AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL

Application for Authorisation of Acquisition of Macquarie Generation by AGL Energy Limited [2014] ACompT 1

IN THE AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION TRIBUNAL | |

APPLICATION FOR AUTHORISATION OF ACQUISITION OF MACQUARIE GENERATION BY AGL ENERGY LIMITED Applicant |

TRIBUNAL: | MR G F LATTA, MEMBER PROF D K ROUND, MEMBER |

DATE OF ORDER: | |

WHERE MADE: |

THE TRIBUNAL DETERMINES THAT:

1. AGL Energy Limited (AGL) be granted an authorisation pursuant to s 95AT of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) to acquire the assets of Macquarie Generation, on the conditions (the Conditions) set out in the Schedule to this Determination and in accordance with the Sale and Purchase Agreement (Macquarie Generation Assets) entered between the State of New South Wales and AGL’s wholly owned subsidiary, AGL Macquarie Pty Ltd, on 12 February 2014.

2. The table titled “Credit exposure and maturity limits” in Annexure 1 to the Conditions must remain confidential and must not be published to any person other than the officers of AGL, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and its officers, and the Approved Independent Auditor appointed pursuant to the Conditions.

3. The acquisition of the assets of Macquarie Generation by AGL be completed by 24 June 2015.

ACT 1 of 2014 |

re: | APPLICATION FOR AUTHORISATION OF ACQUISITION OF MACQUARIE GENERATION BY AGL ENERGY LIMITED Applicant |

TRIBUNAL: | MANSFIELD J, PRESIDENT MR G F LATTA, MEMBER PROF D K ROUND, MEMBER |

DATE: | 25 JUNE 2014 |

PLACE: | ADELAIDE (VIA VIDEOLINK TO SYDNEY AND MELBOURNE) |

REASONS FOR DECISION

INTRODUCTION

1 AGL Energy Limited (AGL) applied on 24 March 2014 to the Australian Competition Tribunal (the Tribunal) for an authorisation under s 95AT of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CC Act) of the proposed acquisition by its subsidiary AGL Macquarie Pty Limited of the assets of Macquarie Generation (Proposed Acquisition). The Proposed Acquisition involves, in essence, acquisition of the Liddell and Bayswater electricity generation plants of Macquarie Generation in New South Wales (NSW). Macquarie Generation is presently wholly owned by the State of New South Wales (the State).

2 Following the lodgement of further documents by AGL, the Tribunal determined AGL’s application to be valid on 27 March 2014. It is common ground that, for the purposes of s 95AZI of the CC Act, a valid application was made on 27 March 2014.

3 The effect of an authorisation is that s 50 of the CC Act – which prohibits acquisitions of shares or assets that would have the effect, or be likely to have the effect, of substantially lessening competition in a market – will not apply to prevent the Proposed Acquisition from taking place.

4 The Tribunal may only grant the authorisation if it is satisfied in all the circumstances that the Proposed Acquisition would result, or be likely to result, in such a benefit to the public that the acquisition should be allowed to occur: s 95AZH of the CC Act.

5 In the process of considering the application, the Tribunal has had the very considerable benefit of the assistance of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), as contemplated by ss 95AZEA and 95AZF of the CC Act. In particular, the ACCC Report provided under s 95AZEA is a substantial and helpful document, to which the Tribunal has had considerable regard. That assistance was provided over a relatively short period of time in order to meet the requirement under s 95AZI that the Tribunal should give its determination on the application within three months of a valid application having been made.

SUMMARY

6 The National Electricity Market (NEM) is established under the National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 (SA) as adopted and applied throughout the States of Australia. The Schedule to that Act is the National Electricity Law (NEL). The objective of the NEL, set out in s 7, is to promote efficient investment in, and efficient operation and use of, electricity services for the long term interests of consumers of electricity with respect to price, quality, safety, reliability and security of supply of electricity and the reliability, safety and security of the national electricity system.

7 The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), established by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), has from 1 July 2009 been responsible (amongst other things) for the NEM operations and systems as prescribed in the NEL, and in more detail in the National Electricity Rules (NER).

8 It is clear that the market for the generation and supply of electricity is a national market.

9 The NEM is centrally operated by the AEMO. All generators in the NEM submit bids to AEMO for the opportunity to supply electricity and, using the sophisticated NEM dispatch engine, AEMO determines how much electricity each generator is to supply in order to meet demand and “dispatches” the lowest cost generator first. It calculates a spot price for each region and for each 30-minute trading interval based on the average bids of the highest-priced generators dispatched to meet demand in each of six five minute intervals. It is a sophisticated process which is explained in more detail below.

10 Further, electricity flows between NEM regions via a series of transmission lines known as interconnectors. The interconnectors have the effect generally of equalising prices between NEM regions, although there are times when prices between NEM regions diverge particularly due to constraints such as capacity limitations or outages. Relevantly for present purposes, NSW has two interconnectors to Queensland and one to Victoria.

11 The Tribunal has found that the relevant retail market for electricity is a NSW one.

12 Retailers pay AEMO the spot price calculated for their region. As retail customers generally pay a flat tariff that does not reflect the spot price, one of the most important roles for retailers is to manage the risk of exposure to high spot prices. This is considered further below. Relevantly for the identification of the geographic extent of the relevant retail market, although there is usually little divergence in spot prices between regions, retail market participants tend to be regionally focused.

13 In NSW, until 30 June 2014, the retail price for electricity to domestic and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) has been regulated so that the retailers to end users have been unable to on-sell electricity to them at above that price. That price regulation is about to be removed, so that competition to acquire the supply of electricity to on-sell to SMEs and to domestic consumers in NSW from 1 July 2014 will not be constrained by price regulation.

14 Macquarie Generation, Origin Energy Limited (Origin), AGL and EnergyAustralia Holdings Limited (EnergyAustralia) are the largest generators in the NEM in terms of capacity, each holding between 10.2% and 12.6% market share. It is not common for any generator to consistently work to its full capacity and different types of generator will be used to a greater or lesser extent depending on their marginal costs of operation (since AEMO dispatches the lowest-cost generators first) and subject to any planned or unplanned outages. The top four generators in the NEM in terms of output are AGL, EnergyAustralia, GDF Suez Australian Energy Pty Ltd (GDF Suez) and Macquarie Generation, which each generated between 11.2% and 13.2% of the energy produced in the NEM in the 2013 financial year. Of the large number of other generators in the NEM, the largest in capacity terms are CS Energy, Delta Electricity, Snowy Hydro Limited (Snowy Hydro) and Stanwell Corporation (Stanwell).

15 The NEM is currently oversupplied with capacity. This has arisen from both increasing new generation capacity and declining demand. The growth in capacity has particularly arisen from increased investment in wind and solar generation encouraged by renewable energy schemes. The fall in demand has been driven by rising retail prices (commonly attributed to increasing costs of transmission infrastructure, solar subsidies and the carbon tax), the closure of energy-intensive industrial users such as aluminium smelters, and the growth in rooftop solar systems. The current oversupply of capacity is expected to continue for some years into the future.

16 The retail market for the supply of electricity in NSW is dominated by three large retailers that together supply about 96% of the retail market: AGL, with approximately a 24% market share and Origin and EnergyAustralia, which account for a further 40% and 32% respectively. Origin and EnergyAustralia are both vertically integrated in that they also hold generation assets in NSW, with 23% and 16.9% of capacity respectively. AGL presently has no generating capacity in NSW but on acquiring Macquarie Generation would hold 29.4% of NSW generation capacity and 35.9% of output. There are a number of other smaller retailers in NSW, some of who are also vertically integrated and others that do not have generation assets. The largest non-integrated generator in NSW (other than Macquarie Generation) is Delta Electricity, with 12.4% of capacity. As supply of electricity to retailers in NSW is in the NEM, there is the potential for supply from generators outside NSW where necessary to meet NSW retailer demand and subject to interconnection constraints. NSW is a net importer of electricity.

17 The ACCC has pointed out to the Tribunal that the Proposed Acquisition would mean that AGL would become a very significant “gentailer”, that is a vertically integrated generator/retailer: it would become the largest generator and remain the third largest retailer in NSW.

The Proposed Acquisition

18 AGL proposes to acquire the following assets from the State and Macquarie Generation by the Proposed Acquisition:

(1) the 2,640 megawatt (MW) coal-fired Bayswater power station located near Muswellbrook in NSW, and its related infrastructure;

(2) the 2,000 MW coal-fired Liddell power station located near Musswellbrook in NSW, and its related infrastructure;

(3) the 50 MW open cycle Hunter Valley gas turbine located near the Liddell power station;

(4) the Liddell solar farm;

(5) the development site known as the “Bayswater B generation development site” which has Concept Approval under the former Part 3A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) for the development of a new (base load) power station with a maximum generating capacity of 2,000 MW powered by either pulverised coal or natural gas, located 4km west of Bayswater, Muswellbrook in NSW;

(6) the development site known as the “Tomago generation development site” for which project approval has expired, located 15 km west of Newcastle;

(7) various contracts entered into by Macquarie Generation including hedge contracts, coal supply and haulage contracts, diesel supply contracts, operations and maintenance agreements, carbon trading agreements and connection and metering services agreements;

(8) various rights, obligations and interests in Macquarie Generation’s registrations and authorisations required to operate the power stations; and

(9) Macquarie Generation’s other assets, rights and liabilities including policies of insurance, intellectual property, real property, equipment, consumables and spares.

(together, the Macquarie Assets).

19 The contracts referred to above include the electricity sale and hedge contracts entered into by Macquarie Generation with Tomago Aluminium Company Limited Pty Ltd (Tomago) on behalf of the of the participants in the Tomago joint venture.

The proceeds of sale

20 The gross sale proceeds from the Proposed Acquisition will be $1.505 billion by way of the purchase price payable by AGL, and a further $220 million by way of cash currently held by Macquarie Generation.

21 The proceeds from the Proposed Acquisition must be paid to the State into the Restart NSW Fund, subject only to specific authorised deductions from the transaction proceeds, as may be approved by the Treasurer of the State.

22 As at 30 June 2013, Macquarie Generation had total borrowings of $710.6 million. On the assumptions that:

(1) debt held by Macquarie Generation of approximately that amount will be repaid from the proceeds of the sale (as is permitted); and

(2) other permitted deductions from the proceeds of the sale will be relatively small;

approximately $1 billion will be transferred to the Restart NSW Fund upon completion of the Proposed Acquisition by AGL.

The possible detriments to competition

23 The Proposed Acquisition, if it is allowed, is suggested by the ACCC to produce significant anti-competitive effects principally because it will inhibit the capacity of other retailers to participate in the retail market, particularly smaller retailers, and partly because AGL will be in a much stronger position to seek to extend its share of the retail market because it will be a vertically integrated entity with the efficiencies that carries with it, including the “natural hedge” (explained in the following paragraph). The ACCC also suggests that AGL as a substantial gentailer will have the inducement to, and capacity to, directly influence the wholesale market for electricity in the NEM.

24 Both generators and retailers are vulnerable to significant price fluctuations or price spikes at short intervals in the wholesale market for electricity, mainly because demand fluctuates very significantly dependent upon circumstances such as severe weather events. Generators and retailers therefore adopt a “hedging” practice. That practice is particularly relevant to the retail market because retailers, dealing with their customers, are committed to supply at a particular price and on particular terms, even though they may be exposed intermittently to very much higher wholesale prices because of the erratic nature of the wholesale market. A gentailer, because it has both generating and retail capacity, has a “natural hedge” because it does not need to seek external hedge contracts to protect it from price fluctuations in the wholesale market to the extent that its generation capacity meets or balances with its share of the retail market. Where contractual hedging is required, the “hedge market” is a very sophisticated market involving long and short-term swap and cap contracts, and a range of other derivative contracts. Those hedging arrangements may be made directly between retailers and generators, or through intermediaries including on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX); there are other entities which participate in ASX trades of those derivatives simply as investors or speculators, both physical and financial. The evidence is that the hedge or derivative trades represent over five times the total generating output for any given period of time.

25 Because AGL after the acquisition would have a natural hedge to the extent of its present retail share, it is apparent that its presently significant demand for hedge contracts (to protect itself as a retailer against wholesale price fluctuations) will be greatly reduced, at least to the extent that it will have a natural hedge. The ACCC has pointed out to the Tribunal that, by that significant reduction, the volume of hedge contracts that may be available for trading in NSW will be significantly reduced, because Macquarie Generation will not be hedging its generating capacity to the same extent because of the natural hedge with the AGL retail market share. The ACCC has suggested that, as other retailers will no longer be able to acquire the hedge contracts they previously acquired from Macquarie Generation either at all or at a sufficiently low price (due to the available hedge contracts being in short supply). small retailers in particular will be unable to compete effectively in the retail market. In addition, because AGL would gain the benefit of the natural hedge, as well as the efficiencies of vertical integration, the ACCC points out that AGL will be able to participate in the retail market more vigorously and again potentially to the detriment of small retailers.

26 The Tribunal has very carefully considered the material on that topic, and has reached the view that, at present (that is pre-acquisition) the “market” for hedge contracts available to retailers in NSW is not a tight one and is not therefore constrained. Whilst it accepts that the number of small retailers in NSW is significantly less than that in Victoria (where in broad terms a not dissimilar wholesale market structure exists, albeit with some different generating firms), the probable cause of that relatively lower participation of smaller retailers is, in part, the consequence of retail price regulation. The Tribunal also accepts that the consequence of retail price regulation may have been to limit the “head room” between the retail price (the regulated price) and all the costs incurred by second tier retailers in servicing their customers. While the Tribunal appreciates that the price of acquiring hedges is a significant component of retail cost, it is of the view that the lower market penetration achieved to date by second tier retailers in NSW compared with Victoria is not caused by a tight market for hedges in NSW.

27 The Tribunal has also reached the view that, post the Proposed Acquisition, retailers of electricity in NSW, including small retailers, will still have available a significant competitive “market” in NSW for the acquisition of hedge contracts.

28 The Tribunal has used the word “market” where it first appears in the preceding paragraph in parenthesis because neither AGL nor the ACCC have suggested that there is a need to consider a separate market for hedge contracts. Rather, hedge contracts are a feature of the separate markets for wholesale and retail supply and sale of electricity, used to protect the participants in those markets from significant price variations in the wholesale market. However, it is a convenient term to use to describe the extent to which hedge contracts are, and will be, available to the participants in the two markets. It is not used hereafter in a technical sense or as a term of art.

29 The reasons for those conclusions are set out in the Tribunal’s detailed reasons.

30 The consequence is that the Tribunal has reached the view that Proposed Acquisition is not likely to result in a significant detriment to the ability of retailers, including small retailers, to compete in the retail market for the supply of electricity in NSW. In addition, it has taken into account that post acquisition there will be three (four, if Snowy Hydro is included) gentailers competing for a share of the business of selling electricity to end users. Their rivalry will produce a vigorous competitive market.

31 Indeed, the Tribunal is satisfied that the risk identified by the ACCC is unlikely to occur. In reaching that view, the Tribunal has accepted the conditions proposed by AGL that it would continue to make available not less than 500 MW of hedge contracts per year to small retailers for a period of seven years. The availability of the conditions has not been critical to the Tribunal’s view, but has been accepted as providing a further additional comfort to address the concerns expressed by some smaller retailers and their representatives.

32 The Tribunal has also considered a range of “without” scenarios. The above comments reflect the Tribunal’s view of the likely future “with” the Proposed Acquisition. First, as AGL says, the State could simply retain and maintain Macquarie Generation as a generating entity from now and for the medium to long term. Second, as the Tribunal considers somewhat more likely, the State would, within two to five years (the medium term), sell or endeavour to sell the Macquarie Assets, either to a pure generator (preserving the structure of the electricity wholesale and retail markets as they now exist), or to a small or large existing retailer, or to a new retailer entering the retail market. The Tribunal is satisfied that none of the “without” scenarios would in any significant way affect the its assessment of any detriments to competition which may arise from the acquisition because none of the “without” cases would cause small retailers to be significantly assisted or impeded in competing in the NSW retail electricity market, compared to the future with the Proposed Acquisition.

33 More generally, whilst it is clear that the Proposed Acquisition, if it proceeds, will result in a not insignificant change in the input supply conditions faced by sellers in the retail market for the supply of electricity in NSW, the Tribunal is satisfied that structural change will not result in material detriment to the public by reason of a lessening of competition in the retail market for the supply of electricity in NSW.

34 The Tribunal has also considered whether AGL will, if the Proposed Acquisition occurs, be in a position to, and have the incentive to, “spike” the spot price or otherwise cause volatility in the wholesale market for electricity in the NEM to the detriment of the public interest. There is some evidence that AGL engaged, or attempted to engage, in such conduct in South Australia (SA) in 2008 to 2010 (when the interconnector function was, on the evidence, less effective and reliable and supply and demand conditions were tighter than at present). The Tribunal is satisfied that there is no real risk of AGL being able to engage in such conduct in NSW or elsewhere in the NEM. It does not find that the Proposed Acquisition will put AGL in a position to exert significant market power in the NEM (or in NSW as a region of the NEM) to spike the spot price or to cause volatility in the wholesale market.

The possible public benefits

35 The public benefits are said by AGL broadly to be in three categories:

(1) the benefits to the State and to the public of NSW of being able to dispose of the Macquarie Assets at a price which reflects their retention value, providing the State immediately with about $1 billion. The proceeds would be put into the Restart NSW Fund established by the Restart NSW Fund Act 2011 (NSW), which dictates its use for the funding of infrastructure improvements for NSW. The State would also be relieved of operating, at least in the short to medium term (or indefinitely as AGL would have it), the Macquarie Assets, which have a limited life and an increasing level of inefficiency and vulnerability to break down. The disposal of the Macquarie Assets would be in circumstances where the State has determined, on the basis of a series of reports extending back to the Owen Inquiry in 2007, that it is in the interests of NSW to do so.

(2) the investment by AGL of $345 million in the efficient operation of the Macquarie Assets, so as to increase their capacity and longevity, and in turn to generate more and cheaper electricity to the wholesale market;

(3) the public benefits arising from AGL being able to operate the Macquarie Assets more efficiently, and to invest significantly in their upgrading to ensure they operate more efficiently and effectively in the medium to longer term. This is said to enable AGL to be better able to compete in the retail market. The interests of ultimate consumers of electricity in NSW, it is said, would be better served by such competition and by the assurance of the longer term more secured life of the Macquarie Assets.

36 The ACCC has pointed out to the Tribunal that those benefits might be obtained whether the acquirer of the Macquarie Assets is AGL or some other entity which may not be a substantial existing retailer and so may not have such a large capacity to benefit from the natural hedge and other efficiencies which would follow the Proposed Acquisition. The Tribunal has carefully considered that contention. It has reached the view that there is no other potential acquirer which would be in a position to acquire the Macquarie Assets in the short term, and, in the short to medium term, there is no other acquirer that would be able to acquire those assets at a price which is reasonably commensurate with the price that AGL has offered. The Tribunal has considered the “without” possibilities referred to above and concluded that the State is unlikely to retain the Macquarie Assets indefinitely, so that, in the future without the Proposed Acquisition, the more likely scenario is that the State would retain and continue to operate the Macquarie Assets but with a view to disposing of them within a few years. The Tribunal accepts that other entities may then seek to acquire those assets, but, being deteriorating assets (particularly without significant expenditure being made on them), they are likely to be worth less than at present. There is evidence upon which the Tribunal finds that AGL, because of particular techniques which it has available to it, is likely to be able to make the Macquarie Assets operate more efficiently than other potential bidders would be able to do. The Tribunal has also had regard to the bidding process adopted by the State and its outcome. It has also had regard to the prospect that another bidder or bidders in the next few years may well include those with a not insignificant retail market share in NSW.

37 Having regard to these matters, the Tribunal is satisfied that there are significant benefits to the public of the character referred to in (1) and (2) of [35] above that are likely to follow from the Proposed Acquisition. The Tribunal’s more detailed reasons for its conclusions are set out later in its determination.

38 While the Tribunal has considered AGL’s claims as to the benefits to the public arising from the efficiencies in the Proposed Acquisition itself, it has not needed to decide them, except in relation to the amount another bidder may be prepared to pay for the Macquarie Assets, having regard to AGL’s ability, with particular techniques, to operate the Macquarie Assets more efficiently and to extend the life of the assets.

Conclusion

39 The Tribunal is satisfied that after the Proposed Acquisition there will be active competition in the NSW retail market, including by small retailers that will have a substantial and adequate hedge market available to them. It anticipates that the retail market will evolve in a similar way as the Victorian market has evolved in an environment where the retail price is not regulated, with an increased number of small retailers and a greater capacity to distinguish offerings to retail and SME end users by price, service and product differentiation. That has been the experience in Victoria where, it is said, the retail market is one of the most competitive retail markets for electricity of those countries where comparisons may fairly be made.

40 It also observes that, post acquisition, there will be three large gentailers (AGL, Origin and EnergyAustralia), and a number of smaller retailers including some with generating capacity who will be participants in the NSW retail market for the supply of electricity and with opportunities for new entrant retailers to participate. If AGL is to materially increase its market share, it must of necessity do so in a competitive way, which would involve it taking market share from the other gentailers. At a general level, such competition should produce a benefit to the public. It may well be, as has occurred in Victoria, that other smaller retailers will also participate in the market and acquire a more significant share of the market through competition against the large gentailers. It notes, for instance, that, after acquiring the Loy Yang A power station and thus a significant natural hedge in Victoria, AGL has lost market share to small retailers. However, the public benefit claimed by AGL under (1) of [35] above is sufficient on its own to warrant the grant of the authorisation sought.

41 As the Tribunal is satisfied that the Proposed Acquisition is likely to result in substantial public benefits and that the public detriments identified by the ACCC are unlikely to arise, the Tribunal is satisfied in all the circumstances that the Proposed Acquisition would result, or would be likely to result, in such a benefit to the public that the acquisition should be allowed to occur.

42 Accordingly, the Tribunal has determined to grant the authorisation AGL seeks for the Proposed Acquisition.

BACKGROUND

AGL

43 AGL is a company listed on the ASX. Its issued capital consists of 558,385,153 fully-paid ordinary shares. It has three shareholders with greater than 5% shareholding: HSBC Custody Nominees (Australia) Limited (14.94%), JP Morgan Nominees Australia Limited (14.41%) and National Nominees Limited (10.45%).

44 AGL produces and supplies gas and electricity for sale in wholesale and retail markets. It variously operates electricity generation and gas production assets and, in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and SA, operates electricity and gas retail businesses.

45 AGL also has coal seam methane production and exploration interests in NSW and Queensland.

46 AGL’s business has 3 main divisions:

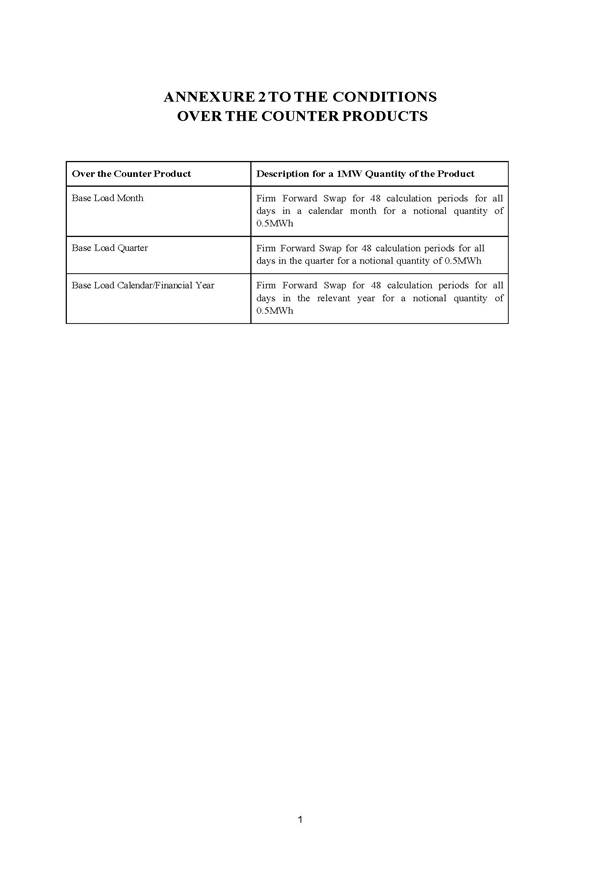

(1) The Merchant Energy division manages AGL’s relationships with its large commercial and industrial customers and develops, operates and maintains AGL’s power generation assets, develops the company’s carbon strategy, and manages the risks related to buying and delivering gas and electricity for AGL’s wholesale and retail customer portfolio. There are four groups within Merchant Energy:

(a) Merchant Operations is responsible for operation and maintenance of AGL’s wind and water powered and gas fired and coal fired generation plants, as well as the coal mine associated with the Loy Yang A power station in Victoria;

(b) Energy Portfolio Management manages the risks associated with procuring gas, electricity and environmental market certificates, administers AGL’s hedge contract portfolio and bids AGL’s electricity generation into the NEM);

(c) Business Customers manages AGL’s business customer accounts; and

(d) Power Development develops wind and solar generation assets.

(2) The Retail Energy division sells and markets natural gas, electricity and energy-related products and services to over 3.8 million residential and small business customer accounts in NSW, Victoria, SA and Queensland. AGL has Australia’s largest retail energy and dual fuel customer base: as at 31 December 2013, it had 2,344,942 retail customers throughout the NEM, 812,883 of whom were in NSW. There are four business units within Retail Energy:

(a) Marketing & Retail Sales develops and implements AGL’s strategic sales and marketing objectives across residential and small to medium enterprise (SME) customers;

(b) Retail Operations is responsible for customer service and back office operations including billing, sales fulfilment, credit management and revenue assurance;

(c) Customer Experience & Digital, which delivers AGL’s customer experience and digital strategy; and

(d) Retail Business Architecture, which works with information technology to design and implement processes and systems for delivery of retail strategies;

(3) The Upstream Gas division invests in and operates gas exploration, development and production tenements and develops and operates gas storage facilities. It manages AGL’s upstream gas assets in Queensland and NSW.

47 AGL says that it does not have a specific volume cut-off to distinguish which customers will be supplied by Retail Energy and which by Merchant Energy. However, it says that, in the electricity industry, residential and SME customers are considered to be those that consume up to 160MWh per year and larger industrial and commercial customers are those whose annual electricity consumption exceeds 160MWh per year.

Macquarie Generation

48 Macquarie Generation is a State-owned corporation established under the Energy Services Corporations Act 1995 (NSW) (ESC Act) and the State Owned Corporations Act 1989 (NSW) (SOC Act). It is administered by the State Minister for Resources and Energy. Section 20H of the SOC Act provides that there must be two voting shareholders in a State owned corporation: the Treasurer and another Minister for the time being nominated by the Premier (the Premier can be nominated as a voting shareholder). There is no issue about its relevant decisions being properly made.

49 Macquarie Generation is one of three electricity generators within the meaning in s 3 of the ESC Act (the other two being Delta Electricity and Eraring Energy). Section 6(2) of the ESC Act provides that the principal functions of electricity generators are:

(a) to establish, maintain and operate facilities for the generation of electricity and other forms of energy, and

(b) to supply electricity and other forms of energy to other persons and bodies.

50 An electricity generator may also provide facilities or services that are ancillary or incidental to its principal functions, and may conduct any business (whether or not related to its principal functions) that it considers will further its objectives (ESC Act, s 6(3)).

51 Macquarie Generation’s principal assets include:

(1) the 2,640 megawatt (MW) black-coal fired baseload generation Bayswater power station (Bayswater), which comprises four 660 MW units commissioned between 1985 and 1986. Bayswater is located approximately 16 km south-east of Muswellbrook. Since FY2004, Bayswater has generated between 14,595 gigawatt hours (GWh) and 17,776 GWh of electricity each year;

(2) the 2,000 MW black-coal fired baseload and shoulder generation Liddell power station (Liddell). The Liddell power station comprises four 500 MW units, commissioned between 1971 and 1973. Liddell is situated adjacent to Lake Liddell, and next to Bayswater. Generation by the Liddell power station is closely linked with Macquarie Generation’s hedging contracts concerning electricity supplied to the Tomago aluminium smelter (Tomago Hedge Contracts);

(3) the Hunter Valley Gas Turbines (Hunter Valley Gas Turbines), which have a capacity of 50 MW;

(4) the development site for an ultra super-critical coal fired or closed cycle gas turbine Bayswater B power station (Bayswater B Development); and

(5) the development site for an open or closed cycle gas turbine Tomago power station (Tomago Development).

52 In 2013, the Bayswater and Liddell power stations represented 10.2% of total electricity generation capacity registered in the NEM, and 12% of total electricity output in the NEM.

ELECTRICITY SUPPLY IN AUSTRALIA

53 The following description of the supply of electricity in the NEM has been largely taken from the Frontier Economics General Industry Report, an expert report that was prepared for and provided to the Tribunal by AGL. The General Industry Report was not contentious and was referred to by both AGL and the ACCC in submissions.

54 The supply of electricity involves generation, transmission, distribution and retail supply. Generation is the production of electrical energy from other energy sources such as coal, gas, wind, the sun or water flow. Transmission is the long distance transport of high voltage electrical energy. Distribution is the transport of electrical energy from transmission networks to customers needing power at low or medium voltages. Retailers manage relationships with end customers, including the issuing of bills for power consumption.

Generators

55 Electricity supplied through the NEM is generated in a number of ways: thermal plants, which burn fuel, such as coal, gas or oil, to heat water and create steam that drives a turbine; gas turbines, in which the turbine is driven by the combustion of fuel; wind turbines and hydroelectric plants, in which the turbine is driven by the wind or water; and solar photo-voltaic (PV) cells.

56 Generators generally fall into one of three categories:

(a) Base load generators, which, due to their typically high sunk costs and relatively low variable costs, are most efficient to run continuously at near maximum output, although output can be reduced to a certain minimum level. Coal-fired power stations such as Bayswater and Liddell are base load generators.

(b) Intermediate or peaking generators have higher variable costs than base load generators and typically minimise their generation when the wholesale electricity price is below the generator’s marginal cost of generation. Gas-fired power stations, such as Delta Electricity’s Colongra power station and Snowy Hydro’s Laverton North power station are examples of this type of generator.

(c) Intermittent generators are those whose output is not readily predictable. This includes solar generators (which depend on sunlight), wind turbine generators (which require the wind to blow) and hydroelectric generators (which are dependent on water availability).

57 Generators in the NEM will also be “scheduled”, “semi-scheduled” or “non-scheduled”. Most large generators in the NEM are scheduled generators. This means that the generator is centrally dispatched by the AEMO. A semi-scheduled generator will have its output regulated by AEMO only at certain times. This generally refers to generators with greater than 30MW capacity but which are intermittent. A non-scheduled generator is not dispatched by AEMO. Generally, smaller generators (less than 30MW capacity), whose output is committed to a particular customer are non-scheduled.

Wholesale supply

58 Wholesale electricity supply in Tasmania, SA, Victoria, NSW and Queensland occurs through the NEM. The five regions of the NEM (each of which currently corresponds to a state) are connected by six interconnectors.

59 The electricity supply industry and the structure and operation of the NEM are formidable topics for the uninitiated. The complexity arises from the nature of electricity itself:

(1) Electricity cannot be stored (except in a very limited way) and its technical characteristics (such as voltage and frequency) mean that supply and demand must be matched at all times to avoid the power system becoming unstable.

(2) Electricity is homogeneous in that, within a network of generators and consumers, it is not possible to determine which generator produced the energy consumed by any customer.

(3) Demand for electricity is highly inelastic, which means that electricity demand is unresponsive to changes in price, especially in the short term. Electricity demand tends to be driven by other factors. For example, daytime electricity demand tends to be significantly higher than overnight demand, and demand increases in hot weather (as people switch on their airconditioners) and in cold weather (when people use more heating).

(4) Electricity supply infrastructure, particularly transmission and distribution networks, exhibits strong natural monopoly characteristics, which means that it may be most efficient for there to be a single provider. For this reason, in most cases, electricity transmission and distribution systems are subject to regulation.

60 The NEM is a “compulsory gross pool”, which means that all power (unless exempted) must be traded through the centralised spot market and all traded power is settled at spot prices. The compulsory gross pool can be compared to the net pool model, in which producers and consumers can enter bilateral contracts for electricity supply and only uncontracted power flows are settled through the market.

61 The NEM is energy-only, which means that generators are paid for energy produced, not capacity. In a “capacity market”, generators receive some compensation for capacity, or the energy they will produce at some point in future. In an energy-only market, generators recover both variable operating costs and fixed capital costs through wholesale spot prices or derivatives settled against spot prices. The spot price must at times rise above the operating cost of the plant that has the highest operating costs in the market to enable that plant to recover its fixed costs.

62 The NEM spot market is managed by AEMO. Generators submit offers to AEMO to supply the market with specific amounts of electricity at particular prices. Offers are submitted every five minutes and AEMO determines how much electricity is to be “sent out” by each generating unit in order to meet demand. The least cost generator is dispatched first and the last generating unit dispatched is the marginal unit and its offer price becomes the clearing price for the whole market.

63 Generators are required to provide AEMO with offers by 12.30 pm Australian Eastern Standard Time (AEST) each day for each half-hour “trading interval” for the following trading day, commencing at 4.00 am AEST. Generators must provide ten choices of prices, known as price “bands”, with subsequent price bands being no lower than the previous band. A “bid stack” consists of the ten escalating price bands, with a specified quantum of electricity offered at each band level. There must be at least one negative price band because, if there is more generation offered at a zero price than is required to meet demand, it may be more economical for some generators to pay (ie receive a negative price) not to be switched off by AEMO than to incur the delay and cost in switching off and on.

64 Once final bids have been submitted, the prices offered in each band cannot be changed and these prices apply over the trading day. However, generators can change or “rebid” how much (in MW) they are willing to supply at each price band and in each trading interval. Rebidding allows generators to manage the risk of not being able to meet the quantities previously promised, such as might occur where there has been a plant failure. Rebidding may also provide a means for generators to attempt to stimulate higher spot prices, which may be profitable, but it is at the risk of that generator not being dispatched by AEMO.

65 While generators are dispatched to minimise the aggregate cost of supply to all loads at all locations across the NEM, prices are determined at specific locations within each of the five NEM regions. Those locations are referred to as “regional reference nodes” (RRN) and the price determined at each RRN is referred to as the “regional reference price” (RRP). The RRP reflects the marginal value or cost of electricity at the RRN and is the price at which electricity sales and purchases for all generators and wholesale customers within that region are settled for the relevant trading interval.

66 Annual average prices in each NEM region since 2012 have ranged from $42.21/MWh to $69.75/MWh but spot electricity prices can be very volatile. The volatility arises because supply and demand in the NEM must be kept in balance at all times. This is a function of the nature of electricity, as it cannot, except to a very limited extent, be stored and the need for voltage and frequency to be kept within narrow ranges in order to maintain system security. The possibility that, where demand outstrips supply, there will be no price at which the market will clear is addressed by the imposition of a market price cap (MPC). The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) calculates the MPC using a formula set out in Rule 3.9.4 of the NER and publishes by 28 February each year the MPC for the following financial year. For the financial year 2013-2014, the MPC was $13,100/MWh and for 2014-2015 it will be $13,500/MWh. The market floor price is set by Rule 3.9.6 at minus $1,000/MWh.

67 Although pricing and settlement is determined regionally (at the RRN), electricity does flow between regions through high voltage transmission lines known as interconnectors. Interconnectors allow generators in one region to supply customers in another, thereby increasing the effective supply of power in the “importing” region and meeting the effective demand in that region. In this way, interconnector power flows can help equalise demand and supply conditions across the NEM.

68 Further, when there are no power system constraints across the NEM, all RRPs in the market will be the same, when the value of electrical losses incurred through the transportation of electricity from one location to another is allowed for. This is because, in the absence of constraints, the marginal cost of meeting an increment of electricity demand at any location in the NEM will be the same (again, allowing for losses). This means that, without any binding constraints, any generator in the NEM could be dispatched to meet an increase in demand anywhere in the 5,000 km-long power system. However, if there are transmission constraints, different regions’ RRPs will diverge, reflecting the fact that the marginal cost of meeting an increase in demand in different regions will vary.

Electricity retailing

69 Retailers purchase electricity through the wholesale exchange operated by AEMO and arrange and pay for the provision of network services required to convey power to the premises of their customers. Retail electricity is a homogeneous physical product, so retailers differentiate and compete on price and ancillary services.

70 Until recently, electricity retailers in all NEM regions other than Victoria were subject to regulation in respect of residential and SME customers. Regulated retail tariffs in these jurisdictions were set by jurisdictional regulators taking account of the level of network tariffs, estimates of energy purchase costs and deemed efficient retail costs and margins. In NSW, the Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal presently sets maximum retail tariffs for customers consuming up to 100 MWh per annum and who are not already on market contracts. However, retail electricity prices will be deregulated in NSW from 1 July 2014. Retail prices were deregulated in SA from 1 February 2013 and the Queensland Minister for Energy and Water Supply has announced an intention to remove retail price regulation in southeast Queensland by 1 July 2015.

71 Retailers generally offer flat tariffs (in c/kWh) that do not vary with prevailing market demand-supply conditions. Retail price variations will bear no relationship to short term fluctuations in wholesale spot prices. Therefore, while most retailers are paid a flat rate per kWh consumed by the customer, the prices they pay for wholesale electricity can vary dramatically on a half-hourly basis (theoretically between minus $1,000 and $13,500 in a single trading interval). A key task for retailers is therefore to manage financial risk.

Risk management

72 The volatility of spot prices in the NEM gives rise to a number of risks for generators and retailers. For present purposes the main risks are:

(1) Volume risk – Generators and retailers do not know in advance how much electricity they have available to sell or need to buy, respectively, in the future. For generators, volume uncertainty arises because the nature of generating plant is such that its operating reliability is less than 100%, so generators tend not to enter binding commitments to sell their entire potential output. While retailers may have some warning of circumstances that may increase demand, such as very hot or cold weather, they will not know the exact level of wholesale electricity they will be required to purchase on any day.

(2) Price risk – Generators are exposed to uncertainty about the price they will be paid for the electricity they produce and retailers are exposed to uncertainty about the price they will have to pay for the electricity they need to purchase to supply their customers. Generators produce electricity for which they are paid the applicable wholesale spot price, so are naturally “long” electricity because they gain if the spot price rises. Retailers purchase electricity for which they must pay the applicable wholesale spot price if their supply is not fully hedged, so retailers (and large customers) are naturally “short” electricity because they gain if the spot price falls.

73 The key ways of managing price risk for NEM participants are vertical integration of generation and retailing activities or the sale or purchase of financial derivative (hedge) contracts.

Vertical integration

74 Vertical integration can be achieved by:

(1) acquisition of existing generation or retail assets – commonly through a merger or government sales process;

(2) developing new generation or retail assets or activities; or

(3) acquisition of rights to the outputs or cashflows of generation or retail activities, such as through a power purchase agreement (PPA) between a retailer and generator, which entitles the buyer to either the physical power supply or the spot market proceeds from the electricity output of the subject generating plant.

75 Vertical integration between a generator and a retailer is often referred to as a “natural hedge” since a retailer’s exposure to high spot prices is offset by the generator’s naturally long position and the generator’s exposure to low spot prices is offset by the retailer’s naturally short position. The risk of the generator to the extent that its capacity equals its retail demand is approximately set off by the risk of the retailer to the extent that its generation capacity equals that demand, so the need for external hedge contracts to cover the risk to that extent is more or less abated.

76 The Tribunal notes the caution urged upon it by AGL in giving meaning to the phrase natural hedge. The use of the phrase in these reasons does not indicate that the Tribunal regards a natural hedge as necessarily being a precise or perfect hedge. Rather, it is used for the sake of simplicity and as a reflection of industry convention, including use of the phrase by AGL itself.

Contractual hedging

77 The two main forms of derivative contract utilised in the NEM are swaps and caps. Options written on these two contracts (swaptions and captions) are also fairly common. More exotic contracts (such as collars and other options) are also available.

78 Swap contracts are broadly defined as a series of financial forward contracts between two parties, whereby one stream of cash flows is “swapped” for another stream of cash flows at regular intervals over the term of the contract. Typically, they involve the swapping of a variable stream of cash flows based on (variable) spot prices with a fixed stream of cash flows based on an agreed strike price. Given that swaps are a form of forward contract, each party to the swap has an obligation to exchange the agreed cash flows on the settlement date.

79 A typical swap contract requires the seller (most often a generator) to pay the buyer (most often a retailer or large industrial customer) the difference between the spot price, which is variable, and a fixed contract strike price. This value is positive when the spot price is greater than the strike price, and negative when the spot price is less than the strike price. Under such an agreement, both the retailer and generator have certainty regarding the ultimate net price they will either pay or receive per unit of energy covered by the contract.

80 By way of illustration, during half-hours when the spot price is above the strike price of the swap the seller of the swap makes difference payments to the buyer. During half-hours when the spot price is below the strike price the seller receives difference payments from the buyer. The swap contract results in a fixed price (the strike price) for both the seller and buyer for a given level of coverage (determined by the size of the contract).

81 Swap contracts thereby allow parties exposed to the spot price to reduce cash flow uncertainty by effectively “locking in” the fixed strike price, which is based on an expectation of future spot prices. Most swap contracts trade at a modest premium to spot prices. This positive premium indicates that participants in the contract markets face asymmetric risk: there is greater potential for spot prices to rise well above contract strike prices than there is for prices to fall well below strike prices.

82 A cap contract is a “one-sided” swap contract which involves the buyer (usually a retailer or large industrial customer) receiving difference payments from the seller (usually a generator) when the spot price exceeds a certain level (the cap strike price). At all other times no difference payments are made. The difference payments made to the buyer are equal to the difference between the spot price and the cap strike price. To acquire this protection the buyer of the cap pays the seller a fixed cap premium in every half-hour of the contract. Cap contracts are typically utilised by electricity retailers to hedge infrequent but extremely costly spot price spikes.

83 Options contracts covering both swaps (swaptions) and caps (captions) give the buyer the right, but not obligation, to enter either a swap or cap as either a buyer or seller on a future date at a pre-determined strike price. To acquire this option, the buyer pays the seller an option premium for every half-hour covered by the underlying swap or cap contract. At the expiration of the option the buyer chooses whether to exercise the option or not. If the buyer chooses to exercise, then the buyer and seller become counterparties in the underlying swap or cap contract. If the buyer chooses not exercise, then the underlying swap or cap contract lapses.

84 An “Asian option” is an option where payment is calculated based on the difference between the strike price and the average spot price over an agreed period.

85 Derivative contracts are purely financial arrangements and are not subject to any physical constraints. As a result, they can be structured in many different ways to meet the risk management requirements of market participants. Examples of structured contracts include “shaped” or “load following” swaps or caps.

86 Under a standard swap, the parties agree on a strike price for a specified volume of electricity over a defined period. A shaped contract allows a retailer to tailor the swap so that the agreed volumes vary at different times of the day to reflect the shape of its exposure, for example the forecast customer demand. A load following swap is even more tailored to the retailer’s customers’ demand and will follow the actual usage of the retailer’s customers over the agreed period. These types of contracts allow the retailer to better manage volume risk, as well as price risk, but are generally more expensive than “vanilla” hedges.

87 Other exotic instruments, such as “weather derivatives” also exist and have been used in the NEM. An example of a weather derivative is a contract that is settled against a particular weather index, such as heating/cool degree days, maximum/minimum temperatures or precipitation over a period of time.

88 Derivative contracts in the NEM are of two main types: over-the-counter (OTC) instruments and exchange-traded futures (ETF) contracts.

89 OTC contracts involve customised bilateral commitments between two parties (generally retailers and generators), either directly or through a broker. OTC instruments tend to be customised to suit the needs of the two contracting parties and are non-transparent since they are negotiated and settled in private. In an OTC arrangement, the parties face the risk of credit default by the counterparty.

90 ETF contracts involve standardised contracts that are bought and sold through a securities exchange. In Australia, ETF electricity contracts were designed and developed by d-cyphaTrade and are sold through the ASX. ETF contracts tend to be highly standardised and transparent and are publicly reported. Due to the presence of a financial intermediary (clearing house) between contracting parties, ETF contracts are not subject to credit default risk.

Basis risk

91 An additional form of risk arises for NEM participants who seek to enter derivative contracts with counterparties located in different NEM regions in that prices between regions can and do diverge. This is referred to as “basis risk”. It is the risk that the price of a commodity bought or sold in the physical market moves differently to the hedge price of that commodity.

92 Standard derivative contracts can be used for hedging spot price volatility when all counter-parties are settled at the same RRP at which the relevant contract is settled. However, participants can be subject to basis risk in the NEM when they have entered into financial contracts with participants located in another region and transmission limits that restrict flows on interconnectors between those regions bind, causing the relevant RRPs to diverge.

93 Participants in the NEM can manage basis risk, at least to some extent, by acquiring inter-regional settlement residue (IRSR) units. Given that electricity usually flows from regions where the RRP is lower to regions with higher RRPs, a residue will accrue from the difference between the price paid to a generator in an exporting region and the price paid for electricity by retailers in an importing region. IRSR units provide their holder with a stream of payments that is based on the flow on a particular interconnector multiplied by the price difference between the relevant RRPs, with payments funded by the NEM settlements process. IRSR units are made available to participants through quarterly settlement residue auctions run by AEMO and can be used to hedge inter-regional price differences.

94 IRSR units do not always provide a reliable or “firm” hedge against divergences in RRPs. Where, for any of a variety of reasons, the flow on an interconnector is constrained, despite the fact that the relevant RRPs have separated, insufficient electricity can flow between regions to fully respond to the separation in RRPs. Participants sometimes respond to this risk by acquiring a greater quantity of IRSR units than their inter-regional exposure, or by discounting the face value of IRSRs to reflect a realistic assessment of the extent of the cover they provide.

THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION

Context of the Proposed Acquisition

95 AGL proposes to acquire the Macquarie Assets from the State and Macquarie Generation.

96 The sale of the Macquarie Assets is one of a number of transactions in the broader process of the privatisation of NSW electricity generators. The genesis of that process may be traced for present purposes back to 2007 and the key recommendation of the Owen Inquiry into Electricity Generation in NSW (Owen Report) that the State should divest itself of all State-owned retail and generation electricity assets. Following the Owen Report, the State in November 2008 decided to proceed with an Energy Reform Strategy involving the sale of the State’s retail businesses and certain development sites, contracting out of State-owned generation, and retention of State ownership of the network and transmission infrastructure. Two subsequent reports – the NSW Financial Audit 2011 (Lambert Inquiry Report) and the Final Report of the Special Commission of Inquiry into the Electricity Transactions (Tamberlin Report) of October 2011 – in general terms affirmed the Electricity Reform Strategy and made recommendations about how to progress its implementation.

97 The contracting out of generation came to be known as the “gentrader” option. The gentrader contracts involved the sale of the wholesale trading rights for certain state-owned generators to the private sector. The owner of those rights (the gentrader) paid capacity charges to the generators, which remained in the hands of the State. The gentrader had the exclusive right to trade the electricity output of the power stations and to all revenue resulting from trading that electricity in the NEM.

98 In 2010 to 2011, Origin and TruEnergy Holdings Pty Ltd (TRUenergy) (now EnergyAustralia) each acquired gentrader contracts and a NSW retail business:

(1) Origin Energy acquired the wholesale trading rights for the Eraring and Shoalhaven power stations (for 22 and 28 years, respectively, from 27 February 2011) and the Country and Integral retail businesses; and

(2) TRUenergy acquired the wholesale trading rights for Delta Electricity’s Mt Piper and Wallerawang power stations (for 33 and 19 years, respectively, from 1 March 2011), the EnergyAustralia retail business and several development sites.

99 The sales of Macquarie Generation and Delta Electricity’s Colongra and Vales Point power stations were not pursued until, following the recommendations of the Tamberlin Report, the Electricity Generator Assets (Authorised Transactions) Act 2012 (NSW) (EGA Act) was passed. The EGA Act authorised and made other provision for the transfer of Eraring Energy, Delta Electricity and Macquarie Generation to the private sector. Among the obligations in the EGA Act is a requirement that the proceeds of any sales made under it be paid into the Restart NSW Fund established under the Restart NSW Fund Act 2011 (NSW).

100 On 15 November 2012, the State Treasurer announced that the sale of the electricity generators would proceed in two stages: first, the sale of the assets of Eraring Energy and the western assets of Delta Electricity (ie, the Eraring, Shoalhaven, Mount Piper and Wallerawang power stations that remained State-owned pursuant to the gentrader arrangements); and second, the sale of the assets of Macquarie Generation and the central coast assets of Delta Electricity’s Colongra and Vales Point power stations.

101 The first stage has been completed. In August 2013, Origin Energy acquired the Eraring and Shoalhaven power stations and in September 2013 EnergyAustralia acquired the Mount Piper and Wallerawang power stations.

102 The sale of the Delta Electricity’s Colongra and Vales Point power station assets is yet to commence.

Genesis of AGL’s application for authorisation

103 The sale process for the Macquarie Assets began on 30 July 2013, with an announcement by the State Treasurer. AGL submitted an expression of interest on 19 August 2013 and on 21 October 2013 submitted an indicative bid.

104 Three entities, including AGL, made binding bids for the Macquarie Assets. AGL made its binding bid on 5 February 2014, offering $1.505 billion, conditional on AGL receiving clearance from the ACCC.

105 The State Government accepted AGL’s bid and on 12 February 2014. AGL entered into a binding agreement with the State of NSW and Macquarie Generation for the sale and purchase of the Macquarie Assets (SP Agreement).

106 On 12 February 2014, the State Treasurer announced in a press release that of the three bids received, AGL Energy was the only one that exceeded retention value and that, should the ACCC not provide clearance to AGL Energy, the State would not proceed with the sale of Macquarie Generation at that time.

Regulatory consideration

107 In the meantime, on 29 November 2013, AGL had lodged a written submission with the ACCC seeking informal clearance of the Proposed Acquisition. An informal clearance is a statement by the ACCC that it does not propose to take action to prevent a merger from taking place because it does not consider that merger is likely to result in a substantial lessening of competition and will thus not contravene s 50 of the CC Act.

108 The ACCC commenced its public review of the Proposed Acquisition on 2 December 2013. Interested parties were invited to make submissions by 18 December 2013. Additional information was provided by AGL and meetings and correspondence between AGL representatives and the ACCC took place.

109 On 6 February 2014, the ACCC released a Statement of Issues, outlining its concerns about the Proposed Acquisition.

110 The ACCC considered that it was relevant to consider the impact of the Proposed Acquisition on a NEM-wide basis because the Proposed Acquisition would raise issues in relation to wholesale electricity supply in the NEM.

111 The ACCC’s principal concern about the Proposed Acquisition was that it would increase barriers to entry and expansion in the retail supply of electricity in NSW by:

(1) significantly reducing liquidity in the supply of hedge contracts since AGL’s retail load would be supported with a natural hedge; and

(2) increasing AGL’s ability and incentive to withhold competitively priced and customised hedge contracts to independent retailers.

112 The ACCC also expressed concern that aggregating Macquarie Generation’s capacity with AGL’s existing generation capacity in the NEM may substantially lessen competition in wholesale electricity markets across one or more of NSW, Victoria and SA, or the NEM.

113 AGL provided further information to the ACCC, including in response to a notice issued under s 155 of the CC Act. On 17 and 18 February 2014, AGL gave the ACCC a proposed undertaking under s 87B of the CC Act that it would make hedge contracts available to market participants following completion of the Proposed Acquisition. The ACCC conducted further market inquiries in relation to the undertaking and AGL provided a submission in response to the Statement of Issues. The proffered undertaking formed the basis for the Conditions that AGL has proposed should apply to the Tribunal’s authorisation of its proposed acquisition of Macquarie Generation, notwithstanding that it does not consider the Conditions to be necessary.

114 On 4 March 2014, the ACCC announced that it would oppose the Proposed Acquisition because it considered that the Proposed Acquisition was likely to result in a substantial lessening of competition in the market for the retail supply of electricity in NSW.

115 The ACCC’s objection to the Proposed Acquisition entitled either AGL or the State to terminate the SP Agreement. On 20 March 2014, the State Treasury wrote to AGL, observing that AGL would not be in a position to complete the Proposed Acquisition unless and until an authorisation was granted by the Tribunal. The State Treasury reserved its termination rights in respect of the SP Agreement and confirmed that the State would continue to engage with other participants in the sales process to establish whether any would be able to transact on terms acceptable to the State, including that the transaction value exceeds the State’s retention value.

116 This application followed those events.

THE TRIBUNAL’S PROCESSES

117 In terms of procedure, the Tribunal in this matter has been sailing relatively uncharted waters. In January 2007, the then President of the Tribunal issued a series of Practice Directions for the making of merger authorisation applications and for the submitting of documents by interested parties and the ACCC. However, AGL’s merger authorisation application is only the second to have been made to the Tribunal and it is the first to have proceeded to determination.

118 The Tribunal is the original decision maker in relation to merger authorisations under the CC Act. The Tribunal’s consideration of a merger authorisation application has something of an inquisitorial character. It is necessary for the Tribunal to inform itself of the issues arising from the application and to obtain evidence going to those issues. The assistance of the ACCC in that process is integral. The role of the Tribunal in merger authorisation matters is quite different to its function in its merits review jurisdiction under the CC Act, where the Tribunal reviews decisions made by certain Ministers or the ACCC are conducted on the material that was before the original decision maker.

119 Section 103 of the CC Act stipulates that, in considering a merger authorisation application, the procedure of the Tribunal is, subject to the CC Act and the regulations, within the discretion of the Tribunal. Proceedings are to be conducted with as little formality and technicality and with as much expedition as proper consideration of the matter permits. The Tribunal is not bound by the rules of evidence.

120 The Tribunal must take into account: any timely submissions made by the applicant, the Commonwealth, a State, a Territory or any other person; any information received pursuant to requests issued by the Tribunal under ss 95AZC or 95AZD; any report by the ACCC given to it under s 95AZEA; and any information or evidence provided to the Tribunal in the course of the ACCC assisting it under s 95AZF: s 95AZG(2).

121 The Tribunal’s role as original decision maker and the requirements of s 103 require the Tribunal to take a more active role in proceedings than would ordinarily be the case if the Tribunal were reviewing a decision or determination of a Minister or the ACCC. However, the scope of the Tribunal’s task is subject to an implicit limitation on the Tribunal’s consideration of the application imposed by s 95AZI.

122 Section 95AZI requires the Tribunal to make its determination within three months beginning on the day a valid application was given to the Tribunal. If the Tribunal has not made its determination within that period, it is taken to have refused to grant the authorisation. The Tribunal may extend the three-month period by not more than three months if it determines in writing that the matter cannot be properly dealt with in that time because of complexity or other special circumstances. (In contrast, the corresponding period for a review by the Tribunal of an authorisation determination by the ACCC is 60 days: see s 102(1A) of the CC Act. For reviews of determinations and decisions under Part IIIA of the CC Act, the period is 180 days: see s 44ZZBC of the CC Act.)

Management of the application

123 AGL’s application is comprised of a document in the form of Form S in Schedule 1 of Part 5 of the Competition and Consumer Regulations 2010 (Form S), eight witness statements and three expert reports plus supporting documents. AGL claimed confidentiality in respect of some of the information in its application. Some of that information was confidential to Macquarie Generation and the State.

124 Following notification of AGL’s application to the ACCC as required by s 95AX, the Tribunal gave general notice of the application pursuant to s 95AY by including the application on its website and on its Merger Authorisation Register.

125 On 31 March 2014 at a case conference the Tribunal set a timetable for the making of any application to intervene, and for interested parties to make submissions. In the event, no person or entity applied to intervene. Several entities made submissions as interested parties. Those submissions were received by the Tribunal, and have been considered in the course of the Determination. In one instance, as a result of AGL and the ACCC having a slightly different view about the status of or clarity of the facts underlying one of those submissions, the Tribunal arranged for a representative of that entity to attend during the hearing to produce some primary records and to give oral evidence: that was Mr Greg Everett, the Chief Executive Officer of Delta Electricity, whose evidence is referred to elsewhere in these reasons.

126 At that case conference, the Tribunal also set in place a timetable (largely as suggested by the ACCC) for the ACCC to provide an Issues List, and its Report as required pursuant to s 95AZEA, as well as for the identification of information which the Tribunal might seek from other entities as well as from AGL under ss 95AZC and 95AZD of the CC Act.

127 The Tribunal also made a request under s 95AD for information from the State concerning its consideration of AGL’s bid and other bids and the State’s possible options if the Tribunal did not authorise the Proposed Acquisition. That information was clearly relevant to the “without” or counterfactual assessment and so to the Tribunal’s overall assessment of the Proposed Acquisition.

128 The Tribunal set down the hearing of the application for up to ten days, with a view to making its determination within the time specified by s 95 AZI.

129 Section 95AZI(2) does not invite a routine extension of time. Each application should be addressed in its particular circumstances. It is clear enough that the time frame imposed reflects a decision that it is in the public interest that a prompt determination is preferred to an exhaustive and prolonged inquiry that might take many months to complete. However, the Tribunal recognises the burden imposed on AGL and on the ACCC by the legislatively imposed time frame. In the context of that time frame, the Tribunal records its appreciation of the assistance of the ACCC in providing the Issues Paper and its Report under s 95AZEA, and for its very substantial assistance at the hearing in testing the evidence adduced by AGL, adducing oral and written evidence, and in its careful and thorough submissions. The Tribunal appreciates the very substantial efforts of the staff and representatives of AGL and the ACCC, which have enabled the Tribunal to make its determination within the statutory deadline.

Confidential information

130 It is appropriate for the Tribunal to comment on the presentation and handling of confidential information within the processes under Div 3 of Part VII of the CC Act. In considering questions of public benefit and, particularly, competitive detriment that may arise from a commercial transaction, it is inevitable that commercially confidential information will need to be considered. Confidential information may be provided by the applicant, by any intervenor or an interested party, and through information obtained by the ACCC. Information may be confidential because its disclosure may be of benefit to competitors in a market, or in other markets, or for other reasons. Section 95AZA, which sets out processes for the handling of confidential information in merger authorisation matters, recognises that that will occur, and identifies certain types of information which it is presumed will be confidential and is not to be published.

131 The provision of confidential information presents practical challenges in its recording and management.

132 In relation to its recording, s 95AZ requires the Tribunal to maintain on its Merger Authorisation Register the application, and documents and submissions provided to the Tribunal, and of course its Determination. Section 95AZA provides a regime for the protection of confidential information. First, it must be identified, and confidentiality claimed, when the information is provided to the Tribunal. Second, it must then be redacted from the information placed on the Register. Thirdly, the Tribunal must decide on the request for confidentiality, and if the request is not acceded to, the information provider or person making the submission must be given an opportunity to withdraw the information or the submission.

133 In response to information requests to seek comprehensive information about the market for hedge contracts in NSW, some information providers claimed confidentiality not simply from publication of the information on the Tribunal’s authorisations register (s 95AZ), but from certain persons seeing it at all. Some other entities (counterparties to hedge contracts) claimed that information provided by one entity contained information confidential to the counterparty, particularly about the identity of the counterparty or about the terms of the hedge contracts, where the information provider had not claimed confidentiality. Ultimately, in the assembly of all that information, especially with respect to hedge contracts, it became apparent that the process would not produce a sufficiently comprehensive data set to enable Mr MacLeod to use it as a firm foundation for the analysis of the hedge market available to retailers that he was proposing to undertake. An alternate basis for his analysis was therefore adopted. As appears later in these reasons, the Tribunal does not consider that, even if the full data set of actual hedge contracts had been obtained, its assessment of the weight to be given to his views would have been different, as its assessment of them depends on other factors. However, obviously there is scope to improve those sorts of inquiries. Also, some information was provided by the State about its tender process, or more accurately its assessment of particular bids or its dealing with particular communications and about its commercial strategies and options, which it sought to be confined to particular persons and on particular terms.

134 Those considerations flow into the issue of management of the information which was confidential. Even if it is not published on the Register, it was necessary to address the extent to which it should be made available to AGL, and, particularly in the case of the information provided by the State, to both AGL and to the ACCC. The State’s information was accepted as being extremely commercially sensitive.

135 Those matters led to quite extensive communications between AGL, the ACCC and others (largely through legal representatives) to address those concerns. The Tribunal was anxious to get as much relevant information as was appropriate. It notes that AGL and the ACCC through their respective legal teams spent considerable time dealing informally with those issues. Whilst the Tribunal was able to decide that the information over which confidentiality was claimed was (in almost all instances) in fact confidential and should be excluded from the Register, that did not resolve the issues about how the Tribunal should manage that information, or more accurately manage access to it. That is also a common issue in commercial litigation. Ultimately, a satisfactory regime for managing the various levels of confidential material was largely agreed upon, and following directions from the Tribunal, duly implemented.

136 That sort of issue is endemic and inevitable in such matters as this, but it is clear that the Tribunal should review its Practice Directions in an endeavour to make the resolution of such issues more efficient.

The hearing

137 It is also appropriate to refer briefly to the progress of the hearing.

138 The Tribunal had the benefit of opening submissions from AGL and the ACCC. It had, of course, read voluminous material in advance of the hearing. The evidence of AGL was then presented, largely documentary and supported by affidavits of a number of its senior management team. Where the ACCC considered that evidence might usefully be tested or challenged, or other information elicited, the AGL witness was asked questions by counsel for the ACCC. The ACCC, as noted earlier, also adduced some documentary material and affidavit material. For its part, counsel for AGL asked several of those persons questions for similar reasons. That process was efficient, focused and helpful.