Federal Court of Australia

Wight (liquidator), in the matter of Responsible Entity Services Limited (in liquidation) [2025] FCA 1219

File number: | VID 842 of 2025 |

Judgment of: | BEACH J |

Date of judgment: | 3 October 2025 |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS — insolvency — secured creditor of another insolvent company — releasing security interests — application for directions as to reasonableness and appropriateness of dealings — application under s 90-15 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) — application under s 477(2A) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) — meaning of “compromise a debt” — observations on modifying securities as to whether a “compromise” — orders made |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 477(2A) Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) s 90-15 |

Cases cited: | Handberg v MIG Property Services Pty Ltd (2012) 92 ACSR 38 Mentha v G E Capital Ltd (1997) 27 ACSR 696; 154 ALR 565 Mercantile Investment and General Trust Company v International Company of Mexico [1893] 1 Ch 484 Re Ansett Australia Ltd [2001] FCA 1439; (2001) 39 ACSR 355 Re Ansett Australia Ltd (No 3) [2002] FCA 90; (2002) 115 FCR 409 Re One.Tel Limited (2014) 99 ACSR 247 Re Spedley Securities Ltd (in liquidation) (1992) 9 ACSR 83 Yeo (liquidator), in the matter of Tuftex Carpets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2025] FCA 1200 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 177 |

Date of hearing: | 3 October 2025 |

Counsel for the Plaintiffs: | Mr Adam Segal |

Solicitors for the Plaintiffs: | Gilbert + Tobin |

Counsel for the Interested Party: | Mr Gavin Rees |

Solicitors for the Interested Party: | Vaikom Law |

ORDERS

VID 842 of 2025 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF RESPONSIBLE ENTITY SERVICES LIMITED (IN LIQUIDATION) (ACN 116 489 420) | ||

BETWEEN: | BARRY WIGHT AND RACHEL BURDETT IN THEIR CAPACITY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL LIQUIDATORS OF RESPONSIBLE ENTITY SERVICES LIMTIED (IN LIQUIDATION) (ACN 116 489 420) First Plaintiff RESPONSIBLE ENTITY SERVICES LIMITED (IN LIQUIDATION) (ACN 116 489 420) Second Plaintiff | |

order made by: | BEACH J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 3 OCTOBER 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 90-15 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations), the first plaintiffs are justified and acting reasonably in receiving $5,975,000 plus GST (secured creditor amount) under the deed of company arrangement between Aaron Lucan in his capacity as the voluntary administrator of each of Pleasure Point Mine Pty Ltd (administrator appointed) (receivers and managers appointed) (PPM) and BRS Quarries Australia Pty Ltd (administrator appointed) (BRS), Swift Mining Resources LLC (Swift), PPM and BRS (PPM DOCA) (a copy of which is at pages 137 to 179 of annexure REB-4 to the affidavit of Rachel Elizabeth Burdett sworn on 12 September 2025 (third Burdett affidavit) in exchange for the first plaintiffs:

(a) executing and performing their obligations and causing the second plaintiff to execute and perform its obligations under the deed poll granted by the first plaintiffs and the second plaintiff in favour of Swift (a copy of which is at pages 180 to 189 of annexure REB-4 to the third Burdett affidavit) (Deed Poll); and

(b) performing any act in connection with releasing the following security interests:

(i) the mortgage dated 6 July 2023 granted by PPM in favour of the second plaintiff (with dealing number 722596019) over the property located at 174 Goldmine Road, Helidon, Queensland (with land title reference 15916016 and land description of Lot 1 on CP CSH133) (a copy of which is at pages 507 to 534 of annexure REB-1 to the affidavit of Rachel Elizabeth Burdett sworn on 2 July 2025 in this proceeding); and

(ii) the security interest over all the issued shares in BRS, which arises from the general security agreement dated 5 July 2021 between PPM and the second plaintiff (a copy of which is at pages 461 to 493 of annexure REB-1 to the affidavit of Rachel Elizabeth Burdett sworn on 2 July 2025), being a security interest registered on the Personal Property Securities Register as registration number 202403150024953.

(together, the Security Interests).

2. To the extent necessary, pursuant to s 477(2A) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) it be approved that the first plaintiffs, on behalf of the second plaintiff, may receive the secured creditor amount in exchange for releasing the Security Interests in accordance with the terms of the PPM DOCA and the Deed Poll.

3. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), until the conclusion of the liquidation of the second plaintiff or until further order, on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, publication of investor names, entities or details in the third Burdett affidavit (including annexures) be prohibited.

4. The first plaintiffs’ costs of and incidental to this application are costs in the liquidation of the second plaintiff.

5. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BEACH J:

1 The first plaintiffs are the joint and several liquidators of Responsible Entity Services Limited (in liquidation) (RES), which is a secured creditor of Pleasure Point Mine Pty Ltd (administrator appointed) (receivers and managers appointed) (PPM) in respect of the financing of a sandstone quarry known as the Pleasure Point Mine located in Helidon, Queensland.

2 On 4 April 2025, the liquidators appointed Mr Matthew Hutton and Mr Mark Holland of McGrathNicol as receivers and managers and agents over the mine and associated land.

3 On 3 July 2025, orders were made pursuant to s 477(2B) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) that the entry by the liquidators into the deeds for the appointment of the receivers be approved nunc pro tunc, and that pursuant to s 90-15 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) (IPS) being Schedule 2 to the Act, the liquidators were justified and acting reasonably in entering into and performing, and causing RES to enter into and to perform, the obligations of the plaintiffs under the appointment deeds.

4 Since that time, the receivers and Mr Aaron Lucan of Worrells, who was appointed voluntary administrator of PPM, have continued to undertake a sale process for PPM and its wholly owned subsidiary BRS Quarries Australia Pty Ltd (administrator appointed) (BRS) concerning the mine and associated land.

5 Before me this morning, the plaintiffs have now made a further application for the following orders.

6 First, they have sought an order pursuant to s 90-15 of the IPS that the liquidators of RES are justified and acting reasonably in receiving $5,975,000 plus GST (the secured creditor amount) under the deed of company arrangement between Mr Lucan in his capacity as the voluntary administrator of both PPM and BRS (the PPM administrator), the entities themselves and Swift Mining Resources LLC (Swift) (the PPM DOCA), in exchange for executing and performing the liquidators’ obligations and causing RES to execute and perform its obligations under a deed poll granted by the plaintiffs in favour of Swift (the deed poll), and performing any act in connection with releasing various security interests, being a mortgage granted by PPM in favour of RES over the mine and relevant land, and the security interest over all the issued shares in BRS, which arises under a general security agreement between PPM and RES that is registered on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR). I will refer to these securities as collectively the security interests.

7 Second, the plaintiffs have sought an order pursuant to s 477(2A) approving the liquidators receiving the secured creditor amount in exchange for releasing the security interests in accordance with the terms of the PPM DOCA and the deed poll. As I have said, a different transaction was the subject of a s 477(2B) order on 3 July 2025.

8 Now when this matter was last before the Court, the receivers had commenced a process to sell the mine and associated land, but since that time the following events have occurred.

9 The receivers and the PPM administrator completed a joint two-stage sale campaign for the recapitalisation or restructure of all or part of PPM and BRS, which resulted in only one proposal that was capable of acceptance, which was a proposal for a deed of company arrangement made by a shareholder of PPM being Swift (the proponent) that ultimately resulted in the PPM DOCA.

10 The PPM DOCA was recommended for approval to creditors by the PPM administrator. At the second creditors meeting of PPM on 5 August 2025, the creditors voted to approve the PPM DOCA.

11 On 26 August 2025, the PPM DOCA was executed by the PPM administrator and the proponent. And relevant to the timing of the present application, a key term of the PPM DOCA is that within 60 days of the execution of the PPM DOCA, the relevant deed contribution, the precise identification of which I will come back to later, will be paid directly by the proponent on account of the secured creditor amount.

12 Now the liquidators of RES abstained from voting in respect of the PPM DOCA and so the PPM DOCA is not binding on RES. But in order to give effect to the terms of the PPM DOCA, the liquidators agreed to sign a deed poll to afford the proponent some comfort that the release of the security interests will occur in exchange for RES receiving the secured creditor amount.

13 For completeness, I should say at this point that the debt owed by PPM to RES as at 12 September 2025 is approximately $32 million. Under the PPM DOCA, RES is to receive payment of the secured creditor amount, in exchange for the release of the security interests under the deed poll.

14 Let me now descend more into the detail and begin with some observations concerning RES.

Matters concerning RES

15 RES held an Australian Financial Services Licence pursuant to which it was authorised to carry on a financial service business to provide general financial product advice for interests in managed investment schemes.

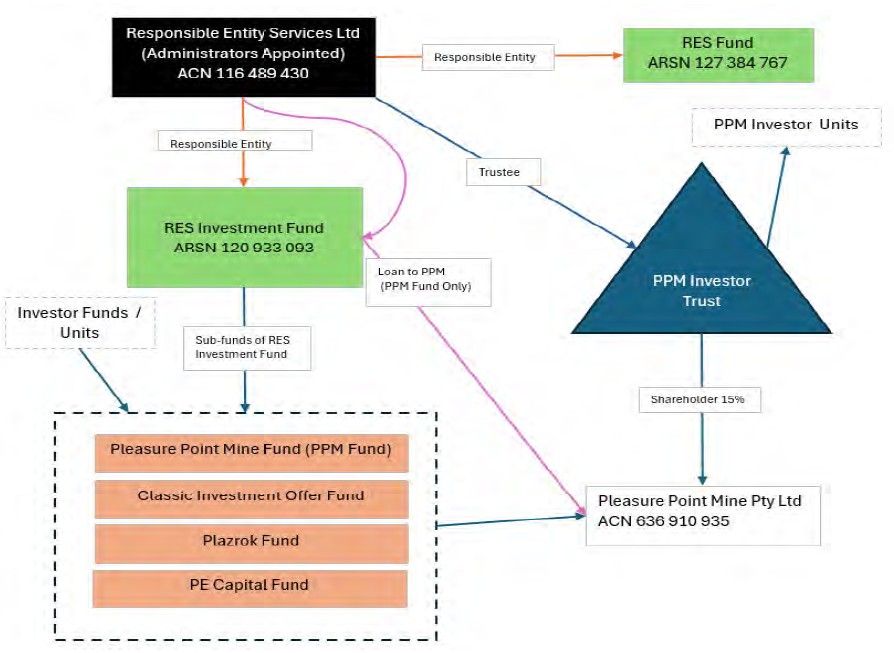

16 RES is the responsible entity for two funds, being the RES Fund which is dormant with no active investments and the RES Investment Fund, the latter of which has four sub funds being the Pleasure Point Mine Fund (PPM Fund), the Classic Offer Investment Fund, the Plazrok Investment Fund and the PE Capital Investment Fund. There are 325 investors in the PPM Fund.

17 The investment mandate for each of the RES Investment sub funds was to loan investor funds to third parties on commercial terms. The outstanding loans within the RES Investment sub funds is primarily in respect of the PPM Fund to PPM.

18 The PPM Fund, being one of the RES Investment sub funds, was established as an investment fund to provide funding to PPM to assist with the establishment and operation of the mine on the relevant land which I will from time to time refer to as the site. RES as responsible entity of the RES Investment Fund provided that funding pursuant to various loan agreements.

19 As I have said, RES holds the security interests to secure such funding given to PPM, which security interests are to be released in exchange for the secured creditor amount.

20 RES also acts as trustee for the PPM Investor Trust (the PPM trustee). As at the date of the liquidators’ appointment there were about 510 unit holdings in the PPM Investor Trust. RES does not hold any units. The unit holders in the PPM Investor Trust are members of the RES Investment Fund.

21 RES holds at least 15% of the shares in PPM in its capacity as the PPM trustee.

22 The following diagram usefully sets this out.

23 Let me switch focus for a moment and say something more about PPM.

Matters concerning PPM

24 PPM operated the mine under a mining lease granted to BRS. The site is owned by PPM and is currently vacant land. A consulting geologist report obtained in mid-2022 assessed the estimated measured resources of the site of up to 40.9 million tonnes of silica.

25 PPM entered into a number of security documents with RES, including loan agreements and variations to loan agreements over the period 2019 to 2023 (the loan deeds) and general security agreements in 2019, 2021 and 2023 (the GSAs).

26 Pursuant to the loan deeds, RES lent funds to PPM (the loan account).

27 In accordance with the loan deeds and the GSAs, RES registered the following security interests being a mortgage over the site on 6 July 2023 and registration on the PPSR of a general security interest over PPM’s assets including the measured recourse of the site.

28 From about 13 December 2019 to September 2023, PPM drew down on the loan account.

29 PPM first defaulted on principal loan repayments in December 2022 and from mid-2023 did not repay its schedule interest and capital repayments on the loan account to RES.

30 In June 2023, PPM advised RES in its capacity as responsible entity of the RES Investment Fund that it intended to sell the site and advised that the process may take between 8 to 12 months.

31 In November 2023, PPM and SA Services International LLC (SASI), an international sulphuric acid physical and financial commodities trader, signalled their intent to enter into a partnership to assist with an informal restructure of PPM.

32 From at least June 2023, PPM failed to make repayments on the loan account in accordance with the loan deeds.

33 On 7 December 2023, RES issued a default notice to PPM detailing the arrears on the loan account of $1,917,924. The loan account became due and payable following PPM’s failure to comply with the default notice dated 7 December 2023.

34 On 23 February 2024, RES sent a letter to PPM detailing an outstanding balance of the loan account of $25,876,899.

35 On 12 September 2024, the liquidators caused a default notice to be issued to PPM detailing the arrears on the loan account in the sum of $12,466,350. The default notice required payment of that amount to be made by PPM by no later than 12 October 2024, failing which RES reserved its right to take enforcement action with respect to the loan deeds, the GSAs any other security held by RES. It also identified that upon an event of default, the entire amount payable by PPM became due and payable in respect o f the first and second loan agreements. PPM did not comply with the default notice.

36 As at 31 October 2024, the loan account balance was approximately $29 million and at the start of July 2025 it was approximately $30 million.

SASI dealings - proposed forbearance on loan

37 Now prior to the appointment of the PPM administrator, PPM had been undergoing an informal restructure outside of a formal external administration process.

38 As part of the PPM restructure, on 24 March 2024, PPM and SASI entered into a strategic alliance agreement by which SASI agreed to provide funding and strategic guidance to PPM during the PPM restructure (the SASI agreement). SASI agreed to provide PPM with funding towards loan repayments of the loan account to RES, outstanding invoices owed by PPM representing unpaid project costs and ongoing costs to ensure the success of the operation of the mine at the site.

39 Further, the SASI agreement purports to issue 1000 new A-class shares in PPM to SASI which would have the effect of providing SASI with 70 percent of voting rights in PPM and a share of profits or dividends described in clause 4.1 of the SASI agreement, in consideration for SASI’s funding of PPM’s liabilities and the mining project.

40 As I have said, RES holds at least 15% of the shares in PPM in its capacity as the PPM trustee.

41 Accordingly, the issue of new PPM shares to SASI under the SASI agreement could have the effect of diluting RES’ PPM shareholding.

42 The liquidators did not agree to or adopt the SASI agreement and have reserved rights in respect of any relief that RES may seek to obtain if RES’ shares in PPM have been diluted.

43 From about May 2024, when RES was in voluntary administration, up to about November 2024, after RES’ creditors resolved to wind up RES, the liquidators, PPM and SASI engaged in negotiations regarding a potential forbearance, whereby RES would forbear from taking enforcement action against PPM in respect of its obligations under the loan deeds and GSAs, to allow for the PPM restructure to take place and the mine to be developed.

44 On or about 7 November 2024, the liquidators, SASI and PPM agreed on a term sheet for the liquidators to present to the creditors and investors of the PPM Fund.

45 On 19 November 2024, the liquidators issued a circular to creditors and investors detailing the key terms of the SASI proposal and that the liquidators believed the SASI proposal was an acceptable option when also considering other alternatives such as enforcement.

46 On 27 November 2024, investors in the PPM Fund attended a virtual meeting to discuss the SASI proposal. In respect of the SASI proposal, the liquidators explained to investors that it is unlikely that investors would receive 100c on the dollar in either a forbearance scenario or enforcement. They explained that RES is in liquidation so the SASI proposal, and a course for recoveries by investors, was favourable. They also explained that enforcement action, if taken by the liquidators, is not without risk that investors may potentially receive no return on their investment or less return than the SASI proposal. And they explained that whilst both the forbearance and enforcement scenarios carry risk, the estimated return on RES’ loan to PPM is more certain and potentially higher in the SASI proposal scenario than if taking enforcement action.

47 During early to mid-December 2024, the liquidators continued to negotiate with SASI but were unable to obtain materially better terms from SASI.

48 On 23 December 2024, the liquidators issued a further circular to creditors and investors, which included SASI’s final proposal. The liquidators recommended a resolution that pursuant to ss 477(2A) and 477(2B), approval be granted for the liquidators of RES to enter into and cause RES to enter into a deed of forbearance substantially in the terms set out in their report. And they called for and convened a meeting in respect of the deed of forbearance resolution.

49 On 5 February 2025, the creditors’ meeting was held and a vote taken in respect of the deed of forbearance resolution. The vote was decided by poll and the deed of forbearance resolution did not pass.

Enforcement action

50 As the deed of forbearance resolution did not pass, the liquidators considered the next step being to take enforcement action against PPM.

51 The liquidators took steps to appoint a voluntary administrator over PPM. But before they could do so, PPM itself appointed the PPM administrator pursuant to s 436A.

52 On 7 March 2025, pursuant to s 436A and as I have said, Mr Lucan was appointed voluntary administrator of PPM by the directors of PPM.

53 On 17 March 2025 the liquidators’ lawyers wrote to the PPM administrator to obtain his consent to RES enforcing its security interests against PPM pursuant to s 440B(2)(a). On 18 March 2025, the PPM administrator provided such consent.

54 On 4 April 2025, and as I have said, the liquidators appointed Mr Hutton and Mr Holland as receivers and managers over the site and all of PPM’s present and after acquired property including anything in respect of which PPM has at any time a sufficient right, interest or power to grant a security interest. Further, the liquidators also appointed them as agents over the site.

Other issues arising

55 On 5 March 2025, SASI, being an entity associated with the proponent, lodged a caveat with the Queensland Department of Resources over the mining lease held by BRS over the site (the SASI caveat).

56 On 17 July 2025, the PPM administrator and the receivers received a letter from Frank Law + Advisory, who have been engaged to act on behalf of the proponent and SASI in relation to the sale process.

57 The 17 July 2025 letter set out the asserted basis of SASI’s interest in BRS and PPM including the SASI agreement, a separate loan deed and a deed of covenant which purported to establish a registrable interest in BRS’ property. The letter put the PPM administrator and the receivers on notice that the parties should not act in contravention of SASI’s caveatable interest, or purport to exercise powers which would interfere with the mining lease. Further, it was said that the DOCA proposed (now, the PPM DOCA) was the only viable outcome that appropriately deals with the purported existing proprietary rights. It was said that should the PPM DOCA not be the preferred proposal, then SASI would take steps to exercise its proprietary and leasehold rights over the subject mineral interests and associated property.

58 On 28 July 2025, the receivers’ solicitors, Gilbert + Tobin, sent a letter to Frank Law in response to the 17 July 2025 letter seeking confirmation and information on various topics. The receivers did not receive a response to the 28 July 2025 letter.

59 On 28 July 2025, the PPM administrator sent a letter to Mr Holland , one of the receivers of PPM. In the administrator’s letter, the PPM administrator states that he had obtained legal advice in relation to the SASI caveat and formed the view that the SASI caveat relates to an equitable interest that arises due to BRS’ acknowledgment of the SASI agreement, the SASI caveat does not appear to secure any monetary amount, and the registration of the caveat is likely a voidable transaction as the granting of the security by BRS.

60 There are grounds that support the validity of the SASI caveat and also grounds that support the displacement of the SASI caveat, such as SASI not complying with the SASI agreement, which would require further factual investigation.

61 In any case, in circumstances that the PPM DOCA was the only option presented to PPM and BRS creditors, and because of the likely costs associated to set aside the SASI caveat even if another viable proposal was available, the PPM DOCA is the most favourable outcome for RES, noting that it does not preclude the liquidators of RES from pursuing other claims it may have against other parties, such as the directors of RES or PPM or those connected with any breaches of the law by RES.

PPM sale process, PPM administrator’s recommendation and second meeting of creditors

62 As I have indicated, the receivers and the PPM administrator have undertaken a joint two-stage sale campaign for the recapitalisation or restructure of all or part of PPM and BRS. The PPM sale process has now been completed.

63 The PPM sale process resulted in three final binding offers of which two were incapable of acceptance and one was a proposal for a deed of company arrangement made by a shareholder of PPM, being Swift Mining Resources Pty Ltd (the proponent), which ultimately resulted in the PPM DOCA.

64 The PPM DOCA was recommended for approval to creditors by the PPM administrator.

65 The PPM DOCA was the only final binding offer put to creditors at the second meeting of creditors of PPM and the second meeting of creditors of BRS, which were both held on 5 August 2025.

66 In the PPM administrator’s report to creditors, the PPM administrator formed the view that PPM was insolvent from at least June 2023, when PPM defaulted on its obligations under various loan deeds.

67 According to the PPM administrator’s report to creditors, the PPM administrator identified potential claims in a liquidation scenario of PPM, including voidable transaction claims, including uncommercial transactions and unreasonable director-related transactions with an estimated value of what appears to be $2,155,656 and insolvent trading claims, with an estimated value of about $582,239.

68 In the PPM administrator’s report to creditors, the potential dividend for secured and unsecured creditors in the PPM DOCA scenario versus a liquidation scenario is said to be as follows:

Secured Creditor (being RES) | Unsecured Creditors | ||||

PPM DOCA | Liquidation (Best Case) | Liquidation (Worst Case) | PPM DOCA | Liquidation (Best Case) | Liquidation (Worst Case) |

19.18c in the dollar | 17.24c in the dollar | 14.19c in the dollar | 23.98c in the dollar | 8.22c in the dollar | 0c in the dollar |

69 The PPM administrator recommended that the PPM DOCA be accepted for the following reasons. First, the PPM DOCA allowed for a higher return to RES as secured creditor than the most likely outcome in a liquidation scenario. Second, the PPM DOCA allowed for a higher return to both RES and the unsecured creditors of PPM than the best-case outcomes in a liquidation scenario. Third, the expected distribution of funds to creditors of PPM and BRS under the PPM DOCA is six months, whereas in a liquidation scenario, distribution of funds would likely take 24 months, that is, following investigations, commencing proceedings and/or negotiating an outcome. Fourth, the PPM DOCA allows for the continued operation of the businesses of PPM and BRS.

70 Now at 10:30am on 5 August 2025, pursuant to s 439A(1), the PPM second meeting of creditors took place via Microsoft Teams.

71 At this meeting, the PPM administrator tabled the PPM administrator’s report to creditors, which included a proposed DOCA and explained to creditors that it was the PPM administrator’s recommendation that creditors of PPM and BRS resolve to accept the PPM DOCA and that the likely outcome for both the secured and unsecured creditors in each scenario, was as set out in the table above.

72 The PPM creditors and BRS creditors were asked to vote on resolutions that: “…the Company [being either PPM or BRS, as the case may be] enter into the proposed Deed of Company Arrangement and that the administrator be the administrator of the Deed of Company Arrangement”.

73 The vote was decided by poll and the PPM DOCA was passed for PPM and BRS. But the liquidators of RES abstained from voting on the PPM DOCA proposal because they thought it prudent to reserve RES’ rights in full in respect of the release of security until they had received approval pursuant to s 477(2A).

74 Let me now say something more about the PPM DOCA and the deed poll.

PPM DOCA

75 The PPM DOCA was executed by the PPM administrator and the proponent on 26 August 2025.

76 The key terms of the PPM DOCA include inter alia the following aspects.

77 First, the PPM DOCA will be binding on both PPM and BRS.

78 Second, the PPM administrator will be appointed as deed administrator under the PPM DOCA.

79 Third, the creditors of PPM and BRS will agree to a moratorium in respect of certain actions against PPM and BRS for the period of the PPM DOCA.

80 Fourth, the deed fund will comprise a deposit contribution in the amount of $630,000 (deposit contribution, a non-refundable contribution of $5,670,000 (deed contribution), and any cash held by the deed administrator.

81 Fifth, the deed fund does not include any plant and equipment owned by PPM that has been recovered by the receivers, and there is nothing in the PPM DOCA which prevents the receivers from realising the PPM plant and equipment for the benefit of RES’ creditors.

82 Sixth, within 1 business day after the execution of the PPM DOCA, the proponent must pay the deposit contribution to the deed administrator, which will be refundable if the liquidators cannot execute a deed poll.

83 Seventh, within 60 days of the execution of the PPM DOCA, the deed contribution will be paid directly by the proponent to the receivers on account of the secured creditor amount, which is $5,975,000.

84 Eighth, within 2 business days of the liquidators signing the deed poll, the deed administrator must apply the deposit contribution, first, to the balance of the secured creditor amount by paying $305,000 to the receivers and, second, as follows. The deed administrator must apply the balance of the deed fund in the following order: (a) $200,000 will be paid to the PPM administrator and deed administrator on account of his reasonable remuneration and expenses; (b) $100,000 will be paid to employees of PPM in satisfaction in full of any claim that they would have been entitled to be paid in priority to the payment of other unsecured claims and general unsecured creditors of PPM on a pro rata basis in full satisfaction of their admitted claims; and (c) $25,000 will be paid to employees of BRS in satisfaction in full of any claim that they would have been entitled to be paid in priority to the payment of other unsecured claims and general unsecured creditors of BRS on a pro rata basis in full satisfaction of their admitted claims. Any surplus remaining in the deed fund following the application of the deed fund as just described will be paid to RES on account of the outstanding debt owed by PPM to RES.

85 Ninth, within 5 business days or as soon as practical following receipt of the secured creditor amount by RES, the receivers will retire and RES will release the mortgage and its security interest in the shares issued in BRS, which arise from the GSAs, that is, the release of security.

86 Tenth, by no later than 6 months after the PPM DOCA is executed, the proponent must have produced all necessary consents to facilitate the transfer of all of the shares in PPM to the proponent, which may include the proponent procuring the deed administrator to obtain an order of the Court for the share transfer pursuant to an application under s 444GA.

87 Eleventh, the share transfer will occur on completion, or failing the share transfer being procured, then subject to RES receiving the secured creditor amount, the deed administrator may take steps to transfer the site to the proponent at the proponent’s costs and transfer BRS’ shares to the proponent, at the cost of the deed administrator.

88 Twelfth, immediately following the share transfer and subject to the preceding point, the PPM DOCA will effectuate and all claims of creditors as against PPM and BRS will be extinguished in full.

89 Thirteenth, the directors, associated parties and associated entities of the proponent will subordinate any claim that they may have against PPM or BRS whether priority or not behind those of the ordinary unsecured creditors.

90 Fourteenth, the PPM DOCA may be terminated prior to effectuation if: (a) one or more of the implementation required to be undertaken prior to completion are not satisfied or waived within the prescribed timelines in the PPM DOCA; (b) the Court makes an order under s 445D terminating the PPM DOCA; (c) the creditors of PPM or BRS resolve to terminate this the PPM DOCA in accordance with ss 445C(b) and 445CA; or (d) a resolution varying the PPM DOCA, which has not been consented to by the proponent of the PPM DOCA, is passed at a meeting of creditors of PPM and BRS.

Deed Poll

91 As I have indicated, the liquidators of RES abstained from voting in respect of the PPM DOCA and so the PPM DOCA is not binding on RES.

92 Accordingly, to give effect to the terms of the PPM DOCA, the liquidators have agreed to sign a deed poll to afford the proponent some comfort that the release of security will occur in exchange for RES receiving the secured creditor amount.

93 The terms of the deed poll are the following. First, subject to the receivers receiving the secured creditor amount in accordance with the PPM DOCA, they will release the RES securities and provide the release documents. Second, the interest in the PPM plant and equipment will be unaffected by the deed poll. Third, subject to the liquidators obtaining approval from the Court for the release of security in exchange for the secured creditor amount, the liquidators will sign the deed poll.

94 Now before dealing with the precise orders sought, let me address the relevant legal principles.

Some relevant legal principles

95 Let me say something first about the direction sought under s 90-15 of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) that the liquidators are justified in entering into and causing RES to enter into and to give effect to the various instruments.

96 As I said earlier this week in Yeo (liquidator), in the matter of Tuftex Carpets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2025] FCA 1200 at [7] to [9], in terms of the Court’s powers to give directions to liquidators or other types of external administrators such as voluntary administrators, one can do no better than refer to the exposition of the relevant principles by Goldberg J in Re Ansett Australia Ltd [2001] FCA 1439; (2001) 39 ACSR 355 at [58] to [66] and in Re Ansett Australia Ltd (No 3) [2002] FCA 90; (2002) 115 FCR 409 at [42] to [67], which dealt with a statutory analogue to the one I am considering.

97 In Re Ansett Australia Ltd (2001) Goldberg J said at [58] to [66]:

The applications are made by way of directions pursuant to s 447D of the Act which is, in substance, in similar terms to s 479(3) of the Act which allows a liquidator of a company to apply to the Court for directions “in relation to any particular matter arising under the winding up”. In Editions Tom Thompson Pty Ltd v Pilley (1997) 77 FCR 141, a company subject to a deed of company arrangement applied to the Court pursuant to s 447D of the Corporations Law seeking directions permitting it to sell goods the title to which were disputed between the company and another party. Lindgren J observed at 149:

“I see no distinction in the present respect between an application by administrators under s 447D and an application by a liquidator under s 479(3). …The procedure afforded by s 447D to administrators under a deed of company arrangement is clearly drawn from, and is in substance the same as, that afforded to liquidators by s 479(3).”

Accordingly, authorities relevant to the construction and application of s 479(3) are also relevant to the present applications. There are a number of authorities which consider the consequences of an order upon the rights of third parties made upon an application by a liquidator for directions under s 479(3) of the Corporations Law. In Re G B Nathan & Co Pty Ltd (in liq) (1991) 24 NSWLR 674, McLelland J considered the genesis and legislative history of s 479(3) of the Corporations Law (the predecessor of the Corporations Act) and observed at 679-680:

“Modern Australian authority confirms the view that s 479(3) ‘does not enable the court to make binding orders in the nature of judgments’ and that the function of a liquidator’s application for directions ‘is to give him advice as to his proper course of action in the liquidation; it is not to determine the rights and liabilities arising from the company’s transactions before the liquidation’: [cases cited omitted].”

…

The nature of the type of directions commonly sought under s 479(3) of the Corporations Law and its predecessors were considered by Young J in Sanderson v Classic Car Insurances (1985) 10 ACLR 115 at 117 as involving:

“(a) guidance to the liquidator on matters of law …

(b) questions involving legal procedure …

(c) whether a liquidator should act on his commercial judgment to postpone a sale because he recognises his legal duty ordinarily requires him to reduce the company’s assets into cash as soon as possible and to distribute …or

(d) where there are two or more competing purchasers for the company’s property and the liquidator can see that it may be alleged that the liquidator has acted mala fide or in an absurd or unreasonable or illegal way …”

Essentially what a court is doing when giving directions under provisions such as s 447D and s 479(3) in relation to a question whether an administrator or liquidator should enter into an agreement, or whether an administrator or liquidator should give effect to an agreement, is to provide the administrator or liquidator with protection against claims that he or she acted inappropriately or unreasonably in entering into, and performing, the agreement.

This consequence was identified by McLelland J in Re G B Nathan & Co Pty Ltd (in liq) (supra) at 679:

“The historical antecedents of s 479(3), the terms of that subsection and the provisions of s 479 as a whole combine to lead to the conclusion that the only proper subject of a liquidator’s application for directions is the manner in which the liquidator should act in carrying out his functions as such, and that the only binding effect of, or arising from, a direction given in pursuance of such an application (other than rendering the liquidator liable to appropriate sanctions if a direction in mandatory or prohibitrary form is disobeyed) is that the liquidator, if he has made full and fair disclosure to the court of the material facts, will be protected from liability for any alleged breach of duty as liquidator to a creditor or contributory or to the company in respect of anything done by him in accordance with the direction.”

…

In a number of authorities, the courts have made it clear that courts should pay regard to the commercial judgment of liquidators when considering compromises of claims or causes of action made by liquidators in respect of which compromises the approval of the court is sought. The Act and its predecessors, entrust to liquidators and administrators the conduct of liquidations and administrations, albeit subject to the ultimate supervision of the court. The Court will generally defer to the commercial judgment of liquidators and administrators. In Re Spedley Securities Ltd (in liq) (1992) 9 ACSR 83, Giles J said at 85-86:

“In any application pursuant to s 377(1) [equivalent to Corporations Act s 477(2A)] the court pays regard to the commercial judgment of the liquidator (Re Chase Corporation (Australia) Equities Ltd (1990) 8 ACLC 1118). That is not to say that it rubber stamps whatever is put forward by the liquidator but, as is made clear in Re Mineral Securities Australia Ltd [1973] 2 NSWLR 207 at 231-2, the court is necessarily confined in attempting to second guess the liquidator in the exercise of his powers, and generally will not interfere unless there can be seen to be some lack of good faith, some error in law or principle, or real and substantial grounds for doubting the prudence of the liquidator’s conduct.

The same restraint must apply when the question is whether the liquidator should be authorised to enter into a particular transaction the benefits and burdens of which require assessment on a commercial basis.”

Put shortly, it is not the role of the Court to make a commercial judgment for the liquidators or administrators or to substitute its judgment for their judgment. The Court is not qualified to do so and it is not part of the judicial function to do so. Street CJ made this point in Re Mineral Securities Australia Ltd (in liq) [1973] 2 NSWLR 207 at 232:

“When the court is required to pronounce upon the commercial prudence of a transaction, it enters upon a slippery and uncertain field. Apart from the lawyer’s disclaimer of expert qualifications in matters of business prudence, the very process of litigation and the necessary limitations upon the scope of admissible evidence restrict the available material to far less than is necessary for the making of a commercial decision.”

As I have pointed out earlier, although courts will not pronounce upon the commercial prudence of a particular transaction, they will act in an appropriate case to protect liquidators and administrators from claims that they have acted unreasonably in entering into particular transactions…

98 Moreover, as Goldberg J pointed out, any protection given to the liquidators concerning the subject matter of the direction is in effect conditional upon and applies so long as the liquidators have made a full and fair disclosure to the Court of all facts material to that subject matter.

99 In that context, Goldberg J cited what Finkelstein J said in Mentha v G E Capital Ltd (1997) 27 ACSR 696 at 702; 154 ALR 565 at 571, which like the Ansett cases also produces a sense of nostalgia.

100 Let me now turn to s 477(2A), which concerns the separate but related aspect of authorization. And to be clear, the grant of authorization does not confer the same protection on a liquidator as a direction under s 90-15 or other statutory analogues as discussed by Goldberg J. It merely empowers a liquidator to enter into the relevant transaction, nothing more.

101 Section 477(2A) provides:

(2A) Except with the approval of the Court, of the committee of inspection or of a resolution of the creditors, a liquidator of a company must not compromise a debt to the company if the amount claimed by the company is more than:

(a) if an amount greater than $20,000 is prescribed—the prescribed amount; or

(b) otherwise—$20,000.

102 The relevant amount now prescribed for the purposes of s 477(2A) is $100,000.

103 In terms of its subject matter, s 477(2A) is to be distinguished from s 477(2B) which latter provision reflects the separate statutory concern that the timing of contractual provisions may be in tension with the expectation that generally a liquidation should proceed as expeditiously as the circumstances permit. But both provisions reflect the necessity for court oversight concerning the conferral or completion of the necessary power to engage in certain transactions albeit with different characterisations. Let me return to s 477(2A).

104 It is appropriate on this occasion to abide by the advice formalised in the well known maxim melius est petere fontes quam sectari rivulose: it is better to go to the fountain-head than to follow the streamlets.

105 The relevant fountain-head in the present context is Re Spedley Securities Ltd (in liquidation) (1992) 9 ACSR 83, where Giles J said at 85 and 86 (omitting citations):

The powers given to a liquidator, either directly by [now s 477(1)] or upon authorisation pursuant to [now s 477(2A)], are directed to achieving the efficient winding up of the company, that is, the collection and distribution of its assets for the general benefit of its creditors. In controlling the exercise of the liquidator’s powers pursuant to [now s 477(2A)], the court looks to the interests of creditors, and where a compromise is in question it must be asked whether it is in the interests of those concerned in the winding up — here the creditors. The same question must be asked when deciding whether to confer authority to enter into the compromise. While the court will seek to ensure that a minority of creditors who do not agree with the compromise will not be treated unfairly, even if some creditors have not assented it may be found that the compromise is for the benefit of all concerned.

Directions given to a liquidator pursuant to [now s 90-15 of the IPS] fulfil a different function from authorisation pursuant to [now s 477(2A)]. Authorisation empowers the liquidator to do what he would otherwise not have power to do, or at least, would not have power to do beyond [now s 477(1)] or authority given by the Committee of Inspection or a resolution of creditors. The nature and scope of an application for directions is … essentially a means whereby the liquidator may be guided in the conduct of the liquidation and protected against allegations of breach of his duty. It is generally not appropriate in an application for directions to make the liquidator’s commercial decisions for him where he has full power to act, and the liquidator should not seek directions as a kind of insurance that he has made the right commercial decision. It is nonetheless common for a liquidator to seek directions as to whether he is justified in entering into a particular compromise, but in the present case I doubt that there is really any separate issue in relation to directions pursuant to [now s 90-15 of the IPS]. If the liquidators are given the authority for which they ask it will follow that they are justified in exercising the power they will then have.

In any application pursuant to [now s 477(2A)] the court pays regard to the commercial judgment of the liquidator. That is not to say that it rubber stamps whatever is put forward by the liquidator. The court is necessarily confined in attempting to second guess the liquidator in the exercise of his powers, and generally will not interfere unless there can be seen to be some lack of good faith, some error in law or principle, or real and substantial grounds for doubting the prudence of the liquidator's conduct. The same restraint must apply when the question is whether the liquidator should be authorised to enter into a particular transaction the benefits and burdens of which require assessment on a commercial basis. Of course, the compromise of claims will involve assessment on a legal basis, and a liquidator will be expected to obtain advice and, as a prudent person would in the conduct of his own affairs, advice from practitioners appropriate to the nature and value of the claims. But in all but the simplest case, and demonstrably in the present case, commercial considerations play a significant part in whether a compromise will be for the benefit of creditors.

It is for these reasons that the attitudes of creditors are important in applications such as the present. The acquiescence of creditors is important.

106 Clearly, the following points are necessarily implied from these observations.

107 First, it is not the Court’s role to take an atomistic approach in assessing each and every factor considered by the liquidator, let alone to re-weight them or to add additional factors as if the Court was making the judgment call for itself, which it is not.

108 Second, and related to this first point, the Court should take a holistic approach and look at the liquidator’s overall assessment.

109 Third, the Court should ask the following questions. Has the liquidator’s inquiry and consideration been thorough? Has the liquidator obtained proper advice on any technical or legal issue that is fundamental to his consideration? But there may be occasions, such as the context before me, where no legal advice is necessary if no substantive legal question is involved in the liquidator forming his judgment if what is involved is purely a commercial judgment call.

110 Fourth, is the decision made by the liquidator one that is within the range of decisions that a reasonable liquidator would or could take in the circumstances? This question may seem watered down in its formulation, but it is explained by the fifth point.

111 Fifth, as Brereton J said in Re One.Tel Limited (2014) 99 ACSR 247 at [26]:

Importantly, the Court’s approval is not an endorsement of the proposed agreement, but merely permission for the liquidator to exercise his or her own commercial judgment in the matter. Thus the approval confers, or completes, the liquidator's power to enter into the transaction, but does not amount to the court approving the transaction itself. The distinction is material, because it means that - unlike a direction under s 479(3) or s 511 - an approval under s 477(2A) or (2B) alone does not exonerate the liquidator from personal liability.

112 In other words, the fourth point is explained by the fact that an exercise of power under s 477(2A) is only giving authorization. It does not provide the protection that is given by a direction under s 90-15 of the IPS.

113 Now before addressing the proposed orders, let me address a topic that is common to a consideration of the appropriateness of both orders.

Liquidators’ views on the PPM DOCA and why the release of security is in the best interests of creditors and investors of RES

114 The debt owed to RES as at 12 September 2025 is approximately $32 million. Under the PPM DOCA, RES will receive payment of $5,975,000 being the secured creditor amount in exchange for the release of security, pursuant to the deed poll, which sum comprises 95% of the deed fund.

115 The liquidators consider that signing the deed poll and proceeding with the release of security as required by the PPM DOCA in exchange for the secured creditor amount is in the best interests of RES’ creditors and investors.

116 The liquidators consider that the PPM DOCA is the highest genuine offer received in the sale process and there is no alternative outcome that would result in a better return to RES, especially in the following circumstances.

117 First, RES will likely receive a better return under the PPM DOCA compared with a best-case liquidation scenario.

118 Second, the receivers and the PPM administrator are of the opinion that the first final binding offer, which was for $29.6 million, is not genuine as: (a) the offeror has no public profile; (b) the sole director of the offeror has no apparent relevant industry profile or experience; (c) the offeror has not paid a requested deposit and has not provided any evidence of their financial capacity to complete the transaction despite several requests; and (d) the offeror has repeatedly amended its offer to avoid any immediate commercial obligations in relation to the offer.

119 Third, the second final binding offer was for $6.1 million plus taxes but was subject to further due diligence; accordingly, the offer would likely have changed.

120 Further, the release of security does not require RES to release any claims it may have against the directors of RES, PPM or BRS, reserving the liquidators’ and RES’ rights and ability to pursue potential further recovery avenues on behalf of creditors and investors.

121 Further, if the PPM DOCA was not the preferred proposal, SASI indicated that it would take steps to exercise its rights which are subject to the SASI caveat. Additionally, it is unlikely that SASI would voluntarily remove the SASI caveat to allow for completion of the sale to a third party, and, accordingly, any bid by a third-party may be negatively impacted by the SASI caveat. Conversely, compelling the removal of the SASI caveat would be a costly and risky process to embark on.

122 Further, given that any realisations from the PPM plant and equipment are not governed by the PPM DOCA and do not form part of the deed fund, any recoveries from the realisations of the PPM plant and equipment by the receivers will be for the benefit of RES.

123 Further, based on the PPM administrator’s report to creditors, the PPM administrator obtained an appraisal of the site, which estimated the value of the site, where the mining lease and EPA permit are not included in the sale, to be between $450,000 and $550,000. RES’ return under the PPM DOCA in the amount of $5,975,000 far exceeds the value of the site provided for in the valuation.

124 Further, notwithstanding that the liquidators consider the PPM DOCA to be in the best interests of all of RES’ creditors and investors, given that the PPM DOCA requires the transfer of all PPM shares, investors in the PPM Fund will not be entitled to share in any profits from the mine if the proponent eventually puts the mine into production and it becomes profitable (the upside protection). Further, it is only a mere possibility that the proponent will be able to put the mine into production and that the mine will be profitable if it is put into production.

125 But the lack of upside protection does not change the liquidators’ view that the PPM DOCA is in the best interests of all of RES’ creditors and investors because none of the final binding offers allow any of the investors in the PPM Fund to retain any interest in the mine or provide the PPM Fund investors with upside protection. Accordingly, regardless of the final binding offer with which the PPM administrator and receivers proceeded, investors in the PPM Fund would not have had upside protection.

126 Further, if there is no PPM DOCA and PPM is put into liquidation, there is no upside protection for PPM’s shareholders.

127 Further, given that the liquidators’ remuneration is $342,985.00 and the liquidators’ fees and expenses, including involving the receivership of PPM, is $1.3 million, it is anticipated that there will be approximately $4.3 million remaining of the secured creditor amount after the liquidators’ fees and expenses are paid.

128 Further, the SASI proposal which was a forbearance proposal, has been the only offer since RES has entered external administration that provided investors in the PPM Fund with the ability to maintain their shareholding in PPM, the ability to maintain some involvement in putting the site into production through a partnership with SASI, and some potential upside from production, being a potential bonus repayment for those who continued with their investment. But RES’ creditors and investors did not pass a resolution in favour of the SASI proposal.

129 In the liquidators’ view, whatever prejudice may be suffered by investors in the PPM Fund is well outweighed by the above considerations and the commercial reality.

130 I have no reason to doubt the legitimacy or reasonableness of any of these views expressed by the liquidators. Let me now turn to the orders sought.

Directions under s 90-15 of the IPS — proposed order 1

131 The liquidators seek directions pursuant to s 90-15 of the IPS that they would be justified and acting reasonably in undertaking the release of the security interests and taking any steps in connection with the release of the security interests.

132 And part of the context explaining their application is that notwithstanding that they consider that the execution and completion of the PPM DOCA is in the best interests of RES’ creditors and investors, they may be subject to criticism, allegations of impropriety or legal action in circumstances where: (a) the release of security is an implementation step required to be taken prior to completion of the PPM DOCA; (b) completion of the PPM DOCA will result in all issued shares in PPM, including the shares currently held by RES in its capacity as the PPM trustee, being transferred to the PPM DOCA proponent; and (c) they are on notice that investors in the PPM Fund may not support the release of security or RES selling or losing its shares in PPM, notwithstanding that there is no greater viable proposal available.

133 Now usually a liquidator annexes confidential legal advice on the relevant compromise to an affidavit seeking approval of this kind. But the compromise being proposed is of a commercial rather than legal nature. So, a legal merits advice has not been sought. I should say that this is a course that I have no difficulty with. I will discuss later the views of a notable commercial judge, Robson J, on this topic, whose views are always highly persuasive.

134 Now as I have indicated, on 5 March 2025, SASI, being an entity associated with the proponent, lodged a caveat with the Queensland Department of Resources over the mining lease held by BRS over the site.

135 Subsequently, SASI and the proponent have put the PPM administrator and the receivers on notice that the PPM DOCA is the only viable outcome that appropriately deals with the purported existing proprietary rights and as such, should be treated as the preferred proposal and that if not given effect, they would exercise their proprietary and leasehold rights over the subject mineral interests and associated property.

136 So, in circumstances that the PPM DOCA was the only option presented to PPM and BRS creditors, and because of the likely costs associated to set aside the SASI caveat even if another viable proposal was available, the liquidators accepted the reasons for the PPM administrator’s view that the PPM DOCA is the most favourable outcome for RES.

137 Further, the PPM DOCA does not preclude the liquidators of RES from pursuing other claims it may have against other parties, such as the directors of RES or PPM.

138 Further, the liquidators have explained their rationale as to why signing the deed poll and proceeding with the release of security, as required by the PPM DOCA, in exchange for payment of $5,975,000 is in the best interests of RES’ creditors and investors.

139 On the basis of the factual matters that I have detailed and the liquidators’ assessment and views, it is appropriate to give the direction sought.

Order under s 477(2A) — proposed order 2

140 Now a point of construction has been raised concerning the phrase “compromise of a debt to the company”. The question is whether the release of the security interests in exchange for the secured creditor amount falls within that phrase in terms of it being a relevant compromise.

141 Now in the context before me I am not concerned with the meaning of “debt to the company” as such. Clearly, there exists and has existed a certain sum that has either been immediately due and payable by PPM to RES or will become due and payable. And nor am I concerned with the aggregation question where there is one compromise transaction of, say, two or more debts which in aggregate meet the statutory threshold but where each singularly is below it.

142 I would make a number of observations about the broader phrase, including the word “compromise” for which there is no statutory definition.

143 First, it should be construed in its broader context and purposively.

144 Second, the word “compromise” should be construed consistently with its other uses under the Act, for example, s 477(1) and also s 411(1). In these other contexts, there is no reason at all to give it any technical or narrow meaning. Indeed, in the scheme of arrangement context with which I am familiar, the essence of a compromise involves a “give and take” which could clearly involve each side giving something to the other or their nominees or more subtly moving to a common position on a matter from differing starting points which would involve each party giving up their opportunity to have their starting point vindicated by whatever means available.

145 But one has to exercise a little caution concerning the meaning of “compromise” in the scheme of arrangement context. Given that under ss 411 and 412 a “compromise” can be imposed on a creditor or shareholder who did not vote on the relevant resolution or indeed voted against it, there may be occasions when a court may draw the line, say, where the scenario involves an investor against his wishes being required to switch his debentures issued by company A to preference shares in company B, where company A had transferred all its assets to company B, and where all rights against company A had been extinguished (see Mercantile Investment and General Trust Company v International Company of Mexico [1893] 1 Ch 484 at 489 per Lindley LJ).

146 But in the present context, I am not concerned with such an outlier scenario. Moreover, under s 477(2A), the implicit assumption is that both the creditor and debtor have acquiesced to the compromise subject to s 477(2A) authorization, albeit that the creditors of the creditor so to speak may not have.

147 Third, if the Court is in doubt as to whether a transaction is a compromise, it should treat it as such. Why do I say that? Well, the liquidator does not suffer a bad hair day if the Court refuses to accept that it is a compromise or indeed positively decides that it is not. If that be so, then the liquidator can proceed in any event with the transaction in the absence of any scrutiny by exercising his powers under s 477(2). Now s 477(2) is subject, inter-alia, to s 477(2A), but the predicate here is that s 477(2A) does not apply because it is not a “compromise”.

148 But accepting all this to be so, nevertheless it is desirable that the Court maintain some oversight and treat s 477(2A) as prima facie applying in scenarios where it has a doubt. But if there is no doubt that there is no compromise, then of course any application under s 477(2A) should be refused.

149 For completeness, I should note one other point. If there is no “compromise” under s 477(2A) and likewise no “compromise” under s 477(1)(d), I do not see the breadth of s 477(2) as in any way denying the applicability of s 477(2) to the transaction given the breadth of, inter-alia, ss 477(2)(c) and (m).

150 Now the liquidators consider that the release of the security interests in exchange for the secured creditor amount may constitute a “compromise” of a debt payable by PPM to RES in excess of $100,000 as contemplated by s 477(2A). I agree. Indeed, I would express it more strongly. In my view there is such a “compromise of a debt”.

151 Of course the compromise does not change the face value of the principal. It does not change the interest provisions. It does not change the term of the loan or the conditions under which it could be called up. And such changes would affect the commercial or time value of the debt.

152 But the compromise does affect the security underlying the debt and hence its commercial value in terms of recoverability.

153 It would be too narrow a view to treat only the first type of change as the subject matter for a compromise but not the second type of change. Indeed, the second type of change may be more commercially fundamental. One could change the face value of the principal but not affect recoverability if the value of the security was still underwater at the same depth.

154 Moreover, the security and the debt go together. Indeed, “debt” could be considered to be a broader term encompassing either a secured debt or an unsecured debt.

155 There is no cogent legislative purpose or commercial reason why a change in security or release of a security in relation to a secured debt, but leaving all else equal, could not amount to a compromise. Indeed, the point of a liquidator entering into the transaction is ultimately to enhance recovery for the creditors. It would be anomalous to exclude security changes that directly impact recoverability in such a context.

156 In my view, the release and exchange of the security interests do involve a compromise.

157 Now as I have already explained, the liquidators consider that the PPM DOCA is in the best interests of RES’ creditors and investors. Further, they do not consider there is a more viable course to recover the balance of the loan account. Further, they are aware that there are third parties from whom the balance of the debt may be recovered.

158 Further, the liquidators consider that it is a purely commercial decision to accept the PPM DOCA, rather than consider alternative recovery options, due to the lack of other options available for recoveries and lack of funding available to pursue any alternative course, if one did exist.

159 So, the liquidators seek, to the extent necessary, approval under s 477(2A) because, given the contentious nature of RES’ liquidation to date, if such approval were not sought, they consider that it may be open to RES’ creditors and investors to attempt to challenge the release of security on the basis that it is a “compromise” of a debt.

160 Let me elaborate on one other topic concerning the liquidators’ decision not to separately procure independent legal advice concerning the appropriateness of the compromise.

161 As I have indicated, the liquidators’ decision to accept the relevant proposal is a purely commercial decision to accept the PPM DOCA, rather than consider alternative recovery options, due to the lack of other options available for recoveries and lack of funding available to pursue any alternative course, if one did exist. And the liquidators have not sought a merits advice in support of the compromise in circumstances where there are no legal proceedings on foot, there are no funds presently available in the liquidation, the compromise being proposed is of a commercial, rather than legal nature, and the decision and judgment to be made in respect of this potential compromise is based on experience of reputable external administrators and the advice and opinions that they have provided, including from the receivers and the PPM administrator who I have identified earlier.

162 As I have indicated, I am prepared to forgo the usual evidence of appropriate legal advice on the merits of the compromise given that the reasons for compromising were essentially commercially based.

163 Indeed, the scenario before me that justifies so proceeding is even stronger than the position pellucidly portrayed by Robson J in Handberg v MIG Property Services Pty Ltd (2012) 92 ACSR 38 at [78] to [80] where he said:

As mentioned in Spedley Securities, where the court’s approval of the compromise of a legal claim is sought, a liquidator will usually be expected to obtain legal advice supporting the compromise from an appropriate practitioner. This approach was summarised in McPherson’s The Law of Company Liquidation, which was cited with approval by Einstein J in Gate Gourmet. Mr Handberg has not deposed to any such advice. Nevertheless, his reasons for compromising are essentially commercially based. If he succeeds on the appeal, he is not confident of recovering any amount of the judgment debt for the reasons I have canvassed. The only assets available to pay the liquidator’s costs and expenses of the liquidation are the claims against MIG, the costs orders against the other defendants, and the funds in court, and these assets are not sufficient to meet the liquidator’s remuneration and expenses, much less future remuneration and expenses.

Accordingly, in the peculiar circumstances of this case, I am prepared to forgo the usual evidence of appropriate legal advice on the merits of the compromise.

I am satisfied that liquidator has entered into the compromise in good faith. I find that in doing so he has not made some error in law or principle. I do not doubt the prudence of the liquidator’s conduct in settling the judgment debt on the basis that he does and in view of the matter.

164 In my context, legal advice is not required. Moreover and overall, I would make the same judgment call as Robson J in judging the liquidators’ position before me in similar terms to Robson J’s assessment in [80] of his reasons.

Urgency and other matters

165 The proponent has executed the PPM DOCA and, accordingly, it must pay the deed contribution by no later than 26 October 2025. So, this application needed to be heard as soon as reasonably practicable for the following reasons.

166 First, given that neither the liquidators nor RES are parties to the PPM DOCA, the proponent would like the commercial certainty of knowing that the liquidators and RES are approved to undertake the release of security well in advance of 26 October 2025.

167 Second, if this application was not heard and determined before 26 October 2025, under the terms of the PPM DOCA, the proponent would be required to pay the deed contribution or risk the PPM DOCA being automatically terminated without any certainty that the liquidators and RES were approved to undertake the release of security.

168 Third, whilst it has not yet been signed by the liquidators or RES, there is a term in the deed poll that requires this application to be made as soon as reasonably practicable following the execution of the PPM DOCA.

169 I should deal with one final matter.

170 Counsel for an investor/creditor of RES turned up this morning. His instructing solicitors had previously indicated that an adjournment of the matter would be sought on the basis that it was proposed to make an application to set aside the PPM DOCA. But I would have refused the adjournment.

171 First, the investor/creditor has significantly delayed in making such an application.

172 Second, the application would have to be made against other parties such as the PPM administrator and other parties who are not parties to the present proceeding.

173 Third, I am addressing the question concerning the position of the liquidators of RES and their authority to enter into certain transactions and the appropriateness of doing so. The assumption on which the present application has proceeded is a valid PPM DOCA. If that assumption turns out not to be valid or the PPM DOCA is terminated, none of the transactions the subject of the present application will occur or at least the orders that I have made will lose their force.

174 Fourth, there is some weeks before the transactions are to occur in any event.

175 In these circumstances, there is no prejudice at all to the matter proceeding today. If the interested party does apply to set aside the PPM DOCA and is successful, no prejudice is caused by making the orders sought today.

176 Counsel for the investor/creditor astutely anticipating such points did not press any adjournment application, although it was indicated to me that an application would be made to either seek to have the PPM DOCA declared invalid or to have it terminated if valid.

Conclusion

177 For the above reasons, I made the orders sought this morning but with some modifications as discussed with counsel.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and seventy-seven (177) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Beach. |

Associate:

Dated: 3 October 2025