Federal Court of Australia

Singh v Aulakh [2025] FCA 1207

File number(s): | VID 368 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | BENNETT J |

Date of judgment: | 2 October 2025 |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS – application for leave to bring a derivative action on behalf of a company under s 237 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) – criteria of good faith, best interests of the company and whether there is a serious question to be tried – appropriateness of leave in the face of deficient proposed pleading – leave granted |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 180, 181, 182, 183, 232, 236, 237, 288, 1317H, 1324 |

Cases cited: | ASIC v Drake (No 2) [2016] FCA 1552; 118 ACSR 189 Angas Law Services Pty Ltd (in liq) v Carabelas [2005] HCA 23; 226 CLR 507 Carr v Finance Corp of Australia Ltd (1981) 147 CLR 246 Cemcon Constructions Pty Ltd v Hall Concrete Constructions (Vic) Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 696 Chahwan v Euphoric Pty Ltd (t/as Clay & Michel) [2008] NSWCA 52; 65 ACSR 661 Fiduciary Ltd v Morningstar Research Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 442; 53 ACSR 732 Goozee v Graphic World Group Holdings Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 640; 42 ACSR 534 Griffiths & Beerens Pty Ltd v Duggan [2008] VSC 201; 66 ACSR 472 Hannon v Doyle [2011] NSWSC 10; 82 ACSR 259 Hart Security Australia Pty Ltd v Boucousis [2016] NSWCA 307; 117 ACSR 408 Herbert & Ors v Redemption Investments Ltd [2002] QSC 340 HM&O v Ingram [2012] NSWSC 684 Maher v Honeysett and Maher Electrical Contractors [2005] NSWSC 859 Re Gladstone Pacific Nickel Ltd [2011] NSWSC 1235; 86 ACSR 432 Ehsman v Nutectime International Pty Ltd [2006] NSWSC 887; 58 ACSR 705 Re Wonga Pastoral Development Co Pty Ltd [2023] NSWSC 133 Re Woodbine Project Pty Ltd [2021] VSC 617 South Johnstone Mill Ltd v Dennis [2007] FCA 1448; 163 FCR 343 Swansson v RA Pratt Properties Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 583; 42 ACSR 313 Tydeman v Asgard Group Pty Ltd, in the matter of Asgard Group Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 486 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 129 |

Date of hearing: | 11 September 2025 |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | I Finch |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | J Auld of Harding Property Law |

ORDERS

VID 368 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | DAMANJEET SINGH Applicant | |

AND: | KULWINDER SINGH AULAKH First Respondent AJIT SINGH Second Respondent KULJIT KAUR AULAKH (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | BENNETT J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 2 October 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Second Respondent is granted leave to rely upon the affidavit dated 12 September 2025.

2. The Applicant be granted leave pursuant to s 237 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) to bring proceedings on behalf of Aulakh BS Pty Ltd against the First and Second Respondents under ss 180 and 181 of the Act identified in the affidavit of Mr Damanjeet Singh dated 6 June 2025.

3. Each party bears its own costs of the proceeding to date.

4. Order 3 be stayed for seven days, and if:

(a) the parties do not file submissions in relation to the order – the order is to take effect after that day; or

(b) the parties file submissions in relation to the order – the order be stayed until further order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BENNETT J:

Background

1 By application dated 6 June 2025 Mr Damanjeet Singh sought leave under s 237 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) to bring proceedings on behalf of a company called Aulakh BS Pty Ltd (the Company). The Company is the trustee of the ABS Unit Trust, which owns and operates a green grocer business in Cairns, Queensland, with the registered trading name “Cairns Local Farmers Market”.

2 There were originally three directors of the Company: Mr Damanjeet Singh (the Applicant or Mr D Singh), Mr Kulwinder Singh Aulakh (the First Respondent or Mr Aulakh), and Mr Ajit Singh (the Second Respondent or Mr A Singh). On 9 October 2024, the Second Respondent was removed as a director. There are six shareholders. The Applicant and First and Second Respondents are each shareholders, as are their wives: Ranjeet Kaur, Kuljit Kaur Aulakh (the Third Respondent), and Mandeep Kaur Mundi (the Fourth Respondent). All shareholders hold one ordinary share.

3 The Company commenced operations in 2021 following initial capital contributions by each of the directors. Mr D Singh’s evidence is that he contributed $86,000, the First Respondent contributed $180,000, and the Second Respondent contributed $157,000. Mr Aulakh’s evidence is that the Applicant contributed $70,000, the First Respondent contributed $180,798, the Second Respondent contributed $157,000 to the business, and they each contributed an additional $16,000 as a guarantee for the lease.

4 There were four bank accounts operated by the Company. Relevantly, one of those accounts was commonly used by the Company for its daily financial processes, held with the National Australia Bank (the NAB Account). Each director was a signatory on that account, and the evidence is that all withdrawals had to be approved by two out of three directors before the transaction would be authorised. After the removal of the Second Respondent as a director, approval of both remaining directors was required for any transactions.

5 An account was opened in or around July 2022 with ANZ Banking Group Ltd (the ANZ Account). The Applicant was not a signatory to that account. It is said that this account was in the name of the First and Second Respondents only, and that funds of the Company were directed to the ANZ Account instead of the NAB Account. The Applicant argues that there are no records showing any authorisation for the deposit of funds to the ANZ Account. The core of this issue is the allegation that there were funds misappropriated into the ANZ Account by the First and Second Respondents and that, in doing so, they acted in breach of their directors’ duties.

6 In February 2025 matters came to a head. The Respondents argue that the Applicant had tried to withdraw funds of the Company for his own benefit, and refused to authorise payments to creditors and staff unless those withdrawals were approved by the First and Second Respondents. The Applicant argued that the First and Second Respondents had misappropriated Company funds into the ANZ Account. On 26 February 2025, the Respondents convened a shareholder meeting to consider a motion to remove the Applicant as a director. The Applicant, through his solicitor, demanded that the meeting be adjourned because insufficient notice had been given. The meeting was adjourned, and, on 28 February 2025, another meeting for the same purpose was scheduled for 24 March 2025.

7 The Applicant made an application to this Court for an injunction freezing the Company’s accounts and preventing him from being removed as a director.

8 On 25 March 2025, Collier J made interim freezing orders restraining the First and Second Respondents from withdrawing, transferring or disposing of certain funds in specified bank accounts, or from opening or using a bank account in the name of the Company without the consent of the Applicant. The Respondents were further restrained from removing the Applicant as a director of the Company, and from taking any steps to diminish the value of the Company, among other matters.

9 On 2 April 2025, the Respondents sought to have the matter relisted before the duty judge. On 7 April 2025, Moshinsky J made orders continuing many of the orders made on an interim basis, as well as requiring that the Applicant file and serve a statement of claim in the proceeding, and for the filing of materials relevant to whether the freezing orders of 7 April 2025 should be maintained.

10 Before me on 22 May 2025, a hearing regarding the Applicant’s application for an injunction took place. Ultimately, the parties consented to the freezing orders being vacated, but certain orders being in place requiring the Company to use certain bank accounts and restraining the removal of the Applicant as director. At the hearing, the solicitor for Mr D Singh accepted that his proposed statement of claim would need to be brought in the name of the Company, and that leave would be required to do so.

11 The proposed statement of claim was annexed to the affidavit of Mr Damanjeet Singh dated 6 June 2025. It is not in dispute that leave is required under s 237 of the Act to proceed with that claim.

Evidence

12 I have before me the following materials:

(1) Affidavits of Mr D Singh dated 24 March 2025, 4 April 2025, 23 April 2025, 6 June 2025, 4 July 2025 and 10 September 2025.

(2) Affidavits of Mr Aulakh dated 3 April 2025, 12 May 2025 and 22 July 2025.

(3) An affidavit of Raj Kumar Joshi dated 22 July 2025.

13 The Second, Third and Fourth Respondents did not file any affidavit material prior to the hearing.

14 It is appropriate to briefly summarise relevant parts of that evidence. Some of the affidavits were filed prior to the present issue, and were (at least partially) relevant to predecessor issues related to the interim injunctions previously in place. They were, nevertheless, all read into evidence in the hearing of this application. Much of the evidence is repetitive and contradictory. No party sought to cross examine any deponent on any aspect of the evidence.

15 At the hearing, the solicitor for the Respondents said that the Second Respondent sought to adopt as his own evidence, the evidence given by the First Respondent. The basis for doing so was not clear, given that the Second Respondent had not filed any evidence of that adoption. Consequently, after the hearing, the Second Respondent filed an application to reopen the hearing for the limited purpose of filing an affidavit, which substantially stated that the Second Respondent “support[s], agree[s with] and rel[ies] on the evidence put forward by the First Respondent”. Although the practice of filing evidence following a hearing should be discouraged (see generally Carr v Finance Corp of Australia Ltd (1981) 147 CLR 246 at 257-258 (Mason J); HM&O v Ingram [2012] NSWSC 684 at [29]-[30] (McDougall J)), in this circumstance I am content to grant leave for that affidavit to be filed, given that it appears to be the basis on which the parties proceeded, and nothing substantially turns on it.

16 On the day before the hearing (10 September 2025), the Applicant sought to file a further affidavit without leave. The affidavit sought to do two things. First, it annexed copies of documents referred to in Mr D Singh’s affidavit of 4 July 2025, which were mistakenly not attached to that affidavit. Second, it provided evidence about a software platform which recorded point-of-sale transactions for the business. It also included correspondence with an external accountant (External Accountant) that was the subject of submission and not the subject of dispute. Save for the correspondence with the External Accountant, I do not consider the additional affidavit particularly relevant. I said that I would address the question of leave to rely upon that affidavit in these reasons. Given I have permitted the Second Respondent to file additional evidence, and given its confined relevance, it is appropriate that the additional affidavit be admitted.

Opening and direction of funds to the ANZ Account

17 Mr D Singh discloses the core of his concern as follows:

I am not 100% certain of the exact dates but I believe that somewhere between July 2022 and April 2024, the First and Second Respondents, without authorisation or disclosure to me, opened a joint personal account with ANZ Bank (BSB 014-577, Account No. 3278-27974), and caused business takings of approximately $343,780 to be deposited into that account.

During the relevant time both of the Respondents and I were directors of the Company.

The deposits were made in a manner intended to bypass the Company's official NAB accounts, in breach of corporate protocols…

18 Statements in respect of the ANZ Account are annexed to Mr D Singh’s affidavit of 24 March 2025. In his affidavit of 6 June 2025, he says these statements show that the re-direction of funds were from wholesale restaurant customers. Mr D Singh argues that it can be inferred that those customers were instructed to deposit funds into the ANZ Account rather than the NAB Account. He says that these payments into the ANZ Account were not disclosed to him, and were not reported in the Company’s financial statements.

19 Mr Aulakh’s evidence was that the Applicant and the First and Second Respondents agreed that the ANZ Account would be opened in or around July 2022. The Applicant’s knowledge of the ANZ Account is discussed below. Mr Aulakh’s evidence was that it was agreed that he and Mr A Singh would be the only signatories to the ANZ Account because they were involved in the day-to-day operation of the business. He deposes that the ANZ Account was used to pay staff, before the balance of the funds were deposited in the NAB Account. It was also stated that all wages paid were recorded in a group WhatsApp chat between the Applicant and First and Second Respondents. However, in the course of the hearing, the solicitor appearing for the Respondents accepted that there was before the Court no definitive record of all money paid on account of wages by (or purportedly by) the Company.

20 Mr D Singh’s evidence was to the effect that the Company’s financial activities were overseen by an External Accountant. His affidavit of 4 July 2025 annexes correspondence between his solicitor and the External Accountant. In correspondence of 28 May 2025, the solicitor sent a letter to the External Accountant asking, among other things, the following:

2. Looking at the Financial Statements prepared by you I note that the company owns and operates a number of Bank Accounts with the NAB. Further, that the only authorized bank accounts for trading are in fact those bank accounts currently held in the NAB. Is this correct?

3. Are you aware that between July 2022 and January 2024 (estimate) Kulwinder and Ajit held a joint bank account in the ANZ. This account was in their own individual names and that between 25 July 2022 and 25 January 2024 in excess of $343,780 (estimate) from the earnings of the company was deposited into this ANZ account?

4. Were you involved, in any way, in the setting up and use of the ANZ bank account by Kulwinder and Ajit?

21 On 12 June, the External Accountant responded as follows:

Q2). We prepare Financial Accounts based on information supplied to us by the company. The draft Financial Statements are based on the following bank account:

NAB. BSB: [REDACTED]. Account: [REDACTED]

The question as to what the authorized bank accounts for trading are a matter for the Board, not ourselves. We prepare Accounts based on what is supplied to us.

Q3). We only became aware of the existence of an ANZ bank account with possible links to the business on 9 February 2024, when Kulwinder Singh forwarded us an email from the ANZ “Information Request – Reference C2401942732”. We have yet to see details of bank transactions in the ANZ Bank and have not had any instructions about the relevance of these to financial accounts of ABS Unit Trust.

Q4). No

22 The External Accountant for the Company states that he was unaware of the ANZ Account until 9 February 2024, approximately 18 months after the ANZ Account commenced being used. The Applicant argues that this makes clear that the Company’s External Accountant had no operational knowledge of the movement of funds into and out of the ANZ Account and thus it can be safely inferred that the ANZ Account was not being used for the purposes of the Company. Of course more complete evidence may provide an explanation for this position. However the present status of the evidence raises a concern about the ANZ Account, and the extent to which funds deposited into it were solely for the benefit of the Company.

Whether the Applicant knew of the ANZ Account

23 The Respondents sought to argue that Mr D Singh was aware of the ANZ Account from its inception, based on evidence of various WhatsApp chats in which the ANZ Account was mentioned. There are two examples of this that the Respondents have pointed to.

24 The first is a WhatsApp message dated 13 July 2023, where a picture of an invoice from the Company to a customer was sent, which contained as the payment details the ANZ Account. Mr D Singh responded “Thanks bro”. Mr D Singh did not provide any evidence as to why he sent this message. However, given that the ANZ Account was not clearly identified in the message, I do not accept that it establishes on the balance of probabilities that he was aware of the ANZ Account at this time.

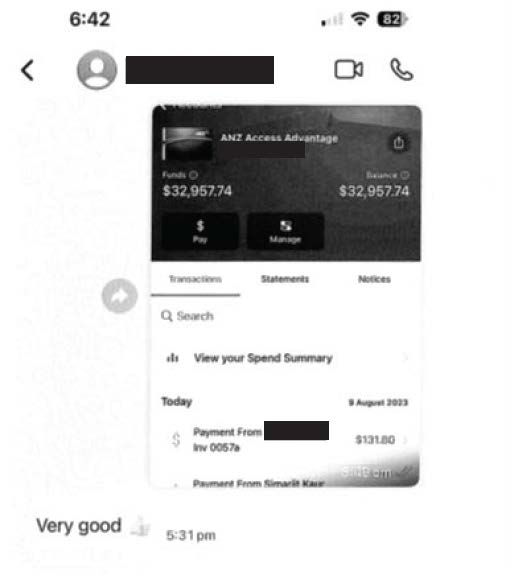

25 The second is the following WhatsApp exchange of 9 August 2023 containing a screenshot of the ANZ Account:

26 It is not in dispute that the message “Very good [thumb up emoji]” was sent by Mr D Singh. It is said by Mr Aulakh that Mr D Singh’s response indicated that he was aware of the ANZ Account.

27 In his affidavit of 6 June 2025, Mr D Singh asserted that the WhatsApp message does not indicate knowledge of the ANZ Account, nor its use for the purposes of the business. He deposed that:

If you look closely at the screen shot it shows ANZ Access Advantage [REDACTED] [REDACTED] and says Balance/Funds of $32,957.74. It also indicates that a payment of $131.80 was received from [REDACTED]. It does not identify the name of the account, or account holder(s) and offers no explanation as to why it was sent. I thought the Second Respondent had simply sent me a screenshot saying “look, I have $32,957.74 in my ANZ Account. That is why I responded with “very good” and gave a thumbs up symbol.

28 Mr D Singh also deposes that the message was sent without context, and on other occasions the First and Second Respondents had sent screenshots of bank accounts of his other business without any apparent relevance to the Company, such that he did not interrogate the messages closely or infer that they were necessarily connected to the Company.

29 This explanation was not the subject of cross examination. It might be an issue that is more completely the subject of evidence, however at this stage it is clear that the issue of Mr Singh’s knowledge is disputed, and that the dispute is credible.

30 Mr D Singh requested access to the ANZ Account in a WhatsApp message on 13 November 2023, and was provided with a temporary password on the same day. It is clear that he was aware of the ANZ Account from at least that date. Mr D Singh contends that, while he was able to view the transaction record from this time, he was not granted access to withdraw from the account or to initiate, approve or conduct transactions.

Circumstances leading up to freezing orders

31 Mr Aulakh deposes that Mr D Singh began extracting a weekly “directors fee” in January 2025, and sought for the payment to be increased to $1,500 in February 2025. Mr Aulakh states that, while he could have cancelled the payments, he did not do so because he was concerned that it would cause Mr D Singh to not authorise “legitimate business expenses”.

32 Mr D Singh sought to transfer a total of $86,000 from the NAB Account between 20 and 22 February 2025, and again on 25 February 2025. Mr Aulakh says that he cancelled the transactions before they were completed. It is clear that the Respondents consider that Mr D Singh attempted to obtain money to which he was not entitled.

33 Mr Aulakh deposes that on 25 February 2025, Mr D Singh stated that he would not authorise any payments to staff or creditors unless the transfer to him was approved.

34 Mr D Singh states that the Respondents have refused to provide him with access to the Company’s accounting software or financial records since the subject-matter of this dispute arose.

Other deficiencies in the operation of the Company

Record keeping

35 Mr D Singh deposes to irregularities in the payment of employees, and in the record keeping of the Company, including that the use of WhatsApp messages to record cash takings and payments to employees does not satisfy the Company’s governance obligations.

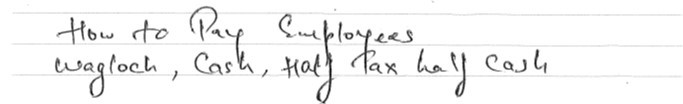

36 Mr Aulakh accepts that running a Company via WhatsApp messages was not “a proper system of financial accounting”, but asserts that the Applicant was aware of these practices. He relies on the evidence of Mr Joshi for that proposition. Mr Joshi is a friend and former workmate of Mr D Singh, and says that he used to assist in the business. Mr Joshi says that he was present at two meetings between the parties, on 13 May 2023 and in March 2024, to discuss the business. He says that Mr D Singh documented the meeting in March 2024 between the parties in handwritten notes. Mr Joshi exhibits a copy of those handwritten notes. Part of the notes appear to state decisions about how to pay employees including that “Family members will get normal pay on public holidays” and, further, the following statement “How to pay employees … cash, half tax half cash”.

Employment of individuals lacking the right to work

37 Mr D Singh deposes that the Respondents “have employed family members in the business, despite some of those individuals not holding visas that permit them to work in Australia”.

38 Mr Aulakh deposes that during periods of “severe understaffing” he sought assistance from some family members for a few days each week, and that none of those people were paid for their time. I interpolate that it is said that the individuals were not paid because they had no right to be paid for work. On its face, these appear to be irregularities in both workplace and immigration matters.

39 It is not clear how evidence of this kind assists the Respondent: it appears to be a concession that the Company was engaging in conduct which could expose it to a liability or penalty by failing to comply with relevant laws and to make provision for appropriate taxation. The awareness (or potential awareness) of the Applicant does not necessarily alter that proposition.

Previous dispute between the parties

40 Mr D Singh gives evidence of correspondence from a time when the Applicant and First Respondent accused the Second Respondent of inappropriate conduct in relation to the Company, including:

(1) the employment of individuals who lack the right to work in Australia;

(2) unaccountable financial withdrawals; and

(3) other irregularities in the conduct of the Company.

41 It is not clear how these allegations relate to the present allegations, save to illustrate that there has, in the recent past, been bad blood between the First Respondent and Second Respondent and that allegations of misconduct have been made by others in the past, including allegations by the First Respondent that the Second Respondent had misappropriated funds of the Company in the past.

Foreshadowed counterclaim

42 Mr Aulakh deposes that, while the Company’s accounts were frozen as a result of orders made in this proceeding, he and Mr A Singh each made a loan to the Company by depositing $30,000 and $34,700 respectively into the ANZ Account.

43 Mr Aulakh states that, if leave to bring the derivative action is granted, the Respondents intend to file a counterclaim for repayment of these loaned amounts.

Overall observations from the evidence

44 The evidence makes clear that the governance of the Company was poor. The use of WhatsApp messages is hardly a system conducive to clear record keeping, and its limitations are evident in this proceeding where it is near-impossible to reconcile amounts of receivables, authorisation for payments, and employee and tax provisions. Given the large array of electronic options available for management of accounts and recording expenses, it is difficult to understand why such poor processes were adopted.

45 That the Applicant may have been aware of these poor governance arrangements is relevant to, but not determinative of, the issues in this application. It does not appear to be in dispute between the parties that the Company was, at times, run in a manner that was inconsistent with taxation and employment obligations.

46 Taken together, the way in which the Company has been operated by the Applicant and Respondents created circumstances giving rise to an opportunity for misappropriation.

47 Mr Aulakh’s assertion that the ANZ Account was opened with the full knowledge and consent of the parties, and for the purposes of the business, is disputed. There is some evidence from the External Accountant that the ANZ Account was not provided to him as part of the accounting of the business: this somewhat undermines the proposition that the use of the ANZ Account was open and transparent, although I note that some of the evidence of the External Accountant was provided late, without the opportunity to respond to it.

48 Mr D Singh asserts that he has repeatedly sought access to the accounts of the Company and been denied. It seems that there has not been a full and frank sharing of information between the parties. There is clearly mistrust and animosity. I am not able to assess the extent to which there has not been full disclosure of relevant documents, but that is not a matter that I need to deal with at the present time.

49 There is a credible dispute about the existence and timing of Mr D Singh’s knowledge of the ANZ Account. I do not accept that it is clear that the Applicant was aware of the ANZ Account from either of the screenshots proffered and relied upon, particularly when considered in the context of the informal nature of communications on WhatsApp, which are intended to be read over a phone and tend to be responded to quickly (making it unlikely that documents were carefully examined). In the circumstances of the test that I am applying, and the responsive evidence of the Applicant, it is not possible to reach a resolved position about the Applicant’s awareness of the ANZ Account at this stage, nor is it appropriate to do so.

50 There are counter-allegations concerning the conduct of Mr D Singh, suggesting that he paid himself a director’s fee, and sought to obtain a repayment of his initial loan, without authorisation. These are issues that are in dispute between the parties. I am not in a position to determine them, but note their existence as part of the overall analysis.

51 In that factual context, I turn to consider the operation of section 237 of the Act.

CONSIDERATION

52 Sections 236 and s 237 of the Act relevantly provide:

236 Bringing, or intervening in, proceedings on behalf of a company

(1) A person may bring proceedings on behalf of a company, or intervene in any proceedings to which the company is a party for the purpose of taking responsibility on behalf of the company for those proceedings, or for a particular step in those proceedings (for example, compromising or settling them), if:

(a) the person is:

(i) a member, former member, or person entitled to be registered as a member, of the company or of a related body corporate; or

(ii) an officer or former officer of the company; and

(b) the person is acting with leave granted under section 237.

(2) Proceedings brought on behalf of a company must be brought in the company's name.

…

237 Applying for and granting leave

(1) A person referred to in paragraph 236(1)(a) may apply to the Court for leave to bring, or to intervene in, proceedings.

(2) The Court must grant the application if it is satisfied that:

(a) it is probable that the company will not itself bring the proceedings, or properly take responsibility for them, or for the steps in them; and

(b) the applicant is acting in good faith; and

(c) it is in the best interests of the company that the applicant be granted leave; and

(d) if the applicant is applying for leave to bring proceedings - there is a serious question to be tried; and

(e) either:

(i) at least 14 days before making the application, the applicant gave written notice to the company of the intention to apply for leave and of the reasons for applying; or

(ii) it is appropriate to grant leave even though subparagraph (i) is not satisfied.

…

53 Neither party relied on a rebuttable presumption that granting leave is not in the best interests of the Company, which is governed by ss 237(3) and s 237(4), so those provisions do not need to be set out.

54 It is not in dispute that the Applicant has standing under s 236(1)(a)(i). Focus in this application was on the criteria for leave set out in s 237(2). It is clear that if I am satisfied of all five matters set out in s 237(2)(a)-(e), then I must grant leave – although I could do so subject to certain conditions (Fiduciary Ltd v Morningstar Research Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 442; 53 ACSR 732 (Morningstar) at [16] (Austin J)).

55 In Tydeman v Asgard Group Pty Ltd, in the matter of Asgard Group Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 486 (Tydeman), Anderson J observed at [31] that:

Leave under s 237 should not be given lightly; applications for leave are not interlocutory, but final; and the applicant bears the onus of establishing all five requirements in s 237(2): Swansson v R A Pratt Properties Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 583; 42 ACSR 313 at [24] per Palmer J; Vinciguerra v MG Corrosion Consultants Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 763; 79 ACSR 293 at [15] per Gilmour J.

56 I have approached this application with this exhortation in mind.

57 It is not in dispute that the Company will not bring the proposed action itself (s 237(2)(a)) and that the Applicant has met the notice requirements set out in s 237(2)(e). The balance of the issues remain in contention. I analyse each in turn.

Is the Applicant acting in good faith?

58 In Swansson v RA Pratt Properties Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 583; 42 ACSR 313 (Swansson) at [38], Palmer J said:

Where the application is made by a current shareholder of a company who has more than a token shareholding and the derivative action seeks recovery of property so that the value of the applicant's shares would be increased, good faith will be relatively easy for the applicant to demonstrate to the Court's satisfaction.

59 The principles in relation to good faith in this provision are “well established” (Cemcon Constructions Pty Ltd v Hall Concrete Constructions (Vic) Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 696 at [15] (Gordon J)). There are at least two interrelated factors to which the court will have regard, which have been described as the minimum content of good faith, namely:

whether the applicant has an honest belief that a good cause of action exists with reasonable prospects of success; and

whether the applicant has a collateral purpose that would amount to an abuse of process.

See Swansson at [36] (Palmer J); Goozee v Graphic World Group Holdings Pty Ltd [2002] NSWSC 640; 42 ACSR 534 at [56] (Barrett J); Herbert & Ors v Redemption Investments Ltd [2002] QSC 340 at [27] (Mackenzie J); Morningstar at [21] (Austin J); Maher v Honeysett and Maher Electrical Contractors [2005] NSWSC 859 at [28] (Brereton J).

60 In South Johnstone Mill Ltd v Dennis [2007] FCA 1448; 163 FCR 343 (South Johnstone), Middleton J noted at [67] (citations omitted):

more than “bald assertion” is required in order to establish an applicant’s honest belief…. In fact, in the present case no applicant has deposed that he or she honestly believes that a good cause of action exists and has a reasonable prospect of success. The applicants’ solicitor, Mr Maitland, has not sought to give hearsay evidence as to the existence of such an honest belief.

61 However, in Tydeman, leave was sought to proceed on behalf of the company so to avoid the rule that the company be represented by a lawyer, and that was held to be an abuse of process, or not in good faith (at [42]-[43]).

62 In this case, Mr D Singh’s evidence does not contain an express statement that he subjectively believes he is acting in good faith.

63 The Applicant’s evidence and submissions did not identify his position with respect to indemnifying the Company for an adverse costs order if the derivative action is unsuccessful. I sought to confirm his position in relation to an indemnity because cases have identified that, while such indemnification is not sufficient, it is an important factor in establishing good faith (Hannon v Doyle [2011] NSWSC 10; 82 ACSR 259 (Hannon) at [110] (Barrett J); Re Woodbine Project Pty Ltd [2021] VSC 617 (Re Woodbine) at [60] (Button J); Re Wonga Pastoral Development Co Pty Ltd [2023] NSWSC 133 at [34] (Black J)). On 12 September 2025 (the day after the hearing), pursuant to a direction of the Court that this issue be clarified, the solicitor for the Applicant emailed saying:

I advise that the Applicant in this matter - Mr Damanjeet Singh has provided instructions that he is willing to give an indemnity, in whatever form the court considers relevant, to AULAKH BS PTY LTD (ACN 648-924-252) against the risk of adverse costs (if any) if the derivative proceedings later fail.

64 While this statement is not in evidence, and no evidence of the Applicant’s financial position has been led substantiating his financial position to make good the undertaking (cf Re Woodbine at [86] (Button J)), I consider that this matter tends in favour of good faith.

65 In South Johnstone, Middleton J was willing to accept that there the applicant was acting in good faith because there were other indicators, even in the absence of a positive statement of subjective belief. In that case, the existence of an indemnity by the Applicant assisted his Honour to conclude that there existed an honest belief in the cause of action with reasonable prospects (at [69]; see also Re Woodbine at [86]).

66 Similarly, here, the evidence of Mr D Singh satisfies me that he has an honest belief in a good cause of action with reasonable prospects. He outlines his long-held concerns as to the governance processes of the Company, and his attempts to raise them with the Respondents. It is clear that he considers that there has been wrongdoing. He has an interest in the financial health of the Company, and in ensuring that its assets are maximised, and not misappropriated.

67 The Respondents argue that there can be no honest belief in the existence of a good cause of action. That is because allegations are poorly articulated and, in many cases, contrary to the evidence disclosed in the affidavit material. The foundation of this argument is the Respondents’ attempt to undermine the evidentiary basis for the allegation in the proposed statement of claim, that the ANZ Account was opened without the knowledge or authorisation of the Applicant. However, as I have outlined above, I do not consider the evidence on that issue to be clear.

68 I consider that the evidence does not disclose a single conclusion about this issue and that it remains contested. The evidentiary dispute does not foreclose a conclusion that the Applicant is acting in good faith.

69 The Respondents further rely on their assertion that the Applicant requested, and was granted, access to the ANZ Account on 16 November 2023. However, again, Mr D Singh’s evidence is that the access was not complete and that in any event he has been hamstrung by a failure to provide him with access to other systems. In addition, the Company’s record keeping was clearly poor, so that access to accounts would not necessarily permit a full understanding of the issues.

70 Further, it is clear from the affidavit of Mr Joshi, among other things, that there was concerningly little formality connected with the administration of the affairs of the Company. WhatsApp was used to exchange photographs of scraps of paper listing employees that would be paid in cash. Such conduct is ripe for concern as to the appropriateness of the corporate governance practices of the Company, and whether funds were being properly applied.

71 Overall, none of these matters persuade me that there is a lack of good faith. I accept, of course, that the onus is on the Applicant, and it is not necessary for the Respondents to establish bad faith (Chahwan v Euphoric Pty Ltd (t/as Clay & Michel) [2008] NSWCA 52; 65 ACSR 661 at [69] (Tobias JA; Beazley and Bell JJA agreeing)).

72 The Respondents also point to a lack of particulars in the proposed statement of claim, which is a matter that is of greater relevance to the question of whether there is a serious question to be tried and the best interests of the Company than to good faith.

73 I have some concern that there is a collateral purpose in this proceeding insofar as Mr D Singh may have a personal interest in obtaining funds (or even personal vindication) from the proceedings.

74 However, the proposed statement of claim seeks declarations and orders in favour of the Company alone, and the Applicant would not have standing to bring the proceeding in his own right (with the exception of the oppression claim discussed at [118]-[119] below); this is therefore a case that is in a different category to that in Tydeman, where a derivative action was sought to avoid the requirement that a company proceed by a solicitor.

75 Accordingly, I am satisfied that the proceeding is contemplated in good faith and that this requirement is satisfied.

Is it in the best interests of the Company for leave to be granted

76 In Swansson at [55]-[56], Palmer J said (emphasis added; citations omitted):

At the outset, it is important to note that s 237(2)(c) requires the Court to be satisfied, not that the proposed derivative action may be, appears to be, or is likely to be, in the best interests of the company but, rather, that it is in its best interests. In this respect, s 237(2) differs significantly from its counterpart in the Canadian legislation, which requires the Court to be satisfied that the proposed derivative action "appears to be" in the interests of the company, and from s 165(3) of the New Zealand Act which requires that the Court "have regard to ... the interests of the company". These provisions seem to have led the Courts of those countries to the view that the best interests of a company need be considered only in a prima facie way…

The requirement of s 237(2)(c) that the applicant satisfy the Court that the proposed action is in the best interests of the company is a far higher threshold for an applicant to cross. It requires the applicant to establish, on the balance of probabilities, a fact which can only be determined by taking into account all of the relevant circumstances.

77 In Morningstar at [51], Austin J held that:

… there is a balance to be struck between the prejudice that the company will suffer if claims are pressed unsuccessfully on its behalf and there is an adverse costs order, and the advantage that it will gain, indirectly for the benefit of its shareholders, if the claims are successful…

78 The Respondents did not seek to rely upon the rebuttable presumption in s 237(3). This is appropriate, given that the Respondents are not a third party (ss 237(3)(a)(i), 237(4)(a)(ii), 228(2)), and because the directors have a material person interest in the decision (s 237(3)(c)(ii)).

79 In Re Gladstone Pacific Nickel Ltd [2011] NSWSC 1235; 86 ACSR 432 at [57], Ball J identified matters relevant to identifying when an action is in the best interests of the company, including the prospects of success of the action, noting:

The requirement that the court be satisfied that it is in the best interests of the company that the applicant be granted leave raises two questions. One is whether it is in the best interests of the company that the action be brought. The other is whether it is in the best interests of the company that it be brought by the applicant. The court must consider the interests of the company as a whole. As Brereton J said in Maher v Honeysett & Maher Electrical Contractors Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 859 at [44]:

The phrase "best interests" directs attention to the company's separate and independent welfare. Charlton v Baber (2003) 47 ACSR 31, [52]; Fiduciary Ltd v Morningstar Research Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 442, [46]. This imports the familiar concept of the interests of the company as a whole. ... Whether the "best interests" of the company as a whole reflect those of the shareholders taken together in light of the corporate objects, or those of the creditors which will prevail in the context of insolvency, will be influenced by the status of the company. Walker v Wimborne (1976) 137 CLR 1; 3 ACLR 529; Spies v R (2000) 201 CLR 603 ; 173 ALR 529 ; 35 ACSR 500; Charlton v Baber (2004) 47 ACSR 31, [53].

80 In considering the best interests of the Company, it is important to consider the prospects of success of the action, the likely costs and the likely recovery if the action is successful, and the consequences if it is not.

81 In oral submissions, the Applicant asserted that the material already before the Court involved most of the material and argument that would need to be deployed, so that the costs of the proceeding would not be significant. No evidence about the likely costs was forthcoming. Nor were there any submissions as to the capacity of the Company to pay the costs of the proceeding, although evidence about the financial position of the Company was before me in terms of the bank statements across the ANZ Account and the NAB Account which show reasonably substantial returns. The Respondents did not argue that the funds were not available to fund the litigation. Their arguments focused on the asserted lack of prospects of the claim.

82 It is important to note that the quantum of approximately $350,000 appears to reflect the amount deposited into the ANZ Account in the relevant period on the basis of the theory that all of the funds deposited in that account were misappropriated or potentially misappropriated. While I consider the evidence as to payment of employees to be deficient, it appears clear that at least some of the funds were likely used for Company purposes. In the course of submissions, the solicitor appearing for the Respondents submitted that the asserted quantum of the claim, being $350,000, could ultimately be higher or lower.

83 There is therefore a degree of uncertainty over the quantum of the claim. Generally speaking, where there is uncertainty, that will tell against the party that bears the burden. However, in this instance, much of the uncertainty arises because of the way in which the Respondents have maintained the Company’s accounts – asserting on their own affidavit material that they used WhatsApp chats as the means of accounting for employee entitlements. The evidence shows scraps of paper with scribbled hours sent between the three directors, apparently showing an entitlement to payment. Given the paucity of records is the main barrier to clearly identifying the quantum of the claim, and the Respondents have had the opportunity to, but have not, clarified their payment of employee entitlements to a sufficient degree, I am inclined to conclude that the quantum of the claim can properly be seen as being in the vicinity alleged – noting the Respondents’ acceptance that it could be a greater or lesser figure.

84 In the course of oral submissions, the solicitor for the Applicant relied upon general governance failings as being a reason of itself to permit the derivative proceeding. I do not accept that submission: the Company is not necessarily well served by undertaking costly and time-consuming litigation to vindicate the theory of good governance which can in any event be enforced by a director using less drastic mechanisms than a derivative suit.

85 It is also relevant here that a counterclaim of over $70,000 is likely. The Respondents submit (with some force) that a claim for approximately $350,000 is not in the Company’s interests given a potential and well-founded counterclaim for over $70,000, when considered in combination with the difficulties in pressing a claim of this size, and the complexity involved in proof that is evident from the filed materials.

86 In oral submissions, the Applicant argued that the factual substratum is common between the claim and the counterclaim so that no real prejudice would arise if the counterclaim proceeded. There is force in this argument, because the common elements concern the use of funds, and how they are accounted for. In order to establish the counterclaim, it would be necessary to show that the loans were made to the Company and that on their terms, they were due and payable by the Company. I accept that the potential counterclaim is likely, and that it will involve increased costs and complexity. However, overall, the irregularities in the conduct of the Company, which are conceded on the material, support the contention that the Company is well served by ventilating the issues, and seeking to recover funds paid inappropriately. If it is unsuccessful, then it will be liable for a costs order which may be substantial. However, the indemnity of Mr D Singh satisfies me that the risk to the Company is manageable.

87 There is no evidence about whether other remedies would be sufficient. This was noted as relevant in Re BCK Holdings Group Pty Ltd [2021] NSWSC 1400 at [36] (Rees J). The present application contemplates an oppression action (as noted below, it is contemplated as being commenced on behalf of the Company – an approach that is clearly not available). However, the entitlement to the funds in question is only said to be available to the Company itself and not to the Applicant.

88 The balance of the issue of the best interests of the Company travels with the question of whether there is a serious question to be tried. That issue is analysed below. For the reasons that I have given, there is a serious question in relation to some parts of the claim and not others. In relation to the confined portions of the claim that I have identified, there are reasonable prospects of success and it is in the best interests of the Company that the proceedings commence.

89 In respect of those parts of the claim which I consider to have prospects of success, it is apparent that the Applicant is the only person able or willing to bring the claim. Insofar as they concern directors’ duties, it is not clear that there is any other person who is able to proceed with them.

90 However, in many respects, the conduct alleged (inappropriate attempts to avoid taxation liability, failure to account for funds) was due to exceptionally lax accounting and governance practices to which the Applicant was a party. While the Applicant disputes that he was aware of the ANZ Account, it is apparent that he was aware of the practice of cash payments, record-keeping and apparent attempts to avoid taxation obligations.

91 I am concerned that if the matter proceeds, the Applicant’s conduct may be shielded from scrutiny. However, given the foreshadowed counterclaim, and the allegations already ventilated in the materials, it appears that this is an unlikely outcome.

Is there a serious question to be tried?

92 The question of whether there is a serious question to be tried requires consideration of the available evidence and the proposed cause of action. This is often done by way of a draft pleading. However, as Austin J in Ehsman v Nutectime International Pty Ltd [2006] NSWSC 887; 58 ACSR 705 explained at [43]-[44]:

Section 237 authorises the court to grant leave to permit a person to bring proceedings on behalf of a company. Part 2F.1A does not explain the word 'proceedings' or give any direct indication of the level of specificity of pleaded allegations and prayers for relief that the applicant for leave must achieve. Typically the applicant will provide the court with a draft statement of claim or (as here) points of claim, or some other document giving particulars of the derivative claims. But in my view it cannot be the case that a full statement of the derivative claims must be presented before the court can consider and determine a leave application. Were that to be required, any subsequent amendments to the pleaded case would need to be treated as a leave application under s 237 to which the criteria in s 237(2) would have to be applied. That, in my view, would be an unnecessary burden for case management.

In my opinion the applicant for leave must identify and describe the proposed proceedings with sufficient precision that the court can properly assess the application having regard to the criteria that it is required to consider under s 237(2), and the opponents can respond to the application in terms of those criteria. That may be achieved by presenting the court with a draft pleading, but it may be achieved in other ways such as by outlining the claims in affidavit evidence. It is not hard to envisage an application that falls so far short of identifying the derivative causes of action to be asserted that the court is left unable to assess, for example, whether it is in the best interests of the company that the applicant be granted leave, and whether there is a serious question to be tried. Here, however, Mrs Ehsman has done enough in her draft points of claim (defective though they are) and in the voluminous evidence that has been adduced, to permit me to identify the causes of action broadly described in paragraphs (A)-(F) above, of which paras (C) and (D) are derivative claims. I am able to consider the application for leave under s 237 as an application for leave to bring proceedings on behalf of Timentel by a statement of claim that would assert the causes of action identified in paras (C) and (D) and seek appropriate equitable and statutory relief.

93 Similarly in this case, where the draft statement of claim (read in combination with the submissions) is sufficient to identify a serious question to be tried in relation to the issue, then the paucity of the pleading is not necessarily a barrier. However, when the deficiencies are more than a matter of form, and go to a failure to identify a substantive or complete cause of action, then a serious question to be tried may not have been disclosed. It is not for the Court to sift through the material to identify if it discloses a case which meets the relevant threshold: it must be articulated appropriately by the party bearing the burden. It is otherwise possible to grant leave for the matter to proceed, based on a condition that it be properly pleaded. Any subsequent pleading can be managed in the same way as any other, and would be susceptible to strike out or other interlocutory process if it failed to disclose a cause of action.

94 The requirement to show that there is a serious question can be equated to the test which applies on application for an interlocutory injunction (Swansson at [25]; South Johnstone at [78]), being that the applicant must make out a prima facie case in the sense that if the evidence remains as it is there is a probability that in a trial of the proposed action the corporation will be entitled to relief (Tydeman at [47] and the cases cited therein). In this instance, the evidence is not complete and it is not appropriate to make findings beyond what is necessary to determine whether this threshold is met.

95 Even though I do not consider that the pleading binds the Applicant, it is still the main form in which he has expressed the proceeding which he proposes to have the Company commence. I have therefore analysed it in its present form.

Due care and diligence: s 180(1) of the Act

96 Section 180(1) of the Act requires that a director or other officer of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they were a director or officer of a corporation in that corporation’s circumstances and occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within the corporation as, the director or officer. The obligation adopts an objective standard. The principles relevant to establishing a contravention of s 180 were summarised by Edelman J in ASIC v Drake (No 2) [2016] FCA 1552; 118 ACSR 189 at [394]-[401] and I do not repeat them here.

97 There is an allegation that the First and Second Respondents have failed to exercise due care and diligence under s 180(1) of the Act by opening a bank account without the knowledge or approval of one director, and allegedly diverting $343,780 of business income. Part of this allegation involves the proposition that the diverted income in the Company was not accounted for and accounts were not made available to the Applicant in his role as director.

98 The allegations are poorly pleaded, but are comprehensible.

99 Given what is conceded by the First and Second Respondents to be the inappropriate use of WhatsApp and handwritten notes as a method of keeping accounts of the Company, at the very least the allegations that there was not appropriate record-keeping appears well founded.

100 The Respondents argue that the allegation that funds were diverted is said to be not well particularised. Given the voluminous affidavit material that gives substance to the allegation, it is appropriate that if the matter proceeds, it be better particularised and pleaded. However, as noted above, given the paucity of accounting, the governance systems adopted were ripe for the kind of mismanagement that is alleged to have occurred. That contributes to my view that there is a prima facie case in relation to this allegation.

101 The Respondents appear to argue that the Applicant was aware of the use of the ANZ Account. For the reasons I have identified I consider that issue to be in dispute. In any event, if it is the case that the Respondents seek to argue that there has been some form of ratification, that will need to be considered in light of the comments in Angas Law Services Pty Ltd (in liq) v Carabelas [2005] HCA 23; 226 CLR 507 at [32] (Gleeson CJ and Heydon J).

Good faith in the best interest of the Company: s 181(1) of the Act

102 Section 181 requires that a director or other office exercise their powers and discharge their duties in good faith in the best interests for the corporation and for a proper purpose.

103 This aspect of the proposed action centres around the alleged diversion of Company income into personal accounts, concerning alleged withdrawals of between $1,500 and $4,000 per week from Company funds by the First and Second Respondent as wages without written contract or resolution.

104 These allegations are denied, and that denial may be well-founded. In particular, the uncontroverted evidence is that the First and Second Respondents worked at the Company for substantial periods of time, and sought compensation for that work. However, this serves to underscore that payments were made in respect of wages, and at present there is a paucity of proper account in relation to those payments: the system adopted by the directors of the Company make it impossible to be clear about the purpose for which funds were used. So much was made clear in my exchange with the solicitor appearing for the Respondents in the course of the hearing, when he was unable to provide an assurance that all of the wages said to have been paid were identified in records of the Company (even of the hand-written and ad hoc nature posted in the WhatsApp chat).

105 While it is the Applicant who bears the burden of showing that there is a prima facie case in the relevant sense, the Applicant has persuaded me that at present, the evidence suggests that there was insufficient documentation to support the various transfers disclosed in the various bank statements. On balance, I consider that the allegations in this respect meet the prima facie threshold.

106 Once again, this is not well pleaded, and it would be necessary for any future proceeding to be based on a substantially amended pleading.

Improper use of position: s 182(1) of the Act

107 Section 182(1) of the Act provides that:

A director, secretary, other officer or employee of a corporation must not improperly use their position to:

(a) gain an advantage for themselves or someone else; or

(b) cause detriment to the corporation.

108 An improper use of position need not be dishonest (Griffiths & Beerens Pty Ltd v Duggan [2008] VSC 201; 66 ACSR 472 at [54] (Pagone J)). In Hart Security Australia Pty Ltd v Boucousis [2016] NSWCA 307; 117 ACSR 408 at [84]-[85] (Meagher JA; Bathurst CJ and Beazley P agreeing) it was accepted that an objective standard had to be applied, and that it was necessary to establish the director’s purpose was to gain a relevant advantage, or to cause detriment.

109 The pleading of this allegation is deficient. It presently provides:

The Respondents have improperly used their position contrary to s 182(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Particulars

(a) the Respondents employed, amongst other people, family members of the Second Respondent in the business despite their visa conditions prohibiting employment.

(b) The Respondents withheld accounting software credentials from the Applicant and or their fellow director Damanjeet Singh to conceal financial misappropriation.

110 There is no pleading that the alleged impropriety was for the benefit an officer or employee or the detriment of the Company. It is therefore not possible to discern which part of s 182(1) is said to be engaged. If it is an improper use for the benefit of the Respondents, it is not clear how such a benefit arose. If it is the detriment of the Company, it is not alleged that it was for a relevant purpose. There are no particulars identifying who was employed around what time and the basis for the allegation that there was non-compliance with visa obligations.

111 These are substantive issues. While a form of pleading may be changed, the Applicant has not identified the way in which it is said the purported cause of action operates, and has therefore not satisfied the burden cast upon him by s 237.

Improper use of information: s 183(1) of the Act

112 Section 183(1) provides:

A person who obtains information because they are, or have been, a director or other officer or employee of a corporation must not improperly use the information to:

(a) gain an advantage for themselves or someone else; or

(b) cause detriment to the corporation.

113 This aspect of the draft statement of claim states as follows:

3.4 The Respondents have improperly used information contrary to the s 183(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Particulars

(a) The Respondents used confidential business financial information to facilitate the redirection and personal use of company income.

114 Again, the pleading is concerningly sparse. The confidential information is not identified in the draft claim or on the evidence. Given the present state of the evidence it cannot proceed, because that fundamental element is not identified. Unlike the prospective claims under ss 180 and 181, the substance of this proposed cause of action is not comprehensible, and there is not a serious question to be tried.

Related party transactions

115 The allegations in this part of the proposed claim are difficult to follow. It provides:

4.1 Section 188 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) requires that financial benefits given to related parties, including directors, be approved by members in accordance with Chapter 2E.

4.2 The Respondents, both directors of the company, are related parties within the meaning of section 228 of the Corporations Act.

4.3 In or about November 2023, the Respondents caused business income, approximately $343,780, to be redirected into a joint ANZ bank account held in their personal names without disclosure to or approval of the Applicant and fellow director Damanjeet Singh and/or without disclosure to or approval of the shareholders and the ABS Unit Trust unit holders.

4.4 The Respondents and their family members received weekly payments from company funds purportedly as wages despite there being no written employment contract or resolution of the board of directors approving the arrangement.

4.5 These transactions constitute the provision of financial benefits to related parties that required member approval, which was not obtained.

4.6 The conduct of the Respondents constitutes a breach of section 188 of the Corporations Act.

116 While the pleading repeatedly refers to s 188, it appears likely that it is intended to refer to s 208 of the Act (s 188 is not relevant as it refers to the responsibility of secretaries for certain corporate contraventions, which has not been raised in evidence or submissions, and cl 4.2 of the proposed pleading refers to the definition of a related party in s 228 of the Act, which is relevant to a contravention of s 208).

117 Section 208 applies to financial benefits given to related parties of public companies. The Company is a small, closely held private company. Section 208 has no apparent operation. No cause of action is identified on the face of the proposed pleading.

Oppression: s 232 of the Act

118 The draft statement of claim includes an oppression claim under s 232 of the Act. Section 232 provides a remedy for, broadly, a member or former member against a corporation. Section 234 sets out who may apply for an order under s 232. Unsurprisingly, it does not permit a corporation to bring a proceeding against itself.

119 This aspect of the draft claim appears incompetent, and leave to proceed in relation to this claim will not be granted.

Conflict of interest and governance breaches

120 Under this heading, it is alleged that the First Respondent convened a shareholders’ meeting to remove Mr D Singh as a director and that he had a conflict of interest in doing so. His failure to recuse himself is said to involve a conflict of interest and to have been undertaken for a collateral purpose. This is said to be a breach of fiduciary duty, to be oppressive under s 232 and “further supports Damanjeet Singh and the Applicant’s standing under s 1317H and /or section 1324”.

121 The structure of these allegations is unclear. It is not clear to whom the fiduciary duty is said to be owed, how it was breached, nor how the standing requirements in s 1317H are said to be relevant.

122 Following discussion in the course of argument it was not clear how this allegation was put (simply that s 1317H and 1324 are perhaps provisions that were intended to be referred to in the prayer for relief). Overall, this part of the claim is incoherent and cannot proceed.

Conclusion on serious question

123 There are significant problems with the proposed pleading. In Hannon, the Court noted that it is not necessary, and was not in that case appropriate, to frame the grant of leave by reference to the precise claims in the existing points of claim. Justice Barrett in that case said (at [113]):

The points of claim are, I think, deficient in several ways. They need to be framed more precisely and with greater particularity, especially as to the relief sought, given the possibility, to which I have referred, that an account of profits or equitable compensation "on the basis of the value to the misappropriating fiduciary" might conceivably be awarded.

124 I consider that the claims articulated in the context of the alleged breach of s 180(1) (a breach of the duty to act in accordance with the obligation of care and diligence) and s 181(1) (an alleged breach of the duty to act in good faith and in accordance with the best interests of the company and for a proper purpose) have been articulated with enough clarity, and are based on sufficient evidence, to meet the prima facie threshold. The balance of the claims, however, have not been articulated with sufficient clarity or do not otherwise meet the prima facie threshold. They ought not proceed.

Conclusion

125 I am persuaded that the criteria in s 237 are met, and so I must grant leave. That leave can be attended by conditions. In this instance, the leave that is granted is limited to allegations of breaches of s 180 and s 181 of the Act identified in the affidavit of Mr D Singh dated 6 June 2025.

126 In attaching this condition, I emphasise that any subsequent pleading must comply with the rules of pleading. This grant of leave is not provided on the basis that the draft statement of claim is appropriately pleaded – merely that it has been a means by which the statutory threshold has been met for the purposes of the s 237 application. Any pleading filed in accordance with this grant of leave will be amenable to any appropriate application to be struck out, if it does not properly comply with the rules of pleading.

127 The Applicant otherwise sought orders that the Respondents pay the costs of the proceeding and otherwise deliver up documents identified. None of those orders are appropriate at this stage.

128 The Company can commence the proposed proceeding in the limited manner that I have identified. In conducting the litigation, the Applicant is bound by the same obligations arising under s 180 and 181 which he seeks to deploy against the Respondents.

129 The Applicant has been successful in this application, albeit in a limited sense. It follows from a series of steps that were taken in the proceeding without having in place the necessary leave to proceed. In the unusual circumstances in which the case has evolved, I propose to make an order that each party bear their own costs of the proceeding to date, subject to consideration of any contrary submission received within seven days of the date of this decision.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and twenty-nine (129) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Bennett. |

Associate:

Dated: 2 October 2025

SCHEDULE OF PARTIES

VID 368 of 2024 | |

Respondents | |

Fourth Respondent: | MANDEEP KAUR MUNDI |