Federal Court of Australia

QGold Pty Ltd v Woods [2025] FCA 1201

File number: | QUD 260 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | DERRINGTON J |

Date of judgment: | 2 October 2025 |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS – application for compulsory acquisition of residual ordinary shares of Carawine Resources Limited – where the applicant is the “90% holder” of the relevant class of securities – where the applicant’s compliance with Division 1 of Part 6A.2 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) is irregular in part – whether appropriate to remediate such irregularities pursuant to s 1322 of the Act – where the applicant lodged a compulsory acquisition notice with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission on 21 March 2024 – where the notice relies upon the opinion expressed in an expert’s report dated 26 February 2024 – whether expert’s report inconsistent with the Act or otherwise deficient – whether applicant has established that the terms set out in the compulsory acquisition notice give a “fair value” for the relevant securities – application granted – costs reserved |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Batoka Pty Ltd v Conocophillips WA-248 Pty Ltd (2006) 198 FLR 93 BG & E Management Pty Ltd v de Abolitz [2016] FCA 1368 Blaze Asset Pty Ltd v Target Energy Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 488 Bromley Investments Pty Ltd v Elkington (2003) 47 ACSR 273 Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 Capricorn Diamonds Investments Pty Ltd v Catto (2002) 5 VR 61 ConocoPhillips WA-248 Pty Ltd v Batoka Pty Ltd (2005) 193 FLR 424 Dolby Australia Pty Ltd v Catto (2004) 52 ACSR 204 Espasia Pty Ltd v Barbarry Pty Ltd (2009) 262 ALR 639 Holt v Cox (1997) 23 ACSR 590 In the matter of Navalo Financial Services Group Limited [2025] NSWSC 317 Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles (2001) 52 NSWLR 705 Re Australian Water Holdings Pty Limited (2016) 306 FLR 40 Re Goodyear Australia Ltd (2002) 167 FLR 1 Re Helios Energy Ltd (2017) 122 ACSR 174 Re Wave Capital Ltd (2003) 47 ACSR 418 Teh v Ramsay Centauri Pty Ltd (2002) 42 ACSR 354 Weinstock v Beck (2013) 251 CLR 396 Winpar Holdings Ltd v Goldfields Kalgoorlie Ltd (2000) 176 ALR 86 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Queensland |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 194 |

Date of hearing: | 6, 8 May 2025 |

Counsel for the Plaintiff: | Mr D Ananian-Cooper |

Solicitor for the Plaintiff: | Arnold Bloch Leibler |

Counsel for the Thirty-Sixth Defendant: | Mr M Bennett |

Solicitor for the Thirty-Sixth Defendant: | Bennett Law |

ORDERS

QUD 260 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | QGOLD PTY LTD ACN 149 659 950 Plaintiff | |

AND: | KERRIN JOHN WOODS First Defendant FAYE LEONIE WOODS Second Defendant MELINDA JANE KIRKWOOD (and others named in the Schedule) Third Defendant | |

order made by: | DERRINGTON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 2 October 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiff’s acquisition of all of the ordinary shares in Carawine Resources Limited (Carawine) not already held by the plaintiff is approved on the terms set out in the notice of compulsory acquisition dated 21 March 2024 (the Compulsory Acquisition Notice).

2. The time for the plaintiff to comply with ss 664C(2)(b) and (3) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) is extended to:

(a) 25 March 2024, in respect of all shareholders of Carawine except those referred to in sub-paragraphs (b) and (c) below;

(b) 11 April 2024, in respect of the 71 shareholders referred to at paragraph [42] of the affidavit of Ann Hunyh (filed 20 May 2024) (the Huynh Affidavit); and

(c) 16 May 2024, in respect of the 3 shareholders identified at paragraph [62] of the Huynh Affidavit.

3. Notwithstanding that the Compulsory Acquisition Notice contravenes s 664C(1)(d) of the Act, neither the notice nor this proceeding are invalidated per s 1322(4) of the Act.

4. Notwithstanding that the list of objectors that was lodged with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission on 30 April 2024 contravenes s 664E(3)(a) of the Act, neither the list nor this proceeding are invalidated per s 1322(4) of the Act.

5. To the extent that the reports prepared by Sherif Andrawes of BDO Corporate Finance (WA) Pty Ltd (dated 26 February 2024) and Lynda Burnett of Valuation and Resource Management Pty Ltd (dated 26 February 2024) (together, the Reports) contravene the Act, neither the Reports, the Compulsory Acquisition Notice nor this proceeding are invalidated per s 1322(4) of the Act.

6. The parties are to be heard on the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

DERRINGTON J:

Introduction

1 On 20 November 2023, QGold Pty Ltd (QGold) became the “90% holder” – as that phrase is defined by ss 664A(1) and (2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) – of ordinary shares in Carawine Resources Limited (Carawine). It now seeks, by an Amended Originating Process filed 28 April 2025, the Court’s approval of the acquisition of all remaining ordinary shares in that company on the terms set out in a notice of compulsory acquisition (dated 21 March 2024) (the Compulsory Acquisition Notice). Such imprimatur is necessary because, despite QGold’s submission that it has “followed” the relevant processes prescribed by Division 1 of Part 6A.2 of the Act, persons who hold at least 10% of the securities that are the subject of the proposed acquisition – being represented by the thirty-sixth defendant, Mr Robert Catto (as per Order 1 of the Orders of 9 August 2024) – object to the terms of such acquisition: s 664F of the Act.

2 In general terms, the nub of the defendants’ objection is that QGold neither complied with the procedural requirements of the Act nor offered a “fair value” for the shares in question. It is, however, somewhat difficult to ascertain precisely all of that of which the defendants complain. For instance, while there was substantial cross-examination about the veracity of the underlying technical valuations that ultimately informed the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice, no relevant criticism appeared in the representative defendant’s written outline of submissions.

3 For the purposes of parsing that which follows, it is important to keep in mind the observations of the Western Australian Court of Appeal in Batoka Pty Ltd v Conocophillips WA-248 Pty Ltd (2006) 198 FLR 93 at 104 [39] (Batoka) (Steytler P, with whom McLure JA and Murray AJA agreed), namely that the scheme of the legislation under consideration has the object “only of ensuring that the shares are acquired at a fair value”. That overarching purpose serves to colour the application of the procedural requirements that the Act impresses upon entities desirous to compulsorily acquire the property of another and, indeed, tends against an understanding that any non-compliance, no matter how inconsequential, should have the result that the relevant processes and procedures must start over. That is, as will be seen, most important.

4 Unless otherwise indicated, all references to Chapters, Parts, Divisions and Sections throughout the course of these reasons should be taken to be references to the Act.

The relevant legislative regime

5 Division 1 of Part 6A.2 concerns the manner in which the 90% holder of securities in a subject entity may compulsorily acquire the residual, minority securities in that entity. The scheme of that Division was helpfully surveyed by Warren J in Capricorn Diamonds Investments Pty Ltd v Catto (2002) 5 VR 61 (Capricorn Diamonds) in the following terms (at 65 [9]):

… The legislative scheme provides that within a specified period of six months after becoming that holder, a 90% holder can give a notice of compulsory acquisition setting out a cash price for the minority securities: see ss 664AA(6), 664C(1). The price must only be cash and not differentiate between minority holders: see s 664B. No benefit outside the price formally notified can be offered to any individual holder at any time: see s 664D. Under the statutory regime, minority holders are entitled to object to the acquisition: see s 664E. Where persons who hold at least 10% of the minority securities object to the acquisition then the acquisition can proceed only if the court gives approval: see ss 664F, 664A(3)(b). The court must approve the acquisition if the 90% holder establishes that the terms set out in the notice “give a fair value for the securities”: see s 664F(3). Where fair value is not established the court must confirm that the acquisition will not take place: see s 664F(3).

6 Self-evidently, such scheme has, as a primary subject, the so-called “90% holder”. That phrase is defined by ss 664A(1) and (2) in the following terms:

90% holder — holder of 90% of securities in particular class

(1) A person is a 90% holder in relation to a class of securities of a company if the person holds, either alone or with a related body corporate, full beneficial interests in at least 90% of the securities (by number) in that class.

90% holder — holder with 90% voting power and 90% of whole company or scheme

(2) A person is also a 90% holder in relation to a class of securities of a company if:

(a) the securities in the class are shares or convertible into shares; and

(b) the person’s voting power in the company is at least 90%; and

(c) the person holds, either alone or with a related body corporate, full beneficial interests in at least 90% by value of all the securities of the company that are either shares or convertible into shares.

Note: Subsection 667A(2) provides that the expert’s report that accompanies the compulsory acquisition notice must support the paragraph (c) condition.

7 Such a person may compulsorily acquire the minority securities in the relevant subject entity in those circumstances prescribed by ss 664A(3) and (4):

90% holder may acquire remainder of securities in class

(3) Under this section, a 90% holder in relation to a class of securities of a company may compulsorily acquire all the securities in that class in which neither the person nor any related bodies corporate has full beneficial interests if either:

(a) the holders of securities in that class (if any) who have objected to the acquisition between them hold less than 10% by value of those remaining securities at the end of the objection period set out in the notice under paragraph 664C(1)(b); or

(b) the Court approves the acquisition under section 664F.

If subsection (2) applies to the 90% holder, the holder may compulsorily acquire securities in a class only if the holder gives compulsory acquisition notices in relation to all classes of shares and securities convertible into shares of which they do not already have full beneficial ownership.

Note: Subsection 92(3) defines securities for the purposes of this Chapter.

(4) This section has effect despite anything in the constitution of the company whose securities are to be acquired.

8 Section 664A(3)(b) relevantly refers to s 664F which, in turn, provides as follows:

664F The Court’s power to approve acquisition

(1) If people who hold at least 10% of the securities covered by the compulsory acquisition notice object to the acquisition before the end of the objection period, the 90% holder may apply to the Court for approval of the acquisition of the securities covered by the notice.

(2) The 90% holder must apply within 1 month after the end of the objection period.

(3) If the 90% holder establishes that the terms set out in the compulsory acquisition notice give a fair value for the securities, the Court must approve the acquisition of the securities on those terms. Otherwise it must confirm that the acquisition will not take place.

Note: See section 667C on valuation.

(4) The 90% holder must bear the costs that a person incurs on legal proceedings in relation to the application unless the Court is satisfied that the person acted improperly, vexatiously or otherwise unreasonably. The 90% holder must bear their own costs.

9 The power of the Court to approve an acquisition under s 664F(3) is premised upon the terms of the relevant compulsory acquisition notice. The obligations which are imposed upon a 90% holder with respect to the drafting and distribution of such a notice are set out in s 664C:

664C Compulsory acquisition notice

Compulsory acquisition notice

(1) To compulsorily acquire securities under section 664A, the 90% holder must prepare a notice in the prescribed form that:

(a) sets out the cash sum for which the 90% holder proposes to acquire the securities; and

(b) specifies a period of at least 1 month during which the holders may return the objection forms; and

(c) informs the holders about the compulsory acquisition procedure under this Part, including:

(i) their right to obtain the names and addresses of the other holders of securities in that class from the company register; and

(ii) their right to object to the acquisition by returning the objection form that accompanies the notice within the period specified in the notice; and

(d) gives details of the consideration given for any securities in that class that the 90% holder or an associate has purchased within the last 12 months; and

(e) discloses any other information that is:

(i) known to the 90% holder or any related bodies corporate; and

(ii) material to deciding whether to object to the acquisition; and

(iii) not disclosed in an expert’s report under section 667A.

(2) The 90% holder must then:

(a) lodge the notice with ASIC; and

(b) give each other person (other than a related body corporate) who is a holder of securities in the class on the day on which the notice is lodged with ASIC:

(i) the notice; and

(ii) a copy of the expert’s report, or of all experts’ reports, under section 667A; and

(iii) an objection form; and

(c) give the company copies of those documents; and

(d) give copies of those documents to the relevant market operator if the company is listed.

Note: Everyone who holds the securities on the day on which the notice is lodged with ASIC is entitled to notice. Under subsection 664E(1), anyone who acquires the securities during the objection period may object to the acquisition.

Time for dispatching notice to holders

(3) The 90% holder must dispatch the notices under paragraph (2)(b) on the day the 90% holder lodges the notice with ASIC or on the next business day.

…

10 Section 664C(2)(b)(ii) relevantly refers to the preparation of an “expert’s report” under s 667A. That latter section provides as follows:

667A Expert’s report

(1) An expert’s report under section 663B, 664C or 665B must:

(a) be prepared by a person nominated by ASIC under section 667AA; and

(b) state whether, in the expert’s opinion, the terms proposed in the notice give a fair value for the securities concerned; and

(c) set out the reasons for forming that opinion.

Note: See section 667C on valuation.

(2) If the person giving the compulsory acquisition notice is relying on paragraph 664A(2)(c) to give the notice, the expert’s report under section 664C must also:

(a) state whether, in the expert’s opinion, the person (either alone or together with a related body corporate) has full beneficial ownership in at least 90% by value of all the securities of the company that are shares or convertible into shares; and

(b) set out the reasons for forming that opinion.

(3) If the person giving the compulsory acquisition notice obtains 2 or more reports, each of which were obtained for the purposes of that notice, a copy of each report must be given to the holder of the securities.

(4) An offence based on subsection (3) is an offence of strict liability.

Note: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

11 In the first Note to the above section, reference is made to s 667C. In broad terms, that section is concerned with the valuation of securities for the purposes of Chapter 6A. It provides:

667C Valuation of securities

(1) To determine what is fair value for securities for the purposes of this Chapter:

(a) first, assess the value of the company as a whole; and

(b) then allocate that value among the classes of issued securities in the company (taking into account the relative financial risk, and voting and distribution rights, of the classes); and

(c) then allocate the value of each class pro rata among the securities in that class (without allowing a premium or applying a discount for particular securities in that class).

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), in determining what is fair value for securities for the purposes of this Chapter, the consideration (if any) paid for securities in that class within the previous 6 months must be taken into account.

Uncontentious background matters

12 There are a number of uncontentious matters in relation to that which has transpired.

13 First, Carawine is an exploration company listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (the ASX). It is said to be primarily focused on gold, copper and base metal deposits, and owns projects in Victoria and Western Australia (in which it relevantly holds several 100% owned tenements).

14 Second, QGold is the “90% holder” of ordinary shares in Carawine. On 20 November 2023, QGold was issued 38,901,620 ordinary shares which (a) increased its shareholding in Carawine from 88.94% to 90.61% of all shares on issue; and (b) were acquired for $0.11 per share.

15 Third, QGold lodged the Compulsory Acquisition Notice with the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) on 21 March 2024. Amongst other things, that document (a) gave notice that QGold proposed to acquire the remaining ordinary shares in Carawine for the cash amount of $0.11 per share; and (b) was lodged within six months of QGold becoming the “90% holder” in relation to that class of securities (see ss 664AA(b) and 664C(2)(a)).

16 It appears also to be common ground that such notice was in the prescribed form and, generally, in compliance with s 664C(1). That being said, it did, however, contain certain irregularities. For instance, the notice included, as Annexure A, a list of transactions between 18 May and 20 November 2023 by which QGold had acquired its shareholding in Carawine and at what price. That annexure contained an error: it recorded QGold as having acquired 38,928,477 ordinary Carawine shares on 20 November 2023; in reality, it had only acquired 38,901,620 such shares.

17 Fourth, and also on 21 March 2024, QGold provided to both Carawine and the ASX:

(1) the Compulsory Acquisition Notice;

(2) an Independent Expert’s Report prepared by a Mr Sherif Andrawes of BDO Corporate Finance (WA) Pty Ltd dated 26 February 2024 (the Andrawes Report), which, amongst other things, appended an Independent Technical Assessment Report of Mineral Assets Owned by Carawine Resources Ltd prepared by a Ms Lynda Burnett of Valuation and Resource Management Pty Ltd (VRM) dated 26 February 2024 (the VRM Report); and

(3) a shareholder objection form,

(collectively, the Compulsory Acquisition Documents).

18 For context, it is noted that Mr Andrawes was one of three persons nominated by ASIC for the purposes of preparing an expert’s report (see ss 667AA and 667A(1)(a)). He was engaged by QGold in December 2023. On his recommendation, QGold subsequently engaged VRM as an independent technical specialist to value the mineral assets of Carawine.

19 In the Andrawes Report, Mr Andrawes relevantly concluded that:

(1) “the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition give a fair value to Shareholders”; and

(2) QGold “has full beneficial interests in approximately 90.61% of Carawine’s shares”.

20 Fifth, between March and May 2024, QGold provided copies of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents to persons who held ordinary shares in Carawine. As discussed below, the issuance of those documents did not occur in accordance with the time period specified by s 664C(3).

21 Sixth, between 31 March and 28 April 2024, QGold received various signed objections vis-à-vis the notice. It lodged each such objection with ASIC and, on 30 April 2024, it lodged a list of relevant objectors (see ss 664E(2) – (3)). It is noted that that list omitted one objector.

22 QGold received objections from persons holding some 16.47% of the securities covered by the Compulsory Acquisition Notice. As such, QGold must seek the Court’s approval of the terms set out in the notice before it may proceed (see ss 664A(3)(b) and 664F).

23 Seventh, QGold has notified Carawine, the shareholders of Carawine, ASIC and the ASX, that it has applied to the Court for approval of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice under s 664F.

The issues for determination

24 Having noted both the statutory and factual contexts that undergird this dispute, it is appropriate to return to the issues that are presently before the Court for determination.

25 At the heart of this matter lies s 664F(3). It is binary in its terms: the Court must approve the Compulsory Acquisition Notice if QGold establishes its terms give a fair value for the securities in question. Otherwise, the Court must confirm the proposed acquisition will not take place. In this context, it was said by Mr Bennett (on behalf of the representative defendant) that QGold had “failed to discharge the onus” impressed upon it by the terms of s 664F(3) because:

(1) the Andrawes Report was inconsistent with the Act or otherwise deficient; and

(2) the price at which the Compulsory Acquisition Notice proposed to acquire the residual ordinary shares in Carawine (being $0.11 per share) did not accord them “fair value”.

26 No comment was passed as to the various irregularities which underlay the plaintiff’s handling of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents and list of relevant objectors. As has been noted:

(1) the Compulsory Acquisition Notice incorrectly identified, at Annexure A, the number of ordinary shares in Carawine that had been acquired by QGold on 20 November 2023 (in breach of s 664C(1)(d)).

(2) copies of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents were not delivered to all holders of affected securities on the day they were filed or the next business day (21 and 22 March 2024) (in breach of 664C(3)). Instead, 254 copies were sent on 25 March 2024, 71 copies were sent between 4 and 11 April 2024 and 3 copies were sent on 16 May 2024.

(3) the list of objectors that was filed with ASIC on 30 April 2024 omitted reference to the details of one objector, a Mr Salvatore Aquilia (in breach of s 664E(3)).

27 A preliminary issue for determination is, therefore, whether it is appropriate, as QGold submits, for the Court to remediate such irregularities pursuant to the power conferred by s 1322(4).

The preliminary question: Is relief under s 1322(4) appropriate?

The relevant provisions

28 Section 1322 is titled “Irregularities”. At subsection (4), it relevantly provides:

(4) Subject to the following provisions of this section but without limiting the generality of any other provision of this Act, the Court may, on application by any interested person, make all or any of the following orders, either unconditionally or subject to such conditions as the Court imposes:

(a) an order declaring that any act, matter or thing purporting to have been done, or any proceeding purporting to have been instituted or taken, under this Act or in relation to a corporation is not invalid by reason of any contravention of a provision of this Act or a provision of the constitution of a corporation;

…

(d) an order extending the period for doing any act, matter or thing or instituting or taking any proceeding under this Act or in relation to a corporation (including an order extending a period where the period concerned ended before the application for the order was made) or abridging the period for doing such an act, matter or thing or instituting or taking such a proceeding;

and may make such consequential or ancillary orders as the Court thinks fit.

29 The exercise of that power is subject to the conditions identified by s 1332(6):

(6) The Court must not make an order “unless it is satisfied” that:

(a) in the case of an order referred to in paragraph (4)(a):

(i) that the act, matter or thing, or the proceeding, referred to in that paragraph is essentially of a procedural nature;

(ii) that the person or persons concerned in or party to the contravention or failure acted honestly; or

(iii) that it is just and equitable that the order be made; and

…

(d) in every case—that no substantial injustice has been or is likely to be caused to any person.

30 The principles to be applied when considering an application under s 1322(4) are well known to the Court: see, eg, Re Helios Energy Ltd (2017) 122 ACSR 174, 176 – 177 [20].

31 For instance, it is settled that the power enumerated within s 1322(4) reflects a legislative policy that the Act should not inflict unnecessary liability or inconvenience or invalidate transactions as a consequence of non-compliance with its requirements where such non-compliance is the product of honest error or inadvertence and if the Court can avoid its effects without prejudice to third parties or to the public interest in compliance with the law: Re Wave Capital Ltd (2003) 47 ACSR 418, 426 [29]; see also Blaze Asset Pty Ltd v Target Energy Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 488, 492 – 493 [30] – [35]; Weinstock v Beck (2013) 251 CLR 396, 419 – 420 [53] – [56].

Consideration

32 The written outline of submissions for the representative defendant records the following:

The plaintiff, by one of its originating affidavits, namely the affidavit of Ann Huynh affirmed 20 May 2024 admits procedural errors contrary to the requirements of the Corporations Act 2001. As such, the plaintiff seeks to rely on an amended originating process seeking orders pursuant to section 1322(4) of the Corporations Act 2001.

The representative defendant makes no submissions in respect of the plaintiffs application for relief for its procedural errors

33 That silence, it may be observed, gives colour to the prejudice, if any, that the aforementioned irregularities (at supra [26]) may have occasioned. Indeed, there is no hint of a suggestion that they were other than of a procedural nature, that they were not honest or that their remediation would not be just and equitable. Nor is there any suggestion that substantial injustice has been, or is likely to be, caused to any person by the irregularities or by an order validating them.

34 First, the overstatement in Annexure A to the Compulsory Acquisition Notice as to the number of shares acquired by QGold on 20 November 2023 is of little moment. The magnitude of the overstatement concerns approximately 27,000 shares out of a total of 39,000,000 (i.e., an error of 0.07%) and it is not easily understandable how such error could be of material consequence. Indeed, there is no suggestion that it occurred other than by inadvertence or that any injustice, substantial or otherwise, could have been caused to any party by reason of it.

35 Second, and similarly, the delay in the provision of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents to shareholders is also of little moment. There is no suggestion that it occasioned any prejudice.

36 It appears that, in early March 2024, a printing firm (MBE Brisbane CBD (MBE)) was engaged, by QGold, to print and issue copies of the documents to Carawine’s shareholders based upon the company’s share register as at 29 February 2024 (which identified 1,154 shareholders). On 6 March 2024, MBE was (a) provided with copies of the Andrawes Report and a shareholders’ objection form; and (b) instructed to commence production (which was estimated to take 8 to 10 business days). On 21 March 2024, the Compulsory Acquisition Notice was given to MBE; that day, the notice was also lodged with ASIC such that, pursuant s 664C(3), the Compulsory Acquisition Documents were to have been sent to all relevant shareholders of Carawine on that date or the next business day (being Friday, 22 March 2024). That did not occur.

37 By close of business on 22 March 2024, 900 copies of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents had been lodged with Australia Post for posting. The evidence suggests that those notices were sent on that day. The remaining 254 copies of the documents were dispatched on Monday, 25 March 2024 (being the first business day after 22 March 2024), such that a mail out to all 1,154 shareholders identified on Carawine’s share register (at 29 February 2024) was then completed.

38 Some one week later, on 3 April 2024, an updated version of Carawine’s share register (as at 29 February 2024) was provided to QGold. It was accompanied by an explanation, appended to the affidavit of a Ms Ann Huynh (filed 20 May 2024), that the earlier version of the register “excluded shareholders with return mail notifications”. A further 71 shareholders were thereby identified; they received copies of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents by 11 April 2024.

39 On 15 May 2024, a further version of the share register (as at 21 March 2024) was provided to QGold by Carawine. It contained an additional three shareholders (compared to the register as at 29 February 2024); accordingly, copies of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents were sent to them by express mail (and, in some cases, email) on 16 May 2024.

40 In the circumstances, it may be said that QGold’s failure to send the Compulsory Acquisition Documents to all intended recipients within the time stipulated by s 664C(3) was unintentional and the product of unforeseen events. There was no lack of honesty in the way in which the provision of the material occurred. Further, there is no hint that any injustice might have been caused by the delay that has transpired. Nor will it follow an order remediating the oversight.

41 In short, it may be said that the delays which occurred were, in context, minimal and, thereby, did not obfuscate the purpose of the communications required by the Act (being, ostensibly, to ensure prompt and contemporaneous communication between the 90% holder, ASIC and the minority shareholders so as to protect the latter’s interests and enhance transparency and market integrity: see Explanatory Memorandum, Corporate Law Economic Reform Bill 1998 (Cth) 41 [7.11]). It follows that it is appropriate to extend the time limits imposed by ss 664C(2)(b) and (3), such that the issuance of the Compulsory Acquisition Documents is not rendered invalid.

42 Third, a further instance of negligible non-compliance with the procedures defined by the Act occurred in relation to QGold’s lodgement of a list of objectors with ASIC on 30 April 2024 (see s 664E(3)). That list was required to set out (a) the names of people who held securities covered by the Compulsory Acquisition Notice and had objected to the acquisition; and (b) the details of the securities that they held (s 664E(3)(a)). It failed to do so in respect of Mr Aquilia.

43 That minor inconsistency has caused no harm to any party nor has the contrary been suggested. The omission of Mr Aquilia was not the result of any lack of honesty and it has not, at least on the evidence before the Court, caused hardship or injustice. Therefore, it is appropriate that an order be made that the filing of a list of objectors with ASIC on 30 April 2024 was not invalid.

44 It must be kept steadily in mind that the length of time between the issuance of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice and the hearing of this application has been substantial (being at least some 12 months). Any person who might have suffered any prejudice by any of the aforementioned procedural irregularities could have come forward to identify whatever damage might have been inflicted upon them by the failings of the plaintiff. As it is, no person did so, nor was it suggested that there exists any inhibition upon them from doing so if they were so minded.

45 In light of that which has been canvassed above, it is plain that these irregularities in QGold’s observance of the Act are appropriately remedied by an exercise of the power under s 1322(4). They are of a procedural character, and occurred without any lack of honesty on the part of any person involved. No injustice has been, or is likely to have been, caused to any party as a result of the errors. In each case, it is just and equitable that a remediating order be made.

Objection (1): the Andrawes Report is deficient in several respects

46 To compulsorily acquire securities under s 664A, the 90% holder must prepare a compulsory acquisition notice in the form prescribed by s 664C(1) and “then”, inter alia, give each person who is a holder of the relevant securities the Compulsory Acquisition Documents (s 664C(2)). Here, those documents include the Andrawes Report. Amongst other things, that report was required to (a) state whether, in Mr Andrawes’ opinion, the terms proposed in the Compulsory Acquisition Notice gave a “fair value” for the securities concerned (as per the procedure in ss 667C(1)); and (b) set out Mr Andrawes’ reasons for forming that opinion (ss 667A(1)(b) – (c)).

47 The defendants submit that the Andrawes Report did not do so for the following reasons – it:

(1) valued the relevant shares at the incorrect date;

(2) did not comply with s 667C(1)(b), because it failed to consider or attribute any value to certain tranches of options which had been issued by Carawine;

(3) did not comply with s 667C(2), because it failed to consider the consideration paid for ordinary shares in Carawine within the previous six months;

(4) did not comply with s 667C(1)(c), because it applied a control premium to the shares;

(5) did not comply with s 667A(1)(c), because it did not disclose Mr Andrawes’ reasoning;

(6) contained technical data that had been incorrectly reported; and

(7) attached an annexure that was ineligible.

Objection (1.1): The Andrawes Report did not value the shares at or about 21 March 2024

48 In the written outline of submissions for the representative defendant, it was said that:

The affidavit of Ann Huynh affirmed 20 May 2024 evidences that the Compulsory Acquisition Notice was dated 21 March 2024. Accordingly the date for valuation by Mr Andrawes ought have been on or about 21 March 2024 and not 26 February 2024.

The [Andrawes Report] does not explicitly state the date at which the valuation is carried out but in cross examination Mr Andrawes confirmed that the valuation was as at the date of the [Andrawes Report] and not the date of the compulsory acquisition notice.

49 That submission appears to rest upon the assertion that the Andrawes Report was required to have undertaken an assessment of the “fair value” of the residual ordinary shares in Carawine having regard, not to the circumstances existing as at the time of the preparation of the report (being formalised on 26 February 2024), but instead the circumstances that may have existed as at the time of the lodgement of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice (being 21 March 2024).

50 Under the framework of Division 1 of Part 6A.2, whether the terms of a compulsory acquisition notice give “fair value” to the relevant class of securities is a question to be answered by both the Court (s 664F(3)) and the expert’s report (s 667A(1)(b)). With respect to the former, and as made clear by Warren J in Capricorn Diamonds, the Court’s task is to be undertaken having regard to the circumstances existing “at or about” the date upon which the relevant compulsory acquisition notice was lodged with ASIC. Specifically, her Honour observed (at 85 [89]):

The independent expert, Appleyard, made the determination of fair value in early May 2001 in the May report, immediately prior to the date on which Capricorn lodged its compulsory acquisition notice with ASIC. Whether the terms set out in the compulsory acquisition notice give fair value for the securities covered by the notice must be assessed at or about the date the compulsory acquisition notice was lodged with ASIC and the notice was dispatched to unit holders as at or about 9 May 2001. Such proposition is supported by the construction of the provisions of Pt 6A of the Corporations Act. It seems to me that the new provisions would be unworkable if it were otherwise.

(Emphasis added).

51 That is, the Court is to determine whether the notice offers a fair price for the relevant securities at or about the time of its lodgement – here, 21 March 2024: Dolby Australia Pty Ltd v Catto (2004) 52 ACSR 204, 206 [4] (Dolby); Re Australian Water Holdings Pty Limited (2016) 306 FLR 40, 42 [2]; In the matter of Navalo Financial Services Group Limited [2025] NSWSC 317 [26], citing BG & E Management Pty Ltd v de Abolitz [2016] FCA 1368 [16] – [21] (de Abolitz).

52 Further comment was passed by Warren J as to the correlation between the issue that the Court is to decide under s 664F(3), being whether “the terms set out in the compulsory acquisition notice give a fair value for the securities”, and the subject of the expert’s report under s 667A(1)(b), being whether “the terms proposed in the compulsory acquisition notice give a fair value for the securities concerned”. In her Honour’s opinion (at 85 [90]):

… Because the inquiry as to fair value is directed to the terms set out in the compulsory acquisition notice both in the case of the expert’s report and in the case of the court’s determination, the time of the notice is the time at which the issue of “fair value” is to be tested. It is the preparation of the notice that initiates the procedure for compulsory acquisition under s 664A(3), and it is the securities to be acquired outstanding at that time that comprise “the securities covered by the compulsory acquisition notice”. The fair value inquiry is in relation to those securities.

53 Though the nature of the task imposed upon the Court and relevant expert are, prima facie, indistinguishable, there are, however, important differences. For instance, the subject of the Court’s assessment – being the compulsory acquisition notice which is lodged with ASIC – as well as its nature – being retrospective – is different from that of the expert. In this respect, it is appropriate to recall the content of s 664C(3), which requires the Compulsory Acquisition Documents, including, relevantly, the expert’s report, to be sent to security holders “on the day the 90% holder lodges the [compulsory acquisition] notice with ASIC or on the next business day”. In this way, the Act does not afford the expert’s report time to opine on the terms of the particular notice that is lodged with ASIC. Instead, it may necessarily only offer an opinion upon the terms that are proposed to be included in such notice; self-evidently, those terms may differ from those which are lodged with ASIC and issued to security holders by the 90% holder.

54 Such conclusion is consistent with the language of s 667A(1)(b), which requires the expert’s report to opine upon whether the terms that are “proposed in the notice give a fair value for the securities concerned” (emphasis added) (cf the subject of s 664F(3): “the terms set out in the [notice]” (emphasis added)). That drafting presumes that the terms “proposed” in the notice will be available to the expert, even if the terms “set out” in the notice lodged with ASIC are not. In other words, Part 6A.2 is structured in such a way so that the drawing of the expert’s opinion is, necessarily, to precede lodgement of any compulsory acquisition notice with ASIC.

55 The following question therefore arises: is the expert’s assessment of the terms proposed to be included in a compulsory acquisition notice to be undertaken by reference to the circumstances that are then before them or the circumstances that they foresee will exist at the time the notice is lodged with ASIC (and dispatched to security holders)? In this regard, it is important to keep steadily in mind the ostensible purpose of an expert’s opinion: to inform and assist, in the first instance, the 90% holder in its assessment of the value of a security and, in the second instance, the relevant security holder(s) in their assessment of the strength of offers made to acquire that security. Necessarily, the former element requires the opinion to be provided before any offer is made (in a compulsory acquisition notice), whereas the latter element calls for some temporal proximity as between the currency of the opinion and the making of the offer.

56 Though it might be thought that such purposes are best achieved by obliging the relevant expert to assess whether the terms proposed will give “fair value” at the time at which the 90% holder intends to lodge the compulsory acquisition notice – as the representative defendant seemingly contends – there are several reasons why that is not a pragmatic construction. First, and most importantly, an expert is no soothsayer. They are not to know when the 90% holder will lodge the notice with ASIC nor can they foresee what vicissitudes might arise between the giving of their opinion and lodgement of the notice, such as delays caused by unforeseen circumstances or changes in markets that affect the company’s value (see, eg, ConocoPhillips WA-248 Pty Ltd v Batoka Pty Ltd (2005) 193 FLR 424, 432 [57] – [58] (ConocoPhillips: being the first instance decision in Batoka)). In this respect, they are in a wholly different position to that of the Court when opining upon fair value (under s 664F(3)), for they do not have the benefit of hindsight. Second, the terms of s 667A(1)(b) are clear: an expert must state whether, in their opinion, the terms proposed in a notice give a fair value for the securities. Cast in the present tense, that provision does not suggest, expressly or implicitly, that an expert is to assess whether the terms will give fair value at some later date or time.

57 That being so, it is quite plainly in the interests of the 90% holder to ensure that the compulsory acquisition notice is lodged (and dispatched to security holders) as soon as reasonably possible following finalisation of the expert’s report. Self-evidently, adoption of such a practice ensures that the opinions of the expert are current when put before the relevant security holders; a lapse of time will, for instance, be particularly poignant in relation to securities which are known to be susceptible to significant fluctuations over short periods of time. Indeed, it might be thought to be a matter of common sense that the greater the discord between the date of (a) finalisation of the expert’s report; and (b) lodgement of the compulsory acquisition notice with ASIC, the more likely it is that the security holders will seek to exercise their right of objection. In doing so, they are expressing disquiet as to the veracity of the expert’s opinion by seeking a secondary opinion – namely, that of the Court. That is entirely consistent with the framework of the Act.

58 The foregoing is consistent with the observations in Batoka, where it was recognised that the relevant expert (GSA) did not have to consider the acquisition price offered in the compulsory acquisition notice lodged with ASIC, but merely the terms proposed in the notice that had been given to it. That case involved the following facts: (a) in July 2003, the 90% holder (CPWA-248) communicated its intent to GSA to acquire certain shares at a price of 78 cents (per share); (b) on 4 August 2003, GSA gave its report to CPWA-248 which identified a valuation range of between 63 to 89 cents and expressed an opinion as to whether 78 cents was fair value; (c) on 7 August 2023, CPWA-248 lodged a compulsory acquisition notice with ASIC that sought to acquire the relevant shares at a price of 89 cents; and (d) on 8 August 2003, CPWA-248 sent the expert’s report and compulsory acquisition notice (of 4 and 7 August 2003, respectively) to the shareholders (see Batoka at 97 – 98 [11] – [14]; ConocoPhillips at 431 – 432 [50] – [60]).

59 As the observations of Steytler P (with whom McLure JA and Murray AJA agreed) make clear, the expert’s report to be sent with the compulsory acquisition notice does not have to express an opinion as to whether the price ultimately offered by the 90% holder is “fair value” (see 103 – 104 [36] – [41]). Their task is to express and explain, in their opinion, whether the terms that are proposed in a notice give fair value for the securities concerned: ss 667A(1)(b) – (c). They may, for example, consider that “fair value” is higher or lower than the acquisition price then proposed; if so, the 90% holder is at liberty to lodge and issue a notice with a term as to price equivalent to the expert’s opinion of “fair value”. Or, as in the case then before the Court, the 90% holder may wish to lodge and issue a notice that offers a price in excess of the expert’s estimation of “fair value” in an effort to dissuade potential objectors: ConocoPhillips 432 [59]. The Court’s acceptance that such a course was open tends to support an understanding of Part 6A.2 that the expert’s report need only express a view upon the terms proposed to be set out in a compulsory acquisition notice having regard to the circumstances that are then before them (it then falling to the 90% holder to promptly act upon such opinion); they need not attempt to do so having regard to the circumstances which may or may not exist at some time in the future.

60 The above construction also accords with the regime of Part 6A.2, for it must be kept in mind that the expert’s opinion about fair value is neither the end of the process nor determinative of it. On the contrary, if more than 10% of eligible shareholders object to a proposed acquisition, it is for the Court to approve the acquisition and, to that end, the applicant must establish the terms set out in the compulsory acquisition notice give a fair value of the securities (s 664F(3)). So, whereas the expert is to express an opinion when completing their report about the terms proposed in a notice for the purposes of the security holders considering the offer of acquisition, where the relevant objection has occurred, the acquisition cannot take place unless the Court is satisfied, as a matter of fact, that the terms of the notice actually issued, do provide fair value.

61 The position may be summarised thus. An expert’s opinion must opine on the terms proposed to be included in a compulsory acquisition notice; that is different to the task of the Court under s 664F(3) which, instead, must assess the terms set out in the notice lodged with ASIC. So as to avoid unnecessary speculation and ambiguity, and having regard to the drafting of s 667A(1), the opinion is to be formed having regard to the circumstances that are then before the relevant expert. It is prudent for a 90% holder to minimise the temporal difference between the date on which the expert formalises their opinion and lodgement of their compulsory acquisition notice (so as to satisfy security holders of the currency of the factual basis on which the expert purports to rely); however, there is no obligation to do so under the Act. That being so, such construction is largely semantic. As an expert’s opinion, within the framework of Part 6A.2, is (a) intended to do no more than allow the reader (be it the 90% holder or some security holder) to rationalise whether a price which is offered for a security accords it “fair value”; and (b) not determinative of whether the terms set out in a compulsory acquisition notice will be endorsed by a Court, it can be accepted that the only tangible consequence of a stale valuation opinion is that security holders will, necessarily, be more likely to object to the compulsory acquisition process. That is appropriate and can be dealt with, by the Court, in its assessment of the notice under s 664F.

Did the Andrawes Report express an opinion upon whether the terms proposed in the notice provided to it gave a “fair value” for the residual ordinary shares in Carawine?

62 The Andrawes Report is dated 26 February 2024. Item 1 is titled “Introduction”. It identifies:

QGold has advised that it intends to proceed with the Compulsory Acquisition. QGold is offering $0.11 cash per share for each Carawine share (‘Consideration’).

The notice of compulsory acquisition to minority shareholders of Carawine is to be accompanied by this independent expert’s report.

(Emphasis in original).

63 In this way, Mr Andrawes identified the terms proposed in the compulsory acquisition notice then before him to be to the effect that the price which QGold intended to offer for the residual ordinary shares in Carawine was $0.11 cash per share. He was, thereby, obliged to express an opinion as to whether that proposed acquisition cost gave “fair value” (per s 667A(1)(b)).

64 Item 2 is titled “Summary and opinion”. It defines the “Requirement for the report” as follows:

2.1 Requirement for the report

The directors of QGold have requested that BDO Corporate Finance (WA) Pty Ltd (‘BDO’) prepare an independent expert’s report (‘our Report’) to express an opinion as to whether the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition notice (‘Notice of Compulsory Acquisition’) give a ‘fair value’ for the securities, to the minority shareholders of Carawine (‘Shareholders’).

Our Report is prepared pursuant to Chapter 6A of the Corporations Act and is to be included in the Notice of Compulsory Acquisition for Carawine in order to assist the Shareholders in their assessment of the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition.

(Emphasis in original).

65 Item 2.2 (“Approach”) notes the report was prepared having regard to various regulatory guides published by ASIC and provides that:

In arriving at our opinion, we have assessed the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition as outlined in the body of this report. To determine if the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition offer a ‘fair value’ for the securities, we have:

• compared the value of a Carawine share (including a premium for control) with the Consideration; and

• set out the reasons for our opinion.

66 The report proceeds to set out the applicable statutory procedures and the requirement for the valuation to be given to the shareholders with the compulsory acquisition notice (see Item 3).

67 At Item 2.3, the Andrawes Report expresses Mr Andrawes’ “Opinion” in the following terms:

2.3 Opinion

We have considered the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition as outlined in the body of this report. We have concluded that the terms of the Compulsory Acquisition give a fair value to Shareholders as the Consideration per share within the range of our assessed value per Carawine share.

68 That Item plainly states the opinion of Mr Andrawes as to whether the terms then proposed by QGold (being, namely, to acquire the residual ordinary shares of Carawine for “$0.11 cash per share”) gave a fair value for the securities at 26 February 2024. That satisfied the requirement imposed upon Mr Andrawes by the terms of s 667A(1)(b). He does not attempt to hypothesise when QGold would lodge a compulsory acquisition notice with ASIC nor does he express any opinion as to whether $0.11 would reflect the “fair value” of an ordinary share in Carawine at that time. There is nothing in the Act to suggest that he was required to do so. If anything, the discord between the date of lodgement of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice and valuation in the Andrawes Report suggests, for the purposes of the Court’s assessment of “fair value” under s 664F(3), that the opinions expressed by Mr Andrawes may carry diminished weight for want of currency at or about 21 March 2024 (but see infra [87], [156] – [157]); it also gives a cogent reason for why the defendants now seek an additional assessment of “fair value” by the Court.

A valuation “at or about” the time of lodgement of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice

69 In any event, and for the avoidance of doubt, it may be said that the Andrawes Report expressed an opinion of value “at or about” the date upon which the Compulsory Acquisition Notice was lodged with ASIC. Necessarily, that which might be said to be proximate to the date of the lodgement of such notice will vary with the circumstances of the case. Where the environment in which the securities that are sought to be acquired are of a nature that price fluctuations occur or are likely to occur, the timing of a valuation which can be described as “at or about the time” of the notice will be shorter than where such fluctuations do not occur or are not likely to.

70 In the present case, some three weeks elapsed between the date of the valuation in the Andrawes Report and the lodgement of the notice. There is no evidence before the Court to suggest either (a) the market for the subject matter of Mr Andrawes’ valuation; or (b) the price of an ordinary Carawine share, exhibited any degree of significant fluctuation during that particular time.

71 It follows that the date of the giving of Mr Andrawes’ opinion is sufficiently proximate to the lodging and issuing of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice. Therefore, the date of the valuation which informed the opinion that was stated in the expert’s report and sent with the Compulsory Acquisition Notice (pursuant to s 664C(2)(b)) undoubtedly met the conditions of s 667A(1)(b).

72 As an aside, in the absence of evidence that there was some significant difference in the value of an ordinary Carawine share between the date of the valuation and lodging of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice, it follows that, even if valuation in the Andrawes Report was stale and did not comply with the Act, no damage or prejudice could possibly have flowed from it.

Objection (1.2): No part of the value of the company was attributed to extant options

73 Section 667C specifies the method for determining what is “fair value” for securities. One step in that methodology is prescribed by subsection (1)(b): the value of Carawine as a whole must be allocated amongst the classes of issued securities (taking into account the relative financial risk, and voting and distribution rights, of the different classes). In relation to this requirement, it is accepted that options granted by Carawine fall within the meaning of “security”: s 92(3)(f).

74 In short, the defendants allege that the valuation contained within the Andrawes Report does not satisfy the requirement in s 667C(1)(b) because Mr Andrawes failed to consider or attribute a value to certain options which Carawine had issued. That objection is misplaced.

75 In his oral evidence, Mr Andrawes indicated that he had considered the existence of the options (indeed, they are contemplated in his report at Item 5.10) but attributed no value to them on the basis that the prices at which they were exercisable were so far in excess of the shares’ market value that it was not foreseeable that they would be exercised. Thus, a nil value was attributed to them and the total value of the company was ascribed to the existing shares. In his words:

HIS HONOUR: Could you just slow down a bit and say that again?---The options that were on issue were reflected in my report and mentioned. However, they were very far out of the money. Had they been in the money, ie, had the – had the exercise price been less than the value I had – I – I had arrived at per share, then I would have taken account of them on a diluted basis.

What do you mean, “out of the money” - - -?---Out of the money means the exercise price is more than the value, so they wouldn’t be exercised.

I see?---And they were quite – they were quite far out of the – out of the money as well.

Right. I see?---And so they had negligible value, if any. And so, in that respect, there was no value to be attributed to them. Had they been – the exercise price been below my value, then I would have taken them into account in terms of attributing value to them. But in this case, it wasn’t appropriate.

76 Mr Andrawes’ evidence on this particular topic should be accepted. It was given in a forthright and considered manner, and no reason was exposed for doubting the veracity of it.

77 Moreover, the logic of his approach is undeniable. As Item 5.10 of the Andrawes Report makes clear, the exercise price per share of the options in question was $0.40 (in respect of 3,000,000 shares) and $0.60 (in respect of 2,250,000 shares). Those prices were, and are, so far above what Mr Andrawes considered to be representative of their “most likely” market value ($0.104 per share; see infra [106] – [107]), that he understood there to be no real chance that they would be exercised. He was not significantly challenged on his evidence in this respect. Accepting his belief that the options would not be exercised, there would be no additional shares in respect of which the value of Carawine could be apportioned. That approach is rational and consistent with s 667C(1)(b). After all, that section is directed to ascertaining what is a “fair value” for the relevant shares by attributing the value of the company to the shareholding. It is not intended to attribute the value among shares which have no real chance of being issued.

78 It was suggested in the written submissions for the representative defendant that at least some part of the value of Carawine should have been attributed to the options given that, as they did not expire until December 2025, there existed at least some potential for their being exercised. That submission is unfortunate in circumstances where it was not put to Mr Andrawes that the length of the option period should have acted as an indicator of the potential for the options, or at least some of them, being exercised. Had that question been put, he may have had a response. That may have been based on the known circumstances, the historical value of the share price or any combination of those matters. In any event, the defendants had the opportunity to examine Mr Andrawes on the topic and did not do so. It is now inappropriate to indirectly criticise him without affording him a chance to explain it: Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67.

79 To that, it might be added that no scenario was postulated in which it might reasonably be suggested that the market price of an ordinary Carawine share would approach $0.40, let alone $0.60, such that the option holders might exercise them. Instead, the evidence established that (a) between 18 May and 17 November 2023, the quoted daily market price of a Carawine share did not exceed $0.1477; and (b) from 17 November 2023, that price did not waver significantly from $0.11. In such circumstances, there was nothing to suggest any error in Mr Andrawes’ approach of assuming that there was no reasonable prospect of the options being exercised.

80 In sum, no error has been shown to exist in the Andrawes Report on the basis that the value of the company was not appropriately allocated among the classes of issued securities.

81 It is a matter worthy of remark that the defendants would seek to rely upon this alleged defect, given that Mr Andrawes’ decision to attribute a nil value to the options necessarily inflated the value to be attributed to the ordinary shares that were the subject of the Compulsory Acquisition Notice. That is a decision which would have plainly enured to the benefit of persons from who the shares were sought to be acquired (the defendants). Moreover, it follows that the price of $0.11 would be even higher than the market price of the shares than Mr Andrawes had believed.

Objection (1.3): Consideration of prior six months trading in the relevant shares

82 It is also alleged that the Andrawes Report did not comply with s 667C(2) which requires that, in any assessment of fair value, the consideration (if any) paid for securities in the class sought to be acquired within the previous 6 months “must be taken into account” (see also Capricorn Diamonds 79 – 80 [72]).

83 The requirement under s 667C(2) is of a procedural character; a matter (the consideration paid for securities in the relevant class within the previous 6 months) must be “taken into account” by the relevant expert(s) in their assessment of “fair value”, though precisely the weight that it carries is a matter for their discretion (Capricorn Diamonds 78 [65]; see also Teh v Ramsay Centauri Pty Ltd (2002) 42 ACSR 354, 360 [27] (Teh)). Thus, to assess whether the Andrawes Report took such a matter “into account” in its determination of “fair value”, regard must be paid to the manner in which the report sought to value the residual ordinary Carawine shares.

84 In this respect, it is noted that Mr Andrawes relied upon an array of valuation methodologies – namely, (a) a “Sum-of-Parts” (SoP) analysis (Item 10.1); (b) a “Quoted Market Price” (QMP) analysis (Item 10.2); and (c) a consideration of the so-called “Subscription Price” (Item 10.3). These reasons will traverse such methodologies, and their differing logics, where appropriate.

The QMP analysis

85 Mr Bennett, in his outline of submissions, took the Court to evidence of the trading of ordinary Carawine shares which “show[ed] consistent trading above 11 cents, including trades on 6 July 2023 and 10 July 2023 at 14 cents per share” and was said to buttress the following assertion:

The legislature [by s 667C(2)] seeks to protect the minorities from precisely what occurred in this matter, that is, the acquisition by the plaintiff of securities at an upper range between 13.5 and 14 cents in the previous 6 months then offering the minority shareholders 11 cents per share.

86 Although the thrust of such characterisation of s 667C(2) may, indeed, be apposite, it does not appear to have any direct bearing upon the present case. It is, with respect, rather pellucid that Mr Andrawes did take into account evidence of historical trading in ordinary Carawine shares. Principally, he did so by considering the quoted market prices for those shares in the six months prior to 20 November 2023, being the date QGold became the 90% holder in Carawine (at Item 10.2). Such a timeframe was nominated to cater for the fact that QGold’s acquisition of a 90% holding could reasonably be expected to artificially distort the market price of Carawine shares thereafter (given that it would then be in a position to compulsorily acquire the residual shares) (at Item 10.2). It is noted that no criticism was made of the decision to confine Mr Andrawes’ analysis of the consideration paid for ordinary Carawine shares to the six months that preceded 20 November 2023 (and not the six months prior the date of his valuation (26 February 2024)).

87 In any event, a supplementary report prepared by Mr Andrawes (and dated 27 February 2025) revealed there to be no significant difference in the consideration paid for a Carawine share in the six months that preceded (a) 20 November 2023; and (b) 21 March 2024 (and, by extension, 26 February 2024). If anything, the effect of QGold acquiring 90% of the shareholding was to exert a downward pressure on the market price for the remaining ordinary shares (e.g., compare the weighted average market price for the six months to 17 November 2023 ($0.132; Item 10.2 of the Andrawes Report) and 21 March 2024 ($0.108; Item 5 of the supplementary report)).

88 The Andrawes Report explained the QMP approach in the following terms (at Appendix 2):

2 Quoted Market Price Basis (‘QMP’)

A valuation approach that can be used in conjunction with (or as a replacement for) other valuation methods is the quoted market price of listed securities. Where there is a ready market for securities such as the ASX, through which shares are traded, recent prices at which shares are bought and sold can be taken as the market value per share. Such market value includes all factors and influences that impact upon the ASX. The use of ASX pricing is more relevant where a security displays regular high volume trading, creating a liquid and active market in that security.

89 Item 10.2 of that report is titled “Quoted Market Prices for Carawine Securities”. It begins by noting that Mr Andrawes’ assessment of the quoted market price of an ordinary Carawine share had been prepared in two parts: “The first part is to assess the quoted market price on a minority interest basis. The second part is to add a premium for control to the minority interest value”. In relation to the former, the Andrawes Report first sets out a chart. It is titled “Carawine share price and trading volume history” and represents the quoted market price of ordinary Carawine shares as between 18 May 2023 to 17 November 2023. It revealed the following information:

(1) the daily price of a Carawine share was at its lowest on 9 June 2023 ($0.0975);

(2) the daily price of a Carawine share was at its highest on 2 October 2023 ($0.1477);

(3) the volume of trading was low, with the largest trade being the acquisition of 2,262,864 shares by QGold on 6 July 2023 (at a price of $0.14 per share).

90 Further analysis followed, including that of the volume of trading in Carawine shares for the six-month period between 18 May 2023 and 17 November 2023. In this respect, the Andrawes Report observed that only 2.06% of Carawine’s current issued capital was traded in that period (being, at least on Mr Andrawes’ view, influenced by QGold’s status as the 90% holder).

91 In the result, Item 10.2 offered the following conclusion:

In the case of Carawine, we consider the shares to display a low level of liquidity, on the basis that less than 1% of securities have been traded weekly on average, with 2.06% of Carawine’s current issued capital being traded over a six-month period and 21.94% when excluding the shares held by QGold. Across the period assessed, there were 62 trading days where there was no trading in the Company’s shares.

Our assessment is that a range of values for Carawine shares based on market pricing is between $0.105 and $0.125.

92 The Andrawes Report then turned to address the QMP value of a Carawine share if a premium for control were to be added and found, in short, that the appropriate range of values for such shares would be between $0.131 and $0.169 (see infra [109]). However, it cautioned against “placing too much reliance on these values … due to the low liquidity of the shares” in question.

Consideration of the Subscription Price

93 In October 2023, Carawine offered all shareholders the opportunity to participate in a pro-rata renounceable entitlement offer of two fully paid ordinary shares for every nine shares (at a price of $0.11 per share (the Subscription Price)) (the 2023 Entitlement Offer). For present purposes, it suffices to observe that Mr Andrawes accounted for such offering in his assessment of the historical market price of Carawine’s shares (at Item 10.3). In so doing, he discounted much of what had transpired in relation to the rights’ issue because, “substantively”, it was only QGold who had subscribed for shares under the 2023 Entitlement Offer. This was said to indicate that the Subscription Price was in excess of that at which other shareholders were willing to transact at and that, had the price been closer to the market price, it would have been reasonable to expect a greater degree of participation from shareholders other than QGold. On that basis, he found that the Subscription Price, of itself, did not reflect a fair market value.

Identification of appropriate methodology to assess “fair value”

94 In its assessment of the value of Carawine shares, Item 10.4 of the Andrawes Report compared the (a) SoP approach; (b) QMP approach; and (c) Subscription Price. In short, Mr Andrawes determined that it was the former which provided the best foundation to identify “fair value”:

The values derived from our Sum-of-Parts and QMP approaches and the Subscription Price are reasonably consistent with one another. Given that the shares of Carawine display a low level of liquidity and that the 2023 Entitlement Offer was only substantively taken up by QGold, we have elected to rely on the value derived from our Sum-of-Parts approach.

Did Mr Andrawes comply with the requirements of s 667C(2)?

95 It is undoubted that Mr Andrawes took into account, in his preparation of the Andrawes Report, evidence pertaining to the historical price paid for ordinary Carawine shares. He did so in the course of his QMP analysis (Item 10.2), as well as in his consideration of the 2023 Entitlement Offer (Item 10.3). Having done so, he discounted it as of utility to an assessment of “fair value” in the circumstances of the case (Item 10.4). He was wholly entitled to do so under the Act.

96 The defendants assert that evidence of such shares being sold for prices in excess of $0.11 (e.g., $0.135 and $0.14) in the six-month period preceding 20 November 2023 had the consequence that the “fair value” of an ordinary Carawine share should have been higher than as determined by Mr Andrawes. That submission, however, fails to appreciate the assessment process and that, whilst s 667C(2) requires that historical prices be taken into account, that evidence is not determinative of “fair value”. Here, the prices received were taken into account; their relevance was, however, considered to have been diminished by reason of the circumstances of the market when the shares were sold and, in particular, the low liquidity of share transactions. It is plain Mr Andrawes gave active, intelligent consideration to the evidence of the historical price of the shares, but it is also clear his reasons for discounting such were substantive and compelling.

97 In the result, there is no substance in this criticism of the Andrawes Report.

Objection (1.4): Use of a “premium for control”

98 Pursuant to s 667C(1)(c), the valuation prepared by the relevant expert is to “allocate the value of each class pro rata among the securities in that class”. Importantly for present purposes, that allocation must not allow a premium, or apply a discount, for particular securities in that class (see Explanatory Memorandum, Corporate Law Economic Reform Bill 1998 (Cth) 42 [7.13]).

99 As has been alluded to, the Andrawes Report undertook an assessment as to the “fair value” of the relevant securities by reference to a “control premium” (see supra [65] and [92]; see also Item 2.4, which identifies the low, preferred and high values of an ordinary Carawine share upon “a control basis (per share)”). It is noted that (a) in his evidence, Mr Andrawes clarified that use of the expression “control basis” was a reference to a “premium for control”; and (b) the valuations set out in Item 2.4 incorporated, in part, assessments undertaken by reference to the Australasian Code for Public Reporting of Technical Assessments and Valuation of Mineral Assets (2015 ed) (VALMIN Code) (per Item 9), such that a reference to “preferred value” may be understood as a reference to a “most likely” market value (VALMIN Code at 30 [8.6]).

100 The defendants submitted that the inclusion of such a premium for control was impermissible, in that it was inconsistent with a regulatory guide that had been published by ASIC – namely, Regulatory Guide 111 (Content of Expert Reports) (RG111) – and contrary to s 667C(1)(c).

101 It is not entirely clear what was sought to be made of this alleged non-compliance with RG111. It appeared to be advanced on the footing that a valuation that did not comply with the guidance set out in RG111 would not be a “valuation” for the purposes of s 667C, with the consequence that, if non-compliance was made out, the section would not be satisfied. No basis for that conclusion was identified and it should be rejected when cast at such a high level of generality. In any event, even if the proposition was correct, there was no non-compliance with RG111.

The SoP analysis (includes an inherent premium for control)

102 Mr Andrawes indicated that his valuation was prepared in accordance with certain regulatory guidelines issued by ASIC, including RG111, for the purposes of assessing the “fair value” of the securities. Indeed, he extracts [RG111.48] – [RG111.49] of RG111 at Item 3.2. Thereafter, he notes RG111 states that a transaction will be “fair” if the value of the offer price is equal to (or greater than) the value of the securities which are the subject of the offer. In turn, this was said to require a comparison between the value of a Carawine share “on a control basis” prior to the compulsory acquisition and the value of consideration being offered per share by QGold.

103 As noted above, Mr Andrawes purported to do so by reference to multiple valuation methods. One such method was the SoP approach. Item 9 of the Andrawes Report relevantly explains:

… In our assessment of the value of a Carawine share we have chosen to employ the following methodologies:

• Sum-of-parts method … which estimates the market value of a company by separately valuing each asset and liability of the company. The value of each asset may be determined using different methods and the component parts are then aggregated using the NAV [Net Asset Value] methodology.

…

104 Item 10.4 provides further clarity as to what such methodology entailed:

[The valuation achieved by the SoP methodology] represents the amount that would be distributed to shareholders if all the Company’s assets and liabilities were sold and settled on an orderly basis.

105 The manner in which Mr Andrawes used the SoP methodology to value an ordinary Carawine share is set out in Item 10.1 (titled “Sum-of-Parts valuation”). That Item begins by noting:

We have employed the Sum-of-Parts methodology in estimating the fair market value of a Carawine share by aggregating the estimated fair market values of its underlying assets and liabilities, having consideration of the following:

• Value of Carawine’s mineral assets; and

• Value of Carawine’s other assets and liabilities.

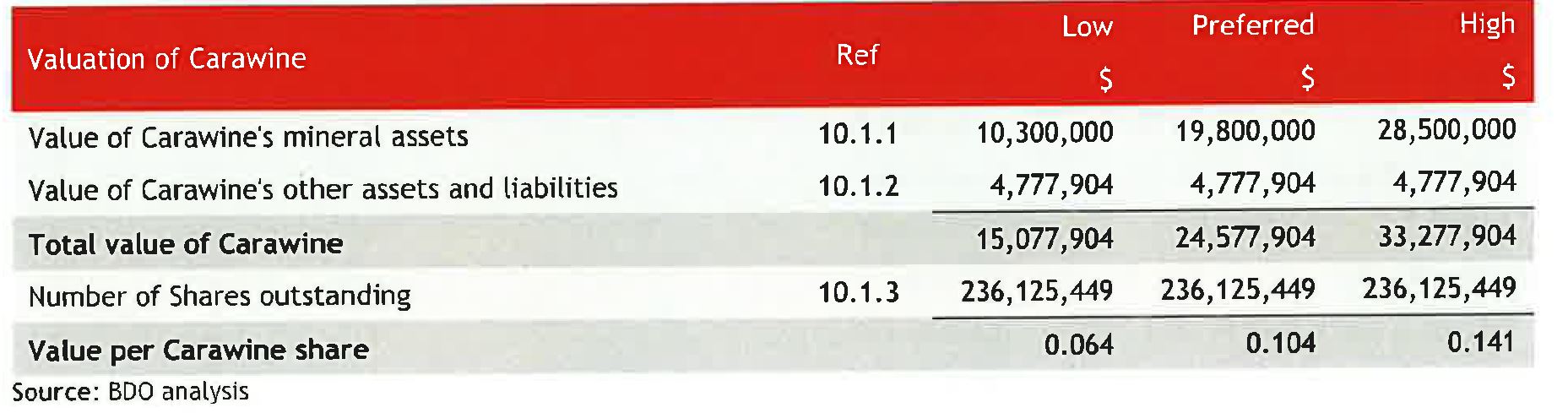

106 The value of those assets and liabilities (at a “low”, “preferred” and “high” range), as well as the value that would be distributed to shareholders if those assets and liabilities were sold and settled on an orderly basis, were set out by Mr Andrawes in the following table:

107 That data informed the following conclusion:

We have assessed the value of a Carawine share (on a controlling interest basis) to be in the range of $0.064 to $0.141, with a preferred value of $0.104.

108 Critically, and unlike the QMP method, no “premium” was subsequently added to the assessed value of a Carawine share (cf supra [92]). Indeed, all that occurred within the SoP process was that the assessed asset value of the company was divided by the number of issued shares.

109 For the purposes of comparison and assessment, Mr Andrawes undertook a QMP valuation of the relevant Carawine shares (Item 10.2). There, he considered the quoted market price of the shares for the six months preceding QGold’s ascendency to 90% holder on a “minority interest basis”, as well as by adding a premium for control. The results of that analysis were as follows:

Low | Midpoint | High | |

$ | $ | $ | |

Quoted market price value | 0.105 | 0.115 | 0.125 |

Control premium | 25% | 30% | 35% |

Quoted market price valuation including a premium for control | 0.131 | 0.150 | 0.169 |

110 However, and as has been noted, Mr Andrawes cautioned against placing too much reliance on the values obtained under such approach due to the “low liquidity of the shares” (Item 10.2).

111 Ultimately, the Andrawes Report preferred the results of the SoP method. At Item 10.4, it said:

We consider the sum-of-parts value, which is a control value, to represent the fair value of Carawine’s shares to Shareholders. This represents the amount that would be distributed to shareholders if all the Company’s assets and liabilities were sold and settled on an orderly basis. In our opinion no premium would be received in excess of the net asset value by selling 100% of the Company noting that RG111.11 requires that any special value of the target to a particular bidder should not be taken into account in the assessment of fairness.

Based on the results above we consider the value of a Carawine share to be between $0.064 and $0.141, with a preferred value of $0.104.

(Emphasis added).

112 The emphasised portion of that conclusion is important in the current context.

Alleged contravention of RG111 and s 667C(1)(c)

113 It was put to Mr Andrawes that the identification of a value of a Carawine share on a “control basis” contradicted RG111 at [RG111.48(c)]. That guidance relevantly provides:

To determine what is ‘fair value’, s667C requires that an expert:

(a) first assess the value of the entity as a whole;

(b) then allocate that value among the classes of issued securities in the company (taking into account the relative financial risk and the voting and distribution rights of the classes); and

(c) then allocate the value of each class pro rata among the securities in that class (without allowing any premium or applying a discount for particular securities or interest in that class).

(Emphasis added).

114 It is a matter worthy of comment that [RG111.48] is not a strict recitation of s 667C(1), for it adds the words “or interest” to subparagraph (c) which seemingly seeks to expand the operation of s 667C(1)(c). The legislative requirement is to the effect that, in the allocation of the value attributed to a class of securities, no premium is to be allowed or discount to be applied vis-à-vis “particular securities in that class”. In other words, all securities within the one class are to be treated equally: Capricorn Diamonds 79 [69] (in this vein, see eg, Winpar Holdings Ltd v Goldfields Kalgoorlie Ltd (2000) 176 ALR 86, 100 [68] – [69] and Re Goodyear Australia Ltd (2002) 167 FLR 1, 20 – 21 [85] – [86]). By contrast, ASIC’s reformulation of s 667C(1) in [RG111.48] has the appearance of attempting to expand subparagraph (1)(c), so as to prevent a premium or discount being applied by reason of a party having an interest in the class of securities as a whole. Experience reveals this instance of overstatement to not be uncommon; indeed, it is most unfortunate that such guides often contain unreliable recitations of the law.