Federal Court of Australia

Thomas v Ejueyitsi [2025] FCA 1167

File number(s): | NSD 1393 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | CHEESEMAN J |

Date of judgment: | 22 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | BANKRUPTCY – sequestration order – where application for review of sequestration order made by Registrar – where review conducted as a hearing de novo – whether petitioning creditors have established onus to prove matters in s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) – whether petitioning creditors have discharged onus on civil standard to establish that Bankruptcy Notice personally served on debtor – whether debtor discharged onus on civil standard to establish able to pay debts within the meaning of s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act – whether sequestration order should be made. Held: sequestration orders made |

Legislation: | Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) ss 40(1)(g), 41(7), 43, 51, 52, Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 35A Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth) r 10(1)(a) Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth) r 7.06 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 1.39, 3.11 |

Cases cited: | Alam v QBE Insurance (Australia) Ltd [2018] FCA 1560 Axon v Axon [1937] HCA 80; 59 CLR 395 Bechara v Bates [2021] FCAFC 34 Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63; 98 ER 969 Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 Coates Hire Operations Pty Ltd v D-Link Homes Pty Ltd [2011] NSWSC 1279 Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing & Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 Culleton v Balwyn Nominees Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 8; 343 ALR 632 Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Bayconnection Property Developments Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 363; 127 ALD 64 Do (Trustee), Andrew Superannuation Fund v Sijabat [2023] FCAFC 6; 295 FCR 584 Ejueyitsi v Thomas & Anor [2022] NSWDC 490 Ejueyitsi v Western Sydney University & Ors [2023] HCASL 143 Ejueyitsi v Western Sydney University [2023] NSWCA 126 Francis v Eggleston Mitchell Lawyers Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 18 Mangano v Bullen [2025] FCAFC 42 Robson as former trustee of the estate of Samsakopoulos v Body Corporate for Sanderling at Kings Beach CTS 2942 [2021] FCAFC 143; 286 FCR 494 Sarina v Council of the Shire of Wollondilly [1980] FCA 175; 48 FLR 372 Shaw v Yarranova Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 88; 252 FCR 267 Szepesvary v Weston as trustee of the bankrupt estate of Aaron Szepesvary [2018] FCAFC 224; 363 ALR 379 Totev v Sfar [2008] FCAFC 35; 167 FCR 193 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | General and Personal Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 115 |

Date of hearing: | 12 September 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicants: | Ms H Cohley |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Clyde & Co |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Mr P Beazley of Beazley Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 1393 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JOY THOMAS First Applicant BARNEY GLOVER Second Applicant | |

AND: | VINCENT EJUEYITSI Respondent | |

order made by: | CHEESEMAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 september 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The estate of Vincent Ejueyitsi (also known as Babatunde Vincent Ejueyitsi) be sequestrated under the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth).

2. The applicant creditors’ costs be taxed and paid from the bankrupt estate of Vincent Ejueyitsi in accordance with the Act.

3. A copy of this order is to be provided by the applicant creditors to the Official Receiver in Sydney within two (2) days.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The date of the act of bankruptcy is 6 July 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

CHEESEMAN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 These reasons concern an application as of right for a de novo review under s 35A(5) and (6) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) of a Registrar’s decision to sequester the estate of the respondent, Vincent Ejueyitsi (also known as Babatunde Vincent Ejueyitsi), under s 43 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth). The applicants, Joy Thomas and Barney Glover, are the petitioning creditors.

2 Mr Ejueyitsi was a litigant in person in this proceeding until 23 May 2025 when he obtained legal representation. Following an adjournment of the hearing on 12 June 2025 to allow additional time to bring into focus the real issues in dispute, the hearing was relisted for hearing in September 2025. The adjournment application was made by Mr Ejueyitsi. It was not opposed by the petitioning creditors.

3 After various iterations of his grounds of opposition, Mr Ejueyitsi ultimately relies on a further amended notice of opposition which raises two grounds of opposition. First, Mr Ejueyitsi contends that he has not committed an act of bankruptcy because he was not personally served with the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024 as claimed. Secondly, Mr Ejueyitsi contends that at the date of the sequestration order, he was solvent and had sufficient funds to pay the petitioning creditors’ debt in full.

4 The present review being conducted de novo requires a judge to take a “fresh look” at the issues on a complete rehearing of the facts and the law. Error does not need to be demonstrated on the part of the Registrar for success in the review.

BACKGROUND

5 The petitioning creditors claim in respect of a debt that arises from costs orders made by the District Court of New South Wales on 20 October 2022: Ejueyitsi v Thomas & Anor [2022] NSWDC 490. The litigation between Mr Ejueyitsi and Ms Thomas and Mr Glover was initiated by Mr Ejueyitsi in the Local Court of New South Wales at Parramatta. The primary claim and the proceedings at each level of appeal have been dismissed, essentially as disclosing no reasonable cause of action, with costs orders being made against Mr Ejueyitsi.

6 In February 2022, Mr Ejueyitsi commenced in the Small Claims Division of the Local Court at Parramatta. Mr Ejueyitsi first issued proceedings against Ms Thomas, who was at the relevant time an employee of Western Sydney University (WSU), in relation to a decision by the WSU to disenroll Mr Ejueyitsi from a course following non-payment of fees. Mr Ejueyitsi alleged that WSU had failed to inform him that a subject he enrolled in was not “covered by Fee-Help/HECS” and sought relief in the amount of $50,000 against Ms Thomas. Mr Ejueyitsi later amended his pleading to add Mr Glover, the then Vice Chancellor of WSU, as the second defendant. In June 2022, Mr Ejueyitsi’s claim was struck out by the Local Court and he was ordered to pay Ms Thomas’ and Mr Glover’s costs as agreed or assessed.

7 In August 2022, Mr Ejueyitsi sought to appeal the decision of the Local Court proceeding to the District Court of New South Wales. In October 2022, the District Court summarily dismissed the appeal as disclosing no reasonable cause of action and ordered costs against Mr Ejueyitsi in the specified gross sum of $13,000 on an ordinary basis up to 15 September 2022 and on an indemnity basis thereafter.

8 In November 2022, Mr Ejueyitsi sought judicial review of the District Court’s summary dismissal in the New South Wales Court of Appeal. In February 2023, Mr Ejueyitsi filed an amended summons adding WSU as a respondent to the Court of Appeal proceeding, notwithstanding that WSU was not a party to the proceedings below. Mr Ejueyitsi was represented at the hearing of the appeal. In June 2023, the Court of Appeal dismissed the summons with costs: Ejueyitsi v Western Sydney University [2023] NSWCA 126.

9 In July 2023, Mr Ejueyitsi applied for special leave to appeal the judgment and order of the Court of Appeal. On 12 October 2023, the High Court of Australia (Gordon and Steward JJ) refused Mr Ejueyitsi’s application for special leave: [2023] HCASL 143.

10 In April 2025, Mr Ejueyitsi commenced a second proceeding against WSU and Ms Thomas in the Local Court Small Claims Division in Sydney alleged to arise from broadly the same facts and circumstances relied upon in the first Local Court proceeding, seeking relief in the reduced amount of $20,000.

BANKRUPTCY PROCEEDING

11 On 21 February, 21 March and 8 April 2024, the solicitors for the judgment creditors sent letters of demand to Mr Ejueyitsi for $13,000, being the debt owed under the lump sum costs order made by the District Court on 20 October 2022. Mr Ejueyitsi did not pay.

12 On 14 June 2024, the judgment creditors arranged for Murray Juchau – a process server – to personally serve Mr Ejueyitsi with a Bankruptcy Notice which had been issued on 10 May 2024 for the total debt amount of $13,000. At the hearing before me, Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor submitted that Mr Ejueyitsi now does not dispute that Mr Juchau attended his home to serve him on that day. However, Mr Ejueyitsi claims he was not at home and was not personally served. Mr Ejueyitsi has not paid the amount of the debt claimed in the Bankruptcy Notice.

13 By a Creditors’ Petition dated 25 September 2024, the petitioning creditors applied for a sequestration order against the estate of Mr Ejueyitsi.

14 On 22 October 2024, the petitioning creditors arranged for the same process server, Mr Juchau, to personally serve Mr Ejueyitsi at his home address with the Creditors’ Petition. On this de novo review, Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor informed the Court that the issue in relation to service was limited to service of the Bankruptcy Notice: T25.6 – T26.12.

15 The matter was listed for hearing before a Registrar on 28 November 2024. Mr Ejueyitsi appeared in person and told the Registrar that he had not received any documents in relation to the proceeding. As mentioned, on this application Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor informed the Court that service of the Creditor’s Petition and the accompanying documents was not in issue. In doing so, Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor observed that Mr Ejueyitsi had appeared at the hearing of the Creditors’ Petition on the date on which it was listed. The Creditor’s Petition was adjourned to 13 February 2025. It appears that the Registrar directed during the hearing that copies of all documents be re-served to Mr Ejueyitsi: T71.

16 On 11 December 2024, the petitioning creditors sent a letter to Mr Ejueyitsi enclosing copies of the Bankruptcy Notice, a sealed copy of the judgment of the District Court issued on 30 April 2024, a sealed affidavit of service of the Bankruptcy Notice, the Creditors’ Petition, a sealed affidavit of service of Creditors’ Petition, an affidavit of Isabella He dated 13 November 2024, an affidavit of Cassandra Bush dated 13 November 2024 and a short bill of costs dated 11 December 2024.

17 The Creditors’ Petition was heard and determined on 13 February 2025. Mr Ejueyitsi attended the hearing and appeared as a litigant in person. The Registrar made orders that Mr Ejueyitsi’s estate be sequestrated under the Bankruptcy Act and that petitioning creditors’ costs fixed in the sum of $10,923.00 be paid from Mr Ejueyitsi’s estate. By order 1 of the Registrar’s orders dated 13 February 2025, the Creditors’ Petition was amended by altering the date of the act of bankruptcy to 6 July 2024 (previously erroneously expressed to be 10 May 2024, being the date of the Bankruptcy Notice).

18 On 25 March 2025, Mr Ejueyitsi filed the present review application.

19 The Official Trustee’s report pursuant to r 7.06 of the Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth) was provided on 2 June 2025 and is in evidence on this application.

EVIDENCE

20 The petitioning creditors rely on the following evidence:

(1) an affidavit of Isabella He, the solicitor for the applicants, affirmed on 23 April 2025;

(2) an affidavit of Mr Juchau dated 16 May 2025 but not sworn until Mr Juchau adopted the affidavit in the witness box on this application on 12 September 2025, which in turn attaches what is described as:

(a) Exhibit MJ-1, an affidavit of Mr Juchau’s sworn on 4 July 2024;

(b) Exhibit MJ-2, another affidavit of Mr Juchau’s sworn on 23 October 2024; and

(c) Exhibit MJ-3, four colour photographs taken by Mr Juchau of Mr Ejueyitsi’s apartment building namely, an intercom system at the entry to the premises, a footpath, a front door and a screen door;

(3) an affidavit of Lachlan Scott, Director of Estate Administration within the Office of the Official Trustee in Bankruptcy, affirmed 2 June 2025 which constitutes the Official Trustee’s report;

(4) Exhibit 1, a Report to Creditors dated 7 May 2025; and

(5) Exhibit 2, the four colour photographs described in Exhibit MJ-3 above and dated by Mr Juchau in the witness box as being taken on 22 October 2024.

21 Included in the Court book is a further affidavit of Mr Juchau which was put to Mr Juchau in cross-examination. The dates on this affidavit vary. It is either dated 1 October 2024 or 2 October 2024. It reproduces the substantive content of Mr Juchau’s 4 July 2024 affidavit.

22 Mr Ejueyitsi relies on the following evidence:

(1) his affidavit affirmed on 2 May 2025 but only paragraphs 1-9 and the annexures to those paragraphs;

(2) his affidavit sworn on 26 May 2025; and

(3) an affidavit of Julie Aitken, a carer, dated 23 July 2025.

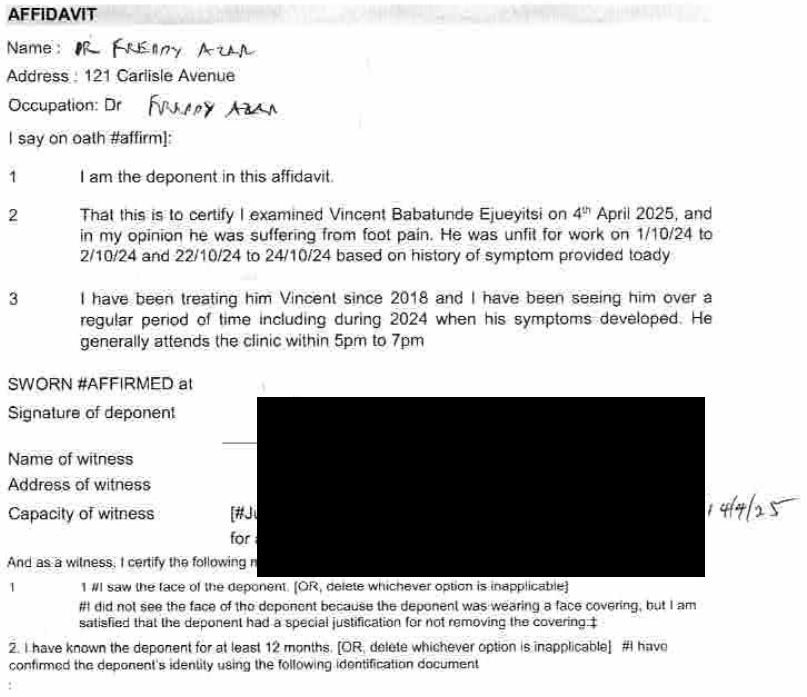

23 Annexed to paragraph 6 of Mr Ejueyitsi’s affidavit of 2 May 2025 is a short document that on its face is described as an affidavit, prepared in the style of “Form 40(version 6) UCPR”, of Dr Freddy Azar. Mr Ejueyitsi did not read this affidavit on this application. I have treated the affidavit as having been tendered by Mr Ejueyitsi. Mr Ejueyitsi was cross-examined on this document on the basis that it was an affidavit.

24 The following witnesses gave oral evidence and Mr Juchau, Mr Ejueyitsi and Ms Aitken were cross-examined:

(1) Mr Juchau;

(2) David Halling, Mr Juchau’s boss;

(3) Mr Ejueyitsi; and

(4) Ms Aitken.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK

25 A party may apply to the Court under s 35A(5) of the FCA Act and r 3.11 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) for review of the exercise of the power of the Court by a Registrar. Such an application must be made within 21 days after the day on which the power was exercised.

26 The sequestration order made by a Registrar takes effect as an exercise of judicial power by the judges of the Court but the exercise of that delegated power depends for its validity upon the availability of review by the judges of the Court: Bechara v Bates [2021] FCAFC 34 at [3] (Allsop CJ, Markovic and Colvin JJ). In contrast, a sequestration order made by a judge pursuant to s 43(1) of the Bankruptcy Act, may only be annulled pursuant to s 153A of the Bankruptcy Act.

27 The nature of delegated judicial power and a de novo review was considered in Robson as former trustee of the estate of Samsakopoulos v Body Corporate for Sanderling at Kings Beach CTS 2942 [2021] FCAFC 143; 286 FCR 494. Justice Colvin (with whom Allsop CJ, Markovic, Derrington and Anastassiou JJ agreed on this issue) said (at [63]):

Further, the de novo review is not to be seen as directed to a consideration of the correctness of the delegate's decision or redressing error by the delegate. On review, the Court hears the case again unaffected by what has gone before. However, the Court does not act as if there is a new appellate proceeding. The review task it undertakes is a determination again of an application that has already been listed for hearing and proceeds in the same manner that would be the case if the power had not been delegated. In consequence, on review, the Court can entertain new arguments, receive new evidence or adjourn the proceeding but only to the extent, and in the circumstances where, it would do so in a matter that had already been set down for determination. Further, the applicant on review is the applicant on the application irrespective of whether the applicant was successful before the delegate. The same onus arises as if the application was being heard for the first time. This has particular significance for the review of a sequestration order. The review is initiated by the debtor (now bankrupt by the order to be reviewed), but proceeds as an application by the creditor on its petition.

28 The Court has power to make a sequestration order on satisfaction of the following criteria pursuant to s 43(1) of the Bankruptcy Act which relevantly provides that:

Jurisdiction to make sequestration orders

(1) Subject to this Act, where:

(a) a debtor has committed an act of bankruptcy; and

(b) at the time when the act of bankruptcy was committed, the debtor:

(i) was personally present or ordinarily resident in Australia;

…

the Court may, on a petition presented by a creditor, make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

29 The act of bankruptcy presently relevant is that described in s 40(1)(g) of the Bankruptcy Act:

Acts of bankruptcy

(1) A debtor commits an act of bankruptcy in each of the following cases:

…

(g) if a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order, being a judgment or order the execution of which has not been stayed, has served on the debtor in Australia or, by leave of the Court, elsewhere, a bankruptcy notice under this Act and the debtor does not:

(i) where the notice was served in Australia--within the time fixed for compliance with the notice; or

…

comply with the requirements of the notice or satisfy the Court that he or she has a counter - claim, set - off or cross demand equal to or exceeding the amount of the judgment debt or sum payable under the final order, as the case may be, being a counter - claim, set - off or cross demand that he or she could not have set up in the action or proceeding in which the judgment or order was obtained;

30 Section 41(7) of the Bankruptcy Act provides:

Where, before the expiration of the time fixed for compliance with a bankruptcy notice, the debtor has applied to the Court for an order setting aside the bankruptcy notice on the ground that the debtor has such a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand as is referred to in paragraph 40(1)(g) , and the Court has not, before the expiration of that time, determined whether it is satisfied that the debtor has such a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand, that time shall be deemed to have been extended, immediately before its expiration, until and including the day on which the Court determines whether it is so satisfied.

31 A failure to comply with s 41(7) of the Bankruptcy Act is not a procedural irregularity capable of cure, but rather is fatal to jurisdiction: Van Eps v Child Support Registrar [2023] FCA 1068 at [31] (Collier J).

32 Section 51 of the Bankruptcy Act provides:

Subject to section 109 [of the Bankruptcy Act], the prosecution of a creditor’s petition to and including the making of a sequestration order on the petition shall be at the expense of the creditor.

33 Section 52 of the Bankruptcy Act relevantly provides:

(1) At the hearing of a creditor’s petition, the Court shall require proof of:

(a) the matters stated in the petition (for which purpose the Court may accept the affidavit verifying the petition as sufficient);

(b) service of the petition; and

(c) the fact that the debt or debts on which the petitioning creditor relies is or are still owing;

and, if it is satisfied with the proof of those matters, may make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

…

(2) If the Court is not satisfied with the proof of those matters, or is satisfied by the debtor:

(a) that he or she is able to pay his or her debts; or

(b) that for other sufficient cause a sequestration order ought not to be made;

it may dismiss the petition.

34 A judge who hears the review application must hear the petition afresh, must be satisfied as to the matters referred to in s 52 of the Bankruptcy Act and be satisfied with the proof of:

(1) the matters stated in the petition;

(2) the service of the petition; and

(3) the fact that the debt or debts on which the petitioning creditor relies is or are still owing.

See Totev v Sfar [2008] FCAFC 35; 167 FCR 193 at [14] (Emmett J), quoted with approval in Bechara at [21].

35 The onus is on the petitioning creditor to prosecute the petition at the rehearing. It is only if the Court is satisfied of the matters in s 52(1), that the person whose estate has been sequestrated will be required to discharge their onus in proving the matters in s 52(2) of the Bankruptcy Act, whether that be with respect to solvency or there being any other sufficient cause: Bechara at [27(d)].

36 Fundamental to the law of bankruptcy is that a sequestration order should not be made against the estate of a person who is solvent: Alam v QBE Insurance (Australia) Ltd [2018] FCA 1560 at [1]-[2] (Lee J), cited in Szepesvary v Weston as trustee of the bankrupt estate of Aaron Szepesvary [2018] FCAFC 224; 363 ALR 379 at [4] (Perry, Moshinsky and Lee JJ). It has been repeatedly affirmed by the Full Court that where a person is able, but unwilling, to pay their debts, the discretion to make a sequestration order will not usually be exercised to make a sequestration order: see Sarina v Council of the Shire of Wollondilly [1980] FCA 175; 48 FLR 372 at 375-376 (Bowen CJ, Sweeney and Lockhart JJ); Francis v Eggleston Mitchell Lawyers Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 18 at [50]-[51] (Rares, Flick and Bromberg JJ); Culleton v Balwyn Nominees Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 8; 343 ALR 632 at [40]-[44] (Allsop CJ, Dowsett and Besanko JJ); and Shaw v Yarranova Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 88; 252 FCR 267 at 290-291 [105]-[109] (North, Perry and Charlesworth JJ).

CONSIDERATION

37 The present application does not appear to have been filed within the requisite time prescribed by r 3.11 of the Rules and accordingly Mr Ejueyitsi requires an extension of time under r 1.39. There is a cryptic reference in the first application that Mr Ejueyitsi filed to an extension of time. I will treat the application for review as extending to an application for an extension of time as well. On this application, the parties each confirmed that they only relied on the latest iteration of their written submissions and did not rely on earlier versions of their respective submissions that had been exchanged and lodged. No submissions were directed to exercise of the Court’s discretion to grant an extension of time to file the application. In these circumstances, having regard to the minimal nature of the extension required, I proposed to deal with the substance of the grounds of opposition raised by Mr Ejueyitsi.

38 Before considering the substance of the grounds of opposition, I will first note that the further amended notice of opposition was filed and served on 17 July 2025 outside of the agreed timetable and absent any orders permitting the filing of a revised notice of objection. This is, in effect, Mr Ejueyitsi’s third attempt to frame his opposition to a sequestration order being made. The original notice of opposition filed on 10 February 2025 raised three grounds of opposition, all of which have since been abandoned. Of the two remaining grounds, one is a new ground — that the respondent was not served with the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024 — and the other — that the respondent was solvent — was introduced in the second iteration of the notice of opposition. Against that, as I have mentioned, Mr Ejueyitsi did not obtain legal representation until May 2025.

Petitioning creditors’ contention that Court has no jurisdiction on this review

39 The petitioning creditors raise a preliminary issue as to jurisdiction. They submit that the Court does not have jurisdiction to set aside the sequestration order because Mr Ejueyitsi did not comply with the time for filing an application to set aside the Bankruptcy Notice, or to extend the time within which to do so, in accordance with s 41(7) of the Bankruptcy Act. The petitioning creditors submit that the non-compliance with s 41(7) is fatal to this Court’s jurisdiction relying on Van Eps at [35] (Collier J). The petitioning creditors contend that Mr Ejueyitsi did not file the relevant application before the date of the act of bankruptcy, being 6 July 2024 and that the Court on the present application has no jurisdiction to set aside the sequestration order.

40 The petitioning creditors’ submission is wholly misconceived. It misapprehends the nature of the present application. This is an application for review of a decision of a Registrar exercising delegated power. It is not an application to extend the time for filing an application to set aside a bankruptcy notice after the time for compliance stipulated by s 41(7) of the Bankruptcy Act has elapsed. As the Full Court stated in Bechara at [2], it is an accepted incident of judicial power that it may be exercised by an order being made by a Registrar pursuant to a delegation, but only if the order may be reversed or otherwise corrected by a judge on review. Such a review is as of right and is by way of a de novo hearing. Fresh evidence may be adduced, as it has been here.

41 I reject the petitioning creditors’ submission as to the Court’s jurisdiction on the present application.

Issues arising for determination

42 The petitioning creditors rely on a total debt of $13,000 owed by Mr Ejueyitsi pursuant to orders of the District Court of New South Wales. That debt is not in dispute.

43 The petitioning creditors contend that Mr Ejueyitsi committed an act of bankruptcy within the meaning of s 40(1)(g) of the Bankruptcy Act, in that: (1) he was served on 14 June 2024 with a Bankruptcy Notice issued on 10 May 2024 and which required payment of $13,000 within 21 days of service of the notice (which if the bankruptcy notice was served on 14 June 2024 as claimed by the petitioning creditors translates to payment being required by 6 July 2024); and (2) he failed to comply with the Bankruptcy Notice. Mr Ejueyitsi contends that he was not personally served with the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024 and therefore he has not committed an act of bankruptcy within the terms of s 40(1)(g) of the Bankruptcy Act. It is not in dispute that at the relevant time Mr Ejueyitsi was personally present and ordinarily resident in Australia and that he has not paid the debt. The only issue in relation to whether Mr Ejueyitsi has committed an act of bankruptcy is whether he was served with the Bankruptcy Notice. The petitioning creditors bear the onus on this issue, and I must assess it afresh based on the evidence presented at this hearing.

44 If I am satisfied that the petitioning creditors have discharged their onus and established that Mr Ejueyitsi was served with the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024 (being within six months of the date it was issued in accordance with r 10(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth)) – with the consequence that he committed an act of bankruptcy on 6 July 2024 – then I must consider whether to make a sequestration order.

45 If I am satisfied that Mr Ejueyitsi committed the relevant act of bankruptcy, then there is no remaining issue in relation to proof of the matters set out in s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act. At the hearing of the application, as I have mentioned, Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor eschewed Mr Ejueyitsi’s earlier contention that he had not been served with the Creditors’ Petition. His sole argument on service was in relation to the Bankruptcy Notice.

46 That being so, if service is determined against Mr Ejueyitsi, then the only issue remaining for determination is whether the Court should dismiss the Creditors’ Petition under s 52(2) of the Bankruptcy Act, on the grounds that Mr Ejueyitsi has established that he is able to pay his debts. Mr Ejueyitsi bears the onus of establishing that he is able to pay his debts. Mr Ejueyitsi does not seek to establish, pursuant to s 52(2)(b), that there is any other sufficient cause for the Court to decline making a sequestration order.

47 Again, in my consideration of this issue, I must consider the issue afresh by reference to the evidence led on this application.

Issue 1: Service of the Bankruptcy Notice

48 The evidence before me on the issue of service is different from that which was before the Registrar.

49 The essential contest on the evidence before me is between Mr Ejueyitsi and Mr Juchau on the service issue. In addition, Mr Ejueyitsi relies on the evidence of Ms Aitken, a friend of his, who said that Mr Ejueyitsi was with her and a friend of hers at Darling Harbour at the time when Mr Juchau says he served the Bankruptcy Notice on Mr Ejueyitsi at his home in St Mary’s. Ms Aitken further says that she was with Mr Ejueyitsi from about 7.30pm to 11.30pm when he dropped her home. Mr Ejueyitsi submits that based on his evidence and Ms Aitken’s evidence, I should reject Mr Juchau’s evidence that he served Mr Ejueyitsi at his home at 8.45pm on that same day.

50 Service of the Bankruptcy Notice is an issue on which the petitioning creditors bear the onus. It is an essential element of proving the act of bankruptcy on which the petitioning creditors rely under s 40(1)(g) of the Bankruptcy Act. Each of the central witnesses on this issue provided affidavits. They were each cross-examined. I had an opportunity to observe each of them carefully during their evidence. I have concluded, applying the civil standard, that the petitioning creditors have discharged their onus. I find that Mr Ejueyitsi was personally served on 14 June 2024 by Mr Juchau at his residential address. My reasons for making that finding of fact are as follows. In making this finding, I should make clear from the outset that I do not make adverse credit findings against Ms Aitken. Rather, in the context of the evidence as a whole and noting the time that had elapsed between 14 June 2024 and when she was asked to provide an affidavit (23 July 2025) and her lack of any contemporaneous note or record, I find that Ms Aitken is mistaken as to the date or time on which she was in Darling Harbour with Mr Ejueyitsi. I will address Ms Aitken’s evidence in more detail below.

51 Mr Juchau’s job as a process server involves repeatedly performing what is essentially a routine task at different addresses in relation to different people, day in and day out. He has worked for Mr Halling as a process server for “years”: T20.14. In this case, he was giving evidence about two episodes of service. The first was about 15 months before he was required to give oral evidence. The second was about 11 months before he was called to give evidence. He had sworn an affidavit in relation to each occasion relatively soon after the event.

52 Not surprisingly given the nature of his job, Mr Juchau in giving his evidence answered by recourse to his usual practice when describing how he goes about serving a person, the way in which he gains access to secure buildings in order to effect service and his practice in relation to swearing affidavits of service. In cross-examination, Mr Juchau outlined his standard procedure when serving documents: he approaches the residence, asks for the named individual, and relies on cues such as a “nod or wink” to confirm identity before presenting the documents. If they indicate they are the person named on the documents, he will then proceed to show them the documents and the name on the documents. For example, when asked how he accessed Mr Ejueyitsi’s flat which was situated in a secure building, he answered by reference to how he usually gained access to secure buildings — by being given access by someone entering or exiting the building or pressing buzzers until someone lets him in. He was candid in acknowledging that he did not recollect how he gained access to Mr Ejueyitsi’s block of flats. That was not a matter that he had noted in his affidavit which addressed this occasion. He was firm in maintaining that he did gain access on both occasions. Given the photographs he took, that line of cross-examination went nowhere.

53 Mr Juchau acknowledged that his affidavits were prepared by Mr Halling, his employer — “He does all the affidavits”: T.17. Mr Juchau did not seek to conceal this fact — he repeatedly said that he does not prepare the affidavits, Mr Halling does. He frankly acknowledged that Mr Halling always has, for years: T.20. Mr Juchau said that the account given in the affidavit in relation to service came from what he told Mr Halling. He said that in the course of his work he reported to Mr Halling by phone or sometimes by email as to what had transpired when he attended to serve documents. He was challenged as to whether his affidavits were prepared based on his usual practice and not what actually happened. He confirmed that his affidavits in relation to serving Mr Ejueyitsi described what actually happened on each of the particular occasions.

54 Mr Juchau first attended Mr Ejueyitsi’s address on 14 June 2024. On that occasion he says he served Mr Ejueyitsi personally with the Bankruptcy Notice. He says that Mr Ejueyitsi accepted service by physically taking the documents from Mr Juchau. He first swore an affidavit deposing to this occasion on 4 July 2024. Mr Juchau deposed that he followed this same approach when serving Mr Ejueyitsi. He deposed that he had the following conversation with Mr Ejueyitsi at the residential address on 14 June 2024 (as written):

I spoke with a male person whos English appeared to be limited.

I said, “Are you Vincent Ejueyitsi?”

He nodded and said, “Yes.”

I then said, “Please check your name (and pointed to the documentation), is this you as mentioned this Bankruptcy notice?”

He looked at the document and his name and nodded, and said, “Yes.”

55 He was challenged on why he had not taken photos when he attended on 14 June 2024. He said he had. He accessed his phone and showed the cross-examiner the photographs on his phone which were taken on 14 June 2024 at 8.10pm and 8.11pm. Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor acknowledged that he would no longer submit that Mr Juchau had not attended the premises on 14 June 2024. Mr Ejueyitsi no longer disputes that Mr Juchau attended his residence on that day for the purpose of serving him with the Bankruptcy Notice. He does however dispute that the Bankruptcy Notice was given to him. He says it could not have been because he was not at home at 8.45pm when service is said to have been effected. He says that Mr Juchau must have given the documents to someone else at his address. Mr Ejueyitsi’s evidence is silent as to whether he shared his rented premises with anyone else or whether anyone else was at his residence on each of the two days on which Mr Juchau attended. That is a matter on which Mr Ejueyitsi could have led evidence. I infer from his failure to do so, that evidence on this topic would not have assisted him.

56 Mr Juchau deposes to serving the Creditors’ Petition on Mr Ejueyitsi in the same manner on 22 October 2024. Mr Juchau deposes as follows in relation to his attendance on 22 October 2024 when he served Mr Ejueyitsi with the Creditors’ Petition (as written):

I spoke with a male person who’s English appeared to be limited.

I know the person served, as I have previously served the defendant in relation to this matter

I said, “Are you Vincent Ejueyitsi?”

He nodded and said, “Yes.”

I said, “I have been here before. This is a Creditor’s Petition, can you check your name (and pointed to the documentation), is this you in the document?”

He looked at the document and to his name, and nodded and replied, “Yes.”

I then handed the documents to Vincent Ejueyitsi, and he accepted service by physically taking the documents from me.

57 Mr Ejueyitsi now accepts that he was served by Mr Juchau on this occasion, but he did for a considerable period of time deny that he was served with the Creditors’ Petition on this date at his home. Mr Juchau was not challenged in cross-examination on the basis that he served a different person on each of the occasions on which he attended Mr Ejueyitsi’s residence. In closing submissions, Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor submitted that I should place weight on the fact that Mr Juchau did not in his oral evidence point to Mr Ejueyitsi in the courtroom and say that he was the person that Mr Juchau served. I do not place any weight on that because I would have attached little if any weight to any attempt by Mr Juchau to identify Mr Ejueyitsi in the courtroom in circumstances where Mr Ejueyitsi had clearly identified himself as the respondent and was sitting behind his solicitor giving instructions.

58 In aid of the submission that it was not Mr Ejueyitsi that Mr Juchau served but someone else, Mr Ejueyitsi submits that he is not a person whose English is limited and so it could not have been him that Mr Juchau served. The contemporaneous records in evidence before me indicate that Mr Ejueyitsi takes umbrage at being described as a person “who’s English appeared to be limited” and when he received Mr Juchau’s affidavits, he went to Mr Juchau’s work address to complain about this amongst other things. In his affidavit, Mr Ejueyitsi responded to the suggestion that his English was limited in the following way (as written):

I have seen an affidavit of service by a process server. The address at which the process server referred is a gated environment/community setup. I had never met the process server once in my life and the process server described the person he served in the affidavits as “Vincent Ejueyitsi”, a person appeared has limited English. I am not limited in English, I am a student of the college/school of law program in Australia and is being conducted in English language by reputable and distinguished professors and doctors from the great University of Sydney that had produced distinguish Justices and renowned scholars. Even at the date the process server claimed he served me I was at the surgery with foot pain. See Annexure and marked attachment ‘A’. To be opportuned to be at the school of law and passed at college of law my English is not limited but with the power and ability to argue as plaintiff/applicant and defendant/respondent with guidance in moot classes as examination requirement.

The only thing the Applicant relied on to proof service was the affidavit of service and the statement in the affidavit which indeed do not tally with my written and speaking ability given the standard in College of Law/School of Law. He must have served a different person and not me. …

59 In cross-examination, Mr Juchau said that he formed the view that Mr Ejueyitsi’s English appeared to be limited because he did not respond clearly. He added that he has experience speaking “to hundreds of people every day” and can therefore “tell by whether their English is poor or whether their English is good”: T18. Mr Juchau was cross-examined on his observation about Mr Ejueyitsi’s limited proficiency in the English language. The ultimate thesis informing the cross-examination was that because Mr Ejueyitsi is in fact proficient in English and could not be mistaken for being otherwise that I should infer that Mr Juchau served someone other than Mr Ejueyitsi. I do not make that inference.

60 I had opportunity to attend closely on Mr Ejueyitsi when he was giving evidence. I repeatedly had to ask him to speak clearly and slowly as it was difficult to understand what he was saying. While he may well be proficient in English, he speaks English with a strong accent and he speaks fast. In answering questions, he goes off on tangents and it was at times difficult to follow what he was trying to communicate. An instance of this was when he was asked if he knew the name of the restaurant where he said he was having dinner in Darling Harbour at the very time when Mr Juchau says he served him at his home and he gave a long answer about not knowing the names of the coffee shops in Macquarie Street, Sydney.

61 I infer that the conversations recounted in Mr Juchau’s affidavits record what he regarded at the time as the salient details of what was said but it is likely that more was said than is recounted, although the extra dialogue may have been perceived by Mr Juchau to be trivial and for that reason it was not recounted verbatim to Mr Halling when Mr Juchau reported back. I do not infer that because Mr Juchau described the person he served as having limited English that it follows that that person was not Mr Ejueyitsi. To the contrary, I think it more likely that Mr Juchau during his brief interactions with Mr Ejueyitsi found it difficult to understand him and concluded based on that difficulty of comprehension that Mr Ejueyitsi had limited English.

62 Mr Juchau deposed that he normally asks the relevant individual whether they live at the specified address named on the document but did not hesitate to accept that if he had asked Mr Ejueyitsi that then he would have said so in his affidavit. He also accepted that he did not have a photograph of Mr Ejueyitsi. When asked how he knew that it was Mr Ejueyitsi, Mr Juchau said:

It was him. Trust me. And he knew exactly all about the documents, and he acknowledged his name. I asked for his name. He gave it to me. I mean, he – he – he nodded in – in agreement when I said, “Are you Vincent” – I can’t pronounce his name. And then I showed him the documents, what they were, and then he took the documents. If it wasn’t him, why did he take the documents?

63 Mr Juchau was not an articulate or sophisticated witness. I do not accept some of the assertions he made in the witness box as to his power to ascertain a person’s true identity. I do however accept that he said “Are you Vincent” and that Mr Ejueyitsi agreed. I accept that he pointed to Mr Ejueyitsi’s name on the documents comprising the Bankruptcy Notice. I accept that Mr Juchau could not pronounce Mr Ejueyitsi’s surname. I accept that after pointing to Mr Ejueyitsi’s name on the documents, that Mr Juchau handed the documents to Mr Ejueyitsi and that Mr Ejueyitsi accepted them. I do not accept Mr Ejueyitsi’s denials in relation to the service of the Bankruptcy Notice for reasons to which I will come.

64 The second occasion on which Mr Juchau attended Mr Ejueyitsi’s address was on 22 October 2024 when he served the Creditors’ Petition. He first swore an affidavit deposing to this occasion on the next day 23 October 2024. He took photos of the building and entry way to Mr Ejueyitsi’s residence which during the hearing were accepted to have been taken on 22 October 2024. Although Mr Ejueyitsi has disputed that he was served on 22 October 2024, and tendered evidence on which he relied to contend that he was not served on 22 October 2024, at the hearing his solicitor confirmed that Mr Ejueyitsi does not now dispute he was served on this date with the Creditors’ Petition.

65 Mr Juchau presented as an honest witness. He made appropriate concessions and was clear when answering questions in differentiating between what he could and could not remember when giving evidence in the witness box. He was somewhat combative in cross-examination but that appeared to me to be as a result of frustration where he did apprehend the question or where he did not understand that certain propositions were being put to him as a matter of procedural fairness given Mr Ejueyitsi’s version of events. When I intervened to explain that aspect of the questioning, Mr Juchau answered the questions put to him in a forthright manner. I took him to be doing his best to answer the questions put to him.

66 I accept Mr Juchau has a practice of reporting to his boss, Mr Halling, on a relatively contemporaneous basis, as to what transpires when he serves a person. I also accept that Mr Halling takes the information provided to him by Mr Juchau and incorporates it into an affidavit, which Mr Juchau later swears. I accept that Mr Juchau followed this practice in relation to the affidavits he swore on 4 July 2024 and 23 October 2024. I regard his affidavits of 4 July 2024 and 23 October 2024 to be reliable evidence in relation to each of the occasions on which he attended Mr Ejueyitsi’s premises. I infer that the affidavits are based on Mr Juchau causing Mr Halling to take a note at a time when Mr Juchau’s recollection was fresh. The affidavit as prepared by Mr Halling was then adopted by Mr Juchau swearing the contents to be true at a time when Mr Juchau had a clear recollection of the events described in the affidavit. In this regard, I note that Mr Halling was called as a witness. His evidence in chief was principally in relation to Mr Ejueyitsi’s communication with and attendance at Mr Halling’s office to complain that he was not served with the Creditors’ Petition on 22 October 2024. Mr Halling was not cross-examined.

67 Mr Juchau offered to produce his phone in the witness box to demonstrate the dates on which he had taken photographs during his attendance at Mr Ejueyitsi’s address. After that was done, Mr Ejueyitsi’s solicitor accepted that Mr Juchau did attend Mr Ejueyitsi’s address on 14 June 2024 but not that the person to whom the Bankruptcy Notice was handed was Mr Ejueyitsi. The issue having reduced to whether Mr Juchau handed the Bankruptcy Notice to Mr Ejueyitsi or another person, there is a problem with Mr Ejueyitsi’s contention that it was not Mr Ejueyitsi who was served. The problem is that Mr Ejueyitsi now accepts that he was served by Mr Juchau on 22 October 2024 with the Creditors’ Petition whereas for a long time he denied that was what had occurred.

68 On the whole of Mr Juchau’s evidence, I am satisfied on the balance of probabilities that Mr Ejueyitsi was served with the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024. The evidence given by Mr Ejueyitsi and Ms Aitken does not cause me to depart from this conclusion. My reasons are as follows.

69 Mr Ejueyitsi was not an impressive witness. He changed his story in a number of material ways. He was prone to give dissembling and argumentative answers. In part, I think that probably reflects his manner of speaking where instead of answering questions directly he would answer by posing a rhetorical question or launching into a rhetorical narrative. But, it was not just a manner of speaking, there were parts of his evidence on important matters that were inconsistent and simply not credible. I will address the shifts in his evidence thematically.

70 First, it was ultimately not in contention that Mr Juchau attended Mr Ejueyitsi’s residence on both the following dates: 14 June 2024 (service of the Bankruptcy Notice) and 22 October 2024 (service of the Creditors’ Petition). Mr Ejueyitsi originally contended that Mr Juchau did not attend his residence on either of these occasions. By the close of evidence, it was submitted on Mr Ejueyitsi’s behalf that he accepted that Mr Juchau did attend his residence on both of these occasions. That concession was made on the basis of Mr Ejueyitsi’s acceptance that Mr Juchau took photos of his apartment building and the door of his flat on these occasions.

71 Second, Mr Juchau maintains that he personally served Mr Ejueyitsi on each of these occasions. He was firm in his evidence that he served the same person on both occasions. Mr Ejueyitsi originally contended that he was not served by Mr Juchau on either of these occasions. However, Mr Ejueyitsi ultimately did not dispute that he was served on the second occasion with the Creditors’ Petition. There is no suggestion in the evidence that anyone other than Mr Juchau was involved in serving Mr Ejueyitsi on either of these occasions. Mr Ejueyitsi does not explain in his evidence when it was that he was served with the Creditors’ Petition if it was not when Mr Juchau attended his residence on 22 October 2024. In reaching that conclusion I have not overlooked that Mr Ejueyitsi asserts he obtained copies of various documents after the first hearing before the Registrar. The point is he now accepts he was served by Mr Juchau with the Creditors’ Petition on 22 October 2024. Given that Mr Ejueyitsi attended at the first return of the Creditors’ Petition before the Registrar, it would have been difficult for Mr Ejueyitsi to maintain that he was not served with the Creditors’ Petition on 22 October 2024.

72 Third, before Mr Ejueyitsi conceded at the hearing that he was served with the Creditors’ Petition, he gave evidence that he could not have been served by Mr Juchau on 22 October 2024 as alleged at his residence. He gave elaborate evidence as to why he could not have been at home on 22 October 2024. His evidence extended to asserting that he had been at a medical appointment with Dr Azar. As I have mentioned, Mr Ejueyitsi relies on a document described as an affidavit of Dr Azar which purports to be sworn or affirmed and which was annexed to one of Mr Ejueyitsi’s affidavits. It is convenient to extract the substantive part of the document (signatures redacted):

73 The document is hand dated 14 April 2025. On its face, Dr Azar appears to certify that Mr Ejueyitsi attended for examination on 4 April 2025 reporting foot pain. In this proceeding, Mr Ejueyitsi’s description as to the nature of the pain has changed over time to include foot pain, arm pain and shoulder pain. But more critically, Dr Azar’s affidavit does little more than record what Mr Ejueyitsi told Dr Azar about being unfit for work on specified dates in October 2024, including the date on which he was served with the Creditors’ Petition. In his oral evidence, he claimed that Dr Azar looked at his electronic records and confirmed that Mr Ejueyitsi had attended his surgery on the dates listed. That is not what is said in this affidavit and appeared to be something that Mr Ejueyitsi made up on the spot when giving his evidence. In the Azar affidavit, Dr Azar expressly records that the dates he has listed derive from the history taken by Dr Azar from Mr Ejueyitsi on 4 April 2025 as to alleged past periods of incapacity in October of the previous year. On the basis of this affidavit, Mr Ejueyitsi did not attend Dr Azar until about seven weeks after the sequestration order was made and some 164 days after the date on which he now accepts that he was served with the Creditors’ Petition. Mr Ejueyitsi was unable to produce a receipt or any other form of documentation to confirm that he attended a consultation on 22 October 2024. Even had he done so, it would not have rendered it impossible that Mr Ejueyitsi was at home and served with the Creditors’ Petition on 22 October 2024, as he now accepts he was.

74 Mr Ejueyitsi’s main contention in relation to service of the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024 is that he was not at home at the relevant time and was not served. He says that he was at dinner at Darling Harbour with Ms Aitken and another friend of Ms Aitken’s.

75 There is no evidence in Mr Ejueyitsi’s affidavits dated 2 May 2025 and 26 May 2025 in relation to his whereabouts on 14 June 2024.

76 In his examination-in-chief, Mr Ejueyitsi said that on 14 June 2024 he saw a doctor temporarily around 5.00pm to 7.00pm and then left to go to the city: T31. He said that he met Ms Aitken at around 8.15pm for dinner in Darling Harbour: T32. Mr Ejueyitsi said that Ms Aitken’s friend, Jenny, who was visiting Australia from Thailand joined him and Ms Aitken for dinner: T32-T33.

77 Mr Ejueyitsi gave evidence that the three of them went to a restaurant for dinner, although, he could not recall the name of the restaurant: T32. He said that he paid for his own portion of the dinner, although when asked if he could produce any proof of payment or any other documentation to confirm that he attended the dinner he said he could not recall if he paid for dinner at all: T34.

78 According to Mr Ejueyitsi, they stayed in Darling Harbour for quite some time, before he drove Ms Aitken back to her home around 11.00pm: T33.

79 Ms Aitken deposed that on 14 June 2024, at about 8.15pm, she met Mr Ejueyitsi at Darling Harbour for dinner. In cross-examination she was more equivocal. She said “he came later, like mid-afternoon”. She then said she met him after 7.30pm and that they were eating “about 8, 8.15. Yes. Just after 8 we were eating”: T56. She said that they did not eat dinner at a restaurant – they just walked around and had something to eat: T55. Ms Aitken said that her friend, Jenny Green, was also there: T56. Critically in relation to how she knew that it was on the 14 June 2024 that she met Mr Ejueyitsi at Darling Harbour, she said (at T56):

I was with my girlfriend. That’s how – how I know it was the 14th. She’s from Thailand, and she was heading back on the 16th.

80 She gave evidence that Mr Ejueyitsi drove her home about 11.30pm: T56.

81 Ms Aitken said that Mr Ejueyitsi could not have been served because he was with her at Darling Harbour. It was put to her she did not have dinner with Mr Ejueyitsi at Darling Harbour on 14 June 2024 because he was at home and was served by a process-server at 8.45pm on that day. Ms Aitken adhered to her evidence.

82 Ms Aitken is a friend of Mr Ejueyitsi’s. She presented as doing her best to answer questions directly and honestly. She was giving evidence from memory about having a dinner with Mr Ejueyitsi about a year earlier. She does not appear to have been asked to recall what she was doing on 14 June 2024 until about a year later when she was asked to provide her affidavit. As I have mentioned, Mr Ejueyitsi did not rely on any evidence from Ms Aitken before the Registrar and did not refer to her in his own affidavits. She had no contemporaneous note or record which referred to the time and or date of the relevant visit to Darling Harbour to 14 June 2024. She hypothesised that it was 14 June 2024 because her friend Jenny was there and her recollection was that her friend Jenny returned to Thailand on 16 June 2024. The circumstances in which Ms Aitken came to provide evidence are such that I think it is probable that she was mistaken as to the time and or date on which she visited Darling Harbour with Mr Ejueyitsi. While I accept that the visit took place some time around 14 June 2024, I find that Ms Aitken is mistaken as to Mr Ejueyitsi being with her at the time when Mr Juchau attended his residence on 14 June 2024 to serve the Bankruptcy Notice. I prefer Mr Juchau’s evidence which is supported by relatively contemporaneous notes in the form of his affidavit and also the photographs which were taken on 14 June 2024.

83 Taking into account the evidence as a whole, I am satisfied to the civil standard that Mr Ejueyitsi was served with the Bankruptcy Notice on 14 June 2024. He committed an act of bankruptcy on 6 July 2024. I am satisfied that the petitioning creditors have established each of the matters on which they bear the onus under s 52(1) of the Bankruptcy Act.

84 I now turn to consider the issue of whether Mr Ejueyitsi is able to pay his debts within the meaning of s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act.

Issue 2: Mr Ejueyitsi is able to pay his debts

85 It is well established that a debtor bears the onus of proving on the civil standard that he is able to pay his debts: Culleton at 644 to 645 [44] (Allsop CJ, Dowsett and Besanko JJ); Coates Hire Operations Pty Ltd v D-Link Homes Pty Ltd [2011] NSWSC 1279 at [66] (White J, as his Honour then was); Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Bayconnection Property Developments Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 363; 127 ALD 64 at [60]-[61] (Robertson J). The nature of the evidence necessary to discharge the onus will vary from case to case — a debtor resisting a creditor’s petition on the basis that they are solvent is ordinarily expected to adduce the most cogent evidence available to them, which evidence would then fall to be assessed in accordance with the principle in Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65; 98 ER 969 at 970 (Lord Mansfield): see Mangano v Bullen [2025] FCAFC 42 at [29]-[30].

86 I have proceeded on the basis that in this context solvency is a question of fact, consistently with Mangano v Bullen at [31]. The parties did not contend otherwise.

87 Where the law requires proof of any fact, the Court must “feel an actual persuasion” of the occurrence or existence of that fact before it can be found: Axon v Axon [1937] HCA 80; 59 CLR 395 at 403 (Dixon J); Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361-363 (Dixon J); Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing & Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 at [31]-[32] (Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ); Mangano v Bullen at [31].

88 I addressed this issue in Mangano v Bullen at [36] as follows:

Section 52(2) relevantly requires the Court to be “satisfied by the debtor … that he or she is able to pay his or her debts”. As to what is required to attain a state of satisfaction in relation to, relevantly, a state of affairs, the observations of Dixon CJ (with whom Taylor J agreed) in Murray v Murray (1960) 33ALJR 521 at 524, are apposite:

What the civil standard of proof requires is that the tribunal of fact, in this case the judge, shall be “satisfied” or “reasonably satisfied”. … But the point is that the tribunal must be satisfied of the affirmative of the issue. The law goes on to say that he is at liberty to be satisfied upon a balance of probabilities. It does not say that he is to balance probabilities and say which way they incline. If in the end he has no opinion as to what happened, well it is unfortunate but he is not “satisfied” and his speculative reactions to the imaginary behaviour of the metaphorical scales will not enable him to find the issue mechanically.

(Bold emphasis added.)

89 Applying the principles to which I have already referred I accept that a sequestration order will not usually be made against a debtor who is able but unwilling to pay their debts but in the present circumstances I am not satisfied in the requisite way that Mr Ejueyitsi is able to pay his debts as is required by s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act.

90 There is limited information about Mr Ejueyitsi’s circumstances revealed by the evidence on this application. The totality of the evidence before me does not enable me to reach the requisite satisfaction that Mr Ejueyitsi is able to pay his debts in accordance with the civil standard. I am left in the unfortunate position of not being able to be satisfied on the topic — to borrow from Dixon CJ in Murray, the evidence is such that I have “no opinion” on the topic. My conclusion in that regard is fortified by reference to the principle in Blatch v Archer.

91 Mr Ejueyitsi is 64 years old. As I have mentioned, he has filed a number of affidavits, parts of which were read on this application. He also gave oral evidence and was cross-examined. As mentioned, Mr Ejueyitsi speaks fast and did not answer questions directly when he gave his evidence. He introduced irrelevancies that were at best tangential instead of answering the question he was asked. His oral evidence was difficult to understand; I intervened to ask that he speak more slowly and clearly so that I may follow his evidence. He appeared to attempt to do so but his oral evidence was hard to follow both as to what he was saying and also in terms of ascertaining what his evidence was as there were inconsistencies in what he said.

92 Mr Ejueyitsi has not lodged a statement of affairs with the Trustee, despite repeated requests. The Trustee has communicated the requirement for the lodgement of, and the consequence of failing to provide, a statement of affairs to Mr Ejueyitsi.

93 Mr Ejueyitsi is divorced and has a 14-year-old child. The evidence does not reveal any information in relation to any liability he has to make child support payments and whether he makes such payments and if so, if he is up to date in making those payments. He works as a taxi driver and operates a company called Oris and Otis Pty Ltd. There was no company search for Oris and Otis in evidence. He says Oris and Otis is his company.

94 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that he earns between $500 and $700 per week from driving a taxi. He has not produced any documentary evidence to support his claimed income from driving a taxi. His evidence on this issue was difficult to follow. At times, he asserted he was paid for his work in driving a taxi, at other times he said that he received no wage but that his company received income from his efforts in driving the taxi. He has not produced any of his personal tax returns or the tax returns of his company in support of his competing accounts of the income that either he or his company earn from his taxi driving efforts. He has not produced any documentation in support of his assertions such as wage records, group certificates or tax returns.

95 Mr Ejueyitsi asserts that he has no personal tax debt. In support of this assertion, he relies on what appears to be a screenshot of an Activity Statement generated from the Australian Taxation Office portal for his company, Oris and Otis. The Activity Statement is dated 26 May 2025 with a debit balance of $481.00. That does not shed any light on his assertion that he does not have any personal tax liabilities. Against this, in the Trustee’s report to creditors, the Trustee deposes to a proof of debt being lodged in Mr Ejueyitsi’s bankrupt estate by the Australian Taxation Office in the amount of $12,873. Mr Ejueyitsi was in a position to call evidence to support his assertion that he has no personal tax liability. He did not do so.

96 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that he has a bank account with Bank of Queensland (BOQ). He has placed only a single bank statement for the period from 19 September 2024 to 18 March 2025 from this account into evidence. Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that he has other bank accounts with St George Bank. Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that the balance of the St George accounts is around $990. In his oral evidence, he said he held another bank account with the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA). Mr Ejueyitsi did not place any statements from the St George or CBA bank accounts into evidence. The St George and CBA bank accounts are not referred to in the Trustee’s report to creditors.

97 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that he is a student of the college of law program conducted by the University of Sydney. In his oral evidence he said under cross-examination that he had a HECs liability. Other than describing his HECs liability as being a “pressing liability”, he provided no other information in relation to that liability.

98 In his oral evidence, Mr Ejueyitsi made a distinction between “pressing” and “non-pressing” liabilities. He acknowledged his HECS debt as a “pressing” liability, whereas he said he had no “non-pressing” liabilities such as electricity and water bills.

99 Mr Ejueyitsi lives in rented accommodation; he says that he pays around $330 per week in rent. He has not produced any documentary evidence in support of his assertion. The single BOQ bank account statement that he has put in evidence does not include meaningful transaction details concerning the debit entries (by way of withdrawal and transfers from the account).

100 He was cross-examined on an entry on his bank statement dated 18 February 2025 with descriptor “Withdrawal WA Govt Garnishee” in the amount of $824.95. Mr Ejueyitsi says that the payment relates to parking fines issued in Western Australia. His oral evidence on this topic was convoluted about the frequency and amounts of the payments and if they were recurring. His oral evidence was not supported by documentary evidence in relation to the garnishee and its present operation.

101 Mr Ejueyitsi is the sole registered proprietor of a real property located in St Mary’s, New South Wales (the Property). The Property was purchased for $460,000 in March 2024. Pepper Finance Corporation Limited holds a first mortgage over the Property. The principal amount of the mortgage was $372,416. As to the value of the Property, Mr Ejueyitsi relies on an internet printout from the Domain property website. The Domain internet printout shows the estimated value of the Property to be in the range “Low $430K Mid $500K High $570K”. There is a dearth of probative evidence before me as to the present value of the net equity that Mr Ejueyitsi may have in this Property.

102 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that the strata fees and rates on his Property are up to date. He did not produce any documentary evidence in support of his assertion. He did not give evidence himself or produce any documentary evidence as to quantum or frequency of his payments for strata fees and rates.

103 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes as to his mortgage repayments of $727.14 per fortnight. He did not produce any account statement to demonstrate that he is meeting his liability to make repayments. On its face, the BOQ statement does not identify any of the transfers out of the account as mortgage payments to Pepper Finance.

104 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that the Property is rented through Ray White St Mary’s and that he receives fortnightly rental payments. Mr Ejueyitsi says that the rental payments are paid into Mr Ejueyitsi’s bank account ending 1853 held with the BOQ (the 1853 Account). The bank statement in evidence for the 1853 Account shows weekly payments of $969.00. There is no evidence relating to fees payable to a real estate agent or property maintenance charges and whether the payments in respect of rent are made into Mr Ejueyitsi’s account on a net basis.

105 Mr Ejueyitsi deposes that he owns a car which he says is worth approximately $28,000. There is no certificate of registration in evidence. In cross-examination, Mr Ejueyitsi gave evidence that he took his car to a car dealer who valued it for him. He could not point to any documentary evidence of a valuation in the amount of $28,000.

106 Mr Ejueyitsi says that other than the “unquantified and unassessed costs orders” in relation to the Local Court proceeding and the Court of Appeal proceeding, Mr Ejueyitsi has no other liabilities.

107 On 27 February 2025, the Trustee withdrew $21,014.61 from the 1853 Account. Mr Ejueyitsi contends that the fact that the funds withdrawn from his account exceeded the debt the subject of the Bankruptcy Notice demonstrates that he was able to meet his debts within the meaning of s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act.

108 Mr Ejueyitsi further submits that I should conclude that he was able as at 13 February 2025 to pay the debt that is the subject of the petitioning creditors’ claim and that is the only debt that is relevant. Further, the fact that he has been unwilling to pay that debt does not bear on whether he is able to pay that debt.

109 I reject Mr Ejueyitsi’s submissions for two principal reasons.

110 First, he proceeds on a misapprehension of what is required under s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. He is required to prove that he is able to pay his debts (plural). Here, what Mr Ejueyitsi is required to prove is not limited to proof that he is able to pay the singular debt which is the subject of the Bankruptcy Notice. While I accept that s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act is directed to an assessment as to whether a debtor is able to pay and not to whether a debtor is willing and able to pay, the focus of that enquiry in not limited to the debt that is the subject of the petition. The debtor is required to prove that he is in fact solvent on a cash flow basis by reference to all of his or her debts. That requires probative evidence to be led, which is then assessed by the Court on an inductive basis and the Court must decide whether on the balance of probabilities the debtor is as a matter of fact able to pay his or her debts. In making such a finding of fact the Court must feel an actual persuasion that the debtor is able to pay his or her debts. Where the evidence does not enable the Court to reach such a conclusion, the debtor will have failed to discharge his or her onus.

111 Second, the evidence led by Mr Ejueyitsi does not enable me to conclude that he is able to discharge his debts. The test for solvency is a cash flow test: Do (Trustee), Andrew Superannuation Fund v Sijabat [2023] FCAFC 6; 295 FCR 584 at [148] (Markovic, Halley and Goodman JJ). It is not sufficient to simply establish that one’s assets exceed one’s liabilities in value: Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd v Foyster [2000] FCA 400 at [17] (Hely J). While Mr Ejueyitsi’s credit resources are properly to be taken into account, the evidence he has led does not supply a probative basis upon which I can form an opinion as to his present equity in the Property. In short, his evidence does not establish on a balance of probabilities that he is solvent on a cash flow basis. Mr Ejueyitsi’s unverified claims of ownership and valuation are not probative of his solvency. That is especially so when his evidence in this proceeding has been inconsistent and variable. The probative value of the evidence is such that I cannot conclude on the civil standard that he is able to pay his debts. The deficiencies in the cross-examination of Mr Ejueyitsi cannot convert the paucity of Mr Ejueyitsi’s evidence on matters that clearly inform whether he is solvent on a cash flow basis into a satisfactory evidentiary foundation for the Court to reach a level of satisfaction to the requisite standard as to his solvency on a cashflow basis.

112 On many issues, including critical matters on which it would be expected that supporting evidence would be led, Mr Ejueyitsi’s evidence does not rise above bare assertion. In other areas, his evidence is inconsistent and blurs the line between his and his company’s affairs. I am left in the position where I have no opinion as to whether Mr Ejueyitsi can or cannot pay his debts. It was within Mr Ejueyitsi’s capability to adduce evidence, if such evidence was available, that would enable the Court to make a cogent assessment of whether he is able to pay his debts. He has not done so. I infer such evidence as was available to him would not have assisted him in establishing solvency. He has not adduced sufficient evidence to support the factual finding for which he contends under s 52(2)(a).

113 As I have said, Mr Ejueyitsi does not contend that there is any other sufficient cause under s 52(2)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act to refuse to make a sequestration order.

114 Mr Ejueyitsi did not submit that there was a sufficient cause not to make the sequestration order for the purpose of s 52(2) of the Bankruptcy Act. Having regard to the whole of the evidence before me, I am satisfied that the discretion to make a sequestration order is enlivened and that it is appropriate to make such an order.

CONCLUSION

115 For the reasons I have given, I will exercise the discretion to make a sequestration order against Mr Ejueyitsi. In short, I am satisfied that the petitioning creditors have established that the Bankruptcy Notice was served on Mr Ejueyitsi on 14 June 2024 and that he committed an act of bankruptcy on 6 July 2024. Being satisfied that the requirements as to jurisdiction under s 43 of the Bankruptcy Act are met and that the petitioning creditors have established each of the matters specified in ss 52(1)(a) to (c) of the Bankruptcy Act, the discretion to make a sequestration order against Mr Ejueyitsi is enlivened. I am not satisfied that Mr Ejueyitsi discharged his onus that he is able to pay his debts in accordance with s 52(2)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act. I am further satisfied that it is appropriate to exercise the discretion arising under s 52(1) of the Act to make a sequestration order. I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and fifteen (115) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Cheeseman. |

Associate:

Dated: 22 September 2025