Federal Court of Australia

Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson's Art Supplies Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 1127

File number: | WAD 255 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | JACKSON J |

Date of judgment: | 12 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY - contraventions of s 18, s 29(1)(g) and s 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law and passing off - declarations - appropriate form of non-pecuniary relief - format of and content of website disclaimer - disclaimer not required to be published in other media COSTS - offers made before trial commenced - applicant's rejection of Calderbank offer not unreasonable - costs as between applicants and first and second respondents to be assessed on a party-party basis - applicant's rejection of offers from third and fourth respondents unreasonable - those respondents entitled to indemnity costs from certain date COSTS - parties each enjoyed some degree of success - whether costs of third and fourth respondents to be assessed separately - overall 15% discount on costs payable by first and second respondents - costs to be assessed on a lump sum basis by a Registrar |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Sch 2 (Australian Consumer Law) ss 18, 29 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 43 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 1.35, 25.01, 25.05, 25.14, 40.12 |

Cases cited: | Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; (2018) 259 FCR 514 Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Limited v ACPA Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 112 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Purple Harmony Plates Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1062 Calderbank v Calderbank [1975] 3 All ER 333 Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd (Costs) [2025] FCAFC 29 Harvard Nominees Pty Ltd v Tiller (No 3) [2020] FCA 1054 Hutchence v South Seas Bubble Co Pty Ltd (1986) 64 ALR 330 Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson's Art Supplies Ltd [2025] FCA 530 Knott Investments Pty Ltd v Winnebago Industries, Inc (No 2) [2013] FCAFC 117 Special Gold Pty Ltd (in liq) v Dyldam Developments Pty Ltd (subject to a Deed of Company Arrangement) (No 3) [2025] FCA 1031 Strzelecki Holdings Pty Ltd v Jorgensen [2019] WASCA 96; (2019) 54 WAR 388 University of Western Australia v Gray (No 21) [2008] FCA 1056 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Western Australia |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Trade Marks |

Number of paragraphs: | 161 |

Date of hearing: | 28 August 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr D Larish |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Bennett |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr T Besanko SC |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Wallmans Lawyers |

Counsel for the Cross-Claimant: | Mr T Besanko SC |

Solicitor for the Cross-Claimant: | Wallmans Lawyers |

Counsel for the Cross-Respondents: | Mr D Larish |

Solicitor for the Cross-Respondents: | Bennett |

ORDERS

WAD 255 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JACKSONS DRAWING SUPPLIES PTY LTD (ACN 008 723 055) Applicant | |

AND: | JACKSON'S ART SUPPLIES LTD First Respondent JACKSON'S ART AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 658 761 776) Second Respondent JACKSON'S ART HOLDINGS AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 658 493 728) Third Respondent PYRMONT CAPITAL PARTNERS PTY LTD (ACN 656 079 140) Fourth Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | JACKSON'S ART SUPPLIES LTD Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | JACKSONS DRAWING SUPPLIES PTY LTD (ACN 008 723 055) First Cross-Respondent MICHAEL FRANCIS BOERCAMP Second Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | JACKSON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 12 september 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. It is declared that each of the first and second respondents, since October 2018 and April 2022 respectively, has contravened s 18, s 29(1)(g) and s 29(1)(h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), and engaged in the tort of passing off, by representing that:

(a) the first respondent and/or the second respondent is the applicant;

(b) the first respondent and/or the second respondent is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by the applicant;

(c) the Australia-specific subdomain jacksonsart.com/en-au of the website www.jacksonsart.com is the applicant's website;

(d) the Australia-specific subdomain jacksonsart.com/en-au of the website www.jacksonsart.com is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by the applicant;

(e) the Australian telephone number +61 (08) 64 580 850 is the applicant's telephone number;

(f) the Australian telephone number +61 (08) 64 580 850 is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by the applicant.

2. On and from 26 September 2025, each of the first and second respondents whether by itself, its officers, servants, agents or otherwise howsoever, is permanently restrained, without the licence or consent of the applicant, from operating, in trade or commerce in connection with the offering for sale or sale of art or craft products under or by reference to the names or marks JACKSON'S and/or JACKSON'S ART SUPPLIES, or any name or mark substantially identical with or deceptively similar thereto:

(a) the Australia-specific subdirectory jacksonsart.com/en-au of the website www.jacksonsart.com (JAS AU Site); and/or

(b) any other website, subdirectory or subdomain that has any one or more of the following characteristics (the Australian characteristics):

(i) being an online store with content specific to Australia;

(ii) Australian dollars as the default currency;

(iii) references to Australian operations (being references to any one or more of an Australian place of business, an Australian telephone number, Australian operating hours or information about Australian Tax, Customs Fees and Duty charges)

(together, Enjoined Website) unless the Enjoined Website displays the words set out in paragraph 3 below (Disclaimer) in accordance with the requirements of paragraph 4 below.

3. The Disclaimer is:

Please note: this website is not affiliated with the Australian company Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd or its website jacksons.com.au.

4. The Disclaimer must:

(a) appear clearly, prominently and legibly to the user in a pop up where:

(i) the pop up appears when the user visits the Enjoined Website, at least once in any given browser session;

(ii) the pop up prevents from access or view any other part of the Enjoined Website until the user has clicked a checkbox acknowledging the Disclaimer;

(iii) apart from the Disclaimer, the pop up may only contain:

A. one or more of the name or mark JACKSON'S, JACKSON'S ART or JACKSON'S ART SUPPLIES (whether in text and/or a logo); and/or

B. text and a button or check box indicating acknowledgement of the disclaimer; and/or

C. any button dismissing the pop up so as to continue to the Enjoined Website;

(iv) the Disclaimer is in a font no smaller than that of any other text used in the pop up; and

(v) there is a reasonable degree of colour contrast between the background of the pop up and the text of the Disclaimer;

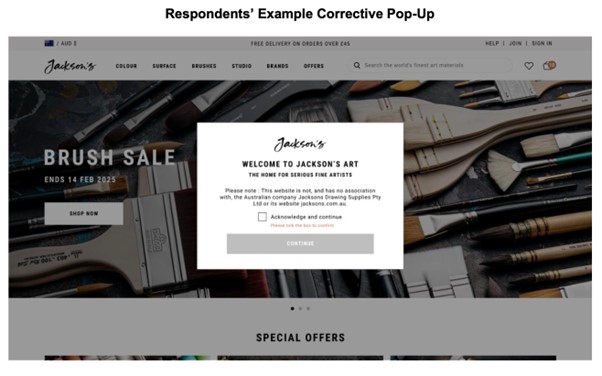

(b) also appear at or near the bottom of each page on the Enjoined Website in a font size no smaller than the size of the body text on the page; and

(c) in all cases, not hyperlink to the site jacksons.com.au.

5. There is to be an inquiry as to pecuniary relief.

6. The applicant's amended originating application is otherwise dismissed.

7. The cross-claimant's amended notice of cross-claim is dismissed.

8. With the exception of costs orders already made, the first and second respondents must pay the applicant's and cross-respondents' costs of the proceeding, up to and including the judgment hearing of 12 September 2025.

9. The costs are to be assessed in a lump sum, with a discount of 15% to be applied to the sum assessed.

10. The assessment of the quantum of the costs, as well as any procedural directions necessary for the assessment, are to be determined by a Registrar of the Court.

11. The assessment and payment of the amount assessed are to occur forthwith.

12. The third respondent and fourth respondent have liberty to apply to the Court in relation to the above costs orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKSON J:

1 In Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson's Art Supplies Ltd [2025] FCA 530 (Main Judgment) I found that the first and second respondents had engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), had made certain false or misleading representations in breach of s 29 of the ACL, and had engaged in the tort of passing off. I decided that claims against the third and fourth respondents, and a cross-claim against JDS and its Managing Director, Michael Boercamp, were to be dismissed. Defined terms from the Main Judgment will be used in these reasons, which assume familiarity with the Main Judgment.

2 At the end of the Main Judgment, I indicated that I would give the parties the opportunity to adduce further evidence and make submissions in relation to the appropriate form of non-pecuniary relief. They took up that opportunity, and on 28 August 2025 a hearing on the question was held. These reasons explain why I will make orders in the terms that appear at the beginning of this judgment.

3 While these reasons assume familiarity with the Main Judgment, a brief recap of the findings as to the liability of JAS and JAA is necessary context to what follows.

4 Those findings followed from the fact that, from October 2018 onwards, JAS offered for sale arts and craft products on the JAS AU Site, being an Australian specific subdomain of its main website. The contraventions concerned certain aspects of that broad conduct, but did not, on JDS's case, concern by itself the fact that the JAS AU Site offered and promoted arts and craft products under the JAS Names that were very similar to the JDS Names in relation to which JDS had traded and developed reputation and goodwill.

5 In view of the way JDS put its case, the contraventions occurred because, in the context of that broader conduct, the JAS AU Site:

(a) had certain Australian characteristics, including prominent and frequent display of the Australian flag and the word AUSTRALIA and the use of AUD as the currency for purchases; and

(b) made reference to Australian operations of JAS, being those conducted by JAA from its warehouse and office in Adelaide - these references were to matters such as the address of the warehouse and an Australian telephone number that customers could use to contact 'Jackson's Art'.

6 In addition to this, JAS's majority-owned subsidiary JAA fulfilled sales from an Australian address and provided customer service in Australia under and by reference to the JAS Names. This was conduct of JAA that was itself contravening, because in the context of the references to the Australian operations on the JAS AU Site it was likely to convey to consumers that the products were being dispatched or the customer service was being provided by an Australian 'Jackson's' which would be taken by some to be JDS. And in the context of the JAA conduct, the other conduct of JAS mentioned above was likely to mislead consumers into equating JAS (and JAA) with JDS.

7 While all of these findings concern sales and other conduct made by way of the JAS AU Site, it was common ground that JAA had made a small number of telephone sales by reference to the JAS Names, over a four month period from October 2022. This aspect of the JAA conduct, having been pleaded in terms that telephone sales involved misleading conduct, misrepresentations and passing off was therefore also made out: Main Judgment at [470].

The orders proposed and the common ground and differences between the parties

8 Each of JDS on the one hand and JAS and JAA on the other have proposed orders by way of final relief (for convenience I will only refer to JAS in connection with the respondents from now on, unless the context otherwise requires). The relief is final, that is, save for the fact that the parties agree that an inquiry as to pecuniary relief is necessary.

9 There are broad areas of both agreement and disagreement between the parties on the orders they propose. First, the broad agreement. Each party accepts that it follows from the Main Judgment that a declaration should be made to the effect that the contraventions summarised above occurred. By the end of the hearing they were also in agreement as to the wording of the declaration, which is the one that will be made.

10 Apart from the inquiry as to pecuniary relief, each party also accepts that there should be orders otherwise dismissing JDS's originating application, and that the cross-claim is to be dismissed.

11 The broad areas of disagreement between the parties concern the terms of the injunction to be granted, and costs. As to the first, in the Main Judgment I foreshadowed that I would be prepared to make an order requiring JAS to publish words on the JAS AU Site that clearly indicate to the users of that site that JAS is not JDS or associated with JDS: Main Judgment at [799]-[805]. All concerned have generally referred to those words as the disclaimer. There are a number of differences between the parties as to the precise form that order should take.

12 As to the second, JDS seeks an order that JAS is required to pay its costs in a lump sum forthwith, that is, before the proceeding is concluded by the grant of pecuniary relief. As explained below, however, while JAS initially contended that the question of costs should await the determination of the entitlement to pecuniary relief, its final position at the hearing was that costs orders should be made giving all of the respondents their costs on an indemnity basis for periods after certain offers of compromise were made.

13 I will now address each of these two areas of disagreement in turn.

The disclaimer order

14 This set of issues concerns the precise terms of the injunction that is to be ordered against JAS. The parties are agreed as to its broad form, that is, that it should restrain JAS from operating the JAS AU Site unless a specified disclaimer is displayed. But they disagreed about most other aspects as to how and when the disclaimer was to be displayed.

The expert evidence

15 Before dealing with each of the specific issues, it is convenient to summarise the expert evidence about websites on which the parties relied. The evidence came from three witnesses.

16 First, Mr Michael Simonetti. His evidence was adduced by JDS, and he also gave evidence at the trial. Mr Simonetti has expertise in the fields of website development, software engineering and online media and marketing, including experience in providing SEO services, optimising client websites and analysing website visitor information.

17 Next is Dr Karen Nelson-Field, whose evidence was adduced by JAS. Her (unchallenged) description of herself was 'a globally-recognised expert in omnichannel attention measurement and attention science, for which my company (Amplified) analyses biometric gaze tracking together with behavioural signals from users (such as scrolling or skipping) to accurately measure human attention to advertising': Nelson-Field affidavit affirmed 16 July 2025 (Nelson-Field I) para 7. Dr Nelson-Field describes her field of expertise as 'attention science', which is 'the study of how people allocate mental focus, what they notice, how long they stay engaged, and what holds or loses their attention … Modern attention science, such as the methods I apply, use large-scale datasets and computational methods to uncover repeatable, predictive patterns that explain how humans engage with media': Nelson-Field I para 7(a). '"Omnichannel attention measurement" … refers to the study of patterns across multiple channels and formats. It covers both digital and non-digital formats': Nelson-Field I para 7(b). Her curriculum vitae includes eight years as Professor of Media Innovation at the University of Adelaide, and lists three books (published by Palgrave Macmillan and Oxford University Press) and numerous articles and other papers.

18 Finally there is Professor Mingming Cheng, whose evidence was also adduced by JAS. Professor Cheng is a Professor of Digital Marketing and Director of the Social Media Research Lab at Curtin University. He is an expert in digital marketing, in particular, search engine marketing in the Asia Pacific region.

19 The evidence of each of these experts was given by affidavit. No party sought to cross-examine (on the agreed basis that the rule in Browne v Dunn would not be invoked). No challenge to qualifications or expertise was made.

20 It is convenient to summarise the expert evidence by reference to certain issues that will be addressed below.

Whether the disclaimer should appear on each page of the JAS AU Site - sticky headers

21 Mr Simonetti's view is that if the disclaimer appears on each page of the JAS AU Site, it would increase the likelihood that visitors to the site will see it, provided that it is sufficiently prominent on the web page. This evidence was given in the context of a since discarded proposal by JAS that the disclaimer should appear only on the 'front page' (that is the home page) of the site. Thus, in referring to an increased likelihood, Mr Simonetti is saying that it would be more likely that the disclaimer would be seen if it were on every page than if it were on the home page alone. That is, with respect, obvious.

22 Mr Simonetti's evidence is, though, that even the fact that an internet user has noticed a disclaimer on a web page does not mean that it will be read. Many internet users are focussed on a specific task and will disregard anything that looks like an ad, pop up or legal text and many internet users click check boxes acknowledging that they have read and understood a particular message even where they have not done so. Mr Simonetti says that this phenomenon is known as 'banner blindness'.

23 Dr Nelson-Field agrees with Mr Simonetti in relation to each of the above two points.

24 According to Mr Simonetti, a technique that is commonly used in order to ensure that a message on a website is noticed is to put it in a 'sticky header'. This is a header that stays in place at the top of the page even as the user scrolls down. Mr Simonetti's view is that these 'are far more likely to be read by internet users than normal headers': Simonetti affidavit sworn 2 July 2025 (Simonetti II) para 20.

25 Dr Nelson-Field's view (Nelson-Field I para 23(a)) is that, as an element that does not require interaction, and which is 'ever-present and visually predictable', sticky headers:

often fade into the background of the browsing experience. As a result, they're typically processed with low levels of attention. Users notice them peripherally but rarely engage meaningfully unless their design or behaviour interrupts the expected flow.

26 According to Dr Nelson-Field, sticky headers have minimal impact on user experience because they are cognitively ignored. They may produce irritation on smaller devices but otherwise go largely unnoticed. Elsewhere, Dr Nelson-Field says that sticky headers are 'seen but rarely read with intent', strictly lacking the friction that is required to engage users so that their 'static, peripheral presence is easily ignored' (para 49(a)). Of an example website she examined, Dr Nelson-Field described the sticky header as 'a textbook case of banner blindness - technically visible, but cognitively ignored' (para 49(b)).

27 Dr Nelson-Field summarises her views about a disclaimer that would appear on every page of the JAS AU Site as follows (para 47) (emphasis in original):

(a) I support placing a disclaimer on all pages of the site for visibility, particularly since many users arrive via subpages. However, mere visibility is not enough. A disclaimer must be seen and cognitively processed to serve its purpose - a sticky banner won't achieve that.

(b) That said, I do not believe returning visitors should be repeatedly exposed to the same disclaimer once it has been actively acknowledged. Repetition in these cases is redundant and risks frustrating the user. A fair and privacy-safe solution is to use unique visitor tagging, enabling the disclaimer to appear only for first-time or unconfirmed users. This approach maintains compliance without unnecessary disruption while respecting jurisdictional rules around the collection and storage of personal information.

The effect of pop ups

28 Mr Simonetti considers (Simonetti II para 25) that:

it is unlikely that the majority of Australian internet users who visit the JAS AU Site would read a disclaimer that appeared in a pop up before the user is taken to the JAS AU Site itself, irrespective of whether the pop up appears on the first or each occasion that the user visits the website.

29 According to him (Simonetti II para 26), although 'most' internet users are likely to notice the pop up, it is 'commonly understood in the digital marketing field' that many if not the majority of them take whatever action is necessary to remove the pop up without actually reading it, because it is interfering with the user's goals in visiting the website. Two exceptions to this are where the user has to choose between two alternatives (such as selecting between countries) or where the user has to provide an electronic signature. In oral submissions it was explained that this can refer to a handwritten signature (written with a mouse, stylus or finger) or a name inserted using the keyboard. But while an electronic signature makes it more likely that the user will notice the message in the pop up, a significant proportion will still provide their signature without reading it.

30 Dr Nelson-Field's opinion is that pop ups 'trigger active attention' (para 23(c)). That is in the context of her evidence that, for a disclaimer to be effective, 'it needs to move from passive to active attention', requiring 'a moment of attentional engagement - something unexpected, interactive, or interruptive enough to cut through the noise' (para 19). Thus, according to her (paras 23(c) and 24) pop ups:

interrupt the browsing experience, demand visual focus, and usually require a user action to dismiss. This interactivity boosts the likelihood of cognitive processing. While pop-ups with skippable functionality aren't necessarily pleasant, they are unavoidable forcing the viewer to pay at least momentary attention in order to exit the ad.

31 For Dr Nelson-Field (para 28):

Pop-ups, on the other hand, do disrupt the experience. This disruption is exactly what gives them their attention value: they hijack the passive scroll and demand interaction. This forced exposure, especially if unexpected or interruptive, leads to more active attention.

32 As for pop ups with which the user must interact, Dr Nelson-Field's opinion is (para 35(b)):

When a user must click, select, or sign, attention is extended and becomes more likely to shift from passive to active. This interaction, even if brief, improves the likelihood that the disclaimer is cognitively processed, not just seen.

33 Thus, specifically in connection with Mr Simonetti's views about the phenomenon of banner blindness, Dr Nelson-Field's evidence (para 40(b)) is that when a pop up includes 'friction' it 'drives a shift from passive viewing to active focus. Without this disruption, users quickly revert to habitual scanning and dismissal, and attention falls back into passive territory'.

34 Dr Nelson-Field otherwise disagrees with Mr Simonetti's view that pop ups are broadly ineffective, repeating her view that the friction they require shows that even the brief active attention that results, is more effective than static messages, so that pop ups are far more effective at ensuring that users see and meaningfully engage with the message.

35 In a responsive affidavit sworn on 4 August 2025 (Simonetti III), Mr Simonetti argues (para 10) that he and Dr Nelson-Field at least agree that neither a pop up nor a sticky header will result in all ('or even the vast majority') of internet users reading the disclaimer, and that the likelihood of it being read would be substantially higher if the disclaimer were contained on both a pop up and a sticky header.

36 Mr Simonetti also considers (para 18(b)):

that it is unlikely that the majority of Australian internet users who visit the JAS AU Site would read a disclaimer that appeared in a pop up before the user is taken to the JAS AU Site itself, irrespective of whether the pop up appears on the first or each occasion that the user visits the website.

37 Mr Simonetti also points out that a pop up disappears once it is dismissed, so the user is no longer able to see or consider it, while a sticky header does not have that disadvantage.

38 Dr Nelson-Field also comments on Mr Simonetti's views about electronic signatures. She considers (Nelson-Field I para 51(c)) that 'comprehension does not require such formality. A few seconds of active attention, prompted by a clearly designed pop-up, are sufficient to support awareness and understanding'.

39 In Simonetti III (para 30), Mr Simonetti responds, to the effect that if the user is required to give an electronic signature, that 'is likely to make a material impact on the probability that a user's "attention is extended" and that the "disclaimer is cognitively processed"'.

How often the pop up should appear

40 According to Dr Nelson-Field (Nelson-Field I para 36):

(a) Showing the pop-up at each visit might aid recall through repeated exposure but attention wears off fast if the format becomes familiar or easy to skip. Like any attention trigger, its effectiveness relies on some level of unpredictability or friction.

(b) Without this friction, users fall back into habitual dismissal, and the attention value quickly erodes.

41 Mr Simonetti's view, expressed in Simonetti III (para 29), is that:

in the case of a pop-up, the benefit of showing the pop-up 'at each visit' is not only to 'aid recall' but, more critically, to increase the likelihood that the message in the pop-up is read. For example, a user who does not read the pop-up on the user's first visit to the website may choose to read it on a subsequent occasion. This also somewhat reduces (although does not eliminate) the effect of one of the disadvantages associated with pop-ups, namely that once dismissed it cannot be re-read - at least on that visit …

42 In the same affidavit (para 43), Mr Simonetti acknowledges that 'it is somewhat more likely that a returning visitor will read the pop-up at least once if repeatedly exposed to the disclaimer'.

Hyperlinking

43 Mr Simonetti's view is that if the URL of the JDS Website is included in the disclaimer, if it is not hyperlinked then many users will not then visit the JDS Website, because they will need to type out the full web address. Even when they begin to type it, the autocomplete function in the search bar is likely to come up with the JAS AU Site. A hyperlink will provide the user with the simplest way to reach the JDS Website.

44 Professor Cheng's evidence essentially went to this question. It was to the effect that if the URL of the JDS Website were to appear in plain text in the disclaimer on the JAS AU Site, it would be unlikely to have a significant direct impact on the SEO of either website. That is, it would be unlikely to have a significant impact on the ranking of each website on the search results page when a Google search is performed, for example. But if an ordinary hyperlink to the JDS Website were in the disclaimer (ordinary in the sense that it is 'dofollow', so that a search engine's web crawler indexing function will follow the hyperlink), that would have a significant impact on the SEO. Both the Google and Bing web search engines treat a hyperlink as a kind of endorsement, so that (Cheng affidavit affirmed 15 August 2025 para 41):

a dofollow hyperlink to JDS's site could confer a measurable SEO benefit to JDS, such as increased crawl frequency, improved domain authority, and better performance in branded or nonbranded search queries. However, this link could also strengthen the perceived association between JAS and JDS in search engine algorithms …

45 There is, however, some uncertainty about whether the search engines will index a hyperlink that appears in a pop up.

The website(s) to be captured by the injunction

46 The first issue between the parties as to the terms of the injunction arose because JAS proposed that the injunction would only restrain it from operating the JAS AU Site identified by reference to its specific current URL, namely jacksonsart.com/en-au. As JDS pointed out, that would mean that if the site were to be moved to another address, or a similar site were to be set up without that particular URL, JAS would not be in breach of the injunction. Such a change could become necessary for entirely legitimate operational reasons.

47 Senior counsel for JAS ended up accepting this concern at the hearing. He agreed with a suggestion that the website to be the subject of the injunction could be defined by reference to having one or more of the 'Australian characteristics' that were the focus of JDS's claim and so of the findings in the Main Judgment. These characteristics were content specific to Australia, using Australian dollars as the default currency, and references to Australian operations. The injunction to be granted adopts that suggestion. When I refer below to the JAS AU Site, unless the context indicates otherwise, I should be taken to refer to the site at jacksonsart.com/en-au and any other website that falls within the description of the sites that are to be enjoined.

The text of the disclaimer and hyperlinking

48 Again, subject to one issue, counsel for the parties reached a sensible agreement as to the wording of the disclaimer.

49 They ultimately agreed that the disclaimer to be found on the JAS AU Site should say:

This website is not affiliated with the Australian company Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd or its website jacksons.com.au.

50 What they did not agree on concerned an additional sentence proposed by JDS, which would say of the JDS Website: 'If you intended to visit that website, please click here'. The word 'here' would then be hyperlinked to the JDS Website. JAS resists the idea that its website should carry any hyperlinks to the JDS Website.

51 This issue also arises as a result of JDS's proposal that the 'sticky banner' it proposes for the JAS Website (see below) should also carry a hyperlink to the JDS Website.

52 For the following reasons, I have determined that the injunction will not require the JAS AU Site to contain any hyperlink to the JDS Website.

53 It is of fundamental importance in this area that injunctive relief to restrain is limited to what is necessary in the circumstances of the particular case: see Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [111]. The purpose of the proposed relief here is to protect consumers: see Main Judgment at [795]. A disclaimer saying that the JAS AU Site is not associated with JDS will help to achieve this; a hyperlink making it easier for the user to go to the JDS Website will not. The effect of such a hyperlink will be to make it easier for the consumer to go to that website after having been disabused of any impression that they were already on it. It is the disabusing that protects the consumer.

54 In truth, the likely effect of hyperlinking will be that it is easier to find JDS on the internet, so that any damage to JDS's commercial interests from JAS's conduct will be reduced. But as explained in the Main Judgment at [769]-[783], JDS delayed in taking steps to protect its commercial interests from any impact of JAS's conduct. So as a matter of the exercise of the discretion, I put little weight on the possible effect of a hyperlink in redressing any damage to those interests. This reasoning applies not just in relation to the ACL case, but also in relation to the question of the equitable relief that might be appropriate in light of the findings as to passing off.

55 It does not advance JDS's position concerning hyperlinking for it to say, as it does, that consumers have been drawn into JAS's 'marketing web' (see Main Judgment at [382]). Even if that has occurred, the only two objectives of possible relevance here are to prevent consumers being further misled and to redress any damage to JDS. A hyperlink to the JDS Website will not promote the first objective. Further, Professor Cheng's evidence establishes that hyperlinking to the JDS Website may increase the likelihood that consumers are misled into thinking that the JDS Website and the JAS Website are the same or are operated by the same business. It could thus be counterproductive. And for the reasons given, I accord no weight to the second objective in this context.

Where and when the disclaimer will appear

56 There was much argument about the location and form of the disclaimer (as distinct from its specific wording). Most of the evidence summarised above goes to this issue.

57 JAS's initial position was that the disclaimer should appear only on the home page of the JAS AU Site. With respect, that was unsustainable, as many internet users will come to the site by way of web searches that link to pages that are 'behind' the home page, and so will never see the disclaimer. JAS had discarded this position by the time of the hearing.

58 Its ultimate position was, rather, that the disclaimer should appear in a pop up that is presented to the user the first time that they visit the JAS AU Site, and only that first time. The user should be required to click a check box to acknowledge the disclaimer. Only after having done that will the user be able to visit any page on the website. In its written submissions, JAS provided an illustrative mock-up of such a pop up, as follows:

59 In oral submissions, as an alternative to the above primary submission, senior counsel for JAS countenanced (but did not positively advance) that in addition to the pop up, the disclaimer could appear at the bottom of each page on the JAS AU Site, in a way that is 'non-sticky' - that is, it will only be visible if the user scrolls to the bottom of the page.

60 JDS's position is that the disclaimer should appear in a clear and prominent sticky header that appears on each page of the JAS AU Site.

61 JDS relied in this regard on certain statements by Allsop CJ (Cowdroy and Jagot JJ agreeing) in Knott Investments Pty Ltd v Winnebago Industries, Inc (No 2) [2013] FCAFC 117 (Winnebago (No 2)). One was (at [4]) that:

the protection of the public and of the respondent's trade reputation requires orders to be made that will prevent any continuation of the capacity of Knott to mislead those people in Australia who have a familiarity with the respondent's reputation and who are likely to be misled by the use of the name and logo.

Another was (at [22]): 'The relief should be such that the court is satisfied it will prevent deception'.

62 The emphases in each of these quotes has been added to reflect where the emphasis in JDS's submissions lays; its counsel submitted that the Court needs to be satisfied that the injunction not 'may' but 'will' prevent consumers being misled or deceived.

63 In written submissions JDS went further, to rely on Hutchence v South Seas Bubble Co Pty Ltd (1986) 64 ALR 330 at 338 to argue that the onus of establishing that a disclaimer will prevent people being misled lies on the party 'relying upon the disclaimer', here JAS. However, in oral submissions counsel for JDS properly accepted that the onus of establishing the need for any relief fell on his client as applicant. The correct way to describe the situation is that JDS is proposing measures which, it says, will ensure that consumers are not misled, and in that context it was, as a practical matter, incumbent on JAS to persuade me that some lesser measure would achieve this. In the end, I did not take JDS to be submitting that Winnebago (No 2) or any other authority lays down hard and fast rules that constrain the exercise of the remedial discretion.

64 Guidance can, however, be found in Winnebago (No 2) at [23] where Allsop CJ, speaking of a requirement in that case for a consumer to sign to acknowledge that they had been informed of a disclaimer, said that he was persuaded that it was 'an appropriate additional protection for the public, that will assist in ensuring as far as reasonably and fairly possible, members of the public are not deceived as to the trade origin of these vehicles and of the business in question'. This confirms that, as important as it is, the objective of consumer protection is not to be achieved at all costs. The relief ordered must be reasonable and fair to the respondent in the particular circumstances of the case at hand.

65 Taking those principles into account, and taking into account the expert evidence summarised above, I do not consider that either of the parties' respective positions should be adopted in full. I have determined that the disclaimer should be in a pop up that appears once every time a new browser session is used to access the JAS AU Site. So it will not appear only the first time when a device (or user) visits the site. It should not appear in a sticky header. I have also determined that it is appropriate for the disclaimer to appear (in a 'non-sticky' way) at the bottom of each page on the JAS AU Site.

66 My reasons for ordering that the disclaimer be presented in that way are as follows.

67 A pop up that appears when the user visits the JAS AU Site, and which must be dismissed before the site can be used, is most likely to arrest the attention of the user. That is, it is more likely than in the case of a sticky banner. The user will be required to acknowledge the pop up before they are able to visit or use the rest of the site. Dr Nelson-Field's evidence is to the effect that a pop up of this kind is more likely to mean that the user reads and understands it than a static message which requires no interaction with the user.

68 Mr Simonetti's view is that most internet users are likely to notice the pop up, but many if not the majority of them will remove it without reading it. Subject to one qualification, I accept that evidence. The qualification is that, while I accept that there is a significant chance that a user will not read a pop up that appears on any given occasion, I do not accept that this means that the majority of people will not read it. Mr Simonetti presents no basis in any research for his inherently ambiguous statements that 'many if not the majority' of people, or perhaps 'even the vast majority' of internet users will not read it.

69 What is important here is that, on the basis of Dr Nelson-Field's opinion, a pop up that must be acknowledged will maximise the chance that the user will read the disclaimer. To the extent that this is inconsistent with Mr Simonetti's evidence, the specificity of Dr Nelson-Field's expertise to the study of human attention in the context of websites leads me to prefer her evidence.

70 The likelihood that the user will read the disclaimer will be reinforced by the need to do so before seeing any other part of the JAS AU Site. While there will still be a significant chance that the user will not read it on any given occasion, that is the main reason why I have decided that it should appear each time a user visits the JAS AU Site during a new browser session. Repeated exposure, if that occurs, will increase the likelihood that the disclaimer will be read. Dr Nelson-Field's views set out at [40] provide no strong basis to reach a contrary conclusion.

71 Repeated exposure will also go some way to redressing the deficiency in any pop up that, once dismissed, it will never be seen again. That will be particularly problematic in many cases where, it can be inferred, visits by consumers to the JAS AU Site will be separated by months or even years so that even if the disclaimer is seen once, by the time of subsequent visits it will have been forgotten.

72 It is true that the import of the expert evidence as a whole is that no technique of presenting the disclaimer can guarantee that it will be read. But a pop up has the best chance of doing so, and with repetition that chance will be increased (see Mr Simonetti at [41]-[42] above). Dr Nelson-Field says as much (see [40] above) and while she says that attention wears off fast if the format becomes familiar, she appears to consider that the 'friction' required by having to acknowledge the disclaimer can ameliorate this. In any event, it can be inferred that many people buy arts and craft supplies infrequently and at irregular intervals, so that for those people, the repetition of the disclaimer will not be such as to lead to the 'blindness' to which the experts attest.

73 Another point should be made about this. The remedies to be granted respond to contraventions of s 18 and s 29 of the ACL. It is trite that the standard as to breach of those provisions and of passing off is an objective one. Judged objectively, a website that contains a clear disclaimer that necessarily presents itself as the sole visual element of a web page before any other page on the site can be viewed will not be misleading. If a given user nevertheless ignores it, that will be the outcome of subjective thoughts and emotions of that user, not any objective characteristic of the website.

74 Turning to the measure proposed by JDS - a sticky banner - that will not significantly improve the likelihood that the disclaimer will be read. It will be intrusive and will damage the user experience of the JAS AU Site, for little countervailing benefit.

75 The intrusiveness will occur in particular on smartphones, where the amount of the screen taken up by a sticky header will be comparatively greater than it will be on a tablet or a desktop device. The paucity of countervailing benefit will arise from the static and highly repetitive nature of a sticky banner, which are the very characteristics that, on the evidence of the experts, produce banner blindness. That is confirmed by Dr Nelson-Field's opinion that a visually predictable and ever present element which requires no user interaction is likely to be ignored. So the presence of the sticky header will interfere with the user's experience of the site while at the same time the content of the disclaimer is likely to be ignored.

76 In submitting that a sticky header is appropriate, JDS relies on Dr Nelson-Field's opinion set out at [27] above, in which she says that she supports placing a disclaimer on all pages of the site for visibility. But read fairly in context, I do not consider that she is expressing an expert opinion that the disclaimer should appear on each page of the JAS AU Site. Rather, in what is probably poor wording, I take her to mean that the disclaimer should not be visible only on the home page of the site, 'particularly since many users arrive via subpages', but at the same time Dr Nelson-Field does 'not believe returning visitors should be repeatedly exposed to the same disclaimer'.

77 While that last point is a matter for the Court, not expert opinion, for the reasons already given I agree that the constant presence of the disclaimer in a sticky header should not be required. As a lesser but still potentially useful measure, though, it will be ordered that in addition to the pop up, the disclaimer must appear at the bottom of each page (in a non-sticky way) in a font size no smaller than the body text of the page. This will go some way to ameliorating the deficiency in a pop up that, once dismissed, it cannot be seen again in any given browsing session. It will also have the advantage that, under the current design of the JAS AU Site at least, the disclaimer will be seen at the foot of the page, close to the references to the Australian operations that were found to contribute to the misleading impression created by the JAS AU Site: see Main Judgment at [350], [437]-[440], [465]-[466] and Appendix 2 item 12.

Electronic signature

78 I have decided not to require that the user must give an electronic signature in order to dismiss the pop up. In this regard JDS relied on the fact that in Winnebago (No 2), the Full Court required that any buyer or hirer of a vehicle supplied by Knott (the contravening party) was to sign a form stating that they had been informed of the disclaimer. But Winnebago (No 2) was a very different case. Unlike this case, it involved high value transactions concerning recreational vehicles. They were transactions that were taking place in person, rather than over the internet, so they were always going to take more time to complete. Another point of difference is that there had been some deliberate exploitation of Winnebago's goodwill: see Winnebago (No 2) at [3]. In contrast, at [786] in the Main Judgment I concluded that JAS built its business in Australia largely on the basis of its own efforts, and not by appropriating JDS's reputation. The degree of consumer interaction that was appropriate to the relief ordered in the specific circumstances in Winnebago (No 2) does not provide sound guidance for the very different circumstances of this case.

79 On the evidence in this case, while it appeared that an electronic signature would increase the likelihood that a user would read and understand the disclaimer, there is no way of knowing whether that increase would be significant. While Mr Simonetti's evidence was that it would make a material impact (see [39] above) he also said that a significant proportion of users will still not read the disclaimer ([29] above), Dr Nelson-Field's evidence casts doubt on whether that proportion will be greater if an electronic signature is not required ([38] above). Again, to the extent that this is inconsistent with Mr Simonetti's evidence ([39] above), I prefer the evidence of Dr Nelson-Field.

80 It is permissible in the exercise of the remedial discretion for the Court to take into account the relative importance of the subject matter of the representations and so of the relief: see for example Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Purple Harmony Plates Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1062 at [33] (Goldberg J). Given the relatively low value of the arts and craft products that are the subject matter here, I consider that it would be disproportionate to require an electronic signature on each new visit to the JAS AU Site. That, together with the above doubts as to its effectiveness, have led me to decline to require it here.

The format and content of the pop up

81 I accept JAS's submission that no specific text size or font should be ordered for the disclaimer. The variety of devices and screens on which it will be viewed, and JAS's likely legitimate desire to change the design aesthetic of the JAS AU Site over time, mean that it will be unduly restrictive to do so and may lead to unintended consequences. JAS's submissions embraced a broader requirement that the disclaimer be clear, prominent and legible and that will be reflected in the orders.

82 Nevertheless, the example pop up provided by JAS (see [58] above) illustrates the dangers of leaving too much to its discretion. For the example presents the disclaimer as fine print which is much less prominent than a logo and marketing messages using the JAS Names. A pop up in that form would significantly increase the likelihood that any given user would not read or comprehend the disclaimer.

83 As such, the order will require explicitly that the size of the text of the disclaimer in the pop up must be no smaller than any other text, and it will keep such other text to a minimum. That will mean that the disclaimer is prominent while at the same time giving sufficient flexibility for the JAS AU Site to evolve over time without requiring an application to the Court.

No requirement to publish the disclaimer in other media

84 The orders proposed by JDS would require JAS to communicate the disclaimer to consumers, not only via the JAS AU Site but over the telephone and in any other form of broadcast or published advertisements, including social media.

85 I will not impose any such requirement. The evidence adduced at trial is to the effect that JAS functions exclusively as an online seller. There are two qualifications to that: it has brick-and-mortar stores in the United Kingdom (which are not relevant here) and there are a small number of telephone sales: see Main Judgment at [302].

86 There is no evidence that JAS has engaged in advertising in traditional broadcast and print channels in Australia, and no suggestion that it intends to do so. There is no reason to think that a consumer will learn of JAS and its business, other than through or by reason of the JAS AU Site. The conduct that has been found to have contravened did not involve the traditional marketing channels. It was not part of JDS's case. No order for the disclaimer to appear in those channels will be made.

87 Nor was social media part of JDS's case. The variety of ways in which social media can be used to promote a business make it impracticable to seek to prescribe how a disclaimer will be included in it, at least in the present case where no particular infringing conduct using social media was pleaded or proved. Further, since social media is online, it is unlikely that any Australian users of it will come to acquire products from JAS other than via the JAS AU Site, where the disclaimer will be unavoidable.

88 As to the telephone sales, the sole basis on which JDS's claim in that regard was upheld was because it was common ground on the pleadings that JAA had made a small number of telephone sales by reference to the JAS Names, over a four month period from October 2022: see Main Judgment at [354], [470]. There was no clear evidence about any phone orders outside that period. Also, it was also not clear whether those orders were made, or could be made, without the customer accessing the JAS AU Site. Even in cases where consumers communicated with JAA by telephone (with service queries) or received their products in packaging to which the JAS Names are affixed, they will almost inevitably have visited the JAS AU Site. Reflecting that, the very text of the disclaimer proposed by JDS concerns the parties' websites and no other sales channels.

89 At the hearing on 28 August 2025, JDS tendered the results of a Google search of the phrase 'jacksons art phone number' in which the top five results appeared to contain the customer service number of JAS. The next two results were hits on the JDS Website. JDS thus submitted that consumers might obtain the telephone number without ever seeing the JAS AU Site and so being exposed to the disclaimer.

90 However, JAS tendered a printout of a Google search for precisely the same phrase which returned as the first three results, under the heading 'Places', the addresses and telephone numbers of JDS physical stores, and which had for the subsequent results a mix of JDS Website, JAS Website and JAS AU Site hits. It therefore seems the results of Google searches are unpredictable and depend on circumstances that were not clear from the evidence. I put little weight on the search results.

91 In any event, it is still unlikely that a consumer will wish to order specific art products from the online retailer JAS without visiting its website and further unlikely that a consumer would just call the number without clicking on the search hits and being taken to the website and the disclaimer. And if the user did do this, any misapprehension on their part would not necessarily have arisen as a result of the JAS AU Site, which is at the heart of the contravening conduct found in the Main Judgment.

92 I consider it far fetched that a consumer will telephone JAA without any exposure to the JAS AU Site. As stated, the number of actual telephone sales established was very small. I do not consider that requiring the disclaimer to be communicated by telephone will serve any utility. No order for it to appear outside the JAS AU Site will be made.

Costs

93 The issue between the parties as to costs evolved over the course of the hearing on 28 August 2025. At the outset of the hearing JDS was pressing for costs orders in its favour, but JAS sought to rely on the fact of a Calderbank offer having been made, as a basis to defer any costs order, without disclosing the terms of the offer.

94 After a somewhat tortuous set of interchanges between bar table and bench which need not be described, JAS accepted that the issue of costs needed to be determined now, and tendered the Calderbank offer as well as two further offers of compromise made under r 25.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). JDS did not object to these tenders; indeed it sought them. As a result, the offers were received into evidence.

95 In addition to the issues as to the effect that should be given to those offers, if any, the parties also disagreed as to what discount, if any, should be applied to the costs to be awarded to JDS as the party that has obtained judgment in its favour. That question arises because JDS was wholly unsuccessful in its claims against the third and fourth respondents and has not obtained the relief it sought against JAS and JAA. There was also an issue about whether the costs of the successful respondents should be assessed separately.

96 A third issue arose at the relief hearing about whether the costs should be assessed on a lump sum: JDS says they should; JAS says that they should be assessed on an itemised basis in the usual way.

97 I will now address each of these issues in turn.

The offers of compromise

98 It is convenient to deal with the offers of compromise in turn, that is, first the offer made on behalf of all four respondents, and then the offers made on behalf of JAH and PCP respectively.

The terms of the offer made on behalf of all four respondents

99 The first offer of compromise is contained in a letter dated 28 March 2024 from JAS's solicitors to JDS's solicitors. It was expressed to have been made in accordance with the principles in Calderbank v Calderbank [1975] 3 All ER 333. The letter commenced with some comments about the status of the proceeding and JDS's prospects. They do not need not be set out because JAS has not relied on them. In the letter, 'JAS' was defined to mean all four respondents, which approach I will also take in referring to the offer.

100 The substantive terms of the offer were set out in a schedule to the letter. Materially, if accepted, JAS would have agreed to permanently cease shipping orders to Western Australia or the Northern Territory in circumstances, in effect, where the order was placed with a business using the JAS Names (or 'phonetic or fuzzy equivalents'). Western Australia and the Northern Territory are what I called in the Main Judgment JDS's 'core markets'. The JAS Website, which includes the JAS AU Site, would have still been accessible to people in those core markets, but any orders placed on those sites would be blocked. There was also an offer to pay JDS a sum of money.

101 While the anfractuous course of the relief hearing does not need to described, I do need to explain why I have not said what that sum of money was. It is because JAS foreshadowed an application for me to recuse myself from determining pecuniary relief if I had seen the sum in question (which I have). I therefore consider that it is preferable at this point not to make the sum known publicly, in case it turns out that another judge does need to deal with the matter. It is not necessary to specify the sum in these reasons. I will only say that counsel for JAS properly accepted in oral submissions that the sum of money in question is small.

102 Coming back to the Calderbank offer, if accepted its effect would have been that JDS released JAS from all known and unknown claims in Australia arising from passing off, misleading or deceptive conduct or 'all tangential rights in connection to their branding, get-up and supply of goods and services to date'. The entirety of the claim was to be dismissed by consent but, explicitly, not the cross-claim. The settlement was to be documented in a deed. This would include a term to the effect that successors and assigns would be bound, and also what the offer described (without more) as 'the usual confidentiality provisions'. The parties were each to bear their own costs. The offer was open for acceptance until 5.00 pm AWST on 22 April 2024.

103 There is no evidence as to whether JDS responded to the offer, and if so how. It can, of course, be inferred that it was not accepted before it expired.

Principles

104 JAS and JAA press for indemnity costs from 22 April 2024 on the basis of the lapsing of the Calderbank offer. The principles that apply in that situation are well established. It is convenient to quote the summary given by Nicholas, Yates and Beach JJ in Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Limited v ACPA Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 112 (most citations removed):

[5] Section 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) confers a broad discretion on the Court to award costs in proceedings. In Re Wilcox; Ex parte Venture Industries Pty Ltd (No 2) (1996) 72 FCR 151, Black CJ at 152 stated the principles applicable to a claim for indemnity costs:

…it is well established that the starting point for any consideration of an application for indemnity costs is that in the ordinary case costs will follow the event and the Court will order the unsuccessful party to pay the costs of the successful party, on a party and party basis, a basis which will fall short of complete indemnity. Nevertheless, the Court has an absolute and unfettered jurisdiction in awarding costs, although the discretion must be exercised judicially. So indemnity costs may properly be awarded where there is some special or unusual feature in the case justifying the Court in exercising the discretion in that way.

[6] A well-established circumstance justifying an award of indemnity costs is an imprudent refusal of an offer to compromise. In such cases, a key question is whether the offeree's refusal of the offer was 'unreasonable' when viewed in light of the circumstances existing at the time the offer was rejected.

[7] The circumstances to be taken into account in determining whether rejection of an offer was 'unreasonable' cannot be stated exhaustively but may include, for example:

(a) the stage of the proceeding at which the offer was received;

(b) the time allowed to the offeree to consider the offer;

(c) the extent of the compromise offered;

(d) the offeree's prospects of success, assessed as at the date of the offer;

(e) the clarity with which the terms of the offer were expressed; and

(f) whether the offer foreshadowed an application for an indemnity costs in the event of the offeree rejecting it.

[8] An unsuccessful party is not liable to pay indemnity costs merely because it received an offer to settle on terms more favourable than it achieved at trial and rejected that offer. As we observed in the Appeal Reasons, albeit in the context of r 25.14(2) of the FCRs, assessment of the 'unreasonableness' of an offeree's refusal of a settlement offer is a broad-ranging inquiry that is not restricted to consideration of the extent or quantum of the compromise offered.

105 It is relevant in the application of these principles to have regard to the fact that the offer here was for the parties to bear their own costs. That is functionally equivalent to an offer of a sum that does not include a separate component to deal with costs or interest (interest is not mentioned in JAS's Calderbank offer at all).

106 The approach to be taken to an offer of that kind was described by French J in University of Western Australia v Gray (No 21) [2008] FCA 1056 as follows:

[34] I accept that the making of a rolled up offer inclusive of costs and interest may detract from the weight to be given to its refusal in the exercise of the discretion. Finn J referred to authorities on the point in GEC Marconi Systems Pty Ltd v BHP Information Technology Pty Ltd (2003) 201 ALR 55 at [34]. His Honour cited single judge decisions to the effect that such offers ought not to be a relevant consideration on the question of costs and would not be considered in the same way as a Calderbank letter. His Honour was invited to depart from that line of first instance authority. However he was not prepared to say it was clearly wrong. Notwithstanding that, in the circumstances of the case he had to decide, his Honour found that:

The fact that the offer gave no indication at all of the breakdown … between the claim, interest and costs blunts significantly the weight to be given the offer.

[35] While respecting the general approach to rolled up offers reflected in the cases to which Finn J referred, such approaches cannot be calcified into rules of law which fetter a general discretion. They simply reflect a common sense proposition that generally speaking such an offer is not unreasonably refused. There may, however, be circumstances where a rolled up offer, refused by an applicant who is unsuccessful, may support a claim for indemnity costs.

Application of principles to the Calderbank offer in this case

107 JAS submitted at the relief hearing that it was unreasonable for the Calderbank offer not to have been accepted. Senior counsel for JAS put his submissions on the basis that this was a necessary precondition for making an order for indemnity costs in favour of his clients.

108 That was qualified, however, by a submission that it was difficult for me to assess the reasonableness of the offer because it includes a term for payment of money, and the quantum of any pecuniary relief has not been determined. However, senior counsel also labelled the monetary term a 'distraction' and identified the term that restricted JAS from selling into the core markets as the 'critical' one.

109 Senior counsel submitted that this term would have kept JAS out of JDS's core markets, in circumstances where JDS did not establish a single sale outside those markets. And it would not have been subject to any temporal limitation. Senior counsel submitted, in effect, that this would have been a more beneficial outcome for JDS than the one it is going to achieve, centred around the publication of the disclaimer on the JAS AU Site.

110 As to the fact that there was no separate costs component for the offer, senior counsel for JAS submitted that it is important not to conflate the sum of money mentioned in the offer with the costs that JDS had incurred up to the date of the offer. He submitted that it was not a straight dollar-for-dollar comparison, because of the significance of the term that would have prevented sales into JDS's core markets. He submitted that it was necessary to look at the offer as a whole, not the particular financial component.

111 Counsel for JDS submitted that there was a key problem with what his opponent called the critical term in that, even if JAS was not selling into the core markets, consumers would still have been misled. In contrast, the objective of the disclaimer now proposed is to prevent that. In that way, he submitted, his clients have done better than the offer. He pointed out that the relief being sought by JDS was to prevent misleading conduct and representations, not sales.

112 Counsel for JDS also pointed out that the offer contained no term as to declarations, which will be made and which he said are important to his client. Accepting the offer also would not have ended the cross-claim. Further, he submitted that the terms of the proposed settlement deed as to the binding of successors and assigns and confidentiality were matters that JAS could not have achieved in the proceeding, which is another reason why it was not unreasonable for JDS not to accept the offer.

113 I agree that it was not unreasonable. That is essentially for the reasons advanced by counsel for JDS, which I adopt without repeating. I would only emphasise the following matters.

114 First, there is clearly room for debate about whether the key term of the Calderbank offer preventing JAS from selling in the core markets would have been a better outcome for JDS than the outcome that will follow from the orders I am going to make. It is not difficult to think of scenarios where consumers in the core markets continue to be misled, even though they could not buy products from JAS. And it is not difficult to think of scenarios where this could have caused problems for JDS, for example because consumers dissatisfied with the restriction wrongly attributed frustrations with the JAS AU Site to JDS. So there is a prima facie case to say that preventing consumers from being misled was the most important aim of the proceeding.

115 It could also be that a nationwide injunction is better for JDS than a localised one would have been, even if the nationwide injunction does not stop sales by JAS in the core markets. For example, JDS may have expansion plans.

116 There was no evidence about these matters and it would be wrong to speculate about them. But there is no need to speculate; they simply illustrate why JAS has failed to discharge its practical onus of establishing that the offer it made would have been better for JDS than the outcome of the trial.

117 Second, that failure is compounded by three further characteristics of the Calderbank offer: it would not have resolved the cross-claim, on which JAS failed at trial; the releases proposed were not mutual, but solely in favour of JAS; and it did not provide for any separate sums of money for costs or interest, as to which see the quote from Gray (No 21) above at [106]. These further exacerbate the uncertainty around the outcome of accepting the offer, and provide further grounds for concluding that JDS did not act unreasonably.

118 Third, these considerations hold regardless of the exact amount of money offered. Or at least they do where, as here, the amount would not on any view have been enough to have compensated JDS for the costs it had incurred up to the date of the offer. There was some evidence of what those costs were, but there is no need to refer to it. The amount offered was small; the costs were not.

119 I accept that, as senior counsel for JAS submitted, the offer needs to be viewed as a whole. But it does not follow from this that comparing the amount offered with the costs incurred involves conflating an offer that may have covered pecuniary relief with the matter of costs. It simply involves assessing, wholistically, the financial dimension of the overall question of whether JDS would have been better off accepting the offer.

120 Nor does the fact that the amount of pecuniary relief has not yet been determined present any difficulty in assessing the reasonableness of the offer. Perhaps that might have been different if the sum that had been offered were substantial or generous. But JAS does not suggest that it was.

121 In the end then, even if it is assumed that JDS ends up recovering no money at all by way of pecuniary relief, when the offer is viewed as a whole in light of the status of the proceedings as at the date of the offer, including the very significant costs incurred, it is clear that the pecuniary component of it presented no good reason to accept it. That is so even if the financial dimensions of the offer are assessed along with the non-pecuniary terms, including the so-called critical term.

122 The essential precondition for the Court to act on the Calderbank offer, in the normal course - that it was unreasonable not to accept it - has not been established. And there is no feature of this case that takes it outside the normal course. In those circumstances, there is no need to run through any list of factors, such as that set out in Anchorage at [7]. No indemnity costs will be awarded in JAS or JAA's favour.

The terms of the offers of compromise made on behalf of JAH and PCP

123 As to the offers made under r 25.01 of the Federal Court Rules, they were each dated 24 April 2024. One was sent on behalf of the third respondent, JAH, the other on behalf of the fourth respondent, PCP. In each case the offer was that the proceeding, in so far as it related to the relevant respondent, would be dismissed with no order as to costs. The offers were open for acceptance for 21 days (seven days longer than the minimum time required under r 25.05(3)).

124 The covering letter to the offers made it clear that they were independent; acceptance of one was possible without accepting the other.

125 In relation to PCP, the covering letter (on which the respondents do rely) pointed out that it was a 10% minority shareholder in JAA and in the absence of further evidence any attempt to 'pierce the corporate veil' in relation to such a shareholder was 'doomed to fail'. The letter said that, likewise, JAH was 'only a shareholder, and no further evidence has been produced of its close personal involvement'.

126 Again, there was no evidence as to any response to these offers, but evidently they were not accepted.

Principles

127 The consequences of any offer made under r 25.01 of the Federal Court Rules are governed by the provisions of Pt 25 of the Rules. In particular, r 25.14(2) says:

If an offer is made by a respondent and an applicant unreasonably fails to accept the offer and the applicant's proceeding is dismissed, the respondent is entitled to an order that the applicant pay the respondent's costs:

(a) before 11.00 am on the second business day after the offer was served - on a party and party basis; and

(b) after the time mentioned in paragraph (a) - on an indemnity basis.

128 So, as the parties here all accepted, the question once again is whether it was unreasonable for JDS not to have accepted each offer. The parties did not suggest that any different standard is to be applied than that applied to Calderbank offers as set out above and the same standard is commonly applied: see e.g. Caporaso Pty Ltd v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd (Costs) [2025] FCAFC 29 at [21] (Katzmann, Wheelahan and Hespe JJ). I need only observe further that in the Appeal Reasons mentioned in Anchorage at [8], the Full Court described the judgment to be made as an evaluative one 'in relation to which the trial judge will usually enjoy a distinct advantage': Anchorage Capital Partners Pty Ltd v ACPA Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 6; (2018) 259 FCR 514 at [224] (Nicholas, Yates and Beach JJ).

Application of principles to Pt 25 offers in this case

129 As to whether it was unreasonable for JDS not to have accepted the offers, its counsel submitted that the Court was to assess whether the claims against JAH or PCP were without merit or had no prospects of success, or were plainly unmeritorious. The Court was to balance that, he submitted, against the extent of the compromise that was offered here: in effect, that no relief would be obtained against those respondents. While acknowledging that JDS has failed to obtain any relief against JAH or PCP, he submitted that the extent of the compromise was, in effect, to release JDS from whatever small costs liability it had incurred against those respondents. Implicit in this submission was the proposition, which I accept, that the cases against them did not form a large part of the time or other resources expended in taking the matter as a whole to trial.

130 Counsel for JDS submitted that the claims were not unmeritorious or unarguable. He pointed out that much of the evidence relevant to the matter was obtained from cross-examination of JAA's Australian-based Executive Director, Franz Baumgartner, and that cross-examination was yet to take place at the time the offers were due to be accepted (which was more than five weeks before trial). He therefore submitted that it was not unreasonable for JDS not to have accepted the offers. He also submitted that the amount of compromise that was offered was small, in that no sums were to be paid by way of compensation and all that was offered was release from a modest potential liability for costs.

131 Senior counsel for the respondents submitted that JAH and PCP did better than the offers, because they are entitled now to the costs of the proceeding, although he conceded that the entitlement was small. He said that the matters set out in the covering letter said why it was unreasonable for the offers not to have been accepted. They boil down to an absence of evidence to support the claims against JAH and PCP. There were amendments to the claims in the course of the trial, but they were after the time of the offers.

132 In my view, it was unreasonable for JDS not to have accepted the Pt 25 offers made here. Counsel for JDS cited no authority for the proposition that, in order to reach this conclusion, I would need to find that his client's cases against JAH and PCP were 'without merit' or 'had no prospects of success', or were 'plainly unmeritorious'. I do not accept these glosses on the broad standard of unreasonableness.

133 In terms of JDS's prospects of success against the respondents as at the time of the offers, my evaluation, as trial judge, is that the claims were weak. My assessment of them is set out in full in the Main Judgment at [552]-[572] and there is no need for me to paraphrase those passages here. I would only highlight that I found that:

(a) the evidence on which JDS relied did not 'come close to persuading me that JAH actually did (or omitted to do) anything that aided, abetted, counselled or procured JAA's contraventions, or that it was knowingly concerned in or a party to those contraventions' (Main Judgment at [553]);

(b) JDS had pointed 'to no act or omission on the part of JAH capable of meeting [the] requirements for knowing involvement' (Main Judgment at [557]);

(c) there was 'no evidence that JAH aided, counselled, directed or joined in the commission of any tort' (Main Judgment at [561]); and

(d) in relation to PCP, JDS had not identified (much less established) any specific act or omission on its part that made JAA's contraventions more likely or meant that PCP was concerned in or party to them (Main Judgment at [570]).

134 In terms of other matters contributing to the evaluation of unreasonableness, the terms of each offer were straightforward and easy to understand and the time provided for acceptance was greater than the minimum required under r 25.05(3). On the other hand, it is true that the extent of compromise offered was uncertain, being limited to the unknown and probably modest amount of costs attributable to JAH and PCP.

135 Most importantly though, properly advised JDS should have known at the time of the offers that its cases against JAH and PCP were weak. All the evidence was in. All it had to rely on were some bare shareholding relationships and common or nominee directorships, and the terms of a Shareholders Deed. It was unreasonable of JDS to take a punt that something more substantial would emerge in cross-examination, and as it turned out, nothing did.

136 Rule 25.14(2) of the Federal Court Rules therefore entitles each of JAH and PCP to an order that JDS pay their costs on a party-party basis up to 11.00 am AWST on 26 August 2024 and on an indemnity basis thereafter. No direct submission was made to the effect that I should exercise the discretion afforded by r 1.35 to make an order that is inconsistent with that requirement: see Caporaso at [21]. I say 'no direct submission' because an issue did arise on the parties' submissions as to whether any entitlement to costs on the part of JAH and PCP should be reflected in separate orders in their favour, with separate assessments of their costs, or whether it should be reflected in a discount on JDS's overall entitlement to receive its costs of the proceeding from JAS and JAA. I will return to that issue in the next section.

Taking account of JDS's less than complete success in the proceeding

137 The next set of issues as to costs arises as a result of the conclusion about JAH and PCP's costs just expressed, and as a result of the incomplete success JDS has had in the proceeding as a whole.

138 Apart from failing against JAH and PCP, JDS has also failed to obtain the principal relief that it sought, which was (broadly) to restrain the respondents from offering arts and crafts products under the JAS Names using an Australian-specific website, or any 'physical presence' in Australia, or an Australian telephone number, or conduct otherwise 'targeted at Australian consumers': see Main Judgment at [642]. It also broadly sought to restrain the respondents from representing in Australia that they were equivalent to or associated with JDS, and to geo-block the JAS AU Site in Australia.

139 I found at [793] of the Main Judgment that if all this relief had been granted, it would have effectively put an end to JAS's business in Australia. On reflection, perhaps I should have said that it would have required JAS to start again to build goodwill in Australia using a name that did not have include the word 'Jacksons'. But nothing turns on that for present purposes; on any view the relief to be granted is significantly more confined than the relief that was sought.

140 The incomplete nature of JDS's success gives rise to two issues. The first is how the failure of its claims against JAH and PCP should be reflected in the costs orders. The second is the extent to which there should be any discount on the costs awarded to JDS to reflect the difference between the injunctive relief it sought against JAS and JAA and the injunctive relief that will be granted.