FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

EIS Gmbh v LELO Oceania Pty Ltd (Liability Trial) [2025] FCA 1111

File number(s): | NSD 376 of 2023 NSD 1411 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | DOWNES J |

Date of judgment: | 18 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | PATENTS – validity – infringement – standard patent entitled “Pressure Wave Massager” – compression wave massage device for sexual stimulation of the clitoris – construction – meaning of claim which refers to device “when used” in a specified way – whether device must be tested when used in that way – whether results of testing established infringement PATENTS – where claim limited by result – whether claims should be revoked for lack of clarity and lack of definition – s 40(2)(b) Patents Act 1990 (Cth) – s 40(3) Patents Act 1990 (Cth) – finding that insufficient information in the patent to enable the person skilled in the art to achieve the claimed stimulating pressure field PATENTS – sufficiency – support – novelty – inventive step – best method – utility – whether arbitrary integer – unjustified threats – s128 Patents Act 1990 (Cth) – whether misleading or deceptive conduct – whether in trade or commerce – s18 of Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (Australian Consumer Law) |

Legislation: | Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth), s 6 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), s 18(1) of Sch 2 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), ss 80, 136 Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) Patents Act 1990 (Cth), ss 7(2), 7(3), 18(1), 40(2)(b), 40(3), 116, 128, 138(3)(b) Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), s 52 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), rr 23.13(1)(b), 23.13(ga) |

Cases cited: | Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2002) 212 CLR 411; [2002] HCA 59 Albany Molecular Research Inc v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2011) 90 IPR 457; [2011] FCA 120 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 226 FCR 324; [2014] FCAFC 99 Austal Ships Sales Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag (2008) 77 IPR 229; [2008] FCAFC 121 Australian Competition & Consumer Commission v Dateline Imports Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 114 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 Axent Holdings Pty Ltd (t/as Axent Global) v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd (2020) 154 IPR 431; [2020] FCA 1373 BlueScope Steel Ltd v Dongkuk Steel Mill Co, Ltd (No 2) (2019) 152 IPR 195; [2019] FCA 2117 Caffitaly System SpA v One Collective Group Pty Ltd (2020) 154 IPR 1; [2020] FCA 803 CPC Patent Technologies Pty Ltd v Apple Pty Limited [2025] FCA 489 Damorgold Pty Ltd v Blindware Pty Ltd (2017) 130 IPR 1; [2017] FCA 1552 Flexible Steel Lacing Company v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 Folding Attic Stairs v The Loft Stairs Company Ltd [2009] EWHC 1221 (Pat) General Tire & Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Company Ltd (1971) 1A IPR 121 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 119 IPR 1; [2016] FCA 608 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 474; [2018] FCAFC 71 GM Global Technology Operations LLC v SSS Auto Parts Pty Ltd (2019) IPR 199; [2019] FCA 97 Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd (2023) 180 IPR 315; [2023] FCA 1017 Illumina Cambridge Ltd v Latvia MGI Tech SIA [2021] EWHC 57 (Pat) Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 (2005) 67 IPR 68; [2005] FCA 1472 JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 68; [2005] FCA 1472 Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61; [2016] FCAFC 27 Lido Manufacturing Co Pty Ltd v Meyers & Leslie Pty Ltd (1964) 5 FLR 443; [1964–5] NSWR 889 Meat & Livestock Australia Ltd v Cargill, Inc (2018) 129 IPR 278; [2018] FCA 51 Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 Nesbit Evans Group Australia Pty Ltd v Impro Ltd (1997) 39 IPR 56 Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360 Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd v Ice TV Pty Ltd (2007) 73 IPR 99; [2007] FCA 1172 Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Limited (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307 NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd (1992) 24 IPR 1 Occupational and Medical Innovations Limited v Retractable Technologies Inc (2007) 73 IPR 312; [2007] FCA 1364 Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (2015) 113 IPR 191; [2015] FCA 634 Pharmacia Italia SpA v Mayne Pharma Pty Ltd (2005) 66 IPR 84; [2005] FCA 1078 Rakman International Pty Limited v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd (2023) 178 IPR 20; [2023] FCAFC 202 Rescare Ltd v Anaesthetic Supplies Pty Ltd (1992) 25 IPR 119 Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd (2017) 126 IPR 427; [2017] FCAFC 138 SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (t/as Database Consultants Australia) v Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd (2024) 176 IPR 391; [2024] FCAFC 6 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (2023) 277 CLR 186; [2023] HCA 8 Sigma Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Ltd v Wyeth (2011) 119 IPR 194; [2011] FCAFC 132 Sydney Cellulose Pty Ltd v Ceil Comfort Home Insulation Pty Ltd (2001) 53 IPR 359; [2001] FCA 1350 U & I Global Trading (Australia) Pty Ltd v Tasman-Warajay Pty Ltd (1995) 60 FCR 26 Vald Pty Ltd v KangaTech Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 333 Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Limited v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd trading as Database Consultants Australia (No 8) [2023] FCA 182 Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 Wellcome Foundation Limited v V.R. Laboratories (Aust.) Proprietary Limited (1981) 148 CLR 262 Williams Advanced Materials Inc v Target Technology Co LLC (2004) 63 IPR 645; [2004] FCA 1405 Zoetis Services LLC v Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc (2024) 306 FCR 19; [2024] FCAFC 145 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and associated Statutes |

Number of paragraphs: | 460 |

Date of hearing: | 10–14, 17–20, 26–27 February 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Ms C Cochrane SC with Mr E Thompson |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Gilbert + Tobin |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Ms K Howard SC with Mr J Samargis |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Douros Jackson Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 376 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | EIS GMBH Applicant | |

AND: | LELO OCEANIA PTY LTD ACN 135 459 782 First Respondent LELOI AB Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | LELO OCEANIA PTY LTD ACN 135 459 782 (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | EIS GMBH Cross-Defendant | |

order made by: | DOWNES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 SEPTEMBER 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Australian Standard Patent No. 2018200317 is invalid.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Pursuant to section 138 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), Australian Standard Patent No. 2018200317 be revoked.

3. The cross-claim otherwise be dismissed.

4. The applicant’s claim be dismissed.

5. In relation to costs:

(a) within 14 days, the parties submit any agreed proposed orders as to costs;

(b) if the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days, each party file and serve a short written submission on costs limited to 5 pages, and within 28 days each party file and serve a short responding written submission limited to 5 pages. The issue of costs will then be determined on the papers.

6. Paragraphs 1 to 4 above be stayed:

(a) for a period of 28 days; or

(b) if any party files a notice of appeal within 28 days, until the hearing and determination of the appeal.

7. This order is taken to be entered on the day that it is authenticated.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1411 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | EIS GMBH Applicant | |

AND: | CALVISTA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Respondent | |

order made by: | DOWNES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 SEPTEMBER 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Australian Standard Patent No. 2018200317 is invalid.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. Pursuant to section 138 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), Australian Standard Patent No. 2018200317 be revoked.

3. The cross-claim otherwise be dismissed.

4. The applicant’s claim be dismissed.

5. In relation to costs:

(a) within 14 days, the parties submit any agreed proposed orders as to costs;

(b) if the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days, each party file and serve a short written submission on costs limited to 5 pages, and within 28 days each party file and serve a short responding written submission limited to 5 pages. The issue of costs will then be determined on the papers.

6. Paragraphs 1 to 4 above be stayed:

(a) for a period of 28 days; or

(b) if any party files a notice of appeal within 28 days, until the hearing and determination of the appeal.

7. This order is taken to be entered on the day that it is authenticated.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[12] | |

[25] | |

[25] | |

[35] | |

[54] | |

[58] | |

[59] | |

[61] | |

[61] | |

[62] | |

[63] | |

[64] | |

[65] | |

[66] | |

[67] | |

[68] | |

[71] | |

[71] | |

[77] | |

[90] | |

[90] | |

[93] | |

[118] | |

7.1 “compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris” | [118] |

[149] | |

[162] | |

[162] | |

[166] | |

[177] | |

[177] | |

[215] | |

[234] | |

[250] | |

[258] | |

[258] | |

[261] | |

[269] | |

[281] | |

[287] | |

[290] | |

[290] | |

[293] | |

[303] | |

[310] | |

[316] | |

[339] | |

[339] | |

[344] | |

[353] | |

[353] | |

14.3.2 Integer 1.5 “wherein the cavity is formed by a single chamber” | [360] |

[363] | |

[367] | |

[371] | |

15.2 Relevant legal principles—misleading or deceptive conduct | [374] |

15.3 Conduct occurring before the commencement of proceedings | [382] |

[382] | |

[384] | |

[388] | |

[389] | |

15.4 Conduct occurring after the commencement of proceedings | [399] |

[459] | |

[460] |

DOWNES J:

1. SYNOPSIS

1 These proceedings involve applications for relief for infringement of Australian Standard Patent No. 2018200317 (Patent) which has a priority date of 4 April 2016. In general terms, the Patent relates to a compression wave massage device for sexual stimulation of the clitoris.

2 The applicant, EIS GmbH (EIS), is the patentee. Before February 2016, EIS sold a device called the Satisfyer Pro, and since about October 2016, it has sold the Satisfyer Pro 2 which is said to be made in accordance with the Patent.

3 The respondents, LELO Oceania Pty Ltd (LELO Australia) and LELOi AB (LELO Sweden), in NSD 376 of 2023 are related companies. The respondent, Calvista Australia Pty Ltd (Calvista), in NSD 1411 of 2023 is an Australian distributor of LELO-branded products. Unless it is necessary to distinguish between the respondents, I will describe them as LELO in these reasons.

4 EIS contends that, in exploiting the compression wave massage devices illustrated in Annexure B to the Amended Statement of Claim (together, the LELO Products), LELO has infringed claims 1 to 7, 9, 10, 15, 19 to 22 and 31 of the Patent directly, or alternatively indirectly (relevant claims).

5 LELO denies that the LELO Products are infringing and has also brought cross-claims seeking to invalidate the claims of the Patent. LELO also alleges that various letters, emails and press releases made by EIS were unjustified threats pursuant to s 128 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) and misleading and deceptive conduct pursuant to s 18(1) of Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), being the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). In relation to certain of these statements, LELO also alleges that EIS breached an undertaking given to the Court on 12 December 2023 to the effect that it would not make threats of infringement proceedings in respect of the Patent in relation to any LELO products until the hearing and determination of these proceedings or further order (December 2023 undertaking).

6 As part of its invalidity case, LELO relies on third party devices called the Womanizer W100 and Womanizer W500 (together, the Womanizer).

7 The present case is to be determined by the Patents Act as amended by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth). Amendments to ss 7 and 40 of the Patents Act apply to the present case as a consequence of Sch 1, item 55 of the Raising the Bar Act.

8 By order of Nicholas J dated 6 December 2023, it was ordered that all issues relating to liability for infringement (including validity), contravention of the ACL and unjustified threats be determined prior to and separately from any issues of election and quantification of pecuniary relief.

9 By order of Nicholas J dated 18 December 2023, it was ordered by consent that the trial in NSD 1411 of 2023 be heard together with NSD 376 of 2023, and that evidence given in the latter proceeding is to stand as evidence given or tendered in the former proceeding.

10 A trial on liability only was held in February 2025.

11 For the following reasons:

(1) the claims do not comply with ss 40(2)(a), 40(2)(b) and 40(3) of the Patents Act. It follows that the Patent is invalid and should be revoked;

(2) the cross-claims should otherwise be dismissed;

(3) none of the LELO Products infringes the relevant claims. This has the consequence that the application should be dismissed.

2. THE PATENT

12 The Patent is entitled “Pressure Wave Massager”.

13 The Abstract states as follows:

A compression wave massage device for body parts is described, particularly for erogenous zones such as the clitoris, comprising a pressure field generation device and a drive device. The pressure field generation device has at least one cavity with a first end and a second end, located opposite the first end and distanced from said first end, with the first end being provided with at least one opening for placement on a body part. The drive device causes a change of the volume of at least one cavity between a minimal volume and a maximal volume such that in at least one opening a stimulating pressure field is generated. The cavity is formed by a single chamber, and the ratio of the volume change to the minimal volume is not below 1/10, preferably not below 1/8.

14 Under the Background, the following is stated:

A device of the type mentioned at the outset is particularly known from DE 10 2013 110 501 Al. In this known device the cavity is formed by a first chamber and a second chamber. The second chamber shows an opening for placement on a body part or on an erogenous zone. The two chambers are connected to each other via a narrow connection channel. The drive device is embodied such that it only changes the volume of the first chamber, namely such that via the connection channel a stimulating pressure field is generated in the second chamber. This construction of prior art shows considerable disadvantages, though. The use with gliding gel or under water is impossible, since the lubricant or the water increases the throttle effect in the narrow connection channel to such an extent that the drive device is choked off. Additionally, the device of prior art fails to comply with the strict requirements of hygiene required here, since the connection channel due to its very narrow cross-section prevents any cleaning of the first chamber located at the inside so that contaminants and bacteria can accumulate there, which then cannot be removed.

The objective of the present invention is to provide a compression wave massage device of the type mentioned at the outset which shows a simple and simultaneously effective design, and additionally meets the strict requirements for hygiene.

15 Under the Summary, there is further discussion of the objective:

This objective is attained in a pressure field generation device, which comprises at least one cavity with a first end and an opposite second end, located at a distance from the first end, with the first end comprising at least one opening for placement on a body part and a drive device, which is embodied to change the volume of at least one cavity between a minimal volume and a maximal volume such that a stimulating pressure field is generated in at least one opening, characterized in that the cavity is formed by a single chamber and the ratio of volume change to minimal volume is not below 1/10, preferably not below 1/8.

Accordingly, the invention is characterized in a single-chamber solution, which shows the advantages of a simpler construction, improved hygiene, particularly due to the ability of easier rinsing of the cavity according to the invention, formed by only a single chamber, and the easy handling with lubricant or under water.

Furthermore, according to the invention the ratio of the minimal volume to the volume change shall not exceed 10, particularly not exceed 8, since it was found that otherwise the suction effect becomes too low. Here, the volume change refers to the difference between the maximal volume and the minimal volume. The volume of the cavity is defined as the volume of a chamber which ends in the proximity of the opening in a virtually planar area, which virtually closes the opening.

16 Accordingly, the invention is characterised in the Patent as a “single-chamber solution”. Furthermore, the above passage discloses that the volume of the cavity “is defined as the volume of a chamber which ends in the proximity of the opening in a virtually planar area, which virtually closes the opening”.

17 The drawings depict a preferred exemplary embodiment of the invention. Under the Brief Description of the Drawings, it is stated that the embodiment is greater detail based on the drawings.

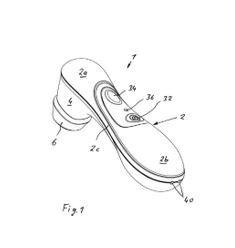

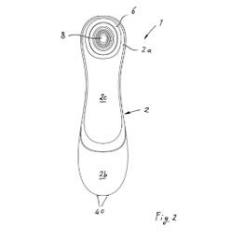

18 It is stated that Figure 1 is a perspective side view of the compression wave massage device according to the invention in a preferred embodiment. Figure 1 is shown below:

19 Figure 2 (reproduced below) is a front view of the compression wave massage device of Figure 1.

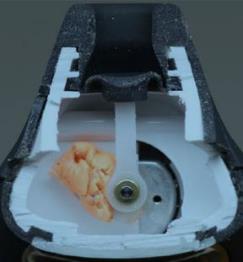

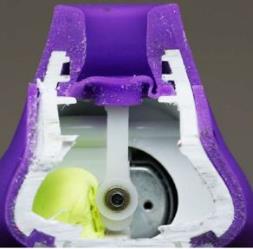

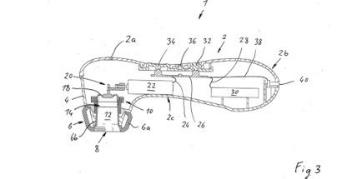

20 Figure 3 (reproduced below) is a longitudinal section through the compression wave massage device of Figure 1.

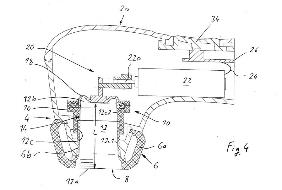

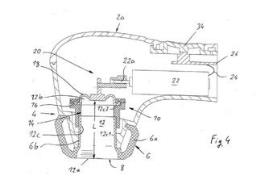

21 Figure 4 (reproduced below) is an enlarged detail of the longitudinal section of Figure 3 in the head section of the compression wave massage device of Figure 1.

22 The Detailed Description provides detailed information about the preferred embodiment as depicted in the Figures, but also refers to other possible designs and preferments.

23 Other aspects of the specification will be addressed later in these reasons.

24 The relevant claims, with integers identified, are as follows:

No. | Integer |

Claim 1 | |

1.1 | A compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris, comprising: |

1.2 | a pressure field generation device comprising at least one cavity with a first end and a second end, located opposite the first end and distanced from the first end, |

1.3 | with the first end being provided with an opening for placement over the clitoris; and |

1.4 | a drive device configured to generate a change of the volume of at least one cavity between a minimal volume and a maximum volume such that in at least one opening a stimulating pressure field is generated, |

1.5 | wherein the cavity is formed by a single chamber |

1.6 | and the ratio of the volume change to the minimal volume is not below 1/10 and not greater than 1. |

Claim 2 | |

2.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

2.2 | wherein the cavity is formed by a single continuous chamber. |

Claim 3 | |

3.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

3.2 | wherein the cavity is limited by a continuous lateral wall connecting the first end with the second end of the cavity. |

Claim 4 | |

4.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

4.2 | wherein the cross-section of the cavity of the chamber defined perpendicular to its length between the two ends is essentially unchanged or at least almost consistent over the entire length between the two ends |

4.3 | such that the air flow is essentially unchanged or at least almost consistent over the entire length of the cavity of the chamber. |

Claim 5 | |

5.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

5.2 | wherein the cavity of the chamber essentially shows the form of a rotary body with a circular or elliptic cross-section. |

Claim 6 | |

6.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

6.2 | wherein the lateral wall of the chamber limiting the cavity and connecting its two ends to each other is free from discontinuations. |

Claim 7 | |

7.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

7.2 | wherein the cavity of the chamber shows the form of a continuous tube. |

Claim 9 | |

9.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

9.2 | wherein the ratio of the width of the cavity of the chamber, defined perpendicular to its longitudinal extension, to the length of the cavity of the chamber, defined in the direction of its longitudinal extension, ranges from 0.1 to 1.0. |

Claim 10 | |

10.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

10.2 | wherein the cavity of the chamber is closed at its second end with a flexible membrane, |

10.3 | preferably made from silicon, |

10.4 | which essentially extends over the entire cross-section of the cavity and |

10.5 | which is moved by the drive device alternating in the direction towards the opening and in the opposite direction thereto. |

Claim 15 | |

15.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

15.2 | wherein the stimulating pressure field shows a pattern of relative vacuum and overpressure stages, which are modulated on a reference pressure. |

Claim 19 | |

19.1 | A device according to claim 15, |

19.2 | wherein the stimulating pressure field shows an essentially sinusoidal periodic pressure progression. |

Claim 20 | |

20.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

20.2 | further comprising a control device which controls the drive device and |

20.3 | comprises at least one control means by which the respective modulation of the stimulating pressure field can be changed. |

Claim 21 | |

21.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

21.2 | wherein the device is a hand-held device. |

Claim 22 | |

22.1 | A device according to claim 1, |

22.2 | wherein the ratio of the volume change to the minimal volume is not below 1/8. |

Claim 31 | |

31.1 | A device according to claim 21, |

31.2 | wherein the device is operated by a battery. |

3. WITNESSES

3.1 Witnesses called by EIS

25 Ms Margaux Hayes is a mechanical engineer and product designer, with over 10 years’ experience in the design and development of consumer products, medical instruments, sexual stimulation devices and percussion devices.

26 Ms Hayes affirmed six affidavits in the proceedings, dated 6 March 2024 (Hayes 1), 15 May 2024 (Hayes 2), 12 September 2024 (Hayes 3), 15 November 2024 (Hayes 4), 15 November 2024 (Hayes 5) and 7 February 2025 (Hayes 6).

27 Between 2014 and 2016, Ms Hayes worked as a sessional lecturer at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), and her work included teaching classes on the design and manufacture of sex toys. During that period, she visited sex toy shops, including for the purposes of her teaching. In 2015 and 2016, she taught undergraduate students at RMIT’s “Future Sex” design studio about product solutions including for the improvement of sexual pleasure. As part of this, Ms Hayes assisted students with the detailed design of a clitoral stimulator.

28 A Sydney Morning Herald Article published in December 2015 entitled “Melbourne’s RMIT University runs design course on how to make sex toys” is in evidence. According to that article, RMIT’s Future Sex design studio was the first university course of its kind which involved industrial design and development of sex toys. Based on that article, Dr Judith Glover, with whom Ms Hayes and Ms Lauren Rigbye worked, believed she was the only person in the world who had a PhD in sex toy design at that time.

29 In 2018, Ms Hayes worked as an assistant researcher for Handii (now called Bump’n) on the design and manufacture of sexual stimulation products for people with disabilities, particularly those with cerebral palsy. As part of that project, she designed and developed prototype clitoral stimulation devices with vibrating components.

30 LELO is critical of the evidence of Ms Hayes and submits that she was biased towards EIS, that she had issues recalling salient facts and that she had withheld relevant and important information when writing Hayes 1 in order to aid EIS’s infringement position. In particular, LELO submits that Ms Hayes was selective in the choice of photographs of the LELO Products which were included in her evidence, and that the ones she chose to include were advantageous to EIS. I do not accept these criticisms as, although I consider that there were some issues with the evidence of Ms Hayes which I address below, I do not consider that Ms Hayes lacked independence or was biased. This is especially as the explanations given by Ms Hayes for why she chose particular photographs (for example) were not unreasonable.

31 LELO also submits that Ms Hayes was incapable of being impartial in respect of the testing performed by Cobalt Design (Cobalt). Ms Hayes worked as a product engineer for Cobalt from 2017 until 2020. Furthermore, in late 2024, Ms Hayes corresponded with Cobalt about a potential employment position. Ms Hayes stated that she ceased all communication with Cobalt once she was informed by the lawyers for EIS that Cobalt had been appointed to undertake the experiments in the proceeding, and that it was inappropriate for her to continue to correspond with Cobalt. Although Ms Hayes was cross-examined about this association by counsel for LELO, it failed to demonstrate that Ms Hayes was biased.

32 Although Ms Hayes appeared to take her role as an expert witness seriously and was independent, much of her written evidence and many of her answers during the hearing lacked precision, were at times vague and confusing and, on occasion, appeared to be based on her own personal experience and knowledge of devices of the kind claimed in the Patent acquired post the priority date, rather than based on the extent of the disclosure, and the terms used, in the Patent and the common general knowledge.

33 Mr Brody Payne is a mechanical design manager and senior mechanical engineer employed by Outerspace Design (Outerspace). Mr Payne was engaged as an independent witness. He affirmed two affidavits addressing the conduct of certain experiments by Outerspace.

34 EIS also relied on various affidavits from its solicitors, including Mr John Lee, Ms Irini Lantis, Mr Connor Jarvis and Ms Vanessa Farago-Diener from Gilbert + Tobin. Their evidence addressed various issues, including the conduct of the experiments, various inspections of prior art products, Wayback Machine searches, and various overseas decisions. None of these witnesses was required for cross-examination.

3.2 Witnesses called by LELO

35 Ms Rigbye is a mechanical engineer. Ms Rigbye affirmed two affidavits on 6 March 2025 (Rigbye 1) and 15 November 2024 (Rigbye 2).

36 Ms Rigbye described her qualifications and experience in relation to sex toys as follows:

From 2014 - 2017, I worked under Dr Judith Glover as a sessional academic, teaching the subject “Engineering for Industrial Design”. Dr Glover’s research work was focussed on sex toy design, and she developed a course on sex toy design (the “Future Sex design studio”), which was delivered to students in 2015. We frequently discussed her work in this field of sex toy design, which is how I became familiar with the industry before 4th April 2016, prior to working with Dr Glover later in 2017 on the first sex toy-based project mentioned above. We discussed some sex toys on the market before April 2016, for example, We-Vibe, Lelo and Iroha devices.

37 Like Ms Hayes, Ms Rigbye was mentored by Dr Glover, and worked for Dr Glover after earning her Bachelor degree. Ms Rigbye also had a practical interest in, and possessed for her own use, sex toys before 4 April 2016 but had not been involved in sex toy design before April 2016.

38 Between 2017 and 2018, Ms Rigbye was involved in two projects which included stimulation devices, albeit that the project in 2017, which involved the insertion of a clitoral stimulator above the male pubic bone, was not considered to be feasible. The other project involved the Handii product (being the same project in which Ms Hayes was also involved).

39 Ms Rigbye’s affidavit evidence and her evidence in the joint expert reports contained detailed, logical and cogent explanations for her opinions. Her oral evidence during the hearing was clear and generally consistent with her written evidence, which evidence was not undermined by the answers given under cross-examination in any significant way. Ms Rigbye made appropriate concessions during the hearing, and was an exemplary expert witness. For these reasons, where the evidence of Ms Rigbye differed from that of the other experts, I prefer the evidence of Ms Rigbye unless indicated otherwise.

40 Mr Michael Duff is an electrical engineer, who affirmed ten affidavits in the proceedings, dated 5 December 2023 (Duff 1), 12 December 2023 (Duff 2), 6 March 2024 (Duff 3), 28 March 2024 (Duff 4), 29 April 2024 (Duff 5), 7 June 2024 (Duff 6), 13 June 2024 (Duff 7), 12 September 2024 (Duff 8), 15 November 2024 (Duff 9) and 18 November 2024 (Duff 10).

41 Mr Duff graduated with a Bachelor of Electronic and Electrical Engineering from the University of Northumbria in 1989. Since 2010, he has worked as an engineer for Armocon Technology (Armocon), in Suzhou, China. LELO has been a customer of Armocon for more than 14 years. Armocon is the Chinese manufacturing partner for LELO, and in particular in relation to the LELO Products.

42 Mr Duff was initially called as a factual witness. The first four affidavits affirmed by Mr Duff did not contain the expert declaration required by r 23.13(1)(b), or the acknowledgement required by r 23.13(ga), of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). It was not until Mr Duff’s fifth affidavit filed in April 2024 that he was provided with the Expert Witnesses Guidelines.

43 In the circumstances, it is difficult to understand how Mr Duff could describe himself as being an independent expert witness in his fifth and later affidavits in light of the connection between his employer and LELO. Further, at times during the hearing, Mr Duff acted in a manner which was demonstrably partisan because he appeared to be taking steps to give evidence which he considered would assist LELO. For example, Mr Duff would interject frequently and ask to comment on a topic despite not being asked to do so. He also tended to give very elaborate answers that were not responsive to the question being asked.

44 Indeed, Mr Duff appeared to appreciate the position that he was in when he gave these answers:

MS COCHRANE: Yes, but also your role in this proceeding was to assist LELO and Armacon to avoid a finding of infringement of the EIS patent.

MR DUFF: It’s – because LELO is a good client of ours, it was of interest to help, yes.

MS COCHRANE: Yes, and it’s of interest to Armacon to avoid a finding that the LELO products infringe the EIS patent, because then they can keep on making them, can’t they?

MR DUFF: That’s correct.

MS COCHRANE: Yes.

MR DUFF: That’s correct.

MS COCHRANE: And it’s very difficult, isn’t it, Mr Duff, for you to apply an open mind to this case, given that you’re employed by Armacon, and it has an interest in ensuring that the LELO products are found not to infringe the EIS patent.

MR DUFF: I’m here as an expert because I’ve been involved in the design with the LELO team in Shanghai on pressure wave devices, and LELO is a good client of Armacon, so it is of my interest to assist and give my expert advise.

MS COCHRANE: Yes. And in particular, you’re conscious that it’s in Armacon’s interest to make sure that the LELO products are found not to infringe the EIS patent.

MR DUFF: I think it’s in the interest of LELO and Armacon.

MS COCHRANE: Yes.

MR DUFF: Is that – it’s in the interest of both, because LELO is a client to Armacon.

45 LELO submits that its justification for calling Mr Duff is that finding an expert working in the field of clitoral pressure wave massage devices in Australia “proved impossible”. LELO also submits that, “[d]ue to these difficulties, Mr Duff was asked by LELO and agreed to share his expertise in the area”. However, no evidence was adduced in support of these difficulties.

46 In any event, Mr Duff’s knowledge exceeded the common general knowledge as at the priority date in relation to compression wave massagers. That is because, while working at Armocon, Mr Duff had experience in building and testing prototypes of designs for “pressure wave vibrators” and assembling the final products from component parts. Mr Duff also attended weekly “New Product Development” meetings hosted by LELO, which were also attended by Mr Filip Sedic (being the named inventor on patents and patent applications in the name of LELO, such as, for example, the patent which is contained in Annexure MD-5 of Duff 1). By these meetings, Mr Duff had extensive exposure to the design of these devices by someone who is inventive. This peculiar knowledge which was derived by Mr Duff through his role at Armocon is therefore not representative of the knowledge of the hypothetical person skilled in the art.

47 For these reasons and unless stated otherwise, I place less weight on Mr Duff’s opinion evidence where it conflicts with that of Ms Hayes and Ms Rigbye. However, I do not accept that Mr Duff gave false evidence when it came to factual matters, as EIS contends. While it is the case that Mr Duff gave inconsistent factual evidence at times, this affected his reliability as a witness (in terms of his recollection) rather than demonstrating his dishonesty.

48 Mr Barry Schoonenberg is a retailer and the owner of the Playhouse Adult Stores, based on the Gold Coast, Queensland (Playhouse). Mr Schoonenberg affirmed two affidavits on 6 December 2023 (Schoonenberg 1) and 15 November 2024 (Schoonenberg 2).

49 Ms Michelle Temminghoff is a retailer and the owner of the shop called “Passionfruit, The Sensuality Shop Pty Ltd” (Passionfruit Shop). Ms Temminghoff affirmed three affidavits on 6 March 2024 (Temminghoff 1), 7 June 2024 (Temminghoff 2) and 15 November 2024 (Temminghoff 3). Ms Temminghoff was not required for cross-examination.

50 Mr Roger Sheldon-Collins is the Managing Director of Calvista. Mr Sheldon-Collins affirmed three affidavits on 6 March 2024 (Sheldon-Collins 1), 2 April 2024 (Sheldon-Collins 2) and 15 November 2024 (Sheldon-Collins 3). Mr Sheldon-Collins’ evidence addressed the introduction of the Womanizer devices into the Australian market and his sale of those devices.

51 Mr Viktor Pilčik is the Global Head of Marketplaces for LELO Adria. Mr Pilčik affirmed one affidavit on 14 November 2024. His evidence addressed the provenance of the Womanizer W100 devices supplied to Mr Duff for the purposes of certain experiments.

52 Mr Dejan Lukac is the director of LELO Oceania Pty Ltd. Mr Lukac swore and affirmed (respectively) two affidavits in the proceeding on 4 December 2023 and 5 June 2024. His evidence addressed the issue of the claimed threats.

53 LELO also relied on affidavits from its solicitor, Mr Peter Douros. Mr Douros swore or, in one instance, affirmed seven affidavits on 9 June 2023 (Douros 1), 29 November 2023 (Douros 2), 6 March 2024 (Douros 3), 6 May 2024 (Douros 4), 13 September 2024 (Douros 5), 2 October 2024 (Douros 6) and 18 November 2024 (Douros 7).

3.3 Court appointed expert

54 On 14 October 2024, I made orders facilitating further experiments to be conducted by a court-appointed, independent testing facility in Australia.

55 On 21 October 2024, I appointed Cobalt to undertake this testing, with the experiments conducted under the supervision of Mr Kynan Taylor, Associate Principal of Cobalt.

56 Cobalt is an engineering and design firm with over 25 years’ engineering and design expertise.

57 Mr Taylor is a registered engineer with over 18 years’ experience. He affirmed one affidavit dated 8 November 2024 annexing a report regarding the conduct of the experiments that were undertaken by Cobalt and a copy of the experimental report prepared by Mr Taylor and Mr Marcus Krigsman, who is a lead engineer at Cobalt and who conducted the testing under the supervision of Mr Taylor.

3.4 Joint expert reports

58 Three joint expert reports were prepared being:

(a) a report addressing the topics of the person skilled in the art (PSA), the common general knowledge (CGK) and construction of the Patent was prepared following a conclave attended by Ms Hayes, Ms Rigbye and Mr Duff (JER 1);

(b) a report addressing the topics of novelty and inventive step was prepared following a conclave attended by Ms Hayes and Ms Rigbye (JER 2);

(c) a report addressing the topics of infringement, utility, s 40 grounds and the experimental evidence was prepared following a conclave attended by Ms Hayes and Mr Duff (JER 3).

3.5 Reasons for rulings

59 During the hearing, certain evidence was the subject of objections. The reasons for admitting or excluding that evidence are contained in Annexure A to these reasons. In Annexure A, I do not address objections where an agreement was reached between the parties about the outcome of an objection or where a party did not press the evidence following an objection being made.

60 In addition, for the reasons explained in EIS GmbH v LELO Oceania Pty Ltd (Expert Evidence) [2024] FCA 1334 (Downes J), the question of whether LELO was entitled to rely upon [14]–[49] of Duff 9 at trial was reserved to the trial. That topic is also addressed in Annexure A.

4. EXPERIMENTS

4.1 Experiments conducted by Outerspace

61 In December 2023, Outerspace, a design and engineering firm in Melbourne, was engaged by the parties, with leave of the Court, to carry out experimental tests (Outerspace experiments). LELO provided unopened samples of the LELO Products to be tested. The Outerspace experiments were carried out between 31 January and 2 February, and 28 February 2024. Representatives from both parties were present.

4.2 Experiments conducted by respondents

62 In late February and early March 2024, the respondents carried out further experiments on alleged prior art devices at Armocon in Suzhou, China (China experiments). The circumstances relating to the China experiments are described in EIS GmbH v LELO Oceania Pty Ltd (Evidence of Experiments) [2024] FCA 713 (Downes J).

4.3 Experiments conducted by Cobalt

63 Further testing was conducted by Cobalt (Cobalt experiments) where LELO provided unopened samples of the LELO Products to be tested. The Cobalt experiments were carried out between 30 October to 1 November 2024. Representatives from both parties were present.

4.4 Experimental protocols

64 The experimental protocols followed in the Outerspace experiments and Cobalt experiments (only) are in evidence. In respect of each LELO Product and at a high level, the protocols involved three tests, as follows.

4.4.1 Volume Measurements

65 These tests were designed to measure whether the ratio of the volume change of the cavity to the minimal volume (i) is not below 1/10 and/or (ii) is not below 1/8. These tests were relevant to integer 1.6 and integer 22.2.

4.4.2 Width/Length Measurements

66 These tests were designed to measure whether the ratio of the width of the cavity of the chamber, defined perpendicular to its longitudinal extension, to the length of the cavity of the chamber, defined in the direction of its longitudinal extension, ranged from 0.1 to 1.0. This is relevant to claim 9.

4.4.3 Cross-Section

67 These tests involved bisecting each LELO Product, leaving the cross-section of the cavity unaffected, and taking photographs. This is relevant to various integers, insofar as they relate to the shape or structure of the cavity and single chamber.

4.5 Conduct and reliability of the experiments

68 Mr Payne gave evidence about the conduct and reliability of the Outerspace experiments and Mr Taylor gave evidence about the conduct and reliability of the Cobalt experiments.

69 Insofar as Mr Duff sought to impugn the conduct and reliability of the Outerspace and Cobalt experiments, I do not accept his criticisms in circumstances where (a) neither Mr Payne nor Mr Taylor were cross-examined and (b) Mr Duff is not independent. In any event, during the trial, Mr Duff accepted that all of his criticisms about the experiments were immaterial.

70 For these reasons and subject to their relevance to the issues raised concerning the construction of the claims and infringement, I accept the veracity of the results of the Outerspace and Cobalt experiments.

5. PERSON SKILLED IN THE ART

5.1 Relevant legal principles

71 The PSA is the hypothetical person to whom the patent specification is addressed and who, generally speaking, works in the art or science with which the invention is connected. It is a notional person who may have an interest in (inter alia) using the products or methods of the invention: see e.g., Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 at [26] (Nicholas J); Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd (2023) 180 IPR 315; [2023] FCA 1017 at [86] (Burley J).

72 The first step in identifying the PSA is to identify the field of knowledge to which the invention relates: see e.g., Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360 at [72]–[74] (Nicholas J). The “subject matter of the invention” is the area “in which the invention is intended to be used”: Neurim at [74]. The “patent specification is directed to those with a real, not a peripheral, interest in its subject matter”: Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Limited (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307 at [157] (Yates J).

73 If the field is defined too narrowly, this would fall into the error identified by Birss J in Illumina Cambridge Ltd v Latvia MGI Tech SIA [2021] EWHC 57 (Pat) at [62], citing Peter Prescott QC in Folding Attic Stairs v The Loft Stairs Company Ltd [2009] EWHC 1221 (Pat) at [33]:

… It is unfair to define an art too narrowly, or else you could imagine absurd cases e.g. “the art of designing two-hole blue Venezuelan razor blades”, to paraphrase the late Mr T.A. Blanco White. Then you could attribute the “common general knowledge” to that small band of persons who made those products and say that their knowledge was “common general knowledge” in “the art”. That would have the impermissible result that any prior user no matter how obscure could be deemed to be common general knowledge, which is certainly not the law.

74 The PSA is the “non-inventive worker in the field”: Wellcome Foundation Limited v V.R. Laboratories (Aust.) Proprietary Limited (1981) 148 CLR 262 at 270 (Aickin J, with whom Gibbs ACJ and Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ agreed); Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 293 (Aickin J, with whom Barwick CJ, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ agreed).

75 Further, the notional PSA may be a team. As observed by Yates J in Novartis at [148]–[151]:

The “person skilled in the art” is a construct that is used to analyse questions that arise in patent law.

It is well-recognised that this construct can be understood as a “team”, particularly if the art is one having a highly developed technology. As such, the construct combines and deploys the knowledge and skills of the members of the “team”. This means that, in real life, the knowledge and skills of some members of the “team” may not be known or shared by others in the “team”. There is, however, but one construct. The person skilled in the art thinks with one mind, speaks with one voice, and draws, when and to the extent necessary, on the disparate knowledge and skills of all the members of the “team”. The person skilled in the art is indivisible.

Depending on the relevant art, the members of the “team” may be highly skilled with research capabilities…

This does not mean, however, that the person skilled in the art, understood as a highly skilled team or a notional research group, exhibits the capacity for invention. The person skilled in the art, even when understood as a highly skilled team or a notional research group, is taken to have no inventive capacity whatsoever, and is constrained to act only with knowledge that is publicly known, and commonly accepted, by those within the calling of the art in question.

(Citations omitted.)

76 The Court may focus on particular characteristics of the PSA depending on the legal issue involved: see e.g., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (2015) 113 IPR 191; [2015] FCA 634 at [127] (Yates J); Axent Holdings Pty Ltd (t/as Axent Global) v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd (2020) 154 IPR 431; [2020] FCA 1373 at [251] (Kenny J).

5.2 Identification of field of knowledge

77 The Abstract of the Patent describes the invention as, “[a] compression wave massage device for body parts is described, particularly for erogenous zones such as the clitoris, comprising a pressure field generation device and a drive device. The pressure field generation device has at least one cavity with a first end and a second end, located opposite the first end and distanced from said first end, with the first end being provided with at least one opening for placement on a body part. The drive device causes a change of the volume of at least one cavity between a minimal volume and a maximal volume such that in at least one opening a stimulating pressure field is generated. The cavity is formed by a single chamber, and the ratio of the volume change to the minimal volume is not below 1/10, preferably not below 1/8”.

78 Similarly, the section entitled “Technical Field” states that, “the invention relates to a compression wave massage device for body parts, particularly erogenous zones such as the clitoris, comprising a device generating a pressure field which shows at least one cavity with a first end and a second end, located opposite thereto and distanced from the first end, with the first end comprising at least one opening for placement on a body part and a drive device, which is embodied to generate a change of the volume of at least one cavity between a minimal volume and a maximal volume such that a stimulating pressure field is generated in at least one opening”.

79 The specification also states that, “[t]he objective of the present invention is to provide a compression wave massage device of the type mentioned at the outset which shows a simple and simultaneously effective design, and additionally meets the strict requirements for hygiene”.

80 Claim 1, which is the only independent claim, claims “[a] compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris…” comprising a pressure field generation device with certain features and which is configured to generate a stimulating pressure field.

81 Thus, the relevant subject matter of the invention relates to a compression wave massage device which has particular characteristics when used on the clitoris.

82 LELO submits that the PSA would be a person working in the field of clitoral pressure wave massage devices. However, I disagree as this would define the field too narrowly in the manner described in Illumina.

83 This conclusion finds support by the agreement reached between the experts as recorded in the JER 1, being that the person or team to whom the Patent is directed or addressed has (at least):

(1) experience designing battery powered handheld therapeutic devices;

(2) knowledge of materials, waterproofing, relevant levels of power output, knowledge of drive systems and battery capacity;

(3) knowledge and experience of the product design process, including reverse engineering;

(4) enough knowledge of manufacturing methods (e.g. injection moulding) and quality control processes to engage with manufacturers;

(5) knowledge of general engineering principles including common mechanisms and basic fluid mechanics;

(6) a degree in mechanical engineering or product design or similar;

(7) exposure to or understanding of sexual stimulation devices through industry or research experience;

(8) industry experience working as a product designer with hands-on experience designing consumer products, including work on therapeutic or medical devices, and using tools such as CAD (computer aided design) programs for detailed design and documentation;

(9) knowledge of anatomy of the clitoris, vulva and perineum;

(10) knowledge of the history and current state of the art in sex toy design – which given the lack of formal published and academic resources on the subject, would have involved discussions with manufacturers, retailers and users of sex toys.

84 Nowhere in the agreement reached by the experts (including Mr Duff) was it stated that the PSA needed to have knowledge of and experience with the design or manufacture of clitoral pressure wave massage devices, or even sexual stimulation devices to be used on the clitoris per se (whether pressure wave or otherwise).

85 For these reasons, the field of knowledge to which the invention relates is the design and manufacture of sex toys or, to put it another way, the design and manufacture of devices for sexual pleasure. Those who work in this field would have a real interest in the subject matter of the Patent irrespective of whether they had any prior knowledge or experience of clitoral pressure wave massage devices.

86 Considering the evidence of Mr Duff concerning his “real life” involvement in meetings at which the development of the design of potential sex toys (and specifically clitoral stimulators) was discussed, I consider that, in this case, the hypothetical PSA would be a team of people who have, as a team, the skills and knowledge identified by the experts. As the experts themselves acknowledged, the PSA would have knowledge of the history and current state of the art in sex toy design, acquired through discussions with manufacturers, retailers and users of sex toys.

87 During the trial, both Ms Rigbye and Ms Hayes gave evidence that retailers of the devices would be consulted by the PSA team, at the least, if not (in the case of Ms Rigbye) being members of the team either “formally or informally”. Ms Hayes said that it was “very common to consult retail experts, among other people, for inputs”. Ms Rigbye explained that “anyone who’s looking at developing a device in any field is going to look at what’s already out there”. Ms Hayes agreed with this, saying that “whenever you get given a brief or a project, if there are any gaps, then go and fill them. And so you would have [the] skills to go and ask the questions…”.

88 Ms Hayes also gave evidence that it was “common practice [to] start consulting with manufacturing experts when you get to the detail design phase. So you might have some crude prototypes already that you’ve put together yourselves to explore – well, to answer questions, whatever they are. I think it’s best practice to engage manufacturing experts earlier, but I think it’s actually uncommon, in my experience of the design industry, to engage them at the concept phase. It usually happens at a detail design phase.”

89 On that basis and having regard to their respective qualifications and work experience as at the priority date, Ms Hayes, Mr Duff and Ms Rigbye each qualified as members of the notional PSA team. That is so even though neither Ms Hayes nor Ms Rigbye was aware of clitoral pressure wave massage devices before the priority date, and Mr Duff’s engineering degree was in electrical engineering rather than mechanical engineering.

6. COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE

6.1 Relevant legal principles

90 The kinds of information that form part of the CGK differ from industry to industry and from one technical field to another. The qualifications of the skilled addressee, the setting in which and the resources with which he or she operates, and the practices and techniques that he or she regards as commonplace and known are important considerations in determining the CGK in any case: Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2002) 212 CLR 411; [2002] HCA 59 at [153] (Kirby J).

91 The fact that a witness, or even a number of witnesses, had particular knowledge at the priority date does not of itself establish that such knowledge was CGK. The witness may be an expert who has specialised expertise and knowledge. At the same time, evidence that an expert, or number of experts, were not aware of certain information may be evidence, depending on the circumstances, that the information was not CGK.

92 Further, material or information cannot be regarded as CGK based upon the personal knowledge of a witness by reason of their individual experiences in the absence of evidence of its general acceptance and assimilation by the bulk of those in the relevant field: see Aktiebolaget at [31]. It follows that, research or other work carried out by witnesses in the course of their employment or matters which became known to them by reason of that employment or individual experiences is not, for that reason alone, knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade, and nor is it probative of CGK.

6.2 CGK as at 4 April 2016

93 In the JER 1, Ms Rigbye, Ms Hayes and Mr Duff provided an agreed statement of the CGK at the priority date as including:

(1) understanding of needs of sex toys: hygiene, pleasure, ease to use, ergonomics, safety;

(2) familiarity with common sex toy architecture (rotary motor, battery, housing, soft touch areas);

(3) understanding of technical needs (e.g., how to specify the motors and batteries in drive systems);

(4) general understanding that there are different waterproofing levels and different ways you might achieve each;

(5) understanding of existing market and how to check that your design is unique, for example a patent search;

(6) familiarity with user testing methods.

94 Ms Hayes and Ms Rigbye generally agreed with the descriptions of the state of the CGK in Hayes 3 ([33]–[47]) and [2.2.1] (Basic engineering principles) of Rigbye 1, Annexure LR-1. The latter concerned evidence which was related primarily to pressure fields, and is aligned with LELO’s Second Further Amended Particulars of Invalidity (invalidity particulars) at [2(c)(i)]. This evidence included:

(1) obtaining reciprocating straight-line motion from a drive engine rotating shaft using an eccentric or con-rod;

(2) creating a pressure field from a piston system or membrane system. As to this, the relationship between pressure and volume is given by Boyle’s law. The piston is often given as a basic example to study change in pressure due to a change in volume. It is widely known that the mechanism of operation of loudspeakers is a membrane system which creates varying changes in air pressure;

(3) a pressure field can be constant or modulating;

(4) a pressure field can be modulating and always positive (pushing);

(5) a pressure field can be modulating and always negative (sucking);

(6) a pressure field can be modulating between positive and negative.

95 The evidence of Ms Hayes was that, based on her reading of the Patent, she understands that the field of the invention is the field of sexual stimulation devices, which she defines as “Field”: Hayes 3 [13]. Ms Hayes was instructed that the PSA was a “skilled but not particularly inventive or imaginative worker in the field, with qualifications, experience, and knowledge of practices and techniques regarded as commonplace and known in the field” and that the CGK was “the general body of knowledge and experience which is available to all in the relevant Field at the relevant time”.

96 With those instructions in mind, Ms Hayes gave evidence of what she considered to be the CGK of a PSA as at the priority date. I have set this out below with a cross-reference to the invalidity particulars, and noting Ms Rigbye’s general agreement to this evidence:

At the Relevant Date, I had a sound understanding of the female sexual anatomy, including the labia majora, labia minora and clitoris, including through the work I performed. In particular, the size and shape of the female sexual anatomy, and the way that stimulation (being direct or indirect) would cause arousal, being the body’s response to sexual stimulation. This information is important in the design of sexual stimulation devices and affects the size and dimensions of the device.

At the Relevant Date, sexual stimulation devices were essentially of two types, that is, devices designed to be used to create stimulation through; (i) insertion into bodily orifices (which were typically phallic in nature and described in the industry as “dildos”); or (ii) vibration on the relevant body area, that is, externally (described in the industry as “vibrators”). At the Relevant Date, some products had both of these functions. [[2(c)(ii)a] invalidity particulars]

Insertable products, before the Relevant Date, typically sought to reflect the male anatomy but the product design of products in the sexual stimulation device market was beginning to shift. At the Relevant Date some new, higher end sexual stimulation devices were being created with user centred design in mind, with more playful shapes and colours, greater focus on ergonomics, and a wider market of end user, not being limited to heterosexual men and women. …

Vibration-type products typically used an electric motor with an off centre weight attached to the driveshaft of the motor to create vibration when the driveshaft spins the attached weight. At the Relevant Date, vibration-type devices were used as external genital massagers. A vibration-type product that I was aware of at the Relevant Date was the Hitachi Magic Wand, which based on my review of industry publications and discussions with industry colleagues before the Relevant Date, I regarded as widely known in the Field, before the Relevant Date. [[2(c)(ii)b], [2(c)(ii)c] and [2(c)(ii)f] invalidity particulars]

At the Relevant Date, there were some sexual stimulation devices that created stimulation through bodily insertion, and through external genital stimulation through vibration. The “rabbit” vibrator was a device that I was aware of at the Relevant Date, which, based on my review of industry publications and discussions with industry colleagues before the Relevant Date, I regarded as known in the Field at the Relevant Date. It comprised both an insertable appendage and a second external appendage for use as a clitoral stimulator, with an electric motor to create vibration in the device. [[2(c)(ii)d] invalidity particulars]

At the Relevant Date, sexual stimulation devices comprised hard plastic ABS was the most common plastic used in this kind of consumer product due to its impact resistance, its stability over time, and its low cost). Only some sexual stimulation devices were covered with silicone, and only on the contact surfaces of the devices. These devices were typically higher end and were more expensive. [[2(c)(ii)h] invalidity particulars]

… At the Relevant Date, I was not aware of sexual stimulation devices that created positive and negative pressure waves for stimulation of erogenous zones (pressure wave stimulation devices). Specifically, at the Relevant Date, I had not seen and had no experience with the Womanizer W100, Womanizer W500, or Satisfyer Pro devices. [[2(c)(ii)e], [2(c)(ii)g] and [2(c)(iii)] invalidity particulars]

For all sexual stimulation devices, it is of paramount importance that the device functions to provide sexual stimulation. The shape, construction and, in the case of powered devices the electronic components, must be optimised to provide stimulation to the intended erogenous zone, such as the clitoris. The development of a sexual stimulation device will involve testing, optimisation, and iteration to obtain a functional final product.

At the Relevant Date, I was aware of product design principles relevant to the design of consumer products, such as sexual stimulation devices. Relevant consumer products typically comprised electromechanical components such as electric motors (including crankshafts and camshafts, used to convert linear motion (up and down or back and forth) to rotational motion, and vice versa), basic electrical circuitry, and the use of printed circuit boards and batteries.

At the Relevant Date, I was aware of general engineering principles relevant to the design and manufacture of consumer products. This included the use of design tools such as CAD and geometrical dimensioning and tolerancing as used in geometric drawings. One application of geometrical dimensioning and tolerancing is to define virtual references called datums. Datums are theoretically exact lines, points, axes, or planes. A datum will often have an associated edge or surface on the part, but the virtual plane itself will extend beyond that edge or surface and is treated as infinite. This is used to define geometry of parts and assemblies.

At the Relevant Date, I was aware of general fluid dynamic principles. That is, what a wave is, and how waves behave in air or liquid fluids.

At the Relevant Date, I was aware of speakers and had a high-level understanding of how they functioned. Speakers were, and are today, typically comprised of a fixed, permanent magnet, a voice coil connected to a power source, a speaker cone, and a flexible material which connects the speaker cone to the assembly. Speakers generate sound waves (which are pressure or compression waves in air) through the movement of the speaker cone backwards and forwards.

At the Relevant Date, and today, I was not aware of any sexual stimulation devices that utilised speaker technology. That is, I was not aware of any sexual stimulation devices that had a mechanism to generate compression waves comprising a magnet, voice coil connected to a power source, and a speaker cone.

As I noted [above], in the Field at the Relevant Date, user-centred design had started to become a more central consideration when designing a sexual stimulation device. User-centred design required that the product be suitable for use on genital areas. This would have required that the shape of the product would be easy to use for consumers and would simply fit into the hand and other bodily areas. Sexual stimulation devices are used on sensitive areas of the body, and body safe silicone was known to be a useful material for the external body contact surfaces of sexual stimulation devices. As gels or lubricants could be used with sexual stimulation devices, the materials comprising these products should be resistant to, or not be damaged by use with, gels or lubricants.

97 While Ms Hayes and Ms Rigbye were familiar with commercially available clitoral stimulation devices, they stated in their respective affidavit evidence that they were not aware of any clitoral stimulation device which used positive and negative airwave pressure to stimulate the clitoris: Hayes 3 [35]–[40], [50], [58]; Rigbye 1, Annexure LR-1 at [2.2.2.7]. They also stated in the JER 2 that, “[o]ur understanding of CGK at the time did not include knowledge of pressure wave massagers”. However, that Ms Hayes and Ms Rigbye were not personally aware of such devices is not definitive, as they were each relatively new entrants to the industry and had limited experience as at the priority date.

98 Nor did the evidence of Ms Hayes and Ms Rigbye support a finding that “suction type stimulation devices that use suction to stimulate the clitoris” were CGK as alleged by LELO: [2(c)(ii)e] invalidity particulars.

99 Mr Duff added some comments in the JER 1 about matters which he considered formed part of the CGK. However, in relation to many of the matters identified by him in the JER 1, Mr Duff described them as matters that would “need to be known”, which indicates that he did not have a proper understanding of the meaning of CGK. Further, in Duff 1 and Duff 9, Mr Duff refers to information of which he became aware in his role at Armocon. However, because of his employment with Armocon and his interactions with LELO, his peculiar or specialised knowledge exceeds that of the notional PSA in relation to the design and manufacture of clitoral devices for sexual stimulation.

100 None of the experts in the JER 1 (including Mr Duff) identified compression wave massager devices as forming part of the CGK at the priority date.

101 However, LELO relies upon the position taken by EIS in opposition proceedings to an application filed by Novoluto GmbH, being EIS GMBH v Novoluto GMBH (2021) 162 IPR 342; [2021] APO 1, as constituting an admission that compression wave massage devices for clitoral stimulation were CGK as at the priority date.

102 In that case, EIS contended, through the evidence of Mr Florian Witt, that “sexual stimulation devices which use alternating positive and negative pressure to stimulate erogenous zones (pressure wave massagers) were [CGK] in the art at the priority date [being 13 March 2015 in that case]”: see [77]. Mr Witt “refers to the Womanizer W100 and its availability before the priority date to support his contention”. Mr Witt also stated that “a Womanizer W100 device was sent to him for analysis before March 2015”: see [95].

103 The delegate did not accept that such devices were CGK having regard to the evidence, including the evidence of the expert called by Novoluto GmbH: see [79]. However, I am not, of course, bound by such a finding, and EIS did not submit that I was.

104 The real question is whether, by the position taken by it in the opposition proceedings, EIS has admitted that compression wave massage devices for clitoral stimulation were CGK as at the priority date in this case (being a date which post-dates the date in those proceedings).

105 No evidence was adduced by EIS to explain the circumstances around the position taken by it in those opposition proceedings, and it is notable that Mr Witt is the named inventor on the Patent. That is, it is not the case that EIS called an independent witness who was not associated with it—rather, it called its own man, as it were. This was no doubt done for the purpose of defending the Patent, and its case on CGK was a central contention advanced by EIS in that proceeding for the purposes of obviousness: see e.g., [81].

106 Nor did EIS contend that the reasons given by the delegate as reported were inaccurate or incorrect.

107 To be an admission under the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), there must be a previous representation that is made by a person who is or becomes a party to a proceeding and is adverse to the person’s interest in the outcome of the proceeding. “Previous representation” (also a defined term) means a representation made otherwise than in the course of giving evidence in the proceeding in which evidence of the representation is sought to be adduced. “Representation” (also a defined term) includes an express or implied representation (whether oral or in writing) and a representation to be inferred from conduct.

108 In this case and by its conduct in the opposition proceedings (including the case which it advanced to the delegate and the evidence which it adduced through Mr Witt), EIS admitted that compression wave massage devices for clitoral stimulation were CGK as at the priority date of the Patent including, in particular, the Womanizer W100. Such an admission is admissible evidence as exceptions to both the hearsay and opinion rules: see s 81 of the Evidence Act.

109 The position taken by EIS in the opposition proceedings accords with the evidence of Mr Sheldon-Collins who gave evidence about the promotion, distribution and sale of the Womanizer products in Australia and New Zealand from February 2015. This timing is consistent with the reported evidence of Mr Witt in the opposition proceedings that “a Womanizer W100 device was sent to him for analysis before March 2015”.

110 By Sheldon-Collins 1, Mr Sheldon-Collins said that “[t]he Womanizer was a gamechanger because it was the first of its kind using pulsed air waves in the adult products market”. He also called it an “instant best seller” and said during the hearing that there was a “90-second club coming out of the States through social media, and that women will climax in under 90 seconds. So that’s how impressive the product was”. He also gave evidence during the trial to the effect that the Womanizer achieved a significant number of sales in 2015 and early 2016 for a product that was being launched and which was brand new. His evidence was to the effect that the promotion by Calvista of the Womanizer prior to the priority date included press releases, electronic direct mail marketing, flyers, magazine advertising, advertising on websites, social media, catalogues, posters and banners.

111 Mr Sheldon-Collins stated that, as at 4 April 2016 and as a result of the matters set out in his affidavit, he believed that all those working in the industry knew about the Womanizer. I accept this evidence. Having regard to his evidence as a whole, I do not accept the submission by EIS that the Womanizer had a “fledgling reputation amongst retailers”. Notably, even if Mr Sheldon-Collins would not have been a member of the PSA team, someone like him would have been consulted by the notional PSA team to ascertain the current state of the art in sex toy design, and the existence of the Womanizer would have been disclosed to the team, if they were not already aware of it.

112 Another person who could have been consulted by the PSA team is a retailer like Ms Temminghoff, who has sold sex toys since 1998. She said that her knowledge “is at the coalface of the sex toy industry” and that, in her view, it was commonly known in Australia in the sex toy industry before 4 April 2016 that sex toys using air pressure waves to stimulate the clitoris were introduced in “about 2014” and the main product was the Womanizer W100. Ms Temminghoff recalls being shown the first Womanizer in 2015 and did not believe it would work; but said that she tried the product and was proved wrong. Included in her evidence is an invoice dated 18 January 2016 showing the purchase by her business of three Womanizer products.

113 Similarly, Mr Schoonenberg could have been consulted by the PSA team. His evidence was that Playhouse was the first importer, retailer and distributor of the Womanizer in Australia, and that it had commenced selling the Womanizer in Australia in January 2015. He said that the Womanizer was “widely publicised” and had “mainstream promotion in Australia”; and that there were also online reviews and online discussion about the Womanizer. Mr Schoonenberg sold the Womanizer through Playhouse and also online, and he saw that the Womanizer won awards internationally in 2015 and January 2016 (which information he saw on the internet at the time).

114 EIS seeks to downplay the evidence of these lay witnesses by, first, pointing to what it says are the low numbers of sales of the Womanizer products before the priority date (which I do not accept having regard to the evidence of Mr Sheldon-Collins referred to above) and, secondly, submitting that public availability for sale, and knowledge by retailers, does not establish that the Womanizer was CGK – that is, it does not establish that there was general acceptance and assimilation by the PSA. While I accept the latter submission, I observe that, even if the Womanizer was not CGK, people like distributors and retailers would have been consulted by the notional PSA team and so (at the least) the Womanizer devices (and the existence of air pressure based clitoral stimulators) would have become known to the notional PSA team asked to design a new sexual stimulation device for women. In any event, the submissions by EIS do not overcome its admission in the opposition proceedings including in relation to the Womanizer W100.

115 For these reasons, the following was CGK at the priority date of the Patent in the art of sexual stimulation devices:

(1) sexual stimulation devices which use alternating positive and negative pressure to stimulate erogenous zones (pressure wave massagers);

(2) the Womanizer W100.

116 The evidence was insufficient to establish that the Womanizer W500 was CGK as at the priority date, especially as this version of the Womanizer device was not the subject of admission by EIS in the opposition proceedings. However, the evidence did establish that sales of the Womanizer W500 occurred in Australia, and so was publicly available, before the priority date: see e.g., Temminghoff 1 [24], Sheldon-Collins 1 [13].

117 Nor did the evidence establish that the Satisfyer Pro was CGK as at the priority date. However, the evidence did establish that it was being sold in Australia in early 2016, and so was publicly available before the priority date.

7. CONSTRUCTION

7.1 “compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris”

118 The first construction debate relates to the meaning of “compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris” in integer 1.1.

119 Claim 1 was amended on 22 December 2017 in order to overcome the Patent Examiner’s objections of lack of novelty and lack of inventive step over the prior art:

A compression wave massage device for when used on body parts, particularly erogenous zones such as the clitoris, comprising…

120 The form of claim 1 prior to its amendment may be taken into account when construing the current wording of claim 1: see s 116 of the Patents Act.

121 LELO submits that the amendment changed the claim from a “for” claim, indicating suitability for a particular use, to a “when used” claim, which it says limits the scope of the claim to the device “when used on the clitoris”.

122 The words used in claim 1 are ordinary English words. Further, by the JER 1, the experts agreed that the phrase is a description of the device, and its function in situ.

123 EIS accepts the construction of the experts and accepts that the phrase “compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris” describes the function of the device. EIS also submits that it is a “compression wave massage device when it’s used on the clitoris” but it submits that, as a matter of construction, the features which are described in the subsequent integers of claim 1 are not referable to its use on the clitoris.

124 However, in my view, on the proper construction of “compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris” in integer 1.1, the device is (that is, it functions as) a compression wave massage device when used on the clitoris and which has certain identified features when it is used on the clitoris. It follows that the words “when used on the clitoris” in integer 1.1 limits the scope of claim 1 to a device “when used on the clitoris” comprising the features identified in integers 1.2 to 1.6. Thus, the words “when used on the clitoris” govern all of the features of the device that follow those words, such that each of those features must be present when the device is used on the clitoris when it is performing its function as a compression wave massage device.

125 This conclusion is supported by the reference in integer 1.3 to the first end being provided with an opening for placement over the clitoris, and the reference in integer 1.4 to the generation of a “stimulating pressure field”. It is difficult to conceive of how such a pressure field can be generated, and how it could be adjudged to be stimulating, other than when using the device on the clitoris.

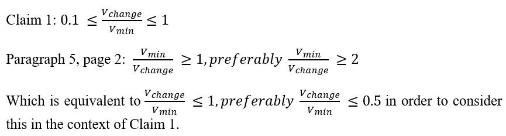

126 To understand how to generate a “stimulating pressure field”, one has particular regard to the interplay between integers 1.4 and 1.6. Integer 1.4 refers to (inter alia) the generation of a change of volume between a minimal volume and a maximal volume such that in at least one opening a stimulating pressure field is generated. Integer 1.6 refers to what the parties and experts called the volume change ratio or VCR. That is, integer 1.6 requires that “the ratio of the volume change to the minimal volume is not below 1/10 and not greater than 1”.

127 The experts agreed in the JER 1 that the VCR is the ratio of minimal volume to volume change, where:

(1) the minimal volume is the smallest volume of the cavity allowed by the device, when the drive device is in its forward-most position;

(2) the maximal volume is the largest volume allowed by the device, when the drive device is in its backward-most position;

(3) the volume change is the difference between minimal volume and maximal volume.

128 The specification also contains statements which describe VCR as being a measure of the strength of the stimulating pressure field when used on the clitoris.

129 In the Patent at page 2 lines 10–12, which forms part of the Summary, it is stated that:

…according to the invention the ratio of the minimal volume to the volume change shall not exceed 10, particularly not exceed 8, since it was found that otherwise the suction effect becomes too low…

130 In context, the reference to the “suction effect” becoming “too low” means that the pressure field is no longer “stimulating”, which can only be a reference to the pressure generated by the device when used on the clitoris.

131 In the Patent at page 2 lines 19–23, which forms part of the Summary, it is also stated that: