Federal Court of Australia

Scenic Rim Regional Council v Cutbush (No 3) [2025] FCA 1103

File number: | QUD 262 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | WHEATLEY J |

Date of judgment: | 8 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY — Bankruptcy notice – Determination of a separate question regarding validity of bankruptcy notice — Where notice contained address of creditor’s solicitors, by way of a post office box — Whether notice invalid by reason of a failure of the creditor to state a street or physical address whereby the judgment debtor may make payment for the amount claimed in notice or where he may make arrangements to the creditor’s satisfaction – Bankruptcy notice valid. |

Legislation: | Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 25C Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth) ss 7, 52, 53 Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) ss 37, 40, 41, 43, 44, 306 Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment Act 1996 (Cth) Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 21 Bankruptcy Rules 1928 (Cth) rr 5, 144 Bankruptcy Rules 1968 (Cth) r 8 Bankruptcy Rules 1996 (Cth) r 8 Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth) Bankruptcy Amendment (Electronic Service) Regulations 2024 (Cth) Bankruptcy Amendment (Service of Documents) Regulations 2022 (Cth) Bankruptcy Regulations 1996 (Cth) reg 4.02 Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth) ss 9, 12, 102 |

Cases cited: | Adams v Lambert (2006) 228 CLR 409; [2006] HCA 10 Anderson Rice (a firm) v Bride, Robert (1995) 61 FCR 529; [1995] FCA 868 Australian Steel Co (Operations) Pty Ltd v Lewis (2000) 109 FCR 33; [2000] FCA 1915 Bonds Industries Ltd v Sing [1999] FCA 1055 Croker v Commonwealth of Australia (2011) 9 ABC(NS) 44; [2011] FCAFC 25 Duarte v Coshott, in the matter of Duarte [2017] FCA 1238 Fuller v Alford (2017) 252 FCR 168; [2017] FCA 782 General Motors Acceptance Corporation Australia v Marshall (2002) 124 FCR 210; [2002] FCA 1006 Guss v Johnstone (2000) 74 ALJR 884; [2000] HCA 26 Hicks v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2003] FCA 757 James v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1955) 93 CLR 631; [1955] HCA 75 Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd v Crowl (1988) 165 CLR 71; [1988] HCA 34 Marshall v General Motors Acceptance Corporation Australia (2003) 127 FCR 453; [2003] FCAFC 45 McInerney v Ghougassian [2020] FCA 1230 Metledge v Hopkins [2020] FCA 561 Nugent v Brialkim Pty Ltd (1985) 61 ALR 725; [1985] FCA 416 Paligorov v Cohen [2006] FCA 1473 Re Celestini; Ex Parte Monte Paschi Australia Ltd (1996) 71 FCR 399; [1996] FCA 1107 Re Haritos; ex parte Hill (1968) 15 FLR 378 Re St Leon; Ex Parte National Australia Bank Limited (1994) 54 FCR 371; [1994] FCA 992 Re Pugliese; Ex parte Chase Manhattan Bank of Australia Ltd (1993) 44 FCR 536; [1993] FCA 733 Sarina v O’Shannassy (No 2) (2021) 359 FLR 1; [2021] FCCA 338 Seller v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (2011) 282 ALR 80; [2011] FCA 865 Seovic Civil Engineering Pty Ltd v Groeneveld (1999) 87 FCR 120; [1999] FCA 255 Sharpe v W H Bailey & Sons Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 738; [2014] FCA 921 Skouloudis v St George Bank Ltd (2008) 173 FCR 236; [2008] FCA 1765 Stec v Orfanos [1999] FCA 457 Veale v Coleman (2024) 304 FCR 182; [2024] FCAFC 83 Walsh v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 156 CLR 337; [1984] HCA 33 Yu v Farrow Mortgage Services Pty Limited (1995) 60 FCR 300; [1995] FCA 889 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Queensland |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | General and Personal Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 151 |

Date of hearing: | 30 April 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr S Tan |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | King & Company Solicitors |

Counsel for the Respondent: | The Respondent appeared in person |

Counsel for the Amicus Curiae: | Ms S Wright |

Solicitor for the Amicus Curiae: | Australian Government Solicitor |

ORDERS

QUD 262 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | SCENIC RIM REGIONAL COUNCIL Applicant | |

AND: | PAUL CUTBUSH Respondent | |

order made by: | WHEATLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 SEPTEMBER 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The Bankruptcy Notice dated 27 October 2023 is valid.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be listed for case management on a date to be fixed, on consultation with the parties.

2. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

WHEATLEY J:

InTroduction

1 The Applicant creditor, Scenic Rim Regional Council (herein after referred to as the Creditor), brought an interlocutory application seeking, in essence, two matters. First, a declaration relating to the validity of the bankruptcy notice, and secondly, orders for substituted service of the creditor’s petition (Application). Only the declaration regarding the validity of the bankruptcy notice remains to be determined as orders for substituted service were made on 24 September 2024.

2 The Application seeks declaratory relief pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and s 306(1) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (the Act).

3 The Creditor accepts that should the bankruptcy notice be found to be invalid, the creditor’s petition should be dismissed. If it is found to be valid, the Creditor then seeks a separate hearing of the creditor’s petition.

4 The Respondent debtor, Mr Paul Cutbush (herein after referred to as the Debtor) also accepts that should the bankruptcy notice be valid, the matter should be set down for a separate hearing of the creditor’s petition, as orders for substituted service of the creditor’s petition have already been made.

5 It should also be observed that the Official Receiver was appointed, by consent, as amicus curiae in relation to the declaratory relief sought by the Creditor. The Official Receiver’s position was that the bankruptcy notice issued in the circumstances of this case was valid.

6 For the reasons given below, the bankruptcy notice issued was valid on the basis of the prescribed requirements in s 41(2) of the Act and s 9 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 2021 (Cth) (the Regulations), together with the prescribed form in Schedule 1 of the Regulations. The current version of the Regulations commenced on 1 April 2021 and it changed the prescribed form of a bankruptcy notice. It is on the basis of the requirements of the Act and the current version of the Regulations that this bankruptcy notice is valid.

background

7 The Official Receiver issued a bankruptcy notice on the Creditor’s application on 27 October 2023. The bankruptcy notice relied on and had attached to it two orders from the District Court of Queensland.

8 The Creditor claims (this is disputed) to have served the bankruptcy notice by way of ordinary post to the Debtor on 31 October 2023.

9 The Creditor then filed the creditor’s petition on 21 May 2024 pursuant to s 44(1)(c) of the Act.

10 The matter came on before Registrar Schmidt on 28 August 2024, who referred any application for declaratory or other relief for hearing by a Judge.

issue

11 The central issue raised in the Application seeking declaratory relief is in relation to the validity of the bankruptcy notice. It concerns the address stated in the bankruptcy notice and whether the completion and provision of a post office box complies with an essential requirement of the Act, the Regulations and the Federal Court (Bankruptcy) Rules 2016 (Cth) (the Rules).

12 The bankruptcy notice dated 27 October 2023 referred to the Creditor and its address on page one (referred to as the recitals), as follows:

Scenic Rim Regional Council ABN 45596234931

PO Box 25, Beaudesert, Queensland, QLD, Australia 4285

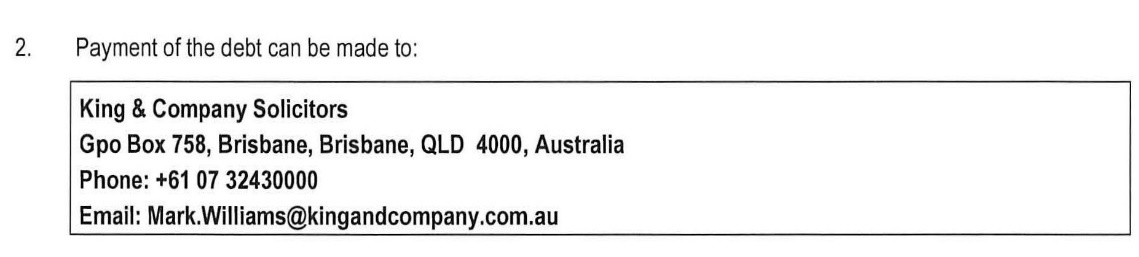

13 In addition to that, on page two of the bankruptcy notice, in numbered section 2 (Section 2), it provided as follows:

relevant principles

14 Section 40(1)(g) of the Act relevantly provides, in relation to a bankruptcy notice, that a debtor commits an act of bankruptcy if (cumulatively):

(a) a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment; and

(b) who has served on the debtor a bankruptcy notice under the Act; and

(c) the debtor does not, within the time specified in the bankruptcy notice, comply with the requirements of the bankruptcy notice.

See also Adams v Lambert (2006) 228 CLR 409; [2006] HCA 10 at [7] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Kirby, Hayne, Callinan and Crennan JJ).

15 Section 43 of the Act provides that where a debtor has committed an act of bankruptcy, the Court may, on a petition presented by a creditor, make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

16 Section 41(1) of the Act empowers an Official Receiver to issue a bankruptcy notice where the requirements of subsection (a) or (b) are satisfied.

17 Section 41(2) of the Act, (after the Bankruptcy Legislation Amendment Act 1996 (Cth), being Act No 44 of 1996 (Amendment Act)), provides as follows:

(2) The notice must be in accordance with the form prescribed by the regulations.

18 Prior to the Amendment Act, s 41 stated: “The notice shall be in accordance with the prescribed form”. In Adams at [9], it was observed that there is no material difference between “shall” and “must”. The language is that of prescription and obligation. However, the prescribed form has changed over time.

19 Furthermore, prior to the Amendment Act, s 41(2) of the Act expressly stated certain matters that shall be included in the prescribed form, being the bankruptcy notice. It was to require the named debtor to (i) pay the judgment debt or sum ordered to be paid in accordance with the judgment or order, or (ii) secure the payment of the debt or sum to the satisfaction of the Court or the creditor or his agent, if any, specified in the notice or compound the debt or sum to the satisfaction of the creditor or agent, again specified in the notice, and to state the consequences of non-compliance: Kleinwort Benson Australia Ltd v Crowl (1988) 165 CLR 71; [1988] HCA 34 at 76 (Mason CJ, Wilson, Brennan and Gaudron JJ). The prescribed form of a bankruptcy notice was then provided by r 8 of the Bankruptcy Rules 1996 (Cth).

20 By the Amendment Act, these express requirements of the prescribed form in the Act were removed. The explanatory memorandum to the Amendment Act observed (at [41.2]) that these provisions were to be repealed and that the bankruptcy notice will be a notice in accordance with a form prescribed under regulations.

21 The relevant section under the Regulations now is s 9, which is as follows:

9 Form of bankruptcy notice

(1) For the purposes of subsection 41(2) of the Act, the form of bankruptcy notice set out in Schedule 1 is prescribed.

(2) A bankruptcy notice must follow that form in respect of its format (for example, bold or italics typeface, underlining and notes).

(3) Subsection (2) does not limit section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901.

Note: Section 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 provides that strict compliance with a form is not required and substantial compliance is sufficient.

22 Schedule 1 to the Regulations provides the prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice and it commenced on 1 April 2021. It is a different form to that which was prescribed under the Bankruptcy Regulations 1996 (Cth). The prescribed form has changed over time.

23 From s 40(1)(g) of the Act, one of the matters upon which an act of bankruptcy is dependant upon is service on a debtor of a valid bankruptcy notice. Given the consequences of a valid bankruptcy notice, “strict compliance with the requisites of a bankruptcy notice” have been insisted upon: Adams at [16]; Kleinwort Benson at 81 (Deane J, who although in dissent, this opening statement of principle was uncontroversial); James v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1955) 93 CLR 631; [1955] HCA 75 at 644 (Williams, Kitto and Taylor JJ).

24 A bankruptcy notice is a nullity if it fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Act or if it could reasonably mislead a debtor as to what is necessary to comply with the bankruptcy notice. It is not necessary that the debtor is in fact misled – it is an objective test: Adams at [25]; Kleinwort Benson at 79; James at 644. If a requirement is made essential by the Act, then a failure to meet that requirement is not a formal defect or irregularity within the meaning of s 306 of the Act. Whether a requirement is made essential is determined by a process of statutory construction: Adams at [28].

25 In Adams, the High Court was considering whether the requirement to state the provision under which interest was being claimed was an essential requirement for the purposes of the Act, including s 306 of the Act. The Court observed that the requirement being considered was established by “three levels of prescription” (at [14]). A failure to comply with a requirement to be found in the Act, as to the information to be furnished by the bankruptcy notice, was held to be a defect or irregularity (at [24]). That misdescription of the relevant section under which interest was being claimed was a formal defect or irregularity which could not have misled the debtor and as such was not fatal to the validity of the bankruptcy notice by application of s 306 of the Act: Adams at [30]-[34].

26 To this can be added the following principles which were distilled by the Full Court from Adams in Veale v Coleman (2024) 304 FCR 182; [2024] FCAFC 83 (Markovic, Halley and Cheeseman JJ) at [32]:

(1) whether a particular defect or irregularity is a “formal defect or irregularity” is a question of statutory construction to be determined in the ordinary way having regard to the text of s 306, the relevant purpose(s) of the Bankruptcy Act and its context when read with other provisions;

(2) a defect or irregularity cannot be a formal defect or irregularity if it:

(a) fails to meet a requirement made essential by the Bankruptcy Act; or

(b) could reasonably mislead a debtor as to what is necessary to comply with the bankruptcy notice; and

(3) whether a requirement is made essential by the Bankruptcy Act is to be ascertained by a process of statutory construction of the relevant requirement. In this regard:

(a) the use of imperative terms such as “must” is not conclusive as to whether a requirement, especially as to form, is essential;

(b) questions which may be relevant, depending on the case, include:

(i) on the true construction of the Bankruptcy Act, having regard to legislative purpose and an evaluation of the significance or importance of the degree and/or kind of error or deficiency in the circumstances of the case, is the requirement which has been breached properly described as being essential; and

(ii) is it the purpose of the legislation that any slip with the breached requirement should invalidate the notice, particularly if the slip could not have misled the recipient of the notice as to what is required to comply with its requirements.

27 Section 306(1) of the Act provides as follows:

306 Formal defects not invalidate proceedings

(1) Proceedings under this Act are not invalidated by a formal defect or an irregularity, unless the court before which the objection on that ground is made is of opinion that substantial injustice has been caused by the defect or irregularity and that the injustice cannot be remedied by an order of that court.

28 A bankruptcy notice is a proceeding under the Act: Adams at [17]; Kleinwort Benson at 77. As such, it can be accepted that in the context of s 306 of the Act, some failure to comply with a requirement of the Act is permissible.

29 The relevant questions to be asked, in relation to the validity of a bankruptcy notice, were summarised by the Full Court in Veale (at [102] and [123]) as follows:

(1) Was the bankruptcy notice defective or irregular?

(2) If so, was the defect or irregularity substantive or formal?

(3) If the defect or irregularity is formal only, had it occasioned substantial injustice?

30 The defect or irregularity complained of must be properly identified to allow the Court to ask and answer these questions.

the parties’ submissions

The Creditor’s Submissions

31 In earlier written submissions, prior to filing the Application, the Creditor quite properly raised a potential preliminary issue regarding whether the bankruptcy notice was valid. This was on the basis of the decision in Metledge v Hopkins [2020] FCA 561 (Lee J). The issue identified by Lee J (at [11]) was whether the address identified in that bankruptcy notice (that is, the post office box) was one at which it was reasonably practicable for the debtor to make payment or to offer to secure or compound the debt. Lee J held that the bankruptcy notice was invalid on the basis that payment could not be affected at the address identified in the bankruptcy notice, being the post office box (at [12]-[17]). The effect of Metledge, the Creditor submits, was to require the bankruptcy notice at Section 2 to state a physical address.

32 The Creditor observes that the details provided in Section 2 of this bankruptcy notice were those of the Creditor’s solicitors, King & Company Solicitors. Further, the Creditor relied on the following passage from Nugent v Brialkim Pty Ltd (1985) 61 ALR 725; [1985] FCA 416 (Lockhart J with whom Northrop and Beaumont JJ agreed) at 727:

The test must satisfy the demands of commonsense in the highly ordered and busy world in which we live, tempered by a consideration of the implications of a bankruptcy notice and the serious consequences that can flow from non-compliance with its requirements. I respectfully agree with the primary judge that the basic principle is that the address given should be one at which during the relevant period it is reasonably practicable for the debtor to make payment or to offer to secure or compound.

33 The Creditor submits that the post office box, together with the other details provided in the bankruptcy notice, were sufficient to satisfy the “basic principle” from Nugent. The Creditor submits that even the provision of a physical street address does not inform a debtor of a method of payment and may not facilitate payment, but simply a location for payment. Further, the Creditor contended that in more recent times, payments of larger amounts would usually be by way of electronic funds transfer, rather than by cash or cheque.

34 The Creditor contends that provision of a post office box still permitted payment by cheque, as was considered and rejected by Lee J in Metledge (at [15]-[16]). Furthermore, the Creditor submits that the physical address of its solicitors, King & Company Solicitors, could have been quite easily found and that firm could have been contacted by telephone or email, as those details were provided in the bankruptcy notice.

35 The Creditor also relies on the observations of Judge Manousaridis in Sarina v O’Shannassy (No 2) (2021) 359 FLR 1; [2021] FCCA 338 and submits that Metledge is plainly wrong. However, the Creditor accepts that unless Metledge is distinguishable as a matter of judicial comity, I should follow Lee J in Metledge, unless I am of the opinion that his Honour is plainly wrong: see French J in Hicks v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2003] FCA 757 at [73]-[76].

36 The Creditor suggests that Lee J did not have the benefit of evidence regarding the prescribed form to be used by an applicant when applying for a bankruptcy notice. The Creditor relies on “screenshots” from the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) website page about applying for a bankruptcy notice. However, the Creditor accepted that such ‘instructions’ could not supplant the requirements of the Act, Regulations and the prescribed form.

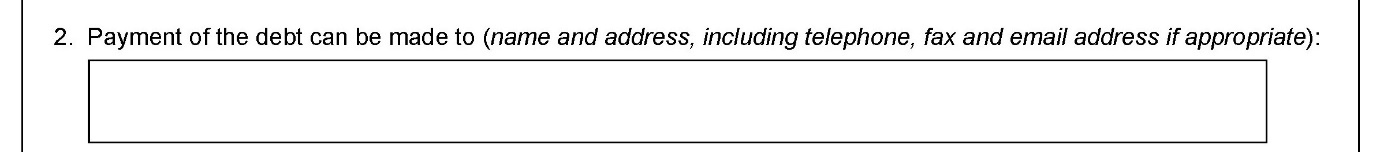

37 Further, relying on the reasoning in Sarina, the Creditor submits that the earlier prescribed form included the words at Section 2 “name and address, including telephone, fax and email address if appropriate”. These words, it was submitted, were part of the prescribed form at the time of Metledge. On this basis and in the alternative, the Creditor seeks to distinguish Metledge as the prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice has changed.

38 Finally, the Creditor submits that taking a “common sense” approach to the details provided in the bankruptcy notice, including the name of the Creditor’s legal representative, telephone number and email address, made it “reasonably practical” for the Debtor to make the payment required and comply with the bankruptcy notice. The Creditor relies on s 306 of the Act to submit that any such non-compliance in relation to this bankruptcy can be cured by s 306 of the Act. This is on the basis that any such non-compliance is a formal defect or irregularity only.

The Respondent’s Submissions

39 The Debtor submits that the bankruptcy notice is invalid due to the address for payment being provided as a post office box and relies on Metledge and Sarina. The Debtor submits that the AFSA website suggests that the Official Receiver will refuse to issue a bankruptcy notice where the creditor has not provided a street address. Further, the Debtor submits he was “banned” from visiting or phoning King & Company Solicitors (as well as the Scenic Rim Regional Council). Although the Debtor observes that the latest form requires less information, the provision of a physical street address, he submits, is still essential.

40 The Debtor has also raised other submissions regarding the bankruptcy process generally and submits that the bankruptcy notice was not validly served, that he has made a payment which is not listed in the bankruptcy notice, the interest calculated is inaccurate and the bankruptcy proceedings are being used as a “debt collection” proceeding.

41 The Debtor raised several other matters, effectively seeking to go behind the judgment by contesting who is the proper creditor and arguing that the creditor’s petition was not filed within the required time.

42 Many of these issues are more properly considered on the hearing of the creditor’s petition. The relevant issue to be determined on this application for a declaration is a narrow one.

The Submissions of the Amicus Curiae

43 The Official Receiver submitted that to resolve the issue of validity, the Court will need to resolve the following three questions, in relation to the contact information, being:

(1) Question 1: Is including more information (than what is in the Notice) a requirement made essential [by the Act] in the context of the whole Act, informed by the general purpose of the legislation, and the particular purpose of the provisions relating to bankruptcy notices? If so, the [bankruptcy notice] is invalid.

(2) Question 2: Could something within the [bankruptcy notice] (which may be incorrect or deficient in some way) reasonably mislead the debtor as to what is necessary to comply with the [bankruptcy notice]? If so, the [bankruptcy notice] is invalid.

(3) Question 3: If the [bankruptcy notice] is not invalid, does it contain a formal defect or an irregularity? If so, has substantial injustice been caused by the defect or irregularity such that the injustice cannot be remedied by an order of that court? If so, the [bankruptcy notice] is invalid.

44 In short, the Official Receiver submits that each question can be answered as follows:

(1) The provision of a street address in the bankruptcy notice is not a requirement made essential by the Act.

(2) There was nothing in the bankruptcy notice, in terms of contact information, which could have reasonably misled the Debtor. There was nothing which was incorrect or deficient in some way. In any event, the Debtor, due to his prior dealings, would have been able to communicate with, or locate the street addresses of, the Creditor.

(3) The non-provision of a street address is a formal defect or irregularity and no substantial injustice has been caused.

45 The Official Receiver supports the above submissions by reference to the text in context of the Act, particularly of ss 40, 41 and 306 of the Act, ss 9 and 102 of the Regulations, and the prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice in Schedule 1. Further, the Official Receiver relies on Nugent, Croker v Commonwealth of Australia (2011) 9 ABC(NS) 44; [2011] FCAFC 25 (Siopis, Tracey and Gilmour JJ), Fuller v Alford (2017) 252 FCR 168; [2017] FCA 782 (Perry J), and McInerney v Ghougassian [2020] FCA 1230 (Markovic J).

46 Furthermore, the Official Receiver sought to distinguish Metledge on the following bases:

(1) the creditor in Metledge was a natural person, not a public body;

(2) the creditor and the payee were the same natural person, whereas here the payee is a firm of solicitors;

(3) Metledge distinguished Croker, where there was a separate creditor and payee;

(4) in Metledge, a phone number and email address were provided for the creditor/payee, in addition to the post office box, but these were not considered in the judgment and nor was the existence of the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth); and

(5) changes have been made to the prescribed form (being the bankruptcy notice) in Schedule 1, since Metledge, which are relevant.

47 The Official Receiver also bought to the Court’s attention two other amendments to the Regulations. First, the Bankruptcy Amendment (Service of Documents) Regulations 2022 (Cth), which added “Note 2” at the end of s 102(1) of the Regulations and commenced on 6 April 2022. Secondly, the Bankruptcy Amendment (Electronic Service) Regulations 2024 (Cth), which repealed and replaced s 102 of the Regulations and commenced on 17 December 2024. As the Official Receiver observed, however, this second amendment was after the date of the bankruptcy notice in this case.

consideration

48 Although the central issue to be considered on this application is identified above at [11], regarding the validity of the bankruptcy notice, the parties did also raise two additional issues, being:

(1) Service of the bankruptcy notice; and

(2) Can the Court go behind the judgment debts?

Service of the Bankruptcy Notice.

49 This issue can be dealt with shortly as both the Creditor and the Debtor accepted at the hearing that on this application for declaratory relief, it was not necessary to determine the issue of service of the bankruptcy notice.

50 The Creditor maintains that the bankruptcy notice was properly served and the Debtor disputes service.

51 This issue will need to be addressed at the hearing of the creditor’s petition. As such, it would not be appropriate to address it further now.

Can the Court go behind the judgment?

52 Again, this issue was raised by the Creditor and the Debtor in written submissions. However, both parties took the sensible and reasonable position that it was not necessary to determine this issue on this application for declaratory relief.

53 The Debtor maintains that the Court should go behind the judgment and the Creditor disputes that position.

54 This issue will need to be addressed at the hearing of the creditor’s petition. As such, it would not be appropriate to address it further now.

Is the bankruptcy notice valid?

55 The Debtor raised two issues regarding the validity of the bankruptcy notice, being that the notice was invalid because of:

(i) an overstatement; or

(ii) the completion and provision of a post office box as the address in Section 2 of the prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice.

(i) Invalid due to overstatement?

56 The Debtor gives evidence (but without contemporaneous documents) in his Affidavit dated 5 November 2024 that he paid over $32,000 for what he describes as “Costs Order 1” from November 2017. The Debtor then describes the costs orders in this Affidavit as follows:

Costs Order 1 – Indemnity Costs – Order of 10 November 2017 - $32,266

Costs Order 2 – Standard Costs – Order of 17 June 2019 - $70,134.45

Costs Order 3 – Indemnity Costs – Order of 14 November 2019 - $43,607.91

57 The Debtor submits, in effect, that there is an overstatement in the bankruptcy notice. This is with reference to the claimed payment of $32,333.75 in May 2021. The Debtor submits that the bankruptcy notice does not record this payment.

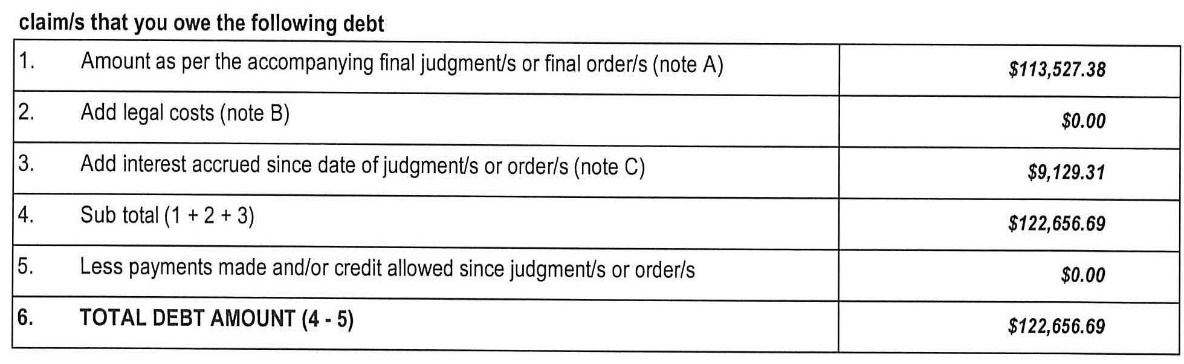

58 Relevantly the bankruptcy notice states as follows:

59 There are two judgments attached to the bankruptcy notice, which are:

(a) for $43,587.82 dated 14 December 2022, pursuant to an Order of Judge Chowdhury dated 17 June 2019; and

(b) for $69,939.56 dated 14 December 2022, pursuant to an Order of Judge Chowdhury dated 14 November 2019.

60 These two judgments add-up to the amount stated in the bankruptcy notice of $113,527.38. The bankruptcy notice was dated 27 October 2023.

61 There is email correspondence from the Debtor to the costs assessor dated 21 December 2022 (the basis of the judgments is the quantification of costs orders in District Court proceedings between the Debtor as plaintiff and the Creditor as defendant) asking if the costs assessor was aware that an amount of $25,000 had already been paid to King & Company Solicitors, being taken from the Debtor’s late mother’s estate. By email dated 21 December 2022, the cost assessor advised the Debtor that he had undertaken a default costs assessment and was not aware of the matter raised in the Debtor’s email correspondence. The costs assessor further stated that the Debtor could seek to set aside the default costs assessment and, in any event, if he had any complaints about the costs assessments he could seek a remedy from the court.

62 There is no evidence of the Debtor making an application to set aside the default costs assessments.

63 The bankruptcy notice does not list any payments made since quantification of the two costs judgments were made. These judgments are dated 14 December 2022. It is apparent that the claimed payment referred to by the Debtor, made in May 2021, does not relate to these two judgments, as these judgments were not made until 14 December 2022. That is, after the claimed payment.

64 The Debtor also refers to an earlier costs judgment, said to relate to an Order dated 10 November 2017. However, it is unclear when the costs pursuant to that order were quantified. In any event, the costs order dated 10 November 2017 is not the subject of the bankruptcy notice.

65 Further, the potential issue regarding overstatement must be considered in the context of s 41(5) of the Act, which provides:

(5) A bankruptcy notice is not invalidated by reason only that the sum specified in the notice as the amount due to the creditor exceeds the amount in fact due, unless the debtor, within the time fixed for compliance with the notice, gives notice to the creditor that he or she disputes the validity of the notice on the ground of the misstatement.

66 A bankruptcy notice will be invalid if a debtor gives notice in accordance with s 41(5) of the Act of an overstatement within the time fixed for compliance that the sum specified in the bankruptcy notice in fact exceeds the amount due to the creditor: Walsh v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1984) 156 CLR 337; [1984] HCA 33 at 339 (Gibbs CJ with whom Mason, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ agreed); Seovic Civil Engineering Pty Ltd v Groeneveld (1999) 87 FCR 120; [1999] FCA 255 at [31]-[32], [36]-[40] and [52] (Hill, Sackville and North JJ); Skouloudis v St George Bank Ltd (2008) 173 FCR 236; [2008] FCA 1765 at [22]-[36] (Edmonds J).

67 However, based on the above authorities, the contrary can also be accepted. If no notice is given by the debtor pursuant to s 41(5) of the Act, then the bankruptcy notice is not liable to be set aside by reason only of the overstatement: Adams at [31].

68 There is no evidence before the Court that any notice of an alleged overstatement of the debt stated in the bankruptcy notice, which is in fact due, was given by the Debtor in accordance with s 41(5) of the Act to the Creditor. As such, in the absence of such a notice, the bankruptcy notice is not liable to be set aside by reason only of an overstatement (if there is one).

69 The Debtor briefly submitted that the interest calculation was inaccurate. This appeared to be based on a suggestion that the interest calculation should have been updated when served with the creditor’s petition in May 2024 or when it was served, by substituted service in September 2024. No authority was cited for this proposition.

70 There is no requirement to update or change the interest calculation in the bankruptcy notice, when it is then served with the creditor’s petition. Furthermore, on the basis of Adams, even if there was an error in the calculation (which I do not accept), that would not, of itself, be sufficient to result in invalidity.

71 Therefore, this bankruptcy notice will not be invalid on these bases.

A post office box as the address

72 The relevant details which were completed and provided by the Creditor in this bankruptcy notice regarding the address at Section 2 are set out above at [12]-[13].

73 The relevant questions to be considered are as follows.

(1) Was this bankruptcy notice defective or irregular?

(2) If so, was the defect or irregularity substantive or formal?

(3) If the defect or irregularity is formal only, did it occasion substantial injustice?

74 Although the questions as posed by the Official Receiver are one way to address this issue, I prefer to adopt and apply the questions as identified by the Full Court in Veale.

75 Before addressing each of these questions, it is necessary to consider the relevant statutory context, the relevant authorities and the particular version of the prescribed form, which required completion, now and at the time of each of the relevant decisions.

76 Section 41 is the relevant section of the Act in relation to bankruptcy notices. Section 41(1) provides when the Official Receiver may issue a bankruptcy notice. It requires a creditor to have a final judgment or order of the kind described in s 40(1)(g) and for such judgment to be for an amount that is more than the statutory minimum or where there are 2 or more judgments or orders which taken together are for an amount of at least the statutory minimum.

77 Section 41(2) of the Act requires that the form of the bankruptcy notice be in accordance with that prescribed by the Regulations. This section uses mandatory language by way of the word “must” and “prescribed”. The use of such mandatory language, however, must be “kept in perspective”: Adams at [14]. This is particularly so when regard is then had to s 9(3) of the Regulations with the express reference to s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), in the context of the Regulations which provides the prescribed form for the purposes of s 41(2) of the Act: Veale at [135].

78 Before considering the Regulations, it is necessary to consider the other statutory requirements imposed by s 41, for relevant context, when considering the question of construction. Section 41(2A) requires the bankruptcy notice to specify a period of time for compliance.

79 Section 41(3) provides that a bankruptcy notice shall not be issued in relation to a debtor, except on the application of a creditor who has obtained against the debtor a final judgment or final order within the meaning of s 40(1)(g) or a person who is deemed to be such a creditor within s 40(3)(d). The bankruptcy notice will not issue if at the time of the application of the bankruptcy notice execution of the judgment or order has been stayed, if the judgment or order was given more than 6 years prior or the operation of the judgment or order has been suspended under s 37 of the Act.

80 Section 41(5) and (6) of the Act are directed towards the validity of the bankruptcy notice in circumstances where the amount stated to be due to the creditor exceeds the amount in fact due. More particularly it provides that if a debtor gives notice to the creditor, within the time fixed for compliance, that he or she disputes the validity of the bankruptcy notice on the basis of that misstatement, the bankruptcy notice will be invalid: Walsh at 339. However, if no such notice is given but the amount specified in the bankruptcy exceeds that in fact due, he or she will be deemed to have complied if, within the time for compliance, he or she takes such action as would have constituted compliance, had the notice in fact specified the correct amount. The relevant context from this is directed towards considerations of timing and that if the bankruptcy notice overstates the amount required to be paid, that will only render the bankruptcy notice invalid, if the required notice is given.

81 This potential defect or error in a bankruptcy notice is relevant as part of the legislative context and gives an indication of the legislative purpose: Adams at [15]. This, together with s 306 of the Act, confers a legislative intent of not requiring strict compliance on a judgment creditor when issuing a bankruptcy notice: Adams at [32].

82 Section 41(6A) provides the sole source of the Court’s power to extend time for compliance with the requirements of a bankruptcy notice: Guss v Johnstone (2000) 74 ALJR 884; [2000] HCA 26 at [62] (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Kirby and Callinan JJ); see also Seller v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (2011) 282 ALR 80; [2011] FCA 865 at [38]-[49] (Flick J). This power, to extend time for compliance, is to facilitate an application to set aside the bankruptcy notice itself: Sharpe v W H Bailey & Sons Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 738; [2014] FCA 921 at [36] (Gleeson J). It is also subject to s 41(6C) of the Act. This context is again directed to the time for compliance with the bankruptcy notice.

83 Finally, s 41(7) provides that where before the expiration of the time fixed for compliance with the bankruptcy notice, the debtor has applied to the Court for an order setting aside the bankruptcy notice on certain grounds and where the Court has not determined that application before the expiration of that time, then time will be deemed to have been extended. Those grounds are that the debtor has a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand as is referred in s 40(1)(g) of the Act.

84 To this must be added s 306 of the Act which makes plain that some instances of non-compliance will not invalidate the bankruptcy notice.

85 The relevant context from these provisions includes (in summary):

(a) a bankruptcy notice can only be issued to a creditor who has a final judgment or order (or 2 or more such judgments or orders) that amount to the statutory minimum, which has not been stayed and is less than 6 years old;

(b) the bankruptcy notice must (but without requiring strict compliance):

(i) be in the prescribed form (by the Regulations, which requires substantive compliance);

(ii) specify the time for compliance, which if served in Australia, is 21 days from being served;

(c) certain matters can be done before the expiration of the time for compliance, which would then not lead to an act of bankruptcy, being that the debtor can give a notice of overstatement, an application to the Court can be made to set aside the bankruptcy notice, where proceedings to set aside the judgment have been instituted bona fide or with due diligence, or where the debtor has a counter-claim, set-off or cross demand of the kind described in s 40(1)(g) of the Act;

(d) certain instances of non-compliance with the requirements of the Act will not necessarily invalidate the bankruptcy notice, this would at least include an overstatement or understatement of the amount to be paid;

(e) there is a temporal imperative. The time period for compliance must be stated and is derived from the Act (see s 5, the definition of statutory period). Any notice of misstatement and any extension of the time for compliance (to apply to set aside the judgment or to set aside the bankruptcy notice) must be given within the time for compliance; and

(f) payment to the creditor of the debt claimed or to make arrangements for settlement of the debt, to the creditor’s satisfaction, again, within the time for compliance.

86 Section 41 of the Act was significantly amended by the Amendment Act. In Adams at [32]-[34], the High Court endorsed the observations of Lee J and Gyles J in the minority in Australian Steel Co (Operations) Pty Ltd v Lewis (2000) 109 FCR 33; [2000] FCA 1915 regarding the question to be addressed regarding the correct completion of the prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice. The Amendment Act was not to create a new regime of strict compliance. As Gyles J observed in Australia Steel at [110], after the Amendment Act, the section was less prescriptive. Although this particular passage of Gyles J was not the subject of express comment by the High Court in Adams, generally the approach of Lee J and Gyles J was preferred: also see the approach of the Full Court in Veale at [143].

87 The Full Court in Veale was considering the validity of a bankruptcy notice in which it was argued that the bankruptcy notice failed to comply with an essential requirement of the Act because of an alleged failure to comply with s 12(3) of the Regulations. It was argued that such a matter was essential because in addition to the emphatic language used, the amount of the Australian currency demanded in the bankruptcy notice played a central role, as stating the amount that the debtor had to pay to comply with the bankruptcy notice. Although the Full Court accepted that the calculation in accordance with s 12(3) was necessary to evaluate whether a bankruptcy notice meets the statutory minimum (the calculation produced an understatement), it was a machinery provision and not an essential requirement of the Act such that failure to comply would render the bankruptcy notice a nullity: Veale at [137]-[142]. This approach of the amount being stated in the bankruptcy notice itself, being either understated (as in Kleinwort Benson) or overstated (as discussed in Adams), provides a consistent approach of not requiring stringent compliance, but one of substantial compliance: Veale at [93]. Although substantial compliance may be all that is required, where there is a specific requirement to state a provision (or some other specific requirement), it is not substantial compliance to state a different provision: Adams at [22]. However, the kind of error must be considered in terms of s 306 of the Act.

88 The prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice has changed over time. It is not necessary to set out all of the different versions. However, to demonstrate the relevant changes for the purposes of this case, the following can be observed.

89 Form 1, pursuant to reg 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations 1966 as amended by the Bankruptcy Amendment Regulations 2000 (No. 1) and Bankruptcy Amendment Regulations 2000 (No. 2) on 1 July 2000 amended the form relevantly as follows:

BANKRUPTCY NOTICE

This Bankruptcy Notice is prescribed, under subs. 41 (2) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (“the Act”), by r. 4.02 of the Bankruptcy Regulations.

Note Words appearing below in italics are for guidance in the completion of this Notice, and are not to be reproduced in the Notice.

To: (name) ____________________

(“the debtor”)

of: (address) ____________________

____________________

____________________

This Bankruptcy Notice is an important document. You should get legal advice if you are unsure of what to do after you have read it.

1. (name) ____________________

(“the creditor”)

of: (address) ____________________

____________________

____________________

…

4. Payment of the debt can be made to:

(name) ____________________

of: (address) ____________________

____________________

____________________

Note The address must be within Australia.

…

90 Relevantly, the form substantively changed with the passing of the Bankruptcy Amendment Regulations 2010 (No. 1) on 9 July 2010 as follows:

…

91 On 1 April 2021 the current Regulations commenced. The Regulations also introduced a new version of the prescribed bankruptcy notice. The opening section and the recitals of the form did not change, where the debtor’s details and the creditor’s details are completed.

92 However, relevantly, at Section 2, the prescribed form is now as follows:

93 It is, of course necessary to have regard to the entire form. However, this section is of particular importance, in the circumstances of this case. There is no longer any reference to a requirement of completing the form with the provision of an address, or to a telephone number, fax number or email address.

94 The prescribed form under the Bankruptcy Regulations 1996, bought into effect in July 2000, not only required completion of the “name” and “address” of where payment of the debt could be made, it also noted that the address must be within Australia. The prescribed form relevantly was amended in July 2010 and included providing details of “name and address, including telephone, fax and email address if appropriate”. The form no longer required that the address identified be one within Australia. The additional inclusion of other contact details would also facilitate the debtor being able to contact the creditor (or creditor’s agent) to make arrangements for payment, either of the debt claimed or to make arrangements to the creditor’s satisfaction for settlement of the debt, as specified in section 1 of the bankruptcy notice. In this regard, it should be observed (as Gyles J did in Australian Steel at [110]) that the requirements in s 41 prior to the Amendment Act are no longer required and s 41 is now less prescriptive. Similarly, Section 2 of the bankruptcy notice form is now less prescriptive.

95 When the current Regulations were made and the current version of the bankruptcy form changed, the Explanatory Statement said the following regarding the form at Schedule 1:

Schedule 1 – Forms

Subsection 9(1) provides that a bankruptcy notice should be in the approved form, which is prescribed in Schedule 1 of the Regulations.

Schedule 1 contains that prescribed Bankruptcy Notice form, for use by persons applying to the Official Receiver for the issue of a bankruptcy notice in relation to a debtor. The form includes space for an applicant to enter certain information, including:

* the name/s of debtors to which the application relates

* the names of the applicant creditor/s

* the total debt amount owing

* (if applicable) the amount of debt converted into foreign currency using the Reserve Bank of Australia exchange rate

* the timeframe within which the debtor is required to settle the debt

* the payment details, and

* the schedule of post-judgment interest calculation.

(emphasis added)

96 The prescribed form in Section 2 no longer requires or specifies that completion of the form in this section is to be by way of providing an address of where the payment can be made. It simply states that the form should be completed by providing details in response to: “Payment of the debt can be made to:”. The evident purpose of Section 2 is to facilitate payment, it being directly under section 1, which identifies the time within which the debtor is required to either pay the amount of the debt claimed or to make arrangement to the creditor’s satisfaction for settlement of the debt. Correct completion of the prescribed form in Section 2 now permits details which facilitates where or how the payment can be made. This accords with a purposive construction to inform the debtor as to what is required to comply with the bankruptcy notice. This, as the Creditor submits, would facilitate payments by way of electronic funds transfer and would allow for the form to be completed by provision of a name (which could include the creditor’s solicitors, as discussed below) and bank account details. In such circumstances, a physical or street address may not be required at all, what is required are “payment details” of where or how “payment of the debt can be made to”. It may be, depending on the particular circumstances of a case, that some other contact details are also required in Section 2, given the terms of section 1(b) of the bankruptcy form. However, it is unnecessary to decide that in this case, given that additional contact details were provided.

97 The bankruptcy notice in Nugent was sought to be set aside on the ground that it failed to give an address at which there was present a person or persons with the authority of the respondents (being the creditor in that case) to receive payment or to secure or compound (Nugent at 726-727). Nugent was decided prior to the Amendment Act (which removed the reference in s 41(2)(a)(ii) to secure or compound the debt) and therefore also required completion of a different version of the prescribed form.

98 The address provided in the bankruptcy notice in Nugent (at 725) was “their registered office at c/- Messrs Lyons, Dunlop and Pratt, 8th Level MLC Centre, Cnr George & Adelaide Streets, Brisbane in the State of Queensland”. Lockhart J, with whom Northrop and Beaumont JJ agreed, observed at 726 that neither the Act nor the Bankruptcy Rules 1996 contained any provision requiring the address of the creditor to be stated in the bankruptcy notice. The requirement was from the form itself, at that time, in the schedule to the Bankruptcy Rules 1996. Lockhart J then stated at 726-727:

Judgments of long standing have held in relation to comparable provisions in the bankruptcy legislation of England and Australian Bankruptcy Act 1924 that a judgment creditor must give an address or addresses where he, or if more than one, they, or one of them, or some agent authorised on his or their behalf, may be found: see Re Beauchamp; Ex Parte Beauchamp [1904] 1 KB 572 and James v FC of T (1955) 93 CLR 631 at 639. The question before this court must be considered in the light of the following passage from James’ case (at p639): “It is the duty of a debtor to seek out the judgment creditor and pay the judgment debt to the creditor if he is in Australia. The debtor has the correlative right to pay the creditor wherever he can find him so that a debtor could be seriously prejudiced if he was led to believe that he was bound to pay the creditor at one particular place.”

As I perceive it, the rationale of these and other decisions is that the address of the creditor must be stated in order to comply with the prescribed form of notice and because non-compliance with the requirements of a bankruptcy notice constitutes an act of bankruptcy and may have quasi-penal consequences.

It is not sufficient that a creditor merely gives an address where he is known. It must be an address at which he can be paid or where an agreement may be made with him or on his behalf to secure or compound it. …

(emphasis added)

99 The Court outlined (at 727) the practicalities of when a person must be available at that address, noting the absurdity of requiring a person (if the home address was given) of being bound to remain there all day and night during the currency of the bankruptcy notice. It is after these observations that the passage relied upon by the Creditor (above at [32]) occurs. The Court in Nugent dismissed the appeal as it had not been established that the address that the creditor had given in the bankruptcy notice was one at which it was not reasonably practicable to make payment or to secure or compound the amount.

100 The prescribed form of the bankruptcy notice relevant in Nugent was different to that which is now prescribed. The prescribed form at the time of Nugent included express reference to the address of the judgment creditor in the “recital” to the bankruptcy notice (as the current version still does) and in the “operative part” of the bankruptcy notice for the debtor to make payment of the judgment amount to the judgment creditor or if the judgment or order requires payment to a court or a person other than the judgment creditor, the name and address of the court or the other person (Nugent at 726).

101 It is worth considering the entire passage from James (part of which is quoted in Nugent), at 639, which was as follows:

Section 53 provides that a bankruptcy notice shall be in the prescribed form. The prescribed form is that contained in Form 5 but rule 6 provides that this form may be varied to meet the particular circumstances. Section 53 also provides that the notice shall require the debtor to pay the judgment debt or sum ordered to be paid in accordance with the terms of the judgment or order. We are here concerned with an order that the plaintiff shall pay the costs to the defendants. It does not provide that the plaintiff must pay the costs to the defendants at any particular place as the bankruptcy notice does. But the prescribed form simply directs the debtor to pay the debt to the creditor “of”. Unless the judgment or order does so the notice should not require the debtor to pay the creditor at a particular place. It is the duty of a debtor to seek out the judgment creditor and pay the judgment debt to the creditor if he is in Australia. The debtor has the correlative right to pay the creditor wherever he can find him so that a debtor could be seriously prejudiced if he was led to believe that he was bound to pay the creditor at one particular place. The objection is not a trifling one particularly in a large geographical area like Australia. It is one of substance…

102 The relevant statutory provisions in James provided as follows. Section 53 of the Bankruptcy Act 1924 (Cth) (1924 Act) stated “A bankruptcy notice under this Act shall be in the prescribed form…”. Rule 144 of the Bankruptcy Rules 1928 (Cth) provided “A bankruptcy notice issued by the Court shall be in accordance with Form 5”. In addition, r 5 provided “The forms in the Schedules to these Rules, where applicable, and where they are not applicable forms of the like character, with such variations as circumstances require, shall be used.” Section 7(1) of the 1924 Act was in similar terms to the current s 306, providing “No proceedings under this Act shall be invalidated by any formal defect or irregularity, unless the court before which objection is made is of opinion that substantial injustice has been caused thereby, and that the injustice cannot be remedied by an order of that Court.”

103 In James at 643-644, the High Court held that the bankruptcy notice was invalid as it failed to comply with s 53 because it wrongly sought to restrict the debtor to paying the debt to the creditors at one particular place and because it did not notify the debtor that he may in the alternative secure or compound the debt.

104 Section 41 is now the relevant provision regarding bankruptcy notices. It is in different terms to s 53 of the 1924 Act. However, there are some similarities between the two provisions, being that the bankruptcy notice:

(a) shall/must be in the prescribed form;

(b) is not invalidated only by reason that the sum specified as the amount due exceeds the amount actually due, unless the debtor within the time allowed for payment gives notice to the creditor that he disputes the validity of the notice on the ground of such misstatement. That is, it is not necessarily invalidated by an overstatement;

(c) but if the debtor does not give such notice, he or she will be deemed to have complied if, within the time for compliance, he or she take such steps as would have constituted compliance had the actual amount due been correctly specified.

105 To those similarities can also be added:

(a) the particular requirements of a debtor committing an act of bankruptcy for non-compliance with a bankruptcy notice, in the circumstances described in s 40(1)(g) of the Act and s 52(j) of the 1924 Act; and

(b) certain formal non-compliances, errors, defects or irregularities will not invalidate the bankruptcy notice unless substantial injustice has been caused: s 306 of the Act and s 7(1) of the 1924 Act.

106 Neither s 41 of the Act nor s 53 of the 1924 Act (noting that it is a question of construction) expressly required that the bankruptcy notice state an address for the judgment creditor.

107 It is worth re-stating the emphasised passage in Nugent, citing and quoting from James, that:

It is the duty of the debtor to seek out the judgment creditor and pay the judgment debt to the creditor if he in Australia. The debtor has the correlative right to pay the creditor wherever he can find him so that a debtor could be seriously prejudiced if he was led to believe that he was bound to pay the creditor at one particular place.

This has been cited with approval in Anderson Rice (a firm) v Bride, Robert (1995) 61 FCR 529; [1995] FCA 868 at 542 (Sackville and R D Nicholson JJ); Stec v Orfanos [1999] FCA 457 at [12] (Beaumont, Branson and Sundberg JJ); Paligorov v Cohen [2006] FCA 1473 at [25] (Tamberlin J); see also Gyles J in Australian Steel at [124] (although in dissent, generally, that reasoning was preferred in Adams).

108 In General Motors Acceptance Corporation Australia v Marshall (2002) 124 FCR 210; [2002] FCA 1006, Gyles J was considering whether certain alleged defects in a bankruptcy notice were such as to not make a sequestration order. One defect alleged was in relation to the interest calculation and Gyles J sought to distinguish Australian Steel. However, relevantly, another defect alleged was that the bankruptcy notice required payment otherwise than in accordance with the judgment (at [22]). Gyles J held (at [25]) that this was not a defect, explaining that the terms of the 1924 Act were no longer part of the Act. As such, it is apparent that Gyles J sought to distinguish that part of the reasoning in James on this basis. It can be accepted that the terms of s 41 of the Act and s 53 of the 1924 Act in this sense are different. As outlined above, some aspects remain similar. Certainly, as Gyles J observed at [25], s 41 no longer requires (as s 53 of the 1924 Act did) that the bankruptcy notice, as well as being in the prescribed form, shall require the debtor to pay the judgment debt or sum ordered to be paid in accordance with the terms of the judgment. Gyles J held at [22] that the procedure adopted in that case, that payment was required to be made to “Canberra Lawyers, Barristers and Solicitors of 7/13 Napier Close, Deakin, ACT” (a telephone and fax number were also provided) being the agent to receive payment, was open. The requirement or nomination to make payment to a law firm did not invalidate the notice (at [23]-[25]). Nothing in this reasoning, however, is contrary to the emphasised passage from James, that it is the duty of the debtor to seek out the judgment creditor and pay the judgment debt to the creditor. Furthermore, the drafting changes to s 41 of the Act from s 53 of the 1924 Act do not appear to be contrary to this long-standing principle.

109 The Full Court in Marshall v General Motors Acceptance Corporation Australia (2003) 127 FCR 453; [2003] FCAFC 45 (by majority Cooper and North JJ, Spender J dissenting) overturned Gyles J on appeal. The majority did so on basis of Australian Steel, regarding the alleged defect concerning the interest claimed on the bankruptcy notice. Cooper J observed (at [49]) that there were no material differences between the circumstances of the bankruptcy notice in that case, and that in Australian Steel, in relation to requiring disclosure of the correct provision which identifies the entitlement to interest. North J similarly observed the central issue (at [61]) as to the validity of the bankruptcy notice was how it dealt with interest on the judgment claimed. As already observed, Australian Steel was overruled by Adams at [4].

110 The central reason that the appeal overturned Gyles J at first instance was following Australian Steel, which is no longer good law. As such, I do not consider that I am bound by the Full Court in Marshall and I prefer the reasoning at first instance of Gyles J in General Motors.

111 Furthermore, it can be observed in passing that this passage from James (at 639) regarding the duty of a debtor to seek out the judgment creditor is referred to in Metledge at [9], by quoting the relevant passage from Nugent.

112 Heerey J was considering the validity of a bankruptcy notice under the Act in Re Pugliese; Ex parte Chase Manhattan Bank of Australia Ltd (1993) 44 FCR 536; [1993] FCA 733 where one of the grounds relied on that the bankruptcy notice was invalid was that it did not state the address of the creditor. The bankruptcy notice was required to be in accordance with the prescribed form (s 41(1)(a) of the Bankruptcy Act) and r 8 of the Bankruptcy Rules 1968 (Cth), which provided that the bankruptcy notice shall be in accordance with Form 4. In the recital of that bankruptcy notice, the address of the judgment creditor was care of its solicitors at “7th Floor, 469 La Trobe Street, Melbourne, in the State of Victoria” (at 537). The bankruptcy notice was held to be valid and his Honour observed at 538 that:

In my opinion, the bankruptcy notice did comply with the Act. The term “address” means, amongst other things, “a place where a person lives or may be reached” (Macquarie Dictionary). The purpose of a bankruptcy notice is to convey to the debtor the amount which the judgment creditor claims and to the debtor the opportunity of paying or securing that amount. For that purpose the judgment debtor must be told what the amount is and where the creditor can be reached to accept payment or security. The requirement of providing the address of the creditor was satisfied in this case by giving the address of the creditor’s solicitors, since that was a place where payment of the debt would be accepted, even though it was not a place where the creditor carried on business.

113 In Re St Leon; Ex Parte National Australia Bank Limited (1994) 54 FCR 371; [1994] FCA 992, Lindgren J considered a preliminary question of whether the omission of an address of the judgment creditor in the bankruptcy notice was a defect which rendered the bankruptcy notice a nullity or a formal defect or irregularity which attracted the operation of s 306 of the Act (at 374). The statement of the address relied upon by the creditor in that case was stated at the foot of the first page and on the second page as “Mallesons Stephen Jaques, Solicitors, Governor Philip Tower, 1 Farrer Place, Sydney NSW 2000”. Lindgren J expressly considered Re Haritos; Ex parte Hill (1968) 15 FLR 378 and Re Pugliese, distinguishing the latter on the basis that a fair reading of the bankruptcy notice in question did not imply that the creditor was calling for payment to the named solicitor, but it was calling payment directly to National Australia Bank (at 376). It can be observed, as the Creditor and Official Receiver submitted, a complete failure to state where or how the payment may be made, may still render a bankruptcy notice invalid. However, what must be considered is the current version of the Act and the requirements of the prescribed form, as a whole and in the particular circumstances.

114 Lehane J gathered the authorities together in Yu v Farrow Mortgage Services Pty Limited (1995) 60 FCR 300; [1995] FCA 889 and made the following relevant observations (at 306-307):

… A number of propositions are, I think, well established. First, failure to state the creditor’s address at all results in a void notice (St Leon, Re Ma). Secondly, it is not necessarily an objection to a bankruptcy notice that the judgment creditor’s address stated in it is care of the offices of its solicitors (Re Nugent; Ex parte Nugent (1985) 5 FCR 161; on appeal Nugent v Brialkim Pty Ltd (1985 61 ALR 725; Re Pugliese; Ex parte Chase Manhattan Bank of Australia Ltd (1993) 44 FCR 536); that will not be a proper statement of the judgment creditor’s address only if the judgment debtor establishes that it is an address at which it is not reasonably practicable to make payment or to secure or compound, the notice must not be so expressed as to require payment at that address to the exclusion of other places where the judgment creditor may be found (James v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1955) 93 CLR 631).

115 The bankruptcy notice being considered by Lehane J did state an address of the judgment creditor, however, it was only stated in the operative part and not in the recitals. On this basis the bankruptcy notice would only be a nullity if the misplacement of the address was apt to mislead the debtor, which Lehane J held it was not (at 307).

116 The Full Court in Croker considered whether a bankruptcy notice where the address identified was a post office box of the respondent creditor’s lawyers, being the Australian Government Solicitor, was apt to misled. The Full Court reasoned as follows:

[17] The trial judge rejected this ground for a number of reasons. The notice had made clear that the Commonwealth’s address for service was the Australian Government Solicitor’s offices and that, had Mr Croker wished to pay the sum owing, he had the option of doing so at those offices. The address was provided. The bankruptcy notice was in the prescribed form. In any event, Mr Croker had never intended to pay the amount claimed and so, in a practical sense, there was no risk that he might be misled about how he should respond to the notice.

…

[27] The bankruptcy notice did not fail to include a sufficient address for service. The notice clearly identified the creditor’s address for service as being that of the Australian Government Solicitor’s Office in Sydney. The notice also advised Mr Croker that payment of the debt could be made at that office. He was not left uncertain as to what he should do to comply with the notice, and to avoid the consequences of committing an act of bankruptcy: see Foote v Mid-West Finance Pty Ltd (1997) 78 FCR 306 at 307. It is permissible, in a bankruptcy notice, for the address for payment to be identified as the office of the creditor’s solicitors, provided that those solicitors are authorised by the creditor to collect payment on its behalf: see Nugent v Brialkim Pty Ltd (1985) 61 ALR 725 at 726-727.

117 However, it does appear from Croker (at [3]) that the identification of the creditor, being the Commonwealth, and the provision of its address as a post office box may have been only in the recitals of the bankruptcy notice. The address for service of the creditor was advised to the debtor as being the Australian Government Solicitor, for which a street address was provided. Further, that bankruptcy notice also specified that payment could be made to the Commonwealth “c/- Australian Government Solicitor”, again providing the street address. As such, the circumstances of Croker are different.

118 In Fuller, Perry J was considering several grounds which were advanced challenging the validity of the bankruptcy notice, including that it failed to specify a correct address (at [4]). In the circumstances of that case, the bankruptcy notice was held to be valid and a sequestration order made. The bankruptcy notice was that prescribed by reg 4.02. The issues of validity of the bankruptcy notice were outlined at [53], which included the alleged failure to specify a correct address because it failed to state the level of the building in the address provided. Perry J at [81]-[82] considered that substantial compliance was sufficient. Further, that where an incorrect address was alleged to have been provided in the bankruptcy notice, the onus rested on the party seeking to impugn the bankruptcy notice (at [84]). Perry J also referred, as the Creditor here relies on, the “basic principle” from Nugent, that the address should be one at which during the relevant period it is reasonably practicable to make payment or secure or compound (noting those were relevant words of the section at the time of Nugent).

119 The relevant address given in the bankruptcy notice in Fuller was that of the creditor’s firm of solicitors, being (together with a telephone number and email address):

Deutsch Miller

53 Martin Pl, SYDNEY, NSW 2000

120 The debtor in Fuller submitted that the insertion of an incorrect address for payment in the bankruptcy notice was a substantive defect and not merely a formal matter. That substantive defect was said to be the failure to include the level or floor of the building at which the firm could be located. The debtor relied on Re Celestini; Ex Parte Monte Paschi Australia Ltd (1996) 71 FCR 399; [1996] FCA 1107 at 403G and Re Haritos at 379 to support the submission that the defect was substantive. The creditor submitted that those decisions should not be followed because of the different legislative regime, they have not been followed in subsequent cases, and these decisions were impliedly overruled by Adams. Perry J agreed with the submissions of the creditor and did not follow those decisions, on the basis, amongst others, of the different legislative regime (at [92]). Applying the primacy of substance over form, Perry J held that the omission of the level or floor of the building in the address was only a formal defect or irregularity (at [97]). Perry J also did not accept that the omission of the level of the building was capable of misleading the debtor (at [99]). Perry J observed that the floor level was stated on the attached judgments, amongst other earlier documents (in the proceedings in which the judgments were obtained), provided to the debtor (at [99]). Furthermore, the floor level for the creditor’s solicitor was stated on their website which could have been readily accessed (at [99]).

121 Finally, it is necessary to consider the decision of Metledge. Lee J at [2]-[3] observed the following about the bankruptcy notice:

[2] The bankruptcy notice referred to the applicant’s twice: first, on page one, where the address of the applicant was notified as being “P. O. Box 226, Strathfield, Sydney (sic), NSW, Australia”; and secondly, on page two, in numbered section 2 (being that part of the approved form of notice dealing with how payment is to be made), the bankruptcy notice provided:

Payment of the debt can be made to:

Mrs Mary METLEDGE

P. O. Box 226, Strathfield, Sydney (sic), NSW 2135

[3] The bankruptcy notice then went on to provide the applicant’s mobile telephone number and email address.

122 Lee J identified the issue as (at [11]) whether the address identified in that bankruptcy notice, being a post office box was one at which, during the relevant period, it was reasonably practicable for the debtor to make payment or to offer to secure or compound the debt. Lee J did not accept the argument that delivering a cheque to that post office box was reasonably practicable in order to achieve compliance.

123 Lee J considered the decision in Croker, noting that the address shown for the creditor, the Commonwealth, was a post office box but that the notice in that case had expressly stipulated that payment of the debt could be made to the creditor at the offices of its lawyers (at [17]). Lee J distinguished the decision in Croker on the basis that the bankruptcy notice in Metledge did not provide any alternative place for payment, even though the address for service was recorded to be that of the creditor’s solicitors, there was no stipulation that payment could be effected at that address, which was different to Croker.

124 Metledge was handed down on 29 April 2020 and although the date of the bankruptcy notice is not stated in the judgment, it would necessarily be dated prior to April 2020. As such, the prescribed form would have been different to that now under consideration. On this basis, it is unnecessary to consider whether or not this decision is plainly wrong. The relevant question of construction in the circumstances of this case is different. This matter is properly distinguishable because of the change in the prescribed form. Those changes have been considered above.

125 The decision of Sarina was handed down on 26 February 2021 in relation to a bankruptcy notice dated 6 March 2020. At [8] of Sarina it is clear that the relevant prescribed form is the same form as that was considered in Metledge. The defect alleged in Sarina was also said to be the identification of a post office box where payment of the debt could be made. The Court in Sarina considered it was bound by Metledge (at [29]).

126 In Ghougassian, an issue was taken with the address identified at which the creditor could be reached for the purposes of making payment (at [126]). The address in the bankruptcy notice was said to be that of the former liquidator (at [128]). Markovic J relevantly referred to Nugent at [139], and at [141]-[143], a decision of Emmett J in Bonds Industries Ltd v Sing [1999] FCA 1055 (which also relied on Nugent) and Metledge. The facts before Markovic J were quite specific in that the relevant creditor for the purposes of that bankruptcy notice, when it was issued, was Mr Arnautovic. The address provided was his and that address remained his address. However, an order was made extending the time for compliance with the bankruptcy notice and by that time Mr Arnautovic was no longer the liquidator. In short, Markovic J was satisfied that the address was one at which during the currency of the bankruptcy notice the debtors could make payment or make arrangements to the creditor’s satisfaction (at [155]; see also [146]-[152]). Further, Markovic J distinguished Metledge (at [153]) on the basis that the address provided although that of the former liquidator, was still an address where arrangements could be made of settlement of the debt or to secure or compound the debt.

127 Finally, as a matter of overarching principle, to this, I gratefully adopt the observations of Bromwich J in Duarte v Coshott, in the matter of Duarte [2017] FCA 1238 at [36], that pre-2006 authority may need to be checked to ensure compatibility with the High Court’s approach to the substance rather than form in the application of s 306 of the Bankruptcy Act: Adams at [34].

128 Therefore, from this survey of the relevant authorities and legislative context, the following relevant principles are to be applied:

(a) the overwhelming preference is one of substance, over form: Adams at [34];

(b) substantial compliance with the requirements of the form is sufficient, however, regard must be had to the particular defect alleged: s 25C of the Acts Interpretation Act, s 9(3) of the Regulations: Adams at [22], Veale at [93];

(c) a formal defect or irregularity in a bankruptcy may not render the bankruptcy notice a nullity by s 306 of the Act: Adams at [24]-[25]; Veale at [32];

(d) if the bankruptcy notice, however, fails to meet an essential requirement of the Act, it is not necessary that the debtor be misled, the bankruptcy notice will be invalid: Adams at [25], Kleinwort at 79; James at 644; Veale at [20] and [32];

(e) whether a requirement is made essential by the Act, is determined by a process of statutory construction: Adams at [28];

(f) a purposive approach for determining invalidity should be undertaken – the purpose is to inform the judgment debtor as to what is required to comply with the bankruptcy notice: Australian Steel (Gyles J) at [122]; Veale at [142]-[143]; Adams at [27].

129 To those overarching matters, in the context of the alleged defect in this matter, the following can be added:

(a) consideration of whether the address is incorrect is that during the currency of the notice the address given should be one at which it is reasonably practicable to make payment or make arrangements to creditor’s satisfaction: Nugent at 163; Fuller at [84]; Ghougassian at [155];

(b) it is the duty of the debtor to seek out the judgment creditor and the debtor has the right to pay the creditor wherever the debtor can find the creditor: James at 639, Nugent at 726-727;

(c) it is acceptable to identify a solicitor or law firm, on behalf of the creditor, at which payment can be made: Pugliese at 538; Yu at 306-307; Metledge at [13]; Croker at [27]; General Motors at [22]; Paligorov at [27]; Anderson Rice at 554 and 556.

Was this bankruptcy notice defective or irregular?

130 It is necessary to consider as a question of construction whether it is a requirement of the Act to provide a complete and correct street address in Section 2 of the prescribed form, being the bankruptcy notice.

131 The question identified by Gyles J in Australian Steel at [102], endorsed in Adams at [32], was whether the correct completion of the form prescribed by the Regulations in every respect is a requirement made essential by the Act. Therefore, in the circumstances of this case, the question is whether the completion and provision of an address, and more particularly by way of a post office box, completes the form prescribed by the Regulations in a way which fails to meet a requirement of the Act. Above at [88]-[96], consideration is given to the changes in the prescribed bankruptcy form and the evident purpose of Section 2 of the bankruptcy notice. Neither the Act, the Regulations nor the prescribed form in Section 2 state that “an address” is to be provided when completing that part of the bankruptcy notice.

132 In this case, the complained of defect is that Section 2 of the operative part of the bankruptcy notice has been completed with the details of a post office box. Section 2 is headed, “Payment of the debt can be made to”. This, it is contended by the Debtor, fails to meet a requirement of the Act because Section 2 is said to require provision of where payment of the debt can be made or where to make arrangements to the creditor’s satisfaction for settlement of the debt. However, for the reasons at [88]-[96] above and the reasons below, I do not accept the Debtor’s submission that this section is now only directed to where payment can be made or where arrangements can be made, it would now also include how payments or arrangements can be made.