FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (No 3) [2025] FCA 1086

File number(s): | VID 350 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | MCELWAINE J |

Date of judgment: | 5 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – alleged multiple contraventions of ss 47, 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) – six vulnerable consumers financed to purchase used motor vehicles – content of various obligations to make reasonable inquiries about a consumer’s requirements and objectives and financial situation and to take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation – whether respondent failed to make inquiries and to verify to the standard of a reasonable lender at the time – whether inquiries and verification required analysis of declared living expenses as an integer of a consumer’s financial situation – Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2020] FCAFC 111; (2020) 277 FCR 343 distinguished – content of licensee obligations to take reasonable steps to ensure its representatives comply with the credit legislation and to ensure its representatives are adequately trained and competent to engage in credit activities authorised by a licence – obligations of a regulator in civil penalty proceedings to explicitly plead and particularise the case. WORDS AND PHRASES – reasonable inquiries – reasonable steps to verify – reasonable steps to ensure representatives comply with the credit legislation –reasonable steps to ensure representatives are adequately trained and competent. EXPERT EVIDENCE – utility of expert evidence where basis for opinions is not exposed – unexplained constructs of reasonable and prudent lender; execution framework and minimum expected practices, inter alia. |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 79 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 37M, 37N National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) ss 47, 128, 129, 130, 131 and 133 Explanatory Memorandum to the National Consumer Credit Protection Bill 2009 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Channic Pty Ltd (No 4) [2016] FCA 1174 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Firstmac Ltd [2024] FCA 737 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Green County Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 367 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey [2011] FCA 717; (2011) 196 FCR 291 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Lanterne Fund Services Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 353 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (Expert Evidence Admissibility) [2025] FCA 75 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (No 2) [2025] FCA 110 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (Trial Ruling No 2 - Witness Unavailability) [2025] FCA 110 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2020] FCAFC 111; (2020) 277 FCR 343 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2019] FCA 1244; (2019) 139 ACSR 25 CAL No 14 Pty Ltd v Motor Accidents Insurance Board [2009] HCA 47; (2009) 239 CLR 390 Dasreef Pty Ltd v Hawchar [2011] HCA 21; (2011) 243 CLR 588 Lang v R [2023] HCA 29; (2023) 278 CLR 323 Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705 Permanent Trustee Australia Ltd v Boulton (1994) 33 NSWLR 735 Rogers v Whitaker [1992] HCA 58; (1992) 175 CLR 479 Rosenberg v Percival [2001] HCA 18; (2001) 205 CLR 434 Wyong Shire Council v Shirt [1980] HCA 12; (1980) 146 CLR 40 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | 790 |

Date of hearing: | 5 –10 February 2025, 12 – 17 February 2025 and 13 March 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr S R Senathirajah KC and Mr R J Boadle |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Australian Government Solicitor |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr C M Caleo KC and Ms C van Proctor |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Clayton Utz |

ORDERS

VID 350 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | MONEY3 LOANS PTY LTD (ACN 108 979 406) Respondent | |

order made by: | MCELWAINE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 september 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The further hearing of the proceeding is adjourned to a date to be fixed.

2. The applicant is to file by 4pm on 10 October 2025, a draft document that sets out the declaratory relief it seeks, consistent with the contraventions as established.

3. A further case management hearing will take place at 10.15 am on 30 October 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

1. Synopsis | [1] |

[15] | |

[15] | |

[23] | |

[41] | |

[41] | |

2.3.2 The process of assessment: ss 128(c), (d), 129 and 130(1)(a)-(c) | [50] |

[57] | |

[61] | |

[77] | |

2.3.6 Minimum necessary expenses, discretionary basics, absolute basics or something else? | [88] |

[128] | |

[141] | |

[147] | |

[147] | |

[154] | |

[163] | |

[164] | |

[169] | |

4.3 Reasonable and prudent conduct is a matter for the Court to determine | [213] |

[219] | |

[219] | |

[267] | |

[268] | |

[294] | |

[332] | |

[333] | |

[388] | |

[400] | |

[401] | |

[401] | |

[423] | |

[423] | |

[426] | |

[449] | |

[450] | |

[450] | |

[452] | |

[459] | |

[460] | |

[460] | |

[464] | |

[470] | |

[471] | |

[471] | |

[509] | |

[509] | |

[514] | |

[533] | |

[534] | |

[534] | |

[536] | |

[538] | |

[539] | |

[541] | |

[545] | |

[546] | |

[546] | |

[579] | |

[579] | |

[583] | |

[602] | |

[603] | |

[603] | |

[605] | |

[606] | |

[606] | |

[608] | |

[614] | |

[615] | |

[615] | |

[643] | |

[650] | |

[676] | |

[677] | |

[677] | |

[678] | |

[679] | |

[680] | |

[682] | |

[683] | |

[698] | |

[720] | |

[720] | |

[744] | |

[744] | |

[769] | |

[790] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MCELWAINE J:

1. SYNOPSIS

1 The Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) brings this proceeding for declaratory relief, injunctions, compliance orders and the imposition of pecuniary penalties against Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (Money3) for contraventions of various responsible lending provisions in the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth). In these reasons, each reference to a statutory provision is to the Act unless otherwise stated.

2 Money3 is a wholly owned subsidiary of Solvar Limited (previously named Money3 Corporation Limited) (ACN 117 296 143), a publicly listed company, and is a member of the Money3 Group (comprising Solvar Limited and its subsidiaries), which is a provider of consumer automotive finance and consumer personal loans across Australia and New Zealand. Money3 provides a range of finance products, including loans to customers through direct access, broker and dealer channels.

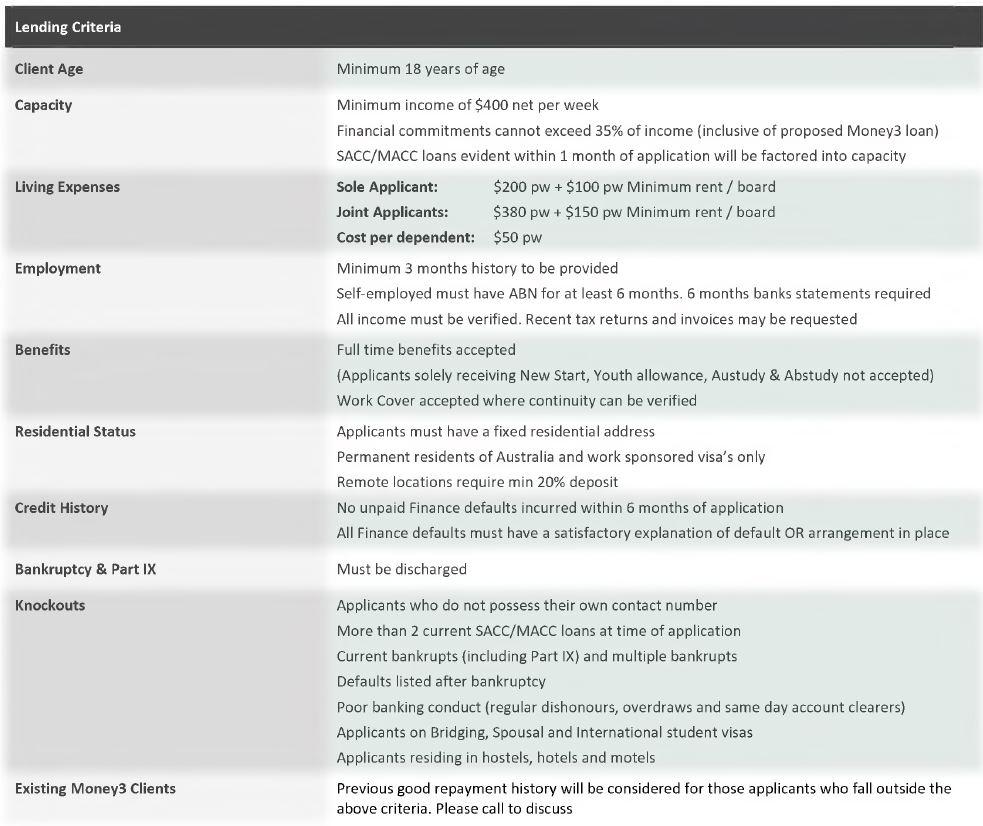

3 Amongst other products, Money3 offers a “Micro Motor” loan. The Micro Motor business of Money3 involves lending to a maximum of $8,000 for a secured product. Subject to other conditions, the product is available to consumers who receive government benefits comprising of up to 100 per cent of their income. Money3 utilised internal documents which set out the features, conditions and lending criteria of the Micro Motor loan. Its form has evolved. Relevant to this proceeding is the Micro Motor Matrix which applied between July 2018 and August 2019. It was replaced by successive versions of Product Guides in August 2019 and October 2020. In evidence, the collective reference Product Guide was often used, including references to the Matrix. These reasons adopt that nomenclature where appropriate. The Product Guides contain “knockout” criteria which used by Money3 to determine whether an applicant is eligible for the product. Amongst other things, the knockout criteria render the product unavailable to applicants with “poor banking conduct” or applicants who have more than two current “payday” loans.

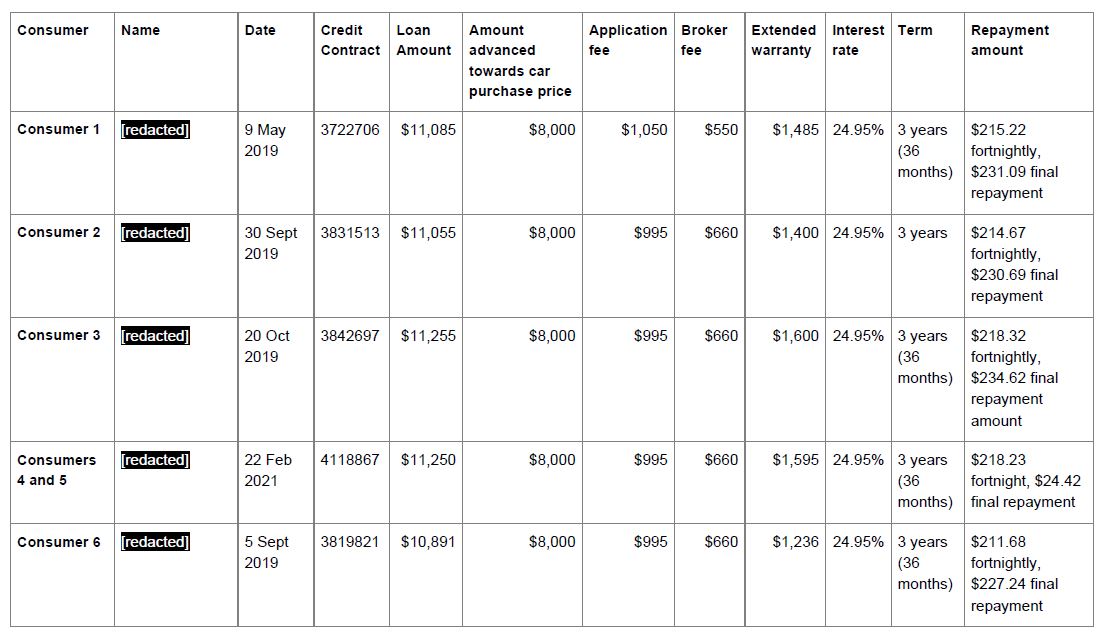

4 ASIC contends that between 8 May 2019 and 18 February 2021 (the relevant period) Money3 contravened its responsible lending obligations. The allegations relate to five Micro Motor credit contracts that Money3 entered into with six consumers (the credit contracts). It is ASIC’s case that shortly after entering the credit contracts each consumer suffered financial hardship. The credit contracts provided for, among other things, finance to purchase second-hand vehicles. Each credit contract comprised an amount of $8,000 advanced to purchase a vehicle, as well as additional amounts of approximately $3,000 for application fees, broker fees, and insurance warranties (add-on fees). Each credit contract was provided by Money3 to the consumer through its broker channel. The credit contracts and the consumers are identified below:

5 There were three versions of the Product Guides at different times during the relevant period:

(1) The July 2018 Matrix, relevant to Consumer 1 (CB 6245);

(2) The August 2019 Product Guide, relevant to Consumer 2, Consumer 3 and Consumer 6 (CB 6377); and

(3) The October 2020 Product Guide, relevant to Consumers 4 and 5 (CB 6624).

6 During the relevant period, Money3 held, and continues to hold an Australian Credit Licence which authorises it to engage in credit activities, including as a credit provider under the credit contracts.

7 In respect of each credit contract, ASIC alleges multiple contraventions of cascading legislative requirements for the six consumers. In all, 15 contraventions are alleged, most of which are pleaded conjunctively and disjunctively for each consumer. Multiple contraventions are alleged of ss 128, 130, 131 and 133 for the five credit contracts plus four contraventions of s 47 which require determination. That does not exhaust the permutations that ASIC advances to establish each contravention. For each, ASIC relies on a plethora of submissions, where acceptance of one establishes a contravention. These reasons resolve 83 separate contentions relating to the credit contracts plus the general conduct contraventions, where ASIC in closing submissions identifies 17 contraventions founded on 81 separate findings of fact. With some grouping, these reasons reduce the general conduct contraventions to 12. Working through the ASIC case to prepare these reasons has consumed an inordinate and disproportionate amount of the judicial and administrative resources of the Court. When a regulator chooses to proceed in this way questions arise as to whether a proceeding is conducted consistently with the overarching purpose at ss 37M and 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act).

8 Stepping back and through an objective lens, the question that s 37M(1) of the FCA Act requires a party to consider, before commencement of a proceeding, is how it may be framed, arranged and prosecuted as quickly, inexpensively and as efficiently as possible. In a civil penalty proceeding, the issue is not how many contraventions (often a related course of conduct) can be established, but how many are material to achieve the purpose of specific and general deterrence? Another question is whether it is efficient to press multiple claims of the same type of conduct where selection of the best (or worst example) run as a separate case will achieve the regulator’s objective? Relatedly, will proceeding by reference to an example case with a limited number of the more egregious contraventions, if established, likely result in an agreed penalty proceeding for the balance of the claims?

9 In any event it is now too late to visit those matters in this proceeding. The Court must deal with the case as framed and prosecuted. In broad summary, ASIC alleges that Money3 contravened:

(1) Section 128(c) because the credit contracts were entered into without making the unsuitability assessment required by s 129;

(2) Section 128(d) because the credit contracts were entered into without having:

(i) made reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives as required by s 130(1)(a);

(ii) made reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation as required by s 130(1)(b); and/or

(iii) taken reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation as required by s 130(1)(c);

(3) Section 130(1) because the inquiries and verification required by s 128(d) (before making the assessment under s 128(c)) were not undertaken;

(4) Section 131(1) because it failed to assess the credit contracts as unsuitable for each consumer on the basis that:

(i) pursuant to s 131(2)(a) it was likely that the consumer would be unable to comply with their financial obligations under the credit contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship; and/or

(ii) pursuant to s 131(2)(b) the credit contracts would not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives if it was entered into;

(5) Section 133(1) because the credit contracts were entered into with each consumer in circumstances where the contract was unsuitable on the basis that:

(i) pursuant to s 133(2)(a) it was likely that the consumer would be unable to comply with the financial obligations under the credit contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship; and/or

(ii) pursuant to s 133(2)(b), the credit contract would not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives if it was entered into;

(6) Section 47(1)(g) and (4) by failing to ensure that its representatives were adequately trained and competent to engage in the credit activities authorised by the Licence during the relevant period; and

(7) Section 47(1)(e) and (4) by failing to take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives complied with the credit legislation (relevantly, ss 128, 130(1), 131(1) and 133(1)).

10 It is ASIC’s case that, at the time of applying for a loan and entering the credit contracts, each consumer was in precarious financial circumstances. Each consumer was unemployed and relied on Government payments or child support for income. Four of the consumers were Indigenous single mothers and several lived in community housing. In each case, the consumers’ debits exceeded or were near-equal to their credits in the 90-day period prior to the loan application. Each consumer sought finance to purchase a second-hand car at a cost of $8,000, and the add-on fees of approximately $3,000 were not part of the consumers’ requirements or objectives in relation to the credit contract. In that regard, ASIC submits that Money3 did not make reasonable inquiries about each consumers’ objectives and requirements in relation to the credit contract or make reasonable inquiries or take reasonable steps to verify the consumers’ financial situation.

11 Another key aspect of ASIC’s case is Money3’s reliance on the expense amounts contained in the Product Guides. The lending criteria that the Money3 credit analysts used in assessing applications for the Micro Motor loans were set out in Product Guides that applied at the time of each finance application. Each includes a ‘minimum living expense’ amount. How the minimum living expense amounts contained in the Product Guides were arrived at by Money3 is in issue.

12 The general conduct, s 47 contraventions, focus on the policies, procedures and training of Money3, which according to an expert report of Mr Michael Hartman dated 19 December 2023 (Expert Report) fell short of the minimum standards of reasonable and prudent lenders at the time. There is a large dispute about the value of the opinions of Mr Hartman which turns on whether he exposed his reasoning process.

13 For the reasons that follow I have concluded that in limited respects, Money3 contravened the responsible lending provisions of the Act, in that its credit analysts did not make reasonable inquiries about the requirements and objectives or the financial situation of the consumers and relatedly did not take reasonable steps to verify the financial situation of each consumer. These are contraventions of ss 128(d) and 130(1) and each occurred during the assessment period. ASIC has failed to establish each other contravention.

14 The appropriate order at this time is to adjourn the proceeding for further hearing and conduct a case management hearing with a laser-like focus on the overarching purpose.

2. LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK

2.1 The provisions in issue

15 As I have noted, ASIC pleads multiple contraventions of the Act. In the legislative scheme, the starting point is Chapter 1, Part 2-2, Division 5 which sets out the general conduct obligations of licensees. Section 47 relevantly provides:

(1) A licensee must:

(a) do all things necessary to ensure that the credit activities authorised by the licence are engaged in efficiently, honestly and fairly; and

(b) have in place adequate arrangements to ensure that clients of the licensee are not disadvantaged by any conflict of interest that may arise wholly or partly in relation to credit activities engaged in by the licensee or its representatives; and

(c) comply with the conditions on the licence; and

(d) comply with the credit legislation; and

(e) take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives comply with the credit legislation; and

(ea) comply with the Reference Checking and Information Sharing Protocol; and

(f) maintain the competence to engage in the credit activities authorised by the licence; and

(g) ensure that its representatives are adequately trained, and are competent, to engage in the credit activities authorised by the licence; and

(h) have an internal dispute resolution procedure that:

(i) complies with standards and requirements made or approved by ASIC in accordance with the regulations; and

(ii) covers disputes in relation to the credit activities engaged in by the licensee or its representatives; and

(ha) give to ASIC the same information it would be required to give under subparagraph 912A(1)(g)(ii) of the Corporations Act 2001 if it were a financial services licensee (within the meaning of Chapter 7 of that Act); and

(i) be a member of the AFCA scheme; and

(j) have compensation arrangements in accordance with section 48; and

(k) have adequate arrangements and systems to ensure compliance with its obligations under this section, and a written plan that documents those arrangements and systems; and

(l) unless the licensee is a body regulated by APRA:

(i) have available adequate resources (including financial, technological and human resources) to engage in the credit activities authorised by the licence and to carry out supervisory arrangements; and

(ii) have adequate risk management systems; and

(m) comply with any other obligations that are prescribed by the regulations.

Assessment of whether compliance is adequate

(2) For the purposes of paragraphs (1)(b), (g), (k) and (l), in considering whether a matter is adequate, the nature, scale and complexity of the credit activities engaged in by the licensee must be taken into account.

16 Chapter 3 is concerned with responsible lending conduct. It commences with the guide at Part 3-1, s 111 which in part provides:

This Part has rules that apply to licensees that provide credit assistance in relation to credit contracts. These rules are aimed at better informing consumers and preventing them from being in unsuitable credit contracts. However, these rules do not apply to a licensee that will be the credit provider under the credit contract.

17 Part 3-2 sets out general rules for licensees that are credit providers under credit contracts. The guide at s 125 provides:

This Part has rules that apply to licensees that are credit providers. These rules are aimed at better informing consumers and preventing them from being in unsuitable credit contracts.

Division 2 requires a licensee to give its credit guide to a consumer. The credit guide has information about the licensee and some of the licensee’s obligations under this Act.

Division 3 requires a licensee, before doing particular things (such as entering a credit contract), to make an assessment as to whether the contract will be unsuitable. To do this, the licensee must make inquiries and verifications about the consumer’s requirements, objectives and financial situation. The licensee must give the consumer a copy of the assessment if requested.

Division 4 prohibits a licensee from entering or increasing the credit limit of a credit contract that is unsuitable for a consumer.

18 In this Part, the relevant provisions commence with s 128 which imposes an obligation to assess unsuitability and where the assessment must comply with s 129:

128 Obligation to assess unsuitability

A licensee must not:

(a) enter a credit contract with a consumer who will be the debtor under the contract; or

(aa) make an unconditional representation to a consumer that the licensee considers that the consumer is eligible to enter a credit contract with the licensee; or

(b) increase the credit limit of a credit contract with a consumer who is the debtor under the contract; or

(ba) make an unconditional representation to a consumer that the licensee considers that the credit limit of credit contract between the consumer and the licensee will be able to be increased;

on a day (the credit day) unless the licensee has, within 90 days (or other period prescribed by the regulations) before the credit day:

(c) made an assessment that:

(i) is in accordance with section 129; and

(ii) covers the period in which the credit day occurs; and

(d) made the inquiries and verification in accordance with section 130.

Civil penalty: 5,000 penalty units.

129 Assessment of unsuitability of the credit contract

For the purposes of paragraph 128(c), the licensee must make an assessment that:

(a) specifies the period the assessment covers; and

(b) assesses whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in that period.

Note: The licensee is not required to make the assessment under this section if the contract is not entered or the credit limit is not increased.

19 Section 130 sets mandatory requirements for the inquiry and verification obligation at s 128(d) and relevantly provides:

130 Reasonable inquiries etc. about the consumer

Requirement to make inquiries and take steps to verify

(1) For the purposes of paragraph 128(d), the licensee must, before making the assessment:

(a) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract; and

(b) make reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation; and

(c) take reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation; and

(d) make any inquiries prescribed by the regulations about any matter prescribed by the regulations; and

(e) take any steps prescribed by the regulations to verify any matter prescribed by the regulations.

Civil penalty: 5,000 penalty units.

…

(2) The regulations may prescribe particular inquiries or steps that must be made or taken, or do not need to be made or taken, for the purposes of paragraph (1)(a), (b) or (c).

20 No regulation has been made for the purposes of s 130(2).

21 A licensee must assess a credit contract as unsuitable where s 131 applies. It relevantly provides:

131 When credit contract must be assessed as unsuitable

Requirement to assess the contract as unsuitable

(1) The licensee must assess that the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract will be unsuitable for the consumer under subsection (2).

Civil penalty: 5,000 penalty units.

Note: Even if the contract will not be unsuitable for the consumer under subsection (2), the licensee may still assess that the contract will be unsuitable for other reasons.

Particular circumstances when the contract will be unsuitable

(2) The contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if, at the time of the assessment, it is likely that:

(a) the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship, if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in the period covered by the assessment; or

(b) the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in the period covered by the assessment; or

(c) if the regulations prescribe circumstances in which a credit contract is unsuitable—those circumstances will apply to the contract if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in the period covered by the assessment.

…

Information to be used to determine if contract will be unsuitable

(4) For the purposes of determining under subsection (2) whether the contract will be unsuitable, only information that satisfies both of the following paragraphs is to be taken into account:

(a) the information is about the consumer’s financial situation, requirements or objectives, or any other matter prescribed by the regulations under paragraph 130(1)(d) or (e);

(b) at the time of the assessment:

(i) the licensee had reason to believe that the information was true; or

(ii) the licensee would have had reason to believe that the information was true if the licensee had made the inquiries or verification under section 130.

22 Division 4 prohibits a licensee from entering into a credit contract if the contract is unsuitable for the consumer. Relevantly, s 133 provides:

133 Prohibition on entering, or increasing the credit limit of, unsuitable credit contracts

Prohibition on entering etc. unsuitable contracts

(1) A licensee must not:

(a) enter a credit contract with a consumer who will be the debtor under the contract; or

(b) increase the credit limit of a credit contract with a consumer who is the debtor under the contract;

if the contract is unsuitable for the consumer under subsection (2).

Civil penalty: 5,000 penalty units.

When the contract is unsuitable

(2) The contract is unsuitable for the consumer if, at the time it is entered or the credit limit is increased:

(a) it is likely that the consumer will be unable to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract, or could only comply with substantial hardship; or

(b) the contract does not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives; or

(c) if the regulations prescribe circumstances in which a credit contract is unsuitable—those circumstances apply to the contract.

…

Information to be used to determine if contract will be unsuitable

(4) For the purposes of determining under subsection (2) whether the contract will be unsuitable, only information that satisfies both of the following paragraphs is to be taken into account:

(a) the information is about the consumer’s financial situation, requirements or objectives, or any other matter prescribed by the regulations under paragraph 130(1)(d) or (e);

(b) at the time of the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased, the information:

(i) the licensee had reason to believe that the information was true; or

(ii) the licensee would have had reason to believe that the information was true if the licensee had made the inquiries or verification under section 130.

Credit contract not unsuitable under regulations

(5) The regulations may prescribe particular situations in which a credit contract is taken not to be unsuitable for a consumer, despite subsection (2).

2.2 General principles

23 There is a large divide between ASIC and Money3 as to the meaning of the unsuitability assessment provisions and how they apply to the credit contracts and consumers in issue. It is of assistance to commence by understanding their structure and interrelationship: a task greatly assisted by the decision of the Full Court in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2020] FCAFC 111; (2020) 277 FCR 343, Middleton, Gleeson and Lee JJ (Westpac). In what follows, I focus only on the requirements applicable to entry into a contract; I do not address the separate credit contract provisions.

24 The central obligation of a licensee is to make an assessment: ss 128(c) and 129. That is a decision which is an evaluative judgment involving a prediction as to the future in two respects. One, the likely ability of a consumer to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract (or whether the consumer could only comply with substantial hardship): s 131(2)(a). There is a rebuttable presumption of substantial hardship if the consumer could only comply with the consumer’s financial obligations by selling the consumer’s principal place of residence: s 131(3).

25 The other, the likelihood that the contract will meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives if the contract is entered into: s 131(2)(b).

26 Each of those requirements is conditioned by when the assessment is undertaken, which is a defined point in time: at the time of the assessment: s 131(2).

27 The assessment is a binary decision. Will the credit contract be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered?: s 129(b). A mandated affirmative answer is required by s 131(1) where the conditions of s 131(2) apply.

28 The assessment is the outcome of a process which begins with the making of the inquiries and undertaking of the verifications in accordance with s 130: s 128(d). Section 130 specifies three steps: (1) making reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract; (2) making reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation; and (3) taking reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation. Although Parliament provided for a prescription mechanism by regulation of what inquiries must be made and verification steps taken (s 130(1)(d)-(e)), none have been promulgated to that effect. As such, these are matters for the licensee to determine: Westpac at [141], Gleeson J; [167], Lee J.

29 What is reasonable is a question of fact. The familiar analysis proceeds prospectively by what was known, or ought to have been reasonably known, at the time. It is an error to determine the content of the reasonableness obligation by analysing what has happened.

30 The reasonable inquiries and taking steps obligations open for consideration a range of matters, though constrained by the purpose of s 130, which as Gleeson J explained in Westpac at [117] by reference to the decision of the primary judge, is:

[T]o ensure that credit providers put themselves in an informed state about the financial position of the consumer before making an assessment of the suitability or otherwise of the loan.

31 Further as Middleton J stated in Westpac at [11]:

Chapter 3 as a whole has a specific purpose to create and enforce a new norm of conduct for credit providers (and brokers) when entering into credit contracts. This context explains the very specific and detailed requirements of the provisions of Pt 3-2, and the very significant penalties to which those contravening those requirements may be subjected. Each of the requirements is a critical part of a sequence leading up to the credit provider making an assessment of unsuitability, by reference to the consumer’s financial situation and requirements and objectives.

32 An obligation to act reasonably as a normative standard of conduct is well understood in the law of negligence, operating as the first prerequisite in a claim for damage caused by careless conduct. Unless a duty to take reasonable care is owed to a plaintiff, there is no cause of action. If there is a duty, the next step requires identification of its content: put simply, what was the defendant required to do in order to satisfy the standard? In simple cases, such as motor vehicle running down claims, the content of the duty that the defendant drove negligently is usually particularised by identification of why the driving fell short of the reasonable care standard. Familiar examples include driving at excessive speed, failing to give way, being under the influence of alcohol or failing to keep a proper lookout.

33 The duty in negligence to exercise reasonable care is not one that requires elimination of all foreseeable risks or to prevent harm from eventuating. The inquiry focuses prospectively on what measures could and should have been taken to address foreseeable risk. The answer is what a reasonable person or corporation in the position of the defendant would have done in response to the risk. Very often the answer to that question is straightforward; as examples, reference is commonly made to industry standards, statutory provisions and accepted practices and procedures in a field of operation.

34 Where the answer is not so clear, identification of the content of the duty may be assisted by expert evidence. The guiding principle is the classic formulation of Mason J in Wyong Shire Council v Shirt [1980] HCA 12; (1980) 146 CLR 40 at 47-48, often referred to as the Shirt calculus:

In deciding whether there has been a breach of the duty of care the tribunal of fact must first ask itself whether a reasonable man in the defendant's position would have foreseen that his conduct involved a risk of injury to the plaintiff or to a class of persons including the plaintiff. If the answer be in the affirmative, it is then for the tribunal of fact to determine what a reasonable man would do by way of response to the risk. The perception of the reasonable man's response calls for a consideration of the magnitude of the risk and the degree of the probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action and any other conflicting responsibilities which the defendant may have. It is only when these matters are balanced out that the tribunal of fact can confidently assert what is the standard of response to be ascribed to the reasonable man placed in the defendant's position.

35 Here, the obligation at s 130 invites a fact specific interrogation of what, if any, inquiries were made and what steps were taken compared with what a reasonable licensee would have done in the same circumstances to be reasonably informed about the individual consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to a prospective credit contract and the consumer’s financial situation in conjunction with taking reasonable steps to verify the consumer’s financial situation.

36 There is an additional element that must be read with the obligation to make reasonable inquiries to obtain the information to be used in the unsuitability assessment at s 131(4). The licensee must subjectively have reason to believe that the information was true or objectively would have had reason to believe that the information was true if the licensee had made the inquiries or verification under s 130.

37 Lurking behind those apparently simple questions is the vice of prescriptively framing the content of the duty, which Hayne J identified in CAL No 14 Pty Ltd v Motor Accidents Insurance Board [2009] HCA 47; (2009) 239 CLR 390 at [68]:

Because the duty relied on in this Court was framed so specifically, it merged the separate inquiries about duty of care and breach of duty. The merger that resulted carried with it the vice of retrospective over-specificity of breach identified in Romeo v Conservation Commission (NT) (1998) 192 CLR 431 at [163]-[164] and in the diving cases of Vairy v Wyong Shire Council (2005) 223 CLR 422 at [29], [54], [60]-[61], [122]-[129], Mulligan v Coffs Harbour City Council (2005) 223 CLR 486 at [50], and Roads and Traffic Authority (NSW) v Dederer (2007) 234 CLR 330 at [65]. The duty alleged was framed by reference to the particular breach that was alleged and thus by reference to the course of the events that had happened. Because the breach assigned was not framed prospectively the duty, too, was framed retrospectively, by too specific reference to what had happened. These are reasons enough to reject the formulation of duty advanced in argument in this Court.

38 This provides a useful analogy, which I consider in detail later in these reasons, in analysing how ASIC particularises the content of the duty, supported by the extensive expert evidence it relies on. Returning to the structural aspects of the provisions in issue, the controlling mechanism for the content of the duty is the unsuitability conclusion, where s 131 is determinative of the outcome if either subparagraph (2)(a) or (b) applies, and the prohibition that a licensee must not enter into a credit contract with a consumer who will be a debtor if the contract is unsuitable for the consumer: s 133. Of course, the difficulty with these provisions is that they turn on a (necessarily evaluative) assessment as to the future: Westpac at [36], Middleton J. Predicting the future is notoriously difficult and often inaccurate. These provisions do not require the licensee to accurately predict the ultimate outcome. That a consumer is subsequently unable to comply with his or her financial obligations under the contract or is only able to do so with substantial hardship is beside the point. So much is clear from s 131(2) which speaks to likelihood at the time of the assessment.

39 There is however a notable difference in the drafting. Section 131(2) requires an unsuitability conclusion (the result of the assessment required by s 131(1)) “if…it is likely that”, (a) or (b) apply: in short, an inability to comply with future contractual obligations or the contract will not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives. In contrast, the prohibition at s 133 that a licensee must not enter a credit contract with a consumer who will be the debtor if unsuitable under subsection (2) confines likelihood to subparagraph (a): the consumer’s inability to comply with the contractual obligations. Subparagraph (b) is expressed definitively: the contract does not meet the consumer’s requirements or objectives. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Channic Pty Ltd (No 4) [2016] FCA 1174, Greenwood J identified the reason for textual difference between “s 131(1) and s 131(2) on the one hand and s 133(1) and s 133(2) on the other hand” as “the temporal element of the time of the assessment in the first case and the time of entry into the contract in the second case” (at [1817]). The prohibition does not apply if the licensee has undertaken the unsuitability assessment required by s 128(c), conformably with s 129, and if the outcome is that the credit contract is not unsuitable having passed by the mandatory assessment outcome required by s 131.

40 I next address the particular construction issues identified by the parties.

2.3 Construction issues

2.3.1 Section 129

41 ASIC contends that guidance on what makes an assessment “compliant” for the purposes of s 129 is found in the consolidated Explanatory Memorandum to the National Consumer Credit Protection Bill 2009 (Cth) at [3.133]-[3.134]:

3.133 In order to make a compliant assessment for the purposes of section 128, the credit provider must specify the period that the assessment covers (which is to be a period which includes the critical day)…

3.134 A compliant assessment must also assess whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered or the credit limit is increased in that specified period…

42 In reliance, ASIC submits that Money3 must specify “in the documents it holds out as constituting its ‘assessment’ for the purposes of s 129, the period covered by the assessment for each of the consumers, as well as assessing whether the credit contract would be unsuitable in that specified period.” ASIC accepts, as it must conformably with Westpac, that s 129 is not prescriptive as to how the assessment must be undertaken or requires that all information acquired by the licensee must be used in the assessment.

43 Money3 submits that ASIC’s first proposition is not supported by the statutory language of s 129, nor the extract of the Explanatory Memorandum relied on. Further, the legislation does not prescribe how an assessment is to be carried out or how it is to be recorded: Westpac at [167] and [171], Lee J.

44 I am unable to accept ASIC’s submission that the assessment must be documented in the broad manner contended. Middleton J explained why in Westpac at [67]:

Section 129 gives content of that assessment by referring back to s 128(c). Whilst the reference in s 129(a) to specifying the period the assessment covered may indicate some sort of written specification, I do not consider in light of its text or context, it has this meaning. Section 129 relates to “making” an assessment, and is an evaluative exercise involving the criteria in s 129(a) (period of time) and s 129(b) (unsuitability). Then s 132 is another separate and discrete provision which clearly refers to a document being provided to the consumer. It creates a separate civil penalty provision, and refers to the written assessment in fact created by the credit provider after carrying out the assessment required under s 128(c).

45 I agree, and would add that the requirement to give the consumer a written copy of the assessment at s 132(1) only arises if the consumer requests it.

46 Although his Honour dissented as to one aspect of the appeal, I do not read the reasons of Gleeson J or Lee J as expressing a contrary view to the effect that the licensee is obligated to specify in the documents it holds out as constituting the assessment, the period and the unsuitability conclusion.

47 Indeed, as explained by Lee J at [167] there are only two requirements at s 129:

There is no textual requirement specifying how the assessment is to be undertaken, and indeed ASIC accepted that “it remains open to a licensee to choose how it conducts the assessment required”. Section 129 spells out only two requirements for an assessment: first, specifying the period covered; and secondly, assessing whether the contract (or an increase in credit limit) will be unsuitable for the consumer.

48 See also his Honour at [171]: the manner of assessment is “left up to a fully informed licensee”.

49 That addresses further arguments of ASIC. It follows that s 129 does not prescribe how the period covered by the assessment must be specified. Nor does it preclude a licensee from engaging in oral communications with a consumer to obtain relevant information as a method of complying with the inquiry and verification obligations.

2.3.2 The process of assessment: ss 128(c), (d), 129 and 130(1)(a)-(c)

50 The submissions of ASIC and Money3 are consistent to a point.

51 ASIC does not submit that the requirements to make reasonable inquiries and to take reasonable steps to verify at s 130 must be completed before the assessment process begins, nor does it submit that the assessment cannot be a process over an extended period of time. Money3 agrees.

52 There is no disagreement that the process must be completed within 90 days of the date on which the licensee enters into the credit contract.

53 Unsurprisingly, there is no disagreement that the reasonable inquiry and verification steps must be completed before the unsuitability assessment is completed as that is the explicit requirement of s 130(1).

54 Something should be said about s 128(c) and s 129. The licensee must, within 90 days before the credit day, make an assessment which covers the period in which the credit day occurs and specifies the period the assessment covers. The drafting could be clearer, but in my opinion the meaning is revealed by commencing with the basal requirement that the assessment is forward looking: the likelihood of unsuitability is assessed as required by s 131(2). The assessment must also specify the period of currency: s 129(a). Although there is no maximum currency period, a credit contract must not be entered into unless there has been an assessment within 90 days before the credit day and it must cover the period in which the credit day occurs.

55 For the six consumers in issue, Money3 specified in each credit contract the date of its preparation (Disclosure Date) and the Settlement Date (when the funds were advanced). If the Settlement Date did not fall within 14 days of the Disclosure Date, Money3 could withdraw from the transaction (an example of the clause in issue is set out at [83]). By this method, Money3 complied with the obligation to make an assessment (putting aside the ASIC contention that it was insufficient) within 90 days of the credit day, that included the credit day and specified the period covered by it – 14 days from the Disclosure Date.

56 I turn to three issues that divide the parties.

2.3.3 Interrelationship of s 130 with s 128(c)

57 Does s 130 provide content to the obligation at s 128(c)? ASIC submits that “antecedent failures” by Money3 to make reasonable inquiries and to take reasonable steps to verify the financial situation of each consumer resulted in Money3 “failing to use (reasonably) accurate/reliable amounts for the consumers expenses in undertaking [the] purported unsuitability assessments”.

58 Money3 interprets this submission as a contention that an unsuitability assessment “that does not reflect, or follow, compliance with the obligations imposed by s 130(1) will not constitute an assessment (at all) for the purpose of s 129, and therefore s 128(c)”. Money3 submits it is only s 129(b) that provides the content to s 128(c), relying on Middleton J in Westpac at [51]. Further, Money3 contends that “whether and how the results of any inquiries and verifications are used to make an assessment are matters for the licensee to decide, provided the licensee assesses whether the contract will be relevantly unsuitable”. In Money3’s submission, ss 128(c) and 129 are not themselves concerned with the inquiries about, or steps taken to verify, a consumer’s financial situation, which is further supported “by the fact that an obligation to have ‘made the inquiries and verification in accordance with s 130’ is specifically and separately imposed by s 128(d)”.

59 I accept the construction submission of Money3. The making of an assessment is distinct from the inquiry and verification process. The prohibition at s 128 does not apply if the licensee, within 90 days before the credit date, has completed two tasks: the making of the assessment in accordance with s 129 and making the inquiries and undertaking the verifications in accordance with s 130. Textually, each requirement is a separate obligation that is only capable of satisfaction “in accordance with” the content requirements of respectively s 129 (the assessment) and s 130 (inquiries and verification). Although in Westpac Middleton J dissented in part, the majority did not express a different view as to the content requirement of s 128(c) that his Honour addressed at [50]-[51], where inter alia he said:

The nature of the assessment required by s 128(c) is as set out in s 129, and the content of the inquiries and verification required by s 128(d) is as set out in s 130. An assessment that does not meet the description in s 129 is not the assessment required to be performed under s 128(c) prior to entering into the relevant credit contract.

Section 129 provides that, for the purposes of s 128(c), the credit provider “must make an assessment that”, relevantly, “assesses whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered”. Section 129(b) provides the content to s 128(c). Further, as the primary judge accepted, there must be an assessment which assesses whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer if the contract is entered into by the consumer and credit provider.

60 Further, once it is understood that the statutory scheme does not prescribe how the licensee is to apply the results of the inquiry and verification in making the assessment of unsuitability (Westpac at [141], Gleeson J; [171], Lee J), it does not follow that any failure (an antecedent failure on the case of ASIC) to comply with the obligation at s 130 has the consequence of failure to make the s 129 assessment.

2.3.4 Is s 130 prescriptive?

61 The second divisive issue is whether the assessments undertaken by Money3 for each consumer complied with s 130(1). That is a factual question, though one which on ASIC’s case is premised on a prescriptive construction of the statutory obligations.

62 ASIC places considerable emphasis on passages in the Explanatory Memorandum as providing “guidance” about the inquiries and verification steps required by s 130 (emphasis in ASIC written closing submissions):

3.138 Consideration of what is reasonable will depend on the circumstances. Generally, the minimum requirement for satisfying reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s requirements and objectives will be to understand the purpose for which the credit is sought and determine if the type, length, rate, terms, special conditions, charges and other aspects of the proposed contract meet this purpose or put forward credit contracts that do match the consumer’s purpose.

…

3.140 Reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation could ordinarily include inquiries about the amount and source of the consumer’s income, determining the extent of fixed expenses (such as rent or contracted expenses such as insurance, other credit contracts and associated information) and other variable expenses of the consumer (and drivers of variable expenses such as the number of dependants and the number of vehicles to run, particular or unusual circumstances). The extent of inquiries will however depend on the circumstances.

3.141 The possible range of factors that may need to be established in relation to a consumer’s capacity to repay credit could include:

* the consumer’s current income and expenditure;

* the maximum amount the consumer is likely to have to pay under the credit contract for the credit;

* the extent to which any existing credit contracts are to be repaid, in full or in part, from the credit advanced;

* the consumer’s credit history, including any existing or previous defaults by the consumer in making payments under a credit contract; and

* the consumer’s future prospects, including any significant change in the consumer’s financial circumstances that is reasonably foreseeable (such as a change in repayments for an existing home loan, due to the ending of a honeymoon interest rate period).

…

3.146 In undertaking the assessment, credit providers are required to take into account information about the client’s financial situation and other matters required by the regulations that they either already possess, or which would be known to them if they made reasonable inquiries and took reasonable steps to verify it. This provision means that credit providers must ask the client about their financial situation and the other matters prescribed in the regulations, and must make such efforts to verify the information provided by the client as would normally be undertaken by a Reasonable and Prudent lender in those circumstances. Conducting a credit reference check is, for instance, likely to be an action that would be reasonable to undertake in most transactions. Credit providers are not expected to take action going beyond prudent business practice in verifying the information they receive.

63 From those statements, ASIC’s submission is:

Accordingly, Money3 must, as part of its obligations under s 130 understand the purpose for which the consumers seek the credit and determine whether the proposed credit contract meets that purpose. Money3 must also make reasonable inquiries about consumers’ variable expenses.

The emphasised passage from [3.146] of the consolidated Explanatory Memorandum also fixes the meaning of the use of the word ‘reasonable’ in s 130. Namely, the practices of ‘a reasonable and prudent lender in those circumstances’ (emphasis added)…

The ‘requirements and objectives’ inquiries forming part of s 130 of the Act extend to making reasonable inquiries into the consumer’s requirement to enter a credit contract which includes financing additional fees. The inquiry into ‘requirements and objectives’ also extends to raising with the consumer the interest rate that would or would be likely to apply to a loan they might take up: cf, in the context of the analogous provision in s 117(1) of the Act, Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Channic Pty Ltd (No 4) [2016] FCA 1174 at [1745], [1750]-[1751], and in the context of s 130 of the Act, at [1806]-[1807] (Greenwood J).

64 What is notable about the submission is how the guidance of the Explanatory Memorandum is transformed into mandatory obligations.

65 I am unable to accept the breadth of the submission. First, it departs from the statutory text, unsupported by context and purpose. There is no requirement to understand the purpose for which a consumer seeks credit. Rather, the obligation is to gather the information by making the s 130 inquiries and verification for the purpose of carrying out the unsuitability assessment: Westpac at [117], Gleeson J. In doing so, the purpose is to obtain information about the consumer’s requirements and objectives in relation to the credit contract and the consumer’s financial situation. There may well be an overlap with the consumer’s purpose in seeking credit, but that is not the statutory text.

66 Second, the Explanatory Memorandum, whilst recognising that what is reasonable is circumstance dependent, then departs therefrom by a prescriptive list of “minimum requirements” for the making of reasonable inquiries. Section 130 does not so provide, though Parliament made provision for it to have that effect by the making of prescriptive regulations in exercise of the power at subsection (1)(d) when read with subsection (2).

67 Third, ASIC’s reliance on the Explanatory Memorandum is inconsistent with Westpac in that it is up to the licensee to determine the scope of the inquiries that are made to satisfy s 130(1)(a) and (b): [141], Gleeson J; [167], Lee J.

68 Fourth, the submission in part mischaracterises the Explanatory Memorandum. At [3.140], the observation is made that reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial situation could ordinarily include inquiries about a range of matters including other variable expenses, concluding that the extent of inquiries depends on the circumstances. This does not support ASIC’s submission that Money3 must make reasonable inquiries about variable expenses. That submission puts aside the important element that what is reasonable is inevitably circumstance dependent.

69 Fifth, and relatedly, the variable expenses submission is inconsistent with the construction that ASIC accepted in Westpac, where at [113] Gleeson J noted:

The primary judge correctly noted (at [5] of his Honour’s reasons) that Div 3 of the Act does not contain an express statement that a credit provider must use the consumer’s declared living expenses in making the unsuitability assessment. Nor did ASIC suggest that, as a matter of construction, s 130 of the Act requires a licensee to obtain the information comprised in “declared living expenses” from a consumer in order to satisfy the requirement of s 130(1)(b) of making reasonable inquiries about the consumer’s financial information.

70 ASIC has not put a submission to me as to why it should not be held to that or why the circumstances are such that a contrary construction of the provision should be adopted in this proceeding.

71 Sixth, the Explanatory Memorandum is no substitute for the statutory text: “Notoriously explanatory memoranda sometimes get the law wrong”: Pearce DC, Statutory Interpretation in Australia (10th ed, LexisNexis, 2024) at [3.27]. Here, despite making provision for regulatory specification of minimum inquiries or verification steps of the type contemplated, none have been promulgated.

72 Seventh, whilst Greenwood J in Channic at [1747] considered on the facts of that case that an aspect of the credit offered necessarily included the payment of interest and: “A critical question would be the amount of interest payable on the borrowed funds and whether each consumer had “a requirement” or “an objective” for a certain rate of interest…”, it is not part of ASIC’s pleaded case that Money3 charged excessive interest or that the inquiries it was obliged to make included the consumer’s requirements and objectives as to the rate of interest to be charged.

73 In my view, Money3 is correct to submit that s 130 does not operate to require that reasonable inquiries must be exhaustive or that, because further inquiries could be made, any failure to do so is a breach of the obligation. That must follow from my earlier general analysis that reasonableness is not a counsel of perfection, does not require the elimination of all risks and does not require that all possible steps must be taken. Nor does s 130 require that all reasonable inquiries and steps must be taken. Justice Downes in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Firstmac Ltd [2024] FCA 737, considered the obligation at s 994E of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) which is concerned with the distribution of financial products and the obligation to take reasonable steps to ensure consistency with target market determinations. Of course, the purpose and objectives of the Corporations Act provisions differs markedly from the promotion of responsible lending practices for consumers. Nonetheless, her Honour’s summary of reasonable steps obligations drawn from various provisions of the Corporations Act is useful by analogy. The summary at [50]-[51] is:

While there are no authorities considering s 994E(3), there are several other provisions in the Corporations Act which contain a “reasonable steps” obligation, some of which have been the subject of judicial consideration, such as ss 961L and 963F. Consistently with the statutory requirement to consider all relevant matters, these authorities indicate that the inquiry is not a narrow one. Some guidance is therefore provided by statements made in these authorities, which I accept would also apply to the obligation in s 994E(5). These are as follows:

(1) what is encompassed by taking all “reasonable steps” will differ depending on the entity, the complexity of the entity’s business and the procedures within the entity: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey (2011) 196 FCR 291; [2011] FCA 717 at [162] (Middleton J);

(2) it is necessary to undertake a holistic analysis, considering the full framework of the entity’s contracts, policies and procedures: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Diversa Trustees Limited [2023] FCA 1267 at [375] (Button J);

(3) the reasonable steps obligation does not require a person to “find and to take the optimal steps”: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v RI Advice Group Pty Ltd (No 2) (2021) 156 ACSR 371; [2021] FCA 877 at [392] (Moshinsky J);

(4) the provision is not expressed as an obligation to take all reasonable steps, and nor does it require identification and performance of either the universe of possible reasonable steps, or the ‘one true path’ that must be followed: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v R M Capital Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 151 at [73] (Jackson J);

(5) positing steps that could have been taken, but were not taken, can be helpful. It is an obvious way of testing the reasonableness of what was (and was not) done. But the focus of the inquiry must always be on whether the steps that were taken in their totality were reasonable: see R M Capital at [80].

Whether the requirement to take ‘reasonable steps’ has been met is to be determined objectively by reference to the standard of behaviour expected of a reasonable person in the regulated person’s position that is (or was) proposing to engage in the relevant retail product distribution conduct regarding the same product, and is (or was) subject to the same legal obligations.

74 Her Honour’s last observation is plainly applicable to the consumers in issue and about which ASIC and Money3 did not disagree. The inquiry in this case must focus on what a reasonable licensee in the position of, and informed by the known characteristics of, Money3 at the time would do in the circumstances: the Shirt calculus.

75 Evidence of acceptable industry practice in addressing that question is relevant and admissible, but not determinative. It is for the Court to determine the standard: Rogers v Whitaker [1992] HCA 58; (1992) 175 CLR 479 at 487. As later explained by Gleeson CJ in Rosenberg v Percival [2001] HCA 18; (2001) 205 CLR 434 at [7]:

[As] Rogers v Whitaker, makes clear, the relevance of professional practice and opinion was not denied; what was denied was its conclusiveness. In many cases, professional practice and opinion will be the primary, and in some cases it may be the only, basis upon which a court may reasonably act. But, in an action brought by a patient, the responsibility for deciding the content of the doctor's duty of care rests with the court, not with his or her professional colleagues.

76 In this proceeding ASIC repeatedly emphasises the practices of reasonable and prudent lenders as the touchstone for determining the standard of inquiry and verification required by s 130. Evidence of those practices on ASIC’s case is set out in the Expert Report of Mr Hartman. Despite the objections of Money3, I ruled the report to be admissible as meeting the thresholds at s 79 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth): Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (Expert Evidence Admissibility) [2025] FCA 75. However, as I noted at [69] of those reasons, whether I accept Mr Hartman’s opinions as correct or ultimately of assistance is a different question.

2.3.5 When does the unsuitability assessment conclude?

77 This is the third divisive issue. ASIC submits in writing that Money3 failed to make reasonable inquiries about and take reasonable steps to verify the financial situation of the consumers before making the unsuitability assessment. In written closing submissions, it relies on answers given by Ms Suzanne Costantini and Ms Daniela Cavar in cross-examination, which it characterises as concessions that the assessment process is complete once a settlement pack is sent to a broker and the settlements team is not responsible for the assessment function. Mr Senathirajah KC maintained that submission orally (T 8 L 21-34, T 517 L18).

78 Money3 submits in writing that by the time the settlements team receives the proposed contract signed by the consumer, a conditional assessment is complete. Money3’s contracts provided that if the circumstances changed or Money3 obtained more information prior to it executing the contract, it could review its offer and may determine not to proceed. In oral submissions, Mr Caleo KC stated that it is not part of his client’s case that the assessment proceeds to the point of the welcome call (T 80).

79 The result of the assessment is the determination of whether the credit contract will be unsuitable for the consumer, if it is entered into: s 129. When the assessment is complete is a mixed question of law and fact. The evidence relied on by ASIC commences with answers given by Ms Costantini in cross-examination (T 426). She was questioned about the Money3 generated application form for Consumer 3 (CB 3150-3154). Her attention was directed to the weekly expenses section which record $0.00 for food and entertainment, travel expenses and home utilities (CB 3151). Her evidence was:

MR SENATHIRAJAH: In the assessment process, the use to which this form is placed, is deployed, is to say, when Money3 is carrying out the assessment of suitability as to give this person a loan, “We are going to be relying on these expenses as being the expenses”; correct?---This was – so this is created after an assessment has been finished.

Afterwards? So you say that the suitability assessment has been finished by the time this document is sent to the consumer to sign?---This document goes out with the loan contracts as – yes. This goes out with the loan contract.

Yes. So it is your evidence that, by that stage, the suitability assessment is completed?---Yes.

Right. And then when this document comes back, is that used, to your knowledge, as a basis for verifying that the customer agrees that these are his or her expenses?---To my knowledge, yes.

80 Ms Cavar was questioned about the welcome call as the last stage of the settlement process (T 465), which she confirmed, and then:

Mr SENATHIRAJAH: Thank you. And within the Money3 Motor Department during the relevant period, that’s 8 May 2019 to February 2021, it was the credit analyst who had the responsibility for carrying out the unsuitability assessment of the loans, correct?---The questions in the system, correct.

Yes. But the analysis, the assessment, that’s done not by the settlement team, is it?---No, assessment is done by the settlements officer.

And I think you’ve said this before, but I just want to check. And it’s your evidence that the procedure that’s described in the settlement procedure document, that only starts after a signed copy from the customer is received by Money3. Correct?---Correct.

Yes, and that’s when the settlement team’s responsibility commences. Correct?---Correct.

81 Money3 submits that these answers responded to conclusionary statements and are not consistent with the business records. If the outcome of the APL capacity calculation is that the consumer has a weekly surplus sufficient to make the calculated repayments, the credit analyst will either generate a pre-approval or the proposed contract documents which are then provided to the broker. A pre-approval is generated if Money3 has not been advised as to the vehicle to be purchased or whether the consumer requires finance for the warranty insurance premium, which was the case for Consumer 1, Consumer 3 and Consumers 4 and 5. Following the finalisation of those details, the credit analyst would then generate the contract documents and deliver them to the broker by email.

82 The pre-approvals for Consumer 2 and Consumer 6 set out nominal amounts for the warranty insurance premium, calculated at 20% of the principal because at the time Money3 did not have information about the vehicle to be purchased and the warranty insurance premium.

83 The credit contracts are in standard form and include this clause (for example, CB 2840, Consumer 1):

We reserve the right to withdraw from this transaction if anything occurs which in our opinion, acting reasonably, makes settlement undesirable or if the Settlement Date does not occur within 14 days of the Disclosure Date our obligations under this Loan Agreement only arise if and when we lend you the loan amount.

84 As stated above, the Disclosure Date is the date the document is generated and the Settlement Date is when the funds are advanced.

85 Money3 also relies on evidence from Ms Cavar (affidavit from [30] CB 1730) to the effect that the settlements team becomes involved once the consumer has signed and the broker has returned the contract documentation, at which time the settlements officer runs through a pre-fund checklist including by regenerating the loan repayment schedule in the APL to check whether it matches with the repayment schedule in the credit contract. As part of this process the settlement officer compares the scheduled repayments in the APL against the total amount of repayments in the credit contract to confirm that the amount in the APL is less than or equal to the amount in the credit contract. If any issue is identified, the matter is returned to the credit analyst.

86 By reason of this procedure, and the standard term in the credit contracts, Money3 submits that by the time the settlement team “receives the proposed contract signed by the consumer, Money3 has completed a conditional assessment” which submission is explained as follows:

[I]n the case of each of the credit contracts in this proceeding, the assessment process was complete when Money3 sent to the broker (acting on behalf of the relevant consumer) the documents that required execution. However, each such assessment was also contingent; if the consumer did not return to Money3 the required list of documents executed without any relevant amendments, the loan application would either not proceed or would need to be sent back to the credit analyst. In either such event, Money3 would not execute the loan contract. The execution by the consumer of the various documents required by Money3 confirm the correctness of the details of those draft documents.

87 This proceeding does not require me to resolve the conditional assessment submission. What I am concerned with is when the unsuitability assessment commenced and was complete for the six consumers in issue. In Parts 5 to 9 of these reasons, I make detailed findings as to that issue for each of the consumers. In no case was any assessment undertaken after the Credit Contract was generated and delivered to the broker. Factually, Ms Costantini and Ms Cavar were correct in their evidence: the point in time at which the assessments in issue were complete was when the credit contracts were generated and delivered to the brokers. That aligns with how ASIC ultimately put the case for each of the consumers (CS at [55]).

2.3.6 Minimum necessary expenses, discretionary basics, absolute basics or something else?

88 This is the fourth divisive issue and a matter of great significance in the examination of the extent of the obligations to make reasonable inquiries and verification of the consumer’s financial situation.

89 I have rejected ASIC’s construction submission that s 130(1)(a), (b) or (c) requires a licensee in all cases to obtain declared living expenses from a consumer or to inquire about and verify actual or likely future living expenses. Consistently with Westpac, the inquiries and verifications are undertaken for the purpose of making the prospective assessment of risk of default and hence the unsuitability conclusion: Westpac at [140]-[141], Gleeson J. Nor is it a universal requirement to inquire about and verify the integers of declared living expenses: Westpac at [138]-[139]. The inquiry is about the consumer’s financial situation generally. However, that does not foreclose inquiries about integers of a consumer’s financial situation. The issue is whether in the circumstances of each consumer as they were known at the time, Money3 acting reasonably should have made those inquiries and verifications about the consumer’s declared living expenses?

90 Those steps precede how the information about a consumer’s declared living expenses are then used by a licensee in answering the s 131 questions, which is a matter for the licensee. That point was made, if I may say so, pellucidly and comprehensively by Perram J as the primary judge in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2019] FCA 1244; (2019) 139 ACSR 25 (Westpac PJ) at [67]-[77]; particularly his Honour’s reference to “wagyu beef…washed down with the finest shiraz” [76].

91 For the six consumers, ASIC makes the submission that having received bank transaction data for the 90-day period to the lodgement of each application for finance, Money3 failed to make any inquiry into the quantum of the consumer’s declared living expenses by reference to the bank transactions. Similarly, it did not use the transaction data to verify the consumer’s declared living expenses. At a more granular level, ASIC in each case recalculates the average living expense of the consumers by adding and then dividing all of the bank debits to derive average expenses to then submit that Money3 failed to comply with the obligations at s 130(1)(b) and (c) because reasonable inquiries and verification required it to reconcile discrepancies between declared living expenses and the quantum and pattern of spending evidenced in the bank statements. For some of the consumers, ASIC steps further by contending that patterns of same day account clearing reasonably should have been considered as relevant to the consumer’s ability to meet future loan commitments.

92 Something must be said about the bank statements for the consumers. Most of the statements are third party compilations from a credit checking and reporting service provider called illion (sic). That entity does not employ the usual grammatical convention for proper nouns of capitalising the first letter. This has caused much confusion in the evidence and submissions where upper and lower case references abound. There is a further grammatical error in that the bank transaction data is described as BankStatements (sic), which plainly they are not and where illion commits the further error of uniting separate words. All of that aside, in these reasons I will refer to illion and interchangeably refer to bank data or bank statements where apposite.

93 Money3 objects to the recalculation as stepping outside the ASIC pleaded case, but in any event submits that interrogation of bank account debits does not reveal much, or indeed anything, about whether each debit is an average weekly expense or a necessary expense that a consumer is unable to forego to meet future loan commitments.

94 This is a large point of difference between the parties. ASIC in submissions variously contends that Money3 failed to inquire into and to verify “living expenses”, “minimum expenses”, “average weekly expenses” and “reasonably necessary expenses”. Very often in submissions, those expressions are used interchangeably, which draws criticism from Money3 for lack of precision in what is meant. ASIC’s written closing submission at [65] – [66] commences with a reference to the “minimum expenses” of each consumer, which is then subdivided for each by reference to their “reasonably necessary expenses”. Of this analysis, Money3 makes the valid criticism:

At AS [65]-[67], ASIC contends that Money3 failed to make an assessment contemplated by s 129 because (it asserts) Money3 did not take into account each consumer’s “minimum expenses”, and then describes these as the consumers’ “reasonably necessary expenses” in AS [66.1] to [66.5]. The evidence that ASIC relies on at AS [66.1] to [66.5] is the same evidence that it lists in fn 28 and describes in the first sentence of AS [64] as ASIC’s calculation of “the Consumers’ average weekly expenses as disclosed from the illion extracts”. It would appear that, in closing submissions, ASIC has now undertaken an analysis (as set out in the schedule items listed in fn 28) that assumes that every debit identified in the illion bank statements is an “expense”, and has used all of the debits listed in the illion bank statements to calculate a purported “average weekly expense” figure for each of the consumers.

95 Money3 contends that this approach is erroneous on two bases. “Problematically” it assumes that every debit in the transaction record is necessarily a component of average weekly expenses. And, more importantly, the contention that it was required to consider all expenses was “categorically” rejected by the Full Court in Westpac at [139]-[140], Gleeson J and [172], Lee J.

96 In reply, ASIC maintains that the “reasonably necessary expenses” of each consumer are those which it identifies, which are the expenses it selects from the illion transaction data (by totalling and then averaging the three month data) to produce an average of weekly expenditure to which is then added the regular deductions from the Centrelink statements. Because each of the consumers were in a “precarious financial circumstance” ASIC then submits:

Those circumstances are such that few if any of the Consumers’ expenses can properly be characterised as relevantly discretionary, as opposed to reasonably necessary expenses. The salient analysis is to identify “reasonably necessary expenses”, not isolate only expenses that are consumer strictly could not live without.

(Emphasis in original).

97 The passage emphasised by Money3 from the decision of Lee J in Westpac at [172] is:

I respectfully agree with the primary judge (see J[71]) that it does not follow that the statutory purpose can only be achieved by taking into account all information collected, regardless of its relevance or materiality to the assessment of unsuitability. Simply labelling an expenditure as a Declared Living Expense, and the fact that the consumer incurs that expense on their current lifestyle, does not necessarily change its nature from being discretionary. It is plain that a consumer may choose to, and can be expected to, forgo particular living expenses in order to meet their financial obligations under a credit contract.

98 That passage must be read in the context that the Court was not concerned with the circumstances of any particular consumer; rather with an automated system which applied a 70% ratio rule, triggered if a consumer’s declared living expenses exceeded 70% of their verified monthly income. That point was made by his Honour at [173]: “this was an unusual case, being a case alleging a serious want of compliance with responsible lending norms, divorced from consideration of any facts about any specific consumers”.