FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hams v Whyalla Ports Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed), in the matter of OneSteel Manufacturing Pty Limited (Administrators Appointed) (No 2) [2025] FCA 1059

File number(s): | VID 420 of 2025 |

Judgment of: | O’CALLAGHAN J |

Date of judgment: | 3 September 2025 |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS – administration – where defendant/cross-claimant sought damages against plaintiff/cross-respondent and its administrators for alleged conversion of personal property located at the Whyalla Port in South Australia – where claim supported by secured creditor of cross-claimant’s property including the assets the subject of the proceeding – whether assets the subject of the cross-claim are fixtures and thus the property of the cross-respondent or chattels and thus the personal property of the cross-claimant – consideration of relevant principles – held: each disputed asset is a fixture |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s 440B(2) Broken Hill Proprietary Company’s Indenture Act 1937 (SA) Harbors and Navigation Regulations 2009 (SA) Sch 3 Whyalla Steel Works Act 1958 (SA) Whyalla Steel Works (Port of Whyalla) Amendment Act 2025 (SA) The Broken Hill Proprietary Company, Limited’s Hummock Hill to Iron Knob Tramways and Jetties Act 1900 (SA) |

Cases cited: | Agripower Barraba Pty Ltd v Blomfield [2015] NSWCA 30; (2015) 317 ALR 202 Australian Provincial Assurance Co Ltd v Coroneo (1939) 38 SR (NSW) 700 Commissioner of State Revenue v Snowy Hydro Ltd (2012) 43 VR 109 Hams v Whyalla Ports Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed), in the matter of OneSteel Manufacturing Pty Limited (Administrators Appointed) [2025] FCA 949 Macrocom Pty Ltd v City West Centre Pty Ltd [2001] NSWSC 374; (2001) 10 BPR 18,631 May v Ceedive Pty Ltd [2006] NSWCA 369 Metal Manufactures Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [1999] FCA 1712; (1999) 43 ATR 375 National Australia Bank Ltd v Blacker (2000) 104 FCR 288 Snowy Hydro Ltd v Commissioner of State Revenue (Vic) [2010] VSC 221; (2010) 79 ATR 118 TEC Desert Pty Ltd v Commissioner of State Revenue (WA) (2010) 241 CLR 576 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 221 |

Date of hearing: | 7, 8, 11, 12, 14 and 15 August 2025 |

Counsel for the Plaintiffs / Cross-Respondents: | Mr B McLachlan with Ms M Salinger and Mr N Dias |

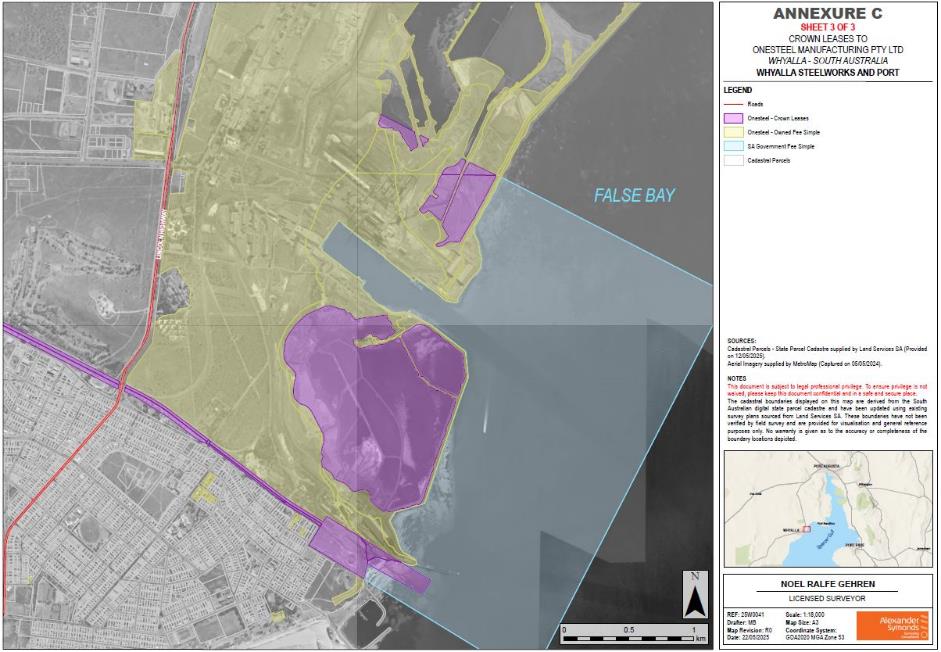

Solicitor for the Plaintiffs / Cross-Respondents: | Arnold Bloch Leibler |

Counsel for the Defendants / Cross-Claimant: | Mr B Dharmananda SC with Mr L Pham |

Solicitor for the Defendants / Cross-Claimant: | King & Wood Mallesons |

ORDERS

VID 420 of 2025 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF ONESTEEL MANUFACTURING PTY LIMITED (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) ACN 004 651 325 | ||

BETWEEN: | SEBASTIAN DAVID HAMS, MARK FRANCIS XAVIER MENTHA, LARA LUISA WIGGINS AND MICHAEL ANTHONY KORDA IN THEIR CAPACITY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL ADMINISTRATORS OF ONESTEEL MANUFACTURING PTY LIMITED (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) ACN 004 651 325 First Plaintiff ONESTEEL MANUFACTURING PTY LIMITED (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) ACN 004 651 325 Second Plaintiff | |

AND: | WHYALLA PORTS PTY LTD (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) (RECEIVERS AND MANAGERS APPOINTED) ACN 153 225 364 First Defendant GOLDING CONTRACTORS PTY LTD ACN 009 732 794 Second Defendant | |

AND BETWEEN: | WHYALLA PORTS PTY LTD (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) (RECEIVERS AND MANAGERS APPOINTED) ACN 153 225 364 Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | SEBASTIAN DAVID HAMS, MARK FRANCIS XAVIER MENTHA, LARA LUISA WIGGINS AND MICHAEL ANTHONY KORDA IN THEIR CAPACITY AS JOINT AND SEVERAL ADMINISTRATORS OF ONESTEEL MANUFACTURING PTY LIMITED (ADMINISTRATORS APPOINTED) ACN 004 651 325 (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | O’CALLAGHAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 3 September 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The first defendant’s cross-claim be dismissed.

2. The first defendant pay the plaintiffs’ costs of the cross-claim.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

O’CALLAGHAN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Whyalla Ports Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (receivers and managers appointed) (WP) seeks damages against OneSteel Manufacturing Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (OneSteel) and its administrators for the conversion of what it alleges is its personal property located at the Whyalla Port in South Australia (the Port). WP and OneSteel have always been part of the same corporate group, although the broader ownership of that group has changed over time.

2 In December 2024, WP guaranteed OneSteel’s indebtedness to a company called Golding Contractors Pty Ltd (Golding) (which had provided mining services to OneSteel) and also granted Golding a security interest over WP’s property to secure repayment of the amount owed. Golding thereby became a secured creditor of WP with potential claims against it in the order of $131.2 million. Golding subsequently appointed receivers and managers over WP’s property, including the assets the subject of this proceeding. Golding supports WP’s claim.

3 OneSteel’s administrators were appointed on 19 February 2025. On 27 March 2025, they gave notice to WP purporting to terminate a lease dated 29 June 2018 (commencing retrospectively on 1 January 2012) which OneSteel had granted to WP over part of the land on which the Port operates (the Lease).

4 On 2 April 2025, OneSteel and its administrators brought this proceeding seeking an order that the Lease was void ab initio, unenforceable and of no legal effect. WP defended the claim, and cross-claimed for damages for conversion of what it alleges are its assets.

5 On 15 May 2025, the South Australian Parliament passed the Whyalla Steel Works (Port of Whyalla) Amendment Act 2025 (SA) (Amendment Act), amending the Whyalla Steel Works Act 1958 (SA) (Whyalla Steel Works Act). The Amendment Act received royal assent on 22 May 2025, which voided the Lease and rendered otiose the claims of OneSteel and its administrators.

6 WP’s cross-claim for damages for conversion remained to be determined. I heard the cross-claim over six days commencing on 7 August 2025. Mr B Dharmananda SC appeared with Mr L Pham of counsel for WP. Mr B McLachlan of counsel appeared with Ms M Salinger and Mr N Dias of counsel for OneSteel and its administrators.

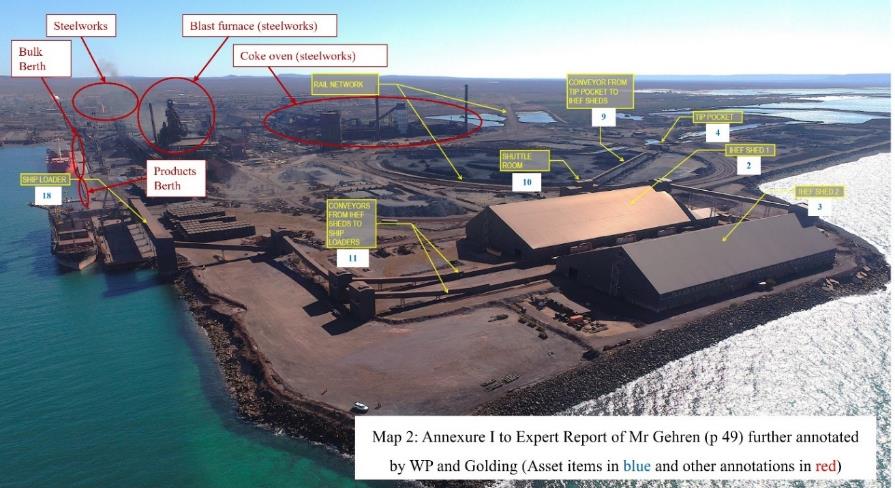

7 The assets ultimately in dispute on the cross-claim were described in a document titled “Updated Attachment 1: Information about the Assets” which was marked as exhibit MFI-P5 (each an Asset; together, the Assets). That document was an amended version of an attachment to WP’s notice of amended cross-claim dated 12 June 2025. The Assets include a tip pocket, two ore storage sheds, conveyors (and their associated transfer towers) and a shiploader. Each of those named Assets (among others) is located on what is called the “inner harbour” of the Port. The Assets were constructed or erected between 2011 and 2012 pursuant to three contracts entered into between WP and two construction companies, Kerman Contracting Pty Ltd (Kerman) and Leighton Contractors Pty Ltd (Leighton). The construction of the Assets was part of a “Port expansion project” being undertaken by the “Arrium group”, a corporate group whose ultimate holding entity was Arrium Limited and whose subsidiaries included WP and OneSteel. Arrium Limited later sold WP and OneSteel (among other entities) to Liberty Primary Metals Australia Pty Ltd (LPMA), the head company of another corporate group called the “Gupta Family Group Alliance” (GFG Alliance).

8 Three issues now arise for determination in this proceeding:

(1) Are the Assets fixtures (and thus the property of OneSteel) or chattels (and thus the personal property of WP)?

(2) If the Assets are chattels, did the Whyalla Steel Works Act, as amended by the Amendment Act, render void and ineffective WP’s personal property interests (on the basis that the Assets were “erected or constructed by or on behalf of [OneSteel] on the prescribed land”: see cl 4(1)(b) of Schedule 4 to the Whyalla Steel Works Act)?

(3) If issues (1) and (2) are answered in favour of WP (which, as OneSteel conceded, would mean that OneSteel has converted and used the Assets, save for three immaterial exceptions), what is the appropriate quantum of damages?

9 It was accepted by both parties that if the Assets are fixtures, questions (2) and (3) need not be answered.

10 For the reasons set out below, in my view each of the Assets is a fixture. WP’s cross-claim will therefore be dismissed.

THE FACTS

The witnesses

11 OneSteel relied on the following evidence at trial:

(a) parts of an affidavit of Mr Michael Korda sworn on 2 April 2025;

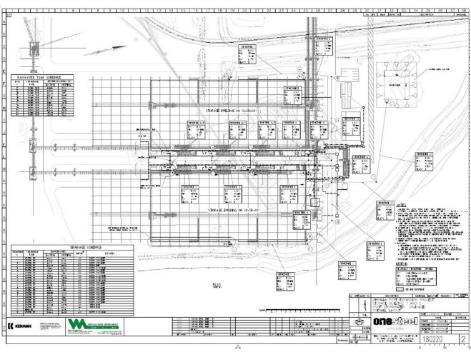

(b) an affidavit of Ms Courtney Price sworn on 28 July 2025;

(c) an affidavit of Mr Kym Drogemuller sworn on 28 July 2025;

(d) two expert reports of Mr Noel Gehren (a surveyor), being an expert report dated May 2025 and a supplementary expert report dated July 2025;

(e) two expert reports of Mr Richard Billett (an engineer), being an expert report dated 28 July 2025 and a supplementary expert report dated 4 August 2025; and

(f) the expert report of Mr David Mitchell (a valuer) dated 30 July 2025.

12 Mr Korda, a partner at KordaMentha, gave evidence on behalf of the administrators of OneSteel about the GFG Alliance, OneSteel’s business operations (which were said to include mining, steelworks and the “[p]rovision of some port services”) and the physical and functional characteristics of the Port.

13 Ms Price, an employee of OneSteel and the port manager at the Port, gave evidence about her former and current roles at the Port since December 2014. She also gave evidence describing the physical characteristics of the Port, the exclusive operation of the Port by OneSteel, and the physical features, location and function of each Asset (including the functional relationship between the Assets). Annexed to her affidavit was a copy of a document titled “Whyalla Port Handbook: August 2013 (version 13)” (the Handbook), which she deposed is “the official document shared with vessels and Port users as to how the Port operates, key contacts requirements and services”.

14 Mr Drogemuller, the manager of commercial services at “SIMEC Mining” (the trading name of OneSteel) and an employee of OneSteel (including its predecessors) since 1979, gave evidence about his previous and current roles at OneSteel, the background to the Port expansion project and the funding mechanism adopted by the Arrium group for that expansion.

15 Mr Gehren, a senior licensed surveyor at Alexander Symonds with over 20 years of experience as a professional surveyor, provided his expert opinion in respect of certain parcels of land at the Port. In his first report, he identified: (i) the land owned, leased or licensed by OneSteel; (ii) the land subject to Crown leases or indentures; (iii) the land purported to have been licenced to WP and/or leased by WP pursuant to the Lease between OneSteel and WP; and (iv) the location of certain Assets on the identified land. In his supplementary report, Mr Gehren identified further Assets situated on the land identified above.

16 Mr Billett is a principal mechanical engineer at Field Engineers with 19 years of experience as a professional engineer. In his first report, Mr Billett provided his expert opinion on the following questions in respect of each Asset:

(a) What is the purpose of the Asset?

(b) What is the means by which the Asset is attached or connected to the land and/or surrounding property or premises?

(c) Is the Asset integrated with the land and/or surrounding property or premises?

(d) What are the steps or processes necessary to remove the Asset from the land and/or surrounding property or premises?

(e) What is the estimated cost of removing and/or dismantling the Asset from the land and/or surrounding property or premises?

(f) What effect will removal of the Asset have on the land and/or surrounding property or premises?

(g) Is the type of Asset typically installed on a permanent basis or as a temporary installation?

(h) Is the Asset bespoke?

17 He gave evidence to the following general effect in his first report:

(a) most of the Assets are bespoke, have been installed on a permanent basis by means of affixation to concrete foundations by bolts and are integrated with the land;

(b) for many of the Assets, removal would likely cause partial damage to the Assets themselves but would not preclude future reuse (albeit with likely modification); and

(c) for most of the Assets, removal “would result in the inability to operate the inner harbour of the port as a whole”.

18 Mr Billett did not provide any calculations in his first report to support or justify his estimates as to removal costs.

19 In his second report, Mr Billett sought to explain the basis for some of the conclusions in his first report — in particular, his conclusions about the removal costs and bespoke nature of each Asset. As regards removal costs, he clarified that his estimates included labour costs based on charge-out rates (not salary rates) and included the cost of “demolition and dumping of the concrete foundations as a waste product, to return the land to a safe and usable condition” which can constitute “30% of the total cost of asset removal from the land”. Mr Billett also provided responses to the views of Mr Connelly, an expert witness called by WP, in relation to removal costs and the resale value of each Asset on the second-hand market.

20 Mr Mitchell is a director of Focus Group Valuations Pty Ltd, where he also works as a certified practising plant and machinery valuer. He has 44 years of professional experience. His report contained his expert opinion on the market value and the liquidation value (assuming an orderly liquidation in one instance, and a forced liquidation in the other) of each of the Assets. The solicitors for OneSteel instructed him to assume for the purposes of his valuation that WP has no right to access the land on which the Assets are located and that, once the Assets are removed from the land, WP will be unable to use the Assets to generate income. His report expressly stated that his valuation was based on the assumption that “WP has no security of tenure in respect of the land, and by extension, no legal right to retain the assets affixed to it in situ”. He noted that “[t]his assumption has materially informed the basis of value adopted and the valuation conclusions reached in this report”. Mr Mitchell calculated the total market value of the Assets to be approximately $92.3 million. After accounting for removal and reinstallation costs (among other things), he calculated the total orderly liquidation value of the Assets to be approximately $1.5 million and the total forced liquidation value to be approximately $1.3 million.

21 Mr Drogemuller, Mr Billett and Mr Mitchell were cross-examined.

22 During the course of the trial, I ruled inadmissible certain parts of the expert reports of Mr Billett and Mr Mitchell. See Hams v Whyalla Ports Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed), in the matter of OneSteel Manufacturing Pty Limited (Administrators Appointed) [2025] FCA 949 (J1).

23 WP relied on the following evidence at trial:

(a) two affidavits of Ms Laura Johns, sworn on 14 April 2025 and 17 April 2025, respectively;

(b) two affidavits of Mr Theunis Victor, sworn on 17 April 2025 and 23 July 2025, respectively;

(c) parts of an affidavit of Mr Nathan Collins sworn on 25 April 2025;

(d) an affidavit of Ms Stacie Starcevich sworn on 26 May 2025;

(e) an affidavit of Mr Ross Mann sworn on 28 July 2025;

(f) an affidavit of Mr Samuel Dundas sworn on 30 July 2025; and

(g) three expert reports of Mr Damian Connelly (an engineer), being an expert report dated 28 July 2025, a further expert report dated 1 August 2025 and a further supplementary expert report dated 10 August 2025.

24 WP also filed an expert report provided by Mr Robert Stainforth, an expert valuer. He gave his expert opinion on the value of each of the Assets and estimated that the aggregated market value of all the Assets, on an “as is where is” basis, is approximately $96.6 million (excluding GST). Counsel did not rely on this expert report at trial, but it contains a number of uncontroversial and helpful photographic depictions of some of the Assets, which I have included later in these reasons.

25 Ms Johns, a solicitor at Norton Rose Fulbright (the former solicitors for WP), gave evidence about the commercial rationale for the Port expansion project, the administration of the Arrium group of companies (including WP and OneSteel), the transfer of Arrium Limited’s shares in WP and OneSteel to the GFG Alliance in 2017, and various business records which purport to identify assets owned by WP and their values.

26 Mr Victor has been a director of certain companies in the GFG Alliance — namely, WP, OneSteel and their current parent company, LPMA — since September 2023. He gave evidence about his former roles within the Arrium group, the commencement of “Project Magnet” in 2005 (through which the Arrium group commercialised the production of magnetite ore at the mines in the Middleback Ranges for use in OneSteel’s steelworks business), the Arrium group’s acquisition in 2011 of a hematite mining project owned by Southern Iron Pty Ltd (which substantially increased the volume of hematite ore available for export from the Port), the commencement of the Port expansion project in 2011 and the incorporation of WP in connection with that expansion, various contracts that WP entered into with Kerman and Leighton for the construction of the Assets at the Port, agreements between WP and OneSteel relating to the operation of the Port and the permitted use of the Assets, WP’s relationships with third party suppliers and customers, the business records of intercompany charges, the status of Golding as a substantial creditor of OneSteel with a security interest in all of WP’s present and after-acquired property pursuant to a General Security Agreement dated 6 December 2024, and the harm to WP’s interests resulting from OneSteel’s re-possession of the land purportedly leased to WP.

27 Mr Collins, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons (the solicitors for WP and Golding), gave evidence about Golding’s interest in this proceeding as a creditor of OneSteel with a general security interest over all of WP’s property, the conduct of WP’s business in connection with the Port expansion project, the construction contracts executed in connection with the expansion (and WP’s ownership of the constructed Assets), the appointment of voluntary administrators to WP and OneSteel, the sale of WP and OneSteel by the Arrium group to the GFG Alliance, the execution of various agreements relating to Port operations, and the financial records purportedly showing the value of a number of assets owned by WP.

28 Ms Starcevich, a solicitor at King & Wood Mallesons, gave evidence to the effect that various assets which belong to WP are not located on “prescribed land” as defined in clause 1 of Schedule 4 to the Whyalla Steel Works Act.

29 Mr Mann, the general manager of finance of Golding, gave evidence about a number of agreements to which WP, OneSteel, LPMA and Golding (among other entities) are party. These agreements, as amended from time to mine, included a Mining Services Agreement dated 17 March 2017, a Standstill Agreement dated 6 December 2024, a Guarantee and Indemnity dated 6 December 2024 and a General Security Agreement dated 6 December 2024. He also deposed that, as at 28 July 2025, the amount owing to Golding under the relevant agreements was over $133 million.

30 In his affidavit dated 30 July 2025, Mr Dundas, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons, gave notice of WP’s intention to request leave (out of an abundance of caution and to the extent necessary) under s 440B(2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) to claim a right to possession of relevant assets at the commencement of the trial. Mr Dharmananda sought that leave on the first day of the trial.

31 Mr Connelly, a principal consulting engineer at METS Engineering, has 50 years of experience working in the mineral processing industry, including over 35 years working as a consultant metallurgical engineer with experience in plant operation, design, construction, commissioning and all unit operations. He has over 30 years of experience in valuation advice in relation to the resale value of second-hand mining and processing equipment.

32 In his first report, Mr Connelly gave the following uncontradicted evidence about his experience valuing relevant plant and equipment:

I have developed equipment lists and data sheets that detail valuations and pricing for equipment usually seen in resource projects around the world. As a result, I have extensive knowledge of plant and equipment of the kind similar to the plant and equipment at the Whyalla Port and the prices for such plant and equipment.

I have been involved in and prepared a number of valuations and due diligence reports in relation to the proposed relocation, and disassembly for relocation, of plant and equipment (including bulk handling facilities) of the kind similar to the plant and equipment at the Whyalla Port. I have also been engaged to source second hand plant and equipment of the kind similar to the plant and equipment at the Whyalla Port for a number of mining clients.

33 He also gave evidence to the following general effect:

(a) all of the Assets can be removed and relocated, with relative ease, for second-hand use without damage to the Asset or the land;

(b) the relative cost of removal does not outweigh the value of each Asset on the second-hand market;

(c) all of the Assets are in working order or in very good working condition and have a substantial remaining useful life; and

(d) the total relevant asset value for the Assets is between approximately $61 million and $70.7 million.

34 In his second report, Mr Connelly gave evidence in response to the expert reports of Mr Billett and Mr Mitchell about the estimated costs involved in the removal of the Assets. In calculating removal costs, he did not include the costs of removing the concrete foundations of the Assets because, as he deposed, concrete structures are usually left behind when assets are removed. (His third report corrected two arithmetic errors contained in the second report.)

35 Only Mr Connelly was cross-examined.

Factual background

Corporate entities

36 Before turning to describe the factual background, it is convenient to explain the different corporate entities involved in the operation of the Port and the related mining and steelworks businesses.

37 As I have already mentioned, OneSteel is currently a wholly-owned subsidiary of LPMA, which is part of the GFG Alliance. OneSteel was formerly a wholly-owned subsidiary of Arrium Limited (which had been known as “OneSteel Limited” from 4 August 2000 to 1 July 2011) until OneSteel and WP were sold by the Arrium group to the GFG Alliance in 2017. (In these reasons, I will use the term “Arrium Limited” to refer to the head company of the Arrium group, regardless of its previous or future names.) OneSteel’s business operations include mining, steelworks and the provision of port services conducted on land at or around the Port.

38 WP was incorporated in September 2011. Mr Victor, a director of WP, deposed in his first affidavit that the incorporation of WP “occurred in connection with upgrades to the port facilities in the period 2012-2014” and that it was the function of WP to “support the increased mining capabilities of the Arrium business via the port facility and concomitantly, to procure and own property and equipment forming part of the port upgrades”. He reiterated in his second affidavit that “the function of WP was to service Arrium’s increased mining capabilities via the Whyalla Port (through the provision of port and logistics services) and to procure and own the existing and new property and infrastructure associated with the Whyalla Port”.

39 OneSteel did not dispute that WP was incorporated in connection with the Port expansion, or that WP contracted for the construction of certain items of infrastructure erected at the inner harbour.

40 When WP and OneSteel were still part of the Arrium group, Arrium Iron Ore Holdings Pty Ltd (Iron Ore Holdings), which was itself a wholly-owned subsidiary of Arrium Limited, owned all the shares in WP.

The Arrium group’s mining business

41 Before 2005, OneSteel produced hematite ore (a type of iron ore) from its mines in the Middleback Ranges, located about 40 kilometres from the Port. The hematite ore was wholly used to feed OneSteel’s steelworks business in Whyalla. During this time, the Port was largely an inbound port that was used to import minerals and coking coal needed for the steelworks.

42 In May 2005, Arrium Limited embarked on a project, called “Project Magnet”, to enable the commercial production of magnetite ore (a lower-grade type of iron ore) from its mines in the Middleback Ranges and to upgrade the steelworks in Whyalla. Following this, the magnetite ore was used to feed the steelworks, and the hematite ore was transported from the mines in the Middleback Ranges to the Port for direct export and sale. As a result, the Port went from being a mainly inbound port to being both an inbound port and an outbound port.

43 The Port is comprised of an outer harbour and an inner harbour. Leading up to 2011, the outer harbour of the Port consisted of a jetty and two sheds, and it was mainly used for sales of pellets and iron ore. Iron ore from the mines in the Middleback Ranges was (and still is) transported by rail to the outer harbour for export. The inner harbour at that time consisted only of the wharf and loading facilities (i.e. berths), and it was used to receive feed products for the steelworks.

The Port expansion project

44 On 22 August 2011, Arrium Limited announced two related initiatives.

45 The first was the Port expansion project, which contemplated the expansion of the export facilities at the Port through the development of bulk export operations at the inner harbour. It was said that the expansion would increase the export capacity of the Port from about 6.5-7 million tonnes per annum to about 12 million tonnes per annum.

46 The second initiative was the acquisition of certain subsidiaries of a company called WPG Resources Limited (WPG), which owned iron ore assets in northern South Australia. This included the acquisition of Southern Iron Pty Ltd, which owned (and still owns) the so-called “Peculiar Knob” mining project about 90 kilometres from Coober Pedy and about 600 kilometres by rail from the Port (the Southern Iron project or, alternatively, the Peculiar Knob project).

47 The announcement also said that Arrium Limited “expected that the new export facilities will be used for export of iron ore from WPG’s Peculiar Knob project, as well as to support existing operations and provide scope for potential increases in exports from [Arrium Limited’s] existing mines”. It was also said that the Port expansion project was estimated to cost $200 million, that the acquisition of the iron ore assets was estimated to cost $346 million, and that Arrium Limited would provide WPG with a secured loan of up to $140 million to facilitate the development of the Peculiar Knob project.

The Limited Agency Agreement

48 On 13 October 2011, WP and OneSteel entered into an agreement titled “Limited Agency Agreement” under which WP, as “Principal”, appointed OneSteel as “Agent” to provide “the Services”, which included conducting and operating the “Principal Business” (being WP’s business of “operat[ing] and own[ing] assets used in the development of a new port development at Whyalla, South Australia, and infrastructure associated with that development”) (the Limited Agency Agreement).

49 The Limited Agency Agreement provided that it commenced on 6 October 2011 and ended on 1 October 2012. It relevantly defined the “Agent Business” (being OneSteel’ business) as the “operat[ion] [of] a steel manufacturing and iron ore business (not including the development of an iron ore mine at Peculiar Knob, South Australia) at Whyalla and other locations in Australia”. It also provided that OneSteel’s “commission” for performing the Services was limited to reimbursement for its costs and preservation of the “Agent Business Profit”, which was defined as “that part of the earnings before interest and income tax generated by the Agent from the conduct and operation of the Agent Business …”.

50 Mr Victor deposed that an “internal business record” dated 20 September 2018, titled “Port Intercompany Contracts”, indicated that WP and OneSteel “agreed to extend the term of the Limited Agency Agreement from 2 October 2012 to 31 August 2017”. But, as OneSteel submitted, there was no sufficient evidence that the parties in fact agreed to such an extension. The latest update from the document was that, as at 21 August 2018, a “draft” of the extension agreement was “to be issued for review” by 28 September 2018. Accordingly, I do not find that the term of the Limited Agency Agreement was extended beyond 1 October 2012.

WP’s construction contracts

51 On 30 November 2011, WP and Kerman entered into an agreement which relevantly provided for the construction at the inner harbour of the site services buildings (Item 1), two sheds (Items 2 and 3), a tip pocket (Item 4), a fire-fighting system (Item 5), a dust collection system (Item 6), a water spray system (Item 7), the sampler equipment (Item 8), conveyors and transfer towers (Items 9, 10 and 11) and the inner harbour control system (Item 34).

52 The Kerman contract stated that WP, as “the Principal”, operates the inner harbour facilities of the Port. It also stated that one of the “key objectives” was to complete the project on time so as to “enable[e] the Principal to safely commence receiving iron ore by rail, from its mining operations at Peculiar Knob and the South Middleback Ranges, and transferring this into vessels as early as possible in the fourth quarter of calendar year 2012”.

53 On 19 April 2012, WP and Leighton entered into an agreement providing for (among other things) the construction of a temporary berth and mooring at the inner harbour of the Port. The only relevant Assets erected and constructed under this contract were the Rolls Royce mooring winches (Item 15).

54 On 25 June 2012, WP and Leighton entered into a second agreement providing for (among other things) the construction of a bulk products berth at the Port. This contract relevantly provided for the construction at the inner harbour of a fire-fighting system (Item 5) and a permanent shiploader (Item 18).

55 The Leighton contracts stated that WP, as “the Principal”, operates the inner harbour facilities with other wholly-owned subsidiaries of Arrium Limited.

56 The first Leighton contract provided that one of the “key objectives” was to complete the works on time so as to “enabl[e] the Principal to safely commence receiving iron ore by the conveyor system being installed [separately] … and transferring the iron ore into vessels via the shiploader being installed [separately] as early as possible in the fourth quarter of calendar year 2012”.

57 The “Introduction” section of the construction contracts stated that each contract forms part of the Port expansion project, and provided the following background to the contracted works:

As a result of a recent acquisition, the Principal now has access to high grade iron ore deposits at the Peculiar Knob mine site available for blending with existing ores and export. This initiative, known as the Whyalla Port Expansion Project, requires the upgrade, augmentation and expansion of [Arrium Limited’s] rail and port facilities at Whyalla Steelworks to facilitate the blending and export of that iron ore.

58 The second Leighton contract only differs in the language used after the first sentence quoted above, viz:

… This initiative, known as the Whyalla Port Expansion Project, requires the engineering, procurement, construction and commissioning of a bulk products berth, including the transfer conveyors and connected utilities to a Shiploader take-over-point, and including the fixed long travel rails on which the Shiploader is mounted at the Whyalla Steelworks for the export of that iron ore.

59 Each of the construction contracts contained in its “Project Definition Statement” the same general performance requirements, including that the constructed infrastructure “shall be capable of … [r]eceiving, storing, blending and transhipping 6.6 Mtpa of Iron Ore Feed Material … while allowing the existing outer harbour to export 6.1 Mtpa inclusive of 0.8 Mtpa of pellet”.

60 Further and in particular, the Project Definition Statement for both the Kerman contract and the second Leighton contract defined “Iron Ore Feed Material” as “bulk, hematite iron ore of 2 product sizes and multiple types”, where “[t]he type is dependent on its source from [Arrium Limited’s] South Middleback Range and Peculiar Knob reserves as well as the blend ratio”. The characteristics of the feed material — namely, its sizing range, moisture, density, angle of repose and flow properties — were also specified.

Financial arrangements and business records

61 Mr Drogemuller deposed that payments to Kerman and Leighton under each of the construction contracts were made from funds “held by OneSteel/Arrium Treasury”. The money borrowed by WP to fund the Port expansion project was recorded in the financial records of WP and Iron Ore Holdings as an intercompany loan from Iron Ore Holdings. Mr Drogemuller accepted in cross-examination that the records did not show any intercompany loan from OneSteel to WP to fund the Port expansion project (T:121.10–15).

62 At the times that the construction contracts were entered into and each of the Assets was constructed, WP did not have a bank account and did not generate any revenue from any Port-related activities. WP acquired a bank account in 2021 and began generating income from Port-related activities that same year (after it entered into a Harbour Towage Licence Agreement dated 27 August 2021 with CSL Australia Pty Ltd).

63 Further, WP’s audited financial report for 2017 reported that WP owed debts comprised of loans from related parties in the amount of about US$159 million as at 30 June 2016 and about US$157 million as at 30 June 2017. It was explained that due to Arrium Limited and its wholly-owned subsidiaries entering into voluntary administration, the intercompany loans were deemed not to be recoverable and were forgiven on 31 August 2017 (so that any purchaser of WP’s shares, having already agreed to give value to Iron Ore Holdings in consideration for acquiring its full shareholding in WP, would not be required to pay an additional sum representing WP’s repayment of the intercompany loan to Iron Ore Holdings). As I have already mentioned, the GFG Alliance purchased all of WP’s shares later that year.

ASX releases, presentations and other reports

64 A copy of Arrium Limited’s ASX release dated 4 October 2012 was in evidence, together with a “Mining Site Tour Presentation” that provided updates about the progress of the Port expansion project and the Southern Iron project. Relevantly, the presentation:

(a) included the slide represented below, which indicated that Arrium Limited’s mining business comprised the “Middleback Ranges”, the “Southern Iron” project and “Port Operations”:

(b) referred to the delivery of a “step change” in Arrium Limited’s mining business through “[i]ncreasing export iron ore sales from ~6Mtpa to ~12Mtpa” and “[m]ore than doubling port capacity from 6Mtpa to ~13Mtpa”;

(c) noted the Port expansion project generated blending and marketing opportunities, including “[b]lending of Peculiar Knob ore with MBR [i.e. Middleback Ranges] ores”; and

(d) referred to the new facilities to be constructed at the inner harbour, including connections to train lines, two ore storage sheds and a bypass conveyor, a temporary bulk products berth and a new bulk products berth with a “4,200 tph travelling ship loader”.

65 It seems that the construction of the works in respect of each contract was nearing completion by November 2012. At the 2012 Annual General Meeting, held on 19 November 2012, Mr Geoff Plummer (Arrium Limited’s managing director and chief executive officer) was recorded in the annual report as having said the following:

I would now like to turn to our growth initiatives in a little more detail. One of the attractions of the Southern Iron and Port expansion was our ability to deliver a step change in iron ore sales quickly to take advantage of generally favourable market conditions.

This involved completing the infrastructure to bring the Peculiar Knob mine into operation and doubling the capacity of our Whyalla Port to 12 million tonnes per annum. Another attraction of the expansion was our ability to generate additional volumes of iron ore for sale through blending high grade ore from Peculiar Knob with lower grade ore from our Middleback Ranges operation, with what we would generally stockpile for beneficiation or would treat as waste. This blending opportunity is expected to provide a very significant contribution towards the cost of the expansion.

66 In an ASX release dated 20 August 2013, Arrium Limited referred to “receiving and transshipping first ores from Southern Iron through the new Whyalla Port facilities in December [2012]” and receiving “first ores from the Middleback Ranges mines on the new narrow gauge rail for blending with Southern Iron ores” in May 2013.

67 And on 18 November 2013, Arrium Limited published its “Mining Quarterly Production Report for the quarter ended 30 September 2013”, which confirmed that “[t]he Whyalla Port Expansion Project was completed in July [2013] with the commissioning of the high capacity travelling ship loader and port capacity has now doubled to ~13Mtpa”.

Role and layout of the Port

68 Ms Price, the manager of the Port, gave the following uncontroversial evidence (parts of which I have already mentioned above) about the role and layout of the Port.

69 The Port is used to export raw and processed iron ore products mined by OneSteel and related Arrium group entities from the Southern Iron project and the Middleback Ranges.

70 The Port is also used to export BHP copper concentrate, and to import raw materials (such as coking coal, dolomite and limestone) for use in the steelworks. The steelworks business is owned and operated by OneSteel. The Port’s infrastructure is integrated with the steelworks, enabling the steelworks to operate as an “end-to[-]end steel manufacturing system”.

71 The Port comprises the outer harbour and the inner Harbour.

72 The outer harbour is positioned at the southernmost point of the Port. It is dedicated exclusively to OneSteel operations and supports the export of hematite ore, magnetite ore and iron ore pellets produced at OneSteel’s pellet plant, which is also situated within this area. The outer harbour has one berth.

73 The inner harbour is relevantly connected by rail to the mining sites at the Middleback Ranges and the Southern Iron project. The product from the mining sites at the Southern Iron project is exported only from the inner harbour, because that product can only be transported by the specific railway gauge that is used at the inner harbour.

74 The inner harbour contains three main berths (and one redundant berth).

75 The three main berths and their functions are as follows:

(a) the “Inner Harbour Export Facility” (which includes two sheds, a tip pocket and a shiploader) is primarily used for the export of hematite ore by the Southern Iron project and OneSteel’s mining operations in the Middleback Ranges;

(b) the “Products Berth” (which consists of a concrete apron with minimal fixed infrastructure) is used for the export of BHP copper concentrate, loading steel products (including slabs and billets) produced by OneSteel at the steelworks, and handling project cargo under one-off agreements (such as wind farm components). Vessels at this berth are serviced by mobile harbour cranes operated by a third party company called Qube Holdings Limited; and

(c) the “Bulk Berth” (which is equipped with a mobile hopper owned by OneSteel) is used for the import of raw materials for the steelworks.

76 At the inner harbour, iron ore is first delivered by train to the tip pocket. The iron ore is then tipped into the tip pocket and transferred via inloading conveyors (and transfer towers) to one of the two sheds for temporary storage. The iron ore is then distributed from the sheds by outloading conveyors (and transfer towers) to the shiploader, which distributes the iron ore onto vessels for export. Iron ore may also be taken directly from the first transfer tower to the shiploader via a bypass conveyor when there is no need to store or blend it.

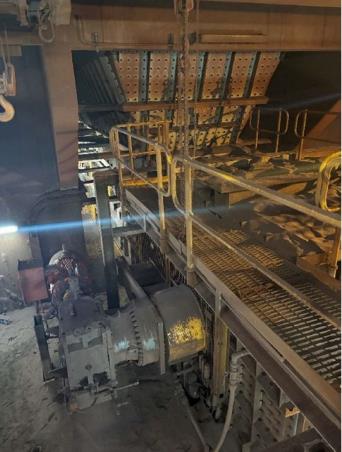

77 The following photograph depicting the inner harbour and the location of some of the Assets was in evidence:

Port operations

78 Ms Price gave the following unchallenged evidence:

The Port, including all of the assets that are located there, is operated exclusively by OneSteel employees and independent contractors who hold roles operating machinery or providing other services relating to the operation of the Port.

To the best of my knowledge, since I commenced working for OneSteel … [WP] has not had any employees at the Port. I have never interacted with, or received any direction from Whyalla Ports, about the operation of the Port or use of any of the assets at the Port.

I have been shown a copy of a document titled “Whyalla Port Handbook: August 2023 (version 13)” … I am familiar with this document, as I have used it while working at the Port. This is the official document shared with vessels and Port users as to how the Port operates, key contacts, requirements and services. This document has been updated from time to time, and I have had input into those updates.

79 In the Handbook to which Ms Price referred, the Port is described as a harbour “owned and operated” by OneSteel.

OneSteel’s property interests

80 As summarised in OneSteel’s written closing submissions, it was uncontroversial that OneSteel conducted (and continues to conduct) its port and logistics operations business on land at the Port through a series of related freehold titles, Crown leases and perpetual licences, as follows:

(a) OneSteel owns land in the Port area in certificates of title 5463/457, 5582/363, 5603/813, 6105/304, 6141/526 and 6144/964;

(b) OneSteel is a lessee of land in the Port area under Crown leases 6189/771, 6213/636, 6268/422 and 6268/421;

(c) OneSteel is a licensee under “Perpetual Licence 319”, which was granted under s 23 of The Broken Hill Proprietary Company, Limited’s Hummock Hill to Iron Knob Tramways and Jetties Act 1900 (SA) (1900 Act). The area the subject of Perpetual Licence 319 forms part of Crown lease 6189/771.

(d) OneSteel is also a licensee under “Perpetual Licence 319A”, which was granted under the Broken Hill Proprietary Company’s Indenture Act 1937 (SA) (1937 Act). The area the subject of Perpetual Licence 319A forms part of Crown lease 6213/636.

The regulatory regime

81 There is a regulatory scheme that confers rights on OneSteel to use, and conduct operations at, the Port. It was fairly summarised in OneSteel’s closing written submissions as follows:

(a) Perpetual Licence 319 confers on OneSteel a right to “occupy, maintain and use all such jetties wharves and quays together with all the works buildings approaches roads ways tramways and conveniences connected therewith as the Company [i.e. OneSteel] have made erected and constructed” or which it shall “make erect and construct” pursuant to the powers contained in s 22 of the 1900 Act.

(b) Perpetual Licence 319A confers on OneSteel a right to “occupy maintain and use all jetties wharves works buildings approaches roads ways tramways and conveniences in which are or shall be erected or constructed by the Company [i.e. OneSteel]” pursuant to the Consolidated Indenture to the 1937 Act.

(c) Clause 7(a) of the Consolidated Indenture to the 1937 Act confers on OneSteel the right to erect, construct, occupy, maintain and use jetties, wharves, channels, works, buildings, approaches, roads, ways, tramways and conveniences reasonably required in connection with the operations of OneSteel within a specified area at or around “False Bay” (being the bay that surrounds the Port). The specified area overlaps with what has ultimately become the inner harbour and outer harbour of the Port. Clause 7(c) provides that OneSteel is entitled to occupy, maintain and use all jetties, wharves, works, buildings, approaches, roads, ways, tramways and conveniences which are erected by it pursuant to the Consolidated Indenture to the 1937 Act.

(d) Clause 25(1) of the Consolidated Indenture to the Whyalla Steel Works Act confers on OneSteel the right to use and occupy the foreshore and sea bed and reclaim the foreshore, sea bed and sea within a specified area at or around False Bay. The specified area overlaps with what has ultimately become the inner harbour and outer harbour of the Port. Clause 25(2) provides that, on the application of OneSteel, the South Australian government will grant OneSteel the fee simple of any land above high water mark within the specified area. The parent titles for three of the certificates of title referred to above at paragraph 80(a) — being certificates of title 5603/813 (parent title 3080/69), 5582/363 (parent title 3971/84) and 5463/457 (parent title 4241/517) — were granted under the Consolidated Indenture to the Whyalla Steel Works Act. The parent title for certificate of title 6144/964 — namely, CL 1013/20 — was subject to Perpetual Licence 319A.

(e) An environmental authorisation in Schedule 3 to the Whyalla Steel Works Act confers on OneSteel the right, among other things, to operate bulk shipping facilities, marinas and boating facilities at various “Locations” (defined to include the “Port of Whyalla”, being the area identified in Schedule 3 of the Harbors and Navigation Regulations 2009 (SA)) and on the “Premises” (defined to include all of the certificates of title identified above at paragraph 80(a)). The environmental authorisation also imposes obligations on OneSteel in respect of the operation of various of the Assets, including the tip pocket (cl 1.2(a)), sheds (cl 1.2(b)–(c)), conveyors (cl 1.5) and shiploader (cl 1.6).

82 The following map, which was in evidence, depicts the land and waters at or around the Port in respect of which OneSteel is the registered proprietor, Crown lessee or licensee:

GOLDING’S INTEREST

83 On 17 March 2017, OneSteel and a company called BCG Contracting Pty Ltd (BCG) entered into a Mining Services Agreement, under which BCG agreed to provide open pit mining services and rehandle services to OneSteel. In December 2020, BCG novated the agreement to Golding. The agreement between OneSteel and Golding was most recently extended and amended by a deed dated 31 January 2025.

84 On 6 December 2024 — due to the significant debt owed by OneSteel to Golding under the Mining Services Agreement — Golding, OneSteel, WP and LPMA entered into a Standstill Agreement. Among other things, this agreement required Golding not to take enforcement action in respect of the amounts owing under the Mining Services Agreement (subject to, among other things, certain payments being made, WP granting Golding a first-ranking security interest over all of its assets and LPMA granting Golding a first-ranking security interest over its shares in WP).

85 On the same day, Golding, WP and LPMA entered into a Guarantee and Indemnity, under which WP and LPMA guaranteed the payment to Golding of all money which OneSteel owed under the Mining Services Agreement and the Standstill Agreement.

86 Critically for present purposes, on 6 December 2024 Golding and WP also entered into a General Security Agreement, under which WP granted Golding a security interest in all of its present and after-acquired property to secure the payment of the money which OneSteel was liable to pay under the agreements mentioned above.

87 Mr Mann’s evidence was that, as at 28 July 2025, the total amount owing to Golding under the relevant agreements was over $133 million.

APPOINTMENT OF ONESTEEL’S ADMINISTRATORS AND INITIATION OF THIS PROCEEDING

88 On 19 February 2025, the South Australian government appointed Michael Korda, Lara Wiggins, Sebastian Hams and Mark Mentha of KordaMentha as joint and several administrators of OneSteel pursuant to s 436C of the Corporations Act.

89 On 27 March 2025, OneSteel served a notice of termination and repossession on WP, purporting to terminate WP’s right to occupy a portion of the land in certificates of title 5463/457, 5582/363, 5603/813, 6105/304 and 6141/526 and any other part of the land owned by OneSteel in South Australia.

90 On 2 April 2025, OneSteel and its administrators brought this proceeding against WP (being the same proceeding in which WP brings the cross-claim with which these reasons are concerned).

91 By points of claim filed on 8 May 2025, OneSteel and its administrators alleged as follows, among other things:

Overview

1 The Second Plaintiff (OneSteel) has exclusive proprietary and other operational rights with respect to the port in Whyalla. It conducts its operations at the port in a geographically landlocked area. The rights asserted by the First Defendant (Whyalla Ports) to portions of land within the port are legally baseless but, also, practically nonsensical given the inability of any third party to physically access those areas.

OneSteel’s business and the port

2 On 19 February 2025, the State Government of South Australia (State) appointed the First Plaintiffs as Administrators of OneSteel.

3 OneSteel occupies land and certain structures on and around the port of Whyalla as part of its business of mining, manufacturing and distributing steel products.

4 OneSteel:

(a) is the registered proprietor of much of but not all of the land comprising the port (better described as: Certificates of Title 6105/304, 6141/526, 5582/363, 5463/457, 5603/813 and 6144/964 and Crown Leases 6213/636, 6189/771 and 6268/422); and

(b) has been granted exclusive rights with respect to that land and the areas around it, including to:

(i) use, occupy, and maintain wharves and jetties constructed by OneSteel (pursuant to Perpetual Licence 319 under The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited Hummock Hill to Iron Knob Tramways and Jetties Act 1900 (SA));

(ii) construct, use, occupy and maintain jetties and wharves, buildings, works, tramways and roads (by virtue of cl 7 of the Consolidated Indenture to the Broken Hill Proprietary Company’s Indenture Act 1937 (SA));

(iii) operate bulk shipping facilities, marinas and boating facilities (under Perpetual Licence 319A (Crown Lease 1013/20)); and

(iv) exclude persons from taking a vessel into specified waters in and around the port (pursuant to the Harbours and Navigation Regulations 2009 (SA)).

5 The effect of the exclusive rights referred to in [4] above is that only OneSteel is authorised to operate the port.

The purported lease

6 A document purporting to be a lease with respect to certain areas within the port was apparently executed by One Steel and Whyalla Ports on 29 June 2018 (the Lease).

7 The Lease purports to grant exclusive possession to certain areas defined in the Lease as the Premises.

8 The Initial Term of the Lease is stated to be 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2018.

9 For the reasons set out below, the Administrators do not consider that the Lease is valid or otherwise of legal effect and, on 27 March 2025, the Administrators caused to be served on Whyalla Ports a Notice of Termination and Repossession.

10 On 28 March 2025 Whyalla Ports asserted that the Lease was operative.

The Lease is prohibited by statute

11 Clause 31 of the Consolidated Indenture to the Whyalla Steel Works Act 1958 (SA) provides, inter alia, that ‘rights, powers, benefits or privileges conferred on [OneSteel] by virtue of this indenture’ or ‘any mineral or other lease held by [OneSteel] at the date of the ratification of this Indenture or acquired by [OneSteel] pursuant to this Indenture’ may be assigned by OneSteel ‘with the consent of the State’.

12 On the proper construction of cl 31:

(a) OneSteel may only assign the relevant rights, powers, benefits, privileges or leases with the consent of the State; and

(b) any purported assignment of rights, powers, benefits, privileges or leases without such consent is void ab initio, unenforceable or of no legal effect.

13 The Lease:

(a) purports to assign rights, powers, benefits or privileges and/or a lease the subject of cl 31 of the Whyalla Steel Works Act 1958 (SA) Consolidated Indenture;

(b) purports to exclude OneSteel from the land and fixtures over which is has exclusive rights to operate its business;

(c) was executed without the consent of the State and, accordingly,

(d) is void ab initio, unenforceable or of no legal effect.

92 They sought, among other things, a declaration that the Lease was void ab initio, unenforceable or of no legal effect, or alternatively that it had been terminated by virtue of the notice of termination and repossession.

93 As I have already said, on 15 May 2025, the South Australian Parliament passed the Amendment Act, amending the Whyalla Steel Works Act, which voided the Lease and rendered otiose the claims of OneSteel and its administrators.

94 On 6 June 2025, WP went into voluntary administration.

THE ASSESTS — THEIR LOCATION, MANNER OF AFFIXING, CONSEQUENCES OF REMOVAL AND VALUE

95 All of the Assets in dispute are located in the inner harbour, save for Item 15 (which has not been in OneSteel’s possession since 2014) and Item 145 (which is in the outer harbour).

96 OneSteel accepted that if I were to find that the Assets are chattels and that the Whyalla Steel Works Act (as amended) does not extinguish WP’s interests in the chattels, then WP is the owner of the Assets.

97 OneSteel also conceded that the Rolls Royce mooring winches (Item 15), the CSL compound potable water filtration skid (Item 140) and the Bis equipment transition (Item 145) are chattels. OneSteel further indicated that it is content for WP to take possession of Items 140 and 145. The position with respect to Item 15 is complicated by the fact that the mooring winches are no longer in OneSteel’s possession and therefore cannot be proffered to WP. For the purposes of these reasons, those three Assets are not contentious.

98 A number of general points can be made about the expert evidence relating to the Assets in dispute.

99 First, as WP submitted, of the experts before me, only Mr Connelly is a qualified expert with significant experience in the removal and resale of plant and equipment used for bulk handling in a second-hand global market for such plant and equipment.

100 Secondly, Mr Connelly accepted — and it is obvious in any event — that most of the Assets (certainly the ones of greater value) were designed to operate in conjunction with each other, and that if one (or more) of them was removed, the Port could not operate. It was equally obvious that many of the Assets were designed to be suitable for the location, ore type and operational requirements of the Port. Mr McLachlan asked Mr Connelly the following questions in cross-examination (T:132–133):

And at the inner harbour, the tip pocket, the conveyors, the transfer towers, the two 30 sheds and the inner harbour shiploader, they were designed to operate in conjunction with each other, weren’t they?---Yes.

They were designed and installed such that iron ore could be taken via the conveyors from the tip pocket to the sheds and then to the shiploader?---Yes, that’s correct. It had that option.

They’re complementary to each other, those individual assets, in that respect, aren’t they?---In the way it was operating, yes.

Yes. So you could say they’re integrated with each other to that extent?---Yes, they all – they form part of the process.

Thank you?---Yes.

Stating the obvious, but without the conveyors, for example, the process of moving an iron ore comes to a halt pretty quickly, doesn’t it?---Absolutely.

And those assets that I’ve just mentioned, they were designed specifically for installation and use at the Port of Whyalla, weren’t they?---Yes, they were, but the conveyors and sheds and shiploaders are generic.

Yes?---Don’t – don’t – wasn’t bespoke.

But those items that I’ve listed off from the top – tip pocket through to the shiploader, they, those particular ones that were installed at the port were designed specifically for installation and use at the Port of Whyalla, weren’t they?---Yes, they were.

And they were custom built for that purpose, weren’t they?---There was a scope of work. Kerman was asked to design and procure and construct, and that’s what they did. Yes.

Yes. And they were designed in that respect for Whyalla Ports’ unloading and loading requirements?---Yes.

And they were designed for Whyalla Ports’ storage requirements, the sheds, for example?---Yes.

And they were designed for Whyalla Ports’ site layout?---Yes. They would have – the engineers would have looked at the site and configured the best configuration to put that together. Yes.

For example, the conveyors are of a particular rise – I beg your pardon, a particular length and rise and motor power, aren’t they, to suit that site and the requirements of that site?---Well, they were designed for a process design criteria for that project. Yes.

Yes.

HIS HONOUR: And you know that because you’ve read the contracts or - - -?---Yes, I’ve read the contracts. Yes. Yes.

And having read them, it was those contracts that informed the answers you’ve just given or something else?---Probably reading the contract and my experience. Yes. But I mean, that process is what normally happens in any resource project where there’s a scope of work and a design criteria, and the engineers design it to achieve the objectives. And that’s exactly what happened there.

101 Thirdly, it cannot be doubted, and Mr Connelly accepted, that the scale of removing some of the larger Assets was significant. He opined in his second report that it would take 21 days to remove the site services buildings (Item 1), 90 days to remove the tip pocket (Item 4), 120 days to remove all of the transfer conveyors (although because WP no longer presses its claim for the conveyors in the outer harbour, that estimate would be less now), 140 days to remove both sheds and 30 days to remove the permanent shiploader (Item 18).

102 Fourthly, WP accepted that “Mr Billett was, for the most part, a conscientious and measured witness, who did his best (based on his different type of expertise), to assist the Court”. See WP’s written closing submissions at [154].

103 Fifthly, there was, generally speaking, and perhaps unsurprisingly, little difference between Mr Billett and Mr Connelly about the degree of annexation of the Assets — that is to say, how they were affixed and what they were affixed to. In his oral closing submissions, Mr McLachlan fairly summarised the evidence about affixation as follows (T:275):

The assets in dispute are affixed to the ground or connected to another structure which is affixed to the land … again, with the exceptions that I’ve made explicitly clear, those three chattel exceptions[.] [T]he tip pocket is partially underground. Conveyor 1, which connects that tip pocket to transfer tower 1, is also partially underground and includes a concrete tunnel. Each of the site-services buildings, the sheds, the inloading conveyor and transfer towers and the outloading bays are bolted to or embedded within concrete foundations. The dust collection system comprises a vacuum pressure building which is mounted on a steel truss structure and, in turn, bolted to a concrete foundation, and ducting which is bolted to the tip pocket shed and into the concrete floor.

One component of the water-spray system is affixed to the land, and another component is affixed to the shed and bunker in the tip pocket. The sampler equipment is affixed to transfer chutes within the uploading conveyor system. The firefighting system comprises water tanks bolted to the concrete foundations and contains underground distribution piping. The inner harbour control system consists of large electrical cabinets, a smaller computer system, underground cabling, and distributes power through the inner harbour. The building in which it is situated is on a steel truss frame and bolted to concrete foundations.

104 Sixthly, as WP submitted, although there were some areas of dispute between Mr Billett and Mr Connelly, Mr Billett also agreed that the Assets: (i) can be removed; (ii) are for the most part bolted on; (iii) are not to remain at the Port indefinitely; and (iv) have a second-hand market.

105 Seventhly, again as WP submitted, Mr Billett accepted that he did not have experience in removing and relocating bulk materials handling plant and equipment for reuse in the second-hand market, and that his engineering specialty is more focused on failure analysis of plant and equipment (T:191.1–3). Accordingly, to the extent that there is any difference between Mr Connelly and Mr Billett on questions of removal (including removal costs), resale value and reuse of the Assets, and intending Mr Billett no disrespect, Mr Connelly’s evidence is to be preferred, and I proceed accordingly.

106 Eighthly, as WP quite properly conceded, Mr Mitchell’s evidence assists insofar as it identifies the depreciated cost value of the Assets (totalling approximately $92.3 million). Mr Connelly provided a lower estimate of the total market value of the Assets (i.e. between $61 million and $70.7 million) but maintained that, on any view, the Assets have significant value.

107 Ninthly, as WP submitted, Mr Mitchell’s decision to value the Assets on a liquidation basis was not justified. In preparing his report, he was instructed by the solicitors for OneSteel to assume that: (i) WP has no right to access the land on which the Assets are located (other than a right to enter the land to remove any Assets which the court determines are WP’s); and (ii) once the Assets are removed from the land, WP will be unable to use the Assets to generate income. Based on these assumptions, Mr Mitchell assumed that the Assets could not be sold in situ and valued them on a liquidation basis. During cross-examination, Mr Mitchell ultimately accepted that the Assets had greater value in situ than they would otherwise have in a liquidation scenario. In my view, WP was correct to contend that OneSteel is a prospective buyer to whom WP could sell the Assets in situ, and in any event, WP was not under pressure to sell the Assets within 9–12 months (for an orderly liquidation) or within 3–4 months (for a forced liquidation). It follows that “the basis of value adopted and the valuation conclusions reached in [Mr Mitchell’s] report”— namely, the liquidation value of the Assets — were misconceived.

108 Tenthly, Mr Mitchell accepted that, although he is aware of a global secondary market for second-hand bulk materials handling plant and equipment (T:204.12–14), he has no experience valuing such assets for reuse by a purchaser (T:204.4–5). Further, and in light of my finding in J1 that Mr Mitchell’s evidence about removal costs is inadmissible, I give little weight to his conclusion (based largely on that inadmissible evidence) that the Assets have “no realisable value”. Accordingly, to the extent that there is any difference between Mr Connelly and Mr Mitchell on questions of the resale value of the Assets, and intending Mr Mitchell no disrespect, Mr Connelly’s evidence is to be preferred, and I proceed accordingly.

109 It follows from what I have said above that I accept that each Asset has the estimated second-hand market value (and associated removal costs) attributed to it by Mr Connelly.

Item 1: Site services buildings

110 The site services buildings are located at the inner harbour on certificate of title 6144/964 held by OneSteel. They include offices, lunchrooms and maintenance workshops, and (at least according to Mr Connelly) also include the SCADA system and the inner harbour control system (Item 34). The buildings are the only protected office area within close proximity to the harbour where staff and contractors at the Port can work and take breaks indoors and access amenities.

111 Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that some of the buildings comprising Item 1 are bolted to steel structures which are, in turn, bolted to concrete foundations or footings, while other buildings are bolted to internal steel frames which are, in turn, bolted to a concrete slab. They also agreed that these buildings can be removed. Mr Connelly’s view is that they could be removed with minimal damage (if any) being done to them. Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that, following their removal, the land could be returned to its original condition.

112 Mr Connelly opined that there is a deep secondary market for assets like the site services buildings. Mr Billett likewise said that the site services buildings are of a standard type and that, at the very least, the demountable offices may be reused. To the extent that there is any significant difference between Mr Connelly and Mr Billett on this question, Mr Connelly’s evidence is to be preferred. This is because, unlike Mr Billett, Mr Connelly has experience in dismantling and removing assets for resale and reuse elsewhere.

113 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of the site services buildings (Item 1) is between $1.08–$1.53 million, and that the cost of removing the site services buildings would not exceed their value.

114 These depictions of Items 1 and 34 were in evidence:

Item 2: Shed 1

115 Shed 1 is located at the inner harbour on certificates of title 5463/457, 5582/363 and 6144/964 held by OneSteel.

116 Shed 1 is a large steel shed which contains loaders, hoppers, apron feeders, conveyors, dust suppression systems, electrical systems and water and air tanks. It is used to store iron ore before transport, protecting it from environmental elements such as wind and rain. It is also used to blend different iron ore grades. Iron ore is received into shed 1 by conveyors (Items 9 and 10) from the tip pocket (Item 4) and is “outloaded” from shed 1 by conveyors (Item 11) to the shiploader (Item 18).

117 Mr Connelly’s evidence is that shed 1 is bolted to steel frames which are, in turn, bolted to the concrete slab sitting on the ground. Mr Billett said that shed 1 is both bolted and partially embedded at a low level into the concrete slab. Nonetheless, both agreed that shed 1 and the plant and equipment in it could be removed.

118 Mr Connelly’s view was that shed 1 (including the plant and equipment within it) can be removed with minimal damage (if any) being done to it. Mr Billett agreed with Mr Connelly’s view, save that he said that the roof and wall sheeting would be damaged upon removal. Unlike Mr Connelly, however, Mr Billett lacks experience in dismantling and removing assets like shed 1 for resale and reuse elsewhere (T:193.27–29). Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that, following the removal of shed 1, the land could be returned to its original condition.

119 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of shed 1 is between $4.5–$5.4 million, and that that the cost of removing shed 1 would not exceed its value. That accords with Mr Connelly’s view that there is secondary market for shed 1 and the apron feeders and reclaim conveyors located within shed 1. Neither Mr Billett nor Mr Mitchell have given admissible evidence as to the cost of removing shed 1.

120 These depictions of Items 2 and 3 were in evidence:

Item 3: Shed 2

121 Shed 2 is located at the inner harbour on certificate of title 6144/964 held by OneSteel.

122 As shed 2 is essentially identical to shed 1 (save that shed 2 does not have a bypass conveyor), what I have said above about shed 1 applies equally to shed 2.

123 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of shed 2 is between $4.5–$5.4 million, and that that the cost of removing shed 2 would not exceed its value.

124 The depictions of Items 2 and 3 that were in evidence are set out above at paragraph 120.

Item 4: Tip pocket

125 The tip pocket is located at the inner harbour on Crown lease 6213/636 (Perpetual Licence 319A).

126 The tip pocket is a train unloading system. It is where railcars are emptied of iron ore for transport onto the conveyors to sheds 1 and 2.

127 The tip pocket is comprised of several component parts, including a steel shed structure, the grates comprising the tip pocket itself and an apron feeder. The train wagons, which have doors on the bottom, come into the shed structure on rails and dump the iron ore into grates below the rail. The iron ore then falls through the grates into a “hopper” (which is a large, funnel-like piece of equipment). The iron ore is then fed through the apron feeder onto conveyors to transport the iron ore to sheds 1 and 2.

128 The hopper sits underground within a concrete cavity, which is a hole in the ground beneath the grates, lined with concrete walls.

129 The manner or method of affixing differs between the component parts of the tip pocket. Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that the steel shed is bolted to steel frames (which sit on the inside of the walls of the shed), the steel frames are bolted to a concrete slab underneath, the hopper is bolted to the concrete walls of the cavity and the apron feeder is bolted directly to the concrete slab beneath it.

130 Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that the component parts of tip pocket can be removed. Mr Connelly’s view was that the component parts of the tip pocket could be removed with minimal damage (if any) being done to them. Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that, following the removal of the tip pocket, the land could be returned to its original condition.

131 Mr Connelly’s view was that there is a secondary market for the component parts of the tip pocket. He said that because there are very few assets of this kind for sale in the secondary market, they would be highly sought after by potential buyers.

132 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of the tip pocket is between $7.2–$8.1 million, and that the cost of removing the tip pocket would not exceed its value. Mr Billett gave no admissible evidence as to removal costs.

133 These depictions of Item 4 were in evidence:

Item 5: Fire-fighting system

134 The fire-fighting system is located at the inner harbour at various locations in and around the site services buildings (Item 1), sheds 1 and 2 (Items 2 and 3) and the tip pocket (Item 4).

135 The fire-fighting system is used for fire suppression in the case of emergencies and comprises two water tanks, a small shed, underground piping, hydrants and hose reels.

136 Mr Connelly’s evidence was that the fire-fighting system sits on its own weight on a concrete slab and is only attached by its pipework (save for the shed in which it is housed, which is attached by bolts to steel frames which are in turn bolted to concrete foundations). Mr Billett said that the water tanks, the shed and the distribution piping, hydrants and hose reels are all bolted to concrete, but they agreed that the fire-fighting system can be removed. Mr Connelly’s evidence is that minimal damage (if any) would be done to the fire-fighting system upon removal, and Mr Billett did not suggest otherwise.

137 Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that, following removal of the fire-fighting system, the land could be returned to its original condition.

138 Mr Connelly said that there is a deep secondary market for assets such as the fire-fighting system which are general purpose. Mr Billett did not suggest otherwise.

139 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of the fire-fighting system is between $540,000–$630,000, and that the cost of removing the fire-fighting system would not exceed its value.

140 These depictions of Item 5 were in evidence:

Item 6: Dust collection system

141 The dust collection system is located at the inner harbour at various locations in and around sheds 1 and 2 (Items 2 and 3) and the tip pocket (Item 4). There are also dust collectors in the transfer towers.

142 The dust collection system is used to maintain air quality and meet environmental standards. It is used to remove nuisance dust created during the movement of iron ore. The dust collection system is essentially comprised of extraction fans, baghouses (which are similar to a bag on a vacuum machine) and ductwork.

143 Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that the component parts of the dust collection system are bolted to steel frames which are, in turn, bolted to concrete foundations. Mr Connelly and Mr Billett also agreed that the dust collection system can be removed through the use of cranes and a truck.

144 Mr Connelly’s view was that, leaving aside the ductwork (which would likely be scrap), the dust collection system can be removed with minimal damage being done to it. Mr Billett did not suggest otherwise. Further, Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that, after removal of the dust collection system, the land could be restored to its original condition.

145 Mr Connelly considered that there is a secondary market for the Asset, including potential buyers in mineral processing and bulk commodities. Mr Billett did not say otherwise.

146 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of the dust collection system (Item 6) is between $1.8–$2.7 million, and that the cost of removing the dust collection system would not exceed its value.

147 These depictions of Item 6 were in evidence:

Item 7: Water spray system

148 The water spray system is located at the inner harbour at various locations in and around sheds 1 and 2 (Items 2 and 3), the tip pocket (Item 4), conveyor 1 (Item 9), the inloading conveyors and transfer towers (Item 10) and the outloading conveyors and transfer towers (Item 11).

149 The water spray system is used to suppress dust generated during the inloading and outloading of iron ore. The water spray system is comprised of water tanks which are connected to a pumping system.

150 Mr Connelly said that the water spray system sits on its own weight on a concrete slab and is only attached by pipework. Mr Billett said that the water tanks are “bolted/pegged” to the land, and that the water pump is bolted to the shed which houses the tip pocket. Both agreed that it can be removed using a crane and a truck.

151 Mr Connelly said that, save for the pipework and ductwork, the removal of the water spray system would not cause any damage to it. Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that it can be removed without damage to the land.

152 Mr Connelly’s evidence is that there is a deep secondary market for assets of this kind.

153 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of the water spray system is between $450,000–$540,000, and that the cost of removing the water spray system would not exceed its value.

154 These depictions of Item 7 were in evidence:

Item 8: Sampler equipment

155 The sampler equipment is located at the inner harbour within the transfer towers connected to the outloading conveyors (Item 11). It is located on certificates of title 5603/913, 5582/363 and 5463/457 held by OneSteel.

156 The sampler equipment is used to collect samples of iron ore to test and verify whether the ore meets required specifications.

157 Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that the sampler equipment is bolted to steel structures which are, in turn, bolted to the transfer towers. They also agreed that it can be removed through unbolting, craning and trucking, with no damage to the land.

158 Mr Connelly’s evidence is that there is a secondary market for the sampler equipment in which it would be readily saleable.

159 Mr Connelly’s evaluative judgment was that the second-hand market value of the sampler equipment (Item 8) is between $270,000–$360,000, and that the cost of removing the sampler equipment would not exceed its value.

160 This depiction of Item 8 was in evidence:

Item 9: Conveyor 1 (from tip pocket to transfer tower 1)

161 Conveyor 1 is located at the inner harbour on certificate of title 5463/457 held by OneSteel and on Crown lease 6213/636 (Perpetual Licence 319A).

162 Conveyor 1 transports the iron ore, commencing underground at the tip pocket (Item 4) and then emerging above ground a short distance thereafter, before extending above ground to the first transfer tower (which forms part of Item 10). Conveyor 1 is comprised of several component parts, being the conveyor belt, the rollers and the steel trusses or frames.

163 With respect to the below-ground portion of conveyor 1, Mr Connelly said that the belt and rollers sit within a steel frame and the steel frame is bolted to concrete foundations. With respect to the above-ground portion, he said that the belt and rollers sit within a steel frame that is housed by steel cladding, which sits on steel structures that are bolted to small concrete footings on the ground.

164 Mr Billett gave similar evidence that these items are bolted onto steel frames.

165 Mr Connelly and Mr Billett agreed that conveyor 1 (Item 9), the inloading conveyors (Item 10) and the outloading conveyors (Item 11) can be treated in the same way.