Federal Court of Australia

Doctors for the Environment (Australia) Incorporated v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2025] FCA 989

File number(s): | VID 527 of 2025 |

Judgment of: | MCELWAINE J |

Date of judgment: | 22 August 2025 |

Catchwords: | ENVIRONMENTAL LAW – application to review decision of National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA) – where Woodside Energy Scarborough Pty Ltd requires approval of an environment plan to undertake offshore petroleum activities – construction of Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2023 – indirect impact of third party GHG emissions into the atmosphere – whether it is a mandatory requirement of an environment plan that the proponent must state what is an acceptable level of GHG emissions from the activity in order for NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied that the environment plan satisfies the environment plan acceptance criteria – held regulatory scheme does not require level of prescription as contended by the applicant. WORDS AND PHRASES – as low as reasonably practicable – to an acceptable level – environmental performance outcome – environmental performance standard – whether specificity or quantification in statements of acceptable level of environmental impact and risk is required for indirect Scope 3 GHG emissions caused by consumption of liquified natural gas produced by the activity. STANDING – where applicant represents medical professionals concerned about the health impacts of climate change – where applicant was extensively consulted by the proponent during formulation of the environment plan in issue – where proponent subsequently contends applicant lacks standing as not having a sufficient interest in declaratory relief – held there is a justiciable controversy and applicant has standing. |

Legislation: | Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) s 5 Australian Meat and Live-stock Industry Act 1997 (Cth) Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) ss (1A)(c), 39B(1) Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974 (Cth) Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) ss 3A, 146B Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (Cth) ss 7, 645, 646(gg) Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2023 (Cth) ss 4, 5, 17, 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26, 33(7), 34, 39, 40, 41, 43, 51 Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 (Cth) Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Legislation Amendment (Environment Measures) Regulation 2014 (Cth) Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Safety) Regulations 2009 (Cth) ss 1.4, 2.5 Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Safety) Regulations 2024 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Animals’ Angels e.V. v Secretary, Department of Agriculture [2014] FCAFC 173; (2014) 228 FCR 35 Australian Conservation Foundation v Commonwealth (1979) 146 CLR 493 Boyce v Paddington Borough Council [1903] 1 Ch. 109 Cooper v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2023] FCA 1158 Disorganized Developments Pty Ltd v South Australia [2023] HCA 22; (2023) 97 ALJR 575 Edwards v National Coal Board [1949] 1 KB 704 Forestry Corporation of New South Wales v South East Forest Rescue Incorporated [2025] HCA 15; (2025) 99 ALJR 794 Hobart International Airport Pty Ltd v Clarence City Council [2022] HCA 5; (2022) 276 CLR 519 Kelly v R [2004] HCA 12; (2004) 218 CLR 216 Ludwig v Coshott (1994) 83 LGERA 22 Munkara v Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 9 Onus v Alcoa of Australia Ltd [1981] HCA 50; (1981) 149 CLR 27 Re Judiciary (1921) 29 CLR 257 Santos NA Barossa Pty Ltd v Tipakalippa [2022] FCAFC 193; (2022) 296 FCR 124 Slivak v Lurgi (Australia) Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 6; (2001) 205 CLR 304 South Western Sydney Local Health District v Gould [2018] NSWCA 69; (2018) 97 NSWLR 513 Tipakalippa v National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (No 2) [2022] FCA 1121 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Administrative and Constitutional Law and Human Rights |

Number of paragraphs: | 186 |

Date of hearing: | 14 – 15 July 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr C Young KC with Ms S Molyneux |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Environmental Defenders Office |

Counsel for the First Respondent: | Mr C Lenehan SC with Mr G Ayres |

Solicitor for the First Respondent: | Australian Government Solicitor |

Counsel for the Second Respondent: | Mr D Clothier KC with Ms J Watson |

Solicitor for the Second Respondent: | Allens |

ORDERS

VID 527 of 2025 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | DOCTORS FOR THE ENVIRONMENT (AUSTRALIA) INCORPORATED Applicant | |

AND: | NATIONAL OFFSHORE PETROLEUM SAFETY AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY First Respondent WOODSIDE ENERGY SCARBOROUGH PTY LTD (ACN 650 177 227) Second Respondent | |

order made by: | MCELWAINE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 august 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding is dismissed.

2. Any application for costs must be made in writing, and if made, responded to in writing as follows:

(a) The application is to be filed by 4 pm on 29 August 2025, limited to no more than three pages;

(b) Any response to an application is to be filed by 4 pm on 5 September 2025, limited to no more than three pages; and

(c) Subject to any further order, the question of costs will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MCELWAINE J:

Synopsis

1 Woodside Energy Scarborough Pty Ltd proposes to develop the Scarborough gas resource in Commonwealth waters approximately 375 km west-northwest of the Burrup Peninsula off the coast of Western Australia. It forms part of the Greater Scarborough gas fields comprising the Scarborough, Thebe and Jupiter fields. Woodside in the language of the regulatory scheme is the titleholder. To proceed with the development lawfully, Woodside must address certain requirements of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2023 (Cth). The administering authority pursuant to the Regulations is the National Offshore Petroleum Safety and Environmental Management Authority (NOPSEMA), continued pursuant to s 645 of the Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage Act 2006 (Cth). In these reasons each reference to a legislative provision is to the Regulations unless otherwise specified.

2 A requirement of the Regulations is the approval of an offshore project proposal by NOPSEMA. If the proposal is approved, a titleholder commits an offence of strict liability if it undertakes a petroleum activity or a greenhouse gas (GHG) activity without an environment plan that is in force for the activity.

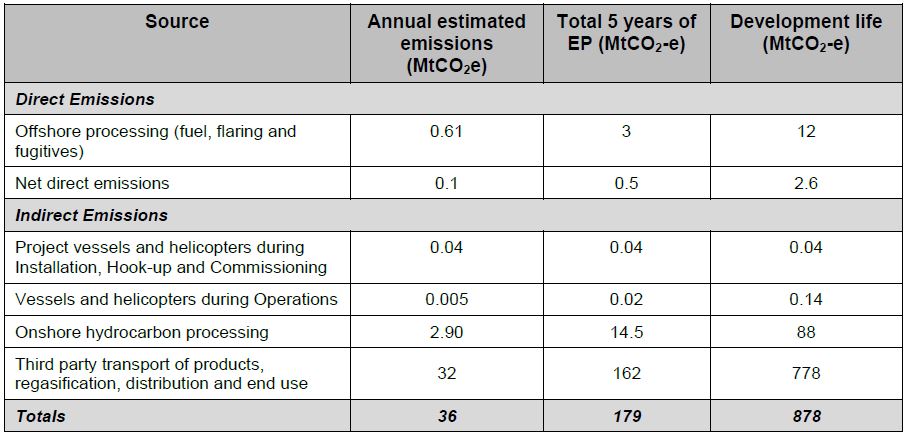

3 On 27 February 2020, Woodside submitted its offshore project proposal to NOPSEMA to develop the Scarborough and North Scarborough gas fields (OPP). On 30 March 2020, NOPSEMA accepted the OPP. Woodside submitted three versions of an environment plan to NOPSEMA, the last in January 2025. It is titled: Scarborough Offshore Facility and Trunkline (Operations) Environment Plan, January 2025 (Revision 3) (EP). The EP is a large document comprising 752 pages plus an appendix. It deals with many environmental impacts and risks of the proposed activity, including GHG atmospheric emissions. The EP contains estimates for GHG third party emissions (commonly known as Scope 3 GHG emissions) of 162 MtCO2-e over the five-year period of the EP and 778 MtCO2-e over the expected combined life of the project.

4 The EP does not dispute the science of human induced climate change since the Industrial Revolution. Amongst other statements in the EP, the following is acknowledged (page 335):

Climate change is caused by the net global concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

…

Human-caused climate change is a consequence of more than a century of net GHG emissions from energy use, land use change, lifestyle patterns of consumption, and production (IPCC 2023). The IPCC has stated that observed increases in GHG concentrations since 1750 leading to climate change are unequivocally caused by human activities and that there’s a near linear relationship between cumulative anthropogenic CO2 emissions and the global warming they cause (IPCC 2023).

5 Doctors for the Environment (Australia) Inc (DEA) is an incorporated association, endorsed as a deductible gift recipient and listed on the Register of Environmental Organisations (administered by the Australian Taxation Office) and registered as a charity with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission. As at 9 May 2025, it had approximately 1,844 members and its total subscribed supporters exceeded 3,500. The objects clause of its constitution in part provides:

To conserve and restore the natural environment because of its relationship to and impact on human health.

To work towards sustainable development which meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

To alert doctors and the public on the health effects of environmental degradation locally and worldwide using the best available scientific evidence and the precautionary principle.

6 The uncontested evidence of Dr Katriona Wylie, the executive director of DEA, is that it is the leading medical voice on health and climate change in Australia, being comprised of members who are medical professionals and students focused on the health impacts of climate change through education and advocacy. Woodside consulted DEA before finalising the EP. DEA expressed concern about the environmental impacts and effects of Scope 3 GHG emissions in consequence of undertaking the project.

7 The Regulations require NOPSEMA to accept an environment plan submitted to it by a titleholder if reasonably satisfied that it meets the environment plan acceptance criteria. In the case of a resubmitted environment plan, s 33(7) applies. On 19 February 2025 a delegate of NOPSEMA decided to accept the EP and later, on 1 April 2025, provided a statement of reasons for that Decision.

8 By an Amended Originating Application accepted for filing on 17 June 2025, DEA seeks judicial review of the Decision pursuant to the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act) and ss 39B(1) and (1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). NOPSEMA is the first respondent and Woodside is the second. Although there are 16 grounds of review, the core contention of DEA is that the EP did not satisfy mandatory requirements of the Regulations, was not therefore an environment plan within the meaning of the Regulations and in consequence it was not open to NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied that it met the environment plan acceptance criteria. Declaratory relief to the effect that the Decision is void and is of no effect is sought together with an order setting aside or quashing the Decision. NOPSEMA and Woodside resist the application.

9 It need hardly be said that it is not the function of this Court to examine the merits of what is the central concern of DEA: the release of materially more GHG into the atmosphere is likely to be catastrophic for the environment and human health. This Court is purely concerned to exercise its Constitutional function to determine on the case as formulated by DEA whether NOPSEMA erred in law or committed jurisdictional error in purporting to be reasonably satisfied that the EP met the environment plan acceptance criteria in the Regulations. It is not for this Court to adjudicate on the existential threat posed by climate change caused by anthropogenic CO2 emissions to the atmosphere.

The Project and the EP

10 Woodside proposes to perform petroleum activities within designated permit areas comprising the hook-up of the Scarborough floating production unit (moorings and subsea system), start-up and commissioning activities, routine production, the export of gas to the Pluto onshore gas plant via a gas export trunkline, inspection, monitoring, maintenance and repair of subsea infrastructure and associated surveys. This is referred to in the EP as the Petroleum Activities Program (PAP) which is addressed in very great detail in section 3 of the EP.

11 Woodside was not required to submit the project for assessment pursuant to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) because, on 27 February 2014, the Minister for the Environment gave final approval for the taking of action under s 146B of the EPBC Act for the strategic assessment of the environmental management authorisation process for petroleum and GHG storage activities as administered by NOPSEMA. The effect is that action undertaken as authorised does not require separate assessment or approval under the EPBC Act.

12 The arguments for DEA focus on the wording and content of the EP to establish the basal proposition that it was not open to NOPESMA to accept it because it failed to include assessments mandated by the Regulations. Thus, it is necessary to set out the provisions of the EP which are in issue.

13 The purpose of the EP (clause 1.3) is to demonstrate that:

(i) the environmental impacts and risks (planned (routine and non-routine) and unplanned) of the PAP are identified;

(ii) appropriate control measures are implemented to reduce environmental impacts and risks of the PAP to as low as reasonably practicable and an acceptable level; and

(iii) the PAP is carried out in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development as set out at s 3A of the EPBC Act.

14 Section 6 of the EP contains the environmental risk assessment, the identification of performance outcomes and standards and measurement criteria. This is mostly taken up with the direct and indirect impacts of the PAP activities, such as impacts on Matters of National Environmental Significance (MNES). Sub-section 6.7.6 addresses Routine and Non-routine GHG Emissions. There will be minor emissions resulting directly from the PAP such as operational flaring and exhaust emissions from internal combustion engines on vessels and helicopters, which may be put to one side. The focus of attention in this proceeding is upon the identification of “GHG emissions associated with onshore processing of Scarborough gas, third-party transportation, regasification and combustion by end users”. Of that group, the EP notes that the main source of indirect emissions is third party use, which is not part of the PAP but is “included for completeness”. That is Scope 3 GHG emissions, sometimes referred to in the EP as third party consumption.

15 Direct and Scope 3 GHG emissions are estimated at Table 6-22 of the EP:

16 The EP identifies management techniques and abatement steps that may be implemented where “practicable given that Woodside does not have operational control over third-party GHG emissions”. The examples are grouped as: Reduce (including supporting customers to reduce emissions via the investment in new energy products and lower carbon services), Substitute (promotion and marketing of the role of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) in displacing higher carbon intensity fuels), Advocate (Woodside aligns its advocacy to support the goals of the Paris Agreement by giving speeches and making submissions), Monitor and Report, and Verification (the verification of assumptions used to estimate third-party emissions, and if the assumptions used in the EP “are found to have varied or are no longer valid, Woodside will undertake a review and re-estimate third-party emissions”).

17 There is a section which sets out the history of the Paris Agreement on climate change, with particular emphasis that LNG from the Scarborough project “is understood to have an ongoing role in supporting customer’s plans to secure their energy needs, while they reduce their emissions” and that LNG has a role to play in reducing dependence on carbon intensive fuels. A consequence of the analysis presented in this section of the EP is this conclusion (page 355):

Global energy demand is expected to increase. Since the availability of gas can support the reduction of more carbo-intensive firming fuel sources such as coal, rather than displacing renewable energy, it cannot be assumed that emissions associated with customer consumption of Scarborough gas would be entirely additive to global atmospheric emissions.

18 This was variously referred to in submissions as the displacement assumption.

19 In addressing the Scarborough contribution to GHG concentrations, the EP in part states (page 357):

The remaining carbon budget to limit global warming to 1.5°C and to 2°C was 500 GtCO2 and 1350 GtCO2 respectively as calculated from 2020 (IPCC 2023).

Since 2020, a portion of this global carbon budget has been consumed by ongoing global CO2 emissions … The last Global Carbon Budget in 2024 estimated that the remaining carbon budget for cumulative global GHG emissions to limit global warming to 1.5°C, and 2°C were 235 GtCO2, and 1110 GtCO2 respectively as at January 2025 (50% likelihood).

…

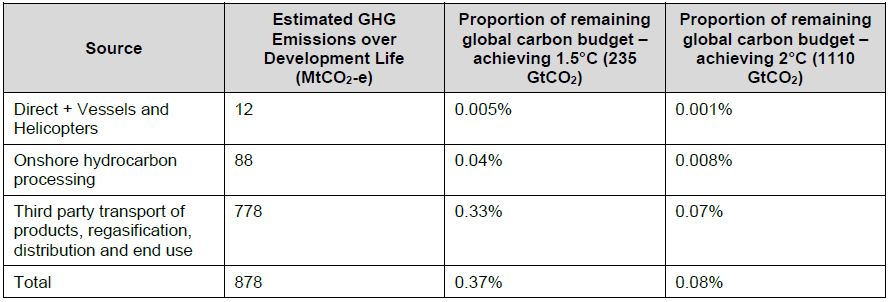

To facilitate a comparison against carbon budgets, a hypothetical scenario where GHG emissions associated with the Scarborough project are treated as entirely additive is considered. This scenario is not expected to eventuate due to reasons described above. The estimated Scarborough GHG emissions over the expected life of the development are compared with remaining carbon budgets expected to achieve the goals of the Paris agreement below. Additionally, no allowance is given for future abatement of GHG emissions associated with the project (such as through future abatement opportunities or future policy requirements), or changes to the carbon budgets which are known to be estimates only. As described above, the carbon budgets are developed based on CO2 only however the comparison below conservatively considers all GHG emissions from the project normalised as CO2-e, the vast majority of which are CO2. Emissions associated with onshore processing of Scarborough gas will also be subject to GHG frameworks which are expected to reduce the estimate from the gross figure used, such as the Federal SGM.

20 That analysis is set out at Table 6-25 (page 358):

21 The analysis continues:

Assuming the scenario in which all GHG emissions associated with the Scarborough project are additive to global GHG gas concentrations, which they may not be, the project’s contribution to the global carbon budget required to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement is de minimis.

22 There is then a statement that “climate science is a rapidly evolving field in which new observations continue to deepen understanding of the current and potential impacts of global warming, and the possible pathways for mitigation and adaptation”. Extensive reference is then made to the CSIRO State of the Climate 2024 Report and the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (2023). None of the science is disputed. The overall significance is assessed as (page 362):

Climate change impacts cannot be attributed to any one activity as they are instead the result of global GHG emissions, minus global GHG sinks, that have accumulated in the atmosphere since the industrial revolution started. They do not take into account the net impact of each project or activity. Even discounting the role gas can play towards customer commitments and plans to decarbonise through the energy transition, emissions associated with the project are expected to have a de minimis impact to global carbon budgets estimated to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

23 In tabular form the EP seeks to demonstrate that the environmental impacts and risks will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable (the EP acronym is ALARP). For Scope 3 GHG emissions the analysis is (from page 365):

Demonstration of ALARP | ||||

Control Considered | Control Feasibility (F) and Cost/ Sacrifice (CS) | Benefit in Impact/Risk Reduction | Proportionality | Control Adopted |

Verify assumptions used to estimate GHG emissions associated with third party transport, regasification, distribution and consumption on an annual basis. Re-estimate these emissions over five year duration of this EP revision | F: Yes CS: Minimal cost | Ensures estimates for these emissions are aligned with best practicable approach and within bounds set in this Environment Plan, noting challenges of procuring actual emissions data from third parties | Proportional, given the availability of data to implement this verification activity. | Yes C 6.19 |

Woodside supports customers to reduce their emissions via the investment in new energy products and lower carbon services, including the progression of corporate Scope 3 targets that apply across Woodside’s portfolio including the following: Scope 3 Investment Target: Woodside has a Scope 3 investment target aiming to invest $5 billion in new energy products and lower carbon services (non LNG) by 2030. Scope 3 Emissions Abatement Target: Woodside has a Scope 3 emissions abatement target, to indicate the potential abatement impact of these products and services upon customer Scope 1 or 2 emissions. This target is to take final investment decisions on new energy products and lower carbon services by 2030, with total abatement capacity of 5 Mtpa CO2-e | F: Yes CS: Cost as reflected in target | Supports customers to reduce their scope 1 and 2 emissions | Proportional at a Woodside corporate level | Yes C 6.17 |

Woodside will undertake an annual review process to address uncertainty in the impact assessment. This process will include: Reassessment of the role of gas in the energy transition and its potential to contribute to the net displacement of more carbon intensive energy sources (for example through review of relevant literature and studies from credible sources, participating in or commissioning studies, assessing relative carbon intensity of energy generation in customer nations, compared to LNG Using data published or available from business partners in the value chain) Application of additional management measures if triggered by conclusion that gas is not displacing more carbon intensive fuels or contributing to the global energy transition (directly or indirectly) | F: Yes CS: Minimal Cost | Supports understanding of the role of gas in the energy transition and the potential for LNG to displace higher carbon intensive fuel sources, addressing uncertainty in the impact assessment and the global carbon budget. In addition, by considering the relevant management measures that can be applied at the time allows for the development of fit for purpose management measures that are applicable to the energy transition at the time. By applying an adaptive management approach, Woodside can manage of the risk so that the corresponding EPO can be achieved. | Proportional | Yes C 6.20 |

Woodside will work with the natural gas value chain to reduce emissions in third party systems (e.g. regasification and distribution), such as through: the adoption and promotion of the Methane Guiding Principles, sharing knowledge of methane reduction via Australian industry forums and other companies in the natural gas value chain Advocacy for stable policy frameworks that reduce carbon emissions. Annual review of the implementation and outcomes of these measures | F: Yes CS: Minimal cost associated with collaboration and advocacy | Supports customers to reduce their scope 1 and 2 emissions | Proportional at a Woodside corporate level | Yes C 6.18 |

24 The EP from pages 374 to 378, provides an analysis of and conclusion that GHG emissions will be as low as reasonably practicable. It includes:

Discussion of ALARP

Risk Based Analysis

Application of Woodside’s Risk Management Procedures, implementation of the Emissions and Energy Management Procedure and Production Optimisation and Opportunity Management Procedure reduces GHG emissions risk to ALARP in design and operations. A range of controls have been considered for both direct and indirect emissions in design and project execution phase, and a system of continual review and improvement is in place for ongoing operations.

Societal Values

Consultation was undertaken for this program to identify the views and concerns of relevant stakeholders, as described in Section 5 and Appendix F Consultation Summary Tables. Some stakeholders expressed strong views on GHG emissions associated with the Scarborough project, which were responded to accordingly. This included provision of further information on direct and indirect GHG emissions, discussion of controls and Woodside’s corporate position, targets and controls via the 2024 Climate Transition Action Plan and 2023 Progress Report.

ALARP Statement:

On the basis of the environmental risk assessment outcomes and use of the relevant tools appropriate to the decision type (i.e. Decision type A and B for direct and indirect emissions respectively), Woodside considers the adopted controls appropriate to manage GHG emissions from the Scarborough facility and indirect emissions sources that Woodside may practicably influence, during the five year term of this EP. The adopted controls meet legislative requirements.

Indirect GHG emissions from onshore processing at PLP are managed under the Pluto Greenhouse Gas Abatement Program, and at Karratha Gas Plant are managed under the NWS Project Extension Greenhouse Gas Management Plan. These require comprehensive reporting and independent auditing of emissions and emission intensities to ensure compliance with contemporary greenhouse gas standards and to maintain transparency and accountability. Greenhouse gas data available to Woodside will be used to verify the onshore hydrocarbon processing estimates once available. These facilities are also subject to complying with the Federal Safeguarding Mechanism (SGM) to manage net emissions under the scheme in line with Australia’s emission reduction targets of 43% below 2005 levels by 2030 and net zero by 2050.

Woodside is implementing programs at a corporate level to manage indirect emissions associated with customer use of gas from the Scarborough project.

As no reasonable additional/alternative controls were identified that would further reduce the impacts without grossly disproportionate cost/sacrifice, GHG emissions from the Scarborough facility and indirect emissions sources that Woodside may practicably influence are considered ALARP.

…

Indirect GHG emissions associated with Scarborough will be managed to ALARP and an acceptable level through the implementation of the controls detailed below.

25 In Part 2 of the EP there is an explanation of the Risk Management Procedures. The EP proceeds on the basis that the principles and guidelines for risk management identified in ISO 31000: 2018 Risk Management Guidelines meet the requirements of the Regulations (page 34). Additionally, Woodside has developed internal risk management procedures consistent with the principles set out in the Guidance on Risk Related Decision Making (Oil and Gas UK, 2014) (page 35). The framework is then discussed, including risk classification as Decision Types A, B or C. Type A risks are well understood and reflect good industry practice. Type B risks involve greater uncertainty and complexity and include higher order risks. Such risks sit outside established practice and require more detailed risk assessments to conclude that risk is reduced to as low as reasonably practicable. Type C risks are typically significant and relate to environmental performance. Such risks involve greater complexity and uncertainty and require implementation of the precautionary principle. There is a risk of significant environmental impact.

26 It will be noticed from the above summary that the EP applies a Type A and Type B risk assessment to direct and indirect GHG emissions. DEA does not contend that, in accepting that part of the analysis, NOPSEMA made a legally unreasonable or irrational decision.

27 The corresponding control mechanisms assume significance to the issues in this proceeding, as do others, which form the basis for Woodside’s demonstration that it achieves as low as reasonably practicable, including the following statements (page 375, 378):

GHG emissions are a global concern, and as such Woodside has undertaken an impact assessment of GHG associated with the Scarborough facility and identified key measures to manage GHG emissions to an acceptable level.

…

Indirect GHG emissions associated with Scarborough are managed to an acceptable level by meeting (where they exist) legislative requirements, industry codes and standards, applicable company requirements, and industry guidelines, and these have been adopted as key controls.

Even discounting the role gas can play towards customer commitments and plans to decarbonise through the energy transition, emissions associated with the project are negligible in the context of existing and future predicted global GHG emissions. As described above, even in the hypothetical scenario when taken to be wholly additive, the GHG emissions created by and associated with the project represent a de minimis contribution to the carbon budgets estimated to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. Further, the project will comply with the relevant Australian carbon management framework, for example the Federal SGM. The impact on national and international emission reduction targets is therefore negligible and acceptable.

28 The control measures in issue are presented in tabular form as respectively environmental performance outcomes, controls, environmental performance standards and measurement criteria. Relevantly (from page 380):

EPOs, EPSs and MC for Scarborough Facility Operations | |||

Environmental Performance Outcomes | Controls | Environmental Performance Standards | Measurement Criteria |

EPO 11 Woodside will support customers to reduce their GHG emissions. EPO 12 Net GHG emissions associated with onshore processing will achieve reduction requirements under the reformed Safeguard Mechanism (inclusive of legislated net zero emissions by 2050). EPO 29 Estimated GHG emissions associated with third party transport, regasification, distribution and end use shall remain below 162 MtCO2-e over 5 year operational span of this EP revision | C 6.4 Onshore facilities which process Scarborough gas apply for and manage GHG emissions in alignment with the relevant baseline under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Safeguard Mechanism) Rule 2015. | PS 6.4.1 Onshore facilities which process Scarborough gas manage GHG emissions in alignment with the accepted baseline, under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Safeguard Mechanism) Rule 2015. | MC 6.4.1 Records demonstrate net emissions of onshore processing facilities have been managed to within the relevant accepted Safeguard Mechanism baseline. |

C 6.20 Woodside will undertake an annual review process to address uncertainty in the impact assessment. This process will include: Reassessment of the role of gas in the energy transition and its potential to contribute to the net displacement of more carbon intensive energy sources (for example through review of relevant literature and studies from credible sources, participating in or commissioning studies, assessing relative carbon intensity of energy generation in customer nations, compared to LNG, using data published or available from business partners in the value chain. Application of additional management measures if triggered by conclusion that gas is not displacing more carbon intensive fuels or contributing to the global energy transition (directly or indirectly). | PS 6.20.1 Assessment of the role of gas in the energy transition undertaken on an annual basis | MC 6.20.1 Records demonstrate annual assessment of the role of gas in the energy transition has been undertaken | |

PS 6.20.2 Adaptive management measures implemented if: gas is not contributing to the global energy transition; or displacing more carbon intensive fuels | MC 6.20.2 Records demonstrate adaptive management measures implemented, if required | ||

C 6.17 Woodside supports customers [75] to reduce their emissions via the investment in new energy products and lower carbon services, including corporate targets that apply across Woodside’s portfolio including the following: Scope 3 Investment Target [76] Invest $5 billion in new energy products and lower carbon services (non LNG) by 2030[77]. Scope 3 Emissions Abatement Target [76] Take final investment decisions on new energy products and lower carbon services by 2030, with total abatement capacity of 5 Mtpa CO2 -e[78]. | PS 6.17.1 Woodside will progress its Scope 3 investment and emissions targets, aligned with stated timeframes. | MC 6.17.1 Progress against targets reported in the relevant annual Woodside disclosures to relevant industry standards and/or requirements. This includes an estimate of abated emissions from currently sanctioned projects. | |

C 6.18 Woodside will work with the natural gas value chain to reduce emissions in third party systems (e.g. regasification and distribution). | PS 6.18.1 Woodside to implement the following: sharing knowledge via Australian industry forums and other companies in the natural gas value chain through; the adoption and promotion of global methane frameworks such as the Methane Guiding Principles and Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter Advocacy for stable policy frameworks that reduce carbon emissions. Annual review of the implementation and outcomes of these measures, this includes consideration of current or new industry forums, initiatives and natural gas value chain participants | MC 6.18.1 Records demonstrate that listed actions have been undertaken and are effective. | |

29 The footnotes state:

76. Scope 3 targets are subject to commercial arrangements, commercial feasibility, regulatory and Joint Venture approvals, and third-party activities (which may or may not proceed). Individual investment decisions are subject to Woodside’s investment targets. Not guidance. Potentially includes both organic and inorganic investment. Timing refers to financial investment decision, not start-up/operations.

77. Includes pre-RFSU spend on new energy products and lower carbon services that can help our customers decarbonise by using these products and services. It is not used to fund reductions of Woodside’s net equity Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions which are managed separately through asset decarbonisation plans.

78. Includes binding and non-binding opportunities in the portfolio, subject to commercial arrangements, commercial feasibility, regulatory and Joint Venture approvals, and third-party activities (which may or may not proceed). Individual investment decisions are subject to Woodside’s investment targets. Not guidance.

Statutory Scheme

30 The Regulations are an instrument made under the Storage Act and commence with a statement of objects at s 4:

The object of this instrument is to ensure that any petroleum activity or greenhouse gas activity carried out in an offshore area is:

(a) carried out in a manner consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development set out in section 3A of the EPBC Act; and

(b) carried out in a manner by which the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

(c) carried out in a manner by which the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level.

31 The reference in (a) to s 3A of the EPBC Act is:

Principles of ecologically sustainable development

The following principles are principles of ecologically sustainable development:

(a) decision-making processes should effectively integrate both long-term and short-term economic, environmental, social and equitable considerations;

(b) if there are threats of serious or irreversible environmental damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation;

(c) the principle of inter-generational equity–that the present generation should ensure that the health, diversity and productivity of the environment is maintained or enhanced for the benefit of future generations;

(d) the conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity should be a fundamental consideration in decision-making;

(e) improved valuation, pricing and incentive mechanisms should be promoted.

32 Part 4 is concerned with the requirements for and content of an environment plan. A titleholder commits an offence of strict liability if it undertakes an activity under the title and an environment plan is not in force for the activity: s 17. It is also an offence of strict liability to undertake the activity in a way that is contrary to the environment plan: s 18. Division 2, s 20, commences with:

This Division sets out the required contents of an environment plan for an activity under a title.

33 Section 21 requires an environmental assessment to address a number of topics: description of the activity, description of the environment, requirements of an environment plan, evaluation of environmental impacts and risks and environmental performance outcomes and standards. Subclauses (5), (6) and (7) are in issue, providing respectively:

(5) The environment plan must include:

(a) details of the environmental impacts and risks of the activity; and

(b) an evaluation of all the environmental impacts and risks, appropriate to the nature and scale of each impact or risk; and

(c) details of the control measures that will be used to reduce the impacts and risks of the activity to as low as reasonably practicable and an acceptable level.

(6) To avoid doubt, the evaluation mentioned in paragraph (5)(b) must evaluate all of the environmental impacts and risks arising directly or indirectly from:

(a) all operations of the activity; and

(b) any potential emergency conditions, whether resulting from an accident or any other cause.

Environmental performance outcomes and standards

(7) The environment plan must:

(a) set environmental performance standards for the control measures identified under paragraph (5)(c); and

(b) set out the environmental performance outcomes for the activity against which the performance of the titleholder in protecting the environment is to be measured; and

(c) include measurement criteria that the titleholder will use to determine whether each environmental performance outcome and environmental performance standard is being met.

34 The definitions central to the content of these requirements are respectively:

control measure means a system, an item of equipment, a person or a procedure, that is used as a basis for managing environmental impacts and risks of an activity.

environment means:

(a) ecosystems and their constituent parts, including people and communities; and

(b) natural and physical resources; and

(c) the qualities and characteristics of locations, places and areas; and

(d) the heritage value of places;

and includes the social, economic and cultural features of the matters mentioned in paragraphs (a), (b), (c) and (d).

environmental impact, of an activity, means any change to the environment, whether adverse or beneficial, that wholly or partially results from the activity.

environmental management system, for an activity, includes the responsibilities, practices, processes and resources used to manage the environmental aspects of the activity.

environmental performance means the performance of a titleholder in relation to the environmental performance outcomes and environmental performance standards mentioned in an environment plan.

environmental performance outcome, for an activity, means a measurable level of performance required for the management of environmental aspects of the activity to ensure that environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level.

environmental performance standard means a statement of the performance required of a control measure.

35 There is no definition of acceptable or of as low as reasonably practicable.

36 Section 22 requires an environment plan to contain an implementation strategy comprising: environmental management system, responsibilities of employees and contractors, monitoring and reporting, oil pollution emergency response, testing oil pollution emergency response arrangements and consultation and compliance. At issue in this proceeding is the environmental management system at subclause (2):

(2) The implementation strategy must contain a description of the environmental management system for the activity, including specific measures to be used to ensure that, for the duration of the activity:

(a) the environmental impacts and risks of the activity continue to be identified and reduced to a level that is as low as reasonably practicable; and

(b) control measures detailed in the environment plan are effective in reducing the environmental impacts and risks of the activity to as low as reasonably practicable and an acceptable level; and

(c) environmental performance outcomes and environmental performance standards in the environment plan are being met.

37 In the course of preparing an environment plan a titleholder must consult with specified agencies and persons (s 25) including (1)(d) and (e):

(d) a person or organisation whose functions, interests or activities may be affected by the activities to be carried out under the environment plan;

(e) any other person or organisation that the titleholder considers relevant.

38 That obligation extends to giving each relevant person “sufficient information to allow the relevant person to make an informed assessment of the possible consequences of the activity on the functions, interests or activities of the relevant person” and relevant persons must be allowed a reasonable period for the consultation: ss 25(2) and (3). When finalised, an environment plan is submitted to NOPSEMA: s 26. As I have noted, the EP in issue is revision 3, which engaged the decision power at s 33(7):

(7) If the titleholder resubmits the plan by the day referred to in paragraph (5)(c), or a later date agreed by NOPSEMA, then, subject to section 16, NOPSEMA must:

(a) if NOPSEMA is reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the environment plan acceptance criteria — decide to accept the plan; or

(b) if NOPSEMA is still not reasonably satisfied that the environment plan meets the environment plan acceptance criteria — decide to:

(i) give the titleholder a further notice under subsection (5) of this section; or

(ii) accept the plan in part (for a particular stage of the activity), or subject to limitations or conditions applying to operations for the activity, or both; or

(iii) refuse to accept the plan.

39 The criteria for acceptance of an environment plan is set out at s 34:

For the purposes of section 33, the criteria for acceptance of an environment plan (the environment plan acceptance criteria) for an activity are that the plan:

(a) is appropriate for the nature and scale of the activity; and

(b) demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable; and

(c) demonstrates that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level; and

(d) provides for appropriate environmental performance outcomes, environmental performance standards and measurement criteria; and

(e) includes an appropriate implementation strategy and monitoring, recording and reporting arrangements; and

(f) does not involve the activity or part of the activity, other than arrangements for environmental monitoring or for responding to an emergency, being undertaken in any part of a declared World Heritage property; and

(g) demonstrates that:

(i) the titleholder has carried out the consultations required by section 25; and

(ii) the measures (if any) that the titleholder has adopted, or proposes to adopt, because of the consultations are appropriate; and

(h) complies with the Act, this instrument and any other regulations made under the Act.

40 These are the central provisions at issue in this proceeding. There are some others that were referenced in argument, the effect of which may be summarised. Division 5 is concerned with revision of an environment plan in defined circumstances. They include submission by the titleholder upon the occurrence of any significant new environmental impact or risk or significant increase in an existing environmental impact or risk (s 39), revision at the request of NOPSEMA, without limitation as to the circumstances when the request may be made (s 40), and revision at the end of each five year period (s 41). Division 6 confers power for NOPSEMA by written notice to the titleholder to withdraw acceptance of an environment plan, including if it determines that the environmental performance outcomes and environmental performance standards in the plan have not been met: s 43(1)(d).

Relevance of Scope 3 GHG emissions to the functions of NOPSEMA

41 It will have been noticed that the Regulations require an environment plan to include details of the environmental impacts and risks of the activity, an evaluation of those impacts and risks appropriate to the nature and scale of each impact or risk and which must extend to evaluating all of the environmental impacts and risks “arising directly or indirectly from” from all operations of the activity: ss 21(5) and (6).

42 The EP proceeds on the basis that Scope 3 GHG emissions emitted by consumption of gas extracted and processed by the activity is an indirect impact and risk to the environment. Table 6-22 (set out above) distinguishes between direct emissions within the control of Woodside as well as Scope 3 GHG emissions not within its control: transport of products, regasification, distribution and end use. Scope 3 GHG emissions are the largest source of GHG emissions associated with the project by a very considerable margin.

43 Mr Young KC for DEA submits that s 21(6) required the EP to address Scope 3 GHG emissions as indirect environmental impacts and risks from the operation of the activity. In oral submissions when I put that proposition to Mr Clothier KC for Woodside, he accepted that for the purposes of this proceeding, the EP treats them as indirect impacts and that I should proceed on that basis. Mr Lenehan SC for NOPESMA did not submit to the contrary, consistently with the statement of reasons at [24(c)(iii)(C), (D) and (E)].

Content of the Decision

44 Although DEA eschews the reasons of the delegate, because on its case the EP did not comply with mandatory requirements of the Regulations and therefore it was not open to NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied as required by s 33(7), it is necessary to understand the delegate’s reasons as contextual and on the arguments of Woodside and NOPSEMA they assume dispositive importance.

45 In the statement of reasons, the delegate relevantly proceeded sequentially through s 34 as follows.

46 As to subparagraph (a), the delegate found that the EP is appropriate to the nature and scale of the activity. More particularly concerning GHG emissions they found at [24(c)]:

i. The EP includes details of the impacts and risks that are relevant to the GHG emissions from the activity and provides an evaluation that is appropriate to the nature and scale of that impact and risk. This titleholder has applied more detail and rigour to the evaluation of higher order impacts and risks and to receptors in the Australian environment that are most vulnerable to impacts from climate change.

ii. The EP applies more detail and rigour to the impact and risk assessments where there is a higher degree of scientific uncertainly in predictions of impacts (i.e. in the potential future emissions and climate change scenarios that may arise) and risks and/or severity of potential consequence of impacts and risks. Information from authoritative sources such as the IEA and IPCC has primarily been relied upon in developing the impact evaluation and analysis of the project's emissions; and in describing the potential future impacts and risks.

iii. The EP (Section 6.7.6 and Table 6-5) contextualises the estimated emissions from the activity against current established Australian national and global emissions budgets that are consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement and with Australia’s Nationally Determined Contributions. These have been derived from authoritative sources such as the Australian National Emissions Projections 2024, the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report, and the Global Carbon Budget 2024. In this respect:

A. The EP estimates that the total lifecycle emissions from the Scarborough Project (an estimated 878 million tonnes CO2-equivalent) are expected to comprise approximately 0.37% of the estimated remaining global carbon budget (in a scenario projected to limit global warming to 1.5°C, consistent with the Paris Agreement objectives).

B. It also estimates that emissions occurring within Australia would comprise approximately 0.9% of the projected remaining national emissions budget to 2030.

C. I noted that the majority of the emissions arising from the Project occur in jurisdictions onshore in Australia (e.g. processing) or overseas (in products use). The legislative and international frameworks that govern these emissions are administered in Australia by State (e.g. WA EPA) and Federal (e.g. Clean Energy Regulator) regulators in delivering Australia’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement via the Safeguard Mechanism and other relevant legislation and policy. Overseas, equivalent regulators administer the legislative frameworks which enact the NDCs of those countries under their own Paris Agreement commitments.

D. While there is some uncertainty inherent in the efficacy and sufficiency of NDCs and their implementation with respect to achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement, it is assumed that the frameworks in place and being administered by appropriate regulators are able to, and must, be relied upon in evaluating the impacts, risks and control measures for this activity. It is noted that mechanisms exist nationally (via advice to government and other measures as described in the Climate Change Act 2022) and internationally (via NDC reporting to the Global Stocktake, the annual Conference of the Parties, and other measures as enacted via the Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC) to evaluate progress against the objectives of the Paris Agreement and to recommend changes as required. It is considered that this national and international framework must be relied upon to reduce emissions, including those from the Scarborough Project; and that the control measures presented in the EP must be, and are, consistent with those frameworks.

E. Advice from government departments (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water [DCCEEW] and the Clean Energy Regulator [CER]) confirmed that emissions from the Scarborough Project that occur in Australia are covered by Australia’s NDCs and mechanisms to support their achievement such as the Safeguard Mechanism. The projected emissions from the project have been included in the 2024 National Emissions Projections, which show that the Safeguard emissions reduction targets are expected to be met. I received advice from DCCEEW that it is unlikely that the Project will affect Australia’s ability to meet its target to reduce emissions by 43% below 2005 levels by 2030.

iv. I also noted that the EP (Section 6.7.6) describes multiple potential future gas demand scenarios from authoritative sources such as the International Energy Agency to reflect the uncertainty associated with energy market prediction. In addition, while describing the theoretical potential for gas to contribute to the displacement of more carbon-intensive energy sources, the EP also acknowledges the uncertainty associated with this expectation and includes measures to monitor and reassess whether this potential has been realises (e.g. Control 6.20).

47 As to subparagraph (b), the delegate found in part (from [29]):

Section 2 and 6 of the EP describes the process applied to evaluate whether impacts and risks are reduced to ALARP. A clear, systematic, and reproducible process for the evaluation of all impacts and risks is outlined, which details the control measures to be implemented, including an evaluation of additional potential control measures, and justifies why control measures are either adopted or rejected (with well-reasoned and supported conclusions) to demonstrate that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be reduced to ALARP. I was reasonably satisfied that the evaluation of the adoption of control measures is based on environmental benefits and the consideration of the feasibility and cost/sacrifice of implementation to demonstrate that impacts and risks will be reduced to ALARP.

…

The evaluation of impacts and risks has informed the selection of suitable control measures to either reduce the severity of the consequence or likelihood of impacts and risks. The control measures outlined in Section 6 of the EP are sufficiently detailed to demonstrate they will be effective in reducing the impacts and risks for the duration of the activity. The level of detail in the ALARP assessment is matched to the nature and scale of the potential impacts and risks. The EP provided a reasonable demonstration, that there are no other practical control measures that could reasonably be taken to reduce impacts and risks any further.

…

There is sufficient detail of the control measures to demonstrate that the measures will be effective in reducing impacts and risks to ALARP for the duration of the EP:

A. All control measures evaluated are described in the demonstration of ALARP table, and those adopted have been detailed in the tables listing EPOs, EPS and MC alongside their relevant EPS. Where applicable, further details of processes have been provided in the implementation strategy for the EP (Section 7).

B. Sufficient details of the control measures are provided such that they can be implemented, compliance monitoring can occur, and their effectiveness can be evaluated. This detail is provided through the combination of information described in control measures, EPS, and the implementation strategy where relevant.

C. Each control measure has been clearly linked to corresponding EPS and MC in Section 6.7.6, with sufficient detail to provide a level of performance that can be monitored for effectiveness.

The EP commits (through the processes described in the implementation strategy, especially Section 7.2.4 and 7.5) to revisiting the evaluation of control feasibility over the life of the activity to identify controls that may become reasonably practicable in future.

48 As to subparagraph (c), the delegate found in part (from [35]):

I was reasonably satisfied the EP demonstrated that the environmental impacts and risks of the activity will be of an acceptable level. This is because specifically, I found that:

a. Section 6 of the EP applies a clear, systematic, and reproducible process for demonstrating how environmental risks will be of an acceptable level and the statements and conclusions drawn by the titleholder in the EP have been sufficiently supported with scientific literature. This process is commensurate with the nature and scale of the activity and the severity of its impacts and risks with more effort and rigour applied to evaluations where there is a higher degree of scientific uncertainty in predictions of impacts and risks and/or severity of potential consequence of impacts and risks.

b. Sections 2 and 6 of the EP describe the process undertaken by the titleholder to determine acceptable levels of impact and risk for the activity. The titleholder considered internal and external policy settings, feedback received by the titleholder during relevant persons consultation, relevant legislative requirements, applicable plans of management, recovery plans, conservation advice and other guidance for matters protected under the EPBC Act, and the principles of ecologically sustainable development as defined in the EPBC Act.

i. In specific relation to GHG emissions, Section 6.7.6 and Table 6-25 include consideration of the relevant requirements that apply to GHG emissions from the activity, including those internal and external to Woodside, and the principles of ESD.

…

f. The titleholder has identified and addressed areas of uncertainty in the impact and risk evaluations (Section 6). Predictions of environmental impact and risk are suitably conservative, supported by appropriate modelling, or subject to measures to validate assumptions and outcomes. Examples to support this reasoning include:…

iii. In specific relation to GHG emissions:

A. The EP impact evaluation (Section 6.7.6) is conducted on the assumption that all emissions predicted for the lifecycle of the activity will be realised; and does not account for potential future emissions reduction projects through technology or operational refinements. It also does not account for the expected emissions trajectory decline that will be required through compliance with the Safeguard Mechanism, or potential future policy requirements that may apply to emissions from the activity.

B. The EP (Section 6.7.6) contains emissions performance monitoring measures to review predictions against realised emissions; including validation of design controls and onshore processing emissions.

C. The EP contains specific controls (e.g. C 6.20) which will assess areas of uncertainty in relation to the stated potential of gas to displace more carbon-intensive energy sources on an ongoing basis and commits to adaptive management measures in the event that this scenario does not occur. This is supported by suitable performance standards and measurement criteria.

D. The EP contains specific measurement criteria (e.g. MC 6.17.1 and MC 6.18.1) to verify that actions are not just implemented, but effective, in contributing towards meeting the EPOs and acceptable levels.

49 As to subparagraph (d), the delegate found in part (from [44]):

I found the EP provided appropriate EPOs, which I considered:

a. Were relevant and addressed all the identified environmental impacts and risks for the activity.

b. When read in conjunction with associated EPSs, established measurable levels for management of environmental aspects of the activity.

c. When read in conjunction with the relevant environmental impact/risk evaluation and adopted management measures, demonstrated that the environmental impacts and risks will be managed to an acceptable level and as low as reasonably practicable.

d. Are consistent with the principles of ESD and relevant requirements (such as plans of management, recovery plans, conservation advice and other guidance for matters protected under the EPBC Act), considering items (a) and (c) above).

…

f. In relation to GHG emissions:

i. The EP includes EPOs (EPO 3, 10, 11, 12, and 29) that are clear, unambiguous and appropriately address all identified impacts and risks relevant to the activity, including the direct and indirect emissions sources identified in the EP. The EPOs appropriately reflect the magnitude of identified emissions sources and are established with reference to the degree of operational control held by the titleholder over those sources; which is a reasonable and practicable approach,

ii. The EPOs demonstrate that impacts and risks will be managed to an acceptable level and reflect a level of environmental performance for management that is achievable. These are consistent with the Australian GHG emissions management frameworks, including the requirements of the NGER Act and the Safeguard Mechanism.

50 Finally, as relevant to this proceeding, as to subparagraph (e), the delegate found in part (from [48]):

I was satisfied that the implementation strategy contains an adequate environmental management system (EMS) for the activity. The implementation strategy outlined in Section 1.9 and Section 7 provides a range of systems, practices and processes (outlined in further detail below) which I was satisfied provided for all impacts and risks to continue to be managed to ALARP and acceptable levels for the duration of the activity.

…

In specific relation to GHG emissions, I am satisfied that the implementation strategy is appropriate for the nature and scale of the activity and the GHG emissions arising from it. This is because it contains specific processes and measures which support implementation of the GHG emissions-relevant controls, and which will be used to continuously manage emissions to ALARP and acceptable levels for the life of the activity. Key features relevant to GHG emissions include:

…

b. The EP also describes the annual process for identification and implementation of emissions reduction opportunities on an ongoing basis (Section 7.2.4.3), which will be used to achieve continuous improvement and reduction to ALARP. The process is described in sufficient detail to assure its implementation; and provides clear commitment to reviewing opportunities for improvement over time.

…

d. In addition, specific measures for indirect GHG emissions management are included (Sections 6.7.6 and 7.5.2) which include the adoption of a corporate emissions abatement target to drive continuous improvement and reduction to ALARP. This is supported by the measures for review and improvement described earlier in this report.

Core submission of DEA

51 The Amended Originating Application sets out 16 detailed, in part overlapping, grounds of review supported by particulars. The essential contentions may be grouped and some grounds put to one side as derivative on the success of others.

52 Standing back from the intense focus of the grounds for a moment, the fundamental complaint is that Scope 3 GHG emissions are an indirect impact of the activity, the EP was required to provide for appropriate environmental performance outcomes (s 34(d)) and to have the statutory character of an environmental performance outcome, the acceptable level of impact must be identified and defined. The EP fails to do so for Scope 3 GHG emissions and therefore it was not open to NOPSEMA to be reasonably satisfied that the EP met the environment plan acceptance criteria: s 33(7)(a).

53 Lurking behind that contention are five “key decision points” as identified by Mr Young in oral submissions:

(1) Global GHG concentrations are an impact, not a potential impact.

(2) As an impact, the GHG concentrations must be evaluated. The content of the evaluation is set out at ss 21(5) and (6), including by the formulation of environmental performance outcomes and control measures.

(3) Woodside did not, and has not, defined the acceptable level of Scope 3 GHG concentrations (by which is meant emissions).

(4) Control measures must actually exist in order to be capable of being said to be used to manage environmental impacts and risks. Unspecified additional measures to be taken in the future cannot be said to be control measures.

(5) Environmental performance outcomes and environmental performance standards are concerned with the environmental outcomes and environmental performance, not about corporate outcomes or corporate performance. They are standards and outcomes set by reference to the environment.

54 With that understanding, the grounds are conveniently grouped as follows. The inadequacy of various control measures is addressed in grounds 1, 2, 6, 7, 11 and 12. Section 21(5) requires an environment plan to include details of the control measures that will be used to reduce the impacts and risks of the activity to as low as reasonably practicable and to an acceptable level and s 21(7) requires that the environment plan must set environmental performance standards for the control measures.

55 The inadequacy of the environmental performance standards is addressed in grounds 3, 8 and 13.

56 Grounds 4 and 9 contend that environmental performance outcomes EPO 11 and EPO 29 fail to comply with the requirement to set out the environmental performance outcomes for the activity by including measurement criteria to determine whether each environmental performance outcome is being met, contrary to s 21(7).

57 Grounds 5, 10 and 14 contend that the EP fails to establish measurement criteria that Woodside will use to determine whether each environmental performance outcome and environmental performance standard is being met, contrary to s 21(7).

58 That leaves grounds 15 and 16 which are parasitic on success of one or more of the prior grounds. Ground 15 is a catchall contention that the EP did not provide for appropriate environmental performance outcomes, environmental performance standards and measurement criteria concerning the environmental impacts and risks of GHG emissions because it did not satisfy the requirements for environmental performance outcomes, environmental performance standards and measurement criteria. Ground 16 contends that the decision of NOPSEMA was neither final nor certain. The point is: if a control measure leaves for later decision and determination by Woodside an important aspect of what measure will be applied to demonstrate that the environmental impacts and risks of GHG emissions will be reduced to as low as reasonably practicable and will be of an acceptable level, then it lacks legal certainty. DEA accepts that if the preceding grounds fail, grounds 15 and 16 fall away and do not require separate consideration.

Standing: a preliminary issue

Submissions

59 The application is framed pursuant to s 5 of the ADJR Act and ss 39B(1) and(1A)(c) of the Judiciary Act. Woodside contends that DEA does not have standing. NOPSEMA makes no standing submission. Pursuant to the former, DEA must be a person aggrieved by the Decision and pursuant to the latter, there must be a matter arising under laws made by the Parliament.

60 I was extensively addressed by Woodside that the relevant test for standing in either case is as set out by Gibbs J in Australian Conservation Foundation v Commonwealth (1979) 146 CLR 493 at 527, expanding on the reference to special damage in Boyce v Paddington Borough Council [1903] 1 Ch. 109. His Honour said:

[R]eference to “special damage” cannot be limited to actual pecuniary loss, and the words “peculiar to himself” do not mean that the plaintiff, and no one else, must have suffered damage. However, the expression “special damage peculiar to himself” in my opinion should be regarded as equivalent in meaning to “having a special interest in the subject matter of the action”.

61 His Honour continued at 530:

A person is not interested within the meaning of the rule, unless he is likely to gain some advantage, other than the satisfaction of righting a wrong, upholding a principle or winning a contest, if his action succeeds or to suffer some disadvantage, other than a sense of grievance or a debt for costs, if his action fails.

62 However, as Gibbs CJ subsequently observed in Onus v Alcoa of Australia Ltd [1981] HCA 50; (1981) 149 CLR 27 at 36, Australian Conservation does not lay down an inflexible rule: “the question what is a sufficient interest will vary according to the nature of the subject matter of the litigation”.

63 More recently, in Forestry Corporation of New South Wales v South East Forest Rescue Incorporated [2025] HCA 15; (2025) 99 ALJR 794, the Court (Gageler CJ, Edelman, Steward, Jagot and Beech-Jones JJ) at [11] stated:

The treatment of standing to enforce public rights, duties or obligations as an aspect of the jurisdiction or the power to invoke the jurisdiction vested in the relevant court is consistent with standing being subsumed within the concept of a "matter" in Ch III of the Constitution. However, leaving aside any constitutional restraints, whether satisfaction of the first limb of Boyce v Paddington Borough Council or the second limb as reformulated by this Court is either sufficient or necessary for a litigant to have standing to commence and maintain proceedings to enforce public rights, duties or obligations is subject to a consideration of the statutory scheme creating and regulating those rights, duties or obligations.

64 The Constitutional requirement of matter has two elements: subject matter and a concrete or justiciable controversy: Hobart International Airport Pty Ltd v Clarence City Council [2022] HCA 5; (2022) 276 CLR 519 at [26]. There is no doubt that the first element is satisfied. The power of NOPSEMA to accept the EP is conferred by the Regulations and is constrained thereby. As to the second, “there can be no matter within the meaning of [ss 75 and 76 of the Constitution] unless there is some immediate right, duty or liability to be established by the determination of the Court”: Hobart at [29], citing Re Judiciary (1921) 29 CLR 257 at 265. This does not however, as demonstrated by Hobart, require that for declaratory relief an applicant must identify an immediate right, duty or liability to be secured in its favour. Why that is so was explained by Gageler and Gleeson JJ in Hobart at [65] and [69]:

Though the expression of standing has been variously in terms of a "sufficient interest", a "sufficient material interest", a "special interest" or a "real interest", the conception of standing developed through that body of case law has been consistent. That conception of standing has involved recognition that a person who does not claim to have a legal right or equitable interest to be vindicated by a declaration or other order that would resolve a controversy about a right or obligation may yet have a material interest in seeking the order. In this context, an interest will be "material" if the person "is likely to gain some advantage, other than the satisfaction of righting a wrong, upholding a principle or winning a contest, if [the order is made] or to suffer some disadvantage, other than a sense of grievance or a debt for costs, if [the order is not made]". Depending on the totality of the circumstances, the material interest that the person has in seeking the order may be sufficient to justify a court entertaining the proceeding in which the order is sought.

Where a person is shown to have a material interest in seeking a declaration or other order, considerations bearing on the public interest can contribute to the sufficiency of that material interest to justify a court entertaining the proceeding in which the order is sought. A weighty public interest consideration, where it is applicable, is that the person's interest is within the scope of interests sought to be protected or advanced by the exercise of a statutory power or executive authority through which the right or obligation in controversy has come into existence. Another weighty consideration, where it is applicable, is that a party by or against whom the right or obligation is held and against whom the declaration is sought is a public authority or an executive government, which "acts, or is supposed to act, not according to standards of private interest, but in the public interest".

65 In my view, DEA has standing in this proceeding by reference to: the overarching nature of what it does, its objects, activities and interests; the engagement by DEA in pursing those activities and interests in the subject matter of NOPSEMA’s decision (which has climate change ramifications); and DEA was recognised as a relevant person by Woodside for the purposes of s 25(1)(d). I explain why.

66 I find the following facts based on the unchallenged evidence of Ms Wylie, from uncontroversial documents in the court book, the statement of reasons and the EP.

67 As previously observed, DEA represents the interests of medical professionals who are at the front line of dealing with the adverse health impacts of climate change as an existential threat to the environment.

68 DEA’s Constitution at clause 2 lists objects of particular relevance to the relief it seeks: particularly, to conserve and restore the natural environment and to alert doctors and the public on the health effects of environmental degradation. In support of its objects, DEA undertakes a range of activities including giving evidence and making submissions to public bodies, such as the Australian Senate Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Inquiry into the Climate Change Amendment (Duty Of Care and Intergenerational Climate Equity) Bill 2023 and the Australian House of Representatives Standing Committee on Climate Change, Energy, Environment And Water inquiry into the transition to electric vehicles. It has developed climate change resources for medical professionals, such as the Hospital Sustainability Project Tracker, which has been incorporated into pilot programs in the Northern Territory by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. It organises conferences and webinars and is consulted by various governments; an example being the inquiry into the National Health and Climate Strategy in 2023. DEA is a member of the Australian Government’s Climate and Health Expert Advisory Group.

69 DEA brings this proceeding in the public interest in that it contends that climate change, driven by GHG emissions, is a material threat to public health. In consequence it is concerned about the approval of projects that contribute or may contribute to the emission of GHG which has an observed relationship to adverse health impacts, physical and mental.

70 To these objects, DEA engaged with Woodside at an early stage in relation to the drafting of various iterations of environment plans for the activity. On 19 December 2023, DEA corresponded with Woodside about the project. It stated that its interests, functions and activities may be affected by the project and sought to be a consulted as a “relevant person” within s 25(1)(d) and or (e). In that correspondence DEA stated, inter alia:

[DEA] is an organisation of medical doctors that recognises the importance of protecting human health through care of the environment with a focus on the issues and events relevant in Western Australia.

[DEA] was formed in 2001, and are guided by the vision ‘Healthy Planet, Healthy People’.

Based on the latest evidence we demonstrate the important health benefits of clean air and water, biodiverse natural places, stable climates and sustainable health care systems.

We raise the alarm and act when public health is threatened by environmental problems such as climate change, air pollution, fossil fuel impacts and deforestation.

We are considered the leading medical organisation in Australia for providing accurate scientific information on the relationships between climate change, other environmental harms, and health.

We educate and alert colleagues, patients, the public, business and industry, and politicians to understand:

• The requirement for a healthy natural environment for good human health.

• The need to prevent and redress environmental degradation locally and globally.

• The need for sustainable development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising future generations.

• The use of the best available scientific evidence as the basis for decisions, and the precautionary principle where the evidence is unclear.

[DEA] is active in areas of publication, education, submissions, research, and advocacy. For examples of these and further information on our interest and activities we refer you to our website https://dev.dea.org.au/.

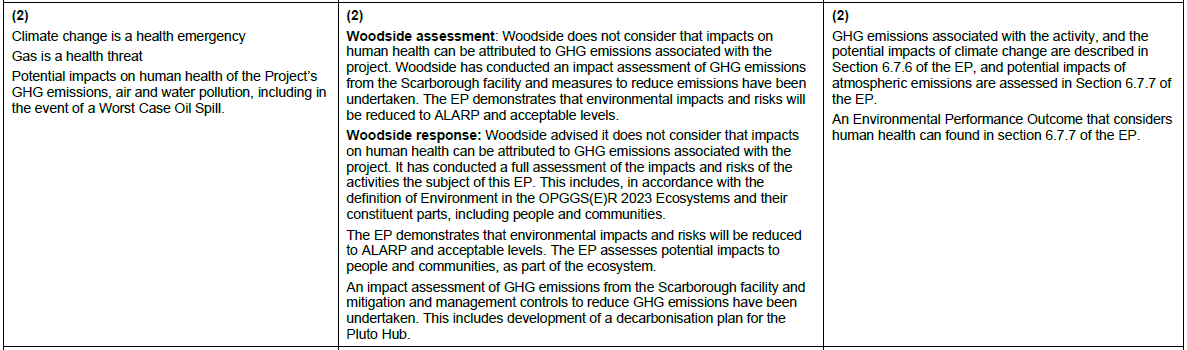

71 Woodside did consult with DEA and accepted that it had demonstrated “an interest with the potential risks and impacts associated with planned activities in accordance with the intended outcome of consultation”: EP Appendix F, page 43. A detailed summary of the consultation between DEA and Woodside and the outcome is set out in Appendix F at pages 416 – 453 of the EP. The consultation occurred between August 2023 and October 2024. To an extent, the views of DEA were included in the EP as demonstrated in the table commencing at page 437. In particular there is this:

72 On those facts, it is surprising that Woodside now contends that DEA does not have standing to challenge the lawfulness of the outcome of the consultation process. Nonetheless, its submission must be addressed on merit.

73 Woodside submits that engaging in consultation, even making representations, is insufficient and places particular reliance on Australian Conservation at 525. However, Australian Conservation concerned a radically different statutory scheme pursuant to the Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974 (Cth) and certain administrative procedures through which the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) had made submissions about a proposal. The salient point made by Gibbs J at 525 was that by making a submission the ACF did not thereby acquire any right “to ensure that [its] comments were taken into account in the final environmental impact statement”. Immediately, the clear distinction with the scheme of the Regulations is apparent. Here, Woodside was bound by s 25 to consult in the preparation of the EP and to include within it a report as to the outcome of each consultation, including an assessment of the merit of any objection or claim about the adverse impact of the activity together with its response, or proposed response, if any: s 24. Understood in that way, the statutory scheme is the foundation for the justiciable controversy between DEA, Woodside and NOPSEMA. It is not necessary for DEA to have a legal or equitable right or interest if it has a material interest in declaratory relief that the EP is void and of no effect.