FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Al Muderis v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (Trial Judgment) [2025] FCA 909

File number(s): | NSD 917 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | ABRAHAM J |

Date of judgment: | 8 August 2025 |

Catchwords: | DEFAMATION – where the applicant is a well-known orthopaedic surgeon – where applicant sues in defamation over a 60 Minutes program broadcast by Nine Network – where publications televised, published online and in print – where 75 defamatory imputations alleged DEFAMATION – defences – substantial truth – justification defence – s 25 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) – where imputations conveyed may be summarised into 9 stings – imputations involving improper sales tactic, misleading osseointegration patients, poor patient selection, negligent post-operative care, illegal procedures in the United States, prioritising money, fame, reputation and numbers, mistreating staff, lying to journalists, unethical conduct case DEFAMATION – defences – contextual truth – s 26 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) – some imputations established as substantially true – whether imputations not substantially true or where there is no truth defence do not further harm the applicant’s reputation – contextual truth considers the facts, matters and circumstances relied upon to support the substantial truth of the contextual imputations rather than the terms of the imputation – defence established

DEFAMATION – defences – public interest – s 29A of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) – consideration of legislative construction – whether the respondents reasonably believed the matters published was in the public interest – flaws in a matter will not necessarily preclude the defence – inform prospective patients about a cohort of the applicant’s patients who had negative experiences – defence established EVIDENCE – observation as to fact-finding, onus and standards of proof – inferences in relation to the failure of a party to call a particular witness: Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298 – principles in Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 (HL) – consideration of contemporaneous documents – consideration of standard practice and inferences that may be drawn – consideration of the impact of mental health issues and trauma on the reliability of evidence |

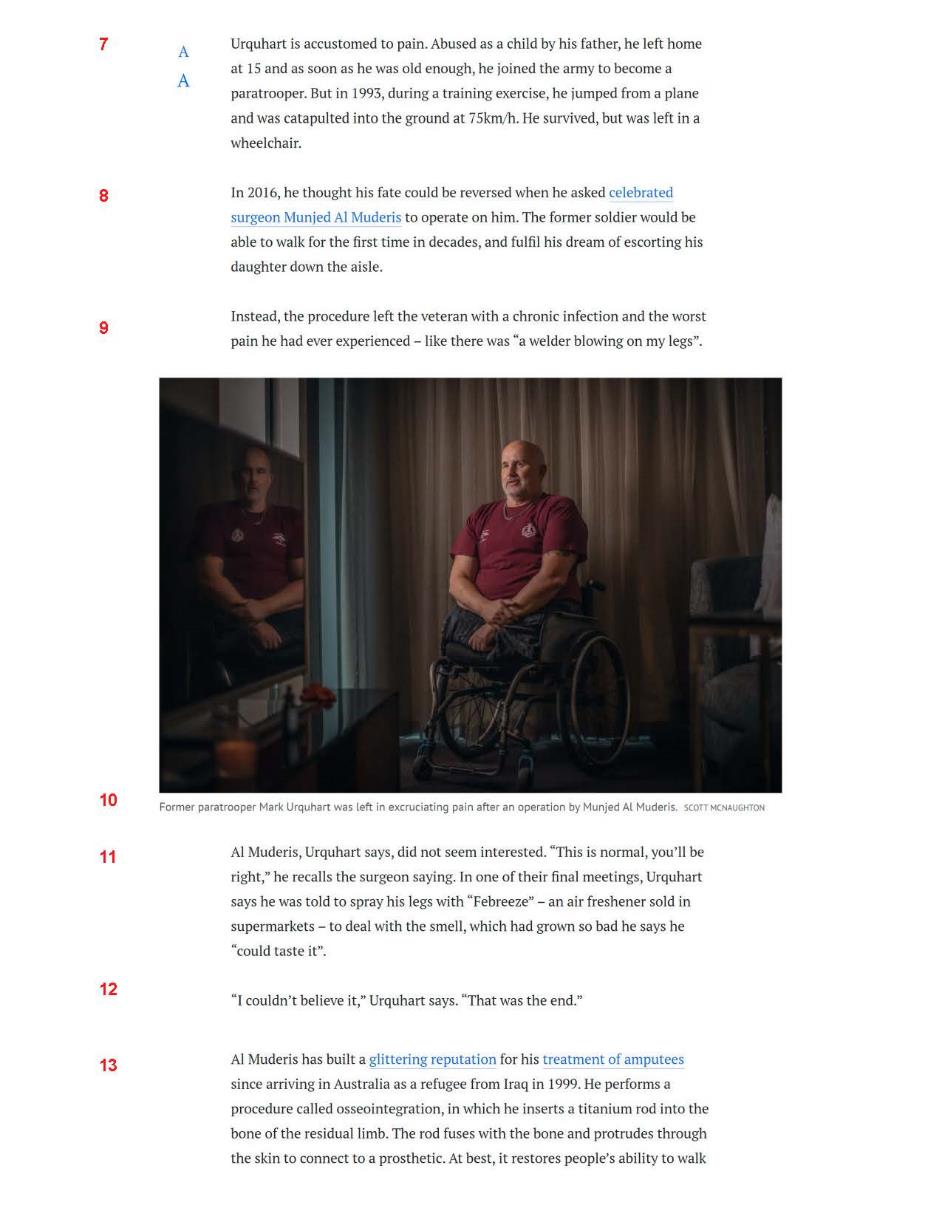

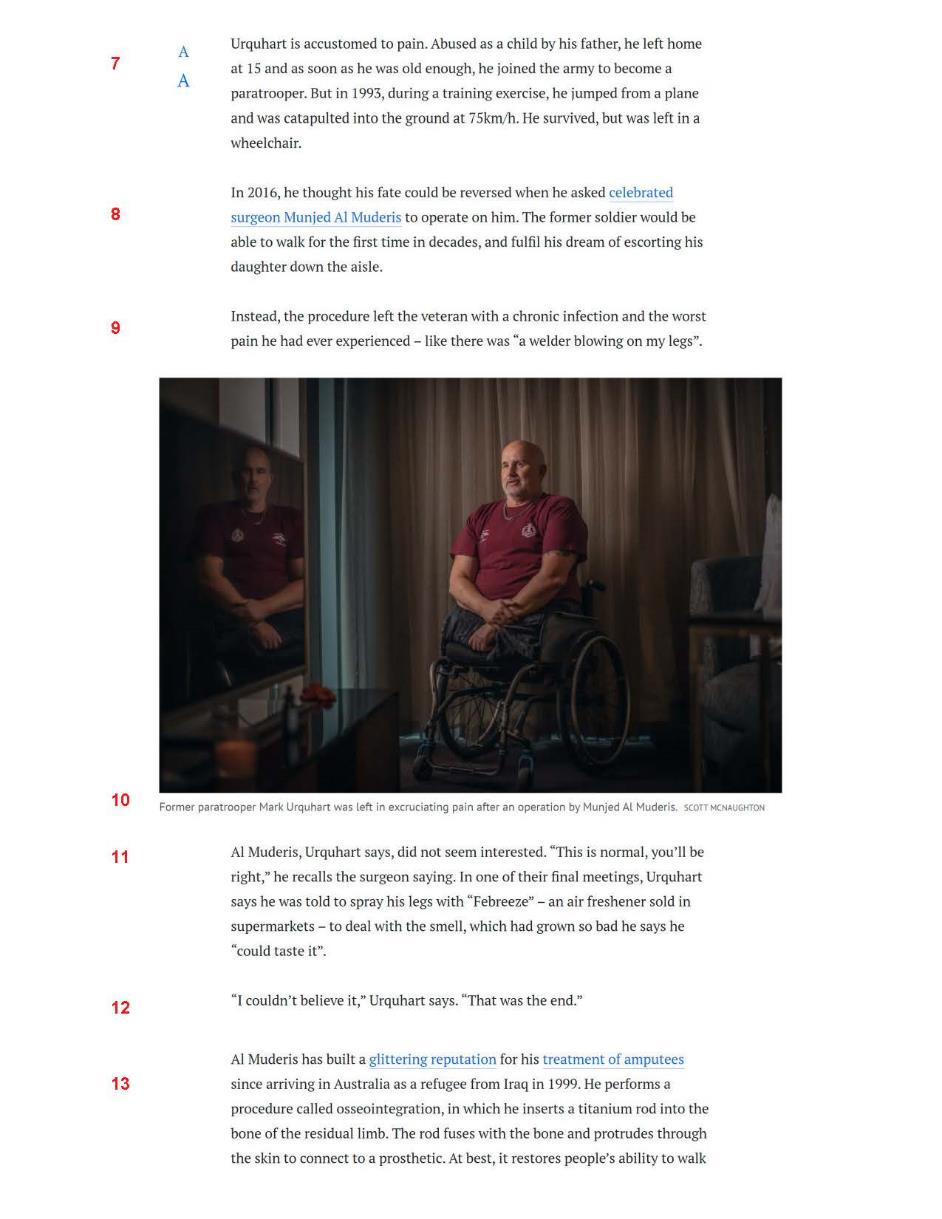

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, Australian Consumer Law, ss 18, 21(4), 33, 54 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 63, 64, 79, 126K, 140, 164(1), 174 Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) ss 3(b), 4, 8, 25, 26, 29A, 30(4), 31 Defamation Act 1974 (NSW) (repealed) s 16 Defamation Act 2013 (UK) s 1, 4 Fla Stat § 456.065 Ky Rev Stat Ann § 311.560 (2017) La Rev Stat Ann § 37:1271 (2018) Medical Practice Act of 1987, 225 Ill Comp Stat 60/3, 60/3.5, 60/50, 60/59 (2017) NY Education Law §§ 6512, 6520-6521 (2018) NY Public Health Law (2018) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 23.13 Explanatory Note, Defamation Amendment Bill 2020 (NSW) |

Cases cited: | Allen v Tobias [1958] HCA 13; (1958) 98 CLR 367 Allianz Australia Insurance Limited v Delor Vue Apartments CTS 39788 [2021] FCAFC 121; (2021) 287 FCR 388 Allied Pastoral Holdings Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1983] 1 NSWLR 1; (1983) 44 ALR 607 Al Muderis v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited [2023] FCA 1623 Al Muderis v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (No 2) [2024] FCA 136 Ange v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd & Ors [2010] NSWSC 645 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Delta Automation Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 880 Axent Holdings Pty Ltd t/a Axent Global v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1373 Banks v Cadwalladr [2019] EWHC 3451 (QB) Banks v Cadwalladr [2022] EWHC 1417 (QB); [2022] 1 WLR 5236 Banks v Cadwalladr [2023] EWCA Civ 219; [2023] 3 WLR 167 Banque Commerciale S.A., En Liquidation v Akhil Holdings Ltd [1990] HCA 11; (1990) 169 CLR 279 Bathurst Regional Council v Local Government Financial Services Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] FCA 1200 Besser v Kermode [2011] NSWCA 174; (2011) 81 NSWLR 157 Betfair Pty Limited v Racing New South Wales [2010] FCAFC 133; (2010) 189 FCR 356 Boyd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1980] 2 NSWLR 449 Bridges v Pelly [2001] NSWCA 31 Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; (1938) 60 CLR 336 Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 Capic v Ford Motor Company of Australia Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 715 CCL Secure Pty Ltd v Berry [2019] FCAFC 81 Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd [1998] HCA 37; (1998) 193 CLR 519 Channel Seven Sydney Pty Ltd v Mahommed [2010] NSWCA 335; (2010) 278 ALR 232 Chau v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2021] FCA 44; (2021) 386 ALR 36 Chau v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 185 Commercial Union Assurance Company of Australia Ltd v Ferrcom Pty Ltd (1991) 22 NSWLR 389 Connor v Blacktown District Hospital [1971] 1 NSWLR 713 Cubillo v Commonwealth (No 2) [2000] FCA 1084; (2000) 103 FCR 1 Dasreef Pty Ltd v Hawchar [2011] HCA 21; (2011) 243 CLR 588 Deeming v Pesutto (No 3) [2024] FCA 1430 Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Shi [2021] HCA 22; (2021) 273 CLR 235 Drummoyne Municipal Council v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1990) 21 NSWLR 135 Duma v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No 3) [2023] FCA 47 Edwards v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 422 Elliott v The Queen [2007] HCA 51; (2007) 234 CLR 38 ET-China.com International Holdings Ltd v Cheung [2021] NSWCA 24 Fairfax Digital Australia & New Zealand Pty Ltd v Kazal [2018] NSWCA 77; (2018) 97 NSWLR 547 Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Gayle [2019] NSWCA 172; (2019) 100 NSWLR 155 Farquhar v Bottom [1980] 2 NSWLR 380 Favell v Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 52; (2005) 219 CLR 165 Flood v Times Newspapers Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 804; [2011] 1 WLR 153 Fonterra Brands (Australia) Pty Ltd v Viropoulos (No 3) [2015] FCA 1050 Ford v Narrabri Shire Council [2022] NSWPIC 119 Fox v Percy [2003] HCA 22; (2003) 214 CLR 118 GLJ v The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore [2023] HCA 32; (2023) 97 ALJR 857 Greek Herald Pty Ltd v Nikolopoulos & Ors [2002] NSWCA 41; (2002) 54 NSWLR 165 Griffiths v TUI (UK) Ltd [2023] UKSC 48; (2023) 3 WLR 1204 Habib v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2010] NSWCA 34; (2010) 76 NSWLR 299 Haddon v Forsyth [2011] NSWSC 123 Hanson v Burston [2023] FCAFC 124; (2023) 413 ALR 299 Harvey v John Fairfax Pty Ltd [2005] NSWCA 255 Herron v HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 68; (2022) 292 FCR 336 Hockey v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited [2015] FCA 652; (2015) 237 FCR 33 House v King [1936] HCA 40; (1936) 55 CLR 499 Hughes v St Barbara Mines Ltd (No 4) [2010] WASC 160 John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Blake [2001] NSWCA 434; (2001) 53 NSWLR 541 Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 9; (1959) 101 CLR 298 Katsilis v Broken Hill Pty Co Ltd (1977) 18 ALR 181 Kazal v Thunder Studios Inc (California) [2023] FCAFC 174 Lehrmann v Network Ten Pty Ltd (Trial Judgment) [2024] FCA 369 Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 M v The Queen [1994] HCA 63; (1994) 181 CLR 487 Maisel v Financial Times Limited (1915) 112 LT 953; 84 LJKB 2145 Masterton Homes Pty Ltd v Palm Assets Pty Ltd [2009] NSWCA 234; (2009) 261 ALR 382 Mirror Newspapers Ltd v World Hosts Pty Ltd [1979] HCA 3; (1979) 141 CLR 632 Morsman (by his next friend Bampton) v State of Victoria (Department of Education and Training) [2020] FCA 763 Murdoch v Private Media Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1275 Nassif v Seven Network (Operations) Ltd [2021] FCA 1286 Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Rush [2020] FCAFC 115; (2020) 380 ALR 432 Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Weatherup [2017] QCA 70; [2018] 1 Qd R 19 Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd [1992] HCA 66; (1992) 110 ALR 449 O’Brien v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2017] NSWCA 338; (2017) 97 NSWLR 1 Oneflare Pty Ltd v Chernih [2017] NSWCA 195 Palios Meegan & Nicholson Holdings Pty Ltd v Shore [2010] SASCFC 21; (2010) 108 SASR 31 Palmer v McGowen [2021] FCA 430 Palmer v McGowan (No 5) [2022] FCA 893 Palram Australia Pty Ltd v Rees [2013] FCA 649 Phelan v Melbourne Health [2019] VSCA 205 Project Blue Sky v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 355 Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton [2009] HCA 16; (2009) 238 CLR 460 Reynolds v Times Newspapers Ltd [2001] 2 AC 127 Reifek v McElroy [1965] HCA 46; (1965) 112 CLR 517 Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No 41) [2023] FCA 555; (2023) 417 ALR 267 Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 67 Rofe v Smith’s Newspapers Ltd (1924) 25 SR (NSW) 4 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 357 Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 496 Russell v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2023] FCA 1223 Sampson in his Capacity as Trustee for the Bankrupt Estate of Tannous v Tannous [2022] FCA 1427 Schellenberg v Tunnel Holdings Pty Ltd [2000] HCA 18; (2000) 200 CLR 121 Schiff v Nine Network News Pty Ltd (No 2) [2022] FCA 1120 Seven Network (Operations) Limited v Greiss [2024] FCAFC 162 Seymour v Australian Broadcasting Commission (1977) 19 NSWLR 219 Slim v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1968] 2 QB 157 State of New South Wales v Wraydeh [2019] NSWCA 192 Sutherland v Stopes [1925] AC 47 SZTAL v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 34; (2017) 262 CLR 362 The Ophelia [1916] 2 AC 206 Thomson v STX Pan Ocean Co Ltd [2012] FCAFC 15 Trkulja v Google Inc LLC [2010] VSC 226 Trkulja v Google LLC [2018] HCA 25; (2018) 263 CLR 149 Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2018] FCAFC 155; (2018) 266 FCR 631 V’landys v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2021] FCA 500 V’landys v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2023] FCAFC 80 Volonakis v Erceg [2019] NSWSC 1875 Wong v National Australia Bank Ltd [2022] FCAFC 155 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Other Federal Jurisdiction |

Number of paragraphs: | 2958 |

Date of last submission/s: | 21 June 2024 |

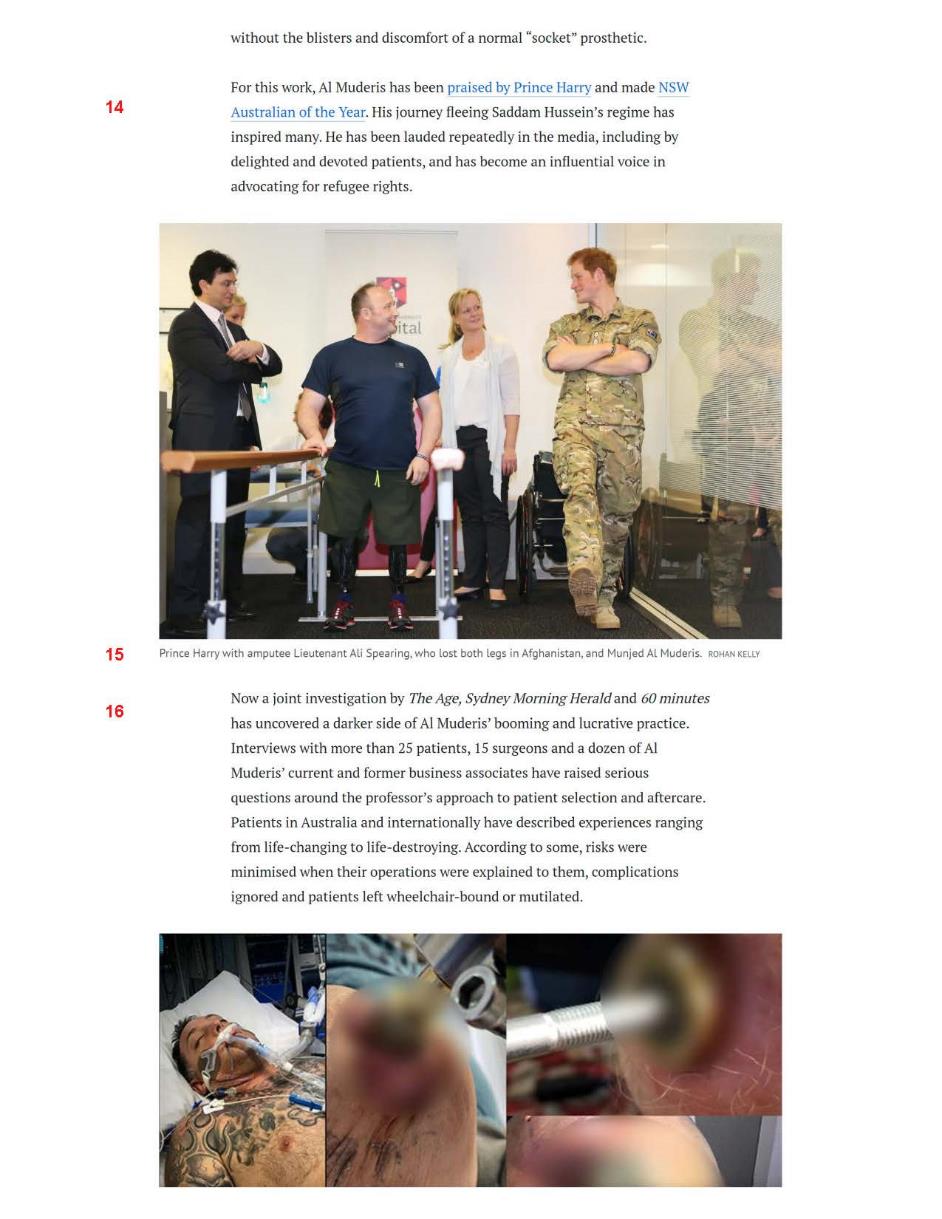

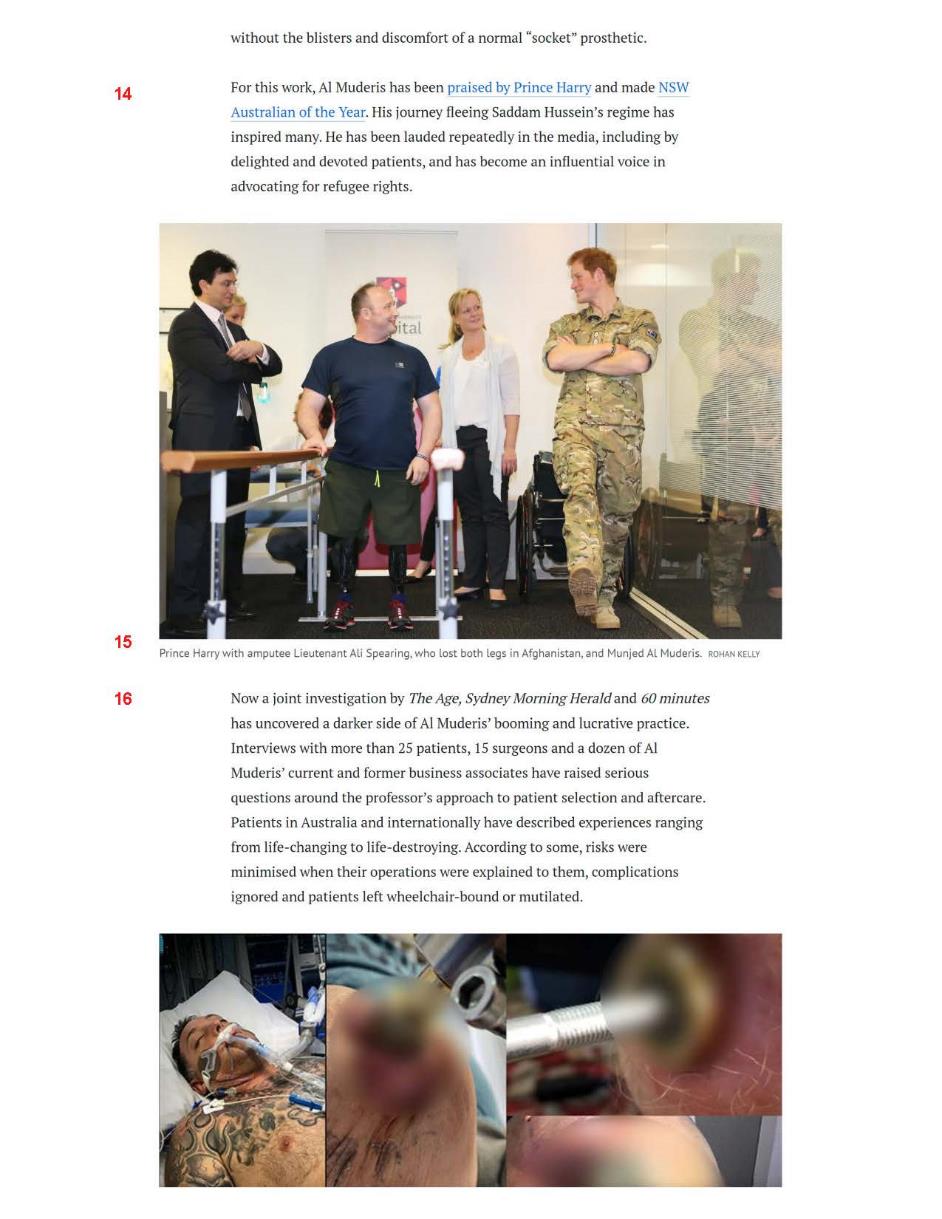

Date of hearing: | 4–5, 8, 11–13, 19–22, 25–29 September 2023, 3–6, 9–13 October 2023, 4–8, 11–15, 18–22, 25–28 March 2024, 2–5, 8–11 April 2024, 7–10, 13–16, 23 May 2024, 3–6, 13 June 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Ms S Chrysanthou SC, Mr N Olson and Mr T Smartt |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | HWL Ebsworth Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Dr M Collins AM KC, Mr D Roche SC, Ms M Marcus, Mr M Mukerjea and Ms C Roberts |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Thomson Geer Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 917 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MUNJED AL MUDERIS Applicant | |

AND: | NINE NETWORK AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED First Respondent FAIRFAX MEDIA PUBLICATIONS PTY LIMITED Second Respondent THE AGE COMPANY PTY LIMITED (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | ABRAHAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 August 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

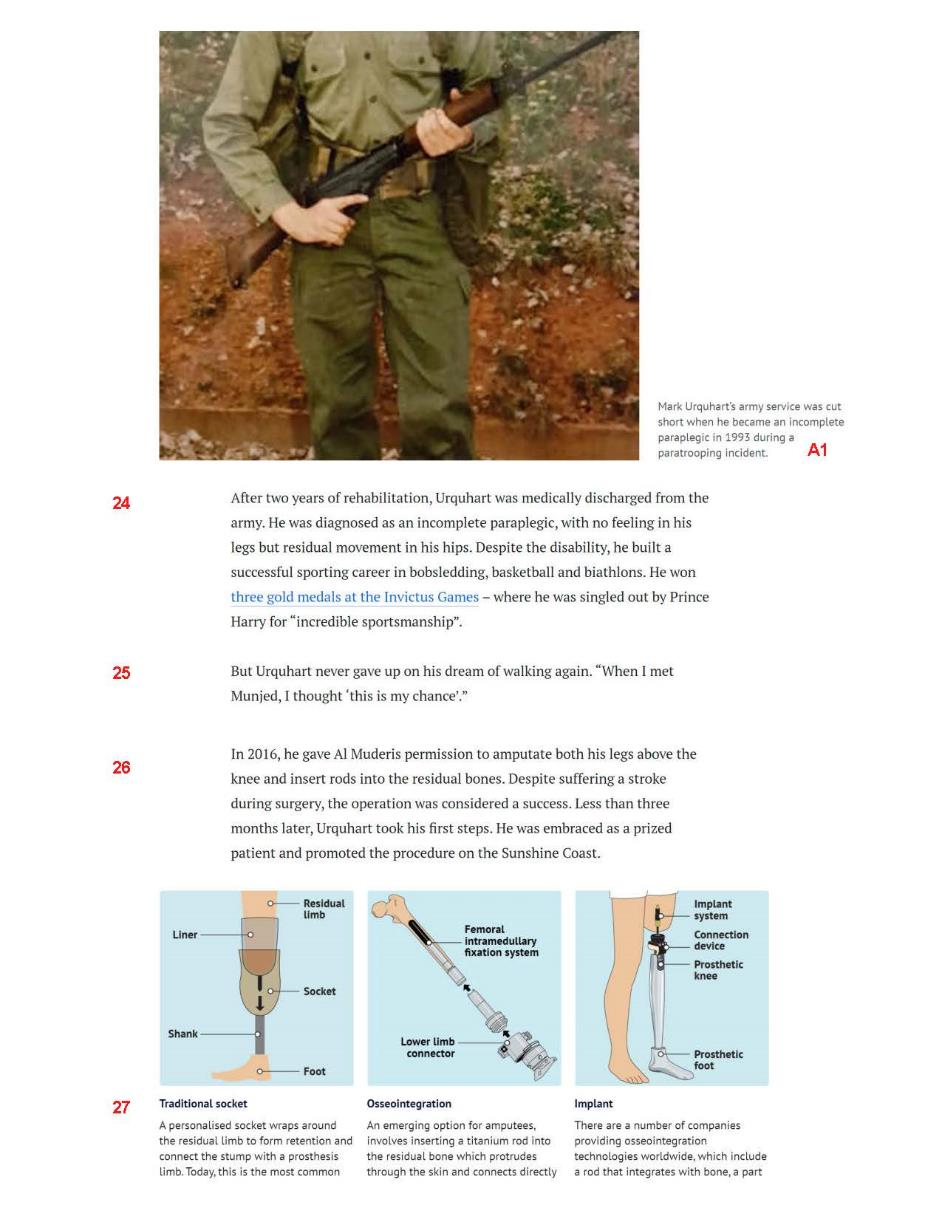

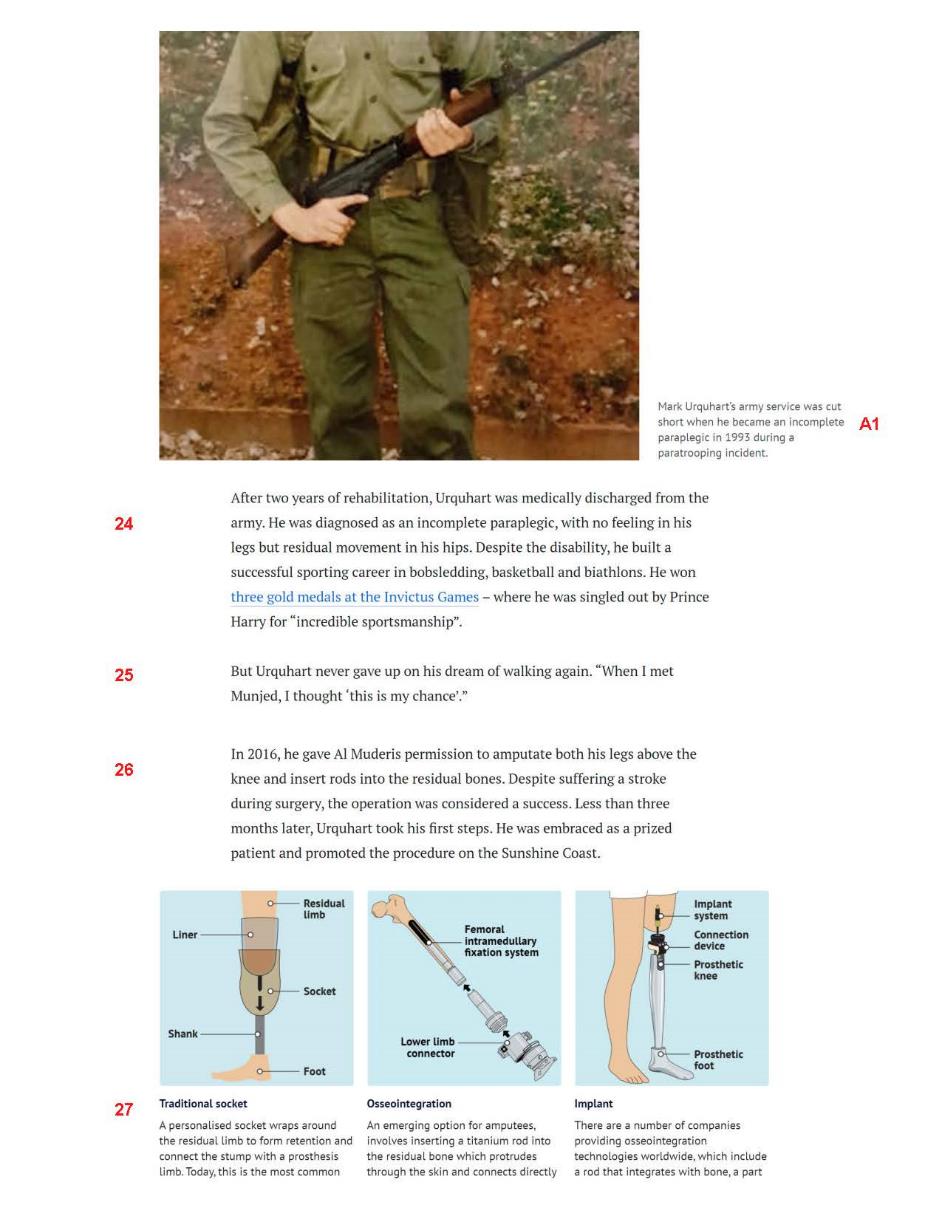

1. The application is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

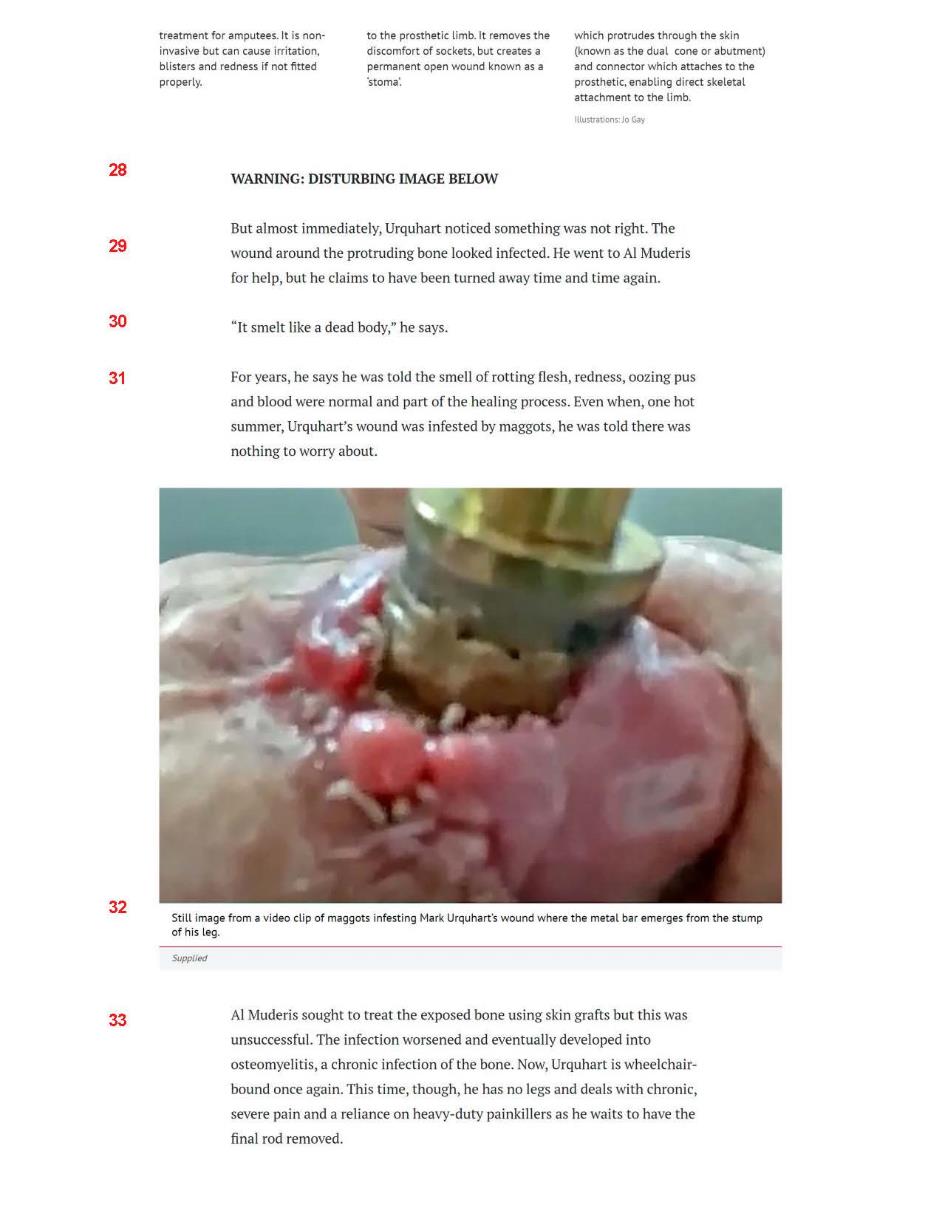

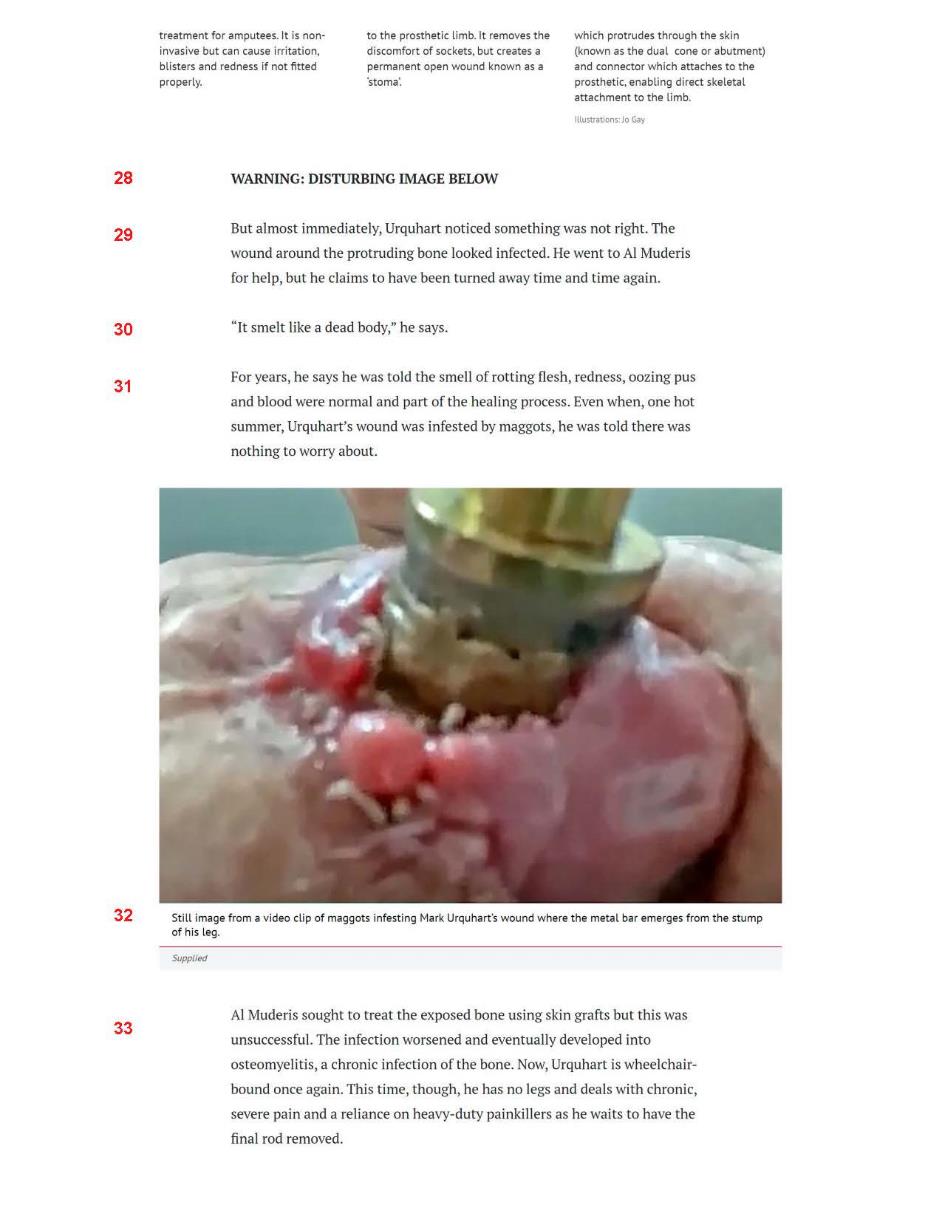

[1] | |

[1] | |

[11] | |

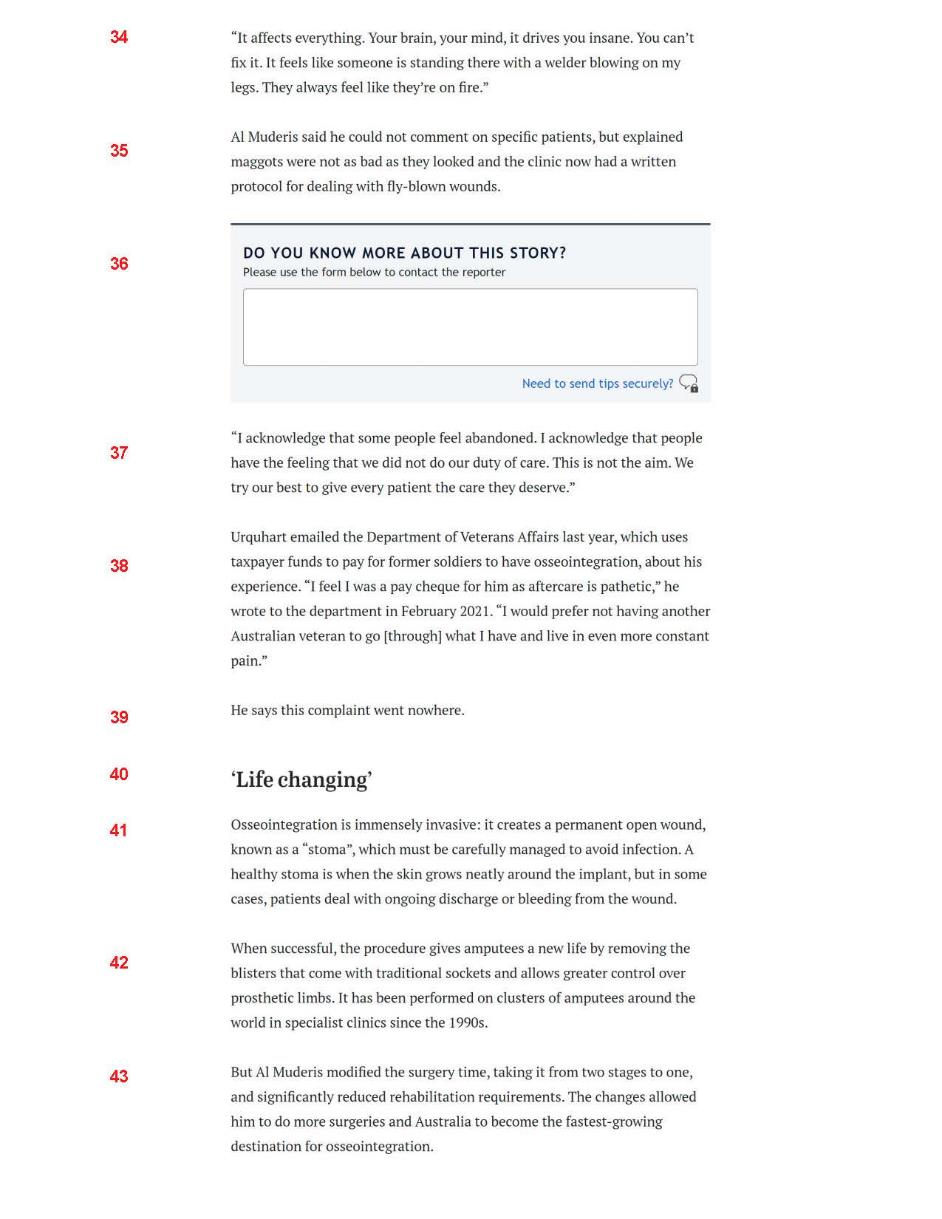

[10] | |

[22] | |

[31] | |

[31] | |

[32] | |

[33] | |

[34] | |

[34] | |

[35] | |

[35] | |

[36] | |

[42] | |

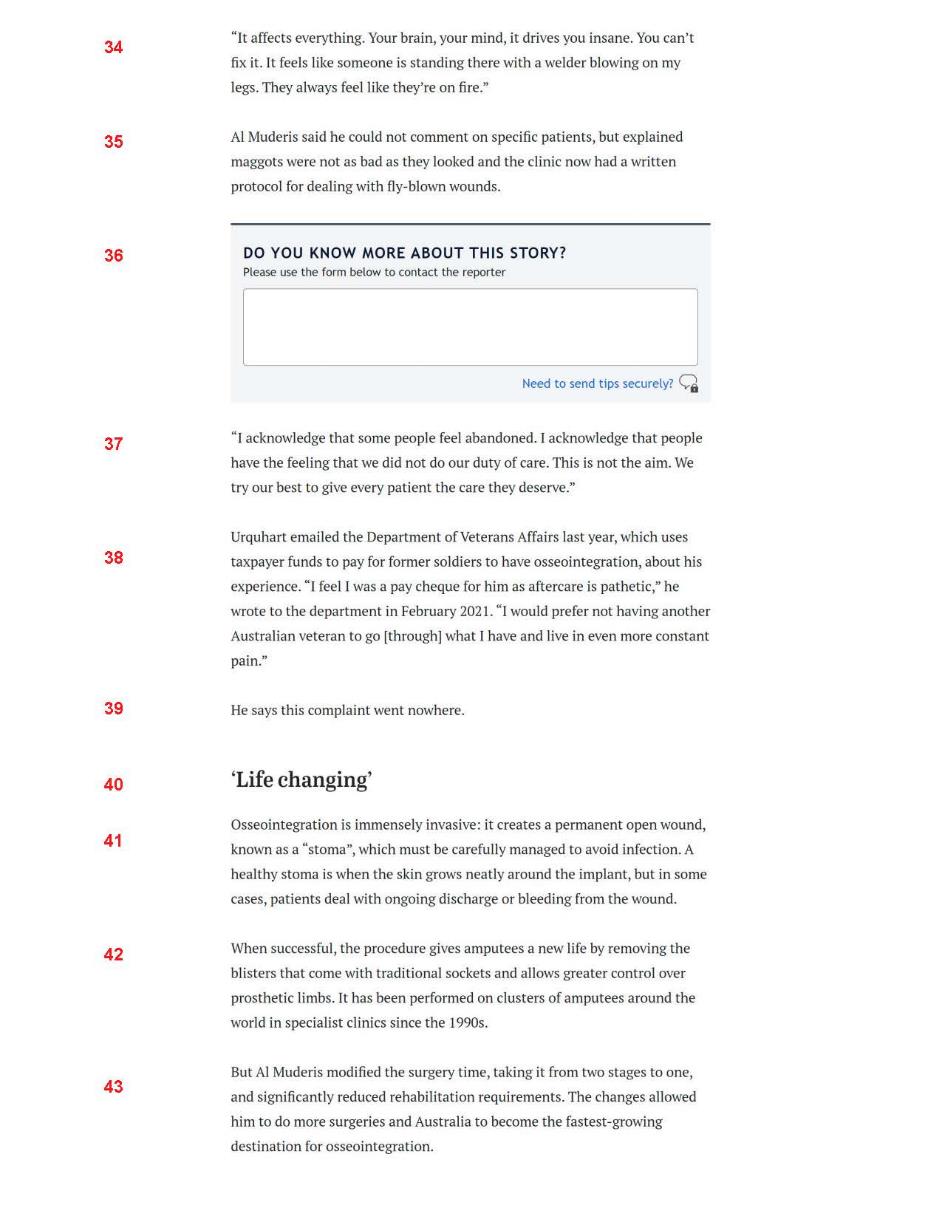

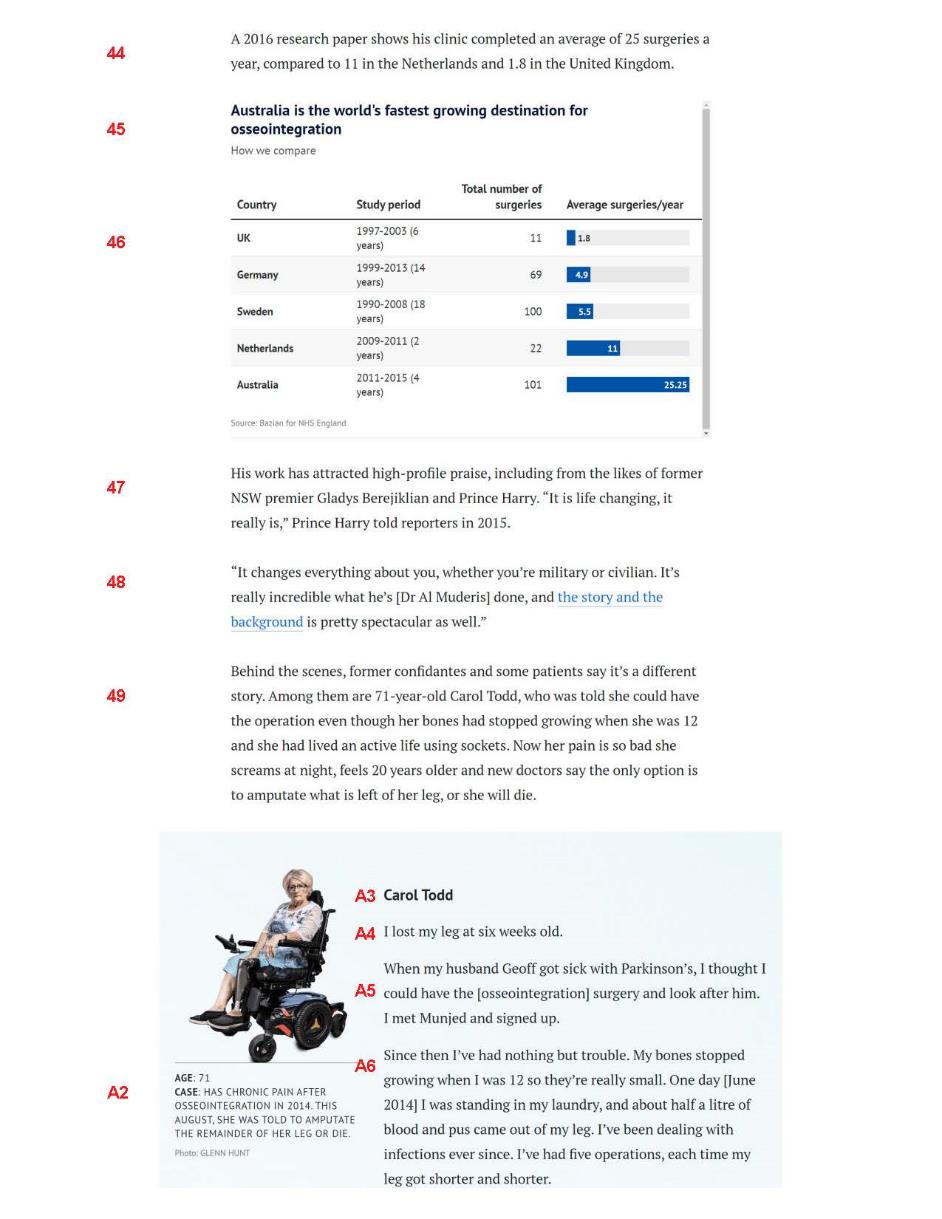

[48] | |

[59] | |

[78] | |

[83] | |

[90] | |

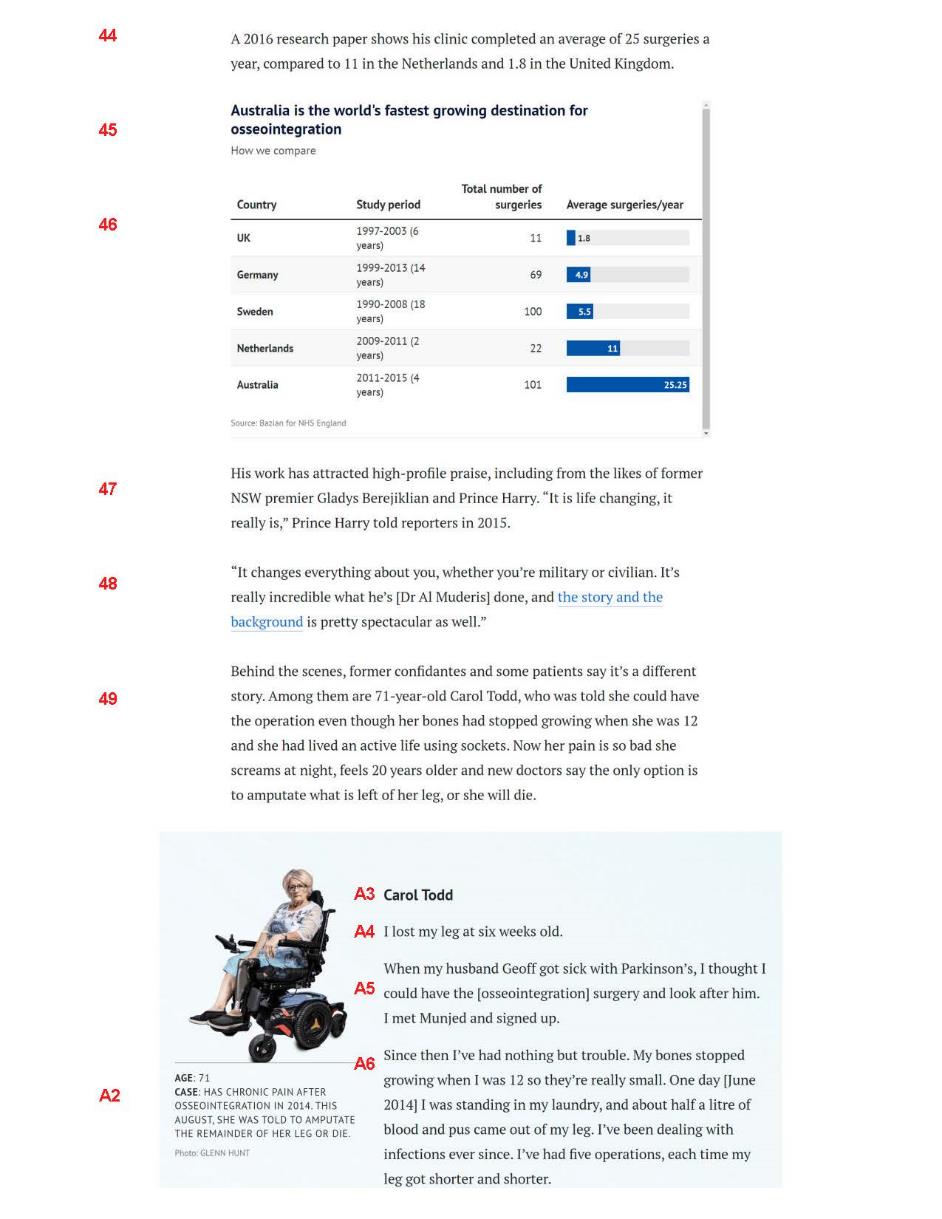

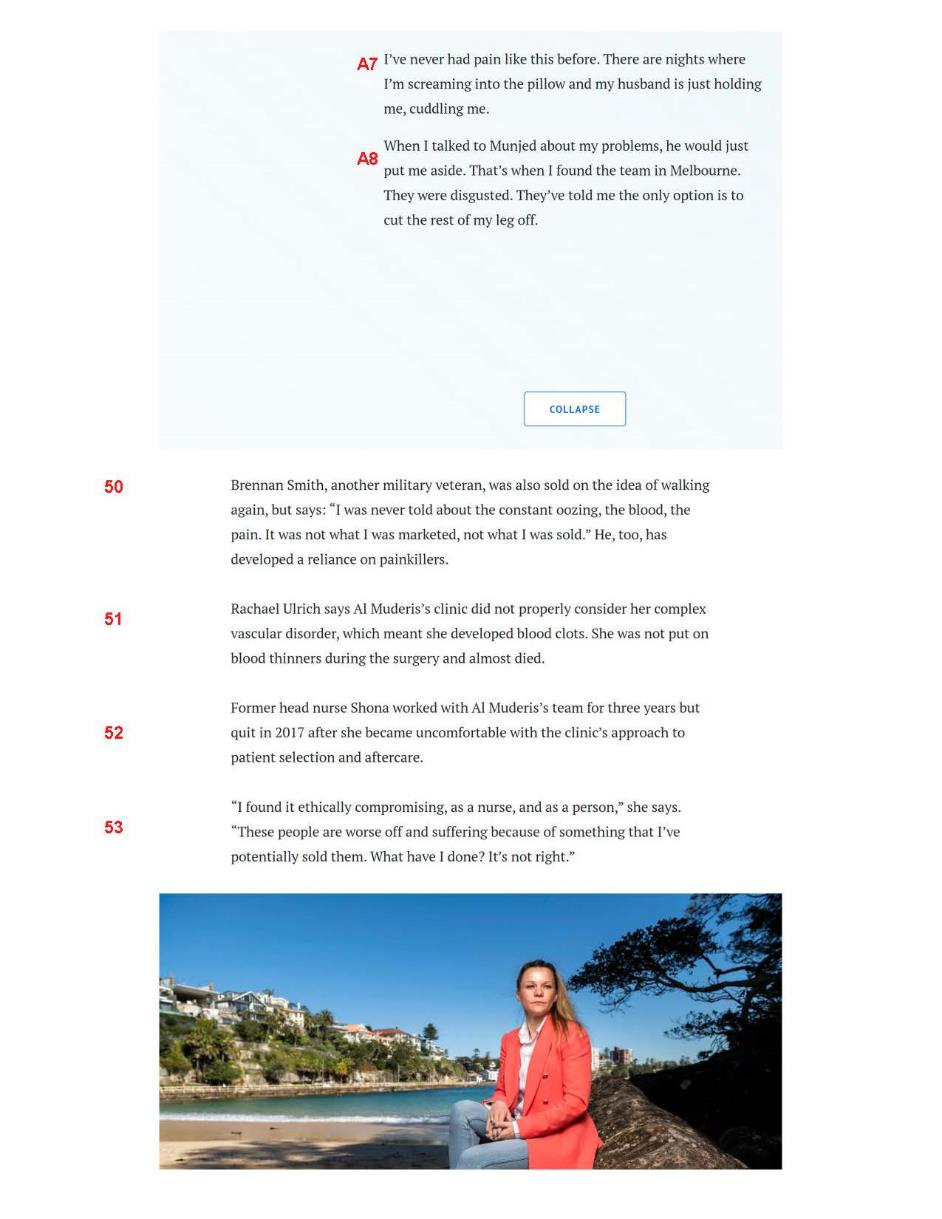

[100] | |

Section 4 — Meaning of “negligence” and “unethical” in the imputations | [101] |

[101] | |

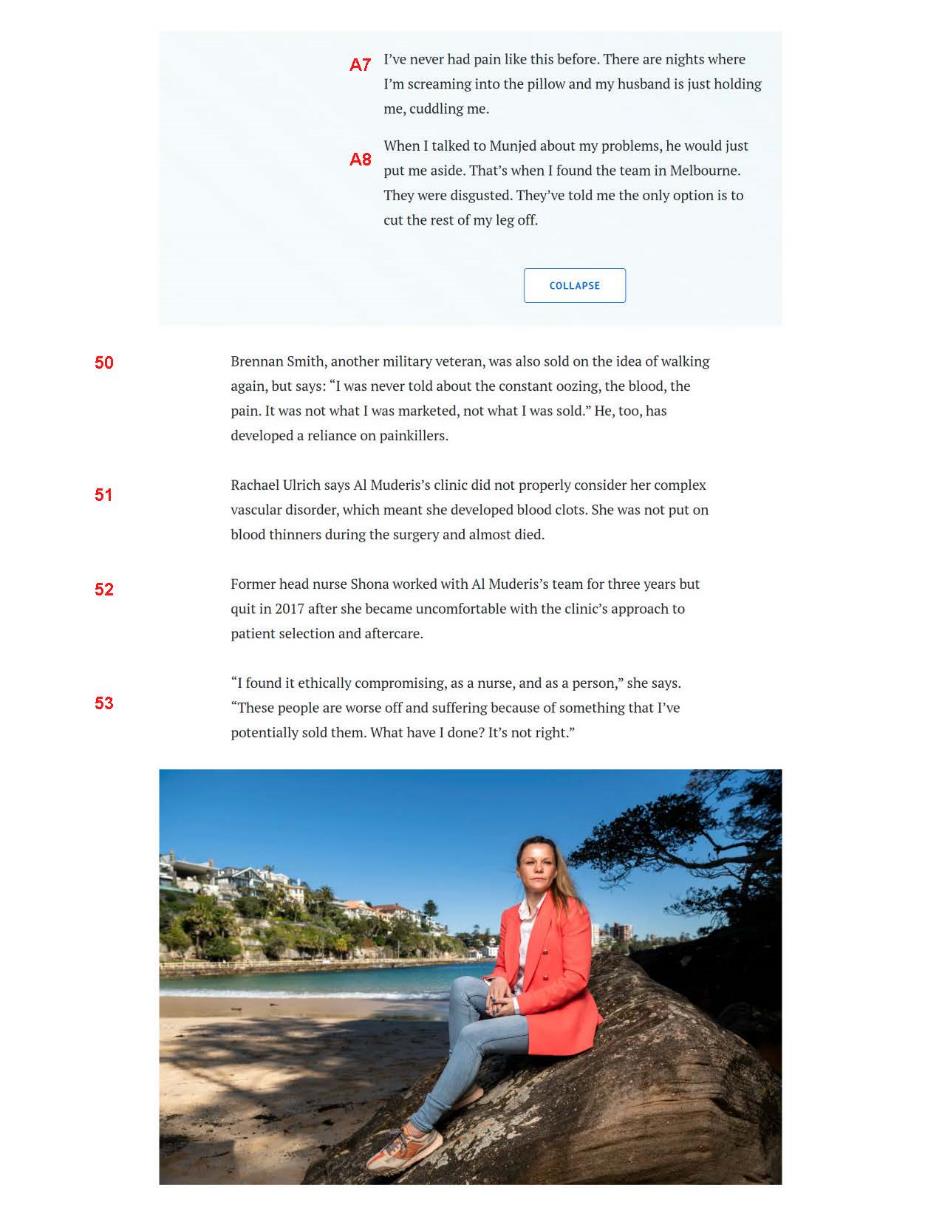

[108] | |

[110] | |

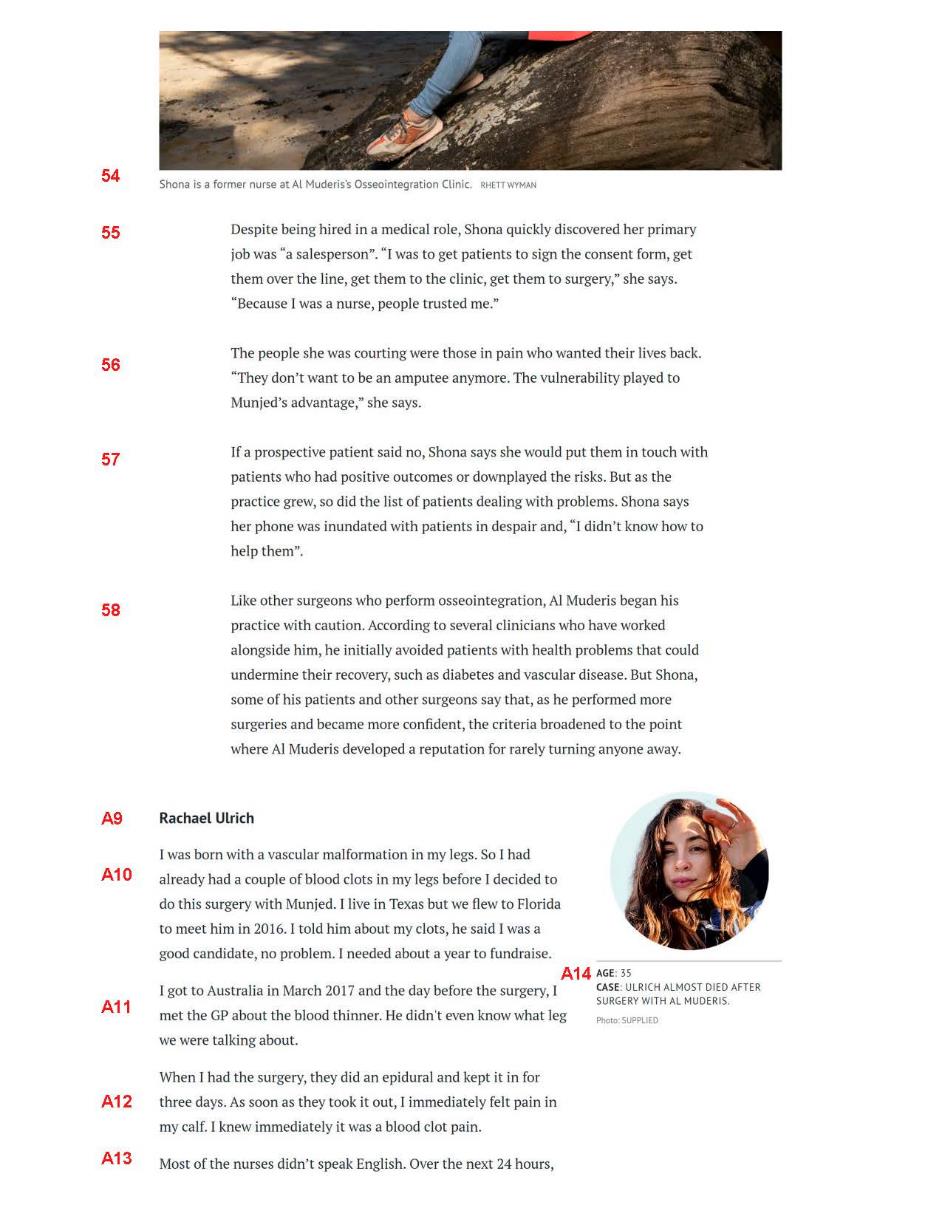

[110] | |

[122] | |

[134] | |

[153] | |

[165] | |

[179] | |

[184] | |

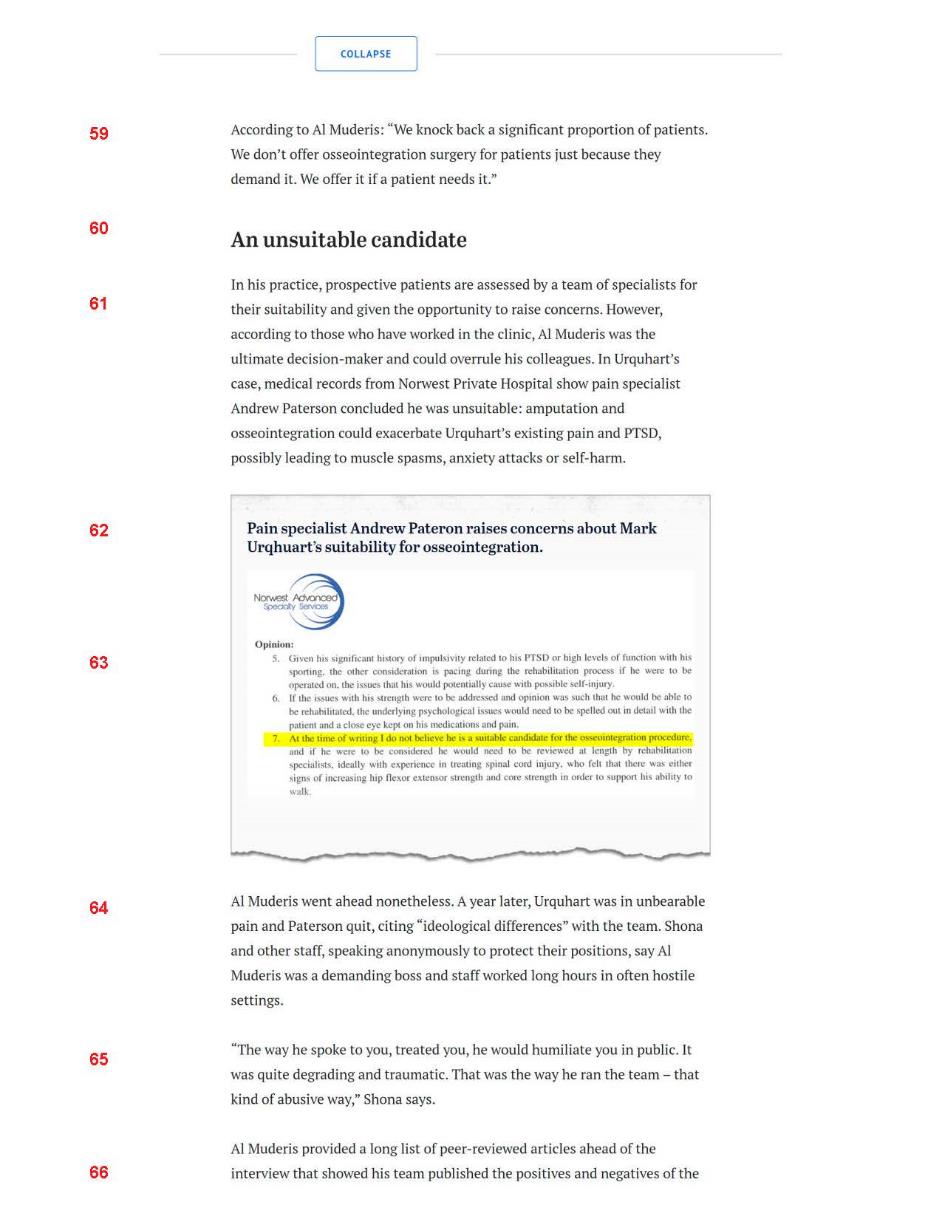

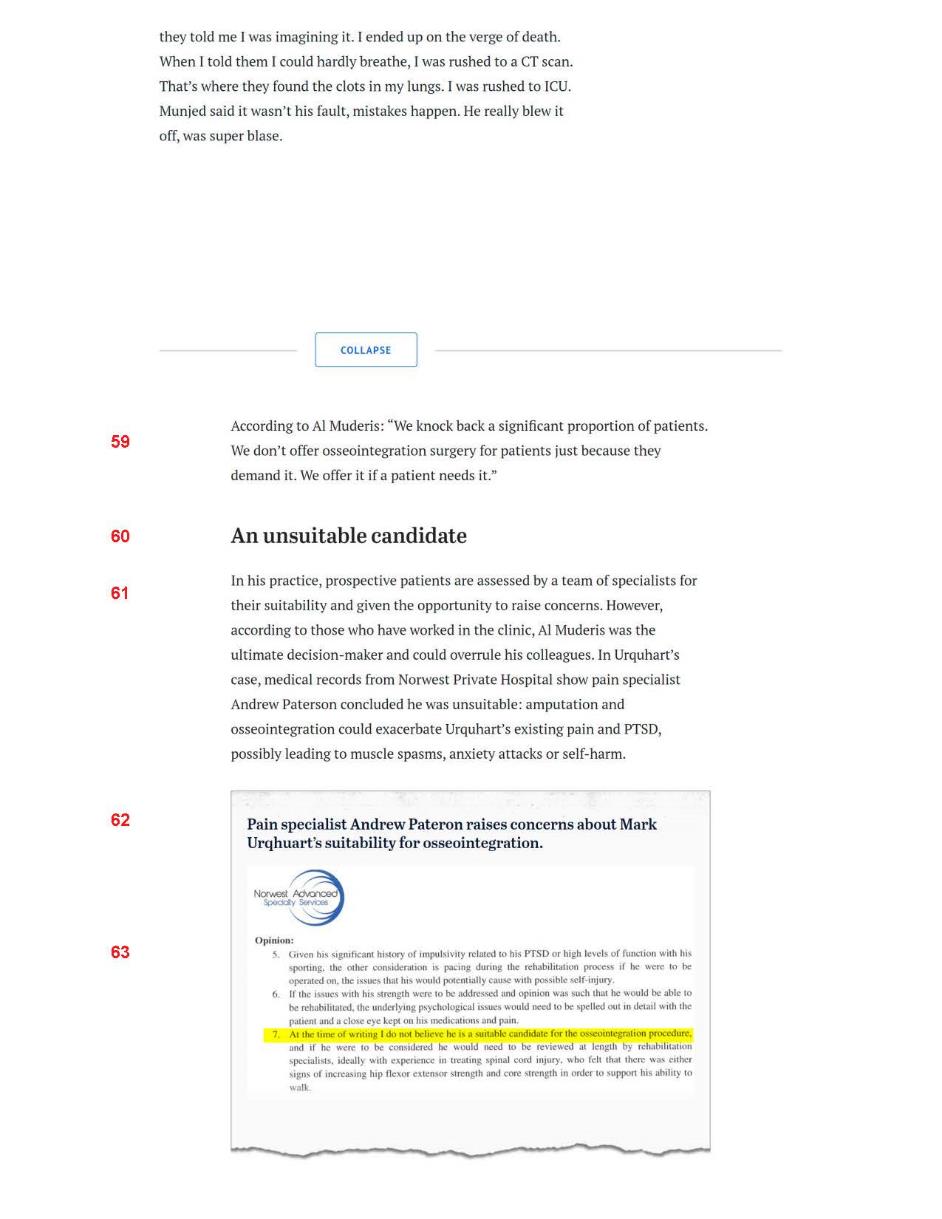

[184] | |

[187] | |

[213] | |

[213] | |

[220] | |

[234] | |

[242] | |

[251] | |

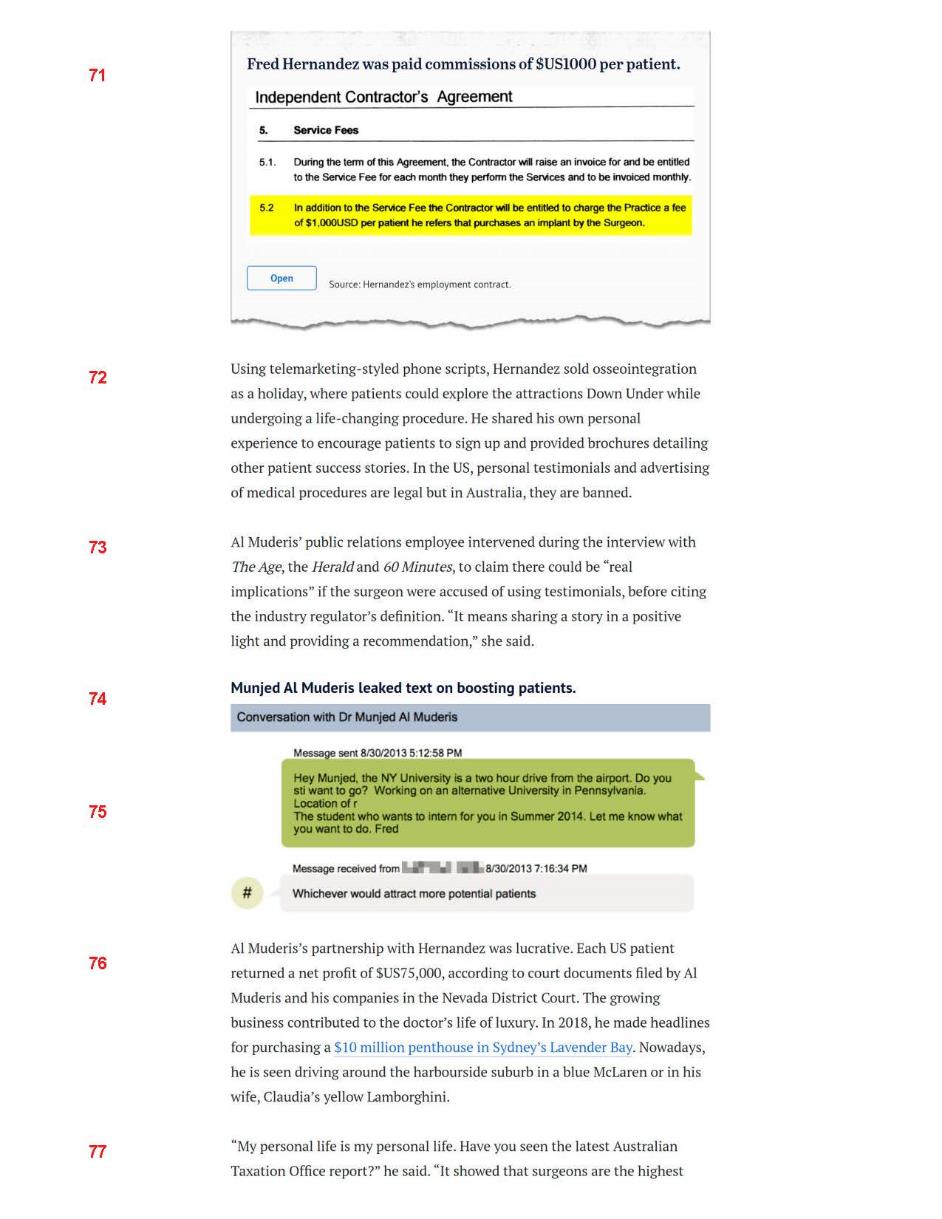

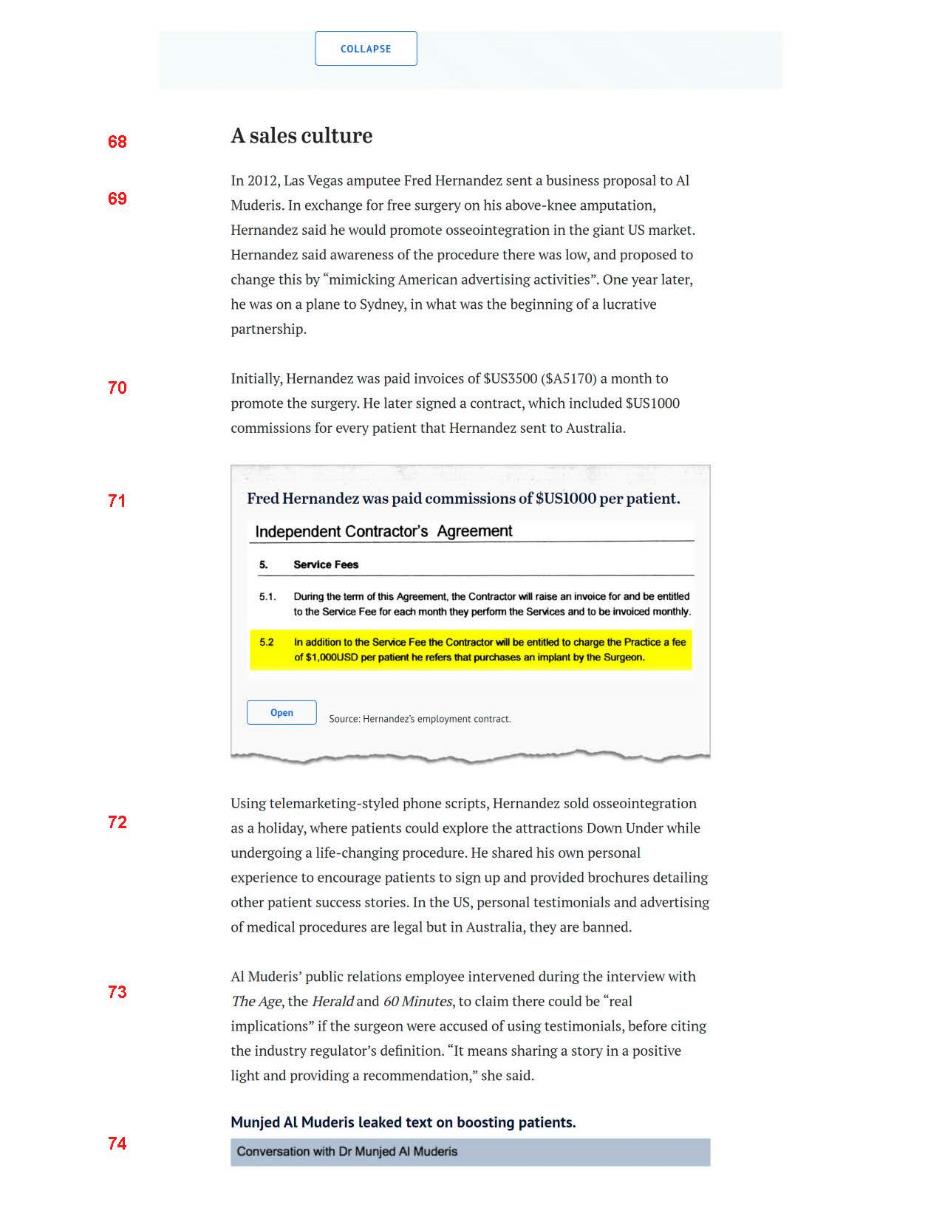

[263] | |

[265] | |

[293] | |

[305] | |

[307] | |

[323] | |

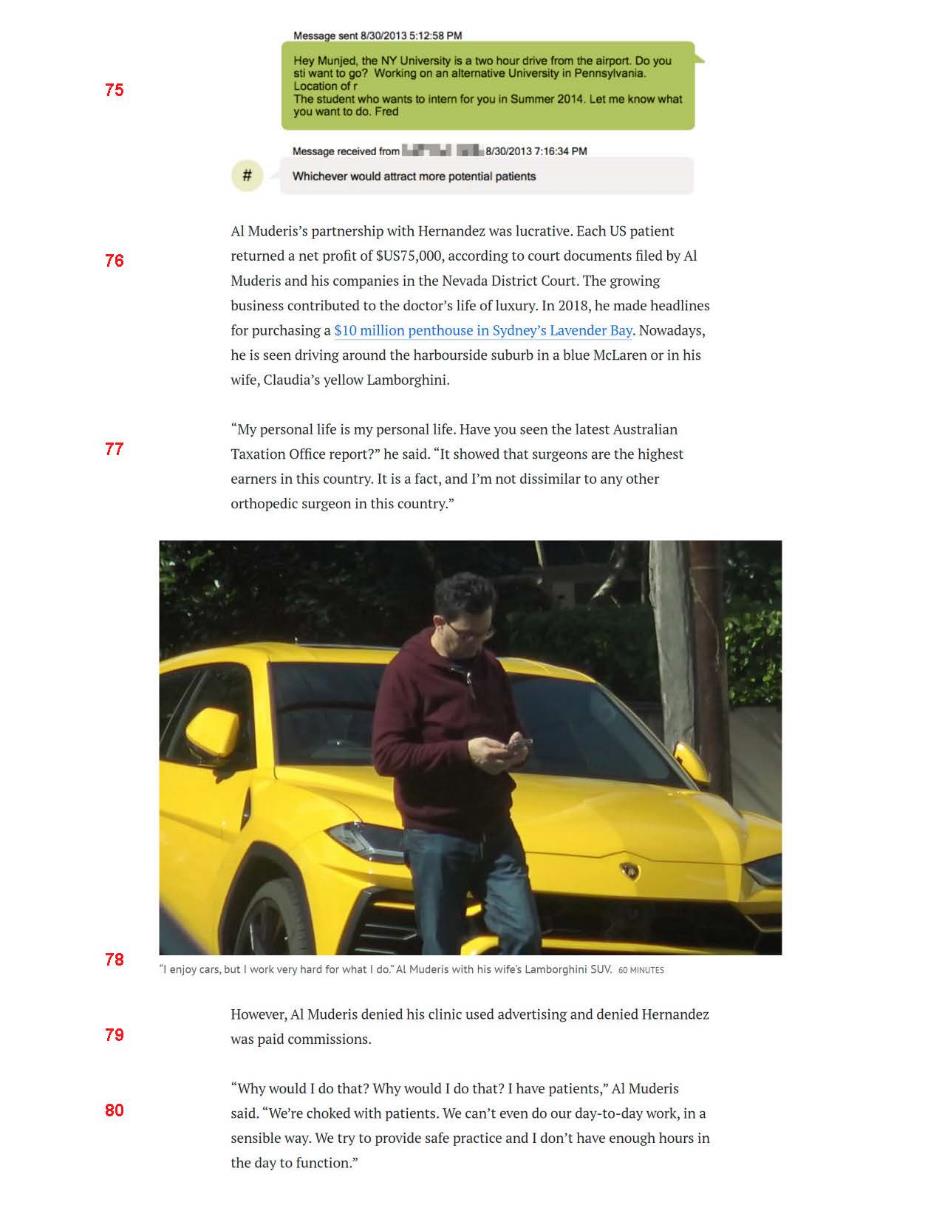

[329] | |

[332] | |

[332] | |

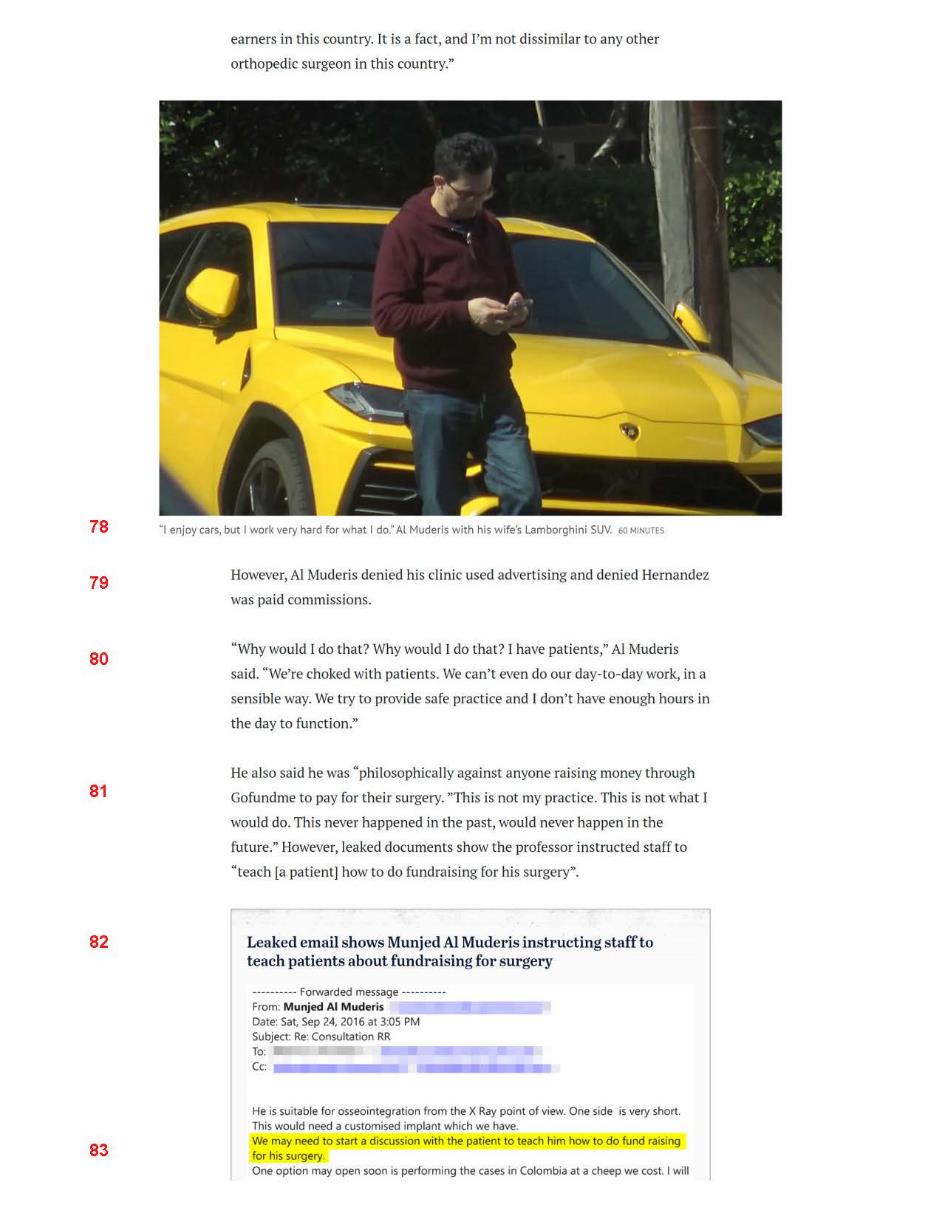

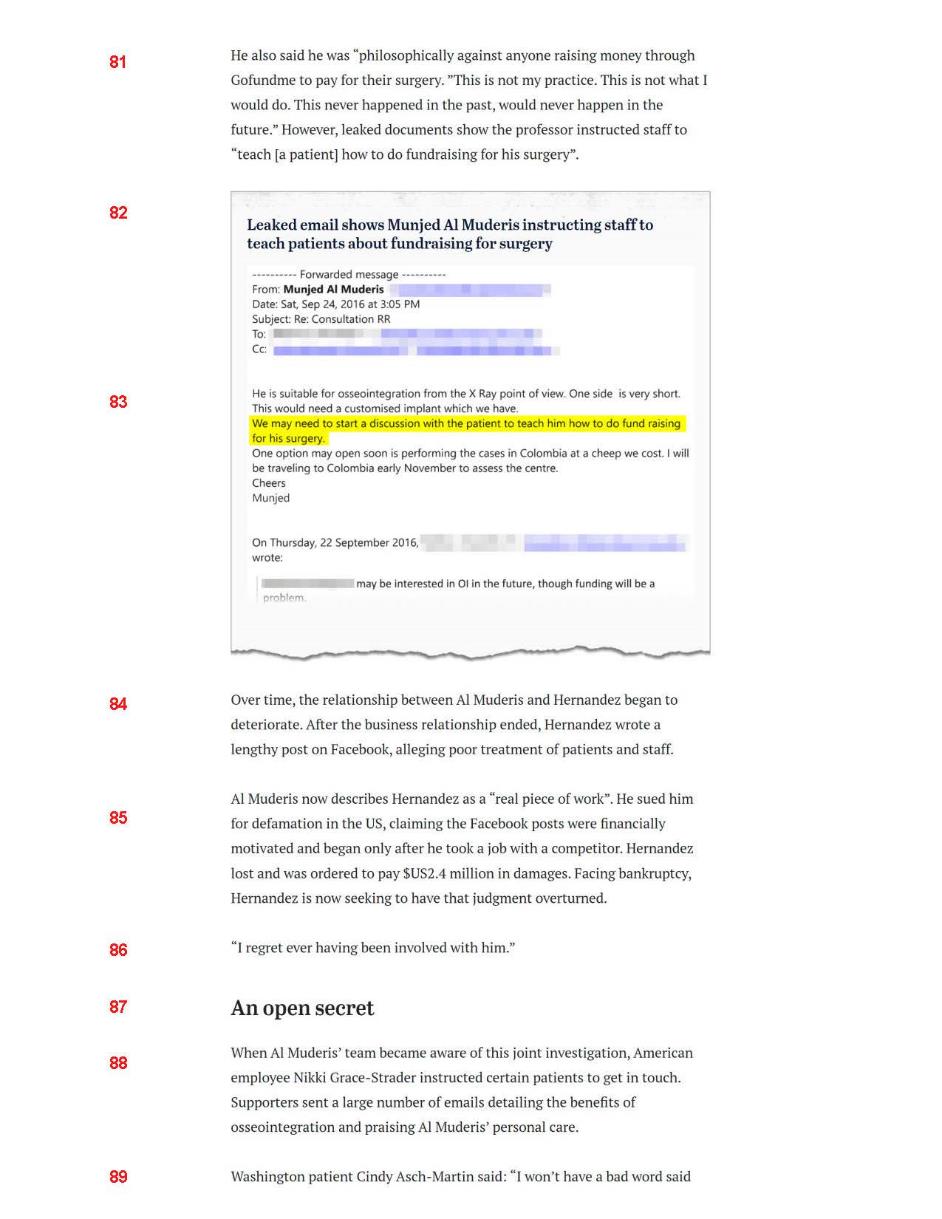

[334] | |

[336] | |

[339] | |

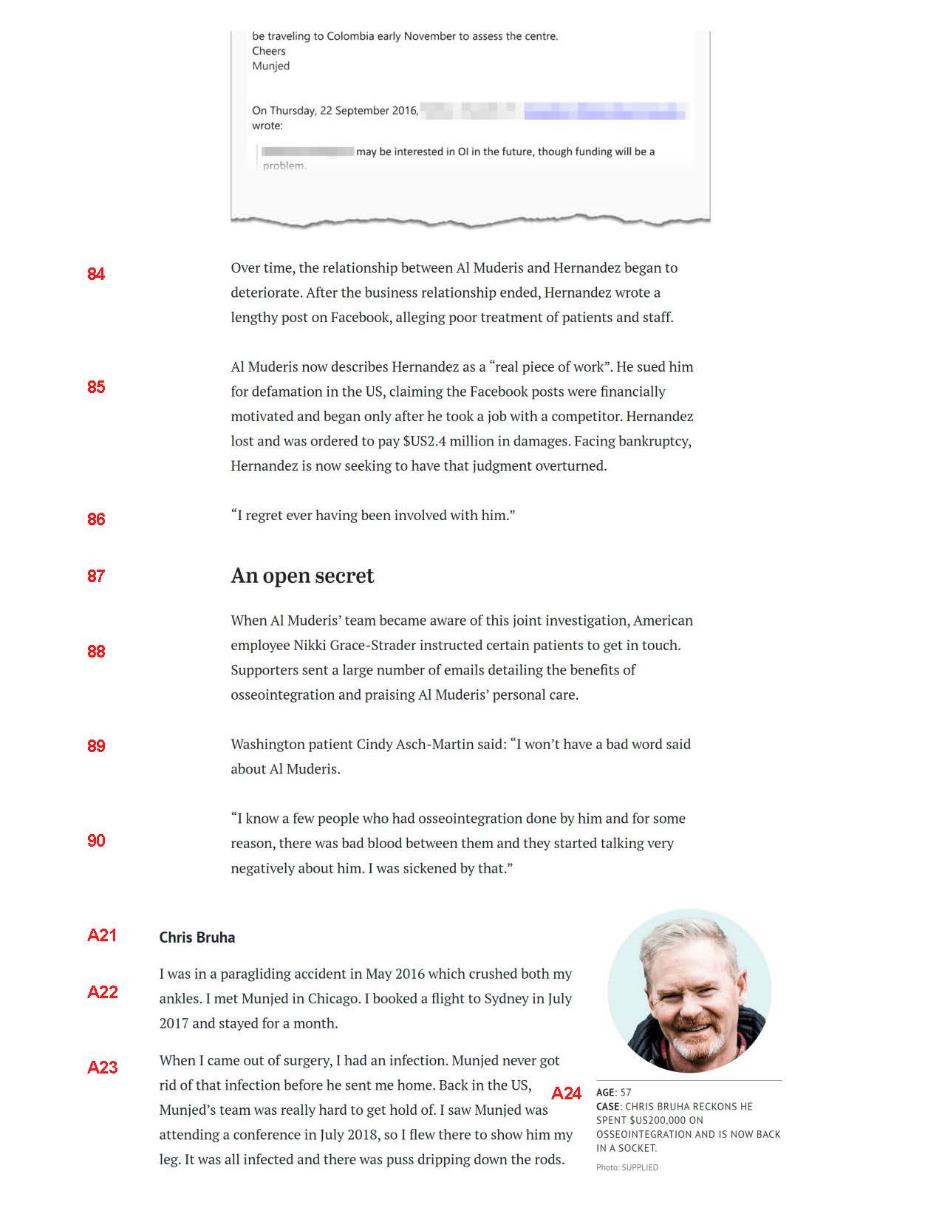

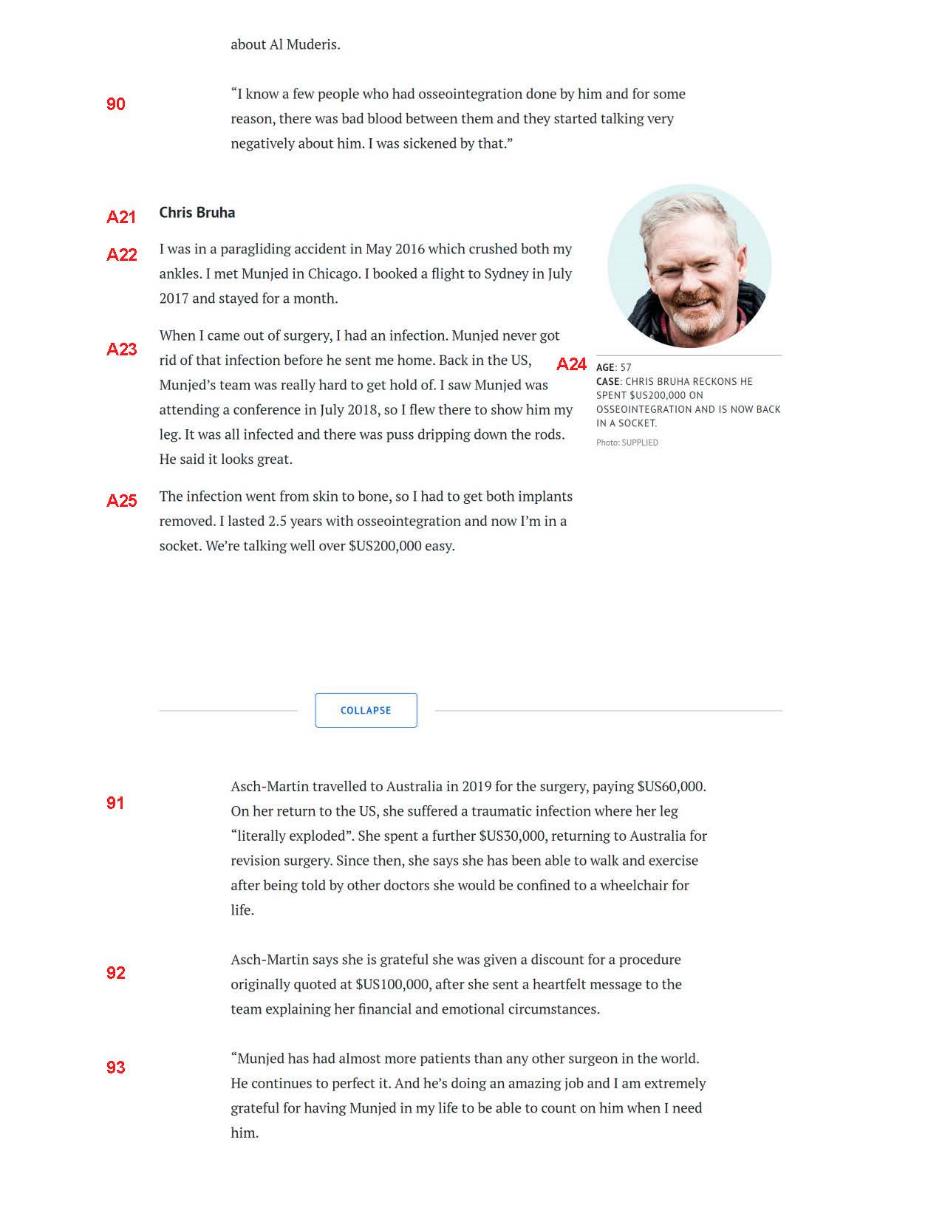

[341] | |

[347] | |

[348] | |

[348] | |

[351] | |

[355] | |

[368] | |

[374] | |

[377] | |

[383] | |

[383] | |

[410] | |

[447] | |

[494] | |

[494] | |

[494] | |

[537] | |

[597] | |

[615] | |

[634] | |

[656] | |

[671] | |

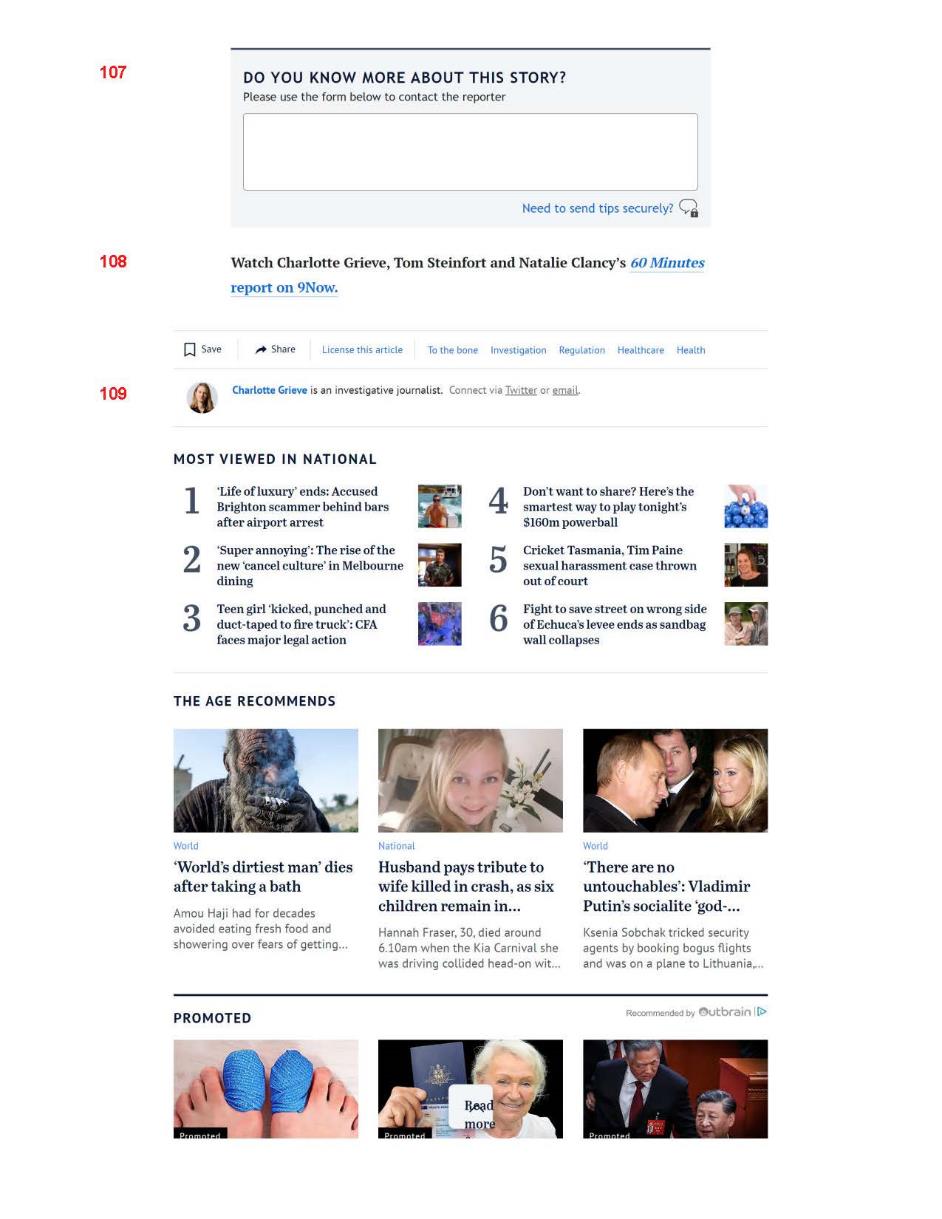

[671] | |

[700] | |

[745] | |

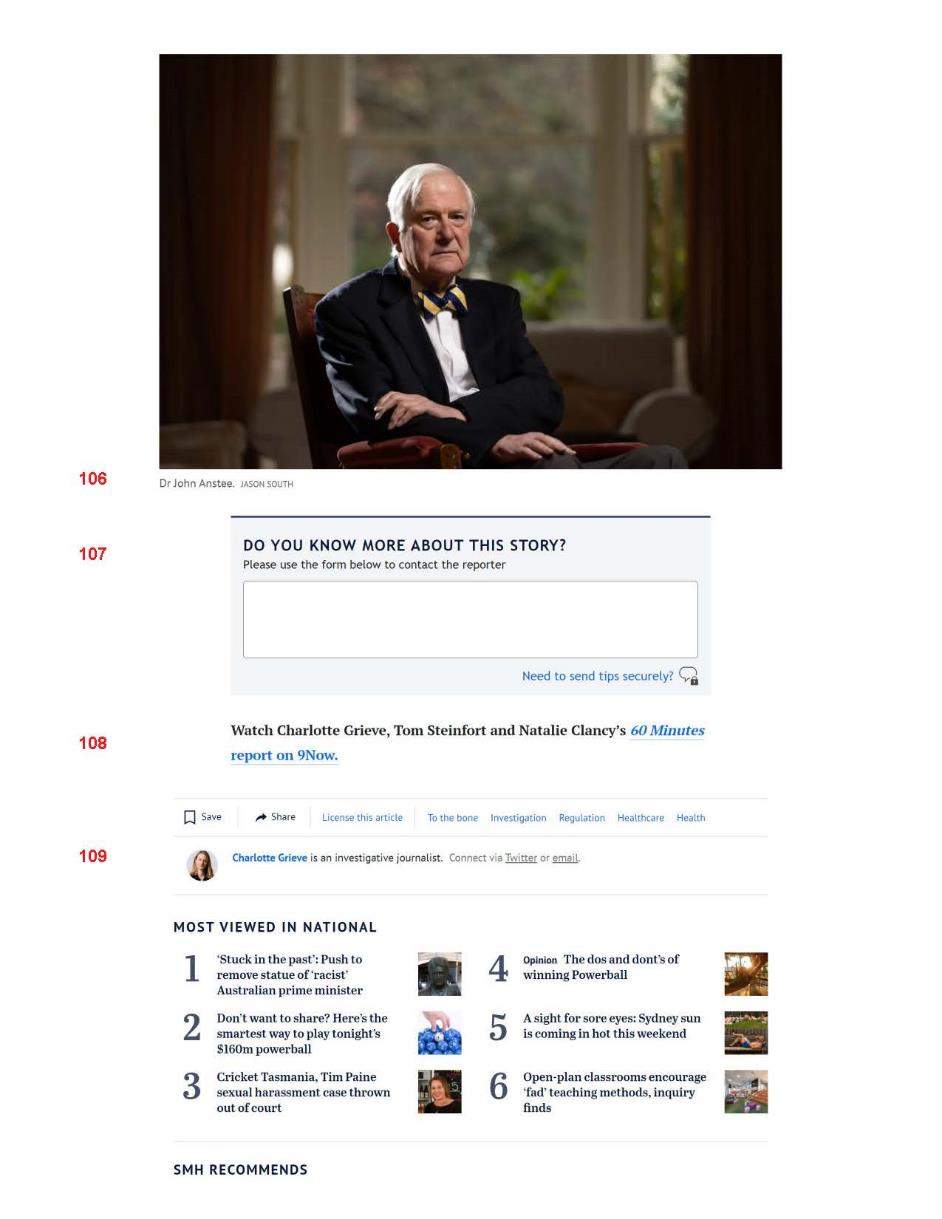

[745] | |

[767] | |

[827] | |

[827] | |

[898] | |

[968] | |

[1071] | |

[1106] | |

[1135] | |

[1148] | |

[1245] | |

[1304] | |

[1342] | |

[1342] | |

[1418] | |

[1508] | |

[1508] | |

[1596] | |

[1693] | |

[1748] | |

[1841] | |

[1887] | |

[1909] | |

[1922] | |

[1922] | |

[2040] | |

[2064] | |

[2106] | |

[2141] | |

[2141] | |

[2151] | |

[2166] | |

[2177] | |

[2187] | |

[2197] | |

[2199] | |

[2210] | |

[2210] | |

[2220] | |

Sting 2 — Misleading osseointegration patients (false promises, downplaying risks and complications) | [2251] |

[2278] | |

[2294] | |

[2348] | |

[2384] | |

[2428] | |

[2434] | |

[2438] | |

[2447] | |

[2453] | |

[2470] | |

[2473] | |

[2476] | |

[2479] | |

[2480] | |

[2482] | |

[2489] | |

[2498] | |

[2506] | |

Section 3 — The parties responsible for the defamatory matters | [2511] |

[2529] | |

[2534] | |

[2546] | |

[2552] | |

[2555] | |

[2562] | |

[2564] | |

[2566] | |

[2569] | |

[2588] | |

[2605] | |

[2606] | |

[2613] | |

[2615] | |

[2619] | |

[2643] | |

[2651] | |

[2699] | |

[2714] | |

[2719] | |

[2724] | |

[2735] | |

[2758] | |

[2767] | |

[2775] | |

[2791] | |

[2813] | |

[2821] | |

[2825] | |

[2870] | |

[2877] | |

[2879] | |

[2880] | |

[2886] | |

[2904] | |

[2905] | |

[2916] | |

[2956] | |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

ABRAHAM J:

PART 1 — INTRODUCTION

Section 1 — Introductory remarks

1 The applicant, Dr Munjed Al Muderis, an orthopaedic surgeon, is suing Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (Nine Network), Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited (Fairfax), The Age Company Pty Limited (The Age Company) and journalists, Ms Charlotte Grieve, Mr Tom Steinfort and Ms Natalie Clancy (together, the respondents), for defamation in relation to television, video and newspaper (print and online) publications published in September 2022.

2 It is not disputed that at the time of publication, Dr Al Muderis had a high profile. He had featured on the television programs 60 Minutes (a separate episode to that the subject of these proceedings), Foreign Correspondent, Inside Story and Anh’s Brush with Fame. On his own account he was one of the busiest orthopaedic surgeons in Sydney. He held several clinical, consultant, academic and other professional appointments. He is a prolific author, accomplished public speaker (including at significant forums), the recipient of many awards for his medical and humanitarian achievements and was the 2020 NSW Australian of the Year. His fame was also because of his backstory; from escaping Iraq as a refugee, to holding the various positions and obtaining the achievements described (expanded upon below). The respondents described his reputation as “glittering”.

3 The matters published stemmed from a joint investigation conducted from May 2022 until the date of publication, between 60 Minutes, The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, into information that had been obtained that portrayed a different picture of Dr Al Muderis. Although the respondents accepted Dr Al Muderis is, to many, an Australian hero who has devoted much of his life’s work to helping amputees walk again, they contended their investigation revealed that there was a significant cohort of unhappy patients. The journalists gave evidence that they found that some of the patients’ experiences with Dr Al Muderis were inconsistent with that portrayed in the media, including experiences where patients were vulnerable and susceptible to pressure tactics, where some patients had not had the risks of the surgery properly explained to them and where some patients said they had not received proper aftercare. After the investigation, a decision was made to publish the impugned matters. The journalists’ evidence is that they believed it was in the public interest to do so. The matters covered topics including allegations that Dr Al Muderis engaged in improper sales tactics, misled patients and downplayed the risks of osseointegration surgery, did not provide proper aftercare, and prioritised money over patient care.

4 There are seven matters sued on:

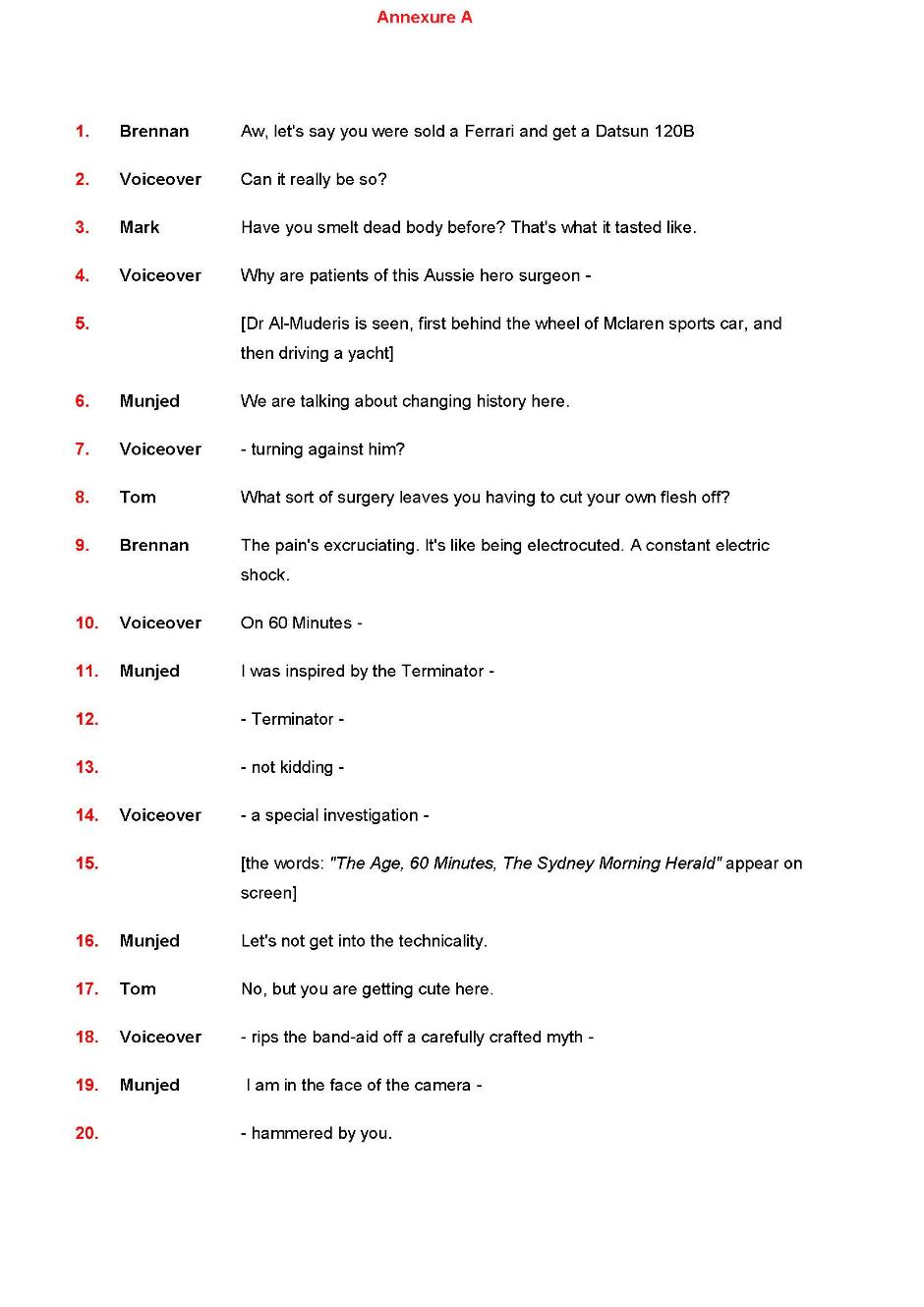

(1) a promotion for the then upcoming episode of 60 Minutes entitled “Sneak Peek: Cut to the Point”, published on 8 September 2022, and on the 60 Minutes Australia YouTube page from about 14 September 2022 (Sneak Peek) (see transcript at Annexure A);

(2) an episode of 60 Minutes entitled “Cut to the Point”, broadcasted on 18 September 2022 (Broadcast) (see transcript at Annexure B);

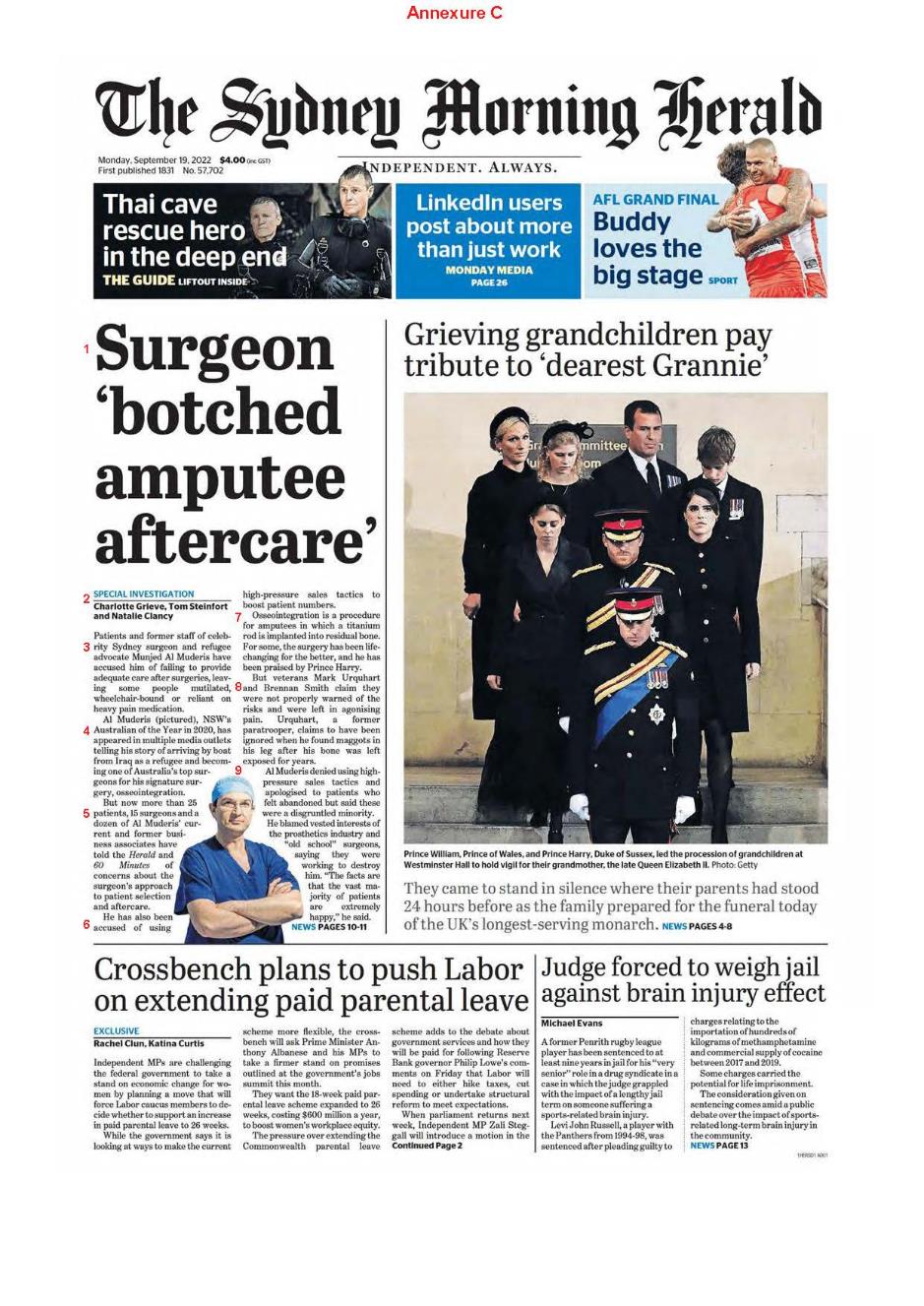

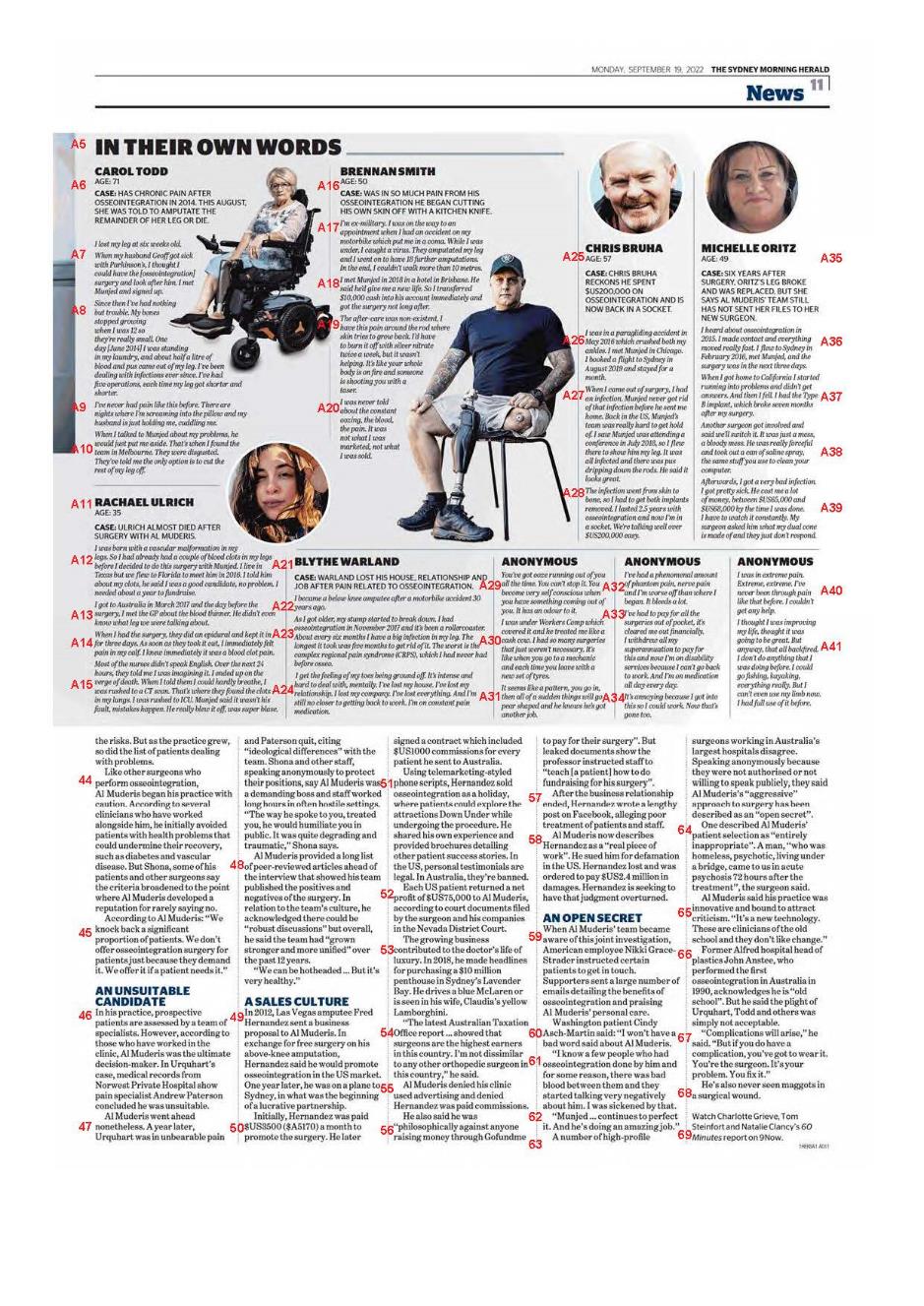

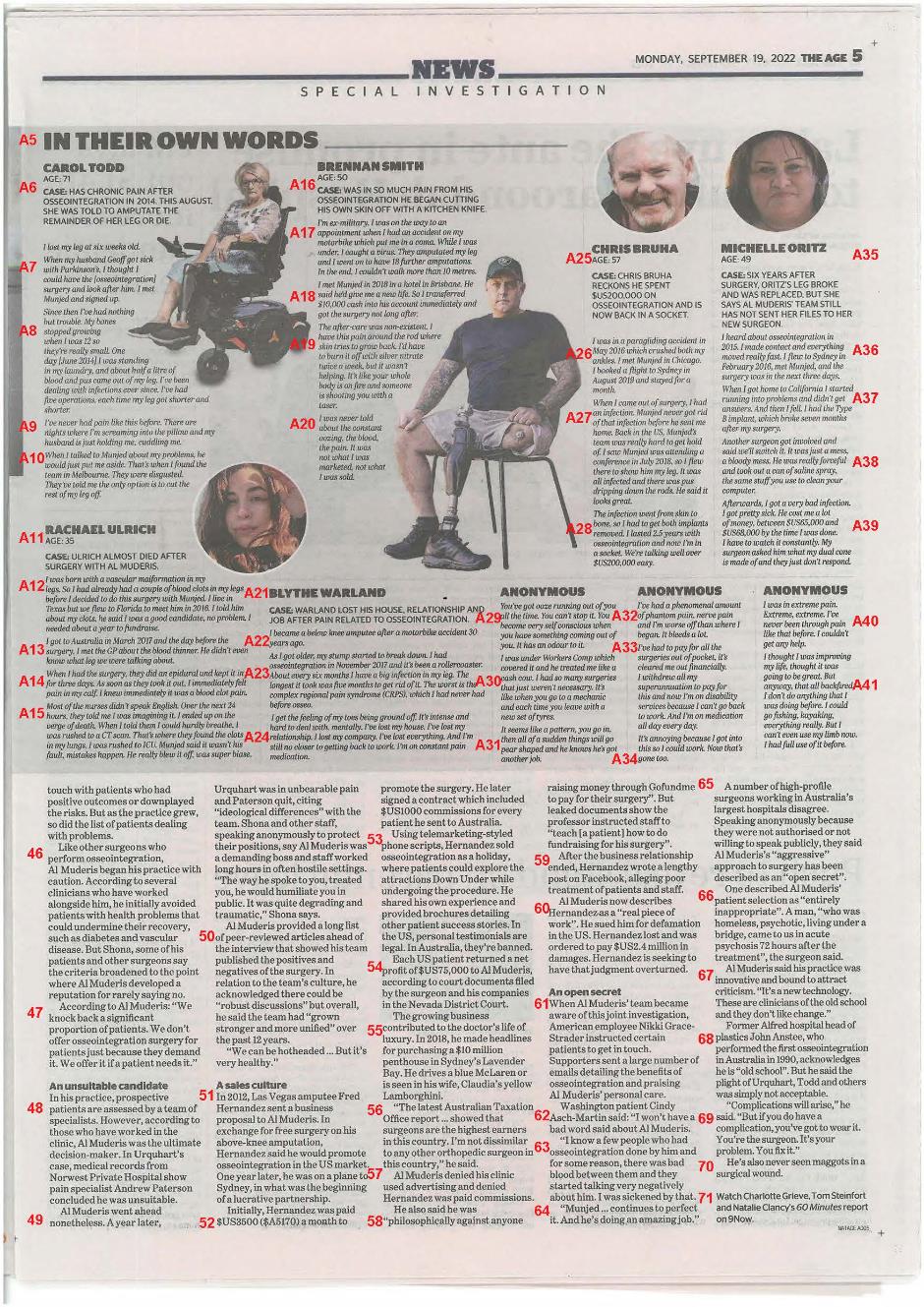

(3) a print article in the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper entitled “Surgeon ‘botched amputee aftercare’”, published on 19 September 2022 (SMH Article) (see Annexure C);

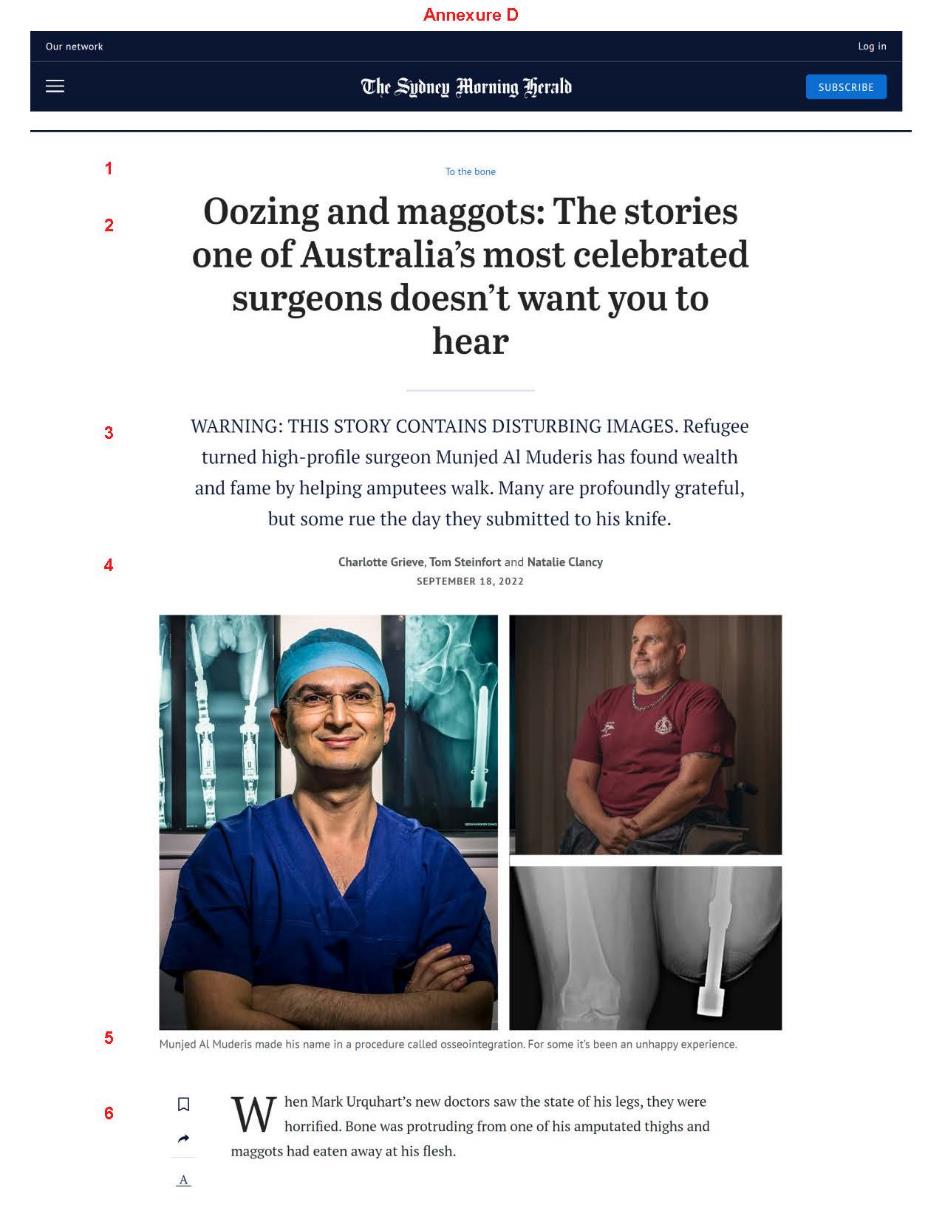

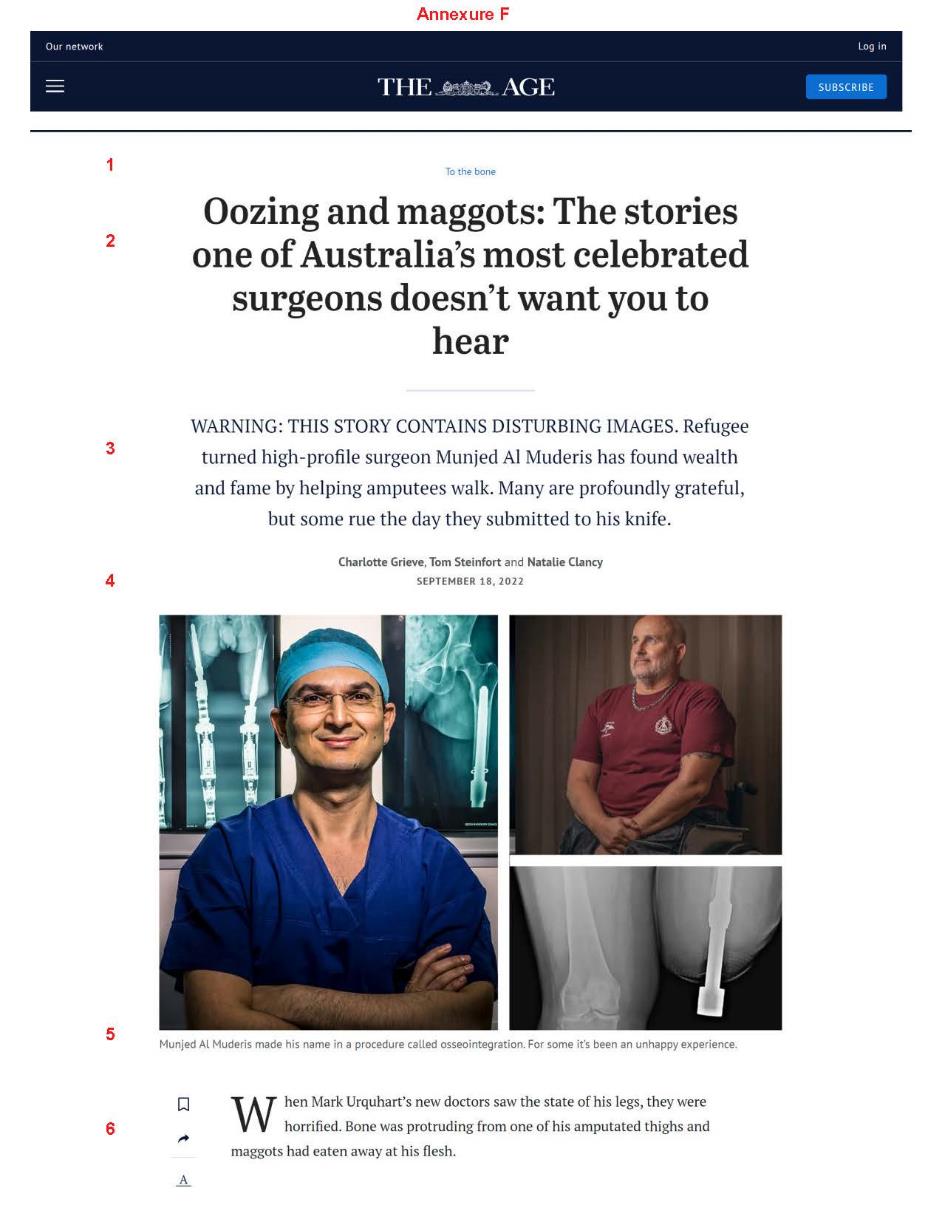

(4) an article on the Sydney Morning Herald’s website entitled “Oozing and maggots: The stories one of Australia’s most celebrated surgeons doesn’t want you to hear”, published on 18 September 2022 (SMH Online Article) (see Annexure D);

(5) a print article in The Age newspaper entitled “Celebrity Surgeon ‘left patients in pain, to rot’”, published on 19 September 2022 (Age Article) (see Annexure E);

(6) an article on The Age’s website entitled “Oozing and maggots: The stories one of Australia’s most celebrated surgeons doesn’t want you to hear”, published on 18 September 2022 (Age Online Article) (see Annexure F); and

(7) a video on The Age’s website entitled “Oozing and maggots: The stories one of Australia’s most celebrated surgeons doesn’t want you to hear”, published on 18 September 2022 (Grieve Video) (see transcript at Annexure G),

(the Publications).

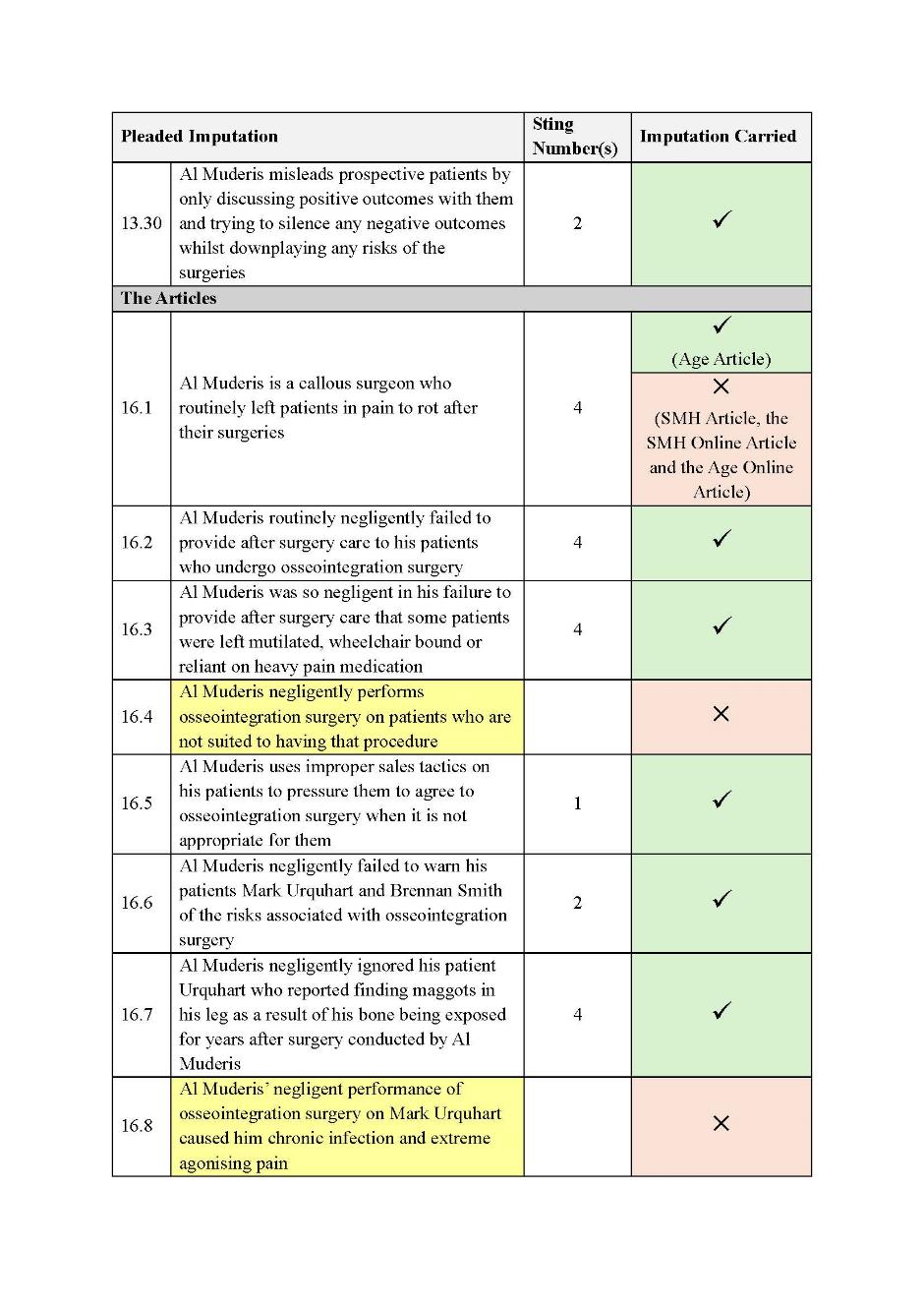

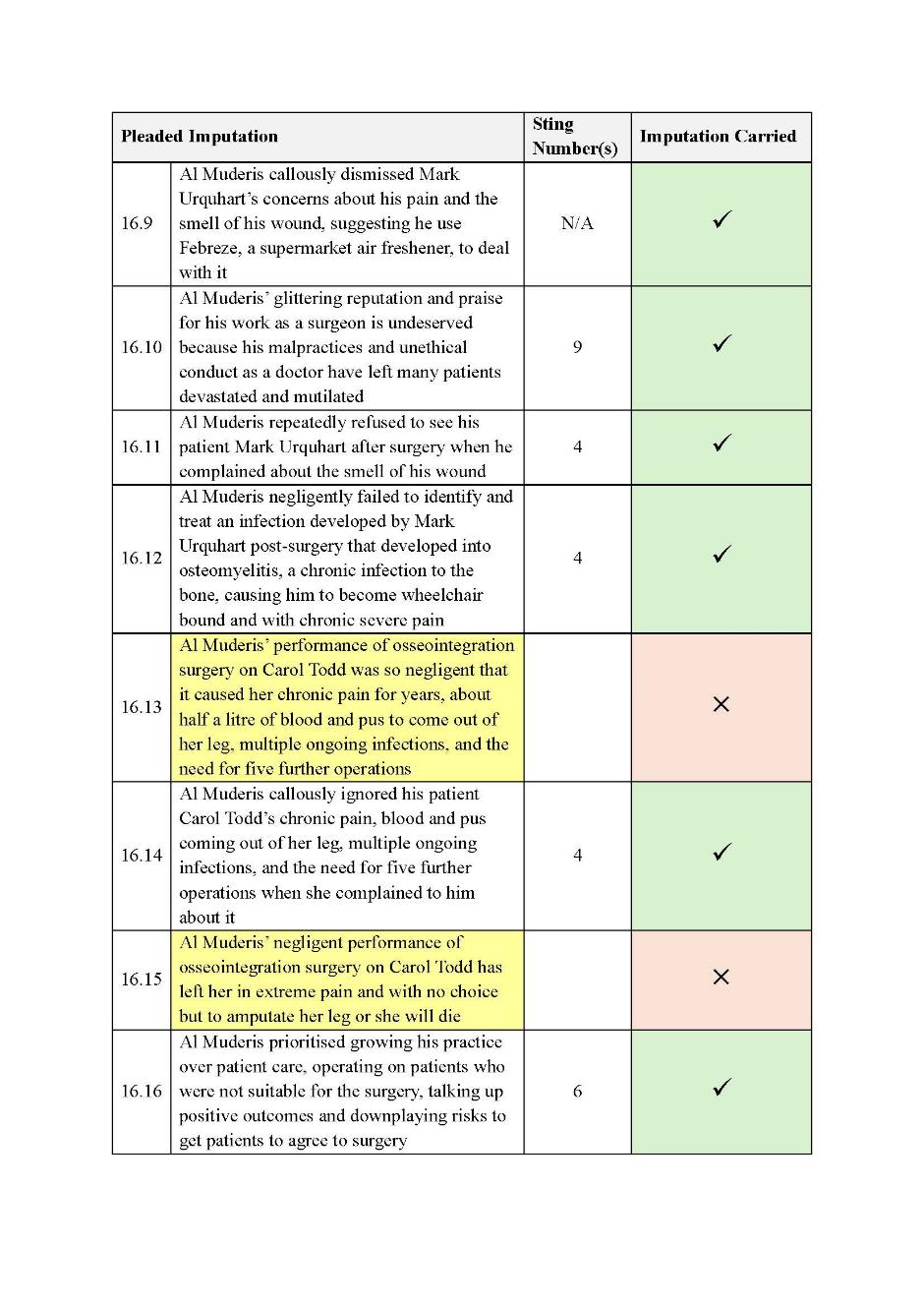

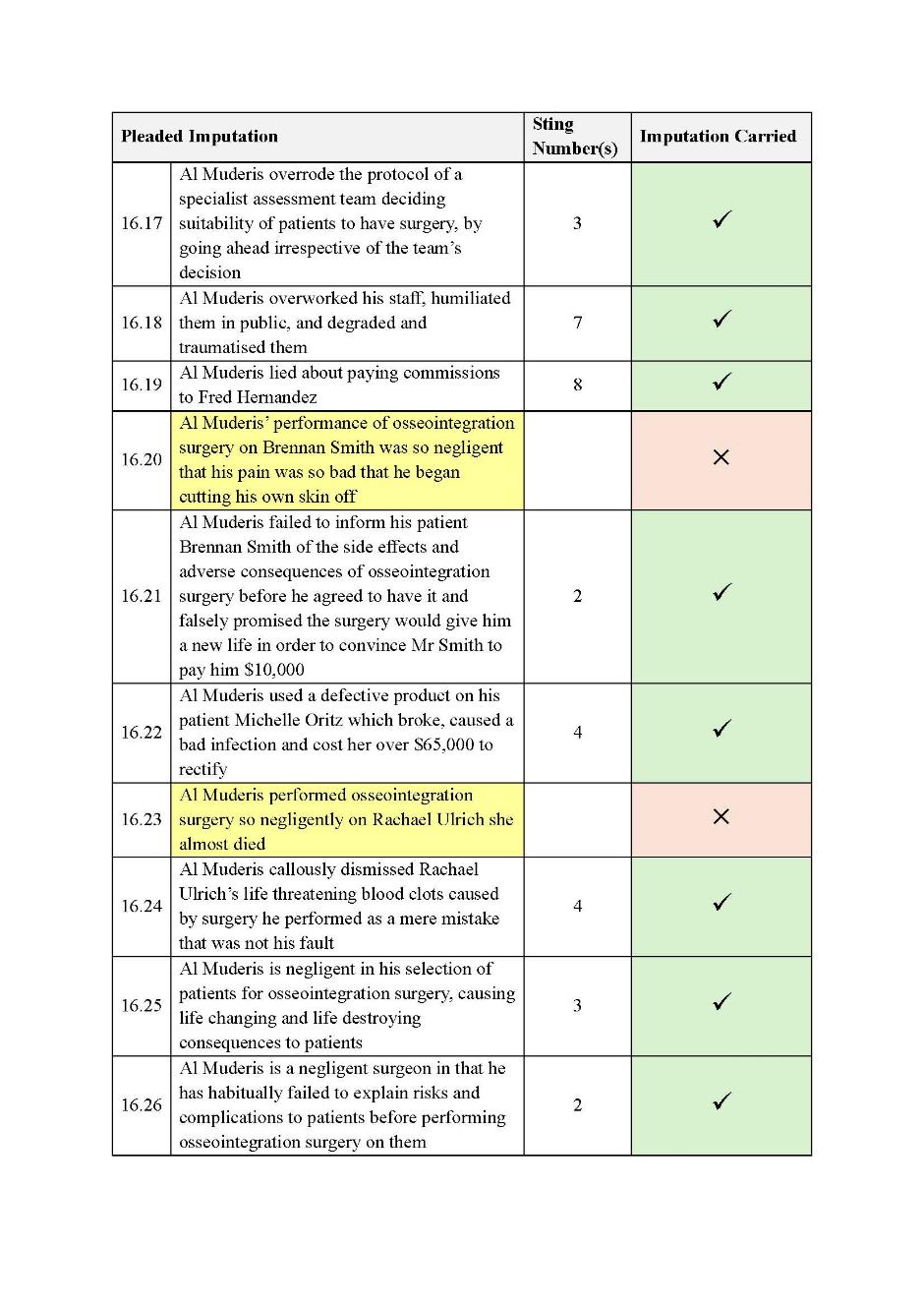

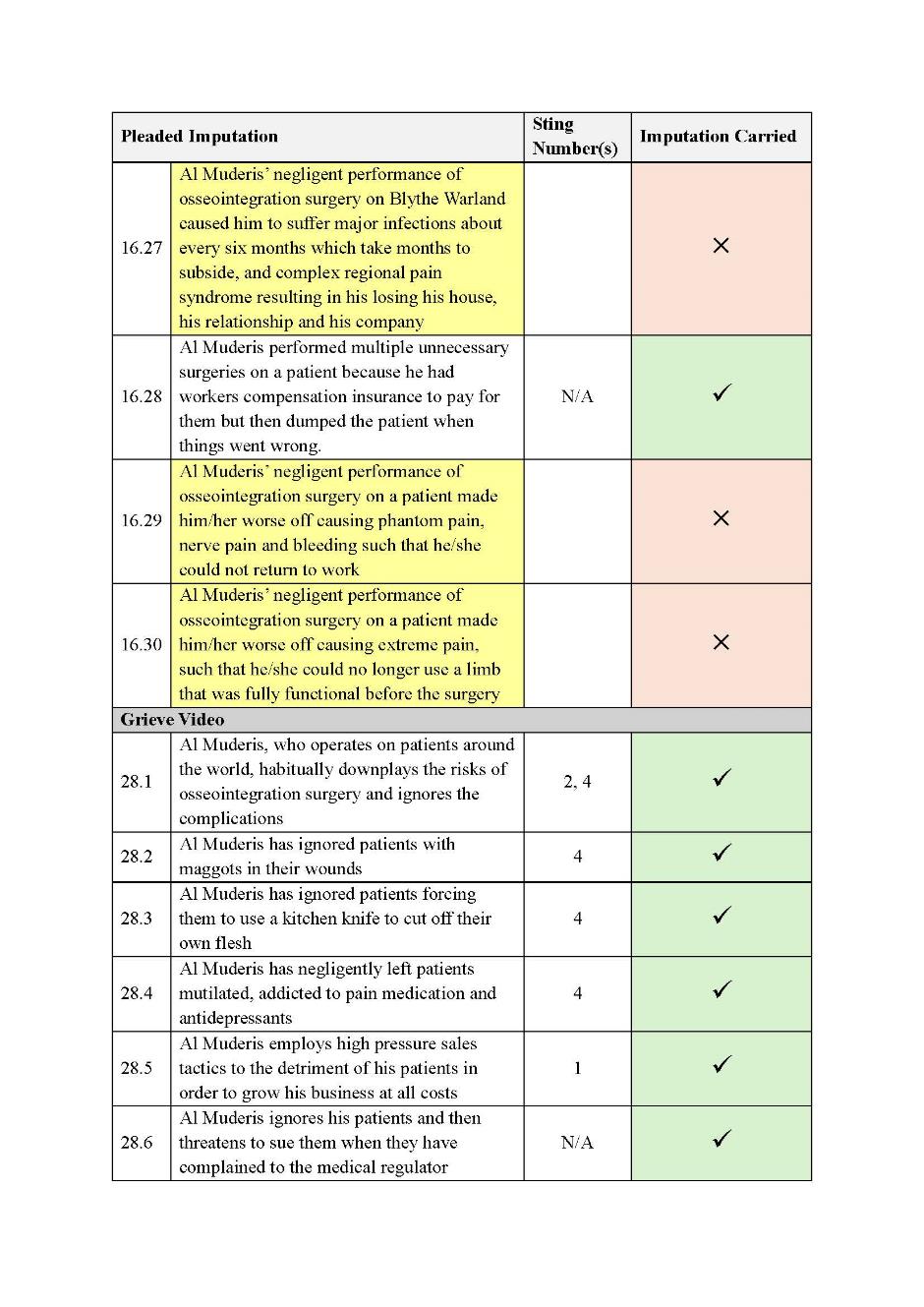

5 The applicant alleges those matters convey 75 defamatory imputations (see a list of the pleaded imputations at Annexure H), some of which are admitted by the respondents to be conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader or viewer (others are disputed). The respondents rely on the defences of justification (substantial truth) to most of the imputations, contextual truth, public interest and honest opinion, relying on ss 25, 26, 29A and 31 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW), respectively.

6 The issues which arise for the Court’s consideration are:

(1) whether the defamatory imputations pleaded at [13.24] and [16.1] (in the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article, and the Age Online Article) of the Statement of Claim (SOC) (together, the Denied Imputations) were conveyed;

(2) whether the defamatory imputations pleaded at [10.1], [10.2], [10.3], [10.4], [10.5], [10.6], [13.2], [13.6], [13.20], [16.4], [16.8], [16.13], [16.15], [16.20], [16.23], [16.27], [16.29] and [16.30] of the SOC (the Disputed Imputations), are confined to the applicant’s performance ‘in the operating theatre’, and if so, whether they were conveyed;

(3) whether the pleaded defamatory imputations in the SOC which are conveyed (save for [13.24], [16.9], [16.28] and [28.6]) are substantially true: defence of justification, s 25 of the Defamation Act. The respondents in oral closing submissions characterised their case as one of contextual truth, not a justification case;

(4) whether some or all the imputations on which the respondents rely as contextual imputations are substantially true and whether, in light of their substantial truth, any residual defamatory imputations do not further harm Dr Al Muderis’ reputation: defence of contextual truth, s 26 of the Defamation Act;

(5) whether the respondents reasonably believed that the Publications were in the public interest: defence of public interest, s 29A of the Defamation Act;

(6) whether the Publications were expressions of opinion on matters of public interest based on proper material: defence of honest opinion, s 31 of the Defamation Act; and

(7) various findings of fact which Dr Al Muderis invites the Court to make in relation to his alleged entitlement to damages and aggravated damages.

7 It is appropriate to observe at the outset that this is not a medical negligence case. The relevant issues are determined based on the principles applicable in defamation proceedings.

8 For the reasons below:

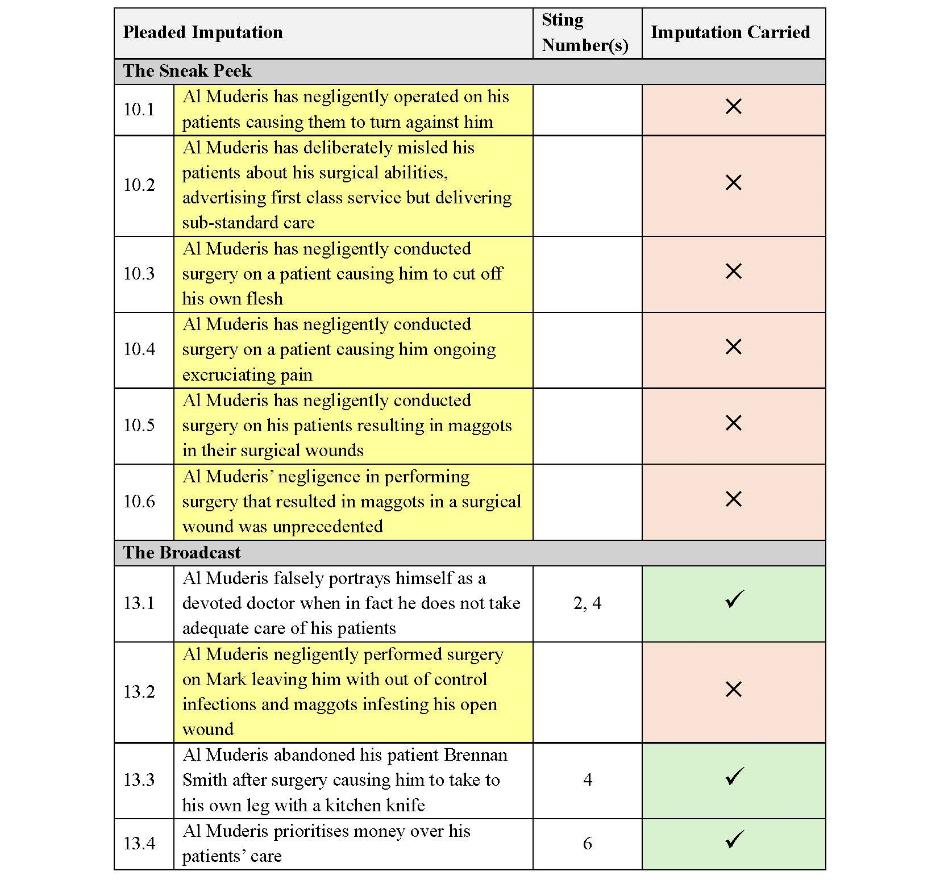

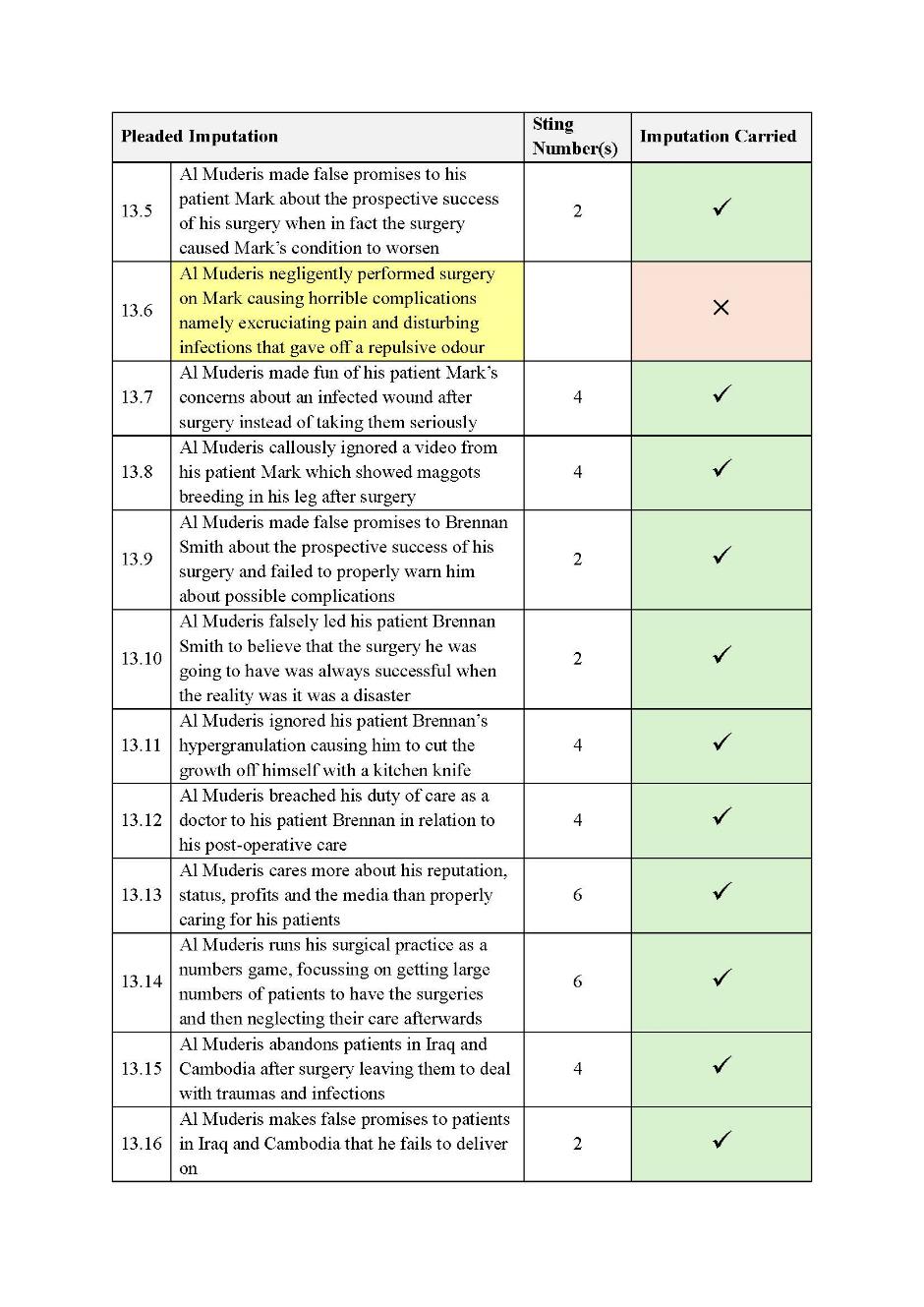

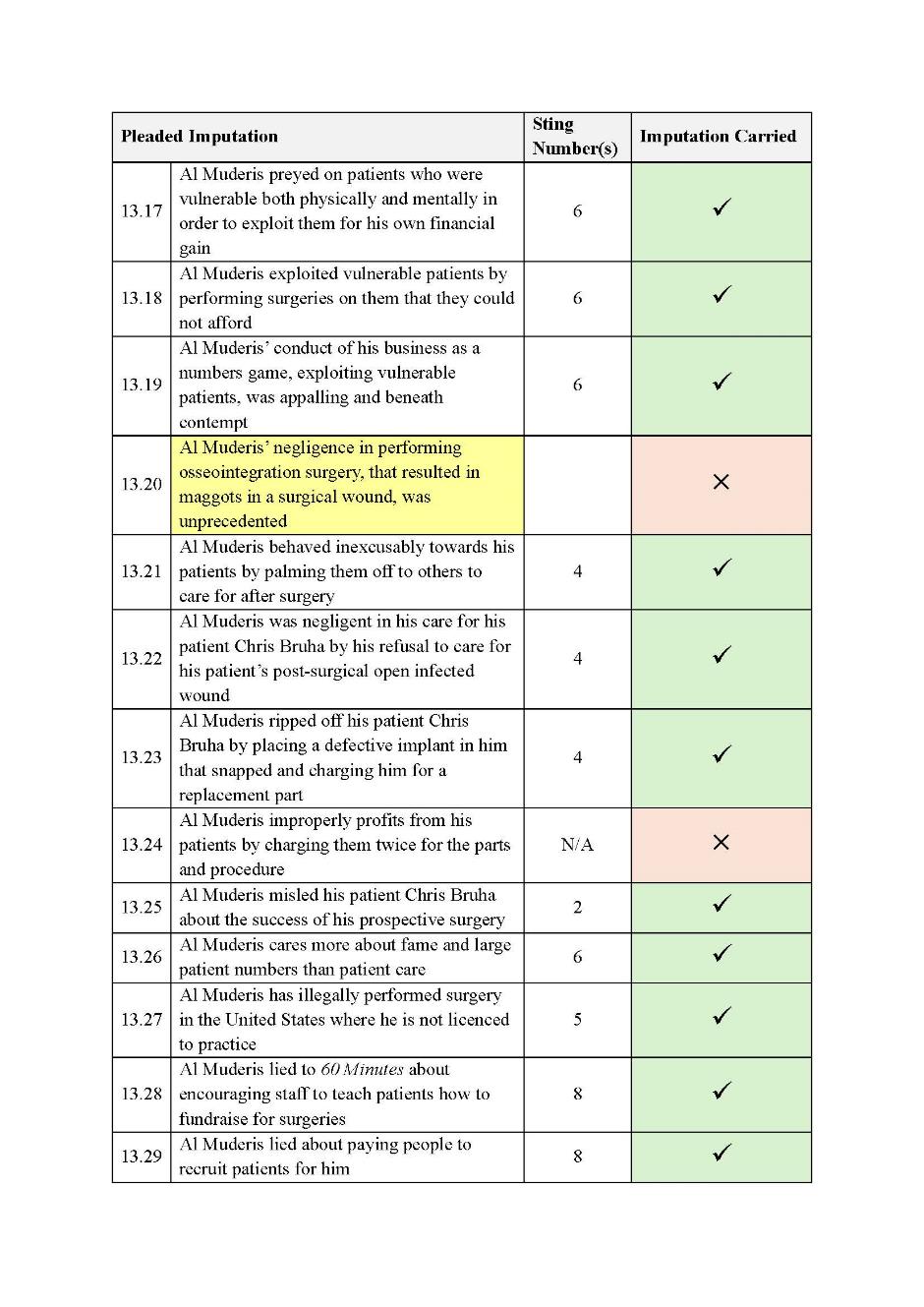

(1) Imputations [13.24] and [16.1] (in respect of the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article and the Age Online Article), are not conveyed by the Publications. The Disputed Imputations, being [10.1]-[10.6] (Sneak Peek), [13.2], [13.6], [13.20] (Broadcast), [16.4], [16.8], [16.13], [16.15], [16.20], [16.23], [16.27], [16.29] and [16.30] (Articles) are not conveyed. The remaining imputations are conveyed;

(2) it follows that in relation to the Sneak Peek, it has not been established that any of the pleaded imputations have been conveyed. The Broadcast, Articles, and the Grieve Video each conveys defamatory imputations;

(3) the respondents have established the defence of contextual truth under s 26 of the Defamation Act in relation to the Publications in which imputations are conveyed;

(4) the respondents have established the defence of public interest under s 29A of the Defamation Act in relation to the Publications in which imputations are conveyed; and

(5) given the above, it is unnecessary to determine the respondents’ claim to the defence of honest opinion.

9 Accordingly, the application is dismissed.

Section 2 — Overview

Dr Munjed Al Muderis

10 Dr Al Muderis was born in Baghdad, Iraq in 1972. He completed his medical studies at the University of Baghdad, graduated in 1996 with the degrees of Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery and was licensed to practice medicine in Iraq shortly afterwards. He came to Australia by boat in November 1999 and was detained at Curtin Detention Centre in Western Australia, where he spent nearly a year before his asylum claim was accepted. He was granted an Australian visa in 2000.

11 From shortly thereafter he has held positions in various hospitals. In 2002, Dr Al Muderis passed the Australian Medical Council’s examinations to earn recognition in Australia of his Iraqi medical qualifications. In 2008, he passed the examinations which qualified him as an orthopaedic surgeon.

12 Dr Al Muderis is a Fellow of the Royal Australian College of Surgeons and the Australian Orthopaedic Association, a Clinical Professor at the Macquarie University Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, and an Adjunct Clinical Professor at the University of Notre Dame Australia School of Medicine. He is also an Honorary Associate in the School of Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering in the Faculty of Engineering and IT at the University of Sydney.

13 He has held consultant positions as an orthopaedic visiting medical officer at Norwest Private Hospital since 2010, Macquarie University Hospital since 2010, Hurstville Private Hospital since 2016 and East Sydney Private Hospital since 2020. He has also held and currently holds numerous leadership and executive positions, including: Member of the MQ Health Clinical Leadership Council since 2019; Member of the Medical Advisory Committee at Macquarie University Hospital since 2021; Member of the MQ Health Clinical Executive Committee since 2021; Head of the Lower Limb Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine Discipline at MQ Health since 2022; and Member of the SydOrth Board Committee since 2022.

14 He has been involved in clinical education and supervision, including as the Chief Supervisor for three fellowship training programs accredited by the Australian Orthopaedic Association, and as Director of Registrar Training at MQ Health since 2019. He is an ambassador for a number of charitable and humanitarian organisations including the Red Cross and Amnesty International Australia; is or has been a patron of a number of other organisations including the Multicultural Disability Advocacy Association of NSW, Asylum Seekers Centre and Amputees NSW; is represented by Saxton Speakers and has been regularly engaged to speak on topics including human rights issues and charitable causes.

15 He has published extensively in the field of orthopaedics generally, and osseointegration in particular, by co-authoring 40 original publications in international peer-reviewed journals (including four on the topic of osseointegration in 2022) and authoring or co-authoring ten textbook chapters on orthopaedics (including seven on the topic of osseointegration in 2022). Dr Al Muderis has also presented academic papers at many medical conferences, in Australia and overseas and has been awarded research grants with a cumulative value of over $7,000,000 over the last decade.

16 In 2022, Dr Al Muderis was awarded the degree of Doctor of Medical Science by the School of Medicine at the University of Notre Dame for his thesis “Osseointegration for Amputees: Past, Present and Future: Basic Science, Innovations in Surgical Technique, Implant Design and Rehabilitation Strategies”.

17 Dr Al Muderis is the inventor of several patents for prosthetic devices, which are held either by him personally or through his company, Osseointegration International Pty Ltd (Osseointegration International). These include patents for an osseointegratable device and other orthopaedic and deformity correction devices. He has also contributed to the design and development of other systems, including an osseointegrated prosthetic limb system.

18 He has been involved in charity and humanitarian work, providing consultations and medical procedures to amputees and other patients (including orthopaedic and osseointegration procedures) in countries including India, Poland, Cambodia, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories in Ramallah and the West Bank, Iraq, Israel and Ukraine.

19 He has been the recipient of numerous awards including the Asia Game Changers Award for humanitarian work in 2018, the GQ Man of the Year Social Force Award in Abu Dhabi for surgical and humanitarian work in 2019 and NSW Australian of the Year for surgical innovations and humanitarian works in 2020.

20 Dr Al Muderis estimated he has performed more than 9,000 orthopaedic procedures since 2012, and over 800 osseointegration procedures.

21 Generally, Dr Al Muderis conducts his consultations at the Limb Reconstruction Centre (LRC) in Macquarie University Hospital (which was formerly at Norwest Private Hospital). He is the Chairperson and Founder of the Osseointegration Group of Australia. His company, Osseointegration International, was incorporated on 20 February 2015.

Osseointegration

22 The Publications featured the experiences of ten of Dr Al Muderis’ osseointegration patients. It is helpful at this stage to briefly address the nature of this surgery.

23 Traditionally, amputees used socket-mounted prostheses to mobilise and regain use of their affected amputated limb. The socket attaches to the amputation stump via suction, meaning that such prostheses do not require invasive surgical procedures. When used for the lower limb, an artificial knee joint and lower leg prosthesis attach to the socket.

24 Osseointegration, is a term that describes the in-growth and integration of living bone onto the surface of an artificial implant, without an intermediate layer of soft tissue. In the 1960s, the concept of osseointegrated reconstruction originated in the dental implant field. In the 1990s, Dr Rickard Brånemark pioneered the use of a screw-fixation implant under the name OPRA (Osseointegrated Prosthesis for the Rehabilitation of Amputees), following which, transdermal osseointegrated implants for attachment of prosthetic limbs were first used. As a procedure, extremity osseointegration is a relatively new major elective and invasive orthopaedic surgery which allows for direct attachment of an external prosthesis to the skeleton through the surgical implantation of an intramedullary device (a device inserted into the medullary cavity of the femur or tibia, i.e. into the central cavity of the bone). The three basic elements of osseointegration are: the residual bone, the metal implant and the transdermal surface. The metal device is implanted into the end of the residual bone of the amputated limb, then exits the soft tissue and skin through a surgically created transdermal opening in the body, known as a stoma, to attach and interface with an external prosthesis. Osseointegrated devices are typically made of titanium, which is a particularly biocompatible material. Bone grows onto and integrates with the surface of the implant, and osseointegration occurs. Over time, this creates a stable and solid connection between implant and bone.

25 Until about 2014, most osseointegration procedures worldwide were performed in two stages: the first stage to insert the intramedullary implant; and the second stage, to create the stoma, allowing for transcutaneous abutment attachment and prosthesis fitting. There were two main approaches for osseointegration procedures: the OPRA system and EndoExo system. Osseointegration using the OPRA system screws the implant into the bone in the first stage with a six to nine-month interval between stages. Implantation of the OPRA system occurs in two stages because the implant is not initially stable and time needs to be given to allow strong osseointegration to occur before load is placed on the implant, otherwise it may fail. By contrast, the EndoExo system inserts a press-fit implant made of cobalt chrome alloy, driven into the medullary cavity with a mallet (instead of being screwed in, per the OPRA system) and requires a four to eight-week interval between stages. A more recent version of the implant is called the Integral Leg Prosthesis (ILP).

26 Dr Al Muderis’ evidence was that he began his practice using the two-stage EndoExo system. In 2013, he designed modifications to the system in collaboration with Permedica S.p.A in Milan and renamed it to Osseointegrated Prosthetic Limb (OPL) system. The OPL system retains the EndoExo press-fit concept, and according to Dr Al Muderis’ description, has several advantageous features.

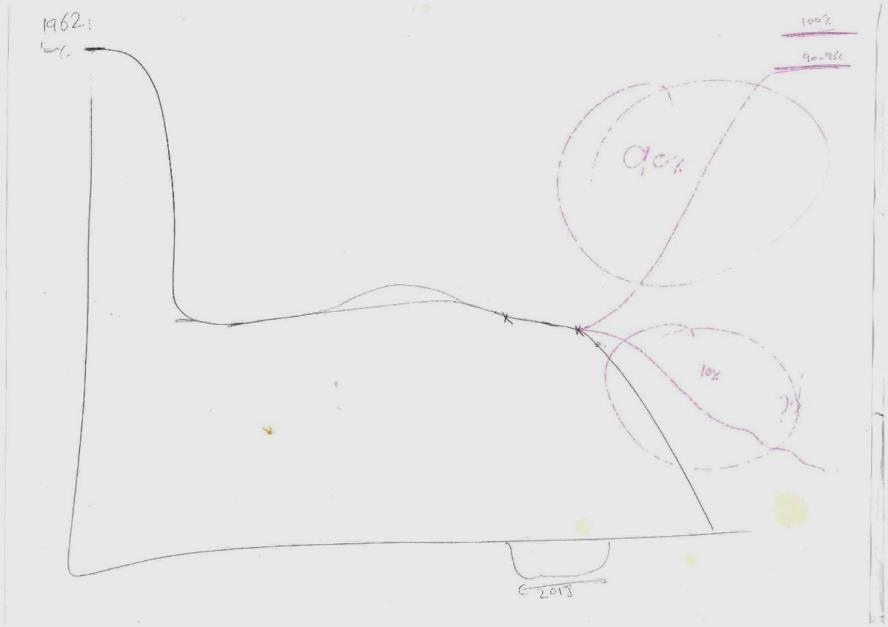

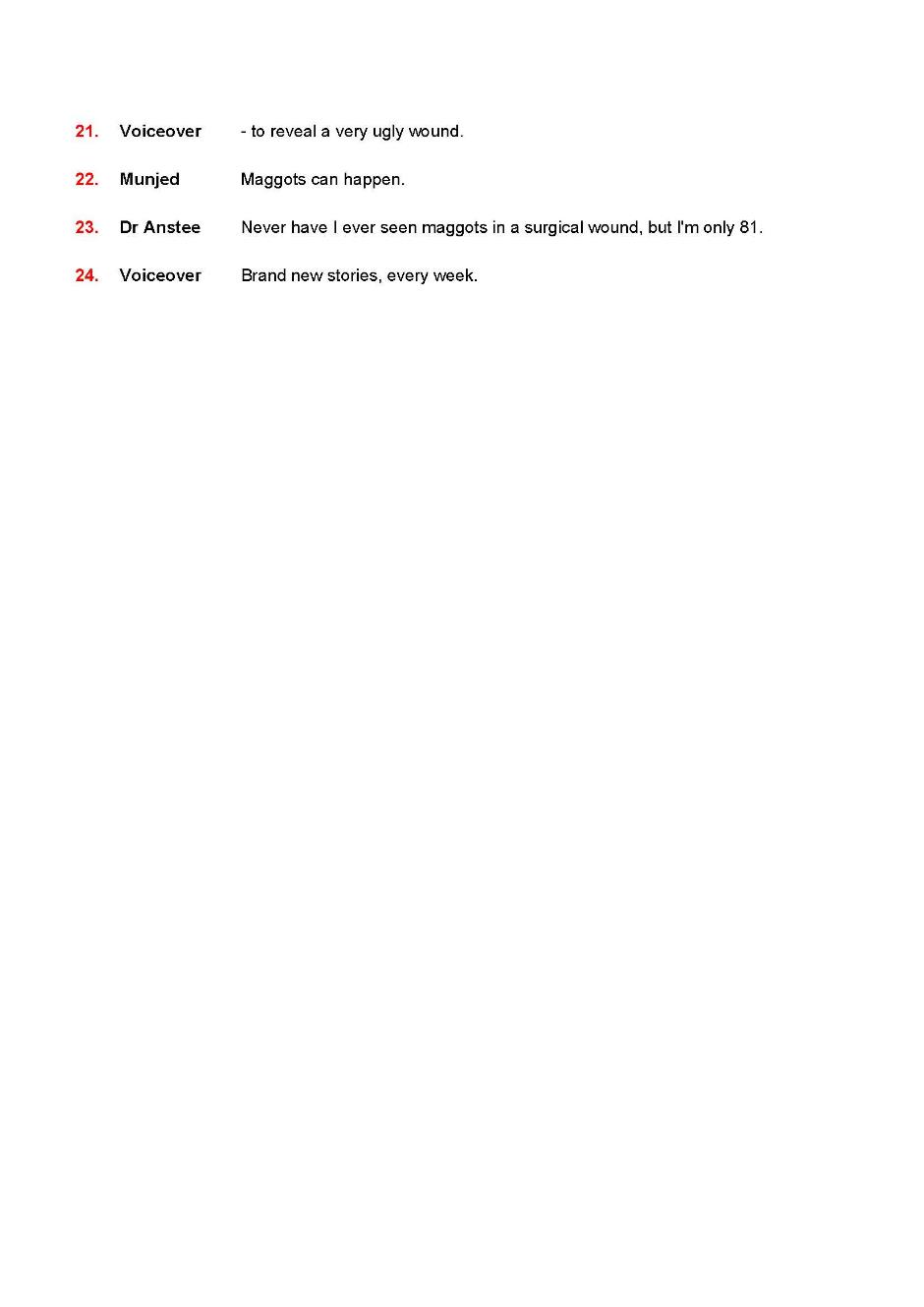

27 The image below depicts the main components of the OPL system used by Dr Al Muderis.

28 The dual cone adaptor connects the intramedullary implant to the external prosthesis and is secured by the internal locking screw. Dr Al Muderis’ evidence is that the dual cone adaptor has a highly polished surface to minimise soft tissue friction, and is coated with Titanium Niobium, which has antibacterial properties. The OPL system includes a “fail-safe” connector, which includes a taper sleeve component that connects on the distal end of the dual cone. The bushing component has two fail-safe pins that slot into matching holes on the taper sleeve. These pins are designed to break away if they are exposed to excessive rotational force, such as in the event of a fall, so that the excessive load can pass through and avoid damage to the implant or patient. The distal locking screw secures both the bushing and the taper sleeve on the dual cone. These three components form an abutment that can be inserted into the connector, which enables the quick attachment of the external prosthetic limb into the osseointegrated implant via the operation of a grub screw. The connector is then distally attached onto compatible commercially available prosthetic limbs via an industry standard four-hole base profile.

29 Since about April 2014, Dr Al Muderis has been performing a single-stage surgery with the OPL system, a modified surgical technique under the Osseointegration Group of Australia Accelerated Protocol-2 and a structured post-operative loading protocol. According to Dr Al Muderis, single-stage implantation is possible with the OPL system because of its design: the fluted proximal section of the OPL implant is both axially and rotationally stable after implantation. Dr Al Muderis owns personally, or through his company (Osseointegration International), the patent for his osseointegration device used in the surgery. His company manufactures the implants.

30 Dr Al Muderis, and various of the expert witnesses gave evidence which addressed the advantages and disadvantages of the different systems for osseointegration surgery. However, it is important to remember that this is not a case about the merits of osseointegration. Nor is it about which is the better system.

The journalists

Ms Charlotte Grieve

31 Ms Grieve is an investigative journalist in The Age’s Investigations Team. In June 2022, she was appointed as a secondee in that team. It was in that context that she conducted the investigation into Dr Al Muderis’ practice. Ms Grieve’s affidavit details her experience including the work undertaken in the roles she has held, the stories she has been involved in, and awards and commendations she has received. She began working in the media in various positions while studying for her Masters of Journalism in 2016 to 2017. She explained she also acted as a freelance journalist during this period, with articles published in The Guardian, The Age, SBS and the Sydney Morning Herald. In October 2018, she commenced as a trainee journalist at The Age. From around December 2019, she worked as a business journalist with the newspaper. She was awarded the 2021 and 2022 Citi award for young business journalist of the year.

Mr Tom Steinfort

32 At the time of the Publications, Mr Steinfort was a journalist with 60 Minutes. He first joined the 60 Minutes team in 2018. Mr Steinfort has been a journalist for nearly 20 years. He has extensive experience in both news and investigative journalism, having worked for various programs, including Today, A Current Affair, Inside Story, 60 Minutes and Nine News. In February 2022, as a senior journalist, he assisted judging the 66th Walkley Awards for excellence in journalism. In August 2022, he won the Kennedy Award for Outstanding Foreign Correspondent for his reporting of the Ukrainian war and was also announced as a finalist in the Outstanding Finance Reporting category. In November 2022, he was part of a group nominated as finalists for the radio/audio feature of “Liar Liar: Melissa Caddick and the Missing Millions” as part of the 67th Walkley Awards for Excellence in Journalism.

Ms Natalie Clancy

33 Ms Clancy joined 60 Minutes in October 2019 as an Associate Producer. In January 2022, she became a Producer of the program. By September 2022, she had been a journalist and a producer in television news and current affairs programs for approximately six years. Ms Clancy detailed in her affidavit the significant stories and investigations in which she had been involved. She was a finalist in the 2018 Walkley awards and the 2018 Kennedy awards, for her reporting in relation to Dr Emil Gayed. In 2021, she won the Paul Lockyer Kennedy award for Outstanding Regional Broadcast Journalism with Gareth Harvey and Liz Hayes for her investigation into healthcare in regional and rural NSW.

Section 3 — The present proceedings

The parties sued

34 It is helpful to set out which respondents are sued in relation to each Publication:

(1) Nine Network is sued in respect of the Sneak Peek and the Broadcast;

(2) Fairfax is sued in respect of the SMH Article and the SMH Online Article;

(3) The Age Company is sued in respect of the Age Article, the Age Online Article and the Grieve Video;

(4) Ms Grieve is sued in respect of all the Publications except the Sneak Peek, that is, she is sued in respect of the Broadcast, the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article, the Age Article, the Age Online Article (together, the Articles) and the Grieve Video;

(5) Mr Steinfort is sued in respect of the Broadcast and the Articles; and

(6) Ms Clancy is sued in respect of the Broadcast and the Articles.

PART 2 — THE DEFAMATORY IMPUTATIONS

Section 1 — The pleaded imputations

35 As mentioned above, the applicant pleaded 75 defamatory imputations in his SOC. I do not propose to recite them here. Rather, they have been annexed to this judgment as Annexure H. There is an issue as to the meaning of certain imputations, and whether they are conveyed (with the conclusions below also being identified in Annexure I).

Section 2 — Legal principles

36 The principles in relation to meaning are well established, and not in dispute between the parties: Favell v Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 52; (2005) 219 CLR 165 at [6]-[12], [17]; Trkulja v Google LLC [2018] HCA 25; (2018) 263 CLR 149 (Trkulja) at [30]-[32]. For application, see, for example, Rush v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 496 (Rush) at [70]-[85] (with there being no suggestion of any error in this collection of principles on appeal to the Full Court); Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Rush [2020] FCAFC 115; (2020) 380 ALR 432; Hockey v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited [2015] FCA 652; (2015) 237 FCR 33 (Hockey) at [63]-[73]; Chau v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 185 at [14]-[27]; Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632 (Wing); V’landys v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2021] FCA 500 (V’landys) at [41]-[55]; Hanson v Burston [2023] FCAFC 124; (2023) 413 ALR 299 at [43]-[48]; Kazal v Thunder Studios Inc (California) [2023] FCAFC 174 (Kazal) at [336]-[337].

37 An applicant bears the onus of establishing on the balance of probabilities that an ordinary reasonable reader, viewer or listener would understand that the publication sued upon bears the alleged defamatory meanings or imputations as pleaded and particularised.

38 The relevant question is whether the publication would have conveyed the alleged meanings to an ordinary reasonable person. It is to be objectively determined. The hypothetical individual is a person with various characteristics, including: they are of fair to average intelligence, experience, and education; are fair-minded and neither perverse, morbid, suspicious of mind, nor “avid for scandal”; and that they do not examine the publication overzealously. While they do not search for hidden meanings or adopt strained or forced interpretations, they nevertheless draw implications, especially derogatory implications, more freely than a lawyer would: Rush at [75]-[77]; Kazal at [336]-[337]. The ordinary reasonable person is also taken to have read the entire publication, considered the context as a whole, and taken into account emphasis that may be given by conspicuous headlines or captions: see Rush at [77]; Trkulja at [32]; and the summary in V’landys at [41]-[55]. They are more likely to consider a publication cautiously and carefully, and less likely to jump to conclusions or engage in loose thinking, where the publications purport to be serious investigative journalism concerning matters of importance (a topic to which I return below). For transient publications such as television broadcasts (even where those publications are available to be viewed or re-viewed via the internet), ordinary viewers are likely to have watched the publication only once, without pausing or going back over it: Chau v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2021] FCA 44; (2021) 386 ALR 36 (Chau) at [35]; V’landys at [73].

39 However, it does not follow that each part of the publication must be given equal significance, as striking words or images may stay with the reader, viewer or listener and give them a predisposition or impression that influences all that follows: V’landys at [51]. A pleaded imputation, and whether it has been proven to be substantially true, requires attention to context, as provided by the balance of the publication and any wider context within which it is to be understood. The natural and ordinary meaning of words is not limited to their literal meaning. The ordinary reasonable person is not a lawyer or be taken to have a detailed understanding of the law: Trkulja at [32]. The imputations are considered by reference to the ordinary meaning, not their legal meanings, because that is the way the terms would be understood by ordinary reasonable people. Words do not necessarily have a fixed meaning that applies in all circumstances; even benign words may convey a worse, or better, impression when regard is had to how and when they are deployed: see, for example, Greek Herald Pty Ltd v Nikolopoulos & Ors [2002] NSWCA 41; (2002) 54 NSWLR 165 at [21]-[27]; Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 at 258. The meaning that an individual would attribute to a publication, or the impression that the reader forms, may be influenced by the overall tone or tenor of the article in question: Rush at [80].

40 Given that the meaning is to be determined objectively, the audience is taken to have a uniform view of that meaning. The publisher’s intended meaning and that understood by individual readers of the matter complained of, are irrelevant: Rush at [84]-[85]. The determination of the natural and ordinary meaning of words involves the application of the “single meaning” rule. Although different people might in fact have understood the meanings conveyed by a matter in different ways, the Court must arrive at a single objective meaning: Slim v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1968] 2 QB 157 at 171-175; Hockey at [73]; Wing at [32]. The issue is the single meaning that an objective audience composed of ordinary reasonable persons should have collectively understood the matter to bear: Wing at [32].

41 A matter is defamatory if it carries a meaning about the applicant which is calculated to: expose him or her to hatred, contempt, or ridicule; lower him or her in the estimation of ordinary right-thinking members of society; or cause others to shun and avoid him or her: Boyd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1980] 2 NSWLR 449 at 452-453; Mirror Newspapers Ltd v World Hosts Pty Ltd [1979] HCA 3; (1979) 141 CLR 632 at 638-639; Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton [2009] HCA 16; (2009) 238 CLR 460 at [5].

Section 3 — Consideration

42 In this case, there are two imputations which the respondents deny are carried: Imputations [13.24] and [16.1] (in relation to the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article and the Age Online Article) (the Denied Imputations). There are a further 18 imputations where the meaning is disputed. If the applicant’s meaning is accepted, the imputations are denied. If the respondents’ meaning is accepted, they admit that meaning is carried, relating to Imputations: [10.1]-[10.6], [13.2], [13.6], [13.20], [16.4], [16.8], [16.13], [16.15], [16.20], [16.23], [16.27], [16.29] and [16.30] (the Disputed Imputations). The remaining imputations are those which the respondents admit are carried, those being imputations [13.1], [13.3]-[13.5], [13.7]-[13.19], [13.21]-[13.23], [13.25]-[13.30], [16.1] (only in relation to the Age Article), [16.2], [16.3], [16.5]-[16.7], [16.9]-[16.12], [16.14], [16.16]-[16.19], [16.21], [16.22], [16.24]-[16.26], [16.28] and [28.1]-[28.9].

43 I accept the respondents’ submission that in assessing the meaning of these imputations that:

Ordinary reasonable viewers and readers of the Publications will have understood that 60 Minutes, the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age are reputable sources of serious news and current affairs. They will have known that these publishers employ reputable and experienced journalists who are not prone to exaggeration and sensationalism. They will have immediately understood that the Publications concerned serious matters of public importance in connection with the provision of medical care to vulnerable members of society. Such persons are not unusually suspicious or avid for scandal and do not search for sinister meanings. They will have approached serious, long-form journalism of this kind with caution and care, and been reluctant to leap to conclusions or engage in loose thinking.

44 That submission was not disputed.

45 In support of the submission, the respondents referred, inter alia, to the observations of Wigney J in V’landys at [72]-[73] (a passage upheld on appeal in V’landys v Australian Broadcasting Corporation [2023] FCAFC 80 at [75], [79] and [82]):

[72] The first general observation is that the report was broadcast as part of an episode of one of the ABC’s flagship news and current affairs programs. That program, 7.30, is a half-hour long program which the ordinary reasonable viewer would understand generally includes well-researched reports by experienced journalists and social and political commentators concerning serious issues of public interest or concern. It should be noted, in this context, that, somewhat unusually for the 7.30 program, the report in question was almost 50 minutes long and occupied the entire episode of 7.30 on 17 October 2019.

[73] Returning to the nature of the program generally, while views may of course differ, the ordinary reasonable viewer of 7.30 would most likely understand that the program was a respected current affairs program which was generally not prone to sensationalism, or loose or imprecise journalism or reporting. The ordinary reasonable viewer of 7.30 would be a person interested in watching a program containing serious and well researched reporting about important issues. Such a viewer would generally be more likely to view the program carefully and be less likely to engage in loose thinking and speculation than viewers of more sensationalist and less informative programs aimed more at entertainment than serious journalism.

46 The Full Court rejected the appellant’s ground that there was no basis for that observation: see [75]. At [81]-[84], Rares J (with whom Katzmann and O’Callaghan JJ agreed) concluded:

[81] The ordinary reasonable reader, listener or viewer is a person whose understanding of what the matter complained of in a defamation action conveys necessarily must be representative of the class of ordinary reasonable members of the community who read, listened or viewed the publication. Different classes of readers, listeners or viewers will have different appreciations of what a publication is saying. Thus, the readers of a technical scientific journal that allegedly conveys a defamatory meaning, and those readers’ characteristics or approach, are not likely to be the same as those of ordinary reasonable persons who read a tabloid newspaper or a weekly gossip magazine.

…

[83] Depending on the nature of the program that the viewer has selected to watch, his or her focus may be to learn from what is broadcast or to be informed, amused, distracted or entertained by it. It is a feature of everyday life that people change their approach to absorbing or comprehending communications that they read, hear or see depending on the context of the publication and the person’s purpose in reading, listening to or viewing it. …

[84] But in every case where the question is whether a video or television publication conveys a defamatory imputation, the hypothetical viewer is an ordinary reasonable member of the type of audience who watches a program of the kind in issue in the way in which such a person ordinarily does. This required his Honour to take into account, in assessing how the viewer would understand the report and whether it conveyed the imputations, the degree to which such a program’s viewers had a proneness to loose thinking.

47 I accept the observations of Wigney J are apt to describe the Articles in The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, as well as the Broadcast by 60 Minutes, which is a public affairs program. This was investigative, long-form journalism on a serious topic of the standard of medical care provided by Dr Al Muderis. The applicant admitted that the Publications were in the public interest. These were not entertainment stories but raised serious concerns and allegations about a serious subject matter of public interest: see Chau at [39].

The Denied Imputations

Imputation [13.24]: Dr Al Muderis improperly profits from his patients by charging them twice for the parts and procedure.

48 This imputation is said to arise from the following statement spoken by Mr Steinfort, in the Broadcast:

Dr Munjed Al Muderis’ business model is ingenious because not only does he carry out the surgery, but he also designs his own implants, so effectively he profits twice by charging for the parts and the procedure.

49 The applicant submitted that while Mr Steinfort did not expressly allege that this arrangement is “improper”, the notion of impropriety was conveyed by: the proximate context of the line to references in the Broadcast of Mr Bruha (one of his patients) saying he felt Dr Al Muderis was “a bit of a cowboy”; Mr Steinfort describing Mr Bruha as feeling like “just another number in a moneymaking machine” and stating that this feeling got worse with “another shocking development”, namely that when one of Mr Bruha’s parts broke, he was charged for the replacement; and Mr Bruha saying that this added “insult to injury”. The applicant also referred to the broader context of the Broadcast, which stated it is “all about the numbers” and referenced Dr Al Muderis going from “rags to riches”, with his expensive penthouse and car. He submitted that the Broadcast’s central theme was that the profits Dr Al Muderis supposedly makes from the components are exploitative, audacious and scandalous. It was submitted that when Mr Steinfort described Dr Al Muderis’ “business model” as “ingenious”, it was not a compliment, rather, the ordinary reasonable viewer would understand “ingenious” in this context to mean “devious” or “crafty”.

50 The respondents submitted that the imputation relates to a short part of the Broadcast lasting seconds and consisting of two sentences (which includes the next sentence being “[i]n fact, court documents from the US reveal that on average his business makes a profit of 110,000 Australian dollars for every American patient”). They submitted there is nothing in Mr Steinfort’s tone, nor the substance of his words, that would have conveyed to ordinary reasonable viewers that there was anything “improper” in the mere practice of Dr Al Muderis profiting from both the performance of osseointegration surgery and the supply of parts for that surgery. Their submission was that ordinary viewers, not avid for scandal, not searching for hidden or sinister meanings, and approaching the Broadcast cautiously with regard to the whole of its contents, will have understood that: (a) osseointegration surgery is “ground-breaking” and “cutting edge surgery”; (b) the surgery is radical, in that it involves implanting a metal rod into an amputee’s residual bone and connecting it to a robotic limb, making them “half-human, half-machine” in order to enable them to walk again; (c) surgery of this kind involves specialist skill and sophisticated hardware, both of which are expensive; (d) Dr Al Muderis is one of the leading exponents of the surgery in the world and has been feted for his performance of the surgery; (e) in the circumstances, Dr Al Muderis would be expected to profit handsomely; and (f) there is nothing inherently improper about that.

51 The respondents submitted the real sting of the Broadcast in so far as it concerns Dr Al Muderis’ business practices was not whether there is anything improper in Dr Al Muderis profiting from both his performance of surgery and his supply of parts but, rather, his practice of allegedly driving up patient numbers, prioritising the growth of his practice over patient care and treating patients like numbers (with the respondents pointing to other aspects of the Broadcast they submitted emphasised this). The respondents also referred to what Dr Anstee said in the Broadcast, where he expressed his opinion as to the propriety of Dr Al Muderis’ marketing practices but cast no judgment on the fact that Dr Al Muderis profits from both the parts and surgery, a matter the respondents argued would not have been lost on ordinary viewers.

52 I accept the respondents’ submission that the imputation as pleaded is not conveyed. An ordinary reasonable viewer would consider this statement in its broader context, considering the whole of the Broadcast. As the respondents submitted, the sting of the Broadcast in respect to Dr Al Muderis’ business practices relates to driving up patient numbers, treating patients as numbers, and prioritising growth of the business over patient care. At best, as the respondents submitted, it might support a finding that the Broadcast imputed that Dr Al Muderis engaged in commercially shrewd or opportunistic conduct in relation to the mechanisms by which he profits from osseointegration surgery. The statement conveys profiteering, but in context, not improperly so.

53 Imputation [13.24] is not carried.

Imputation [16.1]: Dr Al Muderis is a callous surgeon who routinely left patients in pain to rot after their surgeries

54 This imputation is disputed in so far as it is said to be carried by each of the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article, and the Age Online Article. The respondents no longer dispute the imputation is carried in relation to the Age Article.

55 The applicant submitted that it is conveyed explicitly by the front-page headline of the Age Article, “Celebrity surgeon ‘left patients in pain, to rot’”. He submitted that the ordinary reasonable reader would consider this to be callous behaviour by a surgeon towards his patients. The headline conveys that this is routine behaviour because it is expressed in absolute terms: Dr Al Muderis “left patients in pain, to rot”, not just “some patients”. The ordinary reasonable reader would understand that this occurred on more than a few occasions. It was submitted that with the exception of the Age Article headline, the text of the Articles is relevantly the same, and that the Articles presented numerous examples of patients who presented to Dr Al Muderis with complaints of pain or infection but were either ignored or brushed off (with the applicant providing examples thereof). The applicant submitted from the statements identified, that the ordinary reasonable reader would consider that what is described are the actions of a surgeon who is callous towards patients who are in pain and literally “rotting” because of infections. The applicant also submitted that the notion that Dr Al Muderis “routinely” ignores these patients arises in two ways: first, it is suggested that some of the patients profiled in the Articles raised concerns with him on multiple occasions and that he consistently ignored them; and, second, the notion that this kind of treatment is a routine occurrence across Dr Al Muderis’ practice as a whole is conveyed by the accumulation of examples.

56 The respondents accepted that the imputation is conveyed in the Age Article, but contended it is not conveyed in the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article and the Age Online Article. They submitted that each of those publications made no reference to Dr Al Muderis leaving patients to “rot after their surgeries”. The Articles did refer to some of Dr Al Muderis’ patients who had suffered ongoing and severe pain following osseointegration surgery but submitted that none suggested that Dr Al Muderis had left them to “rot” after surgery. They submitted that ordinary readers could only have arrived at such a meaning as a result of applying their own beliefs and prejudices in a search for a hidden or sinister meaning.

57 The SMH Article, the SMH Online Article and the Age Online Article do not contain a reference to “rot”. It is to be recalled that from the passages in the Articles relied on by the applicant in support of his submission, he contended that the ordinary reasonable reader would consider that the patients were “literally ‘rotting’ because of infections”. Considering those passages in the context of the whole of the Articles, I am not persuaded that is what is conveyed.

58 Imputation [16.1] is not carried in the SMH Article, the SMH Online Article and the Age Online Article.

The Disputed Imputations

59 It will be recalled that the Disputed Imputations are [10.1]-[10.6] (Sneak Peek), [13.2], [13.6], [13.20] (Broadcast), [16.4], [16.8], [16.13], [16.15], [16.20], [16.23], [16.27], [16.29] and [16.30] (Articles, noting [16.27], [16.29] and [16.30] are not pleaded in relation to the SMH Online Article and the Age Online Article (together, the Online Articles)). Each of these imputations incorporates words or phrases such as “operated”, “surgical abilities”, “conducted surgery” and “performed surgery”, or slight variations thereof.

60 There is an issue as to the meaning of those terms. As explained below, the applicant proceeded to conduct his case on the basis that those words or phrases mean what occurs in the operating theatre. That is, the conduct of the surgery itself, which they submitted must involve taking a scalpel to a patient. The respondents do not admit the imputations with that meaning. Rather, in their Amended Defence, their admission was only on the basis that ordinary reasonable viewers and readers would have understood them as impugning his surgical practice more generally, including “pre-operative and post-operative consultations, considerations and care” (being the broader meaning). The respondents submitted that the Disputed Imputations are not conveyed if understood in the narrower sense as advanced by the applicant, that is, only concerning Dr Al Muderis’ conduct of surgery in the operating theatre. The respondents submitted that if that is accepted, the applicant’s case in respect of those imputations must fail, because it has not been established that they are conveyed. They submitted that nonetheless, in that circumstance, they rely on the imputations with the broader meaning as contextual imputations. I note that the respondents also submitted that in any event, the evidence adduced at trial supports a finding that Imputations [10.1], [10.2], [10.4], [16.4] and [16.30] are true even in the narrower sense posited by the applicant.

61 In his written closing submissions, the applicant took issue with the respondents’ approach, contending that rather than addressing the issue of which imputations are carried by the matters, the contention about the meaning of “surgery” appears to be directed more to the extent to which certain particulars of justification, even if made good, are relevant to establishing the substantial truth of the imputations of which Dr Al Muderis complains. He submitted that the respondents seek to expand the meaning of “surgery” to broaden the matters which may be relevant to justifying those imputations. During oral submissions, the applicant contended it is for the Court to determine the meaning of “surgery” by reference to what the ordinary reasonable reader or viewer thinks it means. He submitted that as the respondents have admitted the broader interpretation is conveyed, the Court should conclude that meaning, as a minimum, applies and conclude, per the respondents’ case, that those imputations are carried.

62 I do not accept that that is the approach taken by the respondents. Rather, the respondents have addressed as the first step, the question of the meaning of the imputations, contending that the imputations are not conveyed if understood as the applicant contended. The respondents submitted that if that is correct, they are then able to otherwise rely on the Disputed Imputations with the broader meaning (as contextual imputations) for the purposes of their defence of contextual truth. The applicant repeatedly criticised the form of the respondents’ pleading but brought no application challenging its sufficiency or appropriateness, prior to the hearing.

63 An initial issue arises as to what the applicant pleaded in relation to the Disputed Imputations. In the applicant’s oral closing submissions (which I note for context were heard after his written closing submissions were filed), the applicant submitted that he was taken by surprise by the respondents’ approach to this issue, because at no point did he seek to define the meaning of “operation” or “surgical” or “surgery”, and it was not the applicant’s job to do so.

64 As the applicant submitted from the outset, it is his prerogative to choose the battleground by choosing the imputations on which he relies. That choice is a matter for the plaintiff: Wing at [16]-[17].

65 An imputation should identify the act or condition the plaintiff claims was attributed to him, as they would be understood by the ordinary reasonable reader, viewer or listener. The meaning would usually be distilled or inferred from the words used in the publication: Harvey v John Fairfax Pty Ltd [2005] NSWCA 255 at [118]-[132]; Drummoyne Municipal Council v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1990) 21 NSWLR 135 (Drummoyne) at 137. If the publication gives rise to one or more possible meanings of a particular condition attributed to an applicant, the applicant is obliged to specify how and in what respects that condition is conveyed in the imputation: Trkulja v Google Inc LLC [2010] VSC 226 at [19]-[20], citing Gleeson CJ in Drummoyne.

66 As explained above, an applicant bears the onus of establishing that an ordinary reasonable reader, viewer or listener would understand the publication sued upon bears the alleged defamatory meanings or imputations as pleaded and particularised, which is seen to extend to any meanings that are not substantially different from or more serious than those pleaded meanings (often described as a mere shade or nuance of the pleaded meaning, or a permissible variant): Wing at [17]-[18]; Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd [1998] HCA 37; (1998) 193 CLR 519 at [21]-[23], [60], [139]; Nassif v Seven Network (Operations) Ltd [2021] FCA 1286 (Nassif) at [80].

67 The respondents submitted that at least from the case management hearing held on 24 August 2023, the meaning identified by the applicant and relied upon as conveyed is “surgery” and “operation” in the narrow sense, that is, confined to what occurred in the operating theatre. I accept that the position of the parties was apparent from at least that case management hearing (after the pleadings and evidence had been filed, but before the trial).

68 So much was made clear by the applicant in his written opening submissions. He submitted:

Whatever else might be comprehended within those expressions [“operated on”, “conducted surgery”, “performed surgery” and “performed osseointegration surgery”], the natural and ordinary meaning of them, as any ordinary reasonable person would understand them, must involve taking a scalpel to the patient. If the respondents are not in a position to justify the imputations in that sense, particulars about other aspects of medical practice which might form part of an extended notion of “performing surgery”, such as preoperative consultations and informed consent procedures, will not assist them because they will have failed to justify what is obviously a material part of the imputations as pleaded, namely the performance of surgery stricto sensu.

69 The applicant’s oral opening submission was consistent with that. The applicant’s written closing submissions are in the exact same terms. This approach is also reflected in those written submissions that concern whether the justification defence has been established in relation to the imputations in issue. The reasons given in the annexure to the applicant’s submissions addressing why he contended justification is not established in relation to these imputations, refer to the imputations as involving negligent surgery, negligently conducting surgery, or conducting the actual operation. The broader imputation is not addressed.

70 It is in that context that the applicant’s oral closing submission, referred to above, was made. That is, at no point did he seek to define the meaning of “operation” or “surgical” or “surgery”, and it was not his job to do so. He submitted that the meaning of “operation” or “surgery” only becomes relevant for the truth case if there is a dispute about meaning. However, the first issue is whether the applicant has established that the imputation has been carried. If it has not, the occasion for a defence does not arise.

71 The applicant’s oral closing submission was ultimately, that at a minimum, the Court should find that the imputations are carried, even if I accept that the respondents’ view of surgery is correct. He submitted that the respondents have admitted the imputations are carried. He submitted his position as to the meaning of surgery is “not black and white” on every imputation, because of the context in which it occurred. However, in respect to the Disputed Imputations that is not how his case was conducted. For example, the applicant submitted the Sneak Peek, is only talking about surgery in the narrow sense. To illustrate, the applicant accepted that his position in relation to Mr Smith is that surgery meant the operation itself:

That his surgery, as a surgeon, caused Brennan Smith to cut his flesh off, caused him excruciating pain like being electrocuted, caused maggots in a surgical wound, surgery, negligent performance of surgery.

72 That is, Dr Al Muderis negligently conducted the operation which caused Mr Smith to cut off his own skin. His submission on the other imputations is consistent with that; that these imputations all relate to surgery in the narrow sense, and that they could not mean anything else. The applicant’s submission also does not sit with the manner he opened his case wherein he submitted the respondents need to establish the justification defence for these imputations in respect to surgery in the strict sense, without which the justification defence fails.

73 The applicant’s closing submission proceeded on the basis that the respondents admitted the Disputed Imputations are conveyed, but as explained above, the respondents did not admit these imputations were carried by the Publications if the meaning of the terms was construed in the narrow sense, being the operation or performance of the surgery itself.

74 The respondents submitted:

The ordinary reasonable person understands what surgery entails. They know that the surgeon’s role involves much more than the time spent in an operating theatre. They will appreciate that surgical practice involves assessing whether surgery is necessary, what type of surgery, whether the patient is a suitable candidate for that surgery, the disclosure of information about the surgery, the preparation of the patient for surgery, the performance of the surgery itself, and all aspects of ongoing post-surgical care, treatment and rehabilitation. When a person says in common parlance that they are “having surgery”, ordinary reasonable members of the community understand that this is not simply a reference to the process of laying on an operating table to undergo a surgical procedure. It is a reference to an entire process.

75 I accept that submission. As the respondents submitted, the narrow interpretation of the terms also does not reflect either the words or substance of the Publications, which do not contain any express allegation concerning Dr Al Muderis’ performance of surgery “in the operating theatre”. As explained below, in my view, the Publications convey acts which would be understood by the ordinary reader, as within the broader concept of what is involved in having surgery (not confined to what occurred in the operating theatre). Where the word surgery is used (which is limited), in context, would be understood by the ordinary reasonable reader to be referring to surgery of this type, not this operation. Where the word operation is used, it is a reference to the fact of the operation.

76 I accept the respondents’ submission that the applicant conducted his case on the basis of the meaning of the terms in the Disputed Imputations as surgery in the narrow sense (i.e. what occurred in the operating theatre which must involve taking a scalpel to a patient). That is the meaning of the imputations he intended to convey by his pleading, and on which he chose to rely.

77 The issue then becomes whether those imputations (on the meaning pleaded by the applicant, bearing in mind permissible variants) are carried. The relevant question is whether the Publications would have conveyed the alleged meanings to an ordinary reasonable person.

The Sneak Peek

78 The applicant pleaded six imputations in relation to the Sneak Peek, all of which he contended would be understood as having conveyed that Dr Al Muderis negligently operated or conducted surgery on a patient, specifically in the operating theatre. To use the applicant’s language, this “must involve taking a scalpel to the patient”.

79 I do not accept that the ordinary reasonable viewer would have understood this publication to impugn Dr Al Muderis’ conduct of surgery in the operating theatre. That is not what is conveyed by the Sneak Peek. This is a very brief advertisement, promoting and directing attention to an upcoming program “on 60 Minutes”, that is, the Broadcast. The publication directs attention to the substantive broadcast. Given that context, as the respondents submitted, it does not descend to any level of detail as to the type of conduct attributed to Dr Al Muderis. The terms pleaded (being negligent surgery, negligently conducting surgery, or negligence in performing surgery) are not used in that publication, save for one reference to surgery, but not in the sense relied on by the applicant. That sole reference in the Sneak Peek to surgery pertains to the question posed by Mr Steinfort to Mr Smith: “What sort of surgery leaves you having to cut your own flesh off?” As evident from the use of the phrase “sort of surgery”, in context, it conveys a type of surgery as opposed to the conduct or performance of a particular operation. There is no reference to “conducted surgery”, “performing surgery”, “operated on”, or “surgical abilities”, being the terms used in the pleaded imputations. Rather, the publication conveys false promises, broken promises, patients turning against Dr Al Muderis, and complications arising after surgery (e.g. smells akin to a dead body, excruciating pain or needing to cut off flesh).

80 Contrary to the applicant’s submission, the Sneak Peek does not convey that Dr Al Muderis was negligent in the operating theatre during the operation such that it caused Mr Smith to cut his own flesh off and experience excruciating pain likened to being electrocuted.

81 The applicant submitted that as an imputation contains all variant meanings, even if a broad view of surgery is accepted, his case does not fail.

82 That raises the issue of whether, what is conveyed, is a permissible variant. I am not persuaded that surgery in the broad sense is a mere variant or nuance of surgery in the narrow sense. The focus in the latter interpretation is on a confined aspect of conduct (Dr Al Muderis’ conduct in performing the operation) whereas, the Publications had as their focus, the broader concept.

The Broadcast

83 In relation to the Broadcast, the imputations in issue, [13.2], [13.6] and [13.20], all relate to Mr Urquhart, and include the allegation that Dr Al Muderis negligently performed surgery on him.

84 I do not accept that the ordinary reasonable viewer would have understood the Broadcast to impugn Dr Al Muderis’ conduct towards Mr Urquhart in performing the surgery in the operating theatre. The nature of the complaints that supposedly have patients turning against Dr Al Muderis is identified at the outset:

Now a number of the surgeon’s patients are turning against him, accusing him of not taking proper care of them. And when you see the evidence you’ll understand why they’re so angry.

85 That is the framing of the Broadcast. As the respondents submitted, the reference to “care” was sufficiently broad to have been understood as extending to all aspects of Dr Al Muderis’ care for patients.

86 There are several other instances in the Broadcast which support the respondents’ submission. For example (any emphasis is added):

(1) shortly after the above statement, there is a clip of Mr Urquhart with Mr Steinfort referencing out-of-control infections and maggots in a voiceover;

(2) the Broadcast then turns to Mr Smith with Mr Steinfort’s voiceover describing him as “a patient feeling so abandoned he had to take to his own leg with a kitchen knife” over a video to this effect, followed by Mr Smith’s interview where he describes the excruciating pain he experienced;

(3) Mr Steinfort remarks that “[t]hese patients are left feeling like they’re just a number”;

(4) the Broadcast returns to Mr Urquhart with Mr Steinfort referring to the fact that within three months of rehabilitation he was able to walk, but there were “horrible complications” including pain, infections, repulsive odour, what is known as the “Febreze incident” (discussed further below) and maggots;

(5) the Broadcast also returns to Mr Smith, with Mr Steinfort referring to his hypergranulation, with Mr Smith saying “if you take on a job you take it on and start to finish to its entirety, and you got a responsibility and duty of care”, to which Mr Steinfort responds: “Care’s the important word there isn’t it?”;

(6) the Broadcast shows Ms Grieve and Mr Steinfort discussing their joint investigation, and Ms Grieve saying “[s]o we’ve got traumas, infections” followed by Mr Steinfort describing in a voiceover that Ms Grieve interviewed overseas patients “who felt neglected after Dr Al Muderis operated on them”, such that Ms Grieve described a theme of Dr Al Muderis abandoning patients, over-promising and viewing patients as numbers;

(7) following Ms Stewart’s interview, Mr Steinfort remarks that “Shona says once operated on, rehabilitation care for patients was inconsistent”;

(8) in his interview with Dr Anstee, Mr Steinfort notes “[c]omplications will arise. I guess the issue is how well you manage those complications”, to which Dr Anstee responds: “Yeah. And how well you plan to avoid the complications. But if you do have a complication, you’ve got to wear it. That’s your problem until you die or the patient dies.” Mr Steinfort further asks “[i]s there any excuse for a surgeon to – to palm that off to someone else?” and Dr Anstee replies “… you’ve got to look after the patient”;

(9) Mr Steinfort’s voiceover: “While some question how well Dr Al Muderis looks after his patients …”;

(10) the Broadcast later turns to Mr Bruha, and Mr Steinfort’s voiceover remarks “… like a number of other patients, his wound became infected”, Mr Bruha stating in his interview that “[t]hey sent me home with an infection in my leg and an open wound”, and Mr Steinfort’s later voiceover that “Chris Bruha has ongoing issues with pain”;

(11) regarding Ms Cindy Asch-Martin, the Broadcast states “even Cindy admits she did suffer major complications and was sent back to America afterwards with a dangerous infection”; and

(12) in the course of his interview with Mr Steinfort, Dr Al Muderis was asked about abandoning Mr Urquhart, maggots as a complication, downplaying infection and odour by recommending the use of Febreze, performing procedures and hosting medical clinics in the United States potentially in breach of United States laws, high-pressure sales tactics, encouraging staff to teach patients how to fundraise for the surgery, being motivated by money, paying people to recruit patients and mobilising patients to protect his reputation.

87 As the respondents submitted:

Conspicuously absent from all of this was any suggestion, complaint, allegation or accusation that Dr Al Muderis had at any stage acted negligently when performing surgical procedures “in the operating theatre”.

88 I agree with that description. I accept the respondents’ submission that ordinary reasonable viewers would have understood the Broadcast as conveying that Dr Al Muderis has engaged in negligence or other discreditable conduct in his practice as a surgeon generally and specifically in relation to Mr Urquhart, including the disclosure of risks and post-operative care. Again, it is difficult to accept this is simply a mere variant or nuance of the pleaded imputations.

89 I am not satisfied that Imputations [13.2], [13.6] and [13.20] are conveyed.

The Articles

90 In relation to the SMH Article and the Age Article, the Disputed Imputations are [16.4], [16.8], [16.13], [16.15], [16.20], [16.23], [16.27], [16.29] and [16.30].

91 As the respondents submitted, the headline for each article (which for reference are “Surgeon ‘botched amputee aftercare’” and “Celebrity surgeon ‘left patients in pain, to rot’”) are plainly directed to the quality of Dr Al Muderis’ post-operative care. Thereafter, the Articles are virtually the same. The focus on aftercare is reinforced at the commencement of the article:

[Dr Al Muderis] has been accused by patients and former staff of failing to provide adequate care following surgeries, leaving some people mutilated, wheelchair-bound or reliant on heavy pain medication.

92 There are several other examples in the body of these articles which support the respondents’ submission. Given these articles are virtually indistinguishable, the following examples are taken from the contents of the Age Article, which will apply mutatis mutandis to the SMH Article (any emphasis is added).

93 In the introductory portion of the article:

(1) the statement “[b]ut now more than 25 patients, 15 surgeons and a dozen of Al Muderis’ current and former business associates have told the Herald and 60 Minutes of concerns about the surgeon’s approach to patient selection and aftercare” and similarly “[i]nterviews with more than 25 patients, 15 surgeons and a dozen of Al Muderis’ current and former business associates have raised questions about the professor’s approach to patient selection and care”;

(2) the statement “[h]e has also been accused of using high-pressure sales tactics to boost patient numbers”;

(3) the statement “veterans Mark Urquhart and Brennan Smith claim they were not properly warned of the risks and were left in agonising pain”;

(4) the statement “Urquhart, a former paratrooper, claims to have been ignored when he found maggots in his leg after his bone was left exposed for years”; and

(5) the statement “Al Muderis denied using high-pressure sales tactics and apologised to patients who felt abandoned but said these were a disgruntled minority”.

94 In the remainder of the article: