Federal Court of Australia

McCallum v Projector Films Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 903

File number(s): | NSD 1832 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | SHARIFF J |

Date of judgment: | 6 August 2025 |

Date of publication: | 7 August 2025 |

Catchwords: | COPYRIGHT – interlocutory application – dispute over which of two persons is to be attributed and credited as the “principal director” of a documentary to be premiered this week at the Melbourne International Film Festival – moral rights – right of attribution of authorship – false attribution – misleading and deceptive conduct – interlocutory injunctive relief – serious question to be tried – balance of convenience – relief granted |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, Australian Consumer Law s 18 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 189, 191, 195AW(1), 195AW(2), 195AWA |

Cases cited: | Australian Broadcasting Corp v O’Neill [2006] HCA 46; 227 CLR 57 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 63; 208 CLR 199 Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd [1968] HCA 1; 118 CLR 618 Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd v South Australia [1986] HCA 58; 161 CLR 148 Samsung Electronics Co Limited v Apple Inc [2011] FCAFC 156; 217 FCR 238 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Copyright and Industrial Designs |

Number of paragraphs: | 86 |

Date of hearing: | 4 August 2025 |

Counsel for the applicant | Mr A R Lang SC with Mr R Clark |

Solicitor for the applicant | Frankel Lawyers |

Counsel for the respondents | Ms F St John with Ms A O Brodie |

Solicitor for the respondents | Banki Haddock Fiora |

ORDERS

NSD 1832 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | STEPHEN MCCALLUM Applicant | |

AND: | PROJECTOR FILMS PTY LTD First Respondent DAVID ANTHONY NGO Second Respondent | |

order made by: | SHARIFF J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 6 August 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Upon the Applicant providing through his counsel the usual undertaking as to damages, until final determination of these proceedings or further order, the Respondents be enjoined from, in Australia:

(a) causing or authorising the film entitled “Never Get Busted!” which is presently proposed to be screened at the Melbourne International Film Festival 2025 (the Documentary) to be seen and heard in public or communicated to the public, unless the Documentary both contains the credit “Directed by Stephen McCallum” and does not contain the credit “Directed by” for the Second Respondent; and

(b) promoting the Documentary, or causing the Documentary to be promoted, unless (where the promotion contains credits for the Documentary) the promotion both contains the credit “Directed by Stephen McCallum” and does not contain the credit “Directed by” for the Second Respondent.

2. Costs be reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

SHARIFF J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 A documentary film entitled “Never Get Busted!” (the Documentary) is due to have its Australian premiere this week at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). It is scheduled to be screened on Friday, 8 August 2025, and again on Sunday, 10 August 2025. A dispute has arisen between the parties as to who is to be attributed as the “Principal Director” of the Documentary for the purpose of the credits to be displayed at the screening of the Documentary and more generally in the promotion of the Documentary.

2 The proceedings are listed for final hearing before me for three days commencing on 10 September 2025. By the time the proceedings are heard, the Documentary will already have been screened in Australia. This fact, together with an impasse about the credits which are to appear in the version of the Documentary to be shown at the MIFF, have led the applicant (Mr McCallum) to apply for interlocutory relief seeking to enjoin the respondents from taking particular steps in relation to the screening and promotion of the Documentary until the final determination of the proceedings. The hearing of the interlocutory application has fallen to me to resolve as the docket judge.

3 To lay members of the public, the identification of the dispute as to who is the “Principal Director” may beg the question: what is the difference between the Principal Director and a Director of a film? The answer to this question lies in certain interlocking provisions of Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) which deals with “moral rights” of attribution in respect of cinematographic works. Specifically, for the purposes of attribution (and, conversely, proscribing false attribution) of moral rights in respect of a “cinematograph film” where two or more individuals are involved in directing that film, s 191 of the Copyright Act provides that “a reference in this Part to the director … is a reference to the principal director of the film and does not include a reference to any subsidiary director, whether described as an associate director, line director, assistant director or in any other way” (emphasis added). It can thus be seen that, where there is more than one person who is said to be the director of a film, the attribution of a person as the “Principal Director” has considerable significance to the moral rights of the relevant person. As I explain below, whilst these are distinctions that may appear to be an exercise of overwrought pedantry and may well be lost on ordinary members of the public, they are ones which are well understood within the so-described “film industry”.

4 Mr McCallum claims that he is the “Principal Director” of the Documentary to the exclusion of the second respondent (Mr Ngo), though he acknowledges that Mr Ngo may be a subsidiary, associate or other “Director”. In the substantive proceedings, by his Amended Statement of Claim (ASOC), Mr McCallum claims that despite entering into a contract with the first respondent (Projector Films) by which it was agreed that he was to be engaged as, and was in fact, the “Principal Director” of the Documentary, the respondents have failed to recognise him in this capacity in the credits of the Documentary and in promotional materials including in relation to its impending Australian premiere. One version of the Documentary was screened at the Sundance Film Festival in Salt Lake City, Utah, in the United States, which did not refer to Mr McCallum at all. Mr McCallum was also excluded from attending that Festival altogether. The version of the Documentary that is to be screened at the MIFF was also screened at a film festival in Los Angeles known as the “Dances With Films Festival” and whilst this version referred to Mr McCallum as a “Director”, Mr McCallum claims that the credits and promotional materials for that festival conveyed that Mr Ngo was the “Principal Director”. Mr McCallum claims that by this and related conduct, the respondents have infringed his “moral rights” as provided for in the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), and have engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct contrary to s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (as contained in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010), as well as breaching the contract between him and Projector Films.

5 For immediate purposes, Mr McCallum claims that if the respondents do not take steps to attribute him as the “Principal Director” of the Documentary in the credits and promotional materials for the MIFF, he will continue to suffer from irremediable harm to his moral rights, reputation and career prospects. At the very least, Mr McCallum says that there should be an indication that the question of who is the “Principal Director” of the Documentary is the subject of legal proceedings as this would convey the true position and preserve the true status quo between the parties.

6 The respondents deny Mr McCallum’s claims and contend that Mr Ngo is the “Principal Director” of the Documentary. For present purposes, it is common ground that Mr Ngo, together with his wife, Ms Erin Williams-Weir, created the idea for the documentary based on the life of Mr Barry Cooper, who was at one time a Texan based narcotics officer during the height of the “war on drugs” in the United States in the 1990s before he changed stripes to call out corruption in the police force and instructed citizens on how to outsmart law enforcement. It is also common ground that Mr Ngo is the screenwriter of the Documentary and that he and Ms Erin Williams-Weir are the producers (under the auspices of Projector Films). The respondents say that, although it was intended that Mr McCallum would be the “Principal Director” of the Documentary, after a period of time Mr McCallum abandoned his duties or ceased performing essential work, and was otherwise not involved in critical phases in the completion of the Documentary. The respondents say that it is Mr Ngo who has performed substantial aspects of directorial work in the development and production of the final versions of the Documentary that have been screened at the Sundance Film Festival, the Dances With Films Festival, and the version which is due to premiere at the MIFF. The respondents accept that Mr McCallum is a “Director” of the Documentary, but say that he is not the “Principal Director”.

7 The respondents have also filed a cross-claim in which they assert Mr McCallum has disparaged them and/or engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by, amongst other things, asserting to third parties that he is the “Principal Director” of the Documentary.

8 For the purpose of the somewhat boutique or bespoke issue as to who is the “Principal Director” of a “cinematograph film”, it is common ground between the parties that, where there is more than one director of a film, a reference in the credits to the film or in its promotional materials to the film being “Directed by” a person is a reference to the “Principal Director” of the film and a reference to the “Director” is a reference to the non-Principal Director. It is also common ground between the parties that the order or sequence in which the directors are referred to in the opening or title credits and in the end credits also conveys who is the “Principal Director” where there is more than one director of a film.

9 All of this introductory background is to set the scene for what has led to the present interlocutory application. On or about 10 July 2025, and in accordance with earlier orders I made in the case management of the proceedings, Mr McCallum was notified by the respondents that the Australian premiere of the Documentary would occur at the MIFF. The promotional and other materials for the Australian Premiere conveyed that Mr Ngo was the sole “Director” of the Documentary and referred to him as being “at the helm” of it. These promotional materials made no reference to Mr McCallum – not even as a “Director”. Mr McCallum then threatened to seek injunctive relief. Met with the prospect of an interlocutory application, the respondents’ solicitors wrote a letter dated 16 July 2025 to the solicitors for Mr McCallum to make a “without admissions” offer by which they offered to take all necessary steps to amend the credits to identify that the Documentary was “Directed by Stephen McCallum”, being in the same style as the directorship credit that was to be given to Mr Ngo (16 July Proposal). The purported effect of this proposal was said to involve both men being credited as “co-Principal Directors”.

10 Mr McCallum rejected the 16 July Proposal. As explained below, his position is that the 16 July Proposal is meaningless in that it does not, in truth or in substance, convey that he is a “co-Principal Director” and, in fact, together with all the other promotional and contextual materials that have been published to date, the effect of the Proposal is to convey or create the impression that Mr Ngo is the “Principal Director”. As a result, Mr McCallum proceeded to file an interlocutory application on 21 July 2025 by which he seeks orders enjoining the Respondents, until the final determination of the proceedings or further order, from causing or authorising the Documentary to be seen or heard in public, or promoted unless:

(a) it contains the credit “Directed by Stephen McCallum” and does not contain the credit “Directed by David Ngo”; or

(b) alternatively, instead of any directing credits being referred to at all, a statement is made to the effect that the “directing credits are the subject of court proceedings.”

11 During the course of oral argument, Mr McCallum refined the alternative relief he seeks such that the respondents be enjoined, until further order, from causing or authorising the Documentary to be seen or heard in public, or promoted, unless the credits or promotions contain a statement to the effect that “both Stephen McCallum and David Anthony Ngo claim that they are the director and the directing credits are the subject of court proceedings”.

12 The respondents opposed the interlocutory application.

13 As is well established, the two critical questions that arise in the grant of interlocutory relief are:

(a) first, whether the applicant has established that there is a serious question to be tried or a prima facie case, and, in this regard, it suffices to show a sufficient likelihood of success at trial if the evidence remains as it is: Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd [1968] HCA 1; 118 CLR 618 at 622–623 (Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ) as explained by Gummow and Hayne JJ in Australian Broadcasting Corp v O’Neill [2006] HCA 46; 227 CLR 57 at [65] (Gleeson CJ and Crennan J agreeing with this explanation at [19]); Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd v South Australia [1986] HCA 58; 161 CLR 148 (Mason ACJ); Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 63; 208 CLR 199 at [13] (Gleeson CJ) Samsung Electronics Co Limited v Apple Inc [2011] FCAFC 156; 217 FCR 238 at [52]–[74] (Dowsett, Foster, Yates JJ); and

(b) second, whether the balance of convenience favours the granting of the injunction, which involves consideration of matters including, among other things, whether the relief will change the status quo, the potential harm that will be caused, whether damages are an adequate remedy, and whether there is any disentitling conduct: Castlemaine Tooheys Ltd; Samsung Electronics at [52]–[74].

14 For the reasons that follow, I am satisfied that interlocutory relief should be granted. As I will explain, I was initially inclined to grant the alternative relief sought by Mr McCallum as, in my view, this would have more adequately addressed the justice of the case in that it would have recognised that both men laid claim to being the Principal Director of the Documentary and that this matter was the subject of legal proceedings. This would have been an accurate statement as to the true state of affairs and one which genuinely preserved the status quo. However, the respondents did not wish this true position to be conveyed as they considered it to be detrimental to their prospects of selling rights to the Documentary to third parties which, in the present age of streaming and digital platforms, is where the real money is likely to lie rather than at the box office. The respondents urged that, if Mr McCallum established a case for relief (which they stridently opposed), the Court should grant the primary relief sought by Mr McCallum which was said to be preferable to being subjected to the alternative relief. As I will explain, in light of this position, I am satisfied that the primary relief sought by Mr McCallum should be granted even though it will be obvious from this judgment that the question of who is the Principal Director of the Documentary is the subject of legal proceedings and one might expect that the respondents will disclose this fact to third parties (if they did not already know).

2. THE RELEVANT EVIDENCE

15 As mentioned above, the proceedings have been listed for final hearing. By reason of case management orders made by me, the parties have respectively filed and served the evidence upon which they intend to rely in the substantive proceedings. The evidence that the parties have filed is as extensive as it is voluminous, and includes expert evidence. The parties relied upon all of that evidence for the purpose of the interlocutory relief, together with some additional evidentiary materials.

16 Mr McCallum relied on:

(a) three affidavits he affirmed in these proceedings:

(i) the first of which was dated 22 July 2025 and is 100-pages in length (First McCallum Affidavit);

(ii) the second of which was also dated 22 July 2025 and is 11-pages in length; and

(iii) the third of which was dated 27 July 2025;

(b) the affidavit of Ms Needeya Islam dated 21 July 2025 (Islam Affidavit), who is Mr McCallum’s agent;

(c) the affidavit of Mr Greg Duffy dated 22 July 2025, who is Mr McCallum’s solicitor; and

(d) the affidavits of Mr Rolf de Heer dated 23 July 2025 (de Heer Affidavit) and 27 July 2025, who is an accomplished, award-winning Australian film director and producer and whose evidence is in the nature of expert evidence.

17 In turn, the respondents relied on:

(a) the affidavit of Mr Ngo dated 24 July 2025;

(e) the affidavit of Ms Erin Williams-Weir dated 23 July 2025, who is a producer of the Documentary and the wife of Mr Ngo;

(f) the affidavit of Mr Daniel Joyce dated 25 July 2025, who is a producer of the Documentary and is a corporate director of Projector Films;

(g) the affidavit of Mr John Battsek dated 23 July 2025, who is an executive producer of the Documentary;

(h) the affidavit of Mr Julian Hart dated 24 July 2025, who is an editor of the Documentary;

(i) the affidavit of Mr James Cude dated 24 July 2025, who is a story consultant and editor of the Documentary;

(j) the affidavit of Ms Sharyn Grace Eyre dated 22 July 2025, who is an editor of the Documentary;

(k) the affidavit of Mr Simon Walbrook dated 23 July 2025, who is the composer of the Documentary; and

(l) the affidavit of Ms Lucy Maclaren dated 25 July 2025, who is an expert witness with over 40 years’ experience in various roles in the Australian film industry with a particular focus on documentary films (Maclaren Affidavit).

18 As I have noted, and as is self-evident, the affidavit material filed by the parties in these proceedings is extensive. By way of example, the First McCallum Affidavit contains some 714 paragraphs spanning 100 pages. For his part, Mr Ngo’s affidavit is also of considerable length and contains 156 paragraphs across 38 pages and is accompanied by an exhibit which contains 189 stand-alone files. As I have also noted, the exhibits to all of the parties’ affidavits are extensive.

19 Each of the exhibits to the above affidavits were contained in the court book, which I received into evidence as Exhibit 1. The parties also tendered a number of documents, which included promotional material for the MIFF and other related material.

20 For the purposes of what follows, it is neither necessary nor possible for me to rehearse the extensive facts that are in dispute between the parties. Rather, it is sufficient that I point out the following critical facts that contextualise what is to be conveyed and represented at the MIFF in respect of the involvement of Mr McCallum and Mr Ngo as the apparent directors of the Documentary.

21 The evidence indicates there are at least four versions of the Documentary, including:

(a) a thirty-minute promotional cut for the purposes of pitching the project for funding;

(b) an episodic version that contained three episodes;

(c) a 46-minute cut that screened at the Sundance Film Festival (Sundance Version); and

(d) a feature-length version that was screened at the Dances With Films Festival in Los Angeles, California (Feature Version).

22 The Feature Version is relevantly the version that is intended to be shown at the MIFF.

23 The evidence further indicates that the primary footage and interviews of each of these versions of the Documentary was conducted predominantly by Mr McCallum, but that is not exclusively so. For example, other footage and interviews for some of the versions, especially the latter ones, were undertaken without Mr McCallum’s apparent involvement. The editing and other research work, especially that of the latter versions, were at least in part conducted without Mr McCallum’s involvement, as well as some aspects of the aesthetics and overall feel of the film. The respondents also assert that Mr Ngo and Ms Williams-Weir also performed principal parts of the research and content of the interviews that were conducted by Mr McCallum or under his direction. These matters are in contest.

24 It is relevant that Mr de Heer has examined the evidence of both Mr McCallum and Mr Ngo, as well as the other lay evidence of those who have been involved in the editing and other work relating to the Documentary. In doing so, Mr de Heer has examined the documentary records and also viewed the relevant footage and made assessments of them. Having done so, Mr de Heer expresses the opinion that, having regard to his experience and specialised knowledge, Mr McCallum is the Principal Director of the Documentary. He reasons that Mr Ngo’s contributions are not inconsistent with his primary opinion. The respondents dispute this evidence and submit that it cannot be given too much weight given that, whilst Mr de Heer is an accomplished film director, he has limited experience and expertise in the production of documentaries. They rely on the evidence of Ms Maclaren who is said to have considerably more experience in the production of documentaries and who gives evidence as to the different stages involved in such works. Addressing themselves to her evidence, the respondents point out that Mr Ngo has been involved in each of the critical phases of the development of the Documentary especially in the earlier and latter parts such that, in truth, he is the Principal Director.

25 As will be apparent, there is a considerable dispute in the evidence as to a critical factual issue.

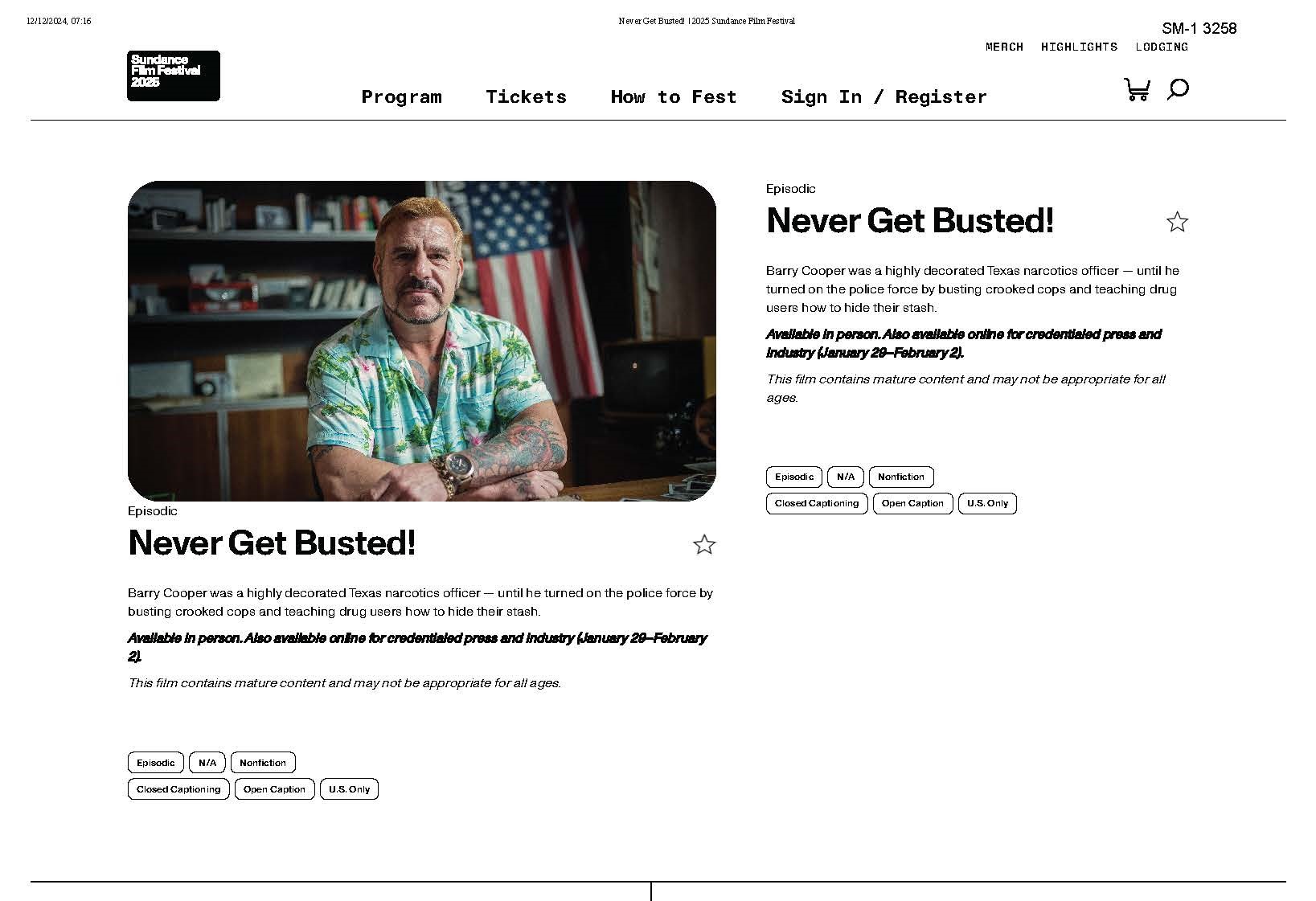

26 The evidence before me includes the various promotional and other materials relating to the Documentary in its various versions. Amongst this evidence is an extract of promotional material connected with the screening of the Sundance Version of the Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival. This relevantly comprised a webpage, at the top of which general information was displayed as follows:

27 The bottom half of the webpage included a section for credits to the Documentary alongside two biographies, including a biography of Mr Ngo:

28 As is evident from the “Meet the Artist” section of the webpage, Mr Ngo is stated to be making his “directorial debut” with the Documentary. As is further evident and conspicuous in its absence, is any reference to Mr McCallum. He does not have a biography, is not credited in the “Credits” section of the webpage, and is not otherwise mentioned at all.

29 In connection with the Sundance Film Festival, the exclusion of Mr McCallum was not limited to the promotional material for the Documentary but appears to have also extended to the premiere at the festival itself. In this regard, Mr McCallum deposes that he was “refused entry into the premiere screening” of the Documentary and that his tickets had been cancelled and would be refunded: First McCallum Affidavit at [701].

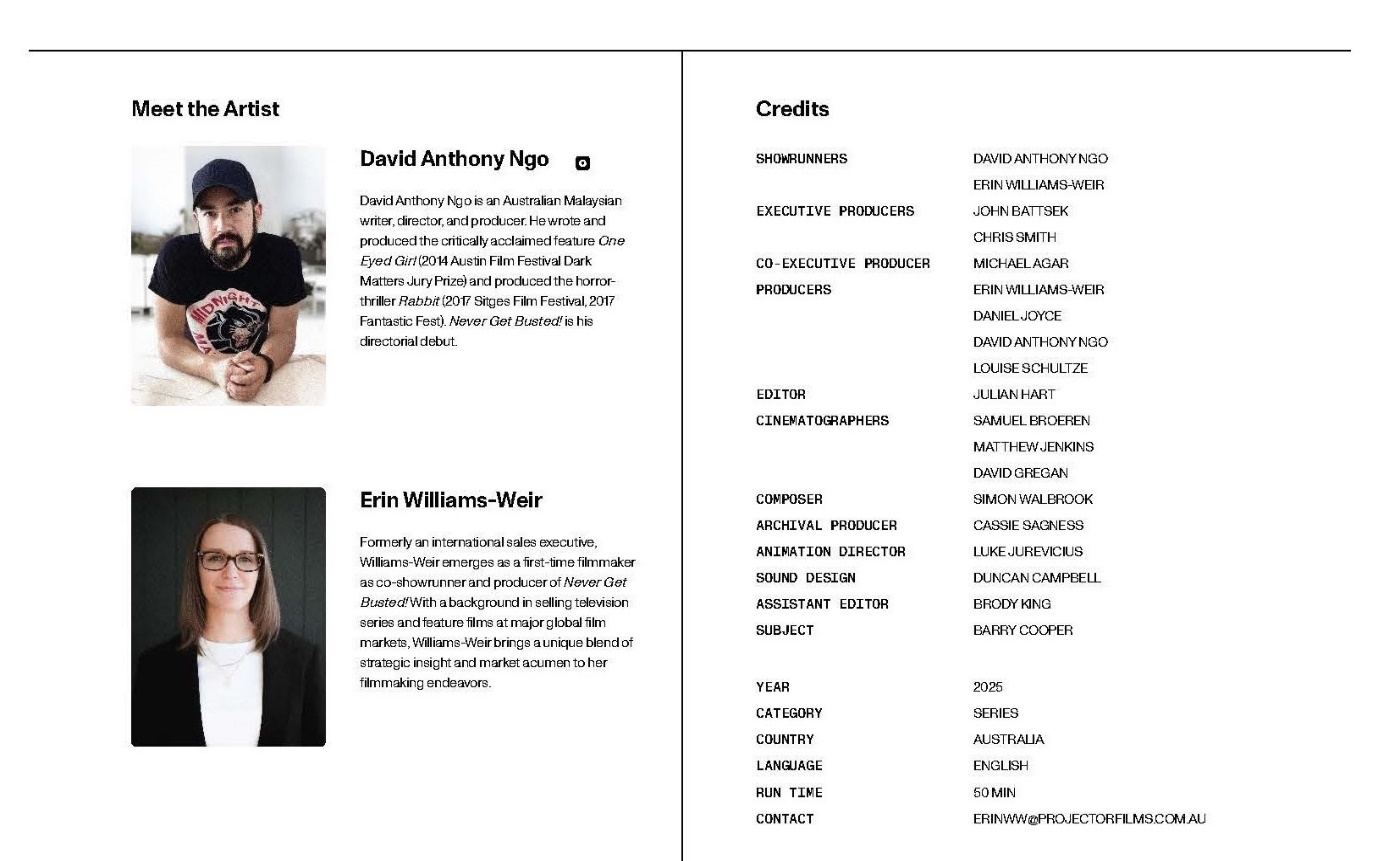

30 I was also directed to further evidence which included an apparent festival program for the Dances With Films Festivals in Los Angeles, which appears as follows:

31 As is evident in the extract above, the program promoted Never Get Busted! as a documentary “by David Anthony Ngo” and represented that the Documentary was “written and directed by David Anthony Ngo”. Although Mr McCallum was mentioned in the program, the attribution was relevantly made with the word “director” rather than the words “Directed by” (the relative significance of which has been adverted to above and is considered in several pieces of lay evidence).

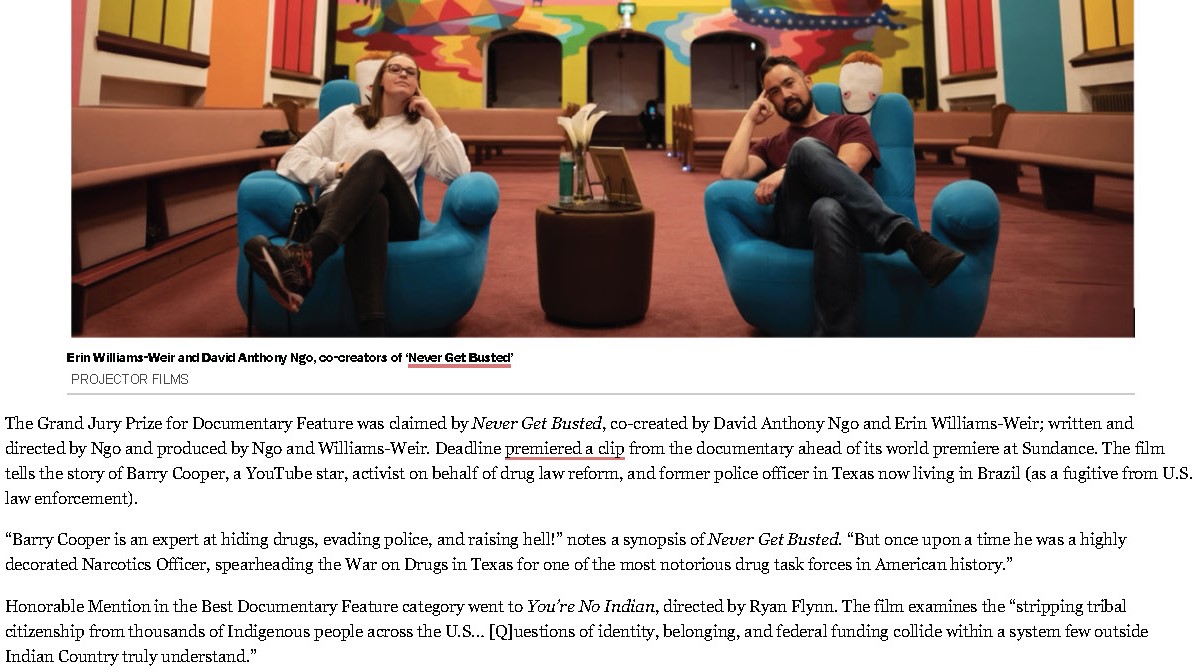

32 In a publication known as Deadline, which was published following the Dances With Films Festival, it was reported that the Documentary had received the “Grand Jury Prize for Documentary Feature” at that festival, was “written and directed by Ngo”, and would be having its “world premiere” at the Sundance Film Festival. As is evident in the extract below, no reference was made to Mr McCallum in the publication:

33 The evidence further included two iterations of promotional material for the Documentary in connection with the MIFF which appears to have been hosted on the MIFF webpage. The first iteration made no reference to Mr McCallum at all. However, it identified Mr Ngo as the sole director of the Documentary in two locations: first, immediately below the headline and, second, in the credits section of the webpage. Further, as is evident in the extract below, it was stated that “David Anthony Ngo helms this Australian production”:

34 It will be apparent from the above that no mention was made of Mr McCallum.

35 As mentioned above, at some point after this first iteration was published on the MIFF website, the respondents made the 16 July Proposal. The letter which conveyed the proposal stated as follows:

We refer to our email dated 10 July 2025 regarding the premiere of the film the subject of these proceedings (Film) at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), and your subsequent email to the Associate on 15 July 2025 foreshadowing an urgent interlocutory injunction in respect of that showing (Foreshadowed Application).

Notwithstanding that we have not been provided with the relief your client actually seeks in respect of the Film at MIFF, we're instructed to make the following without admissions offer to settle the Foreshadowed Application:

1. Projector Films will take all the steps necessary to amend the credits on the Film to be shown at MlFF so that the Applicant is given a "Directed By" credit on the Film in the same style as the directorship credit given to Mr Ngo (save that there is no writing credit for the Applicant) and be shown for the same amount of time;

2. Projector Films will take all steps necessary to ensure that any advertising, marketing or promotional material for the Film at MIFF over which it has control has the "Directed By" credit for the Applicant;

3. all other credits on the Film as shown at MIFF, including the credit given to Mr Ngo, will be at the discretion of Projector Films; and

4. the Foreshadowed Application, insofar as it concerns the Film at MIFF, is withdrawn with no order as to costs.

For your information, our clients estimate that preparing the MIFF version of the Film in accordance with 1 above is likely to cost in the region of $3,000-$5,000 plus at least a day's work cutting and redesigning the credits. If the above is accepted, these would become costs in the cause.

This is an open offer to settle the Foreshadowed Application. Our client reserves the right to tender this letter on the application. It will remain open until orders are made requiring our clients to take steps on the Foreshadowed Application. If the offer is not accepted, then our client intends to rely on the offer on the question of the costs of the Foreshadowed Application.

(Emphasis added.)

36 Following the 16 July Proposal, the second iteration of the MIFF promotional material published on the MIFF website was relevantly identical to the first iteration with an important amendment in that it now made mention of Mr McCallum. As is apparent in the extract below, the material does not explicitly identify the Principal Director, however it is notable that reference was made to the “Director” with the reference to Mr McCallum coming after the reference to Mr Ngo (including in the short byline, “Dir. David Anthony Ngo, Stephen McCallum”):

37 It will be noticeable that the second iteration of the webpage continues to state that Mr Ngo “helms” the documentary.

38 There is also evidence of the program for the MIFF. That program contains the following short synopsis (reflective of the abovementioned byline) in relation to the Documentary:

Never Get Busted!

Dir. David Anthony Ngo, Stephen McCallum Australia

A Texan narc turns maverick decriminalisation activist in this outrageous, colourful, hugely compelling saga set amid America’s drug War.

(Original emphasis retained; additional emphasis added in underline.)

39 It will be apparent that a shorthand for the word “Director” precedes the names of Mr Ngo and Mr McCallum, with Mr Ngo’s name appearing first and Mr McCallum’s name appearing second.

40 In addition, there is evidence that as part of the MIFF, a “Q&A” session has been organised with the “Director” of the Documentary. This includes an email sent to Mr McCallum on 1 August 2025 which states as follows:

Join us for a wildly entertaining documentary with a director Q&A

A Texan narc turns maverick decriminalisation activist in this outrageous, colourful, hugely compelling saga set amid America’s drug and culture wars. Director David Anthony Ngo is a guest of the festival and will attend both session of the film, on Friday 8 and Sunday 10 August.

(Original emphasis retained; additional emphasis added in underline.)

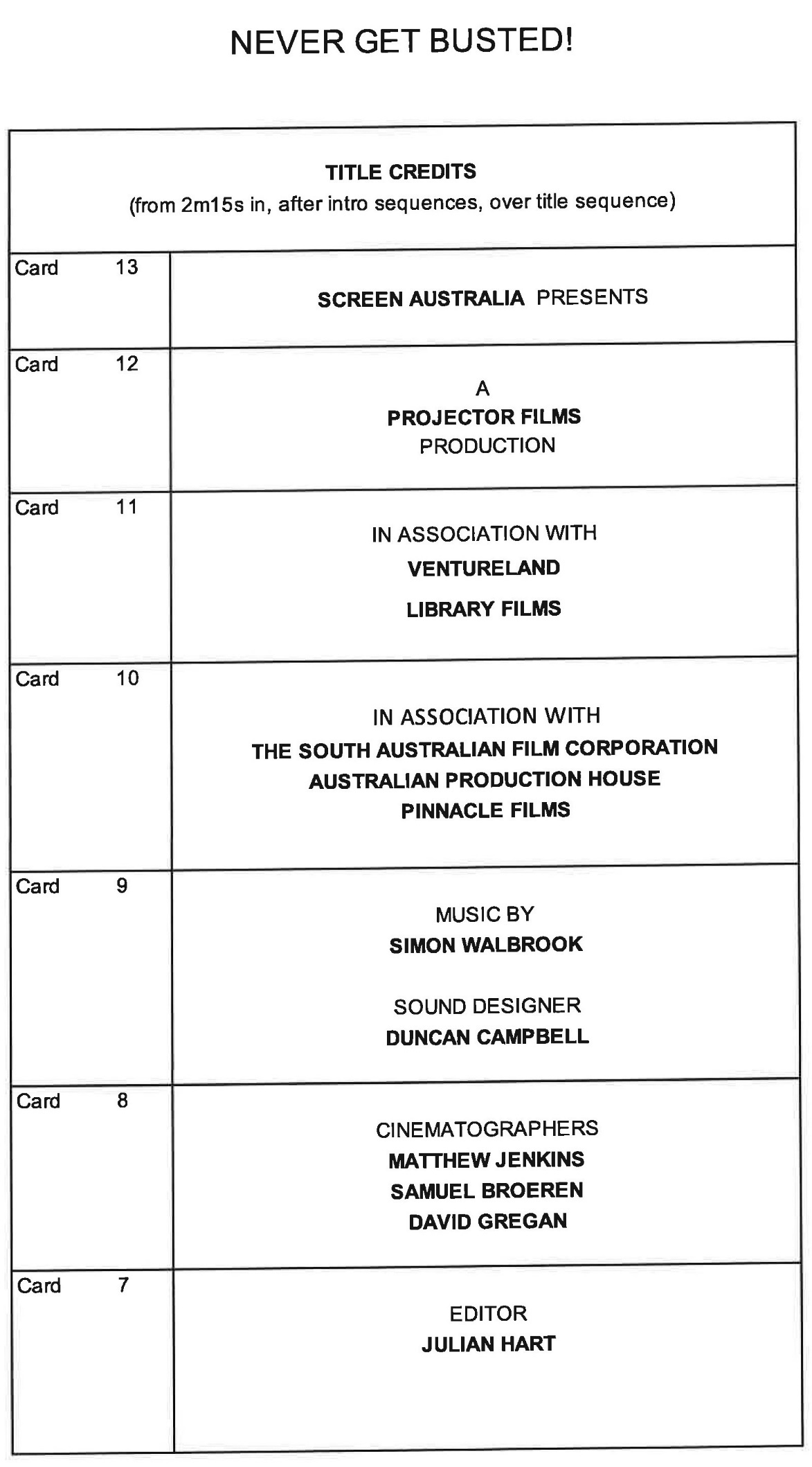

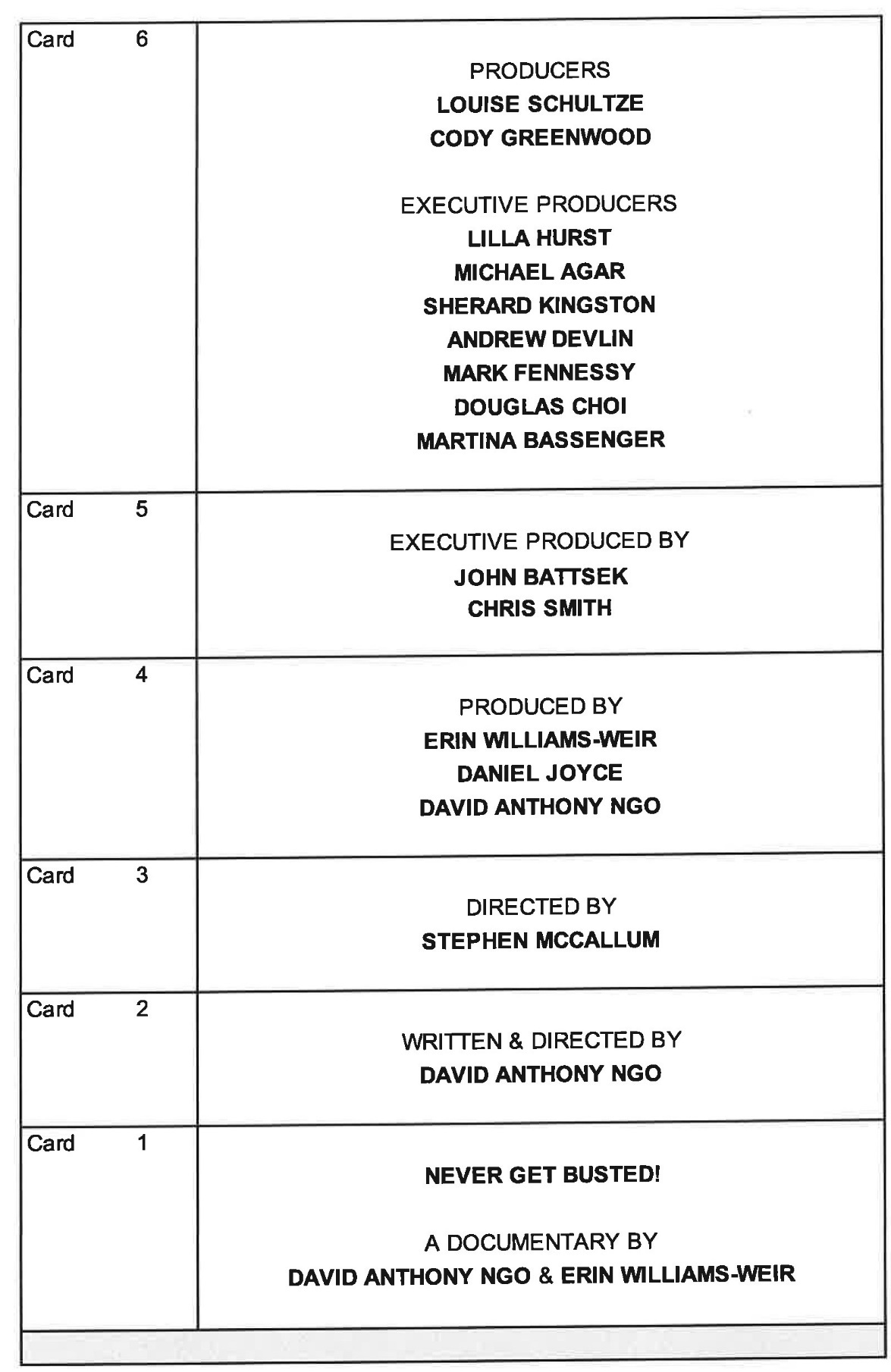

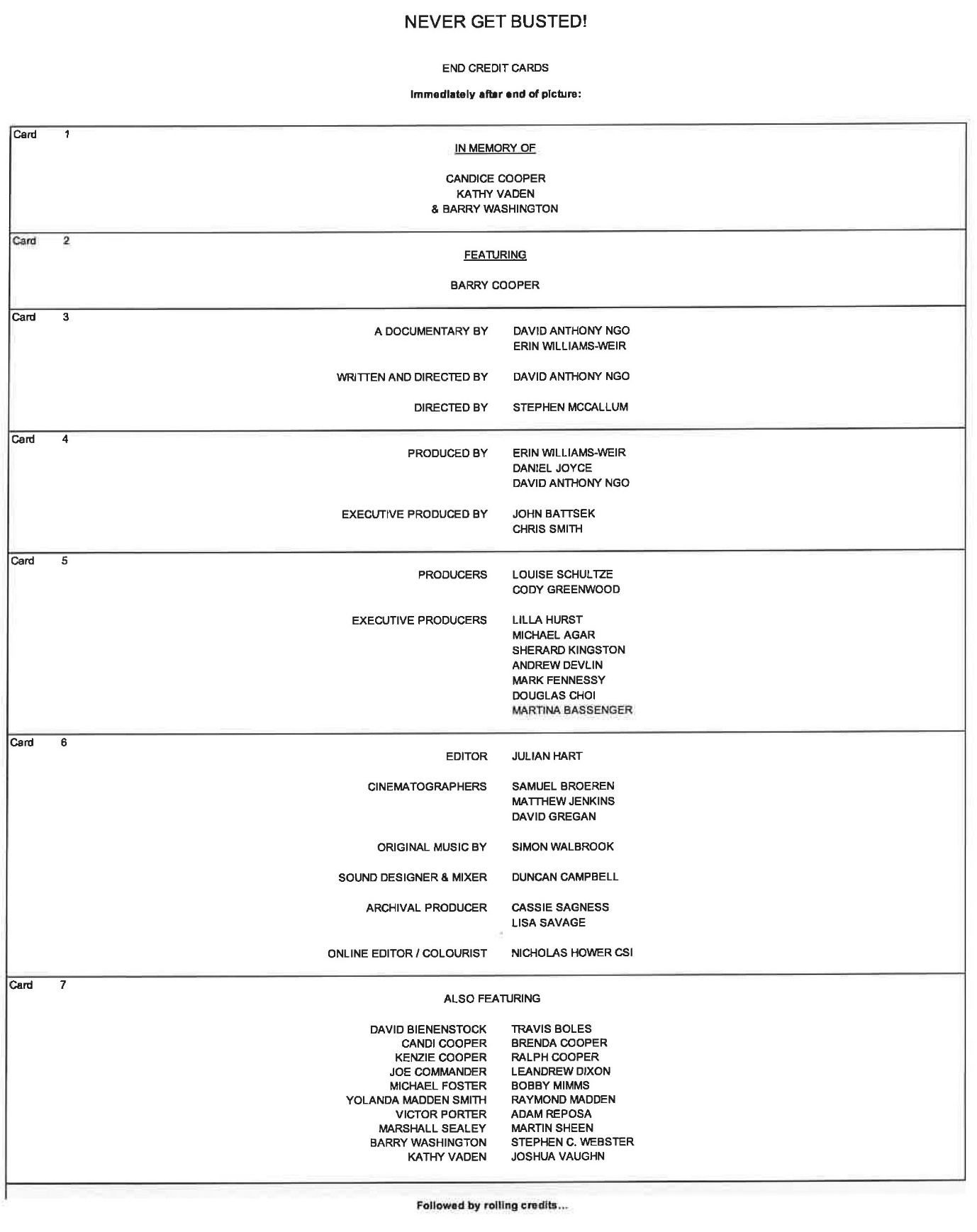

41 Following the 16 July Proposal, Mr McCallum’s solicitor sought clarification as to the opening and end credits that will be displayed in the screening of the Documentary at the MIFF. These are referred to in the nomenclature of the film industry as “credit cards”. The respondents’ solicitors responded by identifying that the following “credit cards” reflected the credits that will be displayed in the opening and end credits:

42 The evidence indicates a level of concurrence between Mr de Heer and Ms Maclaren that the order and sequence of credits conveys prestige and seniority as between the makers of a film. The sequence of the opening and closing credits is inverted: at the start of a film, credits tend to appear in increasing order of seniority and prestige; at the end of a film, the credits tend to appear in decreasing order of seniority and prestige: Maclaren Affidavit at [39]–[40]; de Heer Affidavit at [94]. Thus, it is common ground between the parties that, traditionally, the person who is mentioned last in the opening credits and first in the closing credits is regarded as the Principal Director.

3. SERIOUS QUESTION TO BE TRIED

43 As noted above, Mr McCallum has pleaded three causes of action in the ASOC: (a) infringements of moral rights under the Copyright Act, (b) contraventions of s 18 of the ACL, and (c) breach of contract. For the purposes of the interlocutory application, Mr McCallum did not rely upon the cause of action for breach of contract as a basis for the grant of interlocutory relief. Rather, Mr McCallum maintained that he has established a prima facie case in respect of the alleged contraventions of the Copyright Act and the ACL.

3.1 The parties’ submissions

44 As to contraventions of the Copyright Act, Mr McCallum contends there has been an actual or threatened contravention of his moral rights because of a failure to attribute him as the Principal Director of the Documentary and by falsely attributing Mr Ngo as the Principal Director. As mentioned above, this argument rests upon interlocking provisions of the Copyright Act. In short, s 189 of the Copyright Act (headed “Definitions”) provides that an “author” has three moral rights—the “right of attribution of authorship”, the “right not to have authorship falsely attributed”, and the “right of integrity of authorship”. In the context of the present application, an “author” is relevantly a “maker” of the film, which includes “the director of the film, the producer of the film and the screenwriter of the film”. The meaning of the word “director” of a cinematograph film is affected by s 191 of the Copyright Act, which, as noted above, provides that where two or more individuals were involved in the direction of the film, a reference in the Act to the “director” is a reference to the “principal director” and not to any “subsidiary director” however described. As for the moral rights enjoyed by the Principal Director, each is governed by a series of provisions contained in separate Divisions of the Act. At present, it suffices to mention that Mr McCallum relies upon the right of attribution of authorship (Division 2) and the right not to have authorship of a work falsely attributed (Division 3).

45 Although Mr McCallum does not rely upon his contractual rights as the basis for the grant of contractual relief, he points to the contractual terms as a powerful indicator as to what the parties agreed would be the attribution he would receive as Principal Director of the Documentary. In this regard, Mr McCallum points out that cl 9 of the Director’s Agreement between Projector Films and himself provides as follows:

9. CREDIT

9.1 Provided the Director substantially fulfils and completes all of his obligations under this document, the Producer shall provide the Director with a credit on all positive prints of the Documentary and all paid advertising and paid publicity issued by the Producer or under its control in connection therewith. Such credits shall read substantially as follows:

"Directed by Stephen McCallum"

9.2 Additional directors may be added to the Director’s credit line in a position to be mutually agreed between the Director and the Producer upon completion of the Documentary.

9.3 Any inadvertent failure by the Producer to provide the Director with credits in accordance with this clause shall not constitute a material breach of this document or an event of default.

46 Mr McCallum submits that the agreement that the Documentary would bear credits that it was “Directed by Stephen McCallum” was a recognition and acknowledgment that he was to be the Principal Director of the Documentary and that he has fulfilled that role and discharged his duties as directed by Projector Films. Mr McCallum further submits that the fact that Mr Ngo may have exercised control over aspects of the editing of the Documentary or its footage or has exercised oversight or control over aspects of the finalisation of the Documentary is not inconsistent with Mr McCallum’s role as the Principal Director and his fulfilment of duties to that end. He contends that the performance of some of these functions by Mr Ngo are consistent with him also being a director or exercising the role of a creative producer, which is not uncommon in the film industry. To this end, he also relies upon other clauses of the Director’s Agreement (including cl 2) which reinforce that he was to perform the duties of Principal Director “as required” by the producer, Projector Films, and that it was contemplated that notwithstanding the retention of aspects of creative control by the producer(s), he was the Principal Director. He relies to this end on the opinions expressed by Mr de Heer, both as to industry practice and the work performed by Mr McCallum.

47 Further, Mr McCallum submits that he has, in fact, performed all of the duties required of him. His affidavit evidence in this regard is voluminous and steps through the minutiae of the work he performed including by reference to the objective documentary records. Mr McCallum submits that to the extent that Mr Ngo took over aspects of the editing work and other steps involved in the production of the final version of the Documentary this was done without his knowledge (“behind his back”) and he was effectively sidelined. Mr de Heer has examined the evidence and has expressed opinions that in his assessment Mr McCallum is the Principal Director of the Documentary notwithstanding the work that was performed by Mr Ngo.

48 For their part, the respondents submit that they have a complete answer to Mr McCallum’s claims as to infringement of his moral rights under the Copyright Act. The respondents rely upon cl 6.2 of the Director’s Agreement, which provides as follows:

6.2 Moral Rights

The Director waives all moral or other similar rights in respect of the Documentary or the Development Materials that the Director may be entitled to under the laws of any jurisdiction throughout the world in perpetuity. To the extent that the foregoing waiver is not enforceable in any jurisdiction of the world the Director unconditionally and irrevocably consents, for the benefit of the Producer and all of its assignees, licensees and sublicensees to material alterations to the Documentary (including, without limitation, any copying, editing, adding to, taking from, adapting and / or translating the Documentary in any manner or context) for any purpose.

49 The respondents submit that by cl 6.2 of the Director’s Agreement, Mr McCallum has provided a “written consent” to the infringement of his moral rights within the meaning of s 195AW(1) and (2) of the Copyright Act. Those sections provide as follows in respect of a “cinematograph film”:

(1) It is not an infringement of a moral right of an author in respect of a work to do, or omit to do, something if the act or omission is within the scope of a written consent given by the author or a person representing the author.

(2) A consent may be given in relation to all or any acts or omissions occurring before or after the consent is given.

50 The respondents contend that by contrast to s 195AWA (which applies to other non-film literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works and requires specific consent to be given), ss 195AW(1) and (2) expressly contemplate a general consent may be given to infringements of moral rights and that such consent has been given by reason of the general waiver Mr McCallum gave in cl 6.2 of the Director’s Agreement.

51 The respondents further submit that, in any event, the preponderance of evidence establishes that Mr McCallum abandoned or ceased any relevant involvement with the film at a certain point in time and, from that time onwards, it was Mr Ngo who performed all of the relevant directorial work including managing the editing of the Documentary, research, conducting further interviews, as well as managing and overseeing the sound recording, the animation and other vital steps involved in the finalisation of the Documentary ready for screening. To this end, the respondents rely upon the evidence from Mr Ngo and Ms Williams-Weir. They also rely upon evidence from Mr Hart (editor) and Mr Cude (story consultant) who each say that they met Mr McCallum during an initial Zoom call in early 2022 but otherwise had limited (if any) direct contact with him during the period in 2022 in which they provided services in connection with the Documentary. The respondents also rely on evidence from Mr Eyre, who similarly says that she attended an initial Zoom call with Mr McCallum prior to her engagement as a full-time editor in late-August 2021. Ms Eyre deposes that Mr Ngo and Mr McCallum were both present at most times while she was editing and that “approximately 8 times” during the editing period, Mr McCallum sat alone with her to go through an edit whereas she has no recollection of doing so with Mr Ngo. The respondents further rely on the evidence of Mr Walbrook (composer) who was engaged in March 2024 and says that he primarily dealt with Mr Ngo and deposes to never having communicated with Mr McCallum. Finally, the respondents also rely upon the evidence of Ms Maclaren who expresses opinions as to the ordinary and essential steps involved in the production of a documentary and point out that Mr Ngo has performed all of those functions to establish that he is the Principal Director.

52 Mr McCallum counters the respondents’ contentions as to the alleged waiver of his moral rights by pointing to the legislative history of s 195AW which indicates that Parliament eschewed the concept of “waiver” in favour of the concept of “written consent” in relation to authorising infringements of moral rights. Mr McCallum submits that this is reinforced within the text of cl 6.2, which in its second sentence refers to “consent” by contradistinction to waiver in the first sentence, thereby indicating a contractual intention that the two words signify different concepts. Mr McCallum further contends that cl 6.2 must be read subject to cl 9 which preserves his right to be attributed with a credit as the Principal Director of the Documentary.

53 As to his claim under the ACL, Mr McCallum submits that, when viewed in context, the particular acts of the respondents and their conduct over a period of time conveys the misleading representation and impression that Mr Ngo is the Principal Director which is contrary to the objective facts. The respondents deny these claims on the basis that they say their evidence establishes the contrary facts.

54 Mr McCallum submits that he has established a prima facie case or shown that there is a serious question to be tried that there is an immediate threat that the impending screening of the Documentary at the MIFF will infringe his moral rights and give rise to misleading and deceptive conduct. In this regard, he points to the fact that notwithstanding the steps that the respondents have taken following the 16 July Proposal to now refer to Mr McCallum as a director of the Documentary and to amend the credits to state “Directed by Stephen McCallum” the other promotional materials, especially the opening and end credits, continue to convey the false impression that Mr Ngo is the Principal Director of the Documentary.

55 The respondents submit that Mr McCallum has not established a prima facie case in circumstances where, by implementing the 16 July Proposal, Mr McCallum will receive attribution as a Principal Director of the Documentary.

3.2 Consideration

56 In respect of both of Mr McCallum’s relevant claims – under the Copyright Act and the ACL – one of the core issues is whether in fact Mr McCallum was, or is, the Principal Director. There is a considerable factual dispute about who performed the work as the Principal Director. For the reasons I explain below, despite the considerable contest in the evidence I am satisfied that Mr McCallum has established that there is a serious question to be tried as to whether he has an entitlement to relief which I do not regard as weak but equally I cannot presently assess it to be strong. In coming to the conclusion that Mr McCallum has established a serious question to be tried, I have had regard to the nature and quality of the rights in issue in respect of which there is a threatened infringement: O’Neill at [19] (Gleeson CJ and Crennan J).

57 I accept the respondents’ contention that the case as to the existence and infringement of moral rights has complexity in light of the core factual issue between the parties and by reason of cl 6.2 of the Director’s Agreement relating to the waiver of moral rights. However, in my view those issues need to be weighed against the fact that the terms of the Director’s Agreement record the parties’ intention that Mr McCallum was to be the Principal Director of the Documentary and was to perform work in that capacity as required by Projector Films. The Director’s Agreement has not been terminated. Nor has there been any allegation that it was breached or repudiated. Further, even if cl 6.1 is to be read as giving rise to a “written consent” within the meaning of s 195AW(1) and (2) of the Copyright Act, there is a serious question to be tried as to whether the breadth of that clause is to be read subject to cl 9 which provides that Mr McCallum will, subject to fulfilling his duties as required by Projector Films, receive credit as the Principal Director of the Documentary. Thus, subject to the resolution of the central factual controversy between the parties, I am satisfied that Mr McCallum has established that there is a serious question to be tried as to the existence and infringement of his alleged moral rights.

58 Putting to one side Mr McCallum’s claims under the Copyright Act, I am also satisfied he has established a prima facie case or that there is a serious question to be tried that the respondents have engaged in or are engaging in misleading and deceptive conduct such that there is a threat that this will occur upon the Australian premiere of the Documentary at the MIFF. To explain why this is so, it is necessary to point out the steps the respondents have taken since the 16 July Proposal in a purported attempt to convey that Mr McCallum and Mr Ngo are co-Principal Directors which do not, in fact, have that effect for the following reasons:

(a) first, the present iteration of the MIFF webpage (which is the second iteration overall as referred to above at [36]), merely refers to “Director” and not “Principal Director” or “co-Principal Director”, it places Mr McCallum’s name second in order to Mr Ngo, and continues to state that Mr Ngo helms the documentary – thus, irrespective of whether the webpage and its contents are under the control of the respondents, a central aspect of the promotion of the Documentary is, at best, entirely ambiguous as to who is the Principal Director and, at worst, conveys that it is Mr Ngo and, accordingly, does not achieve the effect of conveying that Mr McCallum was, or is, at least a co-Principal Director;

(b) second, the present program for the MIFF contains a short synopsis for the Documentary which simply reads “Dir. David Anthony Ngo, Stephen McCallum” – this too conveys a similar impression as described in (a) and also does not achieve the effect of conveying that Mr McCallum was, or is, at least a co-Principal Director;

(c) third, material has been disseminated by the organisers of the MIFF in relation to a “Q&A” to be held following each screening of the Documentary and identifies Mr Ngo as the director – this too, by omission, does not achieve the effect of conveying that Mr McCallum was, or is, at least a co-Principal Director; and

(d) fourth, the opening and end credits have been ordered in a sequence in which there is a concurrence between the experts that they will convey that Mr Ngo is the Principal Director and, accordingly, does not achieve the effect of conveying that Mr McCallum was, or is, at least a co-Principal Director.

59 It follows that, if what was intended to be conveyed by the respondents was that Mr McCallum and Mr Ngo are co-Principal Directors, there is a real and not insignificant risk that this is not what will be conveyed by the combination of the above matters.

60 The respondents submitted that none of this matters as the audience will not pick up the nuanced and subtle distinctions that are only known to experts such as Mr de Heer and Ms Maclaren. That contention may be accepted for present purposes, but only so far as it goes. That is because the relevant audience is not limited to the general members of the public who view the promotional materials and the Documentary. The relevant audience extends to the critical members of the film industry including the hosts of the MIFF, the judges who determine the awards to be given for best film or best director etc, the funders and financiers, network and streaming company executives, and so on. It is arguable that this segment of the audience is far more discerning and alive to the nuanced distinctions at issue here and these are the parts of the audience that, if misled, may be causative of the reputational or other loss that Mr McCallum claims.

61 The real contest between the parties is whether Mr McCallum has established a prima facie case or a serious question to be tried having regard to the hotly contested issue as to whether the evidence establishes that he was the Principal Director of the Documentary, and, conversely, that Mr Ngo was not. Having examined the evidence at this interlocutory stage, I do not assess or regard Mr McCallum’s case as weak. Rather, I am satisfied that he has established a prima facie case. Mr McCallum’s position is supported by the opinion of Mr de Heer, who in expressing his opinions has examined the relevant affidavits and documentary records. It may be that at final trial I will not accept Mr de Heer’s evidence but I am assessing the evidence as it presently stands. As a result, at this stage, I am satisfied that there is a serious question to be tried because there is at the very least independent expert evidence supportive of Mr McCallum’s claims. I do not presently regard Mr McCallum’s case as strong. In making that assessment, I have taken into account Mr Ngo’s countervailing evidence and, in particular, evidence of third parties who were involved in the editing and sound recording work who indicate they had limited or no dealings with Mr McCallum.

62 For these reasons, I am satisfied that Mr McCallum has established a prima facie case that there is a present threat and prospect of a contravention of the Copyright Act and the ACL. I am not prepared to characterise the case as strong, but it is not weak.

4. BALANCE OF CONVENIENCE

63 In assessing the balance of convenience, it is of course necessary to take into account the strength of the prima facie case but also weighing that in light of the consequences for the party whose rights are alleged to have been infringed. I am satisfied that the balance of convenience compellingly favours the grant of the primary relief sought by Mr McCallum for the reasons that follow.

4.1 The parties’ submissions

64 Mr McCallum submits that the failure to give him credit as the Principal Director will cause irreparable harm to his reputation and standing within the film industry for which damages would not be an adequate remedy. It is contended that Mr McCallum is a “mid-career director” who has been involved in directing several films and a failure to recognise him as the Principal Director and merely to refer to him as a director or a subsidiary director harms his standing as it would be an indication of a backward step in his career. Further, it is said that this prejudice is particularly acute in circumstances where the respondents have:

(a) at times identified Mr Ngo as the sole Director;

(b) at other times engaged in conduct that identifies Mr Ngo as the Principal Director;

(c) excluded Mr McCallum from being referred to as a director at all, let alone as having any involvement with the Documentary;

(d) at times, engaged in conduct that conveys that Mr McCallum was not the Principal Director, or was merely a subsidiary director; and

(e) since 16 July 2025, engaged in conduct that is productive of reinforcing that he is not the Principal Director, even though purporting to credit him, in effect, as a co-Principal Director.

65 Mr McCallum submits that conveying his role in these various ways is an infringement of his rights, harms his reputation and deprives him of professional opportunities for future film work. This prejudice is said to be exacerbated by the fact that, for the purposes of the impending premiere, Mr McCallum has not been invited as a “Guest of the Festival”, it is Mr Ngo who has been invited to speak as the director of the Documentary at a Q&A session at the MIFF as a “guest of the Festival”, and the respondents have elected not to recognise him as part of the directorship team for these purposes and he will miss opportunities to promote both the Documentary and himself as the Principal Director of the Documentary.

66 Mr McCallum further submits that the relevant prejudice is not cured by the 16 July Proposal because notwithstanding that the respondents assert that they will credit him as a co-Principal Director, this is not in fact what has occurred and not what will be conveyed. That is because all of the promotional material which I have summarised above is productive of ambiguity: he is referred to second in order to Mr Ngo as the “Director” on the present promotional material and the screening credits which do refer to the Documentary being “Directed by Stephen McCallum” are presented in a sequence and order which indicate that he is not in fact the Principal Director.

67 Mr McCallum contends that these matters are to be viewed in the context of the publications that have already been made in the context of the earlier film festivals in the United States.

68 In addition, Mr McCallum submits he has an existing and well-established reputation as a director, and, as such, the prejudice to him is greater than that which might be occasioned to Mr Ngo who is making a directorial debut. In this regard, Mr McCallum submits that Mr Ngo has entered the scene with his “eye wide open” to the risks that might arise in choosing to proceed by not appropriately recognising Mr McCallum’s role: citing Beecham Group Ltd v Bristol Laboratories Pty Ltd [1968] HCA 1; 118 CLR 618 at 626 (Kitto, Taylor, Menzies and Owen JJ).

69 As to his alternative form of relief, Mr McCallum submits that recognising that both men lay claim to being the Principal Director of the Documentary and further noting that the matter is subject to a legal dispute is the fairest and most accurate statement that can be made.

70 The respondents submit that the claimed prejudice to Mr McCallum is overstated. They again submit that virtually no one would appreciate the pedantic distinctions between Principal Director and Director, or understand the significance of the sequencing of credits. It is further submitted that any prejudice that would be occasioned to Mr McCallum applies equally to Mr Ngo as he is making his directorial debut, and in circumstances where he says that he is the principal director. The respondents submit that if Mr McCallum establishes any prejudice, it is the very same prejudice that Mr Ngo will suffer from not being recognised as the Principal Director. It is contended that Mr Ngo too has moral rights and unlike Mr McCallum he has not waived them.

71 It is in these circumstances that the respondents submit that the 16 July Proposal strikes a fair balance of the competing interests between parties. It is further submitted that the most recent promotional materials from the MIFF identified both men as directors, and, as a result, the 16 July Proposal represents the present status quo that should be preserved.

72 The respondents further contend that the alleged prejudice to Mr McCallum arising from the immediate premiere and screening of the Documentary at the MIFF is overstated. First it is submitted that, by reference to the materials published by the MIFF, that Mr McCallum had every opportunity to participate in or at the MIFF and the events organised under its auspices just as any other member of the public or film industry could do. These events include scheduled meetings with relevant persons within the film industry and other organised events for which Mr McCallum could have registered or made submissions in answer to a call for submissions, if he wished to do so. It was submitted that to the extent that a particular session or opportunities no longer existed, the granting of an order now would be futile as it would not address any alleged prejudice.

73 The respondents deny that Mr McCallum has not been able to promote himself as a director of the Documentary and claim that not only does he have the opportunity to do so but that he has done so including through his agent. Next, it is submitted that here is a paucity of evidence about any privileges that Mr McCallum claims arise from the MIFF such as being a “Guest of the Festival” which has been afforded to Mr Ngo which have not been afforded to Mr McCallum.

74 In response to Mr McCallum’s alternative relief, the respondents submitted that it would be even more deleterious to the film, relying upon the evidence of Mr Joyce, a director of Projector Films, which relevantly included the following:

The Applicant seeks as an alternative that the director credits on the Film be changed to "the subject of a legal dispute". If those orders were made, and assuming the changes could be made to the Film in time for it to be shown at MIFF, such a change to the credits would indicate to people at MIFF (including potential buyers and distributors of the Film) that it is obstructed by a legal dispute. That would, in my view, cause it to be less likely to obtain a cinema release or sale for broadcast or streaming. As set out above, the consequences of the Film not being obtained for a cinema release or sold for broadcast or streaming would be catastrophic for all involved in the project.

(Emphasis added.)

75 Relying on this evidence, it is submitted that there is a risk that if the alternative relief were ordered then there would a “cloud hanging over the film” which would impact potential buyers in considering whether to purchase rights in the Documentary and may even deter such persons from approaching the producers at all by reason of the dispute.

4.2 Consideration

76 I accept that, in all of the circumstances, Mr McCallum has suffered and will suffer prejudice unless relief is granted and that the balance of convenience favours the grant of relief.

77 I am satisfied that the prejudice Mr McCallum will suffer is different to, and greater than, any prejudice that Mr Ngo may suffer. That is because, it is Mr Ngo’s directorial debut, the relief claimed by Mr McCallum does not prevent Mr Ngo from being promoted as a Director of the Documentary. Mr Ngo has already, in fact, promoted himself as a Director of the Documentary in various promotional and other materials. Moreover, Mr Ngo’s evidence as to the prejudice he will suffer is all directed to him not being credited as a director of the Documentary. His evidence in this regard is as follows:

254 If the [Documentary] was shown at MIFF without me credited as a director, I anticipate that I could suffer damage in the following ways:

(a) damage to my reputation, particularly being seen as someone who takes a director credit when they are not entitled to it. That would also damage my opportunities I have to work in the industry in the future;

(b) by either removing my credit or having it replaced with a disclaimer stating that the director's credits are the subject of ongoing Court proceedings, that would have the same effect as not having a credit at all;

(c) while the credit may be amended at the end of the case, as set out above, MIFF may be the only time that the attendees see the [Documentary]. Those people may never be disabused of the incorrect impression that I am not a director of the [Documentary] irrespective of the ultimate outcome of this case. The people will include people involved in the film industry, from where I earn my living;

(d) a director of a film being shown at a film festival is usually interviewed by media and takes part in publicity events during the festival. If I was not credited as director of the [Documentary] at MIFF, I would be deprived of that opportunity, which is both an opportunity to promote the film and to promote my services in the industry;

(e) all press that is written about the film at MIFF, particularly reviews, will not list me as the director, which would harm future opportunities I may have in the industry;

(f) in circumstances where I have been credited as a director in all marketing materials and then not listed as director in the film, people that have seen the marketing materials and then seen the [Documentary] at MIFF may conclude that I was dishonest in some way, again damaging my reputation in the industry;

(g) I will also be attending MIFF 37South, the film market attached to MIFF, and are inviting various industry members, including potential investors and financiers in my next projects. By having my credit removed, this would greatly damage my reputation and likely dissuade them to be involved in my next projects;

(h) the credit on the version of the film sent for screening at MIFF has both myself and Stephen as directors. It is possible that the [Documentary] will be nominated for or receive one of the awards handed out at MIFF. If I am not credited as a director on the [Documentary], then I will not be entitled to receive any award at MIFF that I would otherwise be entitled to as a director;

(i) other projects I am involved with will likely have issues screening at future MIFF events as the organisers will be made aware that I was originally credited as a director and then had that credit stripped just before screening. The same might be said of my projects showing at other film festivals if word gets around about what has happened;

(j) the film industry is very small, both within Australia and abroad. I expect that word of the removal or alteration of my credit would quickly spread and be devast[at]ing to my career. The damage to my reputation would be something that I would unlikely be ever to recover from, particularly at a time when I am negotiating my next film. It would indicate to people in the industry that I have been deceitful and do not deserve to be credited as a director on a film that I have worked tirelessly on for the better part of six years.

78 As will be immediately apparent from the above, Mr Ngo has addressed his evidence to not being credited as a “Director” of the Documentary as opposed to not being credited as the “Principal Director”. I do not accept that the references in Mr Ngo’s evidence to being credited as a director should be read as being references to him being credited as the “Principal Director”. Mr Ngo’s evidence was responsive to Mr McCallum’s interlocutory application which clearly contained prayers for relief seeking to enjoin the respondents from crediting Mr Ngo as the “Principal Director”. In those circumstances, I can only infer that Mr Ngo well understood the distinction between a Principal Director and Director and was keen to provide evidence as to the damage he would suffer if he was not credited as a Director of the Documentary.

79 In any event, I am not satisfied that the matters raised by Mr Ngo in paragraph of 254 of his affidavit provide for a compelling case of the damage and prejudice he will allegedly suffer. As to the matters in:

(a) sub-paragraphs 254(a), (f), (i) and (j): it is true that, if interlocutory relief is granted but Mr McCallum is unsuccessful at final hearing, some members of the public or the film industry may come to wrongly have seen Mr Ngo as someone who took credit when he was not entitled to it. However, that may be the position that prevails if Mr McCallum is successful. It is also the position that Mr Ngo has himself permitted to arise. For example, as noted above, notwithstanding that there is now recognition from the respondents that Mr McCallum was at least a Director of the Documentary, there was no mention made of Mr McCallum in the promotional materials for the screening of the Documentary at the Sundance Film Festival and in the first iteration of the material that was published on the MIFF website. The respondents submitted that there was no evidence as to the criteria for submissions made to the Sundance Film Festival that might explain the omission of Mr McCallum’s name or that there was the same significance to this fact. Nevertheless, I can infer that Mr Ngo was aware that Mr McCallum was not being given any attribution of any type in relation to the Documentary. And, none of this explains why Mr McCallum’s name was not mentioned at all in the first iteration of the MIFF materials. I can infer a conscious choice was made to exclude Mr McCallum from being mentioned at all in those materials including in circumstances where there were extant proceedings before this Court putting into issue the question as to the attribution of the authorship of the Documentary. These proceedings were commenced in December 2024 and the respondents have run the risk to reputation that was in their hands to control. Thus, Mr Ngo’s reputation, like Mr McCallum’s reputation, will fall where it falls depending on the ultimate outcome of the proceedings. I do not accept that the effect of the orders that I intend to make is to “strip” Mr Ngo of being credited as a Director of the Documentary. I do not regard these points raised by Mr Ngo to be compelling;

(b) sub-paragraph 254(b): for reasons I will come to, I do not intend to order that Mr McCallum’s name be removed as a Director of the Documentary or for there to be a notation that the director’s credits are the subject of legal proceedings even though I consider the latter to be an accurate and truthful statement of the true state of affairs;

(c) sub-paragraph 254(c): for the reasons stated in (b) above, I do not intend to order that Mr McCallum’s name be removed from the credits of the Documentary. Further, it is to be noted that Mr Ngo has been promoted in present and past publications as the creator and screenwriter of the Documentary, as well as being a producer, and, importantly, has been represented as the Director and having made his directorial debut. That position will continue on the orders that I will make as Mr Ngo will continue to be able to represent and promote himself as a Director of the Documentary and having made his directorial debut, but will only be prohibited from representing that he is the Principal Director;

(d) sub-paragraphs 254(d), (e) and (g): for the reasons stated above, this alleged prejudice too does not arise as I do not intend to order that Mr Ngo be deprived of the opportunity to be promoted as a Director of the Documentary for the purposes of the MIFF, the various MIFF events, or press publications. Further, as I will return to below, Mr Ngo has well and truly had the march over Mr McCallum in this respect; and

(e) sub-paragraph 254(h): I have no evidence as to whether an award for best director at the MIFF will be shared where there is both a Principal Director and a Director, but the converse is equally true that Mr McCallum will be deprived of that opportunity if relief is not granted.

80 By contrast to Mr Ngo’s position, I am satisfied that Mr McCallum has suffered and will continue to suffer irreparable damage and prejudice unless relief is granted. Until 16 July 2025, Mr McCallum was given no recognition at all in relation to the Documentary’s Australian premiere at the MIFF. Other than the credits published in relation to the Dances With Films

Festival, Mr McCallum has received virtually no recognition of earlier screenings of versions of the Documentary, especially at the Sundance Film Festival where he received no recognition at all. The press articles that have otherwise been published in relation to the Documentary have promoted Mr Ngo to the exclusion of Mr McCallum. Further, it is clear that Mr Ngo has had the march over Mr McCallum in respect of his connection and promotion of himself as the Director of the Documentary – Mr Ngo has been identified as a “Guest of the Festival”, will be involved in the Q&A with the audience following the screenings of the Documentary and, on his own evidence, as set out above, has registered to attend and will be attending at least one or more events associated with MIFF (including “MIFF 37South”).

81 Mr McCallum has not done any of these things in circumstances where he has been sidelined. I do not accept the respondents’ contentions that it was open for Mr McCallum to have registered for events at the MIFF. The fact is that Mr Ngo was in a superior position to Mr McCallum to have done so. That is obvious from testing the commonsense proposition as to what would have occurred if Mr McCallum attempted to attend the MIFF as being associated with the Documentary, and as its Principal Director or Director. Prior to 16 July 2025 he would not have been recognised. Further, it is not insignificant that the respondents have cross-claimed against Mr McCallum for having disparaged them or engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by reason of various representations he has made to third parties that, amongst other things, he is the Principal Director of the Documentary. In the face of such a cross-claim, in my assessment, it is entirely unsurprising that Mr McCallum has turned to the Court to seek relief before taking any steps to promote himself at the MIFF. None of this is gainsaid by the fact that there are examples of where Mr McCallum has in fact promoted himself as a Director or even as the Principal Director of the Documentary. To the extent that he has done so, it has been without the backing and authority of the producers of the Documentary which places him in a substantially different position to Mr Ngo.

82 The respondents placed great weight on the 16 July Proposal as remedying Mr McCallum’s prejudice. It was submitted that it was a sensible resolution which permitted both men to promote themselves as the Principal Directors of the Documentary in a way that benefitted its commercial success. However, for the reasons stated above, I do not accept that the 16 July Proposal in fact achieves the effect propounded by the respondents. I also reject the respondents’ contention that the distinction between these concepts is meaningless or of no significance to the audience. As noted above, it is a distinction that has meaning to those within the film industry. This is because part of the audience are members of the film industry, who on the evidence, are likely to understand the significance of the distinction. And, it is this segment of the audience where the prejudice to Mr McCallum would be most acute as these members of the audience are likely to appreciate by the sequencing and order of the credits, as well as the other matters to which I have adverted above, that Mr Ngo is being credited as the Principal Director of the Documentary (even under the 16 July Proposal).

83 For these reasons, I also reject the respondents’ contention that leaving things where they presently stand would be a preservation of the status quo. That status quo does not in fact achieve the result of both men being credited as co-Principal Directors. Further, the 16 July Proposal is to be viewed in the context of all the matters that preceded it and the fact that Mr Ngo has in the meantime had the march over Mr McCallum as set out above. It is also not insignificant, in my view, that the respondents took the course that they did (including in relation to the first iteration of materials published on the MIFF website) in July of this year notwithstanding that these proceedings had been on foot since December last year. They have taken the course that they have with their “eyes wide open” to the fact that there is present litigation on foot.

84 Taking all of the above matters into account, and as I informed the parties at the conclusion of the hearing before me, I would have been satisfied that the justice of the case warranted relief in the form of the alternative orders sought by Mr McCallum which would have had the effect of ensuring that both men could be credited as co-Principal Directors of the Documentary on the proviso that it would be conveyed that the matter was the subject of legal proceedings. However, the respondents, as noted above, resisted the alternative relief and submitted that they would prefer to be subjected to the primary relief sought by Mr McCallum. This submission was advanced on the basis of Mr Joyce’s evidence (as extracted above). The respondents’ submissions in this regard were surprising. I can readily accept that distribution companies, film houses, network and streaming service executives may be discouraged from investing in or acquiring the rights to screen the Documentary when it is the subject of legal proceedings. I can also readily accept that prospect of sale or distribution through streaming services is where the real money lies in respect of the Documentary. However, these proceedings are a matter of public record. It would be inconceivable that Mr Joyce or anyone else associated with the film would not disclose the fact of the legal dispute to any interested acquirers of the rights to republish, distribute or broadcast the Documentary. Again, to the extent that there are consequences in respect of the commercial success of the Documentary, it is a product of the parties’ inability to put aside their differences (be they creative, interpersonal, or based on fact or perception). On the evidence I have reviewed to date, no one party is more or less responsible than the other in this regard.

85 At any rate, it is unnecessary for me to further consider alternative relief sought by Mr McCallum given that the respondents submitted that if I was satisfied that Mr McCallum had established a prima facie case and that the balance of convenience favoured the grant of relief, they would prefer that I make orders in the form of the primary relief sought by Mr McCallum. As I am satisfied that Mr McCallum has established a prima facie case and that the balance of convenience favours the grant of relief, I will make orders in the nature of the primary relief sought by Mr McCallum.

5. DISPOSITION

86 I will make order substantially in the form of prayer 1 of the interlocutory application. I will reserve the question of costs.

I certify that the preceding eighty-six (86) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Shariff. |

Associate:

Dated: 7 August 2025