Federal Court of Australia

Epic Games, Inc v Google LLC [2025] FCA 901

File number: | NSD 190 of 2021 |

Judgment of: | BEACH J |

Date of judgment: | 12 August 2025 |

Catchwords: | COMPETITION LAW — digital technology — Android mobile devices — operating system software — original equipment manufacturers — Google mobile services — anti-fragmentation agreement — Android compatibility commitment —smart phones — tablets — personal computers — native apps — web apps — web browsers — Google’s Play Store — downloading apps — installing apps — app developers — access to platforms — two-sided platforms — platform operators — market definition — market power — mobile OS licensing market — distribution services market — market for payment services — restrictive conduct in distribution market and payments market — security and technology considerations and constraints — misuse of market power — imposition of restrictive contractual conditions — substantial lessening of competition — purpose questions — effects questions — contraventions of s 46 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) — alleged contraventions of ss 45 and 47 — unconscionable conduct — alleged contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) ss 4, 4E, 4F, 4G, 5, 45, 46, 47, 51, sch 2 ss 21, 22 |

Cases cited: | Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Ltd (2014) 319 ALR 388 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Metcash Trading Ltd (2011) 198 FCR 297 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd (2020) 277 FCR 49 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCA 669; (2019) ATPR ¶42-633 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v P T Garuda Indonesia Ltd (2016) 244 FCR 190 Epic Games Inc v. Apple Inc 67 F.4th 946 (2023) (9th Circuit, Court of Appeals) Federal Trade Commission v. Advocate Health Care Network 841 F.3d 460 (2016) (7th Circuit, Court of Appeals) Federal Trade Commission v. Penn State Hershey Medical Centre 838 F.3d 327 (2016) (3rd Circuit, Court of Appeals) Federal Trade Commission v Tenet Health Care 186 F.3d 1045 (1999) (8th Circuit, Court of Appeals) Re Duke Eastern Gas Pipeline Pty Ltd (2001) 162 FLR 1 Re Fortescue Metals Group Ltd (2010) 271 ALR 256 Re Qantas Airways Limited (2004) ATPR 42–027 Re Southeastern Milk Antitrust Litigation 739 F.3d 262 (2014) (6th Circuit, Court of Appeals) United States v. American Express Company 838 F.3d 179 (2016) (2nd Circuit, Court of Appeals) Athey S, Chetty R, Imbens G and Kang H, “The Surrogate Index: Combining Short-Term Proxies to Estimate Long-Term Treatment Effects More Rapidly and Precisely” (2019, Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research) Cameron A and Trivedi P, Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications (Cambridge University Press, 2005) Chandar B et al, “The Drivers of Social Preferences: Evidence from a Nationwide Tipping Field Experiment” (2019, Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research) Davis P and Garcés E, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis (2009, Princeton University Press) Decarolis F, Li M and Paternollo F, “Competition and Defaults in Online Search” (2023, Discussion Paper, Centre for Economic Policy Research) Evans D and Salinger M, “The Role of Cost in Determining When Firms Offer Bundles” (2008) 56(1) The Journal of Industrial Economics 143 Felt A et al, “Improving SSL Warnings: Comprehension and Adherence” (2015, Conference Paper, CHI 2015 Crossings, Korea) Filistrucchi L, “A SSNIP Test for Two-sided Markets: The Case of Media” (2008, NET Institute Working Paper) Filistrucchi L et al, “Market Definition in Two-Sided Markets: Theory and Practice” (2014) 10(2) Journal of Competition Law & Economics 293 Gneezy U and List J, The Why Axis: Hidden Motives and the Undiscovered Economics of Everyday Life (2013, Public Affairs) Haggag K and Paci G, “Default Tips” (2014) 6(3) American Economic Journal 1 Hovenkamp H, The Antitrust Enterprise: Principle and Execution (Harvard University Press, 2005) Katz M and Shapiro C, “Critical Loss: Let’s Tell the Whole Story” (2003) 17(2) Antitrust 49 Kotzias P et al, “How Did That Get In My Phone? Unwanted App Distribution on Android Devices” (2021) (Published at the 42nd IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, California) Lindenberg E and Ross S, “Tobin’s q Ratio and Industrial Organization” (1981) 54(1) Journal of Business 1 Mayrhofer R et al, “The Android Platform Security Model” (2021) 24(3) ACM Transactions on Privacy and Security Salinger M, “A Graphical Analysis of Bundling” (1995) 68(1) Journal of Business 85 Smitizsky G, Liu W and Gneezy U, “The endowment effect: Loss aversion or a buy-sell discrepancy?” (2021) 150(9) Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 1890 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Economic Regulator, Competition and Access |

Number of paragraphs: | 6370 |

Dates of hearing: | 15, 18 to 21, 25 to 28 March, 2 to 4, 8 to 11, 15 to 18, 22 to 24, 29, 30 April, 1, 2, 6 to 9, 13 to 16, 20 to 23, 27 to 30 May, 3 to 7, 11 to 14, 17 to 20, 24 to 28 June, 1 to 5 July 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicants: | Mr N J Young KC, Mr G K J Rich SC, Dr R C A Higgins SC, Mr T O Prince, Mr A d’Arville, Mr A Barraclough, Mr O Ciolek, Ms K Lindeman, Mr B Hancock, Mr J T Waller, Ms J Apel and Mr R R Marsh |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Allens |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr C A Moore SC, Mr R A Yezerski SC, Mr P J Strickland, Ms C Trahanas and Ms W Liu |

Counsel for the Respondents (confidentiality issues only): | Ms E N Madalin and Mr A Hanna |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Corrs Chambers Westgarth |

Counsel for the Respondents (Apple parties) in NSD 1236 of 2020 and VID 341 of 2022: | Mr M J Darke SC, Mr S Free SC, Mr C Bannan, Ms Z Hillman, Ms L Thomas, Ms X Teo and Mr B Lim |

Solicitor for the Respondents (Apple parties) in NSD 1236 of 2020 and VID 341 of 2022: | Clayton Utz |

Counsel for the Applicants in VID 341 of 2022 and VID 342 of 2022 (class actions): | Mr A J L Bannon SC, Mr N De Young KC, Ms K Burke, Mr D Preston, Mr B Ryde and Dr S Chordia |

Solicitors for the Applicants in VID 341 of 2022 and VID 342 of 2022 (class actions): | Phi Finney McDonald and Maurice Blackburn |

ORDERS

NSD 190 of 2021 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | EPIC GAMES, INC First Applicant EPIC GAMES INTERNATIONAL S.A R.L Second Applicant EPIC GAMES ENTERTAINMENT INTERNATIONAL GMBH Third Applicant | |

AND: | GOOGLE LLC First Respondent GOOGLE ASIA PACIFIC PTE LTD Second Respondent GOOGLE PAYMENT AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Third Respondent | |

order made by: | BEACH J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 12 august 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The further hearing of the proceeding be stood over to a date to be fixed.

2. Save for the oral summary of these reasons given by Beach J at the time of delivery of this judgment and any republication in any form of that summary, pursuant to s 37AF(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the ground set out in s 37AG(1)(a), subject to further order, disclosure and publication of these written reasons and the content thereof shall only be made to the parties’ external legal advisors in this proceeding and in proceedings NSD 1236 of 2020, VID 341 of 2022 and VID 342 of 2022, and to no other person.

3. Liberty to apply.

4. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BEACH J:

1 There are four proceedings before me, the joint trial of which took place over a period of four months on questions of liability.

2 In the first proceeding, the Epic parties have made claims against the Apple parties principally concerning alleged contraventions of s 46 and other provisions of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). I have set out the relief that they seek elsewhere.

3 The Epic parties are involved in developing entertainment software for personal computers, smart mobile devices and gaming consoles, with their most popular game being Fortnite. They allege that the Apple parties’ contravening conduct has forced app developers including Epic to only use Apple’s App Store to distribute their software applications (apps) to the broad base of iOS device users, and to only use Apple’s payment system for processing the purchases of their in-app digital content by iOS device users. Apple removed Fortnite from the App Store on 13 August 2020. That step has provoked the present litigation against the Apple parties.

4 I have delivered a separate set of reasons dealing with the first proceeding (Epic Games, Inc v Apple Inc [2025] FCA 900).

5 In the second proceeding, which these present reasons deal with, the Epic parties have made claims against the Google parties principally also concerning analogous alleged contraventions of s 46 and other provisions of the CCA. The relief that they seek is directed at gaining more access to Google’s digital ecosystem which does allow some access but is akin to a nature reserve protected by a large barbed-wire fence.

6 They allege that the Google parties’ contravening conduct has hindered the ability of app developers including Epic to distribute apps to Android devices in a realistic and practical way other than through Google’s Play Store. It is said that Google has achieved this by imposing various contractual and technical restrictions, which stifle or block Android device users’ ability to download app stores and apps directly from developers’ websites and prevent or hinder competition in the distribution of apps to Android devices. It is also said that Google has inappropriately imposed on app developers Google’s payment system for processing the purchases of in-app digital content by Android device users. I will explain the detail of this in a moment. Google removed Fortnite from the Play Store on 13 August 2020. That step has also provoked the present litigation against the Google parties.

7 The third and fourth proceedings are representative proceedings commenced by the representative applicants under Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) where similar allegations have been made by them on behalf of group members against the Apple parties and the Google parties concerning the same contraventions of s 46 of the CCA as alleged in the first proceeding and the second proceeding. One of the class actions is against the Apple parties concerning inter-alia the overcharging of commissions on the App Store. The other class action is against the Google parties concerning inter-alia the overcharging of commissions on the Play Store. In each case it is said that the contraventions caused app developers to pay materially higher commissions on paid app downloads and in-app purchases of digital content than they would otherwise have had to pay had the contravening conduct not occurred.

8 I have delivered a separate set of reasons dealing with both the third and fourth proceedings (Anthony v Apple Inc; McDonald v Google LLC ([2025] FCA 902).

9 I will say something more about the joint trial and how these reasons should be read a little later. But for the moment let me introduce the case against the Google parties in some more detail.

10 Epic’s case is that Google has used its control of the Android ecosystem to stifle competition in app distribution and in payment solutions for Android apps. It is said that as a result of Google’s conduct, Google’s Play Store is the default and predominant distributor of Android apps, and is not meaningfully subject to the forces of competition. And it is said that in exchange for access to the Play Store, app developers are compelled to use Google’s payment solution, Google Play Billing, as their sole supplier of services for facilitating, including accepting, processing, collecting, and remitting, payments for in-app purchases of digital content.

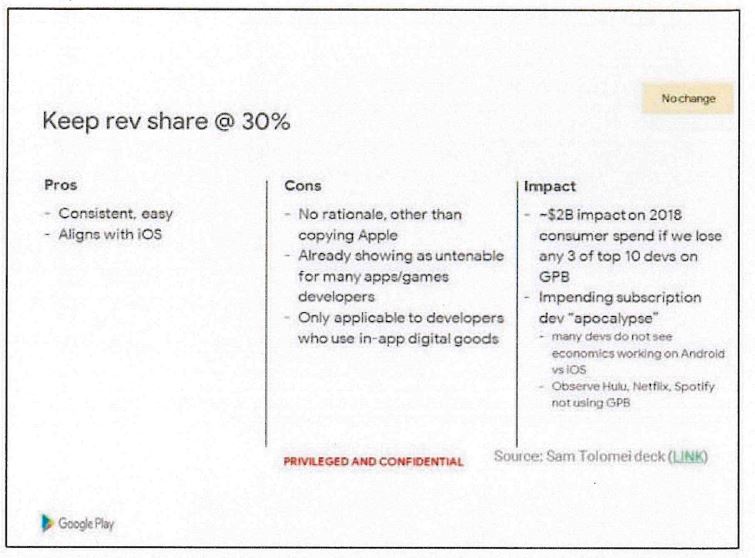

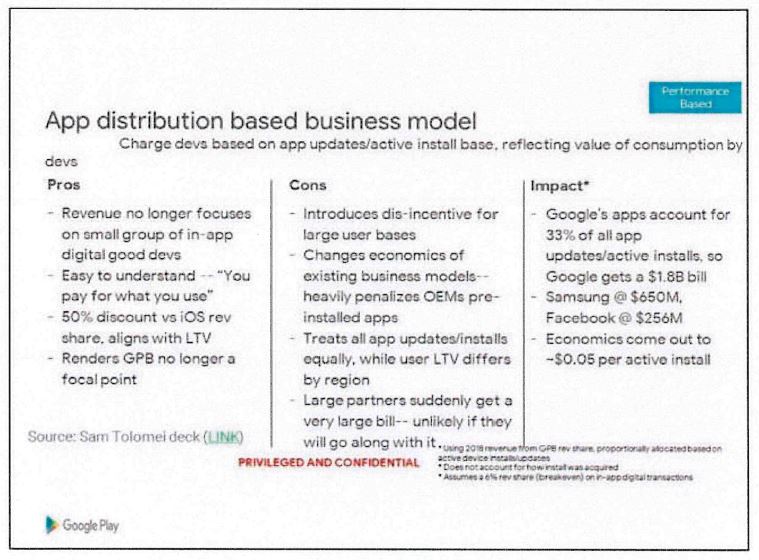

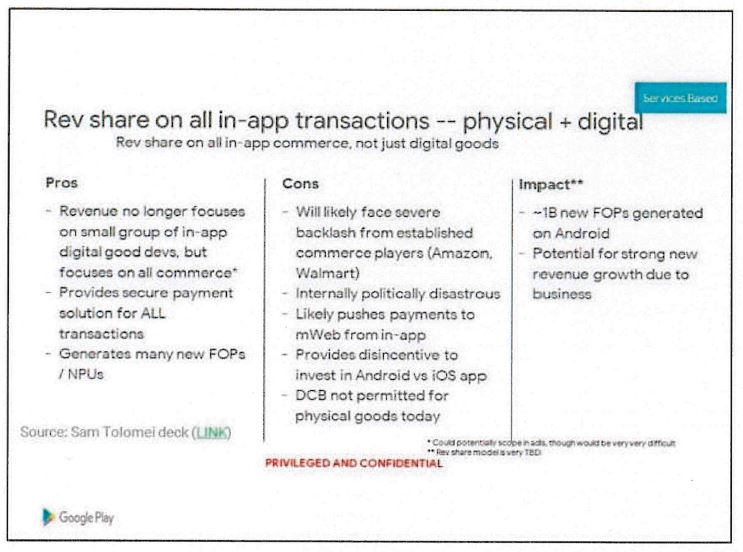

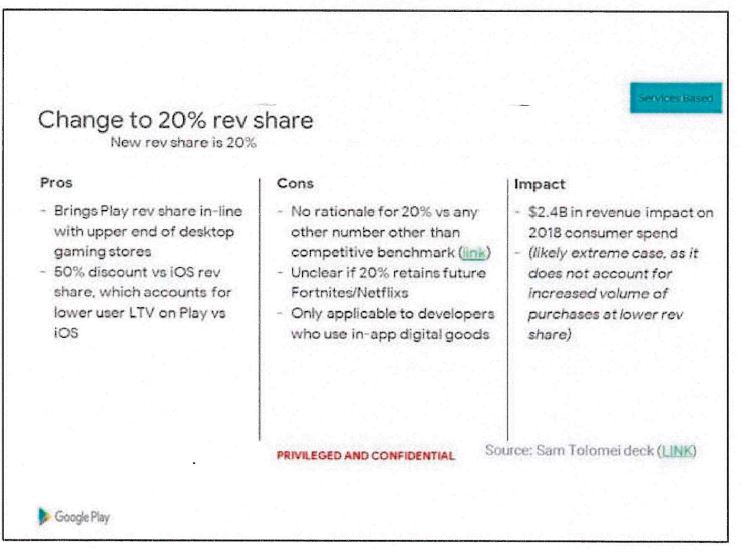

11 Further, it is said that in order to secure, and to prevent any challenger from threatening, Google’s control of app distribution and in-app payment solutions within the Android ecosystem, Google imposes and enforces a set of contractual and related arrangements on app developers and on the original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) of smartphones and tablets.

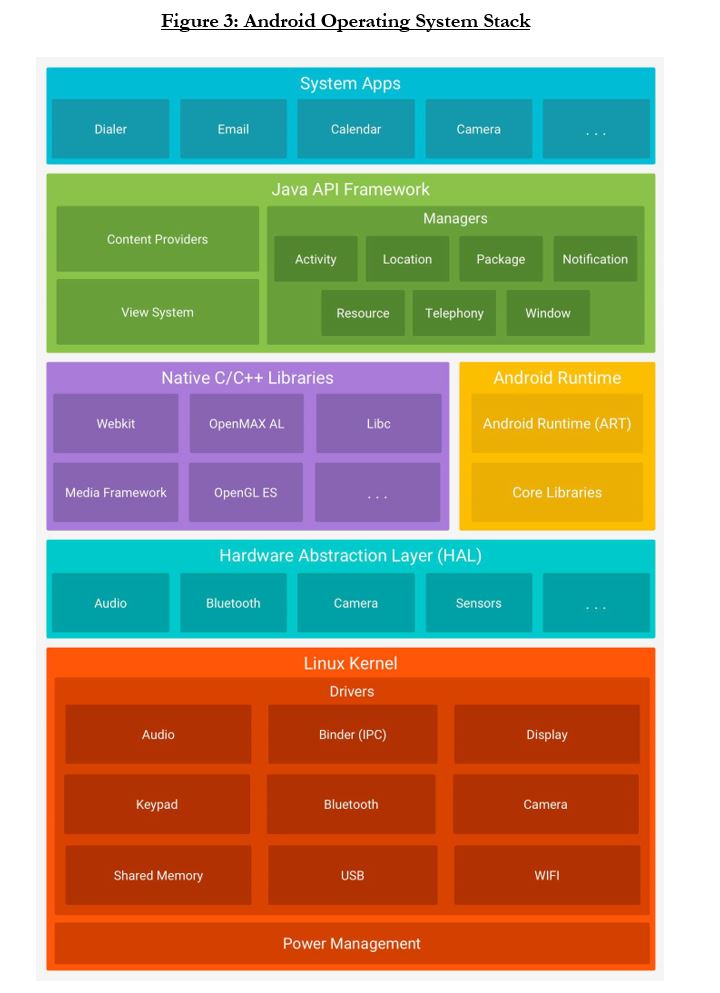

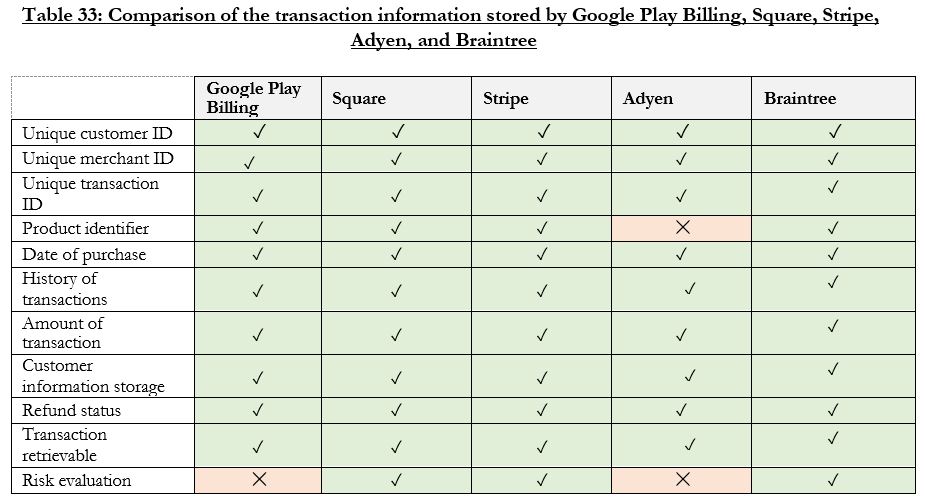

12 Epic’s case is that every OEM that wishes to sell smart mobile devices needs to pre-install an operating system (OS) for those devices. Now the Android OS, which is owned by Google, is an operating system for mobile devices being smartphones and tablets, based on the open source Linux OS.

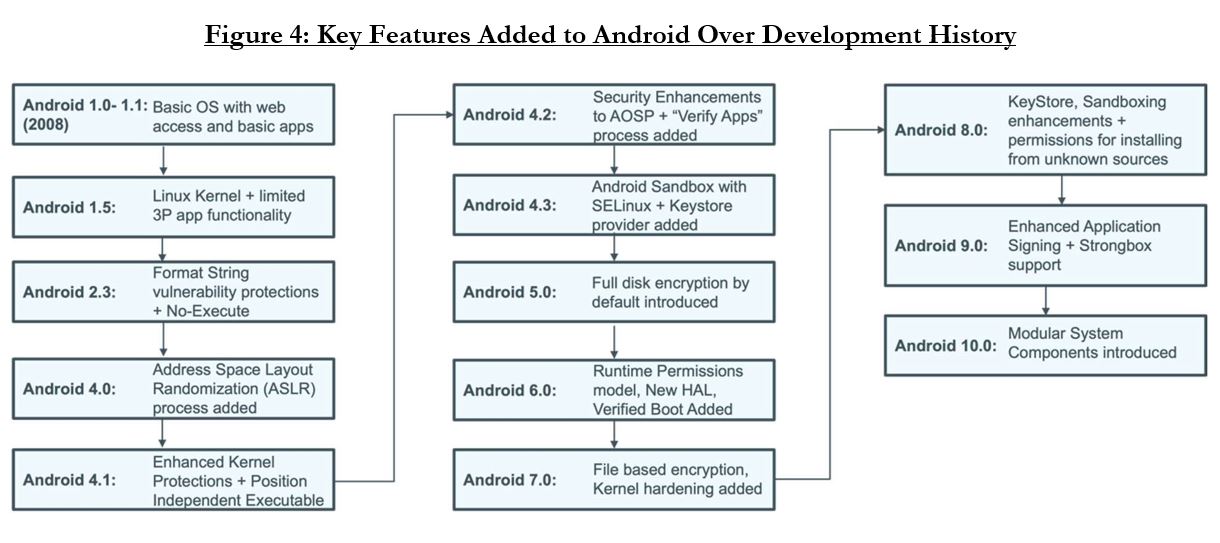

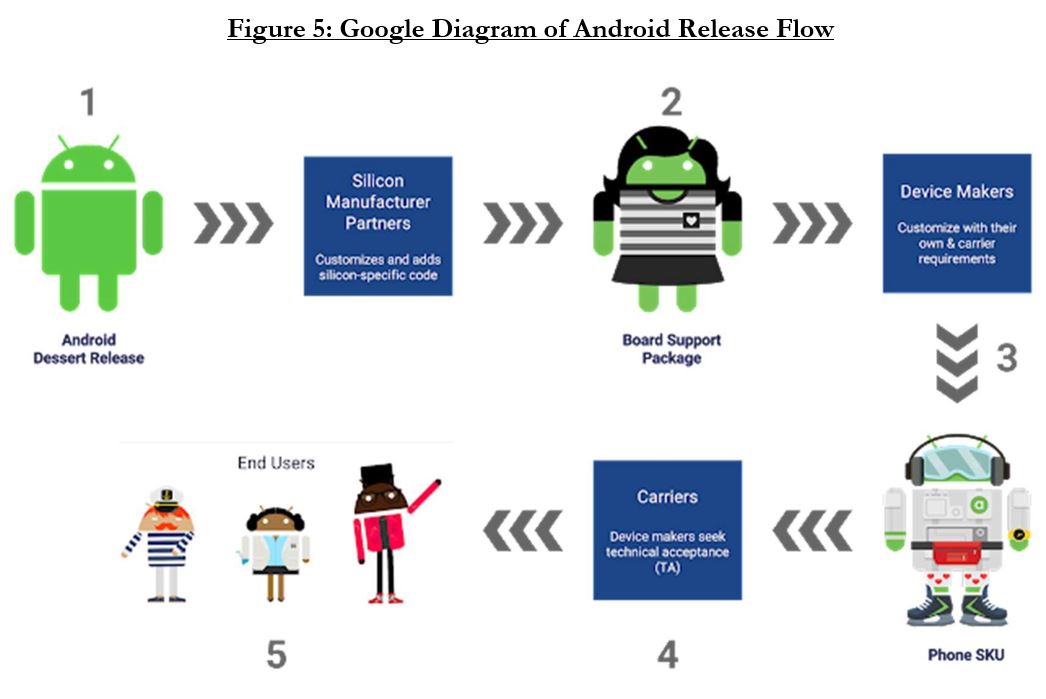

13 Google makes Android OS available for free under an open source licence being the Apache 2.0 licence via the Android Open Source Project (AOSP). So, Google makes the source code for that software publicly available for use and modification. At the time of trial there had been 14 iterations of the Android OS, with Android 15 in beta phase. But apparently Android 15 was released in late 2024. The Android OS is available to be modified by OEMs.

14 The Android OS is the foundation of what has been described as the Android ecosystem, which comprises the Android OS, the products and services that support the Android OS, as well as the participants in that ecosystem, being users, OEMs, developers, carriers and Google.

15 Now the development and success of Android as an OS depends upon its ability to attract OEMs to develop Android-compatible devices, its ability to attract developers to develop apps for Android and its ability to attract users to acquire Android devices and apps, each of which is related to the others.

16 The notion that Android is an ecosystem reflects the fact that there is interdependence between these participants. This dynamic of interdependence is relevant to understanding the commercial realities of any competition or any competitive constraints faced by Google, Android and the Play Store.

17 Android connects OEMs who make Android devices, telecommunications carriers who supply mobile services on Android devices, app developers who develop apps for Android devices, and consumers who use Android devices and Android apps. As I have said in my reasons in the Apple proceeding, multi-sided platforms involve indirect network effects which can create feedback loops across the platform. These indirect network effects manifest strongly with respect to Android. The more consumers that want to acquire Android devices, the greater the incentive for OEMs to make Android devices and for developers to develop apps for the Android OS. The better the range and quality of Android devices and Android apps, the more attractive Android devices become for consumers.

18 These network effects create economic challenges. In particular, the continued success of Android depends upon it overcoming coordination problems and agency problems. Now a coordination problem arises when the value that one participant derives from a platform is linked to the participation of other users on the platform. Further, an agency problem arises in situations where participants are incentivised to act in ways that may harm other participants or the platform overall, such as some OEMs or developers engaging in malicious privacy or security practices that reduce consumers’ willingness to purchase Android devices.

19 Coordination and agency problems manifest in multi-sided platforms due to indirect network effects.

20 In the case of Android, the interests of users, OEMs, developers and carriers must be balanced so that each group is sufficiently incentivised to participate. In the absence of such balance, the Android ecosystem may be unable to attract and sustain sufficient engagement and investment from participants on all sides of the platform, being OEMs, developers, users and carriers. Were that to occur, Android may cease to remain competitive.

21 In the case of Android, risks are mitigated, in part, by the contracts Google enters into with OEMs. These contracts overcome coordination problems, and enhance the attractiveness of Android to both users and developers. By comparison, Apple manages risks through vertical integration.

22 Now as I have said, Google owns the Android OS and makes its source code available to third parties free of charge under an open source licence. I will refer to this version of Android as open source Android. Open source Android does not include a suite of software apps, software development kits (SDKs) and application programming interfaces (APIs) that are owned by Google and known as Google Mobile Services (GMS).

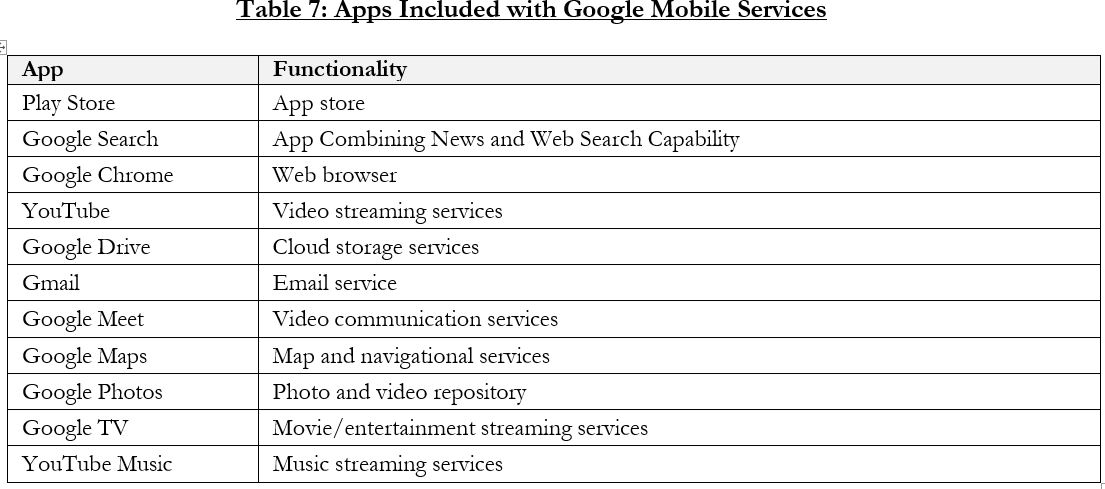

23 A smart mobile device which does not have GMS installed is functionally limited, because most non-iOS apps are built using GMS APIs or SDKs supplied by Google and those apps will only run as intended on devices that have GMS installed. Further, GMS includes six core applications developed by Google that are among the most used apps in the world, being the Play Store, Google Search, Chrome, Google Maps, Gmail and YouTube.

24 In theory, an OEM can do without GMS. It can license an Android fork, which is a modified version of open source Android which does not comply with compatibility standards set by Google. It can also create its own mobile OS. But few OEMs do either of these things and those that do end up with market shares that are miniscule. Instead, the vast majority of non-iOS smart mobile devices distributed outside of China with a licensable mobile OS are pre-installed with a combination of open source Android and GMS. For convenience, I will refer to that combination as GMS Android or Google Android, although I accept Google’s point that this is not supplied by it as a unitary product.

25 Now to obtain the right to distribute devices with GMS Android pre-installed, OEMs must enter into a mobile application distribution agreement (MADA) with Google.

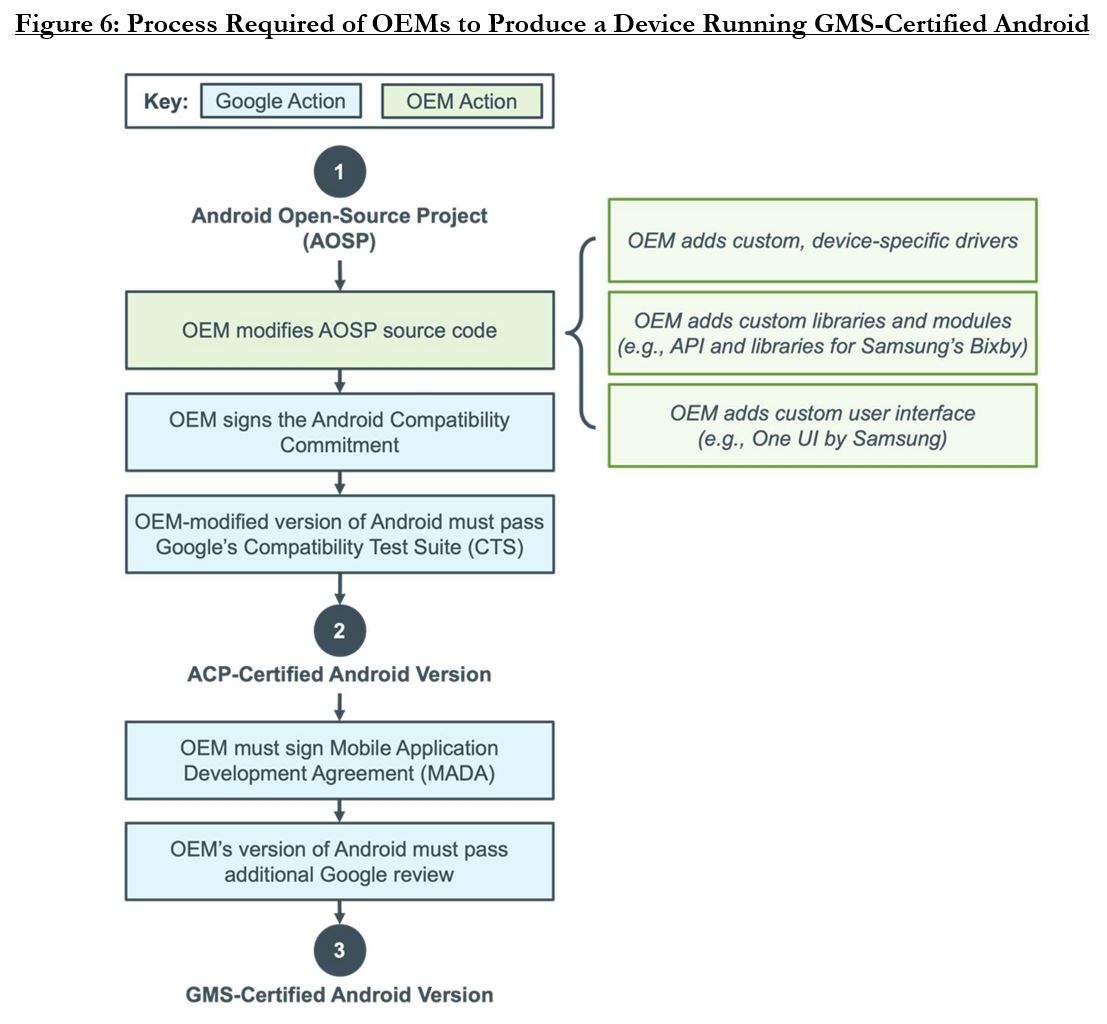

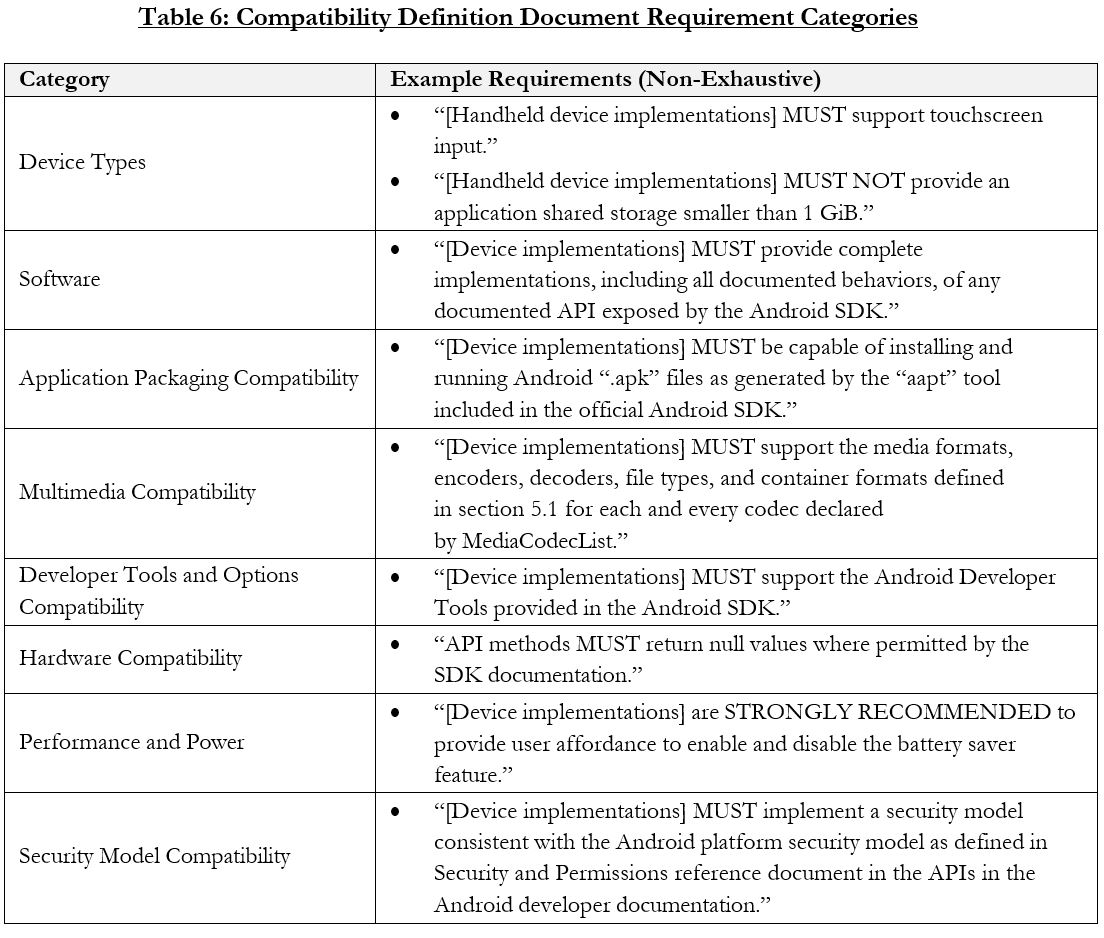

26 The MADA grants OEMs a license to distribute their devices with GMS pre-installed, but on conditions that, first, certain apps nominated by Google, including the Play Store, must be pre-installed on those devices, second, those Google apps must be placed in specified prominent locations on the OEM’s device, third, the OEM must comply, and their devices must be tested for compliance, with numerous technical requirements set by Google, including restrictions on which apps are allowed to install other apps and, fourth, the OEM must ensure ongoing compliance with the Android Compatibility Commitment (ACC) as part of the Android compatibility program.

27 An ACC is a nominally separate contract between the OEM and Google. In general terms, it precludes OEMs from distributing devices that run on an Android fork. It operates together with a MADA so that, for so long as an OEM wants to distribute devices with GMS Android pre-installed, it cannot distribute any devices that run on an Android fork. This explains the dearth of non-Apple smart mobile devices distributed outside China that run on something other than GMS Android.

28 The effect of the anti-fragmentation agreements (AFAs) and the ACCs is that some OEMs have committed to certain core functionality and baseline standards, which ensures that developers and users have a consistent experience in developing for and using Android devices. That is because departures from or modifications to the Android OS source code may result in so-called “forked” devices, being devices on which apps developed for Android either do not function, or do not function correctly.

29 This is the problem of device fragmentation, which arises when there is incompatibility between devices notwithstanding that they notionally operate on the same operating system.

30 As their names suggest, the AFAs and ACCs address the risk of device fragmentation by promoting compatibility between Android devices. Devices that comply with the compatibility standards agreed in the AFAs and ACCs are often referred to as compatible Android devices and are so approved under what has been described as the Android compatibility program. Google did not, and does not, charge OEMs any fee under the AFAs or ACCs.

31 Further, some OEMs have entered into MADAs with Google under which, as discussed above, Google licenses the OEMs to use GMS. That package of software includes familiar Google apps such as Google Maps, Chrome and YouTube. These are high quality apps which certain OEMs want to have on their devices. Google also licenses OEMs to use the “Android” and “Google” trademarks under the MADAs in relation to compatible Android devices. Outside of Europe and Turkey, Google does not charge OEMs a licensing or other fee under the MADAs.

32 Of course, many OEMs do want to develop, manufacture and sell Android devices that satisfy the AOSP compatibility standards, which use GMS and which can be marketed and sold using the Android trademark. Such devices may be referred to as Android devices although they might more accurately be described as GMS devices.

33 That OEMs who wish to develop, manufacture and sell Android devices must enter into a MADA with Google is unremarkable in circumstances where that is the means by which Google licenses OEMs to use Google’s proprietary software, being GMS, and intellectual property.

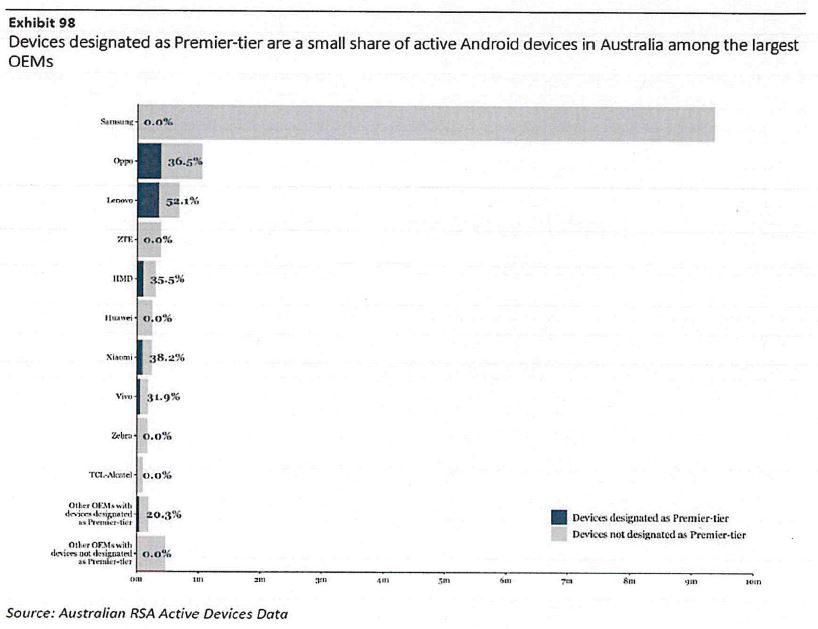

34 According to Epic, to ensure this situation never changes, Google has entered into incentive agreements with most OEMs, whereby they receive a portion of Google’s advertising revenues earned from the OEM’s devices. Such incentives are conditional upon OEMs complying with their MADAs and ACCs. Further, certain OEMs have entered into incentive arrangements which entitle them to a portion of Google’s Play Store revenues, provided the OEMs do not pre-install or promote a competing app store. I will address what have been described as the Premier-tier revenue sharing agreements (RSA3s) and mobile incentive agreements (MIAs) later.

35 Let me now say something about the distribution of Android apps.

36 It is possible to distribute Android apps to Android device users via pre-installation on the device prior to its sale, or else via download to the device after sale, from the Play Store, a third-party app store that may come pre-installed on the device such as the Samsung Galaxy Store, or be directly downloaded onto the device, or via a website. Acquiring an app from a website is referred to as direct downloading or, in some cases, sideloading.

37 Google does not permit third-party app stores or any app that facilitates the distribution of another app to be distributed through the Play Store.

38 Pre-installation requires the agreement of the device’s OEM. Often the agreement of mobile telecommunications carriers is also necessary. Carriers supply devices to users subject to mobile plans, being so-called locked devices, and have a say in what apps are pre-installed on locked devices. Different carriers operate in different territories such that securing pre-installation is a complex endeavour.

39 Although direct downloading of apps and app stores is possible on Android devices, less than 3% of new apps downloaded to Android devices in Australia during 2020 were directly downloaded or downloaded from an app store that was itself directly downloaded. Globally, the relevant proportion was under 12%. Three major challenges attend this distribution method.

40 The first challenge is one of discoverability, that is, of being found or noticed by users. If the app or app store is made available in the vast cyberspace of the internet, rather than within a dedicated and searchable app store that is already installed on users’ devices, it is far less likely to be found by users.

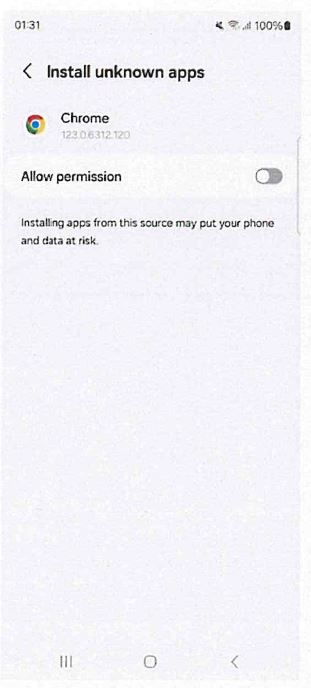

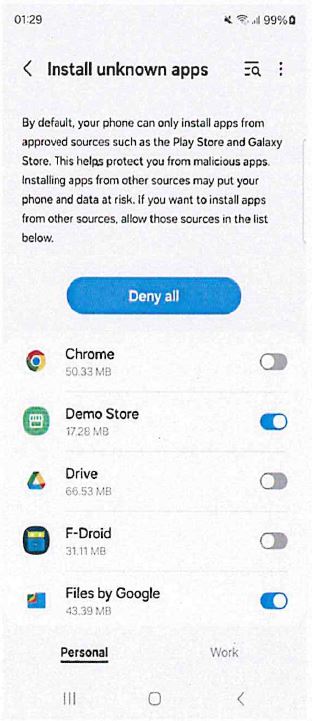

41 The second challenge is that several additional steps and warnings are injected into the sideloading process. These frictions stem from restrictions with which Google requires OEMs to comply as a condition of distributing devices with GMS installed. I will refer to these collectively as the technical restrictions.

42 The third challenge is that directly downloaded apps are functionally deficient, in that they generally do not update automatically. Instead, they must be updated manually, which requires the user to reinstall the app from the original source to obtain the updated version. Until Android 12 was released in October 2021, the same was generally true for apps sourced from a directly downloaded app store. It is only since October 2021 that Google has permitted directly downloaded app stores to update apps automatically.

43 Now it is said by Epic that within this realm, developers like Epic, who wish to distribute apps to the users of smart mobile devices with GMS installed, which for convenience I will refer to as Android devices or GMS devices, have been forced to operate. And it is a realm in which the Play Store is pre-installed in a prominent location on almost every Android device, and in which about 97% in Australia and about 91% globally, excluding China, of new app downloads through Android app stores are undertaken via the Play Store. Its closest rival in Australia, being Samsung’s Galaxy Store, has a share of only about 1.5% of app downloads and its closest rival globally, being Oppo Store, has a share of only about 2.5%.

44 Now it is possible for developers to distribute their apps to Android device users by methods other than app stores. But Epic says that none of those methods are a substitute for distribution through an Android app store. And the only Android app store with a more than negligible market share is the Play Store.

45 Now developers do not need Google’s consent or permission to develop or distribute apps for Android. Developers have a range of alternatives for distributing apps on Android. These include reaching pre-installation or pre-loading agreements with OEMs or carriers, installing via a pre-installed third-party app store, downloading or sideloading apps or app stores from a website, via streaming or in the form of a web app. A web app is an application accessed through a web browser. And developers can distribute through any of these means without entering into any agreement with Google.

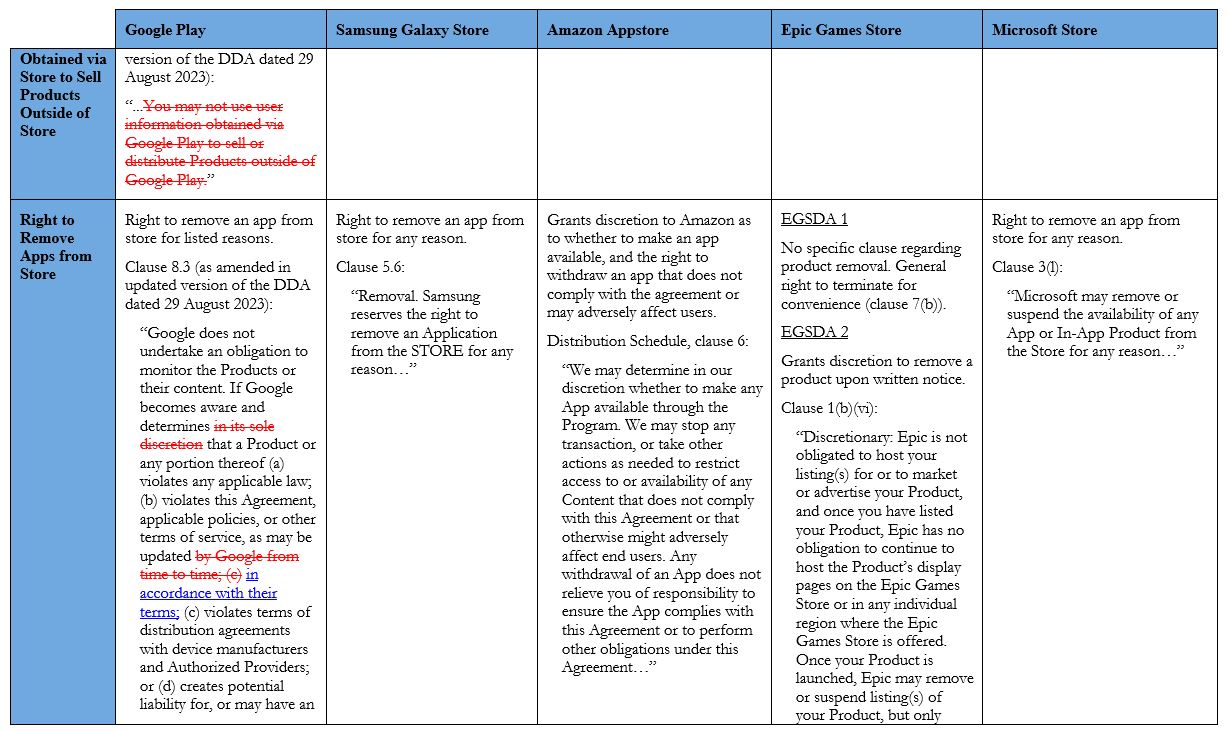

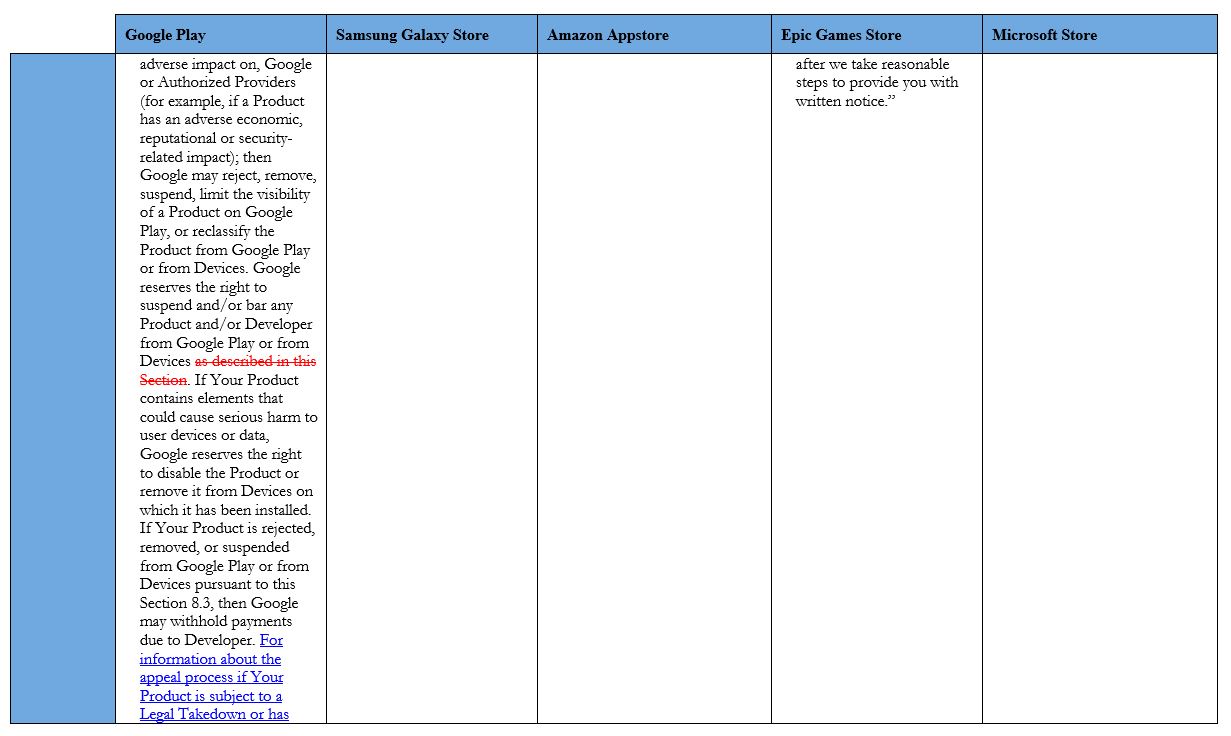

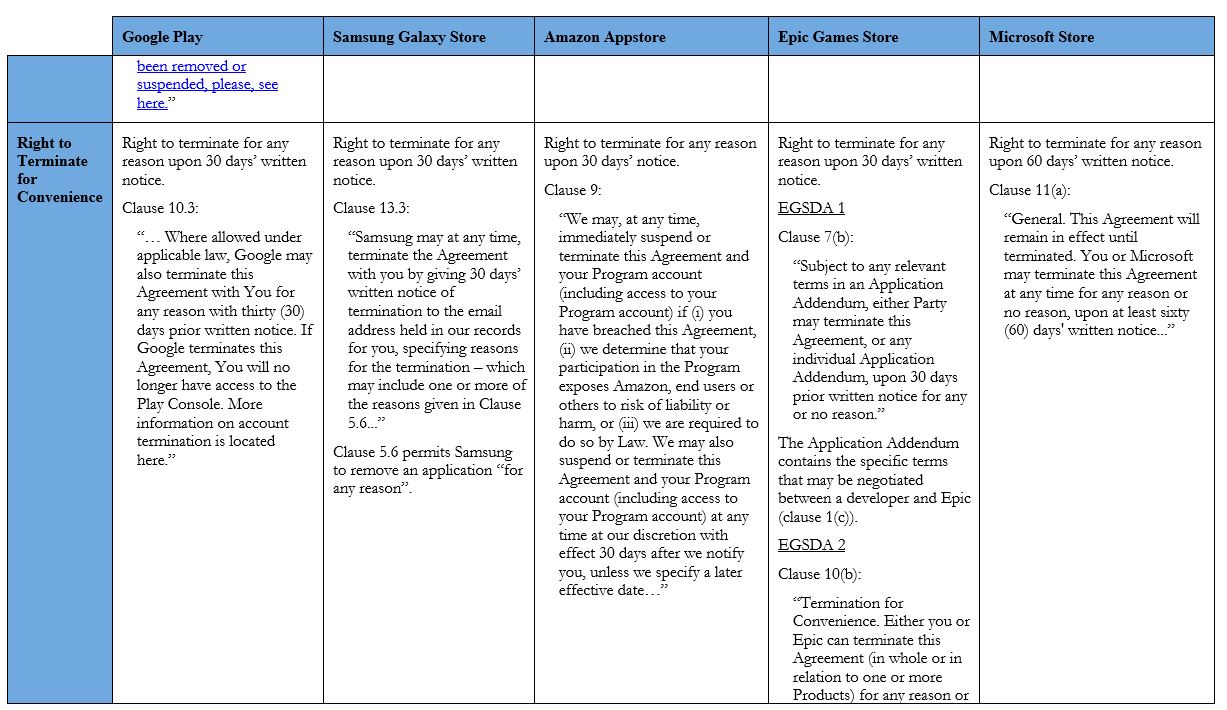

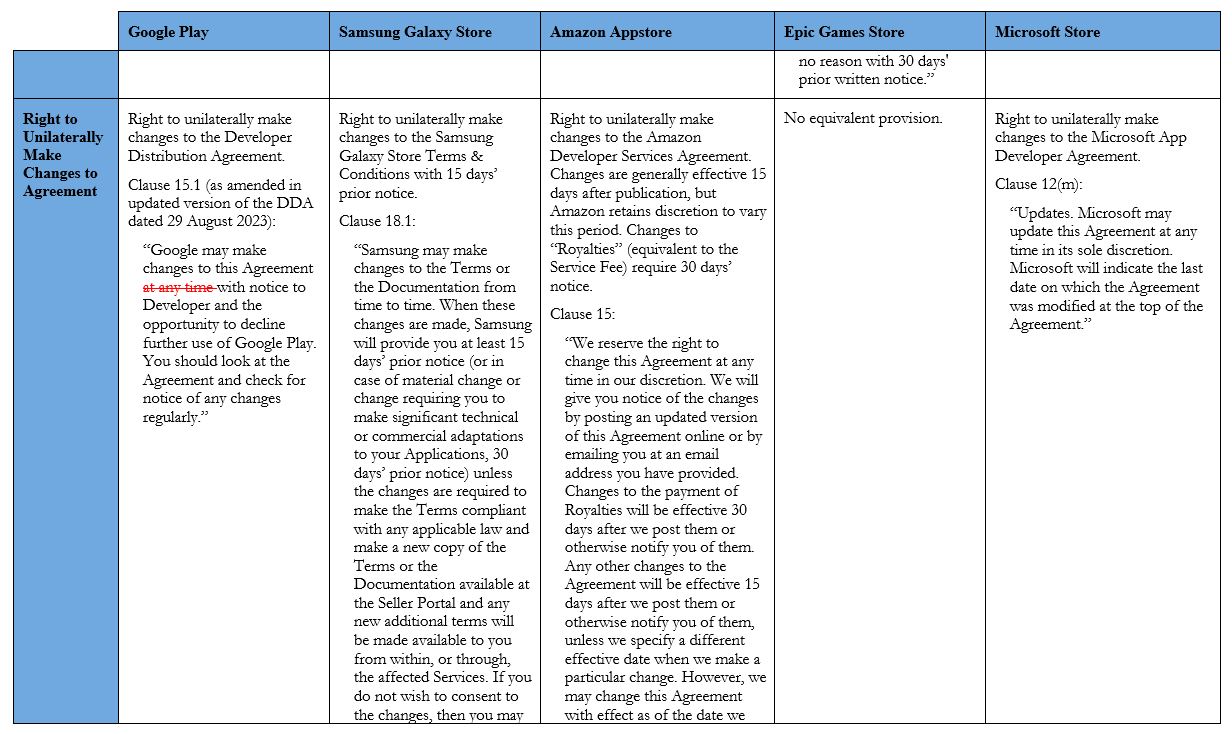

46 But developers cannot distribute their apps through the Play Store unless they enter into a developer distribution agreement (DDA) with Google, the terms of which are essentially non-negotiable.

47 Under the DDA, developers are prohibited from distributing an app store or any app that distributes another app through the Play Store. Google claims this prohibition is necessary for security reasons. The result is that rival Android app stores, and indeed any Android app that distributes another app, are denied access to the Play Store. They cannot be distributed via the most effective means of Android app distribution.

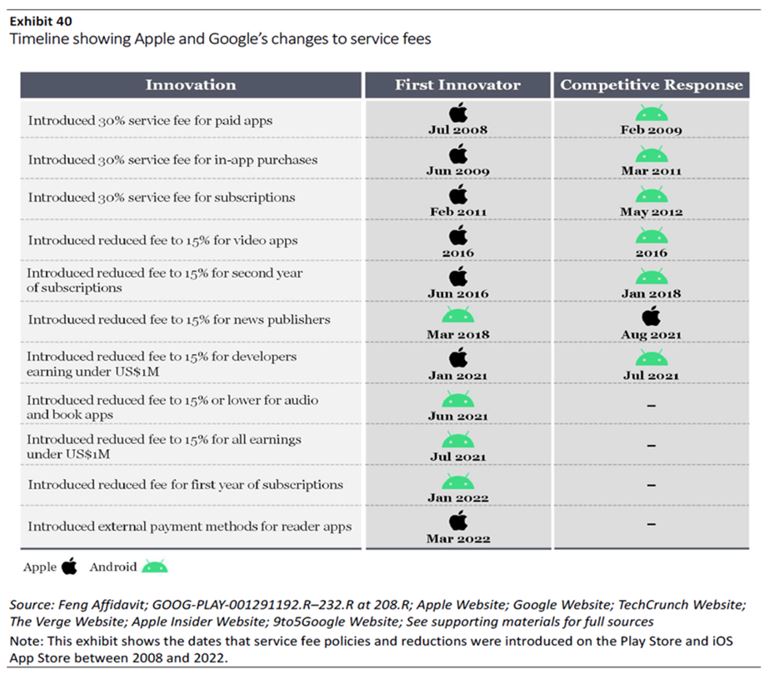

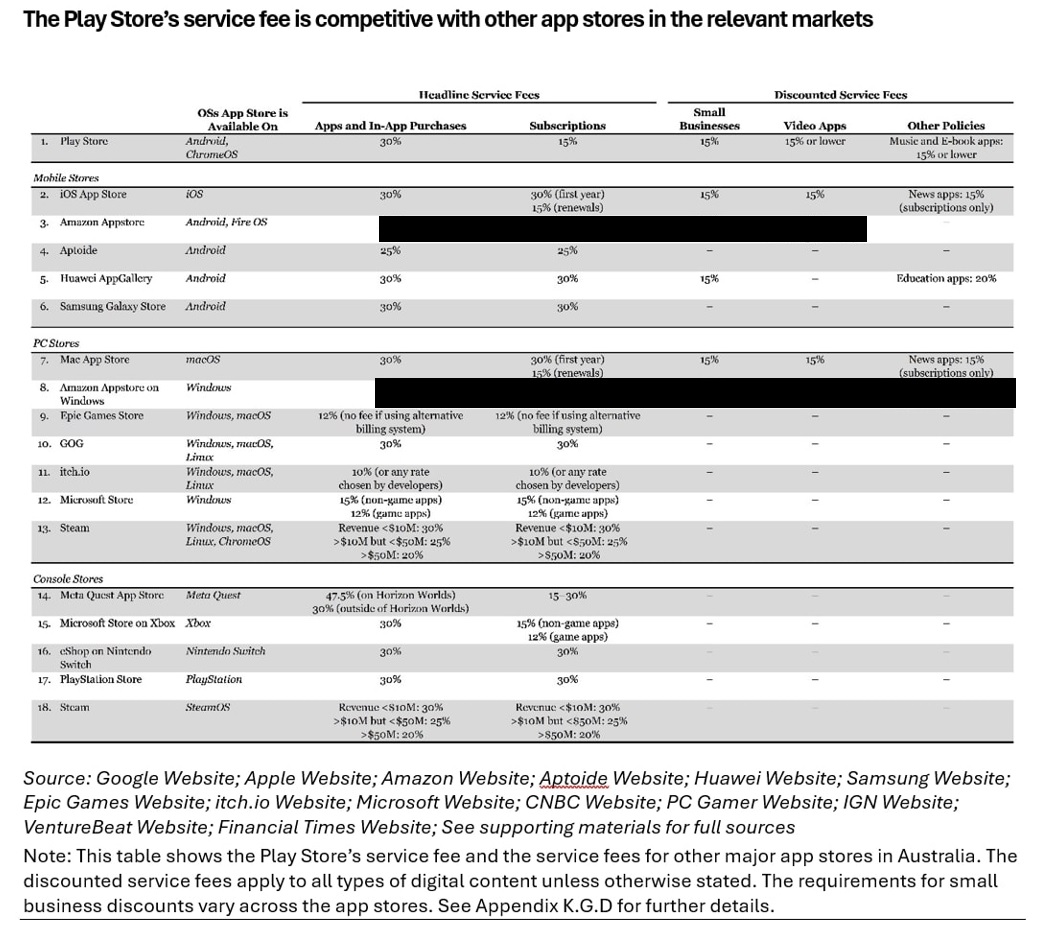

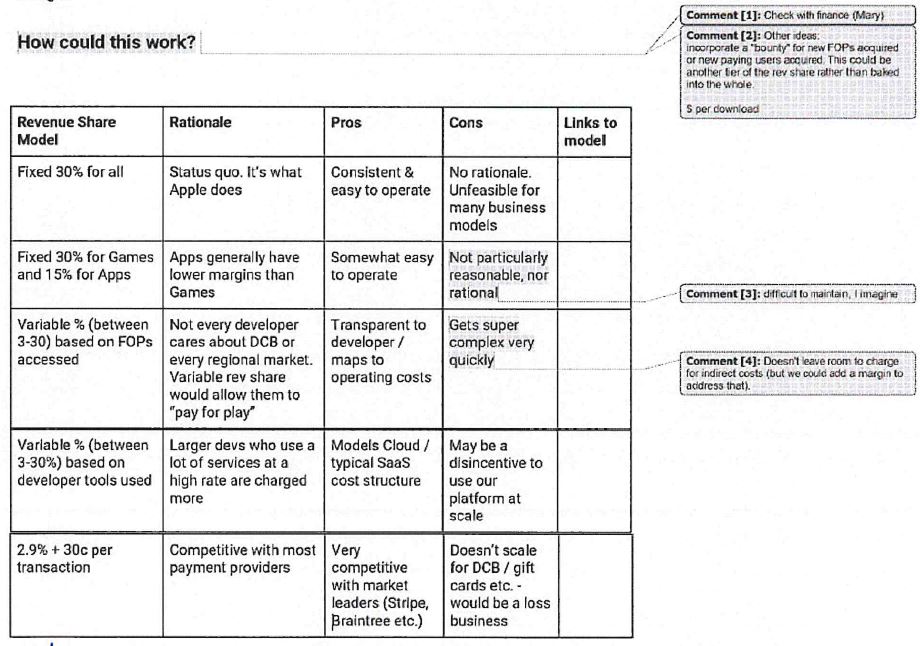

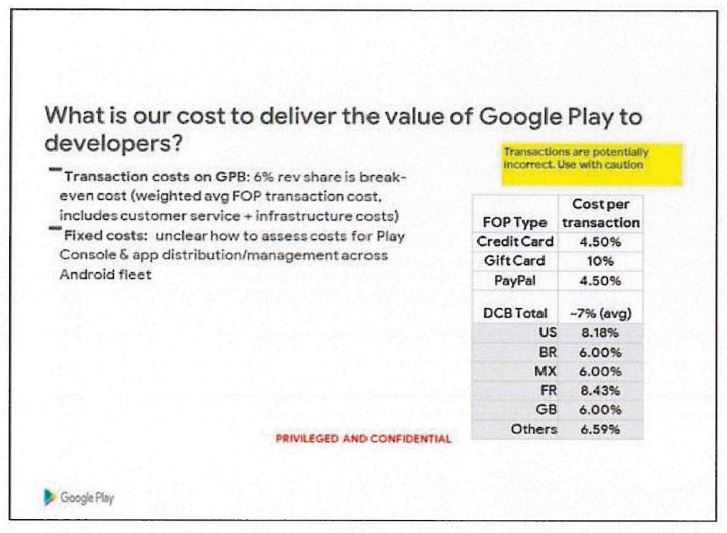

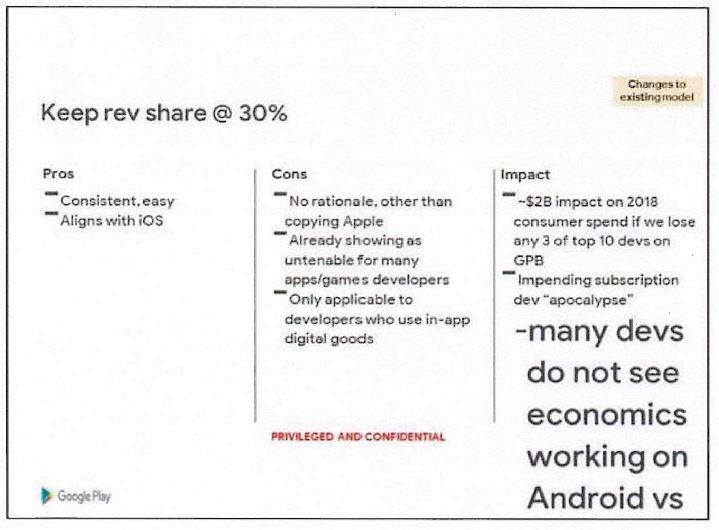

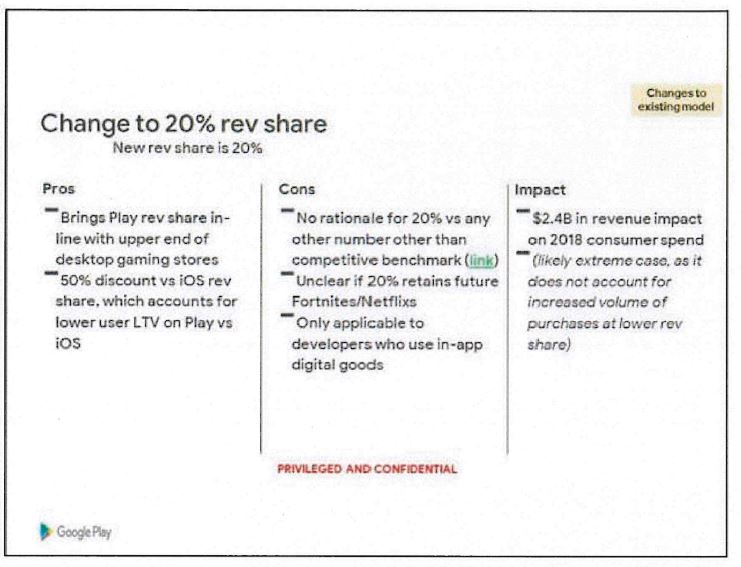

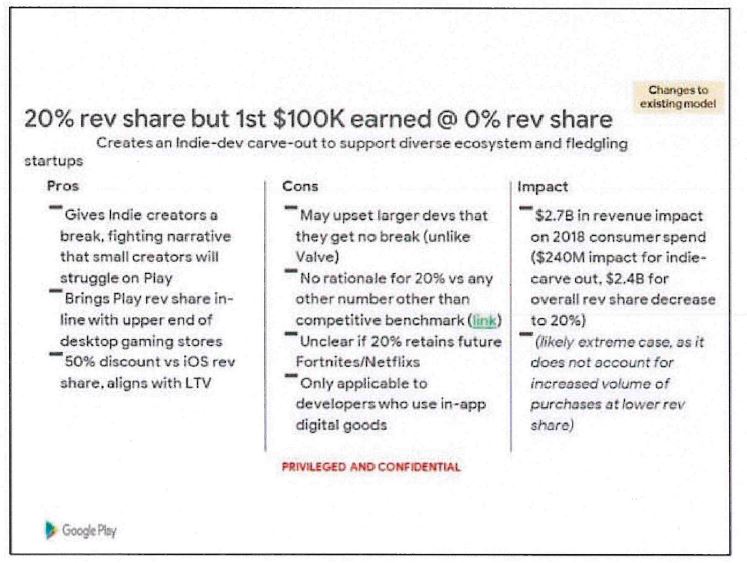

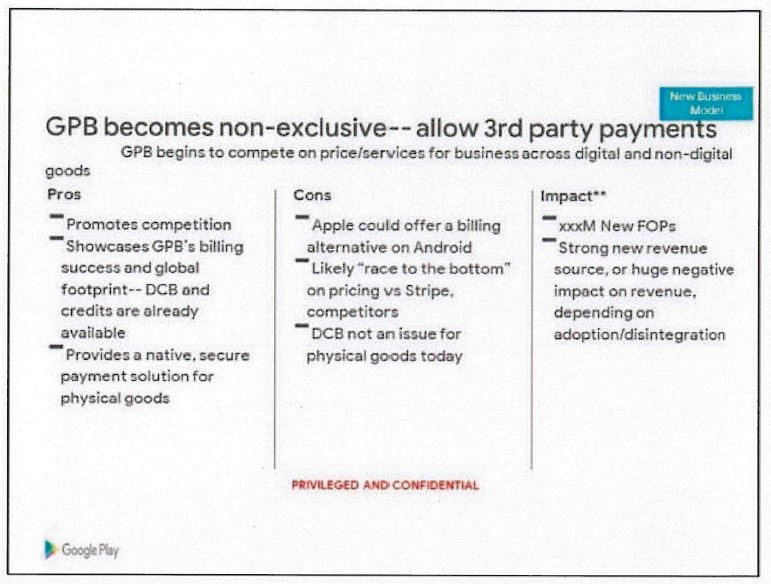

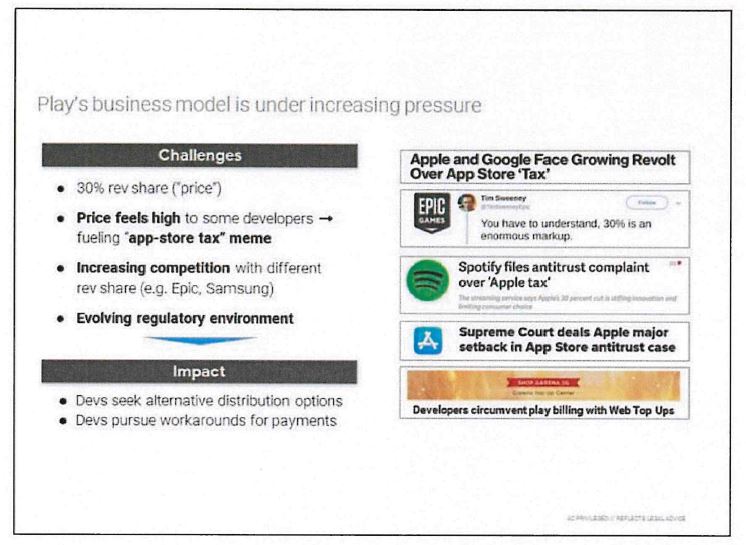

48 The DDA also provides that app developers that monetise their Play Store apps through in-app purchases of digital content must use Google’s own payment solution, Google Play Billing, to facilitate such payments. The parties have described this as the payments tie. When a user makes an in-app purchase of digital content using Google Play Billing, Google charges the developer a service fee, which is ordinarily 30% or 15% of the in-app purchase price.

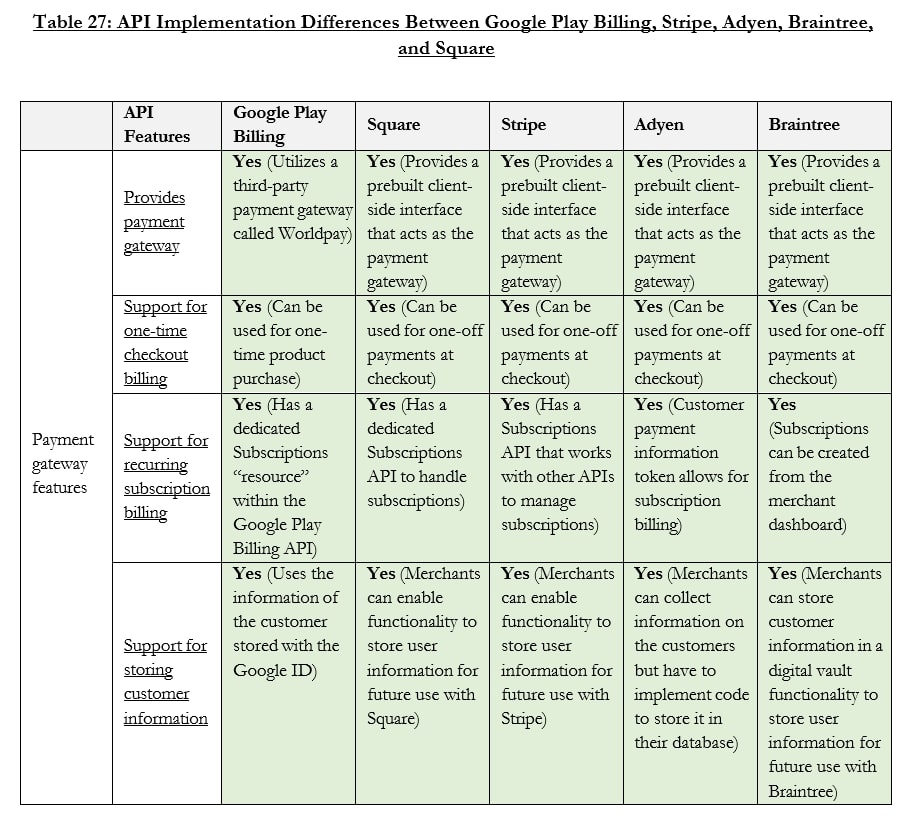

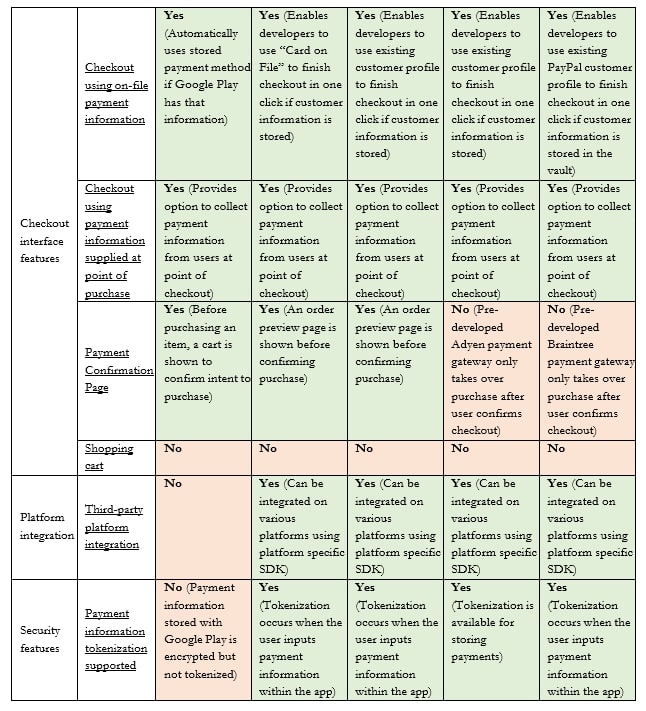

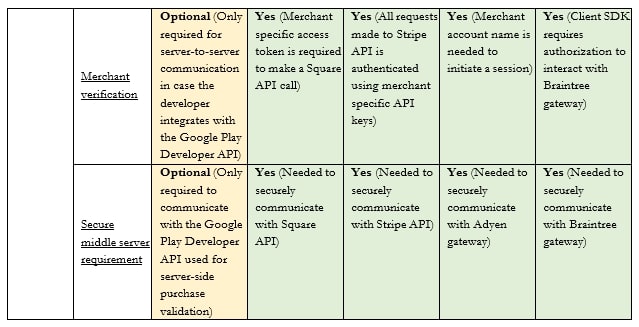

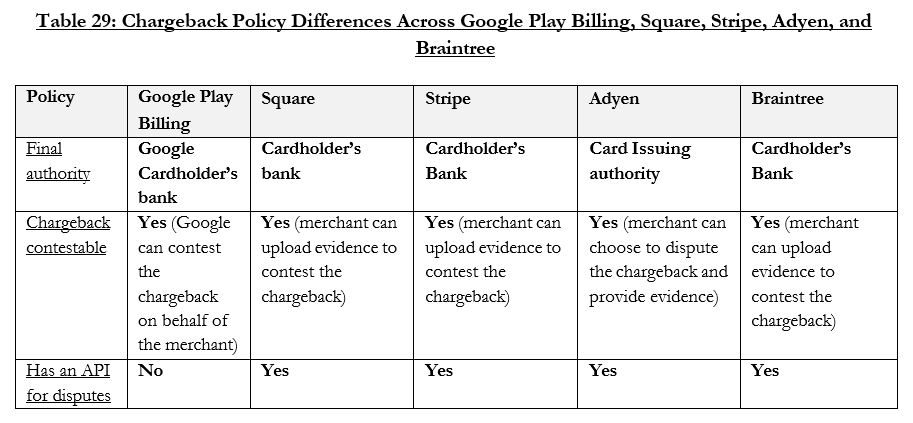

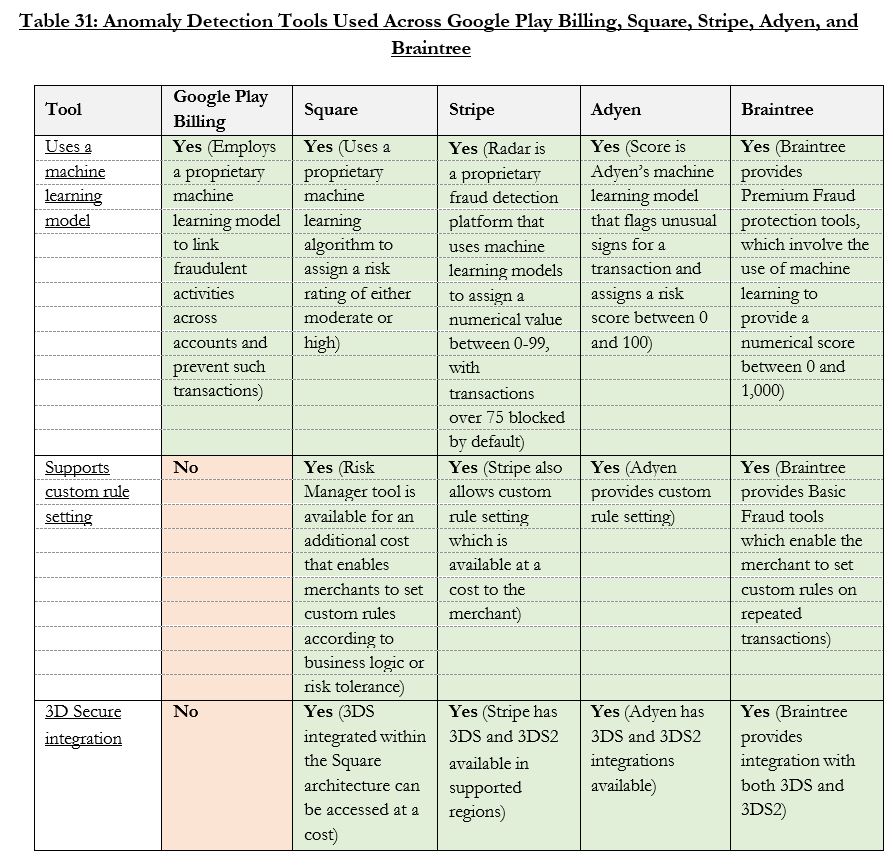

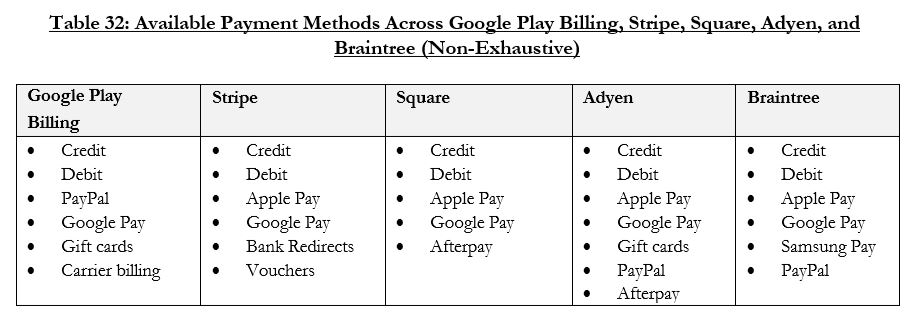

49 Google requires that app developers use Google Play Billing as their payment solution for in-app purchases of digital content within apps downloaded from the Play Store. There are some limited exceptions to this. Google does not require the use of Google Play Billing for in-app purchases of physical goods and services. Other payment solutions including those provided by third-parties such as PayPal, Stripe, Adyen and Braintree are used to purchase physical goods or services within apps distributed through the Play Store.

50 Additionally, the DDA includes an anti-steering rule, which prohibits Play Store apps from leading users to a payment method besides Google Play Billing. So, developers cannot include within their apps a link to a website where payment can be made.

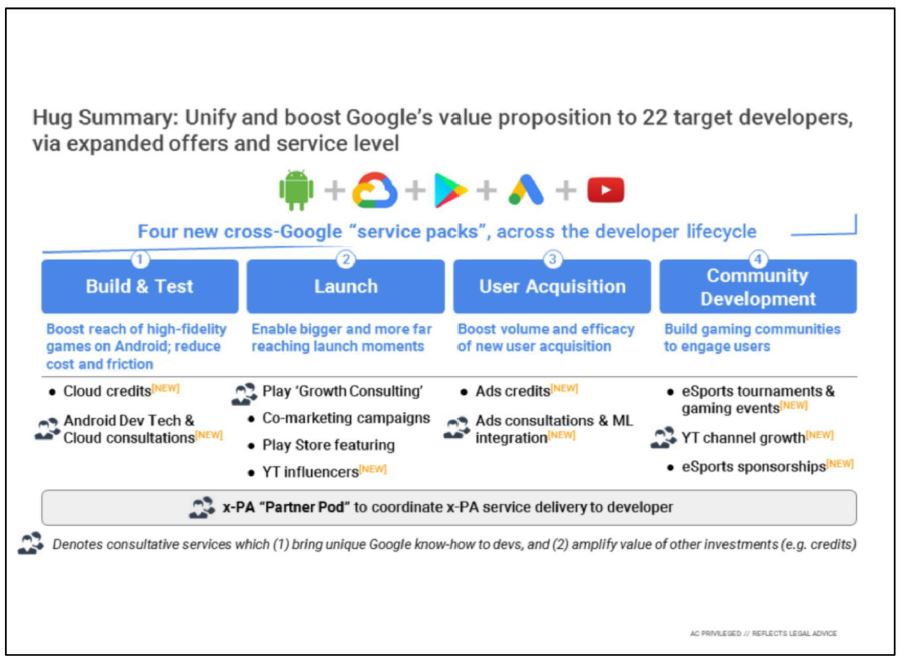

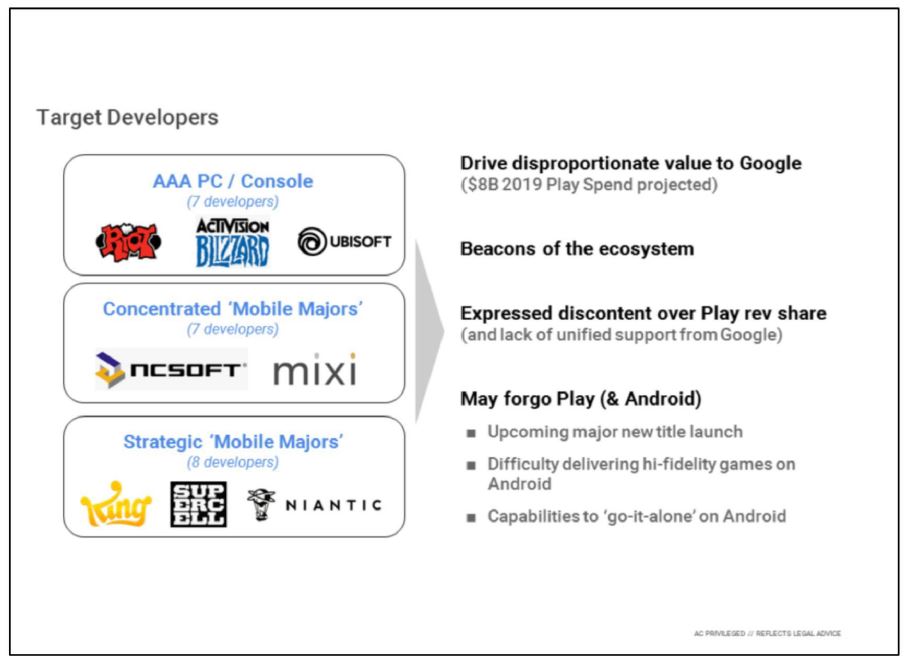

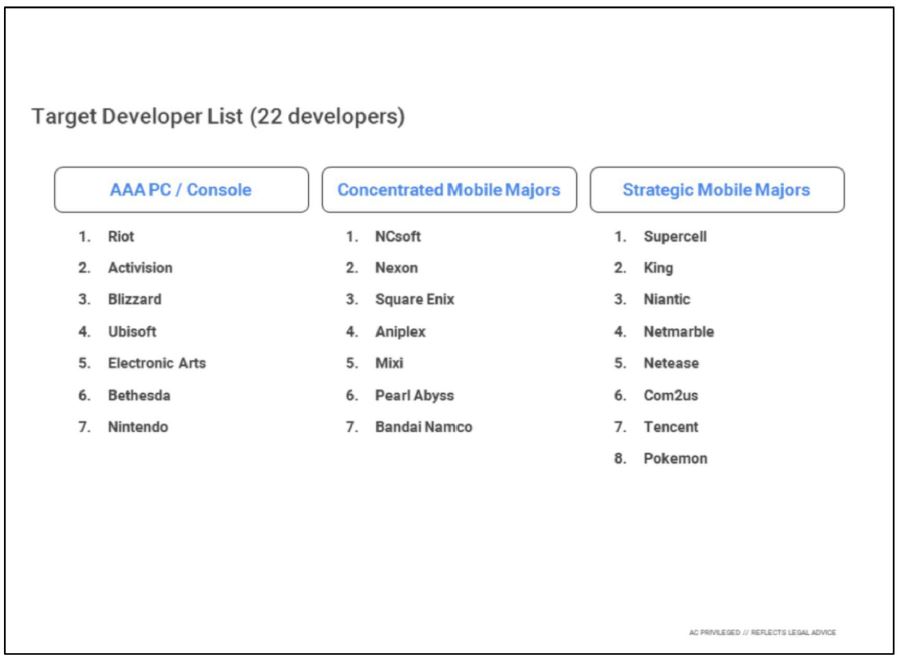

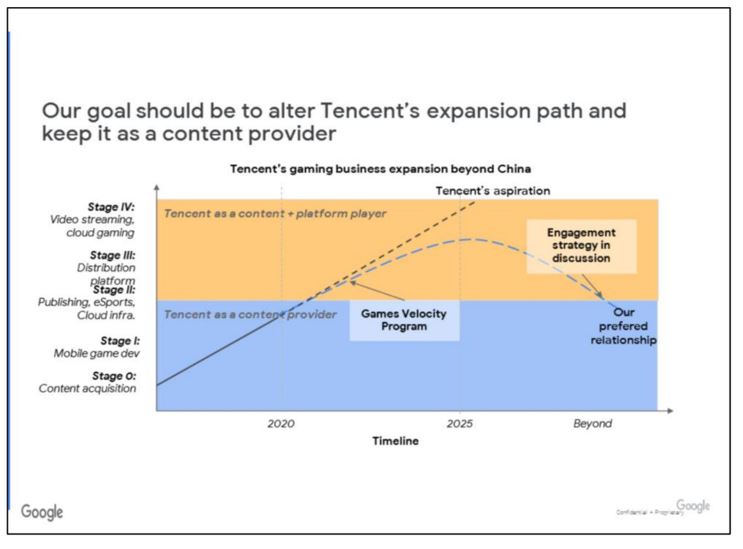

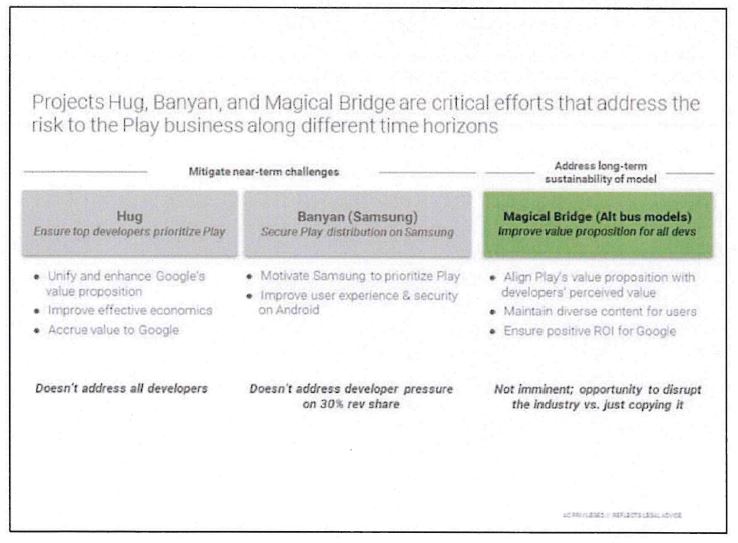

51 The final set of agreements which are of present concern are known as the Games Velocity Program (GVP) agreements and Apps Velocity Program (AVP) agreements, whose genesis was Project Hug which I will describe in detail later. These were made with certain large developers, which were described by Google as “beacons of the ecosystem” and many of whom Google considered to be at risk of distributing their Android apps outside the Play Store.

52 Now it is Google’s conduct in entering into and enforcing these various arrangements which is the subject of these proceedings.

53 Epic says that this conduct occurred in three relevant markets being, first, a market for the supply of mobile OS licenses to OEMs, second, a market for the supply of services for the distribution of Android apps and, third, a market for the supply of services for facilitating payments for the purchase of digital content within Android apps.

54 Now the posited mobile OS licensing market is a market for the supply of licenses for mobile operating systems, where the geographic dimension of the market is a global market excluding China, of which Australia forms part.

55 The posited Android mobile app distribution market is a market for the supply of services for the distribution of Android apps to Android smart mobile device users, with the following elements or dimensions. It is said that the services consist of the provision of services to app developers enabling or facilitating app developers to reach, offer and provide Android smart mobile devices users with Android apps and associated updates and/or the provision of services to Android smart mobile devices users enabling or facilitating Android smart mobile devices users to be presented with or to find, obtain and utilise Android apps and associated updates. And it is said that the geographic dimension of the market is Australia or a global market excluding China, of which Australia forms part.

56 The posited Android in-app payment solutions market is a market for the supply of services to app developers for accepting and processing payments for the purchase of digital content, including by way of subscriptions, within an Android app, with the following elements or dimensions. It is said that the services consist of the provision of services to app developers enabling and/or facilitating app developers to accept and process payments for the purchase of digital content, including by way of subscriptions, within an Android app. And it is said that the geographic dimension of the market is Australia or a global market, excluding China, of which Australia forms part.

57 Now there is an alternative posited to the Android mobile app distribution market. This is the mobile app distribution market, which is said to be a market for the supply of services for the distribution of Android apps and native apps written for iOS to smart mobile device users, with the following elements or dimensions. It is said that the services consist of the provision of services to app developers enabling or facilitating app developers to reach, offer and provide smart mobile device users with native apps and associated updates and/or the provision of services to smart mobile device users enabling or facilitating smart mobile device users to be presented with or to find, obtain and utilise native apps and associated updates. And it is said that the geographic dimension of the market is Australia or a global market excluding China, of which Australia forms part. I will put this alternative to one side for the moment.

58 Now it is said that Google has a substantial degree of power in each of these markets.

59 It is said that the purpose and effect of Google’s conduct in both the mobile OS licensing market and the Android mobile app distribution market has been to ensure that the Play Store remains the predominant supplier of Android app distribution services and to prevent or hinder the emergence and expansion of rival Android app stores. It is said that its conduct has substantially lessened competition in the Android mobile app distribution market. It is said that in the absence of Google’s conduct, rival app stores would enter that market and compete with the Play Store, including by offering developers lower fees. And it is said that existing Android app stores such as the Amazon App Store and the Galaxy Store could compete more effectively.

60 Similarly, it is said that the purpose and effect of Google’s conduct in the Android in-app payment solutions market has been to ensure that Google remains the sole supplier of services for the facilitation of payments for the purchase of digital content within Play Store apps. It is said that its conduct has substantially lessened competition in that market. It is said that in the absence of Google’s conduct, rival payment solutions providers would enter the Android in-app payment solutions market and compete with Google Play Billing.

61 In summary, Epic says that Google has contravened ss 46 and 47, alternatively, s 45 of the CCA on and from 6 November 2017 (the relevant period).

62 It is said that Google has contravened s 46 because it has a substantial degree of power in all three relevant markets and its conduct had the purpose, effect, or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in two of those markets.

63 It is said that Google has contravened s 47 by supplying Android app distribution services to developers via the Play Store on the condition that they not obtain services for the facilitation of in-app purchases of digital content in Play Store apps from anyone besides Google. Alternatively, it is said that Google has contravened s 45 because it has made and given effect to contractual provisions that have the purpose, effect, or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

64 Further, it is said that in all the circumstances, Google has engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law.

Summary of findings

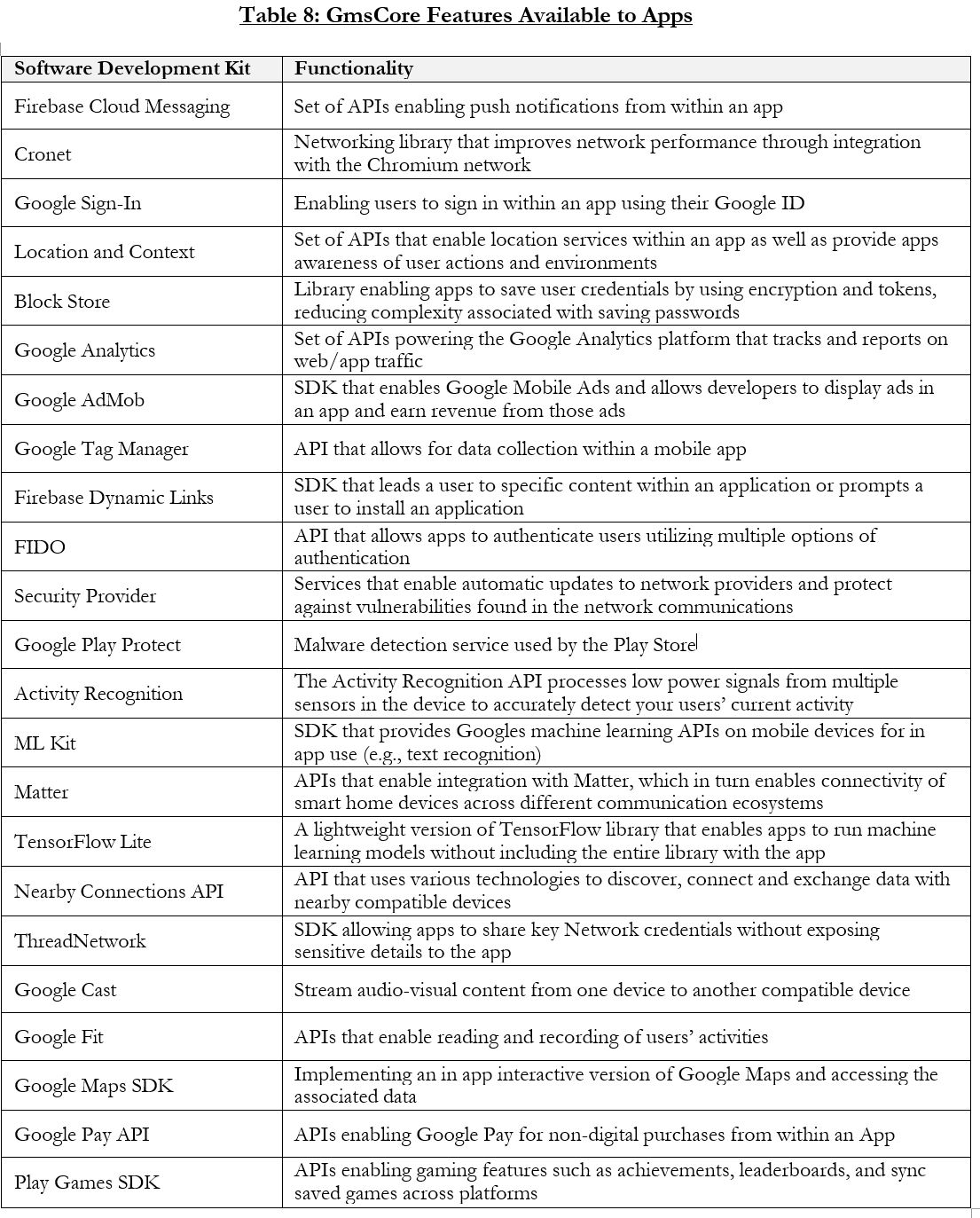

65 In summary, I have made the following key findings.

66 First, I have found in favour of Epic concerning its three posited markets being, first, the mobile OS licensing market, second, the Android mobile app distribution market and, third, the Android in app payment solutions market.

67 And relevant to the question of substitution concerning the second posited market, in my view other Android app stores do provide a competitive constraint on the Play Store such as to be a substitute. Further, there is some substitutability between sideloading of apps and Android app distribution services, but it is not a close constraint, and users and developers do not consider it to be a close substitute. Further, the pre-installation of apps is not a close substitute for Android app distribution services. Further, there is some competition with PC and console operators and mobile app stores, but there is not close substitution. Further, out of app payments say little about the question of substitution for distribution services and in any event would not constrain the hypothetical monopolist of Android app distribution services.

68 Now I should note that the fact that I have found that various other products and services are not close constraints and therefore are not part of the relevant product dimension of market definition does not entail that the availability of such products and services do not provide some form of competitive constraint. In my view they do provide a competitive constraint to some extent although not such as to deny the market definition that I have found or Google’s substantial market power in such a market.

69 Second, I have found in favour of Epic to the effect that at all relevant times Google has and had a substantial degree of power in each market.

70 Third, I have found that contrary to s 46 of the CCA, Google engaged in conduct in the latter two of the three posited markets that has had or is likely to have the effect of substantially lessening competition in such markets being conduct that prevents or prohibits developers and users from using alternative payment methods to Google Play Billing for purchasing digital in app content.

71 In terms of the Google Play Billing restrictions being the payments tie provision and the anti-steering provision, I have found that they were imposed or have been maintained at the start of the relevant period with the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the payment solutions market.

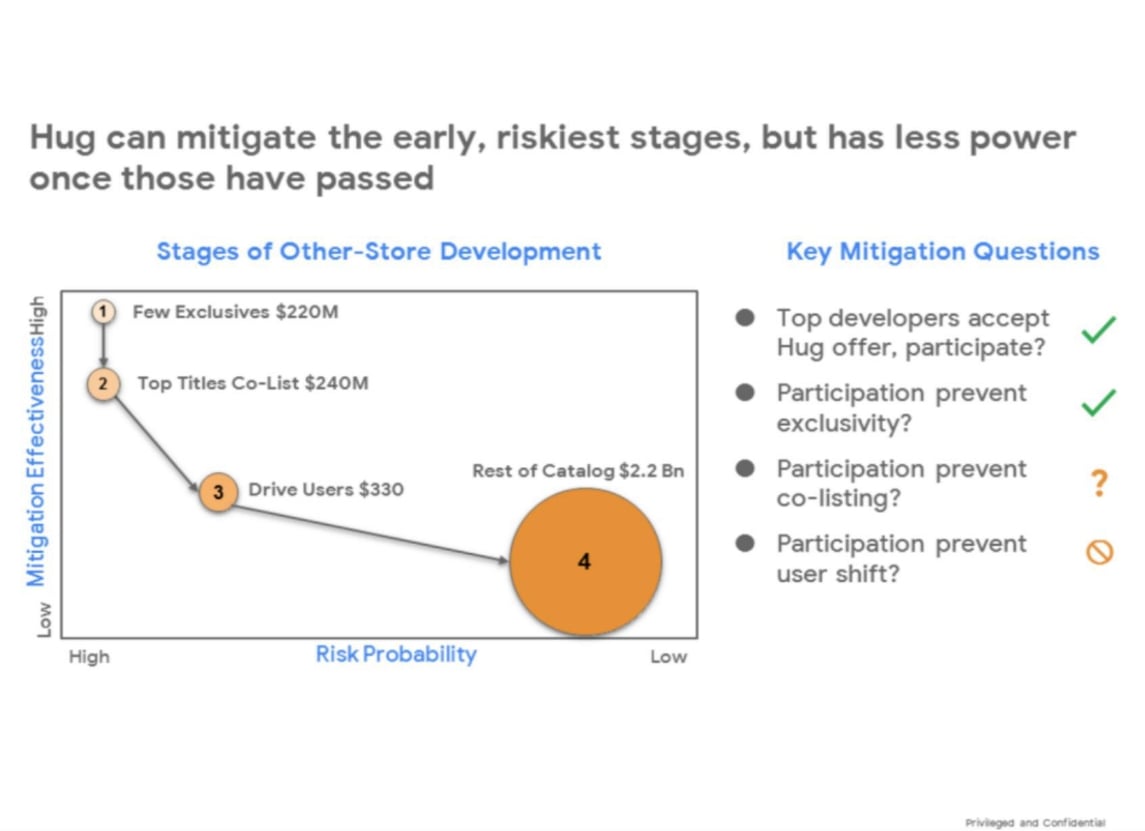

72 Fourth, I am satisfied that Google engaged in conduct concerning Project Hug, the GVP agreements, the AVP agreements and the RSA3s that had the purpose of substantially lessening competition in the Android mobile app distribution market and so contravened s 46. Further, in relation to the conduct constituted by Project Hug and the GVP agreements, I am satisfied that such conduct had a likely effect of substantially lessening competition in that market; I am using “likely” here in terms of a real chance.

73 In all other respects I have not accepted Epic’s case against Google concerning the other alleged contraventions of Part IV of the CCA or its unconscionable conduct case. And to be clear, I have not accepted Epic’s case concerning the technical restrictions or its case concerning clause 4.5 of the DDA. Let me briefly make some observations on these last two matters.

74 As to the first matter in terms of the technical restrictions relating to install flows and frictions, I have concluded the following. First, such technical restrictions caused or imposed by Google are disproportionate to the security risks that Google has sought to protect against. Second and notwithstanding the first point, in my view such technical restrictions were not imposed by Google or sought to be maintained by Google for the purpose of substantially lessening competition. Third, such restrictions do not separately have any actual or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. And fourth, I have also considered these restrictions in combination with other restrictive conduct that Epic has alleged, but in my view no anti-competitive purpose or effect has been shown by the combination.

75 Now as to the second matter in terms of clause 4.5 of the DDA and the ban on, in effect, an app store within an app store, I am not prepared to find that Google imposed this with the purpose or effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the Android app distribution services market.

76 Now, it must be recalled that Google has permitted direct downloading or sideloading of other competing Android app stores. So such competition was not substantially hindered by Google.

77 Further, the clause 4.5 ban is targeted if at all against competitors rather than competition.

78 Further, Google seems to have had various purposes for the clause 4.5 ban. One purpose was to address security risk as Google perceived it. Another purpose was to prevent free riders. And an associated purpose was to protect the asset that it had invested in and built up. Clearly there was no anti-competitive purpose. Moreover, given the other avenues for the direct downloading or sideloading of alternative Android app stores, in my view no actual or likely anti-competitive effect has been shown in the relevant markets.

79 Now I should say here that the position is a little more complicated concerning Apple as it precluded direct downloading or sideloading of alternative iOS app stores.

The joint trial and these reasons – structural aspects

80 Now as I have said, the joint trial before me concerned the concurrent hearing of four proceedings being Epic’s proceeding against Google, Epic’s proceeding against Apple and two class actions, the detail of which I have set out elsewhere.

81 Epic’s two proceedings had been issued out of the NSW Registry of this Court. The two class actions had been subsequently issued out of the Victoria Registry of this Court. The two class actions in terms of competition law liability questions were derivative of or sought to leverage off Epic’s cases and evidence on liability against Apple and Google, save for the question of the overcharging of commissions relating to paid app downloads or in-app digital purchases on the Play Store or Apple’s App Store.

82 Now in terms of the concurrent hearing of all four matters, I made orders that the evidence in one case should be treated as evidence in all other cases unless I indicated to the contrary, say, in respect of an admission made by one party that was not cross-admissible against other parties.

83 As I have said earlier, I have produced three sets of reasons being the present reasons, another set of reasons in the Epic v Apple proceeding and a third set of reasons dealing with and combining my analysis and findings in the two class actions. Now a number of points.

84 First, the sequence in which the reasons should be read for ease of comprehension are my reasons in the Epic v Apple proceeding, the present reasons and then the reasons in the class actions.

85 Second and relatedly, it should also be understood that findings of fact or law in my reasons in the Epic v Apple proceeding form part of the foundation for my present reasons and then my reasons in the class actions, unless I indicate to the contrary. Indeed, all sets of reasons should be read as a composite whole. So, although I have indicated the sequence in which the reasons should be read, which in one sense can be seen as an incremental vertical structure, I also intend for my findings in this proceeding to be treated as findings in the Epic v Apple proceeding as well as findings in the class actions, and for the findings in the class actions to the extent relevant to be findings in this proceeding and the Epic v Apple proceeding.

86 Third, occasionally, my reasons in Epic v Apple and Epic v Google may overlap in relation to a particular topic. This is partly a function of how the cases have been presented. Nevertheless, my conclusions on such a topic in each proceeding have considered and been based upon all the evidence in all proceedings.

87 Fourth, some aspects of my discussion in the reasons in the class actions concerning the relevant counterfactual analysis should be taken as being incorporated by reference in these reasons. But I do accept that to some extent the dimensions to such an analysis are different.

88 In terms of assessing whether the relevant contraventions occurred, one is looking at and comparing the future from the time of the contravention with the relevant impugned conduct against the future from the time of the contravention without such conduct. But of course in looking at the future with and without the relevant conduct you do not just simplistically hold all else equal. But in terms of the class actions where one is considering causation questions involving what would have occurred if the relevant impugned conduct had not been engaged in, a different calculus and standard of proof is required as I have explained in my reasons in the class actions. A different retrospective hypothetical scenario is involved. Nevertheless the two types of analysis overlap and accordingly my reasons here also include aspects of my reasons in the class actions.

89 Fifth, I have dealt with the survey evidence in my reasons in Epic v Apple.

90 Sixth, I have set out all relevant legal principles concerning market definition, s 46 and other provisions of Part IV of the CCA and aspects of the ACL in my reasons in Epic v Apple.

91 Seventh, I have also set out some applicable economic principles in my reasons in Epic v Apple, including on the question of tied products.

92 Eighth, annexed to my reasons in this proceeding and the Epic v Apple proceeding is both a schedule of abbreviations and acronyms and also a dramatis personae which also includes the detail of lay and expert witnesses in terms of their positions at the start of the trial.

93 Now in terms of the venue for and mode of the joint trial, I have made various observations in my reasons in the Epic v Apple proceeding which I will not repeat save as to two matters.

94 As I have said in my reasons in the Epic v Apple proceeding, the trial required the use under my control of the largest electronically fitted out trial court room of its type in Australia with the necessary technical and other assistance from numerous court staff, all of whom were directly answerable to my requirements. What was also necessary was to provide the parties with work spaces, conference rooms and storage facilities on the same level as the court room. All of this was arranged and provided months in advance of the trial starting. If I may say so I am most grateful to the administrative and court staff for making this all possible. I should also express my appreciation to the in court electronic operator for her first class work.

95 Further, let me express my appreciation for the considerable effort put in by Mr Neil Young KC and his team for Epic, Mr Cameron Moore SC and his team for Google, Mr Matthew Darke SC and his team for Apple and the cameo performance of Mr Anthony Bannon SC and his team for the class applicants. The timeliness and quality of the work of counsel and their instructing solicitors was excellent, and the skill of counsel in their notably efficient presentations including the handling of witnesses resulted in this complex and lengthy trial finishing precisely on time.

96 Let me now proceed to the heart of the matter. For convenience I have divided my reasons into the following sections:

(a) The Google entities and background matters – [97] to [148].

(b) Epic, Google and the Play Store – [149] to [191].

(c) The OEM restrictive conduct and the OEM agreements – [192] to [367].

(d) App developer restrictive conduct and the developer distribution agreements – [368] to [545].

(e) Mobile OS licensing and Android mobile app distribution markets – s 46 – [546] to [594].

(f) In app payment solutions restrictive conduct – [595] to [642].

(g) The Android in app payment solutions market – s 46 – [643] to [687].

(h) Google’s lay evidence – [688] to [766].

(i) Market definition concerning Android mobile app distribution – the parties’ cases – [767] to [861].

(j) Some relevant concepts debated by the economic experts – [862] to [1095].

(k) Epic’s posited Android mobile app distribution market – what is the correct focal product? – [1096] to [1280].

(l) The experts’ approaches to HMT quantitative and qualitative analysis – [1281] to [1444].

(m) Fortnite removal event and diversion ratios – [1445] to [1816].

(n) Logit demand model, transition probability analysis and counting of diversion estimates – [1817] to [2017].

(o) Critical loss analysis including the Lerner index – [2018] to [2402].

(p) What are the close substitutes, if any? – [2403] to [2650].

(q) Is there any competitive tension between Google and Apple? – [2651] to [2789].

(r) Market power – Android mobile app distribution – [2790] to [3162].

(s) Market definition and market power concerning the mobile OS licensing market – [3163] to [3376].

(t) The MADAs including questions of anti-competitive purpose and anti-competitive effect – [3377] to [3584].

(u) The revenue share agreements including the RSA3s and MIAs – anti-competitive purpose and anti-competitive effect of the RSA3s – [3585] to [3918].

(v) Project Banyan and Project Hug – purpose and effect of Project Hug and the GVPs – [3919] to [4280].

(w) Clause 4.5 of the DDA – prohibiting the distribution of rival app stores – [4281] to [4406].

(x) Android ecosystem security including Google Play Protect – [4407] to [4596].

(y) Behavioural economics evidence – [4597] to [4716].

(z) The technical restrictions – [4717] to [4815].

(aa) Real world impact of installation frictions – [4816] to [5178].

(ab) The technical restrictions – purpose and effect of SLC – [5179] to [5346].

(ac) Epic’s s 46 case – Android in app payment solutions, contracts and mechanisms – [5347] to [5567].

(ad) In-app payments – some technical evidence – [5568] to [5687].

(ae) Android in-app payment solutions – market definition, market power, purpose and effect of SLC – [5688] to [6057].

(af) Overall purpose and effect of Google’s conduct – Android mobile app distribution – [6058] to [6128].

(ag) The effect of Google’s conduct on Epic and Fortnite – [6129] to [6221].

(ah) Epic’s claims for breach of ss 45, 46 and 47 and for unconscionable conduct – [6222] to [6345].

(ai) Relief and conclusion – [6346] to [6370].

(aj) Schedule of abbreviations and acronyms, dramatis personae of witnesses and other individuals, and other annexures.

The Google entities and background matters

97 The following matters in this section are largely uncontentious, unless I indicate otherwise.

98 Google LLC is incorporated in Delaware, USA and its ultimate holding company is Alphabet Inc., which is also incorporated in Delaware. Google LLC is headquartered in California, USA.

99 Google LLC is the largest of the entities owned by Alphabet. For public financial reporting purposes, Google LLC is divided into two segments, being Google Services and Google Cloud. The core products and platforms which comprise Google Services include what are known as or what have been described as Android, Chrome, Hardware, Gmail, Google Drive, Google Maps, Google Photos, the Play Store, Search and YouTube.

100 Google LLC owns and continues to develop the Android OS. Google LLC also owns and develops GMS and licenses GMS to OEMs. But as Google points out, it does not supply or license a unitary product of both the Android OS and GMS. They are separately supplied, although of course GMS has some relevant OS aspects.

101 Let me at this point say something about GMS Android, which I have used as a convenient composite label, given that both in Australia and globally excluding China, over 99.9% of smart mobile devices which utilise a licensed OS are GMS Android devices, that is, they have the Android OS and GMS. From 2018 to 2021, approximately 4 million smartphones were sold in Australia each year with GMS Android pre-installed. Globally excluding China, approximately 800 million smartphones were sold each year with GMS Android pre-installed.

102 As I have said earlier, GMS is Google’s proprietary software that runs on top of open source Android and is necessary for a number of key OS features not available in open source Android alone.

103 GMS includes key modules being APIs and SDKs collectively known as Google Play Services, which enable core functionality for the device and for many apps and services. Android devices which do not also have GMS installed cannot access Google Play Services and are significantly functionally limited as a result. One limitation is that if app developers build apps using Google Play Services APIs or SDKs, those apps become dependent on GMS and will only run as intended on devices that have GMS installed.

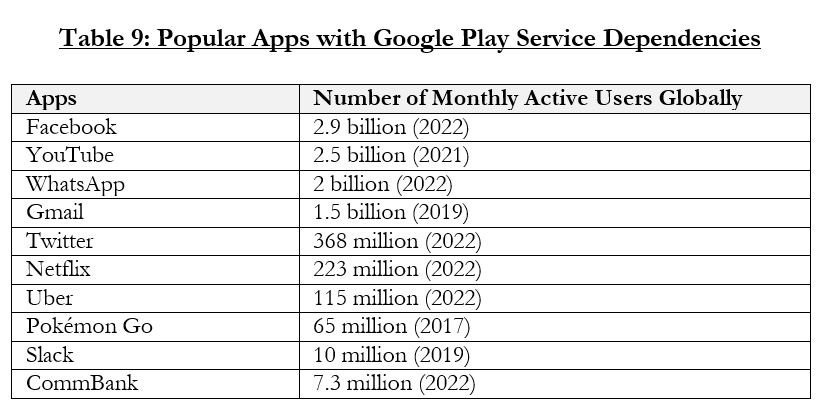

104 So, by using Google Play Services, app developers can design their app to make use of Google Maps functionality, such as features that respond contextually to a user’s location, via specific Google Play Services APIs. But if such an app is installed on a device that lacks GMS, the app will not have that functionality. Many popular apps, such as Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, Gmail, Twitter, Netflix, Uber, Pokemon Go, Slack, and CommBank cannot be run on an Android device that does not have GMS installed.

105 GMS also includes apps developed by Google. Among them are the core applications, being the Play Store, Search, Chrome, Google Maps, Gmail and YouTube. The remaining five core applications were among the top six apps by usage in the Play Store as of April 2023. GMS also includes what are described as flexible applications. These differ between territories and, in Australia, consist of Drive, YouTube Music, Play Movies, Duo and Photos.

106 Now as I have indicated, in Australia and globally excluding China, the vast majority of smart mobile devices which utilise a licensed OS are pre-installed with a combination of open source Android and GMS, which on occasion I will refer to as GMS Android or Google Android.

107 As I have said, Google’s GMS apps are pre-installed under the terms of the MADAs on virtually all Android devices sold outside of China.

108 As I have said, Google licenses OEMs to distribute GMS on their Android devices in accordance with the terms of a MADA. In doing so, more users are introduced to the GMS apps, which include Google Search and the Play Store, and therefore more advertising revenues are derived by Google. This has led Google to make most of its money selling advertising on Google Search and a considerable amount from the Play Store.

109 Such a licence includes the following software and apps. First, a bundle of closed-source, proprietary Google apps including the Play Store, Google Search, Google Chrome, Google Maps, Gmail and YouTube. Second, a Google proprietary software layer that provides background services, SDKs and APIs for the integration of apps with Google Play Services.

110 Google Play Services is an important component of the Android ecosystem and is relied on by many app developers. Its main components are the Google Play Services Android Application Package (APK) and the Google Play Services client library. And without Google Play Services, many Android apps could not function properly.

111 The elements of GMS perform functions that were previously performed by open-source Android OS source code.

112 The GMS apps and Google Play Services are listed in the Google Product Geo Availability Chart, as modified or updated by Google from time to time.

113 Let me at this point say something about the Play Store and Google Play Billing.

114 The Play Store is an app store and is itself a native app. It is owned and was developed by Google. It was originally known as Android Market, which launched in 2008 in the United States and in 2009 in Australia, before being rebadged as the Play Store in 2012.

115 The Play Store distributes Android native apps to Android devices. It is the principal distribution point for Android native apps. Through the Play Store, users can search or browse for apps developed by Google or third-parties, and then download and install such apps onto their devices. There are approximately 3 million apps available to users in Australia for download on the Play Store. Users can discover apps within the Play Store using the search function, and recommended apps are presented to users based on their search and download history. The Play Store also facilitates app updates.

116 From December 2017 to September 2022, the Play Store was pre-installed on between 97.7 and 99.6% of active Android devices in Australia, and between 97.2 and 99.2% of active Android devices worldwide excluding China. Further, in 2020, some 97.9% of new app downloads to Android devices in Australia that occurred through an app store were undertaken via the Play Store, while globally excluding China some 91.4% of new app downloads from an app store occurred via the Play Store.

117 If an app developer wishes to distribute its app via the Play Store, the developer must enter into a DDA with Google.

118 With limited exceptions, app developers who wish to distribute their apps via the Play Store are required to use Google Play Billing to facilitate in-app purchases of digital goods. Google Play Billing enables the facilitation of payments from users in many countries, via a range of payment methods. Google charges developers a fee of up to 30% of the price of in-app purchases made through Google Play Billing.

119 Google Play Billing can only be used on native Android apps that are downloaded from the Play Store and installed on Android devices. Hundreds of thousands of developers monetise their apps through the use of Google Play Billing.

120 Google Play Billing has a function which facilitates the transfer of money from the user to the app developer. Google Play Billing can be considered to be either a payment solution or it can be considered to have a function which includes a payment solution.

121 Let me at this point say something about Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd and Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd.

122 Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd is incorporated in Singapore. Its ultimate holding company is Alphabet Inc. Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd is a party to a payment processing service agreement with Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd.

123 Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd is also the contracting Google entity and marketplace service provider under the DDA with app developers who select to distribute apps through the Play Store to Android users in Australia.

124 The DDA provides that it is a contract between the app developer and “the applicable Google entity based on where [the developer has] selected to distribute” its apps. The “applicable Google entity” is Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd in relation to apps distributed through the Play Store in Australia. And the applicable entity is Google LLC in respect of US distribution. Consequently, a developer that distributes apps through the Play Store in Australia and in the USA enters into the DDA with both Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd and Google LLC.

125 Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd is an Australian corporation and subsidiary of Google LLC. Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd holds an Australian financial services licence which authorises it to offer the Google Payments Service as that term is used in the Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd product disclosure statement. Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd enters into agreements with users of the Google Payments Service who register for that service online. The terms of those agreements are set out in the PDS issued by Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd.

126 By a payment processing services agreement with Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd, Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd has undertaken to perform payment processing functions and services as directed by Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd.

127 Now both Google LLC and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd carry on business within Australia for the purposes of s 5(1)(g) of the CCA. They do so directly and through Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd. As such, the relevant provisions of the CCA apply to their conduct outside Australia. Now by the end of the trial these matters ceased to be contentious. But for completeness it is worth stating the following.

128 The fact that Google LLC carries on business within Australia is evident from the following facts.

129 First, Google LLC supplies services in Australia, including but not limited to the service known as Google Play to Australian users of the Play Store. The Play Store terms of service expressly reflect such a position. Further, the Google terms of service stipulate that “Google services are provided by, and you’re contracting with, Google LLC”. Those “Google services” referred to within the Google terms of service are not confined to the Play Store. They also include Android OS, Chrome, Gmail, Google Maps and Google Search. That such Google services are supplied in Australia is evident from the fact that Australian users of Android OS, Chrome, Gmail, Google Maps and Google Search all use those products on devices physically located in Australia.

130 Second, in addition to the supply of the Google services in Australia, Google LLC also enters into the contracts under which those services are supplied in Australia. In each instance where the Google terms of service and the Play Store terms of service are accepted by users within Australia when they first use the Google services and the Play Store on their Android device, Google LLC can be taken to have entered into that contractual relationship in Australia.

131 As at 30 September 2022, there were more than 1.9 million Android device users in Australia, which is indicative of the number of Android device users who had agreed to the relevant terms of service in Australia.

132 Google LLC’s supply of services and entry into contracts in Australia amounts to business activities carried on by Google LLC in the jurisdiction on a continuous and repetitive basis.

133 Third, and in addition to the services that Google LLC supplies to Australian consumers, Google LLC also supplies, in Australia, various services to Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd. Appendix IV of Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd’s Compliance Manual records that those services include “[s]oftware maintenance and development”, “[o]perations and support” and “hosting” for the “[Google] Wallet account management platform”, “IT support and services for the office environment”, among other services relating to risk management, human resources, auditing and legal services.

134 Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd likewise carries on business within Australia.

135 First, like Google LLC, Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd also supplies services and enters into contracts in Australia.

136 For a developer to distribute apps via the Play Store, the developer must enter into a DDA. Where the developer wishes to have its apps distributed in Australia, the relevant Google counterparty to the DDA is Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd. So, developers located in Australia who wish to distribute apps in Australia via the Play Store must enter into the DDA with Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd. Those developers’ entry into the DDA occurs by the developer accepting the terms of that agreement by accessing a website from their device located in Australia, such that Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd will be taken to have entered into those contractual relationships within Australia.

137 Further, under the DDA, Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd is the relevant entity authorised to make apps available in Australia via the Play Store, such that Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd supplies app distribution services in Australia.

138 Accordingly, Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd’s supply of services and entry into contracts in Australia amounts to business activities carried on by it in the jurisdiction on a continuous and repetitive basis.

139 Second, Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd has contracted with Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd for the provision of payment processing services in Australia in exchange for a service fee, which Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd pays to Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd under that agreement. This ongoing commercial relationship with an Australian entity, the subject matter of which is services supplied by that entity in Australia in consideration for a fee, similarly amounts to the carrying on of business in Australia by Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd.

140 Further, both Google LLC and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd carry on business within Australia by and through Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd.

141 Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd conducts a confined business as one of several Google payment entities used to process payments made on the Play Store. It performs that role pursuant to the terms of the payment processing services agreement between it and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd.

142 The payment processing services agreement provides that Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd shall provide the defined “Services” in consideration for a set fee from Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd. Those “Services” are defined to include “all services, consulting, advice and assistance required by [Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd] in connection with performing payment processing functions and services”. The agreement stipulates that those services shall be provided “as directed by” Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd. The agreement further stipulates that Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd “shall provide other services in relation to the Services as directed by Company”.

143 The fee for which Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd performs these services at the direction of Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd is tied to the amount of operating expenses incurred by Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd in the performance of those services, plus an additional 8% of those expenses.

144 Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd adopts the organisational systems and compliance measures, processes and procedures and the employment and personnel policies of Google LLC, and it considers that its employees are bound by the code of conduct published by Google LLC.

145 Indeed, many of the functions required to deliver its services are provided either in whole or in part by Google affiliate companies. And Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd’s compliance manual lists a multitude of functions that are outsourced to Google LLC and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd.

146 Further, Google LLC has given Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd a financial undertaking so as to enable it to satisfy the requirements of its Australian financial services licence. Similarly, Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd has indemnified Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd in respect of any financial risk, expenses, civil and criminal liability, or any kind of financial liability whatsoever that may be incurred as a result of any third-party litigation in which both entities are named as co-defendants.

147 In summary, both Google LLC and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd carry on business within Australia. And because they carry on business within Australia, Part IV of the CCA and the ACL (other than Part 5-3) apply to conduct engaged in by Google LLC and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd outside Australia.

148 It is convenient in dealing with Epic’s main competition case to refer to Google LLC and Google Asia Pacific Pte Ltd together as Google unless I indicate otherwise; I will not generally put Google Payment Australia Pty Ltd under that label given its more limited function.

Epic, Google and the Play Store

149 I have summarised the nature and evolution of Epic’s business up to the launch of Fortnite on iOS in my reasons in the Apple proceeding. It is unnecessary to repeat that detail here. Let me at this point set out a narrative of some of the relevant dealings between Epic and Google and Epic and various OEMs, the primary facts of which were not contentious unless I state otherwise.

150 Let me begin by saying something about the launch of the Fortnite installer on Android.

151 In August 2018, Epic launched the Fortnite installer on Android. The Fortnite installer was an app from which users could download, and which would thereafter be used to update, another native app, that is, Fortnite.

152 Although initially Fortnite was the only mobile app available for download through the Fortnite installer, Epic’s intention was that the Fortnite installer would be expanded in the future to become the Epic Games App, through which users could download other mobile apps developed by Epic, and ultimately mobile apps developed by third parties.

153 Since the primary function of the Fortnite installer was to distribute and update another app, the DDA prohibited Epic from distributing the Fortnite installer through the Play Store.

154 But it is possible for developers to distribute native apps to Android device users outside the Play Store by reaching arrangements with OEMs to pre-install the app on devices manufactured by that OEM, via third-party Android app stores, or via direct downloads from a website. And given these possibilities, Mr Sweeney proposed launching the Fortnite installer on Android outside the Play Store via a combination of direct downloading from Epic’s website and pre-installation deals negotiated with Android OEMs.

155 Epic ultimately chose not to distribute Fortnite on the Play Store because it believed that Google’s contractual terms would require Epic to use Google’s payment solution, Google Play Billing, for in-app purchases, require Epic to pay Google a 30% commission on those purchases, and prevent Epic from distributing the Fortnite installer as distinct from Fortnite, because the former facilitated the distribution of another app contrary to Google’s contractual terms.

156 Epic saw the Fortnite installer as an initial step towards having its own mobile app store. This was important to Epic, including because Epic was intent on developing its own ecosystem, being a set of developers and users with whom Epic had an ongoing relationship.

157 Let me at this point say something about Epic’s collaboration with Samsung. The following chronology is not contentious in terms of the base facts.

158 From about April to August 2018, Epic negotiated with Samsung and sought its agreement to pre-install the Fortnite installer on Samsung devices. Epic’s original proposal disclosed its intention to later grow the Fortnite installer into a mobile game distribution service for third-party gaming apps. Samsung liked Epic’s intention to disrupt the Play Store but advised that it had to get approvals from Google and various carriers which may not be forthcoming.

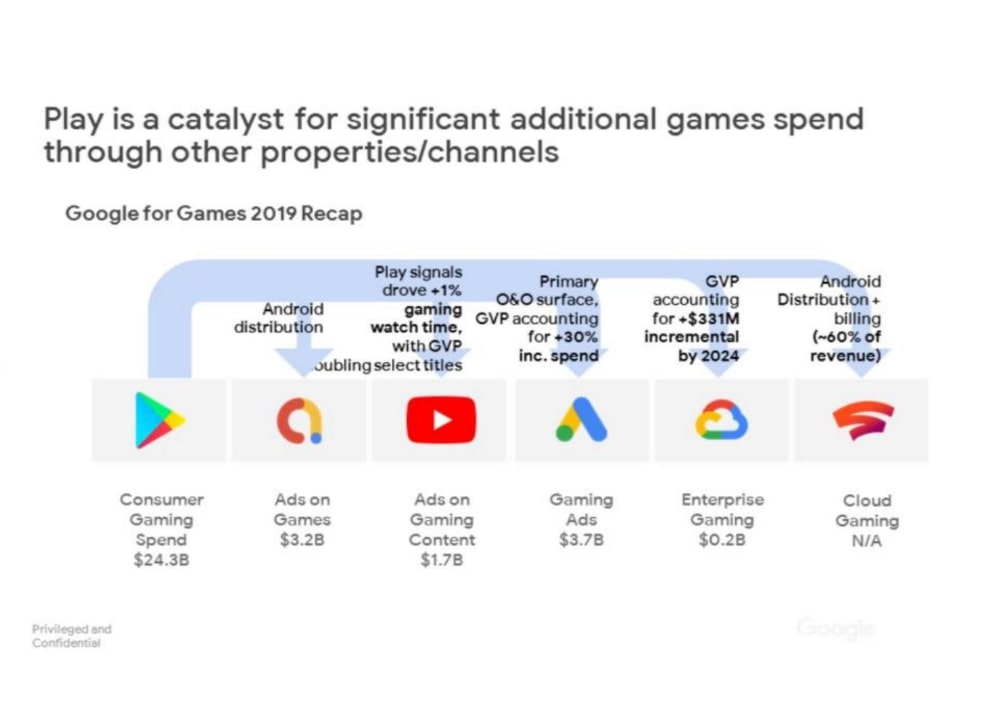

159 Whilst these negotiations were occurring, Epic informed Google of its intention to make Fortnite available on Android outside the Play Store. Soon afterwards, Google, which was concerned with a potential revenue loss of up to USD 3.6 billion if other developers followed Epic in not launching on the Play Store, offered Epic various incentives worth over USD 200 million to reverse that decision.

160 When Epic declined this offer, Mr Lockheimer, the senior vice president, platforms and ecosystems at Google, said to Mr Sweeney that Google viewed any launch of software outside the Play Store as a threat to Google and that Google would have to make changes to Android to protect users.

161 In July 2018, an internal Google presentation titled Project Elektra was prepared. It noted Epic’s plan to launch Fortnite directly to the public, thereby bypassing the Play Store, and observed that a large strategic investment into Epic could help advance broader discussions about using the Play Store for Fortnite.

162 On 19 July 2018, an off-cycle meeting of the Google business council was convened to discuss the proposed investment in Epic. The business council is an internal Google committee which is responsible for reviewing significant deals or transactions being proposed by Google’s various business divisions.

163 In a presentation titled EPIC/Fortnite BC Deal Review of the same date, the objectives of the deal were said to include that “[n]ot having Fortnite on Play creates significant risks for Android ecosystem & Play business, and threatens our business in the long term”. Among the risks identified in the presentation were the “Contagion effect” of other top developers following Epic, “increased rev[enue] share pressure” and “Fortnite may legitimize “Samsung” store & 3rd party stores; fragmenting distribution on Android”.

164 On 21 July 2018, the business council approved the proposal. The proposed investment in Epic did not eventuate.

165 In August 2018, the negotiations with Samsung culminated in Epic entering into the Samsung collaboration agreement. The Samsung collaboration agreement provided that Samsung would distribute the Fortnite installer or the Epic Games App through the Galaxy Store. It also licensed Samsung to pre-install the stub version of the Fortnite installer and, if Epic transitioned to the Epic Games App, the stub version of the Epic Games App on Samsung Galaxy Note 9 and Galaxy Tab S4 devices.

166 These stubs were icons which when clicked took the user to the Galaxy Store, where the user could then initiate a download of the Fortnite installer in the same way that any other app could be downloaded from within a pre-installed Galaxy Store, which had a privileged install permission and so did not confront the technical restrictions.

167 But the Samsung collaboration agreement was limited and did not overcome the discoverability challenges faced by Android apps distributed outside the Play Store.

168 Samsung only agreed to use reasonable efforts to pre-install the stub on two new device models, and to make reasonable efforts to perform an update which would install the app on existing Samsung devices. So, Epic could not compel pre-installation on locked devices, even of the two new models, without the consent of carriers. Further, the Fortnite installer stub was located within Samsung’s Game Launcher, which was located in the app tray and not on the home screen of the relevant Samsung devices. Further, if a user searched for an app via the search bar of their Samsung device, they were redirected to Google Search, the results of which prioritised apps available on the Play Store.

169 Now pursuant to the Samsung collaboration agreement, Fortnite apps and any apps downloaded through the Epic Games App were required to use Samsung’s in-app payment solution. Use of Samsung IAP was not mandatory where Epic’s apps were directly downloaded onto a Samsung device.

170 The agreed revenue shares were as follows. In the scenario of in-app purchases within Fortnite apps, the revenue share was 85% to Epic and a commission of 15% to Samsung for the first 18 months, and an 88/12 percentage split thereafter. And in the scenario of in-app purchases within other apps downloaded through the Epic Games app, the revenue share was REDACTED] to Epic and a commission of [REDACTED] to Samsung for the first REDACTED] months, and a REDACTED] percentage split thereafter.

171 On 10 August 2018, Epic announced the launch of Fortnite on Samsung devices at Samsung’s Galaxy Unpacked event. The Fortnite installer was also made available for Samsung users to download via the Galaxy Store and Epic made an Android version of the Fortnite installer available for direct download from its website.

172 Further, in the period from 2018 to 2020, Epic negotiated with various OEMs besides Samsung, with a view to having the Fortnite installer, and later the Epic Games App, pre-installed on as many Android devices as possible. Epic also negotiated with carriers to pre-install its apps on “locked” Android devices. Epic’s goal in these negotiations was to improve both the discoverability and the install flow of Epic’s apps on old and new, locked and unlocked Android devices.

173 At about the time of these negotiations, Epic launched the Epic Games Store on PC in December 2018 and, in October 2019, Epic began replacing the Fortnite installer with the Epic Games App for Android devices. At that time, the Epic Games App enabled users to download, install, and update another Epic app besides Fortnite.

174 Let me now turn to the question of the launch and subsequent removal of Fortnite on the Play Store.

175 In December 2019, Mr Sweeney contacted Google and advised that Epic would submit a version of Fortnite to the Play Store that used Epic’s own payment solution being Epic Direct Payment (EDP) to facilitate in-app purchases instead of Google Play Billing. The app was duly submitted with EDP installed but Google refused to allow it onto the Play Store and suspended Epic’s publishing status.

176 Following further unsuccessful negotiations, Mr Sweeney concluded that all avenues for negotiating terms with Google to distribute Fortnite on the Play Store using EDP were exhausted. He concluded that Epic’s attempt to connect with a large proportion of Android users outside the Play Store, via direct download, pre-installation, and the Galaxy Store, had been unsuccessful.

177 Mr Sweeney decided that Epic should adopt the same approach toward both Apple and Google, namely, to distribute Fortnite on the Play Store and on the App Store, and then publicly challenge both Apple and Google to alter their policies.

178 On 21 April 2020, Epic launched Fortnite on the Play Store, using Google Play Billing. It continued to make the Epic Games App available on Android through other means, including the Galaxy Store and Epic’s website. The contractual terms which applied to Epic’s distribution of Fortnite through the Play Store were set out in a DDA with Google that was entered into in November 2016.

179 After Fortnite launched on the Play Store, Epic experienced a large increase in new Fortnite users on Android. In the first month after that launch, 3.14 million Fortnite users downloaded the app from the Play Store, and 1.7 million of them were new to Fortnite. Fortnite’s gross revenue from the Play Store in that month was approximately $1.3 million, or about $50,000 per day.

180 In June and July 2020, Mr Sweeney sought Google’s agreement to allow Epic to offer its own payment solution within Fortnite and other Epic apps distributed via the Play Store, and to allow Epic to launch a mobile Epic Games Store app on Android, either via the Play Store or by a direct download process which did not have to confront the technical restrictions. Google declined those requests.

181 On 3 August 2020, Epic submitted Fortnite version 13.40 to Google. This version contained code that would allow Epic to offer EDP as an alternative payment option within Fortnite on Android devices when what has been described as a hotfix was activated. Epic did not disclose the hotfix to Google, because it believed that Google would then not approve the update.

182 On 5 August 2020, Mr Sweeney requested from Mr Lockheimer and Mr Samat that Google support Epic using competing payment options in time for a planned Fortnite price reduction. Lockheimer’s response on 11 August 2020 indicated that Google was not willing to do so.

183 On 13 August 2020, Epic activated the hotfix and thereby made EDP available within Fortnite apps downloaded from the Play Store and the App Store. As a result, Play Store users were presented with a choice when purchasing V-Bucks within the Fortnite app: they could make their purchase using Google Play Billing or using EDP. At the same time, Epic introduced the “Fortnite mega drop”.

184 Within a few minutes of Epic activating the hotfix and implementing the mega drop, Mr Sweeney emailed Mr Lockheimer and other senior executives at Google, informing them that Epic had introduced EDP in the version of Fortnite distributed through the Play Store.

185 Later on 13 August 2020, Google removed Fortnite from the Play Store. Epic later commenced proceedings against Google in the US District Court for the Northern District of California, alleging, among other things, violations of the Sherman Act and California’s Unfair Competition Law.