Federal Court of Australia

Epic Games, Inc v Apple Inc [2025] FCA 900

File number: | NSD 1236 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | BEACH J |

Date of judgment: | 12 August 2025 |

Catchwords: | COMPETITION LAW — digital technology — Apple mobile devices — operating system software — iOS smart phones — tablets — personal computers — native apps — web apps — web browsers — Apple’s App Store — downloading apps — installing apps — app developers — access to platforms — two-sided platforms — platform operators — market definition — market power — distribution services market — market for payment services — restrictive conduct in distribution market and payments market — security and technology considerations and constraints — misuse of market power — imposition of restrictive contractual conditions — substantial lessening of competition — purpose questions — effects questions — contraventions of s 46 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) — alleged contraventions of ss 45 and 47 — unconscionable conduct — alleged contravention of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) ss 4, 4E, 4F, 4G, 5, 45, 46, 47, 51, sch 2 ss 21, 22, Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 10, 31, 126B |

Cases cited: | AHG WA (2015) Pty Ltd v Mercedes-Benz Australia/Pacific Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1022; (2023) 303 FCR 479; (2023) 170 ACSR 1 AHG WA (2015) Pty Ltd v Mercedes-Benz Australia/Pacific Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 86 Air New Zealand Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2017) 262 CLR 207 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cascade Coal Pty Ltd (2019) 374 ALR 90 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Flight Centre Travel Group Limited (2016) 261 CLR 203 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Metcash Trading Ltd (2011) 198 FCR 297 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd (No 2) (2019) ATPR ¶42-633; [2019] FCA 669 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pacific National Pty Ltd (2020) 277 FCR 49 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 356 ALR 582 Australian Gas Light Company v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 137 FCR 317 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kobelt (2019) 267 CLR 1 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (2022) 407 ALR 1 Boral Besser Masonry Limited v Australian Competition & Consumer Commission (2003) 215 CLR 374 Dowling v Dalgety Australia Ltd (1992) 34 FCR 109 Epic Games Inc v Apple Inc, 559 F Supp 3d 898 (ND Cal, 2021) Epic Games, Inc v Apple, Inc, 67 F 4th 946 (9th Cir. 2023) Google LLC v Oracle America, Inc 593 US 1 (2021) Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd v Motorola Solutions Inc (2024) 308 FCR 68; [2024] FCAFC 168 Monroe Topple & Associates Pty Ltd v Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia (2002) 122 FCR 110 News Limited v South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Limited (2003) 215 CLR 563 NT Power Generation Pty Ltd v Power and Water Authority (2004) 219 CLR 90 Ohio v American Express Co 585 US 529 (2018) Olympia Equipment Leasing Company v. Western Union Telegraph Company, 797 F2d 370 (7th Cir, 1986) Oracle America, Inc v Google Inc 750 F.3d 1339 (2014) Productivity Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2024) 419 ALR 30 Queensland Wire Industries Proprietary Limited v The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (1989) 167 CLR 177 Re Queensland Co-operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 25 FLR 169 Re Tooth & Co Ltd [1979] 39 FLR 1 Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd (2009) 182 FCR 160 Singapore Airlines Ltd v Taprobane Tours WA Pty Ltd (1991) 33 FCR 158 United States v Microsoft Corp, 253 F 3d 34 (DC Cir 2001) Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2003) 131 FCR 529 Vogel v R and A Kohnstamm Ltd [1973] QB 133 Aguiar L, “Going mobile: The effects of smartphone usage on internet consumption”, JRC Digital Economy Working Paper, No. 2019-07, European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Seville Ahlborn C, Evans D and Padilla A J, ‘The Antitrust Economics of Tying: A Farewell to Per Se Illegality,’ (2004) 49 (1/2) The Antitrust Bulletin 287 Andrews M, Luo X, Fang Z and Ghose A, “Mobile ad effectiveness: Hyper-contextual targeting with crowdedness” (2016) 35(2) Marketing Science 218 Baumol W, “Predation and the Logic of the Average Variable Cost Test” (1996) 39 Journal of Law & Economics 49 Bishop S and Walker M, The Economics of EC Competition Law: Concepts, Application and Measurement (3rd ed, 2010) Bork R and Sidak J, “The Misuse of Profit Margins to Infer Market Power” (2013) 9(3) Journal of Competition Law & Economics 511 Brunt M, ““Market Definition” Issues in Australian and New Zealand Trade Practices Litigation” (1990) 18(2) Australian Business Law Review 86 Davis P and Garcés E, Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis (Princeton, 2010) Evans D, “Governing Bad Behavior by Users of Multi-Sided Platforms,” (2012) 27(2) Berkeley Technology Law Journal 1201 Evans D and Schmalensee R, “Failure to Launch: Critical Mass in Platform Businesses,” (2010) 9(4) Review of Network Economics 1 Evans D and Schmalensee R, “Markets With Two-Sided Platforms” in Issues in Competition Law and Policy (2008, American Bar Association) Evans D and Schmalensee R, “The Industrial Organization of Markets with Two-Sided Platforms,” (2007) 3(1) Competition Policy International 151 Filistrucchi L et al, “Market Definition in Two-Sided Markets: Theory and Practice,” (2014) 10(2) Journal of Competition Law & Economics 293 Fisher F and McGowan J, “On the Misuse of Accounting Rates of Return to Infer Monopoly Profits” (1983) 73(1) The American Economic Review 82 Ghose A, Goldfarb A and Han S P, “How is the mobile Internet different? Search costs and local activities” (2013) 24(3) Information Systems Research 613 Goldfarb A and Tucker C, “Digital economics” (2019) 57(1) Journal of Economic Literature 3 Han S, Han J K, Im I, Jung S I and Lee J W, “Mapping consumer’s cross-device usage for online search: Mobile-vs. PC-based search in the purchase decision process” (2022) 142 Journal of Business Research 387 Honka E, “Quantifying search and switching costs in the US auto insurance industry” (2014) 45(4) The RAND Journal of Economics 847 Honka E, Hortaçsu A and Vitorino M A, “Advertising, consumer awareness, and choice: Evidence from the US banking industry” (2017) 48(3) The RAND Journal of Economics 611 Hu M, Dang C and Chintagunta P K, “Search and learning at a daily deals website” (2019) 38(4) Marketing Science 609 Jeziorski P and Segal I, “What makes them click: Empirical analysis of consumer demand for search advertising” (2015) 7(3) American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 24 Jullien B and Sand-Zantman W, “The Economics of Platforms: A Theory Guide for Competition Policy” (2021) 54 Information Economics and Policy 1 Jullien B et al, “Two-sided markets, pricing, and network effects,” in K Ho et al (eds), Handbook of Industrial Organization (2021, vol 4) Jung J, Bapna R, Ramaprasad J and Umyarov A, “Love unshackled: identifying the effect of mobile app adoption in online dating” (2019) 43(1) MIS Quarterly 47 Kemp K, “Causation in Misuse of Market Power Claims under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)” (2021) 49 ABLR 208 Lurie N H, Berger J, Chen Z, Li B, Liu H, Mason C H, ... and Venkatesan R, “Everywhere and at all times: mobility, consumer decision-making, and choice” (2018) 5 Customer Needs and Solutions 15 Manne G and Williamson E, “Hot Docs v Cold Economics: The Use and Misuse of Business Documents in Antitrust Enforcement and Adjudication” (2005) 47 Arizona Law Review 609 Motta M, Competition Policy: Theory and Practice (Cambridge, 1993) Posner R, Antitrust Law: An Economic Perspective (1976, University of Chicago Press) Ransbotham S, Lurie N and Liu H, “Creation and Consumption of Mobile Word of Mouth: How Are Mobile Reviews Different?” (2019) 38(5) Marketing Science 773 Scherer F and Ross D, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance (1990, 3rd ed, Houghton Mifflin Company) Sosnick S, “A Critique of Concepts of Workable Competition” (1958) 72(3) The Quarterly Journal of Economics 380 Tucker C, “Network Effects and Market Power: What Have We Learned in the Last Decade?” (2018) Antitrust 72 Whinston M, “Tying, Foreclosure, and Exclusion” (1990) 80(4) The American Economic Review 837 Xu J et al, “News media channels: Complements or substitutes? Evidence from mobile phone usage” (2014) 78(4) Journal of Marketing 97 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Economic Regulator, Competition and Access |

Number of paragraphs: | 6347 |

Dates of hearing: | 15, 18 to 21, 25 to 28 March 2024, 2 to 4, 8 to 11, 15 to 18, 22 to 24, 29, 30 April 2024, 1, 2, 6 to 9, 13 to 16, 20 to 23, 27 to 30 May 2024, 3 to 7, 11 to 14, 17 to 20, 24 to 28 June 2024, 1 to 5 July 2024 |

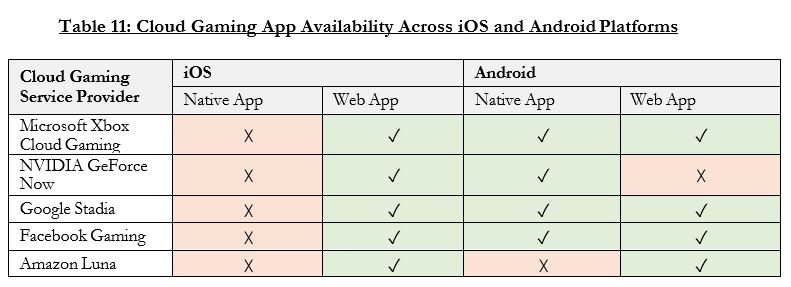

Counsel for the Applicants: | Mr N J Young KC, Mr G K J Rich SC, Dr R C A Higgins SC, Mr T O Prince, Mr A d’Arville, Mr A Barraclough, Mr O Ciolek, Ms K Lindeman, Mr B Hancock, Mr J T Waller, Ms J Apel and Mr R R Marsh |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Allens |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr M J Darke SC, Mr S Free SC, Mr C Bannan, Ms Z Hillman, Ms L Thomas, Ms X Teo and Mr B Lim |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Clayton Utz |

Counsel for the Respondents (Google parties) in NSD 190 of 2021 and VID 342 of 2022: | Mr C A Moore SC, Mr R A Yezerski SC, Mr P J Strickland, Ms C Trahanas and Ms W Liu |

Counsel for the Respondents (Google parties) in NSD 190 of 2021 and VID 342 of 2022 (confidentiality issues only): | Ms E N Madalin and Mr A Hanna |

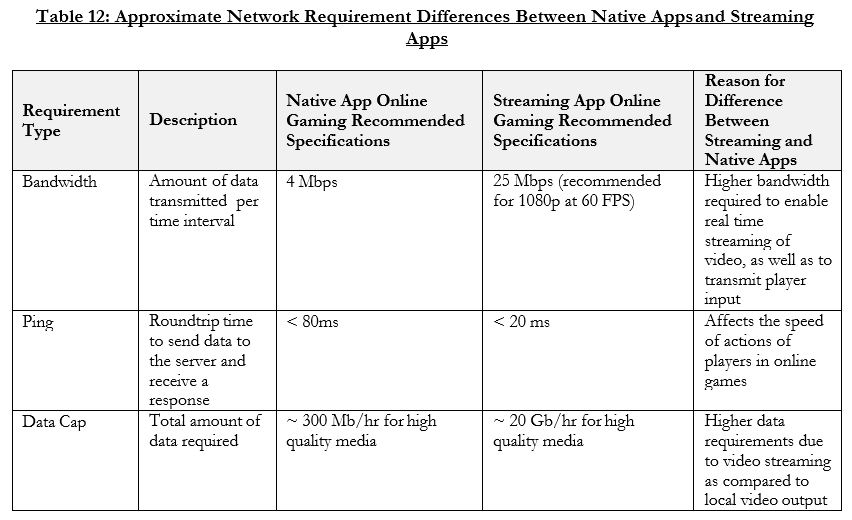

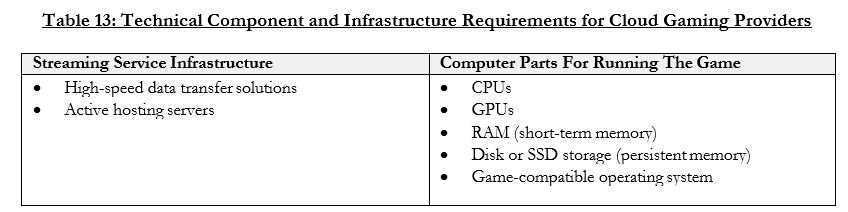

Solicitors for the Respondents (Google parties) in NSD 190 of 2021 and VID 342 of 2022: | Corrs Chambers Westgarth |

Counsel for the Applicants in VID 341 of 2022 and VID 342 of 2022 (class actions): | Mr A J L Bannon SC, Mr N De Young KC, Ms K Burke, Mr D Preston, Mr B Ryde and Dr S Chordia |

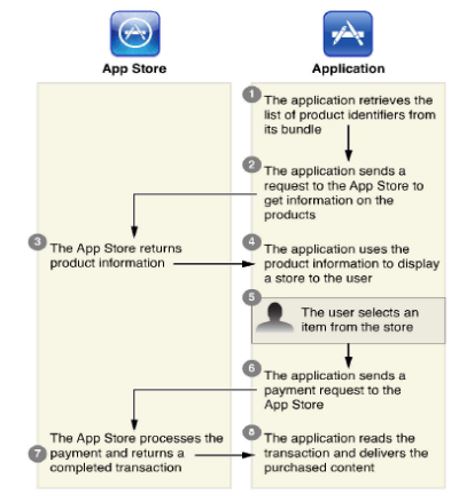

Solicitors for the Applicants in VID 341 of 2022 and VID 342 of 2022 (class actions): | Phi Finney McDonald and Maurice Blackburn |

ORDERS

NSD 1236 of 2020 | ||

| ||

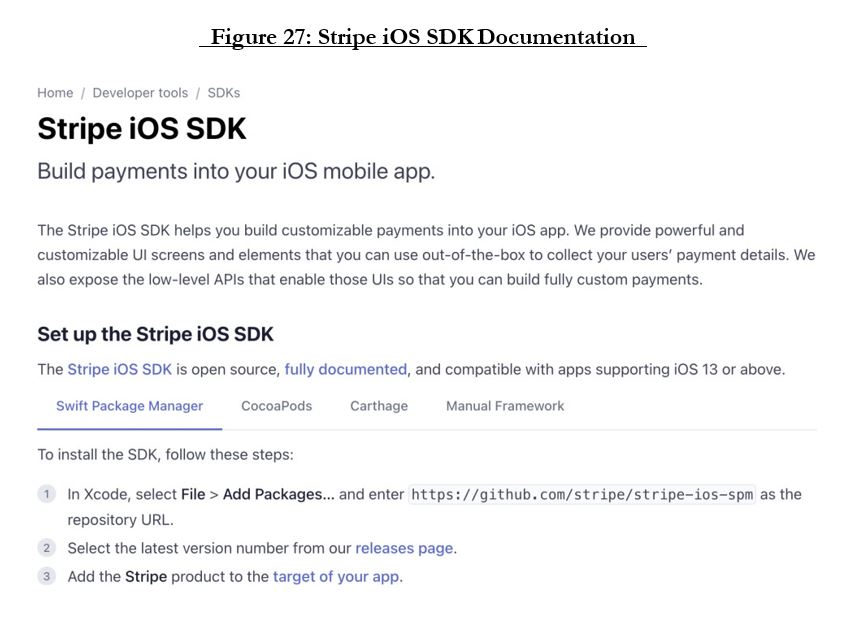

BETWEEN: | EPIC GAMES, INC First Applicant EPIC GAMES INTERNATIONAL S.A R.L Second Applicant EPIC GAMES ENTERTAINMENT INTERNATIONAL GMBH Third Applicant | |

AND: | APPLE INC First Respondent APPLE PTY LIMITED Second Respondent | |

order made by: | BEACH J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 12 august 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The further hearing of the proceeding be stood over to a date to be fixed.

2. Save for the oral summary of these reasons given by Beach J at the time of delivery of this judgment and any republication in any form of that summary, pursuant to s 37AF(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the ground set out in s 37AG(1)(a), subject to further order, disclosure and publication of these written reasons and the content thereof shall only be made to the parties’ external legal advisors in this proceeding and in proceedings NSD 190 of 2021, VID 341 of 2022 and VID 342 of 2022, and to no other person.

3. Liberty to apply.

4. Costs reserved.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BEACH J:

1 There are four proceedings before me, the joint trial of which took place over a period of four months on questions of liability.

2 In the first proceeding, which these present reasons deal with, the Epic parties have made claims against the Apple parties principally concerning alleged contraventions of s 46 and other provisions of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). The relief that they seek is directed at breaching Apple’s walled garden that protects its digital ecosystem.

3 The Epic parties are involved in developing entertainment software for personal computers, smart mobile devices and gaming consoles, with their most popular game being Fortnite. They allege that the Apple parties’ contravening conduct has forced app developers including Epic to only use Apple’s App Store to distribute their software applications (apps) to the broad base of iOS device users, and to only use Apple’s payment system for processing the purchases of their in-app digital content by iOS device users. I will explain the detail of this in a moment. Apple removed Fortnite from the App Store on 13 August 2020. That step has provoked the present litigation against the Apple parties.

4 In the second proceeding, the Epic parties have made claims against the Google parties principally also concerning analogous alleged contraventions of s 46 and other provisions of the CCA. They allege that the Google parties’ contravening conduct has hindered the ability of app developers including Epic to distribute apps to Android devices in a realistic and practical way other than through Google’s Play Store. It is said that Google has achieved this by imposing various contractual and technical restrictions, which stifle or block Android device users’ ability to download app stores and apps directly from developers’ websites and prevent or hinder competition in the distribution of apps to Android devices. It is also said that Google has inappropriately imposed on app developers Google’s payment system for processing the purchases of in-app digital content by Android device users. Google removed Fortnite from the Play Store on 13 August 2020. That step has also provoked the present litigation against the Google parties.

5 I have delivered a separate set of reasons dealing with the second proceeding (Epic Games, Inc v Google LLC [2025] FCA 901).

6 The third and fourth proceedings are representative proceedings commenced by the representative applicants under Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) where similar allegations have been made by them on behalf of group members against the Apple parties and the Google parties concerning the same contraventions of s 46 of the CCA as alleged in the first proceeding and the second proceeding. One of the class actions is against the Apple parties concerning the overcharging of commissions on the App Store. The other class action is against the Google parties concerning the overcharging of commissions on the Play Store. In each case it is said that the contraventions caused app developers to pay materially higher commissions on paid app downloads and in-app purchases of digital content than they would otherwise have had to pay had the contravening conduct not occurred.

7 I have delivered a separate set of reasons dealing with both the third and fourth proceedings (Anthony v Apple Inc; McDonald v Google LLC ([2025] FCA 902).

8 I will say something more about the joint trial and how these reasons should be read a little later. But for the moment let me introduce the case against the Apple parties in some more detail.

9 Apple Inc designs, manufactures and sells smartphones, tablets and personal computers, which are known as iPhones, iPads and Macs respectively, along with various other devices and accessories. Let me say something more about devices before proceeding further.

10 Internet-connected computing devices include smartphones, tablets, PCs such as Windows and macOS, and gaming consoles such as the Microsoft Xbox, Nintendo Switch and Sony PlayStation. Types of computing devices differ in various physical and functional respects depending on their particular use cases and the consumer needs that they are designed to meet. Conveniently one can identify five general characteristics of relevance to the present case.

11 First, one has size and portability. Smartphones are smaller and more portable than consoles. Second, one has methods of power connection. Desktop PCs for example require fixed power connections. Third, one has performance and memory capacity. Smartphones have typically been less powerful than PCs. Fourth, one has input methods. Typically, smartphones have touch screens, consoles require controllers and desktop PCs and some laptops require keyboards and mice or trackpads. And fifth, one has the range of apps that they support. Let me say something by way of introduction about operating systems and apps at this point.

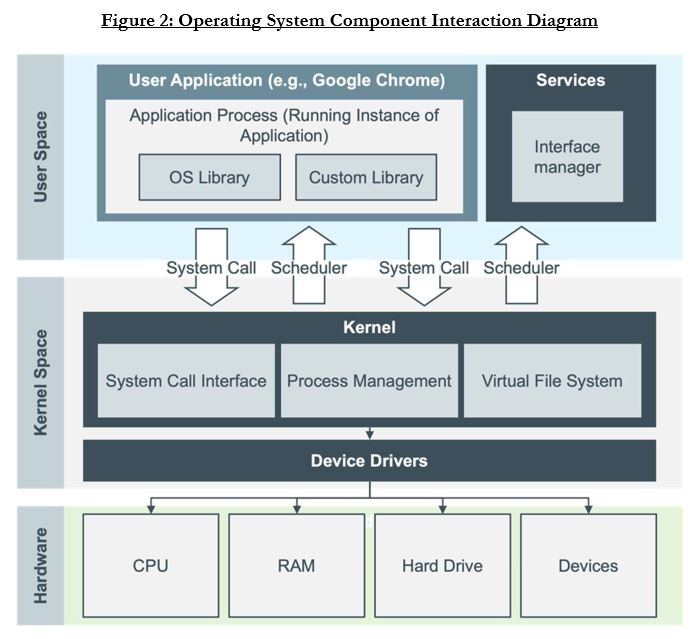

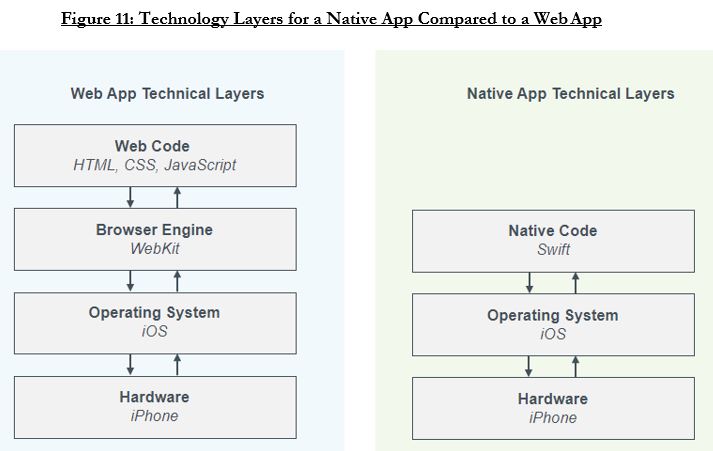

12 For a smartphone, tablet or personal computer to operate, it requires an operating system. Now an operating system, which I have simply referred to as an OS, is a form of software that provides the basic functionality for a device. It facilitates the operation of the device’s hardware and software, manages how apps will run on the device, and manages access to and use of its resources. Both smartphones and tablets as well as PCs require an OS to operate.

13 The two largest operating systems for mobile devices are Apple’s iOS on which iPhones run and with a similar operating system for iPads, and Google’s Android OS on which Android devices run.

14 On each of these devices, users can use applications known as apps for any number of purposes, including news, travel bookings, maps, entertainment and games. Apps developed for a particular OS are referred to as native apps. Apps may also be developed to run through a web browser on any device irrespective of the OS. These are referred to as web apps and can be accessed by users via a web browser.

15 Now apps enhance and optimise the functionality of a device. Generally speaking, three kinds of apps can be run on a modern device being native apps, web apps and streaming apps.

16 As I have indicated, a native app is an OS-specific app that is programmed to run on a particular OS and cannot run on a different OS. To create a native app, a developer will use software development tools that are created for the particular characteristics of an OS. Consequently, it is difficult to port apps between different operating systems.

17 There are now more than 1.8 million native apps available on the App Store for download to iOS devices. Only a small number of these were developed by Apple. The vast majority of iOS apps available in Australia are developed by third-party developers.

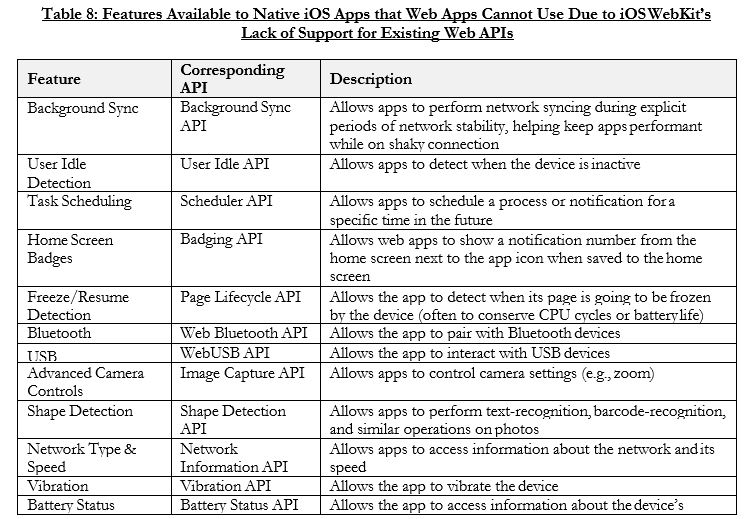

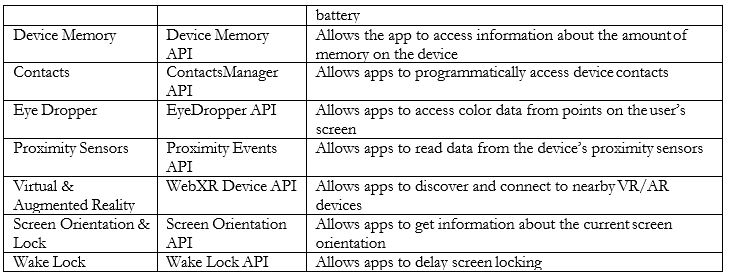

18 In contrast to a native app, a web app is designed to run inside a webpage accessed through a web browser and is platform agnostic. Web apps use web technologies rather than platform specific software and suffer limitations in functionality compared with native apps. These differences are the result of inherent technical limitations that web apps face, as well as browser and operating system level policy decisions made by platforms to extend less functionality to web apps.

19 Any web app can be accessed on an iOS device through a web browser and are not subject to the same guidelines or restrictions that Apple imposes on native apps available through the App Store.

20 A streaming app is run on a remote server but can be viewed and controlled on a user’s device via an associated portal app being either a web app or a native app. Streaming apps respond to user inputs relayed by the portal app and transmit back to the user’s device a live audio-visual feed of the remote streaming app’s output. Generally speaking, for this all to work well, streaming apps require high bandwidth, low latency and reliable network connections which are not always available to mobile users.

21 Now native apps are typically distributed for installation on a device in one of three ways. First, through an app store. Second, by directly downloading the app from a website. Third, by pre-installation on the device.

22 Software developers develop apps and make them available to consumers for use on their devices. Apps are most commonly downloaded onto mobile devices via an app store, itself a type of app that allows users to browse or search a catalogue of apps.

23 Now developers can monetise apps developed for smart mobile devices in three principal ways. First, they can monetise their apps by providing users with the app for free, and monetising the app through other means such as advertisements shown in the app. Second, they can monetise their apps by charging users a fee to download the app. Third, they can monetise their apps by supplying users with apps in which the user can make “in-app” purchases for which the developers can charge.

24 Now in-app purchases are, as the name suggests, purchases that occur within an app, such as purchases of digital content such as subscriptions or in-app currency, and of physical goods and services supplied outside the app such as food deliveries or transportation. Contrastingly, out-of-app purchases require the customer to leave the app and undertake the purchase elsewhere, such as on a website or another device.

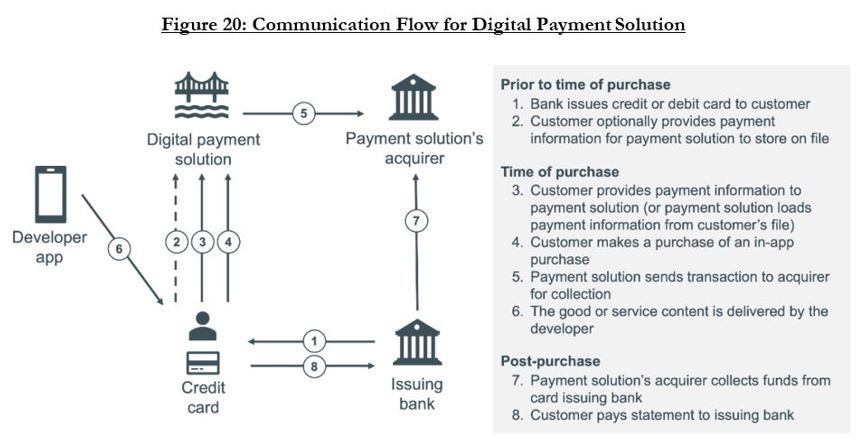

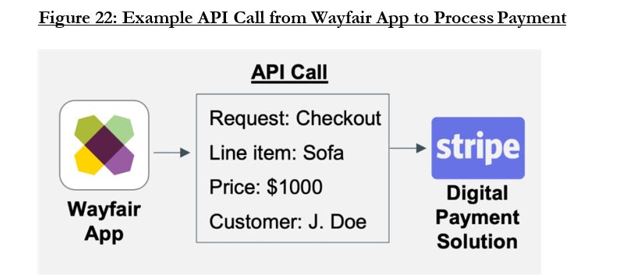

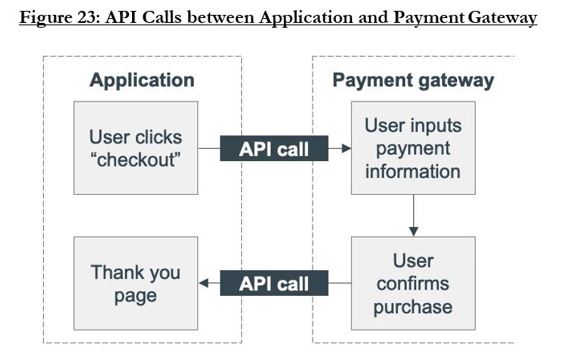

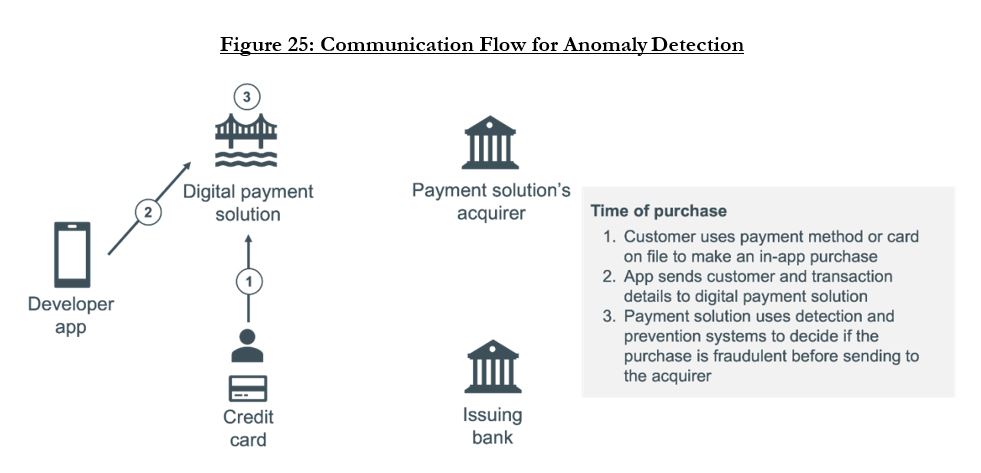

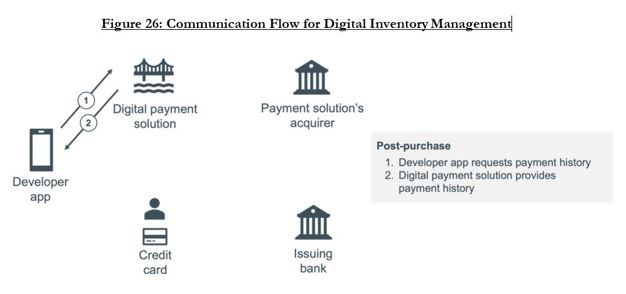

25 Now to offer in-app purchases, app developers require in-app payment solutions. In-app payment solutions are systems by which funds are transferred between a buyer and seller without the user leaving the app.

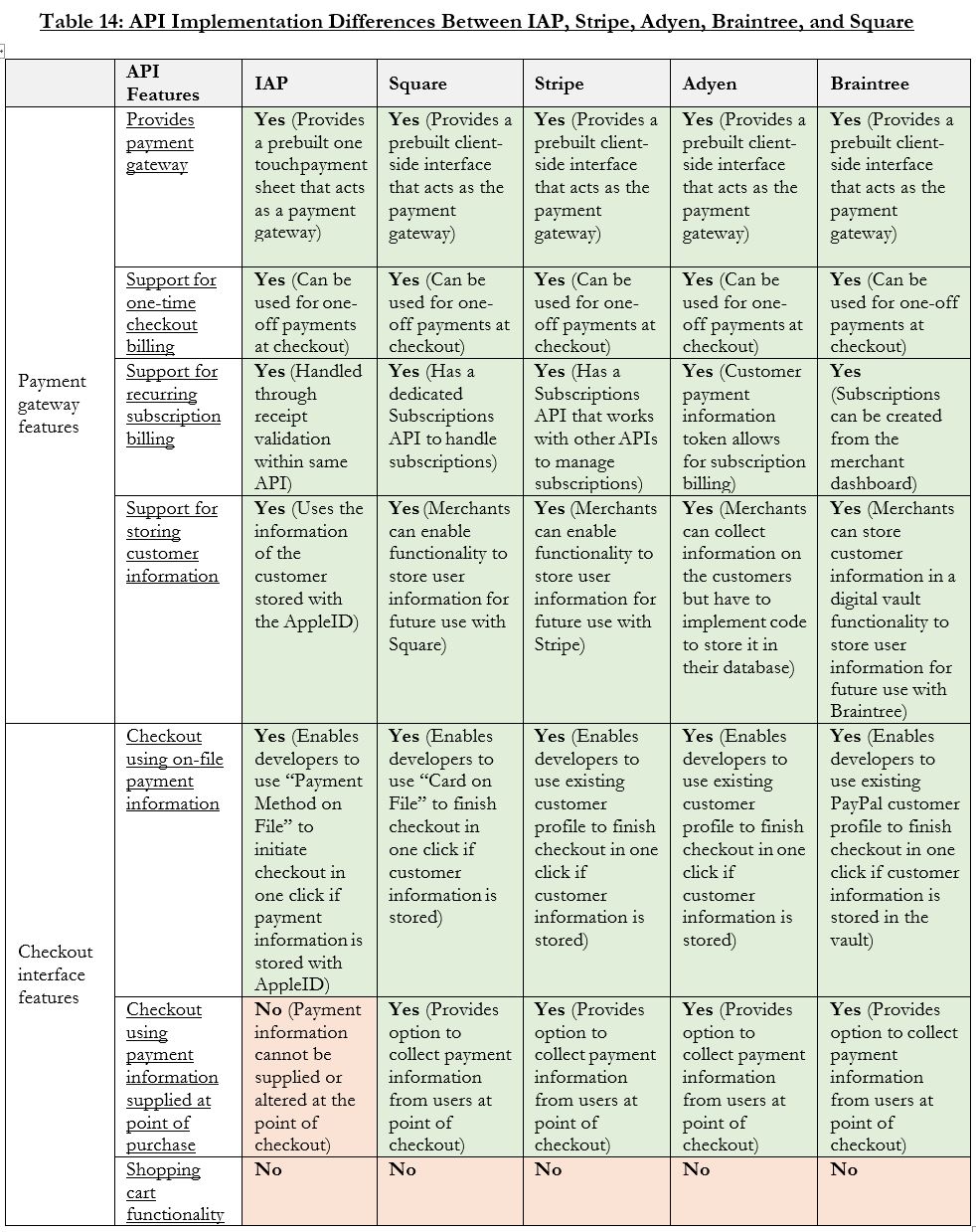

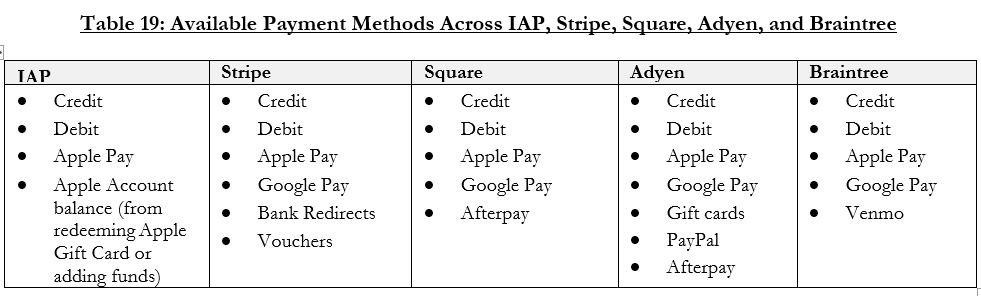

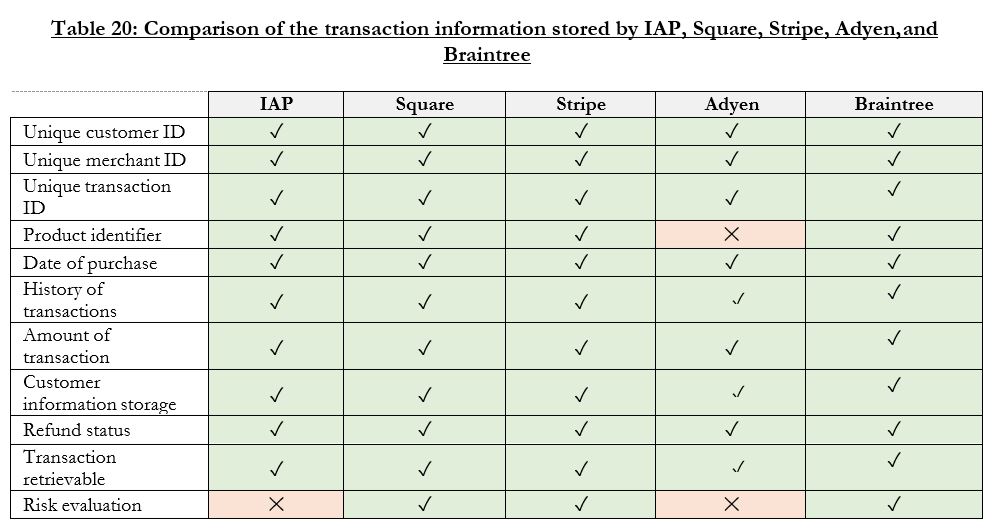

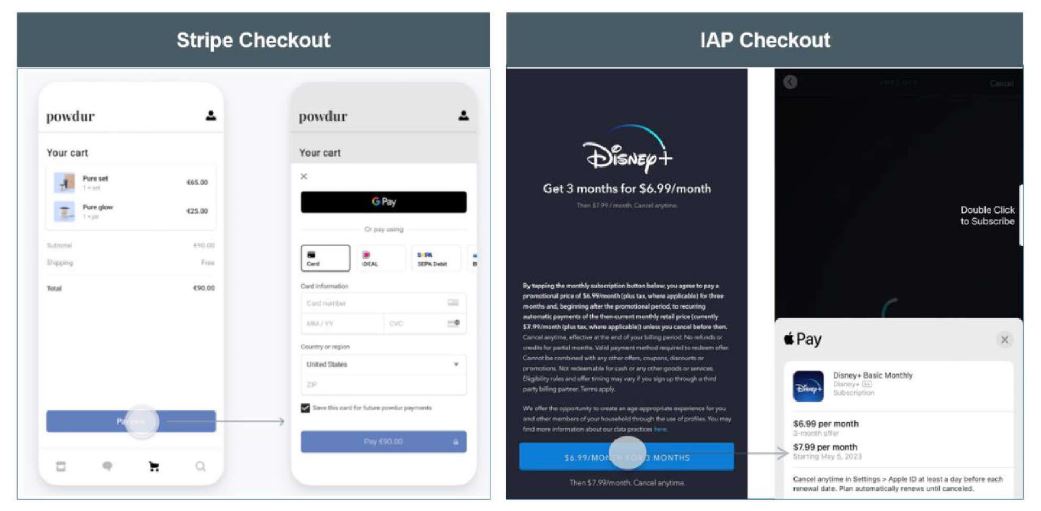

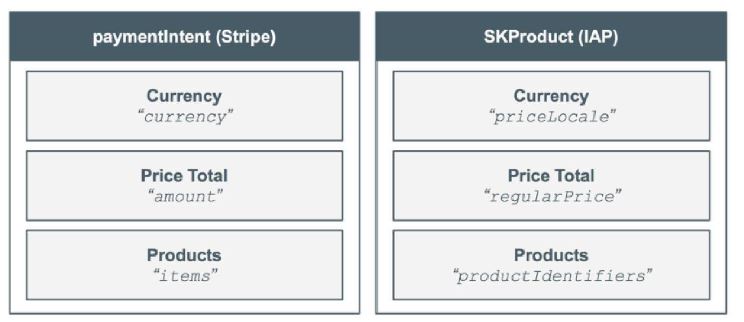

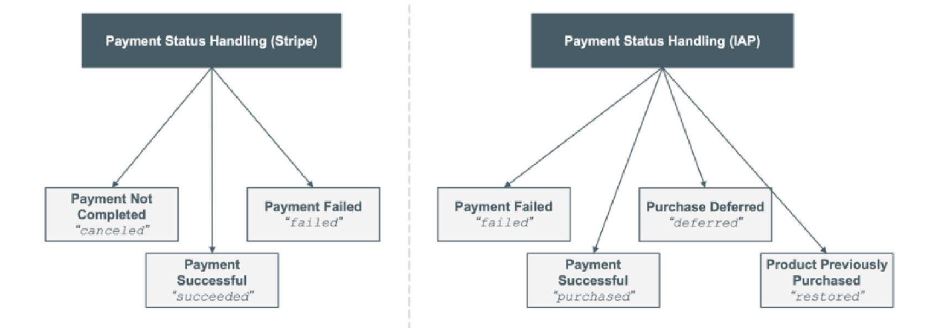

26 App developers can develop their own in-app payment solution or obtain an in-app payment solution from a third-party. Various third-parties supply in-app payment solutions, including Stripe, Square, PayPal and Adyen.

27 Now Apple’s App Store is the exclusive platform by which iOS native apps are distributed. By reason of Apple’s policies and contractual restrictions, as well as technical restrictions encoded in iOS, only native apps from the App Store may be installed on an iOS device apart from certain trivial exceptions.

28 Further, under the terms and conditions of the developer program licence agreement (DPLA) that Apple requires all developers to enter into, Apple does not permit any third-party app store to be distributed on iOS devices in Australia, whether through the App Store or otherwise. Apple also prohibits and makes it technically impossible to directly download apps onto iOS devices. As to pre-installation, Apple pre-installs the App Store and a few native Apple-developed iOS apps on iOS devices supplied by it in Australia, but it does not pre-install any additional third-party apps on iOS devices.

29 Contrastingly, users of Android devices can use more than one app store. They can also download native apps directly from websites, which is referred to as direct downloading or sideloading.

30 But users of apps for iPhone and iPad have no choice. The only means by which iPhone and iPad users can gain access to native apps, and developers can supply them to such users, is via Apple’s App Store, which is pre-installed on all iPhones and iPads.

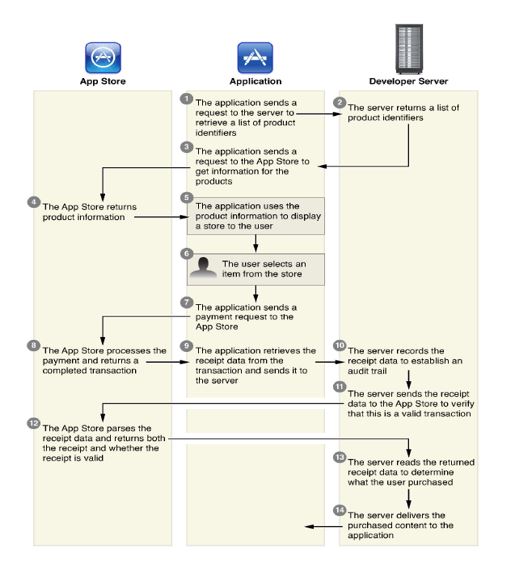

31 Further, app developers that make apps available for download on the App Store are contractually required to use Apple’s in-app payment solution (IAP) exclusively to take payment in respect of iOS apps, whether for the initial download of an app or for an in-app purchase of digital content. Contrastingly, when users make an in-app purchase of physical goods or services, developers can choose the payment solution that they wish to use.

32 Apple does not require the use of IAP for in-app purchases of physical goods and services, such as food or transportation. Indeed, Apple specifically prevents IAP from being used for the payment of such goods and services.

33 Apple charges a commission on paid apps downloaded from the App Store and any in-app purchases of digital content within an app that is downloaded from the App Store, and which purchase is facilitated by the only available payment solution, IAP.

34 Apple achieves all of this by means of restrictive contractual provisions to which developers are required to agree if they wish to distribute iOS apps. Those contractual provisions are supported by technical restrictions at the OS level relating to which apps the OS will permit to run.

35 If a developer wishes to distribute iOS apps, it must enter into two essentially non-negotiable agreements with Apple Inc, being the developer agreement and the DPLA. And subject to some limited exceptions, thereafter the developer is only permitted to distribute apps via the App Store. Further, with limited exceptions and as I have already indicated, iOS will only permit apps to run if they were acquired from the App Store, and will not permit apps other than the App Store to install other apps.

36 Developers are not permitted to submit any alternative app store for listing on the App Store. Further, developers are not permitted to distribute an app by any means other than the App Store including via direct downloading. Further, developers are not, save for limited exceptions, permitted to steer users to payment mechanisms other than the IAP.

37 The entry into and enforcement of these non-negotiable contractual provisions is the Apple conduct which these proceedings concern.

38 Now according to Epic, Apple’s conduct should be assessed in two relevant markets.

39 The first market is said to be an iOS app distribution market, in which Apple provides services related to the distribution of iOS apps. This encompasses the services Apple provides to users in making a large range of apps available for download, and to developers in facilitating the provision of developers’ apps to users. It is said that no services are readily substitutable on either the user side or developer side such that the market should be widened. As posited by Epic, Apple is a monopolist in that market, a position which it brought about through various contractual provisions and technical restrictions.

40 The second market is said to be an iOS in-app payment solutions market, in which Apple provides services to developers including accepting, processing, collecting and remitting payments for digital content within iOS apps. It is said that there are no readily substitutable services for developers which might point towards a wider market. Again, as posited by Epic, Apple is a monopolist in that market.

41 Contrastingly, Apple contends for a market which it describes as a market for app transactions. Further, it denies the existence of any separate iOS in-app payment solutions market.

42 Now as to market power, and as I have indicated, Epic says that Apple is a monopolist in both relevant markets, which manifests itself in the complete foreclosure of any competition in relation to the distribution of iOS apps and also for iOS in-app payment solutions services.

43 Further, according to Epic, in both the iOS app distribution services market and the iOS in-app payment solutions market, Apple has acted to ensure that it remains the only supplier and that this was Apple’s purpose in both markets in engaging in the impugned conduct the subject of this proceeding.

44 As to competitive effect, Epic says that Apple is currently a monopoly supplier in both of Epic’s posited markets. Epic says that if Apple’s contractual restrictions were removed, competitors in both markets would be given the chance to compete. It is said that in both markets there are various examples of app developers who have sought to enter the distribution market or use alternatives to Apple’s IAP, but have been blocked by Apple’s contractual restrictions. More directly, Epic says that it would seek to compete in the iOS app distribution market almost immediately. Epic says that entry into both markets would necessarily lead to greater competition than the current state where there is an absence of competition.

45 Now Apple has resorted to matters of security to justify its contractual provisions and restrictions. But Epic’s case is that the issue of security is not relevant to the question of whether Apple’s conduct has the purpose of or brought about a substantial lessening of competition. Epic says that there is no scope to permit a substantial lessening of competition just because it is balanced by claimed pro-competitive effects elsewhere. Epic says that it is impermissible to assess the relevant question by seeking to weigh up Apple’s asserted advantage arising from the restrictive conduct, being increased security, against the harm arising from the restrictive conduct, being a reduction in competition. Further and in any event, Epic says that in respect of distribution, the effective aspects of Apple’s security measures being OS-level protections and other protections can apply to all apps regardless of their source.

46 Further, Epic says that in respect of payment solutions, there is no good reason why allowing entry of other payment solutions providers would have any effect on security. It is said that Apple presently allows alternative payment solutions providers to operate in respect of payments for physical goods and services ordered through an iOS app using a payment system that is integrated into the app.

47 In summary, Epic says that Apple by engaging in the impugned conduct has breached ss 46 and 47, alternatively s 45, of the CCA from 6 November 2017 (the relevant period). I note that it is not a coincidence that 6 November 2017 is also the commencement date for the present version of s 46.

48 Epic says that Apple has breached s 46 because it has substantial market power in both of Epic’s pleaded markets and has imposed the restrictive contractual conditions. Epic says that the restrictive contractual conditions had the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in one or both of the distribution and payments markets. Further, Epic says that Apple has breached s 47 because it supplies distribution services to iOS app developers on the condition that they not obtain in-app payment solutions for digital content from any other person. And in the alternative to the s 47 case, Epic says that Apple has breached s 45 because it imposes the restrictive contractual conditions.

49 Further, Epic also says that Apple has engaged in unconscionable conduct contrary to s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being schedule 2 to the CCA, by reason of what are said to be the unbalanced contractual terms and technical restrictions which it has imposed on app developers.

Summary of findings

50 In summary, I have made the following key findings.

51 First, I have found in favour of Epic concerning its two posited markets being, first, the iOS app distribution market and, second, the iOS in app payment solutions market. Now I should note that the fact that I have found that various other products and services are not close constraints and therefore are not part of the relevant product dimension of market definition does not entail that the availability of such products and services do not provide some form of competitive constraint. In my view they do provide a competitive constraint to some extent although not such as to deny the market definition that I have found or Apple’s substantial market power in such a market.

52 Second, I have found in favour of Epic to the effect that at all relevant times Apple has and had a substantial degree of power in each market.

53 Third, I have found that Apple has, contrary to s 46 of the CCA, engaged in conduct in either or both markets that had the purpose or had or is likely to have or had the effect of substantially lessening competition in such markets being, specifically, conduct that prevents or prohibits the direct downloading or sideloading of native apps and prevents or prohibits developers and users from using alternative payment methods to IAP for purchasing digital in app content; as to the latter, I have only found in favour of Epic on its effects case.

54 Let me elaborate further on some of my key findings.

55 In my view Apple’s restrictions on direct downloading or sideloading of native iOS apps had the purpose and effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the iOS app distribution services market. Further, in my view such conduct had such a purpose and effect or likely effect in the broader app distribution market, if I am wrong in my primary finding of an iOS app distribution services market.

56 Further, in my view Apple’s conduct in imposing IAP on app developers in the circumstances indicated had the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the payment solutions market.

57 Now I would note in relation to these findings that Apple may in part in imposing these restrictions have sought to address security concerns and risks. But nevertheless, none of that negates my key conclusions. Apple may have had a security purpose in preventing direct downloading or sideloading, but that does not deny other substantial purposes. Moreover, the existence of a security purpose says little about the effect or likely effect of Apple’s restrictive conduct in terms of competition questions.

58 Now before proceeding further I should say something about Apple’s centralised app distribution system. After all, the various contractual constraints and technical restrictions were designed to keep in place and to fortify such a centralised app distribution system.

59 First, it may be accepted that a centralised system has some benefits over a decentralised system in terms of security concerns.

60 Second, I also accept that the quality of Apple’s offerings including its distribution services is in part a function of the premium style security that Apple offers and enshrines in its centralised app distribution system. So, it is a relevant non-price factor. And so, for example, in dealing with any counterfactual commission charges absent the relevant impugned conduct, quality differentials such as concerns security differences need to be considered in terms of Apple’s offerings as compared with other entities’ offerings.

61 Third, the fact that Apple has imposed a centralised app distribution system for the purpose of protecting security does not entail that there is not also a substantial anti-competitive purpose involved.

62 Fourth, in terms of anti-competitive effects, any security beneficial effects in maintaining a centralised distribution system do not necessarily outweigh any anti-competitive effects flowing from Apple’s conduct.

63 Let me say something concerning Apple’s ban on rival app stores within the App Store. As I have indicated, Apple does not permit the direct downloading or sideloading of rival iOS app stores. Contrastingly, Google permits this concerning rival Android app stores.

64 Now I am not persuaded that the restriction precluding rival app stores within the App Store had an anti-competitive purpose relevant to the iOS app distribution services market. Such a ban is targeted if at all against competitors rather than competition. Further, Apple seems to have had various purposes for such a ban. One purpose was to address security risk as Apple saw it. Another purpose was to prevent free riders. And an associated purpose was to protect the asset that it had invested in and built up.

65 But does this restriction have an effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in the iOS app distribution services market?

66 Now given that direct downloading or sideloading of rival iOS app stores was not permitted, it would seem that the combination of such a restriction together with the ban on rival app stores within the App Store had such a likely effect.

67 But of course if I permit the direct downloading or sideloading of rival iOS app stores, then the competition question concerning the ban on rival app stores within the App Store itself is substantially ameliorated. There would then be no effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. A rival app store could enter the market and compete through the direct downloading or sideloading of an iOS app store, albeit that there are imperfections and disadvantages in such a pathway as distinct from being permitted to do this through the App Store. But that less desirable pathway would not give rise to substantial competition consequences.

68 Now there is another way to consider the matter. If I allowed an app store within an app store, that would diminish the quality of Apple’s App Store offering. That would not be a pro-competitive step. Further, to the extent that new security risks were injected by permitting such access, that would also not be a pro-competitive step. These last two concerns may have an anti-competitive effect. For reasons I will later address, in my view Apple’s ban on rival app stores within the App Store itself does not contravene the CCA.

69 In all other respects I have not accepted Epic’s case against Apple concerning the other alleged contraventions of Part IV of the CCA or its unconscionable conduct case under s 21 of the ACL.

The joint trial and these reasons – structural aspects

70 Now as I have said, the joint trial before me concerned the concurrent hearing of four proceedings being Epic’s proceeding against Apple, Epic’s proceeding against Google and two class actions.

71 Epic’s two proceedings have been issued out of the NSW Registry of this Court. The two class actions were subsequently issued out of the Victoria Registry of this Court. The two class actions in terms of competition law liability questions were derivative of or sought to leverage off Epic’s cases and evidence on liability against Apple and Google, save for the question of the overcharging of commissions relating to paid app downloads or in-app digital purchases on the App Store or Google’s Play Store.

72 Now in terms of the concurrent hearing of all four matters, I made orders that the evidence in one case should be treated as evidence in all other cases unless I indicated to the contrary, say, in respect of an admission made by one party that was not cross-admissible against other parties.

73 As I have said earlier, I have produced three sets of reasons being the present reasons, another set of reasons in the Epic v Google proceeding and a third set of reasons dealing with and combining my analysis and findings in the two class actions. Now a number of points.

74 First, the sequence in which the reasons should be read for ease of comprehension are in the order that I have just indicated.

75 Second and relatedly, it should also be understood that findings of fact or law in my present reasons form part of the foundation for my reasons in the Epic v Google proceeding and then my reasons in the class actions, unless I indicate to the contrary. Indeed, all sets of reasons should be read as a composite whole. So, although I have indicated the sequence in which the reasons should be read, which in one sense can be seen as an incremental vertical structure, I also intend for my findings in the Epic v Google proceeding to be treated as findings in this proceeding as well as findings in the class actions, and for the findings in the class actions to the extent relevant to be findings in both this proceeding and the Epic v Google proceeding.

76 Third, occasionally, my reasons in Epic v Apple and Epic v Google may overlap in relation to a particular topic. This is partly a function of how the cases have been presented. Nevertheless, my conclusions on such a topic in each proceeding have considered and been based upon all the evidence in all proceedings.

77 Fourth, some aspects of my discussion in the reasons in the class actions concerning the relevant counterfactual analysis should be taken as being incorporated by reference in these reasons. But I do accept that to some extent the dimensions to such an analysis are different.

78 In terms of assessing whether the relevant contraventions occurred, one is looking at and comparing the future from the time of the contravention with the relevant impugned conduct against the future from the time of the contravention without such conduct. But of course in looking at the future with and without the relevant conduct you do not just simplistically hold all else equal. But in terms of the class actions where one is considering causation questions involving what would have occurred if the relevant impugned conduct had not been engaged in, a different calculus and standard of proof is required as I have explained in my reasons in the class actions. A different retrospective hypothetical scenario is involved. Nevertheless the two types of analysis overlap and accordingly my reasons here also include aspects of my reasons in the class actions.

79 Fifth, I should also note here that the economic concepts including the hypothetical monopolist test that I have discussed in my reasons in Epic v Google apply to my discussion in these reasons, although of course more quantitative analysis was involved in the evidence in that proceeding by virtue of Professor Asker’s detailed analysis.

80 Sixth, annexed to my present reasons and the reasons in the Epic v Google proceeding is both a schedule of abbreviations and acronyms and also a dramatis personae which also includes the detail of lay and expert witnesses in terms of their positions at the start of the trial.

81 Now in terms of the venue for the joint trial, on 24 August 2023 being about 7 months before the trial commenced, I informed the parties that the trial would be in Melbourne so that they could organise their affairs including their selection of counsel. I should say that at this time much of the lay written evidence and expert written evidence had been filed save for the important economic expert evidence which was in the early phases of preparation, which for Apple did not need to be filed until 1 December 2023 and which for Google did not need to be filed until 7 February 2024. But undoubtedly some counsel had already been engaged in the matter for some time, including on various questions that had been resolved by the time that I took control.

82 It is convenient to note here a number of points concerning the venue for the joint trial and how it was run.

83 First, the subject matter of the litigation had nothing to do with particular State geography or location. It concerned Australia wide (at least) digital commerce and markets, rather than say a gas plant explosion where the place of trial usually selects itself.

84 Second, 95% of the management lay witnesses of Epic, Google and Apple were located overseas. Whether they flew into Melbourne or Sydney was a neutral question for both them and the parties whether from the perspective of convenience or expense.

85 Third, 95% of the expert witnesses called by all parties were also overseas witnesses. A similar point can be made.

86 Fourth, the trial was run so that the vast majority of Fridays were non-sitting days so that any Sydney counsel could return to Sydney if they so wished. Order 3 of my orders of 27 September 2023 specifically provided for this. This of course entailed that extended sitting hours applied on all other days. I have annexed to these reasons my chambers’ communication to the parties on 24 August 2023, my orders of 27 September 2023 and part of the transcript of the case management hearing held on 19 September 2023 which sets out the discussion on these matters.

87 Fifth, any Sydney counsel had the option of appearing on a video-link at any time if they so wished. Order 6 of my orders of 27 September 2023 specifically provided for this optionality for Sydney counsel on an unqualified basis.

88 Sixth and importantly, for Apple witnesses and issues, Sydney senior counsel for Google did not need to be physically present. Likewise for Google witnesses and issues, Sydney senior counsel for Apple did not need to be physically present. Indeed, that was my observation. Sydney senior counsel came and went depending upon the particular phase of the trial then being run and what their dance cards looked like.

89 Seventh and in any event, each team had multiple senior counsel involved. So, on many occasions where an Apple issue was being run, not all Apple senior counsel needed to be present. Indeed they were not present. The same position applied for Google issues. As for Epic, it had three senior counsel, being Mr Neil Young KC and two others who operated on a FIFO basis as suited the occasion, namely, Mr Garry Rich SC and Dr Ruth Higgins SC.

90 Eighth, the trial required the use under my control of the largest electronically fitted out trial court room of its type in Australia, with the necessary technical and other assistance from numerous court staff, all of whom were ultimately answerable to my requirements. What was also necessary was to provide the parties with workspaces, conference rooms and storage facilities on the same level as the court room. All of this was arranged and provided months in advance of the trial starting. If I may say so I am most grateful to the administrative and court staff for making this all possible. I should also express my appreciation to the in-court electronic operator for her first-class work.

91 Finally in terms of the running of the trial, let me express my appreciation for the considerable effort put in by Mr Young KC and his team for Epic, Mr Matthew Darke SC and his team for Apple, Mr Cameron Moore SC and his team for Google and the cameo performance of Mr Anthony Bannon SC and his team for the class applicants. The timeliness and quality of the work of counsel and their instructing solicitors was excellent, and the skill of counsel in their notably efficient presentations including the handling of witnesses resulted in this complex and lengthy trial finishing precisely on time.

92 Let me now proceed to the heart of the matter. For convenience, I have divided my reasons into the following sections:

(a) Epic parties and background facts – [94] to [216].

(b) Apple parties and background facts – [217] to [281].

(c) Apple’s relationship with app developers and IAP – [282] to [372].

(d) Google entities and background facts – [373] to [394].

(e) Epic’s pleading – Apple’s conduct and the pleaded markets – [395] to [483].

(f) Lay evidence in the Apple proceeding – [484] to [528].

(g) Apple’s decision-making processes and decision makers – [529] to [583].

(h) Apple’s contractual framework with developers – [584] to [734].

(i) Apple’s intellectual property – access and use by developers – [735] to [861].

(j) Operating systems and security, Apple’s devices and app distribution – [862] to [1297].

(k) Some legal and economic principles – market definition and other matters – [1298] to [1659].

(l) Market definition – the parties’ cases – [1660] to [1800].

(m) Market definition – what is the relevant product? – [1801] to [2032].

(n) Application of the hypothetical monopolist test – [2033] to [2317].

(o) Substitution – behaviour of users, relevant metrics, competitive constraints, out of app payments, iOS v Android, perceived competition between Google and Android, Professor Dhar’s surveys, web apps and streaming, conduct of platforms and developer side responses – [2318] to [3688].

(p) Section 46 – some legal principles – [3689] to [3840].

(q) Apple’s power in the iOS app distribution market – [3841] to [4174].

(r) The App Store’s profitability – evidence of market power – [4175] to [4485].

(s) Core security and threat model – Apple’s justifications – [4486] to [4789].

(t) The purpose of Apple’s conduct in the iOS app distribution market – [4790] to [5063].

(u) The effect of Apple’s conduct in the iOS app distribution market – [5064] to [5442].

(v) In app payments – processing solutions – [5443] to [5623].

(w) The iOS in app payment solutions market and market power – [5624] to [6005].

(x) iOS in app payment solutions – purpose and effect of Apple’s conduct – [6006] to [6113].

(y) The position of Apple Pty Ltd – [6114] to [6137].

(z) Other alleged statutory contraventions – [6138] to [6324].

(aa) The question of relief and conclusion – [6325] to [6347].

(ab) Schedule of abbreviations and acronyms, dramatis personae of witnesses and other individuals, and other annexures.

93 Let me now proceed to deal with some background matters.

Epic parties and background facts

94 Let me now say something about the Epic parties. The following matters are not controversial unless I state otherwise.

95 The first applicant, Epic Games Inc, is a technology company headquartered in Cary, North Carolina, USA. Epic was founded by Mr Timothy Sweeney in 1991. He remains its CEO, controlling shareholder and is the chairman of its board. Other current shareholders of Epic include a subsidiary of Tencent Holdings Ltd, Sony Corporation, KIRKBI A/S (the parent of the Lego Group) and the Walt Disney Company.

96 Epic’s business is multifaceted and includes the following aspects.

97 First, its business includes the development of apps for consumers, including both gaming and non-gaming apps.

98 Second, its business includes the development of software tools that provide other developers with digital content and other resources, and which can be used in a range of commercial settings, including game development, film and television production, architecture, and automotive design. These software tools include Epic’s licensable “game engine”, known as Unreal Engine, the most recent version of which was released in April 2022.

99 Third, its business includes the provision of Epic online services which is a modular set of online services made available for free to other developers for use in multiplayer games. Epic online services enables developers to provide a wide range of functionalities, including those that facilitate “friend” connections and voice communication between users, and the analysis of user activity.

100 Fourth, its business includes distributing and publishing PC apps developed by Epic and third-party developers, which has been facilitated via the Epic Games Store since December 2018.

101 Fifth, its business includes providing an optional payment solution known as Epic Direct Payment (EDP) to process in-app purchases of digital items for developers whose apps are distributed through the Epic Games Store. Epic charges developers that use EDP a 12% commission on in-app purchases, but does not charge any commission for in-app purchases where the developer uses an alternative payment solution.

102 Epic is now a significantly sized company. Its most popular app is Fortnite. In January 2023, there were approximately 1.4 million monthly active users of Fortnite, and approximately 12,000 monthly active users of Unreal Engine, in Australia. A monthly active user is a consumer who ran the app or completed a purchase within the app at least once during a given month.

103 The second applicant, Epic International, is a subsidiary of Epic that is registered in Luxembourg. The third applicant, Epic Entertainment, is a subsidiary of Epic that is registered in Switzerland.

104 Until 2023, Epic International was responsible for certain parts of Epic’s business operations outside the USA. In particular, until 31 December 2022, Epic licensed Epic International to distribute, publish, market and operate games developed by Epic, as well as Unreal Engine, outside the USA. Since 1 January 2023, Epic Entertainment has replaced Epic International in this function.

105 Users in Australia who download and use Epic’s apps on a smart mobile device enter into an end user licence agreement with Epic International from August 2018 to 31 December 2022, or Epic Entertainment since 1 January 2023.

106 At its inception, Epic’s business focused on the development of computer games for PCs, and, from 1998, the provision of Unreal Engine, which Epic licensed and continues to license to other developers. In addition to being a developer in its own right, Epic has consistently sought to foster a competitive environment for third-party developers. Initially, this was for the collective benefit of the gaming industry. More recently its focus has expanded to the app industry as a whole.

107 It has done so in a number of evolving ways. From the outset, Epic sought to support third-party developers by creating innovative product features and software tools that were made available to all developers. So, Epic’s first PC game enabled users to edit and create new versions of gameplay within the game. The Unreal game, which precipitated Unreal Engine, took this concept further and provided users with access to the game’s complete editing interface and scripting language, thereby enabling them to program and then share their own game modifications with other users. The subsequent development of Unreal Engine conferred even more wide-reaching benefits on third-party developers: the engine was designed to enable developers to generate their own components for their own games. This resource provided developers with the necessary capabilities to overcome the significant technical barriers to developing high quality 3D games. More recently, in 2020, Epic launched Epic online services which provides further tools and services to developers to assist them to enhance their games. Epic online services is available for free and is compatible with a variety of game engines beyond Unreal Engine.

108 Upon the launch of the App Store in 2008 and the emergence of native iOS app development, it was anticipated that mobile games would be the next frontier for Epic and should be a central focus of its business strategy. Epic began directing its attention to iOS app development. At the time, most iOS game apps were rendered with simple 2D graphics and yet were popular with users. If Epic could make Unreal Engine compatible with iOS, it could bring more complex and immersive 3D games to iPhone users, and later to Android users, and become the leading game engine for high-quality 3D games on smartphones.

109 In 2010, Epic updated Unreal Engine 3 to include support for iOS and Android apps. In later editions of Unreal Engine, Epic progressively widened its functions and availability and reduced its cost, and it is now used in many business contexts, including film, television, automotive design and the training of surgeons.

110 In or around September 2010, Epic and Apple entered into an Apple developer agreement, which governed how Epic could use information and software provided by Apple, as well as a DPLA, including schedule 2 to that agreement. Together, these set out the terms on which Epic could develop and distribute iOS apps on the App Store.

111 At the same time, Epic opened an Apple developer program account, being the Team ID ’84 account, which was subsequently used for the distribution of Fortnite, among other Epic apps.

112 In 2011, Epic began exploring ways to reposition itself to become a leading developer of “play for free” or “freemium” online games using a “games-as-a-service” model. This involved distributing games directly to users online and continuously updating those games with new content, for example, new maps and characters, without the need to develop sequels. Play for free games can be downloaded and played without charge, but typically offer optional in-app purchases for players to enhance their experience.

113 In about September 2003, Valve Corporation, a game developer, launched an online PC app distribution service called “Steam”, which could be accessed from a web browser or downloaded as a desktop app by PC users. Initially, Steam only distributed PC games developed by Valve itself.

114 In about October 2005, Valve started distributing third-party PC games through Steam, charging a commission of 30% of the gross revenue from the sale of each game downloaded. Within about three years, almost all third-party PC game sales were occurring through Steam. It remained the dominant distributor of PC games for at least another 10 years.

115 In 2013, Epic began negotiating with Valve for the distribution of Fortnite to PC users. Epic had previously distributed PC games in the Unreal series through Steam, paying Valve 30% of its gross revenue from those titles. But there were perceived drawbacks in Valve’s terms. Epic decided that it would not distribute Fortnite through Steam and instead took steps to develop its own PC distribution capability. Epic’s ultimate objective was to develop a multi-platform store for both Epic and third-party titles, with a commission structure that was more favourable to developers than that of Steam. This decision was informed by the fact that Epic was already a relatively successful company which could expect to reach a substantial user base.

116 The first step toward this objective was the launch, in 2014, of the Epic Games Launcher. PC users could download this app free of charge from Epic’s website. It enabled them to access and download to their PC all of Epic’s games and other apps, including Unreal Engine. By June 2015, the Epic Games Launcher had achieved one million unique users and hosted various Epic products.

117 Epic began working on Fortnite in late 2011. The app underwent testing with limited numbers of users in late 2014 and through 2015, and was publicly released on 25 July 2017 as a paid game on PCs such as Windows and macOS, Xbox One, and PlayStation 4. At the time, PCs and consoles were the only devices capable of supporting “AAA” games, being games that, like Fortnite, require high-level graphics, high screen resolutions, and sophisticated input devices or controllers.

118 The original version of Fortnite released on 25 July 2017 was a “player versus environment” (PvE) game, now known as Fortnite: Save the World. PvE games involve a single user playing against a computer-controlled environment or characters. Save the World quickly became popular and, by mid-August 2017, over one million people had played it.

119 In September 2017, Epic launched a new free to play, multiplayer game mode within Fortnite called Fortnite Battle Royale. Within about three weeks of its release, over 12 million people had played Battle Royale. By the middle of January 2018, that number exceeded 40 million. Within a year of the release of Battle Royale, there were approximately 175 million registered Fortnite users. It has since become one of the world’s most popular games. As of February 2023, the number of users who registered a Fortnite account exceeded 500 million, and there were about 62 million monthly active users, being users who log into their Fortnite account at least once per month.

120 In late 2017, Epic introduced various features which allowed real world friends to connect with each other within Fortnite and allowed users to make new connections with other Fortnite users. The ability for users to build strong social connections within the game, and to play with people whom they knew in the real world was an important part of Epic’s strategy to grow the Fortnite user base and maintain user enjoyment over time.

121 By August 2018, Fortnite was available on Windows, macOS, Xbox, PlayStation, Nintendo Switch, iOS and Android and, in September 2018, it became the first AAA gaming app to achieve full cross-play functionality between all of those devices. Cross-play enabled a user playing Fortnite on any one of those devices to play in the same game session as a user of any of those other devices, provided each had installed the latest update to Fortnite.

122 Achieving cross-play functionality was and remains innovative, and required Epic to overcome differences between each platform. It required negotiations with Microsoft and Sony, both of whose standard platform rules had prohibited cross-play functionality. Epic considers cross-play to be an essential part of the Fortnite experience. Without it, users would not be able to play with their friends unless their friends owned the same device hardware, and Fortnite’s user base would be fragmented. For users, cross-play between platforms is one of Fortnite’s popular features.

123 At the same time, Epic introduced cross-progression within Fortnite across PCs, consoles, and mobile devices, which enabled users to access the digital items they had purchased and the rewards they had earned on any platform by logging into their Fortnite account, regardless of the platform on which the items had been purchased or the rewards earned.

124 Epic then progressively introduced cross-wallet within Fortnite, which provided the ability to purchase V-Bucks, being an in-app currency, on one platform and to then use those same V-Bucks on another platform. But Nintendo has never allowed this functionality.

125 Both cross-progression and cross-wallet were innovative technical achievements, and both features remain uncommon among mobile games.

126 In December 2018, Epic launched another mode within Fortnite known as Fortnite Creative. Creative enables users, on their own or with up to 16 friends, to customise and publish their own Fortnite “islands”; that is, virtual worlds, in which users can play Battle Royale-style games, enjoy musical shows and concerts, attend social or educational experiences or artistic installations, or visit virtual tourism destinations. Once these islands are created, other Fortnite users can access and experience them.

127 Creative has been popular with Fortnite users. Between October 2020 and December 2021, Fortnite users spent 30 to 40% of their time in Creative, and 75% of monthly active users played Creative. As at February 2023, over one million creators had published over one million islands.

128 In April 2020, Epic released Fortnite Party Royale, as part of Fortnite’s evolution from a pure gameplay experience to an app with a substantial social and entertainment dimension. Party Royale was a mode in which users could take part in events with other users without participating in gameplay such as music concerts, movie screenings, collaborations with TV shows, fashion brands and athletes, social justice discussions, and film festivals.

129 The result of these iterative developments is that Fortnite has evolved from being a game to being an app that offers each of its many users an immersive social, entertainment, and creative experience.

130 Epic incurs significant costs to maintain and continually improve Fortnite. Battle Royale is regularly updated, with new chapters and seasons, storylines, maps, items, weapons, and challenges. Epic employs approximately 500 to 700 engineers, including teams of platform experts who specialise in platforms such as Xbox, Linux, Mac, Windows, PlayStation, Android and iOS. Of those, some 150 engineers are responsible for the continued development of Fortnite.

131 Now Epic has monetised its apps both through subscriptions and, more extensively, in-app purchases of digital content. Fortnite generates revenue primarily through the sale to users of the in-app currency V-Bucks. V-Bucks can be purchased with real money within the Fortnite app, and they can be purchased outside the app, from the Epic Games Store on PCs, from console stores, physical retailers and online resellers.

132 Once purchased, V-Bucks are stored in a digital wallet linked to a user’s account in the Fortnite app. They are used to buy digital items from a store within the app, which items can then be used in the game. Once purchased, digital items are stored in a user’s “locker”, from which users can select the items with which they want to equip their character at any given time.

133 In addition to V-Bucks, users can purchase a “pack” of digital items for use in Fortnite, whether from other digital storefronts or physical retailers. The digital items contained in a pack can be redeemed from the item shop, within the Fortnite app or through the Epic Games website.

134 In December 2020, Epic introduced the “Fortnite Crew” subscription service which provides users with a “crew pack”, which includes a collection of digital items and 1,000 V-Bucks, each month, in exchange for a monthly fee.

135 Let me turn to the development of Fortnite for mobile devices. In about January 2018, Epic decided to launch Fortnite on Android and iOS mobile devices.

136 To continue to expand the Fortnite user base, Epic considered that it was necessary to make Fortnite accessible to users across as many device types as possible. Making Fortnite available on mobile devices was seen as a means to attract a new class of users who did not own a PC or console, or did not often play games on those devices. Given that most people own a mobile device, but a far smaller proportion of people own a gaming console, Epic considered that the potential audience for Fortnite on mobile was much larger than on consoles. Epic also considered that launching Fortnite on mobile would attract a different audience, including casual gamers, mobile gamers and women, who were less likely to purchase consoles than mobile devices and more likely to play games on mobile devices than on consoles or PCs. In addition, expanding to mobile would allow Epic to engage existing Fortnite users at different times and in different situations, given the portability of mobile devices relative to PCs and consoles.

137 Now building a mobile version of Fortnite took considerable technical work by a team of engineers, to accommodate the differences between mobile devices, consoles and PCs, including the smaller and lower quality displays, and the role of touch screen controls.

138 Epic sought to launch Fortnite on iOS and Android mobile devices at around the same time, because both operating systems had very large user bases and Epic believed users tended not to switch between them. The development process took longer for Android than iOS, including because of the need to ensure compatibility with many different Android devices which are manufactured by a variety of original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) with different characteristics.

139 To launch Fortnite on mobile, Epic created Fortnite native apps for iOS and Android and, for Android only, the Fortnite installer.

140 Although Fortnite can be accessed and streamed on certain devices, including iOS and Android, Epic perceived that running Fortnite as a native app as opposed to a web app or streaming app on mobile was the only viable option to reach a broad new user base and the only way to provide an acceptable experience to all users. Epic considered that offering Fortnite to mobile users via a web app was not viable because web apps suffer from limitations as to speed, performance, functionality, memory and security, which would compromise the user experience.

141 Epic released a beta version of Fortnite as a native app for iOS devices on 14 March 2018. The full release occurred in April 2018.

142 The contractual terms previously agreed between Epic and Apple, as well as technical restrictions which Apple imposed on iOS devices, precluded Epic from ever distributing Fortnite as a native app to iOS device users otherwise than via the App Store. In short, an app cannot be distributed to iOS devices without a certificate from Apple. Further, under the DPLA, Apple prohibits all forms of app distribution outside of the App Store, custom app distribution, ad hoc distribution and beta testing through TestFlight.

143 During the period in which Fortnite was available on iOS, it was consistently one of the most popular apps on the App Store. Throughout 2018 and 2019, Fortnite maintained a top 10 position on the App Store in the “free games” category and was one of the top grossing iOS apps overall. From March 2018 to July 2020, Fortnite’s average monthly active users on iOS devices ranged between 8.3 million and 13.6 million.

144 Let me say something now about the Epic Games Store.

145 For several years prior to 2018, Epic had a goal of developing a store for its own PC games and third-party PC games. This would enable it to distribute its apps without paying commission to a distributor. It would offer app developers a commission structure more favourable to them than Steam’s 30% commission. It would later expand into mobile platforms to create a multi-platform store. And it would expand Epic’s ecosystem by attracting more consumers and developers to Epic’s products.

146 Epic began implementing this strategy in 2018. The Epic Games Store was launched on 6 December 2018. The Epic Games Store is an app store for PCs running Windows and macOS, comprising the Epic Games Store website and the Epic Games Launcher app.

147 Since at least 2020, the Epic Games Store has included non-gaming apps, such as the music streaming app Spotify, the voice-chat and social app Discord, the podcast and radio streaming app iHeart, an app created by Buendea in partnership with NASA to assist NASA research being NASA XOSS MarsXR Editor, and the music streaming app Tidal.

148 Users can browse and purchase gaming and non-gaming apps on the Epic Games Store website, but must download and install the Epic Games Launcher in order to download and install Epic Games Store titles on their PC. The Epic Games Launcher ensures that all apps downloaded from the Epic Games Store can be updated automatically and are stored in the same location on the user’s device. Once installed on a PC, the user can browse and purchase Epic Games Store titles from within the launcher app, without having to navigate to the Epic Games Store website via a web browser.

149 The games and other apps available on the Epic Games Store include first-party titles that Epic developed or owns, second-party titles developed by third-parties with funding from Epic Games Publishing, and third-party titles developed and funded by third-party developers including Spotify.

150 By about January 2024, the Epic Games Store had three first-party titles, six second-party titles, and approximately 2,976 third-party titles. By that time, 262 million total users had interacted with the Epic Games Store at least once and it had reached a peak in December 2023 of 75 million monthly active users.

151 Now in launching the Epic Games Store, Epic sought to disrupt Steam’s dominance in PC app distribution by offering developers a more favourable revenue share model, more closely reflecting the actual costs of app distribution.

152 The revenue share model Epic decided to implement for the Epic Games Store was an 88:12 percentage split, whereby third-party app developers retained 88% of gross revenues generated from the sale of apps and from in-app purchases made within apps downloaded from the Epic Games Store. Epic considered that a 12% commission would cover its costs of distributing third-party apps on the Epic Games Store and earn Epic a profit of about 5% of gross revenues.

153 Now in order to attract developers to distribute their apps via the Epic Games Store and compete with Steam, Epic considered that it would need to offer an attractive revenue share to developers and grow the Epic Games Store user base into a large and engaged audience.

154 Epic’s strategy was to rapidly grow the Epic Games Store user base by leveraging the popularity of Fortnite, and by offering apps that were for a period exclusive to the Epic Games Store on PC. To persuade developers to offer exclusive PC content on the Epic Games Store and forgo Steam’s much larger user base, Epic offered developers minimum guarantees, that is, it promised to pay certain developers a minimum amount regardless of revenue earned in exchange for exclusive Epic Games Store distribution on PC for 12 months. To attract users, Epic also offered games that, for a limited period, could be installed for free and which, once installed, could be retained indefinitely.

155 Now in the months leading up to the launch of the Epic Games Store, Epic met and communicated with about 80 to 90 different app developers and informed them of its intention to launch a rival PC app store with an 88:12 percentage revenue share. About two weeks before launching the Epic Games Store, Epic informed Steam’s owners that Epic was about to announce an 88:12 percentage revenue split.

156 On 1 December 2018, five days prior to the launch of the Epic Games Store, Steam announced the first change to its 70:30 percentage revenue share model in about 13 years, in the form of a tiered commission structure at the following rates: 30% of the first USD 10 million in revenue; 25% of revenue between USD 10 million and USD 50 million; and 20% of revenue over USD 50 million.

157 Other Epic Games Store competitors shortly followed. About eight days after the Epic Games Store launch, Discord, a social and voice-chat company which had launched its own PC app store in August 2018, announced that it would reduce its revenue share from 70:30 to 90:10. In March 2019, about four months after the Epic Games Store launch, Microsoft lowered its commission rate for all non-gaming apps distributed on PC through the Microsoft Store from 30 to 15%. In about May 2019, Microsoft announced a new version of its game subscription service, Xbox Game Pass for Windows PCs, which enabled Microsoft to differentiate the Microsoft Store from the Epic Games Store and Steam.

158 In April 2021, Microsoft announced that it was lowering its commission rate for PC gaming apps to 12%, matching the Epic Games Store’s revenue share.

159 In June 2021, Microsoft announced that, with effect from 28 July 2021, app developers were no longer required to use Microsoft’s payment solution for in-app payments within non-gaming PC apps, and instead could use their own or a third-party commerce platform in their apps, in which case no commission would be payable to Microsoft. This latter announcement also mirrored the approach taken by the Epic Games Store.

160 Now when the Epic Games Store first launched, EDP was used to facilitate purchases of paid apps on the Epic Games Store as well as for in-app purchases of digital goods and services within apps downloaded from the store.

161 EDP was created by Epic, initially for the purpose of facilitating in-app purchases within its own apps. Currently, it is incorporated within most PC apps downloaded from the Epic Games Store and within Epic’s apps on Android devices, save for those downloaded from the Samsung Galaxy Store, both to facilitate the purchase of paid apps and to facilitate in-app purchases of digital goods and services.

162 In around mid-2019, Epic agreed to permit the developer Ubisoft to distribute via the Epic Games Store but with its own payment solution, owing to technical features associated with Ubisoft’s games.

163 In December 2019, Epic decided to allow all third-party developers distributing through the Epic Games Store to choose their own payment solution for in-app purchases within their apps.

164 Third-party developers can build their own payment solution to facilitate in-app purchases, use a payment solution developed by a third-party payment solutions provider such as Paddle, Stripe, Square or PayPal, or use EDP.

165 Where the developer chooses not to use EDP in a given app, Epic does not earn any commission on in-app purchases occurring within that app save where Epic has paid the developer a minimum guarantee or other amount yet to be recouped.

166 EDP allows users to purchase goods and services without leaving the app. EDP accepts payments using about 76 payment methods in 43 different currencies. It connects to payment gateways provided by eight third-party payment processors.

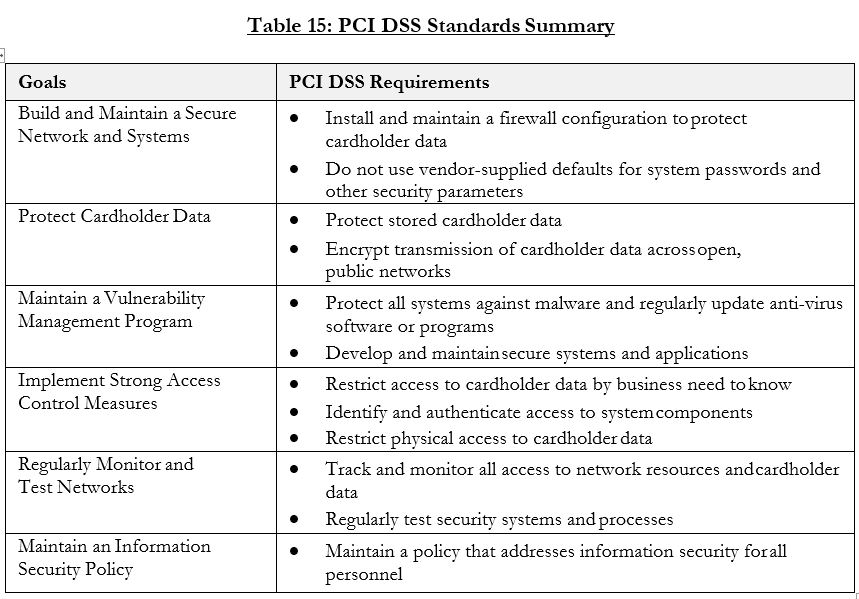

167 EDP is compliant with the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard, as are the third-party payment processors that Epic uses for EDP, and has anti-fraud and transaction data encryption measures in place. Additional anti-fraud checks are run by both the third-party processor and the financial institution. If a user makes a purchase within an app that uses EDP, and that user has not previously provided their payment details, the user will be asked to enter those details and they will be securely stored by the third-party payment processor, not by EDP.

168 Where a third-party developer chooses to use EDP, Epic or Epic International, depending on where the customer is domiciled, generally acts as “merchant of record”. Epic sells the digital goods on behalf of the app developer, takes responsibility for associated licensing and reporting obligations including paying relevant taxes and handles refund requests and other customer complaints.

169 Let me now say something about Epic’s agreements with app developers relating to the Epic Games Store.

170 Since at least 23 August 2023, all developers distributing apps via the Epic Games Store do so under the terms of the current Epic Games Store distribution agreement with Epic. Previously, developers who chose not to use EDP for in-app purchases could enter into an in-game transaction rider, which could sometimes be negotiated. The Epic Games Store distribution agreements do not prohibit the distribution of other app stores on the Epic Games Store and, indeed, two alternative PC app stores are currently distributed through the Epic Games Store.

171 For app developers, the Epic Games Store provides various features and functions, including the following.

172 First, there is a distribution service, whereby Epic hosts developers’ apps on Epic’s servers, displays those apps on the store, and distributes the apps to those users who choose to purchase or download them through the store.

173 Second, there is access to a developer portal, where developers can publish their apps and updates, upload code, access marketing tools and sales and financial data, as well as obtain app development tools such as the Epic online services (EOS) software development kit (SDK). EOS is a modular set of online services which make it easier for developers to successfully launch, operate, and scale high-quality games.

174 Third, subject to user consent, Epic provides developers with their users’ email addresses, which enables developers to share information with users about updates, new features, and titles.

175 Fourth, the developers have the option of promoting their titles to users on the Epic Games Store homepage from time-to-time as part of Epic’s editorial support. Epic does not offer paid or search advertising on the Epic Games Store but provides developers with access to its social media channels and merchandising services.

176 Fifth, there is cross-store PC play support, whereby Epic requires developers to integrate cross-store PC play functionality within their titles, that is, the ability for users to play games with each other regardless of the store from which they downloaded the app, and sometimes provides financial support to developers to cover the engineering work to meet this requirement. Epic has developed and made available an SDK to support cross-store PC play, which it makes available to developers for free.