FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

The NOCO Company v Brown and Watson International Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 887

File number: | VID 264 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | MOSHINSKY J |

Date of judgment: | 7 August 2025 |

Catchwords: | PATENTS – jump starter device for jump starting a depleted or discharged battery (eg in a vehicle) – priority date – where the patents in suit claimed an earliest priority date based on the filing date of a PCT application – where the cross-claimant contended that the patents were not entitled to the asserted priority date – whether, for each asserted claim, the invention in the claim was disclosed in the PCT application PATENTS – jump starter device for jump starting a depleted or discharged battery (eg in a vehicle) – novelty and inventive step –whether the claims in the patents in suit were anticipated by one or other of two documents – whether the claims in the patents in suit would have been obvious to the person skilled in the art in light of the common general knowledge (CGK) alone, or in light of the CGK together with one or other of two documents PATENTS – jump starter device for jump starting a depleted or discharged battery (eg in a vehicle) – best method – where the cross-claimant contended that the patentee had not disclosed the best method known to the patentee for performing the invention – whether the knowledge element was to be determined as at the international filing date or as at the filing date for the patents in suit PATENTS – jump starter device for jump starting a depleted or discharged battery (eg in a vehicle) – infringement – whether the impugned products infringed the claims in the patents in suit – construction issues – whether the claims required that the device automatically start upon satisfaction of preconditions – whether a product that is capable of operating in manual mode falls outside the scope of the claims – whether references to “USB” in the claims encompass USB-C, which had not been released as at the asserted priority date |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), s 136 Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Productivity Commission Response Part 2 and Other Measures) Act 2020 (Cth) Patents Act 1990 (Cth), ss 7, 18, 29A, 40, 43, 79B Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth), regs 3.12, 3.13A, 3.13D |

Cases cited: | Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2002] HCA 59; 212 CLR 411 Allied Pumps Pty Ltd v LAA Industries Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1457; 179 IPR 1 Arbitron Inc v Telecontrol Aktiengesellschaft [2010] FCA 302; 86 IPR 110 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99; 226 FCR 324 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 Austal Ships Sales Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag [2008] FCAFC 121; 77 IPR 229 Bristol-Myers Squibb Company v FH Faulding & Company Ltd [2000] FCA 316; 97 FCR 524 Brugger v Medic-Aid Ltd [1996] RPC 635 Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; 277 FCR 267 Dometic Australia Pty Ltd v Houghton Leisure Products Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1573; 135 IPR 403 Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd [2000] FCA 890; 49 IPR 331 Flour Oxidizing Company Ltd v Carr & Company Ltd (1908) 25 RPC 428 Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] FCAFC 73; 222 FCR 336 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 71; 264 FCR 474 Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd v Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 162; 145 IPR 39 Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd v Motorola Solutions Inc [2024] FCAFC 168 Icescape Ltd v Ice-World International BV [2018] EWCA Civ 2219; [2019] FSR 5 Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 90; 222 ALR 155 Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd (2004) 64 IPR 444 Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 27; 247 FCR 61 Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] HCA 21; 235 CLR 173 MedImmune Ltd v Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd [2013] RPC 27 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp v Wyeth LLC (No 3) [2020] FCA 1477; 155 IPR 1 Miele & Cie KG v Bruckbauer [2025] FCA 537 Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd [1980] HCA 9; 144 CLR 253 Mont Adventure Equipment Pty Ltd v Phoenix Leisure Group Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 84; 176 FCR 575 Multigate Medical Devices Pty Ltd v B Braun Melsungen AG [2016] FCAFC 21; 117 IPR 1 Nichia Corporation v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 2; 175 IPR 187 Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307 PAC Mining Pty Ltd v Esco Corp [2009] FCAFC 18; 80 IPR 1 Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co [2005] FCAFC 224; 68 IPR 1 Rescare Ltd v Anaesthetic Supplies Pty Ltd [1992] FCA 811; 25 IPR 119 Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 980; 49 IPR 225 Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 138; 126 IPR 427 ToolGen Incorporated v Fisher (No 2) [2023] FCA 794 UbiPark Pty Ltd v TMA Capital Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 885 Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel [1961] HCA 91; 106 CLR 588 Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd (1981) 148 CLR 262 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and associated Statutes |

Number of paragraphs: | 413 |

Date of hearing: | 10-14, 17-21 February 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr IP Horak KC with Mr MB Fleming and Ms LE Davis |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Griffith Hack Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr TD Cordiner KC with Mr P Creighton-Selvay |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Ashurst Australia |

ORDERS

VID 264 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | THE NOCO COMPANY Applicant | |

AND: | BROWN AND WATSON INTERNATIONAL PTY LTD Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | BROWN AND WATSON INTERNATIONAL PTY LTD Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | THE NOCO COMPANY Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | MOSHINSKY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 AUGUST 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Claims 1 to 8, 11 to 14 and 16 to 21 of Australian Patent 2020201223 are invalid.

2. Claims 1 to 4, 6 to 12 and 14 to 24 of Australian Patent 2021258059 are invalid.

3. Claims 1 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 26 and 29 to 36 of Australian Patent 2022201338 are invalid.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

4. Claims 1 to 8, 11 to 14 and 16 to 21 of Australian Patent 2020201223 be revoked.

5. Claims 1 to 4, 6 to 12 and 14 to 24 of Australian Patent 2021258059 be revoked.

6. Claims 1 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 26 and 29 to 36 of Australian Patent 2022201338 be revoked.

7. The applicant’s claim be dismissed.

8. Pursuant to s 37AI(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), [371] (third and fourth sentences) and [392]-[395] of the reasons for judgment of the Court dated today be published only to the parties and be kept confidential and not otherwise be disclosed for a period of 30 days. [THIS ORDER HAS SUBSEQUENTLY BEEN VACATED]

9. If any party seeks suppression or non-disclosure orders in respect of those paragraphs, the party may within 10 days file and serve an interlocutory application supported by an affidavit and an outline of submissions. The other party may within a further seven days file any responding material, and the party seeking the order may within a further two business days file any material in reply. The application will then be determined on the papers.

10. In relation to costs:

(a) within 14 days, the parties submit any agreed proposed orders as to costs;

(b) if the parties cannot agree, then within 21 days, each party file and serve a short written submission on costs, and within 28 days each party file and serve a short responding written submission. The issue of costs will then be determined on the papers.

11. Paragraphs 1 to 6 above be stayed:

(a) for a period of 28 days; or

(b) if the applicant files a notice of appeal within 28 days, until the hearing and determination of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

[1] | |

[21] | |

[21] | |

[47] | |

[51] | |

[54] | |

[73] | |

[78] | |

[81] | |

[85] | |

[88] | |

[89] | |

[89] | |

[99] | |

[101] | |

[108] | |

[110] | |

[132] | |

Construction issue 5(ii): Operation across the voltage range | [148] |

[149] | |

[171] | |

[172] | |

Construction issue 10: USB charging circuit including DC-DC converter | [173] |

Construction issue 11: DC-DC converter controlled by microcontroller | [190] |

[191] | |

[192] | |

[193] | |

[196] | |

[198] | |

[208] | |

[216] | |

[225] | |

[233] | |

[239] | |

[255] | |

[256] | |

[259] | |

[264] | |

[283] | |

[306] | |

[311] | |

[317] | |

[321] | |

[337] | |

[347] | |

[355] | |

[362] | |

[369] | |

[399] | |

[400] | |

[413] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 The applicant, The NOCO Company (NOCO), a company organised under the laws of Ohio in the United States of America, is the patentee of (relevantly) three Australian patents titled “Portable vehicle battery jump starter apparatus with safety protection”, namely:

(a) Australian Patent 2020201223 (the 223 Patent);

(b) Australian Patent 2021258059 (the 059 Patent);

(c) Australian Patent 2022201338 (the 338 Patent),

(together, the Patents).

2 In broad terms, each of the Patents relates to a jump starter apparatus for boosting a depleted or discharged battery (eg, a car battery). The specifications of each of the Patents are in substantially the same terms aside from the consistory clauses. In each specification, in the section dealing with the background to the invention, the following problem is outlined at [0003]:

Problems with the prior art arose when either the jumper terminals or clamps of the cables were inadvertently brought into contact with each other while the other ends were connected to a charged battery, or when the positive and negative terminals were connected to the opposite polarity terminals in the vehicle to be jumped, thereby causing a short circuit resulting in sparking and potential damage to batteries and/or bodily injury.

3 In [0013] of the specification of each Patent, it is stated that, while the prior art attempted solutions to the abovementioned problems, each of the prior art solutions suffers from other shortcomings, namely complexity, cost or potential for malfunction; accordingly, there exists a need in the art for further improvements to vehicle jump start devices.

4 Although many claims are in issue in this proceeding, much attention was given to Claim 1 of the 223 Patent, which is in the following terms (with numbers added for ease of reference):

(1.1) A jump starter apparatus for boosting or charging a depleted or discharged battery having a positive battery terminal and a negative battery terminal, the apparatus comprising:

(1.2) a power supply;

(1.3) a positive battery connector for connecting the jump starter apparatus to the positive battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

(1.4) a negative battery connector for connecting the jump starter apparatus to the negative battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

(1.5) a power switch connected in circuit with the power supply and the positive and negative battery connectors, the power switch configured to turn power on or off from the power supply to the positive and negative battery connectors;

(1.6) a control system or circuit connected to and controlling the power switch, the control system or circuit configured (1.6.1) to detect presence of the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors and (1.6.2) to detect polarity of the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors;

(1.7) wherein the control system or circuit switches on the power switch to connect the power supply to the depleted or discharged battery only when (1.7.1) the depleted or discharged battery is present and properly connected between the positive and negative battery connectors and (1.7.2) the depleted or discharged battery is properly connected with a correct polarity between the positive and negative battery terminals.

(Emphasis added.)

5 All of the claims in the Patents are product claims.

6 The filing dates of the Patents were 20 February 2020, 29 October 2021 and 25 February 2022 respectively.

7 The Patents are from the same patent family, each claiming an earliest priority date of 3 July 2014 (the asserted priority date), based on the filing date of PCT/US2014/045434 (PCT434), which was filed on 3 July 2014. A chart showing the relationship between the Patents and earlier filed documents is set out in Annexure C to NOCO’s opening submissions on infringement.

8 NOCO brings this proceeding against the respondent, Brown & Watson International Pty Ltd (B&W), a company incorporated in Australia, alleging infringement of the Patents. The infringement claims relate to four B&W products (branded as “Projecta” jump starters), known as the IS 920, IS 1220, IS 1400 and IS 2000 (the B&W impugned products or the impugned products). It appears that the letters “IS” stand for Intelli-Start.

9 The claims in the Patents relied on by NOCO in opening (the asserted claims) are set out in Annexure F to NOCO’s opening written submissions on infringement and are as follows:

Projecta product | 223 Patent | 059 Patent | 338 Patent |

IS 920 and IS 1220 | Claims 1 to 8, 11 to 14, 16 to 21. | Claims 1 to 4, 6 to 12, 14 to 24. | Claims 1 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 26, 29 to 36. |

IS 1400 | Claims 1 to 8, 11, 12, 14, 16 to 21. | Claims 1, 2, 4, 6 to 8, 10 to 12, 14 to 24. | Claims 1 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 24, 26, 30, 32 to 34, 36. |

IS 2000 | Claims 1 to 8, 11, 12, 14, 16 to 21. | Claims 1, 2, 4, 6 to 8, 10 to 12, 14 to 24. | Claims 1 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 24, 26, 30, 32 to 34, 36. |

10 On day 9 of the hearing (which occupied 10 days), counsel for NOCO indicated that certain claims were no longer pressed by NOCO in respect of some or all of the impugned products (T874-875). As a result of that narrowing of NOCO’s case, the claims that are relied on by NOCO to allege infringement with respect to the B&W impugned products are as follows:

Projecta product | 223 Patent | 059 Patent | 338 Patent |

IS 920 and IS 1220 | Claims 1 to 8, 11 to 14, 16 to 18, 20, 21. | Claims 1 to 4, 6 to 10, 12, 14 to 24. | Claims 1, 2, 5 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 26, 29 to 36. |

IS 1400 | Claims 1 to 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 16 to 18, 20, 21. | Claims 1, 2, 4, 6 to 8, 10, 12, 15 to 19, 21 to 24. | Claims 1, 2, 5 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 22, 24, 30, 32 to 34, 36. |

IS 2000 | Claims 1 to 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 16 to 18, 20, 21. | Claims 1, 2, 4, 6 to 8, 10, 12, 15 to 19, 21 to 24. | Claims 1, 2, 5 to 8, 10 to 14, 16 to 22, 24, 30, 32 to 34, 36. |

11 B&W has cross-claimed against NOCO, alleging invalidity of the asserted claims. In B&W’s opening submissions on invalidity, B&W states in paragraph 1 that it alleges that “all asserted claims” are invalid on multiple grounds. B&W indicated in closing submissions that it pressed its invalidity case in respect of all of the originally asserted claims (T919). I note for completeness that, at a later point in closing submissions, B&W said that the claims it sought to invalidate were those set out in its Consolidated Particulars of Invalidity dated 6 February 2025 (T940). That document refers to a larger group of claims than the asserted claims. For example, in relation to the 223 Patent, it refers to all of the claims in the patent. This is inconsistent with [1] of B&W’s opening submissions on invalidity, which states that B&W alleges that “all asserted claims” are invalid. I propose to deal with B&W’s invalidity case on the basis put forward in [1] of its opening submissions on invalidity, namely that it is directed to all asserted claims (that is, all originally asserted claims). This reflects the way in which I understood the case to be run.

12 B&W relies on the following grounds in its Consolidated Particulars of Invalidity dated 6 February 2025:

(a) lack of novelty;

(b) lack of inventive step;

(c) disclosure does not include best method;

(d) lack of support;

(e) insufficiency; and

(f) lack of utility.

13 B&W contends that the Patents are not entitled to the asserted priority date of 3 July 2014. In summary, B&W contends that the invention claimed in each of the asserted claims is not disclosed in PCT434, as required by s 43 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) and the relevant regulations of the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth) (the Regulations). For the purpose of this proceeding, NOCO accepts that, if any claim is found not to be entitled to the 3 July 2014 priority date, the claim will be invalid for lack of novelty (see NOCO’s opening submissions on invalidity, [61]). I will refer to the issue whether the Patents are entitled to the asserted priority date of 3 July 2014 as the Priority Date issue.

14 A number of issues relating to the correct construction of the Patents are raised in the proceeding. These issues relate to the infringement claim or the invalidity cross-claim or both. The main construction issues are:

(a) There is an issue whether it is a requirement of the claims that the switch turn on (or close) automatically upon satisfaction of a precondition or preconditions. I will refer to this as the Automatic Start issue. For example, in relation to integer 1.7 of Claim 1 of the 223 Patent, the issue is whether the switch may turn on at any time after the preconditions are satisfied (as contended by NOCO), or whether it is a requirement that the switch turn on automatically upon satisfaction of the preconditions (as contended by B&W).

(b) There is an issue whether a device that can be operated in “manual mode” (thereby allowing a user to use the device without resorting to some or all of the safety features) falls within certain claims in the Patents. NOCO contends that the fact that a device can be operated in manual mode does not mean that it falls outside the scope of the relevant claims. B&W contends that such a device does not meet the requirements of the relevant claims. I will refer to this as the Manual Mode issue.

(c) In relation to claims that refer to “USB charging port”, “USB charging circuit”, etc, there is an issue whether these references encompass USB-C, which had not been released at the asserted priority date. NOCO contends that the relevant claims are not specific as to the type of USB and therefore include USB-C. B&W contends that the relevant claims do not include USB-C. I will refer to this as the USB issue.

15 The infringement issues that remained live at the time of closing submissions turned largely, if not entirely, on the outcome of the construction issues.

16 In relation to the lack of novelty ground, B&W relies on its contentions in relation to the Priority Date issue. B&W contends that, in any event, the Patents lack novelty. B&W relies on two pieces of prior art, namely:

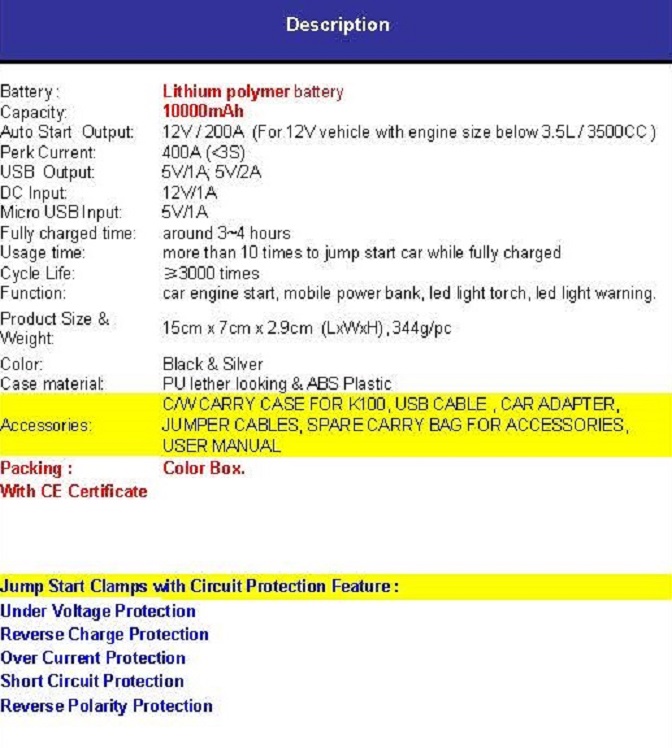

(a) a user manual for the Projecta HP 2012 and HP 2200 jump starters dated 9 August 2013 (the HP Manual). It appears that the letters “HP” in the product name stand for “High Performance”;

(b) a one-page document titled “Multi-Function Power Bank with JUMP START feature” that was circulated by Quitewin Technology Corporation in April 2014 (the QTC Brochure).

17 In relation to the lack of inventive step ground, B&W relies on:

(a) the common general knowledge alone; or

(b) the common general knowledge, together with either the HP Manual or the QTC Brochure (see s 7(2) and (3)(a) of the Patents Act).

18 In relation to the best method ground, a significant issue is the time at which knowledge is to be assessed. B&W contends that NOCO was required to disclose the best method known to it at the time of filing the complete application for each Patent (i.e. dates in 2020, 2021 and 2022). NOCO contends that the knowledge requirement should be assessed as at the filing date of PCT434, namely 3 July 2014.

19 The following is a summary of my conclusions in relation to the main issues in the proceeding:

(a) As to construction issues:

(i) In relation to the Automatic Start issue, in my view Claim 1 of the 223 Patent does not require that the switch automatically turn on upon satisfaction of the preconditions in 1.7.1 and 1.7.2. The same reasoning applies to the asserted claims with comparable wording. It does not apply to all of the asserted claims.

(ii) In relation to the Manual Mode issue, in my view a device that has a manual mode that allows the user to turn on the power switch in circumstances where no depleted/discharged battery is present, or in circumstances where the voltage of the depleted/discharged battery is so low that it cannot be detected, is inconsistent with and therefore outside the scope of Claim 1 of the 223 Patent and the other asserted claims that are relevant to this issue.

(iii) In relation to the USB issue, in my view the expressions in the Patents using “USB” encompass USB-C.

(b) In relation to the Priority Date issue, I consider that, for many of the asserted claims, the invention in the claim is not disclosed in PCT434. It follows that those asserted claims are not entitled to the asserted priority date. Further, it follows from NOCO’s concession that such claims are invalid for lack of novelty.

(c) I consider the particular grounds of invalidity relied on by B&W on the assumption that all asserted claims are entitled to the asserted priority date. On that basis:

(i) In my view, none of the asserted claims are invalid for lack of novelty.

(ii) I consider that all of the asserted claims are invalid for lack of inventive step.

(iii) I conclude that the best method ground is not made out.

(iv) It is unnecessary to consider, and I do not consider, the remaining grounds of invalidity.

20 I then consider the infringement issues on the assumption that (contrary to the above) all the asserted claims are valid. On this basis, I resolve each of the infringement issues raised by the parties. It is not practicable to summarise those conclusions.

Patents

223 Patent

21 The specification states at [0001] that the present invention relates generally to an apparatus for jump starting a vehicle having a depleted or discharged battery.

22 The section relating to the background to the invention has been referred to briefly in the Introduction to these reasons. The problems with the prior art are outlined in [0003] of the specification, which has been set out above.

23 The summary of the invention commences at [0013a], which is a consistory clause reflecting Claim 1. [0013a] is in the following terms:

The present invention provides a jump starter apparatus for boosting or charging a depleted or discharged battery having a positive battery terminal and a negative battery terminal, the apparatus comprising:

a power supply;

a positive battery connector for connecting the jump starter apparatus to the positive battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

a negative battery connector for connecting the jump starter apparatus to the negative battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

a power switch connected in circuit with the power supply and the positive and negative battery connectors, the power switch configured to turn power on or off from the power supply to the positive and negative battery connectors;

a control system or circuit connected to and controlling the power switch, the control system or circuit configured to detect presence of the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors and to detect polarity of the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors;

wherein the control system or circuit switches on the power switch to connect the power supply to the depleted or discharged battery only when the depleted or discharged battery is present and properly connected between the positive and negative battery connectors and the depleted or discharged battery is properly connected with a correct polarity between the positive and negative battery terminals.

(Emphasis added.)

24 [0013b]-[0013u] are consistory clauses that reflect the terms of Claims 2 to 21. [0014]-[0016] state as follows:

[0014] Also described herein is an apparatus for jump starting a vehicle engine, comprising: an internal power supply; an output port having positive and negative polarity outputs; a vehicle battery isolation sensor connected in circuit with said positive and negative polarity outputs, configured to detect presence of a vehicle battery connected between said positive and negative polarity outputs; a reverse polarity sensor connected in circuit with said positive and negative polarity outputs, configured to detect polarity of a vehicle battery connected between said positive and negative polarity outputs and to provide an output signal indicating whether positive and negative terminals of said vehicle battery are properly connected with said positive and negative polarity outputs of said output port; a power switch connected between said internal power supply and said output port; and a microcontroller configured to receive input signals from said vehicle isolation sensor and said reverse polarity sensor, and to provide an output signal to said power switch, such that said power switch is turned on to cause said internal power supply to be connected to said output port in response to signals from said sensors indicating the presence of a vehicle battery at said output port and proper polarity connection of positive and negative terminals of said vehicle battery with said positive and negative polarity outputs, and is not turned on when signals from said sensors indicate either the absence of a vehicle battery at said output port or improper polarity connection of positive and negative terminals of said vehicle battery with said positive and negative polarity outputs.

[0015] In accordance with an embodiment described herein, the internal power supply is a rechargeable lithium ion battery pack.

[0016] A jumper cable device may also be provided, having a plug configured to plug into said output port; a pair of cables integrated with the plug at one respective end thereof; said pair of cables being configured to be separately connected to terminals of a battery at another respective end thereof.

(Emphasis added.)

I note that, unlike [0013a] and Claim 1, which use the language of “only when”, [0014] uses the language of “in response to”.

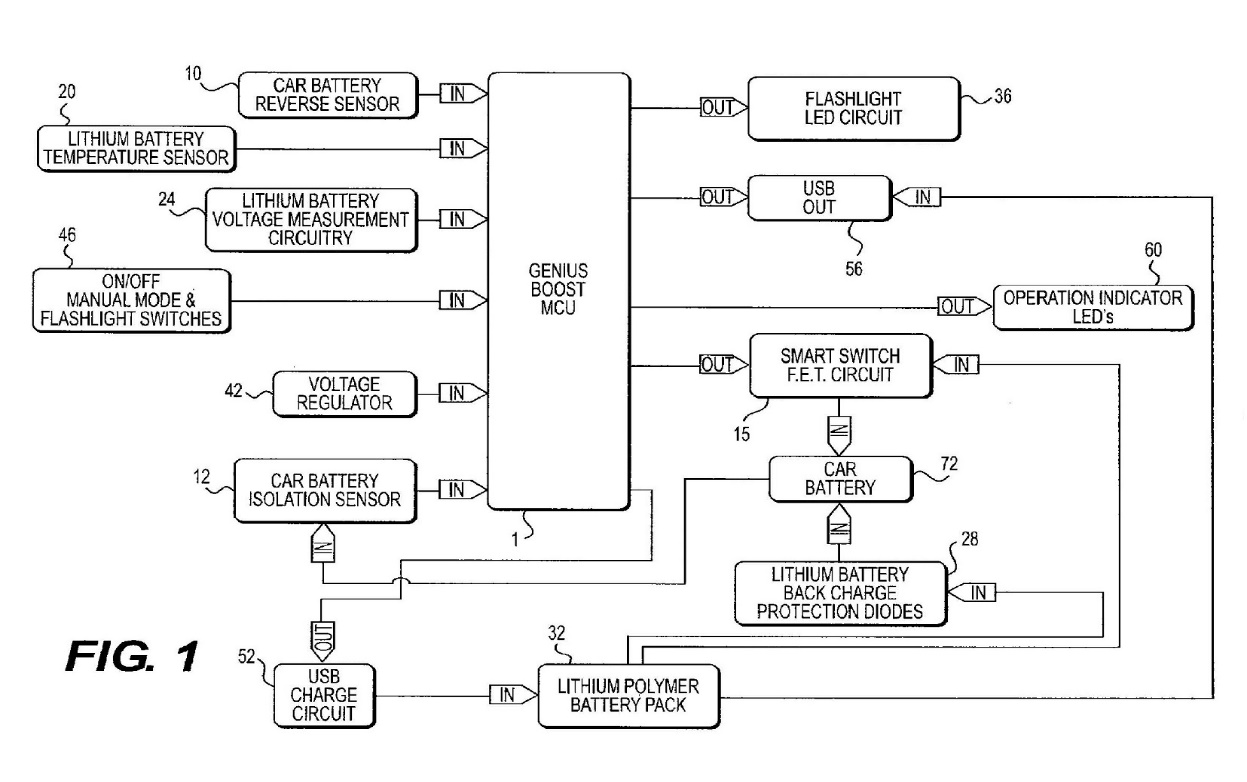

25 At [0018]-[0021], reference is made to Figures 1, 2A-2C, 3 and 4. Figure 1 is described as a functional block diagram of a handheld vehicle battery boost apparatus in accordance with one aspect of the present invention. Figure 1 is as follows:

26 The detailed description of the invention commences at [0022], which states (in relation to the preferred embodiment):

FIG. 1 is a functional block diagram of a handheld battery booster according to one aspect of the invention. At the heart of the handheld battery booster is a lithium polymer battery pack 32, which stores sufficient energy to jump start a vehicle engine served by a conventional 12 volt lead-acid or valve regulated lead-acid battery.

27 The apparatus can be controlled by a programmable microcontroller (MCU) and this unit is described at [0023].

28 Aspects of the operation of the apparatus of one aspect of the invention are elaborated upon at [0024] and [0025] by reference to circuits identified as a car battery reverse sensor (10) and a car battery isolation sensor (12). The isolation sensor is also known as the presence sensor. The specification provides at [0024]:

A car battery reverse sensor 10 monitors the polarity of the vehicle battery 72 when the handheld battery booster device is connected to the vehicle’s electric system. As explained below, the booster device prevents the lithium battery pack from being connected to the vehicle battery 72 when the terminals of the battery 72 are connected to the wrong terminals of the booster device. A car battery isolation sensor 12 detects whether or not a vehicle battery 72 is connected to the booster device, and prevents the lithium battery pack from being connected to the output terminals of the booster device unless there is a good (e.g. chargeable) battery connected to the output terminals.

29 As identified in [0024], the apparatus described operates so as to prevent the lithium battery pack from being connected to the vehicle battery when the terminals of the battery are connected to the wrong terminals of the booster device. This paragraph also refers to the other precondition, relating to presence of a vehicle battery.

30 This is explained further in [0025], which states in part:

A smart switch FET circuit 15 electrically switches the handheld battery booster lithium battery to the vehicle’s electric system only when the vehicle battery is determined by the MCU 1 to be present (in response to a detection signal provided by isolation sensor 12) and connected with the correct polarity (in response to a detection signal provided by reverse sensor 10).

31 The above passage refers to a smart switch “FET” circuit. “FET” stands for Field Effect Transistor. A FET switch is one example of an electrically operable electric switch (as opposed to a mechanically operable electric switch).

32 Features of the apparatus are discussed at [0026], where reference is made to the apparatus having a “manual mode”. That paragraph states in part:

On/Off manual mode and flashlight switches 46 allow the user to control power-on for the handheld battery booster device, to control manual override operation if the vehicle has no battery, and to control the flashlight function. The manual button functions only when the booster device is powered on. This button allows the user to jump-start vehicles that have either a missing battery, or the battery voltage is so low that automatic detection by the MCU is not possible. When the user presses and holds the manual override button for a predetermined period [of] time (such as three seconds) to prevent inadvertent actuation of the manual mode, the internal lithium ion battery power is switched to the vehicle battery connect port. The only exception to the manual override is if the car battery is connected in reverse. If the car battery is connected in reverse, the internal lithium battery power shall never be switched to the vehicle battery connect port.

33 Figure 1 of the specification (set out above) includes a manual mode button at item 46.

34 The specification refers to a USB charging circuit and USB charger power source in the preferred embodiment at [0027]:

USB charge circuit 52 converts power from any USB charger power source, to charge voltage and current for charging the lithium battery pack 32. USB output 56 provides a USB portable charger for charging smartphones, tablets, and other rechargeable electronic devices. Operation indicator LEDs 60 provide visual indication of lithium battery capacity status as well as an indication of smart switch activation status (indicating that power is being provided to the vehicle's electrical system).

35 The way in which the reverse sensor and the isolation sensor (each being optically coupled isolator phototransistors) operate in the preferred embodiment is explained in [0028] and [0029]:

[0028] Detailed operation of the handheld booster device will now be described with reference to the schematic diagrams of Figs. 2A-2C. As shown in Fig. 2A, the microcontroller unit 1 is the center of all inputs and outputs. The reverse battery sensor 10 comprises an optically coupled isolator phototransistor (4N27) connected to the terminals of vehicle battery 72 at input pins 1 and 2 with a diode D8 in the lead conductor of pin 1 (associated with the negative terminal CB-), such that if the battery 72 is connected to the terminals of the booster device with the correct polarity, the optocoupler LED 11 will not conduct current, and is therefore turned off, providing a “1” or high output signal to the MCU 1. The car battery isolation sensor 12 comprises an optically coupled isolator phototransistor (4N27) connected to the terminals of vehicle battery 72 at input pins 1 and 2 with a diode D7 in the lead conductor of pin 1 (associated with the positive terminal CB+), such that if the battery 72 is connected to the terminals of the booster device with the correct polarity, the optocoupler LED 11A will conduct current, and is therefore turned on, providing a “0” or low output signal to the MCU, indicating the presence of a battery across the jumper output terminals of the handheld booster device.

[0029] If the car battery 72 is connected to the handheld booster device with reverse polarity, the optocoupler LED 11 of the reverse sensor 10 will conduct current, providing a “0” or low signal to microcontroller unit 1. Further, if no battery is connected to the handheld booster device, the optocoupler LED 11A of the isolation sensor 12 will not conduct current, and is therefore turned off, providing a “1” or high output signal to the MCU, indicating the absence of any battery connected to the handheld booster device. Using these specific inputs, the microcontroller software of MCU 1 can determine when it is safe to turn on the smart switch FET 15, thereby connecting the lithium battery pack to the jumper terminals of the booster device. Consequently, if the car battery 72 either is not connected to the booster device at all, or is connected with reverse polarity, the MCU 1 can keep the smart switch FET 15 from being turned on, thus prevent[ing] sparking/short circuiting of the lithium battery pack.

36 As explained in the above paragraphs, each of the sensors will provide either a “0” (or low signal) or “1” (or high signal) to the MCU and these inputs can be used by the microcontroller software to determine when it is safe to turn on the power. The outputs from those circuits can be illustrated in the following table (based on NOCO’s opening submissions on infringement, as adjusted during the hearing):

Car battery 72 connection to the handheld booster device | Reverse | Isolation | Smart switch 15 |

Correct polarity | “1” or high | “0” or low | Closed (on) |

Reverse polarity | “0” or low | “1” or high | Open (off) |

Not connected | “1” or high | “1” or high | Open (off) |

37 One configuration of the power switch known as a FET switch is included in the circuit illustrated in the preferred embodiment and discussed at [0030] of the specification.

38 The specification at [0031] discusses the measurement of the voltage of the lithium battery, indicating that if the voltage is too low during discharge operation (or too high during charge) the MCU will not operate.

39 The temperature of the lithium battery is also monitored in the preferred embodiment. This is discussed in [0032]. The MCU will not allow jump starting if the internal lithium battery is too hot. The input of this sensor is shown in Fig 1 as Lithium Battery Temperature Sensor (20).

40 There is reference to a USB output circuit that allows for charging portable electronic devices in the description of the preferred embodiment at [0036]:

A USB output 56 circuit (Fig. 2C) is included to provide a USB output for charging portable electronic devices such as smartphones from the internal lithium battery pack 32. Control circuit 57 from the microcontroller 1 allows the USB Out 56 to be turned on and off by software control to prevent the internal lithium battery getting too low in capacity. The USB output is brought to the outside of the device on a standard USB connector 58, which includes the standard voltage divider required for enabling charge to certain smartphones that require it.

41 There is a further disclosure of a USB charge circuit that allows the internal lithium battery pack to be charged using a standard USB charger. It is stated at [0037]:

The USB charge circuit 52 allows the internal lithium battery pack 32 to be charged using a standard USB charger. This charge input uses a standard micro-USB connector 48 allowing standard cables to be used. The 5V potential provided from standard USB chargers is up-converted to the 12.4VDC voltage required for charging the internal lithium battery pack using a DC-DC converter 49. The DC-DC converter 49 can be turned on and off via circuit 53 by an output from the microcontroller 1.

42 The specification describes the physical features of a handheld device and a jumper cable device of the preferred embodiment at [0039]-[0040] by reference to Figures 3 and 4, which provide a depiction of the device and its jumper cables respectively.

43 The 223 Patent has 21 claims. There are two independent claims, namely Claims 1 and 21. Claim 1 has been set out in the Introduction to these reasons.

44 Claim 12 incorporates a lithium ion battery. Claim 12 is as follows (with numbers added):

(12.1) The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims,

(12.2) wherein the power supply comprises a lithium-ion battery disposed within the jump starting apparatus, and

(12.3) wherein the lithium-ion battery comprises a battery pack comprising multiple lithium ion batteries.

45 Claims 16, 17 and 18 refer to a USB charging port and a USB charging circuit, allowing the internal lithium battery pack to be charged using a USB charger. These claims are in the following terms (with numbers added):

(16.1) The apparatus according to any one of the preceding claims,

(16.2) further comprising a USB charging port configured to provide charging power from an external power source to the power supply.

(17.1) The apparatus according to claim 16,

(17.2) further comprising a USB charging circuit connecting the USB charging port to the power supply.

(18.1) The apparatus according to claim 17,

(18.2) wherein the USB charging circuit comprises a DC-DC converter.

46 Claim 20 has the language “wherein the DC-DC converter is configured to be turned on and off via a circuit by an output from a microcontroller”, anticipating the possibility of the MCU controlling that component.

059 Patent

47 The specification of the 059 Patent, including the description and figures, is largely in the same form as the body of the 223 Patent. The summary of the invention differs in that it contains different consistory clauses, reflecting the different claims.

48 The 059 Patent contains 25 claims. There are five independent claims – Claims 1, 14, 15, 21 and 24.

49 Claim 1 of the 059 Patent is in the following terms (with numbers added for ease of reference):

(1.1) A jump starting apparatus configured for boosting or charging a depleted or discharged battery having a positive polarity battery terminal and a negative polarity battery terminal, the jump starting apparatus comprising:

(1.2) a rechargeable battery;

(1.3) a positive polarity battery terminal connector configured for connecting the jump starting apparatus to the positive polarity battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

(1.4) a negative polarity battery terminal connector configured for connecting the jump starting apparatus to the negative polarity battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

(1.5) a power switch or circuit configured to turn on power from the rechargeable battery to the positive and negative polarity battery terminal connectors;

(1.6) a control system or circuit connected to and controlling the power switch, the control system or circuit configured to detect whether the positive and negative polarity battery terminal connectors have a proper or improper connection with the positive and negative polarity battery terminals of the depleted or discharged battery prior to turning on the power switch or circuit;

(1.7) a USB input charge circuit connected to the rechargeable battery, the USB input charge circuit comprising a DC/DC converter, the USB input charge circuit configured for converting power from a USB charger to increase charge voltage for charging the rechargeable battery; and

(1.8) a USB input connector connected to the USB input charge circuit, the USB input connector configured for connecting to the USB charger and providing charge input from the USB charger through the USB input connector and the USB input charge circuit to the rechargeable battery.

(Emphasis added.)

50 Claim 2 of the 059 Patent then further defines the rechargeable battery as a lithium ion battery.

338 Patent

51 The specification of the 338 Patent, including the description and figures, is also largely in the same form as the body of the 223 Patent. Again, the summary of the invention differs in that it contains different consistory clauses reflecting different claims.

52 The 338 Patent contains 36 claims. There are two independent claims – Claims 1 and 36.

53 Claim 1 of the 338 Patent is in the following terms (with numbers added for ease of reference):

(1.1) A jump starting device for boosting or charging a depleted or discharged battery having a positive battery terminal and a negative battery terminal, the jump starting device comprising:

(1.2) a rechargeable battery;

(1.3) a positive battery connector for electrically connecting the jump starting device to the positive battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

(1.4) a negative battery connector for electrically connecting the jump starting device to the negative battery terminal of the depleted or discharged battery;

(1.5) a power switch or switch circuit connected in series with the rechargeable battery and the positive and negative battery connectors, the power switch or switch circuit configured to switch power on from the rechargeable battery to boost or charge the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors;

(1.6) a USB input connector; and

(1.7) a USB charge circuit electrically connecting the USB input connector to the rechargeable battery, the USB charge circuit comprising a DC-DC converter configured to upconvert voltage from the USB input connector to the rechargeable battery.

The hearing and the evidence

54 The hearing, which was on liability only, occupied ten days.

55 Originally, this proceeding (VID 264 of 2023) was due to be heard together with The NOCO Company v Hong Kong Haowei Technology Co., Ltd. (VID 122 of 2023) (the Carku proceeding). However, that proceeding settled on 6 February 2025, shortly before the hearing was due to commence.

56 The Carku proceeding concerned the same patents as this proceeding and included a cross-claim alleging invalidity of the Patents. There was considerable overlap in the grounds of invalidity, but there were some differences. Prior to the settlement, the parties in both proceedings filed their opening submissions in chief (both on infringement and invalidity). In preparing those submissions, B&W and the Carku parties divided responsibility for the invalidity case. In other words, some grounds of invalidity were dealt with in the submissions of one party rather than by both parties.

57 Following the settlement of the Carku proceeding, B&W adopted some of the grounds of invalidity that the Carku parties had relied on as part of their case, but which had not formed part of B&W’s case. This was reflected in a document titled “Consolidated Particulars of Invalidity” dated 6 February 2025, which made clear which grounds of invalidity B&W relied on in this proceeding. B&W also adopted some of the submissions made by the Carku parties in their outline of opening submissions.

58 In relation to the best method ground, the parties proceeded on the basis that the contentions and submissions comprise or include material that is commercially sensitive. Accordingly, the Consolidated Particulars of Invalidity set out the details of this ground in a confidential annexure. The parties’ outlines of submissions similarly deal with this ground in confidential sections. In these circumstances, the parts of this judgment dealing with factual issues concerning the best method ground will be redacted for an initial period of time. The parties will be given the opportunity to apply for a further suppression or non-publication order in respect of that part of these reasons.

59 NOCO relied on evidence from the following lay witnesses:

(a) Mr James Richard (Rick) Stanfield, the Chief Technical Officer of NOCO. Mr Stanfield is an electrical engineer and one of the named inventors of the Patents;

(b) Mr Gavin Adkins, a solicitor and principal of Griffith Hack Lawyers, the solicitors acting for NOCO in the proceeding. Mr Adkins’s evidence related to B&W jump starters he purchased; and

(c) Ms Ellen Baker, a solicitor employed by Griffith Hack Lawyers. Ms Baker’s evidence related to certain website images.

60 Mr Stanfield was cross-examined during the hearing. Neither Mr Adkins nor Ms Baker was required to attend for cross-examination.

61 Mr Stanfield was a good witness. He gave clear answers to questions and accepted propositions without regard to whether they helped or harmed NOCO’s case. He was careful and considered. I generally accept his evidence. Where there are differences between his affidavit and oral evidence, I prefer his oral evidence.

62 B&W called expert evidence from Mr Jonathan (Jo) Banks, an industrial designer. Although Mr Banks was put forward as an independent expert, he had worked for B&W for many years. I would therefore not regard him as independent. However, I accept that he has considerable experience and expertise as an industrial designer. Mr Banks was cross-examined.

63 Mr Banks was a good witness. He answered questions clearly and succinctly. He was precise in his answers. He gave evidence in a straightforward way and made appropriate concessions. I will consider his evidence later in these reasons.

64 Both parties called evidence that comprised the translation of certain documents from the Chinese (Mandarin) language to the English language.

65 NOCO called evidence from Dr Xiangtong Xu, a registered Chinese patent attorney. Dr Xu prepared two affidavits, which went into evidence. Dr Xu was not required for cross-examination.

66 B&W called evidence from Ms Yang Liu, a registered Chinese patent attorney. Ms Liu’s evidence comprised a translation of Chinese Patent Utility Model Patent CN202696190 (CN190), which was published on 23 January 2013. In its opening submissions, B&W relied on CN190 as prior art for the purposes of its lack of novelty and lack of inventive step grounds. Ms Liu gave evidence by video-conference with the assistance of an interpreter. Ms Liu was cross-examined by one of the junior counsel for NOCO. Following the cross-examination (and, I infer, in light of it) B&W abandoned reliance on CN190. Accordingly, CN190 and Ms Liu’s evidence can be put to one side.

67 Each party called an expert witness in relation to electrical engineering and power electronics issues. The experts were:

(a) Mr Darrin Wilson, an electronic engineer, called by NOCO; and

(b) Professor Grahame Holmes, an electrical engineer, called by B&W.

68 Mr Wilson’s qualifications and experience are summarised in paragraphs 2, 3 and 10 to 14 of his affidavit dated 5 June 2024 (Wilson 1):

A. Engagement

2. I am an Electronic Engineer with over 30 years’ experience in power electronics, analogue and digital electronic hardware design, manufacturing and laboratory management. I have worked across a range of engineering roles, including Senior Project Engineer, Design Engineer and Product Manager and my qualifications are set out further in Section B below.

3. I am currently a Senior Design Engineer at Clevertronics Pty Ltd (Clevertronics). [Clevertronics] is an Australian emergency lighting specialist that designs, prototypes and tests all its luminaires and systems. I am also self-employed and provide consulting services in electronic design and manufacturing.

…

B. Training, study and experience

10. My qualifications and experience are largely in the area of Electronic Engineering. Electronic engineering is a discipline of electrical engineering focusing on low current and voltage electrical circuits (such as battery operated devices, computers, handheld devices, mobile phones and remote controls) and communications systems (such as hardware for radio transceivers and hardware for wireless and wired communications).

11. In my professional career I have worked across a range of engineering roles, including Senior Project Engineer, Design Engineer and Production Manager. My formal qualifications consist of a Bachelor of Engineering in Electronic Engineering from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (1991) and Master of Business Administration (MBA) from Monash University in 2012.

12. A detailed summary of my relevant qualifications and experience are set out in detail in my curriculum vitae (CV). Attached and marked Annexure DJW-47 is a copy of my CV.

13. I have been asked by Griffith Hack Lawyers to summarise my professional work experience up to and including 2014. I have set out that summary in paragraphs 13 to 31 of my First VID122/2023 Affidavit which I have already annexed as Annexure DJW-45.

14. As a result of my training, study and experience I believe that I have developed specialised knowledge of at least the following:

(a) the design and components of electronic engineering systems, including hardware, firmware and software;

(b) the functionality and integration of sensors in electronic engineering systems, including voltage, current, light, temperature and magnetic sensors; and

(c) the functionality and integration of power supply solutions in the design of electronic engineering systems.

69 Professor Holmes is an Honorary Professor of Smart Energy Systems at RMIT University, Melbourne. He has held that position since retiring as Professor of Smart Energy Systems at RMIT in 2020. Professor Holmes’s qualifications and experience are set out in Section B of his affidavit dated 6 September 2024 (Holmes 1). In that section, Professor Holmes states that he is an electrical engineer and that electrical engineering encompasses a range of specialties and sub-areas. Since 1984, he has specialised in power electronics, which is an area of electrical engineering that deals with the control and conversion of electrical energy, and the design of electrical circuits to achieve that control and conversion. Professor Holmes’s relevant experience, as detailed in Section B of that affidavit, is extensive.

70 Each of the experts prepared a number of affidavits.

71 A process was put in place for the preparation of a joint expert report. This process included the expert witness to be called by the respondents to the Carku proceeding, Professor David Ricketts. The three experts – Mr Wilson, Professor Holmes and Professor Ricketts – prepared a joint expert report dated 23 January 2025 (the Joint Expert Report). In circumstances where, because of the resolution of the Carku proceeding, Professor Ricketts was not called to give evidence, an evidentiary issue arose in relation to the parts of the report that were authored by Professor Ricketts. These fall into two categories: in some places, opinions are expressed by Professor Ricketts individually; in other places, opinions are expressed by Professor Ricketts together with one or both of Mr Wilson and Professor Holmes. While it was a straightforward matter simply to not admit into evidence the opinions expressed individually by Professor Ricketts and to treat jointly expressed opinions as the opinions of Mr Wilson or Professor Holmes or both (as applicable), in some cases the opinions expressed individually by Professor Ricketts provided context for opinions expressed by the other experts. In light of this, I made a ruling pursuant to s 136 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) that the Joint Expert Report be admitted into evidence subject to the limitation that all statements attributed to “Professor Ricketts” or “DR” (or “the Experts” to the extent it is a reference to Professor Ricketts) be admitted solely for the purpose of providing context for any response to such statements provided by another expert or experts.

72 Mr Wilson and Professor Holmes gave evidence concurrently during the hearing, over four days. The evidence was structured around a series of topics, as agreed between the parties. Both experts gave evidence in a careful and considered way. Both had a command of the subject matter and were of considerable assistance to the Court.

Person skilled in the art

73 The “skilled addressee”, or “person skilled in the relevant art” (Patents Act, s 7(2)), is a hypothetical person (or team) who has a “practical interest in the subject matter of [the] invention” and who might be “interested in making, constructing, compounding or using the invention”: Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 980; 49 IPR 225 (Root Quality) at [70]-[71] per Finkelstein J.

74 Such a person was described by French CJ in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 at [23] as a “tool of analysis”, and his Honour explained that this hypothetical person is not an “avatar” for the views of the particular expert witnesses who give evidence in a proceeding – it is a “pale shadow of a real person”.

75 The person skilled in the art is assumed to be a skilled but non-inventive worker in the field of the invention: Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd [1980] HCA 9; 144 CLR 253 (Minnesota Mining) at 293 per Aickin J. The person skilled in the art may comprise a team: Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly & Co [2005] FCAFC 224; 68 IPR 1 (Pfizer) at [288] per French and Lindgren JJ; Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307 at [149] per Yates J.

76 In the present case, there is no real issue between the parties as to the identification of the person or team that constitutes the “person skilled in the art”. It is common ground that the “person skilled in the art” is or includes an electrical engineer with experience in power electronics, such as Mr Wilson and Professor Holmes.

77 B&W submits that, in addition, if a company was seeking to design a new jump starter at the asserted priority date, an industrial designer would also be involved. NOCO accepts that the notional team includes a manufacturer (product designer). Thus, it appears to be common ground that, for the purposes of the inventive step issue, the “person skilled in the art” is a team that includes a product designer.

Common general knowledge

78 The common general knowledge may be described as “the background knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade in considering the making of new products, or the making of improvements in old”: Minnesota Mining at 292.

79 Professor Holmes describes the underlying core concepts and well understood components and safety features used in power electronics circuitry before the asserted priority date in Holmes 1 at [69]-[149]. Mr Wilson describes Professor Holmes’s evidence as “reasonably comprehensive” and only seeks to “clarify” a small number of points: see Mr Wilson’s third affidavit (dated 15 November 2024) (Wilson 3) at [16]-[22]. Professor Holmes’s evidence is summarised in B&W’s opening submissions on invalidity at [11]-[17]. In closing submissions, NOCO provided a document headed “NOCO’s Response to CGK alleged in BWI’s Aide-memoire to BWI’s s 7(2) arguments”. It appears from [3.2] and [3.3] of NOCO’s response that it accepts the summary at [11]-[17] of B&W’s opening submissions on invalidity.

80 In light of the above, I find that the common general knowledge relating to power electronics as at the asserted priority date included the matters set out at [81]-[87] below. In addition, I make findings about the common general knowledge at [88]. I will refer to other aspects of the common general knowledge later in these reasons.

Power electronics – basic electrical concepts

81 Power electronics is an area of electrical engineering that deals with the control and conversion of electronic energy, and the design of electrical circuits that achieve that control and conversion.

82 It was common general knowledge in the field of power electronics that current (I) is measured in amps (A) and refers to the amount of flow of electricity in a system, whereas voltage is measured in volts (V) and refers to the degree of force behind current. There are two forms of current – direct current (DC), which refers to circuits with a one-way flow of electricity, and alternating current (AC), which refers to circuits in which the flow of electricity alternates backward and forward and swaps polarity. Energy is the product of voltage and current. The equation for electrical power is Power (P) (being measured in watts (W)) = Current (I) x Voltage (V), (P=IV); so that, for example, 5V applied at 2A gives 10 watts of power. Resistance (R) is measured in Ohms (Ω) and refers to the degree to which a circuit (or, more broadly, any substance or component) impedes the flow of electrical current induced by a particular voltage. Ohm’s law provides that Voltage (V) = Current (I) x Resistance (R).

83 The arrangement of electronic components to achieve a function (i.e., a conversion of power from one type to another) is often described as a topology or circuit topology. Where components are connected in a single path through which energy will flow, they are described as being in series, whereas where components are connected in multiple paths through which electricity may flow simultaneously, they are described as being in parallel.

84 Electrical circuits may deal with signals that are binary (eg, either “0” or “1”, such as a switch that is open or closed) and described as digital; or signals that are continuously variable (eg, a measurement of voltage) and described as analog.

Power electronics – components and protective features

85 By the asserted priority date, there were a range of well-understood components that were routinely used in power electronics circuitry, including:

(a) Integrated circuits (IC), a semiconductor (typically silicon) bearing many transistors and other electronics on a single “wafer” or “board”.

(b) Control circuitry, being the circuit components which handle the processing of inputs and outputs. The most common “programmable” ICs, by the asserted priority date, were microprocessors (sometimes called microcontrollers or MCUs), being digital electronic circuits built into an IC that would be programmed to execute software.

(c) Transistors and switches, being the components used to close (i.e., connect) or open (i.e., disconnect) an electrical circuit (or portion thereof). Switch circuitry controls the flow of energy by withstanding voltage when turned “off” and conducting current when turned “on”. Necessarily, this requires such components to withstand the maximum voltage and current of a product. At the asserted priority date, relevant switches included: (i) solenoids (also called relays), which provided robust switching, but were relatively large and slow; and (ii) semiconductor switches, including field-effect transistors (FET), which could switch faster and were smaller and lighter than solenoid switches.

(d) Sensors and sensing circuits, which are used to measure a parameter, commonly voltage and current (as a direct value and as a proxy for other parameters), and provide an input to an electrical circuit. Voltage and current are both analog signals. At the asserted priority date, the measurement of those signals typically involved electrically isolating the signal, conditioning the signal to a reduced voltage or current suitable for control circuitry, and then converting the analog signal to a digital signal to be “read” by a microcontroller. It was common to measure voltage by using: (i) an optical isolation structure (to isolate the power circuit from the control circuit); or (ii) a resistor divider (to reduce the measured voltage without isolation). It was common to measure current by using a Hall-effect sensor (a device that detects magnetic fields produced by current, with the magnetic field changing as a current changes). There were a very large number of sensors available at the asserted priority date that were purpose built for particular sensing operations.

(e) Isolation components, being components which allow a signal to be transferred between circuitry, without an electrical connection. At the asserted priority date there were a range of isolation components that were commonly used in power electronics circuits. A particularly common isolation component was an optocoupler, being a device with: (i) a light emitting diode (LED), connected to the circuit that is to transmit a signal; and (ii) a phototransistor, which is connected to the circuit that is to receive a signal. If the LED is illuminated, the phototransistor will turn on in response, allowing a signal to transfer from the circuit connected to the LED to the circuit connected to the phototransistor, without an electrical connection between the two.

(f) Power converters, being the electrical components which convert one voltage or current to another voltage or current, including where necessary converting from AC to DC (and vice versa). There were step down or buck converters (where the output voltage was lower than the input voltage) and step up or boost converters (where the output voltage was higher than the input voltage). A common type of power converter was a DC-DC converter.

(g) Analog to digital converters (being the circuitry used to convert a variable analog signal into a binary value) and digital to analog converters (vice versa).

(h) Batteries, being remote energy sources that allow a power electronics circuit to be used when disconnected from a fixed electrical circuit. It was common general knowledge that: (i) power generated by batteries is always DC (and so must be converted to AC where the load being powered requires AC power); (ii) batteries can be single use or rechargeable; and (iii) two common battery chemistries in power electronics were lead acid batteries and lithium-based batteries. The growing availability of lithium-based batteries was a key advance before the asserted priority date, as they could generate higher energy density and currents than lead acid-based batteries (thereby enabling the use of smaller and lighter batteries). To charge a rechargeable battery, it was known that DC current must be used and that as the charge of a battery increases, so does its voltage (such that level of charge can be measured by sensing voltage). Battery control circuitry was commonly used (often in the form of “off-the-shelf” ICs and microprocessors) to: (i) take measurements indicating the status of a battery; (ii) manage the charging process; (iii) prevent excessive charging; and (iv) prevent the battery from discharging too much power.

(i) Connection components, being the components used to electrically connect a power electronics circuit to another circuit. Such connections could be permanent (eg, soldered) or temporary (i.e., “quick fit” connections, such as three-pin wall connectors, USB connectors, and alligator clips).

86 Irrespective of the precise components used, it was common general knowledge at the asserted priority date that an important aspect of power electronics was the potential for hazard and damage if something went wrong. Accordingly, a key aspect of designing a power electronics circuit involved the incorporation of safety features, to avoid hazard or damage if a product was connected or operated improperly.

87 At the asserted priority date, common safety features incorporated in power electronics circuits included: (i) short-circuit protection (a way of detecting and protecting against the over-current created by an unintended direct connection); (ii) controlled shut down (circuits designed to detect a failing input power supply and shut down the system in a controlled fashion); (iii) reverse polarity protection (circuits designed to detect whether a power electronic circuit and load are connected with correct polarity and, in the event of reverse polarity, either prevent power from flowing the wrong way back into the power electronic circuit or avoid connecting the power electronic circuit to the load); and (iv) temperature overload protection (circuits designed to detect excessive heat and either shut down the system or reduce performance of the system to reduce heat).

Lithium batteries

88 During the course of Mr Banks’s oral evidence, reference was made to different types of lithium batteries. Mr Banks gave evidence, which I accept, that the overarching category is lithium ion batteries and that, within that category, one subset is lithium iron phosphate batteries and another subset is lithium cobalt batteries (T403). He also said (and I accept) that the expression lithium polymer batteries would generally be associated with lithium cobalt batteries (T403). Mr Wilson gave evidence to the same effect (T795). Having regard to the context in which Mr Wilson gave that evidence, I find that these categories formed part of the common general knowledge as at the asserted priority date.

Construction issues

Applicable principles

89 In UbiPark Pty Ltd v TMA Capital Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 885, I summarised the applicable principles relating to claim construction at [55]-[63]. I adopt that summary. For ease of reference, I set out that summary in the following paragraphs.

90 In Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd [2005] FCAFC 90; 222 ALR 155, the Full Court of this Court (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) summarised the principles of construction as follows (at [67]):

There is no real dispute between the parties as to the principles of construction to be applied in this matter although there is some difference in emphasis. It suffices for present purposes to refer to the following:

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 at [81] (Flexible Steel Lacing); and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1; 177 ALR 460; 50 IPR 513; [2001] HCA 8 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221 at 224-5; (1938) 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485-6 (Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd); the court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd at 485-6.

91 In Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd v Australian Mud Company Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 162; 145 IPR 39, the Full Court set out, at [93]-[96], a number of key principles that are also relevant here. I refer to those principles without setting them out. I note also the following principles and observations.

92 In GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 71; 264 FCR 474 (GSK), the Full Court (Middleton, Nicholas and Burley JJ) provided the following guidance in relation to purposive construction (at [106]):

More recent cases have continued to emphasise the need to read a patent specification as a whole and in light of the common general knowledge. They also confirm that a patent specification should be read in a practical and common sense way and given a “purposive” construction. This approach to construction requires the court to read the specification through the eyes of the skilled addressee with practical knowledge and experience in the field of work in which the invention was intended to be used and a proper understanding of the purpose of the invention.

93 In GSK (at [108]) the Full Court quoted with apparent approval the following passage from the judgment of Lord Hoffmann in Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd (2004) 64 IPR 444 at [34]:

“Purposive construction” does not mean that one is extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims. The question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean. And for this purpose, the language he has chosen is usually of critical importance. The conventions of word meaning and syntax enable us to express our meanings with great accuracy and subtlety and the skilled man will ordinarily assume that the patentee has chosen his language accordingly. As a number of judges have pointed out, the specification is a unilateral document in words of the patentee’s own choosing. Furthermore, the words will usually have been chosen upon skilled advice. The specification is not a document inter rusticos for which broad allowances must be made. On the other hand, it must be recognised that the patentee is trying to describe something which, at any rate in his opinion, is new; which has not existed before and of which there may be no generally accepted definition. There will be occasions upon which it will be obvious to the skilled man that the patentee must in some respect have departed from conventional use of language or included in his description of the invention some element which he did not mean to be essential. But one would not expect that to happen very often.

94 Consistently with the above, an expert witness cannot assist the court with the meaning of an ordinary English word (or phrase) unless it has a special or unusual meaning within an area of technology: see Minnesota Mining at 272; see also Kinabalu Investments Pty Ltd v Barron & Rawson Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 178 (Kinabalu) at [45] per Sundberg, Emmett and Greenwood JJ.

95 In Commissioner of Patents v Rokt Pte Ltd [2020] FCAFC 86; 277 FCR 267, Rares, Nicholas and Burley JJ explained at [73]:

The role of expert evidence in construing the patent specification and the claims is limited. It is to place the Court in the position of the person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture as at the priority date …

96 To similar effect, in Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd [2000] FCA 890; 49 IPR 331, Hely J stated at [81]:

[T]he construction of the specification is for the court, not for the expert. In so far as a view expressed by an expert depends upon a reading of the patent, it cannot carry the day unless the court reads the patent in the same way.

97 The above passage has been cited with approval by three Full Courts: Kinabalu at [44]-[45]; Austal Ships Sales Pty Ltd v Stena Rederi Aktiebolag [2008] FCAFC 121; 77 IPR 229 at [14]; and PAC Mining Pty Ltd v Esco Corp [2009] FCAFC 18; 80 IPR 1 at [29].

98 In Multigate Medical Devices Pty Ltd v B Braun Melsungen AG [2016] FCAFC 21; 117 IPR 1 at [23]-[28], Bennett, Yates and Beach JJ made a series of related observations about the role of expert evidence in patent cases on issues of construction.

Consideration

99 I will now consider, in turn, each of the construction issues identified in NOCO’s opening submissions on infringement. The issues are relevant to infringement or invalidity or both. Some of the issues have fallen away in light of the narrowing of the parties’ cases during the hearing. This will be indicated below.

100 I will approach the construction issues as at the asserted priority date. That is, I will approach the issues on the basis of how the skilled addressee would have understood the Patents as at that date.

Construction issue 1: sensor to detect polarity

101 Construction issue 1 (as identified by NOCO) relates to integer 1.6.2 in Claim 1 of the 223 Patent (and comparable wording in other asserted claims). That integer requires the control system or circuit to be configured “to detect polarity of the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors”. In B&W’s opening submissions on infringement (which deal with construction issues) this construction issue is discussed in terms that relate to integer 1.6.1 as well as 1.6.2. Integer 1.6.1 requires the control system or circuit to be configured “to detect presence of the depleted or discharged battery when connected between the positive and negative battery connectors”.

102 There is a lack of clarity in the parties’ submissions as to the identification of this issue.

103 NOCO’s submissions are directed to whether detection of polarity is to occur regardless of whether the connectors are connected.

104 B&W submits that “when connected” is a temporal limitation that requires the control system, circuit or sensors (depending on the particular claim) to be configured to make the specific detections (i.e. present or not, correct polarity or not) at the time specified in the asserted claims. However, B&W submits, the asserted claims do not assume battery presence. B&W submits that: the asserted claims are directed to an apparatus, not a method; the control system, circuit or sensors of that apparatus must be “configured” to make the specified detections; the asserted claims encompass such an apparatus, irrespective of whether it is, in fact, connected to a vehicle battery. In B&W’s closing propositions (at [8]) and in its closing oral submissions (at T881) it seemed to be making a different point, namely that a reasonable construction of “when connected” is “upon and while connected”, thus including the time after switch closure.

105 In relation to whether the vehicle battery needs to be connected at the time of detection for the purposes of integer 1.6.2, in my view, the answer is Yes. This is clear from the words “when connected” in integer 1.6.2. Further, as a matter of practicality, detection of polarity can only occur when the vehicle battery is connected. This conclusion is supported by the opinion of both experts expressed in the Joint Expert Report, Section A, page 3, lines 86 to 88, where they state:

All claims that refer to “configured for detection” or “detection of”, “polarity”, “correct polarity”, “proper polarity” and “improper polarity”, require the vehicle battery to be connected to the jumpstarter connectors to make the polarity determination.

106 In relation to whether the asserted claims assume battery presence, I accept that they do not, for the reasons given by B&W in its opening submissions.

107 In relation to whether “when connected” is to be construed as “upon and while connected”, this issue appears to overlap with construction issue 2, which I deal with next.

Construction issue 2: Operation before switch closure

108 This construction issue relates to integer 1.7 in Claim 1 of the 223 Patent (and comparable wording in other asserted claims). NOCO’s contention is that the claim does not concern the operation of the apparatus after the circuit switches on the power switch.

109 B&W questioned Mr Wilson about this issue (eg, at T441, 447-450, 455). Mr Wilson accepted that if you do not detect presence after the switch is turned on, there is a risk that one lead will come off, there will be shorting, and you will not have solved the problems identified in the patent. Notwithstanding this and other concessions in Mr Wilson’s evidence, in my view the focus of Claim 1 is on turning on the power switch. Thus, it is concerned with detection of polarity and presence before that occurs and not after it occurs.

Construction issues 3 and 4: Automatic Start issue