Federal Court of Australia

Watson Webb Pty Ltd v Comino [2025] FCA 871

File number(s): | NSD 1335 of 2021 NSD 1337 of 2021 | |

Judgment of: | HALLEY J | |

Date of judgment: | 30 July 2025 | |

Catchwords: | DESIGN – entitlement – identification of co-designer for purposes of s 13(1)(a) of the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (Designs Act) – whether first respondent was only person whose mind conceived relevant shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation applicable to article in question and reduced it to visible form – where design combined features that could be found in prior art – where a visual feature internal and constrained by function – whether first reduction to visible form can occur via multiple documents created on different occasions – where second applicant co-designer DESIGN – validity – whether designs are new or distinctive over prior art base – whether designs are substantially similar in overall impression – s 16(2) of the Designs Act – s 19 of the Designs Act – regard to freedom to innovate – more weight to be given to similarities than differences – whether confidential document forms part of prior art base – minor visual differences – where designs valid DESIGN – infringement – whether first applicant’s products identical or substantially similar in overall impression to registered designs – relevant test – consideration of similarities and differences – infringement not established – application for relief for unjustified threats pursuant to s 77 of the Designs Act – whether impugned letter constituted a threat or mere notification pursuant to s 80 of Designs Act – operation of s 78 and whether conduct to which the threats relate constitute, or would constitute, infringement – whether discretion should be exercised not to grant relief for unjustified threat – threat not established COPYRIGHT – infringement under s 36 of Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act) – where design drawings copied to obtain design registration – whether respondents had implied licence – whether respondents entered into common design or authorised infringement – application of s 75 and s 77 of Copyright Act to design drawings – infringement established – second applicant entitled to an account of profits and additional damages EQUITY – breach of confidence – whether design drawings possessed necessary quality of confidence – whether drawings were received by respondents in circumstances importing an obligation of confidence – whether duty of confidence conversely owed by respondents to second applicant – breach of confidence established – second applicant entitled to account of profits awarded – whether constructive trust can be imposed over design rights of first respondent – where constructive trust to be imposed CONTRACTS – breach of contract – whether restricted use clause in contract extended to subsequent design drawing – whether intention to induce breach of contract – actual knowledge or reckless indifference – breach of contract not established – tort of inducing breach of contract not established CONSUMER LAW – whether respondents, in trade or commerce, engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or was likely to mislead or deceive contrary to s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) – whether respondents made representations by silence – whether representations were representations as to a future matter and were not made on reasonable grounds pursuant to s 4(1) of the ACL – contraventions established PATENTS – cross-claim for invalidity – patent for brackets used for holding pipes – construction of patent specification – whether specification failed to describe the best method of performing the invention known to patent applicant – whether patent invalid for want of clarity – whether patent invalid for want of sufficiency and support – whether patent invalid for want of novelty or lack of an innovative step – whether prior use of relevant information had been ‘publicly available’ – invalidity established PATENTS – infringement – whether second respondent had an exclusive licence – whether first applicant infringed patent by making, selling, or supplying products within the profile of patent – infringement not established | |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, Australian Consumer Law ss 4, 18, 232, 236, 237 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 35, 36, 74, 75, 76, 77, 77A, 115, 184 Designs Act 2003 (Cth) ss 5, 7, 13, 15, 16, 19, 71, 75, 76, 77, 78, 80, 93 Designs Amendment (Advisory Council on Intellectual Property Response) Act 2021 (Cth) Patents Act 1990 (Cth) ss 40, 122, Sch 1 Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) s 52 (repealed) Copyright (International Protection) Regulations 1969 (Cth) reg 4 | |

Cases cited: | Albany Molecular Research Inc v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2011) 90 IPR 457; [2011] FCA 120 Ansell Rubber Co Pty Ltd v Allied Rubber Industries Pty Ltd [1967] VR 37 Aspirating IP Limited v Vision Systems Limited (2010) 88 IPR 52; [2010] FCA 1061 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Lenah Game Meats Pty Ltd (2001) 208 CLR 199; [2001] HCA 63 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Group Ltd (2020) 281 FCR 108; [2020] FCAFC 162 Bathurst City Council v PWC Properties Pty Ltd (1998) 195 CLR 566 Becton Dickinson Pty Ltd v B Braun Melsungen AG [2018] FCA 1692 Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65 Calix Ltd v Grenof Pty Ltd (2023) 171 IPR 582; [2023] FCA 378 City of Sydney v Streetscape Projects (Australia) Pty Ltd (2011) 94 IPR 35; [2011] NSWSC 1214 Computermate Products (Aust) Pty Ltd v Ozi-Soft Pty Ltd (1988) 20 FCR 46 Council of the City of Sydney v Goldspar Pty Ltd (2004) 62 IPR 274 Cranleigh Precision Engineering Ltd v Bryant [1965] 1 WLR 1293 Crown Resorts Ltd v Zantran Pty Ltd (2020) 276 FCR 477; [2020] FCAFC 1 Décor Corp Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 Del Casale v Artedomus (Aust) Pty Limited (2007) 73 IPR 326; [2007] NSWCA 172 Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky (1992) 39 FCR 31; [1992] FCA 557 Edwards v Liquid Engineering 2003 Pty Ltd (2008) 77 IPR 115 Elwood Clothing Pty Ltd v Cotton On Clothing Pty Ltd (2008) 172 FCR 580; [2008] FCAFC 197 Foster’s Australia Ltd v Cash’s Australia Ltd (2013) 219 FCR 529 Giumelli v Giumelli (1999) 196 CLR 101 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 474; [2018] FCAFC 71 GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd (2022) 166 IPR 551; [2022] FCA 520 Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd (2016) 121 IPR 1 IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458; [2009] HCA 14 Interstate Parcel Express Co Pty Ltd v Time-Life International (Nederlands) BV (1977) 138 CLR 534; [1977] HCA 52 Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298; [1959] HCA 9 Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86; [2005] FCAFC 90 Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1; [2001] HCA 8 Krueger Transport Equipment Pty Ltd v Glen Cameron Storage & Distribution Pty Ltd (2008) 78 IPR 262; [2008] FCA 803 LED Technologies Pty Ltd v Elecspess Pty Ltd (2008) 80 IPR 85; [2008] FCA 1941 Liberty Financial Pty Ltd v Jugovic [2021] FCA 607 Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (2004) 217 CLR 274; [2004] HCA Martin v Scribal Pty Ltd (1954) 92 CLR 17; [1954] HCA 48 Mastec Australia Pty Ltd v Trident Plastics (SA) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 1581 Merck Sharpe & Dohme Corporation v Wyeth LLC (No 3) 155 IPR 1; [2020] FCA 1477 Miele & Cie KG v Bruckbauer [2025] FCA 537 Miller & Associates Insurance Broking Pty Ltd v BMW Australia Finance Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 357 Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253; [1980] HCA 9 Natural Colour Kinematograph Co Ltd (In liquidation) v Bioschemes Ltd (1915) 32 RPC 256 Optus Networks Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2010] FCAFC 21; (2010) 265 ALR 281 Oxworks Trading Pty Ltd v Gram Engineering Pty Ltd (2019) IPR 215; [2019] FCAFC 240 Pearson v Morris Wilkinson & Co (1906) 23 RPC 738 QAD Inc v Shepparton Partners Collective Operations Pty Ltd (2021) 159 IPR 285; [2021] FCA 615 Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd v Astrazeneca AB (2013) 101 IPR 11 S W Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466; [1985] HCA 59. Saltman Engineering Co Ltd v Campbell Engineering Co Ltd (1948) 65 RPC 203 Schering Biotech Corp’s Application [1993] RPC 249 Sheldon v Metrokane (2004) 135 FCR 34; [2004] FCA 19 Shepparton Partners Collective Operations Pty Ltd v QAD Inc [2021] FCAFC 206 Smart EV Solutions Pty Ltd v Guy [2023] FCA 1580 State of Escape Accessories Pty Limited v Schwartz (2022) 166 IPR 242; [2022] FCAFC 63e TCT Group Pty Ltd v Polaris IP Pty Ltd (2022) 170 IPR 313; [2022] FCA 1493 Terrapin Ltd v Builders’ Supply Co (Hayes) Ltd (1959) 1B IPR 777; [1960] RPC 128 ToolGen Incorporated v Fisher (No 2) [2023] FCA 794 Trumpet Software Pty Ltd v Ozemail Pty Ltd (1996) 34 IPR 481 Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2018) 266 FCR 631; [2018] FCAFC 155 Vawdrey Australia Pty Ltd v Krueger Transport Equipment Pty Ltd (2009) 261 ALR 269; [2009] FCAFC 156 Warman International Ltd v Dwyer (1995) 182 CLR 544; [1995] HCA 18 Warner-Lambert Co LLC v Apotex Pty Ltd (No 2) (2018) 129 IPR 205; [2018] FCAFC 26 Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588; [1961] HCA 91 Zetco Pty Ltd v Austworld Commodities Pty Ltd (No 2) [2011] FCA 848 | |

Division: | General Division | |

Registry: | New South Wales | |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property | |

Sub-area: | Copyright and Industrial Designs | |

Number of paragraphs: | 666 | |

Date of last submission/s: | 9 May 2024 | |

Date of hearing: | 8-11, 15-19 April, 14-15 May 2024 | |

Counsel for the Applicants: | Mr P Flynn SC with Mr J Elks | |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Watson Webb | |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr A Fox SC with Ms J McKenzie | |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Bird & Bird | |

ORDERS

NSD 1335 of 2021 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | WATSON WEBB PTY LTD (FORMERLY WATSON CHIARELLA PTY LTD) Appellant | |

AND: | JOHN ALEXANDER COMINO Respondent | |

order made by: | HALLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 July 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties provide to the associate to Halley J agreed or, if not agreed, competing, draft orders giving effect to these reasons, including as to the costs of the proceeding, by no later than 4.00 pm on Thursday, 14 August 2025.

2. The proceeding be listed for a case management hearing for the purpose of resolving any outstanding issue in relation to orders to give effect to these reasons, including as to costs, at 9.30 am on Monday 18 August 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1337 of 2021 | ||

BETWEEN: | ALL VALVE INDUSTRIES PTY LTD First Applicant CAV. UFF. GIACOMO CIMBERIO S.P.A Second Applicant | |

AND: | JOHN ALEXANDER COMINO First Respondent STRONGCAST PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | JOHN ALEXANDER COMINO First Cross-Claimant (First Cross-Claim) STRONGCAST PTY LTD Second Cross-Claimant (First Cross-Claim) | |

AND: | ALL VALVE INDUSTRIES PTY LTD Cross-Respondent (First Cross-Claim) | |

AND BETWEEN: | ALL VALVE INDUSTRIES PTY LTD Cross-Claimant (Second Cross-Claim) | |

AND: | JOHN ALEXANDER COMINO Cross-Respondent (Second Cross-Claim) | |

order made by: | HALLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 July 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended notice of cross-claim filed by the first cross-claimant on 17 May 2022 be dismissed.

2. The parties otherwise provide to the associate to Halley J agreed or, if not agreed, competing, draft orders giving effect to these reasons, including as to the costs of the proceeding, by no later than 4.00 pm on Thursday, 14 August 2025.

3. The proceeding be listed for a case management hearing for the purpose of making directions for the determination of issues as to quantum and resolving any outstanding issue in relation to orders to give effect to these reasons, including as to costs, at 9.30 am on Monday, 18 August 2025.

[Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011]

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

HALLEY J:

A. Introduction

A.1. Overview

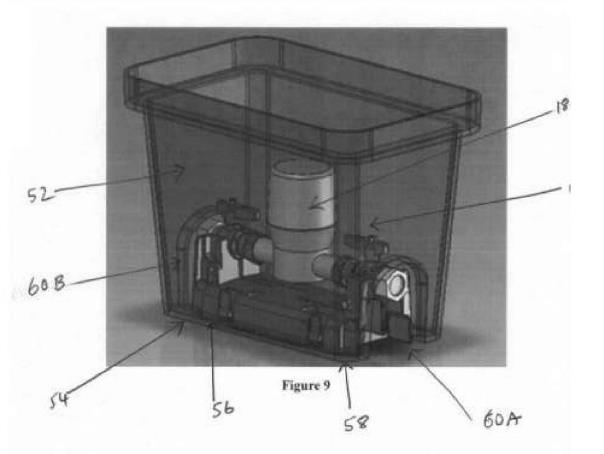

1 These two interrelated proceedings arise from a breakdown in commercial relationships between parties relevantly engaged in the design, fabrication, manufacture, importation and distribution of valves, meter boxes and brackets for water distribution systems.

2 The first proceeding is an appeal by Watson Webb Pty Ltd, as the solicitor for All Valve Industries Pty Ltd (AVI) and Cav.Uff. Giacomo Cimberio S.p.A. from a decision of the Australian Designs Office concerning the ownership of two registered Australian designs for valves numbered 201811005 (005 Design) and 201811810 (810 Design) (together, Designs). The respondent to the appeal, Mr John Comino, is recorded on the Australian Designs Register as the owner of both Designs.

3 In the second proceeding, AVI and Cimberio advance claims against Mr Comino and his company, Strongcast Pty Ltd, for copyright infringement, breach of confidence, breach of contract and inducing breach of contract, contraventions of s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), invalidity of the Designs, and making unjustified threats of design infringement. AVI and Cimberio contend that any rights held by Mr Comino in the Designs are held on constructive trust for Cimberio.

4 There are two cross-claims in the second proceeding. Mr Comino and Strongcast cross-claimed against AVI (First Cross-Claim) for infringement of the Designs by importing into Australia and selling valves that are identical or substantially similar in overall design to the Designs (AVI Ball Valves) and associated water meter assemblies (AVI Water Meter Assemblies) for infringement of claims 1 to 4 in an Australian Innovation Patent with respect to a bracket for holding pipes numbered 2017100757 (757 Patent). Mr Comino was recorded on the Patent Register as the owner of the 757 Patent until it expired on 18 July 2024. AVI, in turn, cross-claims against Mr Comino, claiming that claims 1 to 4 of the 757 Patent are invalid (Second Cross-Claim).

5 In these reasons for judgment, I refer to AVI and Cimberio as the applicants and I refer to Mr Comino and Strongcast as the respondents.

6 The parties have prepared a statement of agreed facts and issues for determination.

7 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that:

(a) Cimberio was (at least) a co-designer of the Designs and an entitled person at the time of the registration of each of the Designs for the purposes of the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (Designs Act);

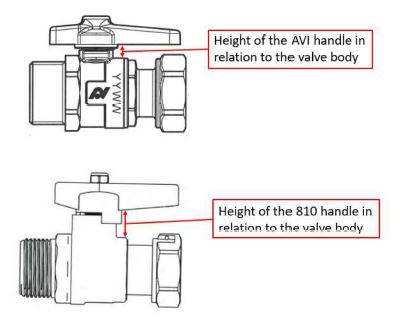

(b) both of the Designs are distinctive over the design of the C6827 Valve (the valve provided by AVI to Strongcast, which AVI had sourced and obtained from Cimberio);

(c) the AVI Ball Valves are not identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the 810 Design;

(d) the letter dated 28 February 2020 that was sent by Foundry Intellectual Property Pty Ltd, on behalf of Mr Comino, to each of the applicants referring to the 005 Design (Foundry IP letter) did not constitute an unjustified threat under s 77 of the Designs Act;

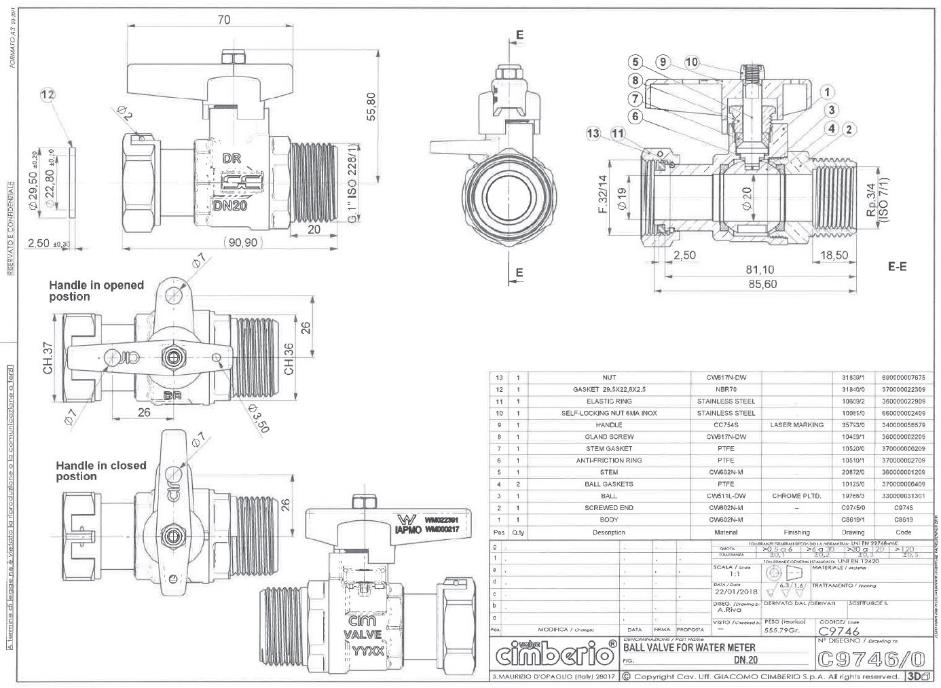

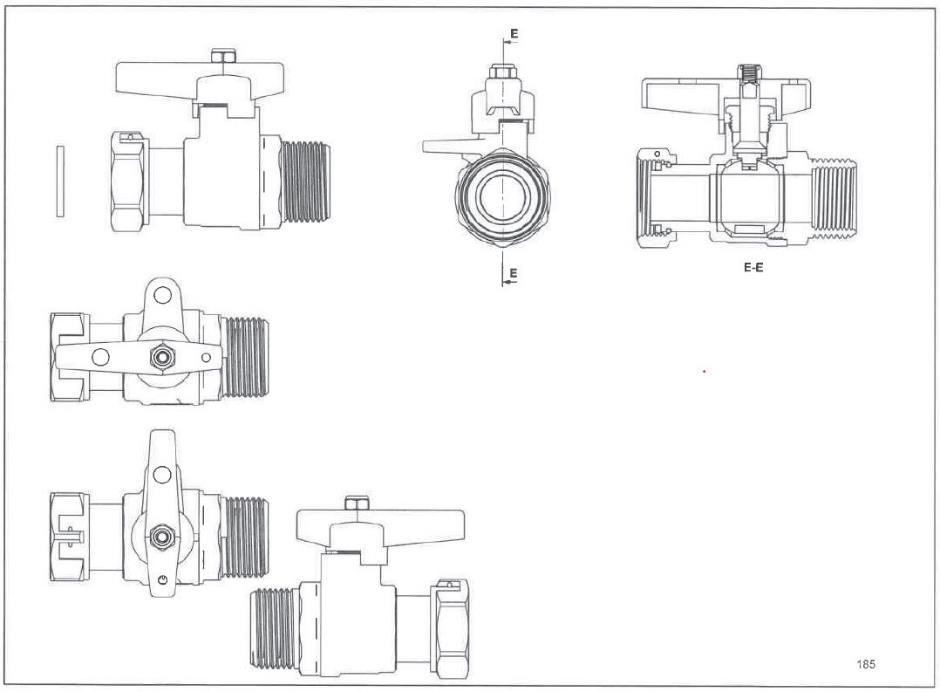

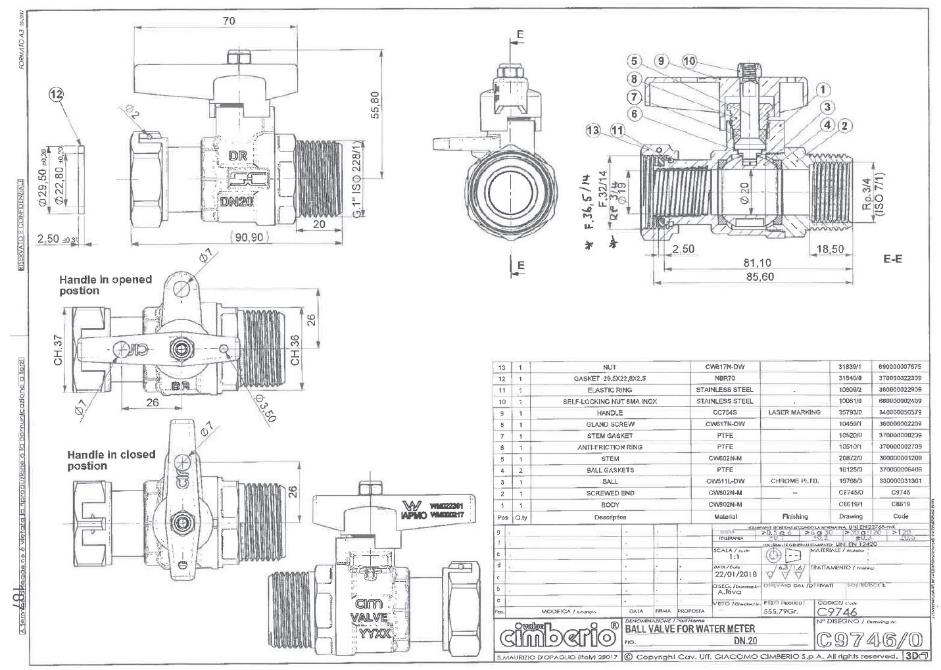

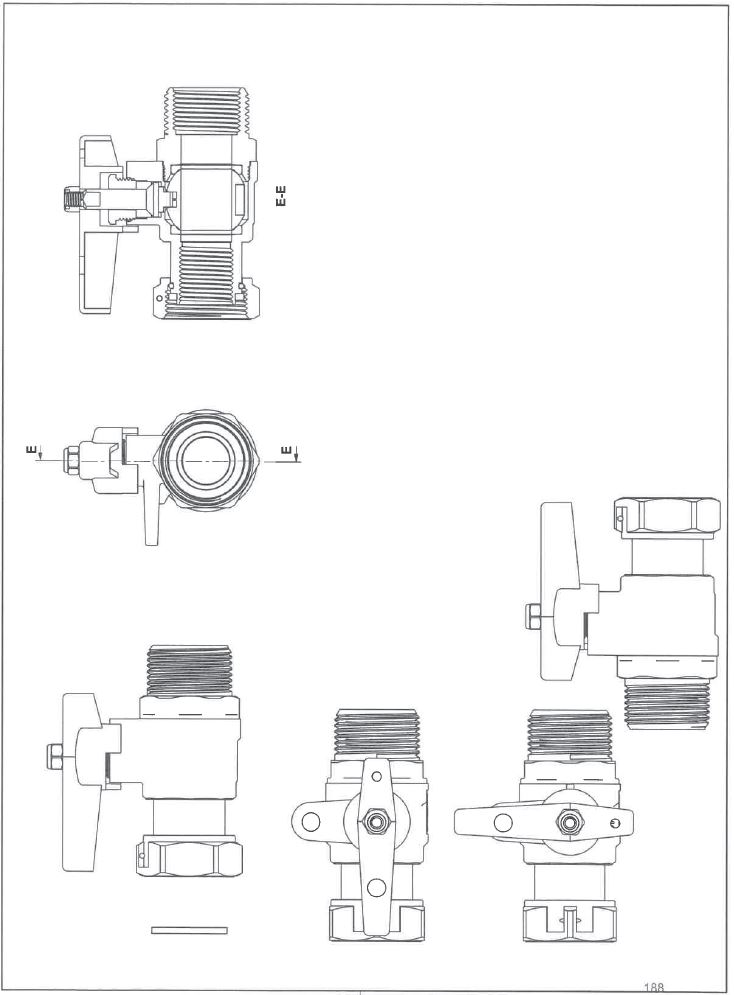

(e) the respondents directly infringed the copyright of Cimberio in the C9746 Design Drawing (a drawing of a valve with a lockable handle and an internal thread numbered C9746/0) by providing it, wholly or in substantial part, to Infinity Design Pty Ltd (Infinity Design) in February 2018, to their patent attorney for the purpose of registering the Designs and by their patent attorney, as their agent, to the Designs Office;

(f) the respondents authorised the infringement by Infinity Design of the copyright of Cimberio in the C9746 Design Drawing in February 2018;

(g) the respondents breached the obligations of confidence that they owed to Cimberio in disclosing the C9746 Design Drawing to Infinity Design, their patent attorney for the purpose of registering the Designs and by their patent attorney, as their agent, to the Designs Office and using it for an extraneous purpose;

(h) the written agreement entered into between Strongcast and AVI on 16 July 2013 entitled “Product Distribution Agreement” (Distribution Agreement) did not extend or apply to the C9746 Design Drawing;

(i) the respondents contravened s 18 of the ACL by making representations to the effect that they would only use the C9746 Design Drawing for the purpose of signing off the drawing prior to manufacture by Cimberio and would not apply for an application to register a design in respect of the C9746 Valve or use the C9746 Design Drawing for that purpose;

(j) claims 1 to 4 of the 757 Patent are invalid and should be revoked as each lacks clarity, support and/or sufficiency under s 40(2)(a) or s 40(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (Patents Act);

(k) had I otherwise found that the 757 Patent was valid, AVI did not infringe the 757 Patent by supplying any of the AVI Brackets or the AVI Water Meter Assemblies.

8 It follows that the applicants have succeeded on design entitlement and infringement, breach of copyright and obligations of confidence, the ACL claims, patent invalidity and, had it otherwise arisen, patent infringement, but not on their design invalidity and breach of contract claims.

9 As for relief, I have concluded that:

(a) Cimberio is entitled to an order for an account of profits, or subject to any election to the contrary, damages, from the respondents with respect to the respondents’ infringement of their copyright in the C9746 Design Drawing;

(b) Cimberio is entitled to additional damages pursuant to s 115(4) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act) from the respondents with respect to the respondents’ infringement of their copyright in the C9746 Design Drawing;

(c) an order is to be made revoking the registration of each of the Designs;

(d) a declaration is to be made that each of Cimberio and Mr Comino was an entitled person in respect of each of the Designs at the time it was registered;

(e) a declaration is to be made that Mr Comino holds his interest in the Designs on a constructive trust in favour of Cimberio and an order should be made that his interest is to be transferred to Cimberio;

(f) the applicants are entitled to damages and/or compensation pursuant to s 236 and/or s 237 of the ACL for any loss they have suffered by reason of the respondents’ contraventions of s 18 of the ACL;

(g) a declaration is to be made that the 757 Patent is invalid;

(h) an order is to be made revoking the 757 Patent.

10 The quantification of the account of profits or damages and additional damages under the Copyright Act and damages and/or compensation under the ACL are to be determined at a subsequent hearing on the quantum of pecuniary relief pursuant to the order separating liability and quantum made by Jagot J on 5 July 2021 in NSD 1337/2021.

A.2. Glossary

11 I have used the following defined terms in these reasons:

Defined Term | Definition |

005 Application | An application for what became upon registration 005 Design filed by Mr Comino’s patent attorney with the Designs Office in Mr Comino’s name on 20 February 2018 |

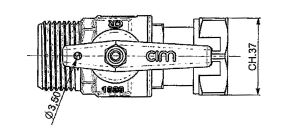

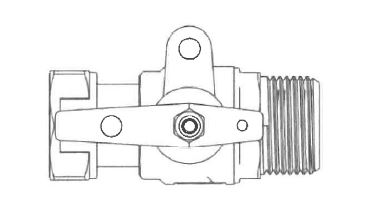

005 Design | Registered design for valve numbered 201811005 |

757 Patent | Australian Innovation Patent with respect to a bracket for holding pipes numbered 2017100757 |

757 Patent Specification | The specification of the 757 Patent published by the Australian Patent Office on 20 July 2020 |

810 Application | An application for what became upon registration 810 Design filed by Mr Comino’s patent attorney with the Designs Office in Mr Comino’s name on 23 March 2018 |

810 Design | Registered design for valve numbered 201811810 |

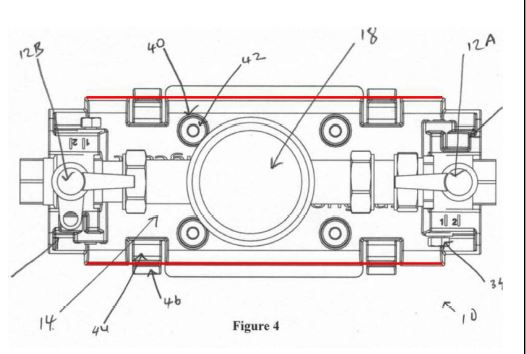

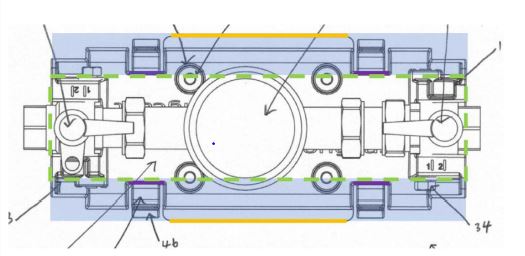

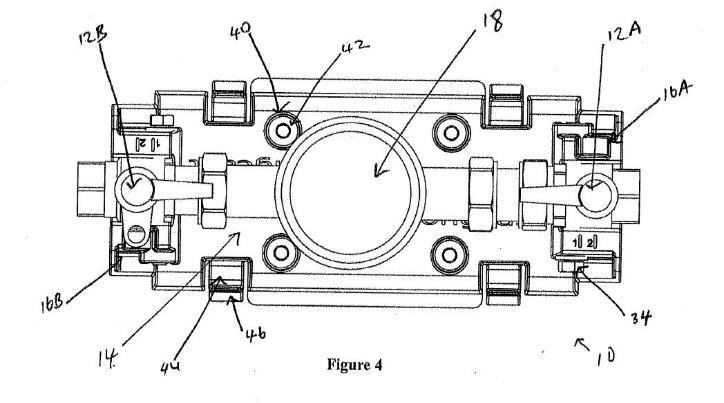

Additional Differences | Three differences between the AVI Ball Valve and the 810 Design identified by Mr Smerdon in addition to the Principal Differences |

Airaga | Airaga Rubinetterie S.p.A. |

Annotated C9746 Design Drawing | An attachment sent by Mr Comino to Mr Murphy which was an annotated version of the C9746 Design Drawing |

Asserted Claims | Claims 1 to 4 of the 757 Patent |

AVI Water Meter Assemblies | Water meter assemblies supplied by AVI with the AVI Ball Vales |

AVI | All Valve Industries Pty Ltd |

AVI Ball Valves | QLD Ball Valve and NSW Ball Valve being valves that the respondents allege are identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to the Valves |

AVI Brackets | First AVI Bracket, the Second AVI Bracket and the Third AVI Bracket, together |

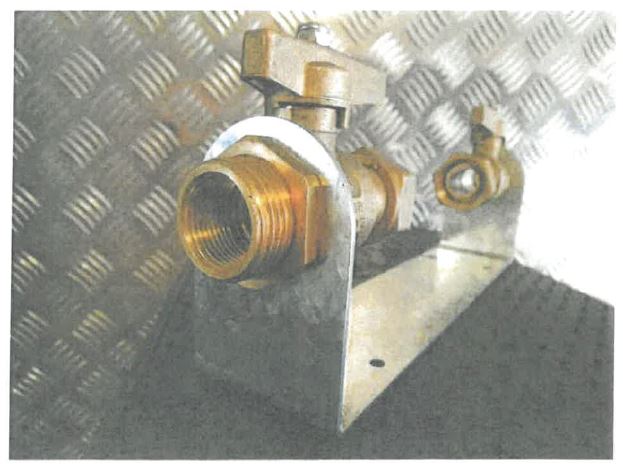

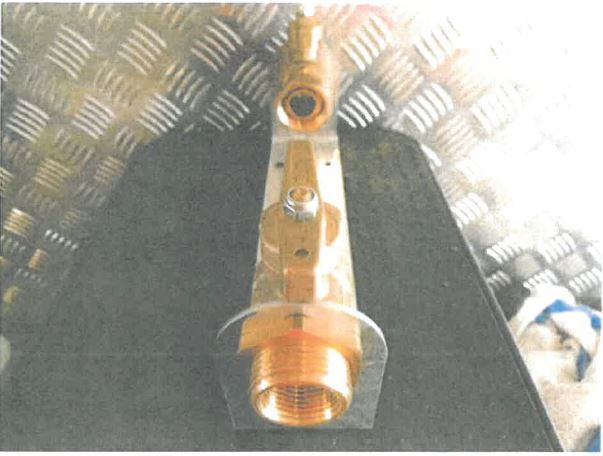

C6827 Valve | A ball valve provided by AVI to Strongcast, which AVI had sourced and obtained from Cimberio |

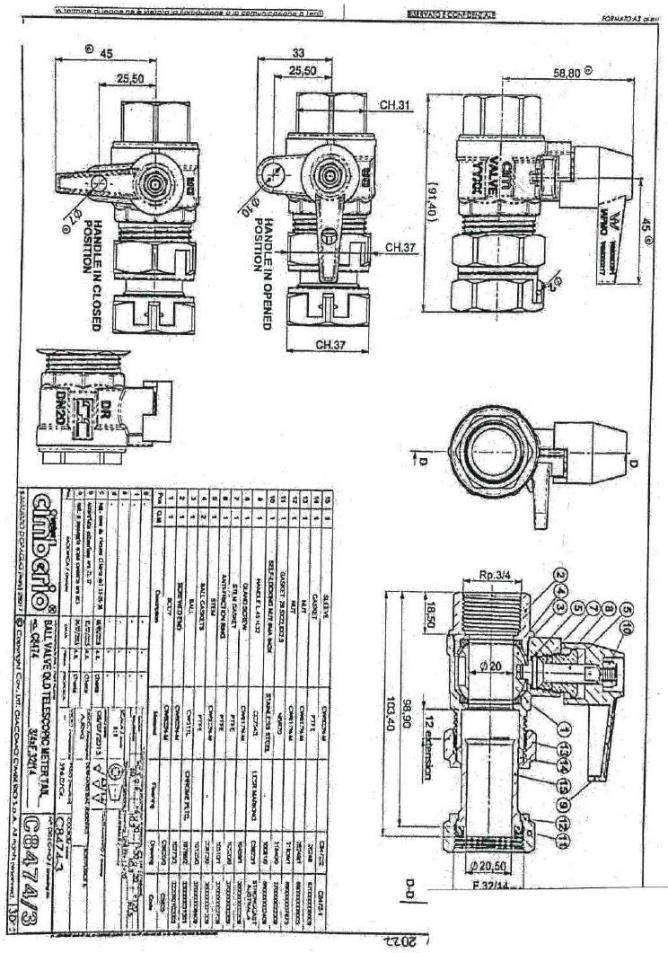

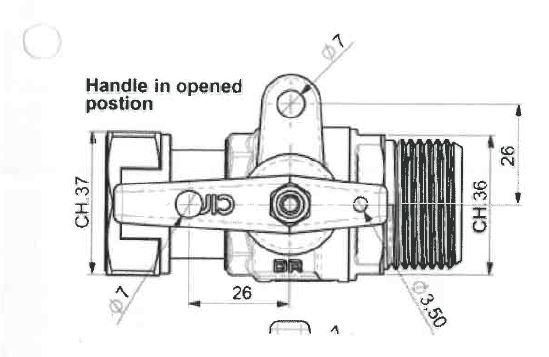

C6827 Design Drawing | Design drawing C6882/0 that has been renumbered as 31820/0 and the item code of which has been changed to Cim C6827 |

C9746 Valve | Valve with a lockable handle and an internal thread |

C9746 Design Drawing | Drawing of a valve with a lockable handle and an internal thread numbered C9746/0 |

Cimberio | Cav.Uff. Giacomo Cimberio S.p.A |

Designs | The 810 Design and 005 Design |

Distribution Agreement | Written agreement entered into between Strongcast and AVI on 16 July 2013 entitled “Product Distribution Agreement” |

Draper | Draper Enterprises Ltd |

Draper Catalogue | Draper new product catalogue printed in approximately January 2015 |

Draper Products | The products marketed in the Draper Catalogue |

Dual Thread Feature | A thread machined into the bore of the nozzle to provide both male and female coupling options |

Elster Metering | Elster Metering Pty Ltd |

First AVI Bracket | A bracket that, during the period from 28 July 2020 to 3 September 2021, AVI sold, offered to sell, kept for those purposes and imported as part of the Inground Water Meter Assembly |

First Cross-Claim | Cross-claim filed by Mr Comino and Strongcast in NSD 1337 of 2021 for infringement of the Designs and for infringement of claims 1 to 4 in an Australian Innovation Patent with respect to a bracket for holding pipes numbered 2017100757 |

First Edited C9746 Design Drawing | An edited version of the C9746 Design Drawing, which was materially the same as the C9746 Design Drawing other than the removal of the Cimberio trademarks and detailing, and the addition of a second female internal thread |

Foundry IP letter | A letter dated 28 February 2020 that was sent by Foundry Intellectual Property Pty Ltd, on behalf of Mr Comino, to each of the applicants which referred to the 005 Design. |

Humes | Humes Limited |

Infinity Design | Infinity Design Pty Ltd |

Inground Water Meter Assembly | A product supplied to customers in Australia by AVI called the “INGROUND WATER METER ASSEMBLY” by reference to the product codes AVMB-2BSP/TD8 and AVMB-1BSP/TD8 |

lnground Water Meter Assembly Brochure | Online advertising by AVI of the Inground Water Meter Assembly |

Machinery Solutions | Machinery Solutions Pty Ltd |

NSW Ball Valve | Valve sold by AVI in New South Wales from approximately December 2019 |

Principal Differences | Visual differences that experts, Mr Smerdon and Mr Hunter, agreed separated the 810 Design from the prior art (namely, the C6827 Valve), being the locking wing with a through hole added to the valve body, a hole in the valve lever and a dual threaded connection in the valve opposite the swivel nut. |

QLD Ball Valve | Valve sold by AVI in Queensland from approximately December 2019 |

QUU | Queensland Urban Utilities |

RCR Laser | A company commissioned by Mr Comino to produce a locking plate |

Representations | The following representations, together, that the applicants allege were made by Mr Comino, on his own behalf, and on behalf of Strongcast, by silence: (a) they would only use design drawings as provided to them in respect of the modified form of the C6827 Valve for the purposes of “signing off” on those drawings prior to their manufacture by Cimberio; (b) one or both of them did not intend or otherwise consider it to be a possibility that they would make an application for one or more registered designs in respect of the modified form of the C6827 Valve; and (c) one or more of them did not intend or otherwise consider it to be a possibility that one or more design drawings with which they were to be provided would be used in an application for one or more registered designs. |

Second AVI Bracket | A modified version of the First AVI Bracket that from 27 May 2021, AVI sold, offered to sell, kept for those purposes and imported |

Second Cross-Claim | Cross-claim filed by AVI in NSD 1337 of 2021 against Mr Comino claiming that claims 1 to 4 of the 757 Patent are invalid. |

Second Edited C9746 Design Drawing | A further edited version of the C9746 Design Drawing, which was materially the same as the drawing, other than the removal of the Cimberio trademarks and detailing |

Strongcast | Strongcast Pty Ltd |

Sub Meter Assemblies | Sub meter assembly kits advertised and sold by AVI with the product codes SMLIM and SMA20M |

Third AVI Bracket | A bracket that AVI has sold, offered to sell, kept for those purposes and imported into Australia from approximately May 2021 |

US 400 | US Patent No. 3,913,400 |

US 548 | US Patent No. 4,809,548 |

A.3. Dramatis personae

12 The following are the principal persons referred to in these reasons for judgment:

Mr Gianni (or Giovanni) Airaga | The Chief Operating Officer of Airaga |

Mr Roberto Cimberio | A director of Cimberio |

Mr John Comino | The sole director of Strongcast, the first respondent, the first cross-claimant in the first cross-claim and the first cross-respondent in the second cross-claim in NSD 1337 of 2021 |

Mr Daniel Dillenbeck | The Marketing Manager at AVI |

Ms Anna Ellis | The manager of Draper |

Mr William Hunter | A mechanical engineer and an expert witness retained by the respondents to provide independent expert evidence in the proceedings in relation to design and patent issues |

Mr Trent Kilner | The managing director of AVI |

Mr Andrea Milani | A representative of Airaga, with whom Mr Comino met in Italy on 19 March 2018 |

Dr George Mokdsi | Patent searcher and a director of The Patent Searcher Pty Ltd |

Mr Dan Murphy | Studio Manager at Infinity Design |

Mr Andrew Nicholls | Currently a landscaper, but in the period between 2013 and 2019, he was employed by Draper in various roles in the family business that had been established by his grandfather |

Mr Alexander Richardson | An industrial designer, currently the managing director and owner of Design Edge and an expert witness retained by the respondents to provide independent expert evidence in the proceedings in relation to design invalidity issues |

Mr Augusto Riva | A technical project development designer for Cimberio |

Mr Kevin Smerdon | A consultant mechanical engineer and product designer, currently the director of AusCreate Pty Ltd, and the expert witness retained by the applicants to provide independent expert evidence in the proceedings in relation to design and patent invalidity and infringement issues |

Mr Alec Tonkin | A solicitor employed by Watson Webb, the solicitor for the applicants |

B. Witnesses

B.1. The applicants’ lay evidence

13 The applicants relied on lay evidence from six witnesses.

14 Mr Trent Kilner is the managing director of AVI. Mr Kilner affirmed three affidavits in the proceedings. In his first affidavit, Mr Kilner gave evidence directed at design issues, addressing AVI’s relationship with Cimberio and Strongcast, the sharing of design drawings between Cimberio, AVI and Strongcast, the involvement of AVI in the development of the C6827 Valve and the C9746 Valve (a valve with a lockable handle and an internal thread), his knowledge of the registration of the Designs by Strongcast, and the complaints made by Strongcast about the AVI Ball Valves. In his second affidavit, Mr Kilner gave evidence on patent issues directed at the holes in the First AVI Bracket (a bracket that, during the period from 28 July 2020 to 3 September 2021, AVI sold, offered to sell, kept for those purposes and imported as part of the Inground Water Meter Assembly), the Second AVI Bracket (a modified version of the First AVI Bracket that from 27 May 2021, AVI sold, offered to sell, kept for those purposes and imported), and the bolts in the Third AVI Bracket (a bracket that AVI has sold, offered to sell, kept for those purposes and imported into Australia from approximately May 2021). Mr Kilner also gave evidence directed at the use of recesses in each of the First AVI Bracket, the Second AVI Bracket and the Third AVI Bracket (together, the AVI Brackets). Mr Kilner was cross-examined.

15 Mr Kilner gave evidence directly and did not seek to engage in any advocacy. He made appropriate concessions, and I was satisfied that he was answering questions honestly and to the best of his recollection. In particular, he accepted that Mr Daniel Dillenbeck, Marketing Manager at AVI, was the main point of contact between AVI and Strongcast, to his knowledge Mr Comino spoke and dealt almost exclusively with Mr Dillenbeck since early 2013 and he personally did not have any discussions with Mr Comino about product design. He also accepted, without prevarication, that two paragraphs in a statutory declaration that he gave to the Designs Office were in error and objectively misleading.

16 Mr Augusto Riva is a technical project development designer for Cimberio. Mr Riva has been employed in Cimberio’s Technical and Design team for almost 30 years and swore two affidavits in the proceedings. Mr Riva gave evidence of the background to Cimberio, the relationship between Cimberio and AVI, the Cimberio design process and his involvement in the design of the C6827 Valve and the C9746 Valve. Mr Riva was cross-examined with the assistance of an interpreter.

17 Mr Riva was an impressive witness. I am satisfied, after giving due allowance for the inherent difficulties of being cross-examined on technical issues through an interpreter, that he answered questions directly and without prevarication. I gave more weight, however, to his oral evidence than his affidavit evidence. As the respondents submitted, Mr Riva’s affidavits were prepared in an unorthodox fashion. Mr Riva’s affidavits were translated from Italian into English with the assistance of Mr Cimberio’s secretary, who is not an accredited translator, and online translation services. As a general principle, if a witness can only give evidence orally with the assistance of an interpreter, it is highly desirable, particularly in giving evidence on technical matters, that accredited translators are used for the purpose of preparing affidavit evidence and the necessary certifications are made on the affidavit.

18 Ms Anna Ellis is the manager of Draper Enterprises Ltd (Draper). Ms Ellis affirmed one affidavit in the proceedings. She gave evidence directed at prior art for the patent invalidity case, in particular, Draper new product catalogue printed in approximately January 2015 (Draper Catalogue), the sale of products featured in the Draper Catalogue, and two invoices for the sale of Draper Products (the products marketed in the Draper Catalogue) in 2013 and 2014. Ms Ellis was cross-examined.

19 Mr Andrew Nicholls is currently a landscaper but in the period between 2013 and 2019, he was employed by Draper in various roles in the family business that had been established by his grandfather. Mr Nicholls swore one affidavit in the proceedings. Mr Nicholls is the brother of Ms Ellis. Mr Nicholls gave evidence of his involvement in the preparation of the Draper Catalogue and the distribution of the catalogue in Australia and New Zealand.

20 Both Ms Ellis and Mr Nicholls were cross-examined as to their personal knowledge of the publication of the Draper Catalogue and the sale of Draper Products before the priority date for the 757 Patent. Both answered questions directly and without prevarication and made appropriate concessions. I was satisfied that I could accept their evidence.

21 In addition, Dr George Mokdsi gave evidence concerning publication dates of two United States designs, and Mr Alec Tonkin, a solicitor employed by the solicitor for the applicants, gave evidence on chain of custody issues for the copy of the Draper Catalogue admitted into evidence. Neither was cross-examined.

B.2. The applicants’ failure to call witnesses

22 The respondents contend that a critical consideration is that neither Mr Roberto Cimberio, a director of Cimberio, who gave evidence before the Designs Office below, nor Mr Daniel Dillenbeck, who was the person at AVI who dealt with Mr Comino and Mr Cimberio, gave evidence for the applicants.

23 The respondents submit that both Mr Riva and Mr Kilner gave evidence of their limited involvement on important issues to be determined, in particular, that Mr Riva did not deal directly with Mr Comino; Mr Cimberio was the person who dealt with the commercial arrangements with clients; Mr Dillenbeck was the AVI representative responsible for AVI’s relationship with Strongcast in the period since early 2013; and Mr Kilner did not have any discussions with Mr Comino about new product design.

24 The respondents submit that the applicants ought to have called evidence from Mr Cimberio and Mr Dillenbeck if they were going to seriously dispute the evidence given by Mr Comino. They submit that the Court should draw appropriate inferences pursuant to the rule in Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298; [1959] HCA 9 at 320-321 that the evidence each would have given would not have assisted the applicants’ cases. They also seek to rely on the rule in Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65 to the effect that all evidence must be weighed according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced and in the power of the other to contradict.

25 The respondents also contend that the Court should draw appropriate inferences from the applicants’ failure to lead evidence from Mr Kilner in relation to the meeting that he attended in Italy with Airaga Rubinetterie S.p.A. (a manufacturer of plumbing equipment) on 19 March 2018, in which the applicants contend that Mr Comino disclosed the C9746 Design Drawing.

26 The rule in Jones v Dunkel only applies, however, where a party is “required to explain or contradict” something: Jones v Dunkel at 321. In the present case, the respondents have not identified, with one exception, any material matter within the knowledge of Mr Cimberio or Mr Dillenbeck that they were required to explain or contradict, for two principal reasons.

27 First, Mr Comino’s dealings with Mr Dillenbeck and Mr Cimberio appear to have been almost exclusively by email, as appears were Mr Cimberio’s dealings with Mr Dillenbeck. Moreover, Mr Comino’s dealings were largely limited to dealings with Mr Dillenbeck with very little direct interaction with Mr Cimberio.

28 Second, Mr Comino did not give any evidence-in-chief of any specific conversations that he had with either Mr Dillenbeck or Mr Cimberio concerning the issues to be determined in the proceedings. As a consequence, there was nothing that either Mr Dillenbeck or Mr Cimberio were required to explain or contradict.

29 The one exception was the decision by the applicants not to lead any evidence from Mr Kilner with respect to the alleged provision of the C9746 Design Drawing by Mr Comino to Airaga prior to, or in the course of, the meeting with Airaga in Italy on 19 March 2018. I address that failure below in connection with the design invalidity issues.

B.3. The respondents’ lay evidence

30 The respondents relied on four affidavits from Mr Comino. Mr Comino gave evidence directed at the ownership of the Designs and the 757 Patent, as well as in response to claims by the applicants involving breach of confidence, copyright infringement and contraventions of the ACL. In particular, Mr Comino’s evidence focussed on his involvement in the design and development of the C6827 Valve and the C9746 Valve, Strongcast’s relationship with AVI, the sharing of design drawings between Cimberio, AVI and Strongcast, and the registration of the Designs by Strongcast.

31 Mr Comino was not an impressive witness. He had a pronounced tendency to be combative and argumentative. He was reluctant to make appropriate concessions when confronted with compelling evidence to the contrary and at times his evidence appeared to change or at least evolve to meet the cases that were being advanced by the applicants.

32 The approach that Mr Comino took to giving evidence is readily apparent in the following exchanges during his cross-examination.

33 When pressed about whether he told Mr Dillenbeck that he was planning to use the C9746 Design Drawing to register the Designs, he gave the following evidence:

And did you tell Mr Dillenbeck before he sent you the drawing on 24 January 2018 that you were planning to go off and register a design based on the drawing?---I don’t recall. But I mean – I don’t recall that happening. I don’t recall if it did or if it didn’t happen. It may have happened.

You say it may have happened, do you?---Look, I can’t recall. I can’t recall. I was very open with AVI with things that I was doing. It may have happened, but I honestly can’t recall.

So your position before his Honour is that you may have told Mr Dillenbeck before 24 January that you were going to go off and register a design; is that right?---I can’t recall if it happened or not, Mr Flynn.

34 Equally, instructive was the following evidence he gave when he was challenged about evidence that he had given to the Designs Office – that, at the time that he had filed the Designs for registration, AVI was aware that he was going to do so:

And the designs were filed in February and March 2018, correct?---Yes.

And it’s false that those designs’ applications were filed with the knowledge of All Valve, do you agree?---This is – I am just trying to catch up here, Mr Flynn. I can see that the dates precede the file date. The – yes. Sorry. Can you ask your question 5 again, please, Mr Flynn?

It’s false that the design applications, which were filed on 20 February 2018 and 23 March 2018, were filed with the knowledge of All Valve; do you agree?---I’m not sure.

Well, Mr Comino, you swore an oath in the Designs Office, saying that they will file with the knowledge of All Valve. And now you’ve sworn an oath before his Honour, and you’re saying you’re not sure. So - - -?---Sorry.

Do you want to respond to that?---I’m just digesting it, Mr Flynn. Look, I’m not sure what to say there. There’s – the dates seem to precede each other. Yes.

You agree it’s false?---I think so.

…

Yes. And so when you said in the Designs Office that these designs applications were filed with the knowledge of All Valve, that was – false, wasn’t it?---I find it to be quite a grey statement. It’s – it’s just difficult because of how many – how many times I communicate with Dillenbeck. I still – I can see that the dates don’t line up, yes.

…

And I want to suggest to you that this email, even though you say, as you know, was the first time you told AVI that you had a registered design. Do you agree?---I’m not sure, Mr Flynn. I – I – I – I know this was probably the first time I – I emailed it, but, I mean, I – I think I’m – I communicated so much with Dillenbeck that it’s – it’s – I find it challenging to know for sure other than if there was any verbal communication about it.

So when you said in the design’s office that the design’s applications were filed with 40 the knowledge of All Valve, is your position that you swore that on oath even though you weren’t sure whether that was true?---Look, I was sure at the time. Like, I was – I – I felt confident that that was the position, but you helping me see things are not looking quite the same.

And you knew when – did you know when you swore this declaration in the Designs Office that you weren’t going to get cross-examined?---Sorry, can you please repeat that? That I wasn’t going to get cross-examined?

Yes?---I – I had no idea about any of these sort of – these proceedings, so - - -

So you haven’t repeated this statement in your affidavit, have you?---I don’t believe so.

And I want to suggest to you you haven’t repeated it because you knew it was wrong; is that right?---I – I’m not sure, Mr Flynn.

35 For these reasons, I approached the evidence given by Mr Comino, in particular his denials, with great caution and gave it comparatively less weight in weighing his evidence against other contemporaneous evidence and the inherent logic of events.

B.4. Expert evidence

B.4.1. Overview

36 Three expert witnesses gave evidence at trial. AVI and Cimberio retained Mr Kevin Smerdon on both design and patent infringement and invalidity. Mr William Hunter was retained by Mr Comino and Strongcast for the purposes of patent infringement and invalidity and design infringement. Mr Comino and Strongcast retained Mr Alexander Richardson on design invalidity.

37 Prior to the trial, the experts prepared four joint expert reports:

(a) Mr Smerdon, Mr Hunter and Mr Richardson prepared a joint expert report on common topics on design invalidity and design infringement;

(b) Mr Smerdon and Mr Richardson prepared a joint expert report on design invalidity;

(c) Mr Smerdon and Mr Hunter prepared a joint expert report on design infringement; and

(d) Mr Smerdon and Mr Hunter prepared a joint expert report on patent infringement and invalidity.

38 The experts gave evidence in concurrent sessions in respect of each of the four joint expert reports. I found that the evidence given by the experts in the concurrent sessions, in the context of their joint expert reports, was of considerable assistance in addressing the principal issues for determination. The concurrent sessions provided an invaluable platform to expose the reasoning of each of the experts and permit it to be tested and evaluated. At times, the experts strayed into positions that appeared to be driven more by advocacy than expertise but I was generally, subject to some exceptions, satisfied that each of the experts was genuinely seeking to assist the court in a non-partisan and constructive manner.

B.4.2. Mr Smerdon

39 Mr Smerdon is a consultant mechanical engineer and product designer, and currently the director of AusCreate Pty Ltd. Mr Smerdon has over 25 years of experience in product development and design experience, including with respect to the design of plumbing products and injection-moulded plastic components. Mr Smerdon has a Bachelor of Engineering (Mechanical).

40 Mr Smerdon was employed by Avtex Pty Ltd, working in the design and manufacture of components for aerospace systems, Viscount Plastics (Australia) Pty Ltd, Islex Australia Pty Ltd (where Mr Smerdon’s design expertise became more plumbing and piping focused), Industrial Plastics (Australia) Pty Ltd, and Everhard Industries Pty Ltd.

41 In his roles at Islex, Industrial Plastics and Everhard, Mr Smerdon was actively involved in the development of plastic products for pipes, plumbing systems and related projects and was required to design water ball valves as part of wider design programs on a regular basis.

42 Mr Smerdon is the named designer on several registered designs in Australia and one patent.

43 Mr Smerdon prepared five affidavits for use in the proceedings in which he addressed design and patent invalidity and infringement issues that had arisen in the proceedings. The manner in which Mr Smerdon’s affidavits were prepared, however, was unsatisfactory and ultimately caused me to place little weight on his affidavit evidence. The approach adopted to the preparation of his affidavits was in summary, to conduct an online conference by Microsoft Teams with Mr Smerdon in which various design and patent issues were discussed and a solicitor present on the conference call would type up a first draft of the affidavit as the conference call progressed. Mr Smerdon was not able to observe on his screen what was being typed by the solicitor. The draft affidavit prepared by the solicitor would then be provided to Mr Smerdon for his review and a second conference call would be arranged. In the course of the second conference call, Mr Smerdon would raise any changes he had to the draft affidavit. A revised draft of the affidavit would then be provided to Mr Smerdon for his final approval.

44 The essential flaw in this procedure is that it has the very real potential to subvert the integrity of the provision of independent expert evidence to the Court. A solicitor with knowledge of the issues in the proceeding and no relevant expert knowledge, with the best will in the world, may well frame the evidence in the initial draft in a manner that fails to reflect the expert’s evidence accurately or free of potential ambiguity. At the same time, an expert reviewing a draft affidavit prepared by a solicitor may be expected to focus more on matters of substance and not appreciate subtle matters of emphasis or positioning that may have been introduced into the initial or subsequent draft of the affidavit.

45 There is a fundamental difference between the orthodox position of an expert preparing an initial draft of their evidence in response to specific questions, and then editing that evidence in response to requests for clarification, or a refining of the questions to be addressed, and the position of an expert relying on a solicitor to prepare an initial and subsequent drafts of their evidence, based on what the expert has stated in the course of a conference, irrespective of whether it is in person or online. I do that accept that the practice adopted by the applicants in this case in preparing Mr Smerdon’s affidavit is consistent with the principles informing the code of conduct enshrined in the Court’s expert practice note or with the principles underpinning the reception of expert evidence in proceedings.

46 Not surprisingly, the oral evidence given by Mr Smerdon in the course of the expert conclave was at times inconsistent with his affidavit evidence.

47 Given the manner in which Mr Smerdon’s affidavits were prepared, I have principally had regard to his oral evidence and the evidence attributed to him in each of the four joint expert reports, rather than his affidavit evidence.

B.4.3. Mr Hunter

48 Mr Hunter is a mechanical engineer with more than 30 years of experience. He has a Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering and a Masters of Engineer Science.

49 Mr Hunter has held a variety of roles including as a mechanical engineer with Hawker Siddeley, a product design consultant with Invetech Pty Ltd and Niche Innovation Pty Ltd (Mr Hunter’s own company), and as a design contractor to product design firms such as Design+Industry and Planet Innovation. During these roles, Mr Hunter worked on various product design projects which related to valves and pumps, including the development of different scientific instruments with air and liquid handling systems, which incorporated various types of valves, including ball valves, and the development of a sand filtration filter for swimming pools which included a gate valve.

50 Mr Hunter prepared four affidavits in the proceedings on design and patent issues, two of which annexed expert reports addressing design infringement and patent issues.

51 Mr Hunter has considerable experience in giving evidence in patent litigation and, at times, in his evidence on design issues, appeared to be focusing more on functionality than visual appearance.

B.4.4. Mr Richardson

52 Mr Richardson is an industrial designer with over 40 years of experience in product design. He is currently the managing director and owner of Design Edge, a product design consultancy business. Mr Richardson has a Bachelor of Engineering (Mining) and a Bachelor of Arts (Industrial Design).

53 Mr Richardson has held a variety of design related positions including senior consultant designer at Design Resource Pty Ltd, consultant designer at Lightmakers Pty Ltd and planning engineer at Utah Development Company.

54 Mr Richardson’s product experience includes working with plumbing, pool equipment, public water stations, water treatment and filtration, irrigation monitoring, electrical equipment, medical equipment and consumer items.

55 Mr Richardson prepared an affidavit in the proceedings annexing an expert report addressing design invalidity issues.

C. Factual Background

56 The following factual background by way of a general overview to the various claims advanced in these proceedings is taken from the Agreed Facts or from evidence that was not the subject of any dispute between the parties

57 AVI is an importer, supplier and distributor of a range of valves, meter boxes and associated goods.

58 Cimberio is an Italian company engaged in the business of design and fabrication for plumbing, heating, air conditioning and gas and water distribution systems, including the design and manufacture of valves for those systems.

59 Mr Comino is the sole director and shareholder of Strongcast, involved in the day-to-day management of the business of Strongcast, and in effective control of the conduct and business of Strongcast.

60 In early 2013, Mr Comino contacted AVI seeking assistance in relation to the manufacture of certain plumbing product components.

61 On 16 July 2013, AVI and Strongcast entered into the Distribution Agreement. At all relevant times, Mr Comino had knowledge of the existence and terms of the Distribution Agreement.

62 The Distribution Agreement remained in force until at least 14 May 2019.

63 From the middle of 2013 to at least 2018, AVI supplied plumbing fittings to Strongcast, including the C6827 Valve.

C.1. AVI Ball Valves

64 From approximately December 2019, AVI sold a Queensland version of a ball valve (QLD Ball Valve) and a New South Wales version of a ball valve (NSW Ball Valve).

65 Airaga is the manufacturer of the AVI Ball Valves.

66 AVI has purchased the AVI Ball Valves from Airaga and imported them into Australia. AVI has sold and offered to sell the AVI Ball Valves, including online with the product code 0194A0606. The product code 0194A0606 correlates with the QLD Ball Valve.

67 AVI is not licenced by either of the respondents to import or sell the AVI Ball Valves.

C.2. Sub Meter Assemblies

68 AVI advertised and offered for sale a sub meter assembly kit online with product codes SMLIM and SMA20M (together, the Sub Meter Assemblies).

69 The SMA20M was supplied with two QLD Ball Valves, and the SLMIM with two NSW Ball Valves.

70 AVI has sold the Sub Meter Assemblies to customers in Australia.

71 AVI is not licenced by either of the respondents to import and sell the AVI Ball Valves as part of the Sub Meter Assemblies.

D. Conduct of the respondents from late 2017 to March 2018

D.1. Overview

72 The applicants contend that Mr Comino’s conduct in the period from 2017 to early 2018 is important to several of the issues for determination in this proceeding, including the appropriateness of constructive trust relief, additional damages for copyright infringement, breach of confidence, and ACL contraventions based on non-disclosure.

D.2. Submissions

D.2.1. Applicants

73 The applicants submit that up until late 2017, AVI and Strongcast had been acting cooperatively on the distribution of their Cimberio-designed and sourced products, in particular the C6827 Valve. They submit that such distribution was governed by the bargained-for Distribution Agreement that was entered into in 2013, whereby Strongcast had been granted exclusive distribution rights in Australia, but Mr Comino had expressly been refused design ownership of the C6827 Valve due to Cimberio’s participation in the design process.

74 The applicants submit that instead of again seeking to negotiate and bargain for exclusivity in late 2017, Mr Comino, believing he did not have exclusivity over the upcoming C9746 Valve, decided to seek registered design rights in relation to the C9746 Valve knowing that such rights would enable him to prevent others (including AVI and Cimberio) from selling the same or similar products in Australia without his consent.

75 The applicants submit that given his knowledge of intellectual property rights and the implications of registration, including copyright since 2012 and patents and designs since 2016, Mr Comino did not inform AVI or Cimberio of his plans to achieve registered design rights with respect to the C9746 Valve prior to receiving the C9746 Design Drawing on 24 January 2018.

76 The applicants submit that Mr Comino sent the C9746 Design Drawing to Mr Kilner on 15 February 2018 “for the purpose of providing them to Airaga”. They submit that the very next day, Mr Comino emailed Infinity Design and asked for a “Skype call”, so he could explain without a written record the actions he wished to be taken in respect of the C9746 Design Drawing, namely, to have images created for the purpose of registering the Designs.

77 Next the applicants submit that Mr Comino knew Mr Riva of Cimberio was the author of the C9746 Design Drawing and that there was a copyright notice on the drawing. They submit that he never asked for permission to use the C9746 Design Drawing despite knowing, when he was filing the two Designs, that Mr Riva had participated in the design process. They submit that Mr Comino continued to “overlook” Cimberio’s copyright markings, not because he thought he owned the copyright in the C9746 Design Drawing, but because he deliberately went ahead regardless of any other parties’ rights. They submit that he was in a rush as he knew that he could not file a registered design, and thus “surreptitiously achieve ownership and exclusivity”, after there had been a non-confidential disclosure to a third party.

78 The applicants then submit that once the 005 Design was filed, Mr Comino considered that he was protected if there were further non-confidential disclosures and therefore, he did not ask whether Mr Kilner had any confidentiality measures in place with Airaga and he did not seek to re-deploy the Strongcast “standard” confidentiality deed before or after his trip to Milan.

D.2.2. Respondents

79 The respondents submit that the applicants have constructed a narrative of the respondents’ conduct in late 2017 to early 2018 which is not supported by the evidence.

80 The respondents submit that the negotiated exclusivity in the Distribution Agreement was only with respect to the two products depicted in the Annexures to the agreement. They submit that Mr Comino’s belief that he did not have any “exclusivity” in the C9746 Valve was only with respect to the provisions of the Distribution Agreement as its terms did not extend to products beyond the C6827 Valve.

81 The respondents submit that the applicants’ narrative ignores Mr Comino’s steadfast belief that the Designs were his own, his steadfast rejection that Airaga was provided with a copy of the C9746 Design Drawing at their meeting, and incorrectly suggests AVI had a claim to ownership of the intellectual property in the C6827 Valve (which Mr Kilner agreed was incorrect).

82 The respondents submit that Mr Comino’s evidence regarding the timing of his dealings with Infinity Design was frank and candid and there was no basis to suggest that his testimony was not honest. They also submit that the suggestion that he “was in a rush – he knew that he couldn’t file a registered design, and thus surreptitiously achieved ownership and exclusivity, after there had been a non-confidential disclosure to a third party” is contradicted by the “true nature” of his state of mind as is clear from his oral evidence.

D.2.3. Consideration

83 Ultimately any acceptance of the applicants’ narrative of Mr Comino’s conduct in late 2017 and early 2018 turns upon Mr Comino’s claimed “steadfast belief” that he was the exclusive designer of the C9746 Valve, the extent of his knowledge of intellectual property rights and the inherent logic of events. I address below Mr Comino’s knowledge of intellectual property rights in the period leading up to late 2017 and early 2018. I address Mr Comino’s “steadfast belief” that he designed the C9746 Valve in the context of the inherent logic of events in addressing issue 1, being the question of entitlement to the Designs.

84 In the course of the negotiation of the terms of the Distribution Agreement, Mr Comino sent an email on 18 April 2013 in which he provided a summary of his proposed changes to the draft agreement, including the following suggested change to the retention of title clause:

The title shall be passed from Company to Client and both will acknowledge the proprietary rights of all modifications made to new and existing products requested by Strongcast. The rights of items will be specified with drawings of products manufactured exclusively for Strongcast.

85 On 30 April 2013, Mr Dillenbeck responded to Mr Comino’s email by marking up responses on it, including the following response to Mr Comino’s retention of title clause comments:

Are you asking something different here compared to what I have already written into the agreement? I have written under Section III - Proprietary Rights that you will have all rights to the housing, however, I don’t believe this should be given to you for the ball valve. The product you came to us with compared to the final product design by Cimberio is significantly different. I’m sure you wouldn’t take it and have it manufactured by someone else, but we need to cover this anyway. You will of course have exclusive distribution of this design under the contract, but Cimberio will still own the design of the ball valve.

86 The exchange is significant because it shows that as early as 2013, Mr Comino understood the importance of intellectual property rights and that the applicants had agreed to give him exclusive distribution rights over “new and existing products requested by Strongcast” but when the product brought by him was “significantly different” to the final product design by Cimberio, Cimberio would own the design of the ball valve.

E. Design issues

E.1. Overview

87 There was significant tension between the entitlement, invalidity and infringement design claims advanced by the parties in the proceeding. The tension was most evident in the approach that the parties and their experts took to “substantial similarity” in addressing the significance of the visual differences between the designs of the ball valves with respect to invalidity and infringement.

88 The applicants, consistently with the evidence of Mr Smerdon, adopted a narrow approach to visual differences on infringement but a broader and more inclusive approach when addressing invalidity. Understandably this gave rise to a submission from the respondents that Mr Smerdon’s evidence on the significance of visual differences in addressing those issues was irreconcilable.

89 Conversely, the respondents adopted a broad, inclusive approach to visual differences on infringement but a narrower, more exclusive approach when addressing invalidity. Unlike the applicants, the respondents did not rely on the one expert to address both invalidity and infringement. In support of infringement, the respondents relied on Mr Richardson’s inclusive and broad approach to visual differences, which contrasted with the narrower approach taken by Mr Hunter to visual differences in addressing invalidity.

90 Ultimately in reconciling the competing evidence given by the experts as to the significance of visual differences between the valves, I have generally adopted a consistent and comparatively more narrow and confined approach to the significance of visual differences in assessing substantial similarity, rather than the broad and inclusive approach advocated by Mr Richardson on infringement and Mr Smerdon on invalidity.

F. Issue 1: Entitlement to 810 and 005 Designs

F.1. Overview

91 Cimberio contends that it was at least the co-designer of each of the Designs for the purposes of s 13(1)(a) of the Designs Act.

92 The respondents contend that Mr Comino was the sole designer of each of the 810 and 005 Designs.

93 It is well established that a designer for the purposes of s 13(1)(a) of the Designs Act is the person whose mind conceives the relevant shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation applicable to the article in question and reduces it to visible form. A person is not a creator, for the purposes of s 13 of the Designs Act, if they have converted a design created by another person into another form, such as a technical drawing: LED Technologies Pty Ltd v Elecspess Pty Ltd (2008) 80 IPR 85; [2008] FCA 1941 at [26] (Gordon J).

94 More than one person may be entered on the register as the registered owner of a design: s 13(3)(a) of the Designs Act. Each of the persons registered must fall within one or more of the categories of persons listed in s 13(1). If not all of the persons entitled to be registered as the owner of the design are included in the registration, the court may revoke the registration: s 93(3)(c) of the Designs Act.

95 It is also well established that a design that combines various features, including where those features can be found in the prior art, is capable of being new and distinctive: LED Technologies at [12].

96 In order to determine whether Cimberio, as the employer of Mr Riva, was at least a co-designer of each of the Designs, it is necessary to determine who created the Designs. In part, that question is informed by an identification of what visual features are new in the Designs over the prior art. In this case, the principal new visual features in the Designs were the lockable handle and the additional internal threads.

97 The applicants accept that Mr Comino proposed the idea of an internal thread, in addition to an external thread, in the C9746 Valve. The addition of an internal thread in the C9746 Valve was replicated in the internal thread in the 810 Design and the two internal threads in the 005 Design. The applicants, however, submit that the internal thread should be given less weight than the integrated lockable handle, as the internal threads are completely constrained by function, given they are standard thread sizes, and the second internal thread in the 005 Design cannot even be seen from the “end view”.

98 The critical question for determination remains to identify which person or persons created the Designs. This necessarily includes a consideration of who conceived the relevant shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation of the integrated lockable handle visual feature, who reduced it to visible form, and the weight to be given to the internal threads as a design feature.

F.2. Factual findings

99 On 11 January 2013, Mr Cimberio raised several questions by email with Mr Dillenbeck in response to his request for quotation for a tap project for Strongcast, including:

2. Do you need the valve to be exact same construction or alike function would suffice (we can offer much better design than this one)

…

5. Since this product will be used on potable water and (I assume) water meter, would a lockable tamper proof handle be preferred?

100 Later that day, Mr Dillenbeck forwarded Mr Cimberio’s email to Mr Comino at strongcast@gmail.com, asking him for his thoughts on the questions that Mr Cimberio had raised, and Mr Comino relevantly responded to Mr Dillenbeck by email to the questions reproduced above:

…

2) I am very interested in seeing what the engineers have in mind with a similar valve of the same functions. The critical element with this project is that Strongcast has exclusive sole rights to the agreed products supplied by All Valves due to it’s unique characteristics. If this can be maintained, I am more than happy to proceed with another design of the same use.

…

5) A lockable tap is certainly an option as long as this addition doesn’t increase the price significantly.

…

If there are elements of the tap design that already exist, it will hopefully speed up the manufacturing and approval processes. If the engineers create some images of their design, I would like to view them before production.

101 On 11 July 2013, Mr Dillenbeck emailed Mr Comino with a series of design drawings, including drawing C6882/0 that had been renumbered as 31820/0, and the item code of which had been changed to Cim C6827 (C6827 Design Drawing). Mr Dillenbeck asked Mr Comino, if he agreed with all the drawings, to sign them and return them to AVI so they could be kept on file.

102 It is common ground that the C6827 Design Drawing is an artistic work under the Copyright Act, the prior art base (for the purposes of the Designs Act) for each of the Designs includes the design of the C6827 Valve and the design of the C6827 Valve is shown in the C6827 Design Drawing.

103 On 31 July 2013, Mr Dillenbeck emailed Mr Comino pictures of Cimberio lockable valves in response to a request from Mr Comino for samples of lockable/tamper-proof valves that AVI had in stock or that Cimberio was able to supply.

104 In late 2014, Mr Comino received “feedback from Unity Water that they wanted a ball valve that could be locked”. Unity Water was a customer of Strongcast.

105 On 25 June 2015, Mr Comino sent an email to Mr Dillenbeck and Mr Cimberio in relation to the introduction of a lockable handle into the C6827 Valve to which he attached 6 photographs of the C6827 Valve with a locking wing made out of rough tin affixed to the valve body as a separate piece. Mr Comino explained in the email:

I have been looking at the lockable handle issue and have attached some images that can be used as an indication for a concept. I believe we can achieve success through the use of a simple brass fitting.

106 On 6 July 2015, Mr Cimberio responded to Mr Comino’s email in the following terms (as written):

yes the pictures where fine an explain the concept well.

Before confirming this is a feasible way, we need to design the parts and make some prototypes to validate the design.

I will get back with some results and test data by end of month.

It is a pleasure and fun to develop products with you. It is not often to work with someone that have similar understanding of the product like you.

107 In or about mid to late 2015, Mr Riva created several designs for lockable handles that he considered were commercially feasible and provided a less expensive lockable solution compared with Cimberio’s existing designs. None of the designs were commercialised because Strongcast informed Cimberio that they were too expensive.

108 On 14 November 2015, Mr Cimberio emailed Mr Dillenbeck drawings of new versions of Cimberio valves, including the C6827 Valve, with the “possibility to lockable handle in the closed position”, where the lockable handle was integrated into the body of the valve, in response to a request from Mr Dillenbeck for concept drawings of the “dog ear handle design”. Mr Cimberio advised Mr Dillenbeck in his email that the dog ear handle was “far too expensive for the application” and stated that Cimberio had redesigned all their valves in an attempt to minimise the impact on price of the addition of a lockable handle.

109 In February 2016, Mr Comino engaged a company called RCR Laser to produce a locking plate which could be retrofitted to the C6827 Valve to lock the handle in a fixed position.

110 On 10 March 2016, RCR Laser produced a drawing for a locking plate for Mr Comino, and subsequently Mr Comino placed an order for the manufacture of 1701 locking plates.

111 In or about March 2016, Mr Comino engaged Machinery Solutions Pty Ltd (Machinery Solutions) to drill 7-millimetre holes into the handles of valves, including C6827 Valves.

112 On 7 May 2016, Mr Dillenbeck forwarded to Mr Comino an email he had received from Mr Cimberio. Mr Cimberio explained in his email that the “last models have been created after John’s visit and we have sent samples for test and approvals”. He then stated:

The gap in the process that has not generated automatically a price construction for these new models is that we have not received formal approval on samples. This is something generated by working crossed between John you and us. A new element we need to implement in our system and improve for future (even if l wish we do not have to go through this mess again in future).

So to make sure we are talking about the right products to quote, I need confirmation on your end.

- Telescopic valve. With John we have designed a lighter version of this valve. Enclosed 2 models C8707 and C8474. Please confirm it is what is requested to be quoted.

(Emphasis in original.)

113 Mr Cimberio then outlined work that had been done with respect to the handle and the new version of the angle valve for the C8719 valve that had been “built based on John’s request” that had been designed with a new handle but that could be replaced with the C8922 valve quoted handle. He also stated that it had been agreed that the valve body mould would be produced for a cost of 3,000 Euros and the cost would be split “1000 Euro each (you me and him) if this product would have failed to sell.”

114 Mr Cimberio concluded his email to Mr Dillenbeck with the following remarks:

I hope this give you a better picture of what was discussed, agreed and developed with John.

If you confirm above on Monday, I will work our prices and send you the quote by Monday night. It will be with you Tuesday morning.

115 The references to “John” in Mr Cimberio’s email were to Mr Comino.

116 On 25 May 2016, Mr Dillenbeck emailed Mr Comino an email he had received from Mr Cimberio in which Mr Cimberio had attached 4 new drawings “for review”, including a drawing numbered C8474/3, featuring an integrated locking wing, and provided short explanations for each drawing, including the following explanation:

Drawing C8474 is for telescopic valve with female end having new body that incorporate a locking wing. This is using standard handle with added hole diameter 7mm. the body is pierced with 10 mm in case you want to use the new special handle in future. If this is not an option the hole can be reduced to 7 mm as well.

117 Mr Cimberio then enquired in his email to Mr Dillenbeck, for Mr Comino’s attention:

Please let me know if the drawings are okay. We can then agree on product price to finalize the quote and hopefully get the order.

118 In or about April 2017, Mr Comino commissioned Machinery Solutions to modify further C6827 Valves by machining a thread into the bore of the nozzle to provide both male and female coupling options (Dual Thread Feature).

119 In or about April 2017, Mr Comino, AVI and Cimberio also engaged in discussions about proposed modifications to the C6827 Valve.

120 On 21 April 2017, Mr Comino sent an email to AVI attaching photographs showing the modified C6827 Valve with the addition of the Dual Thread Feature.

121 On 25 September 2017, Mr Comino sent an email to Mr Dillenbeck in relation to new orders of C6827 Valves and changes he wanted made to the C6827 Valve, including a request for an integrated locking wing. Mr Comino stated in the email:

Lockable Body/Handle

As we have discussed, the lockable aspect of the valves is timely and costly. If we can have a “lockable-wing” added to the valve bodies it will simply mean that we can knock out orders quicker without the assembly and manufacturing currently required. I wish this wasn’t the case, but Unity Water are our largest council for the kits and there isn’t a way around it.

These valves will also need a hole in the handle so it can be locked and if the quantities warrant the new handle it’ll be great. If not, the existing handle will have to do. Keep in mind that this new handle and wing will be of interest with the next C7094 valves we produce too, so more volume again.

122 On 27 September 2017, Mr Dillenbeck sent an email to Mr Cimberio, in dot point form, under similarly worded headings, outlining the requests made by Mr Comino in his email of 25 September 2017. Mr Dillenbeck included in his email to Mr Cimberio the following points for discussion raised by Mr Comino with respect to the locking wing:

Lockable Body/Handle

* We would like to review if the C6827 body can be amended to include a locking wing. I believe it is a Strongcast specific mould?

* We will continue to drill the 7mm holes into the handles to allow a padlock unless there are other viable handle options available.

123 Mr Dillenbeck concluded his email with the following request from Mr Comino:

We will need to order more product very soon, so please let’s review these points asap to see that improvements can be done in the next order.

124 On 24 October 2017, Mr Cimberio replied to Mr Dillenbeck’s 27 September 2017 email. Mr Cimberio attached two drawings of a valve with a “padlock wing” (numbered C6891/0 and C6827/0) and included the following response in his email to the discussion points previously addressed with respect to the locking wing and the valve body:

Lockable Body/Handle

* Attached modified drawing with padlock wing. This would be a special custom made mould for Strongcast. There is a mould cost to consider of approximately 3000 Euro.

* The valve includes 7mm hole in the handle. Other option needs to be evaluated. I believe you have quite a good quantities of solutions to evaluate.

C6827/C6891 Valve Body

* No need for sample. The photo show the concept quite well. My only concern is about the resistance of the thread trapped. Is enough wall on the valve to avoid cracking during installation or service? We would not feel responsible for any issue connected to this activity.

* Attached drawing of valve with female connection and wing for locking. It is the same body as above model. This gives us the flexibility to use different end parts to create different combination. These drawings are already in your hands since last year together with valve quote, but in case I need to review pricing.

125 On 25 October 2017, Mr Dillenbeck forwarded to Mr Comino the email that he had received from Mr Cimberio on 24 October 2017.

126 On 7 November 2017, Mr Dillenbeck responded to Mr Cimberio’s 24 October 2017 email in which he conveyed in red text the responses that he had received from Mr Comino, including the following with respect to the modified drawing with the padlock wing:

The wing needs to come out further to clear the body of the valve, otherwise it is difficult to fit a padlock. Attached is a drawing of a previously drawn model which is correct.

We hope that the price isn’t affected too much with the wing?? if we are paying for the mould, then the additional cost of brass should be very little. If this is not the case, then we are wasting time on reviewing this request. Please check how this affects cost before spending too much time on this solution.

(Emphasis in original.)

127 In his affidavit evidence, Mr Comino gave unchallenged evidence that he provided the instruction in the first paragraph reproduced above but did not directly address the second paragraph. Further, I infer from the context, that is, – the red text, the reference to “additional cost” and the tone of the language – that the second paragraph was also a response that Mr Comino provided to Mr Dillenbeck.

128 The “drawing of a previously drawn model” that was attached to Mr Dillenbeck’s email to Mr Cimberio was Mr Riva’s drawing, numbered C8474/3, which depicts a locking wing integrated into the body of the valve. This drawing had been provided to Mr Dillenbeck by Mr Cimberio and was subsequently emailed by Mr Dillenbeck to Mr Comino on 25 May 2016.

129 On 12 December 2017, Mr Cimberio emailed Mr Dillenbeck his responses, marked in green text, in response to the red text markup in Mr Dillenbeck’s email of 7 November 2017, including the following with respect to the modified drawing with the padlock wing and attached three drawings of a valve with a padlock wing:

Attached drawings with modified wing. This is now longer as you required. I guess it will add as much as 0,25 Euro. If confirmed I can make due calculation.

130 In or about late 2017, Mr Comino procured from Machinery Solutions a new sleeve part for a “dual thread” valve that Machinery Solutions had manufactured from brass on a lathe in which an internal thread was provided on both sides of the valve. It is readily apparent from the photographs of the Machinery Solutions valve admitted into evidence that it did not include a lockable handle.

131 On 24 January 2018, Mr Dillenbeck emailed Mr Comino C9746 Design Drawing. The email had an apparent subject heading “New C9746” and simply stated:

Here is the updated drawing.. working on some prices now.

132 The C9746 Design Drawing included a copyright notice in English, identifying “GIACOMO CIMBERIO S.p.A” as the owner of the copyright in the drawing and a confidentiality notice in Italian “Reservato Confidenziale” but in terms that one might expect would be readily understood by an English speaker.

F.3. Submissions

F.3.1. Applicants

133 The applicants submit that while Mr Comino proposed the idea of an internal thread in the C9746 Valve (which was incorporated into the 810 Design and the two internal threads in the 005 Design), such an act alone is insufficient to render Mr Comino a sole creator of the Designs. They submit that is insufficient because the internal threads (a) are largely not visible, and (b) are completely constrained by function. The applicants therefore submit that the pivotal question one must consider in determining the ownership of the Designs is who “conceived the relevant shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation” applicable to the lockable handle visual feature and reduced it to visible form.