FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Webjet Marketing Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 867

File number: | VID 1304 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | BUTTON J |

Date of judgment: | 28 July 2025 |

Date of publication of reasons: | 29 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – misleading or deceptive conduct – where the respondent represented to consumers on its website, via email and on its social media accounts that they could purchase airfares for promoted prices – where the respondent represented to certain consumers that their airfare bookings were confirmed – where the respondent admitted that it contravened ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law – where the parties jointly proposed declarations and pecuniary penalties |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Sch 2 (Australian Consumer Law) ss 18, 29, 224, 228, 246 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 21, 43 |

Cases cited: | Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; (2017) 254 FCR 68 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABG Pages Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 764 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 146 ALD 385; [2015] FCA 399 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bloomex Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 243 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dell Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 588 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; (2023) 407 ALR 302 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v HealthEngine Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1203 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optus Internet Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1397 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Qantas Airways Limited [2024] FCA 1219 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SmileDirectClub LLC [2022] FCA 1343 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Uber B.V. [2022] FCA 1466 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] FCA 44; [2016] ATPR 42-521 Australian Energy Regulator v AGL Loy Yang Marketing Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1299 Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8; (2008) 165 FCR 560 Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 521; (1991) ATPR 41-076 Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | 94 |

Date of hearing: | 25 July 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | T Spencer Bruce SC with S Martin |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Johnson Winter Slattery |

Counsel for the Respondent: | M Borsky KC with A Lord |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | MinterEllison |

ORDERS

VID 1304 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | WEBJET MARKETING PTY LTD Respondent | |

order made by: | BUTTON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 July 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondent Webjet Marketing Pty Ltd (Webjet) contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (which is sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA)) by representing, in trade and commerce, that it was possible for consumers to purchase flights for prices at or from “$XX” (the Promoted Price or the Promoted Prices), by displaying the Promoted Prices:

(a) on Webjet’s website (the Webjet Website) and Webjet’s mobile application (the Webjet Mobile Application) between 1 November 2018 and 13 November 2023;

(b) in promotional emails sent to consumers who had not previously booked a flight with Webjet between 1 November 2018 and 31 October 2023; and

(c) in social media posts between 31 July 2019 and 30 October 2023,

the displaying of which, in each case, was false or misleading because, in fact, flights could not be purchased for the Promoted Prices without paying additional compulsory services fees, which were charged by Webjet on each booking.

2. Between 10 February 2019 and 1 April 2024, Webjet contravened ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the ACL, by displaying a booking confirmation and sending a confirmation email to 118 consumers, thereby representing that the booking had been confirmed at the price paid, when in fact, the booking was not confirmed.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary Penalty

3. Pursuant to s 224(1) of the ACL, Webjet pay pecuniary penalties to the Commonwealth of Australia, within 30 days of these orders being made, in the amount of:

(a) $8,500,000 in respect of the contravention of s 29(1)(i) referred to in paragraph 1 above; and

(b) $500,000 in respect of the contravention of s 29(1)(i) referred to in paragraph 2 above.

Publication Orders

4. Pursuant to s 246(2)(d) of the ACL, Webjet, at its own expense, and within 14 days of these orders being made, publish on the homepage of the Webjet Website and on the Webjet Mobile Application a corrective notice in the terms and form set out in Annexure A (Notice) ensuring that the Notice complies with the following specifications:

(a) the Notice is viewable by clicking a ‘click-through’ icon (Click-through Icon);

(b) the Click-through Icon:

i. is in the top third of each page on which it appears, and is not obscured, blocked or interfered with by any operation of the website;

ii. contains the words “Corrective Notice ordered by the Federal Court of Australia — Breaches of Australian Consumer Law. Learn More”:

A. in at least 14-pixel black font;

B. in bold text with a font-weight of at least 700; and

C. on a white background; and

iii. has the words “Learn More” operating as a one-click hyperlink to a page containing the Notice; and

(c) the Notice:

i. occupies the entire webpage that is accessible via the Click-through Icon;

ii. must not be displayed as a ‘pop up’ or ‘pop under’ window;

iii. must be crawlable (meaning, its contents must be indexable by a search engine); and

iv. must be maintained for a period of 60 days from the date of publication.

Compliance Orders

5. Pursuant to s 246(2)(b) of the ACL, Webjet, at its own expense:

(a) to the extent that it has not already done so, within the time period specified in Annexure B, review its ACL compliance program and makes any amendments necessary to meet the requirements identified in Annexure B; and

(b) maintain and continue to implement the ACL compliance program for a period of three years from the date on which the amendments in paragraph 5(a) above are made.

Costs

6. Pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), and within 30 days of these orders being made, Webjet pay $100,000 as a contribution to the applicant’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding.

Others Matters

7. The proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BUTTON J:

OVERVIEW

1 These proceedings were commenced by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) against Webjet Marketing Pty Ltd (Webjet), alleging that Webjet contravened ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

2 Webjet has admitted that between 1 November 2018 and 1 April 2024 (the Contravention Period), it engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct and made false or misleading representations, in trade or commerce, thereby contravening ss 18 and 29 of the ACL. The parties have filed joint submissions on liability and relief, and have jointly proposed orders, including declarations and the imposition of civil penalties totalling $9 million in respect of the contraventions.

3 Specifically, the parties sought declarations that Webjet engaged in conduct contravening ss 18 and 29 of the ACL, and orders that:

(a) Webjet pay a total of $9 million in pecuniary penalties to the Commonwealth of Australia;

(b) Webjet publish a corrective notice on Webjet’s website (the Webjet Website) and Webjet’s mobile application (the Webjet Mobile Application) outlining Webjet’s breaches of the ACL;

(c) Webjet review and maintain its ACL compliance program;

(d) Webjet pay a $100,000 contribution to the costs of the ACCC; and

(e) the proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

4 The parties have prepared two joint statements of agreed facts pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), dated 4 July 2025 and 25 July 2025 (SAFAs). The second SAFA was prepared at the Court’s request, to address the question of when the ACCC raised the issue concerning the Booking Failures (explained below) with Webjet. Copies of the SAFAs are annexed to these reasons for judgment. The facts stated in the SAFAs provide the factual foundation for the exercise of the Court’s jurisdiction to make the orders sought.

5 For the reasons below, I am satisfied that the declarations and orders proposed by the parties are appropriate in the circumstances. Orders were made on 28 July 2025, following receipt of the second SAFA after the hearing of the matter.

FACTUAL OVERVIEW AND THE CONTRAVENING CONDUCT

6 Webjet is a wholly owned subsidiary of Webjet Group Limited. Webjet is an online travel agency that:

(a) allows consumers to compare and book flights, hotels, car rentals and travel insurance on its website, the Webjet Website, and on its mobile application, the Webjet Mobile Application (together, the Webjet Platforms); and

(b) manages the Webjet brand and carries out marketing operations via the Webjet Platforms, email and social media.

7 In its capacity as travel agent, Webjet acts as an intermediary between consumers and airlines. Webjet’s other operations are not relevant to this proceeding. Webjet aggregates information about travel products — relevantly airfares — which allows consumers to search for, compare and purchase flights using a single platform. In aggregating the information about available flight bookings, Webjet relies on information provided to it by the airlines in relation to availability and price of a particular ticket class for a particular flight. This airfare information is simultaneously made available by airlines to travel agents globally, as well as directly to consumers via the airlines’ own sales channels. As a result, the airfare information is subject to real-time changes made by airlines.

8 Given the real-time nature of the booking system, sometimes, in the time between the consumer selecting a particular airfare on the Webjet Platforms and the consumer completing the booking, the airfare may become sold out, or the price or availability of the airfare may change, for reasons outside of Webjet’s control (a Booking Failure).

9 The occurrence of a Booking Failure is outside Webjet’s control, but what the customer is told is within Webjet’s control. The process is supposed to operate so that, in the event of a Booking Failure, no confirmation of booking is communicated by Webjet to the customer, and Webjet issues the consumer with a “Customer Service Advice” stating that Webjet has been unable to confirm the booking but is undertaking a process of manually confirming the booking. However, as further detailed below, there was a flaw in Webjet’s back-end processes, which resulted in customers being advised by Webjet that their booking was confirmed when that was not the case.

10 Between at least November 2018 and November 2023, Webjet has charged fees in respect of every booking made by a consumer. These fees, which were between $34.90 and $54.90 per booking in the relevant period, made up a substantial portion of Webjet’s revenue over that period. Those fees were charged as a matter of course and could not be avoided by the consumer. The quantum of fee varied between domestic and international travel but was not affected by the number of airfares included in a booking. These fees were not adequately disclosed by the Webjet Platforms and promotional emails, and were not disclosed at all in Webjet’s social media posts.

11 Webjet took prompt action to cease the conduct of concern after the ACCC raised its concerns regarding pricing disclosures with Webjet in October to November 2023 and, from that time, instituted changes to develop and enhance its training and processes for ACL compliance. Webjet took steps to address the conduct concerning Booking Failures in July 2024, and financially remediated the 118 affected consumers in October 2024, after the matter was raised by the ACCC on 25 June 2024.

Contraventions arising from the making of the Price Representation

12 Between 1 November 2018 and 13 November 2023, Webjet displayed airfare prices at or from “$XX” (Promoted Price) on the Webjet Platforms, social media and in promotional emails. Webjet thereby represented to consumers that it was, in fact, possible to purchase a promoted flight by paying only the Promoted Price (Price Representation). Specifically, Webjet made the Price Representations:

(a) on the Webjet Platforms from 1 November 2018 to 13 November 2023;

(b) in promotional emails sent to consumers who had not previously booked a flight with Webjet from 1 November 2018 to 31 October 2023 (Promotional Emails); and

(c) in 144 posts published on Webjet’s Facebook and Instagram Accounts (Social Media Posts) from 31 July 2019 to 30 October 2023,

(each the Price Contravention Period, as context requires).

13 In each instance, the Promoted Price did not include Webjet’s compulsory “Webjet Servicing Fee” and “Booking Price Guarantee” fee (together, the Webjet Fees) of between $34.90 and $54.90 per booking. The fact that the Webjet Fees were not included was not sufficiently disclosed on the Webjet Platforms or in the Promotional Emails, and was not disclosed at all in the Social Media Posts.

14 In most cases, the Promoted Prices had an asterisk attached. However, this was not always the case, and the information disclosed by a particular asterisk differed in the various contexts (Asterisk Disclosures), as follows:

(1) The Webjet Platforms mostly, but not always, displayed Promoted Prices with an asterisk. This asterisk was not a direct reference to the Webjet Fees but rather notified consumers that prices were “subject to change without notice” and that prices were inclusive of taxes and airline surcharges. While the Webjet Fees were then set out in the next sentence, it was not clear whether the fees were included in, or in addition to, the Promoted Prices.

(2) Most, but not all, of the Promotional Emails contained an asterisk attached to the Promoted Price. However, the corresponding asterisked text described “Terms & Conditions” but did not contain information as to the Webjet Fees. The Webjet Fees were displayed separately, immediately above the text specifying the qualification signified by the asterisk.

(3) Social Media Posts displaying Promoted Prices almost always had an asterisk attached to the Promoted Prices, but, in most instances, there was nothing to explain what the asterisk signified. These posts did not contain any Webjet Fee information. Of the 144 Social Media Posts, 14 contained an asterisk connected to text reading “T&C’s apply”, but did not explain what those “T&C’s” were.

(4) In all cases where information regarding the Webjet Fees was included, it was never explicitly stated that the Webjet Fees were in addition to, and not included in, the Promoted Price.

15 Webjet has admitted that:

(a) it represented to consumers that it was possible to purchase a promoted flight by paying the Promoted Price only — the Price Representation;

(b) the Asterisk Disclosures were not sufficient to displace the Price Representation;

(c) Webjet did not otherwise disclose to consumers, on the Webjet Platforms, in the Promotional Emails or in the Social Media Posts, that the Promoted Prices did not include the Webjet Fees; and

(d) it was, in fact, not possible for a consumer to purchase an airfare at the Promoted Price without the consumer incurring the additional compulsory Webjet Fees.

16 As such, Webjet accepts that the making of the Price Representation was conduct, in trade or commerce, that:

(a) was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, thereby contravening s 18 of the ACL; and

(b) contained a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services (an airfare), thereby contravening s 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

Contraventions arising from the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation

17 As outlined above in paragraph 8, the real-time nature of the Webjet booking system means that in some cases, in the time between a consumer booking an airfare on a Webjet Platform and that consumer completing the booking, the airfare may become sold out, or the price or availability of the airfare may change. In this scenario, rather than sending a booking confirmation, the system is intended to operate so that Webjet would issue a “Customer Service Advice” stating that it has not been able to confirm the booking but is attempting to do so manually.

18 Between 10 February 2019 and 1 April 2024 (Confirmed Bookings Contravention Period), due to an error in its back-end systems, on 118 occasions, Webjet issued a booking confirmation (either by displaying a confirmation page and/or sending the consumer an email) in circumstances where, in fact, these bookings had not been confirmed by the airline and Webjet should instead have issued a “Customer Service Advice”. By issuing those booking confirmations, Webjet represented that the consumer had acquired airfare(s) at the price paid (Confirmed Booking Representation).

19 Webjet has admitted that:

(a) it displayed a confirmation page and/or sent a confirmation email in respect of the 118 bookings, and, on each occasion, made the Confirmed Booking Representation; and

(b) those 118 bookings were, in fact, not confirmed and Webjet should have issued, but did not issue, a “Customer Service Advice” alerting the affected consumers to the Booking Failure.

20 Webjet’s making of the Confirmed Booking Representation in these circumstances was caused by a weakness in Webjet’s systems, specifically its back-end workflow process.

21 Webjet has admitted that, as such, the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation on the 118 occasions in question constituted conduct, in trade or commerce, that:

(a) was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, thereby contravening s 18 of the ACL; and

(b) conveyed a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services (the specific booking), thereby contravening s 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

APPLICABLE PRINCIPLES

Declaratory Relief

22 Section 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (Federal Court Act) grants this Court a “very wide” power to make declarations: Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2009] FCAFC 166; (2009) 182 FCR 160 at [1016] (Dowsett and Lander JJ, Mansfield J agreeing), citing Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 435 (Gibbs J).

23 I have previously set out the principles in relation to declaratory relief, albeit in a different context, in Australian Energy Regulator v AGL Loy Yang Marketing Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1299 (AER v AGL) at [67]:

Where declaratory relief is sought by consent, the Court retains, and must exercise, its discretion in determining whether to make the declarations sought. The questions posed must be real (not hypothetical), the applicant must have a real interest in raising the question, and there must be a proper contradictor: Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421 at 437–8 (Gibbs J); see also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378 at [12]–[19] (Greenwood, Logan and Yates JJ).

24 The making of declarations also serves to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator’s claims, assist the regulator in carrying out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the relevant provisions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bloomex Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 243 at [87] (Anderson J), citing Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; (2017) 254 FCR 68 (ABCC v CFMEU) at [93] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ). In these respects, the fact that the contravening conduct has ceased does not undermine the utility of making declarations.

Civil Penalties

Nature of Civil Penalties

25 In AER v AGL at [69]–[70], I set out the principles governing the imposition of civil penalties as follows:

69 The primary, if not sole, purpose of a civil penalty is to secure deterrence: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450 (Pattinson) at [14]–[19] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Edelman, Steward and Gleeson JJ). Deterrence in this context means both specific and general deterrence: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2018) 262 CLR 157 (ABCC v CFMEU) at [87] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ); Chief Executive Officer, Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre v Westpac Banking Corporation (2020) 148 ACSR 247; [2020] FCA 1538 (AUSTRAC v Westpac) at [23] (Beach J). Penalties are to be set so that the financial disincentives associated with contraventions are sufficiently high as to encourage compliance with the law: Pattinson at [66].

70 Penalties must be set at such a level as to have sufficient “sting or burden” to achieve “the specific and general deterrent effects that are the raison d’être of its imposition”, without being so high that they are oppressive: ABCC v CFMEU at [116] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ); NW Frozen Foods (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ). A penalty must not be so low that it can be regarded as merely a “cost of doing business”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 3) (2018) 131 ACSR 585; [2018] FCA 1701 at [120] (Beach J).

26 Where the parties agree and jointly propose a pecuniary penalty, the approach to be taken by the Court was set out by the Full Court in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 at [125]–[129] (Wigney, Beach and O’Bryan JJ) as follows:

125 First, the Court must be persuaded that the penalty proposed by the parties is appropriate: Fair Work [referring to Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482] at [57]. The agreement of the parties cannot bind the Court in any circumstances to impose a penalty which it does not consider to be appropriate.

126 Second, if the Court is persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the agreed penalty jointly proposed is an appropriate remedy in all the circumstances, it would be highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty: Fair Work at [58]. The desirability of the Court accepting a proposed agreed penalty which it is persuaded is an appropriate penalty derives primarily from a public policy consideration; the promotion of predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings: Fair Work at [46]. Predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation. It should be emphasised, however, that this public policy consideration is but one of the relevant considerations to which the Court must have regard and, more significantly, it cannot override the statutory directive for the Court to impose a penalty that is determined to be appropriate.

127 Third, in considering whether the agreed and jointly proposed penalty is an appropriate penalty, it is necessary to bear in mind that there is no single appropriate penalty. Rather, there is a permissible range of penalties within which no particular figure can necessarily be said to be more appropriate than another. The permissible range is determined by all the relevant facts and consequences of the contravention and the contravener’s circumstances. An agreed and jointly proposed penalty may be considered to be “an” appropriate penalty if it falls within that permissible range: NW Frozen Foods [referring to NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285] at 290-291; Mobil Oil [referring to Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] ATPR 41-993] at 48, 625-48, 626; [47], [51]. It is unlikely to be considered an appropriate penalty if it falls outside that range.

…

129 Fourth, in considering whether the proposed agreed penalty is an appropriate penalty, the Court should generally recognise that the agreed penalty is most likely the result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the regulator, and to reflect, amongst other things, the regulator’s considered estimation of the penalty necessary to achieve deterrence and the risks and expense of the litigation had it not been settled: Fair Work at [109]. The fact that the agreed penalty is likely to be the product of compromise and pragmatism also informs the Court’s task when faced with a proposed agreed penalty….

Pecuniary Penalties

27 The ACL does not provide for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty for a contravention of s 18. However, s 224(1)(a)(ii) states that a Court may order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of pt 3-1 of the ACL (which includes s 29 of the ACL).

28 The penalty imposed is to be that which the Court determines to be appropriate. However, in determining the appropriate penalty, s 224(2) provides that the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

29 Sections 224(3)–(3A) set out that the maximum penalty amount for a body corporate is the greater of:

From the start of Contravention Period until 9 November 2022

(a) $10 million;

(b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission — 3 times the value of that benefit; or

(c) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit — 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred or started to occur.

From 10 November 2022 until the end of the Contravention Period

(a) $50 million;

(b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission — 3 times the value of that benefit; or

(c) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit — 30% of the body corporate’s adjusted turnover during the breach turnover period for the act or omission.

30 While the prescribed maximum penalty operates as a yardstick in a civil penalty context, where a case involves false or misleading representations made on many thousands of occasions, the arithmetic maximum aggregate penalty may become so disproportionately large as to make precise calculation unnecessary, and not helpful to the Court: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 at [155]–[156] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [18], [82] (Allsop CJ); ABCC v CFMEU at [143] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Optus Internet Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1397 (ACCC v Optus) at [27]–[28] (Moshinsky J).

31 Together with the statutory factors listed above at paragraph 28, the Court should have regard to the “French Factors” as set out in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 521; (1991) ATPR 41-076 at [42] (French J), quoted with approval by the High Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450 (Pattinson) at [18] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ):

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

32 The French Factors should not be regarded, however, as a “rigid catalogue of matters for attention”: Pattinson at [19] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ), quoting Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8; (2008) 165 FCR 560 at [91] (Buchanan J). The penalty amount should rather be determined by an instinctive synthesis, whereby the Court identifies all relevant factors and, after weighing these factors, decides on an appropriate penalty: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Qantas Airways Limited [2024] FCA 1219 at [109] (Rofe J), citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 5; (2023) 407 ALR 302 (Employsure) at [42], [50], [53] (Rares, Stewart and Abraham JJ).

33 Other general considerations relevant to this decision are set out below.

34 Firstly, as I outlined in AEC v AGL at [68]:

[p]rovided that the Court is “sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed”, it is desirable that the Court accept agreed penalty submissions in civil penalty proceedings: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (Director, Fair Work) at [46], [58] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ); see also NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 (NW Frozen Foods) at 291 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ).

35 Secondly, where consenting parties are both legally represented and thus able to properly understand and evaluate the terms and desirability of the settlement, it is unexceptional for the Court to accept an agreed submission as to the nature and quantum of relief, subject to the Court being satisfied that, inter alia, the proposed penalty is an appropriate penalty: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 (the Agreed Penalties Case) at [58]–[59] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

36 Thirdly, steps taken by a party to ameliorate loss or damage (like a payment of compensation) are potentially relevant mitigatory considerations: ACCC v Optus at [32] (Moshinsky J), citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2016] FCA 44; [2016] ATPR 42-521 at [166]–[167] (Edelman J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v AGL South Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 146 ALD 385; [2015] FCA 399 at [38] (White J) .

37 Lastly, co-operating with authorities during investigations and subsequent proceedings can properly reduce the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. This is because it frees up the regulator’s resources thereby allowing the regulator to bring other contraveners to justice: ACCC v Optus at [33] (Moshinsky J), citing Agreed Penalties Case at [46] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ); NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 293–294 (Burchett and Kiefel JJ).

Multiple contraventions

38 Additionally, when imposing a penalty for several separate contraventions arising from acts or omissions that are inextricably linked, the “course of conduct” and “totality” principles are of relevance.

39 The course of conduct principle was explained by Moshinsky J in ACCC v Optus at [29]–[31]:

29 It is relevant to refer to the course of conduct principle, which was considered by the Full Court of this Court in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [421]–[428]. The Full Court (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ) stated at [424] that the course of conduct principle is a useful “tool” in the determination of appropriate civil penalties. The Full Court continued:

As we have already indicated, the principal object of the penalties imposed by s 76 of the [Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)] is that of specific and general deterrence. With this in mind, in a civil penalty context, the course of conduct principle can be conceived of as a recognition by the courts that the deterrent effect in respect of a civil penalty (at both a specific and general level) is measured by reference to the nature of the conduct for which it is imposed. It is therefore of paramount importance to identify whether multiple contraventions constitute a single course of conduct or separate instances of conduct, so as to ensure that an appropriate deterrent effect is achieved by the imposition of the penalty or penalties in respect of that particular conduct.

30 In relation to the course of conduct principle, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 (Hillside), Beach J stated at [25]:

… the “course of conduct” principle does not have paramountcy in the process of assessing an appropriate penalty. It cannot of itself operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed for contraventions of the ACL. Further, its application and utility must be tailored to the circumstances. In some cases, the contravening conduct may involve many acts of contravention that affect a very large number of consumers and a large monetary value of commerce, but the conduct might be characterised as involving a single course of conduct. Contrastingly, in other cases, there may be a small number of contraventions, affecting few consumers and having small commercial significance, but the conduct might be characterised as involving several separate courses of conduct. It might be anomalous to apply the concept to the former scenario, yet be precluded from applying it to the latter scenario. The “course of conduct” principle cannot unduly fetter the proper application of s 224.

31 The above passage was cited with approval by the Full Court in [Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 340 ALR 25] at [141].

40 The totality principle requires the Court to perform a last check to ensure that the cumulative total of the penalty imposed is just and appropriate having regard to the contravening conduct as a whole: ACCC v Qantas at [104] (Rofe J), citing Employsure at [52] (Rares, Stewart and Abraham JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Uber B.V. [2022] FCA 1466 at [79] (O’Bryan J), citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53 (Goldberg J).

Non-punitive Orders

41 Pursuant to s 246(1) of the ACL, the Court may, on the application of the regulator, make one or more of the orders described in s 246(2) in relation to a person who has engaged in conduct that contravenes a provision of chapter 2, 3 or 4 (chapter 2 includes s 18 and chapter 3 includes s 29).

42 The parties propose orders pursuant to ss 246(2)(b) and 246(2)(d), requiring that:

(a) Webjet undertake a review of its ACL compliance program and then continue to maintain and implement it for three years; and

(b) Webjet publish a corrective notice on the Webjet Platforms.

43 Orders of this kind have frequently been made: see, eg Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABG Pages Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 764 (Rangiah J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dell Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 588 (Jackman J); ACCC v Optus (Moshinsky J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SmileDirectClub LLC [2022] FCA 1343 (Anderson J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v HealthEngine Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1203 (Yates J).

CONSIDERATION

Declarations

44 The declarations as proposed by the parties are properly established by the facts and admissions as set out in the SAFAs.

45 Additionally, I am satisfied that the three requirements for making declarations by consent are satisfied in that:

(a) there is a real and not hypothetical question;

(b) the ACCC has a real interest in the matter; and

(c) Webjet is a proper contradictor.

46 As such, I consider it appropriate to make declarations substantially in the terms proposed by the parties. The making of these declarations serves to record the Court’s disapproval of Webjet’s contravening conduct, vindicate the ACCC’s regulatory action, and deter others from engaging in similar contravening conduct.

Civil Penalties

47 The parties propose that a penalty of $9 million be imposed, comprising an aggregate penalty of $8.5 million for three courses of conduct by which the Price Representation was conveyed and a $500,000 penalty for the conduct by which the Confirmed Booking Representation was made on 118 occasions. The parties submit, and I accept, that penalties in those amounts are appropriate after considering the relevant factors, set out below.

Maximum Penalty

48 The Price Representation was made between 1 November 2018 and 13 November 2023 for the Webjet Platforms, between 1 November 2018 and 31 October 2023 for the Promotional Emails, and between 31 July 2019 and 30 October 2023 for the Social Media Posts.

49 The Confirmed Booking Representation was made on 118 occasions between 10 February 2019 and 1 April 2024.

50 By making these representations, Webjet contravened s 18 and s 29(1)(i) of the ACL.

51 Given the proceeding was commenced on 28 November 2024, contraventions that occurred prior to 28 November 2018 (specifically, those that occurred between 1 November 2018 and 28 November 2018) are statute barred pursuant to s 228 of the ACL.

52 The period over which the contraventions occurred spans both the former maximum penalty regime (which applied between 28 November 2018 and 9 November 2022) and the current maximum penalty regime (which applied from 10 November 2022 onwards). Both are set out above in paragraph 29.

53 Webjet’s annual average revenue for:

(a) July 2018 to June 2020 was around $119.1 million (including approximately $147.8 million during the 2019 financial year);

(b) July 2020 to November 2022 was $59.5 million; and

(c) November 2022 to June 2024 was $129.3 million.

54 As such, the relevant maximum penalty for each alleged contravention is:

(a) under the former regime: between $10 million (where 10% of Webjet’s annual turnover during the breach turnover period was less than that amount) and approximately $14.7 million (being 10% of Webjet’s annual turnover at its highest during that period, and treating the financial year annual figures as a proxy for the period specified in the previous maximum penalty regime); and

(b) under the current regime: $50 million (being the greater of the relevant amounts).

55 That said, given each occasion on which the Price Representation was made and each occasion on which the Confirmed Booking Representation was made constitutes a distinct contravention, the maximum penalties are so large that they do not constitute a meaningful reference point by which to assess the appropriateness of the penalties proposed. Instead, consideration of the other relevant factors is necessary to assess the appropriateness of the proposed penalties.

Contraventions arising from the making of the Price Representation

56 Course of conduct: I accept the parties’ submission that the contraventions arising from the making of the Price Representation should be considered to comprise three distinct courses of conduct, one in respect of each medium through which the Price Representation was made. That is, the making of the Price Representation on the Webjet Platforms, the sending of the Promotional Emails and the making of the Social Media Posts constitute three separate courses of conduct. While the Price Representation was made through each medium for a similar marketing purpose, the way in which each medium operated was distinct and the Asterisk Disclosures varied across the media. Within each medium, however, the contraventions were inextricably linked and as such should not be treated as distinct.

57 The nature and extent of the breach: the Price Representation was made across three different media: the Webjet Platforms and the Promotional Emails for approximately five years, and the Social Media Posts for approximately four years. The Price Representation was made for both a marketing purpose and as part of the purchasing process.

58 While it is not possible to know with precision how many times a consumer viewed the Price Representation during the Price Contravention Period, and by extension how many contraventions occurred, it is clear that the extent of the conduct was significant and that the Price Representation was made on millions of occasions over the Price Contravention Period.

59 Misleading consumers as to the purchase price of a travel product is a serious matter. Consumers ought to be able to rely on what they are told about the price for which they can acquire goods and services and to be given clear information about any fees that are payable in addition to an advertised price. The making of misleading or deceptive claims about price can severely undermine consumer confidence, not to mention wasting consumers’ time and drawing them in to completing purchases for a higher cost than originally anticipated. Travel agents must ensure the information presented to consumers regarding price is clear, accurate and does not mislead by omission.

60 The nature or extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result: while approximately 4.45 million bookings were made during the Price Contravention Period, it is not possible to quantify the loss or damage suffered as a consequence of Webjet’s contraventions. That is because it is not known how many of those 4.45 million bookings were made by consumers who were misled by the Price Representation.

61 Consumers may have also suffered non-economic damage as a result of the contraventions, including being deprived of the opportunity to make a properly informed decision as to whether to purchase the Webjet airfare, being unaware of the additional Webjet Fees charged until the final stage of booking resulting in a loss of time and effort, and even at the final stage, being unaware of the automatically added Webjet Fees unless they clicked “show details”. It is critical that consumers are made aware of all fees that will be charged so that they can make informed decisions.

62 The circumstances in which the breach took place: although Webjet did not set out to mislead or “hide” the Webjet Fees, the way in which it marketed its airfares was within its control. Webjet made the decision to exclude the Webjet Fees from the Promoted Price and determined the information to be provided to consumers about its products. While Webjet’s senior management team was responsible for signing off on the design of the Webjet Platforms and implementing internal policies and training on price and fee disclosures, there is no suggestion that Webjet’s senior management deliberately sought to mislead consumers. Instead, there is evidence to suggest that Webjet staff misunderstood the relevant pricing and disclosure requirements, and erroneously thought that the use of an asterisk was sufficient to disclose the additional fees.

63 While Webjet did have an ACL compliance program in place during the Price Contravention Period, the contraventions nonetheless occurred across a variety of media and for a prolonged period of time. As such, the compliance program did not prevent the contravening conduct being engaged in, and was not effective as it did not identify and address the contravening conduct.

64 Since the ACCC raised its concerns with Webjet in October and November 2023, Webjet has committed to improving its culture of compliance. Webjet has already appointed an ACL Compliance Officer and conducted an external review of its ACL compliance training, resulting in compulsory ACL training being brought forward, training being conducted more frequently, and specialised training being provided to senior leaders and key business functions. Additionally, Webjet has ceased price-based advertising on social media in circumstances where the Webjet Fees apply and updated its Webjet Platforms and promotional emails to improve disclosure of the Webjet Fees.

65 Whether the respondent has engaged in previous contraventions of a similar nature: Webjet has not previously been found by a court to have contravened the ACL.

66 Size and financial position of the contravener: Webjet operates one of the largest online travel agencies in Australia. Given Webjet’s position in the travel agency market, it is important that the imposed penalty sends a clear signal to other travel companies in Australia that contraventions of the ACL will be penalised. The fact that the contravening conduct went to the core of Webjet’s business model, enticing consumers onto the Webjet Platforms by advertising prices in a misleading manner, provides further reason why the penalty must be substantial.

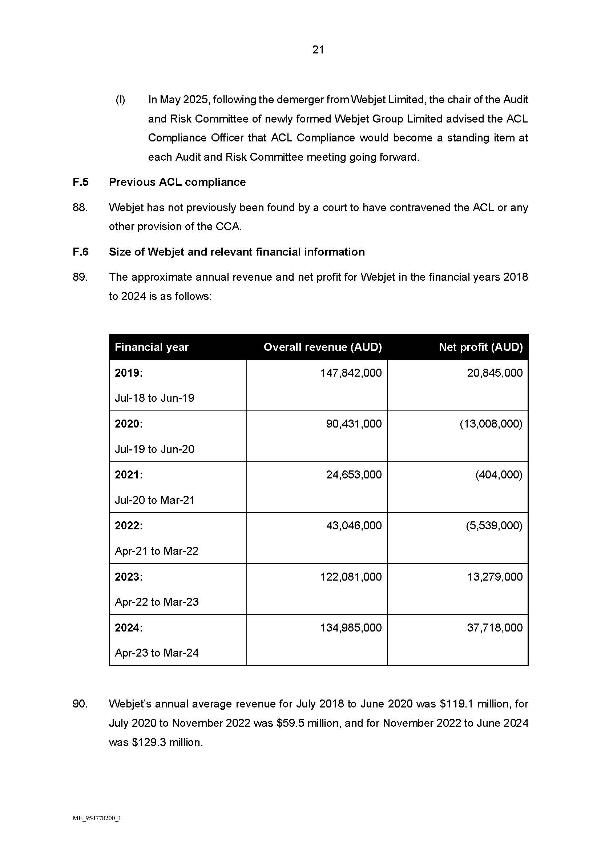

67 Having regard to Webjet’s revenue and net profit as set out in paragraph 89 of the first SAFA, the proposed $8.5 million penalty represents approximately:

(a) 9.1% of Webjet’s average annual revenue for the period from July 2018 to March 2024;

(b) 69% of Webjet’s average annual statutory EBITDA of $12.3 million for the period from July 2018 to March 2024, and 11.5% of Webjet’s overall EBITDA over that period; and

(c) 1.5% of Webjet’s total revenue for the period from July 2018 to March 2024 (noting that Webjet was operating at a financial loss in the financial years 2020 to 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic).

68 I am satisfied that, having regard to Webjet’s size and financial position, the penalties are appropriate in the circumstances. The penalties, while not “crushing”, have sufficient “sting” to serve the purposes of general and specific deterrence.

69 Deliberateness of the contraventions: the contraventions were not deliberate. They were a result of employees having an insufficient understanding of the pricing and disclosure requirements vis-à-vis the marketing of airfares. For example, Webjet’s Marketing Campaign Manager and Marketing Campaign Coordinator, with whom the principal responsibilities regarding promotional content development lay, erroneously considered the use of an asterisk to be sufficient from a legal compliance perspective.

70 The extent of any profit or loss derived as a result of the contraventions: as explained above in paragraph 60, the total value of any profit or loss derived as a consequence of the contravening conduct cannot be quantified. However, over the Price Contravention Period, Webjet earned $167.4 million in Webjet Fee revenue, which accounted for 36% of Webjet’s total revenue.

71 While there is no basis upon which to conclude that any particular proportion of that revenue was generated through the contravening conduct, it is likely that the Promoted Prices led to Webjet attracting consumers that may have otherwise booked airfares through different agents or directly on a specific airline’s website, had they been informed about the additional fees that would be charged.

72 Whether the conduct involved senior management: senior management were not involved in day-to-day decisions about price and fee displays. However, they were responsible for signing off on the design of the Webjet Platforms, which conveyed the Price Representation. Senior management were also responsible for approving Webjet’s formal Code of Conduct, and such processes as were in place to manage risks in marketing activities and implementing policies and training in relation to Webjet’s legal responsibilities regarding pricing and fee disclosure. Clearly, the training and policies did not prevent the contravening conduct. However, there is no suggestion that Webjet’s senior management intended to mislead consumers or that they were aware of any pattern of consumer complaints about the Webjet Fees.

73 Cooperation with the ACCC: upon being notified by the ACCC of its concerns in October and November 2023, Webjet acted promptly — starting in November 2023 — to remediate its internal processes, and started to implement structural and procedural changes to raise awareness of, and better secure compliance with, consumer laws. Webjet cooperated with the ACCC during its investigations and, after the ACCC commenced this proceeding, Webjet swiftly conceded liability and cooperated with the ACCC to prepare the SAFAs and joint submissions, consenting to final orders and costs. Webjet has displayed appropriate contrition.

74 Whether a company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance: Webjet has already taken several steps to improve its disclosure of the Webjet Fees as fees payable in addition to the Promoted Prices (set out at paragraph 87 of the first SAFA). While Webjet already had an ACL compliance program in place, it has conducted a review of its program and has formalised the appointment of an ACL officer. These are all positive steps to ensure that Webjet does not engage in similar conduct in the future.

Contraventions arising from the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation

75 In this section, I have only dealt with factors where the analysis differs from that in the above section on the Price Representation.

76 Course of conduct: I consider the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation on multiple occasions constitutes a single course of conduct. Each of the 118 Confirmed Booking Representations was the result of the same failure in Webjet’s back-end systems.

77 Nature and extent of the breach: the Confirmed Booking Representation was made on 118 occasions, and occurred in circumstances where there were Booking Failures, in that a particular consumer’s airfare was not confirmed but Webjet nonetheless sent the consumer a booking confirmation email and/or displayed a booking confirmation page.

78 Once Webjet identified the Booking Failure associated with each of the 118 bookings, it identified a substitute airfare. It then notified the consumer of the substitute airfare. The median time it took to notify the consumer was 12 hours, but the actual time ranged from 12 minutes to 9 days. On each occasion, Webjet gave relevant consumers two options. Consumers could pay an additional amount to Webjet to book the identified substitute airfare. This additional amount was the net amount required to secure the substitute airfare, after Webjet had contributed $1,000 through the application of Webjet’s Booking Price Guarantee, being the service provided by Webjet in exchange for the Booking Price Guarantee fee. On average, this additional amount was $343.44. The maximum was $2,120.16. Alternatively, consumers could receive a full refund of the amount paid for the affected airfare.

79 In 23 cases, the consumer decided to receive a refund while in the other 95 cases, consumers made additional payments to book the substitute airfare.

80 To put the number of distinct occasions on which the Confirmed Booking Representation was made into context, over the Confirmed Bookings Contravention Period, two million unique consumers made bookings with Webjet. This means that less than 1% of Webjet consumers were affected by the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation.

81 The nature or extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result: the 95 consumers who chose to book alternative airfares paid on average $309.87 each and a total of $29,438.09 in additional airfare costs. These additional costs have now been refunded by Webjet (save for one consumer whose original payment method has expired and who has not responded to Webjet’s request for updated payment details).

82 Consumers affected by the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation may have also suffered non-economic harm such as:

(1) The time spent, and inconvenience of, taking steps to clarify the situation with Webjet.

(2) During the time between the Confirmed Booking Representation being made and Webjet notifying the affected consumer of the issue, some consumers may have incurred other travel costs such as accommodation. These bookings may have been difficult to change or cancel, and it is possible the associated costs may have been nonrefundable. When Webjet then sought additional payment, some consumers may have been placed in the unenviable position of having to choose between paying the additional amount to Webjet or cancelling other arrangements, which may have resulted in additional losses.

(3) Where there was a significant delay in Webjet notifying the affected consumer of the issue arising from the Booking Failure, the affected consumer may have been deprived of the opportunity to secure comparable flights that might have been cheaper or otherwise more suitable than the alternative flights offered by Webjet.

83 The circumstances in which the breach took place: although the cause of the Booking Failures was beyond Webjet’s control, the process of displaying the booking confirmation was within Webjet’s control. That process was not intentionally designed to mislead consumers, although, in relation to the Confirmed Booking Representation, it had that effect. Additionally, Webjet’s senior management team did not address the underlying issue that caused the contraventions, thereby allowing the contraventions to continue throughout the Confirmed Bookings Contravention Period.

84 After the ACCC raised its concerns on 25 June 2024, Webjet updated its back-end workflow process to ensure the issue does not reoccur. The updated process was implemented on 24 July 2024. It is critical that companies understand that system issues need to be identified and addressed promptly. From a general deterrence perspective, the penalty imposed in this case serves to put companies on notice that contraventions arising from inadequate systems or processes will have consequences, particularly where they involve large or sophisticated corporations.

85 Deliberateness of the contraventions: Webjet did not design its booking confirmation process to mislead consumers. The contraventions were the result of a technological issue.

86 The extent of any profit or loss derived as a result of the contravention: while Webjet initially received $29,438.09 from the 95 consumers who decided to book the alternative airfares with Webjet, Webjet ultimately refunded all 95 consumers in full and so did not retain any financial benefit (save for one consumer as explained above at paragraph 81).

87 Whether the contraventions arose from the conduct of senior management: the conduct did not arise directly from conduct on the part of senior management, save to the extent that senior management was ultimately responsible for Webjet’s systems. Those systems were responsible for the back-end error, which was not identified promptly, but in fact persisted over five years.

88 Whether a company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance: after the ACCC raised its concerns, Webjet amended its back-end workflow processes to ensure the issue does not occur again, and remediated affected consumers.

89 Size and financial position of the contravener: relevant facts concerning Webjet’s financial position are set out in paragraph 66 above. The penalty of $500,000 for the relevant contravening conduct reflects the fact that, as a large and sophisticated business, it was not acceptable for Webjet to operate systems that resulted in the technological issue occurring and going unnoticed for such a long period of time.

Synthesis of Factors

90 Having regard to the considerations outlined above, the parties’ proposed penalties are appropriate in all the circumstances. Those penalties are as follows:

(a) $3.5 million for the Social Media Posts course of conduct by which the Price Representation was made;

(b) $2.5 million for each of the Webjet Platforms and Promotional Emails courses of conduct by which the Price Representation was made; and

(c) $500,000 for the course of conduct by which the Confirmed Booking Representation was made on 118 occasions.

91 The $9 million aggregate penalty is sufficiently high to ensure specific and general deterrence, recognising the need to send a strong message regarding misleading advertising of prices and the adequacy of back-end systems and processes. It is vital that the Australian public can rely on the travel industry to advertise real and accurate prices, and to ensure that back-end systems accurately record and communicate the status of a consumer’s booking. The penalty accounts for Webjet’s key role in the travel agent industry, the fact that the contraventions occurred over a long period of time — five years — and Webjet’s strong financial position, while also acknowledging Webjet’s cooperation with the ACCC, Webjet’s contrition and the fact that Webjet has already taken steps to improve its ACL compliance, has refunded the additional costs incurred as a result of the making of the Confirmed Booking Representation, and has agreed to contribute to the ACCC’s costs in this proceeding.

Other Orders

92 The parties also propose that the Court make orders to the effect that:

(1) pursuant to s 246(2)(d) of the ACL, Webjet, at its own expense, publish on the homepage of the Webjet Website and on the Webjet Mobile Application a corrective notice in the terms and form set out in Annexure A to the orders, complying with specifications as outlined in paragraph 4 of the orders;

(2) pursuant to s 246(2)(b) of the ACL, at its own expense Webjet:

(a) review its ACL compliance program to ensure it complies with the requirements in Annexure B to the orders, to the extent that it has not already done so;

(b) maintain and continue to implement its ACL compliance program for a period of three years from the date on which any amendments are made;

(3) pursuant s 43 of the Federal Court Act, and within 30 days of the orders, Webjet pay $100,000 as a contribution to the ACCC’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding; and

(4) the proceeding otherwise be dismissed.

93 I am satisfied that making these additional orders is appropriate in the circumstances.

CONCLUSION

94 It was for the above reasons that I made the declarations and orders on 28 July 2025. The proceeding was otherwise dismissed as the ACCC initially sought, by its originating application, injunctions, but did not press for this relief.

I certify that the preceding ninety-four (94) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Button. |

Associate:

Dated: 29 July 2025