Federal Court of Australia

Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Interlocutory Matters) [2025] FCA 801

File numbers: | VID 222 of 2025 VID 642 of 2025 |

Judgment of: | LEE J |

Date of judgment: | 8 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – litigious morass – where the outstanding issues in the proceedings can be grouped into six categories – where the last four categories of issues fell for determination – where the requirement of the Court to conduct proceedings in a way which facilitates their efficient, cost effective and prompt resolution considered – where the best way of dealing with matters of this type considered – where preliminary applications were unsuccessfully made by the respondents – where prayers for relief that the applicant acted in contempt of court considered – where an informal oral application for judicial review and other matters considered |

Legislation: | Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) s 5 Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) ss 51(1), (2) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ch 2, ss 11, 27, 29(1), 192(2) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 35A(5), 37AF(1)(a), 37AG(1)(a) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 2.26, 29.03, 29.09, 42.11, 42.12 Legal Profession Uniform Law (Vic) Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (Vic) |

Cases cited: | Ferdinands v Registrar Cridland [2022] FCAFC 80 Impiombato v BHP Group Limited [2025] FCAFC 9; (2025) 308 FCR 250 Lantrak Holdings Pty Ltd v Yammine [2023] FCAFC 156 Nyoni v Murphy [2018] FCAFC 75; (2018) 261 FCR 164 Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (No 2) [2025] FCA 646 Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal, in the matter of Kuksal [2025] FCA 508 Victorian Legal Services Borad v Kuksal [2025] FCA 558 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | General and Personal Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 83 |

Date of hearing: | 8 July 2025 |

Counsel for the applicants: | Mr D Collins KC with Ms G Coleman |

Solicitor for the applicants: | Corrs Chambers Westgarth |

Counsel for the respondents: | The respondents were self-represented |

ORDERS

VID 222 of 2025 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | VICTORIAN LEGAL SERVICES BOARD First Applicant DAMIAN NEYLON Second Applicant GORDON COOPER (and another named in the Schedule) Third Applicant | |

AND: | SHIVESH KUKSAL First Respondent LULU XU Second Respondent PETER ANSELL Third Respondent | |

order made by: | LEE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 JULY 2025 |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

1. This order adopts the term ‘Flitner Allegations’ defined in the concise statement filed on 21 May 2025 in the Collateral Proceeding.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

2. The affidavit of Lulu Xu affirmed on 13 May 2025 and filed on 14 May 2025 be removed from the Court file.

3. Absent prior leave by a judge of the Court, any further documents filed or otherwise relied on by the respondents in this proceeding are not to contain or refer to the Flitner Allegations, any part of them, or their substance.

4. Unless and until notices of opposition are filed in a form which properly identifies the grounds of opposition, the respondents are not to issue any notices to produce and are refused leave to issue any subpoenas.

5. Orders 2 to 4 made on 20 June 2025 in this proceeding are vacated.

6. The respondents’ application for judicial review is dismissed.

7. The applications for orders in terms of prayers 5 to 6, and prayers 1 to 5 of Annexure A, of their interlocutory application filed in this proceeding on 23 June 2025 are dismissed.

8. By 4:00pm on Tuesday, 29 July 2025, the respondents file and serve any application alleging a contempt in accordance with r 42.12 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), including:

(a) a statement of charge in accordance with Form 137, specifying the contempt with sufficient particularity to allow the person to answer the charge; and

(b) the affidavits on which the person making the charge intends to rely to prove the charge.

9. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the following parts of the following documents remain confidential for a period of five years:

(a) exhibit A received into evidence at the hearing on 8 July 2025 (being pages 71–72, 297–298 and 306 of the court book);

(b) the following parts of the affidavit of Jared Robert Heath affirmed on 30 June 2025 (Second Heath Affidavit), filed in the Collateral Proceeding and read and relied upon at the hearing on 8 July 2025:

(i) the words underlined in each of sub-paragraphs 7(a) to (d);

(ii) the words underlined in each of sub-paragraphs 14(a) to (e);

(iii) pages 18, 19, 20, and 24 of the confidential annexure JRH-5; and

(iv) confidential annexure JRH-6.

(c) the following parts of the affidavit of Thomas Christian Flitner made and filed on 21 May 2025 in the Collateral Proceeding, and read and relied upon by the Respondents at the hearing on 8 July 2025:

(i) paragraphs 43 to 44, 74 and 77; and

(ii) footnotes 2, 11 and 19.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

VID 642 of 2025 | |

BETWEEN: | VICTORIAN LEGAL SERVICES BOARD Applicant |

AND: | SHIVESH KUKSAL First Respondent PETER ANSELL Second Respondent LULU XU Third Respondent |

order made by: | LEE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 JULY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the following parts of the following documents remain confidential for a period of five years:

(a) exhibit A received into evidence at the hearing on 8 July 2025 (being pages 71–72, 297–298 and 306 of the court book);

(b) the following parts of the affidavit of Jared Robert Heath affirmed on 30 June 2025 (Second Heath Affidavit) filed in this proceeding:

(i) the words underlined in each of sub-paragraphs 7(a) to (d);

(ii) the words underlined in each of sub-paragraphs 14(a) to (e);

(iii) pages 18, 19, 20, and 24 of the confidential annexure JRH-5; and

(iv) confidential annexure JRH-6.

(c) the following parts of the affidavit of Thomas Christian Flitner made and filed on 21 May 2025:

(i) paragraphs 43 to 44, 74 and 77; and

(ii) footnotes 2, 11 and 19.

2. The applicant’s interlocutory application dated 21 May 2025 seeking interlocutory relief in this proceeding is otherwise dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

(Delivered ex tempore, revised from the transcript)

LEE J:

A INTRODUCTION

1 I commenced the hearing of these applications at 9:30am today and, with a truncated break for lunch, I have heard argument and submissions until after 5pm. I have reached a firm view as to the course that should be taken in relation to the applications made in these proceedings and hence have determined to deliver these reasons immediately.

B BACKGROUND

2 The relevant background to the issues that have come before the Court today is set out in several judgments, including Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal [2025] FCA 558 (at [4]–[8] per Meagher J).

3 By way of very broad summary, it appears that in the middle of 2021, the Victorian Legal Services Board (VLSB) is said to have exercised powers under the Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (Vic) and the Legal Profession Uniform Law (Vic) to commence an investigation into the behaviour of Shivesh Kuksal and Lulu Xu relating to the conduct of a business known as “RM Legal Consultants” and “Law Innovation”. Later, the investigations of the VLSB extended to Peter Ansell and related to the conduct of “People Shop Pty Ltd” (People Shop) trading as “New Edge Law” and/or “Erudite Legal”.

4 The VLSB allege that Mr Kuksal and Ms Xu have not been admitted to legal practice and do not hold practising certificates and, although Mr Ansell was admitted to legal practice, it is alleged he ceased to hold a practising certificate from 18 October 2022 onwards.

5 It suffices to note that by August 2022, the VLSB had appointed an external manager to the law practice conducted by People Shop.

6 A slew of litigation ensued in the Supreme Court of Victoria, commencing in 2022. Set out in Annexure A to this judgment is a summary of proceedings which, as I understand it, are being (or have been) conducted in the Supreme Court of Victoria.

7 More relevantly for present purposes, bankruptcy proceedings have been commenced in this Court (VID 222 of 2025) (Bankruptcy Proceeding). This involves an application by the VLSB for sequestration orders against each of Mr Kuksal, Mr Ansell and Ms Xu. These applications are listed for final hearing at the end of this month.

8 The bankruptcy notice, which has given rise to the alleged act of bankruptcy of each of the respondents, is based on judgments arising from various costs orders made in the Supreme Court of Victoria proceedings. As best as it can be understood from the material currently before the Court, the making of sequestration orders is opposed on the basis that the judgment debts were procured by fraud or are otherwise irregular or void, or because there is an intention to appeal from the underlying costs orders or have the costs orders set aside; it is further asserted that the Bankruptcy Proceeding is an abuse of process (in that it was commenced by the VLSB to punish the respondents or to deter them from pursuing complaints of misconduct made against the VLSB).

9 The Bankruptcy Proceeding has been docketed to her Honour, Justice Downes, and, as noted above, the application for sequestration orders has been listed before her Honour on 28 and 29 July 2025. Needless to say, the pending hearing of the application for sequestration orders (quintessentially an application that ought be resolved with celerity) is a further reason for the expeditious resolution of the matters presently before me.

10 Additionally, applications have been brought by the VLSB (VLSB Interlocutory Application) against the respondents in a proceeding commenced by the VLSB on 21 May 2025, being VID 642 of 2025 (Collateral Proceeding).

11 In the Collateral Proceeding, Meagher J made orders on 21 May 2025, the reasons for which are set out in Victorian Legal Services Borad v Kuksal (Meagher J Orders). A number of those orders were expressed to continue in operation “until the hearing and determination of the [VLSB’s] interlocutory application filed in [the Collateral Proceeding] on 21 May 2025 or further order …”. It is common ground between the parties that these aspects of the Meagher J Orders will expire upon my determination of the VLSB Interlocutory Application.

12 I have already said enough to give an indication of the litigious morass that characterises this controversy. A large part of the hearing today was working out what relief each party sought both before me, and in the Bankruptcy Proceeding and Collateral Proceeding generally. In the end, it is possible to group the outstanding issues into six categories:

(1) The application for sequestration orders, including determining the grounds of opposition to the petition provided for by the respondents, that is, the substantive matter listed for final hearing before Downes J later this month;

(2) An application by which the respondents seek the disqualification of Downes J from the further conduct of the Bankruptcy Proceeding and the Collateral Proceeding (Disqualification Application);

(3) Various prayers of relief whereby the respondents contend: that the VLSB has acted in contempt of court by first, improperly influencing or seeking to improperly influence Mr Thomas Flitner against giving evidence and secondly, commencing the Collateral Proceeding in order to “impede the [r]espondents in effectively prosecuting their foreshadowed applications in the [Bankruptcy Proceeding]”; that the solicitors acting on behalf of the VLSB are accessories in the VLSB’s conduct in contempt of court; and a number of ancillary matters including issues identified in a s 78B notice filed by the respondents in the Bankruptcy Proceeding (Filed s 78B Notice);

(4) An informal oral application for judicial review arising from the rejection by Judicial Registrar Schmidt of an affidavit of Mr Kuksal affirmed 23 June 2025, a further s 78B notice dated 30 June 2025 (Rejected s 78B Notice) and an affidavit of Lulu Xu affirmed 30 June 2025 (Rejected Xu Affidavit);

(5) The VLSB’s application which, during the course of argument, has been refined to orders seeking that an affidavit of Lulu Xu made on 13 May 2025 (Xu Filed Affidavit) be removed from the court file and an order that certain allegations referred to in the Xu Filed Affidavit, described as the “Flitner Allegations”, are not made further in the Bankruptcy Proceeding; and

(6) An application that the Court set aside the Meagher J Orders.

13 I deal below with the matters that fall for determination by me, being all or aspects of the last four categories of issues identified above. The first two matters will not be dealt with by me, although I intend to hear from the parties after I have delivered these ex tempore reasons as to appropriate orders readying the Bankruptcy Proceeding for hearing later this month.

C PRELIMINARY REMARKS

14 As might have already become evident, the current controversy between the VLSB and the respondents is a paradigm example of the difficulties currently bedevilling this and other courts in dealing with self-represented litigants and opposing parties who often overcomplicate their response to querulous opponents.

15 The Supreme Court of Victoria proceedings have resulted in many judgments, which I detail at Annexure B. Further, leaving aside the Collateral Proceeding, the Bankruptcy Proceeding has already resulted in the following judgments in this Court: Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal, in the matter of Kuksal [2025] FCA 508 and Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (No 2) [2025] FCA 646.

16 The amount of judicial time which has been involved in attempting to deal with this matter can only be the subject of speculation. On any view, it has involved various judges hearing argument in interlocutory matters, reserving their decisions, and then writing judgments, including lengthy judgments, which then become the subject of further and repeated disputation.

17 Judges of this Court and the Supreme Court of Victoria, like all other superior courts in this country, are now required to conduct proceedings in a way which facilitates the efficient, cost effective and prompt resolution of controversies. The ability of the Court to fulfill its function is significantly challenged if litigation is conducted in a way similar to how this matter has been conducted.

18 It is often said that a person is entitled to his or her day in court, but that does not mean that they are entitled to another person’s day in court. Every hour this Court and the Supreme Court of Victoria has been required to spend on this matter in dealing with interlocutory disputation is another day when justice is delayed for other litigants.

19 Without in any way being critical of how others may have dealt with aspects of this matter, it has become increasingly evident (to me at least) that the best way of dealing with cases of this type is to bring them on for early final hearing as quickly as possible, in order to minimise the amount of interlocutory disputation. A focus on an early final hearing will identify whether there is a real issue or issues to be determined – something which is often obscured by the brume of endless interlocutory applications and collateral disputation. Often the amount of time spent on interlocutory disputation with subsequent applications for leave to appeal or for the setting aside of orders can be minimised if the Court grasps the nettle of listing the matter for early final hearing.

20 Prior to coming to the matters which I must deal with, it is first necessary to deal with a preliminary application made on behalf of the respondents.

21 The respondents commenced the hearing today by seeking an adjournment.

22 This adjournment application was premised on a number of arguments, including that: the respondents had inadequate time to prepare for the hearing; they wished to issue subpoenas for witnesses to give evidence (including Mr Flitner and Mr Anstee); they wished to conduct a foreshadowed cross-examination of a witness called on behalf of the VLSB, Mr Heath, in person rather than at today’s remote hearing from Sydney; they only seek directions in relation to the contempt issue; and that the respondents wished to deal initially with a separate issue (referred to in prayer four of the interlocutory relief initially sought on 17 June 2025 but now referred to in the interlocutory application of 23 June 2025), that is, that the Court separately determine the issues in the Filed s 78B Notice before hearing any other issues.

23 I declined the adjournment application.

24 Ultimately, the issue as to whether or not the application for an adjournment should be granted is dictated by what best facilitates the overarching purpose. A vast array of paper and confusing material has been placed before the Court. The quicker the Court deals with these matters in order to allow the substantive matters to proceed for hearing the better. Further, the Court has become well acquainted to dealing with matters remotely and I am not satisfied that any material prejudice is caused by conducting aspects of the proceedings online.

25 Further, I am not satisfied that it is appropriate to determine any aspect of the proceeding separately, before the hearing of the application for sequestration orders listed on 28 and 29 July 2025, and accordingly, I do not propose to order a separate determination of any issue. Why separate determination of any issue would be consistent with the overarching purpose and the long recognised need for bankruptcy proceedings to be resolved with alacrity is wholly unclear to me.

D THE VLSB’S APPLICATION

26 As originally framed, the application made by the VLSB proposed that orders be made in both the Bankruptcy Proceeding and the Collateral Proceeding restraining the respondents from disclosing any of the Flitner Allegations, irrespective of the forum of disclosure. Further, orders were sought pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(a) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act), being broad suppression or non-disclosure orders, notwithstanding that the information in respect of which those orders were sought has not been the subject of adduction of evidence in the proceedings (subject to some material I identify below).

27 Both aspects of the relief sought by the VLSB seem to me to be misconceived.

28 There is no basis for me to enjoin the respondents outside of the context of the Bankruptcy Proceeding. If allegations like the Flitner Allegations are made other than on occasion of absolute privilege, then the law of defamation would be the appropriate remedy for any actionable damage occasioned. There is no doubt defamatory imputations could be drawn from a publication containing at least some of the Flitner Allegations. The question would then arise as to whether or not there would be a defence to that defamatory publication. By reference to a raft of authority I need not presently set out, it would be, at the very least unorthodox, to grant an application to enjoin peremptorily a possible (but not currently threatened) defamatory publication.

29 The second application is misconceived because suppression and non-publication orders are made with regard to evidence. It is trite that the filing of an affidavit does not involve its adduction into evidence. This only occurs if and when the affidavit is read. In this regard, in Impiombato v BHP Group Limited [2025] FCAFC 9; (2025) 308 FCR 250, I pointed out (at 303 [319]) that “[b]unging an affidavit into a “court book” does not constitute it being adduced into evidence … an affidavit contains representations of a witness called in the proceeding and these representations only form part of the testimonial evidence when the affidavit is read, and the deponent thereby becomes a witness. Reading an affidavit is a necessary and critical step to its receipt as testimonial evidence …”. There is only a need for suppression and non-publication orders to be made at the time the representations contained in the affidavit are adduced into evidence.

30 The Xu Filed Affidavit is only eleven paragraphs long, but attached to it are a large number of email chains and pieces of correspondence, together with transcripts of telephone calls and electronic folders. To say the least, it is not a document which is prepared in an orthodox form.

31 It is common ground that it contains within it what has been described on this application and the previous application before Meagher J as the Flitner Allegations. Those allegations, which I will not repeat in these reasons, are set out in a confidential annexure to the concise statement filed in the Collateral Proceeding and, in a materially similar form, are set out in the court book at pages 297–298 and 306, which, for the purpose of this application, I received into evidence and have marked Exhibit A.

32 By their very nature, the Flitner Allegations are extraordinary and are also highly personal. Meagher J referred to them in Victorian Legal Services Borad v Kuksal (at [14]–[15]) as follows:

Central to this matter are what are described in Mr Heath’s affidavit as the Flitner Allegations. They comprise an email from Mr Flitner to Mr Kuksal (the Flitner email) and a letter from Mr Ansell to the members of the Victorian Legal Services Board, and each of a solicitor and a barrister (the Ansell letter). The Flitner email and the Ansell letter (together the Flitner allegations) contain allegations about a person employed at the Victorian Legal Services Board by the Commissioner (Person One) which Mr Heath deposes are “scandalous, embarrassing and reputationally damaging”. The Flitner allegations include a description of explicit videos. The Flitner email and the Ansell letter are attached to Mr Heath’s affidavit as part of a confidential annexure.

The Ansell letter more broadly sets out a number of grievances that the respondents to this matter and others, including Mr Flitner, have with the applicant. The Ansell letter foreshadows the bringing by the respondents of contempt proceedings against the first applicant in the bankruptcy proceedings and other matters. In that context the Ansell letter accuses the applicant of moving to prevent the respondents (and others) bringing to light what might broadly be described as corruption and collusion on the part of the applicant and others not parties to this matter.

33 Evidence was received on the application from Mr Heath, who is the solicitor for the VLSB. Mr Heath made various contentions as to his belief in relation to the proposed use of these allegations. Mr Kuksal took issue with that material and cross-examined Mr Heath. Although cross-examination was opposed, I adhere to the view that I have expressed a number of times, including most recently in Impiombato (at 302 [317]), that when an interlocutory application is accompanied by affidavit material and evidence is proposed to be adduced by way of affidavit, there is an ability, in accordance with r 29.09 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR), for a party to give notice requiring the deponent of the affidavit for cross-examination. There is no need to ask “permission” to do so.

34 It used to be said (and sometimes still is) that “leave” is required to cross-examine on an interlocutory application, but as I explained as part of the Full Court in Lantrak Holdings Pty Ltd v Yammine [2023] FCAFC 156 (at [28]), this line of authority, which developed in some states prior to the introduction of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) and its cognates, is not the right starting point or frame of analysis because the Evidence Act now applies and s 27 provides that “[a] party may question any witness, except as provided by this Act” and s 29(1) provides that “[a] party may question a witness in any way the party thinks fit, except as provided by [Ch 2 of the Evidence Act] or as directed by the court”.

35 The Court has, of course, an express (s 11) implied power to control the conduct of the proceeding, and given the terms of Ch 2, the question of whether cross-examination should occur on an interlocutory application is more properly framed as whether a direction should be made that it does not occur notwithstanding it is sought. When properly framed, it can be seen the mandatory considerations in s 192(2) of the Evidence Act apply to considering whether a direction ought to be made, and this cannot be reconciled with the notion that a form of “leave” needs to be sought and that such “leave” is normally granted “somewhat sparingly”.

36 Notwithstanding the application of the VLSB, I did not make a direction preventing Mr Kuksal cross-examining on two limited topics, because he wished to challenge the accuracy of the evidence given by Mr Heath, and it seemed to me appropriate that, as a matter of procedural fairness, these matters be put to the witness. They were, but the cross-examination did not assist.

37 Ultimately, the determination of the substantive issue comes down to the question of whether r 29.03 is engaged, such as to allow the party to apply to the Court for an order that the affidavit be removed from the court file. The prohibition in r 29.03(1) is that an affidavit must not contain any scandalous, frivolous or vexatious material, be evasive or ambiguous or otherwise be an abuse of process of the Court.

38 I am amply satisfied that the affidavit does contain scandalous or vexatious material. That conclusion can be reached without forming a final view as to whether or not the affidavit also constitutes a somewhat broader abuse of process of the Court as alleged by Mr Heath.

39 I pressed Mr Kuksal over the course of his lengthy oral submissions to articulate how the Flitner Allegations could conceivably be relevant to the determination of the Bankruptcy Proceeding. His submissions in this regard were diffuse and somewhat difficult to follow. They seemed to consist of two broad arguments, which included contentions that, first, in the Bankruptcy Proceeding, the respondents wished to adduce “tendency evidence” that the VLSB has taken similar action against the respondents as it has against other legal practitioners, which has involved abuses and a “rigging of the system”. This has resulted in a pattern of conduct whereby the Board has threatened legal practitioners and obtained “exorbitant” interlocutory costs orders as a means of placing improper pressure on practitioners and in order to secure judgments, which could ground bankruptcy notices. This is said to be a tactical ploy which involves the Board improperly obtaining costs orders.

40 Secondly, it is said that because the conduct the subject of the Flitner Allegations (insofar as it implicates the Board) is so egregious, that conduct amounts to an abuse of authority, and all actions taken subsequent to the establishment of that abuse of authority were non-operative and are subject to “reversal” or are “open to be set aside”.

41 In one respect, I am at a disadvantage because I have not been taken to any filed notice on behalf of the respondents stating the grounds of opposition to the petition (a Form B5) and accompanying affidavits supporting those grounds which identify, with precision, the matters called in aid in opposition to the petition. Nevertheless, the summary of the grounds of opposition which I have set out above, was accepted by the respondents as an adequate summary of the allegations (notwithstanding they are, on the material I was taken to, imprecise and unparticularised).

42 Sections 52(1) and (2) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) (Bankruptcy Act) provides as follows:

(1) At the hearing of a creditor's petition, the Court shall require proof of:

(a) the matters stated in the petition (for which purpose the Court may accept the affidavit verifying the petition as sufficient);

(b) service of the petition; and

(c) the fact that the debt or debts on which the petitioning creditor relies is or are still owing;

and, if it is satisfied with the proof of those matters, may make a sequestration order against the estate of the debtor.

…

(2) If the Court is not satisfied with the proof of any of those matters, or is satisfied by the debtor:

(a) that he or she is able to pay his or her debts; or

(b) that for other sufficient cause a sequestration order ought not to be made;

it may dismiss the petition.

…

43 This is not the occasion to canvass in any detail the way in which a petitioning creditor who has a prima facie right to a sequestration order (once the matters required by s 52(1) have been proven) can be deprived of the order because of the existence of a discretion to refuse such an order for, inter alia, “other sufficient cause”: see s 52(2)(b). It suffices to note that the concept of “other sufficient cause” is broad, and it is inappropriate to catalogue or circumscribe what these “other sufficient cause(s)” may be. Of course, even if “other sufficient cause” has been shown, that merely enlivens the Court’s discretion to refuse the making of a sequestration order.

44 Notwithstanding the width of the provision, it is presently inconceivable to me how, given the nature of the Flitner Allegations, they could be probative of any rational argument which demonstrates that “other sufficient cause” can be made out, such that sequestration orders ought not be made, including a contention that the Bankruptcy Proceeding constitutes an abuse of process.

45 In reaching this conclusion, I am conscious of the fact that I intend to make a direction that a proper notice of opposition be filed, and I will give the respondents leave to file any properly formulated affidavit material which goes to those identified grounds of opposition, such that any proper argument can be put before the Court.

46 Given the opportunity afforded to the respondents to file properly directed and admissible evidence directed to particularised grounds of opposition, it does not seem to me to be sensible to delineate between those parts of the Filed Xu Affidavit that could conceivably be relevant and non-scandalous or vexatious and those parts that are properly characterised in that way. I am satisfied that the Filed Xu Affidavit should be removed from the court file in its entirety.

47 Further, given the view I have expressed about the nature of the allegations and how they could not be relevant to the determination of the sequestration orders, I also propose to make an order that the Flitner Allegations not be repeated in documents filed in the Bankruptcy Proceeding. If some limited non-vexatious aspect of the Flitner Allegations is conceivably relevant to a later properly articulated ground of notice of opposition (a prospect I very much doubt), then reference to it would need to be subject to the trial judge varying my order in order to allow that limited material to be adduced.

48 Much time was spent today on an application to set aside the Meagher J Orders. It is a waste of time for me to deal with those arguments in circumstances where I have dealt with the application made by the VLSB and, consistently with the joint position of the parties, the substantive operation of the interim orders made by Meagher J will now expire. There was some suggestion made on behalf of the respondents that there could be some issue estoppel or other preclusion arising by reason of the fact that they do not press an application to set the orders aside, but this, again, is misconceived. I am conscious that the way in which the respondents put the application is to set aside the orders ab initio, but I see no reason why I should proceed to take that course.

49 In any event, it appears from the submissions made today that all the material upon which the respondents rely to contend that an error of fact was made by Meagher J, was available prior to the hearing before Meagher J but was not in evidence. The circumstances in which the Court may vary or set aside a judgment or an order after it has been entered are set out in r 39.05. These circumstances can include where the order was obtained by fraud, which generally goes to the evidence relied upon before the Court.

50 Of course, a party asserting an order was procured by fraud must usually show there has been a new discovery of something material in the sense that fresh facts have been found which provide a reason for setting aside the order, and the burden of establishing the matters necessary to warrant the drastic step of setting aside the order lies on the party impugning it. Apart from the fact that I do not consider that fraud has been established, the fraud has not, in any event, been sufficiently particularised, and as I noted above, the utility of the Meagher J Orders will, upon the making of orders arising from this ex tempore judgment, be spent.

E JUDICIAL REVIEW APPLICATION

51 I mentioned above that the orders sought in relation to the rejection by Judicial Registrar Schmidt of an affidavit of Mr Kuksal affirmed 23 June 2025, the Rejected s 78B Notice and the Rejected Xu Affidavit were not formalised.

52 Ordinarily, of course, a Judicial Registrar’s refusal under r 2.26 is a decision of an administrative character and is amenable to review under s 5 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act). No such application has been made in the usual form, but I will proceed on the basis that, in accordance with s 5(1) of the ADJR Act, the respondents are persons who at least allege that they are aggrieved and also allege that the relevant decision was contrary to law.

53 The alternative bases upon which the challenge is made is that the Registrar’s decision amounted to an improper exercise of judicial power or, if this contention is wrong, that the decision is an administrative one which is affected by jurisdictional error.

54 The first argument is untenable. It is well established that the Registrar’s refusal under r 2.26 is administrative and not the exercise of a judicial power pursuant to a delegation: see Nyoni v Murphy [2018] FCAFC 75; (2018) 261 FCR 164 (at 171 [37] per Barker, Banks-Smith and Colvin JJ). It follows that the decision is not reviewable under s 35A(5) of the FCA Act. Insofar as the affidavit material the subject of the judicial review application is concerned, the argument that the decision was judicial seems to be based on the notion that it necessarily involved the Judicial Registrar dealing with matters of evidence and making some form of preliminary ruling in relation to the ability to adduce evidence. In respect of the Rejected s 78B Notice, a related argument is made that the rejection of the notice involved the Judicial Registrar making a determination as to whether or not a s 78B notice should result in notification to the Attorneys General and an adjournment.

55 Both these arguments do not withstand any analysis.

56 It is trite that a Registrar acting under r 2.26 does not have the power to adjudicate under the substantive law whether an application that a party seeks to bring is an abuse of process (or is frivolous or vexatious). Relatedly, the Registrar has no judicial power to determine substantively whether the claim must be dismissed because it is an abuse of process (or is frivolous or vexatious). Rather, the point of the rule is a means by which the administrative requirement is expressed that all documents filed in the Registry must not, in their form and content (irrespective of any substantial assessment of their merit), be an abuse of process of the Court or frivolous or vexatious.

57 In Ferdinands v Registrar Cridland [2022] FCAFC 80 (at [8]), the Full Court referred to White J’s review of the authorities on the meaning of the phrase “an abuse of the process of the Court or is frivolous or vexatious”. It is apparent that a proceeding will be frivolous and/or vexatious if, among other things, it is based on a cause of action which no reasonable person could properly treat as bona fide or is without substance, groundless or fanciful.

58 The conclusion reached by the Judicial Registrar in relation to the affidavit of Mr Kuksal affirmed 23 June 2025 was that he was satisfied, on the face of the affidavit, that it contained material which is clearly vexatious and is an abuse of process of the Court. Again, this affidavit is in a defective form. It produces an electronic folder containing a number of subfolders and audiovisual files. Two of the audiovisual files are titled “Shivesh Explains How Cognitive Biases Affect Judicial Decision-Making” and “An Overview of the Gorton-VLSB Conspiracy to Pervert the Course of Justice in SK’s Court Proceeding”. There are also subfolders titled “complaints against Downes J” and “complaints against Gorton J” with further audiovisual files contained within them. A number of other audiovisual files are put before the Court, apparently in support of the contention that Downes J has unjustly and unjustifiably sought to prevent the respondents from filing interlocutory applications and seeking relief in the current proceedings “…by blatantly abusing the statutory discretion afforded to her in respect of case management decisions”.

59 It was plainly open for the Judicial Registrar to form the view that he did. Apart from its manifest defects in form, the allegations made in the affidavit are clearly open to be characterised as vexatious.

60 The next document is the Rejected s 78B Notice. This notice could accurately be described as constitutional gobbledygook. It is not a s 78B notice in an orthodox form and seeks, rather, to make a series of contentions as to whether the express or inherent (by which, I assume, the respondents mean implied) powers of the Court allow it to act in a way which the respondents suggest is either illegal or improper. In essence, it is a backdoor way of making various complaints about the way in which the proceeding has been conducted. On any view, it was open for the Registrar to conclude that the Rejected s 78B Notice was vexatious and an abuse of process.

61 The third document, being the Rejected Xu Affidavit, annexes documents otherwise provided to the Court and contains various folders concerning correspondence between the parties and the Chambers of Downes, Bennett and Moshinsky JJ in relation to the current proceedings. The deponent seeks to recount various discussions between the respondents and others that took place during their preparation for the hearings, along with document lodgements in the current proceedings and related proceedings in the Supreme Court of Victoria. Again, any rational assessment of that material is one which is open to the conclusion that the affidavit is vexatious and an abuse of process.

62 Accordingly, the informal application for judicial review is denied.

F FURTHER CONDUCT OF THE MATTER

63 The parties should now focus on the substantive issues between them. That is, whether or not the VLSB is entitled to sequestration orders and, more particularly, whether there is some reason why the sequestration orders ought not be made for grounds identified in a proper notice of opposition.

64 To the extent that there are contempt proceedings, they should also be commenced and conducted in such a way as complies with the requirements of the rules. In particular, r 42.11, which provides that an application for punishment of the alleged contempt must be made by a party by interlocutory application in the proceeding if it is a contempt committed in connexion with a proceeding before the Court. Further, pursuant to r 42.12, the application alleging the contempt must be accompanied by a statement of charge, in accordance with Form 137, which specifies the contempt with sufficient particularity so as to allow the person charged to answer the charge.

65 The Court should not entertain, let alone make directions about, a contempt application which is deficient in form.

66 I will, however, make directions allowing any contempt issues to be properly articulated (if they are pursued). It would be a matter for the docket judge in due course as to the case management of any such application, including whether, after it has been properly articulated and filed, compulsory process can be issued to obtain documents apparently relevant to the allegations in the statement of charge.

67 I will hear from the parties shortly as to an appropriate timetable in relation to these steps. Even if it is said the factual allegations which are apparently material to the contempt are also relevant to the opposition to the making of sequestration orders, the necessary steps to bring a properly constituted contempt application are distinct from the orderly and prompt progress of the Bankruptcy Proceedings to the final hearing.

68 The transcript of today’s hearing shows the very wide-ranging and discursive submissions made by the respondents. If they are serious about defending the sequestration proceedings, I can only entreat them to obtain legal representation in order to identify with precision the arguments which they wish to advance and allow those arguments to be developed in a coherent way.

69 I should also mention that Mr Kuksal sought to put before the Court, in relation to the VLSB Application, a variety of material, including various transcripts and recordings of telephone calls between him and Mr Flitner and also Mr Ansell, which show the ways in which the respondents had intended to deal with the Flitner Allegations. Further, an affidavit of Mr Flitner of 21 May 2025 was read and was not the subject of objection. But this affidavit, to the extent it does refer to the Flitner Allegations, should be the subject of properly calibrated confidentiality orders. I have made an interim order, but I direct that the VLSB prepare specific orders which contain non-publication orders which, in my view, are appropriate to extend for a period of five years or until further order. The interim order will continue until I have had the ability to make those orders, which I will make in Chambers.

[THE RESPONDENTS MADE SUBMISSIONS]

70 Consistently with my reasons above, I have asked that the respondents indicate to me a time by which they wish to file a notice stating grounds of opposition to the petition, being a Form B5 and an accompanying affidavit supporting the grounds in proper form, prior to the hearing on 28 and 29 July 2025. I also separately asked whether and when the respondents wished to file a statement of charge in proper form in relation to any contempt proceedings.

71 The first of these requests was met by me being apprised, for the first time, after 6:30pm, of nine applications which Mr Kuksal informs me had been drafted, and which were sought to be filed in order to set aside bankruptcy notices, but which were rejected by the Registry. It is said that this rejection was also improper, and I am told that that is the subject of an application which is listed for hearing in August 2025. I know nothing of the specifics of these alleged applications other than what Mr Kuksal mentioned during his submissions.

72 Doing the best I can, it appears that Administrative Review Tribunal (ART) proceedings have been commenced challenging the decision of the Registrar to reject these nine applications.

73 As I understand the position of the respondents, they say that it would be improper for the hearing of the applicant’s application for sequestration orders to occur prior to the unfiled applications being heard relating to the bankruptcy notices. This seems to be premised on the notion that ART proceedings would be successful in substituting the decision of the Registrar to reject the nine applications. I am unsure of the basis of these applications, but it seems to relate to fees not being paid to file the applications to set aside the bankruptcy notices. But no doubt there is some articulated reason as to why the bankruptcy notices ought to have been set aside. I enquired of Mr Kuksal as to why it was that any substantive matter relied upon in relation to the setting aside of the bankruptcy notices would not be able to be raised in the context of a notice stating the grounds of opposition to the petition and the accompanying material. This did not receive a direct response other than an assertion that it is open for the respondents to seek to allege that the bankruptcy notices ought to have been set aside, and that they are entitled to challenge whether or not an act of bankruptcy has occurred.

74 All of this is further example of the collateral procedural issues and confusion which infects this matter.

75 I am not the docket judge dealing with the Bankruptcy Proceeding. It is a matter for the respondents as to whether or not they wish to file proper material in advance of the currently listed hearing of the Petition or whether they would prefer simply to turn up and seek an adjournment relying upon the existence of unfiled “applications” in relation to the bankruptcy notices and any pending ART proceedings. Needless to say, the respondents should be on notice that, if the trial judge refuses that adjournment, which no doubt will be determined by reference to the overarching purpose and the need for bankruptcy proceedings to be resolved promptly, then these reasons indicate that the respondents were provided ample opportunity of filing a proper notice in opposition to the petition and an accompanying affidavit in advance of that hearing. No doubt, this will be a relevant consideration when it comes to the course that the trial judge may take. Ultimately, however, these are not matters for me.

[THE RESPONDENTS MADE FURTHER SUBMISSIONS]

76 Mr Kuksal has now informed me that they need three weeks in order to file a statement of charge in proper form. He has also informed me that he is content for any supporting affidavit material to be filed within that period. Accordingly, I will make those orders.

[THE RESPONDENTS MADE FURTHER SUBMISSIONS]

77 Other miscellaneous matters have been dealt with at the conclusion of the hearing.

78 On 20 June 2025, Downes J made orders concerning the filing and serving of the respondents’ interlocutory application in the form annexed to those orders, and orders concerning the service of an amended Notice of Constitutional Matter dated 17 June 2025. The orders in the annexed interlocutory application seek various orders relating to contempt and the separate determination of issues identified in the constitutional notice. Downes J made a further order that if such documents were filed in compliance with those orders, then the interlocutory application would be listed for hearing at 9:30am on 18 July 2025. Similar orders listing the Collateral Proceeding for interlocutory hearing on 18 July 2025 were made.

79 As I have noted, the focus of the parties should be in preparing for the hearing of the substantive application for sequestration orders. Given this, and what has occurred today, the 18 July listing appears to me to be unnecessary and contrary to the overarching purpose. Accordingly, that listing should be vacated to the extent it has not been already.

80 I consider that, given the matter is already listed for hearing before Downes J on 17 July 2025, I should leave it to her Honour as to whether, for some reason not currently apparent to me, she wishes to deal, as a separate issue, with the alleged constitutional matters, or alternatively, whether her Honour proposes to deal with those matters (to the extent they are properly justiciable) at the hearing on 28 and 29 July 2025. As I have noted, I do not propose to order a separate determination of any issue.

81 At the risk of repetition, the respondents should not assume that there will be a separate determination of any issue on 17 July at the time that they bring the Disqualification Application and, as I have already indicated, it will be a matter for her Honour as to how she deals with these matters in accordance with the overarching purpose leading up to the hearing of the applications for sequestration orders on 28 and 29 July 2025.

[THE RESPONDENTS MADE FURTHER SUBMISSIONS]

82 A further issue has been raised by the respondents concerning the seeking of compulsory process in aid of the hearing on 28 and 29 July. I do not propose to allow the issue of (or calling upon) any compulsory process and would not do so unless and until a properly articulated notice of grounds of opposition document has been filed so that one may assess the apparent relevance of the documents sought to be produced against articulated arguments to be dealt with at the final hearing. I have provided the respondents the opportunity, on several occasions, to provide me with a date by which they will file such a document well in advance of the hearing (so that any subsequent proper application for compulsory process could then be made). They have not done so. Given that the respondents have not sought a formal order, it will be a matter for them as to when and whether such documents are filed, and whether applications for subpoenas can then be made on properly formulated grounds.

83 I direct the applicant to deliver to my Chambers short minutes of order tomorrow morning, reflecting the orders that I have made.

I certify that the preceding eighty-three (83) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Lee. |

Associate:

Dated: 14 July 2025

SCHEDULE OF PARTIES

VID 222 of 2025 | |

Applicants | |

Fourth Applicant: | HOWARD RAPKE |

ANNEXURE A

ANNEXURE B

S ECI 2022 03994 (Injunction Proceeding) |

1. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Adjournment) [2024] VSC 459 |

2. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Costs and Amendment Application) [2024] VSC 48 |

3. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Recusal and Subpoenas) [2024] VSC 291 |

4. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal [2024] VSC 674 |

5. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Costs) [2024] VSC 746 |

6. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Judiciary Act and Charter Notices) [2024] VSC 461 |

7. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal [2024] VSC 367 |

8. Victorian Legal Services Board v Kuksal (Recusal Application) (No 2) [2023] VSC 698 |

9. VLSB v Kuksal (Recusal Applications) [2022] VSC 648 |

S ECI 2022 04527 (PPP Proceeding) |

None available |

S ECI 2022 04808 (State of Victoria Proceeding) |

1. Kuksal v State of Victoria [2025] VSC 72 |

2. Kuksal v State of Victoria (Costs) [2025] VSC 251 |

1. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board (Further Recusal) [2024] VSC 508 |

4. Kuksal v State of Victoria (Reopening and Recusal Applications) [2024] VSC 253 |

5. Kuksal v State of Victoria (Costs) [2024] VSC 671 |

6. Kuksal v State of Victoria [2023] VSC 438 |

7. Kuksal v State of Victoria [2023] VSC 625 |

S ECI 2023 00183 (Mioch Proceeding) |

None available |

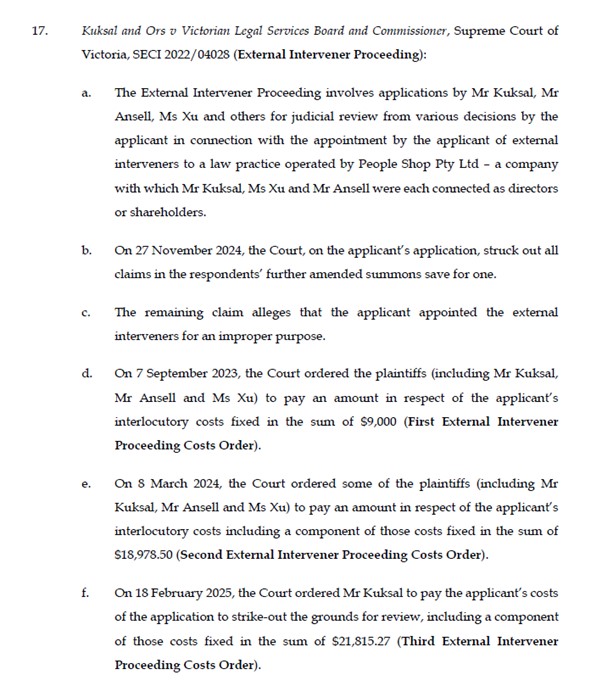

S ECI 2022 04028 (External Intervener Proceeding) |

1. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board (Costs) [2025] VSC 48 |

2. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board (Recusal, Summons and Subpoena) [2024] VSC 418 |

3. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board [2024] VSC 732 |

4. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board (Recusal, Stay and Costs) [2024] VSC 78 |

1. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board (Recusal Appln) [2023] VSC 722 |

6. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board [2023] VSC 495 |

7. Kuksal v Victorian Legal Services Board (No 2) [2023] VSC 526 |