Federal Court of Australia

Pabai v Commonwealth of Australia (No 2) [2025] FCA 796

File number: | VID 622 of 2021 |

Judgment of: | WIGNEY J |

Date of judgment: | 15 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | NEGLIGENCE – representative proceeding on behalf of Torres Strait Islanders against the Commonwealth of Australia – whether the Commonwealth has a duty to take reasonable steps to protect Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change – whether impacts of marine inundation and erosion caused property damage, loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom, and injury, disease or death – whether the loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom, the body of customs, traditions and beliefs distinctive to Torres Strait Islanders which creates a unique spiritual connection with the Torres Strait Islands and surrounding waters, is a compensable loss under the law of negligence – imposition of novel duties of care considered – whether posited duties of care would require the Court to pass judgment on issues of high or core government policy and political judgment – factual findings of the severe impacts of human-induced climate change on the Torres Strait Islands – ecosystems damaged and destroyed – devastating impacts on the traditional way of life and the ability to practise Ailan Kastom EMISSIONS REDUCTION TARGETS – whether Commonwealth owed the applicants and Torres Strait Islanders a duty of care to take reasonable steps to set greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets having regard to the “Best Available Science” which prevent or minimise impacts of climate change in the region – where Commonwealth set greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets and provided those targets to the UN Convention on Climate Change as Nationally Determined Contributions pursuant to Art 4.2 of the Paris Agreement in 2015, 2020, 2021 and 2022 – whether those emissions reduction targets were set having regard to the best available science – where best available science indicates global average temperature increase must be held to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels to limit the worst effects of climate change – whether setting emissions reduction targets are a matter of high or core government policy – whether relationship between the applicants and the Commonwealth more than a relationship between the governing and the governed – whether posited standard of care appropriate – whether any breach of the alleged duty of care in respect of setting emissions reduction targets caused applicants to suffer compensable damage – whether Commonwealth materially contributed to loss or damage suffered by the applicants as a result of climate change – duty of care not established – factual findings that the Commonwealth failed to give genuine consideration of the best available science – Australian emissions reduction targets inconsistent with international obligations and objectives CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION – alleged duty of care to take reasonable care to protect against marine inundation and erosion – standard of care said to require the provision of predictable, adequate funding for the construction of seawalls and the leading and coordinating of a plan for funding – whether delays in funding and consequent delays in construction of seawalls cause or contributed to loss and damaged suffered – evidence incapable of proving inundation events occurring in the relevant periods caused or contributed to loss – funding arrangements concerned allocation of responsibilities between three tiers of government – all requested funding provided – delays in finalisation of funding neither solely attributable to the Commonwealth nor unreasonable – salient features do not support the alleged duty of care – duty of care not appropriate or practical to impose where the Court would need to pass judgment on the reasonableness of government policy, intergovernmental relations and budgetary priorities DECLARATIONS, INJUNCTION – declarations sought regarding the existence and breach of duty / duties of care – declaration has no utility where expressed in abstract terms divorced from the nature of any duty – inappropriate where no finding that breach has caused loss or damage – impermissible interlocutory declaration where claims of group members not finally determined – injunctive relief sought to compel the Commonwealth to implement measures to protect the environment, cultural and customary rights and reduce emissions – subjective and imprecise terms |

Legislation: | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Act 2005 (Cth) Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988 (Cth) Climate Change Act 2022 (Cth) Climate Change Authority Act 2011 (Cth) Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Financial Management Act 1997 (Cth) Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Regulations 1989 (Cth) Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Regulations 2021 (Cth) Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (Cth) Offshore Petroleum and Greenhouse Gas Storage (Environment) Regulations 2009 (Cth) Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 (ACT) Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) Community Services (Torres Strait) Act 1984 (Qld) Constitution Act 1867 (Qld) Crown Proceedings Act 1988 (NSW) Limitation Act 1985 (ACT) Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) Local Government Act 1993 (Qld) Local Government Act 2009 (Qld) Local Government and Other Legislation (Indigenous Regional Councils) Amendment Act 2007 (Qld) Queensland Coast Islands Act 1879 (Qld) Belgian Civil Code Dutch Civil Code |

Cases cited: | Agar v Hyde (2000) 201 CLR 552 Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564 Akiba and Another v Queensland and Others (No 2) (2010) 204 FCR 1 Amica Pty Ltd v Ellis (2010) 240 CLR 111 Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1978] AC 728 Barrett v Enfield London Borough Council [2001] 2 AC 550 Bonnington Castings v Wardlaw [1956] AC 613 Brodie v Singleton Shire Council (2001) 206 CLR 512 Brookfield Multiplex Ltd v Owners Corporation Strata Plan 61288 (2014) 254 CLR 185 Caltex Refineries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Stavar (2009) 75 NSWLR 649 Cattanach v Melchior (2003) 215 CLR 1 Chapman v Hearse (1961) 106 CLR 112 Chappel v Hart (1998) 195 CLR 232 Cole v South Tweed Heads Rugby league Football Club Ltd (2004) 217 CLR 469 CPCF v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2015) 255 CLR 514 Crimmins v Stevedoring Industry Finance Committee (1999) 200 CLR 1 Cubillo v Commonwealth of Australia (No 2) (2000) 103 FCR 1 Dixon v Davies (1982) 17 NTR 31 Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 Dovuro Pty Ltd v Wilkins (2003) 215 CLR 317 Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick (2002) 210 CLR 575 East Suffolk Rivers Catchment Board v Kent [1941] AC 74 Electro Optic Systems Pty Ltd v State of New South Wales; West v State of New South Wales (2012) 273 FLR 304 Evans v Queanbeyan City Council [2011] NSWCA 230 Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd [2003] 1 AC 32 Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89 Fejo v Northern Territory (1998) 195 CLR 96 Gibuma on behalf of Boigu People v State of Queensland [2004] FCA 1575 Graham Barclay Oysters Pty Ltd v Ryan (2002) 211 CLR 540 Haber v Walker [1963] VR 339 Harriton v Stephens (2006) 226 CLR 52 High Country Outfitters Inc v Pitt Meadows (City) [2012] BCJ No 1859; 2012 BCPC 308 Hunt & Hunt Lawyers (a firm) v Mitchell Morgan Nominees Pty Ltd (2013) 247 CLR 613 Jackson v Spittall (1870) LR 5 CP 542 John Pfeiffer Pty Ltd v Canny (1981) 148 CLR 218 John Pfeiffer Pty Ltd v Rogerson (2000) 203 CLR 503 Kent v East Suffolk Rivers Catchment Board [1940] 1 KB 319 La Sucrerie Casselman Inc v Cambridge (Township) [2000] OJ No 4650 Lewis v Australian Capital Territory (2020) 271 CLR 192 Love v The Commonwealth (2020) 270 CLR 152 Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 Mahoney v J. Kruschich (Demolitions) Pty Ltd (1985) 156 CLR 522 March v E & MH Stramare Pty Ltd (1991) 171 CLR 506 Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell [2021] ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339 Milpurrurru v Indofurn Pty Ltd (1994) 54 FCR 240 Minister for the Environment v Sharma (2022) 291 FCR 311 Minister for the Environment v Sharma [2022] FCAFC 35 Modbury Triangle Shopping Centre Pty Ltd v Anzil (2000) 205 CLR 254 Mutual Life & Citizens’ Assurance Company Ltd v Evatt (1968) 122 CLR 556 Namala v Northern Territory (1996) 131 FLR 468 Naoumi v Dannawi (2009) 75 NSWLR 216 Napaluma v Baker (1982) 29 SASR 192 Neilson v Overseas Projects Corp (Vic) Ltd (2005) 223 CLR 331 Northern Territory of Australia v Griffiths (2019) 269 CLR 1 Notre Affaire à Tous v France [2021] No 1904967, 1904968, 1904972, 1904976/4-1 Optus Networks Pty Ltd v City of Boroondara [1997] 2 VR 318 Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Miller Steamship Company Pty Ltd (the Wagon Mound No 2) [1967] 1 AC 617 Overseas Tankship (UK) Ltd v Morts Dock & Engineering Company Ltd (The Wagon Mound) [1961] AC 388 Perre v Apand Pty Ltd (1999) 198 CLR 180 Perrre v Apand Pty Ltd (1999) 198 CLR 180 Pyrenees Shire Council v Day (1998) 192 CLR 330 Roberts v Devereaux (unreported, Supreme Court of the Northern Territory 22 April 1982) Rodriguez & Sons Pty Ltd v Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority trading as Seqwater (No 22) [2019] NSWSC 1657 Rowling v Takaro Properties Ltd [1988] AC 473 Santos N A Barossa Pty Ltd v Tipakalippa (2022) 296 FCR 124 Sharma by her litigation representative Sister Marie Brigid Arthur v Minister for the Environment [2021] FCA 560 Smaill v Buller District Council [1998] 1 NZLR 190 Smith v Fonterra Cooperative Group Limited & Ors (2024) NZSC 5 Stovin v Wise [1996] AC 923 Strong v Woolworths Ltd (2012) 246 CLR 182 Sullivan v Moody (2001) 207 CLR 562 Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman (1985) 157 CLR 424 Tame v State of New South Wales; Annetts v Australian Stations Pty Ltd (2002) 211 CLR 317 Trevorrow v South Australia (No 5) (2007) 98 SASR 136 Urgenda Foundation v the State of the Netherlands (2015) ECLI:NL:RBDHA:20155555:7196 Vernon Knights Associates v Cornwall Council [2014] Env. L.R. 6 Voth v Manildra Flour Mills Pty Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 538 VZW Klimaatzaak v Kingdom of Belgium & Others [2021] 2015/4585/A VZW Klimaatzaak v Kingdom of Belgium & Others [2023] 2021/AR/15gs 2022/AR/737 2022/AR/891 Wallace v Kam (2013) 250 CLR 375 Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 Weston v Woodroffe (1985) 36 NTR 34 Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1 Woolcock Street Investments Pty Ltd v CDG Pty Ltd (2004) 216 CLR 515 Wyong Shire Council v Shirt (1980) 146 CLR 40 Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 Australian Academy of Science, The Risks to Australia of a 3°C Warmer World (Report, March 2021) Australian Academy of Science, The Science of Climate Change: Questions and Answers (Report, February 2015) Climate Change Authority, Reducing Australia’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions – Targets and Progress Review (Final Report, February 2014) DI Armstrong McKay et al, ‘Exceeding 1.5C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points’ (2022) 377(6611) Science 1171 H Burmester, ‘The Torres Strait Treaty: Ocean Boundary Delimitation by Agreement’, (1982) 76 American Journal of International Law 321, 322 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 19 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976) IPCC, 2007: Climate Change 2007: Impacts Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden, and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Field, C.B., V.R. Barros, D.J. Dokken, K.J. Mach, M.D. Mastrandrea, T.E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K.L. Ebi, Y.O. Estrada, R.C. Genova, B. Girma, E.S. Kissel, A.N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P.R. Mastrandrea, and L.L. White (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA IPCC, 2018: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Mason-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 3-24 IPCC, 2019: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. A. Pirani, S.L, Connors, P. Pean, S Berger, N. CAud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R Mathews, T.K. Maycock, T. Wakefiled, O. Yelecki, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCollum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA J Stapleton, “Law, Causation and Common Sense”, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies vol 8 (1988) 111 at 125 Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, opened for signature 16 March 1998, 2303 UNTS 162 (entered into force 16 February 2005) Treaty between Australia and the Independent State of Papua New Guinea Concerning Sovereignty and Maritime Boundaries in the Area Between Two Countries, Including the Area Known as Torres Strait, and Related Matters entered on 18 December 1978, in force from 15 February 1985 (Australian Treaty Series 1985 No 4) United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, GA Res 61/295, UN Doc A/RES/61/295 (2 October 2007, adopted 13 September 2007) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, opened for signature 4 June 1992, 1771 UNTS 107 (entered into force 21 March 1994) United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Paris Agreement 2015 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Other Federal Jurisdiction |

Number of paragraphs: | 1,275 |

Date of hearing: | 5-6, 8-9, 12-13, 15-16 June 2023; |

Counsel for the Applicants: | Ms F McLeod AO SCand Mr T Boston KC with Ms L Barrett, Ms S Martin, Dr J R Murphy, Ms J Dodd, Ms J Wang, Mr T Rawlinson, Ms M Tom and Ms C Aniba |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Phi Finney McDonald |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr S Lloyd SCand Ms Z Maud SC with Ms A Lyons, Mr M Sherman and Ms M Salinger |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Australian Government Solicitor |

ORDERS

VID 622 of 2021 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | PABAI PABAI First Applicant GUY PAUL KABAI Second Applicant | |

AND: | COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

order made by: | WIGNEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 july 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to confer, through their legal advisers, and by no later than six weeks after the delivery of this judgment, provide the Court with either:

(a) agreed draft orders which give effect to this judgment and dispose of the proceeding, including in relation to costs; or

(b) if no agreement can be reached concerning the orders, competing draft orders, together with an outline of submissions (not exceeding ten pages in length) in respect of the competing orders, together with a note as to whether an oral hearing is requested to resolve the outstanding issues in respect of the orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

WIGNEY J:

1 The central issue in this difficult and novel case is whether the common law tort of negligence can and does provide Torres Strait Islanders with a remedy for what they claim has been the Commonwealth of Australia’s unreasonable and inadequate response to the existential risks posed by climate change and the impacts that it is having on the Torres Strait Islands.

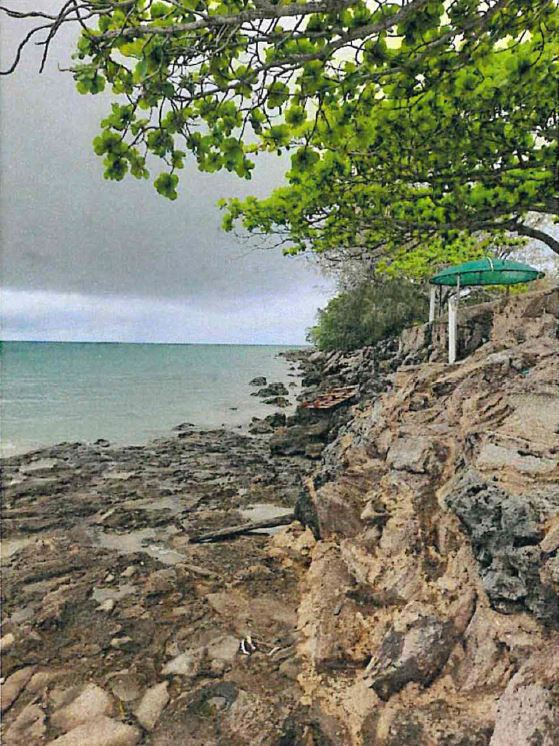

2 The Torres Strait Islands, or the Zenadth Kes, are a cluster of islands located in the Arafura and Coral Seas between Cape York in far northern Australia and Papua New Guinea. Many of the islands, including those that are inhabited, are coral cays or very low-lying sand or mud islands.

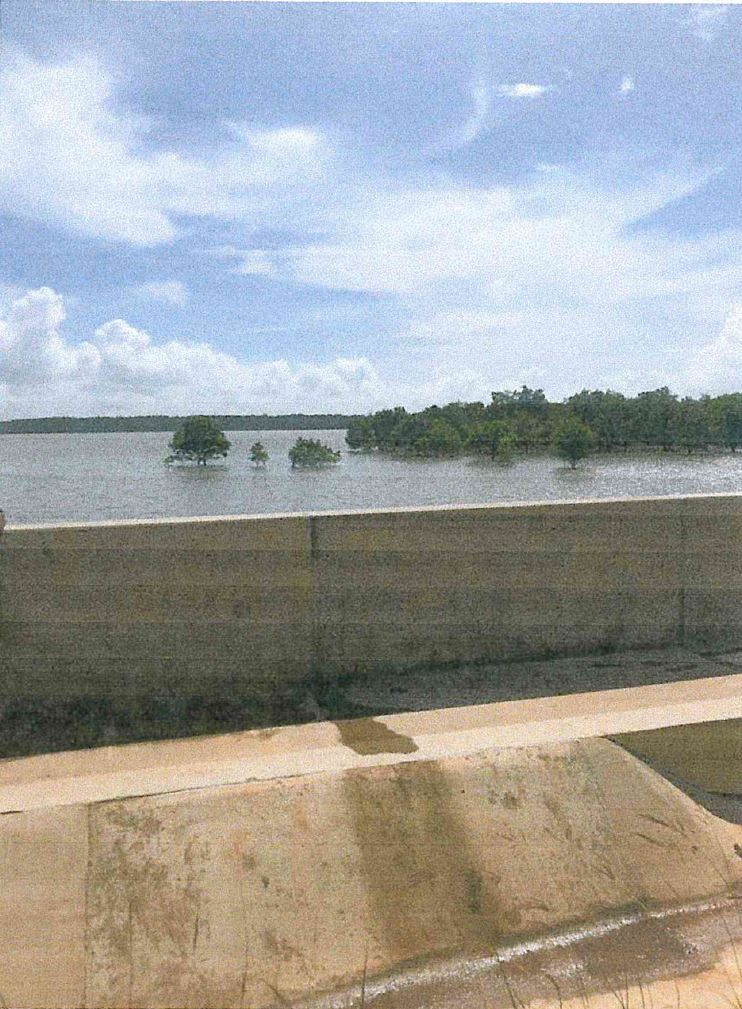

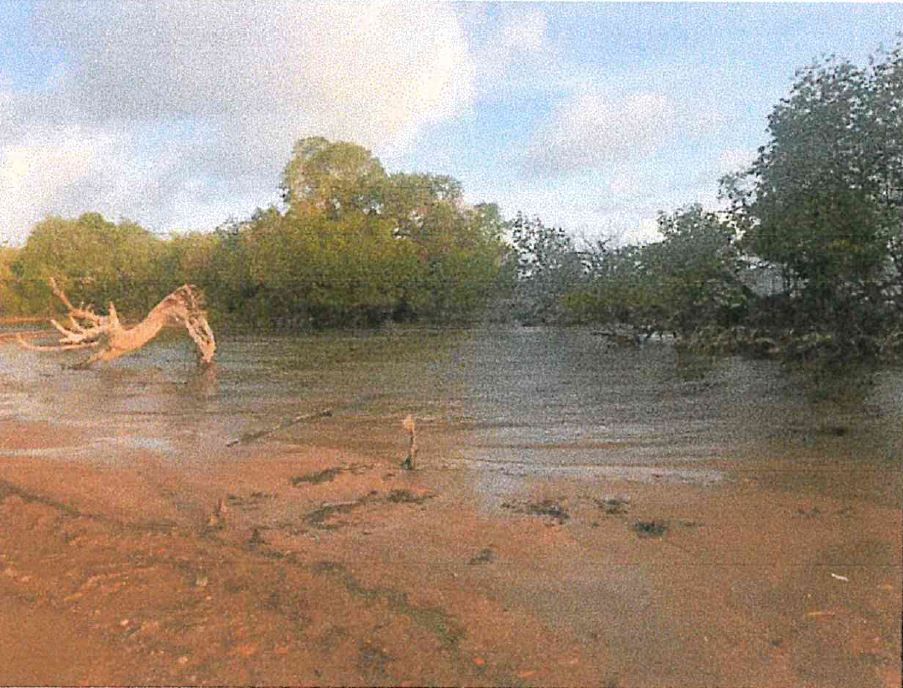

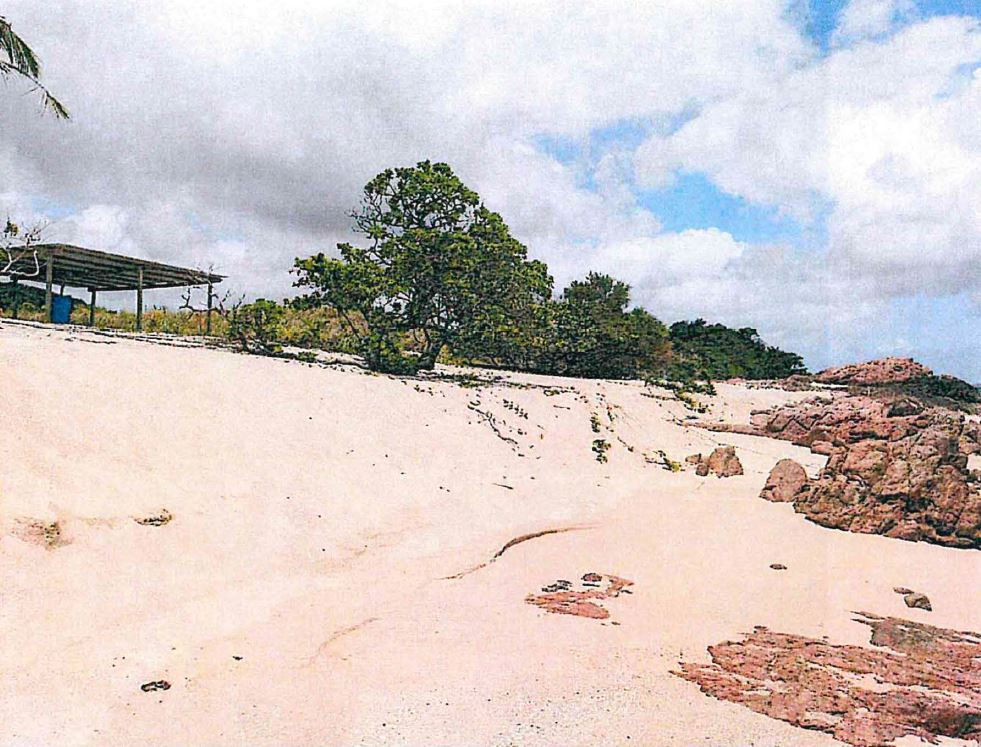

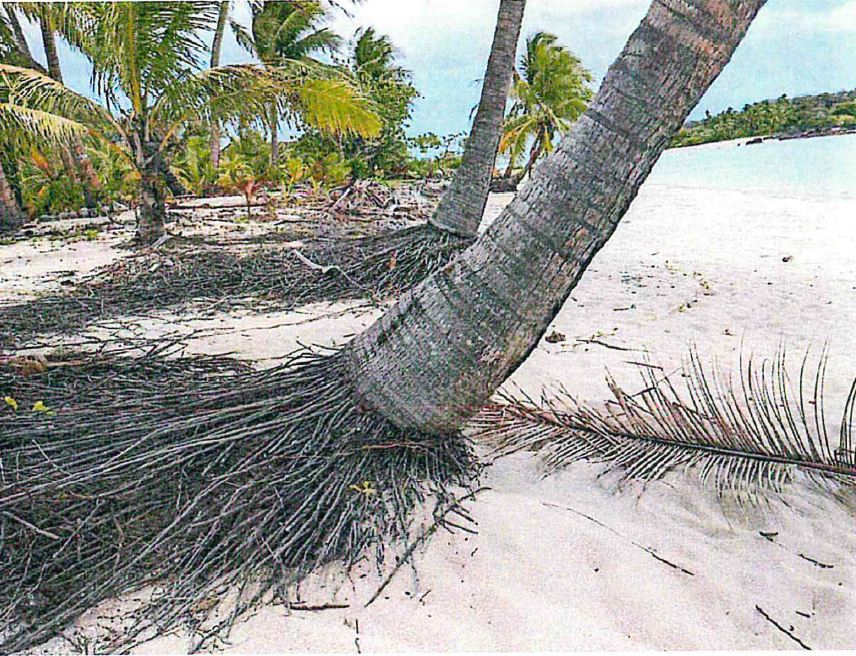

3 The Torres Strait Islands have in recent years been ravaged by the impacts of human-induced climate change. Rising sea levels, storm surges and other extreme water level events have resulted in flooding and seawater inundation on many of the islands. Trees are dying and previously fertile areas have been adversely affected by salination and are no longer suitable for growing traditional crops. Rising sea levels and storms have led to the erosion and the depletion of beaches and the salination of wetlands. Warmer ocean temperatures and ocean acidification have caused coral bleaching and the loss of seagrass beds. Totemic sea creatures like dugong and turtles, once abundant in the region, have become scarce. Seasonal patterns have changed, as have the migratory patterns of birdlife.

4 The impacts of climate change on the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands have had a profound impact on the customary way of life of the inhabitants and traditional owners of the Torres Strait Islands. They are finding it increasingly difficult to practise and observe the body of customs, traditions and beliefs, known generally as Ailan Kastom, which has sustained them for generations. Sacred sites, including burial and ceremonial sites, have been damaged and are constantly at risk of further inundation. The traditional owners who reside on the islands are increasingly unable to source traditional foods or engage in certain cultural ceremonies, particularly those involving hunting and gathering. Changing seasonal, migratory and stellar patterns make it increasingly difficult for elders to pass-on traditional knowledge to the next generations.

5 Climate change poses an existential threat to the whole of humanity. The wellbeing and way of life of many, if not most, communities in Australia are vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The Torres Strait Islands and their inhabitants are, however, undoubtably far more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than other communities in Australia. The many low-lying islands in the Torres Strait are particularly prone to damage and destruction caused by rising sea waters and extreme weather events. The region’s ecosystems are also far more prone to damage and destruction caused by increasing ocean temperatures and ocean acidification. To make matters worse, most Torres Strait Islanders and their communities are socially and economically disadvantaged, at least compared to other Australians and their communities, and often lack access to appropriate resources, infrastructure and services which would enable them to protect themselves from, or adequately adapt to, the impacts of climate change. They understandably feel powerless when it comes to protecting themselves against climate change and its impact on their islands and traditional way of life.

6 There could be little, if any, doubt that the Torres Strait Islands and their traditional inhabitants face a bleak future if urgent action is not taken to address climate change and its impacts.

7 Mr Pabai Pabai, the first applicant in this proceeding, is from the Guda Maluyligal nation. He is 53 years old and has lived almost his entire life on Boigu, a small low-lying island that is closer to Papua New Guinea than it is to mainland Australia. He is a leader in his community. He has witnessed firsthand the impacts of climate change on Boigu in recent times and has experienced the resulting community sadness and loss of Ailan Kastom. He fears that, if something is not done about climate change and its impacts in the Torres Strait Islands, Boigu will lose its ancestral, sacred, and ceremonial sites and he will lose his connection to country and culture.

8 Mr Guy Paul Kabai, the second applicant, is also from the Guda Maluyligal nation and has lived most of the 55 years of his life on Saibai. Saibai, like Boigu, is a tiny low-lying island very close to the coast of Papua New Guinea. Like Mr Pabai Pabai, he is an elder who has observed the damage wrought by climate change on his island and the traditional way of life of its peoples. He too is worried that, if nothing is done in respect of climate change, his community will lose its sacred places, culture and traditions, and he will lose his country and his identity.

9 The Torres Strait Islands are, both literally and figuratively, a world away from Canberra, the home of the Commonwealth Parliament. That is where many of the most important decisions are made about the nation’s response to climate change and its impacts. While there may have been, and perhaps still are, some climate change doubters and deniers among the politicians and bureaucrats who are responsible for making those decisions, it is tolerably clear that the Commonwealth Government has for some time known about the perils of, and ongoing risks posed by, climate change. It has also recognised that it must play a part in the global response to climate change. The Commonwealth has also known and appreciated that the Torres Strait Islands and Torres Strait Islanders are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. But has the Commonwealth’s response to climate change been reasonable and adequate to protect Torres Strait Islanders and their traditional way of life from the ravages of climate change?

10 Mr Pabai Pabai and Mr Kabai contend that the Commonwealth’s response to climate change has been inadequate and that it has not done enough to protect them and other Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change. In this representative proceeding, they claim that the Commonwealth has breached the duty or duties of care that they say the Commonwealth owes them and other Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable steps to protect them from the impacts of climate change. They allege, among other things, that in setting its greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, the Commonwealth has failed, and continues to fail, to have regard to, and act in accordance with, the best available science in respect of climate change, and thereby failed to prevent or minimise its impacts on Torres Strait Islanders in particular. They also claim that the Commonwealth has breached the duty of care it owes them and other Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable steps to implement adaptation measures to prevent or minimise the impacts of climate change in the Torres Strait Islands. They contend, among other things, that the Commonwealth has failed to provide predictable and adequate funding for infrastructure, in particular seawalls, to protect the islands from inundation and flooding.

11 As will be discussed in detail in this judgment, there is merit in many of the factual claims that underly the causes of action in negligence brought by the applicants, both on their own behalf and on behalf of the Torres Strait Islanders who comprise the group members in this proceeding. There could be little doubt that the Torres Strait and Torres Strait Islanders have in recent times been severely impacted by climate change. There is also much to be said for the proposition that many of the decisions that have been made by the Commonwealth Government to address climate change by limiting or reducing Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions have not paid sufficient regard to, or heeded the warnings of, the best available science. There is also something to be said for the proposition that those steps that the Commonwealth have taken to provide appropriate funding for infrastructure to protect some of the Torres Strait Islands from the impacts of rising sea levels and extreme weather events have been too little and too late.

12 The critical question, however, is whether Mr Pabai Pabai and Mr Kabai have established that they, and the group members on whose behalf they have brought this proceeding, have an actionable case in negligence against the Commonwealth. As will be discussed in detail in these reasons for judgment, the applicants face effectively insurmountable legal hurdles and roadblocks in establishing the elements of their cause or causes of action against the Commonwealth in negligence, even if many, if not most, of the factual issues may be resolved in their favour.

13 In short summary, while it may perhaps be accepted that there are certain special and unique features of the relationship between the Commonwealth and Torres Strait Islanders, the duties of care that the applicants contend that the Commonwealth owes Torres Strait Islanders are novel and there are many factors that weigh heavily against the recognition of those novel duties of care. There are also various factors which make it difficult to accept that, despite what might be said to be some failings on the part of the Commonwealth in respect of its responses to climate change and its protection of Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change, those failings constituted a breach of the alleged duties of care. It is equally difficult to accept that those failings materially contributed to the loss or damage suffered by Torres Strait Islanders as a result of the impacts of climate change during the period relevant to the cause of action. Finally, the applicants face a significant hurdle in establishing that the loss of fulfillment of Ailan Kastom that they and other Torres Strait Islanders have collectively experienced as a result of the impacts of climate change is recognised compensable loss or damage under the Australian common law of negligence.

A SHORT NOTE IN RELATION TO TERMINOLOGY

14 During the evidence and submissions, most if not all the Torres Strait Island witnesses were addressed or referred to as either “Uncle” or “Auntie”, depending on their gender, along with their first or given names. The applicants, for example, were referred to or addressed as Uncle Pabai and Uncle Paul, or sometimes just Uncle. Elders in indigenous communities, including Torres Strait Island communities, are frequently referred to as Uncle or Auntie as a mark of respect and in recognition of their wisdom, cultural knowledge and the esteem within which they are held in the community. It is, however, not always appropriate for a non-indigenous person to refer to an indigenous person as Uncle or Auntie. Much depends on the context and circumstances.

15 I have decided that in these reasons I will not refer to or address the applicants and other Torres Strait Island witnesses as Uncle and Auntie. I do not intend any disrespect in not referring to them as such. I understand and accept that they are all elders who are held in esteem in their communities and are recognised as being custodians of deep cultural knowledge and lore. The Commonwealth did not suggest otherwise. In a formal document like the reasons for judgment in this Court, however, I consider it appropriate to refer to them by name and a common and neutral prefix such as Mr or Ms.

16 I have also decided to refer to each of the Torres Strait Island witnesses’ totem and tribe. The evidence indicated that, when they introduce themselves, Torres Strait Islanders would generally state their totem. Their association with particular totems and tribes also indicates their close connection to their island. Finally, where I have used a traditional word or expression which is unique to the Torres Strait Islands, I have generally italicised that word or expression.

OVERVIEW OF THE CASE

17 It is useful to begin by providing a short summary of the applicants’ case and the Commonwealth’s defence to it.

The applicants’ case

18 As has already been noted, this is a representative proceeding which was commenced by the applicants both on their own behalf and on behalf of group members. The group members are defined as being “all persons who at any time during the period from 1985 to the date [the] pleading [was] filed, [who] are Torres Strait Islander (whether by descent or by customary adoption) and suffered loss and damage as a result of the conduct of the [Commonwealth] described in [the pleading]”: Third Further Amended Statement of Claim (3FASOC) at [1].

19 The expression “Torres Strait Islanders” is defined in the 3FASOC (at [54]) as follows:

Torres Strait Islanders include persons:

(a) Indigenous to the Torres Strait Islands within the meaning of the definition in s 4(1) of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005 (Cth) and/or who are Torres Strait Islander by way of customary adoption;

(b) from the Gudang, Kaiwalagal, Maluiligal, Guda Maluyligal, Kulkalgal, and Kemerkemer Meriam Nations;

(c) who may hold native title and/or native title rights and interests (as defined in s 223 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth)) in relation to various parts of the Torres Strait Islands;

(d) who have a distinctive customary culture, known as Ailan Kastom, which creates a unique spiritual and physical connection with the Torres Strait Islands and surrounding waters (Ailan Kastom);

(e) including the Applicants and the Group Members.

(mark-up as a result of amendments not replicated)

20 References in these reasons to Torres Strait Islanders should be taken to be references to the group members as defined in the pleading unless indicated otherwise.

21 The key factual allegations in the applicants’ case are, broadly speaking, relatively straightforward. The complexities arise when it comes to framing those factual allegations in terms of the elements of the tort of negligence. As will be seen in due course, many complex factual and legal issues arise.

22 The starting point of the applicants’ case is climate change and its impacts generally and specifically on the Torres Strait Islands.

Climate change and its impacts on the Torres Strait Islands

23 Climate change is a shorthand expression which is used to describe the increase in the Earth’s temperature and other changes to the Earth’s climate which have and continue to be caused by human activities, in particular the burning of fossil fuels, since the industrial revolution which commenced roughly 150 years ago. The increased emission of greenhouse gases (or GHGs), primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), but also methane and nitrous oxide, has resulted in the accumulation of those gases in the Earth’s atmosphere. That has, through a series of processes, resulted in the rapid heating of the Earth’s lower atmosphere and, in turn, an increase in the temperature of the Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere. It has also led to other significant changes to the Earth’s climate.

24 It will, of course, be necessary to refer to the science in respect of climate change in more detail later in these reasons. It suffices at this point to note that it is scientifically clear and unequivocal that there is a near linear relationship between cumulative anthropogenic (human caused) CO2 emissions and the increase in global surface temperature. It is also scientifically clear and unequivocal that every tonne (and every fraction of a tonne) of CO2 emissions adds to global warming.

25 The science is equally clear and unequivocal about the climate and environmental impacts of global temperature increases caused by CO2 emissions. Those impacts include: the increase in global ocean surface temperature; ocean acidification; melting ice on land and sea; melting permafrost; changing precipitation patterns; sea level rise and the inundation of coastal lands; the increase in the frequency, size and intensity of extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts, bushfires, tropical cyclones, severe storms and flooding; harm and destruction of ecosystems, including coral reefs, and the harm and destruction of non-human species; the greater likelihood of undernutrition resulting from diminished food production; and the increased risk of food, water-borne and vector-borne diseases.

26 The deleterious impacts of climate change are experienced, to a greater or lesser extent, by the whole world and the whole of humanity. It is, however, well recognised that small and low-lying islands and their communities, including the Torres Strait Islands, are particularly vulnerable to many of the impacts of climate change, especially sea level rises, storm surges, tropical cyclones, increasing temperatures and changing rainfall patterns. It is also well recognised that indigenous peoples in Australia, including those in the Torres Strait, are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change by reason of, among other things, their unique and close connection to the land and environment and their relative social and economic disadvantage.

27 To put it bluntly, the applicants contend that it is an incontrovertible truth, and a truth that is not only well known to, but has been acknowledged by the Commonwealth, that Torres Strait Islanders have been, and continue to be, severely and disproportionately impacted by climate change. Their traditional homelands in the islands have been eroded, inundated by seawater, and rendered inarable by salination. The resting places of their ancestors have been desecrated. They have suffered the effects of changing weather patterns and increased temperatures. Animal species that they have traditionally relied on as a source of food, including dugong and turtles, have become scarce. Ecosystems, including coral reefs and seagrasses, have been damaged. The ability of Torres Strait Islanders to practise their sacred traditions and customs – Ailan Kastom – has been severely impacted by the damage to their lands and the island ecosystems.

28 The damage and destruction that has been wrought by climate change, including in the Torres Strait Islands, is not really in dispute. What is in dispute is, in essence, whether the Commonwealth was required to, and has failed to, take reasonable steps to protect Torres Strait Islanders from the ravages of climate change, and whether any failures on the part of the Commonwealth in that regard have materially contributed to any loss or damage that has been suffered by Torres Strait Islanders due to the impacts of climate change. More specifically, and more prosaically, the central issue is whether, by reason of any failings in its responses to climate change, the Commonwealth is liable in the tort of negligence for any loss or damage suffered by Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change.

The Commonwealth’s failure to protect Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change

29 The general thrust of the applicants’ case against the Commonwealth is that, by virtue of the unique and special relationship between the Commonwealth and Torres Strait Islanders, the Commonwealth has a duty to take reasonable steps to protect Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change and has failed to fulfil or discharge that duty. The unique and special protective relationship between the Commonwealth and Torres Strait Islanders was said to essentially flow from the relationship between the coloniser and the colonised. The very purpose of the colonisation of the Torres Strait Islands was, so it was said, to protect the native inhabitants of the islands.

30 As has already been made clear, the applicants’ cause or causes of action against the Commonwealth were in the tort of negligence. In terms of the elements of the tort of negligence, the applicants claimed that the Commonwealth owed them, and Torres Strait Islanders more generally, a duty (or duties) of care to protect them from the impacts of climate change and that the Commonwealth breached that duty (or those duties) and thereby caused them to suffer loss and damage. This is where the applicants’ case becomes complex.

31 The applicants framed their case in negligence in two alternative ways. The central allegation in the applicants’ primary case was that the Commonwealth was required to, but failed to, set appropriate greenhouse gas emissions targets having regard to the best available science (the applicants’ primary or targets case). The central allegation in the applicants’ alternative case was that the Commonwealth was required to, but failed to, provide predictable and adequate funding for infrastructure, in particular seawalls, which would assist Torres Strait Islanders to adapt to the impacts of climate change (the applicants’ alternative or adaptation case).

The applicants’ primary or targets case

32 The applicants’ primary case was, it would be fair to say, pleaded in somewhat broad, elaborate and, at times, convoluted terms. It will be necessary to examine the applicants’ pleaded case in more detail later in these reasons. Expressed in very simple terms, however, the applicants’ case was that the Commonwealth owed Torres Strait Islanders a duty to take reasonable steps to set greenhouse gas emissions targets which, having regard to the best available science in respect of climate change, would prevent or minimise the impacts of climate change in the Torres Strait Islands. That duty of care required the Commonwealth to take reasonable steps to: identify, by reference to the best available science, the global temperature limit necessary to prevent or minimise many of the most dangerous impacts of climate change in the Torres Strait Islands; and identify a best available science target reflecting that temperature limit. The duty of care was also said to require the Commonwealth to implement measures which were necessary to reduce Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions consistent with that best available science target.

33 The applicants contended that the Commonwealth breached that duty of care essentially because the emissions targets that were set by the Commonwealth in 2015, 2020, 2021 and 2022 were not based on, or were not in accordance with, the best available science and therefore did not, or would not, prevent or minimise the impacts of climate change on the Torres Strait. The applicants alleged, in that regard, that from at least 2014, the best available science indicated that, to avoid the worst impacts of climate change on small and low-lying islands, it would be necessary for the global community to limit or hold the long-term average global temperature increase to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels. The applicants contended that there was broad scientific consensus that it was possible for nations such as Australia to calculate, by one of three different methodologies, their share or allocation of remaining cumulative greenhouse gas emissions which would be consistent with an emissions budget that would limit global warming to 1.5℃. The applicants’ case was that, whichever of the three methodologies was adopted in Australia, the greenhouse gas emissions targets that were set by the Commonwealth in 2015, 2020, 2021 and 2022 were inconsistent with Australia’s budget or allocation of remaining greenhouse gas emissions consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels.

34 In short, the applicants claimed that the emissions targets set by the Commonwealth were not in keeping with the best available science concerning climate change and its impacts. That is because they were inconsistent with, and would not contribute to the achievement of, the goal of keeping the global temperature increase to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels, which the best available science indicated was necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, including for Torres Strait Islanders. Indeed, the applicants went so far as to contend that the Commonwealth failed to have any regard at all to the best available science when setting its emissions targets.

35 The applicants’ case was that the Commonwealth’s breach of its duty of care in respect of the setting of appropriate emissions targets caused the Torres Strait Islanders to suffer loss and damage. That loss and damage included physical damage arising from inundation events, and damage relating to the inability to effectively practise their Ailan Kastom. The applicants advanced the following seven-point chain of causation in that regard.

36 First, there is a near-linear relationship between increased global emissions of greenhouse gases and global temperature increases.

37 Second, at relevant timescales, a tonne of CO2 or CO2 equivalent greenhouse gas contributes to global temperature increases irrespective of when, where and by whom it was emitted.

38 Third, it is therefore the cumulative effect of global greenhouse gas emissions that is the cause of global temperature increases.

39 Fourth, the impacts of climate change in the Torres Strait Islands are caused by global temperature increases.

40 Fifth, emissions from Australia are a contributing cause of the impacts of climate change on the Torres Strait Islands, in the sense that emissions from Australia have contributed to the cumulative effect of global greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore contributed to global temperature increases.

41 Sixth, if the Commonwealth had not failed to take reasonable steps in respect of the setting of appropriate emissions targets based on the best available science, Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions would have decreased, which in turn would have lessened its causal contribution to the impacts of climate change on the Torres Strait Islands.

42 Seventh, the Commonwealth’s breach of its duty of care in respect of the setting of greenhouse gas targets therefore materially contributed to the harm suffered in the Torres Strait Islands as a result of the impacts of climate change.

43 In short, the applicants’ case was that the Commonwealth’s failure to set appropriate emissions targets in accordance with the best available science meant that more greenhouse gases were emitted by Australia than would otherwise have been the case and that those additional emissions contributed to global warming and its impacts on the Torres Strait Islands. According to the applicants, it matters not that it may not be possible to measure or quantify the effect that the additional emissions may have had on global temperature increases, or the specific impact that the increase in global temperature referrable to the increased emissions may have had on climate change in the Torres Strait. That is because climate science establishes that the increased emissions by any nation have some effect on global temperature increases and therefore some climate change impact.

44 As for the loss and damage suffered by the applicants and other Torres Strait Islanders, the applicants’ case ultimately focussed primarily on what was said to be the collective loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom suffered by all Torres Strait Islanders arising from the damage to or degradation of the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands. There was very limited evidence in respect of damage to the applicants’ personal or real property.

The applicants’ alternative or adaptation case

45 The applicants’ alternative case in negligence against the Commonwealth was also initially expressed in very broad and general terms. The applicants alleged that the Commonwealth had failed to take reasonable steps to implement “adaptation measures” to prevent or minimise the current and projected impacts of climate change on the Torres Strait Islands. The adaptation measures were initially said to include: adequate infrastructure to protect the Torres Strait Islands from the impacts of sea level rise, storm surges and flooding; adequate infrastructure to protect Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of heatwaves; and “such other measures as are reasonably necessary to protect” the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands, the cultural and customary rights of Torres Strait Islanders, and the health and safety of Torres Strait Islanders.

46 Ultimately, however, the applicants were effectively compelled to fall back on a far more limited case which essentially focussed on what were said to be inadequacies or deficiencies in the Commonwealth’s provision of funding for the construction of seawalls on some of the low-lying islands in the Torres Strait.

47 The applicants alleged that the Commonwealth owed a duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable care to protect them against marine inundation and erosion causing property damage, loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom, and injury, disease or death. That duty of care was said to require the Commonwealth to take reasonable steps to provide predictable and adequate funding for the construction of seawalls on Torres Strait Islands, and to lead, coordinate and establish a coherent plan for the provision of funding for the protection of Torres Strait Islanders from the adverse effects of sea level rise, inundation and erosion through the construction of seawalls.

48 The applicants’ case was that the Commonwealth breached that duty of care because it failed to take any, or any reasonable, steps, to provide predictable and adequate funding to complete planned seawall projects, or to lead and coordinate a coherent plan in respect of the construction of seawalls, on Saibai, Boigu, Poruma, Iama, Masig and Warraber islands.

49 As for causation and damage, the applicants contended that the Commonwealth’s breach of its duty of care in respect of the funding of seawalls caused Torres Strait Islanders to collectively suffer a loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom arising from damage to, or degradation of, the land and marine environment on the islands in question.

The relief sought by the applicants

50 The applicants sought damages from the Commonwealth. They also sought declaratory and injunctive relief.

51 The applicants asked the Court to make two declarations. The first declaration was to the effect that the Commonwealth owes Torres Strait Islanders a duty of care to take reasonable steps to protect them, their traditional way of life and the marine environment in and around the Torres Strait Islands, from the current and projected impacts of climate change. The second declaration was that the Commonwealth had breached that duty of care.

52 The injunction sought by the applicants would, if made, compel the Commonwealth to:

… implement such measures as are necessary to:

a. protect the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands and the cultural and customary rights of the Torres Strait Islanders, including the Applicants and Group Members, from GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions into the Earth’s atmosphere;

b. reduce Australia’s GHG emissions consistent with the Best Available Science Target; and

c. otherwise avoid injury and harm to Torres Strait Islanders, including the Applicants and the Group Members, from GHG emissions into the Earth’s atmosphere.

53 The basis upon which that injunction was sought was that the Commonwealth’s breach of duty was ongoing and that, unless restrained, that ongoing breach of duty would continue to cause Torres Strait Islanders to suffer further loss and damage.

The Commonwealth’s defence

54 The Commonwealth did not dispute or question much of the climate science that lay at the heart of the applicants’ case. It also did not dispute that climate change presents serious threats and challenges to the environment, the Australian community, and the world at large. Nor did it dispute that the Torres Strait Islands were and are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, or that some of those impacts have already been felt in that region. As discussed in more detail later, the Commonwealth was correct to make those concessions. The science of climate change is now broadly accepted and doubted by only those on the very fringes of political and scientific debate. The impacts of climate change are undeniable, as is the particular vulnerability of coastal and island communities and their inhabitants.

55 The central tenet of the Commonwealth’s defence to the applicants’ case was that the tort of negligence is an inappropriate and unsuitable vehicle by which to challenge decisions and actions which involve matters of high or core government policy. The Commonwealth contended that its actions in response to climate change, including the setting of emissions reductions targets and the funding of infrastructure to meet the challenges posed by climate change, were matters of high or core government policy and therefore should not be made the subject of a duty of care. The Commonwealth also contended that it did not in any event owe any such duty or duties of care to Torres Strait Islanders as alleged by the applicants. It also denied that its decisions and actions in response to climate change and its impacts breached any such duty or duties of care and denied that any deficiencies in its decisions or actions in that regard caused Torres Strait Islanders to suffer any compensable loss or damage.

The defence to the primary or targets case

56 The Commonwealth’s defence to the applicants’ case based on the alleged failure by it to set appropriate greenhouse gas emissions targets by reference to the best available science included, in summary, the following propositions.

57 First, the Commonwealth did not owe Torres Strait Islanders any duty of care concerning the setting of appropriate emissions targets, or the implementation of any such targets, essentially because Australia’s response to the global threat posed by climate change, including the setting and implementation of greenhouse gas emissions targets, involved “matters of high government policy, which are unsuited to curial assessment according to the standards of reasonableness”. The Commonwealth also contended that it owed no such duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders because the risk of harm from its conduct was not reasonably foreseeable, and it lacked the necessary control over the relevant risk of harm to Torres Strait Islanders from the impacts of climate change.

58 Second, even if the Commonwealth owed Torres Strait Islanders such a duty of care, it did not breach that duty of care because the setting of a greenhouse gas emissions reduction target is “a question of policy or a value judgement for each country, and there is no consensus approach”. It submitted, in that regard, that there was no consensus that emissions reduction targets must only be set by reference to the best available science. Rather, countries, including Australia, could reasonably set their emissions reductions targets having regard to numerous factors including “economic, social, political and practical factors”. The Commonwealth contended that the targets it set were “reasonable in light of those factors”.

59 Third, even if the Commonwealth breached the alleged duty of care relating to the setting and implementation of emissions reduction targets, the applicants had not shown that the targets that were set by the Commonwealth resulted in more greenhouse gas emissions than would have been the case if targets had been set having regard to the best available science. That was said to be because the applicants had adduced no evidence concerning the measures that the Commonwealth could and should have taken to meet those best available science targets. The Commonwealth also contended that the release of additional greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere that may have resulted from the allegedly inadequate emissions targets “at most cause[d] an increase in risk, and not a contribution to harm” and that, in any event, any increase in risk was not material because it could not be “measured by scientific instruments, let alone discerned by humans”. In short, the Commonwealth contended that the applicants had not established that any breach of the alleged duty of care had caused them or the group members to suffer any harm or damage.

60 Fourth, even if the Court found that the Commonwealth had breached the alleged duty of care, the applicants had not adduced any evidence of any damage to their personal property, or any personal injury, disease or death suffered by them. As for the allegation that Torres Strait Islanders had suffered a loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom, the Commonwealth contended that any such loss was not compensable under the common law of negligence and that any finding of liability for such loss would be contrary to principle.

61 Fifth, even if the Court found that the applicants had a claim against the Commonwealth in negligence, the declaratory and injunctive relief sought by the applicants should not be granted. The declaratory relief should not be granted because, in the absence of any finding that individual group members had suffered loss or damage, the proposed declarations would be in the nature of impermissible interlocutory declarations. The injunctive relief sought by the applicants should not be granted because of its subjective and imprecise terms and the “array of practical difficulties that would arise in seeking to identify the steps required for compliance and supervising adherence to the terms of the order”.

The defence to the alternative or adaptation case

62 The Commonwealth’s defence to the applicants’ case based on the alleged failure by it to implement appropriate adaptation measures involving the funding of seawalls included, in summary, the following propositions.

63 First, the Commonwealth did not owe Torres Strait Islanders any duty of care which required it to take reasonable steps to provide predictable or adequate funding for the construction of seawalls on the Torres Strait Islands, or to lead, coordinate and establish a coherent plan for the provision of funding for the protection of the Torres Strait Islanders through the construction of seawalls. That was said to be because the imposition of any such duty would require the Court to assess the reasonableness of the arrangements between the three tiers of government concerning the allocation of responsibilities in respect of climate change adaptation measures, including the funding of infrastructure, and Commonwealth decision-making regarding the allocation of its budget. The Commonwealth contended that those were matters of “high policy” which would be unsuitable for determination by the Court.

64 Second, if any such duty of care was owed, the Commonwealth did not breach that duty of care. The Commonwealth contended, in that regard, that it considered whether to provide funding for the seawalls project on certain islands in the Torres Strait Islands in accordance with the legal and policy framework applicable to the provision of such funding. It ultimately provided all the funds that were sought from it for the project. It therefore could not be said that it failed to provide predictable or adequate funding for the project.

65 Third, the applicants had not demonstrated that they, or Torres Strait Islanders generally, had suffered any loss or damage which was caused by any breach of the alleged duty of care in respect of the funding of adaptation measures. The Commonwealth contended that there was no evidence that the applicants had suffered any damage to their property, or had suffered any personal injury, as a result of any breach of the adaptation or alternative duty of care. As for the alleged loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom, the Commonwealth contended that there was no authority which supported the proposition that harm of that sort was compensable under the common law of negligence.

66 Fourth, the declaratory and injunctive relief sought by the applicants was not available in respect of the alleged adaptation or alternative duty of care, and its breach, for the same reasons as those given in respect of the alleged targets duty of care and breach.

The common questions

67 After some considerable discussion and debate, the parties eventually agreed on the questions common to all group members that the Court could and should answer at this stage of the representative proceeding. The agreed common questions obviously did not, and did not endeavour to, include every factual question that would need to be determined for the purposes of answering any of the questions. The capitalised terms in the questions are terms that are defined in the final iteration of the applicants’ pleading (the Third Further Amended Statement of Claim or 3FASOC). Those defined terms will be explained shortly.

68 The agreed common questions are as follows.

Duty of care

1. Has climate change had and does it continue to have any or all of the impacts described in paragraph [57] of the 3FASOC and the particulars thereto (the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait)?

2. Will climate change in the future have any of the impacts described in paragraph [59] of the 3FASOC and the particulars thereto (the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait) if Global Temperature Increase exceeds the Global Temperature Limit?

3. At any relevant time, did or does the Commonwealth owe a duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable steps to:

(a) protect Torres Strait Islanders; and/or

(b) protect Torres Strait Islanders’ traditional way of life, including taking steps to preserve Ailan Kastom; and/or

(c) protect the marine environment;

(d) from the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands?

(See paragraph [81] of the 3FASOC)

4. If the answer to question 3 is ‘yes’, did or does any such duty of care require the Commonwealth to take reasonable steps to ensure that, having regard to the Best Available Science, it:

(a) identifies the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands;

(b) identifies the risk, scope and severity of the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands;

(c) identifies the Global Temperature Limit necessary to prevent or minimise many of the most dangerous Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands;

(d) identifies a Best Available Science Target reflecting the Global Temperature Limit identified at subparagraph (c) above to prevent or minimise the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands; and

(e) implements such measures as are necessary to reduce Australia’s GHG emissions consistent with a Best Available Science Target identified at subparagraph (d) above?

(See paragraph [82] of the 3FASOC)

Alternative duty of care

5. At any relevant time, did or does the Commonwealth owe a duty of care to Torres Strait Islanders to take reasonable care to protect against marine inundation and erosion causing:

(a) property damage;

(b) loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom; and/or

(c) injury, disease or death?

(See paragraph [81A] of the 3FASOC)

6. If the answer to question 5 is ‘yes’, did or does such duty of care require the Commonwealth to take reasonable steps to:

(a) provide access to predictable funding, including additional funding as required, that was sufficient to construct seawalls on the Torres Strait Islands;

(b) lead and coordinate and establish a coherent plan for the provision of funding for the protection of the Torres Strait Islanders from the adverse effects of sea level rise, inundation and erosion through the construction of seawalls?

as part of the Seawalls Project Stage 1 and Stage 2 on Saibai, Boigu, Poruma, Iama, Masig and Warraber (the Seawalls Projects).

(See paragraph [82A] of the 3FASOC, the particulars set out in the applicants’ letters dated 12 November 2023 and 20 November 2023 and his Honour’s rulings on 14 and 23 November 2023)

(Note: seawalls includes bunds, wave return walls, geotextile bags and associated coastal protection infrastructure)

Breach of duty of care

7. If the answer to questions 3 and 4 is ‘yes’, did the Commonwealth breach the duty of care by failing to take any, or any reasonable steps to ensure that, having regard to the Best Available Science, it:

(a) identified the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands;

(b) identified the risk, scope and severity of the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands;

(c) identified the Global Temperature Limit necessary to prevent or minimise many of the most dangerous Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands;

(d) identified a Best Available Science Target reflecting the Global Temperature Limit identified at subparagraph (c) above to prevent or minimise the Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands and the Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands; and

(e) implemented such measures as are necessary to reduce Australia’s GHG emissions consistent with a Best Available Science Target identified at subparagraph (d) above;

when:

(f) setting and maintaining Australia’s 2030 Target;

(g) setting and maintaining Australia’s Re-affirmed 2030 Target;

(h) setting and maintaining Australia’s 2050 Target;

(i) setting and maintaining Australia’s Updated 2030 Target?

(See Paragraphs [82] and [83] of the 3FASOC and the particulars thereto)

8. If the answer to question 7 is ‘yes’, is there an ongoing breach of the duty of care?

(See paragraph [89] of the 3FASOC)

Breach of alternative duty of care

9. If the answer to questions 5 and 6 is ‘yes’, did the Commonwealth breach the alternative duty of care by failing to take any, or any reasonable steps to:

(a) provide predictable funding necessary to complete all planned seawalls projects;

(b) lead and coordinate and establish a coherent plan for the provision of funding for the protection of the Torres Strait Islanders from the adverse effects of sea level rise, inundation and erosion through the construction of seawalls;

as part of the Seawalls Project Stage 1 and Stage 2 on Saibai, Boigu, Poruma, Iama, Masig and Warraber (the Seawalls Projects).

(See paragraphs [82A] and [83A] of the 3FASOC, the particulars set out in the applicants’ letters dated 12 November 2023 and 20 November 2023 and his Honour’s rulings on 14 and 23 November 2023)

10. If the answer to question 9 is ‘yes’, is there an ongoing breach of the alternative duty of care?

(See paragraph [89] of the 3FASOC)

Causation, loss, and damage

11. If the answer to question 7 is ‘yes’, was the breach of the duty of care a cause of Torres Strait Islanders collectively suffering loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom arising from damage to or degradation of the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands?

(See paragraph [86] of the 3FASOC)

(Note: this question does not address any specific claims of loss or damage that the applicants or any specific group member may have)

12. If the answer to 8 is ‘yes’, will the ongoing breach of the duty of care, if not restrained, continue to be a cause of Torres Strait Islanders collectively suffering loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom arising from damage to or degradation of the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands?

(See paragraph [86], [87] and [89] of the 3FASOC and the particulars thereto)

(Note: this question does not address any specific claims of any ongoing loss or damage that the applicants or any specific group member may have)

13. If the answer to question 9 is ‘yes’, was the breach of the alternative duty of care a cause of Torres Strait Islanders collectively suffering loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom arising from damage to or degradation of the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands?

(See paragraph [86] of the 3FASOC and the particulars thereto)

(Note: this question does not address any specific claims of loss or damage that the applicants or any specific group member may have)

14. If the answer to question 10 is ‘yes’, will the ongoing breach of the alternative duty of care, if not restrained, continue to be a cause of Torres Strait Islanders collectively suffering loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom arising from damage to or degradation of the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands?

(See paragraph [86] and [89] of the 3FASOC and the particulars thereto)

Relief

15. What statutory law applies to the claims of the applicants and group members?

(See paragraphs [1b], [1c] and [86e] of the Further Amended Defence)

16. Is the loss of fulfilment of Ailan Kastom, arising from damage to or degradation of the land and marine environment of the Torres Strait Islands compensable under the law of negligence?

17. Can the declaratory and injunctive relief sought by the applicants be granted and, if so, should it be granted?

(See prayers 1, 2 and 3 in the Amended Originating Application)

69 It will be readily apparent that, to make any real sense of the common questions, it is necessary to have regard to some of the defined terms in the pleading. Regrettably, the applicants’ pleading is dizzyingly and bafflingly replete with defined terms. Many of the defined terms which are included in the common questions in turn include further defined terms, which in turn include further defined terms. It is unnecessary to reproduce or explain the complete labyrinth of defined terms. That would in any event be productive of confusion. What follows is an attempt to unpack and describe the main defined terms so that some sense may be made of the common questions.

70 The term “Current Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands” is defined in [57] of the pleading as including the following “Impacts of Climate Change” (which term is defined in 3FASOC [10(c) and (d)] as comprising increasing ocean acidity and the impacts of “Global Temperature Increase”, which term is in turn defined in 3FASOC [9] as “the increase in global average surface temperature above pre-industrial levels”) at the “Current Warming Level” (which is defined in 3FASOC [24(b)] as being approximately 1.2℃ above pre-industrial levels): higher average surface temperature than the “Current Warming Level” (which is defined as being “approximately 1.2℃ above pre-industrial levels” and as being “unprecedented in at least 125,000 years”: 3FASOC [24(b) and (c)]); ocean acidification and increase in “Ocean Temperature” (defined as meaning “the increase in the global average ocean surface temperature”: 3FASOC [10(d)(i)]); sea level rise, with consequential impacts including flooding and coastal erosion; increase in the frequency, size and/or intensity of extreme weather events such as terrestrial and marine heatwaves, severe storms, and flooding; harm and destruction of ecosystems and non-human species; and harm to human health. The pleading contains more detailed particulars of those impacts. It is, however, unnecessary for present purposes to reproduce those further particulars.

71 The term “Projected Impacts of Climate Change in the Torres Strait Islands” is defined in [59] of the pleading as meaning (or including) the following Impacts of Climate Change (defined earlier) that are projected to occur in the Torres Strait Islands if Global Temperature Increase (defined earlier) exceeds the Global Temperature Limit (defined in 3FASOC [31] as, in effect, holding the long-term Global Temperature Increase to below 1.5℃): further increase in average surface temperature, above the projected Global Temperature Increase[s] (defined earlier); further ocean acidification and increases in Ocean Temperature (defined earlier); further sea level rise and associated impacts, including inundation, erosion, and contamination of freshwater sources; further increase in the number of intense tropical cyclones, and incidence, intensity and duration of other extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, severe storms and flooding, and associated impacts such as personal injury, property damage, erosion, and impacts to infrastructure, emergency services facilities and roads; further harm and destruction of ecosystems and non-human species, including coral reefs, marine ecosystems and species and mangroves and coastal wetlands; and the greater likelihood of injury, disease, and death due to extreme weather events, increased likelihood of undernutrition resulting from diminished food production, and increased risks from food and water borne diseases and vector-borne diseases.

72 The term Ailan Kastom is defined in [54] and [55] of the 3FASOC as meaning the “distinctive customary culture”, or “body of customs, traditions, observances and beliefs of Torres Strait Islanders generally, or of a particular community or group of Torres Strait Islanders”, including: “connection to the marine and terrestrial environment, including as part of cultural ceremony”; “participating in cultural ceremony”; “use of plants and animals for food, medicine and cultural ceremony”; “burying Torres Strait Islanders in local cemeteries and performing mourning rituals”; “visiting sacred sites, including on uninhabited islands”; and “dugong and marine turtle hunting, and other marine hunting and fishing”.

73 The term “Best Available Science” is defined in [22] of the 3FASOC as meaning reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), World Meteorological Organisation (WMO), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), the (Australian) Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) and the (Australian) Climate Change Authority (CCA) [that] “represent the best available science on the causes and Impacts of Climate Change and the necessary actions to avoid the most dangerous Impacts of Climate Change”.

74 The term “Best Available Science Target” is defined in [45] of the 3FASOC as meaning the “necessary GHG [greenhouse gas] or CO2 emissions reductions for each country to do its part consistent with staying within a Global GHG Budget” (defined as “the total global GHG emissions that can be released into the atmosphere within a particular time period to give a specified probability of limiting Global Temperature Increase to a specified level”: 3FASOC [43A]) “[that] can be determined on the basis of Best Available Science”.

75 The term “Australia’s 2030 Target” is defined in the particulars to [50] of the 3FASOC as being a GHG emissions reduction target, adopted by the Commonwealth in 2015, of 26 to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. The term “Australia’s Re-affirmed 2030 Target” is effectively defined as the Commonwealth’s re-affirmation, in 2020, of Australia’s 2030 Target. The term “Australia’s 2050 Target” is defined as meaning a commitment given by the Commonwealth in 2021, to achieve “Net Zero Emissions” (defined as the point where “a balance is reached between the GHGs emitted and removed from the atmosphere”: 3FSOC [11(b)(ii)]) by 2050. The term “Australia’s Updated 2030 Target” is defined as meaning the Commonwealth’s adoption, in 2022, of a GHG emissions reduction target of 43% below 2005 levels by 2030.

76 While that may all appear to be somewhat confusing at this stage, a further attempt is made later in these reasons to unravel or unpack the applicants’ pleaded case, both in respect of the primary or targets duty case and the alternative duty or adaptation case. The precise nature of the common question will then hopefully be a bit easier to comprehend.

THE TORT OF NEGLIGENCE – RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

77 This is perhaps not the occasion to publish a lengthy dissertation on the law of negligence. The elements of the tort of negligence and the applicable legal principles in relation to those elements were not really in dispute in this case. It was the application of those principles to the unique and complex facts and circumstances of this case that was the main point of contention. It is nevertheless necessary to briefly identify the elements of the cause of action and the legal principles that apply in determining whether those elements have been made out. Before turning to those principles, it is necessary to briefly address common question 15, which is what, if any, statutory law applies to the claims of the applicants and group members?

The applicable law

78 The applicants contended that the law, including the relevant statutory law, of Queensland applied to this proceeding. In particular, they contended that the Civil Liability Act 2003 (Qld) and the Limitation of Actions Act 1974 (Qld) applied in respect of their claims in tort against the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth, however, contended that the law of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) applied to this proceeding, including (potentially) the Civil Law (Wrongs) Act 2002 (ACT) and the Limitation Act 1985 (ACT). The parties ultimately agreed, however, that no substantive issue in the case turned upon the applicable law. The choice of law issue can accordingly be addressed in very brief terms.

79 The law governing questions of substance in tort claims is the lex loci delicti – the law of the place where the tort was committed. In Dow Jones & Co Inc v Gutnick (2002) 210 CLR 575, it was said (at [43]) that “locating the place of commission of a tort is not always easy” and that:

Attempts to apply a single rule of location (such as a rule that intentional torts are committed where the tortfeasor acts, or that torts are committed in the place where the last event necessary to make the actor liable has taken place) have proved unsatisfactory if only because the rules pay insufficient regard to the different kinds of tortious claims that may be made. Especially is that so in cases of omission. In the end the question is “where in substance did this cause of action arise”? In cases, like trespass or negligence, where some quality of the defendant's conduct is critical, it will usually be very important to look to where the defendant acted, not to where the consequences of the conduct were felt.

(Emphasis added; footnotes omitted.)

80 Where the conduct of the defendant which gives the plaintiff cause for complaint is said to involve an omission, the place of the cause for complaint may be “the place of the act or acts of the defendant in the context of which the omission assumes significance”: Voth v Manildra Flour Mills Pty Ltd (1990) 171 CLR 538 at 567 (Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ) referring to Jackson v Spittall (1870) LR 5 CP 542 at 552. As the decision in Voth illustrates, the place where the defendant’s omission assumes significance is not necessarily the place where the plaintiff’s loss or damage occurred.

81 Each case turns on its own facts and it is generally not appropriate to reason on the basis of factual analogies.

82 In relation to the applicants’ primary or targets case, the conduct of the Commonwealth which gave the applicants cause for complaint was, in essence, the setting and communication of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets. The applicants’ central complaint is that in setting those targets, the Commonwealth failed to take certain steps that the applicants claimed the Commonwealth was required to take to meet the standard of care required of it. Ultimately, however, the Commonwealth’s conduct which was the cause of complaint was the making of decisions concerning the targets. That conduct essentially occurred in Canberra in the ACT. That is where the Commonwealth relevantly acted and is also the place where the Commonwealth’s alleged omissions assumed significance. It follows that the applicants’ cause of action in respect of the primary or targets duty of care in substance arose in the ACT.