FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Dyno Nobel Asia Pacific Pty Ltd v Orica Explosives Technology Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 767

File number(s): | NSD 345 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | DOWNES J |

Date of judgment: | 14 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | PATENTS – validity – infringement – standard patent entitled “Wireless detonator assembly, and methods of blasting” – standard patent entitled “Wireless electronic booster and methods of blasting” – standard patent entitled “Selective control of wireless initiation devices at a blast site” – standard patent entitled “A method of underground rock blasting” PATENTS – claim construction – utility – clarity – fair basis – identification of members of notional skilled team – person skilled in the art – where witnesses had peculiar or specialised knowledge – lack of inventive step – novelty – availability of prior art information – date on which prior art is to be construed for purposes of novelty – whether person skilled in the art could be reasonably expected to have ascertained and regarded as relevant certain prior art publications – whether obviousness established on the evidence PATENTS – best method – whether best method disclosed because of failure to disclose details of commercial embodiment of invention – proper characterisation of invention in patent – manner of manufacture – whether statements in patent constituted admissions that matters were known – whether new method disclosed |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 136 Patents Act 1990 (Cth) ss 7(1), 7(2), 7(3), 18(1), 40(2), 117(2), 128, 129, 131 |

Cases cited: | Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2002) 212 CLR 411; [2002] HCA 59 Alcon Research LLC v Actavis Group PTC ehf [2021] EWHC 1026 Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 226 FCR 324; [2014] FCAFC 99 Australian Steel Co (Operations) Pty Ltd v Steel Foundations Ltd (2003) 58 IPR 69; [2003] FCA 374 Axent Holdings Pty Ltd (t/as Axent Global) v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd (2020) 154 IPR 431; [2020] FCA 1373 Betfair Pty Limited v Racing New South Wales (2010) 189 FCR 356; [2010] FCAFC 133 BlueScope Steel Limited v Dongkuk Steel Mill Co, Ltd (No 2) (2019) 152 IPR 195; [2019] FCA 2117 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc v Elanco New Zealand (2021) 164 IPR 17; [2021] FCA 1457 Bradken Resources Pty Ltd v Lynx Engineering Consultants Pty Ltd (2012) 210 FCR 21; [2012] FCA 944 British Acoustic Films Ltd v Nettlefold Productions Ltd (1935) 53 RPC 221 CQMS Pty Ltd v Bradken Resources Pty Ltd (2016) 120 IPR 44; [2016] FCA 847 Dometic Australia Pty Ltd v Houghton Leisure Products Pty Ltd (2018) 135 IPR 403; [2018] FCA 1573 Dyson v Hoover [2002] RPC 22 EI Dupont de Nemours & Co v Imperial Chemical Industries plc (2002) 54 IPR 304; [2002] FCA 230 Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (2002) 54 IPR 449; [2002] HCA 21 General Tire & Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Company Ltd (1971) 1A IPR 121 Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd v Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC (2016) 117 IPR 252; [2016] FCA 169 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 119 IPR 1; [2016] FCA 608 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 474; [2018] FCAFC 71 Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd v Reflex Instruments Asia Pacific Pty Ltd (2022) 167 IPR 515; [2022] FCA 797 Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd (2023) 180 IPR 315; [2023] FCA 1017 Hicks v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs [2003] FCA 757 ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v Lubrizol Corporation Inc (1999) 45 IPR 577; [1999] FCA 345 ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v The Lubrizol Corporation Inc (2000) 106 FCR 214; [2000] FCA 1349 Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd (2017) 134 IPR 1; [2017] FCAFC 196 Illumina Cambridge Limited v Latvia MGI Tech SIA [2021] EWHC 57 Interlego A.G. v Toltoys Proprietary Limited (1973) 130 CLR 461 JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd (formerly known as A’Van Campers Pty Ltd) v Camoflag Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 68; [2005] FCA 1474 Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61; [2016] FCAFC 27 Lido Manufacturing Co Pty Ltd v Meyers & Leslie Pty Ltd (1964) 5 FLR 443; [1964–5] NSWR 889 MedImmune Limited v Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited [2012] EWCA Civ 1234 Merck & Co Inc v Arrow Pharmaceutical Ltd (2006) 154 FCR 31; [2006] FCAFC 91 Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Bondina Ltd [1972] FSR 417; [1973] RPC 491 Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Tyco Electronics Pty Ltd (2002) 56 IPR 248; [2002] FCAFC 315 Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 Mullard Radio Valve Co. Ltd. v British Belmont Radio Ltd. (1939) 56 RPC 1 Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360 Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990) 16 IPR 545; (1990) AIPC 90-670 Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Limited (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307 Occupational and Medical Innovations Ltd v Retractable Technologies Inc (2007) 73 IPR 312; [2007] FCA 1364 Ore Concentration Company Ld v Sulphide Corporation Ld [1914] 31 RPC 206 Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (2015) 113 IPR 191; [2015] FCA 634 Pharmacia LLC v Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (2022) 168 IPR 431; [2022] FCAFC 167 Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC (2015) 240 FCR 85; [2015] FCAFC 179 Rakman International Pty Ltd v Boss Fire & Safety Pty Ltd (2023) 178 IPR 20; [2023] FCAFC 202 Ramset Fasteners (Aust) Pty Ltd v Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd (1999) 44 IPR 481; [1999] FCA 898 Sandoz AG v Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH (2024) 183 IPR 309; [2024] FCAFC 135 Sandvik Intellectual Property AB v Quarry Mining & Construction Equipment Pty Ltd (2017) 126 IPR 427; [2017] FCAFC 138 SARB Management Group Pty Ltd (t/as Database Consultants Australia) v Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd (2024) 176 IPR 391; [2024] FCAFC 6 Schlumberger Holdings Limited v Electromagnetic Geoservice AS [2010] EWCA Civ 819 Sequenom, Inc v Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc (2019) 143 IPR 24; [2019] FCA 1011 Sigma Pharmaceuticals (Australia) Pty Ltd v Wyeth (2010) 88 IPR 459; [2010] FCA 1211 Sydney Cellulose Pty Ltd v Ceil Comfort Home Insulation Pty Ltd (2001) 53 IPR 359; [2001] FCA 1350 Townsend Controls Pty Ltd v Gilead (1989) 16 IPR 469; (1989) AIPC 90-602 U & I Global Trading (Australia) Pty Ltd v Tasman-Warajay Pty Ltd (1995) 60 FCR 26; (1995) 32 IPR 494 Wellcome Foundation Limited v V.R. Laboratories (Aust.) Proprietary Limited (1981) 148 CLR 262 Zoetis Services LLC v Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc (2024) 306 FCR 19; [2024] FCAFC 145 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and associated Statutes |

Number of paragraphs: | 1331 |

Date of hearing: | 30 September 2024, 1–4, 8–11, 14–18, 21–23, 30–31 October 2024, 1 November 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Ms C Cochrane SC with Mr B Mee, Mr J Elks and Ms J Thornton |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Spruson & Ferguson |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr N Murray SC with Ms K Beattie SC, Ms F St John and Ms S Yates |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Davies Collison Cave Law |

ORDERS

NSD 345 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | DYNO NOBEL ASIA PACIFIC PTY LTD (ACN 003 269 010) Applicant | |

AND: | ORICA EXPLOSIVES TECHNOLOGY PTY LTD (ACN 075 659 353) First Respondent ORICA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 004 117 828) Second Respondent ORICA LIMITED (ACN 004 145 868) Third Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | ORICA AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 004 117 828) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | DYNO NOBEL ASIA PACIFIC PTY LTD (ACN 003 269 010) Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | DOWNES J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 JULY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), access to and disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the unredacted text of the reasons for judgment delivered today be restricted to the external legal representatives of the parties, and those persons to whom access is allowed under the terms of the confidentiality regime agreed by the parties, until 12.00pm on 21 July 2025.

2. The parties confer and communicate to the associate to Downes J those parts of these reasons which should be restricted from publication by 4.00 pm on 18 July 2025, with a brief explanation for the proposed redactions.

3. The parties provide to the associate to Downes J agreed or, if not agreed, competing, draft orders giving effect to these reasons by no later than 4.00 pm on 21 July 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[11] | |

[24] | |

[35] | |

[35] | |

[43] | |

[44] | |

[44] | |

[45] | |

[56] | |

[69] | |

[71] | |

[72] | |

[73] | |

[80] | |

[85] | |

[86] | |

[87] | |

[89] | |

[89] | |

[92] | |

6.3 Information capable of forming part of CGK at the priority date | [93] |

[101] | |

[107] | |

[107] | |

[117] | |

[122] | |

[122] | |

[124] | |

[130] | |

[139] | |

[141] | |

[150] | |

[158] | |

[162] | |

[187] | |

[191] | |

[203] | |

[208] | |

[209] | |

[213] | |

[214] | |

[224] | |

[227] | |

[230] | |

[230] | |

[230] | |

[250] | |

[263] | |

[270] | |

[282] | |

[285] | |

[294] | |

[309] | |

[322] | |

[340] | |

[342] | |

A detonator of the type disclosed in the 079 patent (integer 1.1) | [342] |

[354] | |

[358] | |

Internal power source to power the receiving means (integer 1.5) | [359] |

[360] | |

[365] | |

[372] | |

[377] | |

[384] | |

[389] | |

[394] | |

[400] | |

[406] | |

[412] | |

[415] | |

[421] | |

[423] | |

[424] | |

8.2.1 No disclosure of a detonator of the type disclosed in the 079 patent | [429] |

8.2.2 No disclosure of wireless command signal and wireless detonator assembly | [438] |

[450] | |

[453] | |

[455] | |

[457] | |

[458] | |

[459] | |

[468] | |

9.1.2 Removal of wires from detonators was counter-intuitive | [478] |

[484] | |

[494] | |

[495] | |

[497] | |

[499] | |

[504] | |

[522] | |

[530] | |

[533] | |

[537] | |

[538] | |

[540] | |

[544] | |

[562] | |

[570] | |

[575] | |

[582] | |

[600] | |

[608] | |

[609] | |

[626] | |

[628] | |

[628] | |

[632] | |

[637] | |

[639] | |

[647] | |

[649] | |

[659] | |

[661] | |

[673] | |

[675] | |

[678] | |

[683] | |

[689] | |

[691] | |

[693] | |

[695] | |

[697] | |

[698] | |

[699] | |

[714] | |

[722] | |

[724] | |

[724] | |

[725] | |

[725] | |

[734] | |

[745] | |

[745] | |

[750] | |

[759] | |

[767] | |

[767] | |

[771] | |

[772] | |

[773] | |

[776] | |

[779] | |

[790] | |

[797] | |

[810] | |

[813] | |

25.6 Whether claims 1 and 2 were part of the CGK as at 873 priority date | [814] |

[818] | |

[820] | |

[821] | |

[822] | |

Whether a wireless initiation device must include a detonator | [824] |

Whether the detonator in the wireless initiation device is confined to EDs | [853] |

26.1.2 “predetermined group … within a plurality… at a blast site” | [856] |

26.1.3 “transmitting to” and “receiving the wireless command signal” | [860] |

26.1.4 “determining whether… part of the predetermined group” | [864] |

[867] | |

26.2.1 “group identification component” and “stored group identification” | [868] |

[876] | |

[884] | |

[890] | |

[891] | |

[891] | |

[907] | |

[911] | |

[915] | |

[917] | |

[919] | |

[923] | |

[925] | |

[927] | |

[928] | |

[934] | |

[938] | |

[942] | |

[945] | |

[947] | |

[948] | |

[951] | |

[952] | |

[956] | |

[964] | |

[971] | |

[973] | |

[977] | |

[983] | |

[987] | |

[993] | |

[994] | |

[994] | |

[996] | |

[999] | |

[1007] | |

[1020] | |

[1028] | |

[1031] | |

[1033] | |

[1034] | |

[1047] | |

[1047] | |

[1052] | |

[1061] | |

[1062] | |

[1062] | |

[1069] | |

[1076] | |

32.4 Boucher, Papillon, Jacobson and Napier not members of the notional skilled team | [1086] |

[1093] | |

[1097] | |

[1104] | |

[1115] | |

[1122] | |

[1138] | |

[1156] | |

[1157] | |

[1157] | |

[1161] | |

[1172] | |

[1172] | |

35.2 Challenge to validity determined by disclosure in specification | [1184] |

[1186] | |

[1198] | |

[1207] | |

[1215] | |

[1216] | |

[1220] | |

[1223] | |

[1226] | |

[1229] | |

[1232] | |

[1237] | |

[1243] | |

[1244] | |

[1245] | |

[1253] | |

[1257] | |

[1266] | |

[1272] | |

[1278] | |

[1279] | |

[1281] | |

[1289] | |

[1293] | |

[1294] | |

[1294] | |

[1303] | |

[1308] | |

[1310] | |

[1313] | |

[1314] | |

[1318] | |

[1321] | |

[1325] | |

[1326] | |

[1329] | |

[1330] |

DOWNES J:

1. SYNOPSIS

1 The first respondent and cross-claimant (Orica) is the registered owner of the following patents:

(1) Australian Patent No. 2006225079 (079 patent) entitled “Wireless detonator assembly, and methods of blasting”;

(2) Australian Patent No. 2007246165 (165 patent) entitled “Wireless electronic booster, and methods of blasting”;

(3) Australian Patent No. 2010207873 (873 patent) entitled “Selective control of wireless initiation devices at a blast site”; and

(4) Australian Patent No. 2010302943 (943 patent) entitled “A method of underground rock blasting”;

(together, the patents).

2 Since at least 1 June 2021, the applicant and cross-respondent (DNAP) has been making and supplying “CyberDet I” wireless electronic detonators (CyberDet I Device). DNAP has used CyberDet I Devices, and supplied CyberDet I Devices for use, in certain blasts at the Big Bell Mine (Big Bell) from at least 1 June 2021 and AngloGold Ashanti’s Sunrise Dam Mine (Sunrise Dam) from at least 17 October 2021.

3 By its application, DNAP seeks revocation of the claims of the patents, and associated declaratory relief, and relies upon numerous grounds of invalidity.

4 DNAP also contends that Orica made unjustified threats within the meaning of s 128 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) in the period between 26 October 2021 and 7 July 2022. DNAP seeks a declaration, injunction and damages. The claim for additional damages was not pressed.

5 By its cross-claim, Orica alleges that DNAP has infringed various claims of the patents:

(1) 079 patent. Subject to validity, DNAP admits infringement of claims 1, 3, 5, 12, 13, 16, 25, 26, 30 and 31 but denies infringement of claims 2 and 17 (and claims 25, 26, 30, and 31, insofar as they depend on earlier disputed claims);

(2) 165 patent. Subject to validity, DNAP admits infringement of claims 1, 2, 5–10, 12–15, 23, 26–29 but denies infringement of claims 4 and 11 (and claims 26–29, insofar as they depend on claims 4 and 11);

(3) 873 patent. Orica alleges, and DNAP denies, infringement of claims 1–4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 13 and 15;

(4) 943 patent. Orica alleges, and DNAP denies, infringement of claims 1–7, 9, 11, 14 and 19–20 and that DNAP has threatened to infringe claim 8.

6 The hearing on liability only was held in 2024. As the trial concerned discrete issues in relation to the four patents, it is convenient to divide these reasons into the issues as they relate to each of the patents except where otherwise indicated.

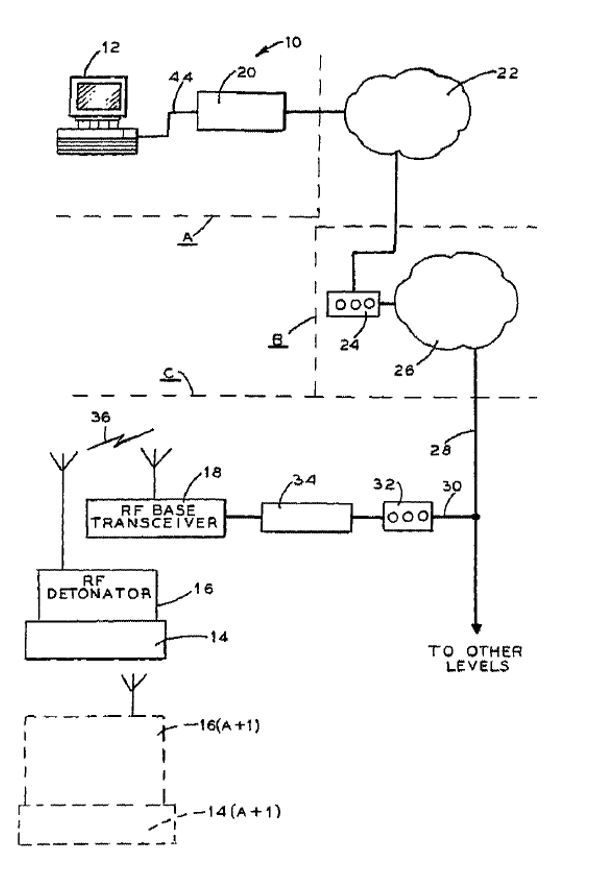

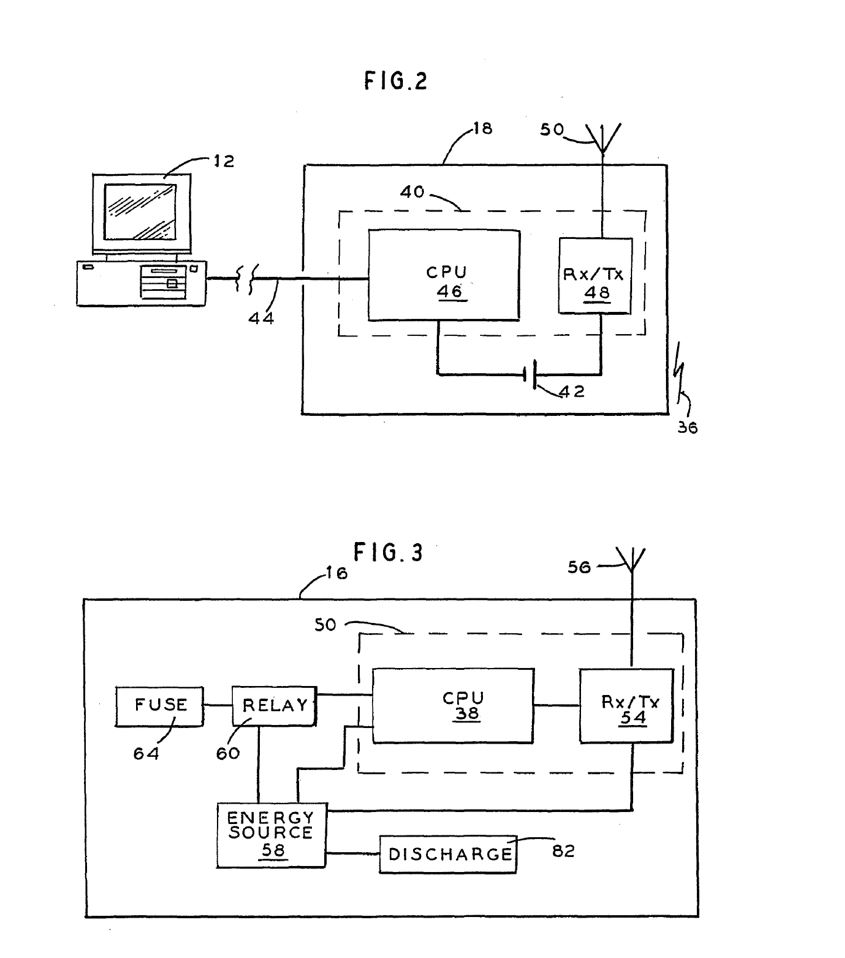

7 It also convenient to identify particular initiation systems which receive regular mention in these reasons.

8 The first of these is the BlastPED system, which was created by Mine Site Technologies Pty Limited (MST).

9 The second is the Rothenbuhler system, versions of which have been supplied by Rothenbuhler Engineering Company (Rothenbuhler).

10 For the reasons which follow, I have concluded that Orica has achieved almost complete success in its infringement case in relation to the 079, 165 and 943 patents, but did not succeed in its infringement case in relation to the 873 patent. DNAP’s validity attacks on the patents have failed completely, as did its claim based on unjustified threats.

2. THE MANNER IN WHICH THE PROCEEDING WAS CONDUCTED

11 When the case was opened by it at trial, DNAP’s then version of its statement of claim, being the Fifth Further Amended Statement of Claim (5FASOC), pleaded an extensive range of validity attacks on each of the patents. The 5FASOC also pleaded matters which DNAP alleged were CGK as at the priority dates of each of the patents. Prior to trial, Orica filed a document entitled “Statement of Particulars: Matters of common general knowledge” (SOP). In the SOP, certain allegations of CGK made by DNAP were admitted but the majority were denied, in their entirety or in part, with explanations given.

12 By its closing submissions, DNAP is critical of Orica’s refusal to admit its allegations concerning CGK, and even submits that Orica sought to “artificially limit the CGK”, which approach should be rejected. However, DNAP bore the onus of establishing its case, and Orica was entitled to either deny or not admit DNAP’s allegations, and to put DNAP to proof. Such an approach is not artificial, as DNAP submits, and whether it should be rejected turns on the evidence.

13 Many of the grounds on which DNAP alleged that one or more of the patents was invalid were abandoned by the close of the trial, namely:

(1) the false suggestion challenge to the 079 and 165 patents;

(2) the entitlement challenge to the 079 patent;

(3) the novelty citation of US Patent No. 5,476,044 entitled “Electronic Safe/Arm Device” (US’044) to the 079 patent;

(4) the novelty and inventive step citations of Australian Patent No. 614183 entitled “Primer” (ICI Primer Patent), published 20 March 1990; United States Patent No. 5,038,682 entitled “Electronic Device”, published 13 August 1991; and United States Patent No. 5,159,149 entitled “Electronic Device”, published 27 October 1992, to the 165 patent;

(5) the clarity challenge to the 943 patent.

14 DNAP was granted leave to file its Sixth Further Amended Statement of Claim (6FASOC) during closing submissions which reflected its abandonment of various grounds of invalidity. At the same time, it relied on extensive written closing submissions which, in certain respects, addressed a different case to that pleaded in the 6FASOC.

15 These proceedings were commenced by DNAP in May 2022, and they relate to four patents. Prior to the trial, DNAP had amended its original statement of claim in June 2022, November 2022, April 2023, June 2023, March 2024, and August 2024. In addition to the SOP, other formal documents had been prepared and exchanged between the parties including novelty tables. DNAP therefore had ample opportunities to plead its case.

16 The proceedings were case managed leading up to trial, with multiple experts engaged and numerous affidavits prepared. Three joint expert conclaves occurred over a number of days resulting in three joint expert reports. It is apparent and is to be expected that this evidence was prepared by the parties having regard to the issues as identified by the pleadings and other documents such as the SOP.

17 Thus, each side went to significant lengths over a long period of time and through various pre-trial steps to identify to the other party and to the Court the case which it intended to advance at trial.

18 Further, the parties took an admirable and pragmatic approach to objections, with no objections being taken to the evidence-in-chief of the experts, which evidence was voluminous. Further, having regard to the welter of issues raised by DNAP in its validity attacks on the patents, with overlapping issues connected with many of the attacks, Orica cannot be criticised for not objecting to questions being asked of the experts during the trial on the grounds of relevance.

19 By its closing submissions, DNAP does not address many of the facts in issue as they arose from the pleadings. This includes the allegations relating to CGK but also extends to the material facts pleaded by it in relation to the alleged bases of invalidity of each of the patents. Instead, DNAP’s closing submissions tend to focus on aspects of evidence given during the hearing, and it presses for numerous findings to be made based on that evidence, some of which fall outside the scope of its pleaded case.

20 As a consequence of DNAP’s approach, the parties’ closing submissions address different issues in many respects. That is, while Orica has addressed DNAP’s pleaded case as well as (to some extent) the case as opened by DNAP, DNAP has made submissions about a different or (in some instances) an expanded case, without proper notice to Orica of that different case.

21 The problem with such an approach is that, had Orica been given notice of that different or expanded case through DNAP’s pleadings or other documents served prior to trial, this could have impacted upon, for example, the evidence-in-chief which Orica adduced from its experts or the questions asked of the expert for the purposes of the joint expert reports or during the trial. In such a complex case as this one with the pre-trial steps identified above, it is not necessarily an answer for DNAP to point to its opening submissions to say that Orica knew the case it had to meet at trial.

22 For these reasons and generally, I have taken the approach to decline to make findings sought by DNAP in closing submissions about a matter which was not pleaded by it, and when objection has been taken by Orica and I was not satisfied that Orica knew the nature of the case it had to meet at trial: see, generally, Betfair Pty Limited v Racing New South Wales (2010) 189 FCR 356; [2010] FCAFC 133 at [49]–[53] (Keane CJ, Lander and Buchanan JJ). I have adopted a similar approach in relation to one aspect of Orica’s infringement case which was not part of its pleaded case.

23 When I have taken this approach, it has been identified in these reasons.

3. 079 PATENT

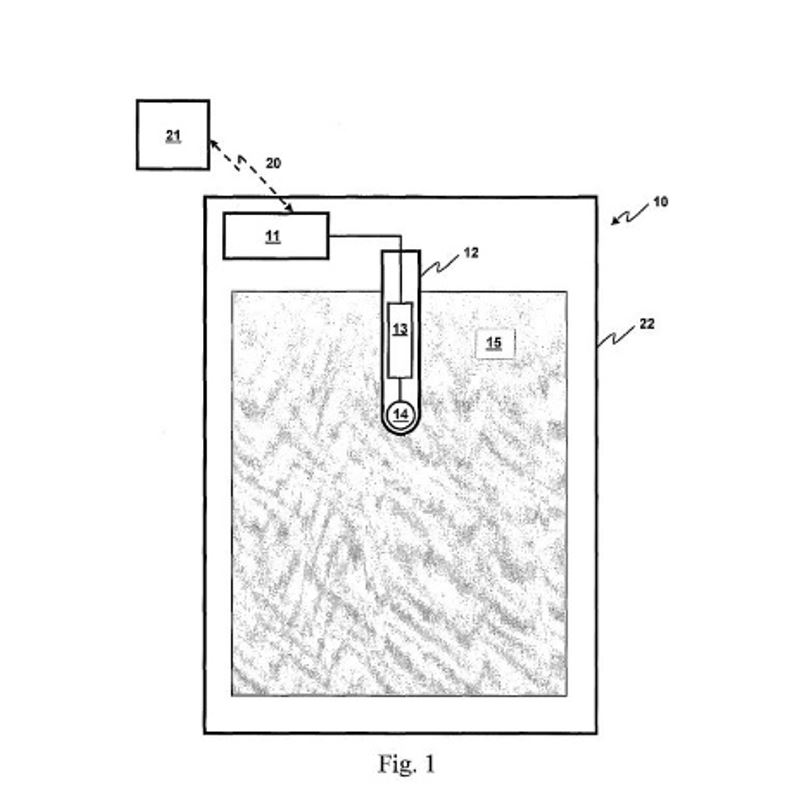

24 The 079 patent is entitled “Wireless detonator assembly, and methods of blasting” and claims a priority date of 18 March 2005 (079 priority date).

25 The invention relates to the field of wireless detonator assemblies and methods of blasting employing such assemblies. In particular, the invention relates to detonator assemblies that are substantially free of physical connections with an associated blasting machine and to improvements in the safety of such wireless detonator assemblies.

26 The abstract of the 079 patent states as follows:

A wireless detonator assembly (10) for blasting arrangements comprising a detonator with a base charge (18), command signal receiving (11) and processing means (12), a charge storage device (13) with a firing circuit (15) for storing electrical energy, at least one power source (14) to power said command signal receiving (11) and processing means (12), and to charge said charge storage device (13), each of said at least one power source (14) capable of supplying a maximum voltage or current that is less than a threshold voltage or current to actuate said base charge (18), and said base charge (18) actuating if a voltage or current in the firing circuit (15) resulting from discharge of the electrical energy from said charge storage device (13) exceeds said threshold voltage or current.

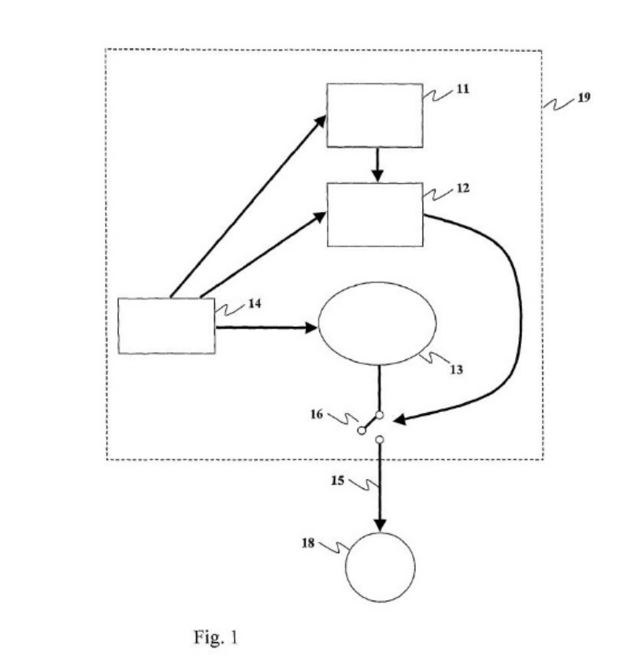

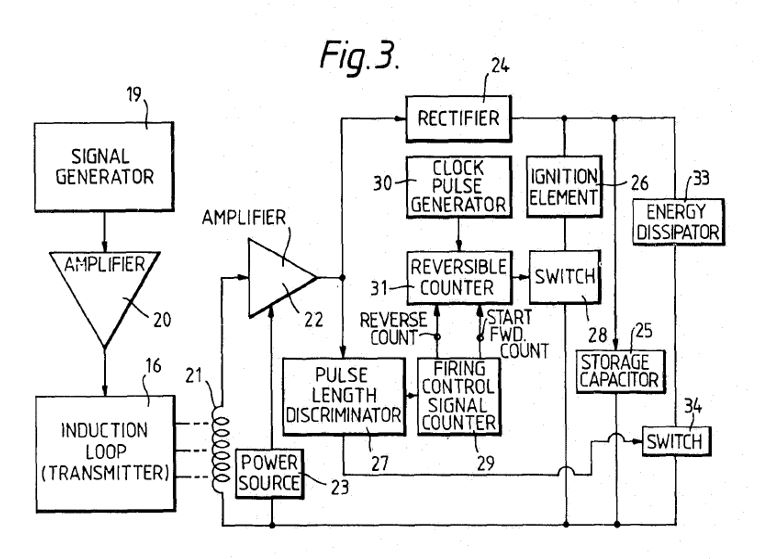

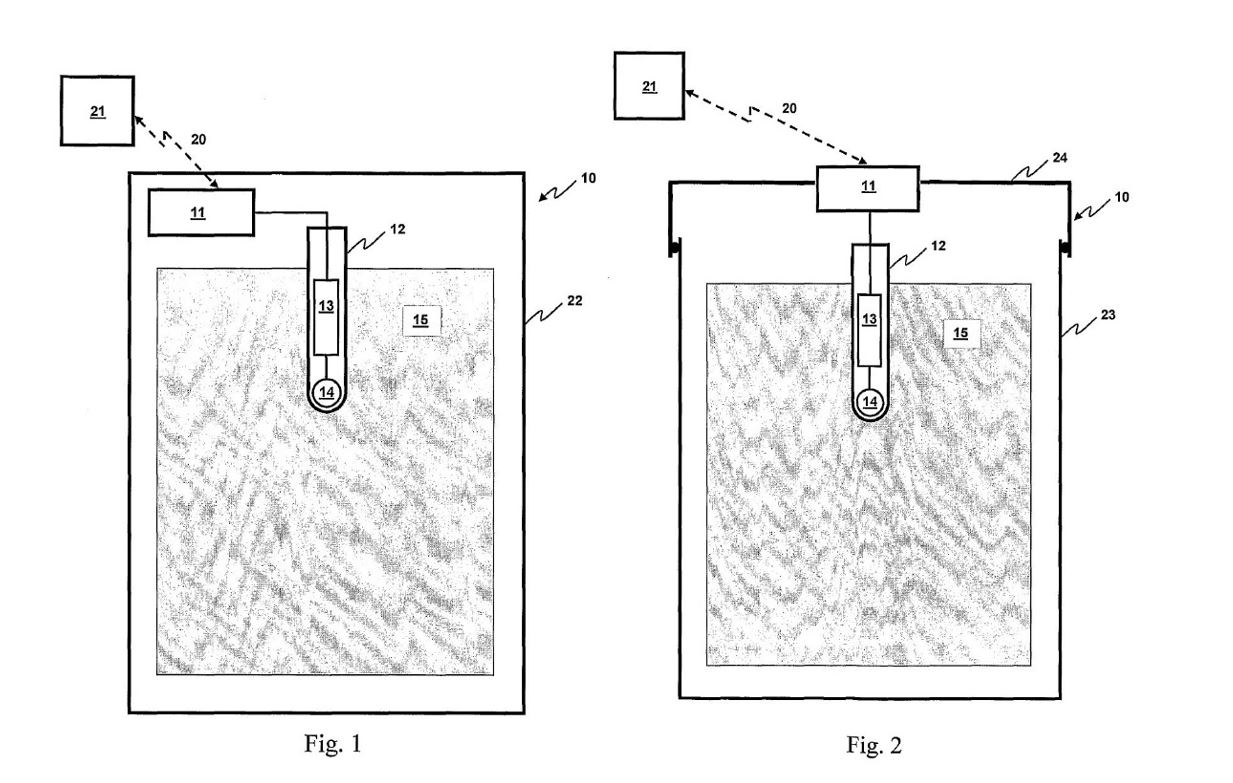

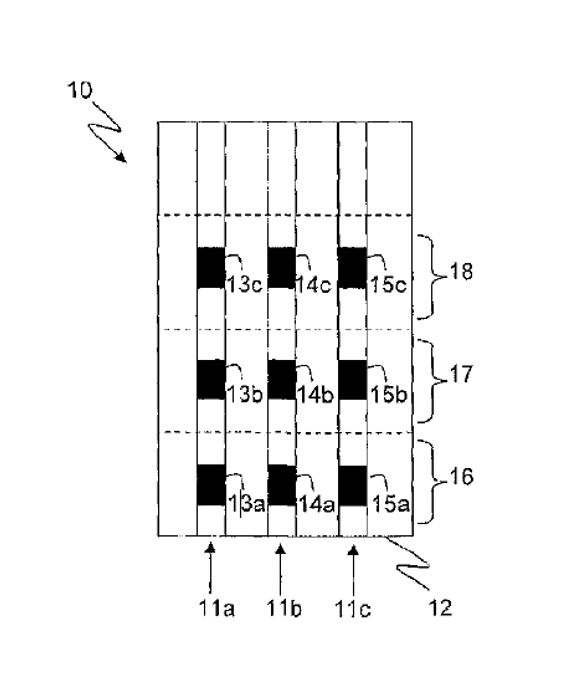

27 Figure 1 of the 079 patent is reproduced below:

28 The Background to the Invention states the following:

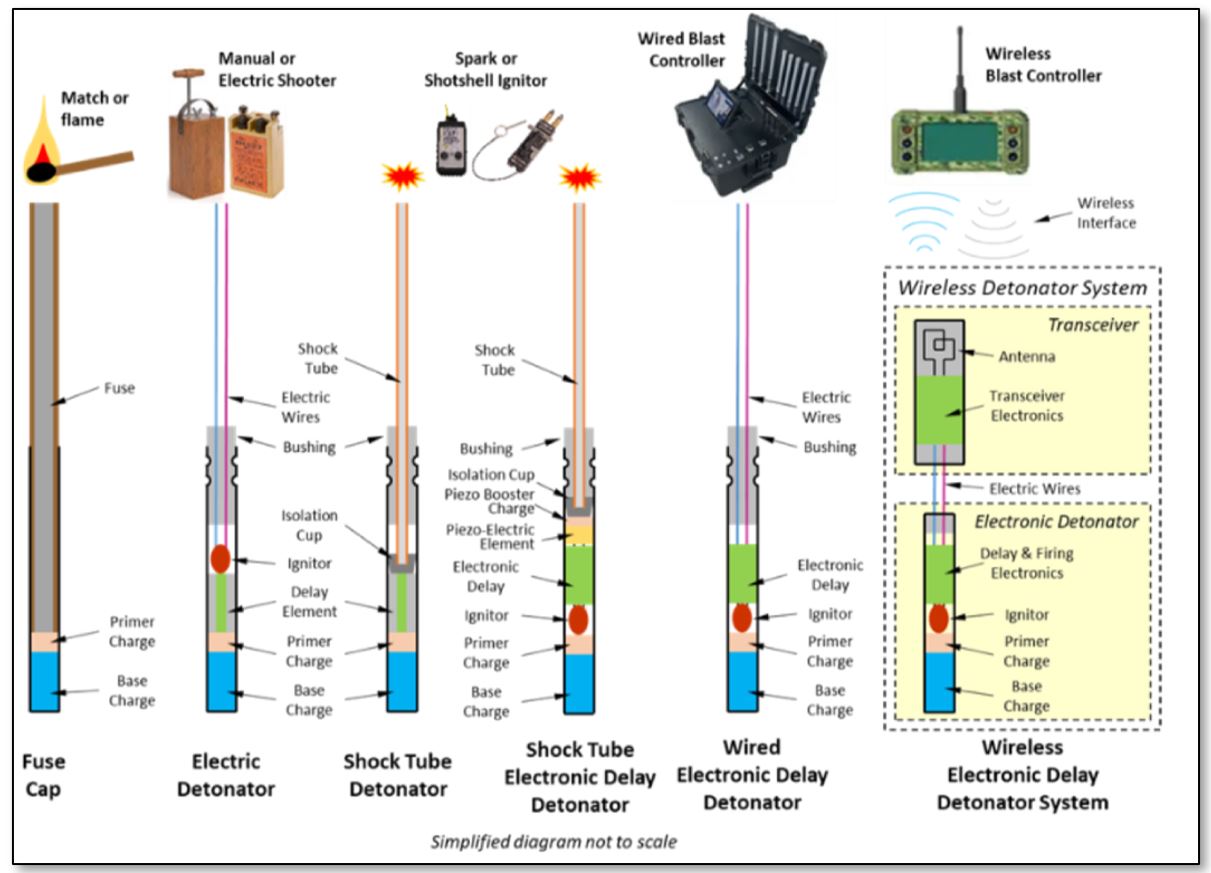

In mining operations, the efficient fragmentation and breaking of rock by means of explosive charges demands considerable skill and expertise. In most mining operations explosive charges are planted in appropriate quantities at predetermined positions within the rock. The explosive charges are then actuated via detonators having predetermined time delays, thereby providing a desired pattern of blasting and rock fragmentation. Traditionally, signals are transmitted to the detonators from an associated blasting machine via non-electric systems employing low energy detonating cord (LEDC) or shock tube. Alternatively, electrical wires may be used to transmit more sophisticated signals to and from electronic detonators. For example, such signaling [sic] may include ARM, DISARM, and delay time instructions for remote programming of the detonator firing sequence. Moreover, as a security feature, detonators may store firing codes and respond to ARM and FIRE signals only upon receipt of matching firing codes from the blasting machine. Electronic detonators can be programmed with time delays with an accuracy of 1ms or less.

The establishment of a wired blasting arrangement involves the correct positioning of explosive charges within boreholes in the rock, and the proper connection of wires between an associated blasting machine and the detonators. The process is often labour intensive and highly dependent upon the accuracy and conscientiousness of the blast operator. Importantly, the blast operator must ensure that the detonators are in proper signal transmission relationship with a blasting machine, in such a manner that the blasting machine at least can transmit command signals to control each detonator, and in turn actuate each explosive charge. Inadequate connections between components of the blasting arrangement can lead to loss of communication between blasting machines and detonators, and therefore increased safety concerns. Significant care is required to ensure that the wires run between the detonators and an associated blasting machine without disruption, snagging, damage or other interference that could prevent proper control and operation of the detonator via the attached blasting machine.

Wireless detonator systems offer the potential for circumventing these problems, thereby improving safety at the blast site. By avoiding the use of physical connections (e.g. electrical wires, shock tubes, LEDC, or optical cables) between detonators, and other components at the blast site (e.g. blasting machines) the possibility of improper setup of the blasting arrangement is reduced. Another advantage of wireless detonators relates to facilitation of automated establishment of the explosive charges and associated detonators at the blast site…

However, the development of wireless blasting systems presents new challenges with regard to safety issues. In one example, each wireless detonator assembly must include some form of communication means to allow the receipt, and processing by the wireless detonator assembly of command signals (e.g. ARM, DISARM, FIRE signals etc.) received wirelessly from an associated blasting machine, and optionally the transmission of signals (e.g. including status information, firing codes, delay times etc.) back to an associated blasting machine. For this purpose, each wireless detonator assembly must include some form of independent power supply (an “operating power supply”) sufficient to power the signal receiving, processing, and transmission components of the assembly. However, the presence of the operating power supply itself presents an inherent risk of inadvertent detonator actuation resulting from accidental or inappropriate application of the operating electrical power to the firing circuitry. This problem is recognized in the art, and several systems have previously been developed to reduce the risk of inadvertent detonator actuation.

…

Progress has been made in the development of wireless detonator assemblies with internal safety features. Nonetheless, existing wireless blasting systems still present significant safety concerns, and improvements are required if wireless blasting systems are to become a more viable alternative to traditional “wired” blasting systems.

29 The Summary of the Invention states the following:

The present invention seeks to provide, at least in preferred embodiments, an assembly comprising a detonator or detonator assembly that is capable of wireless communication with an associated blasting machine.

The present invention also seeks to provide, at least in preferred embodiments, a detonator or detonator assembly in which the risk of inadvertent activation of the firing circuit, and actuation of the base charge is essentially eliminated.

The present invention further seeks to provide, at least in preferred embodiments, a method for wireless communication with a detonator, including an option to fire the detonator, where the risk of inadvertent detonator actuation is substantially eliminated.

The inventors have succeeded in the development of a wireless detonator assembly for use in mining operations, the wireless detonator assembly being capable of communication with a corresponding blasting machine and including features that substantially avoid the risk of accidental detonator actuation resulting from inappropriate use of operating power for communications. In this way, a blast operator working at a blast site can position explosive charges, associate wireless detonator assemblies of the invention with the explosive charges and move away from the blasting site, without the need to establish and lay a multitude of wired connections between the components of the blasting system. Not only does this reduce the time and cost of the blasting operation, but the safety of the overall system is improved.

In one preferred embodiment, the invention includes a wireless detonator assembly comprising a small power source of sufficient strength to power wireless communications circuitry, but insufficient strength to cause actuation of the base charge of the detonator via the firing circuitry. The assembly may further comprise a charge storage device or other form of voltage multiplier that may be charged by the operating power supply, the charge stored therein being discharged to the firing circuitry only in response to a fire signal.

…

Preferably, the “keep alive” command signal comprises a continuous signal transmitted by the blasting machine, the charging switch adopting an open position upon removal of, or in the absence of the continuous signal. Alternatively, the “keep alive” command signal causes the charging switch to maintain a closed position for a time period following receipt of the "keep alive" signal by the command signal receiving and processing means, the charging switch adopting an open position at the end of the time period unless the command signal receiving and processing means has received another “keep alive” signal from the blasting machine during the time period. Preferably, the blasting machine transmits a series of “keep alive” signals to maintain the charging switch in the closed position so that the charge storage device remains at least substantially charged, the base charge being actuatable by discharge of the electrical energy into the firing circuit upon receipt of a command signal to FIRE.

Preferably, the discharging means is in electrical connection with the charging switch, such that when the charging switch is in an open position the charge storage device is connected to the discharging means but is not connected to the power supply thereby to cause bleeding of the charge in the charge storage device, and when the charging switch is in a closed position the charge storage device is connected to the power supply but is not connected to the discharging means thereby to cause charging of the charge storage device.

Preferably, the charge storage device is selected from the group consisting of: a capacitor, diode, rechargeable battery or activatable battery.

Preferably, the command signals are selected from the group consisting of: ARM signals, DISARM signals, FIRE signals, detonator delay times, and detonator firing codes.

Preferably, the wireless detonator assembly further comprises signal transmission means for generating and transmitting at least one communication signal for receipt by the blasting machine. More preferably, each communication signal comprises detonator delay times, detonator firing codes, or detonator status information.

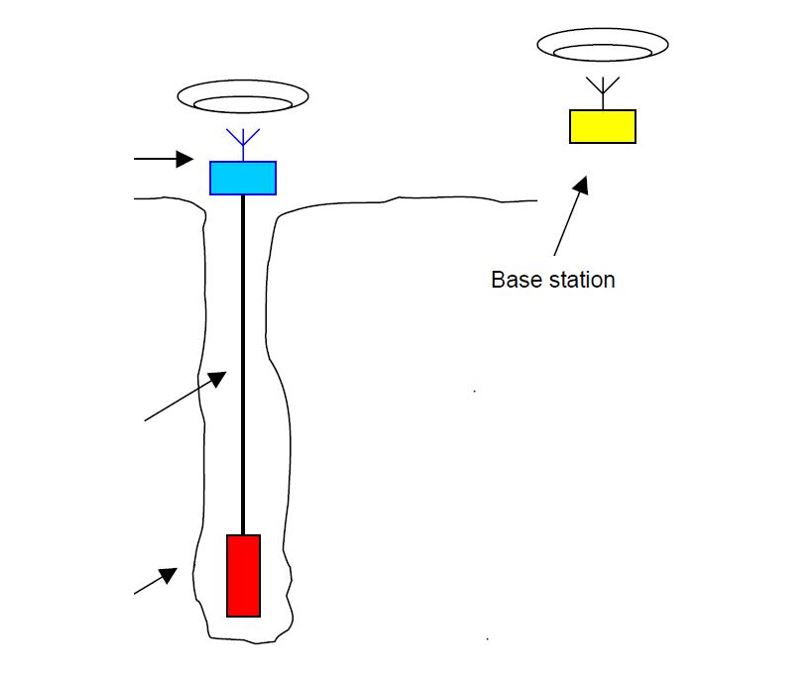

Preferably, in use the base charge is located in a detonator shell down a borehole in association with an explosive charge, and at least the signal receiving and processing means, the charge storage device, and the power supply are located at or near a surface of the ground. More preferably, at least the signal receiving and processing means, the charge storage device, and the power supply are located in a top-box at or near a surface of the ground.

Preferably, the at least one power source comprises an active power source to provide power at least to the signal receiving and processing means, and an energy receiving means for receiving energy from a remote energy source, the energy receiving means transferring the energy to a converting means for converting the energy to electrical energy, the converting means providing the electrical energy to charge the charge storage device.

…

Preferably, in accordance with the methods of the invention, each detonator comprises a stored firing code, and the command signals further comprise firing codes, each detonator firing only if a stored firing code and a firing code from a command signal correspond…

30 Various terms are then defined on pages 11 to 15 of the specification. Where relevant, these are addressed later in these reasons.

31 In the Detailed Description of the Preferred Embodiments, the following is stated:

Wireless blasting systems help circumvent the need for complex wiring systems at the blast site, and associated risks of improper placement, association and connection of the components of the blasting system. However, the development of wireless communications systems for blasting operations has presented significant new challenges for the industry, including new safety issues.

Through careful investigation, the inventors have determined that the wireless detonators and blasting systems of the prior art are problematic with regard to inadvertent or accidental actuation of the detonators. Rapid and accurate communication between a blasting machine, and associated detonators presents a difficult challenge, regardless of the nature of the wireless communication systems. One of the most important signals that must be properly and accurately processed by a wireless detonator is the signal to FIRE. Failure of the communication systems to fire detonators on command, or improper detonator actuation at any other time, can result in a significant risk of serious injury or death for those blast operators working at the blast site. Therefore, prevention of inadvertent or accidental detonator actuation is of paramount importance to blasting operations.

The present invention provides a wireless detonator assembly, a corresponding blasting apparatus comprising the wireless detonator assembly, and a method involving the wireless detonator assembly. The wireless detonator assembly of the present invention utilizes a combination of components to provide a way to substantially avoid inadvertent detonator actuation. In a particularly preferred feature, the wireless detonator assembly of the invention involves the use of a power source of sufficient power to operate the command signal receiving and processing circuitry of the assembly, but of insufficient power to accidentally activate the firing circuitry, or actuate the base charge. In this way, wireless communication by an associated blasting machine with the wireless detonator assembly, for example to communicate ARM, DISARM, or FIRE signals, as well as delay times and firing codes, will substantially avoid inadvertent detonator firing since the intrinsic nature of the detonator is to be in a “safe mode”.

The wireless detonator assembly of the invention generally comprises a detonator comprising a base charge; command signal receiving and processing means for receiving and processing at least one wireless command signal from an associated blasting machine; a charge storage device for storing electrical energy; at least one power source to power said command signal receiving and processing means, and to charge said charge storage device; and a firing circuit in electrical connection with said charge storage device. Upon receipt of a signal to FIRE from an associated blasting machine, electrical energy stored in the charge storage device discharges into the firing circuit to generate an electric current in the firing circuit, thereby to actuate the base charge.

32 By reference to Figure 1 (which appears above) the following is stated:

The wireless detonator assembly 10 further comprises a charge storage device 13 suitable for storing electrical charge and releasing the stored electrical charge as required. The charge storage device 13 may take the form of any suitable device capable of being charged by the application thereto of an electric current, and capable of being discharged in response to a suitable signal, as will become apparent below.

Switch 16 is located between charge storage device 13 and firing circuit 15, which includes base charge 18. In other embodiments, switch 16 may form part of firing circuit 15 to achieve a similar effect. Signal processing means 12 controls the switch 16 to determine whether switch 16 adopts an open state, in which no electrical connection exists between the charge storage device 13 and the base charge 18. However, upon receipt by the receiving means of a wireless command signal to FIRE, the signal processing means 12 provides an electrical signal to cause switch 16 to close, thereby establishing electrical connection between charge storage device 13 and base charge 18. As a result, the charge in charge storage device 13 is discharged into the firing circuit 15, and if the resulting electric current or voltage in the firing circuit is sufficiently high, the base charge is induced to actuate.

Figure 1 also illustrates a particularly preferred embodiment of the invention, which involves the use of a top-box 19. Typically, a top box is a unit for containing selected components of the wireless detonator assembly and retaining those components at or near a surface of the ground when the wireless detonator assembly is in use at a blast site in association with a bore-hole and explosive charge located therein. Top-boxes are typically located above-ground or at least in a position in, at or near the borehole that is more suited to receipt and transmission of wireless signals, and for relaying these signals to the detonator down the borehole. In preferred embodiments, each top-box comprises one or more selected components of the wireless detonator assembly of the present invention. Moreover, use of a top-box allows for sensitive components (e.g. clock components) to be retained away from the bore-hole, and explosive charge contained therein.

In Figure 1, the power supply 14 is shown to supply power to three components, namely the signal receiving means 11, the signal processing means 12, and the charge storage device 13. In this way, the power supply may comprise a voltage sufficient to power the communications devices 11 and 12 of the wireless detonator assembly, and sufficient to supply charge to the charge storage device. However, the power supply 14 has a voltage insufficient to cause actuation of the base charge, under circumstances where the power supply is somehow accidentally or inadvertently in direct contact with

the firing circuit. In this way, the base charge can actuate only in response to a voltage that is higher than a predetermined threshold voltage, and the threshold voltage is higher than any voltage that can be supplied by the power supply. In effect, the charge storage device 13 functions as a voltage multiplier. By accepting electrical energy supplied by the power supply, temporarily storing this energy, and discharging the energy into the firing circuit in response to a FIRE signal, the charge storage device can supply a voltage or current to the firing circuit that exceeds the threshold voltage or current for actuation of the base charge.

In the embodiment illustrated in Figure l, and indeed in any of the embodiments described herein, the power supply 14 may supply power only to the communications components 11, 12 of the wireless detonator assembly. A separate power supply (not shown) may be used to provide power to the charge storage device. This separate power supply may form an integral component of the wireless detonator assembly, and for example may take the form of a battery.

33 The 079 patent has 33 independent and dependent claims, relevantly a wireless detonator assembly (claims 1 to 24); a corresponding blasting apparatus including the wireless detonator assembly (claims 25 and 26); and a method of blasting involving the aforementioned blasting apparatus (claims 27 to 32). Claim 33 is an omnibus claim. The relevant claims are set out below, with integer numbering added.

34 Claim 1 of the 079 patent states as follows (with integers identified):

A wireless detonator assembly for use in connection with a blasting machine that transmits at least one wireless command signal to the wireless detonator assembly, the wireless detonator assembly comprising [integer 1.1]:

a detonator comprising a base charge [integer 1.2];

command signal receiving and processing means for receiving and processing said at least one wireless command signal from said blasting machine [integer 1.3];

a charge storage device for storing electrical energy [integer 1.4];

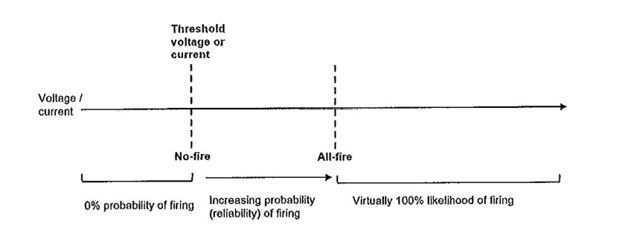

at least one power source to power said command signal receiving and processing means, and to charge said charge storage device [integer 1.5], each of said at least one power source capable of supplying a maximum voltage or current that is less than a threshold voltage or current to actuate said base charge [1.6]; and

a firing circuit in electrical connection with said charge storage device [integer 1.7]; whereupon receipt by said command signal receiving and processing means of a command signal to FIRE causes said electrical energy stored in said charge storage device to discharge into said firing circuit [integer 1.8], said base charge actuating if a voltage or current in said firing circuit resulting from discharge of said electrical energy from said charge storage device exceeds said threshold voltage or current [integer 1.9].

4. PERSON SKILLED IN THE ART

4.1 General legal principles

35 The person skilled in the art (or PSA) is the hypothetical person to whom the patent specification is addressed and who, generally speaking, works in the art or science with which the invention is connected. It is a notional person who may have an interest in (inter alia) using the products or methods of the invention: see e.g. Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28; [2015] FCA 735 at [26] (Nicholas J); Hanwha Solutions Corporation v REC Solar Pte Ltd (2023) 180 IPR 315; [2023] FCA 1017 at [86] (Burley J).

36 The first step in identifying the PSA is to identify the field of knowledge to which the invention relates: see e.g. Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360 at [72]–[74] (Nicholas J). The “subject matter of the invention” is the area “in which the invention is intended to be used”: Neurim at [74]. The “patent specification is directed to those with a real, not a peripheral, interest in its subject matter”: Novartis AG v Pharmacor Pty Limited (No 3) [2024] FCA 1307 at [157] (Yates J).

37 The PSA is the “non-inventive worker in the field”: Wellcome Foundation Limited v V.R. Laboratories (Aust.) Proprietary Limited (1981) 148 CLR 262 at 270 (Aickin J, with whom Gibbs, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ agreed); Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 at 293 (Aickin J, with whom Barwick CJ, Stephen, Mason and Wilson JJ agreed). Evidence must be directed to showing what the notional skilled worker would have known, not what a leading expert in the field would have known: Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd v Reflex Instruments Asia Pacific Pty Ltd (2022) 167 IPR 515; [2022] FCA 797 at [277] (Jagot J). An expert witness should have no “excess of any peculiar or special knowledge” and should not be over-qualified: see JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd (formerly known as A’Van Campers Pty Ltd) v Camoflag Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 68; [2005] FCA 1474 at [91] (Crennan J).

38 The notional PSA may be a team. As observed by Yates J in Novartis at [148]–[152]:

The “person skilled in the art” is a construct that is used to analyse questions that arise in patent law.

It is well-recognised that this construct can be understood as a “team”, particularly if the art is one having a highly developed technology. As such, the construct combines and deploys the knowledge and skills of the members of the “team”. This means that, in real life, the knowledge and skills of some members of the “team” may not be known or shared by others in the “team”. There is, however, but one construct. The person skilled in the art thinks with one mind, speaks with one voice, and draws, when and to the extent necessary, on the disparate knowledge and skills of all the members of the “team”. The person skilled in the art is indivisible.

Depending on the relevant art, the members of the “team” may be highly skilled with research capabilities…

This does not mean, however, that the person skilled in the art, understood as a highly skilled team or a notional research group, exhibits the capacity for invention. The person skilled in the art, even when understood as a highly skilled team or a notional research group, is taken to have no inventive capacity whatsoever, and is constrained to act only with knowledge that is publicly known, and commonly accepted, by those within the calling of the art in question.

The knowledge and skills of the person skilled in the art can be informed by the evidence of expert witnesses. It is important to bear in mind, however, that the person skilled in the art is not a mere avatar of those witnesses.

(Citations omitted.)

39 The combined skills and mind-sets of the real research teams in the identified field make up the notional PSA team: see e.g. MedImmune Limited v Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited [2012] EWCA Civ 1234 at [76]–[77] (Kitchin LJ, Lewison and Moore-Bick LJJ agreeing); Schlumberger Holdings Limited v Electromagnetic Geoservice AS [2010] EWCA Civ 819 at [42] (Jacob LJ); Illumina Cambridge Limited v Latvia MGI Tech SIA [2021] EWHC 57 at [64], [68] (Birss J); Alcon Research LLC v Actavis Group PTC ehf [2021] EWHC 1026 at [30] (Meade J).

40 In Schlumberger, Jacob LJ observed at [42], with reference to Dyson v Hoover [2002] RPC 22 (UK Court of Appeal):

I think one can draw from this case that the Court, in considering the skills of the notional “person skilled in the art” for the purposes of obviousness will have regard to the reality of the position at the time. What the combined skills (and mind-sets) of real research teams in the art is what matters when one is constructing the notional research team to whom the invention must be obvious if the Patent is to be found invalid on this ground.

41 As the PSA team may involve the joint efforts of experts in more than one field, the evidence must deal with the way in which that notional joint effort would have come about. As the Full Court observed in Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Tyco Electronics Pty Ltd (2002) 56 IPR 248; [2002] FCAFC 315 at [91] (Emmett, Hely and Dowsett JJ):

The team approach is, of course, designed to solve a problem which requires the joint efforts of experts in more than one field. Such an approach must involve interaction between or amongst the experts so that common general knowledge can be shared…

42 The Court may focus on particular characteristics of the PSA depending on the legal issue involved: see e.g. Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Generic Health Pty Ltd (No 4) (2015) 113 IPR 191; [2015] FCA 634 at [127] (Yates J); Axent Holdings Pty Ltd (t/as Axent Global) v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd (2020) 154 IPR 431; [2020] FCA 1373 at [251] (Kenny J). The fact that aspects of knowledge from a particular discipline are relevant to understanding a claim does not mean this discipline is necessarily part of the “team”: Novartis at [162].

4.2 PSA – 079 patent

43 In relation to the 079 patent, there is no dispute between the parties, and it was agreed by the relevant experts, that the “qualifications and experience of the hypothetical, skilled but uninventive, person or team who may have had a practical interest in the claimed products and methods of [the 079 patent] and may have wanted to put them into practical use” is a team with “a wide range of experience and qualifications in communication technology and detonator science”, including people with experience or qualifications in (inter alia) systems engineering, electronics engineering, communications engineering, and detonator and explosives engineering, and experience working with a varied customer base, including people in related fields (such as blast or mine site management and blast operators, or technology and operations managers).

5. WITNESSES CALLED BY THE PARTIES

5.1 Witnesses called by DNAP – 079 and 165 patents

44 DNAP relies on the evidence of three expert witnesses in relation to the 079 and 165 patents: Mr Craig Boucher, Mr Anthony Napier and Dr George Mokdsi.

5.1.1 Mr Boucher

45 Mr Boucher affirmed two affidavits in the proceeding dated 18 December 2023 (Boucher 1) and 10 July 2024 (Boucher 2).

46 Mr Boucher has a Bachelor of Computer and Systems Engineering. He retired in 2022 with over 40 years’ experience as an engineer, which includes 34 years as an explosive initiation systems engineer. Mr Boucher has experience in commercial blasting systems and products, including work on projects in the 1990s concerning electronic detonators or EDs and the development of wireless devices. In the late 1990s, Mr Boucher worked on the “Cyberdet” (wireless detonator) project within Ensign-Bickford Aerospace & Defense Company (Ensign-Bickford).

47 Mr Boucher was appointed as an Advanced Development Manager at Ensign-Bickford in 1998. He became the Engineering Vice President at that company in 2011, and in 2017 he became the Chief Engineer. His role as the Advanced Development Manager involved the “advancement of existing explosive initiation systems technologies” and the development of “disruptive explosive initiation systems technology products”. He agreed that by “disruptive”, he meant “disrupting the status quo through innovation”. Mr Boucher’s work on those projects included product concept development and product design.

48 Mr Boucher has professional experience in battlefield electronics, in the development of flight control and air data systems for military aircraft, including the B-2 stealth bomber, and in explosive initiation systems in aerospace, commercial blasting and oil and gas contexts. He has also done pioneering work in laser-initiated and networked ordnance systems, and he has worked on explosive initiation in rockets.

49 Mr Boucher is an inventor of new products in the field of explosive initiation systems. He is the sole inventor of US’044 in the name of Ensign-Bickford. Mr Boucher is also a named inventor on about 20 other patents and patent applications, including at least three other patent applications relating to detonator or initiation technology. He also worked on projects that were the subject of other patent applications in the name of Ensign-Bickford where he was not the named inventor. Mr Boucher accepted during the concurrent evidence session that he is an inventor of new products in the field of explosive initiation systems.

50 Mr Boucher was, in many respects, an impressive witness who often gave detailed oral evidence during the concurrent expert sessions. Subject to below, my perception was that he generally did this because he wished to assist me, rather than because he was seeking to advance a particular stance on behalf of DNAP.

51 However, the weight to be attached to Mr Boucher’s evidence must be reduced for four reasons.

52 First, at least some of Mr Boucher’s opinions were based upon the information and opinions provided by other experts in the case. He conceded during cross-examination that in giving some of his evidence, he had relied on the affidavits of other witnesses and had no direct knowledge of the facts himself. The extent to which he did this is not known, and for this reason, I have concerns about the extent to which Mr Boucher’s opinions are truly his own, and the extent to which they are based on admissible evidence or identified facts. Of particular concern is Mr Boucher’s adoption of opinions expressed by Mr Napier, for reasons I explain below in relation to Mr Napier.

53 Secondly, when expressing opinions, Mr Boucher drew heavily on his own personal experience and knowledge. That included knowledge of confidential, proprietary information that he had acquired during the course of his employment.

54 Thirdly, Mr Boucher is not representative of the PSA as he is too highly qualified and too inventive.

55 Finally, Mr Boucher appeared to take a semantic and overly technical approach to the construction of the words used in the patents considered by him and in this limited regard, he did appear to be acting as an advocate for DNAP on occasion, rather than giving evidence as an independent expert. Further and to some extent, it appeared that his views on construction were influenced by his own understanding of patent law in the USA.

5.1.2 Mr Napier

56 Mr Napier affirmed three affidavits in this proceeding: the first on 6 September 2023 (Napier 1), the second on 19 December 2023 (Napier 2), and a third on 11 July 2024 (Napier 3).

57 Mr Napier is the Chief Operating Officer and Managing Director APAC of Strata Products Australia. Mr Napier has approximately 37 years of experience and expertise with respect to wireless and other communications systems used in mining.

58 Mr Napier does not have expertise in EDs or detonator technology and had no direct involvement with wireless blasting initiation systems after late 2003.

59 Mr Napier held managerial roles at MST between 1992 and November 2003, commencing as a Technical Support Manager and being appointed CEO in mid-2001. In his affidavit evidence, Mr Napier refers to multiple MST company documents that are not pleaded as prior art and are either not pleaded or were not shown to be CGK.

60 MST is the creator of the PED system. The PED system is not a blast initiation system, but is a safety alert system. MST is also the creator of the BlastPED system, which is a variation of the PED system and which has different versions.

61 During the concurrent evidence session, Mr Napier referred to himself as “PED biased” or exhibiting “PED bias”. He also accepted that it was difficult for him to separate his personal knowledge of the BlastPED system from public knowledge when giving his evidence about webpages which appeared on the MST website in 2003 (defined in the 6FASOC as the MST Website 2003).

62 Mr Napier’s personal involvement with the PED system and the BlastPED system is pertinent because, in this proceeding, DNAP alleges that these systems were CGK at the priority date of each of the patents and relies on his evidence to prove that case. DNAP also relies on the MST Website 2003 as prior art with respect to each patent.

63 Because of these matters, Mr Napier is not a proper representative of the PSA insofar as his evidence relates to MST’s products and the MST Website 2003. In particular, his evidence was infected with personal knowledge derived from his work at MST, and his knowledge of its products including knowledge derived from MST’s company documents.

64 For the following reasons, Mr Napier was in many respects an unsatisfactory witness.

65 Firstly, Mr Napier did not appear to recall many of the facts and opinions expressed by him in his affidavits, and often hesitated after being asked questions, appearing to be unsure of what the answer should be. He also gave confusing evidence about certain topics. For example, in Napier 1, Mr Napier deposed that to his knowledge, the Canary Mine Messenger System was “not successfully commercialised in Australia”. However, when it was suggested to Mr Napier during the hearing that the Canary Mine Messenger System could not be CGK because it was not widely sold and taken up by customers, Mr Napier disagreed and said “I don’t know the exact numbers, I believe they were successful. I heard they were successful, the sales and deployments that MST didn’t win, but I couldn’t quantify the numbers”. He then went on to contradict that statement a short time later, saying “in Australia, it would be fair to say Canary was not that well represented”.

66 Secondly, Mr Napier was willing to attest to the truth of facts based on documents which had been supplied to him by DNAP’s solicitors, which shows that he did not understand his role as an independent expert. For example, in Napier 2 at [16], Mr Napier gave evidence to the effect that various devices and systems supplied by Rothenbuhler were promoted, supplied and used in mines in Australia and other countries. However, during the hearing, Mr Napier conceded that this evidence was based on manuals that were provided to him by the lawyers for DNAP, being documents that he had not previously seen, and that he was “a bit aware of Rothenbuhler at the time”.

67 Finally, during the concurrent evidence sessions, Mr Napier gave what appeared to be rehearsed speeches which were not responsive to the questions asked. For example, when Mr Napier was asked about the internal battery source of the remote unit which formed part of the BlastPED system, Mr Napier provided an unresponsive answer that concluded with his expressed view that the remote device was a “top-box configuration”. Mr Napier returned to that topic again, uninvited, shortly afterwards. By volunteering this evidence, it appeared that Mr Napier was anxious to advance the argument that the remote device in the BlastPED system was a top-box within the meaning of the 079 patent, being evidence which was helpful to DNAP’s case.

68 For these reasons and unless otherwise indicated, I generally do not accept the evidence of Mr Napier. As Mr Boucher in turn expressed some of his opinions based upon the evidence of Mr Napier, Mr Boucher’s evidence must be given less weight for the same reasons. As already observed, the extent to which Mr Boucher was influenced by Mr Napier’s evidence is unknown.

5.1.3 Dr Mokdsi

69 Dr Mokdsi is an expert patent searcher and a director of The Patent Searcher Pty Ltd. He holds a Bachelor of Science and a PhD in Chemistry from the University of Sydney and is a Qualified Patent Information Professional. Dr Mokdsi has over twenty years’ experience in the searching of patents and scientific literature using patent databases, search platforms and online scientific literature search tools. Dr Mokdsi affirmed one affidavit in this proceeding on 19 December 2023.

70 The extent to which I accept the evidence of Dr Mokdsi is addressed later in these reasons.

5.2 Other witnesses called by DNAP at trial

71 Additional witnesses called by DNAP were:

(1) Mr Thomas Jacobson in relation to the 873 patent.

(2) Mr Geoffrey Dunstan in relation to the 943 patent.

5.3 Witnesses called by Orica

72 Orica relies on the evidence of two expert witnesses in relation to the 079 and 165 patents: Mr Bryan Papillon and Professor Efstratios (Stan) Skafidas.

5.3.1 Mr Papillon

73 Mr Papillon swore seven affidavits in this proceeding, dated 27 December 2023 (Papillon 1), 11 April 2024 (Papillon 2), 2 May 2024, 19 July 2024 (Papillon 4), 31 July 2024 (Papillon 5), 31 July 2024 (Papillon 6) and 16 September 2024.

74 Mr Papillon is an independent consultant with over 40 years’ experience in the explosives and mining industry. Mr Papillon holds a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering and has specialist knowledge and experience in developing detonators. At the priority dates for the 079, 165 and 873 patents, Mr Papillon was employed by Austin Powder Co in the United States as Director – E-Technology. He led the team responsible for developing Austin Powder Co’s ED initiation system.

75 For the purposes of the 079, 165 and 873 patents and subject to one issue, Mr Papillon is a proper representative of the non-inventive skilled person working in the field (being someone with certain skills of a member of the notional PSA team). Mr Papillon was working on the development and design of an ED for Austin Powder Co at the priority dates. Further, although he had no qualifications in electronics or communications engineering and he had not been involved in the design of an electrical circuit for an ED, he was responsible for and involved with all aspects of the ED, and he acted as a conduit between what the customers wished to do with a detonator in terms of functionality and the technical people who were designing the intricacies of such circuits. Importantly, he did not stand apart from the “technical people” but was in close communication with the “primary inventor of the inner workings” of detonators, the manufacturers of the control equipment, and manufacturers of the wire used in EDs, and was responsible for the design and development of the connector external to the detonator. Mr Papillon has direct experience of blasting and holds a current blasting licence.

76 Mr Papillon’s knowledge exceeded the CGK in Australia in relation to the Rothenbuhler system. That is because, while working at Austin Powder Co, Mr Papillon had purchased some modified Rothenbuhler products for testing. This peculiar knowledge which was derived by Mr Papillon through his role at Austin Powder Co is not representative of the knowledge of the hypothetical PSA in Australia.

77 During the hearing, Mr Papillon gave careful, considered and helpful evidence. Mr Papillon made appropriate concessions and did not at any time appear to be partisan to any party or cause. He was often the subject of cross-examination towards the end of the day (with several hearing days commencing at 9.30am) and this appeared to affect the quality of his answers given at this time, with more detailed answers being given to questions asked of him in the mornings.

78 At times, it did not appear that he could physically hear the cross-examiner or (by the end of the question) recall the entirety of the questions asked of him, some of which were very long and contained more than one question or multiple assumptions. When this occurred, Mr Papillon appeared to answer the final question in the series of ‘questions within a question’, at least on occasion.

79 During the hearing, it was put to Mr Papillon by counsel for DNAP that he was acting as an advocate for Orica. I observe that the fact that Mr Papillon gave answers that did not suit DNAP’s case, or which involved him not agreeing with questions posed to him, does not of itself make him an advocate for Orica, and so the basis for the challenges to his independence during the hearing was and remains opaque. In any event, any such suggestion was abandoned by the time that closing submissions were made when reliance was sought to be placed on Mr Papillon’s evidence for the purposes of the 943 patent.

5.3.2 Professor Skafidis

80 Professor Skafidas swore two affidavits in this proceeding dated 18 July 2024 (Skafidas 1) and 31 July 2024 (Skafidas 2).

81 Professor Skafidas is a Professor of Nanoelectronics at the University of Melbourne, specialising in electrical and electronics engineering and wireless communications. He has attained the following degrees: a Bachelor of Engineering (Honours), a Bachelor of Science, a Masters of Engineering Science, and a PhD in Electrical Engineering. He has worked and researched in the field of electrical and electronics engineering and wireless communications for over 30 years. His core expertise is in electrical and electronic engineering. He has published extensively on hardware circuits and electronic circuits. His experience extends to building commercial products, as well as communications in certain military applications, to propagate signals through earth and reinforced concrete.

82 Professor Skafidas has two areas of expertise that would be brought to bear in the notional skilled team: first, as an electrical engineer, experienced in implementing the types of systems described in the 079 and 165 patents, and secondly, as a wireless communications expert. As Professor Skafidas explained, which evidence I accept, it is necessary to have a wireless communications engineer, with experience in networking, electrical and electronics engineering, in such a team.

83 DNAP was critical of the evidence given by Professor Skafidas because (for example) he had never designed a circuit for a detonator, or an electrical circuit containing a firing capacitor for the purpose of firing a detonator; and had never designed a commercial product (as opposed to a military product) that seeks to communicate wirelessly through the earth (TTE). However, while it is the case that Professor Skafidas had no direct experience of communications systems for underground mining before the 079 priority date, and no expertise in relation to detonators and explosive initiation systems, he has significant experience in electronics and communications, including circuit design and systems for communicating through dirt, soil and underwater.

84 During the concurrent expert sessions, Professor Skafidas appeared to take his role as an expert witness seriously, and (like Mr Boucher) he seemed anxious to ensure that sufficient information was provided in relation to each topic being addressed. Such enthusiasm does not translate to a conclusion that he was being partisan, evasive or argumentative. Nor did he treat the concurrent evidence session as a combative exercise, as DNAP submits. To the contrary, Professor Skafidas was a forthright and genuine witness who was not prepared to agree with scientific propositions which, while technically accurate at a superficial level, could lead to a concealment of what he regarded as being the complete and relevant information necessary to answer a question correctly. That an expert witness took such an approach is to be commended, not criticised; indeed, it is essential that an expert witness give such fulsome evidence.

5.3.3 Mr Campbell

85 Orica also relies on the evidence of Mr Rory Campbell, a registered patent and trade marks attorney. Mr Campbell swore one affidavit in this proceeding dated 11 July 2024 which annexes copies of patent search results regarding relevant patent applications filed by Ensign-Bickford. Mr Campbell was not required for cross-examination.

5.4 Other witnesses called by Orica at trial

86 Additional witnesses called by Orica were:

(1) Mr John Meneghini in relation to the 943 patent;

(2) Mr Peter (Billy) Grace in relation to the 943 patent.

5.5 Joint expert report (079 and 165 patents)

87 Three joint expert reports (JERs) were prepared in this proceeding. The first JER was in respect of the 079 and 165 patents and is dated 6 September 2024 (079 & 165 JER). It followed joint conferences which were attended by Mr Boucher, Mr Napier and Mr Papillon on all topics, and Professor Skafidas in relation to certain topics.

88 As it transpired, the 079 & 165 JER required close scrutiny. That is because, on occasion, a proposition appears in the “Matters agreed” column but when the corresponding comments of the experts are reviewed, it appears that the matter was not agreed, either in its entirety or at all. For example, it is stated that sections C.4 and C.5 of Boucher 1 were “generally agreed” by the experts in response to topic 3a, and yet Mr Papillon stated that “[c]omments on an electronic detonator mirror those as stated in affidavit [sic]” and “it is critically important that one reads this part of the joint expert report having regard to the [passages] from Papillon 4”, which are then identified. The reference to the matters being “agreed” by the experts in the 079 & 165 JER must therefore be read subject to additional statements made by the experts in relation to the topic.

6. COMMON GENERAL KNOWLEDGE

6.1 Overview

89 As the patents pre-date the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth), CGK in this case must be assessed as it existed in Australia before the priority date of the claims of each of the patents: Patents Act, s 7(2).

90 Whilst the CGK in Australia (the patent area) was generally the same as that in North America, this was not the case with respect to all of the matters alleged by DNAP to be CGK. Nor is it the case, as DNAP submits, that the parties advanced their cases on the basis that it was the same in all respects because both parties called experts from the USA. In particular, counsel for Orica sought to differentiate between the knowledge of those skilled in the art located in Australia and the USA in relation to specific topics during the joint expert conferences.

91 The priority date of the 165 patent is 28 April 2006 (165 priority date). As it transpired, neither the experts nor the parties considered that the CGK differed between the priority dates of the 079 and 165 patents, and so I will address them together.

6.2 Lapse of time since 079 and 165 priority dates

92 The priority dates of the 079 and 165 patents are about 18 years before the experts’ affidavits were prepared. In this regard, I note that, by the 079 & 165 JER, the experts agreed by reference to the relevant priority dates that:

The relevant technologies were continuously evolving at the time until today, not everything that is known today was known at that time. It is difficult to pinpoint specific things that were known and understood (or not known or not understood) at that date.

(Emphasis added.)

6.3 Information capable of forming part of CGK at the priority date

93 The kinds of information that form part of the CGK differ from industry to industry and from one technical field to another. The qualifications of the skilled addressee, the setting in which and the resources with which he or she operates, and the practices and techniques that he or she regards as commonplace and known are important considerations in determining the CGK in any case: Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2002) 212 CLR 411; [2002] HCA 59 at [153] (Kirby J).

94 It has been observed that the CGK might include standard texts and handbooks, standard English dictionaries, technical dictionaries relevant to the field, and magazines and other publications specific to the field: ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v Lubrizol Corporation Inc (1999) 45 IPR 577; [1999] FCA 345 at [112] (Emmett J).

95 However, an article or standard reference work is not part of the CGK simply because skilled persons could readily locate and assimilate its contents. It is well-established that information does not constitute CGK merely because it might be found in a journal, even if widely read, or by a literature search. The critical question is whether the contents were known to and accepted by all or the bulk of those skilled in the trade: Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA Inc v Elanco New Zealand (2021) 164 IPR 17; [2021] FCA 1457 at [179] (Besanko J).

96 As Jagot J observed in Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd v Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC (2016) 117 IPR 252; [2016] FCA 169 at [217] (affirmed in Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd (2017) 134 IPR 1; [2017] FCAFC 196 (Nicholas, Beach and Burley JJ) (Idenix FCAFC):

… It may be accepted that instant recall of an article is not required. This does not mean, however, that documents found by searching for a subject-matter, rather than by some form of recall or reminder of what is already known to exist, are common general knowledge. This is so irrespective of the fact that experts in the field read widely. Further, it is not the case that mere publication and republication proves that a document and its contents have entered the common general knowledge. Nor is it the fact that a document and its contents necessarily form part of the common general knowledge merely because one expert knows or has managed to locate it and assimilate its contents. Such a document may or may not form part of the common general knowledge. The relevant inferences are to be drawn on the basis of the whole of the evidence.

(Emphasis added.)

97 Further, as Luxmoore J said in British Acoustic Films Ltd v Nettlefold Productions Ltd (1935) 53 RPC 221 at 250:

In my judgment it is not sufficient to prove common general knowledge that a particular disclosure is made in an article, or series of articles, in a scientific journal, no matter how wide the circulation of that journal may be, in the absence of any evidence that the disclosure is accepted generally by those who are engaged in the art to which the disclosure relates. A piece of particular knowledge as disclosed in a scientific paper does not become common general knowledge merely because it is widely read, and still less because it is widely circulated. Such a piece of knowledge only becomes general knowledge when it is generally known and accepted without question by the bulk of those who are engaged in the particular art; in other words, when it becomes part of their common stock of knowledge relating to the art. Whatever else common general knowledge may be, it has never in my judgment included public knowledge of particular documents reports or scientific papers and the like. The knowledge of a number of individuals that a particular suggestion or particular suggestions has or have been made for the use of biasing in a particular apparatus, or a number of particular apparatus, cannot be held to be common general knowledge. It is certainly difficult to appreciate how the use of something which has in fact never been used in a particular art can ever be held to be common general knowledge in the art.

98 Similarly, while information that has been made available orally or by demonstration, such as at an exhibition or conference, may form part of the CGK, it can only be because a large proportion of people skilled in the relevant field attended the disclosure or the demonstration, or that the information has otherwise been assimilated into the CGK: see Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (2002) 54 IPR 449; [2002] HCA 21.

99 It follows that the fact that a witness, or even a number of witnesses, had particular knowledge at the priority date does not of itself establish that such knowledge was CGK. The witness may be an expert who has specialised expertise and knowledge: British Acoustic Films at 250; Idenix FCAFC at [192]. At the same time, evidence that an expert, or number of experts, were not aware of certain information may be evidence, possibly powerful evidence depending on the circumstances, that the information was not CGK: Elanco at [180].

100 Further, material or information cannot be regarded as CGK based upon the personal knowledge of a witness by reason of their individual experiences in the absence of evidence of its general acceptance and assimilation by the bulk of those in the relevant field: see Aktiebolaget at [31]. It follows that, research or other work carried out by witnesses in the course of their employment or matters which became known to them by reason of that employment or individual experiences is not, for that reason alone, knowledge and experience which is available to all in the trade, and nor is it probative of CGK.

6.4 Mr Boucher’s misunderstanding of CGK

101 Mr Boucher misunderstood the concept of CGK, stating in the 079 & 165 JER that a particular patent represents prior art that should have been known by a PSA. Whether something “should have been known” does not make it CGK.

102 Relatedly, Mr Boucher also gave evidence in the 079 & 165 JER as follows:

The items listed in 3e are building blocks used to create a wireless detonator. Examples of each item existed prior to 2005 where these building blocks were combined to produce a wireless detonator system (PlastPED [sic], ICI, Inco, Rothenbuhler) and had been published in patents, journals, adverts, web sites etc. These are the locations that a PSA would review to stay up-to-date as described in topic 2. So the PSA likely would have seen it. If there were one example this would likely not be CGK, but the number of instances as indicated in Napier AN-2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 39 and 40 indicate strongly that 3e describes CGK.

(Emphasis added.)

103 Before this proceeding, Mr Boucher had not seen the Inco Patent and the ICI Remote Firing Patent (as defined below) and he was not aware of any specific technology sold by Rothenbuhler prior to 2005. Mr Boucher had also not seen the MST Website 2003, and gave oral evidence that he expressed the opinion that a particular patent represents prior art that should have been known by a PSA because the information was contained in a published patent, even though he had not seen the patent himself prior to this proceeding. Mr Boucher therefore appears to have assumed that publication of information is sufficient for the information to be CGK, which assumption is flawed, especially as even he was not aware of it.