FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Paige LLC v Sage and Paige Collective Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 750

Appeal from: | Paige, LLC v Sage and Paige Collective Pty Ltd [2023] ATMO 57 |

File number(s): | NSD 501 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | NEEDHAM J |

Date of judgment: | 10 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | TRADE MARKS – whether composite marks containing the registered mark and other words (Opposed Marks) deceptively similar under s 44 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) – whether the appellant’s trade mark acquired a reputation in Australia before the Priority Date and because of that reputation would likely deceive or cause confusion under s 60 of the Act – whether notional consumer would be caused to wonder whether the Opposed Marks signify a collaboration between brands or that the marks otherwise emanate from the same source |

Legislation: | Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) ss 10, 44, 56, 60, 120 |

Cases cited: | Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 227 FCR 511 Australian Postal Foundation Corporation v Digital Post Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 308 ALR 1; [2013] FCAFC 153 Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658 Bauer Consumer Media Ltd v Evergreen Television Pty Ltd (2019) 142 IPR 1; [2019] FCAFC 71 Beling v Sizty International SA (2015) 228 FCR 194; [2015] FCA 250 Bianca-Moden GmbH & Co. KG v Bianca and Bridgett Pty Ltd [2021] ATMO 30 Caporaso Pty Ltd (as trustee for the Diversity Trust) v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd (2024) 181 IPR 78; [2024] FCA 138 Conde Nast Publications Pty Ltd v Taylor (1998) 41 IPR 505; [1998] FCA 864 Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd [1952] HCA 15 Enagic Co Ltd v Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd (No 3) (2021) 164 IPR 234; [2021] FCA 1512 Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (2023) 407 ALR 473; [2023] FCAFC 44 Eveden Inc v P & Y Halas Pty Ltd [2015] ATMO 116 Hachette Filipacchi Presse v KIND TO ME PTY LTD [2024] ATMO 204 Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc (2020) 385 ALR 514; [2020] FCAFC 235 In-N-Out Burgers, Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd (2020) 377 ALR 116; [2020] FCA 193 Killer Queen LLC and Others v Taylor (2024) 306 FCR 199; [2024] FCAFC 149 Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd’s Application (1936) 6 AOJP 1724 McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick (2000) 51 IPR 102; [2000] FCA 1335 Mond Staffordshire Refining Co Ltd v Harlem (1929) 41 CLR 475 Ocean Spray Cranberries Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2000) 47 IPR 579; [2000] FCA 177 Paige, LLC v Sage and Paige Collective Pty Ltd [2023] ATMO 57 Puma SE v Caterpillar Inc (2022) 407 ALR 446; [2022] FCAFC 153 Re Intel Corporation a Delaware Corporation [2020] ATMO 4 Re John Fitton & Co Ltd’s Application (1949) 66 RPC 110 Re London Lubricants (1920) Ltd’s Application (1925) 42 RPC 264 Rowntree plc v Rollbits Pty Ltd (1988) 90 FLR 398; 10 IPR 539 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (2023) 277 CLR 186 Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407; [1963] HCA 66 Soap & Glory Ltd v Boi Trading Co Ltd (2014) 107 IPR 574; [2014] ATMO 47 Societe Civile et Agricole du Vieux Chateau Certan v Kreglinger (Australia) Pty Ltd (2024) 179 IPR 226; [2024] FCA 248 Starr Partners Pty Ltd v Dev Prem Pty Ltd (2007) 71 IPR 459; [2007] FCAFC 42 Taiwan Yamani Inc v Giorgi Armani SpA (1989) 17 IPR 92 Taylor v Killer Queen LLC & Ors [2025] HCATrans 31 (11 April 2025) Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 237 FCR 388; [2015] FCAFC 156 The Agency Group Australia Ltd v HAS Real Estate Pty Ltd (2023) 174 IPR 153; [2023] FCA 482 Tivo Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 252 Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc (2012) 294 ALR 661; [2012] FCAFC 159 Winnebago Industries, Inc v Knott Investments Pty Ltd (No 2) (2012) 293 ALR 108; [2012] FCA 785 Woods and Another v Teed (2018) 143 IPR 249; [2018] ATMO 121 Woolworths Ltd v BP plc (2006) 150 FCR 134; [2006] FCAFC 52 Australian Trade Mark Law, Burrell & Handler, (3rd ed, LexisNexis) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Trade Marks |

Number of paragraphs: | 116 |

Date of hearing: | 29 April 2025 – 1 May 2025 |

Counsel for the Appellant: | DB Larish with JA McKenna |

Solicitor for the Appellant: | ChrysLegal Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondent: | AEM McDonald |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Zander Dre Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 501 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | PAIGE, LLC Appellant | |

AND: | SAGE AND PAIGE COLLECTIVE PTY LTD Respondent | |

order made by: | NEEDHAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 10 July 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

NEEDHAM J:

Background

1 This is an appeal under s 56 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act) from the decision of a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks to dismiss the appellant’s opposition to the registration of trade marks applications made by the respondent to this appeal, Sage and Paige Collective Pty Ltd (Sage + Paige).

2 Each of the applications is made in respect of clothing-related goods in classes 14, 18 and 25 and services in class 35 (together, specified goods and services).

3 The trade marks which were the subject of the delegate’s decision (the Opposed Marks) are:

Application No. | Trade Mark | Classes | Priority Date |

2094275 |

| 14, 18, | 17 June 2020 |

(275 Application) | 25, 35 | ||

2094276 |

| 14, 18, | 17 June 2020 |

(276 Application) | 25, 35 |

4 The respondent sought registration for specified goods and services for each of the marks as listed in Schedule 1 to this judgment. Broadly speaking, they cover clothing, apparel, handbags and jewellery, and related retail services. Sage + Paige is an online retailer of women’s fashion, based in Australia.

5 The appellant, Paige, LLC is an international fashion house established in California, United States of America and trades under the name PAIGE. It has a presence in the Australian market, including, but not confined to, denim wear. It is the owner of Australian registered trade marks for PAIGE as follows:

Registration No. | Trade Mark | Classes | Priority Date |

1018471 (471 Registration) | PAIGE | 25 | 8 July 2004 |

1168574 (574 Registration) | PAIGE | 3, 18 | 28 March 2007 |

1495028 (028 Registration) |

| 25 | 17 August 2011 |

6 The specified goods and services for which the appellant’s marks are registered are set out in Schedule 2. They broadly cover apparel, handbags, and cosmetics.

7 The grounds of opposition relied on by Paige before the delegate have been narrowed on this appeal to ss 44 and 60 of the Act. Each of these grounds must be assessed as at 17 June 2020 (Priority Date).

8 The appellant contends that, pursuant to s 44 of the Act, the Opposed Marks are deceptively similar to its marks, so that consumers are likely to be caused to wonder whether the trade marks on the respondent’s specified goods and services emanate from the same source as, or are otherwise associated with, the brand PAIGE. Additionally, it contends, pursuant to s 60 of the Act, that the reputation of PAIGE as at the Priority Date was such that the use of the respondent’s Opposed Marks would be likely to deceive or confuse.

9 A particular issue in this case is the impact of the fashion trend of “collabs” or collaborations between brands. The appellant opened its case on the question as to whether:

at least some consumers with knowledge of the mark…PAIGE, who encountered the Opposed Marks for Sage + Paige … would be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the Opposed Marks represent a collaboration between PAIGE and another brand, designer, or celebrity going under Sage.

10 The second ground contended for by the appellant was that that notional consumer may be caused to wonder whether there was, otherwise than a collab, “some form of brand or product variant, compared with the core brand PAIGE”.

11 The appellant relies on the two registered word marks, as indicated by the capital letters. Registration of a word mark provides a monopoly over the word in any notional use of the mark, that is, in any font or style: Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 227 FCR 511 at [18] (Yates J); Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd (2023) 407 ALR 473; [2023] FCAFC 44 at [165] (Yates, Stewart and Rofe JJ). The appellant does not rely on the 028 Registration device mark.

12 The registration of the PAIGE marks by IP Australia pursuant to s 41 of the Act has the effect that the marks were considered inherently distinctive in relation to the goods and services for which they were registered.

13 The respondent’s marks, as seen above, are both composite marks. The 275 application mark comprises the stylised words “Saige + Paige” in serif font against a pink coloured disc, and the 276 application mark comprises just the words “Sage + Paige” set in the same stylised font on their own. It was common ground that the “plus” symbol would be understood, and pronounced, as the word “and”.

14 The appellant submitted that the primary focus in this appeal is on the words themselves given that the degree of stylisation in the respondent’s marks is minimal. The respondent, whilst urging the Court to consider its marks as a whole, including the font and style of the marks, also focused on the comparison between the PAIGE word marks and the respondent’s composite marks.

15 The delegate determined in decision Paige, LLC v Sage and Paige Collective Pty Ltd [2023] ATMO 57 dated 10 May 2023 that the appellant had not established the opposition grounds. The delegate was not persuaded that the marks were deceptively similar merely because the appellant’s word mark is contained in the applied-for trade marks, or that PAIGE was the essential feature of the marks.

16 The delegate considered the impact of the + (“plus”) sign in the Opposed Marks, and whether it indicated an association between two brands; in this case, the appellant’s brand, preceded by another brand called “Sage”. Referring to the IP Australia Trade Marks Manual of Practice and Procedure Part 26 Annex A1, and to a decision of Bianca-Moden GmbH & Co. KG v Bianca and Bridgett Pty Ltd [2021] ATMO 30 (15 April 2021), the delegate considered that “the coupling of given names is shown by the case law to be a trend in the fashion industry, no more likely than not to signal a merger or collaboration of brands” (at [26]).

17 The respondent took the Court to various names in the fashion field which used the “name +/&/and name” convention, such as:

(a) Camilla and Marc

(b) Spencer & Rutherford

(c) Bec & Bridge

(d) Kendall + Kylie

(e) Dolce & Gabbana

to emphasise that two names, used together, do not always signify a collaboration between brands, and would not necessarily demonstrate a contextual context for potential confusion.

18 The appellant appealed on 31 May 2023 and the matter came before me for hearing on 29 April 2025, for three days.

Principles on the appeal

19 While the Notice of Appeal listed various grounds of appeal which were said to be errors on the part of the delegate, this is an appeal de novo: Woolworths Ltd v BP plc (2006) 150 FCR 134; [2006] FCAFC 52; at [30] (Sundberg and Bennett JJ); Bauer Consumer Media Ltd v Evergreen Television Pty Ltd (2019) 142 IPR 1; [2019] FCAFC 71 at [37] (Greenwood J). There is no presumption in favour of the correctness of the Registrar’s decision; however, appropriate weight should be given to the delegate as a skilled and experienced person; Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365; [1999] FCA 1020 at [33], where French J said:

Weight can be given to the Registrar’s opinion without compromising the duty of the Court to construe the relevant legal criteria. When the proper principles are applied to the manner in which a judgment is to be made about an issue such as “deceptive similarity” there is room for a degree of deference to the evaluative judgment actually made by the Registrar. That does not mean the Court is bound to accept the Registrar’s factual judgment. Rather it can be treated as a factor relevant to the Court’s own evaluation.

20 Accordingly, this Court should approach matters “afresh and without undue concern as to the ratio decidendi of the Registrar” (see Registrar v Woolworths at [32] per French J, citing Needham J in Rowntree plc v Rollbits Pty Ltd (1988) 90 FLR 398; 10 IPR 539 at 403, 545).

21 There is a presumption of registrability both before the Registrar and in this Court; Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd (2023) 277 CLR 186 at [10] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ); Registrar v Woolworths at [33]. The onus lies on the appellant, who as the opponent to the registration, needs to prove its case on the balance of probabilities; Telstra Corporation Ltd v Phone Directories Company Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 237 FCR 388; [2015] FCAFC 156 at [133] (Besanko, Jagot and Edelman JJ).

22 Both parties relied with enthusiasm on the text Australian Trade Mark Law, Burrell & Handler, (3rd ed, LexisNexis). In relation to the presumption of registrability as described by the learned authors, they say (at p 54-5):

When deciding whether an application should be accepted for registration, the tribunal will need to reach a point where it is either satisfied on the balance of probabilities that a ground of rejection does not arise, or that it is not satisfied as to this … The effect of the presumption is not that applications should somehow be readily accepted ...

Evidence

23 The appellant called evidence from Walter Lacher, the Chief Financial Officer of Paige, and relied on his affidavit of 31 October 2023. Mr Lacher was cross-examined. In addition, the appellant relied on five affidavits of Thomas Frisina, with two sworn on 16 October 2023, one on 17 October 2023, and two on 20 October 2023.

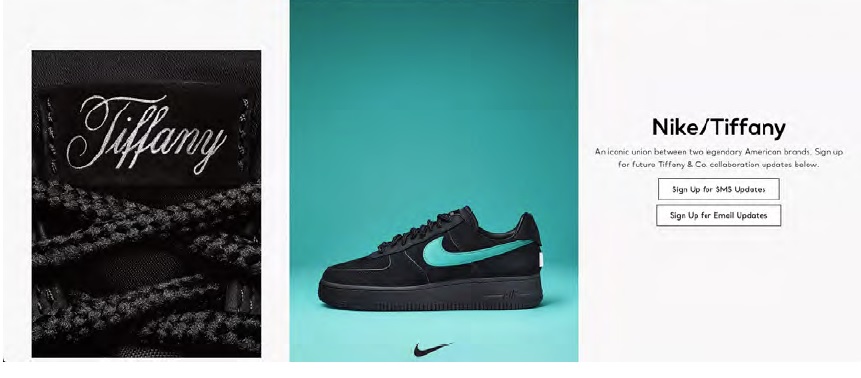

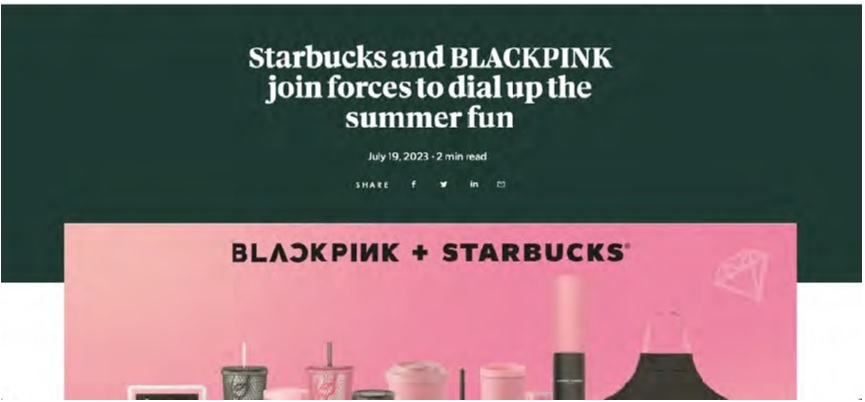

24 The respondent called evidence from Hing Fu (Arthur) Chau, who was cross-examined, and relied on his affidavit of 19 February 2024. Additional affidavits were read from Max Steinhausen of 19 February 2024, and Yishuang (Annie) Lou of 23 February 2024.

25 In reply, the appellant read two affidavits of Lincoln Chrysiliou of 18 April 2024.

26 Mr Lacher had worked for the appellant for some 19 years. He gave evidence that the brand Paige is named after its co-founder and Creative Director, Paige Adams-Gellar. Ms Adams-Gellar worked in fashion as a fit model prior to founding the brand. A fit model is “someone who is hired to model a garment that’s meant to represent the median size of a collection”.

27 Ms Adams-Gellar said in a Marie-Claire article that having her name attached to the brand was “important for [her] to have that emotional connection and create that camaraderie with the women buying [her] jeans”. Mr Lacher gave evidence that the importance of the name “Paige” was because there was a person named Paige “behind the product that they’re wearing”.

28 The brand PAIGE was first used in Australia in around January 2006 when the brand exported jeans through the International Fashion Group Pty Ltd. Paige also sells its products directly to Australian consumers via its website and retailers such as David Jones, General Pants Co, the Iconic, and other boutiques. A number of invoices demonstrating sales to Australia were in evidence. Mr Lacher was taken though the PAIGE items that were imported by International Fashion Group. Most of them were in the category of denim jeans, although there were some other items such as tops, and pants under the designation of the “Edgemont ultra-skinny” which Mr Lacher referred to as a “very fashion-forward product with zippers on it … not a denim pant in a true understanding of this product” because of its low cotton proportion (23%), meaning that was not “as structurally intense as a denim pant”.

29 Even so, Mr Lacher conceded that the Edgemont ultra-skinny may be referred to by some customers as denim, but it did not “feel like denim, does not look like denim … some consumers could call it something completely different”. He was taken to the David Jones website which listed the product under a heading “Denim” but noted that “we don’t control David Jones’ or any customer’s exact words and how they lay out their websites”.

30 The affidavits of Mr Frisina annexed a large number of online articles and webpages published in Australia and elsewhere that reference the PAIGE brand and/or support the concept of collaborations in the fashion industry. Most of the articles were published before the Priority Date. Many are about celebrities or models which mention the PAIGE brand in passing, with a few feature articles on Ms Adams-Gellar, or brand collaborations with PAIGE. The articles which are distinctively Australian from .com.au websites are as follows:

(a) www.vogue.com.au/beauty

(b) www.vogue.com.au/fashion

(c) www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/fashion

(d) www.ragtrader.com.au/news

(e) www.broadsheet.com.au/sydney/fashion/

(f) www.marieclaire.com.au/fashion-collaborations-2018

(g) www.gq.com.au/style/news/the-best-sneakercollaborations-of-2018-so-far

(h) www.broadsheet.com.au/national/fashion/article/worldscollide-five-best-new-fashioncollaborations-shop

(i) au.lifestyle.yahoo.com/priyanka-chopra-teams-little-red-132245206.html

(j) www.gq.com.au/style/news/the-most-influentialcollaborations-of-2019/imagegallery/871e5e3e962267c00e6df3145682e67f

(k) www.marketingmag.com.au/social-digital/broadsheet-the-return-of-qualiy-content-and-the-future/

(l) www.dailytelegraph.com.au/lifestyle/fashion/style-snippets-jasondundas-and-reneebarghs-new-fashioncollab-with-paigedenim/news-Story/ddd6f2163ec7d52705bb70dlf44c03cf

(m) www.theiconic.com.au/paige

(n) www.revolveclothing.com.au/paige/br/13e56b/

(o) www.electriccollective.com.au/reebok-x-gigi-hadid-sydney-launch/

(p) https://www.frankie.com.au/article/a-short-guide-to-collaborations-565202

(q) https://harpersbazaar.com.au/best-romance-was-born-collaborations/

(r) https://insideretail.com.au/business/uncontentional-luxury-brand-collaborations-are-everywhere-heres-why-202308

(s) https://www.pacificmags.com.au/wpcontent/uploads/2018/02/MediaKlt-marieclaire-2018-2.pdf

(t) https://www.newscorpaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/GQ-2019-Media-Kit.pdf

(u) https://www.studioa.org.au/design-partnerships

and make up approximately 43% of the total number.

31 Mr Chau is the Co-Founder and managing director of Sage + Paige. He gave evidence that the respondent was incorporated on 1 November 2019, and he registered the business name “Sage and Paige” on 29 June 2020.

32 While Mr Chau (and his wife Ms Lou, the Co-Founder and Head of Sales and Product of Sage + Paige) are based in Australia, they gave evidence that the business of Sage + Paige is an international business, selling “B2C” (business to consumer) through online shops. “Sage” is the name of Mr Chau and Ms Lou’s daughter, and they first became aware of the name “Paige” through the Instagram account of a makeup artist who has a dog with that name. Mr Chau gave evidence that he thought the names together “have a catchy ring”, and “the use of two girls’ names conveys a sense of friendship”. Instead of an ampersand, they chose a plus sign to convey the brand in a “more unique way”. The plus sign was, Mr Chau said, pronounced as “and”, which is how it appears on the brand’s website https://www.sageandpaige.com.au, in its Instagram handle @sage_and_paige, and on its Facebook profile, @sageandpaige.aus.

33 Mr Chau gave evidence that he was familiar with the sale, promotion, and branding of fashion goods, and in particular with the fashion industry in Australia, and that he was aware of the part of the Sage + Paige website which invited visitors to the site to “collab with us”. He agreed in cross-examination that:

A collaboration is a strategic partnership where two or more fashion brands, or a fashion brand and an individual, work together to create or cross-promote … a product or collection of products that blends one or more of their aesthetics, audiences, and values.

He agreed that “collab” was short for, and interchangeable with, “collaboration” in that specific sense, and that visitors to the website generally would understand “collab” to mean “collaboration”.

34 Mr Chau agreed that collabs enhanced the exposure to Sage + Paige by, among other things, reaching new customer segments. He was asked questions about cross-brand collaborations in particular, and agreed that “branded collaboration represented as the new normal” in fashion before June 2020.

35 Ms Lou provided in her affidavit a number of traders in Australia and the United States using the word PAIGE before the Priority Date in connection with products and brands marketed mainly to women. These marks were variously obtained from the IP Australia Trade Mark Register, the USPTO Trade Mark Register, as well as various websites and social media accounts. Marks relied upon included “HAYLEY PAIGE”, (Australian - jewellery, watches, bridal apparel), “IZLA + PAIGE” (jewellery) and “PAIGE’S CANDLE CO” (candles).

36 Mr Steinhausen is an Australian-registered foreign lawyer and employed by IP Service International Pty Ltd for Sage + Paige. Mr Steinhausen undertook various searches of PAIGE, and Sage + Paige, on purported retailers of the appellant, Facebook advertising and Google. Mr Steinhausen revealed that PAIGE is referred to as “Paige Denim” on the David Jones website and listed the number of PAIGE denim garments retailed on the David Jones and The Iconic webpages. Mr Steinhausen found that none of his searches of the appellant on the Facebook Ads Library in Australia returned results relating to PAIGE (in contrast to 66 results for searches of the respondent) and he provided screenshots of depictions of trade marks in various collaborations, the majority of which were post-Priority Date.

37 In his first reply affidavit, Mr Chrysiliou, a trade marks attorney for the appellant, conducted searches on YouTube and on each party’s website. His searches revealed that both brands stock denim, but noted that only 45.76% of items in the Women’s section of clothing of the appellant’s website were denim items. In his second reply affidavit, Mr Chrysiliou deposed to the refusal and cancellation of a number of trade marks on the USPTO containing the word or mark “Paige”. Several of the trade marks which were refused, abandoned or otherwise cancelled (one of which being the Sage + Paige trade mark) were indeed opposed by Paige.

The legislation

38 The appellant relies on ss 44 (the deceptive similarity ground) and 60 (the reputation ground) of the Act. The relevant sections provide:

10 Definition of deceptively similar

For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

…

Division 2—Grounds for rejecting an application

…

44 Identical etc. trade marks

(1) Subject to subsections (3) and (4), an application for the registration of a trade mark (applicant’s trade mark) in respect of goods (applicant’s goods) must be rejected if:

(a) the applicant’s trade mark is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to:

(i) a trade mark registered by another person in respect of similar goods or closely related services; or

(ii) a trade mark whose registration in respect of similar goods or closely related services is being sought by another person; and

(b) the priority date for the registration of the applicant’s trade mark in respect of the applicant’s goods is not earlier than the priority date for the registration of the other trade mark in respect of the similar goods or closely related services.

Note 1: For deceptively similar see section 10.

…

60 Trade mark similar to trade mark that has acquired a reputation in Australia

The registration of a trade mark in respect of particular goods or services may be opposed on the ground that:

(a) another trade mark had, before the priority date for the registration of the first-mentioned trade mark in respect of those goods or services, acquired a reputation in Australia; and

(b) because of the reputation of that other trade mark, the use of the first-mentioned trade mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion.

Section 44 – are the marks deceptively similar?

Principles

39 A trade mark is deceptively similar to another trade mark if it “so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion”: s 10 of the Act.

40 For the purposes of s 44, it was common ground that:-

(a) subsections (3) and (4) do not arise;

(b) the appellant’s marks have an earlier priority date than the Opposed Marks; and

(c) the designated goods and services are similar to the appellant’s goods.

41 In Puma SE v Caterpillar Inc (2022) 407 ALR 446; [2022] FCAFC 153, the Full Court of this Court adopted a statement of the primary judge (set out at [95] of the Full Court decision) at [90] that “in assessing the likelihood of deception or confusion, it is relevant to consider the relevant trade or business, the way in which the particular goods or services are sold and the character of the probable acquirers of the goods or services …”.

42 The comparative process for assessing deceptive similarity is set out in the decision of Windeyer J in Shell Company of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407; [1963] HCA 66 at 415:

On the question of deceptive similarity a different comparison must be made from that which is necessary when substantial identity is in question. The marks are not now to be looked at side by side. The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. Therefore the comparison is the familiar one of trade mark law. It is between, on the one hand, the impression based on recollection of the [earlier] mark that persons of ordinary intelligence and memory would have; and, on the other hand, the impressions that such persons would get from the [later mark].

43 The test in Shell Co was more recently considered in the context of s 120(1) of the Act by the High Court in Self Care. At [29], Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ said:

The marks are not to be looked at side by side. Instead, the notional buyer’s imperfect recollection of the registered mark lies at the centre of the test for deceptive similarity.

44 The relevant principles to be derived from Self Care are as follows:

(a) The question to be asked is an objective question, based on a construct. The focus is upon the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers: Self Care at [28];

(b) That potential customer is a person:

(i) who has seen the registered mark: Self Care at [29];

(ii) who has no knowledge about any actual use of the registered mark or the business of the owner of the registered mark: Self Care at [28]; and

(iii) who is unaware of any reputation associated with the registered mark: Self Care at [28];

(c) The marks are to be considered both visually and aurally and in the context of the surrounding circumstances; Self Care at [68]; Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658 (Dixon and McTiernan JJ);

(d) The likelihood of confusion/deception is determined by the usual way ordinary people behave, having regard to the character of the customers who would likely buy the goods: Self Care at [31]. Consumers are not credited with “any high perception or habitual caution”, although “exceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded”: Self Care at [31] (citing Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills at 658);

(e) A trade mark is deceptively similar if it “so nearly resembles” the other trade mark that it is “likely to deceive” or “cause confusion”. Deception “implies the creation of an incorrect belief or mental impression”; while causing confusion “may merely involve ‘perplexing or mixing up the minds’ of potential customers”: Self Care at [30]. In Apple Inc Yates J made it clear that Apple would able to use its trade mark of the word sought to be registered (in that case, APP STORE) with whatever font, capitalisation, or stylisation it chose.

(f) The “threshold for confusion is not high”: Australian Postal Foundation Corporation v Digital Post Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 308 ALR 1; [2013] FCAFC 153 at [70], but a mere possibility of confusion is not enough; there must be a real, tangible danger of deception or confusion occurring; Self Care at [32]:

It is enough if the notional buyer would entertain a reasonable doubt as to whether, due to the resemblance between the marks, the two products come from the same source. Put another way, there must be “a real likelihood that some people will wonder or be left in doubt about whether the two sets of products … come from the same source”.

(Emphasis added).

That some people would not be confused is “not to the point”: Puma at [98]; and

(g) “All surrounding circumstances” are taken into consideration. These include the circumstances in which the marks will be used, the circumstances in which the goods or services will be bought and sold, and the character of the probable acquirers of the goods or services: Self Care at [33]; Woolworths at [50].

45 I pause here to note that the appellant submitted that the delegate erred at [23] of the reasons below, in saying:

The opponent’s submission that, on seeing the applied-for trade marks, consumers are likely to understand some economic or organizational link to the Opponent would, in my assessment, only be likely if those consumers knew of the Opponent’s mark…

where the more appropriate formulation would be that the consumer had an “imperfect recollection” of the PAIGE mark. While there is some force in this submission, this is, as noted above, a hearing de novo, and I am not swayed by the finding by the delegate that the lack of confusion he found was on this basis.

Impact of the inclusion of “Paige” in the Opposed marks

46 The appellant submitted that PAIGE is inherently distinctive in respect of clothing goods and services, and disputes the respondent’s suggestion that it is a relatively common female name, relying on the fact that the word mark was registered by IP Australia without any objection. I accept that the word PAIGE is a given name and not descriptive of the relevant goods and services: Energy Beverages at [167].

47 The respondent relied on Winter Holding GmbH & Co KG v SASS Clothing Pty Ltd [2021] ATMO 55 at [22], where a delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks said that trade marks consisting of given names and surnames are “relatively common”. The delegate was of the view that the more distinctive and unusual a name, the greater potential for confusion with other trade marks sharing the same element, but the more common, the less likelihood there is for confusion. This approach is consistent with the Manual: Part 26, Annexure 1A Citing Multiple Names, which provides:

Citations when one mark consists of a given name and the other consist of multiple given names

When comparing a trade consisting of a given name and a trade mark that consists of two or more given names a real and tangible danger of confusion is less likely to occur between trade marks.

In making this decision examiners should consider:

• The relative commonness of the given name;

• The goods and/or services the trade mark will be used on, and the marketplace in which the goods or services are traded;

• Placement or representation of the name in the trade mark;

• Any other factors relevant to a decision of deceptive similarity.

In limited circumstances confusion may be considered likely when the given name between the marks is extremely unusual, rare, or otherwise memorable, such as an invented given name.

(A table from the Manual including examples of names is reproduced in Schedule 3)

48 The delegate’s decision drew on the approaches as to naming conventions as set out in the Manual. In the Bianca and Bridgett case, the delegate considered that Bianca was a not uncommon name, using their own knowledge, as well as determining that the name Bianca was “frequently used in the fashion industry”, that finding being based on a list of fashion labels and a list of Australian trade mark registrations in the relevant category.

49 While I am not bound by the Manual and the approach taken by the delegate, the dot points:

• The relative commonness of the given name;

• The goods and/or services the trade mark will be used on, and the marketplace in which the goods or services are traded; and

• Placement or representation of the name in the trade mark

in the approach taken by the delegate seem a sensible way of approaching the matter.

50 The respondent submitted that “Trade Marks consisting of given names or surnames should be treated with a level of caution”. That submission drew on some decisions of the ATMO and on the approach set out above in Part 26 of the Manual as to the lesser lack of confusion between trade marks using one, and two, names.

51 The appellant contended that the Manual was “no more than a set of administrative guidelines” (see Beling v Sizty International SA (2015) 228 FCR 194; [2015] FCA 250 at [10] (Mortimer J), and that reliance on the Manual may detract from the Court’s task, citing Enagic Co Ltd v Horizons (Asia) Pty Ltd (No 3) (2021) 164 IPR 234; [2021] FCA 1512 at [37] (Charlesworth J)).

52 The respondent sought to rely on Ms Lou’s evidence of other traders using the word “Paige” to demonstrate that “the notional consumer would understand that PAIGE is a name as a matter of common knowledge”. The appellant however submitted that such evidence should not be accepted as it is irrelevant to consider the registration of other trade marks as the context in which these trade marks were registered is not known: Ocean Spray Cranberries Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2000) 47 IPR 579; [2000] FCA 177 at [35] (Wilcox J). Further, it was submitted that evidence from websites containing the word “Paige” has no probative value given that the evidence does not show their exposure to Australian consumers, are post-Priority Date, do not all concern clothing, and that the marks have different a syntactical structure to the marks in dispute.

53 The appellant urged me not to take judicial notice as to the commonality of the name Paige. There was no direct evidence as to the commonality of the name “Paige” before the Court (as the respondent’s evidence of searches of baby name internet sites was rejected). However, I regard the question of whether the name is highly uncommon or relatively common is the kind of matter of which I can take judicial notice pursuant to s 144 of the Evidence Act as urged by the respondent in submissions.

54 It may not be a name which is very frequently encountered, but it is recognisably a woman’s name, which speaks to its being not uncommon. It is not a “fancy” or invented word. The evidence discloses that each of Ms Adams-Gellar, a prospective child of the directors of the respondent, and an influencer’s dog, each have the name “Paige”, which inclines me to the view that it is not highly unusual.

55 As the respondent pointed out, the word “Paige” has no other meaning other than a woman’s name. Further, Mr Lacher accepted that consumers would be aware that “Paige” was a woman’s name, even without specific knowledge of Ms Adams-Gellar. In my view that general evidence, along with the fact that “Paige” is recognisably a woman’s name, leads to the view that it is not so unusual that there would be an immediate identification of PAIGE as the “essential feature” of “Sage + Paige”. It is well-established that elements of a trade mark that is common in both marks and used by a number of traders will be discounted to some extent in the assessment for deceptive similarity, given that the notional consumer would find a less common word more memorable: The Agency Group Australia Ltd v HAS Real Estate Pty Ltd (2023) 174 IPR 153; [2023] FCA 482 at [63] (Jackman J). In Mond Staffordshire Refining Co Ltd v Harlem (1929) 41 CLR 475 at 477 (MONSOL and MUSOL), the plurality found the Court was entitled to consider the circumstance that a number of medicines and pharmaceutical preparations use the suffix “sol” or “ol” and that words commencing with “mul” have been registered as trade marks and used in Australia for some years. See also Cooper Engineering Co Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd [1952] HCA 15.

56 I find, from my review of the above evidence and principles, that:

(a) “Paige” is not a distinctively unusual name;

(b) “Paige” is recognisably a woman’s name and has no other meaning; and

(c) there is some evidence of the use of the name “Paige” by other brands in Australia, however, unlike the delegate in Bianca and Bridgett, I am not able on the evidence to find that “Paige” is a distinctive or a common name in the fashion industry.

57 I have taken into account the fact that each of “Sage” and “Paige” are given names (noting that “sage” as a noun or adjective has other meanings), the fact that “Paige” is the second of the two names in the respondent’s mark, and the fact that each of the marks is used on clothing.

Impact of inclusion of word “Sage” in the Opposed Marks

58 The respondent submits that of the two names, “Sage” is more likely to leave an impression on the notional consumer and the word is “the most interesting of the two names, having multiple meanings and references”, being also a herb and a colour.

59 The respondent relied on Conde Nast Publications Pty Ltd v Taylor (1998) 41 IPR 505; [1998] FCA 864 (Burchett J), which cited with approval at 511, Re London Lubricants (1920) Ltd’s Application (1925) 42 RPC 264 at 279 (Sargant LJ) that “the first syllable of a word is, as a rule, far the most important for the purpose of distinction”. I do not agree with the respondent’s submission that, as a general principle, the first part of the mark is always the most important when assessing deceptive similarity. That could be the case but that question always turns on the facts of the case: Caporaso Pty Ltd (as trustee for the Diversity Trust) v Mercato Centrale Australia Pty Ltd (2024) 181 IPR 78; [2024] FCA 138 at [282] (Charlesworth J).

60 For example, “N-OUT” was found by Katzmann J to be the significant and distinctive feature of the IN-N-OUT BURGER mark (In-N-Out Burgers, Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd (2020) 377 ALR 116; [2020] FCA 193 at [109], with the Full Court agreeing in Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd v In-N-Out Burgers, Inc (2020) 385 ALR 514; [2020] FCAFC 235 at [76]). Similarly, the words “& GLORY” as used in PRIDE & GLORY and SOAP & GLORY were found to be distinctive and therefore the marks were deceptively similar: Soap & Glory Ltd v Boi Trading Co Ltd (2014) 107 IPR 574; [2014] ATMO 47 at [33] (M Kirov).

61 The respondent relied on the decision in Puma, in particular noting that deceptive similarity was found between Puma’s “leaping cat” on PROCAT branded goods (in particular athletic wear and shoes), and clothes including footwear branded CAT by Caterpillar, primarily a heavy equipment manufacturer, even where the consumer had a knowledge of Puma. The relevance of the use of the word “-CAT” in PROCAT, in the evaluative assessment that needs to be undertaken, gave rise to the finding of the primary judge, upheld by the Full Court at [98], that “consumers would be caused to wonder” about the commercial association so implied.

62 In this case, I consider that the word “Sage” does have an impact on the question of whether the two marks are deceptively similar. The fact that sage is a herb, a colour, and a (relatively uncommon) female name, as well as being indicative of wisdom, gives it a much more nuanced and complex impression than merely “Paige” which has no meaning other than a woman’s name. I find that the inclusion of “Sage”, and its placement and rhythm with “Paige”, gives the respondent’s name a distinctive flavour.

Aural features

63 Phonetic similarities between marks will not be important if the words in the marks are not usually spoken: Starr Partners Pty Ltd v Dev Prem Pty Ltd (2007) 71 IPR 459; [2007] FCAFC 42 at [23] (Lindgren, Emmett and Finkelstein JJ). In Taiwan Yamani Inc v Giorgi Armani SpA (1989) 17 IPR 92 the Registrar considered at 96 that aural similarities are not as important as the visual impact of the marks in question in the context of clothing now being selected by customers from a rack as opposed to being purchased verbally over the counter.

64 I find that given the online nature of the respondent’s business, and the relatively minor nature of the appellant’s storefront presence, means that the aural features of the marks are not as important as the visual aspects of the marks.

Trend of two first names

65 The respondent took me to various brands that incorporated two first names in screenshots of a directory of David Jones brands in 2012 and 2017, including “Camilla & Mark”, “Bec & Bridge”, “Kendall + Kylie” and “rag & bone”. The respondent also relied on Hachette Filipacchi Presse v KIND TO ME PTY LTD [2024] ATMO 204 where the delegate of the Registrar found at [64] that ELLE and ELLE & HARPER were not deceptively similar, given the importance of the “HARPER” element of the trade mark, and that consumers would recall the trade mark as two relatively common given names representing a single brand.

66 On the other hand, counsel for the appellant relied on the decision Woods and Another v Teed (2018) 143 IPR 249; [2018] ATMO 121 (VIKTORIA + WOODS and VIKTORIA). In that case, the delegate found at [31] that it is “likely that a person who is aware of the Plus Trade Mark would, on seeing the Trade Mark, speculate that it is a sub-brand of the Plus Trade Mark or a re-branding of the Plus Trade Mark”, and so found the marks to be deceptively similar.

67 There is no set rule as to whether a brand with two first names necessarily is deceptively similar to a brand with one of those names, in the sense that the two-name brand might be thought of as a sub-brand of the single name. The decision will depend on the relevant surrounding circumstances. The evidence in this case as to the extent of the “two names” trend, assisted by the Trade Mark Office cases provided, demonstrates that the plus sign and ampersand are commonly used to connect two names as a brand or trade mark. I am satisfied that the trend of two names being used with a connecting word or mark (such as “and” or “+”) was a trend in the fashion industry as at the Priority Date and is one of the surrounding circumstances that I need to take into consideration in determining the deceptive similarity question.

Collaborations

68 A key surrounding circumstance in these proceedings which I have been asked to consider is the existence of “collaborations” in the fashion industry as at the Priority Date. The evidence is that collaborations are known as “collabs”. The appellant’s position is that the notional consumer is familiar with such a concept and, accordingly, upon seeing the Sage + Paige mark, would be caused to wonder whether they emanated from the same source, or were otherwise associated with PAIGE. The possible confusion which arises from the knowledge of collabs in the fashion industry was at the heart of the appellant’s case.

69 The learned authors Burrell and Handler stated at p 282 that “[t]he ‘surrounding circumstances’ approach means that, when assessing visual and aural similarity, careful attention must be paid to the way in which the goods or services are ordinarily sold and marketed”. In relation to this matter, the considerations to be taken into account must include the trend of collaboration between brands and whether the notional consumer would have a familiarity with collaborations and wonder whether Sage + Paige may be an iteration of the brand “PAIGE”, or that they were two brands “working together”.

70 The appellant submitted that collaborations in the clothing space “have involved some of the best known clothing brands in Australia (and around the world)”. The Court was taken to what may be seen as somewhat unlikely fashion collaborations, such as the fast food business McDonalds with the shoe brand Crocs, and a further Crocs collaboration with the high-fashion house Balenciaga. In evidence were a number of online articles published pre-Priority Date which discuss the trend of collaborations in the clothing industry, one such article authored by Canadian fashion retailer SSENSE noting that “[c]ross-brand collaboration has become one of the defining features of fashion in 2017”. Mr Chau accepted propositions in cross-examination from Mr Larish, counsel for the appellant, that that “before June 2020, branded collaboration represented the new normal in fashion, including in Australia”.

71 The appellant also relied on its own pre-Priority Date collaborations with model Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, which were denoted variously as “Rosie HW x PAIGE”, “PAIGE + RHW” and “PAIGE + ROSIE”.

72 The appellant submitted that marks may be deceptively similar even though the differences between them would be apparent to the consumer: Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v Tivo Inc (2012) 294 ALR 661; [2012] FCAFC 159 at [145] (Nicholas J), citing Re John Fitton & Co Ltd’s Application (1949) 66 RPC 110. Examples include:

(a) where consumers perceive a mark as involving a “collaboration” between two entities: e.g., Re Intel Corporation a Delaware Corporation [2020] ATMO 4 at [30]; Eveden Inc v P & Y Halas Pty Ltd [2015] ATMO 116 at [48]; or

(b) “contextual confusion, where consumers might think that the product bearing the impugned mark is a variant of or related to an existing brand”: Societe Civile et Agricole du Vieux Chateau Certan v Kreglinger (Australia) Pty Ltd (2024) 179 IPR 226; [2024] FCA 248 at [560] (Beach J).

73 The appellant referred to the case of Re John Fitton, where the Assistant-Comptroller referred to confusion “owing to the presence of the common element ‘Jest’ in each mark, in traders and the public being induced to believe that the two sets of goods sold under the marks emanated from one and the same trade source” (at 113). The marks in questions were JESTS and EASYJESTS.

74 This reflects the “the well known trade practice of traders in adopting a certain word as a trade mark and constructing other trade marks for distinguishing characteristics of their goods by using such word as a basis and adding thereto”: Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd’s Application (1936) 6 AOJP 1724.

75 The respondent’s case is that the evidence does not establish that the average Australian consumer was aware of the existence of collaborations as at the Priority Date, and submitted that Mr Chau was not representative of the notional consumer. In cross-examination, Mr Chau agreed that “visitors” to the Sage + Paige website or Instagram page would understand the website’s request “collab with us” as an invitation for “collaboration”. However, counsel for the respondent submitted that this direction or request was directed to people within the fashion industry who would have an understanding of the concept of collaboration and are not reflective of the understanding held by the notional consumer. Moreover, the respondent submitted that the notional consumer is not limited to visitors to its website.

76 The respondent cautioned me against relying on the oral evidence of Mr Chau in relation to consumer understanding of collaborations as Mr Chau was not the notional consumer, nor was he asked about his understanding of the notional consumer.

77 However, I accept that Mr Chau, as the co-founder and managing director of a fashion brand, would have knowledge of the state of collaborations within the fashion industry. His evidence can also be taken to extend beyond this field, given that his own website invites the reader to “collab with us”. The invitees would not be restricted to industry professionals but would include individual consumers or perhaps influencers who may wish to collaborate with the Sage + Paige brand, perhaps to mutual benefit. Mr Chau said in his affidavit that the company’s clients “engage with Sage + Paige directly, often through its social media channels. There is no context in which consumers will view or purchase Sage + Paige’s Goods without direct engagement with Sage + Paige itself.” That evidence, while not directed to the question of the notional consumer’s understanding of collaborations, does underline the way in which Sage + Paige engages with its customers through social media, and the use of the word “collab” is indicative of the relationship between social media and the kind of cross-pollination of marketing which collaborations represent.

78 The appellant submitted that there was no uniform rule as to how collaborations were stylised. I was taken to a number of examples showcasing how collaborating brands choose to stylise their brands, noting that examples were not limited to fashion collaborations. This included, among others, “Heinz x Absolut”, “Blackpink + Starbucks”, and the appellant’s collaborations with Rosie Huntington-Whiteley. The appellant depicted these in its submissions, as shown below:

79 Some examples of collaborations relied on by the respondent were:

80 The evidence demonstrated that collaborations are most often denoted by an “x”, but also sometimes by a “+” or a “/”, and that collaborating brands most often retained their own stylisation but occasionally were rendered by both trade marks and in text. In the Blackpink + Starbucks example, the collaboration logo uses the trade mark stylisation (referred to by counsel for the appellant as having had “something fancy” done to the A, C and N), but the website refers to “Starbucks and BLACKPINK” in text (without the reversed letters in BLACKPINK). The McDonalds x Crocs collaboration also has a stylised, and a plain text, representation.

81 I accept that brands often maintain their individual brand identity in the stylisation of the collaboration, but that is not always the case. The appellant submitted that a uniform stylisation did not rule out a notional consumer wondering whether two names or two brands together may be a collaboration. The evidence in this case is that often the collaboration maintains or includes at least some elements of their familiar stylisation, as can be seen from the use of the PAIGE word in its familiar font in the PAIGE + RHW example above.

82 The notional consumer would, I find, be familiar with the concept of collaborations in the fashion industry as at the Priority Date, as evidenced in the various examples of collaborating brands pre-Priority date in the evidence, as well as Mr Chau’s own evidence as to the existence of collaborations. The plentiful evidence as to the existence of collaborations, most commonly branded but occasionally un-stylised, leads me to accept that the notional consumer would be familiar with the collaboration concept. I find that a collaboration is more often indicated by an “x” (such as the Lego x Levis example), but can also be recognised by the use of an “+” (Blackpink + Starbucks) or a “/” (Nike/Tiffany).

83 The respondent pointed to the different kinds of collaborations – whether it were “two or more fashion brands” or a “fashion brand and an individual” (as discussed by Mr Chau in his evidence). While I accept that these are two different kinds of collaboration, the concept of collaboration covers both. As noted above, counsel for the appellant defined collaboration, and Mr Chau accepted that definition, as:

a strategic partnership where two or more fashion brands, or a fashion brand and an individual, work together to create or cross-promote, a product or collection of products that blends one or more of their aesthetics, audiences, and values.

84 The concept of collaboration is, as demonstrated by the evidence overall, something that was an embedded part of the fashion industry and known to consumers as at the Priority Date, and so is something that can be taken into account as a relevant surrounding circumstance in determining the question of deceptive similarity.

Are the marks “deceptively similar?”

85 The appellant will succeed if I accept that the notional consumer would be caused to wonder whether the Sage + Paige mark was a collaboration, or brand extension, by a brand named Sage with the brand, imperfectly recollected, named PAIGE, in order to succeed. As noted in Self Care at [32], the issue is whether there is a reasonable doubt between the two marks that the products come from the same source, or a real likelihood that some people will be left in doubt as to that.

86 As noted above, the appellant relies significantly on the inherent distinctiveness of the name PAIGE and the possibility that “at least some” consumers would be likely to wonder whether the Saige + Paige marks reflected a collaboration, product, or brand extension involving PAIGE.

87 No evidence has been led as to actual confusion between the marks. I do not take this omission as affecting the respondent parties’ case, given that such evidence is “not essential”: Self Care at [30]. I was provided during the hearing by the appellant with a document entitled “Section 44 and 60 comparisons” which had, in the s 44 section, comparisons of the word PAIGE in the Sage + Paige font, and the same renditions but this time in the pink circle, notionally placed on a t-shirt or cap. This seems to transgress the test expressed by Windeyer J in Shell Co and the High Court in Self-Care (set out in [42] and [43] above) that the marks are not to be looked at side by side: “The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity” (Windeyer J in Shell Co at 414).

88 It seems to me that the use of the word “Sage” as the first element in the respondent’s mark, and the uniform stylisation of the two words, along with a “plus” sign rather than the more common “x” in collaborations, are all factors which weigh against the notional consumer being likely to be caused to wonder about the requisite link with PAIGE in the context of a collaboration or brand extension. Both of the names in the respondent’s mark are given the same visual weight, and the stylisation of the pink circle, while minimal, does not distinguish between the two names in the way in which a collaboration often would. The two names in the Sage + Paige stylised pink circle are vertically stacked, which is not a feature in many of the examples of collaborations in evidence, and so does not tend towards indicating a collaboration in my view.

89 In The Agency Group, Jackman J (at [76]) reasoned that the differences in words between THE NORTH AGENCY and AGENCY, particularly the definite article “THE”, meant that there was no real risk of ordinary consumers wondering whether the real estate services of the former may be an extension of the latter. The use of two names with the same stylisation tend to indicate, in my view, a singular brand name, rather than two separate, collaborating, brand names. The “name + name” trend about which there has been evidence also tends to this conclusion, leading me to consider that the notional consumer would first be attracted to the “two names, one brand” trend rather than a collaboration, and would not thus be caused to wonder about any relationship with an imperfectly recollected brand PAIGE.

90 I am of the view that, while the test for deceptive similarity may seem to be a “low bar”, the question of whether there is a real, tangible danger of deception or confusion occurring has not been answered positively. I would dismiss the appeal on the s 44 ground.

Section 60 - Has PAIGE acquired a reputation in Australia?

91 I now turn to whether PAIGE had acquired a reputation in Australia prior to the Priority Date and whether the use of the Opposed Marks would be likely to deceive or cause confusion due to the reputation of the PAIGE marks.

Principles

92 As Ms McDonald, counsel for the respondent, helpfully explained, s 60 allows someone who is using an unregistered trade mark to still oppose the registration of a trade mark where that person can establish that the trade mark has had a reputation in Australia before the Priority Date.

93 The relevant principles for s 60 can be summarised as follows:

(a) Section 60 involves a two-stage enquiry. First, whether the earlier mark had acquired a reputation in Australia, and second, whether because of that reputation, the mark sought to be opposed would be likely to deceive or cause confusion: Killer Queen LLC and Others v Taylor (2024) 306 FCR 199; [2024] FCAFC 149 (Yates, Burley and Rofe JJ) at [274]

(b) Reputation, which refers to the recognition of a trade mark by the public generally, can be inferred “from a high volume of sales, together with substantial advertising expenditures and other promotions, without any direct evidence of consumer appreciation of the mark, as opposed to the product”: Self Care at [48], citing McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick (2000) 51 IPR 102; [2000] FCA 1335 at [86] (Kenny J).

(c) In the absence of sales, “a mark may acquire a reputation in Australia by the means of direct preliminary marketing, direct advertising, indirect advertising, exposure in radio, film, newspapers and magazines or television, or because the mark has a reputation in another country which can be shown to have extended to Australia”: Vivo at [57].

(d) The standard of “confusion and deception” under s 60 is the same as under s 44(1), that is, there must be a real tangible danger of deception or confusion; a mere possibility is not sufficient: at Killer Queen at [278].

(e) “Even if the conflicting marks are not deceptively similar, the s 60 objection may be established if the reputation of the first mark is such that use of the opposed mark is likely to result in a real risk of confusion in the trade mark sense”. The focus is on the reputation of the first mark: Killer Queen at [275].

(f) “There is no statutory requirement that the reputation in the earlier mark be specific to the goods or services the subject of the opposed mark”: Killer Queen at [277].

(g) The comparison is between the reputation of the prior mark derived from its actual use, and a notional normal and fair use of the mark sought to be opposed in respect of each of the goods or services covered by the specification: Killer Queen at [279].

94 Some elements of the Killer Queen decision are not relevant to this case, since Ms Adams-Gellar’s reputation in the fashion industry was not comparable to that of Katy Perry, whose reputation as a then-earthbound pop songstress underpinned her claim to a s 60 claim in relation to her later branching out into clothing. But the principles listed in the preceding paragraph were not the subject of the recent grant of special leave in Killer Queen – see Taylor v Killer Queen LLC & Ors [2025] HCATrans 31 (11 April 2025).

Evidence of reputation as at Priority Date

95 The delegate reviewed evidence brought on the original application and found as follows at [31]-[32]:

I note that by the Relevant Date, sales were half what they were in 2014. Advertising expenditure is not specific to the Australian market and is a single-digit percentage of the total annual spend. The Opponent’s submission is that notwithstanding the diminishing sales, the brand awareness would remain. The Applicant submits that reputation in the fashion sector is dynamic and potentially short-lived.

My assessment is that the truth lies somewhere between. The evidence indicates that the Opponent’s trade marks have been used principally in respect of denim goods, mainly, jeans for women. The jeans are highly priced and have been bought and worn by various celebrities (again, mainly women) but the confidential sales figures in that period leading up to the Relevant Date are not at all very substantial for the fashion clothing sector. On balance, I find that, on the Relevant Date, the Opponent had a modest reputation in Australia in respect of jeans for women. I find, further, that any possible confusion would be limited to those particular goods, and I find that risk is defrayed by the differences in the trade marks, their lack of deceptive similarity, and (relevantly to s 60) the boutique status of the Opponent’s goods, something bound to stimulate the critical faculties of likely buyers.

96 The appellant submitted that the evidence shows there was a substantial reputation in the name PAIGE before the Priority Date in respect of clothing. The appellant relied on sales figures of PAIGE-branded goods to Australian distributors and marketing expenditure in Australia as well as evidence of PAIGE’s exposure to the Australian public by way of campaigns, social media, and online articles in fashion publications before the Priority Date.

97 While marketing expenses for Paige included marketing in Australia, they were not individually tracked on a country-specific basis. Between 2015-2019, some $8 million USD worth of sales of PAIGE-branded goods were made to Australian distributors. Estimates which appeared to have been prepared for the opposition proceedings below indicated that the advertising/promotional expenditure for the Australian market from 2013 to 2019 was approximately $2.7 million AUD or around $300,000 per annum. The appellant does not break down marketing expenditure by region or by country.

98 While the evidence of specific marketing for the brand in Australia did not demonstrate any targeted specific marketing programmes, Mr Lacher pointed to the promotional activities undertaken by Paige. For example, products bearing the PAIGE logo were included in a designated area in ten David Jones stores in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. Products were displayed on shelves and racks showing the PAIGE logo and there were photographs in evidence of PAIGE goods being featured in David Jones’ storefront windows in Australia in 2014 and 2016.

99 Paige was also part of several in-person promotional events held in Australia, including:

(a) Vogue Australia’s “Fashion’s Night Out” event in 2016 and 2012. At the 2016 event, customised PAIGE-branded cookies in the shape of a jeans pocket were provided to attendees and attendees could win a pair of PAIGE jeans through a game of poker;

(b) Premiere Boutique Trade Show at the Royal Hall of Industries in Sydney in 2012;

(c) A dinner for fashion bloggers in 2017 celebrating PAIGE, where guests received a gift from PAIGE; and

(d) Fashion events at stores in 2013 hosted by bloggers and Ms Adams-Gellar.

100 Social media marketing in Australia was undertaken by International Fashion Group from 2011 to 2019, and Edwards Imports Pty Ltd from 2019 onwards. The International Fashion Group had 4,257 followers on Facebook and 1,306 followers on Instagram as at 22 July 2021. In evidence were a number of posts featuring PAIGE-branded goods on these accounts.

101 Mr Lacher was cross-examined as to the marketing of the brand, and as to Ms Adams-Gellar’s reputation (given that Mr Lacher noted in his affidavit that the brand was intrinsically tied to her reputation in the fashion industry). He was asked as to Ms Adams-Geller’s role as a fit model, as opposed to a runway model who would have a more forward-facing reputation, and agreed that he was not familiar with her work as a fit model. It is fair to say that while Ms Adams-Gellar may not have had a broad reputation in the industry prior to the establishment of her brand, she has been the focus of a number of articles and online publications linking her with her eponymous brand.

102 As mentioned at [30] above, the appellant also relied on a large number of online articles referencing or featuring the PAIGE brand. This included articles from publications including InStyle, Elle Australia, Harper’s Bazaar, Daily Mail Australia and Marie Claire. The articles range from containing only a short reference to the PAIGE brand, to full feature articles in relation to Ms Adams-Gellar or its collaborations with other brands or people.

103 The respondent’s position is that what must be shown is the trade mark having a reputation in Australia, not reputation alone (see Self Care at [13]). The respondent submitted that the appellant’s sales in Australia had been limited, and that no evidence was provided showing the size of these sales in the context of the fashion sector generally. It was also unclear from where the estimated figures for marketing expenditure in Australia originated. The respondent pointed to the lack of evidence as to online sales, submitting that the evidence as to the estimated marketing expenditure was not reliable and that there were limitations in the respondent’s evidence as to PAIGE-related promotional events, online articles and social media presence. The respondent submitted that the appellant had not put on any evidence in relation to whether the online articles referencing PAIGE were in fact seen by Australian audiences.

104 In the absence of actual sales in Australia, reputation has been held to be established by evidence of foreign travel and placement of the mark in publications and advertisements encountered by Australian consumers. The appellant relied in particular on Winnebago Industries, Inc v Knott Investments Pty Ltd (No 2) (2012) 293 ALR 108; [2012] FCA 785 (Foster J), a passing-off case in which spillover reputation was held to subsist in the American caravan brand Winnebago as at 1 June 1982. In that case, Foster J was willing to infer that some visitors to Australia and some Australian residents who visited foreign countries from time to time between 1962 and 1982 came into contact with Winnebago via well-known publications such as the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post when published in their places of origin; that news of Winnebago would have spread in Australia through the conversations and actions of some of the visitors to Australia and some Australian travellers to overseas countries who were aware of Winnebago and its RVs; that there were some advertisements which specifically identified Winnebago and an imported model had been offered for sale; and that, most tellingly, the respondents had used the name and logo of Winnebago in its own motorhome company to “intentionally [hijack] the Winnebago marks in Australia in a bold attempt to pre-empt Winnebago’s opening its doors here” (at [124]-[130]).

105 In discussing the global impact of reputation under s 60, Dodds-Streeton J in Tivo Inc v Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd [2012] FCA 252 at [334]-[335] referred to Lockhart J’s observations in ConAgra Inc v McCain Foods (Aust) Pty Ltd (1992) 33 FCR 302, 373 (which were made in the context of passing off) as follows:

His Honour noted that due to the effect of modern mass media advertising through television, radio, newspapers and magazines which reach people in many different countries and the international mobility of the world population, “[g]oods and services are often preceded by their reputation abroad. They may not be physically present in the market of a particular country, but are well known there because of the sophistication of communications which are increasingly less limited by national boundaries, and the frequent travel of residents of many countries for reasons of business, pleasure or study” (at 342).

The authorities therefore recognise that even in the absence of sales or use, a mark may acquire a reputation in Australia by the means of direct preliminary marketing, direct advertising, indirect advertising, exposure in radio, film, newspapers and magazines or television, or because the mark has a reputation in another country which can be shown to have extended to Australia.

These principles apply, even more so, in the age of Instagram and other easily accessible platforms, such as social media and highly intuitive search engines.

106 The respondent contended to the extent that any reputation existed in the trade mark PAIGE in Australia, such reputation was modest and limited to high-end denim jeans, as evidenced by the references to the appellant being described as a denim label variously in online articles as well as branding as “PAIGE denim” on its own clothes. The appellant accepted that jeans were PAIGE’s “core product” but disputed that the reputation was confined to jeans. Mr Lacher was cross-examined on some of the invoices which revealed that most of the products sold into Australia on those particular invoices were jeans or other products that may be recognised as denim.

107 The evidence was that the marketing activities undertaken in Australia were mainly, but not exclusively, undertaken within the fashion industry. The Royal Hall of Industries stand and the fashion blogger event were not open to the public, and the Vogue Fashion’s Night Out event is a one-off annual event where (generally high-end) retailers offer discounts and experiences (in the case of PAIGE, the denim-pocket branded cookie gift and the chance to win jeans). The David Jones store windows, again, would reach a small audience given the high-end nature of department store shopping, although the David Jones window display was featured on the International Fashion Group Instagram page (which, as noted, had only a small number of followers at the time).

108 As the respondent noted, the evidence shows celebrities or models wearing the PAIGE products pre-Priority Date (including Australian celebrities Chris and Liam Hemsworth and Lara Bingle, and international names such as UK Model Kate Moss, and music icon Beyonce) rather than them being worn “in the wild” by ordinary people. Most of the celebrities are wearing denim products but some are not; for example, Kim Kardashian is shown wearing a PAIGE top, and Nicole Richie, Hilary Duff, and Jessica Alba are shown in “The ultimate fall [2013]’s accessory: PAIGE shirting”. This was possibly because the evidence was taken from the brand’s Instagram account on the basis that the international celebrities there either have name recognition in Australia or would fall within the Winnebago principle that their media coverage would provide for a spillover reputation in Australia. However, there is, as set out by the respondent in its submissions, no evidence of how many Australian followers the account had, nor of the number of followers overall.

109 Mr Lacher’s evidence was that the PAIGE brand was “high-end” and sold at premium prices, their denim jeans selling at around four times the price of the Sage + Paige denim products. The respondent’s products are clearly looking to a different market than the appellant’s. The items for sale are more “fast” fashion, often dresses, priced at less than $100 each, and the style is (from my perusal of the material provided) not the high-end “soft luxury” California denim style of the appellant, but more a breezy romantic girlish style.

110 From a review of the evidence, the reputation of the PAIGE brand in Australia as at the Priority Date was limited. Despite the borderless nature of the Internet, including the Instagram account, the online articles, magazine articles, and the celebrities wearing the products, there is little in the evidence which links the PAIGE brand with a strong presence in Australia. The appellant summarised the evidence as showing that sales of PAIGE-branded goods to Australian distributors in the years 2015 to 2019 (i.e. the year before the Priority Date) were more than US $8 million. However, in that same period, the global sales of PAIGE-branded goods were over US $580 million. The PAIGE Australian market is a relatively small one. The limited evidence of marketing in Australia and the failure to keep country-specific records underlines a general lack of focus on the Australian market.

111 I find that there was no significant reputation in Australia at the Priority Date for the PAIGE goods. Accordingly, the s 60 ground fails at the issue of reputation. If I am wrong in this, and there was a reputation in Australia at the relevant time, then in my view it was limited to denim. The Instagram account shows a preponderance of denim jeans, as well as the PAIGE brand shirts and tops being worn with denim or in the case of Hilary Duff, wearing a denim shirt. The marketing of PAIGE at the Vogue Fashion’s Night Out event was by providing a cookie in the shape of a jeans pocket, and the International Fashion Group marketing of the David Jones campaign window was captioned on Instagram as “Go and Check out our Paige Denim / David Jones Denim Campaign window at the Elizabeth Street store now! #LIVEINIT”. While I note Mr Lacher’s comment that the appellant could not control how Australian stores or marketers advertised their goods, the brand presence in Australia before the Priority Date did seem to be linked with women’s jeans and in particular denim.

Given PAIGE’s reputation in denim, would the notional use of the Opposed Marks be likely to deceive or cause confusion?

112 In relation to the alternative ground of a reputation in denim, the appellant submitted that again, consumers are likely to be caused to wonder whether there is an association or collaboration between PAIGE and the Opposed Marks given the presence of the leading element of “Sage +”. To the extent that PAIGE’s reputation in Australia was limited to denim jeans, the appellant submitted that Sage + Paige’s notional use of the Opposed Marks would extend to denim and the fact that a collaboration may extend to other forms of clothing “would represent a natural and logical extension in the eyes of the consumer”.

113 The delegate found (at [32], set out in context in [95] above) that any confusion would, if the reputation in denim were upheld, need to be limited to those particular goods.

114 In relation to this outcome, the appellant submitted that the reputation would nevertheless deceive or cause confusion in relation to a number of specifications listed in classes 25 and 35 of Sage + Paige’s applications which would potentially comprise of denim, including, for example, “Apparel (clothing, footwear, headgear)”, “Casual clothing”, “Dance clothing” and so on. If so found, the appellant contended that the respondent’s applications as a whole should fail: Apple Inc at [232].

115 The respondent submitted that this was not correct; the mere fact of a finding of a reputation in denim would only be attributed to the notional consumer in making the relevant comparison, and the differences between the PAIGE goods and those of the respondent would “still negate any deception or confusion”. I agree with this submission. A perusal of the websites of the two brands at the relevant time reveals a significant difference in materials, as well as in price and the likely customers for each brand. The differences in the two brands are striking when it comes to the depiction, style, and marketing of their denim products. The “high-end” nature of the appellant’s goods contrasts with the more accessible and Instagram style of the respondent’s.

116 I have found, in my consideration of s 44, that the marks are not deceptively similar. As with my findings on deceptive similarity, the consumer is likely to see the name “Sage + Paige” as a separate brand rather than to be confused or deceived as to a possible collaboration or other brand association with PAIGE. Even if the notional consumer were making the requisite comparison only in relation to denim, I find that they are not likely to be confused by the marks. The appellant bears the onus of proof in demonstrating the elements of s 60, and in my view has not met that onus.

Orders

1. The appeal be dismissed.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and sixteen (116) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Needham. |

Associate:

Dated: 10 July 2025

Schedule 1

275 Application Goods and Services

Class 14: Amulets (jewelry); Bracelets (jewelry); Bracelets made of embroidered textile (jewelry); Brooches (jewelry); Chains (jewelry); Charms for jewelry; Clasps for jewelry; Cloisonne jewelry; Crucifixes as jewelry; Crucifixes of precious metal, other than jewelry; Gold thread (jewelry); Hat jewelry; Ivory jewelry; Jewelry; Jewelry cases (caskets or boxes); Jewelry charms; Jewelry findings; Jewelry hat pins; Jewelry hatpins; Jewelry of yellow amber; Jewelry rolls; Lockets (jewelry); Necklaces (jewelry); Pearls (jewelry); Pins (jewelry); Rings (jewelry); Shoe jewelry; Silver thread (jewelry); Threads of precious metal (jewelry); Wire of precious metal (jewelry)

Class 18: Handbags; Handbags made of imitation leather; Handbags made of leather; Ladies handbags; Travelling handbags; Beauty cases (not fitted); Card cases (notecases); Cases, of leather or leatherboard; Cosmetic cases (not fitted); Credit card cases; Key cases; Leather cases; Make-up cases; Bags for sports; Bags made of imitation leather; Bags made of leather; Casual bags; Clutch bags; Cosmetic bags (not fitted); Evening bags; Gym bags; Jewellery bags (empty); Knitting bags; Leather bags; Luggage bags; Make-up bags; Messenger bags; Pouches (bags); Shopping bags; Shoulder bags; Shoulder bags for use by children; Sling bags; Tote bags; Travel bags; Waist bags; Weekend bags; Wristlets (bags); Clutch purses; Evening purses; Leather purses; Purses; Satchels