FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v M101 Nominees Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 8) [2025] FCA 741

File number: | VID 524 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | BUTTON J |

Date of judgment: | 9 July 2025 |

Catchwords: | BANKING AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS – whether entity associated with the Second Defendant conducted a financial services business without an Australian financial services licence – whether statutory definition of debenture in s 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) is only satisfied where the arrangement would be recognised as a debenture at common law – whether entity operated an unregistered managed investment scheme as defined in s 9 of the Corporations Act, or made available a facility through which investors made a financial investment as defined in s 763B of the Corporations Act, in circumstances where investors’ entitlements were limited to fixed interest payments and the repayment of principal upon maturity of their investment, and no direct investor evidence was adduced – whether no Australian financial services licence required on the basis of arrangements being credit facilities for the purposes of reg 7.1.06A of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) CONSUMER LAW – principles for attributing characteristics to the hypothetical representative member of the class of persons to whom the conduct is directed CORPORATIONS – financial products offered by entities associated with the Second Defendant – whether conduct (particularly the dissemination of promotional and marketing materials) conveyed representations – whether conduct was misleading or deceptive – whether representations were false or misleading – whether entities associated with the Second Defendant contravened s 1041H of the Corporations Act and ss 12DA and 12DB(1)(a) and (e) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) CONSUMER LAW – knowledge required to be an accessory in the sense described in Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 (Yorke v Lucas) in respect of implied representations CORPORATIONS – relief under s 1101B of the Corporations Act – where relief sought against a person other than the primary contravener – whether relief against a person other than the primary contravener is available under s 1101B of the Corporations Act without establishing Yorke v Lucas involvement – whether the Second Defendant was associated with, or involved in, the contraventions – matters relevant to relief under s 1101B of the Corporations Act |

Legislation: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) ss 12BAA, 12BAB, 12BB, 12DA, 12DB, 19, 33 Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Sch 2 (Australian Consumer Law) ss 4, 18, 21, 29 Corporate Law Economic Reform Program Act 1999 (Cth) Sch 3 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 9, 19, 79, 92, 283AA, 283AB, 283AC, 283BF, 283BH, 283DA, 283DB, 283EA, 461, 472, 533, 708, 761A, 761G, 762A, 763A, 763B, 764A, 765A, 766A, 766C, 769B, 769C, 911A, 912C, 1041H, 1101B, 1305, 1324 Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Act 2009 (Cth) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 63 Financial Services Reform Act 2001 (Cth) Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) ss 51A, 52, 75B Treasury Laws Amendment (2023 Law Improvement Package No 1) Act 2023 (Cth) Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) regs 7.1.06, 7.1.06A Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 16.08, 16.33 Explanatory Memorandum, Corporate Law Economic Reform Bill 1998 (Cth) Explanatory Memorandum, Financial Services Reform Bill 2001 (Cth) Revised Explanatory Memorandum, Corporations Legislation Amendment (Financial Services Modernisation) Bill 2009 (Cth) Bills of Sale and Other Instruments Act 1955 (Qld) s 6 |

Cases cited: | ABN AMRO Bank NV v Bathurst Regional Council [2014] FCAFC 65; (2014) 224 FCR 1 Adams v Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2017] FCAFC 228; (2017) 258 FCR 257 Adler v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2003] NSWCA 131; (2003) 46 ACSR 504 All Options Pty Ltd v Flightdeck Geelong Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 588 Anchorage Capital Master Offshore Ltd v Sparkes [2023] NSWCA 88; (2023) 111 NSWLR 304 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 ALR 73 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v IMB Group Pty Ltd [2003] FCAFC 17 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1800; (2001) 115 FCR 442 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Universal Sports Challenge Ltd [2002] FCA 1276 Australian Karting Association Ltd v Karting (New South Wales) Incorporated [2022] NSWCA 188 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Caddick [2021] FCA 1443; (2021) 395 ALR 481 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Dunjey [2023] FCA 361 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Edwards [2004] QSC 344 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Emu Brewery Mezzanine Ltd [2004] WASC 241; (2004) 52 ACSR 168 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Finder Wallet Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 228 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Great Northern Developments Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 1087; (2010) 79 ACSR 684 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hopkins [2024] FCA 1371 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Karl Suleman Enterprises Pty Ltd (in liq) [2003] NSWSC 400; (2003) 45 ACSR 401 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kaur [2023] FCA 599 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v M101 Nominees Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1166; (2020) 147 ACSR 537 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v M101 Nominees Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 354; (2021) 153 ACSR 230 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v M101 Nominees Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 62 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Maxwell [2006] NSWSC 1052; (2006) 59 ACSR 373 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 494 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1630 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 247 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mitchell (No 2) [2020] FCA 1098; (2020) 382 ALR 425 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MLC Nominees Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1306; (2020) 147 ACSR 266 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v NGS Crypto Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] FCA 822 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2009] NSWSC 1229; (2009) 75 ACSR 1 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Secure Investments Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 1463; (2020) 148 ACSR 154 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Sydney Investment House Equities Pty Ltd [2008] NSWSC 1224; (2008) 69 ACSR 1 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Web3 Ventures Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 58 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) [2018] FCA 751; (2018) 266 FCR 147 Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd v Lloyd [2021] FCAFC 187; (2021) 156 ACSR 273 Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Ptd Ltd [2004] HCA 60; (2004) 218 CLR 592 Certain Lloyd’s Underwriters v Cross [2012] HCA 56; (2012) 248 CLR 378 Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 25; (2015) 230 FCR 298 DZY (a pseudonym) v Trustees of the Christian Brothers [2025] HCA 16; (2025) 99 ALJR 806 Edmonds v Blaina Furnaces Co (1887) 36 Ch D 215 Emu Brewery Mezzanine Ltd (in liq) v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2006] WASCA 105; (2006) 32 WAR 204 Fasold v Roberts (1997) 70 FCR 489 Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; (2012) 247 CLR 486 Gillette Australia Pty Ltd v Energizer Australia Pty Ltd [2002] FCAFC 223; (2002) 193 ALR 629 Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2013] HCA 1; (2013) 249 CLR 435 Handevel Pty Ltd v Comptroller of Stamps (Vic) (1985) 157 CLR 177 Harman v Secretary of State for the Home Department [1983] 1 AC 280 Henjo Investments Pty Ltd v Collins Marrickville Pty Ltd (No 1) (1988) 39 FCR 546 Hoh v Ying Mui Pty Ltd [2019] VSCA 203 Invisalign Australia Pty Ltd v SmileDirectClub LLC [2024] FCAFC 46 Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 Keller v LED Technologies Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 55; (2010) 185 FCR 449 Kelly v R [2004] HCA 12; (2004) 218 CLR 216 King v GIO Australia Holdings Ltd [2001] FCA 308; (2001) 184 ALR 98 Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; (2011) 243 CLR 361 Levy v Abercorris Slate and Slab Co (1887) 37 Ch D 260 Lloyd v Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 2177; (2019) 377 ALR 234 Loxton v Moir (1914) 18 CLR 360 Master Wealth Control Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2024] FCAFC 171; (2024) 306 FCR 462 Mawhinney v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 159; (2022) 294 FCR 375 Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 170; (2022) 295 FCR 106 Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy [2003] FCAFC 289; (2003) 135 FCR 1 Mikasa (NSW) Pty Ltd v Festival Stores (1972) 127 CLR 617 National Australia Bank Ltd v Norman [2009] FCAFC 152; (2009) 180 FCR 243 Owners of the Ship “Shin Kobe Maru” v Empire Shipping Co Inc (1994) 181 CLR 404 Productivity Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2024] HCA 27; (2024) 419 ALR 30 Quinlivan v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2004] FCAFC 175; (2004) 160 FCR 1 Re Austral Mining Construction Pty Ltd [1993] 1 Qd R 358 Re Bauer Securities Pty Ltd (1990) 4 ACSR 328 Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in prov liq); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 41 ACSR 72 Re Idylic Solutions Pty Ltd; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hobbs [2013] NSWSC 106; (2013) 93 ACSR 421 Re St George’s Development Company Pty Ltd (in liq) [2022] VSC 295; (2022) 68 VR 110 Re Vault Market Pty Ltd [2014] NSWSC 1641 Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 277 CLR 186 Taco Co of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 Weissensteiner v R (1993) 178 CLR 217 Yorke v Lucas (1985) 158 CLR 661 |

Division: | General |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | 1190 |

Date of last submission/s: | 9 May 2025 |

Date of hearing: | 28 – 31 October 2024, 1, 6 – 8, 12, 15 and 22 November 2024, 5 and 25 – 28 February 2025 |

Counsel for the Plaintiff: | M Borsky KC with C Tran, D Fuller, N Congram and J Nikolic |

Solicitor for the Plaintiff: | MinterEllison |

Counsel for the Second Defendant: | M Pearce SC and J Condon KC with C Thompson, P Donovan, R Campbell and S Crock |

Solicitor for the Second Defendant: | Roberts Gray Lawyers |

ORDERS

VID 524 of 2020 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF M101 NOMINEES PTY LTD

| ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | |

AND: | M101 NOMINEES PTY LTD First Defendant | |

JAMES MAWHINNEY Second Defendant | ||

SUNSEEKER HOLDINGS PTY LTD Third Defendant | ||

order made by: | BUTTON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 July 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to make any further submissions on relief within 21 days of the publication of these reasons, limited to 15 pages.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

1. INTRODUCTION | [1] |

2. BACKGROUND, WITNESSES AND THE REMITTER | [5] |

2.1 Lay evidence | [11] |

2.2 Expert evidence | [13] |

2.2.1 Mr Tracy | [13] |

2.2.2 Mr Meredith | [17] |

2.2.3 Mr Quinn | [19] |

2.2.4 Mr Jahani | [20] |

3. A PRELIMINARY ISSUE: JONES V DUNKEL IN PENALTY PROCEEDINGS | [23] |

4. FACTS | [30] |

4.1 The Mayfair Group business | [31] |

4.2 The main players: who’s who | [33] |

4.3 Dunk Island and the Mission Beach area: Mr Mawhinney’s “tourism mecca” vision | [42] |

4.4 The M Notes | [57] |

4.5 The marketing material by which the M Notes were promoted | [64] |

4.6 The last quarter of calendar 2019: negative media, difficulty settling on acquisitions, obtaining external funding from Naplend | [66] |

4.7 Variations to the Naplend Facility Agreement in January, February and May 2020 | [72] |

4.8 The Security Trustee and the security structure | [82] |

4.8.1 The loan by M101 Nominees to Eleuthera: whether a 10-year term, or advances were payable on 12-month terms | [87] |

4.8.2 The value of the Eleuthera loan given Eleuthera’s balance sheet | [93] |

4.8.3 The debt to equity swap | [95] |

4.8.4 The value of properties held and thereby the units held in the property holding trusts | [131] |

4.9 Liquidity Prudency Policy | [138] |

4.10 Legal advice obtained | [163] |

4.10.1 IPO Capital: accounting and legal advice concerning whether an AFSL was required | [166] |

4.10.2 M Notes: legal advice regarding marketing materials | [175] |

4.10.2.1 Intersection of advice on marketing material and the M Core Notes security structure | [199] |

4.10.2.2 Conclusion on advice regarding the M Notes marketing materials | [209] |

4.10.3 The Liquidity Prudency Policy and the Liquidity Prudency Policy Decision: legal advice regarding disclosure | [213] |

4.10.4 Australian Property Bonds: legal advice regarding marketing materials | [224] |

4.11 Interactions with ASIC | [225] |

4.11.1 Interactions regarding IPO Capital | [226] |

4.11.2 Interactions concerning (or relevant to) the M Notes | [240] |

4.12 Legal proceedings commenced in April 2020 leading to the appointment of liquidators and the making of injunctions | [248] |

4.13 M101 Nominees’ business model | [263] |

4.13.1 The flow of funds | [275] |

4.13.2 The terms of the Eleuthera loan and its recoverability | [279] |

4.13.3 Cashflow: income-producing capacity and redemption assumptions | [283] |

4.13.4 The impact of COVID-19 and ASIC’s actions | [314] |

4.13.5 Conclusions on the M101 Nominees business model | [318] |

5. FINANCIAL SERVICES BUSINESS ALLEGATIONS | [320] |

5.1 Statutory provisions | [322] |

5.1.1 Debentures | [325] |

5.1.2 Unregistered managed investment schemes | [327] |

5.1.3 Financial investment | [330] |

5.2 Relevant facts | [333] |

5.3 Did IPO Capital issue debentures? | [343] |

5.3.1 The parties’ arguments | [344] |

5.3.2 The statutory and common law concept of a debenture | [350] |

5.3.3 Mr Mawhinney’s argument based on other provisions of the Corporations Act concerning debentures | [388] |

5.3.4 The potential “working capital” criterion | [391] |

5.3.5 Mr Mawhinney’s “antecedent debt” argument | [394] |

5.3.6 IPO Capital issued debentures | [400] |

5.4 Did IPO Capital make available a facility by which persons made financial investments? | [410] |

5.5 Did IPO Capital issue interests in a managed investment scheme? | [442] |

5.5.1 Pleading issue | [443] |

5.5.2 Consideration | [448] |

5.6 Did IPO Capital carry on a financial services business? | [471] |

5.7 Mr Mawhinney’s “credit facility” argument | [479] |

5.8 Did IPO Capital carry on a business in this jurisdiction? | [491] |

5.9 Over what period did IPO Capital carry on a financial services business? | [492] |

6. MISLEADING OR DECEPTIVE CONDUCT ALLEGATIONS: GENERAL MATTERS | [502] |

6.1 Principles concerning misleading or deceptive conduct allegations | [502] |

6.2 The characteristics of the hypothetical member (or members) of the class | [505] |

6.3 Whether ASIC’s case was limited to considering all forms of marketing material as a whole in determining whether representations were made | [532] |

6.4 Who engaged in the conduct by which any representations relating to the M Notes were made? | [550] |

6.4.1 The Mayfair Platinum website | [557] |

6.4.2 The Term Deposit Guide website | [562] |

6.4.3 The M Core Notes brochure | [566] |

6.4.4 The M+ Notes brochure | [569] |

6.4.5 The Mayfair Group corporate brochure | [572] |

6.4.6 The newspaper advertisements | [579] |

6.4.7 The EDMs | [588] |

6.4.8 Google and Bing advertising | [593] |

6.5 Representations as to future matters | [601] |

6.6 Did M101 Holdings provide a financial service by issuing the M+ Notes, and did M101 Nominees provide a financial service by issuing the M Core Notes? | [614] |

6.7 Other elements of contraventions regarding the M Notes and the Australian Property Bonds: financial product, jurisdiction in which the conduct occurred | [619] |

7. MISREPRESENTATIONS: BANK TERM DEPOSIT REPRESENTATION | [627] |

7.1 Was the Bank Term Deposit Representation made? | [629] |

7.1.1 The Mayfair Platinum website | [632] |

7.1.2 The Term Deposit Guide website | [644] |

7.1.3 The M Core Notes brochure | [652] |

7.1.4 The M+ Notes brochure | [659] |

7.1.5 The Mayfair Group corporate brochure | [666] |

7.1.6 The newspaper advertisements | [672] |

7.1.7 The EDMs | [679] |

7.1.8 Google and Bing advertising | [689] |

7.2 Was the Bank Term Deposit Representation misleading or deceptive? | [695] |

7.3 Did one or more of M101 Nominees, Australian Income Solutions, M101 Holdings and Online Investments trading as Mayfair 101 contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB(1)(a) and (e) of the ASIC Act? | [700] |

8. MISREPRESENTATIONS: REPAYMENT REPRESENTATION | [702] |

8.1 Was the Repayment Representation made? | [703] |

8.1.1 The Mayfair Platinum website | [704] |

8.1.2 The Term Deposit Guide website | [707] |

8.1.3 The M Core Notes brochure | [710] |

8.1.4 The M+ Notes brochure | [713] |

8.1.5 The Mayfair Group corporate brochure | [715] |

8.1.6 The newspaper advertisements | [717] |

8.1.7 The EDMs | [719] |

8.1.8 Google and Bing advertising | [723] |

8.1.9 Mr Mawhinney’s argument that the Repayment Representation was not made | [724] |

8.2 Was the Repayment Representation misleading or deceptive? | [726] |

8.3 Did one or more of M101 Nominees, Australian Income Solutions and M101 Holdings contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB(1)(a) and (e) of the ASIC Act? | [732] |

9. MISREPRESENTATION: NO RISK OF DEFAULT REPRESENTATION | [735] |

9.1 Was the No Risk of Default Representation made? | [736] |

9.1.1 The Mayfair Platinum website | [737] |

9.1.2 The Term Deposit Guide website | [744] |

9.1.3 The M Core Notes brochure | [745] |

9.1.4 The M+ Notes brochure | [748] |

9.1.5 The Mayfair Group corporate brochure | [752] |

9.1.6 The newspaper advertisements | [754] |

9.1.7 The EDMs | [757] |

9.1.8 Google and Bing advertising | [759] |

9.2 Was the No Risk of Default Representation misleading or deceptive? | [760] |

9.3 Did one or more of M101 Nominees, Australian Income Solutions, M101 Holdings and Online Investments trading as Mayfair 101 contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB(1)(a) and (e) of the ASIC Act? | [770] |

10. MISREPRESENTATIONS: SECURITY REPRESENTATION | [774] |

10.1 Pleading issue | [775] |

10.2 Was the Security Representation made? | [798] |

10.2.1 The Mayfair Platinum website | [800] |

10.2.2 The M Core Notes brochure | [805] |

10.2.3 The M Core launch advertisement | [809] |

10.2.4 The 4 November 2019 EDM | [811] |

10.3 Was the Security Representation misleading or deceptive? | [813] |

10.3.1 M101 Nominees’ bank account | [816] |

10.3.2 M101 Nominees’ other assets (mainly the loan to Eleuthera) | [818] |

10.3.3 Units held by Sunseeker in the unit trusts | [828] |

10.3.4 Assets of the trustees (other than real estate) | [848] |

10.3.5 Single mortgage over real estate | [849] |

10.3.6 Conclusions on whether the Security Representation was misleading or deceptive | [850] |

10.4 Did one or more of M101 Nominees and Australian Income Solutions contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB(1)(a) and (e) of the ASIC Act? | [854] |

11. LIQUIDITY PRUDENCY POLICY CONTRAVENTIONS | [857] |

11.1 Was the omission of reference to the Liquidity Prudency Policy and/or the Liquidity Prudency Policy Decision from the marketing material and investor updates post-11 March 2020 conduct that was misleading or deceptive? | [860] |

11.1.1 ASIC’s allegations | [860] |

11.1.2 Was the continued promotion of the M Notes while failing to disclose the Liquidity Prudency Policy and/or the Liquidity Prudency Policy Decision conduct that was misleading or deceptive? | [870] |

11.1.3 Who engaged in the impugned conduct? | [883] |

11.1.4 Did one or more of M101 Nominees, M101 Holdings and/or Australian Income Solutions contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act and/or s 12DA of the ASIC Act? | [888] |

11.2 Misrepresentations: Redemptions Not Frozen Representation | [890] |

11.2.1 Was the Redemptions Not Frozen Representation made? | [890] |

11.2.2 Was the Redemptions Not Frozen Representation misleading or deceptive? | [895] |

11.2.3 Did one or more of M101 Nominees, Australian Income Solutions and M101 Holdings contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB of the ASIC Act? | [896] |

12. AUSTRALIAN PROPERTY BONDS CONTRAVENTIONS | [899] |

12.1 Was the Property Bonds Security Representation made? | [905] |

12.1.1 The EDMs | [908] |

12.1.2 The Australian Property Bonds brochure and the Australian Property Bond Agreement | [918] |

12.2 Was the Property Bonds Security Representation misleading or deceptive? | [926] |

12.3 Who conveyed the Property Bonds Security Representation (if it was conveyed)? | [937] |

12.4 Did Australian Income Solutions contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB(1)(a) and (e) of the ASIC Act? | [943] |

13. INVESTOR RR CONTRAVENTION | [961] |

13.1 The Wongaling Beach Property Representation | [961] |

13.2 Was the Wongaling Beach Property Representation made? | [962] |

13.3 Was the Wongaling Beach Property Representation misleading or deceptive? | [977] |

13.4 Who conveyed the Wongaling Beach Property Representation? | [980] |

13.5 Did one or both of Australian Income Solutions and Mainland Property Holdings contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB of the ASIC Act? | [984] |

14. THE ON-LENDING TO FAMILY CONTRAVENTIONS | [986] |

14.1 Did the family trusts each receive amounts traceable to funds invested in the M Core Notes? | [992] |

14.2 Conduct case | [1007] |

14.2.1 Was the omission of information relating to the transfer of funds to entities associated with Mr Mawhinney’s family in the M Core Notes brochure by Australian Income Solutions and M101 Nominees misleading or deceptive? | [1007] |

14.2.2 Did one or more of M101 Nominees and Australian Income Solutions contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act and/or s 12DA of the ASIC Act by the omission (in the M Core Notes brochure) of information relating to the transfers to the family trusts? | [1016] |

14.3 Representation case | [1018] |

14.3.1 Was the Core Notes Use Representation made? | [1018] |

14.3.2 Was the Core Notes Use Representation misleading or deceptive? | [1021] |

14.3.3 Did one or both of M101 Nominees and Australian Income Solutions contravene s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the ASIC Act and/or s 12DB of the ASIC Act by making the Core Notes Use Representation? | [1023] |

15. RELIEF | [1024] |

15.1 Preliminary matter: Mr Mawhinney’s request to make further submissions on relief after findings on contraventions | [1024] |

15.2 Principles: s 1101B of the Corporations Act | [1030] |

15.3 The basis upon which ASIC seeks orders under s 1101B of the Corporations Act against Mr Mawhinney: whether Yorke v Lucas involvement must be established | [1040] |

15.4 Mr Mawhinney’s association with, and involvement in, the contravening conduct | [1049] |

15.4.1 Knowledge requirements for Yorke v Lucas “involvement” | [1051] |

15.4.2 Overarching matters concerning Mr Mawhinney’s role in the activities and affairs of the Mayfair Group | [1080] |

15.4.3 Association with IPO Capital’s contravention of s 911A of the Corporations Act | [1085] |

15.4.4 Association with contraventions relating to misleading or deceptive conduct: Mr Mawhinney’s knowledge of the characteristics of the target audience | [1102] |

15.4.5 Association with contraventions concerning the Bank Term Deposit Representation, Repayment Representation and No Risk of Default Representation | [1105] |

15.4.6 Association with contraventions concerning the Security Representation | [1127] |

15.4.7 Association with contraventions concerning the Liquidity Prudency Policy | [1134] |

15.4.8 Association with contraventions concerning the Australian Property Bonds | [1149] |

15.4.9 Association with alleged contraventions concerning Mr RR | [1160] |

15.4.10 Association with on-lending to family alleged contraventions | [1163] |

15.5 Other matters relevant to relief (whether on the “association” basis, or the Yorke v Lucas involvement basis) | [1168] |

16. CONCLUSION | [1190] |

BUTTON J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 ASIC seeks orders under s 1101B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) effectively precluding James Mawhinney, the Second Defendant, from having any involvement in the offering or promotion of any financial product for a period of 20 years. ASIC seeks that relief on the basis of Mr Mawhinney’s alleged involvement in (or association with) a number of alleged contraventions of the Corporations Act and/or the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) by companies in the Mayfair Group (defined below).

2 The contraventions alleged mostly concern the marketing of the M Core Fixed Income Notes (M Core Notes), issued by M101 Nominees Pty Ltd (M101 Nominees), the M+ Fixed Income Notes (M+ Notes), issued by M101 Holdings Pty Ltd (M101 Holdings), and the Australian Property Bonds. The Australian Property Bonds were to be issued by property holding trustee companies in the Mayfair Group (although only two or three such bonds were actually issued). ASIC alleged that misleading or deceptive conduct occurred in the marketing of those products.

3 The date ranges over which the marketing material regarding the M Core Notes and M+ Notes (together referred to as the M Notes) was issued varied, but the broad period in issue is between June 2019 and mid-April 2020. Allegations concerning the alleged failure to disclose that redemptions in the M Notes had been frozen focus on the period from 11 March 2020 to early April 2020. Allegations concerning the Australian Property Bonds focus on the period from 22 April 2020 to late June 2020.

4 ASIC also alleged that, between 2016 and “at least December 2017”, another company associated with Mr Mawhinney, IPO Capital Pty Ltd (IPO Capital), contravened s 911A of the Corporations Act on the basis that it required, but did not have, an Australian financial services licence (AFSL). As may be seen, this set of allegations has a different legal and temporal focus from the allegations concerning the M Notes and the Australian Property Bonds.

2. BACKGROUND, WITNESSES AND THE REMITTER

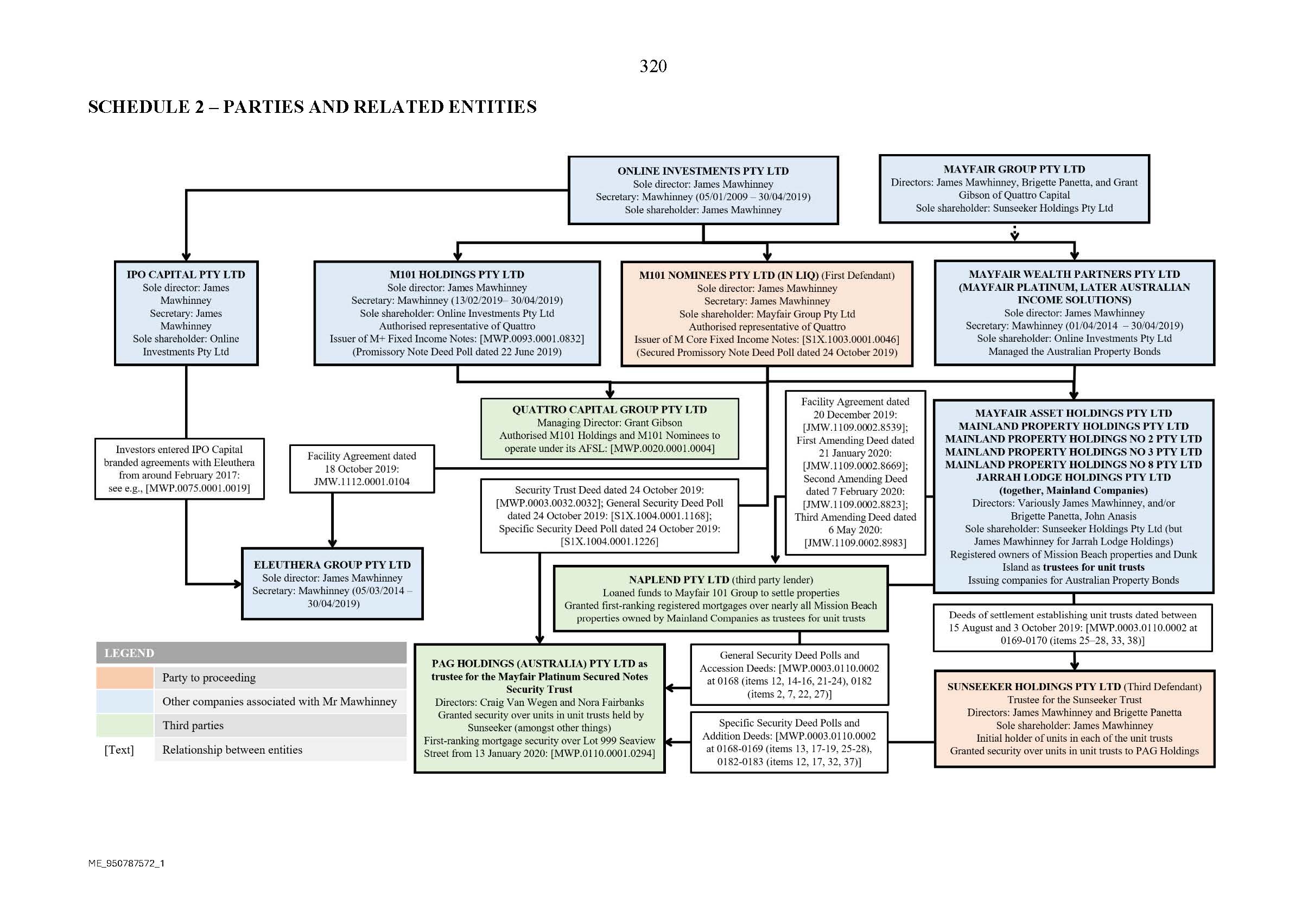

5 The course of the litigation brought by ASIC against Mr Mawhinney and companies in the Mayfair Group is set out in more detail below (at paragraphs 248–262). The companies relevant to the issues in this proceeding, which I refer to as the Mayfair Group, are set out in the corporate structure chart at Annexure A to these reasons (which reproduces the chart prepared by ASIC). It serves, to put the proceeding in context, to record here that the present proceeding was commenced by ASIC on 10 August 2020. By orders made on 19 April 2021, a judge of this Court made final orders under s 1101B of the Corporations Act effectively precluding Mr Mawhinney from pursuing any business involving the soliciting of investments in financial products, including the M Notes and the Australian Property Bonds. Reasons were published: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v M101 Nominees Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 354; (2021) 153 ACSR 230.

6 Mr Mawhinney appealed. On 15 September 2022, the Full Court of the Federal Court allowed Mr Mawhinney’s appeal, concluding that Mr Mawhinney had been denied procedural fairness. There had been a denial of procedural fairness because the primary judge concluded that contraventions of provisions of the Corporations Act had occurred, which contraventions provided the foundation for the exercise of the powers conferred by s 1101B of the Corporations Act against Mr Mawhinney, even though ASIC brought the case on the basis that it was not necessary for it to establish, and it did not allege, that there had been such contraventions: Mawhinney v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 159; (2022) 294 FCR 375 (Mawhinney Full Court).

7 The Full Court’s orders, amongst other things, remitted the proceeding for hearing by a judge other than the primary judge on the basis of such further evidence and submissions as the parties wished to adduce and put respectively, and such further case management orders as the judge to whom the matter was remitted thought fit.

8 It was common ground that, as the proceeding was subject to a remitter (and not an order for an entirely new trial), evidence that had been adduced in the initial trial was still before the Court on the remitter, subject to any orders of the Court disturbing that position.

9 Following the Full Court’s orders allowing Mr Mawhinney’s appeal, ASIC pleaded, fulsomely, its case alleging contraventions of various provisions of the Corporations Act and the ASIC Act. The myriad alleged contraventions, and the plethora of marketing material on which ASIC’s case was based, account for the regrettable length of these reasons. I have summarised my findings with respect to ASIC’s misleading and deceptive conduct allegations in the table at Annexure C to these reasons. While accepting that the evidence in the initial trial was still (other than immaterial exceptions) before me on the trial of the remitter, ASIC essentially jettisoned reliance on the earlier evidence, and built its evidentiary case from the ground up. It tendered an extensive set of documents, called its lay witnesses (many of whom were cross-examined) and relied on fresh expert evidence.

10 I will introduce some aspects of that evidence.

2.1 Lay evidence

11 ASIC relied on the evidence of 12 lay investor witnesses. Those witnesses participated, either personally or through personal corporate or superannuation vehicles, in the investment products at issue in this proceeding. While I have not had much recourse to their evidence in determining the liability issues below, many of them suffered significant financial losses, illustrating the potential harm to which investors were exposed.

12 In its closing submissions, ASIC referred to, and annexed, summaries of the lay witnesses’ evidence, including aspects of their evidence in cross-examination. Mr Mawhinney accepted that ASIC’s summaries were fair summaries of their evidence. Accordingly, it is not necessary for me to resolve any factual disputes about their evidence, or burden these reasons with freshly crafted summaries. ASIC’s summaries of the investor evidence are reproduced as Annexure B to these reasons, with the investors’ full names replaced with their initials, footnotes omitted and investor Mr RR omitted (as his investment is addressed in Part 13 of these reasons).

2.2 Expert evidence

2.2.1 Mr Tracy

13 Mr Jason Tracy is a chartered accountant and registered liquidator. Mr Tracy was engaged by ASIC prior to the commencement of this proceeding and to provide expert evidence in the initial trial of this proceeding on matters including the nature and extent of any security protecting the M Core Notes. He prepared one expert report dated 12 June 2020 and two supplementary reports dated 12 August 2020 and 14 September 2020. These reports were annexed to an affidavit of Mr Tracy affirmed on 24 November 2020, which was read into evidence at the initial trial.

14 Mr Tracy was cross-examined — albeit on limited issues — at the initial trial. By an interlocutory application dated 25 September 2024, Mr Mawhinney sought orders recalling Mr Tracy for further cross-examination on the remitter. Mr Mawhinney submitted that because ASIC had been “permitted to run a very different case” on the remitter, he should not be bound by the forensic decisions made in the initial trial with respect to Mr Tracy’s cross-examination. He also submitted that Mr Tracy made significant concessions in the course of cross-examination in the related Mayfair proceeding (discussed in further detail from paragraph 248 below), which was undefended on liability but defended on penalty. Mr Mawhinney sought to recall Mr Tracy in the present proceeding to obtain those concessions in this proceeding.

15 For reasons given on the transcript, I determined that the application to recall Mr Tracy should be allowed, on a limited basis.

16 Mr Tracy was recalled on 8 November 2024, and was cross-examined on the limited basis permitted. ASIC did not rely on his evidence, having briefed Mr Meredith since the initial trial, although it referred to Mr Tracy’s evidence at two points in its written closing submissions (on the recoverability of the loan made by M101 Nominees to Eleuthera Group Pty Ltd (Eleuthera) and the defects in the security structure; both topics to which I return below).

2.2.2 Mr Meredith

17 Mr Greg Meredith is an experienced forensic accountant. ASIC tendered his report, dated 30 August 2024, along with a letter dated 18 October 2024, in which Mr Meredith made some corrections to his report. His evidence concerned (amongst other matters) how funds obtained from investors were applied, aspects of the M Core Notes security structure, the value of that security and reports provided to the security trustee, PAG Holdings (Australia) Pty Ltd (PAG or Security Trustee).

18 Mr Meredith was cross-examined by Mr Mawhinney’s counsel for the better part of one sitting day, principally in relation to his views on the nature and value of the M Core Notes security structure. I refer to Mr Meredith’s evidence below principally in relation to aspects of the security structure and the debt to equity swap.

2.2.3 Mr Quinn

19 Mr Mark Quinn is an expert property valuer called by ASIC. He prepared an expert report dated 16 August 2024 and a supplementary report dated 30 September 2024. Mr Quinn’s reports concerned the value of properties held by companies in the Mayfair Group. Mr Quinn was cross-examined on how his valuations were conducted (from the “kerbside”), certain of his valuation opinions, changes to the value of properties in the Mission Beach area and rental yields that might reasonably be expected. I refer to Mr Quinn’s evidence in relation to the value of the units held in the property holding trusts and the M101 Nominees business model below.

2.2.4 Mr Jahani

20 Mr Said Jahani was initially appointed, with a colleague, as provisional liquidator of M101 Nominees (the issuer of the M Core Notes) on 13 August 2020, and was then appointed liquidator (again with his colleague) on 29 January 2021. Mr Jahani provided a provisional report dated 24 September 2020 pursuant to directions of this Court (Court Report), a statutory report dated 29 April 2021 (Statutory Report) and a supplementary report dated 15 August 2024 (Jahani Report), the latter of which ASIC tendered on the remitter (over the objection of Mr Mawhinney). ASIC principally relied on Mr Jahani’s evidence regarding the solvency of M101 Nominees on the basis that that topic is relevant to relief under s 1101B of the Corporations Act (cf relying on his reports to establish contraventions).

21 Mr Jahani was cross-examined by Mr Mawhinney’s counsel at length (two full days). Mr Mawhinney has advanced serious criticisms of Mr Jahani, both in relation to his evidence and his conduct, effectively blaming Mr Jahani, and his Court Report in particular, for M101 Nominees being put into liquidation.

22 Mr Jahani’s evidence is addressed in more detail below, where it arises in relation to the issues for determination.

3. A PRELIMINARY ISSUE: JONES V DUNKEL IN PENALTY PROCEEDINGS

23 The trial was conducted on the basis that Mr Mawhinney was entitled to the privilege against exposing himself to a penalty. Given that the trial was conducted on that basis, with ASIC’s concurrence, it is not necessary to scrutinise whether that be so where the “penalty” sought by ASIC comprises orders under s 1101B of the Corporations Act.

24 In commencing his oral closing submissions, counsel for Mr Mawhinney said that “it is not permissible, generally, to draw a Jones v Dunkel inference in a civil penalty proceeding” (referring to the principle derived from Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 (Jones v Dunkel)). Counsel cited Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1800; (2001) 115 FCR 442 (Universal Music) at [33] (Hill J) in support. There, Hill J said (emphasis added):

Where the proceedings are criminal (and the present proceedings are not; they are proceedings, inter alia, for the recovery of a civil penalty) it might be thought that the failure of the accused to go into evidence should not lead to the drawing of Jones v Dunkel inferences. After all it is clear that a witness can not be compelled to give evidence which is likely to incriminate the witness or expose the witness to a penalty. However, even in criminal cases it has been held that the failure of the accused, who is in a position to deny, explain or answer the evidence adduced by the prosecution, to give evidence will permit the jury to draw inferences adverse to the accused more readily: see Azzopardi v The Queen (2001) 205 CLR 50; 179 ALR 349, affirming Weissensteiner v The Queen (1993) 178 CLR 217. A fortiori, therefore, the failure of a respondent to proceedings for recovery of a pecuniary penalty to give evidence on a matter relevant to an issue in the proceeding and deny, explain or answer the evidence adduced against the respondent will permit the Court more readily to draw the inferences to which the decision in Jones v Dunkel refers.

25 While the submission may have initially been framed in rather sweeping terms — or much is contained in the qualification, “generally” — Mr Mawhinney’s position was ultimately that no Jones v Dunkel adverse inference can be drawn against him unless the evidence adduced by ASIC is such that it calls for some evidence to explain, answer or deny that evidence.

26 To that extent, Mr Mawhinney’s submission is consistent with the way Hill J put it in Universal Music at [33]. The submission is also consistent with the observations of Beach J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mitchell (No 2) [2020] FCA 1098; (2020) 382 ALR 425 at [1678]–[1694], citing Weissensteiner v R (1993) 178 CLR 217 at 227, 229 (Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ); Jones v Dunkel at 308 (Kitto J); Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; (2011) 243 CLR 361 at [63] (Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ); and Re HIH Insurance Ltd (in prov liq); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; (2002) 41 ACSR 72 at [447] (Santow J).

27 For its part, and perhaps understanding the submission put by Mr Mawhinney to be more absolute than it turned out to be, ASIC pointed to a number of cases confirming that Jones v Dunkel inferences may be drawn in civil penalty proceedings: Adler v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2003] NSWCA 131; (2003) 46 ACSR 504 at [652]–[661] (Adler v ASIC) (Giles JA, with whom Mason P and Beazley JA agreed); Adams v Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2017] FCAFC 228; (2017) 258 FCR 257 at [147] (North, Dowsett and Rares JJ), citing Adler v ASIC; Master Wealth Control Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2024] FCAFC 171; (2024) 306 FCR 462 at [38] (Sarah C Derrington, Halley and Shariff JJ); Productivity Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2024] HCA 27; (2024) 419 ALR 30 at [276] (Productivity Partners) (Edelman J).

28 I accept that, as submitted by ASIC, a Jones v Dunkel inference may be available in civil penalty proceedings. However, it must always be borne in mind that Jones v Dunkel inferences do not operate at large to fill in gaps in a party’s case and overcome a want of proof. Rather, Jones v Dunkel allows an available inference to be “more confidently drawn when a person presumably able to put the true complexion on the facts relied on as the ground for the inference has not been called as a witness by the [party against whom the inference would be drawn] and the evidence provides no sufficient explanation of his absence”: Jones v Dunkel at 308 (Kitto J); see also 312 (Menzies J) and 320–321 (Windeyer J).

29 ASIC invited the Court to draw Jones v Dunkel inferences in relation to numerous aspects of its case. As will emerge, as I step through the issues, they all either rise or fall on the evidence. In other words, in respect of the allegations on which ASIC has succeeded, its success has not rested on drawing a Jones v Dunkel inference against Mr Mawhinney. Similarly, in respect of allegations on which ASIC has failed, with the exception of the on-lending to family allegations, its failure has not rested on the failure to draw a Jones v Dunkel inference that it had invited.

4. FACTS

30 The disputed issues largely concern characterisation and consequences, rather than facts. Nevertheless, the issues arising for determination fall to be decided in a particular factual context. That factual context is important in considering whether, and if so what, orders should be made under s 1101B of the Corporations Act.

4.1 The Mayfair Group business

31 The Mayfair Group described itself (in a corporate brochure) as a London-based, Australian-owned investment and corporate advisory group founded in 2009. It said it offered — amongst other services — “wealth management”, involving income-generating investments, pre-IPO opportunities, private equity services and more, for wholesale and high-net-worth investors. The brochure identified “Mayfair Platinum and IPO Wealth Pty Ltd” (IPO Wealth) as its best-known Australian operations, which were said to “provide access to a range of cash-investment alternatives typically only accessed by family offices, investment banks, stockbrokers and ultra-wealthy investors”. Prior to the launch of the M Notes products, the IPO Wealth Fund was one of the primary investment products being marketed by the Mayfair Group. Interactions between ASIC and Mr Mawhinney concerning the IPO Wealth Fund were raised by ASIC in this proceeding on the basis that those interactions are relevant to some of the issues concerning the M Notes (see paragraphs 240–243 below). One of the entities within the Mayfair Group is Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd (Mayfair Wealth). This entity traded as “Mayfair Platinum”, and changed its name to Australian Income Solutions Pty Ltd (Australian Income Solutions) on or about 14 June 2020.

32 By the time this brochure was issued, the Mayfair Group’s services were said to be offered as an authorised representative of an AFSL holder. However, earlier on, fixed term, fixed interest investment opportunities were offered by IPO Capital (also a member of the Mayfair Group). IPO Capital did not offer these investments under an AFSL. Whether it was required to operate under an AFSL is one of the issues arising in this proceeding. As detailed further below, IPO Capital’s pitch to investors was that it raised money from third parties (investors) which it used in making investments on its own account by way of providing debt finance to other companies, making equity investments and purchasing assets. This investment vehicle does not, on the evidence, appear to have any obvious connection with the project to redevelop the Mission Beach region and Dunk Island in Queensland, which were central to other Mayfair Group investment opportunities and attracted much focus in the trial on the remitter.

4.2 The main players: who’s who

33 In addition to Mr Mawhinney, there are a number of individuals who are mentioned in these reasons.

34 Brigette Panetta was Mr Mawhinney’s fiancée and held the roles of “Management Accountant” and “Finance Director” at the Mayfair Group. She was also a director of a number of companies associated with Mr Mawhinney: relevantly, Mayfair Group Pty Ltd, Sunseeker Holdings Pty Ltd (Sunseeker, the Third Defendant) and Jarrah Lodge Holdings Pty Ltd.

35 Devin O’Keefe was part of the Mayfair Group’s sales team, holding the roles of “Investor Relations Manager” and “Client Relationship Manager” of Australian Income Solutions.

36 Michael Divens was the Mayfair Group’s Chief Financial Officer.

37 John Anasis was the Mayfair Group’s “Family Office and Institutional Client Manager”. He was also the Managing Director of The Public Listing Co.

38 Kristiina Lumeste held the roles of “Marketing Manager” and “Group Marketing Manager” at the Mayfair Group.

39 Lhamo Johnson was also a member of the Mayfair Group’s marketing team, holding the role of “Senior Marketing Coordinator”.

40 Nora Fairbanks and Craig van Wegen were directors of PAG, the Security Trustee for the Mayfair Platinum Secured Notes Security Trust (relating to the M Core Notes issued by M101 Nominees).

41 Venn King was a solicitor at KHQ Lawyers, who was retained by the Mayfair Group.

4.3 Dunk Island and the Mission Beach area: Mr Mawhinney’s “tourism mecca” vision

42 Mr Mawhinney’s vision was for the Mayfair Group to acquire property in the Mission Beach area in tropical north Queensland, and revitalise that area, to turn it into a “tourism mecca”. While the origins of this vision are not clear, and Mr Mawhinney did not give evidence, it appears that the project — to turn the Mission Beach area into a “tourism mecca” — was active in earnest by mid-2019. At some point, that vision came to encompass acquiring and redeveloping Dunk Island, which is one of a group of islands off the coast of the Mission Beach area. The funds raised by the issue of the M Notes, and the funds that were hoped to be raised by the issue of the Australian Property Bonds, were to support the pursuit of this vision.

43 From August 2019, contracts were signed for the acquisition of a large number of properties in the Mission Beach region (including Mission Beach itself, South Mission Beach, Wongaling Beach and some other localities in the area). Many of these contracts were entered into by Mainland Property Holdings Pty Ltd (Mainland Property Holdings) as trustee for the Mission Beach Property Trust (MBPT), although there were other property holding companies and related trusts that ultimately acquired some property, or which were party to real estate contracts of sale that did not ultimately settle (including Mainland Property Holdings No 2 Pty Ltd (Mainland Property Holdings No 2) as trustee for the Mission Beach Property Trust No 2 (MBPT No 2), Mainland Property Holdings No 3 Pty Ltd (Mainland Property Holdings No 3) as trustee for the Mission Beach Property Trust No 3 (MBPT No 3), Mainland Property Holdings No 5 Pty Ltd as trustee for the Mission Beach Property Trust No 5 (MBPT No 5), Mainland Property Holdings No 8 Pty Ltd as trustee for the Mission Beach Property Trust No 8 (MBPT No 8), and Jarrah Lodge Holdings Pty Ltd (Jarrah Lodge) as trustee for the Jarrah Lodge Trust).

44 The frenetic pace of the Mayfair Group entities’ purchasing in the Mission Beach area was reflected in Mr Mawhinney’s reference (in a WhatsApp message on 16 August 2019) to going on a “shopping expedition at Mission Beach”. The effect of the real estate market in that area being fuelled by acquisitions by Mayfair Group entities is relevant to some issues in the proceeding, including the value of securities held in respect of the M Core Notes and the financial stability and viability of the Mayfair Group investment structure (principally in respect of M101 Nominees).

45 Dunk Island is located about four kilometres from the coast off Mission Beach. It was badly damaged by Cyclone Larry in 2006 and again by Cyclone Yasi in 2011. It was not rebuilt after Cyclone Yasi. Mayfair Asset Holdings Pty Ltd (Mayfair Asset Holdings) as trustee for the Mayfair Island Trust acquired the freehold to most of Dunk Island in September 2019 for $31.5 million. An email from PAG (the Security Trustee) in March 2020 recorded that (allowing for a deposit) the balance of $27.5 million was financed by a vendor loan with a repayment schedule that would have seen the last $3 million paid by September 2021.

46 While there was some infrastructure on the island (including a 900-metre airstrip, and a disused and damaged resort) in 2019–2020, the Mayfair Group’s plans included considering refurbishment and some upgrades, or a more costly alternative, which involved demolishing the existing resort and building a new one. The cost of the demolition and rebuilding option was estimated (at the concept stage) to be about $150 million.

47 Mr Mawhinney tendered a number of documents directed at establishing that the scheme (to use that word in a legally-neutral sense) being pursued by the Mayfair Group had sufficient income producing capacity such that M101 Nominees was not insolvent from the outset, and the fundraising through the M Notes should not be regarded as exposing investors to a high risk that the issuing entities would be unable to pay the interest due on time and/or repay investors’ principal. These documents were also directed at establishing that the plans for the revitalisation of the Mission Beach/Dunk Island region were not merely a pie-in-the-sky “vision” of Mr Mawhinney. Those documents included architects’ schematic plans and more detailed plans for proposed hotel and resort accommodation, promotional videos, as well as documents produced by LSV Hotels, a hospitality and hotel consultancy business.

48 I accept that these documents show that there was significant work being done to develop and present a considered and professionally supported vision for the region. However, and as those documents reveal, the cost of realising those plans — which were so extensive they also included construction of a new inland marina, and extending the airstrip on Dunk Island — was staggering. One document that assessed the economic impact on the region of the proposals put the cost of construction at $1.68 billion. Another document, being a “Masterplan” with related financials, put the capital expenditure at $1.18 billion. Plans for an area known as “Lugger Bay” included construction of the inland marina, a new golf course and built developments. It was estimated that planning and environmental approvals for Lugger Bay alone would take two to three years and cost $2–3 million. The Masterplan anticipated a mix of arrangements with third party operators and in-house operations, as well as leasing and sales.

49 It is clear, and Mr Mawhinney did not shy away from acknowledging, that the tourism mecca vision would take years and hundreds of millions of dollars to realise. The financial projections in evidence, such as they were, did not break down what portion of the overall costs were expected to be borne by third parties. There was no evidence of any cashflow analysis being prepared that showed how it was anticipated that the costs of paying interest to investors, and repaying principal to investors who did not want to roll over their investments, could be met while this vision was being realised. The cashflows that were in evidence are discussed from paragraphs 157 and 291 below. In answer to the question of how it was proposed to fund interest and redemptions due to investors while the vision was being realised, counsel for Mr Mawhinney answered: “Well, to a great extent, with new people coming in, with fresh debt replacing old debt”.

50 Mr Mawhinney also directed attention to two sources of revenue that were expected in the short to medium term: first, income from leasing properties in the Mission Beach area; and second, income from the redevelopment and re-opening of “The Spit” bar on Dunk Island, in advance of the broader revitalisation and redevelopment of Dunk Island.

51 As to leasing income, Mr Mawhinney tendered leases that had been entered into for some of the properties purchased in the Mission Beach area. An aide memoire prepared in respect of the leases confirms that leases were entered into for approximately 23 properties, with terms varying between two months (putting aside one said only to be “periodic”) to one year for non-commercial properties, and between two and five years for the four properties that were described in terms making it clear they were commercial premises (shops). The rent for the non-commercial properties varied from $0 (if the tenant did gardening), $1 (for a two-month lease) to $6,000 plus GST per month for one property, although most were in the $250–$550 per week range. The commercial premises’ rents ranged from $12,000 to $30,000 per annum, excluding GST ($230–$577 per week). Many of the properties acquired were vacant land, which obviously enough would have limited the capacity to obtain income by leasing them.

52 On ASIC’s calculations, if the rental yields based on leases actually entered into were all annualised (even though many of the leases were for less than a full calendar year), the total rental income would not exceed $473,546.52. Mr Mawhinney contended that gross rental yields of about $2 million could realistically have been achieved. I address that specific contention below.

53 While the leasing income actually secured would have provided some funds, even if annualised at its peak, the leasing income would not have provided any realistic source of income by which to meet either the expenses of pursuing the wider redevelopment vision, or meeting interest payments and redemptions due to investors. To put the leasing income in context, the operating expenses (excluding interest payments and redemptions) actually incurred by the Mayfair Group between January and March 2020, recorded in the Mayfair Group “Consolidated Cash Flow” spreadsheet set out at Appendix 21 to the Jahani Report, ranged from approximately $92,000 to over $950,000 per week.

54 Similarly, a document prepared to “pitch” to a third party lender (discussed further below at paragraph 289) recorded anticipated holding costs for the planned property portfolio at $4.06 million per annum against an anticipated gross rental yield for the entire portfolio of $3.21 million. Even on Mr Mawhinney’s vision, holding costs exceeded the rent-generating capacity of the planned portfolio.

55 The Mayfair Group “Consolidated Cash Flow” spreadsheet referred to above recorded weekly redemptions by investors in the “actual” portion of the cashflow, covering 28 January to 5 April 2020. The amount recorded in outflows for redemptions each week varied widely. In some weeks, the figure was $0, but in another week, it was $983,736, with the lowest weekly redemption figure (which was not $0) otherwise being $254,680. Monthly interest expenses in respect of the M Notes holders rose from $310,346 in the first week of February 2020 to $349,215 in the first week of March 2020, and rose again to $433,479 in the week from 30 March to 5 April 2020. I note that the redemptions and interest expenses recorded refer to “M1 Notes” and “M1 Distribution”, and that the M+ Notes were previously named “M1 Notes”. Accordingly, and on its face, these figures would appear to be referable to the M+ Notes even though the document purports to be a Group-wide cashflow, which suggests the figures presented related to the M Notes generally. This ambiguity was not explored in the evidence.

56 As to “The Spit”, that area of Dunk Island was owned by the local council. Mayfair Asset Holdings as trustee for the Mayfair Island Trust entered into a 30-year lease with the local council, which was signed on 9 March 2020, and commenced on the same day. An information memorandum for “The Spit Bar & Deck” was in evidence, dated March 2020. It contained drawings by Hunt Design (architects). Other activities in respect of Dunk Island included an expression of interest document issued by LSV Hotels for the management of the anticipated “brand new upscale” luxury hotel and beach club facilities on Dunk Island. This document included architectural drawings and mock ups of the beach club, villas and other facilities. Expressions of interest were stated to be due on 1 May 2020. On 29 April 2020, Mr Mawhinney received an email from LSV Hotels indicating that some well-known hotel operators were interested and wanted to present their submissions.

4.4 The M Notes

57 The M+ Notes and M Core Notes were two promissory note investment products offered, respectively, by two Mayfair Group companies: M101 Holdings and M101 Nominees. The legal structure by which the M Notes were issued included a Deed Poll for each form of notes. The Promissory Note Deed Poll for the M+ Notes (the M+ Notes Deed Poll) was executed by Mr Mawhinney and dated 22 June 2019. The Secured Promissory Note Deed Poll for the M Core Notes (the M Core Notes Deed Poll) was executed by Mr Mawhinney and dated 24 October 2019. As may be observed, the rolling out of the M Notes coincided with the program of real estate acquisition in the Mission Beach region and the development of plans for the revitalisation of that area.

58 The M+ Notes Deed Poll and the M Core Notes Deed Poll were in similar terms, save that the M Core Notes Deed Poll made reference to the notes being secured and to security being held by a security trustee pursuant to the terms of the Security Trust Deed. Both Deed Polls included, as schedules, an application form, a form to be completed by the issuer company upon acceptance of the application to subscribe for notes, a “Note Certificate” (to be completed with details including the amount invested, term and interest rate), and a “Withdrawal Notice” form.

59 The application form included in each instance a provision stating that the applicant agreed to be bound by the terms of the relevant Deed Poll and (in the case of the M Core Notes Deed Poll) the Security Trust Deed.

60 In each case, the Note Certificate described the investor as the holder of “redeemable promissory notes in the capital of the Company”. Each also contained a statement that:

For value received, the Company promises to pay to the Noteholder the amounts payable in accordance with, and otherwise comply with the obligations contained in, the [Promissory Note Deed Poll/Note Deed and the Security Trust Deed].

61 The Deed Poll for each of the M+ Notes and M Core Notes contained a term (cl 3.5) specifying the “[n]ature of Note obligation”, which stated that “[t]he Notes are debt obligations of the Company owing under [this Deed Poll/this deed]”. Each Deed Poll also provided for the calculation of interest, together with an obligation imposed on the relevant company to pay interest that had accrued, and otherwise to capitalise it and add it to the “Monies Owing”, which term was defined in each Deed Poll in terms that referred to “the amount owing by the Company to a Noteholder” pursuant to a note.

62 Provision was also made in each Deed Poll (cl 5.1(b)) for the notes to roll over for a period equal to the original term if a Withdrawal Notice had not been received by the required date. The provisions concerning early withdrawal included (cl 5.2(b)) an acknowledgement that the issuing company was under no obligation to agree to an early withdrawal request.

63 Each Deed Poll contained the following clause (cl 5.6) concerning “Payment Date extension”, with immaterial differences between the two versions. The clause is important as it relates to the Liquidity Prudency Policy (defined in paragraph 140 below), the invocation of which underlies components of ASIC’s allegations. The version in the M Core Notes Deed Poll was in the following terms (emphasis and underlining in original):

Payment Date extension

(a) Extension - The Company may at any time, extend the Payment Date, if:

(i) insufficient Liquidity - the Company, in its reasonable opinion, considers that it does not have sufficient Liquidity to fund the redemption;

(ii) multiple - the Company has received multiple Withdrawal Notices in a short period which will have a negative impact on its Liquidity; or

(iii) future - the Company considers that if the redemption is paid on the Payment Date, it may affect the Company’s Liquidity to pay future anticipated redemptions of other Noteholders’ Notes.

(b) Timing - Any extension of the Payment Date will be made until the time that the Company considers that it has sufficient Liquidity to pay the Monies Owing on the redemption of the Noteholders’ Notes, and any other upcoming redemptions which the Company reasonably anticipates.

(c) Part-payments - If the Company extends a Payment Date, the Company may, at its discretion, make part payments of the Monies Owing before the extended Payment Date.

(d) Interest continues - Subject to clause 5.5(c), if the Payment Date is extended, then interest under clause 4 will continue to apply to the balance of the Monies Owing, calculated from the original Payment Date until such time as the Monies Owing are paid in full.

4.5 The marketing material by which the M Notes were promoted

64 The M Notes were marketed through a variety of channels. Some forms of marketing were specific to the product, but others promoted the Mayfair Group more generally. The relevant contents of each of the relevant marketing materials is set out in addressing the alleged contraventions. At this stage, it is sufficient to note that the relevant marketing materials were as follows:

(a) the Mayfair Platinum website;

(b) the Term Deposit Guide website;

(c) the M Core Notes brochure;

(d) the M+ Notes brochure;

(e) the Mayfair Group corporate brochure;

(f) newspaper advertisements;

(g) email advertisements (referred to as “electronic direct mail” or EDMs); and

(h) use of sponsored links in Google and Bing web search facilities.

65 Mr Mawhinney elected to go into evidence on some issues, one of which was the legal advice said to have been obtained in relation to the marketing material used to promote the M+ Notes, the M Core Notes and the Australian Property Bonds. I address the legal (and accounting) advice received below from paragraph 163.

4.6 The last quarter of calendar 2019: negative media, difficulty settling on acquisitions, obtaining external funding from Naplend

66 By mid-August 2019, Mr Mawhinney was starting to express concern about how the Mayfair Group sales team was going, as new investments were not being secured at the pace Mr Mawhinney expected. He expressed these concerns in WhatsApp messages. By mid-October 2019, concerns were intensifying. On 15 October 2019, Mr Mawhinney referred to needing to “pull out all stops” to get acquisitions settled “in a clean and timely manner”. Despite that close focus on securing incoming revenue from investors, numerous requests to extend settlement dates on real estate acquisitions (often attracting default rates of interest) were made through October and November 2019. Funds were so tight that settlements and deferrals were being juggled, sometimes on a daily basis, waiting for funds that might come in from new investors that day, in order to decide which property settlements to proceed with and which to defer.

67 On 27 November 2019, Mr Mawhinney informed the team that, while 29 properties had been settled by that time using “our own resources”, he was engaging with financiers to obtain external funding. Mr Mawhinney said the plan was to “draw down on the equity in the properties we currently hold unencumbered and roll this money into new settlements”. Around this time, settlement extensions continued to be requested into December 2019, with some properties requiring more than one extension. Media interest in the Mayfair Group business was evident in December 2019, with questions received from the Australian Financial Review (AFR). Mr Mawhinney described the AFR’s article as a “very low blow” and considered legal action. Mr Mawhinney also approved the provision of a response to The Guardian.

68 Mr Mawhinney’s WhatsApp messages through December 2019 referred to financial “pain”, needing “breathing space to weather this media and ASIC stuff”, and to his plans for promotional activities to “re-focus and re-balance the messaging in the media”. All the while, many property settlement dates were being deferred (although it appears that the acquisitions of some “small blocks” were being accelerated). Mr Mawhinney blamed negative media coverage for the investor pipeline dropping off and for some investors, who were almost over the line, pulling out. Mr Mawhinney engaged with media strategy advisers seeking advice to address negative media articles (particularly in the AFR).

69 In the context of this acute need for cash and negative media coverage, Mr Mawhinney engaged with Naplend Pty Ltd (Naplend) to obtain external funding. Naplend was also referred to as “Napla” in some documents.

70 By a Facility Agreement dated 20 December 2019, Naplend extended a facility with a “Commitment” amount of $8.268 million. The stated purpose of the facility was to enable the “release of equity” in respect of various properties acquired, and to assist with the acquisition of the balance of the properties listed in a schedule to the Naplend Facility Agreement. The term of the facility was four months, unless extended, with one two month extension available, at the lender’s discretion: cl 6.2. Interest was due at 2% per month (2.5% for any period after the stated “Termination Date”) with an additional 1% interest payable if the facility was in default: cl 8. The “Borrower” under the Naplend Facility Agreement was each of the property holding entities that were trustees of the various Mission Beach Property Trusts, as well as Jarrah Lodge: Sch 1. The “Guarantor” was Mayfair Group Pty Ltd and Mr Mawhinney personally: Sch 1. The Naplend Facility Agreement contained, as Sch 7, a list of the properties held by the relevant property holding entities, or for which deposits had been paid.

71 Schedule 8 specified the “Permitted PAG Security” that the Security Trustee could hold. That included only one mortgage over real property (Lot 999 Seaview Street, Mission Beach (the Seaview property)). Otherwise, all but one of the various real properties held were mortgaged to Naplend (excluding the Dunk Island titles, which were mortgaged to the vendor, Family Islands Group Pty Ltd (Family Islands Group)).

4.7 Variations to the Naplend Facility Agreement in January, February and May 2020

72 The Naplend Facility Agreement was formally amended on 21 January 2020, 7 February 2020 and 6 May 2020 (Third Amending Deed). The terms of the amending deeds were mostly relevant insofar as they altered the basis upon which the Borrower could make repayments and obtain releases of Naplend’s mortgages. That matter is principally an issue arising in connection with certain of the misrepresentation claims advanced by ASIC concerning the Australian Property Bonds, and is discussed further below, in addressing that part of the case.

73 There is, however, an issue that requires findings to be made. In substance, Mr Mawhinney contended that the repayment and mortgage release terms that were formalised by the Third Amending Deed from 6 May 2020, were in fact agreed in substance earlier such that, by 23 April 2020, Naplend had agreed that it would discharge mortgages over individual properties without insisting on the conditions set out in the Naplend Facility Agreement.

74 On 21 April 2020, Dentons (solicitors for Naplend) sent Mr Mawhinney and Mr King of KHQ Lawyers drafts, which were subject to client comment, of various documents including the Third Amending Deed.

75 On 23 April 2020, Mr Mawhinney emailed Naplend, referring to a prior discussion, saying that the release schedule would not work with the Mayfair Group’s incoming investors from the “Property Bond” (which I take to be a reference to the investors Mr Mawhinney was expecting would acquire the Australian Property Bonds investment product, which had just been launched). In his email, Mr Mawhinney proposed alternative release arrangements.

76 Naplend replied on 23 April 2020, observing that Mr Mawhinney’s proposal was a “marked difference” from what had been proposed, agreed and documented following an event of default. Naplend said that, nonetheless “we have created a paydown schedule that will allow for individual property releases”. The email contained a table specifying the purchase price, “Release LVR” and “Required Paydown” for properties in three groups (later amended to four groups with adjusted loan to value ratios (LVRs)). The email said that the arrangement would provide “$29.5M of property security to place”. However, the email also stated that a paydown of $2 million was required by 20 May 2020, and a further $5 million by 1 June 2020.

77 This proposal was not accepted by Mr Mawhinney, who replied saying that “the release is still too marginal for the short term inflows”. He specified revised LVRs for three categories of properties. Mr Mawhinney’s counter-offer was then rejected by Naplend, at which point Mr Mawhinney replied “Ok - please proceed”. The Third Amending Deed was then executed, dated 6 May 2020.

78 Email correspondence from 23 to 29 June 2020 (post-dating formalisation of the Third Amending Deed) shows Mr Mawhinney’s communications with Dentons and Naplend seeking a mortgage release in respect of 46 Sanctuary Crescent, which was said to be the property over which security was to be given to the investor in the first Australian Property Bond that was being issued. There was a letter from Dentons, following which Naplend set out a practical proposal for the steps by which mortgages could be released. In addition to expressing a preference for the process to be undertaken in “batches of properties every few days”, Naplend’s process was relatively straightforward: the Mayfair Group would identify the property (or properties) in respect of which a mortgage release was sought, Naplend would confirm the amount required to be transferred to Naplend for it to discharge the relevant mortgage(s), and Naplend would give instructions to Dentons to remove the mortgage(s) once the funds cleared, leaving the Mayfair Group (or more accurately, the specific property holding trustee company with title to the property) free to deal with the property and grant a mortgage to an investor in the Australian Property Bonds.

79 As far as the evidence goes, it does not show Naplend declining to release individual mortgages by relying on the condition in the Third Amending Deed that would have allowed Naplend to refuse a release if a default was continuing under the Facility Agreement. Rather, it was willing to release mortgages over two further properties in respect of which Australian Property Bonds were to be issued (7 Rise Crescent and 23 Sanctuary Crescent) although, for reasons that were never adequately explained, the mortgage over 7 Rise Crescent in favour of an investor, Mr PK, was never registered on title.

80 I find that, from 6 May 2020, entities in the Mayfair Group (relevantly to the Australian Property Bonds issues, Australian Income Solutions and the property holding trustee entities that were anticipated to be the issuers of the Australian Property Bonds) had reasonable grounds for considering that Naplend would be unlikely to invoke its right to refuse to release its first mortgages over specific properties on the basis that there was a continuing default under the Naplend Facility Agreement. Those entities had reasonable grounds for considering that mortgage releases could be obtained from Naplend over specific properties so as to make them available to be mortgaged to investors in the Australian Property Bonds.

81 However, I do not consider that such reasonable grounds existed prior to the execution of the Third Amending Deed on 6 May 2020. Having regard to the email correspondence through which those variations were negotiated, I find that, from the evening of 23 April 2020, Mr Mawhinney was aware that Naplend was prepared to enter into a further variation of the Facility Agreement, which would allow the relevant Mayfair Group entities to procure the release of Naplend’s mortgages over individual properties on the terms specified in Naplend’s email of 3.09pm on 23 April 2020. Nevertheless, Naplend did not give any indication that it would be willing to give effect to those varied release arrangements prior to their being formalised in documentation. Nor was there any evidence tendered of a mortgage release having been made before the Third Amending Deed was finalised on 6 May 2020. On that basis, I do not consider that any of the relevant Mayfair Group entities had reasonable grounds for being confident that Naplend would agree to release its first-ranking mortgage over any particular property prior to 6 May 2020.

4.8 The Security Trustee and the security structure

82 The security arrangements are relevant as the M Core Notes were promoted and issued as secured promissory notes. The Security Trustee was PAG. It was appointed pursuant to a Security Trust Deed dated 24 October 2019, between M101 Nominees (which was the issuer of the M Core Notes) and PAG. There was significant dispute between Mr Mawhinney and ASIC regarding the value of the interests secured in favour of M Core Notes holders through the security structure. On Mr Mawhinney’s case, the value fluctuated between 100% and 119% of the value of the funds of M Core Notes holders. ASIC’s expert, Mr Meredith, was of the view that the securities were insufficient both in monetary terms, and having regard to the various features of the security structure. The opinions of Mr Jahani also come into the frame of this dispute, as further set out below.

83 Under the terms of the Security Trust Deed, the Security Beneficiaries were the holders of the M Core Notes and PAG in its capacity as Security Trustee. The features of the security arrangements that were promoted in connection with the M Core Notes were that the security was “asset-backed”, “dollar-for-dollar”, first-ranking and over assets that were otherwise not encumbered. The promotional statements conveying these features are set out below (see paragraph 798 and following) in addressing the Security Representation.

84 The security interests actually granted in favour of PAG comprised:

(1) A security interest in M101 Nominees’ bank account with ANZ pursuant to a Specific Security Deed Poll dated 24 October 2019. The terms on which this security interest was granted did not prevent M101 Nominees using the funds in its bank account for investment and capital management purposes across the Mayfair Group.

(2) A security interest in the property of M101 Nominees, other than its account with the ANZ Bank, pursuant to a General Security Deed Poll dated 24 October 2019.

(3) A security interest in the units held by Sunseeker in the property holding unit trusts. The trustees of those unit trusts were the Mayfair Group entities that held the title to real estate, although not all of the unit trusts held real property. Pursuant to a series of Deeds of Settlement, Sunseeker held the beneficial interest in the assets of each of the relevant property trusts and, in turn, PAG held a security interest in the units held by Sunseeker. PAG’s security interest was granted by a combination of Specific Security Deed Polls and Addition Deeds which brought those security interests within the “Security Property” covered by the Security Trust Deed.

(4) A security interest in property held by the trustees of the property holding unit trusts, but excluding real estate held by the trustees, granted pursuant to a series of General Security Deed Polls and Accession Deeds.

(5) A mortgage on one property, which was the Seaview property. While this mortgage was lodged on title on 3 January 2020, it only became first-ranking when Naplend’s mortgage was released on 13 January 2020.

85 The units held by Sunseeker over which a security interest was granted included units held by Sunseeker in the Mayfair Island Trust, which was the trust holding the Dunk Island interests.

86 It was common ground that another Mayfair Group company, Eleuthera undertook what might broadly be described as a treasury role in the Mayfair Group. Most of the funds received into M101 Nominees’ bank account from those investing in the M Core Notes were transferred to Eleuthera’s bank account. Eleuthera would then typically provide the funds needed to settle the purchases of real estate by the property holding trustee entities. While M101 Nominees’ bank account was within the security structure, Eleuthera’s bank account was not, and the funds held in M101 Nominees’ bank account was significantly lower than the value of the M Core Notes that had been issued. For example, Mr Meredith’s report identified that the highest balance of M101 Nominees’ bank account at any point was $5.996 million on 20 November 2019. Even at that peak, the balance was far below the face value of the M Core Notes on issue at that time, which stood at $15.733 million.

4.8.1 The loan by M101 Nominees to Eleuthera: whether a 10-year term, or advances were payable on 12-month terms