FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Oobagooma on behalf of the Big Springs Claim Group v State of Western Australia [2025] FCA 592

File number: | WAD 144 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | O'BRYAN J |

Date of judgment: | 5 June 2025 |

Catchwords: | NATIVE TITLE – native title determination application brought jointly on behalf of two separate claim groups who each claim separate and distinct native titles in the claim area – application for consent determination under s 87 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) – relevant considerations in making a consent determination – whether the proposed determination is within the power of the Court – whether s 61(1) enables a single native title determination application to be made on behalf of more than one native title claim group – whether and in what circumstances the common law is able to recognise exclusive native title rights held by more than one native title claim group – observations concerning the use of the word ‘connection’ in native title proceedings |

Legislation: | Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 23 Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth) Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ss 61, 67, 86, 87, 223, 225 |

Cases cited: | Agius v State of South Australia (No 6) [2018] FCA 358 Barunga v State of Western Australia [2011] FCA 518 Carter on behalf of the Warrwa Mawadjala Gadjidgar and Warrwa People Native Title Claim Groups v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 1702 Commonwealth v Clifton (2007) 164 FCR 355 Drury on behalf of the Nanda People v State of Western Australia (2020) 276 FCR 203 Freddie v Northern Territory [2017] FCA 867 Hunter v State of Western Australia [2012] FCA 690 James v State of Western Australia [2002] FCA 1208 Kokatha Native Title Claim v State of South Australia [2006] FCA 838 Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474 Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 Munn (for and on behalf of the Gunggari People) v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109 Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402 Northern Territory v Ward (2003) 134 FCR 16 Smirke on behalf of the Jurruru People v State of Western Australia (No 3) [2021] FCA 1122 Smirke on behalf of the Jurruru People v Western Australia (No 4) [2022] FCA 993 Stuart v South Australia (2023) 299 FCR 507 Stuart v South Australia [2025] HCA 12 Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Western Australia |

National Practice Area: | Native Title |

Number of paragraphs: | 113 |

Date of last submission: | 11 April 2025 |

Date of hearing: | Determined on the papers |

Solicitors for the Applicants: | Kimberly Land Council |

Solicitors for the First Respondent: | State Solicitor for Western Australia |

Solicitors for the Second Respondent: | Self-represented |

Solicitors for the Intervener: | Australian Government Solicitor |

ORDERS

WAD 144 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | DEREK OOBAGOOMA & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE BIG SPRINGS CLAIM GROUP First Applicant PATRICIA JUBOY Second Applicant ELAINE LARAIA (and others named in the Schedule) Third Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA First Respondent JOCK HUGH MACLACHLAN Second Respondent | |

THE ATTORNEY-GENERAL OF THE COMMONWEALTH Intervener | ||

order made by: | O'BRYAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 5 June 2025 |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The Applicant in proceeding WAD 144 of 2024 has made a native title determination application (the Big Springs Application).

B. The Applicant, the State of Western Australia, the other Respondent and the Intervener to the proceeding (the parties) have reached an agreement as to the terms of a determination which is to be made in relation to the land and waters covered by the Big Springs Application (Determination Area).

C. The Applicant has been authorised to enter into the agreement by the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders (as defined in the agreement).

D. Pursuant to subs 87(1), (1A) and (2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA), the parties have filed with the Court their agreement in relation to this proceeding.

E. The terms of the agreement involve the making of consent orders for a determination of native title in relation to the land and waters the subject of this proceeding pursuant to ss 87 and 94A of the NTA.

F. The parties acknowledge that the effect of the making of the determination is that the members of the native title claim group, in accordance with the traditional laws acknowledged and the traditional customs observed by them, should be recognised as the native title holders for the Determination Area as set out in the determination.

G. Pursuant to s 87(2) of the NTA, the parties have requested that the Court determine the proceeding without holding a hearing.

BEING SATISFIED that a determination of native title in the terms set out in Attachment A

would be within the power of the Court and, it appearing to the Court appropriate to do so,

pursuant to ss 87 and 94A of the NTA and by the consent of the parties:

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in terms of the determination as provided for in Attachment A.

2. The Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation (ICN 9400) shall hold the determined native title in trust for the Warrwa Native Title Holders pursuant to s 56(2) of the NTA.

3. The Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation (ICN 10487) shall hold the determined native title in trust for the Worrora Native Title Holders pursuant to s 56(2) of the NTA.

4. There be no order as to costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ATTACHMENT A

DETERMINATION

THE COURT ORDERS, DECLARES AND DETERMINES THAT:

Existence of native title (section 225 Native Title Act)

1. Subject to paragraph 2, native title exists in the Determination Area in the manner set out in paragraphs 4 and 5 of this Determination.

2. Native title does not exist in those parts of the Determination Area that are identified in Schedule Five.

Native title holders (section 225(a) Native Title Act)

3. The native title rights and interests in the Determination Area are held by each of the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders.

The nature and extent of native title rights and interests (sections 225(b) and 225(e) Native Title Act)

4. Subject to paragraphs 7, 8, 9 and 10 the nature and extent of the rights and interests in relation to the Exclusive Area referred to in Schedule Three held conjointly by the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders is the right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the Exclusive Area as against the whole world.

5. Subject to paragraphs 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the Non-Exclusive Area referred to in Schedule Four are the following:

(a) the right to have access to, remain in and use that part. For the avoidance of doubt, some of the ways in which that right may be exercised include but are not limited to the following activities:

(i) to access and move freely through and within that part;

(ii) to live, being to enter and remain on, camp and erect temporary shelters and other structures for those purposes on that part;

(iii) to light controlled contained fires but not for the clearance of vegetation;

(iv) to engage in cultural activities in that part, including the transmission of cultural heritage knowledge; and

(v) to hold meetings in that part;

(b) the right to access and take for any purpose the resources on that part. For the avoidance of doubt, one of the ways in which that right may be exercised includes but is not limited to the following activity:

(i) to access and take water other than water which is lawfully captured or controlled by the holders of pastoral leases;

(c) the right to protect places, areas and objects of traditional significance on that part. For the avoidance of doubt, some of the ways in which that right may be exercised include but are not limited to the following activities:

(i) to conduct and participate in ceremonies in that part;

(ii) to conduct burials and burial rites and other ceremonies in relation to death in that part; and

(iii) to visit, maintain and protect from physical harm areas, places and sites of importance in that part.

6. The native title rights and interests referred to in paragraph 5 do not confer:

(a) possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of those parts of the Determination Area on the Warrwa Native Title Holders or the Worrora Native Title Holders to the exclusion of all others; nor

(b) a right to control the access of others to the land or waters of those parts of the Determination Area.

7. The native title rights and interests are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the laws of the State and the Commonwealth, including the common law; and

(b) the traditional laws and customs of the Warrwa Native Title Holders and/or the Worrora Native Title Holders (as the case may be).

8. Notwithstanding anything in this Determination, there are no native title rights and interests in the Determination Area in or in relation to:

(a) minerals as defined in the Mining Act 1904 (WA) (repealed) and in the Mining Act 1978 (WA), except to the extent that ochre is not a mineral pursuant to the Mining Act 1904 (WA);

(b) petroleum as defined in the Petroleum Act 1936 (WA) (repealed) and in the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Resources Act 1967 (WA); or

(c) water lawfully captured or controlled by the holders of the Other Interests.

9. The native title rights and interests are subject to the Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Resources Act 1967 (WA).

10. For the avoidance of doubt, the native title rights and interests set out in paragraphs 4 and 5 do not confer exclusive rights in relation to water in any watercourse, wetland or underground water source as defined in the Rights in Water and Irrigation Act 1914 (WA) as at the date of this Determination.

Areas where extinguishment is disregarded (section 47B Native Title Act)

11. Section 47B of the Native Title Act applies to disregard any prior extinguishment in relation to the areas described in Schedule Six.

The nature and extent of any Other Interests (section 225(c) Native Title Act)

12. The nature and extent of the Other Interests are described in Schedule Seven.

Relationship between native title rights and Other Interests (section 225(d) Native Title Act)

13. The relationship between the native title rights and interests described in paragraphs 4 and 5 and the Other Interests is as follows:

(a) the Other Interests co-exist with the native title rights and interests;

(b) this Determination does not affect the validity of those Other Interests; and

(c) to the extent of any inconsistency, the native title rights and interests yield to the Other Interests and the existence and exercise of native title rights and interests cannot prevent activities permitted under the Other Interests.

Definitions and Interpretation

14. In this Determination, unless the contrary intention appears:

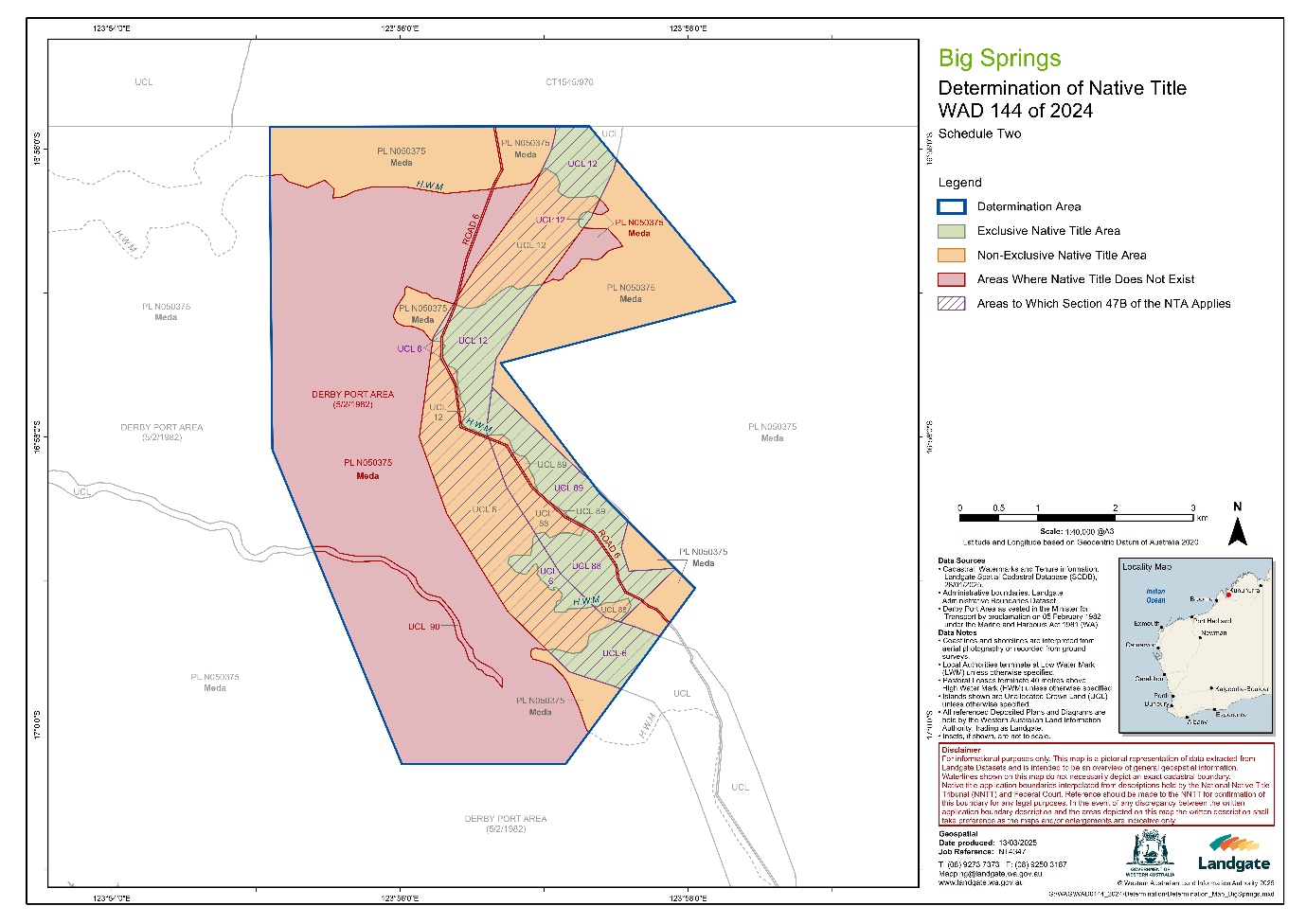

Determination Area means the land and waters described in Schedule One and depicted on the map at Schedule Two;

Exclusive Area means those lands and waters of the Determination Area described in Schedule Three (being areas where any extinguishment must be disregarded) which are not Non-Exclusive Areas or described in paragraph 2 as an area where native title does not exist. Exclusive Areas are generally shown as shaded green on the map at Schedule Two;

high water mark means the mean high water mark at common law;

land and waters respectively have the same meanings as in the Native Title Act;

Native Title Act means the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

Non-Exclusive Area means those lands and waters of the Determination Area described in Schedule Four (being areas where there can only be partial recognition of native title). Non-Exclusive Areas are generally shown as shaded orange on the map at Schedule Two;

Other Interests means the legal or equitable estates or interests and other rights in relation to the Determination Area described in Schedule Seven and referred to in paragraph 12;

State means the State of Western Australia;

Titles Validation Act means the Titles (Validation) and Native Title (Effect of Past Acts) Act 1995 (WA);

Warrwa Native Title Holders means the people described in Schedule Eight and referred to in paragraph 3; and

Worrora Native Title Holders means the people described in Schedule Nine and referred to in paragraph 3.

15. In the event of any inconsistency between the written description of an area in Schedules One, Three, Four, Five, Six or Seven and the area as depicted on the map at Schedule Two, the written description prevails.

SCHEDULE 1

DETERMINATION AREA

The Determination Area, generally shown as bordered in blue on the map at Schedule Two, comprises all land and waters bounded by the following description:

All those lands and waters commencing at a point on the southern boundary of Portion A of Native Title Determination WAD6061/1998 Dambimangari (WCD2011/002) at Longitude 123.918226 East being a point on the boundary of Native Title Determination WAD33/2019 Warrwa Combined Part A (WCD2020/010) and extending southerly, southeasterly, easterly, northeasterly, generally northwesterly and again northeasterly along the boundaries of that native title determination through the following coordinate positions:

LATITUDE (SOUTH) | LONGITUDE (EAST) |

16.968127 | 123.918551 |

17.004533 | 123.933542 |

17.004533 | 123.952459 |

16.984188 | 123.967449 |

16.973124 | 123.956385 |

16.958133 | 123.944963 |

16.950995 | 123.972089 |

Then northwesterly to the southern boundary of Portion A of Native Title Determination WAD6061/1998 Dambimangari (WCD2011/002) at Longitude 123.955215 East; Then westerly along the boundary of that native title determination back to the commencement point.

Note: Geographic Coordinates provided in Decimal Degrees.

Cadastral boundaries sourced from Landgate’s Spatial Cadastral Database dated 28 January 2025.

For the avoidance of doubt the Determination Area excludes any land and waters the subject of:

Native Title Determination WAD6061/1998 Dambimangari (WCD2011/002) as determined in the Federal Court on 26 May 2011.

Native Title Determination WAD33/2019 Warrwa Combined Part A (WCD2020/010) as determined in the Federal Court on 1 December 2020.

Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020)

Prepared by: Geospatial (Landgate) 13 March 2025

Use of Coordinates:

Where coordinates are used within the description to represent cadastral or topographical boundaries or the intersection with such, they are intended as a guide only. As an outcome to the custodians of cadastral and topographic data continuously recalculating the geographic position of their data based on improved survey and data maintenance procedures, it is not possible to accurately define such a position other than by detailed ground survey.

SCHEDULE 2

MAP OF THE DETERMINATION AREA

SCHEDULE 3

EXCLUSIVE NATIVE TITLE AREAS

Areas where native title comprises the rights set out in paragraph 4

The following land and waters (generally shown as shaded green on the map at Schedule Two):

1. Unallocated Crown Land

MapInfo ID | Description |

UCL 006 | That part of UCL 006 that lies landward of the high water mark. |

UCL 012 | That part of UCL 012 that lies landward of the high water mark. |

UCL 088 | That part of UCL 088 that lies landward of the high water mark. |

UCL 089 | That part of UCL 089 that lies landward of the high water mark. |

SCHEDULE 4

NON-EXCLUSIVE NATIVE TITLE AREAS

Areas where native title comprises the rights set out in paragraph 5

The following land and waters (generally shown as shaded orange on the map at Schedule Two):

1. Pastoral leases

Lease Number | Description |

N050375 (Meda) | Those parts of pastoral lease N050375 not subject to the Derby Port Area as vested in the Minister for Transport by proclamation on 5 February 1982 under the Marine and Harbours Act 1981 (WA). |

2. Areas seaward of the high water mark

Any land or waters within the Determination Area which are seaward of the high water mark (and which, for the avoidance of doubt, are not described in paragraph 2 as an area where native title does not exist).

SCHEDULE 5

AREAS WHERE NATIVE TITLE DOES NOT EXIST (PARAGRAPH 2)

Native title does not exist in relation to land and waters the subject of the following interests within the Determination Area which, with the exception of public works (as described in clause 3 of this Schedule), are generally shown as shaded in pink on the map at Schedule Two.

1. Roads

The following dedicated roads, roads set aside, taken or resumed or roads which are to be considered public works (as that expression is defined in the Native Title Act and the Titles Validation Act):

MapInfo ID. | Description | Shown on |

ROAD 006 | Road No. 319 | Gazette 12.02.1891 CPP 507016 CPP 507349 |

2. Port of Derby

The Derby Port Area as vested in the Minister for Transport by proclamation on 5 February 1982 under the Marine and Harbours Act 1981 (WA), other than those areas to which section 47B of the Native Title Act applies as set out in Schedule Six.

3. Public Works

Any other public work as that expression is defined in the Native Title Act and the Titles Validation Act (including the land and waters on which a public work is constructed, established or situated as described in section 251D of the Native Title Act) and to which section 12J of the Titles Validation Act or section 23C(2) of the Native Title Act applies.

SCHEDULE 6

AREAS TO WHICH SECTION 47B NATIVE TITLE ACT APPLIES (PARAGRAPH 11)

Section 47B of the Native Title Act applies with the effect that any extinguishment over the following areas is to be disregarded (these areas are generally shown with purple hatching on the map at Schedule Two):

MapInfo ID | Description |

UCL 006 | Whole of area |

UCL 012 | Whole of area |

UCL 088 | Whole of area |

UCL 089 | Whole of area |

SCHEDULE 7

OTHER INTERESTS (PARAGRAPH 12)

The nature and extent of the Other Interests in relation to the Determination Area are as follows.

Land tenure interests registered with the Western Australian Land Information Authority are current as at 28 January 2025. All other interests are current as at the date of the Determination.

1. Pastoral leases

Lease Number | Station Name |

N050375 | Meda |

NOTE: The rights and obligations of the pastoralist pursuant to the pastoral lease referred to in clause 1 of Schedule Seven above include responsibilities and obligations to adopt and exercise best practice management of the pasture and vegetation resources, livestock and soils within the boundaries of the pastoral lease in order to manage stock and for the management, conservation and regeneration of pasture for permitted uses.

2. Miscellaneous rights and interests

(a) Valid or validated rights and interests, including licences and permits, granted by the Crown in right of the State or of the Commonwealth pursuant to statute or otherwise in the exercise of its executive power and any regulations made pursuant to such statutes.

(b) Valid or validated rights and interests held by reason of the force and operation of the laws of the State or of the Commonwealth including the Rights in Water and Irrigation Act 1914 (WA).

(c) Rights and interests of members of the public arising under the common law including:

(i) the public right to fish;

(ii) the public right to navigate; and

(iii) the right of any person to use any road in the Determination Area (subject to the laws of the State) over which, as at the date of this Determination, members of the public have a right of access under common law.

(d) The international right of innocent passage though the territorial sea.

(e) The right to access the Determination Area by an employee, agent or instrumentality of:

(i) the State;

(ii) the Commonwealth; or

(iii) any local government authority,

as required in the performance of his or her statutory or common law duties where such access would be permitted to private land.

(f) So far as confirmed pursuant to section 212(2) of the Native Title Act and section 14 of the Titles Validation Act as at the date of this Determination, any existing public access to and enjoyment of:

(i) waterways;

(ii) beds and banks or foreshores of waterways;

(iii) coastal waters;

(iv) beaches; and

(v) areas that were public places at the end of 31 December 1993.

SCHEDULE 8

WARRWA NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS (PARAGRAPH 3)

1. The Warrwa Native Title Holders are:

(a) those Aboriginal persons who are:

(i) descended from one or more of the people listed in clause 2 of this Schedule; or

(ii) recognised by the descendants of the people listed in clause 2 of this Schedule as having traditional rights and interests in the Determination Area under traditional law and custom.

2. The people referred to in clause 1(a)(i) of this Schedule are those Aboriginal persons who are the biological or adopted descendants of the following apical ancestors:

(a) Topsy Mouwudjala;

(b) Gudayi and Bobby Ah Choo; and

(c) Nani.

SCHEDULE 9

WORRORA NATIVE TITLE HOLDERS (PARAGRAPH 3)

1. The Worrora Native Title Holders are:

(a) those Aboriginal persons who are:

(i) descended from one or more of the people listed in clause 2 of this Schedule; or

(ii) recognised by the descendants of the people listed in clause 2 of this Schedule as having traditional rights and interests in the Determination Area under traditional law and custom.

2. The people referred to in clause 1(a)(i) of this Schedule are those Aboriginal persons who are the biological or adopted descendants of the following apical ancestors:

(a) Gaana;

(b) Ganbalya;

(c) Charlie Ganbalya; and

(d) Jangara.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

O’BRYAN J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding is a native title determination application made pursuant to s 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) and is known as the Big Springs application.

2 The land and waters covered by the application (the claim area) are located in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The claim area comprises approximately 32.24 square kilometres and is an area of permanent fresh water and vegetation located between the mouths of the Meda and Robinson Rivers. The majority of the claim area is covered by Meda Station pastoral lease, with a corridor of Unallocated Crown Land (UCL) through the centre, and two smaller parcels of UCL in the southeast.

3 The Big Springs application is a single application notionally made on behalf of a single ‘native title claim group’ which is said to comprise ‘Warrwa and Worrora members’. As discussed further below, the reference in the application to the ‘native title claim group’ is somewhat artificial. In substance, the application is brought jointly on behalf of two separate claim groups, whom I will refer to as the Warrwa claim group and the Worrora claim group for convenience, who each claim separate and distinct native titles in the claim area. Each of those claim groups authorised the making of the application, and each of those claim groups authorised four of their members to join in making the application. As such, the application was made by eight persons, four of whom represent the Warrwa claim group and four of whom represent the Worrora claim group.

4 The circumstance that distinct groups of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders may each possess native title rights and interests in the same area has been recognised in a number of cases, and was the subject of discussion by the Full Court in Drury on behalf of the Nanda People v State of Western Australia (2020) 276 FCR 203 (Drury) (see for example at [30] and [36]-[37] (Mortimer and Colvin JJ)). However, as a matter of procedure, it is unusual for a single native title determination application to be made on behalf of more than one native title claim group.

5 The parties to the Big Springs application are the applicant, the State of Western Australia, Mr Jock Hugh Maclachlan (who holds a pastoral lease in the claim area), and the Attorney-General of the Commonwealth of Australia as Intervener.

6 The parties have reached agreement on the terms of a native title determination (proposed consent determination) for the claim area and a form of orders regarded as appropriate to provide recognition of the native title rights and interests held by each of the Warrwa claim group and the Worrora claim group in relation to the claim area. That agreement is recorded in a document filed with the Court on 11 April 2025. The parties have applied to the Court for an order in, or consistent with, the terms of the proposed consent determination pursuant to s 87 of the NTA.

7 In support of the application for a consent determination, the applicant and the State filed:

(a) a minute of proposed orders and determination of native title by consent, signed by each of the parties to the proceeding;

(b) a statement of agreed facts signed by the applicant and the State on 11 April 2025;

(c) an affidavit of Scott Howieson (Senior Lawyer of the Kimberley Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (KLC), the solicitors for the applicant) affirmed on 26 March 2025;

(d) an affidavit of Scott Cox (Senior Project Officer of the KLC) affirmed on 26 March 2025;

(e) an affidavit of Dr Heather Lynes (Senior Anthropologist of the KLC) affirmed on 25 March 2025;

(f) affidavit of Amy Jones (Lawyer of the KLC) affirmed on 8 April 2025;

(g) a nomination of Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC to be the prescribed body corporate and trustee of the Warrwa Native Title, signed by Patricia Juboy on 2 May 2024;

(h) a consent by Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation to the nomination, executed by the directors of Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation on 8 October 2024;

(i) a nomination of Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation to be the prescribed body corporate and trustee of the Worrora Native Title, signed by Leah Umbagai on 18 February 2025;

(j) a consent by Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation to the nomination, executed by the directors of Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation on 18 February 2025; and

(k) a joint submission of the applicant and the State dated 11 April 2025.

8 By orders made today, a determination of native title has been made in respect of the Big Springs application pursuant to the power conferred on the Court by s 87 of the NTA. These are my reasons for making the determination sought by the parties.

Statutory requirements

9 Section 87 of the NTA relevantly provides as follows:

Application

(1) This section applies if, at any stage of proceedings after the end of the period specified in the notice given under section 66:

(a) agreement is reached on the terms of an order of the Federal Court in relation to:

(i) the proceedings; or

(ii) a part of the proceedings; or

(iii) a matter arising out of the proceedings; and

(aa) all of the following are parties to the agreement:

(i) the parties to the proceedings;

(ii) the Commonwealth Minister, if the Commonwealth Minister is intervening in the proceedings at the time the agreement is made; and

(b) the terms of the agreement, in writing signed by or on behalf of the parties to the proceedings and, if subparagraph (aa)(ii) applies, the Commonwealth Minister, are filed with the Court; and

(c) the Court is satisfied that an order in, or consistent with, those terms would be within the power of the Court.

…

Power of Court

(1A) The Court may, if it appears to the Court to be appropriate to do so, act in accordance with:

(a) whichever of subsection (2) or (3) is relevant in the particular case; and

(b) if subsection (5) applies in the particular case—that subsection.

Agreement as to order

(2) If the agreement is on the terms of an order of the Court in relation to the proceedings, the Court may make an order in, or consistent with, those terms without holding a hearing or, if a hearing has started, without completing the hearing.

Note: If the application involves making a determination of native title, the Court’s order would need to comply with section 94A (which deals with the requirements of native title determination orders).

…

10 It can be seen that, under ss 87(1A) and (2), the Court is empowered to make an order in, or consistent with, the terms agreed between the parties without holding a hearing if the following conditions are satisfied:

(a) the period specified in the notice given in the proceeding under s 66 has ended (s 87(1));

(b) agreement has been reached on the terms of an order of the Court between the parties to the proceeding (and, if the Commonwealth Minister is intervening at the time the agreement is made, the Commonwealth Minister) (ss 87(1)(a) and (aa)), and the terms of the agreement, in writing signed by or on behalf of the parties (and, if the Commonwealth Minister is intervening at the time the agreement is made, the Commonwealth Minister) have been filed with the Court (s 87(1)(b)); and

(c) the Court is satisfied that an order in, or consistent with, the terms agreed between the parties would be within the power of the Court (s 87(1)(c)).

11 In the present case, the parties seek an order in which the Court makes a determination of native title. Section 94A stipulates that an order in which the Court makes a determination of native title must set out details of the matters mentioned in s 225. Section 225 is in the following terms:

A determination of native title is a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land and waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area; and

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non-exclusive agricultural lease or a non-exclusive pastoral lease–whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

Note: The determination may deal with the matters in paragraphs (c) and (d) by referring to a particular kind or particular kinds of non‑native title interests.

12 The discretion conferred on the Court under ss 87(1A) and (2) is broad. The Court may make an order in accordance with the agreement of the parties if the Court considers it appropriate to do so. The considerations that may be relevant to the exercise of the discretion have been considered in a number of cases. In exercising the discretion, however, it is important to have regard to the nature and purpose of the power conferred in the context of the NTA. The power conferred is to make an order in, or consistent with, the terms agreed between the parties without holding a hearing. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Native Title Amendment Bill 1997 stated (at [26.23], emphasis added):

The rules about the powers of the Federal Court when the parties reach agreement are substantially the same as in the current Act [section 87]. They take account of the important role that negotiation is intended to play in settling applications made under the Act. If the parties reach an agreement on the terms of an order in relation to the proceedings, the Court may make that order, or one consistent with it, without holding a hearing or without completing the hearing [subsection 87(2)]. If the Federal Court makes an order on terms agreed to by the parties which involves a determination of native title, the order must comply with section 94A, explained directly below (see note under subsection 87(2)).

13 The important role that negotiation is intended to play in settling applications made under the NTA is expressly recognised in the preamble to the NTA which states (emphasis added):

A special procedure needs to be available for the just and proper ascertainment of native title rights and interests which will ensure that, if possible, this is done by conciliation and, if not, in a manner that has due regard to their unique character.

14 Parliament’s intent, that native title rights and interests be ascertained, if possible, through a process of conciliation, has been recognised in the authorities concerning s 87.

15 In Munn (for and on behalf of the Gunggari People) v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109 (Munn), Emmett J observed (at [28]) that, in exercising power under s 87:

… The Court must have regard to the objects and purposes of the Act. One important object and purpose to be found in the Act is resolution of issues and disputes concerning native title by mediation and agreement, rather than by Court determination. Detailed procedures are set out in the Act to achieve those objects.

16 Similarly, in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474 (Lovett), North J said (at [36]):

The focus of the section is on the making of an agreement by the parties. This reflects the importance placed by the Act on mediation as the primary means of resolving native title applications. Indeed, Parliament has established the National Native Title Tribunal with the function of conducting mediations in such cases. The Act is designed to encourage parties to take responsibility for resolving proceedings without the need for litigation. Section 87 must be construed in this context. The power must be exercised flexibly and with regard to the purpose for which the section is designed.

17 Other considerations that may be relevant to the exercise of power under s 87 have been canvassed in many cases. In Agius v State of South Australia (No 6) [2018] FCA 358 (Agius), Mortimer J (as her Honour then was) stated (at [64]):

The concept of “appropriateness” in s 87(1A) also recognises that the determination made by the Court is one made as against the whole world, and not just between the parties to the proceeding: Cox on behalf of the Yungngora People v State of Western Australia [2007] FCA 588 at [3] (French J). The rights conferred are enduring legal rights, proprietary in nature and in recognising them through a determination, the Court must be conscious of their character. The nature of the rights informs considerations such as the clarity of the terms of the determination (as to the claim area, the nature of the native title rights and interests and the manner of affectation on other proprietary interests); the need for appropriate notification and then the free and informed consent of all parties; and finally the State’s agreement that there is a credible and rational basis for the determination proposed.

18 One of the considerations referred to in the above passage is the State’s agreement that there is a credible and rational basis for the determination proposed. It is important to recognise that, while relevant, the consideration is not a statutory condition requiring the parties to adduce evidence with respect to the State’s assessment of the applicant’s claim to native title rights and interests. The origin of the phrases “credible” and “rational” basis for the proposed determination can be traced to Emmett J’s reasons in Munn and North J’s reasons in Lovett. In Munn, Emmet J stated (at [29]-[30]):

29 Next, the Court must have regard to the question of whether or not the parties to the proceeding, namely, those who are likely to be affected by an order, have had independent and competent legal representation. That concern would include a consideration of the extent to which the State is a party, on the basis that the State, or at least a Minister of the State, appears in the capacity of parens patriae to look after the interests of the community generally. The mere fact that the State was a party may not be sufficient. The Court may need to be satisfied that the State has in fact taken a real interest in the proceeding in the interests of the community generally. That may involve the Court being satisfied that the State has given appropriate consideration to the evidence that has been adduced, or intended to be adduced, in order to reach the compromise that is proposed. The Court, in my view, needs to be satisfied at least that the State, through competent legal representation, is satisfied as to the cogency of the evidence upon which the applicants rely.

30 However, that is not to say that the Court would itself want to predict the State's assessment of that evidence or to make findings in relation to those matters. On the other hand, in an appropriate case, the Court may well ask to be shown the evidence upon which the parties have based their decision to reach a compromise. Either way, I would not contemplate that, where the Court is being asked to make an order under s 87, any findings would be made on those matters. The Court would look at the evidence only for the purpose of satisfying itself that those parties who have agreed to compromise the matter, particularly the State on behalf of the community generally, are acting in good faith and rationally.

19 In Lovett, North J paraphrased the above passages by stating that the Court will wish to be satisfied that the State has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application (at [37]).

20 As indicated in the foregoing passages, in exercising power under s 87, the Court’s principal focus is upon the agreement of the parties. In that context, it is relevant to consider whether the State, as the representative of the interests of the community generally, has had independent and competent legal representation and is acting in good faith and rationally. That does not require the Court to embark on its own assessment of the evidentiary basis for the State’s agreement, as such a requirement would undermine the purpose of the power conferred: see Agius at [69]. In a given case, the history of the proceeding, the legal representation of the State, a statement of agreed facts and representations made by the State to the Court, often jointly with the applicant, will be sufficient to satisfy the Court that the State is acting in good faith and rationally in reaching agreement with the applicant: Agius at [71].

Background to the Big Springs application

21 Prior to the Big Springs application being made, the land and waters of the claim area were included within the Warrwa Combined application (WAD 33 of 2019). On 1 December 2020, a determination of native title was made by the Court in favour of the Warrwa people in respect of a large part of the land and waters covered by the Warrwa Combined application (Warrwa Determination): see Carter on behalf of the Warrwa Mawadjala Gadjidgar and Warrwa People Native Title Claim Groups v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 1702 (Carter). At the time of the Warrwa Determination, the prescribed body corporate in respect of the Warrwa Determination was named the Warrwa People Aboriginal Corporation. Subsequently, the name of that corporation was changed to Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation.

22 The Big Springs claim area was one of three areas excluded from the Warrwa Determination. It was excluded on the basis of anthropological research which suggested that, in addition to native title rights and interests claimed by Warrwa people, the area of Big Springs (also known as “Windjidabil” or “Radawal”) may be the subject of native title rights and interests held by Worrora people.

23 Worrora People, along with the other members of the Wanjina-Wunggurr Community, are recognised as native title holders in a determination of native title made on 26 May 2011 (Dambimangari Determination): see Barunga v State of Western Australia [2011] FCA 518 (Barunga). The Dambimangari Determination covers the area immediately to the north of the Big Springs area. The prescribed body corporate in respect of the Dambimangari Determination is the Wanjina-Wunggurr (Native Title) Aboriginal Corporation.

24 As a result of the decision in Carter, the Warrwa Combined application was deemed by s 64(1B) of the NTA to be amended to remove the area of the Warrwa Determination. On 11 September 2023, the Court made orders separating the remaining areas of the Warrwa Combined application into three parts. That part of the Warrwa Combined application that covered the Big Springs claim area was referred to as “Part C”. With respect to Part C, the Court also made orders for the Warrwa Combined applicant to consult with the Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation and Worrora people regarding a proposed consent determination with respect to the area of Big Springs.

25 The Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation is not a registered native title body corporate, although it is a ‘related corporation’ to the Wanjina-Wunggurr (Native Title) Aboriginal Corporation and its objectives include assisting the Wanjina-Wunggurr (Native Title) Aboriginal Corporation to carry out its native title functions in the Dambimangari Determination area and promoting the recognition, protection, use and enjoyment of the native title rights and interests within the Dambimangari Determination area. Its membership is limited to Worrora people.

26 In a joint report to the Court filed on 13 November 2023, the Warrwa Combined applicant and the State informed the Court that:

(a) although the Worrora people had not filed a native title determination application in respect of the Big Springs claim area, they continue to assert native title rights and interests in the area; and

(b) the available anthropological evidence supports the conclusion that Warrwa people and Worrora people are members of separate ‘societies’, each with their own distinct body of traditional laws and customs, and that they each possess native title rights and interests in the Big Springs area separately under their respective laws and customs.

27 Subsequently, in a joint report to the Court filed on 28 February 2024, the Warrwa Combined applicant and the State informed the Court that:

(a) with the State’s support, the Warrwa Combined applicant proposed to discontinue Part C of the Warrwa Combined application and, together with representatives of Worrora people, to file a new native title determination application in respect of the Big Springs area which would claim separate native title rights and interests on behalf of both the Warrwa people and the Worrora people; and

(b) steps would then be taken to authorise and agree a proposed consent determination in respect of the Big Springs claim area on that basis.

28 On 13 June 2024, Part C of the Warrwa Combined application was discontinued by order of the Court. The Big Springs application was filed with the Court on the same day pursuant to s 61 of the Native Title Act. The Big Springs application covers the same area of land and waters as the discontinued Part C of the Warrwa Combined application.

29 The Big Springs application is brought by:

(a) Patricia Juboy, Elaine Laraia, Patrick Lawson and Nathan Lenard who are Warrwa people and represent the Warrwa claim group; and

(b) Derek Oobagooma, Craig Oobagooma, Kirk Woolagoodja and Gary Umbagai who are Worrora people and represent the Worrora claim group.

30 The application separately describes the Warrwa members of the claim group and the Worrora members of the claim group.

31 The Warrwa members of the claim group are, in effect, described in the same manner as in the Warrwa Determination, being those Aboriginal persons who:

(a) are the biological or adopted descendants of the following apical ancestors:

(i) Topsy Mouwudjala;

(ii) Gudayi and Bobby Ah Choo; and

(iii) Nani; or

(b) are recognised by the descendants of the people listed in paragraph (a) as having traditional rights and interests in the claim area under traditional law and custom.

32 It should be noted that Mr Tommy May (Ngarralja) was a named custodian for the Warrwa Determination area on the basis that he was recognised by the native title holders to hold specific, non-transferable rights and interests in the Warrwa Determination area (see Carter at [44]). However, Mr May is now deceased.

33 The Worrora members of the claim group comprise a sub-set of the native title holders recognised in the Dambimangari Determination, being those Aboriginal persons who:

(a) are the biological or adopted descendants of the following apical ancestors:

(i) Gaana;

(ii) Ganbalya;

(iii) Charlie Ganbalya; and

(iv) Jangara; or

(b) are recognised by the descendants of the people listed in paragraph (a) as having traditional rights and interests in the claim area under traditional law and custom.

34 The Big Springs application was certified by Tyronne Garstone, CEO and Director of the KLC, on 31 May 2024 pursuant to s 203BE(1)(a) of the NTA. The certificate stated that the application was authorised at a meeting arranged by the KLC and held at the Mowanjum Community Hall in Mowanjum Community on 1 and 2 May 2024. The claimants agreed that decisions would be made separately by the Warrwa claimants and the Worrora claimants and that each of the Warrwa claimants and the Warrwa claimants would make decisions about the native title claim in accordance with their own adopted decision-making processes. Pursuant to those processes, each of the Warrwa claim group and the Worrora claim group passed resolutions authorising the applicant to make the application and to deal with matters arising in relation to it.

35 As required by s 190A of the NTA, the Big Springs application was assessed against the provisions of ss 190B and 190C of the NTA by a delegate of the Native Title Registrar. The delegate accepted the Big Springs application for registration pursuant to s 190A on 30 August 2024. The Big Springs application was notified by the Native Title Registrar pursuant to s 66 of the NTA. The notification period referred to in ss 66(8) and 66(10)(c) of the NTA ended on 19 February 2025.

Evidence in support of the consent determination

Statement of agreed facts

36 The applicant and the State filed a statement of agreed facts in support of the application for the proposed consent determination. In proceedings under the NTA, a statement of agreed facts may be relied upon by the Court when making a determination of native title by consent under s 87(2) of the NTA, or making an order in relation to a part of a proceeding or a matter arising out of a proceeding under ss 87(3) or (5). Subsections 87(8) to (11) relevantly stipulate:

Agreed statement of facts

(8) If some or all of the parties to the proceeding have reached agreement on a statement of facts, one of those parties may file a copy of the statement with the Court.

(9) Within 7 days after a statement of facts agreed to by some of the parties to the proceeding is filed, the Federal Court Chief Executive Officer must give notice to the other parties to the proceeding that the statement has been filed with the Court.

(10) In considering whether to make an order under subsection (2), (3) or (5), the Court may accept a statement of facts that has been agreed to by some or all of the parties to the proceedings but only if those parties include:

(a) the applicant; and

(b) the party that the Court considers was the principal government respondent in relation to the proceedings at the time the agreement was reached.

(11) In considering whether to accept under subsection (10) a statement of facts agreed to by some of the parties to the proceedings, the Court must take into account any objections that are made by the other parties to the proceedings within 21 days after the notice is given under subsection (9).

37 In accordance with s 87(9), on 17 April 2025 the Chief Executive Officer of the Court gave notice to the other parties to the proceeding that the statement of agreed facts had been filed with the Court. None of those parties made any objection to the statement of agreed facts within 21 days after the notice was given.

38 For the purposes of s 87(10), I am satisfied that the State is the principal government respondent in relation to the proceedings at the time the agreement was reached. Accordingly, in considering whether to make the proposed consent determination under s 87(2), the Court is empowered to accept the statement of agreed facts.

39 The facts that are agreed between the applicant and the State in the statement of agreed facts are largely framed in terms of the ultimate issues which must be determined by the Court in making a native title determination in accordance with s 225 of the NTA.

40 The statement of agreed facts commence with the facts that the date of sovereignty in the claim area is 29 May 1829, but effective sovereignty (being the time at which the lives of Aboriginal people in the claim area began to be impacted by European settlement) in the claim area did not occur until 1885 – 1890. It is agreed that, at the time that Britain asserted sovereignty, the land and waters of the claim area were occupied by Aboriginal persons.

41 The statement of agreed facts includes the following facts with respect to the Aboriginal persons who hold native title in the claim area:

(a) the persons holding the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters of the claim area are the ‘Warrwa Native Title Holders’ and the ‘Worrora Native Title Holders’;

(b) the Warrwa Native Title Holders are the Warrwa members of the claim group as described earlier in these reasons;

(c) the Warrwa Native Title Holders have, since prior to sovereignty and continuing today, rights and interests in, and a connection to, the claim area in accordance with their traditional laws and customs;

(d) the Worrora Native Title Holders are the Worrora members of the claim group as described earlier in these reasons;

(e) the Worrora Native Title Holders have, since prior to sovereignty and continuing today, rights and interests in, and a connection to, the claim area in accordance with their traditional laws and customs.

42 The statement of agreed facts includes the following facts with respect to the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests held by the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders in the claim area:

(a) one or more of the members of the claim group were, for the purposes of s 47B of the NTA, in occupation of those parts of the claim area comprising UCL that lies landward of the high water mark, and which are identified in Schedule Three of the proposed consent determination as UCL parcels 006, 012, 088 and 089, when the Big Springs application was made on 13 June 2024;

(b) s 47B of the NTA applies in relation to the UCL parcels, and, for all purposes under the NTA in relation to the Big Springs application, any extinguishment of the native title rights and interests in relation to the UCL parcels by the creation of any prior interest must be disregarded;

(c) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests that exist in relation to the UCL parcels (being areas where any extinguishment must be disregarded), held conjointly by the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders, confer the right to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of those parts of the claim area to the exclusion of all others;

(d) native title rights and interests have been extinguished and no longer exist in those parts of the claim area set out in Schedule Five of the proposed consent determination;

(e) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests that exist in relation to all other parts of the claim (being areas where there has been a partial extinguishment of native title and where any partial extinguishment is not required to be disregarded) confer on the native title holders:

(i) the right to have access to, remain in and use those parts of the claim area, including, but not limited to the following activities:

(A) accessing and moving freely through and within those parts of the claim area;

(B) living, entering and remaining on, camping and erecting temporary shelters and other structures for those purposes on those parts of the claim area;

(C) lighting controlled contained fires but not for the clearance of vegetation;

(D) engaging in cultural activities in those parts of the claim area, including transmitting cultural heritage knowledge; and

(E) holding meetings in those parts of the claim area;

(ii) the right to access and take for any purpose the resources on that part, including but not limited to the following activities:

(A) accessing and taking water other than water which is lawfully captured or controlled by the holders of pastoral leases; and

(iii) the right to protect places, areas and objects of traditional significance on those parts of the claim area, including but not limited to the following activities:

(A) conducting and participating in ceremonies in those parts of the claim area;

(B) conducting burials and burial rites and other ceremonies in relation to death in those parts of the claim area; and

(C) visiting, maintaining and protecting from physical harm, areas, places and sites of importance in those parts of the claim area;

(f) the native title rights and interests referred to in paragraph (e) do not confer:

(i) possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of those parts of the claim area on the Warrwa Native Title Holders or the Worrora Native Title Holders to the exclusion of all others; nor

(ii) a right to control the access of others to the land or waters of those parts of the claim area.

43 With respect to the nature and extent of other interests in relation to the claim area, the statement of agreed facts records that the other non-native title rights and interests in the claim area are set out in Schedule Seven of the proposed consent determination.

44 With respect to the relationship between the native title rights and interests referred to in paragraph 38 and the other interests referred to in paragraph 39 above, the statement of agreed facts records that:

(a) the other interests co-exist with the native title rights and interests;

(b) a determination of native title does not affect the validity of those other interests; and

(c) to the extent of any inconsistency, the native title rights and interests yield to the other interests and the existence and exercise of native title rights and interests cannot prevent activities permitted under the other interests.

45 I accept the foregoing facts for the purposes of this determination.

Authorisation meeting

46 By their respective affidavits, each of Dr Lynes, Mr Cox and Mr Howieson gave evidence concerning meetings of each of the Warrwa claim group and Worrora claim group held at the Mowanjum Community Hall in Mowanjum Community, Western Australia, on 1 and 2 May 2024. Separate meetings were held by members of each of the Warrwa and Worrora claim groups authorising:

(a) the making of the Big Springs application;

(b) the filing of the consent determination; and

(c) nominating a prescribed body corporate for each of the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders.

Prescribed bodies corporate

47 At the meeting in Mowanjum on 2 May 2024, the Warrwa claim group nominated Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation to be the prescribed body corporate to hold the native title on trust for the Warrwa Native Title Holders. As noted above, Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation is an existing Registered Native Title Body Corporate registered under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth) (CATSI Act) which holds the native title rights and interests that are the subject of the existing Warrwa Determination on trust for the Warrwa Native Title Holders. A consent by Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation to the nomination, executed by the directors of Madanaa Nada Aboriginal Corporation on 8 October 2024, was exhibited to Mr Howieson’s affidavit.

48 At the meeting in Mowanjum on 2 May 2024, the Worrora claim group nominated the Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation to be their prescribed body corporate. The Worrora claim group also resolved that, if Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation withheld its consent to act in that capacity, authority was given to the Worrora members of the applicant to nominate an alternative prescribed body corporate. Mr Howieson gave evidence that the board of Dambimangari Aboriginal Corporation subsequently resolved not to accept the nomination to be the trustee of the Worrora native title for the Big Springs claim area. A further meeting of the Worrora claim group was held on 18 February 2025 in Mowanjum at which a decision was made to nominate Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation to be the prescribed body corporate to hold the Worrora native title in respect of the claim area on trust for the Worrora Native Title Holders. A consent by Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation to the nomination, executed by the directors of Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation on 18 February 2025, was exhibited to Mr Howieson’s affidavit. Ms Jones gave evidence that the Winjoodoorurlbul Aboriginal Corporation was subsequently registered with the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations under the CATSI Act.

Joint submissions of the applicant and the State

49 In support of the application for a consent determination, the applicant and the State filed joint submissions. The joint submissions identified the material taken into account by the State in assessing whether to support the application for a consent determination and summarised aspects of that material.

50 The material that has been considered by the State in considering the application includes:

(a) a report titled “Barddabardda Wodjenangorddee: We’re Telling All of You” (2017), compiled and written in collaboration with Dambimangari People by Valda Blundell, Kim Doohan, Daniel Vachon, Malcom Allbrook, Mary Anne Jebb and John Bornman (Blundell Report 2017);

(b) a report dated January 2018 authored by Dr Bill Kruse and titled “Connection Report in the matter of Warrwa Combined (WAD 258/12) and Warrwa Mawadjala Gadjidgar (WAD 104/2011) Native Title Claims: Warrwa Core Country” (Kruse Report 2018);

(c) a report filed with the Court by the Warrwa Applicant on 15 May 2019 in the Warrwa Combined application titled “A report setting out the outcomes of family consultations and further research with Worora People regarding the Big Springs area” (Court Report 2019), which provided details and outcomes of the family consultations and further research conducted by Dr Kruse in relation to the Big Springs area;

(d) a 2022 report prepared by KLC anthropologist, Dr Heather Lynes, titled “Supplementary Report: Windjidabil/Radawal (Big Springs)” (Lynes Report 2022); and

(e) an affidavit of Patricia Juboy affirmed 20 July 2023in support of the “occupation” requirement in s 47B of the Native Title Act in relation to areas of UCL within the claim area.

51 The joint submissions also place reliance on the reasons of the Court in the earlier Warrwa and Dambimangari Determinations, which relate to the land and waters surrounding the Big Springs claim area. In that regard, s 86(1)(c) of the NTA provides that the Court may adopt any recommendation, finding, decision or judgment of the Court: see also Stuart v South Australia [2025] HCA 12 (Stuart) at [31], [85] (Gageler CJ, Gordon, Edelman, Gleeson and Beech-Jones JJ).

Warrwa people’s rights and interests in, and connection to, the claim area

52 The joint submissions record the following facts and matters concerning the Warrwa people’s rights and interests in, and connection to, the claim area, which have been drawn from the reasons of the Court in Carter (concerning the Warrwa Determination) and the other reports and evidence taken into account by the State (listed above).

53 In Carter, Banks-Smith J noted (at [46]) that Warrwa people are situated within a broader regional society within the West Kimberley region of Western Australia, which includes both Warrwa and Nyikina peoples, amongst others. Religious beliefs, systems of social kinship and language are largely similar across the regional society. Within the regional society, the term ‘Warrwa’ denotes a distinct language as well as a distinct group of people with rights and interests in the land and waters the subject of the Warrwa Determination.

54 The Lynes Report 2022 stated that the ethnographic record indicates the presence of Warrwa-identifying people, including Warrwa apical ancestors Bobby Ah Choo and his mother Gudayi, as well as Topsy Mouwudjala, in the immediate vicinity of the claim area at or before the time of effective sovereignty (circa 1885–1890). The Lynes Report 2022 also noted that many Warrwa claimants and their families lived and worked on Meda station throughout the 20th century, which provided an opportunity for Warrwa people to maintain a physical presence on country, including on and around the claim area. The Kruse Report 2018 noted that pastoral infrastructure was installed at Big Springs in the early 20th century, suggesting that the fresh water available there was utilised by Meda station.

55 The Kruse Report 2018 noted that Big Springs is one of the key ‘nodal areas’ in Warrwa country that was known from pre-sovereignty times, and continues to be known, as a major traditional source of water, game and a ceremonial site. Warrwa People continue to utilise ceremonial and traditional resources extracted from the Big Springs claim area. In her 20 July 2023 affidavit, Patricia Juboy provides the following example:

After my grandmother died, we used to go out to Big Springs a lot with my Dad, Harry Lennard, Maudie Lennard’s son. That was his hunting ground. He used to go out there just about every weekend in the good season. Sometimes he would take the whole family. Sometimes he would just take the boys out there, to teach them hunting…

56 In relation to the known ceremonial site in the claim area, Ms Juboy explains:

My grandmother told me that Warrwa people used to go [to the claim area] for lore, as there is a ceremony place there… The ceremony place is at the top of this area, just to the left of the road. There are three small pools, and then there’s a big spring. They are all fresh water… My grandmother told me that those springs were a meeting place for Ngarinyin, Worrora, Warrwa and Ungami people. My grandmother told me that the old people used to fight out there. The grass is red from the blood, it still grows red there. It’s a significant traditional area for us, one of our main areas, and no-one is allowed to interfere with that place

57 Warrwa woman, Maudie Lennard (who died in 2016) (granddaughter of Topsy Mouwudjala) is known to have had a life history linked to Oobagooma and the claim area. The Kruse Report 2018 noted that Diane Lennard (Maudie’s daughter-in-law) showed Dr Kruse a home video recording of a family trip to Big Springs made with Maudie in the early 2000s. Maudie is shown in the video talking in Warrwa and showing her family around the area.

58 Big Springs features in Bukarrarra (Dreamtime) stories about Warrwa country, with Dr Kruse noting (in the Kruse Report 2018) the following story told by senior Bunuba men George Brooking and Dillon Andrews, and custodian for Warrwa country Tommy May (now deceased):

Marla Marla, he is man, walks in the shallow water, from Sunday Island, he goes to Big Springs and finish there. He goes to little island on Meda River. He travels to Bunuba country, he travels through Warrwa country … Limestone Springs got Billabong there, Dreamtime for women, big fish ... Warrwa and Ungami mix story there. Big Hill, there, Jillunkarti …

59 The Kruse Report 2018 also noted that:

(a) key elements of the restricted male knowledge taught to initiates include Bukarrarra stories for coastal areas, including sites located at Big Springs;

(b) one of the known remaining Warrwa estates, Emama Gnuda, is said to take in the Big Springs Area; and

(c) the site known as Windjidabil or Radawal (Big Springs), as well as Oobagooma, the Robinson River and the southern parts of the Wyndham Ranges, are main points of reference for Warrwa People marking the northern boundary of their traditional country.

Worrora people’s rights and interests in, and connection to, the claim area

60 The joint submissions record the following facts and matters concerning the Worrora people’s rights and interests in, and connection to, the claim area, which have been drawn from the reasons of the Court in Barunga (concerning the Dambimangari Determination) and the other reports and evidence taken into account by the State (listed above).

61 Worrora people are part of the Wanjina-Wunggurr Community which includes people associated with the Worrora, Ngarinyin and Wunumbal languages. In Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402, Sundberg J found that the members of the Wanjina-Wunggurr Community constituted a society and were bound together by a normative system of laws and customs which had continued to be acknowledged and observed by its members in a substantially uninterrupted manner since prior to British assertion of sovereignty over Western Australia. They follow the traditional system of law which comes from the spirit beings known as Wanjina (the supernatural beings that created all things). The Wanjina-Wunggurr system of traditional law and custom, and the native title rights and interests that it gives rise to with respect to the portion of Worrora country which borders the claim area to the north, was recognised by Gilmour J in the Dambimangari Determination.

62 Worrora people define the extent of their traditional country by reference to named estates, which are gained through patrifilial descent in the first instance. The Worrora claim group comprises a relatively small sub-set of the members of the Wanjina-Wunggurr Community who are recognised in the Dambimangari Determination. This is because the claim area is located in close proximity to or within the estate area known as Laddinyoom. The Worrora claim group are those Worrora people who belong to the Laddinyoom estate group. The Laddinyoom estate is referred to in the Blundell Report 2017 and is considered to be the country of the Worrora apical ancestors Gaana and his brothers, Ganbalya and Charlie Ganbalya, each of whom is named in the Big Springs application. The three brothers were all born in the latter part of the 1800s and are described in the Blundell Report 2017 as belonging to ‘bottom Woddordda [Worrora] country’, as well as Jilan and Laddinyoom dambeema [estates]. During the early decades of the 1900s, Gaana and his brothers were looking after the Jilan and Laddinyoom estates. The Blundell Report 2017 refers to Gaana's continuing presence in the country:

The spirits of the country took Gaana away. Some people who were mustering around Oobagooma saw him walking around like a spirit himself. Oobagooma and Kimbolton areas are very powerful spirit country. There are more spirits in this country than other places. They are the Rai and are powerful. Gaana became one of them and is part of the country now.

63 Both Oobagooma and Kimbolton, referred to in the abovementioned extract, run through or in close proximity to the claim area.

64 The Blundell Report 2017 also contains ethno-historical information which provides a credible basis to infer that the other Worrora apical ancestor listed in the Big Springs application, Jangara, had a traditional connection with the claim area at or around the time of effective sovereignty. Jangara, who is listed as an apical ancestor in the Dambimangari Determination, was born in the mid-1800s. Jangara is said to have been an Oonggarddangoowai man from Yampi (today, much of the Yampi peninsula falls within the Yampi Sound Training Area – an Australian Department of Defence facility, which lies immediately to the north of the claim area). According to the Blundell Report 2017, it is likely that Jangara and his wife worked on the stations established on Yampi in the 1880s and also possibly worked on Meda station in the early 1900s. The Lynes Report 2022 states that Jangara and his family lived, for a time until the late 1940s, at Oobagooma, which is just to the north of the claim area.

65 Members of the Worrora claim group continue to have physical and/or spiritual involvement in the claim area, retain knowledge of stories and songs associated with the claim area, undertake traditional practices in the claim area, and pass on that knowledge and practice to younger generations. The Court Report 2019 stated that a meeting in March 2017 between Dr Kruse and a number of senior Worrora representatives ‘identified that present-day Worora persons have traditional information about the Big Springs area and that they identify it as an extension (or part) of an estate area located within the Dambimangari determination’.

66 The Kruse Report 2018 states that Worrora (and Warrwa) traditional names were identified for the claim area by Mrs J Oobagooma (deceased), Mr D Woolagoodja (deceased) and Francis Woolagoodja. Each of these individuals are Worrora speakers associated with country around the Oobagooma part of the Dambimangari Determination area.

67 In the Lynes Report 2022, Dr Lynes recounts a personal communication she had with Dr Kruse in October 2022 in which he shared that his Worrora-identifying informants who went with him on a helicopter trip over Windjidabil / Radawal (Big Springs) in 2019 were able to point out and name locations within the area, and share cultural knowledge.

68 Some of that Worrora cultural knowledge is evident in the Blundell Report 2017. For example, the importance Worrora People place on sharing is highlighted in a dreamtime story about an emu, whose greediness illustrates how people ought not to act and that there are consequences for inappropriate behaviour. Part of the story, as told by senior Worrora man, Mr D Woolagoodja (deceased), centres around Big Springs:

At Big Springs [on Meda station near Derby] all the animals were having a big party and they cut him out, the Emu. They were playing [performing] Walangaddee [a ceremony]. The food was for when they finished dancing. It was a celebration and that is why they were having a feast. The Emu wondered why they didn't include him. So when they all went dancing and singing then he just sat there and ate food – all the food. They chased him and he went south along the marsh and he ended up in the desert. He went inland all the way to Christmas Creek. They were trying to chase him and he was trying to fly. He was flapping and running and flapping and running but he was too heavy. As he ran away flapping his wings they got smaller and smaller and smaller. That's why he is a big bird with no wings to fly.

Shared country

69 An important feature of the present application is that it involves the recognition of two separate groups of native title holders in respect of the claim area, being the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders. By making a single application in respect of the claim area, the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders recognise each other’s rights and interests in the claim area.

70 The joint submissions referred to a meeting held in March 2018 between Warrwa people and Worrora people, that was recorded in the Court Report 2019. The report stated:

The meeting concluded with the Warrwa representatives present stating that they accepted that the Worora people present had rights and interests in Big Springs area and the country was a shared or "crossover" between Warrwa and Worora people. The Worora people present acknowledged the same for the Warrwa persons present.

71 Similarly, the Lynes Report 2022 expressed the opinion that “… due to the fact that Warrwa and Worrora people are neighbours, there is mutual respect for, and participation in, each group's traditional world”.

72 The joint submissions expressed the conclusion that the fact that the Warrwa Native Title Holders and the Worrora Native Title Holders both held rights and interests in the claim area at the time of effective sovereignty is consistent with the ways in which the laws and customs of the neighbouring groups allow for shared rights and interests in bordering parcels of country.

Statutory conditions for consent determination

73 As noted earlier, the Court’s power to make a consent determination under s 87 is enlivened if three conditions are satisfied.

74 The first condition is that the period specified in the notice given in the proceeding under s 66 has ended. As stated earlier in these reasons, the notification period under s 66 in this proceeding ended on 19 February 2025. Accordingly, the first condition is satisfied.

75 The second condition is that agreement has been reached between the parties to the proceeding on the terms of an order of the Court and the terms of the agreement, in writing signed by or on behalf of the parties, have been filed with the Court. A minute of consent determination in respect of this proceeding was filed with the Court on 11 April 2025. The minute records that:

(a) the parties have reached agreement on the terms of orders of the Court set out in the minute; and

(b) the terms of the agreement are that each party consents to the making of orders pursuant to s 87 of the NTA and a determination of native title in the terms set out in the minute.

76 A copy of the proposed consent determination, referred to in the minute, has also been filed with the Court and is the basis for this determination by the Court. Accordingly, the second condition is satisfied.

77 The third condition is that the Court is satisfied that an order in, or consistent with, the terms agreed between the parties would be within the power of the Court. In order to be satisfied that the proposed orders are within the power of the Court, consideration must be given to other restrictions or requirements in the NTA applicable to any determination of native title: Freddie v Northern Territory [2017] FCA 867at [15]. In that regard, I have considered the following requirements:

(a) the requirement in s 61(1) that a native title determination application may be made by “a person or persons authorised by all the persons (the native title claim group) who, according to their traditional laws and customs, hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the particular native title claimed, provided the person or persons are also included in the native title claim group”;

(b) the requirement in s 68 that the area covered by the determination cannot be the subject of a previously approved determination of native title;

(c) the requirement in s 94A that the determination set out the details of the matters required by s 225;

(d) the requirement in s 223(1)(c) that the determination concerns rights and interests which the Australian common law is able to recognise; and

(e) the requirement in s 55 for the Court to make such determinations as are required by ss 56 and 57 at the same time as, or as soon as practicable after, the Court makes the determination, including:

(i) specifying whether the native title is to be held in trust and, if so, by whom;

(ii) if the native title is to be held in trust by a body corporate, that a representative of the native title holders has given the Court a written nomination of a prescribed body corporate together with the written consent of the body corporate to be the trustee; and

(iii) if the native title is not to be held in trust, that a representative of the native title holders has given the Court a written nomination of a prescribed body corporate together with the written consent of the body corporate to be a non-trustee prescribed body corporate.

Section 61 (native title determination application)

78 In Commonwealth v Clifton (2007) 164 FCR 355, the Full Federal Court concluded (at [57]) that s 213(1) discloses a legislative intent that a determination of native title should only be made by the Court in accordance with the procedures set out in the NTA, and that those procedures require that, before any determination may be made that native title is held by a particular group, an application as mentioned in s 13(1) must be made under Pt 3 of the NTA by a person or persons authorised by that group in the manner required by s 61(1). The Full Court further concluded (at [58]) that, where more than one native title claim group seeks a determination that it holds common or group rights and interests constituting the whole or part of the native title to an area, each group must authorise a person or persons to make an application as mentioned in s 13(1).