FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

R and N Hunter Pty Ltd ATF The Hunter Family Superannuation Fund v Count Financial Limited [2025] FCA 544

File number(s): | VID 565 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | HALLEY J |

Date of judgment: | 27 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | REPRESENTATIVE PROCEEDINGS – financial services – application brought by applicant on its own behalf and on behalf of group members – consideration of conflicted remuneration following the introduction of the Future of Financial Advice reforms (FoFA reforms) – whether practice of financial advisers (Representatives) of a financial services licensee (Licensee) continuing to receive commissions or rebates breached fiduciary duties owed to applicant and group members, contravened provisions within Pt 7.7A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) or constituted misleading or deceptive conduct EQUITY – fiduciary obligations – relationship between financial adviser and client – whether Representatives and Licensee owed fiduciary obligations to applicant by reason of undertaking to provide ongoing advice and holding themselves out as expert financial advisers – established categories of fiduciary duty not extended – non-presumptive fiduciary duties owed to applicant by Representatives in relation to certain financial product – fiduciary duty not owed by Licensee – whether advice given to applicant to acquire products that paid commissions or other benefits to the Licensee and Representatives breached fiduciary duties– whether receipt of commission or other benefits, and related conduct, gave rise to insurmountable conflict of interest – whether fiduciary duties attenuated by disclosure and implied agreement – whether fully informed consent provided to alleged breach of fiduciary duties – consideration of “full disclosure in all the circumstances”– fiduciary duties owed to applicant not breached EQUITY – where claimed Representatives and Licensee owed fiduciary obligations to group members by reason of representations made in financial services guide – whether common questions of fact and law able to be determined in proceeding – common questions not able to be determined in proceeding CORPORATIONS – introduction of best interests duty (s 961B) and conflict priority rule (s 961J) pursuant to the FoFA reforms – distinction between fiduciary obligations and statutory obligations pursuant to s 961B and s 961J – effect of “grandfathering” exception in s 1528 of Corporations Act – whether s 961B and s 961J impose requirement to obtain fully informed consent to any conflict or perceived conflict of interest – whether Representatives failed to comply with s 961B and s 961J of the Corporations Act in relation to advice provided to the applicant – contraventions not established CORPORATIONS – whether Licensee contravened s 961L of the Corporations Act – whether Licensee failed to take reasonable steps to ensure that Representatives complied with, relevantly, s 961B and s 961J – consideration of Licensee’s remuneration policy, incentive program, supervision of Representatives, quality assurance processes and standards – contravention not established CORPORATIONS – where group members claim Representatives failed to comply with s 961B and s 961J and Licensee contravened s 961L – whether common questions of fact and law able to be determined in proceeding – common questions proposed by respondent able to be determined in proceeding – contraventions not established CONSUMER LAW – whether Licensee made representations as to future matters to applicant that were likely to mislead or deceive – whether Licensee contravened s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Act 2001 (Cth) or s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law in Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) – contraventions not established CONSUMER LAW – where group members claim Licensee made representations as to future matters that were likely to mislead or deceive – whether common questions of fact and law able to be determined in proceeding – relevant common question not able to be determined in proceeding PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – application for leave to amend agreed fact – leave not granted |

Legislation: | Australian Securities and Investments Act 2001 (Cth) s 12DA Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, s 18 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Ch 7, ss 764A, 769B, 916A, 917, 917B, 917E, 941B, Pt 7.7A, ss 961B, 961E, 961J, 961L, 961M, 963G, 1041H, 1528 Corporations Amendment (Further Future of Financial Advice Measures) Act 2012 (Cth) Corporations Amendment (Future of Financial Advice) Act 2012 (Cth) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss191, 192 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 23, Pt IVA, s 33ZB Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) s 52 Treasury Laws Amendment (Ending Grandfathered Conflicted Remuneration) Act 2019 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | ABN AMRO Bank NV v Bathurst Regional Council (2014) 224 FCR 1; [2014] FCAFC 65 Aequitas Ltd v Sparad No 100 Ltd (formerly Australian European Finance Corp Ltd) [2001] NSWSC 14 Ancient Order of Foresters in Victoria Friendly Society Limited v Lifeplan Australia Friendly Society Limited (2018) 265 CLR 1; [2018] HCA 43 Asirifi-Otchere v Swann Insurance (Aust) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 1355; (2020) 148 ACSR 14 Asirifi-Otchere v Swann Insurance (Aust) Pty Ltd (No 3) [2020] FCA 1885, (2020) 385 ALR 625 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Allied Advice [2022] FCA 496; (2022) 160 ACSR 204 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) (2020) 377 ALR 55; [2020] FCA 69 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Superannuation Limited [2023] FCA 488; (2023) 168 ACSR 206 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Financial Circle Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 1644; (2018) 131 ACSR 484 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v NSG Services Pty Ltd (2017) 122 ACSR 47; [2017] FCA 345 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Wealth & Risk Management Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 59; (2018) 124 ACSR 351 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 2) (2018) 266 FCR 147; [2018] FCA 751 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Securities Administration Ltd (2019) 272 FCR 170; [2019] FCAFC 187 Australian Securities Investments Commission v Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Ltd (2007) 160 FCR 35; [2007] FCA 963 Bennett v Elysium Noosa Pty Ltd (in liq) (2012) 202 FCR 72; [2012] FCA 211 Birtchnell v Equity Trustees, Executors & Agency Co Ltd (1929) 42 CLR 384 Blackmagic Design Pty Ltd v Overliese (2011) 191 FCR 1; [2011] FCAFC 24 Brady v NULIS Nominees (Australia) Limited in its capacity as trustee of the MLC Super Fund (No 3) [2022] FCA 224 Breen v Williams (1996) 186 CLR 71 Bright v Femcare Ltd [2002] FCAFC 243 Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 CLR 592; [2004] HCA 60 Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304; [2009] HCA 25 Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2002) 202 CLR 45; [2000] HCA 12 Clark Boyce v Mouat [1994] 1 AC 428 Casaclang v Wealthsure (2015) 238 FCR 55; [2015] FCA 761 Commonwealth Bank of Australia v Smith (1991) 42 FCR 390 Coope v LCM Litigation Fund Pty Ltd [2016] NSWCA 37; (2016) 333 ALR 524 Daly v Sydney Stock Exchange Ltd (1986) 160 CLR 371 Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky (1992) 39 FCR 31 Dillon v RBS Group (Australia) Pty Ltd (2017) 252 FCR 150; [2017] FCA 896 Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89; [2007] HCA 22 FHR European Venturers Ltd LLP v Mankarious [2011] EWHC 2308 (Ch) Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 GM & AM Pearce & Co Pty Ltd v Australian Tallow Producers [2005] VSCA 113 Gray v New Augarita Porcupine Mines Ltd [1952] 3 DLR 1 Grimaldi v Chameleon Mining NL (No 2) (2012) 200 FCR 296; [2012] FCAFC 6 Henderson v Amadio (No 1) [1995] 62 FCR 1 Henjo Investments Pty Ltd v Collins Marrickville Pty Ltd (1988) 39 FCR 546 Hospital Products Ltd v United States Surgical Corporation (1984) 156 CLR 41 Howard v Commissioner for Taxation (2014) 253 CLR 83; [2014] HCA 21 Imperial Mercantile Credit Association (Liquidators) v Coleman (1873) LR 6 HL 189 Industry Research and Development Board v Phai See Investments Pty Ltd (2001) 112 FCR 24; [2001] FCA 532 J&J Richards Super Pty Ltd ATF The J&J Richards Superannuation Fund v Nielsen [2024] FCA 1472 Johnson Tiles Pty Ltd v Esso Australia Pty Ltd [2003] VSC 27; (2003) ATR 81-692 Kamasaee v Commonwealth of Australia & Ors (No 10) (Issues for trial ruling) [2017] VSC 272 Kimberley NZI Finance Ltd v Torero Pty Ltd [1989] ATPR (Digest) 46,054 Law Society of New South Wales v Harvey [1976] 2 NSWLR 154 Lloyd v Belconnen Lakeview Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 2177; (2019) 142 ACSR 445 Lloyds Bank v Bundy (1975) 1 QB 326 Moussa v Camden Council (No 5) [2023] NSWSC 1135 Naaman v Jaken Properties Australia Pty Ltd [2025] HCA 1: (2025) 421 ALR 227 Nguyen v Rickhuss [2023] NSWCA 249 Oliana Foods Pty Ltd v Culinary Co Pty Ltd (In Liq) [2020] VSC 693 One.Tel Ltd (in liq) v Rich (2003) 45 ACSR 466; [2003] NSWSC 522 Our Lady’s Mount Pty Ltd (as trustee) v Magnificat Meal Movement International Inc (1999) 33 ACSR 163 Pavan v Ratnam (1996) 23 ACSR 214 Perera v GetSwift Ltd (2018) 263 FCR 1; [2018] FCA 732 Porter & Anor v Mulcahy & Co Accounting Services Pty Ltd & Ors [2021] VSC 572 R v Rivkin (2004) 59 NSWLR 284; [2004] NSWCCA 7 Re McGrath & Anor (in their capacity as liquidators of HIH Insurance Ltd) [2010] NSWSC 404; (2010) 266 ALR 642 Real Estate Services Council v Alliance Strata Management Ltd (unreported, NSW Court of Appeal, 8 June 1994) Richmond Valley Council v JLT Risk Solutions Pty Ltd [2021] NSWSC 383 Richmond Valley Council v JLT Risk Solutions Pty Ltd [2021] NSWSC 383 Rodriguez & Sons Pty Ltd v Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority t/as Seqwater (No 5) [2015] NSWSC 1771 Semrani v Manoun [2001] NSWCA 337 Short v Crawley (No 30) [2007] NSWSC 1322 Simpson v Donnybrook Properties Pty Ltd [2010] NSWCA 229 Stack v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 1479; (2021) 401 ALR 113 Thomson v Golden Destiny Investments Pty Ltd [2015] NSWSC 1176 Timbercorp Finance Pty Ltd (in liq) v Collins (2016) 259 CLR 212; [2016] HCA 44 Toyota Motor Corporation Australia Limited v Williams [2023] 296 FCR 514; [2023] FCAFC 50 Traderight (NSW) Pty Ltd v Bank of Queensland Limited (No 17) and 13 related matters [2014] NSWSC 55 Williams v Toyota Motor Corp Australia Ltd (Initial Trial) [2022] FCA 344 Wingecarribee Shire Council v Lehman Brothers Australia Ltd (in liq) [2012] FCA 1028; (2012) 301 ALR 1 Woolworths Ltd v Kelly (1991) 22 NSWLR 189 Wyse & Young International Pty Ltd v Sanna [2019] NSWSC 683 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | 712 |

Date of last submission/s: | 29 April 2024 |

Date of hearing: | 4-7, 11-14, 19-22 March 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr C H Withers SC with Mr T Bagley, Mr B O’Connor and Mr M J Gvozdenovic |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Piper Alderman |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Ms E Collins SC with Mr P Meagher, Mr M Sherman and Mr J Birrell |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Clayton Utz |

ORDERS

VID 565 of 2020 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | R AND N HUNTER PTY LTD (ACN 105 163 522) ATF THE HUNTER FAMILY SUPERANNUATION FUND Applicant | |

AND: | COUNT FINANCIAL LIMITED (ACN 001 974 625) Respondent | |

order made by: | HALLEY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 27 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The common questions filed by the respondent on 2 July 2024 be answered in accordance with “Annexure A” annexed to these orders.

2. The amended originating application filed on 16 December 2020 otherwise be dismissed.

3. The applicant is to pay the respondent’s costs, as taxed or agreed.

ANNEXURE A

[The order entered is available on the Commonwealth Courts Portal, which attaches Annexure A].

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[17] | |

[18] | |

[18] | |

[19] | |

[25] | |

[28] | |

[29] | |

[31] | |

[32] | |

[34] | |

[36] | |

[37] | |

[38] | |

[48] | |

[48] | |

[51] | |

[51] | |

[57] | |

[63] | |

[70] | |

[70] | |

[74] | |

[76] | |

[82] | |

[82] | |

[83] | |

[92] | |

[98] | |

[100] | |

[100] | |

[101] | |

[102] | |

[103] | |

[104] | |

[109] | |

[112] | |

[113] | |

[115] | |

[115] | |

[117] | |

[126] | |

[132] | |

[135] | |

[136] | |

[141] | |

[149] | |

[155] | |

[155] | |

H.9.2. Obtaining the Applicant’s Products without Commissions | [160] |

[168] | |

[177] | |

[178] | |

[178] | |

[180] | |

[199] | |

[199] | |

[202] | |

I.3.3. Extension of established categories of fiduciary relationships | [214] |

I.3.4. Non-presumptive fiduciary duties owed to the Applicant | [221] |

[221] | |

[229] | |

Consideration – fiduciary duties owed by the Applicant’s Representatives | [232] |

[253] | |

[277] | |

[278] | |

[278] | |

[284] | |

[284] | |

[291] | |

[294] | |

[294] | |

[303] | |

[309] | |

[321] | |

[324] | |

[325] | |

[337] | |

[339] | |

[341] | |

[341] | |

[343] | |

[354] | |

[354] | |

[362] | |

[378] | |

[379] | |

[379] | |

[380] | |

[383] | |

[383] | |

[387] | |

[387] | |

[400] | |

[404] | |

[426] | |

[426] | |

[428] | |

[431] | |

[431] | |

[433] | |

[436] | |

[442] | |

[442] | |

[444] | |

[444] | |

[451] | |

[454] | |

[462] | |

[465] | |

[465] | |

[472] | |

[485] | |

[485] | |

[486] | |

[493] | |

[497] | |

[504] | |

[504] | |

[506] | |

[511] | |

[531] | |

[537] | |

[546] | |

[547] | |

[547] | |

[552] | |

[552] | |

[553] | |

[560] | |

[567] | |

[567] | |

[570] | |

[575] | |

[575] | |

[583] | |

[588] | |

[593] | |

[593] | |

[594] | |

[602] | |

[610] | |

[619] | |

[619] | |

[620] | |

[623] | |

[629] | |

[630] | |

[630] | |

[632] | |

[632] | |

[635] | |

[642] | |

[651] | |

[651] | |

[653] | |

[661] | |

[663] | |

[674] | |

[688] | |

[691] | |

[692] | |

[692] | |

[697] | |

[699] | |

[704] | |

[704] | |

[710] | |

[712] | |

[] | |

[] |

HALLEY J:

A. INTRODUCTION

1 The principal issue that arises in this proceeding is whether the practice of financial advisers of a financial services licensee continuing to receive commissions or rebates from product providers following the introduction of the Future of Financial Advice (FoFA) reforms breached fiduciary duties owed to clients, contravened best interests and client priority duties in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) or constituted misleading or deceptive conduct.

2 The Applicant is the corporate trustee of a self-managed superannuation fund (Hunter SMSF), operated for the benefit of Roslyn Hunter (Mrs Hunter), Neal Hunter (Mr Hunter), and their sons, Shaun Hunter and Dene Hunter. Mrs Hunter has been the director and company secretary of the Applicant since 19 June 2003 and at all material times was responsible for the financial affairs of the Applicant and made decisions for the Hunter SMSF.

3 The Applicant brings this proceeding on both its own behalf and as the representative for and on behalf of Group Members.

4 The Respondent (Count) was the holder of an Australian Financial Services License (AFSL) during the period from 21 August 2014 to 21 August 2020 (Relevant Period). Count conducted a franchise business pursuant to which it authorised various corporate entities, partnerships and sole traders (Member Firms) and individuals employed by Member Firms to provide financial advice under its AFSL (together, Count Representatives).

5 Centenary Financial Pty Ltd (Centenary) and three of its employees, Michael Williams, Arthur Duffield and Chad Hohnen (together, Applicant’s Representatives) were authorised representatives of Count.

6 The Applicant acquired four financial products, following the provision of financial advice by the Applicant’s Representatives, that are relevant to this proceeding (Applicant’s Products). Three of the Applicant’s Products were issued to the Applicant prior to the Relevant Period.

7 Each of the Applicant’s Products was a financial product for the purposes of s 764A(1) of the Corporations Act. Both upfront and trail commissions were payable on the products.

8 The Applicant claims that it received personal financial advice from the Applicant’s Representatives on six occasions in relation to the Applicant’s Products during the Relevant Period (Relevant Period Advice).

9 The Applicant contends that the Applicant’s Representatives, and in turn, Count breached fiduciary duties that each owed to the Applicant in relation to the Relevant Period Advice and contravened related best interests and client priority statutory duties owed to the Applicant, and by reason of omissions in the Relevant Period Advice also engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

10 The Applicant does not contend that any of the Applicant’s Products was not suitable or should not have been recommended by the Applicant’s Representatives.

11 For the reasons that follow I have concluded:

(a) the only personal financial advice that the Applicant received with respect to the Applicant’s Products in the Relevant Period was in relation to a life insurance policy with AMP Life Limited (AMP Policy);

(b) having regard to all the relevant circumstances, the Applicant’s Representatives owed fiduciary duties to the Applicant with respect to their recommendation to the Applicant during the Relevant Period to acquire the AMP Policy;

(c) the receipt of commissions and other benefits in connection with the AMP Policy was disclosed to the Applicant and constituted part of the agreed remuneration for the acquisition of the AMP Policy or was otherwise the subject of the informed consent of the Applicant;

(d) Count did not owe any fiduciary duties to the Applicant with respect to the Relevant Period Advice or was not otherwise liable for any alleged breach of fiduciary duties by the Applicant’s Representatives;

(e) the Applicant has not established that the Applicant’s Representatives contravened either s 961B or s 961J of the Corporations Act in relation to the provision of any of the Relevant Period Advice;

(f) the Applicant has not established that Count contravened its statutory supervisory obligations pursuant to s 961L of the Corporations Act in relation to the provision of any of the Relevant Period Advice; and

(g) the Applicant has not established that Count engaged in any misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act, s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) or s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) in relation to the provision of any of the Relevant Period Advice.

12 The Applicant also advances claims on behalf of Group Members that during the Relevant Period, Count and the Count Representatives breached fiduciary duties that each owed to Group Members, contravened related best interests and client priority statutory duties owed to Group Members, and by reason of that conduct also engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct.

13 For the reasons that follow I have concluded that given the breadth and generality of the pleaded Group Member definition advanced by the Applicant and the limited evidentiary foundation on which the claims on behalf of Group Members have been advanced, the scope of the common questions that can be addressed in the proceeding is necessarily narrow.

14 The parties were not able to agree common questions for determination in relation to the claims that the Applicant advanced on behalf of Group Members. For the reasons developed below, the common questions advanced by Count were framed in a manner that the Court was in a better position to answer than those advanced by the Applicant. I have answered each of the common questions as formulated by Count in the First Schedule to these reasons. The common questions advanced by the Applicant, except to the extent they were accepted by Count, raised issues that could not be determined on a common basis given the manner in which the Applicant has advanced its case.

15 The parties have prepared a statement of agreed facts that I have relied upon in preparing these reasons for judgment.

16 The parties have also prepared an agreed list of factual and legal issues for determination at the initial trial. I have specifically addressed each of the agreed factual and legal issues in the course of these reasons. Many of the agreed factual and legal issues, however, were not framed in a manner that could be answered with a simple yes or no. In order not to introduce undesirable prolixity into these reasons for judgment I have answered the agreed factual and legal issues while retaining the numbering used in the parties’ document but have otherwise reproduced the agreed list in the Second Schedule to these reasons.

B. GLOSSARY

17 I have used the following defined terms in these reasons:

Defined Term | Definition |

2FASOC | Second Further Amended Statement of Claim filed on 12 March 2024. |

Advice Non-Disclosures | Together or severally, the factors pleaded at [26] of the 2FASOC which the Applicant contends were not disclosed or contained in any of the advice documents, emails or conversations (as recorded by the file notes). |

AFL | Agreed facts and legal issues for determination |

AFSL | Australian Financial Services License |

AMP Distribution Agreement | Operative distribution agreement dated 20 June 2003 in place at the time in which the AMP Policy was acquired by the Applicant. |

AMP Policy | AMP Elevate Life Insurance Policy no. P811402855, issued by AMP Life Limited. |

AMP Template Agreement | Undated template agreement entitled “AMP Financial Services (AMPFS) Distribution Agreement” |

APL | Count’s Approved Product List |

Applicant’s Common Questions or ACQ | Applicant’s proposed common questions |

Applicant’s Products | The Relevant Products acquired by the Applicant. |

Applicant’s Representatives | The Count Representatives who provided financial services to the Applicant (and were authorised by Count to do so), Centenary Financial Pty Ltd, Michael Williams, Arthur Duffield and Chad Hohnen. |

April 2009 ROA | Record of advice provided by Mr Duffield to the Applicant on 21 April 2009. |

August 2015 ROA | Record of advice completed by Mr Williams and provided to the Applicant on 4 August 2015. |

BAC Review | A preventative audit and review control of financial planning advice files referred to as the Best Interest Duty Assessment and Coaching Review, implemented from or around October 2018 to the end of the Relevant Period. |

Bonus Pool | The pool of funds from which the variable quarterly bonus was paid. |

CBA | Commonwealth Bank of Australia |

CBA Cash Account | Commonwealth Bank of Australia Accelerator Cash Account held by the Applicant. |

CBA Rebate Decision | Standard included in CBA’s licensee standards that when giving personal advice to clients in relation to commissioned financial products, and a conflict existed due to the continued receipt of the Commissions, the adviser must dial down or reduce their advice fee by the amount of the Commission to remove the conflict. |

Centenary | Centenary Financial Pty Ltd |

CFSFs | Licensee service fees, structured in the same manner as LAFs, but used to describe fees paid on a specific Colonial First State wholesale product. |

CMLA | Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society Limited (CMLA trading as CommInsure) |

Commissions | Initial and/or “trail” commissions in relation to the sale of the Relevant Products pursuant to the Distribution Agreements. |

Control Gap Spreadsheet | Spreadsheet entitled “control gap assessment” produced by Count. |

Count | Count Financial Limited |

Count Licensee Standards | Policies, licensee standards, corporate guidance documents and training that Count Representatives were required to comply with during the Relevant Period. |

Count Representatives | Authorised corporate entities, partnerships, sole traders and individuals employed by Member Firms to provide financial advice under Count’s AFSL. |

CTC Benefits | The benefits provided to the Count Representatives under the CTC Program. |

CTC Program | Points based rewards system titled “Contribution to Count” calculated primarily by reference to revenue contributed to Count by the Count Representatives. |

December 2013 ROA | Record of advice prepared by Mr Williams and issued to the Applicant on or around 18 December 2013. |

Distribution Agreements | The contractual arrangements between Count and the issuers of financial products for the sale and distribution of the products. |

FASEA Code of Ethics | Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority Code of Ethics |

Financial Services Guide | Financial services guide issued by Count to clients that was updated from time to time. |

FoFA Reforms | Future of Financial Advice Reforms |

FPA Code of Professional Practice | Code of Professional Practice produced by Financial Planning Association of Australia. |

GBE | Gross Business Earnings |

Grandfathered Member Firms | Member Firms who joined before 1 July 2013 who were subject to specific remuneration policies. |

Hunter SMSF | Hunter Family’s self-managed superannuation fund |

July 2015 Meeting | Meeting between Mr Williams, Mr Hohnen, Zeljko Butorajac and Mrs Hunter on 31 July 2015. |

July 2017 ROA | Record of advice prepared by Mr Williams and provided to the Applicant on 19 July 2017. |

Key Risk Indicators Document | A document produced in May 2018 by Count titled “key risk indicators”. |

LAFs | Fees paid by clients of Member Firms to Count on specific platform products, generally calculated as a percentage of the value of funds under management held by the client in the platform product. |

LSFs | Management fees charged by Member Firms in relation to listed security portfolios, calculated by reference to the sum of those funds under management. |

Macquarie | Macquarie Group Limited |

Macquarie Cash Management Account | Applicant’s cash management account operated by Macquarie Bank Limited. |

Macquarie Cash Management Trust | Macquarie Cash Management Trust, being the precursor to the Macquarie Case Management Account. |

March 2018 SOA | Statement of advice prepared on 5 March 2018 directed at life insurance coverage for Shaun Hunter. |

May 2008 SOA | Statement of advice provided to the Applicant by Mr Williams on 20 May 2008. |

May 2008 TFCA | Total Financial Care Agreement issued by Centenary on 20 May 2008 and provided by Mr Williams to the Applicant in late May 2008. |

Member Firms | Authorised corporate entities, partnerships and sole traders who were part of Count’s franchise business. |

Neal TCP Policy | Policy schedule issued by CMLA on 30 July 2009 for a CommInsure Total Care Plan life insurance policy listing the Applicant as the “policy owner” and Mr Hunter as the insured. |

New Member Firms | Member Firms who joined after 1 July 2013 who were subject to specific remuneration policies. |

November 2015 ROA | Record of advice prepared by Mr Williams and provided to the Applicant on 19 November 2015. |

October 2008 ROA | Record of advice provided to the Applicant by Mr Duffield on 3 October 2008. |

Other Benefits | Payments or items of monetary value other than Commissions and Rebates received by Count or Count Representatives from product providers. |

Pre-Relevant Period Advice | Personal Advice received by the Applicant from the Applicant’s Representatives between 20 May 2008 and 18 December 2013. |

Project Gecko | A project initiated by Count in or about early 2017 in which financial data was analysed to identify Member Firms that had been with Count for five or more years and did not meet commercial viability thresholds. |

QAA | Quality Advice Assurance |

QAA question sets | Standard set of questions issued by Count to Count employees conducting a file review as part of the Quality Advice Assurance process to assist with the performance of the file review, during the Relevant Period. |

Rebates | Volume bonuses for the sale of some of the Relevant Products pursuant to the Distribution Agreements. |

Relevant Period | 21 August 2014 to 21 August 2020 inclusive. |

Relevant Period Advice | The following personal advice received by the Applicant during the Relevant Period: (a) on or around 31 July 2015, from Centenary and Michael Williams which is partially documented in a file note from Michael Williams and a review questionnaire of the same date, signed by Michael Williams; (b) on or around 4 August 2015, from Centenary and Michael Williams which is documented in a Record of Advice; (c) on or around 19 November 2015, from Centenary and Michael Williams which is documented in a Record of Advice; (d) on or around 19 July 2016, from Centenary and Michael Williams which is partially documented in a review questionnaire of the same date, signed by Michael Williams and a file note; (e) on or around 19 July 2017, from Centenary and Michael Williams which is documented in a Record of Advice; and (f) on or around 5 March 2018, from Centenary and Chad Hohnen which is documented in a Statement of Advice. |

Relevant Products | The Relevant Products: (a) consist of policies of insurance and other financial products pursuant to which product issuer(s) agreed to pay Count initial and/or trail Commissions in relation to each of those products; (b) are each financial products within the meaning of s 764A(1) of the Corporations Act; (c) are comprised of three classes, being financial products, insurance products and platforms. |

Representations | The representations pleaded in the 2FASOC at [74] as comprising, collectively, on their own, or in any combination the representations pleaded therein. |

Respondent’s Common Questions or RCQ | Respondent’s proposed common questions |

Retail Entitlement Offer | Retail Entitlement Offer announced by Santos Limited. |

RLAL Communication | Letter and attached schedule provided on subpoena from a Claims Data Manager of Resolution Life Australasia Limited. |

Roslyn TCP Policy | A policy schedule issued by CMLA on 1 May 2009 for a CommInsure Total Care Plan life insurance policy listing the Applicant as the “policy owner” and Mrs Hunter as the insured. |

Scenario 1 | Profit based calculations performed by Mr Cairns for the purpose of quantifying the relief sought by the Applicant in the proceeding. |

Scenario 2 | Loss based calculations performed by Mr Cairns for the purpose of quantifying the relief sought by the Applicant in the proceeding. |

Skandia One Fund | Applicant’s investment portfolio described as the Skandia One Fund. |

Solutions Requirements Document | CBA document issued on 9 October 2015 titled “Solution Requirements Document” for the “Adviser & Conflicted Remuneration – Corporate Guidance” project. |

Splits | Specified percentage of Commissions and adviser service fees deducted by Count before passing fees through to the Member Firm. |

TCP Policies | Roslyn TCP Policy and Neal TCP Policy |

Total Financial Care Agreements | Formal contractual arrangements entered into by the Applicant and Centenary for the provision of ongoing advice services. |

TPD | Total permanent disability |

True Position | The True Position pleaded in the 2FASOC at [75] as comprising, jointly and severally, the facts pleaded therein, during the Relevant Period. |

C. WITNESSES

C.1. Applicant’s lay witnesses

18 The Applicant relied on the evidence of Mrs Hunter and her son, Shaun Hunter.

C.1.1. Mrs Hunter

19 Mrs Hunter affirmed three affidavits in the proceedings and was cross examined. After leaving school, Mrs Hunter worked for the CBA for 12 years as a teller, supervisor and ultimately as a loans officer. She subsequently worked for the Ku-ring-gai Soccer Club, initially as a part-time office administrator and then worked full time for 9 years as an office and financial administrator.

20 Mrs Hunter found the process of cross examination stressful. I have no doubt that Mrs Hunter genuinely believes that the Applicant’s Representatives charged an excessive amount for the services that they provided to the Applicant, both directly under the Total Financial Care Agreements and indirectly through the receipt of Commissions from the providers of the Applicant’s Products. Unfortunately, Mrs Hunter allowed that sense of grievance to colour her evidence, in particular, her oral evidence.

21 In giving her oral evidence, Mrs Hunter had a tendency to be defensive, argumentative and exaggerate her alleged inability to understand the documents with which she was provided by the Applicant’s Representatives. At one stage of her cross examination, when pressed on a particular issue, she responded that she was a “mother who’s just running a superannuation fund for her family” and when confronted with specific disclosures of commission arrangements in documents that had been provided to her, she responded “that doesn’t mean anything to me”, they are “just facts and figures”. I accept that Mrs Hunter had little financial experience but I am satisfied that Mrs Hunter, by reason of her work experience with the CBA and her demeanour in the witness box, was an intelligent and capable person who would have had little difficulty understanding the documents with which she was provided by the Applicant’s Representatives, notwithstanding her testamentary protestations to the contrary.

22 Mrs Hunter steadfastly maintained that all meetings that she attended with Mr Williams, either alone or with Mr Hunter, were initially held annually at Mr Duffield’s house at Christmas time notwithstanding a reference in the May 2008 SOA to previous meetings.

23 Mrs Hunter accepted that parts of documents were expressly drawn to her attention by Mr Duffield and Mr Williams but claimed both in her affidavits and in cross examination that they never told her that Centenary received any Commissions from product providers. When pressed on important details she would often respond to matters that might be thought adverse to the Applicant’s case by stating that she could not recall but if it was otherwise consistent with the Applicant’s case, she would confidently assert that it “would have” happened.

24 Ultimately, given the selective nature of Mrs Hunter’s professed lack of recollection, I have not been able to attribute significant weight to her evidence of contemporaneous conversations, in particular, her contentions that Mr Williams or Mr Hohnen never told her about the payment of Commissions on the Applicant’s Products.

C.1.2. Shaun Hunter

25 Shaun Hunter is the son of Mr and Mrs Hunter and a director of the Applicant since 2010.

26 Shaun Hunter gave evidence of his very limited involvement in the affairs of the Hunter SMSF, his dealings with Mr Hohnen in relation to the purchase of a residential property in Asquith in 2018, and the absence of any disclosure by Mr Hohnen or anyone else at Centenary of any receipt by Centenary of Commissions in exchange for recommending financial products or any of the other matters that the Applicant contends should have been disclosed to it.

27 He was not cross examined on the basis that the Applicant would not take any Browne v Dunn point against Count in relation to his evidence.

C.2. Count’s lay witnesses

28 Count relied on evidence from Mr Williams, Mr Hohnen, Michael Spurr, Karen Peel, Belinda Light, and Cameron Lewis.

C.2.1 Mr Williams

29 Mr Williams gave evidence of (a) his dealings with the Applicant, in particular the advice he provided to the Applicant in records of advice and in connection with the Applicant’s acquisition of the AMP Policy and the Macquarie Cash Management Account, (b) meetings and communications with Mr and Mrs Hunter, (c) Centenary’s remuneration arrangements, (d) the CTC Program, and (e) the Total Financial Care Agreements and certain records of advice. He was extensively cross examined.

30 Mr Williams was an impressive witness. He answered questions directly, concisely and without prevarication. His evidence was given in a relatively dispassionate manner and was consistent with the apparent logic of events. He could not recall the detail of specific conversations that he had with Mr and Mrs Hunter but was able to give cogent and plausible evidence of his usual practice in providing financial services to retail clients. He made appropriate concessions, did not speculate and was not unduly defensive. I was satisfied that his evidence was generally reliable and his evidence as to his state of mind at various times was honestly given.

C.2.2. Mr Hohnen

31 Mr Hohnen gave evidence of (a) his usual practice in providing financial advice to retail clients, (b) his discussions and communications with Shaun Hunter in connection with the issue of the AMP Policy to the Applicant, (c) the preparation of the March 2018 SOA and (d) Centenary’s remuneration arrangements. He was not cross examined on the basis that Count would not take any Browne v Dunn point against the Applicant in relation to his evidence.

C.2.3. Mr Spurr

32 Mr Spurr held various senior executive positions with Count, its subsidiary CountPlus Pty Ltd and the CBA during the Relevant Period, including with CBA as Project Manager in Adviser Remuneration and Incentives. His primary role in that position was to review Count’s existing remuneration model and to consider, develop and implement an alternative remuneration model. He gave evidence of (a) Count’s business model and remuneration policies, (b) the CTC Program, (c) Count’s APL, and (d) the “dialling down” of Commissions. He was cross examined.

33 Mr Spurr responded directly to questions in cross examination without prevarication and made appropriate concessions. He was not argumentative and I am satisfied that he gave truthful evidence to the best of his recollection. I am satisfied that his evidence can be relied upon.

C.2.4. Ms Light

34 Ms Light was employed as a Senior Manager, Supervision & Governance in the Risk Management and Compliance team of Count during the Relevant Period. She gave evidence of (a) Count’s business structure, (b) Count’s risk management framework and risk management function, (c) the framework for adviser supervision and monitoring, including detection measures, and (d) the investigation and consideration of matters of concern. She was briefly cross examined.

35 Ms Light answered questions directly and without prevarication. I am satisfied that her evidence is reliable and given honestly.

C.2.5. Ms Peel

36 Ms Peel was first employed by CBA in 1988 and has held compliance roles in CBA since 2002, including in the period October 2014 to approximately May 2018, Executive Manager, Wealth Risk Management Advice and acting Chief Risk Officer, Wealth Risk Management Advice from approximately May 2018 to approximately June 2019. Ms Peel gave evidence of CBA’s risk and compliance framework as far as it concerned or was applicable to Count, including (a) risk assessment and the testing of process and controls, (b) key governing policies that applied to Count, (c) the regulatory reform program, and (d) CBA’s in-house function. Ms Peel was not cross examined on the basis that Count would not take any Browne v Dunn point against the Applicant in relation to her evidence.

C.2.6. Mr Lewis

37 During the Relevant Period Mr Lewis was variously a Senior Manager, Quality Advice Assurance at CBA for CBA’s licensees, including Count, seconded to other business units of CBA, including in 2018 serving as a Senior Technical Advice Expert for CBA’s Advice Remediation Program which included an assessment of client files of Count, and from 1 October 2019, Senior Manager, Supervision and Monitoring at Count, coinciding with the sale of Count to CountPlus. Mr Lewis gave evidence on (a) contractual relationships between Count and Member Firms, (b) Count’s organisational structure, and (c) Count’s risk and compliance framework. Mr Lewis was not cross examined on the basis that Count would not take any Browne v Dunn point against the Applicant in relation to his evidence.

C.3. Expert witnesses

38 Both the Applicant and Count relied on expert reports addressing relief.

39 The Applicant tendered a report and a reply report from Martin Cairns. Mr Cairns is the managing director of Sapere Research Group Limited and the co-lead of its forensic accounting and valuation team. He has extensive experience in a wide range of business sectors involving audit, accounting, forensic and valuation issues.

40 Count tendered a report from Andrew Ross. Mr Ross is a partner of KordaMentha. He has extensive experience in the provision of financial advice, valuation and forensic accounting.

41 Neither Mr Cairns nor Mr Ross was cross examined.

42 Mr Cairns advanced profit based calculations described as Scenario 1, and loss based calculations described as Scenario 2, for the purpose of quantifying the relief sought by the Applicant in the proceeding.

43 For the three Applicant’s Products that were insurance products, Mr Cairns determined the profit based calculations in Scenario 1 comprised total Commissions referrable to the Applicant’s Products together with pre-judgment interest. In Scenario 2 the loss based calculations were based on decreases in the value of the three Applicant’s Products between the annual premiums payable on those products and the annual premiums that would have been payable had the premiums been subject to maximum dial down rates together with pre-judgment interest.

44 For the Macquarie Cash Management Account, Mr Cairns calculated, for both Scenario 1 and Scenario 2, the difference between the actual interest rate earned by the Applicant from Macquarie, as the product provider, and the interest the Applicant would have received but for the payment of Commissions referrable to the Macquarie Cash Management Account together with pre-judgment interest.

45 In his report, Mr Ross raised numerous concerns with the analysis and methodology adopted by Mr Cairns in his first report.

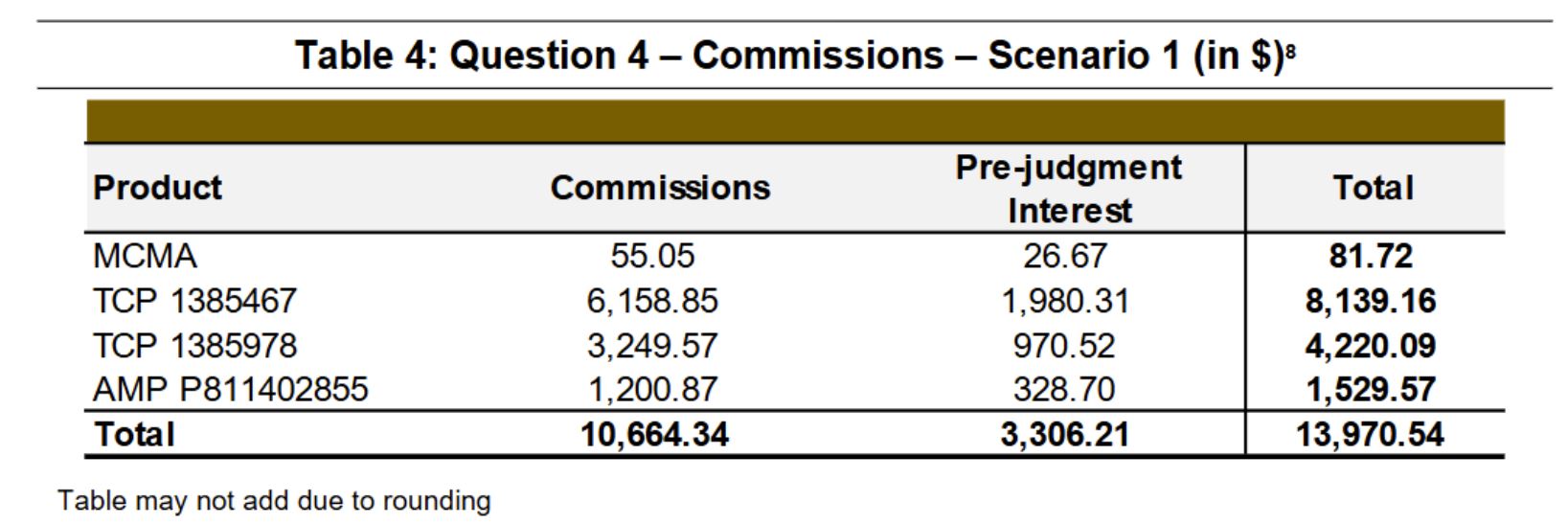

46 In the course of the trial, however, Count accepted that the calculations undertaken by Mr Cairns in Scenario 1 for Commissions could be accepted for the purposes of determining compensation for the Applicant if the Applicant was otherwise successful in establishing any of its causes of action in the proceeding. I set out below the calculations of Commissions and pre-judgment interest in Scenario 1 performed by Mr Cairns in his first report:

47 I note that due to an inadvertent double counting of interest issue, Mr Cairns corrected the figures for Commissions and pre-judgment interest for the Macquarie Cash Management Account in his reply report. The corrected figures for Commissions was $51.32 and for pre-judgment interest was $24.78. As a result of these corrections the aggregate figure advanced by Mr Cairns in Scenario 1 reduced from $13,970.54 to $13,964.92.

D. APPLICATION TO QUALIFY REMUNERATION AGREED FACT

D.1. Overview

48 The statement of agreed facts adduced into evidence pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) included an agreed fact in [24] in the following terms:

Commissions formed part of the way in which financial advisers, including Count Authorised Representatives, were remunerated for the provision of personal advice.

49 On the last day of the initial trial the Applicant foreshadowed that it would seek to qualify the terms of the agreed fact in [24].

50 On 15 April 2024, the Applicant filed submissions seeking leave to amend [24] as follows:

Commissions formed part of the way in which financial advisers, including Count Authorised Representatives, were remunerated for the provision of personal advice to some Group Members.

D.2. Submissions

D.2.1. The Applicant

51 The Applicant accepts that some Count Representatives were remunerated by Count in the form of Commissions and in some cases the Commissions may have constituted remuneration for providing advice to a client but submits that in other cases the Count Representative may have received an upfront or ongoing advice fee by the client and therefore the Commissions would have been in addition to those fees.

52 In these circumstances, the Applicant submits that [24] cannot be read as an admission or concession that Count Representatives in fact received a Commission for work performed for Group Members in all instances for the following reasons. First, it does not have the information to make such an admission on behalf of all Group Members. Second, the Applicant cannot make admissions that affect individual claims for particular Group Members for whom it does not act. Third, it would be contrary to Count’s defence that it admitted it did not require the Count Representatives to provide any service in exchange for Commissions. Fourth, it is inconsistent with the terms of the Distribution Agreements that show that the Commissions were paid to Count Representatives for marketing their products. Fifth, it is not possible to assume that Commissions constituted remuneration if there existed an agreed fee for service, such as the upfront fee of $1,650 and the ongoing fee of $5,500 payable by the Applicant to Centenary as recorded in the May 2008 SOA.

53 The Applicant submits, however, that in order to “obtain certainty” it should be given leave to amend [24] to add the words “to some Group Members”.

54 The Applicant submits that the Court plainly has power to permit the amendment pursuant to s 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act).

55 Next the Applicant submits that given the Court’s Practice Note “Central Practice Note: National Court Framework and Case Management” (CPN-1) recognises that a statement of agreed facts is a “collaborative tool to minimise the length of the trial hearing”, an “innovative tool relating to managing evidence” and is “encouraged by the Court”, it would be “somewhat perverse” if a party seeking to reach “the most effective, efficient and economical way to manage evidence” was prevented from making a submission important to its case because of competing interpretations as to how a paragraph in a statement of agreed facts should be read.

56 The Applicant submits that such a result would be antithetical to the purpose and objective of CPN-1, particularly given (a) the Applicant’s position that no service was provided was well known to Count such that it “would be truly odd” if the Applicant were taken to have suddenly and without any rational explanation abandoned that position in an agreed document ordered by the Court, and (b) there would be no prejudice to Count in permitting the Applicant to make that amendment to [24] simply to clarify an agreed fact that is unclear.

D.2.2. Count

57 On 29 April 2024, Count filed submissions opposing leave to amend or qualify [24] and attached copies of correspondence between the parties’ solicitors with respect to the inclusion of [24] in the statement of agreed facts.

58 Count submits that leave to amend or qualify [24] should be refused for the following reasons.

59 First, the application is misconceived because the power conferred by s 23 of the FCA Act does not extend to “amending” evidence that has been adduced in the proceeding or deeming that a respondent has agreed to a fact that it has not agreed to.

60 Second, the amendment sought to be made to [24] is inconsistent with the case the Applicant pursued at trial. Count submits that the Applicant separately admitted that Count’s payment to Centenary of Commissions received from product providers was a component of Centenary’s remuneration, the Applicant cross examined Mr Williams on the premise that Commissions was a form of remuneration, and Count made both written and oral submissions based on [24] that Commissions were in substance, a form of deferred remuneration.

61 Third, the application is brought extremely late causing prejudice to Count as it prepared and advanced its closing written and oral submissions on the basis that [24] was agreed and uncontroversial. Count submits that it made forensic decisions on that basis, including a decision not to adduce expert evidence.

62 Fourth, the Applicant has not filed any evidence to explain its delay until the last day of the trial to identify any desire to qualify the language of [24] or why it did not seek to adduce any evidence in support of the proposed amendment to the paragraph.

D.3. Consideration

63 I accept that s 23 of the FCA Act confers a broad power on the Court to make orders that it considers appropriate but I am not satisfied for the following reasons that the power should be exercised in the present case to amend unilaterally, in a significant manner, an agreed fact after a three week trial has concluded.

64 First, the Evidence Act provides for a specific procedure by which a party can seek to qualify an admission made in a statement of agreed facts tendered pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act. The procedure does not involve any unilateral amendment to the agreed fact but rather permits a party, subject to the leave of the Court, adducing evidence “to

contradict or qualify an agreed fact”: s 191(2) of the Evidence Act. Such leave may be given on such terms as the Court thinks fit and without limiting the matters the Court can take into account, the Court is required, in determining whether to grant leave, to take into account (a) the impact on the length of the hearing, (b) any unfairness to a party or a witness, (c) the importance of the evidence, (d) the nature of the hearing, and (e) the power, if any, to adjourn the hearing or make any other direction in relation to the evidence: s 192(2) of the Evidence Act.

65 Rather than seek to invoke this procedure the Applicant has asked the Court for consent for it to amend unilaterally an agreed fact. It is not apparent how a Court can, consistently with established principles of justice, make an order retrospectively having the effect of amending a fact that had been admitted into evidence pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act. In substance, the Applicant is asking the Court to impose an agreed fact on a party that has not consented to that fact. That is a fundamentally different proposition to the Court having regard to evidence that it has given leave to adduce pursuant to s 191(2) and s 192 in assessing the weight it might give to an agreed fact.

66 Second, I do not accept that there is any relevant ambiguity in [24]. Moreover, the use of the qualification for “some Group Members” in other paragraphs of the statement of agreed facts emphasises the importance of the absence of such a qualification for [24]. The Court would not readily infer that it was an oversight or accidental. As the correspondence between the parties in relation to the formulation of [24] makes plain, on 7 December 2023 the Applicant proposed that [24] be included in the statement of agreed facts in its exact terms, by letter dated 25 January 2024 Count sought an amendment to [24] but by letter dated 27 February 2024, the Applicant rejected the amendment.

67 Third, and relatedly, the submissions advanced by the Applicant in support of its ambiguity contentions are thinly disguised and impermissible attempts to point to evidence that contradicts or qualifies the agreed fact in [24], contrary to s 191(2) of the Evidence Act or otherwise are not matters that would displace the clear and unambiguous wording of [24].

68 Fourth, I accept [24] is an important agreed fact for the case that the Applicant seeks to advance in the proceeding but I am equally satisfied that it is an important agreed fact that Count relies upon in answer to the claims advanced by the Applicant. In assessing the weight to be given to prejudice to the parties, the unfortunate issue for the Applicant is that it not only agreed to the inclusion of [24], it drafted the precise terms of the paragraph.

69 Fifth, given the application to amend [24] was not made, or even foreshadowed, until after Count had conducted the trial and made its closing submissions, any order made now to amend the agreed fact would likely cause substantial prejudice and unfairness to Count, not least the opportunity to lead evidence to support [24] in its currently agreed form. It would, contrary to the Applicant’s submissions, rather be antithetical to the purpose and objective of CPN 1 to accede to the Applicant’s request to grant leave to permit the Applicant to unilaterally amend [24] given the time at which the application was made.

E. COUNT AND CENTENARY

E.1. Franchise business of Count

70 At all times during the Relevant Period, Count was a holder of an AFSL and conducted a franchise business in which it authorised Member Firms to provide financial advice under its AFSL. The Member Firms included employed advisers of corporate firms and partnerships who were also authorised representatives of Count. Count did not employ any advisers.

71 The number of Member Firms authorised by Count to provide financial advice under its AFSL during the Relevant Period varied between 569 and 936 firms and individuals.

72 Count generated nearly all of its revenue through the Member Firms and the providers of products which were purchased by clients of the Member Firms. In return for Member Firms sharing the revenue they generated from their clients, Count permitted the Member Firms to operate under its AFSL and its brand. In addition, Count provided operational and compliance support and ongoing training to Member Firms.

73 Count was highly reliant on revenue from product providers. In FY14 approximately 64% of Count’s revenue came from platforms. During the Relevant Period, Count received in aggregate $154,863,136.48 in Commissions and the total Commissions and Rebate expenses paid out by Count exceeded $400,000,000.

E.2. Count’s sources of revenue

74 Count obtained revenue from the following principal sources:

(a) membership fees paid by Member Firms;

(b) fees paid by Member Firms for attendance at Count’s annual conference;

(c) Rebates paid by product providers, typically on a minimum volume basis but also subject to other criteria;

(d) Splits, being funds retained by Count on Commissions or advice fees payable to Member Firms by their clients or product providers, at variable rates over time and as between Member Firms;

(e) LAFs, being fees paid by clients of Member Firms to Count on specific platform products, generally calculated as a percentage of the value of funds under management held by the client in the platform product;

(f) CFSFs, being licensee service fees, structured in the same manner as LAFs, but used to describe fees paid on a specific Colonial First State wholesale product;

(g) LSFs, being management fees charged by Member Firms in relation to listed security portfolios, calculated by reference to the sum of those funds under management;

(h) sponsorship and payments from education providers; and

(i) software, paraplanning and other support fees charged to Member Firms.

75 Rebates paid by platform providers were the largest source of revenue, that was retained by Count, during the Relevant Period. The accrual of Rebates was an integer in the calculation of “CTC points” in the CTC Program, but Rebates were not otherwise shared with Member Firms.

E.3. Count’s Representatives

76 Count entered into “Authorised Representative Agreements” with Member Firms.

77 On 25 February 2005, Count authorised Centenary as a Member Firm to provide financial advice, including financial services, on its behalf. During the Relevant Period, up to 3 April 2020, Centenary was a corporate representative of Count, and Michael Williams was an authorised representative of Count, and employee of Centenary. Mr Williams became an authorised representative of Count on 1 June 2006. Mr Duffield was an authorised representative of Count and employee of Centenary from 22 May 2003 until approximately February 2013.

78 Count promoted its Count Representatives to retail clients on its website in the following terms, noting that on or about 20 March 2018, Count amended its website to remove “and independent” from the last sentence below:

WHAT WE OFFER

The right adviser for you depends on your personal requirements. At Count we believe it's essential you find someone you are comfortable with and who you can trust. And [sic] someone who will provide you with professional advice that is based on your best interests.

Why choose a Count adviser?

…

• The peace of mind that comes from dealing with a professional

• We’re working for you.

Count advisers recommend investments and strategies based on their suitability to your specific needs. Each investment we recommend has been through our rigorous and independent research process.

79 Count represented in the December 2013 ROA, March 2018 SOA, and it’s website to prospective retail investors that:

(a) it could help them achieve their financial goals;

(b) its “Count Wealth Accountants” were “looking after your financial life”;

(c) “our advisers operate at the highest industry education standards”;

(d) “we can offer you choice and flexibility to keep your financial future on track”;

(e) “[w]ith access to a wide range of quality investment and insurance solutions, Count advisers can offer you choice and flexibility when it comes to mapping out your financial future”… “a reputation built on trust”; and

(f) “A count adviser can help you: … work out the level of cover you need and … can afford; [p]rovide guidance on where to invest your money.”

80 Centenary represented to the Applicant that (a) “our strategy recommendations will help you achieve your goals and needs” and “our experience is your peace of mind” in its December 2013 ROA, and (b) each of its financial planners were experts in its Financial Services Guides.

81 The majority of Centenary’s revenue was derived from the payment of Commissions. During the Relevant Period, Centenary received more than $2,700,000 in Commissions.

F. THE APPLICANT’S PRODUCTS

F.1. Overview

82 The Applicant’s personal case against the Applicant’s Representatives and Count is directed at the provision of personal advice by the Applicant’s Representatives in relation to the Applicant’s Products during the Relevant Period.

F.2. Macquarie Cash Management Account

83 In or about April or May 2009, Mr Duffield provided the April 2009 ROA, a record of advice dated 21 April 2009 to the Applicant in which he recommended that the Applicant place $260,000 in the Macquarie Cash Management Account from the funds held in the Applicant’s Macquarie Cash Management Trust. The April 2009 ROA was four pages in length.

84 The April 2009 ROA noted that after meeting with Mrs and Mr Hunter, it had been confirmed that their personal situation had either not altered or was deemed not to have altered significantly from that previously recorded and therefore the recommendations were based on the personal and financial information set forth in the May 2008 SOA and the October 2008 ROA (although mistakenly referred to as an October 2009 ROA), each of which is considered at [102] and [109] to [111] below.

85 There was no evidence of any Distribution Agreement, being contractual arrangements between Count and the Issuers of the relevant products for the sale and distribution in force between Macquarie and Count at the time that the Applicant accepted the recommendation by Mr Duffield to place funds in the Macquarie Cash Management Account.

86 Subsequently, however, on or about 30 June 2012, Count entered into a cash products distribution agreement with Macquarie. The agreement provided for the payment of commissions (described as “distribution commission”) to Count, promises by Count to promote Macquarie Cash Management Accounts and a sales target, but did not include any promises by Count to place Macquarie Cash Management Accounts on the APL or include any lapse rate incentive. The agreement provided Macquarie with an unfettered discretion to cease paying commissions if less than 500 new Macquarie Cash Management Accounts were opened in any year, less than $250 million was held in all accounts or the average account balance fell below $30,000. In addition, Macquarie agreed to pay Count up to $6.5 million each year on cash deposit products. The agreement included a clause that Count would keep all information that it might acquire pursuant to the agreement and the distribution commissions payable under the agreement confidential but did not include any confidentiality obligation with respect to the agreement itself.

87 On or about 9 December 2014, the Applicant, through Mrs Hunter, indicated that it wished to close the Macquarie Cash Management Account.

88 On or about 31 July 2015, the Applicant applied to close its Macquarie Cash Management Account.

89 By 4 August 2015, all funds were withdrawn from the Macquarie Cash Management Account. The Applicant otherwise held its Macquarie Cash Management Account until approximately 1 September 2015.

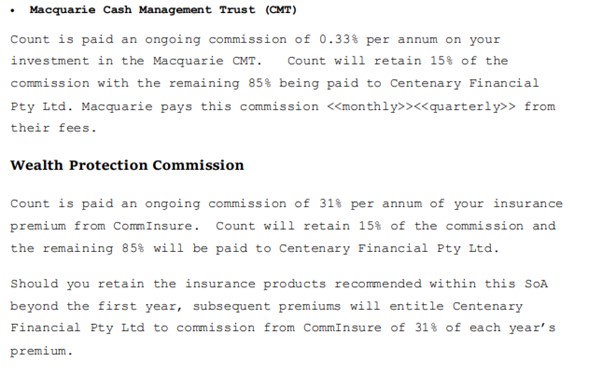

90 In the period between 1 July 2012 and 1 September 2015, Centenary received Commissions with respect to the Macquarie Cash Management Account in the amount of $337.08.

91 During the period of approximately 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015, the Applicant paid ongoing service fees to Count and Centenary, in an amount of $5,500, a proportion of which was retained by Count.

F.3. Roslyn and Neal TCP Policies

92 On or about 1 May 2009, the Roslyn TCP Policy, a new policy schedule, was issued by CMLA for a CommInsure Total Care Plan life insurance policy listing the Applicant as the “policy owner” and Mrs Hunter as the insured. The Roslyn TCP Policy was held until at least 1 May 2020. In the period between 1 May 2013 and 1 May 2020, Centenary received Commissions with respect to the Roslyn TCP Policy in the amount of $3,591.67.

93 On 30 July 2009, CMLA issued a second policy schedule for a CommInsure Total Care Plan life insurance policy, listing the Applicant as the “policy owner” and Mr Hunter as the insured, being the Neal TCP Policy. The Neal TCP Policy was held until at least 30 July 2020. In the period between 1 August 2012 and 1 August 2019, Centenary received commissions with respect to the Neal TCP Policy in the amount of $7,579.78.

94 During the period in which the TCP Policies were in force, the relationship between Count and CMLA was governed by three successive Distribution Agreements.

95 In the period prior to 1 July 2011, the operative Distribution Agreement was a distribution agreement between Count and CMLA dated 3 June 2003. The agreement provided for the payment of Commissions to Count and an asset and renewal commission in relation to the “in force portfolio” but did not include any other provision of incentive rebates, promises by Count to promote CMLA products or place them on the APL, lapse rate incentives or sales targets. The agreement included a clause that Count would keep all information that it might acquire pursuant to the agreement confidential but did not include any confidentiality obligation with respect to the agreement itself. This was the CMLA Distribution Agreement that was in force when the Applicant became the owner of each of the TCP Policies.

96 Subsequently, in the period between 1 July 2011 and 30 June 2012, the operative CMLA Distribution Agreement was a relationship agreement between Count and CMLA dated 15 September 2011, but with effect from 1 July 2011. The agreement provided for the payment of incentive rebates to Count together with lapse rate incentives and sales targets but did not otherwise include any obligation to place them on the APL or promises by Count to promote CMLA products, other than a general “support” obligation that included undertaking “speaking spots and CommInsure branding opportunities” at professional development days, conferences and workshops. The agreement was marked confidential but did not include any confidentiality clauses.

97 Then finally, in the period from 1 July 2012, the operative CMLA Distribution Agreement was a preferred relationship agreement between Count and CMLA executed on 24 April 2013, but with effect from 1 July 2012. The agreement provided for the payment of incentive rebates to Count, together with lapse rate incentives, sales targets and a promise by Count to place CMLA products on the APL, but did not provide for the payment of commissions nor include promises by Count to promote CMLA products, other than a general “support” obligation including at professional development days, State based events and conferences, invitations to CommInsure technical resources to present at plenary sessions and workshops, invitations to attend Count’s annual conferences and the opportunity to engage with Count Representatives at professional development events. The agreement was marked confidential and included a clause that each party agreed, unless otherwise required by law or regulation to keep the terms of the agreement confidential.

F.4. AMP Policy

98 On 2 March 2018, the Applicant acquired the AMP Policy, an AMP Elevate Life Insurance Policy, issued by AMP Life Limited, nominating Shaun Hunter as the insured.

99 The AMP Policy was issued during the Relevant Period. The scope of the advice provided and the extent of the relevant disclosures with respect to the AMP Policy are addressed below in my consideration of the Relevant Period Advice.

G. PRE-RELEVANT PERIOD ADVICE

G.1. Overview

100 As explained above, three of the four Applicant’s Products were acquired prior to the Relevant Period. It is therefore necessary to have regard to the circumstances in which those products were acquired by the Applicant.

G.2. The Applicant’s initial relationship with Centenary

101 In or about 2007, Mrs Hunter, on behalf of the Applicant, first approached Centenary for formal financial advice. Mr Williams was asked, through Mr Duffield, to provide assistance to the Applicant for the purpose of removing Gary Foster and Jill Foster as directors of the Applicant and renaming the Hunter SMSF.

G.3. May 2008 SOA

102 In or about May 2008, Mr Williams provided the May 2008 SOA to the Applicant, a statement of advice dated 20 May 2008. At the time the May 2008 SOA was provided to the Applicant, Mrs Hunter, but not Mr Hunter, had existing life and TPD insurance through the Hunter SMSF. Centenary recommended in the SOA that Mr Hunter take out TPD cover through the Hunter SMSF.

G.4. Financial Services Guide

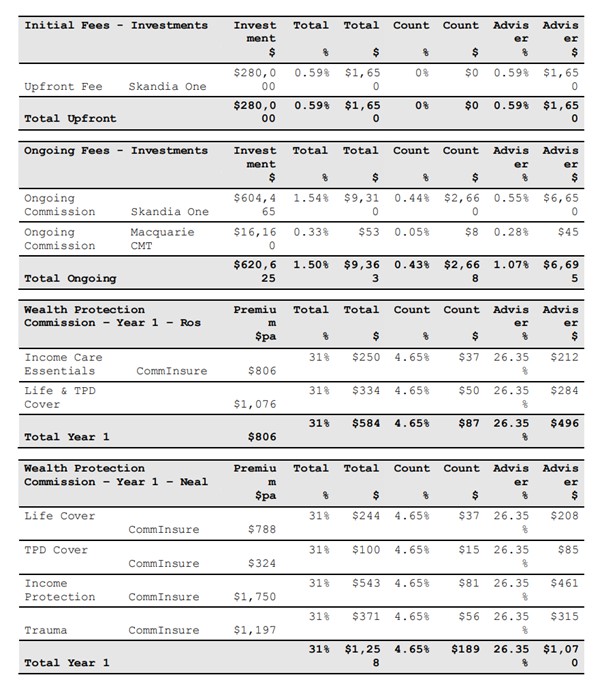

103 Prior to the provision of the May 2008 ROA, Centenary provided the Applicant with a Financial Services Guide. The Financial Services Guide included a high level disclosure of the financial services and products provided by Count and the Count Representatives together with a brief explanation of the franchise basis on which Count’s financial advisers operated.

G.5. Total Financial Care Agreements

104 From late May 2008, the Applicant entered into formal contractual arrangements with Centenary for the provision of ongoing advice services. The contractual arrangements were recorded in a series of agreements which were described as Total Financial Care Agreements. The Total Financial Care Agreements were drafted by Mr Williams based on templates supplied by Count. The templates for at least the Total Financial Care Agreements entered into in 2015 and 2017, provided for the authorised representative of Count to vary the specific services to be provided and the fees payable for those services. Other documents that specified standards for licensees with regard to Total Financial Care Agreements provided for variations to the frequency with which the specific services were to be provided. From approximately March 2018, the Total Financial Care Agreements were known as Ongoing Service Agreements.

105 In late May 2008, Mr Williams provided the May 2008 TFCA to the Applicant, being a Total Financial Care Agreement dated 20 May 2008. The May 2008 TFCA offered the Applicant on a stipulated periodic basis (a) face-to-face interviews reporting on the performance of the Applicant’s portfolio and reporting on wealth protection, income needs, cash flow, budgeting and tax, (b) portfolio reports, and (c) copies of reports prepared by Count.

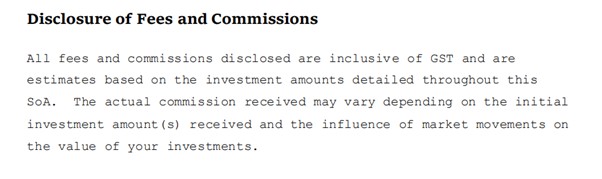

106 The fee that was to be paid by the Applicant under the May 2008 TFCA was an annual fee of 0.55% of the total funds that the Applicant had invested in an investment portfolio described as the Skandia One Fund. The May 2008 SOA had recommended that the Applicant make an additional investment in the Skandia One Fund of $280,000 from funds held in the Applicant’s Macquarie Cash Management Trust. This investment was not made, however, because the Applicant decided not to proceed with it due to market volatility. Had the additional Skandia One Fund investment been made, the annual fee payable to Centenary would have been approximately $3,325 ($604,465 (being $280,000 + $324,465) x 0.55%).

107 During the Relevant Period, the fee that was imposed under the Total Financial Care Agreements was initially an annual fee of $5,500. This fee was subsequently reduced to $2,200 from about July 2017 because the Applicant had liquidated its investment portfolio to purchase an investment property. On or about 6 June 2017, Mr Williams recorded in a file note that the fee was reduced because there would be “less work involved in the investment side”.

108 During the initial trial, Count agreed to repay to the Applicant all fees that had been paid under the Total Financial Care Agreements.

G.6. October 2008 ROA

109 From May 2008, Mr Williams took steps to have the name listed on Mrs Hunter’s life and TPD policy changed to record the change in the name of the Applicant and to arrange life and TPD insurance cover for Mr Hunter.

110 On or about 3 October 2008, Mr Duffield provided the October 2008 ROA to the Applicant, being a record of advice which repeated the recommendation made in the May 2008 SOA that Mr Hunter take out a life and TPD policy with CommInsure. The October 2008 ROA was a five-page document. It was noted in the October 2008 ROA that due to “recent market volatility”, Mr and Mrs Hunter had decided not to proceed with a recommendation made in the May 2008 SOA to invest surplus cash from the Macquarie Cash Management Trust in highly rated managed funds through the Skandia One Fund.

111 The October 2008 ROA noted that after meeting with Mrs and Mr Hunter, it had been confirmed that their personal situation had either not altered or was deemed not to have altered significantly from that previously recorded and therefore the recommendations were based on the personal and financial information set forth in the May 2008 SOA and the Financial Needs Analyser also dated 20 May 2008.

G.7. May 2011 ROA

112 On or about 31 May 2011, Mr Williams issued a further record of advice to the Applicant dated 31 May 2011, being the May 2011 ROA. Mr Williams confirmed in that record of advice that, based on the recommendations made in a record of advice of 10 September 2010 and subsequent discussions in December 2010, all the Applicant’s managed funds had now been liquidated and $140,000 worth of CBA Retail Bonds had been purchased in December 2010 and $247,000 worth of Australian equities had been purchased in March 2011.

G.8. December 2013 ROA

113 On or about 18 December 2013, Mr Williams issued the December 2013 ROA to the Applicant dated 18 December 2013 containing investment recommendations for the Applicant’s share portfolio that was being managed by the Applicant’s Representatives. The December 2013 ROA was an eight page document.

114 The December 2013 ROA recorded that the Applicant’s total investments had a value of $738,321.06, comprising an amount of $13,893.63 in the Applicant’s CBA Cash Account, $463,856.90 in the Applicant’s share portfolio, and cash and term deposits with Macquarie in an aggregate amount of $260,570.53.

H. RELEVANT PERIOD ADVICE

H.1. Overview

115 The Applicant contends that during the Relevant Period it received personal advice on six occasions, constituting the Relevant Period Advice. It contends that the Relevant Period Advice contained an express recommendation to pay or continue to pay Commissions and/or an implicit recommendation to pay or continue to pay Commissions and/or an express or implicit recommendation to pay Commissions in addition to ongoing service fees in relation to the Applicant’s Products.

116 Further, the Applicant contends that the advice provided in the Relevant Period Advice did not disclose or contain the Advice Non-Disclosures, being:

(a) that ongoing Commissions and Other Benefits were being received by the Applicant’s Representatives in relation to the Applicant’s Products;

(b) that the Applicant’s Products would be materially cheaper if the Commissions were “dialled down” or “rebated”;

(c) that the Applicant’s Representatives could “dial down” or “rebate” those Commissions to the benefit of the Applicant, or that the Applicant’s Representative’s fees could be reduced by the amount of the Commissions and/or Other Benefits;

(d) as to the extent of a conflict arising as a result of the payment of Commissions and/or receipt of Other Benefits, including that:

(i) the Applicant’s insurance products would be materially cheaper if the Commissions were “dialled down” or switched off;

(ii) the CTC Program incentivised advisers to recommend products that promoted the interests of Count;

(iii) the Count remuneration policies incentivised advisers to only recommend products that were on the APL;

(iv) the Applicant’s Representatives were ranked by Count on the revenue they generated for Count and financially rewarded for their revenue; and

(v) the Splits, and the variable remuneration received as a result of the Splits could give rise to a conflict;

(e) the reason(s) for any recommendation to continue to pay Commissions or why that recommendation was in the Applicant’s best interests;

(f) that no additional benefits or services would be provided in exchange for the payment of Commissions;

(g) any advice to stop paying the Commissions;

(h) that it was possible to obtain the same products without paying Commissions;

(i) that the adviser’s advice was, or could reasonably be expected to be, influenced by the Commissions and/or Other Benefits;

(j) that the Applicant’s Products would attract a higher premium and/or cost than if the Commissions had been “dialled down”, “switched off” or rebated to the Applicant; and

(k) that the Applicant was paying Commissions in relation to the Applicant’s Products in addition to ongoing service fees.

H.2. 31 July 2015 file note and review questionnaire

117 On 31 July 2015, Mr Williams and Mr Hohnen, together with Zeljko Butorajac, one of the Hunter SMSF’s accountants, met with Mrs Hunter. The matters discussed at the July 2015 Meeting included a request by the Applicant to close the Macquarie Cash Management Account, and personal insurance.

118 Mr Hohnen made both handwritten notes and a typed file note of the July 2015 Meeting. His handwritten notes included the following summary of the discussion of insurance issues (as written):

Discussed INSURANCE However Ros indicated that there was no need to change as cashflow not a issue. We also discussed Restructuring in particular the waiting period as Neal has 12 months Annual leave however Ros indicated she was happy to keep the current set up.

119 Mr Hohnen’s typed file note records that Mrs Hunter had indicated in a document described as an “FNA”, which in context I infer was a Financial Needs Analyser that she had completed, that the first of the “Top of Mind/Goals and objectives” that she wanted was:

1. Review the insurances to make sure they were right and also the most cost effective.

120 Mr Hohnen’s typed file note also recorded the following discussion concerning insurance issues:

Personal Insurance

Had a discussion about their current insurance. Ros indicated that they are happy with the levels of cover they have in place. We indicated to Ros that we completed research however the cost savings would be minimal. Ros indicated they were happy to leave as is however they were concerned about the cost of the current premiums. Ros indicated that Neal almost has 12 months of annual leave. As a result of this we suggested to Ros to increase the waiting period on Neal's cover however she declined. We also discussed changing the structure if cashflow was an issue however Ros indicated that it was not. With regards to cover for Sean and Deane we discussed this however Ros indicated that the boys could not afford this. We then had a further discussion about if something happened to them then Ros and Neal would need to cover them as such this could affewct [sic] them financially and as such impact on their retirement if they had to support them financially. Ros agreed with this and indicated that Shaun had some cover in various Super Fund's that he has. Ros indicated she would send through to us and we could review for her and come back with our suggestions.