Federal Court of Australia

Miele & Cie KG v Bruckbauer [2025] FCA 537

File number: | VID 711 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | ROFE J |

Date of judgment: | 27 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | PATENTS – application to amend claims of a patent application under s 105 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) due to typographical error – correction of obvious mistake PATENTS – infringement – standard patent for a hob with a recess for a device for downwardly removing cooking vapours through suction – claim construction PATENTS – validity – support – sufficiency – novelty – whether a document is publicly available – whether there are multiple forms of the invention – ss 40(2)(a), 40(3) and 43(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) |

Legislation: | Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) Patents Act 1990 (Cth) Patents Act 1952 (Cth) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth) Patents Act 1949 (UK) |

Cases cited: | Airco Fasteners Pty Ltd v Illinois Tool Works Inc (2023) 170 IPR 225 American Home Products Corp v Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd [2001] RPC 8 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 226 FCR 324 AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 257 CLR 356 Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft v Generic Health Pty Ltd (2012) 99 IPR 59 BlueScope Steel Ltd v Dongkuk Steel Mill Co., Ltd (No 2) (2019) 152 IPR 195 Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 Calix Ltd v Grenof Pty Ltd (2023) 171 IPR 582 Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183 CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation v BASF Plant Science GmbH (2020) 151 IPR 181 CSL Ltd v Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (No 2) (2010) 89 IPR 288 Dometic Australia Pty Ltd v Houghton Leisure Products Pty Ltd (2018) 135 IPR 403 Expo-Net Danmark A/S v Buono-Net Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 88 IPR 1 Farmhand Inc v Spadework Ltd [1975] RPC 617 Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Pty Ltd v Avion Engineering Pty Ltd (1991) 22 IPR 1 Fresenius Medical Care Australia Pty Limited v Gambro Pty Limited (2005) 67 IPR 230 Garford Pty Ltd v Dywidag-Systems International Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1039 General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 General Tire and Rubber Co (Frost’s) Patent [1972] RPC 259 HTC Corp v Gemalto SA [2014] EWCA Civ 1335 Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd (2016) 121 IPR 1 Icescape Ltd v Ice-World International BV [2019] FSR 5 Insta Image Pty Ltd v KD Kanopy Australasia Pty Ltd (2008) 239 FCR 117 JMVB Enterprises Pty Ltd v Camoflag Pty Ltd (2005) 67 IPR 68 Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 86 Jusand Nominees Pty Ltd v Rattlejack Innovations Pty Ltd (2023) 176 IPR 336 Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Multigate Medical Products Pty Ltd (2011) 92 IPR 21 Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd (2004) 64 IPR 444 Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2010) 89 IPR 219 Meat & Livestock Australia Limited v Cargill, Inc (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 47 Meat & Livestock Australia Ltd v Cargill, Inc (2018) 129 IPR 278 Mentor Corp v Hollister Inc [1991] FSR 557 Mentor Corp v Hollister Inc [1993] RPC 7 Merck & Co Inc v Arrow Pharmaceuticals Ltd (2006) 154 FCR 31 Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp v Wyeth LLC (No 3) (2020) 155 IPR 1 Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 Multigate Medical Devices Pty Ltd v B Braun Melsungen AG (2016) 117 IPR 1 Mylan Health Pty Ltd v Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd (2020) 153 IPR 199 Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360 Nicaro Holdings Pty Ltd v Martin Engineering Co (1990) 16 IPR 545 Nichia Corp v Arrow Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 699 Novartis AG v Bausch & Lomb (Australia) Pty Ltd (2004) 62 IPR 71 Populin v HB Nominees Pty Ltd (1982) 41 ALR 471 Product Management Group Pty Ltd v Blue Gentian LLC (2015) 116 IPR 54 Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc v Kymab Ltd [2021] 1 All ER 475 RGC Mineral Sands Pty Ltd v Wimmera Industrial Minerals Pty Ltd (1998) 89 FCR 458 Richardson-Vicks Inc’s Patent [1995] RPC 568 Sachtler GmbH & Co KG v RE Miller Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 605 Schering Biotech Corp’s Application [1993] RPC 249 Sunbeam Corporation v Morphy-Richards (Aust) Pty Ltd (1961) 180 CLR 98 The Queen v Commissioner of Patents; Ex parte Martin (1953) 89 CLR 381 Thornhill’s Application [1962] RPC 199 ToolGen Incorporated v Fisher (No 2) [2023] FCA 794 Tramanco Pty Ltd v BPW Transpec Pty Ltd (2014) 105 IPR 18 Unilin Beheer BV v Berry Floor NV [2004] EWCA Civ 1021 Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc (2001) 51 IPR 327 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and associated Statutes |

Number of paragraphs: | 549 |

Date of last submissions: | 31 July 2024 |

Date of hearing: | 6–9, 14–15 August 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicants: | N Murray SC and K Beattie SC |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Davies Collison Cave |

Counsel for the Respondents: | J Hennessy SC and S Hallahan |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Gestalt Law |

ORDERS

VID 711 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MIELE & CIE KG First Applicant MIELE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 005 635 398) Second Applicant | |

AND: | WILHELM BRUCKBAUER First Respondent BORA-VERTRIEBS GMBH & CO KG Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | BORA-VERTRIEBS GMBH & CO KG (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | MIELE & CIE KG (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Respondent | |

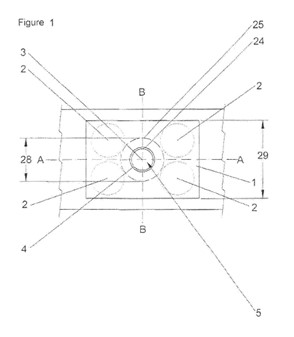

order made by: | ROFE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 27 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are directed to confer and provide a draft order giving effect to these reasons to the Chambers of Justice Rofe by 11 June 2025.

2. In the event that the parties are unable to reach agreement about the form of orders, then the parties are to notify Chambers and provide their own version of a draft order, with the areas of disagreement set out in mark-up.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

ROFE J:

[1] | |

[7] | |

[7] | |

[12] | |

[14] | |

[45] | |

[49] | |

[54] | |

[62] | |

[65] | |

[65] | |

[65] | |

[71] | |

[76] | |

[78] | |

[78] | |

[78] | |

[80] | |

[86] | |

[91] | |

[93] | |

[93] | |

[95] | |

[100] | |

[102] | |

[104] | |

[111] | |

[114] | |

[116] | |

[118] | |

[128] | |

[132] | |

[136] | |

[141] | |

[163] | |

[172] | |

Integer 1.5: ‘downwardly sequentially in a vertical direction’ | [182] |

Integer 1.5.1: ‘a housing for the heating or hob heating and control electronics’ | [195] |

[221] | |

Integer 1.5.3(b): ‘for preparing the cooking vapour stream to be vertically aspirated upwardly’ | [234] |

[242] | |

[246] | |

[249] | |

[252] | |

[260] | |

[267] | |

[278] | |

[279] | |

[282] | |

[286] | |

[293] | |

[295] | |

[297] | |

[315] | |

[315] | |

[332] | |

[348] | |

[380] | |

[385] | |

Section 43(3) — is there more than one form of the invention? | [394] |

[404] | |

[407] | |

[414] | |

[421] | |

[436] | |

[453] | |

[459] | |

[466] | |

[469] | |

[476] | |

[476] | |

[480] | |

[483] | |

[488] | |

[493] | |

[496] | |

[503] | |

[508] | |

[524] | |

[538] | |

[544] | |

[546] |

Overview

1 The applicants (Miele) seek to revoke each of claims 1 to 13 and 15 (relevant claims) of Australian Patent No. 2012247900 entitled “Hob with central removal of cooking vapours by suction-extraction in the downward direction”. Claim 1 is the only independent claim of the Patent.

2 Miele intends to launch its new product models, KMDA 7272 Silence and KMDA 7473 Silence (collectively, the Miele Silence Products) after October 2024. Since at least May 2018, Miele has sold, and continues to sell in Australia the product models, KMDA 7476 FL, KMDA 7774 FL, KMDA 7633 FL, KMDA 7633 FR, KMDA 7634 FL and KMDA 7634 FR (collectively, the Current Miele Products).

3 The respondents (BORA) cross-claim, seeking relief in relation to the infringement of claims 1 and 11 of the Patent (asserted claims). The first respondent/cross-claimant, Mr Bruckbauer is the inventor of the invention claimed in the Patent, and the registered owner of the Patent. BORA - Vertriebs GmbH & Co KG, the second respondent/cross-claimant, is the exclusive licensee of the Patent. BORA also seeks to amend the Patent pursuant to s 105 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) to amend what they describe as “two obvious typographical errors” in the Patent.

4 The only issue on the infringement case relates to the Miele Silence Products, as Miele admits that the Current Miele Products have the features claimed in claims 1 and 11 of the Patent.

5 Miele contends that each of the relevant claims is invalid for lack of support and sufficiency, and that if the invention as claimed is sufficiently described in the Patent, for lack of novelty by reason of a deferred priority date. Further, Miele alleges that amendments to a Chinese patent application were publicly available and disclosed the invention claimed in the Patent.

6 On 28 September 2022, O’Bryan J ordered that all questions concerning the quantum of any award of damages (including any entitlement to, and amount of, additional damages), profits or interest be determined separately from, and after, all other questions in the proceeding. Thus it is not for determination in this part of the proceeding whether additional damages are enlivened.

Patent

Prosecution history

7 The Patent claims a priority date of 28 April 2011, based on an application filed in Germany. It is common ground between the parties that the provisions of the Act which apply to this Patent are those amended by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth).

8 An International Patent Application PCT/DE2012/000458 (WO 2012/146237) (PCT Application) was filed on 28 April 2012. The Patent was granted from Australian Patent Application No. 2012247900 A1 (the A1 Application), which is an Australian national phase application based on the PCT Application. I refer to the A1 Application interchangeably with the PCT Application in this judgment. Section 29A of the Act stipulates that the corresponding PCT Application is to be treated as the complete specification as filed for the corresponding patent.

9 Amendments to the PCT Application were filed when the PCT Application entered national phase in Australia on 12 November 2013. I refer to these amendments as the 2013 Amendments.

10 On 11 November 2015, Mr Bruckbauer, the Patentee, filed amendments to the Patent in response to a first examination report dated 23 September 2015. Those amendments, which I will call the 2015 Amendments, were accepted on 1 December 2015. The Patent was granted on 31 March 2016.

11 As discussed below, the Patentee now seeks to amend the Patent in this proceeding to correct two typographical errors in the specification and claim 1.

Specification

12 The specifications of the Patent and the PCT Application do not have numbered paragraphs or numbered lines. The parties and their experts adopted a numbering scheme to refer to paragraphs in the specification. A reference to a paragraph is by reference to the page number and paragraph number on that page. For example, the first complete paragraph on page 1 will be [1.1] and the second complete paragraph on page 1 will be [1.2]. I will adopt the same paragraph numbering scheme in these reasons.

13 As Miele contends that the 2015 Amendments were not allowable under s 102 of the Act and that the invention claimed in Patent is not entitled to a priority date earlier than 11 November 2015 (Deferred Priority Date), I will start with a consideration of the specification of the PCT Application. Where appropriate, I will set out the relevant differences between the Patent and the PCT Application.

PCT specification

14 The PCT specification begins by noting that the present invention relates to a hob with the features of claim 1. The invention in the Patent relates to “a hob”. Both experts agreed that a ‘hob’ as used in the specification refers to the top part of the cooktop assembly comprising hotplates for heating pots and pans, rather than an entire standalone assembly (i.e., a cooktop).

15 Claim 1 of the PCT claims:

A hob (1) with one or more cooking locations (2), characterized in that, as viewed from above, it exhibits one or more recesses (4) only in the area (25) around its geometric centre (3), which are connected with one or more devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction, wherein these devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction downwardly remove the cooking vapours that arose or arise above the cooking locations (2) by suction in a direction pointing vertically below the hob (1).

16 Claim 1 includes reference to the numbers by which the integers are identified in the figures in the PCT. Figure 1, replicated below, is a top view of a hob (1) according to the preferred embodiment of the invention, with one or more cooking locations (2), a central recess (4) for a device (5) for downwardly removing cooking vapours through suction.

17 BORA places emphasis on the reference to “a device (5)” as providing a basis for a form of the invention with only one fan, as opposed to two fans.

18 The known prior art hob is described as a hob that “exhibits oblong, rectangular suction slits on both sides and on the back, through which cooking vapours that arise in the hob area are downwardly removed through suction”.

19 The known hob is said to have a number of disadvantages, including:

(a) the countertop that carries the hob cannot be completely used for temporary storage or similar purposes, at least right to the side of the hob;

(b) the lateral and rear suction flows cancel each other out completely or at least partially, especially in the centre of the hood;

(c) marked manufacturing and material costs, in particular due to the design of the three suction devices and the foul-air duct system connected with the latter;

(d) high maintenance costs, including maintaining three grease filters;

(e) high noise from three fan motors and low efficiency;

(f) installation is time intensive and expensive.

20 The object of the “present invention” is said at [2.4] to address each of these disadvantages. This object is said to be achieved “in a generic device by the features indicated in the characterizing clause of claim 1”. Whether the skilled reader would understand “device (5)” and the word “device” in this paragraph to be interchangeable with “fan” was a subject of debate between the parties.

21 Both experts agreed that the invention is not restricted to induction heating hobs, the heating elements may be electrical coils or ceramic hotplates.

22 Especially preferred embodiments are said to be the subject of the sub-claims.

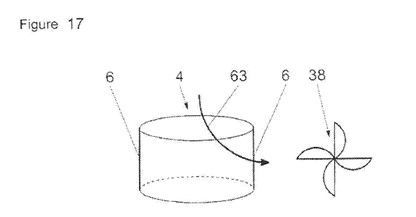

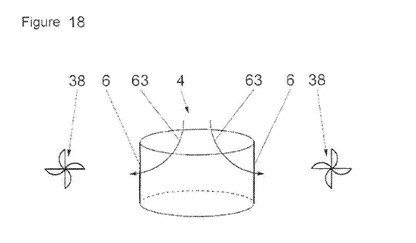

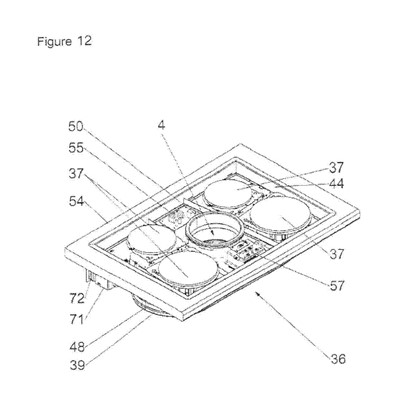

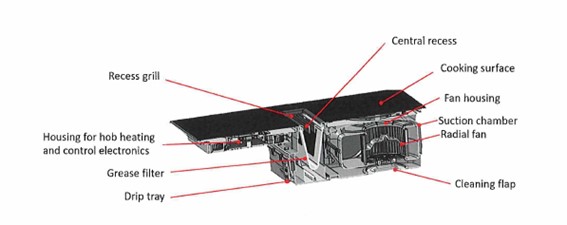

23 There is then a brief description of the drawings. Figures 1 to 11 are various views of a hob according to the invention. Figures 2 to 7, 10 and 11 are schematic cross-sections of a hob. Figures 12 to 16 are of a hob according to the invention which takes the form of an “assembly unit with a device (36)”. The “assembly unit with a device (36)” is described from [10.4] of the Patent. Figures 17 and 18 are said to be a schematic view of a hollow cylindrical grease filter connected with, respectively, a single or two opposing, foul-air vents.

24 At [6.4] the present invention is said to relate to a hob with one or more cooking locations, which, as viewed from above, exhibits one or more recesses only in the area around its geometric centre, but not in its edge area. The specification notes that:

[a]s a rule, these recesses (4) are connected with one or more devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction, wherein these devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction downwardly remove the cooking vapours that arose or arise above the cooking location(s) (2) by suction in a direction pointing vertically below the hob (1).

25 Figures 2 to 7 deal with different options for the configuration of the grease filter insert in the central recess and for the configuration of the floor for collection of grease and oil. Paragraphs [7.1] to [10.3] describe variations of the grease filter, closure options and overflow protection.

26 Miele contends that the PCT specification is not deploying those figures to tell the reader about the fan configuration. Figure 2 is a schematic cross-section of a hob along the A–A line depicted on Figure 1. Figures 3 to 7 are cross-sections along the B–B line depicted on Figure 1. Figures 10 and 11 are cross-sections along the B–B line depicted on Figure 9.

27 After introducing the general features of the hob, the PCT specification then describes the device “for downwardly removing cooking vapours by suction”. From [10.4], the word “device” is used in a different manner, as part of the larger integer, “an assembly unit with a device”. The present invention is said to further relate to:

a hob (1) with a central recess (4), which takes the form of an assembly unit with a device (36) provided on its bottom side (35) for operating the hob (1) and downwardly removing cooking vapours by suction, and can be quickly and easily inserted into a recess of the kitchen countertop (54) whose dimensions correspond thereto.

28 Figures 12 to 16 are of a hob according to the invention which takes the form of an “assembly unit with a device (36)”.

29 It is apparent that the “device (5)” is not the same as the item labelled (36) which is described as “an assembly unit with a device”. Item (36) is the composite assembly, being an assembly unit with device. On the basis that the Patentee has made consistent use of words, the device in the assembly unit would be the “device” in item (5).

30 Later references in the PCT Application appear which are to “the invention designed as an assembly unit with a device (36)”: PCT Application at [13.4].

31 The PCTspecification continues:

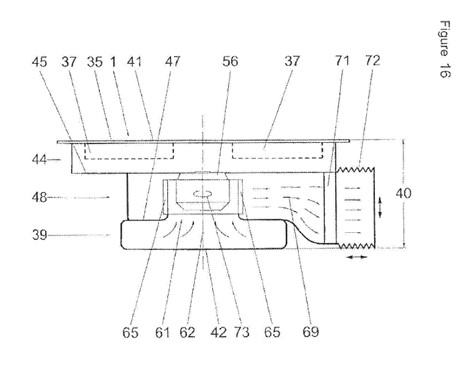

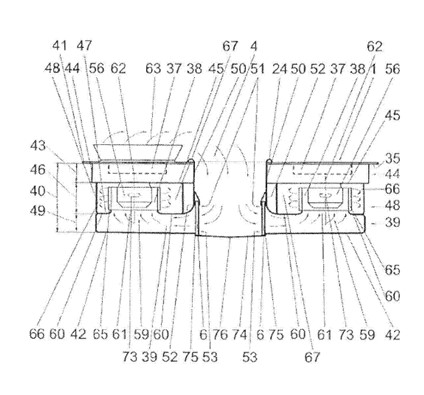

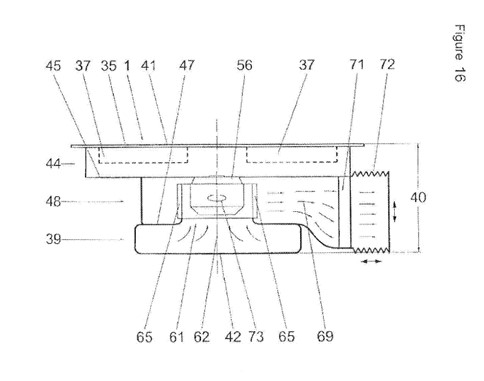

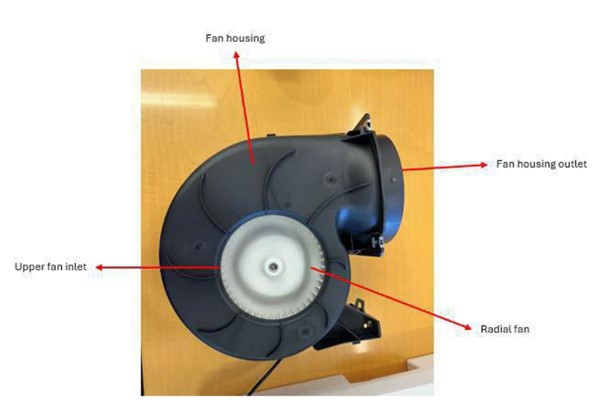

[11.1] As depicted in particular on Fig. 12 to 16, the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) in the device (36) as viewed downwardly sequentially in a vertical direction can encompass a housing (44) for the heating or hob heating and control electronics, a fan housing (48) for two or more radial fans (38), and one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) for horizontally relaying the cooking vapours toward the outside, as well as for preparing the cooking vapour stream to be vertically aspirated toward the top by means of the radial fans (38) provided in the fan housing situated vertically higher.

[11.2] One special advantage to this hob (1) designed according to the invention is that the distance (40) between the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) on the one hand and the bottom side of the floor (42) of the cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) on the other only measures between 110 mm and 260 mm, preferably between 140 mm and 230 mm , in particular between 150 mm and 200 mm.

(Emphasis added.)

32 At [12.1], the PCT Application states that in “preferred embodiments of the hob (1) according to the invention described as an assembly unit with a device (36), two or more deep cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) can be provided downstream from the hollow cylindrical grease filter (6) …”.

33 Figures 14 and 16 are described in [12.2] as showing that

two or more recesses (61) for guiding the cooking vapours (63) from the bottom up to the radial fans (38) provided downstream from the recesses can be provided in the middle areas (59) of the covers (60) of the cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) lying vertically at the top.

34 The housing (44) for the heating or hob heating and control electronics first appears at [11.1]. At [12.3] the specification explains that the radial fan motors can be centrally secured by way of their recesses in the middle areas of the covers of the cooking vapour aspiration chambers to the bottom side of the housing (44) for the heating or hob heating and control electronics. The housing, and what it can, amongst other things, incorporate is discussed at [12.4]:

Among other things, for example, the housing (44) for the hearing or hob heating and control electronics can incorporate the hob heating elements (37), the power electronics (55) for the fan motors (56) and touch-control operating components (57) (see Fig. 12). Among other things, for example, the bottom side of the housing (44) for the hearing or hob heating and control electronics can be provided with a device power supply line (58) (see Fig. 13).

35 Figure 15 is a schematic top view of an assembly unit according to the invention. Figure 15 has two perpendicular lines (A–A) and (B–B) drawn on it which show where the longitudinal sections depicted in Figure 14 and Figure 16 are taken. Figure 14 is a schematic, longitudinal section along the A–A line of the assembly unit depicted in Figure 15, and Figure 16 is a schematic longitudinal view along the B–B line. Figure 15 and Figure 16 are shown below:

36 Figures 14 and 16 are also said to show that the “rotational axes (62) of the radial fan motors (56) can be vertically aligned, and that the cooking vapours (63) aspired vertically upward by the rotating fan wheel (65) can be transported in the fan housing (48) provided above the respective aspiration chamber (39)”. The rotational direction of the two radial fan wheels is preferably opposite to each other: PCT Application at [14.2].

37 The specification notes at [14.3] that:

[t]he advantage to oppositely aligning the rotational directions according to Figure 15 is that the two cooking vapour exhaust flows (69) stream toward the odour filter (71) provided downstream from the space (68) for dividing and aligning the exhaust flows (69), either indirectly by way of air guiding surfaces (70), or in a uniformly direct manner.

38 At [15.2] the specification brings the threads together, commencing “[i]n sum, let it be noted that the present invention provides a hob with a device for removing cooking vapours through suction in a direction lying vertically below the plane of the hob”. It continues: “For the first time ever, a cooking vapour removal device is combined with a hob in the device according to the invention to form a single component, thereby yielding especially low manufacturing and assembly costs”.

39 BORA submits that it is that characteristic which sets apart the invention claimed in the PCT specification from predecessor downdraft extraction products, which were separate products installed adjacent to the hob, rather than being integrated with the hob. This general characteristic is submitted to be independent from the additional, special characteristics of the “assembly unit” (which are described in paragraphs [16.5] to [17.1]).

40 Advantages of the hob according to the invention designed as an assembly unit with a device (36), are said to be, its energy efficiency, quietness, low height, low operating costs, and as it can be completely pre-assembled at the factory, its fast, simple and easy installation.

41 Miele submits that the only device as part of the below hob assembly unit described and disclosed is a device with two or more radial fans, and the advantages of the assembly unit described are confined to the unit with two or more radial fans. The discussion of the “device (5)” at [16.1] speaks of “sufficiently strong suction flows that do not cancel each other out”, consistent with there being two or more fans. The description of the assembly unit that follows at [17.2] and [17.3] refers only to plural radial fans and fan motors.

42 At [17.2] it is noted that:

providing two or more opposing radial fans (38) downstream from the hollow cylindrical grease filter (6) according to Fig. 17 and 18 markedly enlarges the working surface of the grease filter (6) and elevates throughput volume… The advantage to this is that the fan motors (56) of the radial fans (38) can exhibit an especially small, energy-saving, energy-efficient and quiet design. In addition, a lower speed can be selected for the fan motors, as a result of which the radial fans used according to the invention operate in an especially quiet, low-vibration and energy efficient manner.

43 Miele contends that the skilled reader understands [17.2] of the PCT Application to say that the invention of that specification is to use two radial fans in the device forming part of the assembly unit and Figure 17 is used in that aspect by way of contrast or counterexample to illustrate the advantage of the two-fan configuration of the invention (as seen in Figure 18) in comparison to a single fan configuration. BORA contends otherwise and submits that the skilled reader understands [17.2] of the PCT Application as containing a distinct reference to a particular embodiment of the invention claimed in claim 14 of the PCT Application, which is “characterized in that two radial fans as viewed from above are positioned in the fan housing on either side of the tubular foul air line”. BORA submits that a skilled reader would not understand a description of an advantage of this particular, narrow embodiment with two opposing radial fans to effectively be disclaiming any embodiment with one radial fan (which, it submits, is virtually every other claim of the PCT Application which is dependent on claim 1).

44 Figures 17 and 18 are shown below.

PCT claims

45 Claim 1 of the unamended PCT Application and the A1 Application claims:

A hob (1) with one or more cooking locations (2), characterized in that, as viewed from above, exhibits one or more recesses (4) only in the area (25) around its geometric centre (3), which are connected with one or more devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction, wherein these devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction downwardly remove the cooking vapours that arose or arise above the cooking locations (2) by suction in a direction pointing vertically below the hob (1).

(Emphasis added.)

46 Miele observes that there are no references to fans in the PCT claims until claim 11, which claims a fan housing for two or more radial fans. The only reference to radial fans in the claims after claim 11 are to more than one fan (i.e., fans or fan motors).

47 Claim 11 of the unamended PCT Application and the A1 Application is dependent on claims 1 or 2 and claims the following:

The hob (1) according to one of claims 1 or 2, characterized in that the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) is provided with a device (36) for operating the hob (1) and downwardly removing cooking vapours by suction that together with the hob (1) forms an assembly unit, wherein the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) in the device (36) as viewed downwardly sequentially in a vertical direction encompasses a housing (44) for the heating or hob heating and control electronics, a fan housing (48) for two or more radial fans (38), and one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) for horizontally relaying the cooking vapours toward the outside, as well as for preparing the cooking vapour stream to be vertically aspirated toward the top by means of the radial fans (38) provided in the fan housing (48) situated vertically higher, wherein the distance (40) between the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) on the one hand and the bottom side of the floor (42) of the cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) on the other measures between 110 mm and 260 mm.

48 Claim 14 claims:

The hob (1) according to one of claims 1, 2, 11, 12 or 13, characterized in that two radial fans (38) as viewed from above are positioned in the fan housing (48) on either side of the tubular foul air line (50) provided downstream from the central hob recess (4), wherein the rotating directions (73) of the two fan wheels (65) of these two radial fans (38) are opposite to each other, wherein the left fan wheel (65) can be rotatively driven counterclockwise as viewed from above, so that the two pressure chambers (67) of the two radial fans (38) are adjacent to the central foul air line (50), and the two cooking vapour exhaust flows (69) stream toward the odour filter (71) provided downstream from the space (68) for dividing and aligning the exhaust flows (69), either indirectly by way of air guiding surfaces (70), or in a uniformly direct manner.

PCT Amendments (2013 Amendments)

49 Amendments were made to claims 1 and 11 of the PCT Application as filed on 28 April 2012 under article 34 of the Patent Cooperation Treaty (Washington, 19 June 1970) prior to entering national phase in Australia on 12 November 2013. The body of the specification and claims 2 to 10 and 12 to 15 remained identical to the PCT Application. These amendments were made to the A1 Application. As noted above, I refer to these amendments as the 2013 Amendments.

50 The 2013 Amendments replaced the original claims 1 and 11 of the PCT Application. The body of the specification and claims 2 to 10 and 12 to 15 remained identical to the PCT Application.

51 Claim 1 was narrowed to the hob assembly unit claimed in former claim 11 (but with the former limitation as to the ‘compactness’, (i.e., the distance references) of the hob deleted). Claim 11, dependent on claim 1 as amended (i.e., the hob assembly unit) retained the limitation as to the ‘compactness’ of the hob.

52 Following the 2013 Amendments, claim 1 as amended in the PCT Application claimed:

A hob (1) with one or more cooking locations (2), which, as viewed from above, exhibits one or more recesses (4) only in the area (25) around its geometric centre (3), which are connected with one or more devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction, wherein these devices (5) for removing cooking vapours through suction downwardly remove the cooking vapours that arose or arise above the cooking locations (2) by suction in a direction pointing vertically below the hob (1), characterized in that the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) is provided with a device (36) for operating the hob (1) and downwardly removing cooking vapours by suction that together with the hob (1) forms an assembly unit, wherein the bottom side of the hob (1) in the device (36) as viewed downwardly sequentially in a vertical direction encompasses a housing (44) for the heating or hob heating and control electronics, a fan housing (48) for two or more radial fans (38), and one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers (39) for horizontally relaying the cooking vapours toward the outside, as well as for preparing the cooking vapour stream to be vertically aspirated toward the top by means of the radial fans (38) provided in the fan housing (48) situated vertically higher.

53 Following the 2013 Amendments, claim 11 as amended in the PCT Application claimed:

A hob (1) according to one of claims 1 or 2, characterized in that the distance (40) between the bottom side (35) of the hob (1) on the one hand and the bottom side of the floor (42) of the cooking vapour aspiration cambers (39) on the other measures between 110 mm and 260 mm.

2015 Amendments

54 On 11 November 2015, BORA filed the 2015 Amendments discussed above. Pages 1 to 5a of the Patent were added with the 2015 Amendments.

55 Paragraph [1.1] was amended as follows: “The present invention relates to a hob”, with the proceeding phrase “with the features indicated in claim 1” removed. Miele submits that, as such, the present invention was no longer confined to the hob assembly unit having two or more radial fans. Miele contends that this is also apparent in the amendment at [4.2], with the amendments quoted below:

[4.2] PRIOR TO AMENDMENT: Fig. 1 is a top view of a hob (1) according to the invention with a central recess (4) for a device (5) for downwardly removing cooking vapours through suction;

[4.2] FOLLOWING AMENDMENT: Fig. 1 is a top view of a hob (1) according to a preferred embodiment of the invention with a central recess (4) for a device (5) for downwardly removing cooking vapours through suction;

56 The description of the prior art hob and its disadvantages are the same as the PCT Application.

57 The object of the present invention is succinctly stated as being “to substantially overcome or at least ameliorate one or more of the above disadvantages”. The object is no longer to overcome all of the disadvantages specified. Consistently with this amended object, the Patent states that a “preferred embodiment aims to provide a hob with a device for removing cooking vapours through suction in a [direction] lying vertically below the plane of the hob…”.

58 Paragraph [2.5] describes a “first aspect” that is disclosed in the Patent. This “first aspect” is a consistory clause for the invention as claimed in claim 1 of the Patent. A “second aspect" is described at [3.1] which corresponds with claim 10.

59 The Patent states at [4.1] that “[p]referred exemplary embodiments are described in more detail based on the drawings”. Those drawings are Figures 1 to 18, which are described on pages 4 to 6 of the Patent and which appear on pages 1/17 to 17/17, after the claims. The drawings are the same as those in the PCT.

60 Other differences between the PCT and the Patent are:

(a) The narrowing of claim 1 in the Patent by making it substantially the same as claim 11 of the PCT Application, but without the dimension limitation of claim 11 of the PCT Application (that dimension limitation remained in claim 11 of the Patent), which change occurred through the 2013 Amendments;

(b) Changing the description of the fan housing of the invention as claimed in claim 1 of the Patent (i.e., a change from the invention as claimed in claim 11 of the PCT Application) in the following manner: “a fan housing for one, two or more radial fans”, and “by means of the one, two or more radial fans provided in the fan housing” (Emphasis added.);

(c) Adding the words “wherein the fan housing is situated above the one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers” at the end of claim 1.

61 Paragraphs [10.4], [11.1], [11.2], [12.2]–[12.4], [15.1]–[17.3] are the same as those in the PCT Application.

Patent claims

62 BORA adopted a numbering system for the integers of claim 1 of the Patent. I adopt this system herein. Claim 1 of the Patent claims:

1 | A hob |

1.1 | with one or more cooking locations, |

1.2 | which, as viewed from above, exhibits one or more recesses only in the area around its geometric centre, |

1.3 | which are connected with one or more devices for removing cooking vapours through suction, |

1.3.1 | wherein these devices for removing cooking vapours through suction downwardly remove the cooking vapours that arose or arise above the cooking locations by suction in a direction pointing vertically below the hob, |

1.4 | wherein the bottom side of the hob is provided with a device for operating the hob and downwardly removing cooking vapours by suction that together with the hob forms an assembly unit, |

1.5 | wherein the bottom side of the hob in the device as viewed downwardly sequentially in a vertical direction encompasses |

1.5.1 | a housing for the heating or hob heating and control electronics, |

1.5.2 | a fan housing for one, two or more radial fans, |

1.5.3 | and one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers |

1.5.3(a) | for horizontally relaying the cooking vapours toward the outside, |

1.5.3(b) | and one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers for horizontally relaying the cooking vapours toward the outside as well as for preparing the cooking vapour stream to be vertically aspirated upwardly by means of the one, two or more radial fans provided in the fan housing and wherein the fan housing is situated above the one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers |

1.6 | and wherein the fan housing is situated above the one or more cooking vapour aspiration chambers |

63 Following the 2015 Amendments, claim 11 of the Patent claims:

A hob according to one of claims 1 or 2, wherein the distance between the bottom side of the hob on the one hand and the bottom side of the floor of the cooking vapour aspiration chambers on the other measures between 110 mm and 260 mm.

64 Both the expert witnesses proceeded on the basis of the claims as amended through the 2015 Amendments in preparing their evidence.

Witnesses

Experts

William Hunter

65 Mr William Samuel Hunter is a mechanical engineer, with more than 30 years’ experience in the research, development, design, testing and manufacture of various consumer products and systems involving the application of mechanical engineering principles, including those which require the control, manipulation and/or extraction of fluids such as air and liquids.

66 Mr Hunter holds a Bachelor of Engineering Science (Mechanical) (with first class honours) from the University of Melbourne (obtained in 1982) and a Master of Engineering Science, also from the University of Melbourne (obtained in 1985). He has been a member of the Institute of Engineers Australia since 1985.

67 In the course of his work as a mechanical engineer, Mr Hunter has obtained considerable experience with both centrifugal (radial) and axial fans. As a result of his undergraduate studies in mechanical engineering, Mr Hunter has specialised knowledge of fluid (air) flow.

68 As he noted in his first affidavit, Mr Hunter has also provided expert opinions to the Federal Court of Australia in relation patent and design matters, including some fan related matters: a ceiling fan design registration matter (Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd (2016) 121 IPR 1); and centrifugal fans and air conditioning systems (Dometic Australia Pty Ltd v Houghton Leisure Products Pty Ltd (2018) 135 IPR 403). He has also given evidence to the Australian Patent Office related to the design of a retractable blade ceiling fan design.

69 Mr Hunter gave considered evidence on the basis of his qualifications as a mechanical engineer, making concessions where appropriate.

70 BORA made a number of criticisms of Mr Hunter, including that he was not representative of the person skilled in the art and that he was a “professional witness”. I deal with BORA’s specific criticisms of Mr Hunter under the heading “Person skilled in the art” below.

Justin McLindin

71 Mr Justin Joseph McLindin is a retired Product Manager. He has a Bachelor of Applied Science in Industrial Design and a Bachelor of Industrial Design. Mr McLindin began his career as an industrial designer with Email Limited in 1983, working primarily on cookers, ovens, cooktops, hobs, and refrigerators. In 1996, he joined Electrolux Ltd as a design engineer, where he worked on cooking products like freestanding cookers, built-in ovens, cooktops/hobs and rangehoods. In that role, he was involved with the mechanical design and testing of new products which included how the products are made, how they are put together, all the bill of materials, the testing and proving of the product, getting it through compliance testing and having the product ready for production at a target price point.

72 Mr McLindin returned to Electrolux in 2001, after a two-year stint at Hills Industries, where he worked as a senior research and development engineer, within the home and hardware products division of Hills Industries. From 2001 to 2008, he was a Senior Product Design Engineer working on the development of freestanding cookers, built-in overs, cooktops/hobs and ranges/hoods. In 2008 he became Asia Pacific Regional Product Manager, and in 2015 he became Regional Product Manager for barbeques, dishwashers and cooking products.

73 Miele accepted that Mr McLindin was suitably qualified to express an opinion as to matters of product design, it observed that whilst Mr McLindin had extensive experience in hob design and manufacture, he had no experience in downdraft hobs before the priority date other than as a consumer. Mr McLindin also had no expertise in the field of optimising fluid dynamics and would engage a consultant to perform such analysis if required.

74 This proceeding was Mr McLindin’s first engagement as an expert witness.

75 Aspects of Mr McLindin’s evidence evolved through the process of written evidence, joint expert report (JER) and the joint session. He also made extensive written corrections to his responses in the JER. Mr McLindin sought to explain this on the basis that it was his first experience as an expert witness. For example, when questioned about his JER corrections in the joint session:

MR McLINDIN: I did, and I considered that I probably should have reviewed it a little bit more carefully than what I did. Obviously, this process is new to me, so that’s why. I noticed there were a number of things that needed to be corrected in there.

Joint Expert Report

76 On 1 July 2024, Mr Hunter and Mr McLindin prepared a JER in which they addressed questions set by the parties, noting where they agreed or disagreed with each other on particular issues.

77 On 19 July 2024, Mr McLindin prepared a three-page document entitled “Joint Expert Report Clarifications”, which clarified many of his responses in the JER (JER Clarifications).

Lay witnesses

Miele

Marco Wiechert

78 Mr Marco Wiechert is a mechanical engineer employed by a subsidiary of the first applicant. Mr Wiechert has been involved in the advanced development of Miele cooking fume extractors (including the Miele Silence Products) since 2014. Since 2017, Mr Wiechert has been a member and/or co-convenor of the International Electrotechnical Commission standardisation bodies related to cooking fume extractors.

79 Mr Wiechert verified the Miele Silence Products’ description, which set out the products which are alleged by BORA to infringe. He was not cross-examined.

Ji Liu

80 Mr Ji Liu is a Patent Attorney and the Director of the Patent Litigation Department at CCPIT Patent and Trademark Law Office. Mr Liu holds a Bachelor of Science and Masters of Science in Applied Chemistry. He commenced work as a patent engineer with CCPIT in 2001 on completion of his Masters of Science. In 2009, Mr Liu was admitted to the patent bar in China and commenced employment with CCPIT as a qualified Patent Attorney.

81 Throughout his over 23 years of practice, Mr Liu has acquired expertise in relation to the prosecution, enforcement, defence and challenge of Chinese patent applications and granted patents and has become familiar with the systems, practices and procedures of the Chinese National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA).

82 Mr Liu’s affidavits were written in English and were prepared without the assistance of an interpreter. Mr Liu declared that Miele’s solicitors, Davies Collison Cave, provided him with drafting assistance in preparing the affidavits.

83 Mr Liu was cross-examined. Mr Liu at times required the assistance of a Chinese language interpreter, however, when the interpreter asked for clarification on certain questions raised in English, Mr Liu was able to respond to the cross-examiner in English.

84 Mr Liu’s answers to questions were at times unnecessarily prolonged, particularly to ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions. At times, Mr Liu responded to questions with irrelevant and extended answers, which did not answer the question posed.

85 Overall, I found Mr Liu to be a credible and reliable witness.

Sensen Min

86 Mr Sensen Min is a Patent Attorney and a Counsel at the Shanghai office of JunHe law firm, a private partnership law firm in China. He holds a Bachelor of Engineering and a Master of Laws.

87 Mr Min joined JunHe as a junior associate in 2014. In 2017, Mr Min obtained certification as a licensed attorney in China. That same year he became a registered patent agent at the CNIPA.

88 Since 2014, Mr Min’s experience has included drafting and handling Chinese and PCT patent applications, specialising in medical devices, semiconductors, autonomous driving, and intelligent manufacturing. Mr Min has expertise in relation to the prosecution, enforcement, defence and challenge of Chinese patent applications and granted patents across various technology fields, and as a result of his practice, he has become familiar with the systems, practices and procedures of the CNIPA, including in 2015.

89 Mr Min is the co-author of an article published on JunHe’s website on 12 November 2015, the title of which translates to “Analysis of the Public Opinion Procedure in Patent Applications”. This article is discussed below.

90 Mr Min was cross-examined. His answers were responsive to the questions asked and he appeared to be a frank and credible witness. I consider that Mr Min’s answers were more responsive to counsel’s line of questioning than Mr Liu’s.

Xinyu Pei

91 Mr Xinyu Pei is a NAATI qualified translator, certified in relation to Chinese into English and vice versa.

92 Mr Pei translated various documents in this proceeding from Chinese to English. Mr Pei was not cross-examined.

BORA

Paul Ganter

93 Dr Paul Ganter is a partner of Rau, Schneck & Hübner Patentanwälte Rechtsanwälte PartGmbB, BORA’s patent attorneys in Germany. Dr Ganter is a German and European Patent Attorney. He affirmed an affidavit on 30 November 2023 and gave evidence in relation to the application to amend the Patent.

94 Dr Ganter has acted for BORA in relation to intellectual property matters globally since 2015. Dr Ganter was not cross-examined.

Ting Nan

95 Ms Ting Nan is a Patent Attorney and Executive Partner of Cohorizon Intellectual Property Ltd in China. She gave evidence regarding guidelines and practices of the CNIPA.

96 Ms Nan made two affidavits in this proceeding.

97 Ms Nan was cross-examined with the assistance of an interpreter. Ms Nan gave evidence that she had no problem reading or speaking English, and that, in the preparation and drafting of her affidavits filed in this proceeding, she did not have any draft versions of the affidavits translated into Chinese in order for her to understand them. However, when counsel for Miele attempted to cross-examine Ms Nan, Ms Nan required the aid of an interpreter and stated that she required their assistance as she could not understand the cross-examiners’ questions.

98 Ms Nan’s inability to answer questions without the aid of an interpreter, coupled with her unresponsive answers to questions, were suboptimal.

99 Ms Nan gave evidence regarding rule 5.2(2), chapter 4, part 5 of the 2010 Patent Examination Guidelines (2010 Guidelines), that certain Patent claim amendments were not publicly available on the CNIPA website. I deal with Ms Nan’s evidence further below.

Jianguo Wang

100 Mr Jianguo Wang is a Patent Attorney and Partner of Chinable IP in Beijing, China. Mr Wang holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Mechanical Engineering from Xi’an Jiaotong University and a Masters in Law from Peking University. He became a registered patent attorney in 2010. As a consequence of his years of experience as a patent attorney, he has become familiar with and knowledgeable about the systems, practices and procedures of CNIPA and its systems for obtaining access to documents on file in relation to Chinese patent applications.

101 Mr Wang was cross-examined. Initially, Mr Wang gave considered responses when initially cross-examined. However after an adjournment, Mr Wang returned the following week and provided lengthier answers which were often not responsive to questions asked, and at times, argumentative. I elaborate on Mr Wang’s evidence further below.

Daniel McKinley

102 Mr Daniel McKinley is a Principal at Gestalt Law and is the solicitor on the record for BORA in this proceeding. He affirmed an affidavit on 28 March 2024. He gives evidence relating to Miele’s alleged infringement of the Patent, and puts into evidence certain dictionary definitions and correspondence relevant to BORA’s application to amend the Patent.

103 Mr McKinley was not cross-examined in this proceeding.

Mario Blersch

104 BORA sought to tender an affidavit of Mr Mario Blersch, the Intellectual Property Management Team Lead of the second respondent in this proceeding. I did not allow this affidavit to be tendered and I indicated to the parties that I would address this in my reasons.

105 Mr Blersch’s affidavit and the annexures to that affidavit contained a variety of models of BORA downdraft extraction products and modular cooktops which predate the Patent.

106 There was no inventive step challenge in this proceeding. BORA submitted that Mr Blersch’s affidavit was relevant to the consideration of the technical contribution to the art for the purposes of the support challenge made against the Patent under s 40(3) of the Act.

107 The technical contribution of the invention of the Patent is assessed by reference to the invention described and claimed in the Patent. In the case of a product claim, it is the product, not by reference to the state of the common general knowledge. Furthermore, the common general knowledge is used for the purpose of interpreting the disclosure of the specification or priority document and placing it in a context. It is not permissible to use the common general knowledge to go further than eliciting the explicit or implicit disclosure, for the purpose of supplementing that disclosure or adding to it what may seem to be an obvious further feature.

108 The experts did not refer to the BORA products discussed in Mr Blersch’s affidavit in their evidence, including in their discussion of whether they would be able to make a hob assembly unit with one fan, and how they might go about that task.

109 I also note that Mr Blersch’s affidavit, and the material in it, was not mentioned by either party in their written submissions or their oral opening submissions, which were completed before I ruled on the parties’ objections.

110 As such, I do not consider Mr Blersch’s affidavit to be relevant to any matter in issue in this proceeding.

Amendment

111 Mr Bruckbauer seeks to amend the Patent pursuant to s 105 of the Act to correct two clerical errors or obvious mistakes in the Patent.

112 Notice was given to the Commissioner of Patents under s 105(3) of the Act on 26 September 2023. On 27 September 2023, IP Australia advised the Patentee that the Commissioner was prima facie satisfied that the proposed amendments met the requirements of s 102 of the Act, and that the Commissioner did not intend to appear in this proceeding. The proposed amendments were advertised in the Australian Official Journal of Patents on 12 October 2023, in accordance with r 34.41 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

113 Miele does not oppose BORA’s application to amend the Patent. Both Mr McLindin and Mr Hunter considered the Patent as if it has been amended to correct the typographical errors.

The proposed amendments

114 The first error sought to be amended appears in claim 1. The line as written currently reads, “a housing for the heating of hob heating and control electronics”; BORA contends that it should read, “a housing for the heating or hob heating and control electronics” (Emphasis added.). BORA submits that this is clearly the result of a clerical error and an obvious mistake in transcribing claim 1. This is demonstrated by the multiple instances of use of the correct phrase (i.e., “heating or hob heating”) elsewhere in the Patent, such as paragraphs [3.1], [11.1], [12.4], [17.3], and claims 12 and 13.

115 The other error sought to be amended appears on page 2 (at [2.4]). The words “direct ion” should be the word “direction”. BORA contends that this is also clearly the result of a clerical error and obvious mistake.

Relevant sections of the Act

116 Section 105 of the Act relevantly provides:

(1) In any relevant proceedings in relation to a patent, the court may, on the application of the patentee, by order direct the amendment of the patent request or the complete specification in the manner specified in the order.

…

(4) A court is not to direct an amendment that is not allowable under section 102.

117 Section 102 of the Act concerns allowable amendments and relevantly provides:

(1) An amendment of a complete specification is not allowable if, as a result of the amendment, the specification would claim or disclose matter that extends beyond that disclosed in the following documents taken together:

(a) the complete specification as filed;

(b) other prescribed documents (if any).

…

(3) This section does not apply to an amendment for the purposes of:

(a) correcting a clerical error or an obvious mistake made in, or in relation to, a complete specification; or

…

Principles

118 BORA contends that both the amendments are for the purpose of correcting a clerical error or obvious mistake made in, or in relation to, the complete specification of the Patent.

119 The onus to establish that the error is a clerical error or an obvious mistake lies with the patentee seeking the amendment: Expo-Net Danmark A/S v Buono-Net Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 88 IPR 1 at [13] (per Bennett J).

120 Justice Yates distinguished between a “clerical error” and “obvious mistake” in Garford Pty Ltd v Dywidag-Systems International Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1039 at [14]–[19], stating:

14 In The Queen v Commissioner of Patents; Ex Parte Martin (1953) 89 CLR 381, Williams ACJ said (at 395):

… A clerical error, I would think, occurs where a person either of his own volition or under the instructions of another intends to write something and by inadvertence either omits to write it or writes something different. …

15 Fullagar J (with whom Kitto J and Taylor J agreed (at 408)) said (at 406), that the expression “clerical error” is of a “somewhat elastic character”. After considering various dictionary meanings of the word “clerical”, his Honour continued:

… Probably no one would deny that a clerical error may produce a significant, and even profound, effect as for example, in a case in which a writer or typist inadvertently omits the small word “not”. But the characteristic of a clerical error is not that it is in itself trivial or unimportant, but that it arises in the mechanical process of writing or transcribing. …

16 In General Tire & Rubber Company (Frost’s) Patent [1972] RPC 271, Graham J (at 279) considered an “obvious mistake” to be one which:

… involves that the instructed public can, from an examination of the specification, appreciate the existence of the mistake and the proper answer by way of correction.

17 In reaching that conclusion, his Lordship distinguished between such a mistake and a mistake that had been “obviously made”. His Lordship (at 278) explained the distinction as follows:

It is the mistake which must be obvious and not the fact that it has been made. This implies, to my mind, that both the fact of mistake and the correction necessary must be clear to the reader’s mind, and it is not enough if he merely appreciates the presence of a mistake. If, in a mathematical context, it is said “2 and 2 make 5”, the reader would immediately say: “5 is an obvious mistake for 4”. If, however, there is more than one possible correct answer to the question, particularly where the answers may depend on intention or judgment, the reader would say: “Obviously a mistake has been made but I cannot tell you what is the right answer”. The wording of the section itself therefore, to my mind, shows an intention in favour of the first construction rather than the second.

18 In the course of considering that question, his Lordship observed (at 277) that, for the purpose of correcting an obvious mistake:

… it does not matter that the claim may be enlarged by the amendment.

19 Both these cases accept that the correction of clerical errors and obvious mistakes may involve the making of very significant amendments to the specification and, in particular, the claims. Yet, such amendments are allowable if they are truly “clerical errors” or “obvious mistakes”.

121 The characteristic of a clerical error is not that it is in itself trivial or unimportant, but that it arises in the mechanical process of writing or transcribing: The Queen v Commissioner of Patents; Ex parte Martin (1953) 89 CLR 381 at 406 (per Fullagar J).

122 In Expo-Net, Bennett J considered the issue of “obvious mistake” and at [13] approved the statement of Graham J in General Tire and Rubber Co (Frost’s) Patent [1972] RPC 259 at 279 that an obvious mistake is one that “the instructed public can, from an examination of the specification, appreciate the existence of the mistake and the proper answer by way of correction”. Such a mistake is to be distinguished from a mistake that has been “obviously made”, but where the correction is not obvious to the reader.

123 A mistake can be an obvious mistake even where trained minds have failed to notice that mistake for “quite a long time”, as Russell LJ further explained in Farmhand Inc v Spadework Ltd [1975] RPC 617 at 619–20:

One is familiar, in all sorts of realms, with the fact that a person who may be in fact responsible for the production of a document may know perfectly well what he means to say and may well think he has said it, and is therefore the last person who is likely to notice that he has failed to say it by mistake. If one really set a standard… that a mistake cannot be an obvious mistake because a trained mind has failed to notice it, then of course… you could never have an obvious mistake in a patent, because some trained mind at some stage has produced that document and has not noticed the mistake… In some sense it may be true to say that the more glaring (and therefore the more unexpected) the mistake is, the less likely is anybody with a skilled mind to notice it. They simply would not believe that it could be there; and this is just that kind of mistake.

124 Even where the requirements of s 102 are met, the word “may” in s 105(1) of the Act indicates that the Court has a discretion as to whether or not to allow an amendment.

125 The discretion whether to allow the amendment is a broad one. The discretionary factors identified in the cases do not constitute a set of rigid rules to be inflexibly applied: Meat & Livestock Australia Limited v Cargill, Inc (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 47 at [462] (per Beach J). As Yates J observed in Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft v Generic Health Pty Ltd (2012) 99 IPR 59 at [162], what is essentially at issue with respect to s 105 of the Act is “whether, by its conduct, the patentee has abused the monopoly that has been conferred upon it by the grant of the patent in its unamended form”.

126 Even where no public or private detriment is apparent, a reasonable explanation is required where there has been a delay: Novartis AG v Bausch & Lomb (Australia) Pty Ltd (2004) 62 IPR 71 at [135] (per Merkel J). A patent applicant’s relevant knowledge of risk may be informed by its overseas experiences, with the genesis being a PCT Application, and its experiences thereafter being seen not as “a collection of isolated events, but as a continuum against which the applicants’ actual or constructive knowledge of the need for an amendment might be inferred ”: CSL Ltd v Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd (No 2) (2010) 89 IPR 288 at [88] (per Jessup J); BlueScope Steel Ltd v Dongkuk Steel Mill Co., Ltd (No 2) (2019) 152 IPR 195 at [1356] (per Beach J).

127 In Novartis, Merkel J recognised that there appeared to be a distinction in the exercise of the discretion in the authorities between validating amendments to cure otherwise invalid claims, and other amendments, such as deletion amendments involving deleting invalid claims, or the correction of errors or mistakes. At [66], Merkel J observed that a more lenient approach may be adopted for the latter type of amendments, noting that:

… The reason for the leniency was explained by Pearson LJ in [C. Van der Lely NV v Bamfords Limited [1964] RPC 54] at 74–5 where his Lordship observed that a court is prima facie disposed to the deletion of invalid claims because if such claims were to remain in the patent they would constitute a potential “nuisance to industry”. A similar observation can be made in respect of the mere correction of errors or mistakes which are not sought to cure any actual or potential invalidity.

Background to errors

128 The PCT is an English translation of the original PCT Application which was in German. An English translation of amended claims 1 and 11 of the PCT Application which were made under Article 34 of the Treaty prior to entering the national phase in Australia and which were filed with IP Australia on 12 November 2013 when the national phase was entered in Australia

129 The PCT and the 2013 Amendments were examined by IP Australia and an examination report was issued by IP Australia on 23 September 2015. The first error occurred in the course of the preparation of an amended claim set in response to the examination report. According to Dr Ganter, the amended claim set was based on a claim set of a corresponding European patent specification which was identical to the 2013 Amendments except that they included numerals in brackets. The amended claim set contains a typographical error in claim 1 at line 14 where it reads “a housing (44) for the heating of hob heating and control electronics” (Emphasis in original.), instead of “a housing (44) for the heating or hob heating and control electronics” (Emphasis in original.). Dr Ganter places the blame for the error on his secretary. Dr Ganter failed to notice and correct the typographical error when he reviewed and settled the proposed amended claim set.

130 Dr Ganter gave four reasons why he considered the first error to be a typographical error:

(a) The document was setting out amendments to claim 1 of Application No 2012247900 as amended following the 2013 Amendments, and at that time claim 1 of Application No 2012247900 included the words “a housing for the heating or hob heating and control electronics” (emphasis added) and did not include the words “housing for the heating of hob heating and control electronics”.

(b) The Amended Claim Set identifies amendments to the claims of Application No 2012247900 using the Microsoft Word “track changes” function, with additions underlined and deletions struck-through. In line 16, “(44)” is struck-through (indicating a deletion), but there is no strike-through of the word “or” or underlining of the word “of”. That is, there is no indication in the Amended Claim Set that the word “or” was intended to be replaced with the word “of’.

(c) The words “heating of hob heating and control electronics” (emphasis added) did not appear anywhere in the Translated Specification or the 2013 Amendments when the Amended Claim Set was prepared. However, the Translated Specification contains the phrase “a housing for the heating or hob heating and control electronics” (emphasis added) in claim 1 and at pages 12, 14 and 17.

(d) On my understanding of the invention described in the body of the Patent, the appearance of the words “heating of hob heating and control electronics” in claim 1 do not make sense, whereas the appearance of the words “heating or hob heating and control electronics” do make sense.

(Emphasis in original.)

131 The second error is the incorrect spelling of “direction” by the insertion of a space in the middle of the word: “direct ion” which also arose in the course of preparing the amended description pages of the response to the examination report. In the context of the specification, “direction” makes sense whereas “direct ion” is nonsensical. Thus BORA contends that the second error is also an obvious mistake.

Matters relevant to discretion

132 The two errors appeared in the amendments submitted to the Commissioner on 11 November 2015, in response to the examination report of 23 September 2015.

133 Dr Ganter’s evidence is that he first became aware of the two typographical errors on 27 February 2023, some seven years after they appeared. This was in the context of contemplated litigation, after BORA’s lawyers had sent a letter of demand to Miele on 15 February 2023 in respect of the threat of infringement of the Patent by the anticipated Australian launch of the Miele Silence Products. After that threat had dissipated, Gestalt Law wrote to Miele’s lawyers (Davies Collison Cave) on 28 August 2023 regarding the ongoing infringement of the Patent by the offering for sale and sale of the Current Miele Products. That letter noted the presence of the typographical error in claim 1 and stated that BORA would seek to have the error corrected by amendment. Miele commenced this proceeding on 7 September 2023.

134 Mr Bruckbauer sought an amendment of the Patent as part of the cross-claim for infringement which was filed on 22 September 2023.

135 To the extent that there was any delay by Mr Bruckbauer in seeking the amendment of the Patent, BORA submits that the period of delay was between 27 February 2023 and 22 September 2023. BORA contends that there was nothing unreasonable about Mr Bruckbauer not seeking to amend before the letter of demand regarding the Current Miele Products was sent on 28 August 2023.

Consideration

136 The purpose of the proposed amendments is to rectify the two errors. BORA submits that they are both clearly clerical errors. In relation to the first error, in claim 1, the same phrase is used in the body of the specification without the error (see [3.1], [11.1], [12.4] and [17.3] of the Patent). The second error, which I consider is also an obvious error, splits the word “direction” into “direct” and “ion”.

137 Since becoming aware of the errors in February 2023, BORA has moved reasonably promptly to notify Miele and the Commissioner of its intention to amend, and to commence the amendment process prescribed by the Rules.

138 No advantage has been gained by BORA as a result of its failure to notice the relevant errors, or its assertion of the unamended claim. The amendments are not sought to cure an invalid patent.

139 There is no evidence that Miele, or any other person, has been prejudiced by reason of the Patent in its unamended form. No unfair advantage has been sought or obtained. There has been no unreasonable delay in seeking the amendment, and there are no other circumstances which would lead the Court to refuse to make the proposed amendments.

140 In the circumstances I am satisfied that it is appropriate to allow the proposed amendments pursuant to s 105(1) of the Act.

Person skilled in the art

141 The person skilled in the art is not a reference to a specific person but is a legal construct drawn by reference to the available evidence. As French CJ explained in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 257 CLR 356 at [23] (AstraZeneca HC):

The notional person is not an avatar for expert witnesses whose testimony is accepted by the court. It is a pale shadow of a real person — a tool of analysis which guides the court in determining, by reference to expert and other evidence, whether an invention as claimed does not involve an inventive step.

142 Relevant evidence will include the patent specification and, typically, evidence of persons with knowledge and experience in the field of the invention: Neurim Pharmaceuticals (1991) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 5) [2024] FCA 360 at [70] (per Nicholas J).

143 The legal construct may be a single person or may be a team of persons “whose combined skills would normally be employed in that art in interpreting and carrying into effect instructions such as those which are contained in the document to be construed”: General Tire & Rubber Co v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485 (per Sachs, Buckley and Orr LJJ). The hypothetical construct “is unimaginative and without inventive capacity”: General Tire at 485.

144 Miele submits that the Patent describes a device for downwardly removing cooking vapours by suction that, together with the hob, forms a hob assembly unit, including the use of radial (centrifugal) fans to direct the flow of the cooking vapour into, through and out of the device. Accordingly, the person skilled in the art includes, within a skilled team, a mechanical engineer with expertise in centrifugal fans and optimising fluid flow in industrial products. Miele submits that Mr Hunter is appropriately qualified to give relevant evidence in relation to centrifugal fans and air flow dynamics from the perspective of a mechanical engineer.

145 Miele accepts that Mr McLindin can give evidence relevant to the person skilled in the art. Miele observes, however, that as Mr McLindin admits, his expertise is not in the field of optimising fluid (e.g., air) dynamics in hobs or extraction systems and that he would engage an external consultant (like, Miele contends, Mr Hunter), to perform that analysis where required. Mr McLindin had not worked on downdraft extraction fan products before any priority date asserted in the proceeding.

146 BORA seeks to sideline the totality of the evidence of Mr Hunter on two grounds. First, BORA seeks to denigrate Mr Hunter as an expert witness by describing him as a “dual specialist”, on the basis that he had expertise in both mechanical engineering and being an expert witness in patent cases. Second, BORA contends that Mr Hunter is not “representative of the person skilled in the art” as he has not himself actually worked in the area of downflow hobs or been part of a team that did. Accordingly, Mr Hunter’s evidence should be ignored in favour of Mr McLindin’s evidence as he has had significant experience of working in the field. Mr McLindin’s background and experience is said to be “representative” of that of the person skilled in the art.

147 Ultimately BORA’s first ground of complaint about Mr Hunter distilled down to a species of the second:

Mr Hunter also has decades of experience as an expert witness in relation to patent and design cases which do not involve hobs or extractor products. That is also not the experience of the person skilled in the relevant art.

148 It was not suggested, and nor could it be on the evidence, that Mr Hunter was a partisan witness, a “gun for hire”, or that he had tried to hide his previous expert witness experience, or that he had not complied with his obligations as an independent expert witness.

149 BORA sought to impugn Mr Hunter’s qualification to comment on matters of fluid mechanics, on the basis that he studied fluid mechanics as part of his undergraduate engineering studies:

MR HENNESSY: Well, I want to suggest to you that you are rather searching around for a basis upon which to advance yourself as a PSA in this case, and things were so scarce in that regard you had to resort to a subject you undertook as an undergraduate 30 or 40 years ago at university.

MR HUNTER: I don’t agree with you.

150 This line of criticism appeared to proceed from a misunderstanding of the role of mechanical engineers and the concept of the person skilled in the art. The role of a mechanical engineer is to apply their knowledge of engineering principles (acquired during their university studies) to a variety of situations. This was exemplified by Mr Hunter being able to give a description of how induction cooktops worked, with which Mr McLindin agreed, despite not having personal experience working with induction cooktops.

151 BORA also submits that Mr Hunter is not able to construe the ordinary English words of the claims as he is not a person skilled in the art. In this he is to be contrasted with Mr McLindin, who BORA submits, based on his experience, is “representative of the person skilled in the art”.

152 In support of its submission, BORA referred to the comments of Nicholas J in Neurim at [71]–[74], that the person skilled in the art must have practical knowledge and experience in the field of the invention. In this respect, the notional skilled addressee is someone not only with a practical interest in the subject matter of the invention but also the relevant background knowledge and experience shared by those working in the field of the invention. His Honour accepted that it is necessary to identify the field of knowledge to which the invention relates and then identify the notional skilled addressee by reference to that body of knowledge: Neurim at [74] (per Nicholas J).

153 BORA submitted that the relevant field was the design of cooktops and rangehoods. According to BORA, hobs with a downward extraction device forming a single component did not constitute a separate field of knowledge at the priority date. BORA contrasts the background and experience of Mr McLindin in the relevant field of cooktop and rangehood design, with Mr Hunters’ lack of experience in that field to submit that Mr McLindin is “representative” of the person skilled in the art, whereas Mr Hunter is not.

154 In propounding Mr McLindin as being “representative” of the person skilled in the art, rather than populating the legal construct that is the person skilled in the art via relevant evidence, BORA, contrary to the High Court’s directions in AstraZeneca HC, seeks to put forward Mr McLindin as an avatar for the person skilled in the art. Such an approach is not endorsed by Nicholas J’s comments in Neurim noted above. His Honour’s reference to “evidence of persons with knowledge and experience in the field of the invention” was made following express recognition that the person skilled in the art was a legal construct. That tool of analysis, a pale shadow of a real person, guides the Court, by reference to expert and other evidence.

155 No one expert stands in the shoes of, or ‘is a representative of’ the person skilled in the art. Rather, the Court receives evidence from appropriately qualified experts, and armed with that evidence construes the Patent through the eyes of the skilled addressee, or determines other questions referable to the person skilled in the art, such as whether an invention involves an inventive step.

156 I consider that the Patent is addressed to someone who has an interest in hob and extractor design. As the Patent is concerned with extracting or removing cooking vapours by suction, that skilled person will also have knowledge and expertise in fans, including fans and fluid flow.

157 Once the relevant field is identified, evidence from relevantly qualified and experienced expert witnesses is used to frame the tool of analysis that is the person skilled in the art.

158 Mr McLindin has experience in cooktop design and manufacture and can give relevant evidence on matters of hob design. Mr McLindin has no qualifications or experience in designing downdraft rangehoods, or any training or specialised knowledge in fluid flow. When at Electolux, Mr McLindin led a team which included industrial designers and engineers. Mr McLindin’s experience qualifies him to provide admissible evidence as to the person skilled in the art in the boundaries of his experience. However, he is not an avatar or ‘representative’ of the person skilled in the art.

159 Mr Hunter has relevant qualifications and experience in product design, including with axial and radial fans, fluid (air) flow and suction. He is well qualified to provide relevant evidence on radial fans and product design related matters.

160 Lastly, I note that Mr McLindin’s evidence appeared to evolve following the JER and joint conclave. BORA sought to suggest that Mr McLindin’s evidence was more “authentic” as he was a first-time expert witness, unlike the “professional” expert, Mr Hunter. Aside from not being entirely sure what was intended to result from that submission, I do not accept that the evolution of aspects of an expert’s evidence through the JER and joint conclave process, or that witness’s failure to thoroughly check his recorded views in the JER, can be put down to it being his first time as an expert witness, and somehow used as the basis for a submission as to his being a more authentic witness than Mr Hunter, the so-called “professional” witness.

161 Expert witnesses are provided with the Harmonised Expert Witness Code of Conduct at an early stage in their engagement. The Code emphasises the seriousness of the expert witness task and its importance in assisting the Court. It is the expert witness’s ability to comply with their obligations to the Court to provide independent evidence to assist the court that is of importance and relevance to assessing the witness’s testimony, not whether it is their first time as an expert witness

162 There is no inventive step challenge, and the words of the claims in dispute are ordinary English words. Thus the role of the person skilled in the art is more limited in this case than in some cases. However, the person skilled in the art does have primary relevance to the support and sufficiency challenges discussed below.

Construction

163 It is appropriate to consider questions of construction shorn of the distraction of the forensic interests of the parties or, as if the infringer had never been born: Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc (2001) 51 IPR 327 at 333 (per Heerey J); CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd (1994) 51 FCR 260 at 267–8 (per Spender, Gummow and Heerey JJ). Accordingly, in these reasons, I first consider questions of construction before turning to whether or not the Miele Silence Products may be said to infringe the claims.

164 The meaning of each of the following terms within each integer is in issue:

(a) integer 1.5: “viewed downwardly sequentially in a vertical direction”;

(b) integer 1.5.1: “a housing for the heating or hob heating and control electronics”;

(c) integer 1.5.3: “cooking vapour aspiration chambers…”; and

(d) integer 1.5.3(b): “for preparing the cooking vapour stream to be vertically aspirated upwardly by means of” the “one, two or more radial fans”.