FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Monarch Advisory Group Pty Ltd v Puxty (No 4) [2025] FCA 534

File number: | NSD 951 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | MARKOVIC J |

Date of judgment: | 23 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – employment agreements – whether consent given to breach post-employment restraint – whether post-employment restraint reasonable, valid and enforceable – where no consent established – where post-employment restraint enforceable DAMAGES – damages for loss of profits – damages for lost opportunity – basis for calculation of damages – where breach of restraint of trade – where company lost business as a consequence – whether loss of business caused loss of opportunity to sell business at a higher price |

Legislation: | Restraints of Trade Act 1976 (NSW) s 4 |

Cases cited: | Commonwealth of Australia v Amann Aviation Pty Ltd (1991) 174 CLR 64 Ennis Paint Australia Holding Pty Ltd & Anor v Jimmy Poh Wing Lei & Ors [2015] NSWSC 1933 Extraman (NT) Pty Ltd v Blenkinship (2008) 23 NTLR 77 Hanna v OAMPS Insurance Brokers Ltd [2010] NSWCA 267 Houghton v Immer (No 155) Pty Ltd (1997) 44 NSWLR 46 Johnston v Brightstars Holding Company Pty Ltd [2014] NSWCA 150 Birla Nifty Pty Ltd v International Mining Industry Underwriters Ltd (2014) 47 WAR 522 OAMPS Insurance Brokers Ltd v Peter Hanna [2010] NSWSC 781 Orica Investments Pty Ltd v McCartney [2010] NSWSC 488 Stacks Taree v Marshall [No 2] [2010] NSWSC 77 Woolworths Ltd v Olson [2004] NSWCA 372 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Commercial Contracts, Banking, Finance and Insurance |

Number of paragraphs: | 211 |

Date of hearing: | 11-13 March 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr D Mahendra |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Madison Marcus Law Firm |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr V Bedrossian SC and Ms S Erian |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Edge Legal Group |

ORDERS

NSD 951 of 2020 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | MONARCH ADVISORY GROUP PTY LTD Applicant | |

AND: | BRETT JAMES PUXTY First Respondent FRANCIS COGGAN Second Respondent ODYSSEY ADVISORY SERVICES PTY LTD Third Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | BRETT JAMES PUXTY (and another named in the Schedule) First Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | MONARCH ADVISORY GROUP PTY LTD Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | MARKOVIC J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 may 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to Order 2 below, by 6 June 2025 the parties are to provide draft short minutes of order giving effect to these reasons including in relation to the date from which interest should run and on the question of costs.

2. In the event that the parties cannot agree on the form of orders:

(a) by 6 June 2025 they are to provide to my Associate their competing orders and submissions, not exceeding three pages in length, addressing the areas and extent of the disagreement between them; and

(b) the proceeding will be listed for case management hearing to allow all outstanding matters in dispute to be determined and for final orders to be made.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MARKOVIC J:

1 Monarch Advisory Group Pty Ltd, the applicant, operated a financial services business offering financial planning services from 5 March 2012 to 2 February 2021. Tatiana Coulter is the sole director of Monarch.

2 Brett James Puxty and Francis Coggan, the first and second respondents respectively, were employed by Monarch in the period from 7 December 2018 to 31 January 2020. Odyssey Advisory Services Pty Ltd, the third respondent, was incorporated on 18 September 2019. Its directors are Messrs Puxty and Coggan and its shareholders are Mr Puxty and his wife who hold those shares on behalf of a family trust. Odyssey operates a financial planning business.

3 By amended originating application filed on 4 February 2022 (Amended OA) Monarch seeks damages from Messrs Puxty and Coggan for breach of their respective employment agreements.

4 Until the final day of the hearing, in its Amended OA Monarch also sought damages and an account of profits occasioned by an alleged breach of fiduciary duty by Messrs Puxty and Coggan and damages pursuant to s 1317H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), s 236 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) and for passing off.

5 Similarly, in its amended statement of claim filed on 4 February 2022 (ASoC) Monarch pleaded a broader case alleging, in addition to breaches by Messrs Puxty and Coggan of various clauses of their respective employment agreements with Monarch, breach by Messrs Puxty and Coggan of their fiduciary duties owed to Monarch, breach by Messrs Puxty and Coggan of s 182 and s 183 of the Corporations Act and Odyssey’s involvement in such breaches and breach by Messrs Puxty and Coggan and Odyssey (together respondents) of s 18 of the ACL and that the respondents engaged in passing off.

6 On 27 February 2023 Mr Puxty and Odyssey (together cross-claimants) filed an amended notice of cross-claim and amended statement of cross-claim (Amended CC) seeking damages for alleged breach of contract and repayment of a loan of $30,000 which the cross-claimants allege was advanced by Mr Puxty to Monarch. In Monarch’s opening submissions it informed the Court that, without admission of liability, it would consent to an order requiring it to pay Mr Puxty the $30,000 it received from him but says that payment of this amount should await the determination of the relief it seeks in the ASoC (such that the amount could be offset against any monetary judgment made in Monarch’s favour as opposed to it constituting a stand-alone order against it).

7 In oral closing submissions on the final day of hearing, counsel for Monarch informed the Court that Monarch only alleges and relies on breach by each of Messrs Puxty and Coggan of cl 19 of their respective employment agreements, which are post employment restraint clauses, and claims damages for those alleged breaches. Monarch otherwise abandoned all other relief sought and claims made in its Amended OA and ASoC, including in relation to alleged breaches of other clauses of Messrs Puxty’s and Coggan’s respective employment agreements.

8 I return to the detail of the remaining pleaded claim as against Messrs Puxty and Coggan below. Before doing so it is convenient to set out the evidence relied on by the parties and the relevant facts, noting that it is no longer necessary to resolve some of the factual issues that might have arisen. To that end I have only included the evidence insofar as it is relevant to the remaining pleaded and defended claim based on an alleged breach of cl 19 of the employment agreements and the components of the Amended CC that remain in issue and otherwise to the extent it provides background and context.

THE FACTS

Witnesses

9 Monarch relied on evidence given by the following witnesses:

(1) Ms Coulter, the sole director and secretary of Monarch. Ms Coulter obtained a Diploma of Financial Services – Financial Advice in 2003, which enabled her to provide financial advice, and an Advanced Diploma Financial Services from RMIT University in 2005. She has held the following positions:

(a) from about 2001 she worked for AdvantEdge, a subsidiary of MLC Limited, in its call centre providing “no advice” information for investments and superannuation to members of AdvantEdge;

(b) from 2002 to 2003 she was a mortgage broker at MLC;

(c) from 2003 to 2004 she was an education specialist for corporate super at MLC. While undertaking these roles for MLC, Ms Coulter focused largely on superannuation. As an education specialist for MLC superannuation, she travelled around Australia educating members of the MLC Super Fund about the mechanics of investing in super and the investment options available to them. Ms Coulter was not able to provide financial advice to members at the time, but she provided them with financial literacy to assist them in making informed decisions about consolidating their super and member investment choice including if appropriate by providing assistance so that members could tailor the investment approach for their super rather than remaining with the default option. Ms Coulter educated staff from a number of large corporations including Telstra, PwC, Sony, Thales and Australian Defence Industries;

(d) in 2005 she worked as a financial planner at Westpac Banking Corporation providing advice to businesses on strategies and structures such as business insurance, including buy/sell and keyperson insurance, superannuation for individual business owners and group superannuation options for staff, along with other investments outside of superannuation. Ms Coulter advised small to medium enterprises where the businesses employed at least 10 staff and had a minimum turnover of $1,000,000;

(e) in 2006 she moved to AMP where she held the role of business development manager. In that role Ms Coulter assisted AMP aligned advisors (advisors licenced by AMP) with structures and strategies for superannuation, investments and insurance;

(f) in 2007 she moved to Perpetual Private Wealth as business development manager in private wealth and investments where she assisted advisors to structure their client investments through separately managed accounts (SMAs). Ms Coulter worked closely with the investment managers to understand their investment philosophy and the individual stocks they chose for the SMAs so as to assist the advisors to understand how to incorporate the SMAs in their client’s overall investment portfolio;

(g) in 2008 she moved to Macquarie Bank where she held the role of business development manager in insurance. In that role Ms Coulter assisted advisors to understand how to structure complex insurance strategies for their high-net-worth clients, being those requiring in excess of the standard sums insured, for example, $15 million total and permanent disability insurance coverage, $10 million trauma insurance coverage and $60,000 per month income protection. Ms Coulter met with advisors and helped them to understand how to calculate the amounts insured to best present to the underwriter, which for those clients were significantly higher than the industry standard at the time; and

(h) in 2010 she moved to OnePath where she held the role of business development manager in insurance until 2012 when she established Monarch. In that role Ms Coulter spent most of her time with advisors working on the OnePath product. However, there was a comprehensive training program that Ms Coulter and the technical advice manager presented to advisors around business insurance which included presenting strategies to advisors and assisting them to implement the strategies, including in depth underwriting case studies. While Ms Coulter was at OnePath, there was a focus on business insurance. After she left OnePath, Ms Coulter maintained her relationship with the technical managers and would often run strategies by them. Ms Coulter was cross-examined;

(2) Alex Lee, managing partner of Newlane Risk Pty Ltd, a financial planning and advisory business. Mr Lee has over 16 years’ experience as a financial advisor and has owned and operated his own advisory business since about 2017. Mr Lee gave evidence in relation to the calculation of the purchase price for the purchase by Newlane of Monarch’s client book. Mr Lee was not cross-examined; and

(3) Michael Potter, a chartered accountant and a partner of EY. Mr Potter is an accredited business valuation specialist and forensic accountant with over 38 years’ experience. Mr Potter prepared a report in relation to the loss of profit suffered by Monarch during the “Restraint Period as a result of the claimed employment contract breaches” and the question of “whether the claimed employment contract breaches resulted in a reduced [purchase price for the purchase by Newlane of Monarch’s client book] and if so, the quantum of that reduction”. Mr Potter was cross-examined.

10 The respondents relied on evidence given by:

(1) Mr Puxty, who has worked as a financial planner for approximately 20 years. In that capacity he worked for AON Hewitt Australia and WiZDOM Advisory, before moving to Monarch. In 2017-2018 while working for WiZDOM Mr Puxty developed his own client base. He also continued to service some of the clients to whom he had provided services while at AON (some of whom followed him to Monarch) and, in addition, received referrals. Mr Puxty was cross-examined; and

(2) Paul Minett, a director of Martin Minett, with experience in the quantification of economic loss and financial analysis including forensic accounting. Mr Minett prepared a report in response to the report prepared by Mr Potter. Mr Minett was not cross-examined.

11 Messrs Potter and Minett also provided a joint report. Their evidence is dealt with below in relation to the third question for consideration, the measure of damages assuming liability is established.

12 As is apparent, the central witnesses were Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty. They each gave evidence about the development of their professional friendship, the interactions and dealings which led to Monarch’s employment of Messrs Puxty and Coggan and the subsequent termination by Messrs Puxty and Coggan of their employment with Monarch. Much of their evidence centred around their recollections of conversations and meetings which took place in 2018 and 2019 as recounted by them in their respective affidavits which were sworn or affirmed several years later. While I accept that Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty may have some recollection of those events, it is difficult to accept that either of them has the recollection of conversations which they attribute to themselves given the passage of time. That being so while I have, in some instances, recounted their recollections of conversations and meetings, in the absence of contemporaneous documents, I have attributed little weight to that evidence in coming to my conclusions preferring the documentary evidence and what it establishes about the dealings between the parties.

13 Mr Puxty submits that when giving oral evidence Ms Coulter was defensive and evasive and that she was not a credible witness, pointing to several examples which he says highlight concerns about Ms Coulter’s credit. Having regard to the whole of Ms Coulter’s evidence I am not satisfied over all that she was not a credible witness. While I accept that at times she was evasive and had to be challenged to answer questions directly, that did not infect the entirety of her evidence. Nor am I satisfied that Ms Coulter telling the cross-examiner that a proposition put to her was only partially correct impacts on her credit. Ms Coulter was entitled to give that answer where that was so. Thereafter, when questioned, she attempted to explain her position and what aspect of the proposition put was incorrect.

Monarch

14 Monarch was incorporated on 7 February 2012 and commenced operating as a financial planning business specialising in wealth protection on 5 March 2012. Monarch offers financial advice but specialises in the provision of insurance solutions for individuals and businesses.

15 Prior to Monarch commencing its business Ms Coulter spent significant time setting it up. By way of example she:

(1) spent about 18 months researching and interviewing dealer groups through which Monarch could be licensed and completing “white papers”;

(2) created a board of advice made up of various contacts within the industry including a financial advisor, senior personnel from the financial services and other industries (e.g. marketing managers) and potential clients with whom she tested her ideas and strategies about how to operate a business and create a successful financial planning business; and

(3) prepared and developed a business and marketing plan.

16 When Ms Coulter established Monarch she wished to specialise in life risk strategies and advice. Notwithstanding that, she joined a dealer group (Securitor) that was focused on wealth creation and retirement advice. She did so because she did not want Monarch to be “pigeonholed” as a risk only advisor but wanted it to work with a more rounded dealer group that dealt with all facets of financial planning. At the time Ms Coulter’s training had been more holistic and she knew that, whilst her speciality was insurance, she would have to provide advice in all areas of financial planning.

17 At the time of commencement of its business Monarch had no clients. However, Ms Coulter had a number of friends and contacts who were ready to sign up with Monarch as clients and she had lined up referral partners.

18 Ms Coulter spent time networking in the Inner West and CBD areas of Sydney to build up Monarch’s client base and engaged in a number of networking activities including joining business networking groups and arranging for Monarch to sponsor sporting teams. She also built her personal profile in the market through various industry publications and by hosting a segment each week as broadcast host on Eagle Waves Radio called “Risky Business” where she discussed matters associated with risks such as insurance and business risk.

19 Ms Coulter worked to maintain Monarch’s clients, including by sending new clients welcome packs, working long hours to ensure she was available to clients and conducting regular reviews with clients.

20 On or about 13 March 2018 Consolidated Corporate Pty Ltd, the parent company of law firm Madison Marcus, acquired 5,000 of the total 10,000 shares on issue in Monarch. Consolidated’s acquisition of shares in Monarch was with a view to Consolidated and Monarch undertaking a joint venture business in the future by which Consolidated, in the form of the Madison Marcus legal business, was to be a source of referrals for Monarch. Ultimately as explained below, the joint venture did not proceed and on 4 March 2019 Consolidated ceased to be a shareholder of Monarch. Other than the period between 13 March 2018 and 4 April 2019, when Consolidated was a shareholder, Ms Coulter has been the sole shareholder of Monarch.

21 Prior to the sale of Monarch’s business to Newlane (see [112] below), it operated a financial planning business specialising in wealth protection, that is insurance advice. About 85% to 90% of its business was insurance advice and the remainder was superannuation advice. Excluding clients introduced by Mr Puxty, Monarch had about 215 insurance clients of which about 20 were superannuation clients. Its primary client base was “white collar professionals” seeking advice on their insurance needs. Monarch did not advertise. Most of its business came from referrals from existing clients and referral partners.

22 Monarch earned its income via its dealer group. It was initially licensed with (i.e. was an authorised representative of) Securitor and was most recently licensed with RI Advice. The dealer groups earn their remuneration from product providers e.g. insurance companies and superannuation funds. Monarch did not receive payment directly from its clients.

Ms Coulter meets Mr Puxty

23 Ms Coulter met Mr Puxty in about October or November 2010 while she was employed at OnePath. At the time Mr Puxty worked for LIFP Consultants, a business which was subsequently purchased by AON, one of the dealer groups Ms Coulter managed while employed by OnePath. Over the years Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty developed a good friendship.

24 After Ms Coulter established Monarch, from time to time she spoke with Mr Puxty as well as other advisors. She recalls that Mr Puxty would often assist her in dealing with work related issues and, during her regular calls and catch ups with him, they often spoke about Mr Puxty’s role at AON. Ms Coulter formed the view, based on those conversations, that she and Mr Puxty were aligned in the way they wanted to “go over and above” for their clients.

25 Ms Coulter recalls that in about 2013 or 2014 she and Mr Puxty had a conversation during which Mr Puxty informed Ms Coulter that his current employer, Rob Jason, was selling his business, LIFP, to AON. LIFP was a consulting business in which Mr Puxty had an equity stake. At the time Mr Puxty was not enjoying his working relationship with Mr Jason. He informed Ms Coulter that following the sale he would become an employee of AON.

26 Ms Coulter recalls that during the conversation referred to in the preceding paragraph she and Mr Puxty discussed the potential to work together in the future. At the time, Ms Coulter was still in the process of building Monarch’s client base, which was not sufficiently established to employ, or partner with, another person.

27 Mr Puxty worked for AON from August 2014 to September 2017. He commenced working for WiZDOM in October 2017 as a senior financial advisor. The terms of Mr Puxty’s employment with AON included a post-employment restraint which restrained him from soliciting, approaching or accepting any approach or dealing with any person who was, at any time during the last 13 months of employment with AON, a client or potential client of AON (AON Restraint). The AON Restraint operated for a period of 12 months.

28 Ms Coulter recalls that on several occasions after Mr Puxty commenced employment with WiZDOM he informed her that he was not happy with the conditions and processes there.

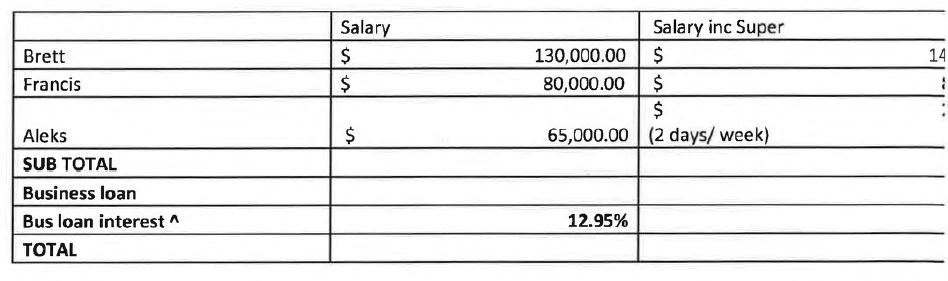

29 Over the years Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty maintained their friendship and, as is apparent from the evidence before me, kept each other apprised of developments in their respective professional lives and from time to time Ms Coulter sought Mr Puxty’s advice on issues that arose in relation to provision of services. It was also evident that the relationship between Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty extended to Ms Coulter informing Mr Puxty of her partnership with Consolidated/Madison Marcus. For example:

(1) on 21 October 2017 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged text messages and, in the course of their exchange, Ms Coulter informed Ms Puxty that “[i]n other news – got my first referral from the lawyers”, where the reference to “the lawyers” was a reference to Consolidated/Madison Marcus;

(2) on 19 January 2018, Ms Coulter sent a text message which read: “[m]eanwhile the lawyers have come to the valuation party”. Ms Coulter agreed in cross-examination that the reference to the “lawyers” was to Madison Marcus and that the valuation to which she referred was part of the process of coming to an agreement about a joint venture with Consolidated/Madison Marcus;

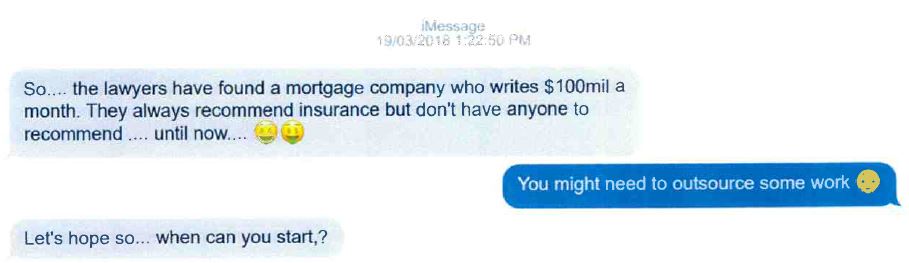

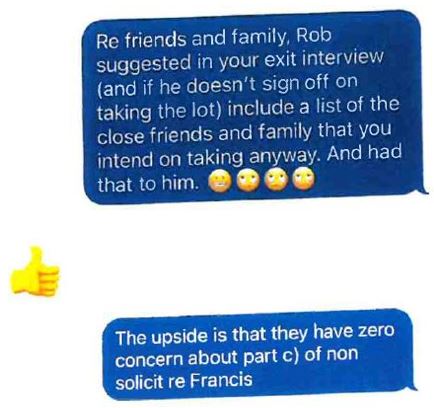

(3) on 19 March 2018 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

Once again Ms Coulter accepted that the reference to “lawyers” in her initial text was to Madison Marcus;

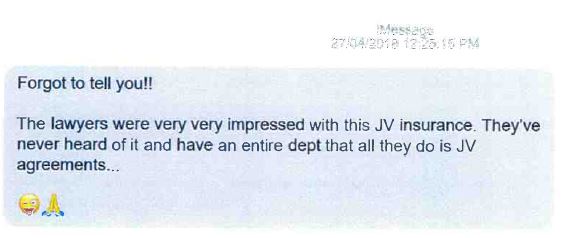

(4) on 27 April 2018 Ms Coulter sent a text to Mr Puxty in the following terms:

The lawyers referred to by Ms Coulter were Madison Marcus. Ms Coulter had passed on to them an idea about JV insurance that Mr Puxty had communicated to her; and

(5) on 4 May 2018 in a text message exchange with Mr Puxty, Ms Coulter told him that she had “Madison Marcus at 4pm followed by their staff meeting over a champers at 5”. Ms Coulter accepted that in her discussions and exchanges with Mr Puxty she used the term “Madison Marcus” to refer to the arrangement with Consolidated.

30 In about March 2018 Ms Coulter and her husband, Rob Coulter, had a conversation with Mr Puxty to the following effect:

Mr Puxty: I received this letter from AON reminding me of the restraint I had with them and demanding that I pay for the clients I have taken. They have asked for about $90,000. This is about 2.7 times the recurring revenue I took. I took about $30,000. I am very concerned about this letter and the consequences. They are my clients, and I didn’t think the restraint would apply to them.

Mr Coulter: Relationships outlast restraints so just stop taking the clients and see out your restraint period.

Mr Puxty explained that about six months into his employment with WiZDOM his family and close friends, amounting to about $30,000 in revenue, followed him to WiZDOM. AON never took any action against Mr Puxty in relation to those clients.

Ms Coulter suggests that Mr Puxty join Monarch

31 In about June 2018, while in Bali, Ms Coulter had an idea about working with Mr Puxty. She thought that if Mr Puxty could bring $200,000 in recurring revenue to Monarch, which was about the same amount of recurring revenue that she generated at the time, they should be able to make working together viable. Ms Coulter was not sure whether she would buy Mr Puxty’s “book” (i.e. his clients and thus recurring revenue) or partner with him. She recalls that she sent Mr Puxty a text message about her idea, and he replied positively.

32 Ms Coulter explained that recurring revenue in the context of financial planning is the income received from an existing client base in the form of commissions from insurance companies or advice fees funded via superannuation funds and that, upon a client taking out an insurance policy for the first time, an initial commission is payable upfront to the advisor, typically at around 66% of the first year’s insurance premium. The recurring revenue is usually 10% to 30% of a premium in the case of renewal commission for insurance, depending on how the policy is set up.

33 On 19 June 2018 Ms Coulter sent a text message to Mr Puxty in which she told Mr Puxty that “Rob [Coulter] wants to talk to you about you coming across to Monarch. Your hours are ridiculous and they can change terms anytime”.

34 On her return to Australia on or about 19 June 2018 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty progressed discussions about Ms Coulter’s idea that they work together, centred around the opening of a Newcastle office. While Consolidated was a shareholder in Monarch at the time, Ms Coulter did not agree that her discussions with Mr Puxty were connected to the fact of her partnership with Consolidated. She maintained that she had been having these types of discussion with Mr Puxty for years because he was unhappy with his current employment.

35 It is difficult to accept that the catalyst for Ms Coulter’s discussions with Mr Puxty in mid 2018 was not connected in some way to Monarch’s partnership with Consolidated/Madison Marcus particularly given the anticipated growth from that partnership. So much is apparent from the following exchange between Ms Coulter and senior counsel for Mr Puxty, Mr Bedrossian SC:

Mr Bedrossian: You accept, don’t you, that, at this point in time, between March 2018 through to June 2018, your anticipation was that this arrangement with Madison Marcus could result in millions of dollars of referred clients; correct?

Ms Coulter: I accept that that part is correct, but not necessarily the reason for employing Brett.

Mr Bedrossian: And to be specific, part of your discussion with Madison Marcus was around the idea of having $1 million of new referrals – that’s new income each year for a five-year straight period; correct?

Ms Coulter: Yes.

Mr Bedrossian: And that, at the end of that five-year period, on that approximate maths, you have a business that would be worth at least $6 million; correct?

Ms Coulter: Yes.

Mr Bedrossian: And there was a proposal – it might have been a concept – that that entity would then be floated on the public stock exchange; correct?

Ms Coulter: Correct.

Mr Bedrossian: And, presumably, if that went well - - -?

Ms Coulter: Mmm.

Mr Bedrossian: - - - huge returns?

Ms Coulter: Yes.

36 At the time of their discussions referred to in [34] above, Ms Coulter informed Mr Puxty that she would need to discuss the proposal with “the board,” which was a reference to the board of Consolidated. For that purpose she asked Mr Puxty to “put some numbers together so that [she could] understand the viability of this going forward” including “expected salaries for [Mr Puxty] and [Mr Coggan], estimated rent in Newcastle, expected revenue”.

37 Ms Coulter said that, as a shareholder in Monarch, Consolidated was entitled to a say in relation to new employees and, given that the board was made up of lawyers, she wanted to obtain their views about employing new staff. At the time, Ms Coulter spoke with Ramy Qutami of Consolidated who gave her the go ahead to look into the viability of expanding the business and working with Mr Puxty.

38 Ms Coulter recalls that when she and Mr Puxty began their discussions about potentially working together, she needed to understand which of the clients from WiZDOM Mr Puxty could bring over and whether they were subject to any restraint. Ms Coulter did not want Monarch to be involved in any dispute between Mr Puxty and his former employer about breaches of restraints. She recalls having a conversation with Mr Puxty to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: Do you think you will have any issues with Clint if you bring clients over?

Mr Puxty: It will be fine I will work it out. These are my clients so I will not have a problem taking them.

The reference to Clint was to Clint Ducat the owner of the WiZDOM. At the time of his discussion with Ms Coulter, Mr Puxty believed, based on his discussions with Mr Ducat, that there be no restraint in relation to clients he brought over to WiZDOM upon commencing his employment there, although that was not reflected in his employment contract with WiZDOM.

39 On 6 September 2018 Ms Coulter attended a meeting (6 September Meeting) with Mr Puxty and Mario Kardum, who Ms Coulter describes as a representative of Consolidated, at the offices of Madison Marcus solicitors. Ms Coulter recalls that during the meeting she had a conversation to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: We need to discuss what this could look like for you Brett. I think that there could be a contingency for you to own a percentage in Monarch provided that you bring enough business over.

Mr Puxty: Okay.

Ms Coulter: If you bring over $200,000 recurring revenue within 12 months, we will give you a shareholding in Monarch. Monarch will purchase your book in $50,000 bundles. When Monarch earns $50,000 of recurring revenue, we will pay you two times the recurring revenue.

Mr Puxty: Okay I agree.

Based on this conversation Ms Coulter understood the agreed incentive program for Mr Puxty would be, among other things, that for every $50,000 of recurring revenue he brought to Monarch from his AON clients and his WiZDOM clients he would receive two times the recurring revenue as a bonus (Incentive Program) and that the $50,000 bundles would come to Monarch each quarter, on average, rather than all at the end of the 12 months.

40 Mr Puxty has a different recollection of the 6 September Meeting. He says that there were no specific discussions in relation to revenue and he did not agree to any particular financial arrangements. He understood that the purpose of the meeting was to introduce him to Madison Marcus. Although Mr Puxty had spoken to Mr Kardum previously, they had never met. Mr Puxty recalls that during the meeting the following exchanges also took place:

Ms Coulter: We will buy your clients at two times revenue and provide you with a 6% ownership in Monarch. We anticipate that the business will be worth about six million dollars in five years’ time.

Mr Kardum: This is correct. We want you to join the business and bring your clients over. We see the business growing to a point where in five years we will look to list on the stock exchange and realise the value. We are willing to also offer a percentage share in the business if the client value we purchase, stays.

And:

Mr Kardum: What is your experience in financial planning?

Mr Puxty: I have been in financial services since 2001 and have been providing advice in all areas of financial planning, apart from gearing strategies. I can provide advice on superannuation, including SMSFs, retirement planning, personal insurance, business insurance, and joint venture protection.

Mr Kardum: What is joint venture protection?

After he explained joint venture protection Mr Puxty said the conversation continued:

Mr Kardum: We have a solicitor here in Madison Marcus that deals solely with joint venture clients. This could be a great opportunity as I do not believe this has ever been discussed.

Ms Coulter: I told you this would be a good opportunity.

Mr Kardum: We are also looking for someone who can do investment, super and financial planning advice. It is good to see that you can do this.

Ms Coulter: Yes, because I am only specialising in insurance.

Mr Kardum: This would be a good fit, as the referrals that we are looking to offer to Monarch are mostly financial planning clients, not insurance-only clients.

41 After the 6 September Meeting Mr Kardum asked Ms Coulter “for verification of the restraint terms in [Mr Puxty’s] contract”. Ms Coulter then spoke with Mr Puxty asking him to provide her with a copy of his employment contract with WiZDOM so that she could check the restraint clause in it.

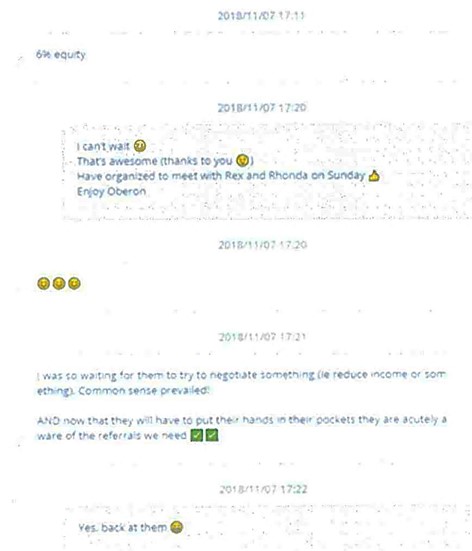

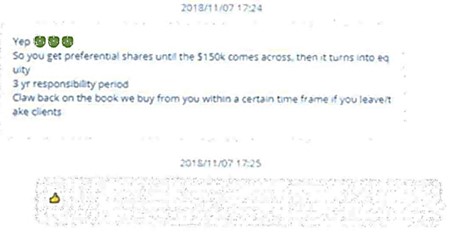

42 On 7 November 2018 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages (as produced in evidence):

Ms Coulter accepted that the reference to “6% equity” was in relation to the proposed future arrangement with Mr Puxty, explained that “Rex and Rhonda” were employees of AON who might become employees of Monarch, accepted that the reference to “them” in the third message was to Consolidated/Madison Marcus and accepted that the viability of the entire partnership arrangement with Consolidated rested upon the flow of referrals, absent which there was no reasons to enter into a 50/50 arrangement with it.

43 A number of things happened on 8 November 2018.

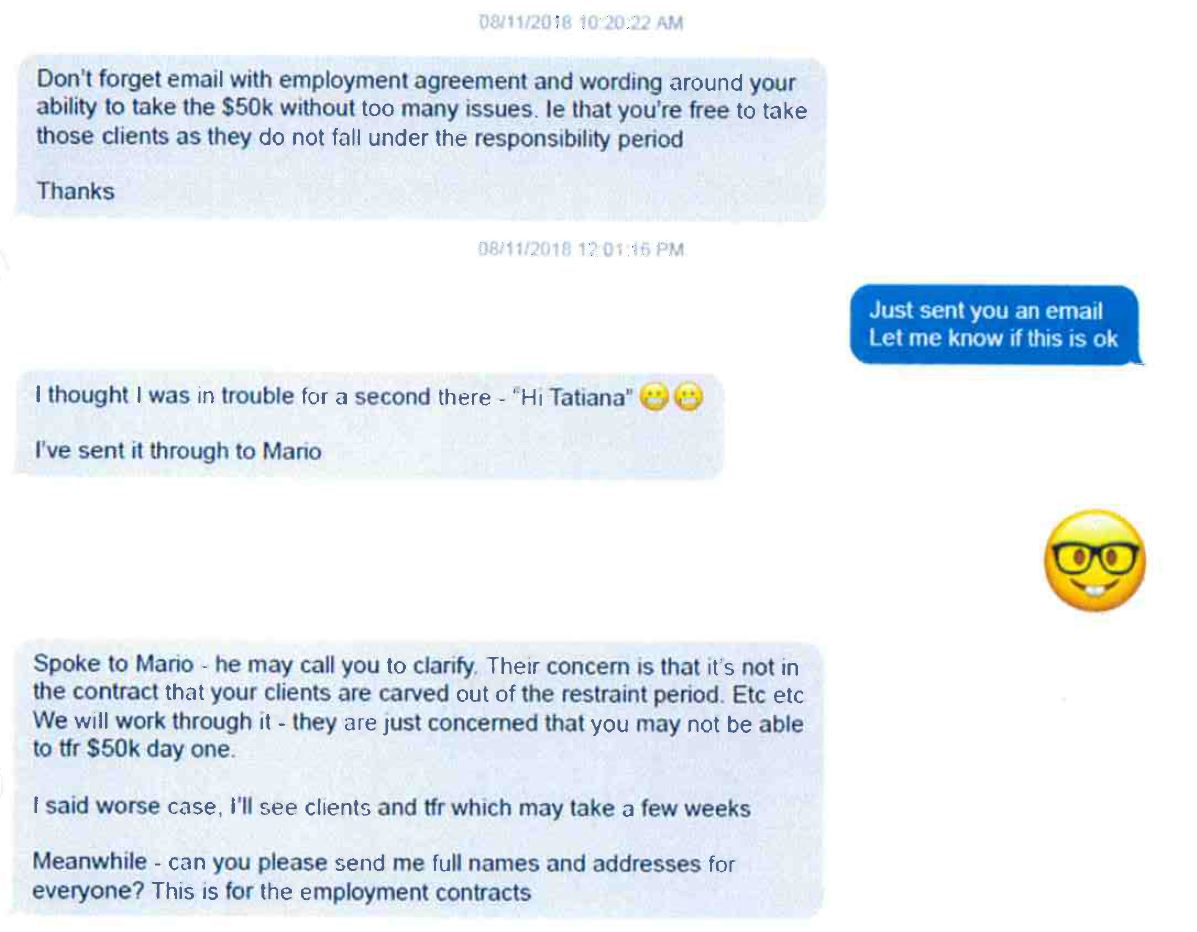

44 First, commencing at 10.20 am Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

Ms Coulter accepted that in suggesting as “a worst case” she would see and transfer clients, she was suggesting that she could chase WiZDOM clients so that, even if Mr Puxty was subject to restraint, she would get the clients across to Monarch.

45 Secondly, as referred to in his text message timed at midday Mr Puxty sent Ms Coulter an email attaching “the wording from [his] current employment contract”. He told Ms Coulter that “the clients that [he] brought with [him] are under a separate code to that of the WiZDOM clients [he had] written” and that the “separate code does not form part of the responsibility period (although not stipulated in the contract)”.

46 Thirdly, after receipt of the email referred to in the preceding paragraph Ms Coulter had a conversation with Mr Puxty to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: The contract says that there is a restraint with WiZDOM. Do you think you can get something from [Mr Ducat] in writing to confirm that there is no restraint?

Mr Puxty: I am not comfortable with that because it will look suspicious and he will know I am looking for employment elsewhere if I ask him about my contract.

Ms Coulter: Well I don’t think the board is going to be comfortable without something in writing.

Mr Puxty: Okay. Let me see what I can do.

47 Fourthly, Ms Coulter attended a meeting with the board of Consolidated to discuss Mr Puxty’s restraint and if and how Monarch could get around it. At that meeting it was agreed that Monarch would not proceed with the Newcastle expansion because of the risks associated with Mr Puxty’s restraint. However, the board informed Ms Coulter that it was open to her to prepare revised figures without any clients from WiZDOM.

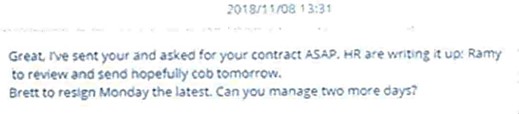

48 Fifthly, at 1.31 pm Ms Coulter sent the following further message to Mr Puxty:

49 On 9 November 2018 Messrs Kardum and Puxty had a telephone conversation which included an exchange to the following effect:

Mr Kardum: Brett, I want to know about your WiZDOM employment contract and bringing your ex-AON clients, who are currently at WiZDOM, over to Monarch. We are hoping that your clients are not subject to restraint and that you can bring them across.

Mr Puxty: There is nothing in my contract with WiZDOM but I will obtain the release of my clients from WiZDOM in writing from the owner of WiZDOM, Clint Ducat.

Mr Kardum: Are you happy with a 6% share offering, the responsibility period and payment occurring in stages where the projected value of clients reaches $50,000.00 lots? We will be looking to hold back 25% of the payment until the revenue is proven to be consistent over a 12-month period.

Mr Puxty: That sounds fair, given it only needs to be proven in a 12-month period.

50 On 11 November 2018 Ms Coulter had a discussion with Mr Puxty to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: The board is concerned. They feel as if you have lied to them about the restraint. I have to go back and speak to them again. Can we readjust the figures to take the restraint into consideration so I can go back to the board.

Mr Puxty: Okay. I have emailed Clint about the restraint. He said as long as the client was on the books for 12 months with WiZDOM, I could take them at the expiry of my restraint period.

Ms Coulter understood, based on that conversation and the email exchange set out at [51] below, that Mr Puxty’s employment agreement with WiZDOM included a restraint over the WiZDOM clients and that WiZDOM was not willing to release those clients to Mr Puxty should he terminate his employment with it.

51 On 14 November 2018 commencing at 10.21 am Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

And:

52 On 14 November 2018 at 8.20 pm Mr Puxty forwarded to Ms Coulter his email exchange with Mr Ducat about the extent of the restraint imposed on him as an employee of WiZDOM. That exchange commenced with an email from Mr Puxty to Mr Ducat sent on 9 November 2018 in which he wrote:

Following from our conversation:

I understand the many business changes that have occurred recently, including the change in the process for transferring clients over to Wizdom, is a way of mitigating risk and I understand the need to protect the business.

This will also limit the number of clients that will potentially be coming over from here on and will also create a push to concentrate on the larger value clients. I also understand this to be strategic and potentially provide a better outcome to the business.

With all these changes, can you please confirm that there is no change to our original agreement that these clients, going forward, still form part of the group of existing clients I have already brought over (ex-Aon clients) and that they all remain quarantined (my introduced clients as a whole) and do not form part of any restraint period.

I’m just after peace of mind that the many changes to the business have and will not affect our original agreement.

Mr Ducat responded on 14 November 2018 in the following terms:

As discussed, I think the fair thing would be that any client introduced to WiZDOM would have a 12 month restraint from initial date that we received revenue to ensure we cover the costs of advice and onboarding.

After the minimum 12 months of revenue then there would be no restraint on the clients that you introduce to WiZDOM directly.

53 Mr Puxty and Mr Ducat then exchanged the following messages on the evening of 14 November 2018. Mr Puxty wrote:

I take it this would be for any clients moving forward under WiZDOM Wealth. I understand due to the change in transfer processes that this has been introduced.

Considering there was no ‘on-boarding’ apart from sending off the transfer form under MyPlanner, I assume these clients (pre Aug 2018) don’t fall under this category and are free from any restraint period. (Majority of these are close to or beyond this anyway).

And Mr Ducat responded:

Yes exactly, although remember that we really want to have an SoA written (simple hold or full review) for the clients transferred under MyPlanner within 12 months (before August 2019).

Mate, I can assure you I’m not going to play silly buggers. As long as everyone plays fair then I’m happy.

Saying this, I know there has been a number of changes and I hope that you plan to hang in there with us through this time.

Once we get the right people and streamline our systems we will be a fair way in front of most of the industry. I’m still very positive about the future.

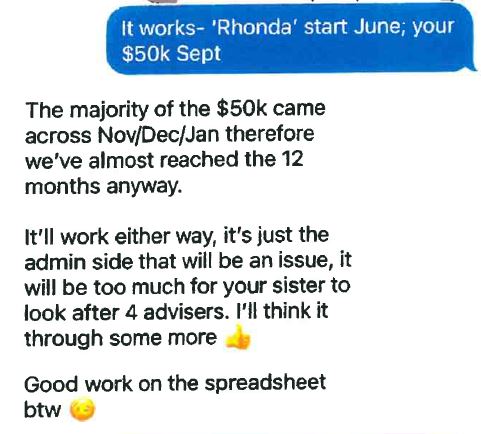

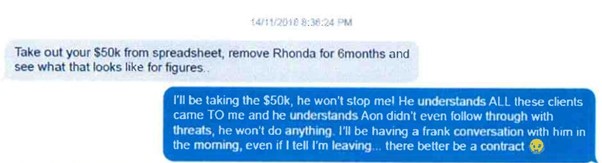

54 Thereafter, on 14 November 2018 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged text messages including:

55 Ms Coulter felt that the Incentive Program would need to be changed. She spoke to Mr Puxty informing him that Monarch could not take the WiZDOM clients into consideration as it did not want to be involved in any disputes about restraints. Following that conversation Ms Coulter proceeded on the basis that she and Mr Puxty had agreed to exclude WiZDOM clients from the Incentive Program and to include only AON clients who were no longer subject to restraint (Amended Incentive Program).

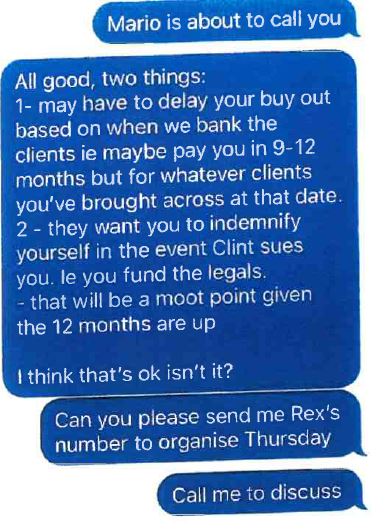

56 On 19 November 2018 at 5.30 pm Ms Coulter sent Mr Puxty the following text messages:

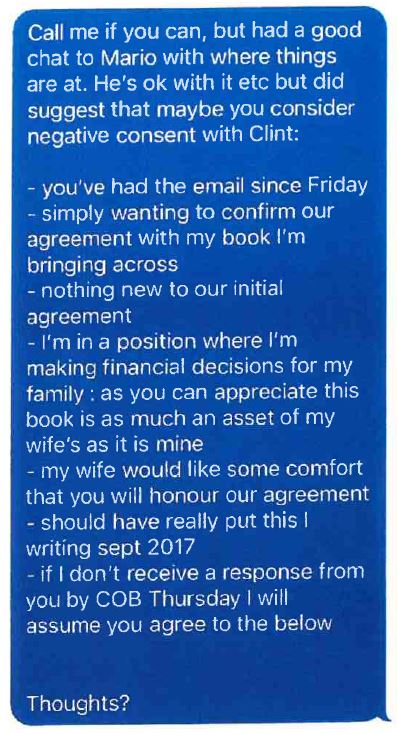

Mr Puxty accepted that at this time his discussions with Ms Coulter related to Monarch’s concerns about becoming involved in litigation about the restraint of trade clause in his employment agreement with WiZDOM and that there was going to be a delay in his acquiring a shareholding in Monarch of about nine to 12 months during which period he could transfer his clients across to Monarch. In other words, Monarch wanted to have the clients transferred to it before Mr Puxty became a shareholder.

57 Ms Coulter said that it was a term of the Amended Incentive Program that if Mr Puxty could bring in recurring revenue and maintain that recurring revenue for a period of twenty-four months, he would acquire a 5% shareholding in Monarch. Ms Coulter recalls that in about mid November 2018 she had a further conversation with Mr Puxty to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: Brett, if we can present figures to the board, based on $150,000 in recurring revenue and excluding the WiZDOM clients, I think we can get this across the line. Based on the initial projections for the Newcastle expansion, I think we should still be able to break even within 12 months. Similar terms would apply in that you can potentially earn 5% equity in the business once you’ve achieved your targets. Monarch would pay you a bonus of 2x for every $50,000 received. Monarch will hold back 20% of the payment for another 12 months to ensure clients remain part of the business.

Mr Puxty I am happy with that.

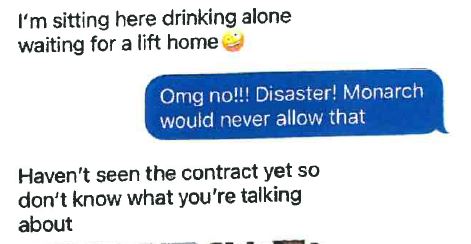

58 On 23 November 2018 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged emails which were light hearted in tone and in which each described what they were doing that evening. That exchange included:

In cross-examination Mr Puxty accepted that, despite the light-hearted nature of the exchange set out above, he was somewhat frustrated because he was yet to receive an employment agreement.

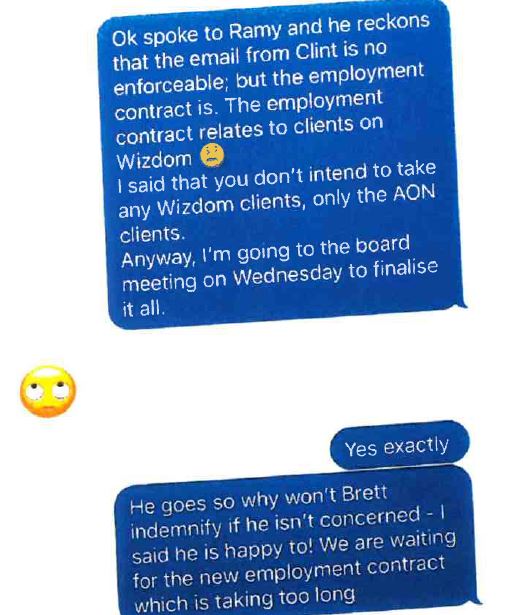

59 On 26 November 2018 at 4.44 pm Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

At this stage of his discussions with Ms Coulter, Mr Puxty believed that, given the passage of time, he could now take his AON clients to Monarch. He had no intention of taking WiZDOM clients.

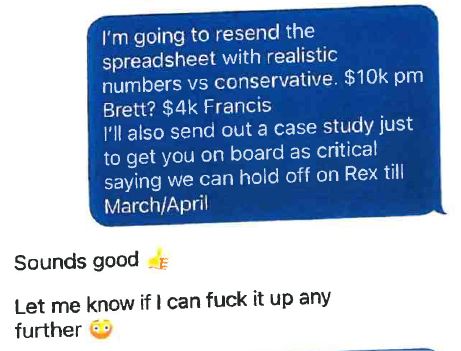

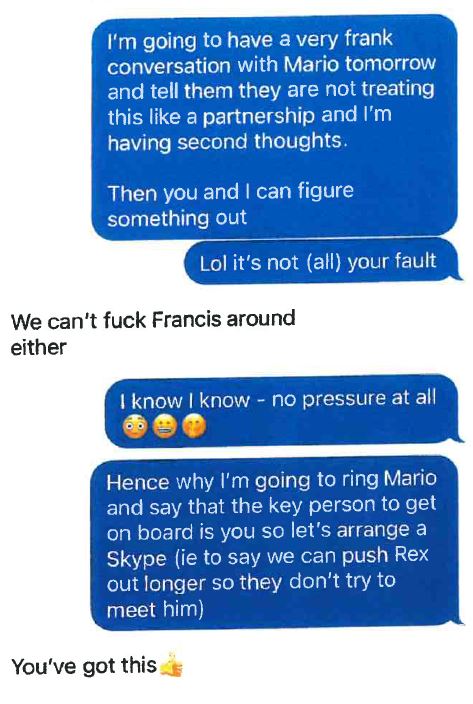

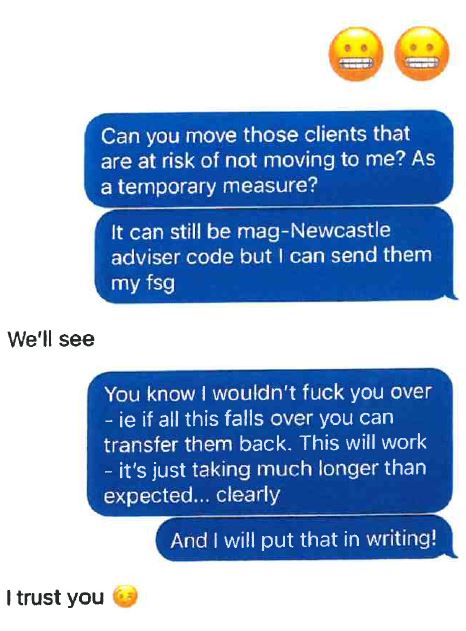

60 Both Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty recall a discussion in late November 2018 about the possible transfer of Mr Puxty’s AON clients to Monarch prior to the finalisation of Mr Puxty’s employment agreement with Monarch. However, they do not agree on the content of that discussion. Given my earlier observations about the weight I can give evidence of this nature, I do not propose to set out their respective versions of the discussion. The better and more reliable evidence of what occurred in late November 2018 is found in the documentary evidence and, in particular, in the following text messages that Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged on 28 November 2018:

(1) at 2.15 pm Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty had the following exchange:

(2) at 4.03 pm Ms Coulter sent Mr Puxty the following message:

(3) commencing at 6.39 pm Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following messages:

61 When asked by counsel for Monarch, Mr Mahendra, about Ms Coulter’s text message in which she stated that she was “going to have a very frank conversation with Mario [Kardum]” the following day, Mr Puxty gave the following evidence:

Mr Mahendra: So you know at that particular point in time that this arrangement with Madison Marcus is not something that was concrete?

Mr Puxty: No. This was to do with the employment contracts.

Mr Mahendra: “… tell them that they are not treating this like a partnership, and I’m having second thoughts”. You say that’s to do with your employment as opposed to the partnership with Madison Marcus?

Mr Puxty: It’s what caused her to get cranky, yes.

62 It is clear from the text messages exchanged on 28 November 2018 that: Ms Coulter wanted Mr Puxty to join Monarch as an employee; she saw the value in Mr Puxty joining both because he had clients he could bring to the Monarch business and because of his skills which he would bring to the business; by November 2018 there were doubts about the viability of the arrangement with Consolidated/Madison Marcus; and the partnership with Madison Marcus was a reason, but according to Ms Coulter not the primary reason, for Mr Puxty joining Monarch. Ms Coulter did not accept that the context in which she sought to persuade Mr Puxty to join Monarch was the fact of her potentially successful arrangement with Madison Marcus and did not accept that the reference in her messages to “if all this falls over” was a reference to the partnership with Consolidated/Madison Marcus. She said the latter was a reference to the entry into of the employment agreements.

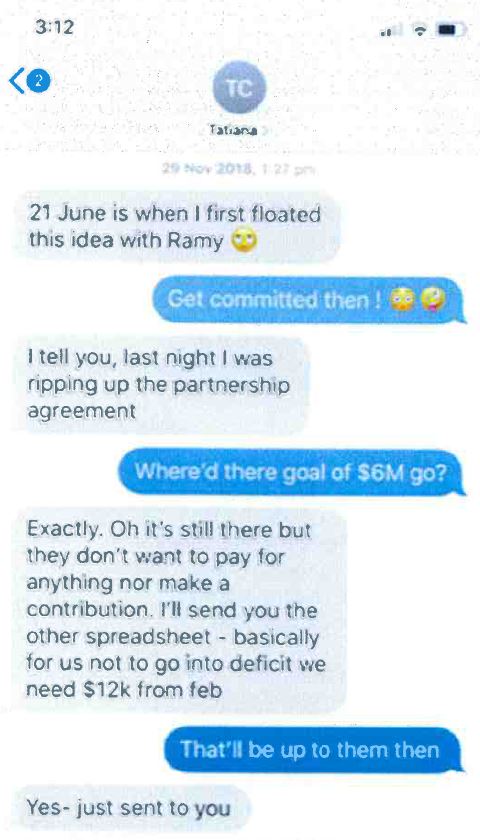

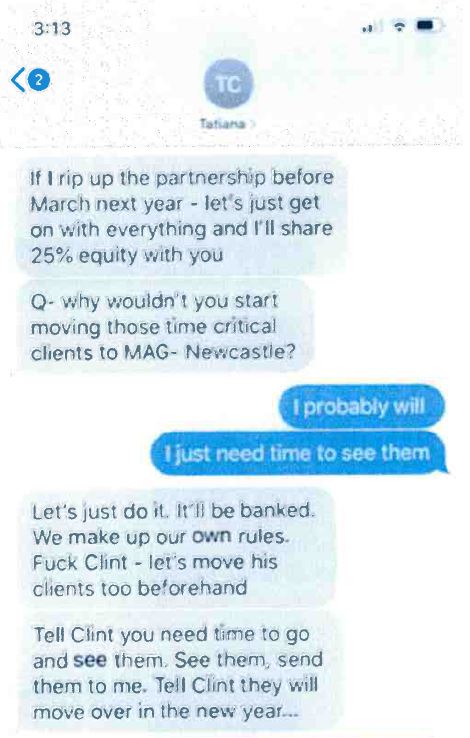

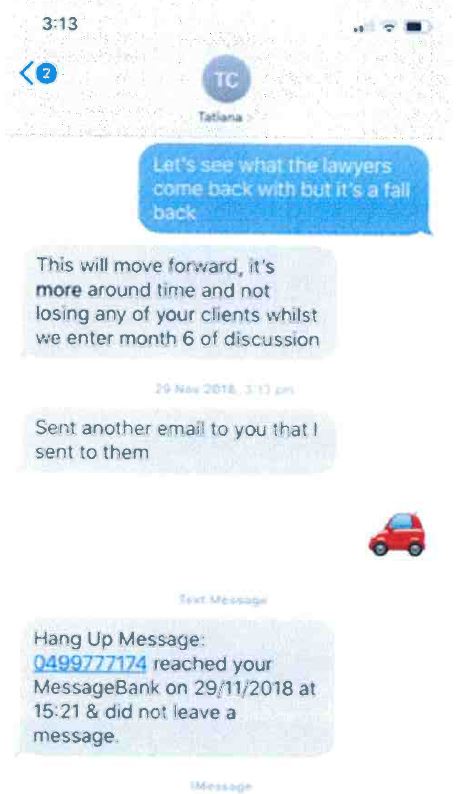

63 On 29 November 2018 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

64 In relation to the exchange set out in the preceding paragraph, Ms Coulter:

(1) explained that her first message referring to 21 June was a reference to the date she first introduced the idea of Mr Puxty joining Monarch to Consolidated;

(2) did not accept that the reference to things falling over in her text message of 28 November 2018 was to the Madison Marcus partnership. This was so despite telling Mr Puxty on 29 November 2018 that “last night” she was ripping up the agreement with Consolidated/Madison Marcus. Ms Coulter maintained that in her exchange on 28 November 2018 she was referring to the employment agreements;

(3) accepted that at the time there was a level of uncertainty as between herself and Mr Puxty which arose because, in turn, there was uncertainty about whether Madison Marcus would come through with referrals and be an ongoing source of referrals; and

(4) explained that the “time critical clients” were those who remained with AON but who wanted to move to Mr Puxty and about whom there was an issue as to whether they should go directly to Monarch, despite Mr Puxty not having signed his employment agreement, or see Mr Puxty at WiZDOM (and hence become clients of WiZDOM).

65 Ms Coulter recalls that in November or December 2018 she informed Mr Puxty that there were potential issues with referrals from Consolidated/Madison Marcus and that she was contemplating ceasing Monarch’s partnership with it. By late 2018 it was becoming apparent to Ms Coulter that, despite her hopes to the contrary, she was unlikely to be able to work something out with Consolidated going forward.

Monarch employs Messrs Puxty and Coggan

66 Monarch agreed to employ Mr Puxty as a senior financial planner and Mr Coggan as a financial planner. On 5 December 2018 Ms Coulter sent each of Messrs Puxty and Coggan a draft employment agreement. After some amendment to the drafts, on 7 December 2018 each of Messrs Puxty and Coggan entered into their respective employment agreement. I will refer to those agreements respectively as the Puxty Employment Agreement and the Coggan Employment Agreement and together as the Employment Agreements. A Performance Review & Bonus document was prepared and provided to Mr Puxty. It was intended to reflect the Amended Incentive Program.

67 Clause 5 of the Employment Agreements is in identical terms and provides:

5. Duties and Accountability

5.1. The Employee shall be responsible for the duties set out at “Appendix A” to the Agreement.

5.2. The Employee shall report to and be accountable to the Managing Director of the Company.

5.3. In performing their duties, the Employee must:

(a) serve the Company faithfully and diligently and exercise all due care;

(b) act in the best interests of the Company at all times;

(c) refrain from acting or giving the appearance of acting contrary to the interests of the Company;

(d) use their best endeavours to protect and promote the Company’s good name and reputation; and

(e) perform their duties to the best of their ability.

68 Clause 15 of each of the Employment Agreements is in identical terms and is titled “Entire Agreement”. It provides:

15. Entire Agreement

15.1 The Agreement together with any

(a) statement of duties; and

(b) Employee handbook

constitutes the entire agreement between the Company and the Employee in relation to the Employee’s employment with the Company and any representations made or agreements arrived at in relation to the performances by the other party of its respective rights and obligations under the Agreement shall, except to the extent they appear in the Agreement, be deemed for all purposes not to have been made or arrived at.

15.2 The Employee acknowledges that they have received from the company all documents referred to above.

69 Clause 19 of each of the Employment Agreements is, save for a cross-referencing error in the Coggan Employment Agreement, in identical terms and concerns “non-competition after the conclusion of employment” (Restraint Clause). That clause provids:

19. Non-Competition after conclusion of Employment

Without the Employer’s prior consent, from the Termination Date, the Employee is not to:

(a) retain, store, copy, utilise or otherwise access the Confidential Information of the Employer, including any client lists, client details, client records, contact details of clients;

(b) solicit, attempt to solicit, or accept any instructions to perform any work from any Client;

(c) solicit, attempt to solicit, entice or encourage any Employer Representative to leave their engagement with the Employer;

(d) encourage, condone or entice any other person or entity, in which the Employee is interested or by which the Employee is engaged, to engage in conduct which, if the engaged in such conduct personally, would cause the Employee to breach this clause 19.

19.2 In this clause 19:

(a) Restraint Period means:

(i) Thirty six (36) months if employed for three (3) years or more;

(ii) Twenty four (24) months if employed for two (2) years or more but less than three (3) years;

(iii) twelve (12) months if employed for one (1) year or more but less than two (2) years;

(iv) six (6) months if employed less than one (1) year.

(b) Client means any person or entity:

(i) to which the Employer provided services during the employment;

(ii) with which the Employer had direct dealings during the employment in relation to the provision (or proposed provision) of services by the Employer to the person or entity;

(iii) which referred business to the Employer during the employment;

(iv) with which the Employee had direct dealings in the course of, or in connection with, their employment with the Employer,

whether or not the Client was introduced to the Employer by the Employee or otherwise.

(c) Employer Representative means:

(i) any director or person involved in the management of the Employer;

(ii) any employee of the Employer who has knowledge of Confidential Information or who reported to the Employee or who was engaged in sales or marketing activities during the Employment;

(iii) any employee of the Employer;

(iv) any independent contractor contracted to the Employer.

19.3 It is acknowledged by the Employee that:

(a) each of the covenants in clause 19.3 shall be construed and have effect as a number of separate covenants which results from combining each covenant. If any such resulting covenant shall be invalid or unenforceable for any reason, such invalidity or unenforceability shall not prejudice or in any way affect the validity or enforceability of any other such resulting covenants;

(b) the restrictions in this clause may be “read down” by a Court, Tribunal or authority of competent jurisdiction to ensure that the remaining clause which has been “read down” is valid and enforceable;

(c) the restrictions in this clause apply to conduct which is either direct or indirect (e.g. done through an agent of any kind) and regardless of whether the conduct is engaged in for the Employee’s own benefit or for the benefit or on behalf of any other person or entity;

(d) the Employer’s rights under this clause 19 are in addition to, and do not derogate from or affect the Employer’s common law rights;

(e) the Employer has invested substantial time and expense in developing its business and all associated goodwill and the Employee acknowledges that the Employer will suffer substantial loss and damage if the Employee fails to adhere to the restrictions;

(f) the business of the Employer is fundamentally built on its relationships with clientele and customers and these restrictions are necessary to protect the goodwill, business, interests and Confidential Information of the Employer

(g) these restrictions are reasonable and go no further than is necessary to protect the goodwill, business, interests and Confidential Information of the Employer;

(h) the Employer has agreed to offer the employment to the Employee and remunerate the Employee in accordance with this Agreement in reliance upon the warranties provided by the Employee that it will comply with the restrictions espoused in this clause;

(i) injunctive relief may be sought by the Employer to enforce these restrictions;

(j) if any of the above restrictions or parts of them are found not to be enforceable then it is agreed that the remainder of the restriction(s) will apply; and

(k) the rights and obligations of the Employer and the Employee in this clause 18 survive termination of this Agreement.

70 There is no definition of the term “Confidential Information” in the Employment Agreements. Clause 1(f) of the Employment Agreements provides that:

Unless otherwise indicated by the context, the following interpretational rules are to apply in the interpretation of the deed:

…

(f) “confidential” has the meaning given to it in Clause 20.1 of the deed;

…

71 However, cl 20 titled “Confidentiality” provides (as written):

The Employee agrees to keep confidential al information of the Company and shall not use such information for her or any other person’s behalf.

72 Ms Coulter gave the following evidence about why the Restraint Clause in each of the Employment Agreements was important to Monarch:

(1) in their roles Messrs Puxty and Coggan had access to all of Monarch’s referral partners and contacts, which was a database Ms Coulter had spent the previous seven years building. They also had access to the entirety of XPLAN, which is the database Monarch used and which contained all client information including, but not limited to, personal details, contact details, family connections, salaries, advice given, where the client was insured, superannuation details and banking details, all of which was confidential and which could be misused by Messrs Puxty and Coggan in the event they left Monarch;

(2) in their roles Messrs Puxty and Coggan would have a high level of autonomy. They were based in Newcastle while Ms Coulter was based in Sydney and thus Ms Coulter would not have complete visibility over their conduct and could not monitor their activities. Given this freedom, Ms Coulter wanted to limit the possibility that either Messrs Puxty or Coggan would create a business of their own within Monarch;

(3) Messrs Puxty’s and Coggan’s role was to bring new business to Monarch. Ms Coulter wanted to make it clear that any business and clients they brought to Monarch was done in their capacity as employees and therefore the business and/or clients belonged to Monarch;

(4) Messrs Puxty and Coggan both held senior roles and managed the Newcastle office together. They had autonomy over a number of decisions regarding the Newcastle office and operated the office while Ms Coulter was in Sydney. She therefore had little visibility over their day-to-day activities;

(5) the business of financial planning is about building trust and developing client relationships which are essential to ensure ongoing business. Ms Coulter thus expected that Messrs Puxty and Coggan would develop and maintain relationships with the clients they managed. In the circumstances, it would take a significant amount of time and work to rebuild the client connection once Messrs Puxty and Coggan left, particularly as they were managing clients in Newcastle meaning Ms Coulter did not have a relationship with most of those clients;

(6) Ms Coulter was aware that, other than Mr Puxty’s shareholding in AON, Messrs Puxty and Coggan had not owned, operated or built a business from scratch as she had. Ms Coulter was concerned that they would not appreciate the hard work, effort and time that went into building client relationships and that this may result in them taking clients if either was to leave. I pause to note that Mr Puxty clarified that he did not have a shareholding in AON as asserted by Ms Coulter but that he did have an equity stake in LIFP; and

(7) Ms Coulter was investing $100,000 into the business which would be operating off Monarch’s client base and income. She wanted to ensure that there was security for Monarch if Messrs Puxty and Coggan left.

73 The Performance Review & Bonus document for Mr Puxty provided under the heading “Bonus”:

The Employee shall be entitled to a bonus calculated at 40% of any revenue generated and received over the agreed hurdle of two (2) times the employees total remuneration package for that financial year. The revenue generated and received in each financial year, for purposes of calculating the bonus payable, will require that a maximum of 50% of the agreed hurdle be a contribution from existing client recurring revenue, excluding any preexisting recurring revenue that the Employee brings to the company from their previous clients whilst the employee was engaged with AON.

Mr Puxty explained that the bonus clause expressly excluded AON clients because those clients were “being purchased” and would contribute to his ability to acquire equity in Monarch. To that end the Performance Review & Bonus document for Mr Puxty relevantly provided under the heading “AON Clients”:

For every $50,000 worth of recurring revenue that the Employee brings to the company from their previous clients whilst the employee was engaged with AON, the company will pay the employee two (2) times recurring revenue (i.e. $100,000) within three (3) months of the recurring revenue coming across to the company. The company will retain 25% (i.e. $25,000) of any such payment in trust for a period of twenty four (24) months.

...

Upon the successful maintaining of $150,000 in recurring revenue that the Employee brings to the company from their previous clients whilst the employee was engaged with AON, noted above, for a period of twenty four (24) months, the Company will grant the Employee 5% profit shareholding in Monarch Advisory Group (A.C.N. 155 549 705).

74 Messrs Puxty and Coggan commenced their employment with Monarch on 20 December 2018. In so doing, Monarch took on a group of clients who had been brought to the business by Mr Puxty from his past roles with AON and/or WiZDOM (Puxty Clients). At the time there was one other employee of Monarch, Ms Coulter’s sister, Aleksandra Miroshnikoff, a paraplanner working two days per week. After Messrs Puxty and Coggan commenced their employment at Monarch, Ms Miroshnikoff moved to full time and worked to assist them four days per week and to assist Ms Coulter on the remaining day.

Mr Puxty and Mr Coggan work for Monarch

75 Mr Puxty recalls that in January 2019 he had a telephone discussion with Ms Coulter in which she expressed her concern about continuation of the partnership with Consolidated/Madison Marcus and, according to Mr Puxty, informed him that if she was to “walk away from Madison Marcus” she would either “put together a deal together between [them], or you can have your clients back and do your own thing”. Ms Coulter denies she made the representation to Mr Puxty about what might happen to his clients should the partnership with Consolidated/Madison Marcus not continue.

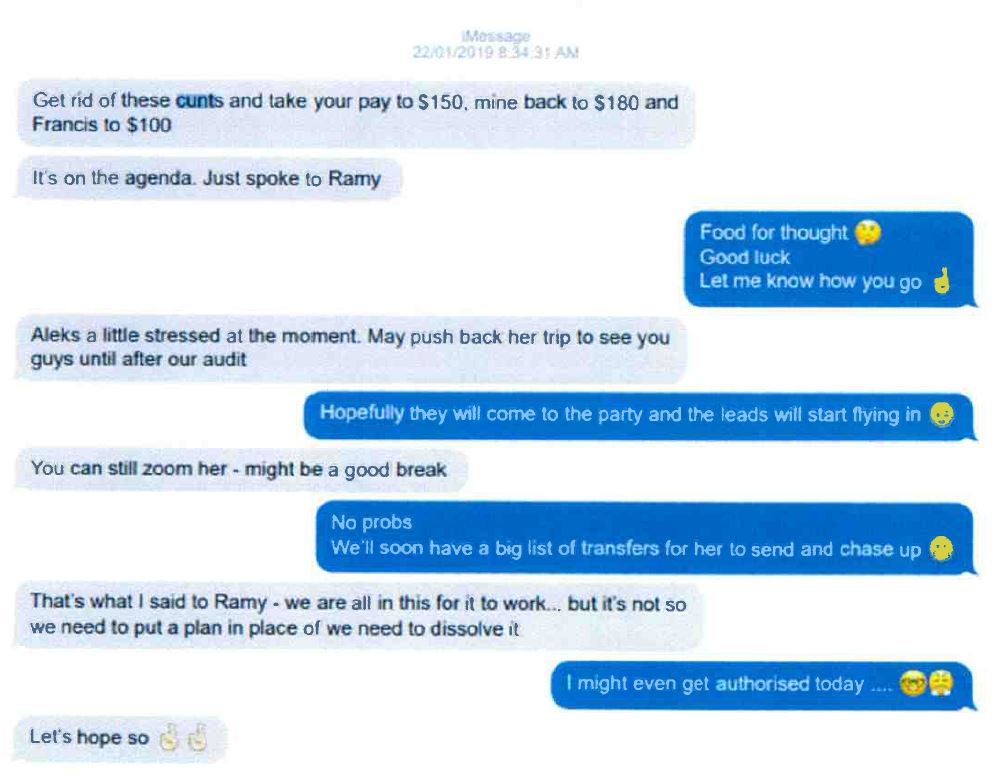

76 On 22 January 2019 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

Ms Coulter accepted that the “these” in the first of her messages was a reference to Madison Marcus and that she seems by her messages to be saying that the Madison Marcus partnership was not going to work.

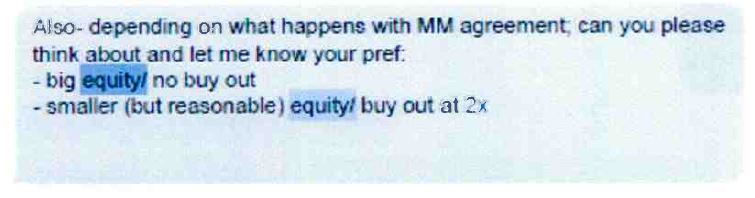

77 On 29 January 2019 Ms Coulter sent two text messages to Mr Puxty, the second of which was in the following terms:

Ms Coulter accepted that if the agreement with Madison Marcus fell over, she would need to have discussions with Mr Puxty about a new arrangement, if there was going to be one going forward.

78 On 11 February 2019 Ms Coulter sent an email to Messrs Qutami and Bechara at Madison Marcus which included:

After considerable reflection I would like to start proceedings to cease our partnership.

Whilst I appreciate our recent meetings and the spirit in which they have been conducted, I don’t feel that MAG is the right fit for MM going forward. This is not a decision I have reached lightly.

The reasons for entering into an agreement with MM were very clear to me and I believed that we were very aligned for the future aspirations for the business. Our discussions that we had leading up to the signing of our agreement 12 months ago, centred around that MM was going to provide significant lead flow to MAG. The joint goal was to create a business valued at $6million in 5 years’ time to coincide with MM listing. All conversations and projections were around MM providing the leads which would result in approx. $1mil in new business each year for 5 years.

As we both acknowledge, the lead flow has not presented itself and has therefore necessitated a different strategy from MM. …

I think both parties agree that MM does not have the capacity to support the growth of MAG through referrals, as initially agreed to.

…

Despite the clear terms of her email, Ms Coulter suggested in cross-examination that the lack of referrals from Madison Marcus was not the reason why she instigated the separation. She gave evidence, which I reject, that Madison Marcus was not happy with the time it was taking to get income into the Newcastle operation. That reason is not recorded in any document to which I was taken and it is not the reason Ms Coulter put to Messrs Qutami and Bechara for wishing to terminate the partnership and bring to an end Consolidated’s 50% shareholding in Monarch.

79 On 13 February 2019 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty had a telephone conversation in which Ms Coulter informed Mr Puxty that Monarch’s partnership with Madison Marcus was to be dissolved.

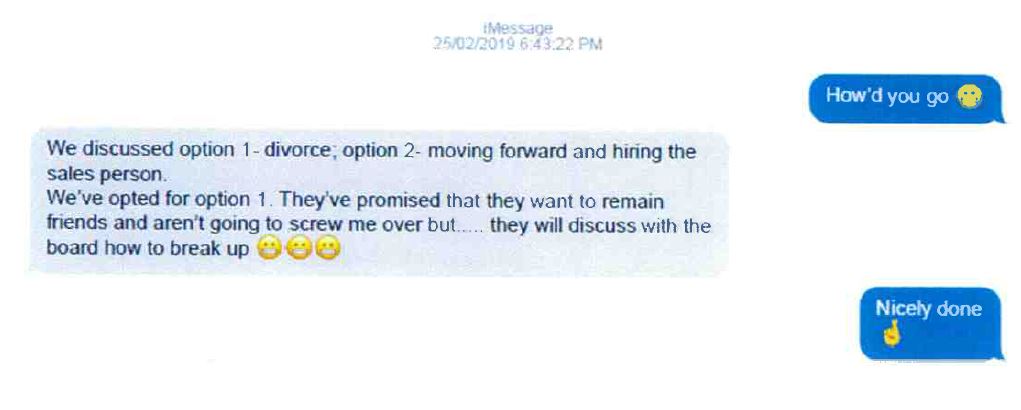

80 On 25 February 2019 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty exchanged the following text messages:

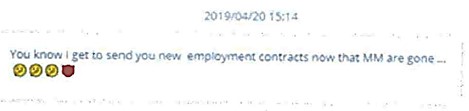

81 On 20 April 2019 Ms Coulter sent the following text message to Mr Puxty:

Ms Coulter accepted, as is reflected in her text, that, given that the partnership with Madison Marcus had been terminated, she needed to come to a new arrangement with Mr Puxty.

82 The Amended Incentive Program required Mr Puxty to bring in $50,000 in recurring revenue bundles quarterly over 12 months. According to Ms Coulter it became clear during the first period of Mr Puxty’s employment that he was not doing so. As a result, Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty had discussions to renegotiate the Amended Incentive Program. On 8 May 2019 Ms Coulter met with Mr Puxty in Pyrmont. Ms Coulter’s husband was also present. During the meeting they had a conversation to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: We need to discuss some alternatives for the incentive program.

Mr Puxty: Okay. I want 50% ownership in Monarch.

Ms Coulter: I don’t think 50/50 is fair. You are joining an existing business. I have worked to build it. It has an existing process; I have paid the set-up costs and I have developed excellent relationships with the dealer groups. I took on all the risks in starting this business, I seeded $100,000 for the expansion and I have a business loan that I am repaying to help fund the Newcastle part of the business so I cannot now give away 50% of it.

Mr Puxty: This is two businesses merging together, not me joining Monarch. It should be 50/50. Do you not think I deserve 50%?

Ms Coulter: It is not two businesses merging together, because we are operating off one P&L/Balance sheet. It has nothing to do with whether or not you deserve it. I cannot compromise myself to give it to you. I will consider a potential 40/60 split, but it needs to be justified by reference to the numbers you bring in and needs to recognise the significant investment I have made into Monarch.

Mr Puxty: I have brought a lot to the table and have helped Monarch improve their processes.

Ms Coulter: With all due respect, the processes needed updating because we went from a team of two to a team of four. Prior to you starting, the processes for Aleks and I were working perfectly well.

83 After some consideration Ms Coulter decided that there might be potential for Mr Puxty to become a shareholder in Monarch. On 13 May 2019 Ms Coulter sent Mr Puxty an email in the following terms (as produced in evidence):

OK....

So, as we discussed, I feel there needs to be some sort of ‘value’ placed on the fact that you have joined an established business. From our discussion last week, it feels that you don’t think there needs to be ‘value’ placed on this.

We are stuck between where I think the split is fair at 60 (T)/40 (B) and what you think is fair at 50/50.

You feel 50/50 is the right balance because the book value that we both bring to the table is approximately the same, along with the expertise you bring - technical/ processes etc etc

I feel 60/40 is right because ultimately I am the founder and CEO of MAG, and that you have been able to join an existing business with its infrastructure, utilise its P&L and balance sheet to get the “Newcastle” office up and running. I have had to fund the initial set up of the Newcastle business and whilst we agree that I will have this all paid back to me, this is a significant amount of money, that realistically won’t get paid back to me any time soon. Money that I don’t have. I have been the one who has had the financial risk and financial stress around this business, and I have been the one that has to worry about how we pay salaries each fortnight. I have had to get a loan to make sure there is a buffer, and it has been my personal exertion that funded this initially (in December the business account had $100k in it). Understand that the intention was to have Madison Marcus fund this, and obviously that didn’t work out (we need to park this), but at the same time we had intentions that we would also have Rex to assist funding the Francis part (we need to park this). So we are where we are.

I have calculated the funding as approx. $200k which includes 5 months of salaries and super for you, Francis and half of Aleks + FP fees (Asic & PI. Not Adviser as this doesn’t kick in until next month) + incidentals such as computers + the NAB loan and interest ($62,600 + interest).

*computers

^Repayments $2110 pm @ 36 months

I don’t think it is fair that we both have the same book, but I am negative a huge amount of money and we end up at 50/50. Hence the 60/40. I basically get paid back the deficit when we sell, OR when we start writing a shit load of new business.

The alternative is that you invest in the business and fund half of the deficit ($100k) and we go 50/50. There is not pay back to either of us, this is simply an investment into our business. And going forward, we take profits from the business 50/50..

We will need to have a strategy meeting to properly understand the way forward as far decision making goes as I get the sense that in some areas we will disagree on things and we can both be stubborn (but I assume this is what you were talking about with the three areas - overall management of the business; Advice component etc etc). We will probably have to constitute a Board of some description so make sure that if we cannot agree, there is a way forward etc etc.

84 Mr Puxty agreed that at the time of receipt of Ms Coulter’s email (see preceding paragraph) there was no change to the arrangement he had with Monarch as set out in the Puxty Employment Agreement and the Performance Review & Bonus document, although at the time the fundamental premise of the latter had, from his perspective, gone away. Ms Coulter’s email put forward an alternative to the Amended Incentive Program recorded in the Performance Review & Bonus document.

85 In June 2019 and subsequently Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty discussed potential business arrangements and how they might move forward.

86 On 7 June 2019 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty had another discussion about Mr Puxty’s employment with Monarch. Ms Coulter recalls that during the discussion she expressed her frustration about Mr Puxty’s financial contributions to Monarch and that he was well short of meeting his target of bringing $200,000 in recurring revenue. Ms Coulter does not recall what she in fact said but recalls telling Mr Puxty that she was frustrated because Monarch had invested so much money into setting up an office in Newcastle for Messrs Puxty and Coggan and they were not meeting their end of the bargain. Ms Coulter recalls that toward the end of their conversation, an exchange to the following effect took place:

Mr Puxty: Francis and I are contemplating leaving. My friendship with you is too important, and it is being affected by being in business together.

Ms Coulter: I think it is too soon to jump the gun given we have come this far and I have invested so much time and money.

Mr Puxty: I will think about it over the weekend.

Mr Puxty says that, insofar as Ms Coulter might be suggesting otherwise, there was no agreement reached about his ongoing involvement in Monarch’s business. According to Mr Puxty, his involvement had always been predicated upon Madison Marcus being a part of the business and, by June 2019, there was no longer any prospect of that.

87 Following the weekend Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty had a further conversation in which Mr Puxty informed Ms Coulter that he and Mr Coggan would stay with Monarch.

88 According to Mr Puxty he met with Ms Coulter on 12 July 2019 at a café in Tuggerah, New South Wales and had a discussion to the following effect:

Ms Coulter: I’ve decided to agree to the ownership split at 50/50 but no name change, or entity change. We still need to discuss finances moving forward and remember, we can only register the change in ownership after my house finance comes through. Can you provide a loan of $50,000.00 to help with a business tax debt?

Mr Puxty: I can lend you $30,000.00 which you can repay from [Monarch] cashflow or within a reasonable time if we can’t come to a partnership agreement.

Ms Coulter: OK, thanks. You know l won’t screw you over.

Ms Coulter denies that she had a conversation in the terms alleged above. She says that she and Mr Puxty never agreed on a 50/50 equity split. I accept Ms Coulter’s evidence. Mr Puxty’s evidence is inconsistent with Ms Coulter’s evidence on this topic and, in particular, with the contemporaneous documentary evidence, namely her email dated 13 May 2019 in which she suggested a 60/40 split in her favour and explained her rationale for doing so (see [83] above).

89 On 15 July 2019 Mr Puxty contacted Ms Coulter. Ms Coulter says that the purpose of the discussion was to discuss a salary increase for Mr Puxty from his current salary of $130,000 plus super, while Mr Puxty says the purpose of the conversation was to discuss the terms and conditions upon which Mr Puxty would consider joining Monarch as a shareholder and thus commit to the business on an ongoing basis. The true purpose of the conversation and what each of Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty recall was said is of little, if any, relevance. The effect of their conversation is best gleaned from the email sent by Ms Coulter to Mr Puxty on 15 July 2019 following their discussion in which Ms Coulter wrote:

Thought I would email you an overview of our discussion this morning.

For us to bring your salary to $150,000 + Super the difference per fortnight will be:

Current

Salary $3528

Super $475

Tax $1472

Proposed

Salary $3999.23

Super $548.08

Tax $1770

Difference per fortnight is $842.

I think we should be able to cover this going forward, and then in the short term (hopefully only this year) we will make up the difference with profit.

Our costs per annum are currently: $580k, this will bring it up to $600k. Obviously this will go up if we ever find you an office space.

However, conservatively, if we assume that my ongoing income is $180k and yours will be around the same, that means $360k pa. If we assume that we both write $150k in new business then there will be approx $60k in profit. I think this is reasonable to expect over this FY, given I usually write between $150 - 180k pa in new business. Last financial year was approx $160k

Any left over profit can go towards the principle debt (your bank loan). I’m not worried about the NAB debt as [Monarch] is paying this back over 3 years.

90 In September 2019 Mr Puxty incorporated Odyssey. At the time of its incorporation all of the shares were owned by Mr Puxty’s family trust. Mr Coggan did not become a director of Odyssey until sometime later.

Messrs Puxty and Coggan have a change of heart

91 On or about 8 November 2019, Mr Puxty informed Ms Coulter that he and Mr Coggan were thinking about leaving Monarch. Following that meeting, Ms Coulter sent Mr Puxty a “spreadsheet” of costs to work through.

92 On 29 November 2019 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty met. While they do not agree on the content of the discussion which took place it is common ground that the purpose of the meeting was to discuss the terms of Messrs Puxty’s and Coggan’s exit from Monarch.

93 On 17 January 2020 Ms Coulter and Mr Puxty met again. Ms Coulter recalls that at this meeting Mr Puxty informed her that Mr Coggan had bought a book with recurring income of just under $500,000 from a Glenda Chase, an opportunity which he had come across at the RI Newcastle advisors’ dinner held in October 2019 and that he was also leaving Monarch.

94 Ms Coulter understood from her conversation with Mr Puxty on 17 January 2020 that they were “on the same page” in that if Mr Puxty was to leave and take his clients with him, he would be required to compensate Monarch for the costs and expenses it had incurred in employing and supporting him and Mr Coggan. Ms Coulter wanted to maintain her friendship with Mr Puxty and to have him leave on good terms. Following their meeting Ms Coulter prepared and sent a spreadsheet to Mr Puxty which set out the costs. The covering email dated 17 January 2020 included:

Have a look and let me know what you think.

I think I have captured everything. I have a line item of “incidentals” which I have added because I’m sure I have missed something like interest paid to ATO/ one off charges in the set up etc.

Note the Xmas party was Coulter funded, not MAG.

The income figures are to 14/1 which do not include this weeks income (approx $1300) - we can add that in when we do the final ‘wash up’ closer to the 31st.

Let me know if anything doesn’t add up and let’s discuss final steps.

Hopefully your discussion goes well with [Mr Coggan] tomorrow. I’ve given Joseph the heads up on where you and I are at, and the fact that I don’t foresee any issues in signing over all your clients on, or leading up to 31/1. Of course, anything that comes over once your (sic) have left I will send across to you. I have no issue in sharing with you the remuneration report for the first month or until you are confident that everything has moved to you.

95 Mr Puxty denies that there was ever any agreement reached to the effect that he would only be entitled to take his clients upon leaving Monarch in return for paying compensation to Monarch. Rather, Mr Puxty was looking to achieve a resolution that was both commercial and which would increase the prospects of preserving his friendship with Ms Coulter.

Messrs Puxty and Coggan resign from Monarch

96 On 20 January 2020 Ms Coulter received letters of resignation dated 17 January 2020 from each of Messrs Puxty and Coggan giving two weeks’ notice of their intention to resign.

97 Messrs Puxty’s and Coggan’s employment with Monarch ended on 31 January 2020. At the time Monarch had about 220 clients in its Sydney office and 140 clients in its Newcastle office.

98 In late January and February 2020 Ms Coulter and Messrs Puxty and Coggan attempted to resolve the issues that arose between them following Messrs Puxty’s and Coggan’s resignations from Monarch. Ms Coulter sought payment to cover costs incurred in return for release of Mr Puxty’s clients. It is only necessary to set out aspects of two of those exchanges on which Mr Puxty relies.

99 First, on 25 February 2020, in response to an email from Mr Puxty sent on 24 February 2020 seeking to resolve their dispute either by payment by Monarch to Messrs Puxty and Coggan of the amount they claimed was due pursuant to the terms of the Performance Review & Bonus document or transfer of the clients they introduced to Monarch, Ms Coulter sent an email which included:

Thank you for your email below.