FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Rainforest Reserves Australia Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water [2025] FCA 532

Review of: | Decision dated 17 June 2024 (EPBC 2021/9066) |

File number(s): | VID 837 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | SHARIFF J |

Date of judgment: | 22 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | ENVIRONMENTAL LAW – where a delegate of the Minister for the Environment and Water granted an approval under ss 130(1) and 133(1) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) to construct, operate and decommission wind turbine generators for a project known as the Gawara Baya Wind Farm (Wind Farm) – where Wind Farm to be located adjacent to but outside the UNESCO-listed Wet Tropics World Heritage Area in North Queensland that is home to various species of protected or endangered species of birds and bats ADMINISTRATIVE LAW – whether s 140 of the EPBC Act creates a jurisdictional fact essential to the exercise of power under ss 130(1) and 133(1) – whether non-compliance with s 140 invalidates a decision made under ss 130(1) and 133(1) of the EPBC Act – whether approval decision involved an improper exercise of power on the basis that it was uncertain within the meaning of ss 5(1)(e) and 5(2)(h) of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) – Held: grounds of review not established PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW – whether the approval decision is inconsistent with Australia’s bilateral treaty obligations with Japan, China and the Republic of Korea (Specified Bilateral Treaties) – where Specified Bilateral Treaties relevantly provide that each nation-state party shall prohibit the “taking” of protected migratory birds and their eggs – whether an innocent, negligent or reckless act which results in the death of migratory birds involves “taking” those birds in a manner inconsistent with the obligations in the Specified Bilateral Treaties – whether the approval of the Wind Farm involves a “taking” of migratory birds protected by Specified Bilateral Treaties – interpretation of multi-lingual bilateral treaties – meaning of the word “taking” – relevance of dictionary definitions in the interpretation of multi-lingual bilateral treaties – where text, context and purpose relevant to the interpretation of the Specified Bilateral Treaties – Held: – decision to approve the Wind Farm is not inconsistent with Specified Bilateral Treaties – application dismissed |

Legislation: | Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) ss 5(1)(e), 5(1)(h), 13(1) Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) ss 3, 12, 13A, 15A, 15B, 15C, 16, 17B, 18, 18A, 20, 20A, 67, 67A 68, 75, 76, 77, 82, 87, 96A, 98, 99, 100, 130, 133, 134, 136, 137A, 138, 139, 140, 140A, 156A, 156B, 156D, 209, 316, 321, 428, 523 Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) s 39B Migratory Bird Treaty Act 1918, 16 USC § 703 Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Korea on the Protection of Migratory Birds, 6 December 2006, Australia–South Korea, 2483 UNTS 459 arts 2, 4, 5, 6 (entered into force 13 July 2007) (ROKAMBA) Agreement between the Government of Japan and the Government of Australia for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Birds in Danger of Extinction and their Environment, 6 February 1974, Australia–Japan, 1241 UNTS 385 arts II, IV, V, VI (entered into force 30 April 1981) (JAMBA) Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Australia for the protection of Migratory Birds and their Environment, 20 October 1986, Australia–China, 1535 UNTS 273 arts II, III, IV (entered into force 1 September 1988) (CAMBA) Convention Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Japan for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Birds in Danger of Extinction, and their Environment, 4 March 1972, Japan–United States, 979 UNTS 149 art 3(1) (entered into force 19 December 1974) Convention Between the United States and Great Britain for the Protection of Migratory Birds, 16 August 1916, Canada–United States, 39 Stat 1702; TS 628 art 2 (entered into force 7 December 1916) Convention for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Game Mammals, 7 February 1936, Mexico–United States, 178 UNTS 309 art 2 (entered into force 15 March 1937) Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, 23 June 1979, 1651 UNTS 333 arts I, V (entered into force 1 November 1983) (Bonn Convention) Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, opened for signature 23 May 1969, 1115 UNTS 331 arts 31, 33 34 (entered into force 27 January 1980) (Vienna Convention) |

Cases cited: | Adan v Secretary of State for Home Department [1999] 1 AC 293 Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 4; 239 CLR 27 Anvil Hill Project Watch Association Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water Resources [2007] FCA 1480; 243 ALR 784 Applicant A v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs [1997] HCA 4; 190 CLR 225 Australia Pacific LNG Pty Ltd v Treasurer, Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships and Minister for Sport [2019] QSC 124 Australian Conservation Foundation Inc v Minister for the Environment and Energy [2017] FCAFC 134; 251 FCR 359 Australian Conservation Foundation Inc v Minister for the Environment [2016] FCA 1042; 251 FCR 308 Avon Downs Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1949] HCA 16; 78 CLR 353 Blue Wedges Inc v Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts [2008] FCA 8; 165 FCR 211 Buzzacott v Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (No 2) [2012] FCA 403; 291 ALR 314 Buzzacott v Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities [2013] FCAFC 111; 215 FCR 301 Cabal v Attorney-General (Cth) [2001] FCA 583; 113 FCR 154 Cabell v Markham 148 F2d 737 (2d Cir 1945) CIC Insurance Ltd v Bankstown Football Club Ltd [1997] HCA 2; 187 CLR 384 Country Carbon Pty Ltd v Clean Energy Regulator [2018] FCA 1636; 267 FCR 126 Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178; 260 FCR 1 Friends of the Gelorup Corridor Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water [2023] FCAFC 139; 299 FCR 236 General Commissioner of Taxation v BHP Billiton Ltd [2011] HCA 17; 244 CLR 325 K&S Lake City Freighters Pty Ltd v Gordon & Gotch Ltd [1985] HCA 48; 157 CLR 309 Kingdom of Spain v Infrastructure Services Luxembourg Sàrl [2021] FCAFC 3; 284 FCR 319 Lawyers for Forests Inc v Minister for the Environment Heritage and the Arts [2009] FCA 330; 165 LGERA 203 Miller v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs [2024] HCA 13; 278 CLR 628 Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Eshetu [1999] HCA 21; 197 CLR 611 NBGM v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs [2006] HCA 54; 231 CLR 52 NBGM v Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs [2006] FCAFC 60; 150 FCR 522 Enfield City Corporation v Development Assessment Commission [2002] HCA 5; 199 CLR 135 Patrick v Australian Information Commissioner (No 2) [2023] FCA 530 Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355 Provincial Insurance v Consolidated Wood (1991) 25 NSWLR 541 R v Connell; Ex parte Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd [1944] HCA 42; 69 CLR 407 Randwick City Council v Minister for the Environment (1998) 54 ALD 682 Sunland Group Ltd v Gold Coast City Council [2021] HCA 35; 274 CLR 325 SZTAL v Minister for Immigration [2017] HCA 34; 262 CLR 362 Television Corporation Ltd v Commonwealth; Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd v Postmaster-General (Cth) [1963] HCA 30; 109 CLR 59 Timbarra Protection Coalition Inc v Ross Mining NL [1999] NSWCA 8; 46 NSWLR 55 Triabunna Investments Pty Ltd v Minister for Environment and Energy [2019] FCAFC 60; 270 FCR 267 Ulan Coal Mines Ltd v Minister for Planning [2008] NSWLEC 185; 160 LGERA 20 US v CITGO Petroleum Corp 801 F3d 477 (5th Cir 2015) Woolworths Ltd v Pallas Newco Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 422; 61 NSWLR 707 Margiotta Broglio C and Ortino F, “Treaty interpretation, multilinguism, and the WTO dispute settlement system: towards the comparative translation paradigm?” (2024) 15(1) Journal of International Dispute Settlement 487 Waeckerle LA, “A Murder Most Fowl: United States v. CITGO Petroleum Corp., 801 F.3d 477 (5th Cir. 2015) and Incidental Killings Under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act” (2018) 96 Nebraska Law Review 742 A New Century Chinese-English Dictionary (Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2004) Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (7th ed, Commercial Press, 2016) Korean-English Learners’ Dictionary (National Institute of Korean Language, 2012) Standard Korean Language Dictionary (1st ed, National Institute of Korean Language, 1999) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Administrative and Constitutional Law and Human Rights |

Number of paragraphs: | 215 |

Date of hearing: | 3–4 April 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant | Mr S Crock with Ms E Faine-Vallantin |

Solicitor for the Applicant | DST Legal |

Counsel for the First Respondent | Mr N Wood SC with Mr T Liu |

Solicitor for the First Respondent | Australian Government Solicitor |

Counsel for the Second Respondent | Mr R Lancaster SC with Mr M Sherman and Ms L Sims |

Solicitor for the Second Respondent | Herbert Smith Freehills |

ORDERS

VID 837 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | RAINFOREST RESERVES AUSTRALIA INC Applicant | |

AND: | MINISTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT AND WATER First Respondent UPPER BURDEKIN WIND FARM HOLDINGS PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

order made by: | SHARIFF J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 22 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended originating application be dismissed.

2. On or by 5 pm on 29 May 2025, the respondents file and serve submissions on the question of costs (to the extent that the respective respondents seek their costs of the proceedings) with any such submissions not to exceed 5 pages.

3. On or by 5 pm on 5 June 2025, the applicant file and serve submissions in reply on the question of costs with such submissions not to exceed 5 pages.

4. On or by 5 pm on 12 June 2025, the respondents file and serve submissions in reply to any submissions filed by the applicant under order 3 with such submissions not to exceed 5 pages.

5. The question of costs be determined on the papers unless one or more of the parties indicate to the court by 12 pm on 16 June 2025 that they wish to be heard on the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

SHARIFF J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 The second respondent (the Proponent) sought the approval of the first respondent (the Minister) for the construction, operation and decommissioning of up to 69 wind turbine generators (WTGs) and ancillary infrastructure as part of the project known as the Gawara Baya Wind Farm (Wind Farm).

2 The Wind Farm is to be located 65 km south-west of Ingham in North Queensland within Kilclooney Station which is currently used for cattle grazing. It is to be located adjacent to but outside the UNESCO-listed Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. This area is made up largely of tropical rainforests and is home to rare and unique marsupials and other animals including a number of protected or endangered species of birds and bats.

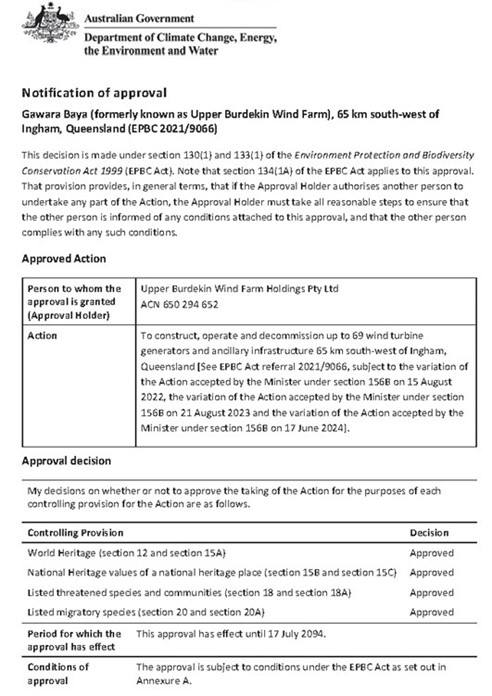

3 On 17 June 2024, a delegate of the Minister made a decision to grant approval to the Proponent (the Approval Decision) to construct, operate and decommission the Wind Farm pursuant to ss 130(1) and 133(1) of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) but subject to certain conditions specified in Annexure A of the decision (the Conditions).

4 The applicant is a not-for-profit environmental charity. It holds concerns that the operation of the WTGs at the proposed Wind Farm will kill, injure or disturb endangered or protected species of birds and bats. It says, amongst other things, that the approval of the Wind Farm amounts to the “taking” of migratory bird species in a manner that is inconsistent with Australia’s obligations under specified international treaties which are protected by the EPBC Act. By a further amended original application, the applicant seeks relief pursuant to s 5 of the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act) and s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).

5 By the time of the hearing before me, the applicant narrowed its case such that it raised the following issues for determination:

(a) whether the Approval Decision is inconsistent with Australia's international obligations for the purposes of s 140 of the EPBC Act and, therefore, invalid because s 140 gives rise to a jurisdictional fact that must be established as a matter of objective fact or because that provision is otherwise jurisdictional such that non-compliance with it gives rise to invalidity: Ground 1 (the Migratory Species Ground);

(b) whether the “action” that was approved went beyond the action that was referred to the Minister by the Proponent: Ground 3 (the Baseline Measures Ground); and

(c) whether certain Conditions make the Approval Decision uncertain (the Uncertainty Grounds), specifically:

(i) whether the "impact trigger threshold" definitions and conditions contained in the Approval Decision are uncertain: Ground 5 (the Impact Trigger Threshold Issue); and

(ii) whether certain other conditions contained in the Approval Decision that provide for further Ministerial approval to be obtained are uncertain in that they give rise to a “secondary consent” process: Grounds 6 and 7 (the Further Ministerial Approval Issues).

6 For the reasons set out below, the further amended originating application should be dismissed and I will hear the parties on the question of cost. For convenience, I have structured my reasons as follows:

(a) Part 2 sets out the salient aspects of the applicable statutory scheme;

(b) Part 3 summarises the relevant facts;

(c) Part 4 addresses the Migratory Species Ground;

(d) Part 5 addresses the Baseline Measures Ground;

(e) Part 6 address the Uncertainty Grounds; and

(f) Part 7 sets out my conclusion.

2. THE SALIENT ASPECTS OF THE STATUTORY SCHEME

7 The objects of the EPBC Act are identified in s 3(1) and relevantly include the protection of the environment, especially matters of national environmental significance (MNES) (s 3(1)(a)), the promotion of ecologically sustainable development (s 3(1)(b)), the promotion of a co-operative approach to the protection and management of the environment involving governments, the community, land-holders and indigenous peoples (s 3(1)(d)) and assisting in the co-operative implementation of Australia’s international environmental responsibilities (s 3(1)(e)).

8 In order to promote these objects, the EPBC Act enacts prohibitions on specified conduct aimed at protecting the environment. It also enacts a sophisticated scheme whereby the Minister may approve of actions that would otherwise contravene or offend the prohibitions. The relevant aspects of this scheme have been considered in a number of previous decisions of this Court: see Australian Conservation Foundation Inc v Minister for the Environment and Energy [2017] FCAFC 134; 251 FCR 359 (ACF Adani FFC) at [2]–[28], [52]–[53] (Dowsett, McKerracher and Robertson JJ); Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178; 260 FCR 1 at [64]–[94] (Mortimer J, as her Honour then was); Triabunna Investments Pty Ltd v Minister for Environment and Energy [2019] FCAFC 60; 270 FCR 267 (Triabunna FC) at [93]–[94] (Mortimer J); Friends of the Gelorup Corridor Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water [2023] FCAFC 139; 299 FCR 236 (Gelorup FFC) at [10]–[31] (Jackson and Kennett JJ) and [100]–[102] (Feutrill J).

9 What follows below is a summary of the key parts of the EPBC Act which are relevant to the present proceedings.

2.1 Prohibitions on certain actions

10 Division 1 of Pt 3 of the EPBC Act contains prohibitions on undertaking any action that has, will have or is likely to have a “significant impact” on particular matters. Each such prohibition is made up of companion provisions: one that gives rise to a civil penalty and the other that creates a criminal offence (see eg ss 12 and 15A, ss 16 and 17B, ss 18 and 18A and ss 20 and 20A). However, each such provision is also subject to exceptions where relevant approvals are in place.

11 Relevantly, for the purposes of the present proceedings, the prohibitions are those contained in ss 20 and 20A of Subdiv D of the EPBC Act. Section 20 provides as follows:

Subdivision D—Listed migratory species

20 Requirement for approval of activities with a significant impact on a listed migratory species

(1) A person must not take an action that:

(a) has or will have a significant impact on a listed migratory species; or

(b) is likely to have a significant impact on a listed migratory species.

Civil penalty:

(a) for an individual—5,000 penalty units;

(b) for a body corporate—50,000 penalty units.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply to an action if:

(a) an approval of the taking of the action by the person is in operation under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(b) Part 4 lets the person take the action without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(c) there is in force a decision of the Minister under Division 2 of Part 7 that this section is not a controlling provision for the action and, if the decision was made because the Minister believed the action would be taken in a manner specified in the notice of the decision under section 77, the action is taken in that manner; or

(d) the action is an action described in subsection 160(2) (which describes actions whose authorisation is subject to a special environmental assessment process).

12 Section 20A of the EPBC Act creates strict liability offences subject to certain exceptions. It provides as follows:

20A Offences relating to listed migratory species

(1) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person takes an action; and

(b) the action results or will result in a significant impact on a species; and

(c) the species is a listed migratory species.

Note: Chapter 2 of the Criminal Code sets out the general principles of criminal responsibility.

(1A) Strict liability applies to paragraph (1)(c).

Note: For strict liability , see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

(2) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person takes an action; and

(b) the action is likely to have a significant impact on a species; and

(c) the species is a listed migratory species.

Note: Chapter 2 of the Criminal Code sets out the general principles of criminal responsibility.

(2A) Strict liability applies to paragraph (2)(c).

Note: For strict liability , see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

(3) An offence against subsection (1) or (2) is punishable on conviction by imprisonment for a term not more than 7 years, a fine not more than 420 penalty units, or both.

Note 1: Subsection 4B(3) of the Crimes Act 1914 lets a court fine a body corporate up to 5 times the maximum amount the court could fine a person under this subsection.

Note 2: An executive officer of a body corporate convicted of an offence against this section may also commit an offence against section 495.

Note 3: If a person takes an action on land that contravenes this section, a landholder may commit an offence against section 496C.

(4) Subsections (1) and (2) do not apply to an action if:

(a) an approval of the taking of the action by the person is in operation under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(b) Part 4 lets the person take the action without an approval under Part 9 for the purposes of this section; or

(c) there is in force a decision of the Minister under Division 2 of Part 7 that this section is not a controlling provision for the action and, if the decision was made because the Minister believed the action would be taken in a manner specified in the notice of the decision under section 77, the action is taken in that manner; or

(d) the action is an action described in subsection 160(2) (which describes actions whose authorisation is subject to a special environmental assessment process).

Note: The defendant bears an evidential burden in relation to the matters in this subsection. See subsection 13.3(3) of the Criminal Code.

13 Sections 20 and 20A both focus on “listed migratory species”. For the purposes of the EPBC Act, the phrase “migratory species” has the meaning given in Art I of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn Convention): s 209(8) of the EPBC Act. Article I provides:

“Migratory species” means the entire population or any geographically separate part of the population of any species or lower taxon of wild animals, a significant proportion of whose members cyclically and predictably cross one or more national jurisdictional boundaries;

14 A “listed migratory species” is a migratory species that is included in the list established by the Minister pursuant to s 209 of the EPBC Act.

15 As is evident from these provisions, the prohibitions contained in ss 20 and 20A do not apply if, relevantly, there is an approval in operation under Pt 9 or there is in force a decision of the Minister under Div 2 of Pt 7 that the provision is not a controlling provision for the action.

2.2 The process of referral, assessment and approval

16 The EPBC Act enacts a process for approvals to be obtained in respect of particular actions. As the Full Court explained in ACF Adani FFC (at [52]–[53]), generally, the process of approval involves “three phases” of decision-making:

... The [EPBC] Act identifies three phases in the process leading to a decision to approve or not approve an action. First, the Minister must decide whether the proposed action needs approval. If he or she so decides, then he or she must identify the relevant controlling provisions. Second, an assessment report will be prepared pursuant to s 47(4), s 84(3) or s 87(4). See s 136(2)(b) and s 130(2). In each case, the assessment report must address the relevant impacts which are, as we have observed, impacts on the protected matters identified by the Minister pursuant to s 75. Third, the Minister makes his or her decision, based upon the matters identified in s 136 and, perhaps, elsewhere in the [EPBC] Act.

The Minister is directed by s 136 to consider, "matters relevant to any protected matter". He or she is not required to decide, at that stage, whether or not a particular event or circumstance is an "impact" or "relevant impact", save for the purpose of deciding whether s 136(2)(e) has been engaged: that is, for the purpose of deciding whether there is material identified by that provision, which material, he or she must consider The identification of controlling provisions and relevant impacts are primarily steps designed to provide a structure within which the assessment of the relevant action may be conducted. Those concepts will generally be irrelevant to the Minister's decision pursuant to s 130…

17 It is necessary to examine each of these three processes.

2.2.1 Phase 1: Referral and initial assessment by the Minister of controlled actions

18 The first phase involves a determination of whether an action requires approval. This is governed by Part 7 of the EPBC Act. The first provision in this Part is s 67, which provides that a proposed “action” is a “controlled action” if the taking of the action without approval under Pt 9 of the EPBC Act would be prohibited by a provision of Pt 3. The provision is described as a “controlling provision” for the action. Section 67A prohibits the taking of a controlled action without approval being obtained.

19 It is relevant that the word “action” is defined broadly in s 523(1) to include a project, a development, an undertaking, an activity or series of activities and an alteration of any of these things.

20 Section 68 of the EPBC Act provides a mechanism for a person to seek Ministerial approval for the controlled action. It provides that a “person proposing to take an action that the person thinks may be or is a controlled action must refer the proposal to the Minister” for a decision on “whether or not the action is a controlled action”: s 68(1). A person proposing to take an action that “the person thinks is not a controlled action may refer the proposal to the Minister for the Minister’s decision whether or not the action is a controlled action”: s 68(2). In either situation, the person must state whether the person thinks the action that is proposed to be taken is a controlled action. As a result, whether “an action is ‘controlled’ or not is therefore a matter for assessment by the Minister”: Gelorup FFC at [12] (Jackson and Kennett JJ).

21 Where there is a referral to the Minister, s 75(1) of the EPBC Act provides that the Minister must decide whether the action that is the subject of the proposal is a controlled action and, if so, which provisions of Pt 3 are controlling provisions for the action. This aspect of the Minister’s functions has been described as an “initial clearing house” or “triage system” which does not “fix in stone all the details of a proposed ‘action’ for the subsequent approval process”: Blue Wedges Inc v Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts [2008] FCA 8; 165 FCR 211 at [22] (Heerey J) citing Anvil Hill Project Watch Association Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water Resources [2007] FCA 1480; 243 ALR 784 at [70] (Stone J).

22 If the Minister believes on reasonable grounds that the referral of a proposal to take an action does not include sufficient information, the Minister may request the person proposing to take the action to provide specified information relevant to making the decision: s 76. However, if the Minister considers that the action is not a controlled action (that is, there are no controlling provisions), then, subject to the operation of s 77, the proponent can take the action and the prohibitions in Pt 3 will not apply as a result of this decision. However, if the Minister considers that the action is a controlled action then further assessment of the action and its impact will be required as set out in Pt 8.

23 The EPBC Act contains a mechanism for the variation of proposals following a referral, which can permit variations until the point of approval: s 156A(2)(d). A person may request that the Minister accept a variation of the original proposal: s 156A(1). The Minister must decide whether or not to accept such a request: s 156B. If a varied proposal is accepted, anything done in relation to the original proposal is taken to be done in relation to the varied proposal: s 156D(1)(b).

2.2.2 Phase 2: Assessment of proposed action by reference to relevant impacts

24 If the Minister decides that an action is a controlled action, the Minister must then proceed to the second phase. This involves an assessment of the “relevant impacts” of the action under Pt 8 of the EPBC Act. The “relevant impacts” of the action are identified in s 82(1) as the impacts that the action has or will have (or is likely to have) on the matter protected by each provision of Pt 3 that the Minister has decided is a controlling provision.

25 The EPBC Act is prescriptive as to how this assessment is conducted. Section 87 requires the Minister to decide on an assessment approach as follows:

87 Minister must decide on approach for assessment

Minister must choose one assessment approach

(1) The Minister must decide which one of the following approaches must be used for assessment of the relevant impacts of an action that the Minister has decided is a controlled action:

(a) assessment by an accredited assessment process;

(aa) assessment on referral information under Division 3A;

(b) assessment on preliminary documentation under Division 4;

(c) assessment by public environment report under Division 5;

(d) assessment by environmental impact statement under Division 6;

(e) assessment by inquiry under Division 7.

26 As specified in s 87(1)(c), one of the available approaches involves an assessment by way of a “public environment report” (PER). Where this assessment approach is selected, Div 5 of Pt 8 provides that a draft PER must be prepared by the proponent in response to written guidelines issued by the Minister (s 96A), public comment must then be sought on the draft PER (s 98), a final report must then be prepared (s 99) and the Secretary must then prepare a recommendation report to the Minister (s 100).

2.2.3 Phase 3: Ministerial approval and decision-making

27 Once an assessment has been made as to the relevant impacts of an action, the third phase of the decision making process requires the Minister to decide whether to approve the taking of action. Part 9 of the EPBC Act governs the approval process.

28 Section 130(1) of the EPBC Act provides that the Minister “must decide whether or not to approve, for the purposes of each controlling provision for a controlled action, the taking of the action.” Relevantly, the decision cannot be made until the Minister has, amongst other things, received the Secretary’s recommendation report.

29 Section 133(1) provides that “[a]fter receiving the assessment documentation relating to a controlled action, or the report of a commission that has conducted an inquiry relating to a controlled action, the Minister may approve for the purposes of a controlling provision the taking of the action by a person.” Section 133(2) relevantly provides that an approval must be in writing, specify the action that may be taken, specify each provision of Pt 3 for which the approval has effect, specify the period for which the approval has effect, and set out the conditions attached to the approval.

30 Sections 134(1) and (2) provide generally for the kinds of conditions that may be imposed. Section 134(3) provides “[e]xamples of kinds of conditions that may be attached” to an approval. In Gelorup FFC, Jackson and Kennett JJ observed (at [28]) that:

Section 136(1) also indicates that the decision as to what conditions should be imposed is at least very closely related to the decision whether approval should be given. Sections 134(1) and (2) reinforce that point: the conditions that may be imposed are those which the Minister thinks are "necessary or convenient" for protecting, or mitigating or repairing damage to, the matters protected by the particular controlling provisions that are in play. At least implicitly, if the Minister is not satisfied that approval of the proposed action as presented is appropriate, they must consider whether an approval subject to identified conditions is appropriate.

31 The EPBC Act contains a series of provisions which govern the considerations relevant (or irrelevant) to the making of a decision under ss 130 and 133. These are located in Subdiv B of Div 1 of Pt 9, which commences with an overarching general provision and is followed by a range of provisions specific to particular circumstances and controlling provisions from Pt 3.

32 The first provision in this subdivision is s 136, which is entitled “General considerations”. It sets out the general matters the Minister must, may and must not consider in deciding whether to approve the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to an approval. Section 136(1) specifies certain “mandatory considerations”. This includes matters relevant to any matter protected by a controlling provision for the action as well as “economic and social matters”. Section 136(2) identifies a number of further factors that the Minister must take into account when considering the matters identified in s 136(1), including the principles of ecologically sustainable development, the PER (if any) and any other information the Minister has as to the relevant impacts of the action: s 136(2)(a), (c) and (e). Section 136(4) identifies permissible considerations to which regard may be had in approving and conditioning an action. These permissible considerations pertain to a person’s suitability by reference to that person’s “environmental history”. And, s 136(5) provides that, in deciding whether or not to approve the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to an approval “the Minister must not consider any matters that the Minister is not required or permitted by this Division to consider” (emphasis added).

33 Sections 137, 137A, 138, 139 and 140 then focus on particular requirements. Each section specifies a number of matters which are each expressed as being matters that the Minister must not do “[i]n deciding whether or not to approve” the taking of an action. Specifically, these provisions state in each respect that “the Minister must not act inconsistently” with particular instruments or relevant plans and obligations pertaining to discrete matters of national environmental significance. As I will return to below, in the present case, s 140 was central to the applicant’s case. It provides as follows:

140 Requirements for decisions about migratory species

In deciding whether or not to approve for the purposes of section 20 or 20A the taking of an action relating to a listed migratory species, and what conditions to attach to such an approval, the Minister must not act inconsistently with Australia’s obligations under whichever of the following conventions and agreements because of which the species is listed:

(a) the Bonn Convention;

(b) CAMBA;

(c) JAMBA;

(d) an international agreement approved under subsection 209(4).

34 Relevantly for the purposes of ss 140(b) and (c), s 428 of the EPBC Act defines CAMBA and JAMBA as follows:

CAMBA means the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the People’s Republic of China for the protection of Migratory Birds and their Environment done at Canberra on 20 October 1986, as amended and in force for Australia from time to time.

JAMBA means the Agreement between the Government of Japan and the Government of Australia for the Protection of Migratory Birds and Birds in Danger of Extinction and their Environment done at Tokyo on 6 February 1974, as amended and in force for Australia from time to time.

35 Also relevant is the Agreement between the Government of Australia and the Government of the Republic of Korea on the Protection of Migratory Birds, which was signed on 6 December 2006 and entered into force on 13 July 2007. This agreement (ROKAMBA) was approved under s 209(4) and is therefore relevant to a decision under s 140(d).

36 For convenience, in these reasons, I have referred to CAMBA, JAMBA and ROKAMBA collectively as the “Specified Bilateral Treaties”.

3. THE RELEVANT FACTS

37 The relevant facts were not in dispute. What follows is a brief summary of them.

38 On 11 October 2021, the Proponent submitted to the Minister’s Department (the Department) a referral pursuant to s 68 of the EPBC Act.

39 The referral proposed the construction, operation and decommissioning of up to 136 WTGs, which was later amended to involve 69 WTGs (the Proposed Action). The details of the Proposed Action were set out in the referral form prescribed by the Department (the Referral Form).

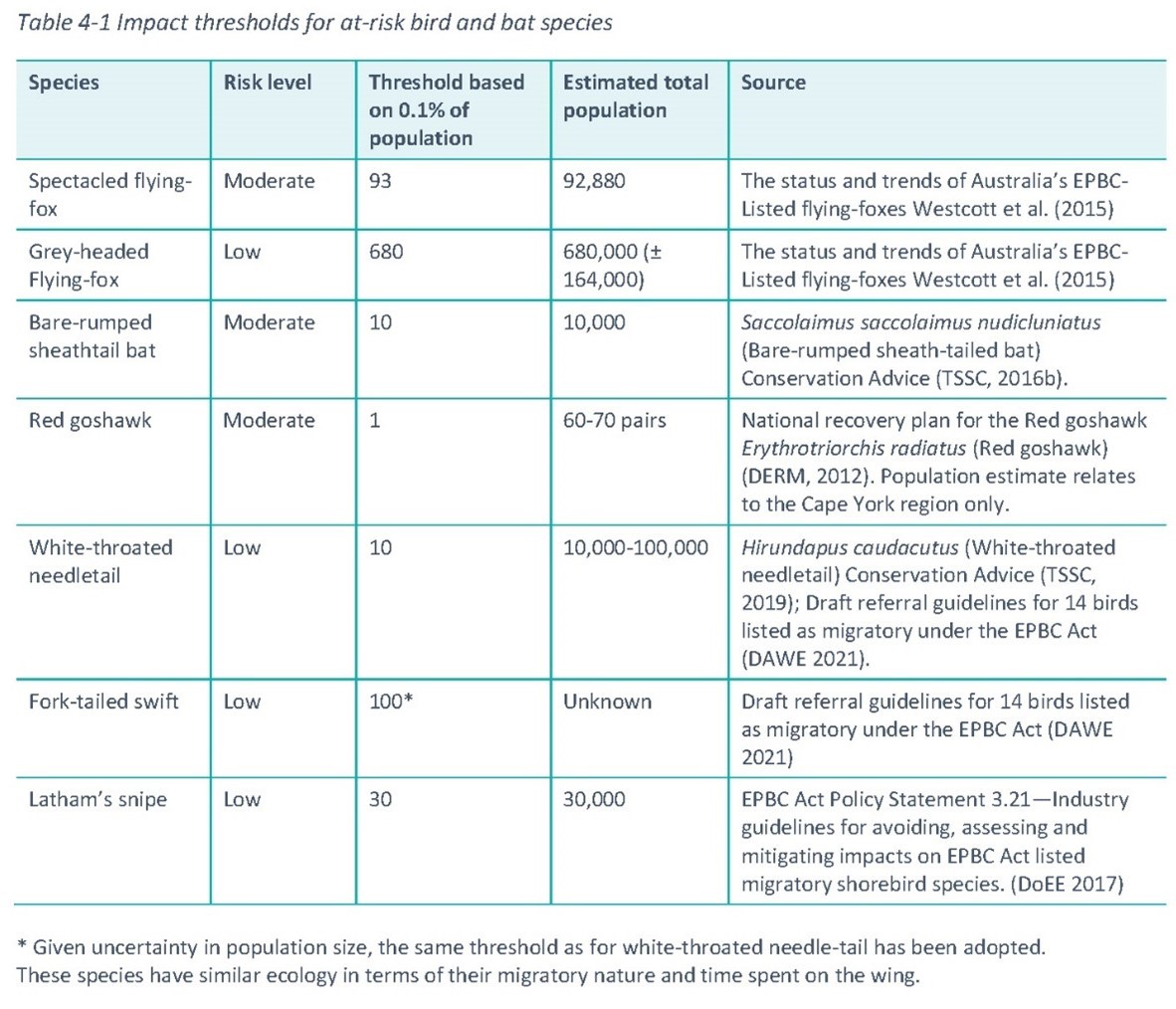

40 The Referral Form attached a number of documents (that were referred to in the body of the referral) including the Significant Impact Assessment for Matters of National Environmental Significance, an Ecological Assessment, and a Biodiversity Management Framework (the BMF). As expanded upon below:

(a) section 4.1 of the Referral Form contained a general description of the measures that the Proponent would undertake to avoid or reduce the impacts from the Proposed Action including avoidance and mitigation measures that would be delivered by the implementation of the BMF and associated management plans; and

(b) in turn, the BMF contained a “Preliminary Bird & Bat Management Plan” (the Preliminary BBMP) which identified four measures to be implemented to address the risk of bird and bat injury and mortality being:

(i) low wind speed curtailment at wind speeds of 0 to 3 ms-1;

(ii) the provision of a collision free zone above the vegetated canopy;

(iii) limitations to the lighting of turbines; and

(iv) the implementation of a fauna injury protocol.

41 On 23 November 2021, a delegate of the Minister decided that the Proposed Action was a controlled action and decided pursuant to s 75(1)(b) that the controlling provisions were: listed threatened species and ecological communities (ss 18 and 18A), listed migratory species (ss 20 and 20A); world heritage values (ss 12 and 15A); and national heritage values (ss 15B and 15C).

42 The delegate determined pursuant to s 87(1) that the proposed action was to be assessed by PER.

43 On 26 April 2022, the Department issued “PER Guidelines” to the Proponent.

44 On 25 July 2022, the Proponent submitted a request to the Department to vary the proposed action under s 156A(1)(b) so as to reduce the number of WTGs from 136 to 82. That request was accepted on 15 August 2022.

45 The Proponent then provided a draft PER to the Department, which was reviewed and commented upon. A revised draft was submitted and found to satisfy the PER Guidelines. It was published and public comment was invited.

46 The applicant commented on the draft PER.

47 On 24 July 2023, following the public consultation period, the Proponent submitted a second request to vary the Proposed Action under s 156A(1)(b) so as to reduce the number of WTGs from 82 to 69, and that variation was accepted on 21 August 2023.

48 On 4 September 2023, the Proponent submitted its final PER. The final PER was prepared with the benefit of updates resulting from the Department’s review and public comment. The final PER reflected the reduction to 69 WTGs and their layout, which followed “further targeted ecology studies, continued public consultation and feedback received on the draft PER”. The final PER attached an “Environmental Management Plan” and a draft “Bird & Bat Management Plan” (the draft BBMP). The draft BBMP that was attached to the final PER identified a range of measures to be implemented to address the risk of injury and mortality to bird and bat species arising from turbine collision along the lines of the measures that had been outlined in the Preliminary BBMP. These measures were referred to as “baseline measures”.

49 Following the publication of the final PER, there were further requests for information from the Department and responses given before a proposed decision (and proposed conditions) were published for comment on 12 April 2024.

50 On 23 May 2024, the Proponent submitted a third request to vary the proposed action under s 156A(1)(b) so as to revise the “Development Corridor” as a result of the proposed conditions. That variation was accepted on 17 June 2024, immediately prior to the delegate’s decision in relation to the proposed action on the same day.

51 On 17 June 2024, the delegate made the Approval Decision, granting approval to take the proposed action subject to conditions. Specifically, the approval imposed 128 conditions which were set out in Annexure A to the Approval Decision (the Conditions). The Conditions were divided into “Part A – Avoidance, mitigation, monitoring and compensation conditions”, “Part B – Administrative conditions” and “Part C – Definitions”.

52 Following the Approval Decision, the applicant requested a written statement of reasons in relation to the decision pursuant to s 13(1) of the ADJR Act. Those reasons were provided to the applicant on 8 November 2024 (the Delegate’s Reasons).

4. THE MIGRATORY SPECIES GROUND

4.1 Overview of the Applicant’s Contentions

53 The applicant’s contentions in support of the Migratory Species Ground rested upon three central submissions.

54 First, the applicant submitted that s 140 of the EPBC Act creates a jurisdictional fact, the existence of which is an essential condition to the exercise of the Minister’s power under ss 130(1) and 133(1) to grant an approval of controlled action. The applicant contended that the relevant jurisdictional fact is that the Minister cannot (as a matter of objective fact) act “inconsistently with” the Specified Bilateral Treaties. The applicant submitted that, as this was a jurisdictional fact, the question of whether the Minister had acted inconsistently with the Specified Bilateral Treaties was not merely a matter in respect of which the Minister’s opinion or satisfaction was sufficient to enliven the exercise of power, but was required to be established as a matter of objective fact and that this was as an essential condition to the exercise of that power.

55 Second, the applicant submitted that s 140 is jurisdictional in the sense that non-compliance with that provision gives rise to invalidity. The applicant submitted that this was the case by reason of the imperative nature of the text of s 140 which indicated a Parliamentary intention that non-compliance with that provision would result in invalidity.

56 Third, the applicant submitted that, as a matter of objective fact, the Minister acted inconsistently with the Specified Bilateral Treaties in that each of those treaties prohibit the “taking” of migratory birds and, on the proper construction of the word “taking”, the Approval Decision has the effect of permitting the “taking” of migratory birds by lifting the prohibitions contained in ss 20 and 20A of the EPBC Act.

57 The Proponent and the Minister (collectively referred to as the “respondents”) disputed the applicant’s contentions.

4.2 Does s 140 of the EPBC Act create a Jurisdictional Fact?

58 It was central to the applicant’s case that s 140 of the EPBC Act created a jurisdictional fact in that it was said to be a necessary condition to the exercise of the Minister’s power to make the Approval Decision. The term “jurisdictional fact” is elusive and complex. In Enfield City Corporation v Development Assessment Commission [2002] HCA 5; 199 CLR 135, Gleeson CJ, Gummow J, Kirby J and Hayne J stated at 148 [28]:

The term “jurisdictional fact” (which may be a complex of elements) is often used to identify that criterion, satisfaction of which enlivens the power of the decision-maker to exercise a discretion.

59 The relevance to the distinction between a jurisdictional fact and a fact or matter that falls for the formation of an opinion by the decision-maker is that it affects the content of judicial review and informs the validity of the relevant exercise of power. In Country Carbon Pty Ltd v Clean Energy Regulator [2018] FCA 1636; 267 FCR 126, Mortimer J (as her Honour then was) adopted (at 165 [166]) the following description of this distinction as stated by Weinberg J in Cabal v Attorney-General (Cth) [2001] FCA 583; 113 FCR 154 at 166 [50]:

The so-called doctrine of “jurisdictional fact” (assuming that it is correct to so describe it) represents an exception to the principles of restraint which normally govern judicial review. “Jurisdictional fact” enables such review whenever the court determines for itself that a statutorily required fact does not exist. Parliament can stipulate that any action which it authorises depends upon the existence of various preconditions. The legislation may require the existence of those preconditions to be established in the mind of the person or body exercising the power, or in the mind of the reviewing court. Where the power depends upon factual requirements being demonstrated to the satisfaction of the person in whom it is reposed, it is that person’s determination of the facts which is decisive. The validity of the exercise of the power is unaffected if the person, acting in good faith and otherwise according to law, considers the facts, and reaches an opinion about them, albeit one which a court would not share. Where the power depends upon the existence of objective facts, the court on judicial review is given the final say as to whether the required facts exist.

60 Whether a particular fact is a jurisdictional fact is a matter that is to be resolved by applying the ordinary processes of statutory construction. As Mortimer J said in Country Carbon, “usually”, it will be easy to identify whether a fact is or is not intended to be a jurisdictional fact as there “will be a clear indication by Parliament that it is the repository’s state of mind which is to be decisive, rather than the objective existence of the alleged fact”: [167]. Ordinarily, this will be the case where the exercise of power is conditioned by the formation of an opinion or state of satisfaction of the relevant decision-maker. As Latham CJ stated in R v Connell; Ex parte Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd [1944] HCA 42; 69 CLR 407 at 430:

[W]here the existence of a particular opinion is made a condition of the exercise of power, legislation conferring the power is treated as referring to an opinion which is such that it can be formed by a reasonable man who correctly understands the meaning of the law under which he acts. If it is shown that the opinion actually formed is not an opinion of this character, then the necessary opinion does not exist…

61 As his Honour further said at 432:

It should be emphasized that the application of the principle now under discussion does not mean that the court substitutes its opinion for the opinion of the person or authority in question. What the court does do is to inquire whether the opinion required by the relevant legislative provision has really been formed. If the opinion which was in fact formed was reached by taking into account irrelevant considerations or by otherwise misconstruing the terms of the relevant legislation, then it must be held that the opinion required has not been formed. In that event the basis for the exercise of power is absent, just as if it were shown that the opinion was arbitrary, capricious, irrational, or not bona fide.

See also Avon Downs Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1949] HCA 16; 78 CLR 353 (Dixon J).

62 However, the distinctions are not always clear cut. As Gummow J stated in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Eshetu [1999] HCA 21; 197 CLR 611 at 651 [130]:

The “jurisdictional fact”, upon the presence of which jurisdiction is conditioned, need not be a “fact” in the ordinary meaning of that term. The precondition or criterion may consist of various elements… the phrase “jurisdictional fact” is an awkward one…

63 The decision of Spigelman CJ (with whom Mason P and Meagher JA agreed) in Timbarra Protection Coalition Inc v Ross Mining NL [1999] NSWCA 8; 46 NSWLR 55 remains seminal on the issue of jurisdictional fact: see Country Carbon at 164 [165]; see also Woolworths Ltd v Pallas Newco Pty Ltd [2004] NSWCA 422; 61 NSWLR 707 at 736–7 [153]. As his Honour there stated at 63–64 [37]–[42]:

The issue of jurisdictional fact turns, and turns only, on the proper construction of the statute: see, eg, Ex parte Redgrave; Re Bennett (1946) 46 SR (NSW) 122 at 125; 63 WN (NSW) 31 at 33. The parliament can make any fact a jurisdictional fact, in the relevant sense: that it must exist in fact (objectivity) and that the legislature intends that the absence or presence of the fact will invalidate action under the statute (essentiality): Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 72 ALJR 841 at 859-861; 153 ALR 490 at 515-517.

“Objectivity” and “essentiality” are two inter-related elements in the determination of whether a factual reference in a statutory formulation is a jurisdictional fact in the relevant sense. They are inter-related because indicators of “essentiality” will often suggest “objectivity”.

Any statutory formulation which contains a factual reference must be construed so as to determine the meaning of the words chosen by parliament, having regard to the context of that statutory formulation and the purpose or object underlying the legislation. There is nothing special about the task of statutory construction with regard to the determination of the issue whether the factual reference is a jurisdictional fact. All the normal rules of statutory construction apply. The academic literature which describes “jurisdictional fact” as some kind of “doctrine” is, in my opinion, misconceived. The appellation “jurisdictional fact” is a convenient way of expressing a conclusion — the result of a process of statutory construction.

Where the process of construction leads to the conclusion that parliament intended that the factual reference can only be satisfied by the actual existence (or non-existence) of the fact or facts, then the rule of law requires a court with a judicial review jurisdiction to give effect to that intention by inquiry into the existence of the fact or facts.

Where the process of construction leads to the conclusion that parliament intended that the primary decision-maker could authoritatively determine the existence or non-existence of the fact then, either as a rule of the law of statutory interpretation as to the intent of parliament, or as the application of a rule of the common law to the exercise of a statutory power — it is not necessary to determine which, for present purposes — a court with a judicial review jurisdiction will inquire into the reasonableness of the decision by the primary decision-maker (in the Wednesbury sense Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 KB 223), but not itself determine the actual existence or non-existence of the relevant facts.

Where a factual reference appears in a statutory formulation containing words involving the mental state of the primary decision-maker — “opinion”, “belief”, “satisfaction” — the construction is often, although not necessarily, against a conclusion of jurisdictional fact, other than in the sense that that mental state is a particular kind of jurisdictional fact: see Craig, Administrative Law, 3rd ed (1994) at 368-370; Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Teo (1995) 57 FCR 194 at 198C. Where such words do not appear, the construction is more difficult.

64 Spigelman CJ then stated at 65 [44]:

The authorities suggest that an important, and usually determinative, indication of parliamentary intention, is whether the relevant factual reference occurs in the statutory formulation of a power to be exercised by the primary decision-maker or, in some other way, necessarily arises in the course of the consideration by that decision-maker of the exercise of such a power. Such a factual reference is unlikely to be a jurisdictional fact. The conclusion is likely to be different if the factual reference is preliminary or ancillary to the exercise of a statutory power. The authorities suggest that an important, and usually determinative, indication of parliamentary intention, is whether the relevant factual reference occurs in the statutory formulation of a power to be exercised by the primary decision-maker or, in some other way, necessarily arises in the course of the consideration by that decision-maker of the exercise of such a power. Such a factual reference is unlikely to be a jurisdictional fact. The conclusion is likely to be different if the factual reference is preliminary or ancillary to the exercise of a statutory power.

65 His Honour further stated at 66 [52]:

One formulation of the relevant distinction is whether the fact referred to is “a fact to be adjudicated upon in the course of the inquiry” as distinct from an “essential preliminary to the decision making process”: Colonial Bank of Australasia v Willan (1874) 5 PC 417 at 443.

66 In Country Carbon, Mortimer J distilled Spigelman CJ’s reasons to the following core propositions (164–5 [165]):

(a) Parliament may make any fact a jurisdictional fact and where it does so, the consequence is that the fact “must exist” objectively (at [37]);

(b) To find that a fact is a jurisdictional fact, the Court must conclude, as a matter of statutory construction, that Parliament intended the presence (or absence) of the fact to invalidate the exercise of power (at [37]);

(c) Both “objectivity” and “essentiality” (Spigelman CJ’s terms) are inter-related elements in the determination of whether a matter is a jurisdictional fact (at [38]), albeit that the ordinary principles of statutory construction are to be applied (at [39]);

(d) A determination that a matter is not a jurisdictional fact involves a conclusion, after the process of construction is completed, that Parliament intended that the primary decision-maker could authoritatively determine the existence or non-existence of the fact, subject to judicial review of that determination (at [41]);

(e) Where “a factual reference appears in a statutory formulation containing words involving the mental state of the primary decision-maker —“opinion”, “belief”, “satisfaction”— the construction is often, although not necessarily, against a conclusion of jurisdictional fact” (at [42]);

(f) The location in the statutory structure of the alleged jurisdictional fact may be critical. Where the alleged fact is located in a provision conferring power, or arises in the course of the consideration by that repository of a power of its exercise, then this may suggest the fact is not intended to be jurisdictional. In contrast, if the fact is located as a preliminary or ancillary matter to the exercise of power, it may indicate Parliament intended the existence of the fact, objectively, to condition the exercise of power (at [44], [51]);

(g) Another way to put this factor is by asking the question whether the fact is “a fact to be adjudicated upon in the course of the inquiry” as distinct from an “essential preliminary to the decision making process” (at [52], referring to Colonial Bank of Australasia v Willan (1874) 5 PC 417 at 443). Spigelman CJ then lists a number of other authorities dealing with this factor (at [53]–[54]);

(h) Other aspects of a given statutory scheme may inform the characterisation the Court must make: see generally [67]–[81], where Spigelman CJ analyses a number of features of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) and the related Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW).

67 As the authorities make plain, the question as to whether a particular statutory provision creates a jurisdictional fact is a matter to be ascertained by the ordinary processes and techniques of statutory construction.

68 Here, it is necessary, as a starting position, to identify the relevant power that was being exercised by the Minister’s delegate. The exercise of that power must be viewed in the context of the particular scheme enacted under the EPBC Act involving the referral and assessment of proposed actions for approval as provided for in Part 9 (Approval of actions) of Chapter 4 (Environmental assessments and approvals) of the EPBC Act.

69 It is relevant that Div 1 of Pt 9 is entitled “Decisions on approval and conditions” and Subdiv A is entitled “General”. The first section of Subdiv A is s 130, which is entitled “Timing of decisions on approval”. Section 130(1) provides (as a “basic rule”) that “the Minister must decide whether or not to approve, for the purposes of each controlling provision for a controlled action, the taking of the action.” The exercise of that power must be read in the context of the period of time within which the Minister must make the decision (s 130(1A)) which, relevantly, is dependent upon when the Minister receives prescribed materials, whether that be the “assessment report”, a PER or otherwise (subject to extensions of time and the like).

70 Sections 133(1) and (1A) empower the Minister to grant an approval as follows:

133 Grant of approval

Approval

(1) After receiving the assessment documentation relating to a controlled action, or the report of a commission that has conducted an inquiry relating to a controlled action, the Minister may approve for the purposes of a controlling provision the taking of the action by a person.

(1A) If the referral of the proposal to take the action included alternative proposals relating to any of the matters referred to in subsection 72(3), the Minister may approve, for the purposes of subsection (1), one or more of the alternative proposals in relation to the taking of the action.

71 Section 133(2A) provides that an approval that is granted “is an approval of the taking of the action specified in the approval by” either “the holder of the approval” or “a person who is authorised, permitted or requested by the holder of the approval, or by another person with consent or agreement of the holder of the approval, to take the action”.

72 Section 133 outlines other requirements including as to:

(a) the content of an approval: sub-s (2);

(b) the notice to be given by the Minister: sub-s (3);

(c) the limitations on publication: sub-s (4); and

(d) importantly, notice of a refusal of approval: sub-s (7).

73 Pausing here, it is plain that it is the combination of ss 130 and 133 that empowers the Minister (or the Minister’s delegate) to grant or refuse an approval of controlled action. So much was not in dispute between the parties.

74 Section 134(1) empowers the Minister to attach a condition to the approval of the action if the Minister is “satisfied” that “the condition is necessary or convenient for” either the protection of a matter protected by Pt 3 or “repairing or mitigating damage to a matter protected by a provision of Part 3” for which the approval has effect “whether or not the damage has been, will be or is likely to be caused by the action”. Amongst other things, s 134(3)(e) provides that an example of a condition that the Minister may attach includes (if certain elections have been made) the requirement for an “action management plan to be submitted to the Minister for approval” and the “implementation of the plan so approved”.

75 Further, as set out above, Subdiv B of Pt 9 sets out the matters to be considered in the exercise of that power; they are not conditions that are a predicate to the exercise of that power. In this regard, s 136 sets out “General considerations” including “Mandatory considerations” (s 136(1)), “Factors to be taken into account” (s 136(2)) and a relevant person’s “environmental history” (s 136(4)). Section 136(5) states that in deciding whether or not to approve the taking of an action, and what conditions to attach to it, the Minister “must not consider any matters that the Minister is not required or permitted” by the Division of Part 9 to consider.

76 Sections 137 to 140 are styled as “Requirements” for particular types of decisions. These provisions are not identical to each other as they relate to different subject matter, but the text of each section specifies that, in deciding whether or not to approve particular types of actions, the Minister “must not act inconsistently with” particular obligations. The general subject of each of sections 137 to 140 is as follows:

(a) s 137 provides “in deciding whether or not to approve” for the purposes of ss 12 or 13A the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to it, the Minister “must not act inconsistently” with Australia’s obligations under the World Heritage Convention or the Australian World Heritage management principles or a plan that has been prepared for the management of a declared World Heritage property under ss 316 and 321;

(b) s 137A provides that “in deciding whether or not to approve” for the purposes of ss 15B or 15C the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to it, the Minister “must not act inconsistently” with the National Heritage management principles or an agreement to which the Commonwealth is a party in relation to a National Heritage place or a plan that has been prepared for the management of a National Heritage place under ss 324S and 324X;

(c) s 138 provides that “in deciding whether or not to approve” for the purposes of ss 16 or 17B the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to it, the Minister “must not act inconsistently” with Australia’s obligations under the “Ramsar wetlands”;

(d) s 139 provides that “in deciding whether or not to approve”, for the purposes of ss 18 or 18A the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to it, the Minister “must not act inconsistently” with Australia’s obligations under particular International Conventions or a recovery or abatement plan; and

(e) as noted above, s 140, which is central to the applicant’s case, relevantly provides that for the purposes of ss 20 or 20A the taking of an action and what conditions to attach to it, the Minister “must not act inconsistently” with Australia’s obligations under the Bonn Convention and the Specified Bilateral Treaties.

77 Section 140A is cast in different terms to ss 137 to 140. It provides that the Minister “must not approve an action consisting or involving the construction or operation of” particular nuclear installations.

78 Division 2 of Pt 9 imposes requirements upon approval holders to comply with the conditions attaching to an approval and creates both civil penalty and criminal offences in respect of contraventions and breaches of those conditions. Division 3 of Pt 9 empowers the Minister to vary, revoke or suspend conditions attaching to an approval and for variations to action management plans. Division 4 of Pt 9 makes provision for the transfer of approvals between persons. And, Div 5 makes provision for the extension of the period of effect of an approval.

79 Stepping back from these provisions, and looking at them as a whole, it is apparent that the text, context and structure of Pt 9 reveals the following central components to the power conferred upon the Minister to grant or not grant an approval:

(a) first, the Minister must decide whether or not to grant approval and must do so within a prescribed period of time;

(b) second, the Minister “may” decide to approve or not approve the taking of a proposed action after receiving the assessment documentation;

(c) third, in deciding whether to approve the taking of a proposed action, the Minister may attach conditions to an approval that are “necessary or convenient”;

(d) fourth, in deciding whether to approve the taking of a proposed action:

(i) the Minister must take into account certain mandatory considerations;

(ii) the Minister may take into account other factors; and

(iii) the Minister must not take into account other matters;

(e) fifth, in deciding whether to grant approval, the Minister must comply with other requirements as to the content of the decision, the notice that is to be given in relation to the approval or decision not to approve the taking of the proposed action, and limits on the publication of a decision to approve the proposed action;

(f) sixth, in deciding whether to grant approval, the Minister must not act inconsistently with particular obligations that Australia has under international or domestic law; and

(g) finally, the Minister must not approve an action relating to particular nuclear installations.

80 This analysis is consistent with what the Full Court stated in ACF Adani FFC at 368 [26]–[28] that:

In summary, in making a decision concerning a proposed action, the Minister:

• must or may consider identified matters;

• must not consider any other matters;

• must not act inconsistently with World Heritage obligations, principles and management arrangements; and

• must not act inconsistently with National Heritage management principles, agreements and plans.

The Minister must also consider the precautionary principle set out in s 391.

There are no criteria as to which the Minister must be satisfied in order to grant approval. By definition, the approval is of an action which has, will have or is likely to have a significant impact upon the protected matters identified by the controlling provisions.

(Emphasis added.)

81 The third and fourth bullet points in the extract above reflect ss 137 and 137A of the EPBC Act but apply equally to s 140.

82 In determining whether s 140 gives rise to a jurisdictional fact, it is relevant but not determinative that the text of s 140 does not expressly refer to words that are indicative that it is a provision that requires the Minister to form an opinion, belief or state of satisfaction as to whether the proposed action is not inconsistent with the Specified Bilateral Treaties: cf Timbarra at 65 [42] (Spigelman CJ). However, in my view, it is more relevant that s 140 is not situated in a “provision conferring power” on the Minister and is instead located within the structure of the EPBC Act which specifies the considerations and requirements that the Minister must take into account in the exercise of the power to grant or refuse to grant an approval: Timbarra at 65 [44] and 66 [51]. The relevant provisions that confer power upon the Ministers are ss 130(1) and 133(1). Neither s 130(1) nor s 133(1) specify that the exercise of power by the Minister in those provisions is conditional upon s 140 as a factual predicate or essential preliminary.

83 In this respect, it is significant that the empowering provisions are located in Subdiv A of Ch 4, Pt 9, Div 1 of the EPBC Act whereas s 140 is located within Subdiv B of the same Division which deals with “Considerations for approvals and conditions” (emphasis added). As noted above, Subdiv B specifies a range of considerations that the Minister must consider and take into account in deciding whether or not to approve the taking of the relevant action. This is reinforced by the specific text of s 140 that is expressed as applying to the Minister “In deciding whether or not to approve for the purposes of section 20 or 20A the taking of an action relating to a listed migratory species, and what conditions to attach to such an approval…”. That text is more consistent with the subject matter of s 140 being a matter that the Minister must consider in deciding whether or not to approve the relevant action and what conditions to attach to such a decision as opposed to it being an essential preliminary or predicate to the exercise of the relevant power. Together, the text of s 140 and its location in the legislative scheme point towards it being one factor of many that must be evaluated in the decision-making process and points away from it being an essential preliminary that must be satisfied before the power in ss 130 and 133 is enlivened.

84 Further, the subject matter of s 140, which involves the Minister “not acting inconsistently with” Australia’s obligations under the Specified Bilateral Treaties, is consistent with it being a matter that requires the formation of an opinion by the Minister as opposed to it being a matter of objective fact as an “essential preliminary to the decision making process”: Timbarra at [52]. The requirement that, in deciding whether or not to approve the taking of the relevant action, the Minister must “not act inconsistently with” Australia’s relevant international obligations is consistent with a task that requires the Minister to form an opinion that the relevant action will not have that effect, as opposed to it being an objective fact that the relevant action is not in accordance with the relevant obligations. As a matter of substance, whether the decision to approve the relevant action is not inconsistent with a legal instrument such as a treaty requires the interpretation of the relevant instrument and its application, which lends itself to being a matter that requires the formation of an opinion, about which reasonable minds may differ. The present matter provides a case in point where, irrespective of the legally correct conclusion, reasonable minds might differ in their view as to whether the relevant action amounts to a “taking” of the protected migratory bird species and, if so, whether that conduct is or is not inconsistent with the Specified Bilateral Treaties.

85 This is especially the case given that the subject matter of s 140 involves an examination of whether the Minister has “not act[ed] inconsistently with” Australia’s obligations under particular legal instruments. As Mortimer J noted in Friends of Leadbeater's Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178; 260 FCR 1 at 54 [215], in the context of a similarly worded provision of the EPBC Act, “a statutory imperative to act ‘not inconsistently with’ is intended by Parliament to be to some extent a softer requirement than an imperative to act ‘in accordance with’” and is intended “to give the responsible Minister more flexibility to impose conditions” which are not the subject of but nevertheless “not inconsistent with” Australia's relevant international obligations. Again, whether the Minister has not acted inconsistently with particular legal instruments lends itself to being a matter of opinion and impression, as opposed to an objective fact.

86 These conclusions are consistent with those reached by Griffiths J in Australian Conservation Foundation Inc v Minister for the Environment [2016] FCA 1042; 251 FCR 308 (Adani), whose conclusions were not the subject of the appeal in ACF Adani FFC (which was, in any event, dismissed). In Adani, Griffiths J considered an argument that a decision by the Minister to approve the construction of a coal mine was affected by error, because, contrary to s 137 of the EPBC Act, the Minister's decision was inconsistent with Australia's obligations under the World Heritage Convention (WHC): at 308 [65]. The Minister's position regarding the proper construction of Art 4 of the WHC was contended by the applicant to be “plainly wrong”: at 336 [85]. Griffiths J stated at 357 [201]–[202]:

The ACF did not suggest that the prohibition imposed by s 137 had the effect of making inconsistency with Australia’s obligations under the WHC a jurisdictional fact. It was a matter for the Minister to form a view, on proper legal grounds, whether or not giving approval to the taking of an action and any conditions which are attached would have the effect of creating an inconsistency with Australia’s obligations under the WHC.

The Minister was mindful of the prohibition imposed by s 137 when he made his decision. It is expressly referred to in [168] to [171] of his statement of reasons and is identified in Annexure A to that statement as one of the statutory provisions he took into account.

87 Although Griffiths J observed that it had not been suggested that s 137 gave rise to a jurisdictional fact, his Honour’s conclusion that the subject matter of the provision was one that required the Minister to “form a view, on proper legal grounds” was dispositive of the contentions that had been advanced by the applicant in that case. In the present case, the applicant contended that Griffiths J’s decision was not on point as it related to a different provision of the EPBC Act and is therefore not binding on me. I accept that contention. Nevertheless, Griffith J’s reasoning is persuasive and accords with the conclusion that I have independently reached as to proper construction of s 140.

88 As Spigelman CJ observed in Timbarra at [38], both “objectivity” and “essentiality” are inter-related elements in the determination of whether a matter is a jurisdictional fact. For the reasons, stated above, viewed within the structure and context of the Pt 9 of Ch 4 of the EPBC Act, s 140 is neither an objective nor essential preliminary or factual predicate to the exercise of power contained in ss 130(1) and 133(1) such that it does not give rise to a jurisdictional fact.

89 It follows that this aspect of the applicant’s challenge to the Approval Decision fails.

4.3 Invalidity

90 The applicant next contended that s 140 was jurisdictional in the sense that non-compliance with that provision leads to invalidity. In support of this contention, the applicant submitted that the text of s 140 was expressed in imperative terms which indicated a Parliamentary intention that non-compliance would result in invalidity. It was further submitted that this was consistent with the structure of the EPBC Act and its objects which included the protection of migratory bird species (ss 3(a)–(c)) and the honouring of international commitments (s 3(e)) such that s 140 was fundamental to these purposes. It was submitted that in view of these matters, it was unlikely that Parliament intended to “permit a scenario where the Minister can misunderstand or ignore the treaties, or even deliberately breach them, and yet produce a valid decision”.

91 I do not accept the applicant’s contentions. The fact that the language of s 140 is expressed in imperative terms (ie, that the Minister “must not act inconsistently with…”) is not determinative as to the question of invalidity. As was explained in Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; 194 CLR 355 at 388–9 [91] (McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ):

An act done in breach of a condition regulating the exercise of a statutory power is not necessarily invalid and of no effect. Whether it is depends upon whether there can be discerned a legislative purpose to invalidate any act that fails to comply with the condition. The existence of the purpose is ascertained by reference to the language of the statute, its subject matter and objects, and the consequences for the parties of holding void every act done in breach of the condition. Unfortunately, a finding of purpose or no purpose in this context often reflects a contestable judgment. The cases show various factors that have proved decisive in various contexts, but they do no more than provide guidance in analogous circumstances. There is no decisive rule that can be applied; there is not even a ranking of relevant factors or categories to give guidance on the issue.

(Emphasis added; citations omitted.)

92 More recently, in Miller v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs [2024] HCA 13; 278 CLR 628, Gageler CJ, Gordon, Edelman, Jagot and Beech-Jones JJ stated at 638 [27]–[29]:

Two other aspects of the principle of statutory construction expounded in Project Blue Sky are of present significance.

The first is that mere use of imperative language to express a condition imports no presumption that non-compliance with the condition is intended to result in invalidity. That is not to deny that juxtaposition of an imperative term (“must”) with a permissive term (“may”) to express different requirements of the one statutory scheme might in an appropriate statutory context indicate that the imperative term is used to express a legislative intention that non-compliance is to result in invalidity whilst the permissive term is used in contradistinction to express a legislative intention that non-compliance is not to result in invalidity.

The second is that identical imperative language might be used in a particular statutory scheme to express a suite of requirements, some of which will admit of one answer to the Project Blue Sky question and some of which will admit of another answer…

(Emphasis added; citations omitted.)

93 In the context of the text and structure of Pt 9 of Ch 4 of the EPBC Act, it is in my view significant that there is a distinction drawn between those obligations that are expressed to be mandatory considerations (as specified in s 136) and others that form part of the balance of matters that the Minister is required to consider including s 140 and which are not framed as mandatory considerations. Moreover, as addressed above, the subject matter and language of s 140, which is cast in terms of a “softer requirement” (than the language of “in accordance with”) and involves the formation of a legal opinion do not lend themselves to matters about which it can be said that there is an objectively ascertainable conclusion from which invalidity will follow.

94 That is not to say that the legality of the Approval Decision may not be challenged on other grounds relating to s 140, for example, if it was contended that the Minister or her delegate had failed to consider s 140. In Adani, Griffiths J did not decide the point whether non-compliance with s 137 of the Act would lead to invalidity but rejected the Minister’s contention “that the issue of compliance with s 137 is non-justiciable in this Court”: at 357 [205]. However, as noted above, Griffiths J concluded that the Minister had given consideration to the matters required by s 140 and the error alleged by the applicant in that case was not established.

95 In the present case, there was no issue taken that the Minister’s delegate had in fact turned his mind to the matters required by s 140 of the EPBC Act (other than that an issue was pressed that the delegate had misdirected himself as to the meaning of the word “taking”, which is dealt with below). The true substance of the applicant’s contention was that the Minister’s delegate had reached the objectively wrong conclusion. However, for the reasons already stated, I do not accept the premise upon which the applicant’s argument was based. That being the case, there was little more to the applicant’s argument as to invalidity than those which were advanced in support of its argument that the provision gave rise to a jurisdictional fact.

96 Accordingly, I am not satisfied as to this aspect of the applicant’s case.

4.4 The Approval Decision was not inconsistent with the Treaties

97 In any event, I am not satisfied that in making the decision to approve the relevant action, the Minister’s delegate acted inconsistently with Australia’s obligations under the Specified Bilateral Treaties.

98 All parties agreed that as a general rule, the Specified Bilateral Treaties were to be construed in accordance with general principles of treaty interpretation, as set out in Art 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969. Relevantly, Arts 31 and 32 provide as follows:

Article 31

General rule of interpretation

1. A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.

2. The context for the purpose of the interpretation of a treaty shall comprise, in addition to the text, including its preamble and annexes: