FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd v Jackson's Art Supplies Ltd [2025] FCA 530

File number: | WAD 255 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | JACKSON J |

Date of judgment: | 23 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY - application for injunctive relief for breaches of s 18, s 29(1)(g) or s 29(1)(h) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Sch 2 (ACL) and passing off - delay by applicant in seeking relief - discretionary refusal of wide injunctive relief CONSUMER LAW - misleading or deceptive conduct - passing off - use of the names 'Jackson's', 'Jackson's Art' and 'Jackson's Art Supplies' to sell art products online - country-specific subdomain for Australia with Australian characteristics - reference to Adelaide warehouse and Australian telephone number on the country-specific subdomain - second respondent dispatched products and communicated with Australian consumers - applicant's reputation online and outside Western Australia and the Northern Territory - accessorial liability of the respondents - representations made - conduct misleading and constituted passing off |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) Schedule 2 (Australian Consumer Law) ss 2, 18, 29, 232, 236, 237, 243 Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 59, 60, 66A, 69, 135, 191 |

Cases cited: | 10th Cantane Pty Ltd v Shoshana Pty Ltd (1987) 79 ALR 299 Apand Pty Ltd v Kettle Chip Company Pty Limited (1994) 52 FCR 474 Ashbury v Reid [1961] WAR 49 Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2016] FCAFC 80; (2016) 248 FCR 280 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Air New Zealand Limited (No 1) [2012] FCA 1355; (2012) 207 FCR 448 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 146; (2007) 161 FCR 513 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 142 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; (2020) 278 FCR 450 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Valve Corporation (No 3) [2016] FCA 196 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v viagogo AG (No 3) [2020] FCA 1423 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd (No 2) [2024] FCA 1086 Australian Woollen Mills Limited v F. S. Walton and Co Limited (1937) 58 CLR 641 Beamer Pty Ltd v Star Lodge Supported Residential Services Pty Ltd [2005] VSC 236 Bed Bath 'N' Table Pty Ltd v Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1587 Bodum v DKSH Australia Pty Limited [2011] FCAFC 98 Bridge Stockbrokers Ltd v Bridges (1984) 4 FCR 460 Brown v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 Burswood Management Ltd v Burswood Casino View Motel/Hotel Pty Ltd (1987) ATPR 40-824 Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 70; (2007) 159 FCR 397 Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; (2000) 202 CLR 45 Cassidy v Saatchi & Saatchi Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 34; (2004) 134 FCR 585 Colorado Group Limited v Strandbags Group Pty Limited [2006] FCA 160 Colorado Group Limited v Strandbags Group Pty Limited [2007] FCAFC 184; (2007) 164 FCR 506 Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Citigroup Global Markets Australia Pty Limited (No 1 - Indictment) [2021] FCA 757 ConAgra Inc v McCain Foods (Aust) Pty Ltd (1992) 33 FCR 302 Crawley v Short [2009] NSWCA 410 Dometic Australia Pty Ltd v Houghton Leisure Products Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1573 Downey v Carlson Hotels Asia Pacific P/L [2005] QCA 199 Emwest Products Pty Ltd v Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union [2002] FCA 61; (2002) 117 FCR 588 Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate Co (1878) 3 AC 1218 Ethicon Sarl v Gill [2021] FCAFC 29; (2021) 288 FCR 338 Federal Treasury Enterprise (FKP) Sojuzplodoimport v Spirits International BV [2024] FCAFC 152 Global Projects Management Ltd v Citigroup Inc [2005] EWHC 2663 Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd v Bed Bath 'N' Table Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 139 Handlen v The Queen [2011] HCA 51; (2011) 245 CLR 282 Harcourts WA Pty Ltd v Roy Weston Nominees Pty Ltd (No 5) [2016] FCA 983 Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Careline Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 105; (2018) 264 FCR 422 ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 In-N-Out Burgers, Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 193 Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 Knott Investments Pty Ltd v Winnebago Industries, Inc [2013] FCAFC 59; (2013) 211 FCR 449 Knott Investments Pty Ltd v Winnebago Industries, Inc (No 2) [2013] FCAFC 117 Lardil, Kaiadilt, Yangkaal, Gangalidda Peoples v State of Queensland [2000] FCA 1548 Leighton Contractors Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] WASC 144 Lindsay Petroleum Company v Hurd (1874) LR 5 PC 221 Los Carnales Pty Ltd, in the matter of Cartel Del Taco Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1053 Makita (Aust) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705 Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1; [2003] FCAFC 289 Metro Business Centre Pty Ltd v Centrefold Entertainment Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1249 Mitolo Wines Aust Pty Ltd v Vito Mitolo & Son Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 902 Moorgate Tobacco Co. Limited v Philip Morris Limited (No 2) (1984) 156 CLR 414 Mortgage House of Australia Pty Ltd v Mortgage House International Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1279 National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90 Natural Waters of Viti Limited v Dayals (Fiji) Artesian Waters Ltd [2007] FCA 200 Optical 88 Limited v Optical 88 Pty Limited (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380 Orr v Ford (1989) 167 CLR 316 Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; (2017) 251 FCR 379 Rafferty v Madgwicks [2012] FCAFC 37; (2012) 203 FCR 1 Ringrow Pty Ltd v BP Australia Ltd [2003] FCA 933; (2003) 130 FCR 569 SAP Australia Pty Ltd v Sapient Australia Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1821 Scandinavian Tobacco Group Eersel BV v Trojan Trading Co Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1086 Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1403 Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 277 CLR 186 Shape Shopfitters Pty Ltd v Shape Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 865 SMA Solar Technology AG v Beyond Building Systems Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] FCA 1483 State Government Insurance Corp v Government Insurance Office of New South Wales (1991) 28 FCR 511 State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 137 Telstra Corporation Limited v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 568 Thai World Import & Export Co Ltd v Shuey Shing Pty Ltd (1989) 17 IPR 289 The Tubby Trout Pty Ltd v Sailbay Pty Ltd (1992) 42 FCR 595 Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd v Gymboree Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 618; (2000) 100 FCR 166 Trivago N.V. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185 Turner v General Motors Australia Pty Ltd (1929) 42 CLR 352 Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirène Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82 viagogo AG v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2022] FCAFC 87 Wardley Australia Limited v The State of Western Australia (1992) 175 CLR 514 World Series Cricket Pty Ltd v Parish (1977) 16 ALR 181 Yorke v Lucas (1983) 49 ALR 672 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Western Australia |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Trade Marks |

Number of paragraphs: | 827 |

Date of hearing: | 24-28 June 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr J Cooke SC with Mr D Larish |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Bennett |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr C Golvan KC with Mr T Besanko |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Wallmans Lawyers |

Counsel for the Cross-Claimant: | Mr C Golvan KC with Mr T Besanko |

Solicitor for the Cross-Claimant: | Wallmans Lawyers |

Counsel for the Cross-Respondents: | Mr J Cooke SC with Mr D Larish |

Solicitor for the Cross-Respondents: | Bennett |

ORDERS

WAD 255 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JACKSONS DRAWING SUPPLIES PTY LTD (ACN 008 723 055) Applicant | |

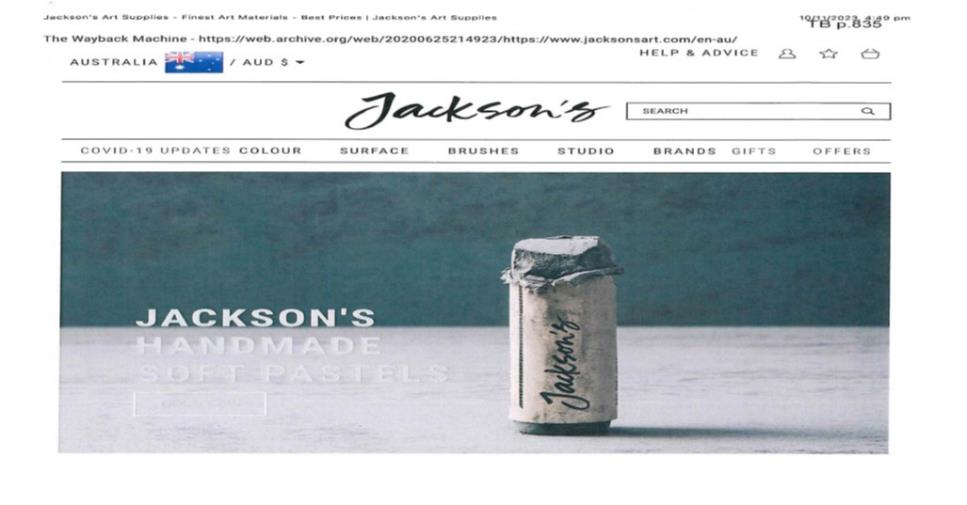

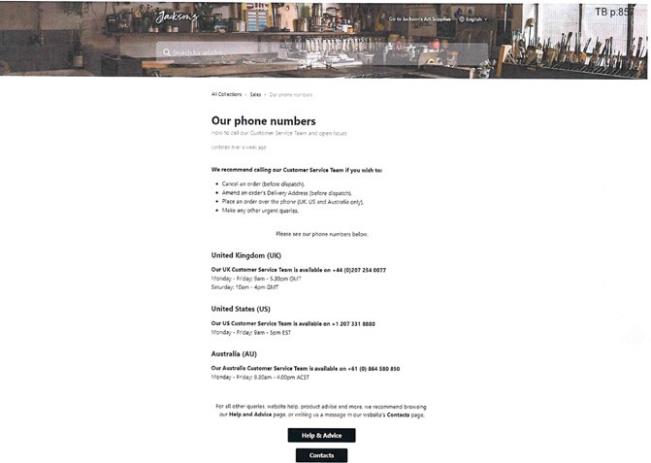

AND: | JACKSON'S ART SUPPLIES LTD First Respondent JACKSON'S ART AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 658 761 776) Second Respondent JACKSON'S ART HOLDINGS AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 658 493 728) Third Respondent PYRMONT CAPITAL PARTNERS PTY LTD (ACN 656 079 140) Fourth Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | JACKSON'S ART SUPPLIES LTD Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | JACKSONS DRAWING SUPPLIES PTY LTD (ACN 008 723 055) First Cross-Respondent MICHAEL FRANCIS BOERCAMP Second Cross-Respondent | |

order made by: | JACKSON J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 MAY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. A case management hearing will be convened to make directions for the determination of the form of non-pecuniary relief.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of Contents

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKSON J:

1 The applicant, Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd (JDS), sells art products from stores located in Western Australia and the Northern Territory, by means of the website www.jacksons.com.au (JDS Website), and also by means of orders placed by account customers.

2 The first respondent, Jackson's Art Supplies Ltd (JAS), is based in the United Kingdom. It sells art products in Australia and elsewhere by means of the website www.jacksonsart.com (JAS Website).

3 JDS trades under the names 'Jacksons' and 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies'. JAS trades under the names 'Jackson's', 'Jackson's Art' and 'Jackson's Art Supplies'. The parties are in dispute about their respective uses of these names, in conjunction with other conduct. No trade mark registered in Australia is involved.

4 JDS commenced this proceeding, alleging breaches of s 18 and s 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) and liability for the tort of passing off. As well as JAS, the respondents to that claim are an Australian company called Jackson's Art Australia Pty Limited (JAA), which is indirectly majority owned by JAS, and the two immediate shareholders of that company, Jackson's Art Holdings Australia Pty Limited (JAH) and Pyrmont Capital Partners Pty Ltd (PCP). JAA is alleged to be liable as a principal wrongdoer and also as an accessory, that is, by reason of being knowingly involved in JAS's alleged breaches of the ACL and as a joint tortfeasor. JAS is likewise said to having accessory liability for JAA's conduct. JAH and PCP are said to be liable as accessories to JAA's conduct.

5 JAS has cross-claimed alleging contravening and tortious conduct against JDS. The Managing Director of JDS, Michael Boercamp, is also named as a respondent by reason of alleged accessory liability.

6 For the following reasons, JDS has established its claim for breaches of the ACL and passing off against JAS and JAA. But I am not prepared to grant injunctive relief in the terms JDS seeks, and further submissions on relief will be necessary after the parties have had an opportunity to consider these reasons. JDS's claim against JAH and PCP will be dismissed. So will JAS's cross-claim against JDS and Mr Boercamp.

I. BACKGROUND

7 Some uncontentious facts can be set out by way of background.

JDS and JAA

8 JDS's business has a long history. From the 1930s to the 1950s, Harry Jackson and George Jordan operated 'Jordans and Jacksons Printers and Stationers' in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. After Mr Jordan's premature death, and the intervention of the Second World War, Harry Jackson withdrew from the printing side of the business and started his first store in Perth in 1955, under the name 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies'. The business has been in continuous operation in the sale of art products since then. JDS was incorporated to carry on the business in 1969.

9 After Harry Jackson's retirement in 1977, control of the business passed to his son, Kevin Jackson. He expanded the retail business into the suburbs of Perth and to regional centres in Western Australia, as well as into the Northern Territory.

10 The second cross-respondent, Mr Boercamp began working for JDS in 1995 as the company accountant. On 30 June 2010 he bought Kevin Jackson out of the business. All the shares in JDS were acquired by Canmore Holdings Pty Ltd, a company of which Mr Boercamp and his wife Jennifer Boercamp are the shareholders and directors. Mr Boercamp has been JDS's Managing Director since then.

11 JDS trades under the names 'Jacksons' and 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd'. It has used the following logos on its physical stores and website from time to time:

12 It will be noted that the second of the names mentioned above is the full company name, which also appears in full in at least two of the logos. However as will be seen, the names that JDS pleads in connection with its alleged reputation are 'Jacksons' and 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies' (JDS Names). Neither party raised any issue connected with the inclusion or omission of the 'Pty Ltd' in the trading name, which I will treat as being of no consequence.

13 When Canmore Holdings Pty Ltd acquired JDS in 2010, JDS had 15 physical stores. Nine of them were in the Perth metropolitan area. Four were in the Western Australian regional centres of Mandurah, Bunbury, Busselton and Geraldton. The others were in Darwin and Alice Springs.

14 Since then, four of the Perth stores have been closed, as has the Geraldton store. An additional store has opened in another Perth suburb. That leaves six stores in the Perth metropolitan area, three stores in Western Australian regional centres and two stores in the Northern Territory.

15 At no time has JDS had any physical stores outside Western Australia and the Northern Territory. While the geographical and other break up of its revenue was controversial, it was not in issue that its overall sales are significant, with average sales revenues of about $11.8 million per annum between 1994 and 2010, and about $9.7 million per annum between 2010 and 2023.

16 JDS registered the domain name for the JDS Website in 2002 and the website was operational and accessible to internet users in Australia (and elsewhere) from about 2006. In fact, JDS operated a website (from a different URL) from 1997.

JAS

17 JAS was incorporated in the United Kingdom in 2000. Both Gary Thompson and Michael Venus have been directors of JAS since its incorporation. Mr Thompson is Executive Director and manages JAS's operations. Mr Venus is not involved in day to day management.

18 Like JDS, JAS sells art products. It does so through retail stores in the United Kingdom and online.

19 JAS trades under the following names (JAS Names):

(a) 'Jackson's';

(b) 'Jackson's Art'; and

(c) 'Jackson's Art Supplies'.

20 It also trades using the following logo:

21 JAS registered the domain name for the JAS Website in 2000 and the website has been in operation since about 2001. It has been accessible to internet users in Australia since that time.

22 From around 2013 to July 2015, consumers were able to select different currencies in which to pay for goods, including Australian dollars (AUD). The default currency was pounds sterling (GBP). The ability to select other currencies was available when the user went to specific products on the JAS Website; it was not apparent on the landing page or home page. However from July 2015 to October 2018, the option of selecting currencies other than GBP, including AUD, became available on the home page.

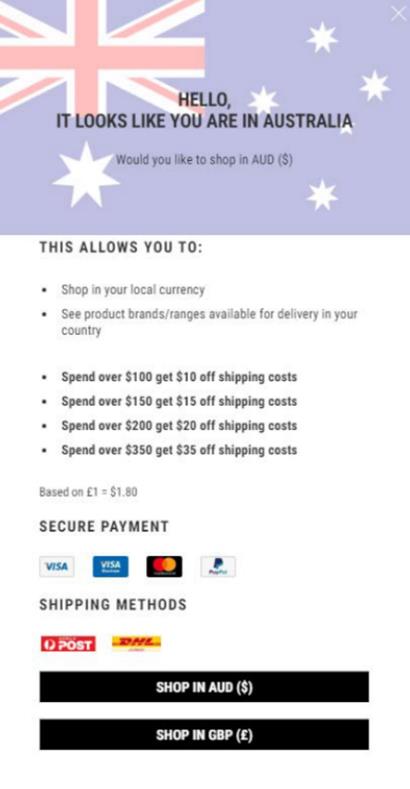

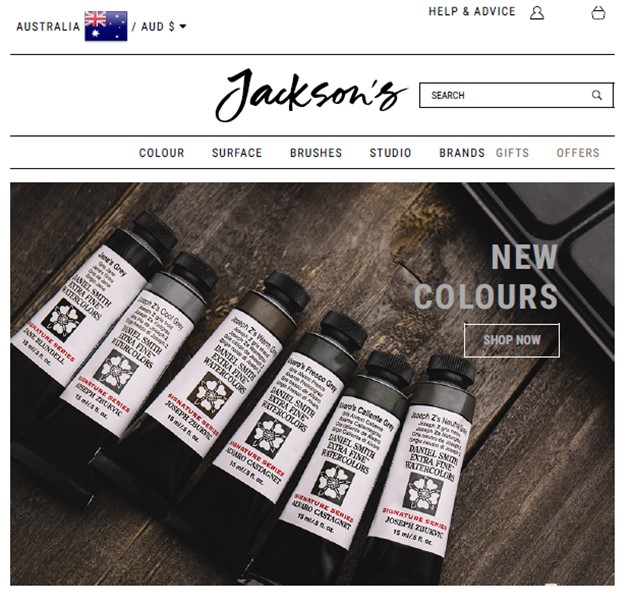

23 From around October 2018 until mid-2023, internet users in Australia who accessed the JAS Website were presented with a pop-up window giving them the option to shop in either AUD or GBP (AU Pop Up). If they selected AUD, they were taken to a subdirectory (jacksonsart.com/en-au, the JAS AU Site) which presented an Australia-specific store front with Australian dollars as the default currency. It was 'Australia-specific' in the sense that the particular content and configuration of web pages found on the JAS AU Site was only presented to customers who were identified as accessing it from devices in Australia.

24 The second respondent, JAA was incorporated in April 2022. Its principal place of business is in Campbelltown, a suburb of Adelaide. The directors of JAA are Mr Thompson, Mr Venus and Mr Baumgartner. Mr Baumgartner is Executive Director of JAA and is involved in its day to day management. Its shareholders are the third respondent, JAH (as to 90%) and the fourth respondent, PCP (as to 10%).

25 JAH is controlled by Mr Thompson, Mr Venus and Michelle Varley (Mr Thompson's sister, who lives in Western Australia). Its sole shareholder (as at 13 December 2022) is a company called Jacksons Art Supplies Ltd (ACN 658 493 737) whose address is in London. PCP is controlled by Franz Baumgartner and his wife Magrifa Sadri, who are based in Adelaide. Its shareholders are Mr Baumgartner (50%) and Ms Sadri (50%) (as at 13 December 2022).

26 Since mid-2022, the JAS AU Site has referred to Adelaide at the bottom of each page, has provided an Australian phone number with Australian Central Standard Time opening hours, has referred to the dispatch of goods from an Australian warehouse, and has indicated that phone orders can be placed in Australia. Although JAA has operated that warehouse from mid-2022, at no time has JAS had any physical stores in Australia. The evidence about JAS and JAA's presence in Australia will be described in more detail in Section V below.

II. THE ISSUES

The issues in detail - JDS's claim

27 The following issues arise on the pleadings, as modified by the parties' submissions and a statement of agreed facts between them. While that statement did not follow the formal requirements of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), the parties treated it as having established the facts that are set out in it, and by analogy to s 191(2)(a) I will proceed on the basis that evidence is not required to establish those facts.

JDS's reputation and trading names

28 The first area of dispute concerns the extent to which JDS has marketed its goods under the names 'Jacksons' or 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies'. JDS pleads that since commencing operations, it has 'extensively advertised, marketed, promoted, offered, sold and supplied arts and crafts products' under those names (Second Further Amended Statement of Claim filed 25 June 2024 (SOC) para 8). The respondents deny this. They also deny JDS's allegation that it has enjoyed significant success and its sales have been and continue to be extensive. However it was clear from opening submissions that the respondents do not dispute that JDS has a substantial reputation connected with sales to customers in the stores based in Western Australia and Northern Territory (JDS's core markets). In issue are JDS's reputation outside those core markets, and its online presence.

29 Also in dispute is whether Australian consumers have referred to JDS as 'Jacksons Art' or 'Jacksons Art Supplies'. JDS pleads that this has been so since at least 2010. JAS denies it.

30 As a result, JAS denies JDS's plea that at all material times it has had and continues to have 'a substantial reputation and goodwill in Australia in each of "JACKSONS", "JACKSONS DRAWING SUPPLIES", "JACKSON'S ART" and "JACKSONS ART SUPPLIES" in relation to the supply and sale of arts and crafts products' (SOC para 12). However, consistently with what has just been said, it does not appear that JAS disputes that JDS has a substantial reputation and goodwill in its core markets in connection with the first two of those trading names.

31 In large part, JAS's resistance to JDS's pleas as to its reputation and goodwill is founded on four contentions:

(a) JDS does not have any reputation in 'Jackson's Art' or 'Jackson's Art Supplies', being the names under which JAS has traded;

(b) JDS's reputation in 'Jacksons' and 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies' is mostly connected to in-store sales and to direct order sales (for example by schools or government agencies) in its core markets;

(c) JDS's online business is small; and

(d) JDS has not established that it has any reputation outside its core markets.

JAS's website and Australia

32 The next area of dispute concerns the JAS Website and its connection to Australia. JAS pleads that it has sold art supplies to customers in Australia through that website since at least 2005 and 'has established a reputation in Australia trading in art supplies and affiliated products' under the names and logo set out at [19] above (Amended Third Defence filed 27 June 2025 (Defence) para 13.1).

33 While, on its face, that involves the offering and sale of the same kinds of products as JDS, JAS has adduced evidence that it offers 'fine art supplies'. It appears that while JAS accepts that both it and JDS sell art products, so that there is a substantial overlap in the kinds of products they respectively sell, JAS maintains that its character as a fine art supplier, and as a company that does not sell craft supplies, is one feature of its business that is likely to lead consumers to differentiate it from JDS. It will become apparent below that I do not accept that the distinction drawn by JAS is significant for the purposes of this case. The products that each of JAS and JDS offer for sale will be referred to as art supplies.

34 JDS joins issue with these matters, and denies similar allegations made in the cross-claim. It appears from objections to evidence that JDS made that it puts JAS to proof on these matters. However JDS made no concerted attempt at trial to contradict or disprove JAS's claims about its reputation.

The conduct of JAS that JDS impugns

35 JDS divides the conduct of JAS that it impugns into three categories. The respondents sought to hold JDS to a very specific case about the conduct it alleged was misleading or deceptive. I will need to examine that aspect of the pleadings in detail in Section VII below.

36 At present, it is enough to say that the conduct of JAS which JDS seeks to impugn is comprised of the offering, promotion and sale of art supplies on the JAS Website using the JAS Names, but only by reference to specific characteristics of the website that were introduced in October 2018 and further characteristics that were introduced in mid-2022. The first of these were, broadly, offering AUD as a choice of default currency for the JAS AU Site (from June 2023 AUD (with New Zealand dollars) was the only currency offered on that subdirectory) and references to Australia on the site. The characteristics introduced in mid-2022 were, broadly, references to JAA's operations in Australia. Those matters are alleged to have constituted misleading or deceptive conduct in conjunction with JAA's conduct in dispatching orders using the JAS Names and doing other things.

37 The respondents do not dispute these bare facts, although they do maintain that other characteristics of its website are relevant and must be taken into account, including what they say are frequent references to JAS's origins and character as a United Kingdom-based company. They deny that their conduct is misleading.

The alleged representations - JDS's claims

38 JDS pleads that three combinations of the conduct impugned in the SOC has resulted in certain Representations being made to Australian consumers. Each of those three combinations is said to have had this result in the context of JDS's substantial reputation and goodwill in connection with each of the JDS Names.

39 The Representations are:

(a) JAS and/or JAA is JDS;

(b) JAS and/or JAA is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by JDS;

(c) the JAS AU Site is a website of JDS;

(d) the JAS AU Site is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by JDS;

(e) the telephone number shown on the JAS AU Site is JDS's telephone number;

(f) that telephone number is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by JDS;

(g) the person or entity offering for sale and/or selling the products via the JAS AU Site is JDS;

(h) the person or entity offering for sale and/or selling the products via the JAS AU Site is associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by JDS;

(i) the person or entity offering for sale and/or selling the products via the Australian telephone number is JDS; and

(j) the person or entity offering for sale and/or selling the products via that telephone number is a person or entity associated with or endorsed, approved, licensed or sponsored by JDS.

40 In the case of JAA, it is pleaded to have made the Representations, in the context of JDS's reputation and goodwill in the JDS Names, by reason of either:

(a) a combination of the references to Australian operations on the JAS AU Site and the further alleged conduct of JAA in dispatching orders etc; and

(b) further or alternatively, solely because of that further alleged conduct.

41 The reason it will be necessary to return to these pleas in more detail is because, as foreshadowed, the respondents seek to confine JDS's case to the specific conduct said to have commenced from October 2018, so that it is not a case that rests on JAS trading under the JAS Names where they are the same or similar to the JDS Names. For that trading was taking place in Australia for some 20 years before the proceeding was commenced.

42 In any event, the respondents deny that they have made the Representations. While they do not give particulars of those denials in the Defence, the respondents refer to the difference between JDS marketing itself as a Western Australian enterprise, as distinct from JAS's promotion of London/United Kingdom base and strong international focus. The respondents say that the reputation that JAS has built in Australia means that it is unlikely to be confused with JDS. The respondents rely on the different branding and store signage used by the two businesses. They also emphasise JAS's character as a predominantly web-based seller (it has two brick-and-mortar stores in the United Kingdom, but neither party made anything of that). In contrast, the respondents submit, JDS's web-based sales have always been small, as it mainly trades through its stores in its core markets and by means of direct orders placed by schools and other institutions by fax or email. The respondents also submit that the changes to JAS's online presence in Australia that were made in 2018 and in 2022 made no material difference.

43 The respondents accept that JDS has a substantial reputation in its core markets in respect of sales from the stores located in those places. But they say that JDS's reputation is geographically limited, while JAS's reputation is (relevantly) Australia-wide.

44 Insofar as there is overlap between the geographic extent of those reputations, the respondents' submission is that JAS has been carrying on business for some 20 years in an area that includes JDS's core markets, and it would not be appropriate to grant an injunction restraining it from continuing to do so.

45 The respondents say further that it is JDS's own conduct (the subject of the cross-claim) that may be leading consumers into error.

The Representations are pleaded to be false

46 To return to the SOC, JDS pleads matters that falsify each of the Representations; essentially, that JDS is not JAS and there is no affiliation between them. The respondents admit the truth of those matters, but deny having made the Representations. So the issue is not whether the Representations were false; it is whether they were made at all.

47 JDS submits that a large number of consumers have in fact been misled. It says that while this is not necessary to be proved in order to establish misleading or deceptive conduct or passing off, it does stand as evidence of those things.

Breaches of the ACL

48 JDS then pleads, in effect, that the Representations were misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the ACL. It also pleads breaches of prohibitions in s 29(1) of the ACL on making false or misleading representations that:

(a) goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits (s 29(1)(g)); and

(b) the person making the representation has a sponsorship, approval or affiliation (s 29(1)(h)).

Each of JAS and JAA are said to have contravened these provisions.

49 Again, all of that is denied.

50 It was made clear in opening submissions that the respondents do not dispute that if the Representations were made, they were made in trade or commerce. Nor do they take any point that the Representations were not made in Australia, or not made in the course of carrying on business in Australia. Finally, the respondents do not dispute that if the Representations as pleaded were made, they concerned, among other things, the subject matter covered by each of s 29(1)(g) and s 29(1)(h) of the ACL.

51 As a result, if JAS or JAA did make any of the Representations, and if they were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, then breaches of each of s 18, s 29(1)(g) or s 29(1)(h) would be established (noting that in this case, at least, there is no relevant difference between the prohibition on conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, and the prohibition on making false or misleading representations: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; (2020) 278 FCR 450 (TPG FCAFC) at [20]-[21]; Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; (2023) 277 CLR 186 at [84]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2014] FCA 634 at [40].

Accessory liability

52 JDS alleges that each of JAS and JAA has been involved in the contraventions of the other, by aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring it, by being directly or indirectly knowingly concerned in it, or by being party to it. These pleas are based on the pleas as to the shareholding relationship between JAS and JAA along with the pleaded role that each is said to have taken in operating the JAS AU Site and fulfilling orders and providing Australian customer service.

53 Further, each of JAH and PCP, the shareholders in JAA, are said to have been involved in JAA's contravening conduct. JDS pleads their involvement by reason of directors in common with JAA, being Mr Thompson and Mr Venus for JAH and Mr Baumgartner for PCP. JDS also relies on obligations which arise under a Shareholder Deed concerning JAA that was executed in April 2022 (SOC paras 4, 5).

54 The respondents deny all these pleas of involvement. They say that the allegations about JAH and PCP's liability should be struck out and the claims against those respondents dismissed.

Passing off

55 JDS effectively relies on the same alleged conduct in order to plead that each of JAS and JAA have engaged in the tort of passing off. JAA's alleged involvement in the making of the Representations is said to make it a joint tortfeasor with JAS. The various shareholding relationships, and the Australian information on the JAS AU Site, are said to mean that each of JAS and the third and fourth respondents are joint tortfeasors with JAA.

56 Again, all this is denied and, further, it is said that the claims against the third and fourth respondents should be dismissed.

Relief

57 JDS then pleads that the respondents will continue with their conduct if not restrained and that they have refused to give undertakings. It pleads that it has suffered and is likely to continue to suffer loss and damage, including misappropriation of its goodwill, damage to reputation of its business, lost sales, an (unspecified) lost licensing opportunity, and user damages. It is also pleads that the respondents have profited from the conduct. All this is denied. The respondents submit that JDS has adduced no evidence of actual loss.

58 It will not necessary to quantify either loss or damage or profits in these reasons. An order has been made that all issues of liability, including entitlement to (but not quantum of) damages, are to be heard and determined prior to the question of the quantum of any pecuniary relief to be awarded.

Delay

59 In addition to the denials already mentioned, the respondents plead some further defences, based on lapse of time. JDS joins issue with each of them.

60 The respondents plead a limitation defence in respect of both the ACL and the tort of passing off. They accept that in in the ACL context, however, this only affects the claim to damages (see s 236(2)), since there is no six year limit on the grant of injunctive relief (see s 232).

61 JDS's primary position on the limitation defence is that the conduct of which it complains only started in October 2018, so it is within the six year limitation period. It makes no claims for any damage suffered before that time.

62 The respondents also rely in a different way on what they say is JDS's delay in seeking relief. It is pleaded that JDS has been aware of JAS's business in Australia since about 2010, alternatively since 2015 or 2019 and (in effect) did not object to it or take action for redress against JAS until 2022.

63 The awareness in 2010 is said to have come about because Mr Thompson emailed Mr Boercamp in that year telling him that JAS was undertaking trade in Australia and Mr Boercamp acknowledged receipt. Alternatively, Mr Boercamp's knowledge of JAS's activities in Australia should be inferred from his activities in 2015 registering certain domain names containing the text strings 'jacksons' and 'art' and 'supplies. Alternatively, on Mr Boercamp's own evidence he became aware of those activities in 2019.

64 While the respondents pleaded estoppel or waiver as a result of this delay, they identified no change of position on its part in reliance on anything JDS did or omitted to do, and those claims were not pressed. The respondents rely on the alleged delay as a reason why the Court should decline relief as a matter of the exercise of its discretion.

65 JDS joins issue with JAS's allegations of delay. It submits that JAS's trading in Australia changed materially when the JAS AU Site was launched in October 2018, and further changed materially when JAA's business operations, and what JDS pleads as JAS's 'Australian physical presence', commenced in mid-2022. It made demand in June 2022 and commenced this proceeding in December 2022. So it says that there has been no delay.

66 As for JDS's knowledge of JAS's activities, it admits that Mr Boercamp knew from 2010 that there was an online business selling art supplies, but contends that he (and JDS) did not know that JAS was selling products to Australian consumers until 2019.

67 The respondents also rely on the matters raised in their cross-claim as a further discretionary consideration against granting relief. I will describe those shortly.

68 JDS raises in answer to any discretionary ground that it is not in the public interest to permit consumers to continue to be misled, and this would be contrary to the purposes of the ACL.

Relief claimed by JDS

69 JDS's amended originating application claims:

(a) declarations of contravention;

(b) a permanent injunction restraining each of the respondents from offering, promoting or selling in Australia (in effect) arts and craft products under the JAS Names:

whereby such conduct involves:

(i) using an Australian sub-domain or a website with content specific to Australian users;

(ii) operating a warehouse, distribution facility or other physical presence located in Australia;

(iii) the operation of an Australian telephone number, or is otherwise targeted at Australian consumers;

or from being involved in or joint tortfeasors in such conduct;

(c) a permanent injunction restraining the respondents from making the Representations in Australia (or involvement or being joint tortfeasors);

(d) an order for a corrective notice;

(e) an order that JAS geo-block access to the JAS AU Site by persons located in Australia;

(f) delivery up (of what is unclear);

(g) damages under s 236 of the ACL;

(h) damages or an account of profits for passing off;

(i) interest; and

(j) costs.

70 The respondents deny that JDS is entitled to any relief.

71 As has been said, the trial did not concern the quantum of any pecuniary relief to be awarded.

The issues in detail - the cross-claim

JDS's various uses of the JAS Names

72 JAS cross-claims against JDS and Mr Boercamp. The cross-claim relies on many matters alleged in the pleadings for the principal claim, and here I will only describe the issues that have not already been joined as a result of those pleadings.

73 The cross-claim essentially arises out of what is said to have been JDS's use of the names 'Jacksons Art' and 'Jacksons Art Supplies' from about May 2022. JAS pleads that JDS did not use those names before that time. The cross-respondents deny this, relying on their contention that JDS has been known as 'Jacksons Art' and 'Jacksons Art Supplies' for many years.

74 It is common ground that on 23 May 2022, JDS applied for and obtained registration of the business name 'Jacksons Art'. JDS submits, however, that it is not misleading to register a business name and there is no evidence that JDS has actually used it.

75 JDS also submits that whether the conduct is misleading is to be assessed as at when it commenced, and that the evidence does not establish that in May 2022 consumers in Australia had sufficient awareness of the JAS Names to mean that any use of them by JDS was misleading. JDS says further that to the extent that JAS did develop a reputation in Australia, that ought to be disregarded for the purposes of the cross-claim, as it is the result of JAS's own wrong. These submissions apply, not only to the registration of the business name, but to the other kinds of misleading conduct pleaded in the cross-claim as are about to be described.

76 It is also common ground that from August 2022 to the present, the 'About Us' page of the JDS Website contained the following paragraph:

Whether you're a painter looking for the best brushes, an illustrator looking for coloured pencils or even someone who wants to get into pottery, Jacksons Drawing Supplies Pty Ltd, ('Jacksons' or also known as 'Jacksons Art Supplies') has all the art supplies you need …

77 JAS pleads that this is an ongoing representation that JAS and JDS were one and the same or that JDS was affiliated with JAS. The cross-respondents deny this and allege that it was in any event true that JDS was known as 'Jacksons Art Supplies'.

78 It is further common ground that on 22 May 2022 JDS registered the following domain names:

(a) jacksonsart.com.au;

(b) jacksonsartaustralia.com.au;

(c) jacksonsartsupplies.com.au; and

(d) jacksonsartsupplies.com;

and the following further domain names on 27 July 2022:

(e) jacksonsart.au;

(f) jacksonsartaustralia.au; and

(g) jacksonsartsupplies.au.

(all together, Contested Domains). It is also common ground that all of the above domains redirect to the JDS Website.

79 The cross-respondents say that since May 2015, JDS has registered similar domain names and that the above registrations were part of that conduct, which commenced earlier. However the respondents are time barred from making a claim based on that earlier conduct.

80 The cross-respondents deny in any event that this was misleading or deceptive conduct. As well as their submissions as to JAS's Australian reputation or lack thereof, they submit that the Contested Domains do not show up in an internet search, and that consumers are not likely to enter them into a browser.

81 It is further common ground that on 8 August 2022, Mr Boercamp caused a company called Jacksons Art Supplies Pty Ltd to be incorporated in Australia, with him as its sole director and Canmore Holdings Pty Ltd its sole shareholder. JAS denies that the mere incorporation of a company can be misleading, and it is common ground that the company has never traded.

82 It is also common ground that at some time before July 2022, JDS updated the metadata keywords of the JDS Website to include 'Jacksons Art Supplies'. The particulars to this allegation say that '"metadata keywords" or "meta tags" are tags which provide search engines, such as Google, information about the content of the website to assist in search engine optimisation (i.e. high[sic] a particular website ranks in the results when a particular search term is used)': Statement of cross-claim filed on 24 June 2024 (SOCC) para 13.

83 The cross-respondents deny these allegations on the basis of their submissions about JAS's Australian reputation and also because it says that the particular metadata keywords had no impact on the results of a web search.

84 To be clear, while the bare elements of the above conduct are largely common ground, the knowledge with which the cross-respondents engaged in it is not. They essentially deny that they knew from 2010 that JAS was selling products to Australian customers using the JAS Names.

JDS and Mr Boercamp's liability

85 JAS pleads that all of the above conduct was conduct in trade or commerce that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in breach of s 18 of the ACL, and also that it contravened s 29(1)(h) (misrepresentations regarding sponsorship, approval or affiliation).

86 The cross-respondents admit that their conduct was in trade or commerce, but deny that it was misleading or deceptive or involved misrepresentation.

87 JAS further pleads that JDS engaged in the conduct with the alleged knowledge, and intending to mislead consumers into believing that JAS and JDS were one and the same or affiliated, and that in purchasing products from JDS they were purchasing from JAS or a business associated with it, so as to wrongfully divert business away from JAS. The cross-respondents deny this. It appears that the knowledge with which the conduct occurred is said to be relevant to relief.

88 The conduct is also said to be passing off by JDS.

89 Mr Boercamp is pleaded to be liable under the ACL because of involvement in JDS's impugned conduct, or as a joint tortfeasor. While the cross-respondents deny this in their defence to the cross-claim, in opening their senior counsel properly accepted that if JDS is found to be liable for misleading or deceptive conduct or passing off, then Mr Boercamp would also be liable, as a person involved in the conduct for the purposes of s 2 of the ACL, or as a joint tortfeasor.

Loss or damage and relief

90 Whether the conduct of JDS and/or Mr Boercamp caused JAS to suffer loss and damage is also in issue.

91 The relief that JAS claims in the cross-claim is:

(a) declarations that JDS and Mr Boercamp have contravened s 18(1) and s 29(1)(h) of the ACL;

(b) mandatory and prohibitory injunctions of various kinds;

(c) damages pursuant to s 236(1) of the ACL and at common law;

(d) interest; and

(e) costs.

The issues in overview

92 In overview, then, the Court needs to determine the following questions:

(1) The extent to which JDS has a reputation in Australia under the names 'Jacksons' or 'Jacksons Drawing Supplies' and, also, the extent to which it has a reputation and goodwill as 'Jacksons Art' or 'Jacksons Art Supplies'. In particular, JDS's reputation as an online vendor of art supplies, and its reputation generally outside its core markets. It will be convenient when dealing with this issue to identify the class of persons who were aware of that reputation. The effect of JAS's alleged conduct on ordinary and reasonable members of that class will need to be assessed in order to determine whether the conduct is misleading or deceptive.

(2) The extent to which JAS has traded in and acquired a reputation in Australia since 2005. It is part of JDS's case that JAS's activities in Australia were not substantial, or known to JDS, until after the introduction of the JAS AU Site in 2018. Mr Boercamp's evidence is that he did not become aware that JAS was 'targeting the Australian market' until May 2019. As described immediately below, the extent and nature of JAS's reputation in Australia is also relevant to JAS's case that Australian consumers have not been led to believe that JAS was or was associated with JDS. JAS's reputation is also relevant to its argument that, as a matter of discretion, the Court should not grant an injunction restraining it from trading under the JAS Names anywhere in Australia.

(3) Whether, by the specific conduct alleged to have occurred since October 2018, JAS or JAA have made the Representations, which are broadly to the effect that they are, or are associated with, JDS, or that the products they offer are products of JDS. JAS maintains that the primary brand names used respectively by JDS and JAS are distinguishable. It contends that it had its own reputation attached to the JAS Names so that using those names is likely to lead consumers to correctly identify JAS as the company that is offering and selling its goods. JAS further seeks to distinguish its reputation from that of JDS by emphasising the entirely online nature of its business in Australia, combined with its promotion of itself as a United Kingdom based company. This is compared with what JAS says is JDS's largely brick-and-mortar presence, confined to its core markets. The respondents also characterise JAA as a mere 'fulfilment provider', and so not making any Representations itself.

(4) Whether, if the Representations were made, they were misleading or deceptive, or constituted the tort of passing off. It is not really in issue that if JAS did indeed represent that it was or was associated with JDS, that was wrong, and therefore misleading. But it will be necessary at this point to consider voluminous evidence about confusion or error on the part of individuals.

(5) Whether JAS and JAA were involved in each other's alleged contraventions, or were joint tortfeasors, and whether the third and fourth respondents were involved in JAA's alleged contraventions, or were joint tortfeasors.

(6) Whether the conduct by JDS that is the subject of JAS's cross-claim - referring to itself as 'Jacksons Art Supplies' on the JDS Website, registering 'Jacksons Art Supplies' as a business name, registering the Contested Domains, incorporating Jacksons Art Supplies Pty Ltd and adding 'Jacksons Art Supplies' to the metadata of the JDS Website - misrepresented that JDS was JAS or affiliated with it, or that the products it was offering were products of JAS, or whether that conduct was passing off.

(7) JDS's entitlement to relief if the contraventions of the ACL or the tort of passing off are established. Also, in particular, whether JDS's alleged delay in acting means that its claims are time barred, or whether it is a reason to refuse discretionary relief. More broadly, whether the injunctions sought are appropriate, including because of the effect they will have on what is said to be JAS's established trade in Australia. Further, whether the conduct alleged in the cross-claim is a reason to refuse discretionary relief.

(8) JAS's entitlement to relief on the cross-claim, including whether it has suffered loss or damage.

93 After commenting briefly on the witnesses, these reasons will be structured by reference to the above list of the issues in overview.

III. THE WITNESSES

94 It is only necessary to comment briefly on my general impression of each of the witnesses.

The lay witnesses

Michael Franciscus Boercamp

95 Mr Boercamp is the sole director and Managing Director of JDS and, with his wife Jennifer, the effective owner of the company. He has run the business and owned it with his wife since buying it from Kevin Jackson in 2010. For some 15 years before that, he worked in senior positions at JDS. He evidently has a dedication to the business and is proud of its long history.

96 Mr Boercamp's credibility did come under attack. I will address those attacks in more detail when I make findings of fact. For now, it is sufficient to say that I consider that he was an honest witness. He struck me as a careful person who was doing his best to give his evidence truthfully. He was notably prepared to make concessions about matters that harmed JDS's case including, as mentioned below, that JDS had presented no evidence of actual sales outside of its core markets. To the extent that attacks on his credibility pertained to the reliability of his memory rather than the honesty of his evidence, I do not consider that his memory was any more or less reliable than one would expect of a person in his position.

97 It is true that at times, Mr Boercamp displayed a level of wariness in responding to the cross-examiner that got in the way of giving straightforward answers to questions. But that is unremarkable on the part of a person who, I expect, had little experience in the witness box. Such a person is naturally going to be defensive when interacting with counsel representing his opponent.

98 It is also worth noting my impression that, during his time as Managing Director of JDS, Mr Boercamp has not been very focussed on the World Wide Web. According to his evidence, he was sufficiently acquainted with it to have developed JDS's early websites. But there is no suggestion that those websites were especially sophisticated or complex. His evidence concerning more recent years displayed an awareness of the web, but no great knowledge of how it and commerce on it work, nor any great interest in that matter.

99 This impression I formed cuts both ways for JDS. It tends to support its case that Mr Boercamp was unaware of JAS's activities in selling art products in Australia. But it also lends credence to the respondents' case that JDS's presence on the web was an insignificant part of its business.

100 There was a peripheral controversy about the fact that JDS's Marketing Manager and Mr Boercamp's daughter, Ashleigh Burstein, did not give evidence. I will deal with that below. Subject to that, there was no suggestion that Mr Boercamp delegated the web commerce side of JDS's business to anyone with more expertise in that area.

Gary Thompson

101 The other main protagonist in the litigation, Mr Thompson, also gave evidence. Mr Thompson is a director of JAS and, as Executive Director, is involved in the day to day operations and management of JAS's business. He is responsible for the technology and development, marketing, sales and general operations arms of the business.

102 Mr Thompson was relaxed in the witness box. He listened to the questions asked and answered them carefully without undue hesitation or qualifications. He readily made a number of concessions, mostly about the role of JAA and the company through which JAS controls it, the third respondent JAH. Mr Thompson did not argue with the cross-examiner. He presented as a sophisticated business person, as one would expect of someone who appears to have built a successful worldwide online art supply business.

103 Although there was no direct challenge to the honesty of Mr Thompson's evidence, he was challenged on the appropriateness of his conduct in connection with the alleged confusion (at least) that customers experienced between JDS and JAS. Mr Thompson was unperturbed by those challenges, and his answers in connection with them had the ring of truth. I will deal with JDS's criticisms of Mr Thompson's conduct to the extent necessary below; for now I only need record that in my view, Mr Thompson gave his evidence honestly.

Franz Christoph Baumgartner

104 Mr Baumgartner is one of three directors of JAA and, together with his wife Magrifa Sadri, is responsible for JAA's operation in Australia. He is also a director and shareholder (along with Ms Sadri) of PCP, the fourth respondent and 10% shareholder of JAA. Mr Baumgartner's evidence was not challenged. Essentially, he was cross-examined in order to adduce evidence about matters which, JDS says, support the primary and accessory liability of JAA and the accessory liability of PCP. His answers and demeanour in the witness box were straightforward and I accept that he gave his evidence truthfully.

Michael Venus

105 Along with Mr Thompson, Mr Venus is the other founding director of JAS. Mr Venus does not have an operational role. He gave his evidence by video link from England. His credibility was not challenged, although the reliability of his evidence about the alleged exchange of emails alleged to have taken place between Mr Thompson and Mr Boercamp in 2010 was. I will comment on that below; for now it is enough to say that, as with the other witnesses, I did not form the view that Mr Venus's memory was either more or less reliable than one would expect of a person in his position. I am satisfied that he gave his evidence honestly.

The expert witnesses

Ryan Jones

106 Mr Jones was the sole expert witness called by the respondents. By agreement, he gave his evidence before the evidence of JDS's sole expert witness, Michael Simonetti. That is because Mr Simonetti's evidence took the form of commentary on Mr Jones's.

107 Mr Jones is an expert in digital marketing with over twenty years' experience in the area. He has expertise in search engine optimisation (SEO) which his report describes as follows:

Search engine optimisation, or SEO, is the process of improving the quality and quantity of website traffic to websites or a specific web page from search engines. It is about making a website more visible and attractive to search engines, so that it ranks higher in search results and gets more organic (not-paid) traffic.

108 In broad terms, Mr Jones's evidence concerned the presence on the World Wide Web of each of JDS and JAS. He gave evidence about the 'organic' traffic to each site (meaning web users finding a site through search engine queries or other avenues that do not involve paid or sponsored/advertising links). He also gave evidence about the traffic to each site as revealed by Google's Analytics service - or not revealed, as the subject was controversial and will take up much space below. Another subject of Mr Jones's evidence was the relative ranking of each of the two websites when various keywords were used to conduct web searches. Finally, he gave some evidence about how the JAS Website has been configured.

109 Mr Jones's expertise to give evidence in each of these areas was not challenged and I accept that he was suitably qualified to give it. What was challenged (albeit not strongly) was Mr Jones's impartiality and independence. I did form the view that Mr Jones was minded to give evidence that favoured the respondents' case where possible. That was not because he was especially argumentative in the witness box. It was because, on the subject of the reliability of Google Analytics, he appeared to draw conclusions adverse to JDS from the evidence about the traffic on the JDS Website, and a different conclusion, favourable to the respondents, from the evidence about the traffic on the JAS Website, when the difference between the two pieces of evidence was not apparent on its face. Mr Jones gave no real explanation for why apparently similar evidence led to different conclusions. I will explain further when I come to consider the Google Analytics evidence in Section V below.

110 I also had a broader concern that Mr Jones did not adequately explain the course of reasoning behind his evidence, as an expert witness should do: see e.g. Makita (Australia) Pty Ltd v Sprowles [2001] NSWCA 305; (2001) 52 NSWLR 705 at [67]-[68]. There was no objection to the admissibility of Mr Jones's evidence on this basis, but it has affected the weight I give that evidence.

Michael Joseph Peter Simonetti

111 As has been indicated, Mr Simonetti was the expert called by JDS to respond to Mr Jones's report. Mr Simonetti is the founder of a digital marketing agency called AndMine Pty Ltd. He has over 25 years' experience in the fields of website development, software engineering and online media and marketing. He has computer science, software engineering and telecommunications qualifications. His experience includes providing SEO services, optimising client websites and analysing website visitor information through platforms such as Google Analytics.

112 Once again, no issue has been raised about Mr Simonetti's expertise to answer the questions asked of him in this proceeding. He presented as calm and impartial in the witness box. He answered confidently but without veering into advocacy. Despite a very thorough cross-examination, his evidence was largely unshaken. And as discussed below, that evidence was generally supported by reasoning albeit reasoning I have not accepted in every respect. I have generally been disposed to put weight on Mr Simonetti's evidence and, where it conflicts with that of Mr Jones, have been disposed to prefer the evidence of Mr Simonetti.

IV. JDS'S TRADING AND REPUTATION IN AUSTRALIA

Principles

113 As already explained, in this proceeding there are issues as to the nature and extent of JDS's reputation. A question also arises about the time at which it is to be assessed.

114 Reputation is of the essence of the cause of action of passing off (Scandinavian Tobacco Group Eersel BV v Trojan Trading Co Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 1086 at [101] (Allsop CJ)), but it is not a necessary precondition to a claim under s 18 of the ACL: Cadbury Schweppes Pty Ltd v Darrell Lea Chocolate Shops Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 70; (2007) 159 FCR 397 at [99]. Nevertheless, it will be common that the basis on which the use of a name is said to be misleading is that the trading name of the applicant has sufficient reputation among a relevant class of persons to mean that they associate the name with the applicant: see e.g. Shape Shopfitters Pty Ltd v Shape Australia Pty Ltd (No 3) [2017] FCA 865 at [91] (Mortimer J).

115 For this purpose, evidence of sales can suffice to establish reputation. In Natural Waters of Viti Limited v Dayals (Fiji) Artesian Waters Limited [2007] FCA 200 at [58], Bennett J explained:

In McCormick & Co Inc v McCormick (2000) 51 IPR 102; [2000] FCA 1335 at [81]-[88], Kenny J discussed the evidence necessary or sufficient to establish reputation in a trade mark. Her Honour pointed out that evidence of sales and advertising may be sufficient to establish reputation despite the absence of any direct evidence of consumer appreciation of the mark, as opposed to the product: 'public awareness of and regard for a mark tends to correlate with appreciation of the products with which the mark is associated, as evidenced by sales volume, among other things': McCormick at [86]. Such factors may also establish the reputation necessary to found a case for passing off and contravention of s 52 of the [Trade Practices] Act: for example, Pacific Publications Pty Ltd v Next Publishing Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 127; 65 IPR 58; [2005] FCA 625 at [12]-[14].

116 Other matters that are typically relied on to establish reputation are the extent and nature of the advertising, marketing and promotional activities of the applicant and the length of time, and geographical area, in which these activities have taken place: Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirène Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82 at [238] (O'Bryan J).

117 Ultimately, the question of reputation is a question of fact that depends on the evidence in the particular case. In Knott Investments Pty Ltd v Winnebago Industries Inc [2013] FCAFC 59; (2013) 211 FCR 449 (Winnebago (No 1)) at [14], Allsop CJ summarised the position as follows:

What is required is proof of a substantial number of persons (whether residents or visitors) who were aware of the applicant's product and who were thus potential customers. Such persons represent, in a real sense, a commercial advantage available to be turned to account were the applicant to commence business: ConAgra at 346 (Lockhart J), at 372 (Gummow J) and at 377 (French J). The size and extent of the class of such potential customers may vary according to the circumstances of the case and will be measured by reference to the relevant group or section of the public likely to be potential customers. Here, such persons would be prospective buyers, hirers or users of recreational vehicles, being the class of persons who would be likely customers, whether direct or indirect. The relevance and importance of there being a substantial number flows from the need to show real damage by the deception caused by the respondent's conduct.

118 In my respectful view, the following passage from French J's judgment in ConAgra Inc v McCain Foods (Aust) Pty Ltd (1992) 33 FCR 302 at 380-381 sheds light on the meaning of 'a substantial number of persons' in this context:

The nature of the question to be asked about McCain's conduct for the purposes of s 52, Trade Practices Act is to be borne in mind in considering the correctness of the approach taken by his Honour. The question is one of characterisation of the conduct, not of the reactions of consumers or others to that conduct. So where some express representation is made and that representation is demonstrably false, it is not usually necessary to go beyond that finding in order to conclude that it is misleading or deceptive. The case of an obvious puff might be taken as an exception. Where conduct depends upon context or surrounding circumstances to convey a particular meaning, then those factors must be taken into account but only as a way of characterising the conduct. Where the name and get-up of a product are in issue, the question for the purposes of s 52 is whether they are misleading or deceptive in the circumstances. The fact that some members of the relevant public may be aware of a similar product in another country does not affect the characterisation of the conduct if that number is small. The word 'insignificant' was used by his Honour to identify the threshold of public awareness below which such conduct is not misleading for the purposes of the section. That word is normative but not for that reason inappropriate. Attention must be paid to the policy of the relevant provision which, as the heading to Pt V and many of its provisions indicate, is one of consumer protection. If the similarity complained of is commercially irrelevant having regard to the number of people who know of it, then it can be concluded that the use of the name and/or getup complained of is not misleading or deceptive. That is essentially the kind of evaluation which underpinned his Honour's finding in this case and on the primary facts that he found I am not persuaded that he erred in his approach.

119 As to the interaction between the formulations 'substantial number of persons' and 'not insignificant number of persons' see the analysis of Yates J in Optical 88 Limited v Optical 88 Pty Limited (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380 at [335]-[342]. I respectfully agree that the differences between the two phrases in the present context are differences of expression rather than substance.

120 The requirement in these authorities that there be a substantial (or not insignificant) number of persons aware of the applicant's reputation might be thought to be inconsistent with the subsequent clarification by Full Courts that, at least at the stage of assessing contravention, there is no need to show that the impugned conduct is likely to have misled or deceived any 'not insignificant number' of members of the class of persons in question: TPG FCAFC at [23]; and Trivago N.V. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185 at [192].

121 However that thought would not be correct. The requirement of a substantial number of persons concerns the extent of the applicant's reputation as a contextual element of a claim of misleading conduct which is important in cases like the present one. It is the existence of a sufficiently extensive reputation connected with a name, mark or get up that leads to people being misled, if the impugned conduct associates the respondent with that reputation. If a reputation of that kind is not established, then the alleged conduct may well be, in French J's words, 'commercially irrelevant' (ConAgra at 380-381). That is the effect of the analysis of this point which Beach J conducted, in the context of another misleading conduct claim analogous to passing off, in State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 137 at [730]-[744].

122 The different principle confirmed in TPG FCAFC simply acknowledges that it is no part of the statutory prohibition now found in s 18 of the ACL that any minimum number of people are to be misled.

123 JDS submits that it is not necessary to establish that it had a reputation in connection with the JDS Names in order to succeed in its claim. But while that might be correct as an abstract statement of the content of the statutory prohibition on misleading conduct, for the reasons just explained, I do not consider that it takes matters very far in practice. As will be seen, the essence of the claim made by JDS is that by conduct involving the use of the trading names which are the same as or similar to the JDS Names, JAS conveyed to consumers of art products that it was or was associated with JDS. It is impossible to see how those consumers could have been led into such error if they did not already associate the JDS Names with JDS's business. And to say that a substantial (or not insignificant) number of consumers made that association is to say that JDS's business had a reputation that was associated with the JDS Names.

124 Consistently with that, as set out below JDS adduced evidence to establish that it had such a reputation. While the respondents did not contest that in respect of consumers located in Western Australia and the Northern Territory, the extent to which JDS had a reputation in Australia outside those jurisdictions was controversial. The respondents submit that the evidence only establishes a reputation for JDS within its core markets.

125 I will consider that evidence below. But before doing so it is necessary to discuss a matter on which JDS relies which is not evidence, namely the Full Court authority of Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; (2017) 251 FCR 379. JDS submits this case means that to establish a substantial reputation in Western Australia is to establish a reputation in the rest of Australia. That is so at least in the context of a national industry and particularly so where the industry concerns specialised products or services. JDS relies on Pham heavily, and in relation to points of critical importance, so it is necessary to examine the case closely.

126 Pham involved disputes about registered trade marks but also claims of breach of s 18 and s 29 of the ACL and passing off. While most of the findings about to be described were made in the trade mark context, the Full Court said that its analysis of the factual substratum was relevant to the misleading or deceptive conduct and passing off issues as well: Pham at [58].

127 It was common ground that the mark of the respondent, Insight Clinical Imaging (ICI), had acquired a reputation in and around Perth before the relevant time, in respect of radiology services: Pham at [60]. The evidence also established that Insight Clinical Imaging 'had extended its marketing and advertising beyond the boundaries of its operations within Western Australia through its website and promotions at national conferences': Pham at [62]. That included evidence of Google Analytics data, another controversial topic that will be addressed below.

128 The primary judge had found that 'whilst some radiology providers may carry on business in a localised area, they operate in a national industry so that there is a potential for deception or confusion even if Insight Clinical Imaging's marks had not acquired a reputation beyond Western Australia': Pham at [65]. Her Honour found that the marks had not acquired a 'substantial reputation' outside that state: Pham at [65]. Her Honour found, however, that 'the likelihood of deception or confusion is not mitigated by the different geographical locations in which the parties have been conducting business because they operate in a national industry': Pham at [65] (emphasis added).

129 The Full Court (Greenwood, Jagot and Beach JJ) found that there was ample basis to support the finding just emphasised: Pham at [69]. At [71] the Full Court said:

The nature of the good or service in question which the mark is to distinguish necessarily informs the identification of the relevant class of persons who may be deceived or confused. It also informs an understanding of the characteristics of that class which will be relevant to the potential for deception and confusion. As a result it necessarily informs an evaluation of the sufficiency of the number of persons within the relevant class who are likely to be deceived or confused. Accordingly, an evaluation of the sufficiency of ICI's reputation across Australia necessarily called for consideration of the nature of the service which ICI's marks distinguished. The national nature of radiological services, as found by her Honour and not challenged in this appeal, was (and is) fundamental to the issue of the sufficiency of ICI's reputation across Australia.

130 Similarly, the fact that Insight Clinical Imaging was conducting a business in Australia in specialised field which operates at a national level was a 'fundamental point': Pham at [79].

131 The Full Court also held that it was neither necessary nor appropriate to lead 'specific evidence' that people participating in the industry (including patients) frequently moved around Australia. And at [79] their Honours said (paragraph references being to the primary judgment):

In particular, in the present case:

(1) it was common ground that ICI had a substantial reputation in its mark in Western Australia;

(2) the primary judge found that ICI's mark distinguished its services in the specialised field of radiological or clinical imaging service (at [88]), and there is no challenge to that finding;

(3) the primary judge found that this specialised market operated on a national basis (at [89] and [146]), and there is no challenge to that finding; and

(4) it is common knowledge and not reasonably open to question that people travel freely between the States and Territories in Australia and, as such, proof of that fact was unnecessary under s 144 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

132 After quoting from ConAgra, their Honours proceeded as follows (emphasis added):

[81] ConAgra was decided 25 years ago. In 1992 the World Wide Web was in its infancy. There were no publicly available internet browsers. There was no Google, no Seek, no web browsing or the like. With the internet and travel both overseas and within Australia now ubiquitous in the lives of Australian people, the essential conceptual underpinning of IR's [the appellant's] case is unsound. IR accepted that, before IR conceived of the IR composite mark, ICI had acquired a substantial reputation in its marks in Western Australia. IR's case depended on the proposition that ICI's reputation in its marks did not extend outside Western Australia and IR would accept any condition or limitation not to use its marks in Western Australia. We accept that the Act permits a condition or limitation to this effect to be imposed (discussed below). But the reality of modern life, with widespread use of the internet for advertising, job seeking, news gathering, entertainment, and social discourse and free and frequent movement of people across Australia for work, leisure, family and other purposes, necessarily impacts on both the acquisition of a reputation in a mark and the likelihood of the use of another mark being likely to deceive or confuse because of that reputation. Given current modes of communication and discourse and free and unfettered rights of travel within Australia, a substantial reputation in Western Australia in this national industry constituted a sufficient reputation in and across Australia for s 60(b) [of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth)] to be engaged. IR's attempts to subdivide the nation into its component States and Territories, in the present context at least, could not succeed. Its approach resonates with sentimental notions of pre or early Federation train track gauge differences.

[82] With these matters in mind, we consider that the primary judge correctly concluded that ICI's reputation across Australia was sufficient to render IR's proposed disclaimer, condition or limitation irrelevant for the purpose of s 60. ICI's reputation within Western Australia, given the national market and its specialised nature, was itself a reputation in Australia because of which IR's composite mark would be likely to deceive or cause confusion amongst a sufficiently substantial number of the relevant class which, as we have said, must have included radiographers and radiologists, and was not confined to referrers and patients; further, her Honour correctly held that ICI's marks also had some reputation outside Western Australia.

133 The Full Court applied these conclusions to the ACL and passing off cases, without modification or further discussion: Pham at [95]-[96]; see also at [108].

134 It is important, of course, not to confuse the ratio of Pham, which if applicable is binding on me, with findings of fact based on the particular evidence before the Court in that case. The question of reputation is, after all, a question of fact: Urban Alley at [238]. In my respectful view, the statement that is not necessary to prove that people travel freely between the States and Territories in Australia is part of the ratio of Pham, and I will proceed on that basis. Other general observations about the impact of such freedom of movement and of the internet on the acquisition of a reputation also contain, with respect, much that is well known and common sense, and while the Full Court does not expressly say so, I consider that proof of those matters is not required either.

135 But I have emphasised other phrases in the quotes above to highlight how care must be taken before moving from judicial notice of those broad matters, to any general proposition that to establish a reputation in one state is to establish a reputation in them all. It was central to the Full Court's views that Insight Clinical Imaging was operating in a 'national industry' with particular characteristics such as national registration for radiographers, a national industry association, a national regulatory body, the exchange of radiology images for assessment and interstate recruitment: see Pham at [66]-[69]. I will return to the effect of Pham when considering the evidence of the extent of JDS's reputation below.

At what time to assess JDS's reputation (and JAS's conduct)?

136 It is necessary to identify a time at which the nature and extent of JDS's reputation is to be assessed. A company's reputation among consumers may fluctuate so the time that is identified may prove to be important.

137 JDS submits, and I accept, that the Court must assess the applicant's reputation, and the respondent's allegedly misleading conduct, at the time at which the conduct commenced: see Mortgage House of Australia Pty Ltd v Mortgage House International Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 1279 at [63] (Beaumont J); Optical 88 Limited at [328]-[334]; Los Carnales Pty Ltd; in the matter of Cartel Del Taco Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1053 at [8]-[9] (Goodman J) and authorities cited there; Global Retail Brands Australia Pty Ltd v Bed Bath 'N' Table Pty Ltd [2024] FCAFC 139 (Bed Bath 'N' Table FC) at [67] (Nicholas, Katzmann and Downes JJ).

138 The way in which JDS has run its case here, however, begs the question: 'which conduct?'. JAS has used the JAS Names in selling art products to Australian consumers from at least 2005. But JDS does not impugn any conduct before October 2018. It submits that only then did JAS start to 'target Australian consumers'. Does its pleading mean that the latter date is the one at which reputation and conduct are to be assessed?

139 Many statements can be found in the authorities to the effect that the conduct in question is the conduct of which complaint is made: Thai World Import & Export Co Ltd v Shuey Shing Pty Ltd (1989) 17 IPR 289 at 302 (Gummow J); Toddler Kindy Gymbaroo Pty Ltd v Gymboree Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 618; (2000) 100 FCR 166 at [123] (Moore J); Mortgage House at [63]; Telstra Corporation Limited v Phone Directories Company Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 568 at [459]-[460] (Murphy J). In the last two of these cases, at least, there appears to have been a question as to when that conduct commenced.

140 In Telstra Corporation, Telstra had pleaded that the respondents' conduct from 2005 was misleading or deceptive, but at trial it also tried to rely on a reputation it said it had developed from 1996. Murphy J was disposed to hold Telstra to the date that it had pleaded, but in the end took a 'cautious approach' and considered Telstra's reputation as at both 1996 and 2005: see Telstra Corporation at [464]-[465].

141 In Mortgage House, Beaumont J looked to the originating application, and identified that the conduct complained of included the use of the name 'Mortgage House International' and any other name including the words 'Mortgage House'. His Honour entertained several alternatives that had been put by the parties as to when this conduct had in fact commenced. In the end he did not need to choose between those alternatives because whatever the choice, he found that the conduct complained of commenced before the applicant had established the necessary reputation to support an action in passing off or under the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth): see Mortgage House at [63]-[71].

142 In neither case did the Court find it necessary to identify a single relevant time. At a level of principle, though, I respectfully agree with the following observations of Goodman J in Los Carnales at [12]: