FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

SMBC Leasing and Finance, Inc v Flexirent Capital Pty Ltd (Discovery) [2025] FCA 459

File number(s): | NSD 543 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | NEEDHAM J |

Date of judgment: | 8 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – Application for discovery of documents alleged to be subject to legal privilege – whether sufficient evidence that documents satisfy dominant purpose test – whether the Court should inspect relevant documents or a sub-set thereof to determine privilege claim – principles of efficient case management. PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – Discovery of documents said to underly opinions created as conditions precedent allegedly subject to a joint privilege – whether such a joint privilege arises – where agreement explicitly precludes the creation of a solicitor/client relationship – where parties are better characterised as counterparties to an agreement. PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – Discovery of documents – where documents traversed in affidavits and exhibits are said to give rise to relevancy – whether underlying documents are relevant on the pleadings – consideration of Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 20.14 – requirement for direct relevance. |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 118, 119 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 37M(2)(R), 43 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 20.14, 20.20(2), 20.31, 20.32, 40.13 |

Cases cited: | Adelaide Brighton Cement Limited, in the matter of Concrete Supply Pty Ltd v Concrete supply Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement (No 3) [2018] FCA 1058 Andrianakis v Uber Technologies Incorporated & Ors; Taxi Apps Pty Ltd v Uber Technologies Inc & Ors [2022] VSC 196 Archer Capital 4A Pty Ltd v Sage Group Plc (No 2) (2013) 306 ALR 384; [2013] FCA 1098 Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Limited v Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (No 2) [2025] FCA 34 AWB Ltd v Cole and Another (No 5) (2006) 155 FCR 30; [2006] FCA 1234 AWB v Cole (2006) 152 FCR 382; [2006] FCA 571 Bailey v Department of Land and Water Conservation (2009) 74 NSWLR 333; [2009] NSWCA 100 Balabel v Air India [1988] Ch 317 Banksia Securities Ltd v The Trust Co [2017] VSC 583 at [43] Barnes v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (2007) 242 ALR 601; [2007] FCAFC 88 Cargill Australia Ltd v Viterra Malt Pty Ltd and Ors [2017] VSC 126 Daniels Corporation International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) 213 CLR 543 DSE (Holdings) Pty Ltd v InterTAN Inc (2003) 135 FCR 151; [2003] FCA 1191 Dye v Commonwealth Securities Ltd (No 5) [2010] FCA 950 Edwards v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (No 4) [2022] FCA 1496 Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1999) 201 CLR 49 Farrow Mortgage Services Pty Ltd (in liq) v Webb & Ors (1996) 39 NSWLR 601; NSWSC 259 Fuji Xerox Australia Pty Ltd v Whittaker (No 2) [2021] FCA 696 Giasoumi (as liquidator of Skalt Pty Ltd) [2024] VSC 250 Grant v Downs (1976) 135 CLR 674; [1976] HCA 63 Hall v Arnold Bloch Leibler (a firm) [2020] FCA 1495 Hancock v Rinehart (Privilege) [2016] NSWSC 12 Kayler-Thomson v Colonial First State Investments Limited (No 2) (2021) 153 ACSR 663; [2021] FCA 854 Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185; [2004] FCAFC 337 Kenquist Nominees Pty Ltd v Campbell [2018] FCA 853 Nipps (Administrator) v Remagen Lend ADA Pty Ltd in the matter of Adaman resources Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (No 3) (2021) 152 ACSR 196; [2021] FCA 628 O’Keeffe Nominees Pty Ltd v BP Australia Ltd (No 2) (1995) 55 FCR 591; [1995] FCA 109 Power Pty Limited (No 4) [2012] FCA 143 Rich v Harrington (2007); 245 ALR 106; [2007] FCA 1987 Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No 42) [2023] FCA 750 Setka v Dalton (No 2) (Legal Professional Privilege) [2021] VSC 604 Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2005] FCA 142 Sharpe v Grobbel [2017] NSWSC 1065 Westpac Banking Corporation v Forum Finance Pty Limited (in liq) (Liability) [2024] FCA 1176 Woollahra Municipal Council v Westpac Banking Corporation (1994) 33 NSWLR 529 Legal Professional Privilege in Australia (Desiatnik, 4th ed, Lexis Nexis Butterworth, 2025) Phipson on Evidence (Phipson, 14th ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 1990) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Commercial Contracts, Banking, Finance and Insurance |

Number of paragraphs: | 134 |

Date of hearing: | 23 October 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr M. Izzo SC with Ms K. Dyon |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Jones Day |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr D.R. Sulan SC with Ms J. Ibrahim |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Bridges Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 543 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | SMBC LEASING AND FINANCE, INC. ARBN 602 309 366 Applicant | |

AND: | FLEXIRENT CAPITAL PTY LTD ACN 064 046 046 First Respondent HUMM GROUP LIMITED ACN 122 574 583 Second Respondent | |

order made by: | NEEDHAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 MAY 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondents to file and serve a revised discovery list and affidavit in support by 29 May 2025.

2. The Interlocutory Application filed on 23 June 2024 otherwise be dismissed.

3. Costs reserved and to be the respondents’ costs in the cause.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[3] | |

[10] | |

[16] | |

[16] | |

[18] | |

[24] | |

[38] | |

[50] | |

[58] | |

[72] | |

[76] | |

[79] | |

[84] | |

[90] | |

[103] | |

[107] | |

[107] | |

B. The parties’ submissions on the Managed Services Documents | [111] |

[123] | |

Further Review Exercise and Production of a Revised Discovery List | [126] |

[131] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

NEEDHAM J:

1 Before the Court is an interlocutory application for discovery (Discovery Application) made by SMBC Leasing and Finance Inc (SMBC or the applicant) on 21 June 2024, pursuant to r 20.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FC Rules). As originally filed, the application sought expansive orders for production of documents against Flexirent Capital Pty Ltd and Humm Group Limited (together, the respondents):

2 As will be discussed below, during the course of preparing for the hearing of the Discovery Application, and subsequent to the hearing itself, the orders originally sought narrowed substantially.

Background

3 The factual background set out below is not intended to be exhaustive and seeks only to traverse the issues with sufficient depth so as to answer the questions necessary to resolving the Discovery Application.

4 SMBC brings its claims against Flexirent as a result of a 2018 receivables financing agreement, under which SMBC purchased receivables and related assets from Flexirent that arose under contracts purportedly entered into by an agent of Flexirent, Forum Enviro (Aust) Pty Ltd (Forum), and Veolia Environmental Services (Veolia).

5 SMBC claims that those receivables and assets did not exist, and that the purported contracts between Forum and Veolia were forged. Flexirent acknowledges that the relevant contracts were forged, but does not admit that the receivables and assets did not exist. A comprehensive history of the backdrop in front of which this particular drama unfolded can be found in Westpac Banking Corporation v Forum Finance Pty Limited (in liq) (Liability) [2024] FCA 1176, in which Cheeseman J described an “audacious fraud” as having taken place (at [1]).

6 SMBC also brings claims against Humm under a Deed of Cross Guarantee. Humm is the ultimate holding company of Flexirent.

7 A range of breaches and consequent remedies are pleaded and sought by SMBC, including (in very brief summary) breach of warranty, negligence, negligent misrepresentation, misleading conduct, and breach of duty.

8 Standard discovery was ordered by Lee J in December 2023, which was required to take place pursuant to the agreed Discovery Protocol, which was agreed to on 12 February 2024.

9 The proceedings are listed for hearing in September 2025 before Thawley J, the docket judge, and, apart from the resolution of this Discovery Application, are ready for hearing.

The Discovery Application

10 The Discovery Application arises from what the applicant casts as failures in the discovery exercise conducted by the respondents. They allege that these failings comprise:

(a) withholding documents on the basis of misconceived privilege claims;

(b) failure to discover relevant documents; and

(c) failure to comply with the discovery protocol that had been agreed between the parties.

11 There has been considerable back and forth between the parties in respect of perceived defects and delays to discovery. These delays and the correspondence arising from them have had the benefit of significantly narrowing the issues between the parties, as evidenced by the most recent revised schedule of documents which was provided on 16 December 2024 (December Schedule).

12 The December Schedule revealed that 109 of the 279 documents subject to the Discovery Application were “not relevant” and should not have been discovered. This left 170 documents in the December Schedule, of which 168 were subject to challenge.

13 The effect of this refinement was that the applicant now seeks:

(a) inspection of communications over which privilege has been claimed by the respondents, involving:

(i) Bianca Spata, the Head of Group Funding and Group Treasurer of Flexi Group during the relevant period (Spata Communications) and, separately,

(ii) Matthew Beaman, who filled each of the roles of a member of the Board of Directors of Flexirent, Group General Counsel, and Group Head of Operational Risk and Compliance of Humm during the relevant period (Beaman Communications)

(the Category 2 documents);

(b) inspection of communications over which privilege has been claimed by the respondents with King & Wood Mallesons, which came into existence as a result of the issuing of opinions which were provided to both the applicant and the respondents in order to satisfy a condition precedent of relevant contracts (KWM Documents);

(c) discovery of the Managed Services Documents relating to Humm’s Managed Services Financing (MSF) business unit which SMBC asserts are relevant to the issues raised in the proceedings;

(d) an Order that the respondents file and serve a revised discovery list which conforms with the discovery protocol as agreed between the parties; and

(e) an Order that the respondents file and serve a further affidavit confirming their compliance with their discovery obligations.

14 In support of the Discovery Application, the applicant relied on affidavits of Maria Yiasemides dated 21 June 2024 (Yiasemides 1), 27 September 2024 (Yiasemides 2), and 22 October 2024 (Yiasemides 3), with the exhibits to those affidavits being tendered into evidence, without objection. Ms Yiasemides is a partner of Jones Day, the applicant’s lawyers.

15 The respondents relied on affidavits of Robert Bruce Wright dated 11 September 2024 (Wright affidavit), Phillip Noel Parker dated 13 September 2024 (Parker affidavit), Andrew Azzi dated 15 October 2024 (Azzi Affidavit), and Karina Elizabeth Carter dated 15 October 2024 (Carter affidavit), with the exhibits to the Wright and Parker affidavits being tendered into evidence, without objection. Mr Wright is an executive of the second respondent, Mr Azzi an accountant employed by the first respondent, and Mr Parker and Ms Carter are respectively a partner and an employed solicitor with Bridges, the respondents’ lawyers.

Discovery of the Category 2 documentsCategory 2 documents

A. The documents over which privilege is claimed

16 As stated above at [13], SMBC has grouped the Spata Communications and Beaman Communications, and no other legal personnel, into the Category 2 documents. In the December Schedule, the Category 2 documents have been further divided by the respondents into Group A, allegedly comprising external legal representative correspondence between Bridges Lawyers and the respondents, and Group B, comprising the respondents’ correspondence or documents. On my reading of the schedule, there are 20 documents remaining in Group A, 147 documents in Group B, and one document which is classified as both.

17 The 21 Group A documents are said by Ms Carter to deal with Bridges lawyers “advising the First Respondent in connection with the liquidation of Forum and the termination of contractual arrangements as between the First Respondent and Forum, and associated draft documents prepared by Ms Griffiths and Ms Amy Nicholls of Bridges Lawyers”.

B. Privilege legal principles

18 It is well established that legal professional privilege attaches to confidential communications brought into existence for the dominant purpose of:

(a) obtaining or providing legal advice; or

(b) use in reasonably anticipated legal proceedings.

See Hall v Arnold Bloch Leibler (a firm) [2020] FCA 1495 at [11] citing Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (1999) 201 CLR 49 and Daniels Corporation International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) 213 CLR 543 at 552.

19 “Dominant purpose” means the prevailing or paramount purpose, or one which predominates over other purposes: AWB v Cole (2006) 152 FCR 382; [2006] FCA 571 at [105] (Young J); Archer Capital 4A Pty Ltd v Sage Group Plc (No 2) (2013) 306 ALR 384; [2013] FCA 1098 at [11] (Wigney J). Privilege extends to documents from which the nature and content of a legally privileged communication may be inferred: Kenquist Nominees Pty Ltd v Campbell [2018] FCA 853 at [13].

20 Privilege is to be determined at the time when the document came into existence: see Barnes v Commissioner of Taxation (Cth) (2007) 242 ALR 601; [2007] FCAFC 88 at [5] (per Tamberlin, Stone and Siopis JJ).

21 Legal advice privilege does not only protect formal advice on the law. While it does not extend to advice that is purely factual or commercial, it includes professional advice as to what a party should prudently or sensibly do in a relevant legal context: see Balabel v Air India [1988] Ch 317 at [323], [330]; DSE (Holdings) Pty Ltd v InterTAN Inc (2003) 135 FCR 151; [2003] FCA 1191 at [45]; AWB at [100].

22 As Tamberlin J said in Seven Network Ltd v News Ltd [2005] FCA 142 at [3], it is generally appropriate that the person from whom the document or the request for it originated give evidence supporting any privilege claim, so that those assertions can be tested in cross-examination. Brereton J, in one of his series of useful judgments in the Hancock v Rinehart disputes (this being Hancock v Rinehart (Privilege) [2016] NSWSC 12) said (at [7]):

To sustain a claim of privilege, the claimant must not merely assert it; but must prove the facts that establish that it is properly made. Thus a mere sworn assertion that the documents are privileged does not suffice, because it is an inadmissible assertion of law; the claimant must set out the facts from which the court can see that the assertion is rightly made, or in other words “expose … facts from which the [court] would have been able to make an informed decision as to whether the claim was supportable”. The evidence must reveal the relevant characteristics of each document in respect of which privilege is claimed, and must do so by admissible direct evidence, not hearsay.

(references omitted)

23 In order to be effective, any evidence put up in support of a claim for privilege must be capable of permitting a conclusion to be drawn as to the dominant purpose of the creation of any particular document: see Kennedy v Wallace (2004) 142 FCR 185; [2004] FCAFC 337 at [171] per Allsop J. The question of whether a document has such a dominant purpose is a question of fact: see Kennedy v Wallace at [157], [211].

C. The respondents’ submissions

24 As the onus lies on the respondents to establish the facts upon which the privilege claim is based (Grant v Downs (1976) 135 CLR 674; [1976] HCA 63 at 689 (Stephen, Mason and Murphy JJ)), it is convenient to deal with their submissions first.

25 The starting point of that evidence is the Parker affidavit. At [24], Mr Parker states that “The Respondent’s privilege position with respect to the ‘Category 2’ documents is as state[d] in the Bridges 30 August Letter” from Bridges to Jones Day. That document can be found in annexure 2 of the Parker Affidavit. Under the sub-heading “Category 2”, Mr Parker first outlines the nature of the roles filled by Ms Spata and Mr Beaman within the business, which accords with what is stated above [13(a)].

26 Mr Parker goes on to assert at [12] of the Bridges 30 August letter that, in respect of the documents where a claim for privilege or part privilege is maintained, such documents meet the criteria set out in s 118 or 119 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). He also states their claims of privilege are not limited to circumstances where the parties to the document are internal legal counsel acting in their capacity as a lawyer, and that claims are maintained in circumstances where the document discloses the contents of a confidential document prepared for the dominant purpose of their clients being provided with professional legal services relating to this dispute.

27 The Wright Affidavit is in somewhat similar terms and sets out the roles of the relevant persons including Mr Beaman and Ms Spata, and notes that Ms Spata:

… held the role of Head of Group Funding and Group Treasurer for Flexi Group. In this role Ms Spata would have had both an operational role and a legal role. As such, Ms Spata would have provided legal advice from time to time to the Respondents. By way of example, Ms Spata was involved in liaising with King and Wood Mallesons on the transactions the subject of these Proceedings.

28 Ms Carter notes that Ms Spata was, at the time of the hearing of the Discovery Application, on maternity leave. She was “Head of Group Funding” from 1 November 2017 to 31 December 2019, and from 1 January 2020 was Group Treasurer. In each role, she had responsibilities in relation to funding strategy and activities. Ms Carter further notes that Mr Beaman was no longer employed by the respondents or any entity associated with them. Prior to 10 September 2018, Mr Beaman was Group General Counsel, and after that date until 19 November 2021, he was Head of Operational Risk & Compliance, and in that role he “over[saw] and identif[ied] legal and regulatory risk issues and the management of legal and regulatory risk compliance”.

29 Each of Mr Beaman and Ms Spata held a practising certificate at the relevant time.

30 The most comprehensive source of evidence as to the content of the documents is the Carter affidavit. That affidavit, at [24], sets out Ms Carter’s assessment of the subject matter of the documents as follows:

(a) seeking and obtaining advice in relation to the respondents’ potential exposure to the Applicant as a result of the transactions involving the First Respondent, the Applicant and Forum: see e.g. document nos. 792-806 and 1890-1891;

(b) internal communications between inter alia Mr Beaman and Ms Spata concerning compliance with a subpoena issued at the request of the Applicant in separate proceedings against Forum: see e.g. document nos. 766, 785, 807, 849, 877, 882, 1383 and 1510; and

(c) advice given by Mr Beaman in connection with disclosures to be made in the Second Respondent's annual report: see e.g. document nos. 1767, 1772, 1805, 1869 and 1925.

31 Ms Carter says that she categorised the documents on the basis that they were prepared for the relevant purposes of legal advice, or for litigation purposes. Ms Carter was not the creator of any of the documents. She does not say, apart from her process of categorisation, how she made the determinations as to the relevant purposes.

32 The respondents suggest that an inference can be drawn from objective material in the evidence, including the nature of the documents and the evidence such as the statement in an ASX announcement dated 9 July 2021 relating to the Forum Finance issue having arisen, and a statement that “investigations are continuing”. The statement contained an assessment of the likely exposure to be suffered by Humm. Mr Sulan SC, senior counsel for the respondents, submitted that an inference arose that there were “plainly going to be legal matters the subject of legal advice privilege and litigation privilege being discussed with internal and external solicitors concerning those matters”. Mr Sulan SC then submitted:

So when your Honour goes to [what became the December Schedule], and glances briefly at the document date, column D, your Honour can see that almost all of them [date] from at least that July period, when the issues with Forum broke, and your Honour is not limited in determining: a) the privilege challenge, and; b) whether or not to exercise the discretion to inspect to direct evidence.

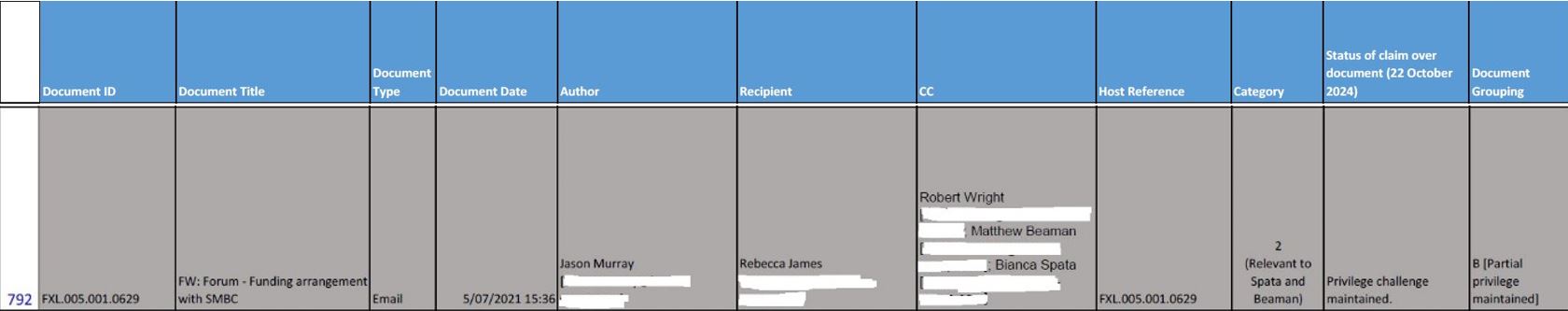

33 This submission used document 792 (which remains as one of the contested documents in the December schedule) as an example. That document appears in the below table (email addresses removed):

34 The documents following document 792 are dated 2018. Ms Carter deals with these in [24(a)] of the Carter affidavit and says:

24. The documents that have been grouped as “B” include documents dealing with the following subject matters:

(a) seeking and obtaining advice in relation to the respondents’ potential exposure to the Applicant as a result of the transactions involving the First Respondent, the Applicant and Forum: see e.g. document nos. 792-806 and 1890-1891 …

35 It was submitted that the Court could find, using the description from Ms Carter and inferences from surrounding events, that the email document no 792 was seeking legal advice on the issues which were current at July 2021 and the attached historical documents attained a privileged flavour because of the privileged nature of the email to which they were attached.

36 In support of this submission the respondents referred to Kenquist Nominees at [13], [15], [16] and [17] in support of their submission that in a complex situation where information is passed between lawyers and clients “as part of a continuum” aimed at keeping information current for the purpose of providing advice, privilege may attach. The “lead email” is the relevant one for the purpose of this inquiry (Kenquist Nominees at [19]). It was submitted that Ms Carter’s categorisation of the documents is “admittedly, hearsay, but [also] her review of the documents”.

37 The fact that Mr Beaman and Ms Spata are not available was, it is submitted, not a factor militating against the sufficiency of the evidence, given the inferences that can be drawn from the history of the matter, Ms Carter’s review, and her experience of some 20 years. (see Andrianakis v Uber Technologies Incorporated & Ors; Taxi Apps Pty Ltd v Uber Technologies Inc & Ors [2022] VSC 196 at [71]). They submitted that to the extent that the Court was unsatisfied with the evidence, this dissatisfaction could be remedied through the Court utilising its power to examine the documents for itself, a power which they submit is not one which the Court should be hesitant in exercising: see Grant v Downs at [52].

D. The applicant’s submissions

38 The applicant submitted that while the Category 2 documents may attach a draft document prepared by Bridges Lawyers, none of them involved Bridges Lawyers as an email sender or recipient. The applicant contended that in the absence of evidence as to the circumstances in which the relevant communications came into existence or their dominant purpose, the privilege claims in relation to these documents must fail.

39 Regarding the remaining five documents in Group A, the applicant asserted that the privilege claims must fail due to the lack of evidence raised as to the basis on which they are said to be privileged.

40 The applicant submitted that the respondents’ assertion of privilege over the Group B documents is reliant on the involvement of Ms Spata or Mr Beaman. The applicant contended that there were a number of reasons why Ms Carter’s evidence to this effect did not go far enough to establish those privilege claims. Senior counsel for the applicant, Mr Izzo SC, described the respondents’ approach as being “…exactly what the authorities say you can’t do. Which is just make short-form assertions of privilege”.

41 The applicant asserted that while the evidence demonstrated that Ms Spata and Mr Beaman had roles that had some legal character, a bare description of those roles does not allow for a conclusion to be drawn that the preparation of a particular document was undertaken for the dominant purpose of giving legal advice or providing legal services in the conduct of litigation.

42 The Court’s attention was brought to a number of decisions containing examples of the topics that are typically addressed in evidence in contests of this nature concerning the function of the in-house legal team. This can cover evidence which demonstrates:

(a) the structure, functions and roles of the in-house legal team: see Uber at [142]; Dye v Commonwealth Securities Ltd (No 5) [2010] FCA 950 at [21]; Rich v Harrington (2007); 245 ALR 106; [2007] FCA 1987 at [48]; Cargill Australia Ltd v Viterra Malt Pty Ltd and Ors [2017] VSC 126 at [53(d)], [53(l)], [53(p)];

(b) the professional nature of the in-house lawyer’s duties and responsibilities within the in-house legal team and business at large: see Archer at [82]; Banksia Securities Ltd v The Trust Co [2017] VSC 583 at [43]; Rich v Harrington at [49]; Cargill at [53(c)];

(c) the reporting lines of the in-house lawyer: see Archer at [82]; Banksia Securities at [43]; Rich v Harrington at [49]; Cargill at [53(c)];

(d) the separate storage of the legal team’s files in a way that is inaccessible to the other teams in the business: see Archer at [82]; Cargill at [52(b)];

(e) the terms in the in-house lawyer’s contract of employment: see Archer at [82]; Dye at [21] and;

(f) whether the in-house lawyer’s remuneration is linked to how the business performs: see Cargill at [54(a)].

43 The applicant went on to submit that there is no direct evidence concerning the roles in which Ms Spata and Mr Beaman acted in relation to the creation of each document. To the extent that evidence is adduced, it is significantly qualified. In the Wright Affidavit, Mr Wright acknowledged that Ms Spata was not employed by either of the Flexirent Parties in a professional capacity as a lawyer. This is reflected in the Carter Affidavit as set out in [28] above. The applicant submitted that there was no explanation for their absence other than a “high-level” one as to Ms Spata being on parental leave, and Mr Beaman no longer working at Humm.

44 The applicant submitted that any evidence of Ms Spata’s supposed involvement is speculative, fails to engage meaningfully with how Ms Spata’s position could be said to encompass a legal role, and provides no direct evidence to support the conclusion that Ms Spata was acting in a professional capacity as a lawyer in relation to the communications the subject of the December Schedule.

45 Additionally, the applicant pointed to a paucity of evidence in the Carter affidavit which could be said to establish that the Group B documents were prepared for the dominant purpose of giving legal advice or providing legal services in the conduct of litigation.

46 While conceding that Mr Beaman held an in-house Counsel role at Humm during the relevant period, the applicant submitted that the Flexirent parties have neglected to explain:

(a) the extent that Mr Beaman’s participation in the relevant communications was couched in his role as in-house lawyer, rather than his capacity as a director of Flexirent;

(b) the extent to which Mr Beaman’s in-house counsel role was solely a legal role, or whether the position picked up both legal and non-legal functions; and

(c) the dominant purpose of each of the relevant communications.

47 Mr Izzo SC also relied on Kenquist Nominees and noted that where the “lead email” (for example in document 792) was not an email between lawyers, it does not fall within the analysis of dominant purpose in email chains. In that decision, Thawley J said (at [19(2)]

If the dominant purpose of the lawyer notionally making the copy of the email chain beneath the lead email was to provide the email chain to the client as part of the communication of legal advice, that email chain is privileged.

48 The applicant submitted that it was happy to accept redactions in email chains, particularly where whole email chains were asserted to be privileged but clearly it was possible that parts of it (for example, non-legal forwarding of emails to someone else in the organisation) were not.

49 In response to the inferences relating to the need for legal advice or litigation preparation in relation to the ASX announcement, the submission was that while that inference was “irresistible”, it did not assist in the formation of a view, on the balance of probabilities, that any particular one of the emails was a document seeking legal advice, or prepared with litigation in mind.

E. Whether the Court should inspect

50 The parties disagree as to whether the Court should exercise the discretion to inspect the documents – or a manageable, representative subset of them – to ascertain the issue of privilege.

51 In its reply submissions, the applicant outlined the legal principles surrounding when the Court should exercise its discretion to inspect, which principles are not fundamentally in dispute, and are briefly summarised below.

52 The power should be exercised to enable a claim to be scrutinised and tested, not in order to facilitate proof by a claimant, citing Rinehart (Privilege) at [31], and Edwards v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited (No 4) [2022] FCA 1496 at [31] (Katzmann J).

53 A further difficulty with the Court’s inspection of documents in order to determine the privileged or other nature of them is the lack of procedural fairness afforded to (in this case) the applicant; it cannot make submissions on the content of documents if it has not been able, as the Court has, to see them – see Rinehart (Privilege) at [18]. As per Giles J in Woollahra Municipal Council v Westpac Banking Corporation (1994) 33 NSWLR 529 at 542:

The Court should be able to proceed upon evidence describing the documents and the circumstances of their creation, and should not unnecessarily pay regard to material which cannot be known to the party challenging the claim to privilege.

54 Material that is in evidence should be considered before deciding whether inspection is appropriate, citing Nipps (Administrator) v Remagen Lend ADA Pty Ltd in the matter of Adaman resources Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (No 3) (2021) 152 ACSR 196; [2021] FCA 628 at [28] per Banks-Smith J.

55 Allsop P said, in Bailey v Department of Land and Water Conservation (2009) 74 NSWLR 333; [2009] NSWCA 100 at [62]:

Parties should not assume that a Judge will put himself or herself to the time and trouble of examining a multitude of documents if the relevant party cannot muster sufficient interest in the protection of its rights to provide an affidavit in support of its claim.

56 If the power of inspection is exercised, the Court will need to recognise that it does not have the benefit of submissions or evidence that might place the document in its proper context, citing AWB Ltd v Cole and Another (No 5) (2006) 155 FCR 30; [2006] FCA 1234 at [44(12)] per Young J.

57 Taking the above statements into account, it first falls to be determined whether the respondents have sufficiently made out a case for establishing the relevant tests of privilege, so as to decide whether to inspect the documents.

F. Competing submissions on inspection

58 As the respondents are requesting that the Court exercise its discretion to inspect, it is convenient to summarise their submissions first.

59 In requesting that the Court undertake inspection, the respondents submitted that when one is dealing with historical material, the Court can look at the totality of the evidence, including inferences that can be drawn from the objective material and the timing of the creation of the documents, to satisfy itself of the need to inspect.

60 The Court’s attention was drawn to [71] of the decision by Matthews AsJ in Uber, in which his Honour stated:

Therefore, the evidence relied on by the Defendants has its limitations and they are such as to mean that it is imperative for me to inspect the Sample Documents. I accept, however, that there is sufficient evidence led to mean that I should do so and that while the power of inspection is not to be used as a substitute for evidence, privilege may be established by the Court drawing inferences based on the documents themselves.

61 The following points were raised in oral submissions in support of this position which it was said, in the aggregate, would satisfy me to the standard necessary to inspect the documents:

(a) the timing of the creation of the documents in light of the history of litigation in the matter (timing point);

(b) the experience and evidence of Ms Carter (expertise point); and

(c) the necessity for efficient case management in matters such as this with voluminous case material and unavailable witnesses (case management point).

62 On the timing point, I have dealt with the submissions as to the ASX announcement at [32] above. It is entitled “Potential historic exposure to Forum Finance via decommissioned flexigroup Managed Services business”. Counsel for the respondents drew my attention to the fourth paragraph which states “investigations are continuing”, and went on to note the material under the subheading “Impact to [Humm]”.

63 I was then taken to [35] of the Statement of Claim filed on 7 July 2023, which demonstrated that the first demand for indemnification by SMBC to Flexirent was made on 1 September 2021.

64 Counsel for the respondents invited a conclusion that, when taken together, these documents made clear that from at least this point, and potentially prior to the date of the announcement, a legal issue had arisen from which legal matters the subject of legal advice privilege and litigation privilege would flow, including discussions with internal and external solicitors concerning those matters. Counsel for the respondents submitted that:

It is not one of those cases where there is some sort of accident, and one is trying to work out whether the investigation has legal professional privilege by reason of lawyers being involved in the investigation, and there might be difficulty as to whether or not the actual event was something that could create legal professional privilege in all the communications. This is a fraud, which obviously my client was looking into in terms of its exposure and had retained external solicitors.

65 On the expertise point, the respondent relied on the Carter affidavit. Counsel observed that Ms Carter is a solicitor of 20 years’ experience who, in swearing her Affidavit, had undertaken a review of the documents in what was a precursor to the December Schedule, which had the effect of reducing the number of privilege claims being made by the respondent, as well as grouping the remaining documents into the categories described at [39] to [40] above.

66 The respondents submitted that in light of a solicitor of her long experience swearing an affidavit describing the undertaking of this exercise, grouping the documents in the manner described above, and forming a view on whether or not they are privileged given the descriptions and details, an available inference is that the documents in the December Schedule are so privileged.

67 In oral submissions it was observed that:

She doesn’t seek…. to be exhaustive, but one is dealing with a huge quantum of documents for the purposes of this privilege claim, so the categorisation process, we would suggest, is eminently sensible and in accordance with case management principles. But importantly, in paragraph 21, Ms Carter again says she has reviewed all the documents and categorised them marked A on the basis of, admittedly hearsay…

68 This fed into the third point, which sought to rely on the principles of efficient case management. My attention was brought to [81] of Setka v Dalton (No 2) (Legal Professional Privilege) [2021] VSC 604, where Daly AsJ said the following:

The authorities that talk about the nature and quality of the evidence, and sometimes they can be hard to reconcile. Each case stands on its own facts, but principles of efficient case management also loom large, particularly where there are a large number of documents where claims for legal professional privilege are in dispute.

(emphasis added)

69 Counsel for the respondents utilised this excerpt as the basis for a submission that a supposed dearth of evidence as to whether the documents are privileged should be considered in light of the whole of Ms Carter’s evidence, and informed by the principles of efficient case management.

70 The applicant submitted that that the respondents have failed to establish that there is sufficient, or indeed any, evidence which would satisfy the onus of establishing the dominant purpose of the creation of the relevant documents (see Barnes at [18]). They argued that this failure has persisted in spite of significant prompting in correspondence, and that production of the documents to SMBC is the desirable outcome rather than further burdening the Court with an extensive review exercise.

71 The applicant cited Rinehart (Privilege) at [17] where Brereton J said:

Thus the evidence tendered by Mrs Rinehart, while it establishes that there were in contemplation at the relevant time proceedings between her and the first plaintiff, communications relating to which could potentially fall in the class of personal privileged documents of Mrs Rinehart as distinct from trust documents, does not begin to establish that the Schedule 1 documents comprised or included such communications. There is no testimonial or documentary evidence – save potentially the disputed documents themselves, to which I shall shortly come – as to the circumstances in and purpose for which they were created.

G. Disposition of Category 2 Disposition of Category 2

72 Sections 118 and 119 of the Evidence Act provide:

118 Legal advice

Evidence is not to be adduced if, on objection by a client, the court finds that adducing the evidence would result in disclosure of:

(a) a confidential communication made between the client and a lawyer; or

(b) a confidential communication made between 2 or more lawyers acting for the client; or

(c) the contents of a confidential document (whether delivered or not) prepared by the client, lawyer or another person;

for the dominant purpose of the lawyer, or one or more of the lawyers, providing legal advice to the client.

119 Litigation

Evidence is not to be adduced if, on objection by a client, the court finds that adducing the evidence would result in disclosure of:

(a) a confidential communication between the client and another person, or between a lawyer acting for the client and another person, that was made; or

(b) the contents of a confidential document (whether delivered or not) that was prepared;

for the dominant purpose of the client being provided with professional legal services relating to an Australian or overseas proceeding (including the proceeding before the court), or an anticipated or pending Australian or overseas proceeding, in which the client is or may be, or was or might have been, a party.

73 I have during both the hearing and the preparation of these reasons found the arguments finely balanced. There are indeed, as proposed by the applicant, significant issues with the way in which the respondent has provided evidence in support of its claims for privilege of the Category 2 documents. On the other hand, the submissions as to the timing, expertise, and case management points are fairly compelling.

74 On balance I have determined that I should uphold the claim of privilege in relation to the Category 2 documents. Ms Carter’s evidence, upon which she was not cross-examined, while not evidence by the authors of the disputed documents, is sufficient for a determination that documents created at the time of the events referred to above were created at a time when legal advice, both as to the legal position of the respondents and the strategy required to respond to issues such as subpoenas, would have been given. I particularly rely on the evidence given in [24] of Ms Carter’s affidavit (set out at [30] and [31] above).

75 The overarching purpose of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FC Act) as to efficient conduct and the just resolution of disputes includes at sub-s 37M(2)(e) “the resolution of disputes at a cost that is proportionate to the importance and complexity of the matters in dispute”. This is not a case where the evidence “does not begin to establish” a basis for a submission as to privilege (cf Rhinehart (Privilege) cited at [71] above). On the contrary, there are a number of aspects of the evidence, based on the evidence of Ms Carter and by way of sensible inference, to establish the position that the documents are subject to privilege. While some of Ms Carter’s evidence may be based on hearsay, her evidence as to her assessment and categorisation of each document is not. On that basis, it appears to me that the Setka approach favouring efficient case-management is the appropriate one to take.

Discovery of the KWM DocumentsDocuments

76 By proposed order 4, SMBC seeks that the Court determine whether the KWM Documents, which are agreed to be prima facie privileged, are subject to a joint privilege between Flexirent and SMBC, meaning that privilege cannot be asserted by one party against the other.

77 The applicant submitted that, where there is evidence that supports the conclusion that documents are subject of a joint privilege held with a party seeking production, then the party objecting to production must establish that there is no joint privilege, citing Colvin J in Kayler-Thomson v Colonial First State Investments Limited (No 2) (2021) 153 ACSR 663; [2021] FCA 854 at [52]. They argued that there is sufficient evidence for such an onus to exist, and that the respondents have failed to discharge that onus.

78 The respondents contended that this submission is wrong, as it is contrary to the terms of the relevant contracts, as well as the opinions themselves.

A. The relevant background for the KWM Documents

79 On 6 August 2018, 28 September 2018, 23 October 2018 and 19 December 2018, legal opinions were provided to SMBC and Flexirent by KWM (KWM Opinions).

80 The KWM opinions were conditions precedent in respect of each offer letter to be delivered by Flexirent to SMBC under the receivables financing arrangement, addressed to SMBC in relation to the material transaction document. Clause 2.1 of the Supplemental Deed of 2 August 2018 required that Flexirent (as Seller) deliver to SMBC (as Purchaser):

(e) legal opinions addressed to the Purchaser, among others, as follows:

(i) from Ashurst confirming, among other things, due execution and enforceability of the MRASA [master receivables acquisition and servicing agreement] and this document, and that the Purchaser will be the owner of Receivables and Related Assets purchased in accordance with the Transaction Documents ...

81 The KWM opinions are each marked “Private and confidential” and are addressed to both SMBC and Flexirent.

82 The applicant seeks discovery not of the opinions themselves (which they have) but documents created in furtherance of the obtaining of the KWM Opinions. The question then is whether there is a joint privilege, not only in the KWM Opinions, but in documents which were created in furtherance of that process.

83 In their written submissions, the applicant summarised the matters on which KWM provided their opinion as follows:

97. At section 5 of the KWM Opinions, KWM provides its legal opinion on nine separate matters, in summary:

(a) that the Obligors under the receivables financing arrangement (Flexirent, Forum and Veolia) were duly incorporated;

(b) that the Obligors had the corporate power to enter into the relevant transaction documents;

(c) that entry into the transaction documents and performance of the Obligors’ obligations under those documents would not breach any laws;

(d) that the transaction documents were duly executed by the Obligors and constituted binding and enforceable obligations on the Obligors;

(e) that Forum was duly authorised by transaction approvals executed by Flexirent to execute the relevant contacts with Veolia as undisclosed agent for Flexirent;

(f) that government approval was not required to enable entry into the transaction documents by the Obligors;

(g) that the filing or registration of the transaction documents was not required by law;

(h) that relevant registrations had been made; and

(i) that the receivables rights and related assets expressed to be assigned by Flexirent to SMBC would be effectively assigned.

B. Joint privilege principles principles

84 The principles surrounding joint privilege were summarised by the applicant in their submissions and, while the existence of such a privilege here is contested, the principles themselves do not appear to be in dispute.

85 A joint privilege arises where two or more parties join in communicating with a legal advisor for the purposes of retaining their services or obtaining their advice. The privilege which protects these communications from disclosures belongs to all parties who joined in seeking the service or obtaining the advice: see Farrow Mortgage Services Pty Ltd (in liq) v Webb & Ors (1996) 39 NSWLR 601; NSWSC 259 at 608 per Sheller JA with Waddell AJA agreeing.

86 Brereton J in Sharpe v Grobbel [2017] NSWSC 1065 at [15] noted that a joint retainer is not strictly necessary for such a privilege to arise, with the privilege extending to circumstances in which multiple parties have a common interest in the subject matter of the communication, even if only one retains the solicitor.

87 A claim of privilege cannot be sustained against a party who has a joint interest in the subject matter of the communication at the time it comes into existence if that communication was made by a party in furtherance of the joint interest then in existence: Sharpe at [17].

88 If a joint privilege arises, any waiving of privilege requires concurrence from all those to whom it belongs: Farrow at 608.

89 In Giasoumi (as liquidator of Skalt Pty Ltd) [2024] VSC 250, Attiwill J considered (at [117]) the position of two or more persons who communicate with a legal advisor for the purpose of retaining advice. Attiwill J said:

[117] Whether a lawyer has been jointly retained can also be determined by looking at the relationship between the parties, the relationship between the parties and the lawyer and the factual context of the retainer and/or advice (see Tabcorp [122] (Sifris J)). In Doran Constructions Pty Limited (in Liquidation) [2002] NSWSC 215 (Doran), Campbell J considered whether a joint privilege existed in the context of a group of companies. Campbell J said:

[62] I should also say that Mr Freeman’s evidence [ie the lawyer’s evidence], that during the meeting he was not asked to provide legal advice to Doran Constructions, is of little assistance. It is perfectly possible for there to be a conclusion that there was a retainer by, amongst others, Doran Constructions, even if no one in the course of the meeting said words to the effect of, “Will you please now advise Doran Constructions”.

…

[76] In my view, there was a joint retainer in the present case. While the impetus for the transaction was, I accept, that Doran Holdings had been asked by its financiers to clean up its intercompany loan accounts, that “cleaning up” process required co-operative action on the part of all four companies involved. There is no basis for believing that any of the companies whose co-operation was involved, were excluded from the advice which was given. Certainly none of them sought advice from anyone other than Mr Freeman. That Doran Holdings was the impetus for the transaction, but all the companies needed to cooperate, is well captured by Mr Joyce’s statement [ie the financial controller’s statement] at the meeting, “Holdings wants to do a series of transactions to take the loans out of Holdings and place them in the Constructions group. Chris what are your thoughts on how we should go about it?” …

[118] These observations of Campbell J were referred to with approval by the Court of Appeal in Great Southern Managers Australia Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (in liq) v Clarke (2012) 36 VR 308 (Great Southern) at [18] (Buchanan and Osborn JJA and Beach AJA). Campbell J in Doran also said:

[72] …whether there is a communication made to, or from, a solicitor in his or her joint capacity is decided by objective evidence about whether the occasion for the communication was one where the solicitor was being asked to advance the purpose for which he or she was jointly consulted…

C. Submissions on joint privilege

90 The applicant submitted that, adopting the reasoning set out in Farrow and Sharpe, a joint interest in being satisfied of the matters that were the subject of the KWM Opinions arises as between Flexirent and SMBC, as well as a joint interest in satisfying the condition precedent associated with receipt of those opinions.

91 The 2 August 2018 KWM Opinion was addressed to each of SMBC and Flexirent, and commenced:

We refer to the Facility in respect of which we have acted as legal advisers to Flexirent.

This opinion is given to you on the instructions of our client (Flexirent). It does not create a solicitor/own client relationship between us and any person to whom this opinion is addressed. We expressly exclude any duty to any addressee in connection with the Facility or this opinion beyond any which arises from the maters stated in this opinion.

92 This formula was repeated in each of the KWM Opinions. In correspondence from Bridges to Jones Day on 27 June 2024 Mr Parker observed that the above paragraph of the KWM opinion “… does not amount to a waiver of privileged documents between our client and KWM with respect to the preparation of the KWM opinions”.

93 The applicant submitted that the terms of the KWM Opinions do not go far enough to prevent a joint interest, and subsequently a joint privilege, from arising, as the KWM opinions are addressed to both SMBC and Flexirent. The respondent relies on the above formulation to exclude any joint privilege.

94 The Court was taken to the decision of Brereton J in Sharpe, expanding on the principles set out in the applicant’s written submissions. At [17] and [18] his Honour states:

… both the nature of the relationship between those said to have a “common interest”, and the purpose of the communication between one of them and the solicitor, are relevant to determining whether there is a relevant “common interest”.

Whether there is a sufficient “common interest” in the relevant communications has to be decided on the facts of the individual case.

(Citations omitted)

95 It was submitted that the satisfaction of the condition precedent referred to in [80] above, specifically ensuring that both parties are comfortable that there were valid and binding transaction documents, is what gives rise to the joint interest, and thus the joint privilege.

96 Rather than this joint interest catching just the KWM Opinions, it was argued that the KWM Documents, having been created in furtherance of that interest, must also be caught by the joint privilege.

97 In resisting the applicant’s claim, the respondents sought to rely on the terms of the Supplemental Deed which caused the KWM Opinions to issue. Clause 2.1 of the Supplemental Deed required Flexirent to deliver various documents and evidence to SMBC prior to the delivery of any offer letter, with Flexirent being obliged to deliver a legal opinion, addressed to SMBC, “from counsel of the seller with respect to the Material Documents”.

98 The respondents submitted that each condition in cl 3.1 of the 2018 MRASA, which covered the conditions precedent in the Supplemental Deed, was for the sole benefit of SMBC, and there could therefore be no joint interest arising from the arrangement. They argued that the terms of the opinions themselves (discussed further below at [101]) underscore this conclusion, and that there can be no cause to go behind what they contended are wholly self-contained opinions, with no further regard needing to be had to any other document for them to be understood.

99 In his oral submissions, counsel for the respondents took the Court again to Sharpe where at [18], Brereton J quotes a passage from the 14th edition of Phipson on Evidence as indicative of the circumstances in, and that basis on, which a joint interest may be found:

No privilege attaches to communications between solicitor and client as against persons sharing a joint interest with the client in the subject-matter of the communication, eg as between partners; a company and its shareholders; trustee and cestui que trust; lord and tenants of a manor as to customs of manor; a lessor and lessee as to production of the lease; reversioner and tenant for life as to common title; two persons stating a case for their joint benefit; or a husband and wife who are not genuinely, but collusively, in contest. Nor does any privilege attach as between joint claimants under the same client – eg between claimants under a testator as to communications between the latter and his solicitor.

Thus where two persons agree to divide the profits made by one of them on contracts made with third parties, the person who does not make the contracts is entitled to production from the person who does of, for example, the opinions of counsel relating to litigation between the contractor and a third party.

But where the communications relate to matters outside the joint interest, they are privileged even as against a person bearing the expense of the communications – eg communications between a plaintiff corporation and its solicitors, against a defendant ratepayer as to matters not connected with rates; or between a company and its solicitors consisting of confidential advice to the former in an action against a shareholder; or between a trustee and his solicitor as against the cestui que trust, where the communication is not made for the former's guidance in the trust, but to enable him to resist litigation by the latter; or where it concerns his character, not as trustee, but as mortgagee of the client.

100 While acknowledging that this is not an exhaustive nor exclusive list, the respondents submitted that the examples provide an outline of the type of formal legal relationship where a common interest can be said to arise, such as a partnership.

101 The respondents submitted that the contractual arrangements between the parties, whom they stated are best conceptualised as “counterparties to a commercial transaction”, cannot reasonably be said to arise from a common purpose, such that the provision of an opinion leads to the applicant being able to access the KWM Documents that sit behind or flowed from the KWM Opinions. Rather, they submitted that it is the opposite of a common interest, noting that the chapeau of the KWM Opinion dated 6 August 2018 expressly excludes “…any duty to the addressee [which includes SMBC] in connection with the facility beyond any which arises from the matter stated in opinion”.

102 In dealing with the applicant’s comparison of the present situation with that found in [18] of Sharpe, noting that the situation therein of two persons agreeing to divide the profits made by one of them on contracts made with third parties was not too far removed from the one in which the parties found themselves in, the respondents contended that the timing was of no assistance to the applicant’s position. In fact, there was to be no transaction until the KWM opinion was provided; it was, it will be recalled, a condition precedent to the entry into the transaction.

D. Disposition of KWM Documents issue

103 It seems to me that the answer to this issue lies in an analysis of the creation of the KWM opinion. It does not matter that Flexirent paid for the opinion. As the learned author of Legal Professional Privilege in Australia (Desiatnik, 4th ed, Lexis Nexis Butterworth, 2025) says (at 258):

Joint legal professional privilege is a concept for which it may be said it is the thought that counts, rather than money, for it extends to those who bona fide believe on reasonable grounds that the person giving the advice was their solicitor (see Global Funds Management (NSW) Ltd v Rooney (1994) 36 NSWLR 122 at 130 per Young J) and it does not depend on who paid for the solicitor’s services.

104 The applicant does not put this case as being one where KWM acted as SMBC’s solicitors. Nor is there anything in the facts as they are set out in the evidence that would indicate that provision of the various KWM Opinions operated as a waiver of any privilege in the underlying documents. Instead, SMBC put the matter as it having a joint interest in obtaining the KWM Opinions, and so, even though it appears that Flexirent was the party who both retained and instructed KWM, they are entitled to the underlying documents.

105 I do not think that this is correct. The Opinions themselves are careful to exclude a solicitor/client relationship between SMBC and KWM, and the fact that no commercial relationship could exist unless and until the KWM Opinions were provided, speak against there being any joint privilege which extends to documents underlying the pre-contractual advice.

106 For that reason the application in relation to the documents said to be subject to a joint privilege fails.

The Managed Services Documents

A. Background and legal principleslegal principles

107 In order to resolve this issue, the applicant seeks a determination as to whether the Managed Services documents are directly relevant to the issues raised by the pleadings, so that they fall within the respondents’ standard disclosure obligations.

108 The applicant submitted that these documents comprise:

(a) documents relating to the “off-site” conference in relation to Humm’s MSF Business unit held in December 2019: see [15] of the Affidavit of Alexander Colbert of 31 May 2024 (Colbert 1);

(b) documents relating to “MS Summit” held on 4 February 2020: see [15] of Colbert 1; and

(c) documents relating to the review and closure of the MSF business unit, including the cessation of the employment of Mr Colbert: see the Wright affidavit.

109 The applicant argued that the documents are plainly relevant to their claim against Flexirent and should thus be disclosed as a part of their standard discovery process.

110 Standard discovery is governed by r 20.14 of the FC Rules, with the sections relevant to these proceedings reading as follows:

20.14 Standard discovery

(1) If the Court orders a party to give standard discovery, the party must give discovery of documents:

(a) that are directly relevant to the issues raised by the pleadings or in the affidavits; and

(b) of which, after a reasonable search, the party is aware; and

(c) that are, or have been, in the party’s control.

(2) For paragraph (1)(a), the documents must meet at least one of the following criteria:

(a) the documents are those on which the party intends to rely;

(b) the documents adversely affect the party’s own case;

(c) the documents support another party’s case;

(d) the documents adversely affect another party’s case.

B. The parties’ submissions on the Managed Services Documents on the Managed Services Documents

111 The applicant submitted that, in devoting a considerable portion of their lay evidence to the issue of the Managed Services Documents, Flexirent has conceded that they are relevant. They contended that this concession has been furthered by their exhibiting to this lay evidence documents related to the MSF business unit.

112 It was argued that this gives rise to an entitlement to the applicant to test the evidence given by Mr Colbert and Mr Wright, not just on the documents that the parties have exhibited, but by reference to the underlying documents. The applicant submitted that it is entitled to test evidence in relation to the closure of the MSF business unit in Colbert 1 and the Wright affidavit by reference to the underlying documents, not just those exhibited by the respondents. They submitted that this evidence given in Colbert 1 and the Wright affidvait is intended to contextualise Mr Colbert’s departure from Humm and his dealings with Forum in respect of the 2020 receivables financing arrangement prior to his departure; something that SMBC is entitled to test.

113 This point was expanded on further in oral submissions through specific reference to Yiasemides 1, in which Ms Yiasemides referred to the evidence given by Mr Wright and Mr Colbert about the offsite conference, managed services summit, presentation slides, and the absence of these documents in those discovered by the respondents. It was reiterated by the applicant that in circumstances where the Wright and Colbert affidavits deal at length with the closure of MSF business unit, which it was submitted “ran … these very transactions”, the materials must be relevant.

114 Further, the applicant submitted that the Managed Services Documents would be relevant to SMBC’s negligent misrepresentation claim, which is pleaded at [49] to [53] of the ASOC, as well as SMBC’s negligence case as pleaded at [69] of the ASOC. In oral submissions, this argument was restated by Counsel as:

They are relevant because in a world where we’re running a negligence claim … which deals with the inquiries that were made by the respondent and how they managed these transactions, what they did before they brought an offer letter to us, what sort of due diligence they undertook to work out whether Veolia was legitimately a party to any of this, … is going to be or likely to be caught up in documents that exist about how the business functioned and that reviews the functioning of the business in connection with its closure.

115 Finally, the applicant argued that discovery of the documents should be given as, to the extent that the respondents have any Ongoing Arrangements Documents in their control, these would have the capacity to expose the enquiries made by the respondents in relation to the operation of the 2018 receivables financing arrangement, and issues relevant to the respondents’ knowledge.

116 The respondents submitted that, when having proper regard to the particular categories of documents identified in order 6 of the Discovery Application, the applicant’s contention that the documents are directly relevant should be rejected. In doing so, they cite the principles set out by Colvin J in Fuji Xerox Australia Pty Ltd v Whittaker (No 2) [2021] FCA 696 at [6], referring to Besanko J’s summary in Adelaide Brighton Cement Limited, in the matter of Concrete Supply Pty Ltd v Concrete supply Pty Ltd (Subject to Deed of Company Arrangement (No 3) [2018] FCA 1058 at [4] to [11], with Colvin J emphasising:

(1) Only documents that are directly relevant to the issues raised by the pleadings are within the scope of standard discovery.

(2) For documents to be directly relevant they must meet at least one of the following criteria: (a) the documents are those on which the party intends to rely; (b) the documents adversely affect the party’s own case; (c) the documents support another party’s case; and (d) the documents adversely affect another party’s case.

(3) The criterion that “the documents support another party’s case” means the strengthening of a position, contributing to success, preventing failure or corroborating or substantiating a claim.

(4) The notion of direct relevance requires that the documents in question be directly on point, in that they tend to prove or disprove the allegation in issue.

(5) The “Peruvian Guano train of inquiry test” is no longer applied in determining whether the documents in question should be discovered.

117 They submitted that any reference to particular events in an affidavit, such as those referenced above at [112], does not amount to a concession that the documents relevant to that event are directly relevant to an issue on the pleadings. The respondents argue that the applicant has not sufficiently spoken to how the unspecified documents are directly relevant to issues raised by the pleadings within the meaning of r 20.14(2), as opposed to relevant in some other more tangential or contextual way.

118 They note that the direct relevance test is framed by reference to pleadings, not to affidavits, citing Katzmann J in Power Pty Limited (No 4) [2012] FCA 143 at [18] where her Honour stated:

A document will be directly relevant, within the meaning of r 20.14, if it tends to prove or disprove a matter in issue, not if there is only a chance it will or if it merely tends to prove or disprove something that might be relevant to a matter in issue.

119 They also contended that the applicant’s assertion to an entitlement to test the respondents’ witnesses by reference to other unspecified documents is flawed, in that it assumes the existence of some relevant issue in the pleadings upon which that evidence may bear.

120 The respondents submitted that the speculative nature of the applicant’s statements on the question of the Managed Services Documents, cast in the language of “will be relevant” should be rejected. In doing so, they pointed to [49], [53] and [90] of the ASOC as failing to meaningfully ground SMBC’s submissions, casting them as “… quintessentially, fishing.”

121 When raised in oral submissions, the respondents largely elected to rely on their written submissions. However, they did reiterate their position on standard discovery and direct relevance, stating that in the absence of “a particular breach or negligence that’s related to the closure of the business for example”, the test for direct relevance cannot be said to have been met.

122 In their reply submissions, SMBC restated its assertion that the Managed Services Documents were directly relevant, relying on the submissions advanced in their written submissions at [108] to [124], as summarised above at [111] to [115].

C. Disposition

123 Having had regard to the terms of the ASOC and to the pleadings of negligent misrepresentation ([49] and [53] of the ASOC) and the negligence case pleaded at [69] of the ASOC, and the submissions of the applicant (at [123] of its submissions) that the documents “have the capacity to throw light on the question of whether Flexirent failed to make reasonable enquiries …”, it is difficult see why the Managed Services Documents are directly relevant to an issue on the pleadings. The documents reveal the way in which the MSF Unit “operated over time”, and because of that are not directly relevant to the way in which the matter is pleaded.

124 I am further not persuaded that the mere fact of the documents being traversed in the evidence of the respondents gives rise to a right to discovery. As legal practitioners would understand only too well, the inclusion of material in an affidavit is not always indicative of that material being relevant, either to an issue in the proceedings or to credit.

125 The above conclusions do not rule out whether the Managed Services Documents are amenable to production on notice to produce (FC Rules r 20.31) or on subpoena, the test for a subpoena being whether the documents are sought for a “legitimate forensic purpose” – see Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No 42) [2023] FCA 750 at [27] where Besanko J said:

An issuing party need not establish that the documents being sought will definitely advance his or her case and it is sufficient if the documents could possibly throw light on the issues or it appears to be “on the cards” that they will do so.

Further Review Exercise and Production of a Revised Discovery List

126 At the time of the hearing of the Discovery Application, the respondents proposed to re-review their discovery to confirm whether there are any further documents which should have been produced for inspection, and to file and serve a revised discovery list.

127 The applicant submitted that this fell short of the relief sought in order 9 of the Discovery Application, which sought that the respondents re-review their discovery to confirm whether there are any further documents which should have been discovered, and file a further affidavit verifying that discovery.

128 The applicant asserted that the respondents appeared to be relying on r 20.20(2) of the FC Rules to withhold discovery of documents despite making no claims for privilege over any of the documents created after the proceedings commenced and it is unclear whether or not the documents withheld would meet the requirements for a successful privilege claim.

129 The applicant submitted that the respondents have failed to comply with the agreed Discovery Protocol. In particular, the applicant contended that the custodian and author information of 22 electronic host documents should be provided in the respondents’ revised discovery list.

130 Given that the respondents intend in effect to comply with their obligations to provide ongoing discovery, I will not make an additional order requiring them to do so, but will order that any such revised discovery list and affidavit in support should be filed and served by 29 May 2025. Any application in relation to the sufficiency of the revised discovery list should be raised before the docket Judge, Thawley J, unless there are any issues of privilege, in which case the matter can return before me.

Costs

131 Costs are of course discretionary. Section 43 of the FC Act confers a wide discretion on the Court. As Perry J said in Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Limited v Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (No 2) [2025] FCA 34 at [13], this discretion:

must be exercised judicially, consistently with the purpose of the power and with regard to all relevant facts and circumstances: see Kazar (Liquidator) v Kargarian; In the matter of Frontier Architects Pty Ltd (in liq) [2011] FCAFC 136; (2011) 197 FCR 113 at [4] (Greenwood and Rares JJ); AOU21 v Minister for Home Affairs (No 2) [2021] FCAFC 212 at [7] (Griffiths, Mortimer and Perry JJ).

132 This is an interlocutory application. The usual position in relation to costs of an interlocutory application is that costs be reserved, and become part of the usual order for costs to the benefit of the successful party in the litigation. The award of costs should, however, “reflect the justice of the situation”: O’Keeffe Nominees Pty Ltd v BP Australia Ltd (No 2) (1995) 55 FCR 591; [1995] FCA 109 at 598 (Spender J). In O’Keeffe, Spender J observed (at 598):

This circumstance reinforces the not uncommon position that in respect of the payment of costs of an interlocutory application, it is not necessarily just that the costs of an interlocutory application should follow the result of that interlocutory application but rather should be determined by the result of the principal litigation of which the interlocutory application forms but a part.

133 Further, the FC Rules provide that, absent an order to the contrary, an interlocutory costs order not be taxed until the conclusion of the proceedings: FC Rules r 40.13. I have not been asked to vary that position.

134 The respondents have been substantially successful (and indeed wholly successful on the three main aspects of the Discovery Application, being the Category 2 documents, the KWM documents, and the Managed Services Documents). I will make an order that the costs of this application be reserved and be the respondents’ costs in the cause.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and thirty-four (134) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Needham. |

Associate:

Dated: 8 May 2025