FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v HCF Life Insurance Company Pty Limited (Penalty) [2025] FCA 454

File number(s): | NSD 413 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | JACKMAN J |

Date of judgment: | 8 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | INSURANCE – pecuniary penalty order under s 12GBB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) for misleading the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability of financial services – where no intention to engage in misleading conduct – where no evidence of consumer loss or damage – where risk of harm merely theoretical – where insurance products were presented as less desirable than they actually were – where defendant derived no financial benefit from contraventions – where legal advice was sought and did not raise possibility that clause may be misleading – consideration of what weight should be attributed to obtaining legal advice in determining a suitable penalty – weight will depend on all circumstances of the case including nature of contravention, nature of advice obtained and degree of certainty or qualification with which it is expressed – where misleading product disclosure statements remained available on website and defendant delayed providing corrective notices following Liability Judgment – specific deterrence largely achieved by declarations of contravention – general deterrence largely achieved by insurers now being on notice that contractual terms may mislead consumers if their operation is modified by or inconsistent with the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) – pecuniary penalty of $750,000 appropriate |

Legislation: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) Private Health Insurance Act 2007 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Australian Building and Construction Commission v Pattinson [2002] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; (2018) 262 CLR 157 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 145 ALR 36 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Equifax Australia Information Services and Solutions Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1637 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2017] FCA 1018 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v HJ Heinz Company Australia Limited (No 2) [2018] FCA 1286 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Allianz Australia Insurance Limited [2021] FCA 1062; (2021) 156 ACSR 638 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 69; (2020) 377 ALR 55 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2018] FCA 155 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Dover Financial Advisers Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 170; (2021) 150 ACSR 185 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Firstmac Limited (Penalty Hearing) [2025] FCA 12 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v HCF Life Insurance Company Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1240 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey (No 2) [2011] FCA 1003; (2011) 284 ALR 734 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v La Trobe Financial Asset Management Ltd [2021] FCA 1417; (2021) 158 ACSR 363 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MobiSuper Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 990 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Web3 Ventures Pty Ltd (Penalty) [2024] FCA 578 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Web3 Ventures Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 58 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2019] FCA 2147 Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 Couch v Attorney-General (No 2) [2010] NZSC 27; [2010] 3 NZLR 149 Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53; (2018) 260 FCR 68 Giannarelli v Wraith (No 2) (1991) 171 CLR 592 Gilfillan v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] NSWCA 370; (2012) 92 ACSR 460 Ingot Capital Investments Pty Ltd v Macquarie Equity Capital Markets (No 6) [2007] NSWSC 124; (2007) 63 ACSR 1 Markarian v R [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 170; (2022) 295 FCR 106 Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; (2004) ATPR 41-993 NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v ACCC (1996) 71 FCR 285 Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076 Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCAFC 193; (2003) 131 FCR 529 Campbell JC, “Unenforceable Exclusions in Travel Insurance” (2018) 29 Insurance Law Journal 71 Heydon JD, Cross on Evidence (LexisNexis Australia, 14th Australian ed, 2024) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Commercial Contracts, Banking, Finance and Insurance |

Number of paragraphs: | 114 |

Date of hearing: | 28 April 2025 |

Counsel for Plaintiff | Mr R Hollo SC Mr H Atkin |

Solicitors for Plaintiff | Norton Rose Fulbright |

Counsel for Defendant | Mr D Thomas SC Ms E Bathurst |

Solicitors for Defendant | Herbert Smith Freehills |

ORDERS

NSD 413 of 2023 | ||

IN THE MATTER OF H C F LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY PTY LIMITED | ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Plaintiff | |

AND: | HCF LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY PTY LIMITED ACN 001 831 250 Defendant | |

order made by: | JACKMAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 May 2025 |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

In these orders, the following definitions apply:

ASIC Act means the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth).

FCA Act means the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

Product Disclosure Statement means any of the First Cash Back PDS, First Income Protect PDS, First Smart Term PDS, Fourth Cash Back PDS, Income Assist PDS, Second Cash Back PDS, Second Income Protect PDS, Second Smart Term PDS, and Third Cash Back PDS as defined in the orders of the Honourable Justice Jackman made on 28 October 2024.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Paragraphs 8 to 15 and 17 of the Originating Process filed 11 May 2023 be dismissed.

2. Pursuant to s 12GBB of the ASIC Act, the defendant (HCF Life) pay a pecuniary penalty to the Commonwealth in the amount of $750,000.

3. Pursuant to s 12GNB of the ASIC Act and/or s 23 of the FCA Act, HCF Life, at its own expense, is, within 14 days of the date of this order, to publish, or cause to be published, in a prominent place on the following website, www.hcf.com.au/insurance/life-recover-cover, (Website) a corrective notice in the terms set out in Annexure 1 to these orders (Website Notice) such that:

(a) the Website Notice shall be viewable by clicking a “click-through” banner located on the Website;

(b) the “click-through” banner is to be:

(i) prominently located in the top third of the Websites and viewable upon opening the Website without scrolling down; and

(ii) not obscured, blocked or interfered with by any operation of the Websites, other than during periods of IT outages or maintenance;

(c) the “click-through” banner box shall contain the wording “Notice ordered by the Federal Court of Australia – Life Insurance policies” with a “Learn More” button within the banner box in white and in the same font and centred on a red background.

(d) the “click-through” banner is to remain on the Website for a period of no less than 180 days from the date the Website Notice is published;

(e) the “click-through” banner is to operate in the form of a one-click hyperlink to the Website Notice;

(f) the Website Notice shall occupy the entire webpage that is accessed via the “click-through” banner;

(g) the Website Notice shall be in bold, red, and in size 15, Whitney font;

(h) the Website is to be maintained or otherwise kept active for the period during which the Website Notice is required to remain on the Websites, other than during periods of IT outages or maintenance; and

(i) the Website shall not have in place any mechanism which would preclude search engines from indexing the pages or scanning the pages for links to follow.

4. Pursuant to s 12GNB of the ASIC Act and/or s 23 of the FCA Act, HCF Life, at its own expense, is, within 14 days of the date of this order, to publish, or cause to be published the Website Notice (or otherwise the “click-through” banner referred to in paragraph 3 of these orders) on each webpage of the Websites where the Product Disclosure Statements are published for so long as policyholders are able to make a claim under the policy referable to the Product Disclosure Statements.

5. There is liberty to apply, as necessary, in relation to paragraphs 3 and 4 of these orders.

6. HCF Life pay 50% of ASIC’s costs incurred up to 28 October 2024.

7. HCF Life pay ASIC’s costs incurred after 28 October 2024.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

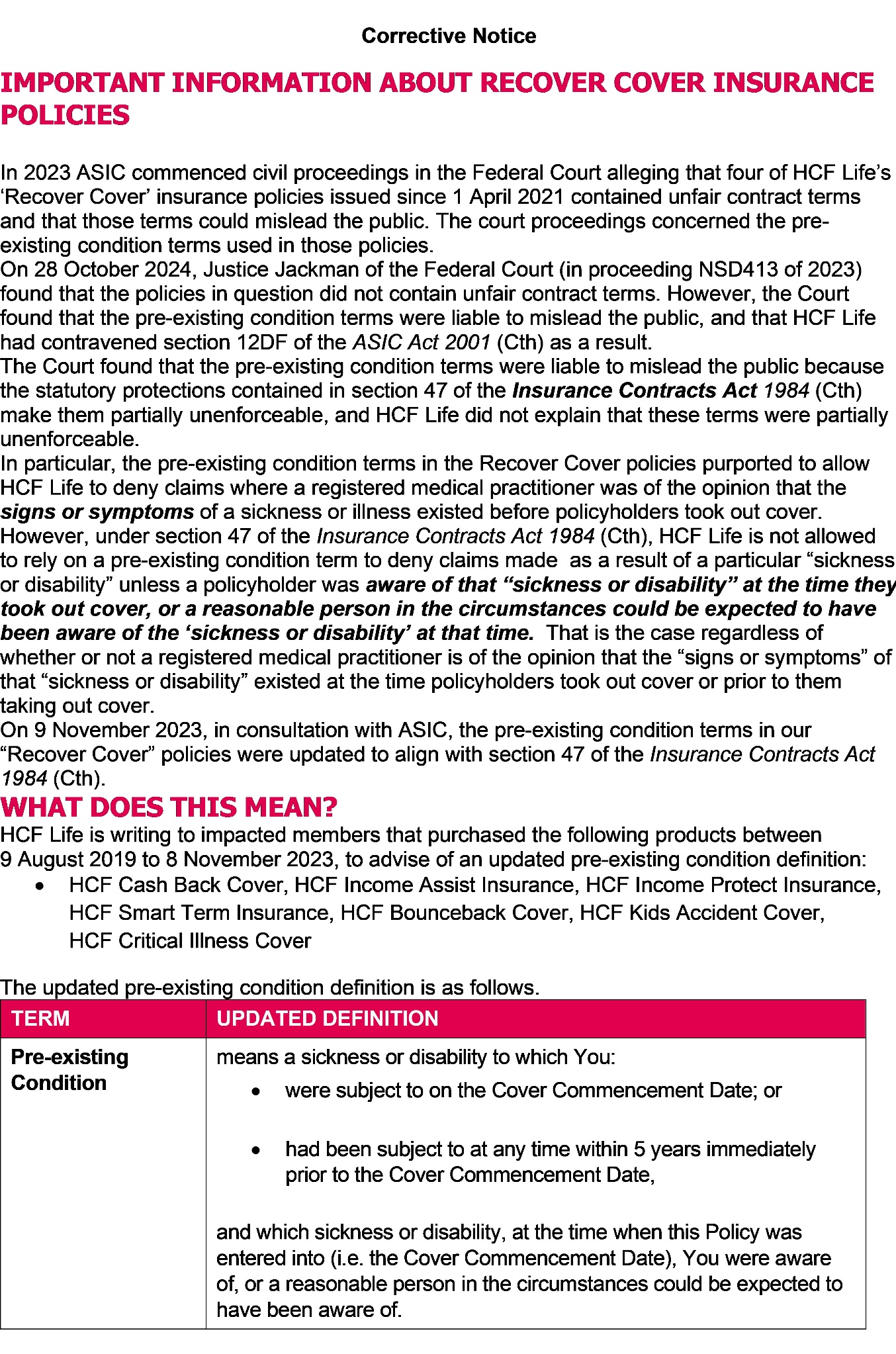

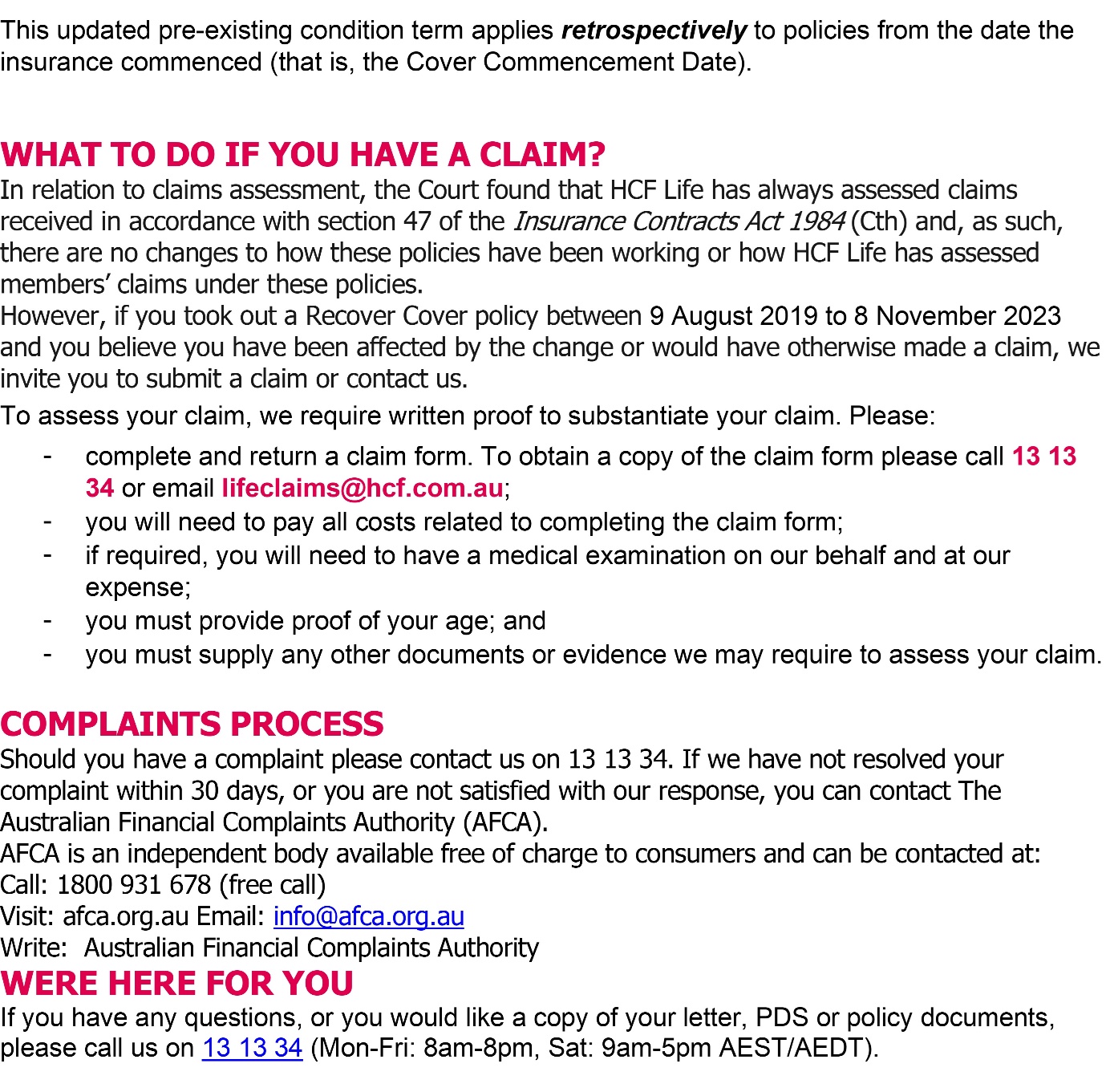

ANNEXURE 1

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKMAN J:

Introduction

1 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v HCF Life Insurance Company Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1240 (the Liability Judgment), I found that HCF Life had contravened s 12DF of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) by engaging in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability of financial services in misrepresenting exclusions, referred to as the Pre-Existing Condition Terms, in the Recover Cover Product Disclosure Statements (PDSs). ASIC now seeks a pecuniary penalty order under s 12GBB of the ASIC Act. In these reasons I have adopted the same defined terms as in the Liability Judgment.

2 The parties have agreed a Further Amended Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (SAF2). They have also prepared further affidavits.

Principles for Pecuniary Penalties

3 The salient principles relating to the assessment of pecuniary penalties were not the subject of significant dispute between the parties, and may be stated as follows.

4 The purpose of a civil penalty regime is primarily, if not solely, the promotion of the public interest in compliance with the provisions of the relevant Act by the deterrence, specific and general, of further contraventions: Australian Building and Construction Commission v Pattinson [2002] HCA 13; (2022) 274 CLR 450 at [9], [15] and [31] (Pattinson) (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ); Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; (2018) 262 CLR 157 at [87] (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ).

5 The penalty must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by the offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Pattinson at [17]. In other words, those engaged in trade and commerce must be deterred from the cynical calculation involved in weighing up the risk of penalty against the profits to be made from contravention: Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; (2012) 287 ALR 249 at [63] (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ). However, the penalty should not be greater than is necessary to achieve the object of deterrence, and severity beyond that is oppression: Pattinson at [40] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ). The penalty should be proportionate in the sense of striking a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity: Pattinson at [41].

6 Further guidance as to the approach to be adopted in assessing the quantum of an appropriate penalty is to be drawn from the joint reasons of Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ in Pattinson as follows:

(a) The prescribed maximum penalty is one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied and must be treated as one of a number of relevant factors (at [54]).

(b) The maximum penalty is not to be reserved for the most serious cases and there is no place for the notion that the penalty must be proportionate to the seriousness of the conduct that constituted the contraventions (at [10], [49] and [51]).

(c) The required relationship between the statutory maximum and the penalty in a particular case is established where the penalty as imposed does not exceed what is reasonably necessary to achieve general and specific deterrence (at [10]).

(d) Neither retribution nor rehabilitation has any part to play in economic regulation where civil penalties are to be imposed where there is a failure to comply with the regulatory requirements (at [15] and [39]).

(e) Factors pertaining to the character of the contravening conduct and the character of the contravener may be considered, but there is no legal checklist and the task is to determine the appropriate penalty in the circumstances of the particular case (at [19] and [44]).

(f) The discretion to assess the appropriate penalty must be exercised fairly and reasonably for the purpose of protecting the public interest by deterring future contraventions (at [40] and [48]).

(g) The penalty must not be oppressive by being greater than is necessary to achieve the object of deterrence and, in that particular sense, must be proportionate (at [40]–[41]).

(h) Concepts from criminal sentencing such as totality, parity and course of conduct may be usefully deployed in the assessment of what is reasonably necessary to deter further contravention (at [45]).

(i) It will be appropriate to consider whether the conduct involves a deliberate flouting of the law, whether the person responsible was aware of the law and whether they have been disciplined for their conduct (at [46]).

7 What is required is “some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed”: Pattinson at [10]. That relationship is established where the maximum penalty does not exceed what is reasonably necessary for specific and general deterrence of future contraventions of a like kind by the contravener and by others: Pattinson at [10]. This may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravener and the contravening conduct: Pattinson at [55].

8 The penalty that is appropriate by way of general deterrence may be moderated by factors of the kind adverted to by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076 to the extent that they bear upon an assessment of what is required to deter future contraventions: Pattinson at [47]. However, these must not be considered a “rigid catalogue of matters for attention”: Pattinson at [19]. Those factors (which substantially overlap with the mandatory factors in s 1317G(6) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act)) are, relevantly, (1) the nature and extent of the contravening conduct, (2) the amount of loss or damage caused, (3) the circumstances in which the conduct took place, (4) the size of the contravening company, (5) the degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market, (6) the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended, (7) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level, (8) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance, and (9) whether the company has co-operated with the relevant regulator in relation to the contravention.

9 A court will usually give significant weight to what the regulator, as ASIC is here, considers necessary to achieve specific and general deterrence: Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; (2004) ATPR 41-993 at [51] in which the Full Court distilled the key propositions which emerged from NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v ACCC (1996) 71 FCR 285. The task for the court is to satisfy itself that the submitted penalty, or disqualification period, is appropriate: Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; (2015) 258 CLR 482 at [48].

10 Where there is an interrelationship between the factual and legal elements of two or more contraventions, consideration might be given to whether or not it is appropriate to impose a single overall penalty for that course of conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2017] FCA 1018 at [36] (Beach J); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [217]–[234] (ACCC v Yazaki) (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ). As Middleton and Gordon JJ expressed the matter in Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 at [39] (Cahill) (emphasis in original), the course of conduct principle:

recognises that where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality. That requires careful identification of what is “the same criminality” and that is necessarily a factually specific enquiry. Bare identity of motive for commission of separate offences will seldom suffice to establish the same criminality in separate and distinct offending acts or omissions.

11 As their Honours said in Cahill at [41], however, the principle is only a tool of analysis which can, but need not, be used in any given case in order to ensure an appropriate deterrent effect. The course of conduct principle does not operate as a de facto limit on the penalty to be imposed, and the maximum penalty for the course of conduct is not restricted to the prescribed maximum penalty for any single contravention: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [24]–[25] (Beach J), approved in ACCC v Yazaki Corporation at [230]–[232]. As Lee J expressed the point in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Equifax Australia Information Services and Solutions Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 1637 at [86], the principle is:

merely a discretionary tool or analytical expedient along the way to determining an appropriate penalty. A precise allocation of the number of courses of conduct is not some sort of calculus which results in various outcomes, depending upon the characterisation of the contravening conduct, as falling into one or other of the identified courses of conduct.

12 In addition, the totality principle requires the court to review the “aggregate” penalty to ensure that it is just and appropriate, and not out of proportion to the contravening conduct considered “as a whole” or the “totality of the relevant contravening conduct”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation [2019] FCA 2147 at [272] and [308] (Wigney J). It involves a “final overall consideration of the sum of the penalties determined” by consideration of all the relevant factors, and requires the court to make a final check of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd [1997] FCA 450; (1997) 145 ALR 36, 53 (Australian Safeway Stores) (Goldberg J). The totality principle will not necessarily result in a reduction from the penalty that would otherwise be imposed. In cases where the court considers that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too low or too high, the court should alter the final penalties to ensure that they are just and appropriate: Australian Safeway Stores at 53. The totality principle is distinct from the course of conduct principle in performing a check at the end of the reasoning process.

13 Courts in civil penalty proceedings have applied the parity principle, which recognises that equal justice requires that, as between co-offenders (in a criminal context), there should not be marked disparity which gives rise to a “justifiable sense of grievance”: Gilfillan v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] NSWCA 370; (2012) 92 ACSR 460 at [185]-[186] (Sackville AJA, with whom Beazley and Barrett JJA agreed); see also Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey (No 2) [2011] FCA 1003; (2011) 284 ALR 734 at [125]-[126] (Middleton J). However, penalties imposed in other cases, especially under other legislative schemes, can only be of limited analogical value and must be treated with caution: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2018] FCA 155 at [22(2)] (Middleton J).

14 In fixing a pecuniary penalty, the court will engage in an “intuitive or instinctive synthesis” of all the relevant matters by weighing together all relevant factors, rather than engage in a sequential, mathematical process: Markarian v R [2005] HCA 25; (2005) 228 CLR 357 as applied to civil penalty proceedings in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [6] (Allsop CJ).

Additional Salient Facts

The Recover Cover PDSs and Contracts

15 The Recover Cover PDSs were published on the HCF Life website and the Recover Cover Products were available for purchase during the following period(s) (SAF2 [7]):

(a) "Smart Term Insurance” on 1 April 2021 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 April 2021 and 30 September 2021) and 1 October 2021 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 October 2021 and 24 March 2023);

(b) “Cash Back Cover” on 1 April 2021 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 April 2021 and 30 September 2021), 1 October 2021 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 October 2021 and 30 August 2022), 1 September 2022 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 September 2022 and 24 March 2023) and 25 March 2023 (applicable to policies purchased on or after 25 March 2023);

(c) “Income Assist Insurance” on 1 April 2021 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 April 2021 and 30 September 2021); and

(d) “Income Protect Insurance” on 1 October 2021 (applicable to policies purchased between 1 October 2021 and 24 March 2023) and 25 March 2023 (applicable to policies purchased on or after 25 March 2023).

16 From 5 April 2021 to 27 April 2023, HCF Life entered into a total of 12,265 Recover Cover Contracts with members of the public, of which 7,022 remained in force as at 10 December 2024: SAF2 [14].

17 Of the products HCF Life currently sells, only Income Protect Insurance and “Critical Illness Cover” (which was not one of the products the subject of the proceeding) contain a Pre-Existing Condition Term of any kind: SAF2 at [8]–[9]. The Pre-Existing Condition Term for Income Protect Insurance was subject to a further amendment on 4 April 2024: Affidavit of Mr Reville of 17 March 2025 at [25]–[27]. On the same day, HCF Life replaced the Pre-Existing Condition Term in the Cash Back Cover for new policies for new insureds with a “Waiting Period”: SAF2 [13]; Affidavit of Mr Reville of 17 March 2025 at [31]–[33].

18 The Income Protect Insurance and Cash Back Cover PDSs that were the subject of the proceeding still appear on HCF Life’s website at http://www.hcf.com.au/lifeinfo: SAF2 at [35]–[36].

19 Notwithstanding that the Liability Judgment was delivered on 28 October 2024, HCF Life’s website does not contain any reference to:

(a) the existence or effect of the Liability Judgment;

(b) the existence or effect of s 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (ICA); or

(c) the fact that the PDSs were and are liable to mislead the public: Affidavit of Ms Bradley of 25 February 2025, Ex GKB–1, Tabs 1–7. I deal with the broader context pertaining to that matter below.

The financial position of HCF Life and its parent company

20 The income, revenue and profit position of HCF Life is addressed at SAF2 at [15]–[16]. In each of FY20 to FY24, HCF Life received premium revenue between approximately $39m and $45m, and derived profits of between $2.3m and $5.9m (except for FY22, when it experienced a loss of approximately $5.3m). Despite the loss in FY22, the appointed actuary of HCF Life explained in the Financial Condition Report for that financial year that HCF Life’s risk business continued to provide strong underlying profitability and attributed the unfavourable experience to one-off project costs in relation to a product which is not the subject of these proceedings, and an increase in discount rates and the inflation assumption.

21 The profit (loss) figures in SAF2 at [15]–[16] do not include the distributions made to HCF Life’s parent company, The Hospital Contribution Fund of Australia Limited (HCF Ltd) by way of commissions for distribution of HCF Life’s products and a profit share arrangement. The commission payable for each product sold amounts to up to 40% of the first year’s premium plus an additional commission of 80% of HCF Life’s underwriting profit each year calculated as premiums less claims and expenses: Affidavit of Mr Keane of 17 March 2025 at [27]. For FY24 this profit share paid to HCF Ltd was $4.2m.

22 The Financial Statements show that HCF Life had net assets of approximately $80.3m as at 30 June 2024, $74.4m as at 30 June 2023 and $71.1m as at 30 June 2022 (p 14 of the FY24 Financial Statement at Annexure A of SAF2).

23 The Recover Cover Products the subject of these proceedings are issued out of HCF Life’s Statutory Life Fund No 1, which is currently the only statutory fund it operates in respect of its life insurance business. HCF Life also maintains a Shareholders’ Fund. The Financial Condition Report of HCF Life prepared for FY24 by its appointed actuary indicated that it held net assets in excess of capital requirements as follows:

(a) $50.216m above regulatory capital requirements as at 30 June 2024; that is, in excess of its prescribed capital amount (see also note 24, p 49, to the FY24 Financial Statement at Annexure A to SAF2). This represented a capital adequacy multiple (CAM) at an entity level of 349%, and a CAM of 341% for Statutory Fund No 1;

(b) $45.857m above regulatory capital requirements as at 30 June 2023. This represented a CAM at an entity level of 382%, and a CAM of 367% for Statutory Fund No 1; and

(c) $32.432m above “enterprise” (ie internal target) capital requirements as set by the Board of HCF Life as at 30 June 2024. As at 30 June 2023, this figure was $31.183m.

24 The Appointed Actuary concluded in the FY24 Financial Condition Report, without allowance for the impact of these proceedings, that HCF Life was expected to have assets in excess of regulatory capital and enterprise capital requirements and generate profits over the projection horizon.

25 The financial position of HCF Ltd is addressed at SAF2 at [17]–[21]. HCF Ltd’s primary business is as a not-for-profit private health insurer. In addition, HCF Ltd has a diversified business, which includes HCF Life’s life insurance business. HCF Life’s insurance products are designed to complement the benefits provided under HCF Ltd’s private health insurance policies: SAF2 at [18(b)].

26 HCF Ltd has a 13.33% share of the Australian private health insurance market by premium revenue: SAF2 at [19]. It has received annual income of between approximately $3bn and $4bn from FY20 to FY24 and derived annual group profits of between $(81m) and $171m in that period: SAF2 at [20].

27 In the period comprising FY20 to FY24, the financial statements show that HCF Ltd had net assets of between about $1.75bn and $2.24bn.

The involvement of HCF Ltd in the management of HCF Life’s affairs

28 More than 90% of Recover Cover customers were HCF Ltd private health insurance fund members at any given time: Liability Judgment at [53].

29 Mr Keane (the Chief Officer Member Services of HCF Life) gave evidence that (Affidavit of Mr Keane of 19 December 2023 at [26] and [49]):

HCF Life outsources its front-line operations such as sales, marketing, advertising, member services and product design and some of its support functions including risk, legal and compliance, company secretarial, information technology, people and culture, and some finance functions to HCF.

…

The Head of Product (Diversified Business) of HCF, is responsible for the

development and management of HCF Life's products.

HCF Ltd provides these services under a Master Services Agreement, which includes design and distribution obligations in relation to HCF Life’s products (Affidavit of Mr Keane of 17 March 2025 at [14]).

30 The Master Services Agreement also refers to an Agency Agreement dated 5 May 2014 between HCF Life and HCF Ltd, as amended from time to time. Under the Agency Agreement HCF Life appointed HCF Ltd as its agent, among other things, to promote and sell products issued, or offered by HCF Life. HCF Ltd’s obligations under the Agency Agreement include compliance with relevant laws, rules and industry codes, including “Relevant Acts” which are defined to include the ASIC Act and ICA.

31 In FY24, each of the directors of HCF Life were directors of HCF Ltd (although some directors of HCF Ltd were not directors of HCF Life): Affidavit of Mr Keane of 17 March 2025 at [12].

Legal advice sought and received by HCF Life prior to 23 March 2023

32 The Recover Cover PDSs issued in 2019, which included the 2019 PEC Clause, were reviewed by external lawyers acting for HCF Life as part of a review of HCF Life’s Recover Cover PDS documents for compliance with financial services laws prior to the PDSs being issued. In that review, HCF Life’s external lawyers did not advise that the draft PDSs (including the proposed 2019 PEC Clause) were potentially misleading or deceptive. HCF Life’s external lawyers did not raise the possibility that the proposed 2019 PEC Clause may be misleading due to the clause’s failure to advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA: SAF2 at [29A].

33 The same is true of the Recover Cover PDSs issued in 2021 and 2023, which contained the 2021 PEC Clause and 2023 PEC Clause respectively, although it should be noted that the 2023 review by HCF Life’s external lawyers occurred prior to 23 March 2023: SAF2 at [29B]–[29C].

ASIC’s letter of 23 March 2023

34 On 23 March 2023, HCF Life received a letter from ASIC which read as follows:

Proposed amendments to Recover range of insurance policies issued by HCF Life Insurance Company Pty Ltd (HCF Life)

I refer to HCF Life’s 30 January 2023 production in response to ASIC notice barcoded N1C221722, and HCF Life's 8 March 2023 productions in response to ASIC notices barcoded NTC2317720 and NTC2317719.

I note that HCF Life’s productions in response to those notices include an explanation and wording of proposed amendments to the pre-existing condition term within various HCF Life insurance policies (within its Recover range of products) due to take effect on or after 25 March 2023 (Proposed Amendments).

ASIC’s concerns

ASIC is concerned that the Proposed Amendments do not accurately describe the rights and obligations arising under the HCF Life policies. In particular, ASIC is concerned that the Proposed Amendments do not adequately set out how the pre-existing condition term would operate given the effect of s47 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (ICA).

ASIC encourages HCF Life to review the wording of the Proposed Amendments against s47 of the ICA and consider whether further revisions are necessary.

ASIC reserves its rights including in respect of any action it might take against HCF Life concerning the current wording of the HCF Life policies and/or any amendments (including the Proposed Amendments).

35 The 23 March 2023 letter came to be received by HCF Life in the following circumstances:

(a) ASIC and HCF Life had corresponded in the period July 2020 to February 2021 in relation to ASIC’s review of unfair contract terms in insurance contracts, and ASIC conducted investigations in the period 24 March to 21 November 2022 relating to that topic (Affidavit of Mr Keane of 17 March 2025 at [48]–[49]).

(b) on 27 July 2022, ASIC had issued a notice to HCF Life under s 912C of the ASIC Act, with category 1 of that notice requiring HCF Life to:

Provide an explanation of what legitimate interests of the Licensee are protected by the Pre-existing Condition Term in each of the HCF Life Policies issued by the Licensee. As part of the explanation, specifically address what legitimate interests of the Licensee for each of the HCF Life Policies are protected by including in the scope of the Pre-Existing Condition Term conditions, illnesses or ailments where the signs or symptoms existed at any time before the insurance policy was entered into even if a diagnosis had not been made.

(c) on 17 August 2022, HCF Life provided a response to ASIC’s notice of 27 July 2022;

(d) on 18 October 2022, ASIC requested by email that HCF Life provide further detail in response to the notice of 27 July 2022:

In particular, ASIC requests HCF Life to provide further detail in relation to the second part of the question, to ‘specifically address what legitimate interests, for each of the HCF Life Policies are protected by including in the scope of the Pre-Existing Condition Term conditions, illnesses or ailments where the signs or symptoms existed at any time before the insurance policy was entered into even if a diagnosis had not been made’ (emphasis added). It is not clear from the response dated 17 August 2022 how inclusion of this part of the definition is necessary to protect HCF Life's legitimate interests, so any further information or clarification that can be provided in this regard would assist.

[emphasis in original email]

(e) on 4 November 2022, HCF Life provided a further response to the notice of 27 July 2022 by way of supplementation of its original response. HCF Life’s supplementary response made reference to the fact that “HCF Life acts, and applies the Pre-Existing Condition Term, in accordance with s47 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth)”. The supplementary response went on to say:

any determination of a pre-existing condition at any stage of the claims assessment process will be excluded from our final decision if s47 of the Insurance Contacts Act 1984 (Cth) applies.

(f) on 2 December 2022, ASIC issued a notice under s 33 of the ASIC Act to HCF Life which required production of pages of HCF Life’s website, certain PDSs, and “Welcome Packs” provided to consumers. The notice referred to suspected contraventions of ss 12DA, 12DB and 12DF of the ASIC Act and s 1041H of the Corporations Act, this being the first time ASIC had alleged suspected contraventions of provisions dealing with misleading or deceptive conduct (as distinct from provisions dealing with unfair contract terms).

(g) on 13 December 2022, ASIC issued:

(i) a notice to HCF Life under s 33 of the ASIC Act, with category 1 requiring production (inter alia) of:

To the extent not already produced, copies of each version of the pages on the Company's website published in Australia during the Relevant Period which refer to the:

a. Pre-Existing Condition Term or pre-existing conditions generally; and

b. IC Act.

(ii) a notice to HCF Life under s 912C of the ASIC Act, with category 6 requiring information of the following kind:

During the Relevant Period:

a. describe where there is any reference to the IC Act that was published or appeared on the Licensee’s website; and

b. state the length of time that there was any reference to the IC Act that was published or appeared on the Licensee’s website.

(h) on 30 January 2023, HCF Life had informed ASIC of its proposal to alter the definition of “Pre-Existing Condition” in its Recover Cover Products. That letter appended a response to ASIC’s notices of 13 December 2022 which stated “HCF Life has made no disclosures on its website in relation to the IC Act, during the Relevant Period” and “HCF Life has not referenced the IC Act on our website during the Relevant Period”;

(i) on 22 February 2023, ASIC issued compulsory notices under s 33 of the ASIC Act and s 912C of the ASIC Act requiring production of any draft or final PDSs containing a revised Pre-Existing Condition Term, and various other documents and information concerning the proposed amendments and the process that had led to them; and

(j) on 8 March 2023, HCF Life complied with those notices, and produced copies of the PDSs proposed to be issued.

36 In his affidavit of 17 March 2025, Mr Keane gives evidence at [55] that ASIC’s letter of 23 March 2023 was, to his knowledge, “the first occasion on which ASIC had specifically raised concerns with the interrelationship of HCF Life's Pre-Existing Condition Terms with s 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act”. ASIC accepts that proposition.

37 Mr Keane gives evidence of steps taken by HCF Life to review the 2021 PEC Clause in the lead up to the introduction of the 2023 PEC Clause on 25 March 2023, in light of the concerns expressed by ASIC in relation to unfair contract terms: Affidavit of Mr Keane of 19 December 2023 at [132]–[152]. However, by its letter of 23 March 2023, ASIC was now encouraging a review of the PEC Clause from a different perspective, namely whether the proposed clause accurately reflected the operation of s 47 of the ICA. I therefore do not accept HCF Life’s submission (at [32] of its written submissions) that HCF Life had already done what it thought ASIC was encouraging in its letter of 23 March 2023.

HCF Life’s decision to issue the 2023 PDSs despite ASIC’s statement of concerns

38 On 23 March 2023, within an hour of receiving ASIC’s letter, Mr Barnard (the Head of Legal and Compliance of HCF) forwarded the letter to HCF Life’s external solicitors by email.

39 On 24 March 2023, Mr Barnard indicated to the external solicitors that HCF Life still wished “to push ahead”, apparently in reference to the proposed launch of new Recover Cover PDSs the following day. The external solicitors sent an email that afternoon after a telephone discussion with Mr Barnard and Mr Keane, suggesting an interim response to ASIC, and referring also to additional information that could be used to supplement the applicable PDSs as follows:

In relation to the meaning of a pre-existing condition, please note that a statutory restriction applies in circumstances where the insured was not aware of, and a reasonable person in the circumstances could not be expected to have been aware of, the sickness or disability at the time when the contract was entered into.

The email then pointed out that if HCF Life did insert that additional information, it would “constitute a quasi-admission”.

40 About half an hour later, Mr Barnard sent an internal email within HCF Ltd and HCF Life as follows:

Kevin [Keane] and I spoke with ASIC [sic: the parties agreed this should be a reference to HCF Life’s external solicitors, not ASIC] earlier and while they believe we do not have an issue, they have suggested we send an email to ASIC tonight as set out below (with a view to sending a fuller response later). They are anxious that ASIC are lifting the bar on PDS disclosures by asking for s 47 to be addressed (not normally dealt with in a PDS) and are again trying to flex their enforcement power.

To mitigate the risk they have also provided some additional text to supplement the applicable PDS’ (see below) however they do note if we do this it would be seen as a quasi-admission by HCF Life. ASIC could issue a stop order [an apparent reference to s 1020E of the Corporations Act] but ASIC must convene a hearing first (we get a chance to defend our position) unless they issue an interim order (where no hearing is held but they can only do this if a delay in holding a hearing causes material prejudice to the public).

At first instance, are you okay for me to send the suggested email to ASIC? We can discuss whether we amend the applicable PDS’ on Monday.

41 There was considerable debate at the penalty hearing as to the proper construction of that email as to the advice which had been given by the external solicitors. Read literally, the external solicitors were advising that there was not even an issue as to whether the relevant PDSs adequately reflected the effect of s 47 of the ICA, but it would appear unlikely that the external solicitors would have given advice in such absolute terms, and the reference to mitigating risk suggests that there was a recognition of at least some risk of a contravention. While the risk being mitigated may well have included the risk of ASIC commencing proceedings or issuing a stop order (or interim stop order), in my view the better construction is that the risk extended to the risk of a contravention of one or more financial services laws being established.

42 The evidence of Mr Keane establishes that the new Recover Cover PDSs had been printed for the launch by this time and were in distribution (presumably meaning that they had been sent out to various branches of HCF Life) by 21 March 2023, ahead of the effective date of the launch of 25 March 2023 (Affidavit of Mr Keane of 17 March 2025 at [56(b)(ii)]).

43 On 25 March 2023, HCF Life issued the Recover Cover PDSs containing the 2023 PEC Clause: Liability Judgment at [37].

44 On 28 March 2023, Mr Barnard wrote an email to HCF Life’s solicitors saying that the company wanted to respond to ASIC and explain “why we did not pull the products last Friday, noting that it was too late in the process to do so”, and saying that at the executive level, “the thinking was better to go now with some product changes even if we have to update later”.

45 On 31 March 2023, the CEO & Managing Director of HCF Ltd sent a letter to ASIC which had been settled by its solicitors (who “agree with the approach”), and included the following:

As ASIC is aware, HCF Life chose to proceed with the Amendments on 25 March 2023. This decision was considered seriously by HCF Life after receipt of the ASIC Letter, including by myself and my executive team. Our decision to proceed as planned on 25 March 2023 was due to two main factors:

a) first, HCF Life considered the issue and maintains that the material substance of section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act 1984 (Cth) (Insurance Contracts Act) has been disclosed in the revised pre-existing condition term following the implementation of the Amendments. In particular, HCF Life considers that the Amendments accommodate the limitations under section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act, given that the definition of a Pre-Existing Condition fixes only upon signs and symptoms already existing within 5 years of the Cover Commencement Date. This means that a person who had, in the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, experienced the signs, symptoms or treatment of a sickness or disability in that period would be either aware, or reasonably expected to have been aware, of the sickness or disability, in accordance with the limitations under section 47. Accordingly, HCF Life considers that the pre-existing condition term does sufficiently disclose how the pre-existing condition term would operate in practice, both in accordance with its terms and section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act; and

b) second, from a timing perspective, the ASIC letter was only received by HCF Life two days prior to the proposed launch. This was part of a broader and complex IT release that included several different items and hence trying to stop it at the last moment would have had other consequences for the business and the IT processes. Given this short timeframe, HCF Life was of the opinion that, on balance and given both a) above and the imminence of launch, the Amendments should proceed.

46 The letter went on to thank ASIC for raising its concerns and concluded by confirming “that HCF Life is currently considering ASIC’s comments and what further enhancements could be made to its disclosures on the pre-existing condition term”.

47 On 12 April 2023, Mr Keane sent an email to the external solicitors referring to HCF Life planning ahead on the assumption that HCF Life would amend the four remaining PDSs, containing PEC Clauses, and write to all impacted policyholders (ie holders of policies purchased since 5 April 2021), referring to the preliminary wording provided in Mr Bernard’s email on 24 March 2023. No explanation is apparent from the evidence as to why the assumed or proposed communication to those policyholders was not sent at the time. The external solicitors responded on 17 April 2023 as follows:

We’ve taken another look at the existing PEC disclosure (using Cash Back as an example but note they are all materially the same). In our view, the definition of the PEC still remains appropriate and so, the best way to address ASIC’s concerns is perhaps through some additional explanation of the PEC (e.g. in the “HOW A PRE-EXISTING CONDITION WORKS” section).

For example, the existing definition and explanations around PEC can be bolstered by adding text to the following effect:

We will assess if an Insured Person has a Pre-existing Condition when You make a claim. In accordance with insurance law, we will only decline Your claim based on a Pre-existing Condition if, based on the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, You were aware or should have reasonably been aware of the condition, illness or ailment giving rise to the Pre-existing Condition.

This way, we are explaining the effect of section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act and how it works clearly, without the need to actually refer to the legislation, which is less consumer-friendly. In our view, this is more effective than the footnote route, particularly given we don’t really use footnotes throughout the PDSs (again, due to the clear, concise and effective disclosure lens).

48 On 19 April 2023, Mr Barnard responded by email saying that HCF was considering making the proposed amendments now, and asked whether it was appropriate to ask ASIC to confirm the amendment, that being HCF Life’s preferred approach, as otherwise further amendments may have to be made if ASIC rejected the proposal. The external solicitors responded the same day saying that it was appropriate to ask ASIC to confirm the amendment, but that ASIC were unlikely to do so as their standard approach is to say that they do not approve disclosure. The external solicitors suggested some changes to the draft letter to ASIC to “help give HCF some comfort”.

49 On 21 April 2023, HCF Life sent the letter to ASIC as settled by the external solicitors reiterating its view “that our current PEC disclosure is appropriate and captures the operation of section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act”. The letter proposed to address ASIC’s comments through some additional explanation of the Pre-Existing Condition Term, by adding the following text to the PDSs:

We will assess if an Insured Person has a Pre-existing Condition when You make a claim. In accordance with insurance law, we will only decline Your claim based on a Pre-existing Condition if, based on the opinion of a registered medical practitioner, You were aware or should have reasonably been aware of the condition, illness or ailment giving rise to the Pre-existing Condition.

HCF expressed the belief that that was a clear way of explaining the effect of s 47 of the ICA “without referring to complex legal jargon or legislation, which is less consumer friendly”. HCF Life requested any comments ASIC may have on that approach. ASIC did not respond until 10 August 2023, as set out below.

50 On 1 May 2023, the external solicitors responded to an email from HCF Life that relevantly asked whether a decision had been made as to where to add the proposed new text in the PDSs and whether that was the only change currently required to be made, referring to the language which had been proposed in the letter to ASIC of 21 April 2023. The external solicitors responded suggesting where the wording be included and stating that it was the only change required from their perspective, but noted that “we have also informed ASIC of the approach, so may be worthwhile to see if they respond before finalising the approach”.

51 On 11 May 2023, these proceedings were commenced, without ASIC having responded to HCF Life’s letter of 21 April 2023, making allegations as to misleading conduct in relation to financial services and unfair contract terms.

52 On 10 August 2023, ASIC responded to HCF Life’s letter of 21 April 2023. Although the letter is marked “without prejudice”, both parties have agreed to waive the privilege which would otherwise have been attached to the letter (and they have taken the same approach to a letter dated 17 October 2023 by HCF Life’s external solicitors which is also marked “without prejudice”). In the letter of 10 August 2023, ASIC said that it was not clear how the text of the further proposed amendment would be introduced into the relevant PDSs and also expressed some preliminary concerns about the proposed amendment. ASIC suggested that another way of addressing ASIC’s concerns may be to alter the definition of Pre-Existing Condition so as to incorporate the relevant elements of s 47(2). ASIC also said that they understood that the proposed amendments would only be introduced for new sales of products, and that it was unclear whether HCF Life intended to take any steps to ensure that existing policyholders were made aware of the effect of s 47 on HCF Life’s ability to rely upon a Pre-Existing Condition Term to deny a claim.

53 On 18 August 2023, HCF Life completed its Financial Condition Report for the year ended 30 June 2023, being a document required to be submitted by HCF Life to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, and which is not made public by HCF Life. In that report, the Appointed Actuary of HCF Life commented on the litigation commenced by ASIC against HCF Life on 11 May 2023, in which it was alleged that the Pre-Existing Condition Terms were unfair contract terms and could mislead the public. The report stated that HCF Life was currently considering its legal position, and that potential penalties, remediation costs or increased capital requirements were expected to be less than the excess assets of HCF Life. The report later stated that a wide range of potential outcomes was possible, ranging from:

• HCF Life defending the case and winning;

• HCF Life defending the case and losing; or

• HCF Life accepting guilt.

54 On 17 October 2023, HCF Life’s external solicitors responded to ASIC’s “without prejudice” letter of 10 August 2023 in a letter also marked “without prejudice”. That letter addressed, among other things, HCF Life’s rationale for its amendments. On 17 October 2023, HCF Life also wrote an open letter to ASIC indicating that it proposed to “amend” the Recover Cover PDSs to address the concerns that ASIC had expressed in the proceedings. The letter attached a draft form of PDS which included the amendments.

55 On 9 November 2023, HCF Life issued revised PDSs for the Cash Back Cover and Income Protect Insurance policies containing the Current PEC Clause for policies issued from that date: Liability Judgment at [46]. The changes to the Pre-Existing Condition Terms in the PDSs which were issued from 9 November 2023 did not alter the Pre-Existing Condition Terms in the Recover Cover Contracts the subject of the contraventions found in these proceedings.

56 On 10 November 2023, ASIC replied to HCF Life’s letter of 17 October 2023 indicating that the “Proposed PDS largely addresses ASIC’s concerns” and making some further comments and queries as to aspects of the drafting.

The nature and extent of the contraventions

57 It is common ground, which I accept, that HCF Life’s contravening conduct should be regarded as objectively serious. There is no dispute that the conduct occurred over more than three years in relation to entry into new policies, and concerned PDSs and Recover Cover Contracts for over 12,000 consumers. It is also common ground that the conduct involved misrepresentation of the operation of an important exclusion in life insurance policies, and that the misrepresentations were made in PDSs which consumers were entitled to regard as reliable documents, containing accurate and sufficient information as to the circumstances in which benefits would be payable (see s 1013D(1)(b) of the Corporations Act). It is also common ground that the contraventions should be viewed as part of a single continuing course of conduct, even though the conduct varied over time, as the Pre-Existing Condition Terms were amended, and the circumstances of the contravention changed, especially after 23 March 2023.

58 However, it should also be noted that it is common ground that HCF Life had no intention to engage in misleading conduct: SAF2 at [31]. The conduct arose from a desire to make the terms “clearer for policyholders to understand”, as I found in the Liability Judgment at [34]. While that desire miscarried as matters transpired, the intention of HCF Life was, in itself, a commendable one.

The nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contraventions

59 It is common ground that there is no evidence that any consumer suffered any direct loss or damage because of the contraventions. Indeed, as I found in the Liability Judgment at [122], the impugned conduct presented the Recover Cover Products as less desirable than they actually were. The contraventions therefore stand in contrast to the more typical misleading conduct case in which a product or service is presented as more desirable than it actually is, and induces consumers to enter into the relevant transaction on that basis. It is also common ground that there is no evidence that any consumer was dissuaded from bringing a claim on a policy that they could have brought, or was prejudiced in their ability to prosecute a claim that they had brought (for example, by disputing the refusal of a claim).

60 In the Liability Judgment at [124], I referred to the evidence of Mr Goodsall, a highly experienced actuary engaged by HCF Life to give independent expert evidence, to the effect that, in his experience, insureds: (i) claim on policies without having read their terms, or (ii) claim on policies even when aware that an exclusion clearly says the claim is not eligible. I accepted that Mr Goodsall’s second proposition was probably true for the vast majority of insureds when deciding to make a claim, but I accepted ASIC’s submission that Mr Goodsall’s evidence suffers from the usual limitation of inductive reasoning, namely that persons who read policy terms and do not make claims when they understand an exclusion applies are, by definition, unlikely to come to attention. I also noted that Mr Goodsall’s report was not admitted as evidence of invariable policyholder behaviour. It thus follows that there was a possibility that the contravening conduct might have had the potential to dissuade at least some consumers from making, or persisting with, claims that HCF Life would have been obliged to pay.

61 In terms of the significance of such a possibility in the assessment of pecuniary penalties, ASIC relies on two recent cases. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Dover Financial Advisers Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 170; (2021) 150 ACSR 185 at [57], O’Bryan J said in the context of assessing a pecuniary penalty that it was relevant to consider the extent to which the contravening conduct had the potential to cause consumers loss and damage. However, in the following paragraph at [58], O’Bryan J found that the relevant conduct had “real potential” to mislead consumers, and that the erroneous belief thereby generated could have caused consumers very great loss. His Honour was thus concerned with realistic, rather than merely theoretical possibilities. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v MobiSuper Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 990 at [119]–[120], Charlesworth J referred to the seriousness of the contravening conduct in that case as lying in the failure of the Defendants to ensure compliance so as to guard against the risk that loss and damage might ensue, being the risk that consumers may lose the benefit of insurance cover as a result of a decision to consolidate their superannuation. However, the point of her Honour’s remarks was to reject a submission that the absence of evidence concerning financial loss or damage being suffered in fact should operate as a mitigating factor. As her Honour said at [119], whether or not loss or damage might be suffered after consumers had lost the benefit of insurance cover attached to their existing superannuation was a matter of happenstance, and one that may not play out until some time had passed. Moreover, as her Honour said at [120], on the admitted facts in that case, there were two instances where consumers had in fact lost insurance cover previously provided under existing superannuation upon their decision to consolidate their superannuation.

62 The difficulty in the present case is that there is little evidence to indicate (whether directly or by inference) the extent, if any, to which the relevant possibility (ie that some consumers may have been dissuaded by the contravening conduct from making or persisting with claims that HCF Life would have been obliged to pay) was a realistic one. In many cases, that will be a matter of inference from the nature of the contravention in light of ordinary experience. Mr Goodsall’s evidence points in the direction of the possibility being speculative and remote, but his evidence cannot entirely eliminate the theoretical possibility. Although I found at [123] of the Liability Judgment that the probability of a mismatch between s 47 of the ICA and the Pre-Existing Condition Terms is real and not speculative, that objective likelihood does not bear on the present issue, which concerns potential decisions by insureds as to whether to make or persist with a claim, not simply whether there is a disparity between s 47 and the language of the policies.

63 I note that corrective notices have now been issued by HCF Life, together with an invitation to submit a claim or contact HCF Life if consumers believe that they were affected by the change to the Pre-Existing Condition Term or would have made a claim under a policy, had the updated Pre-Existing Condition Term been in place. If those notices had been issued promptly after delivery of the Liability Judgment (as would seem to be generally desirable), and well before the hearing as to civil penalties, then evidence would now be available as to whether any consumers claim to have been affected by the contravening conduct. However, ASIC indicated a preference at the liability hearing to defer the question of appropriate corrective notices until the penalty hearing (Liability Hearing Transcript of 11 September 2024, T60.6–19; ASIC’s written submissions of 1 August 2024 at [172]), in which HCF Life acquiesced, and thereby deprived itself of the potential opportunity of ascertaining by now whether any consumers claimed to have been affected by the contravening conduct, for example in not previously making or persisting with a claim. ASIC bears the onus of establishing whether the risk to consumers on which it relies was a realistic possibility, rather than one which is merely theoretical, fanciful or speculative (as ASIC accepted at the penalty hearing at T18.45 and T100.18–23). In my view, ASIC has not discharged that onus. I therefore approach the matter on the basis that the risk of a consumer being detrimentally affected by the contravening conduct has not been shown to be more than theoretical.

64 ASIC also submits that persons who claim on life insurance policies face inherent disadvantages in preparing and prosecuting an insurance claim, given that they are facing exigencies such as being sick, injured, disabled, recently unemployed or recently bereaved. ASIC submits that a mistaken understanding as to whether the consumer can claim on the policy and, if so, what must be established to do so, is liable significantly to compound these existing disadvantages. I do not regard that consideration as sufficient to discharge the onus of establishing that the relevant risk of loss or damage in the present case was a realistic one.

Any benefit derived because of the contravention

65 There is no evidence of HCF Life having derived any financial benefit from the contraventions, nor does ASIC suggest that HCF Life intended to derive such a benefit.

66 Mr Reville, who is now the General Manager of HCF Life, conducted a review of the financial records of HCF Life and found no reference to any expected or projected financial impact to HCF Life (either positive or negative) from the Pre-Existing Condition definitional changes in 2019 or in 2021: Affidavit of Mr Reville of 17 March 2025 at [45] and [48]. As to the change in 2023, this change (which involved introducing a 5-year look-back limitation on the term) was not put forward to mitigate HCF Life’s risk exposure or reduce HCF Life’s loss ratios, and in fact, before making the change, HCF Life estimated that introduction of the 5-year limitation period under the 2023 PEC Clause would increase its annual claims costs by about $200,000 per year: Affidavit of Mr Reville of 17 March 2025 at [50]. That evidence is consistent with the finding in the Liability Judgment at [34] that internally within HCF Life, it was not intended that these changes to the policy would change how claims were to be assessed.

67 The parties have agreed facts concerning HCF Life’s revenue from net premiums, loss ratio and profit margins for the Recover Cover Products between the financial years ended 30 June 2020 and 30 June 2023: SAF2 at [25]. The total product profitability for the Recover Cover Products between April 2021 and April 2023 was a total of $4,464,924: SAF2 at [26]. Those agreed facts, however, have been supplemented by the evidence of Mr Reville concerning the “scaled product profitability” for the 12,265 policies issued by HCF Life for the period April 2021 to April 2023 (including contracts issued containing the Pre-2019 PEC Clause), which shows an overall loss of $144,598: Affidavit of Mr Reville of 17 March 2025 at [67]. Mr Reville explains that “scaled product profitability” has been calculated as the actual revenue earned for the 12,265 policies as a proportion of the total revenue for the four relevant products across the relevant period, with that proportion applied to the total claims and expenses for those products in the period. The proportion of the actual premium paid for the 12,265 policies, to total revenue for the four relevant products across the relevant period, is then applied to apportion claims, reserves and expenses to the 12,265 policies: at [68]. In my view, the concept of “scaled product profitability” is an appropriate way of assessing whether HCF Life derived any profit from the 12,265 policies at all. The fact that HCF Life incurred a loss based on that measure reinforces the conclusion that it did not derive any benefit from the contraventions.

The circumstances in which the contraventions took place

Circumstances prior to 23 March 2023

68 ASIC places considerable reliance on an article by the Honourable J C Campbell KC entitled “Unenforceable Exclusions in Travel Insurance” (2018) 29 Insurance Law Journal 71. That article criticised the practice of including partially enforceable exclusions in respect of pre-existing conditions (including those which depended upon the existence of signs or symptoms) in insurance products as “deceptive market behaviour” (at 125). As I indicated in the Liability Judgment at [119], Mr Campbell KC stated (at 127) that making a practice of issuing standard form contracts that contain unenforceable terms seems likely to contravene s 12DF(1) of the ASIC Act. However, ASIC acknowledges that there is no evidence that anyone at HCF Life was aware of the arguments put forward in Mr Campbell KC’s 2018 article at the time of the adoption of the 2019 PEC Clause, the 2021 PEC Clause or the 2023 PEC Clause. In my view, even the most diligent officer of a life insurer cannot reasonably be expected to be aware of, and to read and absorb, an article in an academic legal journal apparently pertaining to travel insurance, even one written by a distinguished author of Mr Campbell KC’s eminence. ASIC accepted that at T16.23–17.11.

69 Importantly, for each of the Recover Cover PDSs issued in 2019, 2021 and 2023, HCF Life sought and obtained legal advice from external lawyers as to the compliance of those PDSs with financial services laws, which must have included s 12DF of the ASIC Act and other provisions dealing with misleading or deceptive conduct. It is an agreed fact between the parties that in none of those advices did the external lawyers raise the possibility that the proposed 2019, 2021 and 2023 PEC Clauses may be misleading due to the failure to advert to, or explain, the existence or effect of s 47 of the ICA, or that those PEC Clauses were partially unenforceable: SAF2 at [29A]–[29C]. ASIC acknowledges the significance, on the question of penalty, of HCF Life’s external lawyers failing to identify the misleading nature of its PDSs. ASIC cites without criticism or challenge my reasoning in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Web3 Ventures Pty Ltd (Penalty) [2024] FCA 578 at [36]–[41] and [62] (ASIC v Web3 (Penalty)): ASIC’s written submissions on penalty at [57]. Those observations were made in the context of accepting an application under s 1317S(2) of the Corporations Act for relief from liability for contravention of a civil penalty provision, but they are also applicable to the assessment of the amount (if any) of a pecuniary penalty. I note that the Full Court in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Web3 Ventures Pty Ltd [2025] FCAFC 58 at [140]–[141] (O'Callaghan, Abraham and Button JJ) referred to my reasoning on this issue at first instance, saying only that a defendant who seeks to contend either that they should be relieved from liability to pay a pecuniary penalty for contraventions of the Act, or that a penalty should be fixed in an amount lower than it otherwise would be, because they have received relevant legal advice would “ordinarily” need to give evidence about what advice they had in fact received. The present case falls within what might be regarded as the ordinary case, and the agreed facts provide such evidence.

70 ASIC submits, and I accept, that the relevance and weight to be attributed to the obtaining, by the contravener, of legal advice will necessarily depend upon all of the circumstances of the case, including the nature of the contravention and the nature of the advice obtained, and including the degree of certainty or qualification with which it is expressed. There is no inflexible rule: Flight Centre Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53; (2018) 260 FCR 68 at [64] (Allsop CJ, Davies and Wigney JJ). The present case is clearly distinguishable from Universal Music Australia Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] FCAFC 193; (2003) 131 FCR 529 at [307]–[308] (Wilcox, French and Gyles JJ), where the Full Court regarded the fact that the contravener had received favourable and unqualified legal advice as a matter which was to be given minimal weight in the assessment of penalty because the contravening conduct “was plainly and deliberately anti-competitive in its intent” and “ran a serious risk of being in breach of the Act”. In the present case, the fact that HCF Life sought a review by external lawyers of the relevant PDSs as a whole for their compliance with financial services laws before they were issued evinces an intention by HCF Life to comply with those laws, including s 12DF of the ASIC Act. In my view, HCF Life acted responsibly and commendably in that regard. The present case is also clearly distinguishable from Mayfair Wealth Partners Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2022] FCAFC 170; (2022) 295 FCR 106 (Jagot, O’Bryan, Cheeseman JJ), where the only evidence was that the impugned document had been “reviewed and approved by the solicitors for the Mayfair Parties” (at [235]–[236]).

71 Despite acknowledging the significance of HCF Life’s external lawyers failing to identify the misleading nature of the PDSs, ASIC advances four submissions of a supposedly countervailing effect.

72 First, ASIC draws attention to the Pre-2019 PEC Clause substantially mirroring the language of s 47 of the ICA, giving rise to an inference that HCF Life had, at some point in its corporate history, considered it desirable that the PEC Clause align with s 47 of the ICA, but that this aspect of HCF Life’s corporate knowledge appears to have been forgotten or overlooked at the time HCF Life adopted the 2019 PEC Clause. I do not regard that matter as anything more than inadvertence on the part of HCF Life. Further, that inadvertence should be viewed against the background that the change from the Pre-2019 PEC Clause to the 2019 PEC Clause was motivated by a desire to bring the clause into line with private health definitions and make the policies “easier to understand” and “improve transparency and member centricity”: Liability Judgment at [27]–[34]. The 2019 PEC Clause is clearly adapted from s 75-15 of the Private Health Insurance Act 2007 (Cth).

73 Second, ASIC submits that HCF Life’s Claims Manager from February 2019 only became aware of the existence of s 47 in late 2019, in the course of a complaint to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA), and thus was ignorant of the existence of s 47 at the time that the 2019 PEC Clause was adopted on 9 August 2019. Similarly, ASIC submits that HCF Life’s General Manager from 2020 to 2024 only became aware of the existence of s 47 in 2022 when dealing with a complaint to AFCA. However, neither of those employees was responsible for the wording change in 2019, and the submission seems to me to go nowhere in the context of the external legal advice which was obtained. Further, the knowledge or ignorance of the Claims Manager and the General Manager is of minimal relevance in circumstances where the contravening conduct did not involve the failure of HCF Life to apply s 47 correctly when assessing claims made under the Recover Cover Contracts, and, as I found in the Liability Judgment at [68], HCF Life did in fact assess claims consistently with s 47 throughout the whole of the relevant period.

74 Third, ASIC submits that HCF Life had subscribed to the Life Insurance Code of Practice (LICOP) in July 2018, which contained a provision in cl 3.5(a) to the effect that where a life insurance policy has an exclusion clause for a pre-existing medical condition, the insurer will provide to insureds details of how the exclusion works and when the exclusion applies and the potential implications of this in plain language. However, ASIC does not submit that HCF Life did not genuinely attempt to comply with that provision. Further, Mr Keane’s evidence is that since around September 2022, HCF Life has conducted quarterly reviews of both the Claims and Product Teams to ensure compliance with the relevant provisions of the LICOP and, as part of that review, HCF Life ensures that its terms and member-facing communications are consumer-centric and in plain language: Affidavit of Mr Keane of 19 December 2023 at [63].

75 Fourth, ASIC submits that the Pricing and Product Management Framework in place at the time required that changes to conditions be subject to actuarial advice and approval by the board and that the framework expressly provided that the General Manager had no delegation to make changes to product conditions. ASIC submits that it appears that approval of the Board was not sought at the time that the 2019 PEC Clause was adopted, nor does it appear that any actuarial advice was sought in relation to the change. ASIC submits that, consistently with the Liability Judgment at [33], the board of HCF Life was updated about policy changes, which included the 2019 PEC Clause on 28 August 2019. However, it should be noted that the 2019 PEC Clause, despite being the clause that introduced the fundamental flaw, is not in fact the contravening clause. The contravening clauses are the 2021 PEC Clause and the 2023 PEC Clause. HCF Life submits, and I accept, that given the change from the Pre-2019 PEC Clause to the 2019 PEC Clause was not expected to involve any financial impact to HCF Life (either positive or negative), it is not surprising that there was no actuarial review of this change. In any event, ASIC accepts that HCF Life followed its internal governance procedures with respect to the introduction of the 2021 and 2023 PEC Clauses: ASIC’s written submissions on penalty at [71]–[72].

76 In short, in my view, the circumstances in which the contraventions took place before 23 March 2023 do not in themselves warrant the imposition of any pecuniary penalty.

Conduct following 23 March 2023

77 ASIC’s letter of 23 March 2023 implicitly expressed a concern that HCF Life’s proposed amendments to the Pre-Existing Condition Term may be misleading, by stating that the proposed amendments “do not accurately describe the rights and obligations arising under the HCF Life policies”, and in particular, that the proposed amendments do not adequately set out how the Pre-Existing Condition Term would operate given the effect of s 47 of the ICA. ASIC encouraged HCF Life to review the wording of the proposed amendments against s 47 of the ICA and consider whether further revisions were necessary. It is clear from HCF Life’s response of 31 March 2023 and the unchallenged evidence of Mr Keane (Affidavit of Mr Keane of 17 March 2025 at [68]) that HCF Life did not agree with ASIC’s concern and did not consider at the time that it issued the 2023 PDSs, from 25 March 2023, that it was contravening the law.

78 ASIC submits that its letter of 23 March 2023 must have caused HCF Life to at least appreciate there to be a “substantial risk” that the Recover Cover PDSs were misleading, being a risk that until then had not been raised by their external lawyers, given the expression of concern by the regulator that it considered a statement in the PDSs not to be accurate. I accept that the letter of 23 March 2023 caused HCF Life to be aware of a risk that the Recover Cover PDSs may be misleading or liable to mislead. So much is apparent from HCF Life’s internal email of 24 March 2023 referring to the advice given that day by the external solicitors. However, I do not think that ASIC has established that, in the period before 11 May 2023, when ASIC commenced proceedings, HCF Life was aware of any particular level or extent of the risk or that the risk was “substantial”. ASIC’s letter is expressed in relatively mild terms, saying that it was “concerned”, and that it “encourages” HCF Life to review the proposed amendments against s 47 of the ICA and “consider whether” further revisions are necessary. There is no evidence that officers of HCF Life understood from the 23 March 2023 letter that ASIC had arrived at a concluded position that the Pre-Existing Condition Terms were misleading. There is no reason, in the absence of any cross-examination, to doubt the sincerity of HCF Life’s generally dismissive response of 31 March 2023, maintaining its belief that “the material substance” of s 47 had been disclosed in the revised wording and that “HCF Life considers that the pre-existing condition term does sufficiently disclose how the pre-existing condition term would operate in practice, both in accordance with its terms and section 47 of the Insurance Contracts Act”.

79 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 at [131], Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ said that if any degree of awareness of the actual or potential unlawfulness of the conduct is proved then, all other things being equal, the contravention is necessarily more serious. The Full Court also said (at [131]) that it is for the party asserting any particular state of mind to prove its assertion. ASIC accepts that it bears the onus of establishing that HCF Life was conscious of the risk of contravention (T65.24–30).