FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Han v St Basil’s Homes (No 2) [2025] FCA 448

File number: | NSD 1226 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | SHARIFF J |

Date of judgment: | 6 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – claims made by employee for orders as to compensation and penalties following determination that her employer had contravened ss 340(1)(a) and 351(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) – claim for compensation made under s 545(2)(b) of the FW Act – where employee claimed she suffered mental harm – where employee further claimed compensation for past and future economic loss, non-economic loss, past and future out of pocket expenses and past and future gratuitous care because of the contraventions – where employer opposed payment of any compensation despite clear findings of contravention – where neither party challenged the opposing party’s expert and other evidence – where the parties’ respective positions as to compensation were ambitious and untethered to statutory norms – assessment of appropriate compensation – where inconsistent expert evidence adduced but not challenged – evidentiary foundation lacking – claim for penalties to be imposed under s 546 of the FW Act – where employee sought the imposition of penalties – where employer opposed the imposition of penalties – Held: compensation awarded for economic loss, non-economic loss and out of pocket expenses – penalties imposed because they are necessary for the promotion of the public interest in securing compliance with the provisions of the FW Act |

Legislation: | Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ss 336, 340, 340(1)(a), 341, 346, 351, 351(1), 361(1), 545, 545(2)(b), 546(1), 546(3)(c), 557 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 37N(1)-(2), 37M(1), 37M(2)(b) Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act 1986 (Cth) ss 46PO(4), 46PO(4)(d) International Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature 21 December 1965, 660 UNTS 195 arts 2, 4 (entered into force 4 January 1969) |

Cases cited: | Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABB Transmission and Distribution Ltd [2001] FCA 383; ATPR ¶41-815 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd (t/as Bet365) (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 3) [2005] FCA 265; 215 ALR 301 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73 Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers Association v International Aviation Service Assistance Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 333; 193 FCR 526 Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8; 165 FCR 560 Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Melbourne Precast Concrete Nominees Pty Ltd (No 3) [2020] FCA 1309 Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39 Construction, Forestry, Mining, and Energy Union v Hail Creek Coal Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1032 Dafallah v Fair Work Commission [2014] FCA 328; 225 FCR 559 Enzed Holdings Ltd v Wynthea Pty Ltd (1984) 4 FCR 450 Fair Work Ombudsman v Ho [2024] FCAFC 111 Fair Work Ombudsman v Maritime Union of Australia (No 2) [2015] FCA 814; 252 IR 101 Finance Sector Union of Australia v Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2002] FCA 1035 Flavel v RailPro Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCCA 1449 Gill v Australian Wheat Board [1980] 2 NSWLR 795 Gill v Ethicon Sàrl (No 5) [2019] FCA 1905 Goldburg v Shell Oil Co of Australia Ltd [1990] FCA 494; 95 ALR 711 Griffiths v Kerkemeyer [1977] HCA 45; 139 CLR 161 Grincelis v House (2000) 201 CLR 321 Gutierrez v MUR Shipping Australia Pty Limited [2023] FCA 399; 324 IR 58 Hall v A & A Sheiban Pty Ltd [1989] FCA 65; 20 FCR 217 Han v St Basil’s Homes [2023] FCA 1010 Harriton v Stephens [2006] HCA 15; 226 CLR 52 Hughes t/as Beesley and Hughes Lawyers v Hill [2020] FCAFC 126; 277 FCR 511 JLW (Vic) Pty Ltd v Tsiloglou [1994] 1 VR 237 Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080; 166 IR 14 Kennewell v MG & CG Atkins (t/as Cardinia Waste & Recyclers) [2015] FCA 716 Leggat v Hawkesbury Race Club Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 1658 Maritime Union of Australia v Fair Work Ombudsman [2015] FCAFC 120 Morgan v Gibson [1997] NSWCA 212 Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 3; 216 CLR 388 Netline Pty Ltd v QAV Pty Ltd [2022] WASCA 131 Patrick Stevedores Holdings Pty Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (No 4) [2021] FCA 1481 Patrick Stevedores Holdings Pty Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (No 3) [2021] FCA 348 Plancor Pty Ltd v Liquor Hospitality and Miscellaneous Union [2008] FCAFC 170 Planet Fisheries Pty Ltd v La Rosa [1968] HCA 62; 119 CLR 118 Qantas Airways Ltd v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; 167 FCR 537 Qantas Airways Ltd v Transport Workers Union of Australia [2023] HCA 27; 278 CLR 571 Registrar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations v Matcham (No 2) [2014] FCA 27; 97 ACSR 412 Richardson v Oracle Corporation Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 82; 223 FCR 334 Sayed v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2016] FCAFC 4; 239 FCR 336 Shizas v Commissioner of Police [2017] FCA 61 Taupau v HVAC Constructions (Queensland) Pty Ltd [2012] NSWCA 293 TCN Channel Nine Pty Ltd v Hayden Enterprises Pty Ltd (1989) 16 NSWLR 130 Todorovic v Waller [1981] HCA 72; 150 CLR 402 TPG Internet Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 190; 210 FCR 277 Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR ¶41–076 Van Gervan v Fenton [1992] HCA 54; 175 CLR 327 Watts v Rake [1960] HCA 58; 108 CLR 158 White v Benjamin [2015] NSWCA 76 |

Division: | Fair Work Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Employment and Industrial Relations |

Number of paragraphs: | 224 |

Date of hearing: | 15 October 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr D P O’Dowd |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Gillis Delaney Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr H Pararajasingham |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | McPhee Kelshaw |

ORDERS

NSD 1226 of 2020 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | WEI HAN Applicant | |

AND: | ST BASIL’S HOMES Respondent | |

order made by: | SHARIFF J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 6 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The respondent pay compensation to the applicant under s 545(2)(b) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) in the following amounts:

(a) $175,000 for past economic loss;

(b) $61,559.62 for future economic loss;

(c) $75,000 for general damages; and

(d) $10,000 for future out of pocket expenses.

2. The respondent pay pecuniary penalties under s 546 of the FW Act in the following amounts:

(a) $45,000 in respect of the contravention of s 351(1) of the FW Act; and

(b) $15,000 in respect of the contravention of s 340(1) of the FW Act.

3. The pecuniary penalties in Order 2 be paid to the applicant pursuant to s 546(3)(c) of the FW Act.

4. The matter be listed for case management immediately upon delivery of the reasons for judgment dated 6 May 2025 to enable the parties to be heard as to whether:

(a) the applicant presses any claim for interest in respect of the amounts in Order 1(a); and

(b) any party makes a claim for costs under s 570 of the FW Act or any other applicable law.

5. If no claims are made under Order 4, the proceedings be otherwise dismissed.

6. If a claim is made under Order 4:

(a) the applicant is to file and serve submissions not exceeding 3 pages on the issue of interest and costs by 4.00 pm on Thursday, 8 May 2025;

(b) the respondent is to file and serve submissions not exceeding 3 pages on the issue of interest and costs by 4.00 pm on Tuesday, 13 May 2025; and

(c) the applicant is to file and serve submissions in reply, if any, not exceeding 3 pages by 4.00 pm on Thursday, 15 May 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

SHARIFF J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 The applicant (Ms Han) is a former employee of the respondent (St Basil’s). Ms Han worked for St Basil’s as a registered nurse on a permanent part-time basis at its aged care facility in Lakemba, Sydney (Lakemba Facility). St Basil’s terminated Ms Han’s employment on 23 January 2020. Ms Han then commenced proceedings in this Court alleging contraventions of ss 340(1)(a) and 351(1) the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act). The proceedings were allocated to the docket of Rares J, who decided to hear and determine all questions of liability before and separately to the determination of questions as to penalty and compensation.

2 On 28 August 2023, Rares J handed down a decision in which his Honour found that St Basil’s contravened ss 340(1)(a) and 351(1) of the FW Act: see Han v St Basil’s Homes [2023] FCA 1010 (Liability Judgment or LJ). His Honour made orders for the service of evidence and submissions in relation to the questions of remedy. Shortly prior to his Honour’s retirement from the Court, the matter was allocated to my docket. Since that time, there were delays involved in listing the hearing before me due to disputes between the parties in arranging for Ms Han to be assessed by an independent medical practitioner at the request of St Basil’s.

3 The parties’ respective positions as to the orders that should now be made were both ambitious. The claims made on Ms Han’s behalf paid little attention to the statutory norm at stake. They also paid little attention to the findings made by Rares J and the actual evidence before me. Ms Han advanced a claim for compensation and penalties totalling $2,471,381.65. The Damages Schedule provided in support of Ms Han’s claim lacked precision and bore little relationship to the statutory and evidentiary foundations for the amounts claimed.

4 In response, St Basil’s contended that nothing more than a nominal amount of compensation should be awarded and that no penalties should be imposed. That position too was ambitious. It paid scant regard to the fact that Rares J had found that St Basil’s contravened important provisions of a Commonwealth law designed to protect workers like Ms Han from exactly the type of detriment to which she was subjected. Ms Han was entitled to protection from the taking of adverse action against her because of her exercise of workplace rights and because of her race. These propositions are as obvious as they are fundamental to the protections afforded by the FW Act.

5 I am satisfied that Ms Han has made out a claim for the payment of compensation and the imposition of penalties, but not to the extent of her claims. These are my reasons for ordering that St Basil’s pay to Ms Han the following amounts:

(a) $175,000 for past economic loss;

(b) $61,559.62 for future economic loss;

(c) $75,000 for general damages; and

(d) $10,000 future out of pocket expenses.

6 I have structured my reasons as follows:

(a) Part 2 sets out the relevant evidence;

(b) Part 3 summarises the salient findings made by Rares J in the Liability Judgment;

(c) Part 4 addresses the claims for compensation;

(d) Part 5 addresses the claims for the imposition of penalties; and

(e) Part 6 sets out my disposition of the proceedings.

2. THE EVIDENCE

7 The evidence before me was contained in a Joint Court Book, which also included the parties’ pleadings and submissions. The Joint Court Book also included the evidence that was before Rares J. The affidavits contained in that Joint Court Book were read without objection, the outlines of evidence were tendered (again without objection) and the various expert reports were also tendered, again, without objection.

8 In support of her claims before me, Ms Han relied upon the findings made by Rares J in the Liability Judgment, which I summarise in Part 3 below. In addition, Ms Han primarily relied upon the following further evidence in support of her claims for compensation and the imposition of penalties:

(a) an affidavit deposed to by Ms Han on 19 February 2021;

(b) the outlines of evidence of:

(i) Ms Han dated 23 September 2021 and 30 November 2023;

(ii) Ms Zaki Alahiotis dated 23 September 2021;

(iii) Mr Cosgrove (Ms Han’s partner) dated 1 December 2023;

(iv) Ms Macy Han (Ms Han’s niece) dated 1 December 2023; and

(v) Mr Yuchen Hu (Ms Han’s son) dated 1 December 2023; and

(c) the expert reports of:

(i) Dr Richa Rastogi (Consultant Psychiatrist) dated 30 April 2021;

(ii) Dr Abhishek Nagesh (Consultant Psychiatrist) dated 12 September 2023 (First Report) and 30 July 2024 (Reply Report);

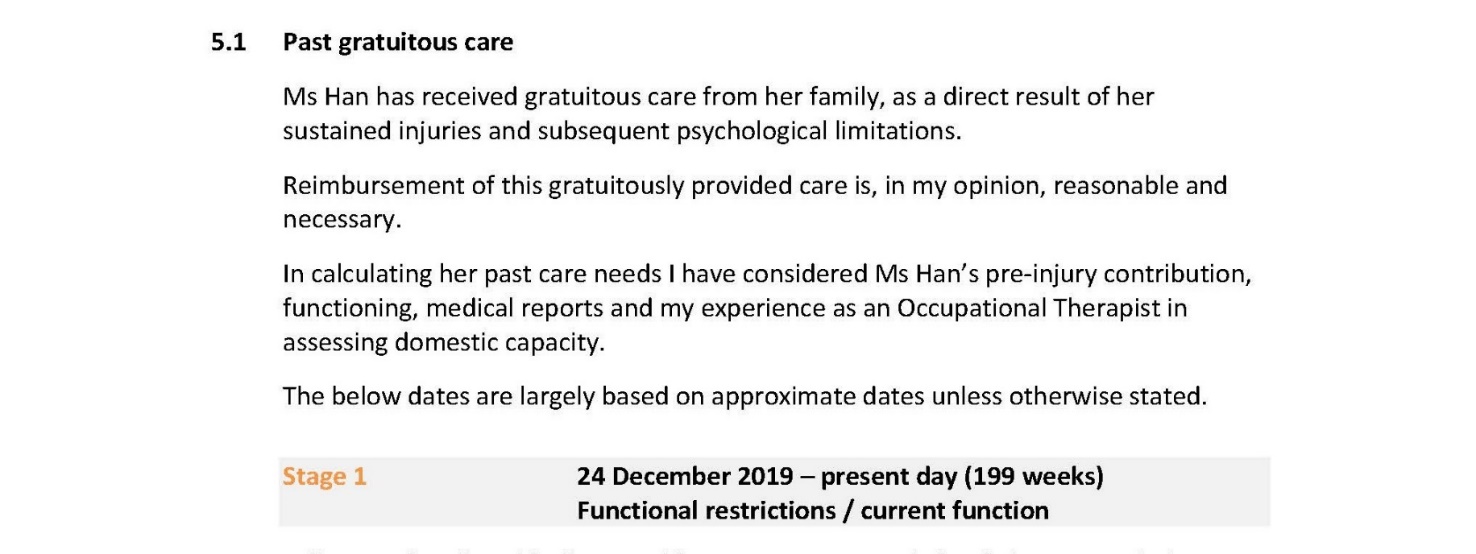

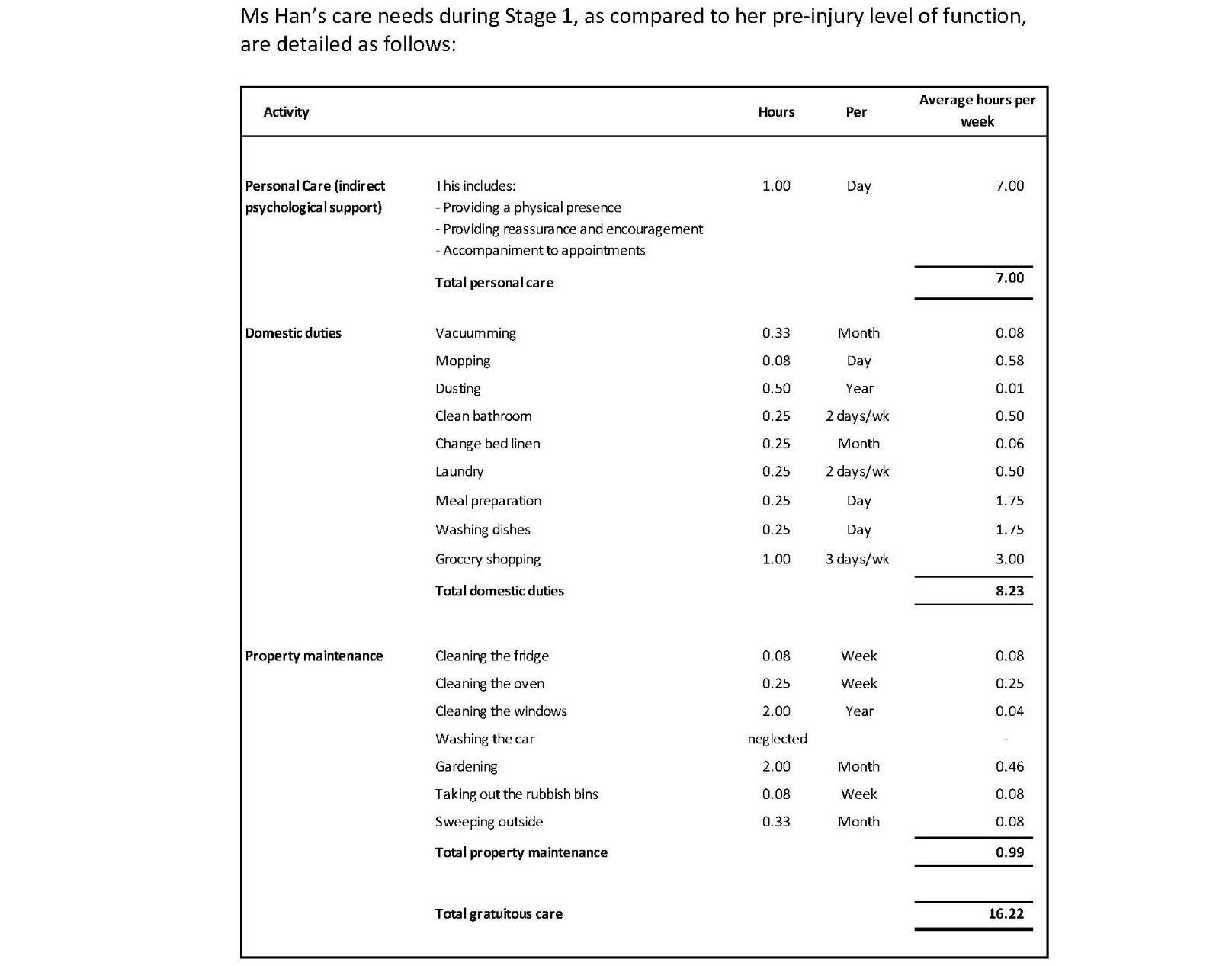

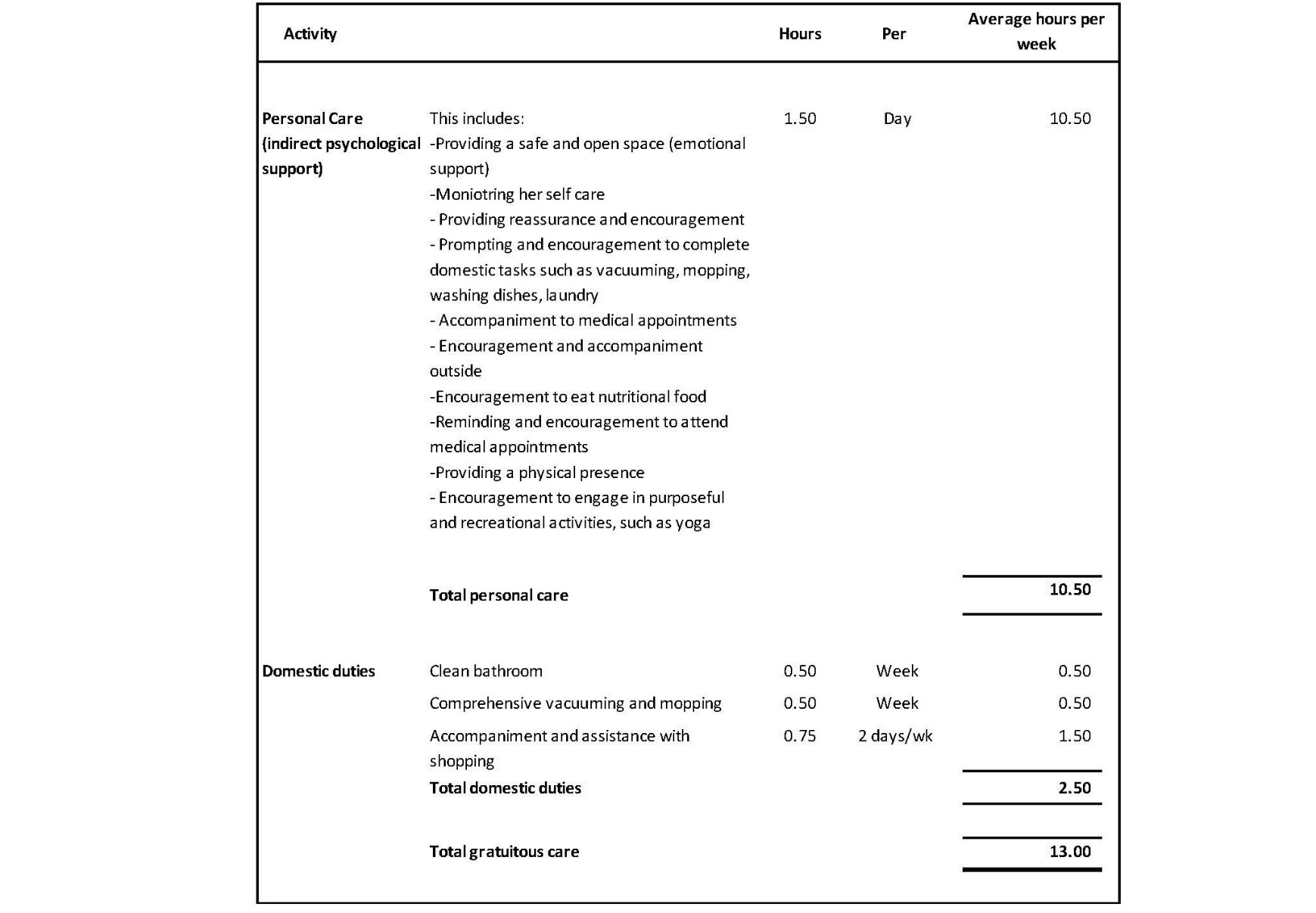

(iii) Ms Kayleen Engelsman (Occupational Therapist) dated 13 October 2023 (Past and Future Care Report);

(iv) Ms Lucinda Smith (Occupational Therapist) dated 16 November 2023 (Vocational Assessment Report); and

(v) Mr Abinash Dhungel (Forensic Accountant) dated 16 November 2023 (Earnings Assessment Report).

9 St Basil’s relied upon the following evidence:

(a) an affidavit of Mr James Jordan (St Basil’s, Board Chairman) sworn on 13 May 2024;

(b) an expert report of Dr Ian Sherman (Consultant Psychiatrist) dated 17 April 2024; and

(c) a joint expert report of Ms Yolla Makhoul (Psychologist, Vocational Consultant and Labour Market Researcher) and Mr James Hill (Vocational Consultant, Labour Market Researcher and Rehabilitation Counsellor) dated 26 April 2024 (Earning Capacity Assessment Report).

10 As already noted, all of the evidence was received without objection, including the outlines of evidence (which were essentially treated by the parties as witness statements). None of the experts were required for cross-examination. The only witness who was cross-examined was Ms Han. That cross-examination was brief.

11 Whilst the parties are to be commended for the efficient way in which they conducted the proceedings, as I will return to below, it has not necessarily made the fact-finding process straightforward. Before returning to these matters, I will first provide an overview of the findings on liability.

3. THE SALIENT FINDINGS MADE IN THE LIABILITY JUDGMENT

12 Both parties drew attention to and emphasised different aspects of the Liability Judgment as being relevant to their submissions as to the appropriate compensation to be awarded and the penalty to be imposed. It is unnecessary to rehearse every finding made in the Liability Judgment, but it is necessary to identify the essential findings as they are relevant to the issues before me.

13 Before turning to these essential findings, it is necessary to say something about the context. As noted at the outset, Ms Han is a registered nurse. By the time of the termination of her employment, Ms Han had worked for St Basil’s for over nine years on a permanent part-time basis. Ms Han is Chinese and is also known by the name, Casey.

14 In the period leading up to the termination of her employment, Ms Han claimed that she had been subjected to discriminatory and bullying conduct because she was Chinese. The specific context was that a number of other staff who worked at the Lakemba Facility were Filipino and, in Ms Han’s perception of things, were operating as a clique that “ganged up” on her: see, eg, LJ [84] and [111]. In particular, Ms Han claimed that the General Manager, Ms Mota, who was Filipino, as well as other managers, preferred the Filipino workers who worked at the Lakemba Facility: see, eg, LJ [238]. The other Filipino workers who worked at the Lakemba Facility included Ms Alcantara (LJ [37], [39]), Ms Pandey (LJ [43]), Ms Bangao (LJ [43]), Mr Dhungana (LJ [43]), Ms Lee (LJ [74]), Mr Agbada (LJ [153]) and Ms Young (LJ [153]).

15 Whilst Ms Han made assertions as to bullying and discrimination, her pleaded case fell within a narrow compass. As Rares J pointed out at LJ [2], Ms Han’s pleaded case asserted two instances of adverse action, being:

(a) the issuing of a warning to Ms Han on 10 September 2019 (the First and Final Warning); and

(b) the termination of Ms Han’s employment, which took immediate effect on 23 January 2020.

16 Ms Han’s case was that St Basil’s had engaged in these two instances of adverse action for one or both of the following reasons (LJ [2]):

(a) because she had exercised her workplace right to make a complaint or inquiry in relation to her employment in contravention of s 340(1)(a) of the FW Act; and/or

(b) because of her Chinese race in contravention of s 351(1) of the FW Act.

17 By reason of the operation of the statutory presumption contained in s 361(1) of the FW Act, the question before Rares J was whether St Basil’s had discharged its onus of rebutting the presumption that it had engaged in the alleged adverse actions for the substantial and operative reasons alleged by Ms Han, or for reasons that included those proscribed reasons.

18 Rares J upheld Ms Han’s claim that St Basil’s contravened both ss 340(1)(a) and 351(1) in relation to the adverse action constituted by the termination of her employment, but rejected Ms Han’s case in relation to the adverse action constituted by the First and Final Warning.

19 It is now necessary to say something by way of summary as to the essential findings that Rares J made in reaching this conclusion.

20 Rares J’s essential findings relating to the First and Final Warning are set out at LJ [42]–[82]. The incident that led to Ms Han being issued with the First and Final Warning was one that occurred on 4 August 2019. At the time, a co-worker, Ms Bangao (an aged care worker), was introducing a new staff member, Mr Dhungana, to Ms Han: LJ [42]. It was alleged that during that conversation, Ms Han had called Ms Bangao a “bitch”, which Ms Han did not deny but said her comment had been taken out of context and was not intended to be offensive: LJ [42]–[44]. A complaint was made about Ms Han’s conduct and it was investigated: LJ [46]–[49]. It is sufficient to note that the investigation process involved:

(a) the receipt of the complaint and corroborating information: LJ [47]–[49];

(b) a letter of allegations being sent to Ms Han, which did not disclose the full details of the incident: LJ [50];

(c) Ms Han asking for further details: LJ [52];

(d) Ms Han attending a meeting to discuss the allegations in general terms: LJ [55];

(e) a further letter being sent, which set out more details of allegations and informing Ms Han that the complaint had been substantiated: LJ [56];

(f) Ms Han being required to attend a show cause meeting: LJ [56]–[58]; and

(g) the First and Final Warning being issued to Ms Han: LJ [60].

21 Rares J found that Mr Rooke (Chief Operating Officer at the Lakemba Facility), Ms Darwich (Director of Care at the Lakemba Facility) and Ms Mota were each involved in the decision and/or were the decision-makers in relation to the issuing of the First and Final Warning: LJ [77]. His Honour was satisfied that each of these persons decided to give the First and Final Warning because they believed that Ms Han had breached St Basil’s Code of Conduct by calling Ms Bangao “a bitch”: LJ [76], [78]. Rares J arrived at this conclusion notwithstanding that his Honour had formed unfavourable views about Ms Mota and, to a lesser extent, Ms Darwich: LJ [79]. His Honour observed that the decision to give the First and Final Warning may have also “suited a wish or desire of Ms Mota to prefer Filipino employees to the Chinese, Ms Han, in allocation of work and shifts” but was satisfied that this “congruence” was “not any part of Ms Mota’s substantial and operative reasoning for her decision on this occasion”: LJ [81]. Rares J concluded that Ms Han had not established her case that each of Ms Rooke, Ms Mota and Ms Darwich had taken the action of issuing the First and Final Warning for a substantial and operative reason that included that Ms Han had complained about the discriminatory conduct to which she claimed to be subjected or because of her race: LJ [81]–[82].

22 The findings in relation to Ms Han’s case in respect of the decision to terminate her employment are addressed at LJ [83]–[240]. Those paragraphs disclose a careful and detailed analysis of the documentary and testimonial evidence before Rares J. That analysis reveals that Ms Han had made complaints about various matters to either or both of Ms Darwich and Ms Mota and, up until a point in time, it appeared that St Basil’s was looking into her concerns, but then the “tables were turned”. One of the matters about which Ms Han had complained was turned into an allegation against her that she had not afforded appropriate or adequate clinical care to a resident of St Basil’s. It was this allegation that led to the termination of Ms Han’s employment. Ultimately, Rares J was not satisfied that St Basil’s had rebutted the presumption arising under s 361(1) of the FW Act that it had made the decision to terminate Ms Han for proscribed reasons. It is unnecessary to repeat Rares J’s analysis in detail here. It is sufficient to highlight some of the essential steps that led his Honour to these conclusions.

23 At a meeting on 26 September 2019 with Ms Darwich and Ms Mota, Ms Han provided a note to them of over six pages which raised concerns about various matters including understaffing and her increased responsibilities, as well as her feeling that she was being discriminated against and “ganged up” on by other staff who were Filipino: LJ [84] ff. At this time, Ms Han asked for her complaints to be investigated: LJ [86].

24 On 16 November 2019, Ms Han recorded an incident based on a complaint received from the daughter of one of the residents at the Lakemba Facility, which Ms Han considered to amount to elder abuse: LJ [91]. On 23 November 2019, Ms Han made a record of a further incident, being that she had observed another resident with bruises on both arms: LJ [93]. Ms Han took a photo documenting the bruising: LJ [93].

25 On 1 December 2019, Ms Han sent an email to Ms Mota in which she stated that she would “like to make a formal complaint” and listed a number of grievances, including three particular incidents that caused her concern: LJ [98]–[100]. Rares J referred to this email as the “1 December Complaint”. Ms Han concluded her list of grievances by stating that she felt she was being “repeatedly targeted by” Ms Pandey and “no longer [felt] safe to work at St Basils”: LJ [101]. Ms Mota acknowledged Ms Han’s email and indicated that her concerns would be escalated, and proposed to meet on 12 December 2019 to discuss the issues raised: LJ [102].

26 On Sunday, 15 December 2019, a number of incidents occurred during a shift that Ms Han worked at the Lakemba Facility. These incidents became a point of attention for further complaints she made, and, for different reasons, one of the incidents became the “catalyst” for the events that led to the termination of her employment: LJ [118] ff. The first event occurred when Ms Han asked Mr Agbada to help her in moving a resident who was sitting on the floor: LJ [121]. Ms Han claimed that instead of helping her, Mr Agbada walked away: LJ [121]. The second event related to Ms Han’s recording and reporting of a clinical incident. Relevantly it was reported to Ms Han that during the previous shift there had been no second signatory recorded in the “schedule 8 medicine register book” for obtaining and administering to a resident of “Targin”, a drug of addiction for pain relief: LJ [122]. The sole signatory was Ms Lee, but Ms Han considered that a second signatory was required and believed she was reporting a substantive error: LJ [122]. Rares J observed that reporting in these circumstances was required at law and under St Basil’s internal policies: LJ [122].

27 The final incident proved to be significant. Ms Han was assisting a resident to go to the toilet when she received a call from Ms Young to inform her that another resident’s vitals were showing an “oxygen saturation level” of 87%: LJ [123]–[124]. This resident was relevantly located in a different wing of the Lakemba facility, some five minutes away: LJ [124]. Ms Han told Ms Young that she was occupied with another resident but would come immediately to assist, but that the resident to whom Ms Young was attending may need to be transferred to a hospital and in the meantime to apply oxygen to that resident and inform her family and the relevant doctor: LJ [124]. Almost immediately after that call ended, Ms Young called Ms Han back and asked her to call the doctor. Ms Han then “ran down” to where Ms Young was, but found that she was not with the relevant resident: LJ [122]. Ms Han then assessed the resident’s condition as stable and telephoned the resident’s daughter and the treating doctor, who both told her that it was the resident’s “advanced care directive” to receive treatment at the Lakemba Facility and not at a hospital, and Ms Han was instructed by the doctor to administer oxygen to the resident at the Facility: LJ [124]. Ms Han then approached Ms Young to inform her about the treating doctor’s orders and asked her to administer oxygen to the resident, but Ms Young told Ms Han that she had finished work and needed to go home: LJ [124]. Ms Han felt that Ms Young would not let her talk and repeatedly told Ms Han that she was going home: LJ [124]. Ms Han then went and administered oxygen to the resident herself: LJ [124].

28 On 24 December 2019, Ms Han sent an email to Ms Mota and made two complaints about the lack of teamwork she had experienced on 15 December 2019: LJ [129]. Rares J referred to these complaints as the “24 December complaint”. These complaints related to the lack of assistance Ms Han had received in turn from Mr Agdaba and Ms Young (who she only identified in her written complaint as “T/L [team leader]”): LJ [129]. As things transpired, this was the final day that Ms Han worked at St Basil’s.

29 On 2 January 2020, Ms Mota telephoned Ms Han and asked her to attend a meeting with her and Ms Darwich on 6 January 2020, but Ms Han indicated that she was on annual leave until the end of January: LJ [131]. In the intervening period between 6 and 13 January 2020, it appears that Ms Mota sought out the accounts of Mr Agdaba, Ms Young and another employee, Ms Kakias, who was a witness to parts of the events of 15 December 2019: LJ [131].

30 Rares J found that by 13 January 2020, Ms Mota had “turned the tables” in the sense that, instead of investigating the 24 December complaint, Ms Mota had used the information from that complaint to investigate Ms Han’s conduct which was a “trumped up attack”: LJ [152]–[155]. By a letter to Ms Han dated 13 January 2020, Ms Mota wrote that Ms Han was required to attend “an outcomes meeting” and that the purpose of the meeting was to discuss Ms Han’s professional role in relation to her job description and the “quality of clinical care” being provided to “consumers of St Basil’s”: LJ [155]. Ms Han, who was then on annual leave, felt stressed by the letter and sought to re-schedule the proposed meeting to 23 January 2020: LJ [164]. There were then telephone discussions between Ms Han and Ms Darwich on 17 January 2020 where Ms Han explained she was unwell: LJ [166]–[167]. Eventually, during a phone call late on the evening of 17 January 2020, Ms Darwich told Ms Han that she was suspended from her employment: LJ [167]. No explanation was provided to Ms Han as to the reason for the suspension, but she was told that there was an investigation that was pending: LJ [168]. A meeting was arranged for 23 January 2020 but Rares J considered that there was a “deliberate opacity” in the communications with Ms Han about the allegations that were being made against her: LJ [170]. Ms Han was sent a letter of suspension on 20 January 2020, which provided no details as to the allegations being made other than to assert that the suspension had come about due to the “serious nature of allegations” made against her: LJ [170].

31 On 21 January 2020, Ms Mota sent Ms Han a letter requiring her to attend an “outcomes meeting” on 23 January 2020: LJ [171]. Rares J found (at LJ [172]) that St Basil’s provided “no clue” to Ms Han as to what was to be discussed at the “outcomes meeting”, let alone whether any disciplinary action would be considered: LJ [172].

32 The meeting on 23 January 2020 was attended by Ms Han, Ms Mota and Ms Darwich. At the commencement of the meeting, Ms Han gave to Ms Darwich a letter she had prepared the previous day that set out Ms Han’s detailed recollection of the events of 15 December 2019: LJ [178]. Ms Darwich informed Ms Han that the purpose of the meeting was to address the care she had given to the resident on 15 December 2019: LJ [182]. The essence of the allegation made against Ms Han was that she had failed to discharge her professional duties to provide appropriate clinical care to the relevant resident by leaving it to a team leader (who did not have appropriate qualifications) to apply oxygen to that resident and to contact the relevant medical officer and the resident’s family: LJ [182].

33 Ms Han was informed during the meeting that her employment was being terminated with immediate effect. Ms Han responded by saying that the termination was unfair and she would challenge it. Ms Darwich told Ms Han should could speak to Father Nicholas Stavropoulos, who then was the chief executive officer (CEO) of St Basil’s: LJ [189]. Within minutes of leaving the 23 January meeting with Ms Darwich and Ms Mota, Ms Han went to see Father Nicholas: LJ [196]. Father Nicholas gave evidence that described his role in Ms Han’s termination as being “to audit the process and to make sure due diligence had been exercised, and that the matters were conducted fairly and properly”: LJ [196]. He said he did not investigate the termination of Ms Han’s employment beyond whatever was involved in the ‘briefing’ that he received from others: LJ [196]. As the CEO, Father Nicholas had the ultimate authority to affirm or review Ms Darwich’s decision earlier on 23 January 2020 to terminate Ms Han’s employment: LJ [204]. Ms Han “begged” him to overturn the decision (LJ [198]), but he instead affirmed the decision because, as Rares J found, he considered that Ms Han was doing no more than seeking to justify her conduct and was raising other complaints in an inappropriate way: LJ [204].

34 Later that same day, Ms Darwich lodged an online complaint about Ms Han with AHPRA, which was subsequently referred to the Health Care Complaints Commission and the Nursing and Midwifery Council of New South Wales: LJ [205]–[208]. She did so because of Father Nicholas’ instruction.

35 On 5 February 2020, Ms Han texted Ms Darwich asking for a letter that confirmed the termination of her employment: LJ [210]. Ms Darwich replied, early on 6 February 2020, that she would ensure that Ms Han received a letter that day.

36 On 7 February 2020, Ms Mota emailed the 6 February letter that she had signed as general manager to Ms Han which, relevantly, stated (LJ [211]):

Dear Wei (Casey),

RE: Termination of Employment

The purpose of this letter is to inform you that we have made the decision to terminate your employment with St Basil’s Homes.

Our thorough investigation process took into account:

1. Opportunities for you to understand and respond to the allegations, including at our meetings on 12/12/2019 and 23/01/2020.

2. Interviews and obtaining statements from staff members; and

3. Work undertaken to review and investigate your claims and assertions made during our interviews.

Our investigation found that you failed to provide the necessary care to residents of St Basil’s Nursing home, particularly the late Helen Toliopoulos, resulting in the delay of treatment to assist a resident with transition into active palliative care

In addition to this, we also identified that you had instructed unqualified staff to offer therapy which was outside of their scope of practice.

After the completion of the investigation and responses received from you on 23/01/20 St Basil’s reviewed the serious nature of these findings and also took into consideration your performance history with our organization. Based on these considerations, we have decided to terminate your employment, with an effective date of 23/01/2020.

(Original emphasis removed.)

37 In April 2020, the complaint that had been made to AHPRA was resolved on the basis that no further action was required: LJ [218]. This was confirmed by the Nursing and Midwifery Council in a letter which stated, amongst other things, that:

…the allegations imposed by the employer around your performance and conduct were imprecise and did not raise significant concerns about performance to warrant immediate action

38 In these circumstances, Rares J was satisfied that Ms Han had exercised a workplace right to make complaints, including those in her 1 and 24 December complaints: LJ [224]–[237]. However, his Honour was not satisfied that there was any, or any proper, investigation of these complaints: LJ [224]–[237].

39 Rares J was not satisfied as to a number of explanations given by Ms Mota and Ms Darwich about the events leading to the termination of Ms Han’s employment, including by reference to various inconsistencies in their evidence. Rares J concluded that he was not satisfied that St Basil’s discharged its onus of proof to displace the presumption in s 361(1) of the FW Act that, when it took the adverse action of terminating Ms Han’s employment on 23 January 2020, it did so because she had exercised her workplace right to make a complaint or inquiry in relation to her employment or because of her Chinese race: LJ [240].

4. THE CLAIMS FOR COMPENSATION

4.1 Applicable principles

40 Section 545 of the FW Act provides as follows:

(1) The Federal Court or the Federal Circuit Court may make any order the court considers appropriate if the court is satisfied that a person has contravened, or proposes to contravene, a civil remedy provision.

(2) Without limiting subsection (1), orders the Federal Court or Federal Circuit Court may make include the following:

…

(b) an order awarding compensation for loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention…

(Emphasis and additional emphasis added.)

41 The text of these provisions makes clear that the discretionary power to make remedial orders is conditional upon those orders being “appropriate” and upon the Court being satisfied that there has been a contravention of the FW Act. The text of s 545(2)(b) further makes plain that the discretionary power to order compensation applies in respect of loss that a person has suffered “because of” the relevant contravention. Each of these textual matters is important and operate cohesively together to empower the Court to make orders for compensation for loss suffered by a person where it is appropriate to do so and where that loss is suffered because of that contravention—ie, there is a causal connection between the loss suffered and the specific contravention that has been found.

42 In Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ stated at 190 [103]:

…the starting point of the process must be the text of s 545(1) read in the context of the Fair Work Act as a whole and, in particular, in light of s 546. So approached, the first and most immediate point of significance is the breadth of the terms in which s 545(1) empowers the court to make any order the court considers appropriate. What is “appropriate” for the purpose of s 545(1) falls to be determined in light of the purpose of the section and is not to be artificially limited. As the ABCC submitted, such broad terms of empowerment are constrained only by limitations that are strictly required by the language and purpose of the section…

(Footnotes omitted; emphasis added.)

43 The governing consideration is what the Court considers “appropriate”: Dafallah v Fair Work Commission [2014] FCA 328; 225 FCR 559 at [148]–[161] (Mortimer J, as her Honour then was). The statutory requirement that an order is “appropriate” highlights the necessity that any order is one the Court considers to be judicially appropriate, or “just”: Patrick Stevedores Holdings Pty Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (No 4) [2021] FCA 1481 at [18] (Lee J). Such a power leaves room for a Court to find in a given case that less than full compensation might be appropriate: Dafallah at [157].

44 The approach to be taken in identifying compensable loss was considered in Maritime Union of Australia v Fair Work Ombudsman [2015] FCAFC 120 at [28] ff (Allsop CJ, Mansfield and Siopsis JJ). There, the Full Court stated at [28]–[29]:

The task of the primary judge, having found the relevant contraventions, was to assess the compensation, if any, that was causally related to those contraventions. That involved not an examination of what did happen, but an assessment of what would or might have occurred, but which could no longer occur (because of the contraventions). Subject to any statutory requirement to the contrary, questions of the future or hypothetical effects of a wrong in determining compensation or damages are not to be decided on the balance of probability that they would or would not have happened. Rather, the assessment is by way of the degree of probability of the effects — the probabilities and the possibilities: Malec v JC Hutton Pty Ltd [1990] HCA 20; 169 CLR 625 at 642–643; Sellars v Adelaide Petroleum NL [1994] HCA 4; 179 CLR 332 at 352–356. The above proposition must be qualified by the recognition that, where the fact of injury or loss is part of the cause of action or wrong, it must be proved on the balance of probability. Compensation is generally awarded for loss or damage actually caused or incurred, not potential or likely damage: Tabet v Gett [2010] HCA 12 ; 240 CLR 537; Sellars at 348; Wardley Australia Ltd v Western Australia [1992] HCA 55; 175 CLR 514 at 526; that is equally so here under ss 807(1)(b) and 545(2)(b).

Difficulties sometimes arise in relation to the distinction between these two principles: see Sydney South West Area Health Service v Stamoulis [2009] NSWCA 153, discussed in Evans v Queanbeyan City Council [2011] NSWCA 230 at [54] per Allsop P, [59]–[61] per Hodgson JA, and [100]–[103] per Basten JA. Here, the statutes provide for an order requiring the defendant to pay an amount “as compensation for damage suffered by the other person as a result of the contravention“: s 807(1)(b) of the WR Act; and an order “awarding compensation for loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention“: s 545(2)(b) of the FW Act…Thus, there must be proved, on the balance of probability, to have been some “damage suffered…as a result of the contravention” and some “loss…suffered because of the contravention.” The wording is not dissimilar to the wording and structure of s 82(1) of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth), which was dealt with by the High Court in Sellars: “A person who suffers loss or damage by conduct of another person that was done in contravention of a provision…may recover the amount of the loss or damage.”

(Original emphasis removed; Emphasis added.)

45 As the Full Court stated, determining whether there is a causal connection involves “not an examination of what did happen, but an assessment of what would or might have occurred, but which could no longer occur (because of the contraventions)” and has been subsequently stated by Lee J to involve “(as with causation inquiries in other areas of the law) consideration of the counterfactual”: Patrick Stevedores Holdings Pty Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (No 3) [2021] FCA 348 at [30]; see also Australian Licenced Aircraft Engineers Association v International Aviation Service Assistance Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 333; 193 FCR 526 at 592 [423] (Barker J). It has also been observed that the focus of such an order is “in a loose sense, the restoration of those affected by a contravention to the positions they would have occupied but for its occurrence”: Shizas v Commissioner of Police [2017] FCA 61 at [209] (Katzmann J).

46 However, it has also been observed that “compensation must not be based on remote connections” or “[d]ouble satisfaction”, “‘double dipping’ … must not be permitted” and that “[e]xemplary or punitive compensation” should not be awarded: Construction, Forestry, Mining, and Energy Union v Hail Creek Coal Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1032 at [43] (Reeves J).

47 The principles of mitigation may also be brought to account. In International Aviation Service, in determining the appropriate award, Barker J took into account that the applicant had sought to mitigate his loss by attempting to obtain alternative employment in his field. Similarly, in Flavel v RailPro Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2013] FCCA 1449, Perry J took into account the applicant’s duty to mitigate his loss by taking steps to obtain other suitable employment: see also Kennewell v MG & CG Atkins (t/as Cardinia Waste & Recyclers) [2015] FCA 716 at [84].

48 In any application for compensation under s 545(2)(b), focus must remain on the statutory wrong that is the source of the contravention. As the Full Court stated in Maritime Union of Australia at [30], “[w]hat such damage or loss is (in the present context) that must be proved on the balance of probability will be governed by an understanding of the statute” and the “protective purpose” of the relevant provisions. In the context of s 346 of the FW Act (which deals with whether a person is or is not a member of an industrial association or is or is not engaging in industrial activity, etc), the Full Court stated:

What such damage or loss is (in the present context) that must be proved on the balance of probability will be governed by an understanding of the statute. Given the evident protective purpose of provisions such as s 792 of the WR Act and s 346 of the FW Act, there would be no sensible statutory purpose in denying a proposition that the damage or loss in relation to prospective employment can be constituted by the loss of an opportunity or chance to be considered for employment as a result of, or because of, the contravention (which then has to be given a value to inform the order for compensation); and there would be no sensible statutory purpose in limiting the compensation to damage or loss proved by reference to the proof of events that would, on the balance of probability, have or have not occurred. Thus, if the relevant contravention by a party has prejudiced a person in prospective employment, it would conform entirely with the statutory purpose to identify the damage or loss by reference to, indeed as, that prejudice. Depending on the circumstances, such prejudice may best be seen as the loss of the chance or opportunity of particular employment. That certainly was the relevant prejudice here, and it can be seen to have been proved on the balance of probability — indeed, to the point of demonstration.

49 Section 545 is to be considered in light of the breadth of the statutory purposes promoted by the multitude of civil penalty provisions of the FW Act, but ultimately such an order must be appropriate to the particular contravention in question. As Mortimer J explained in Dafallah at [148]:

The language of s 545 is broad, allowing the court to provide remedies which meet the circumstances of any given contravention, taking into account the range of parties who may have brought proceedings in relation to the contravention, and the actions which might in any given circumstance be required to remedy the contravention, or to ensure it does not occur again. Awarding compensation for loss is but one example and may not be appropriate, depending on what other action has been taken in respect of any losses. Each case will turn on its facts in that sense.

50 Her Honour further pointed out at [149] that “fixing compensation under s 545 is a statutory task, and the court must not substitute that task with approaches derived from the general law” (citing Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 3; 216 CLR 388 at [44]; Qantas Airways Ltd v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; 167 FCR 537 at [94] per French and Jacobson JJ).

51 The approaches taken in the “general law” including in the assessment of contractual or tortious damage may not always be appropriate. In Qantas Airways Ltd v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; 167 FCR 537, the Full Court considered similar statutory compensation provisions under s 46PO(4) of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Act 1986 (Cth). French and Jacobson JJ observed at [94] that the:

…damages which can be awarded under s 46PO(4) of the HREOC Act are damages “by way of compensation for any loss or damage suffered because of the conduct of the respondent”. Such damages are entirely compensatory. In many cases, as in damages awarded under s 82 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Ch) the appropriate measure will be analogous to the tortious. That may not be every case. Ultimately it is the words of the statute that set the criterion for any award. In any case the discretionary character of the remedy allows an award of an amount “by way of compensation” which does not fully compensate for the loss suffered. In that respect, however, we are not satisfied that his Honour made any error.

52 Consistent with this, in Richardson v Oracle Corporation Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 82; 223 FCR 334, Kenny J (with whom Besanko and Perram JJ agreed) expressed approval of the trial judge’s approach to assessing damages, observing (at [30]) that “the trial judge based his inquiry firmly on the terms of s 46PO(4)(d) and drew on tortious principles only to inform (but not define) the manner in which the statutory task was to be accomplished, to the extent that such principles were capable of providing appropriate guidance in the particular case”, which was relevantly “the approach sanctioned by previous Full Courts”: see generally at [25]–[30].

53 To a similar effect, in Hall v A & A Sheiban Pty Ltd [1989] FCA 65; 20 FCR 217 at 238–9, Lockhart J considered the approach to be taken to the assessment of compensatory damages under anti-discrimination legislation and observed (at 239) that it “would be unwise to prescribe an inflexible measure of damage in cases of this kind, and, in particular, to do so exclusively by reference to branches of law that are not the same, though analogous in varying degrees, as discrimination law”.

54 Before turning to the application of these principles to the present case, it is necessary to say something about the nature and quality of the evidence adduced by and on behalf of Ms Han and make findings as to the matters relevant to the determination of her claims as to compensation under s 545(1)(b) of the FW Act.

4.2 Ms Han’s case as to compensation and the nature and quality of the evidence in support of it

55 As noted in Part 2, I received a considerable body of evidentiary materials in the Joint Court Book. There was no challenge to any of that evidence by way of cross-examination. However, it does not follow that I am bound to necessarily accept that evidence. As Burley J stated in Gutierrez v MUR Shipping Australia Pty Limited [2023] FCA 399; 324 IR 58 at 76 [61]:

A trial judge is not required to accept evidence merely because it is unchallenged in cross examination, however, the fact that evidence is unchallenged may provide a cogent reason for its acceptance. As observed in Hull v Thompson [2001] NSWCA 359 at [21] (Rolfe AJA, Sheller JA and Davies AJA agreeing), “prima facie, if there is no cross-examination of an expert … there is no basis for a Judge not to accept the unchallenged evidence”. However, as the court there noted, it depends on the evidence in question, and where a report is ex facie illogical or inherently inconsistent, where it is based on an incorrect or incomplete history, or where the assumptions on which it is founded are not established, the report may be rejected or subject to criticism or doubt. But “in the absence of some such matters, there is no rational reason not to accept unchallenged evidence”; see Taupau v HVAC Constructions (Queensland) Pty Ltd [2012] NSWCA 293 at [130] (Beazley JA, Macfarlan and Basten JJA agreeing); Lloyd v Thornbury [2019] NSWCA 154 at [152] , [153] (Gleeson JA, Meagher and White JJA agreeing).

56 Burley J referred to the following relevant passages from Taupau v HVAC Constructions (Queensland) Pty Ltd [2012] NSWCA 293 at [132]–[133] and [135], where Beazley JA said (Macfarlan and Basten JJA agreeing):

…a trial judge placed in that position by the parties, is required to analyse the evidence in order to make findings on the issue to which the experts’ evidence is directed. This may and usually does involve the acceptance of one expert or group of experts over another, not on the basis of a demeanour finding, which is unavailable when none of the experts is cross-examined, but on the cogency of the evidence, given the issues addressed.

…The trial judge is required to engage with the issues canvassed and to explain why one expert is accepted over the other: see Archibald v Byron Shire Council [2003] NSWCA 292; 129 LGERA 311 at [54] per Sheller JA. This approach to the consideration of expert evidence and the determination of issues to which the expert evidence related is well-established in Australian jurisprudence, as the summary of cases in Wiki v Atlantis Relocations demonstrates. See also Waterways Authority v Fitzgibbon [2005] HCA 57; 221 ALR 402 at [129] –[130] per Hayne J…

…

In my opinion, this approach applies a fortiori where there has been no cross-examination. There has to be a reasonable basis as to why some evidence is accepted and other evidence is not. In that regard, the evidence cannot be considered in isolation from other evidence. The cogency of the experts’ evidence is dependent upon there being a basis established in the evidence for the views expressed.

57 As I explain further below, in some respects, the evidence adduced by Ms Han was inconsistent with other evidence adduced on her behalf and aspects of it were based on assumptions or histories that were not established by other evidence before me. This impacted upon my assessment of the cogency of that evidence.

58 More importantly, the evidence adduced by and on behalf of Ms Han did not tether itself to the statutory norm. Much of the evidence appeared to be directed to a common law claim for personal injury, as opposed to a claim for compensation under s 545(2)(b) of the FW Act. The logic of Ms Han’s case proceeded on the premise that Ms Han had suffered personal injury by way of a recognisable mental harm caused by her workplace circumstances, including alleged instances of bullying and discrimination, being overworked and by being discriminated against in the allocation of shifts, and that St Basil’s was therefore obliged to compensate her for a range of losses she had suffered by reason of that injury.

59 This frame of analysis was not the correct one.

60 The fallacy with the approach taken on Ms Han’s behalf was that it did not situate itself in the statutory framework within which the Court is to exercise its discretion under s 545(2)(b). As explained above, the criterion for the exercise of the discretionary power under s 545(2)(b) is that it applies to empower the Court to make orders that are appropriate “if the court is satisfied that a person has contravened…a civil remedy provision” and in respect of the loss suffered by the other person “because of” that contravention: ss 545(1) and 545(2)(b). The subsection necessarily directs attention to the loss that is causally connected to the contravention and as to what is appropriate in the circumstances. As I will explain, Ms Han’s claims here assumed that the personal injury was caused by the contravention, without examining the actual contravention as found and the evidence before the Court as to the factors that caused Ms Han’s injury.

61 The starting point is to consider the statutory rights that were infringed. The true rights that were infringed were those located in Part 3-1 of Chapter 3 of the FW Act. As the titles to the Chapter (“Rights and responsibilities of employees, employers, organisations etc”) and the Part (“General Protections”) of the FW Act indicate, these are parts of the Act which establish general protections in respect of particular rights.

62 One set of rights protected by Part 3-1 are those that carry the statutory term “workplace rights” as contained in Division 3 (s 341). It has been observed that “341(1) is not a definition of ‘workplace right’ in the sense that it cannot be said that s 341 merely ‘shortens, but is part of, the text of the substantive enactment to which it applies’”: Qantas Airways Ltd v Transport Workers Union of Australia [2023] HCA 27; 278 CLR 571 at [32] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gleeson and Jagot JJ). The relevant “workplace rights” include those specified in s 341(1)(c)(ii), being, where a person is an employee, that he or she “is able to make a complaint or inquiry…in relation to his or her employment”. The protection of these rights is afforded by making unlawful any “adverse action” taken because of, or for reasons including, the exercise or proposed exercise of those rights (ss 340 and 341).

63 Another set of rights protected by Part 3-1 are those set out in Division 5 (s 351) relating to the protected characteristics and attributes pertaining to a person. The protection of these rights is afforded by s 351 which makes it unlawful for “adverse action” to be taken because of, or for reasons including, the relevantly protected characteristics and attributes.

64 The “rights” protected and promoted by Part 3-1 may have as their source other laws or contractual arrangements between the parties. As the title of the Part indicates, the relevant provisions are cast in terms of general protections from the taking or threatening of adverse action, which includes termination of employment. The purpose of the relevant protections is to promote and protect those rights and their exercise, and the scope of the freedoms they entail. This purpose is made plain by the objects of Part 3-1, which are identified in s 336 as follows:

336 Objects of this Part

(1) The objects of this Part are as follows:

(a) to protect workplace rights;

(b) to protect freedom of association by ensuring that persons are:

(i) free to become, or not become, members of industrial associations; and

(ii) free to be represented, or not represented, by industrial associations; and

(iii) free to participate, or not participate, in lawful industrial activities;

(c) to provide protection from workplace discrimination;

(d) to provide effective relief for persons who have been discriminated against, victimised or otherwise adversely affected as a result of contraventions of this Part.

65 These provisions and similar earlier analogues have a long and complex history in Commonwealth industrial and employment regulation. As stated in Qantas Airways at [20]:

There is a long and complex history of provisions in Commonwealth industrial legislation that protect workplace participants against unfair treatment. At a high level of generality, the historical arc of the protections against adverse action has generally tended to expand the scope of workplace rights, the classes of persons who are covered by the general workplace protections, and the limits upon adverse action. For example, the current Act is not limited by an equivalent of s 792(4) and (8) of the former Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) which required that, for conduct to contravene the predecessors to the adverse action provisions, the entitlement to the benefit of an industrial instrument must have been the “sole or dominant reason” for the conduct. The Explanatory Memorandum to the Fair Work Bill 2008 (Cth) notes that the provisions in Pt 3-1 were “intended to rationalise, but not diminish, existing protections”, and that, “[i]n some cases, providing general, more rationalised protections has expanded their scope”. It went on to explain that “the new provisions protect persons against a broader range of adverse action”.

(Footnotes omitted.)

66 The object and purpose of these provisions and the protections they afford are “secured through civil regulatory remedies enforceable by the Fair Work Ombudsman and affected parties”: Qantas Airways at [22].

67 Returning to the present case, Ms Han’s pleaded case was she had exercised workplace rights by making complaints about her employment and that she had a further right to be protected from the termination of her employment because of her race. In more specific terms, her case was that she was entitled to have made workplace complaints and to participate in her workplace irrespective of her race and was entitled to be protected from adverse action taken by her employer because she had these rights or had exercised them. This was the pleaded case that Rares J decided.

68 Rares J ultimately found that Ms Han’s rights were infringed as St Basil’s had terminated her employment because of those rights. The case for compensation under s 545(2)(b) had to be directed to the appropriate orders for compensation by reference to the loss that was causally connected to the contraventions as found by Rares J.

69 The contraventions alleged by Ms Han did not require there to be a determination that she had actually been bullied or been subjected to discrimination in her workplace. The pleaded case was about the protection of her rights to complain about those matters. Nor were the alleged contraventions ones which required there to be a finding that Ms Han was actually overworked or less favourably treated relative to her Filipino peers, as opposed to protecting her right to complain about those matters. The subject matter of Ms Han’s complaints were contextual facts which informed her exercise of her workplace rights.

70 The contravention of s 351 was of a different character. It required an assessment as to whether a substantial and operative reason for the termination of Ms Han’s employment was because of her race and whether St Basil’s had rebutted the statutory presumption to that effect. Nevertheless, the relevant adverse action for the purpose of s 351 was confined to the act of termination and not to the broader contextual acts alleged by Ms Han to the effect that she had been unfavourably treated on other occasions.

71 In relation to each of these alleged contraventions, the question before Rares J was whether, having regard to the overall context, St Basil’s had rebutted the presumption in s 361(1) of the FW Act that it had not acted for the proscribed reasons.

72 Viewed within this statutory context, any personal injury suffered by Ms Han is not compensable because the personal injury had arisen due to Ms Han’s workplace circumstances. Rather, the relevant question is whether that personal injury was caused by the contraventions that were found by Rares J. It is important in this respect to reiterate that the text of s 545(2)(b) directs attention to the “loss that a person has suffered because of the contravention” (emphasis added).

73 As I explain below, whilst I accept that the evidence before me establishes that Ms Han suffered an injury, the evidence establishes that it was an injury that was, at least in part, one she had suffered prior to the termination of her employment (being the adverse action that was alleged and found to have occurred by Rares J). There were other causes that contributed to that injury. As I will explain, all the relevant experts accepted that the termination of Ms Han’s employment was one factor that caused her to suffer the relevant injury.

74 Ms Han’s submissions did not engage with these matters. Instead, reliance was placed upon the decision of Rares J in Leggat v Hawkesbury Race Club Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 1658 at [218]–[219]:

The Parliament did not limit the Court’s powers to award compensation under s 545(2)(b) or make orders that it considers appropriate under s 545(1). The Parliament contemplated that claims to the Fair Work Commission for an order to stop bullying can be made under Pt 6-4B of the Fair Work Act that will attract the remedies from the Commission that Pt 6-4B provides. The federal Act is not constrained in respect of the compensation that can be awarded by the separate operation, in a different sphere, of the State Workers Compensation Act. In my opinion, the Club’s conduct, through Mr Rudolph, effectively destroyed Mrs Leggett’s life. She cannot work and, as the joint experts agreed, is permanently incapacitated from doing so because of Mr Rudolph’s and the Club’s conduct. That conduct caused a very serious psychiatric illness that may never be cured, or ameliorated to any significant degree. That injury occurred in no small part because Mrs Leggett’s breaking point was Mr Rudolph’s treatment of her on 9 and 10 October 2016. That included his reaction in his 10 October email that he sent to her because she exercised a workplace right. He subsequently acted to drive the nail home later, as I found on the second s 340 claim, by persisting in his bullying conduct throughout the balance of Mrs Leggett’s employment, ignoring the Club’s contractual and statutory obligations to her and taking adverse action against her because she had both taken sick leave and exercised her workplace right to make a complaint about his behaviour. As Perram J, with whom Collier and Reeves JJ agreed, asked rhetorically in Hughes v Hill (2020) 277 FCR 511 at 521 [47], in a case of sexual harassment contrary to s 28A of the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth), “what is the ruin of a person’s quality of life worth?” (see too at 521 [47]–[48]).

I am of opinion that Mrs Leggett should be awarded $200,000 pursuant to s 545(1) and (2)(b) of the Fair Work Act for the loss she has suffered by reason of the Club’s contraventions of the Act and in all of the circumstances.

75 Rares J was in these passages considering an award of “general damages”. His Honour’s reasoning here was directing itself to the very point I have addressed above (at [72]), which is that, there, Rares J considered the award of general damages that was connected with the particular conduct that gave rise to the contravention.

76 Before turning to the relevant evidence, it is necessary to observe that the evidentiary case advanced on behalf of Ms Han took a non-discriminating approach to the determination of the loss she had suffered because of the contraventions. This evidentiary case involved the tender of three reports from two psychiatrists (Dr Rastogi and Dr Nagesh), a report from an Occupational Therapist, a report from a Vocational Assessor, and a report from an Accountant. As I will explain further below, some of these reports contradicted each other, and others made assumptions that were not proved. These reports, and Ms Han’s submissions which relied upon them, did little to tie themselves back to the actual contraventions that were found.

4.3 Findings relevant to Ms Han’s claims as to compensation

4.3.1 Ms Han’s diagnosis and prognosis

77 Ms Han claimed that she had suffered an injury in the nature of mental harm by reason of St Basil’s conduct. I received both lay and expert evidence as to the nature and extent of that injury, its impact upon Ms Han’s capacity to work and earn income, and her prognosis towards full recovery. However, as I have noted above, and explain further below, this evidence did not discriminate as to when that injury was suffered relative to the contraventions that were found.

78 Prior to June 2019, Ms Han enjoyed her duties working as a registered nurse and led an active social life. She was social, outgoing and took pride in her appearance. She had no health issues of any concern. She remained healthy and fit by engaging in regular activities such as yoga (twice a week), Zumba (once a week), going to the gym (three times a week) and occasionally swimming. She attended to domestic chores and tasks including cleaning, grocery shopping, laundry and gardening.

79 Ms Han’s evidence was that her life took a turn from in or about June 2019. Prior to that time, she had not suffered from any psychological symptoms nor had she experienced any difficulties in her work or her relationships with her fellow workers. However, her evidence was that, since then, she has suffered such symptoms and breakdowns in relationships. She has become more detached and no longer enjoys work or the other activities she previously engaged in. Ms Han no longer socialises, rarely goes out with her family, and feels embarrassed and ashamed about what has happened to her. She no longer takes the same level of care of herself or her appearance as she did prior to June 2019. Ms Han has experienced various symptoms such as feelings of self-doubt, loss of confidence, poor concentration, feelings of victimisation, impaired motivation, fatigue, agitation and irritability, impaired sleep and nightmares, panic attacks, headaches and palpitations, forgetfulness and hypertension. At times, her anxiety has been acute, and Ms Han was admitted into St George Hospital on 20 July 2020 and Sutherland Hospital on 30 November 2020 due to panic attacks related to the loss of her employment.

80 Ms Han has felt less inclined to undertake any domestic duties, and she does not shower regularly or change her clothes often. The majority of the domestic duties that Ms Han had previously performed are now performed by her son and her niece. The duties that Ms Han’s niece and son have been performing include meal preparation (though Ms Han now eats many ready-made or purchased meals), changing bed linen, vacuuming monthly, grocery shopping and irregular cleaning. Other domestic tasks have not been performed such as the cleaning of her car and gardening.

81 The evidence given by Mr Cosgrove, Mr Han and Ms Hu largely corroborated Ms Han’s evidence. Mr Cosgrove considered that his relationship with Ms Han has become strained. All three witnesses have observed the manifestations of the symptoms that Ms Han described.

82 It will be immediately apparent from Ms Han’s evidence that the relevant turning point for her was June 2019. That is not the time at which it was alleged, or found, that St Basil’s had taken adverse action against her and thereby contravened the FW Act.

83 I received conflicting expert opinions as to Ms Han’s diagnosis and prognosis.

84 Dr Rastogi’s report was first in time as it was dated 30 April 2021. His diagnosis is that Ms Han is suffering from an “Adjustment disorder with anxious distress with exacerbation” which qualifies as a DSM-V recognised disorder. Dr Rastogi’s opinion is that this disorder “was wholly attributed [to] and arose during” Ms Han’s employment with St Basil’s. It will be apparent that Dr Rastogi did not here identify when the relevant disorder was caused or the particular causes of it other than in general terms. Dr Rastogi expressed the opinion that Ms Han’s “vocational ability is limited” and that her “grievances need to be addressed for her to move on as legal issues are further perpetuating her condition”.

85 In Dr Nagesh’s First Report dated 12 September 2023, Dr Nagesh expressed the opinion that Ms Han met the criteria for “major depression of moderate degree with anxious distress”. Dr Nagesh was asked to opine as to the causes of the condition. The question asked of Dr Nagesh and his response were as follows:

5. Your opinion as to the relationship between our client's condition and the allegations in the course of employment, particularly focusing on the findings of adverse action against our client in regard to her race and her exercising her right to make a workplace complaint.

In my opinion, your client's alleged psychological injury is due to the alleged stressors at her employment where she was bullied, harassed, targeted, ignored, humiliated, and discriminated against by her colleagues. There was an increased workload. There was a lack of support from the management team. Your client was falsely accused of misconduct, and she was deprived of exercising her right to make a workplace complaint.

It has given rise to her alleged psychological injury.

86 As will be apparent, the question asked of Dr Nagesh was put on the basis of the relationship between Ms Han’s condition and the “allegations in the course of [her] employment, particularly focusing on the findings of adverse action…”. Dr Nagesh’s opinion was that the cause of the condition he had diagnosed was the “alleged stressors” in Ms Han’s employment where “she was bullied, harassed, targeted, ignored, humiliated, and discriminated against by her colleagues”, had an “increased workload”, given a “lack of support” and “falsely accused of misconduct” and deprived of exercising her right to make a workplace complaint. Dr Nagesh did not confine the cause of the condition to the particular adverse action that was found and his opinion as to the causes included those that were “alleged”.

87 Dr Nagesh considered Ms Han’s prognosis to be “guarded” as she had been symptomatic for three and a half years. He expressed the opinion that Ms Han will need the care of a psychiatrist on a monthly basis and psychologist on a fortnightly basis for the next 12 to 24 months.

88 Dr Sherman was engaged as an independent expert by St Basil’s. He examined Ms Han on 20 March 2024. Dr Sherman’s diagnosis was that Ms Han is suffering from an “Adjustment Disorder with Mixed Anxiety and Depressed Mood” which met “DSM 5TR criteria”. His opinion is that Ms Han’s condition was caused by several actions taken by St Basil’s. The question asked of Dr Sherman and his response was as follows:

Question 6: If the answer to Question 5 is in the positive, what is the reason, cause and/or basis for said symptoms and/or mental health conditions?

In my opinion the reason, cause and basis for the adjustment disorder were several actions taken by the employer which included:

1. Increasing her workload by 30% (adding 11 patients to a workload of over 30);

2. Removing some of her weekend shifts that she had been accustomed to doing for a long time and giving them to a relative of the manager;

3. Perceptions that there was constant favouring of relatives of one of the managers and attempts to give them the tasks or hours which Ms Han had been accustomed to doing;

4. Falsely accusing her of misconduct in relation to supervising the provision of oxygen to a patient with a terminal illness and reporting this to the nurses’ registration board, a matter which was then dismissed by the Healthcare Complaints Commission;

5. Subsequently terminating her employment in circumstances which have been deemed illegal by the Federal Court and relate to Ms Han having made complaints or inquiries about her employer as well as relating to her race.

89 As with Dr Nagesh, and in a relatively more fulsome way, Dr Sherman’s view was that Ms Han’s condition was caused by “several actions” which went beyond those limited to the contraventions that were found by Rares J and included matters relating to Ms Han’s “perceptions” of events.

90 Dr Sherman expressed the opinion Ms Han was fit for part-time work for up to 24 hours per week. Dr Sherman further expressed the opinion that Ms Han did not yet have full capacity to return to pre-injury duties but that “once the legal proceedings have concluded” he expected Ms Han would recover in “no less than 12 to 24 months”. However, this recovery was subject to Ms Han continuing to be treated, which he considered to involve fortnightly sessions with a clinical psychologist for the next 12 months at the cost of $250 per session or approximately $7,000 per annum.

91 In his Reply Report dated 30 July 2024, Dr Nagesh provided an update on the previous opinions he expressed and responded to Dr Sherman’s report. Dr Nagesh’s view was that Ms Han remained depressed. He expressed the further view that Ms Han “has had reasonable treatment” and could continue to see a “psychologist or GP on a monthly basis for the next 6-12 months” and if her condition remained stable, she could be discharged back to the care of a GP. As to questions of causation, Dr Nagesh was asked, and answered, the following question:

5. Whether you are of the opinion that our client’s symptoms and disabilities continue to relate to the allegations of bullying and harassment, which she experienced in the course of employment and particularly in regard to the adverse action against our client in regard to her race and her exercising her right to make a workplace complaint.

I am of the opinion that your client's symptoms and disabilities continue to relate to the allegations of bullying and harassment, which she experienced in the course of her employment and particularly in regard to adverse action against your client with regard to her race and exercising her right to make a workplace complaint. My rationale is I could not identify any other factors outside of her employment, which have given rise to her alleged injury.

92 As will be evident, Dr Nagesh’s opinion continued to be that the relevant symptoms and disabilities related to the “allegations” of bullying and harassment.

93 In response to Dr Sherman’s report, Dr Nagesh opined as follows:

I have reviewed the report of Dr Sherman. I do agree with [Dr Sherman’s] diagnosis of adjustment disorder with depressed and anxious mood but in my opinion an appropriate diagnosis would be one of major depression of moderate degree with anxious distress. My rationale is [Ms Han’s] symptoms have persisted beyond 6 months in spite of being away from the alleged stressors at a workplace. I do also agree with [Dr Sherman’s] opinion regard to causation. However, I do partially agree with regard to [Dr Sherman’s] opinion regarding capacity. My rationale is, in my opinion Dr Sherman has opined that Ms Han can work up to 24 hours per week which I partially agree with. In my opinion, the client can work only up to 15 to 20 hours per week as working more than 20 hours per week can be detrimental to your client's mental state. [I] also agree with [Dr Sherman’s] recommendations regarding treatment.

94 St Basil’s relied upon the Earning Capacity Assessment Report of Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill. Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill expressed the opinion that, although Ms Han was not fit to work 38 hours per week, she was fit to work 30 hours per week. This report also concluded that Ms Han’s capacity to work “can improve” including by “resolution” of her legal claims. It was also recommended that Ms Han would benefit from 6-12 sessions of cognitive-behavioural approaches and a psychiatrist’s review may also be beneficial. Based on these various assessments, Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill identified three working options that would be available to Ms Han: first, as a registered nurse, the second as a “Care Manager” and the third as a Pathology Collector / Phlebotomist. Based on their labour market research, Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill estimated particular ranges of earnings that Ms Han could expect to earn in each of those three working options on the assumption that Ms Han worked for 30 hours per week.

95 As will be evident from the foregoing, all three psychiatric experts (Drs Rastogi, Nagesh and Sherman) agreed that Ms Han had suffered an injury. All of these experts also generally agreed that Ms Han’s condition had been caused by various contributing factors that were not limited to the “adverse action” actually found by Rares J, which related to the termination of Ms Han’s employment because of her exercise of workplace rights. There were, however, differences between the three experts as to the particular condition that Ms Han had suffered from and in the opinions expressed as between Dr Nagesh, Dr Sherman and Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill as to Ms Han’s present capacity to perform work and her prognosis.

96 Without the benefit of these experts being cross-examined, I have had to consider the reports to determine which opinions to prefer. In conducting this assessment, I have closely examined each of the reports and have concluded that Dr Sherman’s opinion is preferable. My conclusion is supported by several matters, which includes the following. First, although Dr Sherman was retained by St Basil’s as an independent expert, he was nonetheless prepared to express opinions that were adverse to St Basil’s. Next, Dr Sherman’s report was slightly more fulsome than the respective reports of Dr Rastogi Dr and Nagesh. Further, Dr Nagesh had the opportunity to respond to Dr Sherman’s report and expressed the view that he largely agreed with him, with only limited areas of disagreement. In view of these factors, I have afforded greater weight to Dr Sherman’s opinion than I have to the opinions of Dr Rastogi and Dr Nagesh.

97 In relation to Ms Han’s present and future capacity to return to work, I consider that the Earning Capacity Assessment Report of Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill should be preferred to each of the reports of Dr Rastogi, Dr Nagesh and Dr Sherman. Whereas each of the psychiatrists had expressed their opinions based upon their expertise as medical professionals in assessing mental health conditions and their impact, Ms Makhoul and Mr Hill had expressed their views by reference to their expertise as Vocational Counsellors with greater attention being given to the functional aspects of Ms Han’s profession as a registered nurse. Ms Makhoul had also done so with the benefit of her additional qualifications as a registered psychologist.