FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Mond v The Age Company Pty Limited [2025] FCA 442

File number(s): | VID 228 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | WhEELAHAN J |

Date of judgment: | 8 May 2025 |

Catchwords: | DEFAMATION – publication of print and online newspaper articles – whether the print and online articles were defamatory – ordinary reasonable reader’s understanding of the articles – alternative Hore-Lacy meanings – some of the print and online articles were defamatory of the applicant – whether the fourth respondent was a publisher of the articles – the fourth respondent was a publisher – publication is not confined to composing or writing the defamatory matter – the process of publication – the serious harm element in s 10A of the Defamation Act 2005 (Vic) – whether the applicant established serious harm to reputation as a result of the defamatory publications – serious harm to reputation established – harm to reputation in an objectively important aspect of the applicant’s standing – extent of publication significant – whether the respondents established any defences to the publication of the matters – defences of common law and statutory justification – s 25 of the Defamation Act 2005 – defence of justification not made out – defences of honest opinion or fair comment – s 31 of the Defamation Act – defences of honest opinion and fair comment not made out – defence of public interest – s 29A of the Defamation Act – not reasonable to believe publication was in the public interest – defence of public interest not made out – assessment of damages – damages for non-economic loss under s 35 of the Defamation Act 2005 – whether increased damages on account of aggravating conduct should be assessed – absent a lack of justification or impropriety ordinary features of litigation do not sound in aggravation – no aggravated damages awarded PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – findings of defamatory meaning must be fairly within the pleadings – permissible variants of defamatory meaning within the pleadings – Court will not look for imputations outside of bounds of pleaded case |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 78, 126K, 136 Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth) s 79 Defamation Act 1974 (NSW) Defamation Act 2005 (Vic) ss 3(c), 10A, 11(2), 25, 29A, 31, 31(4)(c), 34, 35, 36, 47 Justice Legislation Amendment (Supporting Victims and Other Matters) Act 2020 (Vic) s 21 Transport Accident Act 1986 (Vic) s 93(2)(b) Workplace Rehabilitation and Compensation Act 2013 (Vic) s 327 Defamation Act 2013 (UK) s 1 |

Cases cited: | Advertiser-News Weekend Publishing Company Ltd v Manock (2005) 91 SASR 206 Alcan (NT) Alumina Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Territory Revenue [2009] HCA 41; (2009) 239 CLR 27 Amaca Pty Ltd v Booth [2011] HCA 53; 246 CLR 36 Amaca Pty Ltd v Ellis [2010] HCA 5; 240 CLR 111 Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd v Marsden (No 2) [2003] NSWCA 186; 57 NSWLR 338 Amersi v Leslie [2023] EWCA Civ 1469 Anderson v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2001] VSC 335; 3 VR 619 Associated Newspapers Ltd v Dingle [1964] AC 371 Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hellicar [2012] HCA 17; (2012) 247 CLR 345 Backwell v AAA [1997] 1 VR 182 Banks v Cadwalladr [2023] KB 524; [2023] EWCA Civ 219 Bauer Media Pty Ltd v Wilson (No 2) [2018] VSCA 154; (2018) 56 VR 674 Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65; 98 ER 969 Bonnick v Morris [2002] UKPC 31; [2003] 1 AC 300 Bonnington Castings Ltd v Wardlaw [1956] AC 613 Brandi v Mingot (1976) 12 ALR 551 Bus v Sydney County Council (1989) 167 CLR 78 Carson v John Fairfax & Sons Ltd (1993) 178 CLR 44 Cassell & Co Ltd v Broome [1972] AC 1027 Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd [1998] HCA 37; (1998) 193 CLR 519 Channel Seven Adelaide Pty Ltd v Manock [2007] HCA 60; (2007) 232 CLR 245 Chappell v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1984) Aust Torts Reports ¶80-691 Cheng Albert v Tse Wai Chun Paul [2000] HKCFA 35; [2000] 4 HKC 1 Cherneskey v Armadale Publishers Ltd [1979] 1 SCR 1067 Cooke v MGN Ltd [2015] 1 WLR 895; [2014] WHC 2831 Cooper v Lawson (1838) 8 A and E 746; 112 ER 1020 Coyne v Citizen Finance Ltd (1991) 172 CLR 211 David Syme & Co Ltd v Hore-Lacy [2000] VSCA 24; 1 VR 667 Deeming v Pesutto (No 3) [2024] FCA 1430 Drummoyne Municipal Council v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1990) 21 NSWLR 135 Economou v De Freitas [2018] EWCA Civ 2591 Fairfax Digital Australia and New Zealand Pty Ltd v Kazal [2018] NSWCA 77; (2018) 97 NSWLR 547 Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Kermode [2011] NSWCA 174; (2011) 81 NSWLR 157 Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Voller [2021] HCA 27; 273 CLR 346 Favell v Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 52; (2005) 221 ALR 186 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Consolidated Media Holdings Ltd [2012] HCA 55; (2012) 250 CLR 503 Gardiner v John Fairfax & Sons Pty Ltd (1942) 42 SR (NSW) 171 Greenwich v Latham [2024] FCA 1050 Harbour Radio Pty Ltd v Trad (2012) 247 CLR 31 Hayson v The Age Company Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1538 Herald & Weekly Times Ltd v Popovic [2003] VSCA 161; (2003) 9 VR 1 Howden v Truth & Sportsman Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 416 Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 Lachaux v Independent Print Ltd [2020] AC 612; [2019] UKSC 27 Lewis v Australian Capital Territory [2020] HCA 26; 271 CLR 192 Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 Lloyd v David Syme & Co Ltd [1986] AC 350 London Artists Ltd v Littler [1969] 2 QB 375 Lower Murray Urban and Rural Water Corporation v Di Masi [2014] VSCA 104; (2014) 43 VR 348 Massoud v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2022] NSWCA 150; (2022) 109 NSWLR 469 Mirror Newspapers Ltd v Harrison (1982) 149 CLR 293 Mirror Newspapers Ltd v World Hosts Pty Ltd (1979) 141 CLR 632 Nassif v Seven Network (Operations) Ltd [2021] FCA 1286 Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Rush [2020] FCAFC 115; 380 ALR 432 O'Shaughnessy v Mirror Newspapers Ltd (1970) 125 CLR 166 Palmer v McGowan (No 5) [2022] FCA 893; 404 ALR 621 Peros v Nationwide News Pty Ltd (No 3) [2024] QSC 192 Pervan v North Queensland Newspaper Co Ltd (1993) 178 CLR 309 Planet Fisheries Pty Ltd v La Rosa (1968) 119 CLR 118 Praed v Graham (1889) 24 QBD 53 Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 355 Purkess v Crittenden (1965) 114 CLR 164 Rader v Haines [2022] NSWCA 198 Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton (2009) 238 CLR 460 Ratcliffe v Evans [1892] QB 524 Reader’s Digest Services Pty Ltd v Lamb (1982) 150 CLR 500 Rofe v Smith’s Newspapers Ltd (1924) 25 SR (NSW) 4 Rogers v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2003] HCA 52; (2003) 216 CLR 327 Russell v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (No 3) [2023] FCA 1223; (2023) 303 FCR 372 Selkirk v Wyatt [2024] FCAFC 48; (2024) 302 FCR 541 Shakil-Ur-Rahman v ARY Network Ltd [2017] 4 WLR 22; [2016] EWHC 3110 (QB) Sharma v Singh [2007] EWHC 2988 (QB) Shi v Migration Agents Registration Authority [2008] HCA 31; (2008) 235 CLR 286 Sivananthan v Vasikaran [2022] EWHC 2938 (KB) Sobrinho v Impresa Publishing SA [2016] EWHC 66 (QB) Soultanov v The Age Co Ltd [2009] VSC 145; (2009) 23 VR 182 Stead v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 15; 387 ALR 123 Steele v Mirror Newspapers Ltd [1974] 2 NSWLR 348 Sube v News Group Newspapers [2018] EWHC 1234 (QB) Supaphien v Chaiyabarn [2023] ACTSC 240 Sutherland v Stopes [1925] AC 47 SZTAL v Minister for Immigration & Border Protection [2017] HCA 34; (2017) 262 CLR 362 Templeton v Jones [1984] 1 NZLR 44 Teubner v Humble (1963) 108 CLR 491 Transport Accident Commission v Katanas [2017] HCA 32; 262 CLR 550 Triggell v Pheeney (1951) 82 CLR 497 Trkulja v Google LLC [2018] HCA 25; (2018) 263 CLR 149 “Truth” (New Zealand) Ltd v Holloway [1960] 1 WLR 997 Uren v John Fairfax & Sons Pty Ltd (1966) 117 CLR 118 Webb v Bloch (1928) 41 CLR 331 WIC Radio Ltd v Simpson [2008] 2 SCR 420 XL Petroleum (NSW) Pty Ltd v Caltex Oil (Aust) Pty Ltd (1985) 155 CLR 448 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Other Federal Jurisdiction |

Number of paragraphs: | 532 |

Date of hearing: | 19 – 20, 23 – 27 October 2023, 1 – 2 November 2023, 9 February 2024 |

Counsel for the applicant | Mr A T Strahan KC with Ms N Hickey |

Solicitor for the applicant | Sinisgalli Foster |

Counsel for the respondent | Ms R L Enbom KC with Mr M J Hoyne |

Solicitor for the respondent | Thomson Geer |

ORDERS

VID 228 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | DAVID MOND Applicant | |

AND: | THE AGE COMPANY PTY LIMITED First Respondent FAIRFAX MEDIA PUBLICATIONS PTY LIMITED (ACN 003 357 720) Second Respondent STEPHEN BROOK (and another named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | WHEELAHAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 8 May 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 4.00pm on 12 May 2025, the respondents file and serve submissions on the questions of interest, costs and permanent injunction, limited to four pages, in 1.5 spacing and 12 point font.

2. By 4.00pm on 14 May 2025, the applicant file and serve submissions in response, limited to four pages, in 1.5 spacing and 12 point font.

3. The outstanding questions, including the terms of final orders, be fixed for hearing at 10.15am on 15 May 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

[1] | |

[4] | |

[9] | |

[10] | |

Issue (1): did the fourth respondent publish the matters the subject of this proceeding? | [33] |

[49] | |

[54] | |

[59] | |

[64] | |

[72] | |

[92] | |

[93] | |

[106] | |

[117] | |

[129] | |

[131] | |

[132] | |

[133] | |

[135] | |

[138] | |

[139] | |

[140] | |

[152] | |

[153] | |

[154] | |

[156] | |

[158] | |

[159] | |

[159] | |

[162] | |

[163] | |

[164] | |

[165] | |

[166] | |

[167] | |

[168] | |

[172] | |

Witnesses not called | [175] |

[182] | |

[217] | |

[220] | |

[223] | |

[224] | |

[234] | |

[239] | |

The apology issued by the board of the Caulfield Shule to Mr Adam Slonim | [248] |

[294] | |

The circumstances surrounding the publication of the articles | [301] |

[302] | |

[309] | |

[310] | |

[331] | |

[352] | |

[365] | |

[386] | |

Serious harm – 13 December 2021 and 18 February 2022 articles | [387] |

[387] | |

[390] | |

[397] | |

[413] | |

[421] | |

The applicant did consult Rabbi Genende | [425] |

[433] | |

[442] | |

[446] | |

[447] | |

[450] | |

[454] | |

[466] | |

[470] | |

[489] | |

[497] | |

[517] | |

[531] |

WHEELAHAN J:

Introduction

1 The applicant is a Melbourne businessman and accountant. At the times relevant to this proceeding, he was the president, and then immediate past president, of the Caulfield Hebrew Congregation Inc, which is also known as the Caulfield Shule. The applicant seeks damages and other relief in respect of the mainstream publication of print and online articles which he alleges were defamatory of him.

2 There are four respondents. The first respondent, The Age Company Pty Ltd (The Age), is the publisher of The Age newspaper and of the content on its website, www.theage.com.au and is alleged to be vicariously liable for the conduct of the third respondent, Mr Stephen Brook. The second respondent, Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (Fairfax Media), is the publisher of the content on the website associated with The Sydney Morning Herald, www.smh.com.au and is alleged to be vicariously liable for the conduct of the fourth respondent, Ms Samantha Hutchinson. The third respondent, Mr Brook, is a journalist employed by The Age, and is one of two journalists under whose by-line the articles were published. The fourth respondent, Ms Hutchinson, is a journalist employed by Fairfax Media, and is the other journalist under whose by-line the articles were published. No issue in relation to the allegations of publication arises in relation to the first, second, or third respondents. However, Ms Hutchinson denies that she was a publisher of the articles, and that issue therefore falls for determination.

3 The trial of the proceeding was fragmented. This occurred because the estimated trial length given by the parties at the case management hearing, and the time that the Court set aside for the trial between its other commitments, proved to be insufficient. At the conclusion of evidence, and at the request of the Court, the parties presented an agreed list of issues, comprising 55 in number. Within those 55 issues were sub-issues, and issues that were contingent upon the determination of other issues. I mention this to indicate that there were some complexities in the case, which have taken some time to consider.

The publications

4 There are seven distinct articles that comprise the matters that are the subject of the applicant’s claims. The articles were published in the “CBD” column of The Age newspaper and online. The seven articles can be grouped into three sets of publications –

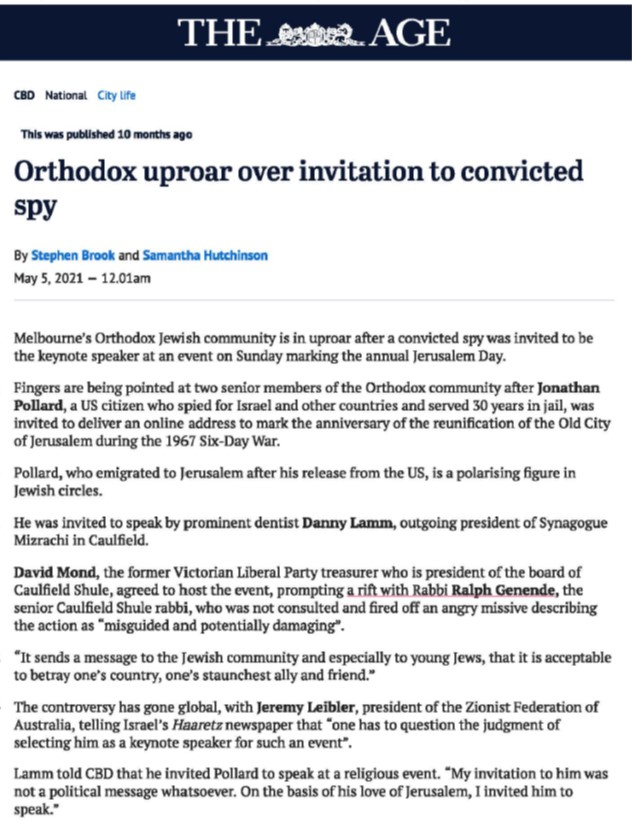

(1) the 5 May 2021 articles, comprising –

(a) a print article published in The Age newspaper dated 5 May 2021 and titled, Uproar over invitation to convicted spy (the first matter); and

(b) an online article published on The Age website dated 5 May 2021 and titled Orthodox uproar over invitation to convicted spy (the second matter);

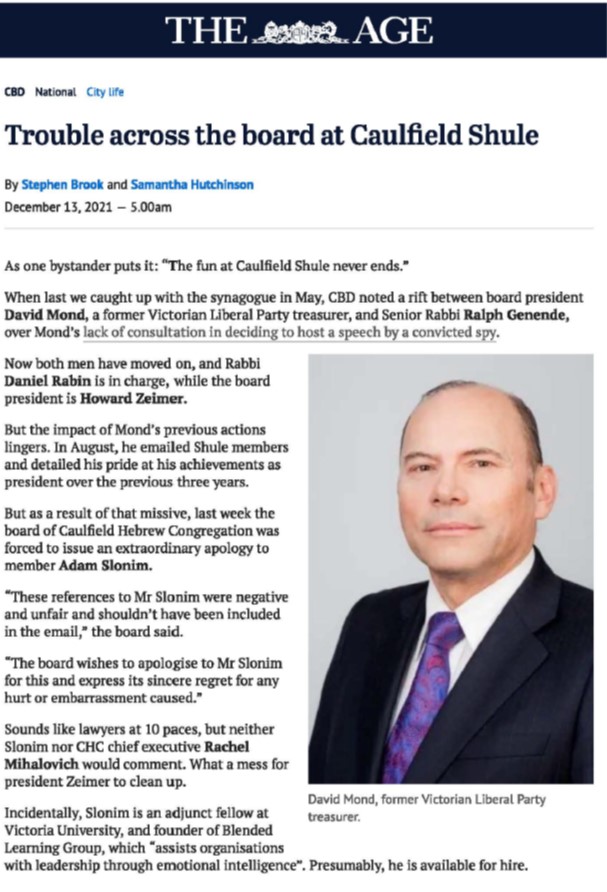

(2) the 13 December 2021 articles, comprising –

(a) a print article published in The Age newspaper dated 13 December 2021 and titled, Trouble across the board in Caulfield (the third matter); and

(b) an online article published on The Age website dated 13 December 2021 and titled Trouble across the board at Caulfield Shule (the fourth matter); and

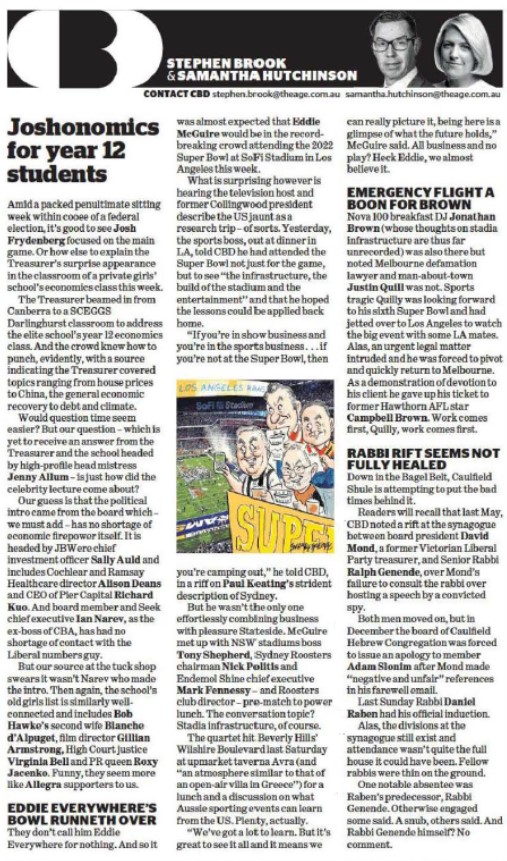

(3) the 18 February 2022 articles, comprising –

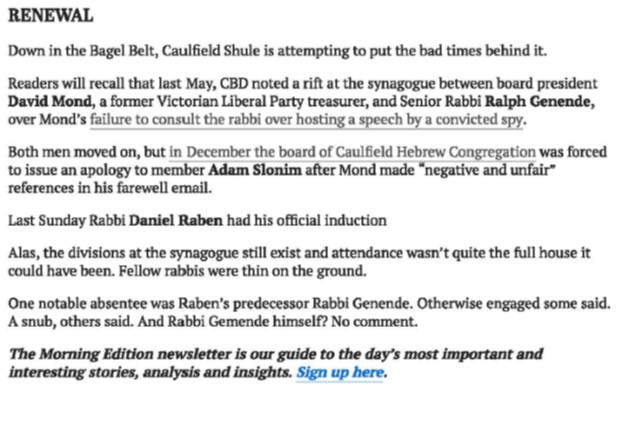

(a) a print article published in The Age newspaper dated 18 February 2022 and titled, RABBI RIFT SEEMS NOT FULLY HEALED (the fifth matter);

(b) an online article published on The Age website dated 18 February 2022 and titled RENEWAL (the sixth matter); and

(c) an online article published on The Sydney Morning Herald website dated 18 February 2022 and also titled RENEWAL (the seventh matter).

5 In addition to the primary publication of the seven matters, the applicant alleges that the first, second, third and fourth matters were subsequently published by hyperlinks appearing in the online versions of the later articles.

6 The text of each of the seven matters is set out in the schedules to this judgment, together with copies of the pages in which the articles were published so as to show how they would have appeared to the ordinary reasonable reader.

7 There are some material differences between the first and the second matters dated 5 May 2021 to which I will refer later. The text of the third and the fourth matters that were dated 13 December 2021 is the same, although the headings differ slightly. And the text of the three matters dated 18 February 2022 is the same, although the heading of the print matter is different from the online matters.

8 I will address the imputations that the applicant alleges were conveyed by the matters later in these reasons. It will also be necessary to consider alternative imputations alleged by the respondents in support of their statutory and common law defences.

Overview of the issues in the proceeding

9 As I mentioned above, the agreed list of issues itemised 55 issues for determination. I have given attention to all the issues raised by the parties, but I have addressed them within my own framework of analysis. In broad outline, the main issues that arise for determination are as follows –

Issue (1):

Was the fourth respondent, Ms Hutchinson, a publisher of any of the articles?

Issue (2):

Did the articles convey any, and if so what, imputations that were defamatory of the applicant, and which are within the applicant’s pleaded case?

Issue (3):

In respect of any defamatory publication occurring after 1 July 2021, has the applicant established that he suffered serious harm to his reputation as a result of the relevant publication?

Issues (4), (5), and (6):

If any of the articles were defamatory of the applicant, and if (where relevant) he suffered serious harm to his reputation as a result, then have the respondents established any of their positive defences, namely –

(a) common law or statutory justification;

(b) honest opinion or fair comment; or

(c) public interest in respect of publications after 1 July 2021?

I have grouped these issues together because their resolution is inter-dependent.

Issue (7):

If the applicant has established any cause of action, in what sum should damages be assessed, and is the applicant entitled to the remedy of an injunction?

Brief background

10 Before going to the issues in more detail, I will set out some background, which comprises findings that I make on some basic issues. When addressing the facts in more detail, it will be necessary to make further findings.

11 The applicant is a practising accountant, and is aged in his early 70s. He is married to his wife Betty, and is close to his brother, Barry Mond. He was born in Melbourne, where he grew up. Over the years, he has had a successful career in business and in his profession of accountancy. He is a former treasurer of the Victorian Liberal Party. He has been part of the social fabric of the community of Melbourne, including as a follower of AFL football, being for many years an enthusiastic supporter of the Carlton Football Club.

12 Growing up, the applicant and his family were members of the congregation of a shule in North Carlton, before the applicant moved with his wife to Doncaster in 1981, and then to Caulfield in 1989. Upon moving to Caulfield, the applicant became a member of the Caulfield Shule, with which his extended family had an existing association, with his brother Mr Barry Mond having been involved with the Caulfield Shule since 1981. The Caulfield Shule is one of many congregations in Caulfield, and in terms of membership is one of the largest in Victoria.

13 The applicant’s faith is a very significant part of his everyday life. At the times relevant to this proceeding, the applicant attended the Caulfield Shule almost daily, and developed close social relationships with many other members of the Congregation. The applicant’s involvement with the Caulfield Shule extended to his election as president of the Congregation, which was an office that he held from September 2018 to October 2021.

14 Although I will use the terms Caulfield Shule and Caulfield Hebrew Congregation interchangeably, it is necessary to identify that Caulfield Hebrew Congregation Inc is an incorporated association, and has a constitution which provides for such things as its purposes, membership, a board of management, an executive, meetings, and diverse powers of both the Congregation and its board of management. The board of management is elected, and is responsible for the control and management of the business and affairs of the Congregation.

15 The constitution of the Congregation provides for the appointment by the board of officials of the Congregation, such as ministers, assistant ministers, chazzanim (or cantors), and other officers. However, the constitution makes no express reference to such persons having a role on the board or the executive of the Congregation. Officials of the Congregation are guided in the performance of their duties and in all matters affecting the interests of the Congregation by directions from the president. However, in spiritual matters, officials of the Congregation are not subject to any direction of the board.

16 The evidence was that there are different ways in which members of the Jewish community practise and express their faith. The Caulfield Shule is a modern Orthodox congregation that was established after the Second World War by many Holocaust survivors. Under its constitution, one of its purposes is to uphold and foster the aims of Zionism, which is elaborated upon in its constitution. There are other congregations in Melbourne where members practise their faith with different emphases, and which will be well-known to members of the Jewish community and others. One such congregation is under the umbrella of the Mizrachi Organisation. Mizrachi also has a shule in Caulfield, which is located close to the Caulfield Shule. Mizrachi has some common features with the Caulfield Shule, including its adherence to the Ashkenazi rites, and the promotion of Zionism, but there is no formal association between the two organisations.

17 During the time the applicant served as president of the Caulfield Shule in 2020 and 2021, the State of Victoria was subject to lockdowns, social distancing requirements, and other restrictions as a result of the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus. These restrictions affected people’s ability to attend religious services and to pray in places of worship. The restrictions presented many challenges to the Caulfield Shule, including their effect on fundraising, because members of the Shule were not able to use their synagogue seats. Funds raised from synagogue seats comprised the bulk of the Caulfield Shule’s revenue. The applicant had to confront these issues, and took a number of steps to address them such as personally making financial contributions, and making hundreds of calls to members of the Congregation. Ms Rachel Mihalovich, the Chief Executive Officer of the Shule at the time, spoke highly in her evidence of the applicant’s leadership of the Shule during this difficult period, and during his term as president generally.

18 On 14 April 2021, Dr Danny Lamm, who was the president of Mizrachi, spoke to Mr Mond at an event organised by Mizrachi to mark Israeli Independence Day, known as Yom Ha’atzmaut. Although organised by Mizrachi, the event was held at the Caulfield Shule, which had a larger capacity than the Mizrachi Shule and was more suitable having regard to COVID-related capacity restrictions that were in place at the time. Dr Lamm asked Mr Mond whether Mizrachi could also use the Caulfield Shule for an upcoming event to be held on 9 May 2021 to mark Jerusalem Day, which is known as Yom Yerushalayim, to which the applicant agreed. At the conclusion of the Independence Day event Dr Lamm announced to those present that the Jerusalem Day event would also be celebrated at the Caulfield Shule.

19 A week later, on 21 April 2021, Dr Lamm left a voicemail message for Mr Mond in which he told him that the guest speaker for the Jerusalem Day event would be Jonathan Pollard. The proposal was that Mr Pollard would speak at the event from Israel by means of a recorded video.

20 Jonathan Pollard is an Israeli resident who is a controversial figure within Jewish circles. It is well known within sections of the Jewish community in the United States and Australia that Mr Pollard is a United States citizen who was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 30 years in the United States from about 1987 for spying for Israel and other countries. Mr Pollard was released from prison in about 2015, and in about late 2020 after completing his parole he left the United States to live in Israel.

21 In a sermon given at The Great Synagogue in Sydney in January 2021, Rabbi Dr Benjamin Elton, who was called as a witness by the respondents, explained his view that Mr Pollard should not be celebrated, valorised, or honoured, and that to do so would severely damage the standing of diaspora Jews. Rabbi Elton said that Australian loyalties matter, and that it was essential that everyone understand that they matter. Of Mr Pollard, Rabbi Elton said in his sermon –

Not only was he a traitor, but he undermined the central platform of diaspora Zionism, that we support the State of Israel but we are implacably loyal to our home nations, until such time as we choose to live in Israel and become Israeli citizens. Pollard’s actions blew a hole in that delicate understanding.

22 In evidence, Rabbi Elton went further, and stated his opinion that it would be contrary to the teachings of the Torah in a broad sense to celebrate someone like Mr Pollard, while acknowledging that his view was not one that was universally held.

23 The proposal that Mr Pollard speak at the Jerusalem Day event at the Caulfield Shule led to differences of opinion between some members of the Jewish community, and between members of the board of the Shule. Rabbi Genende, who was the spiritual leader of the Congregation at the time, spoke to the applicant of concerns relating to the proposal. The board engaged in some email exchanges upon being informed that Mr Pollard would be the speaker at the Jerusalem Day event. Subsequently, Rabbi Genende sent an email to the board expressing his opposition to having Mr Pollard speak, which was expressed in fairly direct terms, supported by reasoning. At a meeting on 3 May 2021 which Rabbi Genende attended, the board discussed the Rabbi’s concerns. A motion that the Congregation withdraw from the event was defeated by a majority.

24 In the meantime, the proposal to have Mr Pollard speak at the Jerusalem Day event was reported in the media, initially in Israel, and then in Melbourne. On 3 May 2021, the Israeli Haaretz newspaper reported online that the invitation to Mr Pollard to speak at the event in Australia had raised controversy. Haaretz attributed to Mr Jeremy Leibler, president of the Zionist Federation of Australia, views that were opposed to having Mr Pollard speak. The Haaretz article also referred to the email that Rabbi Genende had sent to the board of the Caulfield Hebrew Congregation expressing his opposition to the proposal to have Mr Pollard speak, and set out some extracts from the email. The Haaretz article also claimed that the congregational rabbi, who was identified as Rabbi Genende, had not been consulted.

25 Two days later, on 5 May 2021, the first and second matters were published in The Age newspaper in print and online as part of its CBD column, which was a weekday column that normally appeared prominently on page two of the print edition of The Age newspaper. The general subject matter of these articles was the controversy that the invitation to Mr Pollard had generated. Mr Mond claims that these publications were defamatory of him in meanings that I will set out later and consider. There were other print and online articles at around this time that reported on the controversy surrounding the Jerusalem Day event, including in The Australian Jewish News.

26 The Jerusalem Day event proceeded at the Caulfield Shule on 9 May 2021. Mr Pollard spoke at the event via a recorded video, and the event was well attended.

27 Mr Mond and other board members decided to retire from the board of the Congregation at the Annual General Meeting that was to take place on 29 August 2021. This was reported by The Australian Jewish News on 6 August 2021 under the headline “CHC mass resignation”. The article included some quotations that were attributed to a member of the Congregation, Mr Adam Slonim, that were disparaging of the board. The claim of mass resignation was later retracted by The Australian Jewish News, which issued a correction stating that the members of the board were not resigning but were retiring. In that context, on 13 August 2021 the applicant sent a circular email to the members of the Congregation addressing the circumstances of the retirement of the members of the board. In the course of that email, the applicant made some references to Mr Slonim. Mr Slonim claimed that the applicant’s circular email was defamatory of him, and engaged solicitors who on 17 August 2021 served a concerns notice addressed to the Congregation and the applicant.

28 After the applicant and the old board had retired from their positions, and a new board was elected, the new board made an apology to Mr Slonim. The new board published its apology to Mr Slonim by a circular email to the members of the Congregation dated 8 December 2021.

29 On 13 December 2021, the third and fourth matters were published in the CBD column of The Age in print and online. Amongst other things, the third and fourth matters alluded to the first and second matters, and to the applicant’s circular email that referred to Mr Slonim, and to the board’s apology to Mr Slonim. Again, I will identify and consider later in these reasons the meanings that the applicant claims the matters conveyed.

30 In late 2021, Rabbi Genende’s term as senior rabbi of the Caulfield Shule came to an end, and a new rabbi, Rabbi Rabin, commenced his term of appointment. On 12 February 2022, a ceremony to inaugurate Rabbi Rabin as the senior rabbi was held at the Caufield Shule.

31 On 18 February 2022, the fifth, sixth, and seventh matters were published in the CBD column in print in The Age newspaper, and online on The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald websites. These matters alluded to the earlier matters published in the CBD column and claimed that attendances at the inauguration ceremony for Rabbi Rabin were low, and that divisions in the synagogue still existed. The applicant claims that these matters were defamatory of him in meanings that I will set out later and consider.

32 Fairfax Media is also alleged to be liable for the publication of the online articles of 5 May 2021 and 13 December 2021 on the ground that its online article of 18 February 2022 contained hyperlinks to those articles.

Issue (1): did the fourth respondent publish the matters the subject of this proceeding?

33 The first issue to address is whether the fourth respondent, Ms Hutchinson, was a publisher of the seven matters. As I have mentioned, Ms Hutchinson, who was a journalist with The Sydney Morning Herald, denies that she is liable as a publisher. I will set out the circumstances in which that dispute arises.

34 The print and online articles were published with by-lines that identified both Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson. In addition, the print articles were published in The Age newspaper under a banner which contained photographs of Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson and which is reproduced below –

35 An editorial code of conduct titled “Australian Metro Publishing – Editorial Code of Conduct”, which applied to all Australian Metro Publishing editorial employees, including staff at The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, provided under a heading that referred to plagiarism and attribution –

Bylines should be carried only on material that is substantially the work of the bylined journalist.

36 Both Ms Hutchinson and Mr Brook accepted that the Code of Conduct applied to them, and Ms Hutchinson accepted that both she and Mr Brook were held out as co-columnists of the CBD column.

37 However, Ms Hutchinson’s case essentially is that Mr Brook composed those parts of the CBD columns on which the applicant’s claims are founded, and that she did not take responsibility for anything that Mr Brook wrote. Ms Hutchinson’s case is that because she did not compose the words sued upon, she is not liable as a publisher.

38 The applicant made the following allegations in the further amended statement of claim –

(a) the CBD column is a marquee gossip column published prominently by The Age online and in print and Fairfax Media, relevantly, online, of which Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson are or were at all material times the columnists; and

(b) in the particulars to the allegations of publication of the matters by the respondents, that the “lead authors” of the matters were Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson.

39 By their further amended defence the respondents denied that Ms Hutchinson was an author of, or in any way involved in, or otherwise published or caused the articles to be published.

40 Prior to trial, the solicitors for the parties engaged in correspondence in relation to the question of publication. In a letter to the solicitors for the respondents dated 16 August 2023, the solicitors for the applicant claimed that Ms Hutchinson was an active participant in the publication of the matters. This claim was made in support of an invitation to the respondents to admit that Ms Hutchinson was a publisher of the matters. In support of this invitation, the solicitors for the applicant relied on the following claims that were said to be based upon their review of discovered documents –

It is apparent that Ms Hutchinson participated actively in the production of each of the relevant CBD Columns. Her approval of and overt participation in the matters complained of is apparent from the following:

1. The content of the CBD Column was published jointly under the names of Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson.

2. The columnists worked up the matters to be published in a joint document.

3. Ms Hutchinson was on notice at all material times of all the content that was to go out under her name, whether or not she wrote it.

4. The practice of the journalists was to amend each other’s work if they had an issue with it. They also sometimes wrote content jointly. Other times they did not amend each other’s work.

5. When they did not amend each other’s work, it can be readily inferred that it was because they had nothing to add or change and thereby sanctioned the contents.

6. Ms Hutchinson chose not to amend the matters complained of even though she had the opportunity to do so. She thereby sanctioned and endorsed the contents.

7. Further, in relation to the December 2021 publications, Ms Hutchinson formatted the topic ideas which included the word SHUL, and formatted the document as a whole.

8. Further, in relation to the February 2022 publications, Ms Hutchinson wrote the term “Shule” in the Melbourne column, and formatted the document as a whole.

41 The letter then referred to the leading High Court authorities concerning liability for publication of defamatory matter.

42 In the applicant’s written opening at trial, counsel for the applicant stated that the case against Ms Hutchinson was that she and Mr Brook worked on a joint document, knowing that it would be published under their joint by-lines, and that Ms Hutchinson was therefore liable as a publisher. On the other hand, counsel for the respondents in their written and oral openings pointed to the applicant’s allegation in the particulars of the further amended statement of claim that the fourth respondent was an “author” of the articles, and stated that Ms Hutchinson was not an author, but that Mr Brook was the sole author.

43 Both Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson gave evidence in relation to the composition of the articles the subject of this proceeding. Ms Hutchinson gave evidence in a straight-forward manner, and in relation to her evidence as to primary facts, impressed me as being reliable. On issues other than publication, Mr Brook’s evidence will be considered later. For present purposes, there is no aspect of the presentation of either Mr Brook or Ms Hutchinson as witnesses that bears upon my evaluation of the evidence of primary facts going to publication. Those facts include admitted facts arising from the applicant’s service of a notice to admit and the respondents’ response to that notice, being an amended notice of dispute. In referring to primary facts, I am excluding the evidence of Ms Hutchinson and Mr Brook that used the term “author”, and its derivatives, because that is an ultimate conclusion. Both addressed questions from counsel and gave evidence that used the word “author”, which in context must be taken to have referred to the actual composition or writing of the articles. By way of example, Ms Hutchinson denied that she was an “author” of the articles.

44 The following are my findings in relation to the disputed claims of publication of the articles based upon the evidence and the relevant admitted facts.

45 At the time each of the matters was published, Mr Brook was employed at The Age in Melbourne, and Ms Hutchinson was employed by The Sydney Morning Herald in Sydney. Both were engaged as columnists for the CBD column, which was published by both newspapers and on their respective websites. However, the published columns were not usually identical because they were tailored to the different markets of Sydney and Melbourne. Many items in the CBD column were published only in The Age or The Sydney Morning Herald, but not both. However, sometimes items that had a national flavour were published in the CBD columns of both newspapers. Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson worked together on the CBD columns in this way until about May 2022 when Ms Hutchinson left to join the Australian Financial Review.

46 The system for the preparation of the CBD columns commenced with a shared Google document that was created by either Mr Brook or Ms Hutchinson. This was a document stored in the cloud to which Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson had access. I understood the evidence to be that both could work on a Google document concurrently, and that it was possible for each to see the other person’s changes to the document in real time, depending upon what part of the document was viewable on the screen. As Ms Hutchinson put it, “we would be one on top of the other”. Later in the process, an editor was also given access to the shared document.

47 The Google documents that led to the CBD columns for 5 May 2021, 13 December 2021, and 18 February 2022, evolved. They evolved from the planning stages, where ideas for content were recorded in a table containing separate columns for Sydney and Melbourne. Each of Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson then entered text in the shared document as it developed. The text included drafts of what became components of the CBD columns. Through this process, Mr Brook composed each of the matters the subject of the applicant’s claims. Ms Hutchinson did not contribute to their composition. Nor did she contribute any ideas, or research any of the matters in issue.

48 After the Google documents were completed, the text was transferred to a publishing platform known as “Ink”. For the CBD column, two publishing shells within Ink were created: one for Sydney, and the other for Melbourne. Editorial and production staff of The Sydney Morning Herald then worked on the Sydney shell, and corresponding staff at The Age worked on the Melbourne shell. That process of production through the Ink platform typically resulted in several more versions of the columns before final publication.

Publication of the 5 May 2021 articles

49 Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson worked on a shared Google document for the 5 May 2021 CBD column. In the planning table under “Melbourne” Mr Brook entered “Shul”. There were at least five different versions of the column prior to publication. The column was published online at 12.01 am on 5 May 2021, and in the print edition of The Age of 5 May 2021.

50 Mr Brook gave evidence, which I accept, that he and Ms Hutchinson spoke to each other about the 5 May article at an early stage. The substance of that conversation was that Mr Brook informed Ms Hutchinson what he was planning to write, in response to which Ms Hutchinson stated that she knew nothing about the matter, and had no contacts or information that would be helpful, and that she would leave the research and the writing to Mr Brook.

51 In a Google document for the CBD column dated 4 May 2021 and time-stamped at 13:41, both Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson worked in the document. Mr Brook wrote a draft of the matter that is in issue. Ms Hutchinson did not make any revisions to Mr Brook’s draft.

52 In a Google document for the CBD column dated 4 May 2021 and time-stamped at 17:59, Mr Brook amended the draft of the matter in issue, Ms Hutchinson did not amend the draft of the matter, and there was another matter in the document drafted by Ms Hutchinson concerning the Society restaurant that Mr Brook did amend.

53 Mr Brook created the Ink shell for the 5 May 2021 article published in The Age. There were no revisions by Ms Hutchinson to the column on the Ink shell.

Publication of the 13 December 2021 articles

54 As with the 5 May 2021 article, Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson worked in a joint document that led to the 13 December 2021 publications. There were at least four different versions of the column prior to publication. The CBD column was published online at 5:00 am on 13 December 2021, and in the print edition of The Age of 13 December 2021.

55 In a Google document for the CBD column dated 12 December 2021 and time-stamped at 14:18, each of Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson contributed topic ideas. In the “Mel” column Mr Brook wrote “SHUL”, and each of Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson suggested other ideas in the draft.

56 In a Google document for the CBD column dated 12 December 2021 and time-stamped at 17:22, Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson deleted some of the topic ideas, Mr Brook amended the draft of the matter in issue, Ms Hutchinson did not make any revisions to the draft of the matter in issue, and Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson both contributed to an item concerning Alan Jones.

57 As with the 5 May 2021 article, Mr Brook created the Ink shell for the 13 December 2021 article. Ms Hutchinson did not make any revisions to the article within the Ink shell.

58 Neither Mr Brook nor Ms Hutchinson gave evidence of any conversation with each other about the 13 December 2021 article.

Publication of the 18 February 2022 articles

59 In relation to the 18 February 2022 articles, Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson worked on a joint draft document. There were at least seven different versions of the column prior to publication. The column was published online at 5:00 am on 18 February 2022 on The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald websites, and in the print edition of The Age dated 18 February 2022.

60 In a Google document for the CBD column dated 17 February 2022 and timestamped at 12:10, Ms Hutchinson wrote the term “Shule” in the Melbourne column.

61 In a further version of the Google document dated 17 February 2022 and timestamped at 17:28, Mr Brook wrote a draft of the matter that is in issue. Ms Hutchinson did not make any revisions to the draft. Mr Brook made amendments to content that Ms Hutchinson drafted in relation to another item concerning Josh Frydenberg and Eddie McGuire, and Ms Hutchinson made amendments to Mr Brook’s text in relation to another matter concerning the Superbowl.

62 Mr Brook also created the Ink shell for the 18 February 2022 article, and Ms Hutchinson did not make any revisions to the article within the Ink shell.

63 Neither Mr Brook nor Ms Hutchinson gave evidence of any conversation with each other about the 18 February 2022 article.

The fourth respondent was a publisher of the matters

64 At trial, counsel for the respondents maintained that the applicant’s pleaded case in relation to Ms Hutchinson’s liability for publication was confined to authorship of the matters, relying on the applicant’s pleas that the “lead authors” of the articles were Mr Brook and Ms Hutchinson, which reflected the fact that their names appeared in the by-lines. Counsel for the respondents submitted that, on the evidence, Ms Hutchinson was not an author of any of the matters, and that she had nothing to do with their writing.

65 It is trite that liability for publication is not confined to those who compose or write defamatory matter. The following statement from the old text Folkard on Slander and Libel (5th ed, 1891) was approved by Isaacs J in Webb v Bloch (1928) 41 CLR 331 at 363–364 –

The term published is the proper and technical term to be used in the case of libel, without reference to the precise degree in which the defendant has been instrumental to such publication; since, if he has intentionally lent his assistance to its existence for the purpose of being published, his instrumentality is evidence to show a publication by him.

66 More recently, in Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Voller [2021] HCA 27; 273 CLR 346 (Voller), Kiefel CJ, Keane and Gleeson JJ at [23] described publication as “the process by which a defamatory statement or communication is conveyed”. Any act of participation in the communication of defamatory matter to a third party is sufficient to make a respondent a publisher, such that, as their honours held at [32] –

a person who has been instrumental in, or contributes to any extent to, the publication of defamatory matter is a publisher. All that is required is a voluntary act of participation in its communication.

67 To similar effect, Gageler and Gordon JJ held at [62] –

every intentional participant in a process directed to making matter available for comprehension by a third party is a “publisher” of the matter upon the matter becoming available to be comprehended by the third party.

68 The references to intention and voluntary participation relate to the process of publication, and not to any intention to publish defamatory matter or knowledge of the defamatory nature of the matter. Intention in that sense is not relevant to liability for publication, because the tort is one of strict liability and the actionable wrong is the publication: see Voller at [27], [66].

69 Ms Hutchinson worked at The Sydney Morning Herald from August 2020 to May 2022 as a senior columnist for the CBD column. From February 2021, she worked on the CBD column with Mr Brook in the way described at [45]–[62] above. True, she did not herself type into the joint Google document the words that comprised the articles. But she actively and voluntarily participated in the process by which the joint document evolved. She was at the relevant times a voluntary and active participant in the process by which those columns were published. Ms Hutchinson gave evidence in cross-examination that she knew that the CBD columns were published under the joint by-line, and that she did not object to that process at any point in time. I find that at all relevant times Ms Hutchinson knew that the publication which resulted from the joint Google documents on which she and Mr Brook worked would be published under their joint names, and that she authorised publication of the CBD column in this form. Ms Hutchinson thereby gave her imprimatur to the publication of each of the matters in issue. For these reasons, Ms Hutchinson was a publisher of the articles in the legal sense explained in the majority judgments in Voller.

70 Further, Ms Hutchinson may be described as an author of the articles. The respondents’ case treated the concept of authorship in a narrow sense, as being synonymous with the primary composition of, or the primary writing of the actual words used in the articles. It was on this basis that Ms Hutchinson denied in evidence-in-chief that she was the author of any of the articles. But this is only one sense in which there might be authorship. Ms Hutchinson gave her imprimatur to the articles by her agreement to the process of publication in which she participated in the planning stages, and worked on the joint Google document, knowing that she would be named in the by-line as one of the writers of the CBD column. By doing so, Ms Hutchinson was an author in the sense of being one of two co-authors with Mr Brook, neither of whom wrote everything, but both of whom assumed authorship for what was published. For these reasons, the findings of publication of the articles by Ms Hutchinson are within the scope of the applicant’s pleaded case.

71 It follows that Fairfax Media is vicariously liable for the publications in issue to the extent that Ms Hutchinson is found to be liable.

Issue (2): the imputations

72 The significance of words is in their meaning. Until the meanings of the matters in issue are determined, and unless it is held that a matter is defamatory in some meaning about which an applicant complains, there is no occasion to address serious harm (which is an element of the cause of action in relation to publications on and after 1 July 2021), or to address defences such as justification, honest opinion, fair comment, or public interest.

73 The principles applicable to the ascertainment of defamatory meaning are not controversial. The meaning of written words, and the question whether in the meanings so found a matter is defamatory, are evaluated against the objective standard of the ordinary reasonable reader. The ordinary reasonable reader is an ordinary decent person, being of ordinary intelligence, experience, and education, who brings to the question his or her general knowledge and experience of worldly affairs: Radio 2UE Sydney Pty Ltd v Chesterton (2009) 238 CLR 460 (Radio 2UE) at [4]–[6], [39]–[40] (French CJ, Gummow, Kiefel and Bell JJ). The ordinary reasonable reader is a lay person, and not a lawyer, and does not examine an impugned publication over-zealously, but is someone who views the publication casually and is prone to a degree of loose thinking. The understanding of the ordinary reasonable reader is not the same as a lawyer’s understanding. Therefore, a publication such as a newspaper column should not be approached as if it were an exercise in statutory construction, where “a court construing a statutory provision must strive to give meaning to every word of the provision”: Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 355 at [71] (McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

74 The imputed knowledge of worldly affairs allows for the ordinary reasonable reader to read between the lines, and to draw inferences, implications, and conclusions much more freely than a lawyer, especially derogatory implications: Mirror Newspapers Ltd v World Hosts Pty Ltd (1979) 141 CLR 632 at 641 (Mason and Jacobs JJ, Gibbs J and Stephen J agreeing); Favell v Queensland Newspapers Pty Ltd [2005] HCA 52; (2005) 221 ALR 186 at [11]; Trkulja v Google LLC [2018] HCA 25; (2018) 263 CLR 149 at [32] (Kiefel CJ, Bell, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ). Therefore, it is often the case that it is the broad impression conveyed by an impugned publication that falls for consideration, and not the meaning of each word under analysis: Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 at 285 (Lord Devlin). There are, however, limits on the extent to which the ordinary reasonable reader may engage in loose thinking or reading between the lines. While the ordinary reasonable reader’s knowledge and experience in worldly affairs will permit the drawing of inferences, available meanings might not extend to a meaning that is the result of drawing an inference upon an inference that is not suggested by a reasonable reading of the language, or to a meaning that would be understood by some readers only as a result of some prejudice: see Mirror Newspapers Ltd v Harrison (1982) 149 CLR 293 at 301–302 (Mason J). Of course, everything depends upon the words that are used in the publication and the broad impression that the publication conveys.

75 Because meaning is to be determined by reference to an objective standard, the audience to whom a matter is published is taken to have a uniform view of meaning. Although different people might in fact have understood the meanings conveyed by a matter in different ways, the Court must arrive at a single objective meaning. The test is not what an ordinarily reasonable reader could understand the matter to mean, as with the question of capacity arising in interlocutory disputes about pleadings or whether a case should be left to a jury. For that reason, care must be exercised in applying some judicial statements that are concerned with interlocutory questions of capacity, as distinct from the factual question of actual meaning. Thus, it is not sufficient for an applicant to demonstrate that some members of the audience might have understood the matter in the way alleged, or that the publication was reasonably capable of bearing the defamatory meanings alleged, for they are not the issues. The issue is the single meaning that an objective audience composed of ordinary decent persons should collectively have understood the matter to bear. The single meaning rule, coupled with the objective standard of the ordinary reasonable reader, is an important stabilising element of the cause of action in defamation, and has been described as representing “a fair and workable method for deciding whether the words under consideration are to be treated as defamatory”: Bonnick v Morris [2002] UKPC 31; [2003] 1 AC 300 at [21] (Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead).

76 The single meaning rule does not mean that an applicant is confined to a single imputation or sting arising from a defamatory matter. That is not what the single meaning rule is about. As the Full Court explained in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing (2019) [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632 (ABC v Wing) at [33], an applicant may allege two or more distinct defamatory imputations, and may allege imputations in the alternative: see also Massoud v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2022] NSWCA 150; (2022) 109 NSWLR 469 (Massoud) at [57] (Leeming JA, Mitchelmore JA and Simpson AJA agreeing).

77 Whether words in the meanings found to be conveyed are defamatory of an applicant is also determined objectively by reference to the standards of the community generally: Reader’s Digest Services Pty Ltd v Lamb (1982) 150 CLR 500 at 507 (Brennan J, with whom Gibbs CJ, Stephen J, Murphy J and Wilson J agreed). What is involved is a loss of standing in some respect amongst ordinary decent persons who will apply general community standards: Radio 2UE at [39]–[40]; Harbour Radio Pty Ltd v Trad (2012) 247 CLR 31 at [54] (Gummow, Hayne and Bell JJ). The reference to loss of standing includes by reason of disparagement of an applicant, and by imputations that have a tendency to cause people to shun and avoid an applicant. In addition, in relation to matters published after 1 July 2021, by operation of s 10A of the Defamation Act 2005 (Vic), actual damage to reputation in the form of “serious harm” must be demonstrated as an element of the cause of action. However, because the tort of defamation is concerned with the supposed impact of a matter on an applicant’s reputation amongst those to whom it is communicated, it is not concerned with the publication of matter which is merely false, or which embarrasses an applicant, or which results in injury to feelings. Embarrassment or injury to feelings may result from a publication, but publication of defamatory meaning in the estimation of the ordinary reasonable reader, and (since 1 July 2021) resultant serious harm to reputation, is the essence of the cause of action.

78 All of the imputations alleged by the applicant are said to arise from the natural and ordinary meaning of the articles. There is no reliance on any true innuendoes. Therefore, no imputations are alleged to turn on what the articles conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader with knowledge of any special facts that would be known to members of the Caulfield Hebrew Congregation, or the Orthodox Jewish community more generally: see Duncan and Neill on Defamation (Butterworths, 1983) at [4.18(b)].

79 It is well to remember that under the Defamation Act, and corresponding uniform legislation across Australia, it is the publication of defamatory matter that constitutes the cause of action, and not the publication of imputations. Under s 8 of the Act, the publication of a matter gives rise to a single cause of action even if more than one defamatory imputation is conveyed. The object of adopting on a uniform basis the common law position that it is the publication of defamatory matter that constitutes the actionable tort was to do away with the complexities that had arisen in New South Wales, where under the Defamation Act 1974 (NSW) each imputation was a separate cause of action: see the extra-curial observations of Levine J recorded in the Second Reading Speech of the New South Wales Bill, set out in Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd v Kermode [2011] NSWCA 174; (2011) 81 NSWLR 157 at [37] (McColl JA). However, the ascertainment of the defamatory meaning of a matter by a court is not at large. An applicant’s case is shaped by the meanings alleged in the statement of claim, which will generally confine the questions of meaning for determination: Chakravarti v Advertiser Newspapers Ltd [1998] HCA 37; (1998) 193 CLR 519 (Chakravarti) at [17]–[21] (Brennan CJ and McHugh J). Although it is the publication of the matter that constitutes the tort, the pleading of meanings identifies the field of inquiry at trial: Advertiser-News Weekend Publishing Company Ltd v Manock (2005) 91 SASR 206 at [76] (Doyle CJ, with whom Vanstone J and White J agreed). At least as far as an applicant’s meanings are concerned, the case may extend to meanings that are comprehended in, or are less injurious than, or are a mere shade or nuance of the pleaded meaning: Chakravarti at [21]–[22] (Brennan CJ and McHugh J), [60] (Gaudron and Gummow JJ), [139] at points 3 and 4 (Kirby J). Whether, and to what extent, an applicant may be permitted at trial to depart from the pleaded meanings will be resolved by considerations of fairness and practical justice.

80 At trial the Court is concerned with making findings directed to the single natural meaning that would be conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader and is not concerned with identifying the outer boundaries of possible meanings. The terms of the imputations alleged by an applicant are therefore important. An applicant is entitled to bring a proceeding for defamation seeking vindication on some point which will usually be the subject of a pleaded imputation: see the discussion by the Full Court in ABC v Wing at [87], citing Associated Newspapers Ltd v Dingle [1964] AC 371 at 396 (Lord Radcliffe). In framing imputations, an applicant is entitled to disclaim meanings as being outside the pleaded case, at least where those other meanings are separate and distinct and not bound up with or material variants of the meanings that have been pleaded, as the facts of Templeton v Jones [1984] 1 NZLR 448 illustrate. There is often a tension between what defamatory meanings an applicant alleges a matter conveys, and those meanings in respect of which a respondent might maintain defences such as justification or fair comment. Framing imputations therefore carries risk. If an applicant pleads imputations that are strained, or which incorporate contestable or extravagant elements, or which are otherwise contrived for the purpose of establishing the serious harm element or heading off defences to more natural or less serious imputations, an applicant runs the risk that a court will find that the applicant has failed to establish a defamatory meaning within the bounds of the pleaded case: see for example Stead v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 15; 387 ALR 123 at [53] (Lee J).

81 In this case, the respondents have pleaded their own meanings in relation to all of the matters as an alternative to their denial of the applicant’s imputations. The respondents rely on their alternative meanings in support of defences of common law justification, the statutory defence of honest opinion, and the common law defence of fair comment. These alternative meanings are referred to colloquially as Hore-Lacy meanings: see David Syme & Co Ltd v Hore-Lacy [2000] VSCA 24; 1 VR 667. This form of pleading is permissible for the reasons, and to the extent, explained in ABC v Wing at [15]–[23]. A collateral incident of a respondent pleading an alternative meaning may also be to make explicit the respondent’s ground for denying the applicant’s pleaded imputations: Chakravarti at [8] (Brennan CJ and McHugh J). The principles explained in ABC v Wing may extend to Hore-Lacy meanings in support of a common law defence of fair comment: see Soultanov v The Age Co Ltd [2009] VSC 145; (2009) 23 VR 182 (Kaye J). That is because, like justification, a fair comment defence is a defence of confession and avoidance where the ascertainment of defamatory meaning is the first step in scrutinising the elements of the defence, such as whether the publication amounted to comment, whether the comment was based upon true facts, and whether the comment was one that could reasonably be made by an honest person: Channel Seven Adelaide Pty Ltd v Manock [2007] HCA 60; (2007) 232 CLR 245 (Manock) at [83]–[85] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ). Similar considerations may arise in relation to the statutory defence of honest opinion under s 31 of the Defamation Act. For the statutory defence to operate, the defence must be addressed to the matter in its defamatory sense: see Lloyd v David Syme & Co Ltd [1986] AC 350 at 365 (PC); Nassif v Seven Network (Operations) Ltd [2021] FCA 1286 at [180] (Abraham J). However, it is the matter and not the language of the court’s findings as to defamatory meaning which is the subject of scrutiny for the purposes of considering whether the statutory defence of honest opinion is made out: Massoud at [194]–[195]. The rationale of allowing the pleading of alternate meanings is to permit a respondent to defend the publication of the matter in meanings which are comprehended by, or which are a variant of and not more injurious than one of the meanings alleged by the applicant and which, on the respondent’s case, are true, or amount to fair comment or honest opinion. A Hore-Lacy plea within these permissible bounds will be a pleading of a defence to the matter in a meaning on which the applicant would be entitled to succeed at trial.

82 The task of the Court is therefore to make findings about whether the applicant has established by reference to the standard of the ordinary reasonable reader that the matters conveyed a meaning that was defamatory of the applicant that is fairly within the bounds of his pleaded case. In making findings as to meaning, I have given careful attention to whether the meanings found are fairly within the case argued at trial. That is because it would be procedurally unfair to the respondents to allow the applicant to succeed on a defamatory meaning that was not fairly within the imputations that the applicant pleaded and which the respondents addressed at trial, including by formulating and advancing defences to alternative meanings. I have also had regard to the fact that some meanings are alleged by the applicant to be primary meanings, and others are alleged cumulatively and in the alternative.

83 At trial, senior counsel for the applicant submitted that while the applicant maintained reliance on his imputations in the terms in which they were formulated, and disputed the respondents’ alternative meanings, the applicant would nonetheless be entitled to succeed if the Court found that a publication was defamatory of him in a meaning that was a permissible variant of one of the imputations that had been pleaded. On the other hand, senior counsel for the respondents submitted in closing that the applicant did not seek a “verdict” on the respondents’ alternative meanings because the applicant claimed that they were not conveyed. The word “verdict” is apt to a jury trial, but I understood senior counsel for the respondents to be referring to a judgment of the Court.

84 I do not accept the respondents’ submissions on this issue, and I accept the applicant’s submissions in part. There are two important points. First, the cause of action in defamation is constituted by the publication of the matter, and not the imputations. The imputations pleaded by the applicant shape the issues at trial, but the issues at trial are also informed by the respondents’ pleadings. In this respect, it is noteworthy that the respondents’ further amended defence, which maintained their reliance on alternative meanings, was filed on 20 October 2023, which was the second day of trial.

85 Secondly, in Chakravarti at [19] Brennan CJ and McHugh J stated that a plaintiff may not seek a “verdict” on a meaning different to that pleaded, but the terms of what their Honours said are important –

A plaintiff who pleads a false innuendo thereby confines the meanings relied on. The plaintiff cannot then seek a verdict on a different meaning which so alters the substance of the meaning pleaded that the defendant would have been entitled to plead a different issue, to adduce different evidence or to conduct the case on a different basis.

(Emphasis added.)

86 The emphasised words highlight that the different meaning which their Honours had in contemplation was one that so altered the substance of the meaning pleaded by the plaintiff that it raised different issues by way of defence. A similar observation was made by Gaudron and Gummow JJ at [60] –

As a general rule, there will be no disadvantage in allowing a plaintiff to rely on meanings which are comprehended in, or are less injurious than the meaning pleaded in his or her statement of claim. So, too, there will generally be no disadvantage in permitting reliance on a meaning which is simply a variant of the meaning pleaded. On the other hand, there may be disadvantage if a plaintiff is allowed to rely on a substantially different meaning or, even, a meaning which focuses on some different factual basis. Particularly is that so if the defendant has pleaded justification or, as in this case, justification of an alternative meaning. However, the question whether disadvantage will or may result is one to be answered having regard to all the circumstances of the case, including the material which is said to be defamatory and the issues in the trial, and not simply by reference to the pleadings.

(Emphasis added.)

87 In this case a fundamental premise of the respondents’ pleading of their alternative Hore-Lacy meanings is that, as an alternative to their denial that the applicant’s meanings were conveyed, the respondents must be taken to advance their meanings as being bound up with the applicant’s imputations, and as being permissible variants in the way explained in ABC v Wing such that they are meanings on which the applicant would be entitled to succeed at trial. It is only on this premise that the respondents are able to plead defences that are directed to their own alternative meanings.

88 As Gaudron and Gummow JJ indicated in Chakravarti at [60], there will often be no unfairness in treating an alternative meaning advanced by a respondent as being within the applicant’s case. There are qualifications, three of which I will mention. The first is where an applicant, expressly or by implication, nails his or her colours to the mast and thereby excludes any meanings other than those in the strict terms pleaded by the applicant. This has arisen in cases involving the guilt/suspicion dichotomy where an imputation of guilt may be pleaded by an applicant in terms which necessarily exclude lesser or different imputations. In those circumstances, to entertain findings in relation to lesser or different imputations such as reasonable suspicion or reason to investigate would be to engage with false issues, and might result in a denial of procedural fairness to a respondent who may not have advanced positive defences to lesser, unpleaded imputations. The second is where the imputations formulated by an applicant contain necessary elements, the absence of which materially changes the substance of the case. It is to be recalled that the framing of imputations by an applicant is an area of choice for the applicant: see ABC v Wing at [16]. In framing imputations, the applicant defines the territory on which the applicant’s claims of defamatory meaning are to be considered. The third qualification is that while there might be no unfairness in treating a respondent’s alternative meaning as a permissible variant of an applicant’s meaning, unfairness may arise if the Court were to go further and entertain variants on variants, that is, variants of the respondent’s alternative meanings. These are examples only, and there are no hard and fast rules for dealing with these types of issues because circumstances will differ.

89 Because of the importance of pleadings, and the way in which a trial is conducted to the making of findings of defamatory meaning, if an applicant fails to establish a defamatory meaning within the bounds of the pleaded case, the Court will not be expected to pick over the carcasses of the applicant’s failed imputations and piece together a different case.

90 The applicant has primarily advanced his meanings, or meanings not different in substance. The applicant disputed the terms of the respondents’ alternative meanings. The formulations of both sides constitute the boundaries within which questions of defamatory meaning may fairly be determined, but bearing in mind that the respondents’ meanings are advanced only as alternative expressions of the applicant’s case, and on the premise that the respondents’ primary position is to deny that the matters were defamatory in the meanings alleged by the applicant. Therefore, the respondents’ alternative meanings do not constitute admissions by the respondents.

91 The pleadings show that while the applicant’s primary position was to deny the alternative imputations pleaded by the respondents, the applicant advanced an alternative position on the premise that the Court found the matters to be defamatory in the Hore-Lacy meanings alleged by the respondents. This is apparent from paragraphs 7, 8, and 9 of the applicant’s reply dated 18 August 2022 to the respondents’ defence. In those paragraphs the applicant made allegations that are contingent upon the Court accepting the alternative meanings alleged by the respondents. This is consistent with the position taken by senior counsel for the applicant in closing submissions. It is also consistent with the position taken by senior counsel for the applicant in opening, where he accepted in response to a question from the Court that the applicant’s elaborate imputations included permissible lesser variants. Therefore, this is not a case where the applicant disclaimed, expressly or by implication, reliance on the respondents’ alternative meanings as permissible variants of his own meanings on which he was entitled to succeed. And because the respondents advanced positive defences by reference to their own alternative meanings, there is no injustice to the respondents should the Court entertain making findings that are variants of the applicant’s meanings which are within the bounds of the respondents’ alternative meanings.

Imputations – the 5 May 2021 articles

92 The 5 May 2021 articles are set out in the First Schedule. There is a difference between the text of the print article which appeared in The Age newspaper, and the online article. In evidence, Mr Brook stated that the difference was likely the result of editorial staff reducing the length of the print article in order to fit within the available space in the newspaper. There are also differences between the imputations which are alleged in respect of the two articles. I will therefore address the first and second matters separately.

Imputations – the 5 May 2021 print article

93 In relation to the first matter, the applicant alleges in paragraph 9 of the further amended statement of claim that it was defamatory of him and conveyed the following meanings, or meanings not different in substance –

(a) Mr Mond is a person so lacking in judgment that he recklessly agreed to host a convicted spy at an important event for Melbourne’s Orthodox Jewish community without appropriate consultation;

...

(c) Mr Mond is a disruptive person who has caused uproar within the Orthodox Jewish community by reason of the matters alleged in (a);

(d) further and alternatively to (c), Mr Mond is a disruptive person who has caused uproar within the Orthodox Jewish community by recklessly agreeing to host a convicted spy at an important event for Melbourne’s Orthodox Jewish community without appropriate consultation.

94 In opening, the applicant submitted that permissible variants of imputation (c) that were applicable to the 5 May 2021 print and online articles were –

(a) Mr Mond is a disruptive person who has caused uproar within the Orthodox Jewish community by recklessly agreeing to host a convicted spy at an important event for Melbourne’s Orthodox Jewish community without appropriate consultation.

(b) Mr Mond is a disruptive person who has caused uproar within the Orthodox Jewish community when he condoned treason by supporting and sanctioning the conduct of Jonathan Pollard who is a convicted spy. [Online version only]

95 The respondents submitted that the applicant’s pleaded imputations in respect of all of the publications were unduly convoluted and rolled-up. Embedded within most of the imputations are multiple stings. As I will identify, there is also a degree of overstatement in elements of the imputations alleged by the applicant, including the applicant’s variant imputations that were advanced in argument. Each of the above imputations in relation to the first matter rolls up different charges in a compendious way. Imputation (a) rolls up lacking in judgment, recklessness, and the absence of appropriate consultation. Imputation (c) adds to the list of rolled-up charges by introducing a charge that the applicant was a disruptive person. Imputation (d), which was introduced by amendment, is an alternative way of putting imputation (c), but as with the other imputations and variant imputation (a), relies on the absence of appropriate consultation as a necessary element.

96 I am required to assess how the ordinary reasonable reader would regard the CBD column. The applicant characterised the CBD column in the further amended statement of claim as a “marquee gossip column”. As a result of this plea, the question whether the CBD column comprised gossip became a point of contention at trial, with Mr Brook rejecting that characterisation, equating gossip with unconfirmed information.

97 I do not accept the evidence of Mr Brook that the CBD column was not in the nature of a gossip column. Gossip is not accurately characterised as being limited to unconfirmed information. Contrary to the evidence of Mr Brook, the CBD columns that were in evidence clearly comprised gossip. That is because often the source of information in the columns was not disclosed. All of the articles about the Caulfield Hebrew Congregation conveyed the exposure of disagreements behind the scenes, thereby giving the appearance of gossip. Other topics covered by the CBD columns in evidence included:

(1) when the Society restaurant in Melbourne was likely to open;

(2) an account of a City of Stonnington council meeting, where there was a quotation attributed to the Stonnington mayor referring to the CBD column as a “gossip column in The Age”;

(3) a suggestion that a federal member of Parliament, Mr Katter might be planning for a life outside politics;

(4) a reference to what Christmas gifts were given to Sky News staff;

(5) an account of the then federal Treasurer Mr Josh Frydenberg attending a secondary school and addressing an economics class, accompanied by speculation as to what connections with the school secured Mr Frydenberg’s attendance and a reference to “our source at the tuck shop”; and

(6) an account of Mr “Eddie Everywhere” Maguire attending the Super Bowl in the United States.

98 One of the items was even written about the respondents’ solicitor in this proceeding, referring to him as a “man-about-town” and “sports tragic” who also jetted over to the Super Bowl only to be forced to return to Melbourne to attend to a legal matter and who gave his Super Bowl ticket to a former Hawthorn AFL footballer. All this might have been of interest to the readers of The Age in Melbourne, and I am not to be taken as being critical of the CBD column, or the engaging style in which it was written. But however well written, this was not public interest journalism or reporting the news of the day. It was gossip.

99 The ordinary reasonable reader would regard the style of the CBD column as conveying a mixture of facts and opinions, and as incorporating some elements that were mocking in tone. The column was written in a way that attracted attention and was easily absorbed by a reader. The items in the CBD column “name checked” people by placing their names in bold, thereby drawing attention to their identities. Each item within the CBD column was usually short in length. The first matter was typical. It was pithy. As a result, the ordinary reasonable reader would have read the first matter quickly and in its entirety. The ordinary reasonable reader would have taken away the main points. It was not the type of piece that the ordinary reasonable reader would have analysed in any depth. The same observations apply to each of the other matters on which the applicant sues. As a result of these characteristics, it is more the impression conveyed by each of the matters that is important, rather than any deep analysis of the individual words that made up the items.

100 The overall impression conveyed by the first matter was to inform the reader of the existence of disputation in the Orthodox Jewish community in relation to a decision to have Mr Pollard, a convicted spy, speak at a Jerusalem Day event. On the one hand, Rabbi Genende and Mr Jeremy Leibler were presented as opposing the decision. Against that, Dr Lamm, who was said to have extended the invitation to Mr Pollard, was presented as defending the decision.

101 The imputations alleged by the applicant in relation to the first matter were not conveyed to the ordinary reasonable reader. As I have mentioned, the focus of the article is on the existence of a controversy, or “uproar” in the Orthodox Jewish community as a result of Dr Lamm inviting Mr Pollard to speak at an event which the applicant agreed to host. Mr Pollard is described in the article as a controversial figure. Controversy attracted controversy. Two sources of that controversy were identified: Rabbi Genende who described the proposal as “misguided and potentially damaging” and in respect of whom a “rift” was said to have resulted; and Mr Jeremy Leibler who said that one had to question the judgment of selecting Mr Pollard as a keynote speaker for the event.