FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Green County Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 367

File number(s): | NSD 204 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | SHARIFF J |

Date of judgment: | 15 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – alleged contraventions of National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (NCCP Act) and National Credit Code (Code) – where first and second respondents engaged in “credit activity” associated with the provision of credit to small business borrowers – where credit was provided to two consumers who asserted that they were establishing small businesses – application of the Code to the circumstances of those two consumers – examination of divergent judicial views as to the operation of s 5(1)(b) of the Code – whether first and second respondents engaged in credit activity without a licence – whether credit provided for wholly or predominantly domestic, household or personal purposes – operation of statutory presumptions in s 13 of the Code – whether “business purpose declarations” effective – making of “reasonable inquiries” – whether “reasonable inquiries” would have disclosed the true loan purpose – whether the two consumers had entered into multiple contracts or single contract – where resolution of the question of the number of contracts is dependent on identification of the relevant contract(s) under which debt is deferred – contraventions established in most part subject to hearing from the parties as to the application of s 183 of the NCCP Act CORPORATIONS – alleged contraventions of director’s duty of care and diligence under s 180(1) of the Corporations Act – where third respondent a director of first respondent and officer of second respondent – where it is alleged that policies, procedures and systems did not accord with a “Required Framework” and “Minimum Arrangements” based on the opinions of an expert – limited weight to be given to expert’s opinions – whether essential elements of risk calculus established – essential aspects of the pleaded case not established |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) ss 180(1), 180(2) Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) s 4AA Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 140 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 37AF(1)(a) National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) ss 5, 5(1)(b), 5(1)(b)(i), 5(1)(b)(ii), 5(4), 6(1), 29, 29(1), 183, 183(1), 306; Schedule 1 (National Credit Code) ss 3, 3(2), 4, 11(1), 13, 13(1), 13(2), 13(3), 13(3)(a), 13(3)(b), 13(4), 13(5), 17(4), 17(6), 32A, 32A(1), 40 Treasury Laws Amendment (Strengthening Corporate and Financial Sector Penalties) Act 2019 (Cth) National Consumer Credit Protection Regulations 2010 (Cth) reg 68 Consumer Credit (New South Wales) Act 1995 (NSW) s 5 Consumer Credit (Queensland) Act 1994 (Qld) app (repealed) Consumer Credit (South Australia) Act 1995 (SA) s 5 Consumer Credit (Victoria) Act 1995 (Vic) s 5 Legal Practice Act 1996 (Vic) (repealed) Consumer Credit (New South Wales) Code ss 5, 6, 11 Consumer Credit (Queensland) Code ss 6(1), 6(5) Consumer Credit (South Australia) Code s 6 Consumer Credit (Victoria) Code s 4(1) Explanatory Memorandum, National Consumer Credit Protection Bill 2009 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cassimatis (No 8) [2016] FCA 1023; 336 ALR 209 Australia and New Zealand Banking Group v Fink [2015] NSWSC 506 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2009] NSWSC 1229; 236 FLR 1 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Adler [2002] NSWSC 171; 168 FLR 253 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Healey [2011] FCA 717; 196 FCR 291 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v King [2020] HCA 4; 270 CLR 1 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mariner Corporation Ltd [2015] FCA 589; 241 FCR 502 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Maxwell [2006] NSWSC 1052; 59 ACSR 373 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mitchell (No 2) [2020] FCA 1098; 382 ALR 425 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Money3 Loans Pty Ltd (Expert Evidence Admissibility) [2025] FCA 75 Axon v Axon [1937] HCA 80; 59 CLR 395 Bahadori v Permanent Mortgages Pty Ltd [2008] NSWCA 150 Balanced Securities Limited v Dumayne Property Group Ltd [2017] VSCA 61; 53 VR 14 Bank of Queensland Ltd v Dutta [2010] NSWSC 574 Beckley v Consumer, Trader and Tenancy Tribunal [2009] NSWSC 703 Benjamin v Ashikian [2007] NSWSC 735 Bradshaw v McEwans Pty Ltd (1951) 217 ALR 1 Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; 60 CLR 336 Brown v New South Wales Trustee and Guardian [2012] NSWCA 431; 10 ASTLR 164 Cassimatis v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2020] FCAFC 52; 275 FCR 533 Citadel Financial Corporation Pty Ltd (admin apptd) v Action Scaffolding & Rigging Pty Ltd (in liq) [2019] FCAFC 145 Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing & Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 Conway v O’Brien 111 F 2d 611 at 612 (2nd Cir, 1940) Dale v Nichols Constructions Pty Ltd [2003] QDC 453 Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Sara Lee Household & Body Care (Australia) Pty Ltd [2000] HCA 35; 201 CLR 520 G v H [1994] HCA 48; 181 CLR 387 Geeveekay Pty Ltd v Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria [2008] VSC 50; 19 VR 512 George v Rockett [1990] HCA 26; 170 CLR 104 GLJ v The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore [2023] HCA 32; 97 ALJR 857 Hawkes Menangle Pty Ltd v Brennan [2023] NSWSC 1095 Haynes v St George Bank [2018] SASCFC 51; 130 SASR 551 Hillam v Iacullo [2015] NSWCA 196; 90 NSWLR 422 Husqvarna Forest & Garden Ltd v Bridon NZ Ltd [1997] 3 NZLR 215 Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; 101 CLR 298 Jonnson v Arkway Pty Ltd [2003] NSWSC 815; 58 NSWLR 451 Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; 243 CLR 361 Lauvan Pty Ltd v Bega [2018] NSWSC 154; 330 FLR 1 Linkenholt Pty Ltd v Quirk [2000] VSC 166; ASC ¶155–040 Mag Financial Investment Ventures Pty Ltd v El-Saafin [2022] VSCA 286; 70 VR 400 Martin v Osborne [1936] HCA 23; 55 CLR 367 MB v Protective Commissioner [2000] NSWSC 717; 217 ALR 631 Mondelez Australia Pty Ltd v Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union [2020] HCA 29; 271 CLR 495 Morley v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 331; 274 ALR 205 Mount Bruce Mining Pty Ltd v Wright Prospecting Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 37; 256 CLR 104 NOM v DPP [2012] VSCA 198; 38 VR 618 Ozzy Loans Pty Ltd v New Concept Pty Ltd [2012] NSWSC 814 Park Avenue Nominees Pty Ltd v Boon (on behalf of Weir) & Anor [2001] NSWSC 700 Park Avenue Nominees Pty Ltd v Boon [2001] NSWSC 700 Permanent Building Society (in liq) v Wheeler (1994) 11 WAR 109 Permanent Trustee Australia Ltd v Boulton (1994) 33 NSWLR 735 Power v Hamond [2006] VSCA 25 Queensland Bacon Pty Ltd v Rees [1996] HCA 21; 115 CLR 266 Rafiqi v Wacal Investments Pty Ltd [1998] ASC ¶155–024 Sagacious Legal Pty Ltd v Wesfarmers General Insurance Ltd [2011] FCAFC 53 Shafron v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 18; 247 CLR 465 Shakespeare Haney Securities Limited v Crawford [2009] QCA 85; 2 Qd R 156 State of Queensland v Ward [2002] QSC 171 Story v National Companies and Securities Commission (1988) 13 NSWLR 661 Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165 Vrisakis v Australian Securities Commission (1993) 9 WAR 395 WA Pines Pty Ltd v Bannerman (1980) 30 ALR 559; 41 FLR 175 Wyong Shire Council v Shirt [1980] HCA 12; 146 CLR 40 Bolitho H, Howell N and Patterson J, Duggan & Lanyon’s Consumer Credit Law, (2020) 2nd Edition, LexisNexis Butterworths Edwards and Sweeney, Application of the Consumer Credit Code and the Purpose Test (1996) 11 Australian Banking Law Bulletin 85 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | 519 |

Date of last submission/s: | 25 September 2024 |

Date of hearing: | 9–13, 17–18 September 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr J Giles SC with Ms K Morris |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Clayton Utz |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr J Williams SC with Mr B Hancock |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Ronayne Owens Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 204 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | GREEN COUNTY PTY LTD ACN 619 832 816 First Respondent MAX FUNDING PTY LTD ACN 616 549 725 Second Respondent MS IVY TANG GY NG Third Respondent | |

order made by: | SHARIFF J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 15 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. By 5 pm on 29 April 2025, the parties are to provide the Associate to Shariff J competing or consent short minutes of order to deal with the case management matters relating to the next steps arising in the proceedings as a result of the reasons published today in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Green County Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 367.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

SHARIFF J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 This case involves an examination of the conduct of two companies engaged in the business of lending to small businesses. The two companies are the first respondent (Green County) who provided credit to small business borrowers and the second respondent (Max Funding) who referred prospective borrowers to Green County. The case also involves an examination of the conduct of the third respondent (Ms Ng) who was a director of Green County and an officer of Max Funding.

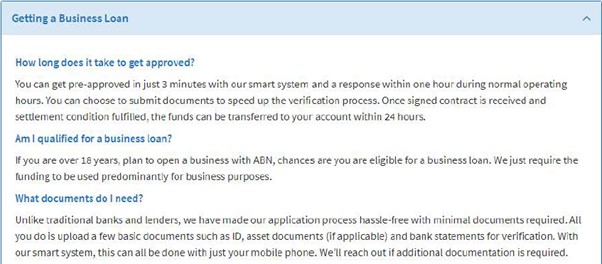

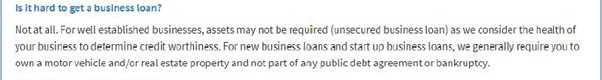

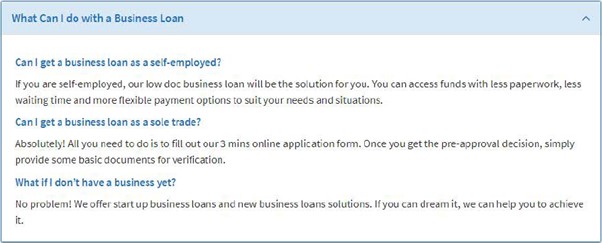

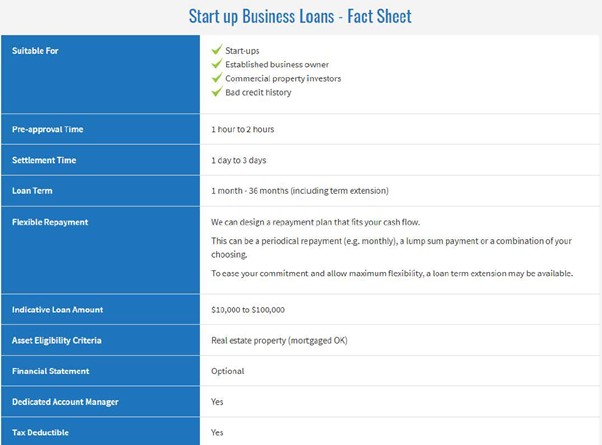

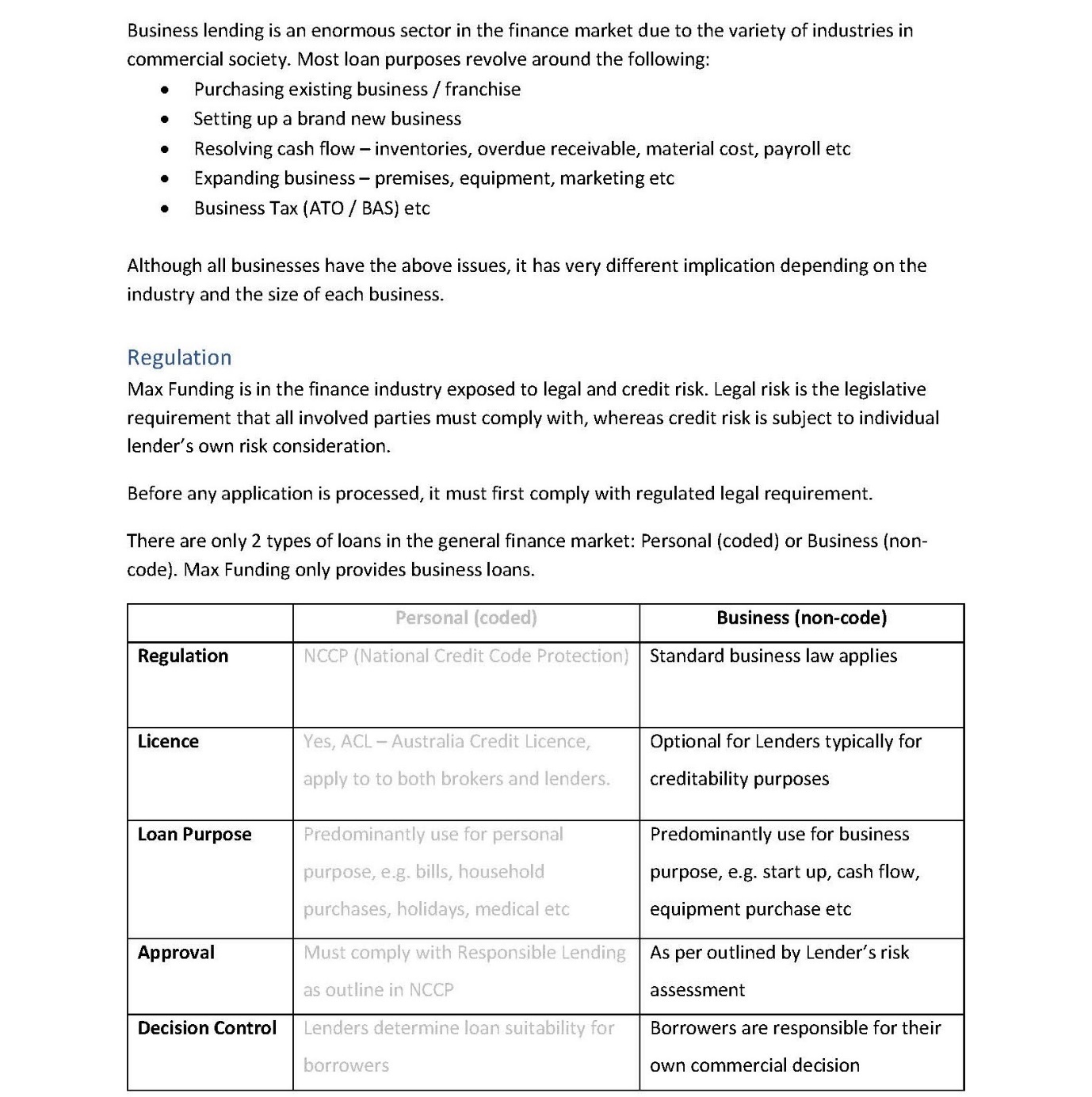

2 Max Funding operated a website which stated that it was involved in providing “Small Business Loans” in Australia. It made available an online application form for prospective borrowers to complete, which represented to them that a decision could be made within “3 minutes (24/7)” and could give rise to “same-day funding”. It was further represented that applications would be accepted even if prospective borrowers had “bad credit” or were seeking to establish a “new business”. If a loan application was approved, Max Funding would refer the prospective borrowers to a lender, including Green County, who would then enter into loan agreements with the borrowers.

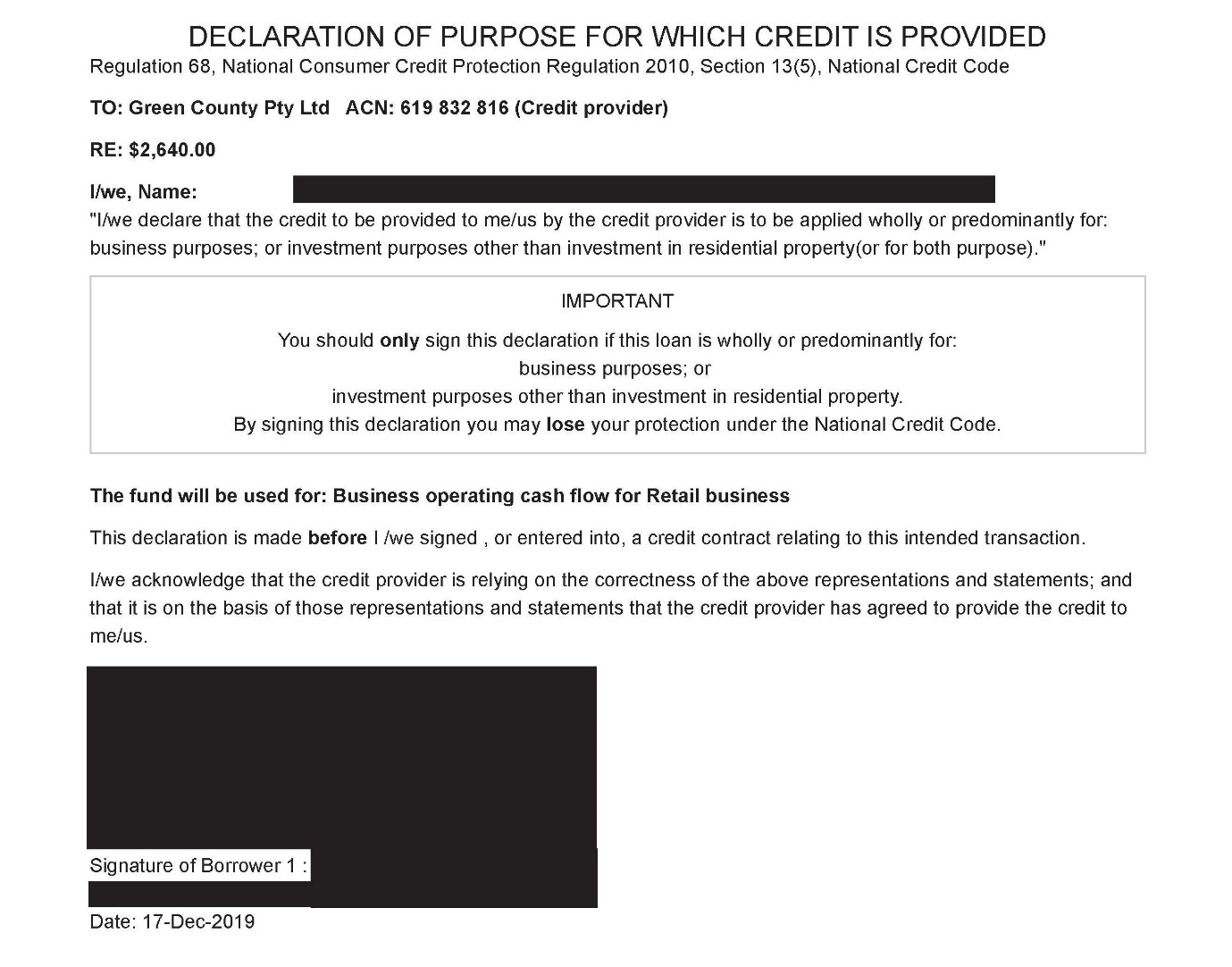

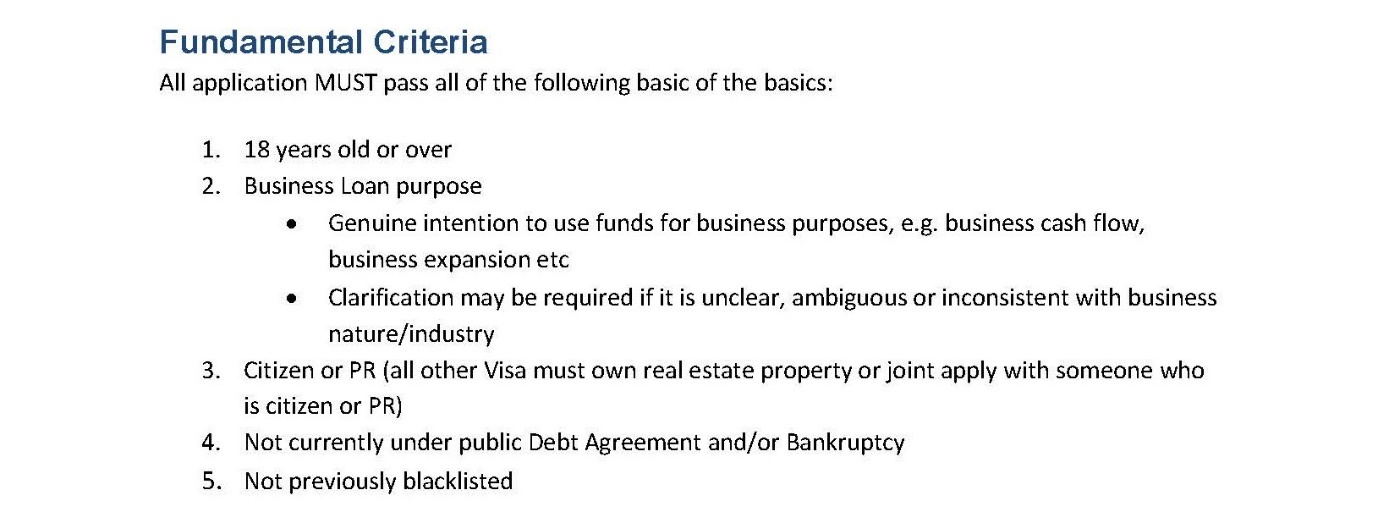

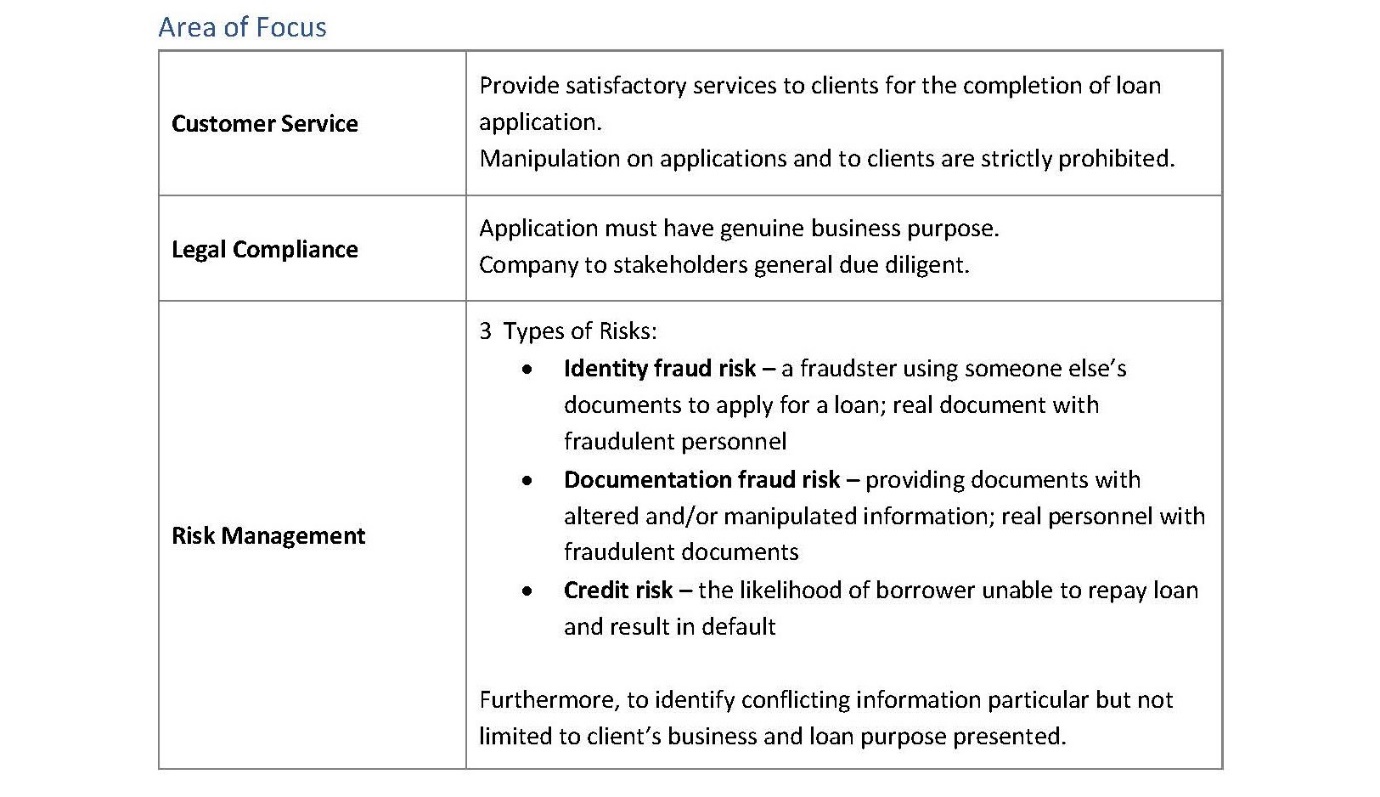

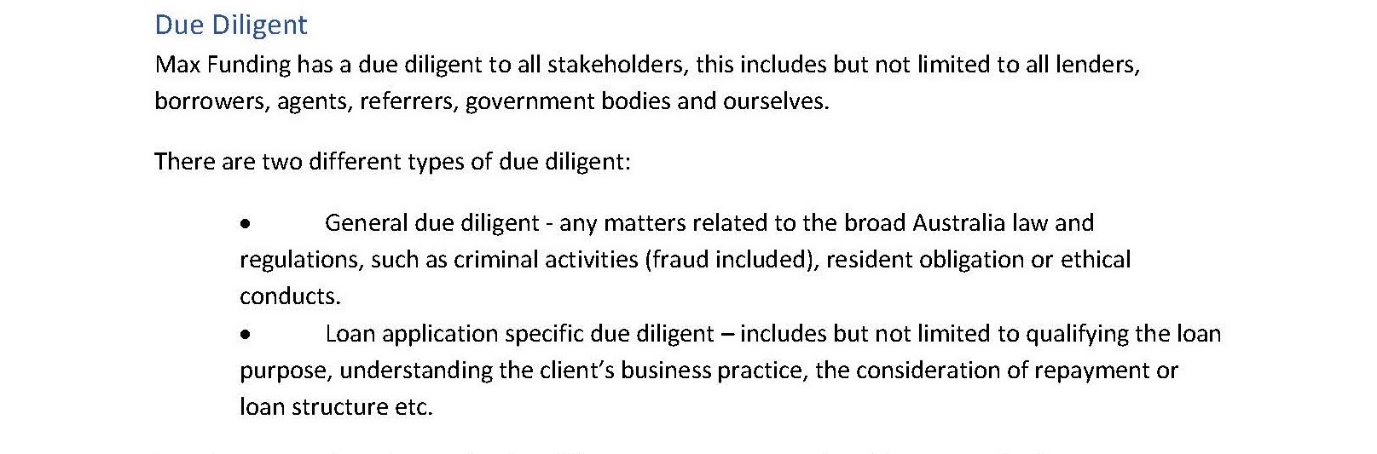

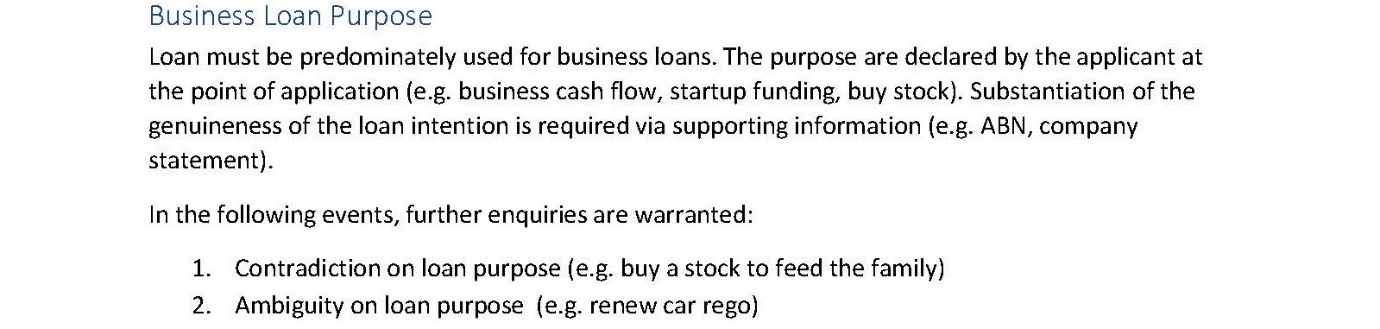

3 Neither Green County nor Max Funding (who I have from time to time referred to as the corporate respondents) hold a credit licence under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (NCCP Act). Nor do they seek to comply with the National Credit Code (Code) which forms Schedule 1 to the NCCP Act. That is because, by way of shorthand, the relevant parts of the NCCP Act and Code only apply when credit is provided wholly or predominantly for “personal, domestic or household purposes” and do not apply when it is declared by a borrower that the credit is to be used wholly or predominantly for business purposes (unless the declaration is found to be ineffective). Neither Green County nor Max Funding purported to be involved in the provision of credit for “personal, domestic or household purposes”. Green County made it a condition of the provision of credit to borrowers that they made a “business purpose declaration” by which they declared that the purpose for which they were seeking credit and the purpose for which it would be applied was wholly or predominantly for business purposes.

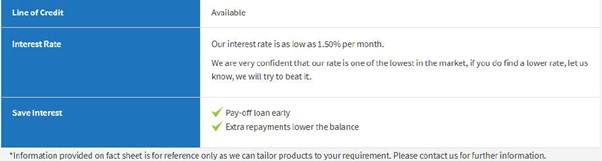

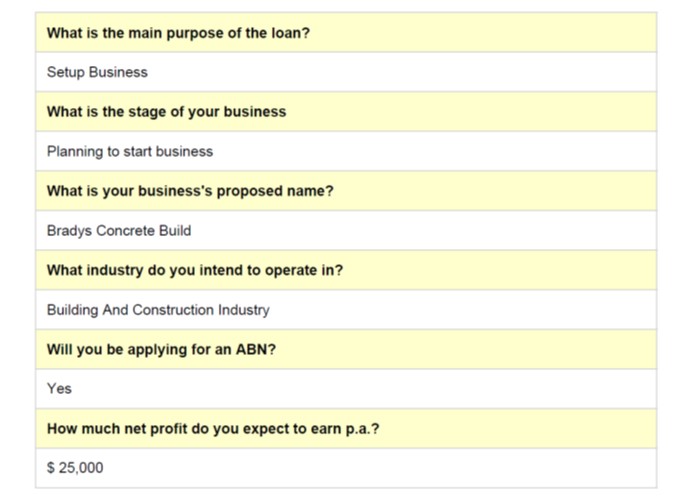

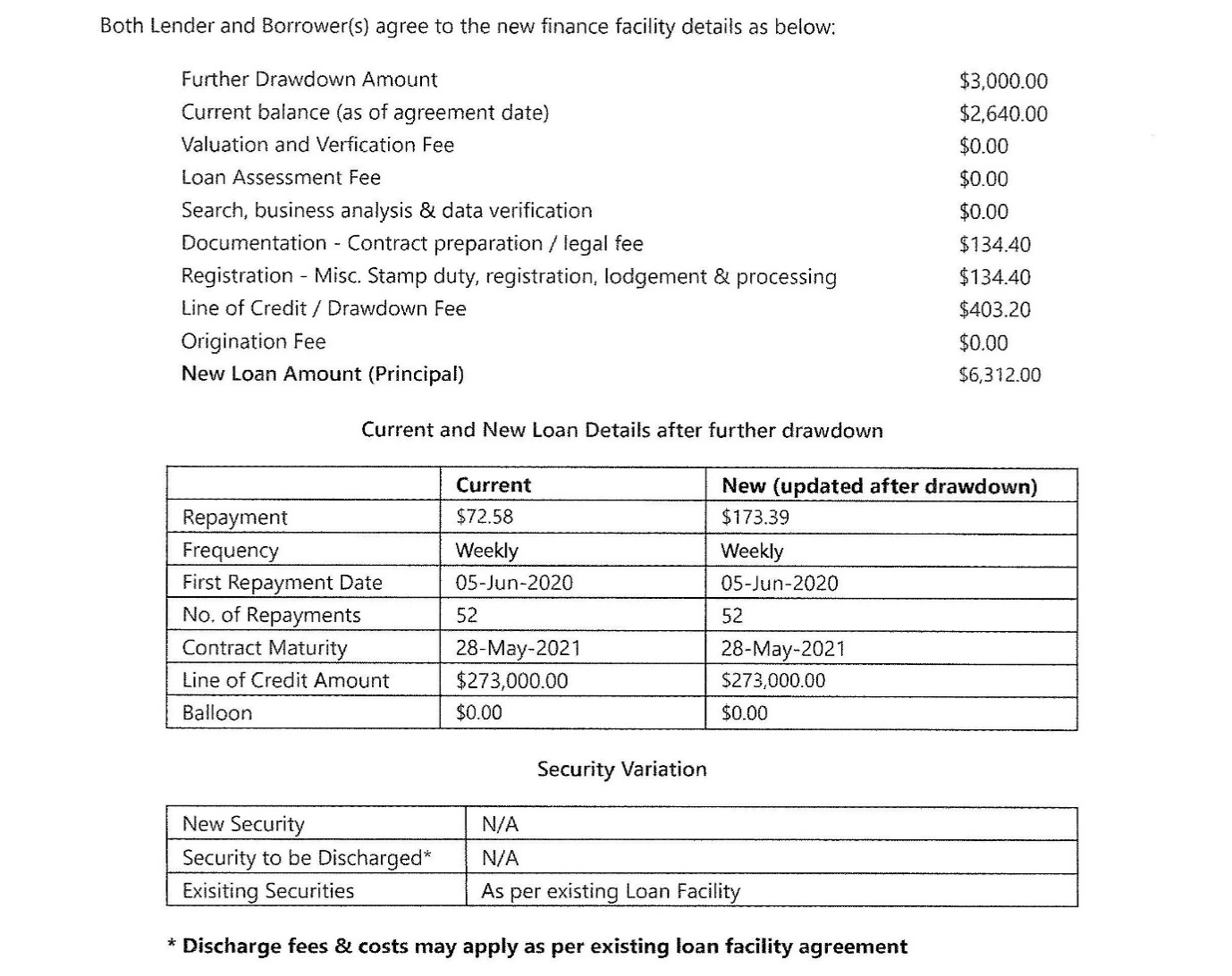

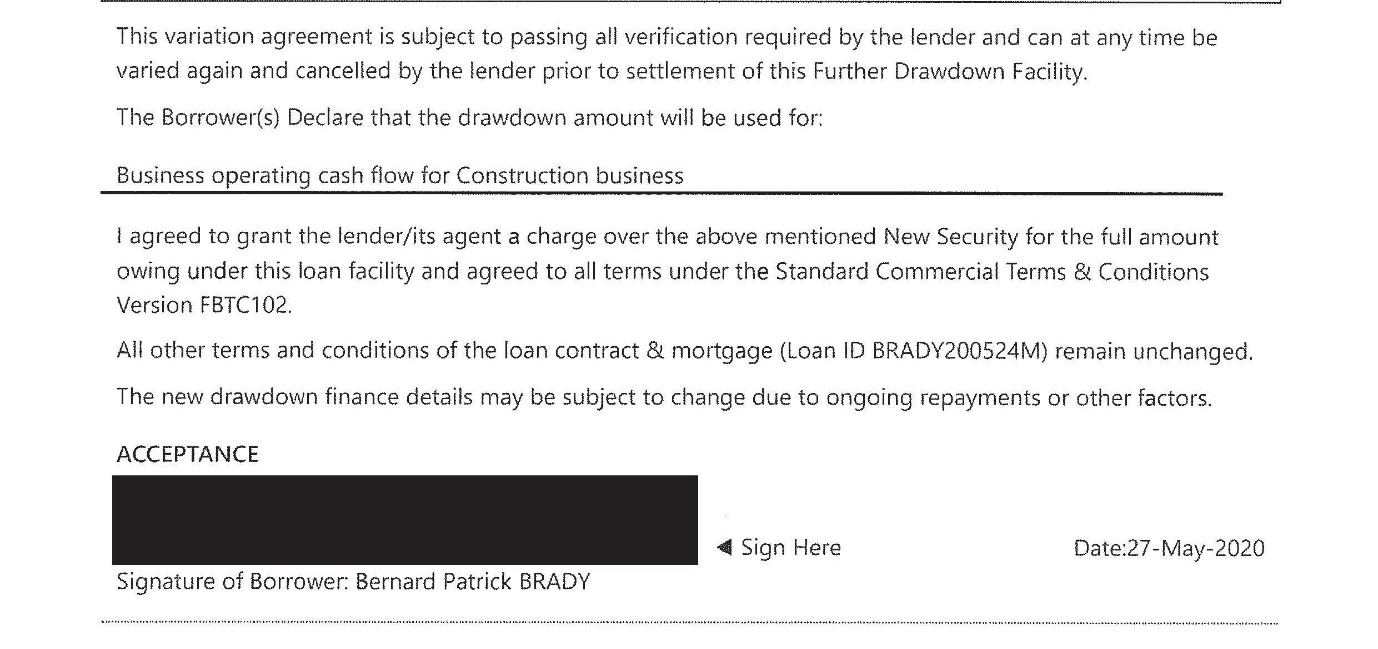

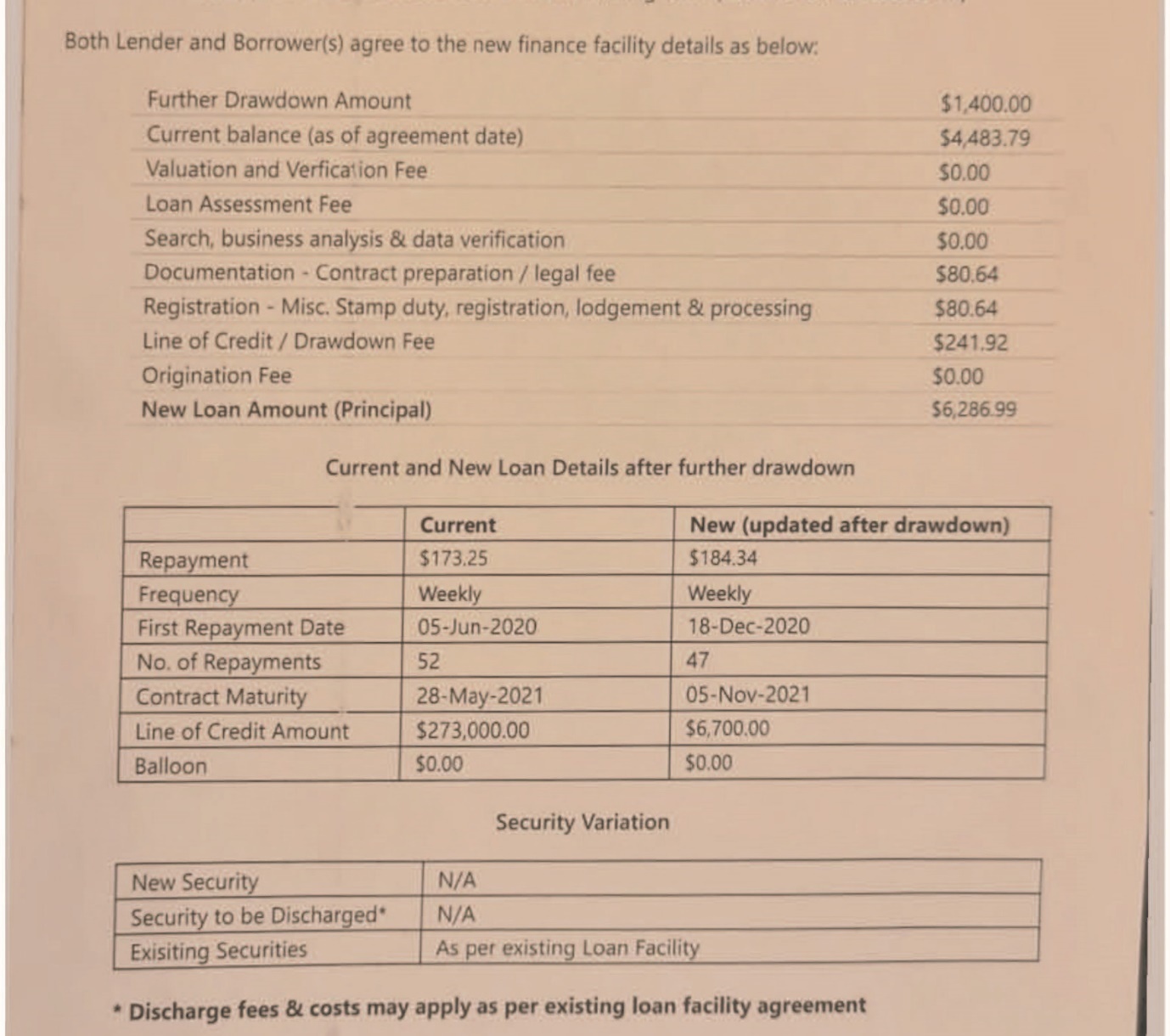

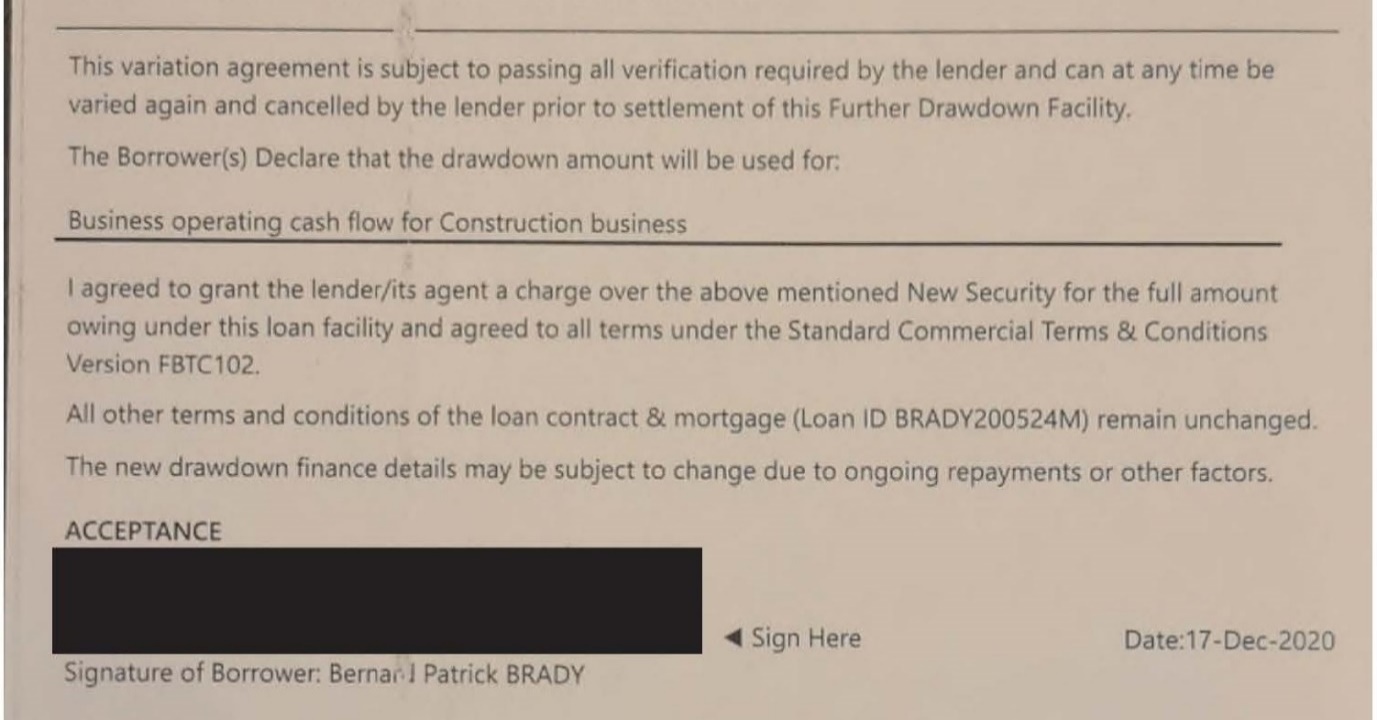

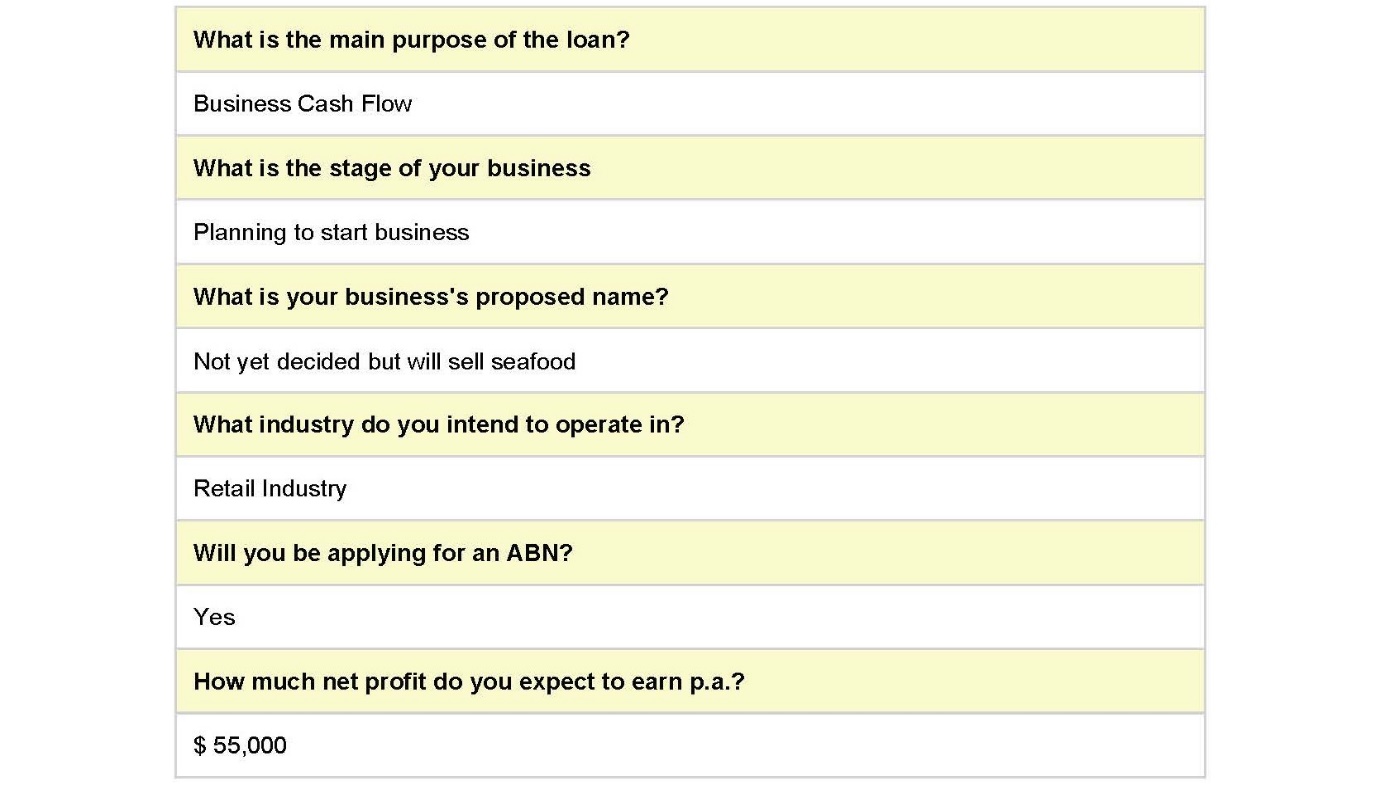

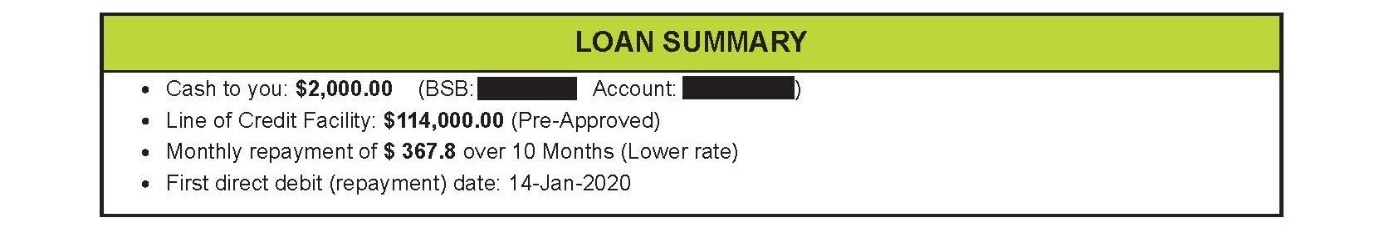

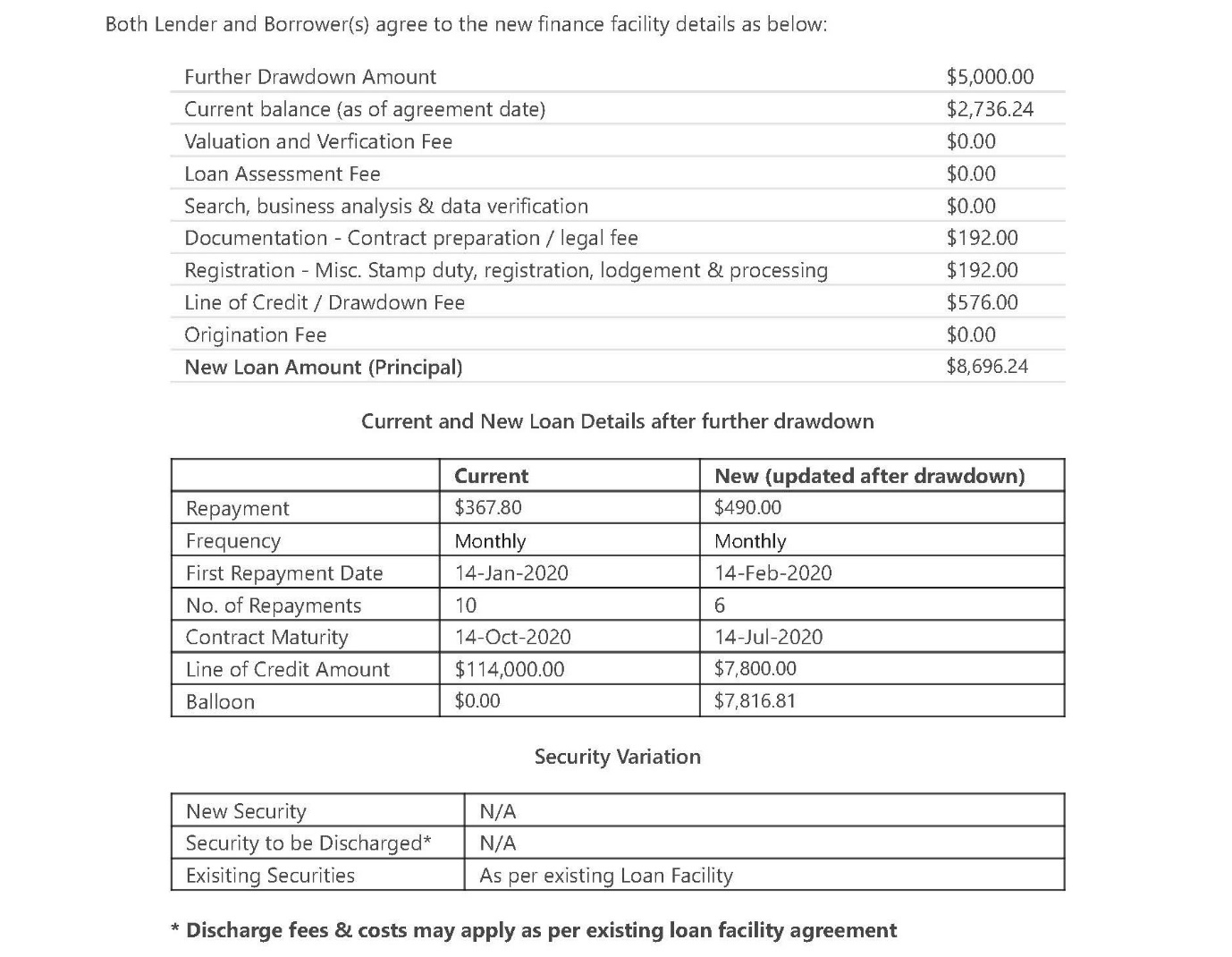

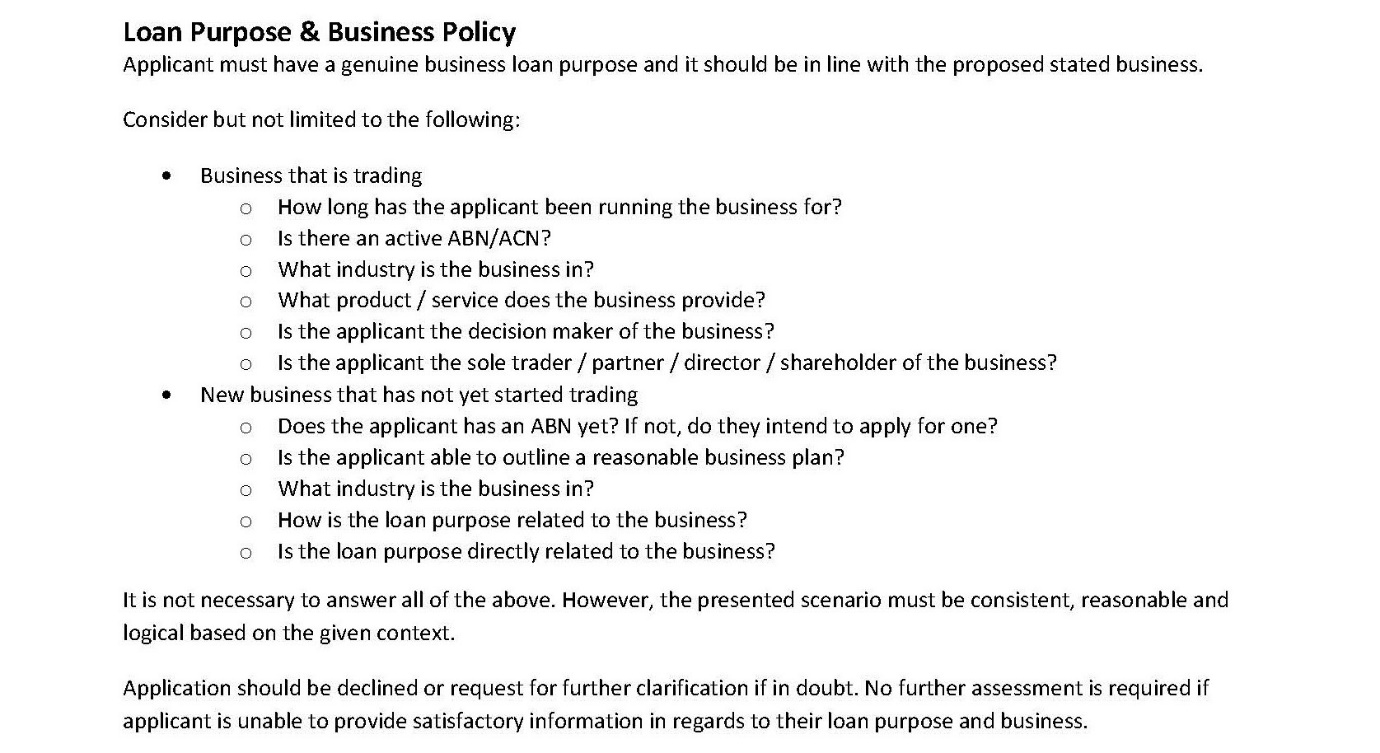

4 Despite this, in its Amended Statement of Claim (ASOC), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) alleged that, during the period from 19 June 2017 to 4 May 2021 (the Relevant Period), Green County and Max Funding contravened the NCCP Act and the Code. ASIC’s case against Green County and Max Funding focusses upon their respective activities in relation to two consumers who, for convenience, I have referred to as Consumer 1 and Consumer 2. Consumer 1 is a person who at the relevant time was suffering from a gambling addiction. Consumer 2 is a person who at the relevant time was under financial distress. Both Consumers 1 and 2 submitted online application forms to Max Funding asserting that they were seeking loans to establish new businesses. Consumer 1 represented that he would be starting up a concreting business and Consumer 2 represented that she would be starting up a retail business selling seafood. Both Consumers 1 and 2 signed declarations confirming they were seeking loans for business purposes. ASIC’s case is that both Consumers 1 and 2 lied, but that these lies would have been detected had Green County and Max Funding made “reasonable inquiries” of both of them.

5 As a result, ASIC alleges that, in fact, Green County and Max Funding were involved in providing credit to Consumers 1 and 2 for wholly or predominantly “personal, domestic or household purposes” within the meaning of s 5 of the Code. It contends that Green County and Max Funding thereby each contravened s 29(1) of the NCCP Act by engaging in a credit activity without holding a licence authorising them to do so in respect of the entry into three credit contracts with Consumer 1 and two credit contracts with Consumer 2. ASIC further alleges that Green County contravened ss 17(4), 17(6) and 32A of the Code by entering into the credit contracts with Consumers 1 and 2 which did not comply with certain requirements of the Code, namely, the cap on maximum interest rates that could be charged as contained in s 32A(1) of the Code and the prescribed disclosures as to interest rate charges as required by ss 17(4) and (6) of the Code.

6 A central issue in the case against the corporate respondents is whether the credit arranged by Max Funding and ultimately provided by Green County to Consumers 1 and 2 was for “personal, domestic or household use” (which, as explained below, is referred to as a “Code purpose”) or for business purposes (which is a “non-Code purpose”). The determination of this aspect of the case involves an examination of interrelated provisions of the Code, including the operation of statutory presumptions that apply when a lender obtains “business purpose declarations” from a borrower and what, if anything, would have been revealed about the borrower’s purpose had “reasonable inquiries” been made.

7 A further substantive issue between the parties relates to the number of credit contracts that Consumers 1 and 2 entered into. The resolution of that issue turns upon a determination of the contractual source of the respective debts that were incurred by Consumers 1 and 2. The resolution of that question also has an impact upon the operation of the statutory presumptions contained in the Code.

8 The case against Ms Ng alleges that, as a director of Green County and an officer of Max Funding, she failed to discharge the statutory duty contained in s 180(1) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) by failing to take the steps that a reasonably careful and diligent person in her position would have taken to have in place policies, procedures, guidelines and frameworks the object of which was to ensure that Green County and Max Funding did not engage in credit activities that they were not licenced to provide. ASIC’s case in this respect focusses upon the “business model” that it claims was operated by Green County and Max Funding whereby credit was provided to borrowers in respect of whom they had, amongst other things, obtained little information as to business purpose, where those borrowers had bad credit histories and found themselves in circumstances of financial distress, especially where those borrowers were claiming to “plan” or “set up” a new business. This aspect of the case involves close attention being paid to the case pleaded by ASIC and the evidence upon which it relied. In a defence filed by her after the close of ASIC’s case on 2 July 2024, Ms Ng foreshadowed that if an adverse finding was made under s 180(1), she relied upon the business judgment rule in s 180(2). Ms Ng also contended that Green County had resolved to ratify her conduct such that she could not be liable for a contravention of s 180(1), if such a finding was made by the Court.

9 Separately, the corporate respondents pleaded in their defence that if either of them are found to have contravened the NCCP Act or the Code, they relied upon s 183(1) of the NCCP Act to relieve them wholly or partly from any liability that would otherwise be imposed on them because of the contravention(s). Ms Ng in her defence relied upon ss 1317S and 1318 of the Corporations Act to contend that she should be fairly excused from liability.

10 The parties agreed that the question of whether the corporate respondents had contravened the NCCP Act and the Code and whether Ms Ng had contravened the Corporations Act should be determined prior to the determination of any other questions that would thereafter arise such as to the determination of the appropriate penalty, if any, to be imposed or the application of the statutory provisions invoked by the respondents to relieve or excuse them from any liability that might be imposed on them. I have proceeded on that basis.

11 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded that ASIC has established its case against Green County and Max Funding in part in relation to Consumer 1 and in whole in respect of Consumer 2. However, ASIC has not established its case against Ms Ng and the claims against her should be dismissed.

12 For convenience, I have organised my reasons as follows:

Part 2 which addresses the applicable statutory provisions including the circumstances in which the Code applies and the operation of the statutory presumptions;

Part 3 sets out my factual findings including in relation to Consumers 1 and 2;

Part 4 addresses whether Consumers 1 and 2 entered into a single credit contract or multiple credit contracts;

Part 5 addresses the contraventions pleaded against Green County and Max Funding in relation to Consumers 1 and 2;

Part 6 addresses the contraventions pleaded against Ms Ng; and

Part 7 sets out my proposed disposition of the proceedings.

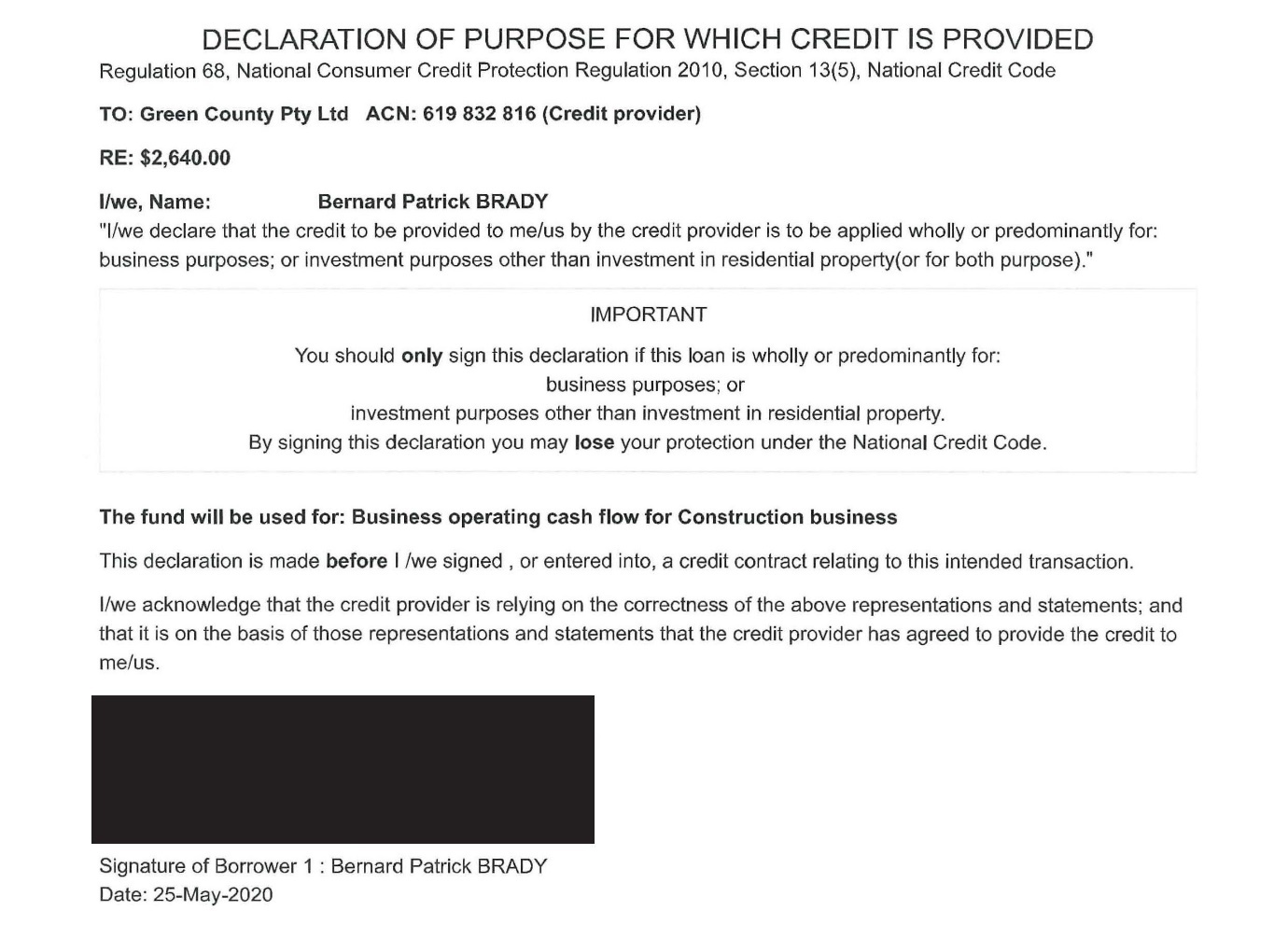

13 Before turning to address the substantive matters, it is necessary to observe that during the course of the proceedings I made suppression and non-publication orders under s 37AF(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) in respect of information that reveals the names of Consumer 2 (including any names associated with Consumer 2 and where her names, or parts thereof, are included in phrases). No such order was made in relation to Consumer 1, Mr Brady. However, during the course of writing my reasons, it became more convenient to refer to Mr Brady as Consumer 1. I have in the course of these reasons redacted parts of the judgment which disclose Consumer 2’s identity, or which disclose the signatures of either Consumers 1 and 2 or any of their more personal details.

2 THE APPLICABLE STATUTORY PROVISIONS

2.1 Overview of Salient Provisions

14 Section 29(1) of the NCCP Act provides that a person must not engage in a “credit activity” if the person “does not hold a licence authorising the person to engage in the credit activity”. It is a civil liability provision. For convenience, I have referred to such a licence as a “credit licence” or an “ACL” (meaning an Australian Credit Licence).

15 There was no dispute between the parties that Green County was engaged in a “credit activity” because it provided credit to borrowers. Nor was there any dispute that Max Funding is engaged in credit activity by providing a “credit service” by way of providing credit assistance or acting as an intermediary in respect of the credit contracts pertaining to Consumers 1 and 2.

16 The critical issues in dispute between the parties related to whether the Code applied and, if so, how many credit contracts were entered into by Green County with each of Consumers 1 and 2. For this purpose, relevantly, “credit activity” is defined in s 6(1) of the NCCP Act to include being a credit provider under a “credit contract” or the carrying on a business of providing credit. For the purpose of s 6(1) of the NCCP Act, “credit contract” has the same meaning as in s 4 of the Code, which provides.

4 Meaning of credit contract

For the purposes of this Code, a credit contract is a contract under which credit is or may be provided, being the provision of credit to which this Code applies.

17 “Credit” is defined by s 3 of the Code as follows:

(2) For the purpose of this Code, credit is provided if under a contract:

(a) payment of a debt owed by one person (the debtor) to another (the credit provider) is deferred; or

(b) one person (the debtor) incurs a deferred debt to another (the credit provider).

(Emphasis in original.)

18 The Code applies to the provision of credit in the circumstances set out in s 5, which provides as follows:

5 Provision of credit to which this Code applies

(1) This Code applies to the provision of credit (and to the credit contract and related matters) if when the credit contract is entered into or (in the case of precontractual obligations) is proposed to be entered into:

(a) the debtor is a natural person or a strata corporation; and

(b) the credit is provided or intended to be provided wholly or predominantly:

(i) for personal, domestic or household purposes; or

(ii) to purchase, renovate or improve residential property for investment purposes; or

(iii) to refinance credit that has been provided wholly or predominantly to purchase, renovate or improve residential property for investment purposes; and

(c) a charge is or may be made for providing the credit; and

(d) the credit provider provides the credit in the course of a business of providing credit carried on in this jurisdiction or as part of or incidentally to any other business of the credit provider carried on in this jurisdiction.

(2) If this Code applies to the provision of credit (and to the credit contract and related matters):

(a) this Code applies in relation to all transactions or acts under the contract whether or not they take place in this jurisdiction; and

(b) this Code continues to apply even though the credit provider ceases to carry on a business in this jurisdiction.

(3) For the purposes of this section, investment by the debtor is not a personal, domestic or household purpose.

(4) For the purposes of this section, the predominant purpose for which credit is provided is:

(a) the purpose for which more than half of the credit is intended to be used; or

(b) if the credit is intended to be used to obtain goods or services for use for different purposes, the purpose for which the goods or services are intended to be most used.

(Emphasis added.)

19 Section 13 of the Code contains statutory presumptions as to “Code purpose”. It provides as follows:

13 Presumptions relating to application of Code

(1) In any proceedings (whether brought under this Code or not) in which a party claims that a credit contract, mortgage or guarantee is one to which this Code applies, it is presumed to be such unless the contrary is established.

(2) It is presumed for the purposes of this Code that credit is not provided or intended to be provided under a contract wholly or predominantly for any or all of the following purposes (a Code purpose):

(a) for personal, domestic or household purposes;

(b) to purchase, renovate or improve residential property for investment purposes;

(c) to refinance credit that has been provided wholly or predominantly to purchase, renovate or improve residential property for investment purposes;

if the debtor declares, before entering the contract, that the credit is to be applied wholly or predominantly for a purpose that is not a Code purpose, unless the contrary is established.

(3) However, the declaration is ineffective if, when the declaration was made, the credit provider or a person (the prescribed person) of a kind prescribed by the regulations:

(a) knew, or had reason to believe; or

(b) would have known, or had reason to believe, if the credit provider or prescribed person had made reasonable inquiries about the purpose for which the credit was provided, or intended to be provided, under the contract;

that the credit was in fact to be applied wholly or predominantly for a Code purpose.

(4) If the declaration is ineffective under subsection (3), paragraph 5(1)(b) is taken to be satisfied in relation to the contract.

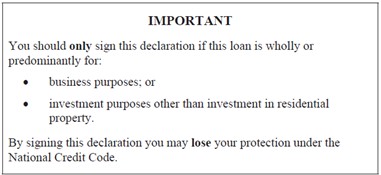

(5) A declaration under this section is to be substantially in the form (if any) required by the regulations and is ineffective for the purposes of this section if it is not.

(6) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person engages in conduct; and

(b) the conduct induces a debtor to make a declaration under this section that is false or misleading in a material particular; and

(c) the declaration is false or misleading in a material particular.

Criminal penalty: 2 years imprisonment.

(7) Strict liability applies to paragraph (6)(c).

Note: For strict liability, see section 6.1 of the Criminal Code.

20 For the purposes of sections 13(3) and 13(5) of the Code, reg 68 of the National Consumer Credit Protection Regulations 2010 (Cth) (Regulations) provides as follows:

68 Declaration of purposes for which credit provided

(1) For subsection 13(5) of the Code, the form of the declaration is:

‘I/We declare that the credit to be provided to me/us by the credit provider is to be applied wholly or predominantly for:

• business purposes; or

• investment purposes other than investment in residential property.’

(2) The declaration must contain the following warning immediately below the words of the declaration mentioned in subregulation (1) or, if the declaration is to be made by electronic communication, prominently displayed when (but not after) the person signs:

(3) The declaration must contain:

(a) the signature of each person making the declaration; and

(b) either:

(i) the date on which the declaration is signed; or

(ii) the date on which it is received by the credit provider.

Note: The Code applies only to credit provided or intended to be provided for:

(a) personal, domestic or household purposes; or

(b) the purchase, renovation or improvement of residential property used for investment purposes; or

(c) the refinancing of credit that has been provided wholly or predominantly for the purchase, renovation or improvement of residential property used for investment purposes.

2.2 Application of the Code

21 Section 5(1)(b)(i) is expressed such that the Code is to apply in respect of the provision of credit if that credit is provided or intended to be provided wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes or to purchase, renovate or improve residential property for investment purposes. The focus of this subsection is upon the purpose of the provision of the credit. There is also a temporal aspect to the determination of whether the Code applies. Namely, the focus in this regard is the time when the credit contract is entered into, or, in the case of a proposed contract, when it is proposed to be entered into.

22 Despite the apparently obvious text of s 5(1)(b)(i), which directs attention to ascertaining the purpose of the provision of the credit, or proposed provision of credit, at the point in time it is provided or proposed to be provided, there have been divergent views expressed as to the appropriate legal test by which such a purpose is to be determined. Is the purpose to be determined by reference to purpose of the credit provider or the debtor, or both? Is the purpose to be determined by undertaking an objective or subjective assessment of the facts known to the credit provider or the debtor, or both? Does the purpose have to be ascertained by reference to the facts known to all parties to the credit contract or proposed credit contract? And, relatedly, is purpose able to be ascertained by reference to what the borrower actually (or subjectively) intended to do with the credit (even if undisclosed to the credit provider) and by reference to how the credit is then actually used by the debtor (even if that too is not disclosed to the credit provider)?

23 One reason for the divergent views that have been expressed is because s 5(4) of the Code provides that, for the purposes of s 5 of the NCCP Act, the predominant purpose for which credit is provided is the purpose for which more than half of the credit is “intended to be used” or, where it is intended to be used to obtain goods or services for different purposes, the purpose for which the goods or services are “intended to be most used”.

24 Many of the divergent views have been expressed in the context of predecessors to the Code including the Uniform Consumer Credit Code (UCCC) enacted under State laws. Whilst the relevant provisions have changed somewhat over time (especially as to the operation of the statutory presumptions to which I will return), the governing provisions as to the application of the Code remain largely the same.

25 One such view was expressed by Brabazon QC DCJ of the District Court of Queensland in Rafiqi v Wacal Investments Pty Ltd [1998] ASC ¶155–024, which was a case concerning the application of s 6(1) of the Consumer Credit (Queensland) Code, as set out in the Appendix to the (now repealed) Consumer Credit (Queensland) Act 1994 (Qld) (Queensland Code). His Honour relevantly stated (at ¶148,574) that in determining whether “credit is provided or intended to be provided wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes” an “objective approach” should be adopted, which involves assessing what a reasonable person standing in the shoes of the credit provider would have understood to be the provision of the credit. This approach was reasoned to be consistent with the necessity for examination as to “what was communicated to the credit provider by the debtor”: at ¶148,574, relying upon Edwards and Sweeney, Application of the Consumer Credit Code and the Purpose Test (1996) 11 Australian Banking Law Bulletin 85. Brabazon QC DCJ further observed that “any other interpretation would place an intolerable burden on the credit provider”. The decision in Rafiqi was followed in Park Avenue Nominees Pty Ltd v Boon [2001] NSWSC 700 (Harrison M).

26 A different view was taken in a later decision of the District Court of Queensland in Dale v Nichols Constructions Pty Ltd [2003] QDC 453, with McGill DCJ observing (at [23]) that: “whether credit is provided for a particular purpose for the purposes of s 6(1) depends on the intention of the borrower at the time the credit is provided” (emphasis added). McGill DCJ stated that the reference to the actual intention of the borrower did not mean the test is subjective (at [31]). In coming to this conclusion, McGill DCJ accepted that s 6(1)(b) of the Queensland Code (which was similar to s 5(1)(b)(i) of the Code) was not “framed by reference (relevantly) to the use to which the money is ultimately put” and was “framed by reference to the purpose for which the credit is provided or intended to be provided”. However, his Honour relied upon s 6(5) (which was similar to s 5(4) of the Code) to reason that the relevant test depended on “the purpose or the intended purpose of the borrower at some particular time…[which] can only be a reference to the borrower’s intention at the relevant time as to the use to be made of the money when borrowed”. His Honour further reasoned that an interpretation focussing upon the purpose of the debtor not only did not impose an “intolerable burden” on the credit provider, contrary to what was stated by Brabazon QC DCJ in Rafiqi, but also fit more readily with the statutory presumptions then contained in s 11(1) because, inter alia, it would otherwise be possible for a credit provider to avoid the operation of the Code merely by ensuring that it never became aware of the purpose for which the debtor was borrowing the money. Thus, on this interpretation, the credit provider could manage its burden by requiring the debtor to make and provide a business purpose declaration.

27 These authorities brought to attention a sharp tension in the application of the UCCC. In Linkenholt Pty Ltd v Quirk [2000] VSC 166; ASC ¶155–040 at ¶200,341, Gillard J of the Supreme Court of Victoria took a different approach altogether. His Honour was there dealing with an application to set aside a default judgment and, in doing so, was called upon to consider the merits of a defence that asserted that the relevant loan the subject of the claim was governed by the Consumer Credit (Victoria) Code as enacted by the Consumer Credit (Victoria) Act 1995 (Victorian Code). By s 5 of this Act, the Victorian Code was prescribed to be that which was set out in the Appendix to the Consumer Credit (Queensland) Act 1994—ie, the Victorian Code was an adoption of the Queensland Code: Linkenholt at [53]. Turning to consider whether the Victorian Code applied to the loan, Gillard J stated at [98]:

[I]t is appropriate to consider what the money was used for in order to determine the purpose of the provision of the credit. In considering the question it is important to consider the substance of the transaction in the context of its performance.

(Emphasis added.)

28 As this passage reveals, the approach taken by Gillard J not only called for an examination of the substance of the transaction, but also an examination of the context of its performance, including the use of the credit by the debtor as one aspect of the overall context. In Jonnson v Arkway Pty Ltd [2003] NSWSC 815; 58 NSWLR 451, Shaw J considered the New South Wales counterpart of the same provision, being s 6 of the Consumer Credit (New South Wales) Code, as implemented by s 5 of the Consumer Credit (New South Wales) Act 1995 (NSW Code). As in Victoria, the Queensland Code was adopted as law in New South Wales. His Honour observed (at [28]) that “divergent views” had been expressed, but preferred the approach taken by Gillard J in Linkenholt and reasoned that “insufficient attention has been given to the need to broadly and liberally interpret beneficial legislation of this kind”.

29 In Benjamin v Ashikian [2007] NSWSC 735, Smart AJ at [74] also agreed with Gillard J in Linkenholt that the court must consider “the substance and the reality of the transaction”. This is also the approach that Davies J preferred in Beckley v Consumer, Trader and Tenancy Tribunal [2009] NSWSC 703 at [76] and in Bank of Queensland Ltd v Dutta [2010] NSWSC 574 at [120]. In Beckley, Davies J stated at [76] that an “examination of what the money was used for produces the result that the credit was provided wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes”.

30 Subsequent intermediate appellate authorities have expressed a preference for an objective test in dicta, albeit considered dicta. In Shakespeare Haney Securities Limited v Crawford [2009] QCA 85; 2 Qd R 156, Muir JA (with whom Mullins and Douglas JJ agreed) observed at [31]-[36], in relation to s 6(1)(b) of the Queensland Code that:

An approach to the construction of s 6(1)(b) which considers the substance of the subject transaction and requires an objective assessment would, in my view, be preferable to one which looks to the actual intention of either the borrower or the lender. Plainly, “the purpose” for which credit is provided or intended to be provided has nothing to do with the lender's general commercial purposes: the reference is to the use to which the credit is to be put. In the great majority of transactions there would be no difficulty in determining the relevant purpose by reference to the terms of the application for credit and of the approval. If the borrower requests credit for a stated purpose and the lender approves the request and makes the loan, there should be no difficulty in concluding that the purpose for which the loan was made was the purpose for which it was requested.

The focus of s 6(1)(b) is on the provision of credit rather than on the obtaining of credit. That is inconsistent with a construction which looks to the debtor's state of mind. Also, one would think that if the legislature had in mind that, in determining the purpose for which credit was provided, the debtor's intention was the governing consideration, s 6(1)(b) would have been worded along these lines:

“The debtor intended to apply the credit wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes.”

Section 6(1)(b) however cannot be construed in isolation. Section 6(4), in effect, deems an “investment” not to be “a personal, domestic or household purpose”. It is consistent with the view that the “purpose” is to be determined objectively by reference to the substance of the transaction. Sections 6(5) and 11, however, may cast doubt on the correctness of this construction. The focus of s 6(5) is on the use rather than the provision of credit. Section 6(5)(a) deems the predominant purpose for which credit is provided to be “the purpose for which more than half of the credit is intended to be used”. Where “the credit is intended to be used to obtain goods or services for use for different purposes”, subs (5)(b) deems “the predominant purpose for which [the] credit is provided” to be “the purpose for which the goods or services are intended to be most used”.

It is arguable that the intention with which each limb of s 6(5) is concerned is that of the debtor. It may be thought exceedingly rare that a debtor would not have an intention to use credit acquired by him or her in a particular way but that is not necessarily true of the lender. Particularly in small transactions, the lender may be indifferent to the use to which the subject monies may be put.

It may be arguable that the intentions to which subs (5) refers are the intentions of the parties to be objectively ascertained as if ascertaining the intention of the parties in construing a contract. But the intentions referred to in subs (5) are intentions as to use of credit in the case of subs (5)(a) and as to the use of goods and services in the case of subs (5)(b). If the words of these paragraphs are construed literally they appear to relate to the actual intention of the debtor. In the case of subs (5)(b), in many cases, the lender would not know or care about the intended differing uses of goods and services but, presumably, the provision is intended to operate even if a lender has no relevant knowledge and the loan documentation does not address the matter.

Subsections (2) and (3) of s 11 also seem to make relevant the debtor's intention. The declaration by the debtor that the purpose or purposes to which the debtor intends to apply the credit are wholly or predominantly for business or investment purposes is a combined statement of the debtor's intended conduct and an expression of opinion. In subs (3) the reference to the credit provider's knowledge “that the credit was in fact to be applied … for personal, domestic or household purposes” would appear to refer to the credit provider's knowledge of what was intended by the debtor. Arguably s 11, in itself, does not provide much support for the view that the purpose for which credit is provided depends on the debtor's state of mind: it merely provides a mechanism by which a credit provider may ensure that the Code has no application to a proposed credit transaction as long as it and its agents are unaware that the credit is in fact to be applied “wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes”. Where no declaration pursuant to s 11(2) is obtained, the Code is presumed to apply in proceedings in which a party claims that the Code applies.

31 Ultimately, Muir JA concluded at [37] that the provisions gave rise to considerable difficulty, which it was unnecessary to resolve because the same outcome would be reached irrespective of the approach that was applied.

32 It will be apparent that Muir JA preferred the application of a test that involved an objective assessment of the subject transaction, albeit with attention needing to be paid to the intention of the debtor given the existence of s 6(5) of the Queensland Code (the equivalent of which is now contained in s 5(4) of the Code).

33 In Bahadori v Permanent Mortgages Pty Ltd [2008] NSWCA 150, Tobias JA (with whom Giles and Campbell JJA agreed) also considered the divergent views which have emerged: see [132]-[138], [148]-[154] and [182]-[186]. In relation to the operation of ss 5 and 11 of the NSW Code, Tobias JA observed (at [183]-[186]) that an approach which focussed on the objective circumstances known to the credit provider had “force”:

In this context, s 11(1) is relevant insofar as it provides that in any proceedings in which a party claims that a credit contract is one to which the Code applies, it is presumed to do so unless the contrary is established. It follows that for the purposes of s 6(1)(b) of the Code, there is a rebuttable presumption that when the subject credit contracts were entered into, the credit to which they referred was intended to be provided wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes. The issue which then arises is whether Permanent and Conway have established the contrary. In my view they have not.

I accept for the purposes of this exercise that the test most favourable to Permanent and Conway is an objective one based upon what a reasonable person would, in all the circumstances, consider to be the purpose for which the loans were intended to be provided. Such a person would be entitled to take into account all the objective circumstances which would otherwise fall for consideration under s 11(3).

Conway submitted that the use of the expression “provided or intended to be provided” required the issue to be determined from the perspective of the credit provider. This was because a lender “provides” credit whereas a borrower “obtains” it. Accordingly, it was contended that the only objective circumstances which are relevant are those known to the credit provider.

There is some force in this submission and for present purposes I am prepared to accept it. However, in my view it makes no difference to the outcome.

34 Tobias JA’s reasons may be taken as expressing a preference for the application of an objective assessment to be applied from the perspective of, and to the facts known to, the credit provider.

35 In Haynes v St George Bank [2018] SASCFC 51; 130 SASR 551, the Full Court of the Supreme Court of South Australia (Kourakis CJ, Blue and Doyle JJ) considered the construction of s 6 of the Consumer Credit (South Australia) Code, as implemented by the (now repealed) Consumer Credit (South Australia) Act 1995. By s 5 of that Act, the Queensland Code was adopted as law in South Australia which was in materially the same terms as s 5 of the Code, but did not include the same statutory presumptions as now apply in s 13: see [41]. Kourakis CJ (with whom Blue and Doyle JJ agreed) said at [44]-[45]:

Section 6 is the primary provision governing the applicability of the UCCC. Section 6 of the UCCC must be read distributively to apply to both entering into a credit contract and to pre-contractual obligations. The opening lines of s 6(1) of the UCCC operate differentially to fix the relevant time for the application of the criterion in subpara (b) to the time of entry into the contract or to the time at which a contract is proposed. Accordingly, in the case of a contract that has been entered into, the question is whether the credit is provided wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household purposes and not whether it is “intended” to be so provided. The question of intention arises only in the application of the UCCC to a proposed credit contract. In the case of the actual provision of credit pursuant to credit on a contract, the test is whether on an objective assessment the credit was provided for the prescribed purpose.

The intention of the debtor is not determinative. As Gillard J observed in Linkenholt Pty Ltd v Quirk “the substance of the transaction in the context of its performance” must be considered.

(Footnotes omitted; emphasis added.)

36 Thus, the Court in Haynes also expressed a preference for the application of an objective assessment and stated in this regard that the intention of the debtor is not determinative (but did not say that it was irrelevant).

37 Subsequently, and more recently, in Mag Financial Investment Ventures Pty Ltd v El-Saafin [2022] VSCA 286; 70 VR 400 the Victorian Court of Appeal (constituted by McLeish, Sifris and Walker JJA) considered the operation of the Code in its current form. In examining s 5(1)(b)(ii), their Honours stated at [112]:

The text of s 5(1)(b)(ii) of the Code requires attention to the use to which the credit is to be put: the credit must be provided ‘to purchase, renovate or improve’ residential property, ‘for investment purposes’. The word ‘to’ shows that this sub-paragraph turns on the immediate purpose for which the credit is provided. We accept that the section does not in terms identify, restrict or place any limitation on who ultimately makes use of the funds for the identified purpose. However, in our opinion, when read as a whole the section is inextricably tied to the debtor — that is, it is directed to the provision of credit to the debtor (as identified in para (a)) and it is implicit in para (b)(ii) that the credit is provided for use by the debtor to purchase, renovate or improve residential property for investment purposes.

(Emphasis added.)

38 Their Honours then stated at [118] that:

The parties submitted, and we accept, that s 5(1)(b) requires consideration of the substance of the transaction and requires an objective assessment of whether the provision of credit has the relevant immediate purpose. The bulk of the authorities to which we were referred, and which were discussed by the trial judge, adopted that objective approach.

(Emphasis added.)

39 Their Honours did not regard the actual or ultimate use of the funds as being determinative and relevantly stated at [121]:

As we have said, the statutory question is not directed to the ultimate use of the funds, but to whether the immediate purpose of the loan is to provide funds which are themselves to be used by the debtor for the relevant purpose. The ultimate use to which the funds are actually put may be relevant in ascertaining the purpose of the loan, but it is not determinative.

(Emphasis added.)

40 In a footnote to the last sentence of [121] (being footnote 31), their Honours further stated:

Indeed, it cannot be determinative, because the relevant time for assessing whether the credit contract is one to which the Consumer Credit Act applies is the date on which the contract is entered into, a time at which the ultimate use to which the funds are put will not be known.

41 However, it is necessary to observe that in Mag Financial their Honours were dealing with s 5(1)(b)(ii) of the Code and considered that little assistance could be obtained from cases dealing with s 5(1)(b)(i): at [125]. Their Honours stated at [125(a)] that “s 5(1)(b)(i) is framed differently from s 5(1)(b)(ii); it does not require that the credit be provided for the immediate purpose of undertaking a particular activity for a particular ultimate purpose. Rather, it is solely directed to the purpose for which the credit was provided”. Despite the reservations there expressed, in my view, their Honours’ approach has some relevance to the approach to be taken to s 5(1)(b) of the Code.

42 Thus, a line of intermediate appellate authorities across different States have expressed a preference for the application of an objective assessment as to the purpose for which the credit is provided, without regarding the intention of the debtor or the use to which the funds are ultimately put as being determinative. There, however, remain nuanced differences between the appellate authorities as to whether the focal point should be on the purpose of the credit being provided as being viewed from the perspective of the credit provider or the debtor, and separately whether the objective assessment is limited to the facts known only to the credit provider.

43 Other than Mag Financial, none of the appellate authorities have considered the operation of the Code in its present form. When Parliament came to enact the NCCP Act, the Explanatory Memorandum to the National Consumer Credit Protection Bill 2009 (Cth) (NCCP EM) stated at [8.34] that:

The question of whether or not credit is provided or intended to be provided wholly or predominantly for a purpose which will result in the credit being regulated by the Code is to be determined consistently with the objectives of the Code. It would not be expected that it can be resolved simply by considering either the actual use of the credit by the borrower or by the purpose of the credit provider.

(Emphasis added.)

44 It has been observed that this passage of the NCCP EM “specifically rejects both the Rafiqi and Linkenholt formulations”: Bolitho H, Howell N and Patterson J, Duggan & Lanyon’s Consumer Credit Law, (2020) 2nd Edition, LexisNexis Butterworths at p 70. In cases that have involved the application of the Code in its present form, it has been concluded that it was strictly unnecessary to decide upon the correct approach: see eg Australia and New Zealand Banking Group v Fink [2015] NSWSC 506 at [90]-[98] (Adamson J); Lauvan Pty Ltd v Bega [2018] NSWSC 154; 330 FLR 1 at [256] (Gleeson JA).

45 In the present case, the evidence indicated, and it was not in dispute, that both Consumers 1 and 2 applied the credit provided by Green County for personal purposes and not for any business purpose. Thus, the application of a test that regards the actual use of the credit as being relevant and determinative would be dispositive of an issue before me. The respondents urged against the application of this test. They contended that I should apply an objective test. The respondents submitted as follows:

Three key propositions emerge from consideration of the authorities considering s 5(1)(b) and its analogues. First, the analysis required by s 5(1)(b) is as to the objective purpose for which credit is provided. Secondly, in conducting that analysis, regard should be had to the substance of the transaction, including the surrounding circumstances known to both parties. The Court is not limited to considering the text of the agreement, the way it may be in construing a contract, but an objective analysis requires that, for a matter to be relevant, it must be known to both parties. Third, a transaction involving a request for credit for a stated purpose that is then approved, is strong evidence that the credit was provided for that purpose.

46 ASIC’s submissions as to these points ultimately contended that the proper construction of s 5(1)(b)(i) had to take into account the existence of the statutory presumptions in s 13 of the Code. ASIC submitted as follows:

The language of section 13(3) is important both in considering the proper construction of the section (and sections 4 and 5) and in considering the significance of authorities directed to the predecessor legislation. Section 5 of the Code is directed to the purpose for which credit is provided or intended to be provided. That has led to debate as to whose purpose is relevant. The lender’s purpose has been rejected (Shakespeare Haney tentatively at [31], and more conclusively Haynes at [46]). The preference was generally but not conclusively, for the anthropomorphic construct of the purpose of the transaction. However, in a case on the current form of the legislation, but without reference to section 13 (or suggesting a departure from relevant authority), the Victorian Court of Appeal in Mag Financial held that it was the use or proposed use by the borrower which was determinative: Mag Financial at [112] (although Mag Financial at [118] cites the earlier authorities).

At least where a declaration has been obtained, section 13(3) necessarily resolves that issue as it is directed to how the credit is “in fact to be applied”. It looks to the application (i.e. use) of the credit (considered at the time the declaration was made which is no later than the time of entry into the credit contract: section 13(2)). Care must be taken to recognise this distinction when considering the application of authorities directed to the assessment of purpose in section 5 (and its predecessor – section 6 UCCC); noting that it is in that context that the debate as to the subjective or objective test has primarily arisen.

Before turning to that distinction, section 13(3) should be construed in accordance with the language used. The relevant actual or attributed state of mind of the lender is as to whether “the credit was in fact to be applied wholly or predominately for a Code purpose”. The section is directed to something that the borrower was to do, which necessarily directs attention to the borrower’s intention (putting to one side how that is determined). In light of section 13(4) it might be thought to be coherent that section 5(1)(b)(i) also direct attention to the borrower’s intention, although it is not necessary to take that step for the purpose of these proceedings which involve circumstances in which the Corporate Respondents did obtain declarations substantially in the form prescribed for the purpose of section 13(2) (but only for the initial credit agreements). Nonetheless, it is relevant to observe that construction does give s 5(1)(b)(i) a grammatical construction: “provided” is agnostic as to whether the “stipulation” or “understanding”, or “condition” or “supposition” (Macquarie Dictionary (8th edn at 1227) is that of the lender or borrower, and is consistent with the use of “intended” in section 5(4). But as already observed, it is unnecessary to resolve that question. If the lender has the state of mind as to the use to be made (by the borrower) as identified in section 13(3), then the credit is conclusively deemed to be for personal, domestic or household purposes: section 13(4).

(Footnotes omitted.)

47 As ASIC’s submissions pointed out, at least in relation to the initial contracts (referred to below as the First Credit Contracts for each of Consumers 1 and 2), the result is governed by whether the “business purpose declarations” made by Consumers 1 and 2 were effective and, if not, the result would be deemed by the operation of s 13(4). However, the position is different in relation to the subsequent credit contracts if they were, as I have found them to be, separate credit contracts. That is because in relation to those subsequent credit contracts, the corporate respondents did not obtain “business purpose declarations”, but relied upon the fact of those declarations as evidencing the stated purpose of the respective borrowers. Hence, in relation to these subsequent credit contracts, the governing presumption was that contained in s 13(1) of the Code and raises a question as to whether the corporate respondents rebutted the presumption for the purpose of these proceedings. That does require resolution of the question raised by s 5(1)(b)(i) of the Code. Necessarily, that question needs to be resolved with regard to the existence of ss 13(2), (3) and (4) of the Code, but with the obvious limitation that those subsections do not govern the outcome in respect of the subsequent contracts.

48 In my view, the preferred approach to be taken for the purpose of s 5(1)(b)(i) involves an objective assessment of the facts and circumstances of the provision of the credit and its intended use at the time that the credit contract is entered into or proposed to be entered into. I do not regard the dichotomy between the provision of the credit and its intended use as being in tension, but one that is necessitated by the operation of s 5(1)(b)(i) and s 5(4). This approach accounts for the bilateral concepts that emerge from s 5(1)(b)(i) which is focussed upon the purpose of the provision of the credit and s 5(4) which is focussed upon the intended use of the credit. It thereby marries the duality involved being, on the one hand, the provision of credit and, on the other, its intended use. The ultimate question to be answered by the objective assessment is the purpose as divined from that assessment. In the application of this approach, the focus is not myopic to the perspective of only the credit provider or only the debtor, but involves an objective assessment of the substance of the transaction between the credit provider and the debtor including the surrounding circumstances (as contended for by the respondents). The substance of the transaction between the credit provider and debtor and its surrounding circumstances would include an objective assessment as to the dealings and communications, as well as the contractual terms, as between those parties.

49 In my view, the task of ascertaining the relevant purpose for s 5(1)(b)(i) is not a task in respect of which authorities addressing the objective theory of contract strictly apply (as was urged upon me by the respondents), but I accept that those authorities provide some guidance as to the objectively divined intention of the parties: cf Toll (FGCT) Pty Ltd Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 52; 219 CLR 165 at [40] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ per curiam); Ozzy Loans Pty Ltd v New Concept Pty Ltd [2012] NSWSC 814 at [47]-[49] (Campbell J). That objective purpose ordinarily is the purpose of a reasonable person in the position of the contracting parties. As I have already indicated, the objective purpose may need to be divined from matters that extend beyond the four corners of a written credit contract and include an examination of the dealings and communications between the parties, including the terms of the contract between the parties. In this regard, it is to be recalled that s 5(1)(b) and s 5(4) are also applicable to credit contracts that are not yet entered and therefore apply to the proposed provision and use of credit. In that instance, it will follow that regard will need to be had to matters that extend beyond the contractual terms in ascertaining purpose.

50 I do not regard the actual use to which the credit is put or expended as being determinative of the objective assessment that is required, which is consistent with what was said in Mag Financial. It is important to bear in mind that s 5(4) is concerned with the intended use of the credit, as opposed to its actual use. However, it may be that in some cases, consideration may be given to the debtor’s actual use of the funds as an evidentiary matter, to shed light on or from which to infer matters that are relevant to an objective assessment of the purpose in question. In this regard, it is important to reiterate that the task involves ascertaining the purpose for which the credit is provided including by reference to the intended use of that credit.

51 There is considerable force in the position advanced by the respondents that the objective assessment should be limited to the facts known to both the credit provider and the debtor, and must exclude the undisclosed intentions on the part of the debtor. However, at least one difficulty with this contention is that it runs the risk of tending towards a subjective assessment of the facts the particular credit provider has elected to consider which was a vice that McGill DCJ adverted to in Dale. As McGill DCJ pointed out, such a contention runs contrary to the way in which the statutory presumptions are intended to operate. What is called for is an objective assessment of all of the facts including those which a reasonable person in the position of the credit provider would have known or is likely to have known, even if the particular credit provider did not advert to or recognise them. Thus, for example, the fact that a debtor asserts the intended use of the credit is for a business purpose would need to be objectively assessed as against the other material and information provided by the debtor to the credit provider and which was in the possession of the credit provider, though not adverted to or considered by the credit provider. There may be cases where the debtor’s asserted business purpose is falsified by other information provided by the debtor to the credit provider. And, equally, there may be cases where the debtor’s falsely asserted business purpose governs the outcome. As I return to below in Part 2.4, these observations are no more than to say that it is not possible to state a governing rule or organising principle as to how the objective assessment would be affected by what are, quintessentially, fact dependent assessments.

52 Further, as I explain below, in the present case, the outcome largely depends on the application of the statutory presumptions and whether one or other party has been able to rebut them. It is now necessary to examine those presumptions.

2.3 The Statutory Presumptions

53 Section 13 of the Code is concerned with matters of presumption and onus.

54 Section 13(1) of the Code applies in the context of “proceedings” and has the effect of creating a presumption that is rebuttable (that is, it operates “unless the contrary is established”). Notably, the presumption in s 13(1) does not operate by reference to a declaration of the kind contemplated in s 13(2). Section 13(1) thereby envisages that a credit provider may have other means of displacing the presumption that the Code applies in “proceedings”.

55 The presumption in s 13(2) is directed to “the purposes of the Code”. It operates if, prior to the entry into a credit contract, the debtor declares (for convenience, referred to as a “business purpose declaration”) that the credit is to be applied wholly or predominantly for a purpose that is not a Code purpose. The presumption applies unless the contrary is established (subject to a finding that the declaration is ineffective by reason of s 13(3)). Once this presumption arises, it is for the party claiming the declaration is ineffective (usually the debtor) to make good their claim: Ozzy Loans at [41]. For the purpose of s 13(2), the declaration is not effective unless it is substantially in the form required by the regulations: s 13(5); r 68 of the Regulations. If a declaration is ineffective, s 13(4) deems s 5(1)(b) to be satisfied in relation to the credit contract.

56 The interaction between ss 13(1) and 13(2) is that, in proceedings, absent a business purpose declaration that is substantially in the required form, the credit provider bears the onus of rebutting the presumption contained in s 13(1).

57 It is important to bear in mind that the present form of s 13 of the Code is different to its predecessors in relation to the circumstances in which a business purpose declaration is not effective. The predecessors to s 13 of the Code were limited to circumstances where the credit provider “knew, or had reason to believe…that the credit was in fact to be applied wholly or predominantly [for Code purposes]”. Section 13(3)(b) expands the operation of the provision by extending the circumstances in which the declaration is ineffective to include cases where the credit provider “would have known, or had reason to believe, if the credit provider or prescribed person had made reasonable inquiries about the purpose for which the credit was provided, or intended to be provided…”.

58 Section 13(3) in its current form was enacted to address what were considered “abuses” of business purpose declarations: NCCP EM at [8.56]. Such abuses were considered by Ambrose J in State of Queensland v Ward [2002] QSC 171: see NCCP EM [8.61]. The NCCP EM relevantly stated at [8.59], [8.60], [8.64] and [8.65]:

8.59 Under the UCCC the presumption was conclusive, except in limited circumstances. The decisive effect of the presumption enabled credit providers to rely on it as an effective means of excluding the application of the UCCC; borrowers were not readily able to set side the effect of the declaration as they needed to argue that the credit was for personal use, and therefore that they had signed a false declaration.

8.60 The result was that the declaration could be largely relied upon by credit providers to prevent borrowers being able to exercise rights under the UCCC, even where the credit was used for personal, domestic or household purposes…

…

8.64 This amendment will provide an effective response to the problems previously associated with the abuse of declarations as:

• where, before the contract was entered into, the credit was to be applied for a Code purpose it would be unlikely that this would not be known or ascertainable by reasonable inquiry by the credit provider; and

• credit providers who do not make any reasonable inquiries into the use of the credit will find it difficult to rely on a declaration where the credit was in fact applied for a Code purpose.

8.65 It is specifically provided that if a declaration is ineffective under subsection 13(4), that paragraph 5(1)(b) of the Code is taken to be satisfied in respect of the contract, that is, the borrower does not still need to establish that the credit was provided for a Code purpose. The Code still may not apply to the credit contract, but only where it fails to meet some other criteria.

59 ASIC submitted that the examples provided by the NCCP EM “plainly contemplate that a credit provider must proactively take steps to make reasonable inquiries if it wishes to avoid the consequences of sections 13(3)-(4)”. In support of this submission, ASIC pointed to the following examples contained in the NCCP EM:

Example 8.1: Whether the lender made reasonable inquiries

The borrower obtains a loan of $250,000 from Lender A, with $200,000 used to pay out their existing home loan, and with the further $50,000 to be used for a business purpose. Lender A makes reasonable inquiries to establish that the $50,000 is for a business purpose, but makes no inquiries into the purpose of the remainder of the funds. Lender A would not meet the criteria for making reasonable inquiries.

Example 8.2: Whether the lender made reasonable inquiries

The lender receives an application submitted by a finance broker seeking a loan of $50,000 for business purposes. The application form is signed by the borrower and states that the borrower has an Australian Business Number (ABN), acquired two days before the loan application. The date an ABN was issued can be easily checked. The application gives no details of the business. In fact, the borrower uses the money to pay arrears on their home loan. It is unlikely that the lender would meet the criteria for making reasonable inquiries if it failed to verify the existence of any business said to be carried on by the borrower.

(Emphasis in original.)

60 Whilst these examples are useful indicators as to purpose, the task remains to give effect to the statutory text and purpose as divined from the Act. Explanatory memoranda are potentially useful for discerning the mischief to which legislation is directed, but they cannot displace the meaning of the statutory text and cannot be substituted for the text: Mondelez Australia Pty Ltd v Automotive, Food, Metals, Engineering, Printing and Kindred Industries Union [2020] HCA 29; 271 CLR 495 at [70] (Gageler J).

61 Section 13 does not impose any positive statutory obligation on a lender to make reasonable inquiries. Rather, the concept of reasonable inquiries operates as a mechanism to render ineffective a declaration as provided for by s 13(3)(b).

62 Section 13(3)(a) provides for the circumstances in which a declaration will be ineffective. It focusses upon the knowledge of the credit provider. Relevantly, for the purpose of this limb, the declaration is ineffective where the credit provider has actual knowledge that, despite the declaration, the credit was to be applied wholly or predominantly for a Code purpose. It also applies to, what has been conveniently described as, constructive knowledge: Ozzy Loans at [49]. That is because the text of s 13(3)(a) (as with the text of s 13(3)(b)) contains the words “had reason to believe”. The label of “constructive knowledge” needs unpacking.

63 ASIC submitted that the words “had reason to believe” require an objective assessment of the state of mind of the credit provider by reference to the facts known by the credit provider. In support of this contention, ASIC relied upon the unanimous decision of the High Court in George v Rockett [1990] HCA 26; 170 CLR 104 at 112 and 116 (Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ) to contend that the words “had reason to believe” direct attention to whether, on such an objective assessment, the facts were sufficient to “incline the mind” of the credit provider towards accepting rather than rejecting a particular proposition. For their part, the respondents urged caution in applying George v Rockett. That is because George v Rockett examined legislation involving the circumstances where a warrant could be issued. The relevant legislation provided that a warrant could be issued if it appeared to the relevant person that there were “reasonable grounds for suspecting” that, in a relevant location, there was anything “as to which there [were] reasonable grounds for believing that it will … afford evidence as to the commission of any offence”: at 107. The respondents submitted that care should be exercised in distinguishing between reasonable grounds for believing something and reasonable grounds for suspecting something. This was a distinction to which the High Court was alive in George v Rockett. At 115-116, the High Court quoted with approval the reasons of Kitto J in Queensland Bacon Pty Ltd v Rees [1996] HCA 21; 115 CLR 266 at 303, where his Honour had said:

A suspicion that something exists is more than a mere idle wondering whether it exists or not; it is a positive feeling of actual apprehension or mistrust … Consequently, a reason to suspect that a fact exists is more than a reason to consider or look into the possibility of its existence. The notion which ‘reason to suspect’ expresses in sub-s (4) is, I think, of something which in all the circumstances would create in the mind of a reasonable person in the position of the payee an actual apprehension or fear that the situation of the payer is in actual fact that which the sub-section describes…

64 By contrast to a suspicion, the High Court in George v Rockett reasoned as follows in relation to the words “reasonable grounds for believing”:

The objective circumstances sufficient to show a reason to believe something need to point more clearly to the subject matter of the belief, but that is not to say that the objective circumstances must establish on the balance of probabilities that the subject matter in fact occurred or exists: the assent of belief is given on more slender evidence than proof. Belief is an inclination of the mind towards assenting to, rather than rejecting, a proposition and the grounds which can reasonably induce that inclination of the mind may, depending on the circumstances, leave something to surmise or conjecture.

65 The words “reason to believe” are commonly used in different statutory contexts: eg, see Story v National Companies and Securities Commission (1988) 13 NSWLR 661 at 674 (Young J); see also WA Pines Pty Ltd v Bannerman (1980) 30 ALR 559; 41 FLR 175 at 184 (Lockhart J). In Power v Hamond [2006] VSCA 25, Chernov JA (with whom Maxwell P and Ormiston JA agreed on this aspect) considered the use of these words in the Legal Practice Act 1996 (Vic) (repealed) as relevantly applicable to the circumstances in which the Legal Ombudsman could commence an investigation. His Honour stated:

105 …It is now settled law that the question whether there is “reason to believe” a specific matter in a context such as the present is to be determined by the person concerned on an objective basis and that the correctness of the conclusion may be tested in court. Thus, for example, it was said in George v Rockett that “[w]hen a statute prescribes that there must be ‘reasonable grounds’ for a state of mind — including suspicion and belief — it requires the existence of facts which are sufficient to induce that state of mind in a reasonable person.” Consequently, in order to have launched the impugned investigation lawfully the Ombudsman had to conclude, on an objective basis, that Power’s failure to obtain insurance might amount to misconduct or unsatisfactory conduct. The question, therefore, is whether, in all the circumstances, a reasonable Ombudsman would have so concluded.

106 …the belief must rest on objective facts that would induce the relevant state of mind in a reasonable person.

66 Care must of course be exercised in examining the statutory context. That is particularly the case where the words “reason to believe” are used in other contexts as a condition to the exercise of a statutory or administrative power. The respondents submitted that the words “reason to believe” did “not pose a negligence test” and that “knowledge of facts from which a reasonable person might suspect the relevant conclusion cannot be enough”: citing, in a different statutory context, Husqvarna Forest & Garden Ltd v Bridon NZ Ltd [1997] 3 NZLR 215 at 226. It was further submitted that the “relevant constructive knowledge is not constructive knowledge on the basis of negligence” and that “[r]eason to believe” is not to be equated with “reasonable grounds to suspect”.

67 I accept that the words “reason to believe”, as contained in s 13(3), require a state of knowledge beyond that of a suspicion. In my view, the words require an objective assessment of the facts known to the credit provider and whether those facts incline the credit provider’s mind as to whether the debtor would be using, or proposing to use, the funds for a Code purpose. This requires a state of satisfaction that is more than a suspicion, and more than an apprehension, though it does not require conclusive proof and leaves some room for “surmise or conjecture”.

68 Section 13(3)(b) poses a hypothetical question. As I have already observed, it does not impose a positive obligation to undertake reasonable inquiries. The question that arises here is what would the credit provider have known or have reason to believe if it made reasonable inquiries, and, relevantly, would it have known or had reason to believe that the credit was in fact to be applied for a Code purpose. The parties accepted that this posed a counterfactual as to what would have been conveyed to the credit provider if it had made objectively “reasonable inquiries”. The parties agreed that this calls for an objective analysis, but were in dispute as to the application of that approach to the facts.

69 Much will depend on what reasonable inquiries are, which will in turn depend on the facts. The word “reasonable” is adjectival and indicates that the relevant inquiries are those that would have been made by a “reasonable person” in the circumstances of the credit provider. The inquiries are not limited to those that the particular credit provider might have subjectively regarded as “reasonable”. The standard of reasonable inquiries is in this sense objective and fact dependent.

70 The legislature has neither defined nor prescribed what inquiries are “reasonable” for the purpose of s 13(3)(b) of the Code. However, it is an expression that appears elsewhere in the NCCP Act and, in particular, is a core component of “responsible lending” obligations imposed under Chapter 3 of the NCCP Act: see, for example, ss 117, 130, 140 and 153 of the NCCP Act, each of which obliges licensees to make reasonable inquiries about, and to take reasonable steps to verify, a consumer’s financial situation.

71 In that context, the content of the obligation to make “reasonable inquiries” has been considered on several occasions. For instance, in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cash Store Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2014] FCA 926 at [28], Davies J observed in relation to s 117 that “‘reasonable’ inquiries about, and ‘reasonable’ steps to verify, the consumer’s financial situation must be such inquiries and steps as will be sufficient to enable to the credit assistance provider to make an informed assessment as to whether the consumer will be able to comply with the consumer’s financial obligations under the contract without substantial hardship” (referring to and relying on ss 118(2)(a) and 123(2)(a)). Consistent with this, Perram J separately observed that “the purpose of s 130 is to ensure that credit providers put themselves in an informed state about the financial position of the consumer before making an assessment of the suitability or otherwise of the loan”: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corp (Liability Trial) [2019] FCA 1244; 139 ACSR 25 at [59]. On appeal, the Full Court affirmed the decision of Perram J: see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corp [2020] FCAFC 111; 277 FCR 343 (Middelton, Gleeson and Lee J). Relevantly, Gleeson J noted (at [141]) that the NCCP Act is not overly prescriptive as to what “reasonable inquiries” entail before observing that:

the Act leaves it open to the licensee to decide:

(1) what inquiries it will make under s 130(1)(a) and (b), provided that those inquiries are reasonable;

(2) what steps it will take to verify the consumer’s financial situation under s 130(1)(c), provided that those inquiries are reasonable;

72 In separate reasons, Lee J described the overarching operation of Divs 3 and 4 of Pt 3-2 of the responsible lending regime and observed (at [170]) that “s 130 imposes an initial duty to undertake inquiries and investigations into the consumer’s requirements and objectives, and financial situation (obligations directed to ‘knowing the customer’)”. In this, it can be seen that the investigative exercise contemplated by provisions such as ss 117 and 130 is multi-faceted in nature and obliges licensees to undertake processes of inquiry and verification.

73 Returning to s 13(3) of the Code, Green County and Max Funding submitted that ASIC’s contentions effectively converted an obligation to make “reasonable inquiries” into a process of verifying loan purpose. It was contended that there was no express obligation to do so, as contradistinct from the obligations imposed by the responsible lending provisions considered above.