FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 6) [2025] FCA 363

File number: | QUD 17 of 2019 |

Judgment of: | O'BRYAN J |

Date of judgment: | 17 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | NATIVE TITLE – application for determination of native title – separate questions concerning the existence of native title – where trial of separate questions conducted between the applicant and the State of Queensland – where subsequent to trial the parties engaged in mediation and reached agreement on a statement of agreed facts – leave granted to re-open the trial for the purposes of adducing the statement of agreed facts in evidence, together with a supplementary expert report – consideration of the legal effect of the statement of agreed facts – determination of the separate questions undertaken on the basis of the evidence adduced at trial and in light of the statement of agreed facts – consideration of the use of the word “society” in expert anthropological evidence, including the use of the terms “regional society”, “core society” and “associative society” – explanation of the meaning of the term “society” in native title jurisprudence and the limits of its usefulness in anthropological evidence |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 191 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ss 61(1), 87, 223, 225 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 30.01 |

Cases cited: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission v BHF Solutions Pty Ltd (2022) 293 FCR 330 Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2023] FCA 600 Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland (No 4) [2024] FCA 425 Bodney v Bennell (2008) 167 FCR 84 CG (Deceased) on behalf of the Badimia People v State of Western Australia [2015] FCA 204 Croft (on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group) v South Australia [2015] FCA 9 Daniel v Western Australia [2003] FCA 666 De Rose v South Australia (No 2) (2005) 145 FCR 290 De Rose v State of South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 Drill on behalf of the Purnululu Native Title Claim Group v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 1510 Gumana v Northern Territory of Australia (2005) 141 FCR 457 Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 Malone on behalf of the Clermont-Belyando Area Native Title Claim Group v State of Queensland [2023] FCAFC 190 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland [2020] FCA 1188 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2020] FCA 1414 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2022] FCA 827 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (2021) 287 FCR 240 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 4) [2025] FCA 36 Malone v State of Queensland (The Clermont-Belyando Area Native Title Claim) (No 5) [2021] FCA 1639 McLennan on behalf of the Jannga People #3 v State of Queensland (2023) 301 FCR 452 Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 Neowarra v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 1402 Northern Territory v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 442 Sandy on behalf of the Yugara People v State of Queensland (2017) 254 FCR 107 Starkey v South Australia (2018) 261 FCR 183 State of Western Australia v Fazeldean on behalf of the Thalanyji People (No 2) (2013) 211 FCR 150 State of Western Australia v Sebastian (2008) 173 FCR 1 Stuart v South Australia [2025] HCA 12 The Nyamal Palyku Proceeding (No 8) [2024] FCA 11 Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council v Minister for Lands (NSW) (No 2) (2008) 181 FCR 300 Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229 Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v State of Queensland [2016] FCA 777 Wyman v Queensland (2015) 235 FCR 464 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Queensland |

National Practice Area: | Native Title |

Number of paragraphs: | 612 |

Dates of hearing: | 30 and 31 August 2022, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 15 and 16 September 2022, 24 November 2022, 8 December 2023, 23 March 2024, 10 October 2024, 12 December 2024, 31 January 2025 and 6 March 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | V Hughston SC with C Athanasiou |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | P & E Law |

Counsel for the First Respondent: | A Duffy QC with L Kruger (until 23 March 2024) A Y Tarrago with L Kruger (after 23 March 2024) |

Solicitor for the First Respondent: | Crown Law |

ORDERS

QUD 17 of 2019 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JONATHON MALONE & ORS ON BEHALF OF THE WESTERN KANGOULU PEOPLE Applicants | |

AND: | STATE OF QUEENSLAND and others named in the Schedule Respondents | |

order made by: | O'BRYAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions that, on 6 December 2017, the Court ordered to be determined separately from any other questions in the proceeding, be answered as follows:

(a) But for any question of extinguishment of native title, native title exists in the land and waters of the claim area.

(b) The persons holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are the biological or adoptive descendants of one or more of the following people:

(i) Polly aka Polly Brown aka Polly McAvoy;

(ii) John 'Jack' Bradley;

(iii) Hanny of Emerald;

(iv) Nannie, mother of Nelly Roberts; and

(v) Annie/Nanny Duggan and Ned Duggan,

who identify as Western Kangoulu People and who are recognised as such by the Western Kangoulu People.

(c) The nature and extent of the native title rights and interests are the following non-exclusive rights and interests in the claim area:

(i) the right to access, be present on, move about on, and travel over the claim area;

(ii) the right to camp on the claim area, and for that purpose, erect temporary shelters on the claim area;

(iii) the right to take natural resources from the land and waters of the claim area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(iv) the right to take the Water of the claim area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(v) the right to maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the Western Kangoulu People under their adapted laws and customs, and protect those places and areas, from physical harm;

(vi) the right to teach Western Kangoulu People members the physical and spiritual attributes of the claim area;

(vii) the right to bury Western Kangoulu People members within the claim area;

(viii) the right to assemble and conduct ceremonies and other cultural activities on the claim area; and

(ix) the right to light fires on the claim area for cultural, spiritual or domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation.

2. In these orders, the following words have the following meanings:

(a) Animal means any member of the animal kingdom (other than human) whether alive or dead;

(b) claim area means the area of land and waters described in Schedules B and C of the amended native title determination application filed by the Applicant on 15 August 2017;

(c) natural resources means:

(i) any Animals and Plants found on or in the lands and waters of the claim area; and

(ii) any clays, soil, sand, gravel or rock found on or below the surface of the claim area,

that have traditionally been taken by the Western Kangoulu People and their ancestors, but does not include:

A. Animals that are the private personal property of any person;

B. crops that are the private personal property of another; and

C. minerals as defined in the Mineral Resources Act 1989 (Qld);

D. petroleum as defined in the Petroleum Act 1923 (Qld) and the Petroleum and Gas (Production and Safety) Act 2004 (Qld);

(d) Plant means any member of the plant or fungus kingdom, whether alive or dead and standing or fallen;

(e) Water means:

(i) water that flows, whether permanently or intermittently, within a river, creek or stream;

(ii) any natural collection of water, whether permanent or intermittent; or

(iii) water from an underground water source; and

(f) Western Kangoulu People has the meaning given in order 1(b).

3. The proceedings be referred to a Judicial Registrar of the Court for further mediation on the residual issues for determination.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

O’BRYAN J:

A. INTRODUCTION

The application

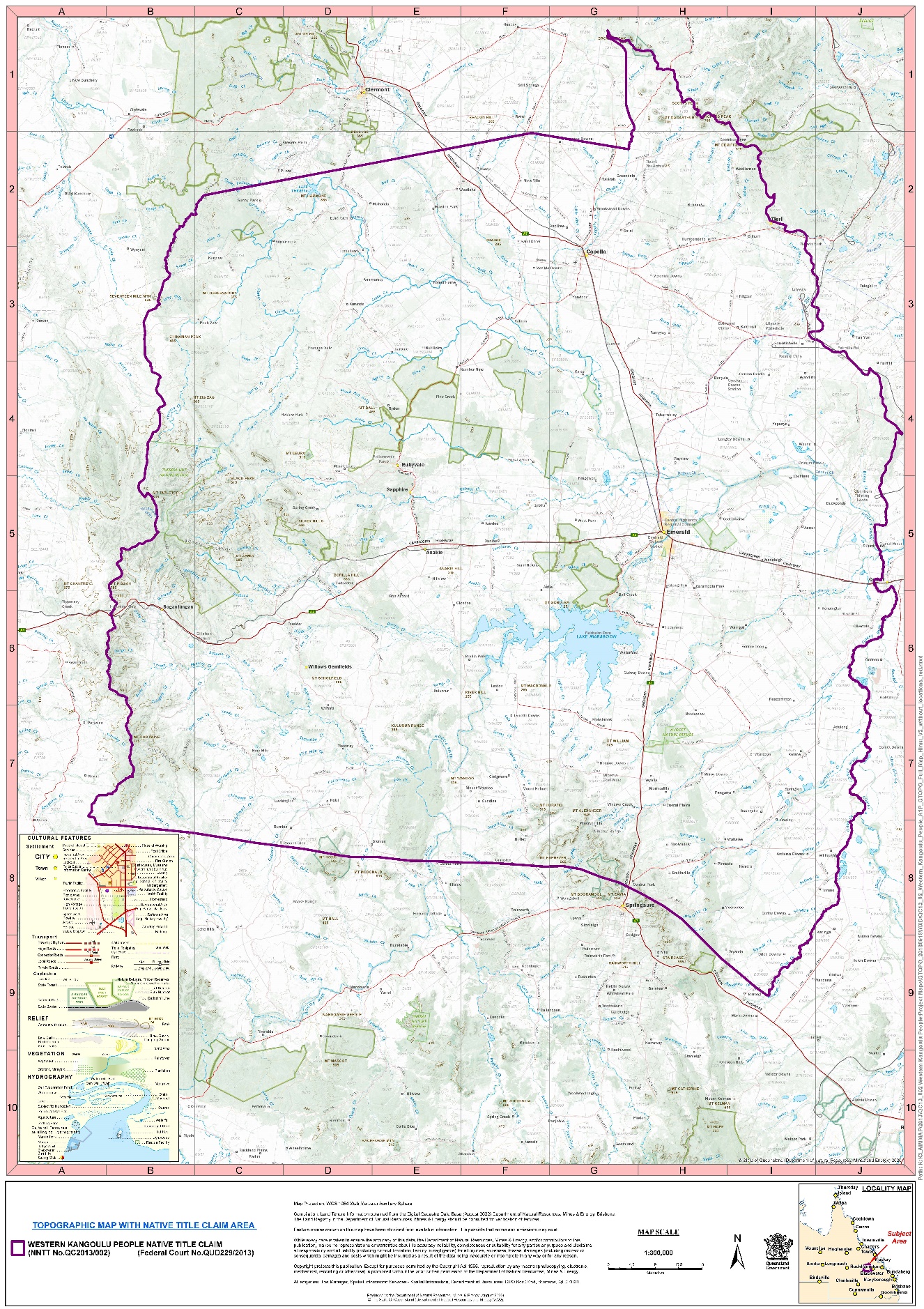

1 The applicant seeks a determination of native title under s 61(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Native Title Act) in respect of an area of land surrounding the township of Emerald in the western part of the Central Highlands in Queensland. The application identifies the named applicants as Jonathon Malone, Hedley Henningsen, Cynthia Broome and Karen Broome. The claim is made on behalf of the Western Kangoulu people and is known as the Western Kangoulu native title claim. The Western Kangoulu native title application was originally filed on 9 May 2013 and given the file number QUD 229 of 2013. The most recent form of the application was filed on 15 August 2017. The proceeding was given the new file number QUD 17 of 2019 on 10 January 2019.

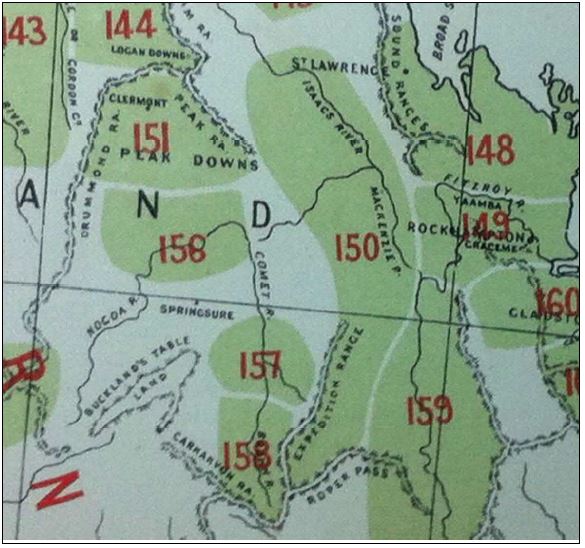

2 The claim area is depicted in the map attached to these reasons as Annexure A. The applicant’s anthropological expert, Dr Richard Martin, provided the following description of the claim area which is uncontroversial:

The claim area is divided along the east-west axis by a main road and railway line connecting the coast at Rockhampton with other inland centres to the west. The town of Emerald, with a population of about 15,000, sits on this axis in the eastern part of the claim area. It is by far the largest population centre in the claim area.

Other towns and localities in the claim area include:

• Capella

• Sapphire

• Rubyvale

• Bogantungan

• Gordonstone

The Nogoa River is the principal waterway on the claim area. Its headwaters are in the Dividing Range to the south of the claim area. It flows into the claim area in a north-easterly direction, passing through Emerald and exiting the claim on its eastern boundary where it joins with the Comet River to form the Mackenzie River.

The western extent of the claim area is marked by the Drummond Ranges, which is the source of a number of creeks that run west to east through the claim area. All the creeks traversing the claim area eventually flow into the Nogoa River. In terms of watersheds, the claim area is the westernmost extent of the Fitzroy Basin, which is a large drainage area that sees its waters flowing into the ocean through the Fitzroy River.

The natural flow of the Nogoa River was substantially altered in the early 1970s through the construction of Fairbairn Dam just to the south of Emerald. The artificially expanded Lake Maraboon has since allowed irrigation farming in this area of highly variable rainfall.

3 The native title claim group is described in Schedule A to the application as follows:

The group of persons claiming to hold the common or group rights comprising the native title is the Western Kangoulu People.

A person is a Western Kangoulu person if and only if the other Western Kangoulu People recognise that he or she is biologically descended from a person who they recognise as a Western Kangoulu ancestor, including the following deceased persons:

• Polly aka Polly Brown aka Polly McAvoy;

• John ‘Jack’ Bradley;

• Hanny of Emerald;

• Nannie, mother of Nelly Roberts; and

• Annie/Nanny Duggan and Ned Duggan.

4 The applicant revised its description of the claim group in the course of the hearing, although not in any fundamental way. The identification of apical ancestors has remained consistent, and inclusion through cognatic descent has remained central. The applicant’s further amended statement of facts and matters dated 15 September 2022, which was filed during the trial, redefined the claim group as:

the descendants of the apical ancestors who identify as Western Kangoulu People and who are recognised as such by the Western Kangoulu People.

where the word “descendants” was defined to mean:

those persons who are biologically descended from, or have been adopted by, Western Kangoulu people.

5 This revised description of the native title claim group introduces the following additional elements:

(a) the expansion of descent to include adoption;

(b) a requirement for self-identification as Western Kangoulu; and

(c) a requirement of recognition by other Western Kangoulu people as someone who is a Western Kangoulu person (which may or may not differ from the description in the application).

6 The application describes the Aboriginal people who were associated with the land and waters of the claim area at the time of the assertion of British sovereignty as being part of a broader regional society. The application states:

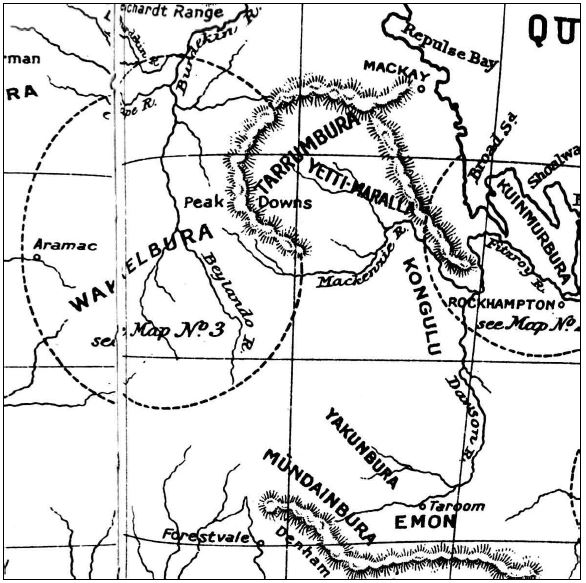

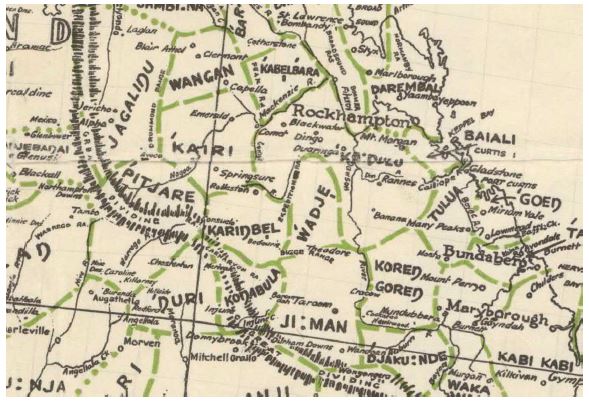

5. At the time the crown acquired legal sovereignty over the Application Area, there was a body of Aboriginal people who were associated with the land and waters of the Application Area.

6. The Aboriginal people who were associated with the land and waters of the Application Area were part of a broader regional society, but were a localised constituent part of this society confining their primary territorial interests to the lands and waters of the Application Area. The contemporary members of the claim group have adopted the name “Western Kangoulu” to explicitly distinguish their localised interests from those of their regional neighbours to whom they have close social and cultural ties dating from the pre-sovereignty period.

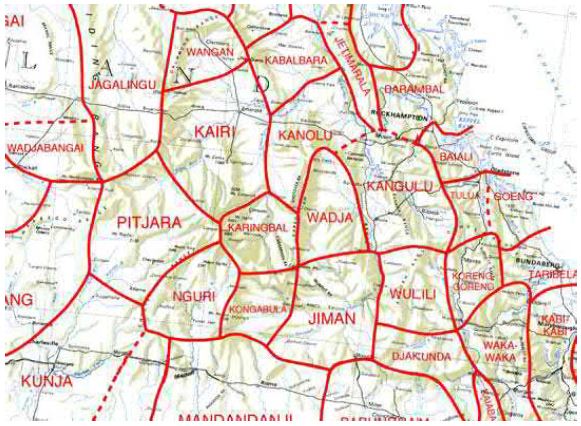

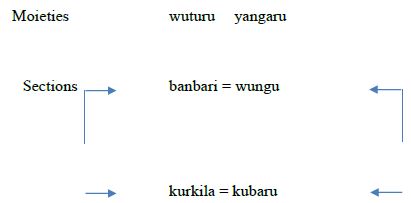

7. The areas surrounding Western Kangoulu country belonged to groups who have or were identified as: the Jagalingu, Wangan, Karingbal, Kanolu, Wadja and Gangalu amongst others. Together these groups and the Western Kangoulu formed an interconnected cluster of distinct groups who interacted for cultural and social purposes, and shared common spiritual beliefs, religious institutions, social organisation and classificatory kinship systems, and common laws and customs. Together, these groups form what may be termed a regional society situated within the cultural bloc often referred to as the Maric cultural bloc by linguists and anthropologists so named for the common word for human (“Mari”) shared throughout much of this bloc.

7 A description of the native title rights and interests claimed in relation to the claim area is set out at Schedule E to the application, as follows:

The Western Kangoulu People claim the rights to:

(a) access, be present on, move about on and travel over the application area;

(b) camp on the application area and, for that purpose, erect temporary shelters on the application area;

(c) take (including by hunting and gathering) and use traditional natural resources from the application area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(d) to assemble and conduct religious and spiritual activities and ceremonies on the application area;

(e) maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the native title holders under their traditional laws and customs and protect those places and areas, by lawful means, from physical harm;

(f) teach on the application area the physical and spiritual attributes of the application area;

(g) light fires on the application area for traditional purposes and in accordance with traditional law and custom;

(h) be buried on the application area in accordance with traditional law and custom;

(i) hunt, fish, travel in or on, and gather from, the water for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes; and

(j) take and use the water for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes.

8 The claim area is not overlapped by any other native title claim and there are no Aboriginal respondent parties to the application.

Separate questions

9 On 6 December 2017, the Court made orders under r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that the following questions (the Separate Questions) be determined separately from any other questions in the proceeding:

1. But for any question of extinguishment of native title, does native title exist in relation to any and, if so, what land and waters of the claim area?

2. In relation to that part of the claim area where the answer to (a) above is in the affirmative:

(a) Who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title?

(b) What is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

10 Thus, issues of extinguishment and the nature and extent of other interests in the claim area (including questions arising under subs 225(c), (d) and (e) of the Native Title Act) are to be determined after the determination of the Separate Questions.

11 At the same time, orders were made to progress the matter to a hearing of the Separate Questions including:

(a) orders requiring any respondent, other than the State, that wished to participate in the hearing of the Separate Questions to nominate themselves;

(b) orders requiring the service of pleadings in respect of the Separate Questions; and

(c) orders requiring the filing of lay and expert evidence for the purposes of the hearing.

12 While there are almost 100 respondent parties to the proceeding, only the State elected to participate in the hearing of the Separate Questions.

13 These reasons answer the Separate Questions.

Orthography

14 The applicant’s anthropological expert, Dr Martin, observed that, over the years, the name “Ganggalu” has appeared in the ethnographic and historical record with a variety of spellings to refer to an Aboriginal group. While most of these names vary somewhat from the modern spelling of the word Ganggalu, Dr Martin expressed the opinion that the different names can be seen as antecedents for the current Ganggalu people, which include the Western Kangoulu people.

15 Dr Martin’s preferred spelling of the group name is Ganggalu. Dr Martin explained that he has included the phoneme ‘ng’ (Ganggalu, as in the English sing) as well as the dorso-velar consonant ‘g’ (i.e. Ganggalu) to reflect the way in which contemporary claimants tend to pronounce this word, as Ga/ng/g/alu. Dr Martin observed that the word could alternatively be spelt Gangkalu or Kangkalu, with the letters ‘g’ and ‘k’ identifying the same sound.

16 Dr Martin noted that the witnesses in the proceeding used a variety of spellings to describe the Ganggalu people, including the spelling Kangoulu with which the native title claim was registered. When making reference to these statements, and also in making reference to the application for the recognition of native title, Dr Martin used the spelling adopted by those who made the application, i.e. Western Kangoulu.

17 In contrast, when referring to the evidence given by a witness, these reasons adopt the spelling used by the witness; when referring to the native title claim more generally, these reasons adopt the spelling with which the application was made, Western Kangoulu; when referring more generally to the tribal group from whom the GNP claim group and Western Kangoulu claim group are descended, these reasons adopt Dr Martin’s preferred spelling, Ganggalu.

Procedural history

18 The determination of the Separate Questions has a lengthy procedural history which has caused delay in the publication of these reasons. An understanding of the procedural history is necessary for a full understanding of these reasons. Accordingly, it is addressed at the outset.

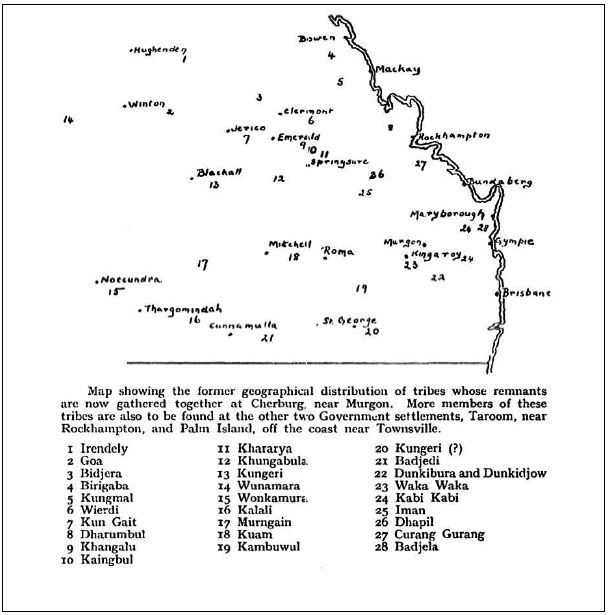

The “Ganggalu cluster” native title claims

19 The preparation of expert evidence for the Western Kangoulu claim occurred in parallel with the preparation of expert evidence in, and conferral with respect to, a number of related native title applications made over areas that were close to, but did not overlap, the area of the Western Kangoulu claim. The related native title claims were:

(a) the Gaangalu Nation People native title claim (QUD 33 of 2019, referred to herein as the GNP claim);

(b) the Wadja native title claim (QUD 28 of 2019, referred to herein as the Wadja claim); and

(c) the Wulli Wulli People #3 (Part A) claim (QUD 619 of 2017, referred to herein as the Wulli Wulli 3A claim).

20 Those claims and the Western Kangoulu claim have been collectively described as the “Ganggalu cluster” claims (or with the alternative spelling “Gaangalu cluster”, or the abbreviated “GNP cluster”). Part of the eastern boundary of the Western Kangoulu claim area abuts the western boundary of the GNP claim area and part of the southern boundary of the GNP claim area abuts the northern boundary of the Wadja claim area and the northern boundary of the Wulli Wulli 3A claim area.

21 The applicants in each of the Ganggalu cluster claims retained different anthropologists as expert witnesses:

(a) Dr de Rijke was retained by the applicant in the GNP claim and prepared a number of expert reports in respect of that claim including an application report in 2012 and a connection report in 2014;

(b) Mr McCaul was retained by the applicant in the Wadja claim and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim in 2013;

(c) Mr McCaul was also previously retained by the applicant in the Western Kangoulu claim and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim in 2015;

(d) Dr Martin and Dr Gorring were subsequently retained by the applicant in the Western Kangoulu claim in place of Mr McCaul and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim dated 13 September 2018; and

(e) Dr Powell was retained by the applicant in the Wulli Wulli 3A claim and prepared an expert report in respect of that claim dated 13 September 2018.

22 In 2018, the applicants in the Western Kangoulu, GNP and Wadja claims commissioned Dr Martin, Dr Gorring, Dr de Rijke and Mr McCaul to produce a joint statement of their respective opinions on the nature and extent of the relevant society or societies in relation to the GNP claim, the Wadja claim and the Western Kangoulu claim, and how the society or societies may be defined, considering:

(a) its constituent groups and geographical extent;

(b) the traditional laws and observed customs which underpinned the relevant society or societies, including with respect to land tenure;

(c) whether some or all of the native title claim groups described in the GNP claim, the Wadja claim and the Western Kangoulu claim were part of the same society, or separate societies with social and cultural links arising from their regional proximity; and

(d) the continuing functioning and status of the constituent groups as a society or societies since the acquisition of British sovereignty.

23 The joint statement prepared by Dr Martin, Dr Gorring, Dr de Rijke and Mr McCaul in response is dated 21 May 2018.

24 Subsequently, the applicants in the Western Kangoulu and GNP claims commissioned Dr de Rijke, Dr Martin and Dr Gorring to produce a joint statement concerning:

(a) the evidence/ethnography and historic record regarding the apical ancestors in common to the GNP claim and the Western Kangoulu claim and their descendants including any contemporary assertions of rights in the claim area of the GNP claim;

(b) whether this evidence provides support for the proposition that the descendants of those ancestors today hold traditional rights and interests in the GNP claim area;

(c) to the extent that the proposition above is supported, the strength of this support, and the nature and geographic extent of such rights; and

(d) whether any omission of the common apicals from the claim group description of the GNP claim would be contrary to the evidence, including consideration of the society for the GNP claim.

25 The joint statement prepared by Dr Martin, Dr Gorring and Dr de Rijke in response is dated 31 May 2018.

Pleadings

26 Following a dispute that arose between the parties regarding the form of pleadings (details of which are set out in Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland [2020] FCA 1188 (Malone No 1)), on 30 March 2020 orders were made providing for a different means of defining the issues in dispute between the parties. Pursuant to those orders, the applicant was required to prepare a statement of facts and matters which it sought the State to admit, and the State was required to prepare a responsive document. These documents were to supersede all pleadings filed in relation to the Separate Questions.

27 In accordance with those orders, on 17 April 2020 the applicant filed a statement of facts and matters. The State filed its response on 8 May 2020. The applicant subsequently filed an amended statement of facts and matters on 10 August 2022 and the State filed an amended response on 25 August 2022. On 15 September 2022, toward the end of the trial of the Separate Questions, the applicant filed a further amended statement of facts and matters.

28 As discussed further below, on 6 March 2025 leave was given to the applicant to tender a statement of agreed facts executed by the applicant and the State of Queensland on 19 February 2025 and to file and serve a (awkwardly named) further further amended statement of facts and matters dated 20 February 2025.

Expert evidence and subsequent conferral and conciliation

29 Under timetabling orders made by the Court and the supervision of a Registrar of the Court, the applicant and the State prepared expert evidence in respect of the Separate Questions and the experts participated in a process of conferral. As noted above, this process occurred in parallel with the preparation of expert evidence in, and conferral with respect to, the Ganggalu cluster native title claims. For present purposes, it is sufficient to note that:

(a) on 14 September 2018, the applicant filed an anthropological report co-authored by Dr Richard Martin and Dr Dee Gorring and dated 13 September 2018 and a genealogical report of Dr Hilda Maclean also dated 13 September 2018; and

(b) on 9 November 2018, the State filed an anthropological report of Dr Anna Kenny.

30 On 21 and 22 February 2019, conclaves were held between the expert anthropologists retained by the applicant in this proceeding, by applicants in the other Ganggalu cluster claims, and by the State in each of those proceedings. Those conclaves resulted in two joint expert reports directed to the Separate Questions. In those joint reports, agreement was expressed by the experts appointed by the applicant and by the State (Dr Kenny) that the applicant holds native title in the Western Kangoulu claim area. Notwithstanding that agreement, the State informed the applicant that: it did not accept the conclusions expressed by the experts in the joint reports; it was not satisfied that there was a credible basis for the native title application; and, therefore, it was unwilling to negotiate a consent determination under s 87 of the Native Title Act. In those circumstances, the State elected not to call Dr Kenny as a witness in the trial of the Separate Questions.

31 By an interlocutory application filed on 22 May 2020, the applicant sought an order striking out the State’s response to the applicant’s statement of facts and matters which would have had the effect of summarily removing the State’s opposition to the Separate Questions (in circumstances where the State was the only party actively participating in the determination of the Separate Questions and, therefore, the only contradictor). For the reasons set out in Malone No 1, I did not accept the applicant’s contentions and ultimately dismissed the interlocutory application. An application for leave to appeal against that decision was refused by a majority of the Full Court: Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (2021) 287 FCR 240 (Malone FC) at [242] per White and Stewart JJ (Rangiah J would have granted leave but dismissed the appeal).

32 On 1 October 2020, the Court made orders requiring the parties to take steps with the aim of facilitating conciliation of the native title claim between the applicant and the State. The reasons for those orders are discussed in Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2020] FCA 1414. Unfortunately, the conciliation failed to bring about agreement between the applicant and the State with respect to the Separate Questions at that time.

Filing of supplementary expert evidence for trial

33 In preparation for the trial of the Separate Questions, the applicant filed supplementary expert evidence. As noted above, Dr Martin originally prepared a joint anthropological report with Dr Gorring dated 14 September 2018. However, Dr Gorring was not available to give evidence at the hearing. Dr Martin prepared a supplementary report dated 20 August 2021 and also prepared a revised version of the report originally co-authored with Dr Gorring which is dated 18 March 2022. As discussed further below, the applicant also sought to tender at the hearing a range of other expert material, which is the subject of evidentiary rulings made in Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2022] FCA 827 (Malone No 3). Dr Maclean also prepared two further genealogical reports on specific issues.

Trial of the Separate Questions

34 At the trial of the Separate Questions, the State adduced no evidence. It argued, however, that the evidence adduced by the applicant at the hearing was not such as would persuade the Court that a determination of native title should be made.

35 The trial of the Separate Questions occurred over the course of 10 hearing days. Between 30 August 2022 and 7 September 2022, the Court heard evidence in Emerald and other locations within the claim area from lay witnesses called by the applicant. On 15 and 16 September 2022, the Court heard expert evidence from Dr Martin and received the reports from Dr Maclean (who was not required for cross-examination). On 24 November 2022, the Court heard closing submissions. At the conclusion of the hearing, I reserved judgment.

Post-trial mediation

36 On 11 August 2023, the Court received an email communication from the solicitors for the State informing the Court that the applicant and the State had met on a without prejudice and confidential basis to discuss whether an agreement to settle the proceeding was possible in advance of the Court’s decision on the Separate Questions. The parties requested time to continue discussions and the relisting of the matter to update the Court at a later date.

37 On 6 October 2023, the solicitors for the State advised the Court by email that the parties were continuing to confer and requested further time for those discussions. As a result, a case management hearing was listed for 8 December 2023.

38 At the case management hearing on 8 December 2023, the applicant informed the Court that the applicant and the State had discussed the principles upon which a possible settlement might occur, but that it would be necessary for the applicant to seek authorisation from the claim group in order to determine whether it had authority to proceed. The applicant also informed the Court that, if the applicant was given authority to proceed on the basis of the principles that had been discussed with the State, it might take the parties a further 12 months to negotiate the agreement as it would involve the National Native Title Tribunal processes. The applicant requested that the Court withhold delivering judgment on the Separate Questions in order for those processes to continue. The State informed the Court that it supported the applicant’s request. At the case management hearing, I informed the parties that the Court would act in accordance with their request.

39 On 27 February 2024, the Court received an email communication from the solicitor for the applicant informing the Court that the negotiations between the applicant and the State had concluded without a settlement being reached. At the time of receiving this email, I was scheduled to take a period of extended leave from the Court. In those circumstances, I convened a further case management hearing on 23 March 2024 to ask the parties whether they would be willing to engage in further mediation before a Registrar of the Court whilst I was on leave. The applicant informed the Court that it was prepared to engage in mediation, and the State informed the Court that it was not resistant to engaging in mediation. In the circumstances, I made orders pursuant to s 86B(5) of the Native Title Act referring the proceeding to mediation before a Judicial Registrar of the Court, for the mediation to be conducted by 31 May 2024 and for the mediator to report to the court whether the mediation had resulted in a settlement of the proceeding or had not resulted in a settlement of the proceeding within three days after mediation had been completed. Given the circumstance that the Court had reserved judgment on the Separate Questions, I also made an order that the mediator was not to appear before the Court in relation to the proceeding or provide any report to the Court in relation to the proceeding other than as contemplated by the order.

40 On 24 May 2024, the applicant and the State reported to the Court that they wished to continue the mediation and an order extending the mediation was made by the Court on 29 May 2024.

41 On 30 August 2024, the applicant and the State reported to the Court that they wished to continue the mediation and a further order extending the mediation was made by the Court on 3 September 2024.

42 On 23 September 2024, the applicant and the State reported to the Court that they wished to seek orders to:

(a) have the matter remain in mediation;

(b) give leave to the applicant to file a further supplementary report of Dr Martin;

(c) give leave to the applicant to file a statement of agreed facts that would replace earlier pleadings in respect of the Separate Questions; and

(d) have the matter listed for a further case management hearing on a date no earlier than 6 December 2024.

43 In response to that report, a case management hearing was listed for 10 October 2024 at which the proposed orders were discussed. At the case management hearing, the applicant and the State informed the Court that they contemplated being in a position jointly to seek leave to re-open the hearing of the Separate Questions to adduce a further supplementary report of Dr Martin and to tender a statement of agreed facts that would replace earlier pleadings in respect of the Separate Questions, and which would either eliminate or substantially narrow the issues in dispute between them. No formal orders were made at that case management hearing, but the Court requested the parties to file any such application by 6 December 2024.

Joinder application

44 On 28 November 2024, Michael Paul Huet filed an interlocutory application seeking an order that he be joined as a respondent party to the proceedings pursuant to ss 84(5) and 84(5A) of the Native Title Act. The application was supported by an affidavit made by Mr Huet on 3 December 2024 and an affidavit made by Raymond Alfred Martin on 2 December 2024.

Application for leave to re-open the trial

45 On 6 December 2024, the applicant filed the foreshadowed application for leave to re-open the trial of the Separate Questions for the purpose of:

(a) filing and adducing in evidence a further supplementary expert report of Dr Richard Martin entitled “Short Report in relation to Society and Boundaries in the Western Kangoulu native title claim” dated 26 July 2024; and

(b) filing and tendering in evidence any statement of agreed facts executed by them.

46 The application was supported by an affidavit of David John Knobel, the solicitor for the applicant, made on 6 December 2024. The affidavit exhibited a copy of Dr Martin’s further supplementary report.

47 On 12 December 2024, a further hearing was conducted. At the hearing, the applicant sought leave to re-open the hearing of the Separate Questions to file and adduce in evidence Dr Martin’s further supplementary report. The State did not oppose the grant of leave. The State also informed the Court that it considered it would not be appropriate to proceed with the application relating to the proposed statement of agreed facts in circumstances where Mr Huet’s application to be joined to the proceeding as a respondent had not been determined. At the conclusion of the hearing, I made orders:

(a) granting the applicant leave to reopen the hearing of the Separate Questions for the purpose of adducing in evidence Dr Martin’s further supplementary report;

(b) timetabling the joinder application for hearing on 31 January 2025; and

(c) requiring any application for leave to reopen the hearing of the Separate Questions for the purpose of adducing in evidence a statement of agreed facts and/or to amend the pleadings with respect to the Separate Questions to be filed and served no later than 21 February 2025.

48 On 31 January 2025, I heard and dismissed the joinder application filed by Mr Huet with reasons published in Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 4) [2025] FCA 36.

49 On 20 February 2025, the applicant filed an application for leave to reopen the hearing of the Separate Questions for the purpose of:

(a) filing and adducing in evidence a statement of agreed facts dated 19 February 2025 executed by the applicant and the State; and

(b) filing and serving a further further amended statement of facts and matters dated 20 February 2025.

50 The application was supported by an affidavit of David John Knobel, the solicitor for the applicant, made on 20 February 2025. The affidavit exhibited a copy of the statement of agreed facts and the further further amended statement of facts and matters. Mr Knobel deposed that the applicant and the State sought the Court’s leave to file the statement of agreed facts as evidence of their preparedness to resolve the entire proceeding, including the Separate Questions, by way of a determination by consent under s 87 of the Native Title Act.

51 On 6 March 2025, a further hearing was conducted. At the hearing, the applicant sought leave to re-open the hearing of the Separate Questions to file and tender in evidence the statement of agreed facts and to file and serve the further further amended statement of facts and matters. The State supported the grant of leave. At the conclusion of the hearing, I made orders granting the leave sought by the applicant.

52 The statement of agreed facts and its effect on the determination of the Separate Questions is discussed below.

Issues for determination at the time of trial

53 The issues to be determined at the time of trial of the Separate Questions were defined by the applicant’s further amended statement of facts and issues dated 15 September 2022 and the State’s earlier responsive document dated 25 August 2022.

54 It is fair to describe the State’s position on the Separate Questions as putting the applicant to proof. In response to most of the allegations of fact made by the applicant in its further amended statement of facts and issues, the State said that it did not know and therefore could not admit the allegation. As noted above, the State adduced no evidence at the trial of the Separate Questions, other than by way of tender of a relatively small number of documents in the course of cross-examination.

55 The primary issues that were required to be determined on the basis of the evidence adduced at trial were the following:

(a) Who were the Aboriginal persons who held rights and interests in the land and waters of the claim area pursuant to their traditional laws and customs prior to the assertion of British sovereignty over that area?

(b) What were the traditional laws and customs of the Aboriginal persons referred to in question (a), so far as can be known?

(c) Under the traditional laws and customs of the Aboriginal persons referred to in question (a), were rights and interests in the land and waters of the claim area acquired by descent?

(d) If so, are the members of the Western Kangoulu claim group the descendants of the Aboriginal persons referred to in question (a)?

(e) If so, does the Western Kangoulu claim group continue to acknowledge and observe the traditional laws and customs under which rights and interests in the land and waters of the claim area are possessed and by which they have a connection to the land and waters of the claim area?

(f) If so, what are those rights and interests?

56 The answer to question (a) has been a contentious issue in both this proceeding and in the “Ganggalu cluster” native title claims. The applicant’s anthropological expert, Dr Martin, explained in evidence that there is a relatively limited ethnographic record with respect to Aboriginal people in the claim area and surrounding areas, in comparison to other regions within Queensland and Australia. Dr Martin commented that, while a number of useful historical sources exist, first-hand anthropological and other socio-cultural research relating to the traditional laws and customs of Aboriginal people in the area is lacking.

57 Dr Martin’s opinion with respect to the identification of the Aboriginal people who occupied the claim area at sovereignty underwent some development over time, resulting from additional research undertaken by Dr Martin. It is, of course, entirely appropriate for an expert witness to amend their opinion in response to further data or research. That was the case with Dr Martin. The development in Dr Martin’s opinions did not cause me to doubt his expertise or the reliability of the opinions he expressed.

58 At the time of trial, and reflecting Dr Martin’s opinion at that time, the applicant contended that the Aboriginal people who occupied the Western Kangoulu claim area at sovereignty were part of a “broader Ganggalu regional society”, which “may have included people who identified as Wadja or Garingbal”. This reference to a broader Ganggalu regional society was based on early historical and ethnographic material that suggested that Ganggalu people occupied both the Western Kangoulu claim area and a broader area, including the claim area of the GNP claim, and that Wadja and Garingbal people may also have been part of the broader Ganggalu regional society.

59 As noted earlier, part of the eastern boundary of the Western Kangoulu claim area abuts the western boundary of the GNP claim area and the two claim areas can be described as adjacent, with the Western Kangoulu claim area being to the west and the GNP claim area being to the east. On 15 June 2023, Rangiah J concluded that the applicants in the GNP claim were unable to establish that they hold native title in the claim area: Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2023] FCA 600 (Blucher No 3). His Honour found (at [1243]) that, under their traditional laws and customs, the Gaangalu people occupied much of the GNP claim area at sovereignty, but were dispossessed of their land through European settlement and violent dispersal, and then by legislative and executive actions. His Honour concluded that native title does not exist today because the Gaangalu people were not able to prove that they continue to acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs under which they possess native title rights and interests. On 30 April 2024, Rangiah J made a negative determination of native title in respect of part of the GNP claim area, declaring that native title does not exist in relation to any part of the claim area to the west of the Dawson River: Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland (No 4) [2024] FCA 425 (Blucher No 4). An appeal has been brought by the GNP applicant against the decisions made in Blucher No 3 and Blucher No 4 but, at the date of these reasons, no judgment on the appeal has been delivered.

60 The answer to questions (e) and (f) has been equally contentious in this proceeding for two reasons. First, a question arises about the extent to which the Western Kangoulu claim group continues to acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs. Second, and relevantly for present purposes, a question arises about the identification of the Western Kangoulu claim group as, in effect, a sub-group of the “broader Ganggalu regional society”.

61 At the time of trial, Dr Martin expressed the opinion that, at sovereignty, the claim area was occupied by patrilineal local descent groups who were typically referred to in local languages with the use of the suffix ‘-bara/-burra/-bora[-bura]’ meaning ‘of’ or ‘belonging to’. Each such group occupied its own local areas within the broader area occupied by the regional society. With respect to the position today, Dr Martin expressed the opinion that:

Knowledge of such local groups and their territories has been lost across the Western Kangoulu claim group since colonisation, with Aboriginal people of the claim area today identifying with the label ‘Western Kangoulu’ which is derived from a linguistic or ‘tribal’ label rather than the name of a local group, in an adaptation of traditional law and custom. My opinion is that the label Western Kangoulu represents an amalgamation or coalescing of local groups with traditional connections to the Western Kangoulu claim area. In my opinion, Western Kangoulu people are the landholding group today rather than the patrilineal groups which existed at colonisation.

62 On the question whether the GNP claim group might also hold rights and interests in the Western Kangoulu claim area, Dr Martin expressed the opinion that:

… claimants recognise a shared identity with members of the Gaangalu Nation People. However, my revised opinion is that this shared identity does not indicate the holding of rights in common across the territory thought to belong to the larger language speaking or ‘tribal’ group. My revised opinion is that such things as the right to identify as a Kangoulu/Ganggalu people and to teach children about the Kangoulu/Ganggalu people do not relate to the holding of rights in country, and should not be described as ‘generic’ native title rights.

Absence of any competing native title claim to the claim area

63 In this proceeding, the applicant placed some reliance on the fact that there is no competing native title claim to the claim area and the claim by the Western Kangoulu people is not opposed by any Aboriginal respondent. The applicant’s anthropological expert, Dr Martin, expressed the opinion that the lack of overlapping claims or other legal disputes relating to the Western Kangoulu people’s native title claim indicates tacit support for the claim amongst neighbouring groups.

64 The absence of a competing native title claim should be acknowledged, but the inference sought to be drawn by the applicant from that fact must be treated with some caution. There may be a number of explanations for the absence of a competing native title claim.

65 It is correct that native title claimants in surrounding areas have not sought to oppose the Western Kangoulu claim. In particular, the claimants in the GNP claim (discussed above) made a claim in respect of an area that abuts the eastern boundary of the Western Kangoulu claim area, but have not claimed rights and interest in respect of the Western Kangoulu claim area or sought to oppose the Western Kangoulu claim. As noted above, the GNP claim was dismissed on 15 June 2023, with the Court concluding that the Gaangalu people were not able to prove that they continue to acknowledge and observe traditional laws and customs under which they possess native title rights and interests. Similarly, the claimants in the Clermont-Belyando Area native title claim (QUD25/2019) have not sought to oppose the Western Kangoulu claim. The claim area for that native title claim abuts the western and northern boundaries of the Western Kangoulu claim area. The claim was filed on behalf of a claim group calling itself the Wangan and Jagalingou people. Subsequently, a native title claim was filed on behalf of the Jangga people (QUD296/2020) which partly overlapped the claim area of the Clermont-Belyando Area native title claim. The question whether native title existed in the claim area of the Clermont-Belyando Area native title claim was heard by the Court over a period from 2019 to 2021. On 23 December 2021, Reeves J concluded that neither claim group had established that the ancestors of its members held rights and interests in the land and waters of the claim area under their traditional laws and customs at the time of the assertion of British sovereignty over the land and waters: Malone v State of Queensland (The Clermont-Belyando Area Native Title Claim) (No 5) [2021] FCA 1639; 397 ALR 397 (Clermont-Belyando No 5) (at [1220] and [1221]). An appeal from that decision was dismissed on 12 December 2023: see Malone on behalf of the Clermont-Belyando Area Native Title Claim Group v State of Queensland [2023] FCAFC 190 in respect of the Clermont-Belyando Area native title claim and McLennan on behalf of the Jannga People #3 v State of Queensland (2023) 301 FCR 452 in respect of the Jannga people native title claim.

66 It should be acknowledged that native title applications have previously been made in respect of part or all of the Western Kangoulu claim area. Those applications are the Kangoulu People claim #1 (QUD6195/1998), the Wangan/Jagalingou People claim (QUD78/2005), the Garingbal Kara Kara claim (QUD23/2006) and the Bidjara People #7 claim (QUD644/2012). Each of those applications was either withdrawn or dismissed by the Court. Evidence was given about the background to some of those claims, but it is unnecessary to refer to that evidence in any detail. The evidence establishes, however, that members of the Western Kangoulu claim group have asserted native title rights and interests in the claim area from soon after the enactment of the Native Title Act.

67 In its closing submissions at trial, the State placed some emphasis on the fact that the Bidjara People #7 claim (which overlapped the Western Kangoulu claim area) was dismissed as an abuse of process in Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v State of Queensland [2016] FCA 777 (Wyman No 6 and 7). In Wyman No 6 and 7, the Court concluded that the Bidjara People #7 claim was an attempt to relitigate an issue of fact which had been determined adversely to the Bidjara in the earlier decision Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229 (Wyman No 2). In Wyman No 2, the Court concluded that, while at sovereignty the Bidjara held rights and interests in Carnarvon Gorge and Carnarvon National Park under their traditional laws and customs, the people who now identify as Bidjara no longer do so. The Court was not satisfied that a body of traditional law and customs, as opposed to attenuated or transformed fragments of law and customs, had continued (at [672]). An appeal against the conclusion in Wyman No 2 was unsuccessful: Wyman v Queensland (2015) 235 FCR 464 (Wyman FC). In Wyman No 6 and 7, the Court concluded that the earlier finding in Wyman No 2, that the traditional laws and customs of the Bidjara had not continued, was fatal to its claim in respect of the area that overlapped the Western Kangoulu claim area.

68 It can be accepted, as the State submitted, that the dismissal of the Bidjara People #7 claim did not involve any consideration by the Court of whether the Bidjara held rights and interests in the Western Kangoulu claim area at sovereignty. The claim was dismissed because the Court had earlier found (in respect of a different claim area) that the traditional laws and customs of the Bidjara were no longer acknowledged and observed to an extent that would sustain a finding of native title. However, some account can be taken of the fact that the Bidjara have not sought to oppose the Western Kangoulu claim. Despite the dismissal of the Bidjara People #7 claim, a representative of the Bidjara would have been legally entitled to become a respondent to the Western Kangoulu claim in order to oppose the claim (on the basis that the claim area was the traditional country of the Bidjara at sovereignty). It is therefore of some significance that no representative of the Bidjara people, or any other Aboriginal community, took that step.

The parties’ post-trial agreement

69 As discussed above, following the conclusion of the hearing of the Separate Questions, the applicant and the State engaged in mediation which culminated in the execution and filing of a statement of agreed facts addressing the Separate Questions. The applicant also filed a further supplementary expert report of Dr Martin which supports the conclusions stated in the statement of agreed facts, and the applicant filed a further further amended statement of facts and matters which brought the applicant’s claim into line with the statement of agreed facts. Each of those documents is summarised below.

Statement of agreed facts

70 The facts agreed in the statement of agreed facts are reproduced in full in Annexure B to these reasons. In summary, the applicant and the State have reached agreement with respect to the following facts for the purposes of, and as contemplated by, s 87(8) of the Native Title Act (which is discussed further below).

71 First, the parties agree that it is likely that the following persons (apical ancestors) held rights and interests in the claim area under the pre-sovereignty laws and customs acknowledged and observed by the Aboriginal people associated with the claim area, as at, or shortly after, effective sovereignty:

(a) Polly aka Polly Brown aka Polly McAvoy;

(b) John 'Jack' Bradley;

(c) Hanny of Emerald;

(d) Nannie, mother of Nelly Roberts; and

(e) Annie/Nanny Duggan and Ned Duggan.

72 Second, from generation to generation since effective sovereignty, the Western Kangoulu people have likely continued to acknowledge and observe most of the pre-sovereignty laws and customs related to rights and interests in the claim area. Although the pre-sovereignty laws and customs have undergone varying degrees of loss, change and adaptation, the contemporary system of laws and customs under which rights and interests are held in the claim area remain rooted in the pre-sovereignty laws and customs. Those laws and customs include:

(a) an understanding of the mythology of the claim area, including the spiritual forces inhering in the land or waters of the claim area;

(b) a system of inheritance of identity and rights in land through different genealogical links, including adoption;

(c) an understanding of spirits in the landscape, including appropriate ways of managing spiritual presence;

(d) an embodied relationship between people and their land and waters;

(e) the inalienability of rights in land and waters;

(f) a variety of responsibilities to manage and protect the land and waters;

(g) the customary use of natural resources;

(h) recognition of gender specific and other sensitive significant sites at which certain access protocols apply;

(i) a kinship system; and

(j) a system of authority emphasising the role of senior people.

73 Third, by the foregoing laws and customs that they continue to acknowledge and observe, the Western Kangoulu people likely have a connection to, and hold native title rights and interests in, the land and waters of the claim area.

74 Fourth, those native title rights and interests are the following non-exclusive rights and interests in the claim area:

(a) the right to access, be present on, move about on, and travel over the claim area;

(b) the right to camp on the claim area, and for that purpose, erect temporary shelters on the claim area;

(c) the right to take natural resources from the land and waters of the claim area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(d) the right to take the water of the claim area for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes;

(e) the right to maintain places of importance and areas of significance to the Western Kangoulu people under their adapted laws and customs, and protect those places and areas, from physical harm;

(f) the right to teach Western Kangoulu people the physical and spiritual attributes of the claim area;

(g) the right to bury Western Kangoulu people within the claim area;

(h) the right to assemble and conduct ceremonies and other cultural activities on the claim area; and

(i) the right to light fires on the claim area for cultural, spiritual or domestic purposes including cooking, but not for the purpose of hunting or clearing vegetation.

Further supplementary expert report of Dr Martin

75 As noted above, on 12 December 2024, I granted the applicant leave to re-open the trial of the Separate Questions for the purpose of filing and adducing in evidence a further supplementary expert report of Dr Martin.

76 The further supplementary expert report of Dr Richard Martin provided expert anthropological support for the statement of agreed facts. The report reflects a further development of Dr Martin’s opinion with respect to the “broader Ganggalu regional society” at sovereignty and the Western Kangoulu people today. Again, the development of Dr Martin’s opinion is based on additional information he received and additional research he undertook. Having reviewed the report, the development in Dr Martin’s opinion does not cause me to doubt Dr Martin’s expertise or the reliability of the opinions he has expressed. By agreeing to the statement of agreed facts, it is apparent that the State has reached the same conclusion.

77 In the further supplementary report, Dr Martin explained that he no longer considered that the concept of a broader regional society at sovereignty encompassing Gaangalu, Wadja and Garingbal people to be relevant. The observations concerning such a regional society arose from the substantial similarities of law and custom between those groups. However, it is Dr Martin’s view that, at sovereignty:

Gaangalu/Kangoulu people, that is, members of the Western Kangoulu and Gaangalu Nation People, were themselves a society 'which is united in and by law and custom' and comprised of 'people who share that common identity and language as Ganggalu people’ …

78 With respect to the position today, Dr Martin expressed the opinion that Western Kangoulu people today comprise a “society” (within the meaning of that word in native title jurisprudence). Dr Martin explained that:

Data from the lay evidence hearing indicate that Western Kangoulu people consistently describe themselves as united by their group identity, their laws and customs and their connection to the claim area through their ancestors. These data further demonstrate that Western Kangoulu people understand themselves to comprise a distinct group notwithstanding their broader view that they also share a common linguistic identity and traditional laws and customs which unites them with the adjoining Gaangalu Nation People.

Further further amended statement of facts and matters

79 By its further further amended statement of facts and matters, the applicant removed from its claim the contention that the Aboriginal people who occupied the claim area at sovereignty were part of a broader Ganggalu regional society which included people who identified as Wadja or Garingbal. In its place, the applicant inserted the contention that the Aboriginal people who occupied the claim area at sovereignty shared traditional laws and customs with a broader group of Gaangalu people who occupied land and waters extending from the Mackenzie and Comet Rivers east to the Dawson River. The applicant also clarified its contention that, today, the members of the Western Kangoulu claim group continue to be united in and by the pre-sovereignty laws and customs, as adapted, and continue to possess rights and interests in all of the land and waters of the claim area.

The legal effect of the statement of agreed facts

80 The agreement reached by the applicant and the State on the facts recorded in the statement of agreed facts is a significant milestone in this proceeding. The statement of agreed facts alters in a fundamental way the factual issues that were previously in dispute between the applicant and the State, and records the agreement between the applicant and the State on the central factual issues that are the subject of the Separate Questions. As the procedural history outlined above shows, it has taken a long period of time for the applicant and the State to reach agreement on these factual issues. It is commendable that the applicant and the State have committed themselves to the arduous process of research and analysis of the applicant’s claim to arrive at this point. In doing so, the applicant and the State have demonstrated their commitment to the principles recorded in the preamble to the Native Title Act, including the emphasis given to the role of conciliation as a means of justly and properly ascertaining native title rights and interests.

81 The evidentiary effect of a statement of agreed facts that is tendered in evidence is governed by s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) which stipulates that, in a proceeding, evidence is not required to prove the existence of an agreed fact and evidence may not be adduced to contradict or qualify an agreed fact, unless the court gives leave.

82 In proceedings under the Native Title Act, a statement of agreed facts may also be relied upon by the Court when making a determination of native title by consent under s 87(2) of the Native Title Act, or making an order in relation to a part of a proceeding or a matter arising out of a proceeding under ss 87(3) or (5). Subsections 87(8) to (11) relevantly stipulate as follows:

Agreed statement of facts

(8) If some or all of the parties to the proceeding have reached agreement on a statement of facts, one of those parties may file a copy of the statement with the Court.

(9) Within 7 days after a statement of facts agreed to by some of the parties to the proceeding is filed, the Federal Court Chief Executive Officer must give notice to the other parties to the proceeding that the statement has been filed with the Court.

(10) In considering whether to make an order under subsection (2), (3) or (5), the Court may accept a statement of facts that has been agreed to by some or all of the parties to the proceedings but only if those parties include:

(a) the applicant; and

(b) the party that the Court considers was the principal government respondent in relation to the proceedings at the time the agreement was reached.

(11) In considering whether to accept under subsection (10) a statement of facts agreed to by some of the parties to the proceedings, the Court must take into account any objections that are made by the other parties to the proceedings within 21 days after the notice is given under subsection (9).

83 In the statement of agreed facts, the applicant and the State recorded that the facts relating to the Separate Questions have been agreed for the purpose of a proposed consent determination under s 87 of the Native Title Act. That intention is also recorded in Mr Knobel’s affidavit dated 20 February 2025. However, the parties are not yet in a position to file an agreement on the terms of a consent determination under s 87 as issues of extinguishment and the nature and extent of other interests in the claim area (including questions arising under s 225(c), (d) and (e) of the Native Title Act) are to still to be finally determined. The final determination of those matters may take some time (perhaps 12 months).

84 In the present circumstances, the Court has a choice whether to wait for the parties to reach agreement on the terms of a consent determination pursuant to s 87 and finalise the proceeding exercising the powers conferred on the Court under s 87, or proceed to answer the Separate Questions taking into account the statement of agreed facts that has now been tendered. I have determined that the Court should proceed to answer the Separate Questions. While there is a high likelihood that the parties will be able to finalise an agreement on the terms of a consent determination pursuant to s 87, that result cannot be regarded as certain. There remains a possibility of disagreement with respect to the other issues that must be determined in the proceeding (issues of extinguishment and the nature and extent of other interests in the claim area). A decision on the Separate Questions has been reserved for a lengthy period and I consider it unsatisfactory for the decision to remain reserved for another lengthy period. By answering the Separate Questions, the Court will provide the parties with certainty about that aspect of the proceeding, which is likely to assist the parties in reaching agreement on the remaining issues to be determined.

85 In determining that the Court should proceed to answer the Separate Questions, I am also influenced by the fact that the parties have tendered the statement of agreed facts on the central factual issues that are the subject of the Separate Questions. As noted above, the evidentiary effect of tendering a statement of agreed facts is that evidence is not required to prove the existence of the agreed facts and evidence may not be adduced to contradict or qualify the agreed facts unless the Court grants leave.

86 That does not mean that the Court is bound to make findings in accordance with the agreed facts. As observed by the Full Court in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v BHF Solutions Pty Ltd (2022) 293 FCR 330 (at [24]), the effect of s 191 of the Evidence Act is to admit the agreed facts as evidence but it still remains for the Court to determine whether the facts are to be accepted as true and to determine what weight to attribute to that evidence. In the present case, the Court has heard extensive evidence with respect to the Separate Questions. That evidence cannot be ignored and the statement of agreed facts does not supplant that evidence. However, the Court is entitled to consider and weigh that evidence in light of the facts that have now been agreed between the parties.

87 A somewhat analogous circumstance arose in The Nyamal Palyku Proceeding (No 8) [2024] FCA 11 (Nyamal No 8). Justice Colvin conducted a trial to answer separate questions whether native title rights and interests existed in the claim area and, if so, the identity of the persons who held those rights. After the trial of the separate questions was completed and his Honour had reserved judgment, the parties reached agreement on the terms of a consent determination pursuant to ss 87 and 87A of the Native Title Act. In support of the consent determination, the parties filed a statement of agreed facts. Justice Colvin accepted the agreed facts, but his Honour also had regard to the evidence received during the hearing of the separate questions for the purpose of considering whether there is any aspect of that evidence that might mean that it is not appropriate to make the order sought without, at least, receiving further submissions from the parties (at [21]).

88 The present case differs from Nyamal No 8 because the parties are yet to reach agreement on the terms of a consent determination under s 87. I am answering Separate Questions, with the benefit of the statement of agreed facts, rather than exercising the powers conferred under s 87 to make a consent determination. Accordingly, it is necessary in the present case to assess all of the evidence before the Court, but to do so in light of the facts that have now been agreed between the parties.

89 At the hearing on 6 March 2025, the applicant and the State did not oppose the Court proceeding to answer the Separate Questions.

90 For completeness, it is noted that on 7 March 2025, the Chief Executive Officer of the Court gave notice to the other parties to the proceeding that the statement of agreed facts had been filed with the Court, in accordance with s 87(9) of the Native Title Act. None of those parties made any objection to the statement of agreed facts within 21 days after the notice was given. That fact will become relevant if and when the parties file an agreement on the terms of a determination pursuant to s 87(1) and the Court is requested to make an order consistent with the terms agreed by the parties pursuant to s 87(2).

B. APPLICABLE LEGAL PRINCIPLES

The statutory provisions

91 By the application filed pursuant to s 61(1) of the Native Title Act, the applicant seeks a determination of native title in relation to the claim area. A “determination of native title” is defined in s 225 of the Native Title Act as:

… a determination whether or not native title exists in relation to a particular area (the determination area) of land or waters and, if it does exist, a determination of:

(a) who the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title are; and

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in relation to the determination area;

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests in relation to the determination area; and

(d) the relationship between the rights and interests in paragraphs (b) and (c) (taking into account the effect of this Act); and

(e) to the extent that the land or waters in the determination area are not covered by a non‑exclusive agricultural lease or a non‑exclusive pastoral lease—whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of that land or waters on the native title holders to the exclusion of all others.

92 The Separate Questions concern only paragraphs (a) and (b) of that definition. The Separate Questions require the Court to determine:

(a) whether, but for any question of extinguishment, native title exists in relation to any and, if so, what land and waters of the claim area; and

(b) if so, who are the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising the native title and what is the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests?

93 Section 223(1) of the Native Title Act provides the following definition of the terms “native title” and “native title rights and interests”:

(1) The expression native title or native title rights and interests means the communal, group or individual rights and interests of Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders in relation to land or waters, where:

(a) the rights and interests are possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders; and

(b) the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders, by those laws and customs, have a connection with the land or waters; and

(c) the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

Judicial explication of native title rights and interests

94 As the plurality (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ) observed in Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria (2002) 214 CLR 422 (Yorta Yorta) at [32], [45], [75]-[76], the native title rights and interests to which the Native Title Act refers are rights and interests finding their origin in pre-sovereignty traditional law and custom; they are not a creature of the common law and they are not created by the Native Title Act. Their Honours observed (at [76]):

The Native Title Act, when read as a whole, does not seek to create some new species of right or interest in relation to land or waters which it then calls native title. Rather, the Act has as one of its main objects (s 3(a)) “to provide for the recognition and protection of native title” (emphasis added), which is to say those rights and interests in relation to land or waters with which the Act deals, but which are rights and interests finding their origin in traditional law and custom, not the Act …

95 Australian courts have long recognised that the connection which Aboriginal people have with their country, emanating from their traditional laws and customs, is essentially spiritual. In Western Australia v Ward (2002) 213 CLR 1 (Ward HC), the plurality (Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Gummow and Hayne JJ) said (at [14], citations omitted):

As is now well recognised, the connection which Aboriginal peoples have with “country” is essentially spiritual. In Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd, Blackburn J said that:

“the fundamental truth about the aboriginals’ relationship to the land is that whatever else it is, it is a religious relationship … There is an unquestioned scheme of things in which the spirit ancestors, the people of the clan, particular land and everything that exists on and in it, are organic parts of one indissoluble whole”.

It is a relationship which sometimes is spoken of as having to care for, and being able to “speak for”, country. “Speaking for” country is bound up with the idea that, at least in some circumstances, others should ask for permission to enter upon country or use it or enjoy its resources, but to focus only on the requirement that others seek permission for some activities would oversimplify the nature of the connection that the phrase seeks to capture. The difficulty of expressing a relationship between a community or group of Aboriginal people and the land in terms of rights and interests is evident. Yet that is required by the NTA. The spiritual or religious is translated into the legal. …

96 The plurality in Ward HC explained that the statutory definition of native title provided by s 223 has the following elements (at [17]):

(a) first, the rights and interests may be communal, group or individual;

(b) second, the rights and interests must be in relation to land or waters;

(c) third, the rights and interests are those possessed under the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders;

(d) fourth, by those laws and customs (in other words, the traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders under which the rights and interests are possessed), the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders have a connection with the land or waters; and

(e) fifth, the rights and interests are recognised by the common law of Australia.

97 Each of those elements of the definition has been the subject of detailed explication in the authorities.

Traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed

98 The phrase “traditional laws acknowledged, and the traditional customs observed, by the Aboriginal peoples or Torres Strait Islanders” in s 223(1)(a) is a reference to laws and customs having a normative content, being a body or system of normative rules that existed before the assertion of British sovereignty: Yorta Yorta at [38]-[40] and [46]. To speak of rights and interests possessed under an identified body of laws and customs is to speak of rights and interests that are the creatures of the laws and customs of a particular society that exists as a group which acknowledges and observes those laws and customs: Yorta Yorta at [50]). Laws and customs and the society which acknowledges and observes them are inextricably linked: Yorta Yorta at [55].

99 A “traditional” law or custom is one which has its origins in the normative rules of the relevant Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander society that existed before the assertion of British sovereignty and which has been passed from generation to generation in the society, usually by word of mouth and common practice: Yorta Yorta at [46]. The reference to rights or interests in land or waters being possessed under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the peoples concerned requires that the normative system under which the rights and interests are possessed (the traditional laws and customs) is a system that has had a continuous existence and vitality since sovereignty: Yorta Yorta at [47].

100 The plurality in Yorta Yorta was careful to note that reference to a normative system of traditional laws and customs may be distracting if undue attention is given to the word ‘system’, particularly if it were to be understood as confined in its application to systems of law that have the characteristics of a European body of written laws (at [39]). Nonetheless, the plurality observed that the term recognises the fundamental premise from which the decision in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 proceeded, that the laws and customs of the indigenous peoples of Australia constituted bodies of normative rules which could give rise to, and had in fact given rise to, rights and interests in relation to land or waters (at [40]). Accordingly, the laws and customs in which the relevant rights or interests are founded must be laws or customs having a normative content and deriving from a body of norms or normative system that existed before sovereignty (at [38] and [42]). In Wyman No 2, Jagot J observed (at [455]) that “normative content” means established behavioural norms in accordance with the recognised and acknowledged demands for conformity of a society.