FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Clorox Australia Pty Limited [2025] FCA 357

File number: | VID 315 of 2024 |

Judgment of: | NESKOVCIN J |

Date of judgment: | 14 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – alleged contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law – where representations made that kitchen tidy bags and garbage bags were made of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, when that was not the case – where parties jointly proposed agreed declarations of contravention, a pecuniary penalty and corrective advertising notice – whether relief sought is appropriate in all the circumstances – relief granted in the form proposed |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, Australian Consumer Law ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g), 33, 232, 224, 246(2)(b) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 21, 43 |

Cases cited: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mercer Superannuation (Australia) Limited [2024] FCA 850 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v LGSS Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 587 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd [2024] FCA 308 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd (No 2) [2024] FCA 1086 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68; [2017] FCAFC 113 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450; [2022] HCA 13 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Private Networks Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 384 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) 258 FCR 312 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640; [2013] HCA 54 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 278 FCR 450; [2020] FCAFC 130 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482; [2015] HCA 46 Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421; [1972] HCA 61 ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1; [2003] FCAFC 289 Self Care IP Holdings v Allergan Australia (2023) 277 CLR 186; [2023] HCA 8 Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v ACCC (2012) 287 ALR 249; [2012] FCAFC 20 Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Ltd (1995) ATPR 41-375 Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Number of paragraphs: | 114 |

Date of hearing: | 7 February 2025 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | O Bigos KC, A Muhlebach and L Schuijers |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Norton Rose Fulbright |

Counsel for the Respondent: | M Darke SC and A Smith |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Corrs Chambers Westgarth |

ORDERS

VID 315 of 2024 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | CLOROX AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED Respondent | |

order made by: | NESKOVCIN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 14 APRIL 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

Kitchen Tidy Bag Products

1. The Respondent, on multiple occasions between about June 2021 and July 2023, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA);

(b) in connection with the supply, possible supply, and promotion of the supply of its products, made false or misleading representations as to:

(i) the composition of its products, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL;

(ii) the environmental benefits of its products, in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(c) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, and the characteristics of its products, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL,

in that it supplied and promoted each of the small, medium and large sizes of the “GLAD to be Green” “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled” kitchen tidy bag product packaged as shown in Annexure One thereby representing that the product was comprised of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea; when in fact, the products were not comprised of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea. Rather, each size of the product was comprised of:

(d) plastic resin at least 50% of which was derived from recycled plastic that had been collected from communities with no formal waste management systems situated up to 50 kilometres from a shoreline;

(e) plastic resin not derived from recycled plastic; and

(f) processing aid and dye/ink.

Garbage Bag Products

2. The Respondent, on multiple occasions between about May 2022 and July 2023, in trade or commerce:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s18 of the ACL;

(b) in connection with the supply, possible supply, and promotion of the supply of its products, made false or misleading representations as to:

(i) the composition of its products, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL;

(ii) the environmental benefits of its products, in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(c) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, and the characteristics of its products, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL,

in that it supplied and promoted each of the large and extra-large sizes of the “GLAD to be Green” “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled” garbage bag products packaged as shown in Annexure One thereby representing that the product was comprised of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, when in fact the products were not comprised of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea. Rather, each size of the product was comprised of:

(d) plastic resin at least 50% of which was derived from recycled plastic that had been collected from communities with no formal waste management systems situated up to 50 kilometres from a shoreline;

(e) plastic resin not derived from recycled plastic; and

(f) processing aid and dye/ink.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary penalties

3. The Respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $8.25 million in respect of the contraventions of ss 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g), and 33 of the ACL declared by the Court, within thirty (30) days of the date of these orders.

Injunctions

4. The Respondent, whether by itself, its officers, agents or employees, be restrained from making representations to consumers in Australia that its products comprise or contain recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, unless the products actually comprise or contain (as the case may be, and in the proportions stated) recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea.

Compliance Program

5. The Respondent, at its own expense:

(a) within 90 days of the date of these orders, establish and implement an ACL compliance program which meets the requirements set out in Annexure Two to these orders; and

(b) for a period of three years, maintain and continue to implement the ACL compliance program referred to in order 5(a) above.

6. The Respondent serve on the Applicant:

(a) an affidavit verifying that it has carried out its obligations under order 5(a), within 14 days after the end of the 90 day period referred to in order 5(a); and

(b) an affidavit verifying that it has carried out its obligations under order 5(b), at the end of each 12-month period, for each of the three years referred to in order 5(b).

Corrective Publication Notice

7. The Respondent:

(a) within 14 days of the date of these orders, publish (or cause to be published) a colour copy of a corrective notice on its website www.glad.com.au and its corresponding Facebook and Instagram social media channels, in the form set out in Annexure Three to these orders; and

(b) for at least a period of 90 days from the date on which the notice referred to in order 7(a) is first published, maintain the corrective notice on the website and social media channels referred to in order 7(a).

8. The Respondent serve on the Applicant:

(a) an affidavit verifying that it has carried out its obligations under order 7(a), within 7 days after the end of the 14 day period referred to in order 7(a);

(b) an affidavit verifying that it has carried out its obligations under order 7(b), within 14 days after the end of the 90 day period referred to in order 7(b).

Other orders

9. The Respondent pay the Applicant’s costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, fixed in the amount of $200,000, within thirty (30) days of the date of these orders.

10. A copy of the reasons for judgment, with the seal of the Court thereon, be retained in the Court for the purposes of s 137H of the CCA

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANNEXURE ONE

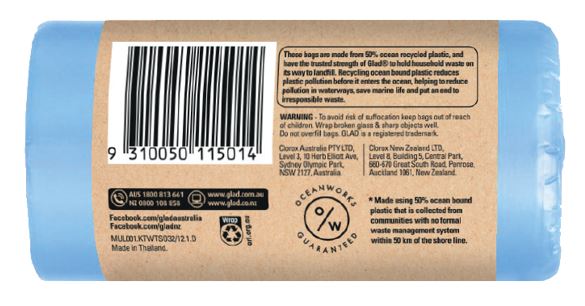

ORIGINAL PRODUCT PACKAGING (KITCHEN TIDY BAGS)

Applicable between about June 2021 and a date in 2022 (respectively, about 13 November 2022 for the small kitchen tidy bags, 29 May 2022 for the medium kitchen tidy bags, and 6 March 2022 for the large kitchen tidy bags).

These images show the packaging for the small kitchen tidy bags. The packaging for the medium and large kitchen tidy bags was comparable, save for the displayed size and dimensions.

Front

Side

Back

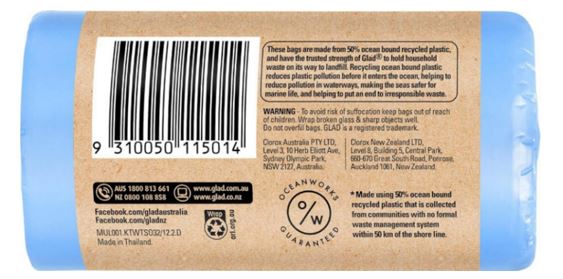

UPDATED PRODUCT PACKAGING (KITCHEN TIDY BAGS)

Applicable between a date in 2022 (respectively, about 13 November 2022 for the small kitchen tidy bags, about 29 May 2022 for the medium kitchen tidy bags, and about 6 March 2022 for the large kitchen tidy bags) and July 2023.

These images show the packaging for the small kitchen tidy bags. The packaging for the medium and large kitchen tidy bags was comparable, save for the displayed size and dimensions.

Front

Side

Back

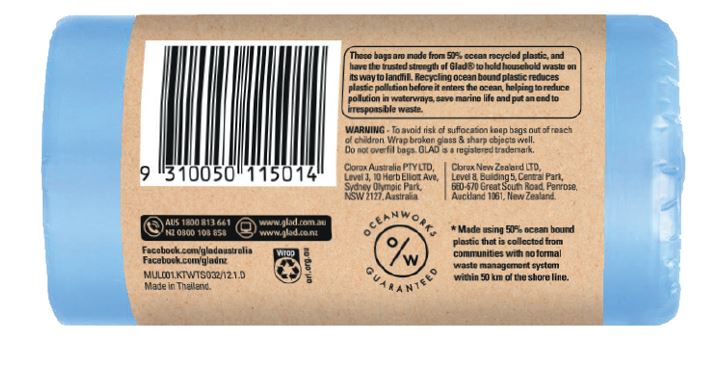

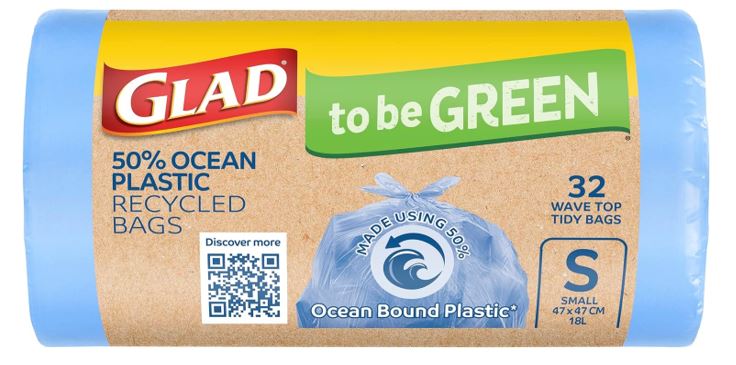

GARBAGE BAG PACKAGING

Applicable between about May 2022 and July 2023.

These images show the packaging for the large garbage bags. The packaging for the extra-large garbage bags was comparable, save for the displayed size and dimensions.

Front

Side

Back

ANNEXURE TWO

Clorox Australia Pty Ltd (“Clorox Australia”) – Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”) Compliance Program

Following the Federal Court proceeding VID315/2024, ACCC v Clorox Australia Pty Ltd, relating to Clorox’s “Glad to be Green 50% Ocean Recycled Plastic” kitchen tidy and garbage bags, Clorox Australia will establish and implement an ACL compliance program (ACL Compliance Program) that meets the following requirements.

ACL Compliance Program will be in addition to Clorox Australia’s obligations under Clorox Global compliance policies

1 The ACL Compliance Program will take account of – and apply in addition to – the global compliance systems and policies of the Clorox group of companies (Clorox Global) to which Clorox Australia, the Australian affiliate (operating subsidiary), is subject. Those systems and policies, including the Code of Conduct and any other relevant Clorox Global Policies as adopted and updated from time to time, are referred to as the “Global Policies”, and are summarised in paragraphs 2 to 7 below.

2 Commitment to compliance with laws including laws relating to truthful advertising and marketing and related matters, including:

Confidential Code of Conduct including Business Partner Code of Conduct (“Code of Conduct”)

Confidential Corporate Policy: MKTG-003 Advertising Standards in Ethics and Standards Category (“Advertising Standards Global Policy”)

Confidential Corporate Policy: MKTG-001 Company Advertising in Ethics and Standards Category (“Company Advertising Global Policy”)

Confidential Corporate Policy: LE-012 Social Media in Communications and Information Security Category (“Social Media Global Policy”)

Confidential Corporate Policy: LE-008 Antitrust and Global Competition Law Compliance Policy

3 Policies requiring personnel to meet various standards relating to ensuring truthful advertising and marketing, including:

Code of Conduct

Advertising Standards Global Policy

Company Advertising Global Policy

Social Media Global Policy

4 The availability and regular use of knowledgeable and experienced in-house advertising and marketing lawyers (“MarComm lawyers”), including as referred to in the policies and documents below:

Code of Conduct

Company Advertising Global Policy

Social Media Global Policy

Confidential International MarComm Review Process and Training Materials

5 The availability and regular use of knowledgeable and experienced Australian qualified external lawyers, including as referred to in the policies and documents below:

Code of Conduct

Company Advertising Global Policy

6 Policies requiring relevant training of personnel, and the carrying out of that training, including:

Code of Conduct

Confidential Code of Conduct training for all new inductees and on an annual basis by all personnel

MarComm lawyers regular training sessions

7 Consumer complaints and whistleblower protection policies including:

Code of Conduct

Confidential Corporate Policy: MKTG-004 Consumer Response (“Consumer Response Global Policy”).

Statement by Clorox Australia of commitment to compliance with the ACL

8 Clorox Australia will issue an internal policy statement confirming its commitment to compliance with the ACL as reflected in this Program document. It will continue to be mandatory for Clorox Australia to comply with the Global Policies. In addition, it will be mandatory for Clorox Australia to comply with any additional specific requirements set out in this document as Local Compliance measures.

Means by which Clorox Australia will realise its commitment to compliance

9 In addition to compliance with the Global Policies which includes compliance with Australian law, Clorox Australia will realise its commitment to compliance by the following steps:

(a) Local Compliance: Clorox Australia will appoint Clorox Australia’s Company Secretary to act as its Compliance Officer. The Compliance Officer will be responsible for generating and maintaining records in relation to the Compliance Program including receiving and recording complaints or concerns by consumers and others of any ACL non-compliance (received on the confidential24/7 Compliance Hotline2 or otherwise), supporting the investigation, where appropriate, of any such complaints or concerns, facilitating the required ACL training program, and providing regular reports to Clorox Australia’s senior leadership on the continuing effectiveness of the Compliance Program;

(b) Local Compliance: Clorox Australia will ensure that staff have access to external legal advice where questions about ACL compliance arise;

(c) Local Compliance: All Clorox Australia staff including new inductees will complete regular ACL compliance training at least annually which will be provided by a suitably qualified compliance professional or legal practitioner with expertise in consumer law.

Complaints Handling

10 Local Compliance: In addition to standard procedures for dealing with complaints in accordance with the Consumer Response Global Policy, for local product related complaints including on ACL compliance issues, Clorox Australia will continue to offer customer care contact points, such as telephone helplines and online systems on GLAD website3.

Obligation of Clorox Australia to report non-compliance concerns

11 Local Compliance: In addition to the obligation to report non-compliance with Global Policies using the Compliance Hotline and Clorox Legal Services (Code of Conduct, and Social Media Global Policy), Clorox Australia will require all local personnel to report any ACL non-compliance issues or concerns of which they become aware to the Compliance Officer.

Whistleblower protection

12 Local Compliance: Clorox Australia strictly prohibits retaliation against anyone who in good faith reports suspected misconduct, including under the Code of Conduct.4 This whistleblower protection will continue to apply to Australian personnel coming forward with ACL complaints or reporting of ACL issues or concerns.

Consequences of non-compliance

13 Local Compliance: Any suspected breaches of the Global Policies, which includes compliance with Australian law, will continue to be investigated, as appropriate under applicable policies, and subject to applicable law, individuals found to have breached the Global Policies may face disciplinary action as described in the Code of Conduct.5

ANNEXURE THREE

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Corrective Notice

Following proceedings by the ACCC and settlement terms agreed with Clorox Australia Pty Ltd (Clorox Australia), the Federal Court of Australia has declared, by consent, that Clorox Australia contravened the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) by supplying and promoting its ‘50% Ocean Plastic Recycled’ kitchen tidy bags and garbage bags in its ‘GLAD to be GREEN’ range, packaged including as shown in the images attached to this corrective notice, thereby making false or misleading representations that the bags were made of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, when this was not the case.

In fact, the GLAD kitchen tidy and garbage bags were made from 50% recycled plastic waste that was collected from communities with no formal waste management system up to 50 kilometres from a shoreline, and not from plastic waste that was collected from the ocean or sea.

Clorox Australia made the representations about its kitchen tidy bags between about June 2021 and July 2023, and about its garbage bags between about May 2022 and July 2023. Clorox withdrew the supply of both products to retailers in July 2023.

The Federal Court has ordered that Clorox Australia:

pay a penalty of AUD$8.25 million and make a contribution of AUD$200,000 towards the ACCC’s costs;

refrain from making similar representations in the future;

implement an ACL compliance program; and

issue this corrective notice.

While Clorox did not intend to mislead consumers that the 50% recycled plastic waste was collected from the ocean or sea, it apologises to any consumers who were misled.

Further information about the Court’s decision can be found on the website of the Federal Court of Australia [link] and in the ACCC’s media release [insert].

Kitchen Tidy Bags | |

|

|

|

|

Garbage Bags | |

| |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

NESKOVCIN J:

1 By originating application and concise statement filed on 18 April 2024, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) alleged that Clorox Australia Pty Ltd engaged in conduct which contravened ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

2 The impugned conduct concerned Clorox’s supply and promotion of its “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled” kitchen tidy bags and garbage bags in its “GLAD to be GREEN” range, packaged in a way that represented that the bags were made of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, when that was not the case.

3 Clorox admitted the alleged contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL and the parties agreed to a resolution of the proceeding, including a pecuniary penalty.

4 The parties filed and relied on:

(a) a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (SAFA) setting out the facts agreed between the parties pursuant to s 191(3)(a) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) and Clorox’s formal admissions of contravention; and

(b) Joint Submissions on liability and relief.

5 The parties jointly sought declarations of contravention, an order that Clorox pay a pecuniary penalty of $8.25 million in respect of the contraventions of ss 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL, an injunction under s 232 of the ACL, orders in relation to a compliance program and corrective advertising notice, and an order that Clorox pay a contribution towards the ACCC’s costs.

6 For the reasons that follow, I consider the proposed relief to be appropriate in all the circumstances, including the proposed penalty, and that it is appropriate to make the orders proposed by the parties.

BACKGROUND

Clorox and The Clorox Company

7 Clorox is the local operating company of the Clorox Group, whose ultimate parent company is The Clorox Company (Clorox US).

8 Clorox’s sales and marketing activities include marketing GLAD-branded products to consumers in Australia, and supplying those products to retailers (including major supermarkets and online retailers), which in turn sell those products to consumers in Australia.

9 Clorox employs approximately 60 people. Clorox’s sales revenue for the financial years ending 30 June 2021, 30 June 2022 and 30 June 2023 was $109,535,905, $120,423,694 and $123,626,719 respectively. It had net assets in the same periods of $60,141,764, $64,494,251 and $59,038,338.

10 Clorox US is listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE:CLX) and is included in the S&P 500. In its annual report for the financial year ending 30 June 2022, which was published on the stock exchange, Clorox US referred to the launch in Australia and New Zealand of its “GLAD to be GREEN ocean bound plastic recycled trash bags” “that incorporate plastic waste at risk of becoming ocean pollution” as an “FY22 product innovation highlight”.

11 Clorox US’s net sales and net earnings for the financial years ending 30 June 2021, 30 June 2022 and 30 June 2023 were as set out in the table below:

FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | |

Net sales (USD) | $7,341,000,000 | $7,107,000,000 | $7,389,000,000 |

Net earnings (USD) | $719,000,000 | $471,000,000 | $161,000,000 |

The Products and Product Packaging

12 Between about June 2021 to July 2023 (Relevant Period), Clorox marketed and supplied kitchen tidy bags and garbage bags, of various sizes, in Clorox’s “GLAD to be GREEN” “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled” range (Products) to consumers in Australia.

13 Clorox supplied the kitchen tidy bag Products, in small, medium and large sizes, in the ‘Original Product Packaging’ from the start of the Relevant Period to a date between 6 March and 13 November 2022. Clorox supplied the kitchen tidy bag Products in the same sizes in the ‘Updated Product Packaging’ for the balance of the Relevant Period. The date on which Clorox ceased to supply the kitchen tidy bag Products in the Original Product Packing, and then supplied the Products in the Updated Product Packing, varied as between the small, medium or large sized bags, as noted in Annexure One of the orders that have been made.

14 Clorox also supplied the garbage bag Products in the ‘Garbage Bag Packaging’ from between about May 2022 to July 2023.

15 Selected images showing the front of the Original Product, Updated Product and Garbage Bag Packaging (collectively, the Packaging) are reproduced below:

Original Product Packaging (Kitchen Tidy Bags)

Updated Product Packaging (Kitchen Tidy Bags)

Garbage Bag Packaging

16 The key features of the Original Product Packaging, the Updated Product Packaging and the Garbage Bag Packaging were as follows:

(a) The Original Product Packaging:

(i) displayed, on its front:

(A) at the top, the text “GLAD to be GREEN” in large font, with a green coloured background underlaying the words “to be GREEN”; in the centre, the text “50% OCEAN PLASTIC RECYCLED BAGS” in large blue font; at the bottom, in smaller font, the text “MADE USING 50% Ocean Plastic*” around an image of a wave, overlayed on an image of a blue coloured waste disposal bag;

(ii) displayed, on its side:

(A) text and design elements mirroring the front of the packaging as described in subparagraph (a)(i) above, all oriented sideways relative to the front of the pack; the “50% OCEAN PLASTIC RECYCLED BAGS” text was in larger font than the text on the front of the packaging;

(iii) displayed, on its back, in smaller font and oriented sideways relative to the front:

(A) “These bags are made from 50% ocean recycled plastic, and have the trusted strength of Glad® to hold household waste on its way to landfill. Recycling ocean bound plastic reduces plastic pollution before it enters the ocean, helping to reduce pollution in waterways, save marine life and put an end to irresponsible waste”; and

(B) “*Made using 50% ocean bound plastic that is collected from communities with no formal waste management system within 50 km of the shore line.”; and

(iv) revealed the actual Product, which was a blue colour.

(b) The Updated Product Packaging was relevantly the same as the Original Product Packaging save that, on the Updated Product Packaging:

(i) the text at the bottom of the packaging on the front and side of the Product said “MADE USING 50% Ocean Bound Plastic*” rather than “MADE USING 50% Ocean Plastic*”;

(ii) the text displayed on the back of the packaging (still in smaller font and oriented sideways relative to the front of the sleeve), was updated to say:

(A) “These bags are made from 50% ocean bound recycled plastic, and have the trusted strength of Glad® to hold household waste on its way to landfill. Recycling ocean bound plastic reduces plastic pollution before it enters the ocean, helping to reduce pollution in waterways, making the seas safer for marine life, and helping to put an end to irresponsible waste.”; and

(B) “*Made using 50% ocean bound recycled plastic that is collected from communities with no formal waste management system within 50 km of the shore line”; and

(c) The Garbage Bag Packaging:

(i) displayed, on its front:

(A) at the top, the text “GLAD to be GREEN” in large font, with a green coloured background underlaying the words “to be GREEN”; below that text, the text “50% OCEAN PLASTIC RECYCLED GARBAGE BAGS” in large blue font; to the right of that text, in smaller font, the text “MADE USING 50% Ocean Bound Plastic*” around an image of a wave, overlayed on an image of a blue coloured waste disposal bag;

(ii) displayed, on its side, text and design elements mirroring the front of the packaging as described in subparagraph (c)(i) above;

(iii) displayed, on its back, in smaller font:

(A) “*Made using 50% ocean bound recycled plastic that is collected from communities with no formal waste management system within 50 km of the shore line.”; and

(B) “These strong garbage bags are made from 50% ocean bound recycled plastic, and have the trusted strength of Glad® to hold waste on its way to landfill. Recycling ocean bound plastic reduces plastic pollution before it enters the ocean, helping to reduce pollution in waterways, making the seas safer for marine life, and helping to put an end to irresponsible waste.”; and

(iv) revealed the actual Product, which was a blue colour.

The Ocean Plastic Representation

17 Clorox admits that, by supplying and promoting the Products in the Packaging, Clorox represented that the Products were comprised of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea (Ocean Plastic Representation), when that was not the case. Rather, the recycled plastic resin in the Products was derived from recycled plastic that had been collected from communities in Indonesia with no formal waste management system situated up to 50 kilometres from a shoreline and the Products were otherwise comprised of non-recycled plastic, dye and processing aid.

18 As can be seen from the images reproduced above, the statement “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled …” appeared on the front of each type of Packaging. The phrase “ocean bound plastic” appeared in smaller font on the side of each type of Packaging and on the front of the Updated Product Packaging and the Garbage Bag Packaging, but not on the front of the Original Product Packaging. The parties agreed that the prominent statement “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled …” on the front of the Packaging was not dispelled by any of the other information provided on the Packaging. The parties also agreed that the change, to include “ocean bound plastic” on the front of the Updated Product and Garbage Bags Packaging, was not effective to prevent the revised packaging from conveying the misleading representation, including because Clorox still retained the headline “50% Ocean Plastic” claim in a larger font, in a more prominent position.

Commercial context in which the contravening conduct occurred

19 In late 2020, Clorox had begun work on ‘Project Billy’ which, according to the project “Charter”, was intended to involve development of “a range of Trash management products using ocean recovered plastic that advance Glad’s position in driving authentically sustainable solutions and are readily understood and desired by the consumer”. Project Billy, which ultimately resulted in the production of the Products, was one of several initiatives over the preceding approximately 5 years which resulted in Clorox bringing to market in Australia a range of products that it considered could contribute to reducing the environmental impact of consumer products.

20 Clorox’s internal “Charter” for Project Billy further identified that the business objectives for Project Billy included:

(a) helping consumers to feel more positive about their choices by offering a product that contributes to minimising adverse environmental impacts;

(b) recruiting new consumers to GLAD branded products; and

(c) migrating existing consumers of GLAD branded products to “more sustainable (and profitable) options”.

21 “Key requirements” of Project Billy (that is, things the Charter identified that the Project “must deliver to drive success”) included that the products’ claim about the use of ocean plastic differentiate Clorox’s product from its competitors, that consumers prefer the products overall to competitors’ products, and that consumers be willing to pay a premium for those products.

22 In late 2020 and continuing into 2021, Clorox made enquiries and had discussions with a supplier, Oceanworks, regarding the different types of recycled plastic that could potentially be used in its Products.

23 On its website and in Oceanworks’ business and contractual documents, Oceanworks:

(a) used the term “ocean plastic” as a general description to encompass various categories of collected used plastic material, including categories it described as “ocean bound”, “waterway”, “coastal”, “nearshore” and “high seas”. Each of these categories referred to used plastics collected from various locations that had some connection to the ocean, sea or water. For example, the “nearshore” and “high seas” categories referred to plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea; and

(b) used the category “ocean bound” to refer to plastics “collected from communities with no formal waste management <50 km of the shore line”.

24 In April 2021, Clorox consulted with Oceanworks in relation to a question from a retailer in New Zealand regarding the composition of the Products. Oceanworks confirmed to Clorox that there was essentially “no ocean recovered material” in the resins Clorox had decided to use for its Products, and that all of the resins Clorox had decided to use were classified as “ocean bound” under Oceanworks’ collection zone definitions.

25 As a result of the matters in paragraphs 22 – 24 above, when the Products were being manufactured and then offered for sale, Clorox considered the Oceanworks’ “ocean bound” resins to be a kind of “ocean plastic” but knew that no plastic recovered from the ocean or sea had been, or was being, used to manufacture the Products.

Products sold

26 Clorox sold more than 2.2 million units of the Products during the Relevant Period.

27 Clorox’s recommended retail price for the Products was generally higher than its recommended retail price for its standard range of household trash bags.

28 Clorox discontinued supply following the commencement of the ACCC’s investigation and before this proceeding was commenced, and the Products are no longer supplied in Australia.

STATUTORY FRAMEWORK

29 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides:

18 Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

30 Section 29(1)(a) and (g) of the ACL provide:

29 False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

(a) make a false or misleading representation that goods are of a particular standard, quality, value, grade, composition, style or model or have had a particular history or particular previous use; or

…

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits;

31 Section 33 of the ACL provides:

33 Misleading conduct as to the nature etc. of goods

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

32 Sections 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL are civil penalty provisions, which enlivens the Court’s power to order the payment of a pecuniary penalty for contravention of those sections.

33 The principles governing liability under these provisions are well-established. They were recently summarised by the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings v Allergan Australia (2023) 277 CLR 186; [2023] HCA 8 at [80]–[81] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Gordon, Edelman and Gleeson JJ) and have been applied in other cases, including recently in the context of claims about the environmental credentials of certain financial products and services: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd [2024] FCA 308 at [21] (O’Bryan J); Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mercer Superannuation (Australia) Limited [2024] FCA 850 at [57] (Horan J) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v LGSS Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 587 at [25] (O’Callaghan J).

34 Adapting those principles to the provisions and facts relevant to this case:

(a) the first step is to identify with precision the “conduct” said to contravene the provisions – that is, the relevant representation that was made in relation to the composition or particular benefits of the goods;

(b) the second step is to consider whether the identified conduct or representation was engaged in or made in “trade or commerce”;

(c) the third step is to consider what meaning that conduct or representation conveyed to its intended audience;

(d) the fourth step is to determine, in light of that meaning, whether the conduct or representation was false or misleading in the requisite sense for the purposes of ss 18 and 29(1)(a) and (g) or whether the conduct was liable to mislead the public in the requisite sense for the purpose of s 33 of the ACL.

35 The third and fourth steps require an objective characterisation of the conduct or representation viewed as a whole and its notional effects, judged by reference to its context, on the state of mind of the relevant person or class of persons. That context includes the immediate context — relevantly, all the words in the document or other communication and the manner in which those words are conveyed, not just a word or phrase in isolation — and the broader context of the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances. Where the conduct was directed to the public – as is expressly contemplated by s 33 – those steps must be undertaken by reference to the effect or likely effect of the conduct on the ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of persons, so as to avoid assessing the effect or likely effect by reference to the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable, or those credited with habitual caution or exceptional carelessness, or by considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful: Self Care at [82]-[83].

36 The terms ‘misleading’, ‘misleading or deceptive’, and ‘false or misleading’ as they appear in the different statutory provisions, can be treated as synonymous and the principles governing liability are the same: Self-Care at [84]; Vanguard at [21]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Private Networks Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 384 at [13]-[16] (Middleton J).

37 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 278 FCR 450; [2020] FCAFC 130, the Full Court (Wigney, O’Bryan and Jackson JJ) relevantly observed at [22]:

… The central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter): Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd (1982) 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell) at 200 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 (Puxu) at 198 per Gibbs CJ; Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 (Campomar) at [98]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (TPG Internet) at [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; Campbell at [25] per French CJ. A number of subsidiary principles, directed to the central question, have been developed:

(a) First, conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility of it doing so: see Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 (Global Sportsman) at 87, referred to with apparent approval in Butcher at [112] by Gleeson CJ, Hayne and Heydon JJ; Noone v Operation Smile (Australia) Inc (2012) 38 VR 569 at [60] per Nettle JA (Warren CJ and Cavanough AJA agreeing at [33]).

(b) Second, it is not necessary to prove an intention to mislead or deceive: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 228 per Stephen J (with whom Barwick CJ and Jacobs J agreed) and at 234 per Murphy J; Puxu at 197 per Gibbs CJ; Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 (Google) at [6] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

(c) Third, it is unnecessary to prove that the conduct in question actually deceived or misled anyone: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ; Google at [6] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ. Evidence that a person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible and may be persuasive but is not essential. Such evidence does not itself establish that conduct is misleading or deceptive within the meaning of the statute. The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is objective and the Court must determine the question for itself: see Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ.

(d) Fourth, it is not sufficient if the conduct merely causes confusion: Taco Bell at 202 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ; Puxu at 198 per Gibbs CJ and 209-210 per Mason J; Campomar at [106]; Google at [8] per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

(e) Fifth, where the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [101]-[105]; Google at [7] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

CLOROX’S CONTRAVENING CONDUCT

38 The Ocean Plastic Representation was a representation about the nature and composition of the Products, the manufacturing process used to produce them, and the Products’ characteristics, in that it represented that the Products were comprised of 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, when that was not the case.

39 Clorox admits that, each time it made the Ocean Plastic Representation in trade or commerce, it:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or was likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the ACL;

(b) made a false or misleading representation with respect to the composition of the Products, in contravention of s 29(1)(a) of the ACL, that the Products were comprised of at least 50% recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea;

(c) made a false or misleading representation with respect to the environmental benefits of the Products, in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL, as the asserted composition of the Products, involving the claimed use of recycled plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea, was a ‘benefit’ for the purposes of s 29(1)(g); and

(d) engaged in conduct which was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, manufacturing process and characteristics of each Product, in contravention of s 33 of the ACL.

40 The Ocean Plastic Representation represented that the Products had a particular environmental benefit, in that, as the Products were made using plastic waste collected (and so removed) from the ocean or sea, production and sales of the Products contributed to removing plastic pollution from the ocean or sea.

41 Conduct of this kind is known as “greenwashing”, which broadly speaking involves making false or misleading environmental or sustainability claims in order to make a company or its business appear more environmentally friendly, sustainable or ethical, particularly in order to induce consumers to purchase its products or services or to invest in the company: Mercer at [3] (Horan J).

42 In LGSS, O’Callaghan J observed at [2]:

Some American authors have said that the origin of the term “greenwashing” can be traced to an unpublished 1986 essay by an environmentalist named Jay Westerveld, in which he is claimed to have:

described a hotel sign urging patrons to use fewer towels to reduce their environmental impact. Despite the hotel’s purported concern for the environment, Westerveld opined that the hotel’s true incentive for posting the sign was to save money by not having to launder as many towels. Based on the term “whitewashing” - using white paint to cover up dirt - environmental groups adopted the term “greenwashing” to signal misleading environmental claims.

(footnotes omitted)

See Peterson VJ, “Gray Areas in Green Claims: Why Greenwashing Regulation Needs an Overhaul” (2024) 35(1) Vill Env’t LJ 177 at 179. Professor Miriam A Cherry, however, suggests that the story described by Ms Peterson may be apocryphal. See Cherry MA, “The Law and Economics of Corporate Social Responsibility and Greenwashing” (2014) 14 UC Davis Bus LJ 281 at 284 (and footnote 5).

43 The parties accept that environmental claims about consumer products will likely continue to be attractive to both manufacturers and suppliers seeking to differentiate their products and achieve a competitive advantage over their competitors, and to consumers seeking to make a positive contribution to environmental protection. These are important contextual matters in assessing the contravening conduct and whether it is appropriate to make the orders proposed by the parties.

DECLARATORY RELIEF

44 The Court has a broad discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act).

45 The parties seek a declaration in the terms set out in the proposed orders.

46 As observed by the Full Court in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2017) 254 FCR 68; [2017] FCAFC 113 at [90] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ), the fact that the parties have agreed that a declaration of contravention should be made does not relieve the Court of the obligation to satisfy itself that the making of the declaration is appropriate. The Full Court also stated at [93]:

Declarations relating to contraventions of legislative provisions are likely to be appropriate where they serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct, vindicate the regulator’s claim that the respondent contravened the provisions, assist the regulator to carry out its duties, and deter other persons from contravening the provisions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; [2007] ATPR 42-140 at [6], and the cases there cited; Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; (2003) 216 CLR 53 at [95].

47 In Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421; [1972] HCA 61, Gibbs J stated, at 437–438, that before making declarations three requirements should be satisfied:

(a) the question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(b) the applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(c) there must be a proper contradictor.

48 I am satisfied the ACCC has a real interest in seeking declaratory relief in this proceeding. Declaratory relief serves to record the Court’s disapproval of the relevant conduct and to vindicate the ACCC’s claim that Clorox contravened the ACL, which was alleged and is now admitted in the SAFA. Clorox is a proper contradictor, notwithstanding that the parties have reached agreement on the SAFA, which provides a sufficient factual foundation for the making of the declaration.

49 The Court is not bound by the form of the declaration proposed by the parties and must determine for itself whether the form is appropriate. The parties submitted, and I accept, that the Court has the power, and it is appropriate, to make the declarations in the form of the declaration in the proposed orders. The proposed declarations relate to conduct that contravenes the ACL and contains sufficient indication of how and why the relevant conduct is a contravention of the ACL.

INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

50 The Court has the power to grant injunctions pursuant to s 232 of the ACL. The Court’s power under s 232(1) allows it to grant an injunction in such terms as the Court considers appropriate, if, relevantly, the Court is satisfied that a person has engaged in conduct that constitutes or would constitute a contravention of ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) or 33 of the ACL (being provisions of Chapters 2 and 3 of the ACL).

51 The Court’s power to grant an injunction under s 232 which would restrain a person from engaging in conduct is broad and may, pursuant to s 232(4), be exercised:

(a) whether or not it appears to the Court that the person intends to engage again, or to continue to engage, in conduct of a kind that constitutes or would constitute a contravention of a relevant provision (here ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) or 33 of the ACL);

(b) whether or not the person has previously engaged in conduct of that kind; and

(c) whether or not there is an imminent danger of substantial damage to any other person if the person engages in conduct of that kind.

52 The purpose of an injunction of this kind is not to restrain an apprehended repetition of contravening conduct but to deter an offender from repeating the offence: ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 at 268 (French J).

53 I am satisfied that the proposed injunction is appropriate within the meaning of s 232 for the following reasons. First, the injunction closely reflects the contravening conduct. Secondly, the injunction is designed to deter any repetition of that conduct. Thirdly, the injunction is clearly expressed and may readily be obeyed without any need for Court supervision.

PECUNIARY PENALTIES

The statutory power to impose a pecuniary penalty

54 The Court has power to order pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 224(1)(a)(ii) of the ACL.

55 Section 224(1)(a)(ii) provides that if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a provision of (relevantly) Part 3-1 of the ACL (which includes ss 29 and 33), the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty, in respect of each act or omission to which section 224(1)(a)(ii) applies, as the Court determines to be appropriate.

56 Section 224(2) provides that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court to have engaged in any similar conduct.

57 Section 224(4) of the ACL provides that if conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more of the provisions to which s 224 applies, a person is not liable to pay more than one pecuniary penalty under s 224 in respect of the same conduct.

Where the parties have agreed a pecuniary penalty

58 The practice and approach to making orders proposed by agreement in a civil penalty proceeding was explained by the High Court in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482; [2015] HCA 46. The plurality (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ) stated, at [58], that it was consistent with principle and highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal as to an agreed penalty, subject to the Court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty proposed is “an appropriate remedy in the circumstances”.

59 In considering whether the proposed agreed penalty is an appropriate penalty, the Court should generally recognise that the agreed penalty is most likely the result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the regulator, and to reflect, amongst other things, the regulator’s considered estimation of the penalty necessary to achieve deterrence and the risks and expense of the litigation had it not been settled: Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2021] FCAFC 49; (2021) 284 FCR 24 at [129], referring to Fair Work at [109] (Wigney, Beach and O’Bryan JJ).

Applicable principles

60 The civil penalty regime in the ACL is similar in form to the civil penalty regimes in other Commonwealth statutes including the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act (2001) (Cth), and the provisions have been construed in a similar manner across the different statutes. The principles relevant to the interpretation of these provisions were recently summarised by O’Bryan J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Vanguard Investments Australia Ltd (No 2) [2024] FCA 1086 at [33] to [37]. I gratefully adopt his Honour’s summary and repeat the principles relevant to this proceeding below.

61 First, the Court may impose a penalty in respect of each act or omission that constitutes a contravention, subject to the maximum penalty which is stated to apply to each act or omission.

62 Secondly, the penalty to be imposed is a penalty that the Court considers appropriate. In that regard, the principal object of imposing a pecuniary penalty is deterrence; both the need to deter repetition of the contravening conduct by the contravener (specific deterrence) and to deter others who might be tempted to engage in similar contraventions (general deterrence): Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v ACCC (2012) 287 ALR 249; [2012] FCAFC 20 at [62]-[63] (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640; [2013] HCA 54 at [65] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Fair Work at [55] (French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ) and at [110] (Keane J) and Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450; [2022] HCA 13 at [15] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ).

63 Thirdly, in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, s 242(2) of the ACL requires the Court to have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court to have engaged in any similar conduct.

64 The relevant matters under s 224(2) of the ACL are non-exhaustive. Other factors that are relevant to the assessment of the appropriate penalty in this proceeding are:

(a) the size of the contravening company;

(b) the deliberateness of the contravention;

(c) whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level;

(d) whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the ACL as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and

(e) whether the company has shown a disposition to cooperate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

65 Fourthly, in considering the sufficiency of a proposed civil penalty, regard must ordinarily be had to the maximum penalty. The maximum penalty provides a “yardstick”, to be taken and balanced with all other relevant factors: Pattinson at [53]-[54] and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 ALR 25 at [155] - [156] (Jagot, Yates and Bromwich JJ).

66 Fifthly, in determining the appropriate penalty for a multiplicity of civil penalty contraventions, the Court may have regard to two common law principles that originate in criminal sentencing: the “course of conduct” principle and the “totality” principle: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; (2018) 262 FCR 243 at [226] (Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ). Under the “course of conduct” principle, the Court considers whether the contravening acts or omissions arise out of the same course of conduct or the one transaction, to determine whether it is appropriate that a “concurrent” or single penalty should be imposed for the contraventions: Yazaki Corporation at [234]. Whether multiple contraventions should be treated as a single course of conduct is a question of fact and degree: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 269 ALR 1 (Cahill) at [39] (per Middleton and Gordon JJ), and the application of the principle requires an evaluative judgement in respect of the relevant circumstances: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; (2017) 258 FCR 312 at [425] (Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ). The principle guards against the risk that the respondent is punished twice in respect of multiple contravening acts or omissions that should be evaluated, for the purposes of assessing an appropriate penalty, as a lesser number of acts of wrongdoing: Cahill at [39].

67 As noted by the Full Court in Yazaki Corporation (at [227]), however, it is not appropriate or permissible to treat multiple contravening acts or omissions as just one contravention for the purposes of determining the maximum limit dictated by the relevant legislation. Accordingly, the maximum penalty for the course of conduct is not restricted to the prescribed statutory maximum penalty for each contravening act or omission: Reckitt Benckiser at [141]; Yazaki Corporation at [229]-[235].

68 The parties submitted that the contravening conduct can appropriately be characterised as involving three separate courses of conduct as follows, attracting a total penalty of $8.25 million:

(a) the making of the Ocean Plastic Representation in connection with the supply of the kitchen tidy bag products (all sizes) in the Original Product Packaging, in the period from about June 2021 until a date in 2022;

(b) the making of the Ocean Plastic Representation in connection with the supply of the kitchen tidy bag products (all sizes) in the Updated Product Packaging, in the period from a date in 2022 until about July 2023; and

(c) the making of the Ocean Plastic Representation in connection with the supply of the garbage bag products (large and extra-large sizes) in the Garbage Bag Packaging, in the period from about May 2022 to July 2023.

69 The “totality” principle operates as a “final check” to ensure that the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, are just and appropriate and that the total penalty for related offences does not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct in question: Trade Practices Commission v TNT Australia Pty Ltd (1995) ATPR 41-375 at 40,169 (Burchett J) and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 (Goldberg J).

Maximum penalty

70 During the Relevant Period, the maximum pecuniary penalty payable by a body corporate in respect of a contravention of ss 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 was, relevantly:

(a) From the start of the Relevant Period (i.e. about June 2021) until 9 November 2022, the greater of:

(i) $10 million;

(ii) if the Court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate and any related body corporate obtained that is reasonably attributable to the relevant act or omission – three times the value of that benefit;

(iii) if the Court cannot determine the value of that benefit – 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred or started to occur.

(b) From 10 November 2022 until July 2023 (i.e. the end of the Relevant Period), the greater of:

(i) $50 million;

(ii) if the Court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any related body corporate, obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the relevant act or omission – three times the value of that benefit;

(iii) if the Court cannot determine the value of that benefit – 30% of the body corporate’s adjusted turnover during the breach turnover period for the act or omission.

71 As noted above, the contraventions straddled periods both before and after 10 November 2022 when the maximum penalties increased. It is not possible, however, to determine precisely how many contraventions occurred before and from that date.

72 Clorox admits that a separate Ocean Plastic Representation was made by Clorox each time a Product was supplied, presented for sale or viewed. Accordingly, based on the total units sold, Clorox made the Ocean Plastic Representation on more than 2.2 million occasions during the Relevant Period. The number of times the Ocean Plastic Representation was made is likely to be higher than this figure, given the representation was also made to consumers who viewed, but did not ultimately purchase, the Products. As a result, it is not possible to estimate the total number of contraventions with any greater precision.

73 Given the inability to estimate the precise number of contraventions in this case, there is no the theoretical maximum penalty. The theoretical maximum would be large and not a meaningful guide in any event.

Consideration of the relevant matters

Nature and extent of the contravening conduct

74 Clorox accepts that by reason of the packaging of the Products, Clorox represented that the Products were comprised of plastic resin, at least 50% of which was derived from recycled plastic that had been collected from the ocean or sea, when that was not the case. Rather, the recycled plastic resin in the Products was derived from recycled plastic that had been collected from communities in Indonesia with no formal waste management system situated up to 50 kilometres from a shoreline and the Products were otherwise comprised of non-recycled plastic, dye and processing aid.

75 The contravening conduct occurred over a period of just over two years and involved the supply of more than 2.2 million Products displaying the Ocean Plastic Representation to consumers through the major Australian supermarket chains and online retailers.

76 Clorox accepts that the claimed environmental benefits were a key feature of the Products. The Ocean Plastic Representation was the dominant, headline message conveyed by the Products’ Packaging. The front of the Packaging bore the prominent statement “50% Ocean Plastic Recycled …”. The blue colour of the Products, and the image of waves on the Packaging, connoted a relationship between the Products and the ocean. The reference to ‘green’ on the Packaging connoted environmental-friendliness. These are important contextual matters in assessing the contravening conduct. Making representations about the environmental benefits of the Products has significance to competing manufacturers and suppliers and consumers, and is a matter of particular seriousness where, as in this case, consumers have limited or no access to information to test the accuracy of such claims.

The amount of loss or damage caused

77 The loss or damage to be considered is not limited to financial or economic harm. For example, in Vanguard (No 2) and Mercer, the relevant loss was characterised as investors’ loss of opportunity to invest in accordance with their investment values. Further, in Volkswagen, the Full Court at [190] recognised that “[i]t is open and often appropriate for the Court to assess penalties for contraventions of the Consumer Law having regard to the need to deter conduct that results in non-economic forms of societal harm”, where the relevant harm included harm to the environment.

78 As the parties submitted, there is a particular societal harm that arises when conduct undermines consumers’ confidence in environmental claims. Many consumers care about their environmental impact and environmental claims are often key factors for consumers in deciding how to spend their money. The development of products that minimise adverse environmental impacts is beneficial. However, any environmental benefits must be accurately represented. Environmental claims are useful for consumers only if they are accurate. Further, false or misleading environmental claims cause competitive disadvantage to businesses making genuine environmental claims and undermine the efforts of businesses to pursue environmental goals accurately and fairly.

79 The Ocean Plastic Representation deprived consumers of the opportunity to make informed purchasing decisions, free from the false impression conveyed by the Ocean Plastic Representation, about whether they would buy a kitchen tidy bag and/or garbage bag product at all, and, if so, which particular product they would buy. Absent the Ocean Plastic Representation, consumers might have purchased alternative products, including from Clorox’s competitors, and may have purchased products that offered substantiated environmental benefits, or that were cheaper than the Products, noting that the recommended retail price of the Products was generally higher (and included a premium, as Clorox intended) than the recommended retail price of Clorox’s ordinary rubbish bag products.

80 Further, Clorox promoted the Products as having a particular benefit, in terms of reducing the environmental problem of plastic in the ocean, and sought to gain an advantage over its competitors, including suppliers of products that were marketed based on substantiated environmental claims. Suppliers of products which competed with the Products, including suppliers of products that were marketed based on accurate and substantiated environmental benefits, may have suffered harm to the extent that the Ocean Plastic Representation put them at a competitive disadvantage to Clorox, including loss of market share.

The circumstances in which the conduct took place, including deliberateness

81 The parties submitted, and I accept, that the contravening conduct, while serious, is not in the most serious category of environmental misrepresentations, as Clorox genuinely believed the Products would contribute to the reduction of plastic waste in the ocean and did not deliberately engage in a strategy to mislead consumers as to the composition of the Products.

82 The circumstances in which the conduct arose were that, as part of Project Billy, Clorox sought to develop a range of products using ocean recovered plastic and achieve a commercial advantage by supplying products with particular environmental benefits.

83 Clorox made enquiries of and had discussions with its supplier, Oceanworks, regarding the different types of recycled plastic that could potentially be used in its Products. Oceanworks used the term “ocean plastic” as a general description to encompass various categories of collected used plastic material, including categories it described as “ocean bound”, “waterway”, “coastal”, “nearshore” and “high seas”. Each of these categories used plastics collected from various locations that had some connection to the ocean, sea or water. The “nearshore” and “high seas” categories referred to plastic waste collected from the ocean or sea. The category “ocean bound” referred to plastics “collected from communities with no formal waste management <50 km of the shore line”.

84 Clorox decided to use “ocean bound” resins supplied by Oceanworks to manufacture the Products and Oceanworks’ “ocean bound” resins were used in the Products. Oceanworks had confirmed to Clorox that there was essentially “no ocean recovered material” in the resins Clorox had decided to use, and that all of the resins Clorox had decided to use were classified as “ocean bound” under Oceanworks’ collection zone definitions.

85 As a result, when the Products were being manufactured and then offered for sale, Clorox considered the Oceanworks “ocean bound” resins to be a kind of “ocean plastic” but knew that that the Oceanworks resin in the Products was not made from waste plastic collected or recovered directly from the ocean or sea.

Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level

86 As will be explained, senior management of Clorox were involved in the contravening conduct.

87 In April 2021, the Products were approved for launch and supply in Australia by the Regional Innovation Team (the RIT). The RIT comprised regional senior managers of the Clorox Group (one of whom was also a director of Clorox), the region in this case being AMEA (comprising Asia, the Middle East, Europe, Australia and New Zealand), and was responsible for providing approval for projects involving expenditure on the development of new products.

88 Documents provided to the RIT to support the request for the RIT’s approval of the Products displayed images of the Original Product Packaging. They included information that the Products were comprised of resin supplied by Oceanworks that were classified by it as “ocean bound” and referred to certain findings from consumer market research undertaken by Clorox showing that the packaging design clearly communicated “ocean recycled” to the surveyed consumers, that the surveyed consumers saw “ocean bound recycled plastic as a preventative to reducing ocean plastic” and that the surveyed consumers expected to pay a small premium for sustainable products.

89 The “Clorox Australia Senior Management” comprised the “Clorox ANZ Leadership Team” (which included two directors of Clorox), a third director of Clorox (who was also a member of the RIT) and other senior management of Clorox. At the time the launch of the kitchen tidy bag Products was approved in April 2021, Clorox Australia Senior Management and other members of the RIT were aware, first, that Clorox sought, through Project Billy, to sell household garbage bag products that would make a contribution to the problem of plastic waste in the ocean and appeal to environmentally conscious consumers. They were also aware that Clorox intended that such products would be sufficiently profitable to be commercially viable and provide an improved gross profit margin over Clorox’s household garbage bag products made without recycled plastic waste resin, and that would enable it to gain an advantage over its competitors. Furthermore, they were aware that the Products were made, as to at least 50%, with resin produced from recycled plastic collected from communities with no formal waste collection, within 50 kilometres of the shoreline, and were not made with plastic recovered from the ocean or sea.

90 At the time the launch of the kitchen tidy bag Products was approved, there was a concern among at least two members of Clorox Australia Senior Management about not calling out on the front of the Original Product Packaging that the Products were made using ocean bound plastic. Those members felt that Clorox should be upfront, on the front of the Products’ packaging, about the fact that 50% of the Product comprised ocean bound plastic, “in order to be authentically sustainable in what we say and do so as to never mislead the consumer”.

91 After those concerns were raised, it was decided by members of Clorox Australia Senior Management that a change would be made to identify on the front of the Original Product Packaging that the kitchen tidy bag products were made using ocean bound plastic, which would have the effect of providing additional transparency to consumers regarding the composition of the Products. It was decided, however, that that change would not be made prior to the initial launch of the Products, because, while there was no deliberate strategy to mislead in doing so, in order to make the change, already packaged Products would have needed to be repackaged in new artwork and Clorox would then not have met its planned timeline for launching the Products.

92 Thus, members of Clorox Australia Senior Management were aware that the Products were made with resin produced from recycled plastic collected from communities with no formal waste collection within 50 kilometres of the shoreline, and were not made with plastic recovered from the ocean or sea. Furthermore, while Clorox Australia Senior Management held concerns about Clorox not calling out on the front of the Original Product Packaging that the Products were being made using “ocean bound” plastic, and decided the packaging would be changed, the launch of the Products went ahead. The Updated Product Packaging was phased in as the Products in the Original Product Packing sold out.

93 The proposed penalty takes into account the involvement of senior management of Clorox and the Clorox Group in the contravening conduct.

The size and financial position of Clorox and Clorox US

94 As mentioned above, in the periods when the contraventions occurred, Clorox’s sales revenue exceeded $100 million and its net assets exceeded $59 million. Clorox US, the parent company, is listed on the New York Stock Exchange and has substantial financial resources.

95 The size of Clorox and its ultimate parent, Clorox US, points to the need for a substantial penalty, in order to ensure that the penalty is not simply regarded by Clorox, Clorox US, or any other comparably sized business, as a cost of doing business in Australia.

Whether Clorox has previously been found by a court to have engaged in any similar conduct

96 Clorox has carried on business supplying and promoting consumer household products in Australia for more than 25 years and has not previously been found to have engaged in any similar conduct, or otherwise to have contravened any provision of the CCA or ACL.

Whether Clorox has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the ACL

97 While Clorox had in place global and local compliance measures, including a policy on truthful advertising and marketing related matters, it did not have a dedicated ACL compliance program in place during the Relevant Period, and the compliance measures it did have in place did not prevent Clorox from engaging in the contravening conduct.

Whether Clorox has shown a disposition to cooperate

98 Clorox has offered a high degree of cooperation to the ACCC in relation to the conduct the subject of this proceeding, including by voluntarily providing documents and information to the ACCC, initiating settlement discussions before the commencement of the proceeding and making the admissions in the SAFA at an early stage in the proceeding. This has spared significant resources and costs that would otherwise have been incurred by the ACCC and the Court in preparing for and holding contested hearings on liability and relief.

99 Clorox has demonstrated contrition through the degree of cooperation it has provided to the ACCC, and to the extent that it discontinued the Products in July 2023, following commencement of the ACCC’s investigation leading to this proceeding.

100 Clorox’s cooperation and contribution have been factored in to the proposed penalty.

Deterrence

101 Clorox’s net profit before tax, from sales of the Products in Packaging conveying the Ocean Plastic Representation, was $365,614. Clorox estimated that it made a net loss on the sale of the Products once expenditure on advertising and promotional activities was taken into account. Clorox noted that it also incurred costs in discontinuing the Products.

102 There is a need for specific deterrence in this case, because Clorox operates a substantial business, responsible for the supply and promotion of ubiquitous brands used by Australian consumers, and a subsidiary of a parent company with significant financial resources. Furthermore, while Clorox did not engage in any deliberate strategy to mislead, the contravening conduct occurred in circumstances where the Products were developed and taken to market as part of a broader initiative seeking to achieve commercial advantage by supplying products with particular environmental benefits. Clorox succeeded in at least some of its commercial objectives for Project Billy, in that its recommended retail prices for the Products were generally higher (and included a premium, as Clorox intended) than its standard product range of household rubbish bags, and Clorox increased its market share in the garbage bag segment in the six month period following launch of the garbage bag Products.

103 The proposed penalty reflects that Clorox is a substantial company and that a substantial penalty is necessary to achieve specific deterrence.

104 There is also a need for general deterrence in this case, given the information asymmetry between consumers and suppliers and the likelihood that environmental claims will continue to be attractive to both manufacturers and suppliers of consumer goods seeking to differentiate their products and achieve a competitive advantage over their competitors, and to consumers seeking to make a positive contribution to environmental protection.

105 The proposed penalty of $8.25 million materially exceeds the total gross and net profit and is more than twice the revenue that Clorox made from sales of the Products. In these circumstances, the proposed penalty ought not be regarded by Clorox or a comparably sized business as an acceptable cost of doing business, and could be expected to deter any potential wrongdoer from engaging in similar contravening conduct.

COMPLIANCE PROGRAM

106 The Court may, on application of the ACCC, make an order under s 246(2)(b) in relation to a person who has contravened ss 18, 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) or 33 of the ACL directing the person to establish a compliance program for employees or other persons involved in the person’s business.

107 The parties sought an order pursuant to s 246(2)(b) requiring Clorox to establish, implement, and maintain an ACL compliance program for a 3-year period that accords with the requirements set out in the proposed orders.

108 I am satisfied that an order in the terms proposed is appropriate in circumstances where Clorox’s existing compliance processes did not include an ACL-specific component and the compliance measures that were in place did not prevent the contravening conduct in this case.

CORRECTIVE NOTICE

109 The parties sought an order requiring Clorox to publish a corrective advertising notice.

110 The Court has the power under s 246(2)(d) of the ACL to require Clorox to publish, at its own expense and in the way specified in the order, an advertisement in the terms specified in the order.

111 Corrective advertising notices play a role in educating the public, including consumers and competitors, as to the type of conduct that might contravene the ACL: Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy (2003) 135 FCR 1; [2003] FCAFC 289 at [49]-[53] (Stone J).