FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Rose v Secretary of the Department of Health and Aged Care [2025] FCA 339

File number: | NSD 349 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | KATZMANN J |

Date of judgment: | 10 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – applications for summary dismissal and strike out of third further amended statement of claim – where applicants allege former Minister and senior public servants acted negligently in relation to provisional approvals of certain COVID-19 vaccines and/or committed tort of misfeasance in public office – where third further amended statement of claim over 800 pages long – whether pleading discloses reasonable cause of action – whether pleading is evasive, ambiguous, likely to cause prejudice embarrassment or delay in proceeding – whether applicants should have leave to replead if pleading struck out PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – application for security for costs – whether security for costs should be ordered – where applicants are impecunious but have benefit of litigation funding agreement – where not suggested litigation funder lacks means to meet adverse costs order – where litigation funder does not stand to profit from proceeding – where proceeding has public interest considerations |

Legislation: | Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 31A, 37N, 37M, 56 Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) s 61A Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) rr 16.02, 16.44(2), 19.01, 20.13, 26.01 Australian Solicitors Conduct Rules 2023 (Qld) r 21.4 Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015 (NSW) r 21.4 Legal Profession Uniform Conduct (Barristers) Rules 2015 (NSW) rr 64 and 65 2011 Barristers’ Rules (Qld) rr 63 and 64 |

Cases cited: | Abbott v Zoetis Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCA 462; 369 ALR 512 All Class Insurance Brokers Pty Ltd (in liq) v Chubb Insurance Australia Ltd [2020] FCA 840 Alpert v Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Defence) (No 2) [2024] FCA 447 Augusta Ventures Limited v Mt Arthur Coal Pty Limited [2020] FCAFC 194; 283 FCR 123 Batistatos v Roads and Traffic Authority of New South Wales [2006] HCA 27; 226 CLR 256 Brett Cattle Company Pty Limited v Minister for Agriculture [2020] FCA 732; 274 FCR 337 Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; 60 CLR 336 Bruce v Odhams Press Limited [1936] 1 KB 697 Cowell v Taylor (1885) 31 Ch D 34 Crimmins v Stevedoring Industry Finance Committee [1999] HCA 59; 200 CLR 1 Dare v Pulham [1982] HCA 70; 148 CLR 658 Eastman v Director of Public Prosecutions (ACT) [2003] HCA 28; 214 CLR 318 Farah Custodians Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2018] FCA 1185 Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2012] HCA 39; 247 CLR 486 Fuller v Toms [2012] FCAFC 155 Graham Barclay Oysters Pty Ltd v Ryan [2002] HCA 54; 211 CLR 540 Green v CGU Insurance Ltd [2008] NSWCA 148; 67 ACSR 105 Jazabas Pty Ltd v Haddad [2007] NSWCA 291, 65 ACSR 276 Karlsson v Griffith University [2022] FCA 591 Kelly v Willmott Forests Ltd (in liq) [2012] FCA 1446 Knight v Beyond Properties Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 764 Knowles v Commonwealth of Australia [2022] FCA 741 KP Cable Investments v Meltglow Pty Ltd [1995] FCA 76; 56 FCR 189 KTC v David [2022] FCAFC 60 Lee v Parker (No 2) [2022] FCA 582 Livingspring Pty Ltd v Kliger Partners (2008) 20 VR 377 Madgwick v Kelly [2013] FCAFC 61; 212 FCR 1 Meckiff v Simpson [1968] VR 62 Minister for Fisheries v Pranfield Holdings Ltd [2008] 3 NZLR 649 Minister for the Environment v Sharma [2022] FCAFC 35; 291 FCR 311 Northern Territory v Mengel [1995] HCA 65; 185 CLR 308 Nyoni v Shire of Kellerberrin [2017] FCAFC 59; 248 FCR 311 Obeid v Lockley (2018) 98 NSWLR 258 Oztech Pty Ltd v Public Trustee of Queensland [2019] FCAFC 102; 269 FCR 349 Plaintiff M83A/2019 v Morrison (No 2) [2020] FCA 1198 PNJ v The Queen [2009] HCA 6; 83 ALJR 384; 252 ALR 612; 193 A Crim R 54 PS Chellaram v China Ocean Shipping Co [1991] HCA 36; 5 ACSR 633; 65 ALJR 642; 102 ALR 321 Ratepayers and Residents Action Association Inc v Auckland City Council [1986] 1 NZLR 746 Rogers v The Queen [1994] HCA 42; 181 CLR 251 Rosenfield Nominees Pty Ltd v Bain & Co (1988) 14 ACLR 467 Salvation Army (New South Wales) Property Trust v Commonwealth of Australia [2015] FCA 674; 147 ALD 677 Sanders v Snell (No 2) [2003] FCAFC 150; 130 FCR 149 Shelton v National Roads and Motorists’ Association Ltd [2004] FCA 1393; 51 ACSR 278 South Australia v Lampard-Trevorrow (2010) 106 SASR 331 Spencer v Commonwealth of Australia [2010] HCA 28; 241 CLR 118 Stewart v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2010] FCA 402; 76 ATR 66; 367 ALR 637 Three Rivers District Council v Bank of England (No 3) [2003] 2 AC 1 Trade Practices Commission v David Jones (Australia) Pty Ltd [1985] FCA 373; 7 FCR 109 Troiano v Voci (2019) 61 VR 511 Turner t/as Classic Gourmet Sausages v Leda Commercial Properties Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 389 UBS AG v Tyne as Trustee of the Argo Trust [2018] HCA 45; 265 CLR 77 White Industries Australia Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2007] FCA 511; 160 FCR 298 Wride v Schulze [2004] FCAFC 216 Young Investments Group Pty Ltd v Mann [2012] FCAFC 107; 293 ALR 537 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Other Federal Jurisdiction |

Number of paragraphs: | 191 |

Date of last submission/s: | 20 December 2024 |

Date of hearing: | 2 December 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicants: | Mr M Robinson SC with Mr J M Manner and Mr AC White |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | NR Barbi Solicitor Pty Ltd |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Ms K Eastman SC with Mr H Cooper |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Australian Government Solicitor |

ORDERS

NSD 349 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | ANTHONY LEITH ROSE First Applicant ANTONIO DEROSE Second Applicant GARETH O'GRADIE Third Applicant | |

AND: | SECRETARY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND AGED CARE, BRENDAN MURPHY First Respondent JOHN SKERRITT IN HIS FORMER CAPACITY AS DEPUTY SECRETARY OF HEALTH PRODUCTS REGULATION GROUP Second Respondent CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER, PAUL KELLY (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | KATZMANN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 10 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The third further amended statement of claim be struck out.

2. No other amended statement of claim be filed without the leave of the Court.

3. The respondents’ application for security for costs be dismissed.

4. The applicants pay 80% of the respondents’ costs of the interlocutory application filed on 17 June 2024.

5. These orders be entered forthwith.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

KATZMANN J:

INTRODUCTION

1 This is a representative proceeding, commonly known as class action, brought against the Commonwealth of Australia and four officers of the Commonwealth. The officers are Professor Brendon Murphy AC, the former Secretary of the Department of Health and Aged Care; Professor John Skerritt. the former Deputy Secretary of the Department; Professor Paul Kelly, the former Chief Medical Officer; and the Honourable Greg Hunt, the Minister for Health and Aged Care in the Morrison Government (the Commonwealth officers). The applicants are three men who claim damages for injuries they say they sustained as a result of receiving vaccines sponsored by Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd, Moderna Australia Pty Ltd and AstraZeneca Pty Ltd which received provisional approval on various dates between January 2021 and January 2022. They sue in their own right and on behalf of “all natural persons” in Australia (both adults and children), who were injected with one or more of the same vaccines and other, later approved vaccines, and suffered “a serious adverse event” “partly or wholly” for that reason, excluding “current” ministers of the Crown (Federal, State or Territory) and judicial officers (the group members). They claim that their injuries were caused by the negligence or misfeasance of one or more of the Commonwealth officers and that the Commonwealth is vicariously liable for the conduct of those officers. The allegedly tortious conduct is said to have occurred in relation to the provisional approval of the vaccines for use in Australia and in public statements made by the Commonwealth officers or issued by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) or the Department. A more precise summary of the applicants’ claims cannot be given for reasons which will soon become apparent.

2 The proceeding was commenced in April 2023 by the filing of an originating application and a 652-page statement of claim. Since then, the statement of claim has been amended four times. Still, the pleading remains prolix. The latest version, the third further amended statement of claim (3FASOC), is 819 pages long. It is dense and extremely difficult to follow. Substantial parts of it are impenetrable.

3 The relief sought is “compensation and/or damages” with interest plus costs. The basis of the claim for compensation, as distinct from damages, is obscure. A claim is made in the pleading, but not in the originating application, for exemplary damages but that claim is not particularised, contrary to the requirement in r 16.44(2) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) that, where such a claim is made, the pleading must also “state particulars of the facts on which the claim is based”. Despite the misfeasance claim, no declaration is sought that anything allegedly done by any of the Commonwealth officers was unauthorised, invalid or beyond power.

4 On 17 June 2024, after extensive correspondence with the applicants in an endeavour to understand and appropriately respond to their pleadings, the respondents filed an interlocutory application seeking:

(1) summary judgment and in the alternative an order that the statement of claim be struck out without leave to replead; or

(2) in the event that the matter is allowed to proceed, an order that within 20 days $312,000 (exclusive of GST) be paid as initial security for costs, that the proceedings be stayed until the security is paid, and that the proceeding be dismissed if the applicants fail to provide the security within the specified time.

5 The interlocutory application is supported by two affidavits affirmed by Emma Gill on 17 June 2024 and 29 November 2024. Ms Gill is a solicitor with the Australian Government Solicitor (AGS) with over 20 years’ experience conducting complex civil litigation for AGS, including representative proceedings and large common law negligence claims against the Commonwealth. The applicants relied on two affidavits relevant only to the security for costs application. Those affidavits were affirmed by Dr Melissa McCann, who has a funding agreement with the applicants, and Christopher Grisenti, a costs law specialist.

6 Written submissions were filed by both parties which were supplemented by oral argument. The written submissions were from the respondents in chief, the applicants in response and the respondents in reply. I have given careful consideration to those submissions. Shortly before the hearing commenced a further submission was filed on behalf of the applicants purportedly in reply to the respondents’ reply. I declined to grant leave to permit the applicants to file such a document but indicated that I would treat the document as “speaking notes” and that it was open to senior counsel for the respondents to address me on any part of them if he wished to.

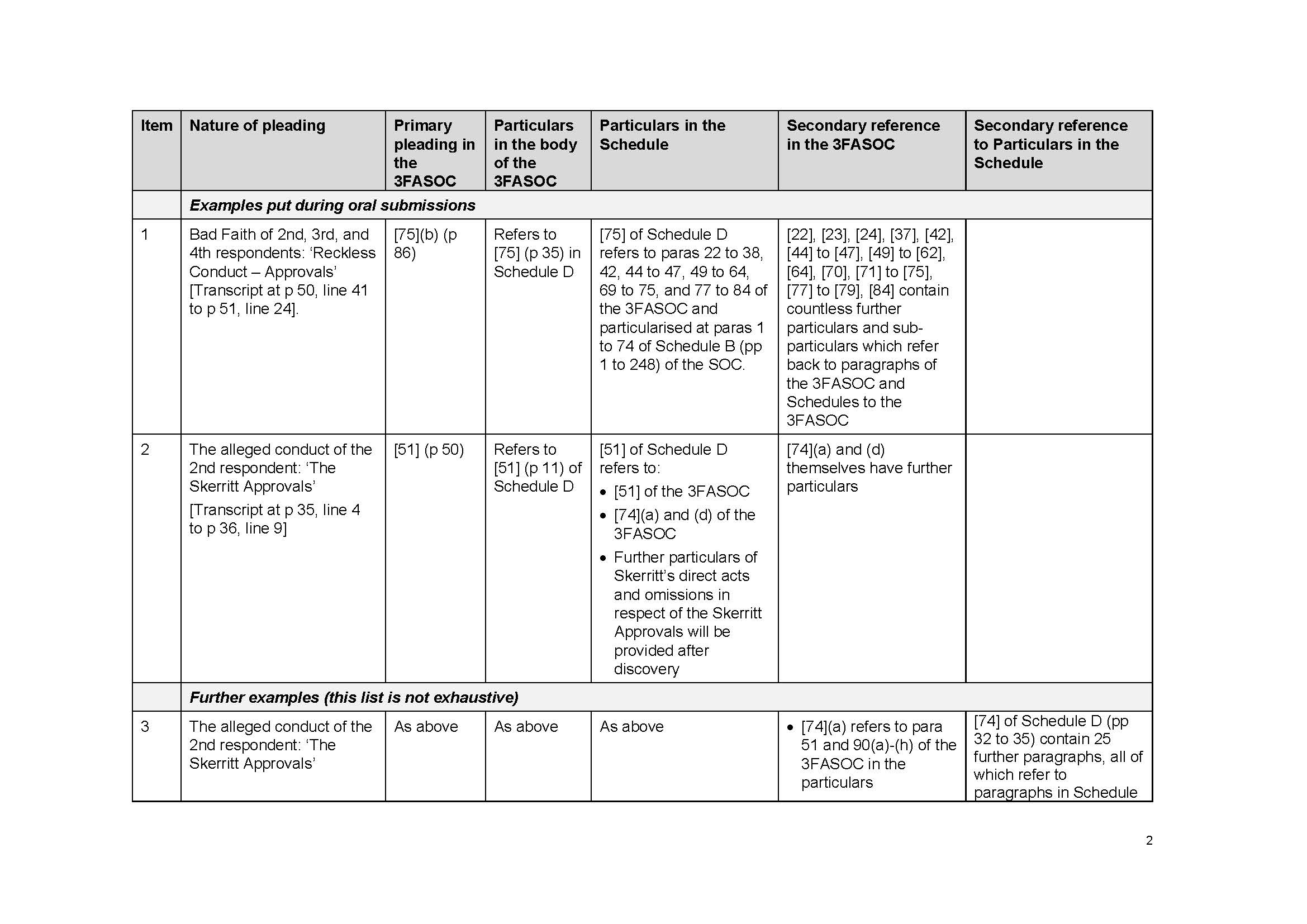

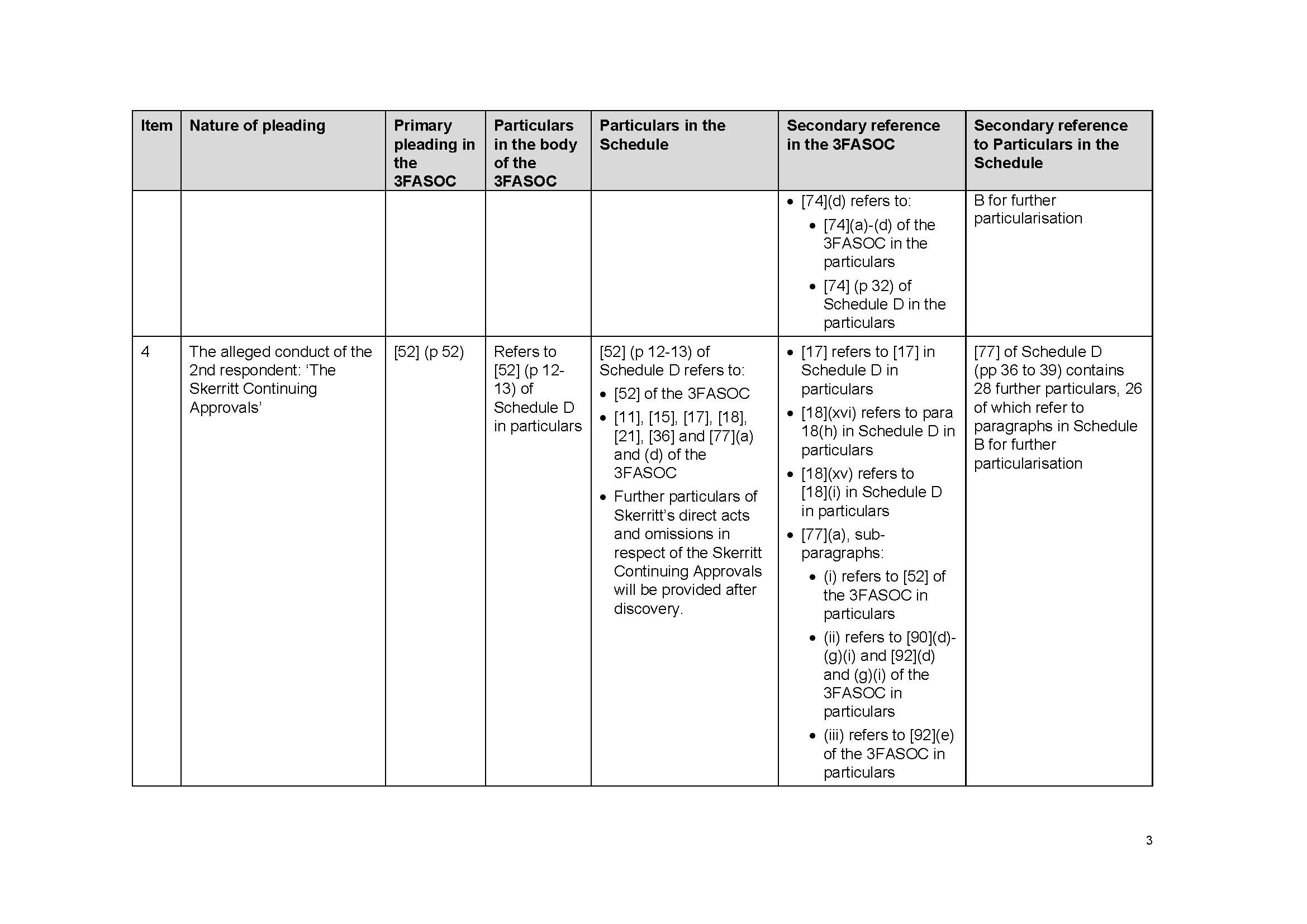

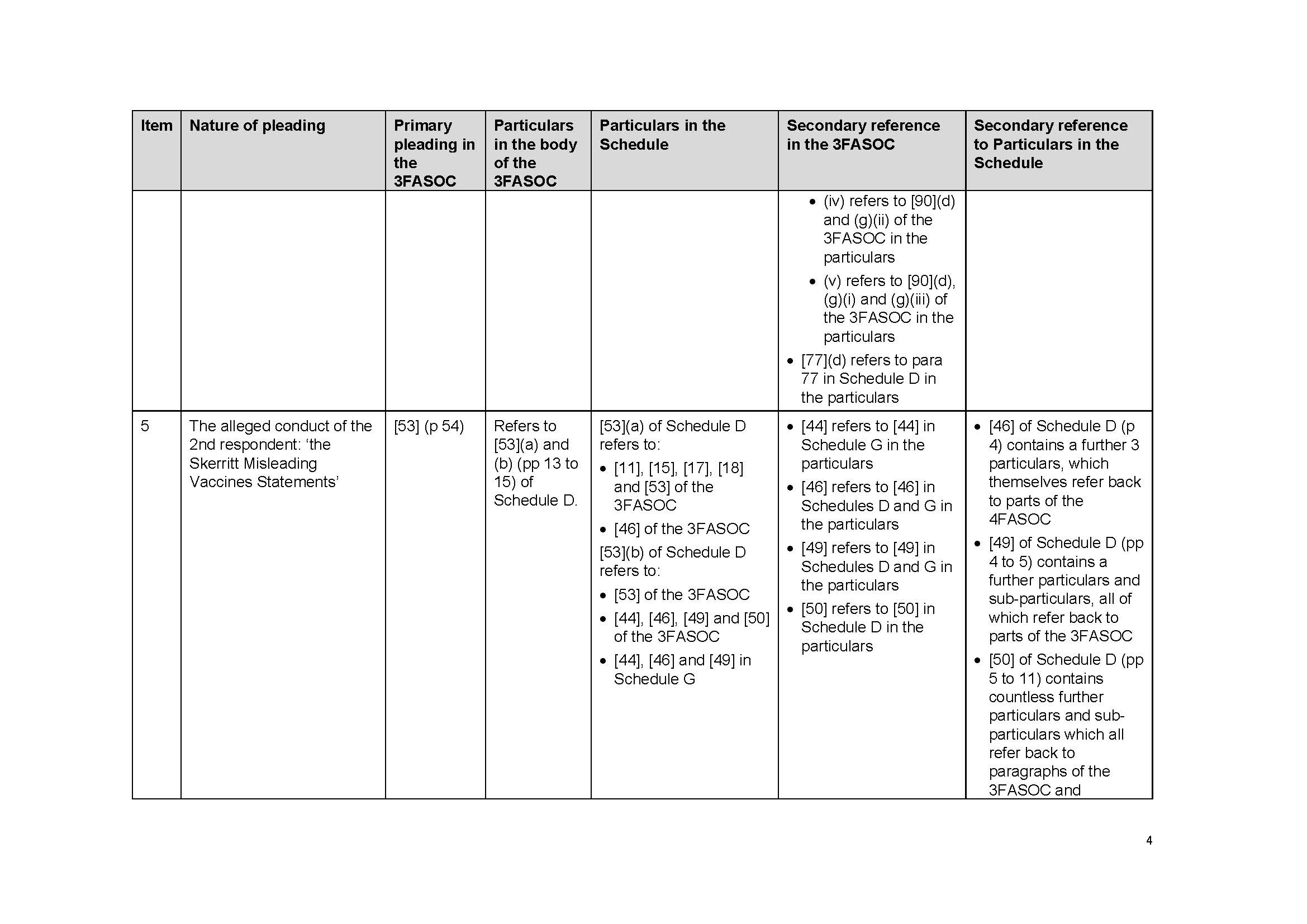

7 At the conclusion of the hearing I made orders requiring the respondents to file and serve four documents to assist me in that process, namely: (1) a chronology of relevant background events and procedural history; (2) a table of alleged issues with the pleading in relation to the questions of knowledge and bad faith, annexed to these reasons; (3) a table identifying the alleged deficiencies in the amended statement of claim which continue to be present in the 3FASOC; and (4) references to any authorities interpreting s 61A of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (TG Act) or an analogous section in other legislation. At the same time I gave the applicants the opportunity to file any amended version of the respondents’ chronology; to identify any alleged errors in the respondents’ tables; and to provide any references to additional authorities on the interpretation of s 61A or analogous provisions.

8 The following day, senior counsel for the applicants informed my associate that his instructions had been withdrawn. The documents subsequently filed by the applicants were signed by the more senior of the applicants’ junior counsel.

9 Two of the three documents filed by the applicants did not comply with the terms of the orders. The applicants frankly acknowledged as much in relation to the document purporting to respond to the second table, stating:

The below does not engage in a response to the error or otherwise of the complaints made with respect to the ASOC, but rather as to the error of those complaints, the substance of which the Respondents now say subsist in the current Pleading.

10 What follows is some 56 pages seeking to defend the pleading.

11 The document filed by the applicants which purportedly responds to the respondents’ table of alleged issues with the pleading on knowledge and bad faith is 24 pages long and goes well beyond the terms of the order.

12 I propose to have no regard to these documents. They should not have been submitted or accepted for filing. The Rules did not authorise this course, the Court did not give the applicants leave to file them and the applicants did not seek leave. If leave had been sought, I would have refused it for the same reasons McHugh J proffered in Eastman v Director of Public Prosecutions (ACT) (2003) 214 CLR 318 at [27]–[31] in similar circumstances with respect to a seven-page submission forwarded to the High Court, after it had heard argument and while judgment was reserved. In that case, like the present, the appellant had informed the court that he had withdrawn his instructions to the senior counsel who had represented him at the hearing. The observations McHugh J made in Eastman at [29] and [31] apply equally here:

Parties to matters before the Court need to understand that, once a hearing in the Court has concluded, only in very exceptional circumstances, if at all, will the Court later give leave to a party to supplement submissions. Parties have a legal right to present their arguments at the hearing. If a new point arises at the hearing, the Court will usually give leave to the parties to file further written submissions within a short period of the hearing ordinarily seven to fourteen days. But a party has no legal right to continue to put submissions to the Court after the hearing. In so far as the rules of natural justice require that a party be given an opportunity to put his or her case, that opportunity is given at the hearing.

…

Once the hearing has concluded, the workload of the Court makes it impossible for the Court to give leave to file further submissions — with all the attendant delay in the Court's business by a fresh round of submissions. Efficiency requires that the despatch of the Court's business not be delayed by further submissions reflecting the afterthoughts of a party or — as perhaps is the case in this appeal — some dissatisfaction with the arguments of the party's counsel.

THE APPLICATION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT/STRIKE-OUT

The respondents’ contentions

13 The respondents’ contention is that summary judgment should be entered in their favour because the proceeding has no reasonable prospect of success; the 3FASOC fails to disclose any reasonable cause of action; and the proceeding is an abuse of process.

14 Alternatively, the respondents contend that the pleading should be struck out in full because it contains scandalous material, is embarrassing, evasive and ambiguous, and an abuse of process, and it fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action.

15 The respondents contend that the negligence claim is bound to fail because the applicants have no reasonable prospect of establishing the existence of the pleaded duty; the allegations of bad faith have not been adequately pleaded or properly particularised; the allegations of breach are vague, generalised, embarrassing and inappropriate; and the pleading makes no attempt to link the alleged breaches of duty to the harm allegedly suffered by the applicants. The respondents contend that the misfeasance claim is fatally flawed in a number of respects.

The evidence

16 The evidence from Ms Gill relevantly discloses the following matters.

17 Five days after the originating application and statement of claim were filed, the applicants served an amended statement of claim. Two months later, on 5 July 2023, AGS wrote a lengthy letter to the applicants’ lawyers drawing attention to “the inadequacy and fundamental flaws” of the document. Many of the matters raised are equally applicable to the latest pleading. For example:

The ASOC, at 654 pages, is extremely lengthy. It would assist the Court and the respondents to navigate the ASOC if it included an index, a glossary of key terms/expressions and an overarching statement outlining the essential elements of the claims.

…

The ASOC fails to comply with the ordinary rules of pleadings. It is incumbent on the applicants to plead all relevant facts and identify a proper basis for an allegation with respect to a person’s states of mind fully and clearly. This requires more than asserting a ‘material fact’ at such a high level of generality as to leave the respondents in real doubt as to the case they have to meet. Such a pleading is embarrassing and liable to be struck out.

…

I take the reference to “relevant” to mean “material”.

18 AGS also drew the applicants’ attention to the obligations of the parties under s 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) and pointed out that “proper pleading discipline is critical to the management of civil cases, in which the ‘primary rule of evidence is that a court will receive, and only receive, evidence that is relevant to the issues as defined by the pleadings’”. AGS asserted:

On the basis of the current ASOC, the pre-trial processes in this matter would be extremely time-consuming and costly. For example, the lack of pleading specificity would make the proper scope of discovery unclear. For those reasons, the respondents consider it essential that both the applicants and the Court give early consideration to the adequacy of the pleadings.

19 AGS proceeded to identify numerous problems it detected with the pleading, foreshadowing the filing of an application for “strike out and summary judgment” unless the claims were satisfactorily repleaded.

20 Two days later I made an order by consent, among other things, requiring a further amended statement of claim to be filed and served by 21 August 2023. On 11 August 2023 I extended the time for filing, again by consent, to 4 September 2023 and on 4 September 2023 the duty judge extended the period to 18 September 2023. These orders also made provision for the respondents to request further and better particulars, for the applicants to reply to any such request, and for corresponding extensions to the filing dates.

21 On 18 September 2023 the applicants filed and served their Further Amended Statement of Claim (FASOC). It ran to 991 pages.

22 On 17 November 2023 AGS sent a 28-page letter to the applicants’ lawyers identifying numerous problems with the FASOC and asked them whether they proposed conducting “a further review and revision of the FASOC”. The author, Alison Thomson, a Senior Executive Lawyer, went on to say:

20. In the meantime, we note the existing Court orders require the respondents to make requests for further and better particulars of the FASOC. Although we are further concerned that requesting particulars of the FASOC is an inefficient use of the parties’ time and costs, we intend to comply with the Court’s orders.

21. As such, we have targeted our request for particulars on key areas of the FASOC where we consider the deficiency in pleading is most grievous. As noted above, the respondents do not consider that provision of further particulars can remedy the applicants’ failure to properly plead the material facts required to establish each element of the relevant causes of action. However, we have taken this approach to provide the applicants with the opportunity to attempt to remedy these flaws, to the extent possible, through the provision of particulars, before we obtain instructions as to whether to proceed with an application for summary dismissal/strike out.

23 Ms Thomson drew particular attention to the manner in which the putative knowledge of the respondents had been pleaded, reminding the applicants of the relevant rules of court. Among other things, she informed the applicants’ lawyers that none of the decisions to approve the vaccines was made by any of the Commonwealth officers. She requested 166 further and better particulars.

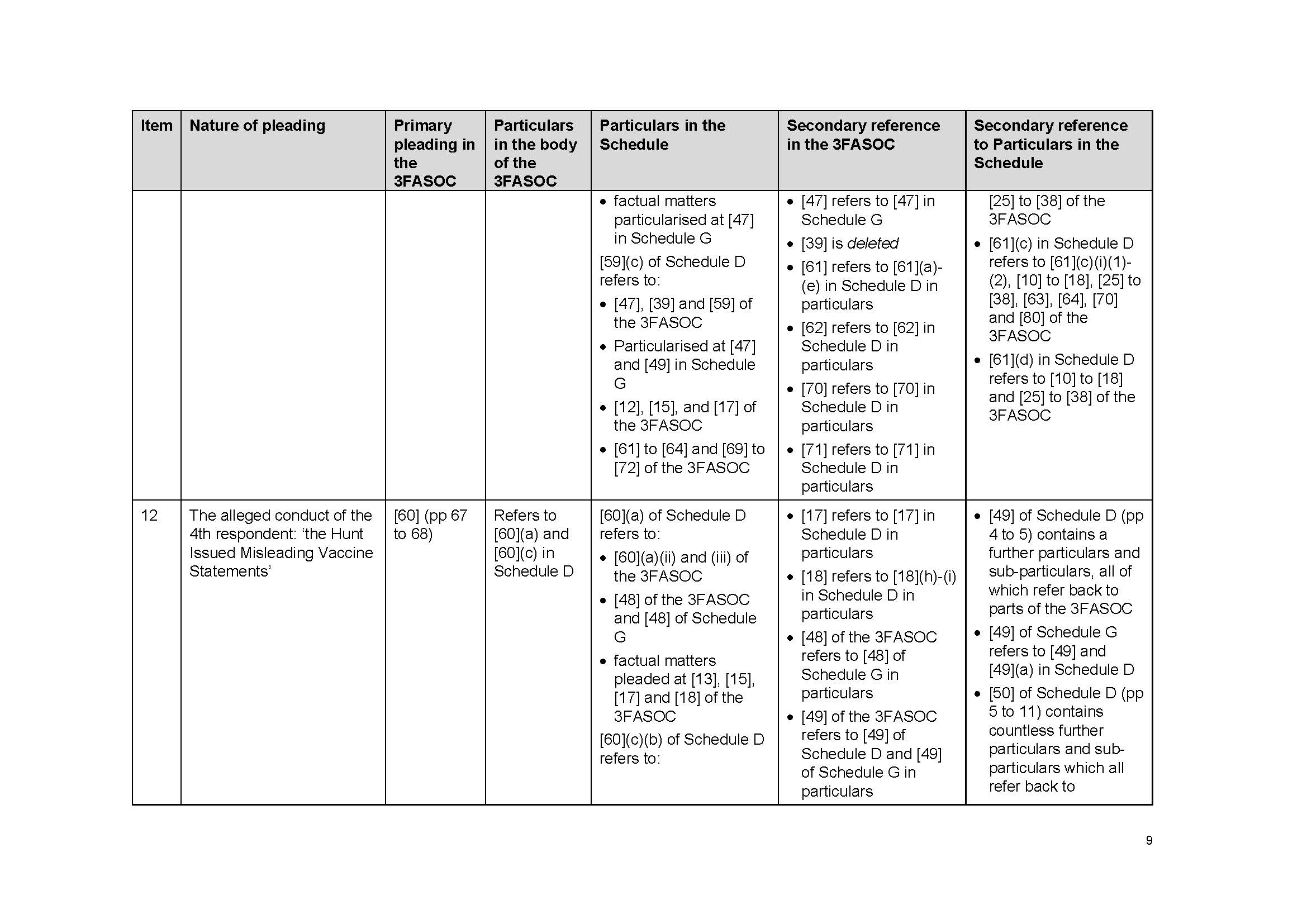

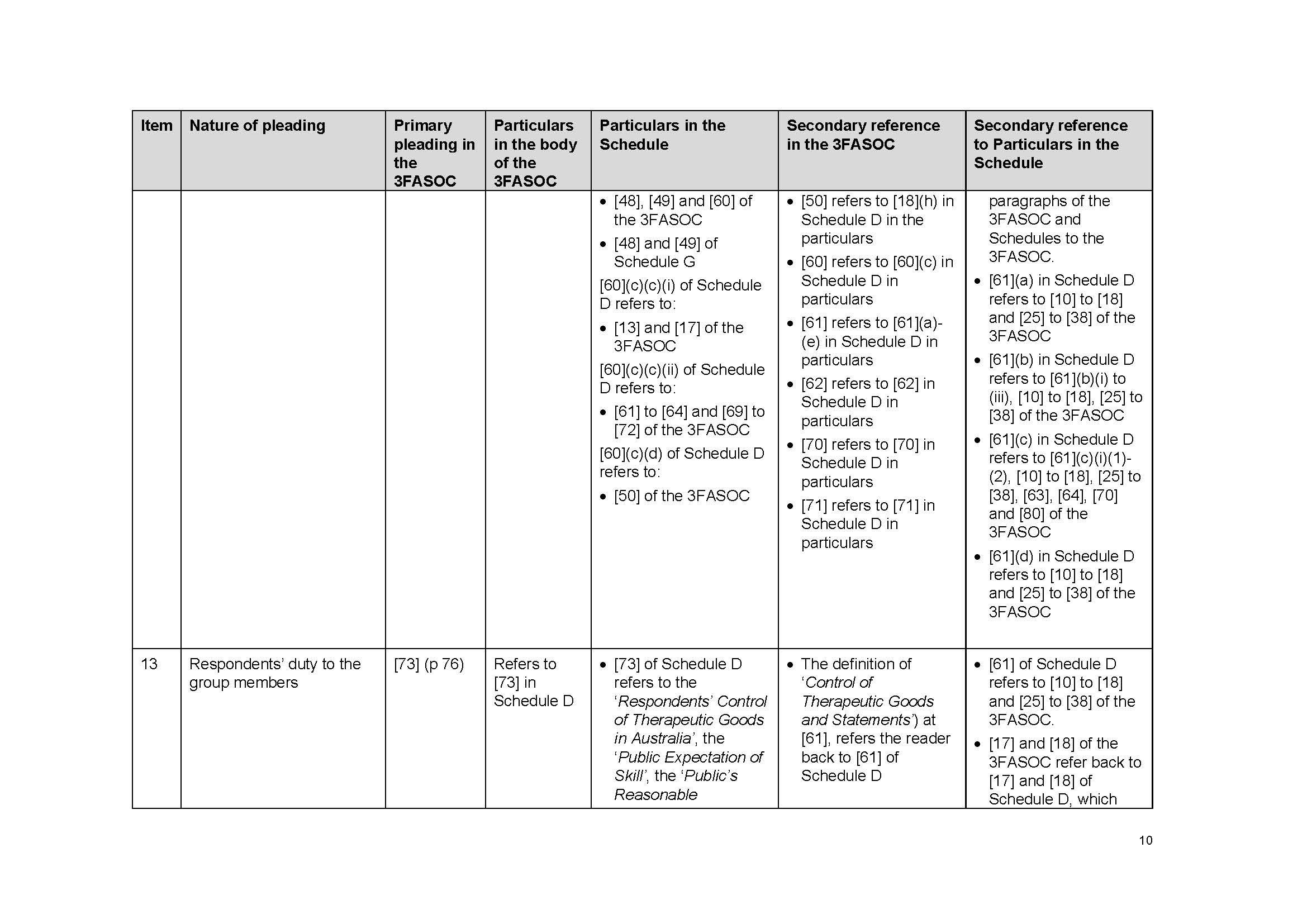

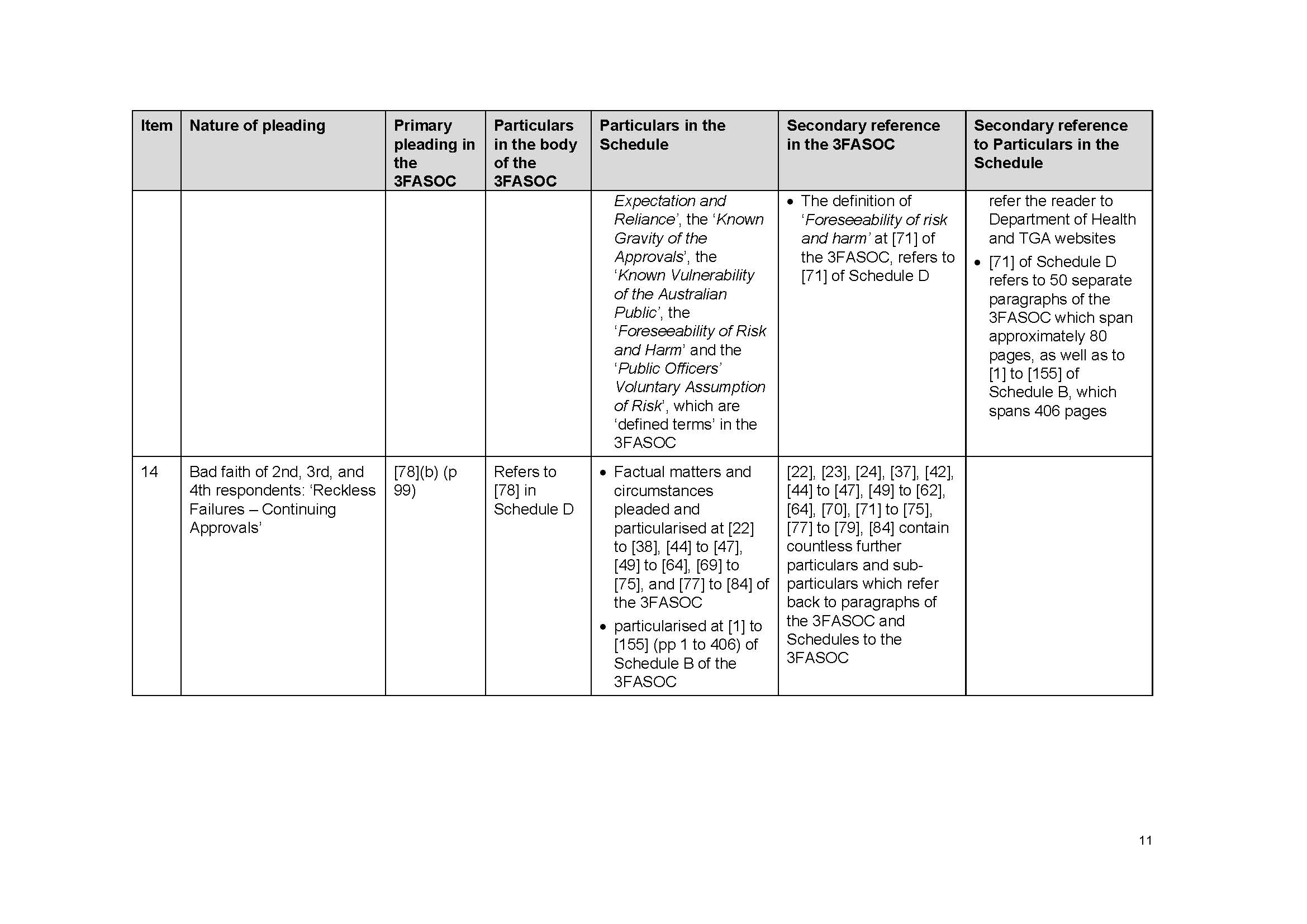

24 On 14 December 2023 I made various orders by consent, among other things, giving the applicants additional time to reply to the respondents’ request for particulars.

25 On 24 January 2024 the applicants’ lawyers wrote to AGS advising that they had considered the issues raised in its letter of 17 November 2023, and proposed filing a second further amended statement of claim which would incorporate the further and better particulars as requested. Unwisely, as it turned out, the respondents agreed to this course and on 9 February 2024 I made orders in chambers by consent enabling the applicants to file any second further amended statement of claim by 1 March 2024 and the respondents to file and serve any interlocutory application for orders for summary judgment and/or striking out the pleadings by 12 April 2024.

26 On 4 March 2024 the applicants filed the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim (2FASOC). It ran to 1025 pages.

27 Three weeks later, on 26 March 2024, the applicants’ lawyers wrote to AGS seeking to “further refine the 2FASOC” and on 28 March 2024 provided AGS with a draft 3FASOC.

28 On 8 April 2024 AGS wrote to the applicants’ lawyers seeking confirmation that the applicants intended to rely on the draft 3FASOC and informing them, among other things, that the respondents would consent to the filing of the 3FASOC but reserved their rights to bring applications for strike out and summary dismissal with respect to the amended pleading. The next day, the applicants’ lawyers informed AGS that they had retained senior counsel (Mark Robinson SC), that he had advised that further amendments to the proposed 3FASOC were desirable, and that they denied that their claims were “fundamentally defective”. On 11 April AGS sent a letter to the applicants’ lawyers indicating that the respondents would consent to the filing of the proposed 3FASOC but reserved their rights to bring applications for strike out and summary judgment with respect to that pleading.

29 On 17 April 2024 I made orders requiring the applicants to file any 3FASOC and a concise statement by 7 May 2024, the latter in the pious hope that it might clarify the applicants’ claims.

30 The 3FASOC was filed on 7 May 2024.

31 The 3FASOC is nearly 200 pages longer than the original statement of claim, albeit that 629 pages are incorporated as “schedules”. While it contains an index (curiously titled “index of contents”), it does not include a glossary of key terms/expressions. It is apt to confuse. At the first case management hearing, I asked the applicants to provide me with a glossary. No such document was ever provided. Instead I received a document listing the defined terms and the paragraphs in the statement of claim where the definitions could be found. On the last working day before hearing of the interlocutory application, a reworked version of the same document was filed. It was even less helpful than the first.

The applicants’ arguments

32 The applicants emphasised the need for caution in exercising the power to award summary judgment and the heavy onus on the party who seeks it. They contended that the “timing and nature” of the respondents’ application was “misconceived” because no defence has been filed. They asserted that where, as here, there are mixed questions of fact and law, “the complexity requires a full hearing”. They refuted the respondents’ characterisation of their pleadings, contending that “on their face” they demonstrate the “baselessness of the respondents’ assertions” because “the pleadings make clear the case against them”. The applicants submitted that the relief the respondents seek should be refused “because the legal and factual issues the Court must decide have not crystallised”.

33 I will refer in due course to the particular arguments concerning the pleaded causes of action. Before doing so, however, it is necessary to identify the relevant powers, rules and principles.

The relevant powers, rules and principles

34 Section 31A of the FCA Act relevantly provides that:

(2) The Court may give judgment for one party against another in relation to the whole or any part of a proceeding if:

(a) the first party is defending the proceeding or that part of the proceeding; and

(b) the Court is satisfied that the other party has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding or that part of the proceeding.

(3) For the purposes of this section, a defence or a proceeding or part of a proceeding need not be:

(a) hopeless; or

(b) bound to fail;

for it to have no reasonable prospect of success.

(4) This section does not limit any powers the Court has apart from this section.

35 The principles governing the exercise of this power are set out in Spencer v Commonwealth of Australia (2010) 241 CLR 118. There is a difference between “no reasonable prospect” and “no real prospect” (the expression in the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 of England and Wales), as the “negative admonition” in s 31A(3) makes clear: Spencer at [51]–[52] (Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ). The former requires an assessment of the prospects of success, the latter calls for a determination that the action is certain to fail: Ibid at [54]. The power is not to be exercised lightly: Ibid at [60]; [24] (French CJ and Gummow J). An action should not be summarily dismissed merely because the Court considers the applicant is unlikely to succeed on a factual issue. Similarly, if the success of the proceeding depends on a proposition of law, the fact that case law, other than a judgment of the High Court, appears to preclude an applicant from succeeding “may not always be the end of the matter” as “[e]xisting authority may be overruled, qualified or further explained”: Spencer at [25] (French CJ and Gummow J). A “practical judgment” is called for: Spencer at [25].

36 By r 26.01, read with r 1.40, the Court may also order summary judgment in favour of a respondent if the applicant has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding or part of the proceeding or the proceeding is frivolous or vexatious, discloses no reasonable cause of action, or is an abuse of process.

37 Pleadings are covered by Pt 16 of the Rules. The key features include the following matters. First, a pleading must be as brief as the nature of the case permits: r 16.02(1)(b). Second, it must identify the issues the party wants the Court to resolve: r 16.02(1)(c). Third, it must state the material facts on which the party relies that are necessary to give the opposite party fair notice of the case against it but not the evidence by which the material facts are to be proved: r 16.02(d). Fourth, it must state the provisions of any statute relied on: r 16.02(e). In addition, a pleading must not ask for relief that is not claimed in the originating application: r 16.02(4).

38 Importantly, not all relevant facts are “material facts”. A fact is material if it is essential to the cause of action, that is to say, if it is a fact which, in combination with other facts, gives rise to a right to sue: Bruce v Odhams Press Limited [1936] 1 KB 697 at 710–712 (Scott LJ). In other words, a fact is material if it is essential to prove that fact in order to make out the cause of action or put another way, it is an element of the cause of action.

39 The elements of a cause of action in negligence are the existence of a duty of care, breach of duty, damage and a causal connection between the breach and the damage. The elements of a cause of action for misfeasance in public office are an invalid or unauthorised act; done maliciously; by a public officer; in the purported discharge of their public duty; which causes loss or harm to the applicant: Northern Territory v Mengel (1995) 185 CLR 308 at 370 (Deane J). In contrast to the tort of negligence, misfeasance in public office is a “deliberate tort in the sense that there is no liability unless either there is an intention to cause harm or the officer concerned knowingly acts in excess of his or her power”: Mengel at 345 (Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron and McHugh JJ).

40 In Mengel at 356 Brennan J discussed what was necessary to establish that a purported exercise of a power was invalid or unauthorised and the consequences of such a finding:

A number of elements must combine to make a purported exercise of administrative power wrongful. The first is that the purported exercise of power must be invalid, either because there is no power to be exercised or because a purported exercise of the power has miscarried by reason of some matter which warrants judicial review and a setting aside of the administrative action. There can be no tortious liability for an act or omission which is done or made in valid exercise of a power. A valid exercise of power by a public officer may inflict on another an unintended but foreseeable loss — or even an intended loss — but, if the exercise of the power is valid, the other’s loss is authorised by the law creating the power. In that case, the conduct of the public officer does not infringe an interest which the common law protects. However, a purported exercise of power is not necessarily wrongful because it is ultra vires. The history of the tort shows that a public officer whose action has caused loss and who has acted without power is not liable for the loss merely by reason of an error in appreciating the power available. Something further is required to render wrongful an act done in purported exercise of power when the act is ultra vires.

41 Malice can be made out if the act is done (or omitted to be done) either:

(a) with the specific intention of causing injury to a person or persons in the knowledge that the act (or omission) was invalid or done without power and in the knowledge that it would, or would be likely to cause injury (sometimes referred to as “targeted malice”); or

(b) with reckless indifference or deliberate blindness to the illegality of the act and likelihood of injury (sometimes referred to as “untargeted malice”).

See, for example, Mengel at 356–7 (Brennan J); 370–1 (Deane J); Three Rivers District Council v Bank of England (No 3) [2003] 2 AC 1 at 191E-F (Lord Steyn), 197 (Lord Hope of Craighead); and Sanders v Snell (No 2) (2003) 130 FCR 149 at [95]-[96] (Black CJ, French and von Doussa JJ).

42 Mere foreseeability of harm is insufficient: Obeid v Lockley (2018) 98 NSWLR 258 at [153]-[171] (Bathurst CJ, Beazley P agreeing at [206], and Leeming JA agreeing at [213], [226]-[242]). As Bathurst CJ and Leeming JA explained in Obeid, the contrary view (expressed in South Australia v Lampard-Trevorrow (2010) 106 SASR 331 at [263]–[264]) is based on a misreading of a passage of the reasons of the plurality in Mengel at 347.

43 Rares J explained in Brett Cattle Company Pty Limited v Minister for Agriculture (2020) 274 FCR 337 at [270] (original emphasis):

Relevantly, [misfeasance in public office] is a tort that requires the claimant to establish that the public officer abused or misused his or her office intentionally, that is by either intending to cause harm (the first limb) or knowingly acting in excess of his or her power (the second limb): Mengel at 345; Sanders 196 CLR 329 at [37]-[38], [42] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, Kirby and Hayne JJ; Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Futuris Corporation Ltd (2008) 237 CLR 146 at [11], [55] per Gummow, Hayne, Heydon and Crennan JJ. The intention or state of mind of the public officer when exercising the power, which he or she appears to hold, is critical to the ascertainment of whether he or she misused the public office in that exercise.

44 Each limb involves the exercise of a public power in bad faith. As Lord Steyn put it in Three Rivers at 191E–F, the first involves bad faith in the sense of the exercise of the power for an improper or ulterior motive, the second occurs where a public officer acts knowing that he has no power to do so and that the act will probably injure the plaintiff (applicant). In the second case, the bad faith is an absence of an honest belief that his act is lawful. This is consistent with, and reflects, the analysis of Brennan J in Mengel at 357 to which his Lordship referred at 192E-F.

45 In Mengel at 357 Brennan J put it this way:

[T]he mental element is satisfied when the public officer engages in the impugned conduct with the intention of inflicting injury or with knowledge that there is no power to engage in that conduct and that that conduct is calculated to produce injury. These are states of mind which are inconsistent with an honest attempt by a public officer to perform the functions of the office. Another state of mind which is inconsistent with an honest attempt to perform the functions of a public office is reckless indifference as to the availability of power to support the impugned conduct and as to the injury which the impugned conduct is calculated to produce. The state of mind relates to the character of the conduct in which the public officer is engaged — whether it is within power and whether it is calculated (that is, naturally adapted in the circumstances) to produce injury … It is the absence of an honest attempt to perform the functions of the office that constitutes the abuse of the office. Misfeasance in public office consists of a purported exercise of some power or authority by a public officer otherwise than in an honest attempt to perform the functions of his or her office whereby loss is caused to a plaintiff. Malice, knowledge and reckless indifference are states of mind that stamp on a purported but invalid exercise of power the character of abuse of or misfeasance in public office. If the impugned conduct then causes injury, the cause of action is complete.

(Emphasis added.)

46 Where serious allegations of dishonesty, fraud or acting with malice or bad faith are made, the allegations must be pleaded “specifically and with particularity”: Plaintiff M83A/2019 v Morrison (No 2) [2020] FCA 1198 at [56] (Mortimer J).

47 As the Full Court (Siopis, Gilmore and McKerracher JJ) said in Fuller v Toms [2012] FCAFC 155 at [17]:

The general principles of pleadings in the modern context are well-established. The function of a pleading is to state, with sufficient clarity, the case that a party must meet thereby rendering procedural fairness, as well as defining the issues for decision. Both aspects are important: Banque Commerciale SA En Liquidation v Akhil Holdings Limited (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 286.

48 In order to provide procedural fairness to a respondent in a representative action, the basic function of the statement of claim is to set out “in comprehensible terms” the material facts in the applicant’s case and, “at a high level of generality”, the claims of group members: Abbott v Zoetis Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCA 462; 369 ALR 512 at [21] (Lee J).

49 Rule 16.02(2) provides that a pleading must not:

(a) contain any scandalous material; or

(b) contain any frivolous or vexatious material; or

(c) be evasive or ambiguous; or

(d) be likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding; or

(e) fail to disclose a reasonable cause of action or defence or other case appropriate to the nature of the pleading; or

(f) otherwise be an abuse of process of the Court.

50 A pleading which answers any of these descriptions is liable to be struck out either on the application of a party or at the initiative of the Court: rr 16.21, 1.40.

51 In Karlsson v Griffith University [2022] FCA 591 at [43] I observed that:

These categories overlap. For example, a proceeding will be frivolous, if, among other reasons, the applicant has no reasonable prospects of successfully prosecuting it (Spencer v Commonwealth of Australia (2010) 241 CLR 118 at [22] per French CJ and Gummow J) or because no reasonable cause of action is disclosed (Karlsson v Griffith University per Wright J at [87]) and a proceeding may be an abuse of process if it is “vexatious and oppressive for the reason that it is sought to litigate anew a case which has already been disposed of by earlier proceedings”: Walton v Gardiner (1993) 177 CLR 378 at 393 (Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ). A reasonable cause of action is a cause of action with some chance of success if regard is only had to the allegations in the claimant’s pleading: Polar Aviation Pty Ltd v Civil Aviation Authority (2012) 203 FCR 325 at [41]–[43] (Perram, Dodds-Streeton and Griffiths JJ).

52 A pleading is “likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay” where it is “unintelligible, ambiguous, vague or too general, so as to embarrass the opposite party who does not know what is alleged against him” (Meckiff v Simpson [1968] VR 62 at 70 per Winneke CJ, Adam and Gowans JJ); if it merely asserts a conclusion to be drawn from facts which are not stated (Trade Practices Commission v David Jones (Australia) Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 109 at 114–115 per Fisher J); if it contains inconsistent or irrelevant allegations or alternatives that are “confusingly intermixed” (Shelton v National Roads and Motorists’ Association Ltd [2004] FCA 1393; 51 ACSR 278 at [18] per Tamberlin J). And, as Wigney J remarked in KTC v David [2022] FCAFC 60 at [121]:

A pleading may be considered to be embarrassing if it suffers from narrative prolixity or irrelevancies to the point that it is not a pleading to which the other party can reasonably be expected to plead to: Fuller v Toms (2012) 247 FCR 440; [2012] FCA 27 at [80]-[84]. A party cannot be expected to respond to mere context, commentary, “history, narrative material or material of a general evidentiary nature”: Fuller v Toms at [83].

53 In Oztech Pty Ltd v Public Trustee of Queensland (2019) 269 FCR 349 at [28]–[32] Middleton, Perram and Anastassiou JJ observed:

The question of whether a pleading adequately raises a claim or defence is not concerned with the expression of the pleading as a matter of style, or of phrasing, or the structure of the pleading. Neither is it concerned with the formality of the process by which the issues in the proceeding are identified; be it a statement of claim, statement of contentions, concise statement, points of claim or points of defence. The verbal formulation of the allegations of fact, or the contentions of law, need not conform to a particular style guide or to any pro forma template.

The sole objective of a pleading is to clearly identify matters in dispute and difference by and between the parties to the dispute. This objective necessarily involves expressing the factual basis of each claim or defence. It is necessary that the legal elements of each cause of action or defence are expressed by reference to allegations of fact required to establish each element. It is not necessary to plead the legal conclusions that follow from the facts, but it is often convenient to do so. These are trite propositions but nevertheless vital to ensuring that the pleading serves its purpose.

There should be no doubt about whether any particular cause of action is relied upon. At a minimum, the pleading should be pellucidly clear about the causes of action, or claims, relied upon by the applicant, including any claims made upon an alternative hypothesis. The explicit clarity with which a claim is expressed should ensure that there be no need for the opposite party to closely scrutinise the pleading in a process of textual construction to determine whether a particular fact is relied upon, or the purpose for which it is alleged, much less to decide whether a particular cause of action is raised. The same basic requirement applies to any defence raised in answer to a claim.

Clarity in pleading is by no means an unattainable objective, even in the most complex litigation. Often the elements of a cause of action require careful and precise identification to ensure that the relevant integer is properly characterised having regard to the context in which the claim arose. The pleading should always be a bespoke articulation of the dispute between the parties, even though the warp and the weft of its fabric may be the same as other claims based upon the same, or a similar, cause of action.

…

(Emphasis added.)

54 A “reasonable cause of action” for present purposes means “one which has some chance of success if regard is had only to the allegations and the applicant’s pleading”: Wride v Schulze [2004] FCAFC 216 at [25] (Spender, Tamberlin and Bennett JJ).

55 Although the categories of cases which will constitute an abuse of process are not closed, it has long been accepted that any of the following circumstances will suffice: where the court’s processes or procedures are invoked for an illegitimate or collateral purpose; where the use of the court’s processes or procedures would be unjustifiably oppressive to a party; or where the use of the court’s processes or procedures would bring the administration of justice into disrepute: Rogers v The Queen (1994) 181 CLR 251 at 286 (McHugh J); Batistatos v Roads and Traffic Authority of New South Wales (2006) 226 CLR 256 at [9], [15] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Crennan JJ). See also PNJ v The Queen [2009] HCA 6; 83 ALJR 384; 252 ALR 612; 193 A Crim R 54 at [3] (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ) and UBS AG v Tyne as Trustee of the Argo Trust (2018) 265 CLR 77 at [1] (Kiefel CJ, Bell and Keane JJ).

56 The power to strike out a pleading is to be exercised with caution and only in a clear or obvious case. In Young Investments Group Pty Ltd v Mann [2012] FCAFC 107; 293 ALR 537 at [6] Emmett, Bennett and McKerracher JJ summarised the relevant principles:

In an application to strike out a pleading, all of the facts alleged in the relevant pleading are to be accepted as true, and it is to be taken for granted that, on all other points, the pleading is unassailable. Provided that a pleading fulfils its basic function of identifying the issues, disclosing an arguable cause of action and apprising the other party of the case that it has to meet at trial, the pleading should be allowed to stand and the proceeding should be allowed to go to trial. Further, a court of first instance should be careful not to risk stifling the development of the law by summarily dismissing a claim where there is a reasonable possibility that, as the law develops, a cause of action may be held to lie.

57 Although a reasonable cause of action may be available, the pleadings may fail to disclose it. In that event, the question for the Court is whether the applicants have been given a reasonable opportunity to articulate the cause or causes of action upon which their application is based. See, for example, Plaintiff M83A at [47]. “A failure after ample opportunity to plead a reasonable cause of action may suggest that none exists and therefore that the applicant has no reasonable prospects of success”: White Industries Australia Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (2007) 160 FCR 298 at [47] (Lindgren J) cited with approval by French CJ and Gummow J in Spencer at [23].

58 Last but not least, any power conferred by the FCA Act or Rules must be exercised in a way that best promotes the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions: FCA Act, s 37M(3). That purpose is described in s 37M(1) and (2):

(1) The overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions is to facilitate the just resolution of disputes:

(a) according to law; and

(b) as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

(2) Without limiting the generality of subsection (1), the overarching purpose includes the following objectives:

(a) the just determination of all proceedings before the Court;

(b) the efficient use of the judicial and administrative resources available for the purposes of the Court;

(c) the efficient disposal of the Court’s overall caseload;

(d) the disposal of all proceedings in a timely manner;

(e) the resolution of disputes at a cost that is proportionate to the importance and complexity of the matters in dispute.

59 Moreover, parties to a civil proceeding have a duty to conduct the proceeding in a way that is consistent with the overarching purpose (s 37N(1)); a party’s lawyer is obliged to take that duty into account and assist the party to comply with it (s 37N(2)); and a failure to comply with that duty must be taken into account in the exercise of the discretion to award costs (s 37(4)).

The pleading

60 I reject the submission that it is premature for the Court to entertain the respondents’ application. The task of responding to the 3FASOC is a formidable one. As the respondents put it in their reply submissions, both the preparation of the defence and the provision of discovery would be “exceptionally onerous and expensive”. Applications for summary judgment and/or striking out a statement of claim are often, if not commonly, made before a defence is filed and before discovery is sought. The respondents acted appropriately, and in accordance with their obligations under s 37N of the FCA Act, by making their application when they did.

Should the third further amended statement of claim be struck out?

61 The answer to this question is an emphatic yes. This is a clear and obvious case.

62 It is true, as the applicants submitted, that this is a complex case. But the 3FASOC makes it impossibly complex, so much so that it defies the fundamental principles of pleading. It is not only likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment and delay, it is inevitable that it will have those results. Large parts of it are incoherent, unintelligible, ambiguous, impenetrable and/or expressed at a high level of generality. In critical aspects it lacks precision. It suffers from both narrative prolixity and the inclusion of irrelevant detail such that it is not a pleading to which the respondents can reasonably expect to plead. In argument at the hearing senior counsel for the applicants candidly and accurately described it as “tortuous”. He expressed “trepidation” at the “[un]pleasant exercise” of taking the Court to it. It is a pleading of the kind described by Perram J in Stewart v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2010] FCA 402; 76 ATR 66; 367 ALR 637 at [33]:

[It] is filled with irrelevancies and allegations which reveal the absence either of comprehension or application or both. The task of identifying what, if any, case the applicants have has been very much hampered by the pleadings put forward on their behalf, which is, of course, precisely the opposite effect which pleadings are intended to achieve see: Gould and Birbeck and Bacon v Mount Oxide Mines Ltd (in liq) (1916) 22 CLR 490 at 517 per Isaacs and Rich JJ; Banque Commerciale SA, En Liquidation v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 286 per Mason CJ and Gaudron J; Cordelia Holdings Pty Ltd v Newkey Investments Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 48 at [148] per Black CJ, French and Tamberlin JJ. Anyone who seeks to wrestle with the mysteries of the proposed further amended statement of claim will see that it is more akin to a Chinese puzzle box than a succinct statement of the applicants’ cases.

63 To allow the case to proceed on the present pleading or anything like it would not be the way that best promotes the overarching purpose of the civil practice and procedure provisions – far from it. Rather, to refrain from striking out the pleading would be to act in defiance of that purpose.

64 When the matter first came before the Court for case management in April 2024, I was informed that the applicants had recently engaged senior counsel and that he was undertaking a final review of the pleading with a view to further truncating and refining it. While the odd paragraph was omitted, the 3FASOC (which carries the endorsement that it was prepared by senior and junior counsel) neither truncated nor refined the pleading in any significant respect and certainly did not make it any easier to digest.

65 One of the functions of pleadings and particulars is to provide “a statement of the case sufficiently clear to enable the other party [or parties] a fair opportunity to meet it”. Another is to define the issues for resolution in the litigation, so as to enable the trial judge to rule on the admissibility of evidence. See Dare v Pulham (1982) 148 CLR 658 at 664 (Murphy, Wilson, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ). The 3FASOC fulfils neither function.

66 The 3FASOC is replete with recitations of immaterial facts; untethered, acontextual references to legislation; and a morass of infuriating cross-referencing which makes the critical allegations nigh impossible to decipher. Reading it is a herculean task. Trying to make sense of it could drive the reader mad. Identifying the material facts is like looking for a needle in a haystack. It would be oppressive to require the respondents to plead to it. If it were permitted to stand, it would likely severely delay a fair trial and prejudice the respondents in attempting to mount a defence: see Fuller v Toms at [18].

67 It beggars belief how some of the allegations could be made, such as the allegations about the state of knowledge of “the public officers and the Australian public” (in para 69). Some of the allegations are tendentious.

68 The schedules are confusing and, in some instances, misleading. Some of them have no place in a pleading and merely serve to contribute to the prolixity of the document.

69 Frequently, rolled-up allegations are made in a single paragraph.

70 Frequently, too, allegations are pleaded in a cascading series of alternatives apparently seeking to cover every conceivable way a respondent might or might not have engaged in certain conduct. At para 51, for example, the applicants allege that Prof Skerritt:

(a) “personally and directly” granted the approvals;

(b) further or alternatively that he “either directly or through direction given to an employee of the Commonwealth, expressly or impliedly advis[ed]” the Secretary and [the Minister] and/or advised, sanctioned or directed “any other person imbued with the actual or delegated authority to grant the Approvals” that the approvals be granted or ought to be granted, that the grant of the approvals would satisfy the requirements of the TG Act and Regulations, that at the date of the respective approvals the “Critical Vaccine requirements” (defined in para 42) had been “rationally established”, that all available information, data and material accumulated by the TGA, the Department and Prof Skerrit and/or reasonably available to him “rationally established that the Vaccines at the time of the Approvals met the Critical Vaccine Requirements”, and that he was “rationally satisfied” of those matters;

(c) further or alternatively, by failing or refusing at any time to “expressly or impliedly, either directly or through direction given to an employee of the Commonwealth” advise the Secretary or the Minister “and/or advise, sanction or direct any other person imbued with the actual or delegated authority to grant the Approvals” that the approvals not or ought not to be granted, that the grant of the Approvals would not satisfy the requirements of the TG Act and Regulations, that the “Critical Vaccine Requirements had not been rationally established” and that he was rationally satisfied of those matters; and

(d) in each instance that Prof Skerrit “undertook any or all of the acts and/or omissions” pleaded in each instance he “intended, knew, expected and considered it likely that as a natural and probable consequence of those acts or omissions” that the approvals would be granted and that the vaccines would be widely distributed and received by the Australian public; and he caused as a direct consequence the approvals to be granted, the vaccines to be distributed to the Australian public and the vaccines to be received by the group members.

71 Substantially identical allegations are made against Prof Murphy and Prof Kelly in paras 54 and 57. Similar cascading alternatives appear in relation to the continuing approval allegations made in paras 52, 55 and 58.

72 These parts of the pleading are incoherent. While it is not impermissible to plead claims in the alternative, as the plurality (French CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Kiefel JJ) observed in Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2012) 247 CLR 486 at [27]:

The task of the pleader is to allege the facts said to constitute a cause of action or causes of action supporting claims for relief. Sometimes that task may require facts or characterisations of facts to be pleaded in the alternative. It does not extend to planting a forest of forensic contingencies and waiting until final address or perhaps even an appeal hearing to map a path through it. In this case, there were hundreds, if not thousands, of alternative and cumulative combinations of allegations. As Keane CJ observed in his judgment in the Full Court (36):

“The presentation of a range of alternative arguments is not apt to aid comprehension or coherence of analysis and exposition; indeed, this approach may distract attention from the central issues.”

(Emphasis added.)

73 As I mentioned earlier, the pleading is riddled with cross-referencing, a good deal of which sends one running around in circles. From time to time reference is made to a non-existent sub-paragraph.

74 Paragraph 75 of the 3FASOC is a good example. It reads:

By reason of the factual matters and knowledge pleaded and particularised in paragraph 74 herein above, the Reckless Conduct – Approvals undertaken by Skerritt, the Secretary and the Chief Medical Officer respectively failed to observe the limits of their respective powers and their said actions were:

a) so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so acted or failed to act, or in the alternative, they were legally unreasonable;

b) conducted in bad faith.

Particulars

Para. 75 in Schedule D of the SOC.

75 The allegation in para 75 must be read with the allegations contained in para 74 and the particulars in para 75 of Sch D. However, these two cross-references do little on their own to explain the basis on which the allegation is made, and contain no fewer than 150 cross-references. To make out the allegation of bad faith in para 75 of the pleading, the “particulars” in para 75 of Sch D contain cross-references to “those factual matters and circumstances pleaded and particularised at paras 22 to 38, 42, 44 to 47, 49 to 64, 69 to 75, and 77 to 84 (inclusive) of the SOC and particularised at paras 1 to 74 of Schedule B to the SOC”. That is, the “particulars” contain cross-references to 53 separate paragraphs or sub-paragraphs of the pleadings and 74 paragraphs of Sch B.

76 The other cross-reference contained in para 75, which is to para 74 of the pleadings, is no less expansive. Paragraph 74 contains cross-references to 58 paragraphs (some more than once), including a cross-reference to the “particulars” in para 74 of Sch D. Those “particulars” in turn refer to some 64 individual paragraphs of Sch B (mentioned repetitively across at least 280 cross-references).

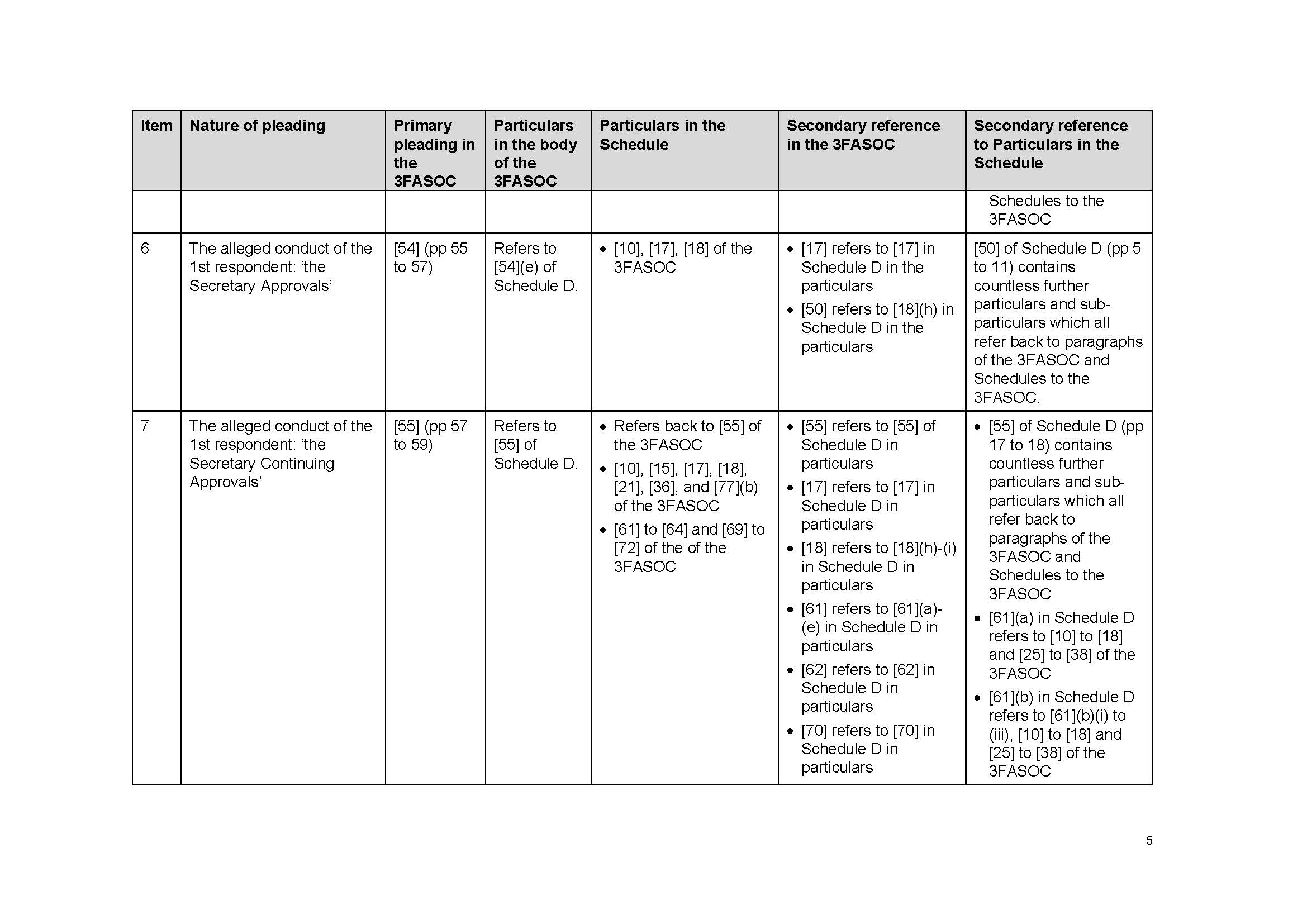

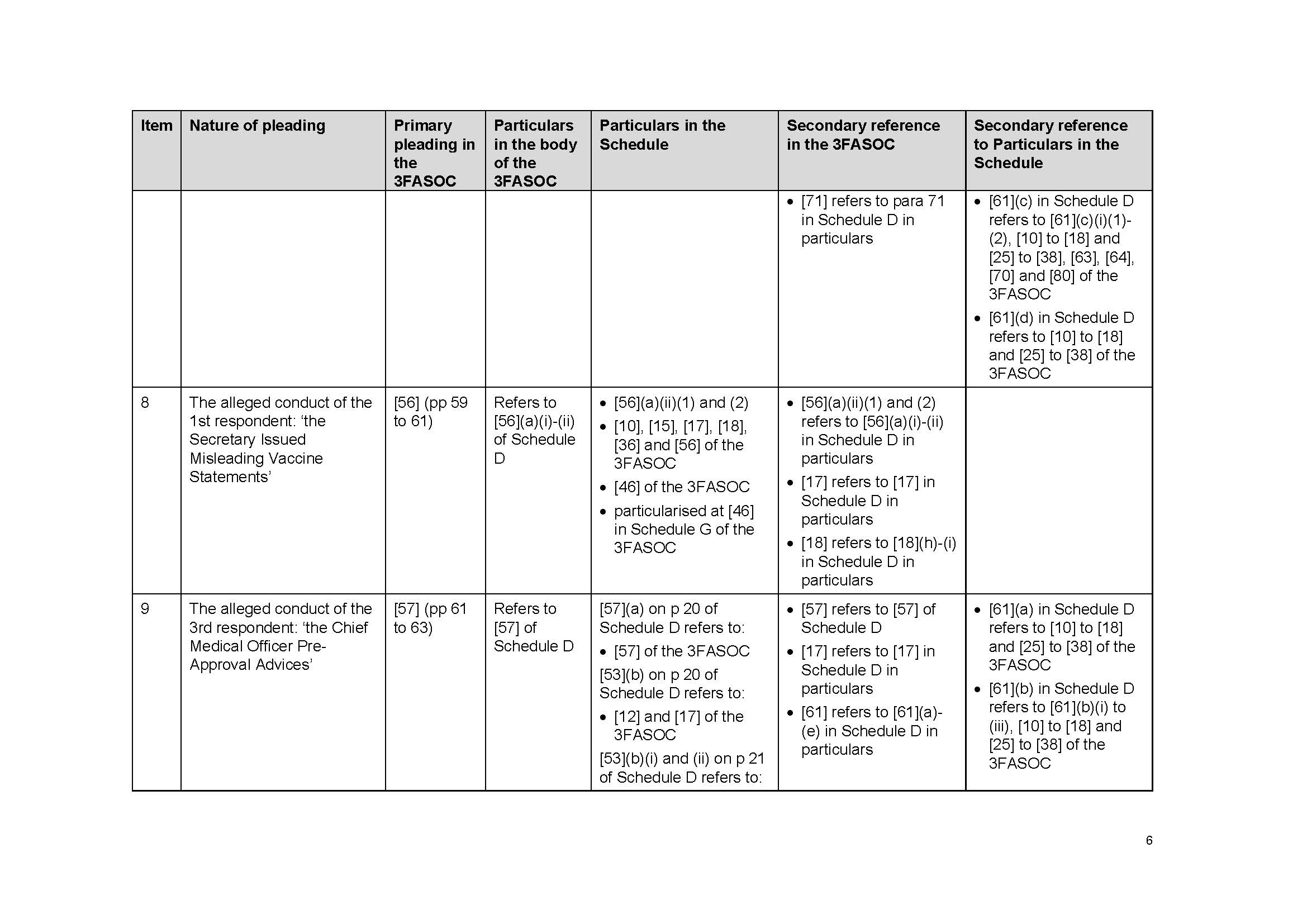

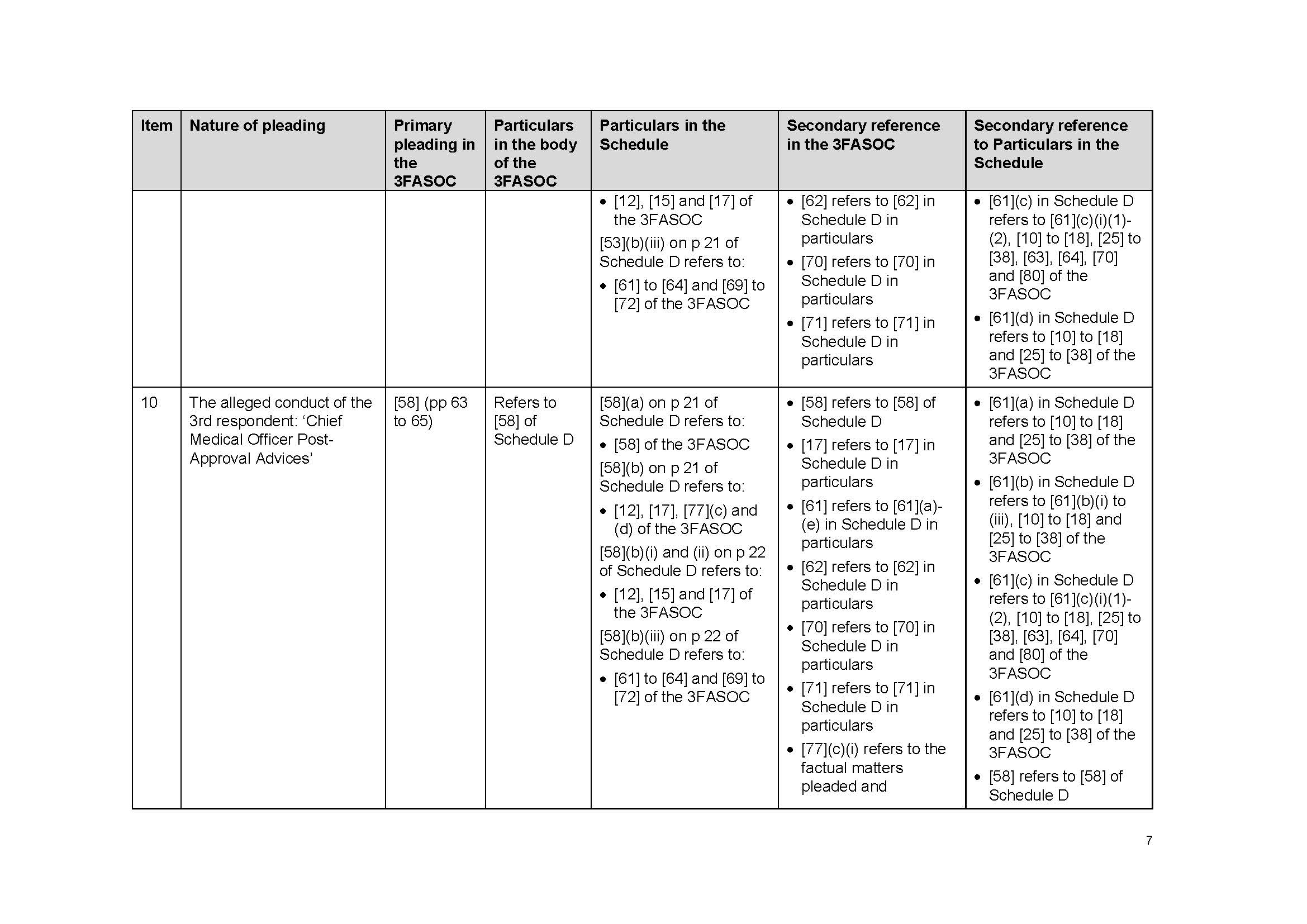

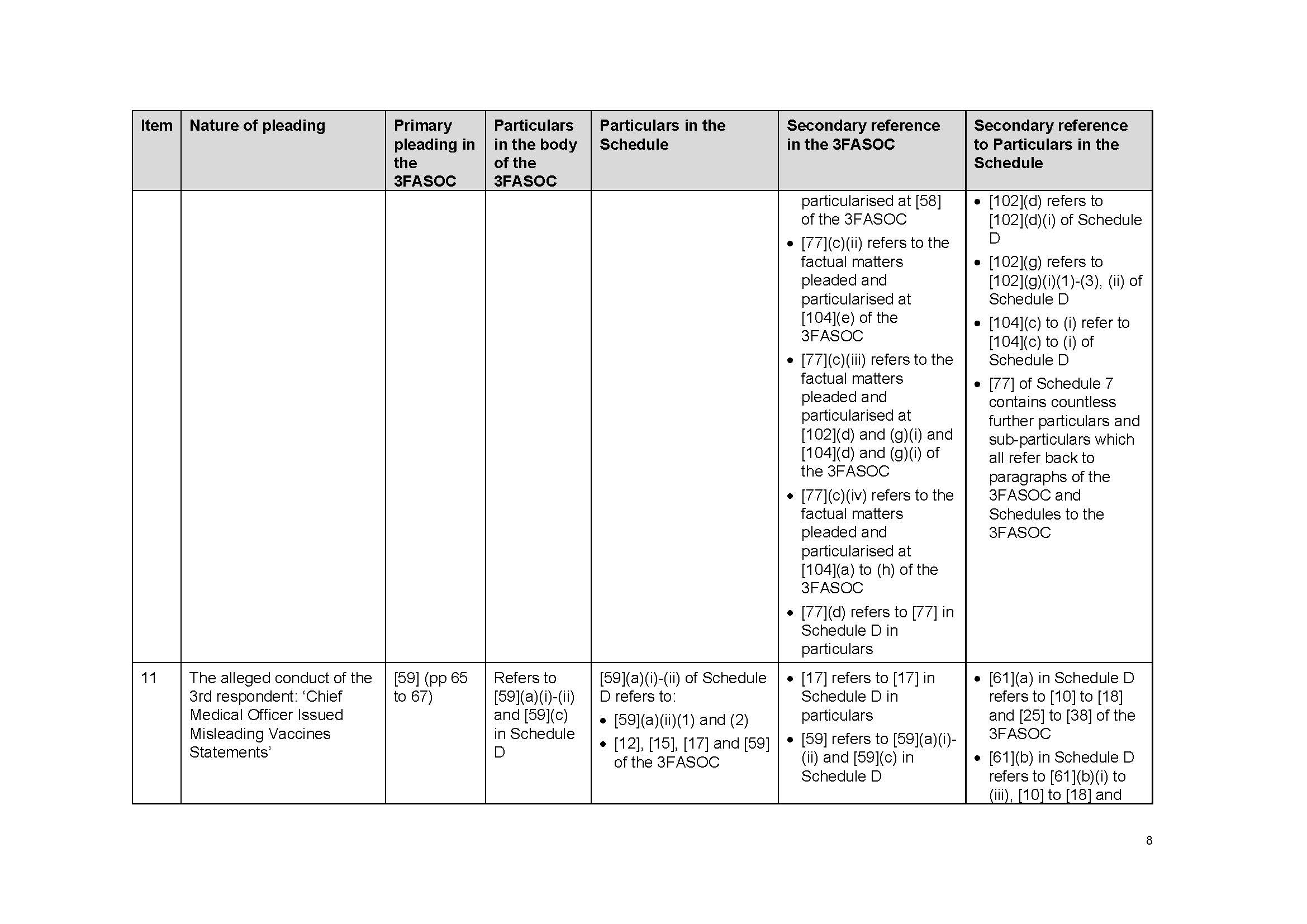

77 This is not an isolated example, as the annexure to these reasons indicates. This is a vice which permeates the pleading.

78 Further, the 3FASOC contains allegations that the respondents made numerous misleading statements but does not allege that any of the applicants read or heard any of them, let alone that they relied on any of them. Many of the statements relied upon are statements made by the TGA, not by any of the Commonwealth officers.

79 One has to read 67 pages before the first cause of action (negligence) is pleaded and then it is not until eight pages later, in para 73, that the duty of care is described. The duty of care is said to be owed to the group members (and not the applicants) and the way in which it is expressed is troubling. Paragraph 73 reads:

By reason of the factual matters and the circumstances of the relationship between the Public Officers and the Group Members pleaded herein, the Public Officers were under a duty to the Group Members to exercise reasonable care and skill and to avoid or minimise the risk of harm when undertaking acts and omissions which would directly or indirectly cause (“the Respondents’ Duty”):

a) a therapeutic good to become lawfully available to the Group Members;

b) a therapeutic good to remain lawfully available to the Group Members;

c) the distribution of a therapeutic good to the Group Members;

d) public statements to the Group Members as to the safety, efficacy and necessity of a therapeutic good.

Particulars

Para. 73 in Schedule D of the SOC.

80 This articulation of the duty is problematic.

81 The duty makes no reference to damage. Yet, “[a] postulated duty of care must be stated by reference to the kind of damage that a plaintiff will suffer”: Minister for the Environment v Sharma (2022) 291 FCR 311 at [8] (Allsop CJ) and the cases referred to there.

82 But this is by no means the only problem.

83 The relationship between the Commonwealth officers and the group members is no different from the relationship between the respondents and any member of the Australian public. “The factual matters and circumstances” in the preceding pages, insofar as they are relevant to the duty of care, are all directed at “the Australian public” or “the Australian population (or people)” albeit that at para 41 the applicants plead that the references to those terms includes the group members. In the result, properly understood, the duty of care is said to be owed to the entire population of the country. In these circumstances, the potential liability of the respondents and the class of persons to whom the duty is owed is indeterminate which tells against the existence of a duty of care: see, for example, Sharma at [706]ff (Beach J).

84 The particulars make no sense. They read:

1. Respondents’ Control of Therapeutic Goods in Australia;

2. Public Expectation of Skill;

3. Public’s Reasonable Expectation and Reliance;

4. Known Gravity of the Approvals;

5. Known Vulnerability of the Australian Public;

6. Foreseeability of Risk and Harm;

7. Public Officers’ Voluntary Assumption of Risk

One has to trawl through the earlier part of the pleading to remind oneself of the meaning intended to be conveyed by these expressions.

85 The misfeasance claim is pleaded over 74 pages, not including other parts incorporated by reference. As the respondents put it, it suffers from a number of “fatal” flaws. The first is what the respondents correctly described as the “hopelessly vague” manner in which the acts and omissions are pleaded. It is impossible to discern from the pleading precisely what acts or omissions associated with the approvals processes are said to be invalid or unauthorised or why. As the respondents submitted, even if the public officers made misleading statements, that is insufficient to establish that the statement was beyond power. I also accept the respondents’ submission that the pleading of malice is manifestly deficient because of its lack of specificity and particularity. By no stretch of the imagination do the schedules compensate for this. They simply send the reader on a wild goose chase.

86 At various places in the 3FASOC allegations are made against the Commonwealth officers collectively. Yet, “it is impermissible to plead a case of misfeasance in public office based on a composite or aggregate of the conduct and states of mind of a number of individual officers”: Farah Custodians Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [2018] FCA 1185 at [147] (Wigney J).

87 Assumptions are made (for example in Sch C) that every statement attributed to the TGA or one of the Commonwealth officers was known to every respondent merely because of the positions held by the officers, such that the knowledge of one officer or one employee in the Department is attributed to all of the respondents.

88 In their written submissions the respondents contended that the applicants have no reasonable prospect of proving that the respondents were recklessly indifferent to the absence of legal authority and the likelihood of injury to the applicants. The applicants’ response did not address the thrust of the submission, particularly the following substantive points:

(1) reckless indifference requires subjective recklessness; in other words, it is necessary to show that the respondents believed or suspected that their conduct was invalid and likely to cause injury but dishonestly proceeded regardless (Farah Custodians at [105]);

(2) a finding of intentional wrongdoing cannot be inferred from facts, matters or circumstances that could be equally consistent with an absence of intentional wrongdoing, such as inadvertence, negligence or even incompetence (Farah Custodians at [105], Plaintiff M83A at [57]–[60]; [115] (Mortimer J);

(3) nor is it sufficient to prove that the respondents’ conduct was legally contentious and potentially subject to challenge (Minister for Fisheries v Pranfield Holdings Ltd [2008] 3 NZLR 649 at [114]–[121]) per O’Regan, Ellen France and Baragwanath JJ)); and

(4) since the relevant decision makers did not have the applicants in mind when exercising powers under the TG Act and/or Regulations or (making or endorsing any of) the allegedly misleading statements, which were directed not to them but to the public at large, to succeed the applicants would have to show that they knew that it was likely that the Australian public would be harmed by their conduct but proceeded regardless; it would not be enough to show that there was some risk, however remote, for some people.

89 The applicants submitted that it is open to the Court to infer malicious intent from the allegations in the statement of claim that the respondents acted with reckless indifference, citing Alpert v Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Defence) (No 2) [2024] FCA 447 at [99] (Snaden J). With respect, that is a preposterous submission. And it is not supported by the cited source. In Alpert at [99] Snaden J merely observed that “a court may infer a malicious intent from a respondent’s reckless indifference to the limits of the powers attaching to his or her office”. That much may be accepted, subject to the qualification that in a case like this where serious allegations are made with potentially serious repercussions, any such inference should be direct, not indirect, and should not be drawn from “inexact proofs” or “indefinite testimony”: Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362 (Dixon J).

90 The applicants also submitted that an act done for lawful purposes could still be an abuse of power when done for an improper purpose. But that submission is based on a misrepresentation or misunderstanding of what North and Rares JJ said in Nyoni v Shire of Kellerberrin (2017) 248 FCR 311 at [96]. The point their Honours were making is that an improper purpose is an abuse of power even if the officer “could have decided to do the same act for a lawful or proper purpose”.

91 The applicants proceeded to cite the paragraphs of the pleading in which they allege that the respondents were actuated by an improper purpose. One of those paragraphs was 90(e) where the applicants alleged that:

the Skerritt Approvals were undertaken by Skerritt:

i) purportedly for the proper purpose incident to his office that his actions in that office be undertaken consistently with:

(1) the Department Overarching Purpose;

(2) the TGA’s Statutory Purpose;

(3) his duty to act for the public good;

ii) in circumstances wherein, the Skerritt Approvals were in fact inconsistent with the Department Overarching Purpose and the TGA’s Statutory Purpose because they were made in the circumstances of the facts of and Skerritt’s knowledge of the Pre-Approval Established Critical Defects;

iii) thereby for an improper purpose:

(1) contrary to the public good;

(2) in breach of a duty to act for the public good.

Particulars

Para. 90(e) in Schedule D of the SOC.

92 Five additional allegations of the same kind are made against Prof Skerritt elsewhere in para 90 and also in paras 92 and 94. Six such allegations are made against Prof Murphy, seven against Prof Kelly and one against Mr Hunt. All are said to have been actuated by the same improper purpose or purposes “contrary to the public good” and/or “in breach of a duty to act for the public good”.

93 Putting aside the error in the submission referred to at [90] above, like other allegations in the 3FASOC, some of these allegations are barely comprehensible; others are altogether incomprehensible.

94 Finally, although no allegations are made anywhere else in the pleading that unidentified public officers committed any tort, para 114 states:

In the premises each of the acts done so as to render the Commonwealth liable in law for the actions of the Public Officers and any and all unidentified officers of the Commonwealth.

(Emphasis added.)

95 That pleading is plainly embarrassing.

Should the proceeding be summarily dismissed or should the applicants be granted leave to replead?

96 The applicants argued that, if the Court were persuaded to strike out the 3FASOC, they should have leave to replead.

97 I have no confidence that the applicants, at least as currently advised, are able to produce a statement of claim that conforms to the Rules sufficient to enable each of the respondents to know precisely the case they have to meet and is capable of pleading to it.

98 Little has changed since the original pleading. If anything, the position has worsened. Furthermore, the applicants have had multiple opportunities to propound a cogent argument capable of persuading a court that they had a reasonably arguable case against each of the respondents but failed to do so. They did not do so in any of their correspondence with AGS. They did not do so in their concise statement. They did not do so in their written submissions. Nor did they do so in oral argument. And they did not proffer a fourth proposed amended statement of claim which rectified the numerous deficiencies of those proffered to date. Moreover, save for some minor concessions, they doggedly maintain that their pleading is acceptable.

99 It is evident from the way in which the claims based on the approvals of the vaccines is pleaded that the applicants do not know who approved the vaccines. In para 51, for example, Prof Skerritt is alleged to have “granted, caused or materially contributed to the grant of each of the respective Approvals” and the various ways in which he might conceivably have done so are then listed. The same allegation is made against Prof Murphy in para 54. In a letter to the applicants’ lawyers on 17 November 2023 AGS wrote:

In relation to the alleged ‘Approvals Misfeasance’ for each of the first, second and third respondents, we are instructed that none of the first, second or third respondents was the decision-maker for the ‘Approvals’ as defined in para 20 of the FASOC. Accordingly, we consider the applicants will be unable to properly plead the material facts to establish that each of the first, second or third respondents was exercising a public power for the purposes of the alleged ‘Approvals Misfeasance’.

100 The applicants filed the 3FASOC on 7 May 2024 — almost six months after AGS informed their lawyers that none of the individual respondents approved the vaccines. In these circumstances, the allegations of misfeasance in connection with the approvals are scandalous. I fail to see how it was reasonably open to the applicants’ lawyers, consistent with their professional obligations, to make the allegations of misfeasance relating to the approvals. It is no answer to point to the “asymmetry of information” or the availability of discovery as the applicants did both in correspondence and submissions.

101 The Legal Profession Uniform Conduct (Barristers) Rules 2015 (NSW) relevantly provide that “[a] barrister must not allege any matter of fact in … any court document settled by the barrister … unless the barrister believes on reasonable grounds that the factual material already available provides a proper basis to do so”: see r 64.

102 Moreover, r 65 provides that:

A barrister must not allege any matter of fact amounting to criminality, fraud or other serious misconduct against any person unless the barrister believes on reasonable grounds that:

(a) available material by which the allegation could be supported provides a proper basis for it; and

(b) the client wishes the allegation to be made, after having been advised of the seriousness of the allegation and of the possible consequences for the client and the case if it is not made out.

103 Identical rules appear at rr 63 and 64 of the 2011 Barristers’ Rules (Qld) as amended, notified under s 225 of the Legal Profession Act 2007 (Qld).

104 Similar provisions appear in the Solicitors’ Conduct Rules: see Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015 (NSW), r 21.4; Australian Solicitors Conduct Rules 2023 (Qld), r 21.4.

105 Discovery is not available as a matter of right, only upon application to the Court, and then only after a defence has been filed: Rules, r 20.13. It is true, as the applicants submitted, that there is authority for the proposition that, where the facts are peculiarly within the respondent’s knowledge, a cause of action should not be dismissed because of gaps in the applicant’s case if the necessary evidence might be obtained as a result of discovery (or, for that matter, other curial processes): see, for example, Turner t/as Classic Gourmet Sausages v Leda Commercial Properties Pty Ltd (2000) 97 FCR 313 at [39] (Gallop J), cited with approval by Jagot J in Salvation Army (New South Wales) Property Trust v Commonwealth of Australia [2015] FCA 674; 147 ALD 677 at [3]. But discovery cannot be used to determine whether an applicant has a case.

106 In the absence of evidence that the respondents took any steps to identify the actual decision makers, despite having been informed that none of the Commonwealth officers made any of the approval decisions, one is left to wonder whether at least that aspect of the proceeding has been brought against those respondents for an ulterior purpose.

107 It is also doubtful whether the applicants would get to first base in their negligence suit.

108 The duty is pleaded in the following terms:

73. By reason of the factual matters and the circumstances of the relationship between the Public Officers and the Group Members pleaded herein, the Public Officers were under a duty to the Group Members to exercise reasonable care and skill and to avoid or minimise the risk of harm when undertaking acts and omissions which would directly or indirectly cause …

a) a therapeutic good to become lawfully available to the Group Members;

b) a therapeutic good to remain lawfully available to the Group Members;

c) the distribution of a therapeutic good to the Group Members;

d) public statements to the Group Members as to the safety, efficacy and of a therapeutic good.

Particulars

Para. 73 in Schedule D of the SOC.

The term “Public Officers” is defined in para 14. It refers to the Commonwealth Officers.

109 With good reason, the respondents complain, amongst other things, that, “in reality, the duty alleged would be one owed to every potential vaccine recipient, and thus potentially to the entire Australian population”.

110 That is apparent from the particulars.

111 Paragraph 73 of Sch D to the 3FASOC reads:

1. Respondents’ Control of Therapeutic Goods in Australia.

2. Public Expectation of Skill;

3. Public’s Reasonable Expectation and Reliance;

4. Known Gravity of the Approvals;

5. Known Vulnerability of the Australian Public;

6. Foreseeability of Risk and Harm;

7. Public Officers’ Voluntary Assumption of Risk.

112 These so-called particulars are in fact references to the allegations made in paras 61 to 64 and 69 to 72 of the 3FASOC.

113 In para 61, one can find the allegations about the respondents’ control of therapeutic goods in Australia. There, the applicants allege, among other things, that the Commonwealth officers had absolute control of whether or not a therapeutic “good” in Australia, including the vaccines, could be lawfully used and the conditions in which and the period over which they could be used; of access to the vaccines by the Australian public (including the group members); of “all statements made to the Australian public (including the group members) for and on behalf of the Commonwealth)” in relation to the safety, efficacy, risk-benefit profile and necessity for use; “and of any other matter relating to the approvals, continuing approvals, and the vaccines”.

114 In para 62, the applicants plead that these matters were generally known by the group members and the Australian public and promoted publicly by the TGA and the Commonwealth officers.

115 The “Public’s Reasonable Expectation and Reliance” is pleaded in para 63. In short, there the applicants allege that, because of the respondents’ control of therapeutic goods and the public’s knowledge of it, the respondents knew first, that the Australian public (including the group members) relied on the Commonwealth officers to perform their functions “with reasonable care, in good faith, in fulfilment of the objects of the Act, and for the public good” and second, to provide true and accurate public statements about the vaccines, including “exhaustive representations as to what was known by them about those matters”, and to make “representations solely based upon rationally determined matters in which the respective [Commonwealth officer] had formed a rational belief”.

116 The “Public Expectation of Skill” is a reference to the matters pleaded in para 64. The pleading is unnecessarily lengthy. In substance, it relates to the alleged expectation of “the Australian population” (including the group members) that the Commonwealth officers would exercise the powers, discretions and functions with which they, others acting on their authority, and the TGA were invested with “reasonable care, professionally and in good faith” and in compliance with the TG Act and Regulations and “publicly declared policy including the TGA Policies”.

117 In para 69 the applicants allege that the Commonwealth officers and the Australian public knew that “the [Commonwealth officers] and those acting under authority” were invested with the power, functions and discretion relating to the approval of, the provision of, advices and public statements in respect of, and the wide distribution to the Australian population of therapeutic goods (including the vaccines); that the conduct of those functions would be significant and material to the Australian population (including the group members) and would expose them to a deleterious and extreme risk of harm if the functions and powers were exercised without reasonable care, “extraneous to power”, for an ulterior or improper purpose, with knowledge or reckless indifference to the absence of statutory power or otherwise to undertake those functions, to the risk of injury to the group members and to “the misleading or false nature of statements made”; and in bad faith.

118 The “Knowledge of Vulnerability of Australian Public to TGA Actions” is pleaded in para 70 as knowledge that any decision or act taken or omission by the Public Officers or those under their authority and direction would directly affect the following: the lawful access of the Australian public (including the group members) to the vaccines; whether they were injected with the vaccines; whether the vaccines were safe and effective for their intended use and had “a positive risk-benefit profile”; the health and well-being of those who were injected; and the likelihood they would suffer serious personal injury and harm.

119 The “Foreseeability of Risk and Harm” is pleaded in para 71. There the applicants allege that it was reasonable that the group members would rely and act upon “the Misleading Vaccines Statements”; “apprehend and believe the Misleading Public Message”, and “determine thereby to take one or more of the Vaccines”. They also allege that it was reasonably foreseeable that the impugned conduct would cause vaccines to be available “for use not otherwise available”; that the group members would use the vaccines when otherwise they would not; that the group members would suffer injury, loss and damage and “pervasive and serious negative consequences upon the health and well-being of the Australian population (including the Group Members)”; and that in the absence of reasonable care there was a “real probability and likelihood” that the group members would suffer “serious or catastrophic personal injuries” and loss and damage.

120 In para 72 the applicants plead that, by the various statements and public messages which they allege were misleading, the Commonwealth officers “publicly and unequivocally” claimed that the vaccines were “safe, effective and necessary for the Group Members” and “thereby personally assumed responsibility for … harm to the Group Members” arising from the administration of any of the vaccines.