Federal Court of Australia

Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd (Trial) [2025] FCA 314

File number: | NSD 943 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | STEWART J |

Date of judgment: | 4 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | TRADE AND COMMERCE – share sale transaction of financial planning business with Australian Financial Services Licence – where purchase price was calculated on the basis of adjusted EBIT – where first tranche of shares was acquired by buyers for $2 million – where actual value of the shares turned out to be less than as agreed based on representations as to expected performance – where parties subsequently fell into dispute which was resolved with a court-ordered repurchase of the shares by the vendor of shares for $282,239 CONSUMER LAW – misleading or deceptive conduct claim – where buyers seek damages for the difference paid and the sum received from repurchase – where buyers allege vendors made representations concerning revenue and other matters which turned out to be false – whether representations were made and if so whether they were subsequently qualified CONTRACTS – breach of share sale agreement – where buyers also allege breach of share sale warranties and contractual disclosure obligations on the part of the vendors – whether vendors adequately disclosed matters in communications and in due diligence data room such that no breach occurred DAMAGES – quantification – where buyers rely on a “no transaction” counterfactual for both statutory and contractual heads of damages – where buyers have not expressly pleaded “true value” for the purposes of the contractual measure EVIDENCE – admissibility and status of referee’s report in earlier related proceeding – where report adopted to determine value of the shares – whether findings in the report are findings in the claim for statutory compensation or contractual damages |

Legislation: | Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth), ss 12BB, 12DA, 12GF Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2 (Australian Consumer Law) ss 4, 18, 236 Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), ss 796C, 962A, 1041H, 1041I Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), ss 55, 91, 135 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), ss 51A, 54A(3)(a) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), rr 1.34, 28.67 |

Cases cited: | All Fasteners (WA) v Caple [2007] FCA 1252 Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1625; 396 ALR 415 Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd (Costs) [2022] FCA 361 Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd (Issues Ruling) [2024] FCA 1016 Cessnock City Council v 123 259 932 Pty Ltd [2024] HCA 17; 418 ALR 304 CH Leaman Investments Pty Ltd v Tuesday Enterprises Pty Ltd as trustee for the Steele Investment Trust [2024] WASCA 142 Commonwealth v Amann Aviation Pty Ltd [1991] HCA 54; 174 CLR 64 Davis v Perry O’Brien Engineering Pty Ltd [2023] QSC 243 Davis v Perry O’Brien Engineering Pty Ltd [2025] QCA 18 DSE (Holdings) Pty Ltd v InterTAN Inc [2004] FCA 1159 DTZ Worldwide Ltd v AIG Australia Ltd [2025] NSWSC 12 Eastgate Group Ltd v Lindsey Morden Group Inc [2002] EWCA Civ 1446; [2002] 1 WLR 642 Fink v Fink [1946] HCA 54; 74 CLR 127 Frith v Gold Coast Mineral Springs Pty Ltd [1983] FCA 27; 47 ALR 547 Gates v City Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd [1986] HCA 3; 160 CLR 1 Gold Coast Mineral Springs Pty Ltd v Frith [1983] FCA 224; (1983) ATPR ¶40-394 Harris v Smith [2008] NSWSC 545; 14 BPR 26,223 Haswell v Commonwealth [2020] FCA 915 Henville v Walker [2001] HCA 52; 206 CLR 459 Howe v Teefy (1927) 27 SR (NSW) 301 HTW Valuers (Central Qld) Pty Ltd v Astonland Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 54; 217 CLR 640 Karim v Wemyss [2016] EWCA Civ 27 Karpik v Carnival plc (The Ruby Princess) (Initial Trial) [2023] FCA 1280 King v Muriniti [2018] NSWCA 98; 97 NSWLR 991 L Shaddock & Associates Pty Ltd v Parramatta City Council [No 1] [1981] HCA 59; 150 CLR 225 Lifehealthcare Distribution Pty Ltd v Nicholas [2011] NSWSC 661 Luna Park (NSW) Ltd v Tramways Advertising Pty Ltd [1938] HCA 66; 61 CLR 286 Mills v Walsh [2022] NSWCA 255 Murphy v Overton Investments Pty Ltd [2004] HCA 3; 216 CLR 388 National Mutual Life Association of Australasia Ltd v Grosvenor Hill (Qld) [2001] FCA 237; 183 ALR 700 Potts v Miller [1940] HCA 43; 64 CLR 282 Robinson v Harman (1848) 1 Ex 850 at 855; 154 ER 363 Sanrod Pty Ltd v Dainford Ltd [1984] FCA 170; 54 ALR 179 Stav Investments Pty Ltd v Taylor; LK Group Investments Pty Ltd v Taylor [2022] NSWSC 208 Wyzenbeek v Australasian Marine Imports Pty Ltd [2019] FCAFC 167; 272 FCR 373 Edelman J, Varuhas J and Higgins A, McGregor on Damages (22nd ed, Sweet & Maxwell, 2024) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Commercial Contracts, Banking, Finance and Insurance |

Number of paragraphs: | 188 |

Date of hearing: | 2-5 and 9 September 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicants: | M A Karam and Q M Noakhtar |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Bartier Perry Lawyers |

Counsel for the Respondents: | T Cox KC and R Ross-Smith |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | DW Fox Tucker Lawyers |

ORDERS

NSD 943 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | BRIDGING CAPITAL HOLDINGS PTY LTD First Applicant ARI BEN MOSES Second Applicant | |

AND: | SELF DIRECTED SUPER FUNDS PTY LTD First Respondent CHRISTOPHER STEVEN HARRIS Second Respondent | |

order made by: | STEWART J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 4 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be judgment for the applicants against the respondents, jointly and severally, in the sum of $1,717,761.

2. There be interest on the judgment sum in order 1 as prescribed under s 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) from 8 June 2021 until the date of judgment.

3. The respondents, jointly and severally, pay the applicants’ costs of the proceeding.

4. There be liberty to apply, limited to the relief in orders 2 and 3, by the filing and service of brief submissions within 14 days of the authentication of these orders.

5. In the event that the liberty in order 4 is exercised by any party within the prescribed time, orders 2 and 3 not be entered until further order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

STEWART J:

Introduction

1 This case arises from a fallout between two businesspeople following the sale of the shares in the business of one of them to the other. The share sale agreement (SSA) was concluded on 11 March 2021.

2 The companies comprising the business and whose shares were the subject of the SSA were Exelsuper Pty Ltd and Exelsuper Advice Pty Ltd (together, the Exelsuper companies). Exelsuper was a trading company which carried on a financial planning business in Adelaide. Exelsuper Advice held the Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) under which Exelsuper was authorised to provide financial services and advice to clients of the business and to invest clients’ money. In the words of its principal, the business “had grown substantially in the previous 10 years from a small average sized financial advice provider to become a large, specialised provider of self-managed super[annuation] services.”

3 Putting a minority shareholding to one side (being irrelevant for present purposes), prior to the SSA the shares in Exelsuper were owned by Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd (SDSF), the first respondent, and in Exelsuper Advice by Christopher Steven Harris, the second respondent. Mr Harris was the sole shareholder and director of SDSF. By the SSA, SDSF and Mr Harris agreed to sell their shares to Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd (BCH), the first applicant, the sole shareholder and director of which was Ari Ben Moses, the second applicant. Mr Moses was a party to the SSA as the guarantor of BCH’s obligations.

4 The SSA provided for the shares to be paid for and transferred in two tranches. The price for the shares was calculated as a factor (x 6) of what was referred to as the adjusted earnings before interest and tax (ie, adjusted EBIT or AEBIT). The EBIT of a business reflects, in essence, the operating profit. The actual EBIT for the business from the preceding accounting period was adjusted (based on information provided by Mr Harris) for expected changes in the EBIT in the current accounting period arising from changes in the business, most notably from actual and expected sales and acquisitions. The adjustments led to an AEBIT of $1.56 million and hence a purchase price representing the value of the goodwill of the business of $9.36 million. The dispute centres on the accuracy of, and the reasonableness of the basis for, the adjustments to the EBIT that resulted from the information given by Mr Harris.

5 Payment of the first part of the purchase price, amounting to $2 million, and the transfer of the first tranche of shares, roughly 45% of the total issued shares in the Exelsuper companies, occurred on 8 June 2021. That was referred to in the SSA as First Completion. Under the terms of the SSA and a corresponding shareholders agreement (SHA), Mr Harris and Mr Moses then became joint directors of the Exelsuper companies until Second Completion when BCH would pay for and receive transfer of the balance of the shares and Mr Moses would gain exclusive control of the Exelsuper companies. The balance of the purchase price was approximately $7.36 million.

6 Second Completion, however, never occurred because shortly after First Completion the two protagonists fell into dispute. That led to BCH and Mr Moses, as minority interests in the companies, commencing an oppression suit on 14 October 2021. The originating process included final orders for the winding up of the companies, or alternatively for the purchase of BCH’s interests in the Exelsuper companies. That suit was resolved on the basis that SDSF and Mr Harris would buy back the shares that were the subject of First Completion at a market value to be determined by the Court. On 22 November 2021, orders were made by consent appointing a referee to undertake an inquiry and to report to the Court on the market value of the shares in the business as a going concern as at 8 November 2021. The referee was instructed to value the shares on two alternative bases, namely with and without a minority shareholding discount.

7 The referee appointed by the Court was Nicholas Stagno Navarra, a Chartered Accountant. Mr Navarra reported on 8 December 2021. On 20 December 2021, there was a hearing on the adoption of Mr Navarra’s report, and particularly on whether his valuation with or without a minority discount was the best reflection of fair market value. The parties on both sides of the case otherwise sought the adoption of the report without variation. On the following day, 21 December 2021, I delivered judgment adopting Mr Navarra’s report without variation and determining the fair market value of the shares to be Mr Navarra’s valuation without a minority discount: Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 1625; 396 ALR 415. That gave a value of $282,239 for the shares to be transferred back to SDSF and Mr Harris, being approximately only 14% of what BCH had paid for them six months earlier. Subsequently, the respondents acquired BCH’s shares in the Exelsuper companies and Mr Moses ceased to be a director of Exelsuper.

8 Having heavily overpaid for the first tranche of shares and being some $1.7 million out of pocket excluding wasted transaction costs, BCH and Mr Moses commenced the present proceeding on 2 November 2022. At the time of the adoption of the referee’s report in December 2021, they had indicated that they intended bringing the present claims in that proceeding, but on it being indicated by counsel for the respondents that no Anshun estoppel issue would be taken if the claims were brought in a fresh proceeding, and it clearly being neater and more convenient to do so, the applicants brought the claims in a new proceeding. The present proceeding nevertheless merely litigates a different component of the same underlying dispute between the parties, being the dispute that arises from their conclusion of the SSA. That was discussed in my reasons for judgment on the costs of the oppression suit: Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd (Costs) [2022] FCA 361 at [20]-[23]. As will be seen, that has significant consequences for the status of the referee’s report in the present proceeding.

9 Although the proceeding was filed in the NSW registry of the Court, the trial was held in Adelaide as a compromise in response to the respondents’ application for the matter to be transferred to the South Australian registry of the Court. The business of Exelsuper was centred in Adelaide and principally conducted in South Australia.

The pleaded claims

10 The applicants plead that Mr Harris made a number of representations to Mr Moses prior to the conclusion of the SSA which Mr Moses and, through him, BCH relied on in entering into the SSA. They say that but for one or more of those representations they would not have concluded the SSA. They say that the representations were misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act) and s 1041H of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act). There is no dispute that those prohibitions against such conduct applied in the circumstances. The applicants also plead that the representations amounted to unconscionable conduct contrary to the prohibition against such conduct in s 12CB of the ASIC Act, although that claim was not pursued in closing submissions.

11 Separately, the applicants plead that the representations, and the failure to disclose certain matters in the lead-up to the conclusion of the SSA, were in breach of warranties in the SSA. I will identify those matters shortly. In the meantime, it is necessary to identify the pleaded representations.

12 First, there is the Recurring Revenue Representation by which it is pleaded that Mr Harris represented that the recurring revenue of the business would be no less than its current actual revenue. That representation is pleaded to have been made by Mr Harris at a meeting between Mr Harris and Mr Moses on Zoom on 11 November 2020 as well as in several email communications. The applicants allege that the recurring revenue was subsequently represented to be in the order of $2.361 million. Understood in context, the allegation is that the representation was as to recurring revenue in the form of fees that were payable to the business under an “ongoing fee arrangement” within the meaning of s 962A of the Corporations Act on an annualised basis in FY21 as compared with the actual recurring revenue in FY20. The representation is pleaded to be a continuing representation in that the respondents did not later retract or qualify it in circumstances where a reasonable person in the applicants’ position would have expected to have been informed if it became incorrect or required revision.

13 Secondly, there is the Future Revenue Representation by which it is pleaded that Mr Harris represented that the future annual revenue of Exelsuper would be worth approximately $3.5 million when future acquisitions that were planned by Mr Harris were completed, based on the current actual revenue of the business. That representation is pleaded to have been made by Mr Harris in the 11 November 2020 meeting. The representation is also pleaded to be a continuing representation which was not later qualified or retracted.

14 Thirdly, there is the AEBIT Representation by which it is pleaded that Mr Harris represented that the goodwill component of the purchase price for the business was to be determined on the basis that it would be six times the business’s adjusted earnings before interest and taxes (ie the AEBIT referred to above) and that for the purposes of calculating the goodwill component of the purchase price for the business, an AEBIT figure of approximately $1.5 million would be utilised. That representation is pleaded to have been made by Mr Harris in the 11 November 2020 meeting and in writing on numerous subsequent occasions, and that it was a continuing representation which was not later qualified or retracted. The representation has considerable overlap with the Recurring Revenue and Future Revenue Representations (which the applicants accepted), as an AEBIT of $1.5 million would not be an accurate measure of business performance to the extent that the recurring revenue or future revenues were not as represented. Nevertheless, the applicants agreed to use an AEBIT of $1.5 million to calculate the purchase price, so there is nothing misleading or deceptive in the respondents’ conduct in representing that that figure would be used – it was in fact used. The real question is whether the applicants were misled or deceived into agreeing to that figure. That is the subject of the other pleaded representations. For those reasons, it is not necessary to consider the AEBIT Representation separately. Counsel for the applicants accepted as much: T362:33-363:12.

15 Fourthly, there is the Compliance Representation by which it is pleaded that Mr Harris represented that the business was legally compliant with all requirements for the provision of financial services and in relation to the AFSL and had an excellent compliance history. It is pleaded that Mr Harris made that representation in an Information Memorandum (IM) provided by Mr Harris to Mr Moses, through a business sales broker, shortly before the 11 November 2020 meeting and on subsequent occasions, with the respondents failing to correct or qualify the representation by giving a fuller account of the business’s compliance issues.

16 The applicants plead that each of the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue, AEBIT and Compliance Representations was false, inaccurate and misleading. In brief, the applicants say that Exelsuper’s performance as a business was substantially less than what was represented as part of the adjustments to the EBIT and that the specific representations made turned out to be false. As part of this, the respondents are said to have remained silent as to the existence of liabilities arising from the acquisition of certain businesses by Exelsuper. As for the Compliance Representation, the applicants say it is established by evidence of regulatory and legal breaches in the provision of advice by Exelsuper.

17 The applicants also plead that the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue and AEBIT Representations were with respect to “future matters” within the meaning of s 4 of the ACL, s 12BB of the ASIC Act and s 769C of the Corporations Act. The effect of those provisions is that unless the respondents adduce evidence that there were reasonable grounds for making those representations (to the extent that they were in respect of future matters), the representations will be taken to be misleading, noting, however, that the overall onus as opposed to the evidentiary burden is not shifted to the respondents in the event that such evidence is adduced: Mills v Walsh [2022] NSWCA 255 at [93] per Brereton JA with whom Bell CJ and White JA agreed; see also Karpik v Carnival plc (The Ruby Princess) (Initial Trial) [2023] FCA 1280 at [722]-[723] and the cases cited there.

18 The applicants’ breach of warranties case is more complicated. They plead reliance on a substantial number of warranties in the SSA. In summary, each of the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue, AEBIT and Compliance Representations referred to above is said to be reflected in the express warranties given in the SSA. As will become apparent, the conduct which grounds the applicants’ misleading or deceptive conduct case is also relied on to establish that the warranties were not true and accurate and were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. The applicants also point to the respondents’ alleged failure to disclose the adverse effect of issues arising between Exelsuper and Praemium, the supplier of separately managed account (SMA) technology, which ultimately led to the termination of the commercial arrangement between them, thus failing to comply with the disclosure obligations in cl 7.4 of the SSA (henceforth referred to as the Praemium issues).

19 The respondents dispute the falsity of any of the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue, AEBIT and Compliance Representations. The statements giving rise to the Recurring Revenue Representation are said to concern what recurring revenue was at that time, rather than what future recurring revenue would be. Further, the respondents say that none of the line items relating to recurring revenue were mischaracterised as recurring revenue. The respondents also say that the Future Revenue Representation was not made, and that in any event, for the same reasons as the Recurring Revenue Representation, it was not erroneous. The AEBIT Representation is said to have been “merely expressions of a negotiating stance to which the applicants had to agree before any figure would actually be utilised”, and not a representation of a past or present fact or future matter. Finally, the Compliance Representation is said not to arise on the pleaded communications and that in any event the purported instances of non-compliance in the business would not materially establish the falsity of that representation.

20 The respondents also dispute that causation and reliance on the representations has been established. The applicants are said to have failed to prove that entry into the SSA caused them any loss, noting that the acquisition of shares occurred on 8 June 2021 (with entry into the SSA on 11 March 2021) and the applicants had “very broad rights” to terminate the SSA prior to First Completion in the event of a material breach or Material Adverse Effect, which was ultimately not exercised to stop the acquisition. Mr Moses is further said to have believed the value of the business was $5 million, rather than the $9.36 million which he agreed to pay, such that the applicants would have entered into the SSA regardless of whether the alternative figures described in the applicants’ case were represented at the time of transacting.

21 With respect to the breach of warranties claims, the respondents advanced a number of different arguments in defence in opening submissions. Some were subsequently abandoned by the respondents, and their entitlement to rely on the balance was disputed by the applicants having regard to the form of the pleadings. I made a ruling on that matter on 3 September 2024, such that the only specific argument available to the respondents on the SSA terms, aside from a general denial of breach, is that “each Warranty is given subject to and the Sellers have no liability in respect of any Claim arising in respect of any fact, matter, event or circumstance to the extent Disclosed (clause 1.2 of Sch 3); Buyer agrees it is aware / deemed to have actual knowledge of all matters Disclosed, including in the data room (clause 28.3)”: Bridging Capital Holdings Pty Ltd v Self Directed Super Funds Pty Ltd (Issues Ruling) [2024] FCA 1016. The argument turns on whether or not information falsifying the representations was adequately disclosed in the due diligence process and in other communications.

22 Against that disclosure defence, the applicants further rely on cl 28.8 of the SSA which stipulates that limitations on the vendor’s liability in respect of warranties do not apply “to the extent that there has been fraud, dishonesty or wilful concealment” on the part of the respondents or their agents or advisers. The applicants allege only wilful concealment.

23 Aside from the SSA terms, the respondents assert that the applicants have not properly pleaded how their alleged loss has flowed from the specific breaches of warranty complained of. Instead, the respondents note the applicants have simply run a “no transaction” counterfactual in relation to the breach of warranties claims like they have done for the misleading or deceptive conduct claims, giving no particulars of the contractual measure of damages.

24 For completeness, I note that the respondents had asserted a cross-claim but it was discontinued on the second day of the trial.

The issues

25 The following key issues are in dispute (as formulated by the parties):

Misrepresentations

(1) Whether each of the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue, AEBIT and Compliance Representations was made by Mr Harris during the Zoom meeting on 11 November 2020, and whether any of those representations was repeated on subsequent occasions;

(2) Whether those representations (or related conduct) were misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive for the purposes of s 18 of the ACL, s 12DA of the ASIC Act or s 1041H of the Corporations Act (or, if taken as representations as to future matters, s 4 of the ACL, s 12BB of the ASIC Act and s 769C of the Corporations Act);

(3) Whether the applicants relied on the representations when deciding to execute the SSA on 11 March 2021.

Praemium issues in contract

(4) Whether the applicants were informed of, or could have learned of, the Praemium issues prior to around late-June 2021 and whether the respondents were aware of those issues from around June 2020;

(5) Whether those issues could reasonably be considered relevant to the business of the Exelsuper companies and to have an adverse effect on the companies;

(6) Whether the respondents failed to comply with cl 7.4 of the SSA in failing to notify the applicants of the Praemium issues.

Breach of warranty

(7) Whether the respondents breached cll 28.1.1 and 28.1.2 of the SSA because the relevant warranties at Schs 1 and 2 were not true and accurate and were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive;

(8) Whether there has been any fraud, dishonesty or wilful concealment on the part of the respondents or their agents and advisers for the purposes of cl 28.8.

Entitlement to relief

(9) Whether the applicants are ultimately entitled to damages in the form they seek, should contravention or breach of warranty be established.

The witnesses

26 The principal witnesses on each side of the case were Mr Moses and Mr Harris, respectively. They were the only witnesses who were required for cross-examination, and each was cross-examined at length.

27 Mr Moses (also referred to by his middle name, Ben) is a financial services professional specialising in wealth management, mergers and acquisitions, remediation, licensing and practice management projects. Born in Ghana in 1986, he emigrated to Australia in 2013. Since then, he has had extensive professional work experience in the financial services industry, having worked as a financial adviser both at firms owned by others and self-employed at his own businesses. As referred to above, Mr Moses is the sole shareholder and director of BCH, and is also the controller of several other vehicles used in his business ventures.

28 Mr Moses was, for the most part, an impressive witness. He gave straightforward answers. He was, on occasion, a little argumentative, or showed some frustration or impatience with the questions he was expected to answer. However, those factors do not detract from my overall impression of him as an honest witness with good recall of the material events, particularly noting that these often involved complex financial arrangements in respect of which perfect recollection could not be expected. He is apparently a big-picture person who left the finer details to his advisers, notably his accountants and lawyers. He was content to pay six times the AEBIT as the purchase price for the shares on the basis that the adjustments to EBIT were fair and reasonable. He did not concern himself with checking the figures that he was given by Mr Harris as he left that to his accountants as part of the financial due diligence process and he considered that his and BCH’s positions were protected by the terms of the SSA. It is that protection that Mr Moses called on in bringing this proceeding.

29 Mr Harris has also worked in the financial services industry, in his case for over 40 years, principally in management roles at financial planning businesses. In such roles, he has overseen many mergers and acquisitions of financial planning and advice businesses. He is the sole shareholder and director of SDSF and controlled (including through SDSF) the Exelsuper companies.

30 Unfortunately, I was not left with confidence in the honesty of Mr Harris’s evidence. It was established in evidence that he was dishonest in his presentation of key details about the Exelsuper companies in the IM that formed the basis for future discussion between him and Mr Moses. He admitted as much in cross-examination. His approach to dealing with Mr Moses and his advisers was, at least in part, to give some information directly and to simply put other material information that might detract from the soundness of his adjustments to the EBIT into the voluminous data room. That was apparently with the dual hope that its significance was not noticed and that if any issue of non-disclosure subsequently arose it would be sufficient for him to have disclosed it in the data room. Mr Harris had to change his evidence on occasion when it was pointed out that his self-serving answers were incorrect.

31 For instance, Mr Harris was questioned on why he failed to disclose contingent or actual liabilities of the business in answer to a direct query raised with him by Rasika Day, Mr Moses’s accountant, on 2 December 2020. Mr Harris’s initial answer in cross-examination was that he did not disclose such liabilities because he did not consider that there were any (T277:30). When shown that there were such liabilities, he changed his evidence to say that he had not disclosed them in answer to Mr Day’s inquiry because “the actual documents relating to those transactions were also uploaded to the due diligence data room” (T277:40). Also, as mentioned and as will be seen, Mr Harris made several false statements in the IM.

32 The result is that I must approach Mr Harris’s evidence with caution. Where there is a conflict between his evidence and Mr Moses’s evidence, unless there is some contemporaneous document or other objective evidence to support the contrary, Mr Moses’s evidence is to be preferred.

The key events

33 Between late-October 2020 and early-November 2020, Mr Moses decided he wanted to build a wealth management business. To this end, he contacted financial services business brokers, one of whom was Steve Prendeville of Forte Asset Solutions. Mr Prendeville became the go-between for Mr Moses and Mr Harris, conveying the former’s interest in the purchase of the Exelsuper business. On 3 November 2020, Mr Moses caused BCH to be incorporated for the purposes of undertaking the acquisition of the Exelsuper companies.

34 On 6 November 2020, Forte provided Mr Moses with the IM for review and comment ahead of a meeting with Mr Harris to further discuss “cultural alignment and fit.” Although it was dated May 2019, in cross-examination Mr Harris confirmed that the IM had been updated from an earlier draft in preparation for that November meeting.

35 The IM stated that in February 2020 Exelsuper commenced a project to increase its scale and profitability by acquiring other assets or businesses. It noted that “[t]o date Exelsuper has completed two transactions”, being the acquisition of Prism Financial Planning in September 2020 and Shortland Wealth Management in October 2020. The IM also mentioned the forthcoming acquisition of “QFP” for which “[a] full understanding of terms has been agreed” and completion anticipated in January 2021, as well as two more assets of “RV WM” and “MJ PL Mount Gambier” for which terms had not yet been agreed.

36 The Shortland acquisition was stated to have been funded using “existing Cash Reserves” thereby implying that the price had already been paid as was accepted by Mr Harris in cross-examination (T241:4-8). That was false because, in fact, payment was made on a vendor-finance basis such that the liability was paid from revenue over a period of time. Thus, the figures given for the projected revenue following the acquisition were misleading as they overstated the position to the extent of the outstanding liability. Mr Harris accepted as much (T278:1-2). The Navarra report discloses that the true position was that there would be no revenue received to the credit of Exelsuper for 24 months following the acquisition as the purchase consideration included 24 monthly payments equivalent to the previous month’s revenue.

37 As for the Prism acquisition, the business had not been acquired as a whole. Instead, Prism was brought on board as an “authorised representative” of Exelsuper. As explained by counsel for the respondents, an authorised representative (AR) is an external financial adviser in an arrangement with Exelsuper whereby the AR is able to make use of the “licensing umbrella” of Exelsuper’s AFSL. The fees earned by the AR are recorded as part of Exelsuper’s revenue, in exchange for commission and other overheads being paid by Exelsuper (ie, cost of sales) (T54:43-55:10). The consequence of Prism being an AR instead of an outright acquisition was that commission was still payable to Prism in exchange for the recurring revenue obtained with the net revenue being limited (T145:29-39, T147:10-13, 31-41).

38 In relation to the so-called completed transactions, the IM noted:

The Directors of Exelsuper understand that the historic Profit and Loss statements of Exelsuper are outdated, given the recent acquisitions. Despite this, the directors therefore wish to disclose that the AEBIT uplift of these acquisitions has been included in this IM. Terms of sales and all DD documents conducted prior to completion including sale agreements will be supplied during DD.

As these transactions have occurred part way through FY2021, the projected AEBIT will not be reflected in Exelsuper’s P&L’s on an annualized basis until FY2022. As such, Exelsuper has prepared detailed pro-forma profit and loss statements showing itemized income components and expense consolidation of each asset listed as a COMPLETED TRANSACTION, which is supplied with this IM.

39 The IM further provided the figures of “$3,800,000 plus” for recurring revenue and AEBIT of more than $1.75 million. It stated that the business had a “[f]ully operational AFSL with excellent compliance history and low risk activities.” The IM did not, when referencing the Prism and Shortland acquisitions, make reference to any extant liabilities. Rather, as mentioned, it stated that the acquisitions had been completed and that the liability on the Shortland acquisition had been paid. Mr Harris conceded in cross-examination that those statements were false (T237:33-41; 240:13-14; 241:4-8).

40 Elsewhere in the IM an AEBIT of $1,972,094 was projected for the 2021 calendar year, apparently on the assumption that other proposed acquisitions detailed in the IM were completed. That figure was calculated as the difference between the projected Gross Revenue of $4,217,237 and the projected Normalised Expenses of $2,245,143. It was not explained how the figure for Normalised Expenses was arrived at, although a list of Key Expenses adds up to $2,711,395. It does not include any acquisition expenses which leads to the inevitable inference that the lower figure for Normalised Expenses also did not include acquisition expenses. The same set of figures gives the Recurring Revenue as $4,193,237 for the 2021 calendar year, which is not dissimilar to the “$3,800,000 plus” figure given earlier for recurring revenue.

41 On 11 November 2020, Mr Moses participated in a Zoom video conference call with Mr Harris and others. Aspects of the information given in the IM were discussed in the meeting. Both Mr Moses and Mr Harris gave evidence that Mr Harris explained that the revenue of the business was lower in the previous financial year (FY20) and that Mr Harris was in the process of pursuing several acquisitions to increase revenue. He explained that the AEBIT on which the sale price of the business would be calculated was based on the annualised anticipated revenue in the current financial year (FY21) which would include the revenue from any completed acquisitions. Mr Harris addressed the figures contained in the IM, including confirming the AEBIT of $1.75 million increasing to $1.972 million if the planned acquisitions went ahead. I accept Mr Moses’s evidence that Mr Harris said that the future annual revenue of the business would probably be about $3.5 million when the anticipated business acquisitions were finalised. There was no revision of the information in the IM during the meeting.

42 On 17 November 2020, the parties executed a non-binding term sheet. The purchase price was expressed as being a 6-times multiple of AEBIT, less a deduction (which is presently not relevant). An “Estimated AEBIT” figure of $1.972 million was given, “assum[ing] the completion of proposed acquisitions as disclosed [in the IM]” where, if the acquisitions did not proceed, the estimated AEBIT would be $1.509 million. The term sheet envisaged that there would be two phases to due diligence; first, “AEBIT confirmation” by 27 November 2020 and “Legal Due Diligence” by 15 December 2020, with completion scheduled for 1 January 2021. Further Q&A between the parties occurred via email following the term sheet.

43 On 30 November 2020, the applicants’ legal and financial advisers were granted access to the due diligence data room. Mr Day and Dasun Kulatunge of the firm Australian Accountants acted for Mr Moses as his financial due diligence advisers on the transaction.

44 On 2 December 2020, Mr Day requested further information from Mr Harris including the details of acquisitions and demergers undertaken by the business since 2015 including any “legal issues or contingent or actual liabilities remaining or arising from these acquisitions”, and “[r]easons for not proceeding with the Malborne [sic] acquisition.”

45 Mr Harris confirmed in cross-examination that he prepared a table in answer to the request for details of acquisitions and demergers which he sent to Mr Day. The table referred to revenue figures from various acquisitions and contained some discussion of legal issues, including litigation arising from the “sale” of clients to Enva Advisory Pty Ltd. Other referenced transactions included the acquisition of Shortland and another business under the name of David Frost (previously an AR of Exelsuper). The table did not refer to any liabilities arising in relation to these transactions despite details of liabilities having been specifically requested. The significance of that omission will become apparent below.

46 On 4 December 2020, Mr Harris responded to further due diligence related queries sent by Mr Day on behalf of Mr Moses. One of the requested items was the profit and loss for 5 months to 30 November 2020. Mr Harris replied by referring to “the disclosed adjustments which have been articulated in the documents provided so far” and referred to further revenue “coming online” and still “to be transferred in full.” He did not refer to any corresponding liabilities.

47 Also on 4 December 2020, Mr Prendeville, on behalf of Mr Harris, requested that Mr Moses confirm that he was content with the AEBIT figure prior to the commencement of Legal Due Diligence, ie the second phase of due diligence. Mr Prendeville stated:

In order to assist you on this matter I have again attached Exelsuper’s AEBIT calc based on FY 2020 actuals which includes adjustments only for transactions that have completed since 30 June 2020 and ignores any acquisitions that are in the pipeline, but not yet complete. As such we have calculated AEBIT to be $1,560,591. Before we proceed to provide further DD Documents, please confirm that your accountant has confirmed that this figure is a fair representation of the future AEBIT. Our agreement is that the sale price is 6 X AEBIT, thus valuing the transaction at $9,363,456. [Second emphasis added.]

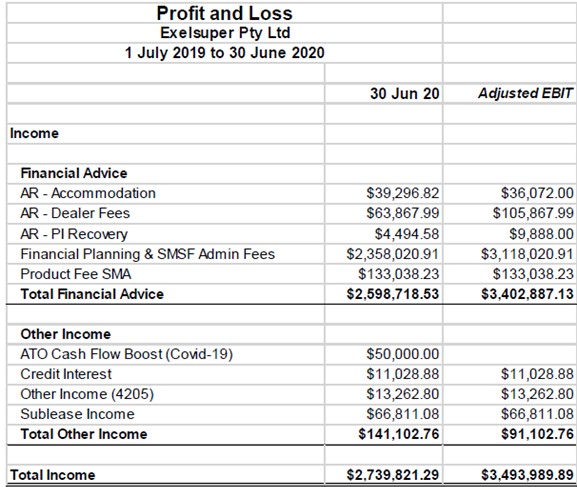

48 The attached spreadsheet prepared by Mr Harris (the AEBIT spreadsheet) was a profit and loss statement for the Exelsuper business for the financial year that ended on 30 June 2020 (ie FY20) with an additional column of figures reflecting the “Adjusted EBIT” as follows (insofar as income is concerned):

49 The line-items “Financial Planning & SMSF Admin Fees” and “Product Fee SMA” taken together amount to recurring revenue. (As will be seen, that is how Mr Navarra treated them.) Thus, it was represented that annualised recurring revenue for FY21, based on the actuals for FY20, would be $3,251,059 (ie $3,118,021 + $133,038 in the right hand column). It can also be observed that recurring revenue is the principal revenue source accounting for some 96% of income deriving from “Financial Advice”.

50 Adjacent to the “Adjusted EBIT” column were a number of notes explaining the adjustments. The adjustments included:

+$42,000 in relation to income for “AR – Dealer Fees.” The note about this adjustment stated: “The intention is to complete the sale of Prism FP to Exelsuper by completions, however I f [sic] sale is not complete they will remain on board as an AR and pay dealer fees etc”;

+$760,000 in relation to income for “Financial Planning & SMSF [Advice].” The note about this adjustment stated: “This includes Prism Revenue, Harris Shortland Revenue and David Frost Revenue recently acquired”; and

-$314,000 in relation to “AR – Advisor Commissions.” The note about this adjustment stated: “Removes D Frost as his client base has ben [sic] pruchased [sic] by Exelsuper but includes payments to Doherty, Mills, and adds Prism FP who became an AR on 1/11.”

51 Later that day, Mr Moses responded with the following:

Please note we have not disagreed on the AEBIT and that was the premise of the initial discussion and also this transaction. At the moment, we are expecting final feedback from our private equity firm hopefully next week for us to move forward and give each other comfort.

…

We’re happy to perform limited DD so far as we are both protected by the contract upon exchange.

52 This prompted the following from Mr Harris:

Just for clarity, we insist that you do full DD on all aspects of the business, however we simply ask that you prioritise AEBIT DD to ensure that you are happy to proceed on the agreed purchase price.

53 Negotiations over the draft SSA occurred from early January 2021. During this time, it was understood that due diligence had virtually concluded.

54 On 25 January 2021, the parties participated in another Zoom video conference, discussing the AEBIT and the financials of the business. Mr Harris continued to note that all acquisitions had been completed, including the Shortland and David Frost acquisitions, and the revenue of Prism as an AR added. It was confirmed in that meeting that financial due diligence had been completed which carried the implication that Mr Harris’s AEBIT had been accepted by Mr Moses.

55 On 10 February 2021, Mr Harris emailed to his solicitor, copying Mr Moses, a communication containing the following passage:

Ben has expressly confirmed with me that he is happy with the clawback provisions, and that I have agreed that the baseline recurring revenue will be as per the document attached which clearly shows recurring revenue to 31/1/2021 as $2,361,382. This of course only includes 3 months Prism Revenue which when extrapolated over 12 months gives Ben substantially more revenue than disclosed. As per the Agreement, Prior to completion, we need to provide a final recurring revenue figure, which I have now done to 31/1/2021. I have uploaded this document to the DD Data Room.

(Emphasis added.)

56 The attached spreadsheet showed recurring revenue for each of the 12 months from February 2020 to January 2021 which, added together, came to the figure given, namely $2,361,382 (more precisely expressed as $2,361.381.20 in subsequent communications discussed below). That is the figure relied on by the applicants in their pleaded Recurring Revenue Representation and not the figure of $3,251,059 in the AEBIT spreadsheet discussed above (see [49] above). Significantly, that figure is given as at 31 January 2021 and not on an annualised basis. Expressing it on an annualised basis would require adding another five months’ revenue which should take it well over the figure of $3,251,059 that had been given on 4 December 2020.

57 Also on 10 February 2021, Australian Accountants completed their financial due diligence report in respect of Exelsuper. That report noted their reliance on the integrity of the information and data supplied to them by the respondents, and that independent verification did not occur unless otherwise stated. Their analysis based on actual revenue from July to November 2020, excluding recent acquisitions, resulted in a total valuation of $5 million.

58 On 15 February 2021, Mr Harris emailed Mr Moses the following:

As per our discussion re recurring revenue, so that you have absolute clarity re the recurring revenue figures the following information is provided in support of our disclosure

1) As per the attached recurring revenue report, the recurring revenue to 31/1/2021 is $2,361,381.20 however this does not include acquisitions that came on board in October 2020, or Prism who came on Board in November 2020.

2) As you can see, in October the purchase of Harris Shortland Wealth Management was completed and was added to our recurring revenue. This amount was $280,000 per annum

3) In November Prism came onboard as an AR which added a further $550,000 to recurring revenue

4) In December David Frost client base was acquired which contains $100,000 in recurring revenue

It is anticipated that total RR to 31/1/2022 should total about $2,900,000. However, as previously stated our only representation on this matter is what exists now, without any further acquisitions, etc.

59 The following day, in an internal email to Mr Harris from Chris Gill (a Chartered Accountant and adviser at Exelsuper), Mr Gill made a number of comments on the above email pointing out to Mr Harris that he had given inflated revenue figures to Mr Moses. Using the same numbering, his comments were:

(1) “This is not correct – November 2020 onwards revenue figures include Harris Shortland Revenue and also from November 2020 onwards includes PRISM revenue (November contained part amounts from Infocus) – To be clear the figures in this report are GST inclusive as its gross cash receipts”;

(2) “Average gross receipts for three months 31 January 2021 is $22,498 or $270k p.a (ex GST)”;

(3) “Average gross receipts for two months 31 January 2021 is $43,555 or $522,660 p.a (ex GST) – only did two months as November only contained part month income from Infocus”; and

(4) “Average gross receipts for three months 31 January 2021 is $5,646 or $67,762 p.a (ex GST).”

60 To be clear, Mr Gill was pointing out to Mr Harris that his email to Mr Moses wrongly represented the financial position of the business in the following respects:

(1) Mr Harris’s figure for recurring revenue of $2,361,381.20 was overstated as:

(a) it included GST without saying so;

(b) it included the Shortland and Prism revenues from November 2020 onwards although Mr Harris stated that it did not;

(2) Mr Harris gave an additional amount (ie, in addition to the $2,361,381.20 figure) of $280,000 for recurring revenue from Shortland which was wrong because part of the Shortland revenue (for three months) was already included in the first amount and the annualised amount was in any event overstated by Mr Harris by $10,000;

(3) Mr Harris gave a further additional amount of $550,000 for recurring revenue from Prism which was wrong because part of the Prism revenue (for two months and part of a month) was already included in the first figure and the annualised amount was in any event overstated by Mr Harris by about $25,000; and

(4) Mr Harris gave an additional amount of $100,000 for recurring revenue from David Frost which was overstated by about $32,000.

61 Mr Gill also commented, “we should also make it clear that we also pay out 100% of the average amount $337,762 to David Frost and Harris Shortland (no GST) as capital payments.” That is to say, the business was at that time receiving no revenue from David Frost and Shortland because that revenue was all being paid as the purchase price for those acquisitions.

62 Having noted these misstatements, Mr Gill advised that Mr Harris should make the true position “clear”. In his email response to Mr Gill, Mr Harris stated that he would upload Mr Gill’s email to the data room. Although that apparently occurred (T366:39-41), Mr Harris had no explanation for why he did not correct the position directly with Mr Moses which would have been the obvious and honest thing to do (T329:18-38). Instead, Mr Moses was left with the materially false position set out by Mr Harris in his email which was not corrected and would not have been corrected unless Mr Moses or his advisers found the proverbial needle in the haystack. Mr Harris’s conduct in that regard was deliberately deceptive.

63 Even aside from the misrepresentations of the true position by him, Mr Harris unequivocally stated that the recurring revenue to 31 January 2021 (ie for seven months) was $2,361,381.20. Even simply annualising that amount without taking account of the increasing revenue in later months would yield an annual recurring revenue of $4,048,082 (ie ($2,361,381.20 / 7) x 12).

64 The SSA was finally executed on and dated 11 March 2021. It provided for legal due diligence to complete in 7 business days from the date of execution. However, legal due diligence continued after this time, resulting in a number of variations to the SSA in order to extend the timeframe for legal due diligence.

65 The third variation deed to the SSA, on or about 22 April 2021, extended the First Completion Date to 30 April 2021. It also provided at cl 1.2 that the parties agreed that all conditions precedent to First Completion had been satisfied, and that the accounts annexed to the deed were accepted as the completion accounts for the purposes of the SSA terms. Clause 1.2.3 also provided that “[f]or the purposes of clause 16.3.2 of the [SSA], [BCH] accepts [SDSF]’s calculation of the Recurring Revenue as at First Completion in the amount of $2,361,381.20.” That was thus the figure to be used to calculate the second instalment amount (cl 16.2).

66 First Completion occurred as ultimately rescheduled on 8 June 2021. As explained at the outset, this led to the applicants paying $2 million and BCH acquiring a shareholding of 43.2% of Exelsuper and 45% of Exelsuper Advice, and Mr Moses becoming a director of Exelsuper.

67 On 27 June 2021, Mr Harris informed Mr Moses by email that Exelsuper had received notice that Praemium was “not wishing to continue with our SMA and Badged version of their product.” Notices of termination from Praemium were also attached dated 24 June 2021. Mr Harris responded by letter to those notices on 28 June 2021, stating “the understanding and agreement formed between Exelsuper and Praemium resulting from Exelsuper’s conversation with Michael Ohanessian [the CEO of Praemium] this time last year has now been abandoned.” The letter went on:

Exelsuper was informed 12 months ago … that it was Praemium’s desire to end our Model Manager relationship, and it was Praemium’s desire to terminate the Exelsuper Super Essentials Super SMA and ExelPrivate SMA agreements.

…

We discussed altering the terms of the agreement to ensure compliance with conflicted remuneration regulations, and Mr Ohanessian committed to ensure that the Praemium team would work with us to implement changes from an MER based Model Management fee to a Dealer Model Management fee.

…

In light of the above information, it is clear that it is in neither Exelsuper’s nor Praemium’s interest to continue a relationship based on past difficulties. I trust that we can conclude our relationship with sensible action and cooperation, and as such ask, that if you still intend to terminate the Agreements utilising the steps outlined in your recent correspondence, please provide information regarding the following in accordance with 8.5 of the Distribution Deed.

68 That was followed by a number of questions as to the transitional arrangements to occur between the parties following termination.

69 Although Mr Harris had known of Praemium’s intention to end its relationship with Exelsuper since mid-2020, Mr Moses was not advised of that until 27 June 2021, well after First Completion.

70 Following this time, Mr Moses and Mr Harris fell into dispute before subsequent steps required under the SSA could be completed in order to effect Second Completion and finalise the transaction. That was the subject of the oppression suit detailed above, leading to the applicants relinquishing their shares in the Exelsuper companies.

The status of the referee’s report

71 During the hearing, I heard submissions on the status of the referee’s report of Mr Navarra, which, as mentioned, was adopted by the Court pursuant to s 54A(3)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) and r 28.67(1)(a) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) in the course of the earlier oppression proceeding. It was argued on behalf of the respondents that the report should be excluded from evidence on various bases, including relevance (including insofar as it commented on issues going beyond what was pleaded) (T96:37), hearsay (T110:15-17), that insufficient notice had been given of Mr Navarra as a witness in the event he was to be called (T110:17-23; 209:12-14), that if the report is to be given the status of a judgment or its findings given the status of findings of the Court then it is excluded by s 91 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (T207:31-33) and that it is unfairly prejudicial to the respondents and should be excluded under s 135 of the Evidence Act (noting in particular that the respondents would not be in a position to undertake proper cross-examination) (T107:19; 178:41-44; 209:14-15).

72 As mentioned, the Navarra report concludes that the Exelsuper shares in the hands of the applicants at 8 November 2021 (the date of agreement of repurchase) were worth $282,000, in contrast to the $2 million which had been paid at First Completion. The content of the report deals at length with why the value of the shares did not accord with what had been paid for them, including that the AEBIT figure which would have been appropriate for the business was different to the amounts that were presented as part of the accounts from which the purchase price was formulated. Annexed to the report are detailed exhibits which particularise the financial information of the business, as well as summaries of responses to Q&As conducted by Mr Navarra with Mr Harris.

73 On 4 September 2024, I made a ruling that admitted the Navarra report subject to what use the Court would make of it being subsequently addressed in closing submissions. The report is a historical document having been produced as a referee report. The report is relevant in the sense of s 55 of the Evidence Act, having a direct bearing on key matters in the present dispute, including the AEBIT calculation and the revenue-related representations pertinent to the valuation of the Exelsuper companies. Any prejudice to the respondents is outweighed by the utility of the report in disposing of the issues in dispute.

74 The claim of prejudice also fails because of the following considerations. The respondents participated in the referee’s inquiry that led to the report, they consented to its adoption by the Court without variation at a time when they were on notice of the applicants’ intention to claim damages including the difference between what they had paid and the value of the shares as determined by the referee, and they were on notice of the applicants’ intention to rely on the report long before the trial.

75 To the extent that the Q&As exhibited to the report might be captured and therefore excluded by r 28.67(2) of the Rules, I dispensed with that rule under r 1.34. I can see no reason why the recorded questions to and answers by Mr Harris and Mr Moses on matters pertinent to this dispute between them should not be admissible.

76 In any event, I do not consider the report to be witness evidence requiring Mr Navarra to be called and cross-examined; indeed, I would not have considered it appropriate for him to be cross-examined. The provenance of the Navarra report means it is a document recording findings of the Court that are relevant to the present proceeding. As noted by Lee J in Haswell v Commonwealth [2020] FCA 915 at [7] and [21], by adopting the report the Court, either explicitly or implicitly, made the findings of fact and law recorded in it. For the same reasons I do not consider the report to be inadmissible hearsay.

77 This does, however, raise (as the respondents did) the question of the effect of s 91 of the Evidence Act. Subsection (1) states “[e]vidence of the decision, or of a finding of fact, in an Australian or overseas proceeding is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact that was in issue in that proceeding.” The section is not applicable unless there are two separate proceedings: King v Muriniti [2018] NSWCA 98; 97 NSWLR 991 at [14] per Basten JA with whom Gleeson JA agreed. National Mutual Life Association of Australasia Ltd v Grosvenor Hill (Qld) [2001] FCA 237; 183 ALR 700, which the respondents cite (relying in particular on [46] and [48]), is not to the point because it dealt with a separate proceeding. As already explained, the Navarra report was adopted in respect of the same matter (in the sense of justiciable controversy) as the matter in the present proceeding. That happened to have been in a different proceeding in the sense of being under a different case number and commenced by a separate originating process, but that was merely for convenience. In substance, it is the same proceeding and s 91 is therefore not engaged.

Statutory misleading or deceptive conduct claims

Whether the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue, AEBIT and Compliance Representations were made

78 Unsurprisingly, the key point of difference between the parties is whether the impugned representations as pleaded were made at the meeting on 11 November 2020 and thereafter. The applicants’ case fails if this is not established.

Recurring Revenue Representation

79 Beginning with the Recurring Revenue Representation, although the respondents’ amended defence denies that the representation was made, it is notable that the respondents in closing submissions do not argue on the evidence that the express representation was not made by Mr Harris to Mr Moses in the meeting on 11 November 2020.

80 Mr Moses in his affidavit evidence deposed that Mr Harris told him that “the recurring revenue of the Exelsuper Business would be around the same as what was stated in the [IM]”. Mr Moses understood “recurring revenue” to mean “the fees payable to a financial planning practice or a sole financial advisor under an ongoing fee arrangement or commission payments.” Mr Harris in his affidavit evidence deposed to speaking to the figures contained in the IM and in particular the quantum of recurring revenue in the Exelsuper business. Although Mr Harris did not specifically depose to the Recurring Revenue Representation being made orally at that meeting, I accept Mr Moses’s evidence to that effect. It will be recalled that the figures given in the IM for recurring revenue were “$3,800,000 plus” and $4,193,237 (see [40] above).

81 On 10 February 2021, Mr Harris’s email reflected that he had agreed that “the baseline recurring revenue will be as per the document attached which clearly shows recurring revenue to 31/1/2021 as $2,361,382” (emphasis added). A subsequent email of 15 February 2021 from Mr Harris to Mr Moses (being the email discussed at [58] above) then contained the words “[a]s per the attached recurring revenue report, the recurring revenue to 31/1/2021 is $2,361,381.20”, that is, a quantum equivalent to being no less than the Exelsuper business’ current actual recurring revenue. This figure was repeated in subsequent versions of the AEBIT spreadsheets prepared by Mr Harris leading up to April 2021. The SSA at cl 25.1 of Sch 1 also repeated it in the form that “[t]he Recurring Revenue as at First Completion will be no less than $2,361,000.” It does not appear on the evidence that these statements were qualified by other statements from the respondents to contrary effect.

82 Against this evidence, the respondents say that the statements relied on do not give rise to the pleaded representation as they relate to past, rather than future, recurring revenue. In other words, the statements relied on as to recurring revenue make no assertion about what revenue would be in the future and are simply statements of current actual revenue (a backward-looking calculation). That cannot be correct where Mr Harris’s own email of 10 February 2021 noted that “baseline recurring revenue will be as per the document attached” (emphasis added), that document containing the $2,361,382 figure. Also, Mr Harris’s email of 15 February 2021 (see [58] above) spoke of “anticipated … total [recurring revenue] to 31/2/2022” (ie a year into the future). Indeed, the very concept of AEBIT is future looking – it provides for adjustments to the actual present EBIT on account of what the figures in the future are expected to be.

83 Hence, I find that the Recurring Revenue Representation was indeed made from time to time and was not withdrawn. I further find that the Recurring Revenue Representation, while initially expressed generally, ultimately became that the current actual recurring revenue of Exelsuper was $2,361,381.20 and that the recurring revenue on an annualised basis in FY21 would be at least that amount (a representation as to a future matter based on the former matter being true).

84 The difficulty for the applicants here is that the figure of $2,361,382 was taken as the actual recurring revenue as at 31 January 2021 at a time when entry into the SSA and First Completion were expected to follow soon thereafter. At that time, as explained, the annualised recurring revenue calculated from that figure would have been well in excess of $4 million. However, the same figure was ultimately used even though First Completion did not occur until 8 June 2021, which was only three weeks from the end of the financial year. To annualise the figure at that stage would not increase it by much. The result is that with the passage of time, what commenced as a grossly inflated recurring revenue figure became less so and, as will be seen, was ultimately not much different from the actual recurring revenue that was achieved.

Future Revenue Representation

85 As dealt with above (see [41]), the figures in the IM were discussed by Mr Moses and Mr Harris in their 11 November 2020 meeting, and the figures were not revised. Also, Mr Harris stated that the future revenue of the business would probably be about $3.5 million when the then anticipated business acquisitions were finalised.

86 The difficulty with this representation is that it is not clear on the finalisation of which anticipated business acquisitions it was conditioned. It would appear that at that time it may have been the “pending” acquisitions referred to in the IM, being “RV WM”, a Melbourne-based financial planning business, and “MJ PL Mount Gambier.” However, those acquisitions were not finalised so the condition was never fulfilled. It is possible that it was at that time a reference to the Prism, Shortland and QFP transactions notwithstanding that they were referred to in the IM under the heading of “Completed Transactions.” That is because it was stated in the IM that for Prism the “entire share transaction will complete by no later than 31 January 2021”, that Shortland was stated to have only recently been acquired and that the QFP transaction was not yet complete and still subject to due diligence.

87 Whatever the intended reference was, the evidence is not clear enough. It is simply not possible to say with any degree of confidence what “anticipated business acquisitions” were being referred to. In the circumstances, the Future Revenue Representation, as pleaded, fails.

88 For completeness, having addressed the Recurring Revenue and Future Revenue Representations and for the reasons discussed at [14] above, it is not necessary to address the AEBIT Representation.

Compliance Representation

89 Unlike the other representations concerning revenue, the Compliance Representation is pleaded as an implied representation arising from the IM’s description of Exelsuper having a “[f]ully operational AFSL with excellent compliance history and low risk activities”, combined with the assumed premise that the transaction would entail Exelsuper being compliant with the law and where Mr Harris did not qualify or retract such an assumption. More specifically, the representation is said to be repeated in the SSA warranties as to compliance by Exelsuper with “all laws and orders (including the Corporations Act, the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) and fair trading legislation).”

90 Beginning with the IM, it is unclear that the description of a “fully operational AFSL” has much content to it other than stating that an AFSL is in place at the time of writing. It would not seem to rise to a representation that the business was “legally compliant with all requirements for the provision of financial services” in the terms pleaded by the applicants, which could have a broader meaning depending on the nature of the “financial services” to be provided. It cannot be assumed that the IM’s reference to “excellent” compliance history is in relation to that attaching to the provision of “financial services” in this broader sense. On that basis, the representation as pleaded in the form of the Compliance Representation is not made out on the content of the IM.

91 Nor does Mr Harris’s conduct throughout the commercial negotiations suggest on the evidence that the Compliance Representation was made in the form pleaded. If anything, the evidence on discussions between the parties as to compliance history was limited. There may be more to the argument that the Compliance Representation was made in the SSA warranties. However, the wording of the relevant warranty at cl 6.1 at Sch 1 of the SSA is limited to bare compliance with laws at time of warranty rather than anything approaching compliance with all requirements for the provision of financial services, or an excellent compliance history.

92 I therefore find the Compliance Representation was not made out.

Whether there was misleading or deceptive conduct

93 As noted before, the applicants’ case for each of the Recurring Revenue, Future Revenue and AEBIT Representations was put as both that of conventional misleading or deceptive conduct, and also misleading or deceptive conduct in respect of a future matter. With respect to those representations, the respondents accepted that if made out as pleaded, they would all be as to future matters. The Compliance Representation, by contrast, was not framed as a representation concerning a future matter. In the event, only the Recurring Revenue Representation has been made out. The evidentiary effect of s 4 of the ACL, s 12BB of the ASIC Act and s 769C of the Corporations Act must be applied to that representation.

94 It is unnecessary to set those provisions out in detail or to discuss their construction here (otherwise see above [17]). Suffice to say, the burden lies on the respondents to adduce at least some evidence of reasonable grounds for the Recurring Revenue Representation. It is the applicants’ submission that the respondents have failed to discharge their evidentiary burden in this respect, with the result that the representation made would be taken to be misleading.

95 As these reasons have already canvassed, a substantial volume of evidence was put before the Court by both sides concerning the quantum and derivation of the recurring revenue figures for the Exelsuper business from time to time, not least the matters recorded in the Navarra report on precisely this issue. It could not be said that there has been a bare failure by the respondents to discharge their evidentiary burden. It is necessary to evaluatively engage with the substance of that material, even if it might be true that the respondents have not squarely set out the reasonable grounds relied on for making the Recurring Revenue Representation. The overall onus, as stated at [17] above, remains on the applicants.

96 The applicants put their substantive case with regard to the Recurring Revenue Representation being misleading or deceptive in a variety of ways.

97 First, they submit that the issue was conclusively determined by Mr Navarra in his report. They refer to the conclusion that “there appears to be no reasonable basis on which I would consider the BCH Share Acquisition Projection … to be a reasonable representation/forecast of Exelsuper’s near term financial performance.” However, what Mr Navarra refers to as the “BCH Share Acquisition Projection” is what I have referred to as the AEBIT spreadsheet. It will be recalled that the projected, or adjusted, recurring revenue figure in that spreadsheet was $3,251,059 which is not the figure relied on in the pleaded and established representation, namely $2,361,381. Mr Navarra’s conclusions with regard to the larger figure are therefore not to the point for present purposes.

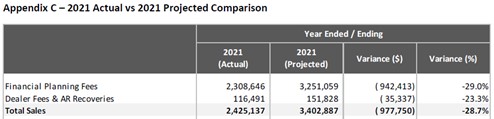

98 Secondly, the applicants go on to submit that in any event the impugned conduct was likely to mislead or deceive the applicants within the meaning of the statutory prohibition. They draw attention to many difficulties underlying Mr Harris’s projection of recurring revenue, and in particular with the adjustments recorded in the AEBIT spreadsheet. They also refer to Mr Navarra’s conclusion that a comparison of the FY21 actual results against the FY21 projected results showed a negative variance of $977,750, ie the business underperformed relative to the projected performance by that amount. Mr Navarra’s figures are relevantly presented as follows:

99 It can immediately be seen that the projected figures used by Mr Navarra are taken from the AEBIT spreadsheet. His figure for projected FY21 “Financial Planning Fees” is the same as annualised recurring revenue for FY21 represented in the AEBIT spreadsheet. His conclusion as to variance is therefore not the variance between the figure relied on in the Recurring Revenue Representation and actual performance. Actual performance was, as can be seen, $2,308,646 which, as against the representation of $2,361,381, shows a negative variance of only $52,735. That is a negligible difference. I am not satisfied that had Mr Moses known that the projection was out by that small amount he would have acted any differently.

100 As Mr Navarra’s report documents, the actual performance of the business fell very considerably short of what Mr Harris had projected in other respects. But that is not the case that the applicants pleaded, ran and established. Their pleaded Recurring Revenue Representation, which is the only one of the pleaded representations that I have found was made, is quite specific and narrow. It is founded on projected recurring revenue of approximately $2.361 million. As it happens, that is very nearly the actual recurring revenue achieved by the company. While that is not necessarily determinative of whether the Recurring Revenue Representation, pleaded as a future matter, was misleading or deceptive, it does focus attention on what the actual recurring revenue was at the time of the representation being made and whether that supplied reasonable grounds for doing so.

101 Mr Navarra’s report states that the actual recurring revenue in FY20 was $2,491,059. This aligns with the actual recurring revenue in FY20 that was recorded in the AEBIT spreadsheet provided by Mr Harris to Mr Moses. The adjustments noted in the AEBIT spreadsheet contemplated as affecting that recurring revenue figure included +$760,000 for acquisitions, including Prism, Shortland and David Frost. As mentioned at [37] above, Prism came onboard as an AR and added its revenues to that of Exelsuper. Shortland was funded by vendor finance, yet still represented recurring revenue for accounting purposes, even if they would not give a net benefit until 24 monthly payments had been made (ie, at the very least, the Shortland acquisition did not foreshadow a fall in recurring revenue). The David Frost revenues should indeed not have been added as an adjustment, since those revenues were already accounted for as David Frost was an existing AR. Yet that too, did not necessarily mean that there was reason to think the recurring revenue would fall below $2,361,381.20 when the actual for FY20 was $2,491,059 with other, genuine incremental streams of revenue incoming in the form of Prism.

102 The above analysis illustrates that there were doubtless many problems with the adjustments made to the EBIT in Mr Harris’s AEBIT spreadsheet. He failed to show a reasonable basis for the adjustments which led to the AEBIT of $1.5 million. As just mentioned, the reality was that there should not have been an upward adjustment for David Frost revenue since it was already an AR. The propriety of a specific upward adjustment for the Shortland revenue (feeding into the purchase price) may also be doubted in circumstances where it would have represented no net revenue for 24 months. And, strictly speaking, Prism had only come onboard as an AR and not as a full-fledged acquisition at the time such that it could not be regarded as unencumbered revenue for which the EBIT could be linearly adjusted. At the very least, these matters should have been noted in the AEBIT spreadsheet.

103 Of equal, if not greater, importance is the omission of any adjustment to recurring revenue in the AEBIT spreadsheet to reflect the loss of Enva revenue from the sale of clients to that firm. That is so despite the fact that Mr Harris had been aware of this transaction prior to the preparation of the AEBIT spreadsheet, and that client base had represented revenues of some $513,000 per year. This was also considered a significant factor in material declines in revenue of the business in FY20 and FY21 by Mr Navarra, accepted by Mr Harris in cross-examination (T323:34-324:25).

104 Yet, it bears repeating that that is not what has been pleaded by the applicants. Where they rely on the Recurring Revenue Representation and the figure of $2,361,381.20 framed within it, these matters do not go to whether there would have been reasonable grounds to represent that the projected recurring revenue of the business would exceed that amount. Even if the particulars of the forecast recurring revenue were overly optimistic (which they were), there was ample reason to think the target would be met – which it ultimately was, as shown in Mr Navarra’s report.

105 The deficiencies identified by Mr Gill as to projected recurring revenue on 15 February 2021 do not go to the case pleaded by the applicants. The instances of overstatement and double counting go largely to the falsity of the recurring revenue of $2,361,381.20 at that time. But, taken as an annual figure for FY21, or for FY21 to 8 June 2021, that figure was close to the mark, even if the other matters represented by Mr Harris in the email to Mr Moses were not correct and not subsequently qualified other than by way of upload to the data room.

106 Separately from the pleaded representations, the applicants in their submissions also put a misleading or deceptive conduct by silence case on the basis that there were ongoing liabilities relating to the Shortland and David Frost acquisitions which were not disclosed. This partly arises out of inaccuracies in the IM pertaining to the manner in which those acquisitions were carried out. It also relates to the capital payments to be made to Shortland and David Frost, as noted by Mr Gill (see [60] above). Be that as it may, this alternative case on silence does not go to whether the Recurring Revenue Representation was misleading or deceptive. That is what, on the applicants’ pleadings, forms the substance of their claim for misleading or deceptive conduct by silence. In other words, the applicants have not squarely pleaded this other basis for misleading or deceptive conduct by silence relying on undisclosed liabilities not tied to the Recurring Revenue Representation. Capital expenditures or extant liabilities for acquisitions would not on their own factor into the bases for recurring revenue as a matter of accounting practice, although it is possible that they could have affected any adjustments so as to result in a modified AEBIT. These were nevertheless material omissions. The significance of these undisclosed liabilities or capital expenditures will become relevant in the consideration of disclosure under the SSA warranties further below.

Whether there was reliance and causation

107 In light of the conclusion above on the Recurring Revenue Representation as pleaded not being misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, it is not strictly necessary to consider reliance and causation. However, in the event that I am wrong on the Recurring Revenue Representation, my conclusion on these matters is set out below, as whether or not the applicants relied on the representation is a question separate from its falsity or deceptiveness.

108 Reliance is an aspect of causation for statutory misleading or deceptive conduct. The relevant principles were recently summarised by Applegarth J in Davis v Perry O’Brien Engineering Pty Ltd [2023] QSC 243 at [218]-[219] (appeal dismissed in Davis v Perry O’Brien Engineering Pty Ltd [2025] QCA 18, where no error was identified in the approach his Honour took to causation: at [49] per Bradley J with whom Flanagan JA and Brown J agreed):