FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Scidera, Inc. v Meat and Livestock Australia Limited [2025] FCA 308

File number: | VID 1007 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | ROFE J |

Date of judgment: | 7 April 2025 |

Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – application to strike out statement of claim – whether pleading or parts of the pleading are ambiguous, likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay, or fail to disclose a reasonable cause of action – whether the pleading fails to comply with rr 16.21 and 34.42 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) |

Legislation: | Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Patents Act 1990 (Cth) Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) |

Cases cited: | Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc v Sequenom, Inc (2021) 159 IPR 371 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pauls Ltd [1999] FCA 1750 Australian Mud Co Pty Ltd v Globaltech Corporation Pty Ltd (No 3) (2022) 169 IPR 1 Banque Commerciale SA (En Liquidation) v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 Barclay Mowlem Construction Ltd v Dampier Port Authority (2006) 33 WAR 82 Commissioner of Taxation v White (No 2) [2024] FCA 1291 Dare v Pulham (1982) 148 CLR 658 EIX20 v State of Western Australia [2022] FCA 1357 Forrest v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2012) 247 CLR 486 Gall v Domino's Pizza Enterprises Ltd (No 2) (2021) 391 ALR 675 KTC v David [2022] FCAFC 60 Magman International Pty Ltd v Westpac Banking Corporation (1991) 32 FCR 1 Meat and Livestock Australia v Cargill, Inc (2018) 129 IPR 278 Meat and Livestock Australia v Cargill, Inc (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 47 Murdock v Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 569 Nomura International Plc v Granada Group Ltd [2007] EWHC 642 Oztech Pty Ltd v Public Trustee of Queensland (2019) 269 FCR 349 Polar Aviation Pty Ltd v Civil Aviation Safety Authority (2012) 203 FCR 325 Seiko Epson Corporation v Calidad Pty Ltd (2017) 133 IPR 1 Sequenom, Inc. v Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. (2019) 143 IPR 24 Stone (liquidator), in the matter of Ironbark Blacksmithing Pty Ltd (in liq) v Mizzi [2024] FCA 696 Thomson v STX Pan Ocean Co Ltd [2012] FCAFC 15 Trade Practices Commission v Pioneer Concrete (Qld) Pty Ltd (1994) 52 FCR 164 Upaid Systems Ltd v Telstra Corp Ltd (2013) 220 FCR 182 Wardley Australia Ltd v Western Australia (1992) 175 CLR 514 Wride v Shulz [2004] FCAFC 216 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Patents and associated Statutes |

Number of paragraphs: | 219 |

Date of last submissions: | 21 August 2024 |

Date of hearing: | 16 September 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | C Dimitriadis SC, M Evetts |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | K&L Gates |

Counsel for the First Respondent: | C Cunliffe |

Solicitor for the First Respondent: | King & Wood Mallesons |

Counsel for the Second Respondent: | K Beattie SC |

Solicitor for the Second Respondent: | Norton Rose Fulbright |

Counsel for the Third Respondent: | P Flynn SC, B Mee |

Solicitor for the Third Respondent: | Allens |

Counsel for the Fifth Respondent: | D Larish |

Solicitor for the Fifth Respondent: | Lander & Rogers |

ORDERS

VID 1007 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | SCIDERA, INC. Applicant | |

AND: | MEAT AND LIVESTOCK AUSTRALIA LIMITED ACN 081 678 364 First Respondent AGRICULTURAL BUSINESS RESEARCH INSTITUTE ACN 058 555 632 Second Respondent ZOETIS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD ACN 156 476 425 (and others named in the Schedule) Third Respondent | |

order made by: | ROFE J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 April 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory applications dated 19 April 2024 filed by the first respondent, second respondent, third respondent and fifth respondent are dismissed.

2. The applicant has leave to file an amended statement of claim substantially in the form annexed to my reasons, subject to amendments which I have indicated are necessary.

3. Once the amended statement of claim is filed, Genotyping Australia Pty Ltd ACN 632 605 817 trading as Xytovet be joined as the sixth respondent in this proceeding.

4. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs thrown away by reason of the 9 May 2024 hearing.

5. The parties’ costs of and incidental to the proposed amendments to the statement of claim and the 16 September 2024 hearing be costs in the cause.

6. The proceeding be listed for a case management hearing on the week of 14 April 2025.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

ROFE J:

1. Introduction

1 By way of interlocutory applications dated 19 April 2024 (Applications), the respondents, Meat and Livestock Australia Limited, Agricultural Business Research Institute, Zoetis Australia Pty Ltd and DataGene Limited, seek orders pursuant to r 16.21(1) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that Scidera, Inc.’s statement of claim (SOC) filed on 1 December 2023, or parts thereof, be struck out.

2 Pursuant to the respondents’ request for further and better particulars of the applicant’s SOC, on 25 March 2024 Scidera filed a response to the respondents’ request for particulars (Response). On 6 May 2024, Scidera filed further particulars of SOC (Further Particulars).

3 Subsequent to an initial hearing at which the respondents ventilated their concerns with the SOC, on 9 May 2024, I made orders for Scidera to serve a draft amended statement of claim (ASOC), and for the respondents to indicate whether they opposed leave being granted to Scidera to file the ASOC.

4 The claims against the fourth respondent, Dairy Australia Limited, were dismissed on 28 June 2024.

5 Scidera prepared an ASOC, which it now seeks to file, which it says addresses the respondents’ concerns. Amongst others, the ASOC adds a sixth respondent, Xytovet, deletes reference to any non-party testing laboratories, and deletes any claims against the fourth respondent. The ASOC integrates into the pleading the detail from Scidera’s Further Particulars document dated 6 May 2024, which is now superseded.

6 The respondents opposed leave being granted, as such, this proceeding was listed for interlocutory hearing to determine the respondents’ Applications, however with the focus turned to the deficiencies of the ASOC, rather than the SOC. The respondents contend that the ASOC is noncompliant with rr 16.06, 16.02(1) or (2), and 34.42(3)(b) of the Rules. The ASOC is annexed to these reasons as Annexure A.

7 Scidera contends that the respondents’ criticisms are misplaced. Scidera submits that the claims in the ASOC are clearly pleaded, set out in considerable detail and supported by extensive particulars. According to Scidera, the ASOC is much more detailed than is conventional for a pleading of patent infringement, and goes well beyond what is required under the Rules.

8 Each of the parties filed submissions in support of its position. Each of the respondents rely on the submissions of the other respondents.

9 The third respondent, Zoetis, filed an affidavit of Mr Frederick Schwenke, Zoetis’s Director — Livestock Business Unit, made on 10 September 2024. The document was tendered, not for the truth of its contents, but as an example of the type of evidence that would be filed by Zoetis in the proceeding.

2. Background

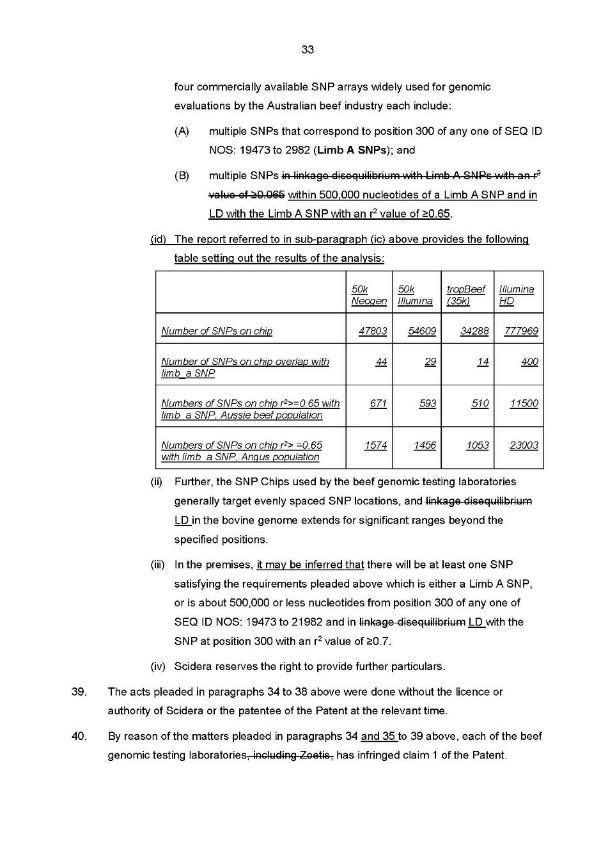

10 This proceeding is a patent infringement case which relates broadly to the use of a method or system to identify or infer a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of the bovine subject, comprising identifying in the nucleic acid sample an occurrence of at least three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) wherein each of the at least three SNPs satisfies particular requirements identified in the claims in suit.

11 Scidera is the patentee of the patent in suit: Australian Standard Patent No. 2010202253 (Patent).

12 The proceeding is at an early stage. No defences have been filed. There has been no discovery and no evidence has been filed.

2.1 Patent history

13 The patent application, which became the Patent in suit, was the subject of pre-grant opposition proceedings involving MLA and the former fourth respondent to this proceeding, Dairy Australia. Justice Beach published two judgments regarding those proceedings in which the patent application (which on grant became the Patent), the relevant technical background, the construction of the claims and a range of other issues were considered: Meat and Livestock Australia v Cargill, Inc (2018) 129 IPR 278; Meat and Livestock Australia v Cargill, Inc (No 2) (2019) 139 IPR 47.

2.1.1 ASOC structure

14 Paragraphs [1] to [6A] identify the parties. [6A] introduces the proposed sixth respondent, the second genomic testing laboratory, Xytovet.

15 Paragraphs [7] to [21A] plead the Patent and its term, and the relevant background to the Patent, being the opposition, the parties to the opposition, the appeal from the opposition, and the amendment of the patent application.

16 Part II of the ASOC relates to the “Beef Cohort Claims”, starting at [22] and finishing at [74]. The allegations of infringement against MLA and ABRI are found in the Beef Cohort Claims section of the ASOC.

17 Part III of the ASOC relates to the “Dairy Cohort Claims”, starting at [75] and continuing to [121]. The allegations against DataGene are found in the Dairy Cohort Claims.

18 Both the Beef Cohort Claims and the Dairy Cohort Claims follow the same pattern of pleading. Both cohorts are applicable to Zoetis and Xytovet.

2.2 Scidera’s allegations

19 Scidera makes a direct infringement claim against Zoetis (and the proposed sixth respondent, Xytovet). Zoetis is one of two genomic testing laboratories which is alleged in the ASOC to have provided genomic selection services in Australia for identifying bovine traits of economic interest in beef and dairy cattle, using high density SNP chips to perform SNP testing of genetic material. Zoetis and Xytovet are alleged to have provided those genomic selection services in a manner compatible with the systems provided or promoted by the remaining respondents as discussed below.

20 Indirect infringement claims are made against the remaining three respondents: MLA, ABRI, and DataGene. The indirect infringement claims involve an allegation that the three respondents have authorised the direct infringement by the genomic testing laboratories within the meaning of s 13(1) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) or are liable for that direct infringement as joint tortfeasors.

21 Scidera alleges that MLA, ABRI and DataGene (collectively, the secondary respondents) have had various involvements in the promotion and facilitation of the SNP testing performed by Zoetis and the other genomic testing laboratories. In particular, Scidera alleges that these respondents have been engaged in various acts relating to the implementation of genetic evaluation systems known as the BREEDPLAN System (for MLA and ABRI with utility for beef cattle breeders) and the DATAGENE System (for DataGene with utility for dairy cattle breeders).

22 Software has also been developed for use in the BREEDPLAN System and DATAGENE System, respectively termed the BREEDPLAN Software and DATAGENE Software. Broadly speaking, these systems are utilised to facilitate the testing performed by Zoetis and Xytovet and the provision of results and analysis of the testing to cattle breeders. Further, these use the BREEDPLAN Software and DATAGENE Software respectively granted to third parties pursuant to the terms of the accompanying BREEDPLAN Licence and DATAGENE Licence.

23 Broadly, those genetic evaluation systems enable:

(1) genetic material to be processed and sent to the genomic testing laboratories;

(2) the genomic testing laboratories to perform genotyping on the genetic material to identify genetic traits and provide the results;

(3) the analysis of the genotyping results to calculate breeding values for the animals tested; and

(4) the results of the analysis to be reported to the cattle breeders.

24 Scidera’s case is that the secondary respondents have been involved in the provision of the BREEDPLAN and DATAGENE Systems in various manners, through which cattle breeders and others have been encouraged to submit genetic material for cattle genotyping and such testing has been facilitated in a way that infringes the patent.

3. Principles

25 The role of pleadings in litigation and the requirements for a proper pleading are well settled. For the sake of completeness, these principles, and the relevant Rules of this Court which outline their requirements are discussed below.

26 Rule 8.21 of the Rules states:

8.21 Amendment generally

(1) An applicant may apply to the Court for leave to amend an originating application for any reason, including:

(a) to correct a defect or error that would otherwise prevent the Court from determining the real questions raised by the proceeding; or

(b) to avoid the multiplicity of proceedings; or

(c) to correct a mistake in the name of a party to the proceeding; or

(d) to correct the identity of a party to the proceeding; or

(e) to change the capacity in which the party is suing in the proceeding, if the changed capacity is one that the party had when the proceeding started, or has acquired since that time; or

(f) to substitute a person for a party to the proceeding; or

(g) to add or substitute a new claim for relief, or a new foundation in law for a claim for relief, that arises:

(i) out of the same facts or substantially the same facts as those already pleaded to support an existing claim for relief by the applicant; or

(ii) in whole or in part, out of facts or matters that have occurred or arisen since the start of the proceeding.

…

(2) An applicant may apply to the Court for leave to amend an originating application in accordance with paragraph (1)(c), (d), (e) or subparagraph (g)(i) even if the application is made after the end of any relevant period of limitation applying at the date the proceeding was started.

(3) However, an applicant must not apply to amend an originating application in accordance with subparagraph (1)(g)(ii) after the time within which any statute that limits the time within which a proceeding may be started has expired.

(Notes omitted.)

27 Rule 16.06 of the Rules provides:

16.06 Inconsistent allegations or claims

A party must not plead inconsistent allegations of fact or inconsistent grounds or claims except as alternatives.

28 Rule 16.21 of the Rules states:

16.21 Application to strike out pleadings

(1) A party may apply to the Court for an order that all or part of a pleading be struck out on the ground that the pleading:

(a) contains scandalous material; or

(b) contains frivolous or vexatious material; or

(c) is evasive or ambiguous; or

(d) is likely to cause prejudice, embarrassment or delay in the proceeding; or

(e) fails to disclose a reasonable cause of action or defence or other case appropriate to the nature of the pleading; or

(f) is otherwise an abuse of the process of the Court.

(2) A party may apply for an order that the pleading be removed from the Court file if the pleading contains material of a kind mentioned in paragraph (1)(a), (b) or (c) or is otherwise an abuse of the process of the Court.

29 Rule 34.42 of the Rules provides:

34.42 Applications under section 120(1) of Patents Act

(1) An applicant who wants an order under section 120(1) of the Patents Act must serve the application and the accompanying document required by rule 8.05 at least 14 days before the return date fixed for the proceeding, on:

(a) the respondent in the proceeding; and

(b) if the applicant is an exclusive licensee, the patentee; and

(c) the Commissioner.

(2) If the application relates to an innovation patent, the accompanying document must state the date on which the innovation patent was certified.

(3) The accompanying document must include particulars of the alleged infringements:

(a) in a proceeding for infringement of a standard patent—specifying which of the claims of the complete specification of that patent are alleged to be infringed; and

(b) giving at least one instance of each type of infringement alleged.

(4) A respondent relying on a defence under section 144(4) of the Patents Act must give particulars of:

(a) the date of, and the parties to, a contract on which the respondent intends to rely for the defence; and

(b) the provision of the contract that the respondent asserts is void.

30 The power to strike out pleadings is discretionary. The power to strike out a pleading should be exercised sparingly and only in a clear case: Trade Practices Commission v Pioneer Concrete (Qld) Pty Ltd (1994) 52 FCR 164 at 175 (per Sheppard J, Jenkinson J agreeing at 175, Drummond J agreeing at 176); KTC v David [2022] FCAFC 60 at [125], [228] (per Wigney J).

31 The decision whether to strike out a pleading is a case specific enquiry. The application of the principles will differ depending on the case and on the pleading. The approach of the Court in a strike-out application is informed by the overarching purpose contained in s 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

32 In Oztech Pty Ltd v Public Trustee of Queensland (2019) 269 FCR 349 at [28]–[30] (per Middleton, Perram and Anastassiou JJ), it was observed:

The question of whether a pleading adequately raises a claim or defence is not concerned with the expression of the pleading as a matter of style, or of phrasing, or the structure of the pleading. Neither is it concerned with the formality of the process by which the issues in the proceeding are identified; be it a statement of claim, statement of contentions, concise statement, points of claim or points of defence. The verbal formulation of the allegations of fact, or the contentions of law, need not conform to a particular style guide or to any pro forma template.

The sole objective of a pleading is to clearly identify matters in dispute and difference by and between the parties to the dispute. This objective necessarily involves expressing the factual basis of each claim or defence. It is necessary that the legal elements of each cause of action or defence are expressed by reference to allegations of fact required to establish each element. It is not necessary to plead the legal conclusions that follow from the facts, but it is often convenient to do so. These are trite propositions but nevertheless vital to ensuring that the pleading serves its purpose.

There should be no doubt about whether any particular cause of action is relied upon. At a minimum, the pleading should be pellucidly clear about the causes of action, or claims, relied upon by the applicant, including any claims made upon an alternative hypothesis. The explicit clarity with which a claim is expressed should ensure that there be no need for the opposite party to closely scrutinise the pleading in a process of textual construction to determine whether a particular fact is relied upon, or the purpose for which it is alleged, much less to decide whether a particular cause of action is raised. The same basic requirement applies to any defence raised in answer to a claim.

(Emphasis added.)

33 A pleading must state all material facts necessary to establish a reasonable cause of action. A “reasonable cause of action” means one which has some chance of success if regard is had only to the allegations and the pleadings: Polar Aviation Pty Ltd v Civil Aviation Safety Authority (2012) 203 FCR 325 at [41] (per Perram, Dodds-Streeton and Griffiths JJ).

34 The fundamental purpose of pleadings is to state with sufficient clarity the case that must be met so as to ensure the basic requirement of procedural fairness that a party should have the opportunity of meeting the case against them: Murdock v Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 569 at [19] (per Burley J), citing Banque Commerciale SA (En Liquidation) v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 at 286 (per Mason CJ and Gaudron J); Dare v Pulham (1982) 148 CLR 658 at 664 (per Murphy, Wilson, Brennan, Deane and Dawson JJ).

35 In Wride v Shulz [2004] FCAFC 216, Spender, Tamberlin and Bennett JJ stated at [25]:

[T]he the pleadings must disclose a reasonable cause of action against the party against whom the cause of action is brought and must state all material facts necessary to establish that cause of action and the relief sought. A “reasonable cause of action” for this purpose means one which has some chance of success if regard is had only to the allegations and the pleadings relied on by the applicant.

36 Justice Banks-Smith summarised the current position on pleadings in the context of modern case management principles in EIX20 v State of Western Australia [2022] FCA 1357 at [19]–[26]. At [19] her Honour cited the observations of Greenwood, McKerracher and Reeves JJ in Thomson v STX Pan Ocean Co Ltd [2012] FCAFC 15 at [13]:

For these reasons, the courts do not, at least in the current era, take an unduly technical or restrictive approach to pleadings such that, among other things, a party is strictly bound to the literal meaning of the case it has pleaded. The introduction of case management has, in part, been responsible for this change in approach: see the observations of Martin CJ in Barclay Mowlem Construction Ltd v Dampier Port Authority (2006) 33 WAR 82 (at [4]-[8]). …

37 In EIX20 at [20], Banks-Smith J noted that it was worth repeating the comments of Martin CJ in Barclay Mowlem Construction Ltd v Dampier Port Authority (2006) 33 WAR 82:

[5] … [T]he contemporary role of pleadings has to be viewed in the context of contemporary case management techniques and pre-trial directions. In this Court, those pre-trial directions will almost invariably include; firstly, a direction for the preparation of a trial bundle identifying the documents that are to be adduced in evidence in the course of the trial; secondly, the exchange well prior to trial of non-expert witness statements so that non-expert witnesses will customarily give their evidence-in-chief only by the adoption of that written statement; thirdly, the exchange of expert reports well in advance of trial and a direction that those experts confer prior to trial; fourthly, the exchange of chronologies; and fifthly the exchange of written submissions.

[6] Those processes leave very little opportunity for surprise or ambush at trial and, it is my view, that pleadings today can be approached in that context and therefore in a rather more robust manner, than was historically the case; confident in the knowledge that other systems of pre-trial case management will exist and be implemented to aid in defining the issues and appraising the parties to the proceedings of the case that has to be met.

[7] In my view, it follows that provided a pleading fulfils its basic functions of identifying the issues, disclosing an arguable cause of action or defence, as the case may be, and appraising the parties of the case that has to be met, the Court ought properly be reluctant to allow the time and resources of the parties and the limited resources of the Court to be spent extensively debating the application of technical pleadings rules that evolved in and derive from a very different case management environment.

[8] Most pleadings in complex cases, and this is a complex case, can be criticised from the perspective of technical pleading rules that evolved in a very different case management environment. In my view, the advent of contemporary case management techniques and the pre-trial directions, to which I have referred, should result in the Court adopting an approach to pleading disputes to the effect that only where the criticisms of a pleading significantly impact upon the proper preparation of the case and its presentation at trial should those criticisms be seriously entertained.

38 In EIX20 at [21], Banks-Smith J also noted the earlier observation of O’Loughlin J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Pauls Ltd [1999] FCA 1750 at [10] that:

The modern system of pleading requires only that the material facts on which a party’s claim is based be stated; the claim is not expected to be formulated as an elegant model of legal purity: Carr v McDonald's Australia Ltd (1994) 63 FCR 358 at 367 and there is now a tendency against taking a pedantic approach to a pleading: Coshott v Kam Tou Mak (Wilcox J, 3 March 1998, unreported).

39 Justice Banks-Smith observed at [22] that such an approach conforms with s 37M of the FCA Act, which sets out that the overarching purpose of civil practice and procedure is to facilitate the just resolution of disputes according to law and as efficiently as possible. This includes the objective of the efficient use of judicial resources and the efficient disposal of the Court’s overall caseload.

4. The amendments to the SOC

40 Scidera contends that in large part the amendments to the SOC in the ASOC involve the pleading of facts which were previously asserted in the particulars to the allegations in the SOC, the provision of additional detail in relation to matters which were already pleaded or particularised, and claims for relief based on those facts. According to Scidera, the claims in the ASOC arise out of the same or substantially the same facts as those already pleaded in the SOC.

41 Scidera categorises the principal proposed amendments as follows.

(1) The existing pleading alleges direct infringement by a number of genomic testing laboratories including Zoetis. The amendments join one of the other genomic testing laboratories, Xytovet, as a respondent and delete the allegations against the other non-party laboratories: see ASOC at [6A], [22], [75].

(2) The amendments address the case against Zoetis and Xytovet in greater detail. This includes integrating into the pleading the detail from Scidera’s Further Particulars; and addressing Zoetis’s assertion regarding conduct outside Australia: see, in particular, ASOC at [33B]–[33E], [83A]–[83D] (Zoetis); [33F]–[33I], [83E]–[83H] (Xytovet).

(3) The amendments address the indirect or secondary infringement claims against the other secondary respondents (MLA, ABRI and DataGene) in greater detail. This is based on matters which are already pleaded or particularised in the existing pleading relevant to the knowledge and conduct of those particular secondary respondents: see ASOC [21A], [23A]– [33A], [62]–[67], [77A]–[83], [112]–[117].

(4) Finally, the amendments introduce an additional basis for the allegations of patent infringement. This additional allegation of patent infringement is directed at the same patent claims as the existing pleading, but involves a combination of steps undertaken by Zoetis/Xytovet and ABRI/DataGene, as opposed to steps undertaken by just Zoetis/Xytovet. Again, Scidera submits that this is based on matters already pleaded or particularised. This was referred to by the respondents as the “in concert” infringement case: see, in particular, ASOC [34A], [41A], [49A], [52A], [55A], [84A], [91A], [99A], [102A], [105A].

5. Submissions

42 Each of the respondents’ submissions with respect to their Applications are detailed below. As a general point, I note from the outset that the respondents’ submissions overlap with one another’s to some extent. However, each submission is described below in full.

5.1 MLA

5.1.1 Direct infringement against the laboratories

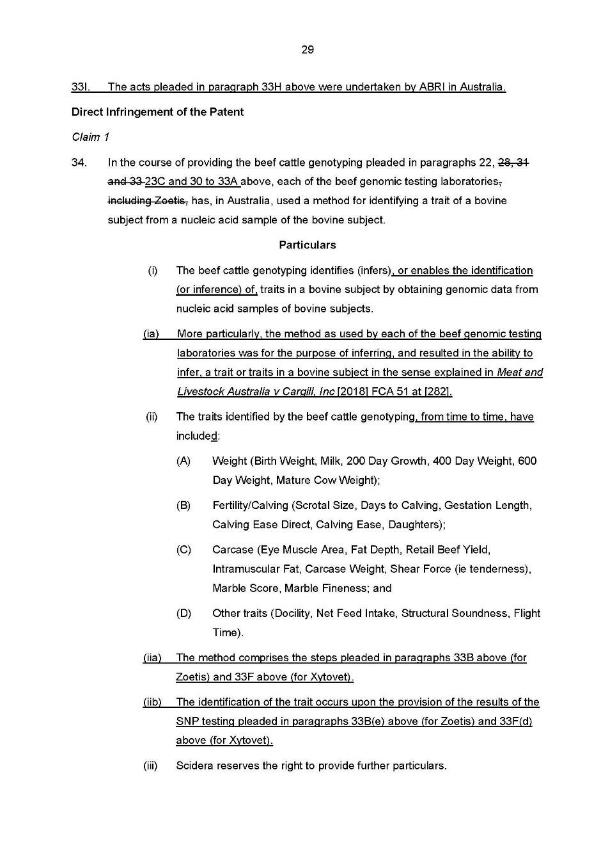

43 MLA submits that the nature of the activities encompassed by “beef cattle genotyping” are central to the allegation of infringement against the laboratories as they are referred to throughout the ASOC: [22], [23C], [30]–[33A], [33B], [33C], [33F], [33G], [34] of ASOC.

44 MLA contends that it is unclear what Scidera means by the phrase, “beef cattle genotyping” and it notes that, in [22] of the ASOC, Scidera defines beef cattle genotyping as “genomic selection services in Australia for identifying bovine traits of economic interest in beef cattle by performing single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) testing of genetic material”. By doing so, MLA submits that Scidera is suggesting that each instance of a SNP test involves genomic selection services, citing [34]–[40] of the Response.

45 MLA separately submits that it appears from [33B] and [33C] of the ASOC that Scidera is asserting that the following may constitute “beef cattle genotyping”:

(1) providing DNA Sample Kits;

(2) receiving genetic material;

(3) extracting genetic material;

(4) determining the quality and quantity of the material is sufficient to enable it to be used to generate SNP genotypes;

(5) transferring the results of SNP testing to a database maintained by ABRI; and

(6) receiving payment.

46 MLA submits that this is at odds with the definition of “beef cattle genotyping” in [22] of the ASOC, which requires the act of SNP testing of genetic material being performed in Australia.

47 Further, in [34] of the ASOC, Scidera pleads that, in the course of providing “beef cattle genotyping”, each of Zoetis and Xytovet has used a method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of the bovine subject. Previously, the particulars to that paragraph specified that the “beef cattle genotyping” identifies (infers) traits in a bovine subject. They now provide in the alternative that the “beef cattle genotyping” may enable the identification of a trait.

48 MLA notes it appears Scidera alleges that, by providing DNA Sample Kits; receiving, extracting and determining the quality and quantity of the genetic material extracted; transferring results of SNP testing (which has been performed elsewhere) to a database and receiving payment, the laboratories have infringed the claims even if they have not performed SNP testing in Australia or analysed the results. MLA submits that this involves an expansive view of the claims and that Scidera has not sufficiently explained how this collection of actions could fall within the scope of the Patent’s claims.

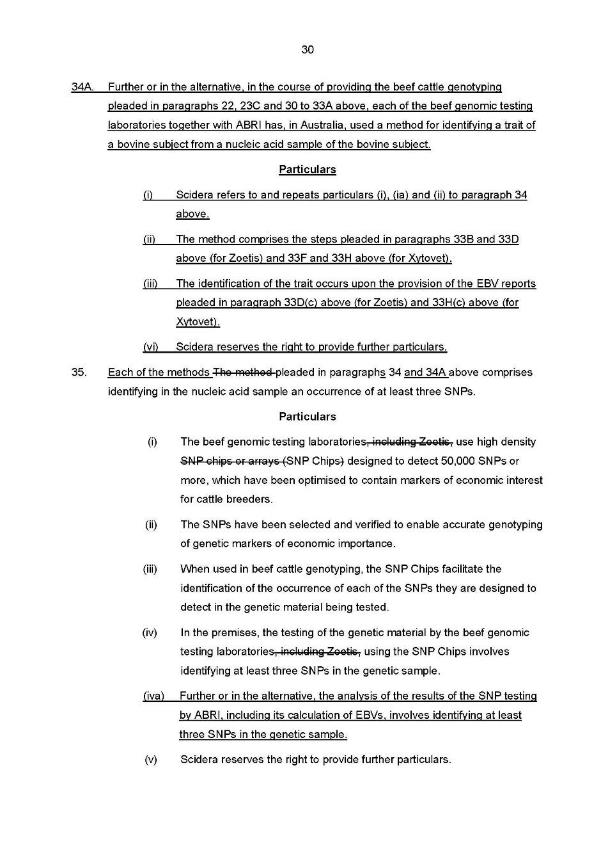

5.1.2 Case against ABRI and the laboratories compared to the case against the laboratories

49 MLA draws attention to the fact that Scidera stated on several occasions that the claim against ABRI was a case of indirect infringement, and now, Scidera asserts, further and in the alternative to its broad case against the laboratories, that the laboratories acting in concert with ABRI have directly infringed claim 1: [33D], [33H], [34A], [35], [40A] of ASOC.

50 MLA submits that this is not a claim that arises out of the same facts, or substantially the same facts as those already pleaded. This has consequences for the date on which the amendments might take effect, if they were otherwise allowed. Further, since the claim is expressed as being further to (as well as in the alternative to) the case against the laboratories, Scidera’s construction of the claims is unclear. MLA submits that it appears in its case against the laboratories, Scidera asserts that actions which go some of the way to enabling the identification of traits (but not as far as testing or undertaking identification) enliven the claims. As against the laboratories and ABRI, Scidera’s case appears to be that the identification of traits is an essential element. MLA contends that the pleading, as put, contains confusingly intermixed alternatives so that the pleading is embarrassing and ambiguous for the following reasons.

(1) It is unclear what is meant by “beef cattle genotyping”, but it may not require SNP testing to be performed, or analysis of the results of SNP testing to be conducted to identify traits.

(2) It is unclear what construction Scidera is giving the claims, since the case against Zoetis and Xytovet suggests that analysis of the SNP test results is not essential but the case against the laboratories and ABRI suggest that the identification of traits by analysis is essential. These allegations are not characterised as simple alternatives.

(3) It appears Scidera is advancing two inconsistent claim constructions, but it is not clear.

5.1.3 Allegation that MLA cooperated with or encouraged the laboratories

51 Scidera alleges that MLA has cooperated with the laboratories: [33A] of the ASOC. MLA alleges that the basis for this allegation is unclear, noting that the pleading cross-refers to [23]–[32] of the ASOC. Those paragraphs, and the particulars to them, are said to not provide any basis for the conclusion that MLA has any relationship with the laboratories.

52 Scidera alleges that MLA encouraged each of the beef genomic testing laboratories to provide the beef cattle genotyping ([63A] of the ASOC) through:

(1) MLA’s development, use and promotion of the BREEDPLAN Software; and

(2) MLA’s grant of a licence to ABRI to use the BREEDPLAN Software.

53 MLA highlights that there is no separate allegation in the pleading that MLA used the BREEDPLAN Software, and MLA’s “promotion” of the BREEDPLAN System and Software seems to be based on the facts that MLA mentioned the BREEDPLAN System and Software in its annual report; and MLA included some information about BREEDPLAN on a website aimed at breed associations, breeders and seed stock producers.

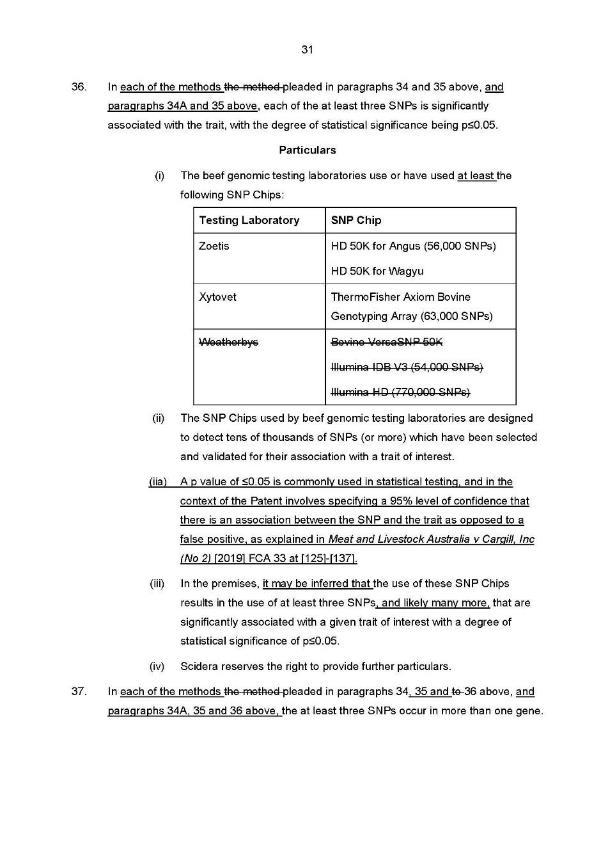

54 MLA contends that the alleged foundational facts cannot establish the allegation that MLA encouraged the laboratories by developing the BREEDPLAN Software, licensing it to ABRI and telling breeders about it, as these alleged facts do not establish a relationship between MLA and the laboratories.

55 Further, MLA submits that the allegation that it had the power to prevent beef genomic testing laboratories from providing beef cattle genotyping ([63C] of the ASOC) is farfetched. This is because this allegation turns on the particulars that:

(1) MLA retains control over, access to and delivery of the BREEDPLAN Software and the BREEDPLAN System;

(2) MLA had the power not to participate in the provision of the BREEDPLAN System, including by not permitting the BREEDPLAN Software to be used or preventing its use for particular purposes, or by not granting or revoking the BREEDPLAN Licence, or by not promoting the BREEDPLAN System; and

(3) if MLA had exercised its power, the BREEDPLAN System could not be provided and beef cattle genotyping could not have occurred, or would not have occurred to the same extent as it otherwise did.

56 The ASOC sets out the key terms of the BREEDPLAN Licence at [26]. MLA relies on the following part of the discussion of the ‘Operational Plan’ on page 169, which was not included in the key terms and includes a summary of Clause 22: “The owners do not have the power to terminate the licensing agreement, convert the licensee’s rights from exclusive to non-exclusive, or purchase the Improvements unless they do so jointly”.

57 MLA contends that a decision by it not to promote the BREEDPLAN System to breeders would not have affected, in any way, the laboratories’ ability to provide testing. Further, it argues that the documents on which Scidera relies do not support the proposition that MLA retained control over access to, and delivery of, the BREEDPLAN Software and BREEDPLAN System.

58 MLA also notes that it had no power to prevent the laboratories from undertaking beef cattle genotyping even if the BREEDPLAN Software and BREEDPLAN System were not available, with particular (v) to [63C] of the ASOC implying this. Additionally, MLA asserts that Scidera does not plead that the BREEDPLAN Software or BREEDPLAN System cannot be used without the use of SNP Testing.

5.1.4 The particularised documents do not support the allegation that MLA controlled ABRI

59 Scidera makes the following allegations against MLA:

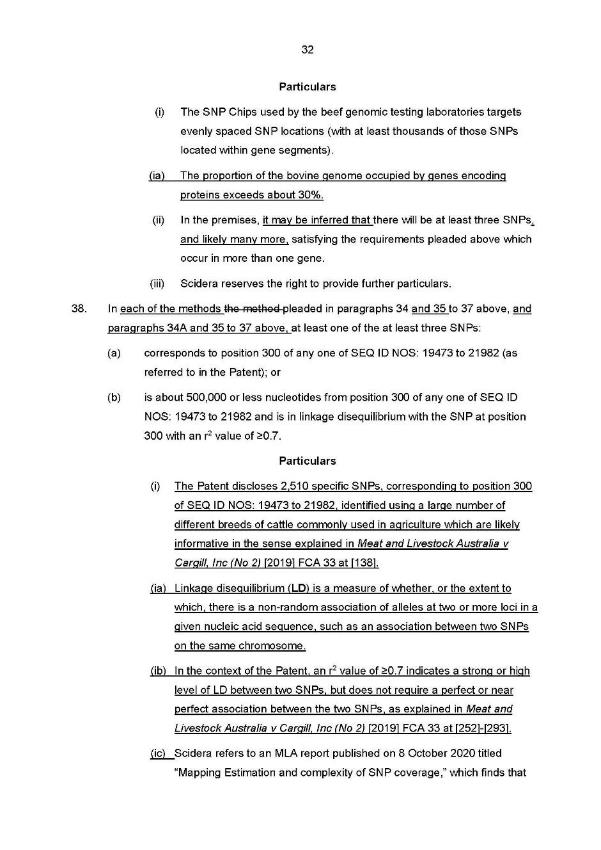

(1) MLA, the University of New England and the New South Wales Department of Primary Industry (together, the owners) developed software for use in a genetic evaluation system for beef cattle breeders ([23] of the ASOC);

(2) MLA retains control over access to and delivery of the BREEDPLAN Software and the BREEDPLAN System ([24A] of the ASOC);

(3) The BREEDPLAN Licence includes a term that in October each year, ABRI must provide the owners with an ‘Operational Plan’ for the next three years that sets out, for each module of the BREEDPLAN Software, the target audience and performance criteria, a description of the manner in which the commercialisation, exploitation and delivery of the module will relate to the delivery of other genetic improvement technologies or other technologies of interest to the Australian beef industry, and the marketing strategy for the module, including proposed expenditure on marketing ([26(f)] of ASOC).

60 MLA contends that these assertions listed above at [59] are unsupported by the particularised documents, on the respective bases.

(1) The particulars to [23] of the ASOC do not support the proposition that MLA, together with the University of New England and the NSW Department of Primary Industry, developed the BREEDPLAN Software for use in the BREEDPLAN System.

(2) Particular (i) to [24A] of the ASOC refers to the particulars of [24]. These particulars refer to certain pages from a document, the BREEDPLAN Final Report dated August 2017, which states: “It has been agreed that modifications to the terms of the licensing agreement with ABRI […] or termination of that agreement can only be effected upon the unanimous consent of the Owners”. The following page includes two bullet points to the same effect. MLA notes that these statements are inconsistent with the proposition that MLA, by itself, retains control over the BREEDPLAN Software or the BREEDPLAN System. The other particulars to [24A] of the ASOC recite a statement that MLA wants to retain some control. That statement does not prove that MLA has any control, let alone sufficient control.

(3) Although no particulars for [26] of the ASOC are provided, [25] of the ASOC (which refers to the BREEDPLAN Licence) cites pages 168 and 169 of the BREEDPLAN Final Report August 2017, which set out the Key Terms and Conditions of the Core Analytical Software Agreement. These key terms include the clauses cited in [26] of the ASOC. However, the ASOC does not refer to parts of documents which indicate that MLA can render the licence non-exclusive in certain circumstances.

61 For these reasons, MLA contends that the documents Scidera particularises in support of its allegations about the BREEDPLAN Licence do not support it. The allegations are alleged to be embarrassing, since the particularised documents undermine the proposition that MLA has control over the BREEDPLAN System or Software. MLA purports that the 2017 BREEDPLAN Report discussed above indicates that MLA does not have the power to reject the Operational Plan due to any steps ABRI takes in relation to beef cattle genotyping.

62 MLA also relied on the submissions of each of the Zoetis and ABRI. MLA further relied on DataGene’s submissions on the terms “together with” which, MLA contends, applies equally to the use of that term for the “Beef Cohort Claims” at ASOC [22]–[74]. These submissions are discussed at 5.2.1.2.2 and 5.3 below.

5.2 Zoetis

63 Zoetis submits that the ASOC is defective for at least the following reasons:

(1) the amendments propound confusingly intermixed, inconsistent and/or untenable acts of infringement and associated implicit constructions of the Patent, contrary to r 16.06, and 16.02(2)(c), (d) and/or (e) of the Rules;

(2) the amendments do not sufficiently plead any basis for Zoetis to be liable for acts of infringement said to be done by other respondents on the basis of joint tortfeasorship, contrary to r 16.02(1)(d) and 16.02(2)(c), (d) and/or (e) of the Rules; and

(3) the amendments still do not sufficiently particularise “instances of infringement” in accordance with r 34.42(3)(b) of the Rules.

5.2.1 Confusingly intermixed, inconsistent, and untenable acts of infringement and associated implicit constructions

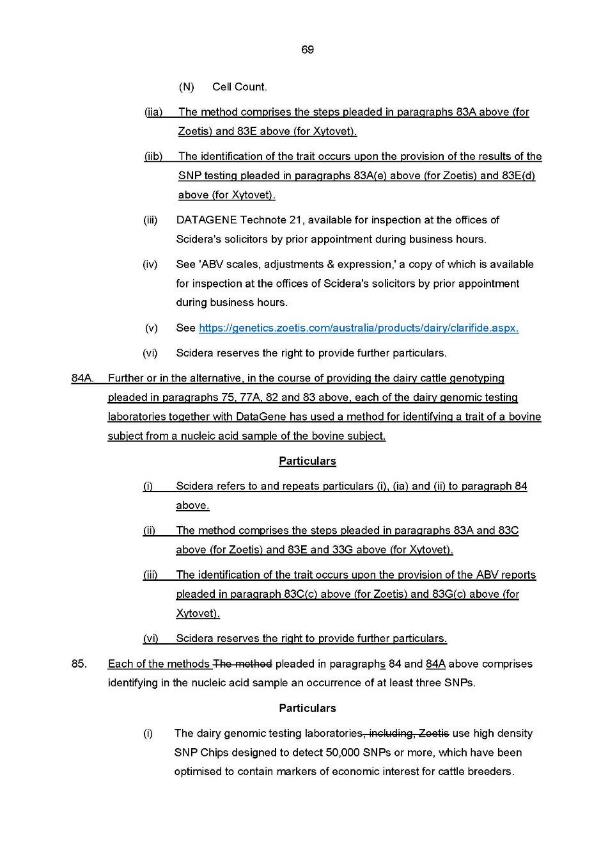

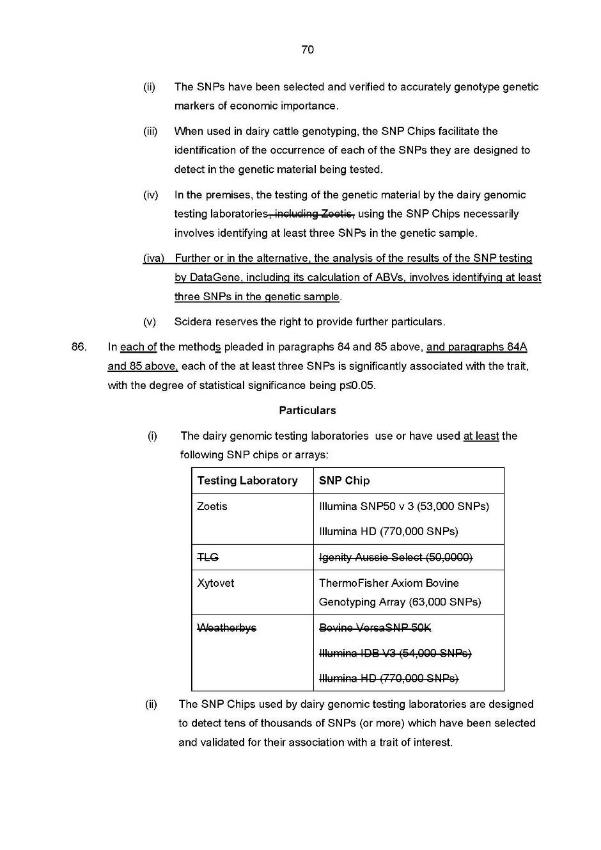

64 Zoetis directed its written submissions to the key proposed amendments in relation to the “beef cohort” of respondents and claim 1 of the Patent. However, Zoetis and DataGene both submitted that similar defects afflict corresponding aspects of the ASOC on the “dairy cohort” and the pleading of infringement in relation to other claims of the Patent.

65 Claim 1 of the Patent involves the concept of “identification” in two different integers, firstly in the integer “[a] method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample” (Trait Identifying Integer), and secondly, comprising “identifying in the nucleic acid sample an occurrence of at least three single nucleotide polymorphisms” (SNP Identifying Integer).

5.2.1.1 Acts said to meet the Trait Identifying Integer

66 Zoetis submits that the ASOC propounds a confusing intermix of different acts, and thus different, inconsistent, implicit constructions of the Trait Identifying Integer, together with an ambiguous and oppressive mix of language apparently pleading some combination of primary and secondary infringement, as follows:

(1) as against Zoetis alone, an act depending upon an implicit construction:

(a) that an act of identification of the trait is not required, but only that an act of identification of a trait is enabled ([34(i)] and [34(iib)] of the ASOC);

(b) that an act of identification of the trait is required and is met “upon the provision of the results of the SNP testing”, which is said to be “transferred, either directly or through the relevant beef cattle breed association … to a database maintained by ABRI” (particular (iib) to [34], picking up [33B(e)] of the ASOC);

(2) either in addition to, or instead of, [66(1)(b)] above — further or in the alternative, as against Zoetis “together with ABRI”, that an act of identification of the trait is required and is said to occur upon the provision of the Estimated Breeding Value reports (particular (iii) to [34A] of the ASOC).

67 Zoetis contends that, by its ASOC, Scidera now seeks to propound as cumulative cases, at least three inconsistent constructions of the Trait Identifying Integer. Zoetis submits that these constructions are contrary to r 16.06 of the Rules, with such a wide construction relying on various alternatives being improper.

68 Further, Zoetis notes that, given the fact that there are multiple respondents who are alleged to have committed various acts, the multiple and overlayed constructions which are broadly alleged against a number of respondents leaves the respondents in a state of uncertainty, being unable to pinpoint to precise allegations and constructions levelled against them. Particularly given the chain of events in this matter, with steps occurring in Australia and the United States, and with different respondents carrying out different acts, Zoetis submits that it is vital that there be absolute clarity as to who is alleged to have committed what act, and at which point an act is said to constitute performance of a method.

69 Zoetis further contends that, the meaning of “together with” in the ASOC, is entirely ambiguous. This is particularly in the context where the matters in [34A] of the ASOC are then said to, in part, ground the pleading of “acting in concert” in [40A] based on acts allegedly done by Zoetis “together with” ABRI, in circumstances where not all of the other acts relied upon in [40A] (namely all of the acts in each of [34A], [35], [36], [37], [38] and [39] of the ASOC) are pleaded in those paragraphs to be done by Zoetis.

70 Zoetis notes that confusingly, this pleading of “acting in concert” and “together with” in [40A] of the ASOC, is in a section headed “Direct Infringement of the Patent”, in contrast to the section headed “Authorisation, inducement, procurement and common design” (beginning at [62] of the ASOC). Zoetis submits that the language of “in concert” is the language of joint tortfeasorship, but no common design or procurement by Zoetis of the acts of others is pleaded.

71 Further, the pleading at [62]–[67] of the ASOC relates to knowledge or procurement by other respondents of each other’s acts or the acts of Zoetis — not the knowledge of, or procurement by, Zoetis of the specific acts of other respondents now said to be done by other respondents (particular (iva) to [35] of the ASOC). To be liable as a joint tortfeasor, Zoetis notes that the alleged joint tortfeasors must agree on a common action and the act of infringement must be in furtherance of that agreement, with the mere facilitation of an infringement being insufficient. Therefore, Zoetis submits that the pleading of “in concert” is mere ipse dixit and does not allege sufficient material facts or disclose a reasonable cause of action.

72 Consequently, Zoetis submits that the ASOC is entirely ambiguous and inconsistent as to what construction of the Patent the proceeding is brought upon, what acts infringe the Patent, which party such acts were committed by and the basis on which Zoetis is alleged to be liable for the acts not committed by Zoetis.

73 Zoetis notes that a pleading is likely to cause prejudice or embarrassment for the purposes of r 16.21(1)(d) of the Rules if it is susceptible to various meanings, contains inconsistent allegations, or includes various alternatives which are confusingly intermixed. Zoetis also contends that such a pleading could equally be characterised as evasive or ambiguous for the purposes of r 16.21(1)(c) of the Rules.

5.2.1.2 Territoriality issue and acts said to meet the SNP Identifying Integer

74 Zoetis contends that similar difficulties as those outlined at 5.2.1.1 above also arise from the ASOC of the relevant acts said to meet the SNP Identifying Integer. Zoetis submits that the case previously propounded against it depended only upon the act of testing of the genetic material using SNP Chips by Zoetis as being the relevant act of “identifying in the nucleic acid sample an occurrence of at least three [SNPs]” (particular (iv) to [35] of the SOC). Zoetis highlights that Scidera has now sought to make two key amendments apparently directed at the issue of territoriality of infringement raised by Zoetis, with Zoetis inferring that this amendment is made in light of Zoetis’s assertion that it does not perform the SNP testing in Australia.

5.2.1.2.1 Alternative pleading that Zoetis did not perform the act of SNP testing

75 Zoetis notes that [33C(b)] of the ASOC includes an alternative pleading to the effect that Zoetis did not perform the act of SNP testing (i.e. the act pleaded in [33B(d)] of the ASOC) in Australia. Zoetis submits that it is entirely unclear whether the “daisy chain” of cross-references culminating in the infringement pleading in [40] and [40A] of the ASOC, continues to encompass an allegation that a relevant act of Zoetis is relied upon to meet the SNP Identifying Integer, and hence infringement, is an act of testing of the genetic material using SNP Chips by Zoetis outside Australia. To illustrate this point, Zoetis notes the following example from the ASOC regarding the pleading of infringement:

(1) [40] of the ASOC refers to [34];

(2) the chapeau to [34] (which alleges “in Australia”) expressly does not pick up anything after [33A], and particular (iia) to [34] refers to [33B] but not [33C]; and

(3) [33C] purports to provide elaboration as to [33B], however none of [33A], [33B] or [34] refers to, or incorporates, [33C].

76 This form of cross-referencing at [75(1)]–[75(3)] above is described by Zoetis as being entirely confusing and ambiguous, and does not make it clear which paragraphs the ultimate cross-reference in [40] to [34] of the ASOC is intended to pick up. In particular, whether it is intended to pick up [33C(b)] of the ASOC and allege infringement on the basis of the matters in [33C(b)]. Zoetis submits that such ambiguity on a crucial issue necessitates the refusal of leave.

77 Zoetis further notes that, to the extent that Scidera now contends the ASOC does allege infringement, this allegation discloses no reasonable cause of action, as all essential integers of the method must be performed in Australia. Zoetis notes that this point has practical implications, even though Scidera also seeks to make a new primary allegation that the act of testing genetic material using SNP chips was done by Zoetis in Australia ([33C(a)] of the ASOC).

5.2.1.2.2 New pleading “further or in the alternative” in particular (iva) to [35] of the ASOC

78 Zoetis also raises further issue with an amendment to make an entirely new allegation in particular (iva) to [35] of the ASOC, “[f]urther or in the alternative” (i.e. cumulative with or instead of particular (iv) to [35]), to the effect that the SNP Identifying Integer is met by “the analysis of the results of the SNP testing by ABRI, including its calculation of EBVs”, which it is said “involves identifying at least three SNPs in the genetic sample”.

79 Zoetis contends that at least three difficulties arise from the proposed new pleading in particular (iva) to [35] of the ASOC.

(1) To the extent that the SNP Identifying Integer is said to be met by “analysis of the results of the SNP testing by ABRI, including its calculation of EBVs”, the construction of the SNP Identifying Integer implicitly disclosed is said by Zoetis to be inconsistent with the case in particular (iv) to [35], where it is said to be “further” to. Zoetis alleges that this inconsistency with the pleading in particular (iv) to [35] arises from the fact that the pleading in particular (iva) to [35] now departs from a technical act of identifying an SNP in the nucleic acid sample. This is said to apparently open up as an alleged act of infringement subsequent dealings with mere information derived from the genetic sample.

(2) The implicit construction in particular (iva) to [35] of the ASOC is wholly unmoored from any “nucleic acid” sample, but the integer requires “identification in the nucleic acid sample”. Accordingly, Zoetis submits that this construction is untenable and has no reasonable prospect of success in relation to claim 1, and is entirely nonsensical in relation to claims 8 and 12. Further, if allowed to proceed it would immensely expand the scope of factual inquiries in the proceeding from the case originally brought.

(3) As pleaded, the act of analysis in particular (iva) to [35] is an act undertaken solely by ABRI. However, [40] of the ASOC pleads that as a matter of direct infringement, all of the acts in [35], including particular (iva) to [35], results in direct infringement by Zoetis for an act only alleged to be done by ABRI. Paragraph [40A] of the ASOC then pleads “[f]urther or in the alternative”, by reason of matters including [35] (including apparently the act in particular (iva) to [35] only done by ABRI), that Zoetis “together with ABRI, acting in concert”, has infringed claim 1 of the Patent, as a matter of direct infringement, when no acts of procurement or common design in relation to the act of analysis are pleaded.

80 Zoetis submits that the pleading of “together with” or “acting in concert”, does not allege sufficient material facts to comply with r 16.02(1)(d) of the Rules. Zoetis alleges that the pleading is also ambiguous, prejudicial or embarrassing, and does not disclose a reasonable cause of action based on joint tortfeasorship, despite the adoption of the verbiage of joint tortfeasorship, contrary to r 16.02(2)(c), (d) or (e), of the Rules.

81 Zoetis alleges that each corresponding allegation of “acting in concert” in the ASOC suffers from the same deficiencies, citing [48A], [51A], [54A], [61A], [90A], [98A], [101A], [104A], [111A] of the ASOC.

5.2.2 Failure to comply with r 34.42(3)(b) of the Rules

82 Zoetis claims that the ASOC still fails to give proper particulars of the instances of infringement. For example, it notes that the ASOC at particular (iv) of [33B] states:

Scidera relies on each instance of the provision by Zoetis of beef cattle genotyping involving the use of a high density SNP Chip designed to detect 50,000 SNPs or more, including all versions of the HD 50K for Angus and HD 50K for Wagyu SNP Chips and any similar SNP Chips known by other names.

83 Zoetis submits that this general statement is insufficient to satisfy r 34.42(3)(b) of the Rules, not least because it depends upon the defined term “beef cattle genotyping” (which Zoetis alleges now has more ambiguities than it did prior to the proposed amendments). Citing the case of Upaid Systems Ltd v Telstra Corp Ltd (2013) 220 FCR 182 at [45] (per Yates J), Zoetis contends that this statement refers to nothing more than “generally described acts [which do] not themselves engage with the specific features of the invention defined in” the asserted claims. Further, Zoetis notes that this statement fails to engage with any of the features of claim 1 of the Patent, including by giving any instance of any trait that is said to have been identified, or of any at least three SNPs that are said to have been identified.

5.3 ABRI

84 ABRI submits that the ASOC is defective for at least the following reasons.

(1) The ASOC is likely to cause real prejudice because it pleads multiple alternatives, and sometimes inconsistent acts, which are said to infringe the Patent.

(2) The new allegations in relation to ABRI acting “together with” the laboratories are ambiguous and embarrassing.

(3) Each new claim and each existing claim supported by new facts purports to relate to acts occurring more than six years ago: ASOC [68]. Section 120(4)(b) of the Patents Act prohibits such proceedings.

5.3.1 Inconsistent acts said to infringe the Patent

85 ABRI notes that the ASOC now alleges multiple acts which are said to constitute:

(1) “a method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of the bovine subject” as required by claim 1 of the Patent; and

(2) “a method of inferring a trait in a bovine, comprising hybridizing a nucleic acid sample from a bovine subject to a system” as required by claim 8 of the Patent; and

(3) “a system for determining nucleotide occurrences of nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a bovine population comprising a hybridisation substrate” as required by claim 12 of the Patent.

86 The acts alleged to constitute the use of each method and system claimed in claims 1, 8 and 12 of the Patent are alleged on a “further or in the alternative” basis in [34] and [34A] of the ASOC as follows.

(1) In the course of providing “beef cattle genotyping”, each laboratory alone used each method and system, which methods and system “identifies (infers)” traits in a bovine subject by obtaining genomic data from nucleic acid samples of bovine subjects, wherein the “identification of the trait occurs upon the provision of the results of the SNP testing”: particular (i) to [34], particular (iib) to [34] of the ASOC.

(2) In the course of providing “beef cattle genotyping”, each laboratory alone used each method and system, which methods and system “enables the identification (or inference) of” (or results “in the ability to infer”) traits in a bovine subject by obtaining genomic data from nucleic acid samples of bovine subjects (although, sub-paragraph (iib) of the particulars to this allegation confusingly allege that the “identification of the trait occurs upon the provision of the results of the SNP testing”: particular (i) to [34], particular (iib) to [34] of the ASOC.

(3) Further (i.e. in addition), in the course of providing “beef cattle genotyping”, each laboratory and ABRI used each method and system, where the “identification of the trait occurs upon the provision of the EBV reports” by ABRI alone: particular (i) to [34A], particular (iii) to [34A], cross-referencing [33D(c)] of the ASOC.

(4) In the alternative, in the course of providing “beef cattle genotyping”, each laboratory and ABRI used each method and system, where the “identification of the trait occurs upon the provision of the EBV reports” by ABRI alone: particular (i) to [34A], particular (iii) to [34A], cross-referencing [33D(c)] of the ASOC.

87 ABRI submits that the multiple, “further or in the alternative” acts which are now alleged to constitute the use of each relevant method and system appear to involve inconsistent allegations of fact or claims which are pleaded in a manner prohibited by r 16.06 of the Rules. These inconsistencies are said to be wholly embarrassing and opaque, with ABRI providing the following examples in support.

(1) It is uncertain how the “identification of the trait” can occur by “the provision of the results of the SNP testing” by each laboratory alone ([34(iib)] of the ASOC) and “further” by the “the provision of the EBV reports” by ABRI alone: [34A] of the ASOC.

(2) If each laboratory alone uses each relevant method and system, it is unclear what additional acts are said to be carried out by ABRI in relation to the use of such methods and system “together with” each laboratory.

(3) Paragraph [34A] of the ASOC cross-references the conduct of MLA alleged in [33A] of the ASOC. It is uncertain what the relationship between the conduct of MLA is said to have to the use of the methods and system by each of the laboratories “together with ABRI”, as alleged in [34A] of the ASOC.

88 Consequently, ABRI contends that the ASOC gives rise to real prejudice because it is unclear what the patentee, Scidera, is saying the claims of its Patent mean, such that ABRI cannot know the scope and boundaries of the claim for the purpose of preparing a defence and any cross-claim.

89 By its ASOC, ABRI contends that Scidera appears to attempt to reserve an ability to argue the claims of its Patent have multiple, sometimes inconsistent, meanings. In total, ABRI submits that the various further and alternative combinations of pleaded constructions leads to up to nine different combinations of acts conducted by different actors which are alleged to lead to infringement. This conduct is said by ABRI to be oppressive and unreasonable, as well as inconsistent with Scidera’s obligations pursuant to s 37N of the FCA Act.

5.3.2 New allegations of primary infringement by ABRI are ambiguous and embarrassing

90 ABRI contends that the ASOC involves a fundamental reformulation of the case against it given that the SOC as pleaded brought strictly a case of secondary infringement against it. Now the ASOC brings new claims of combined primary infringement against ABRI. ABRI contends that this claim is a new case against it and is based on new facts.

91 ABRI submits that the new allegations in the ASOC that ABRI “acting in concert with” the laboratories has committed a primary infringement of the Patent ([40A], [48A], [51A], [54A], [61A] of the ASOC) also give rise to significant ambiguity and embarrassment. ABRI lists the following reasons in support of its submission.

92 First, ABRI submits it is unclear which party is said to have committed which acts alleged to infringe the Patent. As an example, ABRI notes two separate combinations of alternative allegations below.

(1) [34A] of the ASOC is said to occur “in the course of providing beef cattle genotyping”. The laboratories, not ABRI, are alleged to provide “beef cattle genotyping”: [22] of the ASOC. ABRI is said to have “co-operated” with the laboratories in the provision of beef cattle genotyping by, it appears (although it is not clear), promoting the BREEDPLAN System: [33] of the ASOC. However, the cross-referencing here relates to alleged conduct of both ABRI ([30], [33] of the ASOC) and MLA ([31], [31A], [33A] of the ASOC).

(2) [34A] then alleges that the “method for identifying a trait of a bovine subject from a nucleic acid sample of the bovine subject” comprises the steps pleaded in [33B] (Zoetis) and 33D (ABRI). However, particular (iii) to [34A] alleges that the “identification of the trait occurs upon the provision of the EBV reports” by ABRI and new particular (iva) to [35] alleges that “further or in the alternative”, the analysis of the results of the SNP testing by ABRI “involves identification of at least three SNPs in the genetic sample”.

93 In the circumstances alleged in [92(2)] above, ABRI alleges that it is not clear what separate act or acts “in the course of providing beef cattle genotyping” the laboratories (and/or, perhaps MLA) are said to have performed “acting in concert with” ABRI to infringe the Patent: [40A] of the ASOC. Further, ABRI submits that there are no particulars which indicate that it has acted “in concert”, with this term having a specific meaning in law, citing Bateman v Newhaven Park Stud Ltd (2004) 207 ALR 406 at [17] (per Barrett J).

94 Second, ABRI alleges that the cross-referencing with respect to claims 8 and 12 is confusing and nonsensical. ASOC [42] and [56] allege respectively that hybridizing a nucleic acid sample from bovine subject to a system (claim 8) or a system comprising a hybridisation substrate (claim 12) is, by cross-reference to [35] of the ASOC, performed “further or in the alternative” by the analysis of the results of the SNP testing by ABRI.

95 Third, ABRI alleges that the relationship between the two different allegations of ABRI’s actions are problematic. These actions are ABRI’s authorisation of, and joint tortfeasorship with (by inducing, procuring or engaging in a common design) each of the laboratories as alleged at [64] and [66] of the ASOC (the Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations), and the new allegations of ABRI acting “together with” the laboratories (e.g. [34A] of the ASOC) and “acting in concert” with the laboratories ([40A] of the ASOC) (the New Joint Tortfeasor Allegations). ABRI notes that this relationship is problematic for the following reasons.

(1) The Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations, which have been said by Scidera to relate to secondary infringement only, and the New Joint Tortfeasor Allegations of primary infringement, are pleaded cumulatively.

(2) The Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations (of secondary infringement) now rely by cross-reference on each material fact and conclusions of law alleged to constitute primary infringement in relation to the New Joint Tortfeasor Allegations. ABRI submits this is circular and embarrassing.

96 Fourth, ABRI submits that Scidera does not identify any material facts it relies on to provide a foundation for the New Joint Tortfeasor Allegations. ABRI infers that it may be that the material facts will be said to be the same as those alleged with respect to the Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations at [62]–[63B] of the ASOC, but that is said to only make the relationship between the Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations and the New Joint Tortfeasor Allegations even more circular and recursive.

5.3.3 Limitations on new claims

97 The Patent was granted on 3 December 2020. Scidera filed its SOC on 1 December 2023. In doing so, ABRI infers that Scidera sought to rely on the period for commencing patent infringement proceedings in s 120(4)(a) of the Patents Act. That is, by commencing proceedings within 3 years from the day on which the Patent was granted, Scidera alleges it is entitled to relief in respect of all acts occurring after the day the application for the Patent became open for public inspection on 24 June 2010: [68] of the ASOC. At least in so far as it relates to ABRI, Scidera purports to bring proceedings in relation to acts that occurred “since at least 2012”: Response at [63].

98 The High Court in the United Kingdom held that it is an abuse of process to issue an originating application or statement of claim in circumstances where the applicant was not in a position to properly identify each of the elements of the cause of action: Nomura International Plc v Granada Group Ltd [2007] EWHC 642 at [37] (per Cooke J). In Nomura, it was observed that the effect of issuing proceedings in such circumstances is to stop the limitation period running and thus deprive the respondent of a potential limitation defence and unilaterally, by the applicant’s action, extend the time allowed by statute for the commencement of an action even though the applicant was not in a position properly to formulate a claim against the respondent within the time permitted by statute.

99 ABRI submits that the observations in Nomura are equally apt in this case and that Scidera is now seeking to reformulate its claim with respect to ABRI by significant amendments to the SOC. ABRI summarises that broadly, the proposed amendments to the ASOC relate to:

(1) new claims of primary infringement against ABRI acting “in concert” with Zoetis arising out of new facts, which ABRI contends is a different case, and it is a significant change, for example [34A], particular (iva) to [35] and [40A] of the ASOC;

(2) the addition of Xytovet, which will have effect from the date of any joinder;

(3) new claims of primary infringement against ABRI “in concert” with that new respondent, Xytovet, which similarly will have effect from the date of any joinder;

(4) new facts (as pleaded in [63B] of the ASOC) to provide a foundation for the Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations (in [64] and [66] of the ASOC), in circumstances where, as previously framed, the Former Joint Tortfeasor Allegations were liable to be struck out.

100 ABRI notes that at the same time, Scidera still purports to bring the new claims and rely on these new facts outlined at [99] above in relation to conduct occurring since as early as 2012: [68] to [70] of the ASOC.

101 ABRI and Zoetis both assert that, if Scidera is permitted to file the ASOC, the amendments allowed should be allowed only in relation to acts occurring within six years from the date of any amendment. ABRI contends that this is by reason of s 120(4)(b) of the Patents Act which prohibits the new claims and claims arising out of new facts in relation to acts occurring earlier than that date: r 16.53(2) and/or 16.54 of the Rules.

102 Further, ABRI and Zoetis contend that any orders should make clear that the amendments to the ASOC take effect on the date any amendment is made.

5.4 DataGene

103 DataGene submits that the causes of action against it are tied up with the causes of action against Zoetis and the new proposed sixth respondent, Xytovet.

104 The ASOC asserts the following causes of action against DataGene:

(1) direct infringements, “together with” and “acting in concert” with Zoetis and Xytovet ([90A], [98A], [101A], [104A], [111A] of the ASOC). DataGene notes that the SOC did not previously allege that it had engaged in any direct infringements;

(2) that DataGene authorised Zoetis and Xytovet to infringe the patent ([114]–[115] of the ASOC); and

(3) that DataGene induced, procured or engaged in a common design with Zoetis and Xytovet to infringe the Patent ([116]–[117] of the ASOC).

105 In response, DataGene raises the following alleged deficiencies in the ASOC.

106 First, DataGene notes that the ASOC has introduced the ambiguous phrase “together with” in the allegations at [84A], [91A], [99A], [102A] and [105A]. DataGene, like MLA, ABRI and Zoetis, contends that it is not clear what the words “together with” mean in the context of these allegations. For example, DataGene notes that it is not clear whether this pleading alleges that DataGene itself used the alleged method.

107 Second, the “together with” phraseology is also used in [90A], [98A], [101A], [104A], [111A] of the ASOC. DataGene further submits that it is not clear what the words “together with” mean in the context of these allegations, stating again that it is unclear whether it is alleged that DataGene itself used an infringing method.

108 Third, DataGene contends that it is not clear what difference, if any, there is between the causes of action that: DataGene has “together with” Zoetis/Xytovet and “acting in concert”, infringed the Patent; and DataGene has induced, procured or engaged in a common design with Zoetis/Xytovet to infringe the Patent. DataGene notes that both causes of action appear to concern different expressions used in the context of joint tortfeasorship: see e.g., Australian Mud Co Pty Ltd v Globaltech Corp Pty Ltd (No 3) (2022) 169 IPR 1 at [204]–[206] (per Rofe J); Seiko Epson Corp v Calidad Pty Ltd (2017) 133 IPR 1 at [440]–[441] (per Burley J). However, DataGene observes that the allegation of “acting in concert” appears in the “direct infringement” section of the ASOC.

109 For these reasons, DataGene submits that Scidera should not be given leave to file the ASOC.

110 In the alternative, if leave to file the ASOC is granted, DataGene adopts the other respondents’ submissions as to limitation issues, the application of s 120(4) of the Patents Act and the date at which any amendments are to take effect.

5.5 Scidera

111 Scidera submits that the respondents’ criticisms regarding the ASOC are misplaced. The claims in the ASOC being clearly pleaded, set out in considerably more detail than a standard patent infringement case, and supported by extensive particulars, to leave the respondents in no doubt of the case that they have to meet in preparing their respective defences.

112 Scidera submits that the ASOC is much more detailed than is conventional for a pleading of patent infringement and goes well beyond what is required under the Rules. Without accepting the validity of the various criticisms raised by the respondents to date, Scidera contends that, consistent with modern case management principles, it has adopted a pragmatic approach to laying out its case at this early stage in order to facilitate the matter moving forward on its merits.

5.5.1 General response to criticisms

113 Scidera submits that the ASOC more than adequately addresses the matters raised by the parties and the Court on the last occasion. Consistently with this, the criticisms raised by the respondents in their submissions are almost all new criticisms principally directed to the further infringement claims.

114 Scidera contends that it is necessary to approach the respondents’ criticisms of the ASOC with a recognition of the fact that this matter is at an early stage. The respondents have not filed any defences or otherwise engaged substantively with Scidera’s claims. Scidera has not had production of any documents. The ASOC is based on Scidera’s investigations and publicly available material supporting the allegations of infringement.

115 Against that background, Scidera submits that the respondents’ new criticisms strive to find lack of clarity and ambiguity in the detail of the ASOC, including via the particulars and cross-references, in order to construct grounds of objection which, on a fair and common sense reading of the pleading, do not arise.

116 Scidera observes that other objections raised by the respondents seek to criticise or query the construction of the claims of the Patent which they apprehend will be advanced by Scidera. It submits that this approach is misconceived, having regard to the nature and function of the ASOC and the stage this proceeding is at. Scidera submits that it is not the function of the pleading to set out, much less crystallise, Scidera’s construction of the claims. The material facts which are alleged to give rise to infringement need to be pleaded clearly and in detail. Scidera submits that issues of claim construction can and will be addressed later, and it may be explored during the course of a trial or during the interlocutory stages of a matter. Scidera contends that it should not occur now, prior to the filing of any defences.

117 Scidera also contends that the respondents are wrong to assert that the ASOC involves Scidera adopting “inconsistent” claim constructions. A party does not adopt “inconsistent” claim constructions merely by advancing more than one basis on which a particular claim is said to be infringed. Questions of infringement turn not only upon issues of construction, but also upon the nature and characterisation of the conduct which is alleged to give rise to infringement as revealed by the evidence. Additionally, Scidera submits that it is not at all unusual, or impermissible, for a party to advance a case which involves more than one possible construction of a patent claim. Scidera states that, where appropriate, the ASOC makes it clear that the different claims advanced by Scidera against the respondents are put “further or in the alternative”.

118 Scidera accepts that the second basis of infringement is new in the ASOC. It does not accept that the claim is not based on facts already pleaded, and on that basis, it does not accept that the claim cannot date back to the date of the original SOC. In any event, Scidera submits that the “relation back” issue is not a reason not to allow the amendments. It is an issue that should be dealt with at trial.

119 Further, Scidera submits that some of the respondents’ criticisms of the ASOC are not concerned with matters of pleading at all, but rather would be matters for trial, or potentially, matters to be considered on a summary judgment application, were such an application to be brought by them. These include matters such as whether the allegations of fact pleaded in the ASOC are supported by the documents in the particulars. Another example is the application of limitation periods, which Scidera submits, is a matter for trial. Scidera further contends that the respondents’ objections are misplaced, but the key point is that they are not matters to be addressed at this point in time for this application, and are not matters which should preclude the grant of leave to Scidera to file the ASOC.

120 Scidera contends that the construction of the Patent propounded by it is that of Beach J in Cargill at [282], as set out in particular (ia) to [34] of the ASOC.

121 According to Scidera, infringement is put on two bases:

(1) That the acts carried out by each of the genomic testing laboratories, Zoetis and Xytovet, constitutes a use of the claimed method; and

(2) A “combined infringement case” based on the steps carried out by the genomic testing laboratories, plus the further steps carried out by ABRI or DataGene when they receive the text file of the results of the SNP testing, upon which they analyse the results and provide a report in which the traits are inferred.

122 Ultimately Scidera contends that the ASOC is clearly pleaded, logically set out and does more than enough to put each of the respondents on notice of the case put against them.

5.5.2 “Acting in concert” pleading

123 Scidera addresses the particular complaint emphasised by each of ABRI, Zoetis and DataGene relating to the paragraphs in the ASOC which allege infringement on the basis of the genomic testing laboratories, Zoetis and Xytovet, “acting in concert” with ABRI and DataGene to perform the steps of the claimed method or use the claimed system: [40A], [48A], [51A], [54A], [61A], [90A], [98A], [101A], [104A], [111A] of the ASOC.

124 These paragraphs relate to, what Scidera calls the “combined infringement case”, as explained above at [121(2)].

125 The paragraphs which relate to the “combined infringement case” are said by ABRI, Zoetis and DataGene to be confusing, because they appear under the heading “direct infringement” but involve allegations of joint tortfeasance, and also because they overlap with other allegations of indirect infringement in the pleading. It is also said by Zoetis that the paragraphs are not properly supported by a pleading of material facts or particulars against it.

126 Scidera submits that these paragraphs do involve allegations of joint tortfeasance, in that they allege infringement by two parties acting in concert to carry out a series of steps, some of which are undertaken by one of them and some of which are undertaken by the other. Scidera contends that the respondents plainly understand this.

127 Scidera contends that the paragraphs are included where they are in the pleading for convenience and ease of reference and appear at the end of each run of paragraphs which relate the pleaded conduct to the integers of the claims, immediately following a similar paragraph (e.g., [40] of the ASOC) which asserts infringement on the basis of the narrower set of steps undertaken by just Zoetis/Xytovet (reflecting the basis on which the allegation of infringement is put in the existing pleading).

128 Scidera submits that the fact that these paragraphs appear under headings referring to “direct infringement of the Patent” (e.g., before [34] of the ASOC) does not introduce any lack of clarity. Rather, what this section of the pleading deals with are the bases on which Scidera contends that the respondents have used the methods and systems of the claims.

129 Further, Scidera submits that the allegations of infringement by joint tortfeasance in [40A] of the ASOC and corresponding paragraphs are adequately pleaded in the context of the ASOC as a whole. That is particularly so given the other facts and matters pleaded elsewhere in the ASOC which support Scidera’s case that the parties are acting together. However, even if the Court were not to accept this, Scidera submits that [40A] of the ASOC and corresponding paragraphs could be excised without undermining the combined infringement case. That is supposedly so because the later, more detailed pleadings of joint authorisation and joint tortfeasance in [62]–[67], [112]–[117] of the ASOC assert infringement on the basis of that case as well as the narrower set of steps.

130 With respect to ABRI’s submissions, Scidera contends that it is incorrect that it is not clear which party is said to have committed which acts alleged to infringe. The acts giving rise to the use of the claimed methods and system are identified in the ASOC noting, for example, [33B] (steps carried out by Zoetis) and [33D] (steps carried out by ABRI) of the ASOC. This conduct together is said to constitute a use of the claimed method on the “combined infringement case”: particulars (ii) and (iii) to [34A(ii)] of the ASOC.