FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Briggs on behalf of the Boonwurrung People v State of Victoria (No 2) [2025] FCA 279

File number(s): | VID 363 of 2020 | ||

Judgment of: | MURPHY J | ||

Date of judgment: | 31 March 2025 | ||

Catchwords: | NATIVE TITLE –whether six named First Nations women living in the 1800s were members of the Boonwurrung People who, at effective sovereignty, held rights and interests in the Boonwurrung claim area under traditional laws and customs – whether five named persons are contemporary descendants of some of the named First Nations women living in the 1800s – evidentiary issues regarding onus and standard of proof, inferential reasoning, primacy of Aboriginal lay witness evidence, and the weight appropriate to be given to conflicting expert evidence – whether Justice Brennan’s dicta in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1 at 70 regarding “mutual recognition” is an element of native title law, either under common law or under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) – whether, as a question of fact, at sovereignty, membership of the Boonwurrung People required “mutual recognition” as described by Brennan J in Mabo v Queensland (No 2). | ||

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 60(1), 73(1)(d), 79(1), 140 Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ss 61, 86, 223, 253 | ||

Cases cited: | AB (deceased) on behalf of the Ngarla People v Western Australia (No 4) [2012] FCA 1268; 300 ALR 193 Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakay Native Title Claim Group v Northern Territory of Australia [2004] FCA 472; 207 ALR 539 Aplin on behalf of the Waanyi Peoples v Queensland [2010] FCA 625 Ashwin on behalf of the Wutha People v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2019] FCA 308; 369 ALR 1 ASIC v Big Star Energy Ltd (No 3) [2020] FCA 1442; 389 ALR 17 Attorney-General (NT) v Ward [2003] FCAFC 283; 134 FCR 16 Blatch v Archer [1774] EngR 2; 1 Cowp 63; 98 ER 969 Bodney v Bennell [2008] FCAFC 63; 167 FCR 84 Briggs on behalf of the Boonwurrung People v State of Victoria [2024] FCA 288 Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; 60 CLR 336 Brodie v Singleton Shire Council [2001] HCA 29; 206 CLR 512 Commonwealth v Tasmania [1983] HCA 21; 158 CLR 1 Commonwealth v Yarmirr [1999] FCA 1668; 101 FCR 171 Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 Daniel v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 666 De Rose Hill v South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 De Rose v South Australia [2003] FCAFC 286; 133 FCR 325 Dempsey v State of Queensland (No 2) [2014] FCA 528; 317 ALR 432 Dhu v Karlka Nyiyaparli Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (No 2) [2021] FCA 1496 Drill v Western Australia [2020] FCA 1510 Gumana v Northern Territory [2005] FCA 50; 141 FCR 457 Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31; 238 ALR 1 Helmbright v Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs (No 2) [2021] FCA 647; 287 FCR 109 Henderson v Queensland [2014] HCA 52; 255 CLR 1 Ho v Powell [2001] NSWCA 168; 51 NSWLR 572 Jango v Northern Territory of Australia [2006] FCA 318; 152 FCR 150 Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; 101 CLR 298 Lee v The Queen [1998] HCA 60; 195 CLR 594 Leslie v Graham [2002] FCA 32 Lithgow City Council v Jackson [2011] HCA 36; 244 CLR 352 Love v Commonwealth; Thoms v Commonwealth [2020] HCA 3; 270 CLR 152 Luxton v Vines [1952] HCA 19; 85 CLR 352 Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland [2021] FCAFC 176; 287 FCR 240 Malone on behalf of the Western Kangoulu People v State of Queensland (No 3) [2022] FCA 827 Malone v State of Queensland (No 5) [2021] FCA 1639; 397 ALR 397 Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58; 214 CLR 422 Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (1971) 17 FLR 141 Mitchell v MNR [2001] 1 SCR 911 Narrier v Western Australia [2016] FCA 1519 Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd [1992] HCA 66; 67 ALJR 170 Neowarra v Western Australia [2003] FCA 1399; 134 FCR 208 Nona v Queensland (No 5) [2023] FCA 135 Payne v Parker [1976] 1 NSWLR 191 Qantas Airways Ltd v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; 167 FCR 537 Quick v Stoland Pty Ltd [1998] FCA 1200; 87 FCR 371 Registrar of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Corporations v Sonia Murray, Mervyn Brown, Leonie Dickson and Verna Nichols [2015] FCA 346 Rrumburriya Borroloola Claim Group v Northern Territory [2016] FCA 776; 255 FCR 228 Sampi on behalf of the Bardi and Jawi People v State of Western Australia [2010] FCAFC 26; 266 ALR 537 Sampi v State of Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 Shaw v Wolf [1998] FCA 389; 83 FCR 113 Smirke v Western Australia (No 2) [2020] FCA 1728 Westbus Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) v Ishak [2006] NSWCA 198 Western Australia v Ward [2002] HCA 28; 213 CLR 1 Wyman on behalf of the Bidjara People v Queensland (No 2) [2013] FCA 1229 Yarmirr v Northern Territory (No 2) [1998] FCA 771; 82 FCR 533 | ||

Division: | General Division | ||

Registry: | Victoria | ||

National Practice Area: | Native Title | ||

Number of paragraphs: | 1199 | ||

Date of last submission/s: | 23 October 2023 | ||

Date of hearing: | 10-14 July 2023 | ||

Counsel for the Applicants: | Mr R Levy | ||

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Massar Briggs Law | ||

Counsel for the Bunurong respondents: | Mr C Athanasiou | ||

Solicitor for the Bunurong respondents: | Logie Legal Pty Ltd | ||

Counsel for the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung respondents: | Mr P Willis SC and Ms A Sheehan | ||

Solicitor for the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung respondents: | Slater + Gordon Lawyers | ||

Counsel for the Gunaikurnai respondents: | Mr A McLean | ||

Solicitor for the Gunaikurnai respondents: | Marrawah Law | ||

Counsel for the State of Victoria: | Ms R Webb KC and Mr R Kruse | ||

Solicitor for the State of Victoria: | Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office | ||

Counsel for the Commonwealth of Australia: | Mr D O’Leary SC | ||

Solicitor for the Commonwealth of Australia: | Australian Government Solicitor | ||

ORDERS

VID 363 of 2020 | ||

BETWEEN: | CAROLYN MARIA BRIGGS First Applicant SYLVIA FAY MUIR Second Applicant | |

AND: | STATE OF VICTORIA and others listed in the Schedule Respondent | |

order made by: | MURPHY J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 31 MARCH 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The separate questions be answered as follows:

Question 1(a): Were each of the following persons members of a group comprising Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) People who, at sovereignty, held rights and interests in any part of the land and waters covered by the Boonwurrung Application under traditional laws and customs?

(i) Louisa Briggs;

Answer: Yes. (This is an agreed fact).

(ii) Ann Munro;

Answer: No.

(iii) Elizabeth Maynard;

Answer: Yes.

(iv) Eliza Nowan (also known as Eliza Nowen);

Answer: Yes.

(v) Marjorie Munro (also known as Marjorie Munroe and Marjorie Munrow);

Answer: Yes. (This is an agreed fact).

(vi) Jane Foster;

Answer: No.

Question 1(b): If the answer to Question 1(a)(iii) is yes, are Robert Ogden and Jarrod West the descendants of Elizabeth Maynard?

Answer: Yes. (This is an agreed fact).

Question 1(c): If the answer to Question 1(a)(iv) is yes, are Tasma Walton and/or Gail Dawson the descendants of Eliza Nowan?

Answer: Yes.

Question 1(d): If the answer to Question 1(a)(vi) is yes, is Sonia Murray the descendant of Jane Foster?

Answer: Unnecessary to decide.

Question 1(e): At sovereignty did membership of the Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) People require “mutual recognition” as described by Justice Brennan in Mabo No 2 at 70? For the avoidance of doubt, this question is not limited to a legal question as to whether Justice Brennan’s dicta regarding “mutual recognition” is an element of native title law, either under common law or under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). It includes the question as to whether, as an issue of fact, membership of the Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) claim group requires “mutual recognition” as described by Brennan J.

Answer: At sovereignty, Boonwurrung traditional laws and customs had the following relevant normative elements:

(a) membership of the Boonwurrung group was, by default, automatic based on patrifiliation. Primary and secondary rights in the group were derived from that patrilineal system governing the transmission of rights;

(b) once patrilineal descent was established, no more was needed to be a member of the Boonwurrung group. That is, if a person was born to a Boonwurrung father, that person was a member of the Boonwurrung group and no further step was required to activate membership;

(c) rights of membership of the Boonwurrung group were not lost even if the person was absent from Boonwurrung country for an extended period. Provided, upon the person’s return, he or she was remembered the person was accepted as Boonwurrung;

(d) in particular circumstances, a person who did not hold primary rights and interests in Boonwurrung country by patrilineal descent may be accepted into the Boonwurrung group and in such circumstances elders or others with traditional authority had authority to decide issues of membership. Any such decision involved collective decision-making guided by elders of local Boonwurrung groups, and it would not be a decision for a single elder; and

(e) there is, however, no evidence that elders or others with traditional authority had authority to exclude a person from membership of the Boonwurrung group where the person was Boonwurrung by patrilineal descent.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | |

1 INTRODUCTION | [1] |

2 THE PROCEEDING AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND | [12] |

2.1 The proceeding | [12] |

2.2 The Preservation Evidence hearing | [17] |

2.3 The Separate Questions | [18] |

2.4 The Agreed Facts | [24] |

2.5 Separate Questions hearing | [27] |

2.6 The application to adduce further expert evidence | [29] |

3 THE EVIDENCE | [30] |

3.1 The lay evidence | [30] |

3.2 The expert evidence | [34] |

3.3 The documentary evidence | [39] |

4 EVIDENTIARY ISSUES | [49] |

4.1 Onus and standard of proof | [49] |

4.2 Inferential reasoning | [62] |

4.3 The lay evidence | [67] |

4.4 The expert evidence | [77] |

4.4.1 Dr Clark | [83] |

4.4.2 Dr D’Arcy | [86] |

4.4.3 Mr Wood | [90] |

4.4.4 Dr Pilbrow | [132] |

4.4.5 Other expert opinions | [134] |

5 ELIZABETH MAYNARD - SEPARATE QUESTION 1(a)(iii) | [143] |

5.1 The parties’ positions | [146] |

5.2 The locations | [148] |

5.3 The historical records and secondary sources | [150] |

5.3.1 Abduction related records | [151] |

5.3.2 Other records | [191] |

5.4 The lay evidence | [212] |

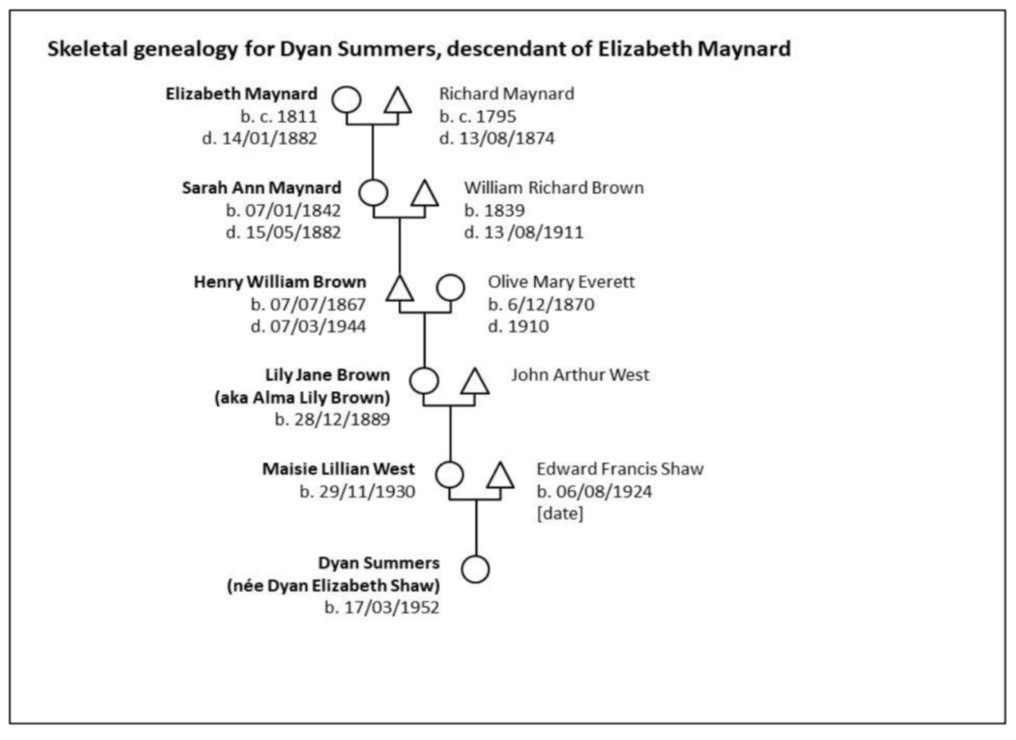

5.4.1 Ms Dyan Summers | [213] |

5.4.2 Mr Robert Odgen | [233] |

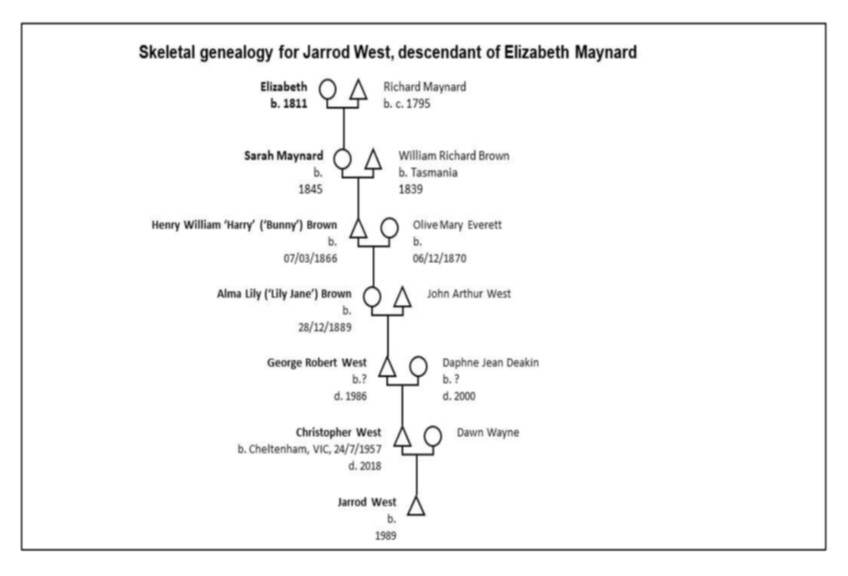

5.4.3 Mr Jarrod West | [241] |

5.5 The expert evidence | [250] |

5.5.1 Dr Clark | [250] |

5.5.2 Mr Wood | [303] |

5.5.3 Dr Pilbrow | [308] |

5.5.4 Dr D’Arcy | [325] |

5.6 The applicant’s submissions | [332] |

5.7 Consideration regarding Elizabeth Maynard | [376] |

5.7.1 The Meredith Abduction | [382] |

5.7.2 Whether Richard Maynard’s unnamed “Port Phillip” Aboriginal female partner in January 1837 was one of the abductees in the Meredith abduction | [384] |

5.7.3 Whether Richard Maynard’s “Port Phillip” Aboriginal female partner in January 1837 was the woman later known as Elizabeth Maynard also known as “Granny Betty”) | [395] |

5.7.4 Whether Elizabeth Maynard was a member of the Boonwurrung People who, at effective sovereignty, held rights and interests in the Boonwurrung claim area under traditional laws and customs | [431] |

6 MARJORIE MUNRO - Separate Question 1(a)(v) | [502] |

7 LOUISA BRIGGS - Separate Question 1(a)(i) | [504] |

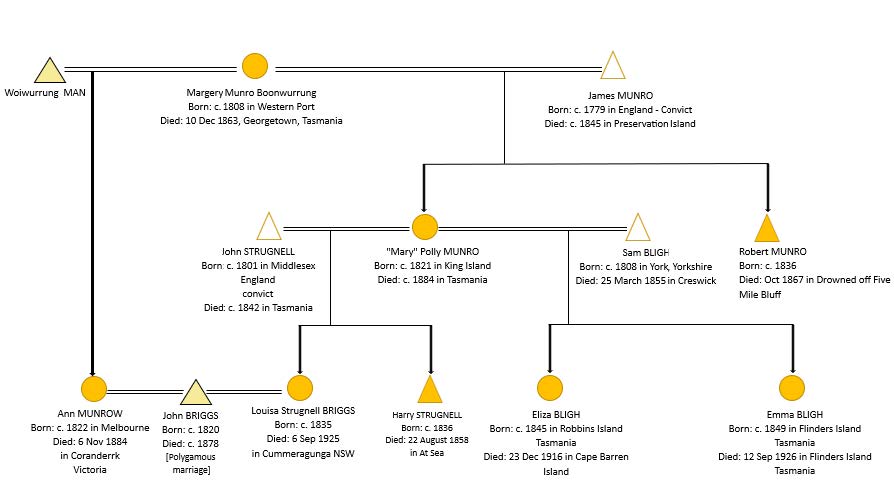

8 ANN MUNRO - Separate Question 1(a)(ii) | [515] |

8.1 The parties’ positions | [517] |

8.2 The pleadings | [523] |

8.3 The historical records and secondary sources | [526] |

8.4 The lay evidence | [559] |

8.5 The expert evidence | [564] |

8.5.1 Dr Clark | [564] |

8.5.2 Mr Wood | [611] |

8.5.3 Dr Pilbrow | [615] |

8.5.4 Dr D’Arcy | [627] |

8.6 Consideration regarding Ann Munro | [630] |

8.6.1 Whether the evidence is sufficient to show that Ann Munro was Marjorie Munro’s daughter | [630] |

8.6.2 The Wurundjeri respondents’ contention that Ann Munro was a Boonwurrung woman with rights and interests in Boonwurrung country | [661] |

8.6.3 The Wurundjeri respondents’ contention that Ann Munro should be found not to have been a Woiwurrung woman | [666] |

8.6.4 Whether Ann Munro’s cognatic descendants are Boonwurrung People | [671] |

9 ELIZA NOWAN - Separate Question 1(a)(iv) | [673] |

9.1 The parties’ positions | [675] |

9.2 The historical records and secondary sources | [678] |

9.3 The lay evidence | [693] |

9.3.1 Ms Tasma Walton | [694] |

9.3.2 Ms Gail Dawson | [710] |

9.4 The expert evidence | [720] |

9.4.1 Dr Clark | [720] |

9.4.2 Mr Wood | [748] |

9.4.3 Dr Pilbrow | [754] |

9.4.4 Dr D’Arcy | [772] |

9.5 The applicant’s submissions | [773] |

9.6 Consideration regarding Eliza Nowan/Gamble | [784] |

10 JANE FOSTER - SEPARATE QUESTION 1(a)(vi) | [823] |

10.1 The parties’ positions | [825] |

10.2 The historical records and secondary sources | [828] |

10.3 The lay evidence | [837] |

10.4 The expert evidence | [841] |

10.4.1 Dr D’Arcy | [842] |

10.4.2 Dr Clark | [857] |

10.4.3 Mr Wood | [868] |

10.4.4 Dr Pilbrow | [873] |

10.5 The Bunurong respondents’ submissions | [882] |

10.6 Consideration regarding Jane Foster | [887] |

11 Robert Odgen and Jarrod West - Separate Question 1(b) | [915] |

12 Tasma Walton and Gail Dawson - Separate Question 1(c) | [917] |

13 Sonia Murray - Separate Question 1(d) | [919] |

14 Mutual recognition - Separate Question 1(e) | [921] |

14.1 Whether Justice Brennan’s dicta regarding “mutual recognition” is an element of native title law either at common law or under the NTA | [922] |

14.1.1 The applicant’s submissions | [924] |

14.1.2 Consideration regarding mutual recognition as a question of law | [931] |

14.2 Whether Justice Brennan’s dicta regarding “mutual recognition” applied at sovereignty as an issue of fact | [956] |

14.2.1 The Boonwurrung lay evidence | [957] |

14.2.2 The Bunurong lay evidence | [1027] |

14.2.3 The expert evidence | [1049] |

14.2.4 The applicant’s submissions | [1110] |

14.2.5 Consideration regarding mutual recognition as an issue of fact | [1131] |

15 Conclusion | [1199] |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

MURPHY J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 The substantive proceeding is a native title determination application brought by Dr Carolyn Briggs AM and Ms Sylvia Fay Muir (the applicant) on behalf of the Boonwurrung People (Boonwurrung Application). These reasons concern separate questions set by the Court (Separate Questions), directed at deciding a dispute primarily between the applicant and the 12th to 16th respondents, the Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation (BLC), Ms Gail Dawson, Mr Robert Ogden, Ms Tasma Walton and Mr Jarrod West (the Bunurong respondents).

2 The Separate Questions centrally concern whether six named First Nations women who lived in the 1800s were members of the Boonwurrung People (also called the Bunurong People) who, at effective sovereignty in the mid-1830s to 1840s, held rights and interests under traditional laws and customs in the lands and waters covered by the claim area in the Boonwurrung Application (Boonwurrung claim area). The dispute is not just of historical interest. Behind it lies the fact that there are hundreds of contemporary descendants of the named women who, if the women are found to have been members of the Boonwurrung People, may be entitled to membership of the native title claim group in the Boonwurrung Application and able to share in the benefits of native title if the Boonwurrung Application is successful.

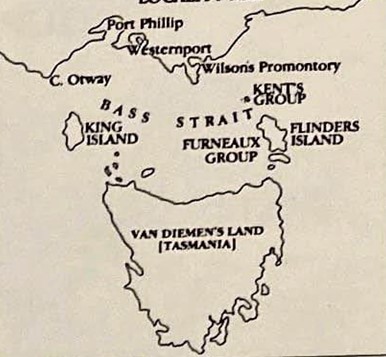

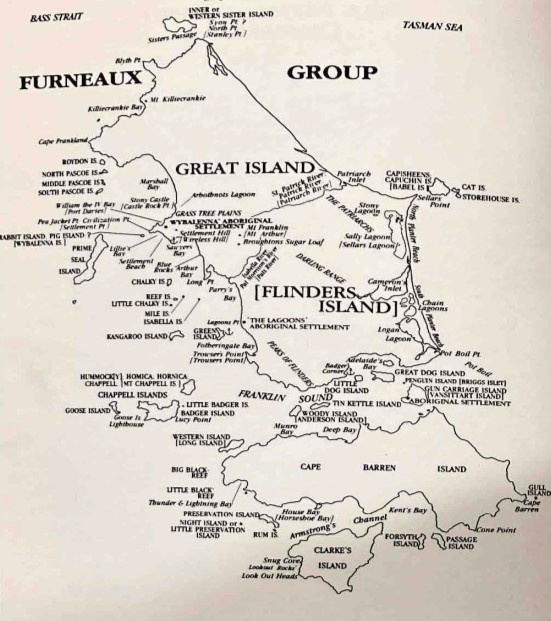

3 The evidence in the case reveals a shameful period in Australia’s history. It shows that from at least the early 1800s to the 1840s, a great number of Aboriginal girls and women were abducted by white sealers and others from coastal Victoria and Tasmania, then called Van Diemen’s Land (VDL), and from other parts. Some of the Aboriginal girls or women whom this case is about were abducted by sealers and taken to remote islands in Bass Strait between Victoria and VDL from where sealing was undertaken, and others were taken more than 3,000 kilometres away to islands off the coast of Albany, Western Australia. The sealers treated the women as slaves; they sold and traded them, they used them as free labour and for sex, and they had many children with them. Some of the women became the de-facto partners of the men.

4 The historical records are replete with evidence of this terrible period. George Augustus Robinson, then the Commandant of the Wybalena Aboriginal settlement on Flinders Island in Bass Strait (and soon to be Chief Protector of Aboriginals at the Port Phillip settlement) wrote the following in a 12 January 1837 report to the Colonial Secretary of VDL:

It is and [sic] indubitable fact that at Port Phillip, Portland Bay, Western Port, and other recently formed settlements; and indeed at every accessible spot where boats have visited along the south coast of New Holland, they, the Aboriginal Inhabitants have experienced a series of persecution, and have been harshly treated, not only be the sealing men who have forcibly taken their wives and children from them, and sent them to distant isles doomed to captivity, but also similar in addition to the sealers, similar aggressions have been perpetrated by whalers, barkers, stockmen, shepherds, and others….

5 NJB Plomley, who transcribed Robinson’s journals and reports, wrote the following:

The slaves of these men were aboriginal women of Van Diemen's Land and New Holland. The practice of using native women to help work the boats, to catch seal, kangaroo and mutton birds, and to tend the wants of their masters must have begun very early in the history of the straits, but one of the earliest references to it is the statement by James Kelly in 1816 that ‘the custom of the sealers in the Straits was that every man should have two to five of these native women for their own use and benefit, and to select any of them they thought proper to cohabit with as their wives, and a large number of children had been born as a consequence of these unions - a fine, active, hardy race. The males were good boatmen, kangaroo hunters, and sealers; the women extraordinarily clever assistants to them’. In fact, these women not only provided for the sexual life of their masters but were indispensable for the physical life they led: as James Munro remarked to Robinson, no white woman would have put up with the conditions of existence or would have worked as they did.

The sealers obtained their native women, largely if not entirely, by raiding. As Robinson states, a party of sealers would surprise a tribe of natives at an encampment and carry off the women.

(Emphasis added.)

: Plomley, NJB, Friendly Mission; the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1966) p 1008.

6 The tragedy of the case is plain when for tens of thousands of years the Boonwurrung People occupied a huge swathe of fertile lands and abundant waters of southern coastal Victoria, stretching from around what is now Werribee to around Wilsons Promontory. The size of their traditional country and the abundance of available food and other resources means that it is likely they were a numerous people. Yet the evidence shows that now the only remaining members of the Boonwurrung People are the descendants of a handful of women who were abducted by sealers and taken in captivity to far away islands.

7 When the Separate Questions were set they primarily concerned whether the evidence is sufficient to establish that it is more likely than not that six named women were members of the Boonwurrung People at effective sovereignty. As the case proceeded two of the women were agreed by the parties to have been Boonwurrung, and the dispute then primarily concerned the remaining four women.

8 Somewhat surprisingly, the evidence is voluminous. It is plain that a great many girls and women were kidnapped and taken away from their country by sealers and others in the relevant period. But it is one thing to infer from archival records and ethnographic studies that many Aboriginal girls and women were abducted and taken away to island where they bore children to their abductor or to other men to whom they were traded, and another to establish that it is more likely than not that a particular woman was so taken, and that the abducted woman was a member of the Boonwurrung People who, at effective sovereignty, held rights and interests in Boonwurrung country under customary laws and practices.

9 Further, the central factual matters in dispute between the parties took place up to 190 years ago. There are limitations in the evidence including because of the effluxion of time, and that the historical records that exist are colonial records that are not focussed on issues of Aboriginal group identity. Other limitations can be traced to the devastating impact of European colonisation which resulted in the displacement and dispossession of the Boonwurrung People, a dramatic demographic decline through massacres and killings, the introduction of new diseases and practices, and profound damage to Boonwurrung culture and their capacity to transmit knowledge and culture by oral tradition.

10 The party which seeks an affirmative answer to each Separate Question has the onus to establish that on the evidence. The relevant standard is the balance of probabilities. As Mortimer J (as her Honour then was) explained in Drill v Western Australia [2020] FCA 1510 at [13], in a case like the present which involves a level of historical reconstruction, the Court’s task is not to decide what the ‘truth’ is in any absolute sense. The Court is not in that sense “the arbiter of history”. Instead, the Court must reach a decision as to whether the party which must prove the necessary facts has shown that the facts it contends for are more likely than not to have existed. That exercise is to be carried out on the basis of the evidence adduced, and inferences which can reasonably be drawn from that evidence, including to decide whether the available evidence is sufficient to enable a decision to be reached on the balance of probabilities. In short, the Court must assess what reasonably and rationally can be made of the evidence before it.

11 For the reasons I explain below, I consider the evidence is sufficient to reach the following findings on the Separate Questions:

Question 1(a): Were each of the following persons members of a group comprising Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) People who, at sovereignty, held rights and interests in any part of the land and waters covered by the Boonwurrung Application under traditional laws and customs?

(i) Louisa Briggs;

Answer: Yes. (This is an agreed fact).

(ii) Ann Munro;

Answer: No.

(iii) Elizabeth Maynard;

Answer: Yes.

(iv) Eliza Nowan (also known as Eliza Nowen);

Answer: Yes.

(v) Marjorie Munro (also known as Marjorie Munroe and Marjorie Munrow);

Answer: Yes. (This is an agreed fact).

(vi) Jane Foster;

Answer: No.

Question 1(b): If the answer to Question 1(a)(iii) is yes, are Robert Ogden and Jarrod West the descendants of Elizabeth Maynard?

Answer: Yes. (This is agreed).

Question 1(c): If the answer to Question 1(a)(iv) is yes, are Tasma Walton and/or Gail Dawson the descendants of Eliza Nowan?

Answer: Yes.

Question 1(d): If the answer to Question 1(a)(vi) is yes, is Sonia Murray the descendant of Jane Foster?

Answer: Unnecessary to decide.

Question 1(e): At sovereignty did membership of the Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) People require “mutual recognition” as described by Justice Brennan in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) [1992] HCA 23; 175 CLR 1 (Mabo No 2) at 70? For the avoidance of doubt, this question is not limited to a legal question as to whether Justice Brennan’s dicta regarding “mutual recognition” is an element of native title law, either under common law or under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). It includes the question as to whether, as an issue of fact, membership of the Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) claim group requires “mutual recognition” as described by Brennan J.

Answer: At sovereignty, Boonwurrung traditional laws and customs had the following relevant normative elements:

(a) membership of the Boonwurrung People was, by default, automatic based on patrifiliation. Primary and secondary rights in the group were derived from that patrilineal system governing the transmission of rights;

(b) once patrilineal descent was established, no more was needed to be a member of the Boonwurrung group. That is, if a person was born to a Boonwurrung father, that person was a member of the Boonwurrung group and no further step was required to activate membership;

(c) rights of membership of the Boonwurrung group were not lost even if the person was absent from Boonwurrung country for an extended period. Provided, upon the person’s return, he or she was remembered the person was accepted as Boonwurrung;

(d) in particular circumstances, a person who did not hold primary rights and interests in Boonwurrung country by patrilineal descent may be accepted into the Boonwurrung group and in such circumstances elders or others with traditional authority had authority to decide issues of membership. Any such decision involved collective decision-making guided by elders of local Boonwurrung groups, and it would not be a decision for a single elder; and

(e) there is, however, no evidence that elders or others with traditional authority had authority to exclude a person from membership of the Boonwurrung group where the person was Boonwurrung by patrilineal descent.

2. THE PROCEEDING AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

2.1 The proceeding

12 The applicant commenced this native title determination application (the Boonwurrung Application) on 1 June 2020. The application defines the native title claim group as the biological descendants of Louisa Briggs (circa 1832-1925) and Ann Munro (circa 1824-1884).

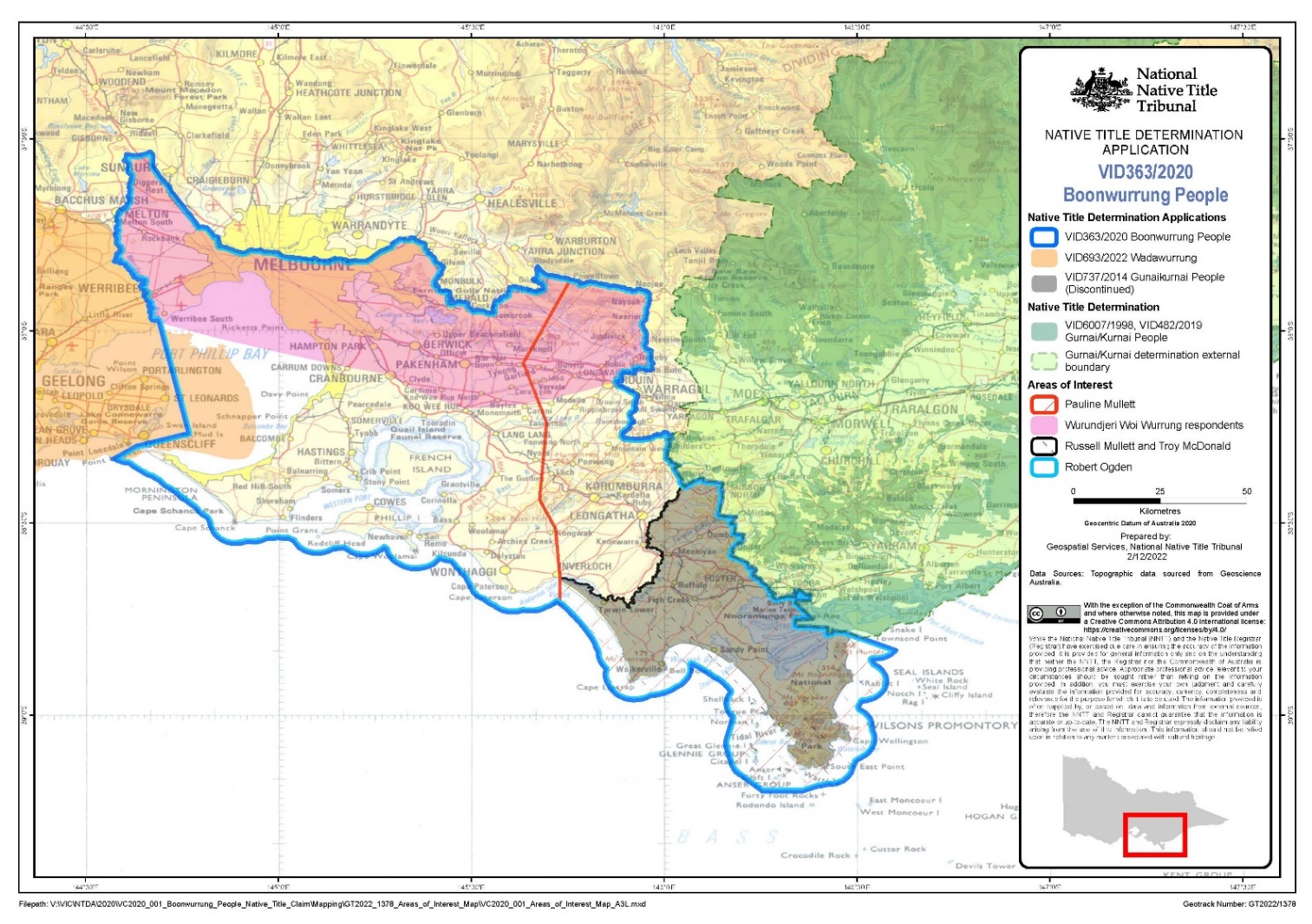

13 The Boonwurrung claim area takes in the coastal land and waters around Melbourne, from the mouth of the Werribee River in the west, extending east along the coast of Port Phillip Bay taking in part of the Melbourne CBD and Greater Melbourne and including the waters of the bay, extending north to Melton, and following the coast east up to and including Wilsons Promontory and the adjacent waters, thus taking in the whole of the Mornington Peninsula, the coastal areas of Western Port and Phillip Island (and extending inland from the coast to the Dandenong ranges). The extent of Boonwurrung country is contested by neighbouring First Nations peoples, the Gunaikurnai, the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung and the Wadawurrung, and the Separate Questions are not directed to deciding the extent or boundaries of their respective countries. Reproduced below is a is a map showing the Boonwurrung claim area, and where it is overlapped by the competing claims of other First Nations peoples.

14 The active respondents in the Separate Questions hearing were:

(a) the first respondent, the State of Victoria (State);

(b) the second respondent, Commonwealth of Australia (Commonwealth);

(c) the 12th to 16th respondents, the Bunurong respondents, who effectively represent the claimed contemporary descendants of Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan, Marjorie Munro and Jane Foster who are alleged to have been members of the Boonwurrung People who, at effective sovereignty, held rights and interests in the Boonwurrung claim area under traditional laws and customs;

(d) the 17th to 19th respondents, Mr Ronald Jones, Mr Perry Wandin and the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation (the Wurundjeri respondents), who allege that they are members of the Wurundjeri Woiwurrung People who hold rights and interests in relation to the northern part of the Boonwurrung claim area under traditional laws and customs; and

(e) the 20th and 21st respondents, Mr Troy McDonald and Mr Russell Mullett (the Gunaikurnai respondents), who allege that they are members of the Gunaikurnai People who hold rights and interests in relation to the land and coastal waters of Wilsons Promontory, and the 24th respondent, Ms Pauline Mullett, who alleges that she is a member of the Gunaikurnai People but asserts a larger area for Gunaikurnai country. On the basis that the Court would not make findings in relation to the boundaries or extent of Boonwurrung or Gunaikurnai country, the Gunaikurnai respondents took a limited role in the Separate Questions hearing. Ms Mullet took no role.

15 It is necessary to understand that the Boonwurrung and the Bunurong are not different First Nations peoples. They are the same people and the names “Boonwurrung” and “Bunurong” just reflect different preferred spellings and pronunciations. For clarity I generally use the “Boonwurrung” variation, except where the context indicates otherwise. That choice is not material to the decision.

16 Although the Boonwurrung and the Bunurong are the same people, the native title claim group in the Boonwurrung Application and the group ‘represented’ by the Bunurong respondents are different. The claim group in the Boonwurrung Application is limited to the descendants of Louisa Briggs and Ann Munro and does not include the descendants of Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan/Gamble or Jane Foster. The group ‘represented’ by the Bunurong respondents includes the descendants of Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan/Gamble and Jane Foster, but not of Louisa Briggs and Ann Munro.

2.2 The Preservation Evidence hearing

17 Preservation evidence was heard ‘on country’ from 5 to 9 December 2022 (Preservation Evidence hearing). The evidence in that hearing related to issues going beyond the dispute between the applicant and Bunurong respondents and thus only some of it is relevant to the separate questions.

2.3 The Separate Questions

18 Following the Preservation Evidence hearing, efforts were made to resolve the overlapping claims by agreement. The Court was told that mediation regarding the correct boundaries of the overlapping claims was unlikely to be effective until the dispute between the applicant and the Bunurong respondents was resolved. All attempts directed at resolving the dispute between the applicant and the Bunurong respondents by negotiation or mediation failed.

19 The Court decided to set separate questions aimed at deciding the dispute between the applicant and the Bunurong respondents. By orders made on 7 March 2023, the Court set the following separate questions for decision (as amended on 19 June 2023, and amended again in relation to Separate Question 1(e) during the course of the hearing) (Separate Questions):

Boonwurrung / Bunurong Separate Questions

1. Pursuant to r 30.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the following questions (Separate Questions) are to be decided separately from any other question in native title determination application VID 363 of 2020 (Application):

(a) Were each of the following persons members of a group comprising Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) people who, at sovereignty, held rights and interests in any part of the land and waters covered by the Application under traditional laws and customs?

(i) Louisa Briggs;

(ii) Ann Munrow;

(iii) Elizabeth Maynard;

(iv) Eliza Nowan, also known as Eliza Nowen;

(v) Marjorie Munro, also known as Marjorie Munroe and Marjorie Munrow; and

(vi) Jane Foster.

(b) If the answer to 1(a)(iii) is yes, are Robert Ogden and Jarrod West the descendants of Elizabeth Maynard?

(c) If the answer to 1(a)(iv) is yes, are Tasma Walton and/or Gail Dawson the descendant of Eliza Nowan?

(d) If the answer to 1(a)(vi) is yes, is Sonia Murray the descendant of Jane Foster?

(e) At sovereignty did membership of the Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) people require “mutual recognition” as described by Justice Brennan in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 at 70? For the avoidance of doubt, this question is not limited to a legal question as to whether Justice Brennan’s dicta regarding “mutual recognition” is an element of native title law, either under common law or under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). It includes the question as to whether, as an issue of fact, membership of the Boonwurrung (also described as Bunurong) people requires “mutual recognition” as described by Justice Brennan.

20 The Separate Questions ask whether the named women were members of the Boonwurrung People at sovereignty, which was asserted in 1788. But it is common ground that the questions require to be answered at effective sovereignty. It is an agreed fact that effective sovereignty was asserted over the Boonwurrung claim area during the period from the mid-1830s to the 1840s.

21 By orders made on 7 March 2023 (March 2023 Orders) any respondent party who intended to actively participate in the hearing of the Separate Questions was required to file a notice indicating that they wished to do so, other than the State and the Bunurong respondents who had already indicated their participation. Following that process the participating parties were the applicant, the Bunurong respondents, the State, the Commonwealth, the Wurundjeri respondents, the Gunaikurnai respondents and Ms Mullet.

22 Pursuant to the March 2023 Orders, unless a participating party gave notice to other participating parties by 6 April 2023 that it intended to rely upon the evidence given by witnesses in the Preservation Evidence hearing, and that party identified the particular evidence upon which it intended to rely, the party was not permitted to adduce that evidence in relation to the Separate Questions.

23 Under the March 2023 Orders the applicant and the Bunurong respondents were directed to file and serve outlines of any further lay evidence they wished to adduce for the Separate Questions hearing (lay witness outlines) by no later than 2 June 2023. Only the Bunurong respondents served lay witness outlines. Any participating party that intended to respond to that evidence was directed to file responsive lay witness outlines by 9 June 2023. No other party put on responsive lay witness outlines. Thus the applicant relied on the lay witness evidence it adduced in the Preservation Evidence hearing.

2.4 The Agreed Facts

24 The participating parties filed a Statement of Agreed Facts and Issues dated 4 July 2023 (SOAFI), centrally based on parts of the Report of Conference of Experts in this proceeding convened on 20 and 21 June 2023 in which the participating expert witnesses, Dr Timothy Pilbrow, Dr Jacqueline D’Arcy, Dr Ian Clark and Mr Ray Wood provided their opinions (BW Joint Experts’ Report).

25 The SOAFI relevantly provides:

Agreed Facts

Boonwurrung/Bunurong people at Sovereignty and Effective Sovereignty:

1. ‘Boonwurrung’ and ‘Bunurong’, and names spelled a variety of other ways are contemporary names used for the group that inhabited at least part of the area of the land and waters covered by the Boonwurrung Application (claim area) under traditional laws and customs.

2. Those parts of the claim area that were inhabited by Boonwurrung at sovereignty and effective sovereignty included coastal land and waters from Mordialloc Creek to the western shore of Anderson Inlet.

3. ‘Boonwurrung’ refers to the group that existed as part of the larger Eastern Kulin Nation at the time of effective sovereignty of the British Crown in the Boonwurrung claim area.

4. British sovereignty was asserted over the claim area in 1788.

5. Effective sovereignty was asserted over the claim area during the period from the mid-1830s to the 1840s.

6. At effective sovereignty, the systems of laws and customs of the Boonwurrung and other peoples that make up the Eastern Kulin Nation governing the distribution of rights and interests in land and waters were the same in all their essential features as they were at sovereignty.

7. At effective sovereignty Eastern Kulin (which included the Boonwurrung) recognised patrilineal descent as the principle by which primary rights in land and waters were acquired.

8. In addition, Eastern Kulin recognised secondary matrifilial rights held by people in their mother's country that were the complement of patrilineal primary rights.

9. At effective sovereignty, Eastern Kulin customary title was communal, inalienable, and perpetually transmitted by descent. It was inclusive of all classes of use and access rights, to the exclusion of all other people. In so far as there were distinctions between different classes of rights and interests, these were genealogically determined within the group, pivoting in particular on the distinction between the rights of matrifilial and patrifilial kin.

10. At effective sovereignty, due to prevailing exogamous marriage practices of the Eastern Kulin Nation, if an Aboriginal girl or woman present on Boonwurrung country was married to a Boonwurrung man, such a girl or woman may not have been Boonwurrung by descent.

11. At effective sovereignty, if a child's father was not Aboriginal, they would take their Aboriginal cultural identity from or through their mother and her kin relationships.

12. At effective sovereignty, Boonwurrung law and custom was regulated by male elders within the local group and by male elders collectively in larger gatherings. Such headmen were referred to as ‘ngurangaeta’ or ‘ngarweet’ or ‘arweet’.

13. There is no evidence in the historical record that, at effective sovereignty, a particular headman or elder had authority, or the sole role to decide whether an Aboriginal person was a member of the Boonwurrung or not.

14. At effective sovereignty, Boonwurrung law and custom extended to relationships with other Aboriginal people and included conceptions of Aboriginal people as kin (such as kin relations with neighbouring groups) or as strangers/foreigners (such as persons they encountered from lengthy geographic and social distance).

Marjorie Munro

15. At effective sovereignty, the woman known as Marjorie Munro (also known as Marjorie Munroe and Marjorie Munrow) was a member of the group comprising Boonwurrung people who, at effective sovereignty, held rights and interests in any part of the claim area, under traditional laws and customs.

Eliza Gamble

18. Tasma Walton and Gail Dawson are descendants of Eliza Gamble.

26 As is apparent, it was agreed in the SOAFI that Marjorie Munro was a member of the Boonwurrung People at effective sovereignty.

2.5 Separate Questions hearing

27 The hearing of the Separate Questions took place from 10 July 2023 to 14 July 2023.

28 On the fourth day of the hearing, the parties agreed that Louisa Briggs was a member of the Boonwurrung People at effective sovereignty.

2.6 The application to adduce further expert evidence

29 Following the close of the Separate Questions hearing, and after written closing submissions had been filed, the applicant brought an interlocutory application dated 22 February 2024 seeking leave to adduce an additional expert witness report in relation to the Separate Questions. I refused that application: see Briggs on behalf of the Boonwurrung People v State of Victoria [2024] FCA 288. The applicant sought leave to appeal that decision but subsequently discontinued that application.

3. THE EVIDENCE

3.1 The lay evidence

30 In the Preservation Evidence hearing the Boonwurrung applicant relied on the following lay witness affidavits:

(a) the Amended Affidavit of Dr Carolyn Maria Briggs dated 10 November 2022, and further affidavits dated 1 December 2022 and 2 December 2022. After the Preservation Evidence hearing the applicant filed a further affidavit dated 28 July 2023. (Respectively, the first, second, third and fourth Briggs affidavits);

(b) the Amended Affidavit of Ms Sylvia Fay Muir dated 10 November 2022;

(c) the Amended Affidavit of Ms Elsie May Anderson dated 15 November 2022; and

(d) the Amended Affidavit of Ms Beryl Dorothy Nellie Philp (née Carmichael) dated 2 December 2022.

Each gave evidence and was cross-examined in that hearing. Pursuant to the March 2023 Orders their evidence is evidence in relation to the Separate Questions.

31 For the Preservation Evidence hearing the Wurundjeri respondents relied on a lay witness affidavit by Ms Joyce Enid Murphy AO dated 4 November 2022. She gave evidence and was cross-examined in that hearing. Pursuant to the March 2023 Orders her evidence is evidence in relation to the Separate Questions.

32 The Bunurong respondents relied on the following lay witness outlines for the Separate Questions hearing:

(a) Ms Dyan Summers dated 2 June 2023;

(b) Mr Jarrod West dated 2 June 2023;

(c) Mr Robert Ogden dated 2 June 2023;

(d) Ms Tasma Walton dated 4 June 2023; and

(e) Ms Gail Dawson dated 7 June 2023.

Each gave evidence in the Separate Questions hearing and was cross-examined. The Bunurong respondents also relied upon [13] to [15] of Ms Murphy’s affidavit filed by the Wurundjeri respondents, and parts of her evidence in the Preservation Evidence hearing.

33 Under the March 2023 Orders the parties were directed to identify the evidence from the Preservation Evidence hearing which they wished to rely on in the Separate Questions hearing. The parties identified various parts of the evidence from the Preservation Evidence hearing.

3.2 The expert evidence

34 The applicant relied on:

(a) two reports prepared for the proceeding by Dr Clark, a historical geographer, titled Expert Report on Boonwurrung / Bunurong Separate Questions dated 29 May 2023 (Clark 2023) and Genealogical Report on Ms Sonia Murray dated 14 June 2023 (Supplementary Clark 2023);

(b) two earlier reports by Dr Clark, titled An Assessment of Boonwurrung Interests from Genealogical and Territorial Perspectives dated 11 September 2002 (Clark 2002), and An Assessment of Boonwurrung Interests from Genealogical and Territorial Perspectives: Supplementary Report (2003) (Clark 2003), upon which Dr Clark drew in Clark 2023; and

(c) a report prepared for the proceeding by Mr Wood, an anthropologist and linguist, titled Anthropology Report on Pre-Sovereignty Laws and Customs relating to the Boonwurrung Native Title Application VID 363/2020 dated 1 June 2023 (Wood 2023).

35 The Bunurong respondents relied on:

(a) two reports prepared for the proceeding by Dr Pilbrow, an anthropologist, titled Bunurong Ancestral Connections and Group Membership dated 2 June 2023 (Pilbrow 2023) and Responsive Report dated 8 June 2023 (Pilbrow Response);

(b) two reports prepared for the proceeding by Dr D’Arcy, a historian, titled Report on Separate Questions regarding Jane Foster and Louisa Briggs dated 1 June 2023 (D’Arcy 2023) and Dr Jacqueline D’Arcy Response to ‘Expert Report on Boonwurrung / Bunurong Separate Questions’ Dr Ian D Clark, filed 1 June 2023 dated 8 June 2023 (D’Arcy Response); and

(c) three earlier reports by Dr D’Arcy, titled Bunurong Land Council Historical and Genealogical Report dated 14 October 2005 (D’Arcy 2005), An Historical Study Prepared for the Bunurong People dated 8 September 2006 (D’Arcy 2006) which is an attachment to D’Arcy 2023, and Genealogies of Senior Bunurong Elders Descended from Apical Ancestors Marjorie Munroe, Jane Foster and Elizabeth Maynard dated 26 June 2007 (D’Arcy 2007), upon which Dr Darcy drew in D’Arcy 2023.

36 No other participating party filed expert evidence for the Separate Questions hearing.

37 A conference of the Boonwurrung and Bunurong expert witnesses was convened on 20 and 21 June 2023 (BW Joint Experts’ Conference). Each of Dr Clark, Mr Wood, Dr Pilbrow and Dr D’Arcy participated in that conference, which produced the BW Joint Experts’ Report.

38 Dr Clark, Mr Wood, Dr Pilbrow and Dr D’Arcy gave evidence in the Separate Questions hearing, doing so in concurrent session on 13 and 14 July 2023. Each was cross-examined.

3.3 The documentary evidence

39 The documentary evidence is voluminous. Pursuant to the March 2023 Orders each participating party was directed to file and serve a copy of any document which it proposed should be received as evidence in relation to the Separate Questions, including in accordance with s 86 of the NTA. Following a procedure for the notification and resolution of any objections to evidence between the parties, Order 18 provided that the documents or parts of the documents that are not identified as objected to may be received as evidence (emphasis added). The notified objections were to be considered by the Court at the commencement of the Separate Questions hearing.

40 Order 38 directed the Boonwurrung applicant to file and serve a draft index for the hearing book for the Separate Questions hearing (Hearing Book), including, amongst other things, the documentary evidence which was likely to be regularly referred to. Unfortunately, the parties took the approach that if a document might be referred to it should be included in the Hearing Book. That resulted in a Hearing Book comprising 23 volumes, taking up approximately 12 lever arch binders, which was completely unsatisfactory.

41 Order 42, however, provided that a document included in the Hearing Book:

(a) shall not form part of the evidence at the trial unless specifically tendered and admitted into evidence; and

(b) shall be treated as tendered and admitted if relied on at the trial (including in written or oral submissions) and no objection is taken.

In circumstances where the parties had taken an overly expansive view of the documents likely to be relied on, Order 42 at least provided for some restriction on the documents required to be considered by the Court.

42 After the Separate Questions hearing, upon the Court’s urging, the parties agreed on a reduced set of documents which comprised five lever binder folders, the Consolidated Hearing Book. Although the Consolidated Hearing Book does not include all of the documents which were admitted into evidence in the Preservation Evidence hearing, or through the process under Order 42, it is appropriate to infer that it comprises the documents the parties consider to be the most salient.

43 Without seeking to exhaustively list all the documents tendered into evidence and included in the Consolidated Hearing Book, they comprise several broad categories.

44 First, reports and writings by anthropologists, ethnographers and historians, including:

(a) a publication by Dr Marie Fels, an anthropologist, titled I Succeeded Once: The Aboriginal Protectorate on the Mornington Peninsula, 1839-1840 (ANU E Press, Canberra, 2011);

(b) Dr Pilbrow’s field notes documenting an interview with Nanette Shaw on 3 March 2023;

(c) three joint experts’ reports from Court-convened joint experts’ conferences in another native title proceeding, Gunaikurnai People v State of Victoria VID737/2014 (the Gunaikurnai proceeding). Some of those joint experts’ conferences and reports involved some of the same expert witnesses as this proceeding and touch upon some of the same issues:

(i) a joint experts’ report dated 7 September 2018 from a conference of experts convened on 3 and 4 September 2018, setting out the opinions of anthropologists Dr Mahnaz Alimardanian, Ms Kathleen Lothian, Dr Suzi Hutchings, Dr Valerie Cooms, Mr Wood and Mr James Annand (First GK Joint Experts’ Report);

(ii) a joint experts’ report dated 31 May 2019 from a conference of experts convened on 24 and 25 May 2019, setting out the opinions of anthropologists Dr Pilbrow, Ms Lothian, Dr Hutchings, Dr Cooms, Mr Wood, Dr Deane Fergie and Mr Annand (Second GK Joint Experts’ Report); and

(iii) a joint experts’ report dated 31 May 2019 from a conference of experts convened on 27 and 28 May 2019, setting out the opinions of anthropologists Dr Pilbrow, Mr Wood, Mr Annand, Ms Lothian, Dr Hutchings, Dr Cooms and Dr Fergie (Third GK Joint Experts’ Report);

(d) a report by Mr James Annand, an anthropologist, prepared for the Gunaikurnai proceeding, titled GunaiKurnai Native Title Claim (VID737/2014) Research Report: Ancestry, Genealogy, and Connection to Wilsons Promontory dated April 2019 (Annand 2019);

(e) extracts from the reports prepared by anthropologists and ethnographers Mr Norman Tindale and Mr Joseph Birdsell from the Harvard-Adelaide Universities Anthropological Expedition 1938-39 to Cape Barren Island Station, 19-29 January 1939 (Tindale 1939);

(f) extracts from a publication by Tindale titled Growth of a People: Formation and Development of a Hybrid Aboriginal and White Stock on the Islands of Bass Strait, Tasmania, 1815-1949 (Records of the Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston, 1953) (Tindale 1953);

(g) excerpts from genealogical research conducted by anthropologists Mr Bill Mollison and Ms Carol Everitt regarding the Bass Strait islands, The Tasmanian Aborigines and their Descendants (Chronology, Genealogies and Social Data) (Hobart, 1978) (Mollison and Everitt); and

(h) a 1985 essay by the anthropologist Dr Dianne Barwick about Louisa Briggs, titled “This Most Resolute Lady: A Biographical Puzzle” in Reay M and Beckett J, Metaphors of Interpretation: Essays in Honour of W.E.H Stanner (Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1985) (Barwick 1985).

45 Second, three compilations of records of births, deaths and marriages and genealogies relating to the ancestry of Ms Walton, Ms Dawson, Mr West, Ms Summers, Mr Ogden and Ms Murray, being:

(a) Compilation of Relevant Birth, Death and Marriage Certificates in relation to the Descent Line of Eliza Nowan (Gamble Compilation);

(b) Compilation of Relevant Birth, Death and Marriage Certificates in relation to the Descent Line of Elizabeth Maynard (Maynard Compilation); and

(c) Compilation of Relevant Birth, Death and Marriage Certificates in Relation to the Descent Line of Jane Foster (Foster Compilation).

46 Third, historical journals and reports and early relevant writings, including:

(a) extracts from the journals and reports of George Augustus Robinson, the Commandant of the Wybalena Aboriginal settlement on Flinders Island in Bass Strait in the relevant period, and his report to the Colonial Secretary of Van Diemen’s Land titled Report on Port Phillip Women dated 12 January 1837 (Robinson’s Report);

(b) extracts from the journal of Mr William Thomas, Assistant Protector of the Aborigines of Port Phillip & Guardian of the Aborigines of Victoria 1839 to 1867, some from Stephens, M, (ed) The Journal of William Thomas, Assistant Protector of the Aborigines of Port Phillip & Guardian of the Aborigines of Victoria 1839 to 1867 (Vol 1, Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages, 2014), and others from secondary sources;

(c) extracts from Rosenman, H, (ed) An Account in Two Volumes of Two Voyages to the South Seas by Captain (later Rear Admiral) Jules S-C Dumont D 'Urville of the French Navy to Australia, New Zealand, Oceania 1826-1829 in the Corvette Astrolabe and to the Straits of Magellan, Chile, Oceania, South East Asia, Australia, Antarctica, New Zealand and Torres Strait 1837-1840 in the Corvettes Astrolabe and Zelee (Melbourne University Press, 1987);

(d) correspondence from Mr John Helder Wedge of Port Phillip to John Montagu, Colonial Secretary, in 1836, which is recorded in Fels, M, I Succeeded Once;

(e) an article from the Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal dated 8 October 1842, titled “Remarks respecting the Islands on the Coast of S.W. Australia”;

(f) extracts from Mr John Lort Stokes, Discoveries in Australia (Vol 2, T. & W. Boone, London, 1846);

(g) extracts from a book by Mr Robert Brough Smythe, first secretary of the Board for the Protection of Aborigines, titled The Aborigines of Victoria (Vol 1, John Ferres, Government Printer, Melbourne, 1878) at pp 94-95;

(h) extracts from a book by Mr James Backhouse from his tour of the Australian colonies between 1832 and 1838, titled A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, 1853 (Facsimile Edition, 1967);

(i) extracts from the Minutes of Evidence taken before the 1881 Colonial Board of Inquiry into the Condition of the Aboriginal Station at Coranderrk (Coranderrk Inquiry);

(j) extracts from a book by Commander Crawford Pasco, titled, A Roving Commission - Naval Reminiscences (London, 1897);

(k) extracts from the book by NJB Plomley, titled Weep In Silence: A History of the Flinders Island Aboriginal Settlement (Blubber Head Press, Hobart, 1987) which includes extracts from Robinson’s journal, Robinson’s Report, and from James Backhouse’s journal from his tour of the Australian colonies between 1832 and 1838; and

(l) excerpt from Mr Pat MacWhirter, Harewood, Western Port (Hilaka Press, Notting Hill, Victoria, 2016).

47 The parties filed comprehensive written closing submissions with detailed references to the evidence. Early in the process of preparing these reasons I reached the view that if a document admitted into evidence was not important enough for a party to rely on it in closing submissions, then the Court should not be required to consider it. I raised that view with the parties and all parties other than the applicant agreed to that course. The applicant contended that the proposed approach would be “inappropriate and misplaced”, including because the closing submissions were subject to a page limit which it said “precluded explicitly identifying all evidence which pertains to the separate questions”. I do not accept that when the applicant’s written closing submissions comprised 58 pages, but in light of the applicant’s position I did not proceed with that approach. It was therefore necessary for me to consider documents which I ultimately concluded had little significance. The fact that I have not referred to a document should not be taken to indicate that I have not considered it.

48 I apologise for my use of the regrettable terms “full blood” and “half-caste” Aboriginal in the reasons which follow. Their use cannot be avoided as the evidence is replete with those terms.

4. EVIDENTIARY ISSUES

4.1 Onus and standard of proof

49 The Separate Questions are centrally questions of fact. The party who asserts those facts has the onus to establish them on the evidence.

50 The standard of proof required of a party under the NTA is the civil standard under s 140(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act), being the balance of probabilities. Section 140(2) provides that when determining the degree of persuasion required for it to be satisfied that a party has proved its case on the balance of probabilities, the Court is to take into account the nature of the cause of action or defence, the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding, and the gravity of the matters alleged.

51 Section 140(2) does not only relate to issues of proof regarding the entire case of a party; it also applies to individual elements of the case: Leslie v Graham [2002] FCA 32 at [57] (Branson J). The section recognises that the strength of the evidence necessary to establish a fact in issue on the balance of probabilities will vary according to the nature of what is sought to be proved and the circumstances in which it is sought to be proved: Qantas Airways Ltd v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; 167 FCR 537 at [139] (Branson J). It reflects Dixon J’s guidance in Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; 60 CLR 336 at 362 where his Honour explained (although speaking of the common law position) that the gravity of the consequences flowing from a particular finding is a consideration which must affect the answer to the question as to whether the issue has been proved.

52 The parties disagree as to the significance of the mandatory considerations under s 140(2) in the circumstances of this case. That provision reflects a legislative intention that courts must be mindful of the forensic context in forming an opinion as to its satisfaction about matters in evidence. Ordinarily, the more serious the consequences of what is contested in the litigation, the more a court will have regard to the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence before reaching a conclusion on that evidence: Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; 162 FCR 466 at [30] (Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ) (CEPSU v ACCC).

53 Authoritative judicial statements have often been made to the effect that “clear or cogent or strict proof” is necessary before so serious a matter as, for example, fraud is to be found. But as Gageler J (as his Honour then was) explained in Henderson v Queensland [2014] HCA 52; 255 CLR 1 at [91] (citing Neat Holdings Pty Ltd v Karajan Holdings Pty Ltd [1992] HCA 66; 67 ALJR 170 at 171 per Mason CJ, Brennan, Deane and Gaudron JJ, those statements should not be understood as directed to the standard of proof; rather they reflect the conventional perception that members of our society do not ordinarily engage in fraudulent or criminal conduct, and a judicial approach that a court should not lightly make a finding that, on the balance of probabilities, a party to civil litigation has been guilty of such conduct. Thus, the standard of proof remains the balance of probabilities.

54 The applicant submitted that a finding that any of Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan/Gamble and Jane Foster were, at effective sovereignty, members of the Boonwurrung People will result in additional apical ancestors in the Boonwurrung Application and an expansion of the Boonwurrung native title claim group. It contended that the question of membership of a native title claim group goes to the heart of the existence of native title and the practical operation of the native title regime. On the applicant’s argument, given the seriousness of the consequences of the findings sought by the Bunurong respondents, s 140(2) of the Evidence Act requires that there be cogent or coherent proof before the Court can be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that those findings should be made.

55 I do not accept that the findings the Bunurong respondents seek have such gravity that the mandatory considerations under s 140(2) have work to do. While the operation of the s 140(2) is not limited to such cases, it is relevant that the case does not involve allegations of fraud, criminal conduct, civil penalties or the like. If any of the named women are found to have been members of the Boonwurrung People at effective sovereignty, that may confer a range of rights and privileges under the NTA upon their contemporary and future descendants, but it will not remove the rights and privileges available to existing members of the Boonwurrung native title claim group, as presently defined. In my opinion the nature of the case, the questions of group membership and descent that arise in the case, and the broad circumstances of the case brought as it is under the auspices of an application for a determination of native title under the NTA, do not impose a requirement for clear, cogent or strict proof pursuant to s 140(2) before a state of satisfaction on the relevant issues can be reached on the balance of probabilities.

56 For their part, the Bunurong respondents and the State submitted that findings that any of the four named women were not, at effective sovereignty, members of the Boonwurrung People is likely to have grave consequences for any contemporary descendants of those women, including the Bunurong respondents themselves. They said, and I accept, that there is no evidence that would tie any of the named women (with the possible exception of Ann Munro) to any particular Aboriginal group outside of the Boonwurrung People, and if they are not found on the evidence to have been Boonwurrung then their Aboriginal group identity is unknowable and is likely lost to history.

57 They contended that the serious consequences of an order which would effectively operate to exclude from membership of the Boonwurrung People current and future generations of Aboriginal people who trace their ancestry back to the named women, means that having regard to s 140(2) the Court should not lightly reach such findings. They submitted that the Court should carefully scrutinise the opinion and documentary evidence put forward by the applicant to rebut an inference that the named women were Boonwurrung.

58 They cited Shaw v Wolf [1998] FCA 389; 83 FCR 113 at 124C) (Merkel J) as support for this argument. In that case the applicant petitioners for an electoral challenge had the onus to prove that 11 candidates in regional council elections for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission were not Aboriginal. Under the relevant legislation a person that asserted that they were Aboriginal was taken to be Aboriginal unless proved otherwise. His Honour found (at 125) that:

…given the serious consequences for the defending respondents of an adverse finding, in the present case, good conscience and principle require that the Court should not lightly make a finding on the balance of probabilities, that any of those respondents is not an Aboriginal person as defined in the Act.

(Emphasis in original.)

59 It is plain from the evidence of the Boonwurrung and Bunurong lay witnesses that they hold a strong conviction that they are members of the Boonwurrung (or Bunurong) People, and that they each have a connection to their asserted country. In different ways they have each strived to be recognised and accepted as Boonwurrung. I am persuaded that their Boonwurrung/Bunurong identity is of real importance to them. I accept that a finding that their claimed ancestors were not members of the Boonwurrung People, and therefore that they are not Boonwurrung by descent, is likely to have a deleterious impact on their cultural identity and/or their relationships with their family and community who identify as Boonwurrung. Such a finding would also mean they may be excluded from enjoying the rights, privileges and legal recognition and identity that group membership carries under the NTA, and also under Victorian legislation such as the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic) and the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic).

60 Even so, I do not accept that the findings that the Bunurong respondents and the State seek mean that the mandatory considerations under s 140(2) have work to do. Again, while the operation of s 140(2) is not limited to such cases, it is relevant that the case does not involve allegations of fraud, criminal conduct, civil penalties or the like. The nature of the case, the questions of group membership and descent that arise in the case, and the broad circumstances of Separate Questions to be decided in a native title determination application, do not indicate a requirement for clear, cogent or strict proof before a state of satisfaction may be reached on the balance of probabilities in relation to the relevant issues.

61 Further, the Bunurong respondents have the onus to establish that Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan/Gamble and Jane Foster were, at effective sovereignty, members of the Boonwurrung People. The serious consequences to which the Bunurong respondents and the State point only arise if the Bunurong respondents fail to meet their onus. And the Bunurong respondents did not contend that s 140(2) requires that they must adduce clear, cogent or strict proof to establish the claimed Boonwurrung identity of Elizabeth Maynard, Eliza Nowan/Gamble and Jane Foster. On their argument, the section only indicates such a requirement in relation to the applicant’s evidence aimed at rebutting the inferences the Bunurong respondents seek. I do not accept that the applicant faces a more stringent standard than that faced by the Bunurong respondents. The decision in Shaw can be distinguished from the present case because it involved a reverse onus of proof, which is not the position here.

4.2 Inferential reasoning

62 The Separate Questions are centrally focused upon facts identifiable at effective sovereignty in the mid-1830s to 1840s. They fall to be answered by reference to factual findings based in lay evidence, historical records and expert evidence, including inferences that can reasonably be drawn from facts found. The Court’s task involves a level of historical reconstruction from limited evidence, and from inferences that can reasonably be drawn from that evidence. As earlier noted, in Drill Mortimer J explained that in such cases the Court is not “the arbiter of history” and it does not decide what the truth is in any absolute sense. Rather, the Court must reach a view about what, on the evidence before it, are more likely than not to be the facts.

63 In approaching its task, and in drawing inferences from the evidence, the Court must first be satisfied that there is evidence of some fact, the existence of which is sufficient to justify the drawing of an inference. An inference is not drawn by conjecture or hypothesis if there is no evidence of basal facts. But an inference that is reasonably available on the evidence ought not be discounted because of conjecture about competing explanations of the evidence, unless there is evidence of facts supporting that contrary explanation. In a case like this the paucity of historical information, and conjecture about alternative possibilities that cannot be proved or disproved on the evidence, should not stand in the way of the Court drawing reasonable and rational inferences from the evidence that is available.

64 As Gageler J explained in Henderson at [89], [91]:

[89] Generally speaking … a party who bears the legal burden of proving the happening of an event or the existence of a state of affairs on the balance of probabilities can discharge that burden by adducing evidence of some fact the existence of which, in the absence of further evidence, is sufficient to justify the drawing of an inference that it is more likely than not that the event occurred or that the state of affairs exists. The threshold requirement for the party bearing the burden of proof to adduce evidence at least to establish some fact which provides the basis for such a further inference was explained by Kitto J in Jones v Dunkel:

‘One does not pass from the realm of conjecture into the realm of inference until some fact is found which positively suggests, that is to say provides a reason, special to the particular case under consideration, for thinking it likely that in that actual case a specific event happened or a specific state of affairs existed.’

…

[91] The process of inferential reasoning involved in drawing inferences from facts proved by evidence adduced in a civil proceeding cannot be reduced to a formula. The process when undertaken judicially is nevertheless informed by principles of long standing which reflect systemic values and experience. One such principle, forming ‘a fundamental precept of the adversarial system of justice’, is that ‘all evidence is to be weighed according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced, and in the power of the other to have contradicted’. Another such principle, ‘reflecting a conventional perception that members of our society do not ordinarily engage in fraudulent or criminal conduct’, is that ‘a court should not lightly make a finding that, on the balance of probabilities, a party to civil litigation has been guilty of such conduct’.

(Citations omitted.)

65 In drawing an inference the Court must be persuaded that it is more probable than not that the particular fact or state of affairs exists, and it cannot choose or elect between competing possibilities, that is, rival facts that are equally plausible on the evidence. In Lithgow City Council v Jackson [2011] HCA 36; 244 CLR 352 at [94] Crennan J said:

Whilst ‘a more probable inference’ may fall short of certainty, it must be more than an inference of equal degree of probability with other inferences, so as to avoid guess or conjecture. In establishing an inference of a greater degree of likelihood, it is only necessary to demonstrate that a competing inference is less likely, not that it is inherently improbable.

66 All of the circumstances must be considered together at the final stage of the reasoning process and where the competing possibilities are of equal likelihood, or the choice between them can only be resolved by conjecture, the allegation is not proved. The standard of proof is not met if the circumstances appearing in the evidence do not give rise to “a reasonable and definite inference”, but at most give rise to “conflicting inferences of equal degree of probability, so that the choice between them is a mere matter of conjecture”: Westbus Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) v Ishak [2006] NSWCA 198 at [20] (Giles JA with whom Handley and Tobias JJ agreed), citing Luxton v Vines [1952] HCA 19; 85 CLR 352 at 358 (Dixon, Fullagar and Kitto JJ); CEPSU v ACCC at [38] (Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ).

4.3 The lay evidence

67 The evidence of the Boonwurrung and the Bunurong lay witnesses appeared to be given candidly and to reflect their genuinely held beliefs. In cross-examination no party attacked the credit of any of the lay witnesses or suggested that they were not telling the truth. On most issues the evidence of each Boonwurrung witness was broadly corroborative of other Boonwurrung witnesses, and the same was true of the Bunurong witnesses. Even so, their evidence cannot just be uncritically accepted. I will set out my view of each witness’s evidence when I deal with it.

68 I will, however, raise Ms Walton’s testimony at this point because, regrettably, she was the subject of adverse online commentary following her testimony, including some abuse and implicit threats. Ms Walton has a public profile as an Australian actor and she gave evidence during a period of heightened interest in indigenous issues in the lead up to the Voice referendum. Because of the online commentary and abuse, posted by keyboard warriors who did not have the courage to put their name to it, Ms Walton gave consideration to withdrawing as a party, but did not ultimately do so.

69 I am sorry that Ms Walton was forced to endure that commentary. I found her to be an honest witness who gave evidence which reflected her genuinely held beliefs. I gave directions for a Judicial Registrar to review the online commentary and report as to whether, in the Registrar’s view, it was appropriate to institute proceedings for contempt of Court. The Registrar did not recommend commencement of a contempt proceeding.

70 The proof of events in relation to allegedly abducted Aboriginal women born around 200 years ago, and of the asserted genealogical connection to people living today, may not be readily established by reference to official records. In the early 1800s the births and deaths of Aboriginal people were not officially recorded, but as that century progressed they were. There are some relevant official records but other evidence regarding Aboriginal descent is based in lay evidence of family histories passed down over the generations, by oral tradition. Both the Boonwurrung and the Bunurong parties relied on the testimony of Aboriginal witnesses based in oral histories they had received from parents, grandparents, uncles/aunties and “old people”. There was no objection to that evidence, and in any event hearsay nature of the lay witness evidence as to their family history attracts the exception in s 73(1)(d) of the Evidence Act relating to evidence of reputation concerning family history or a family relationship. Such evidence is prima facie admissible: see e.g. Yarmirr v Northern Territory (No 2) [1998] FCA 771; 82 FCR 533 at 544E-F (Olney J).

71 In some instances the lay witness evidence can be said to be inconsistent with historical records, but the authorities are clear that the Court should be cautious in relying on historical records to disprove a version of ancestry, history or customary law and practice based on oral history. In the present case some parts of the lay evidence were concerned with traditional laws and customs, some parts were concerned with stories allegedly passed down regarding family history, and some parts concerned relatively contemporary events. The authorities provide that Aboriginal evidence regarding their traditional laws and customs is of the utmost importance (see Sampi v State of Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 at [48] per French J at first instance) and I can see no reason in principle why the same does not apply to family histories passed down by oral tradition.

72 In Narrier v Western Australia [2016] FCA 1519 at [318], Mortimer J (as her Honour then was) cited the Full Court’s remarks in De Rose v South Australia [2003] FCAFC 286; 133 FCR 325 at [264]-[265] (Wilcox, Sackville and Merkel JJ) and explained as follows:

There is no difficulty in a Court preferring, as more reliable and persuasive, the evidence of Aboriginal witnesses over the evidence of anthropologists or anthropological sources. In De Rose at [264]-[265], the Full Court said:

‘As the primary Judge made clear at several points in the judgment, it was because of the testimony of the Aboriginal witnesses that he was prepared to find that the four-fold test for determining Nguraritja was acknowledged by the traditional laws and customs of the Western Desert Bloc. He plainly regarded that evidence as more cogent and persuasive than the writings of Professor Berndt on this particular issue.

His Honour took this view notwithstanding that he was by no means uncritical of the evidence of Aboriginal witnesses. As we have noted, he rejected the evidence of certain witnesses on important issues. His Honour’s acceptance of their evidence as to the ways of becoming Nguraritja plainly took account of his assessment of their reliability and understanding of the questions. His Honour must also have taken into account the fact that they were recounting elements of an oral tradition.’

73 Not only is there no reason to privilege documentary evidence or expert evidence over the evidence of Aboriginal witnesses derived from oral tradition, there are reasons to regard such lay evidence in native title proceedings as the most important evidence: see Commonwealth v Yarmirr [1999] FCA 1668; 101 FCR 171 at [348]-[351] (Merkel J); Members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v Victoria [2002] HCA 58; 214 CLR 422 at [63] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow and Hayne JJ); De Rose Hill v South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 at [351] (O’Loughlin J); Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v State of Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31; 238 ALR 1 at [386] (Lindgren J); Daniel v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 666 at [149] (Nicholson J); Sampi at [48] (French J); Dempsey v State of Queensland (No 2) [2014] FCA 528; 317 ALR 432 at [298]-[300] (Mortimer J as her Honour then was); Rrumburriya Borroloola Claim Group v Northern Territory [2016] FCA 776; 255 FCR 228 at [69] (Mansfield J); Ashwin on behalf of the Wutha People v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2019] FCA 308; 369 ALR 1 at [108]-[110] (Bromberg J).

74 In Dempsey at [298] Mortimer J cited the remarks in Yarmirr, Daniel and Shaw with approval, and observed that:

Care must always be taken when relying upon historical records in native title cases. In Anglo-Australian culture, greater value has traditionally been placed on written material than on oral accounts: Commonwealth v Yarmirr (2000) 101 FCR 171; 168 ALR 426; [1999] FCA 1668 at [348] (Yarmirr) per Merkel J. Certainly, oral accounts may fill the ‘silences’ in the historical records (see Daniel v Western Australia [2003] FCA 666 at [149] (Daniel) per RD Nicholson J), but they may do more than that. It may be oral accounts which provide the only continuous narrative. Oral accounts may explain or give context to any historical records and, in some cases, may qualify or rebut them.

75 Other jurisdictions required to grapple with evidence based in indigenous oral histories have taken similar approaches. In the Canadian decision of Mitchell v MNR [2001] 1 SCR 911 at [37]-[39], McLaughlin CJ (with whom Gonthier, Iacobucci, Arbour and LeBel JJ agreed) explained that the oral testimony of indigenous witnesses should not be devalued or deprived of its evidential force merely on the basis that the account is not verifiable by reference to a documentary record.

76 It is accepted that taking proper account of the oral testimony of Aboriginal lay witnesses provides a basis for drawing inferences about traditional laws and customs at or near effective sovereignty: see e.g., Gumana v Northern Territory [2005] FCA 50; 141 FCR 457 at [194]-[201] (Selway J); AB (deceased) on behalf of the Ngarla People v Western Australia (No 4) [2012] FCA 1268; 300 ALR 193 at [724] (Bennett J); Narrier at [314]-[318] (Mortimer J); Dempsey at [802] (Mortimer J).

4.4 The expert evidence