Federal Court of Australia

Nangalaku on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe People v Northern Territory [2025] FCA 217

File number(s): | NTD 23 of 2022 |

Judgment of: | O'BRYAN J |

Date of judgment: | 28 March 2025 |

Catchwords: | NATIVE TITLE – interlocutory application brought by applicant to amend native title determination application – interlocutory application brought by the Northern Territory to strike out native title determination application pursuant to s 84C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) – whether evidence established that the claimant application had been authorised by the native title claim group as required by s 61 of the NTA – whether claimant application only authorised by a sub-group of the claim group – application to amend dismissed – claimant application struck out for want of authorisation by the native title claim group |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 167 Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) s 31A Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) ss 61, 62, 64, 66B, 84C, 84D, 251B |

Cases cited: | Attorney-General (NT) v Maurice (1986) 161 CLR 475 Bodney v Bropho (2004) 140 FCR 77 Champion v Western Australia [2009] FCA 1141 De Rose v South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 Dieri People v State of South Australia (2003) 127 FCR 364 Drury v Western Australia (2000) 97 FCR 169 Grant v Minister for Land & Water Conservation for New South Wales [2003] FCA 621 Harrington-Smith v Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31 Hazelbane v Northern Territory of Australia [2008] FCA 291 Hazelbane v Northern Territory [2014] FCA 886 Hazelbane v Northern Territory of Australia [2016] FCA 408 Hua Wang Bank Berhad v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (No 15) (2013) 217 FCR 26 Landers v South Australia (2003) 128 FCR 495 Lawson v Minister for Land and Water Conservation [2002] FCA 488 Lawson v Minister for Land and Water Conservation for the State of New South Wales [2002] FCA 1517 Melville on behalf of the Pitta Pitta People v State of Queensland [2022] FCA 387 Noble v Mundraby, Murgha, Harris and Garling [2005] FCAFC 212 Torres v Western Australia [2012] FCA 972 Precision Plastics Pty Ltd v Demir (1975) 132 CLR 362 Risk v National Native Title Tribunal [2000] FCA 1589 Sampi v Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 Sandy on behalf of the Yugara/Yugarapul People v State of Queensland [2012] FCA 978 Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Robertson [2024] FCAFC 58 Strickland v Native Title Registrar [1999] FCA 1530 Strickland v Western Australia [2013] FCA 677 Thardim v Northern Territory [2016] FCA 407 Tilmouth v Northern Territory (2001) 109 FCR 240 Velickovic v Western Australia [2012] FCA 782 Walker v South Australia [2014] FCA 962 Western Australia v Strickland (2000) 99 FCR 33 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Northern Territory |

National Practice Area: | Native Title |

Number of paragraphs: | 156 |

Date of hearing: | 30 September 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | R Bonig |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Finlaysons |

Counsel for the Respondent: | C Taggart |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Solicitor for the Northern Territory |

ORDERS

NTD 23 of 2022 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JOAN GROWDEN NANGALAKU (NEE PETHERICK) ON BEHALF OF THE DAK DJERAT GUWE PEOPLE Applicant | |

AND: | NORTHERN TERRITORY OF AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

order made by: | O'BRYAN J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 28 MARCH 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory application of the applicant seeking orders:

(a) to amend the claimant application in the form of Annexure JG2 to the affidavit of Joan Growden Nangalaku dated 11 September 2024; and

(b) to replace Thomas Edward Petherick (deceased) with Gregory Munar as an applicant to the claimant application (jointly with Joan Growden Nangalaku),

be dismissed.

2. The claimant application in the proceeding be struck out pursuant to s 84C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

O’BRYAN J:

A. Introduction

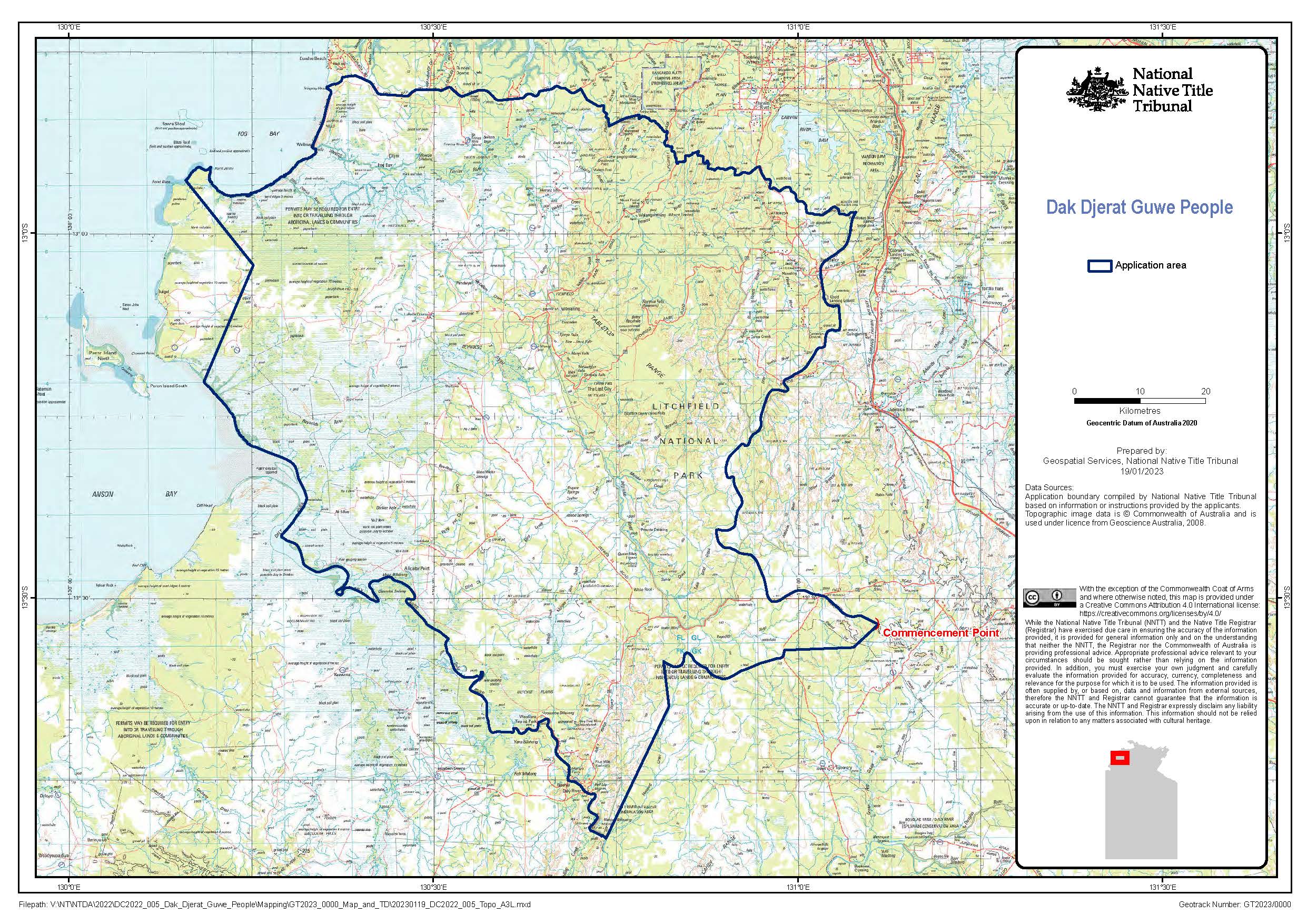

1 On 26 October 2022, Joan Growden Nangalaku (who refers to herself as Ms Growden) and her now deceased brother, Thomas Edward Petherick, signed a native title claimant application on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe people and lodged it for filing the next day (Dak Djerat Guwe claim). It was accepted for filing on 15 November 2022. At that time, Ms Growden and Mr Petherick were self-represented. The area covered by the claim was depicted in a map attached at Annexure C to the application, but which was of very poor quality. The application stated that the claim area is generally described as the entire watershed of the Reynolds River and the Finniss River through to the coast.

2 On 30 January 2023, Ms Growden and Mr Petherick filed an interlocutory application seeking leave to amend the claim. At that point in time, the claim had not been accepted for registration under Part 7 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). That application was supported by affidavits affirmed by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick on that date. The proposed amended claim was annexed to Ms Growden’s affidavit. It contained a clearer map of the claim area, which is attached to these reasons as Annexure A.

3 Subsequently, on 20 June 2023, the respondent to the claim, the Northern Territory (Territory), lodged for filing an interlocutory application seeking orders, amongst others:

(a) requiring Ms Growden and Mr Petherick to file and serve evidence that they were authorised to make and to amend the claim; and

(b) requiring the Territory to bring forward any application to strike out the claim including pursuant to s 84D of the NTA.

4 On 23 June 2023, the applicants appointed Finlaysons Lawyers to act on their behalf.

5 Mr Petherick died in or around August 2023.

6 The parties first appeared before me on 30 June 2023 in relation to the above interlocutory applications. Between that first appearance and 30 September 2024, the applicant was provided with a number of opportunities to address the concerns raised by the Territory with respect to the authorisation of the claim. It is necessary to refer to aspects of that procedural history, and the evidence filed on behalf of the applicant at various stages, which is set out below. Ultimately, the Territory was not satisfied with the evidence adduced by the applicant to establish that the applicant was authorised to bring the claim by the native title claim group as required by s 61 of the NTA, and applied to strike out the application under s 84C.

7 In Hazelbane v Northern Territory of Australia [2008] FCA 291 (Hazelbane 2008), Mansfield J discussed the competing considerations whether to hear and determine an application to strike out a claimant application for want of authorisation at an early stage of the proceeding. His Honour said:

13 As has been often observed, proper authorisation of a native title claimant application is fundamental to the legitimacy of the claim (see for example Quall v Risk [2001] FCA 378 at [67]; Dieri People v South Australia (2003) 127 FCR 364 at [55]; Quandamooka People (No 1) v State of Queensland [2002] FCA 259 at [25]; Moran v Minister of Land and Water Conservation for New South Wales [1999] FCA 1637 at [48]; Daniel v Western Australia [2002] FCA 1147 at [11]).

14 It is, therefore, hard to resist the temptation of determining such a fundamental issue as authorisation before a full trial of the native title determination application with the very substantial resources which are then involved. To do so has the attraction of expedition and economy. Certain recent decisions of the Court have illustrated that proper authorisation is a matter which should not be overlooked, and the possibility of a challenge, at an early point in the proceeding: see e.g. Risk v Northern Territory [2006] FCA 404; Harrington-Smith v Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1. The mere complexity of an issue, or the fact that extensive argument may be necessary to demonstrate that the claim is untenable, is not a reason not to dispose of an application summarily: General Steel Industries Inc v Commissioner for Railways (NSW) 112 CLR at 130 per Barwick CJ.

15 Section 84C(2) requires the Court to consider an application under s 84C(1) before any further proceedings take place in relation to the main application. But that does not require the Court to hear and determine the question as to whether the application has, in fact, been authorised as required by s 251B in all cases. It is only where the application is obviously without merit, that is, where there is no realistic prospect on the material before the Court of the authorisation being shown to have existed at the time it was purportedly granted, that an order will be made summarily dismissing or striking out the main application under s 84C. Sometimes an applicant faced with an application under s 84C may seek to amend the application to cure an identified deficiency (as discussed by Lander J in Williams v Grant at [57]). Where the application is not clearly without merit, so that it is not dismissed summarily or struck out, the Court may consider directing that an application under s 84C be heard and determined at the same time as the main application. That is a course of action which Wilcox J in Bodney v State of Western Australia [2003] FCA 890 at [45] suggested. The Court may also consider directing that the question of authorisation be heard and determined as a separate question, and be heard and determined prior to the hearing of the main application, under O 29 of the Federal Court Rules. That is a matter for each particular case and its particular circumstances. Whether such an order were appropriate would depend upon the extent to which there would be an overlap in the evidence likely to be called relating to authorisation and on the main application and a range of factors. The apparent attraction of expedition and economy may be misleading. Very often, the proposed evidence of authorisation is to be given by persons who also will give “connection” evidence and evidence of traditional laws and customs. There are often sound reasons in such circumstances why the separate trial of issues should not be ordered: Rocklea Spinning Mills Pty Ltd v Anti-Dumping Authority (1995) 56 FCR 406; Energy Australia v Australian Energy Ltd [2001] FCA 1049 at [8] per Stone J. There are also countervailing considerations of potential delay through splitting of issues and the separate processes which follow that course: Tallglen Pty Ltd v Pay TV Holdings Pty Ltd (1996) 22 ACSR 130. So, not uncommonly, as occurred in both Risk and Harrington-Smith (referred to above) the issue of authorisation was heard and determined as part of the principal hearing of the main application.

8 A hearing was conducted on 30 September 2024 in respect of two interlocutory applications before the Court. The first was the applicant’s interlocutory application to amend the claim. At the time of the hearing, the application to amend was to:

(a) add Gregory Munar as a named applicant in place of the late Mr Petherick; and

(b) replace the filed application with the application annexed to Ms Growden’s affidavit dated 11 September 2024.

9 The second was the Territory’s interlocutory application to strike out the claim under s 84C on the ground that it does not comply with ss 61 or 62.

10 For the reasons set out below, the claimant application should be struck out. The evidence adduced by the applicant concerning authorisation does not persuade me that the 7 ritual elders that authorised Ms Growden and Mr Munar to make the claim have the authority, under the traditional laws and customs of the Dak Djerat Guwe people, to make decisions on behalf of all of the 22 clans that comprise the claim group. The requisite authority cannot be assumed in favour of the applicant. The result is that the claim has only been authorised by a sub-group of the claim group.

11 Two matters concerning the evidence filed on behalf of the applicant on the interlocutory applications should be noted.

12 First, the evidence contains variations in the spelling of the names of claim group members and ancestors. The variations in spelling are relatively minor, and no confusion arises with respect to the persons being referred to. When referring to the evidence of a particular witness, these reasons adopt the spelling used by that witness.

13 Second, the applicant adopted a practice of filing affidavits to which other affidavits were annexed. The effect of annexing one affidavit to another person’s affidavit is equivalent to tendering the annexed affidavits as documentary evidence, as opposed to adducing testimonial evidence. As explained by Perram J in Hua Wang Bank Berhad v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (No 15) (2013) 217 FCR 26 at [14], when an affidavit is tendered in evidence, as opposed to being read (as a form of testimonial evidence), the affidavit constitutes hearsay evidence but may be admissible if an exception to the hearsay rule is engaged. A further consequence, as noted by Perram J, is that the opposing party does not have a right to cross-examine the maker of the affidavit (s 27 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) does not apply because the maker of the affidavit is not giving evidence as a witness). Nevertheless, pursuant to s 167 of the Evidence Act, the opposing party may request the party tendering the affidavit to call the maker of the affidavit as a witness so that the maker can be cross-examined about the contents of the affidavit. In the present matter, the Territory did not object to the manner in which the affidavits were provided to the Court or make a request to cross-examine any of the deponents of the affidavits. In those circumstances, all of the affidavits have been received into evidence on the interlocutory applications. However, it should be recorded that the approach taken by the applicant is unorthodox. The affidavits that were annexed to other affidavits should have been filed as individual affidavits.

B. Legislative framework

Claimant applications and their amendment

14 The form and content of native title determination applications are regulated under Div 1 of Pt 3 of the NTA.

15 Relevantly, s 61(1) stipulates the types of applications that may be made under Div 1 and the persons who may make the applications. In respect of native title determination applications, the persons who may make the application relevantly include:

(1) A person or persons authorised by all the persons (the native title claim group) who, according to their traditional laws and customs, hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the particular native title claimed, provided the person or persons are also included in the native title claim group; or

Note 1: The person or persons will be the applicant: see subsection (2) of this section.

Note 2: Section 251B states what it means for a person or persons to be authorised by all the persons in the native title claim group.

16 A native title determination application that has been authorised to be made by a native title claim group is called a “claimant application” (see s 253). The person or persons who make the application on behalf of the claim group are called the “applicant” (see s 61(2)).

17 Section 251B governs the manner in which an application may be authorised. It provides as follows:

251B Authorising the making of applications

For the purposes of this Act, all the persons in a native title claim group or compensation claim group authorise a person or persons to make a native title determination application or a compensation application, and to deal with matters arising in relation to it, if:

(a) where there is a process of decision‑making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind —the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group authorise the person or persons to make the application and to deal with the matters in accordance with that process; or

(b) where there is no such process — the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group authorise the other person or persons to make the application and to deal with the matters in accordance with a process of decision‑making agreed to and adopted, by the persons in the native title claim group or compensation claim group, in relation to authorising the making of the application and dealing with the matters, or in relation to doing things of that kind.

18 Section 251BA stipulates that the persons who authorise a claimant application in accordance with s 251B may impose conditions on the authority.

19 Section 62(1) governs the information that must be included in or accompany a claimant application. Relevantly, the claimant application must be accompanied by an affidavit sworn by the applicant stating the matters mentioned in subsection (1A) which include:

(e) the details of the process of decision‑making complied with in authorising the applicant to make the application and to deal with matters arising in relation to it;

20 Section 62A stipulates that an applicant in respect of a claimant application may deal with all matters arising under the NTA in relation to the application, subject to any conditions imposed on the authority of the applicant as provided for in s 251BA.

21 The central question in dispute on this application is whether the applicant was authorised to make the claimant application by “all the persons (the native title claim group) who, according to their traditional laws and customs, hold the common or group rights and interests comprising the particular native title claimed”.

22 As set out above, the process of authorisation is governed by s 251B which addresses two circumstances: where there is a process of decision‑making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the persons in the native title claim group, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind, and where there is not. Although s 61 requires the applicant to have been authorised by all of the persons who hold the native title rights and interests that are claimed, s 251B specifies how that requirement is to be fulfilled: Lawson v Minister for Land and Water Conservation for the State of New South Wales [2002] FCA 1517 (Lawson) (at [25]). It will not always be necessary for all persons who hold the native title rights and interests that are claimed to meet and approve the applicant. For example, where s 251B(a) applies, the process of decision-making under the traditional laws and customs of the native title claim group may not require (or allow) participation by all members of the claim group. For example, in Strickland v Native Title Registrar [1999] FCA 1530; 168 ALR 242, French J (as his Honour then was) found that there was no evidence before the Court to contradict the assertion made in the application that all relevant authority was vested in the two elders of the relevant native title claim group who had made the application (at [57]). That conclusion was upheld on appeal in Western Australia v Strickland (2000) 99 FCR 33 (at [77]-[78]). So too, where s 251B(b) applies, the process of decision-making agreed to and adopted by the native title claim group may not require unanimous approval by all members of the claim group: Lawson at [25].

23 The claimant application in the present case states that the claim was authorised in accordance with a process that complied with the traditional laws and customs of the native title claim group. It will become necessary to consider the sufficiency of the evidence adduced with respect to that process.

Amendment of claimant applications and the replacement of an individual applicant

24 Section 64 addresses some aspects of the amendment of claimant applications. Relevantly for present purposes, s 64(3) states that the fact that the Native Title Registrar is considering the claim under s 190A (which concerns registration of the application) does not prevent amendment of the application.

25 Section 66B addresses the manner in which one or more of the persons who comprise the applicant on a claimant application can be replaced. Relevantly, s 66B(2A) states that one or more members of the native title claim group may apply to the Court for an order under subsection (2B) if a person (the ceasing member) who is, either alone or jointly with one or more other persons (the continuing members), the current applicant dies. Relevantly, subsection 66B(2B) states that, where:

(a) a member of the claim group is authorised by the claim group to make the application and to deal with matters arising in relation to it because of the death of the ceasing member; and

(b) the authority of any continuing members continues (despite the death of the ceasing member),

the Court may order that the current applicant be replaced by that member and continuing members.

Striking out applications for failure to comply with requirements of this Act

26 Section 84C empowers the Court to strike out claimant applications which do not comply with the requirements of the Act. The section provides as follows:

Strike‑out application

(1) If an application (the main application) does not comply with section 61 (which deals with the basic requirements for applications), 61A (which provides that certain applications must not be made) or 62 (which requires applications to be accompanied by affidavits and to contain certain details), a party to the proceedings may at any time apply to the Federal Court to strike out the application.

Note: The main application may still be amended even after a strike‑out application is filed.

Court must consider strike‑out application before other proceedings

(2) The Court must, before any further proceedings take place in relation to the main application, consider the application made under subsection (1).

Federal Court Chief Executive Officer to advise Native Title Registrar of application etc.

(3) The Federal Court Chief Executive Officer must advise the Native Title Registrar of the making of any application under subsection (1) and of the outcome of the application.

Other strike‑out applications unaffected

(4) This section does not prevent the making of any other application to strike out the main application.

27 The strike out power under s 84C is supported by other procedural powers conferred by s 84D which provides as follows:

(1) The Federal Court may make an order requiring:

(a) a person who, either alone or jointly with another person, made an application under section 61, to produce evidence to the court that he or she was authorised to do so; or

(b) a person who has dealt with a matter, or is dealing with a matter, arising in relation to such an application, to produce evidence to the court that he or she is authorised to do so.

(2) An order under subsection (1) may be made:

(a) on the Federal Court’s own motion; or

(b) on the application of a party to the proceedings; or

(c) on the application of a member of the native title claim group or compensation claim group in relation to the application.

(3) Subsection (4) applies if:

(a) an application does not comply with section 61 (which deals with the basic requirements for applications) because it was made by a person or persons who were not authorised by the native title claim group to do so; or

(b) a person who is or was, or one of the persons who are or were, the applicant in relation to the application has dealt with, or deals with, a matter arising in relation to the application in circumstances where the person was not authorised to do so.

Note: Section 251B states what it means for a person or persons to be authorised to make native title determination applications or compensation applications or to deal with matters arising in relation to them.

(4) The Federal Court may, after balancing the need for due prosecution of the application and the interests of justice:

(a) hear and determine the application, despite the defect in authorisation; or

(b) make such other orders as the court considers appropriate.

28 The exercise of the strike out power under s 84C has been considered in many cases. The applicable principles governing its exercise can be summarised as follows.

29 First, the burden of showing that the claimant application does not comply with a requirement of the NTA lies on the party bringing the application under s 84C: Bodney v Bropho (2004) 140 FCR 77 (Bodney) at [27] (Branson J); Melville on behalf of the Pitta Pitta People v State of Queensland [2022] FCA 387 at [17] (Mortimer J, as her Honour then was).

30 Second, s 84C is concerned with matters of form and authority, not with the merit of the claimant application: Bodney at [33] (Branson J).

31 Third, the test to be applied on a strike out application under s 84C is equivalent to the test to be applied on a summary judgment application under s 31A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act); that is, it should be approached with caution and should only be allowed where a clear case has been made: Bodney at [57] (Stone J, with whom Spender and Branson JJ agreed); Walker v South Australia [2014] FCA 962 at [20] (Mansfield J); Thardim v Northern Territory [2016] FCA 407 (Thardim) at [97] (Mansfield J).

32 Fourth, as with applications for summary judgment, it is permissible to adduce evidence on the application and the fact that extensive argument may be required is not a barrier to the success of a strike out application: Bodney at [52] (Stone J, with whom Spender and Branson JJ agreed).

33 Fifth, where the application is affected by a possible defect in authorisation, the Court retains a discretion under s 84D whether or not to strike out the application: Lawson v Minister for Land and Water Conservation [2002] FCA 488 at [7]. The Court is empowered by s 84D(4)(a) to hear and determine the application despite the defect in authorisation, and is empowered by s 84D(4)(b) to make such other orders as the Court considers appropriate such as requiring the applicant to conduct another authorisation process in order to cure a defect in authorisation: see generally Sandy on behalf of the Yugara/Yugarapul People v State of Queensland [2012] FCA 978 (Sandy).

C. Earlier native title applications

34 The Territory’s submissions drew attention to the fact that the late Mr Petherick had previously made a number of native title claimant applications which have been struck out by the Court: Hazelbane 2008, Hazelbane v Northern Territory [2014] FCA 886 (Hazelbane 2014), Hazelbane v Northern Territory of Australia [2016] FCA 408 and Thardim. Those earlier native title claims provide some context to the present strike out application, albeit that the decisions made in respect of those earlier claims are not determinative of the present application.

35 The claimant applications in the Hazelbane proceedings concerned the town of Batchelor which is on the eastern border of the claim area of the present claim. Mr Petherick was a named applicant (together with May Stevens) on behalf of a claim group comprising two out of eight clans which were identified as the “Finnis River Brinkin Group” (FRBG). The two clans were the Emu clan (of which the late Mr Petherick claimed to be a member) and the Blue Tongue Lizard clan (of which May Stevens claimed to be a member).

36 In Hazelbane 2008, Mansfield J observed (at [24]), in words that remain pertinent to the present application:

What is apparent is that the FRBG comprises at least the eight clan groups referred to in [2] above, and for many years has been seeking to have its interest in the claim area of the Town of Batchelor No 2 application, in Litchfield National Park, and in surrounding areas recognised firstly by the Aboriginal Land Rights Commissioner under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act (1976) (Cth) and, secondly, in various claims made under the Act in relation to areas in which the FRBG claims to have an interest in a number of areas, including the Bachelor area. Both the Aboriginal Land Rights Commissioner in relation to the Finniss River Land Claim 1980 and the Northern Land Council (the NLC) as the representative body responsible for the area in which the relevant claims under the Act have been made, have declined to recognise that interest. The NLC has also declined to provide financial or other support to the FRBG to pursue its claims, variously to pursue its claimed interests in the Batchelor and other areas. Consequently, but not surprisingly, the Town of Batchelor No 2 application and other documents prepared by and on behalf of the FRBG have some unsatisfactory aspects. The process of making such an application is complex and the information required is detailed. It is not surprising that the FRBG or more specifically the Petherick family, who appear to have been carrying the primary responsibility for furthering the interests of the FRBG, have not completed that process in a way which a more formal analysis and professional care might have done.

37 Ultimately, Mansfield J determined that the FRBG application should be summarily dismissed because some of the named applicants did not claim native title rights and interest in the claim area (at [29]-[30]). His Honour also determined that there was no evidence that Mr Petherick was authorised to bring the application (at [34]). For those reasons, and others, his Honour determined that the application should be struck out, but gave the applicant leave to make an application to overcome the identified deficiencies (at [38]).

38 The FRBG applicant subsequently applied for leave to amend the application and to adduce further evidence of authorisation. That application was the subject of the decision in Hazelbane 2014 in which Mansfield J refused to grant leave for the application to be amended, with the result that the original application was struck out pursuant to the decision in Hazelbane 2008. The first reason for the refusal was that the FRBG application was made on behalf of only the members of the Emu clan and the Blue Tongue Lizard clan, whereas Mr Petherick’s own evidence made clear that the native title holding group was a wider group (being possibly members of some 20 clans) (Hazelbane 2014 at [124]). The second reason was that Mansfield J did not consider that there was a reasonable foundation for Mr Petherick showing that he had been authorised as required by s 251B to act as the applicant on behalf of the FRBG, or even on behalf of the Emu clan and the Blue Tongue Lizard clan (at [125]). His Honour observed that there had been no conventional meeting of all members (or all eligible members) of the Emu clan and there was no anthropological evidence to support Mr Petherick’s claim that the traditional laws and customs of the Emu clan enabled him to act in effect unilaterally on behalf of its members to bring such a claim (at [128]). The third reason was that the anthropological evidence adduced in the proceeding contradicted the claim that members of the Emu clan, or the FRBG, hold native title rights and interests over Batchelor (at [136]).

39 The Thardim decision concerned six claims that related to an extensive area, including land and waters to the west of the Stuart Highway, to the north of Daly River and to the south of the Finnis River. The applicants to those claims sought leave to amend the applications, and the Territory sought orders dismissing the applications pursuant to s 84C. Broadly, the amendments were to expand the claim group for each application to comprise eight clans that were identified as the FRBG, being the Long Necked Turtle, Catfish, Red Kangaroo, Werak Goanna, Marri (Cycad/Glider Possum), Emu, King Brown Snake and Blue Tongue Lizard clans, and a ninth clan identified as the Freshwater Crocodile clan. Justice Mansfield refused to allow the amendments and dismissed each of the applications, largely for the reasons given in Hazelbane 2014. First, the findings made in Hazelbane 2014 were that the relevant native title holding groups probably included members of some 20 or so clans, not the eight or nine clans propounded in the six claims. Second, the six claims were inconsistent with the evidence and findings made in Hazelbane 2014, and the applicants had not adduced anthropological evidence to cast doubt on those findings. Third, the evidence did not establish that the claim groups met collectively and authorised the making of each of the claims.

40 As already noted, the foregoing decisions are not determinative of the present strike out application. First, the Territory did not ask the Court to adopt any of the findings made in the foregoing decisions pursuant to s 86 of the NTA, and the Territory did not contend that the applicant on the present claim was bound by any finding made in those decisions. Second, in the foregoing decisions, the evidence adduced by the applicant was contested by both cross-examination and contrary evidence adduced by respondent parties, whereas on the present application, the evidence adduced by the applicant was not the subject of cross-examination and nor was any contrary evidence adduced. The Territory’s strike out application in the present proceeding was based on alleged deficiencies in the evidence adduced by the applicant with respect to the authorisation of the claim and the application to amend it.

41 Nevertheless, the foregoing decisions highlight a significant issue on the present application. It is well-established that a sub-group of a native title holding group is not permitted to bring a claimant application on behalf of the native title holding group: Risk v National Native Title Tribunal [2000] FCA 1589 at [60]; Tilmouth v Northern Territory (2001) 109 FCR 240 at 241-242; Dieri People v State of South Australia (2003) 127 FCR 364 at [56]; Landers v South Australia (2003) 128 FCR 495 at 504; Harrington-Smith v Western Australia (No 9) [2007] FCA 31; 238 ALR 1 at [1209]-[1217]. As discussed below, the claimant application the subject of the present proceeding propounds that there are 22 clans that comprise the Dak Djerat Guwe claim group, but the claim has only been authorised by persons described as the ritual elders of 7 of those clans. The applicant contends that, under the traditional law and custom of the Dak Djerat Guwe people, the ritual elders of those 7 clans have the authority to make the decision to bring the claim on behalf of all clans because “some descendants of our ancestors are not directly involved in Dak Djerat Guwe traditional business, or there may be no living descendants”. An important issue that arises on the present applications is whether there is sufficient evidence before the Court to support the contention that the ritual elders of 7 of the 22 clans that comprise the claim group have the authority to approve the applicant to bring the claim on behalf of the claim group. If not, the Court could not be satisfied that the claim has been authorised by the native title claim group and the application would contravene the principle that a sub-group of a native title holding group is not permitted to bring a claimant application on behalf of the native title holding group.

D. The claimant application and evidence concerning authorisation

Native title determination application dated 26 October 2022

42 In the claimant application dated 26 October 2022, the native title claim group, the Dak Djarat Guwe People, are described as the biological descendants of 45 named male ancestors, 27 named female ancestors and one person said to have been “adopted under their traditional lore” (Captain Waditj). That description implied that membership of the claim group is by cognatic descent from any of the named ancestors. The application stated that the claim area is divided into clan areas making up pre-sovereignty traditional estates for each clan. The application further stated that the claimant group still maintain their clan system structure which is stated to comprise the following 22 clans: Marri (Cycad/Glider Possum); Emu; Blue Tongue Lizard; Werak Goanna (Pulimi); Long Neck Turtle; Catfish; Red Kangaroo; King Brown Snake; Goose; Freshwater Crocodile; Barramundi; Hairy Yam; Tree; Short Neck Turtle; Water Rat; Darter Bird; Water Snake; Wip Snake; Echidna; Waniwun; Blowfly; Saltwater Crocodile. It appears from the application that the clan names are totemic and the application states that the totems are essential to traditional marriage law and custom which continues to be observed.

43 The application did not include an anthropological report. However, annexed to the application (as Annexure T) was a document prepared by Edward Raymond Petherick titled “History of Aboriginal Habitation of the Litchfield National Park and Environs” dated March 2018. In the document, the author states that:

I spent 70 years living in an area generally bounded by the Finniss and Reynolds River systems which join the sea north of the Daly River and West of Darwin.

At the end of my service in the Australian Army after World War II I came to the Northern Territory and took up timber cutting, mining and crocodile hunting in an environment of rocky escarpments, untouched spring fed rainforests and pristine floodplains. Then fate dealt me a splendid hand.

I married Rosie Nungalaku, a member of the local descent group, the paperbark (Guwe) people, who are traditionally, culturally and spiritually connected with the broader family, (22 Clan Groups).

This book is a presentation of the prehistoric and post contact history of Australian aboriginals from the area of the Finniss and Reynolds Rivers southwest of Darwin in the Northern Territory of Australia.

44 Elsewhere in the report, the name “Nungalaku” is spelt “Nangalaku” (which is the spelling used by Ms Growden). I understand that the named applicants on the original claim, Ms Growden and the late Mr Petherick, are the children of Edward Raymond Petherick and his wife, Rosie Nangalaku. It is apparent from the report that Edward Raymond Petherick is of European heritage.

45 The application stated that the applicant is entitled to make the application “as persons authorised by the native title claim group by a process of decision-making that, under the traditional laws and customs of the native title claim group, must be complied with in relation to authorising things of that kind”. Annexed to the application were affidavits made by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick on 27 October 2022 in relevantly identical terms and in which they each deposed as follows:

4. The process of decision-making complied with in authorising me to make the application and to deal with matters arising in relation to it consisted of a process of authorisation given by the Ritual Elders of the Dak Djerat Guwe People, Gregory Muna (Goanna Clan), Richard Tcherna (Marri Clan), Peter Amitil (Longneck Turtle Clan), Thadius Dartingu (Freshwater Crocodile Clan), May Stevens (Blue Tongue Lizard Clan), Virgil Wanirr (King Brown Snake Clan), Raymond Bangun (Catfish Clan) and Kenneth Mulumbuk (Red Kangaroo Clan).

5 These people are the only current Ritual Elders, and are the traditional and customary decision makers for the Dak Djerat Guwe People.

6 A special meeting was held at Wadeye on 15 December 2018 with the Ritual Elders above, with the exception of May Stevens, and at that meeting this application was specifically authorised by them.

7 A photograph of the Ritual Elders attending that meeting can be seen at photo 142 page 189 of attachment T.

8 I have consulted with May Stevens over many years, she has undoubtedly given me the authority to make this application, and she is the only living person from, the Blue Tongue Lizard Clan known to me.

9. …

10. I know that our traditional people are aware that the Ritual Elders are the only persons that can give the authority necessary for this application … .

46 The photograph that appears at page 189 of Attachment T is titled “Elders authorisation meeting at Wadeye 15 December 2018” and lists those present in the photograph as Colin Wanirr, Leonard Dulla, Barnie Narjic, Peter Amital, Ambrose Jongman, Thaddeus Dartinga, Gabriel Thardim, Virgil Wanirr, Gregory Munar and Richard Tcherna.

47 As is apparent, there is a significant time lapse between the purported authorisation meeting (on 15 December 2018) and the filing of the native title determination application (on 27 October 2022). There are also a number of inconsistencies between the contents of the photograph and the evidence given by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick about the authorisation meeting. Those inconsistencies are:

(a) the following persons identified in the photograph are not referred to by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick: Colin Wanirr, Leonard Dulla, Barnie Narjic, Ambrose Jongman, and Gabriel Thardim; and

(b) the following persons referred to by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick are not identified in the photograph: Raymond Bangun and Kenneth Mulumbuk.

48 The application was not certified by a representative body under s 203BE of the NTA.

Amendment application dated 30 January 2023

49 On 30 January 2023, the applicant filed an application to amend the native title determination application. The application was supported by affidavits of Ms Growden and Mr Petherick made the same day. The proposed amendment was to substitute the form of the application at Annexure JG3 to Ms Growden’s affidavit.

50 In their affidavits, Ms Growden and Mr Petherick deposed (in identical terms) that they attended a meeting at the Darwin office of the Northern Land Council (NLC) on 8 October 2022 which was convened to authorise a native title claim on behalf of the “Werat group” (being the descendants of King Dick Parak) over areas subject to Exploration Permit Application (EP(A)) 218. Ms Growden and Mr Petherick deposed that the claim area for the Werat group “was in the middle of the traditional land of the Dak Djerat Guwe People”. They further deposed that, on 27 October 2022 and immediately prior to the filing of the claim on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe people, the NLC filed the following two native title determination applications:

(a) NTD 20/2022 (Rosemary Timber and another on behalf of the Werat Group v Northern Territory) (Werat claim); and

(b) NTD 21/2022 (Kamu and Wagiman v Northern Territory) (Kamu claim).

51 Ms Growden and Mr Petherick deposed that the claim areas of the Werat claim and the Kamu claim overlap the traditional country for the Dak Djerat Guwe people and that, on 7 December 2022, the Solicitor for the Territory wrote to the National Native Title Tribunal (Tribunal) suggesting that the Dak Djerat Guwe claim should be amended to exclude the area claimed in the Werat claim before registration. They also deposed that the Solicitor’s letter also questioned whether the Dak Djerat Guwe claim was properly authorised. A copy of that letter was not in evidence.

52 In relation to authorisation, Ms Growden and Mr Petherick each deposed as follows:

14. The Dak Djerat Guwe People maintain their traditional lore and that requires strict adherence to the traditional decision making processes that must be followed when decisions are made in relation to country.

15. There are only eight ritual elders empowered with the authority to authorise me to make this application and decisions in relation to it, and that authorisation took place on 15 December 2018 in conjunction many years of meetings and consultation, for example see pages 58, 70, 76- 78, 90, 83, 93, 107, 120, 122, 126, 129, 140 of Attachment T of the application.

16. The eight ritual elders named in my affidavit of 27 October 2022 carry the necessary authority as male elders under traditional lore, with exception of May Stevens who I believe is the last living member of her clan, others have deceased or do not follow their traditional law.

17. May Stevens carries the authority because she is the last known person of the Blue Tongue Lizard Clan.

53 The proposed amended claim contained a number of amendments, including with respect to the claim area, the description of the claim group and the description of the authorisation process.

54 The claim area was amended to exclude those areas which are the subject of the Werat claim and the Kuma claim.

55 The description of the claim group was amended in a number of ways. First, three male ancestors and eight female ancestors were removed from the list of apical ancestors. Neither the affidavits of Ms Growden and Mr Petherick nor the amended application explained the process by which the decision had been made to exclude those apical ancestors. Second, a clan group identity was assigned to each of the apical ancestors. Third, an explanation of the basis upon which descendants of the apical ancestors acquire rights and interests in the claim area was added in the following terms:

The biological descent basis upon which the members of the native title claim group can be identified is patrilineal.

In the circumstance of a person having biological descent from a male person outside of the native title claim group, the biological descent basis is determined upon descent from that persons' mothers' father.

Should it be the case that the mothers' father is also outside of the native title group, the biological descent basis is determined upon descent from the persons' grandmothers' father who belongs to the native title claim group.

56 That description involved a significant change from the claim that was filed, which implicitly defined membership on the basis of cognatic descent from the named male or female ancestors. The new description defined membership on the basis of patrilineal descent, including descent from a person’s mother’s father, or a person’s grandmother’s father where they were members of the claim group. On that description, it is unclear why the list of apical ancestors continued to include female ancestors.

57 The description of the authorisation process was amended to state that “[e]xtensive consultation with existing clan members regarding the making of this claim has taken place in the past and present, and for more than a decade”, with reference being made to meetings conducted during 2014. The description continued with the statements that “[e]very effort has been made to identify and consult with all adult members of the Claimant Group” and that “[t]he consensus of the Claimant Group is that all identifiable members should, if they hold native title rights and interests, be included in the Claimant Group”. The description was also amended to include the following statements made by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick in their affidavits:

The Dak Djerat Guwe People maintain their traditional lore and that requires strict adherence to the traditional decision making processes that must be followed when decisions are made in relation to country.

There are only eight ritual elders empowered with the authority to authorise me to make this application and decisions in relation to it, and that authorisation took place on 15 December 2018 in conjunction many years of meetings and consultation, … .

The eight ritual elders named in my affidavit of 27 October 2022 carry the necessary authority as male elders under traditional lore, with exception of May Stevens who like so many of the blood lines of the original 22 clans is the last of their clan, deceased or who do not follow their traditional law.

May Stevens carries the authority because she is the last known person of the Blue Tongue Lizard Clan.

58 The application also included a statement that “Attachment T also contains a Summary from Anthropoogist [sic] Jacinta Warland BSSc.Arc. M.ADR”. Included within Annexure T is an untitled and unsigned four page document, with the name Jacinta Warland appearing at the bottom. The status of the document is unclear, but it appears to be in the nature of a draft document. The document contains no substantive information, analysis or opinions, and consists of generalised statements concerning the need for further research to be completed in relation to the claim made by the Dak Djerat Guwe people. Attached to the document is a list of male and female apical ancestors for the “Dak Djerat Guwe clans”. That list differs from the list contained in the proposed amended claimant application in the following ways:

(a) First, the following ancestors are not included in the list of male ancestors attached to Ms Warland’s document but are included in the list of male ancestors in the claimant application and the proposed amended application: Tedak, Thalagan, Thulumbun, Tiger Jongman, Tjinjabat, Tommy Julmun, Tommy Moyle Kurungu, Wangine and Willy Gaden. It is possible that there is a page missing from Ms Warland’s document which explains the exclusion.

(b) Second, the following ancestors are not included in the list of female ancestors attached to Ms Warland’s document but were included in the list of female ancestors in the claimant application and excluded from the list in the proposed amended application: Minimuk, Namitjanganga, Nanaga, Parmgulla, Pilen, Poiyiri, Tjuwainh and Wurriyende;

(c) Third, the following ancestor is included in the list of male ancestors attached to Ms Warland’s document, and is included in the list of male ancestors in the claimant application, but is excluded from the proposed amended application: Guman Daua (Jessie).

The Territory’s application for evidence of authorisation

59 On 20 June 2023, the Territory filed an interlocutory application seeking orders, amongst others, requiring Ms Growden and Mr Petherick to file and serve evidence that they were authorised to make and to amend the claim. The application also foreshadowed an application by the Territory to strike out the claim (depending upon the evidence adduced by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick). The interlocutory application was supported by an affidavit of Kalliopi (Poppi) Gatis made the same day which exhibited documentation relating to the Werat and Kamu claims.

60 In submissions dated 16 June 2023, the Territory referred to the apparent inconsistencies in the statements made about the authorisation process for the Dak Djerat Guwe claim. Relevantly, the affidavits of Ms Growden and Mr Petherick, and the application itself, state that the Dak Djerat Guwe people maintain their traditional law which requires strict adherence to the traditional decision making processes that must be followed when decisions are made in relation to country, and that there are only eight ritual elders empowered with the authority to authorise the application and decisions in relation to it. Those eight persons are identified as the following male elders – Gregory Muna (Goanna clan), Richard Tcherna (Marri clan), Peter Amitil (Longneck Turtle clan), Thadius Dartingu (Freshwater Crocodile clan), Virgil Wanirr (King Brown Snake clan), Raymond Bangun (Catfish clan) and Kenneth Mulumbuk (Red Kangaroo clan) – as well as May Stevens who is said to have authority as the last known person of the Blue Tongue Lizard clan. Ms Growden and Mr Petherick also deposed that the claim was authorised at a meeting held at Wadeye on 15 December 2018 and identified a photographic of the people attending the meeting.

61 As the Territory observed, and as noted earlier, the evidence concerning the meeting on 15 December 2018 is inconsistent. Not all of the claimed ritual elders are shown in the photo, and the photo includes people who are not claimed to be ritual elders. The evidence concerning May Stevens’ authority is also vague, both as to her status as a female ritual elder and the date on which she purportedly gave her authorisation. The evidence of Ms Growden and Mr Petherick that they consulted May Stevens over many years begs the question of what, precisely, did Ms Stevens authorise?

62 As the Territory also observed, Ms Growden and Mr Petherick referred to conducting consultations with the Dak Djerat Guwe people and this appears to be put forward in the application as further evidence of authorisation. However, the purpose of such consultations is unclear in circumstance where Ms Growden and Mr Petherick asserted that decisions in relation to country can only be made by the eight ritual elders. Further, such consultations appear to have occurred a long time ago (possibly in 2014) which again begs the question of what, precisely, was the subject of consultation.

Hearing on 30 June 2023

63 The interlocutory applications filed by the applicant and by the Territory were listed for mention on 30 June 2023. Prior to that hearing, the parties proposed orders by consent which were made. Those orders required Ms Growden and Mr Petherick to file and serve, by 28 July 2023, evidence that they were authorised to make and to amend the native title claimant application. The orders then provided for the parties to file submissions with respect to any orders sought on the issue of authorisation, with a hearing to be conducted on 21 August 2023. The timetable was extended by orders made on 8 August 2023, with a hearing to be conducted on 11 September 2023.

Applicant’s further evidence on 9 August 2023

64 On 9 August 2023, Jane Louise Welsh, a solicitor at Finlaysons acting for the applicant, made an affidavit which annexed affidavits made by:

(a) Peter Amital, Daniel Jongman, Kenneth Mullumbuk, Richard Tcherna and Virgil Wanirr on 26 July 2023;

(b) Ms Growden on 9 August 2023; and

(c) Gregory Munar on 9 August 2023.

65 Ms Welsh deposed that the affidavits were provided for the purposes of the Court’s order requiring evidence that Ms Growden and Mr Petherick were authorised to make and to amend the claimant application.

66 The affidavits made on 26 July 2023 are in materially identical terms. Each of the deponents deposed that the following seven persons are the ritual elders of the following clans:

(a) Gregory Munar - Goanna clan;

(b) Peter Amital - Long Neck Turtle clan;

(c) Thadius Dartinga - Freshwater Crocodile clan;

(d) Virgil Wanirr - King Brown Snake clan;

(e) Richard Tcherna - Cycad/Sugar Glider clan;

(f) Ambrose Jongman - Emu clan;

(g) Raymond Bangun - Catfish clan,

and also deposed that “some descendants of our ancestors are not directly involved in Dak Djerat Guwe traditional business, or there may be no living descendants”. The meaning of that statement is unclear. It can be noted that Kenneth Mullumbuk is not identified as a ritual elder. Each deponent also deposed to their belief that May Stevens is the last living elder of the Blue Tongue Lizard clan.

67 The affidavit made by Gregory Munar on 9 August 2023 is in substantially the same form, save that Mr Munar did not list himself as a ritual elder and deposed that Kenneth Mullumbuk is a ritual elder for the Red Kangaroo clan. However, later in the affidavit, Mr Munar deposed that:

Under our traditional laws and customs there is one ritual elder who holds authority over the current male ritual elders of each of our clans, and that is me.

68 It is not clear from that statement whether Mr Munar is asserting authority over the other ritual elders of the Dak Djerat Guwe clans.

69 Each of the deponents (including Ms Growden) deposed that:

The traditional decision-making process for the Dak Djerat Guwe about a question that affects native title interests in Dak Djerat Guwe country, is a traditional decision-making process that is made together with the current male ritual elders of each of our clans.

70 Each affidavit (including Ms Growden) also deposed that an authorisation meeting was held at Wadeye on 15 December 2018 attended by Peter Amital, Colin Wanirr, Thaddeus Dartinga, Gabriel Thardim, Virgil Wanirr, Richard Tcherna, Gregory Munar, Ambrose Jongman, Leonard Dulla and Barnie Narjic. In some of the affidavits (but not all), Ambrose Jongman is described as deceased, and yet in those same affidavits he is described as being a “current ritual elder”. Each of the affidavits contain a statement that:

At this meeting, by the traditional decision-making process of the Dak Djerat Guwe that under traditional law must be complied with in relation to a question that affects native title interests in Dak Djerat Guwe country, authorisation was given:

(a) to make a claim for Native Title Determination over the traditional land of the Dak Djerat Guwe People; and

(b) to Joan Growden Nungalku nee Petherick and Thomas Edward Petherick Meering to be the applicants making the claim on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe, and to deal with any matters arising in relation to the making of the Claim.

71 It can be observed that the foregoing evidence concerning the attendees at the meeting on 15 December 2018 is inconsistent with the evidence of Ms Growden and Mr Petherick in their affidavits of 27 October 2022. In particular, the foregoing evidence excludes Raymond Bangun and Kenneth Mullumbuk and includes Colin Wanirr, Gabriel Thardim, Ambrose Jongman, Leonard Dulla and Barnie Narjic.

72 It can also be observed that Raymond Bangun is said to be a ritual elder of the Catfish clan, but did not make an affidavit concerning authorisation and, on the foregoing evidence, did not attend the meeting on 15 December 2018.

73 Nor was there an affidavit from Ambrose Jongman. As already noted, some of the affidavits described Ambrose Jongman as deceased, but then inconsistently listed him as a current ritual elder. In his affidavit, Daniel Jongman listed his occupation as “ritual elder” and deposed that he is a traditional elder for the Emu clan. However, he also deposed that Ambrose Jongman is a current ritual elder for the Emu clan, although later he described Ambrose Jongman as deceased.

74 Nor, at that time, was there an affidavit from Thadius Dartinga. However, as discussed below, Mr Dartinga made an affidavit on 12 September 2023.

75 No evidence was given concerning Leonard Dulla and Barnie Narjic, including with respect to the clans they belong to and the reason why they attended the meeting on 15 December 2018.

76 Given the extent of inconsistencies, the evidence adduced on the issue of authorisation can only be described as unsatisfactory.

77 The affidavit made by Ms Growden differed from the other affidavits and contained additional evidence. Not all of it is relevant to the question of authorisation. Nevertheless, the following matters should be noted.

78 First, Ms Growden deposed that:

I have authority under our traditional laws and customs to make decisions and to act on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe people as the descendant of my great grandfather Thulumbun, and my grandmother Dididi, and my mother Rosie Petherick Nangalaku, born 1925.

79 By that paragraph, Ms Growden appears to assert authority to make decisions for and to act on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe people by reason of descent from her great grandfather. None of the other deponents stated that they have that authority. Rather, each refers to their responsibility for Dak Djerat Guwe country.

80 Second, Ms Growden deposed that the proposed amendments to the list of apical ancestors in the native title claimant application resulted from Ms Growden conducting “enquiries amongst our group”. Ms Growden deposed that there is a lack of recorded evidence or knowledge of clan membership for some of the listed ancestors, and “it seemed prudent” to remove those people from the list. Ms Growden further deposed that, subsequent to the enquiries, it has been confirmed that Minimuk, Parmgulla and Pilen are recognised as Dak Djerat Guwe ancestors, and therefore should remain as such in the claim.

81 Third, Ms Growden deposed that the claimant group had engaged an anthropologist and secured legal representation. Despite that, no anthropological evidence has been adduced on behalf the applicant at any stage.

Territory’s submissions on 23 August 2023

82 In accordance with the orders of the Court, on 23 August 2023 the Territory filed written submissions on the issue of authorisation. By those submissions, the Territory sought an order that the claim be dismissed without prejudice to the rights of the applicant to commence a further proceeding.

83 The Territory’s submissions drew attention to the inconsistencies and deficiencies in the applicant’s evidence, which have been identified earlier in these reasons. Those inconsistencies and deficiencies can be summarised as follows.

84 First, the evidence is that the traditional decision-making process for the Dak Djerat Guwe people about a question that affects native title interests in Dak Djerat Guwe country is a traditional decision-making process that is made together with the current male ritual elders of each of “our clans”. The evidence indicates that there are more than 20 clans, but only seven male ritual elders, and one female elder, authorised the making of the claim.

85 Second, the evidence is that the relevant authorisation decision was made at Wadeye on 15 December 2018, but the evidence concerning the attendees at that meeting and their authority to make a decision to bring the claim is inconsistent.

86 Third, the evidence does not explain what is involved in the traditional decision-making process. As noted above, the amended claim states that “[e]xtensive consultation with existing clan members regarding the making of this claim has taken place in the past and present”, that “[e]very effort has been made to identify and consult with all adult members of the Claimant Group” and that “[t]he consensus of the Claimant Group is that all identifiable members should, if they hold native title rights and interests, be included in the Claimant Group”. No evidence was adduced about that consultation process. Further, no evidence was given about the process of making the relevant decision at Wadeye on 15 December 2018, including what information was provided to the ritual elders about the claim (which was not made until almost 4 years later).

87 Fourth, there is no evidence concerning authorisation of the amendments to the claim, which amendments include substantive matters such as a reduction in the claim area and the removal of a number of apical ancestors.

88 On the basis of the foregoing, the Territory submitted that there had been a failure to comply with s 62 of the NTA so as to give details of the asserted decision-making process.

89 The Territory also drew attention to the shifting description of the claim group. The first description was given in the native title claimant application. The second description was given in the proposed amended application, which proposed the removal of the names of 11 ancestors. A third description was given in the list attached to Jacinta Warland’s note that was annexed to the proposed amended application which, as discussed earlier, is not entirely consistent with the proposed amended application. A fourth description was given in Ms Growden’s affidavit dated 9 August 2023, which proposed the reinstatement of the names of three ancestors, which is inconsistent with the proposed amended application and Ms Warland’s list. The evidence concerning the manner in which the list of ancestors was formulated and changed is vague. The evidence does not establish that the list included in the claimant application was approved at the meeting at Wadeye in 2018, and there is no evidence that any of the changes to the list have been authorised.

90 Having regard to the foregoing matters, the Territory submitted that there is no reasonable basis upon which it can be concluded that the claim is authorised, either as made or in its amended form.

Hearing on 10 November 2023

91 Mr Petherick died in or around August 2023 which caused the parties to seek an adjournment of the hearing scheduled for 11 September 2023.

92 On 4 September 2023, orders were made by consent for the matter to be listed for case management on 10 November 2023.

93 At the hearing on 10 November 2023, orders were made listing for hearing the Territory’s interlocutory application seeking the striking out of the claimant application under s 84C. The applicant was also given leave to file any further evidence in response to that application, and for the Territory to file any evidence in reply.

Applicant’s further evidence in February 2024

94 Pursuant to the orders of the Court made on 10 November 2024, Ms Growden filed a further affidavit affirmed by her on 8 February 2024. The statements made by Ms Growden do not add substantively to the evidence previously given by her. However, Ms Growden also exhibited to her affidavit the following additional affidavits:

(a) an affidavit of Thaddeus Dartinga made on 12 September 2023; and

(b) a further affidavit of Gregory Munar made on 8 February 2024.

95 Mr Dartinga’s affidavit made on 12 September 2023 is in substantially the same form as the affidavits made on 26 July 2023, discussed earlier. One difference is that Mr Dartinga deposed that Kenneth Mullunbuk is a ritual elder (for the Red Kangaroo clan), whereas none of Peter Amital, Daniel Jongman, Richard Tcherna, Virgil Wanirr or even Kenneth Mullumbuk himself gave that evidence.

96 In his affidavit made on 8 February 2024, Mr Munar gave further evidence about the meeting held at Wadeye on 15 December 2018. Mr Munar deposed that Raymond Bangun and Kenneth Mullumbuk were not able to attend that meeting because of ill health, but their absence “did not affect the ability of those present to make decisions or give authority by means of our traditional decision making process”. No explanation was provided by Mr Munar with respect to that statement. Specifically, no evidence was given with respect to the traditional decision making process of the Dak Djerat Guwe people and the persons who must be present or must be consulted before decisions can be made.

Applicant’s further submissions in February 2024

97 Pursuant to the orders of the Court, the applicant also filed a written submission addressing the issue of authorisation to make and to amend the claim. Those submissions, and my findings with respect to the submissions, follow.

Absence of authorisation

98 The applicant submitted that, in cases concerning native title, the testimony of Indigenous people, either by affidavit or on oath in court, is the best evidence to determine the existence of traditional decision-making processes and other native title claim issues (citing Attorney-General (NT) v Maurice (1986) 161 CLR 475 at 492; Sampi v Western Australia [2005] FCA 777 at [48]; De Rose v South Australia [2002] FCA 1342 (De Rose) at [351]). Historical evidence and the evidence of experts is secondary to the testimony of Indigenous people in relation to the existence of their traditional laws and custom (citing De Rose at [351]). The submission should be accepted in so far as the evidence concerns the laws and customs presently acknowledged and observed by the Indigenous witnesses, and how the Indigenous witnesses came to learn of those laws and customs. The submission may be overstated in so far as the evidence concerns laws and customs acknowledged and observed at or around the time of European settlement of Australia or other historical facts.

99 The applicant submitted that the evidence of the witnesses establishes that:

(a) Ms Growden and Mr Petherick were authorised to bring the claim on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe people following a meeting of the ritual elders of the clans (with the exception of Raymond Bangun and Kenneth Mulumbuk who were unable to attend) held on 15 December 2018 at Wadeye;

(b) there are only 8 ritual elders remaining in the claim group as some clan groups are not involved in the Dak Djerat Guwe traditional business;

(c) as the last living member of the Blue Tongue Lizard clan known to Dak Djerat Guwe people, May Stevens possesses the requisite authority to authorise the applicants and has affirmed her intention to do so; and

(d) the conferral of authority on Ms Growden and Mr Petherick to bring the claim and to deal with matters arising in relation to it has been further confirmed by 7 of the 8 ritual elders in the affidavits filed.

100 The difficulty with that submission is that it does not address the numerous inconsistencies and deficiencies in the evidence concerning authorisation as discussed earlier in these reasons. Those inconsistencies and deficiencies include:

(a) the meeting at Wadeye occurred nearly 4 years prior to the claim being filed and there is no evidence concerning what was authorised (for example, there is no evidence concerning the apical ancestors considered at that meeting);

(b) the persons who attended the meeting at Wadeye do not correspond with the persons who are now said to be the ritual elders with authority to make decisions for the Dak Djerat Guwe people, and at least two of the persons who are now said to be the ritual elders with authority to make decisions for the Dak Djerat Guwe people were not present at the Wadeye meeting (Raymond Bangun and Kenneth Mullumbuk);

(c) two of the persons said to be ritual elders with decision making authority have not given evidence affirming that fact (Raymond Bangun and Ambrose Jongman);

(d) it is not clear from the evidence whether May Stevens is considered to be a ritual elder of the Blue Tongue Lizard clan (being the last living member) who is required to participate in the decision making process, noting that there is also no evidence given by May Stevens and the evidence given by Ms Growden and Mr Petherick concerning May Stevens’ approval of the claim is vague and inadequate; and

(e) the claim is brought on behalf of 22 Dak Djerat Guwe clans but only 6 (or possibly 7, if the Blue Tongue Lizard clan is counted) ritual elders approved the original claim.

Existence of a mandatory decision-making process

101 The applicant submitted that the proof of the existence of a traditional decision-making process for the purposes of s 251B of the NTA need not be onerous, citing Noble v Mundraby, Murgha, Harris and Garling [2005] FCAFC 212 at [18]. That case concerned proof of the conduct of a meeting at which a claim was authorised and does not support the breadth of the submission made. The difficulty faced by the applicant is the paucity of the evidence adduced with respect to the traditional decision making process of the Dak Djerat Guwe people.

102 The applicant further submitted that the various affidavits of the ritual elders affirm the traditional decision making process of the Dak Djerat Guwe about a question that affects native title interests as one “made together with the current male ritual elders of each of our clans” and that “there is one ritual elder who holds authority over the current male ritual elders of each of our clans,” that being Gregory Munar. Each of those propositions is problematic. The first proposition is that decisions must be “made together” with the current ritual elders of “each of our clans”. The claim identifies some 22 clans of the Dak Djerat Guwe people but approval has only been given by 6 (or 7) ritual elders. The evidence concerning the exclusion of the other clans is vague, being that “some descendants of our ancestors are not directly involved in Dak Djerat Guwe traditional business, or there may be no living descendants”. There is no positive evidence that the other clans have ceased to exist because there are no living descendants, and the statement that other clans are not directly involved in the Dak Djerat Guwe traditional business is question begging. There is no explanation of why or how, under traditional law and custom, a clan would cease to have a decision-making role because the members of the clan have ceased to be involved in unspecified traditional business. The second proposition, that Gregory Munar holds authority over the current male ritual elders of each of the clans, is only supported by Mr Munar’s affidavit. No other witness refers to Mr Munar having such authority and the evidence of the other witnesses, referring to the ritual elders making decisions together, is inconsistent with the proposition.

103 The applicant also placed reliance on the document apparently authored by Jacinta Warland which is attached to the proposed amended claim. The document has no evidentiary value. It is unsigned and appears to be in the nature of a draft document. Furthermore, as noted earlier, the document contains no substantive information, analysis or opinions, and merely consists of generalised statements concerning the need for further research to be completed in relation to the claim made by the Dak Djerat Guwe people.

Authorisation to amend the application

104 The applicant submitted that, once Ms Growden and Mr Petherick were authorised to make the claim on behalf of the Dak Djerat Guwe people, there is no legal requirement for them to obtain further authorisation to amend the claim. In that regard, the applicant placed reliance on s 62A which provides that, in the case of a claimant application, the applicant may deal with all matters arising under the NTA in relation to the application (subject to any conditions imposed by the persons who authorised the making of the application as per s 251BA). The applicant submitted that this includes an amendment to reduce the area claimed (citing Drury v Western Australia (2000) 97 FCR 169 at [12]; Grant v Minister for Land & Water Conservation for New South Wales [2003] FCA 621 at [32]; Champion v Western Australia [2009] FCA 1141 at [1]-[12]; and Torres v Western Australia [2012] FCA 972 at [12]) and an amendment to the composition of the native title claim group (citing Velickovic v Western Australia [2012] FCA 782 at [37]; and Strickland v Western Australia [2013] FCA 677 at [12]).

105 As a matter of principle, the applicant’s submission must be accepted.

Inconsistencies in the native title claim group description

106 The applicant submitted that the inconsistencies in the descriptions of apical ancestors put forward by the applicant are not so substantial as to invalidate the claim. The applicant submitted that the evidence shows that Ms Growden and Mr Petherick made enquiries among the Dak Djerat Guwe people and identified a lack of recorded evidence or knowledge of clan membership for some of the ancestors which necessitated the removal of names from the list.

107 As discussed earlier in these reasons, the evidence concerning the basis upon which the list of ancestors was originally formulated and then changed is vague. The evidence does not establish that the list included in the claimant application was approved at the meeting at Wadeye in December 2018.

Territory’s submissions on 29 February 2024

108 The Territory filed further submissions on 29 February 2024, which principally relied on the Territory’s earlier written submissions. The Territory maintained its contention that the applicant had failed to identify the process of traditional decision-making required to be followed when authorising the making of the claim and, in that context, to provide evidence establishing that the applicant is authorised to bring the claim on behalf of the “native title claim group” as defined by s 61 of the NTA. The Territory emphasised that the applicant relied upon a decision said to have been made at Wadeye in December 2018, nearly four years prior to the claim being made, and in circumstances where the applicant has now advanced a number of different descriptions of the claim group, all of which were formulated after the asserted authorisation meeting.

Hearing on 4 March 2024

109 The interlocutory applications filed by the applicant (to amend the claim) and by the Territory (to strike out the claim) came on for hearing on 4 March 2024. At that hearing, I informed the applicant that the evidence concerning the authorisation of the claim was lacking in detail. The purported authorisation meeting occurred in December 2018, the claim was not filed until October 2022, there was no clear evidence about the traditional decision making processes of the claim group, and there was no evidence about the information that was before the asserted decision makers or the content of the decision.

110 At the hearing, I raised with the parties the prospect that the dispute could be resolved in another manner, specifically by the applicant convening a new meeting to authorise the claim and adducing evidence of the authorisation process including: the calling and holding of the meeting; the information provided to the meeting concerning the details of the claim (including the claim area, the claim group and the native title rights and interests claimed); and the decision making process at the meeting. I invited submissions on the question whether the Court is empowered by s 84D(4) to make orders for the convening of a further authorisation meeting in order to rectify any failure to comply with ss 61 or 62 of the NTA.

111 Following an adjournment, the applicant requested an opportunity to call a further authorisation meeting in respect of the claim and adduce evidence of the further authorisation. The applicant indicated that, at the further authorisation meeting, the relevant decision makers would also appoint an applicant to replace the late Mr Petherick. The applicant informed the Court that the earliest feasible date for such a meeting would be June 2024. That request was not, in substance, opposed by the Territory.

112 As a result, at the hearing the Court made orders:

(a) adjourning the Territory’s interlocutory application to strike out the claim until 2 August 2024;

(b) granting the applicant leave to seek the authorisation by the native title claim group, in accordance with s 251B of the NTA, of the claimant application as filed or as sought to be amended and the addition or replacement of one or more persons to constitute the applicant for the claim; and

(c) requiring the applicant to file evidence of the authorisation by 12 July 2024.

113 The Court subsequently made orders by consent extending the time by which the applicant was required to file its further evidence until 12 September 2024, with the hearing of the applications rescheduled to 30 September 2024.

Applicant’s further evidence on 12 September 2024