FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 208

File number: | WAD 56 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | FEUTRILL J |

Date of judgment: | 18 March 2025 |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – declaratory relief under s 545 and pecuniary penalties under s 546 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) – multiple breaches of obligations to provide training under enterprise agreements – multiple contraventions of s 50 of the Act – course of conduct under s 547 of the Act – principles applicable to pecuniary penalties – application of criminal law sentencing principles – single course of conduct principle – totality principle |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) s 4AA Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 191 Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ss 3,14, 43, 44, 45, 50, 52, 280, 323, 539, 545, 546, 557; Chs 2, 4; Pts 2-2, 2-5, 4-1 Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) s 305 |

Cases cited: | Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Huddy (No 2) [2017] FCA 1088 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Registered Organisations Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 232; 283 FCR 404 Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd (ABN: 46 123 021 492) [2023] WAIRC 00976 Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd [2024] WAIRC 00220 Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 194 IR 461 Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Williams [2009] FCAFC 171; 191 IR 445 Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCAFC 59; 229 FCR 331 Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2016] FCA 413 Fair Work Ombudsman v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (Kiama Aged Care Centre Case) (No 3) [2023] FCA 1324 Forster v Jododex [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421 Gibbs v Mayor, Councillors and Citizens of City of Altona [1992] FCA 553; 37 FCR 216 Maritime Union of Australia v Qube No 1 Pty Ltd [2017] SAIRC 5 Parker v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2019] FCAFC 56; 270 FCR 39 QR Ltd v Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union (Cth) [2010] FCAFC 150; 204 IR 142 Rocky Holdings Pty Ltd v Fair Work Ombudsman [2014] FCAFC 62; 221 FCR 153 Royer v Western Australia [2009] WASCA 139; 197 A Crim R 319 Sayed v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2016] FCAFC 4; 239 FCR 336 Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc [1993] FCA 105; 41 FCR 89 |

Division: | Fair Work Division |

Registry: | Western Australia |

National Practice Area: | Employment and Industrial Relations |

Number of paragraphs: | 101 |

Date of hearing: | 17 September 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr P Boncardo |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union (the Maritime Union of Australia Division) |

Counsel for the Respondent: | Mr M Follett SC with Ms H Millar |

Solicitor for the Respondent: | Corrs Chambers Westgarth |

ORDERS

WAD 56 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | CONSTRUCTION, FORESTRY, MARITIME, MINING AND ENERGY UNION Applicant | |

AND: | QUBE PORTS PTY LTD (ACN 123 021 492) Respondent | |

order made by: | FEUTRILL J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 March 2025 |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

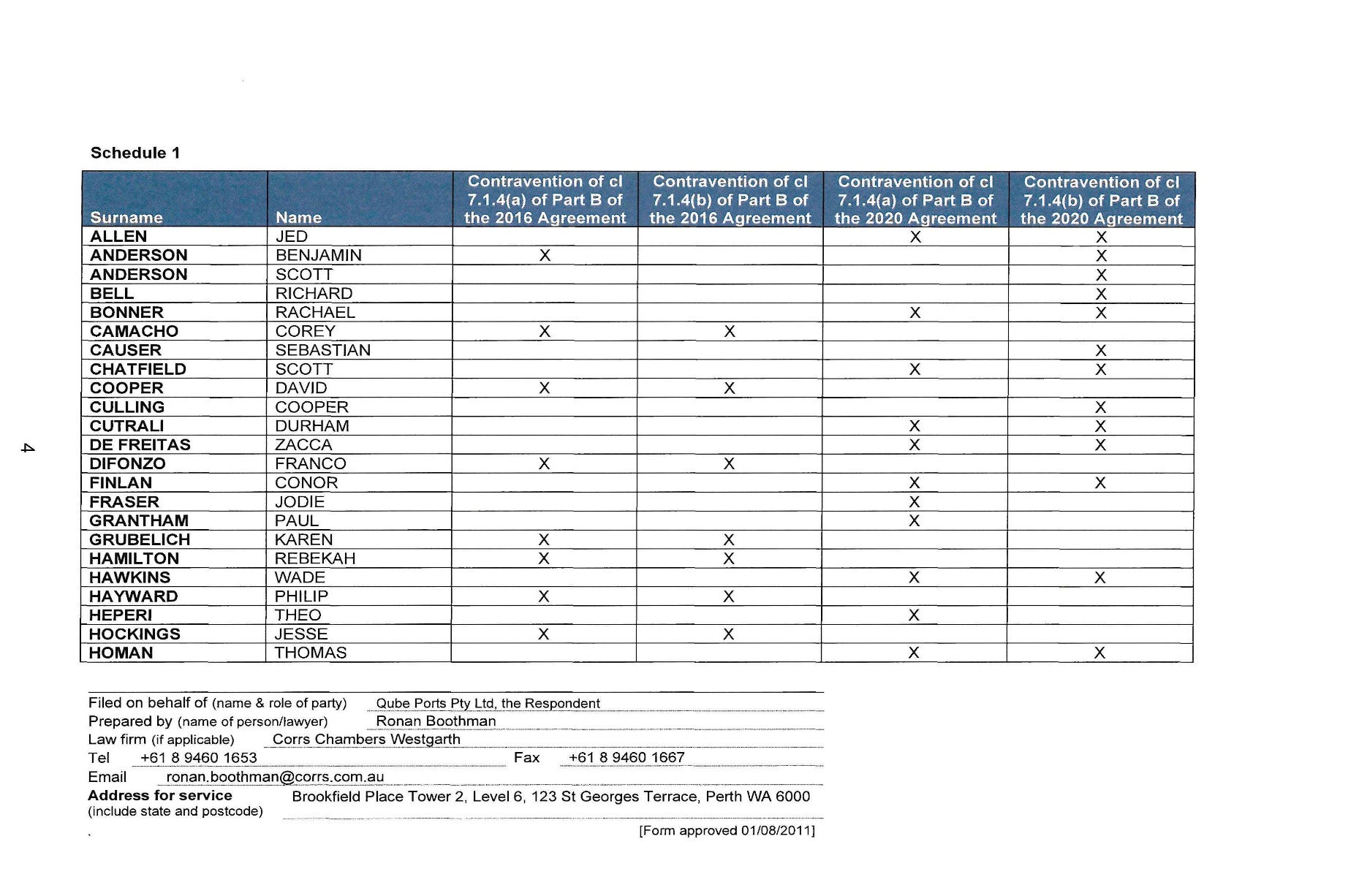

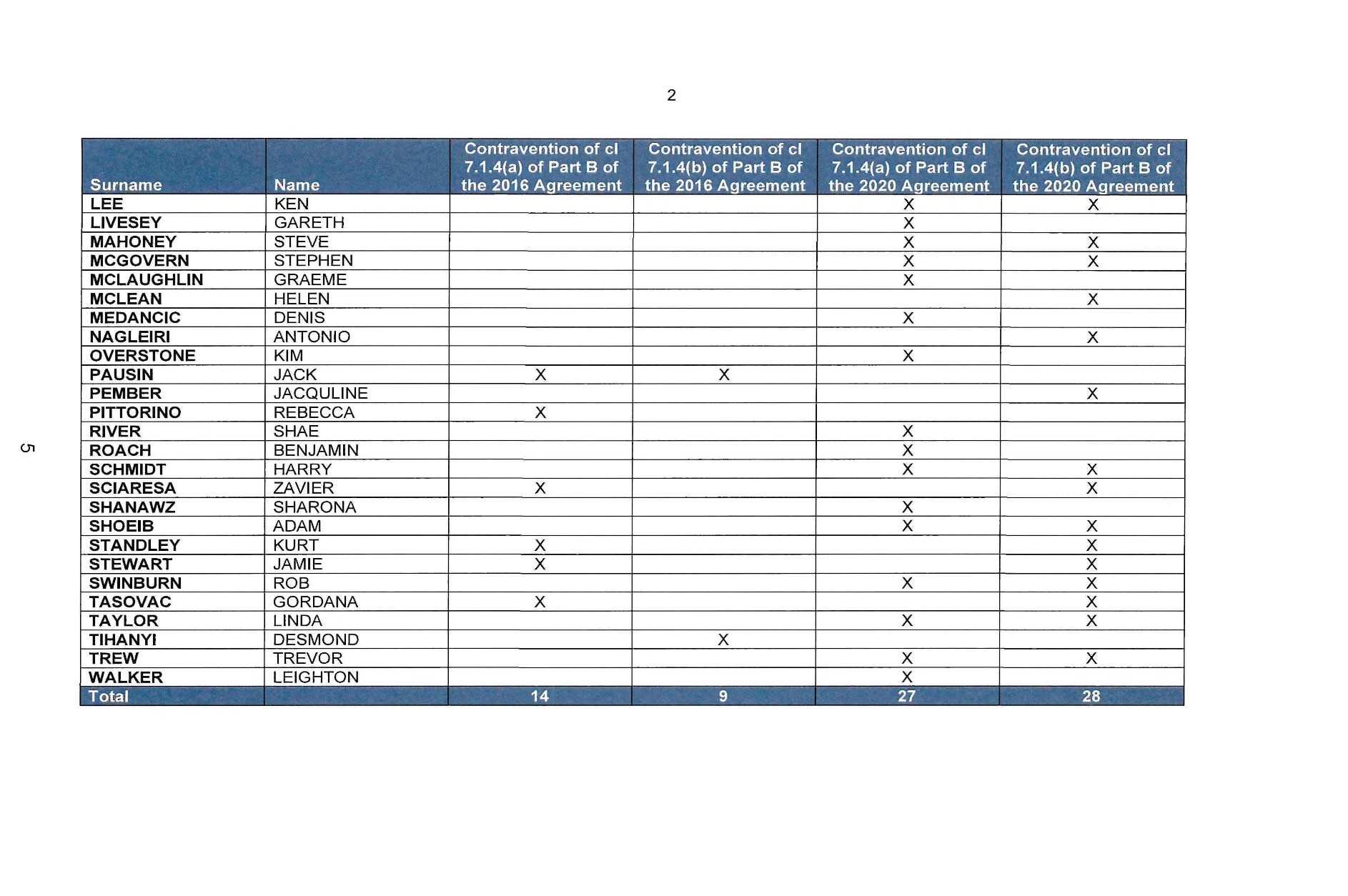

1. The respondent (Qube Ports Pty Ltd) contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) by failing to provide training to 14 guaranteed wage employees in a skill (being grade 3 or higher) within 6 months of the employees becoming a guaranteed wage employee in accordance with clause 7.1.4.a of Part B of the Qube Ports Pty Ltd Port of Fremantle Enterprise Agreement 2016 during the operation of that enterprise agreement.

2. The respondent (Qube Ports Pty Ltd) contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) by failing to provide training to 9 guaranteed wage employees in a skill (being grade 3 or higher) within 12 months of the employees becoming a guaranteed wage employee in accordance with clause 7.1.4.b of Part B of the Qube Ports Pty Ltd Port of Fremantle Enterprise Agreement 2016 during the operation of that enterprise agreement.

3. The respondent (Qube Ports Pty Ltd) contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) by failing to provide training to 27 guaranteed wage employees in a skill (being grade 3 or higher) within 6 months of the employees becoming a guaranteed wage employee in accordance with clause 7.1.4.a of Part B of the Qube Ports Pty Ltd Port of Fremantle Enterprise Agreement 2020 during the operation of that enterprise agreement.

4. The respondent (Qube Ports Pty Ltd) contravened s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) by failing to provide training to 28 guaranteed wage employees in a skill (being grade 3 or higher) within 12 months of the employees becoming a guaranteed wage employee in accordance with clause 7.1.4.b of Part B of the Qube Ports Pty Ltd Port of Fremantle Enterprise Agreement 2020 during the operation of that enterprise agreement.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant’s name in the proceeding be amended to ‘Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union’.

2. The respondent pay a pecuniary penalty of $12,600 in respect of its contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) referred to in paragraph 1 of the declarations made in these orders.

3. The respondent pay a pecuniary penalty of $12,600 in respect of its contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act referred to in paragraph 2 of the declarations made in these orders.

4. The respondent pay a pecuniary penalty of $23,310 in respect of its contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act referred to in paragraph 3 of the declarations made in these orders.

5. The respondent pay a pecuniary penalty of $23,310 in respect of its contravention of s 50 of the Fair Work Act referred to in paragraph 4 of the declarations made in these orders.

6. The pecuniary penalties set out in paragraphs 2 to 5 of these orders be paid to the applicant.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

FEUTRILL J:

Introduction

1 Section 546 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) provides that the Court may order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the Court considers appropriate if satisfied that the person contravened a civil remedy provision. Section 50 of the Act is a civil remedy provision and it provides that a person must not contravene a term of an enterprise agreement.

2 It is not in issue that the respondent contravened two terms of two enterprise agreements multiple times in the period between September 2017 and April 2023 and, thereby, contravened s 50 of the Act. In that period two enterprise agreements applied to the respondent’s employees at the port of Fremantle. An enterprise agreement the Fair Work Commission approved on 2 May 2017 (2016 Agreement) and an enterprise agreement the Commission approved on 21 December 2021 (2020 Agreement). The relevant provisions of those Agreements were in the same terms and one clause required the affected employees to receive certain training within six months of commencing employment and the other clause required the provision of certain other training within 12 months of commencing employment. The respondent failed to meet the training requirements within the six-month and 12-month periods resulting in breaches of the two separate clauses of the 2016 Agreement and the 2020 Agreement. It is also not in issue that, in the circumstances of this case, by operation of s 557 of the Act, the multiple contraventions of each clause of each Agreement are taken to constitute a single contravention of s 50. Therefore, for the purposes of s 546, there are relevantly four contraventions of s 50 of the Act. I am satisfied that the Court’s power to order the respondent to pay a pecuniary penalty is enlivened. It is also not in issue that it is appropriate that the Court make declarations concerning the four contraventions. I am satisfied that is appropriate. The issue in the proceeding is limited to what pecuniary penalty, if any, is appropriate for each contravention of s 50. These are my reasons for ordering the respondent to pay pecuniary penalties for each contravention and the amount of each penalty.

3 The principal point of difference between the parties concerns the manner in which breaches of essentially the same terms of each of the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement should be treated for the purposes of the imposition of penalties. The respondent contends that the breaches formed part of one course of conduct and, therefore, the Court should treat the breaches of each clause of each Agreement in a consolidated manner so that, in effect, there were two contraventions. The applicant contends that approach is not permitted under s 546 and the Court cannot deal with multiple breaches in a consolidated or ‘global’ manner. The other points of difference between the parties relate to the characterisation of the respondent’s conduct and the magnitude of appropriate penalties.

4 For the reasons that follow, it is appropriate to order the respondent to pay a pecuniary penalty for each of the four contraventions of s 50 of the Act. I have decided an appropriate penalty for each of the contraventions individually having regard to, amongst other things, criminal sentencing principles to the extent these are relevant to balancing oppression and deterrence and determining the penalty reasonably necessary to achieve general and specific deterrence. As a consequence, I have taken into account the ‘course of conduct’ or ‘one transaction’ principle and the ‘totality’ principle in deciding appropriate penalties for the individual contraventions to the extent that those principles are relevant to the circumstances and facts of this case.

5 While I have had regard to criminal sentencing principles, I have not considered the individual penalties constrained by any notion of proportionality between the penalty and the seriousness of the contravening conduct or that the maximum penalty is a yardstick according to which the maximum may be imposed only in a case involving the worst category of contravening conduct. I have arrived at an appropriate penalty for each contravention having regard to what is reasonably necessary to achieve the purpose of s 546; namely, deterring the respondent and others from engaging in contraventions of a like kind. Moreover, to have a deterrent effect, the penalty imposed must not be such as to be regarded by the respondent or others as ‘an acceptable cost of doing business’: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 at [8]-[10], [17], [41] (Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ). The factors to which reference is made in these reasons have informed the penalty I consider proportionate (in the sense of a balance between oppression and deterrence) and reasonably necessary for general and specific deterrence. These factors tend towards or away from the maximum penalty by increasing (aggravating) or decreasing (mitigating) the penalty reasonably necessary to deter future contraventions.

Legislative framework

6 Section 3 provides that the object of the Act is to provide a balanced framework for cooperative and productive workplace relations that promotes national economic prosperity and social inclusion of all Australians.

7 Chapter 2 of the Act contains provisions relating to the National Employment Standards, modern awards, enterprise agreements and workplace determinations. The main terms and conditions of employment of an employee that are provided for under the Act are set out in the National Employment Standards [Pt 2-2], a modern award [Pt 2-3], an enterprise agreement [Pt 2-4], or a workplace determination [Pt 2-5] that applies to an employee: s 43 of the Act. An employer must not contravene a provision of the National Employment Standards: s 44. A person must not contravene a provision of a modern award: s 45. A person must not contravene a term of an enterprise agreement: s 50. A person must not contravene a workplace determination: s 280.

8 Chapter 4 of the Act deals with compliance and enforcement. Part 4-1 makes provision for civil remedies for contraventions of certain obligations imposed on persons under the Act. Each of ss 44, 45, 50 and 280 is a civil remedy provision: s 539. The Court also has power to make any order it considers appropriate if satisfied that a person has contravened, or proposes to contravene, a civil remedy provision: s 545.

9 The Act makes provision for the Court to make orders for a person to pay a pecuniary penalty. Section 546 of the Act provides, relevantly (notes omitted):

546 Pecuniary penalty orders

(1) The Federal Court, the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) or an eligible State or Territory court may, on application, order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the court considers is appropriate if the court is satisfied that the person has contravened a civil remedy provision.

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(2) Subject to this section, the pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is an individual—the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2); or

(b) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2).

10 Section 539(1) of the Act provides that a provision referred to in column 1 of an item in the table in s 539(2) is a civil remedy provision. Relevantly, column 1 of item 4 in the table identifies s 50 as a civil remedy provision and column 4 refers to a maximum penalty of 600 penalty units ‘for a serious contravention’ or otherwise 60 penalty units. Therefore, the maximum penalty for a corporation is 3,000 penalty units for a serious contravention or otherwise 300 penalty units. At the relevant time, penalty units were calculated by reference to s 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). Until 30 June 2020 a penalty unit was $210. From 1 July 2020 a penalty unit, calculated in accordance with an indexation formula based on a three-year movement in the All Groups Consumer Price Index number published by the Australian Statistician, was $222. Accordingly, for contraventions during the relevant period, the maximum penalties for contraventions of s 50 by a corporation were $630,000 and $666,000 for a serious contravention and otherwise $63,000 and $66,600.

11 A contravention of a civil remedy provision is a serious contravention if the person knowingly contravened the provision or was reckless as to whether the contravention would occur. A person is relevantly reckless if they are aware of a substantial risk that a contravention would occur and having regard to the circumstances known to that person, it is unjustifiable to take the risk: s 557A of the Act. While there was no allegation of a knowing or reckless contravention in this case, the maximum penalty for contraventions involving such conduct provides an indication of the level of pecuniary penalty that the legislature considered appropriate to deter knowing or reckless contraventions as opposed to the level appropriate to deter careless, inadvertent or other non-serious contraventions. Broadly, the differences in maxima reflect an underlying concept that, the more blameworthy the conduct involved in the contravention, the greater the necessity for specific and general deterrence of like conduct in the future.

12 Section 557 of the Act provides, relevantly, that two or more contraventions of s 50 are taken to constitute a single contravention if the contraventions ‘are committed by the same person’ and ‘arose of out a course of conduct by that person’ provided that a court has not imposed a pecuniary penalty on the person for an earlier contravention of s 50. Therefore, the effect of s 557 is that the maximum penalty for multiple contraventions of s 50 is limited to the maximum penalty for a single contravention in certain circumstances.

Evidence

13 The applicant tendered a statement of agreed facts made pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). By the statement of agreed facts the parties agree that the respondent breached terms of enterprise agreements and contravened s 50 of the Act.

14 The applicant also tendered affidavits of Paul Stephen Brett affirmed 10 March 2023 and 27 May 2024 and an affidavit of Luke Edmonds affirmed 3 June 2024. The respondent tendered affidavits of Michael Kranendonk affirmed 2 August 2024 and Anthony Mancini affirmed 2 August 2024. A number of relevant documents were also exhibited to the statement of agreed facts and affidavits. That evidence was largely directed towards and relevant to the question of pecuniary penalties.

15 Mr Brett is a union organiser and employee of the applicant. His evidence-in-chief in his first affidavit was largely agreed as part of the statement of agreed facts. His evidence-in-chief in his second affidavit addressed the manner in which the respondent engaged new employees and, thereafter, promoted them to higher positions. That evidence is directed to the nature and extent of any harm the respondent’s employees may have suffered as a result of breaches of the enterprise agreements and contraventions of s 50 of the Act. There was no cross-examination of Mr Brett and I accept his evidence.

16 Mr Edmonds is a legal officer and employee of the applicant. His evidence-in-chief concerned previous findings against the respondent or admissions by the respondent of contraventions of the Act and orders for pecuniary penalties imposed on the respondent for those breaches. There was no cross-examination of Mr Edmonds and I accept his evidence.

17 Mr Kranendonk is the national asset manager and employee of the respondent. During the period relevant to the contraventions of s 50 of Act, Mr Kranendonk was the Western Australian state manager for the respondent. In that role he had responsibility for the respondent’s operations for the ports of Fremantle, Ashburton and Dampier. Mr Kranendonk has been an employee of the respondent since 1999. He gave evidence of the respondent’s operations in Australia, about the 2016 and 2020 Agreements, the respondent’s trainers, methodology for allocating employees in various categories to shifts, failure to train employees in accordance with the 2016 and 2020 Agreements and an explanation for that failing. He also gave evidence relating to the nature and extent of any harm the respondent’s employees may have suffered resulting from that failing, the context in which the other contraventions referred to in Mr Edmonds’ affidavit took place, and to the importance of training and compliance to the respondent. There was no cross-examination of Mr Kranendonk and I accept his evidence.

18 Mr Mancini is the national training and development manager and employee of the respondent. He was employed in May 2023. That is, after all of the conduct that contravened s 50 of the Act had taken place. He gave evidence of the nature of his role and the steps the respondent has taken that he considers should ensure that there are not breaches of cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement in the future. There was no cross-examination of Mr Mancini and I accept his evidence.

Agreed facts

19 Although expressed as a statement of agreed facts for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act, the statement of agreed facts is a mixture of agreed facts and agreed legal consequences of those facts. The agreed facts and legal consequences may be summarised as follows.

20 The applicant (CFMEU) was and is a registered organisation under the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth); an employee organisation for the purposes of s 539(2), item 4(c) of the Act; and an employee organisation to which each of the Qube Ports Pty Ltd Port of Fremantle Enterprise Agreement 2016 (2016 Agreement) and Qube Ports Pty Ltd Port of Fremantle Enterprise Agreement 2020 (2020 Agreement) apply within the meaning of s 52 of the Act during the life of both agreements.

21 The respondent (Qube Ports Pty Ltd) was and is a corporation incorporated under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and liable to be sued in its own name, a national system employer as defined in s 12 and s 14 of the Act and an employer to which each of the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement applies within the meaning of s 52 of the Act during the lives of those agreements.

22 The respondent was and is a major integrated port services provider in Australia with bulk and general handling facilities in over 40 Australia, New Zealand and South-East Asia ports, conducts operations, including stevedoring operations at all major Australian and New Zealand ports. It conducts operations at the port of Fremantle in the State of Western Australia. It had revenue from its continuing operations of $406,987,192, profit of $41,616,917 and net assets of $144,262,514 in the financial year ending 30 June 2023.

23 On 2 May 2017 the Commission approved the 2016 Agreement. That enterprise agreement operated from 9 May 2017 to a nominal expiry date of 30 June 2020. It applied to employees of the respondent employed in the classifications set out in Sch 2 of Pt A of that agreement who were employed at the port of Fremantle from 9 May 2017 until 27 December 2021.

24 On 21 December 2021 the Commission approved the 2020 Agreement. That enterprise agreement operated from 28 December 2021 and has a nominal expiry date of 30 June 2024. It applies to employees of the respondent employed in the classifications set out in Sch 2 of Pt A of that agreement who were employed at the port of Fremantle from 21 December 2021.

25 Both the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement provide for the employment of employees in the classification ‘Guaranteed Wage Employee’ and define that classification as ‘an Employee irregularly engaged to work and who is guaranteed a minimum payment in accordance with cl 9.7 of [the] Agreement’.

26 Clause 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement and cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement are in the same terms and provide:

[Guaranteed Wage Employees] will be trained in:

a. A skill (grade 3 skill or higher) within 6 months of becoming a [Guaranteed Wage Employee];

b. In a second skill (grade 3 skill or higher) within 12 months of becoming a [Guaranteed Wage Employee].

27 The reference to ‘grade 3 skill or higher' is a reference to any of the tasks set out in Sch 2 of Pt A of each of the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement.

28 The respondent was at all relevant times aware of the terms of the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement and the requirements of cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of each of those agreements.

29 The respondent failed to provide training to each of the employees set out in the Schedule to these reasons who were Guaranteed Wage Employees in accordance with cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement and (or) cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement. As set out in the Schedule, the respondent failed to provide each of the employees with training in a skill (grade 3 skill or higher) within 6 months of those employees becoming a Guaranteed Wage Employee and (or) failed to provide each of those employees with training in a second skill (grade 3 skill or higher) within 12 months of those employees becoming a Guaranteed Wage Employee.

Other findings of fact

30 Based on the uncontested affidavit evidence of the witnesses to which reference has been made earlier in these reasons, the statement of agreed facts and the documents tendered in evidence, I make the following findings of fact relevant to the question of pecuniary penalties.

Nature and extent of contravening conduct

31 There were 49 employees to whom training was not provided as cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the Agreements required. That resulted in 14 breaches of cl 7.1.4.a (training within six months) and nine breaches of cl 7.1.4.b (training within 12 months) of Pt B the 2016 Agreement (that is, breaches up to 27 December 2021) and 27 breaches of cl 7.1.4.a and 28 breaches of cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement (that is, breaches after 27 December 2021). There were 11 employees in respect of which only cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement was breached. There were four employees in respect of which cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of both the 2016 and 2020 Agreements was breached. There were 34 employees in respect of which only cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement was breached.

32 It follows that there were multiple breaches of cl 7.1.4.a and cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement and there were multiple breaches of cl 7.1.4.a and cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement. Each of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements is an ‘enterprise agreement’ within the meaning of the Act.

33 As explained later in these reasons, the majority of the breaches took place with respect to 42 employees who were employed in the seventeen-month period from November 2020 to April 2022. There were seven employees who were employed between March 2017 and December 2019 who were not trained within six months or 12 months. As a consequence, seven of the 14 breaches of cl 7.1.4.a and seven of the nine breaches of cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement took place by January 2021. The remaining breaches of both Agreements took place from 2 May 2021 when the cohort of 42 employees employed in the seventeen-month period were employed. The contravening conduct for the first cohort of seven employees took place between 24 September 2017 and 2 December 2020. The contravening conduct for the second cohort took place between 2 May 2021 and 26 April 2023.

34 Of the 49 employees all except five, who resigned, received the training to which they were entitled under cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the Agreements, but that training was not received within six months or 12 months as required. In the second cohort of 42 employees, in the case of the first training: nine received the first training within six months; nine others received that training within eight months; and 24 received the training after more than eight months. In the case of the second training: seven received that training within 12 months; 15 others received training within 14 months; three resigned; 14 received the training after more than 14 months; and it is unclear when the last three received their training. In the first cohort of seven employees: none received the first training within eight months; two resigned and the remaining five did not receive the second training within 14 months.

Consequences of contravening conduct

35 Clause 9 of the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement set out a number of categories of employment. These are Full Time Salaried Employees, Provisional Full Time Salaried Employees, Variable Salary Employees, Provisional Variable Salary Employees, Guaranteed Wage Employees and Supplementary Employees.

36 New employees are generally engaged as Supplementary Employees. Supplementary Employees are similar to casual employees in other industries. They have no guarantee of regular engagement, they accrue no leave entitlements (other than long service leave), are engaged to work after all other classifications and are generally engaged to perform work with a lower skill category. A Supplementary Employee may be promoted to the role of Guaranteed Wage Employee after a period of approximately 12 months working as a Supplementary Employee.

37 A Guaranteed Wage Employee receives a guaranteed minimum wage and is required to be available for irregular allocation for work. A Guaranteed Wage Employee is entitled to a guaranteed minimum salary per annum (equal to 28 ordinary hours at the weekly grade 2 rate) and is paid fortnightly. A Guaranteed Wage Employee is required to work sufficient shifts to match the amount he or she is paid each fortnight. A Guaranteed Wage Employee must be available to work irregular shift allocations. However, as a result of the allocation system described later in these reasons, Guaranteed Wage Employees have a lower chance of receiving a shift allocation than Provisional Variable Salary Employees, Variable Salary Employees, Provisional Full Time Salaried Employees and Full Time Salaried Employees.

38 A Variable Salary Employee is a permanent employee position engaged on a minimum annual salary. As with a Guaranteed Wage Employee, a Variable Salary Employee must be available for irregular shift allocation as required, but they generally receive higher pay that a Guaranteed Wage Employee. A Guaranteed Wage Employee that is promoted will generally be promoted to a Variable Salary Employee.

39 A Full Time Salaried Employee is a permanent employee position engaged on a salary with a requirement to work 1820 hours inclusive of all forms of approved leave. A Full Time Salaried Employee is generally the highest paid and most skilled employee engaged under the 2016 and 2020 Agreements.

40 Each year there is a labour review conducted in accordance with cl 14 of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements. Amongst other things, the labour review involves an assessment of whether certain triggers for the creation of an additional Provisional Variable Salary Employee position or Provisional Full Time Salaried Employee position set out in cl 13.5 of the Agreements have been met. If so, a process is followed in accordance with Schedule 1 of Pt A of the Agreements to fill the position. Schedule 1 also applies where a vacancy arises.

41 Schedule 1 contains certain selection criteria and prerequisites and exclusions. It involves advertising for the position internally and inviting applications from existing employees. Applicants are assessed, in part, on the number of points received for six selection criteria. Each criterion is allocated a number of points and the total for all criteria is 100 points. Skills is one of the criteria. An applicant may receive up to 25 points for that criterion of which 13 points are allocated to the skills required for the role and 12 points are allocated for performance from feedback scores.

42 It follows that if a person who is a Guaranteed Wage Employee wants to apply for a position that would be a promotion, that person’s chances of obtaining that position are enhanced if the skills required for the role include grade 3 skills in that it would contribute towards the employees’ score as part of the prerequisites and fitness for the role. Although it is not determinative, it may contribute towards an employee’s prospects of successfully obtaining promotion. Put another way, the practical effect of these provisions of the Agreements is that a Guaranteed Wage Employee who has received training in grade 3 skills in accordance with cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements has a better chance of obtaining promotion to Provisional Variable Salary Employee or Provisional Full Time Salaried Employee and thereafter becoming a Variable Salary Employee or Full Time Salaried Employee.

43 The 2016 and 2020 Agreements also contain provisions which provide for the order in which employees will be engaged to perform work: cl 10.2 Pt A, cl 5.3.2 Pt B of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements. The practical effect of these provisions is that the more skills an employee has and the higher the employee’s classification, the more likely they are to be engaged to perform work.

44 The respondent has a software system, referred to as ‘Microster’, which it uses to allocate shifts to stevedore employees. The allocation process is based on the allocation rules set out in cl 10 Pt A and cl 5 Pt B of the 2020 Agreement. (The allocation process and rules for the 2016 Agreement were materially the same.) The sequence of allocation is: first, to Full Time Salaried Employees who have not met their Annualised Accumulated Hours; second Provisional Full Time Salaried Employees who have not met their Annualised Accumulated Hours; third Variable Salary Employees who have not met their Annualised Accumulated Hours; fourth Provisional Variable Salary Employees who have not met their minimum engagement; fifth Guaranteed Wage Employees who have not met their minimum guarantee; sixth, Supplementary Employees, seventh B Supplementary Employees, and last outsourced labour hire employees. Each day information about the nature of the vessels scheduled to come into port, the skills required to work on it, and the number of stevedores and skills required for the gang’s shift is entered into Microster. Based on the allocation priorities an allocator using Microster allocates employees to the shift.

45 As a consequence of the operation of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements, a Guaranteed Wage Employee who had received training in accordance with cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the Agreements had a greater opportunity to be trained in further skills, to be allocated work and work attracting a higher rate of pay, and for promotion to a higher classification.

46 While Mr Kranendonk and Mr Brett gave evidence to the effect of the matters set out in paragraphs [36] to [45] and I accept their evidence, in substance, it is no more than inference drawn from the objective effect of the provisions of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements. Further, it is not evidence from which an inference can be drawn or a finding made that any particular employee was denied any particular opportunity because that employee was not trained within the timeframes cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of each of the Agreements requires.

47 Mr Brett also gave evidence regarding seven employees who were employed as a Guaranteed Wage Employee under the 2020 Agreement. In the case of four employees, they received training within the 6-month and 12-month timeframes as cl 7.1.4 requires and three were promoted to Provisional Full Time Salaried Employees within three years and one was promoted to Provisional Variable Salary Employee within three years. Three other employees were not trained as required and they remain in the position of Guaranteed Wage Employee after three years. The difference in annual earnings between the employees in the Provisional Full Time Salaried Employee positions and Guaranteed Wage Employee positions is about $60,000.

48 Although I accept that evidence, it is not in evidence that the three employees were not promoted because of a failure to train them. Mr Kranendonk gave unchallenged evidence that one of the three employees had not applied for any promotion. In the case of another of the three employees, Mr Kranendonk said that employee had applied for a promotion after he had received all training and was not successful. In the case of the last of the three employees, that employee applied for promotion twice and was unsuccessful each time. At the time of the second application, he had received all training, but was unsuccessful. Otherwise, there was no evidence regarding the points that the employee had received and the extent to which any lack of training affected the application. On the basis of this evidence, I am not satisfied that any employee was denied the opportunity of promotion because of a failure to train that employee within the timeframes cl 7.1.4 of Pt B requires.

49 It follows that I make no finding that any employee has suffered any specific harm as a consequence of a breach of a term of an enterprise agreement. However, I do not regard breaches of cl 7.1.4 of Pt B, even in the absence of evidence of specific harm, to be trivial. As a matter of objective construction of the provisions of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements, the right to receive and obligation to provide training to a person employed as a Guaranteed Wage Employee is an important component of the enterprise agreements as a whole. The purpose and object of the obligation is self-evidently to facilitate an employee gaining additional skills that will increase the opportunity for the employee to be promoted or, otherwise, be engaged in higher paid work.

50 Objectively, failure to provide training within the required time involves the loss of an important benefit for a Guaranteed Wage Employee for the period during which that employee is deprived of the training. In the case of the first cohort of seven employees, with the exception of the two employees who resigned, that deprivation was for a significant period. In the case of the second cohort of 42 employees, taking into account the three who resigned, that deprivation was significant for about half of the cohort.

51 It is also relevant that the nature of the breach of the enterprise agreement was a failure to perform within the time required. It was not a failure to perform at all. That is a factor that mitigates the harm – real or potential – that flows from the breach and contravention of s 50 of the Act. In general, time is not considered to be of the essence and involves the breach of a non-essential term, or warranty, and not a condition of a contract. Although the delay in performance was significant in many cases, that nature of the relevant breach was delayed performance is a factor that also informs the severity of the breach of the Agreements and contravention of s 50 of the Act.

Circumstances in which the contravening conduct took place

52 The respondent employs approximately 1,800 employees nationally at 19 ports. The respondent is the employer under 19 separate enterprise agreements relating to each port. The enterprise agreement consists of Pt A, which applies to all ports, and Pt B which is specific to each port.

53 Employee payments under each enterprise agreement are managed through a central, national payroll team. However, as each port has different terms in Pt B of the enterprise agreements, each port is managed separately for the purposes of compliance with the enterprise agreement for that port. In the case of the port of Fremantle, compliance with the requirements of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements was the immediate responsibility of the respondent’s Fremantle operations team.

54 The respondent’s breaches of cl 7.1.4 Pt B took place between 2017 and 2023. As already mentioned, the affected employees may be separated into two cohorts. The first cohort of seven were employed between March 2017 and December 2019. The second cohort of 42 were employed between November 2020 and April 2022. Regarding the first cohort, there was no evidence, except for Mr Kranendonk’s speculation, to explain how or in what circumstances these breaches took place. Regarding the second cohort, Mr Kranendonk gave evidence from which I make the following findings.

55 At the commencement of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) and during the period that the Western Australian border was closed the respondent lost a number of its experienced and qualified stevedores who gained employment in other industries leading to a skills shortage at the port of Fremantle. In response, the respondent hired a pool of approximately 40 employees as Guaranteed Wage Employees. In normal circumstances these employees would have been employed as Supplementary Employees, but in the prevailing economic circumstances, in order to encourage people to accept employment and remain in employment with the respondent, the cohort were employed as Guaranteed Wage Employees. In making that decision the respondent’s Fremantle operations team did not take into account that, unlike the conditions in other ports, the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement required training of the Guaranteed Wage Employees within the six-month and 12-month timeframes and that there were operational and other difficulties that would be encountered that would likely prevent completion of the training within the required periods.

56 The terms of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements require the respondent to have assigned to the port of Fremantle one ‘Technical Trainer’ and three to five ‘Workplace Trainers’. A Technical Trainer is a training professional with experience in training provision and management. A Workplace Trainer is an employee who is able to work, on a nominated shift, as a stevedore and a workplace trainer. Workplace Trainers are subject matter experts in relation to the tasks and duties stevedores carry out at the port. In the case of the port of Fremantle, Workplace Trainers were also stevedores.

57 The respondent encountered logistical challenges co-ordinating shift allocations of Guaranteed Wage Employees with shift allocations of Workplace Trainers because the Workplace Trainers were also stevedores who were being allocated shifts according to the allocation procedure described earlier in these reasons. In other words, due to the relatively infrequent allocation of shifts to Guaranteed Wage Employees these allocations had to occur when a Workplace Trainer was allocated to the same shift in order for training to take place. Further, to acquire additional skills it was necessary for the training to take place over more than one shift which added to the logistical challenges. Between 2020 and 2022, the port of Fremantle was busy and often running at full capacity and utilisation, which had the effect of reducing the opportunity for training during shifts. The logistical challenges and operational needs together with the large number of Guaranteed Wage Employees contributed to training not taking place within the six-month and 12-month periods.

58 In addition, there were 78 days of protected industrial action in the form of total work bans from 30 July 2021. No training of Guaranteed Wage Employees took place during that period.

59 Once the respondent was behind on training during the six-month period it inevitably became more difficult to complete the training during the 12-month period. Ultimately, all Guaranteed Wage Employees, except five who resigned, received the required training, but not within the required timeframes.

60 As already mentioned, the applicant has not asserted that the admitted contraventions were knowing or reckless. In any event, the evidence Mr Kranendonk gave about the circumstances in which the breaches of the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement took place does not support an inference that the respondent intentionally, knowingly or recklessly failed to comply with its obligations under the Agreements. Nonetheless, the facts reveal an intention to induce the second cohort of employees to accept or remain in the employ of the respondent in the position of Guaranteed Wage Employees in circumstances in which it ought to have been apparent to those responsible for employing them that there was a real risk that the training requirements of the Agreements would not be achieved for such a large cohort in the prevailing operational and economic environment at the port of Fremantle. These facts, at least, indicate carelessness on the part of the respondent in its approach to timely performance of its training obligations with respect to the second cohort of 42 employees. Thus, except for the period of protected action, Mr Kranendonk’s evidence is not exculpatory with respect to the second cohort. Otherwise, Mr Kranendonk’s evidence provides no explanation of the circumstances in which the breaches involving the first cohort of seven employees took place. Therefore, there is no exculpatory evidence at all with respect to the first cohort.

Response to contravening conduct

61 Mr Kranendonk expressed regret, on the part of the respondent, for not training Guaranteed Wage Employees within the required timeframes.

62 Mr Kranendonk gave evidence that after the issue of non-compliance was raised with him in or around August 2022, he endorsed a decision that from that point onwards, the respondent would only engage new employees as Supplementary Employees. There are no timeframes within which Supplementary Employees must be trained in any particular skill. That is, the respondent ceased to induce employees to accept roles as Guaranteed Wage Employees with conditions of employment that the respondent was unlikely to meet.

63 Mr Kranendonk, again on behalf of the respondent, said:

The importance of training and compliance

64. I have always wanted every Qube stevedore to be trained in every skill relevant to their particular port. In my experience, having stevedores trained in as many skills as possible means Qube can allocate shifts to a broader pool of stevedores, which in turn means there are more stevedores capable of covering periods of leave, there is reduced fatigue risks, and Qube can tender for more work by letting clients know we have a highly skilled workforce capable of servicing their vessels. This upskilling and training is, in this sense, as much in Qube's interests as it is in the interests of each individual stevedore[.]

65. Qube has worked hard to get all stevedores trained but this proceeding is evidence that it has not done enough yet. Qube will continue to look at ways it can improve its training of stevedores and its systems for ensuring that training is carried out in a timely way.

66. That Qube has not been able to upskill all of its stevedores in a timely manner is deeply regrettable to me. It is something Qube is working hard to make sure never happens again. It is in our interests to have all our stevedores as well trained as possible and it is our responsibility to ensure we comply with the agreements we have entered into. I fully acknowledge and accept that.

None of that evidence was challenged. As I have already mentioned, I accept Mr Kranendonk’s evidence.

64 Mr Mancini gave evidence concerning changes the respondent had taken to its allocation and monitoring system. His evidence was not challenged and I accept it.

65 The effect of Mr Mancini’s evidence is that there are three elements to the changes the respondent has implemented. First, the respondent has increased its training budget. Second, since July 2024 changes have been made to the Microster system with specific allocators assigned to each port. The intended effect of this change is to have the allocators become familiar with the rostering and requirement of the port assigned to them and to allocate shifts in a manner that allows for training to take place in a timely manner. The allocators are to provide the management personnel at the relevant port with a monthly list of employees who require training, the nature of the training required, how long it will take and any relevant deadlines by which it needs to be completed.

66 Last, the respondent is in the process of implementing systems intended to improve monitoring of training. The respondent is working on adapting the functionality of Microster to add a feature that will allow allocators to monitor the progress of employees’ training and for automated messages to be sent to operational personnel (the relevant employees) reminding them of upcoming training requirements. The respondent has invested more than $3 million in a new training and learning management system known as ‘INX Intuition’. INX Intuition is an integrated learning management system. It will provide easy access for the respondent’s employees to their training records and will allow management personnel to oversee and manage employees’ competencies, skills, compliance with obligations relating to certification and training. It will include information about training achieved, training requests and upcoming deadlines for new training or re-training.

67 It is also of relevance that the respondent has not put the contraventions in issue in this proceeding.

Previous contraventions of the Act

68 The respondent has been found to have contravened s 50 of the Act a number of times.

(a) In Maritime Union of Australia v Qube No 1 Pty Ltd [2017] SAIRC 5, the respondent contravened s 50 and s 323 of the Act in August 2014 by underpaying two employees their redundancy entitlement upon their retrenchment in August 2014. No penalty was imposed.

(b) In Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd (ABN: 46 123 021 492) [2023] WAIRC 00976, the respondent contravened s 50 and s 323 of the Act by underpaying an employee in Dampier an amount of $159.25 on 2 June 2022 and a penalty of $11,300 was imposed for that contravention.

(c) In Construction, Forestry and Maritime Employees Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd [2024] WAIRC 00220, the respondent contravened s 50 of the Act on 17 January 2022 by underpaying an employee an amount of $229.83 and a penalty of $1,500 was imposed for that contravention.

(d) In Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd (M95 of 2023), the respondent contravened s 50 of the Act by failing to train employees to the level required pursuant to Pt A, cl 46.2(b) of the Port of Port Hedland Enterprise Agreement and a penalty of $936 was imposed for that contravention.

69 In addition to this proceeding, the respondent has admitted to the following contraventions of the Act.

(a) In the Western Australian Industrial Magistrate Court application M76 of 2022 - Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd the respondent has admitted one contravention of each of s 50 and s 323 of the Act by underpaying an employee the amount of $234.78 on 1 January 2022.

(b) In the Western Australian Industrial Magistrate Court application M91 of 2022 - Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd the respondent has:

(i) admitted four contraventions of s 50 of the Act by:

(A) deducting personal leave on 25 December 2020 contrary to the terms of the relevant enterprise agreement;

(B) failing to pay a worker for the 26 December 2020 public holiday leave contrary to the terms of the relevant enterprise agreement;

(C) failing to pay a worker for the 28 December 2020 public holiday leave contrary to the terms of the relevant enterprise agreement; and

(D) for failing to pay a worker a day of her personal leave upon termination of her employment leave contrary to the terms of the relevant enterprise agreement;

and

(ii) admitted one contravention of s 323 of the Act for failing to pay a worker at least monthly and in full in relation to the payments for the 26 and 28 December public holidays.

(c) In the Western Australian Industrial Magistrate Court application M119 of 2022 - Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Qube Ports Pty Ltd, the respondent has admitted one contravention of s 50 of the Act for failing to pay an employee for public holidays and closed port days contrary to the terms of the relevant enterprise agreement.

70 It follows that no pecuniary penalty had been imposed on the respondent for breach of s 50 of the Act at the time of the relevant contraventions. Further, by and large, the prior contraventions of s 50 or admitted conduct involve underpayment of entitlements under enterprise agreements or the National Employment Standards in relatively modest amounts. However, there is at least one other failure to train employees in accordance with the requirements of an enterprise agreement.

Financial resources of the respondent

71 Although there was no direct evidence regarding the financial resources of the respondent, it is an agreed fact that it is a major integrated port services provider with bulk and general handling facilities in over 40 Australian and New Zealand and South-East Asian ports and conducts operations, including stevedoring, at all major Australian and New Zealand ports. As already mentioned, the respondent employs approximately 1,800 employees nationally at 19 ports. It has very substantial revenue, profit and net assets. I infer from these facts that the respondent has significant financial resources and that imposition of the maximum penalties would not result in financial hardship for the respondent.

Applicable principles

72 The parties largely agree on the principles applicable to the relief sought in the originating process.

Declaratory relief

73 The Court has power under s 545 to make a declaration to the effect that a person has contravened a civil remedy provision. The Court also has jurisdiction and power to make such a declaration under s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth): see, Forster v Jododex [1972] HCA 61; 127 CLR 421 at 437-8 (Gibbs J); Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc [1993] FCA 105; 41 FCR 89 at 99-100 (Sheppard J); Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113; 254 FCR 68 at [90]-[93] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ). It was common ground that declarations in the terms that the applicant requested are appropriate. I agree.

Factors relevant to appropriate pecuniary penalty

74 The principles applicable to ordering a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the Court considers is ‘appropriate’ in respect of a contravention of a civil remedy provision were explained in the joint reasons of Kiefel CJ, Gageler, Keane, Gordon, Steward and Gleeson JJ in Pattinson. These may be summarised as follows.

(1) Civil pecuniary penalty provisions of the kind enacted in s 546 have a statutory function of securing compliance with the provisions of the statutory regime: [14].

(2) Although the Court may adapt principles which govern criminal sentencing to civil penalty regimes, the differences between criminal prosecutions and civil penalty proceedings mean that there are limits to transplanting principles from the criminal into the civil penalty context. The most important difference is that, unlike criminal sentences, civil penalties are imposed primarily, if not solely, for the purpose of deterrence: [15]-[16].

(3) There is both a specific and general deterrent component to determining an appropriate penalty. Amongst other things, a civil penalty must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by the offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business: [17]. Also, an inadequate sanction de facto punishes all who do the right thing. Therefore, an important aspect of deterrence is to encourage the corresponding virtue of voluntary compliance: [41].

(4) Like all judicial discretions, the power must be exercised judicially; that is, fairly and reasonably having regard to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the legislation. In the context of a civil penalty provision, insistence upon the deterrent quality of a penalty should be balanced by insistence that it not be so high as to be oppressive. Put another way, as deterrence is the object, the penalty should be no greater than that which is necessary to achieve that object; severity beyond that would amount to oppression: [40].

(5) The concept of proportionality – understood to refer to a penalty that strikes a reasonable balance between deterrence and oppressive severity – is embedded within the power in s 546. Within that framework and with that understanding of proportionality, factors that are commonly taken into account in the context of criminal sentencing may be adapted to the civil penalty regime to the extent relevant to the balance between deterrence and oppression. However, notions of retribution, rehabilitation and protection of the community (except to the extent that forms part of deterrence) have no place in the determination of a civil penalty: [41]-[62].

(6) Matters pertaining to both the character of the contravening conduct and the character of the contravenor may be relevant to the balance. Factors that may be relevant to deterrence include the following: [18]-[19], [46]-[48]

(a) The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

(b) The amount of loss or damage caused.

(c) The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

(d) The size (and financial resources) of the contravening company.

(e) The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it took place.

(f) Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

(g) Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act.

(h) Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with regulators in relation to the contravention.

(7) The maximum penalty is a ‘yardstick’ that is one of the relevant factors that must ordinarily be applied. However, the maximum does not constrain the exercise of the discretion beyond requiring some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed. The relationship of 'reasonableness’ may be established by reference to the circumstances of the contravenor as well as by the circumstances of the conduct involved in the contravention. That is so because either set of circumstances may have a bearing upon the extent of the need for deterrence in the penalty imposed and may overlap: [49]-[55].

Number of pecuniary penalties and applicable maxima

75 The main point of difference between the parties concerned the approach the Court should take to the number of contraventions of s 50 of the Act and, therefore, the number of pecuniary penalties the respondent may be ordered to pay. The difference arises because the breaches were over a period during which both the 2016 Agreement and 2020 Agreement were in place and involved two separate sub-clauses of each enterprise agreement.

76 It was common ground that s 557 of the Act applies in that the contraventions were committed by the same person (the respondent), arose out of a course of conduct of that person (the respondent) and no pecuniary penalty had been imposed for any earlier contraventions of s 50 at the time the contravening conduct was committed. As a consequence, all breaches of cl 7.1.4.a of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement are to be treated as one contravention of s 50. Likewise, all breaches of cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement are to be treated as one contravention, all breaches of cl 7.1.4.a of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement are to be treated as one contravention, and all breaches of cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2020 Agreement are to be treated as one contravention of s 50. Accordingly, there are up to four breaches of s 50 involving two separate sub-clauses of two separate enterprise agreements. Further, during the period of the applicable course of conduct the maximum penalty for contraventions of the relevant kind increased from $63,000 to $66,600.

77 Section 50 of the Act provides: ‘A person must not contravene a term of an enterprise agreement’ (emphasis added). The applicant, relying on Rocky Holdings Pty Ltd v Fair Work Ombudsman [2014] FCAFC 62; 221 FCR 153, contends that s 50 applies to each breach of a separate term of an enterprise agreement. In that case, the Full Court held that a contravention of s 45, which applies to a modern award and uses similar language to s 50, applied to each separate term of a modern award: Rocky Holdings at [13] (North, Flick and Jagot JJ). The applicant submits, and the respondent accepts, by parity of reasoning, s 50 must apply to each term of an enterprise agreement. It was also common ground that for the purposes of cl 7.1.4 of Pt B of the 2016 and 2020 Agreements, each of cl 7.1.4.a and cl 7.1.4.b was a term of an enterprise agreement for the purposes of s 50 of the Act as it applies to each obligation of an enterprise agreement: see, e.g., Rocky Holdings at [17] citing Gibbs v Mayor, Councillors and Citizens of City of Altona [1992] FCA 553; 37 FCR 216 at 223 (Gray J).

78 The applicant submits that the Court is not authorised under s 546 to impose a single global penalty for multiple contraventions of s 50 of the Act. In support of that submission it cites Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Huddy (No 2) [2017] FCA 1088 at [67]-[72] (White J), citing and applying by analogy the Full Court’s construction of s 49 of the Building and Construction Industry Improvement Act 2005 (Cth) in ABCC v CFMEU (2017) at [125]-[126], [148]-[149] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ); Director of the Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2016] FCA 413 at [50] (White J); Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2015] FCAFC 59; 229 FCR 331 at [43] (Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ); Fair Work Ombudsman v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (Kiama Aged Care Centre Case) (No 3) [2023] FCA 1324 at [33] (Katzmann J) also relying on ABCC v CFMEU (2017) at [149]. Also, Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Registered Organisations Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 232; 283 FCR 404 at [78]-[96] (Bromberg, Rangiah and Bromwich JJ) with respect to s 305(1) of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act.

79 The respondent submits that in circumstances in which there are multiple breaches of multiple terms of enterprise agreements, it is open to the Court, in an appropriate case, to take into account, as a matter of discretion, the circumstance that the same acts or omissions have resulted in multiple contraventions of s 50 of the Act by imposing a lesser penalty or even no penalty in respect of some contraventions while imposing a substantial penalty in respect of other contraventions: QR Ltd v Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union (Cth) [2010] FCAFC 150; 204 IR 142 at [48]-[49] (Keane CJ, Gray and Marshall JJ).

80 I accept that s 546 does not authorise the Court to impose a global penalty for multiple contraventions of the Act. However, there are at least two circumstances in which it may be appropriate for the Court to impose a single penalty for multiple contraventions. First, ‘in an appropriate case’ the Court may impose a single penalty for multiple contraventions where that course is agreed or is accepted as appropriate by the parties. For example, it may be appropriate where identifying separate contraventions is difficult or there are so many that imposing individual penalties is not feasible: ABCC v CFMEU (2017) at [148]-[149]; Kiama Aged Care Centre Case at [33]. Second, where there are multiple contraventions arising from the same acts or omissions, even if s 557 does not apply to those acts or omissions, it may be appropriate, as a matter of discretion, to adjust the individual penalties in such a manner that results in a substantial penalty for one contravention and no penalty or minimal penalty for all remaining contraventions: QR Ltd at [49]. Neither of these circumstances is inconsistent with the operation of s 546 but is a means of giving effect to that provision in particular circumstances involving multiple contraventions.

81 The weight of authority also supports the proposition that, in deciding an appropriate penalty under s 546, the Court may take into account and adapt principles of criminal sentencing such as the single course of conduct principle and (or) totality principle: e.g., Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Williams [2009] FCAFC 171; 191 IR 445 at [14]-[19], [31] (Moore, Middleton and Gordon JJ); Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 194 IR 461 at [35]-[47] (Middleton and Gordon JJ); QR Ltd at [62]-[63]; Parker v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2019] FCAFC 56; 270 FCR 39 at [268]-[286] (Besanko and Bromwich JJ). While authorities that precede Pattinson must be approached with caution to the extent that they invoke criminal notions of punishment beyond deterrence, they remain authoritative on adapting the course of conduct and totality criminal sentencing principles to the industrial civil penalty context. These authorities, read with that caution, support the following approach to deciding an appropriate penalty under s 546 of the Act where the single course of conduct or totality principle could be engaged.

82 The Court must first decide the appropriate civil pecuniary penalty for each individual contravention. Next, the Court must decide whether any individual penalty should be reduced having regard to any interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more contraventions. In this stage the Court may take into account that a ‘course of conduct’ or ‘one transaction’ may have the technical legal result of multiple contraventions for essentially the same civil penalty conduct. In the criminal context, that may lead to imposition of concurrent or partially concurrent sentences to avoid punishing an offender more than once for the same criminality. Concepts like avoidance of ‘punishment’ and ‘criminality’ do not translate easily into the civil penalties context. However, following Pattinson, the underlying concept of avoiding duplication of penalties for essentially the same wrongful conduct may be adapted and applied in the civil penalties context so as to avoid imposing penalties that go beyond what is reasonably necessary for achieving general and specific deterrence. Therefore, in a circumstance involving multiple contraventions for essentially the same wrongful conduct, it might be appropriate to adjust the individual civil pecuniary penalties to balance oppression and deterrence in an appropriate manner to achieve deterrence.

83 Last, the Court may have regard to the separate, but related, concept of totality. That principle involves considering the overall result of the sentencing exercise (here, the penalty imposition exercise) and the need sometimes to depart from the literal application of the outcome of that exercise where multiple penalties are imposed as a consequence of contraventions that arise from related facts or circumstances which may, but need not, be characterised as a single course of conduct: Parker at [273]-[274] citing Royer v Western Australia [2009] WASCA 139; 197 A Crim R 319 at [21], [30] (Owen JA). See, also, Williams at [14]-[19], also citing Royer at [21]-[25], [28], [30]-[31] (Owen JA). The necessity to depart from the literal application in the civil pecuniary penalties context will be informed, again, by the balance between oppression and deterrence and the extent to which individual penalties in aggregate are reasonably necessary to achieve deterrence.

84 Although I have described the approach in a way that suggests distinct steps or stages, it is part of an evaluative, not mathematical, exercise. The description of steps or stages is to aid conceptualising the process of reasoning. But, in practice, the concepts are taken into account simultaneously along with all other competing factors and considerations when arriving at decision as to the appropriate penalty for each contravention in the exercise of the Court’s discretion under s 546 of the Act.

Consideration

85 As already mentioned, it was not in issue that the breaches of each clause of the 2016 Agreement and each clause of the 2020 Agreement comprised a course of conduct for the purposes of s 557 of the Act. Consequently, there were four contraventions of s 50 of the Act for the purposes of s 546. Although a ‘course of conduct’ was not in issue insofar as it relates to the application of s 557, I do not accept that all breaches of cl 7.1.4.a of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement form part of a single course of conduct or one transaction for the purposes of adapting and applying criminal sentencing principles. Likewise, I do not accept that all breaches of cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement form part of a course of conduct or one transaction for that purpose. There were two distinct cohorts of employees to which the breaches of the 2016 Agreement related. It is not appropriate, for the purpose of adapting and applying the criminal sentencing principles, to treat both cohorts as part of a single course of conduct.

86 Insofar as the second cohort is concerned, there is a sense in which each separate breach and each separate contravention flows from essentially the same failing; namely, employing Guaranteed Wage Employees in circumstances in which there was a real risk that the respondent would be unable to train them within the timeframes required in the Agreements. Therefore, the criminal sentencing concept of a single course of conduct may be applicable to that cohort because the individual breaches of cl 7.1.4.a of Pt B or cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of the 2016 Agreement or of the 2020 Agreement does not have any real bearing on specific deterrence of the respondent as there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of all breaches of the Agreements and all contraventions. The multiplicity of breaches of cl 7.1.4.a and cl 7.1.4.b of Pt B of each Agreement was a mere function of when the employee was employed and which enterprise agreement was in force at six and 12 months from that date. As a consequence, duplication of the pecuniary penalty for breaches of essentially the same obligations in the same circumstances under consecutive enterprise agreements concerning the same cohort of employees would have the effect of penalising the respondent more than once for essentially the same wrongful conduct. Therefore, the circumstances of this case may warrant some adjustment to the individual pecuniary penalties imposed on the respondent for contraventions of s 50 of the Act associated with the second cohort to the extent necessary to balance oppression and deterrence. However, that logic and reasoning does not apply to the first cohort.

87 The first cohort was not evidently employed as Guaranteed Wage Employees for the same reasons as the second cohort. Nor were there the same logistical or operational difficulties associated with training them. There was no explanation for the failure to comply with the requirements of the 2016 Agreement as it applied to them. There was no evidence of the number of Guaranteed Wage Employees employed in that period or the extent to which the respondent performed its obligations under the 2016 Agreement with respect to any other Guaranteed Wage Employees employed in that period. There was no evidence regarding what steps, if any, the respondent had taken to audit, check or ensure that it was meeting its training obligations or the process it used, if any, to ensure that it complied with those obligations under the 2016 Agreement.

88 In my view, there is no reason to treat the respondent’s conduct that resulted in breaches with respect to the first cohort of employees as falling within the same course of conduct that applied to the second cohort. Therefore, insofar as the first cohort is concerned, there is no sense in which there is duplication of pecuniary penalties associated with breaches of the 2016 Agreement (with respect to the first cohort) and breaches of the 2016 and 2020 Agreement (with respect to the second cohort) because it is not part of the same wrongful conduct.

89 It follows that I accept that the criminal sentencing concept of a single course of conduct may be adapted to the circumstances of the contraventions of s 50 of the Act in this case. However, I do not accept that all breaches of the Agreements should be considered part of one transaction or a single course of conduct. On the evidence, the failings resulting in the breaches concerning the two cohorts of employees were separate and distinct. Therefore, I do not accept that the four contraventions should be treated as two contraventions, as the respondent submits, to avoid penalising the respondent twice for essentially the same wrongful conduct.

90 Nonetheless, in deciding the penalties for the four contraventions, I have taken into account that the breaches of the 2016 Agreement primarily relate to the first cohort and the breaches of the 2020 Agreement all relate to the second cohort and it was common ground that s 557 applied to the breaches of each clause of each of the Agreements. Accordingly, in deciding appropriate penalties for the contraventions associated with breaches of each limb of cl 7.1.4 of the 2016 Agreement I have approached the penalty for those contraventions from the perspective that the penalty is that which is reasonably necessary to deter contraventions of a kind like those associated with the first cohort and that the maximum penalty in the period for nearly all of those contraventions was $63,000. In deciding appropriate penalties for the contraventions associated with breaches of each limb of cl 7.1.4 of the 2020 Agreement I have considered the penalty reasonably necessary to deter contraventions of a kind like those associated with the second cohort (whether or not they are technically breaches of the 2016 or 2020 Agreement) and that the maximum penalty in the period of those contraventions was $66,600.

91 Regarding the first cohort, in the absence of any explanation, the respondent’s conduct is, at least, indicative of failings of its systems, policies, procedures and culture and the necessity for a degree of specific deterrence to discourage future neglect of like enterprise agreement obligations. Regarding the second cohort, as already mentioned, the respondent’s failure to train that cohort was a consequence of, at least, carelessness in timely performance of its obligations under the applicable enterprise agreement and the terms of the enterprise agreements breached were not trivial. The breaches were driven by the conditions of the labour market in Western Australia associated with the COVID-19 pandemic and border closures coupled with the port of Fremantle operating at or near capacity. Employees were offered positions as Guaranteed Wage Employees because the conditions of employment in that role intended to encourage them to accept and remain in the respondent’s employment. At the same time, the respondent’s management personnel ought to have known that there was a real risk that respondent would not be able to meet the training requirements of cl 7.1.4 of Pt B under the Agreements that were part of the provisions that made the position of Guaranteed Wage Employee attractive. In my view, breaches in those circumstances cannot be described as inadvertent or of diminished blameworthiness. In the context of non-serious contraventions, carelessness is a factor that firmly indicates an increased necessity for specific and general deterrence.

92 In the case of the second cohort, the seriousness of the breaches was partly mitigated by the short period of delay in training for about half that cohort. In the case of both cohorts, the seriousness of the breaches was also partly mitigated by ultimate performance of the obligation to train all relevant employees. Ultimate performance also ensured that the potential consequences and harm to the affected employees was mitigated. But, in the case of the first cohort and half the second cohort, the delay in completion of the required training was significant. The nature of the term of the enterprise agreement breached and of the consequences of breach are relevant factors in that, the more serious the breach and consequences, the greater the necessity for general and specific deterrence of like contraventions in the future.

93 The respondent submits that it has never had a finding made against it in relation to the port of Fremantle. The previous contraventions and other conduct took place over a decade in five different ports. In each case, the contraventions were minor in nature, contained and could not be described as significant or deliberate. They took place in a context of employment of approximately 1,800 employees at 19 locations within Australia and each location had different management responsible for enterprise agreement compliance. The respondent submits that the prior contraventions should, in that context and those circumstances, be afforded significantly less weight as prior contraventions from a deterrence perspective. I do not accept that submission.

94 In my view, that previous breaches of the Act took place at other locations and were the result of the action or inaction of other managers of the respondent is not a factor that diminishes the significance of prior contraventions. The conduct of agents of the respondent, wherever located, is attributed to the respondent, as principal and body corporate, for the purposes of s 50 of the Act. Therefore, it was conduct of the respondent wherever it took place. I also do not consider that some sort of calculus based on the number of previous contraventions compared against the number of employees and locations offers a compelling reason to reduce the weight that would otherwise be afforded to previous contraventions. Contraventions are not only the consequence of intentional or deliberate conduct but carelessness, oversight and inadvertence. Part of deterrence involves encouraging employers to implement and maintain systems, policies, procedures and a culture aimed at preventing careless, unintentional or ignorant contraventions of the Act. Therefore, the size and spread of an employer’s operation is not a reason for diminishing corporate responsibility for historical contraventions as these may be indicative of systemic or underlying failings in corporate systems, policies, procedures and culture and, therefore, of an ongoing and enhanced risk of future contraventions. Otherwise, I accept the respondent’s characterisation of the prior contraventions and admissions as minor, contained and not deliberate. But, overall, the respondent’s prior conduct and the conduct the subject of this proceeding reveals a not insignificant number of contraventions over an extended period of time. That is a factor suggesting an increased necessity for specific deterrence.

95 I regard the financial resources of the respondent to be a neutral factor. The maximum penalty reflects the legislature’s view of a penalty that will have the required deterrent effect upon a corporate respondent irrespective of its financial resources. Therefore, bearing in mind that the penalty imposed should not be at a level that could be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business, there is no reason to regard the maximum penalty as more than is reasonably necessary to have the required deterrent effect where the corporate wrongdoer is well-resourced. Put another way, there is no reason, in this case, to reduce the penalty that would otherwise be appropriate because financial hardship would result in an imbalance between oppression and deterrence.