Federal Court of Australia

Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Jemena Networks (ACT) Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 203

File number(s): | NSD 1279 of 2023 |

Judgment of: | NEEDHAM J |

Date of judgment: | 17 March 2025 |

Catchwords: | INDUSTRIAL LAW – penalty determination – where respondents failed to consult with applicant prior to amending the procedure for recording live work on or near the low voltage network and failed to establish a Safety Committee in contravention of enterprise agreement, s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) and ss 47(1) and 47(2) Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (ACT) – where respondents admit to contraventions – where parties have submitted agreed range of civil penalty – consideration of appropriate penalty where not all facts are agreed – discretionary factors to be taken into account where an appropriate range is agreed |

Legislation: | Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 136 Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) ss 50, 437, 545, 546, 557 Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) ss 21, 23 Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (ACT) ss 47, 48, 49, 82 |

Cases cited: | Application by Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia [2023] FWC 2539 Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450; HCA 13 Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v QR Ltd (2010) 198 IR 382; FCA 591 Davids Distribution Pty Ltd v National Union of Workers (1999) 91 FCR 463; FCA 1108 Fair Work Ombudsman v Ho [2024] FCAFC 111 Fair Work Ombudsman v NSH North Pty Ltd (t/as New Shanghai Charlestown) (2017) 275 IR 148; FCA 1301 QR Ltd v Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union (2010) 204 IR 142; FCAFC 150 Secretary, Department of Health v Medtronic Australasia Pty Ltd (2024) 305 FCR 433; FCA 1096 The Australian Federation of Air Pilots v HNZ Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 755 Volkswagen Akitiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2021) 284 FCR 24; FCAFC 49 Kayis D, Gluer E and Walpole S (eds), The Law of Civil Penalties (Federation Press, 2023) |

Division: | Fair Work Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Employment and Industrial Relations |

Number of paragraphs: | 153 |

Date of hearing: | 11, 12, 18 November 2024 |

Counsel for the Applicant: | Mr O Fagir |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Hall Payne |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr M Minucci |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Ashurst |

Table of Corrections | |

20 March 2025 | The figure in [152(b)] and Order 1(b) of the Orders made on 17 March 2025 is amended from $4,596.00 to $4,695.00 in accordance with rr 39.04 or 39.05 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth). |

ORDERS

NSD 1279 of 2023 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | COMMUNICATIONS, ELECTRICAL, ELECTRONIC, ENERGY, INFORMATION, POSTAL, PLUMBING AND ALLIED SERVICES UNION OF AUSTRALIA Applicant | |

AND: | JEMENA NETWORKS (ACT) PTY LTD First Respondent ICON DISTRIBUTION INVESTMENTS LTD Second Respondent | |

order made by: | NEEDHAM J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 17 March 2025 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 50 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), the respondents, jointly and severally liable:

(a) pay $32,865 in relation to the breach of the requirement to consult contained in the Evoenergy and Combined Unions Enterprise Agreement 2020, and

(b) pay $4,695.00 for the failure to convene the Safety Committee as required by the Evoenergy and Combined Unions Enterprise Agreement 2020,

to the applicant, within 28 days of the making of this order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

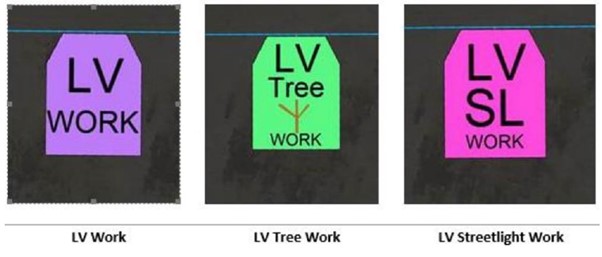

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

NEEDHAM J:

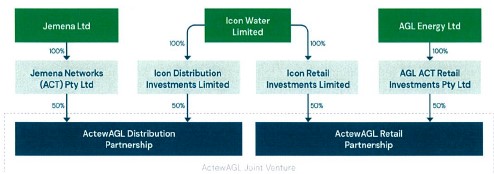

1 These proceedings came before the Court for determination of the appropriate penalty to be imposed by reason of admitted contraventions of an enterprise agreement by the respondents (Jemena Networks (ACT) Pty Ltd) (the first respondent) and Icon Distribution Investments Ltd (the second respondent, formerly the third respondent) who are partners in the ActewAGL Distribution partnership and who trade as Evoenergy.

2 The relevant agreement is the Evoenergy and Combined Unions Enterprise Agreement 2020 (2020 Agreement), an enterprise agreement made under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act). Section 50 of the FW Act provides that a breach of an enterprise agreement incurs a civil penalty.

3 The 2020 Agreement covers the applicant (the Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia or CEPU), Evoenergy, and employees listed in clause 3.1 of the 2020 Agreement.

4 The CEPU is an employee organisation registered under the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth); and entitled to represent the industrial interests of the employees who fall within its eligibility rule, including Network Controllers, electricians, and electrical trades assistants.

These proceedings

5 By its Amended Originating Application and Amended Statement of Claim, the applicant sought declarations and orders pursuant to ss 21 and 23 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and ss 545(1) and 545(2)(a) of the FW Act relating to changes to the procedure for the recording of live work on or near the low voltage network (Live Work Procedure) on 23 October 2023. The changes were implemented without consulting with workers who carried out work for the ActewAGL Distribution partnership and who were likely to be directly affected by a matter relating to work health or safety. The applicant contended that the changes breached ss 47(1) and 47(2) of the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (ACT) (WHS Act), s 50 of the FW Act, and cl 67 of the 2020 Agreement. The changes to procedure and the lack of consultation was referred to in argument as the LV Tag Issue. Additionally, it was contended that the respondents contravened cl 68 of the 2020 Agreement and s 50 of the FW Act by failing to establish and maintain a Joint Management/Union Health, Safety and Environment Policy Committee (the Safety Committee Issue).

6 The Defence to the Statement of Claim raises a number of issues, but in a sense, much of the detail of the matters denied or not admitted now fall away, because the breaches comprising the LV Tag Issue and the Safety Committee Issue are now admitted and what is left for me to determine is a small number of factual issues, and the appropriate penalty. The parties have agreed a penalty range which it is said is appropriate, and the parties have urged me to come to the higher, or the lower, figure respectively. I say more below about the approach I should take in relation to civil penalties, but I am satisfied that the appropriate penalty does in fact fall within the agreed range.

Range of penalty

7 The parties are agreed that a penalty should be imposed for the two admitted breaches. The CEPU does not press the balance of alleged contraventions pleaded in the Amended Originating Application of 9 February 2024.

8 The parties agreed that the two admitted contraventions noted in [57] of the Statement of Agreed Facts (Statement of Facts or SAF) (see [13], [81] and [85] below) are not to be treated as a single course of conduct for the purposes of s 557 of the FW Act.

9 In relation to the LV Tag Issue, the parties are agreed that the appropriate penalty range is 20% – 50% of the maximum penalty (which is $93,900 – see s 546 of the FW Act).

10 In relation to the Safety Committee Issue, the parties are agreed that the appropriate penalty range is 5% – 20% of the maximum penalty.

Legislation

11 At the time of the alleged breach (23 October 2023) the relevant sections of the WHS Act read as follows:

Division 5.2 Consultation with workers

47 Duty to consult workers

(1) The person conducting a business or undertaking must, so far as is reasonably practicable, consult, in accordance with this division and the regulation, with workers who carry out work for the business or undertaking who are, or are likely to be, directly affected by a matter relating to work health or safety.

Maximum penalty:

(a) in the case of an individual—$20 000; or

(b) in the case of a body corporate—$100 000.

Note Strict liability applies to each physical element of this offence (see s 12A).

(2) If the person conducting the business or undertaking and the workers have agreed to procedures for consultation, the consultation must be in accordance with those procedures.

(3) The agreed procedures must not be inconsistent with section 48.

48 Nature of consultation

(1) Consultation under this division requires—

(a) that relevant information about the matter is shared with workers; and

(b) that workers be given a reasonable opportunity—

(i) to express their views and to raise work health or safety issues in relation to the matter; and

(ii) to contribute to the decision making process relating to the matter; and

(c) that the views of workers are taken into account by the person conducting the business or undertaking; and

(d) that the workers consulted are advised of the outcome of the consultation in a timely manner.

(2) If the workers are represented by a health and safety representative, the consultation must involve that representative.

49 When consultation is required

Consultation under this division is required in relation to the following health and safety matters:

(a) when identifying hazards and assessing risks to health and safety arising from the work carried out or to be carried out by the business or undertaking;

(b) when making decisions about ways to eliminate or minimise those risks;

(c) when making decisions about the adequacy of facilities for the welfare of workers;

(d) when proposing changes that may affect the health or safety of workers;

(e) when making decisions about the procedures for—

(i) consulting with workers; or

(ii) resolving work health or safety issues at the workplace; or

(iii) monitoring the health of workers; or

(iv) monitoring the conditions at any workplace under the management or control of the person conducting the business or undertaking; or

(v) providing information and training for workers;

(f) when carrying out any other activity prescribed by regulation for the purposes of this section.

12 Similarly, as at 23 October 2023, the relevant sections of the FW Act read as follows:

50 Contravening an enterprise agreement

A person must not contravene a term of an enterprise agreement.

Note 1: This section is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

Note 2: A person does not contravene a term of an enterprise agreement unless the agreement applies to the person: see subsection 51(1).

…

437 Application for a protected action ballot order

Who may apply for a protected action ballot order

(1) A bargaining representative of an employee who will be covered by a proposed enterprise agreement, or 2 or more such bargaining representatives (acting jointly), may apply to the FWC for an order (a protected action ballot order) requiring a protected action ballot to be conducted to determine whether employees wish to engage in particular protected industrial action for the agreement.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply if the proposed enterprise agreement is:

(a) a greenfields agreement; or

(b) a cooperative workplace agreement.

(2A) Subsection (1) does not apply unless there has been a notification time in relation to the proposed enterprise agreement.

Note: For notification time, see subsection 173(2). Protected industrial action cannot be taken until after bargaining has commenced (including where the scope of the proposed enterprise agreement is the only matter in dispute).

Matters to be specified in application

(3) The application must specify:

(a) the group or groups of employees who are to be balloted; and

(b) the question or questions to be put to the employees who are to be balloted, including the nature of the proposed industrial action; and

(c) the name of the person or entity that the applicant wishes to be the protected action ballot agent for the protected action ballot.

Note: The protected action ballot agent for the ballot must be an eligible protected action ballot agent unless there are exceptional circumstances: see section 444.

(5) A group of employees specified under paragraph (3)(a) is taken to include only employees who:

(a) will be covered by the proposed enterprise agreement; and

(b) either:

(i) are represented by a bargaining representative who is an applicant for the protected action ballot order; or

(ii) are bargaining representatives for themselves but are members of an employee organisation that is an applicant for the protected action ballot order.

Documents to accompany application

(6) The application must be accompanied by any documents and other information prescribed by the regulations.

………..

546 Pecuniary penalty orders

(1) The Federal Court, the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) or an eligible State or Territory court may, on application, order a person to pay a pecuniary penalty that the court considers is appropriate if the court is satisfied that the person has contravened a civil remedy provision.

Note 1: Pecuniary penalty orders cannot be made in relation to conduct that contravenes a term of a modern award, a national minimum wage order or an enterprise agreement only because of the retrospective effect of a determination (see subsections 167(3) and 298(2)).

Note 2: Pecuniary penalty orders cannot be made in relation to conduct that contravenes a term of an enterprise agreement only because of the retrospective effect of an amendment made under paragraph 227B(3)(b) (see subsection 227E(2)).

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(2) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is an individual—the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2); or

(b) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the relevant item in column 4 of the table in subsection 539(2).

Payment of penalty

(3) The court may order that the pecuniary penalty, or a part of the penalty, be paid to:

(a) the Commonwealth; or

(b) a particular organisation; or

(c) a particular person.

Recovery of penalty

(4) The pecuniary penalty may be recovered as a debt due to the person to whom the penalty is payable.

No limitation on orders

(5) To avoid doubt, a court may make a pecuniary penalty order in addition to one or more orders under section 545.

Statement of Facts and Statement of Issues

13 The parties have helpfully reached a joint position on the breaches. The Statement of Facts was marked Exhibit 1. The below factual background to the matter is based upon those agreed facts. Additionally, the parties have agreed to a Statement of Factual and Legal Issues for Determination (Statement of Issues), which was marked Exhibit 2, for which I am also grateful. The parties are agreed that those issues are as follows (amended slightly for readability and sub-headings inserted):

A. Factual issues

LV Tag Issue

1. What were the nature of the amendments to the policy known as the “Recording of Live Work On Or Near the LV Distribution Network” procedure introduced on 23 October 2023 by … Evoenergy?

2. Did Evoenergy introduce changes to the Live Work Procedure without consultation in circumstances where it knew that consultation and training were required before the change was introduced?

3. Prior to 23 October 2023, were Control Room Workers aware of how to use Personnel Working Notes in the Advanced Distribution Management Systems software?

4. Following the introduction of the amendments to the Live Work Procedure, when an incident occurred, were there any material differences in the steps Control Room Workers were required to undertake where the location of the relevant worker(s) was recorded with a Personnel Working Note, rather than with a LV Tag?

Safety Committee Issue

5. Prior to these proceedings being commenced, did the Applicant, other employee representatives or employees of Evoenergy raise any concerns with Evoenergy regarding the lack of a separate joint management/union health, safety and environment policy committee during the period the … 2020 Agreement was in operation?

B. Legal issues

LV Tag Issue

6. What is the appropriate penalty to be imposed on Evoenergy in respect of the admitted contravention of clause 67 of the 2020 Agreement noting the parties have agreed to submit that the appropriate penalty to be imposed in respect of this contravention is between 20% and 50% of the maximum penalty?

Safety Committee Issue

7. What is the appropriate penalty to be imposed on Evoenergy in respect of the admitted contravention of clause 68 of the 2020 Agreement noting the parties have agreed to submit that the appropriate penalty to be imposed in respect of this contravention is between 5% and 20% of the maximum penalty?

14 The proceedings ran for some three days before me in mid-November 2024. A number of witnesses deposed to affidavits, were called, and cross-examined. They were:-

(a) for the applicant:

(i) Mr Michael Birchall, a Network Controller; and

(ii) Mr Matthew Brown, a Network Controller.

(b) for the respondents:

(i) Mr Matthew Capoulade, (in November 2023) Acting Group Manager, Network Services;

(ii) Ms Bronwen Butterfield (in October 2023) Incident Controller – Incident Management Team, Protected Industrial Action;

(iii) Ms Zoe Dougall, Group Manager, Safety, Risk and Compliance; and

(iv) Mr Peter Billing, General Manager of Evoenergy.

15 A number of affidavits had documents exhibited to them, which became exhibits in the proceedings.

16 The applicant also read affidavits from Mr Jarred Pearce, an Evoenergy employee and union organiser, and Ms Madeleine O’Brien, solicitor for the CEPU, neither of whom was required for cross-examination.

17 There were a number of objections to evidence, but the agreed position was that I would determine those objections during the course of preparation of these reasons, and that evidence objected to on the basis of relevance or hearsay be admitted provisionally. That approach enabled the hearing to be conducted efficiently, and evidence to be concluded in the two days allotted. Most of the objections were to hearsay, relevance, or opinion evidence. The determination of those objections is found in the Schedule to these reasons.

Factual background

The 2020 Agreement

18 The 2020 Agreement is found in the evidence as part of Exhibit CB9 to Mr Brown’s affidavit of 2 November 2023 (and also appears in Mr Pearce’s affidavit of that date). The definitions in cl 2.2 include:

Consultation means more than a mere exchange of information. For consultation to be effective the participants must be contributing to the decision-making process not only in appearance but in fact.

…

Workplace Change refers to significant changes identified by either party to the way work is done and includes changes to corporate procedures, work processes and practices and the introduction of new equipment or technology.

19 Clause 7 of the 2020 Agreement provides that:

7. Agreement to be Comprehensive

7.1. Subject to the terms of this Agreement, this Agreement exhaustively states the terms and conditions of employment of the employees covered by this Agreement.

20 Clause 8 notes that “Policies and Corporate Procedures” are not incorporated into, and do not form part of, the 2020 Agreement. Clause 8.2 provides:

Employees and their unions will be consulted when changes are contemplated to corporate procedures and policies that affect employees in their employment.

21 Clause 10 provides a process for Enterprise Agreement Implementation, and cl 11 deals with various kinds of consultations, including cl 11.5 which deals with “Major workplace changes” and requires management to “consult … on major workplace changes that are likely to have a significant effect on employees …”. Clause 11.8 provides that “[e]very effort will be made to ensure the consultation period takes no longer than four weeks”.

22 Clauses 67 and 68 deal with “Health, Safety and Environment” and require Evoenergy to comply with all relevant legislation in the field, and (by cl 68.1) to maintain the Safety Committee.

The industrial dispute

23 The respondents are an electricity distributor and manage the low voltage (LV) electricity distribution network in the ACT. Mr Capoulade, who was at the time the Acting Group Manager of Network Services, noted that Evoenergy supplied electricity to more than 210,000 customers, including “public and private hospitals, nursing homes, water sites and Commonwealth infrastructure”. The General Manager, Mr Billing, set out a diagram of the structure of the ActewAGL joint venture in [6] of his affidavit of 30 September 2024, reproduced below:

24 Between 9 February 2023 and 30 November 2023, the respondents were in the process of bargaining with their employees and their representatives, including the CEPU, for a new enterprise agreement to replace the 2020 Agreement. There were a number of processes in the Fair Work Commission (FWC) (as set out in [18] of the Statement of Facts). An agreement known as the Evoenergy Enterprise Agreement 2023 (2023 Agreement) was approved by a majority of Evoenergy employees on 23 November 2023. The 2023 Agreement was approved by Deputy President Dean on 30 November 2023, and it commenced operation, replacing the 2020 Agreement, on 7 December 2023.

LV Tag Issue

25 One of the processes in the FWC resulted in a protected action ballot order (see Application by Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia [2023] FWC 2539) which order was made on 4 October 2023. The order authorised the following action by employees of the respondents who were members of the CEPU:

(a) an unlimited number of indefinite or periodic bans on Control Room workers placing or removing LV work tags;

(b) an unlimited number of indefinite or periodic bans on Control Room workers placing or removing LV tree work tags; and

(c) an unlimited number of indefinite or periodic bans on Control Room workers placing or removing LV streetlight work tags,

(together, LV Tag Action).

26 Mr Pearce referred to the LV Tag Action as a “tagging ban”. The effect of the LV Tag Action was that no work on the LV network could be undertaken if LV tags could not be placed. Mr Capoulade expressed the dilemma by recounting that Mr Billing, the General Manager, advised him:

…if Control Room Workers will not use LV tags and there is no workaround set out in its procedures, then no LV work will be undertaken across the LV network.

27 Mr Capoulade expressed the view that the LV Tag Action would have significant impacts for Evoenergy and its customers. The work of tag placement was only carried out by Network Controllers, so as to control the “source of truth for the network at any one time”. Mr Capoulade, a former linesman, appreciated the fact that it was critical for the network to be accurately represented to the control room at any particular time.

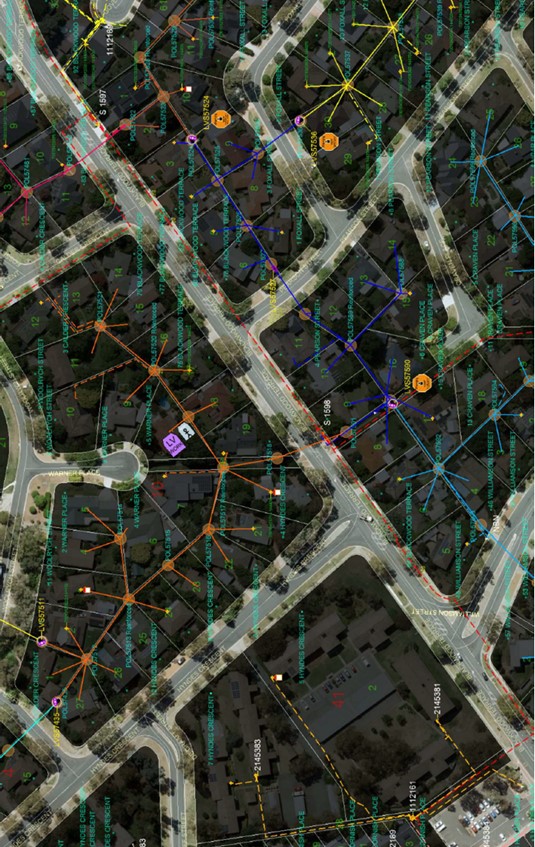

28 The LV Tag Action was part of the Live Work Procedure which was undertaken by Control Room workers. Part of the Control Room workers’ duties was to identify, by placing an electronic tag known as an LV tag, on the map of the LV network, so as to alert other users of the LV network to their presence. This is done by using the Advanced Distribution Management Systems (ADMS) Software. If no tag were placed, then the Live Work Procedure could not be complied with.

29 Mr Birchall, a Network Controller, gave evidence that the relevant part of the ADMS is:

a real time graphic representation of the network and network equipment as a diagram on a screen. This is in simple terms a geographic map overlayed with the network map with various symbols representing equipment. Network controllers monitor the network through screens which display the low voltage and high voltage networks.

30 As pointed out by Mr Capoulade, however, the “real-time” aspect of the Control Room in relation to the LV network is dependent on information provided by workers, and notifications by members of the public, to identify system issues and to allocate workers to attend as necessary.

31 The following description of the Live Work Procedure, and the role of the Live Work Procedure in ensuring the safety of workers, is taken from the Statement of Facts.

C. LIVE WORK PROCEDURE

8. Evoenergy has a set of Electrical Safety Rules. The Electrical Safety Rules specify the safe working requirements and minimum standards for working on, near, or in the vicinity of Evoenergy’s transmission and distribution network facilities in the ACT and the surrounding region into which Evoenergy’s electricity network extends.

9. Rule 9.1 of the Electrical Safety Rules requires any worker that is undertaking LV Work to notify the Control Room. The workers are required to identify all work intended to be performed on the LV network, regardless of whether it is energised or de-energised work, before accessing the distribution network for any overhead or underground works.

10. Evoenergy maintains a procedure which was previously known as the Recording of “Live Work in the Vicinity or Near the LV Network” and at the commencement of these proceedings was known as the “Recording of Live Work On Or Near the LV Distribution Network” procedure (Live Work Procedure).

11. The Live Work Procedure is a safety procedure, and Evoenergy’s position is that it falls within the PO07 Evoenergy Asset Management Policy document suite.

12. The Live Work Procedure is required to ensure the safety of all Evoenergy personnel, contractors and external parties working on or near live LV Evoenergy assets.

13. Prior to 23 October 2023, the Live Work Procedure provided as follows:

(a) prior to performing any field work on or near the LV network, the work crew are required to contact the Control Room;

(b) the work crew then state their name, telephone number and the location at which they are working;

(c) the Control Room worker will locate the area in the ADMS Software, and advise of any currently known risks in the area;

(d) the Control Room worker then places a LV tag in the ADMS Software on the map at the location where the working crew is performing work;

(e) the Control Room worker is required to enter the name and contact details of the person performing work, together with the details of the worker’s employer (if any); and

(f) once work on the LV network is completed, the working crew is required to contact the Control Room, and the LV tag will be removed.

14. There are three types of LV tags that can be placed in the ADMS Software, which reflect the different types of work being undertaking [sic] on the LV network. They are:

(a) LV tree tags (where tree trimming or other vegetation management work is being undertaken near the network);

(b) LV street light tags (where work is being undertaken on street lights); and

(c) LV work tags (other work on the LV network).

15. A screenshot of the three types of LV tag is included below:

32 In case this judgment is reproduced in black and white, the LV Work tag is jacaranda purple, the LV Tree Work tag is light jade green, and the LV Streetlight Work tag is a bright “Barbie” pink.

33 The Personnel Working Note (PWN) on the other hand is a pale grey, and has a drawing of a “stick person” on it in black. Mr Birchall and Mr Brown gave evidence that the PWN had historically been used to log the location of workers for security purposes (for example, when entering a particular area such as a substation, for cleaning or inspection). They were not used to record people working on the network. Mr Brown said that there are eight other different note types in the ADMS, including the Shift Change Note, the Contingency Plan Note, and the Verification Required Note.

34 Mr Birchall gave evidence that the ADMS is configured to display the LV tags so that they are visible at any zoom level, but that was not the case with other tags and representations on the network diagram. His evidence was that the PWNs were not visible at particular zoom levels, although changes to the ADMS in late October 2023 has now provided that function. Mr Birchall was not cross-examined on this aspect of his evidence. Mr Brown noted that the LV tags also disappeared at some zoom level.

35 Mr Birchall gave helpful oral evidence as to the practical application of the Live Work tagging procedure and how the LV tags operated in the context of the Control Room. I found Mr Birchall to give thoughtful evidence and I was impressed by his demeanour and care in answering questions.

36 Mr Brown gave evidence that he was one of around 12 Evoenergy employees authorised to place LV work tags in the ADMS. He has been a Network Controller since around 2016, employed by Evoenergy, as has Mr Birchall. Mr Brown provided a useful summary of the Live Work Procedure in his evidence. Mr Brown noted that the Live Work Procedure:

… is a virtual tagging process. It is unrelated to any physical lock-out tag-out process which may occur at a location where electrical work is being performed.

Workers (e.g. electricians, linesmen, cable jointers, tree contractors, and TCCS contactors undertaking work on streetlights) will contact the Control Room to advise of the work they are performing on the network and their address. Some but not all of those workers are Evoenergy employees. The work is usually “live”, which means it is work on or near energised electrical wires.

…

As a Network Controller, I used the information provided by the worker to create and place an LV work tag in ADMS for that work. To do that, I bring up the map in ADMS, navigate to the location, locate the piece of electrical equipment being worked on, and place a tag on that piece of electrical equipment at the location. I enter information in a free text field as part of the process for creating that tag. The LV work tag remains in place in the ADMS until the worker has completed their work and contacts us to remove the tag.

([12], [13], [15] of Mr Brown’s affidavit of 2 November 2023).

37 Mr Brown gave some more detail about his role in the Control Room in his oral evidence. From a review of both his written and oral evidence, he was able to give the following overview.

38 The Network Controller can filter and search the LV tags in the ADMS, and see quickly which workers are doing what kind of work in any section of the network. This is useful when fielding calls from customers as to whether work (eg, cutting down or trimming trees near the network) is authorised, and to alert workers in case of a network outage and re-energisation, as a safety process. Mr Birchall gave an example of an issue where a power outage was caused by an accident with a worker. While the worker was safe on that occasion, Mr Birchall was able to contact the crew quickly through the use of LV tags and ascertain the safety of the workers, and work to have the network reinstated, as around 60 customers were without power.

39 Mr Brown’s affidavit of 5 September 2024 included examples of the LV Work Tag Summary screen, including the use of “filters” and “notes”, and a map showing what a PWN, and an LV tag (in this case, a purple LV Work Tag) look like in the ADMS. That map (p 430 of the Court Book (CB)) is Attachment A to these reasons.

40 Mr Brown said, in relation to this map:

It is possible to tell from this view that the person whose location is represented by the LV Work Tag is performing streetlight work at a particular location.

It is not possible to tell from this view what the person whose location is represented by the personnel working note is doing. To understand that it would be necessary to click on the note and read the text field.

If I zoomed out of this map, beyond a certain point the [PWN] icon would disappear. The LV Work Tag icon would always remain visible to a different zoom level.

41 Mr Birchall noted that while the policy documents governing the placement of LV Work Tags or notes indicated that “only one … may be placed for any working crew at any one time”, the map at Attachment A showed both an LV tag and a PWN. He said in his oral evidence that this was unlikely to be an accurate depiction of the ADMS but that the note or the tag had probably been placed “as a representation to show that it could be put on there” (ie, for demonstration purposes of the differences in appearance between an LV tag and a PWN). Mr Brown (whose document the map attachment A was) confirmed that he had placed the two tags in a way which would not have been representative of the way the ADMS works, for the purpose of demonstrating the visual effect of each tag. Notwithstanding that the placement did not reflect the practice of the Network Controllers, I found the map at Attachment A (and the documents at CB 427–429) very helpful as an illustrative aid.

42 Mr Brown noted that the PWN and the LV tag on the map were of slightly different sizes, and confirmed that “if you zoom out, the note disappears before the LV tag”.

43 Each of Mr Brown and Mr Birchall had concerns as to the differences between the filters and the summaries used across the ADMS in relation to LV tags and PWNs. An example of an LV Work Tag Summary is found at CB 427. Filters are a way of seeing the PWNs placed on the network, and a filter is personal to the Network Controller. Tag summaries are the same across all of the Network Controllers. Mr Brown agreed with counsel for the respondent that he had “known at least since April 2023 about how the notes worked and the fact that [he] could use filters to reduce their appearance in [the list of tags]”.

44 As with Mr Birchall, I found Mr Brown to be a helpful witness who was impressive and knowledgeable about his work. He was cross-examined by Mr Minucci, counsel for the respondents, on his choice to engage in protected industrial action, and by so doing his refusal to “participate in a process that [he] considered a safety process”. I do not consider that the cross-examination on that point affected his credit adversely, as the protected industrial action was just that – an action which had been authorised by the Fair Work Commission (see Statement of Facts at [21]).

45 Mr Capoulade contested that the type of LV work being performed was vital information carried by the LV tag, and said, “In most cases, the type of LV work being performed (that being either tree work, streetlight work, or general LV work) is irrelevant”. He also took issue with whether PWNs became invisible, and understood that they could be configured to be always visible when zoomed in or out, much as the LV tags are. He said that he came to that understanding through a demonstration of the ADMS (also referred to in the evidence as a “workshop”, and dealt with at [66] below).

46 The CEPU notified the respondents in accordance with the FW Act that its members intended to take the protected LV Tag Action between 23–25 October 2023, and between 6–10 November 2023.

47 In order to attempt to mitigate the effects of the LV Tag Action, the respondents determined to amend the Live Work Procedure to provide an alternative method of recording workers’ locations when working on the LV network. The respondents amended two policy documents:

(a) PO07339 Recording of Live Work in the Vicinity or Near the LV Network (also renamed “Recording of Live Work on or Near the LV Distribution Network); and

(b) PO070501 Servicing Manual.

48 The witnesses for the respondents described the amendments to the policy documents as a “workaround”. It was one of a number of options for “managing work on the LV network if workers decided to engage in protected industrial action involving the LV tag action” (as per [40] of Mr Capoulade’s affidavit of 6 November 2023).

49 In considering the various options, Ms Butterfield, in her affidavit of 30 September 2024, listed the difficulties that Evoenergy experienced as a result of protected industrial actions taken by employees during the negotiation period. She said (at [7], after setting out a table of the protected industrial actions engaged in by employees, totalling 745 actions):

As a direct result of the above engaged in [protected industrial action], Evoenergy was required to cancel or reschedule 480 jobs during the relevant period. This included 122 cancellations to customer service connections which required rescheduling to a future date between 6– 8 weeks ahead. In some instances, this meant customers had no power to their homes for more than a month.

50 However, Ms Butterfield did not identify which of the protected industrial actions related to the cancelled customer services, and I note that the majority of industrial actions were stoppages of work, and only three were exercises of the LV Tag Action. These took place on 23 October 2023 (one employee) and on 25 October 2023 (two employees). The LV Tag Action does not seem to have been a significant brake on the actions of the respondents, and Ms Butterfield’s statement that “[i]n some instances, this meant customers had no power to their homes for more than a month” cannot be sheeted home, without direct evidence to that effect, to the exercise of the protected industrial action of the tagging ban.

51 In her cross-examination, Ms Butterfield agreed that she knew, as at 10 October, that the applicant would, in her words, “arc up” about any unilateral safety changes. Mr Capoulade also had it in mind that the union would object to the changes. He agreed that the changes had been implemented with an eye to mitigating one of the protected industrial actions, and that the consultation time had been reduced because of the time pressures associated with the impact of the bans. Ms Butterfield’s explanation for the lack of consultation was the identification of the changes as a “Category 3 change” which did not require that consultation be undertaken, but instead, provided for communication to the relevant workers (in this case the Control Room workers) and other administrative requirements and approvals.

52 Ms Butterfield indicated that because of “switching” bans, Evoenergy planned increasing work on the LV network, and was concerned that a backlog of work would increase were it not to find a workaround to the Live Work Procedure.

53 The effect of the amendments (which are set out in full in SAF [27] and [29]) was that, in lieu of a LV tag being placed to record work being done on, near, or in the vicinity of the LV network, or to record entry to electrical stations or buildings, the respondents directed that a PWN should be placed instead.

54 Clause 2.1 of PO07339 provided (relevantly):

2.1 Personnel Working note

The Personnel Working Note is not task specific and may be used to record any type of work on, near, or in the vicinity of the Evoenergy distribution network, or entry to electrical stations or buildings.

This note shall be used for entry to electrical stations and wherever other tags are unable to be applied or are not appropriate.

This may include any work tasks at electrical stations, chamber/indoor substations, distribution substations, pits, pillars, POEs, and on or near LV distribution mains.

…

55 The underlining indicates that the inclusion of the PWN procedure was new to the PO07339 policy. Otherwise, the process of placing a PWN was similar to that of an LV tag. Clause 3 included the restriction:

Only one Work Tag or Personnel Working Note LV work tag may be placed for any working crew at any one time.

56 Again, the underlining and strikeout indicate the amendments to the policy.

57 Further provisions were made for the duties of the LV Controller relating to different procedures between the PWN and the LV tags; for example, the previous version of the policy required the LV Controller to maintain a filtered list of all currently placed LV tags, whereas the amended policy required the LV Controller to use the ADMS network diagram to identify and confirm the welfare of any crews, should there be an incident.

58 The PO070501 Servicing Manual document was amended (by underlining and strikeout) as follows:

Prior to working on or near the LV accessing the distribution network for any overhead or underground service works, workers must inform System Control of works being undertaken in accordance with the Evoenergy Safety Rules. a LV tag is required to be issued by Dispatch.

Following the completion of works, workers must inform System Control to notify that the LV works are complete. this LV tag must be cancelled via Dispatch. To get an LV tag ring Dispatch on 6270 7557.

59 The amendments to the Live Work Procedure were not the subject of any consultation with Evoenergy’s employees prior to 22 October 2023. The changes were notified when a communication was sent to the leadership email group, on 22 October 2023, under the heading “Protected Industrial Action – Guidance on the Ban on Use of LV Tags”. and a briefing was provided to the Control Room Workers regarding the changes. The applicant by its National Legal Officer sought an undertaking, sent to Mr Capoulade, that Evoenergy would not replace the existing Live Work Procedures until a consultation had been held.

60 At 6.38 pm on 23 October 2023, Mr Capoulade gave that undertaking to the CEPU, and confirmed that Evoenergy had commenced a consultation process. In his oral evidence, Mr Capoulade conceded that he had it “in mind” that the union may object to the changes in procedures, on the basis that it mitigated one of the protected industrial actions, and he agreed that he was aware, but not with any degree of certainty, that the applicant would object to the proposed changes, as at 23 October 2023.

61 Over the next few days there was correspondence about the way in which the changes would be managed. On 25 October 2023, two consultation sessions were held with employees to discuss the proposed changes. These sessions were held at 7.30 am and 3.15pm. A total of 101 workers attended the two sessions, either in person or by Microsoft Teams. The applicant was not invited to participate, but the consultation memorandum was forwarded to the Electrical Trades Union on 26 October 2023 at 9.26 am. Mr Birchall was on leave over that period, and did not find out about the changes to the LV Tag Procedure until his return to work on 9 November 2023.

62 Mr Brown attended one of the consultation sessions, and asked questions of Mr Capoulade and Ms Butterfield. Some of his concerns were based on the “Tag Summary” and “Note Summary” documents attached to the consultation invitation, which he said did not reflect how he used the ADMS. Mr Brown was told that the “subject matter experts” who worked on the changes were Mr Warren Wood (Acting System Operations Manager), Mr Leylann Hinch (Group Manager, Strategy and Operations) and Mr Gavril Lendeczki (Principal Real Time Systems Engineer). Mr Brown responded to the effect that none of those persons was a user of the ADMS, nor did they issue tags as part of their roles. Mr Capoulade in his oral evidence noted Mr Wood as the person from whom he sought advice on the way in which the ADMS operated in relation to the placing of tags.

63 Mr Pearce attended a meeting with Union members at 7.30 am on 26 October 2023. He noted that “at least 10 members raised concerns with the new tagging procedure”.

64 Further discussions on the changes were held:

(a) on 26 October 2023, at another meeting of the Evoenergy Consultative Forum held at 8.30 am, Mr Pearce raised the safety implications, and the issue of consultation at this meeting; and

(b) on 30 October 2023, the Acting Manager System Control, Mr Wood, held a meeting with the Control Room workers to discuss the proposed changes.

65 Mr Pearce noted that there were no discussions of the proposed changes to the Live Work Procedure discussed at the previous Consultative Forum which had been held on 28 September 2023. Nor were the changes listed for discussion in the agenda for the 26 October 2023 Consultative Forum meeting. Mr Capoulade was cross-examined on why the applicant was not formally consulted on the changes until the morning of 26 October, when a consultation memorandum was sent to Mr Pearce at 9.26 am, given that the consultation closed at 4 pm that day. His answer was that he was aware that a number of employees who had been consulted were members of the union, or delegates of the union, and that the union would therefore be aware of the consultation in any event.

66 On 27 October 2023, a number of employees including Ms Butterfield and Mr Capoulade attended a demonstration of the ADMS to “consider the feedback provided by employees during the consultation process”. The employees listed by Mr Capoulade in his affidavit of 6 November 2023 at [75] do not include any Network Controllers or employees who used the ADMS on a regular basis. The conclusion reached at that demonstration was that there was no significant difference between the Live Work Procedures involving LV tags, and that involving the placement of PWNs. There was some dispute in the evidence about the validity of the conclusions reached at the demonstration. Mr Capoulade noted that the workshop or demonstration was held in a hybrid way from the Fyshwick office of Evoenergy, and online, and while the control room is at the Fyshwick office, it was not held in the control room itself.

67 On 27 October 2023, Mr Van Der Walle, whose email signature block notes he was the “People Business Partner (Evoenergy) | People and Legal”, wrote to Ms Heffernan, of the Electrical Trades Union, disputing that cl 68 of the 2020 Agreement required consultation on the changes. He noted that the changes to procedure were “operational in nature [and] fall under the Evoenergy Asset Management policy suite of procedures. They are not procedures of the Work, Health, Safety, Environment, and Quality policy suite of procedures”. Mr Van Der Walle was not called to give evidence, but Ms Butterfield noted in her oral evidence that she had input into this correspondence.

68 The issue of whether the Live Work Procedure and the placing of tags was a safety issue, or whether it was merely operational, and whether it was a primary or secondary concern, assumed some importance in the evidence, both written and oral, to a somewhat surprising extent. Surprising, when so many of the facts of this matter were otherwise agreed, and in particular in light of the facts agreed in paragraphs [8]–[12] of the Statement of Facts which is extracted in [31] above.

69 Mr Capoulade noted in his affidavit that the two policy documents which were amended to form the new Live Work Procedure “form part of the Evoenergy Asset Management policy suite. They do not form part of the Work, Health, Safety, Environment and Quality policy suite”. However, Mr Capoulade retreated from that position somewhat, answering a question from counsel for the applicant with the statement that the “Live Work Procedures or the recording of those Live Work Procedures form a safety control … for performing live work”. He was then asked, “[T]he procedure was required to ensure the safety of all Evoenergy personnel, etcetera?” He replied, “Yes, agree with that”. He said he believed that the policy documents were operational documents “at the time”.

70 Mr Capoulade was pressed quite strongly on this point, and whether he lied to the workers about whether the procedures were safety, or administrative, procedures. I accept his assertion in oral evidence that while the live tagging procedure had safety elements, he took the view as at 25 October 2023 that it was an operational procedure which fell within the Asset Management suite of policies. He noted that he was not “trying to deny that it is – has safety elements or a safety procedure”. He did give evidence that he heard Ms Butterfield, at the meetings called to discuss the changes on 25 October 2023, say that it was not a safety procedure. He did not correct that assertion at the time.

71 Mr Capoulade was also asked about the differences between notes and filters on the ADMS, and the safety issues when a Network Controller had to look at two different areas of the system, as opposed to just checking the LV tags summary, and whether the change was “minor or immaterial” (which is how Mr Capoulade said he viewed it). He was taken by counsel for the applicant to the differences in view between that point and the views taken by Mr Brown and Mr Birchall as to the differences between PWNs and LV tags, and maintained his view that he understood the way that the ADMS was able to be operated to have both processes viewable through the use of filters.

72 The respondents advised the workers of the outcome of the consultation process on 30 October 2023, by email which attached a summary of the feedback received and the consideration of that feedback by Evoenergy. Evoenergy considered that the consultation process was complete and brought the Live Work Procedure changes into effect at 5.00 pm on 31 October 2023. On 30 October 2023, Mr Wood held a meeting with the Control Room workers to further discuss the changes. He reported to Mr Capoulade that around ten System Operations staff attended the meeting. Mr Wood was not called in these proceedings, and Ms Butterfield gave evidence that he no longer worked for Evoenergy, that she had endeavoured to locate him, and that he currently lives in Dubai. She was unable to get in contact with him.

73 Mr Brown took issue with the completeness of the consultation, and said that his emails of 26 October 2023 (while the consultation was open) and 31 October 2023 (after the consultation was closed) raised a series of practical queries and safety concerns that went unanswered (although this was not accepted by Mr Capoulade). Mr Brown had a series of safety concerns set out in his affidavit of 2 November 2023 (at [45] ff) and raised the issues of the use of summaries as opposed to filters, and the visibility of all notes on the system, in an email to Mr Wood and Mr Hinch on 31 October 2023. He noted in that email that the use of filters at all times “would be a change to how most LV and [High Voltage] Controllers currently operate”.

74 One of the concerns expressed by Mr Brown in his affidavit was that the LV work tags were immediately recognisable as to the kind of work being done, and where. The PWN only indicates that a worker is in a particular location, not (for example) whether the worker was connecting a device to a network, or working on trees. To find out that information, the Network Controller must click into the note itself. If there are tags, and notes, on the system, the Network Controller must look in two places as the two systems would be used concurrently (notwithstanding the requirement that, in the usual course, only one tag be placed on any particular location at once, as noted in [41] above). Mr Brown gave evidence of his concern that, where Network Controllers were not familiar with the PWN system, workers could be at risk. There was some dispute about this aspect from witnesses from the respondent, although Mr Capoulade conceded that “[w]hilst the Personnel Working Note may not provide the same visual indication of the work type, it provides visual indication of work occurring at a particular point on the LV network, and requires minimal time and effort to review”.

75 Mr Capoulade noted that “[l]ike LV tags, it is necessary to click on the Personnel Working Note to bring up the information in the note regarding the contact details of the worker working on or near the network”. Mr Brown on the other hand, pointed out that irrelevant LV tags could quickly be disregarded where necessary because of the colour-coding related to various kinds of work.

76 The respondent did not implement any training for the Network Controllers on the PWN procedures in lieu of the LV tag procedures. Mr Capoulade expressed the view that the changes to the Live Work Procedure involving the PWNs were “relatively minor in nature” and was “a mechanism that was already used by, and familiar to, Control Room workers”.

77 On 31 October 2023 the applicant requested, pursuant to s 82 of the WHS Act, that WorkSafe ACT (the work health and safety regulator) resolve the issue of whether the consultation undertaken by Evoenergy was sufficient for the purposes of the WHS Act. The regulator concluded that “suitable consultation” had been conducted, and that no regulatory actions would be taken by WorkSafe ACT.

78 The proceedings were commenced by CEPU seeking an urgent interlocutory injunction filed at 11.30 pm on 1 November 2023. An interim regime was agreed upon and the application for the injunction was withdrawn on 7 November 2023.

79 The effect of the interim regime was that there was no occasion on which any employees were required to use PWNs rather than LV tags after 1 November 2023, and the LV Tag Action was not taken thereafter. Accordingly, issue numbers 3 and 4 in the Statement of Issues need to be determined in the theoretical sense, rather than having regard to actual work done or actual incidents (except for the three incidents of LV Tag Action noted above in [50]).

80 As noted above, the 2023 Agreement was approved in November 2023, and came into operation on 7 December 2023.

81 Paragraph 57(a) of the Statement of Facts notes that Evoenergy admits that it:

(a) contravened clause 67 of the 2020 Agreement, and thereby contravened s 50 of the FW Act, by introducing a change to their procedures for the recording of live work near the low voltage network on 23 October 2023, without consulting with workers who carry out work for the ActewAGL Distribution partnership and who are likely to be directly affected by a matter relating to work health or safety in circumstances where s 47(1) of the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 (ACT) required:

The person conducting a business or undertaking must, so far as is reasonably practicable, consult, in accordance with this division and the regulation, with workers who carry out work for the business or undertaking who are, or are likely to be, directly affected by a matter relating to work health or safety

Safety Committee Issue

82 Clause 68.1 of the 2020 Agreement required that Evoenergy should maintain a joint Management/Union “Health, Safety and Environment Policy Committee (HSEPC)” (Safety Committee). The Safety Committee would have the following terms of reference:

(a) advise the Senior Management on policy matters concerning HSE within Evoenergy;

(b) advise the Senior Management on projects and programs to implement relevant Evoenergy policies and practices;

(c) develop, monitor and review Evoenergy’s HSE policy and procedures;

(d) advise on broad priorities that should apply to proposed HSE projects and programs, taking into account any resource implications;

(e) monitor outcomes and review actions taken to implement HSE policies and practices;

(f) review regularly:

(i) HSE reports including overall trends in accidents, injuries and diseases; and

(ii) summaries of matters discussed at the local HSE Committee meetings;

(g) provide information and advice to local committees; and

(h) develop procedures to govern its operation.

83 No such Safety Committee was established or maintained by Evoenergy while the 2020 Agreement was in operation.

84 Mr Pearce gave evidence, from his experience as an electrical worker from 2013–2023, and as a union delegate from 2021–2023, that “when there is a safety committee, information exchange and consultation is more effective and efficient and workers have more of a practical opportunity to influence safety outcomes”.

85 The Statement of Facts sets out the existence, and terms of reference, of some other consultative bodies maintained by Evoenergy. These include:

(a) The Evoenergy Field Safety Committee; and

(b) The Evoenergy Consultative Forum.

86 Mr Pearce took the view that the Consultative Forum fulfilled a different role from the Safety Committee, in that the Forum was not safety-specific and deals with company-wide issues that affect different groups of workers, not only those with a particular interest in safety such as frontline electrical workers.

87 The respondents initially took the view in these proceedings that the Evoenergy Field Safety Committee “under[took] the role of the [Safety Committee] for the purposes of clause 68 of the Enterprise Agreement”. Mr Capoulade was cross-examined about whether there was a direction from management that the Field Safety Committee and the Consultative Forum performed the functions of the Safety Committee. Mr Capoulade maintained this view in his updating affidavit of 30 September 2024 (noting that the Consultative Forum also had discussions of matters contemplated by cl 68 of the 2020 Agreement) but in cross-examination, noted that this was not correct, even though it was his understanding at the time.

88 Ms Dougall (Group Manager Safety, Risk and Compliance) was a management representative on the Field Safety Committee. She too initially took the view that that committee, and the Consultative Forum, dealt with safety issues, and allowed workers to place matters on the agenda for either body. She was not, as at 30 September 2024, aware of any issues raised by the lack of a Safety Committee.

89 Mr Pearce said, in his reply affidavit, that his reference in a conversation with Ms Butterfield to cl 68 of the 2020 Agreement was a reference not only to consultation about the change but also to the lack of a Safety Committee. This does not in my view appear to be an obvious inference from the terms of the conversation deposed to, as Mr Pearce’s comment “[l]ook at clause 68 of the agreement” was in the context of the lack of consultation in relation to the changes.

90 It does not seem to me that there was at any point any specific consideration of the need for the Safety Committee or a deliberate decision not to establish one; nor was there a deliberate decision that the other available committees could, and should, undertake that work.

The current position

91 Evoenergy has now established a standalone Safety Committee, and the Terms of Reference were in evidence (see Exhibit ZD-1, pp 23–24).

92 Paragraph 57(b) of the SAF notes that Evoenergy admits that it contravened cl 68 of the 2020 Agreement, and thereby contravened s 50 of the FW Act, by failing to maintain the “Management/Union Health, Safety and Environment Policy Committee” required by that clause.

93 As set out in the factual narrative above, the respondents accepted – once Ms Heffernan had written to them seeking an undertaking – that consultation on the changes to the LV tag procedures was required. Mr Billing described that consultation as “fulsome”. I will leave aside the fact that the formal meaning of the word “fulsome” (being excessive; gushing; insincere – Macquarie Dictionary Online) is not lexically apposite here, and will take it that it has been used in the more informal sense of being thorough or expansive. Even doing so, I am of the view that the consultation was not “fulsome”. It was brief, did not include all the workers with an interest in it, and did not appear to have been undertaken with a view to seeking constructive criticism.

94 I come to this view partly because of the insistence by management that the Live Work Procedure policy changes were changes to Asset Management policies and not a safety process. Clearly the notification of the location of, and work being undertaken by, workers is a significant safety issue. While Mr Billings noted that once discussion had taken place with the workers on the morning of 23 October 2023, it “became apparent that consultation should have been undertaken”, there appeared to be an ongoing resistance to the concept that the Live Work Procedure was indeed a safety procedure regardless of whether the policy documents were held in the Asset Management suite of policies. Indeed, the applicant’s application for injunction was initially resisted on that basis.

95 Mr Billing also sought to set out the steps that had been undertaken after the contraventions. He noted at [15] of his affidavit of 30 September 2024 that:

…Evoenergy has taken the following steps to ensure that such breaches do not occur in the future:

(a) Senior managers have been briefed on the requirements to ensure consultation occurs in line with the WHS Act …

96 However, the applicant called within these proceedings for documents evidencing or relating to the briefing referred to by Mr Billing, by letter of 9 October 2024. Ms O’Brien, in her affidavit, recorded that:

On 14 October 2024, Benjamin Bromfield of Ashurst sent an email to Mr Kennedy [Ms O’Brien’s supervising solicitor] in response to that letter which stated: “We are instructed that there are no documents which evidence or relate to the briefings provided to senior managers referred to in paragraph 15(a) of the affidavit of Peter Billing or which relate to those briefings”.

97 I accept that Evoenergy was, as noted by Mr Billing, concerned to balance the rights of its employees to take protected industrial action during bargaining for the 2023 enterprise agreement, with the safety of the Evoenergy customers, maintenance of the infrastructure, and management of the LV network, as set out by Mr Billing at [9] of his affidavit of 30 September 2024. However, I am of the view that the main reason for the “workaround” of the PWNs and the lack of consultation with the workers was to avoid the impact of the protected industrial action and in effect to sideline the effectiveness of that action.

98 Evoenergy, through its General Manager Mr Billing, has accepted responsibility for its acts and omissions leading to the contraventions, and “apologises to the Court and to its employees”. The apology was not fulsome, in either sense of the word, but I accept that Mr Billing was genuine in his contrition and understands the importance of proper consultation.

Considerations of credit of the respondents’ witnesses

99 I note I have dealt with the credit of Mr Birchall and Mr Brown above in [35] and [44] respectively.

100 Mr Capoulade generally answered questions in a straightforward manner, and made, as I have said, some concessions. However, he did tend to revert to a “corporate” position at times (in particular, in insisting on the position that a safety procedure contained in an operational document was somehow different in quality to a safety procedure which was documented within the safety policies). I do not accept, as the applicant suggested to him in the witness box, that he engaged in deliberate falsehoods and “that Evoenergy had no regard for the truth” when communicating with the applicant as to the nature of the policies. I do take the view that the evidence supports a finding that Evoenergy, in seeking to fast-track the policy changes to avoid the impact of the LV Tag Action, did so in a way which resulted in a failure to consult when that requirement should have been apparent. But that view is not based on a lack of truthfulness in Mr Capoulade.

101 Ms Butterfield, likewise, seemed to give occasionally evasive answers where the straight answer would not have assisted the respondent’s case. As noted above, some of her evidence seems overstated. I do not accept that her evidence should be accepted over that of the evidence of Mr Pearce, Mr Birchall, or Mr Brown. In particular, I am of the view that she knew that consultation was required in relation to safety procedures (see her answers to questions in the transcript of Day 2, page 4, lines 27–28) and that the LV tag procedures were detailed in the Servicing Manual which identified those works as ensuring “the safety of the public, workers and equipment” (see transcript of Day 2, page 5, lines 16–32). She remained staunch in cross-examination however that there was no immediate safety risk in the change in the LV tag procedures without training in the new PWN placement procedure. Likewise, she took the position that it was not until Ms Heffernan sent her letter that Evoenergy “decided that [it needed] to consult at that time”. It seems to me that the evidence given as to the urgency of the need to find a workaround for the LV Tag Action combined with the conclusion above that the need for consultation should have been easily apparent indicates that Ms Butterfield took a technical approach when a practical, safety-focussed approach was required.

102 Ms Dougall on the other hand was straightforward and thorough in her responses. Mr Billing, the general manager, while not as forthcoming, did answer questions in my view honestly. He accepted propositions about the value of consultation, and also accepted that the reason for the change was the “neutralisation” of the LV work tag ban. He was cross-examined at length on the “primary” and the “secondary” motivations of the company, but it seems to me that he, along with the other witnesses for the respondents, were focused more on finding an outcome which would allow work on the LV network to continue despite the protected industrial action relating to LV tags, rather than the need for consultation or the technical nature of the changes.

Submissions

The applicant’s submissions

LV Tag Issue

103 In relation to the LV Tag Issue, the applicant submitted that the respondent should pay a penalty at the higher of the agreed range on the basis that the respondents breached the 2020 Agreement and the legislation for the purpose of “getting around” the effect of the protected industrial action. The changes to the LV tag process were introduced quickly and on the day on which the LV Tag Action was due to commence. The lack of consultation was pointed to by Mr Brown in particular as being something that caused an issue with safety, given that the respondent did not seek to mitigate the introduction of the PWN system with consultation, discussion, training, and resolution of the filters/notes/summaries issue.

104 It was submitted that the consultation, when it happened, was rushed, insufficient, did not cover the workforce, and did not result in any changes to the procedures. Counsel characterised the changes as a “shoddy workaround”. It was submitted that the consultation was not conducted as required by the WHS Act or the agreement, because a number of workers were not at work during that time. Nor was there, as required by the WHS Act, any consultation with the Field Safety Committee or the Consultative Forum. It was submitted that the admission of a breach as “technical breaches” when the breaches were, in truth, substantial, pointed to a higher penalty.

105 The applicant submitted that the stance taken by the respondents that the Live Work Procedure was not a safety procedure is representative of the positions taken by the parties to this dispute – it says that the position was (as expressed on the front page of the procedure document) that the procedure was required for safety purposes, and the assertion that in fact it was an administrative policy was disingenuous. The position taken by the applicant was that the respondents always knew of the requirement to consult, and that it chose to “take the odds” in not doing so. However, Mr Fagir, for the applicant, conceded that it may not matter very much whether the contraventions were knowing, or “merely careless”.

106 The approach taken by the respondents, it was submitted, was to defend the allegations (which the applicant says was indefensible) “for as long as it took to preserve its tactical advantage in the industrial dispute”. The applicant further takes issue with the expression of contrition.

107 The applicant puts the proper level of penalty as being “a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act” – Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450; HCA 13at [15]. In agitating for a penalty at the higher end of the agreed range, the applicant points to the importance of consultation and the fact that it should not be treated “perfunctorily or as a mere formality” (Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v QR Ltd (2010) 198 IR 382; FCA 591 at [43] (Logan J); The Australian Federation of Air Pilots v HNZ Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 755 at [30] (Mortimer J)). The applicant points to the 2020 Agreement itself which requires that consultation must involve participants in decision-making “not only in appearance but in fact” (clause 2.2).

108 The discussions prior to the implementation of the changes to the LV Procedure, and prior to consultation commencing, did not involve any workers, but only senior managers.

109 The applicant made submissions about the differences between the LV tags and the PWN process, and pointed to the greater amount of immediately available information from the LV tags. Those differences, it was submitted, resulted in a unilateral variation of a safety procedure with “self-evident” risks. There was, it was submitted, confusion amongst the Network Controllers, and no assistance provided by way of the failure to update the Servicing Manual until 23 October 2023. The applicant highlighted how the use of filters was an unsatisfactory solution to the challenges caused by the changes.

110 In setting out the steps taken by way of consultation (in [46] of the applicant’s written submissions and [82] of its written outline of closing submissions), it is contended that the consultation was fairly brief, did not include all Network Controllers (the workers who were affected by the change), and neither of the committee or forum dealing with safety was consulted. The fact of the continued insistence of the changes not being a safety procedure was maintained during the consultation process. It is submitted that the abridged safety consultation was in stark contrast to the usual timeline for consultation, which can take a number of months.

111 The applicant drew my attention to the comments of the Full Court in QR Ltd v Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union (2010) 204 IR 142; FCAFC 150 (QR v CEPU) at [80] and [81] (Gray J) which stresses that “real opportunities” need be given for employees to suggest proposals, and requires that consultation not be “a formality”.

Safety Committee Issue

112 The applicant pointed to the formal consultative procedures including the Safety Committee (which was never convened) and the Consultative Forum as vehicles for the consultative process. The lack of a Safety Committee – with its agreed mandate to “develop, monitor and review Evoenergy’s policies and procedures” – was, it was submitted, in itself a serious contravention.

113 It was submitted that there was “never … any defence” to this contravention. The 2020 Agreement, by cl 68, requires the establishment of the Safety Committee, and it is not apposite to say that the existence of the Field Safety Committee or the Consultative Forum – which were not consulted in relation to the changes to the Live Work Procedure – had some crossover responsibilities. I accept Mr Pearce’s evidence – on which he was not cross-examined – on why a dedicated Safety Committee would have been more effective for consultation.

Submissions as to penalty

114 The applicant contends for a penalty of 50% of the maximum for the LV Tag Issue, and 20% of the Safety Committee Issue. In its closing submissions the applicant pointed to the following five factors which it says are relevant to the assessment of the penalty:

(a) the conduct was objectively serious, in amending a safety policy without consultation;

(b) the process leading to the amendment without consultation involved the whole of Evoenergy’s senior management;

(c) Evoenergy had continued to defend its conduct despite knowing it contravened the 2020 Agreement, thereby weighing against any suggestion of Evoenergy’s contrition of insight;

(d) the respondent continued to seek to minimise its contravention and the changes made to the Live Work Procedure and Servicing Manual; and

(e) there is no evidence that the respondents have taken steps to avoid any recurrence of the contravention.

115 As for the Safety Committee issue, the applicant contends that a penalty of 20% is sufficient, as it was a “simple, unexplained and unrepentant failure” to comply with the 2020 Agreement. The applicant submitted that there has been no explanation for the failure, and no “insight or contrition”.

The respondents’ submissions

The LV Tag Issue

116 The respondents submitted that the nature of the amendments to the Live Work Procedure were “minimal”, at best. They contend that the changes to the Live Work Procedure served only to create an additional or supplementary way to record the location of persons working on or near the LV network, to be used in circumstances in which other tags were unable or unsuitable to be applied. They submitted that they considered the amendment to the Live Work Procedure to be “a minor change to an administrative process” which “would not impact on the health and safety of workers” ([12(b)] of the Respondent’s written submissions, citing Mr Capoulade’s affidavit of 6 November 2023, a proposition which he somewhat retreated from in cross-examination). Further, the respondents take issue with the magnitude and importance of the changes to the Live Work Procedure. They submitted that the Control Room does not monitor the LV network “in real time”, but relies on information provided by workers, and members of the public, to identify issues. They submitted that there was no material difference between the process of the placing of a tag or a note, and no real difference between the ability of a Control Room worker to read or otherwise act on the note as opposed to the tag.

117 The respondents are open about the fact that the changes in the LV tag procedure were initiated in order to mitigate the effects of the LV Tag Action. It was submitted that “[e]mployers are entitled to seek to mitigate the effects of protected industrial action being taken by its employees by implementing measures to reduce the impacts of that action on their operations” – citing Davids Distribution Pty Ltd v National Union of Workers (1999) 91 FCR 463; FCA 1108 at [87].

118 The respondents say, in mitigation, that once the lack of consultation was brought to their attention, Evoenergy ceased the implementation of the changes and a consultation process commenced. They contend that the conduct was not “deliberate” in the sense of whether they “consciously disregarded” their consultation obligations as provided for in s 47(1) of the WHS Act. The state of mind at the time was that the change was administrative or minimal, and that relevant participants considered that no consultation was required. They submitted that the changes were introduced with the “legitimate reason” to “continue to undertake critical work on and near the low voltage network” and mitigate the effects of the Live Tag Action. Additionally, the respondents had conducted a health and safety risk assessment prior to introducing the changes, which militates against any conclusion that the failure to consult was deliberate.

The Safety Committee Issue

119 In relation to the Safety Committee, it was submitted that “the functions of the committee were relevantly subsumed by other existing committees that were operating during the relevant period” and referred to the descriptions of the Field Safety Committee and the Consultative Forum in the Statement of Facts.

120 The respondents relied on Ms Dougall’s evidence that the applicant did not raise any issues relating to the failure to maintain a Safety Committee, prior to the commencement of these proceedings.

Submissions as to penalty

121 The respondents submitted that a single penalty in respect of each of the contraventions should be imposed on Evoenergy (that is, the partnership, rather than each of the respondents having a separate penalty):

(a) As to 20% of the maximum penalty for the LV Tag Issue; and

(b) As to 5% of the maximum penalty for the Safety Committee Issue.

122 The respondents contended that the low range of penalty is informed by the lack of any need for deterrence, the fact that the respondents admitted a breach at the early stage and have expressed appropriate remorse and contrition, the lower (or in the case of the Safety Committee Issue, the lowest) range of the seriousness of the breaches, and the need for judicial restraint in imposing penalties. The respondents further submitted that the consultation process was not deficient, as argued by the applicant and that the Safety Committee Issue was merely a “technical contravention”.

Consideration of the principles relating to agreed penalties

123 While there is some level of dispute in this matter as to the amount of the penalty, the parties have agreed on a range. The principles, dealt with below, as to consideration of an agreed penalty are equally applicable to a circumstance where a range has been agreed; see Fair Work Ombudsman v NSH North Pty Ltd (t/as New Shanghai Charlestown) (2017) 275 IR 148; FCA 1301 (Bromwich J) at [44].

124 As I noted in Secretary, Department of Health v Medtronic Australasia Pty Ltd (2024) 305 FCR 433; FCA 1096 at [107]: