FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Davis v Wilson [2025] FCA 108

ORDERS

First Applicant MR GEOFFREY WILLIAM DAVIS Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Second Respondent ERNST & YOUNG (A PARTNERSHIP) ABN 75 288 172 749 Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or by 7 March 2025 the parties are to provide to the Associate to Shariff J consent orders, including answers to the Common Questions, giving effect to the reasons for judgment dated 21 February 2025 and, if consent cannot be reached, each party is to by that time provide its competing set of orders (including their respective answers to the Common Questions).

2. The parties are to confer as to the appropriate costs order to be made and, if consent cannot be reached:

(a) any party wishing to make an application for costs must make such an application by sending an email to that effect to the Associate to Shariff J on or by 7 March 2025 and, at the same time, file and serve on each affected party any affidavits and submissions in support of that application (with such submissions not to exceed five pages in length);

(b) on or by 21 March 2025, any party that opposes the costs orders sought by the party that has made an application for costs under Order 2(a) file and serve on each other affected party any affidavits and submissions in support of its position (with such submissions not to exceed five pages in length);

(c) on or by 28 March 2025, the parties are to file any affidavits and submissions in reply to each other, if they consider it necessary to do so (with such submissions not to exceed three pages in length).

3. Unless the Court considers a hearing is necessary, or a party so requests with good reason, any applications for costs will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

SHARIFF J:

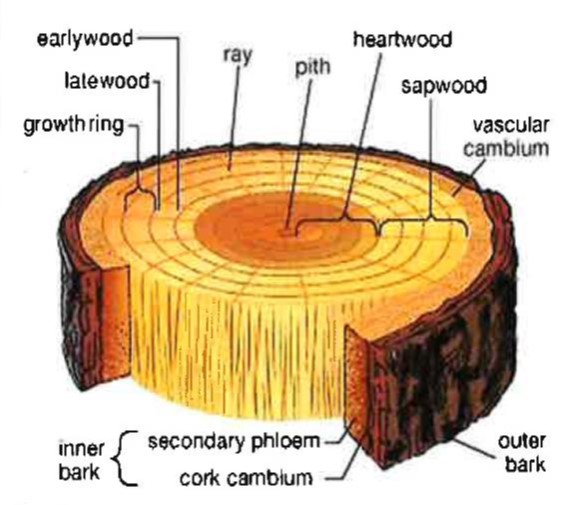

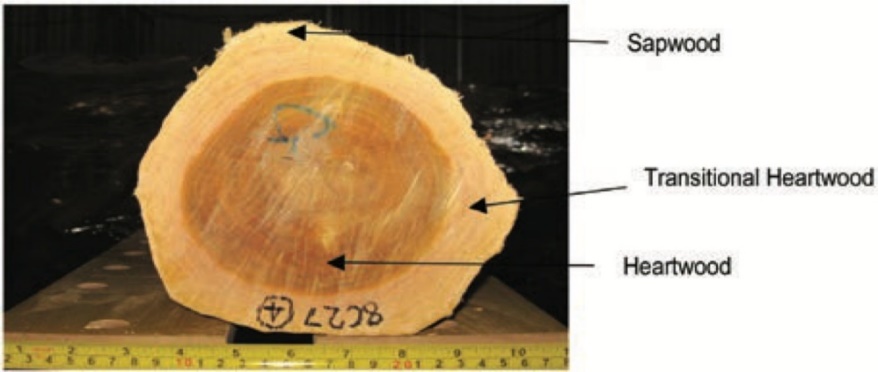

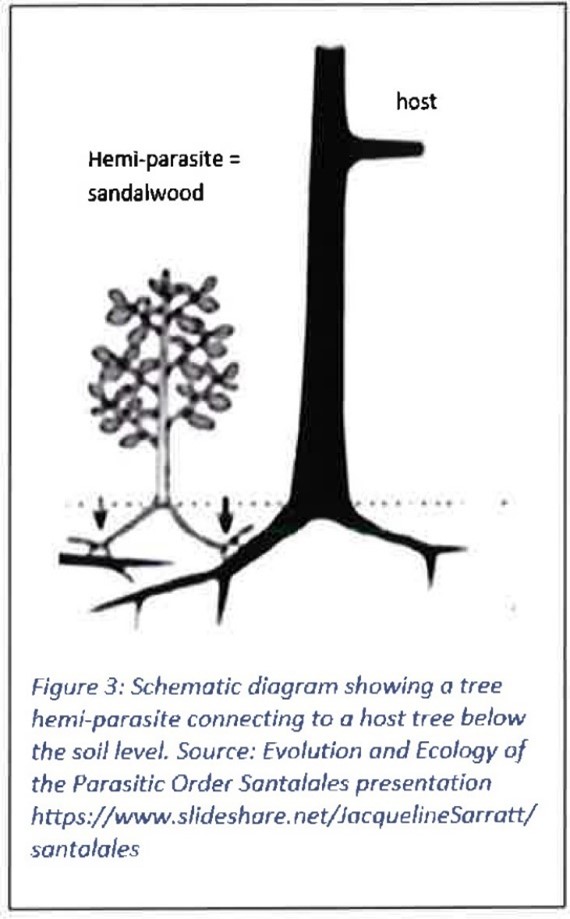

1 Indian Sandalwood (Santalum album) (sandalwood) is a hemi-parasitic tree belonging to the botanical family Santaceae. It produces fragrant oil which may be distilled from the core of the tree, known as its heartwood, through a process of cultivation and manufacture. The fragrant oil produced from sandalwood trees, and its equally fragrant timber, have been used over many centuries for traditional, religious, ornamental and medicinal purposes, and, in more recent times, in the manufacture of commercial products such as perfumes, soaps and cosmetics.

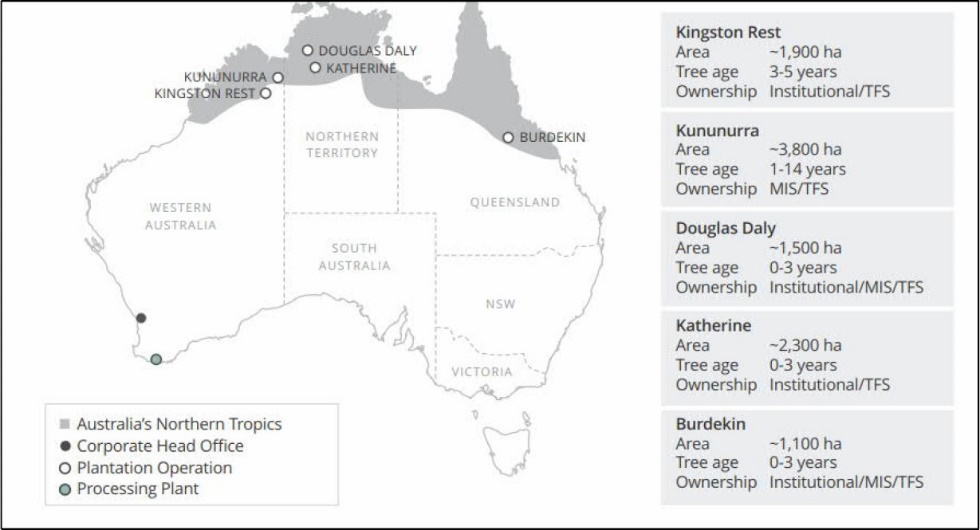

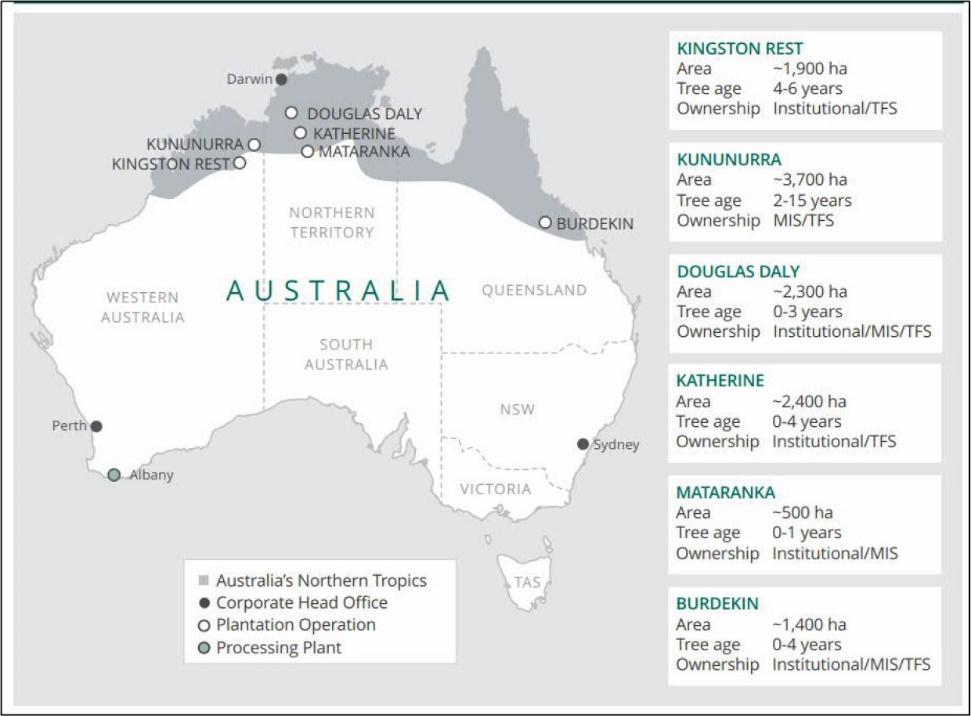

2 Sandalwood trees are native to India and Indonesia, but a handful of wild sandalwood trees were discovered to be growing in natural conditions in the Northern Territory. Historically, there had been no commercial plantations of sandalwood trees in Australia or elsewhere, and sandalwood timber and oil was generally produced from wild stocks in forests. That changed in the 1990s. Through various successive agencies of the (then) Western Australian Government, trials were established to determine, amongst other things, the viability of commercial plantations of sandalwood trees in Ord River Irrigation Area (ORIA) in North-Eastern Western Australia and close to the Northern Territory border, and, specifically, at Kununurra. These trials were conducted in various conditions and configurations to test their efficacy. As the results of the early trials started to be reported in academic journals and research papers, commercial operators entered the scene.

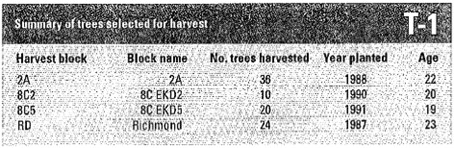

3 Quintis Ltd (Quintis) (formerly TFS Corporation Ltd (TFS)) was one of the earliest operators to have established commercial sandalwood plantations. Its first commercial plantation was established in 1999. By 2004, it was listed on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX). Under the irrepressible driving force of its founder, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and Managing Director, Mr Frank Cullity Wilson (Mr Wilson), Quintis had considerable success in the marketplace. By 2006, it had established the largest commercial plantation of sandalwood in the world. Quintis had also secured investments from many sophisticated, high net worth and institutional investors as part of various managed investment schemes (MISs) by which those investors came to own a large portion of the sandalwood plantations which Quintis managed. Quintis directly owned the balance of the plantations. By 30 June 2015, Quintis had 10,583 ha of sandalwood plantations under management, of which it directly owned 2,533 ha. By 30 June 2016, this had grown to an area of 12,182 ha under management, of which it directly owned 2,638 ha.

4 Quintis also achieved success in the marketplace. Well before its first commercial harvest (which did not occur until 2014) Quintis had entered into contracts for the sale of its products with customers, including a contract entered into in about 2008 with the cosmetics retailer, Lush Ltd. During 2014, it achieved an even greater commercial breakthrough when, through one of its subsidiaries, Santalis Pharmaceuticals Inc (Santalis), Quintis entered into a contract with Galderma SA (Galderma), which, in turn, was a subsidiary of Nestlé SA. The Galderma Contract provided for, amongst other things, the supply of sandalwood oil to Galderma for a period of 20 years at a price of US$4,500 per kg plus annual CPI (capped at 3%). The purpose of the contract was to facilitate the use of sandalwood oil in Galderma’s therapeutic products, including those intended to address skin conditions. Then, in early 2016, Quintis entered into a further substantial contract with a Chinese buyer of sandalwood timber. Together with other agreements said to have been entered into at the time, Quintis announced to the marketplace in an ASX announcement dated 26 February 2016 that it had signed new multi-year agreements to supply sandalwood to buyers in China and India “at prices broadly equivalent to US$4,500 per kg of oil” and that the “signing of these agreements means that 100% of the 2016 and 2017 harvests already owned by TFS, over 300 tonnes of heartwood, has been forward sold”.

5 Quintis’ share price traded as high as $1.74 and it had a market capitalisation which reached as high as $594,000,000. It was admitted into the “ASX 300”. Various market analysts were covering Quintis, including UBS, and making recommendations to “buy” shares in Quintis at target prices that were above its (then) trading price. Things were, as one might say colloquially, “on the up” and progressing swimmingly. But then things turned. Regrettably for its investors, Quintis’ fate as a publicly listed company proved to be yet another example of a share market Icarus.

6 On 22 March 2017, Glaucus Research Group California, LLC (Glaucus) released a report valuing Quintis shares at $0 and made several allegations in relation to Quintis’ business and operations (First Glaucus Report). Glaucus alleged, amongst other things, that Quintis exhibited characteristics similar to that of a “Ponzi scheme” and that is assets of sandalwood trees were effectively worthless. On 27 March 2017, Quintis shares were put into a trading halt by the ASX at Quintis’ request. Quintis denied the allegations made in the First Glaucus Report and described Glaucus as a self-interested short-seller seeking to make a financial gain at Quintis’ expense. On 28 March 2017, Quintis announced the resignation of Mr Wilson as Managing Director and, on 29 March 2017, Glaucus released a further report valuing Quintis shares at $0 (Second Glaucus Report).

7 On 15 May 2017, Quintis shares were put into a further trading halt, following which shares in the company never resumed trading.

8 On 20 January 2018, Quintis entered voluntary administration. On or about 29 June 2018, the company exited voluntary administration and entered into a deed of company arrangement (DOCA). The DOCA had the effect that Quintis was recapitalised and restructured into a private company. Quintis members at the time of the trading halt received a nil return from the DOCA.

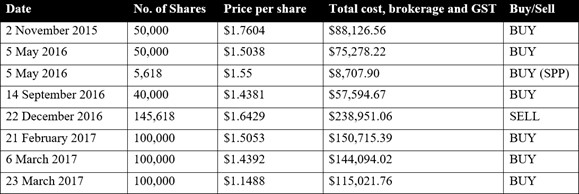

9 The applicants in these proceedings are Mr Geoffrey Peter Davis (Mr Davis Snr) and Mr Geoffrey William Davis (Mr Davis Jnr) (together, the Davis Applicants). The Davis Applicants are trustees of the Davis Superannuation Fund (Davis Fund) who purchased and sold shares in Quintis, on behalf of the Davis Fund, between 2 November 2015 and 23 March 2017.

10 The Davis Fund, as with other investors, acquired shares in Quintis which are now worthless.

11 Other investors acquired shares in Quintis which they sold at a loss.

12 The Davis Applicants bring the proceedings as representative proceedings pursuant to Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act) and as representatives of an open class (Davis Group Members), each of whom acquired an interest in ordinary shares of Quintis in the period commencing on 31 August 2015 and concluding on 15 May 2017 (including those who already had an interest in ordinary Quintis shares before 31 August 2015).

13 The proceedings concern alleged contraventions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) by Mr Wilson. They also concern alleged contraventions of the Corporations Act and the general law by Ernst & Young (EY), the auditor of Quintis’ accounts in the financial years ending 30 June 2015 and 30 June 2016 (together, FY15 and FY16). Initially, the applicants in the proceedings also claimed against Quintis itself, however, as a result of a settlement between the Davis Applicants and Quintis approved by Lee J on 1 July 2022 (see Davis v Quintis Ltd (Subject to a Deed of Company Arrangement) [2022] FCA 806), the remaining active respondents are Mr Wilson and EY (together, the Respondents).

14 The proceedings were heard concurrently with another set of representative proceedings brought against the Respondents by Excel Texel Pty Ltd (as trustee for the Mandex Family Trust) (Excel Texel) and Mr Andrew John Wyma (NSD1983/2017, or the Excel Texel Proceedings). On 16 July 2024, after the conclusion of evidence but before closing submissions had been heard, my chambers were informed that the parties to the Excel Texel Proceedings had executed a deed containing a proposed settlement of those proceedings, and an application for approval of the settlement under s 33V of the FCA Act was thereafter allocated to the docket of Wigney J. I took no further part in the Excel Texel Proceedings.

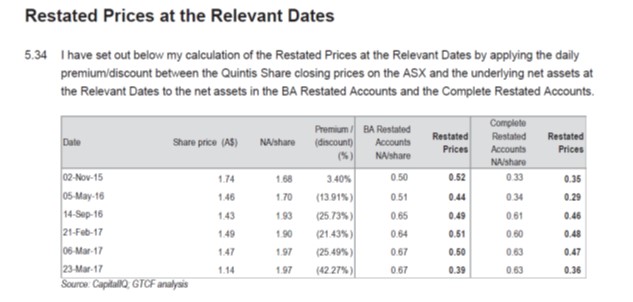

15 In short, the Davis Applicants alleged that they (and the Davis Group Members) acquired Quintis shares, either on market or via a share purchase plan, between 31 August 2015 and 15 May 2017 at an inflated price due to misleading or deceptive statements made in Quintis’ financial reports for FY15 and FY16 (respectively, the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports). Those allegedly misleading statements centre on the value of Quintis’ principal cash generating asset, sandalwood trees, which were referred to in Quintis’ financial statements as its “biological assets”. The Davis Applicants alleged that Quintis materially overstated the value of its biological assets in the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports by reason of various inputs adopted in the discounted cash flow model (DCF Model) which it used to value those assets. These inputs were assumptions which Quintis made for the purposes of measuring and reporting the fair value of its assets, as required by the Corporations Act and the Australian Accounting Standards (Accounting Standards or AASBs).

16 The allegations of misleading conduct against Mr Wilson (as contained in the Davis Applicants’ Fifth Further Amended Statement of Claim (FFASOC)) can be summarised as the conduct engaged in by him, as a director of Quintis, by joining in the resolutions of the directors of Quintis in each of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports, of representing that he was of the opinion that:

(a) the Financial Reports had: (i) been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Corporations Act, including that they complied with the Accounting Standards; and (ii) gave a true and fair view of the financial position and performance of Quintis; and that those opinions were held on a reasonable basis and were the product of the application of reasonable care and skill by Mr Wilson (together, the Wilson FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations);

(b) Quintis had: (i) in FY15, total assets of $1,173,335,000 and net assets of $574,523,000; and (ii) in FY16, total assets of $1,491,958,000 and net assets of $747,222,000; and that those opinions resulted from the application of the Accounting Standards and were held on a reasonable basis and were the product of the application of reasonable care and skill by each director of Quintis, including Mr Wilson (together, the Wilson FY15 and FY16 Assets Representations); and

(c) Quintis had post-tax profit: (i) for FY15 of $113,021,000; and (ii) for FY16 of $90,143,000; and that those opinions resulted from the application of the Accounting Standards and were held on a reasonable basis and were the product of the application of reasonable care and skill by Mr Wilson (together, the Wilson FY15 and FY16 Profit Representations),

(collectively, the Wilson Representations).

17 As will be apparent from the above, the case against Mr Wilson was that the opinions he expressed carried an implied representation that he had reasonable grounds for the expression of those opinions, and that they were made as the product of the application of reasonable care and skill. The Davis Applicants claimed that each of the Wilson Representations was misleading because there were no reasonable grounds for the opinions Mr Wilson expressed or because they were not the product of the exercise of reasonable care and skill by Mr Wilson. The Davis Applicants asserted that this was the case because the assumption Quintis adopted in its DCF Model as to predicted average heartwood yield was materially higher than that which a market participant would assume; the assumption as to the costs of processing sandalwood oil was understated; and that these assumptions had the effect of materially overstating the accounts as reported in each of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports. It was therefore asserted that the accounts did not represent fair value, and that, as a result, there was non-compliance with the requirements of the Accounting Standards.

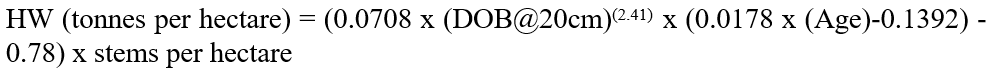

18 As a preliminary matter, Mr Wilson denied that he made any of the Wilson Representations, and, therefore, denied that he engaged in any misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of the Corporations Act. This necessitates resolution of the question as to whether, by joining in the resolutions by which Quintis’ directors came to make the declarations contained in each of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports, Mr Wilson personally conveyed the Representations that were alleged against him. Mr Wilson further submitted that, even if he had made the Representations, the Davis Applicants had not made out any of the essential factual predicates to establish that his conduct was misleading and deceptive. Mr Wilson did not give evidence but contended that the evidence before the Court did not support the case advanced by the Davis Applicants as to the alleged flaws in the DCF Model or that he should have known, or ought reasonably to have known, about these flaws.

19 As for the case against EY, it was common ground that the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports each contained statements of opinion expressed by EY that these Reports were in accordance with the Corporations Act, including by: (a) giving a true and fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance; and (b) complying with the Accounting Standards. Those representations were respectively defined in the FFASOC as the FY15 and FY16 Audit Opinions. EY admitted that it expressed these opinions.

20 The Davis Applicants alleged that, by issuing the FY15 and FY16 Audit Opinions in the circumstances pleaded, EY represented to members and potential investors in Quintis that those opinions were: (a) opinions held on a reasonable basis and the product of the application of reasonable care and skill by EY; and (b) formed after EY had conducted an audit in accordance with the Australian Auditing Standards (Auditing Standards or ASAs). These representations were respectively defined together in the FFASOC as the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations. It was contended that these Representations were misleading because EY had not in fact conducted an audit in accordance with the Auditing Standards, and did not have a reasonable basis for expressing the FY15 and FY16 Audit Opinions. That is because, it was alleged, EY did not take the steps that a reasonable auditor in its position would have taken in conducting the FY15 and FY16 audits. EY denied that it made any of these Representations, and further denied that the Davis Applicants had made out the factual predicates of the misleading and deceptive conduct alleged.

21 As a result of each of these allegedly misleading statements, the Davis Applicants alleged that Mr Wilson and EY each contravened ss 1041H or 1041E of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). They also alleged that EY breached a common law duty of care owed to both current and future members when carrying out the FY15 and FY16 audits of Quintis’ accounts.

22 In respect of each of the cases against Mr Wilson and EY, the Davis Applicants accepted that they needed to establish causation by making out their pleaded counterfactual case. In each case, this required them to establish that the “heartwood yield assumption” that should have been adopted was approximately 6 to 8 kg and that the “processing costs assumption” should have been $229.72 per litre of oil for FY15 and $597 per litre of oil for FY16.

23 The Davis Applicants advanced a “direct reliance” case, contending that they acquired shares in Quintis in reliance on the alleged misrepresentations by Mr Wilson and EY when they would not otherwise have done so. They also advanced an indirect “market-based causation” case on behalf of themselves and the Davis Group Members, contending that they acquired shares in Quintis in a market that was artificially inflated by reason of the misrepresentations alleged against each of Mr Wilson and EY.

24 For the reasons which follow, I have concluded that the Davis Applicants’ case and that of the Davis Group Members for the recovery of loss and damage must fail, even though I have concluded that, in part, they have established their case as to liability against each of Mr Wilson and EY. My reasons for so concluding contain many nuances borne of the factual and legal complexity of the proceedings. It is not possible to fairly or accurately summarise all of my reasons by way of an introduction. Limiting myself to the critical reasons, at a high level, and in brief, I have concluded that the Davis Applicants have:

(a) established that the heartwood yield assumption used by Quintis in the DCF Model in respect of trees aged under five was unrealistic and was an assumption that lacked reasonable foundation;

(b) established that Mr Wilson did make the Wilson Representations, and did not have reasonable grounds for making those Representations;

(c) established that the heartwood yield assumption used by Quintis in the DCF Model in respect of trees aged under five was a significant assumption but was not a reasonable one, such that I am satisfied that EY ought reasonably to have evaluated it as an assumption that was not reasonable as that is what a reasonable auditor would have done in the same circumstances, and, further, it was established that EY failed to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence so as to, in turn, obtain reasonable assurance that the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports were free from the audit risk of material misstatement to an acceptably low but not absolute level;

(d) established that EY did not have a reasonable basis to make the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations and that they were not the product of reasonable care and skill exercised by EY;

(e) established in light of each of the above (and for the other reasons set out below) that Mr Wilson and EY each contravened s 1041H of the Corporations Act and that EY additionally contravened s 12DA of the ASIC Act;

(f) not established their counterfactual case that the heartwood yield assumption that should have been used was approximately 6 to 8 kg per tree;

(g) not established causally connected loss for the purpose of s 1041I of the Corporations Act and s 12GF of the ASIC Act as against either Mr Wilson or EY, or for the purpose of the negligence claim against EY.

25 To explain why I have reached these conclusions, the balance of these reasons are set out as follows:

(a) Chapter A concerns a number of preliminary matters:

(i) in Part 2, I set out an overview of the pleaded case against each of the Respondents;

(ii) in Part 3, I determine a preliminary but fundamental dispute between the parties as to the scope of the pleaded case against the Respondents, which came to be referred to by the parties as the “binary issue”;

(iii) in Part 4, I deal with questions of onus and make general findings as to the evidence and credit of the various lay and expert witnesses;

(b) Chapter B concerns factual matters:

(i) in Part 5, I lay out the chronological facts relevant to the proceedings. Many of these facts were not in dispute, but where they were, this section contains my findings on those factual disputes;

(ii) in Part 6, I set out further facts specific to the FY15 and FY16 audits and the allegations against EY, again resolving factual disputes where relevant;

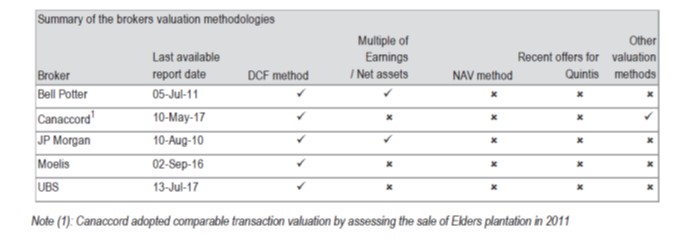

(iii) in Part 7, I set out the reports of a number of market analysts who covered Quintis during the relevant period and make findings as to the significance of these reports;

(c) Chapter C concerns the applicable Accounting and Auditing Standards:

(i) in Part 8, I set out the relevant Accounting Standards and make determinations in respect of the requirements of these standards where these were in dispute;

(ii) in Part 9, I set out the relevant Auditing Standards and similarly make determinations and resolve disputes as to what they require;

(d) Chapter D concerns the accuracy of Quintis’ accounts:

(i) in Part 10, I consider the pleaded attack on the DCF Model by which Quintis valued its biological assets;

(ii) in Part 11, I consider the question of whether Quintis’ accounts were materially overstated and not in accordance with the Accounting Standards for each of FY15 and FY16;

(a) in Part 12, I consider the counterfactual case advanced by the Davis Applicants as to what Quintis’ accounts allegedly should have disclosed;

(e) Chapter E concerns questions of liability:

(i) in Part 13, I turn to the case against Mr Wilson and determine whether the statutory contraventions pleaded against him are made out;

(ii) in Part 14, I turn to the case against EY and determine whether the statutory contraventions and breaches of the general law pleaded against it are made out;

(f) Chapter F concerns questions of causation, loss and relief:

(i) in Part 15, I deal with questions of causation and loss, to the extent they arise; and

(ii) in Part 16, I conclude and dispose of the proceedings.

26 For convenience, given the length of this judgment, a glossary of terms defined in the judgment (as well as other abbreviations and shorthand of common terms that are not defined) is attached as a Schedule to these reasons. The glossary also identifies the key persons referred to in the judgment.

27 Before turning to set out my reasons in detail, it is necessary to make some observations at the outset about the Davis Applicants’ case. The trial was heard before me over 24 days including seven days of oral closing submissions (which included some half days). The parties filed hundreds and hundreds of pages of written opening and closing submissions, as well as supplementary written submissions. The proceedings were conducted efficiently and the parties assisted me in getting to the heart of the complex factual issues that were raised. Other than in particular respects to which I will return, the Davis Applicants brought great efficiency to their case by refining their pleadings and abandoning or not pressing various aspects of their case. All parties and their representatives are to be commended for the way in which the proceedings were conducted.

28 However, as will become apparent from what follows much later in these reasons, it is necessary for me to record one lament at the very outset. The Davis Applicants maintained a case against Mr Wilson under each of ss 1041H and 1041E of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act, and maintained a case against EY under each of the same provisions as well as a case in negligence. In respect of each of these various causes of action, the Davis Applicants’ factual case was largely the same, with some subtlety. In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Fortescue Metals Group Ltd [2011] FCAFC 19; (2011) 190 FCR 364, Keane CJ said at [16]:

I should note here that, at trial and in this Court, the case was complicated by ASIC’s presentation of a number of arguments. Some of these arguments are strong, while others are not. The presentation of a range of alternative arguments is not apt to aid comprehension or coherence of analysis and exposition; indeed, this approach may distract attention from the central issues…

29 The Davis Applicants did not take heed of these observations. Having pleaded a case under s 1041H of the Corporations Act, and (as I will in due course come to in these reasons) another one that they did not adequately address under s 12DA of the ASIC Act, the Davis Applicants additionally propounded a case under s 1041E of the Corporations Act involving a number of considerations that are far from self-evident. The observations made by Keane CJ in Fortescue have as their focus the impact of an over-pleaded case as between the parties to litigation and the Court. I would add to those observations that over-pleading also has a considerable impact upon other litigants. The pursuit of multiple and overlapping causes of action, especially where these are not adequately addressed by the parties, occasions a burden upon the resources of the Court, not just in terms of the time required to address multiple causes of action but also because of the time that is thereby deprived to other litigants.

2. AN OVERVIEW OF THE PLEADED CASE

30 The pleadings in this case were complex and lengthy and raised numerous issues for determination. The salient features of the pleaded case against the Respondents, and the key issues which emerged, were as follows.

31 First, it was pleaded, uncontroversially, that:

(a) Quintis was required to prepare financial reports, including financial statements, for FY15 and FY16, in compliance with the Corporations Act and the Accounting Standards: FFASOC [11]-[13];

(b) each of those financial reports was required to give a fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance for the relevant year: FFASOC [17]; and

(c) each of the financial reports was required to include a declaration by the Directors of Quintis as to whether, in the Directors’ opinion, the financial statements and notes complied with the Accounting Standards and gave a true and fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance for the relevant year: FFASOC [18].

32 Second, the pleadings set out the alleged requirements of each of the Accounting Standards on which the Davis Applicants relied: FFASOC [19]-[25]. One of the issues in the proceedings was the proper construction of these standards and what they required, to which I will return below in Part [8].

33 Third, the pleadings set out the requirement under the Corporations Act for Quintis to have its financial reports for FY15 and FY16 audited and to obtain an auditor’s report in respect of each financial year, and record the fact that EY conducted such an audit of Quintis’ accounts in FY15 and FY16: FFASOC [30]-[32]. The pleadings then set out the requirements of such an audit, including, importantly, that EY was required to (FFASOC [33]-[40]):

(a) form an opinion and report to members about whether the relevant financial reports were in accordance with the Corporations Act, including by complying with the Accounting Standards and giving a true and fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance; and

(b) conduct the audit in accordance with the Auditing Standards.

34 Fourth, the pleadings set out the alleged requirements of each of the Auditing Standards on which the Davis Applicants relied: FFASOC [41]-[65]. Again, the proper construction of these standards and what they required was an issue for determination in the proceedings to which I return below in Part [9].

35 Fifth, the pleadings provided an overview of Quintis’ business, business model and investment products: FFASOC [66]-[91]. These matters were largely not in dispute and are relevantly set out below in Part [5].

36 Sixth, the pleadings set out alleged facts surrounding the publication and content of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports: FFASOC [92]-[109] and [121]-[137]. Significantly, it was pleaded that issuing each Report included lodging it with the ASX, publishing it on the ASX Market Announcements Platform, publishing it on Quintis’ website and distributing it to Quintis’ shareholders: FFASOC [94] and [122]; and that EY knew that its Audit Opinions would be contained in the Reports: FFASOC [95] and [123].

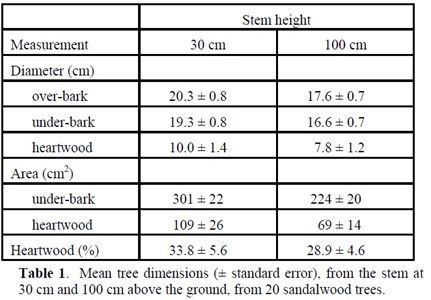

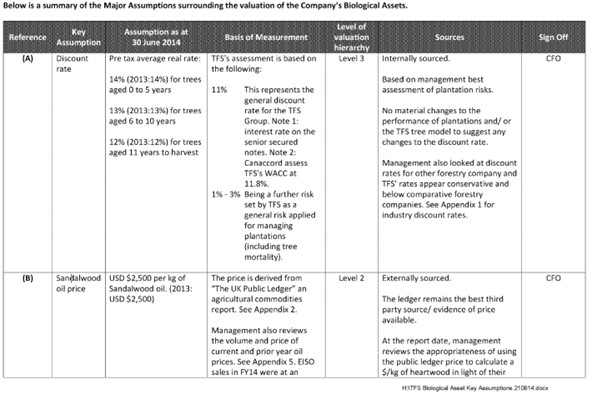

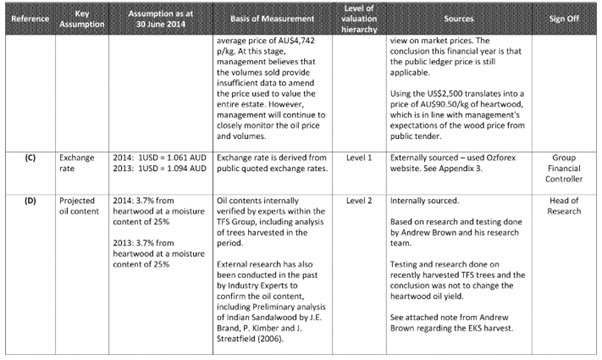

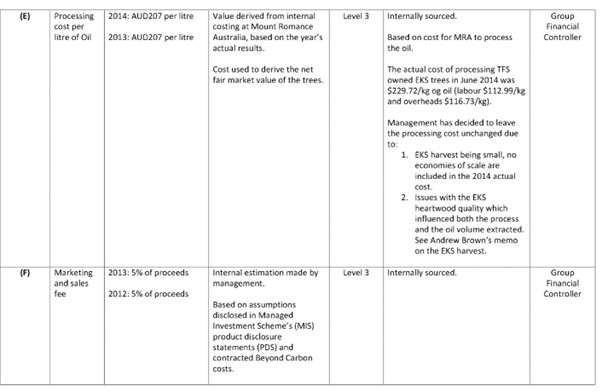

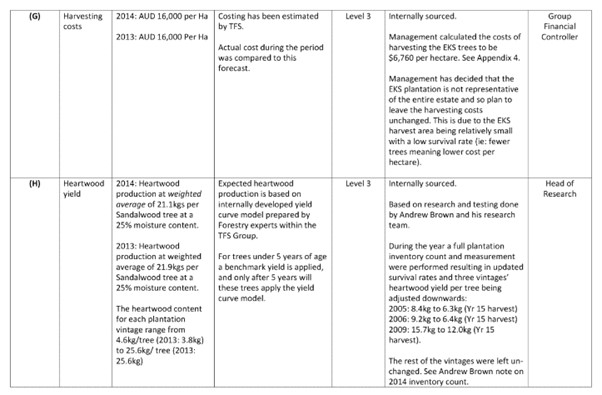

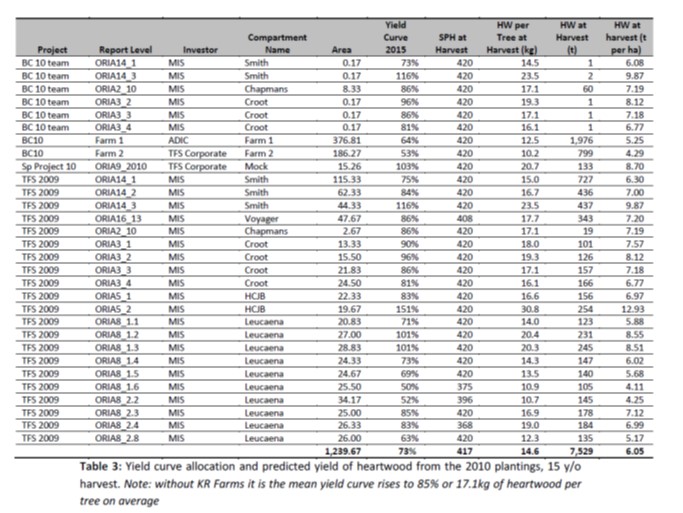

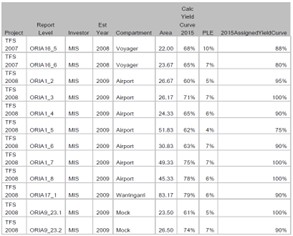

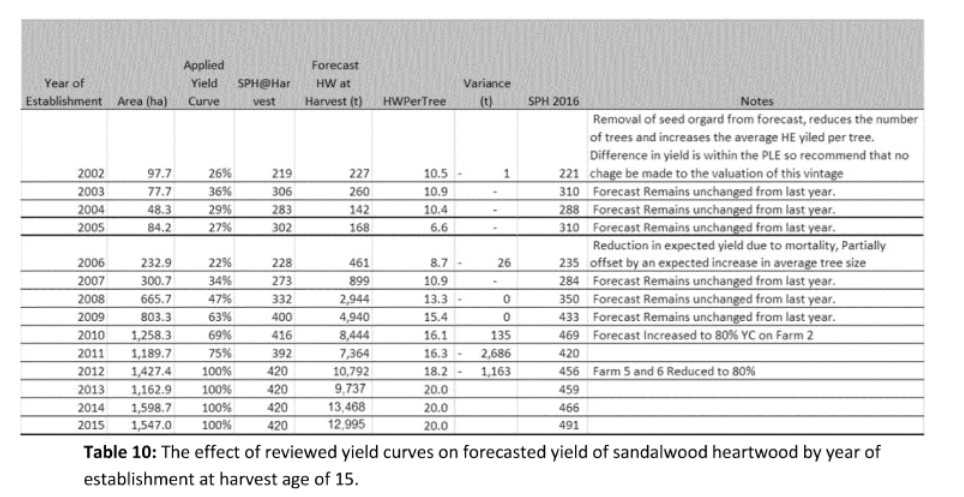

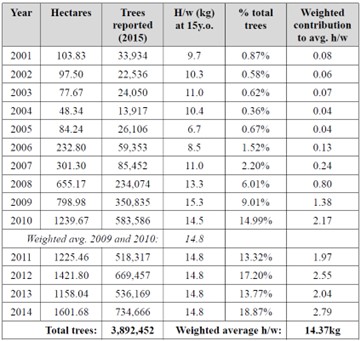

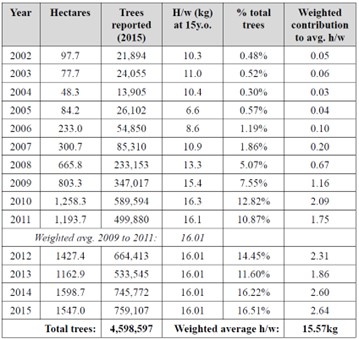

37 Seventh, and critically, it was pleaded that the FY15 Financial Report reported that Quintis’ total biological assets had a value of $624,574,000 (which was defined as the FY15 BA Carrying Value), derived using a DCF Model (FFASOC [97]-[99]), and that the significant inputs into that model were, amongst other things (FFASOC [100]):

(a) weighted average heartwood production of 20.8 kg for trees harvested between 14 and 16 years;

(b) expected heartwood per tree at harvest being based on the application of a yield curve to all trees, whereby:

(i) trees less than five years of age were placed on a theoretical yield curve which assumed the trees would yield 100% of the predicted heartwood production of a tree harvested at 15 years;

(ii) trees aged five years or more were each assigned individual yield curves which predicted heartwood production at harvest, being a percentage of the theoretical yield curve, based on data from tree growth obtained from annual tree counts, past harvests, trial results and sample testing, and judgements as to expected tree growth and heartwood yield for particular plantations provided by Quintis’ Head of Research, Mr Andrew Brown (Mr Brown), following each annual tree count;

(c) estimated cost of harvesting and processing of $207 per litre of oil; and

(d) a post-tax average real discount rate of:

(i) 14% for trees aged 0 to 5 years;

(ii) 13% for trees aged 6 to 10 years; and

(iii) 12% for trees aged 11 years to harvest age.

38 It was recorded that Quintis’ total assets for FY15 were reported as $1,173,335,000 and net assets as $574,523,000: FFASOC [104]; and total post-tax profits for FY15 were reported as $113,021,000: FFASOC [105].

39 Eighth, it was pleaded that the FY15 Financial Report contained a declaration (the FY15 Directors’ Declaration), that, in the Directors’ opinion, the Report had been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Corporations Act and the Accounting Standards, and that that declaration had been signed on behalf of each of the Directors of Quintis, including Mr Wilson: FFASOC [106]-[107]. It was also pleaded that the FY15 Financial Report included the FY15 Audit Opinion, and that that opinion was signed on behalf of EY: FFASOC [108]-[109]. There was a corresponding declaration (the FY16 Directors’ Declaration) and a corresponding audit opinion (the FY16 Audit Opinion) for FY16: FFASOC [134]-[135] and [136]-[137].

40 Ninth, it was pleaded that:

(a) by making the FY15 Directors’ Declaration, Mr Wilson made the Wilson FY15 Financial Report Representation: FFASOC [113]-[114];

(b) by authorising the issuing of the FY15 Financial Report in the circumstances pleaded, Mr Wilson made the Wilson FY15 Assets Representation and Wilson FY15 Profit Representation: FFASOC [115]-[118]; and

(c) by issuing the FY15 Audit Opinion in the circumstances pleaded, EY made the EY FY15 Financial Report Representation: FFASOC [119]-[120].

41 Whether, by their pleaded conduct, Mr Wilson and EY did make the alleged Representations, were significant issues in dispute between the parties to which I return to in detail below.

42 Tenth, the pleaded case in relation to the FY16 Financial Report and related Representations was substantively the same, save for the following matters:

(a) Quintis’ total biological assets reported in the FY16 Financial Report had a value of $771,208,000 (defined as the FY16 BA Carrying Value): FFASOC [125];

(b) total assets for FY16 were reported as $1,491,958,000 and net assets as $747,222,000: FFASOC [132]; and total post-tax profits for FY16 were reported as $90,143,000: FFASOC [133].

43 Eleventh, the pleadings set out alleged facts relating to the publication of Quintis’ financial report for the financial year ending 30 June 2017 (FY17 Financial Report), including that for FY17 (FFASOC [159]-[165]):

(a) Quintis’ biological assets experienced a $307,371,000 loss on revaluation, driven primarily by changes in the significant inputs into the valuation models for FY15 and FY16;

(b) the pre-tax average real discount rates applied to net cash flows were varied to:

(i) 17% for trees aged 0 to 5 years;

(ii) 16% for trees aged 6 to 10 years; and

(iii) 15% for trees aged 11 years to harvest age;

(c) the assumed weighted average heartwood production was varied to 14.6 kg per tree; and

(d) the FY17 Financial Report did not identify any event that had occurred since the FY16 Financial Report was issued which caused the changes to those significant inputs.

44 Twelfth, and critically, at FFASOC [169] it was pleaded that the DCF Model used to derive the FY15 BA Carrying Value adopted assumptions of inputs that:

(a) assumed predicted heartwood yield per tree that was “materially higher than what a market participant would have assumed”;

(b) assigned a yield curve for trees under 5 that assumed the trees achieving 100% of the predicted heartwood yield at harvest, and trees five years of age and older that assumed the trees achieving heartwood yield as a percentage of the theoretical yield of a tree under five years of age, which did not accurately represent the biological assets in their current location and condition; or

(c) understated the cost of processing per litre of sandalwood oil.

45 The particulars to FFASOC [169] stated that “the assumptions which should have been adopted [were] approximately”:

(a) as to assumed average heartwood yield for a tree harvested at 15 years, “around 6 to 8 kg”; and

(b) as to assumed estimated cost of harvesting and processing, $229.72 per litre of oil.

46 The pleadings later set out a counterfactual scenario based on these assumptions, namely that, had the DCF Model been developed and applied in accordance with the Accounting Standards, it would have contained the following, or approximately the following, assumptions (FFASOC [193]-[193A]):

(a) average predicted heartwood yield per tree for a tree harvested at 15 years of “around 6 to 8 kg”; and/or

(b) estimated cost of harvesting and processing at $229.72 per litre of oil for FY15 and $597 per litre of oil for FY16.

47 It was pleaded that, had those significant inputs been used, the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports would have recorded materially lower BA Carrying Values, materially lower revaluation gains, materially lower total asset and net asset values, and materially lower post-tax profits than were in fact reported: FFASOC [194]-[195].

48 A significant dispute arose between the parties as to whether, in order to establish liability on the part of the Respondents for the pleaded contraventions, it was necessary for the Davis Applicants to establish the specific assumptions particularised in FFASOC [169], or if it was sufficient to simply establish that the assumptions used by Quintis were “materially higher” than those which a market participant would have used (as was pleaded). I resolve this issue, which came to be referred to as the “binary issue”, in the following section.

49 FFASOC [169A] set out the equivalent inputs for FY16 which were substantively the same as for FY15, except that for FY16 the particulars specified that the estimated cost of harvesting and processing should have been $597 per litre of sandalwood oil.

50 Thirteenth, it was pleaded that, as a result of the above (FFASOC [170]-[176]):

(a) the Directors’ assessments in each of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports overstated the fair value of Quintis’ biological assets;

(b) each of the Reports therefore did not comply with the pleaded requirements of the Accounting Standards;

(c) the misstatements of the BA Carrying Values in each Report had the effect of overstating the carrying value of Quintis’ most valuable asset, and therefore Quintis’ assets in each financial year, and of leading to revaluation gains being recognised (FY15 and FY16 Revaluation Gains), and by reason of these matters, overstating Quintis’ income and profit in each financial year; and

(d) each Report did not give a true and fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance and did not comply with the requirements of the Corporations Act and Accounting Standards.

51 The particulars to FFASOC [170] specified that:

(a) in the FY15 Financial Report, Quintis’ biological assets were overstated by approximately $448,997,000; and

(b) in the FY16 Financial Report, Quintis’ biological assets were overstated by approximately $560,869,000.

52 Fourteenth, it was pleaded that, in authorising the issuing of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports in the pleaded circumstances, and in making the Wilson Representations alleged against him, Mr Wilson engaged in conduct in relation to a financial product or service within the meaning of ss 1041E and 1041H of the Corporations Act, and in trade or commerce in relation to a financial service within the meaning of s 12DA of the ASIC Act: FFASOC [223]-[224].

53 Fifteenth, it was pleaded that Mr Wilson (FFASOC [225]-[232] and [256]-[263]):

(a) knew the matters pleaded in FFASOC [100], [128], [169] and [169A] regarding the assumptions in the DCF Model, or ought reasonably to have known those matters;

(b) knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the significant inputs pleaded at FFASOC [100] and [128] were unrealistic or otherwise did not meet the Accounting Standards;

(c) did not have reasonable grounds for being of the opinion that the BA Carrying Values were fair value;

(d) did not have reasonable grounds for representing that the Financial Reports had been prepared in accordance with the Accounting Standards;

(e) engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and/or s 12DA of the ASIC Act because he did not have reasonable grounds for representing that the Reports had been prepared in accordance with the Accounting Standards;

(f) further or alternatively, did not have reasonable grounds for representing that the Reports gave a true and fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance; and

(g) engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and/or s 12DA of the ASIC Act because he did not have reasonable grounds for representing that the Reports gave a true and fair view of Quintis’ financial position and performance.

54 Similar allegations were pleaded against Mr Wilson in respect of the FY 15 and FY16 Wilson FY15 and FY16 Assets Representations and the Wilson FY15 and FY16 Profit Representations in each financial year: FFASOC [241]-[243] and [272]-[274].

55 It was further pleaded that each of the Wilson Representations was likely to either induce persons in the jurisdiction to acquire financial products, being shares in Quintis; or have the effect of increasing, reducing, maintaining or stabilising the price for trading in Quintis’ shares on the ASX, for the purposes of s 1041E of the Corporations Act. It was pleaded that Mr Wilson either knew or ought reasonably to have known that those Representations were materially misleading and that, by making the Representations, Mr Wilson contravened s 1041E of the Corporations Act: FFASOC [246]-[255] and [277]-[286].

56 Mr Wilson’s state of knowledge for the purposes of these various alleged contraventions was a significant issue in dispute which I make findings on below.

57 Sixteenth, a series of counterfactuals as to what would have occurred had Mr Wilson not engaged in the conduct pleaded against him were pleaded at FFASOC [287]-[290A], to the effect that the Reports would not have been issued, would only have been issued without the Wilson Representations, or would have been issued with materially lower total and net assets.

58 Seventeenth, it was pleaded that, in issuing the FY15 and FY16 Audit Opinions in the pleaded circumstances, and in making the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations, EY engaged in conduct in relation to a financial product or financial service within the meaning of ss 1041E and 1041H of the Corporations Act, and in trade or commerce in relation to financial services within the meaning of s 12DA of the ASIC Act: FFASOC [291]-[292].

59 Eighteenth, the Davis Applicants set out what, it was said, a reasonable auditor auditing the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports would have done, and compared this to what EY allegedly did: FFASOC [293]-[309] and [332]-[348]. Importantly, one step which it was alleged a reasonable auditor would have taken was to engage a suitably qualified independent expert in sandalwood to report on the validity of Quintis’ heartwood yield predictions, in order to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence concerning the reasonableness of this input into the DCF Model: FFASOC [301A(d)] and [340A(d)]. Whether this and other steps would actually have been taken by a reasonable auditor, and whether, by failing to take these steps, EY fell below the standard required of it to comply with the Auditing Standards, was a significant issue in the case against EY. Specifically, there was a dispute about whether it was pleaded that EY could have expressed a qualified audit opinion as a true alternative to requiring Quintis to obtain an independent expert.

60 Nineteenth, it was pleaded that, in light of the above matters, EY’s conduct in making the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and/or s 12DA of the ASIC Act because the opinions expressed were not held on a reasonable basis and as the product of the application of reasonable care and skill by EY; and/or formed after EY had conducted an audit in accordance with the Auditing Standards: FFASOC [321] and [360]. It was further pleaded at FFASOC [322]-[331] and [361]-[370] that:

(a) the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations were likely to either induce persons in the jurisdiction to acquire financial products, being shares in Quintis; or have the effect of increasing, reducing, maintaining or stabilising the price for trading in those shares on the ASX;

(b) those Representations were materially misleading; and

(c) EY knew or ought to have known matters which meant that it ought to have known that those Representations were materially misleading, such that its conduct in making the Representations was in contravention of s 1041E of the Corporations Act.

61 An audit counterfactual was then pleaded as to what would have occurred had the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations not been issued, namely that the Financial Reports would not have been issued, or would only have been issued along with an audit opinion if they did not contain the material misstatements concerning the BA Carrying Values: FFASOC [371]-[374].

62 Twentieth, it was pleaded that in conducting the FY15 and FY16 audits, EY owed and breached a common law duty of care to existing and potential shareholders in Quintis to exercise reasonable care and skill in the conduct of the audits and in preparing the FY15 and FY16 Audit Opinions, to avoid the risk of harm in the form of economic loss by buying shares or further shares in Quintis in a misinformed market and at above their true value: FFASOC [383]-[388]. Whether such a duty was owed by EY and, if so, whether it was breached and causative of loss, were further significant issues in the case against EY to which I return below.

63 Finally, the pleadings set out allegations as to causation, loss and damage. The Davis Applicants pleaded a case of direct “reliance-based causation”, specifically that the Davis Applicants in fact relied upon one or more of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports, the Wilson Representations and the EY FY15 Financial Report Representations in their decision to acquire interests in Quintis shares: FFASOC [401]-[404].The Davis Applicants pleaded a case of direct “reliance-based causation”, specifically that the Davis Applicants in fact relied upon one or more of the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports, the Wilson Representations and the EY FY15 and FY16 Financial Report Representations in their decision to acquire interests in Quintis shares: FFASOC [401]-[404].

64 It was pleaded that the Davis Applicants and Davis Group Members would not have acquired an interest in Quintis shares at the time they did, or for the price they did, or at all, if the pleaded contraventions had not occurred; and that they now either still hold Quintis shares which are worthless, or sold their shares for a loss, and accordingly claim damages to compensate them for that loss: FFASOC [405]-[408].

65 The Davis Applicants also pleaded a case of indirect or “market-based causation”, specifically that (FFASOC [395]-[400]):

(a) shareholders including the Davis Applicants acquired their interests in Quintis shares in a misinformed market and that if the correct information had been disclosed, it would have had a material negative effect on the price of Quintis shares; and

(b) the pleaded contraventions caused the market price of Quintis shares to be substantially greater than their true value or the market price that would have prevailed but for the contraventions.

66 The availability of market-based causation and what needed to be established to make good such a case was another issue in dispute which I have addressed below.

3. A PRELIMINARY MATTER ARISING FROM THE PLEADINGS

67 As adverted to above, there was a dispute between the parties as to the precise effect of the pleadings and particulars at FFASOC [169] and [169A].

68 The Davis Applicants submitted that their case as to liability required only that they establish that the heartwood yield assumption was materially higher than that which a market participant would have assumed and that the costs of processing per litre of sandalwood oil were understated. The Davis Applicants accepted that their case as to causation required them to establish that a market participant would have used a heartwood yield assumption of 6 to 8kg at 15 years and costs of processing of $229.72 per litre of oil in FY15 and $597 per litre of oil in FY16, but submitted that these counterfactual scenarios did not affect their case as to liability.

69 The Respondents disputed that the Davis Applicants’ contentions reflected the way the case had been pleaded, particularised and run at trial. The Respondents submitted that unless the Davis Applicants established that a market participant would have used a heartwood yield assumption that 6 to 8 kg of heartwood would be produced at 15 years and the costs of processing would be as particularised at FFASOC [169]-[169A], the case against them as to liability must fail.

70 Mr Wilson submitted that the various contraventions alleged against him had as their common thread (at FFASOC [225]-[226] and [256]-[257]) that Mr Wilson knew, or ought reasonably to have known, the matters pleaded at FFASOC [100], [169] and [169A] (regarding the assumptions in the DCF Model). Mr Wilson pointed out that, in relation to the alleged contraventions of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act, the allegations contained in the FFASOC at [225]-[226] and [256]-[257] were expressly pleaded as the “premises” to the allegations that in various respects Mr Wilson “knew or ought reasonably to have known” certain matters and “did not have reasonable grounds for” the various opinions it is alleged he held or expressed, or the representations he made. The allegations contained in the FFASOC at [225]-[226] and [256]-[257] were also the basis upon which it was pleaded that Mr Wilson had contravened s 1041E because it was those paragraphs that were relied upon to support the assertion that he knew or ought reasonably to have known that the various representations made by him were materially misleading. Mr Wilson submitted that these central allegations in the FFASOC at [225]-[226] and [256]-[257] linked directly back to the pleaded assertions at FFASOC [100], [169] and [169A].

71 Relying upon these matters, Mr Wilson submitted that the Davis Applicants had to prove, relevantly, that Mr Wilson:

(a) knew or ought reasonably to have known that the:

(i) heartwood yield assumption was not only “materially higher than what a market participant would have assumed” but also that the market participant would have adopted an assumption of an average heartwood yield for a tree harvested at 15 years of approximately 6 to 8 kg; and

(ii) cost of processing per litre of sandalwood oil was not only “understated” but that the market participant would have adopted an assumption that the cost was $229.72 per litre of oil in FY15 and $597 per litre of oil in FY16; and

(b) on these bases only, did not have reasonable grounds for the various opinions he was alleged to have held or expressed, or the representations he was alleged to have made.

72 EY advanced similar arguments. It was submitted that the particulars to the FFASOC at [169] and [169A] were not “mere” particulars as they “are the only content given in the FFASOC to the allegation that a market participant would have used a different heartwood yield assumption”. It was submitted that the purpose of particulars is to limit the issues of fact to be investigated: Mummery v Irvings Pty Ltd [1956] HCA 45; (1956) 96 CLR 99 at 110. It was submitted that the point was one of procedural fairness and that the particulars here defined the issues at trial: Thomson v STX Pan Ocean Co Ltd [2012] FCAFC 15 at [13]; Dare v Pulham [1982] HCA 70; (1982) 148 CLR 658 at 664. In support of these contentions, EY relied on the decision of the High Court in Berry v CCL Secure Pty Ltd [2020] HCA 27; (2020) 271 CLR 151. Berry involved a claim by an agent that he was misled into agreeing to a termination of his agency agreement. The respondent pleaded by way of defence that, in any event, it would have terminated the agency agreement, even if the agent had not agreed to it. Particular emphasis was placed on the reasons of Gageler and Edelman JJ at [72]-[73], where their Honours stated:

[72] “The function of pleadings is to state with sufficient clarity the case that must be met” and thereby to “ensure the basic requirement of procedural fairness that a party should have the opportunity of meeting the case against him or her and … to define the issues for decision”. A plaintiff should be expected to plead all material facts on which the plaintiff relies to constitute the statutory cause of action, including any counterfactual on which that plaintiff relies to establish the requisite causal link between identified loss or damage and identified misleading or deceptive conduct. In the same way, a defendant resisting the statutory action should be expected to plead any different counterfactual on which that party might rely to deny the causal link. Unless and to the extent that the parties choose to depart from the pleadings in the way they go on to conduct the trial, choice between the competing pleaded counterfactuals on the balance of probabilities should then exhaust the fact-finding that is required to be undertaken by the court on the issue of causation.

[73] The error of the Full Court, in an otherwise meticulous judgment, was sourced in the observation that there was “no reason to assume in the counterfactual that Securency would not have acted to terminate the Agency Agreement at the time when that agreement would otherwise have been automatically renewed”. The way the issue of causation had been joined on the pleadings was reason enough to confine consideration of whether Securency would have terminated the Agency Agreement to whether Securency would have terminated the Agency Agreement for the reasons Securency sought to advance through the evidence of Mr Brown. No broader factual inquiry was warranted.

(Emphasis added).

73 Relying on these passages, EY submitted that the Court would need to make a finding as to the Davis Applicants’ pleaded counterfactual case, which entirely relied upon the expert opinion of Dr Elizabeth Barbour (Dr Barbour). It was submitted that the Court would:

… make a finding on that ‘yes’ or ‘no’, and that exhausts [the Court’s] fact-finding task on the relevant issue. It’s not a matter for [the Court] to determine, in circumstances where neither defendant has put some alternative counterfactual, as to whether it might have been 15 [kg], 16 [kg] or anything else.

74 The Davis Applicants disputed the way in which the Respondents had construed the pleading and their case. Senior Counsel for the Davis Applicants sought to distinguish between issues relevant to establishing liability and those relevant to causation and loss. Senior Counsel also emphasised that the relevant matters for the purpose of liability were those pleaded in FFASOC [169] and [169A], as opposed to the particulars to those paragraphs. In their written closing submissions, the Davis Applicants argued the point as follows:

7. The central allegation pleaded against Mr Wilson and EY has two components. The first is that the accounting value attributed to Quintis’ biological assets did not comply with the accounting standards (particularly AASB 13 on fair value) and did not give a true and fair view of the financial position and performance of Quintis. The second is that the Respondents each made statements that were false, misleading, or deceptive by: (i) making representations in the FY15 and FY16 financial reports as to the financial performance and net assets of the company – in the case of Mr Wilson; and (ii) making statements that the company’s statutory accounts in FY15 and FY16 were audited in accordance with the auditing standards and that they were free from material misstatement. Those statements of opinion were false, misleading or deceptive because the Respondents knew or ought reasonably have known that the accounting value attributed to Quintis’ biological assets did not comply with the accounting standards (particularly AASB 13 on fair value) and did not give a true and fair view of the financial position and performance of Quintis.

8. That leaves the issues of causation and loss for determination. The Applicants plead counterfactuals which identify inputs they allege should have been adopted in Quintis’ discounted cashflow model. Those inputs arise from the particulars of contravention in [169]-[169A] (4FASOC, CB p. 78-81) and are put disjunctively (such that it is not necessary to establish all of them to find the value was materially overstated) and approximately (such that it is not necessary to establish them precisely): [169]-[169A] (4FASOC, CB p. 78-81). The amount by which the Applicants allege the biological assets were overvalued is then put qualitatively (it is alleged the value should have been “materially less” than what was reported) and quantitative particulars are provided of an approximate “true position”: at [194]-[195] 4FASOC CB p. 98-100.

75 These issues were further elaborated upon by Senior Counsel for the Davis Applicants during oral closing submissions, as encapsulated by the following exchanges (at T1804.4-8; T1805.4-8, T1806.1-18):

Your Honour, therefore, needs first to determine whether the accounts were prepared in accordance with the Standards. If not, breach or contravention is established. Your Honour then needs to deal with causation. In doing so, determine what the counterfactual accounts would have looked like or, on the balance of probability, what the range would look like.

…

MR HUTLEY: Your Honour, I’m going to come to it. I’m quite happy to be held at a causation damages to the true form of the accounts that should have been put was approximately six to eight. Got no problem with that. That’s the case that’s pleaded. What I have a problem with, and I’m going to, is that is not, however, a contravention breach.

…

HIS HONOUR: But don’t you have to prove that that was materially higher? So that – necessarily, that’s a relative examination.

MR HUTLEY: Quite, and you might – your Honour might say it’s obviously on the face of the evidence that they had before them that the Heartwood yield of 20 was materially higher than they could, on the material before them, reasonable think was able to be supported.

HIS HONOUR: But you have put a case to this court that it was materially higher because a market participant would have assumed approximately six to eight.

MR HUTLEY: With respect

HIS HONOUR: That is the case you’ve put.

MR HUTLEY: Well, your Honour, that – we have put the case that it was materially higher than the market, and I’m content to deal with that at the point of causation, but not at the point of breach.

76 The Davis Applicants maintained their position that the pleaded case did not require them to establish liability on the basis that the Respondents knew or ought to have known that the assumption a reasonable market participant would have adopted was approximately 6 to 8 kgs of heartwood per tree, but accepted that this would be relevant to questions of causation and loss.

77 The Davis Applicants’ submissions should be accepted. There is a fundamental difference between the purposes served by pleadings and particulars: Trade Practices Commission v David Jones (Australia) Pty Ltd (1985) 7 FCR 109 at 112–114 (Fisher J). As Fisher J stated in David Jones, it is the purpose of a pleading to assert the material facts and “it is not the function of particulars to take the place of the necessary averments in a statement of claim”: citing Lord Justice Scott in Pinson v Lloyds and National Provincial Foreign Bank Ltd (1941) 2 KB 72 at 75. The function of particulars is to put the opposing parties on guard and prevent them from being taken by surprise at the trial of an action, but the “material facts” must be pleaded: Pinson at 75. The material facts are those that are necessary for the purpose of formulating the cause of action: David Jones at 112-114. This is reinforced by rule 16.02(1)(d) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) that provides that a pleading “must” state the “material facts on which a party relies that are necessary to give the opposing party fair notice of the case to be made against the party at trial, but not the evidence by which the material facts are to be proved”. This was reinforced by the Full Court stated in STX Pan Ocean Co at [13]:

It is well-established that the main purposes of pleadings are to give notice to the other party of the case it has to meet, to avoid surprise to that party, to define the issues at trial, to thereby allow only relevant evidence to be admitted at trial and for the trial to be conducted efficiently within permissible bounds: see, eg Dare v Pulham (1982) 148 CLR 658 (at 664-665). However, it is also well-established that pleadings are not an end in themselves, instead they are a means to the ultimate attainment of justice between the parties to litigation: see Banque Commerciale SA (in liq) v Akhil Holdings Ltd (1990) 169 CLR 279 (at 293) per Dawson J who cites Isaacs and Rich JJ in Gould and Birbeck and Bacon v Mount Oxide Mines Ltd (in liq) (1916) 22 CLR 490 (at 517). For these reasons, the courts do not, at least in the current era, take an unduly technical or restrictive approach to pleadings such that, among other things, a party is strictly bound to the literal meaning of the case it has pleaded. The introduction of case management has, in part, been responsible for this change in approach: see the observations of Martin CJ in Barclay Mowlem Construction Ltd v Dampier Port Authority (2006) 33 WAR 82 (at [4]-[8]). Even before the widespread use of case management, the High Court reflected this approach in decisions such as Leotta v Public Transport Commission (NSW) (1976) 50 ALJR 666 (at 668-669) per Stephen, Mason and Jacobs JJ and Water Board v Maustakas (1988) 180 CLR 491 (at 497) per Mason CJ and Wilson, Brennan and Dawson JJ.

78 More conventionally, debates about the distinction between pleadings and particulars tend to arise in the context of applications for strike out or summary dismissal and usually in relation to whether particulars can fill gaps in the absence of pleaded material facts; and reinforcement of the trite proposition that an opposing party is not required to plead to particulars, as opposed to material facts. However, the central idea remains that the material facts must be pleaded.

79 Here, the Davis Applicants contended that the material facts that they relied upon to establish liability were those that were pleaded in the FFASOC [169] and [169A], as opposed to those that were particularised. The body of the FFASOC respectively asserted as material facts that the “discounted cash flow model used to derive” the FY15 and FY16 BA Carrying Values and FY15 and FY16 Revaluation Gains “adopted assumptions of inputs” that “assumed predicted heartwood yield per tree at harvest that was materially higher than what a market participant would have assumed” and “understated the cost of processing per litre of sandalwood oil” (emphasis added). Those assertions of material fact were relevant to the further pleaded allegations at FFASOC [170]-[176] including that, by reason of the assumptions that Quintis had used, the Directors’ assessments “overstated the fair value of Quintis’ biological assets in each of the FY15 Financial Report and FY16 Financial Report” (emphasis added): FFASOC at [170]. And, it was pleaded that the overstatement of the biological assets:

(a) did not yield a value of biological assets that represented fair value;

(b) did not yield a value of biological assets that represented the price that would be received to sell the biological assets in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date;

(c) did not yield a value of biological assets that represented the price that would be received to sell the biological assets in their current location and condition;

(d) had the effect of overstating the most valuable asset on Quintis’ balance sheet and therefore overstating Quintis’ assets;

(e) had the effect of overstating the value of the gain recognised in respect of the increase in the fair value of Quintis’ biological assets in the income statement in each of FY15 and FY16 and therefore overstating Quintis’ income and profit in each of the relevant financial years; and

(f) in each of the FY15 Financial Report and the FY16 Financial Report did not give a true and fair view of the financial position and financial performance of Quintis and did not comply with the requirements of the Accounting Standards.

80 As will be apparent, each of the subsequently pleaded allegations of overstatement depended on the earlier allegation that Quintis had used a heartwood yield assumption that was materially higher than what a market participant would have assumed and understated the cost of processing per litre of sandalwood oil. Those respective allegations of material fact that one assumption was materially higher and another one was understated were essential integers to the basis upon which it was pleaded that Mr Wilson and EY did not have reasonable grounds, or failed to exercise care, in the expression of their respective opinions in relation to the FY15 and FY16 Financial Reports.

81 Therefore, it follows that in determining whether the Davis Applicants have established their case as to liability, it is necessary to make findings as to the material facts they pleaded at FFASOC [169]-[169A] and [170]-[176] as essential steps in deciding whether Mr Wilson and EY had reasonable grounds and exercised reasonable care in respect of the opinions they expressed.

82 This position is to be contrasted to the Davis Applicants’ case as to causation and the counterfactual case pleaded in this regard at FFASOC [193]-[193A]. In these paragraphs, the Davis Applicants pleaded as material facts (and not by way of particulars) that had the DCF Model been developed in accordance with AASB 141 and AASB 13, it would have assumed an average predicted heartwood yield per tree for harvest at 15 years of around 6 to 8 kg and estimated costs of harvesting and processing at $229.72 per litre of oil in FY15 and $597 per litre of oil in FY16. Thus, for the purpose of the case as to causation, it is necessary to decide these material facts.

83 Whilst I have here accepted the Davis Applicants’ characterisation of their pleaded case as to liability and causation, it is well to observe at the outset the trite proposition that they thereby carried the onus of establishing to my satisfaction that (a) the heartwood yield assumption was materially higher than that which a market participant would have assumed, (b) the processing costs were understated, and (c) by reason of these assumptions, a number of things were overstated including the carrying value of the biological assets, the net assets, the revaluation gains, the profits, and the fair value of the assets. Each of these concepts of materially higher, understatement and overstatement are relative ones. They are also question-begging. For example, materially higher than what? And, understated or overstated by reference to what? As noted above, Senior Counsel for the Davis Applicants submitted that I would answer these questions by reaching a state of satisfaction that, if “obviously on the face of the evidence” I am satisfied about them – for example, that the heartwood yield of 20 kg was materially higher than Mr Wilson and EY could, “on the material before them, reasonabl[y] think was able to be supported”. I accept that submission and it is the case that I will decide, and to which the Davis Applicants are to be held.

4. ONUS, INFERENCES, EVIDENCE AND CREDIT

84 The Davis Applicants carried the onus to establish the essential elements of their pleaded case. It is trite that, in a civil proceeding such as this, that case had to be proved on the balance of probabilities: s 140(1) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act). As Dixon J (as his Honour then was) said in Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361-2, that requires the affirmative of the relevant allegation to be “made out to the reasonable satisfaction” of the Court. Reasonable satisfaction is not reached “by inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences”: at 362. Actual persuasion is required and it cannot be found “as a result of a mere mechanical comparison of probabilities independently of any belief in its reality”: at 361; see also, NOM v DPP [2012] VSCA 198; (2012) 38 VR 618 at [123]; Morley v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2010] NSWCA 331; (2010) 274 ALR 205 at [749]-[751]; and Citadel Financial Corporation Pty Ltd (admin apptd) v Action Scaffolding & Rigging Pty Ltd (in liq) [2019] FCAFC 145 at [57]. In Roberts-Smith v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd (No 41) [2023] FCA 555; (2023) 417 ALR 267 at [104], Besanko J recently drew attention to the less cited passages from Briginshaw of Latham CJ who said at 343:

There is no mathematical scale according to which degrees of certainty of intellectual conviction can be computed or valued. But there are differences in degree of certainty, which are real, and which can be intelligibly stated, although it is impossible to draw precise lines, as upon a diagram, and to assign each case to a particular subdivision of certainty.

85 The civil standard of proof is not one of mathematical scales. The resolution of a controversy depends on reaching a state of satisfaction: see Hodgson DH, “The Scales of Justice: Probability and Proof in Legal Fact-finding” (1995) 69 ALJ 731. As Lee J put it recently in Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Qantas Airways Ltd [2021] FCA 873; (2021) 308 IR 244 at [284]-[288], when the law requires proof of any fact, the tribunal of fact must feel actual persuasion as to its occurrence or existence before it can be found. A party bearing the onus will not succeed unless the whole of the evidence establishes a reasonable satisfaction on the preponderance of probabilities such as to sustain the relevant issue: citing Axon v Axon [1937] HCA 80; (1937) 59 CLR 395 at 403 (Dixon J). His Honour drew attention to GLJ v The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Lismore [2023] HCA 32; (2023) 97 ALJR 857, where Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Jagot JJ observed at [60] (quoting from Brown v New South Wales Trustee and Guardian (2012) 10 ASTLR 164 at [51] and Bradshaw v McEwans Pty Ltd (1951) 217 ALR 1 at 5):

… “To satisfy an onus of proof on the balance of probabilities is not simply a matter of asking whether the evidence supporting that conclusion has greater weight than any opposing evidence … It is perfectly possible for there to be a scrap of evidence that favours one contention, and no countervailing evidence, but for the judge to not regard the scrap of evidence as enough to persuade him or her that the contention is correct.” The evidence must “give rise to a reasonable and definite inference” to enable a factual finding to be made; mere conjecture based on “conflicting inferences of equal degrees of probability” is insufficient…

(Citations omitted).

86 It goes without saying that rejection of one side’s case or arguments does not involve acceptance of the other side’s case or arguments. Nor is the Court bound to make findings one way or the other. As Besanko J observed in Roberts-Smith at [117]:

There is no doubt that a court is not bound to accept the case of one or other of the parties. It may reject the case of both parties. In Kuligowski v Metrobus [2004] HCA 34; (2004) 220 CLR 363, the High Court said (at [60]):

In general, disbelief in a witness’s evidence does not establish the contrary. Similarly, disbelief in the case presented by the moving party does not necessarily permit the court to conclude that the positive case of the opposing party is correct. In particular cases it may not be possible to reach a conclusion either way:

[T]he judge is not bound always to make a finding one way or the other with regard to the facts averred by the parties. He has open to him the third alternative of saying that the party on whom the burden of proof lies in relation to any averment made by him has failed to discharge that burden.

[Rhesa Shipping Co SA v Edmunds (The Popi M) [1985] 1 WLR 948 at 955; [1985] 2 All ER 712 (Rhesa Shipping v Edmunds) at 718.]

A failure to find a matter alleged does not establish the truth of the contrary of that which is alleged…

(Emphasis added).

87 Although these matters are well settled to the point of being trite, it is necessary to steadily bear them in mind in the context of essential aspects of the Davis Applicants’ case. That is especially so in respect of the Davis Applicants’ contentions as to whether the heartwood yield assumptions used by Quintis were materially higher than those a market participant would have assumed, and that the fair value of Quintis’ biological assets was overstated. It also applies to the Davis Applicants’ counterfactual case that the heartwood yield assumption that should have been applied was approximately 6 to 8 kg. There are a range of possible outcomes as to what Quintis or a market participant may or should or would have done. Accepting that Quintis’ approach to the valuation of its biological assets was ambitious does not equate with a state of satisfaction that the heartwood yield assumption was materially higher than that which a market participant would have assumed. Likewise, accepting that the heartwood yield assumption was materially higher than that which would have been assumed by a market participant does not lead to the conclusion that the heartwood yield assumption that should have been applied was 6 to 8 kg. And, neither of those propositions, if accepted, necessarily leads to a conclusion that the Davis Applicants have satisfied me that the fair value of Quintis’ biological assets was overstated.

88 The common law test of balance of probabilities “is not satisfied by evidence which fails to do more than establish a possibility” (emphasis added): Seltsam Pty Ltd v McGuiness [2000] NSWCA 29; (2000) 49 NSWLR 262 at [80] citing St George Club Ltd v Hines [1962] ALR 39; (1961) 35 ALJR 106 at 107 at 41. Here, on their counterfactual case it was not sufficient that the Davis Applicants persuaded me that the heartwood yield assumption used by Quintis was materially higher than that which a market participant would have used. Nor is it sufficient that the Davis Applicants persuade me that Quintis should have used a different, and more conservative, heartwood yield assumption. To succeed in their counterfactual case, the Davis Applicants had to establish that a heartwood yield of approximately 6 to 8 kg would or should have been used. They have not succeeded in establishing this part of their case. That being the case, the remainder of the myriad possibilities are not a matter to be entertained in a Court of record where the parties are bound by their pleadings.

89 As will become apparent throughout these reasons, the Davis Applicants focussed all of their attention on seeking to falsify two of the DCF Model assumptions, to in essence contend that, ipso facto, there was an overstatement of the fair value of the biological assets. There was no challenge to any other integer of the DCF Model. Whilst there was evidence adduced about what would have been an appropriate heartwood yield assumption and processing costs assumption, there was no pleaded case about what other assumptions a reasonable market participant would have made, including as to matters such as oil price, exchange rate, discount rates and mortality. These were each matters which the Davis Applicants did originally challenge, but none of which were ultimately pressed.

90 In respect of these matters, it was not for the Respondents to establish what those assumptions would have been. Notwithstanding that the Respondents contended that Quintis’ approach to the valuation of its biological assets was sound and without error, as Besanko J pointed out in Roberts-Smith, the Court is not bound to accept the case of one or other of the parties and may reject the case of all parties. As it happens, whilst I am satisfied that the assumption used by Quintis as to heartwood yield was materially overstated, I am not satisfied that the Davis Applicants have established what the other inputs should have been used had the correct heartwood yield assumption been applied, such that I am unable to positively conclude that the accounts in each of FY15 and FY16 did not represent fair value. Whilst the fair value of the biological assets may well have been overstated, by not contesting the validity of the other DCF Model assumptions, and not leading any evidence as to why those assumptions would remain the same if a different heartwood yield assumption was used, the Davis Applicants failed to discharge their onus to persuade me to a state of positive satisfaction that Quintis’ accounts were, in fact, overstated. These are matters developed through the body of these reasons.

4.2 Inferences including Jones v Dunkel

91 As I will explain below, Mr Wilson did not give evidence in the proceedings and EY did not call any evidence from the personnel that were involved in auditing Quintis’ accounts in FY15 and FY16. Unsurprisingly, the Davis Applicants invited me to draw adverse inferences in accordance with the principle in Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298. The Davis Applicants also invited me to draw the same inference against EY.

92 The rule in Jones v Dunkel is that “the unexplained failure by a party to call a witness may, in appropriate circumstances, support an inference that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted the party’s case”: Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd [2011] HCA 11; (2011) 243 CLR 361 (Heydon, Crennan and Bell JJ) at [63]. That is particularly so where it is “the party which is the uncalled witness”: Kuhl at [63]. The failure to call such a witness may also “permit the court to draw, with greater confidence, any inference unfavourable to the party that failed to call the witness if that uncalled witness appears to be in a position to cast light on whether the inference should be drawn”: Kuhl at [63]. However, the rule in Jones v Dunkel permits an inference not that evidence not called by a party, would have been adverse to the party “but that it would not have assisted the case”: Kuhl at [64]. In this regard, as Heydon J explained in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Hellicar [2012] HCA 17; (2012) 247 CLR 345 at [232]:

… two consequences can flow from the unexplained failure of a party to call a witness whom that party would be expected to call. One is that the trier of fact may infer that the evidence of the absent witness would not assist the case of that party. The other is that the trier of fact may draw an inference unfavourable to that party with greater confidence. But Jones does not enable the trier of fact to infer that the evidence of the absent witness would have been positively adverse to that party.