FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd v Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co Ltd [2025] FCA 44

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to ss 37AF(1)(b) and 37AG(1)(a) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), access to and disclosure (by publication or otherwise) of the unredacted text of the reasons for judgment delivered today be restricted to the external legal representatives of the parties until further order of the Court.

2. By 7 February 2025, the parties confer to determine whether any paragraphs of these reasons require redaction before being publicly released and provide a draft order to the chambers of Downes J concerning the publication of these reasons.

3. The parties are directed to confer and provide a draft order giving effect to these reasons to the chambers of Downes J by 12 February 2025.

4. If the parties are unable to reach agreement about the form of orders, then the parties are to notify chambers and provide their own version of a draft order, with the areas of disagreement set out in mark-up.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DOWNES J:

1. OVERVIEW

1 The first respondent/cross-claimant, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Otsuka Japan), is the patentee of Australian Patent No. 2004285448, entitled “Controlled release sterile injectable aripiprazole formulation and method” (Patent) which has a priority date of 23 October 2003. The Patent was filed on 18 October 2004.

2 The second respondent/cross-claimant is an exclusive licensee, and the third and fourth respondents/cross-claimants are sub-licensees, pursuant to a deed dated 7 May 2024. In these reasons, I will describe the respondents as Otsuka unless it is necessary to distinguish between them.

3 The Patent describes and claims controlled release formulations which contain aripiprazole as the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). In particular, the therapeutic effect (or mechanism of action) of the API in the formulations is the binding of the aripiprazole molecules to receptors (primarily D2 receptors) in the brain, which is useful in treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.

4 On 13 August 2014, Otsuka Japan sought an extension of the term of the Patent (Request). The Request was based on a single alleged “pharmaceutical substance”, predicated on part of claim 16 of the Patent, and two products listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) on 25 July 2014. Both of these ARTG products are kits, comprising (inter alia) aripiprazole (as monohydrate) 300 [or 400] mg powder and solvent for prolonged release suspension for injection vial [or pre-filled syringe], named ABILIFY MAINTENA (ARTG Goods).

5 On 30 September 2014, IP Australia rejected the Request, stating that (inter alia) the “substance” in the ARTG Goods was aripiprazole itself, which was first included in the ARTG on 21 May 2003 (being Otsuka’s earlier aripiprazole product, the ABILIFY tablet product). After further correspondence, the Request was granted, so that the Patent presently expires on 25 July 2029 (Extension).

6 In this proceeding, the applicant/cross-respondent, Sun Pharma ANZ Pty Ltd (Sun Pharma), contends that the Extension was wrongly granted and/or is wrongly existing in the Patent Register and should be removed. There is no dispute that Sun Pharma has standing to seek rectification of the Register by removal of the Extension under s 192 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), as a “person aggrieved”.

7 In response, Otsuka relies on eight claims of the Patent (which the parties described as the PTE Claims), or parts thereof, and ten asserted pharmaceutical substances per se.

8 The PTE Claims are exemplified by two different types of claims: (i) those involving controlled release liquid (i.e. ready to use) injectable formulations (being claims 1, 3, 6 and 14) (Controlled Release Injectable Formulation Claims); and (ii) those involving freeze-dried (i.e. lyophilised) controlled release formulations (being claims 16, 19, 21 and 25) (Freeze-dried Controlled Release Formulation Claims). The formulations which are referred to in these claims are the Controlled Release Injectable Formulations and the Freeze-dried Controlled Release Formulations respectively.

9 Otsuka relies on the following pharmaceutical substance(s) per se for the purposes of this proceeding (which I will describe as the asserted pharmaceutical substances per se):

(I) a controlled release sterile aripiprazole injectable formulation, comprising aripiprazole having a mean particle size of about 1 to 10 microns or alternatively about 2 to about 4 microns;

(II) further or in the alternative, (I) above, wherein the aripiprazole is in the form of a monohydrate or alternatively Aripiprazole Hydrate A;

(III) further or in the alternative, (I) or (II) above, also comprising sodium carmellose (carboxymethyl cellulose), mannitol, monobasic monohydrate sodium phosphate and sodium hydroxide;

(IV) further or in the alternative, (III) above, also comprising water for injection;

(V) further or in the alternative, (IV) above, which upon injection releases aripiprazole over at least about one week;

(VI) a sterile lyophilised/freeze-dried aripiprazole formulation comprising aripiprazole having a mean particle size of about 1 to 10 microns or alternatively within the range from about 2 to about 4 microns;

(VII) further or in the alternative, (VI) above, wherein the aripiprazole is in the form of a monohydrate or alternatively Aripiprazole Hydrate A;

(VIII) further or in the alternative, (VI) or (VII) above, also comprising sodium carmellose (carboxymethyl cellulose), mannitol, monobasic monohydrate sodium phosphate and sodium hydroxide;

(IX) further or in the alternative to (VIII) above, which upon constitution with water forms a sterile injectable formulation;

(X) further or in the alternative to (IX) above, which upon injection releases aripiprazole over a period of at least about two weeks.

10 The lack of reference to “controlled release” in substance VI (and accordingly for substances VII–X) is an obvious typographical error, given that it was included in substance I. As this proceeding was brought on an urgent basis, and no point was taken by Sun Pharma in relation to it, I will proceed on the basis that the words “controlled release” are to be inserted before the word “sterile” in substance VI.

11 Sun Pharma contends that the Extension is invalid because none of the asserted pharmaceutical substances per se, nor the PTE Claims (or parts thereof) on which they are predicated, meet the requirements of s 70 of the Patents Act. It advances eight discrete bases for its contention that the Extension is invalid. Those were summarised in an aide memoire which was handed up during opening submissions, and which document became the focus of the parties’ closing submissions. That is so notwithstanding that the parties had filed an Agreed Statement of Issues on 21 October 2024. As to this, certain of the agreed issues no longer required resolution by the time of hearing (namely those in [1], [3] and [8]).

12 The aide memoire identified the following bases:

(1) The Freeze-dried Controlled Release Formulations (relevantly, claims 16, 19, 21 and 25) do not satisfy s 70(2)(a) of the Patents Act because such formulations do not meet the definition of “pharmaceutical substance”.

(2) Insofar as the Controlled Release Injectable Formulations (relevantly, claims 1, 3, 6 and 14) are capable of being a “pharmaceutical substance” (which is denied), the ARTG Goods do not contain or consist of such substance, because the ARTG Goods comprise a freeze-dried powder in a vial (cf s 70(3) of the Patents Act).

(3) Insofar as the PTE Claims claim anything other than the active ingredient aripiprazole simpliciter, such claims are not claims to a “pharmaceutical substance”, as the definition of “pharmaceutical substance” (properly construed) is confined to active ingredients and does not include formulations with excipients.

(4) If the Court determines that the definition of “pharmaceutical substance” does include formulations, neither the Freeze-dried Controlled Release Formulations nor the Controlled Release Injectable Formulations qualify, because the excipients within those formulations are not for a “therapeutic use” as defined and/or do not have an “application (or one of whose applications) [which] involves a chemical interaction, or physico-chemical interaction, with a human physiological system”.

(5) The majority of the asserted pharmaceutical substances per se impermissibly do not take all of the integers of the PTE Claims, and thus cannot be relied upon for the purposes of s 70.

(6) Relatedly, when regard is had to all of the integers of the PTE Claims, they include process features and/or features which limit the use of the formulations, contrary to Full Court authority.

(7) Contrary to s 70(3) of the Patents Act, the ARTG Goods do not take the Relevant Features [which term is defined below].

(8) Each of the PTE Claims is invalid and should be revoked for lack of clarity and/or lack of definition pursuant to s 40(3) and/or s 40(2)(b) of the Patents Act. Accordingly, none of the PTE Claims is available to form the basis for an extension of term under s 70 of the Patents Act.

13 Items 3 and 4 in the aide memoire require a particular construction of the Patents Act to be accepted. Whether that construction is correct was also in issue in Cipla Australia Pty Ltd v Novo Nordisk A/S [2024] FCA 1414, which decision was delivered during the trial of this case. The impact of Cipla on the issues in this case was addressed by the parties, both in writing and in oral closing submissions. Notably, although Sun Pharma’s written submissions contended that aspects of Cipla were plainly wrong such that I should decline to follow it, those submissions were withdrawn. Instead, Sun Pharma reserves its position in any appeal to contend that Cipla was wrongly decided.

14 Sun Pharma has applied to register and intends to sponsor and supply a product registered on the ARTG which is a generic version of the ABILIFY MAINTENA (400 mg) powder and solvent for injection. It wishes to launch that product on 1 April 2025 and requested that this decision be delivered as soon as possible. There was therefore some urgency in having this proceeding heard and determined.

15 Otsuka cross-claimed for threatened infringement in respect of Sun Pharma’s proposed generic product. In an effort for this proceeding to be heard and determined expeditiously, Sun Pharma did not contest the claim of threatened infringement (if the Extension and the PTE Claims were found to be valid) by making certain admissions for the purposes of this proceeding. Those admissions were made without prejudice to Sun Pharma’s position on the proper construction of each of the claims, and in circumstances where it maintained its position concerning the invalidity of the PTE Claims and the Extension: see, in particular, [25]–[30], [35], [37], [39]–[41] and [46] of the Amended Defence to Cross-Claim. Contrary to Otsuka’s submission, the admissions by Sun Pharma do not assist Otsuka’s case for this reason.

16 Otsuka also cross-claimed for threatened infringement of s 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), which claim was denied.

17 For the reasons which follow, I have determined that the PTE Claims and Extension are invalid, and that the Cross-Claim should be dismissed. That is because:

(1) Substances I–IV and VI–IX do not in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims as required by s 70(2)(a) of the Patents Act.

(2) The PTE Claims are invalid as they fail to comply with ss 40(2)(b) and 40(3) of the Patents Act.

18 As many aspects of the written and oral evidence were restricted by reasons of confidentiality, orders will be made which restrict access to these reasons and provide the parties with an opportunity to address which aspects should remain confidential.

2. WITNESSES CALLED BY THE PARTIES

19 Sun Pharma adduced expert evidence from two experts:

(1) Professor Gerhard Johannes Winter, a Professor and former Chair of the Pharmaceutical Technology and Biopharmaceutics group of the Department of Pharmacy at Ludwig Maximillians University of Munich. Professor Winter affirmed two affidavits, dated 19 July 2024 (Winter 1) and 15 October 2024 (Winter 2) although Sun Pharma did not read [38]–[45] of Winter 2;

(2) Professor Guy Manning Goodwin, psychiatrist and Emeritus Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Oxford and the Chief Medical Officer at Compass Pathways. Professor Goodwin swore two affidavits dated 19 July 2024 (Goodwin 1) and 9 October 2024 (Goodwin 2) although Sun Pharma did not read [19]– [25] of Goodwin 2.

20 Sun Pharma also relied on an affidavit of its solicitor, Ms Nina Fitzgerald, dated 19 July 2024.

21 Otsuka adduced expert evidence from Professor Allan Mark Evans, a pharmaceutical scientist and a clinical pharmacologist, and an Adjunct Professor at the University of South Australia. Professor Evans affirmed two affidavits, dated 20 September 2024 and 26 November 2024. All references in these reasons to the affidavit evidence of Professor Evans is to the affidavit dated 20 September 2024.

22 The experts prepared a joint expert report dated 5 November 2024 (JER).

23 Of the witnesses, only Professor Winter and Professor Evans were required for cross-examination, and they gave concurrent expert evidence on 2, 3 and 4 December 2024.

24 Of these two experts, Professor Winter was, by far, the more impressive expert, both on paper and in person. Professor Winter has a vast amount of experience in the formulation of drug products, including lyophilised products, and he is by far the more qualified of the two experts. I also found that Professor Winter’s evidence was more direct and on point, whereas the evidence of Professor Evans often avoided dealing with an issue squarely. Some of his affidavit evidence is, in particular, obfuscatory insofar as it purports to respond to the evidence of Professor Winter. That is because, while it refers to particular aspects of Professor Winter’s evidence expressly, it does not identify any disagreement with it or explain the reasons for that disagreement.

25 Further, in addition to having superior qualifications and experience to that of Professor Evans, Professor Winter displayed such a depth of knowledge and understanding of the topics being addressed that I found his views to be more compelling, well-reasoned, consistent and logical than those of Professor Evans. Further, all of Professor Winter’s oral answers to questions were dispassionate and he made appropriate concessions. He was an exemplary expert witness.

26 Otsuka was critical of Professor Winter and contended that he did not approach and interpret the Patent in the same way as a person skilled in the art would have engaged in this task. However, I reject all of these criticisms. Generally, Professor Winter raised genuine concerns about lack of data in the Patent, which concerns should have been able to be addressed by Professor Evans if they were excessive or unduly critical, but that did not occur.

27 By contrast to Professor Winter, Professor Evans did, on occasion, become antagonistic when giving his answers, and at times it seemed that his answers were intended to protect the PTE Claims from the invalidity attack.

28 More significantly, it did not appear that the affidavit evidence of Professor Evans provided the full picture of the work which he had done, and a full statement of the reasons for the opinions expressed by him.

29 Professor Evans states that his analysis in respect of Example 4 and Figure 3 of the Patent was “based only on the information provided in the 448 patent, in particular, Example 4 and Figure 3”: Evans, [117]. However, it emerged during the hearing that the analysis was not so limited, particularly as his analysis was heavily predicated on a 28-day “proposed clinical use”. During the concurrent evidence session, Professor Evans accepted that “the 28-day dosing interval was not disclosed in example 4 or figure 3” and could not recall whether it was disclosed or suggested to him by Otsuka’s legal representatives to use the 28-day dosing interval in his calculations based on ABILIFY MAINTENA.

30 It also transpired that Professor Evans had performed calculations using “multiple dosing at a range of doses” using Microsoft Excel, but this was not contained in his affidavits, or referred to by him as forming part of his reasons for his conclusions, contrary to clauses 3(d) and 3(e) of the Harmonised Expert Witness Code of Conduct which is Annexure A to the Expert Evidence Practice Note (GPN-EXPT). As recognised by [2.4] of that Practice Note, such matters affect the weight to be attached to this expert’s opinion evidence.

31 For these reasons and for further reasons given below, I have preferred the evidence of Professor Winter to that of Professor Evans where the two experts disagreed as I attach less weight to the evidence of Professor Evans.

3. THE PATENT

3.1 Release from the depot and absorption into central compartment

32 The following matters formed part of the common general knowledge in Australia as at 23 October 2003.

33 In general terms, one can differentiate drug release profiles in the following way:

(1) immediate release: where a drug substance is released almost immediately upon administration; and

(2) controlled release: any formulation wherein the release of the drug substance differs from an immediate release formulation in that the release of the drug substance is retarded, for example due to the construction of the formulation (like a coated tablet or polymer-based formulations).

34 A type of controlled release formulation is an extended release formulation wherein the drug is released over time, rather than immediately. By extending the release profile of a drug, a formulator can (amongst other things) reduce the frequency of dosing required.

35 Aqueous suspensions are typically made up of a poorly soluble drug substance, one or more excipients, and water. Upon combination with the water, the drug substance forms a suspension whereby the particles of drug substance do not dissolve but exist as (undissolved) solid particles within the liquid. The formulation is then administered to a patient by injection.

36 Since the drug substance is poorly soluble in physiological conditions, it forms a physical “depot” at the injection site.

37 A depot is an injectable formulation that releases a given amount of drug substance slowly over time. The depot, when used in the context of an aqueous suspension formulation, is the collection of particles of drug substance that are trapped at the site of administration. Over time, molecules of the drug substance dissolve from the particles of drug substance in the depot and, depending on the site and route of administration, must cross a number of biological membranes before entering the “central compartment”, which is the blood plasma and organs (such as the liver) that receive a very rich blood supply and turnover of blood.

38 The process of dissolution of a drug substance from a depot is often referred to as “release”, whereas the entry of the drug substance into the central compartment is often referred to as “absorption”.

39 For aqueous suspension formulations, the process of dissolution (or release) of a particulate drug substance is dictated by the following (non-exhaustive) factors:

(1) The size of the drug substance particles: the larger the size of a drug particle, the longer it will take for all of the drug substance to dissolve (or release) from the depot.

(2) The physico-chemical properties of the drug: for example, drugs with lower aqueous solubility (and, more specifically, with lower solubility at physiological conditions) will typically take longer to dissolve upon administration, and so will release drug molecules over a longer period than drugs with higher aqueous solubility.

(3) Any modifications made to the drug substance to decrease its solubility at physiological conditions.

(4) The site of administration of the formulation. This is because of reasons associated with the amount of mechanical force to which a site is subjected and the tissues neighbouring the injection site. Suspension formulations are more prone to be affected by these factors than other extended release formulations, which can impact the time that it takes for a drug substance in particulate form to completely dissolve upon administration.

(5) The volume of formulation being injected. The pressure associated with the administration of larger volumes (2 ml or more) of formulation can cause the formulation to disperse over a greater volume of space inside the body, which can decrease the time that it takes for the drug to completely dissolve from the formulation.

(6) The shape and nature of the drug substance particles, which can stimulate an immune response and delay the time that it takes for the drug to dissolve and be transported away from the site of the injection.

(7) The concentration and dosage of the drug substance.

40 The process of absorption can occur in three main ways:

(1) Often when a formulation is administered by injection, the process of injection causes capillaries at the site of injection to rupture. Due to the body’s self-healing processes, these ruptures will be sealed off quickly. Nevertheless, a small amount of the drug substance may be transported from the site of injection immediately through these ruptured capillaries.

(2) After the suspension formulation has been injected and some of the particulate drug substance has dissolved, the dissolved molecules will diffuse from the tissue or interstitial tissue across one or more biological membranes into surrounding capillaries, and then be transported into the central compartment.

(3) The dissolved drug molecules can also diffuse into the lymphatic tubes that are present in skeletal muscles, and enter the lymphatic transport system, from where they are eventually transported to and absorbed into the central compartment.

41 A drug may be released from the depot but not absorbed due to physico-chemical reasons. For example, it is energetically preferable for drugs that are lipophilic to remain in the fatty tissue. Therefore, a lipophilic drug substance may be in solution at the site of administration but, if administered subcutaneously, it will be energetically favourable for that drug substance to remain in the fatty tissue rather than diffusing across biological membranes to enter the bloodstream.

42 The mechanisms and timeframes involved in the process of absorption of a drug substance (once released from the depot) will vary depending on a range of factors, including the following:

(1) The chemical composition of the drug substance and any modifications made to it to increase its lipophilicity or ionisation at physiological conditions.

(2) The site and route of administration and the pathway to the central compartment. The time taken for molecules of a drug substance to enter the central compartment will depend on the length of the pathway to the central compartment (including the number and types of membranes that it needs to pass), which in turn depends on the site and route of administration (as well as the physical and chemical characteristics of the drug substance). The time taken for the drug substance molecules to enter the central compartment will also depend on the presence or absence of phagocytotic cell types, and the velocity of any transport fluids that the drug substance is exposed to, such as the velocity of blood in the blood stream or the velocity of the lymphatic flow. Typically, formulations that are administered intramuscularly will be absorbed faster than if injected subcutaneously because the diffusion path length from the site of administration to the central compartment is shorter for drugs administered intramuscularly.

43 Several factors can affect the amount of a drug in the blood plasma. In particular, the blood plasma levels of a drug substance will depend on (inter alia) the amount of the drug administered, the bioavailability of the a drug substance, the site of administration, the time it takes for the drug molecules to dissolve, and then to be absorbed, upon administration, and the rates at which the drug is metabolised, distributed and excreted upon administration.

3.2 The specification

44 Aripiprazole is an antipsychotic agent useful in treating schizophrenia. Aripiprazole itself is not the invention claimed in the Patent, nor was it a “new” substance as at the filing date – rather, it was the subject of US Patent No. 5,006,528 (a compound patent) granted over a decade earlier in 1991. Rather, the Patent is directed to controlled release aripiprazole formulations and methods for preparing and using such formulations.

45 The Field of the Invention relevantly states:

The present invention relates to a controlled release sterile freeze-dried aripiprazole formulation, an injectable formulation which contains the sterile freeze-dried aripiprazole and which releases aripiprazole over at least a one week period, a method for preparing the above formulation, and a method for treating schizophrenia and related disorders employing the above formulation.

46 In the Background of the Invention, the following is stated:

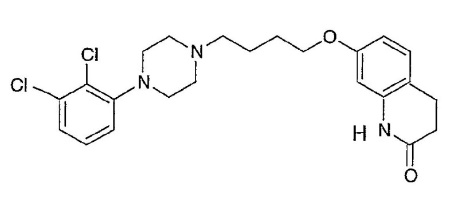

Aripiprazole which has the structure

is an atypical antipsychotic agent useful in treating schizophrenia. It has poor aqueous solubility (<1μg/mL at room temperature).

47 The Background also states, “A long-acting aripiprazole sterile injectionable formulation has merit as a drug dosage form in that it may increase the compliance of patients and thereby lower the rate of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia”.

48 The formulations described and claimed in the Patent include (a) freeze-dried controlled release aripiprazole formulations that need to be reconstituted with water to form an injectable formulation before administration; and (b) controlled release injectable formulations that are administered as aqueous “ready-to-use” suspensions.

49 A Brief Description of the Invention includes the following statements about the freeze-dried controlled release aripiprazole formulations:

Disclosed herein is a sterile freeze-dried aripiprazole formulation which upon constitution with water for injection releases aripiprazole, in therapeutic amounts, over a period of at least about one week, and preferably over a period of two, three or four weeks and up to six weeks or more. The freeze-dried aripiprazole formulation may include:

(a) aripiprazole, and

(b) a vehicle for the aripiprazole,

which formulation upon constitution with water forms an injectable suspension which, upon injection, preferably intramuscularly, releases therapeutic amounts of aripiprazole over a period of at least one week, preferably two, three or four weeks, and up to six weeks or more.

50 After referring to five different aspects of the invention, the following is stated:

A mean particle size of the freeze-dried aripiprazole formulation within the range from about 1 to about 30 microns is essential in formulating an injectable which releases aripiprazole over a period of at least about one week and up to six weeks or more, for example up to 8 weeks.

It has been found that the smaller the mean particle size of the freeze-dried aripiprazole, the shorter the period of extended release. Thus, in accordance with the present invention, when the mean particle size is about 1 micron, the aripiprazole will be released over a period of less than three weeks, preferably about two weeks. When the mean particle size is more than about 1 micron, the aripiprazole will be released over a period of at least two weeks, preferably about three to four weeks, and up to six weeks or more. Thus, in accordance with the present invention, the aripiprazole release duration can be modified by changing the particle size of the aripiprazole in the freeze-dried formulation.

The term “mean particle size” refers to volume mean diameter as measured by laser-light scattering (LLS) methods. Particle size distribution is measured by LLS methods and mean particle size is calculated from the particle size distribution.

51 The specification then refers to the controlled release injectable formulations as follows:

Also disclosed herein is a controlled release sterile injectable aripiprazole formulation in the form of a sterile suspension, that is, the freeze-dried formulation of the invention suspended in water for injection, is provided which, upon injection, preferably intramuscularly, releases therapeutic amounts of aripiprazole over a period of at least one week, which includes:

(a) aripiprazole,

(b) a vehicle therefor, and

(c) water for injection.

The controlled release sterile injectable formulation of the invention in the form of a sterile suspension allows for high drug loadings per unit volume of the formulation and therefore permits delivery of relatively high doses of aripiprazole in a small injection volume (0.1 - 600 mg of drug per 1 mL of suspension).

52 The Brief Description also states:

As an unexpected observation, it has been discovered that a suspension of aripiprazole suspended in an aqueous solvent system will maintain a substantially constant aripiprazole drug plasma concentration when administered by injection; preferably as an intra-muscular injection. No large “burst phenomenon” is observed and it is considerably surprising that a constant aripiprazole drug plasma concentration can be maintained from one (1) to more than eight (8) weeks employing the aripiprazole suspension of the invention. The daily starting dose for an orally administered aripiprazole formulation is fifteen (15) milligrams. In order to administer a drug dose equivalent to one (1) to more than eight (8) weeks of the oral dosage quantity requires the administration of a very large amount of the drug as a single dose. The aqueous aripiprazole injectable formulation of the invention may be administered to deliver large amounts of the drug without creating patient compliance problems.

The aripiprazole injectable formulation of the invention may include anhydrous or monohydrate crystalline forms of aripiprazole or an admixture containing both. If the monohydrate is used, the maintenance of an extended drug plasma concentration is possible.

The aripiprazole injectable formulation of the invention can be administered as an aqueous ready-to-use suspension; however, by freeze-drying this suspension a more useful drug product can be supplied.

53 In the Detailed Description, the following is stated:

The controlled release sterile injectable aripiprazole formulation of the invention will include aripiprazole in an amount within the range from about 1 to about 40%, preferably from about 5 to about 20%, and more preferably from about 8 to about 15% by weight based on the weight of the sterile injectable formulation.

As indicated, desired mean particle size of the aripiprazole is essential in producing an injectable formulation having the desired controlled release properties of the aripiprazole. Thus, to produce desired controlled release, the aripiprazole should have a mean particle size within the range from about 1 to about 30 microns, preferably from about 1 to about 20 microns, and more preferably for about 1 to about 10 to 15 microns.

Where the desired controlled release period is at least about two weeks, up to six weeks or more, preferably about three to about four weeks, the aripiprazole will have a mean particle size within the range from about 1 to about 20, preferably from about 1 to about 10 microns, more preferably from about 2 to about 4 microns, and most preferably about 2.5 microns.

54 It also stated that:

The aripiprazole formulation of the invention will preferably be formed of:

A. aripiprazole,

B. a vehicle therefor, which includes:

(a) one or more suspending agents,

(b) one or more bulking agents,

(c) one or more buffers, and

(d) optionally one or more pH adjusting agents.

The suspending agent will be present in an amount within the range from about 0.2 to about 10% by weight, preferably for about 0.5 to about 5% by weight based on the total weight of the sterile injectable formulation. Examples of suspending agents suitable for use include, but are not limited to, one, two or more of the following: sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose, carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxypropylethyl cellulose, hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose, and polyvinylpyrrolidone, with sodium carboxymethyl cellulose and polyvinylpyrrolidone being preferred. Other suspending agents suitable for use in the vehicle for the aripiprazole include various polymers, low molecular weight oligomers, natural products, and surfactants, including nonionic and ionic surfactants, such as cetyl pyridinium chloride, gelatin, casein, lecithin (phosphatides), dextran, glycerol, gum acacia, cholesterol, tragacanth, stearic acid, benzalkonium chloride [etc]…

Carboxymethyl cellulose or the sodium salt thereof is particularly preferred where the desired mean particle size is about 1 micron or above. …

The bulking agent (also referred to as a cryogenic/lyophilize protecting agent) will be present in an amount within the range from about 1 to about 10% by weight, preferably from about 3 to about 8% by weight, more preferably from about 4 to about 5% by weight based on the total weight of the sterile injectable formulation. Examples of bulking agents suitable for use herein include, but are not limited to, one, two or more of the following: mannitol, sucrose, maltose, xylitol, glucose, starches, sorbital, and the like, with mannitol being preferred for formulations where the mean particle size is about 1 micron or above. It has been found that xylitol and/or sorbitol enhances stability of the aripiprazole formulation by inhibiting crystal growth and agglomeration of drug particles so that desired particle size may be achieved and maintained.

The buffer will be employed in an amount to adjust pH of an aqueous suspension of the freeze-dried aripiprazole formulation to from about 6 to about 8, preferably about 7. …Examples of buffers suitable for use herein include, but are not limited to, one, two or more of the following: sodium phosphate, potassium phosphate, or TRIS buffer, with sodium phosphate being preferred.

The freeze-dried formulation of the invention may optionally include a pH adjusting agent which is employed in an amount to adjust pH of the aqueous suspension of the freeze-dried aripiprazole within the range from about 6 to about 7.5, preferably about 7 and may be an acid or base depending upon whether the pH of the aqueous suspension of the freeze-dried aripiprazole needs to be raised or lowered to reach the desired neutral pH of about 7. …

The freeze-dried aripiprazole formulations may be constituted with an amount of water for injection to provide from about 10 to about 400 mg of aripiprazole delivered in a volume of 2.5 mL or less, preferably 2 mL for a two to six week dosage.

55 Reference is also made to the “desired crystalline form of the aripiprazole” which exists in monohydrate form (Aripiprazole Hydrate A) as well as in a number of anhydrous forms, namely Anhydride Crystals B–G. The specification identifies methods of manufacturing Aripiprazole Hydrate A and preparing Aripiprazole Anhydride Crystals B, and then identifies preferred injectable formulations in the form of aqueous suspensions. It is then stated that:

The aripiprazole formulations of the invention are used to treat schizophrenia and related disorders such as bipolar disorder and dementia in human patients. The preferred dosage employed for the injectable formulations of the invention will be a single injection or multiple injections containing from about 100 to about 400 mg aripiprazole/mL given one to two times monthly. The injectable formulation is preferably administered intramuscularly, although subcutaneous injections are acceptable as well.

56 Four examples are then set out which are said to represent preferred embodiments of the invention.

57 In Examples 1 and 2, there is a description of two ways to prepare an aripiprazole injectable (IM Depot) aqueous suspension (200 mg aripiprazole/2 mL, 200 mg/vial), one by media milling (Example 1) and the other by impinging jet crystallisation (Example 2).

58 Example 3 (Animal PK Data) relates to injecting the formulation in Example 1 into 15 rats and 5 dogs. Reference is made to Figures 1 and 2 as showing “mean plasma concentrations vs. time profiles”. Reference is then made to “PK profiles” (with PK being a reference to pharmacokinetics) and it is stated that:

Mean aripiprazole rats’ serum concentration-time profiles are shown graphically in Fig.1. Aripiprazole aqueous suspensions showed steady serum concentration for at least 4 weeks in the rats’ model.

Mean aripiprazole dogs’ serum concentration-time profiles are shown graphically in Fig.2.

Aripiprazole aqueous suspensions showed steady serum concentration for 3-4 weeks in the dogs’ model.

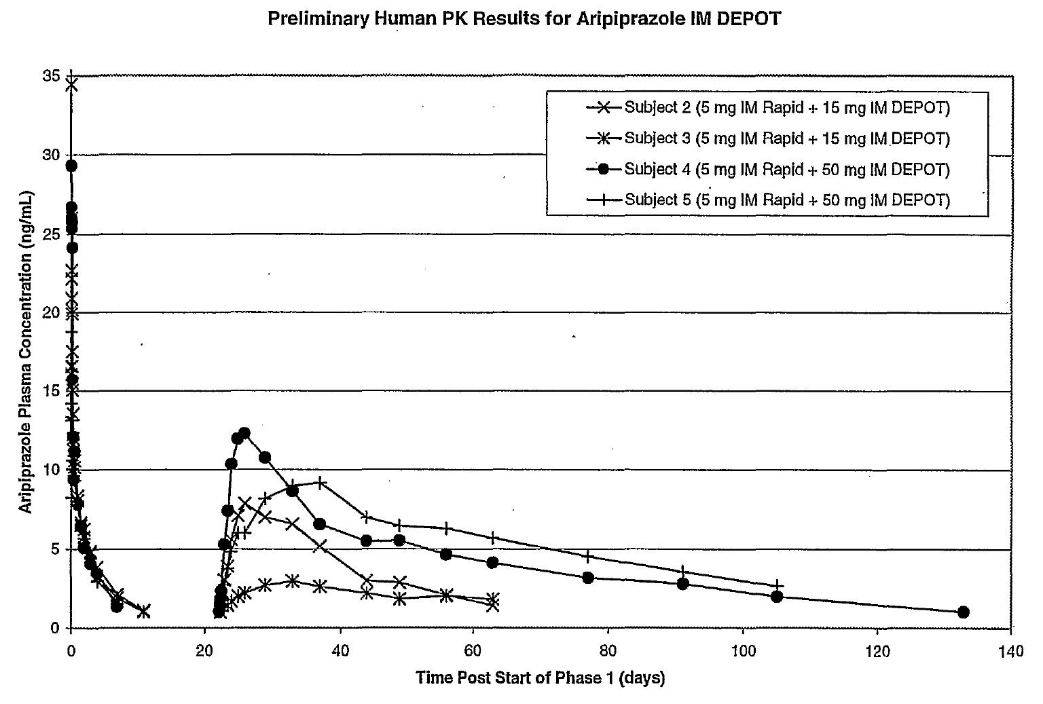

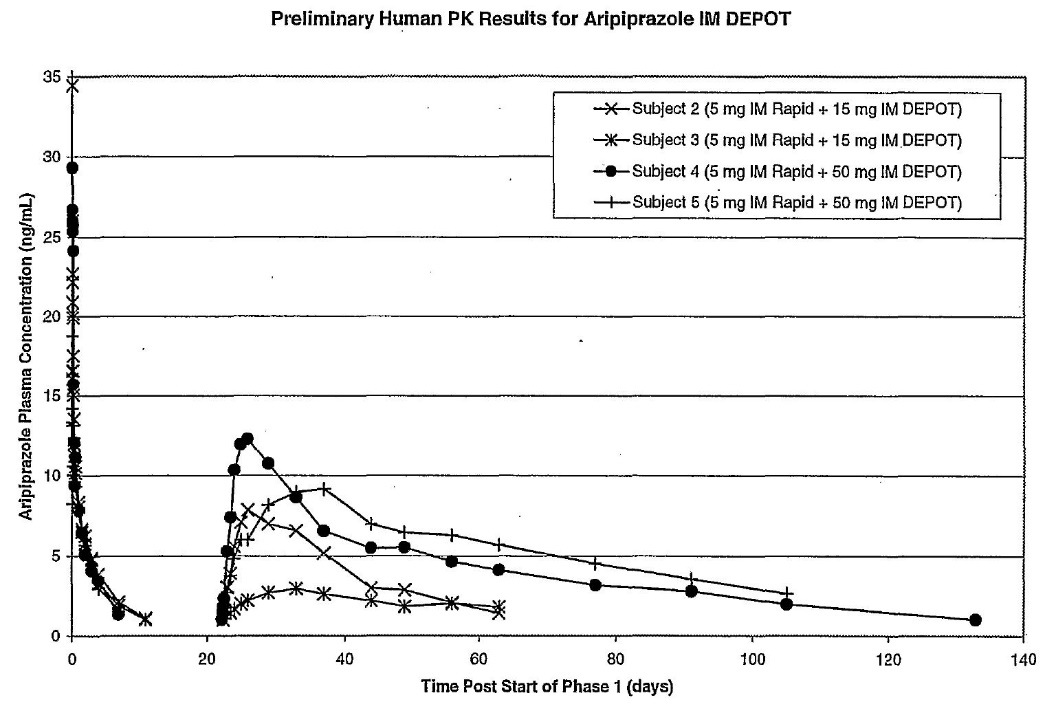

59 Example 4 (Human PK Data) relates to a single-dose IM Depot study. The following is the entirety of the information relating to Example 4:

Aripiprazole I.M. depot formulation prepared in Example 1 was administered intramuscularly to patients diagnosed with chronic, stable schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder at [sic]. The study design included administration of a 5-mg dose of aripiprazole solution to all subjects followed by a single dose of IM depot at 15, 50, and 100 mg per patient. Samples for PK analysis were collected until plasma concentrations of aripiprazole were less than the lower limit of quantification (LLQ) for 2 consecutive visits.

Figure 3 shows mean plasma concentrations vs. time profiles of aripiprazole in subjects 2 and 3 dosed with 15 mg of IM Depot, and subjects 4 and 5 who received 50 mg of IM Depot. In all cases aripiprazole plasma levels showed a fast onset of release and sustained release for at least 30 days.

60 Figure 3 (which appears after the claims) shows the following:

61 The reference to IM Rapid appears to be a reference to the 5-mg dose of aripiprazole solution referred to in Example 4.

62 There are 74 claims, but only eight of these matter for this case (being the PTE Claims).

63 The Controlled Release Injectable Formulation Claims are exemplified by claim 1, which is as follows:

1. A controlled release sterile aripiprazole injectable formulation which upon injection releases aripiprazole over a period of at least one week, which comprises:

(a) aripiprazole having a mean particle size of about 1 to 10 microns,

(b) a vehicle therefor, and

(c) water for injection.

64 The other Controlled Release Injectable Formulation Claims are as follows:

3. A controlled release aripiprazole injectable formulation which upon injection releases aripiprazole over a period of at least one week, which comprises:

(a) aripiprazole having a mean particle size of about 1 to 10 microns, and

(b) a vehicle therefor, said vehicle comprising:

(1) one or more suspending agents,

(2) optionally one or more bulking agents, and

(3) optionally one or more buffering agents, and

(c) water for injection.

…

6. The formulation as defined in any one of claims 3 to 5 wherein the aripiprazole has a mean particle size within the range from about 2 to about 4 microns.

…

14. The formulation as defined in any one of claims 1 to 13 wherein the aripiprazole is in the form of a monohydrate.

65 The Freeze-dried Controlled Release Formulation Claims are exemplified by Claim 16, which is as follows:

16. A sterile freeze-dried controlled release aripiprazole formulation which comprises:

(a) aripiprazole having a mean particle size of about 1 to 10 microns, and

(b) a vehicle therefor,

which formulation upon constitution with water forms a sterile injectable formulation which upon injection releases aripiprazole over a period of at least about two weeks.

66 The other Freeze-dried Controlled Release Formulation Claims are as follows:

19. The freeze-dried formulation as defined in any one of claims 16 to 18 wherein the aripiprazole has a mean particle size within the range from about 2 to about 4 microns.

…

21. The freeze-dried formulation as defined in any one of claims 16 to 20 wherein said vehicle comprises:

(a) one or more suspending agents,

(b) one or more bulking agents, and

(c) one or more buffering agents.

…

25. The freeze-dried formulation as defined in any one of claims 16 to 24 wherein the aripiprazole is in the form of a monohydrate.

67 The PTE Claims do not claim (a) any specified dosages; (b) that such dosage be of a “therapeutic amount”; nor (c) any dosage interval (frequency). Nor do they refer to, or identify, a claimed blood plasma concentration.

3.3 Relevant Feature

68 Having regard to the letter of instructions to the experts for the purposes of preparing the JER, the reference in each of the PTE Claims to “which upon injection releases aripiprazole over a period of [a specified time]” (or equivalent) is referred to as the Relevant Feature.

69 Professor Evans and Professor Winter agreed that the Relevant Feature in each of the PTE Claims follow a common structure and all refer to three elements:

(1) a process of injection (i.e. the injection of the claimed formulation; whether it is a subcutaneous or intramuscular injection is not specified). (Professor Evans notes that the Patent states that the route of administration is preferably intramuscularly and the Examples provided relate to intramuscular administration);

(2) a parameter for the release of aripiprazole (which is the dissolution of aripiprazole molecules from the aripiprazole particle depot at the injection site); and

(3) a defined discrete boundary for release expressed in weeks (e.g. in multiples of seven days, plus/minus 10% where the term “about” is used).

70 It is apparent from this evidence that the Relevant Feature is not to be construed as “mean plasma concentration” or some other drug concentration metric.

71 Further, by this evidence, it is apparent that a person skilled in the art would understand that “release”, as it is to be understood in the context of the PTE Claims and the specification as a whole, means the dissolution of aripiprazole molecules from the aripiprazole particle depot at the injection site.

4. ISSUES OF STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION

72 Before dealing with the contentions by Sun Pharma concerning the validity of the Extension, certain issues of statutory construction which arose in this case will be addressed.

4.1 The Patents Act

73 Section 70 of the Patents Act requires three conditions to be satisfied by a patentee seeking a term extension, each of which must be satisfied in respect of a “pharmaceutical substance”.

74 Schedule 1 of the Patents Act defines “pharmaceutical substance” as follows:

pharmaceutical substance means a substance (including a mixture or compound of substances) for therapeutic use whose application (or one of whose applications) involves:

(a) a chemical interaction, or physico-chemical interaction, with a human physiological system; or

(b) action on an infectious agent, or on a toxin or other poison, in a human body;

but does not include a substance that is solely for use in in vitro diagnosis or in vitro testing.

75 Schedule 1 defines “therapeutic use” as follows:

therapeutic use means use for the purpose of:

(a) preventing, diagnosing, curing or alleviating a disease, ailment, defect or injury in persons; or

(b) influencing, inhibiting or modifying a physiological process in persons; or

(c) testing the susceptibility of persons to a disease or ailment.

76 The first condition operates to identify a candidate patent for extension and is set out in s 70(2) as follows:

Either or both of the following conditions must be satisfied:

(a) one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

(b) one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

77 Sun Pharma alleges that the first condition was not satisfied by reference to s 70(2)(a). It was common ground that s 70(2)(b) did not apply in this case; however, as will be seen, that section is relevant to the proper construction of s 70(2)(a).

78 The second condition (relevantly to this case) is whether the pharmaceutical substance is contained in a good on the ARTG. In this regard, s 70(3) provides:

Both of the following conditions must be satisfied in relation to at least one of those pharmaceutical substances:

(a) goods containing, or consisting of, the substance must be included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods;

(b) the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years.

79 Sun Pharma alleges that the second condition was not satisfied because s 70(3)(a) was not satisfied. Sun Pharma also submits that s 70(3)(b) was not satisfied only if, contrary to the Full Court authorities, Otsuka is permitted to rely upon aripiprazole alone as satisfying the requirements of s 70(2)(a).

80 The third condition is that the term of the patent must not have been previously extended: s 70(4). It is common ground that the third condition was satisfied.

81 Pursuant to s 78 of the Patents Act, following the grant of an extension under s 70, it is not an infringement of the patent to exploit any form of the invention other than a pharmaceutical substance per se that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification. The operation of s 78 has been recognised as narrowing a patentee’s monopoly in the extended term: see, for example, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp v Sandoz Pty Ltd (2022) 291 FCR 26; [2022] FCAFC 40 at [109] (Allsop CJ, Yates and Burley JJ). As will be seen, this is relevant to the proper construction of s 70.

4.2 Meaning of “pharmaceutical substance per se”

82 Section 70(2) refers to “one or more pharmaceutical substances per se”. The meaning of pharmaceutical substance per se has been addressed in a number of decisions of this Court, and in passing by the High Court.

83 The term “pharmaceutical substance per se” means the pharmaceutical substance “by or in itself, intrinsically, essentially”, or “taken alone; essentially; without reference to anything else”: Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH v Commissioner of Patents (2001) 112 FCR 595; [2001] FCA 647 at [34], [37] (Wilcox, Whitlam and Gyles JJ) (Boehringer FC).

84 The Full Court in Boehringer FC stated at [37] that the decision of Heerey J, the primary judge, was “correct, substantially for the [following] reasons”, which reasons were reproduced at [17] of its decision:

The 1990 Act in its present form manifests a policy which draws a distinction between, on the one hand, a pharmaceutical substance that is the subject of a patent claim and, on the other hand, a pharmaceutical substance that forms part of a method or process claim. The specific exception to the latter (an exception which proves the rule) is the provision for recombinant DNA technology in s 70(2)(b).

Broadly speaking, a claim in relation to a pharmaceutical substance can be made in three ways:

(i) a new and inventive product alone;

(ii) an old or known product prepared by a new and inventive process;

(iii) an old or known product used in a new and inventive mode of treatment.

What is clear in s 70 is that only the first type of claim to a pharmaceutical product is to be subject to extension rights. So far as a new process is concerned, it is only when the new process answers the particular description in s 70(2)(b) (recombinant DNA process) that it can be the subject of an extension. As counsel for the Commissioner submitted, the policy to be deduced in the light of the legislative history is that Parliament has decided that what is intended to be fostered is primary research and development in inventive substances, not the way they are made or the way they are used, with the sole (and important) exception of recombinant DNA techniques, this being an area particularly worthy of assistance for research and development.

In the light of this history, the relevance of the expression ‘per se’ becomes clear. Section 70(2)(a) is only to make extension rights available when the claim is for a pharmaceutical substance as such, as opposed to a substance forming part of a method or process.

(Emphasis added.)

85 The Full Court in Boehringer FC continued at [38]–[40]:

There are serious difficulties about the appellant’s argument. One is that it effectively reads out of s 70(2)(a) the words “per se”. On the appellant’s argument, it is enough that the complete specification disclose one or more pharmaceutical substances, whether as the sole element in an invention or in combination with other elements. If that had been the legislative intention, the paragraph could have read: “one or more pharmaceutical substances must in substance be disclosed”. There would have been no need for “per se”.

Second, the Second Reading Speech and the Explanatory Memorandum provide no support to the appellant’s argument; quite the contrary. The Second Reading Speech speaks about the “development of a new drug” and the research and testing required before “the product” can enter the market. This is plainly a reference to the drug itself; not to the drug in combination with other elements.

Similarly, the Explanatory Memorandum says that claims to “pharmaceutical substances per se, would usually be restricted to new and inventive substances”. The Explanatory Memorandum excludes the application of the new provisions to “new processes of making pharmaceutical substances or new methods of using pharmaceutical substances, where the substances themselves are known”.

(Emphasis original.)

86 In Prejay Holdings Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (2003) 57 IPR 424; [2003] FCAFC 77, the Full Court concluded that it is not enough to constitute a claim for a pharmaceutical substance per se that a pharmaceutical substance “appears in a claim in combination with other integers or as part of the description of a method (or process) that is the subject of a claim”: see [24] (Wilcox and Cooper JJ) and [35]–[36] (Allsop J). At [40] and [42], Allsop J added the following:

… The definition refers to a substance, which must have a purpose or use — therapeutic use, and whose application involves the other matters identified in the definition. The definition is of a particular kind of substance, but it is of a substance, and only a substance.

…

While the secondary materials are not entirely internally consistent, the above result and the above construction accord with what appears to me to be the burden of the secondary materials, exemplified by the following part of the explanatory memorandum, referred to by the Full Court in Boehringer at [24]:

The extension of term provisions will be available for patents that include claims to pharmaceutical substances per se provided the other criteria are met. These claims to pharmaceutical substances per se, would usually be restricted to new and inventive substances. Patents that claims [sic], will not be eligible unless the process involves the use of recombinant DNA technology. Claims which limit the use of a known substance to a particular environment, for example claims to pharmaceutical substances when used in a new and inventive method of treatment, are not considered to be claims to the pharmaceutical substance per se…

(Emphasis original.)

87 In Pharmacia Italia SpA v Mayne Pharma Pty Ltd (2006) 69 IPR 1; [2006] FCA 305, Weinberg J stated at [96]:

…If a claim, properly understood, is, in effect, intended to protect some novel process or method, no extension can be granted. The claim, when read sensibly, and as a whole, must be to a “pharmaceutical substance per se”. At least in circumstances where the substance itself is known, the claim must not be, in essence, to a new process of making that substance, or a new method of using it.

88 His Honour also observed at [98] and [101]:

The matter must largely be one of impression, and degree. Reasonable minds may differ as to whether the legitimate boundaries of a “pharmaceutical substance per se” have been crossed.

…

Patent rights, and in particular the right to an extension, are very much dependent upon the language of the claim which defines the invention. When construing a claim, in order to determine whether the requirements set out in s 70(2)(a) are satisfied, it is appropriate to have regard to the reason why any reference to process has been included in the claim as formulated. There is a difference between seeking to protect a process (which can be the subject of a patent, but cannot be the subject of an extension), and merely referring incidentally to some elements of process, that are not themselves novel, in order to better describe the new and inventive substance. Section 70(2)(a) provides that a new and inventive substance that is a “pharmaceutical substance per se” can be the subject of an extension. …

89 In Spirit Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Mundipharma Pty Ltd (2013) 216 FCR 344; [2013] FCA 658 at [45], Rares J approved the approach taken in Pharmacia at [101].

90 In H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd (2009) 177 FCR 151; [2009] FCAFC 70 (Alphapharm FC), Bennett J (with whom Middleton J agreed) referred to the requirements of s 70 at [242] and stated at [243] that:

A patent may be obtained if it discloses and claims, for example, a new method of preparation, or purification that results in greater efficacy, or improvement in the delivery of a known pharmaceutical substance already listed on the ARTG. The scheme of the 1990 Act does not provide for the extension of term of each such patent which relates to the same substance.

91 In Commissioner of Patents v AbbVie Biotechnology Ltd (2017) 253 FCR 436; [2017] FCAFC 129 (Besanko, Yates and Beach JJ), the Full Court at [28] cited the Explanatory Memorandum for the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Bill 1997 (Cth), which inserted the current s 70 into the Patents Act as follows:

The extension of term provisions will be available for patents that include claims to pharmaceutical substances per se (provided that the other criteria are met) [i.e. a product claim]. These claims to pharmaceutical substances per se would usually be restricted to new and inventive substances. Patents that claim pharmaceutical substances when produced by a particular process (product by process claims) will not be eligible unless that process involves the use of recombinant DNA technology. Claims which limit the use of a known substance to a particular environment, for example claims to pharmaceutical substances when used in a new and inventive method of treatment, are not considered to be claims to pharmaceutical substances per se.

92 The Full Court in AbbVie emphasised at [49] that the “cases have recognised that the [concern of s 70(2)(a)] is with inventions that are products, not inventions that are methods or processes” and referred to Boehringer Ingelheim International v Commissioner of Patents (2000) AIPC 91-670; [2000] FCA 1918, before stating at [53]–[57]:

In Prejay Holdings Ltd v Commissioner of Patents (2003) 57 IPR 424 (Prejay), Wilcox and Cooper JJ commented on the Full Court’s observation in Boehringer Ingelheim [International GmbH v Commissioner of Patents (2001) 112 FCR 595], saying (at [24]):

As is apparent from the context of these words, especially the Full Court’s references to the legislative history of s 70, the Full Court was saying that, for a substance to fall within s 70(2)(a) it must itself be the subject of a claim in the relevant patent. It is not enough that the substance appears in a claim in combination with other integers or as part of the description of a method (or process) that is the subject of a claim. The policy adopted in s 70 was to confine extensions to patents that claim invention of the substance itself.

Once again, their Honours were addressing one policy objective. Importantly, their Honours went on to consider the significance of s 70(2)(b) in that regard, saying (at [25]):

This conclusion is not negatived by the terms of s 70(2)(b) of the Act … that paragraph does not require disclosure of a process. Rather, it requires the disclosure of “one or more pharmaceutical substances” that are produced by a particular process.

(Emphasis in original.)

This observation is significant because it acknowledges that s 70(2)(a) and s 70(2)(b) address the same concern — extensions of term in relation to claims directed to pharmaceutical substances, not methods or processes involving pharmaceutical substances. The only exception is the one specifically acknowledged by s 70(2)(b), where pharmaceutical substances can be produced by a process that involves recombinant DNA technology. But, even so, the matter claimed must be the pharmaceutical substance or substances so produced, not other methods or processes involving those substances.

…Nonetheless, each provision’s concern is with pharmaceutical substances, not additional or other matter concerning or involving the use of pharmaceutical substances. In this way, s 70(2)(b) can be construed conformably with s 70(2)(a), and both provisions can be given an harmonious operation, directed to the same end.

This understanding is consistent with the passage in the Explanatory Memorandum quoted at [28] above. The passage emphasises that the extension of term provisions are directed to new and inventive substances — not the method or process by which they are produced (other than involving recombinant DNA technology). Of particular significance is the specific acknowledgement that claims to pharmaceutical substances when used in new and inventive methods of treatment are not intended to be part of the extension of term regime. This passage in the Explanatory Memorandum refers to “pharmaceutical substances per se”, but its reference to product by process claims, and to recombinant DNA technology in particular, signifies that both limbs of s 70(2) are being discussed: see also Section 8 on p 9 of the Explanatory Memorandum, and [7] and [10] of the Notes on Clauses in Sch 1 thereto.

93 In Cipla, Perram J summarised the effect of the Full Court authorities, stating at [5]:

…Although not directly relevant to this case, it is useful to know for some of the arguments to be considered that the words ‘per se’ have been held by the Full Court of this Court to entail that an extension cannot be granted for a patent which discloses claims for a method and is confined (subject to presently immaterial exceptions) to patents claiming products: Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH v Commissioner of Patents [2001] FCA 647; 112 FCR 595 (‘Boehringer (FC)’) at [37] per Wilcox, Whitlam and Gyles JJ, affirming the decision of Heerey J in Boehringer Ingelheim International v Commissioner for Patents [2000] FCA 1918 (‘Boehringer’); Commissioner of Patents v AbbVie Biotechnology Ltd [2017] FCAFC 129; 253 FCR 436 at [49] per Besanko, Yates and Beach JJ…

94 In the High Court decision of Alphapharm Pty Ltd v H Lundbeck A/S (2014) 254 CLR 247; [2014] HCA 42 (Alphapharm HC at [23], Crennan, Bell and Gageler JJ stated:

A little more needs to be said about the Escitalopram Patent. Lundbeck, a Danish pharmaceutical company, applied for the Escitalopram Patent on 13 June 1989 (the expiry date of which became 13 June 2009), for an invention entitled “(+)-Enantiomer of citalopram and process for the preparation thereof”. There are six claims – claims 1 to 5 are product claims and claim 6 is a method claim, which, for present purposes, can be put to one side. Claim 1 claims a compound (an enantiomer) known as “(+)-citalopram” and its non-toxic acid addition salts, and claims 3 and 5 claim a pharmaceutical composition comprising, as an active ingredient, that compound. The pharmaceutical substance disclosed in the complete specification, (+)-citalopram, is used to treat depression.

(Emphasis added; footnotes omitted.)

95 The emphasised sentence in [23] of Alphapharm HC was accompanied by footnote 40:

Relevantly, the extension of term scheme under the Act covers standard patents for pharmaceutical substances per se pursuant to s 70(2)(a), hence patents for pharmaceutical methods or tablets do not fall within the scheme. It can be noted that pharmaceutical substances produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, the subject matter of s 70(2)(b), are not relevant to this case.

96 About these aspects of the reasons in Alphapharm HC, Perram J stated the following in Cipla at [175]–[176]:

The statement that patents for pharmaceutical methods cannot be a patent for a pharmaceutical substance per se accords with the manner in which the words ‘per se’ has been interpreted in this Court in the authorities noted at [5] above…

…The statement is that tablets cannot be a pharmaceutical substance per se. Since this appears immediately after an explanation of the uncontroversial proposition that a patent for a pharmaceutical method cannot be a pharmaceutical substance per se and since there is no reference to tablets in s 70(2) at all, I read this footnote as exhibiting a conclusion that a patent for a tablet is a patent for a pharmaceutical method of delivery. If not read that way, the reference to ‘tablet’ seems to come from nowhere although an alternative view may be that it derives from the passage in explanatory memorandum for the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment Act 2006 set out above which also refers to tablets. But wherever the reference to a tablet comes from, it is clear that the conclusion in footnote 40 is about the proposition that a method patent will not disclose a pharmaceutical substance per se within the meaning of s 70(2).

97 Because it was irrelevant to the issue in dispute between the parties in that case, Perram J stated at [178] of Cipla that:

…It is not necessary to consider whether footnote 40 is a seriously considered dicta of the High Court which I am bound to follow (see Hill v Zuda Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 21; 275 CLR 24 at [26] per the Court) or just an obiter dictum made in passing. Given its presence in a footnote in a section headed ‘The background facts’ in a case having nothing to do with this issue, I would tend to favour the latter characterisation…

98 His Honour concluded that it was not a considered obiter dictum and that he was not legally required to follow it, but noted at [181] that, “[o]bviously, anything said by the High Court, even if a footnote, must be taken into account”.

99 The following emerges from these authorities for the purposes of identifying a claim for a pharmaceutical substance per se (which are not mutually exclusive):

(1) only a claim for a pharmaceutical substance as such or alone will qualify;

(2) a pharmaceutical substance which forms part of a method or process does not qualify;

(3) an existing pharmaceutical substance prepared by a new and inventive process does not qualify;

(4) a pharmaceutical substance when produced by a particular process (product by process claim) does not qualify;

(5) a new and inventive method of using an existing pharmaceutical substance (such as in a new method of treatment) does not qualify. This could extend to a new and inventive pharmaceutical method of delivery.

4.3 Meaning of “in substance fall within the scope of the claim[s]”

100 Sun Pharma submits that the expression “in substance fall within the scope of the claim[s]” in s 70(2)(a) requires that the pharmaceutical substance per se must take all of the essential integers of the claim. Otsuka submits to the contrary and contends that, provided the pharmaceutical substance per se is included amongst the things claimed, that will suffice.

101 In Boehringer FC, the appellant urged the Full Court to only focus on part of the claim that was directed to the “substance”. In doing so, the appellant argued that s 70(2)(a) means “no more than that the pharmaceutical substance must be a specific claimed feature of the invention”, and that it “does not matter that the substance appears only as one element in a combination of elements”: see [26]. It also argued that “[t]he expression mandates nothing more than that the claims include as an essential feature the pharmaceutical substance”: see [27] (emphasis original). In response, the respondent submitted (see [31], [35]):

The effect of s 70(2)(a) insisting that substances fall within the scope of the claims of the specification is to prevent any extensions of term from having a broadening effect on the claims of the extended patent. This policy of not allowing any broadening by extensions is demonstrated by the new s 78. To extend the patent in this case would have that very effect of widening when it did not, during its primary term, include protection for the substance alone. This would make an infringement something which was not previously an infringement…

…

...the words “in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims” of the specification, refer to the elements that make up the claim or claims. They point out that, if one essential integer is removed from a patent claim, the effect is to broaden the claim. They note their opponents concede that the use of the pharmaceutical substance itself would not be an infringement; it would be necessary for the infringer also to replicate the additional elements of any claim that was said to be infringed. It follows, according to counsel, that the pharmaceutical substance, standing alone, does not “in substance fall within the scope of” any claim of the specification.

102 As to this, the Full Court stated at [37]–[38] that:

The submissions made on behalf of the respondent are clearly to be preferred… [and there] are serious difficulties about the appellant’s argument. One is that it effectively reads out of s 70(2)(a) the words “per se”. On the appellant’s argument, it is enough that the complete specification disclose one or more pharmaceutical substances, whether as the sole element in an invention or in combination with other elements. If that had been the legislative intention, the paragraph could have read: “one or more pharmaceutical substances must in substance be disclosed”. There would have been no need for “per se”.

103 Further, the Full Court relied on the effect that the respondent’s construction of s 70(2)(a) would have on the monopoly of a patentee in the extended term by reason of s 78, with the result that it regarded the appellant’s construction of s 70 as “anomalous”: at [41]. At [42], the Full Court concluded that:

The appellant’s best point is that in ordinary usage a necessary integer of a whole would be regarded as falling within the scope of that whole. However, in the context of s 70(2)(a), we think that falling within the scope of a claim in a patent specification means included amongst the things claimed. Here, the substance, in itself, is not a thing claimed in the patent sense.

104 Pausing there, it is apparent that the precise submission advanced by Otsuka in this case was also advanced by the appellant in Boehringer FC and was rejected by the Full Court. At [42] of that decision, the Full Court referred to what it considered was the appellant’s “best point”, stating that it “is that in ordinary usage a necessary integer of a whole would be regarded as falling within the scope of that whole”. The Full Court then rejected that “best point”, stating that “[h]owever, in the context of s 70(2)(a), we think that falling within the scope of a claim in a patent specification means included amongst the things claimed. Here, the substance, in itself, is not a thing claimed in the patent sense” (emphasis added). In other words, the Court was referring to a claim which was comprised of the pharmaceutical substance per se with no other integers. When the reasons of the Full Court are read in context, that is the correct representation of the Full Court’s finding.

105 The reasoning in Boehringer FC was followed by the Full Court in Prejay at [23]–[24], which stated at [24] that:

…the Full Court [in Boehringer FC] was saying that, for a substance to fall within s 70(2)(a) it must itself be the subject of a claim in the relevant patent. It is not enough that the substance appears in a claim in combination with other integers or as part of the description of a method (or process) that is the subject of a claim. The policy adopted in s 70 was to confine extensions to patents that claim invention of the substance itself.

106 The reasoning in Boehringer FC and Prejay was adopted by the Full Court in AbbVie at [52]– [54].

107 Between Prejay and AbbVie, the decision of Alphapharm FC was handed down. In that case, the Court was addressing the question of whether Cipramil (being the goods on the ARTG) “contains or consists of” the (+)-enantiomer molecule, which was the pharmaceutical substance for the purposes of s 70(2)(a): see [231], [239]. At [240], Bennett J stated that “[w]hat is required is an analysis of whether there are goods containing or consisting of (+)-citalopram”. In that same paragraph, her Honour also observed that “[t]here is no suggestion from the words of s 70(3) that the relevant “goods” could or must include no more than one pharmaceutical substance”. It was in that context that Bennett J stated at [242] that “[i]n my view, s 70 recognises that the pharmaceutical substance per se may not equate with the subject matter of the claim of the patent in terms”.

108 Otsuka relies upon the statement in Alphapharm FC at [242]. However, once again, when read in context, the statement at [242] in Alphapharm FC was not addressing the construction of the expression “in substance fall within the scope of the claim[s]” in s 70(2)(a) and nor was it purporting not to follow Boehringer FC and Prejay. Rather, the Full Court considered that, provided the pharmaceutical substance per se was contained in the goods listed on the ARTG, whether alone or with other substances, that would suffice for the purposes of s 70(3): see [240]–[244].

109 For these reasons, Sun Pharma’s position is the correct one, namely that the expression “in substance fall within the scope of the claim[s]” in s 70(2)(a) requires that the pharmaceutical substance per se must take all of the essential integers of the claim.

4.4 Whether the definition of “pharmaceutical substance” excludes formulations

110 In Cipla, it was held that “pharmaceutical substance” includes formulations: see, for example, the findings at [38], [183]–[186]. The reasons for doing so included that both Pharmacia and Spirit have as part of their ratio decidendi that a pharmaceutical substance may include a formulation: see [181].

111 In closing, Sun Pharma submits that the decision in Cipla on this issue of construction is incorrect but does not seek a finding that it was “plainly wrong”. Sun Pharma expressly reserves its position (in any appeal from this decision) to argue that Cipla was wrongly decided.

112 Although it provided a non-exhaustive list of the reasons why it contended that the construction in Cipla was incorrect, I did not understand it to be necessary that I address those submissions, especially as they were not the subject of oral submissions. In any event, addressing such arguments lacks utility in circumstances where no party urges that I reach a conclusion that Perram J was plainly wrong such that I ought not follow Cipla.

113 This has the consequence that I should, and will, follow it for the reasons given by French J in Hicks v Minister for Immigration & Multicultural & Indigenous Affairs [2003] FCA 757 at [75]–[76].

114 For these reasons, the definition of “pharmaceutical substance” includes formulations.

4.5 Whether formulations can only include substances which have therapeutic use

115 In Cipla, Perram J characterised Cipla’s “alternative case” as follows ([187]–[188]):

…It becomes necessary in light of this conclusion to consider Cipla’s alternative case that, even if ‘pharmaceutical substance’ is capable of encompassing formulations, it does not encompass either of the relevant formulations claimed by the 862 Patent.

The pith of Cipla’s alternative case is that here, unlike in Spirit, the excipients do not individually or together have a therapeutic use in the formulations separate from the liraglutide itself. As already noted, there are two limbs to this point: first, somewhat obscurely, whether it is necessary that the excipients in a formulation themselves be for a therapeutic use in order that the formulation be a ‘pharmaceutical substance’; and secondly, if so, whether the excipients in the formulations claimed by the 862 Patent are for a therapeutic use.

(Emphasis added.)

116 His Honour then addressed the “first limb” of that case at [189]–[191]:

The reader may be forgiven for struggling to understand this submission. As I understood it, the submission emerged as an illustration derived from the judgment of Rares J in Spirit and went as follows: in Spirit, the active ingredient was oxycodone but it was formulated as a controlled release tablet. This outcome was achieved by including the oxycodone in a substance (a deliberately neutral word) which resisted the process of digestion in the gastrointestinal tract and slowed the release of the oxycodone. Rares J held that the formulation was a pharmaceutical substance. Cipla’s point, which was very briefly, perhaps vanishingly, expressed, seemed to be that if, contrary to its primary submission, a formulation including excipients could be a pharmaceutical substance then, as a matter of law, such a situation was confined to the circumstances obtaining in Spirit, that is to say, the situation where the excipient was for therapeutic use.

Unpicked in this way, this submission is revealed as a repetition of Cipla’s primary argument that a formulation can never be a pharmaceutical substance. The effect of Rares J’s conclusion that the controlled release excipient was for a therapeutic use inevitably entails that the controlled release excipient satisfied the definition of a pharmaceutical substance. Thus, whilst Cipla glancingly posits this as an alternative legal case to its broad contention that every element in a formulation must be for a therapeutic use, the facts of Spirit show that it was a case where every element of the formulation did have that quality.

Thus, when the fog lifts on this legal contention, it turns out to be the same as Cipla’s primary submission and is to be rejected for the same reasons. If the submission means anything else, then I do not understand it and reject it for that reason. Having cleared this out of the way, the remaining issues are the factual ones raised by Novo Nordisk on the assumption, contrary to my conclusion, that each excipient must be for therapeutic use in its own right.

117 By its written closing submissions, Sun Pharma submits that, to the extent that the decision in Cipla is a holding that the excipients in a formulation need not have a “therapeutic use”, then it is plainly wrong and should not be followed. During oral submissions, Sun Pharma retreated from this position, instead submitting that Perram J misunderstood Cipla’s argument and so had failed to address it, no relevant holding was made by his Honour and so it is not necessary to conclude that his Honour was plainly wrong.

118 I do not accept this characterisation of the reasons in Cipla.

119 Once Perram J found that a formulation including excipients or non-active ingredients could be a pharmaceutical substance, a submission that all excipients must be for a therapeutic use is (in truth) a repetition of the primary argument, as his Honour found at [190].

120 Further and as Otsuka submits, Perram J did hold that the excipients in a formulation need not have or “be for” a “therapeutic use in its own right” in order for the formulation to be a pharmaceutical substance. That is apparent from, at the least, the final sentence of [191].

121 Nor do I accept that such a finding was plainly wrong for the following reasons.

122 Firstly, the conclusion reached in Cipla accords with the decision of Pharmacia at [107], in which Weinberg J stated that:

…Almost every pharmaceutical product will consist of a combination of individual substances, some of which may be intrinsically therapeutic (active ingredients), while others serve different, albeit essential, roles. To restrict the capacity to extend a patent to those unlikely cases where every component of the compound is itself therapeutically useful would be to deprive [s 70] of any real utility, and largely defeat the purpose of its enactment.

123 Secondly, at [125]–[126] of Cipla, Perram J addressed the ordinary meaning of the text of the statutory definition of pharmaceutical substance, stating that: