Federal Court of Australia

Australian Energy Regulator v Callide Power Trading Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 32

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | CALLIDE POWER TRADING PTY LTD (ACN 082 468 719) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The conduct of the respondent referred to in the declarations in paragraphs 1 and 2 below is the “same conduct” for the purposes of s 67 of the National Electricity Law.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The respondent contravened r 4.15(a)(1) of the National Electricity Rules (the NER) by failing to ensure that the Callide C4 generating unit met or exceeded cl 3.6 of the applicable performance standards dated 29 August 2008 (performance standards), in that, on 25 May 2021:

(a) the protection systems for the Callide C4 generating unit (Callide C4 protection systems) included:

(i) the 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection system;

(ii) the X generator transformer differential protection system; and

(iii) the Y overall differential protection system;

(b) the operator of Callide C4 (CS Energy Limited) undertook a planned battery charger replacement procedure at Callide C Power Station, during the course of which:

(i) it continued to operate the generating unit throughout;

(ii) it disconnected the C4 battery charger and battery; and

(iii) the generating unit obtained its DC power supply from the Station battery charger and battery;

(c) at approximately 13:33, in the course of that battery charger replacement procedure:

(i) the Callide C4 battery charger was reconnected;

(ii) the Station battery charger and battery were disconnected;

(iii) the new Callide C4 battery charger failed to respond quickly enough to maintain the required DC voltage as intended; and

(iv) where the C4 battery had not yet been reconnected, the DC power supply to the Callide C4 protection systems went out of service;

(d) subsequently:

(i) immediately after the events referred to in (c), an element within the protection zones of the Callide C4 protection systems, namely the generating unit, experienced faults when it (among other things): (1) lost excitation; and (2) experienced a reverse power flow, where the generating unit began motoring asynchronously instead of generating; and

(ii) at approximately 14:06, among other things, at Callide C4 there was: (1) a two-phase short circuit fault at the generating unit; (2) a three-phase short circuit fault at the generator stator; and (3) a single phase-to-ground short circuit fault, followed by a double phase-to-ground short circuit fault, both within the 275kV system, each being elements within the protection zones of the Callide C4 protection systems;

(e) because the Callide C4 battery was disconnected, the Callide C4 protection systems, a purpose of which was to operate in respect of such faults:

(i) lacked an alternative (redundant) DC power supply (DC power supply redundancy);

(ii) did not have sufficient redundancy to ensure that the faulted elements were disconnected from the power system within the applicable fault clearance times, as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements; and

(f) in the circumstances, the Callide C4 protection systems failed to disconnect the faulted elements from the power system.

2. The respondent contravened cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER by failing to ensure that the Callide C4 generating unit was planned, designed and operated to comply with cl 3.6 of the performance standards in that, on 25 May 2021:

(a) in the circumstances set out in paragraph 1 above; and

(b) because the Callide C4 protection systems lacked DC power supply redundancy (as an incident of their planning and design, and their mode of operation on 25 May 2021),

the Callide C4 protection systems did not have sufficient redundancy to ensure that the faulted elements were disconnected from the power system within the applicable fault clearance times, as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

3. Pursuant to s 44AAG(2)(a) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), within 28 days of the making of this Order, the respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a civil penalty in the amount of $9,000,000 in respect of the respondent’s contraventions of r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER.

4. Pursuant to s 43 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), within 28 days of the making of this Order, the respondent pay the applicant’s costs of, and incidental to, this proceeding, agreed in the amount of $150,000.

5. There be liberty to the parties to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DERRINGTON J:

Overview

1 By an originating application dated 9 February 2024, the Australian Energy Regulator (the AER) sought declarations in respect of conduct by the respondent, Callide Power Trading (CPT), which was said to have contravened the National Electricity Rules (the NER). It also sought the imposition of civil penalties and orders that CPT take certain actions to remedy its contraventions and to prevent a recurrence of those contraventions.

2 CPT has since admitted to two of the major contraventions alleged by the AER, and the parties have reached an agreement as to the terms on which they consider the proceedings should be resolved. The parties are agreed as to the factual circumstances in which the contraventions occurred, the principles to be applied by the Court and, subject to the Court’s discretion, the terms of the declarations, the quantum of the penalties and an order for costs. They have jointly filed written submissions and a statement of agreed facts and admissions within the meaning of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

3 The Callide C Power Station is a coal-fired power station which generates electricity at Mount Murchison, Queensland. It comprises the Callide C3 and C4 generating units, the latter of which is the subject of the present proceeding. As is explained further below, CPT is not the owner or operator of the Callide C Power Station — it is a Scheduled Generator and a Registered Participant under Ch 2 of the NER in the capacity as an intermediary on behalf of the parties to the “Callide Joint Venture”. The operator of the Callide C4 unit is CS Energy Limited (CSEL), which is relevantly required to ensure services are provided in compliance with all aspects of the applicable performance standards and as otherwise required by the NER. Terms that are italicised in these reasons have the same meaning as provided in Ch 10 of the NER.

4 On 25 May 2021, there was a catastrophic failure and destruction of the Callide C4 generating unit. Though there is some technical complexity to the nature and circumstances of the contravening conduct, in broad terms, when that failure occurred, the protection systems for the Callide C4 generating unit failed to operate in the manner required. This breached the generator performance standards and CPT’s obligations under the NER to:

(a) ensure that the Callide C4 generating unit met or exceeded the applicable performance standards (see r 4.15(a)(1) of the NER); and

(b) ensure that the Callide C4 generating unit was planned, designed and operated to comply with applicable performance standards (see cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER).

5 As a result, Callide C4 was placed out of service from 25 May 2021 until approximately 1 May 2023. It remained offline as at the date of the hearing, although that was said to be a result of separate, unrelated incidents.

6 Though the contraventions appear, at first blush, to be minor technical breaches, they were, in fact, very serious. In broad terms, they arose as a result of a substantive failure of major infrastructure to operate within the Callide C4 unit. The consequences included the destruction of valuable equipment, the potential for loss of life, loss of power to the grid, and significant, long-term and wide-ranging impacts on the National Electricity Market (the NEM).

7 Whilst, in the determination of the appropriate relief to be granted, including the quantum of any penalty, the Court is to exercise its own discretion, a degree of weight should be accorded to the position taken by the AER in respect of those matters. In particular, where a civil penalty is proposed by consent, a measure of deference can properly be accorded to the opinion of the regulator, which can be taken to have a unique understanding of, and expertise in, the area of business activity that it is responsible for monitoring: see Clean Energy Regulator v E Connect Solar & Electrical Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1082 [2] (E Connect Solar).

8 For the reasons that follow, it is appropriate to make the declarations proposed by the parties, and to impose on CPT a civil penalty in the amount of $9,000,000, that being an amount to which the parties have also agreed.

The statutory context

9 It is useful to commence with a brief consideration of the statutory context to the contravening conduct that occurred in this case.

10 The AER is a body corporate established under s 44AE of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA). It has the functions and powers referred to in s 15 of the National Energy Law (the NEL), which is set out in a Schedule to the National Electricity (South Australia) Act 1996 (SA), and applies as a law of Queensland (with certain modifications) as the National Electricity (Queensland) Law pursuant to s 6 of the Electricity—National Scheme (Queensland) Act 1997 (Qld).

11 Section 44AAG of the CCA empowers the Court, on the application of the AER, to make orders declaring that a person is in breach of a “State/Territory energy law”, as that term is defined in s 4 of the CCA. A State energy law includes both the NEL and the NER, the latter of which has the force of law by reason of s 9 of the NEL. If such a declaration is made, the Court may also order, amongst other things, that the person pay a civil penalty determined in accordance with the law.

12 Certain provisions of the NER are prescribed as being civil penalty provisions. For present purposes, it suffices to note that r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER are each civil penalty provisions: see s 2AA(1)(c) of the NEL and reg 6(1) of, and Sch 1 to, the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations (SA).

Key aspects of the NEL and the NER

13 The following consideration of the key aspects of the NEL and the NER, including CPT’s obligations under r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER, is taken from the parties’ careful and considered submissions.

14 The “national electricity objective” is set out in s 7 of the NEL. At the relevant time, it provided that the objective of the NEL is to:

… promote efficient investment in, and efficient operation and use of, electricity services for the long term interests of consumers of electricity with respect to—

(a) price, quality, safety, reliability and security of supply of electricity; and

(b) the reliability, safety and security of the national electricity system.

Chapter 4 of the NER

15 Rule 4.15 is contained within Ch 4 of the NER, which is headed, “Power System Security”. Among other things, Ch 4 provides the framework for achieving and maintaining a secure power system: cl 4.1.1(a)(1): and has aims to, amongst other things:

(a) detail the principles and guidelines for achieving and maintaining power system security; and

(b) establish processes to enable AEMO to plan and conduct operations within the power system to achieve and maintain power system security.

See cll 4.1.1(a)(3)(i) and (iii).

16 Chapter 4 deals with the acceptance of, and compliance with, performance standards: see rr 4.14 and 4.15. Critically to this proceeding, r 4.15(a)(1) provides:

4.15 Compliance with Performance Standards

(a) A Registered Participant must:

(1) ensure that its plant meets or exceeds the performance standard applicable to its plant; and

…

17 Registered Participant is defined (with certain exclusions or extensions) as a person who is registered by AEMO in any one or more of the categories listed in rr 2.2 to 2.7 of the NER. Relevantly, this includes a Generator: see r 2.2.

18 Chapter 10 provides a series of contextual definitions of plant, of which the following definition is applicable:

In relation to a connection point, [plant] includes all equipment involved in generating, utilising or transmitting electrical energy.

19 As for the definition of performance standard, Ch 10 provides the following:

A standard of performance that:

(a) is established as a result of it being taken to be an applicable performance standard in accordance with clause 5.3.4A(i); or

(b) is included in the register of performance standards established and maintained by AEMO under rule 4.14(n),

as the case may be.

20 Relevantly, r 4.14(n) provides that AEMO must establish and maintain a register of the performance standards applicable to plant as advised by Registered Participants in accordance with cl 5.3.7(g)(1), cl 5.3.9(h) or established in accordance with r 4.14.

21 In simple terms, the performance standards dealt with by rr 4.14 and 4.15 apply to certain Registered Participants and are designed to maintain power system security. As the parties submitted, compliance with generator performance standards is critical to the safe and secure operation of the power system.

22 A contravention of r 4.15(a) will be made out if it is established that a Registered Participant has failed to ensure that its plant either meets or exceeds the performance standard that is applicable to that plant.

Chapter 5 of the NER

23 The second relevant provision to this proceeding, being cl 5.2.5 of the NER, is located within Ch 5 which is headed, “Network Connection Access, Planning and Expansion”. Most relevantly:

(a) Pt B of Ch 5 (rr 5.2 to 5.5) deals with network connection and access;

(b) Sch 5.2 deals with conditions for connection for Generators; and

(c) cl 5.2.5 concerns a Generator’s obligation to comply with performance standards applicable to facilities.

24 Part B of Ch 5 has a number of aims set out in cl 5.1A.1(a)(2), including:

(iv) to establish processes to ensure ongoing compliance with the technical requirements of this Part B to facilitate management of the national grid.

25 Clause 5.1A.2 then sets out the following principles relating to connection to the national grid (with emphasis added in bold):

…

(a) all Registered Participants should have the opportunity to form a connection to a network and have access to the network services provided by the networks forming part of the national grid;

(b) the terms and conditions on which connection to a network and provision of network service is to be granted are to be set out in commercial agreements on reasonable terms entered into between a Network Service Provider and other Registered Participants;

(c) the technical terms and conditions of connection agreements regarding standards of performance must be established at levels at or above the minimum access standards set out in schedules 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 5.3a, with the objective of ensuring that the power system operates securely and reliably and in accordance with the system standards set out in schedule 5.1a; [Note: In version 21 of the NER, which applied at the date of the Callide Standards, an equivalent provision was found at cl 5.1.3(c).]

(d) [Deleted]

(e) the operation of the Rules should result in the achievement of:

(1) long term benefits to Registered Participants in terms of cost and reliability of the national grid; and

(2) open communication and information flows relating to connections between Registered Participants themselves, and between Registered Participants and AEMO, while ensuring the security of confidential information belonging to competitors in the market.

26 A Generator’s connection agreement must include the applicable performance standards: see cll 5.3.7(b), (g). A performance standard may be one of three types: a minimum access standard, an automatic access standard, or a negotiated access standard. When construing the performance standards, the concept of good electricity industry practice is relevant.

27 Most relevantly, by cl 5.2.5(a)(1), a Generator (as distinct from a Registered Participant) must ensure compliance with performance standards in the following manner:

(a) A Generator must plan and design its facilities and ensure that they are operated to comply with:

(1) the performance standards applicable to those facilities;

…

28 A Generator is defined as a person who engages in the activity of owning, controlling or operating a generating system that is connected to, or who otherwise supplies electricity to, a transmission system or distribution system and who is registered by AEMO as a Generator under Ch 2.

29 Properly construed, cl 5.2.5(a)(1) imposes two distinct obligations upon a Generator: first, to “plan and design” its facilities to comply with the applicable performance standards; secondly, to “ensure” that the facilities are “operated” to comply with those performance standards.

30 The term, facilities, is defined as follows:

A generic term associated with the apparatus, equipment, buildings and necessary associated supporting resources provided at, typically:

(a) a power station or generating unit;

(b) a substation or power station switchyard;

(c) a control centre (being a AEMO control centre, or a distribution or transmission network control centre);

(d) facilities providing an exit service.

31 On the facts of this matter, the terms facilities (as used in cl 5.2.5(a)(1)) and plant (as used in r 4.15(a)(1)) are substantially interchangeable.

Elements of r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1)

32 To establish a contravention of r 4.15(a)(1) by CPT, it must be established that:

(a) CPT is a Registered Participant; and

(b) CPT’s plant did not meet or exceed a performance standard that applied to that plant.

33 To establish that CPT contravened cl 5.2.5(a)(1), it must be proven that:

(a) CPT is a Generator; and

(b) either:

(i) CPT failed to plan and design its facilities to comply with an applicable performance standard; or

(ii) CPT failed to ensure that its facilities were operated to comply with an applicable performance standard.

34 There is clearly some significant overlap between each of r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1). In each case, the critical issue is whether the relevant performance standard has been complied with. Depending on the circumstances, it may be that one or all of the separate obligations under r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) are breached in connection with any given event.

The agreed facts

35 The following facts are taken from the joint statement of agreed facts and admissions.

The ownership and management of the Callide C Power Station

36 As mentioned above, CPT does not own or operate the Callide C Power Station. At all relevant times, both:

(a) the shares in CPT; and

(b) the Callide C Power Station itself,

were owned 50-50 by Callide Energy Pty Ltd (CEPL) and IG Power (Callide) Ltd (administrators appointed) (IGPC) under a joint venture structure (the Callide Joint Venture).

37 The ultimate owner of CEPL is CSEL, and the ultimate holding company of IGPC is OzGen (UK) Limited.

38 The Callide Joint Venture was established under a Joint Venture Agreement dated 11 May 1998 (as subsequently amended) between CEPL and IGPC as “Participants” on the one hand, and Callide Power Management Pty Ltd (CPM) as the “Manager” on the other.

39 Under a “Management Agreement” and the “Shareholder Agreement” in respect of CPM, the Callide Joint Venture appointed CPM as the manager of the Callide C4 generating unit.

40 CPM, as agent for CEPL and IGPC, separately appointed CSEL to act as the operator of Callide C4 under an Operation and Maintenance Agreement dated 11 May 1998 (as subsequently amended) and a Station Services Agreement dated 11 May 1998 (as subsequently amended). As operator, CSEL is responsible for all necessary operation and maintenance of Callide C4.

41 Pursuant to two separate Market Trader Agreements dated 11 May 1998 (both as subsequently amended), which CPT executed respectively with IGPC and CEPL, CPT is responsible for trading electricity produced by the Callide C4 generating unit into the NEM.

42 Under a Deed of Service dated 17 January 2018, CSEL provides certain services to assist CPT to perform its obligations under the Market Trader Agreements and the NER, and to ensure services are provided in compliance with all aspects of the applicable performance standards and as required by the NER. The services provided by CSEL under the Deed of Service include, inter alia:

(a) developing, maintaining and implementing a Generator performance standards compliance program (as contemplated by r 4.15(b) of the NER);

(b) ensuring that the plant was operated to comply with the applicable performance standards;

(c) monitoring the plant and performing relevant testing, and taking action where possible to remedy any shortfalls; and

(d) notifying CPT of any breaches of the applicable performance standards and the program to remedy those breaches.

CPT’s obligations under the NER

43 At all relevant times CPT was registered as a Scheduled Generator and a Registered Participant under Ch 2 of the NER. Further, pursuant to cl 2.9.3 of the NER, it was an intermediary registered by AEMO as a Generator on behalf of the parties to the Callide Joint Venture — that is, CEPL and IGPC. The parties submitted that CPT was therefore regulated by the NER in two respects: as a Generator and as a Registered Participant.

44 There was some initial difficulty in ascertaining how it was that an entity such as CPT, which does not own, operate or control a generating system can be subject to compliance obligations in respect of it and exposed to civil penalties if it fails to meet the obligations. Following the hearing of this matter, the parties filed joint supplementary submissions addressing this issue.

45 The first plank of the submissions relied upon s 11(1) of the NEL, which provides:

A person must not engage in the activity of owning, controlling or operating, in this jurisdiction, a generating system connected to the interconnected national electricity system … unless:

(a) the person is a Registered participant in relation to that activity; or

(b) the person is the subject of a derogation that exempts the person, or is otherwise exempted by AEMO, from the requirement to be a Registered participant in relation to that activity under this Law and the Rules.

(Note omitted).

46 A similar requirement applies under the NER which provides by cl 2.2.1 that:

(a) Subject to clause 2.2.1(c), a person must not engage in the activity of owning, controlling or operating a generating system that is connected to a transmission system or distribution system unless that person is registered by AEMO as a Generator.

…

(c) AEMO may, in accordance with guidelines issued from time to time by AEMO, exempt a person or class of persons from the requirement to register as a Generator, subject to such conditions as AEMO deems appropriate, where (in AEMO’s opinion) an exemption is not inconsistent with the national electricity objective.

…

(Note omitted).

47 The parties agreed that CPT was, at all relevant times, a Registered Participant and a Scheduled Generator for the Callide C Power Station and an intermediary registered by AEMO as a Generator in respect of the parties to the Callide Joint Venture.

48 The parties’ supplementary submissions referenced cl 2.9.3(a) of the NER which permits a party (referred to as the “applicant”) who is required to be registered under the NEL or the NER as a Generator, to apply to be exempt from registration. By cl 2.9.3(b) of the NER, AEMO must allow that exemption if:

(a) the applicant notifies AEMO of the identity of a person (an intermediary) to be registered instead of the applicant;

(b) the applicant provides AEMO with the written consent of the intermediary to act as intermediary in a form reasonably acceptable to AEMO; and

(c) AEMO notifies the applicant that it approves of the intermediary.

49 By cl 2.9.3(c) of the NER, AEMO is required to approve an intermediary if the applicant for exemption establishes (to AEMO’s reasonable satisfaction) that, from a technical perspective, the intermediary can be treated for the purpose of the NER as the applicant with respect to the relevant generating system with which the applicant is associated.

50 In this case, the parties relied upon the following facts in support of CPT being an intermediary of the joint venturers who operate the Callide Power Station:

(a) Each of the parties to the Callide Joint Venture are owners of the Power Station (which was a generating system) such that they were required to be registered under s 11(1) of the NEL and cl 2.2.1 of the NER unless they were exempt;

(b) CPT is currently registered as a Generator in respect of the Callide C Power Station;

(c) Each of the joint venturers nominated CPT as their intermediary and were accordingly exempt from the requirement to register as a Generator; and

(d) The operator of the Power Station is CSEL. Pursuant to a deed between CSEL and CPT, CSEL provides services to assist CPT to perform its obligations under the NER and the Callide Standards.

51 The parties also relied upon the operation of cl 2.9.3(d) of the NER. Subsection (1) provides that if an exemption is granted by AEMO, then, “provided the intermediary satisfies all relevant registration requirements that the applicant would have been required to satisfy, AEMO must register the intermediary as a Registered Participant as if it were the applicant”. The effect was that the intermediary would be treated as if it were the applicant, including that all acts and omissions of the intermediary will be deemed to be the acts of and omissions of the applicant. In this respect, cl 2.9.3(d)(5) of the NER relevantly provides that the intermediary and the applicant will be jointly and severally liable for the acts and omissions of the intermediary in its capacity as a Registered Participant.

52 Clause 2.9.3 of the NER has been the subject of limited judicial consideration. In Origin Energy Limited v Commissioner of Taxation (No 2) [2020] FCA 409 [28] – [29], Thawley J observed the following:

28 A person required to be registered as a Generator in relation to a particular generating system may apply for exemption from registration as a Generator if that applicant notifies AEMO of another person who consents to act as “Intermediary” in relation to the generating system and AEMO, being satisfied that the Intermediary can be treated as the applicant for the purposes of the NER with respect to the relevant generating system, approves of that person to be registered as the Generator in relation to the generating system – see: cl 2.9 NER.

29 A person who is registered as an Intermediary can bid the sent out generation for the generating system. Subject to various exceptions (including that the applicant is jointly and severally liable for the acts, omissions, statements, representations and notices of the Intermediary as Registered Participant: cl 2.9.3(d)(5)), the Intermediary is treated as the applicant in relation to the generating units owned by the applicant – see: cl 2.9.3(d)(2) of the NER. It is sufficient to note for the purposes of the present matter that the Intermediary has, as a practical matter, the rights and obligations of the Generator applicant so far as concerns the operation of the NEM.

53 More recently, in Australian Energy Regulator v AGL Loy Yang Marketing Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 1299 [31], Button J made the following obiter comment:

… AGLL is registered as an intermediary on behalf of the AGL Loy Yang Partnership, which owns and operates the Loy Yang A power station. For the purposes of the NER, an intermediary is treated as the owner, operator and controller of the relevant generating unit: cl 2.9.3(d).

54 On the basis of the foregoing, the parties submitted that CPT (as the intermediary) became a Registered Participant instead of the joint venture parties given that it was registered in their stead, which thereby exempted them from registration. As such, they asserted that CPT is to be treated as the participant instead of the joint venture parties, with the consequence that it is to be treated as the parties in respect of the obligations imposed by the NEL and the NER.

55 In this latter respect the parties claimed that CPT is to be treated as having the obligations of the joint venturers in respect of their obligations under r 4.15(a)(1) of the NER in respect of “its plant” to meet or exceed the applicable standards. The reference to “its plant” is a reference to the plant of the participants for whom CPT is the intermediary. Similarly, under cl 5.2.5(a) of the NER, the obligation that a Generator must plan and design “its facilities” and ensure that they are operated to comply with the applicable performance standard, falls upon CPT as the intermediary, but in respect of the plant and facilities belonging to the joint venturers, namely the Callide C Power Station.

56 In this case, AEMO has accepted CPT as the intermediary of the joint venture parties and has registered it as a Registered Participant. On that basis, CPT has apparently acted as the Registered Participant and Generator (as intermediary). It can be presumed that AEMO has determined that CPT qualified to be accepted as the intermediary which should be registered for the joint venture parties in respect of their plant and which would be liable for any failure to meet the obligations imposed by the NEL or NER. Whilst it was not explained how it was that AEMO was reasonably satisfied that, “from a technical perspective”, CPT could be treated for the purposes of the NER as being the joint venture parties, where there is no evidence to the contrary, it is appropriate to presume that CPT’s registration as an intermediary was regularly made.

57 In such circumstances, albeit with more than a modicum of hesitation, it should be accepted that CPT qualifies as and is the intermediary of the joint venture parties for the purposes of the current application. On that basis, it is appropriately accepted as being liable “as” the owner, operator and controller of the relevant generating unit for the purposes of this proceeding.

Other relevant entities

58 Two other relevant entities to note are AEMO and Powerlink:

(a) AEMO is, and at all relevant times was, the independent market and system operator for the NEM, covering the interconnected power system in Australia’s eastern and south-eastern seaboard and Tasmania.

(b) Powerlink is the registered trading name of Queensland Electricity Transmission Corporation Ltd, a transmission network service provider which operates most of the high voltage electricity transmission network in Queensland, which is also connected to New South Wales via the Queensland-NSW Interconnector and the Terranora Interconnector. That transmission network comprises some 15,000 kilometres of transmission lines and associated substations (including the relevant substation at Calvale).

The relevant obligations

59 As mentioned, CPT has admitted to having contravened r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER, which broadly require it to ensure that its plant and facilities respectively (being those for which it is accorded responsibility), comply with the applicable performance standards.

60 At all relevant times from 29 August 2008 onwards, there was a document dated 29 August 2008 and titled, “Performance Standards for Callide Power Plant”, setting out performance standards which applied to the Callide C Power Station generating system, including Callide C4 (the Callide Standards).

61 The relevant obligation in the Callide Standards with which CPT failed to comply is set out in cl 3.6 of that document, and is extracted below:

3.6 Protection That Impacts on Power System Security (S5.2.5.9)

(Standard determined under Rules clause 4.16.5(c)(4)) Each generating unit has primary protection systems to disconnect from the power system any faulted element within the protection zones that include the connection point, the generating unit stator winding or any plant connected between them. To clear faults within these protection zones, the Generator’s protection system issues an intertrip signal to the Network Service Provider’s protection system within the following times to achieve the respective fault clearance times:

Plant | Intertrip time (ms) | Fault clearance time (ms) |

X generator transformer differential protection | 25 | 100 (Standard determined under Rules clause 4.17.3) |

Y overall differential protection | 35 | 110 (Standard determined under Rules clause 4.17.3) |

19.5 kV and 6.6 kV plant | as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements | as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements |

Each primary protection system has sufficient redundancy to ensure that a faulted element within its protection zone is disconnected from the power system within the applicable fault clearance time with any single protection element (including any communications facility upon which that protection system depends) out of service.

(Standard determined under Rules clause 4.16.5(c)(4)) Breaker fail protection systems for the 275 kV circuit breaker are provided by the Network Service Provider and do not depend on the Generator’s facilities. Breaker fail protection systems are provided to clear faults that are not cleared by the generator circuit breaker or the unit transformer 6.6 kV circuit breaker in sufficient time to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements.

62 In summary, cl 3.6 of the Callide Standards requires each generating unit to have a primary protection system that: first, disconnects the power system where there has been a faulted element within the protection zones that include the connection point, the generating unit stator winding or any plant connected between them; and, secondly, has sufficient redundancy to ensure disconnection, even if any single protection system is out of service.

63 The three specific protection systems in place for the Callide C4 unit are described in more detail below.

The Callide C Power Station and the connection point

64 Although the following part of the parties’ joint statement of agreed facts is lengthy, due to the level of technicality, it is appropriate to set it out verbatim. It should be noted that references to the “Callide C PS” are references to the Callide C Power Station, and that the annexures referred to therein have not been reproduced.

D THE CALLIDE C PS AND THE CONNECTION POINT

D1 The Callide C PS

20. Callide C PS is a coal-fired power station which generates electricity at Mount Murchison, Queensland. It comprises the Callide C3 generating unit and the Callide C4 generating unit, which share a common control room.

21. The Callide C4 generating unit relied on two key electrical systems: the alternating current (AC) system and the direct current (DC) system. The AC system powered key equipment required for the operation of the turbine generator, including the equipment that provides lubrication oil to the bearings, equipment that provides cooling for the unit and equipment that opens and closes valves. The DC system supplied the unit’s protection, control and monitoring systems, and supplies backup equipment, such as the emergency lubrication oil pumps.

22. The DC system was supplied by a battery charger and a battery. The battery charger was the primary source of supply to the DC system, with the battery providing redundancy should the battery charger cease to operate.

23. There was a third electrical system called Station. Station AC provided supply for plant common to unit C3 and C4, while Station DC primarily provided redundancy to both units. Station DC had its own battery charger and battery, while Station AC received its power from the units.

D2 The Callide C4 generating unit

24. Callide C4 is a synchronous generating unit at Callide C PS. On 25 May 2021 and at all relevant times, the infrastructure at Callide C4 was as set out in this Part D.

25. Key components of the infrastructure associated with Callide C4 and the adjoining Calvale substation (operated by Powerlink) are set out in a document titled “Callide C Power Station – 3 unit (4 unit similar) – 275kV grid connection – protection interface diagram” (annexed as Diagram A).

26. Generating unit: The Callide C4 generating unit was a coal-fired steam turbine, capable of generating up to 420MW of AC electricity at a voltage of 19.5kV. The generating unit is depicted on Diagram A by a G placed above a tilde, within a circle.

27. Auxiliary plant: The generating unit had various auxiliary plant, which operated on AC power at 6.6kV or 415V, and included mechanisms to support the safe operation, cooling and lubrication of the generating unit.

28. Circuit breakers:

(a) A circuit breaker is a mechanical switching device which, when operated, creates a physical break in an electrical circuit under normal current and fault-current conditions. Among other functions, where the current exceeds that which the circuit can safely carry, the circuit breaker is intended to break the flow of current in order to protect the circuit and associated plant.

(b) 19.5 kV “Generator” circuit breaker: The 19.5 kV circuit breaker is depicted just above the generating unit on Diagram A, and just below the generator transformer: see [29](c) below.

(c) 6.6 kV incomer circuit breakers: These circuit breakers are depicted as items 18 and 20 on the diagram titled “AC Auxiliary System – Electrical System Diagram for Full Load Operation (annexed as Diagram B).

(d) 275 kV circuit breakers: These circuit breakers are located at the Calvale substation, operated by Powerlink, and are depicted on Diagram A as items Q10 and Q30. If there was a fault at Callide C4, then both the Q10 and Q30 circuit breakers were intended to open in conjunction (depending on the fault type and location).

29. Transformers:

(a) A transformer is a device that transfers electric energy from one circuit to another, and either increases or decreases the voltage at which it is transmitted.

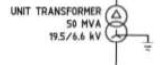

(b) A transformer between the generating unit and the auxiliary plant converted the AC power voltage down from 19.5kV to 6.6kV to supply that plant (unit transformer). This is depicted on Diagram A to the right of the generating unit.

(c) A further transformer between the generating unit and the connection point converted the AC power voltage up from 19.5kV to 275kV in order to connect to the power system (generator transformer). This is depicted on Diagram A above both the generating unit and the generator circuit breaker.

D3 DC power supply to Callide C4

30. The Callide C PS also had systems for controlling and monitoring the generating unit, and protection systems, which required 220V DC power.

31. Callide C4 could obtain DC power from the Callide C4 battery charger and battery, or from the shared Station battery charger and battery, which were used as a standby source of power. Each of the battery chargers required 415V AC power to maintain the charge of the batteries and output to the DC loads. If a battery charger were to fail, then DC power could be supplied temporarily from the battery, assuming that both were connected.

D4 The connection point

32. Connection point: The Callide C4 switchyard had a connection point, at which it connected and supplied electricity to the transmission network (via the Calvale substation) and the power system more generally, at a voltage of 275kV. As stated at [16] above, the Calvale substation is operated by Powerlink.

D5 The Callide C4 protection systems

33. On 25 May 2021 the Callide C4 generating unit had a number of protection systems.

34. Specifically, these included:

(a) the 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection systems;

(b) the X generator transformer differential protection system; and

(c) the Y overall differential protection system,

where (b) and (c) together are the X and Y Differential Protection Systems, and (a), (b) and (c) together are the Callide C4 protection systems.

35. The Callide C4 protection systems had concurrent operation across three “protection zones”. The protection zones included the:

(a) generator;

(b) generator transformer;

(c) Phase Isolated Bus (PIB);

(d) unit auxiliary transformer; and

(e) excitation transformer.

36. The boundary of the zones were:

(a) the generator transformer 275kV terminals;

(b) the unit auxiliary transformer 6.6kV terminals; and

(c) the excitation transformer LV terminals.

37. The X and Y Differential Protection Systems protected all devices inside the protection zones.

38. The 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection systems:

(a) The 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection systems protected specific plant, including the generating unit (which operates at 19.5kV), and provided protection from events such as loss of excitation and reverse power. Such events can cause a generating unit to operate in an unstable fashion, threatening the secure and stable operation of the power system and with the potential for significant plant damage.

(b) The 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection systems are dealt with in the third row of the table in cl 3.6 of the Callide Standards.

39. The X and Y Differential Protection Systems:

(a) The X and Y Differential Protection Systems were designed to detect differential current flows throughout the protection zone, including as a result of short circuit faults. They are dealt with in the first and second rows of the table in cl 3.6 of the Callide Standards.

40. For the purposes of the Callide Standards:

(a) for each of the protection zones, the “elements within the protection zone” included the generating unit; and

(b) the “protection elements” of each of the protection systems, as that term is used in the Callide Standards, relevantly included the supply of DC power (in the sense that the protection systems could not function without it).

41. The applicable fault clearance times, as set out in the table in cl 3.6 of the Callide Standards, were as follows:

(a) for the 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection systems, “as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements”;

(b) for the X generator transformer differential protection system, 100 ms; and

(c) for the Y overall differential protection system, 110 ms.

The events of 25 May 2021

65 As mentioned, the present proceeding arises from the catastrophic events which occurred at the Callide C Power Station on 25 May 2021. It is appropriate to recite verbatim the parties’ agreed facts regarding the events which gave rise to the admitted contraventions.

E THE EVENT ON 25 MAY 2021

E1 The battery charger replacement project

42. On 25 May 2021, CS Energy, the operator of Callide C4, was engaged in the procedure of replacing the C4 battery charger. The replacement procedure had been completed without incident in relation to the C3 and Station battery chargers by that date. The previous day, in the course of that procedure, the operator had configured Callide C4 so that DC power was supplied (via an interconnector switch on its main 220V DC switchboard) by the Station battery charger and battery. The effect of this was to combine the Station and Callide C4 DC system into a single electrical system.

43. By 25 May 2021, the C4 battery charger had been replaced and was ready to be brought into service by being reconnected to the C4 DC system. This involved a preplanned sequence of steps called a “switching sequence”. The switching sequence involved:

(a) on 24 May 2021, connecting the battery charger to the existing C4 battery to bring it to a full state of charge overnight;

(b) on 25 May 2021, disconnecting the replacement battery charger from the existing battery;

(c) connecting the replacement battery charger to the C4 DC system;

(d) disconnecting the Station DC supply from the C4 DC system; and

(e) connecting the existing C4 battery to the C4 DC system.

44. The Callide C4 generating unit was not powered down while the switching sequence was undertaken. Rather, it continued generating at 278 MW.

45. By 13:32 on 25 May 2021, the first three steps of the switching sequence had been carried out successfully.

46. The events described in paragraphs [47] to [65] are referred to as the Event.

E2 The 13:33 faults

47. At about 13:33 on 25 May 2021, the operator switched Callide C4’s DC power supply (via an interconnector switch on its main 220V DC switchboard) from being connected to the Station battery and battery charger to being connected to the C4 battery charger. The C4 battery was not connected to the system before the switching sequence began, as the design of the DC system did not permit the C4 battery and Station battery to be connected to the same electrical system at the same time.

48. The DC system included a “trapped key interlock system” that prevented two batteries being connected to the same DC system. Accordingly, the C4 battery could not be connected to the C4 system prior to the disconnection of the Station DC supply.

49. Prior to the interconnector being opened, the Station battery charger and C4 battery charger had been operating in parallel. When operating in parallel, the battery chargers did not share load and operated independently. This meant that the charger with the highest output voltage, the Station battery charger, provided all the load, while the C4 battery charger voltage decayed to 120 volts. When the interconnector was opened to initiate the switching sequence, the C4 battery charger failed to respond quickly enough to maintain the necessary DC voltage. The DC voltage then rapidly decayed to ~0 volts. Because the C4 battery was not yet reconnected, it was not available as an alternative source of DC power supply.

50. There was a drop in the voltage of the DC power supplied to the control circuits of the 6.6kV incomer circuit breakers. The circuit breakers tripped, and there was a loss of AC power supply to the 6.6kV system. There was also a loss of DC power supply to the generating unit’s monitoring and control systems, and to the Callide C4 protection systems.

51. There was a loss of AC power supply to all 415V switchboards on Callide C4, including the 415V input supply to the C4 battery charger.

52. The C4 battery charger could not recover DC voltage and resume DC power supply.

53. There was a loss of AC power to the auxiliary plant, which ceased to function.

54. The Callide C4 generating unit lost steam, stopped generating and began motoring asynchronously. Relevantly:

(a) the C4 generating unit lost excitation – that is, the DC power supply used to ensure that the rotor and stator of the generating unit remain magnetically linked, ceased to function; and

(b) there was reverse power, where the C4 generating unit began motoring instead of generating – that is, it began to draw power into itself from the power system, rather than exporting power onto it.

(together, the 13:33 faults).

55. However, because there was no DC power supply, the Callide C4 protection systems failed to operate. Relevantly, at about 13:33, despite the events referred to in [54] above, the Callide C4 protection systems failed to cause the generator circuit breaker to disconnect the Callide C4 generating unit from the power system, as they should have done.

56. As a result of the matters in [47] to [55] above, the Callide C4 generating unit was operated asynchronously and without cooling, lubrication, protection or monitoring systems for an extended period of time, which ultimately led to critical short circuit faults and its catastrophic failure and destruction.

57. At 13:40, the operator informed AEMO of a possible fire at Callide C4.

58. At 13:44, the Callide C3 generating unit tripped from 417 MW and the operator contacted AEMO to confirm there was a fire in the Callide C turbine hall.

59. Between 13:49 and 14:04, CS Energy evacuated the Callide C PS, in light of risks to the personal safety of the operating staff.

60. Relevantly, in the period up to 14:06:

(a) Supervisory and Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) data from Calvale substation indicated that Callide C4 was absorbing MW and MVAr, but the SCADA data from Callide C indicated that Callide C4 was still generating at approximately 278 MW. The operator's staff believed (incorrectly) that the generating unit had tripped and was offline;

(b) AEMO had multiple conversations with the operator and Powerlink staff respectively, seeking to confirm the status of Callide C4, and whether Powerlink should open the circuit breakers at Calvale substation in order to disconnect Callide C4;

(c) AEMO and Powerlink were not aware that Callide C4 was operating without DC and AC power supplies;

(d) The operator, Powerlink and AEMO were not aware that the Callide C4 protection systems were not operating; and

(e) The operator was still attempting to determine the situation and status of the Callide C4 generating unit – these attempts were impeded by the loss of certain operator systems as a result of the loss of DC power, and the inability to physically check on the generating unit.

E3 The 14:06 faults

61. At 14:06, the excessive wear caused by the operation of the generating unit in the manner described above caused the rotor to catch on the casing. This impact caused the rotor shaft to tear apart at nine locations. A piece weighing more than two tonnes was thrown five metres across the floor of the turbine hall. The force of the impact also caused remnants of coupling covers, bearings and sections of the shaft to be ejected.

62. After this occurred, the C4 generating unit was still connected to the grid for approximately 40 seconds. During that time, large electrical arcs started to form, vaporising the copper conductors, and causing the generating unit to draw 300 MW and over 1,400 MVars from the grid.

63. At 14:06, among other things, as a result of that electrical arcing, at Callide C4 there was:

(a) a two-phase short circuit fault at the generating unit;

(b) a three-phase short circuit fault at the generator stator; and

(c) a single phase-to-ground short circuit fault, followed by a double phase-to-ground short circuit fault, both within the 275kV system

(together, the 14:06 faults),

where each of the generating unit, generator stator and the 275kV system were elements within the protection zones of the Callide C4 protection systems.

64. However, because there was no DC power supply, the Callide C4 protection systems failed to operate. At about 14:06, the Callide C4 protection systems failed to disconnect the generating unit (and the 275kV plant, in respect of faults referred to in [63](c) above) from the power system in response to the short circuit faults referred to in [63] above, as they should have done.

65. Rather:

(a) all lines out of the Calvale 275kV substation tripped at the remote ends only; and

(b) Callide C4 disconnected from the power system only when the entire Calvale 275kV substation was disconnected, thus clearing the sustained fault.

66. By this stage, the Callide C4 generator and generator transformer had been destroyed. The operator’s remaining staff on-site were then evacuated.

E4 Non-operation of the Automatic Changeover Switch

67. By way of additional context, on the day of the Event, an Automatic Changeover Switch (ACS), which was designed to transfer some DC systems automatically to the standby supply of DC power (i.e., the Station battery) upon a loss of the preferred supply (in this case, the C4 battery charger) of DC power, was available for manual operation but was not operated.

68. The ACS did not operate automatically as it had been rendered inoperable in automatic mode due to damage sustained in a dual unit trip incident in January 2021.

69. However, even if the ACS had operated, it may have only partially restored DC supply and not AC supply. This would not have prevented the significant damage caused by the loss of supply to the lubrication and cooling systems. However, on the restoration of DC supply, it is likely that the Y generator protection system (i.e. part of the 19.5kV plant protection system) would have responded and disconnected the C4 generating unit from the grid.

E5 Prior risk assessment

70. The operator had carried out an Operations Plant Risk Assessment on 18 January 2018 in respect of the replacement of the battery charger. However, that assessment examined only the risks associated with not replacing the Callide C4 battery charger, and did not assess the risks of carrying out the replacement itself.

E6 Compliance prior to the Event and the Deed of Service

71. As described in Part B2 above, CPT does not own or operate Callide C PS. At all relevant times, CPT traded electricity produced by the Callide C4 generating unit into the NEM, pursuant to two separate Market Trader Agreements between it and each of the JV Parties. CPT had no direct involvement in the operation of the Callide C PS at the time of the Event. The Callide Joint Venture appointed CPM as the manager of the Callide C4 generating unit and CPM, as agent for the JV Parties, separately appointed CS Energy as operator of Callide C4.

72. CPT was the Registered Participant with regulatory responsibility for compliance with r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1). Pursuant to a Deed of Service between CPT and CS Energy, CPT required CS Energy to undertake various steps (described in paragraph 14 above), designed to ensure the plant operated in compliance with the Callide Standards. In the present case, those steps were not sufficient to avoid the admitted contraventions.

66 CPT has admitted that it contravened r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER in the above circumstances. The precise manner in which those contraventions occurred is set out in the declarations proposed by the parties (which are discussed further below). However, in broad terms, the plant and facilities did not comply with, meet or exceed cl 3.6 of the Callide Standards on 25 May 2021, by reason of the failure of the Callide C4 protection systems to disconnect the faulted elements from the power system during the battery charger replacement.

The impact of the Event

67 The Event led to the catastrophic failure and destruction of the Callide C4 generating unit, requiring the evacuation of all staff. As mentioned, this resulted in Callide C4 being out of service from 25 May 2021 until approximately 1 May 2023.

68 Aside from the impact on Callide C4 itself, the Event also had various impacts on the NEM, energy consumers and spot prices. The joint statement of agreed facts detailed those impacts as follows:

G2 Impact on the NEM and on energy consumers

79. The Callide C4 generating unit’s prolonged period of asynchronous operation (and the resulting short circuit faults) was followed by:

(a) its absorption of a large amount of reactive power (at its highest, 1,417 MVAr) for at least 30 minutes;

(b) the 14:06 faults;

(c) widespread under-voltages and over-voltages on the NEM in Central Queensland;

(d) the tripping of nine major generating units;

(e) a drop in system frequency;

(f) the loss of 3,045 MW in generation – in context, this was almost one fifth of the installed generation capacity in the entire Queensland region of the NEM (approximately 17 GW);

(g) as a result of that loss of generation, customer load shedding of approximately 2,300 MW, disconnecting customers in Queensland and northern New South Wales (where Queensland regional operational demand prior to the Event was approximately 5,310 MW); and

(h) the tripping of major transmission lines, including the synchronous separation of Queensland from the rest of the NEM.

80. In relation to the impact of the load shedding on consumers, some 488,501 customers were disconnected.

G3 Activation of the RERT

81. Further, the chain of events set out at [79] posed a risk to the stability of the power system and led to AEMO declaring a forecast Lack of Reserve 2 (LOR2) condition at 15:02. A LOR2 condition exists where reserve levels are lower than the single largest supply resource in a state. Once a forecast LOR2 is declared, AEMO has the power to activate the Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader (RERT) mechanism to improve the supply demand balance. At 16:13, AEMO advised the market of its intention to commence RERT contract negotiations for the period from 17:30 to 20:00.

82. RERT is an intervention mechanism under the NER that allows AEMO to contract for emergency reserves, such as generation or demand response, that are not otherwise available in the market. AEMO uses RERT as a safety net in the event that a critical shortfall in reserves is forecast. RERT is activated when all market options have been exhausted, typically during periods when the supply demand balance is tight.

83. The total cost to market participants of the exercise of AEMO’s RERT functions was $461,018, which includes pre-activation costs ($103,000), activation costs ($332,699), and intervention costs ($25,319).

G4 Impact on spot prices

84. Following the events on 25 May 2021, the spot price for electricity in Queensland ranged between $5,124/MWh and $15,000/MWh for the 4.30 pm to 5.30 pm trading intervals, and between $2,542/MWh and $6,848/MWh in New South Wales for the 5 pm to 5.30 pm trading intervals. This is in contrast to the 12 hour forecast spot prices for these periods, which were between $169/MWh and $425/MWh in Queensland and $43/MWh - $69/MWh in New South Wales.

69 The statement of agreed facts also sets out the steps taken since the date of the Event, and the size and financial position of CPT and its related entities. These matters are considered where relevant.

70 Before turning to the relief sought by the AER, it is important to note that CPT denies, and the AER no longer presses, the balance of allegations made in its concise statement. For the avoidance of doubt, this includes the allegation that CPT failed to comply with cl 3.7 of the Callide Standards concerning asynchronous operation. Further, it was agreed that the contraventions were not deliberate, and that CPT did not obtain any benefit from them.

The declarations sought

71 The AER seeks two declarations, each relating to a contravention of a particular clause of the NER. CPT agrees to the making of the declarations in the terms proposed. The first provides as follows:

1. [T]he respondent contravened r 4.15(a)(1) of the National Electricity Rules (NER) by failing to ensure that the Callide C4 generating unit met or exceeded cl 3.6 of the applicable performance standards dated 29 August 2008 (performance standards), in that, on 25 May 2021:

(a) the protection systems for the Callide C4 generating unit (Callide C4 protection systems) included:

(i) the 19.5kV and 6.6kV plant protection system;

(ii) the X generator transformer differential protection system; and

(iii) the Y overall differential protection system;

(b) the operator of Callide C4 undertook a planned battery charger replacement procedure at Callide C Power Station, during the course of which:

(i) it continued to operate the generating unit throughout;

(ii) it disconnected the C4 battery charger and battery; and

(iii) the generating unit obtained its DC power supply from the Station battery charger and battery;

(c) at approximately 13:33, in the course of that battery charger replacement procedure:

(i) the Callide C4 battery charger was reconnected;

(ii) the Station battery charger and battery were disconnected;

(iii) the new Callide C4 battery charger failed to respond quickly enough to maintain the required DC voltage as intended; and

(iv) where the C4 battery had not yet been reconnected, the DC power supply to the Callide C4 protection systems went out of service;

(d) subsequently:

(i) immediately after the events referred to in (c), an element within the protection zones of the Callide C4 protection systems, namely the generating unit, experienced faults when it (among other things) (1) lost excitation; and (2) experienced a reverse power flow, where the generating unit began motoring asynchronously instead of generating; and

(ii) at approximately 14:06, among other things, at Callide C4 there was (1) a two-phase short circuit fault at the generating unit; (2) a three-phase short circuit fault at the generator stator; and (3) a single phase-to-ground short circuit fault, followed by a double phase-to-ground short circuit fault, both within the 275kV system, each being elements within the protection zones of the Callide C4 protection systems;

(e) because the Callide C4 battery was disconnected, the Callide C4 protection systems, a purpose of which was to operate in respect of such faults:

(i) lacked an alternative (redundant) DC power supply (DC power supply redundancy); and

(ii) did not have sufficient redundancy to ensure that the faulted elements were disconnected from the power system within the applicable fault clearance times, as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements; and

(f) in the circumstances, the Callide C4 protection systems failed to disconnect the faulted elements from the power system.

(Emphasis in original).

72 The second proposed declaration is in the following terms:

2. [T]he respondent contravened cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER by failing to ensure that the Callide C4 generating unit was planned, designed and operated to comply with cl 3.6 of the performance standards in that, on 25 May 2021:

(a) in the circumstances set out in paragraph 1 above; and

(b) because the Callide C4 protection systems lacked DC power supply redundancy (as an incident of their planning and design, and their mode of operation on 25 May 2021),

the Callide C4 protection systems did not have sufficient redundancy to ensure that the faulted elements were disconnected from the power system within the applicable fault clearance times, as necessary to prevent plant damage and meet stability requirements.

73 The AER has established a contravention by CPT of both r 4.15(a)(1) and cl 5.2.5(a)(1) of the NER on 25 May 2021.

74 The relevant source of the Court’s power to make these declarations lies in s 44AAG(1) of the CCA. Section 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) is an alternative source of power.

75 Although CPT agrees to the making of the declarations, the Court must itself be satisfied that it is appropriate to make them.

76 The parties’ joint submission that the three prerequisites for the making of declarations have been met in this case should be accepted. They were explained in Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 CLR 421, 437 – 438 and Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564, 581 – 582. Their application in the present case can be summarised as follows:

(a) There is a real and not hypothetical question before the Court in relation to the contraventions of the NER. The proposed declarations relate to the contravening conduct and, as the foregoing reasons reveal, the matters in issue have been identified by the parties with precision.

(c) As the regulator responsible for the civil enforcement of the NER, the AER has an obvious interest in seeking the declarations in the discharge of its statutory functions. In particular, it is in the public interest for the AER to seek the declarations it does.

(d) CPT is a proper contradictor to the AER’s allegations. It, being the entity alleged to have contravened the NER, has an interest in opposing the making of the proposed declarations, notwithstanding its admissions and agreement: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commissioner v MSY Technology Pty Ltd (2012) 201 FCR 378, 387 [30] – [33].

77 No less importantly, the declarations are appropriate as they:

(a) serve to record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct;

(b) vindicate the AER’s claim that CPT contravened the NER, and will assist the AER (and the AEMO) to carry out the duties conferred upon them by the NER and the NEL;

(c) will deter other people (specifically other Generators and Registered Participants) from contravening the NER;

(d) will serve the public interest in defining the type of conduct that constitutes a contravention of the NER and, in particular, in highlighting the importance of compliance with performance standards; and

(e) will inform the public of the contravening conduct and the harm arising from it. This is particularly important in circumstances where the public was affected by the conduct in question.

See Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Axis International Management Pty Ltd (2009) 178 FCR 485, 495 – 496 [42] – [43]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 [78].

78 The observations of White J in Australian Energy Regulator v Pacific Hydro Clements Gap Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 733 also apply to this case. In particular, the declarations contain appropriate and adequate particulars as to how and why the conduct in question contravened the relevant provisions of the NER. They articulate, beyond doubt, the particular nature of the contraventions, which may serve an educative purpose in indicating to others involved in the generation of electricity how and why the contraventions occurred.

79 It follows that, given that the facts, to which the parties agreed and which the Court accepts for the purposes of this application, disclose that CPT engaged in the relevant breaches of the identified clauses of the NER, the declarations sought should be made in the form proposed by the parties.

The appropriate penalty

80 The AER seeks an order that CPT pay a civil penalty of $9,000,000 in respect of the contraventions. Before considering whether that order should be made, it is necessary to briefly address some preliminary matters of principle.

The significance of the penalty being agreed

81 In Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482 (Commonwealth v Fair Work), the High Court reaffirmed the practice of courts acting upon submissions as to an agreed penalty, as had been explained previously in Trade Practices Commission v Allied Mills Industries Pty Ltd (No 5) (1981) 60 FLR 38, NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Consumer and Competition Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] ATPR ¶41-993. The Court emphasised (at 503 – 504 [46]) that there is:

… an important public policy involved in promoting predictability of outcome in civil penalty proceedings and that the practice of receiving and, if appropriate, accepting agreed penalty submissions increases the predictability of outcome for regulators and wrongdoers. As was recognised in Allied Mills and authoritatively determined in NW Frozen Foods, such predictability of outcome encourages corporations to acknowledge contraventions, which, in turn, assists in avoiding lengthy and complex litigation and thus tends to free the courts to deal with other matters and to free investigating officers to turn to other areas of investigation that await their attention.

82 The plurality observed that, subject to the Court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and highly desirable in practice for the Court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty: Commonwealth v Fair Work at 507 [58]. Their Honours later considered (at 508 [60]) the value of the imprimatur of a specialist regulator when the parties before the Court submit an agreed penalty to be imposed, though the submissions will be considered on the merits in the usual manner.

83 As was observed recently in E Connect Solar (at [38]), these reasons do not contradict the fundamental proposition that the Court ultimately bears responsibility for the imposition of civil penalties. It must satisfy itself that, as a matter of law, its power to impose such penalties has been enlivened, and that the circumstances do properly warrant the imposition of the agreed penalty.

84 The principles were recently summarised and restated by the Full Court in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2021) 284 FCR 24, 44 – 45 [125] – [129] (Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft). Their application is now well entrenched in this Court: see, for example, Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Colonial First State Investments Limited [2021] FCA 1268 [73]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v General Commercial Group Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 24 [77]: and it is not necessary to recite them.

The centrality of the role of deterrence

85 It is undoubted, following Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson (2022) 274 CLR 450 (Pattinson), that the primary purpose of civil penalties is deterrence, both specific and general. That is, “to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene”: Commonwealth v Fair Work at 506 [55]. However, in seeking to ensure compliance, the penalty imposed should not be so great as to be oppressive, nor should it be so low as to be regarded by the contravener as an acceptable cost of doing business.

86 It has been said that any penalty should be “proportionate” and “appropriate” so as to strike a balance between oppressive severity and deterrence in the particular circumstances of the case: Pattinson at 467 – 468 [40] – [41], 470 [46].

Contraventions of multiple civil penalty provisions

87 Section 67 of the NEL addresses cases where a person’s conduct is in breach of more than one civil penalty provision. It provides the following:

(1) If the conduct of a person constitutes a breach of 2 or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted under this Law against the person in relation to the breach of any one or more of those provisions.

(2) However, the person is not liable to more than one civil penalty under this Law in respect of the same conduct.

(Note omitted).

88 In this case, the two contraventions admitted by CPT arise from the same facts. The Court can be satisfied, and the parties have agreed, that the two contraventions are in respect of the “same conduct” for the purposes of s 67.

Relevant factors in determining penalty

89 Section 64 of the NEL provides that the civil penalty must be determined having regard to “all relevant matters”. It identifies an inclusive list of factors that the Court must take into account in determining the penalty, which relevantly includes: the nature and extent of the breach, the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the breach, the circumstances in which the breach took place, whether the wrongdoer has engaged in any prior similar conduct, and whether the wrongdoer had pre-existing compliance programs approved by the AER or required under the NER, and whether it was complying with those programs.

90 These factors overlap to some extent with the factors set out by French J in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Limited [1991] ATPR ¶41-076, 52,152 – 52,153 (and quoted with approval in Pattinson at 460 [18]), which also provide a guide as to matters that the Court may take into account.

The factors in this case

The maximum available penalty

91 Relevant to the assessment of the appropriate penalty is the maximum penalty prescribed by the legislature for a contravention of the statutory provision in question: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Lactalis Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2023] FCA 839 [8].

92 At the relevant time, r 4.15(a) and cl 5.2.5(a) were each “tier 1 civil penalty provisions”, prescribed for the purposes of s 2AB(1)(c) of the NEL: see reg 6(2) of, and Pt 1 of Sch 1 to, the National Electricity (South Australia) Regulations (SA). As a result, the maximum penalty available on the basis of the agreed facts is $10,000,000.

The circumstances in which the contraventions took place

93 The Event is set out in detail above. Further to the matters set out there, the failure of Callide C4’s protection systems occurred in a context where the relevant ACS (automatic changeover switch) was inoperable in automatic mode.

94 That ACS was damaged in January 2021 and had not been fixed by the time of the Event in May 2021. CSEL was aware of this at the time of the Event. If the ACS was operational, though it still would not have provided the necessary DC power supply redundancy, the impact of the failure of the C4 battery charger may have been mitigated. In substance, while Callide C4 may not have been disconnected before the plant was damaged (contrary to what is required by cl 3.6 of the Callide Standards), the generating unit might have ceased motoring much earlier, avoiding the greater destruction of the generating unit and the broader power system consequences which followed at 14:06 on 25 May 2021.

95 As the parties jointly submitted, being aware of the absence of DC power supply redundancy during the battery charger replacement procedure, and of the additional risk where the ACS was not functioning, the appropriate step would have been to take Callide C4 offline whilst the battery charger replacement procedure was undertaken.

The nature and extent of the contraventions

96 The relevant provisions that have been contravened by CPT each relate to compliance with generator performance standards. As was submitted by the parties, there are a number of reasons as to why the contraventions should be regarded as “very serious”.

97 First, the provisions are designated as tier 1 civil penalty provisions. As mentioned, generator performance standards are directed to matters which may impact fundamentally on the stability and security of the power system. Indeed, compliance with the standards is critical to the safe and secure operation of the power system.

98 Secondly, there is the potential for catastrophic consequences arising from contraventions of the relevant provisions. Indeed, the explosions and fire which occurred in the Callide C turbine hall caused extensive damage and could have resulted in significant personal injuries.

99 Finally, the seriousness of the contraventions is heightened by the circumstances surrounding the conduct referred to above — in particular, the fact that CSEL was aware of the inoperable ACS, and should have been aware of the increased risk of carrying out the changeover while Callide C4 remained online.

100 These matters weigh in favour of imposing on CPT a penalty that is at the higher end of the permissible range.

The nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the contraventions

101 An exacerbating factor is that the contraventions not only had significant impacts on the operation of Callide C4, but also on the NEM. The parties’ submissions identified that the impacts were the precise kind that the protection systems were designed to avoid. Though they are identified in detail above, in summary, they included:

(a) the loss of service of Callide C4 for some two years;

(b) the tripping of nine major generating units;

(c) the loss of almost one fifth of the installed generation capacity in the entire Queensland region of the NEM;

(d) as a result of this loss of generation, customer load shedding which disconnected customers in both Queensland and northern New South Wales (affecting more than 488,000 customers on 25 May 2021 alone);

(e) the tripping of major transmission lines, including the synchronous separation of Queensland from the rest of the NEM;

(f) causing AEMO to activate the RERT at the expense of approximately $461,000 to market participants; and

(g) significant increases to the spot price for electricity in Queensland and New South Wales for the 4:30 pm to 5:30 pm trading intervals, in comparison to the forecast prices.

102 These are matters which should substantially increase the amount of the appropriate penalty.

Whether CPT has engaged in similar conduct in the past

103 A mitigating factor is that CPT has not engaged in any similar conduct in the past. It has not previously been found to have breached any provisions of the NEL, the NER, or the Regulations in respect of that conduct. However, prior good character ought not be given significant weight where, as here, general deterrence is an important consideration.

Whether CPT had in place, and was complying with, a compliance program

104 As a Registered Participant, CPT was required to institute and maintain a compliance program in respect of the Callide Standards. Pursuant to a Deed of Service between CPT and CSEL, CPT required CSEL to undertake various steps designed to ensure the plant operated in compliance with the Callide Standards. CS Energy had a compliance program in place in respect of Callide C, and CPT had its own internal compliance framework to ensure that CSEL maintained such a program.

105 Despite this, the program was not sufficient to avoid the admitted contraventions and, crucially, failed to identify any risk that the plant did not comply with the Callide Standards.

The size and financial position of CPT and its related entities