FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Commissioner of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission v Valmar Support Services Ltd [2025] FCA 11

ORDERS

NSD 1293 of 2023 | ||

COMMISSIONER OF THE NDIS QUALITY AND SAFEGUARDS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | VALMAR SUPPORT SERVICES LTD (ACN 060 125 340) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. By failing to ensure that each worker listed in schedule “A” to these orders had the necessary qualifications, training, and/or competence to provide mealtime supports to each of Mr H, Mr K and Mr I (each a “participant” known to the respondent (Valmar) to be at risk of choking) in the period from 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2020 (Relevant Period), Valmar contravened:

(a) sections 73J and 73V of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth) because Valmar failed to comply with s 6(1)(c) of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Code of Conduct) Rules 2018 (Cth) in that, it did not provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill, because it failed to ensure that the support worker, who provided mealtime supports to each participant, had been trained as to:

(i) what food and drink to offer each participant, each being a person with a disability that made them susceptible to being at risk of choking and each being a participant with specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar;

(ii) how the food and drink should be prepared for, and provided to, each participant, including the size of the pieces and texture of the food; and

(iii) how to support each participant in consuming that food and drink.

(b) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 10 of Sch 1 of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Provider Registration and Practice Standards) Rules 2018 (Cth) in that it failed to manage the risk that each participant may choke on the food or drink provided by the support worker;

(c) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 15 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to ensure that each participants’ support needs as to:

(i) what food and drink each participant could consume as a person with a disability that made them susceptible to being at risk of choking and each being a participant with specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar;

(ii) how that food and drink was prepared and provided to each participant for consumption including their specific requirements known to Valmar as to size of the pieces and texture of the food; and

(iii) support during the process of consuming food and drink in the event that they experienced a choking event,

were met by workers who are competent in their role, hold relevant qualifications, and have relevant expertise and experience to provide that person centred support;

(d) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 21 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to provide each participant with competent and appropriate supports to meet their needs, where appropriate supports included:

(i) what food and drink each participant could consume as a person with a disability that made them susceptible to being at risk of choking, including each participant’s specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar;

(ii) how that food and drink was prepared and provided to each of them for consumption, including their specific requirements known to Valmar as to size of the pieces and texture of the food; and

(iii) support during the process of consuming food and drink in the event that they experienced a choking event.

2. By failing to supervise the support workers who provided mealtime supports to Mr H, Mr K and Mr I to ensure that those support workers complied with each participant’s specific requirements for eating and drinking (which, for Mr H and Mr K, were recorded in their dietitian plans which incorporated their eating and drinking plans, and, for Mr I, was recorded in his dietitian plan which incorporated his mealtime management plan) and/or failing to audit compliance by those support workers with participant’s specific requirements for eating and drinking in the Relevant Period, Valmar contravened:

(a) sections 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, in that, it did not provide mealtime supports and services in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill because it did not ensure that support workers who provided mealtime supports complied with each participant’s specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar; and

(b) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 10 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to manage the risk that each participant may choke on the food or drink provided by the support worker.

3. By failing at all times in the Relevant Period to engage a speech pathologist to review Mr H’s swallowing, as had been recommended by his qualified dietitian, Ms Curlewis on 9 March 2017, and again on 30 June 2017, following her professional observation that Mr H was having difficulty with fluids, Valmar contravened:

(a) sections 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, in that, it did not provide supports and services to Mr H in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill because it did not take the necessary steps for it to know (and therefore did not know) if Mr H’s specific requirements for fluids had changed and if those requirements had changed, how they had changed, and what it was required to do to ensure that the fluids it provided to Mr H were safe for him to consume;

(b) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 10 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to manage the risk that Mr H could choke while swallowing fluids provided by Valmar; and

(c) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 21 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to provide Mr H with competent and appropriate supports to meet his needs where those appropriate supports included engaging a speech pathologist to understand if Mr H’s specific requirements for supports in swallowing fluids had changed and if so, how they had changed.

4. By failing at all times in the Relevant Period to engage a new dietitian for each of Mr H, Mr K and Mr I, (having terminated the services of the previous dietitian on 11 September 2018), Valmar contravened:

(a) sections 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, in that, it did not provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill, because it did not take the necessary steps for it to know (and therefore it did not know) if each participant’s specific requirements for eating and drinking had changed and if those requirements had changed, how they had changed, and what it was required to do to ensure that the food and drink it provided to each participant was safe for that participant to consume;

(b) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 10 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to manage the risk that each participant may choke on the food or drink provided by Valmar; and

(c) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 21 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to provide each participant with competent and appropriate supports to meet their needs, where those appropriate supports included ensuring that Mr H’s and Mr K’s dietitian plans (which incorporated their eating and drinking plans) and Mr I’s dietitian plan (which incorporated his mealtime management plan) were up to date so that it knew whether each participant’s eating and drinking requirements had changed and if so, how they had changed.

5. By notating Mr K’s eating and drinking plan dated 1 July 2017 with the words “Plan remains current. Feb 2020”, when that was not correct, Valmar contravened s 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 12 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to ensure that Mr K’s information was accurately recorded.

6. In providing mealtime supports to each of Mr H, Mr K and Mr I in the way that it did in the Relevant Period, Valmar contravened:

(a) sections 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, in that, it did not provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill, in that it:

(i) provided mealtime supports to each participant by workers who did not have the appropriate qualifications and/or training in providing mealtime supports to each participant, each being a person with a disability that made them susceptible to being at risk of choking and each being a participant with specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar;

(ii) failed to ensure that each participant’s dietitian plans were up to date so that it knew each participant’s then current eating and drinking requirements and whether the food and drink it provided to each participant was safe for that participant to consume;

(iii) failed to engage a speech pathologist to review Mr H’s swallowing to ensure that it knew if his requirements for swallowing fluids had changed; and

(iv) did not adhere to Mr H’s and Mr K’s dietitians plan, which incorporated their eating and drinking plans and to Mr I’s dietitian plan, which incorporated his mealtime management plan.

(b) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 10 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to manage the risk that each participant may choke on the food or drink provided by Valmar. That risk was ultimately realised for Mr H on 14 May 2020 when he choked on a toasted salami and cheese sandwich that was prepared for him and given to him by a Valmar support worker;

(c) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 15 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, it failed to ensure that each participant’s support needs as to what food and drink each participant, each being a person with a disability that made them susceptible to being at risk of choking and each being a participant with specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar, including by:

(i) ensuring that each participant’s dietitian plan was up to date;

(ii) ensuring that Mr H and Mr K consumed food and drink that complied with their dietitian plans, which incorporated their eating and drinking plans; and

(iii) ensuring that Mr I consumed food and drink that complied with his dietitian plan, which incorporated his mealtime management plan,

were met by workers who were competent in their role, held relevant qualifications and had relevant expertise and experience;

(d) section 73J of the NDIS Act because Valmar failed to comply with cl 21 of Sch 1 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, Valmar failed to provide each participant with competent and appropriate supports to meet their needs where those appropriate supports included:

(i) ensuring that support workers who provided mealtime supports had appropriate qualifications and/or training in providing mealtime supports to each participant, each being a person with a disability that made them susceptible to being at risk of choking and each being a participant with specific requirements for eating and drinking that were known to Valmar;

(ii) ensuring that each participant’s dietitian plan was up to date so that it knew each participant’s then current eating and drinking requirements and whether the food and drink it provided to each participant was safe for that participant to consume;

(iii) ensuring that Mr H and Mr K consumed food and drink that complied with their dietitian plans, which incorporated their eating and drinking plans; and

(iv) ensuring that Mr I consumed food and drink that complied with his dietitian plan, which incorporated his mealtime management plan.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 82(3) of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth), read with s 73ZK of the NDIS Act, Valmar pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $1,916,250 for the contraventions of ss 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act which are the subject of the six declarations above.

2. Valmar pay the Commissioner’s costs as assessed or agreed.

SCHEDULE A

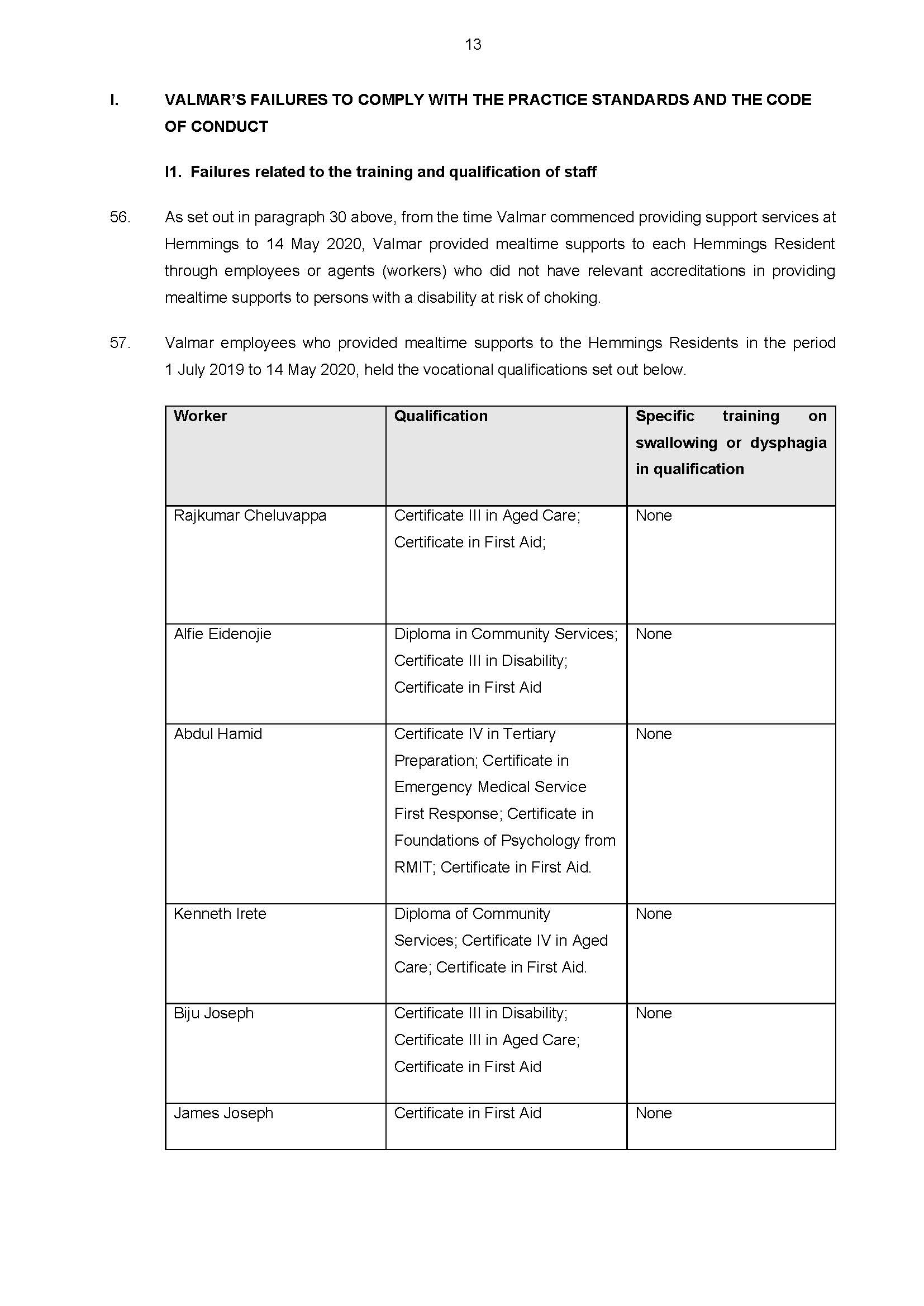

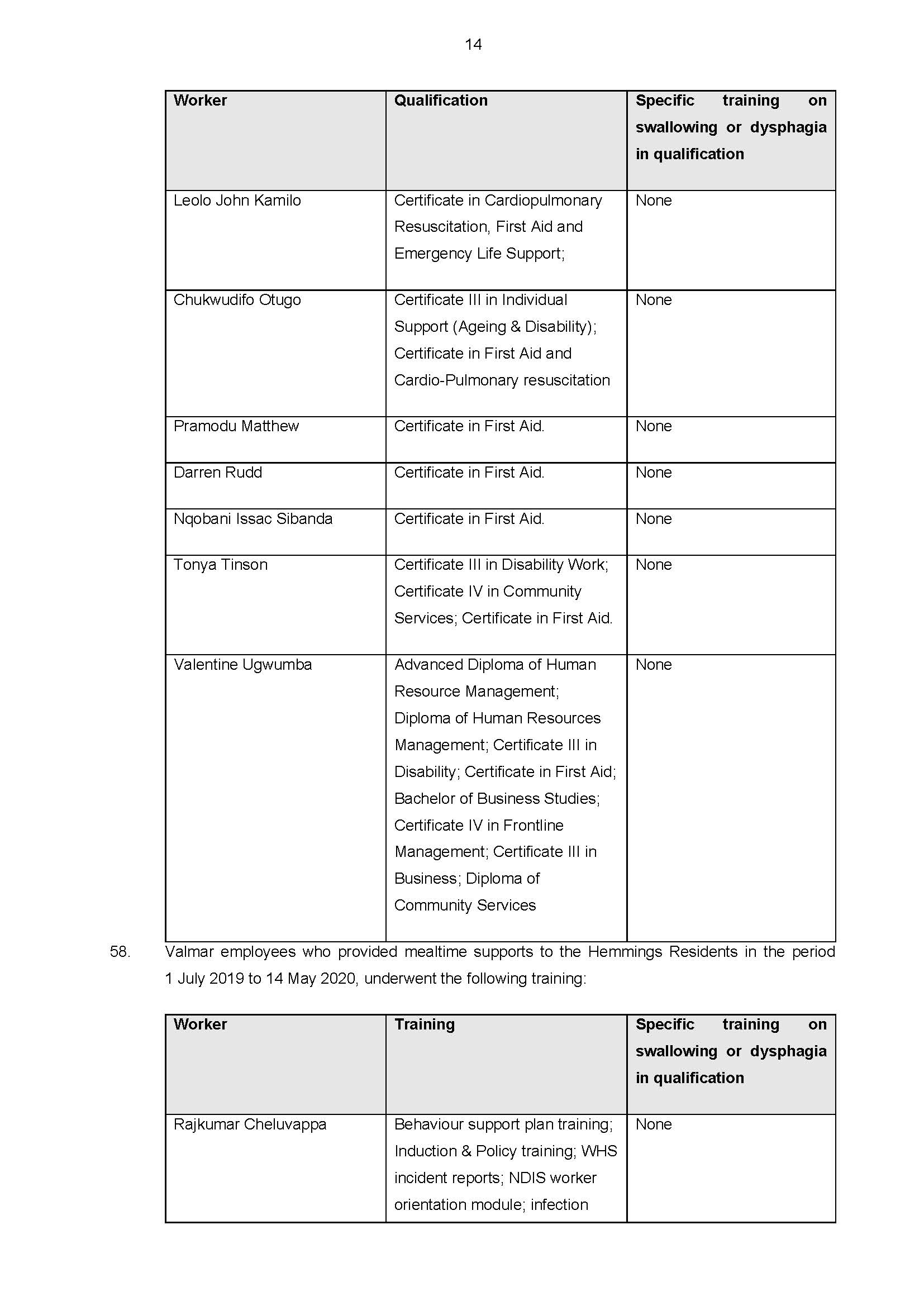

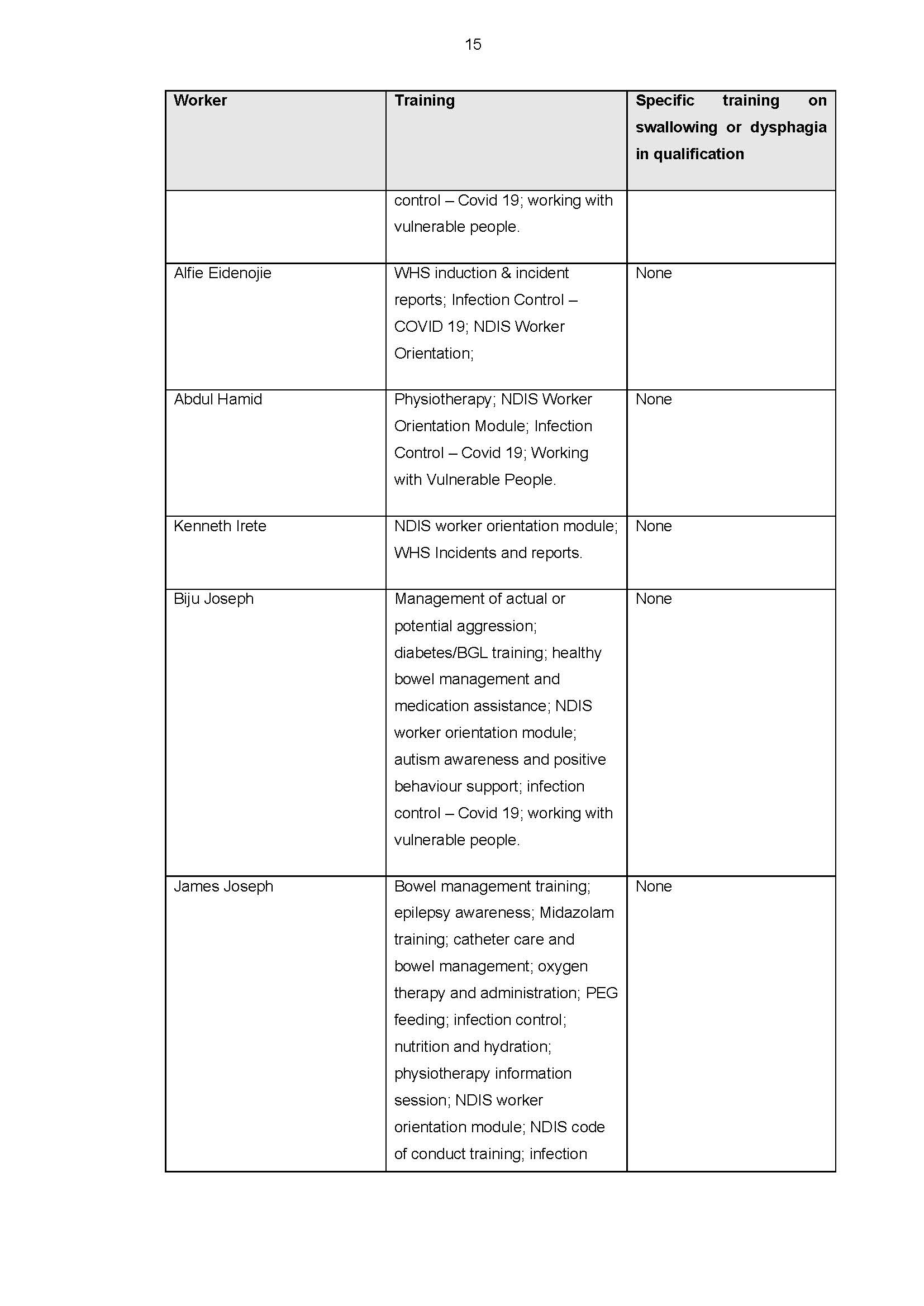

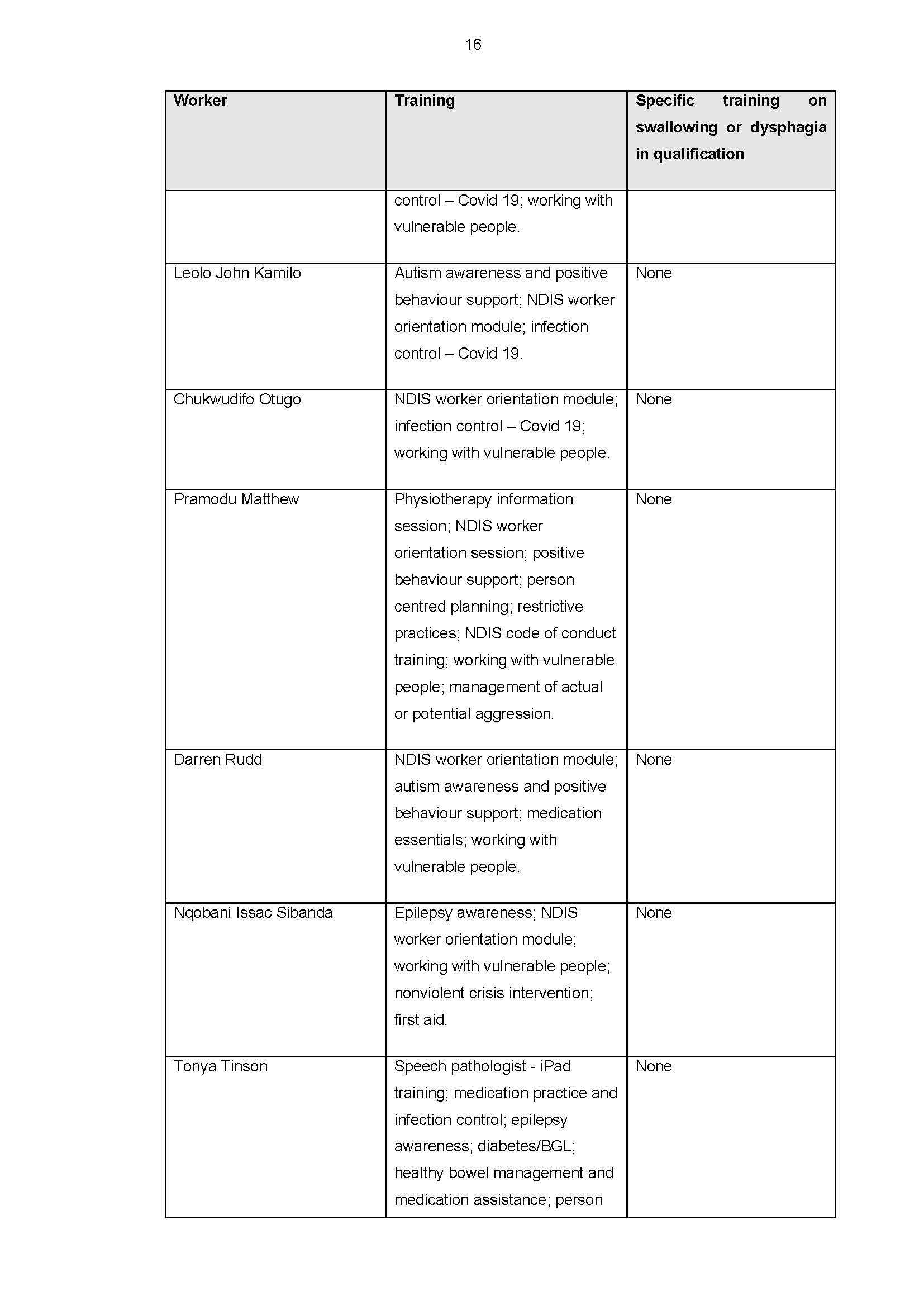

1. Rajkumar Cheluvappa

2. Alfie Eidenojie

3. Abdul Hamid

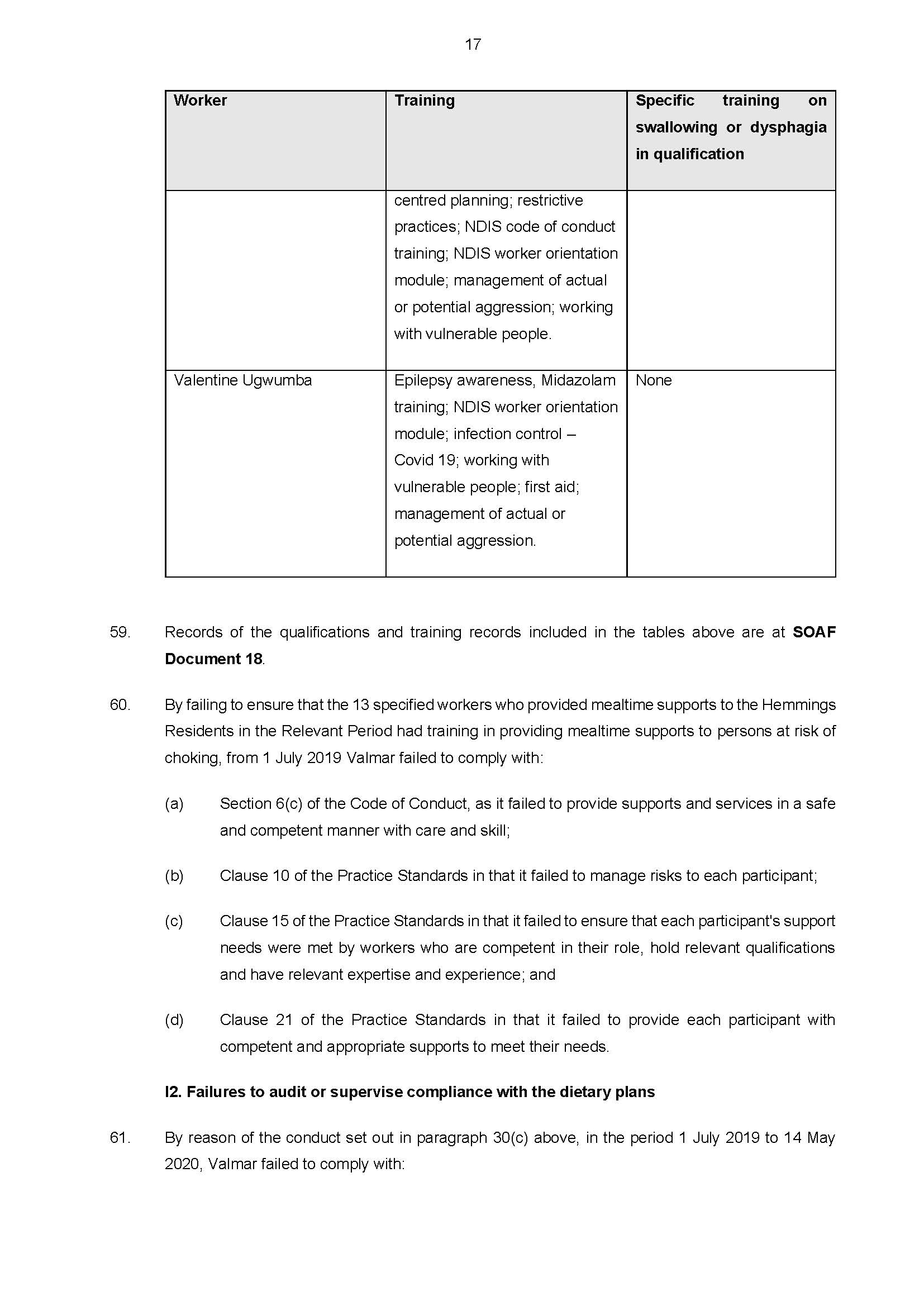

4. Kenneth Irete

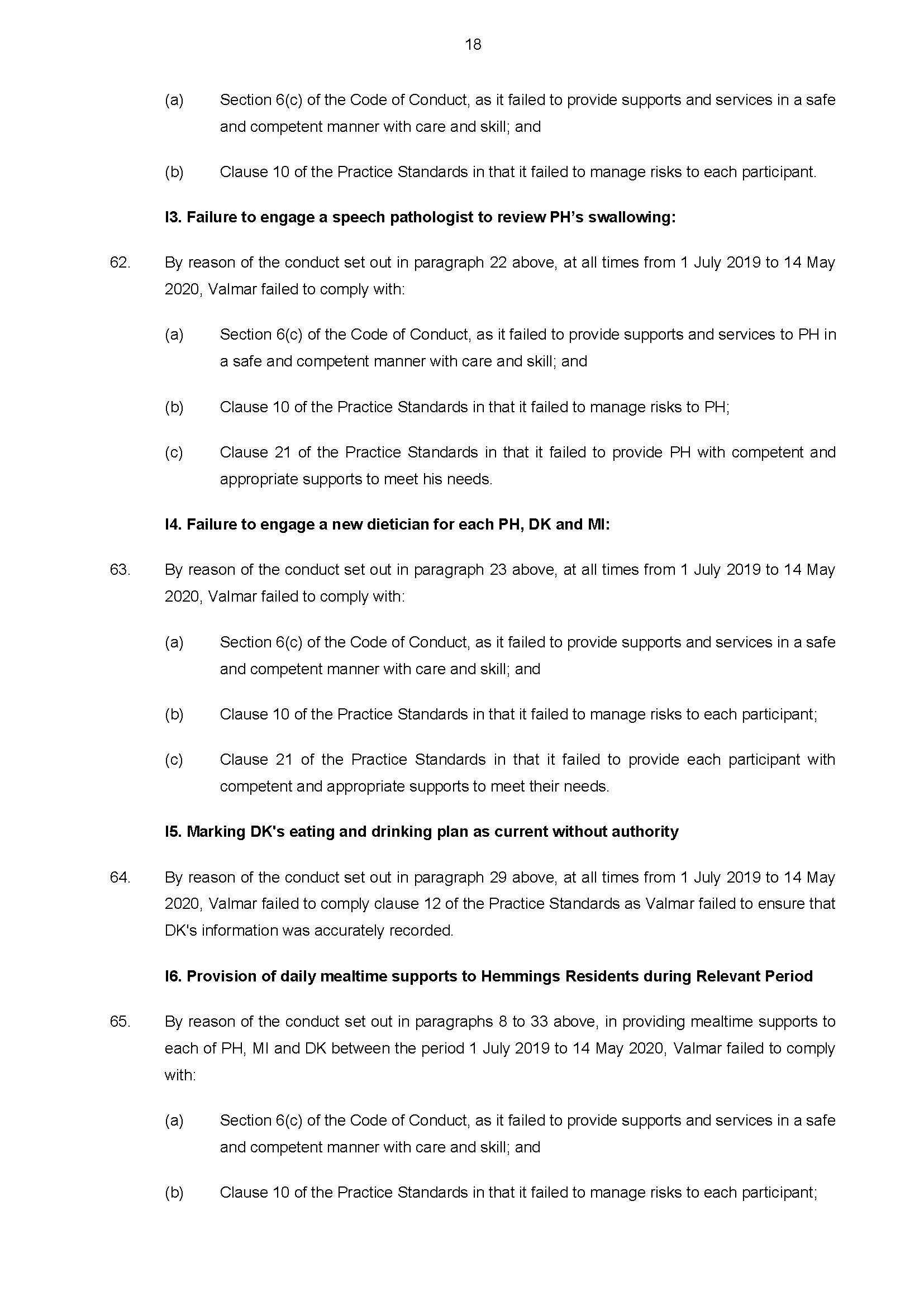

5. Biju Joseph

6. James Joseph

7. Leolo John Kamilo

8. Chukwudifo Otugo

9. Matthew Pramodu

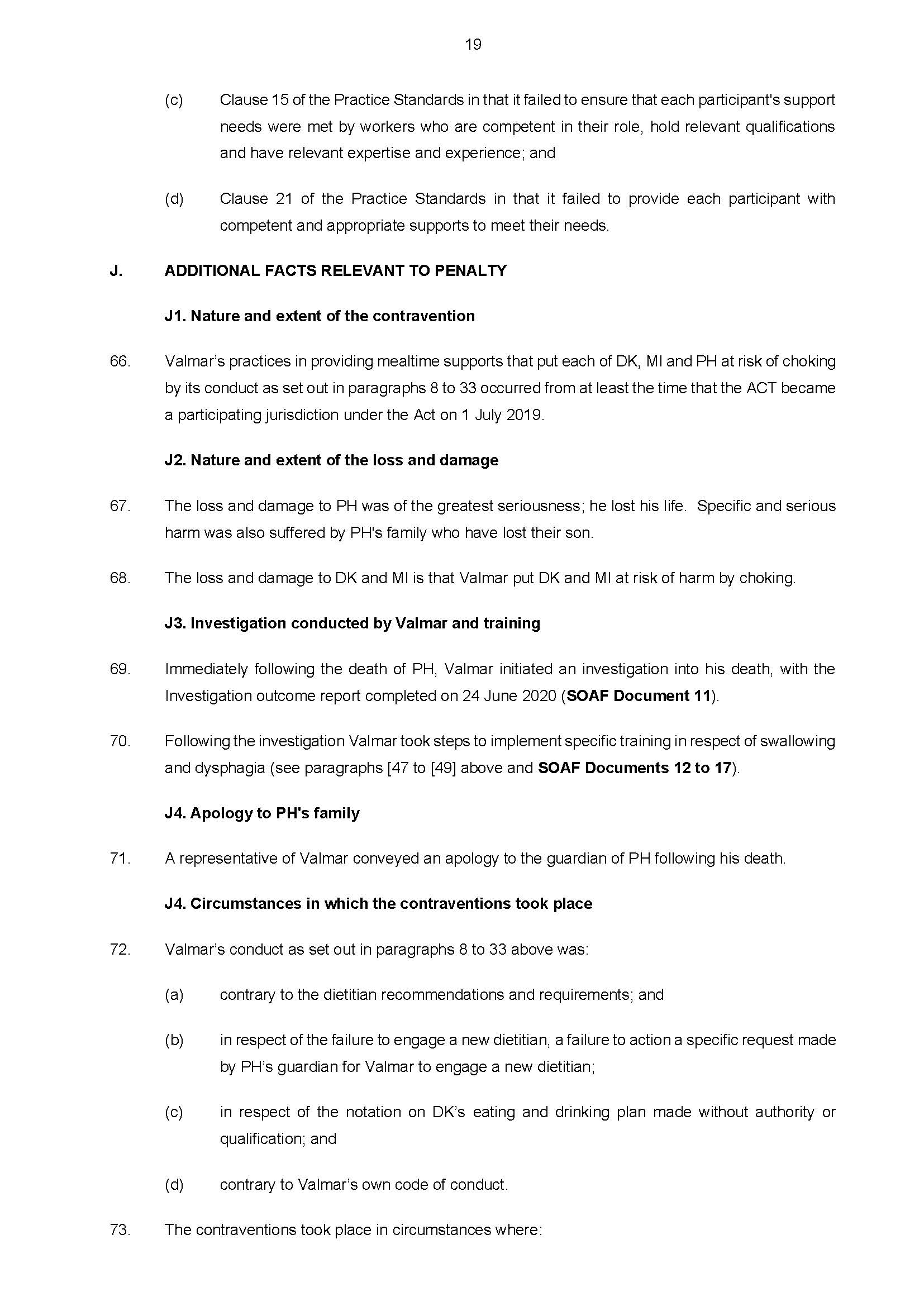

10. Darren Rudd

11. Nqobani Issac Sibanda

12. Tonya Tinson

13. Valentine Ugwumba

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

RAPER J:

1 In the period between February 2016 and May 2020, the respondent, Valmar Support Services Ltd, operated a residential group home in Hemmings Crescent, Richardson in the Australian Capital Territory. Three National Disability Insurance Scheme participants, Mr H, Mr K and Mr I, being men in their mid-40s, resided there (the Hemmings Residents). Each of the Hemmings Residents had intellectual disabilities and were known by Valmar to be at risk of harm by choking when they consumed food or drink. Despite this, none of the support workers who attended to their care had any formal training with respect to this risk. On many occasions, Valmar exposed (or increased) the risk that the Hemmings Residents would choke on their food. On 14 May 2020, a terrible event occurred. Mr H choked and collapsed while eating food, that had been prepared for him, and where the management plan meant to ensure his safety was not complied with. Mr H died three days later. His cause of death was recorded to be choking on food.

2 Valmar did not provide the level of supports they were required to provide under the NDIS, leading to very grave and tragic circumstances where one of the residents died. Valmar also exposed Mr K and Mr I to considerable risk of harm over a long period. Valmar has accepted it is liable for numerous breaches of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth).

3 These proceedings concern the resolution of three questions, which, for the following reasons, are all answered in the affirmative: (1) is the Court satisfied that liability is established? (2) is it appropriate for the Court to make the declarations sought? and, (3) is it appropriate for the Court to impose the civil penalties sought.

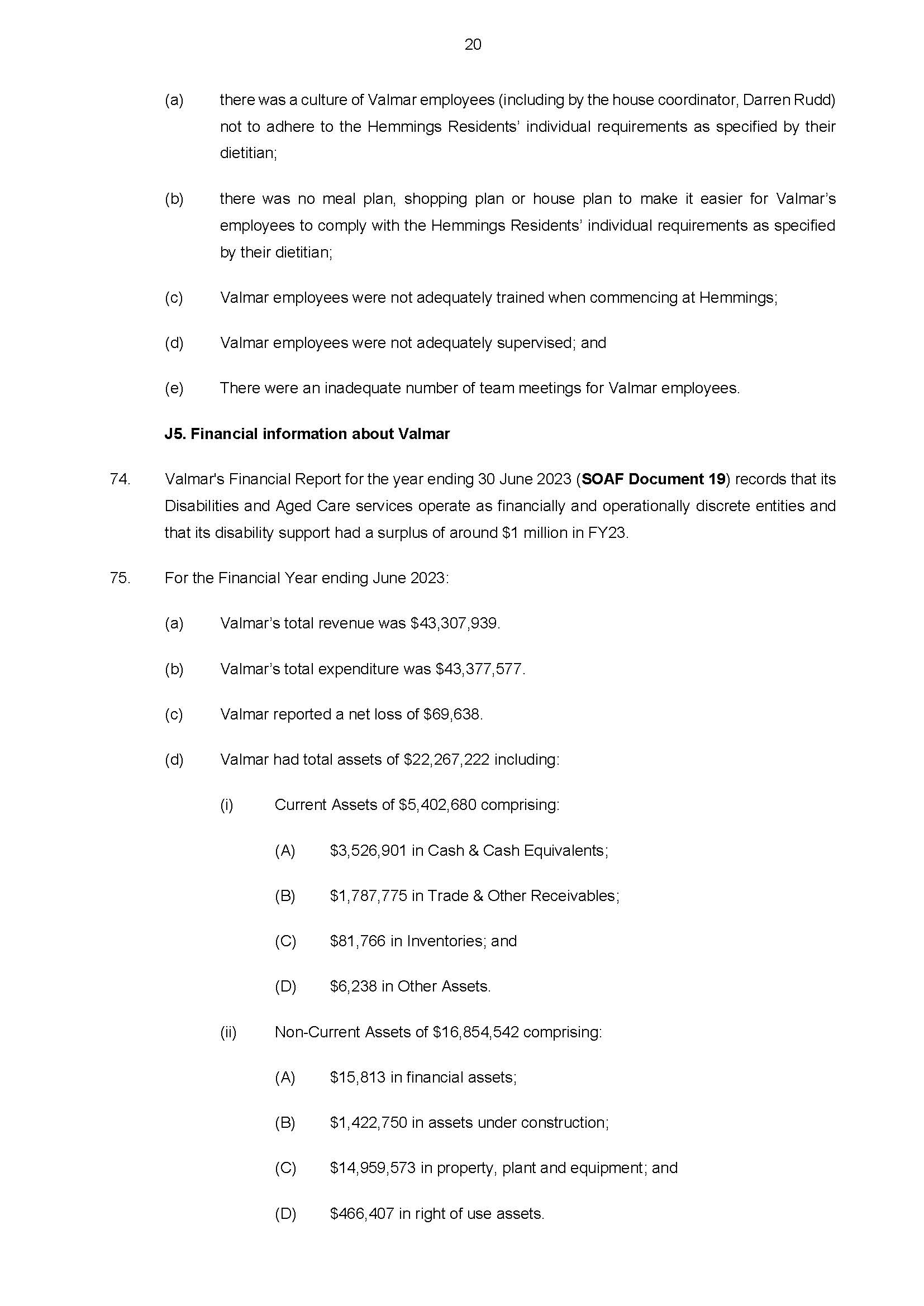

The applicable legislative provisions

4 The purpose of the NDIS is to enable persons with disability, through the provision of tailored high quality and innovative support services that are safe (funded by the Australian government), to exercise their autonomy, facilitate their inclusion in the community, and the prevention of harms caused by support or service providers engaging in poor quality or unsafe practices: NDIS Act ss 3, 4. To achieve this end, registered NDIS providers are subject to statutory conditions and obligations. Compliance is policed by the applicant, Commissioner of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission, through the functions prescribed by ss 181C–181H of the NDIS Act.

5 Section 73F of the NDIS Act obliges registered providers to comply with conditions, including applicable standards and other requirements of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Provider Registration and Practice Standards) Rules 2018 (Cth). Those standards include identifying and managing risks to participants (NDIS Act s 73F(2)(c), NDIS Practice Standards cl 10 of Sch 1, Pt 3); ensuring that there are identifiable, accurately recorded, current and confidential information concerning each participant (NDIS Act s 73F(2)(c), NDIS Practice Standards cl 12 of Sch 1, Pt 3); ensuring that each participant’s needs are met by workers who are competent in their role, by holding the relevant qualifications and having the relevant expertise and experience to provide person-centred supports (NDIS Act s 73F(2)(c), NDIS Practice Standards cl 15 of Sch 1, Pt 3); ensuring each participant can access competent and appropriate support for their needs (NDIS Act s 73F(2)(c), NDIS Practice Standards cl 21 of Sch 1, Pt 4).

6 Section 73J of the NDIS Act provides that a person contravenes this section if the person is a registered NDIS provider and breaches a “condition” (including those captured by s 73F) to which the registration of the person is subject.

7 Section 73V of the NDIS Act provides for the making of, and compliance with, an NDIS Code of Conduct which is contained in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (Code of Conduct) Rules 2018 (Cth) and relevantly includes an obligation that any supports and services are provided in a safe and competent manner, with care and skill: NDIS Code of Conduct s 6(1)(c).

8 Where a provider contravenes ss 73J or 73V of the NDIS Act, they are liable to be penalised pursuant to s 82(3) of the Regulatory Powers (Standard Provisions) Act 2014 (Cth) read together with s 73ZK of the NDIS Act.

What the Commissioner seeks from this Court

9 The Commissioner seeks declarations that Valmar, in connection with its operation of Hemmings between 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2024 (the relevant period), committed multiple contraventions of ss 73J and 73V of the NDIS Act and, for pecuniary penalties to be imposed for that contravening conduct pursuant to s 82(3) of the NDIS Act, read together with s 73ZK of the RP Act.

10 The parties attended mediation with a Judicial Registrar of this Court which resulted in Valmar admitting liability before the service or filing of evidence. The parties produced a Statement of Agreed Facts to the Court for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). The SOAF is attached to these reasons in full as Annexure A. The SOAF was accompanied by a bundle of supporting documents (SOAF documents) which the parties sought to tender in the proceeding. The Commissioner submitted that the SOAF sets out Valmar’s contravening conduct and why it constitutes 21 contraventions and three “course of conduct” contraventions of the NDIS Act (the 24 contraventions). Valmar accepts it committed the 24 contraventions.

11 During the course of the hearing, the Court sought further evidence as to the nature of Valmar’s business and greater detail as to its remediation steps. After the hearing, the parties filed a supplementary SOAF and supplementary SOAF documents. The supplementary SOAF forms Annexure B to these reasons.

12 The Commissioner has sought a single penalty of $1,916,250 in respect of the 24 contraventions and submitted that the declarations it seeks, accompanied by the penalty, will specifically deter Valmar and generally deter others; in turn, upholding and promoting the health, safety and wellbeing of persons with disability receiving supports under the NDIS scheme. Valmar agreed that the penalty sought by Commissioner is an appropriate one.

Summary of the agreed 24 contraventions

13 The parties helpfully provided the Court with a joint list of the agreed 24 contraventions, with a corresponding reference to the relevant parts of the SOAF which are said to establish the contraventions. This is the list:

No. | Contravention description | Section of NDIS Act | Practice Standard (PS) or NDIS Code of Conduct (Code) | SOAF paragraphs |

1–13. | Failing to ensure that the 13 relevant support workers had the necessary qualifications, training and (or) competence to provide mealtime supports to Messrs H, K and I (Hemmings Residents) being participants in Valmar’s care and known to Valmar to be at risk of choking. | 73J 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | As to requirements [15]–[21]; as to deficiencies [30]; [31]–[37]; [41(d)]; 44(b)] and [44(d)]; [46(a)], [56]–[60] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 15 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

14. | Failing to audit or supervise compliance with Mr H’s dietitian plan, incorporating his eating and drinking plan. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [9], [13(a)]; [15]; [18]–[19]; [30(c)]; [40(a)]; [44(e)]; [45(b) and (c)]; [46(c)]; [61(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

15. | Failing to audit or supervise compliance with Mr K’s dietitian plan, incorporating his eating and drinking plan. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [10], [13(b)]; [16]; [18]; [20]; [30(c)]; [45(c)]; [46(c)]; [61(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

16. | Failing to audit or supervise compliance with Mr I’s dietitian plan, incorporating his mealtime management plan. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [11], [13(c)]; [17]; [18]; [21]; [30(c)]; [45(c)]; [46(c)]; [61(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

17. | Failing to engage a speech pathologist to review Mr H’s swallowing as recommended by Mr H’s dietitian. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [22]; [62(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

18. | Failing to engage a new dietitian for Mr H following the termination of the services of the previous dietitian. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [19]; [23]; [63(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

19. | Failing to engage a new dietitian for Mr K following the termination of the services of the previous dietitian. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [20]; [23]; [63(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

20. | Failing to engage a new dietitian for Mr I following the termination of the services of the previous dietitian. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [21]; [23]; [63(a)] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

21. | Notating Mr K’s eating and drinking plan dated 1 July 2017 with the words ‘plan remains current. Feb 2020’ when it was not. | 73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 12 | [29]; [43(d)]; [64] |

22. | Course of conduct in providing mealtime supports to Mr H in the way that it did from 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2020 (Relevant Period). | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [9], [13(a)]; [15]; [18]–[19]; [22]–[25]; [30]–[37]; [40(a)]; [41(c), (d)]; [43(b), (c)]; [44(a)–(f)]; [45(b)] [46(a)–(d)]; [56]–[60]; [65] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 15 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

23. | Course of conduct in providing mealtime supports to Mr K in the way that it did during the Relevant Period. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [10], [13(b)]; [16]; [18]; [20]; [23]; [24]; [26]; [29]; [30]; [41(c), (d)]; [43(b), (c)]; [44(a), (b), (f)]; [46(a), (b)]; [56]–[60]; [65] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 15 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||

24. | Course of conduct in providing mealtime supports to Mr I in the way that it did during the Relevant Period. | 73J and 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | [11], [13(c)]; [17]; [18], [21]; [23]; [24]; [27]; [30]; [41(c), (d)]; [43(b), (c)]; [44(a), (b), (f)]; [46(a), (b)]; [56]–[60]; [65] |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 15 | |||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 |

Should the Court order the penalties sought by the parties?

14 The Court’s power to order pecuniary penalties payable to the Commonwealth arising from the contraventions of the NDIS Act, stem from, and are governed by, Pt 4 of the RP Act: NDIS Act s 73ZK.

15 Relevantly, ss 82 to 87 of the RP Act prescribe the power to award a penalty (s 82), including matters the court must take into account (s 82(6)), its enforcement (s 83), when to fix only one pecuniary penalty where the relevant conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more civil penalty provisions (s 84) and the making of a single penalty where the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character (s 85).

16 The relevant provisions of the RP Act are as follows:

82 Civil penalty orders

Application for order

(1) An authorised applicant may apply to a relevant court for an order that a person, who is alleged to have contravened a civil penalty provision, pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

(2) The authorised applicant must make the application within 6 years of the alleged contravention.

Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty

(3) If the relevant court is satisfied that the person has contravened the civil penalty provision, the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty for the contravention as the court determines to be appropriate.

Note: Subsection (5) sets out the maximum penalty that the court may order the person to pay.

(4) An order under subsection (3) is a civil penalty order.

Determining pecuniary penalty

(5) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision; and

(b) otherwise—the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision.

(6) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the court must take into account all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign country) to have engaged in any similar conduct.

83 Civil enforcement of penalty

(1) A pecuniary penalty is a debt payable to the Commonwealth.

(2) The Commonwealth may enforce a civil penalty order as if it were an order made in civil proceedings against the person to recover a debt due by the person. The debt arising from the order is taken to be a judgement debt.

84 Conduct contravening more than one civil penalty provision

(1) If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted under this Part against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of those provisions.

(2) However, the person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this Part in relation to the same conduct.

85 Multiple contraventions

(1) A relevant court may make a single civil penalty order against a person for multiple contraventions of a civil penalty provision if proceedings for the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character.

Note: For continuing contraventions of civil penalty provisions, see section 93.

(2) However, the penalty must not exceed the sum of the maximum penalties that could be ordered if a separate penalty were ordered for each of the contraventions.

Has the Court been sufficiently persuaded as to the accuracy of the agreed facts and consequences?

17 Whilst it has been recognised that parties have considerable scope to agree on the facts and consequences of conduct that leads to the enlivening of the Court’s power to order (and governs the scope of an appropriate range of) pecuniary penalties, the Court must be “sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed”: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (Agreed Penalties Case) [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 at [57]–[58] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ.

Valmar’s knowledge, over a long period, of Mr H’s risk of choking

18 Mr H was born in 1972. From 1995, until his untimely death in 2020, Mr H lived in disability accommodation services, which included at the Hemmings Residence. Mr H had received supports from Valmar from the time it commenced operating the Hemmings Residence in February 2016. Mr H had an intellectual disability, autism, type 2 diabetes, and Prader-Willi syndrome. Mr H was also non-verbal.

19 The parties’ SOAF described, in stark terms, Valmar’s knowledge of Mr H’s risk of choking, from as early as 2008, and repeating of the existence of that risk on numerous occasions:

(a) A Client Profile for Staffing dated March 2008 that records “Choking risk when eating. Cut up food into small pieces, Maintain high supervision”.

(b) An ACT Government Community Services Checklist dated October 2014 recording that Mr H required a “swallowing mealtime management plan”.

(c) A Valmar One Page Profile dated February 2018, recording “Choking risk whilst eating – see meal time management plan” and “Choking hazard when eating. [Mr H] generally does not chew a great deal. Food is to be cut into bite size pieces and dampened with a sauce if necessary. Monitoring is required when [Mr H] is eating Mr H also has Prada Willi – this will see [Mr H] consume a range of items, which may not even be a food type. Again, monitoring is imperative”.

(d) An undated Quick Reference Guide recording “It’s important that I’m supervised when eating, as sometimes I force food into my mouth too fast and a choking hazard is present.”

(e) A Meal and Snack Management Plan dated 11 January 2020 recording Mr H’s “Choking Risk”.

(f) A positive behaviour support plan dated 23 March 2020, recording “Mr H has a meal and eating plan, as sometimes he eats too fast, which causes a choking risk.”

(references omitted)

20 I am satisfied by my review of the underlying supporting materials that these agreed facts accurately describe the circumstances.

Valmar’s failure to accord with the requirements of the dietitian’s plans

21 At hearing, the Commissioner emphasised the content of the dietitian’s plans, of 5 May 2016, 27 June 2017, 29 November 2017 and 1 June 2018. I note that the last of the dietitian plans was made on 1 June 2018. Additionally, in an eating and drinking plan dated 5 May 2016, it is recorded that Mr H did not chew and was at risk of choking. His food must be soft, cut-up into small bite-sized pieces and moist. Dietician plans dated 3 February 2017 and 1 June 2018 record the requirement that Mr H’s food is to be cut up in bite-sized pieces and must be soft in bold text.

Valmar’s failure to adhere to the numerous requests of the dietitian that a speech pathologist be engaged given Mr H’s issues with swallowing

22 Sadly, the evidence revealed that these plans, and the correspondence from the dietitian, indicated the need, from March 2017, for a speech pathologist assessment to be undertaken given “some issues with swallowing”. The dietitian made a request for a referral on numerous occasions thereafter in 2017, both in the updated eating plans and by email in June and September 2017. The dietitian’s services were terminated in September 2018. No further dietitian was retained, and no speech pathologist was engaged to conduct an assessment.

Mr Rudd’s creation of a meal plan for Mr H without consultation with an expert

23 Thereafter, the evidence revealed that Mr Rudd, a co-ordinator for High Need Accommodation, created his own meal plan, for each of the residents, including Mr H, without consulting a nutritionist or dietitian, nor a speech pathologist (who may assist regarding swallowing difficulties).

24 That meal plan was created on or around January 2019 (a year before Mr H’s death), whilst it identified that Mr H was a “choking risk” and referred the reader to his dietitian plan, it did not set out which dietitian plan was the then current plan, or where it was to be found, and the plan otherwise failed to record that Mr H’s food was to be “soft” (nor recorded what that meant or how it was achieved), cut into bite-sized pieces and moist, as specified in his eating and drinking plan. Inconsistent with the dietitian’s repeated requirements for the food to be “soft” and “moist”, the meal plan stated that Mr H could eat biscuits, fruit, sandwiches and cake without any qualification.

The tragic circumstances leading to Mr H’s death

25 The parties’ SOAF recited the tragic events leading up to Mr H’s death in the following terms:

31. On 14 May 2020, … an employee of Valmar on duty at Hemmings at the time prepared a toasted salami and cheese sandwich and gave it to Mr H to eat.

32. The toasted sandwich was cut into nine pieces but it was not soft, or moist. ….

33. At about 12.20pm on 14 May 2020, Mr H choked and collapsed while eating the salami and cheese toasted sandwich prepared by [the employee].

34. [The employee] called 000 and commenced CPR until paramedics arrived.

35. The ACT Ambulance Report recorded that there was a complete obstruction of Mr H’s airway, that he was not breathing and had no palpable pulse.

36. Mr H was transported to Canberra Hospital. He remained unconscious and died in hospital on 17 May 2020.

37. The Order and Certificate in respect of an inquest and dispensing with a hearing dated 26 June 2020 records that the manner and cause of Mr H’s death was that he “choked on food”.

(references omitted)

26 As revealed above, these proximate tragic circumstances must be understood, in the wider context referred to above. Valmar had known for a long time of Mr H’s risk of choking, there were specific dietitian plans which emphasised this and gave directions as to how the risk could be reduced. Valmar had received specific advice, on numerous occasions to arrange for a speech pathologist assessment to be undertaken, this was not done. Further, confusion was caused by Mr Rudd’s creation of a new plan which failed to record that Mr H was to be given “soft” food, what this meant and how it was to be achieved.

Valmar’s knowledge, over a long period, of Mr K’s risk of choking

27 Mr K was born in 1977 and has resided at Hemmings since 2012. Mr K has received supports from Valmar from the time it commenced operating the Hemmings group home. Mr K has an intellectual disability, type 2 diabetes, and mental health concerns which require a psychiatrist. Mr K also has limited communication skills.

28 The parties’ SOAF described the similar extent of Valmar’s knowledge of Mr K’s risk of choking in the following terms:

(a) By letter dated 21 June 2017, Valmar by its employees [HB and DR] (who was then the Coordinator of Hemmings) reported to Dr [W] that “[Mr K’s] food is cut small, and staff monitor [Mr K’s] eating for each meal to lessen the risk of choking”.

(b) His Valmar One Page Profile dated February 2018 records:

(i) Under the heading Critical Information: “Risks and Alerts: Choking Risk””

(ii) Under the heading Eating and Drinking: “[Mr K] consumes his food very fast and this in the past has caused choking. [Mr K] requires full time supervision when eating, and all food needs to be cut up in bite size pieces.”

(c) His Valmar Program Risk/Behaviour Assessment Form dated 13 March 2018 records as a risk behaviour “Eating fast which is a potential choking risk”.

(d) Reports provided by Carmel Curlewis of Advantage Nutrition to Valmar dated 1 June 2018,17 September 2018, 20 March 2019, record Mr K’s “choking risk”.

(e) A Meal and Snack Management Plan dated 11 January 2020 records Mr K’s “Choking Risk”.

(references omitted)

29 Mr K’s eating and drinking plan, prepared by a dietitian (dated 1 July 2017) records that he does not chew his food and hangs his head and that he is at risk of choking if his food is not cut up into small, bite-sized pieces (being 1.5cm by 1.5cm). This information was also recorded in bold text on Mr K’s dietitian plans of 1 June 2018, 17 September 2018 and 20 March 2019.

30 In the plan created by Mr Rudd, in January 2019, again, like the circumstances of Mr H, the plan referred to Mr K being a “choking risk” and referred the reader to a dietitian plan but did not set out which dietitian plan was the then current plan, or where to find it. The plan also failed to record Mr K’s specific food requirements.

Mr Rudd’s incorrect notation on Mr K’s eating and drinking plan as to its currency where it was done without authority or qualification

31 Notably, in February 2020, Mr Rudd made a notation on Mr K’s eating and drinking plan, dated 1 July 2017, that “Plan remains current Feb 2020” despite the fact that Mr K had not been seen by a dietitian since at least March 2019 and the fact that Mr Rudd otherwise had no authority or qualification to do so.

Valmar’s knowledge, over a long period, of Mr I’s risk of choking

32 Mr I was born in 1973 and has lived at the Hemmings Residence since approximately 1997. Mr I has received supports from Valmar from the time it commenced operating the Hemmings group home. Mr I has an intellectual disability, autism, and PICA, a condition which results in him placing inedible objects in his mouth and swallowing them.

33 With unfortunate similarity to that of Mr H and Mr K, Valmar’s knowledge, over a long period, of Mr I’s risk of choking was accurately described in the SOAF in the following way:

(a) His Valmar One Page Profile dated February 2018 records:

(i) Under the heading Critical Information: “Risks and Alerts: Choking due to PICA”

(ii) Under the heading Eating and Drinking: “[Mr I] also requires his food cut up into small pieces. [Mr I] generally does not chew, therefore the small [sic] the better to ensure safety. He prefers his food with a sauce. Dry foods should generally not be given”.

(b) His CHAP dated 3 September 2018 records “Mr I does not chew his food – his meals are cut into small pieces.”

(c) A Meal and Snack Management Plan dated 11 January 2020 records Mr I’s “Choking Risk”.

(references omitted)

34 Mr I has a mealtime management plan dated 20 October 2009, prepared by a speech pathologist, which is referred to in his dietitian plan dated 27 June 2017. The plan records Mr I having a very high risk of choking, and that his food must be soft, easily broken up with a fork, and served moist in very small pieces.

35 Similarly, with Mr I, Mr Rudd created a meal plan in January 2019, without expert consultation, which failed to record his specific requirements and identified foods that he was able to eat which did not accord with the requirements previously specified by the dietitian.

The compounding effect of other common systemic failures

36 The evidence established that, from when Valmar commenced providing support services at the Hemmings Residence, until the end of the relevant period, it provided those support services where the support workers had not had any specific training as to how to provide supports to persons with a disability that were at risk of choking. There was no menu plan or shopping plan in place at the Hemmings Residence, despite the workers requesting one, which limited their ability to provide meals to Mr H and Mr K which complied with their eating and drinking plans, and for Mr I that complied with his mealtime management plan. There was no adequate supervision, nor a safety audit conducted to ensure compliance with Mr H’s and Mr K’s eating and drinking plans and Mr I’s mealtime management plan. Further, on many occasions, (as found upon investigation after Mr H’s death), workers provided both Mr H and Mr K with food that did fall within the requirements of their eating and drinking plans and Mr I with his mealtime management plan. By this conduct, each of the residents were exposed to a risk, or alternatively, an increased risk, of choking on their food.

Valmar’s failures to ensure the support workers were properly trained

37 Valmar accepts, and I am satisfied on the evidence, that by failing to ensure that the 13 specified workers who provided mealtime supports to the Hemmings Residents, over the relevant period, had training in providing mealtime supports to persons at risk of choking, Valmar failed to comply with:

(a) section 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, as it failed to provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner with care and skill;

(b) clause 10 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to manage risks to each participant;

(c) clause 15 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to ensure that each participant's support needs were met by workers who are competent in their role, hold relevant qualifications and have relevant expertise and experience; and

(d) clause 21 of the Practice Standards in that it failed to provide each participant with competent and appropriate supports to meet their needs.

Valmar’s failures to audit or supervise compliance with the dietary plans

38 By reason of there being no adequate supervision, nor a safety audit concerning compliance with Mr H’s and Mr K’s eating and drinking plans and Mr I’s mealtime management plan, during the relevant period, I am satisfied that Valmar failed to comply with:

(a) section 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, as it failed to provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner with care and skill; and

(b) clause 10 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to manage risks to each participant.

Valmar’s failure to engage a speech pathologist to review Mr H’s swallowing:

39 By reason of Valmar’s failure to adhere to the numerous requests of the dietitian that a speech pathologist be engaged given Mr H’s issues with swallowing (referred to above), I am satisfied that, during the relevant period, Valmar failed to comply with:

(a) section 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, as it failed to provide supports and services to Mr H in a safe and competent manner with care and skill;

(b) clause 10 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to manage risks to Mr H; and

(c) clause 21 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to provide Mr H with competent and appropriate supports to meet his needs.

Valmar’s failure to engage a new dietician for each Mr H, Mr K and Mr I:

40 I am satisfied that it has been established on the evidence that Valmar failed to engage a new dietitian after it terminated the services of Ms Curlewis in September 2018. By reason of this failure, I am satisfied that Valmar failed to comply with:

(a) section 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, as it failed to provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner with care and skill;

(b) clause 10 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to manage risks to each participant; and

(c) clause 21 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to provide each participant with competent and appropriate supports to meet their needs.

Valmar’s failure to accurately record Mr K's eating and drinking plan as current without authority

41 I am satisfied that the evidence establishes that, in February 2020, Mr Rudd made a notation on Mr K’s eating and drinking plan, dated 1 July 2017, that “Plan remains current Feb 2020” despite the fact that Mr K had not been seen by a dietitian since at least March 2019 and the fact that Mr Rudd otherwise had no authority or qualification to do so. By reason of this conduct, I am persuaded that the evidence establishes that Valmar failed to comply with clause 12 of the NDIS Practice Standards, in that, Valmar failed to ensure that Mr K’s information was accurately recorded.

Failure to provide daily mealtime supports to Hemmings Residents during Relevant Period

42 By reason of the conduct referred to above, in providing mealtime supports to each of Mr H, Mr I and Mr K during the relevant period, I am satisfied that the evidence establishes that Valmar failed to comply with:

(a) section 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, as it failed to provide supports and services in a safe and competent manner with care and skill;

(b) clause 10 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to manage risks to each participant;

(c) clause 15 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to ensure that each participant's support needs were met by workers who are competent in their role, hold relevant qualifications and have relevant expertise and experience; and

(d) clause 21 of the NDIS Practice Standards in that it failed to provide each participant with competent and appropriate supports to meet their needs.

Revisiting the legislative context

43 The Court’s power to order pecuniary penalties payable to the Commonwealth arising from the contraventions of the NDIS Act, stem from, and are governed by, Pt 4 of the RP Act: NDIS Act s 73ZK.

44 Relevantly, ss 82–87 of the RP Act prescribe the power to award a penalty (s 82), including matters the court must take into account (s 82(6)), its enforcement (s 83), when to fix only one pecuniary penalty where the relevant conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more civil penalty provisions (s 84), and the making of a single penalty where the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character (s 85).

45 The relevant provisions of the RP Act are as follows:

82 Civil penalty orders

Application for order

(1) An authorised applicant may apply to a relevant court for an order that a person, who is alleged to have contravened a civil penalty provision, pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

(2) The authorised applicant must make the application within 6 years of the alleged contravention.

Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty

(3) If the relevant court is satisfied that the person has contravened the civil penalty provision, the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth such pecuniary penalty for the contravention as the court determines to be appropriate.

Note: Subsection (5) sets out the maximum penalty that the court may order the person to pay.

(4) An order under subsection (3) is a civil penalty order.

Determining pecuniary penalty

(5) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is a body corporate—5 times the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision; and

(b) otherwise—the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision.

(6) In determining the pecuniary penalty, the court must take into account all relevant matters, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the contravention; and

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contravention; and

(c) the circumstances in which the contravention took place; and

(d) whether the person has previously been found by a court (including a court in a foreign country) to have engaged in any similar conduct.

83 Civil enforcement of penalty

(1) A pecuniary penalty is a debt payable to the Commonwealth.

(2) The Commonwealth may enforce a civil penalty order as if it were an order made in civil proceedings against the person to recover a debt due by the person. The debt arising from the order is taken to be a judgement debt.

84 Conduct contravening more than one civil penalty provision

(1) If conduct constitutes a contravention of 2 or more civil penalty provisions, proceedings may be instituted under this Part against a person in relation to the contravention of any one or more of those provisions.

(2) However, the person is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty under this Part in relation to the same conduct.

85 Multiple contraventions

(1) A relevant court may make a single civil penalty order against a person for multiple contraventions of a civil penalty provision if proceedings for the contraventions are founded on the same facts, or if the contraventions form, or are part of, a series of contraventions of the same or a similar character.

Note: For continuing contraventions of civil penalty provisions, see section 93.

(2) However, the penalty must not exceed the sum of the maximum penalties that could be ordered if a separate penalty were ordered for each of the contraventions.

Are the penalties appropriate?

46 A penalty will be an appropriate one where there is a “reasonable relationship” with the theoretical maximum, in the sense that, it goes no further than may be thought reasonably necessary to deter future conduct (by the contravener and others) of a like kind: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Pattinson [2022] HCA 13; 274 CLR 450 at [9] and [55]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 at [156].

47 Whilst the single civil penalty sought was agreed between the parties following mediation, I am not bound to accept it. However, the High Court opined, in the Agreed Penalties Case, as to the public interest in bringing litigation to an end, that it is “highly desirable in practice” for the Court to do so when “sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances”: at [46].

48 Justice Abraham, in Commissioner of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission v Australian Foundation for Disability [2023] FCA 629 (Afford) at [45], explained:

45 The nature of the court’s task in imposing a civil penalty under s 82 of the RPA, is to impose such pecuniary penalty as the court determines to be appropriate, having regard to all relevant matters, including those set out in s 82(6) of the RPA. That process involves an intuitive or instinctive synthesis of all of the relevant factors: ACCC v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [6]; TPG Internet Pty Ltd v ACCC [2012] FCAFC 190; (2012) 210 FCR 277 at [145]. Instinctive synthesis is the method by which the judge identifies all the factors that are relevant to the penalty and, after weighing all of those factors, reaches a conclusion that a particular penalty is the one that should be imposed: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25, [37]: and see Viagogo AG v ACCC [2022] FCAFC 87; at [129]–[133], [148]–[151]. Section 82(6) sets out the factors required to be taken into consideration. In Balasubramaniyan at [93], the Court recognised that those factors are not exhaustive of what may be relevant, and the factors identified in other civil penalty contexts may also be relevant (recognising presently that there is overlap with the s 82(6) factors). The factors identified additionally include matters such as: the seriousness of the conduct; the size of the contravening company; the deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended; whether further contraventions are likely; whether the contravention arose out of conduct of senior management; whether the contravenor has a corporate culture conducive to compliance as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention; and whether there has been co-operation with the authorities, including in the context of the proceedings.

49 The parties submitted the Court could be satisfied the proposed penalty is an appropriate one in the circumstances of this case by reference to the following considerations developed in the authorities.

The breakdown of the penalties sought

50 As stated above, the Commissioner submitted that the SOAF sets out Valmar’s contravening conduct and why it constitutes 21 contraventions and three “course of conduct” contraventions of the NDIS Act. Valmar accepts it committed the 24 contraventions.

51 The Commissioner sought a single penalty of $1,916,250 in respect of the 24 contraventions, apparently arrived at by a mathematical exercise, devised in the following way:

No. | Contravention description | Section of NDIS Act | Practice Standard (PS) or NDIS Code of Conduct (Code) | Max Penalty | Proposed Penalty | % of Maximum |

1–13 | Failure to ensure 13 relevant support workers had the necessary training during the relevant period. | 73J & 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | $3,412,500 ($210 x 1,250) x 13 | $1,023,750 ($78,750 per employee) | 30% |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 15 | |||||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||||

14–16 | Failure to audit or supervise compliance with each of Mr H, Mr K and Mr I’s dietitian plans from 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2020. | 73J & 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | $787,500 ($210 x 1,250) x 3 | $157,500 | 20% |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3 cl 10 | |||||

17 | Failure to engage a speech pathologist for Mr H. | 73J & 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | $262,500 ($210 x 1,250) | $78,750 | 30% |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||||

18–20 | Failure to engage a new dietitian for Mr H, Mr K and Mr I from 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2020 (having terminated previous dietitian on 11 September 2018). | 73J & 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | $787,500 ($210 x 1,250) x 3 | $157,500 | 20% |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 | |||||

21 | Notating a plan prepared by a dietitian with the words 'plan remains current. Feb 2020'. | 73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 12 | $262,500 ($210 x 1,250) | $26,250 | 10% |

22–24 | Contravention by reason of the mealtime supports provided to Mr H, Mr K and Mr I between the period of 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2020. | 73J & 73V | Code, s 6(1)(c) | $787,500 ($210 x 1,250) x 3 | $472,500 For Mr H: $120 x $1,250 X 100% For Mr I & Mr K: 2 x $210 x $1,250 x 40% | 100% of the statutory maximum for one contravention for the course of conduct that lead to Mr H's death; 40% of the statutory maximum for the course of conduct relating to Mr K and Mr I respectively |

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 10 | |||||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 3, cl 15 | |||||

73J | PS, Sch 1, Pt 4, cl 21 |

52 In arriving at the single penalty, calculated on the basis of the above grouping of contraventions and the associated percentages and dollar figures, the Commissioner submitted that they had regard to:

(a) the 21 distinct contraventions and the three separate course of conduct contraventions;

(b) the fact that the maximum penalty for the 21 distinct contraventions is $5,512,200;

(c) as to the maximum penalty for the three course of conduct contraventions, it was not possible to calculate the number of mealtime supports provided to each Hemmings Resident over the 10 month period. Nonetheless, it was submitted that the statutory maximum of $262,500 for each separate contravention operates as a guide as to the level of seriousness of each wrong: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 at [230], [247] per Allsop CJ, Middleton and Robertson JJ;

(d) the required “reasonable relationship” between the theoretical maximum and the proposed penalty, said to be established by the circumstances of the contravening conduct and the circumstances of the contravener, where the contraventions were of the upmost seriousness, Valmar has co-operated with the Commissioner, has no prior contravening history, and has taken steps to ensure that the conduct does not reoccur: Pattinson at [9], [55];

(e) the need for the penalty to be no greater than necessary to achieve the object of deterrence: Pattinson at [10], [55];

(f) the similar penalties incurred in like cases, applying the percentages used in Commissioner of the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (Cth) v LiveBetter Services Ltd [2024] FCA 374 and by reference to Afford; and

(g) the operation of the totality principle.

The appropriate fixing of penalties to conduct

53 As is evident from the above table, the parties have submitted that the penalties be affixed to the relevant conduct in particular ways. For example, the relevant conduct attached to contraventions one to 13 (as they relate to each of the support workers who it is agreed Valmar failed to provide adequate training and/or competence to provide mealtime supports to each of the Hemmings Residents), is submitted to give rise to the affixing of 13 penalties, despite there being four separate breaches of the NDIS Act.

54 The RP Act and the common law make provision for how the Court is to affix penalties. By operation of s 84(2) of the RP Act, the Court cannot order a person liable for more than one pecuniary penalty under Pt 4 in relation to the same conduct, namely where the same acts or omissions constitute an element of more than one contravention. “Conduct” means an act or a failure to act—the physical elements of a contravention: s 4; Commissioner of Taxation v Balasubramaniyan [2022] FCA 374 at [98]. Separate contraventions arising from separate acts should ordinarily attract separate penalties. However, the common law course of conduct principle, gives focus to similar or related conduct rather than the same conduct. The principle is a discretionary tool of analysis which the Court is not compelled to use: Balasubramaniyan at [99]. It is distinct from the purpose of s 84(2) which is concerned with the same acts or omissions constituting an element of more than one contravention—it means that consideration may be given to whether it is appropriate that a single penalty be imposed for more than one contravention arising from a single course of conduct. Its purpose is to ensure that the contravener is not punished twice for essentially the same conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159; 258 FCR 312 at [421]–[424].

55 The determination of whether a number of contraventions should be treated as being a single course of conduct involves a factual enquiry having regard to all the circumstances of the case. It is a tool of analysis (which has no paramountcy in the process of assessing penalty nor operates as a de facto limit on the penalty imposed) which requires evaluative judgment of the relevant circumstances: Balasubramaniyan at [101] citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd t/a Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [25].

56 The contravening conduct falls into six categories:

(1) A failure to ensure that the 13 support workers were adequately trained as to what food and drink to offer each of the Hemmings Residents given the high risk of each of them choking and how to prepare that food (contraventions 1 to 13);

(2) A failure to audit or supervise compliance with each of the Hemmings Residents’ dietitian plans (contraventions 14 to 16);

(3) A failure to engage a speech pathologist for Mr H (contravention 17);

(4) A failure to engage a new dietitian for each of the Hemmings Residents (contraventions 18-20);

(5) The misleading notation on a dietitian’s plan that it was current (contravention 21);

(6) The manner in which Valmar, in fact, provided mealtime supports to each of the three residents, in the way that they did, between 1 July 2019 and 14 May 2020 (contraventions 22 to 24).

57 In this case, each of the contraventions 1 to 13, are founded on a failure to ensure that the 13 support workers, who worked at the Hemmings Residence had the necessary training during the relevant period (between 1 July 2019 and 14 May 2020). Each of those separate failures relating to each of the support workers, constituted 4 separate contraventions of ss 73J and 73V of the Act. However, I accept that each of those failings give rise to the four separate contraventions, but they concerned the same omission, constituting an element of more than one contravention, such that s 84(2) applies and therefore one penalty ought be affixed to the conduct as it relates to each worker.

58 Contraventions 14 to 16 concern Valmar’s failure to audit or supervise compliance of each of the Hemming Residents’ dietitian plans from 1 July 2019 to 14 May 2020. As a consequence of that failure Valmar breached ss 73J and 73V by non-compliance with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct, which required it to ensure any supports and services are provided in a safe and competent manner. I accept that the failure to audit and supervise dietitian plans is different from the ensuring of necessary training. In addition, this failure constitutes a breach of s 73J by breaching a registration condition, namely the identification of and managing risks to participants (cl 10 of Sch 1, Pt 3 of the NDIS Practice Standards). However, the two contraventions again rise from the same omission and it is appropriate that one penalty is affixed to the conduct.

59 Contravention 17 concerns the failure to engage a speech pathologist for Mr H which was urged upon Valmar, by his dietitian numerous times. By this failure, the Commissioner contends, and I accept, there are three separate contraventions of ss 73J and 73V by non-compliance with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct to ensure any supports and services are provided in a safe and competent manner. In addition, this failure constitutes a breach of s 73J by breaching a registration condition, namely the identification of and managing risks to participants (cl 10 of Sch 1, Pt 3 of the NDIS Practice Standards). It also comprises a breach of s 73J by failing to ensuring Mr H could access competent and appropriate support for his needs (s 73F(2)(c), cl 21 of Sch 1, Pt 4 of the NDIS Practice Standards). However, the three contraventions again rise from the same omission and it is appropriate that one penalty is affixed to the conduct.

60 Contraventions 18 to 20 concern the failure, after September 2018, for Valmar to engage a new dietitian for each of the Hemmings Residents from 1 July 2019. This failure manifested in three contraventions of s 73J and 73V by non-compliance with s 6(1)(c) of the NDIS Code of Conduct to ensure any supports and services are provided in a safe and competent manner; of s 73J by breaching a registration condition, namely the identification of and managing risks to participants (cl 10 of Sch 1, Pt 3 of the NDIS Practice Standards); and of s 73J by failing to ensure each Hemmings Resident could access competent and appropriate support for his needs (s 73F(2)(c), cl 21 of Sch 1, Pt 4 of the NDIS Practice Standards). However, the three contraventions again rise from the same omission and it is appropriate that one penalty is affixed to the conduct.

61 Contravention 21 concerns the notation on a plan prepared by a dietitian with words “plan remains current. Feb 2020”, for which a single contravention is sought.

62 Contraventions 22 to 24 concern the manner in which Valmar, in fact, provided mealtime supports to each of the three residents, in the way that they did, between 1 July 2019 and 14 May 2020, the four contraventions again rise from the same omission and it is appropriate that one penalty is affixed to the conduct with respect to each resident.

63 Further, there is no evidence before the Court as to the actual number of times that each participant was provided with food or drink, which did not comply with each of the residents’ most up-to-date, eating and drinking plan. Although Valmar’s investigation in 2020 revealed that non-compliance with the plans as being, in effect, ordinary. As a consequence, as Allsop J has opined, where there are many contraventions it is not helpful to seek to make a finding as to the precise number or to calculate a maximum aggregate penalty by reference to such a number, but rather to determine the penalty assisted by a certain number of courses of conduct leading potentially to a number of contraventions: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 at 546 [18].

The circumstances in which the contraventions took place - the nature and extent of the contraventions (s 82(6)(a)–(c))

64 For the reasons set out above, each of the claimed contraventions has been established based on the agreed facts.

65 The Court is required, by s 82(6) of the RP Act, to take into account all relevant matters including those set out in the sub-section, which include:

(a) the nature and extent of the contraventions;

(b) the nature and extent of any loss or damage suffered because of the contraventions;

(c) the circumstances in which the contraventions took place.

66 As will be apparent from the above, it is indisputable that the nature and extent of the contraventions were of the upmost seriousness.

67 The families of Mr H, Mr K and Mr I, entrusted the care of these three men, to Valmar. Each of these men had complex disabilities. Each were known to be at significant risk of choking. Valmar had known of this risk for a long time, had received expert advice from a dietitian (and in one instance a speech pathologist) as to the simple ways that could be taken to avert this risk, by the provision of and preparation of food (reinforced on a number of occasions).

68 Here, the parties propose penalties, with respect to the three separate course of conduct contraventions, which represent 100% of the statutory maximum for one contravention for the course of conduct that lead to Mr H’s death and 40% of the maximum with respect to the course of conduct as relating to Mr K and Mr I. No submission was made as to why only 40% of the maximum applied to the other conduct relating to the other two residents.

69 It was said with respect to each of the other contraventions (as they relate to the failure to ensure the 13 workers were trained, there was failure to audit or supervise compliance with the dietitian plans, to engage a speech pathologist or engage a new dietitian and by making a false notation as to the currency of a plan) that it was appropriate to award a penalty that was approximately 20% or 30% of the maximum when taking into account the Court’s approach in Livebetter.

70 The Court is concerned about this approach.

71 First, care must be taken to not reduce the highly evaluative exercise to a mathematical one. No doubt by providing the table, the parties sought to be of assistance to the Court. However, a great degree of caution must be exercised by this approach. The affixing of penalties is not a mathematical exercise. The determination of an appropriate pecuniary penalty is a highly evaluative exercise. As observed by Wigney J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2016] FCA 1526 at [144]:

The metaphoric scales, however, do not produce one correct answer. Minds may well differ about the weight and significance to be given to some of the facts and circumstances. Equally, minds may well differ as to the size of the penalty required to achieve the object of specific and general deterrence in all the circumstances. These are not matters of science, mathematics or pure logic. As was pointed out earlier, it is well accepted that the evaluative process involved in determining an appropriate penalty may produce a range of possible penalties, none of which could definitively be said to be more appropriate than any other within that range. Any penalty within that range could be accepted to be an appropriate penalty, even though it may not be able to be said to be the only appropriate penalty.

72 Ultimately, the evaluative exercise involves a consideration of the relevant facts, circumstances and considerations specific to the contravener to determine whether the proposed agreed penalties are within the range of possible appropriate penalties.

73 Secondly, the approach appears to misapprehend the degree of seriousness of the first contravention and is not reflected in the proposed penalty. The gravamen of the contravening conduct was the failure by Valmar to train its employees at all as to how to safely feed these men with known risks of choking. It is not a case where there was some but inadequate training undertaken, rather none at all. There is no explanation for this. There cannot be. To understand just how serious this contravening conduct was, is by remembering the purpose of the scheme: To enable persons with disability, through the provision of tailored high quality and innovative support services, to exercise their autonomy and be included in the community. The entire scheme centres around the provision of high quality support services. Such services cannot be provided, if the workers who provide them, are given no training. The whole scheme fails.

74 The seriousness of this failing cannot be understated. It is from this fundamental failure, that a number of the other contraventions arose.

75 Thirdly, it is problematic to impose a penalty by reference to a percentage said to be referrable to what is perceived to be percentages accepted by the Court in another case. This is particularly so when on any view, the circumstances of this case are more serious than those in LiveBetter—here there was no training of staff (as opposed to a deficiency in training), repeated warnings of the risk of choking, the halting of the provision of the dietitian’s services, and not even adherence to the dietitian’s previous advice, but a changing of the dietary plans (without authority or expertise) in contradiction with the previous expert advice given.

76 As was foreshadowed by Bromwich J in Fair Work Ombudsman v 85 Degrees Coffee Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 1317 at [24], an unfortunate by-product of greater resort to agreed penalties than might otherwise have been the case is that there will be fewer decided cases in which judicial reasoning in support of particular levels of penalty imposition emerge to provide a body of penalty imposition yardsticks to develop the jurisprudence in this area. Here, the circumstances are more stark. There have only been two decisions, both of which, where the penalties were agreed. There has therefore been no proper judicial evaluation of the particular levels of penalty that ought be imposed.

77 It may also be accepted that the other contraventions were objectively serious. Each relating to a discrete underlying obligation that gives rise to the ultimate statutory cloak of protection. It is obvious that there is a need to send a clear message both to Valmar and to other disability support providers as to the consequences of a failure to train and audit or supervise compliance with the relevant dietitian plans.

78 On any view, the amount proposed by the parties, is at the lowest end of the range that could be deemed appropriate, even taking the parties’ submissions and evidence at its highest as to the circumstances of the contravener. The Court would warn against future resort, by extrapolation, to the mathematical manner in which the penalties were agreed (and a suggestion of being in the “range” by reference to this decision and the previous authorities).

79 Ultimately, however, when all of the relevant facts and circumstances (together with all relevant considerations) are weighed in the balance, reluctantly it is my view the agreed penalty is within the range of what could be considered an appropriate penalty, but is at the very lowest possible end of the range. I have, in this regard, also taken into account the fact that a regulator, in this context, is not disinterested, and it can be assumed that the Commissioner has fashioned the penalty submissions, including the agreed amount, “with an overall view to achieving that objective and thus perhaps, if not probably, with one eye to considerations beyond the case at hand”): Agreed Penalties case at [60].

Prior contraventions (s 82(6)(d))

80 I have also taken into account that Valmar has no prior history of contravening the NDIS Act.

81 Account must also be taken of Valmar’s co-operation in these proceedings, agreement as to liability and as to the penalties to be awarded.

Conduct since the contraventions occurred

82 In addition, I have taken into account, when considering the need for general and specific deterrence, the steps Valmar has taken following Mr H’s death.

83 The SOAF (and supplementary SOAF) revealed the following. First, shortly after Mr H’s death, Valmar initiated an investigation which considered whether employees involved had breached Valmar’s Code of Conduct. In the report, dated 24 June 2020, Ms Carr reported that with respect to the relevant support worker, the alleged breaches were not sustained because there was a past practice of Mr H being provided with like (inappropriate) food and inappropriately prepared food. Further, Mr Carr reported finding that various breaches of the Code had been sustained by reason of Mr Rudd’s conduct. Ms Carr recommended: (a) the provision of training to all group homes as to what constituted bite sized and soft food in line with the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative; (b) a formal induction process (in each house); (c) the implementation of meal plans and house plans across all group homes; (d) the introduction of a process that ensured that house coordinators and other coordinators of supports arranged appointments and attendance with specialists for NDIS participants according to their plans; (d) enhanced administrative reporting including that a process capture records/notes of phone conversations with relevant specialists and the creation of an up-to-date “yellow folder” for each client in the house; (e) ensure that team meetings were held according to Valmar policy; and (f) that coordinators and managers ensured any non-compliance be recorded and repeat non-compliance be formally addressed.

84 Secondly, Valmar has, through a registered nurse, implemented training including in relation to shallowing and choking risks. Between November 2020 and May 2021, 200 hundred staff completed the (then) standalone dysphagia training. Staff were informed in May 2021, that with respect to those staff who had not completed the training, they were required to do so that month and if they did not they would not be permitted to work on any shifts with residents who had identified dysphagia or swallowing risk. Further sessions were held in November 2021. From January 2022, the training regarding dysphagia and swallowing issues was incorporated within the “Health Essentials training” that was mandatory for all new starters and was recommended as a refresher course to existing staff. Between 22 February 2022 and 1 October 2024, 314 Valmar staff attended the Health Essentials training, which incorporated the dysphagia training. Given that Valmar employs approximately 566 staff, the evidence reveals that a significant majority of employees (taking into account staff turnover) will have completed some form of dysphagia training.

85 Thirdly, Valmar has implemented additional initiatives to ensure that support workers are not only well trained in the management of choking risks, but to enable them to identify and escalate any signs which might increase a resident’s risk of choking, even if that resident has not previously been identified as suffering from dysphagia. These include the creation of a service induction and initial induction checklist which required that each new staff member and service coordinator confirm that each new staff member had completed the relevant training referred to above. This induction checklist also requires that buddy shifts be completed. In addition, the Mealtime and Dysphagia Policy has been implemented. This Policy:

(a) sets minimum standards for staff training including requiring all staff whose role includes supporting clients at mealtimes to undertake swallowing and dysphasia training;

(b) provides that all clients must have a Nutrition and Swallowing Risk Assessment conducted annually, and if a risk is identified, a speech pathologist is to be engaged for formal assessment and a Mealtime Management Plan is to be developed;

(c) provides that all clients with a Mealtime Management Plan must be reviewed by a speech pathologist annually (or more frequently if determined by the speech pathologist or when an issue is identified); and

(d) specifies mealtime requirements for clients with swallowing issues including as to the implementation of a Mealtime Management Plan, ongoing monitoring and observation during mealtimes, recording of those observations and reporting.

86 As to the Nutrition and Swallowing Risk Assessment, this directs the person completing the checklist to have a General Practitioner or allied health professional review the “Summary of Results” if any question were answered with the words “Yes” or “Unsure/Do Not know” to prescribe action to be taken.

87 Recently, Valmar has created a Mealtime Management Observation record which is to be utilised by service coordinators and managers to perform ad hoc observations of how staff are supporting clients during mealtimes in accordance with their individual needs.

88 Accordingly, it is now mandatory that annual Nutrition and Swallowing Risk assessments are conducted for all residents, with escalation to a speech pathologist if any risk is identified. Furthermore, mandating that all clients already under a Mealtime Management Plan have annual reviews by a speech pathologist, and more frequent reviews if a risk is identified.

89 Accordingly, while in the circumstances of this case, I find that the proposed agreed penalty is appropriate (and at the very bottom of the range), it arose where it was agreed and proposed by the parties. It, therefore, may be assumed that in future, that the Court is likely to impose much higher penalties for like conduct.

Should the Court make the declarations sought?

90 Furthermore, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to make the detailed declarations proposed by the Commissioner (and agreed to by Valmar). They make clear the circumstances of the contravening conduct.

91 The nature of the power and purpose for making declarations was succinctly and pithily described by Abraham J in Afford (at [39]):