Federal Court of Australia

Pacific Current Group Limited v Fitzpatrick [2024] FCA 1480

ORDERS

PACIFIC CURRENT GROUP LIMITED (ACN 006 708 792) Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent ANDREW STUART MCGILL Second Respondent PETER ROBERT KENNEDY (and others named in the schedule) Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 DECEMBER 2024 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant’s proceeding against the first and third to fifth respondents be dismissed.

2. The applicant pay the first and third to fifth respondents’ costs of and incidental to this proceeding concerning the applicant’s claims against those parties.

3. There be a stay on the operation of order 2 until further order.

4. Any period stipulated under the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) for the filing and service of any notice of appeal from orders 1 and 2 be suspended until further order.

5. A case management hearing be fixed at 9.30 am on 7 February 2025 to determine the procedure under which any outstanding issues concerning, inter-alia, any of these orders, the case against the second respondent, any cross-claim between the respondents or any other costs question are to be resolved.

6. To the extent necessary, any prior confidentiality orders made in this proceeding or proceeding VID 608 of 2019 are varied so as to allow public access to and public dissemination of the reasons of the Court published today.

7. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 This proceeding concerns a merger that was completed on 25 November 2014 between Pacific Current Group Ltd (PAC) and Northern Lights Capital Partners LLC (Northern Lights). As part of the merger, each of PAC and Northern Lights transferred substantially all of their assets to a unit trust known as the Aurora Trust in exchange for units.

2 PAC has brought the present proceeding against the then directors of PAC who approved the merger asserting that those directors breached their various statutory and other duties as directors.

3 Now by way of background, in the decade leading up to 2014, the business of PAC involved making investments by taking minority shareholdings in fund managers who were not aligned with major institutions. In these reasons I will refer to these fund managers as boutiques.

4 By 2012, PAC’s boutiques were regarded as too Australian-centric as most were located in Australia and specialised in Australian asset classes. Further, PAC’s income and consequently its ability to pay dividends to its own shareholders largely depended on two mature boutiques. The board of directors recognised that PAC needed to diversify its boutiques including by geography and by asset class.

5 From 2012 to late 2013, PAC endeavoured to diversify, including by merging with or taking over one of its competitors being Pinnacle Investment Management Ltd. This was without success as I will detail later when I discuss the sequence of discussions with representatives of its holding company, Wilson HTM Investment Group Limited (WIG).

6 Now Northern Lights and its related entities had for several years prior to 2014 conducted a similar business to PAC’s business but predominantly in the United States.

7 It was perceived to be advantageous to both PAC and Northern Lights to merge their businesses. And as I have identified, in November 2014 PAC and Northern Lights merged their businesses. PAC and Northern Lights transferred their respective interests in various boutique fund managers to a new, unlisted Australian company, being Aurora Investment Management Pty Limited (the Aurora trustee) in exchange for units in the Aurora Trust.

8 As part of the merger, PAC held approximately 61% of the units in the Aurora Trust and Northern Lights including the interest of BNP Paribas Asset Management Inc held approximately 39% of the units in the Aurora Trust.

9 Now in the proceeding before me PAC asserts that the then directors of PAC who approved the merger breached s 180 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and various other cognate duties at four key decision points. The relevant directors at the time are respondents to the present proceeding.

10 The four key decision points identified by PAC are the following. First, on 24 February 2014 the board of directors resolved that it execute a terms sheet to formalise negotiations for the merger. Second, on 16 April 2014 the board resolved that PAC sign a revised terms sheet. Third, on 23 July 2014 the board resolved that the merger be approved. And fourth, on 16 November 2014 the board signed a circular resolution to proceed with completion of the merger.

11 PAC says that at each of these four key decision points, and particularly on 23 July 2014 when the board resolved that the merger be approved, the directors failed to exercise their powers and discharge their duties with the degree of care and diligence required under the general law and s 180 of the Act.

12 Further, it is said that the directors failed to seek and obtain the approval of PAC’s shareholders to the merger as required by PAC’s constitution and listing rule 11.2 of the ASX listing rules.

13 Let me at this point say something more about the respondents to the proceeding.

14 Mr Michael Fitzpatrick was a director of PAC between 5 October 2004 and 1 March 2019, and the chairman of PAC’s board and a member of PAC’s audit committee at the relevant time.

15 Mr Andrew McGill was the managing director and chief executive officer of PAC between 30 August 2013 and 28 August 2015.

16 Mr Peter Kennedy at the time of trial was a director of PAC and had been from 4 June 2003. He was also the chairman of PAC’s audit committee during the relevant period.

17 Ms Melda Donnelly was a non-executive director and member of PAC’s audit committee from 28 March 2012 to the time of trial.

18 Mr Reubert Hayes was a director of PAC between 22 February 2007 and 31 March 2015, and a member of PAC’s audit committee at the relevant time.

19 Now generally speaking, Mr McGill and Mr Fitzpatrick were largely responsible for effecting the merger. The other non-executive directors, Mr Kennedy, Ms Donnelly and Mr Hayes, were less involved in the proposed merger. I should also note that Mr Hayes was overseas for some of the period in which the key decisions concerning the merger occurred.

20 Before proceeding further and given the wholesale attack made by PAC against the then directors, let me make various observations concerning how the board of PAC operated around the time of the merger and its management practices based upon the voluminous witness and documentary evidence led before me.

21 First, members of the board had both the necessary and sufficient complementary commercial backgrounds, motivations, personalities and skill sets. The productive yield of this was an operative and direct intellectual diversity as between the individuals, which by several orders of magnitude trumped any superficial ex facie diversity or irrelevant self-referential identification. This advantageously reflected itself in the decision-making processes of the board and the debates which took place.

22 Second, given that the time frame of the decision-making processes under consideration was over ten years ago, there was little in the way of meretricious mission statements and correlative performative processes that one normally associates with public companies these days.

23 Third, the board operated a relatively lean management structure where shareholders’ funds were efficiently managed and spent for proper purposes. This was all quite refreshing when one compares this to many boards of public companies today that even go so far as to pride themselves on allocating shareholders’ funds to social causes of the directors for which they have an affinity or affection, with such expenditure or donation of others’ money purportedly justified by little more than humbug and adding no real economic value to the company and its shareholders.

24 Fourth, meta-themes concerning social licence theory can be put to one side. They are a superfluous add-on to the legislative regime applying to directors and companies. It is not necessary to cite Milton Friedman to state the obvious. Any so-called social licence granted on incorporation has its boundaries and content provided by the company’s constitution and the detailed legislative regime, albeit ultimately built upon social policy. Nothing more, nothing less.

25 In summary, and notwithstanding the litany of complaints made by PAC against the then directors, in my view the board of PAC and the management of PAC appears to have been well run, generally speaking.

26 Now each of the directors gave evidence and was cross-examined at trial. Further, I directed that Mr Fitzpatrick be recalled for further cross-examination to address some matters that arose during Mr McGill’s cross-examination. I will say something more about their evidence later.

27 Now in its third further amended statement of claim, PAC alleges that by voting in favour of specific resolutions in relation to the merger in 2014, each of the directors breached his or her statutory duty under s 180 of the Act and their common law and equitable duties to PAC to exercise reasonable care, thereby causing it loss. For the moment I will not distinguish these duties by characterisation but merely refer to their characterisation in the singular. The directors have denied such breaches.

28 The first claim of breach of duty concerns the decision to vote in favour of the resolution passed at the board meeting on 24 February 2014 that PAC enter into a non-binding terms sheet with Northern Lights in the form contained in the board papers for that meeting.

29 The second claim of breach of duty concerns the decision to vote in favour of the resolution passed at the board meeting on 16 April 2014 that PAC sign a revised terms sheet with Northern Lights in the form put before the board.

30 The third claim of breach of duty concerns the decision to vote in favour of the resolution passed at the board meeting on 23 July 2014 that approved the merger subject to various conditions being satisfied or waived. I will refer to this as the transaction documents execution resolution.

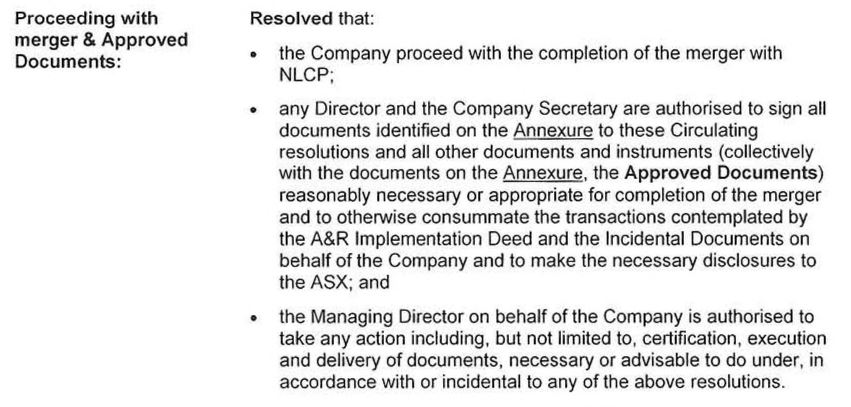

31 The fourth claim of breach of duty concerns the signing by each of the directors on or prior to 16 November 2014 of the circular resolution to proceed to complete the merger and to authorise execution of the documents necessary to achieve completion.

32 The fifth claim of breach of duty concerns the decision to vote in favour of the transaction documents execution resolution and the signing of the circular resolution without first causing PAC to seek or obtain approval of the merger from PAC’s shareholders in an extraordinary general meeting as allegedly required by PAC’s constitution and rule 11.2 of the listing rules of the ASX. A related claim involves PAC seeking restitution of the value of PAC’s assets allegedly dissipated as a result of the contraventions. PAC alleges that by failing to obtain shareholder approval, the transaction documents execution resolution and the circular resolution were ultra vires. Further, it is alleged that by failing to obtain shareholder approval, the directors breached their duty in equity to exercise care and diligence to ensure that PAC’s assets were applied in accordance with PAC’s constitution.

33 Now I should at this point note various allegations which are no longer pressed by PAC.

34 First, it is no longer pressed that the directors breached their duties of care and diligence by voting in favour of the merger in the absence of any analysis of the broader US funds management market including regulatory risk.

35 Second, it is no longer said that the directors breached their duties in failing to seek shareholder approval, even in circumstances where, on an alternative scenario to PAC’s principal case, such approval may not have been required by the listing rules or PAC’s constitution.

36 Now in addition to the claims against all directors, PAC has made separate allegations against Mr McGill claiming that he breached his duties in the following respects. First, it is said that he failed to give the non-executive directors the Deloitte due diligence report. Second, it is said that he failed to bring to the non-executive directors’ attention two versions of the financial model prepared by Gresham Advisory Partners Limited (Gresham) and information concerning risks as to whether WHV Investment Management Inc (WHV) would make a distribution to Northern Lights. WHV was formerly known as Wentworth, Hauser and Violich, Inc.

37 Mr McGill has also filed a cross-claim against Mr Fitzpatrick in respect of the alleged failures concerning WHV and the financial modelling of WHV’s value in the merged business and the alleged failures to bring matters to the attention of the other board members prior to them resolving to enter into the merger.

38 Now the present trial has focused on the principal liability issues, with issues such as relief and specific statutory questions including potentially under s 1317S or s 1318 postponed to a second stage to the extent necessary.

39 In summary and for the reasons that follow, in my view PAC’s claims against Mr Fitzpatrick, Mr Kennedy, Ms Donnelly and Mr Hayes have not been made out. PAC’s case against them will be dismissed.

40 And as to PAC’s case against Mr McGill, in my view the only part of its case that it has made out against Mr McGill concerns various issues relating to the WHV dividend and appreciation rights agreement and the question of the potential dividends and distributions. I will hear further from Mr McGill and PAC concerning any outstanding questions including as to relief.

41 Now before proceeding further, I should deal with one other matter by way of background. On 20 February 2020, orders were made by Moshinsky J in proceeding VID 608/2019 pursuant to s 237 of the Act granting leave to Mr Michael de Tocqueville and ASI Mutual Pty Ltd, two shareholders of PAC, to bring proceedings on behalf of PAC against certain of its directors and former directors. Pursuant to those orders, those shareholders commenced the present proceeding before me on behalf of PAC.

42 Now in terms of my detailed reasons, it has been convenient to divide my discussion into the following topics:

(a) Some relevant background – ([43] to [148]).

(b) Relevant witnesses and evidentiary questions – ([149] to [222]).

(c) General principles: directors’ duties – ([223] to [302]).

(d) The sequence of events – ([303] to [754]).

(e) The alleged breaches of directors’ duties – ([755] to [1253]).

(f) The question of shareholder approval — listing rule 11.2 – ([1254] to [1422]).

(g) General principles concerning listing rule 11 – ([1423] to [1509]).

(h) The ultra vires question – ([1510] to [1628]).

(i) Relevant facts concerning WHV – ([1629] to [1858]).

(j) The various issues concerning WHV – ([1859] to [2193]).

(k) The terms of the implementation deed – ([2194] to [2257]).

(l) Voting in favour of the circular resolution – ([2258] to [2265]).

(m) Causation – ([2266] to [2304]).

(n) Some aspects of potential loss and damage — Pinnacle and WIG – ([2305] to [2446]).

(o) Sections 1317S and 1318 potential application – ([2447] to [2453]).

(p) Conclusion – ([2454] to [2455]).

Some relevant background

43 Prior to the merger, PAC was an ASX-listed investment and financial services business based in Australia.

44 PAC, which was until 18 October 2015 known as Treasury Group Limited, was at all material times engaged in the business of investing in fund managers. Its business model involved investing capital in and providing support services to fund managers or boutiques. In these reasons and for convenience I will simply refer to PAC.

45 As at 12 November 2013, PAC’s business insofar as it involved investing in fund managers comprised holding interests in the following boutique fund managers being Investors Mutual Ltd (IML), Orion Asset Management Ltd, RARE Infrastructure Ltd (RARE), Celeste Funds Management Ltd, Aubrey Capital Management Ltd, Evergreen Capital Partners Ltd, Octis Asset Management Pte Ltd, Treasury Asia Asset Management Ltd, Global Value Investors Limited and AR Capital Management Pty Ltd.

46 As at 21 February 2014, approximately 60 per cent of PAC’s forecast financial year 2014 earnings were generated from its 40 per cent ownership of RARE, and approximately 30 per cent of PAC’s forecast financial year 2014 earnings were generated from its ownership of IML.

47 If the owners of the remaining 60 per cent of RARE put it up for sale, PAC had a right of first refusal to purchase the 60 per cent it did not own. If it did not exercise its right to purchase the remaining 60 per cent, it could be obliged to sell its 40 per cent interest to the purchasers of the 60 per cent interest.

48 At around this time, there was an increasing possibility of RARE being divested within the next 12 months. If RARE was divested, PAC’s earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) would fall by approximately 85 per cent. PAC’s net profits after tax (NPAT) might fall by a lesser amount depending upon whether or not the RARE divestment proceeds were returned to shareholders. If the divestment proceeds were retained, interest income would have become the largest component of NPAT until there were significant new investments completed.

49 Now I note that there was an inherent risk in investing in boutiques and of PAC’s own expertise in selecting investments in boutiques. So, between 2003 and 2014, PAC made 10 investments that failed or meandered until being sold for no profit, during which period PAC made 3 investments which were successful. This experience of investing in boutiques in a volatile industry is significant to some of my later discussion. What PAC alleges were “red flags” were regarded by the directors for the most part as matters which needed to be considered when making a decision to merge.

PAC before the merger

50 In early 2014 PAC was a small but profitable company in ASX terms. It had a small paid-up capital, a small number of shareholders, a five-member board including the CEO, a small number of executives, a small number of employees and an office which was part of one floor of a building in Martin Place, Sydney.

51 In the financial year (FY) ended 30 June 2014, PAC had issued capital of 23,697,498 $0.50 shares. PAC’s top 20 shareholders consistently held over 50% of PAC’s shares. PAC’s NPAT for FY14 was $13.06 million.

52 In 2014 PAC had a workforce of 16, being 3 executives, 6 managers and 7 other employees.

53 In 2014, board meetings usually occurred in PAC’s Sydney office, but the board regularly held meetings where some or all directors participated by telephone.

54 Mr Fitzpatrick ran board meetings in a collegiate manner. The board papers were delivered a few days ahead of a board meeting. Mr Fitzpatrick would take agenda items in the order that suited the board or executives or advisers attending the meeting. On any given agenda item he asked each of the other directors what he or she thought and he encouraged dialogue. After every director, including him, had had a say, he would summarise what the board decision was to ensure it reflected the discussion. He was careful about formal board resolutions and often discussed the wording with the directors slowly until they all agreed upon it.

55 There were various board committees. In 2014, and as I have said, each of the non-executive directors was a member of PAC’s audit committee.

A little about boutiques

56 A boutique obtains funds from sources including institutional investors such as industry superannuation funds and life insurance companies, employers on behalf of employees and retail investors including high wealth individuals and people who manage their own superannuation funds.

57 A boutique typically invests the funds in a particular asset class or classes such as Australian or international equities, bonds and infrastructure assets according to the boutique’s investment strategy.

58 The boutique makes its money by charging the investors a fee for managing the funds. Ordinarily, a substantial part of the fee is calculated as a percentage of the funds under management. In addition, performance fees may be charged if the boutique outperforms industry benchmarks.

59 A boutique is usually founded by one or two people with investment or industry experience. Most founders have worked for some years as an investment manager or merchant banker for an institutional investor and have an established record and reputation as an investor or advisor.

60 When a boutique commences, one of the challenges to its business is finding the money to pay expenses until the boutique generates sufficient income to break even. PAC provided to boutiques those funds by investment or loan.

61 Further, back-office management issues such as regulatory compliance needed to be solved. Until a boutique became mature and able to employ the necessary staff, a boutique would solve these issues by outsourcing them to a service provider which was paid for performing the back-office functions. PAC provided such services for a fee to boutiques in which it invested.

62 Now another aspect of the varying skills of the founders of a boutique was their ability to attract funds under management.

63 In the funds management industry the process of obtaining institutional or retail funds to manage is called distribution or sales. A start-up boutique would need assistance with distribution and it usually did this by hiring a distribution team or by paying third parties for distribution services.

64 Now once a boutique started to generate income it took time for it to break even. For each boutique there is a funds under management figure at which it breaks even and covers its expenses.

65 It can take up to 3 years for boutiques to break even. The challenge facing the boutique is financing its operations up to the break-even point. So, it can take a long time for a start-up boutique to impact on PAC’s profitability.

66 Once the boutique starts operating and is receiving investment funds, performance is very important. Institutional investors will move their money from one fund manager to another if the manager’s investment strategy is not producing returns at the level predicted, and will move it even quicker if performance is below the average return of fund managers generally.

67 The problem of funds under management outflows is not so great with retail funds because retail investors tend not to change investments so often and so quickly, which is why money from retail investors is termed sticky money by fund managers.

68 Poor performance comes about either because the boutique is invested in the wrong market sector, for example, in Australian equites at a time when equities in the United States outperformed Australian equities, or the boutique simply makes poor choices.

69 Poor performance ultimately leads to more distribution problems. As the funds under management shrinks, it is harder for a distributor to persuade an institutional investor to invest funds in what the market may perceive as a sinking ship.

70 Boutiques do not have shareholders with the resources of institutional fund managers and so stagnating or outflowing funds under management for a few years often leads to closure.

71 On the other hand, if the boutique exceeds estimated returns or the market average rates of return or wins an industry award, funds under management inflows occur and can do so rapidly. This can make the boutique very profitable relatively quickly because once the boutique reaches a level of funds under management that allows it to break even or reach the funds under management threshold for performance fees to be payable, the expenses do not proportionally increase. Rather, the same investment team just makes larger investments without the boutique employing extra investment personnel.

72 After a boutique reaches a break-even, it takes about a further 1 or 2 years before it can be said with confidence that the boutique will be successful, bounce along breaking even or fail. It can take longer. Events like the global financial crisis make it more difficult to determine whether a boutique will fail because funds under management disappear for all fund managers.

73 By FY14 PAC’s business had been investing in boutiques and providing distribution, regulatory compliance and other services to boutiques for a fee via PAC’s subsidiary Treasury Group Investment Services Ltd.

74 PAC usually invested by taking a minority shareholding in a boutique, but PAC also provided seed capital by making loans to boutiques until they broke even. PAC was not itself a fund manager. It did not receive funds from institutions or others to invest on their behalf.

75 PAC monitored the boutique by usually having one of PAC’s directors or executives sit on the board of the boutique. The boutiques reported to PAC regularly about their performance.

76 Because PAC was not taking a controlling interest in a boutique in which it invested, there was always a shareholders’ agreement which provided a mechanism for PAC to buy out the founders and vice versa if certain events occurred. A typical triggering event was a proposed sale by either the founders or by PAC of their shareholding in a boutique. If either wanted to sell, the other could acquire the shareholding. If founders wanted to sell their shareholding, PAC’s policy has always been to sell its shareholding to the purchaser.

77 Now valuing a boutique, particularly in its start-up phase, is difficult for several reasons.

78 First, most of the market sectors in which boutiques operate are volatile, which means funds under management can move to or from a boutique quickly if the market changes or changes relative to other sectors. So an investor in a boutique is making assumptions about the sustainability or viability of the boutiques’ chosen investment sector.

79 Second, the value of the boutique depends on its ability to attract and retain funds under management. This largely depends on the founders’ skills. They have to obtain mandates and have a good investment performance. This in turn depends upon the founders staying with the business and keeping the investment team together. Boutiques are really about the founders. An investor is making a judgment about the founders’ ability to do these things. A lot depends on experience and reputation of the founders prior to them wanting to start a boutique, and the only way to assess these sorts of matters is to meet the founders and discuss strategies, performance and expectations.

80 Until the merger, the role of the CEO and his executive team was to identify and evaluate a potential boutique investment. Sometimes the founders would approach PAC because of PAC’s model, but usually PAC’s management learned that a well-known institutional investment executive was thinking of starting a boutique and PAC approached the executive. After due diligence, PAC management would advise the board about an investment if one was potentially advantageous to PAC. PAC’s executives and some of its employees were skilled at providing an assessment of the calibre and potential of founders and their boutiques.

81 The progress with respect to potential investments was reported on regularly by the CEO. By 2013 a regular document in the papers for a board meeting was a deal pipeline memorandum which listed management’s progress with potential investments in boutiques.

82 A recommendation to invest in a boutique was usually contained in a separate paper to the board. PAC had a rigorous approach to assessing potential boutiques and PAC ended up investing in very few of them. The papers took different forms but contained much the same detail.

83 Now investing in boutiques is inherently risky as I have indicated. From 2003 to 2014 PAC’s investments showed mixed results.

84 PAC’s investment in IML in 2003 was very successful. PAC’s stake in IML varied to up to 50% over the years. IML specialised in long only investing in Australian equities. IML was based in Sydney.

85 IML’s funds under management at 30 June 2014 were $4.9 billion.

86 PAC sold its 40% stake in IML in FY18 for $120 million. PAC made more than 30 times the value of its original investment in IML.

87 PAC acquired 40% of RARE in 2007. After a slow start RARE’s funds under management increased extremely rapidly from 2009 and it became one of PAC’s best investments.

88 RARE specialised in the investment and management of securities in the global listed infrastructure sector, including airports, gas, electricity, water and roads. RARE had product offerings in Europe, North America and Australia.

89 RARE’s funds under management at 30 June 2014 were $9.1 billion.

90 In FY16, PAC sold 75% of its interest in RARE, retaining 25%. So after the sale, PAC held 10% of RARE. PAC received $112 million up front with the right to further payments up to $42 million depending on RARE’s performance. Coupled with the dividends and trust distributions from RARE, the return on the sale of the 30% stake in RARE meant a cash return of 33 times PAC’s investment. PAC sold its remaining 10% stake in FY19 for $21.5 million plus dividends.

91 ROC Partners Pty Ltd was based in Sydney and specialised in investing in Asia Pacific markets. PAC invested in ROC in FY14 and had an initial holding in ROC of 15% which it increased to 30%. ROC’s funds under management at 30 June 2015 were $5.3 billion.

92 Let me say something about investments that succeeded at first and then failed.

93 Orion Asset Management Ltd was an example of a boutique which had been very successful for about 10 years and paid good returns to PAC, which fell out of favour with institutions very quickly after poor investment returns and reputational damage as a result of one of its employees being charged with and being later convicted of insider trading.

94 PAC originally invested in Orion in FY02 and increased its holding in Orion from the original 19% to 42% by FY06. Orion specialised in investing in Australian equities. Orion was based in Sydney. Orion closed its fund management operations in FY14.

95 Further, many of PAC’s investments failed or were not successful usually due to a failure to attract sufficient funds under management.

96 Confluence Asset Management Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY04, specialised in investing in ASX listed companies that had a small capitalisation. Confluence was based in Melbourne. By FY06 Confluence’s funds under management were $233m and in FY07 they were $376m. Confluence was not sustainable at those levels of funds under management and its operations were wound down in FY08. PAC lost its investment.

97 Global Value Investors Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY05, was a Melbourne based boutique. GVI specialised in investing in global equities.

98 Treasury Asia Asset Management Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY06, was based in Sydney and also had offices in Singapore. TAAM specialised in investing in Asian and Pacific equities. TAAM failed because of deteriorating investment performance. PAC sold its stake in TAAM in FY14 at a price that recovered PAC’s capital outlays without any profit.

99 Cannae Capital Partners Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY08, was based in Sydney. Cannae failed and was merged with IML in FY10. Mr Hugh Giddy, Cannae’s founder, went to work for IML. PAC wrote off its investment in Cannae in FY10.

100 AR Capital Management Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY10, was Melbourne based and specialised in investing in Australian equities. AR Capital never attracted sufficient funds under management to survive and once its founders left in FY12 it was doomed. AR Capital ceased trading in FY14 and was wound up in FY15.

101 Celeste Funds Management Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY10, was based in Sydney and invested in Australian equities. PAC sold its investment in Celeste in 2018 for $1.6 million.

102 Aubrey Capital Management Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY10, was based in Edinburgh and specialised in investing in global equities. Aubrey never attracted sufficient funds under management to break even.

103 Evergreen Capital Partners Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY12, was based in Melbourne and specialised in investing in Australian equities. Evergreen was another boutique that did not attract enough funds under management to survive. In FY14 Evergreen merged with a property fund manager, Freehold Investment Management Ltd, and PAC obtained an interest in Freehold. PAC sold its interest in Freehold in October 2019 for book value.

104 Octis Asset Management Pty Ltd, in which PAC invested in FY13, specialised in investing in Asian equities. Octis was based in Singapore. Octis was not able to attract sufficient funds under management to continue. PAC’s 20% interest in Octis was sold in FY16 with PAC’s outlaid capital being recovered but with no profit.

General

105 PAC’s share price and its ability to pay dividends to PAC’s shareholders depended on the dividends, distributions and interest that it received from its boutiques and to a lesser extent on the fees it received for PAC’s services.

106 PAC’s dividends paid for FY13 and FY14 were $0.40 and $0.50 per share respectively.

107 There was a significant increase in the dividends paid by PAC over the period from FY09 to FY14 due to the performance of IML and RARE and the dividends and distributions they paid PAC.

108 The challenge with PAC’s investment model was that PAC had to continue to find and make boutique investments with the aim that one of them would succeed and replace the income that would be lost if one of PAC’s mature successful boutiques was sold or collapsed like Orion.

109 If PAC could not make a series of new boutique investments, PAC risked a mature boutique like IML or RARE being sold. Whilst such a sale might produce a one-off significant taxable capital gain for PAC in one FY, as it ultimately did with IML and RARE, going forward PAC would lose the revenue it had been receiving from that boutique. Consequently PAC’s share price would suffer as its ability to pay dividends would diminish.

110 Now in July 2011 the board had recognised that PAC’s investments were too Australian focused, both in terms of the locations of its boutiques and in terms of investment sectors. Because the majority of PAC’s boutiques specialised in Australian equities, PAC risked funds under management stagnating or shrinking if other sectors outperformed Australian equities.

111 The board had already started to address the problem of PAC being too focused on Australia before Mr McGill became CEO in July 2011 with the acquisition of Aubrey in FY10. However, being located in Australia made it difficult for PAC to form the relationships with northern hemisphere founders that might lead to an investment in a boutique.

112 Let me at this point say something about Northern Lights and its boutiques.

Northern Lights

113 Northern Lights was founded in 2006 and headquartered in Seattle, USA. At all material times, Northern Lights was a private limited liability company incorporated under the laws of Delaware, and carried on the business of funds management and investing in fund managers, including in the USA and UK until 25 November 2014. Its assets which were illiquid were investments in private boutique fund managers.

114 First, prior to the merger there were holdings in several boutique fund managers, including Seizert Capital Partners LLC (Seizert), Alphashares LLC (Alpha), del Rey Global Investors LLC, Elessar Investment Management LLC, Tamro Capital Partners LLC (Tamro), and Aether Investment Partners LLC (Aether).

115 Second, there were a number of investments in immature and alternative boutique fund managers including Blackcrane Capital LLC (Blackcrane), EAM Global Investors LLC (EAM), Goodhart Partners LLP (Goodhart), Nereus Holdings LP (Nereus), Northern Lights Alternative Advisors LLP, and Raven Capital Management LLC (Raven).

116 Third, I should say something about WHV. Northern Lights had no equity interest in WHV, only certain contractual rights pursuant to a dividend and appreciation rights agreement. I will return to discuss this in more detail later.

Implementation of the merger

117 Between July and November 2014, PAC and Northern Lights and the Aurora trustee entered into a series of agreements to implement the merger. Those agreements included the following: a deed of amendment to the Aurora Trust; a replacement constitution of the Trustee; an implementation deed between PAC and Northern Lights and an implementation agreement and restatement deed between PAC and Northern Lights; PAC’s implementation deed – disclosure letter and Northern Lights’ implementation disclosure letter; a securities sale agreement between PAC and the Trustee; a PAC other assets contribution deed and PAC other assets services deed; an exchange deed between PAC, Northern Lights and Class B parties; a unitholders deed between PAC, Northern Lights, NL Sub Y LLC (NL Sub Y), BNP Paribas Asset Management Inc (BNP Paribas), various key employees and the Trustee; a partnership allocation deed between PAC, Northern Lights, NL Sub Y, BNP Paribas and the Trustee; a securities sale deed between PAC and Treasury RARE Holdings Pty Ltd; a contribution agreement between Northern Lights and Northern Lights Midco LLC (Northern Lights Midco) and first amendment to contribution agreement; an amended and restated limited liability company agreement of Northern Lights Midco; a subscription agreement between NL Sub Y, LLC and the Trustee; a contribution and assignment agreement between Northern Lights, NL Sub Y and NL Sub LLC (NL Sub); a first amendment to dividend and appreciation rights agreement; a securities sale agreement between Northern Lights and the Trustee; a Medley committed loan notice; an Aether purchase agreement; an Aether securities purchase agreement; an Aether third amended and restated limited liability company arrangement; and a Seizert promissory note.

118 The key agreements and deeds were executed on or around 4 August 2014 and between 21 and 24 November 2014. I will analyse aspects of these instruments later.

119 As part of the merger, PAC and Northern Lights created the Aurora Trust and the Aurora trustee. And PAC and Northern Lights transferred substantially all of their boutiques to the Aurora Trust in exchange for units. Let me set out some of the detail concerning the merger.

120 PAC was given consideration in the form of units in the Aurora Trust of $255,624,260 for the transfer of its net assets to the Aurora Trust.

121 Northern Lights was given consideration in the form of units in the Aurora Trust of $161,925,984 for the transfer of its net assets to Northern Lights Midco which became a wholly owned subsidiary of the Aurora Trust.

122 Northern Lights and BNP Paribas were issued 32,771,555 and 9,228,445 class X redeemable preference units respectively in the Aurora Trust with an aggregate issue price of USD 42 million (XRPUs).

123 NL Sub Y, a company owned 99% by Northern Lights and 1% by NL Sub, and BNP Paribas were issued 11,704,127 and 3,295,873 class Y redeemable preference units respectively in the Aurora Trust with an aggregate issue price of USD 15 million (YRPUs).

124 A debt of USD 45.6 million was drawn down by Northern Lights Midco to fund cash payable in relation to additional equity in Seizert and Aether.

125 The Aurora Trust issued debt notes with an aggregate value of USD 17.5 million on completion of the acquisition of Seizert.

126 Now at the completion of the merger the following was the position.

127 PAC was issued 23,837,479 class A units in the Aurora Trust representing 61.22% of all the units in the Aurora Trust and 2,065,000 class A-1 units in the Aurora Trust.

128 Northern Lights and BNP Paribas were issued 11,782,095 and 3,317,830 class B units in the Aurora Trust, representing 38.78% of all the units in the Aurora Trust, and 2,140,503 and 235,194 Class B-1 units in the Aurora Trust.

129 Further, as part of the merger, the following transactions also took place.

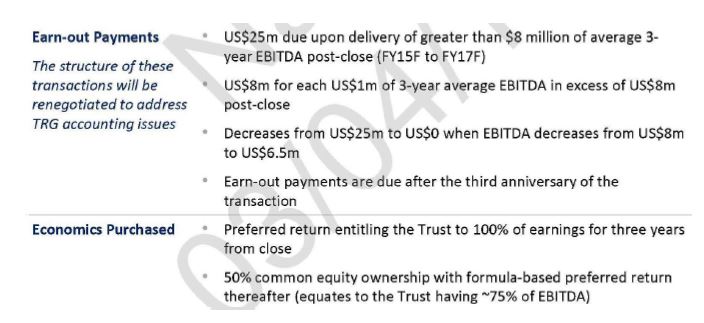

130 First, let me say something about the Aether transaction. Northern Lights Midco and a further Northern Lights subsidiary, Northern Lights Earn Out Co LLC (Earn-Out Co) acquired the remaining equity in Aether for consideration of USD 40 million plus additional earn-out payments and further cash consideration of USD 3.7 million. And the Aether company management agreement was amended so that Northern Lights Midco, which was the manager of Aether, and Earn-Out Co had rights to certain income distributions.

131 Second, let me say something about the Seizert transaction. Northern Lights Midco acquired the remaining equity in Seizert in exchange for Seizert debt notes, being notes with an aggregate value of USD 17.5 million, and upfront cash consideration of USD 21 million, and deferred cash consideration of USD 7 million (USD 6 million to be paid by PAC and USD 1 million by Northern Lights). Further units were issued to the Seizert employees.

132 Now as part of the merger, the Aurora trustee assumed debts of approximately AUD 131,191,729, comprising the following.

133 First, on 24 November 2014, Northern Lights entered into a debt facility of USD 47 million with Medley Capital Corporation (the Medley loan). The facility was entered into to fund the acquisition of additional equity in Seizert and Aether. The Medley loan was repaid by the Aurora Trust on 4 January 2016 for USD 45.85 million.

134 Second, the Aurora Trust issued debt notes amounting to USD 17.5 million to the former owners of Seizert as part of the consideration for the acquisition by Northern Lights Midco of the equity interest in Seizert. The Seizert debt notes were paid in 2018 and 2020.

135 Third, as I have indicated, 42 million XRPUs were issued to Northern Lights and BNP Paribas. The repayment obligations were contingent on the performance of certain boutiques contributed to the Aurora Trust. At the merger date, the XRPUs had a value of USD 35 million.

136 Fourth, as I have indicated, 15 million YRPUs were issued to NL Sub Y and BNP Paribas with a total redemption price of USD 15 million.

Events subsequent to the merger

137 The first meeting of the Aurora trustee’s board saw a report from Mr McGill, who was its CEO, dated 3 December 2014 which indicated, inter-alia, the following matters.

138 First, following the merger, group liquidity was very low.

139 Second, critical cash inflow assumptions for December and January included, as a top priority, the WHV dividend of USD 2 million in December 2014.

140 Third, if actual cash receipts were lower than the inflow assumptions then this could potentially have significant liquidity consequences for Aurora.

141 No WHV dividend was declared or distribution paid in 2014.

142 By 30 June 2015, the Aurora Trust’s interest in WHV was written off.

143 Following the merger, PAC’s interest in the Aurora Trust was increased. On or around 13 April 2015, PAC’s interest in the Aurora Trust increased to 64.03%. And on or around 7 September 2015, PAC’s interest in the Aurora Trust increased to 65.15%.

144 On 13 April 2017, the Aurora Trust became wholly owned by PAC.

145 In the period between the merger closing on 24 November 2014 to 30 June 2017, the Trustee wrote down the carrying value of the former Northern Lights boutiques by approximately AUD 218,340,159.

146 This is reflected in the following table:

Impairments (AUD) | |||

Boutique | Period to 30.6.15 | Year to 30.6.16 | Year to 30.6.17 |

Nereus | 8,878,967 | 11,212,884 | 7,647,988 |

WHV | 16,806,616 | ||

Raven | 9,659,917 | 417,705 | |

Alpha | 3,030,325 | ||

TAMRO | 1,713,430 | ||

Seizert | 85,307,202 | 15,860,138 | |

Aether | 51,318,027 | ||

Blackcrane | 3,699,459 | ||

Goodhart | 14,564 | ||

NL Alternative | 368,815 | 2,404,122 | |

Annual Total | 25,685,583 | 111,292,573 | 81,362,003 |

Total to 30 June 2017 | 218,340,159 | ||

147 In the year ending 30 June 2016, PAC reported a net loss of AUD 48.2 million.

148 I will return later to discuss the specific and relevant sequence of events.

Relevant witnesses and evidentiary questions

149 Let me say something about the respondent directors.

Evidence of the directors

150 As at 2014 Mr Kennedy had been the longest serving of the directors having been appointed a director on 4 June 2003. At the time of trial he still remained a director. He had extensive experience in commercial law and had been a director of other public and private companies.

151 Mr Kennedy was careful in his evidence during cross-examination. He answered questions directly, although he was a little feisty at times in response to some of my gentle queries. Nevertheless he was an impressive and reliable witness.

152 Mr Fitzpatrick was a director of PAC from 5 October 2004 until 1 March 2019 and its chairman for most of that period. Through his companies in 2014 he owned about 11.45% of PAC’s shares. Mr Fitzpatrick had had extensive experience in the funds management sector. He had also had considerable experience as a company director.

153 Mr Fitzpatrick made numerous concessions in cross-examination, particularly where he accepted his inability to recall discussions and events from 2013 and 2014. Mr Fitzpatrick’s evidence was thoughtful and reliable.

154 Mr Hayes was a director from 22 February 2007 to 26 November 2012. He had been the founder of Ausbil Dexia Ltd, a boutique, and part of Barclays Bank’s Australian investment operations. Mr Hayes had an extensive knowledge and understanding of boutiques and investment operations generally.

155 Mr Hayes was the first to acknowledge that there were limitations on his ability to give detailed evidence due to his failing memory. Mr Hayes was 80 at the time of giving evidence. Despite these difficulties, Mr Hayes’ high level evidence on factors that caused him to vote in favour of the merger was generally reliable.

156 Ms Donnelly joined the board on 28 March 2012. Her background was in accounting and tax and then funds management. She held management positions at Australia New Zealand Banking Group Limited and Queensland Investment Corporation.

157 Since finishing as CEO at QIC, she had established, and then sold, her own company which educated investment executives in the superannuation and funds management industry world-wide.

158 She has held numerous directorships on the boards of public and private fund managers and has held positions on the investment committees of government and private investment bodies and industry superannuation funds.

159 Ms Donnelly, although she was prepared to make concessions, was firm in what she recalled. She gave short and sharp reliable answers. I accept Ms Donnelly’s evidence unequivocally.

160 Mr McGill was PAC’s chief executive officer. He had been employed as CEO by PAC in July 2011. He was appointed as a director of PAC in August 2013. He ceased to be a director on 28 August 2015.

161 Mr McGill had an impressive employment history with decades of experience in investment banking before coming to PAC. His experience included being a strategy consultant at LEK Partnership, holding senior roles in Macquarie Bank’s corporate finance and direct investments teams and then being the founding partner at Crescent Capital, which was an independent specific purpose private equity firm, and where he worked from 2000 to 2010.

162 Most of Mr McGill’s evidence was honestly given, although there were some problematic aspects which I will discuss in more detail later concerning the reliability of his evidence on the WHV question.

163 It is necessary at this point to identify some other individuals and entities who are relevant to the events.

PAC executives and employees

164 Mr Joe Ferragina was PAC’s chief financial officer and had extensive business qualifications. By 2014 Mr Ferragina had been PAC’s CFO for about 10 years. Before that he had extensive experience in finance roles at large organisations.

165 Mr Ferragina’s responsibilities included all of the financial aspects of PAC’s business such as the preparation of financial statements. He was also involved in analysing potential investments that PAC may make in a boutique.

166 Mr Ferragina’s regular reports to the board included reports about PAC’s finances. His reports were incorporated into Mr McGill’s CEO reports to the board.

167 Based on his work the board considered Mr Ferragina to be a very capable financial officer with a good knowledge of funds management. He sat on the boards of some of PAC’s boutiques.

168 Mr Andrew Howard was PAC’s chief investment officer. He started at PAC in August 2013.

169 Mr Howard had qualifications in business and in finance before working for PAC. Mr Howard was chief investment officer for the Asia Pacific region at Mercer (Australia) Pty Ltd, part of an international firm specialising in investment consulting, wealth management and associated professional financial services. He had 15 years’ experience in assessing fund managers’ performance.

170 Mr Howard’s role at PAC was to assist in identifying and assessing boutiques which PAC might invest in. Mr Howard developed PAC’s portfolio of investment products and identified and reported on new boutique investment opportunities.

171 Ms Ramswarup was PAC’s company secretary before and during 2014. Her involvement in the merger was peripheral in that she took board minutes, circulated some emails about board meetings and undertook general administrative functions for, and at the request of, the board.

172 Ms Batoon had an accounting qualification. In 2014 she was PAC’s finance manager. She reported to Mr Ferragina. She had previously worked and had experience in accounting for, and integrating finance activities relating to, mergers and acquisitions, minority interests and various types of financial instruments.

Northern Lights’ executives

173 Mr Paul Greenwood was a managing director of Northern Lights.

174 Mr Jack Swift was a managing director of Northern Lights and the sales and distribution manager of WHV.

175 Mr Timothy Carver was an executive director and co-founder of Northern Lights and a director of WHV from around the beginning of 2013.

176 Mr Trent Erickson was the chief financial officer of Northern Lights.

177 Mr David Griswold was the general counsel and chief compliance officer of Northern Lights.

178 Mr Jeff Vincent was a non-executive director of Northern Lights. He was also the CEO of Laird Norton Investment Management, Inc., which was a major shareholder in Northern Lights and the sole shareholder of WHV. Mr Vincent was also a director of WHV.

179 Mr Andy Turner was a non-executive director of Northern Lights and one of the original founding partners of Northern Lights. He was a significant shareholder, owning approximately 25% at about May 2014. However his direct involvement with Northern Lights was relevantly through the running of WHV as CEO since the beginning of 2013 and as a board member of Northern Lights.

Gresham

180 Gresham was a typical merchant bank type advisor and was highly regarded in its field.

181 PAC had retained Gresham between 2011 and 2013 with respect to the proposed acquisition of Pinnacle Investment Management Ltd and so the directors were familiar with the quality of Gresham’s analysis and work product. In particular, Gresham had valued both Pinnacle and WIG, which owned about 83% of Pinnacle, in 2012 and 2013, respectively.

182 The project name given to the merger and which was used by Gresham and others was Project Bondi. The Gresham executives advising PAC with respect to Project Bondi were Mr Charles Graham (managing director), Mr Alistair Pollock (associate director), Mr Darren MacGregor (executive director) and Mr Timothee Moulin (executive).

Herbert Smith Freehills

183 HSF was PAC’s legal advisor in respect of the merger. Like Gresham, HSF had advised PAC with respect to Pinnacle and WIG in 2012 and 2013.

184 The responsible partner at HSF was Mr Peter Dunne and the senior associate assisting Mr Dunne was Ms Shing Lo.

Deloitte

185 There are several entities with the name “Deloitte” involved in the merger to various extents and for different parties.

186 First, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu (Deloitte Australia) were PAC’s auditor and assisted PAC in accounting aspects of the merger. Mr Stuart Alexander, Mr Stephen Connors and Mr Jack Lee were responsible for coordinating with their US counterpart and advising PAC management on accounting issues with the merger.

187 Second, Mr Mark Goldsmith of Deloitte Tax Services Pty Ltd (Deloitte Tax Australia) advised PAC on the tax aspects of the merger. Deloitte Tax Australia’s role is of marginal relevance to the proceeding.

188 Third, Deloitte Tax Australia co-ordinated tax issues with its US counterpart (Deloitte Tax USA) which was acting for Northern Lights. Deloitte Tax USA’s involvement is of no relevance.

189 Fourth, Deloitte & Touche LLP (Deloitte USA) was also involved. The role of Deloitte USA developed into a significant part of PAC’s case as the trial proceeded. Deloitte USA provided the following.

190 It provided a quality of earnings (QoE) data book to Northern Lights which was subsequently provided to PAC management and Gresham on 14 May 2014.

191 Further, it provided the Deloitte due diligence report provided to PAC management on 18 June 2014.

192 Mr Alan Warner, Mr Bruce Gibbens, Mr Masaki Noda and Ms Erika Mitchell of Deloitte USA were primarily responsible for advising Northern Lights. They were also in frequent contact with PAC management.

William Blair

193 William Blair were the financial advisors to Northern Lights, providing Northern Lights with valuations of boutiques, assistance with the due diligence and managing the debt raising aspects of the merger, for example, obtaining loans to acquire majority interests in Seizert and Aether.

Expert witnesses

194 I should say something briefly at this point concerning the expert witnesses.

195 Mr Graham Bradley was an expert called by PAC. As a professional company director and chairman since 2003, he was called to give an expert view as to how reasonable directors in the position of PAC’s directors ought to have acted concerning various aspect of the merger.

196 Now according to the respondents, Mr Bradley allowed himself to become effectively an adviser on how PAC’s claim should be formulated which tainted his evidence.

197 The respondents point to the fact that on at least four occasions Mr Bradley’s report used words strikingly similar to PAC’s particulars. Apparently Mr Bradley had assisted to formulate those particulars. According to the respondents, Mr Bradley’s evidence understandably adopted pleadings which he assisted in formulating.

198 Further, the respondents say that on numerous occasions where Mr Bradley selected quotes from the Howard assessment, which I will discuss later, he did so in a manner that distorted the original text of document. Mr Bradley agreed that he had used incomplete sentences and accepted that he should have quoted full sentences.

199 Further, the respondents say that Mr Bradley was prepared to rely upon supposedly damaging examples of accounting outcomes from the Deloitte due diligence report which, when explained to him, he accepted were incorrect.

200 But I agree with PAC that these criticisms are somewhat over-stated.

201 Mr Bradley’s evidence was that he had a discussion with PAC’s solicitors, where he communicated his views about the documents he had reviewed. PAC then subsequently drafted its particulars in a way that was consistent with the views communicated by Mr Bradley. Mr Bradley otherwise did not have any involvement in drafting the particulars. There is nothing untoward about this approach.

202 First, in some cases where the reverse occurs, namely if the documentary trail reveals that an expert has revised and tailored their expert opinion so as to match the pleadings on which the party retaining that expert relies, it may be possible to impugn the independence of the expert. The sequence of events here was the other way around.

203 Second, there is nothing unusual about discussing issues with an expert, including the questions to be formulated for their report to address.

204 As to the criticism concerning whether Mr Bradley distorted the original text of the Howard assessment, Mr Bradley explained in his evidence that the purpose of the passages that he identified was to highlight red flags that the directors should have taken seriously. Although counsel for Mr McGill may have put to Mr Bradley other aspects of the text that provided a favourable picture of certain boutiques, Mr Bradley’s purpose was to identify statements that he considered should have put the directors on further enquiry. Now I accept that explanation. But of course there were many parts of the Howard assessment that supported the respondent directors’ case.

205 In my view, Mr Bradley was a competent and straight-forward expert, but his evidence did have its limitations. He seemed not to be clear about PAC’s business. PAC was not a funds manager but rather an investor in funds managers, usually with a minority interest. Further, he had little if any experience in running or investing in boutique managers. More generally he collapsed the distinction from time to time between the business of investing in boutiques and the business of funds management. Further, he was not aware of documents dealing with weekly meetings between PAC, Gresham personnel and others.

206 In my view, on the substance, there were significant limitations in the use and therefore the weight that I could place on his evidence.

207 I will address aspects of his evidence in more detail later.

208 Mr Barry Lewin was an expert relied upon by the respondents. He had a background as a lawyer and professional director. He covered the same topics as Mr Bradley.

209 In my view Mr Lewin was also a competent and straight-forward expert. But like Mr Bradley, his evidence also had its limitations. Moreover, he did not have direct expertise in the type of business PAC was conducting, with perhaps one exception.

210 I will discuss some aspects of his evidence in more detail later.

The quantum/valuation experts

211 There were two such experts which I will say something more about later concerning valuation questions dealing with WHV.

Jones v Dunkel, adverse inferences and other matters

212 The unexplained failure by a party to call a witness or tender a document may, in appropriate circumstances, support an inference that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted that party’s case. The principle in Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 is one of common sense. But by itself the inference is frequently somewhat barren, for knowing that the evidence of a witness would not have assisted tells one nothing about what the witness’s evidence affirmatively would have been.

213 Now PAC has largely conducted a documentary case, which is explicable partly because this is a derivative proceeding. That context justifies me in not drawing the usual Jones v Dunkel inferences because there is not the same control or capacity to adduce evidence from former PAC executives or consultants in a co-operative fashion.

214 Let me address one specific matter. Now the directors assert that I am entitled to draw an inference that evidence given by Mr Dunne, a partner of HSF, would not have assisted PAC’s case. But no Jones v Dunkel inference of the type adverted to by the directors is available in the circumstances of this case.

215 Three conditions must be satisfied for the principle in Jones v Dunkel to apply, namely, that the missing witness would be expected to be called by one party rather than the other, the witness’ evidence would elucidate a particular matter, and the witness’ absence is unexplained. But even if all three conditions are satisfied, I am not required to conclude that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted the party’s case

216 Now care is required in assessing the degree to which any particular witness can be said to be in the camp of a party. In the present case there can be no realistic suggestion that PAC was the party expected to call Mr Dunne or that Mr Dunne’s knowledge is to be regarded as the knowledge of PAC or that Mr Dunne is in PAC’s “camp”.

217 The directors’ submission ignores the reality of this proceeding. The proceeding is a derivative one, brought with leave of the Court, which was resisted by PAC, and where PAC acting in a different capacity instructed Mr Dunne’s firm to represent PAC separately in the proceeding. The directors include current directors of PAC.

218 As I observed during the trial, PAC has largely had to reconstruct events from the documentary record, whilst the relevant corporate knowledge was within the heads of the directors. And as I also observed, there is no reason why the directors could not have approached HSF directly. A common sense assessment of the circumstances of the case does not suggest that PAC could be regarded as the party expected to call Mr Dunne.

219 Let me deal with one other matter concerning the question of the content of board minutes.

220 The requirements for the content of minutes include that a minute of a directors’ meeting is not meant to be a report. They must be as concise as circumstances permit. Further, speeches, disagreements and reasons for resolutions are not normally to be recorded.

221 I reject PAC’s assertion that to the extent that the non-executive directors say that they considered matters not recorded in the board minutes, their contention should not succeed because the absence of any record of any discussion of important matters tends to show that they were not, or at the best scantly, discussed.

222 Such an assertion misconceives the purpose of minutes being to concisely record key outcomes of discussions. Moreover, the absence of reference to a specific matter being discussed is little if any positive evidence in and of itself that the matter was not discussed. One must consider the omission in its proper context.

General principles: directors’ duties

223 Section 180 of the Act provides:

Care and diligence—directors and other officers

(1) A director or other officer of a corporation must exercise their powers and discharge their duties with the degree of care and diligence that a reasonable person would exercise if they:

(a) were a director or officer of a corporation in the corporation’s circumstances; and

(b) occupied the office held by, and had the same responsibilities within the corporation as, the director or officer.

Business judgment rule

(2) A director or other officer of a corporation who makes a business judgment is taken to meet the requirements of subsection (1), and their equivalent duties at common law and in equity, in respect of the judgment if they:

(a) make the judgment in good faith for a proper purpose; and

(b) do not have a material personal interest in the subject matter of the judgment; and

(c) inform themselves about the subject matter of the judgment to the extent they reasonably believe to be appropriate; and

(d) rationally believe that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation.

The director’s or officer’s belief that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation is a rational one unless the belief is one that no reasonable person in their position would hold.

(3) In this section:

business judgment means any decision to take or not take action in respect of a matter relevant to the business operations of the corporation.

224 Section 180(1) is normative and cast in mandatory terms. The section imposes an obligation to meet a statutory standard of care and diligence applicable to the exercise of all of the powers and the discharge of all of the duties of a director or officer, whatever the source. If the required degree of care and diligence is not met, then the section will have been contravened.

225 Section 180(1) creates an objective test, as I said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mitchell (No 2) (2020) 382 ALR 425 at [1397]. The “reasonable person” is an ordinary person who possesses the knowledge and experience of the relevant director.

226 The core duty of the director is to take reasonable steps to place themselves in a position to guide and monitor the management of the company. The directors must become familiar with the fundamentals of the business in which the corporation is engaged and are under a continuing obligation to keep informed about the activities of the corporation. Directorial management requires a general monitoring of corporate affairs and policies. The directors should maintain familiarity with the financial position of the corporation.

227 The duty mandates, at its core, that a director’s involvement in the company’s management requires ordinary competence or reasonable ability. Equivalently, the duty of diligence requires directors to take reasonable steps to place themselves in a position to guide and monitor the company’s management.

228 The purpose of s 180(1) is not to punish the making of mistakes or errors of judgment. Directors and officers are expected to take calculated commercial risks. However, they must exercise care and diligence in the assessment of risk and reward.

229 As stated by Robson J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Lindberg (2012) 91 ACSR 640 at [72]:

Section 180(1) does not seek to punish the mere making of mistakes or errors of judgment. Making mistakes does not by itself demonstrate lack of due care and diligence. The business judgment rule in s 180(2) also recognises that business judgments made in good faith and on a proper basis do not fall within s 180(1). Directors and officers of corporations are expected to take calculated commercial risks. A company run on [the] basis that no risks were ever taken would be unlikely to be successful. The proper taking of risk in making business decisions is entirely consistent with exercising care and diligence. The proper assessment of the risks and potential rewards is a matter that demands the exercise of care and diligence. The two concepts complement each other in the management of corporations.

230 Now in order for an act or omission of the director to be capable of constituting a contravention of s 180(1) there must be reasonably foreseeable harm to the interests of the company caused thereby.

231 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mariner Corporation Ltd (2015) 241 FCR 502, I said (at [447] to [452]):

It is wrong to assert that if a director causes a company to contravene a provision of the Act, then necessarily the director has contravened s 180.

No contravention of s 180 would flow from such circumstances unless there was actual damage caused to the company by reason of that other contravention or it was reasonably foreseeable that the relevant conduct might harm the interests of the company, its shareholders and its creditors (if the company was in a precarious financial position) (see ASIC v Maxwell at [99]-[110] and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Macdonald (No 11) (2009) 230 FLR 1; 256 ALR 199 at [236]).

In order for an act or omission of the director to be capable of constituting a contravention of s 180 there must be reasonably foreseeable harm to the interests of the company caused thereby.

Further, relevant to the question of breach of duty is the balance between, on the one hand, the foreseeable risk of harm to the company flowing from the contravention and, on the other hand, the potential benefits that could reasonably be expected to have accrued to the company from that conduct.

Not only must the Court consider the nature and magnitude of the foreseeable risk of harm and degree of probability of its occurrence, along with the expense, difficulty and inconvenience of taking alleviating action, but the Court must balance the foreseeable risk of harm against the potential benefits that could reasonably be expected to accrue from the conduct in question.

After all, one expects management including the directors to take calculated risks. The very nature of commercial activity necessarily involves uncertainty and risk taking. The pursuit of an activity that might entail a foreseeable risk of harm does not of itself establish a contravention of s 180. Moreover, a failed activity pursued by the directors which causes loss to the company does not of itself establish a contravention of s 180.

232 Observations resonating with these themes were made by Edelman J in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Cassimatis (No 8) (2016) 336 ALR 209 at [675] where he said that the Court must balance “the foreseeable risk of harm to any of the interests” of the company against “the magnitude of that harm, together with the potential benefits that could reasonably have been expected to accrue to the company from the conduct in question, and any burdens of further alleviating action”.

233 Further, as Thawley J observed, the balancing exercise is not confined to balancing competing commercial considerations or their varying financial consequences, but extends to considering “all of the interests of the corporation, including its continued existence and its interest in pursuing lawful activity” (Cassimatis v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2020) 275 FCR 533 at [459]). I should say for completeness that State intermediate appellate courts have applied Cassimatis; see DSHE Holdings Ltd (Receivers and Managers) (in liq) v Potts (2022) 163 ACSR 23 at [112] to [115] per Leeming and Kirk JJA and Basten AJA.

234 In Mariner Corporation I also said (at [440] and [441]):

It is not in doubt that the circumstances of the particular company concerned inform the content of the duty. These include the size and type of the company, the size and nature of the business it carries on, the terms of its constitution, and the composition of the board of directors.

It is also not in doubt that in considering the acts or omissions of a particular director, one looks at factors including the director’s position and responsibilities, the director’s experience and skills, the terms and conditions on which he has undertaken to act as a director, how the responsibility for the company’s business has been distributed between the directors and the company’s employees, the informational flows and systems in place and the reporting systems and requirements within the company.

235 Further, it may be necessary, when examining the corporation’s circumstances for the purposes of s 180(1)(a), to have regard to whether the company is listed or unlisted (Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich (2009) 75 ACSR 1 at [7201] per Austin J).

236 Now the responsibilities referred to in 180(1)(b) include the responsibilities that the director has within the corporation, regardless of how those responsibilities came to be imposed on that director. As such, it is not the case that “responsibilities” refer only to specific tasks delegated to the relevant director.

237 Let me say something about the position of chairman as it is relevant to Mr Fitzpatrick’s position.

238 I outlined the specific role and responsibilities of the chairman in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Mitchell (No 2) at [1398] to [1426] in which I identified the usual powers and responsibilities, including having the power, authority and responsibility where relevant to manage board meetings, to ensure that the board has before it sufficient information, to ensure that sufficient time is allowed for the discussion of complex or contentious matters and to ensure that there is appropriate communication with and taking into account the interests of members of the company. It is worth setting out again with necessary modification what I said at [1398] to [1426].

239 The Act does not make any express reference to the roles or functions of a chairman of the board, although there are legislative rules able to be displaced or modified by a company’s constitution (s 135 and also Chapter 2G) concerning formalities or procedural matters involving the chairing of directors’ meetings or shareholders’ meetings.

240 Further, there was regulatory guidance around the relevant time in the form of the ASX’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations. Recommendation 2.5 (3rd edition, 2014) provided that the chairman of a listed entity should be an independent director, and should not be the same person as the CEO. The commentary to Recommendation 2.5 (3rd edition, 2014) described the responsibilities of the chairman:

The chair of the board is responsible for leading the board, facilitating the effective contribution of all directors and promoting constructive and respectful relations between directors and between the board and management. The chair is also responsible for setting the board’s agenda and ensuring that adequate time is available for discussion of all agenda items, in particular strategic issues.

241 The prior version (2nd edition, 2007 with 2010 amendments) had a similarly worded but differently numbered Recommendation 2.2. The commentary to it provided:

The chair is responsible for leadership of the board and for the efficient organisation and conduct of the board’s functioning.

The chair should facilitate the effective contribution of all directors and promote constructive and respectful relations between directors and between board and management.

Where the chair is not an independent director, it may be beneficial to consider the appointment of a lead independent director.

The role of chair is demanding, requiring a significant time commitment. The chair’s other positions should not be such that they are likely to hinder effective performance in the role.

242 In AWA Ltd v Daniels (t/as Deloitte Haskins & Sells) (1992) 7 ACSR 759, Rogers J said at 867:

The chairman is responsible to a greater extent than any other director for the performance of the board as a whole and each member of it. The chairman has the primary responsibility of selecting matters and documents to be brought to the board’s attention, for formulating the policy of the board and promoting the position of the company. In discharging his or her responsibilities the chairman will cooperate with the managing director if the two positions are separate or otherwise with senior management.

243 This judgment was appealed, but the Court of Appeal did not question these observations (see Daniels (formerly practising as Deloitte Haskins & Sells) v Anderson (1995) 37 NSWLR 438).

244 In Woolworths Ltd v Kelly (1991) 22 NSWLR 189 at 225, Mahoney JA said:

…a person who is a chairman of the board of directors has additional rights and duties and additional opportunities. Ordinarily it is the function of a chairman to settle the agenda of the meetings of the board: at least he exercises a significant influence upon it. He is in a position, in the sense here relevant, to ensure that proposals are brought forward for consideration by the directors at their meetings. And this, in a particular case, may affect the content of fiduciary duties which he owes to his company.

245 Let me delve a little deeper into the position of the chairman of the board.

246 Clearly, he has no power or authority to manage the corporation. His primary function is to preside at board meetings and accordingly to exercise procedural control. But save for that, and his power to exercise a casting vote (if applicable), he has no greater authority than an ordinary director. He is not some sort of directorial overlord. But he does have the power and authority to manage board meetings and to that extent he may have greater responsibility for the performance of the board as a whole.

247 But the chairman does have the power, authority and responsibility for setting the agenda items for board meetings, although these may be added to by the agreement of other directors. He can also discharge that responsibility in consultation with the CEO.

248 He also has the power, authority and responsibility to ensure that the board has before it sufficient information, whether presented in written or oral form, such as to be able to meaningfully consider, discuss and decide on the agenda items before the board at the relevant meeting taking into account the context of the decision required or consideration necessary by the board at that meeting. Of course, he may discharge such a responsibility in consultation with the CEO.

249 The chairman also has the power, authority and responsibility to manage the board to ensure that sufficient time is allowed for the discussion of complex or contentious matters; for this purpose it may be necessary to arrange meetings outside board meetings so that board members are thoroughly prepared.

250 Further, the chairman is there to ensure that the board members work effectively together and to ensure that their skill sets and personalities complement each other. Moreover, he should endeavour to facilitate the effective contribution of each director.

251 Further, the chairman is there to ensure workable and harmonious relations between the executive and non-executive directors, and more generally to ensure workable and harmonious relations between the board on the one hand and the executive management on the other hand, particularly the CEO. It should go without saying that the relationship between the chairman and the CEO needs to be productive and harmonious; the chairman should facilitate this.