FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hampden Holdings I.P. Pty Ltd v Aldi Foods Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 1452

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be listed for a case management hearing on a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 The first applicant, Hampden Holdings I.P. Pty Ltd (Hampden) and the second applicant, Lacorium Health Australia Pty Ltd (Lacorium) sue the respondent, Aldi Foods Pty Ltd (Aldi) for breach of copyright in relation to certain artistic works used on the packaging for children’s food products.

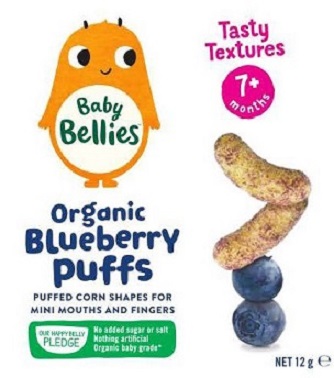

2 Hampden is an intellectual property holding company. It licenses intellectual property to a related company, Every Bite Counts Pty Ltd (EBC), which sells children’s food products under the BABY BELLIES, LITTLE BELLIES and MIGHTY BELLIES brands (also referred to together as the BELLIES brand).

3 In 2017 and 2018, EBC undertook a re-design of the packaging of the BELLIES brand. To this end, it engaged a United Kingdom design firm, B&B Studio Limited (B&B Studio), to design new packaging. Also, once the new designs had been finalised, EBC engaged Lacorium, an Australian company that provided design services, to design the packaging for certain additional products in the BELLIES range based on the designs that had been developed by B&B Studio.

4 In about September 2018, EBC began using the new packaging on BELLIES products that it sold in Australia.

5 Relevantly for the purposes of this proceeding, the new BELLIES packaging included the following nine artistic works. The first five works (the B&B Works) were created by B&B Studio. The other four works (the Mota Works) were created by Bruno Mota Chaves (Mr Mota), an employee of Lacorium, using the designs that had been created by B&B Studio. The following images of the works are drawn from the applicants’ further amended statement of claim (FASOC). They correspond to items 1 to 9 in the Schedule to the applicants’ outline of opening submissions and were the works relied on by the applicants at the hearing of the proceeding.

A. B&B Works

1 |

| 2 |

|

3 |

| 4 |

|

5 |

|

B. Mota Works

6 |

| 7 |

|

8 |

| 9 |

|

6 I will refer to the nine artistic works set out above as the Applicants’ Works, but I note that one of the issues in this proceeding is whether the applicants own the copyright in the works. Further, I will refer to the three works relating to puffs products (i.e. items 1, 6 and 7) as the Applicants’ Puffs Works and the balance of the works set out above as the Applicants’ Non-Puffs Works.

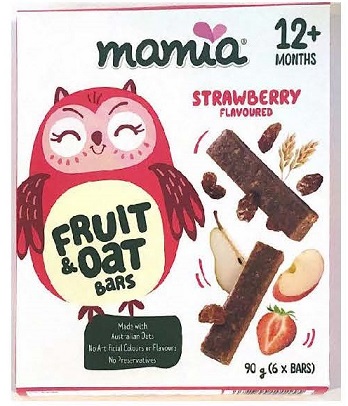

7 Aldi is the general partner of Aldi Stores (A Limited Partnership) (Aldi Stores). Aldi Stores operates around 590 Aldi supermarkets across Australia. The parties proceeded on the basis that, for the purposes of the proceeding, there was no relevant distinction between Aldi and Aldi Stores. A significant majority of the products sold in Aldi supermarkets are sold under Aldi’s house brands (also known as private label brands). One of these is MAMIA, Aldi’s baby portfolio, which comprises nappies, wipes, wet food and dry food.

8 In late 2018 and in 2019, Aldi undertook a re-design of the packaging for the MAMIA range. Aldi engaged Motor Brand Design (Motor Design) to carry out the re-design. In April 2019, Aldi instructed Motor Design to use the LITTLE BELLIES brand as the “benchmark” for the re-design of the packaging for the MAMIA dry food range (also referred to as the snacking range). The sense in which the expression “benchmark” was used by Aldi is discussed later in these reasons. In any event, it is clear that Motor Design (on behalf of Aldi) had regard to the BELLIES packaging in the course of designing new packaging for the MAMIA snacking range.

9 In about February 2020, Aldi began selling some products in the MAMIA snacking range in the new packaging. In June 2020 and December 2020, further products in that range commenced to be sold in the new packaging. In 2020 and 2021, Aldi developed a new product – baby puffs – to be sold in the MAMIA snacking range. Aldi engaged Motor Design to develop packaging for the baby puffs. In doing so, Motor Design continued to use the BELLIES packaging as the “benchmark”. In about August 2021, Aldi began selling MAMIA baby puffs.

10 In this proceeding, the applicants contend that 11 works (the Impugned Works) used on the packaging for products in the MAMIA snacking range infringed the copyright in the Applicants’ Works. The following images of the Impugned Works are drawn from the FASOC and correspond to the works set out in Schedule 1 to the applicants’ outline of closing submissions. The Impugned Works are grouped into two categories by the applicants: the Impugned Non-Puffs Works (comprising eight works) and the Impugned Puffs Works (comprising three works). The works set out in that Schedule are not numbered. For ease of reference in these reasons, the works set out below have been numbered. The Impugned Works are:

A. Impugned Non-Puffs Works

1 |

| 2 |

|

3 |

| 4 |

|

5 |

| ||

6 |

| ||

7 |

| ||

8 |

| ||

B. Impugned Puffs Works

9 |

| 10 |

|

11 |

|

11 It should be noted that the applicants’ claims in the proceeding are limited to breach of copyright claims. The applicants do not claim that Aldi has engaged in passing off or misleading or deceptive conduct.

12 Aldi cross-claims against Hampden, alleging that Hampden has made unjustifiable threats of copyright infringement.

13 Aldi no longer sells any products under the Impugned Works.

14 An order was made that all questions of liability (including liability for additional damages) be heard and determined separately from and in advance of all issues of the quantum of any pecuniary relief.

15 There is no issue that the Applicants’ Works are artistic works or that copyright subsists in those works.

16 The main issues to be determined are:

(a) whether (for each of the Applicants’ Works) Hampden and/or Lacorium is the owner of the copyright;

(b) whether (for each of the Impugned Works) Aldi infringed copyright by reproducing a substantial part of one or more of the Applicants’ Works;

(c) if all or part of the copyright claim is made out, whether Aldi is liable for additional damages; and

(d) whether Aldi’s cross-claim (relating to unjustifiable threats) is made out.

17 For the reasons that follow, I have concluded in summary that:

(a) In relation to the B&B Works, Hampden has the right to bring its claims for breach of copyright. In relation to the Mota Works, Lacorium and Hampden have the right to bring their claims for breach of copyright.

(b) The Impugned Puffs Works reproduce a substantial part of the Applicants’ Puffs Works. However, the Impugned Non-Puffs Works do not reproduce a substantial part of any of the Applicants’ Works.

(c) Aldi is liable for additional damages.

(d) Subject to the assumption in [239] below being correct, the cross-claim is to be dismissed.

The pleadings and the hearing

18 This proceeding was commenced by Hampden on 3 February 2022. In the initial statement of claim, Hampden sued in relation to the Impugned Puffs Works and certain other designs that had been developed (but not implemented) by Aldi involving a monkey character. Subsequently, Lacorium was added as an applicant and the claims were extended to the Impugned Non-Puffs Works.

19 The parties’ latest pleadings in relation to the applicants’ claim are:

(a) the FASOC;

(b) the defence to further amended statement of claim dated 15 May 2023; and

(c) the amended reply dated 24 October 2022.

20 In the applicants’ reply, they indicate that they do not press the allegations in paras 87 to 95 of the statement of claim. Those paragraphs alleged infringement in relation to MAMIA packaging with a monkey device.

21 Aldi filed its cross-claim on 29 March 2022. The latest pleadings in relation to the cross-claim are the statement of cross-claim dated 29 March 2022 and the defence to cross-claim dated 22 April 2022.

22 The hearing took place over four days.

23 At the outset of the hearing, the applicants indicated that they did not press their claim in relation to items 10 to 14 in the Schedule to the applicants’ outline of opening submissions. The applicants offered to prepare amended pleadings, but I said that this was not necessary.

24 On the first day of the hearing, senior counsel for Aldi handed up an undertaking that Aldi was prepared to give. It was in the following terms:

By its counsel, the Respondent, Aldi Foods Pty Limited, undertakes to the Court without admissions as to liability, that it will permanently refrain from offering for sale in Australia products bearing the packaging depicted in paragraphs 51, 63, 75, 86A, 86B, 86C, 86K, 86L, 86T, 86U, 86V, 87, 90 and 93 of the Further Amended Statement of Claim filed on 1 May 2023.

The proposed undertaking covers all of the Impugned Works, as well as some works that are no longer in issue.

The evidence

25 At the hearing, the applicants relied on affidavit evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Clive Sher, a Director and co-founder of Hampden and a Director and co-founder of EBC;

(b) Shaun Clifford Bowen, a Director and founder of B&B Studio;

(c) Mr Mota, a designer employed by Lacorium and the head designer/creative specialist of EBC; and

(d) Patrick Martin, a paralegal at Gestalt Law, the solicitors for the applicants.

26 Each of the above witnesses other than Mr Martin was cross-examined.

27 Mr Sher gave evidence in a clear and straightforward way. I accept his evidence.

28 Mr Bowen gave evidence by video-conference from the United Kingdom. He gave evidence in a frank and honest manner and I accept his evidence.

29 Mr Mota responded to questions in a clear way and made sensible concessions. I accept his evidence.

30 Aldi relied on affidavit evidence from the following witnesses:

(a) Nicole Paquet, who was a Buying Director employed by Aldi Stores at the relevant times; since then, she has moved to Germany and has commenced work for ALDI AHEAD GmbH in the role of Director Buying – International Product Organisation; and

(b) Lucy Hartland, a solicitor employed by Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers, the solicitors acting for Aldi.

31 Ms Paquet was cross-examined, but Ms Hartland was not.

32 Although Ms Paquet now resides in Germany, she gave evidence in person at the hearing. She was familiar with the material and gave evidence in a clear and confident manner. As discussed below, I have difficulty in accepting some parts of Ms Paquet’s evidence; specifically, the evidence she gave in relation to “benchmarking”. Otherwise, I accept her evidence.

33 I note that Aldi was proposing to call as a witness Monique Avdalis, who was a Buying Director at Aldi at the relevant times. However, after Ms Paquet concluded her evidence, Aldi indicated that it would not be calling Ms Avdalis. The applicants tendered a redacted version of Ms Avdalis’s affidavit dated 10 July 2024 (on the basis that it contained admissions). This was admitted into evidence. The applicants contend that an adverse inference (in the sense discussed in Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; 101 CLR 298) should be drawn against Aldi from its failure to call Ms Avdalis.

34 As noted above, the Impugned Works were designed for Aldi by Motor Design. Nicole Bartholomeusz was the Client Services Director and Partner at Motor Design responsible for undertaking the re-design of the packaging for the MAMIA children’s food products. She was not called to give evidence. The applicants contend that an adverse inference (in the sense discussed in Jones v Dunkel) should be drawn against Aldi from its failure to call Ms Bartholomeusz to give evidence.

35 The parties prepared a statement of agreed facts and issues (SOAF), which was admitted into evidence.

36 During the hearing, the applicants tendered physical exhibits that comprised each of the Applicants’ Works (Exhibit A10) and each of the Impugned Works (Exhibit A11). In resolving the issues in this case, I have had regard to these physical exhibits. The physical exhibits provide a clearer depiction of the works than the images appearing in the pleadings, submissions and evidence.

37 The parties prepared an electronic Court Book for the purposes of the hearing. This was later revised (and further revised). In some cases, the documents in the Court Book include electronic notes or comments that were made by persons at the time of the relevant events. It was common ground between the parties that these notes or comments formed part of the material in evidence and the Court could have regard to them (T191-192).

Factual findings

General matters

38 EBC carries on a business of producing and distributing children’s food products. EBC’s children’s food products include product ranges branded BABY BELLIES, LITTLE BELLIES and MIGHTY BELLIES. Hampton licenses intellectual property to EBC.

39 In 2010, EBC conceived of the brand name, LITTLE BELLIES for baby and toddler-specific snacks. This became the key focus of EBC’s business.

40 Aldi supermarkets are operated in Australia by Aldi Stores. Aldi supermarkets sell a very diverse range of products, including:

(a) meat, fish and seafood;

(b) fresh fruit and vegetables;

(c) delicatessen foods;

(d) dairy products;

(e) bread and bakery goods;

(f) preserved foods, such as canned and jarred foods:

(g) snack foods and confectionery;

(h) tea, coffee and other drinks;

(i) alcoholic beverages;

(j) house cleaning products and laundry products;

(k) health, beauty and hygiene products;

(l) baby foods and other products such as nappies and wipes;

(m) pet foods:

(n) homewares;

(o) camping and outdoors; and

(p) automotive.

41 The first Aldi supermarket in Australia opened in 2001. Aldi has opened many supermarkets across Australia since 2001. There are currently 590 Aldi supermarkets across New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory, Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. There are also four “Aldi Cornerstores”, which are in a smaller format than the standard Aldi supermarket.

42 Aldi supermarkets include a number of features, which are typical of Aldi supermarkets but unusual for other supermarkets, including:

(a) the products are left in their outer cartons;

(b) a smaller range of core products than that of a major supermarket (1,800 lines for an Aldi supermarket compared with 30,000 for a major supermarket);

(c) Special Buy products are arranged in the middle of the store;

(d) there is a long till belt, compared with those of other supermarkets;

(e) overall smaller in size than other supermarkets; and

(f) shopping trolleys require use of a token.

43 A significant majority of the products sold in Aldi supermarkets are sold under Aldi’s house brands (also known as private label brands). Aldi’s private labels are not available for purchase at any other retail stores in Australia.

Events in 2017

44 In about July 2017, EBC made a decision to rebrand LITTLE BELLIES products. The Directors of EBC felt that the existing branding could be improved. Mr Sher felt that the then-current LITTLE BELLIES branding was too product-driven and that the brand was lost within the design. He also felt that the branding lacked unique or compelling features that adequately communicated to consumers the message that LITTLE BELLIES products were healthy, natural and free from additives.

45 CTD in the Bag was EBC’s exclusive distributor in the Australia/New Zealand region at the relevant times. CTD in the Bag assisted EBC in the rebrand of LITTLE BELLIES. The marketing director of CTD in the Bag was Georgie Scott.

46 EBC, with the help of CTD in the Bag, looked around at potential branding companies. EBC initially consulted some local companies, but Mr Sher felt that their branding vision was limited in scope. He decided to engage a United Kingdom company.

47 In about August 2017, CTD in the Bag approached B&B Studio to discuss having the studio consult, advise and design a comprehensive rebrand of the LITTLE BELLIES brand. B&B Studio is an independent design agency specialising in the creation and development of brands with a focus on visual identity and packaging design.

48 On 31 August 2017, B&B Studio sent CTD in the Bag (with the contact being Ms Scott) a proposal. The Project Description was: “Brand, Visual identity and Packaging for Little Bellies / Mighty Bellies”. The work comprised nine stages. The first five were: Kick off session and immersion; Brand Positioning, Range Architecture and Creative Strategy; Concept Generation; Design Development; and Design Finalisation.

49 On 22 September 2017, Ms Scott sent an email to B&B Studio (copied to Mr Sher of EBC) stating that she had spoken to Mr Sher and “we” would like to go ahead with the project.

50 Mr Bowen was the Creative Director at B&B Studio for the project.

51 On 30 September 2017, Kerry Bolt of B&B Studio sent Mr Sher of EBC and Ms Scott of CTD in the Bag a revised proposal. B&B Studio also provided a copy of B&B Studio’s Terms and Conditions of Business (B&B Studio Terms and Conditions) (part of Annexure CS-24). Clause 3 provided:

3. Intellectual Property

3.1 In these Terms “Intellectual Property Rights” or “IPR” means all copyright and related rights, trade marks, service marks, trade, business and domain names, rights in trade dress or get-up, rights in goodwill or to sue for passing off, unfair competition rights, rights in designs, rights in computer software, database right, patents, moral rights, rights in confidential information (including know-how and trade secrets) and any other intellectual property rights, in each case whether registered or unregistered and including all applications for and renewals or extensions of such rights, and all similar or equivalent rights or forms of protection in any part of the world; and “Supplies” means all data, information, artwork, photographs, visuals, models and any other materials that we provide to you as part of the Services, but does not include any material (“Client Material”) that has been obtained from you.

3.2. Subject to clause 3.3 below, all Intellectual Property Rights arising out of or in connection with the Services, other than IPR in the Client Materials, shall be owned by B&B.

3.3 The Intellectual Property Rights in the final design that we provide to you on completion of the Services shall be assigned to you on payment of the Price in full and cleared funds. Immediately upon the assignment of such IPR to you, you hereby grant to B&B a non-exclusive, royalty-free perpetual licence to use such IPR in all publicity and marketing materials used by B&B to promote its services.

3.4 We reserve the exclusive right to use any Intellectual Property Rights attaching to the Supplies in any field or industry outside that covered by this Proposal.

3.5 You agree that nothing in the Contract shall be taken to prevent B&B from using any expertise acquired or developed during the performance of the Services in the provision of services for other clients or on its own behalf.

3.6 Unless expressly agreed in writing and supported by a retainer fee, B&B does not work on an exclusive basis for any client.

(Emphasis added.)

52 There does not appear to be any real issue that the revised proposal was accepted or that the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions formed part of the contract. However, there is an issue between the parties whether B&B Studio’s contract was with EBC (as contended by the applicants) or with CTD in the Bag (as contended by Aldi). I consider that the contract was with EBC and that CTD in the Bag was merely acting as EBC’s agent. The revised proposal was sent to both EBC and CTD in the Bag. In circumstances where EBC was the company that produced and sold the products and CTD in the Bag was its distributor (matters that, it can be inferred, were known to the parties), the contracting party was (objectively) intended to be EBC rather than CTD in the Bag. I note that this is consistent with subsequent dealings between the parties, as detailed below.

53 In October 2017, Mr Sher and Ms Scott travelled to the United Kingdom to meet with B&B Studio. B&B Studio then commenced work on the project.

54 In December 2017, B&B Studio delivered a concept presentation to EBC. The evidence includes a PowerPoint presentation titled “LITTLE BELLIES Concept Presentation” (Annexure SB-10). This presentation related to the BABY BELLIES, LITTLE BELLIES and MIGHTY BELLIES brands or ranges and provided a number of brand concepts. Concept 3b in the presentation included drawings of a character that is similar to the character ultimately adopted (as seen in the Applicants’ Works set out above). Some of the B&B Studio documents refer to the character as an animal. During the hearing of this proceeding, the parties and some witnesses referred to the character as a monster. In the Concept Presentation, the monster character was depicted at three ages: a baby monster for the BABY BELLIES brand, a young monster for the LITTLE BELLIES brand and a fully-grown monster for the MIGHTY BELLIES brand.

55 In December 2017, EBC provided feedback on those concepts. This was included in a PowerPoint presentation (Annexure CS-8). On a page headed “Preferred Concept” (CB 493), it was stated:

Our preference is for 3b because out of all the concepts it best alludes to the ‘Natural Progression’ and it is obvious how the brand world could work best and be extended into useful content for social and digital …

56 It was noted that there were some elements of concepts 3a and 4 that worked well and could be considered. Detailed additional feedback was provided. In relation to Concept 3b, the detailed feedback included:

Think this is the logo that best delivers visually on the ‘bellies brand’ given that the brand name is actually sitting in the belly of the character.

57 Following the feedback from EBC, B&B Studio further developed and refined Concept 3b.

Events in 2018

58 In February 2018, B&B Studio delivered a Development Presentation to EBC. A copy of the PowerPoint presentation is in evidence (Annexure CS-9) (the February 2018 Development Presentation). This presentation included an explanation of the proposed brand architecture and revised drawings of product packaging that took into account the feedback that had been provided by EBC.

59 On 12 April 2018, B&B Studio provided four final artworks (the First Final Artworks) with associated files to EBC (Annexure BMC-3). These were the final designs for: LITTLE BELLIES Organic Animal Biscuits; BABY BELLIES Organic Berry & Apple Softcorn; BABY BELLIES Organic Blueberry puffs; and LITTLE BELLIES Organic Tomato Fiddlesticks.

60 Upon the completion of each of the stages of work referred to above, B&B Studio delivered invoices to EBC, which were paid by EBC. These invoices are in evidence. The amounts are substantial.

61 The B&B Works were each made by one or more employees and/or directors of B&B Studio. The employees of B&B Studio contributed to the creation of the works pursuant to the terms of their employment by B&B Studio. When each of the B&B Works was made, each of the relevant employees and directors was a citizen or resident of the United Kingdom.

62 In operating its business, EBC utilises resources from Lacorium (a company run by Mr Sher’s brother).

63 In or about May 2018, Mr Sher (or someone else at EBC) requested Mr Mota (who was employed by Lacorium) to create further packaging designs for additional BELLIES products based on the B&B Works.

64 Mr Mota explains in his affidavit that when new packaging was (and is) required to be developed for the BELLIES brand, he received (and receives) a direction with specifications for the new label and packaging. Mr Mota gives evidence (which I accept) that: he followed (and follows) these specifications; the specifications did not (and do not) include details of the artwork, because his standing instructions are to produce designs that are consistent with the packaging designs developed by B&B Studio; the adjustments to the artwork that are made are dictated by product and flavour and his standing instructions are to introduce no new creative elements.

65 Mr Mota gave the following evidence (in his affidavit and during cross-examination) (which I accept) in relation to the creation of each of the Mota Works:

(a) In or about May 2018, he was directed to create packaging for BABY BELLIES Organic Apple & Cinnamon puffs. The result is the work depicted in item 6 of the Applicants’ Works. The process of creation of the work involved replicating the design for BABY BELLIES Organic Blueberry puffs that had been provided by B&B Studio in the First Final Artworks and adapting the text and food ingredient photography and layout to be used for the Organic Apple & Cinnamon puffs product. To reflect the new product/flavour, he selected images of the food ingredients apple and cinnamon from image libraries and an image of the product taken in-house. He arranged the images in the work. The text colour was also changed to reflect the food ingredients/flavour. Mr Mota decided on the shade of green that was used. During cross-examination, Mr Mota accepted that he made only four changes to the design prepared by B&B Studio: a change in the name of the flavour to Apple & Cinnamon; a change in the colour of the text; a change in the food images in the bottom right; and a change in the puff images.

(b) In or about May 2018, Mr Mota was directed to create packaging for BABY BELLIES Organic Carrot puffs. The result is the work depicted in item 7 of the Applicants’ Works. The process of creation of the work involved replicating the design for BABY BELLIES Organic Blueberry puffs that had been provided by B&B Studio in the First Final Artworks and adapting the text and food ingredient photography and layout to be used for the Carrot puffs product. To reflect the new product/flavour, he selected images of the food ingredient carrot from image libraries and an image of the product taken in-house. He arranged the images in the work. The text colour was also changed to reflect food ingredient/flavour. Mr Mota decided on the shade of orange that was used. During cross-examination, Mr Mota accepted that he made only four changes to the design prepared by B&B Studio: a change in the name of the product; a change in the colour of the text; a change in the food images; and a change in the puff images.

(c) In or about May 2018, Mr Mota was directed to create packaging for LITTLE BELLIES Organic Cheese & Herb Fiddlesticks. The result is the work depicted in item 8 of the Applicants’ Works. The process of creation involved replicating the design for LITTLE BELLIES Organic Tomato Fiddlesticks that had been provided by B&B Studio in the First Final Artworks and adapting the text and food ingredient photography and layout to be used for the product. To reflect the new product/flavour, he selected images of the food ingredients cheese and herbs from image libraries and an image of the product taken in-house. Mr Mota arranged the images in the work. The text colour was also changed to reflect food ingredient/flavour. He decided on the shade of yellow that was used. During cross-examination, Mr Mota accepted that he made only five changes to the design prepared by B&B Studio: a change in the name of the flavour; a change in the colour of the text; a change in the food images in the bottom right; a change in the food images above the monster; and a change of the food image below the monster.

(d) In or about May 2018, Mr Mota was directed to create packaging for LITTLE BELLIES Organic Gingerbread Men. The result is the work depicted in item 9 of the Applicants’ Works. The process of creation involved replicating the design for LITTLE BELLIES Organic Animal Biscuits that had been provided by B&B Studio in the First Final Artworks and adapting the text and food ingredient photography and layout to be used for the Organic Gingerbread Men product. The images of the product were taken in-house. Mr Mota arranged the images in the work. The text colour was changed to reflect the ginger spice ingredient/flavour. He decided on the shade of orange that was used. During cross-examination, Mr Mota accepted that he made only the following changes to the design prepared by B&B Studio: the name of the product; the text for the description of the biscuits underneath the name; the colour of the text; the change from the butterfly biscuit to a gingerbread man in the middle towards the right of the monster; a change to a gingerbread man on the bottom right and two gingerbread men instead of two biscuits on the bottom left.

66 During cross-examination, Mr Mota accepted that in the course of creating the above works he received input or directions about some matters from Ms Scott of CTD in the Bag and Mr Sher. Further, it is apparent that Mr Mota received feedback or input from B&B Studio (via Ms Scott) as part of the process of preparing the above works (as evidenced by the documents at Ex R4, tabs 4 and 6). I do not consider that these matters meant that Mr Mota was not an author of these works.

67 The Mota Works were each made by Mr Mota having regard to works developed by one or more employees and/or directors of B&B Studio. When each of the Mota Works was made, Mr Mota was an employee of Lacorium. Mr Mota contributed to the creation of the works pursuant to the terms of his employment with Lacorium.

68 On 7 August 2018, B&B Studio sent a letter to Mr Sher at EBC (Annexure CS-23) (the 7 August 2018 Letter). The letter stated:

This letter confirms that we acknowledge full payment from you against our agreed proposal.

As per our terms, IP now passes to you:

3.3 The Intellectual Property Rights in the final design that we provide to you on completion of the Services shall be assigned to you on payment of the price in full and cleared funds. Immediately upon the assignment of such IPR to you, you hereby grant to B&B a non-exclusive, royalty-free perpetual license to use such IPR in all publicity and marketing materials used by B&B to promote its services.

(Emphasis added.)

69 The above letter quoted clause 3.3, which referred to the “final design”. I infer that, by the time of this letter, the final design of each of the B&B Works had been provided by B&B Studio to EBC (see, eg, Annexure BMC-3, Annexure SB-14).

70 In about August 2018, B&B Studio presented EBC with guidelines from which further product packaging could be created. The evidence includes a copy of the guidelines (Annexure CS-10). (Although the index to Mr Sher’s first affidavit states that these guidelines were provided in February 2018, the index to the Court Book indicates that they were provided in about August 2018. Ultimately, nothing turns on this.) The “Design Architecture” page indicates that the BABY BELLIES brand is for babies aged 0-1 years, the LITTLE BELLIES brand is for toddlers aged 1-3 years, and the MIGHTY BELLIES brand is for kids aged 3+. On a page headed “The Logo” there are drawings of the monster character at three different ages. The document states: “The logo is an illustrated character, which much like a child, changes as it grows up”. It is also stated: “The illustration subtly evolves across the different ranges, but retains a consistent look and feel”.

71 In or about September 2018, EBC began distributing the BELLIES products in packaging bearing the Applicants’ Works.

72 In late 2018, Aldi commenced a re-branding process in relation to the MAMIA range of products (being a range of baby products). As noted above, the MAMIA portfolio comprised nappies, baby wipes and baby food (wet food and dry food). The baby dry food range was also referred to as the snacking range. The Buying Director for the MAMIA portfolio at this time was Ms Avdalis.

Events in 2019

73 In late January 2019, Ms Paquet became aware that she would become the Buying Director for the MAMIA portfolio (taking over from Ms Avdalis). In January and February 2019, Ms Paquet had various discussions with Ms Avdalis about the portfolio and her work to date, so that she (Ms Paquet) could get up to speed on what was occurring in the portfolio.

74 In about March 2019, Ms Paquet became the Buying Director for the MAMIA range of products. She therefore took over the re-branding process for the MAMIA product range.

75 From about March 2019, Ms Paquet, together with her buying assistant, Davina Fernandez, worked with Motor Design on the re-design of the MAMIA product range. The person at Motor Design with whom Ms Paquet worked predominantly was Ms Bartholomeusz. The design process involved several meetings over the period of the re-design to discuss the various design documents that Motor Design prepared.

76 The re-design process considered all products in the MAMIA product range including nappies and wipes. The range of products had differing requirements, particularly as between the nappies and wipes (on the one hand) and food (on the other). It should be noted that, at this stage, the MAMIA baby food products did not include baby puffs. These products were introduced later (as discussed below).

77 On 9 April 2019, Ms Bartholomeusz sent an email to Ms Paquet with the subject line “Mamia Baby Food Framework Estimate”. The email included:

I have attached where we are at with the Organics and Entry Level food. Also attached is the Market Review for the snacking range.

If you could send through your feedback regarding the benchmarks we will get started. Originally the entry level was to benchmark Rafferty’s. For the Organics range we were benchmarking Little Ones. The Snacking Range market leader was Little Bellies.

(Emphasis added.)

78 In her oral evidence, Ms Paquet accepted that she understood that BELLIES was the market leader in 2019 for the snacking range of products.

79 The attachments to the 9 April 2019 email included a document prepared by Motor Design titled “Mamia Baby Snacking Market Review”. This included a page (CB 1111) headed “Current Packaging & Market References”. One of the images on that page was the packaging for BABY BELLIES Organic Carrot puffs (the same work as item 7 of the Applicants’ Works).

80 On the same day, 9 April 2019, Ms Paquet responded to Ms Bartholomeusz. In her responding email, Ms Paquet stated:

In regards to the benchmarks:

…

Snacking Benchmarking – Little Bellies

https://bellies.com.au/

81 In oral evidence, Ms Paquet said that, in directing Ms Bartholomeusz to the BELLIES website, she had already reviewed it herself.

82 Although Ms Paquet’s email referred to LITTLE BELLIES (as distinct from the BELLIES brand more generally) as the benchmark, the website link she provided was for the BELLIES brand generally, and (as will be seen below) the benchmark adopted by Motor Design included both BABY BELLIES and LITTLE BELLIES packaging. There is evidence (which I accept) in the second affidavit of Mr Martin that all of the Applicants’ Works were depicted on the website around that time. I will discuss the sense in which Aldi used the expression “benchmark” later in these reasons.

83 On about 30 April 2019, Motor Design sent Aldi a document titled “Brandstorm – MAMIA Baby Food Redesign” (part of Annexure NP-3). This included a section with the title page “Snacking Range”. The next page (CB 942) was headed “MAMIA Baby Food Redesign – BENCHMARK” and comprised the following images of BELLIES products:

It is to be inferred that, in designing the new packaging for the MAMIA snacking range, Motor Design (on behalf of Aldi) had regard to the above images from the BELLIES range. This inference arises from a consideration of the sequence and contents of the documents discussed in these reasons. I note that the above page includes items 1, 2 and 9 of the Applicants’ Works.

84 Following feedback from Aldi, on or about 14 May 2019, Motor Design provided to Aldi a further document titled “Brandstorm – MAMIA Baby Food Redesign” (Part of Annexure NP-3). This included a section for the “Snacking Range” that included a design for MAMIA Fruit & Oat Bars. Two designs were presented (options 1 and 2), each utilising an owl character (CB 952). At the foot of that page, under the heading “Market”, there were images of BABY BELLIES Organic Berry & Apple Softcorn and BABY BELLIES Organic Banana Softcorn. Neither of those BELLIES products is relied on by the applicants in this proceeding, but the design is broadly similar to item 1 of the Applicants’ Works.

85 Ms Paquet states in her first affidavit that she provided feedback on the above drawings to Ms Bartholomeusz, including that she (Ms Paquet) wanted the product image to be clearly visible when in the outer carton, and she wanted the flavour of the product to be more prominent. I accept this evidence. The feedback was most likely given at a meeting on 15 May 2019, referred to below.

86 On 15 May 2019, Ms Bartholomeusz made electronic meeting notes of a meeting that day with Ms Paquet (Ex A13, tab 8). The notes commence: “Nicole is so happy with the Mamia rebranding”. It may be inferred that “Nicole” is a reference to Ms Paquet. Ms Bartholomeusz’s notes include, in relation to the MAMIA baby food re-design:

Snacking range architecture needs to follow Baby Bellies with real photography.

During cross-examination, Ms Paquet accepted that this was part of the feedback she gave to Ms Bartholomeusz.

87 The electronic Court Book includes a comment made by Ms Bartholomeusz on the page referred to above (CB 952) in the 14 May 2019 presentation. The comment reads:

Option 1 is the preferred option.

Please follow the architecture of Baby Bellies and use photographic imagery.

This appears to be another record of feedback given by Ms Paquet during the meeting on 15 May 2019.

88 On the basis of the above matters, I find that Aldi instructed Motor Design to follow the architecture of the BABY BELLIES packaging and use photographic imagery. I take the word “follow” in this context to mean seek to resemble. I take the word “architecture” in this context to refer to the layout or structure of the packaging design.

89 On or about 21 May 2019, Motor Design provided to Aldi a further presentation (part of Annexure NP-3). This included two further designs (options 1 and 2) for MAMIA Fruit & Oat Bars (CB 957). These designs included writing in the belly of the owl. (I note that the BELLIES packaging included writing in the belly of the monster.) One of the designs (option 1) was structured with the owl character on the left side and images of the product and ingredients in a formation on the right side. At the foot of the page, under the heading “Market” were images of three BELLIES products, namely BABY BELLIES Organic Berry & Apple Softcorn; BABY BELLIES Organic Banana Softcorn; and LITTLE BELLIES Organic Gingerbread Men. (The first two of these images are not within the Applicants’ Works, but they are broadly similar to item 1 of the Applicants’ Works. The third image is one of the Applicants’ Works.)

90 In an email dated 21 May 2019, from Ms Bartholomeusz to Ms Paquet, Ms Bartholomeusz stated (in an apparent reference to options 1 and 2 referred to in the presentation of the same date):

For the Snacking Range we have visualised two layouts as Baby Bellies has two different architectures.

91 This email indicates that Motor Design was seeking to resemble the layout of the BELLIES packaging.

92 Ms Paquet states in her first affidavit that: she provided feedback to Motor Design; this included that option 1 was preferable to option 2 because the product was more prominent; to this point, the designs had related to MAMIA Fruit & Oat Bars; Ms Paquet now asked Motor Design to prepare a pack design for Rice Cakes. I accept this evidence.

93 The electronic Court Book includes a comment made by Ms Bartholomeusz on the page referred to above (CB 957) in the 21 May 2019 presentation:

Option 1 is preferred with the below [edits]:

1. Make the owl more friendlier (sic).

2. Please conceptualise the Mamia Apple Rice Cakes (reference in folder).

94 These comments appear to record feedback or instructions given to Ms Bartholomeusz by Aldi (most likely by Ms Paquet).

95 On or about 28 May 2019, Motor Design provided a further presentation to Aldi (part of Annexure NP-3). This included further refinement of the design for the Fruit & Oat Bars. The design retained writing in the belly of the owl. Also retained was the overall structure of the design, with the owl on the left side and the product and ingredients on the right side. A similar format was adopted for the Rice Cakes.

96 In May and June 2019, Aldi contacted CTD in the Bag to see whether CTD in the Bag would be interested in having BABY BELLIES products stocked by Aldi as part of Aldi’s seasonal program. Ultimately, however, the idea was not pursued as CTD in the Bag indicated that they would be unable to supply Aldi due to capacity constraints.

97 Several further iterations of the designs for the MAMIA snacking range were provided by Motor Design to Aldi over the following months.

98 By the end of 2019, the re-design for the MAMIA snacking range was substantially complete.

Events in 2020

99 During 2020, the re-designed packaging for the MAMIA snacking range was launched. The SOAF contains the following details of the dates when Aldi commenced selling products in the re-designed packaging:

(a) in about February 2020, Aldi began selling the MAMIA Rice Cakes in the re-designed packaging (i.e. items 1 and 2 of the Impugned Works) (see SOAF, Part A, para 12);

(b) in about June 2020, Aldi began selling the MAMIA Fruit Snack Cereal Bars in the re-designed packaging (i.e. items 6, 7 and 8 of the Impugned Works) (see SOAF, Part A, para 13 and T218); and

(c) in about December 2020, Aldi began selling the MAMIA Fruit & Oat Bars in the re-designed packaging (i.e. items 3, 4 and 5 of the Impugned Works) (see SOAF, Part A, para 14).

100 In about June 2020, Aldi decided to develop baby puffs products within the MAMIA range. On 2 June 2020, Aldi requested Motor Design to develop designs for the new baby puffs products that were consistent with the recently re-designed MAMIA snacking range packaging.

101 On 9 July 2020, Motor Design provided initial designs for three baby puffs products (namely, blueberry, apple cinnamon and carrot). Consistently with the re-design of the MAMIA dry food products referred to above, the proposed designs for the new baby puffs products included an owl with writing in its belly on the left side and images of the product and ingredients on the right side. It is to be inferred (from the documents referred to below) that Motor Design continued to use the BELLIES brand as the “benchmark”.

102 Ms Paquet was on maternity leave from November 2020 until July 2021. She was therefore unable to give any direct evidence as to the design process in relation to the baby puffs products during that period.

Events in 2021

103 On about 5 January 2021, Motor Design provided to Aldi designs for MAMIA Baby Puffs. The drawings are dated 5 January 2021 and are referred to as “version 4” in an email of that date (Ex A13, tab 18). The designs related to three products: Apple Cinnamon Baby Puffs; Blueberry Baby Puffs; and Carrot Baby Puffs. The design for the Apple Cinnamon Baby Puffs (Ex A12, tab 21) was:

104 On 14 January 2021, Ms Fernandez of Aldi sent an email to Motor Design in relation to the artwork for the MAMIA baby puffs (Ex A13, tab 19). The email stated:

Unfortunately I have received feedback that this particular artwork is too close to our benchmark, I understand we are now on V5 of artwork rounds.

Motor this artwork will need to be updated with the below requirements:

1. Baby Puffs to be removed from inside owl & placed under Mamia Organics

2. Rearrange the layout of packaging, so the owl puff imagery is in a different position.

I infer that the reference to the “benchmark” is to the BELLIES brand. (There is no suggestion that the benchmark had changed.) I also infer that the feedback related to version 4 of the artwork, that is, the version dated 5 January 2021. (I take the reference in the email to V5 (version 5) to be a reference to the next iteration that would be produced.)

105 In response, Emily Styles of Motor Design sent an email on the same day (14 January 2021) saying that she had passed this on to Nicole (a reference, it may be inferred, to Ms Bartholomeusz) who would work on a revised design.

106 Ms Fernandez sent an email in response on the same day that stated:

Thanks, although our whole range is consistent this in particular is too close.

107 The evidence includes a copy of the artwork for the MAMIA Apple Cinnamon Baby Puffs (version 4) with an electronic Sticky Note written by Ms Bartholomeusz (Ex A13, tab 20). Ms Bartholomeusz’s Sticky Note reads:

ALDI have now had legal come back to them and state this design is too close to the benchmark – no shit!

ALDI would like to see the below edits made:

- ‘Baby Puffs’ removed from the owl’s belly and placed under Mamia Organic

- rearrange the layout of the pack so the owl and the imagery is in a different location. Best to just swap them around so at least there is some consistency across the range

Reference to the benchmark is in the folder.

The copy of the above note in evidence is dated 29 August 2024. However, that date is likely to be when the document was printed for the purposes of the proceeding. The content of the Sticky Note is substantially the same as the email from Ms Fernandez to Ms Styles dated 14 January 2021 referred to above. Further, in the email from Ms Styles of the same date, she stated that she would pass that on to Nicole (i.e. Ms Bartholomeusz). In light of these matters, it may be inferred that Ms Bartholomeusz’s Sticky Note was written on or shortly after 14 January 2021.

108 On 21 January 2021, Belinda Eames of Aldi (who was assisting in the design process while Ms Paquet was on maternity leave) sent an email to Motor Design with further comments on the design for the MAMIA Apple Cinnamon Puffs (Ex A13, tab 21). Ms Eames’s email included a picture of the then current design (which had the words “Apple Cinnamon” in the owl’s belly). Ms Eames’s email included:

We believe the current concept is still very similar to the branded product, and would like to suggest the following changes.

- Move the wording from the owls belly to a different location

- Revise the positioning of the puff and owl imagery, possible the owl sitting on top off the puff?

I infer that the reference to “the branded product” is to the BELLIES brand. (There is no suggestion that any other branded product was being used as the benchmark.)

109 On the same day (21 January 2021), Ms Bartholomeusz sent an email to Ms Eames (Ex A13, tab 22):

Emily passed your feedback through in regards to the Baby Puffs.

I have had the creative team update this for you. Please see attached. Now that the owl doesn’t have text in his tummy I think this should move it far enough away from the benchmark.

(Emphasis added.)

I infer that the reference to “the benchmark” is to the BELLIES brand.

110 In or about August 2021, Aldi began offering for sale and selling MAMIA baby puffs products in packaging bearing the works depicted in items 9, 10 and 11 of the Impugned Works (see SOAF, Part A, para 15).

111 The Impugned Works were created for Aldi by Motor Design. (To the extent that the applicants and Aldi differed over the wording of para 16 of Part A of the SOAF, I prefer the applicants’ wording; I consider that the applicants’ wording better accords with the evidence.)

112 Motor Design created the Impugned Works having regard to instructions given by one or more employees of Aldi Stores. The final designs of the Impugned Works were approved by one or more employees of Aldi Stores. It is agreed between the parties that these actions of the employees of Aldi Stores are, for the purposes of this proceeding, taken to have been done by and on behalf of Aldi.

113 On 1 October 2021, B&B Studio and Hampden executed a Copyright assignment deed (Annexure CS-13) (the B&B Studio to Hampden Assignment Deed). Although executed on 1 October 2021, the deed is stated to have an effective date of 7 August 2018. The Recitals state that: B&B Studio (referred to as the “Assignor”) created various artistic works for use in the EBC business; B&B Studio is the owner of the copyright in the Works (as defined in the deed); and B&B Studio has agreed to assign to Hampden (referred to as the “Assignee”) the copyright in the Works. “Works” is defined in the deed as meaning “artistic works created by the Assignor for use in the Every Bite Counts Business including the artistic works listed in Schedule 1”. Schedule 1 includes items 1, 2 and 3 of the Applicants’ Works and works that are very close to (but not the same as) items 4 and 5 of the Applicants’ Works. (Given the general definition of “Works”, nothing turns on the fact that the Schedule does not contain works that are the same as items 4 and 5.) Clause 2.1 of the deed is in the following terms:

2. ASSIGNMENT OF COPYRIGHT

2.1 In consideration for the Fees, the Assignor hereby assigns, transfers and sets over to the Assignee from the Effective Date:

(a) the entire ownership of any and all past, present and future rights, title, interest in Copyright (including future copyright) in the Territory subsisting in the Works;

(b) all Copyright in any amendments, adaptions, alterations or variations which the Assignor has made or may in the future make to the Works; and

(c) all rights, if any, that the Assignor has to take actions against third parties for infringement of Copyright in the Works whether or not such infringement took place prior to the date of this Deed.

Although the term “Effective Date” is not defined in the clause setting out definitions (cl 1.1), it is apparent from the beginning of the deed that the Effective Date is intended to be 7 August 2018.

114 On 18 October 2021, Gestalt Law, on behalf of Hampden, sent a letter of demand to Aldi contending that Aldi had infringed Hampden’s copyright in the three artistic works relating to the puffs products (Annexure NP-5).

115 On 29 October 2021, Gestalt Law, on behalf of Hampden, sent a letter to Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers (acting on behalf of Aldi) (Annexure LH-2). This letter responded to a letter dated 28 October 2021.

116 On 17 November 2021, Gestalt Law sent a further letter to Spruson & Ferguson Lawyers (Annexure LH-3). This letter responded to a letter dated 3 November 2021.

117 In December 2021, Aaron Nolan of Aldi requested Motor Design to prepare an amended design for the MAMIA baby puffs. This was in response to objections to the design that had been raised by Hampden in the correspondence referred to above. The key changes to the design were: to change the character from an owl to a monkey and to change the fonts used for the writing.

118 On 22 December 2021, EBC and Hampden executed a Deed of Assignment (Ex A12, tab 14) (the EBC to Hampden Assignment Deed). The Recitals are as follows:

A. On or about 7 August 2018 B&B Studio Limited (B&B Studio) assigned to EBC intellectual property rights owned by B&B Studio in relation to works created by B&B Studio for EBC (Works).

B. On or about 1 October 2021, but with an effective date of 7 August 2018, B&B Studio assigned to Hampden rights in relation to the Works (to the extent that B&B Studio retained any such rights), including:

I. the entire ownership of any and all past, present and future rights, title, interest in all copyright or similar rights now or in the future subsisting in the world (Copyright) (including future copyright) in the world subsisting in the Works;

II. all Copyright in any amendments, adaptations, alterations or variations which B&B Studio has made or may in the future make to the Works; and

III. all rights, if any, that B&B Studio has to take actions against third parties for infringement of Copyright in the Works whether or not such infringement took place prior to the date of the assignment.

C. In or about May 2018, Bruno Mota, an employee of EBC, created the works depicted in the Schedule to this Deed (collectively, the Mota Works).

D. EBC is the owner of copyright in the Mota Works.

E. It is the intention of both EBC and Hampden that Hampden be the owner of all rights in relation to the Works and the Mota Works, including copyright and the right to sue for past infringements of copyright.

F. Accordingly, EBC and Hampden have agreed that any and all rights in relation to the Works and the Mota Works that are currently held by EBC are to be assigned to Hampden.

119 The operative terms of the deed are as follows:

Assignment

1. EBC hereby assigns, transfers and sets over to Hampden:

(a) the entire ownership of any and all past, present and future rights, title, interest in all Copyright (including future copyright) in the world subsisting in the Works;

(b) all Copyright in any amendments, adaptations, alterations or variations which B&B Studio has made or may in the future make to the Works;

(c) all rights, if any, that EBC has to take actions against third parties for infringement of Copyright in the Works whether or not such infringement took place prior to the date of this Deed.

2. EBC hereby assigns, transfers and sets over to Hampden:

(a) the entire ownership of any and all past, present and future rights, title, interest in all Copyright (including future copyright) in the world subsisting in the Mota Works;

(b) all rights, if any, that EBC has to take actions against third parties for infringement of Copyright in the Mota Works whether or not such infringement took place prior to the date of this Deed.

Events in 2022

120 In August 2022, Ms Paquet requested Motor Design to prepare a further amended design for the MAMIA baby puffs. Ms Paquet gives evidence in para 67 of her affidavit that this request was made in an attempt to resolve the proceedings, notwithstanding that she considered that both the original design and the revised design (with the monkey) were different from the BELLIES design. The key changes requested were to change the playful writing, have the puffs and food elements interact differently, and not to use a character or animal with a “belly”. The updated artwork was released to the supplier in September 2022.

Benchmarking

121 As noted above, in April 2019, Aldi instructed Motor Design to use the LITTLE BELLIES brand as the “benchmark” for the re-design of the MAMIA snacking range. Further, in Motor Design’s presentations to Aldi, Motor Design used images from both the BABY BELLIES brand and the LITTLE BELLIES brand as the “benchmark”.

122 In para 24 of her first affidavit, Ms Paquet gave the following description of benchmarking:

… development of a Private Label product (or rebranding an existing Private Label product) also involves consideration of the packaging used by competitors. As part of this process a benchmark product is usually identified within the market. This is a product selected by Aldi or the Agency from amongst the range of on-trend products within an on-trend category which have been identified during the market investigation process I have described above. The purpose of the benchmark is to enable us to identify cues that customers may associate with the product type generally and then adapt them to develop the Aldi Private Label product. These cues can include:

(a) the packaging size;

(b) the use of colours known to relate to quality or characteristics – for example, purple is used for salt and vinegar flavours; and

(c) the presentation of aspects of packaging such as product name and key ingredients, and also the expected age range for consumers of the product.

(Emphasis added.)

123 In para 41 of her affidavit, Ms Paquet stated that “[t]he objective was not to produce a copy or variant of the benchmark product and I did not instruct Motor to do so”.

124 In the course of cross-examination, Ms Paquet gave the following responses to questions about benchmarking:

Well, as at February 2019, your experience as a buying director included the fact that in developing private label product packaging, a benchmark product was usually identified within the market; correct?---Correct.

And that would be a product selected by Aldi or its agency from a range of on-trend products?---Correct.

And the purpose of that benchmark was to enable Aldi to identify cues that customers may associate with a product type?---Correct.

And then to adapt them to develop the product packaging?---Sorry, where are you reading from?

No, I’m asking you a question?---What’s the question?

Do you understand that the purpose of selecting a benchmark was to enable Aldi to identify cues that customers may associate with a product type and then adapt to develop the Aldi private label product?---Yes, to identify cues.

So are you baulking at adapting them?---We – we would benchmark to identify cues.

Are you baulking at the use of the word “adapt”?---No, I just think that it’s more holistic; that it’s about understanding how the consumer buys the product and what the cues are.

125 After some further questions, the following propositions were put to Ms Paquet:

… I want to suggest to you that the idea of adapting is all about creating a design that resembles the market leader’s, in this case, packaging?---No.

I want to suggest to you that the trick in all of this is to make sure that, in adapting, that Aldi’s design doesn’t too closely resemble the market leader’s packaging?---Say that again.

Isn’t the trick in – or the art form, if you like, in engaging in the process you say Aldi engages in of benchmarking that, in adapting a design, you’re mindful not to have the Aldi design too closely resemble the market leader’s packaging design?---No. It’s about understanding how the consumer buys the product.

126 It was put to Ms Paquet that understanding how a consumer buys a product is a distinct piece of analysis. She rejected that proposition. The following exchange took place:

Are you resisting the proposition that Aldi has regard to a so-called benchmark product – a market leader’s product in order to re-design its own packaging to resemble that market leader’s packaging?---Aldi does not re-design packaging to resemble market leading packaging.

127 Ms Paquet also gave the following evidence on the topic of benchmarking:

HIS HONOUR: I’ve just got a question. So, Ms Paquet, if you feel you can’t answer this, don’t – just say so. I’m just wanting to ask a question about the usage of the word benchmark?---Yes.

So when I’ve looked up the Macquarie dictionary definition, one of the definitions of benchmark is a point of reference from which quality, excellence, quantity, etcetera, is measured?---Yes.

So my question is, when you’re using the word benchmark, are you using it in that sense or in some other sense?---In terms of artwork, it’s more to do with a market reference, whereas benchmarking in that sense would be to do with industry standard results would be X and our result is Y. So quantitative benchmarking versus this process which is more around a market reference and understanding what’s happening in the market.

128 I have difficulty in accepting some parts of Ms Paquet’s evidence set out above. Having regard to the contemporaneous documents (as set out above) recording instructions given by Aldi to Motor Design (including the instruction that the snacking range architecture needs to follow BABY BELLIES), I infer that Aldi used the expression “benchmarking” to refer to a process of developing a packaging design that resembled the packaging of the benchmark product (albeit not too closely, because that would infringe the law). To that extent, I do not accept Ms Paquet’s evidence.

The process undertaken by Motor Design

129 On the basis of the contemporaneous documents (set out above), I infer that the process undertaken by Motor Design was to design packaging for the MAMIA snacking range that resembled the packaging of the benchmark product (the BELLIES range) (albeit not too closely, because that would infringe the law). This inference arises from the identification of the BELLIES range as the “benchmark”, the inclusion of images of BELLIES products in the presentations prepared by Motor Design for Aldi, the instructions from Aldi to Motor Design (including to follow the architecture of BABY BELLIES), and the internal Motor Design documents (including Ms Bartholomeusz’s Sticky Note set out at [107] above, which implicitly acknowledges the closeness of the new puffs designs to the benchmark).

130 The applicants submit that an adverse inference (in the sense discussed in Jones v Dunkel) should be drawn from Aldi’s failure to call Ms Bartholomeusz. Although Ms Bartholomeusz did not work for Aldi, I consider that, in the circumstances, it was reasonable to expect Aldi to call her as a witness. She worked for Motor Design, which was engaged by Aldi to create the relevant designs. I infer that Ms Bartholomeusz’s evidence would not have assisted Aldi’s case. This gives me added comfort in drawing the inference that the process undertaken by Motor Design was to design packaging for the MAMIA snacking range that resembled the packaging of the benchmark product (the BELLIES range) (albeit not too closely, because that would infringe the law).

Failure to call Ms Avdalis

131 Insofar as the applicants contend that an adverse inference (in the sense discussed in Jones v Dunkel) should be drawn from the failure of Aldi to call Ms Avdalis, I do not accept that submission. Ms Paquet replaced Ms Avdalis as the Buying Director for the MAMIA range from about March 2019. The critical relevant period in relation to the re-design of the snacking range took place after Ms Paquet commenced in that role. In these circumstances, I consider that it was sufficient for Aldi to call Ms Paquet and no adverse inference should be drawn from the failure to call Ms Avdalis.

Ownership of copyright

132 The first issue that arises is whether (for each of the Applicants’ Works) Hampden and/or Lacorium is the owner of the copyright.

Applicable principles

133 The ownership of copyright in artistic works is dealt with in s 35 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Section 35(2) relevantly provides that, subject to the section, the author of an artistic work is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work by virtue of this Part (namely Pt III). Section 35(6) relevantly provides that where an artistic work is made by the author in pursuance of the terms of his or her employment by another person under a contract of service or apprenticeship (i.e. is an employee or apprentice), then that other person (i.e. the employer) is the owner of any copyright subsisting in the work.

134 It is relevant for present purposes to refer to some of the provisions of the Copyright Act relating to works of joint authorship. The expression “work of joint authorship” is defined in s 10(1) as meaning (unless the contrary intention appears) “a work that has been produced by the collaboration of two or more authors and in which the contribution of each author is not separate from the contribution of the other author or the contributions of the other authors”. Division 9 of Pt III of the Copyright Act deals with works of joint authorship. Section 78 provides that (subject to Div 9 of Pt III) a reference in the Act to the author of a work shall, unless otherwise expressly provided by the Act, be read, in relation to a work of joint authorship, as a reference to all the authors of the work. Thus, under s 35(2), each author of a work of joint authorship is conferred with ownership of the copyright subsisting in the work: Milwell Pty Ltd v Olympic Amusements Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 63; 85 FCR 436 (Milwell) at [32] per Lee, von Doussa and Heerey JJ.

135 “Collaboration” does not require the authors to work directly with one another. As the applicants submit, alterations made by Person A to an earlier work created by Person B can, depending on the circumstances, result in a work of joint authorship of Person A and Person B together.

136 Copyright is personal property and (subject to s 196 of the Copyright Act) is transmissible by assignment, by will and by devolution by operation of law: s 196(1). An assignment of copyright (whether total or partial) does not have effect unless it is in writing signed by or on behalf of the assignor: Copyright Act, s 196(3).

137 A contentious issue in the present case is whether an assignment of copyright can be given retrospective operation as against a third party. The applicants submit that it can; Aldi disputes that contention. In Allam v Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 34; 95 IPR 242 (Allam), a Full Court comprising Bennett, Middleton and Yates JJ stated at [430]-[431]:

430 A similar question arose in Film Investment Corporation of New Zealand v Golden Editions Pty Ltd (1994) 28 IPR 1. In that case Burchett J said (at 15):

But it seems to me there are even more fundamental flaws in the scheme embodied in the deed of 13 November 1990. In the first place, it is not possible, if the exclusive licences purportedly held by FICNZ were not valid, for Mr Wass and FICNZ to make them so retrospectively. What had been written in 1988 had been written, and they could not change a line except for the future. They did not have Parliament’s power of retrospective legislation. So any exclusive licence or assignment brought into existence by the deed of 13 November 1990 could only have operation as from that date. (I am speaking, of course, of the effect of a licence or assignment so far as third parties are concerned, which is what is in issue here.)

431 In our view that passage is determinative of the present question. It was not competent for ATA to extend unilaterally the liability of third parties (in this case, the appellants) for damages to ATI and AI via the head distribution agreement, whatever effect that agreement might have had on the rights of the parties inter se.

(Emphasis added.)

138 It appears to have been accepted in the above passage that an assignment cannot be given retrospective operation as against a third party. See also, to similar effect, MSA 4x4 Accessories Pty Ltd v Clearview Towing Mirrors Pty Ltd [2024] FCA 24 at [299] per Downes J. I will proceed on that basis.

139 There is an issue between the parties as to whether the right to sue for past copyright infringement (i.e. infringement that occurred before the date of the assignment) can be assigned, such that the assignee can sue on the infringement. In my view, it accords with principle that the right to sue for copyright infringement (whether the infringement occurred before or after the assignment) can be assigned prospectively, at least in a case where the copyright is also assigned (prospectively): see the discussion (albeit in the context of a strike out application) in Global Brand Marketing Inc v Cube Footwear Pty Ltd [2005] FCA 479; 65 IPR 44 at [47]-[60] per Goldberg J. Such an assignment operates prospectively, albeit that it relates to a past infringement. I see no inconsistency between this proposition and the passage from Allam set out above.

Consideration

140 I will first consider the issue of ownership in relation to the B&B Works, and then consider the issue in relation to the Mota Works.

B&B Works

141 The applicants contend that, since 7 August 2018, Hampden has been the sole owner of copyright in the B&B Works. There does not appear to be any issue that B&B Studio was the owner of the copyright in the B&B Works at the time they were created, pursuant to s 35(6) of the Copyright Act. The applicants’ contentions can be summarised as follows:

(a) The applicants’ primary position is that copyright in the B&B Works was assigned by B&B Studio to EBC (by the 7 August 2018 Letter and the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions) and then by EBC to Hampden (by the EBC to Hampden Assignment Deed executed on 22 December 2021).

(b) In the event that the Court finds that the 7 August 2018 Letter and the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions were ineffective, the applicants rely in the alternative on the B&B Studio to Hampden Assignment Deed executed on 1 October 2021.

142 I am satisfied that the combined effect of the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions and payment in full by EBC to B&B Studio was to assign copyright in the B&B Works from B&B Studio to EBC, with effect from about 7 August 2018. The relevant terms of the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions have been set out at [51] above. The expressions “Intellectual Property Rights” and “IPR” were defined to mean (among other things) copyright (clause 3.1). Clause 3.2 provided that, subject to clause 3.3, all Intellectual Property Rights arising out of or in connection with the Services (other than IPR in the Client Materials) “shall be owned by B&B”. However, clause 3.3 relevantly provided:

The Intellectual Property Rights in the final design that we provide to you on completion of the Services shall be assigned to you on payment of the Price in full and cleared funds.

143 As set out above, I infer that, by 7 August 2018, the final design of each of the B&B Works had been provided by B&B Studio to EBC.

144 Although cl 3.3 states that the rights “shall be assigned”, which may suggest that a further step (i.e. an assignment) is required to assign the rights, I consider that, construed in context, the clause operates as an immediate assignment upon payment of the Price in full and cleared funds (which occurred here on or shortly before 7 August 2018). The construction of the contract is to be determined objectively. The relevant context includes the word “shall” in clause 3.2, which expresses the general position as regards ownership of copyright (from which clause 3.3 is an exception). Also, the words “on payment of the Price in full and cleared funds” in clause 3.3 suggest that the assignment takes effect automatically on the occurrence of that event. Aldi referred to Acohs Pty Ltd v Ucorp Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 16 at [193]-[195] for the proposition that the words “shall assign” are a promise to assign at a future time, not words of present assignment. However, a case considering words in a different contract is of limited assistance. As set out above, I consider that having regard to the context of the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions, clause 3.3 effects an immediate assignment upon payment in full. Accordingly, I consider that copyright in the B&B Works was assigned by B&B Studio to EBC on or about 7 August 2018.

145 The next question is whether there was an assignment from EBC to Hampden of the copyright in the B&B Works and, if so, from what date. In my view, the EBC to Hampden Assignment Deed was effective to assign copyright in the B&B Works from EBC to Hampden with effect from the date of execution of the deed (22 December 2021). The relevant terms of the deed have been set out at [118] above. Clause 1(a) states that EBC “hereby assigns … the entire ownership of any and all … rights … in all Copyright ... in the Works”. The expression “Works” is defined so as to include the works created by B&B Studio for EBC. On their face, these provisions amount to an assignment of copyright in the B&B Works from EBC to Hampden. It is true that earlier, on 1 October 2021, B&B Studio and Hampden executed the B&B Studio to Hampden Assignment Deed, which purported to assign copyright in the works (including the B&B Works) from B&B Studio to Hampden. However, given the conclusion I have reached in relation to the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions (namely that it was effective to assign copyright in the B&B Works to EBC), the B&B Studio to Hampden Assignment Deed had no relevant effect in relation to the B&B Works. I therefore consider that the EBC to Hampden Assignment Deed was effective to assign copyright in the B&B Works from EBC to Hampden with effect from 22 December 2021.

146 While the EBC to Hampden Assignment Deed was effective to assign copyright from 22 December 2021, it did not purport to have, and did not have, retrospective operation. However, in addition to an assignment of copyright in the B&B Works, the deed assigned all rights of action in respect of copyright in the B&B Works whether the infringements took place before or after the date of the deed (clause 1(c)). Accordingly, as from the date of the deed, Hampden had the right to bring actions for breach of copyright in respect of the B&B Works. This is sufficient to give Hampden the right to bring a claim for breach of copyright in the B&B Works in respect of infringements before 22 December 2021 (as well as infringements after that date).

147 It is therefore unnecessary to consider (in relation to the B&B Works) the applicants’ alternative case based on the B&B Studio to Hampden Assignment Deed.

148 For these reasons, I conclude that Hampden has the right to bring its claims for breach of copyright in respect of the B&B Works.

Mota Works

149 The applicants contend that the Mota Works are works of joint authorship of Mr Mota and the relevant employees of B&B Studio, such that Lacorium (as the employer of Mr Mota) and B&B Studio (as the employer of the B&B employees) were the owners of the copyright in the Mota Works when they were created. The applicants further contend that Hampden is the assignee of B&B Studio’s rights (on the basis of the assignment documents referred to above). Aldi accepts that Lacorium (as the employer of Mr Mota) is the owner of copyright in the Mota Works (see Aldi’s outline of opening submissions, para 53), but otherwise disputes the applicants’ contentions.

150 In my view, the Mota Works were works of joint authorship between the relevant employees at B&B Studio and Mr Mota. The artistic works created by Mr Mota were based on designs that had been prepared by B&B Studio and involved only limited input from Mr Mota. Nevertheless, his contribution was sufficient to constitute him as an author (and there does not appear to be any issue about this, noting that Aldi accepts at para 50 of its written closing submissions that Lacorium owns copyright in the Mota Works). B&B Studio employees created the designs upon which the Mota Works were based and B&B Studio employees provided feedback to Mr Mota on drafts that he prepared (see [66] above). Having regard to those facts, I am satisfied that there was collaboration between the B&B Studio employees and Mr Mota and that the Mota Works were works of joint authorship.

151 It follows that, at the time of the creation of the Mota Works (about May 2018), the copyright was held jointly by B&B Studio (as the employer of the B&B Studio employees) and Lacorium (as the employer of Mr Mota).

152 Unlike the B&B Works, I am not satisfied that copyright in the Mota Works was assigned from B&B Studio to EBC on or about 7 August 2018. This is because cl 3.3 of the B&B Studio Terms and Conditions refers to the assignment of rights in the “final design” provided by B&B Studio to EBC. It does not appear that final designs of the Mota Works were provided by B&B Studio to EBC.

153 However, I consider that the B&B Studio to Hampden Assignment Deed (executed on 1 October 2021) was effective to assign B&B Studio’s copyright in the Mota Works to Hampden from the date of the deed. The relevant terms of that deed are set out at [113] above. The expression “Works” is defined as meaning “artistic works created by the Assignor for use in the Every Bite Counts Business …”. I consider this to be sufficient to cover the Mota Works (in circumstances where, as discussed above, B&B employees were authors of those works). Clause 2.1(a) of the deed provided that the Assignor (B&B Studio) “hereby assigns … the entire ownership of any and all … Copyright … in the Works”. This was an effective assignment of copyright as from the date of the deed. Also assigned were all rights to take action against third parties (cl 2.1(c)). This was effective to assign from B&B Studio to Hampden all rights of action in respect of copyright in the Mota Works, whether the infringement occurred before or after the date of the deed. This is sufficient to give Hampden the right to bring a claim for breach of copyright in the Mota Works in respect of infringements before 1 October 2021 (as well as infringements after that date).

154 For these reasons, I conclude that Lacorium and Hampden have the right to bring their claims for breach of copyright in respect of the Mota Works.

Infringement of copyright

155 The next issue is whether (for each of the Impugned Works) Aldi infringed copyright in one or more of the Applicants’ Works. The applicants rely on both s 36 and s 38 of the Copyright Act.

Applicable principles

156 Section 36(1) of the Copyright Act provides:

36 Infringement by doing acts comprised in the copyright

(1) Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorizes the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

157 Section 31(1)(b) provides that (unless the contrary intention appears) copyright, in the case of an artistic work, is the exclusive right to do all or any of the following acts: (i) to reproduce the work in a material form; (ii) to publish the work; and (iii) to communicate the work to the public.

158 Section 14(1) provides:

14 Acts done in relation to substantial part of work or other subject-matter deemed to be done in relation to the whole

(1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears: