FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Stillwater Pastoral Company Pty Ltd v Stanwell Corporation Ltd [2024] FCA 1382

ORDERS

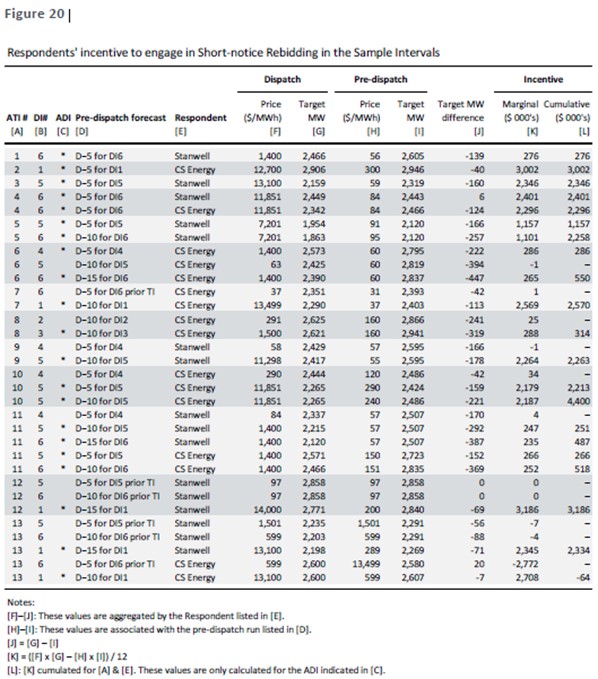

STILLWATER PASTORAL COMPANY PTY LTD ACN 101 400 668 Applicant | ||

AND: | STANWELL CORPORATION LTD ACN 078 848 674 First Respondent CS ENERGY LTD ACN 078 848 745 Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Common Questions to be determined at the Initial Trial be answered as follows:

Common Question 1

At all times during the Conduct Period, was the relevant market for the purposes of s 46 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) the market as pleaded in paragraph 22 of the Statement of Claim (Market)?

Yes.

Common Question 2

During the Conduct Period, did Stanwell have a substantial degree of power in the Market within the meaning of s 46(1) of the CCA?

No.

Common Question 3

During the Conduct Period, did CS Energy have a substantial degree of power in the Market within the meaning of s 46(1) of the CCA?

No.

Common Question 4

During the Conduct Period, for the purposes of s 46(2) of the CCA, did Stanwell and CS Energy together have a substantial degree of power in the Market?

No.

Common Question 5

During the Conduct Period, did each of Stanwell and CS Energy engage in Short-notice Rebidding in relation to the electricity they offered for dispatch in the Queensland Region of the National Electricity Market in any and if so in which of the alleged ATIs?

No.

Common Question 7

If the answer to Common Questions 2, 3 or 4 and to Question 5, is yes, did Stanwell and/or CS Energy, by engaging in the Short-notice Rebidding, take advantage of their market power?

Unnecessary to answer but No.

Common Question 8

If the answer to Common Question 7 is yes, did Stanwell and/or CS Energy take advantage of their market power for the purpose of deterring or preventing a person from engaging in competitive conduct in the Market?

Unnecessary to answer but No.

Common Question 11

If the answer to Common Question 8 is yes, did this constitute a contravention of s 46 of the CCA?

Unnecessary to answer but No.

2. The proceeding be dismissed.

3. The matter be adjourned to a date in March 2025 for the determination of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SARAH C DERRINGTON J:

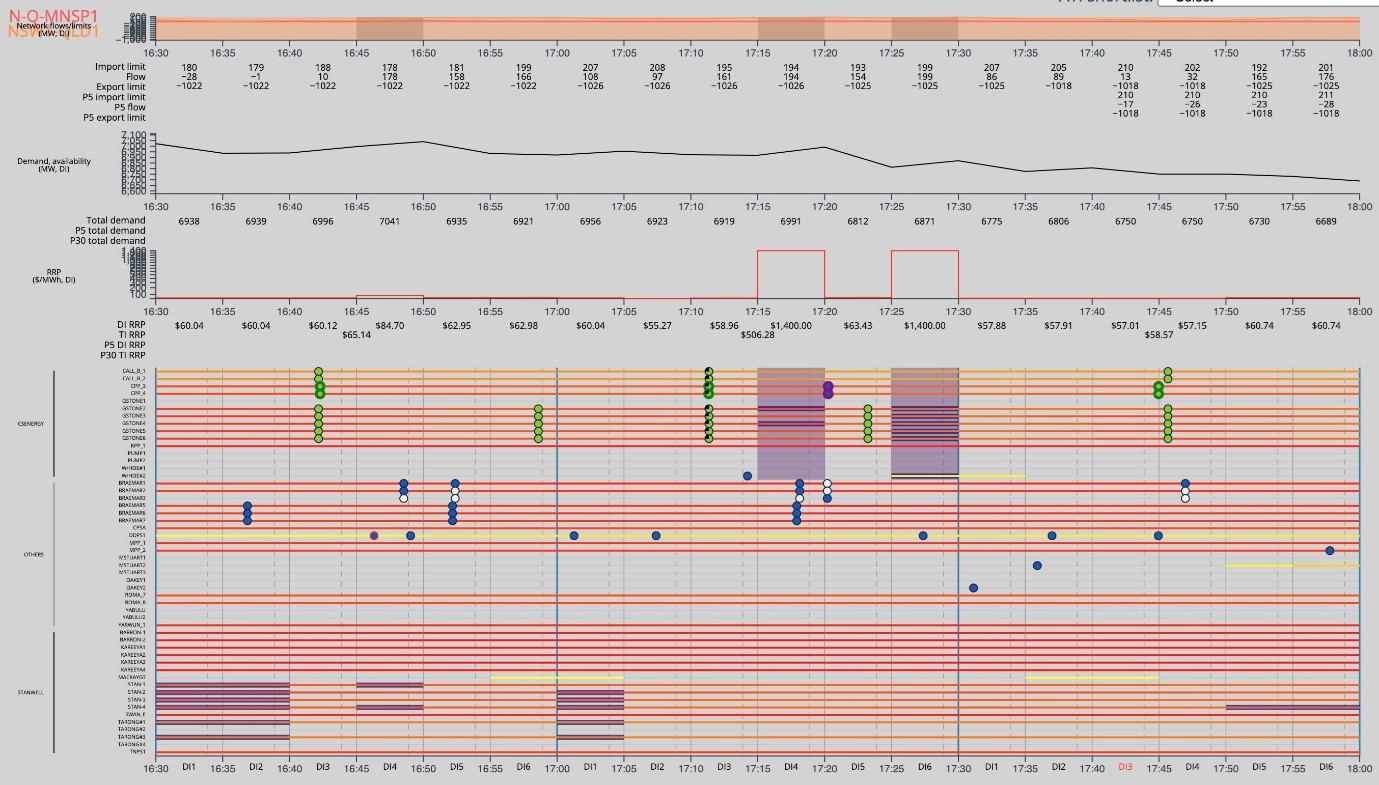

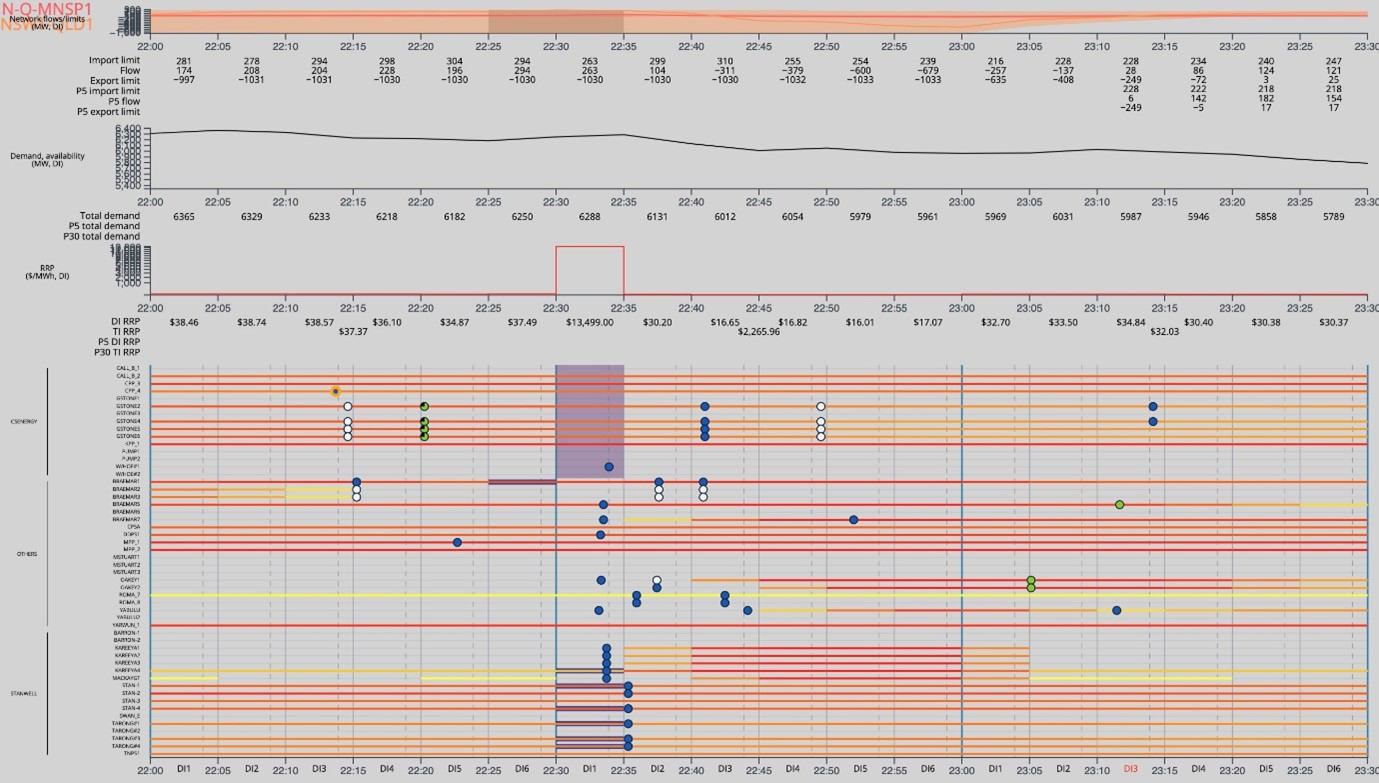

1 Queensland summers are hot and sultry. Demand for electricity is high and tends to peak in the afternoons when many Queenslanders turn on air-conditioners to make the late afternoon heat tolerable. Summer is the season during which Queensland electricity-generating firms (Generators) can maximise gross revenue. For that reason, at least two Generators, Stanwell Corporation Ltd ACN 078 848 674 and CS Energy Ltd ACN 078 848 745, the Respondents, have developed trading strategies to maximise gross revenue during the summer months. In broad terms, the strategies employed by Stanwell and CS Energy encourage their electricity traders to cause the electricity price to spike when the traders observe certain trends in the course of each Spot Market Trading Day. Those trends include forecast high temperatures, higher than forecast demand, low flow from interstate interconnectors, price volatility, and aggressive bidding by competitor firms. A Trading Day is a 24-hour period commencing at 04:00 and finishing at 04:00 the following day. Price spikes may be caused by Generators changing the quantity of electricity available for dispatch within ten pre-determined price bands, within one or more of the forty-eight 30-minute Trading Intervals (TI) by which a Trading Day is divided (Rebidding). If a Generator is able to cause a price spike in a TI, the effect will be to increase the Spot Price for that TI – being the time weighted average of the dispatch prices for each of the six five-minute Dispatch Intervals (DI) within the TI. The Generator that causes the price spike may, but not always, benefit from the price spike through a significant increase to its own revenue, at least for so long as the price spike endures, which is typically very short-lived. All Generators who have been dispatched in a given TI within their geographic region are paid the Spot Price. Those who make the very cheapest offers benefit from an elevated Spot Price.

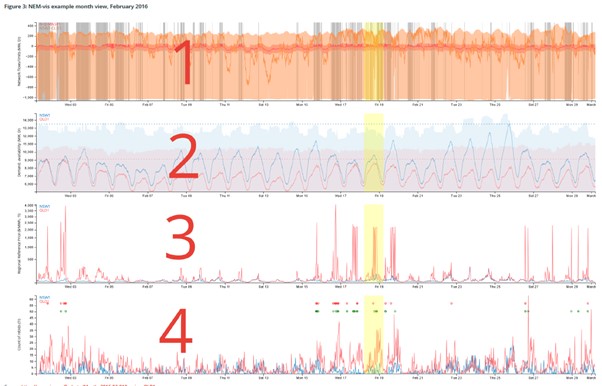

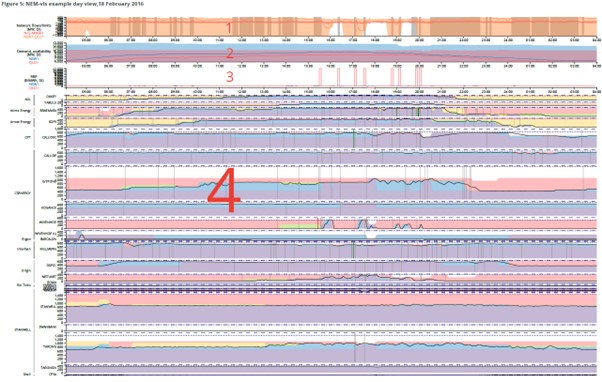

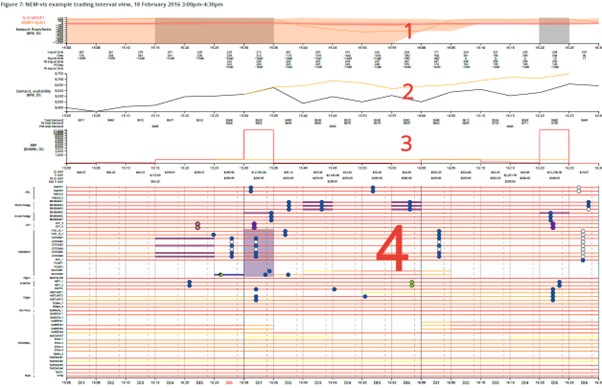

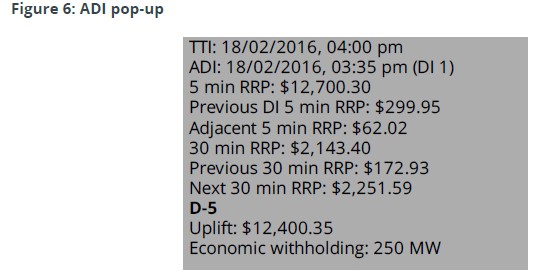

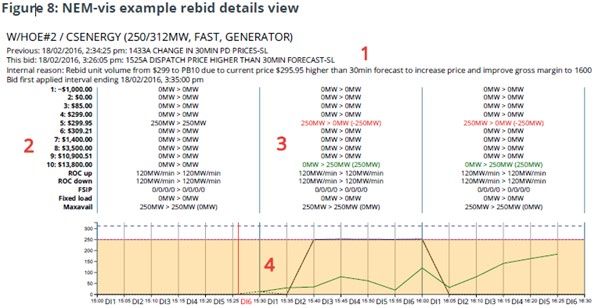

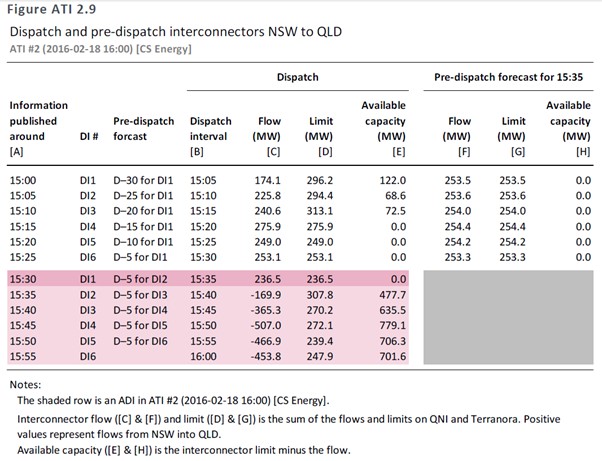

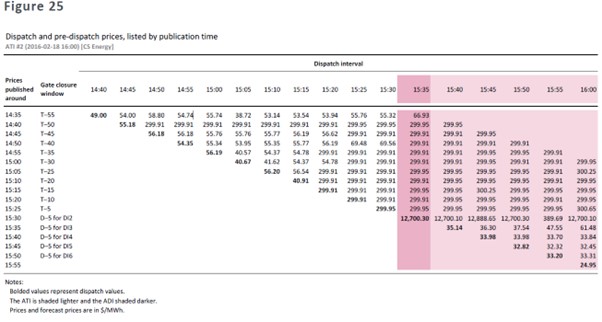

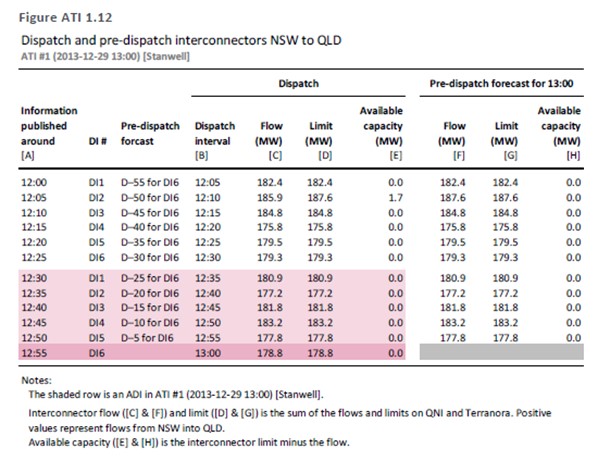

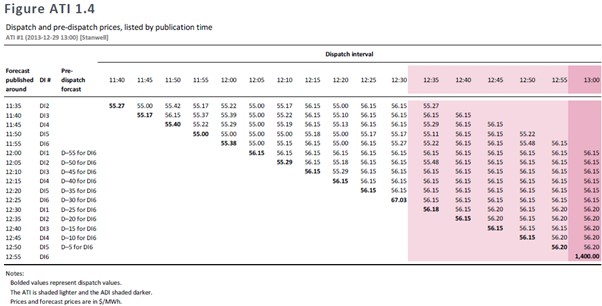

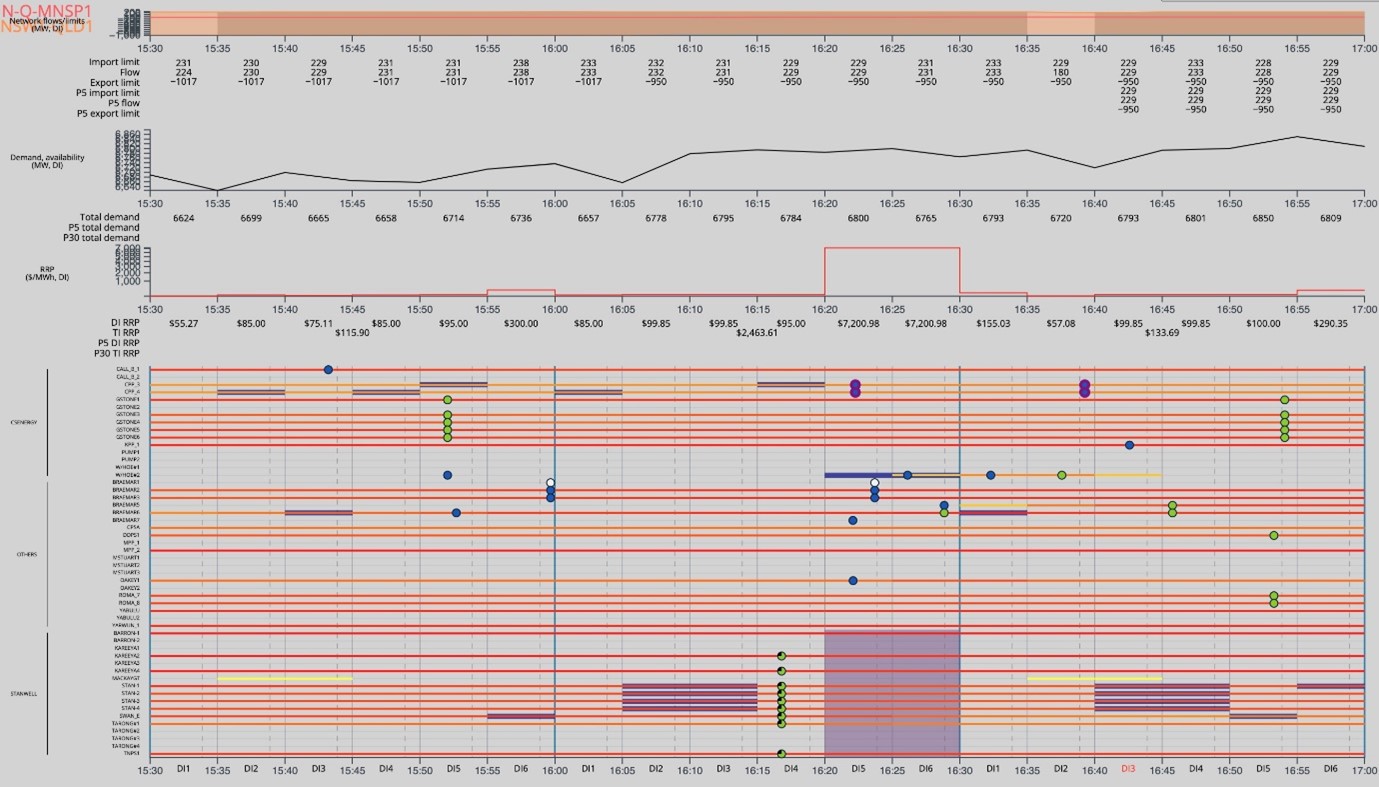

2 Thursday 18 February 2016 was a typical summer day in Queensland. Traders were provided with information throughout the day by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), particularly in relation to forecast demand, pre-dispatch forecast prices, and actual prices for prior TIs. At 15:00, the 30-minute pre-dispatch price forecast for the 30-minute TI ending at 15:30 was $55.20MWh. For the TI ending at 16:00, the AEMO forecast was $299.95MWh. Having noticed the significant change in the pre-dispatch price forecast, CS Energy “rebid” at 15:26 to move 250MW previously offered from one of its generating units (referred to in some evidence as Dispatchable Unit Identifiers, or DUIDs) from the $299.95 price band to the $13,800 price band. In the next DI (being DI1 in the TI ending 16:00), CS Energy moved 250MW from the $13,800 price band to the $0 price band for DI2 of that TI. The effect of the rebid was to reduce supply in the mid-tier price bands and force the National Energy Market Distributor Equation (NEMDE) to look for additional supply in the higher price bands. In DI1, being the DI ending at 15:35, the price spiked to $12,700.30MWh. That elevated price was therefore the dispatch price for DI1, as compared with the pre-dispatch forecast of $299.95MWh. That had the consequence of causing the Spot Price (or Trading Price) for the TI ending at 16:00 to be $2,143.40, as compared with $172.93 in the previous TI.

3 The foregoing is a high-level overview of the conduct about which the Applicant complains. Stillwater Pastoral Company Pty Ltd ACN 101 400 668, the Applicant, sues on its own behalf and on behalf of a group comprising the various categories of consumers of electricity in the Queensland Region of the National Energy Market (QRNEM) during the period between 20 January 2015 and 20 January 2021 (Claim Period). In broad terms, the Court was asked to interrogate 13 examples, similar in many respects to the rebid scenario just described, and which are referred to as Affected Trading Intervals #1 - #13 (ATIs). The 13 ATIs (together, the Sample Intervals) were, it seems, chosen by Stillwater’s expert, Dr Shaun Ledgerwood. The Sample Intervals are a subset of 353 ATIs, identified by Dr Ledgerwood, during which the impugned conduct was said both to have taken place and to have had a quantum effect on the Spot Price in the relevant ATI. The 353 ATIs were identified from amongst the 571,392 DIs during the period from 1 January 2012 to 6 June 2017 (Conduct Period), the latter date being when a Ministerial Direction under s 257 of the Electricity Act 1994 (Qld) was issued to Stanwell, restricting the maximum price of its rebids.

4 At the heart of the claim is the allegation that the two largest Generators in the QRNEM, being the State-owned corporations, Stanwell and CS Energy, contravened s 46 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). Stillwater contends that each of Stanwell and CS Energy enjoyed advantages, relative to other potential suppliers of wholesale electricity in or into the QRNEM, that translated to a substantial degree of market power for each of them. The other Generators offering supply into the QRNEM during the Conduct Period included AGL, Alinta Energy, Arrow Energy, Callide Power Trading (CPT), Ergon Energy Queensland, InterGen, Origin Energy, Rio Tinto and Shell. Stillwater alleges that, during the Conduct Period, the Respondents took advantage of that market power, for the purpose of deterring or preventing other Generators from engaging in competitive conduct, by their conduct comprised of two elements, which is described as Short-notice Rebidding. The two elements said to comprise Short-notice Rebidding are:

(i) the placing by the Respondents of rebids that repriced, to very high prices, volumes of electricity that formerly had been offered at much lower prices – “economic withholding”; and

(ii) the delaying of placing rebids until just before a bidding “window” closed (gate closure – on average 67 seconds prior to commencement of the next DI), such that other Generators had either no opportunity to respond, or insufficient opportunity to adjust their own generation rates and rebids in such a way as would have prevented the Respondents from achieving very substantial net revenue gains from their rebidding conduct.

5 The scope of this trial (Initial Trial) was confined to the question of whether either, or both, of the Respondents contravened s 46 of the CCA. Questions of causation or quantification of loss have been deferred. Central to the issue of whether the Respondents contravened s 46 is an understanding of what it means to “engage in competitive conduct” in the National Electricity Market (NEM), or a relevant subset thereof, the QRNEM. The word “competition” is not defined in the CCA, but is well understood (as used throughout the CCA) in a commercial or economic sense best described by reference to its aim, mechanism, and effect. The views of the Trade Practices Tribunal, expressed in 1976 in Re Queensland Co-operative Milling Association Ltd (1976) 8 ALR 481 (Re QCMA), remain important to understanding what is meant by “competition” in the context of Australian competition law. The Tribunal said, at 511:

… “[C]ompetition” is such a very rich concept (containing within it numbers of ideas) that we should not wish to attempt any final definition which might, in some market settings, prove misleading or which might, in respect to some future application, be unduly restrictive. Instead we explore some of the connotations of the term.

6 The Tribunal continued:

Competition may be valued for many reasons as serving economic, social and political goals. But in identifying the existence of competition in particular industries or markets, we must focus upon its economic role as a device for controlling the disposition of society’s resources. Thus, we think of competition as a mechanism for discovery of market information and for enforcement of business decisions in the light of this information. It is a mechanism, first, for firms discovering the kinds of goods and services the community wants and the manner in which these may be supplied in the cheapest possible way. Prices and profits are the signals which register the play of these forces of demand and supply. At the same time, competition is a mechanism of enforcement: firms disregard these signals at their peril, being fully aware that there are other firms, whether currently in existence or as yet unborn, which would be only too willing to encroach upon their market share and ultimately supplant them.

(Emphasis added.)

7 In Rural Press Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2003] HCA 75; 216 CLR 53 at 73, Gummow, Hayne, and Heydon JJ drew attention to the importance of the views and practice of those within a particular industry, “not only on the question of achieving a realistic definition of the market, but also on the question of assessing the quality of particular competitive conduct in relation to the level of competition”.

8 There was no dispute that the NEM is an “energy-only” market. There is no separate “capacity market” to ensure that Generators’ fixed costs and investments in capacity are remunerated. Thus, the only source of remuneration for costs associated with generation is the revenue earned from the dispatch of electricity or the provision of ancillary services. Accordingly, transiently high spot prices are required to ensure that Generators can recover both their variable and fixed costs, including higher costs generation that is primarily used during peak periods of demand. This feature of the NEM was expressly acknowledged by the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) in 2012 when considering whether major Generators were exercising substantial market power with the purpose or effect of increasing wholesale spot and contract prices such that a change to the National Electricity Rules (NER) was warranted. The AEMC said (AEMC, Draft Rule Determination – Potential Generator Market Power in the NEM, 7 June 2012, at i) (AEMC Draft Determination 2012):

Efficient wholesale prices, averaged over time, can be expected to be at the level required to recover the cost of building new generation or transmission capacity to satisfy growth in consumer demand. The Commission acknowledges that prices above this level for a sustained period of time may be more than is necessary to compensate for the various costs and risks borne by generators. If a generator(s) is able to increase average wholesale spot or contract prices above an efficient level for a sustained period of time, those prices are likely to flow through to retail prices and increase the costs to electricity consumers.

However, wholesale prices will not reflect an efficient level at every moment in time and variations in price are an outcome of the dynamic conditions of supply and demand in the NEM. In order to be useful in a real world setting, particularly in the context of a sector like electricity that requires ‘lumpy’ non-divisible capital investments, a time dimension needs to be recognised.

In addition, for short periods of time, transient but significant increases in the wholesale price of electricity may occur. A generator’s transient ability to significantly increase prices for short periods should not be considered a basis for a rule change unless that power is exercised to such an extent or with sufficient frequency that it causes long term average prices to be above the efficient level for a sustained period of time.

(Emphasis added. Citations omitted.)

9 This is the broad context in which the present proceeding arises.

10 By Order of the Court dated 29 April 2024, a List of Common Issues articulates the questions of facts or law that are common to the claims of Stillwater (as lead applicant) and the group members, and which were to be determined at the Initial Trial.

11 The scope of the Initial Trial was narrowed further by Order of the Court dated 19 December 2022 which directed that Stillwater nominate the Sample Intervals from amongst the 353 ATIs. The Sample Intervals were examined during this Initial Trial.

THE LIST OF COMMON ISSUES OF LAW OR FACT

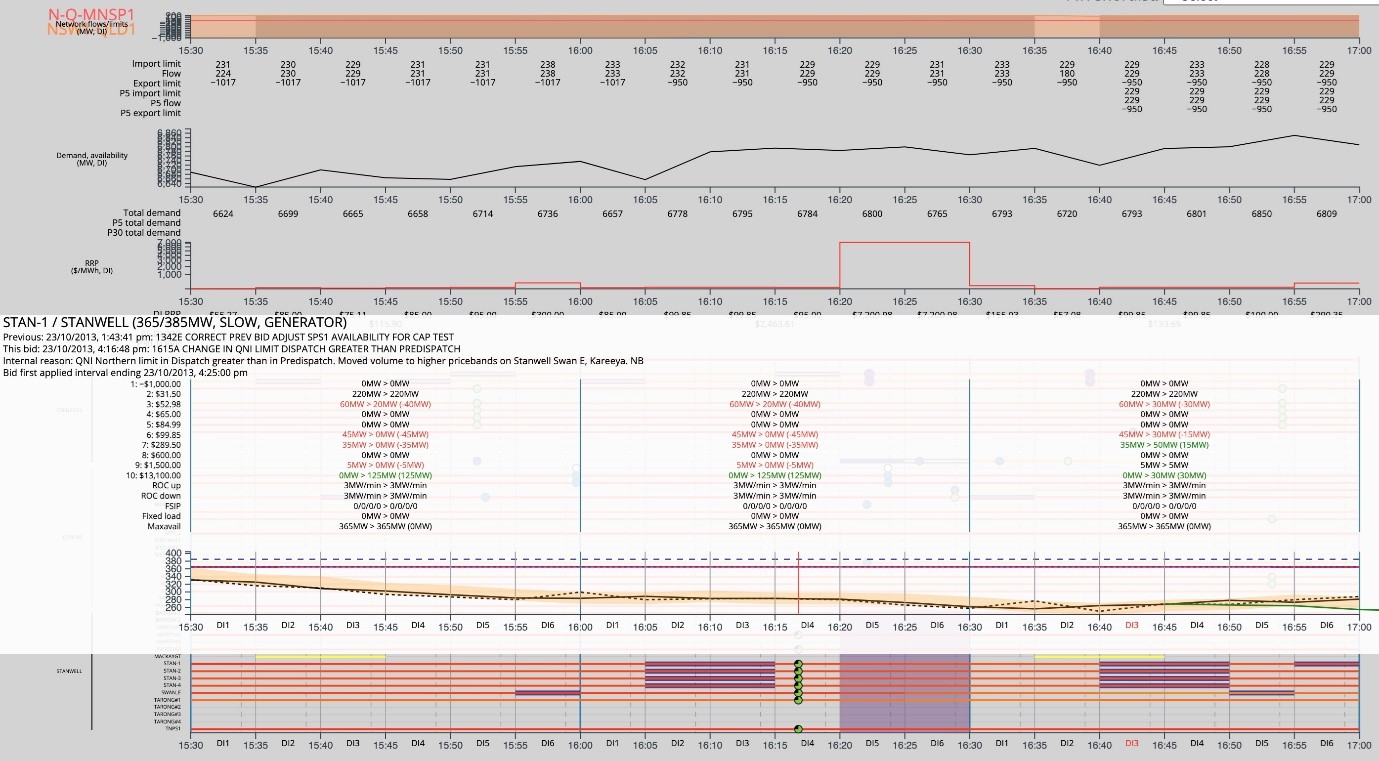

12 The List of Common Issues was settled by the parties. With cross references to the Third Further Amended Statement of Claim (3FASOC), that list is as follows:

The relevant “Market” for the purposes of s 46

1. Common Question 1: At all times during the Conduct Period, was the relevant market for the purposes of s 46 of the CCA the market as pleaded in paragraph 22 of the SOC (Market)? [SOC, [22]]

Substantial degree of power in the Market

Market power of each Respondent

2. Common Question 2: During the Conduct Period, did Stanwell have a substantial degree of power in the Market within the meaning of section 46(1) of the CCA? [SOC, [34]]

3. Common Question 3: During the Conduct Period, did CS Energy have a substantial degree of power in the Market within the meaning of section 46(1) of the CCA? [SOC, [41]]

Market power of each Respondent by reason of s 46(2)

4. During the Conduct Period, were Stanwell and CS Energy “related” within the meaning of s 4A of the CCA? [SOC, [7], [42(a)]]

5. Common Question 4: During the Conduct Period, for the purposes of s 46(2) of the CCA, did Stanwell and CS Energy together have a substantial degree of power in the Market? [SOC, [42(b)], [43]]

6. During the Conduct Period, did each of Stanwell and CS Energy, individually, by reason of s 46(2) of the CCA, have a substantial degree of market power in the Market? [SOC, [43]]

The Conduct

Common Question 5: During the Conduct Period, did each of Stanwell and CS Energy engage in Short-notice Rebidding in relation to the electricity they offered for dispatch in the QRNEM in any and if so in which of the alleged ATIs?

7 – 21. In relation to each Sample Interval did Stanwell and/or CS Energy as the case may be

a. submit a Short-notice Rebid? [SOC, [44(a)]]

b. time the Short-notice Rebid expecting and intending, or in circumstances where Stanwell and/or CS Energy can reasonably be inferred to have expected and intended, that by reason of the lateness of the rebid, competing Generators would be impacted in any of the ways pleaded in paragraphs 44(b)(i),(ii) or (iii) of the SOC? [SOC, [44(b)]]

c. submit the Short-notice Rebid in circumstances not materially different from:

i. the circumstances existing when Stanwell and/or CS Energy’s Timely Offer was made; or

ii. the circumstances existing when a Timely Offer could have been but was not made? [SOC, [44(c)]]

Taking advantage of market power

Common Question 7:

22. If question 20 above is answered in the affirmative, did Stanwell, by engaging in Short-notice Rebidding in relation to any and if so which of the Sample Intervals relating to it, take advantage of its substantial degree of power in the Market? [SOC, [51]]

23. If question 20 above is answered in the affirmative, did CS Energy, by engaging in the Short-notice Rebidding in relation to any and if so which of the Sample Intervals relating to it, take advantage of its substantial degree of power in the Market? [SOC, [51]]

Proscribed purpose

Common Question 8:

24. If the answer to question 22 above is affirmative, did Stanwell, in any and if so which of the Sample Intervals, take advantage of its substantial degree of power in the Market for the purpose of deterring or preventing competing Generators from engaging in competitive conduct in the Market (Proscribed Purpose)? [SOC, [53(a)]]

25. If the answer to question 23 above is affirmative, did CS Energy, in any and if so which of the Sample Intervals, take advantage of its substantial degree of power in the Market for the Proscribed Purpose? [SOC, [53(b)]]

Contravention of s 46

Common Question 11:

26. If the answer to question 24 above is in the affirmative, did Stanwell contravene s 46 of the CCA? [SOC, [53(a)]]

27. If the answer to question 25 above is in the affirmative, did CS Energy contravene s 46 of the CCA? [SOC, [53(b)]]

13 On 2 November 2023, the parties filed an extensive Statement of Agreed Facts (SAF).

14 The Court was assisted in answering these questions by five experts, who gave evidence in two “hot tubs”, following the preparation of joint expert reports in two expert conclaves facilitated by Counsel appointed by the Court. The first conclave focussed on the economic theory and principles relevant to the issues in the case (Economic Conclave). It produced the Joint Experts’ Report Conclave No 1 – Economic Experts dated 26 April 2024 (JtEcER). The second conclave focussed on the structure and operation of the electricity market, particularly the NEM (Electricity Market Conclave). It produced the Joint Experts’ Report Conclave No 2 – Electricity Market Experts dated 29 April 2024 (JtEMER).

15 Stillwater engaged Dr Ledgerwood, a Principal of the economic consulting firm, The Brattle Group. Dr Ledgerwood holds a Doctor of Philosophy, Master of Arts, and Bachelor of Arts, all in Economics, from the University of Oklahoma and a Juris Doctor from the University of Texas. Prior to joining The Brattle Group, he worked as an economist and attorney in the Office of Enforcement for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). His more than 30-year career has focussed on issues related to regulation and competition in energy markets. Dr Ledgerwood has had wide experience testifying as an expert witness in the Federal Courts of the United States and in Canadian Courts. As an Adjunct Professor at the University of Oklahoma Department of Economics, College of Law, and Price College of Business, he has taught undergraduate and graduate courses in microeconomic theory, law and economics, regulation, anti-trust, and contractual and tortious remedies. He also served as an Affiliated Faculty member at the Georgetown University Public Policy Institute. Dr Ledgerwood is widely published.

16 In these proceedings, Dr Ledgerwood has provided the following reports:

(a) the First Ledgerwood Report dated 4 October 2022 (1LedgerwoodR);

(b) the Second Ledgerwood Report dated 21 November 2023, updated by a Report dated 20 March 2024 (2LedgerwoodR);

(c) an analysis of the Hypothetical Monopolist test dated 28 March 2024 entitled, “Brattle note – Ledgerwood Figures for the Conclave Questions”; and

(d) the Fourth Ledgerwood Report dated 13 June 2024 (4LedgerwoodR).

17 Dr Ledgerwood participated in both the Economic Conclave and the Electricity Market Conclave and contributed to both the JtEMER and the JtEcER.

18 The two other participants in the Economic Conclave were Mr Euan Morton and Mr Derek Holt.

19 Mr Morton was engaged by Stanwell. He is a Principal at Synergies Economic Consulting and holds a Bachelor of Economics (Hons I), Bachelor of Commerce, and Bachelor of Laws (Hons) from the University of Queensland. He was admitted as a Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Queensland in 1991. Mr Morton has been appointed as an expert and to numerous expert panels including: the Expert Panel for the COAG Energy Council, 2015 Review of Governance Arrangements for Australian Energy Markets; the Expert Panel for Ministerial Council on Energy 2005 Report on Energy Access Pricing; and as an Independent Expert for NER, 2001. He has been a Member of the Competition and Consumer Law Committee of the Law Council of Australia. Mr Morton has had over 30-years’ experience preparing expert reports relating to competition matters, particularly in the energy sector, and in providing expert evidence.

20 In these proceedings, Mr Morton has provided the following Reports:

(a) Report of Euan Morton dated 28 February 2024 (1MortonR); and

(b) Supplementary Report of Euan Morton dated 6 June 2024 (SuppMortonR).

21 Mr Holt is a Partner of AlixPartners UK LLP. He holds a Master of Science with Distinction from the London School of Economics, an honours degree in economics and finance from McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and a postgraduate Diploma with Merit in Competition Economics from King’s College London. Mr Holt has practised as an economist for over 28 years, acting as an expert and economic advisor in the fields of competition litigation and economic regulation. He has appeared as an expert witness before the High Court of England and Wales, the Competition Appeal Tribunal, the Competition and Markets Authority of the United Kingdom, the Swedish Patent Court, the South African Competition Tribunal, the Hong Kong Competition Tribunal, and the European Commission.

22 In these proceedings, Mr Holt has provided the Expert Report of Derek Holt dated 23 February 2024 (Holt Report).

23 Dr Ledgerwood has had an extensive and impressive career as an economist. He has been particularly focussed throughout his career on issues of anti-competitive conduct and market manipulation. In his 2015 co-authored book, Gary Taylor, Shaun Ledgerwood, Romkaew Broehm and Peter Fox-Penner, Market Power and Market Manipulation in Energy Markets: From the California Crisis to the Present (Public Utilities Reports, Inc. 2010) at 8, Dr Ledgerwood et al, “build on the seminal work of … [Ledgerwood], creating a framework that helps categorize different types of market manipulation …”: see, Ledgerwood, Shaun D, “Screens for the Detection of Manipulative Intent (SSRN, December 2010). Chapter 9 of Market Power and Market Manipulation (at 189) proposes a diagnostic framework to expand “the traditional physical-goods market power conceptual model into one that more naturally incorporates the role of short-term information and financial products”. The authors (at 189) posit that the framework “helps to resolve a tension in the literature, often noted by economist experts such as Professor Pirrong [Bauer College of Business, University of Houston], between market power-based and fraud-based manipulations”. In his 2010 paper (at 2), Dr Ledgerwood attributed to Professor Pirrong what he referred to as “[e]ntrenchment in the literature of the perception that the execution of a ‘market-based manipulation’ requires traditional market power”. This apparent difficulty was picked up, and expanded upon, in Market Power and Market Manipulation (at 196), where in the context of an act of economic withholding by a seller, the authors say:

A successful market-power-triggered manipulation therefore requires that the seller must have the ability to thwart [competitive pressures to return the price to competitive levels] to prevent this participation from occurring, such as by taking advantage of size, entry barriers, or through implementing other restraints of trade – the hallmarks of traditional monopoly power.

Contrast this with the seller who dumps uneconomic volumes of product into the market at sub-competitive prices. Absent arbitrage opportunities … other sellers are not positioned to stop this behaviour and may be driven out of business if it is allowed to persist. Whereas the exercise of market power requires (and is in part defined by) the ability to prevent other sellers from participating in the market and thus thwart the effect of the exercise on the price, the reaction of other sellers to uneconomic trading faces no such immediate resistance. This means that successful manipulations triggered by uneconomic trading can be executed by firms with much smaller market concentrations than traditional anti-trust economics would deem relevant. The ability to make such sales profitably is not a function of market power, but rather of the willingness of the actor to absorb losses in the primary market …

(Emphasis added.)

24 More recently, in Shaun D Ledgerwood, James A Keyte, Jeremy A Verlinda, and Guy Ben-Ishai, “The Intersection of Market Manipulation Law and Monopolization under the Sherman Act: Does it Make Economic Sense?” (2019) 40 Energy Law Journal 47 (2019 ELJ article), Dr Ledgerwood and his co-authors (at 65), drew a distinction between “traditional market power acquired through some form of market dominance or through some ephemeral market power acquired circumstantially, such as when a generator is ‘pivotal’ in hours when system constraints bind”. As the authors explain, the Sherman Act (15 USC §§ 1-7) is often the source of private causes of action for manipulative acts. The Sherman Act is a close analogue of s 46 of the CCA although it is by no means in identical terms. Section 1, however, requires proof of collusion, whereas s 2 does not (at 49). Section 2 requires proof of “market dominance within a well-defined product and geographic market” in order to establish an abuse of monopoly power (at 56). The authors observe, consequently, that “the ephemeral nature of the distortions that are typically produced by such behaviour seems less suited to causes of action under Section 2 of the Sherman Act” (at 66).

25 The reason for setting out in some detail these features of Dr Ledgerwood’s academic writings is to attempt to shed light on some of the economic opinions expressed by Dr Ledgerwood during the Initial Trial which appeared both contrary to economic orthodoxy and contrary to his own previously expressed statements of economic principle. It is tolerably clear that, from about 2010, Dr Ledgerwood has felt unease with his perception that competition law, at least in the United States, does not deal adequately with cases of the type with which we are presently concerned, and which he described continually throughout the Initial Trial as “conduct cases”. He has posited a new approach to the detection of market-manipulation cases and has advocated for courts, and legislators, to adopt his approach. That has not yet happened. It is unfortunate that he did not clearly articulate his theory and debate it with the other economic experts. Rather, he strained existing orthodoxy by commencing with the result he wished to achieve and then constructed a theoretical framework by which that result would be achieved. This was most obvious when Dr Ledgerwood disavowed the appropriateness in this case of the “classic” test for substantial market power, which he and his co-authors had adopted in Market Power and Market Manipulation (at 13), because “it loses all meaning” in what he described as a “conduct case”.

26 That led Dr Ledgerwood to a theory that the competitive process compels Generators to increase output to sell at higher prices and that a responsive Rebid was “competitive” only if it might thwart, abate or mitigate a price spike. This was not through any malicious intent. It is clear that Dr Ledgerwood considered the behaviour of Stanwell and CS Energy to be obnoxious – as to which reasonable minds may differ. But, as Senior Counsel for Stanwell put it, Dr Ledgerwood’s approach emerged as one more akin to that of a prophet or an evangelist than that of an independent expert economist.

27 For these reasons, there are many instances where I have been compelled to reject Dr Ledgerwood’s opinion and have generally preferred the orthodox opinions expressed by Messrs Morton and Holt. Both gave considered and thoughtful evidence. Their reports were thorough and compelling. Both were prepared to make concessions where appropriate and to explain the limits of their evidence and of their expertise.

28 The participants in the Electricity Market Conclave, in addition to Dr Ledgerwood, were Dr Ian Rose and Mr Daniel Price.

29 Dr Rose is an Associate Partner at Ernst & Young. He holds a Bachelor of Electrical Engineering (Hons), Master of Engineering Science in Electrical Engineering from the University of Queensland, a Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering from the University of Waterloo, Canada, and a Graduate Certificate in Management from the Mount Eliza Business Management School in Victoria. Dr Rose is a Fellow of the Institution of Engineers Australia; a Life Member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, New York; a Member of the International Council on Large Electric Systems (CIGRÉ), Paris; and was a Member of CIGRÉ Australian Panel APC5 Committee – Electricity Markets and Regulation from 2000 to 2022. Dr Rose spent the first half of his career working primarily for the Queensland Electricity Commission, commencing in 1972, then for Queensland Generation Corporation (Aust Electric) from 1995 to 1999, before embarking on his consulting career. Dr Rose was involved in developing an energy management system for Queensland to manage the Queensland electricity grid from a new control centre in Brisbane. That centre became the Northern Control Centre for the NEM. Dr Rose has had extensive experience providing expert advice on a range of large electrical projects across Australia and has given expert evidence in disputes concerning transmission upgrades, marginal loss factors, bidding rules, transmission constraints, coal supplies, and power station operation.

30 In these proceedings, Dr Rose provided the following reports:

(i) Response to the First Ledgerwood Report dated 28 February 2023 (1RoseR);

(ii) Second Expert Report of Dr Ian Rose dated 26 February 2024 (2RoseR); and

(iii) Supplementary Report of Dr Ian Rose dated 28 May 2024 (SuppRoseR).

31 Mr Price was engaged by CS Energy. He is the co-owner and Managing Director of Frontier Economics Pty Ltd based in Melbourne, a position he has held since 1999. Mr Price holds a Bachelor of Agricultural Economics from the University of Sydney. Prior to commencing his consulting career, Mr Price had over 30 years’ experience in Australian energy reform design and implementation, including: as a principal economist at the New South Wales Electricity Commission (in which role he worked on the development and reform of the NEM Rules from 1988 until 1992); as a senior economics consultant at London Economics (advising on fundamental energy market design and reform in several countries, and reviewing the early trial of the NEM); as lead advisor to the Queensland Electricity Reform Unit (overseeing the entry of Queensland into the NEM); and as a consultant with Frontier Economics, to the NSW Market Implementation Group. He has provided advice to the Tasmanian, Western Australian, and South Australian governments on a variety of energy issues within those States.

32 In these proceedings, Mr Price has provided the following reports:

(i) Response to Ledgerwood Report dated 28 February 2023 (1PriceR);

(ii) Second Report of Daniel Price dated 26 February 2024 (2PriceRiceR); and

(iii) Supplementary Report of Daniel Price dated 25 March 2024 (SuppPriceR).

33 Despite Dr Ledgerwood’s primary field of expertise being economics, he also gave evidence as an expert in the operation of electricity markets, and more particularly, in relation to the operation of the NEM as relevant to the issues in these proceedings. His knowledge of electricity markets has been acquired largely in the context of his involvement in matters involving anticompetitive and manipulative market behaviour, including in relation to regulatory issues. The vast majority of his experience relates to energy markets in the United States, of which he readily agreed most are “capacity” markets rather than “energy-only” markets. His prior Australian experience was in assisting the Western Australian electric regulator with the development of screens to detect anticompetitive behaviour in its future capacity market design.

34 Dr Ledgerwood conceded that, prior to these proceedings, he had had no experience with the operational aspects of the NEM. Despite his obvious diligence in attempting to get across the minutiae of this extremely complex market, he was at a significant disadvantage as compared with Dr Rose and Mr Price, both of whom had been intimately involved with the NEM since its creation. As an example, Dr Ledgerwood sought to identify the impugned rebids as exercises in economic withholding creating what he referred to as an “artificial scarcity”, whereby no capacity is in fact withheld, merely repriced. As Stanwell submitted, in one sense, every price band above the lowest is an economic withholding in one sense, but the design of the NEM is that this can and should occur. As Mr Price put it, when asked about the difference between his opinions and those of Dr Ledgerwood:

It's not a dispute between me and Dr Ledgerwood. It’s a dispute between the whole National Electricity Market design and the agencies and governments whose market it is and Dr Ledgerwood. All I’m doing is reflecting the design of the market as it has been operating for 30 years. The market Dr Ledgerwood is talking about is not ours.

(Emphasis added.)

35 Where Dr Ledgerwood’s opinions were based on assumptions about matters material to the operation of the NEM, both in relation to the physical aspects of the market and in relation to the operation of the Spot Market, which differed from those of Dr Rose and Mr Price, I had much greater confidence in the opinions of the latter and accept their evidence.

Sample intervals which include Callide C – a preliminary issue

36 The methodology used by Dr Ledgerwood to identify the ATIs, from which Stillwater selected the Sample Intervals will be discussed shortly. Ultimately, in the First Ledgerwood Report, and the Second Ledgerwood Report, Dr Ledgerwood identified 352 ATIs. This number was revised in his later Report to 353, with 113 attributed to Stanwell and 311 to CS Energy, less the number of ATIs in which both Respondents were implicated (2LedgerwoodR at [1433]).

37 There is, however, a preliminary issue which concerns how many of the ATIs should in fact be attributed to CS Energy. This issue arises from the circumstances relating to the ownership and control of the Callide C power station. By the 3FASOC, Stillwater asserts that, during the Conduct Period, CS Energy owned or controlled the output of the Callide C. That contention is relied upon by Stillwater in support of its allegation that CS Energy (and CS Energy together with Stanwell) had a substantial degree of market power (3FASOC at [35]).

38 CS Energy submitted that when the rebids wrongly attributed to it are removed, the number of ATIs which concern CS Energy is reduced from 311 to 200. In relation to ADIs attributed to CS Energy, the number reduces from 363 to 235.

39 Callide C is located in Biloela, south-west of Gladstone, Queensland. It is one of two power plants that comprise Callide Power Station (Callide B and Callide C). Each of Callide B and Callide C have two generating units (referred to as CALL_B1 and CALL_B2, and CPP_3 and CPP_4, respectively).

40 CS Energy disputed that it owned or controlled Callide C. By its Amended Defence and Further Amended Defence (CSE FAD), it maintains Callide C is owned and operated by an unincorporated joint venture company between a wholly owned subsidiary of CS Energy (Callide Energy Pty Ltd) and another, entity, IG Power (Callide) Ltd (IGPC), the latter being a subsidiary of InterGen. It also asserts that, during the Conduct Period, electricity generated by Callide C was traded by another joint venture company, CPT, via separate bidding processes by each owner.

41 In response to the 3FASOC, CSE FAD pleads the arrangement of entities involved in the ownership structure of Callide C in the following way:

[35] As to paragraph 35 of the Statement of Claim, the Second Respondent:

(a) denies the allegations in subparagraph (a) and says further that:

(i) during the Conduct Period the Second Respondent directly or indirectly owned or controlled some or all of the Nameplate Capacity of the following Generating Systems:

CSE Generating System | Generating units DUID | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

Scheduled and Semi-Scheduled Generating Systems (MW) | ||||||||

Callide C | CPP 3 CPP 4 | 950 | 900 | 900 | 900 | 900 | 900 | |

Callide B | CALL B 1 CALL B 2 | … | … | … | … | … | … | |

… | ||||||||

…

(iii) during the Conduct Period:

(1) Callide Energy Pty Ltd (Callide Energy), a wholly owned subsidiary of the Second Respondent, and IG Power (Callide) Ltd (IGP) were 50/50 participants in an unincorporated joint venture which owned and operated Callide C (including the two generating units CCP_3 and CPP_4;

(2) Callide Power Trading Pty Limited (CPT) was a 50/50 joint venture company owned by Callide Energy and IGP;

(3) CPT was (and is) the Registered Participant for CPP_3 and CPP_4; and

(4) CPT traded the electricity generated from Callide C on the basis of bids submitted by each owner;

…

(Emphasis in original.)

42 Relevantly, in its Reply to CSE FAD, Stillwater admits, at [8], that CPT was a joint venture company owned by Callide Energy and IGPC, and that it was the Registered Participant for the two Callide C generating units CPP_3 and CPP_4 throughout the Conduct Period, but otherwise denies CS Energy’s plea of the joint ownership of Callide C and joins issue with respect to the structure of ownership and control of Callide C pleaded by CS Energy. It has not pleaded an alternative structure, but alleges that CS Energy was the operator of Callide C during the Conduct Period.

Findings on the basis of assumptions

43 For the purpose of preparing the First and Second Ledgerwood Reports, Stillwater instructed Dr Ledgerwood to assume that CS Energy owned or controlled Callide C. However, for the purpose of the Economic and Electricity Market Conclaves, Stillwater instructed him to adopt an alternative assumption, namely that Callide C was, in fact, owned and operated in the manner articulated by CS Energy. In the Fourth Ledgerwood Report (4LedgerwoodR at [80]), Dr Ledgerwood corrected Figure SDL9, noting:

The First Callide C Assumption assumes that CS Energy owned or controlled the output of Callide C.

The Alternative Callide C Assumption assumes that CS Energy was responsible only for the offers identified in Exhibit SB-3 as being triggered by instructions submitted by Callide Energy; and owned or controlled 50% of the capacity of Callide C.

*InterGen owns both Millmerran Energy trader and IG Power (Callide) (IGPC).

44 In its oral opening submissions, Stillwater submitted that it was unnecessary for the Court to make findings in relation to the ownership and control of Callide C as part of the Initial Trial. Senior Counsel for Stillwater submitted that it “[did] not consider that [it was] a useful deployment of [the Court’s] time for this trial to be taxed with the issues about how to treat Callide C”, and that the Court should assume that the structure of ownership or control of Callide C is as set out in the evidence tendered by CS Energy. This submission was put on the basis that “there’s a wider issue that we would need to deal with down the track” and so Stillwater “wishes to reserve its rights”. The nature and import of the “wider issue” were not explained. To the extent that Stillwater submitted there is “another round of factual problems” that have been identified, these were not elaborated upon either in oral or written submissions. It is relevant to observe that Stillwater has been on notice of CS Energy’s position since the filing of the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim on 20 March 2023 and cannot be said to have been taken by surprise by CS Energy’s position. Discovery and particulars have been provided, on 14 April 2023 and 28 June 2023 respectively, and interrogatories have been answered, on 21 February 2024. Two affidavits of Mr Stephen Beauchamp, affirmed on 22 February 2024 (First Beauchamp Affidavit) and 1 March 2024 (Second Beauchamp Affidavit), attesting to the manner in which Callide C’s output was traded as between Callide Energy and IGPC, have been filed and served. Mr Beauchamp was not required for cross-examination. A Notice to Admit Facts in relation to Callide C was served on 25 March 2024. Stillwater disputed all but two of the facts in the Notice to Admit.

45 CS Energy addressed the issue at some length in its written closing submissions and in closing addresses. As CS Energy submitted, Stillwater’s proposal to proceed on the basis of an assumption was unsatisfactory, not least because, as I have already said, the ownership and control of Callide C is one of the material facts pleaded by Stillwater in support of its allegation that CS Energy had a substantial degree of market power throughout the Conduct Period. It is basal to Common Question 3. There is also a plea of aggregated market power between the Respondents, the success or otherwise of which depends on their respective degrees of individual market power.

46 Further, the Court has been invited (3FASOC at [44(b)]) to infer from, inter alia, the “frequency” of the rebids made by CS Energy, that CS Energy timed the Short-notice Rebids “intending” to prevent or deter competing Generators from responding in a timely way. Absent a finding as to whether CS Energy, or in fact some other entity, made the several rebids on which that plea was founded, the Court is not in a position to draw any inference as to the frequency of those rebids. As CS Energy submitted, the effect of the impugned analysis in the Second Ledgerwood Report (the allegedly erroneously attribution of rebids) is understood as follows:

(a) for the 45 ATIs identified in Annexure A, 61 ATIs in Annexure B and 10 ATIs in Annexure B1 to CSE FAD, the impugned rebids of CS Energy include rebids of Callide C generating units that were made by InterGen, not CS Energy;

(b) when rebids wrongly attributed to CS Energy are omitted, then:

(i) the total number of ATIs involving CS Energy reduces from 311 to 200 (a difference of 111 ATIs); and

(ii) the total number of ADIs alleged against CS Energy is reduced from 363 to 235 (a difference of 128 ADIs).

47 It would be an astonishing proposition for the Court to proceed to make critical findings of fact, upon which significant aspects of Stillwater’s case rest, based on no more than an assumption that the structure of ownership and control of Callide C is as set out in the evidence tendered by CS Energy. Were the Court to do so, there would be nothing to prevent Stillwater from re-running significant components of the Initial Trial. There would be no issue estoppel.

48 Stillwater admits that CPT was a 50/50 joint venture company owned by Callide Energy and IGPC and that CPT was (and is) the Registered Participant for CPP_3 and CPP_4.

49 Despite [289] of the SAF, which states, as pleaded in [35(a)(iii)(1)] of CS Energy’s Amended Defence, “Callide Energy Pty Ltd (Callide Energy), a wholly owned subsidiary of CS Energy, and IG Power (Callide) Ltd (IGPC) were 50/50 participants in an unincorporated joint venture which owned and operated Callide C”, Stillwater has denied that plea. It did not apply for leave to withdraw the admission (Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 22.06). Nevertheless, Stillwater pleads that during the Conduct Period, CS Energy was the operator of Callide C on behalf of the joint venture.

50 As to that allegation, the evidence demonstrates first, that Callide Energy, IGPC and Callide Power Management Pty Limited (CPM) entered into a Joint Venture Agreement dated 11 May 1998 (as amended) (CPP Joint Venture). It did not appear to be controversial that IGPC was part of the InterGen Group of companies. The recent spate of decisions in this Court concerning the administration of IGPC makes that proposition unarguable.

51 Secondly, Callide Energy and IGPC appointed two main corporate vehicles in relation to the CPP Joint Venture, one of which was CPM. The rights of Callide Energy, IGPC, and CPM are set out in the CPP Joint Venture. Relevantly for present purposes, pursuant to the CPP Joint Venture:

(a) each of CS Energy and IGPC held a 50% interest (cl 2.4);

(b) each of CS Energy and IGPC had an undivided entitlement to use a proportion of the generation of the capacity of the Power Station, in the proportion of that Participant’s interest (cl 2.8);

(c) CPM was appointed the Manager of the CPP Joint Venture to manage “Joint Venture Activities”, which included the operation of Callide C (cl 3.1);

(d) an Operation and Maintenance Agreement dated 11 May 1998 (as amended) was entered into (cl 3.4) pursuant to which CPM, as agent for the joint venture Participants, engaged CS Energy as the Operator to operate and maintain Callide C; and

(e) a Station Services Agreement dated 11 May 1998 (as amended) was entered into (cl 3.5) between CS Energy and CPM (also as agent for the joint venture Participants) to provide certain station services required for, inter alia, the operation of Callide C. Pursuant to cl 62, Sch 2 specified the services to be supplied, which included the transport of coal, procurement of ignition oil, the supply of water for various purposes, the provision of various chemicals, the provision of various facilities, and disposal and removal of waste.

52 Pursuant to the Operation and Maintenance Agreement the subject of cl 3.4, relevantly:

(a) “Station Owners” are defined to mean Callide Energy Pty Limited ACN 082 468 746 and IG Power (Callide) Ltd ABN 53 082 413 885 together, and each of them is a “Station Owner”;

(b) “InterGen Australia” means IG Power (Callide) Ltd ABN 53 082 413 885 a Station Owner;

(c) the Operator (CS Energy) was prohibited, inter alia, from describing itself as agent or representative of the Manager or the Station Owners (cl 2.5);

(d) provision was made for liaison with and flow of information between the Operator and InterGen Australia at all times (cl 16.5);

(e) the services provided under the Operation and Maintenance Agreement pursuant to cl 6.3, as set out in Schedule 3, included:

(i) operating, maintaining, and repairing the Facility in accordance with the standards and requirements of the Operation and Maintenance Agreement;

(ii) providing the skills and resources necessary for the provision of the Services;

(iii) optimising the effective life of the Facility;

(iv) undertaking reviews of and (where appropriate) updating the methods of operation and maintenance employed having regard to, inter alia, world best practice;

(v) performing routine maintenance and testing of plant and equipment;

(vi) co-operating with the Manager, the Station Owners and Callide Power Trading Pty LTD ACN 082 468 710 and all Authorities;

(vii) maintaining operating and maintenance records for plant and equipment;

(viii) reporting on the performance of the Facility and providing forward projections on operations and maintenance;

(ix) providing all engineering required to operate and maintain the Facility including long term asset management; and

(x) maintaining sufficient personnel, expertise, and resources and using best endeavours to maximise returns to the Station Owners.

53 Although CS Energy was the contractual operator of Callide C, having been engaged by the Manager of the CPP Joint Venture, it was the “operator” only within the confines of the Operation and Maintenance Agreement. None of the services specified within the scope of that agreement, or the Station Services Agreement, resemble the functions to be carried out by CPT and by which the Station Owners were able to bid their generation into the NEM. For these reasons, CS Energy did not control the whole of the generating capacity of Callide C as alleged in [24] and [35] of the 3FASOC.

54 The other corporate entity was CPT which, pursuant to cl 6.1 of a Shareholder Agreement between Callide Energy and IGPC dated 11 May 1998 (as amended) (CPP Shareholder Agreement), was appointed the exclusive agent for Callide Energy and IGPC (at the time, named Shell Coal Power (Callide) Ltd), in accordance with the terms of a Market Trader Agreement (Sch 8 to the CPP Shareholder Agreement), entered into by each Participant with CPT (see Recital D of the Market Trader Agreement) to sell each of their shares of electricity in accordance with the terms of that agreement. The requirement for trading guidelines was established pursuant to the Market Trader Agreement (cl 5.2). Clause 5.3 provided that such guidelines must, inter alia, “state whether the Station Owner has adopted a Common Trading Strategy or a Differential Trading Strategy”. Relevantly, cl 7.2 of the Market Trading Guidelines provided:

There are two trading regime options available to the owners, Common Trading and Differential Trading.

Differential Trading

Differential Trading is the default trading option. The Owners bid their generation into the NEM on different terms through the Bidding System, where neither Owner is permitted to see the other Owner’s bid. Further, the Owners agree that Available Plant Capacity is to be dispatched into the NEM based on Differential Trading as the normal trading condition, except for those instances where Common Trading is implemented as described below.

Under differential trading the revenue for each owner is split according to the following rules:

1. When the Power station is operating at or below minimum load, 50% for each owner;

2. When the power station plant capacity is bid inflexible, for example where a fixed load is required for testing, 50% for each owner.

3. When the unit is above minimum load the portion for each owner is determined by the individual owner’s bids. (refer to settlements section for detail)

Common Trading

Where both owners agree that Common Trading is to be implemented, CPT will offer bids to AEMO directly through the AEMO web-portal in accordance with pre-agreed templates as detailed in attachment 1. The Common Trading regime has not been used to date and is not expected to be used under normal circumstances. Under Common Trading revenue will be apportioned 50% to each owner.

(Emphasis added.)

55 The manner in which the Market Trader Agreement and the Trading Guidelines were operationalised in practice was explained by systems engineer, Mr Beauchamp, in his two affidavits. Between approximately 2004 and 2012, Mr Beauchamp held various IT roles with InterGen (Australia) Pty Ltd (First Beauchamp Affidavit at [7]). In around 2009, he was seconded from InterGen to CPT on a full-time basis to develop the CPT Offer System (COS) (First Beauchamp Affidavit at [7]). As described by Mr Beauchamp, at [10]:

COS is an automated system utilised by CPT for submitting energy offers to AEMO. In the usual course, each offer to AEMO requires the following inputs:

(a) an “Owner offer” submitted by Callide Energy to CPT through COS in relation to Callide Energy’s share of Callide C;

(b) an “Owner offer” submitted by IGPC to CPT through COS in relation to IGPC’s share of Callide C; and

(c) an “availability profile” submitted by either CPT personnel or unit operators which contain the unit limits of each of the generating units of the Callide C power station (CPP_3 and CPP_4).

56 Mr Beauchamp deposed that, on or about 18 August 2022, he accessed the COS production database and extracted the historical data relevant to the Conduct Period (at [13]). That data showed whether CS Energy or IGPC issued CPT with instructions for any given rebid at a particular point in time (at [19](e)). As explained in the Second Beauchamp Affidavit, at [7], some “[o]perator availability” rebids were triggered by CPT personnel or unit operators.

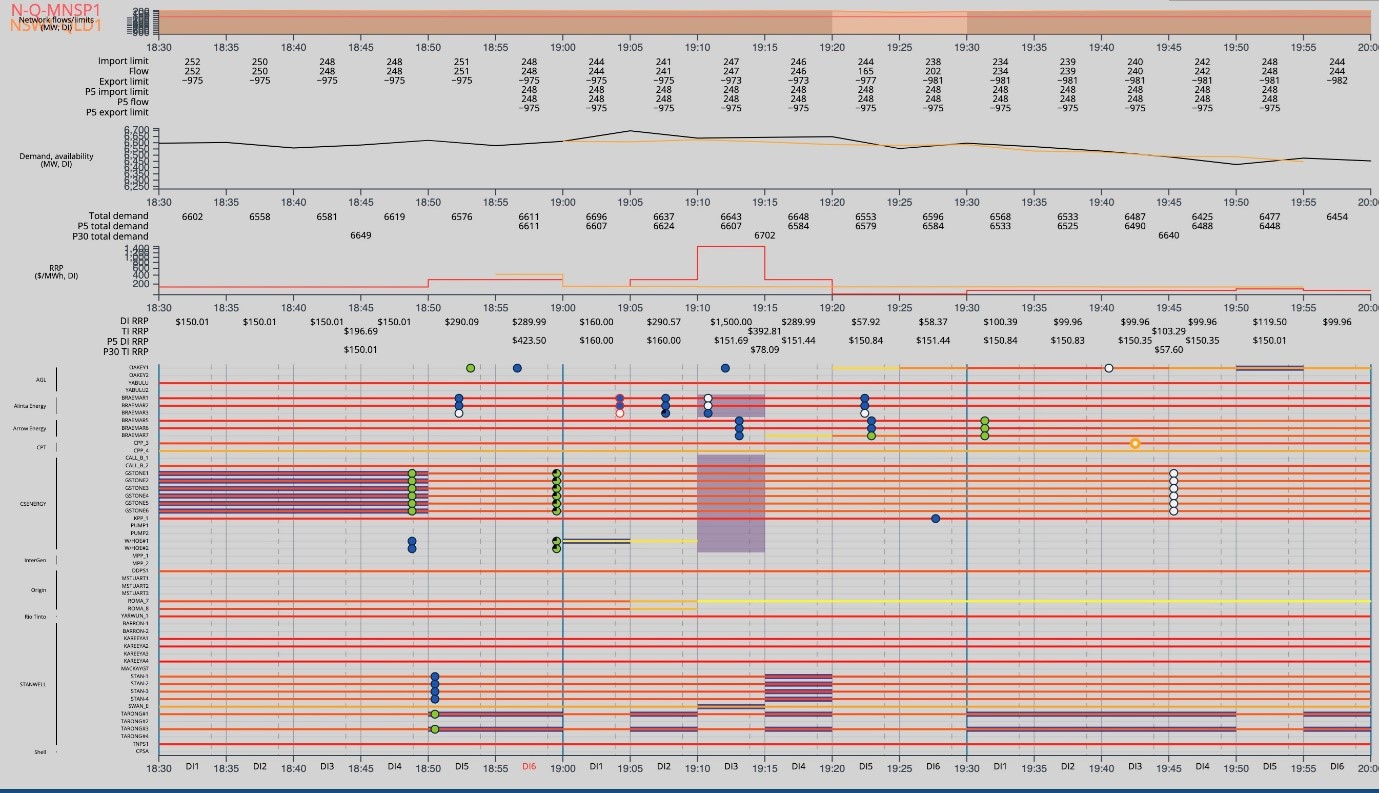

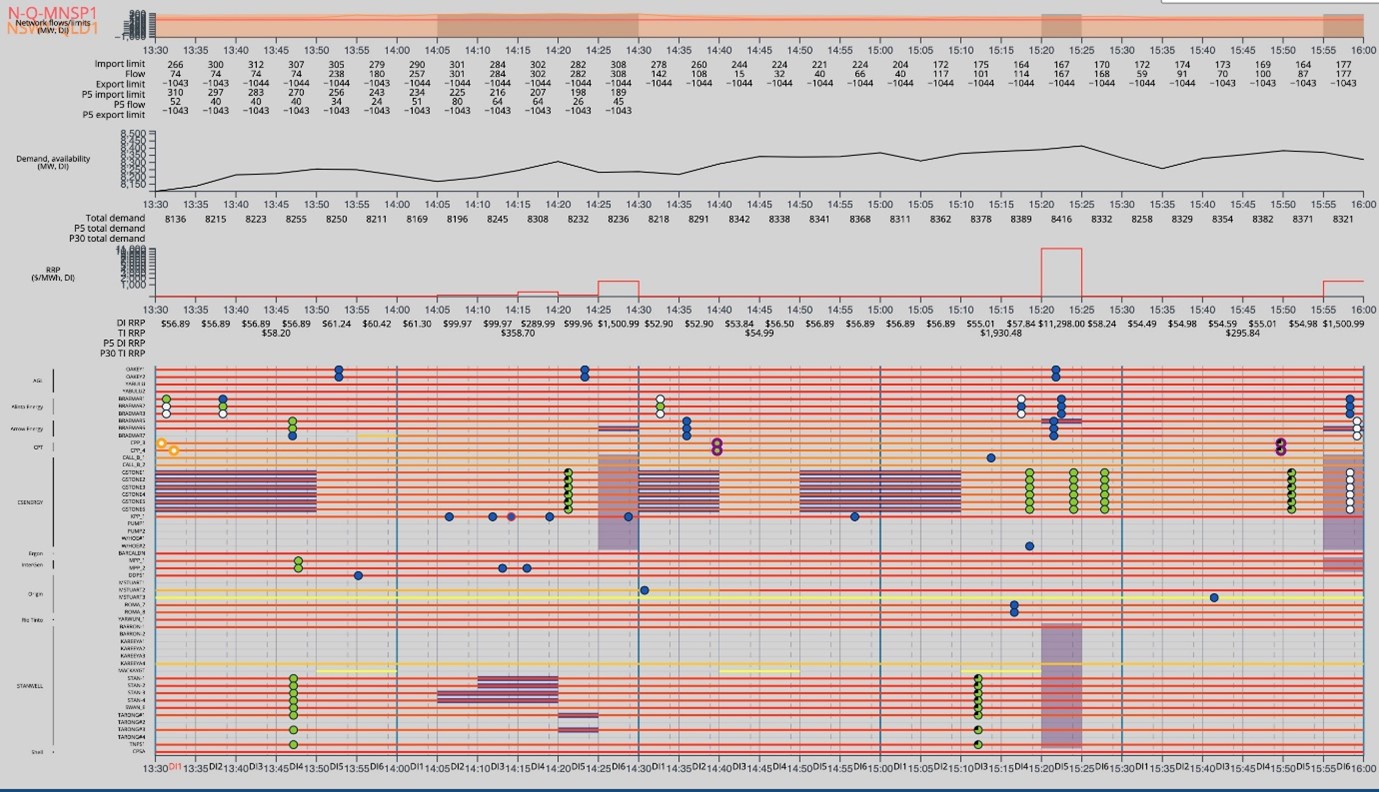

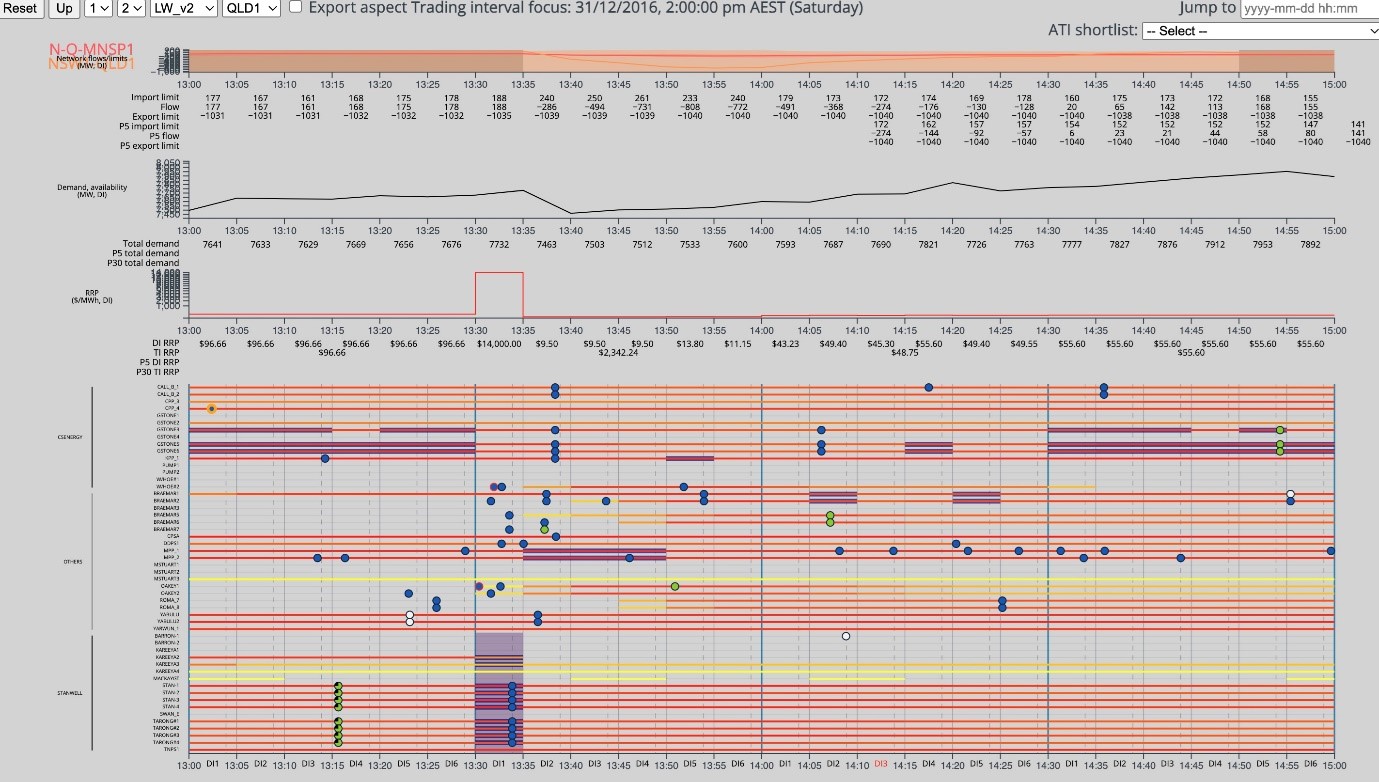

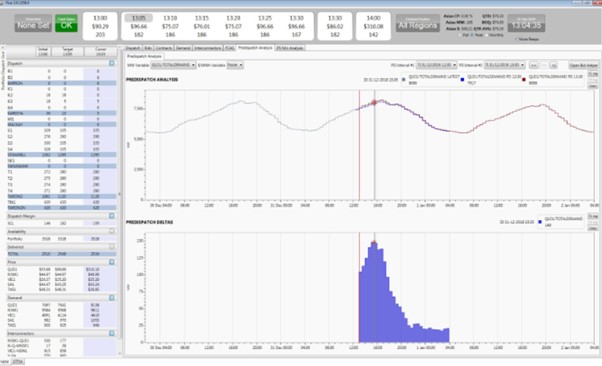

57 The COS data was used, together with other public data, to assist Mr Price to compile the Nem-vis visualisation tool (2PriceR at [76]-[77]), which is discussed further below. In Nem-vis, rebids submitted by CS Energy to CPT through COS are shown with a green border. Rebids submitted by IGPC to CPT through COS have a purple border. Operator availability rebids have an orange border (2PriceR at [93](d)).

58 As I have already observed, Mr Beauchamp’s evidence was unchallenged. I accept that CPT traded the electricity generated from Callide C on the basis of bids submitted by each owner and that, consequently, for the purpose of this proceeding, the number of ATIs referable to CS Energy is 200 and the number of ADIs referable to it is 235.

Methodology for choosing the ATIs

59 A significant attack was mounted by Stanwell and CS Energy on the manner in which Dr Ledgerwood selected the ATIs as described in the First Ledgerwood Report. That report responded to a Letter of Instructions (Ledgerwood Instructions) from the solicitors for Stillwater dated 19 September 2022. Dr Ledgerwood was first briefed on 3 February 2022 with, inter alia, Stillwater’s Further and Better Particulars of the Statement of Claim dated 25 August 2021, the data referred to in those Particulars, and the Amended Statement of Claim dated 27 September 2021 (ASOC) as background information, pending the provision of “the scope of your assignment and your specific instructions in due course”. The Ledgerwood Instructions noted that the Court-ordered timetable required his report to be filed 4 days later, by 4:00pm on 23 September 2022 but that an extension until 14 October 2022 had been requested from the Court.

60 I pause to observe that I was troubled about the approach to soliciting Dr Ledgerwood’s opinion, given the sequencing of the various letters of instructions, his ultimate approach to the selection of the ATIs, and the theory he adopted in impugning the conduct. Nevertheless, all parties adopted what has been accepted by the Full Court as the provision of “a final letter of instructions, containing the final form of the questions to be answered by an expert, to be prepared shortly before an expert report is finalised”: New Aim Pty Ltd v Leung [2023] FCAFC 67; 410 ALR 190 at [87] (Kenny, Moshinsky, Banks-Smith, Thawley and Cheeseman JJ). In what was a novel case, however, the process skirted very close to what the Full Court identified as an inversion of the process – using the expert’s specialised knowledge in order to identify the questions that should have been asked and the assumptions that should have been given. As Lee J said in BrisConnections Finance Pty Ltd (recs and mgrs apptd) v Arup Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1268; 252 FCR 450 at [71], and with which the Full Court agreed, at [89]:

The integrity of the expert evidence process and the independence of experts is best facilitated by transparency in what is being asked of experts prior to, or at the time, they are forming their opinions and, if the questions need to change because they are misdirected, a record being made by way of supplementary instructions as to what has changed.

61 I do not say it occurred in this case, but attempts to shield the actual instructions given to an expert witness, and perhaps also to shield draft opinions, give little comfort to a Court which expects to be able to rely on expert evidence given honestly, dispassionately, and impartially.

62 The Ledgerwood Instructions sought Dr Ledgerwood’s expert opinion on three questions:

Q1. In your opinion, what is the appropriate methodology for assessing whether the Respondents (or either of them) engaged, during the Conduct Period, in conduct of the kinds described in the ASOC as Late Rebidding and Early Spiking:

(a) at all; and

(b) if it occurred (and subject to paragraph 15 below) – in a manner indicating an exercise of market power residing in the Respondents or either of them?

Q2. Having regard to your answer to Question 1, what is your opinion as to whether the Respondents (or either of them) did engage, during the Conduct Period, in conduct of the kinds described in the ASOC as Late Rebidding and Early Spiking:

(a) at all; and

(b) if they did (and subject to paragraph 15 below) – in a manner indicating an exercise of market power residing in the Respondents or either of them?

Q3. If the Respondents (or either of them) did engage in conduct of the kinds described in the ASOC as Late Rebidding and Early Spiking, please identify, for each Respondent, the Trading Intervals in which such conduct occurred.

(Emphasis added.)

63 Paragraph 15 of the Ledgerwood Instructions relevantly reads:

We note that the three questions above concern only your assessment of the Trading Intervals that in your opinion suggest conduct of the kinds described in the ASOC as Late Rebidding or Early Spiking that warrant further investigation as potential exercises of market power … we expect that we will later make a request for a further expert report or reports opining on whether any conduct identified in this first report:

15.1 has had any and if so what impact on Spot Prices (or other ‘downstream’ prices) in the market; and

15.2 reflects the exercise of market power by either Respondent.

(Emphasis added.)

64 Relevantly, the ASOC pleaded, at [30], that during the Conduct Period, each of Stanwell and CS Energy engaged in a trading strategy, described as Late Rebidding, which had certain features. Amongst those features were that “shortly prior the commencement of either the … fifth or sixth” DI of the “Targeted Trading Interval”, Stanwell or CS Energy made a withholding rebid (ASOC at [30](e)). The ASOC pleaded that “by reason of the late submission of the Rebid” competing Generators could not respond quickly enough to be instructed to dispatch electricity (ASOC at [30](f)).

65 In response to a request for particulars of Stillwater’s methodology used to identify the impugned TIs, by letter dated 25 August 2021 (Particulars of ASOC), Stillwater said, inter alia, that:

(a) with respect to Late Rebidding – “a screen was performed to identify the Trading Intervals in which a Rebid was made by Stanwell and/or CS Energy withholding large volumes of generation capacity to higher price bands, within 5 minutes of Dispatch Interval 6”; and

(b) with respect to Early Spiking - “a screen was preformed to identify the Trading Intervals in which a Rebid was made by Stanwell and/or CS Energy withholding large volumes of generation capacity to higher price bands, within 5 minutes of Dispatch Interval 1”.

(Emphasis added.)

66 The screens applied to the data set were described Part IIC of the First Ledgerwood Report. Dr Ledgerwood identified “two essential elements common to both the Late Rebidding and the Early Spiking strategies”. These were described at [45]:

(a) First, on the occasions when these trading strategies were put into effect, one or other or both of the Respondents submitted one or more bids that withheld capacity (that is, caused capacity that had previously been offered at a low price to be offered at a high price).

(b) Second, the Respondents submitted the withholding bid close to the start of the dispatch interval for which the withholding bid caused the dispatch price to be elevated, thereby limiting the ability of competing generators to mount a competitive response to the withholding.

(Emphasis added.)

67 It is observed that Dr Ledgerwood apparently broadened the scope of Stillwater’s methodology as described in the Particulars of ASOC beyond a period of “within 5 minutes” of DI6 or DI1 to a period described by him as “close to the start of the dispatch interval for which the withholding bid caused the dispatch price to be elevated”, a period which he considered to be 15 minutes (1LedgerwoodR at [36(c)]).

68 In order to test for the conduct described in the ASOC, Dr Ledgerwood applied eight screens to a data set sourced from publicly available data from the AEMO Market Management System Data Model comprised of all bids submitted by the Respondents during the Conduct Period (1LedgerwoodR at [19], [24]). The screens removed:

(1) all rebids not associated with Stanwell and/or CS Energy (at [50]);

(2) all rebids for TIs where the Trading Price was greater than or equal to $8,000MWh and all rebids for the first and last DIs of a TI where the Trading Price was greater than or equal to $8,000MWh in the prior and subsequent TI respectively (at [51]);

(3) all rebids and DI combinations in which the Queensland dispatch price was less than twice the New South Wales dispatch price (at [52]);

(4) all rebids that were not either D-5, D-10 or D-15 rebids for at least one DI (at [53]);

(5) all combinations of rebids and DIs that, aggregated over all Stanwell D-5 bids for the DI did not withhold a positive quantity and all Stanwell D-10 and D-15 rebids for the DI, and to CS Energy D-5, D-10, and D-15 rebids for the DI (at [54]);

(6) all DIs where the dispatch price in the preceding DI was less than $0MWh (at [55]);

(7) all combinations of rebids and DIs for which the dispatch price elevation was less than $600MWh (at [56]); and

(8) all combinations of rebids and DIs for which the dispatch price elevation is greater than the dispatch price (at [57]).

69 It is important to observe that Dr Ledgerwood was asked only about the conduct of Stanwell and CS Energy. As he said during cross-examination, he had not been asked to assess the conduct of any other market participant during the Conduct Period. It is therefore not possible to know whether, had these screens been applied to any other market participant, the extent to which similar conduct attributable to those others may have been similarly impugned.

70 By the screens applied to all rebids in the Conduct Period by Stanwell and CS Energy, Dr Ledgerwood identified 2,006 rebids that were not eliminated by any of the screens. From those 2,006 rebids, Dr Ledgerwood identified 352 TIs for which the rebids were effective (at [60]). The number was subsequently amended to 353. It was from those 353 TIs that the 13 Sample Intervals were chosen.

71 I consider it more probable than not that Dr Ledgerwood himself chose the Sample Intervals. He equivocated on that question over the course of his cross-examination. On one occasion, he said that he had chosen the Sample Intervals as “good examples of the behaviour … that we have picked up in the screens”. On another occasion he said, “we did not select the sample intervals”. On yet another occasion, Dr Ledgerwood said he “made recommendations with respect to the sample intervals”. Nothing of any great moment turns on these contradictory statements, except to the extent that no clear explanation for why these particular 13 intervals were chosen ever really emerged. Dr Ledgerwood denied that they were intended to be statistically representative of the ATIs, saying they were “just … representative examples”. I infer that they were the “best” examples of the application of Dr Ledgerwood’s theory to the conduct of which he disapproves.

72 Dr Ledgerwood opined (1LedgerwoodR at [14]) that:

Each of the 352 trading intervals had elevated dispatch prices that were influenced by withholding bids submitted by the Respondents. The fact that I was able to identify these intervals using the screens described in Section II of my report suggests that Respondents engaged in the conduct of the kinds described in the ASoC in a manner indicating an exercise of market power.

73 In cross-examination, Dr Ledgerwood was careful to maintain that, at the stage when the First Ledgerwood Report was written, he was not asserting that the withholding bids identified by the screens caused the subsequent price spike, merely that the latter was proximate to the former. Dr Rose made the point that in some years within the Conduct Period, “there is up to eight months between two five-minute intervals that have been identified. So it’s a very long period to sit waiting, if you have got market power”.

74 Stanwell criticised Dr Ledgerwood’s approach on the basis that, inter alia, he did not identify conduct satisfying the pleaded conduct by scrutinising Stanwell’s rebid reasons in the context of the NEM and the applicable regulations. Rather, any rebid that passed the screens has been identified as having been made with the alleged state of mind and in the absence of a timely material change in circumstances. Mr Price said (1PriceR at [17]):

The approach Ledgerwood uses to come to his conclusions involves focussing on bidding in the spot market, which is just one aspect of market behaviour. He considers only snapshots in time and does not consider the way the market actually operates and the rules that govern the market.

75 CS Energy’s criticisms were similar. It was put to Dr Ledgerwood in cross-examination that the majority of the screens did not, and could not, identify the behaviour that had been pleaded, rather they were directed at identifying an outcome. Dr Ledgerwood agreed that only screens 1, 5, and 6 were concerned with behaviour.

76 Both Dr Rose and Mr Price pointed out that the screens could not accommodate circumstances leading up to the rebid, nor could they have regard to the rebidding activities of other market participants, who were engaged in similar conduct. Being applied ex post facto, the screens rather assumed that a trader would know when the rebid would become effective, that there would be price elevation of above $600MWh, and that price separation from New South Wales would occur. None of these factors could be known to a trader at the time of submitting a rebid.

77 Further, as was observed by Dr Rose, six of the eight Sample Intervals which concern Stanwell were during the period when the carbon tax was in force. Stanwell had to recover that impost. He also observed that all of the Sample Intervals occurred in the Queensland summer in Queensland’s peak period. Many were outliers, occurring for example, on 29, 30 and 31 December, when several generating units are typically offline for maintenance, and it is a period of “drought and record temperatures”. Similarly, Mr Price observed that 73% of the impugned TIs occurred in the top decile of demand for the relevant calendar year (1PriceR at [16]). Dr Ledgerwood was clear that, by Screen 2, he did not screen for periods of “actual scarcity” by reference to very high demand, as may be created by such environmental conditions, although he opined that “it doesn’t seem correct to impugn a rebid that is made in that environment”.

78 Ultimately, what became clear in the course of Dr Ledgerwood’s evidence was that he had designed the screens in such a way as to capture the conduct that he considered to be egregious. That was made clear by Dr Ledgerwood where he said (2LedgerwoodR at [1101]):

The screens used in the First Ledgerwood Report were designed to focus only on instances when the Respondents submitted successful withholding rebids (i.e., ones which produced an elevated price) in such a way as to limit the opportunity of other market participants to rebid in response to the withholding. The screens did this by capturing only withholding rebids submitted approximately 15 minutes [FN 492: That is, in the last three gate closure windows before dispatch] or less before dispatch in a DI that resolved with an elevated dispatch price. The screens excluded any rebids that were submitted more than 15 minutes before dispatch.

79 I have already alluded to the difference between the Particulars of ASOC and Dr Ledgerwood’s decision to screen out rebids that occurred more than 15 minutes before the relevant DI. He was not able to explain how he had arrived at 15 minutes as the outer limit of the time period in which it would be legitimate to make a withholding rebid, other than to say that, after the passing of 15 minutes, “[y]ou have now given three intervals for rebids if you go to a D-20. That’s plenty of time”. He continued:

I don’t recall from the standpoint of characterisation of late rebidding and early spikings as to whether they specified 15 minutes. But I know that, in my own logic, the basis for using the short-notice rebids made sense and so that’s what I used.

80 Dr Ledgerwood conceded that in settling on 15 minutes, he did not take into account the performance characteristics of other Generators in the NEM. He also conceded that the time taken for a trader to rebid would vary according to relevant circumstances.

81 In settling on $600 as the relevant price elevation level, Dr Ledgerwood conceded that he was not comparing actual dispatch price with a counterfactual dispatch price had the withholding rebid not been made, or been made earlier than D-15. Rather, he screened to identify a $600 or greater difference between the pre-dispatch forecast price and the actual dispatch after the rebid. As CS Energy submitted, that was “not comparing apples with apples”. Dr Ledgerwood maintained that the “unbiassed measure of what the dispatch price is going to be prior to the rebid being put into the market is the pre-dispatch price. So we are comparing the dispatch price and the pre-dispatch price with the screen”. The difficulty with that comparison was elucidated by reference to ATI#12, which was a D-15 rebid. As was apparent from Dr Ledgerwood’s Figure ATI 12.3 in the Second Ledgerwood Report, the pre-dispatch forecast immediately prior to the rebid was $199.99. Immediately after the rebid had been made, it was $310.10. The “zero-minute” pre-dispatch forecast had resettled at $199.99. The difference between pre-dispatch price forecast and post rebid pre-dispatch price forecast not being $600 or greater, Dr Ledgerwood’s screen would not have captured this ATI. Dr Ledgerwood described such an outcome as “absurd”. Dr Ledgerwood accepted that he knew the NEMDE pre-dispatch algorithm differed from the algorithm used for the actual dispatch price but could not explain why he adopted prices using different algorithms. He denied that he was using different algorithms.

82 Having identified the 353 ATIs by the application of his eight screens, Dr Ledgerwood developed six “profiles”, which were designed to illustrate the range of timings of the various rebids (2LedgerwoodR at [140]). In cross-examination, Dr Ledgerwood said that he developed the Profiles before classifying the ATIs by reference to the Profiles. This made the basis for the selection of the Sample Intervals rather more opaque. The Profiles move from straightforward “no-notice” (or D-5) rebids to increasingly more complex rebids and out to D-15 rebids. Senior Counsel for Stillwater explained in opening submissions that this was deliberate “because part of the purpose of the selection of the Sample Intervals is, to put it bluntly, to test the limits of the legal rules that apply for resolving the dispute between the parties”. Each of the Sample Intervals falls within one of the six profiles.

83 Profile 1 is comprised of four Sample Intervals – ATI#1, #2, #3, and #4 – which share common characteristics. Dr Ledgerwood identifies those (2LedgerwoodR at [196]) as:

a. first, either one or both of the Respondents submitted withholding rebids very close to, or after, the start of the TI. As a result, AEMO did not prepare any pre-dispatch forecasts for DIs of the TI that reflected the Respondents’ withholding rebids until those withholding rebids had first been used in dispatch for a DI of the TI;

b. second, the rebids withheld a sufficiently large amount of capacity sufficiently quickly that AEMO calculated an elevated dispatch price the first time those rebids were used in dispatch; and

c. third, the rebids did not give rise to elevated dispatch prices in later DIs (unless the Respondents submitted additional withholding rebids).

84 Dr Ledgerwood explained that, consequently, there was no opportunity for other participants to rebid in response so as to influence the dispatch price in the ADI (2LedgerwoodR at [197]).

85 The ATIs in Profile 2 differ from those in Profile 1 in that the rebids caused an elevated dispatch price in a subsequent DI that was not associated with any additional withholding rebid. Dr Ledgerwood explained that the TIs in Profile 2 have the following three features (2LedgerwoodR at [477]):

a. first, either one or both of the Respondents submitted withholding bids very close to, or after, the start of the TI. As a result, AEMO did not prepare any pre-dispatch forecasts for DIs of the TI that reflected the Respondents’ withholding bids until those withholding bids had first been used in dispatch for a DI of the TI;

b. second, the rebids withheld a sufficiently large amount of capacity sufficiently quickly that AEMO calculated an elevated dispatch price the first time those rebids were used in dispatch;

c. third, the rebids also gave rise to elevated dispatch prices in at least one later DI without the Respondents submitting additional withholding rebids.

86 Consequently, explained Dr Ledgerwood, there was no opportunity for other participants to rebid in response in time to influence the dispatch price in the first ADI (2LedgerwoodR at [478]).

87 Sample Intervals 7, 8, and 9 fall within Dr Ledgerwood’s Profile 3. They are said to share the following characteristics (2LedgerwoodR at [607]):

a. first, either one or both of the Respondents submitted withholding rebids close to, or after, the start of the TI. As a result, AEMO prepared either:

i. one pre-dispatch forecast for DIs of the TI that reflected the Respondents’ withholding rebids (if the rebids were submitted in the T–10 gate closure window); or

ii. no pre-dispatch forecasts (if submitted in a later gate closure window);

before those withholding rebids were first used in dispatch for a DI of the TI;

b. second, the rebids withheld a sufficiently large amount of capacity sufficiently quickly that AEMO calculated an elevated dispatch price either the first time those rebids were used in dispatch (if the rebids were submitted in the T–10 gate closure window) or the second time those rebids were used in dispatch (if the rebids were submitted later than the T–10 gate closure window).

88 The consequence of this combination of factors was said to be that there was only one gate closure window in which other participants could respond in time to influence the dispatch price in the ADI (2LedgerwoodR at [608]).

89 Sample Intervals 10 and 11 are included in Profile 4. Dr Ledgerwood explains that the ATIs in Profile 4 have the following three features (2LedgerwoodR at [744]):

a. first, either one or both of the Respondents submitted withholding bids close to, or after, the start of the TI. As a result, AEMO prepared either:

i. one pre-dispatch forecasts for DIs of the TI that reflected some of the Respondents’ withholding rebids (if the earliest rebids were submitted in the T–10 gate closure window); or

ii. no pre-dispatch forecasts (if the earliest rebids were submitted in a later gate closure window);

before those withholding rebids were first used in dispatch for a DI of the TI.

b. second, either one or both of the Respondents submitted further withholding bids in the gate closure window following the gate closure window in which the earliest withholding rebids had been submitted.

c. third, the rebids withheld a sufficiently large amount of capacity sufficiently quickly that AEMO calculated an elevated dispatch price either the first time the earliest of those rebids were used in dispatch (if the earliest rebids were submitted in the T–10 gate closure window or the second time those rebids were used in dispatch (if the earliest rebids were submitted later than the T–10 gate closure window).

90 Consequently, there was only one gate closure window for other participants to rebid in response to the earliest rebid, but no opportunity to rebid in response to the later rebid in time to influence the dispatch price in the ADI (2LedgerwoodR at [745]).

91 Sample Interval 12 is the only Sample Interval in Profile 5. Dr Ledgerwood explained that the ATIs in Profile 5 have the following features in common (2LedgerwoodR at [832]):

a. first, either one or both of the Respondents submitted withholding rebids close to, or after, the start of the TI. As a result, AEMO prepared either:

i. two pre-dispatch forecasts for DIs of the TI that reflected the Respondents’ withholding rebids (if the rebids were submitted in the T–15 gate closure window); or

ii. one pre-dispatch forecast for DIs of the TI that reflected the Respondents’ withholding rebids (if the rebids were submitted in the T–10 gate closure window); or

iii. no pre-dispatch forecasts (if submitted in a later gate closure window);

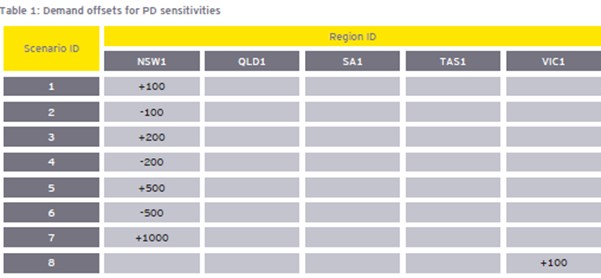

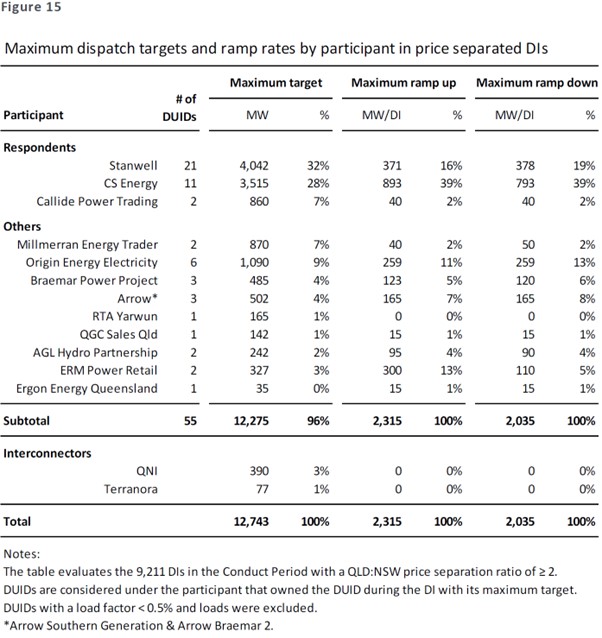

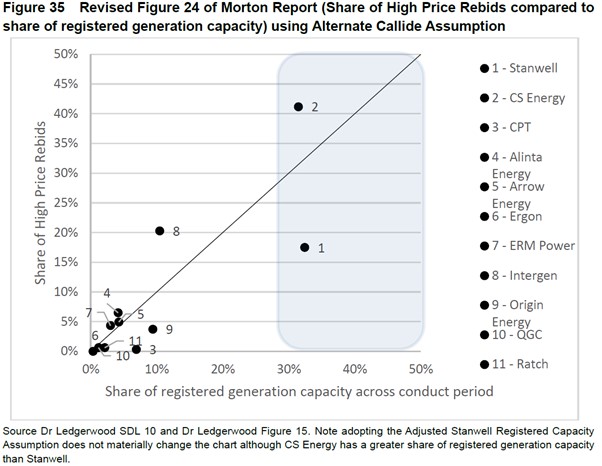

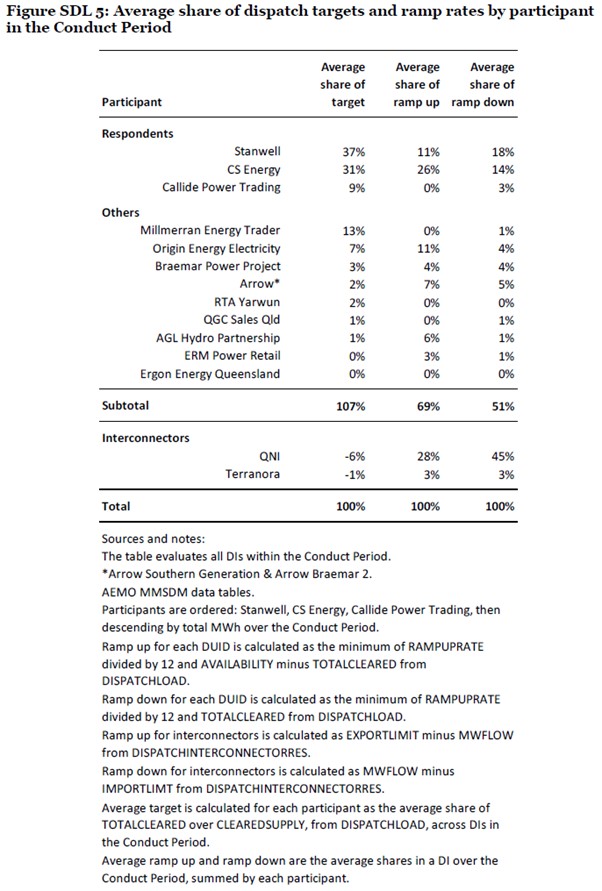

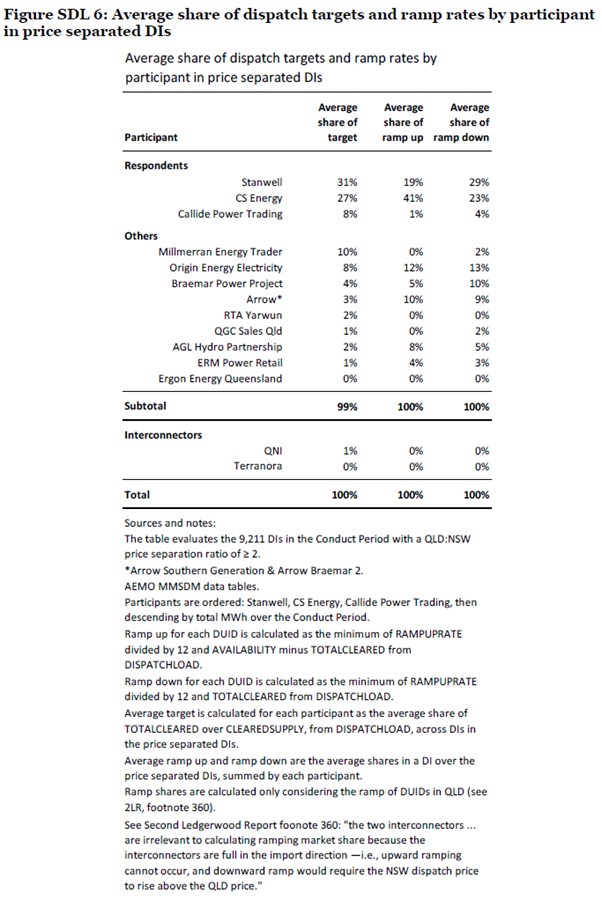

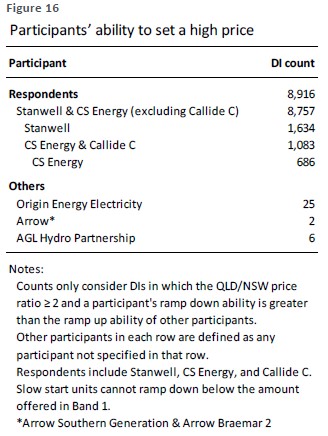

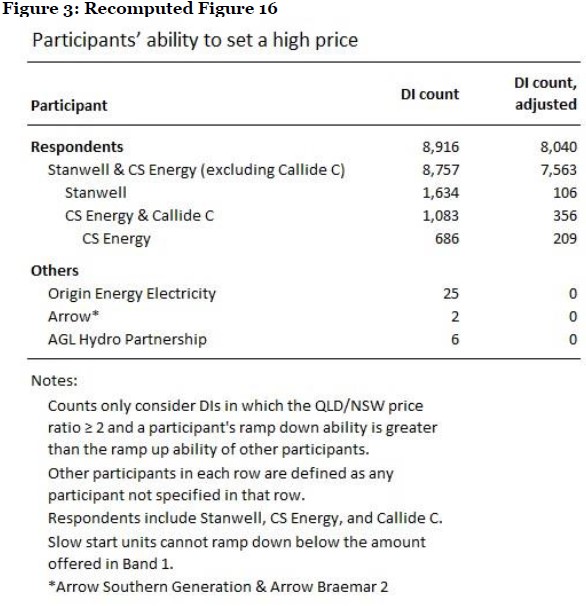

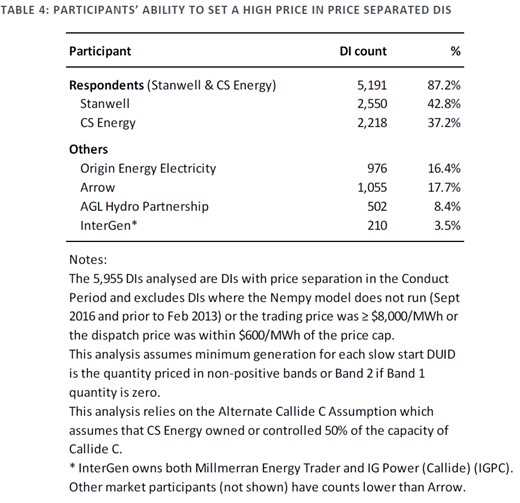

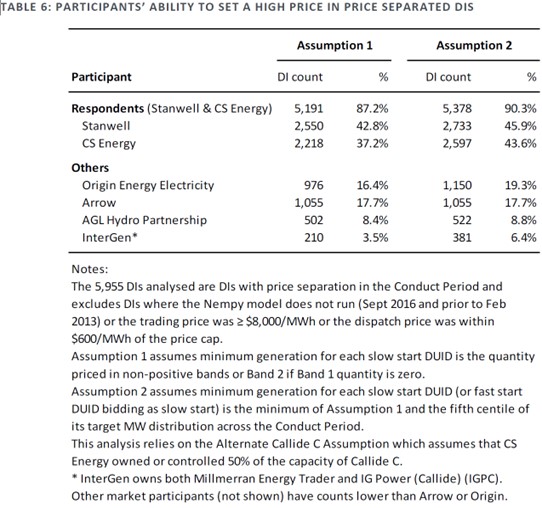

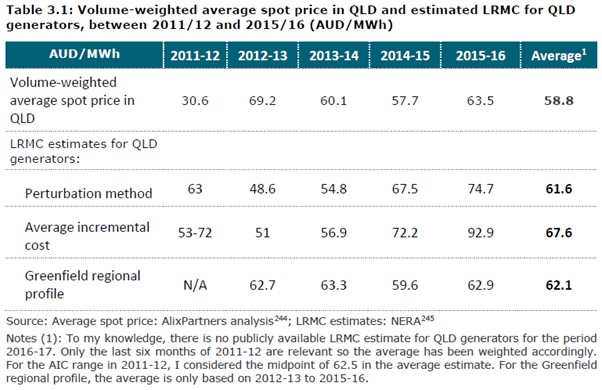

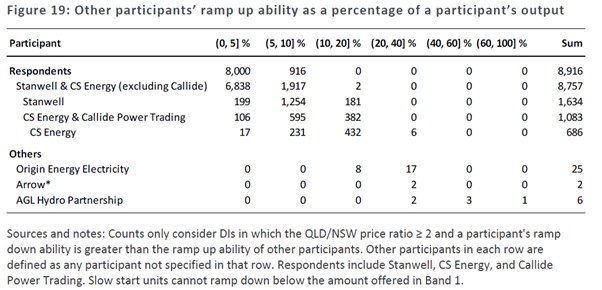

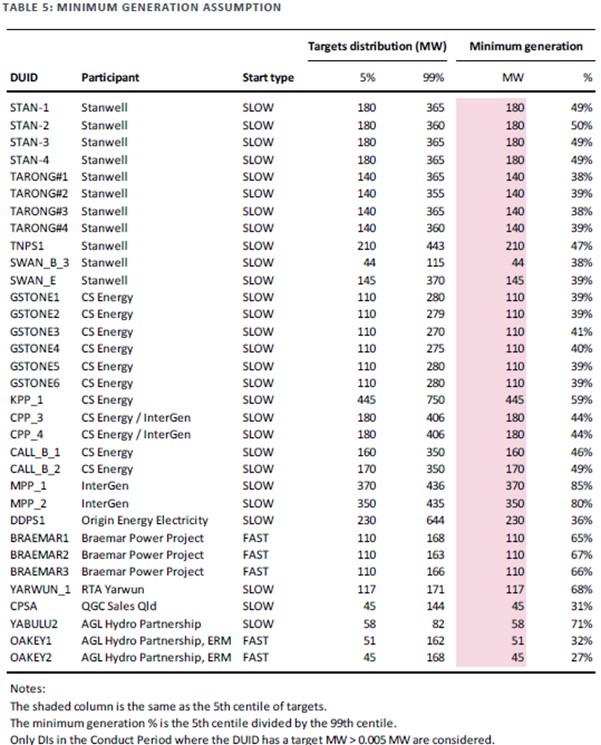

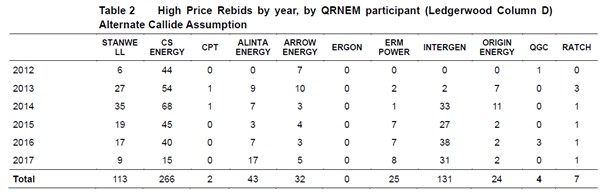

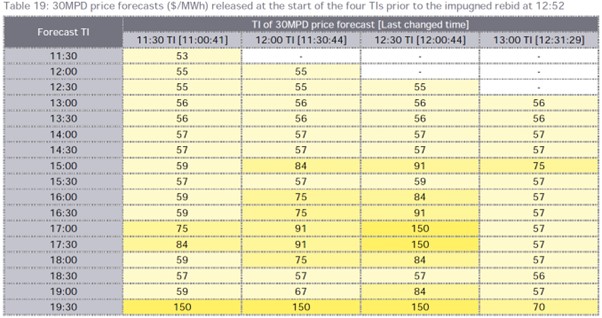

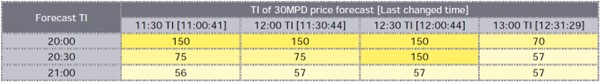

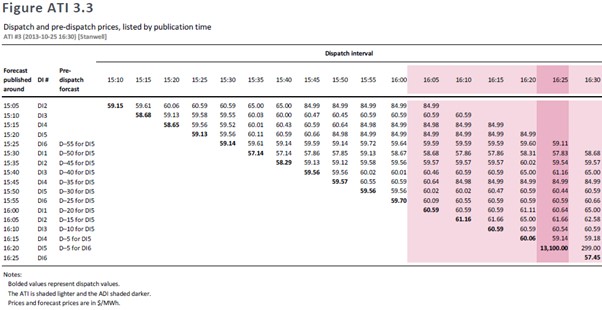

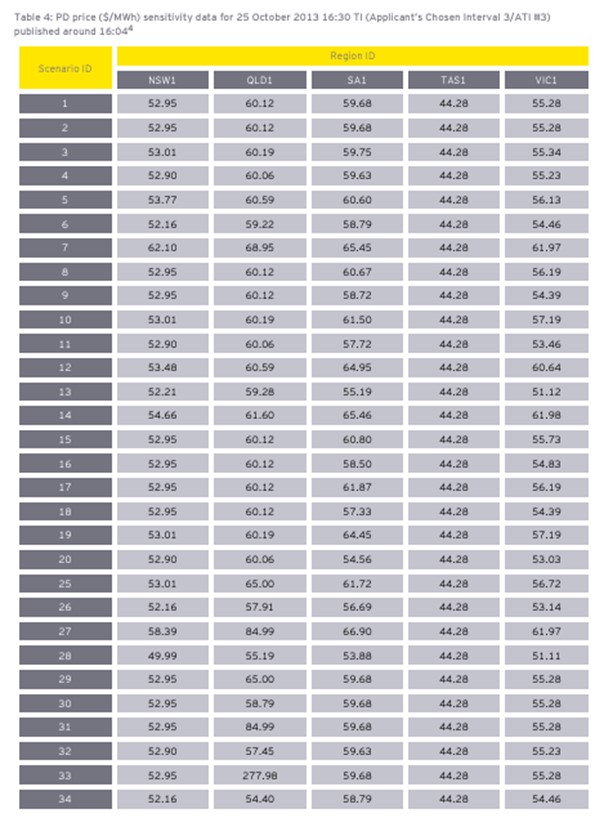

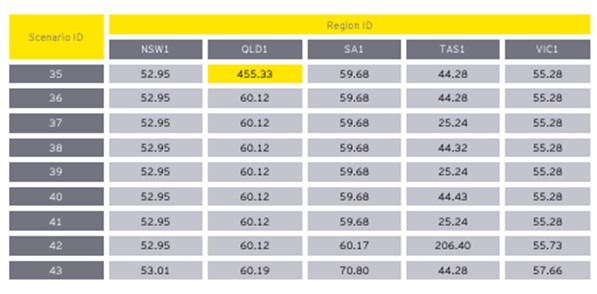

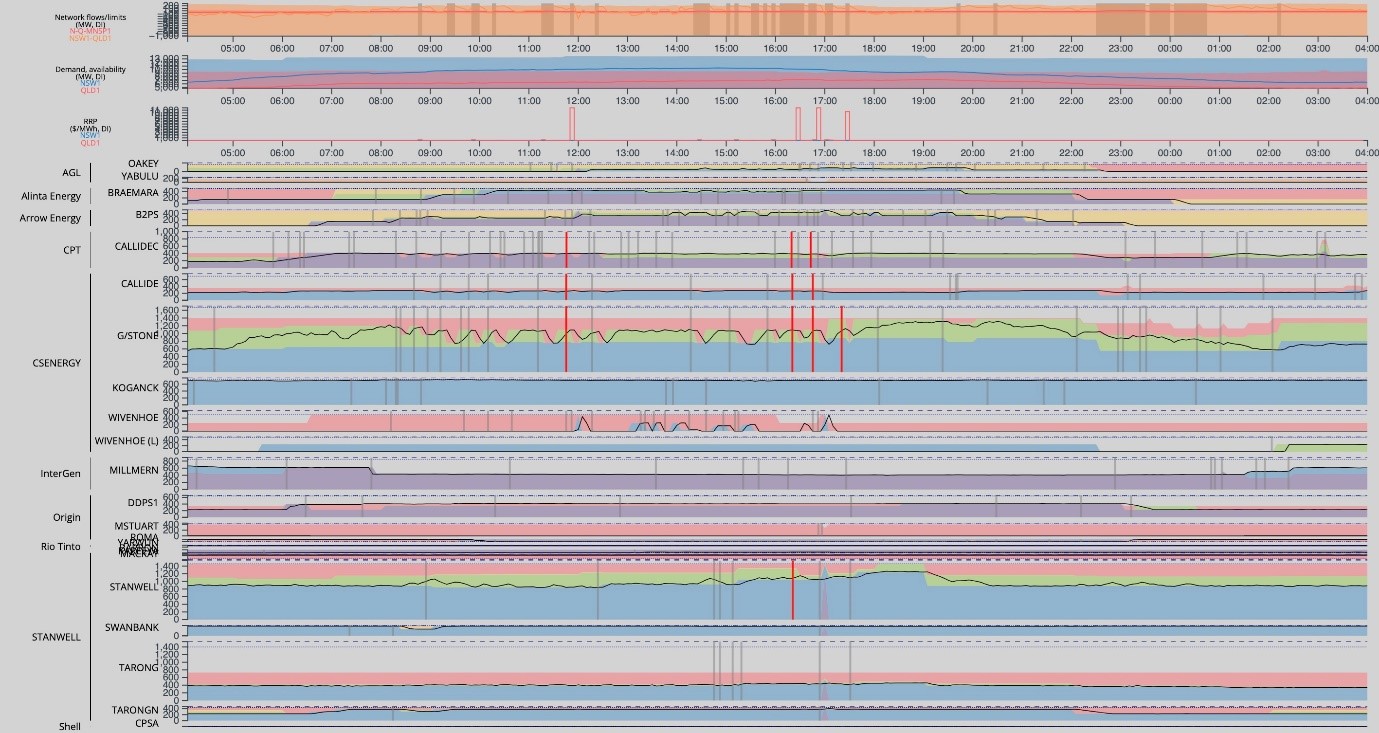

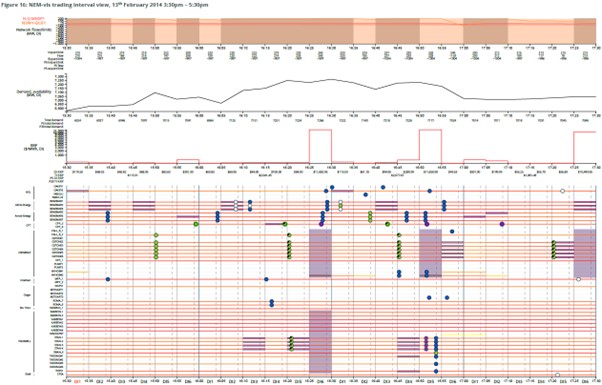

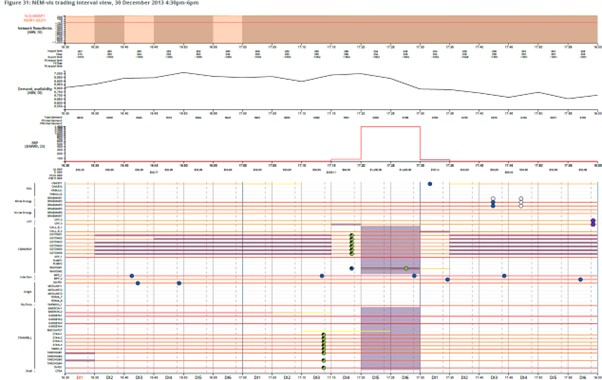

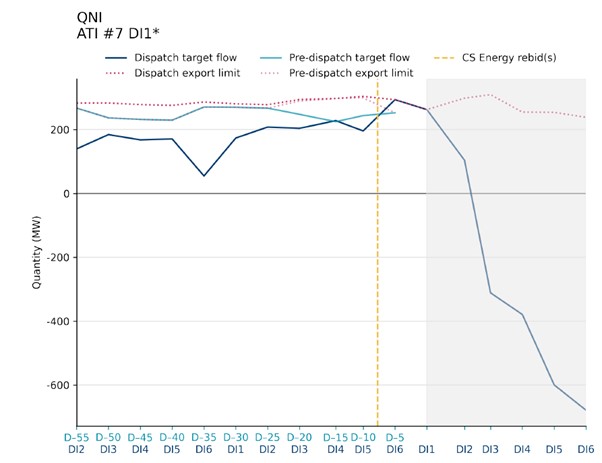

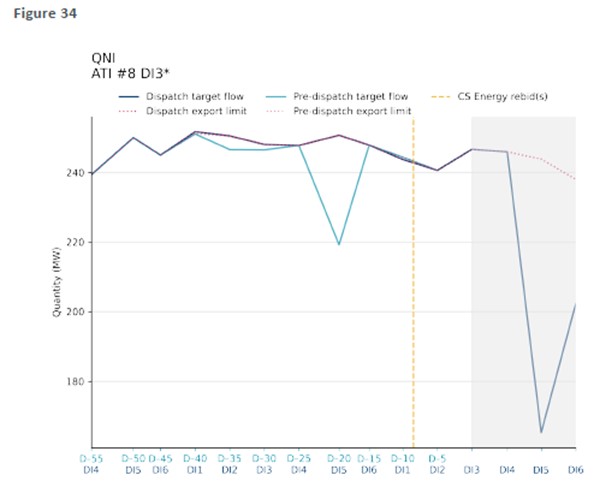

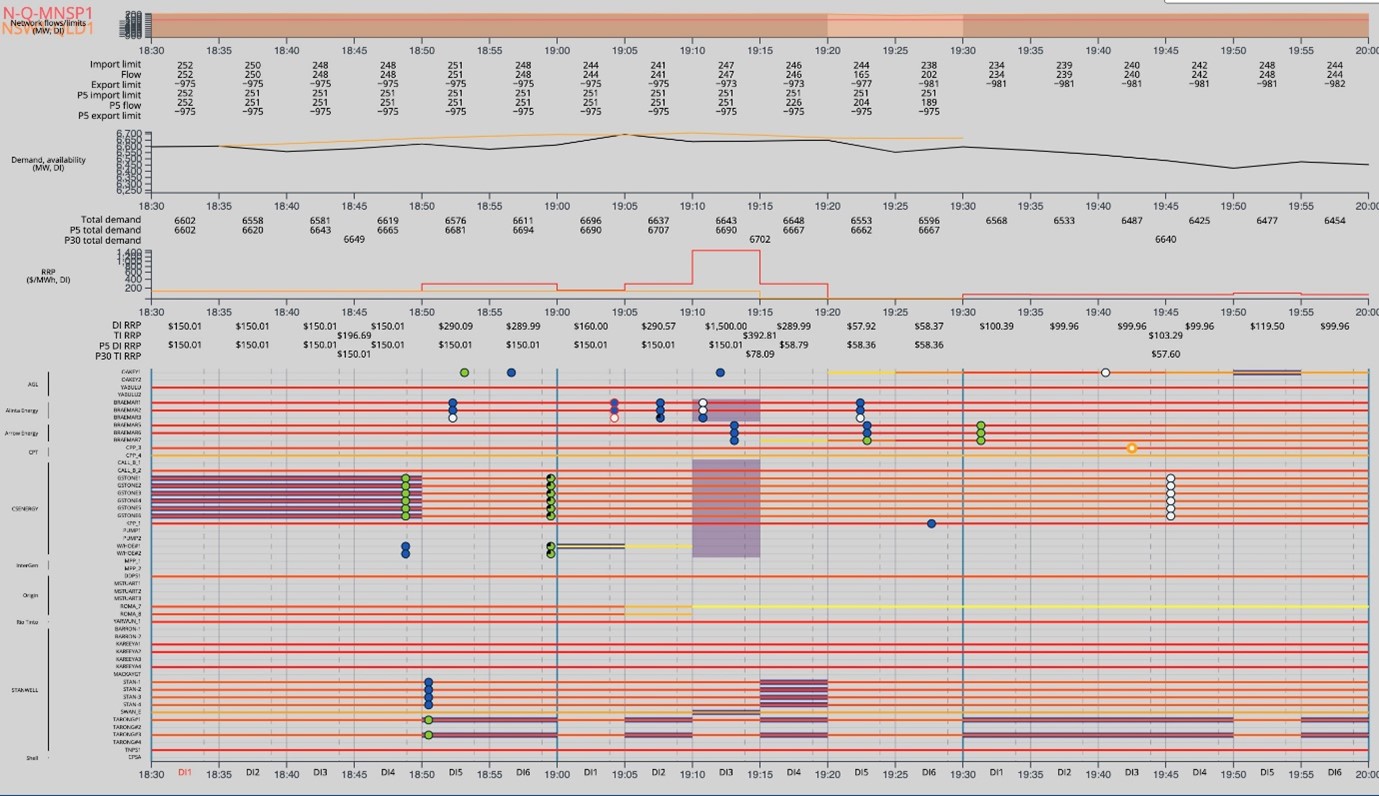

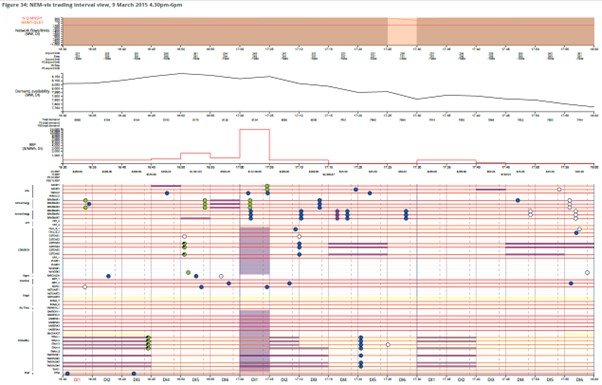

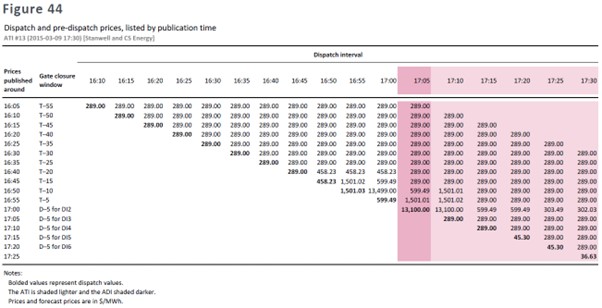

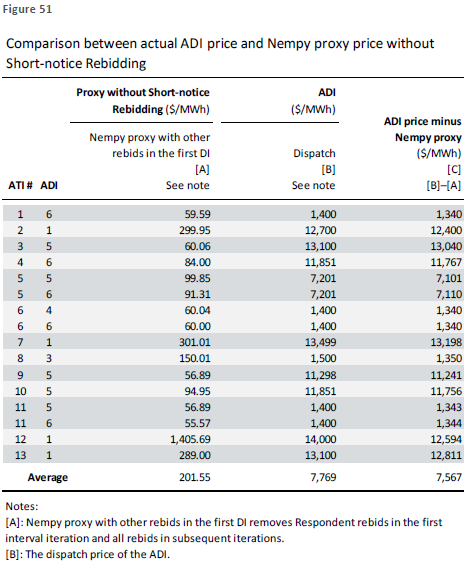

before those withholding rebids were first used in dispatch for a DI of the TI;